Bone Marrow vs. Adipose Tissue: A Comparative Analysis of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Sources for Research and Therapy

This article provides a comprehensive, up-to-date analysis of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from bone marrow and adipose tissue, the two most prevalent sources for research and clinical applications.

Bone Marrow vs. Adipose Tissue: A Comparative Analysis of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Sources for Research and Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, up-to-date analysis of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from bone marrow and adipose tissue, the two most prevalent sources for research and clinical applications. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it systematically explores the fundamental biology, isolation methodologies, and characterization of BM-MSCs and AD-MSCs. It delves into their comparative differentiation potential, secretory profiles, and immunomodulatory properties, underpinned by direct comparative studies. The content further addresses critical challenges in the field, including donor variability, manufacturing standardization, and therapeutic efficacy, while highlighting advanced optimization strategies such as genetic engineering, preconditioning, and the emerging paradigm of cell-free therapies. This review synthesizes evidence to guide the selection and enhancement of MSC sources for specific therapeutic and regenerative applications.

The Biological Blueprint: Understanding MSC Origins and Fundamental Properties

The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) has generated markedly increasing interest across a wide variety of biomedical disciplines, positioning them as cornerstone tools in regenerative medicine and immunomodulatory therapy [1] [2]. However, for years, investigators reported studies using different isolation methods, expansion protocols, and characterization approaches, creating significant challenges in comparing and contrasting research outcomes [1]. This heterogeneity threatened to hinder progress in the field, necessitating the development of standardized criteria.

To address this critical need, the Mesenchymal and Tissue Stem Cell Committee of the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) established minimal criteria to define human MSCs, creating a foundational framework that has guided research and clinical development since its publication in 2006 [1]. This landmark position statement provided the scientific community with a unified reference point, enhancing the credibility and comparability of MSC studies worldwide [3]. The clarification of MSC nomenclature further refined scientific communication, establishing the distinction between "mesenchymal stromal cells" for the plastic-adherent population and reserving "mesenchymal stem cells" only for subsets meeting rigorous stem cell criteria [4].

This technical guide comprehensively details the ISCT criteria, explores their practical implementation in research settings, examines evolving standards in the field, and discusses the implications of recent advances in MSC biology for their definition and therapeutic application.

The ISCT Minimal Criteria: A Three-Pillar Framework

The ISCT established three fundamental criteria that must be satisfied to define human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells [1]. These criteria serve as the cornerstone for MSC identification and characterization across diverse tissue sources and experimental applications.

Plastic Adherence Under Standard Culture Conditions

The first criterion requires that MSCs must be plastic-adherent when maintained in standard culture conditions [1] [3]. This fundamental property refers to the ability of MSCs to adhere to and proliferate on standard tissue culture plastic surfaces, forming characteristic fibroblast-like colonies. This adherence property enables the selective expansion of MSCs from heterogeneous cell mixtures obtained during tissue isolation procedures, serving as a primary purification step before further characterization.

Plastic adherence distinguishes MSCs from hematopoietic cells and other non-adherent cell populations present in source tissues like bone marrow, adipose tissue, or dental pulp. When placed in culture, MSCs attach to the plastic surface within 12-48 hours and begin to proliferate, eventually forming colonies that can be expanded through serial passaging while maintaining their fundamental characteristics.

Specific Surface Marker Expression Profile

The second criterion defines a specific immunophenotypic profile based on cluster of differentiation (CD) marker expression [1] [2]. According to ISCT standards, MSCs must demonstrate positive expression (≥95% of the population) of specific surface markers while simultaneously lacking expression (≤2% positive) of hematopoietic and monocytic markers.

Table 1: Required Surface Marker Profile for MSCs According to ISCT Criteria

| Marker Status | Surface Markers | Expression Requirement | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Markers | CD105, CD73, CD90 | ≥95% positive | Identifies core MSC phenotype |

| Negative Markers | CD45, CD34, CD14 or CD11b, CD79α or CD19, HLA-DR | ≤2% positive | Excludes hematopoietic lineages |

CD105 (endoglin) is a type I membrane glycoprotein essential for cell migration and angiogenesis [2]. CD90 (Thy-1), an N-glycosylated glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein, mediates cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions, contributing to intercellular adhesion and migration [2]. CD73 functions as a 5'-exonuclease, catalyzing the hydrolysis of adenosine monophosphate into adenosine and playing a role in cell signaling within the bone marrow microenvironment [2].

