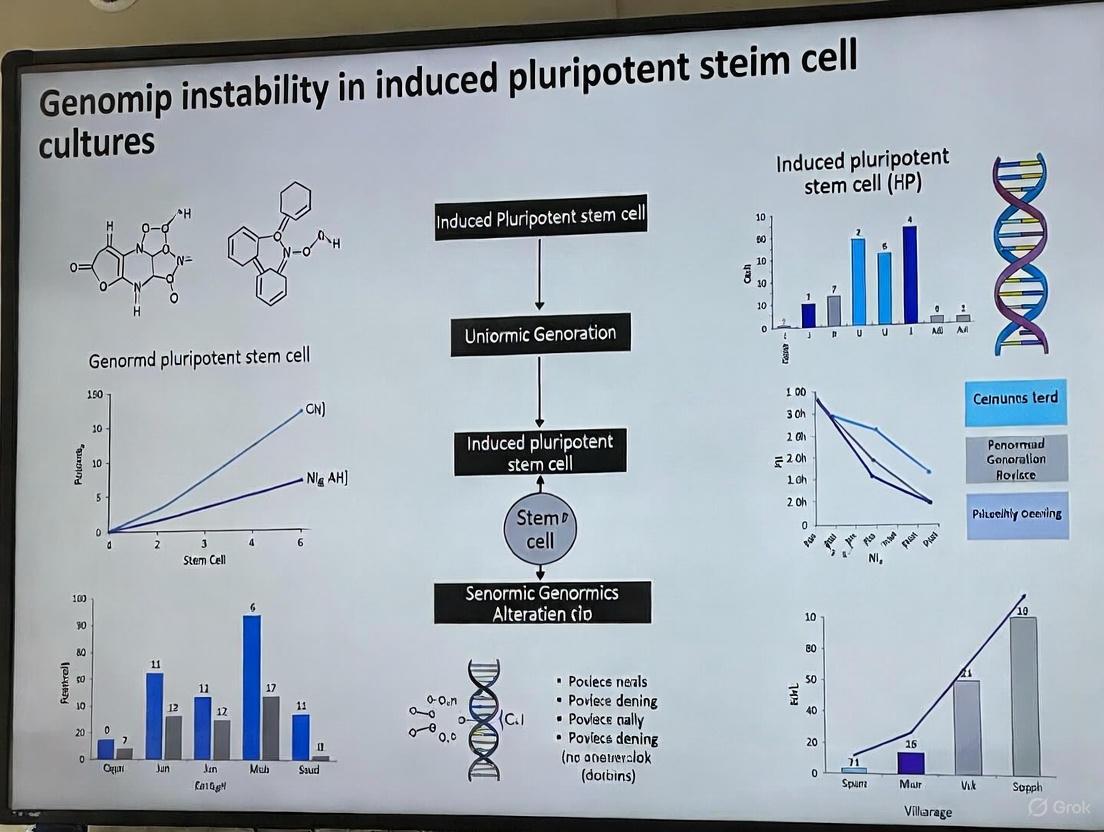

Addressing Genomic Instability in iPSC Cultures: Mechanisms, Monitoring, and Mitigation Strategies for Research and Therapy

The profound therapeutic potential of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) is tempered by the significant challenge of genomic instability, which can compromise experimental results and pose serious risks in clinical...

Addressing Genomic Instability in iPSC Cultures: Mechanisms, Monitoring, and Mitigation Strategies for Research and Therapy

Abstract

The profound therapeutic potential of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) is tempered by the significant challenge of genomic instability, which can compromise experimental results and pose serious risks in clinical applications. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the molecular origins of instability—from reprogramming-induced replication stress to culture-adapted aneuploidies. It details state-of-the-art methodologies for robust genomic monitoring and compares the fidelity of different reprogramming techniques. Furthermore, the article outlines practical strategies for optimizing culture conditions to minimize instability and establishes a framework for the rigorous validation and safety profiling of iPSC lines destined for preclinical and clinical use.

The Origins and Mechanisms of Genomic Instability in iPSCs

The process of reprogramming somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) places tremendous stress on the cellular machinery, particularly on the fundamental process of DNA replication. This replication stress represents a significant source of genomic instability in iPSCs, potentially compromising their research and therapeutic applications. Central to this phenomenon are the reprogramming factors themselves, especially the oncogene c-Myc, which plays a paradoxical role as both a powerful facilitator of reprogramming and a potent inducer of genomic instability. When activated, c-Myc triggers a cascade of molecular events that can lead to slowing and stalling of replication forks, ultimately resulting in DNA damage and genomic alterations [1]. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing strategies to minimize genomic instability in iPSC cultures, thereby enhancing their safety profile for biomedical applications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is replication stress in the context of iPSC reprogramming?

Replication stress refers to the inefficient progression of DNA replication due to slowing, stalling, or collapse of replication forks. During reprogramming, the forced expression of oncogenes like c-Myc creates an environment where the DNA replication machinery encounters obstacles, leading to incomplete genome duplication and potential DNA damage. This is mechanistically distinct from the normal replication process and can compromise genomic integrity [1].

Q2: Why is c-Myc still used in reprogramming if it causes replication stress?

c-Myc remains a component of many reprogramming protocols because it significantly enhances reprogramming efficiency. It functions as a "double-edged sword" by promoting the transition to pluripotency while simultaneously increasing the risk of genomic instability. Research indicates that c-Myc can be dispensable for reprogramming, though its exclusion typically results in substantially lower efficiency [2] [3].

Q3: Are there safer alternatives to using c-Myc in reprogramming?

Yes, several alternatives exist. L-Myc has been identified as a promising substitute that promotes reprogramming with significantly lower transformation activity compared to c-Myc. Additionally, specific c-Myc mutants (such as W136E) that retain reprogramming enhancement while lacking strong transformation capacity have been developed. These alternatives provide researchers with options to balance efficiency and safety concerns [3].

Q4: How does replication stress lead to genomic instability in iPSCs?

Replication stress can directly cause DNA breaks and mutations. When replication forks stall, the DNA becomes vulnerable to breakage, which may result in copy number variations (CNVs), chromosomal rearrangements, and other genetic abnormalities. These alterations can persist in the iPSC population and potentially confer selective growth advantages, leading to their expansion during culture [4] [5].

Q5: What are the practical consequences of replication stress for iPSC-based research?

From a practical standpoint, replication stress-induced genomic instability can compromise experimental reproducibility and disease modeling accuracy. In clinical applications, this instability raises significant safety concerns due to the potential for tumor formation. Research has identified recurrent genomic alterations in iPSCs that overlap with cancer-associated genes, highlighting the importance of careful genomic monitoring [4] [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Replication Stress

Problem: High Rates of Genomic Instability in Reprogrammed iPSCs

| Troubleshooting Step | Implementation Details | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Alternative Myc Factors | Use L-Myc instead of c-Myc, or utilize c-Myc mutants (W136E) with reduced transformation potential [3]. | Reduced replication stress and tumorigenicity while maintaining reprogramming efficiency. |

| p53 Pathway Modulation | Utilize temporary p53 suppression (e.g., mp53DD dominant-negative mutant) rather than complete knockout [7]. | Enhanced reprogramming efficiency without completely removing critical DNA damage checkpoint. |

| Non-Integrating Methods | Employ Sendai virus or episomal vectors instead of integrating viral systems [7]. | Reduced risk of insertional mutagenesis compounding replication stress-induced damage. |

| Optimized Culture | Avoid prolonged culture; use early passage cells; maintain optimal colony density [8]. | Minimized accumulation of culture-acquired genetic variations. |

| Monitoring Protocols | Implement regular karyotyping and CNV analysis at different passages [4] [6]. | Early detection of genomic abnormalities enabling selective expansion of stable clones. |

Problem: Poor Reprogramming Efficiency When Reducing Replication Stress

| Troubleshooting Step | Implementation Details | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Myc Optimization | When using CytoTune Sendai system, optimize Klf4 MOI (try KOS:c-Myc:Klf4 ratios of 5:5:3, 5:5:6, or 10:10:6) [7]. | Balanced reprogramming efficiency with acceptable stress levels. |

| Small Molecule Enhancement | Incorporate small molecules that enhance reprogramming (e.g., ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 for cell survival) [9]. | Improved survival of reprogramming cells without genetic manipulation. |

| Parental Cell Selection | Use early passage ( | More efficient reprogramming with reduced baseline genomic abnormalities. |

| Feeder Condition Optimization | Consider feeder-dependent systems for initial reprogramming (higher efficiency), then adapt to feeder-free [9]. | Maximized reprogramming efficiency before transitioning to defined conditions. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Assessing Replication Stress in Reprogramming Cells

DNA Fiber Assay Protocol (Adapted from [1])

This protocol measures replication fork progression, a direct indicator of replication stress.

