Advanced CRISPR Gene Editing Protocols for Precision Correction of Stem Cell Mutations

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the latest CRISPR-based strategies for correcting disease-causing mutations in stem cells.

Advanced CRISPR Gene Editing Protocols for Precision Correction of Stem Cell Mutations

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the latest CRISPR-based strategies for correcting disease-causing mutations in stem cells. It covers the foundational principles of stem cell biology and CRISPR technology, details cutting-edge methodological approaches including AI-designed editors and prime editing, addresses critical troubleshooting aspects like delivery and off-target effects, and outlines robust validation frameworks. By synthesizing recent advances and practical protocols, this resource aims to accelerate the translation of edited stem cells into reliable research tools and transformative clinical therapies.

Stem Cell Biology and CRISPR Fundamentals: From Mechanisms to Disease Modeling

The convergence of stem cell biology and precision gene editing represents a transformative frontier in biomedical research and therapeutic development. Pluripotent stem cells, including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), alongside adult stem cells such as mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) and neural stem cells (NSCs), provide versatile platforms for modeling human disease and developing regenerative therapies. The integration of CRISPR-based technologies with these cellular platforms has dramatically accelerated our ability to correct disease-causing mutations, create precise disease models, and develop next-generation cell therapies. This article provides a comprehensive overview of current protocols, applications, and reagent solutions for gene editing across NSC, iPSC, and MSC platforms, with a specific focus on CRISPR-Cas9 methodologies for correcting stem cell mutations.

Stem Cell Platforms for Gene Editing: A Comparative Analysis

The selection of an appropriate stem cell platform is fundamental to experimental design in gene editing research. Each platform offers distinct advantages and limitations based on origin, differentiation potential, and therapeutic applicability.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Stem Cell Platforms for Gene Editing

| Platform | Origin | Differentiation Potential | Key Advantages | Primary Applications | Editing Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPSC | Reprogrammed somatic cells | Pluripotent (all germ layers) | Autologous source, unlimited self-renewal, patient-specific disease modeling | Disease modeling, drug screening, regenerative medicine | High editing efficiency, but requires careful characterization to maintain pluripotency |

| MSC | Bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord | Multipotent (osteocytes, chondrocytes, adipocytes) | Immunomodulatory properties, trophic factor secretion, clinically relevant | Immunomodulation, tissue repair, graft-versus-host disease | Primary MSCs have limited expansion; iPSC-derived MSCs offer superior scalability [1] |

| NSC | Fetal brain, iPSC-derived | Multipotent (neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes) | Region-specific subtypes, relevant for neurological disease modeling | Neurodegenerative disease modeling, CNS repair | Editing must preserve neuronal differentiation capacity |

The emergence of iPSC-derived cell types (iPSC-MSCs or iMSCs, iPSC-NSCs) has created exciting new opportunities by overcoming limitations of primary cell sources. Studies demonstrate that iMSCs generated from urinary epithelial cells show homogeneous autologous highly proliferative characteristics and may provide an alternative source to primary MSCs for treating various diseases [1]. These iMSCs maintained MSC characteristics without chromosomal abnormalities even at later passages (P15), during which umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) started losing their MSC characteristics [1].

CRISPR Gene Editing Approaches and Workflows

CRISPR-Cas9 Systems and Delivery Methods

CRISPR-Cas9 has become the predominant system for gene editing in stem cells due to its precision and programmability. The system consists of two core components: the Cas9 nuclease enzyme that creates double-strand breaks in DNA, and a guide RNA (gRNA) that directs Cas9 to specific genomic sequences [2]. Editing outcomes depend on the repair pathway employed:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): Error-prone repair resulting in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function, suitable for gene knockouts.

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): Precise editing using a DNA repair template to introduce specific point mutations or insertions, requiring a donor template.

Table 2: Advanced Gene Editing Systems for Stem Cell Research

| Editing System | Editing Mechanism | Key Advantages | Efficiency in Stem Cells | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 (Nuclease) | Creates double-strand breaks | High efficiency for gene knockout | 50-90% in various setups [2] | Gene knockout, large insertions |

| Base Editing | Chemical conversion of single bases (C→T or A→G) | No double-strand breaks; reduced off-target effects | 26-92% base conversions reported [3] | Point mutation correction |

| Prime Editing | Search-and-replace editing using reverse transcriptase | Versatile; all12 possible base-to-base conversions | Varies based on cell type and target | Transition and transversion mutations |

Recent advances in delivery systems have significantly improved CRISPR efficiency in stem cells. Lipid nanoparticle spherical nucleic acids (LNP-SNAs) have demonstrated enhanced delivery, entering cells up to three times more effectively than standard lipid particles and boosting gene-editing efficiency threefold while reducing toxicity [4]. For difficult-to-transfect cells, electroporation of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes (Cas9 protein pre-complexed with gRNA) remains the gold standard, minimizing off-target effects and reducing time spent in culture.

Inducible Gene Editing Systems

Traditional constitutive expression of editing enzymes can lead to unwanted cellular stress, genotoxicity, and selection against edited cells. Inducible systems provide temporal control over editor expression, enabling editing within a specific time window. A recent protocol describes the generation of iPSCs with doxycycline-inducible ABE8e adenine base editor expression at the AAVS1 safe harbor locus [3]. This system enables:

- Temporal control: Editing only during desired time windows

- Reduced cellular stress: Avoids prolonged editor expression

- Tunable expression: Doxycycline concentration modulates editing levels

- Multiplexed editing: Simultaneous editing of multiple genomic loci

The workflow for establishing inducible editing lines involves electroporation of the donor plasmid (containing the inducible editor cassette) alongside AAVS1-specific zinc-finger nuclease plasmids, followed by puromycin selection and junction PCR verification of correct integration [3].

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Editing in Human iPSCs

This protocol adapts established methods for precise gene editing in human iPSCs [5], optimized for high efficiency while maintaining pluripotency.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell Gene Editing

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Notes for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Culture Media | Essential 8, mTeSR Plus, StemFlex | Maintains pluripotency and self-renewal | Feeder-free formulations recommended for editing workflows |

| CRISPR Delivery | Lipofectamine Stem Transfection Reagent, Neon Transfection System | Introduces CRISPR components into cells | RNP electroporation preferred for minimal off-target effects |

| gRNA Design | CRISPR-GPT AI tool [6] | Optimizes guide RNA sequences for specificity and efficiency | AI tools can predict off-target effects and suggest improvements |

| Base Editing Systems | Inducible ABE8e system [3] | Enables precise single-base changes without double-strand breaks | Doxycycline-inducible systems allow temporal control |

| Characterization | Alkaline phosphatase kits, Pluripotency markers (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2) | Validates stem cell quality and pluripotency post-editing | Essential quality control step before and after editing |

Step-by-Step Procedure

iPSC Culture and Preparation:

- Maintain iPSCs in mTeSR Plus medium on Matrigel-coated plates at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [3].

- Passage cells at 70-80% confluency using EDTA or enzyme-free dissociation reagents to maintain viability.

- Ensure cells have >90% expression of pluripotency markers (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2) before editing.

gRNA Design and Complex Formation:

- Design gRNAs using AI-assisted tools like CRISPR-GPT, which leverages 11 years of published data to optimize experimental design and predict off-target effects [6].

- For RNP delivery, complex purified Cas9 protein with synthetic gRNA at 3:1 molar ratio and incubate 10-15 minutes at room temperature.

Electroporation:

- Harvest iPSCs as single cells using Accutase.

- Resuspend 1×10⁶ cells in 100μl R buffer with prepared RNP complexes (10-20μg Cas9 protein).

- Electroporate using Neon Transfection System (1300V, 30ms, 1 pulse) [3].

- Plate transfected cells in pre-warmed Essential 8 medium with 10μM ROCK inhibitor.

Selection and Clonal Isolation:

- For HDR edits, begin antibiotic selection 48 hours post-electroporation.

- For clonal isolation, perform single-cell sorting into 96-well plates 5-7 days post-editing.

- Expand clones for 2-3 weeks with medium changes every other day.

Genotype Validation:

- Screen clones by PCR amplification of target locus and Sanger sequencing.

- Confirm HDR edits by restriction fragment length analysis if silent cutter site was introduced.

- Validate biallelic editing through TA cloning or next-generation sequencing.

Pluripotency Confirmation:

- Verify edited clones maintain pluripotency markers via immunocytochemistry (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2, TRA-1-60, SSEA4) [1].

- Perform in vitro trilineage differentiation potential assay to confirm developmental capacity.

Protocol: Generation of iMSCs from Edited iPSCs

This protocol describes the differentiation of gene-edited iPSCs into mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (iMSCs) for regenerative applications [1].