The negative markers serve to exclude hematopoietic cells: CD45 is a marker for all white blood cells; CD34 identifies hematopoietic stem cells and endothelial cells; CD14/CD11b are expressed on monocytes and macrophages; CD79α/CD19 are markers of B cells; and HLA-DR is an MHC class II molecule found on antigen-presenting cells with strong immunogenic properties [2] [3].

Multilineage Differentiation Potential In Vitro

The third criterion requires that MSCs must demonstrate the capacity to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondroblasts under standard in vitro inducing conditions [1]. This trilineage differentiation potential confirms the multipotent character of MSCs and provides functional validation of their stemness beyond surface marker expression.

Osteogenic differentiation is typically induced using culture medium supplemented with dexamethasone, ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, and β-glycerophosphate [5] [6]. Successful differentiation is confirmed by the formation of mineralized extracellular matrix detectable by Alizarin Red or Von Kossa staining.

Adipogenic differentiation requires induction with dexamethasone, isobutylmethylxanthine, indomethacin, and insulin [5] [6]. Differentiated adipocytes accumulate lipid vacuoles that can be visualized using Oil Red O staining.

Chondrogenic differentiation generally occurs in pellet or micromass culture systems with transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) supplementation [5] [6]. Successful chondrogenesis is demonstrated by the production of cartilage-specific extracellular matrix components detectable by Alcian Blue or Safranin O staining.

This trilineage differentiation capacity must be demonstrated under controlled in vitro conditions to meet the ISCT definition, providing functional evidence of multipotency that complements the immunophenotypic characterization.

Evolving Standards: Beyond the Minimal Criteria

While the ISCT minimal criteria established a crucial foundation, the field continues to evolve with emerging research revealing complexities in MSC biology that necessitate refined characterization approaches.

Tissue-Specific Variations and Functional Heterogeneity

Recent investigations have demonstrated that while MSCs from different sources share the core ISCT-defined characteristics, they exhibit significant biological variations based on their tissue of origin [5]. For instance, dental pulp-derived MSCs (DPSCs) consistently demonstrate smaller cell size, Nestin positivity, higher proliferation rates, and notably, a diminished capacity for adipogenic differentiation compared to adipose tissue-derived MSCs (ADSCs) [5]. This tissue-specific functional variation indicates that ontogeny significantly influences MSC properties, suggesting the need for tissue-specific characterization benchmarks alongside the core ISCT criteria.

Secretome analysis further reveals substantial differences in the profiles of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors between MSC populations from different tissues [5]. These variations extend to microRNA expression patterns, with DPSCs expressing microRNAs primarily involved in oxidative stress and apoptosis pathways, while ADSCs produce microRNAs that play regulatory roles in cell cycle and proliferation [5]. Such fundamental differences in secretory profiles have profound implications for selecting appropriate MSC sources for specific therapeutic applications.

Impact of Donor Physiology and Disease Status

The biological properties of MSCs are significantly influenced by donor characteristics, including age, health status, and disease conditions [6]. Comparative studies of ADSCs from healthy versus type 2 diabetic (T2D) donors reveal that while both populations meet the core ISCT criteria, they exhibit functional differences in specific differentiation capacities and pro-angiogenic potential [6]. Diabetic ADSCs demonstrate enhanced chondrogenic differentiation and pro-angiogenic properties compared to those from healthy donors, while showing reduced adipogenic differentiation potential [6].

These findings have crucial implications for autologous MSC therapies, particularly for patients with underlying metabolic conditions. They underscore the importance of donor-specific functional characterization beyond minimal criteria to predict therapeutic efficacy and inform clinical applications. The demonstration that diabetic MSCs retain significant functional capacity under diabetic culture conditions supports their potential use in autologous therapies for diabetic patients [6].

Advances in Characterization and Potency Assays

Contemporary MSC research increasingly recognizes the need for potency assays that reflect the intended mechanism of action in specific therapeutic contexts [7] [8]. While the ISCT minimal criteria focus on defining MSC identity, clinical translation requires demonstration of biological activity relevant to the target condition. Current analysis indicates that assessment of functionality remains limited in clinical trial reporting and does not always relate to the likely mechanism of action [7].

The ISCT continues to address these evolving needs through workshops and updated recommendations. A 2024 workshop on "Cell Therapies for Autoimmune Diseases: MSCs from Biology to Clinical Application" emphasized the need for standardization in design, conduct, and reporting of MSC clinical trials, including product characterization and key manufacturing parameters [8]. These developments highlight the ongoing evolution from minimal identity criteria toward comprehensive characterization frameworks that encompass identity, purity, viability, and clinically relevant potency measures.