Step 1: Pulse-labeling with Nucleotide Analogs

- Expose reprogramming cells to sequential pulses of CldU (25 μM for 20 minutes) and IdU (250 μM for 20 minutes)

- Ensure precise timing to accurately measure replication speed

Step 2: DNA Fiber Preparation

- Harvest cells and resuspend at low concentration (1,000 cells/μL)

- Spot cells on glass slides and lyse with spreading buffer (0.5% SDS, 200 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 50 mM EDTA)

- Tilt slides to spread DNA fibers, air dry, and fix in methanol:acetic acid (3:1)

Step 3: Immunodetection and Analysis

- Denature DNA with 2.5M HCl, block with 5% BSA

- Incubate with anti-CldU and anti-IdU antibodies sequentially

- Visualize with fluorescence microscopy and measure fiber lengths

- Interpretation: Shorter fiber lengths in c-Myc-expressing cells indicate replication fork slowing, characteristic of replication stress [1]

Safer Reprogramming Using L-Myc Protocol

This protocol leverages L-Myc for efficient reprogramming with reduced genomic instability [3].

Step 1: Preparation of Parental Cells

- Plate human dermal fibroblasts at 50-80% confluence in 6-well plates

- Use early passage cells (

Step 2: Transduction with Reprogramming Factors

- Prepare retroviral vectors encoding Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and L-Myc

- Perform transduction using standard viral delivery methods

- Critical Note: L-Myc generates significantly fewer non-iPSC colonies compared to c-Myc, indicating more specific reprogramming

Step 3: iPSC Selection and Culture

- Transfer transduced cells to feeder layers or feeder-free matrices 3-5 days post-transduction

- Change to human ESC culture medium supplemented with bFGF

- Begin monitoring for iPSC colony appearance at 2-3 weeks

Step 4: Validation

- Pick colonies with ESC-like morphology

- Verify pluripotency markers (Tra-1-60, Tra-1-81, SSEA-3, Oct3/4)

- Perform teratoma assay to confirm differentiation potential

- Key Advantage: iPSCs generated with L-Myc produce high-percentage chimeras competent for germline transmission without increased tumorigenicity [3]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Research Need | Recommended Reagents | Specific Function |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming with Reduced Risk | CytoTune-iPS 2.1 Sendai Kit (with L-Myc) [7], Epi5 Episomal Kit (with L-Myc/Lin28) [7] | Non-integrating delivery of reprogramming factors with safer Myc alternatives. |

| c-Myc-Specific Reagents | c-Myc antibodies (for monitoring), c-Myc inhibitors (e.g., 10058-F4) | Detection and functional manipulation of c-Myc in experimental systems. |

| Replication Stress Detection | Antibodies against pCHK1, pRPA, γH2AX [1], nucleotide analogs (CldU/IdU) [1] | Markers for monitoring replication stress and DNA damage response activation. |

| Cell Culture Matrices | Geltrex, Matrigel, Laminin-521 [9] | Defined substrates for feeder-free culture supporting pluripotent stem cells. |

| Culture Media | StemFlex Medium, mTeSR Plus, Essential 8 Medium [8] [9] | Optimized formulations for maintaining iPSCs in defined conditions. |

| Cell Survival Enhancement | ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 [9] | Improves survival of dissociated iPSCs and reprogramming cells. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

c-Myc-Induced Replication Stress Mechanism

Safer Reprogramming Experimental Workflow

Data Tables

Comparison of Myc Family Members in Reprogramming

| Property | c-Myc | L-Myc | N-Myc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Efficiency | High | High (superior to c-Myc in human cells) [3] | Moderate |

| Transformation Potential | High | Low | High |

| Specificity (iPSC vs. non-iPSC colonies) | Low | High (significantly higher proportion of true iPSCs) [3] | Low |

| Tumorigenicity in Chimeras | High (increased mortality) [3] | Low (no marked increase) [3] | Not reported |

| Germline Transmission | Promotes | Promotes (comparable quality to ESCs) [3] | Not reported |

| Key Advantages | High efficiency | Specific reprogramming, low tumorigenicity | - |

| Key Limitations | High tumorigenic risk, genomic instability | Less studied | Similar risks to c-Myc |

Common Genomic Alterations in iPSCs and Cancer Associations

| Genomic Region | Type of Alteration | iPSC Context | Cancer Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| chr20q11.21 | Amplification/CNV | Most recurrent CNV hotspot in iPSCs and ESCs [4] [6] | Frequently amplified in various cancers [4] |

| chr12p | Gain/Trisomy | Frequent in both iPSCs and ESCs [4] | Hallmark of testicular germ cell tumors [4] |

| chr8 | Amplification | Common aneuploidy in pluripotent stem cells [4] | Associated with multiple cancer types |

| chr1, 2, 3, 16 | CNVs | Recurrent regions in hiPSCs across studies [6] | Overlap with cancer-associated genes [6] |

| Key Genes Affected | ID1, BCL2L1, DNMT3B (chr20); NANOG (chr12) | Enriched in pluripotency and anti-apoptosis [4] [6] | Cancer development and progression |

Epigenetic Remodeling and Chromatin Dynamics During Somatic Cell Reprogramming

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main epigenetic barriers that resist somatic cell reprogramming? Reprogramming factors must overcome several potent epigenetic barriers to induce pluripotency. Key barriers include:

- Repressive Histone Modifications: Broad heterochromatic regions enriched with H3K9me3 are refractory to initial transcription factor binding and require extensive remodeling for activation [10]. The histone methyltransferase G9a (EHMT2) recruits DNA methyltransferases to pluripotency loci to block their expression [11].

- DNA Methylation: Promoters of key pluripotency genes like OCT4 and NANOG are often hypermethylated in somatic cells. The de novo DNA methyltransferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B act as barriers, and their knockdown improves reprogramming efficiency [11].

- Large Organized Chromatin Modifications (LOCKs): These are large chromosomal regions enriched in H3K9me2 that are prevalent in differentiated cells and cover many lineage-specific genes. They are markedly decreased in pluripotent stem cells, and their persistence impedes reprogramming [10] [12].

Q2: How does the chromatin accessibility of target genes influence the reprogramming timeline? The initial chromatin state of OKSM target genes determines the kinetics of their activation during reprogramming. These targets can be categorized into three classes [10]:

- Class I (Open Chromatin): Genes with an "open" chromatin state (e.g., somatic genes and early MET genes) are characterized by active H3K4me2/3 marks and are bound by OKSM immediately.

- Class II (Permissive Enhancers): Distal regulatory elements with features like H3K4me1 that require additional chromatin remodeling for activation.

- Class III (Refractory Domains): Core pluripotency genes (e.g., NANOG, SOX2) located within broad heterochromatic regions enriched for H3K9me3. These regions are resistant to initial OKSM binding and are the last to be activated, requiring the most extensive chromatin remodeling [10].

Q3: What are the primary sources of genomic instability in iPSC cultures? Genomic instability in iPSCs arises from three main origins [4]:

- Pre-existing Variations: Low-frequency genetic variants present in the parental somatic cell population that are fixed and expanded during the clonal selection of iPSCs.

- Reprogramming-Induced Mutations: Mutations that occur during the reprogramming process itself, which is associated with replication stress and other cellular stresses.

- Passage-Induced Mutations: Mutations that accumulate during prolonged in vitro culture, often due to selective pressures that favor faster-growing variants.

Q4: What methods can improve the safety profile of iPSCs for clinical applications? To enhance safety, focus on using non-integrating reprogramming methods and omitting oncogenes [13]:

- Reprogramming Methods: Use non-integrating methods such as episomal vectors, Sendai virus, or mRNA transfection to avoid insertional mutagenesis [13].

- Factor Selection: Reprogramming with factors that exclude known oncogenes like c-MYC and LIN28 can reduce tumorigenic risk. Some protocols successfully use Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 alone or in combination with small molecules [13].

- Rigorous Screening: Implement comprehensive genetic and genomic screening (e.g., G-banding, CGH/SNP array, whole-genome sequencing) to fully characterize master cell banks before clinical use [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Reprogramming Efficiency

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inefficient epigenetic resetting. Repressive marks at pluripotency loci are not being adequately removed.

- Cause: Suboptimal transcription factor delivery/expression.

- Solution: Utilize a non-integrating, high-efficiency method like Sendai virus or mRNA transfection for robust initial factor expression. For episomal methods, ensure the vectors contain factors like l-Myc or p53 shRNA to boost efficiency without significantly increasing oncogenic risk [13].

- Cause: Inadequate culture conditions.

Problem 2: High Rates of Genomic Instability in Established iPSC Lines

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Selective pressure during prolonged culture.

- Solution: Minimize the number of cell passages. Regularly karyotype cells and use genetic screening to monitor for common aberrations. Be aware that certain mutations, such as gains on chromosome 12 (which contains the NANOG gene) or 20q11.21 (containing BCL2L1 and DNMT3B), confer a growth advantage and can rapidly take over a culture [4].

- Cause: Mutations carried over from parental somatic cells.