Materials and Reagents

- Edited iPSC line with validated genotype and pluripotency

- MSC differentiation medium: DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% GlutaMAX, 1% NEAA

- MSC characterization antibodies: CD73, CD90, CD105 (positive markers); CD34, CD45 (negative markers)

- Trilineage differentiation kits: adipogenic, osteogenic, chondrogenic

Step-by-Step Procedure

Initiate Differentiation:

- Harvest edited iPSCs as small clumps using Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent.

- Transfer to ultra-low attachment plates in MSC differentiation medium.

- Culture for 7 days as embryoid bodies with medium changes every other day.

Select MSC Progenitors:

- Plate embryoid bodies on 0.1% gelatin-coated plates in MSC differentiation medium.

- Allow outgrowth of mesenchymal-like cells over 7-10 days.

- Passage adherent cells using trypsin-EDTA upon reaching 80% confluency.

Expand and Characterize iMSCs:

- Culture expanded cells through multiple passages to enrich for MSC population.

- Confirm MSC phenotype by flow cytometry for CD73, CD90, CD105 (≥95% positive) and CD34, CD45 (≤5% positive).

- Validate trilineage differentiation potential by culturing in specific induction media:

- Adipogenic: Lipid droplet formation with Oil Red O staining

- Osteogenic: Mineralization with Alizarin Red staining

- Chondrogenic: Glycosaminoglycan production with Alcian Blue staining

Functional Assays:

- Perform migration assays to confirm wound-healing capacity [1].

- Evaluate immunomodulatory function through T-cell suppression assays.

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Even with optimized protocols, researchers may encounter challenges in stem cell gene editing. Common issues and solutions include:

- Low editing efficiency: Optimize gRNA design using AI tools like CRISPR-GPT; increase RNP concentration; test different delivery methods.

- Poor cell viability post-electroporation: Reduce RNP concentration; optimize cell density; ensure prompt plating with ROCK inhibitor.

- Incomplete HDR: Increase repair template concentration; use single-stranded DNA donors; synchronize cells in S-phase.

- Loss of pluripotency: Limit culture time post-editing; minimize single-cell passaging; frequently validate pluripotency markers.

The integration of advanced CRISPR systems with pluripotent and adult stem cell platforms has created unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine. The protocols outlined here provide a foundation for efficient gene editing in iPSCs, NSCs, and MSCs, while highlighting critical reagent solutions and troubleshooting approaches. As the field progresses, emerging technologies including AI-assisted experimental design [6], improved delivery systems [4], and more precise base editors [3] will further enhance our ability to harness pluripotency for therapeutic genome engineering. The ongoing clinical translation of these approaches, evidenced by the growing number of FDA-authorized trials involving edited stem cells [7], underscores the transformative potential of these combined technologies for addressing previously untreatable genetic disorders.

The application of CRISPR-based gene editing technologies has revolutionized stem cell research, enabling precise genetic modifications for disease modeling, drug discovery, and therapeutic development. These technologies offer complementary approaches for manipulating the genome of stem cells, including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), with varying levels of precision, versatility, and practical implementation requirements. CRISPR-Cas nucleases introduce double-strand breaks (DSBs) that are repaired by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR). Base editors (BEs) facilitate direct chemical conversion of one base to another without DSBs, while prime editors (PEs) offer precise "search-and-replace" functionality through a reverse transcriptase-mediated process. Each system presents distinct advantages and limitations for stem cell engineering applications, with selection dependent on the specific research goals, desired precision, and available delivery methods.

The selection of appropriate CRISPR technology is particularly critical for stem cell research, where maintaining genomic integrity is paramount. iPSCs derived from somatic cells of patients with genetic disorders like Alzheimer's disease (AD) can be reprogrammed into disease-relevant cell types, creating powerful models for studying pathogenesis and screening therapeutics. The integration of stem cell technology with precise gene editing enables researchers to correct pathogenic mutations in genes such as APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2, which are implicated in familial AD, providing insights into disease mechanisms and potential regenerative medicine approaches.

Technology Comparison and Selection Guide

Comparative Analysis of CRISPR Systems

Table 1: Comparison of Major CRISPR-Based Gene Editing Technologies

| Technology | Editing Mechanism | Editing Outcomes | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Stem Cell Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Nucleases | Creates DSBs repaired by NHEJ or HDR | Insertions, deletions, gene knock-ins, knock-outs | Broad applicability, efficient gene disruption | Off-target effects, indel byproducts, low HDR efficiency in stem cells | Gene knock-out studies, disease modeling via mutation introduction |

| Base Editors (BEs) | Direct chemical conversion without DSBs | C•G to T•A or A•T to G•C point mutations | High efficiency, no DSBs, low indel formation | Restricted to specific base changes, bystander editing, limited targeting scope | Correcting point mutations in monogenic diseases, introducing specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) |

| Prime Editors (PEs) | Reverse transcription of edited sequence from pegRNA | All 12 possible base substitutions, small insertions, deletions | Versatile editing, no DSBs, high precision, reduced off-target effects | Variable efficiency, complex pegRNA design, large construct size | Precise correction of pathogenic mutations without donor DNA templates |

Performance Metrics for Technology Selection

Table 2: Efficiency and Specificity Metrics of CRISPR Systems

| Parameter | CRISPR-Cas Nucleases | Base Editors | Prime Editors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editing Efficiency Range | 10-80% (highly variable by cell type) | 10-70% (dependent on sequence context) | 10-50% (improving with newer versions) |

| Indel Formation Rate | High (5-60%) | Very low (<1%) | Minimal (<1%) |

| Off-Target Effects | Moderate to high | Moderate (DNA/RNA deaminase activity) | Low |

| Targeting Scope | Limited by PAM availability | Restricted by editing window position | Broadest (flexible PAM requirements) |

| Stem Cell Viability Post-Editing | Variable (DSB-induced toxicity) | Generally high | Generally high |

Application Notes for Stem Cell Engineering

CRISPR-Cas Nuclease Applications

CRISPR-Cas nuclease systems remain widely utilized for stem cell engineering applications where complete gene knockout is desired. The technology is particularly valuable for functional genomics screens in stem cells, enabling researchers to identify genes essential for pluripotency maintenance, differentiation, and disease pathogenesis. In Alzheimer's disease research, CRISPR-Cas9 has been employed to introduce disease-associated mutations in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 genes into healthy stem cells, creating isogenic disease models that recapitulate pathological features including Aβ plaque formation and tau hyperphosphorylation.

The implementation of virus-free editing methods using synthetic guide RNAs and electroporation has significantly improved the safety profile of CRISPR-Cas9 in therapeutic applications. This approach avoids random viral integration into the host genome and reduces unwanted DNA edits, making it particularly suitable for clinical translation. Research demonstrates that this method enables efficient knock-in of large DNA sequences, including chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) for cancer immunotherapy, with high specificity and cell viability.

Base Editing Applications

Base editors provide a powerful alternative to nuclease-based approaches for precise single-nucleotide modifications in stem cells without inducing DSBs. These systems are particularly valuable for correcting point mutations associated with genetic disorders or for introducing protective polymorphisms that may modify disease risk. In stem cell models of Alzheimer's disease, base editors can precisely modify risk genes such as TREM2, CD33, and ABCA7, which are primarily expressed in microglia and play important roles in neuroinflammation.

The application of base editing in stem cells is especially advantageous for modifications that require high efficiency with minimal genotoxic stress. Since base editors do not rely on HDR, which is inefficient in many stem cell types, they can achieve higher correction rates while maintaining cell viability and pluripotency. However, the potential for bystander editing, where adjacent nucleotides within the editing window are unintentionally modified, requires careful consideration and design optimization.

Prime Editing Applications

Prime editing represents the most versatile precise editing technology, capable of installing all possible base-to-base substitutions, small insertions, and deletions without DSB formation. This technology is particularly valuable for correcting pathogenic mutations in stem cells with high precision, making it ideal for generating genetically corrected patient-specific iPSCs for regenerative medicine applications. The ability to perform precise edits without donor DNA templates simplifies the editing process and reduces the risk of random integration.

Recent advancements in prime editing systems have significantly improved their efficiency for stem cell applications. The development of engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) with structured RNA motifs at the 3' end protects against degradation and improves editing efficiency by 3-4-fold across multiple human cell lines, including primary fibroblasts. Additionally, the split prime editor (sPE) system addresses delivery challenges associated with the large size of traditional prime editors by allowing nCas9 and reverse transcriptase to function independently, enabling delivery via dual AAV vectors.