MSC Characterization: Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Workflow for MSC Characterization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive experimental workflow for isolating and characterizing MSCs according to ISCT criteria and contemporary standards:

Detailed Methodologies for Core Characterization Assays

Immunophenotyping by Flow Cytometry

Immunophenotypic analysis represents a critical component of MSC characterization, typically performed using flow cytometry. The standard protocol involves:

Cell Preparation: Harvest MSCs at 70-80% confluence (typically passages 3-6) using standard dissociation reagents like trypsin-EDTA [6]. Wash cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and adjust concentration to 1×10⁶ cells/mL in flow cytometry buffer.

Antibody Staining: Incubate cell aliquots with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, CD14, CD19, and HLA-DR for 30 minutes at 4°C in the dark [6]. Include appropriate isotype controls for compensation and background determination.

Analysis: Analyze stained cells using a flow cytometer, collecting a minimum of 10,000 events per sample. Evaluate positive marker expression (CD73, CD90, CD105) as ≥95% positive, while negative markers must demonstrate ≤2% expression to meet ISCT criteria [1] [3].

Trilineage Differentiation Assays

The functional multipotency of MSCs must be demonstrated through directed differentiation toward osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic lineages using established induction media [5] [6].

Table 2: Standardized Protocols for Trilineage Differentiation of MSCs

| Differentiation Pathway | Induction Media Components | Differentiation Period | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osteogenic | DMEM, 10% FBS, 50 µM ascorbic acid-2 phosphate, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1 µM dexamethasone [5] | 21-28 days | Alizarin Red S staining for mineralized matrix |

| Adipogenic | DMEM, 10% FBS, 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxanthine, 1 µM dexamethasone, 10 µM insulin, 200 µM indomethacin [6] | 14-21 days | Oil Red O staining for lipid vacuoles |

| Chondrogenic | High-glucose DMEM, 1% ITS+ Premix, 50 µM ascorbic acid-2 phosphate, 0.1 µM dexamethasone, 10 ng/mL TGF-β3 [6] | 21-28 days | Alcian Blue staining for sulfated proteoglycans |

For osteogenic differentiation, seed MSCs at 3×10³ cells/well in 48-well plates and culture until 60-70% confluence before switching to osteogenic induction medium [5]. Replace differentiation medium every 3-4 days for 21-28 days. Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde and stain with 2% Alizarin Red S solution (pH 4.2) for 20 minutes to detect calcium deposits [6].

For adipogenic differentiation, culture confluent MSCs in adipogenic induction medium for 3 days followed by 1-3 days in maintenance medium, repeating this cycle for 2-3 weeks [6]. Fix cells and stain with filtered 0.3% Oil Red O solution in 60% isopropanol for 15 minutes to visualize lipid droplets.

For chondrogenic differentiation, pellet 2.5×10⁵ MSCs in conical polypropylene tubes and culture in chondrogenic induction medium with medium changes every 2-3 days [6]. After 21-28 days, fix pellets, embed in paraffin, section, and stain with 1% Alcian Blue in 3% acetic acid (pH 2.5) to detect sulfated glycosaminoglycans.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for MSC Characterization and Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | αMEM, DMEM, Basic Medium with supplements [5] [6] | MSC expansion and maintenance |

| Serum Supplements | Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), Human Platelet Lysate (hPL) [5] [6] | Support MSC growth and proliferation |

| Dissociation Reagents | Trypsin-EDTA, TrypLE Select [5] [6] | Cell passaging and harvesting |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Anti-CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, CD14, CD19, HLA-DR [6] [3] | Immunophenotyping per ISCT criteria |

| Osteogenic Inducers | Ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, β-glycerophosphate, Dexamethasone [5] | Osteogenic differentiation |

| Adipogenic Inducers | Isobutylmethylxanthine, Dexamethasone, Insulin, Indomethacin [6] | Adipogenic differentiation |

| Chondrogenic Inducers | TGF-β3, ITS+ Premix, Dexamethasone [6] | Chondrogenic differentiation |

| Differentiation Stains | Alizarin Red S, Oil Red O, Alcian Blue [5] [6] | Detection of differentiated phenotypes |

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Gaps in Current Characterization Standards

Analysis of clinical trial reporting reveals significant limitations in MSC characterization, with approximately 33% of studies including no characterization data and only 13% reporting individual values per cell lot [7]. Viability was reported in just 57% of studies, while differentiation capacity was discussed for osteogenesis (29%), adipogenesis (27%), and chondrogenesis (20%) [7]. This substantial characterization deficit in clinical reporting highlights the disconnect between theoretical standards and practical implementation.