- Solution: Perform deep sequencing of the parental somatic cell population to identify pre-existing variants. When possible, generate multiple iPSC clones and screen them to select clones with the cleanest genetic background [4].

- Cause: Oxidative and replication stress during reprogramming.

- Solution: Use antioxidants and culture conditions that mitigate cellular stress. The p53 pathway is a key mediator of stress response during reprogramming; transiently modulating this pathway can reduce mutation rates, but requires careful control [4].

Problem 3: Incomplete Reprogramming and Residual Differentiation

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Failure to fully activate the core pluripotency network.

- Solution: Extend the reprogramming timeline and ensure exogenous factor expression is maintained long enough for stable endogenous network activation. Analyze the expression of late-pluripotency genes like UTF1 and SOX2 as markers of fully established pluripotency [10] [15].

- Solution: Use advanced assays like ATAC-seq to monitor the chromatin state of key pluripotency loci (e.g., NANOG, SALL4). This reveals whether these genes have transitioned from a "closed" (H3K9me3-rich) to an "open" (accessible) chromatin configuration [10] [16].

- Cause: Persistent expression of somatic genes.

- Solution: Ensure that the silencing of somatic genes, which is an early event in reprogramming, has occurred. This can be facilitated by the recruitment of repressive complexes like PRC2 (which deposits H3K27me3) to somatic loci [10].

The tables below summarize key quantitative findings on genetic instability and chromatin dynamics from the research.

Table 1: Common Genetic Variations in Human iPSCs

| Variation Type | Recurrent Aberrations | Frequency in iPSCs | Potential Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosomal Aberration | Trisomy 12, Trisomy 8, Gain of X [4] | Not remarkably different from human ESCs [4] | Selective growth advantage; linked to pluripotency genes (NANOG on Chr12) and cancer [4]. |

| Copy Number Variation (CNV) | Amplification of 20q11.21 [4] | Common hotspot in both iPSCs and ESCs [4] | Contains anti-apoptosis (BCL2L1) and epigenetic (DNMT3B) genes, promoting survival [4]. |

| Single Nucleotide Variant (SNV) | Varies, low recurrence reported [4] | ~10 protein-coding mutations per line [4] | Origins include pre-existing somatic mutations and errors during reprogramming [4]. |

Table 2: Dynamics of Chromatin States During Reprogramming

| Chromatin Category | Description | Example Genes/Regions | Change in Gene Expression During Naïve Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-to-Open (CO) | Regions that transition from closed in fibroblasts to open in iPSCs [16]. | DPPA3, KLF4, POU5F1 (OCT4) [16] | Significant and consistent upregulation [16]. |

| Open-to-Closed (OC) | Regions that transition from open in fibroblasts to closed in iPSCs [16]. | AMOTL1, RUNX2 [16] | Marked decrease from day 8 onwards [16]. |

| Permanently Open (PO) | Regions that remain accessible throughout reprogramming [16]. | Genes in TGF-β signaling, apoptosis [16] | Negligible changes [16]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Chromatin Accessibility with ATAC-seq

This protocol is used to map genome-wide chromatin accessibility and identify open, closed, and dynamically changing regions during reprogramming [16].

- Cell Harvesting: Harvest intermediate cell populations at defined time points (e.g., days 6, 8, 14, 20, 24) during reprogramming, along with the starting somatic cells and final iPSCs.

- Nuclei Isolation: Lyse cells using a mild detergent to isolate intact nuclei. Keep samples on ice to prevent degradation.

- Tagmentation: Incubate the nuclei with the Tn5 transposase. This enzyme simultaneously fragments DNA and inserts adapter sequences exclusively into accessible genomic regions.

- DNA Purification: Clean up the tagmented DNA using a commercial purification kit.

- Library Amplification: Amplify the purified DNA by PCR using primers compatible with the adapters added by Tn5.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence the libraries on a high-throughput platform. Align sequences to the reference genome and call peaks to identify regions of significant accessibility. Compare peaks across time points to define CO, OC, and PO regions [16].

Protocol 2: Tracking Reprogramming Trajectories via Integrated ATAC-seq and RNA-seq

This integrated approach reveals the relationship between chromatin remodeling and transcriptional changes [16].

- Parallel Sampling: From the same sample of reprogramming cells, split the population for simultaneous ATAC-seq and RNA-seq analysis.

- RNA-seq Library Prep: For the RNA-seq arm, extract total RNA. Convert RNA to cDNA and prepare sequencing libraries using a standard kit (e.g., poly-A selection for mRNA).

- Multi-Omics Data Integration: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the combined ATAC-seq and RNA-seq datasets to visualize the trajectories of naïve and primed reprogramming.

- Correlation Analysis: Correlate ATAC-seq signals from promoter or enhancer regions with expression levels of associated genes. A positive correlation confirms the functional relevance of the observed chromatin changes [16].

Key Signaling and Regulatory Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core molecular mechanism of transcription factor-driven somatic cell reprogramming to pluripotency, highlighting the key stages and epigenetic barriers.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Reprogramming and Epigenetic Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Ectopic expression to initiate reprogramming. | OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) or OSNL (Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, Lin28); Use non-integrating delivery systems (Sendai virus, episomal vectors, mRNA) for clinical relevance [15] [13]. |

| Chromatin Remodelers | Enzymes that restructure nucleosomes to open chromatin. | Chd1 (necessary for open chromatin in PSCs); esBAF (ESC-specific SWI/SNF complex) colocalizes with Oct4, Sox2, Nanog [12]. |

| Histone Modifying Enzymes | "Writers" and "Erasers" of histone marks. | Inhibitors of G9a/Dot1L (reduce H3K9me/H3K79me) can enhance reprogramming. PRC2 deposits H3K27me3 to silence somatic genes [10] [11]. |

| DNA Methylation Modulators | Regulate DNA methylation levels at key loci. | DNMT Inhibitors (e.g., 5-azacytidine) promote demethylation of pluripotency gene promoters. DNMT3A/B knockdown improves efficiency [11]. |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Chemical compounds that improve efficiency/safety. | Used to replace transcription factors (e.g., c-Myc), enhance MET, or inhibit epigenetic barriers (e.g., HDAC inhibitors) [13]. |

| ATAC-seq Kit | To map genome-wide chromatin accessibility dynamics. | Critical for identifying CO, OC, and PO regions during reprogramming [16]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Managing Culture Dominance by Karyotypically Abnormal Cells

Problem: A rapidly proliferating subpopulation of cells is overtaking your culture, suspected to be a common variant (e.g., trisomy 12, 17, or 20q11.21 gain).

| Observation | Possible Affected Chromosome | Underlying Cause & Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid culture overgrowth | Trisomy 12 | Increased dosage of pluripotency (e.g., NANOG) and cell cycle genes confers a proliferative advantage [4]. |

| Increased clonal survival post-dissociation | Trisomy 17 (17q25) | Overexpression of ARHGDIA reduces apoptosis and increases clonality after single-cell passaging [17]. |

| Resistance to apoptosis under standard conditions | 20q11.21 Amplification | Overexpression of the anti-apoptotic gene BCL2L1 (Bcl-xL) enhances cell survival [18] [19]. |

| Impaired neuroectodermal differentiation | 20q11.21 Amplification | BCL2L1 overexpression dysregulates TGF-β and SMAD signaling, blocking ectoderm commitment [19]. |

Step-by-Step Diagnostic & Mitigation Protocol:

Detection and Confirmation:

- Karyotyping (G-banding): Perform regular checks (e.g., every 10 passages) to detect gross chromosomal abnormalities. This is a standard first-line test [4].

- High-Resolution Analysis: Use technologies like SNP arrays or array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH) to identify smaller copy number variations (CNVs), such as the 0.56 Mb amplification at 20q11.21, which may be missed by karyotyping [18] [20] [4].

- PCR or FISH Validation: Confirm specific aberrations, such as the gain of ARHGDIA on 17q25 or BCL2L1 on 20q11.21, using targeted methods [17].

Mitigation Strategies:

- Modify Passaging Technique: Avoid routine single-cell enzymatic passaging, which imposes strong selective pressure. Switch to bulk/clump passaging methods where possible [17].

- Optimize Culture Conditions: Supplement culture medium with a ROCK inhibitor (ROCKi) during single-cell passaging. This can reduce the selective advantage conferred by aberrations like trisomy 17 by promoting general cell survival, thereby allowing normal cells to compete [17].

- Limit Culture Time: Establish a strict schedule for regenerating new cultures from low-passage frozen stocks to prevent the outgrowth of spontaneous mutants [4].