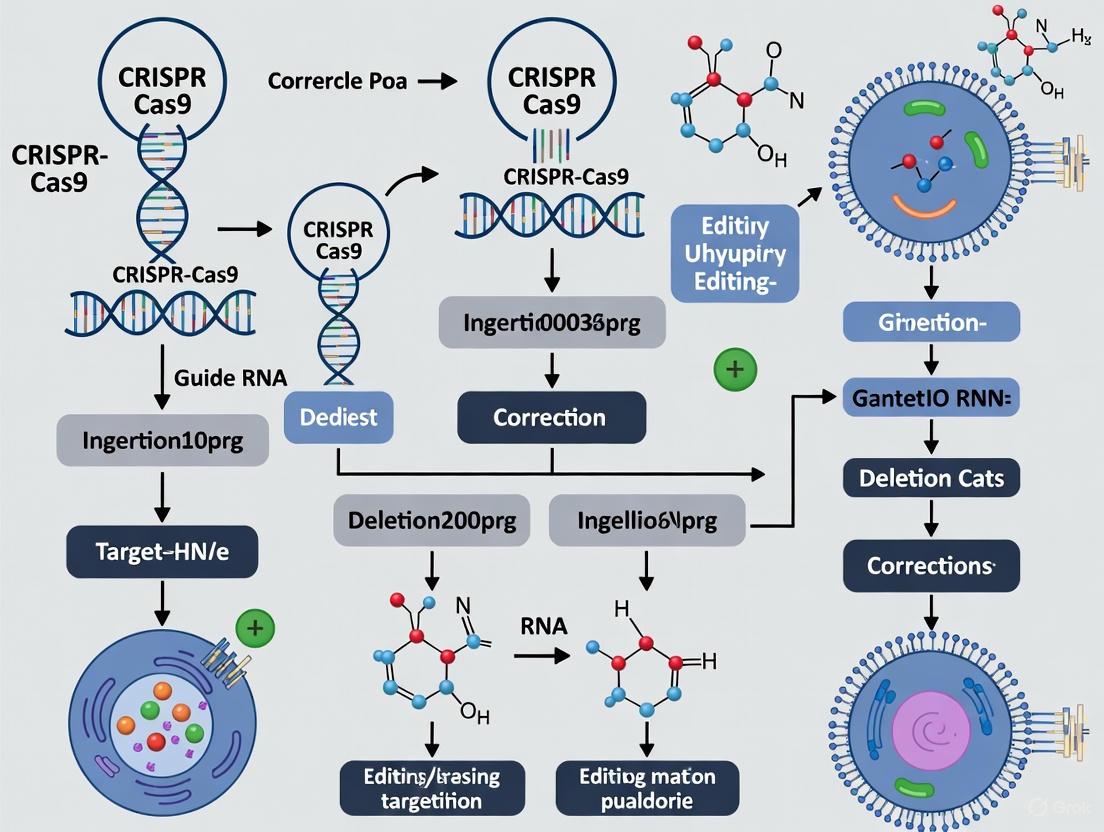

Prime editing workflow showing the stepwise process of precise genome editing.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Virus-Free CRISPR Editing in Stem Cells Using Synthetic gRNA

This protocol describes a method for editing stem cells using synthetic guide RNAs and electroporation, eliminating the need for viral vectors and reducing the risk of off-target integration.

Materials Required:

- Cultured stem cells (iPSCs, NSCs, or MSCs)

- Synthetic guide RNA (synthesized commercially)

- Cas9 protein (commercially available)

- Electroporation system (e.g., Neon Transfection System)

- Stem cell culture medium with appropriate supplements

- DNA donor template (for HDR-mediated editing)

- Validation reagents (T7 Endonuclease I, sequencing primers)

Procedure:

Guide RNA Design and Preparation:

- Design gRNAs targeting the genomic region of interest using established design tools

- Order synthetic gRNAs with chemical modifications to enhance stability

- Resuspend gRNAs in nuclease-free water to a working concentration of 100 μM

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Formation:

- Combine 10 μg of Cas9 protein with 5 μg of synthetic gRNA in electroporation buffer

- Incubate at room temperature for 15-20 minutes to allow RNP complex formation

Stem Cell Preparation:

- Culture stem cells to 70-80% confluency in appropriate conditions

- Dissociate cells using enzyme-free dissociation reagent to maintain viability

- Wash cells twice with PBS and resuspend in electroporation buffer at a concentration of 1×10^7 cells/mL

Electroporation:

- Mix 10 μL of cell suspension with 5 μL of RNP complex

- Transfer to electroporation cuvette and electroporate using optimized parameters (typically 1300-1600V, 10-30ms for stem cells)

- Immediately transfer cells to pre-warmed culture medium

Post-Transfection Culture:

- Plate transfected cells onto matrix-coated plates at appropriate density

- Monitor cell viability daily and change medium after 24 hours

- Allow 48-72 hours for expression and editing before analysis

Validation of Editing:

- Extract genomic DNA 72 hours post-transfection

- Amplify target region by PCR using flanking primers

- Analyze editing efficiency using T7 Endonuclease I assay or sequencing

Virus-free CRISPR editing workflow using synthetic gRNA and electroporation.

Protocol 2: Prime Editing in Stem Cells Using epegRNAs

This protocol outlines the implementation of prime editing in stem cells using engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) to enhance editing efficiency through improved RNA stability.

Materials Required:

- Prime editor expression plasmid (PE2, PE3, or newer versions)

- epegRNA expression vector or synthetic epegRNA

- Stem cell line of interest

- Transfection reagent (lipofection or electroporation system)

- Appropriate antibiotics for selection

- Validation primers for targeted sequencing

Procedure:

epegRNA Design and Preparation:

- Design pegRNA with spacer sequence (17-20 nt) and RTT encoding desired edit

- Incorporate evopreQ1 or mpknot RNA motifs at 3' end to enhance stability

- For plasmid-based expression, clone into appropriate backbone with U6 promoter

- For synthetic epegRNA, order with chemical modifications and resuspend to 100 μM

Stem Cell Transfection:

- Culture stem cells to 60-70% confluency in optimal conditions

- For lipofection: Combine 2 μg prime editor plasmid + 1 μg epegRNA plasmid with transfection reagent

- For electroporation: Mix 5 μg prime editor mRNA + 3 μg synthetic epegRNA with cells in buffer

- Transfert using optimized method and parameters for specific stem cell type

Post-Transfection Culture and Selection:

- Culture transfected cells for 48 hours in standard conditions

- If using selection markers, apply appropriate antibiotic 24 hours post-transfection

- Maintain selection for 5-7 days, changing medium every 2-3 days

Editing Efficiency Analysis:

- Harvest cells 7 days post-transfection for genomic DNA extraction

- Perform PCR amplification of target locus

- Use targeted next-generation sequencing to quantify editing efficiency

- Analyze sequencing data for precise edit incorporation and byproduct formation

Clone Isolation and Validation (Optional):

- For single-cell analysis, perform limiting dilution or FACS sorting

- Expand individual clones for 2-3 weeks

- Screen clones by PCR and sequencing to identify correctly edited isolates

- Validate pluripotency markers in edited clones to ensure stemness maintenance

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Stem Cell Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for CRISPR-Based Stem Cell Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | Cas9 Nuclease (S. pyogenes), HiFi Cas9 variants | DNA cleavage for gene disruption or HDR | HiFi variants reduce off-target effects in sensitive stem cell applications |

| Base Editors | BE4max, ABE8e | Direct base conversion without DSBs | BE4max for C->T conversions; ABE8e for A->G conversions with improved efficiency |

| Prime Editors | PE2, PE3, PE6 systems | Precise search-and-replace editing | PE6 systems with compact RT show improved efficiency and delivery capability |

| Editing Validation | T7 Endonuclease I, Authenticase, Next-generation sequencing kits | Detection and quantification of editing events | Authenticase outperforms T7 Endo I in detecting diverse mutation types |

| Delivery Systems | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), Electroporation systems, AAV vectors | Introduction of editing components into cells | LNPs show promise for in vivo delivery; electroporation preferred for ex vivo stem cell editing |

| Stem Cell Culture | Matrices (Matrigel, Laminin), Defined media, Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor | Maintenance of pluripotency and viability | ROCK inhibitor improves survival post-editing procedures |

The integration of advanced CRISPR technologies with stem cell biology has created powerful platforms for disease modeling, drug discovery, and therapeutic development. The evolving CRISPR toolbox, encompassing nucleases, base editors, and prime editors, provides researchers with multiple options for genetic manipulation, each with distinct advantages for specific applications. Selection of the appropriate technology depends on the required precision, efficiency, and practical considerations for stem cell engineering.