The extent of characterization in published trials shows no correlation with clinical phase of development, indicating that even late-phase trials often lack comprehensive product characterization [7]. Furthermore, assessment of functionality remains limited and frequently does not relate to the likely mechanism of action, representing a critical gap in the translational pathway [7].

Toward Next-Generation Characterization Standards

The emerging understanding of MSC heterogeneity and tissue-specific properties necessitates evolution beyond the minimal criteria toward more comprehensive characterization frameworks [5] [8]. Future standards will likely incorporate:

- Tissue-specific benchmarks that acknowledge biological variations while maintaining core identity criteria

- Mechanism-relevant potency assays that predict therapeutic efficacy for specific indications

- Secretome profiling to characterize paracrine activity, increasingly recognized as a primary therapeutic mechanism [5] [2]

- Standardized manufacturing protocols to control for process-induced variability [8]

- Donor screening criteria that account for health status and physiological factors influencing MSC function [6]

International standards organizations have begun addressing these needs through technical specifications for specific MSC types, such as the ISO/TS 24651:2022 for bone marrow-derived MSCs and ISO/TS 22859-1:2022 for umbilical cord-derived MSCs [3]. These documents outline requirements for collection, isolation, culture, characterization, quality control, and distribution, representing important steps toward global standardization.

The ISCT minimal criteria for defining MSCs have provided an essential foundation for standardizing research and clinical development in the field. The three pillars of plastic adherence, specific surface marker expression, and trilineage differentiation capacity continue to serve as the fundamental reference point for MSC identification across diverse tissue sources and applications. However, the evolving understanding of MSC biology reveals substantial tissue-specific variations, donor-dependent characteristics, and functional heterogeneity that necessitate refinement of characterization standards.

Future directions will require integration of core identity criteria with mechanism-relevant potency assays, comprehensive secretome profiling, and standardized manufacturing protocols to ensure predictive characterization and reliable therapeutic outcomes. As the field advances toward more personalized applications and precision medicine approaches, the definition of MSCs will continue to evolve, incorporating deeper understanding of their biological complexity while maintaining the standardized framework that enables scientific communication and progress.

Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs) represent a cornerstone of regenerative medicine research due to their multipotent differentiation potential, immunomodulatory properties, and therapeutic versatility. While MSCs can be isolated from various tissues including adipose tissue, umbilical cord, and dental pulp, bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) remain the most extensively characterized and historically significant source [9]. First identified in the 1960s by Friedenstein and colleagues as plastic-adherent, fibroblast-like cells capable of forming bone colonies, BM-MSCs were the founding population that established the entire MSC field [10] [11]. The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) established minimal criteria for defining MSCs primarily based on BM-MSCs, cementing their role as the reference standard against which other MSC sources are compared [12] [9]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of BM-MSC isolation, characterization, and fundamental biological properties within the broader context of MSC source comparison.

Fundamental Characteristics and Defining Criteria

BM-MSCs are multipotent stromal cells residing in the bone marrow niche, where they function as structural and regulatory components that support hematopoiesis [11]. According to ISCT standards, human BM-MSCs must fulfill three minimal criteria:

- Plastic adherence under standard culture conditions

- Specific surface marker expression: Positive for CD105, CD73, CD90; negative for CD45, CD34, CD14/CD11b, CD79α/CD19, and HLA-DR

- Multilineage differentiation potential: Ability to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondroblasts in vitro [12] [9]

Beyond these minimal criteria, BM-MSCs exhibit distinctive biological properties that position them uniquely among MSC sources. They demonstrate a characteristic spindle-shaped, fibroblastic morphology with extensions projecting from a small cell body [12] [10]. While adipose tissue contains a higher frequency of MSCs per unit volume, BM-MSCs are renowned for their robust osteogenic differentiation capacity, which often exceeds that of adipose-derived MSCs (AD-MSCs) [11]. BM-MSCs also possess potent immunomodulatory functions, influencing both innate and adaptive immune responses through cell-cell contact and secretion of bioactive factors [12] [13].