Guide 2: Addressing Poor Differentiation Efficiency

Problem: Your iPSC line differentiates poorly into a specific lineage (e.g., neuronal cells), while other lineages form normally.

| Symptom | Potential Genetic Cause | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Failure to form neuroectodermal progenitors | 20q11.21 Amplification | BCL2L1 overexpression drives transcriptomic changes that impair TGF-β-dependent signaling, a pathway critical for neuroectoderm commitment [19]. |

| General inefficiency across multiple lineages | Trisomy 12 | Altered balance of pluripotency factors and differentiation regulators can disrupt the coordinated exit from pluripotency [4]. |

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol:

- Genetic Screening: Prioritize genetic screening for 20q11.21 amplification if neuroectodermal defects are observed [19].

- Control Experiment: Differentiate a genetically normal iPSC line in parallel. If the normal line differentiates correctly, the defect is likely intrinsic to the problematic line.

- Lineage Commitment Analysis: Use flow cytometry or qPCR for early lineage-specific markers (e.g., SOX1 for neuroectoderm, SOX17 for endoderm) to pinpoint the differentiation block [19].

- Final Action: If a recurrent aberration is identified and confirmed to impair your target differentiation, bank a new, genetically normal cell line for your experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do the same aberrations (trisomy 12, 17, 20q) appear so frequently in different labs?

These aberrations are recurrent because they are not random. They confer a selective advantage under standard culture conditions. The genes within these amplified regions enhance survival (e.g., BCL2L1, ARHGDIA) and proliferation (e.g., genes on chromosome 12), allowing cells carrying them to outcompete normal cells and dominate the culture over time [17] [18] [4].

FAQ 2: My karyotype is normal. Are my cells genetically pristine?

Not necessarily. Conventional karyotyping has limited resolution (typically detecting aberrations >5-10 Mb). Higher-resolution methods like SNP arrays or NGS can detect cryptic lesions (e.g., small CNVs) and low-grade mosaicism, where a subset of cells carries an abnormality [20] [4]. A culture can test normal by karyotype but still contain a small, growing population of aberrant cells.

FAQ 3: Where do these genetic mutations in iPSCs come from?

They can arise from several sources [4]:

- Pre-existing in Somatic Cells: Rare variants present in the parental somatic cell population can be captured and expanded during reprogramming.

- Reprogramming-Induced: The reprogramming process itself can be mutagenic, inducing point mutations and CNVs.

- Culture-Acquired: Mutations can occur during prolonged in vitro expansion, with selective pressure allowing advantageous variants to take over.

FAQ 4: Are these genetically abnormal iPSCs tumorigenic?

They are not necessarily cancerous, but they carry a "first hit" toward oncogenesis. The same genes that provide a culture advantage (e.g., anti-apoptotic BCL2L1) are also frequently amplified in cancers [18]. Transplanting differentiated cells derived from these abnormal iPSCs could pose a long-term risk if these cells acquire additional mutations in vivo.

Experimental Protocols for Cited Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Competition Assay to Model Culture Dominance

This protocol is adapted from experiments investigating the selective advantage of ARHGDIA-overexpressing cells [17].

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the fitness advantage of a test cell population (e.g., mutant or gene-edited) against a reference wild-type population in co-culture.

Materials:

- Wild-type (WT) iPSC line

- Test iPSC line (e.g., with a specific aberration or genetic modification)

- Standard iPSC culture medium

- ROCK inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632)

- Enzyme for single-cell dissociation (e.g., Accutase)

- Flow cytometer

Method:

- Cell Preparation: Maintain WT and test iPSC lines separately. If the test line expresses a fluorescent marker (e.g., GFP), this simplifies tracking.

- Initial Seeding: Mix WT and test cells at a defined ratio (e.g., 1:1). Enzymatically dissociate the mixture into single cells and seed onto culture plates. Culture with and without ROCKi supplementation.

- Serial Passaging: Passage the co-culture every 3-5 days. At each passage, dissociate the culture into single cells.

- Quantification: Analyze an aliquot of cells by flow cytometry to determine the percentage of test cells (e.g., GFP-positive) in the population.

- Data Analysis: Plot the percentage of test cells over multiple passages. A consistent increase indicates a selective advantage.

Protocol 2: Clonal Survival Assay at Low Density

This protocol measures the ability of individual cells to survive and form colonies, a key characteristic of cells with aberrations like trisomy 17 [17].

Purpose: To assess the clonogenicity and survival of iPSCs after low-density seeding, a condition that induces stress.

Materials:

- iPSC lines to be tested

- iPSC culture medium with ROCKi

- Enzyme for single-cell dissociation

- Hemocytometer or automated cell counter

Method:

- Cell Dissociation: Harvest and dissociate iPSCs into a single-cell suspension.

- Low-Density Seeding: Count cells and seed at a very low density (e.g., 500-1,000 cells per well of a 6-well plate) in medium containing ROCKi.

- Culture: Allow cells to grow for 7-10 days, changing the medium every other day. Do not disturb the plates to allow colony formation.

- Analysis: Fix and stain colonies with crystal violet or directly count under a microscope. Compare the number and size of colonies formed by different lines. Lines with a selective advantage will show significantly higher colony-forming efficiency.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram: BCL2L1-Mediated Impairment of Neuroectoderm Differentiation

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Genetic Instability Monitoring

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| ROCK Inhibitor (ROCKi) | Critical for increasing survival of dissociated iPSCs. Used during passaging to reduce the selective pressure that favors aneuploid cells. Mitigates the advantage of mutations in ARHGDIA [17]. |

| SNP/Array CGH Kits | High-resolution tools for detecting copy number variations (CNVs), including the cryptic 0.56 Mb amplification at 20q11.21, which may be missed by standard karyotyping [18] [20] [4]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Provides the most comprehensive genetic analysis. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) can detect single nucleotide variants (SNVs), CNVs, and structural variants, revealing the full spectrum of genomic instability [4] [21]. |

| Lentiviral ORF Constructs | Used for functional validation. For example, to overexpress candidate genes like ARHGDIA or BCL2L1 in normal iPSCs to test if this recapitulates the selective or differentiation-defective phenotype [17] [19]. |

| qPCR Assays | Rapid, quantitative method to validate gene expression changes associated with aberrations (e.g., elevated BCL2L1 or ARHGDIA mRNA levels) without the need for full genomic screening [17] [19]. |

Within the context of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) research, genomic instability presents a significant challenge for clinical applications. A critical aspect of maintaining genomic integrity is the faithful repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), with the two major pathways being non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR). Understanding the balance between these pathways is crucial, as their efficiency and fidelity can be altered during cellular reprogramming and prolonged culture of iPSCs. This technical support article provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers identify and address issues related to DNA repair pathway shifts in their iPSC cultures.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: What is the relative efficiency and kinetics of NHEJ versus HR in normal human cells?

Answer: In actively cycling normal human fibroblasts, NHEJ is a faster and more efficient DSB repair pathway than HR.

- Kinetics: NHEJ of compatible ends (NHEJ-C) and NHEJ of incompatible ends (NHEJ-I) are fast processes, completing in approximately 30 minutes. In contrast, HR is much slower, taking 7 hours or longer to complete [22].

- Relative Contribution: The ratio of repair events in cycling cells is approximately NHEJ-C : NHEJ-I : HR = 6 : 3 : 1. This makes NHEJ-C twice as efficient as NHEJ-I and three times more efficient than HR [22].

Table 1: Comparison of NHEJ and HR Efficiency and Kinetics [22]

| Repair Pathway | Description | Approximate Completion Time | Relative Efficiency in Cycling Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ-C | NHEJ of compatible DNA ends | ~30 minutes | 6 |

| NHEJ-I | NHEJ of incompatible DNA ends | ~30 minutes | 3 |

| HR | Homologous Recombination | ≥7 hours | 1 |

FAQ: What types of genomic instability are commonly observed in iPSCs?

Answer: iPSCs are prone to acquiring several types of genetic variations, which pose a safety concern for therapeutic use. The main categories are [4] [6]:

- Chromosomal Aberrations: Numerical changes (aneuploidy) and large structural changes. Common recurrent anomalies include trisomy of chromosome 12, and amplifications of chromosomes 8, 20, and X [4].

- Copy Number Variations (CNVs): Deletions or duplications of DNA segments. A recurrent CNV hotspot is an amplification on 20q11.21, a region enriched with genes associated with pluripotency and anti-apoptosis (e.g.,

DNMT3B,ID1,BCL2L1) [4] [6]. - Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs): Point mutations in the protein-coding regions. Studies have identified an average of ~10 protein-coding mutations per human iPSC line [4].

FAQ: What are the origins of genetic variations in iPSCs?

Answer: The genetic variations found in iPSCs can originate from three main sources [4]:

- Pre-existing Variations: Somatic mutations present at low frequency in the parental cell population can be captured and clonally expanded during the reprogramming process.

- Reprogramming-Induced Mutations: The reprogramming process itself can induce DNA damage and mutations, partly due to replication stress caused by the expression of reprogramming factors [23].

- Passage-Induced Mutations: Genetic changes can accumulate during prolonged in vitro culture of established iPSC lines.

Troubleshooting: How can I reduce replication stress and genomic instability during iPSC reprogramming?