Future developments in CRISPR-stem cell applications will likely focus on enhancing editing efficiency, specificity, and delivery methods. The emergence of newer prime editing systems with improved efficiency and reduced size addresses current limitations, potentially enabling broader therapeutic applications. Additionally, advances in delivery systems, particularly lipid nanoparticles and virus-free methods, will facilitate safer clinical translation. As these technologies mature, their integration with stem cell research promises to accelerate the development of personalized regenerative therapies for genetic disorders, including neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's.

The ability to recapitulate human pathology in vitro is a cornerstone of modern biomedical research. Gene-edited stem cells have emerged as a powerful platform for this purpose, enabling the precise investigation of genetic contributions to disease mechanisms and the development of novel therapeutic strategies. The integration of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) technology with stem cell biology has been particularly transformative, allowing for the creation of highly accurate and standardized disease models. These models are instrumental for drug discovery, functional genomics, and personalized medicine, providing a human-relevant context that is often lacking in animal models [8] [9].

This protocol details the application of CRISPR-Cas9 for introducing disease-relevant mutations into mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) to model complex neurodevelopmental disorders, as exemplified by recent research into autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [8]. The methodology can be adapted to model a wide range of genetic conditions, providing a robust framework for studying pathology in a controlled, scalable system.

Key Quantitative Data from a Representative Study

A recent large-scale study created a bank of 63 mouse embryonic stem cell lines, each with a distinct autism spectrum disorder (ASD)-associated mutation, providing a standardized platform for pathological investigation [8]. Key quantitative outcomes from the characterization of these models are summarized below.

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes from a CRISPR-Edited mESC Disease Model Bank

| Parameter | Result / Value | Context and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Cell Lines | 63 | A bank of mESC lines, each with a different genetic variant strongly associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) [8]. |

| Model Fit (R-value) | 0.97 | Demonstrates a high-efficiency, precise editing outcome in a monoclonal cell line derived from a single cell [10]. |

| Protein Reduction (Therapeutic Effect) | ~90% reduction | Observed in clinical trials for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) using an LNP-delivered CRISPR therapy, showcasing the therapeutic potential of this approach [11]. |

| Key Discovered Pathology | Disrupted protein quality control in neurons | A key pathological mechanism identified through the mESC model bank; neurons were unable to eliminate misshapen proteins [8]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Design and Production of CRISPR Constructs

This protocol covers the initial design and cloning steps for preparing the CRISPR-Cas9 components for stem cell transfection.

Materials:

- gRNA Design Tool: CRISPR-GPT AI tool or similar design software [6].

- Plasmid Backbone: e.g., PX330 (Addgene) for expressing Cas9 and sgRNA [9].

- Oligonucleotides: For synthesizing target-specific guide RNA (gRNA) sequences.

- Cloning Enzymes: Restriction enzymes, ligase, etc.

Method:

- gRNA Design: Identify a 20-nucleotide target sequence adjacent to a 5'-NGG-3' Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) in the gene of interest (e.g., Tex15 for infertility studies) [10]. Tools like CRISPR-GPT can predict optimal gRNA sequences and potential off-target effects [6].

- gRNA Cloning: Synthesize and anneal oligonucleotides corresponding to the target sequence. Ligate them into the gRNA cloning site of the Cas9 plasmid (e.g., PX330) using appropriate restriction enzymes [9].

- Validation: Transform the ligated plasmid into competent bacteria. Select positive clones and validate the plasmid sequence via Sanger sequencing.

Protocol 2: Culturing and Transfection of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

This protocol outlines the maintenance and genetic modification of mESCs.

Materials:

- Cell Line: Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells (mESCs) [8].

- Culture Medium: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin [10].

- Transfection Reagent: Lipid-based transfection reagent (e.g., DNAfectin) [10].

- Selection Antibiotic: e.g., Puromycin.

Method:

- Cell Culture: Maintain mESCs in pre-coated T-25 flasks with complete DMEM medium. Incubate at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ environment. Passage cells upon reaching 90% confluence using trypsinization [10].

- Antibiotic Optimization: Perform a cytotoxicity assay to determine the optimal concentration of puromycin (e.g., range of 5.0 μg/mL to 0.01 μg/mL) required to eliminate 95% of non-transfected cells within 48 hours [10].

- Transfection: Plate cells in a multi-well plate. The following day, transfect the cells with the CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid complexed with the lipid-based transfection reagent at an optimized ratio (e.g., a 1:3.5 DNA:DNAfectin ratio) [10].

- Selection: Apply the pre-determined optimal concentration of puromycin 24-48 hours post-transfection to select for successfully transfected cells.

Protocol 3: Validation of Gene Editing

This protocol describes the confirmation of successful genetic modifications in the stem cell population.

Materials:

- Lysis Buffer: For genomic DNA extraction.

- PCR Reagents: Polymerase, primers flanking the target site, dNTPs.

- Restriction Enzyme: For mutation site enzyme cut analysis if the edit disrupts a restriction site.

- Sanger Sequencing Reagents.

Method:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest transfected and selected cells. Extract genomic DNA using a standard lysis-protocol precipitation method.

- Initial Screening: Amplify the target genomic region by PCR. Perform a restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assay if the edit alters a restriction site. Cleavage failure indicates potential indel mutations [10].

- Sequence Verification: Purify the PCR product and subject it to Sanger sequencing. Analyze the sequencing chromatograms for the presence of insertions or deletions (indels) around the cut site, which indicate a successful knockout. For heterozygous edits, two distinct indel variants may be present [10].

- In-silico Analysis: Use software to translate the DNA sequence and predict the effect of indels on the reading frame and protein function.

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for creating and differentiating a gene-edited stem cell disease model, from design to pathological analysis.

The pathological mechanism discovered through this workflow, specifically for certain autism models, involves a critical disruption of protein quality control in neurons. The diagram below outlines this key signaling and cellular process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Stem Cell Disease Modeling

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Plasmid | Expresses both the Cas9 nuclease and the single-guide RNA (sgRNA) for targeted DNA cleavage. | The PX330 vector is a widely used example [9]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A non-viral delivery system for in vivo delivery of CRISPR components; shows promise for future clinical applications. | Effective for liver-targeted therapies; allows for re-dosing [11] [9]. |

| Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells (mESCs) | A self-renewing cell type that can be differentiated into various cell lineages, serving as the foundation for in vitro disease models. | Used to create a standardized bank of 63 ASD models [8]. |

| Lipid-based Transfection Reagent | Facilitates the delivery of CRISPR plasmid DNA into stem cells in vitro. | A 1:3.5 DNA:DNAfectin ratio was identified as optimal for SSCs [10]. |

| AI Design Tool (CRISPR-GPT) | An AI agent that assists in designing CRISPR experiments, predicting off-target effects, and troubleshooting. | Speeds up experimental design and flattens the learning curve [6]. |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | A viral delivery vector with high transduction efficiency, but limited packaging capacity. | Commonly used in gene therapy; packaging capacity is a key constraint [9]. |

The convergence of CRISPR-based gene editing with stem cell biology represents a transformative paradigm in therapeutic development, enabling researchers to move beyond symptom management toward curative interventions. This approach allows for the precise correction of pathogenic mutations in patient-derived stem cells, creating powerful disease models and autologous cell therapies. For monogenic disorders, the strategy often involves direct correction of the causal variant, while for complex diseases, it requires targeting key genetic nodes within pathological networks. The protocols outlined in this application note provide a framework for identifying these therapeutic targets and executing their correction using state-of-the-art CRISPR technologies, with particular emphasis on stem cell applications relevant to drug development and clinical translation.

Therapeutic Target Classification and Prioritization

The strategic selection of therapeutic targets is fundamental to successful gene editing outcomes. Targets can be systematically categorized based on disease etiology, with distinct editing strategies employed for each category.

Table 1: Classification of Gene Editing Therapeutic Targets

| Target Category | Disease Examples | CRISPR Strategy | Editing Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monogenic Loss-of-Function | Spinal Muscular Atrophy, Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency [12] | HDR-mediated correction [12], Base Editing [13] | Restore protein function |

| Monogenic Gain-of-Function | Early-onset Alzheimer's (APP, PSEN1/2 mutations) [14] | NHEJ-mediated knockout [15], Base Editing [13] | Disrupt pathogenic allele |

| Risk Alleles in Complex Diseases | Late-onset Alzheimer's (APOEε4, TREM2) [14] | Gene silencing (CRISPRi), Base Editing [13] | Modulate disease susceptibility |

| Regulatory Elements for Cell Therapy | Universal CAR-T [16], Hypo-immunogenic stem cells [16] | Multiplex gene knockout (HLA disruption) [16] | Evade immune rejection |

The prioritization of targets for stem cell-based protocols requires additional considerations, including gene expression in relevant stem cell derivatives, the feasibility of achieving high editing efficiency without compromising stemness, and the ability to differentiate corrected stem cells into therapeutically relevant cell types.