Table 1: Key Surface Markers for Identifying Human BM-MSCs

| Marker Category | Marker Examples | Expression in BM-MSCs | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Markers | CD73, CD90, CD105 | Positive | Mesenchymal lineage commitment; ectoenzyme activity |

| CD29, CD44, CD166 | Positive | Cell adhesion and migration | |

| CD146, STRO-1 | Positive (subsets) | Primitive/perivascular phenotype | |

| Negative Markers | CD34, CD45 | Negative | Exclusion of hematopoietic lineage |

| CD14, CD11b | Negative | Exclusion of monocyte/macrophage lineage | |

| CD19, CD79α | Negative | Exclusion of B-cell lineage | |

| HLA-DR | Negative (unless stimulated) | Exclusion of activated immune cells |

Isolation Protocols and Methodologies

Bone Marrow Aspiration and Initial Processing

Bone marrow for BM-MSC isolation is typically obtained from the iliac crest, vertebral body, sternum, or femoral shaft [10]. For human isolation, iliac crest aspiration is most common, performed aseptically after obtaining informed consent [12]. The basic workflow begins with collection of bone marrow into anticoagulant-treated tubes, followed by centrifugation to separate the buffy coat from red blood cells and plasma [12].

Core Isolation Techniques

Several methods have been established for isolating BM-MSCs from the initial marrow aspirate:

Density Gradient Centrifugation This represents the most widely used isolation technique, providing effective separation of mononuclear cells from erythrocytes and granulocytes [12] [9].

- Protocol: The buffy coat or diluted bone marrow is carefully layered onto an equal volume of density gradient medium (Ficoll-Paque or Percoll)

- Centrifugation: 400-450 × g for 20-30 minutes at room temperature

- Cell recovery: Mononuclear cells forming a distinct interface ring are collected, washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and counted

- Advantages: Effective removal of erythrocytes and granulocytes; high cell viability

- Disadvantages: Can co-isolate other mononuclear cells requiring further purification [12]

Plastic Adherence Selection This method exploits the fundamental property of MSC adhesion to tissue culture plastic, providing a simple purification approach that can be used alone or following density gradient separation [9] [11].

- Protocol: Washed mononuclear cells are plated on standard tissue culture-treated flasks or plates

- Culture medium: Typically Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) or αMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) or human platelet lysate and antibiotics

- Incubation conditions: 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO₂ for 48 hours

- Medium exchange: Non-adherent cells (primarily hematopoietic) are removed after 48-72 hours by PBS washing; medium is exchanged every 3-4 days thereafter

- Advantages: Technically simple; no specialized equipment required

- Disadvantages: Slow selection process; potential hematopoietic cell contamination in early passages [12] [11]

Enzymatic Digestion Approach For bone marrow fragments or whole bone samples, enzymatic digestion liberates stromal cells from the matrix [10].

- Protocol: Marrow plugs or bone fragments are treated with collagenase type I or II (typically 1-3 mg/mL) for 30-60 minutes at 37°C

- Termination: Enzyme activity is neutralized with serum-containing medium

- Cell recovery: Released cells are collected by centrifugation and plated

- Advantages: Higher yield from compact bone sources; preserves perivascular MSC populations

- Disadvantages: Potential enzyme-induced cell surface marker alteration; requires optimization [10]

Immunodepletion or Positive Selection Advanced isolation employs antibody-based strategies to deplete hematopoietic cells (using anti-CD45, anti-CD34) or positively select MSC populations (using anti-STRO-1, anti-CD271, anti-CD106) via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) [11].

- Advantages: Highly pure populations; ability to select specific MSC subpopulations

- Disadvantages: Technically demanding; expensive; requires specialized equipment [11]

Diagram 1: BM-MSC isolation workflow. The process begins with bone marrow aspiration, followed by various isolation methods that converge on culture expansion and final characterization.

Characterization and Functional Validation

Morphological Assessment

BM-MSCs exhibit a characteristic homogeneous fibroblastic morphology with a small cell body and extensions projecting in opposite directions [12] [10]. Under phase-contrast microscopy, early passage cells appear heterogeneous with distinct colony formation, gradually developing a more uniform spindle-shaped appearance with increased proliferation [12]. Murine BM-MSCs are notably smaller than human, canine, and feline BM-MSCs, demonstrating species-specific morphological variations [10].

Immunophenotyping by Flow Cytometry

Comprehensive surface marker analysis is essential for BM-MSC identification and quality control. Standard protocol involves:

- Cell preparation: Harvest P2-P3 cells at 80-90% confluence using enzymatic detachment; wash with PBS containing 1% BSA

- Antibody staining: Incubate 10⁵ cells/tube with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, CD14, and appropriate isotype controls

- Analysis: Acquire data on flow cytometer; analyze ≥10,000 events using appropriate gating strategies

- Interpretation: ≥95% positive for CD73, CD90, CD105; ≤2% positive for hematopoietic markers [12]

Table 2: Growth Kinetics and Senescence of BM-MSCs from Different Species

| Species | Population Doubling Time (PDT) | Senescence Characteristics | Proliferation Marker Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | <48 hours (early passage, P1-P5) >96 hours (late passage, P6+) | SA-β-Gal presence in late passages (P6+) | Ki67 negative in cultured cells |

| Canine | Increases to ~100 hours after 25 days | SA-β-Gal increases with passage number | Ki67 positive |

| Rat | 20-30 hours (P1-P3) 50-130 hours (P4-P5) | SA-β-Gal absent at PD100 Present in P6 | Ki67 positive |

| Mouse | >80 hours at week 4 and 8 (P2) | Low senescence in P3-P4 | Information limited |

Trilineage Differentiation Potential

Functional validation of BM-MSCs requires demonstration of adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation capacity using specific induction media.