Problem: High levels of replication stress during reprogramming lead to increased DNA damage and de novo CNVs in resulting iPSC lines. Solution:

- Genetic Strategy: Increasing the levels of the checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1), which helps manage replication stress, has been shown to reduce DNA damage and increase reprogramming efficiency [23].

- Chemical Strategy: Supplementing the culture medium with nucleosides during reprogramming provides the raw materials for DNA synthesis, which reduces the replication stress load. This approach has been demonstrated to lower the levels of DNA damage (γH2AX) and reduce the number of de novo CNVs in the resulting human iPSC lines [23].

Table 2: Strategies to Limit Reprogramming-Induced Genomic Instability [23]

| Strategy | Method | Effect on Reprogramming | Effect on Genomic Instability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increase CHK1 | Genetic overexpression | Increases reprogramming efficiency | Reduces replication stress and spontaneous chromosomal fragility |

| Nucleoside Supplementation | Chemical supplement | Does not increase efficiency | Reduces DNA damage load and de novo CNVs |

FAQ: How does the disruption of NHEJ impact the repair of fragmented chromosomes?

Problem: In an experimental model of chromothripsis (catastrophic chromosomal shattering), cells lacking core NHEJ components (e.g., LIG4 or XLF) show dramatically reduced survival and decreased frequencies of genomic rearrangements [24].

Solution & Interpretation:

- Canonical NHEJ is the primary DSB repair pathway responsible for reassembling shattered chromosomes and generating complex genomic rearrangements.

- In the absence of NHEJ, alternative end-joining or recombination-based pathways are rarely engaged, leading to persistent DNA damage in the form of 53BP1-labeled "MN bodies" and subsequent cell cycle arrest [24].

- This highlights the critical, and sometimes exclusive, role of NHEJ in repairing severe, clustered DNA breaks.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comparing NHEJ and HR Efficiency Using Fluorescent Reporters

This protocol is adapted from a study comparing the kinetics and efficiency of NHEJ and HR in human cells [22].

1. Principle: Chromosomally integrated GFP-based reporter constructs are used. Upon induction of a site-specific DSB by the I-SceI endonuclease, successful repair via NHEJ or HR leads to the reconstitution of a functional GFP gene, which can be quantified by flow cytometry.

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- Reporter cell lines (HCA2-hTERT with single integrated copies of NHEJ-I, NHEJ-C, or HR constructs)

- Plasmid encoding I-SceI endonuclease

- Plasmid encoding DsRed (transfection control)

- Transfection reagent (e.g., Amaxa Nucleofector)

- Flow cytometer

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Culture reporter cell lines under standard conditions.

- Step 2: Co-transfect cycling cells with 5 µg of I-SceI plasmid and 0.1 µg of DsRed plasmid to control for transfection efficiency.

- Step 3: Incubate cells for 4 days post-transfection.

- Step 4: Harvest cells and resuspend in cold PBS.

- Step 5: Analyze the samples using a flow cytometer to quantify the percentages of GFP-positive (repaired) and DsRed-positive (transfected) cells.

- Step 6: Calculate repair efficiency as the ratio of GFP+ cells to DsRed+ cells for each independent cell line.

4. Data Analysis:

- The kinetics of repair can be analyzed by performing FACS at multiple time points after transfection (e.g., from 0.5 hours to 24 hours).

- Compare the ratios between different repair pathways to determine their relative contributions.

Protocol 2: Assessing Genomic Integrity in iPSCs Using Copy Number Variation (CNV) Analysis

This protocol outlines methods for detecting structural variations in iPSC lines [4] [6].

1. Principle: Array-based technologies (aCGH or SNP arrays) or next-generation sequencing (Whole Genome Sequencing) are used to identify copy number variations across the genome, revealing regions of amplification or deletion that may have been acquired during reprogramming or culture.

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- iPSC genomic DNA

- aCGH/SNP array platform or NGS platform

- Associated DNA labeling and hybridization kits or NGS library prep kits

3. Step-by-Step Procedure (for array-based methods):

- Step 1: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from iPSC lines and reference control DNA.

- Step 2: Label test and reference DNA with different fluorescent dyes (e.g., Cy5 and Cy3).

- Step 3: Hybridize the labeled DNA mixture to a microarray slide containing probes spanning the genome.

- Step 4: Wash the slide to remove non-specifically bound DNA.

- Step 5: Scan the slide with a microarray scanner to measure fluorescence intensities.

- Step 6: Use dedicated software to calculate log2 ratios of fluorescence intensities and identify genomic regions with significant deviations from the control, indicating CNVs.

4. Data Analysis:

- Focus on recurrent regions of CNVs reported in iPSCs, such as 20q11.21.

- Cross-reference identified CNVs with databases of known cancer genes, fragile sites, and genes involved in pluripotency.

Pathway Diagrams

Origins and Mitigation of Genomic Instability in iPSCs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying DNA Repair in iPSCs

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Reporter Constructs (NHEJ/HR) | In vivo, real-time monitoring of specific DSB repair pathway activity. | Comparing the relative efficiency and kinetics of NHEJ vs. HR in different cell types [22]. |

| I-SceI Endonuclease Plasmid | Induction of a specific, reproducible DNA double-strand break at a defined genomic locus. | Activating the repair process in reporter cell lines to measure NHEJ/HR efficiency [22]. |

| Array CGH or SNP Arrays | Genome-wide detection of copy number variations (CNVs) at kilobase resolution. | Identifying acquired structural variations in iPSC lines after reprogramming or extended passaging [4] [6]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (WGS/WES) | Comprehensive detection of genetic variations (SNVs, CNVs, indels) at single-nucleotide resolution. | Profiling the full spectrum of mutations in iPSCs and tracing their origin (parental vs. acquired) [4]. |

| CHK1 Expression Vector | Genetic manipulation to increase levels of the checkpoint kinase 1. | Reducing replication stress during reprogramming to lower genomic instability in resulting iPSCs [23]. |

| Nucleoside Supplement | Chemical provision of substrates for DNA synthesis. | Limiting replication stress during reprogramming to reduce DNA damage and de novo CNVs [23]. |

| sgRNAs Targeting DSB Repair Genes | CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of specific DNA repair factors (e.g., LIG4, XLF, POLQ). | Functionally characterizing the role of specific pathways in processing DNA damage in iPSCs [24]. |

The Impact of Culture Conditions and Selective Pressure on the Emergence of Aneuploid Clones

FAQs on Aneuploidy in Stem Cell Cultures

What are the signs that my iPSC culture is developing aneuploidy? While karyotype analysis is needed for confirmation, certain culture observations can signal potential genomic instability. Aneuploid clones often acquire a growth advantage, manifesting as changes in colony morphology, accelerated proliferation rates, and an increased propensity to dominate the culture over passages [4]. Specific recurrent aneuploidies, such as trisomy of chromosome 12 or gains of chromosome 20q11.21, are frequently observed and are associated with genes that promote pluripotency and cell survival [4].

Why does aneuploidy persist in my cultures even though it often reduces cellular fitness? Although aneuploidy can cause proteotoxic stress and reduced fitness under standard conditions, it can provide a crucial selective advantage under specific culture stresses [25]. The extra chromosomes may harbor genes that help cells cope with the culture environment. Consequently, even if aneuploid cells grow slower initially, they can rapidly outcompete normal cells if the culture conditions impose stresses that their specific aneuploidy helps to overcome [4] [25].

Which chromosomes are most commonly gained in iPSC cultures and why? The most recurrent aneuploidies in iPSCs are not random [4]. The table below summarizes the frequently observed chromosomal gains and the key genes within those regions that are thought to drive their selection.

| Chromosomal Abnormality | Key Genes in the Region | Proposed Selective Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Trisomy 12 | NANOG | Enhances reprogramming efficiency and pluripotency [4]. |

| Gain of 20q11.21 | DNMT3B, ID1, BCL2L1 | Promotes anti-apoptosis and supports pluripotent state [4]. |

| Amplifications of Chromosome 8 and X | - | Frequently recurrent; specific advantages area of active investigation [4]. |

How do my culture practices influence the emergence of aneuploid clones? Two key culture factors are passaging techniques and passage number.

- Passaging: Practices that encourage clonal expansion from single cells or that create uneven colony sizes can increase the risk of an aneuploid clone taking over the culture [8].