Experimental Protocols for Target Validation and Correction

Protocol: In Vitro Disease Modeling using Patient-Derived iPSCs

Application Note: This protocol is essential for studying disease mechanisms and screening candidate therapeutic targets, particularly for neurological disorders like Alzheimer's disease where patient neurons are inaccessible [14].

Workflow Diagram:

Methodology:

- iPSC Generation: Reprogram patient dermal fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells using non-integrating Sendai virus or episomal vectors expressing OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC. Culture established iPSC lines in mTeSR1 or Essential 8 medium on Matrigel-coated plates [14].

- CRISPR-mediated Gene Correction: Design a sgRNA targeting within 50 bp upstream of the pathogenic mutation. For base editing applications, ensure the target base falls within the activity window (typically positions 4-8 for ABE, 3-9 for CBE) of the editor [13]. Deliver ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes comprising 5 µg SpCas9 protein and 2 µg synthetic sgRNA via nucleofection (Lonza 4D-Nucleofector).

- Neural Differentiation: Differentiate corrected and uncorrected iPSCs into cortical neurons using a dual-SMAD inhibition protocol. Treat cells with 100 nM LDN-193189 and 10 µM SB431542 for 10 days to induce neural induction, followed by maturation in neurobasal medium containing BDNF, GDNF, and cAMP for 6-8 weeks [14].

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Aβ42/Aβ40 Ratio: Quantify using ELISA from conditioned media at day 50 of differentiation. A significant reduction in the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio in corrected lines indicates phenotypic rescue [14].

- Tau Phosphorylation: Perform western blot analysis using antibodies against phosphorylated tau (AT8, PHF-1) and total tau. Calculate the p-tau/total tau ratio.

- Synaptic Function: Assess using multi-electrode array (MEA) to measure spontaneous neural activity.

Protocol: HDR-Mediated Correction in Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs)

Application Note: This ex vivo editing protocol is foundational for treating monogenic blood disorders and can be adapted for introducing protective mutations. The use of HDR allows for precise nucleotide conversion.

Workflow Diagram:

Methodology:

- HSC Pre-stimulation: Isolate CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells from human mobilized peripheral blood using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS). Pre-stimulate cells in StemSpan SFEM II medium supplemented with 100 ng/mL SCF, 100 ng/mL TPO, and 100 ng/mL Fit3-L for 48 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂ [16].

- RNP Complex Formation: Combine 40 µg HiFi Cas9 protein with 30 µg synthetic sgRNA (resuspended in nuclease-free water) and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes to form RNP complexes.

- HDR Donor Design: Design a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) donor template with ~100 bp homology arms flanking the correction. Incorporate silent mutations (PAM-disruption) within the protospacer to prevent re-cleavage. Add a 5' phosphorothioate modification to enhance stability.

- Electroporation: Mix 2×10⁵ pre-stimulated CD34+ cells with the RNP complex and 2 µL of 100 µM ssODN donor. Electroporate using the Lonza 4D-Nucleofector (pulse code DS-138) in 20 µL P3 Primary Cell Solution.

- Engraftment and Functional Assessment: Transplant 5×10⁵ edited CD34+ cells into sublethally irradiated (250 cGy) NSG mice via tail vein injection. After 16 weeks, analyze bone marrow for human CD45+ cell engraftment by flow cytometry. Assess lineage-specific correction rates via next-generation sequencing of colony-forming unit (CFU) assays [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Stem Cell Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Product/System | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | HiFi Cas9, SpCas9-NG [15], ABE8e [13] | Target gene knockout, base editing | PAM flexibility (NG/G), reduced off-targets, high efficiency |

| Stem Cell Culture | mTeSR1, Essential 8, Matrigel, Recombinant Vitronectin | iPSC maintenance and expansion | Support pluripotency, xeno-free formulations |

| Delivery Systems | Lipoplex nanoparticles [16], Neon Transfection System, 4D-Nucleofector | RNP/sgRNA delivery to stem cells | Cell viability, editing efficiency, scalability |

| HDR Enhancers | NHEJ inhibitors (e.g., SCR7), RS-1 [16] | Improve precise editing rates | Cytotoxicity optimization required |

| Validation Tools | T7 Endonuclease I, Next-Generation Sequencing, Flow Cytometry | Edit efficiency and off-target analysis | Multiplexed amplicon sequencing for comprehensive profiling |

Advanced Editing Modalities for Complex Disease Targets

For complex diseases influenced by multiple genetic and environmental factors, targeting individual pathogenic mutations is often insufficient. Instead, strategies focus on modulating key pathways or creating protective genetic modifications.

Base Editing for Pathogenic Transition Mutations

Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) and Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) enable precise conversion of C•G to T•A and A•T to G•C base pairs, respectively, without inducing double-strand breaks. These editors theoretically correct ∼95% of pathogenic transition mutations cataloged in ClinVar [13]. In a recent preclinical study for Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (AATD), a single dose of CRISPR base editor CTX460 achieved over 90% mRNA correction and restored circulating protein more than five-fold in rodent models [16].

Application Workflow:

- Target Analysis: Confirm the pathogenic single-nucleotide variant (SNV) is within the activity window of the selected base editor.

- Editor Selection: For A•T to G•C corrections, use ABE8e; for C•G to T•A corrections, use BE4max. For enhanced specificity, employ high-fidelity versions with reduced off-target effects [13].

- Delivery: For in vivo applications, package ABE mRNA into liver-tropic LNP formulations (10 mg/kg dose). For ex vivo stem cell editing, use electroporation of RNP complexes.

- Validation: Perform deep sequencing of the target locus and computationally predicted off-target sites. Assess protein restoration via ELISA or mass spectrometry.

Multiplexed Editing for Cell Therapy Engineering

The creation of universal allogeneic cell therapies requires simultaneous disruption of multiple genes to prevent immune rejection while introducing therapeutic transgenes. This approach has been successfully applied to engineer "universal" regulatory T cells for off-the-shelf transplant therapy by using CRISPR to disrupt HLA class I and II genes while inserting an HLA-E fusion protein [16].

Protocol Overview:

- gRNA Array Design: Clone up to 7 gRNAs targeting HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, and CIITA into a multiplex tRNA-gRNA vector system [15].

- Stem Cell Editing: Electroporate hematopoietic stem cells or T cells with Cas9 RNP complexes and AAV6 donor vectors containing the HLA-E transgene.

- Selection and Expansion: Use FACS to isolate HLA-negative populations. Expand cells in GMP-grade media with cytokines (IL-2, IL-7, IL-15).

- Functional Validation: Perform mixed lymphocyte reaction assays to confirm reduced alloreactivity. Evaluate in vivo persistence in humanized mouse models.

The systematic identification and validation of therapeutic targets across the disease spectrum, combined with optimized CRISPR editing protocols for stem cells, provides a powerful roadmap for developing transformative genetic medicines. The integration of base editing and multiplexed gene disruption technologies enables addressing both monogenic disorders and complex diseases with unprecedented precision. As delivery technologies continue to advance and long-term safety data accumulate, these protocols will form the foundation for a new generation of stem cell-based therapeutics that move beyond palliative care to offer durable, potentially curative outcomes for patients with previously untreatable genetic conditions.

Cutting-Edge Editing Techniques and Workflows for Stem Cell Correction

The development of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-based systems has revolutionized biomedical research, providing scientists with an unprecedented ability to manipulate genetic material with precision. For researchers focused on correcting stem cell mutations, selecting the appropriate gene-editing protocol is paramount to experimental success. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of four fundamental genome-editing approaches: homology-directed repair (HDR), non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), base editing, and prime editing. Each technology offers distinct advantages and limitations, with optimal selection dependent on specific research goals, target cell types, and desired editing outcomes. Understanding the mechanistic basis, efficiency, and applications of these systems is essential for designing effective stem cell gene correction strategies, particularly as these technologies advance toward clinical applications in precision medicine [17].

The evolution from traditional nuclease-based systems to newer precision editing tools reflects the field's ongoing pursuit of greater specificity and reduced unintended consequences. While early programmable nucleases like zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) established the feasibility of targeted genome manipulation, their intricate design requirements limited widespread adoption [18]. The discovery of RNA-programmable CRISPR systems dramatically accelerated gene-editing applications due to their remarkable efficiency, ease of programmability, and versatility [17]. This review focuses on the current state of genome-editing technologies, with particular emphasis on their applicability to stem cell research, where precision and safety considerations are of utmost importance.