Adipogenic Differentiation Protocol

- Induction: Culture confluent BM-MSCs for 1-3 weeks in adipogenic differentiation medium (typically containing insulin, dexamethasone, indomethacin, and IBMX)

- Staining: Fix cells with 4% formaldehyde; stain lipid droplets with Oil Red O (0.5% in isopropanol) for 10-15 minutes

- Visualization: Microscopic observation of red-stained intracellular lipid vacuoles

- Quantification: Oil Red O elution with 100% isopropanol and spectrophotometric measurement at 510 nm [12]

Osteogenic Differentiation Protocol

- Induction: Culture confluent BM-MSCs for 3-4 weeks in osteogenic medium (typically containing dexamethasone, ascorbate-2-phosphate, and β-glycerophosphate)

- Staining: Fix with 4% formaldehyde; stain calcium deposits with 2% Alizarin Red S (pH 4.1-4.3) for 5-10 minutes

- Visualization: Microscopic observation of orange-red mineralized nodules

- Quantification: Alizarin Red extraction with 10% cetylpyridinium chloride and spectrophotometric measurement at 562 nm [12] [14]

Chondrogenic Differentiation Protocol

- Induction: Pellet or micromass culture of 2.5×10⁵ BM-MSCs in chondrogenic medium (typically containing TGF-β3, dexamethasone, ascorbate-2-phosphate, proline, and insulin-transferrin-selenium)

- Duration: 3-4 weeks with medium changes every 2-3 days

- Staining: Fix pellets with 4% formaldehyde; embed in paraffin; section; stain with 1% Alcian Blue (pH 2.5) for 30 minutes

- Visualization: Microscopic observation of blue-stained proteoglycan-rich extracellular matrix [15]

Diagram 2: BM-MSC characterization workflow. The validation process requires confirmation of morphological features, specific surface marker expression, and demonstrated trilineage differentiation potential.

Culture Conditions and Expansion Considerations

Media Formulations and Supplements

Traditional BM-MSC expansion employs basal media (DMEM or αMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS, which provides essential growth factors and attachment factors but introduces batch-to-batch variability and xenogenic risks [13]. For clinical applications, serum-free media (SFM) and xeno-free media (XFM) have been developed using defined components including recombinant growth factors, lipids, and proteins [13]. Human platelet lysate (hPL) has emerged as an effective FBS alternative, promoting superior proliferation while eliminating xenogenic concerns [13].

Seeding Density and Population Doubling

BM-MSCs exhibit density-dependent growth inhibition and should be seeded at 1,000-5,000 cells/cm² for optimal expansion [13]. Population doubling time (PDT) varies by species and passage number, with human BM-MSCs typically demonstrating PDT of <48 hours in early passages (P1-P5) increasing to >96 hours in later passages (P6+) [10]. Serial passaging beyond P6-8 often leads to replicative senescence characterized by enlarged morphology, slowed proliferation, and increased SA-β-Gal activity [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for BM-MSC Isolation and Characterization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Isolation Reagents | Ficoll-Paque Percoll Collagenase Type I/II Antibodies (CD45, CD34) | Density gradient separation Density gradient separation Enzymatic digestion of bone fragments Hematopoietic cell depletion |

| Culture Media & Supplements | αMEM/DMEM Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) Human Platelet Lysate (hPL) Penicillin/Streptomycin | Basal culture medium Traditional growth supplement Xeno-free growth supplement Antibiotic prevention of contamination |

| Characterization Reagents | Anti-CD73, CD90, CD105 Anti-CD34, CD45, CD14 Oil Red O Alizarin Red S Alcian Blue | Positive marker flow cytometry Negative marker flow cytometry Adipogenic differentiation staining Osteogenic differentiation staining Chondrogenic differentiation staining |

| Differentiation Kits | StemPro Adipogenesis Kit StemPro Osteogenesis Kit StemPro Chondrogenesis Kit | Standardized adipogenic differentiation Standardized osteogenic differentiation Standardized chondrogenic differentiation |