- Prolonged Culture: The number of cell passages is a major risk factor. The longer iPSCs are maintained in culture, the more time there is for mutations to occur and for fitter, potentially aneuploid, clones to expand. One study noted that the number of copy number variations (CNVs) was high in early passages but decreased during cell passaging as a result of selective pressure, with deletions of tumor-suppressor genes common early on and duplications of oncogenic genes increasing during later passages [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Suspected Aneuploidy Due to Rapidly Overgrowing Clones

Potential Causes and Solutions

| Observation | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| A subset of colonies appears morphologically distinct and grows significantly faster, outcompeting others. | Emergence of an aneuploid clone with a proliferative advantage. | Verify Genomic Integrity: Perform karyotyping or SNP array analysis on the culture. Isolate Individual Clones: Manually pick and expand colonies with normal morphology away from the overgrowing areas. Bank Early: Use low-passage stocks to minimize culture-induced instability. |

| Culture becomes dominated by a single clone type after several passages. | Selective pressure from suboptimal culture conditions favoring an adapted (possibly aneuploid) clone. | Review Culture Conditions: Ensure media is fresh and not expired. Avoid over- or under-confluency during passaging [8]. Reduce Stressors: Minimize the time culture plates are out of the incubator [8]. |

| Spontaneous differentiation increases concurrently with changes in growth rates. | Genomic instability may be compromising lineage commitment. | Remove Differentiated Areas: Physically scrape or chemically remove differentiated regions before passaging [8]. Check Key Signaling Pathways: Ensure growth factors in media are active and at correct concentrations. |

Problem: Genomic Instability During Reprogramming and Differentiation

Background: Genomic alterations can be introduced during the reprogramming of somatic cells into iPSCs and during subsequent differentiation into target cells. One study found that the reprogramming method itself influences stability, with Sendai virus (SV)-derived iPSCs showing a higher frequency of copy number alterations (CNAs) and single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) compared to those generated with episomal vectors (Epi) [26].

Prevention and Monitoring Strategies

| Phase | Risk | Quality Control Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming | Introduction of CNAs and SNVs [26]. | Choose a Non-Integrating Method: Use episomal vectors over integrating viruses where possible [26]. Characterize Multiple Clones: Genomically screen several independent iPSC clones to select the most stable line. |

| Differentiation | Acquisition of mutations during the process to target cells (e.g., mesenchymal stem cells) [26]. | Monitor Genomic Integrity: Perform spot-checks for CNAs and SNVs in the final differentiated cell product [26]. |

| Long-Term Culture | Passage-induced mutations [4]. | Bank at Low Passages: Create a master cell bank of your iPSC line at an early passage. Limit Passages: Use the lowest possible passage number for final experiments or differentiation. |

Experimental Protocols for Monitoring Genomic Integrity

Protocol 1: Karyotype Analysis by G-Banding

Purpose: To detect numerical chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., trisomy) and large structural changes (e.g., translocations) at a resolution of ~5-10 Mb [4].

- Procedure:

- Cell Harvesting: Treat logarithmically growing iPSCs with a mitotic inhibitor (e.g., colcemid) to arrest cells in metaphase.

- Hypotonic Treatment: Expose cells to a hypotonic solution to swell them and disperse the chromosomes.

- Fixation: Fix the cells repeatedly with a methanol:acetic acid solution.

- Slide Preparation: Drop the fixed cell suspension onto glass slides to achieve well-spread metaphase chromosomes.

- Staining: Stain slides with Giemsa stain to produce a characteristic banding pattern (G-banding) for each chromosome.

- Analysis: Analyze at least 20 metaphase spreads under a microscope to identify chromosomal abnormalities [4].

Protocol 2: Detection of Copy Number Variations (CNVs) using SNP Array

Purpose: To identify submicroscopic copy number gains and losses across the genome at a higher resolution (kilobase level) than karyotyping [4].

- Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from iPSCs and a reference control.

- Digestion and Amplification: Digest the DNA, amplify fragments, and label with fluorescent dyes.

- Hybridization: Co-hybridize the labeled test and reference DNA to a microarray slide containing hundreds of thousands of oligonucleotide probes representing SNPs across the genome.

- Scanning and Analysis: Scan the array to measure fluorescence intensities. Use specialized software to analyze the log intensity ratios and make copy number calls, identifying regions of deviation from the diploid state [4].

Key Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Clonal Expansion of Aneuploid Cells

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual process of how a spontaneous genetic variation can lead to the dominance of an aneuploid clone under selective culture conditions.

Experimental Workflow for Tracking Genomic Instability

This workflow outlines a comprehensive strategy for monitoring the emergence of genomic alterations from reprogramming through to the final differentiated cell product, based on published studies [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Genomic Stability Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| KaryoStat+ Assay | A commercial SNP-based array solution for comprehensive CNV detection in stem cells. |

| mTeSR Plus Medium | A feeder-free, defined culture medium optimized for the maintenance of hPSCs, helping to reduce undefined culture stressors [8]. |

| ReLeSR Passaging Reagent | A non-enzymatic dissociation reagent for gentle passaging of hPSCs as clusters, minimizing single-cell stress and supporting genomic stability [27]. |

| Vitronectin XF | A defined, human-derived substrate for cell culture, replacing mouse feeder cells or Matrigel to create a more consistent and controlled environment [8]. |

| STEMdiff Mesenchymal Progenitor Kit | A standardized, serum-free kit for the directed differentiation of iPSCs into mesenchymal progenitor cells, enabling controlled studies of instability during differentiation [26]. |

| Dendra2 Protein/Plasmid | A photo-convertible fluorescent protein used in live-cell imaging to track the fate of specific cells, such as those with micronuclei, over multiple divisions [28]. |

Advanced Methods for Detecting and Monitoring Genomic Aberrations

In the field of genomic research, particularly in the study of genomic instability in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) cultures, high-resolution genotyping platforms are indispensable tools. Array-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) and Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) microarrays enable genome-wide detection of chromosomal abnormalities at a significantly higher resolution than conventional cytogenetic methods [29]. These technologies have become fundamental for identifying genomic variations that arise during iPSC reprogramming and long-term culture, where genomic instability is a major concern for therapeutic applications [30].

The fundamental difference between these platforms lies in their detection capabilities. While aCGH is primarily designed to detect copy number variations (CNVs), SNP arrays can simultaneously identify CNVs, loss of heterozygosity (LOH), and uniparental disomy (UPD), and determine ploidy status [29] [31]. This technical distinction makes each platform uniquely suited for specific research applications, particularly in monitoring the genomic integrity of iPSC cultures intended for regenerative medicine.

Array-Based Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH)

The principle of aCGH is based on the quantitative comparison between a reference DNA and test DNA, typically labeled with Cyanine 3 (green) and Cyanine 5 (red) fluorescent dyes, respectively [32]. The labeled DNA samples are mixed and competitively hybridized to a microarray chip containing thousands of known target DNA sequences. After hybridization, the fluorescence ratio at each probe is measured to detect CNVs throughout the genome [32]. Chromosomal regions with increased copy number in the test sample will show higher green fluorescence, while regions with decreased copy number will show higher red fluorescence [33].

SNP Microarray

SNP microarray technology represents a high-throughput, large-scale genetic testing platform designed for the detection of single nucleotide polymorphisms [33]. The working principle involves the hybridization of fragmented single-stranded DNA to an array containing hundreds of thousands of unique nucleotide probe sequences. SNP arrays take advantage of the differences in SNP loci between individuals. Unlike aCGH, SNP arrays utilize probes featuring different SNP variations that specifically match with SNP sites, allowing determination of the genotype at each locus by measuring hybridization signal intensity [33]. A key advantage of SNP arrays is their ability to detect copy number neutral events such as long contiguous stretches of heterozygosity (LCSH) and uniparental isodisomies, which are undetectable by aCGH alone [29].

Table 1: Key Technological Differences Between aCGH and SNP Microarrays

| Feature | aCGH | SNP Microarray |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Detection | Copy number variations (CNVs) | SNPs and CNVs |

| Genotyping Capability | No | Yes |

| Copy-Neutral LOH Detection | No | Yes |

| Ploidy Determination | Limited | Yes |

| Chimerism Detection | Limited | Yes [29] |

| Resolution | Can detect single-exon CNVs with custom designs [31] | Limited by known SNP distribution [31] |

| Reproducibility | >99.9% for validated SNPs [34] | >99.9% for validated SNPs [34] |

Workflow and Experimental Protocols

Standard Workflow for SNP Microarray

The general workflow of SNP microarray consists of several critical processes that must be carefully optimized for reliable results [33]:

Probe Design: This initial step involves collecting genomic sequence information from target SNP loci. Known SNP information is aligned with the reference genome sequence to determine the position and variable bases of SNP sites. Using sequence information around the SNP sites, specific probes are designed to selectively pair with the variable bases. Probes are typically 20-70 bases in length to ensure stable hybridization and reliable signal detection [33].

SNP Chip Fabrication: Predesigned oligonucleotide probes are arranged orderly and in high density on a solid carrier (usually glass) to create microarrays. Fabrication methods include light-guided in-situ synthesis, chemical spray method, contact dot coating method, and non-contact micromechanical printing. Modern high-density arrays can contain over 400,000 different DNA molecules on a 1 cm² chip [33].