Mechanism of Action and Key Applications

Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways: HDR and NHEJ

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is a high-fidelity DNA repair pathway that utilizes a homologous donor template to enable precise genetic modifications, including targeted insertions, deletions, and substitutions. When a double-strand break (DSB) occurs, the MRN complex (MRE11–RAD50–NBS1) identifies the break and initiates limited end resection with CtIP, creating 3' single-stranded overhangs [18]. Further resection by Exo1 and the Dna2/BLM helicase complex generates extended 3' ssDNA tails, which are protected by replication protein A (RPA). RAD51 then displaces RPA to form nucleoprotein filaments that perform a homology search and initiate strand invasion using a donor template, leading to precise DNA repair through synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) or double-strand break repair (DSBR) pathways [18]. A significant limitation for stem cell research is that HDR is predominantly active in the S/G2 phases of the cell cycle, making it inefficient in many therapeutically relevant cell types, including quiescent stem cells [17].

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) represents the cell's primary "first responder" to DSBs and operates throughout all cell cycle phases. In canonical NHEJ, the Ku70–Ku80 heterodimer immediately recognizes and binds to broken DNA ends, preventing extensive resection and recruiting DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) [18]. The complex may employ nucleases like Artemis to process ends and polymerases such as Pol μ or Pol λ to fill small gaps before XRCC4 and DNA ligase IV perform final ligation [18]. While NHEJ is highly efficient and effective for gene disruption strategies, it is inherently error-prone, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the target site. In stem cell research, NHEJ is particularly valuable for creating gene knockouts, though its unpredictable outcomes present challenges for precision applications.

Alternative repair pathways such as microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) also contribute to DSB repair outcomes. MMEJ utilizes microhomologies (2-20 nucleotides) to guide annealing of opposing DNA ends, typically mediated by DNA polymerase theta (Pol θ) and PARP1 [18]. This pathway often generates moderate-to-large deletions and is considered highly error-prone, further complicating editing outcomes when using DSB-dependent approaches.

Precision Editing Without Double-Strand Breaks: Base and Prime Editing

Base Editing enables direct chemical conversion of one DNA base to another without requiring DSBs or donor DNA templates. Base editors are modular fusion proteins comprising a catalytically impaired Cas9 nickase (nCas9) fused to a nucleotide deaminase enzyme [17]. Two primary classes have been developed: cytosine base editors (CBEs), which mediate C•G to T•A conversions using a cytidine deaminase domain, and adenine base editors (ABEs), which facilitate A•T to G•C conversions using an engineered tRNA-specific adenosine deaminase (TadA) [17] [19]. When the complex binds to target DNA, the deaminase chemically alters bases within a narrow editing window, achieving highly efficient point mutations with minimal indel formation [17]. This makes base editors particularly suitable for correcting specific pathogenic point mutations in stem cells without activating DNA damage response pathways.

Prime Editing represents a more versatile "search-and-replace" technology capable of introducing all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, small insertions, and deletions without requiring DSBs or donor DNA templates [19]. The system employs a prime editor protein consisting of a Cas9 nickase (H840A) fused to an engineered reverse transcriptase (RT), programmed with a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) [19] [20]. The pegRNA both specifies the target site and contains an extended reverse transcriptase template (RTT) encoding the desired edit. After nicking the target DNA, the released 3' flap hybridizes with the primer binding site (PBS) on the pegRNA, priming reverse transcription using the RTT as a template [20]. The resulting edited flap is then incorporated into the genome through cellular repair processes. This multi-step hybridization process enhances editing specificity while providing unprecedented versatility for precise genetic modifications in stem cells [19].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Features of Genome Editing Technologies

| Feature | HDR | NHEJ | Base Editing | Prime Editing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Break Type | Double-strand break | Double-strand break | Single-strand nick | Single-strand nick |

| Donor Template Required | Yes | No | No | No (encoded in pegRNA) |

| Editing Precision | High | Low (error-prone) | High | Very High |

| Primary Applications | Precise gene correction, insertions | Gene knockouts, disruptions | Point mutations (C>T, A>G) | All point mutations, small insertions/deletions |

| Theoretical Editing Scope | Unlimited | Disruptions only | Transition mutations only | All 12 possible base substitutions, insertions, deletions |

| Stem Cell Efficiency | Low (cell cycle dependent) | High | Moderate to High | Variable (improving with newer systems) |

| Indel Formation | Low (but competing NHEJ) | High | Very Low | Very Low |

| Key Limitations | Low efficiency, cell cycle dependence | Unpredictable outcomes, indels | Restricted to specific base changes, bystander edits | Efficiency challenges, complex pegRNA design |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

HDR-Mediated Gene Correction in Stem Cells

Protocol Overview: This protocol describes HDR-based precise gene correction in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) using CRISPR-Cas9 and single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) donor templates. The procedure spans 7-10 days from nucleofection to genotyping.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- gRNA Design and Validation: Design gRNAs targeting adjacent to the mutation site using established tools (e.g., CRISPOR, ChopChop). Select targets with high on-target and low off-target scores. Validate editing efficiency using a T7E1 or tracking indel/decomposition by evolution (TIDE) assay before proceeding with HDR experiments.

Donor Template Design: Design ssODN donor templates (90-200 nt) with the desired correction flanked by homologous arms (35-90 nt each). Incorporate silent mutations in the PAM site or protospacer to prevent re-cutting of corrected sequences. Include a restriction site for diagnostic digestion if possible.

Stem Cell Preparation: Culture hPSCs in feeder-free conditions, ensuring >90% viability and optimal growth. Passage cells 2 days before nucleofection to ensure actively dividing cultures, which improves HDR efficiency.

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Formation: Combine 10 µg of purified Cas9 protein with 5 µg of synthetic gRNA in nucleofection buffer. Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to form RNP complexes.

Nucleofection: Harvest 1×10^6 hPSCs using gentle dissociation reagent. Centrifuge and resuspend in stem cell-optimized nucleofection solution. Add RNP complexes and 2-4 µM ssODN donor to cell suspension. Transfer to nucleofection cuvette and electroporate using manufacturer's recommended program (e.g., CA-137 for hPSCs).

Post-Transfection Recovery: Immediately transfer cells to pre-warmed culture medium with 10 µM ROCK inhibitor. Plate at appropriate density on matrix-coated plates. Refresh medium after 24 hours, removing ROCK inhibitor.

HDR Enrichment (Optional): For difficult-to-edit cells, implement chemical enrichment using 1-5 µM NU7026 (DNA-PKcs inhibitor) or 1 µM Scr7 (Ligase IV inhibitor) for 48-72 hours post-nucleofection to suppress NHEJ and favor HDR.

Clonal Isolation and Screening: After 5-7 days, harvest and dissociate cells to single-cell suspension. Seed at low density (1-10 cells/cm²) for clonal expansion. Pick individual colonies after 10-14 days, expand, and genotype using PCR/restriction digest and Sanger sequencing to identify correctly modified clones.

Troubleshooting Notes: Low HDR efficiency may be improved by optimizing donor design, using chemical enhancers, or synchronizing cells in S/G2 phase. High cytotoxicity may require titration of RNP concentrations or alternative delivery methods.

Prime Editing in Stem Cells

Protocol Overview: This protocol describes prime editing in hPSCs using the PEmax editor system with optimized pegRNA designs. The complete workflow requires 10-14 days from transfection to genotyping.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- pegRNA Design: Design pegRNAs with 10-15 nt primer binding site (PBS) and 10-30 nt reverse transcriptase template (RTT) containing desired edits. Use computational tools (PE-Designer, pegFinder) to optimize designs. Select pegRNAs with predicted strong binding and minimal secondary structure.

Stabilized pegRNA Construction: Incorporate evopreQ1 or mpknot RNA motifs at the 3' end of pegRNAs to enhance stability and resist degradation. Synthesize as chemically modified RNA or clone into expression vectors with appropriate RNA polymerase III promoters.

Prime Editor Delivery: For hPSCs, use ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery of PEmax protein complexed with pegRNA. Combine 15 µg PEmax protein with 7.5 µg stabilized pegRNA and 5 µg nicking gRNA (for PE3b system) in nucleofection buffer. Incubate 15 minutes at room temperature.

Stem Cell Nucleofection: Harvest 1×10^6 log-phase hPSCs. Resuspend in P3 Primary Cell Nucleofector Solution with supplement. Add RNP complexes and transfer to nucleofection cuvette. Electroporate using program CA-137.