When positioned within the broader landscape of MSC sources, BM-MSCs demonstrate distinct advantages and limitations. Adipose tissue provides approximately 500 times more MSCs per unit volume than bone marrow, and extraction via liposuction is considered less invasive than bone marrow aspiration [15]. However, BM-MSCs possess superior documented clinical history with more extensive clinical trial data across various disease indications [16]. The biological performance also varies, with AD-MSCs demonstrating enhanced angiogenic potential in some diabetic models, while BM-MSCs maintain robust osteogenic capability [15] [11]. Importantly, bone marrow aspiration collects additional beneficial cell populations including hematopoietic stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells, which are absent in adipose-derived isolates [16].

BM-MSCs represent the foundational reference standard for mesenchymal stromal cell research, characterized by well-defined isolation protocols, comprehensive characterization criteria, and extensive clinical validation. Their robust osteogenic potential, documented safety profile, and historical precedence continue to make them invaluable for regenerative medicine applications. While newer MSC sources offer advantages in terms of accessibility and abundance, BM-MSCs remain essential for both basic research and clinical development, providing the benchmark against which alternative MSC sources are evaluated. As the field advances toward serum-free culture conditions and more precise subpopulation identification, BM-MSCs will continue to be a critical tool for understanding MSC biology and therapeutic mechanisms.

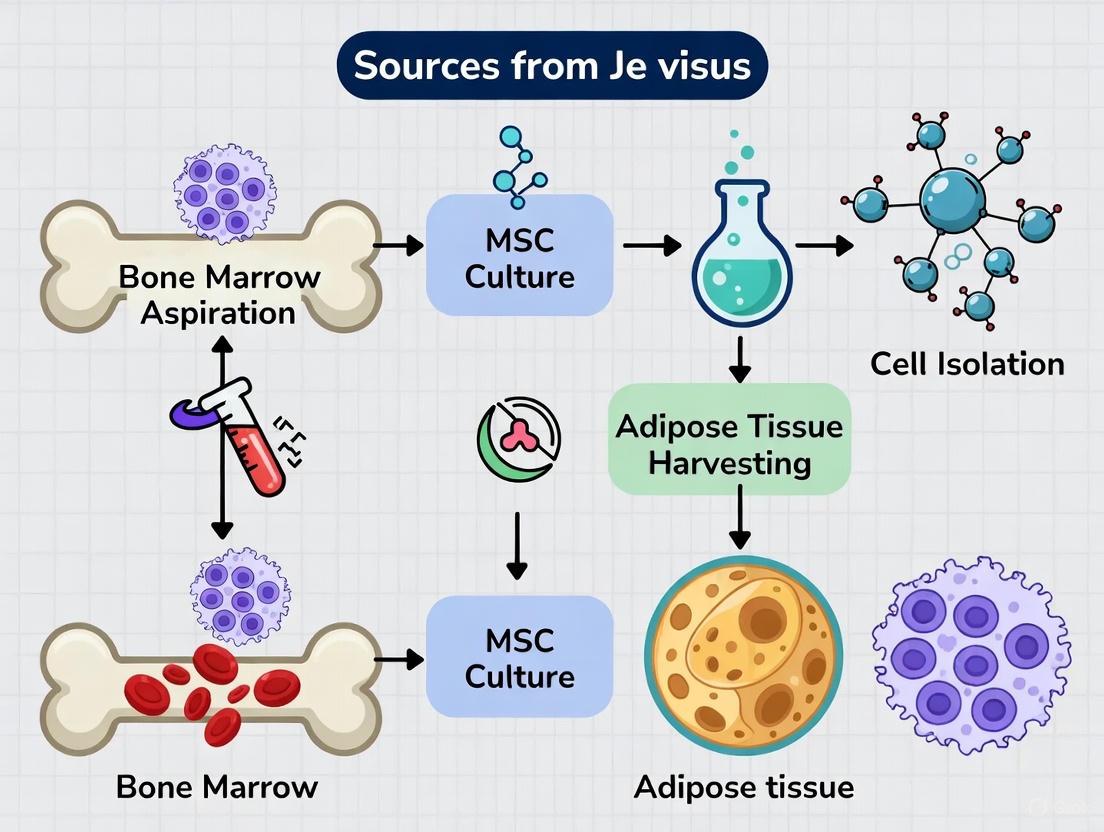

Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD-MSCs), also referred to as adipose-derived stromal cells or adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs), are a population of multipotent progenitor cells residing in adipose tissue. They are a subtype of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) that have garnered significant interest in regenerative medicine due to their accessibility, abundance, and robust regenerative capabilities [17] [18]. According to the latest recommendations from the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT), these cells should be precisely identified by their tissue of origin [19]. AD-MSCs are defined by a triad of key characteristics: their ability to adhere to plastic surfaces under standard culture conditions, specific surface marker expression, and trilineage differentiation potential into adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes in vitro [2] [20].