Sample Genomic DNA Preparation: High quality and high molecular weight genomic DNA should always be used, as it directly affects labeling efficiency [32]. The concentration and purity of DNA samples are paramount, typically assessed using spectrophotometric techniques. The A260/280 ratio should be >1.8, and the A260/230 ratio should be in the range of 2.0-2.2 [32]. For short-term storage, DNA should be kept at 4°C to avoid freeze/thaw cycles that can break chromosomes [32].

Labeling, Hybridization, and Scanning: DNA is labeled with fluorescent dyes, with the efficiency of the labeling reaction being critical for success. The labeled genomic DNA hybridizes with the SNP microarray under optimized reaction conditions (temperature, salt concentration, hybridization time). Post-washing, fluorescence is scanned with a specialized scanner, and data is processed through computer image analysis for bioinformatics interpretation [33].

Diagram 1: SNP microarray workflow

Standard Workflow for aCGH

The aCGH workflow shares similarities with SNP arrays but has distinct critical steps:

DNA Quality Assessment: The quality of results is strictly dependent on the quality of probes hybridized on the microarray. Beyond spectrophotometric measurements, DNA integrity should be verified using gel electrophoresis or automated electrophoresis systems [32].

Labeling Reaction Optimization: The labeling reaction typically involves incorporation of cyanine dyes into newly synthesized DNA by random priming. Both denaturation and primer extension steps are crucial. Changing, particularly shortening, the reaction time causes inefficient and incomplete incorporation of Cyanine-labeled deoxynucleotides [32].

Purification and Quality Control: After labeling, DNA must be purified to remove unincorporated nucleotides. This can be achieved through silica membrane-based purification columns, columns with cellulose membranes, or classical DNA precipitation. Ethanol precipitation with NaOAC is preferred for better removal of free nucleotides [32].

Probe Quality Verification: Before hybridization, labeling efficiency should be checked using a NanoDrop in Microarray Measurement Mode. Key parameters include DNA yield (>5.0 µg), dye incorporation (>300 pmoles Cyanine 3 or >200 pmoles Cyanine 5), and specific activity (>60 pmol/µg for Cy3, >40 pmol/µg for Cy5) [32].

Hybridization and Stringency Control: The hybridization mix must be prepared following array manufacturer instructions. The amount of Cot-1 DNA (which blocks non-specific interactions), buffer stringency, and incubation temperature critically affect final results. Incorrect conditions lead to low signal, elevated background, and poor signal-to-noise ratio [32].

Diagram 2: aCGH workflow

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

DNA Quality and Preparation Issues

Problem: Poor DNA quality affecting labeling efficiency

- Potential Cause: Protein or organic compound contamination, or DNA degradation.

- Solution: Re-purify DNA samples if A260/280 ratio is <1.8 or A260/230 ratio deviates from 2.0-2.2. Verify DNA integrity using gel electrophoresis. For freeze/thaw cycles that break chromosomes, store aliquots at -20°C and keep aliquots in use at 4°C for short-term storage [32].

Problem: Suspected DNA contamination with inhibitors

- Solution: Clean up gDNA using the following procedure:

- Add 0.5 volumes of 7.5 M NH4OAc and 2.5 volumes of absolute ethanol (stored at -20°C) to gDNA

- Vortex and incubate at -20°C for 1 hour

- Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 20 minutes at room temperature

- Remove supernatant and wash pellet with 80% ethanol

- Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 5 minutes

- Repeat 80% ethanol wash once more

- Resuspend pellet in reduced EDTA TE Buffer [34]

Labeling and Hybridization Issues

Problem: Low signal intensity after hybridization

- Potential Causes: Inefficient labeling reaction, insufficient DNA input, or suboptimal hybridization conditions.

- Solution: Ensure labeling reaction follows manufacturer guidelines for volumes, concentrations, timing, and incubation temperatures. Check dye incorporation and specific activity before hybridization. For limited DNA samples, use specialized labeling kits designed for low input (e.g., 50 ng of DNA) [32].

Problem: Wave effect pattern in hybridization intensities

- Potential Cause: GC content bias of probes or potential bias during DNA isolation.

- Solution: Optimize the amount of Cot-1 DNA and ensure proper denaturing step prior to labeling [32].

Problem: Dye-specific signal reduction

- Solution: Protect Cyanine 5 from ozone effects, which are more pronounced at elevated environmental temperatures. Cyanine 3 is generally not affected by this phenomenon [32].

Data Quality Issues

Problem: High derivative log ratio (DLR)

- Potential Cause: Poor DNA quality and/or labeling efficiency.

- Solution: DLR should be <0.2 for optimal data quality. High DLR values correlate with poor data quality and reduce accurate identification of chromosomal abnormalities [32].

Problem: Suspected sample contamination

- Solution: Check for possible cross-sample contamination using genome analysis software. SNP arrays can detect DNA contamination through genotyping patterns [29] [35].

Table 2: Quality Control Metrics and Thresholds for Array Experiments

| Parameter | Optimal Value | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| DNA A260/280 Ratio | >1.8 | Indicates protein contamination |

| DNA A260/230 Ratio | 2.0-2.2 | Indicates organic compound contamination |

| Signal Intensity | >200 | Measurement of overall fluorescence |

| Background Noise | <25 | Standard deviation of negative controls |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | >30 | Ratio between probe signal and background |

| Derivative Log Ratio | <0.2 | Measure of array quality and variation |

| Dye Incorporation (Cy3) | >300 pmoles | Critical for labeling efficiency |

| Dye Incorporation (Cy5) | >200 pmoles | Critical for labeling efficiency |

Application in Genomic Instability Research in iPSCs

The study of genomic instability in induced pluripotent stem cells represents one of the most critical applications of high-resolution genotyping platforms. Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) are known to acquire genomic changes as they proliferate and differentiate, raising concerns about the safety of hPSC-derived cell therapies [30]. Research has shown that hPSCs accumulate specific genomic abnormalities during culture adaptation, with late passage hPSCs being twice as likely to have genomic changes than early passage cells [30].

SNP genotyping has been particularly valuable in identifying common genomic changes in iPSCs, including:

- Recurrent chromosomal abnormalities: Trisomies of chromosomes 1, 12, 17, and X

- Subchromosomal amplifications: Such as the common amplification of 20q11.21, which contains the BCL2L1 (Bcl-xL) gene that enhances hESCs survival

- Copy number variations (CNVs): Both in hESCs and hiPSCs [30]

A recent study systematically investigating genomic alterations from iPSC generation through induced mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (iMS) differentiation observed a total of ten copy number alterations (CNAs) and five single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) during reprogramming, differentiation and passaging [26]. Notably, iPSCs generated using the Sendai virus (SV) method exhibited a higher frequency of CNAs and SNVs compared with those generated with episomal vectors (Epi) [26]. All SV-iPS cell lines exhibited CNAs during reprogramming, while only 40% of Epi-iPS cells showed such alterations [26].

For clinical applications, regulatory agencies require extensive preclinical safety trials in animals to determine whether hPSCs become cancerous or induce cancers [30]. To minimize effects of acquired mutations on cell therapy, it is strongly recommended that cells destined for transplant be monitored throughout their preparation using high-resolution methods such as SNP genotyping [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for High-Resolution Genotyping

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CYTAG TotalCGH Labeling Kit | Allows SNP arrays in addition to standard CGH arrays | General purpose labeling for CGH and SNP detection |

| CYTAG SuperCGH Labeling Kit | Designed for limited starting material (e.g., 50 ng DNA) | Ideal for iPSC clones where material may be limited [32] |

| Puregene DNA Blood Kit | DNA extraction from peripheral blood | Standardized DNA extraction for consistent results [31] |

| NH4OAc and Absolute Ethanol | DNA cleanup procedure | Removes inhibitors from gDNA preparations [34] |

| Reduced EDTA TE Buffer | DNA resuspension after cleanup | Maintains DNA integrity for labeling reactions [34] |

| Cot-1 DNA | Blocks non-specific hybridization | Critical for reducing background in hybridization [32] |

| AluI and RsaI Restriction Enzymes | DNA digestion for SNP detection | Enables detection of SNPs located at enzyme recognition sites [31] |

| 8x60K and 4x180K CGH Arrays | Microarray formats for hybridization | 8x60K allows 8 samples/chip; 4x180K provides higher resolution [32] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which platform is more suitable for detecting genomic instability in iPSC cultures - aCGH or SNP array? SNP arrays are generally preferred for comprehensive monitoring of genomic instability in iPSCs because they can detect both copy number variations and copy-neutral events such as loss of heterozygosity (LOH) [29] [30]. aCGH may be preferred when targeting specific genes at exon-level resolution is required [31]. For clinical applications, some laboratories use combined arrays that incorporate both CGH and SNP probes to maximize detection capabilities [31].

Q2: What are the critical quality control metrics for array experiments, and what are their acceptable thresholds? Key QC metrics include: DNA purity (A260/280 >1.8, A260/230 2.0-2.2), DNA yield (>5.0 µg for labeling), dye incorporation (>300 pmoles Cy3, >200 pmoles Cy5), specific activity (>60 pmol/µg Cy3, >40 pmol/µg Cy5), signal intensity (>200), background noise (<25), signal-to-noise ratio (>30), and derivative log ratio (<0.2) [32].