Post-Nucleofection Recovery: Plate cells in pre-warmed stem cell medium with 10 µM ROCK inhibitor. Refresh medium after 24 hours. Allow recovery for 48-72 hours before assessing editing efficiency.

Efficiency Assessment: Harvest a portion of cells (day 3-4) for initial efficiency assessment using next-generation sequencing or droplet digital PCR. For quantitative analysis, extract genomic DNA and amplify target region with barcoded primers for sequencing.

Clonal Isolation: At day 7, dissociate to single cells and plate at clonal density (0.5-1 cell/well) in 96-well plates. Expand colonies for 14-21 days with regular medium changes.

Screening and Validation: Screen clones by PCR and sequencing of the target locus. Validate top candidates through expanded culture and functional assays where appropriate.

Optimization Notes: Editing efficiency can be improved by using engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs), optimizing PBS length (12-16 nt typically works best), and including MMR suppression agents such as dominant-negative MLH1 (MLH1dn) for certain edits [21]. The PE3 system, which includes an additional nicking gRNA to the non-edited strand, typically provides 2- to 4-fold higher editing efficiency but may slightly increase indel rates [19].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Editing Technologies

| Parameter | HDR | NHEJ | Base Editing | Prime Editing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Efficiency in Stem Cells | 0.5-5% | 20-80% | 10-70% | 1-50% (version-dependent) |

| Indel Formation Rate | 5-30% (at target site) | 20-60% | <1-5% | 0.5-5% |

| Editing Purity | Low (mixed outcomes) | High (disruptions) | High (specific conversions) | High (precise edits) |

| Off-Target Effects | DSB-dependent off-targets | DSB-dependent off-targets | DNA/RNA off-target deamination | Minimal reported |

| Optimal Delivery Format | RNP + ssODN | RNP | RNP or mRNA | RNP with epegRNA |

| Time to Clonal Isolation | 10-14 days | 10-14 days | 10-14 days | 10-14 days |

| Key Efficiency Factors | Cell cycle, donor design, NHEJ inhibition | gRNA efficiency, cell health | Editing window, sequence context | pegRNA design, MMR status |

Pathway Diagrams and Editing Mechanisms

Diagram 1: Genome Editing Pathway Selection. DSB-dependent methods (HDR, NHEJ) rely on double-strand breaks, while newer precision techniques (base editing, prime editing) avoid DSBs to enhance safety and reduce unwanted mutations.

Diagram 2: Prime Editing Mechanism. The prime editing process involves target recognition, DNA nicking, hybridization with the primer binding site (PBS) of pegRNA, reverse transcription using the RT template (RTT), and final incorporation of the edit through flap resolution.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Genome Editing in Stem Cells

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations for Stem Cell Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editor Proteins | S. pyogenes Cas9-NLS, BE4max, PEmax, PE6 variants | Core editing enzymes | Purified proteins for RNP delivery reduce off-target effects and immune activation |

| Guide RNAs | Synthetic sgRNAs, pegRNAs, epegRNAs with stability motifs | Target specification | Chemically modified RNAs enhance stability; epegRNAs improve prime editing efficiency |

| Delivery Tools | Neon Transfection System, Amaxa Nucleofector | Physical delivery method | Stem cell-optimized programs and solutions maximize viability and editing efficiency |

| Stem Cell Media | mTeSR Plus, StemFlex, Essential 8 | Cell culture maintenance | Chemically defined media supports pluripotency during editing workflow |

| Enhancer Compounds | ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632), NHEJ inhibitors (NU7026, Scr7) | Improve cell survival and editing outcomes | ROCK inhibitor critical for single-cell survival; NHEJ inhibitors favor HDR in dividing cells |

| Validation Tools | T7E1 assay, TIDE analysis, NGS panels, ddPCR | Edit confirmation and quantification | Multiplexed approaches recommended to assess on-target efficiency and potential off-target effects |

The selection of an appropriate genome-editing protocol for correcting stem cell mutations requires careful consideration of research goals, technical constraints, and desired outcomes. HDR remains valuable for large insertions but suffers from low efficiency in many stem cell types. NHEJ is highly efficient for gene disruption but inappropriate for precise correction. Base editing offers exceptional efficiency for specific point mutations but is restricted to transitional changes. Prime editing provides unprecedented versatility for diverse edits but requires optimization and efficiency improvements.

Future developments in genome editing will likely focus on enhancing efficiency and specificity while addressing delivery challenges. For base editing, ongoing efforts aim to expand targeting scope and minimize off-target deamination [17]. Prime editing systems are evolving rapidly, with newer versions (PE4, PE5, PE6) showing marked improvements in efficiency through engineered reverse transcriptases and suppression of DNA mismatch repair pathways [21] [20]. The development of smaller editor proteins, such as those utilizing Cas12f1, may alleviate delivery constraints for therapeutic applications [22].

For stem cell researchers, the optimal editing strategy often involves matching the technology to the specific mutation being corrected. Base editing excels for known transition mutations, while prime editing offers a more versatile approach for diverse corrections without DSBs. As these technologies continue to mature, they promise to unlock new possibilities for modeling and treating genetic diseases through precise manipulation of stem cell genomes.

The advent of artificial intelligence has catalyzed a paradigm shift in the development of genome-editing technologies. AI-designed gene editors, such as OpenCRISPR-1, represent a new class of molecular tools that bypass evolutionary constraints to offer optimized properties for research and therapeutic applications. These proteins are not simple modifications of natural systems but are generated de novo by large language models (LLMs) trained on vast biological datasets [23] [24]. For researchers focused on correcting stem cell mutations, these editors provide a platform with the potential for enhanced specificity, reduced immunogenicity, and tailored functionality that can improve the efficacy and safety of stem cell therapies.

The development of OpenCRISPR-1 demonstrates the power of this approach. Created by Profluent Bio, OpenCRISPR-1 is a functional Cas9-like nuclease that maintains the prototypical Type II Cas9 architecture but contains 403 amino acid differences from the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) and is nearly 200 mutations away from any known natural CRISPR-associated protein [25] [26]. This significant sequence divergence translates to tangible functional benefits, including reduced off-target effects and lower immunogenicity, while maintaining robust on-target activity comparable to SpCas9 [23] [27].

Key Advantages for Stem Cell Research

For researchers developing protocols to correct stem cell mutations, AI-designed editors offer several distinct advantages that address critical challenges in the field:

Enhanced Specificity: OpenCRISPR-1 demonstrates a 95% reduction in off-target editing across multiple genomic sites compared to SpCas9, with median indel rates of 0.32% versus 6.1% for SpCas9 [24]. This high precision is crucial when editing therapeutically relevant stem cells, where off-target mutations could have profound consequences.

Reduced Immunogenicity: Initial characterizations indicate that OpenCRISPR-1 lacks immunodominant and subdominant T cell epitopes for HLA-A*02:01 that are present in SpCas9 [24]. This suggests potentially lower immune recognition in therapeutic contexts, a valuable property for ex vivo stem cell editing and subsequent transplantation.

Functional Flexibility: OpenCRISPR-1 has been successfully adapted for base editing applications when combined with deaminase enzymes, demonstrating its compatibility with diverse editing modalities [23] [25]. This versatility enables researchers to employ the same editor backbone for different types of genetic corrections required in stem cell research.

Novel PAM Compatibilities: While OpenCRISPR-1 maintains similar PAM preferences to SpCas9 (NGG), the AI-driven design approach can generate editors with tailored PAM specificities [23] [24]. This expands the targetable genomic space for correcting disease-causing mutations in stem cells.

Experimental Characterization and Performance Data

Comparative Performance Analysis

Independent evaluations have provided quantitative data on OpenCRISPR-1's performance relative to other CRISPR systems. A comprehensive 2025 study systematically compared FrCas9, SpCas9, and OpenCRISPR-1 across multiple genomic loci using GUIDE-seq and AID-seq methodologies [27]. The results provide critical insights for researchers selecting appropriate editors for stem cell applications.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of CRISPR-Cas9 Systems

| Editor | On-Target Efficiency (Median Indel %) | Off-Target Activity (Median Indel %) | Specificity (Log2 Ratio On:Off Target) | Key PAM Preferences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OpenCRISPR-1 | 55.7% | 0.32% | -2.06 | NGG (69.33%), NGA (17.1%) |

| SpCas9 | 48.3% | 6.1% | -3.95 | NGG (76.89%), NGA (12.23%) |

| FrCas9 | Higher than SpCas9 | Fewer off-targets | 4.12 | NNTA (93.93%) |

Structural Validation

Structural analysis through AlphaFold2 predictions confirmed that over 80% of AI-generated proteins, including OpenCRISPR-1, had high-confidence folds (pLDDT > 80), with structural architectures highly similar to natural Cas9 proteins despite significant sequence divergence [23] [26]. Core functional domains including the HNH and RuvC nuclease domains, PAM-interacting domain, and target recognition lobe were preserved in most generated proteins at rates comparable to natural sequences [24].