Q3: How can we detect low-level mosaicism in iPSC cultures using these platforms? Genomic aberrations smaller than 10Mb can be successfully detected in samples with as low as 10% mosaicism using optimized aCGH protocols [32]. SNP arrays generally show higher sensitivity for detecting low-level mosaic aneuploidies and chimerism compared to aCGH [31].

Q4: What is the typical reproducibility and concordance rate of these technologies? For validated SNPs on quality-controlled arrays, reproducibility rates typically exceed 99.9% among different experiments, and Mendelian consistency rates are approximately 99.96% [34].

Q5: How does the choice of reprogramming method affect genomic instability in iPSCs? Research indicates that Sendai virus (SV)-derived iPSCs show higher frequencies of copy number alterations and single nucleotide variations compared with episomal vector (Epi)-derived iPSCs [26]. All SV-iPS cell lines exhibited CNAs during reprogramming, while only 40% of Epi-iPS cells showed such alterations [26].

Multiplex Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (M-FISH) for Karyotypic Analysis

Multiplex Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (M-FISH) is a powerful 24-color karyotyping technique that has become indispensable for the comprehensive detection of complex chromosomal rearrangements. In the context of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) research, where genomic instability is a primary concern, M-FISH provides a critical tool for identifying numerical and structural abnormalities that may arise during reprogramming or prolonged cell culture [4] [36]. This technical support guide addresses common experimental challenges and provides detailed methodologies to ensure accurate detection of chromosomal aberrations, enabling researchers to maintain genomic integrity in their stem cell cultures.

Troubleshooting Common M-FISH Experimental Issues

The following table outlines frequently encountered problems during M-FISH experiments, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Issue | Potential Causes | Troubleshooting Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Poor or No Signal [37] | Inefficient probe labeling, suboptimal denaturation/hybridization, inadequate permeabilization, low probe concentration | Check probe design and labeling efficiency. Optimize denaturation and hybridization conditions. Ensure complete sample permeabilization. Increase probe concentration or hybridization time [37] [38]. |

| High Background Noise [37] [38] | Incomplete stringent washes, non-specific probe binding, cross-reactivity, sample drying during hybridization | Increase stringency of post-hybridization washes (adjust temperature, salt concentration, and duration). Verify probe specificity and use Cot-1 DNA to block repetitive sequences. Ensure a humidified chamber to prevent drying [37] [38]. |

| Weak or Faded Signal [37] | Fluorophore sensitivity, signal quenching, over-fixed or over-permeabilized samples, improper mounting | Use sensitive fluorophores and anti-fade mounting medium. Minimize light exposure during staining and imaging. Optimize fixation and permeabilization times [37]. |

| Uneven or Patchy Hybridization [37] | Non-uniform probe distribution, air bubbles during mounting, uneven denaturation or permeabilization | Ensure even application of the probe and avoid hard pressure on coverslips. Remove all air bubbles when mounting. Verify consistent sample preparation across the slide [37]. |

| Morphological Distortion [37] | Over-fixation, over-permeabilization, harsh cell dissociation methods | Optimize fixation and permeabilization conditions. Use gentler methods for cell dissociation and spreading [37]. |

| Chromosomal Misclassification [39] | "Flaring" or overlapping fluorescence at translocation junctions, poor chromosome preparations, algorithmic interpretation errors | Corroborate complex rearrangements with whole-chromosome painting (WCP). Ensure high-quality metaphase spreads and optimal hybridization conditions to minimize flaring [39]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How does M-FISH differ from traditional FISH and why is it particularly useful for iPSC research?

Unlike traditional FISH, which typically identifies one or a few targets simultaneously, M-FISH allows for the simultaneous visualization of all 24 human chromosomes in a single experiment using combinatorially labeled whole-chromosome painting probes [40] [36]. This is crucial for iPSC research because it enables the detection of complex chromosomal rearrangements and subtle structural changes that are often missed by other techniques [4] [36]. Identifying these aberrations is essential for ensuring the safety of iPSCs in downstream applications like regenerative medicine.

2. What are the inherent limitations of M-FISH in karyotype analysis?

A key limitation is that M-FISH cannot detect intrachromosomal rearrangements, such as deletions, duplications, or inversions, unless they involve a change in chromosomal paint [39]. Additionally, the technique can produce erroneous interpretations due to "flaring"—the overlapping of fluorescence signals at the junctions of translocated segments, which can lead to false identification of small inserted segments [39]. The resolution for detecting insertions/translocations on metaphase spreads is approximately 1 Mb [39].

3. What steps can be taken to improve the reproducibility of M-FISH results?

To ensure consistent and reproducible results, it is critical to standardize the sample preparation and FISH protocol steps [37]. This includes using healthy, actively growing cells for optimal chromosome morphology, carefully controlling fixation and denaturation times, and using appropriate positive and negative controls with each experiment [37] [38]. Consistent reagent quality and storage conditions are also vital [37].

4. Our M-FISH analysis suggests a complex, multi-chromosomal rearrangement. How can we confirm this finding?

When M-FISH indicates a complex rearrangement, it is highly recommended to validate the result using single-color whole-chromosome painting (WCP) for the specific chromosomes involved [39] [41]. This orthogonal technique helps confirm the origin of chromosomal material and can clarify ambiguities caused by fluorescence flaring, ensuring an accurate karyotype interpretation [39].

Essential M-FISH Protocol for Karyotypic Analysis

This protocol provides a robust methodology for conducting M-FISH, with particular attention to steps critical for analyzing iPSCs.

Sample Preparation and Metaphase Spread Creation

- Cell Culture and Mitotic Arrest: Use healthy, actively growing cells (e.g., iPSCs) at ~75-80% confluency. Treat with Colcemid (e.g., 100 ng/mL for 3 hours) to arrest cells in metaphase [42].

- Hypotonic Treatment: Collect mitotic cells and resuspend the pellet in a pre-warmed hypotonic solution (e.g., 75 mM KCl) and incubate for 15 minutes at 37°C. This swells the cells and helps spread the chromosomes [42].

- Fixation: Centrifuge the cells and fix them in freshly prepared Carnoy's fixative (a 3:1 mixture of methanol to acetic acid). Perform at least two changes of fixative, resuspending the pellet each time. Drop the fixed cell suspension onto clean glass slides and air dry [42].

Slide Pretreatment and Denaturation

- Pretreatment: Treat slides with RNase A and pepsin to remove RNA and digest proteins, respectively, then post-fix in formaldehyde. Dehydrate slides through an ethanol series (70%, 85%, 100%) [38] [41].

- Denaturation: Denature chromosomal DNA by incubating slides in 70% formamide in 2x SSC at 72°C for approximately 2 minutes. Immediately dehydrate through another cold ethanol series and air dry [38] [41].

Probe Hybridization and Washing

- Probe Application: Denature the commercially available 24-color M-FISH probe mix (e.g., SpectraVision Assay) at 72°C for 10 minutes. Apply the denatured probe to the denatured slide, cover with a coverslip, and seal with rubber cement [41].

- Hybridization: Incubate slides in a humidified chamber at 37°C for 48 hours to allow for specific hybridization of the probes to their target chromosomes [41].

Post-Hybridization Washes and Counterstaining

- Stringent Washes: Remove coverslips and wash slides in a solution of 0.4x SSC with detergent (e.g., IGEPAL) at 72°C for 2 minutes, followed by a rinse in 2x SSC with detergent at room temperature [41]. This critical step removes unbound or weakly bound probes, reducing background.

- Counterstaining and Mounting: Apply a counterstain such as DAPI (0.14 μg/mL in an anti-fade mounting medium) to stain all chromosomal DNA. Cover with a coverslip and store in the dark prior to imaging [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| M-FISH Probe Cocktail [40] [36] | A mixture of whole-chromosome painting probes, each labeled with a unique combination of fluorophores, allowing for 24-color discrimination. | Commercial kits like the SpectraVision Assay (Vysis) are commonly used [41]. |

| Colcemid [42] | Inhibits microtubule polymerization, arresting cells in metaphase to enrich for chromosomes in their most condensed form. | Typically used at ~100 ng/mL for 2-4 hours [42]. |

| Carnoy's Fixative [42] | A 3:1 mixture of methanol and acetic acid that preserves chromosome morphology and prepares cells for spreading. | Must be prepared fresh for optimal results [42]. |

| Formamide [41] | Used in the denaturation buffer to unwind double-stranded chromosomal DNA, making it accessible for probe hybridization. | Used in 70% concentration at 72°C [41]. |

| DAPI (Counterstain) [37] [41] | A DNA-binding fluorescent dye that stains the entire nucleus, providing a reference for overall chromosome and nuclear morphology. | Visualized in the blue channel, distinct from the M-FISH probe colors [37]. |