Protocol: Implementing OpenCRISPR-1 in Stem Cell Editing

Molecular Cloning and Vector Design

To implement OpenCRISPR-1 in your stem cell research, begin with proper molecular cloning strategies:

Expression Vector Construction: Clone the OpenCRISPR-1 sequence (publicly available through AddGene) into your preferred mammalian expression backbone under the control of a constitutive promoter such as EF1α or CAG [25] [24]. The OpenCRISPR-1 coding sequence is 1,380 amino acids in length and should be human-codon optimized for efficient expression in stem cells.

Guide RNA Design: Utilize the companion AI-generated guide RNA sequences specifically designed for OpenCRISPR-1, which are available alongside the editor sequence [25]. Alternatively, design custom sgRNAs using the standard 20-nucleotide spacer length, as OpenCRISPR-1 maintains compatibility with conventional guide RNA architectures.

Delivery Vector Selection: For hematopoietic stem cells, consider lentiviral delivery systems with appropriate safety profiles. For induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), plasmid or mRNA delivery may be preferable to minimize genomic integration concerns.

Delivery Methods for Stem Cells

Different stem cell types require optimized delivery approaches:

Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Delivery: For primary hematopoietic stem cells, consider mRNA-based LNP delivery systems. Formulate OpenCRISPR-1 mRNA and sgRNA into LNPs using commercially available kits, with optimization of the N:P ratio for stem cell transfection.

Electroporation of Ribonucleoprotein (RNP): For precise editing with minimal off-target effects, complex purified OpenCRISPR-1 protein with sgRNA to form RNP complexes. Electroporate using stem cell-optimized settings (e.g., 1600V, 10ms, 3 pulses for human iPSCs).

Viral Delivery: For difficult-to-transfect stem cell populations, package OpenCRISPR-1 and sgRNA into lentiviral or AAV vectors. Note that AAV capacity limitations may require dual-vector systems or the use of smaller editors.

Validation and Quality Control

Comprehensive validation is essential for stem cell editing:

On-Target Efficiency Assessment: Extract genomic DNA 72-96 hours post-editing and amplify target loci via PCR. Quantify editing efficiency using T7E1 assay or TIDE analysis, or through next-generation sequencing for absolute quantification.

Off-Target Profiling: Employ GUIDE-seq or AID-seq for genome-wide off-target detection [27]. Focus particularly on sites with 1-4 nucleotide mismatches to your target sequence, as OpenCRISPR-1 shows variable tolerance to mismatches depending on their position.

Stem Cell Potency Validation: After editing, confirm that stem cells maintain their differentiation potential and colony-forming capacity through appropriate functional assays specific to your stem cell type.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Implementing AI-Designed Editors

| Reagent/Catalog | Supplier | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| OpenCRISPR-1 Expression Plasmid | AddGene (publicly available) | Source of AI-designed editor for cloning and expression |

| Stem Cell-Specific Lipofectamine | Thermo Fisher | Chemical delivery of plasmids or RNPs to stem cells |

| Human Stem Cell Nucleofector Kit | Lonza | Electroporation reagent optimized for stem cell delivery |

| Cas9 ELISA Kit | Multiple suppliers | Detection and quantification of OpenCRISPR-1 expression |

| GUIDE-seq Kit | Integrated DNA Technologies | Genome-wide identification of off-target editing events |

| StemFlex Medium | Thermo Fisher | Culture medium supporting pluripotency during editing process |

| Recombinant Albumin | Sigma-Aldrich | Serum-free culture supplement for edited stem cells |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Implementing novel editors like OpenCRISPR-1 may require protocol adjustments:

Low Editing Efficiency: If observing suboptimal editing rates, verify OpenCRISPR-1 expression via Western blot using anti-Cas9 antibodies. Ensure sgRNA is specifically designed for OpenCRISPR-1 rather than SpCas9, as the AI-designed guide RNAs may show optimized performance [25].

Cellular Toxicity: Monitor stem cell viability and proliferation rates post-editing. If toxicity is observed, consider reducing RNP concentrations or switching to mRNA delivery, which typically shows transient expression and reduced cellular stress.

Inconsistent Editing Between Clones: For single-cell derived clones, screen multiple colonies to account for heterogeneity. Consider using early-passage stem cells with robust growth characteristics to minimize variability.

Future Perspectives

The successful implementation of OpenCRISPR-1 marks the beginning of a new era in precision genome editing. The AI-driven design process that created OpenCRISPR-1 can generate millions of diverse CRISPR-Cas proteins, representing a 4.8-fold expansion of diversity compared to natural CRISPR-Cas proteins [23]. This vast sequence space enables researchers to potentially request editors tailored to specific stem cell applications, with custom PAM preferences, size constraints, or enzymatic activities.

Furthermore, the integration of AI tools like CRISPR-GPT can assist researchers in designing optimal editing strategies for their specific stem cell mutation correction projects [28]. These systems can select suitable CRISPR systems, design guide RNAs, and recommend delivery methods based on the target cell type and desired edit.

As the field progresses, we anticipate the development of specialized AI-designed editors optimized for particular stem cell types—such as hematopoietic stem cells with enhanced editing in quiescent populations or neural stem cells with improved nuclear import characteristics. These advances will expand the therapeutic potential of stem cell gene editing for treating genetic disorders.

Prime editing is a versatile "search-and-replace" genome editing technology that enables the precise installation of targeted insertions, deletions, and all 12 possible base-to-base conversions without requiring double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) or donor DNA templates [29]. This technology combines a Cas9 nickase (H840A) fused to an engineered reverse transcriptase (RT) with a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) [30]. The pegRNA both specifies the target site and contains the desired edit, serving as a template for the reverse transcriptase [29]. The editing process initiates when the Cas9 nickase domain creates a single-strand nick at the target DNA site. The exposed 3' end then hybridizes to the primer binding site (PBS) on the pegRNA, allowing the reverse transcriptase to synthesize a DNA flap containing the edited sequence using the reverse transcription template (RTT) of the pegRNA [30] [31]. This newly synthesized edited flap is then incorporated into the genome through cellular DNA repair mechanisms [31].

Compared to traditional CRISPR-Cas9 approaches, prime editing offers significantly greater precision with minimal indel formation and reduced off-target effects [30] [32]. While base editing can efficiently correct certain point mutations, it is restricted to specific transition mutations (C•G to T•A, A•T to G•C, and C•G to G•C) and can cause unwanted bystander editing within its activity window [30] [29]. Prime editing overcomes these limitations, enabling correction of a much broader range of mutations, including transversions, small insertions, and small deletions, without the constraint of a narrow editing window [30] [29]. Its mechanism also makes it less dependent on cellular replication and endogenous DNA repair pathways than homology-directed repair (HDR), allowing for more efficient editing in non-dividing cells [31].

Evolution of Prime Editing Systems

Since the initial development of the PE1 system, successive optimizations have substantially improved prime editing efficiency:

- PE2: Incorporates an engineered M-MLV reverse transcriptase with five mutations that enhance thermostability, processivity, and template binding, resulting in a 1.6- to 5.1-fold increase in editing efficiency compared to PE1 [30] [29].

- PE3/PE3b: Adds a second nicking sgRNA to nick the non-edited strand, biasing DNA repair to use the edited strand as a template and increasing editing efficiency 2-3 fold compared to PE2 [30] [29]. PE3b designs the nicking sgRNA to target the edited strand specifically, reducing indels by 13-fold [29].

- PE4/PE5: Incorporates transient inhibition of mismatch repair (MMR) through a dominant-negative MLH1 variant to prevent repair of the heteroduplex back to the original sequence, improving editing efficiency by 7.7-fold (PE4) and 2.0-fold (PE5) compared to PE2 and PE3, respectively [29] [31].

- PEmax: Features a codon-optimized RT, additional nuclear localization signals, and Cas9 mutations that improve nuclease activity and editor expression [29].

- PE6: Includes specialized prime editors derived from evolved RT domains (PE6a-d) and Cas9 domains (PE6e-g) for improved efficiency with specific edit types and size constraints [29].

- epegRNAs: Incorporate RNA pseudoknots at the 3' end of pegRNAs to protect against degradation and improve stability, thereby enhancing prime editing efficiency [29].

Prime Editing Application: Correcting PRPH2 Splice Site Mutations

PRPH2 and Inherited Retinal Diseases