Within the broader thesis on MSC sources, AD-MSCs present a compelling alternative to the more traditionally studied bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs). While BM-MSCs were the first discovered and are the most extensively characterized, AD-MSCs offer distinct practical advantages, primarily their ease of harvest from abundant adipose tissue and a less invasive isolation procedure, often yielding a higher number of cells per gram of starting tissue [18] [20]. This positions AD-MSCs as a highly viable and efficient cell source for research and clinical applications in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine [21].

Isolation and Culture Protocols

The isolation of AD-MSCs primarily relies on the enzymatic digestion of adipose tissue, a method that allows for the release of the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) containing the stem cells.

Core Isolation Methodology

The standardized protocol for isolating AD-MSCs from human adipose tissue involves a series of critical steps to obtain a viable and pure cell population [19] [22].

Table: Key Steps in the Isolation of Human AD-MSCs

| Step | Description | Key Reagents/Equipment |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Tissue Harvesting | Adipose tissue is obtained via liposuction (e.g., power-assisted) or surgical resection from subcutaneous deposits [19]. | -- |

| 2. Washing & Mincing | Tissue is washed with physiological saline or PBS to remove blood and contaminants, then minced into small fragments [22]. | Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), Antibiotics (e.g., Penicillin/Streptomycin) |

| 3. Enzymatic Digestion | Minced tissue is digested with collagenase (e.g., Type I or II) at 37°C for 30-60 minutes with agitation [19] [22]. | Collagenase Type I/II, Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), Serum |

| 4. Digestion Neutralization | Enzyme activity is halted by adding culture medium supplemented with serum [19] [22]. | Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) |

| 5. Centrifugation | The digest is centrifuged to separate the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) pellet from mature adipocytes and lipids [19] [22]. | Centrifuge |

| 6. Erythrocyte Lysis & Filtration | The SVF pellet is treated with NH4Cl to lyse red blood cells and filtered through a 100 μm sieve [19]. | NH4Cl solution, Cell strainer (70-100 μm) |

| 7. Plating & Culture | The processed SVF is resuspended in growth medium and plated on a tissue culture flask [22]. | Culture flask, DMEM, FBS, Antibiotics |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete isolation and initial characterization workflow for AD-MSCs:

Characterization and Key Properties

Rigorous characterization is essential to confirm the identity and quality of isolated AD-MSCs, following international standards.

Surface Marker Profile

AD-MSCs are defined by a specific immunophenotype. The following table summarizes the positive and negative markers used for their identification via flow cytometry [19] [2] [20].

Table: Standard Surface Marker Profile for Human AD-MSCs

| Marker Category | Specific Markers | Presence | Significance / Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Markers | CD73, CD90, CD105 | ≥ 95% Expression | Core defining markers per ISCT; involved in purinergic signaling (CD73), cell-cell/matrix adhesion (CD90), and angiogenesis (CD105) [2]. |

| Negative Markers | CD11b, CD14, CD19, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR | ≤ 2% Expression | Absence of hematopoietic (CD11b, CD14, CD19, CD34, CD45) and potent immunogenic (HLA-DR) markers [19] [2]. |

| Other Common Markers | CD29, CD44, CD49d | Variable Expression | Associated with adhesion and migration [20]. |

| Other Negative Markers | Stro-1 | Low/Absent Expression | A marker often found on BM-MSCs, typically low on AD-MSCs [20]. |

Trilineage Differentiation Potential

A functional hallmark of AD-MSCs is their ability to differentiate into multiple mesodermal lineages. The standard protocol involves culturing the cells in specific inductive media [22] [20].

Table: Standard Protocols for Trilineage Differentiation of AD-MSCs

| Lineage | Key Inductive Factors | Differentiation Timeline | Common Verification Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adipogenic | Dexamethasone, Indomethacin, IBMX, Insulin [20]. | 14-21 days | Oil Red O staining of lipid vacuoles [22] [20]. |

| Osteogenic | Dexamethasone, Ascorbate-2-phosphate, β-Glycerophosphate [20]. | 14-21 days | Alizarin Red S staining of calcium deposits, Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) activity assay [20]. |

| Chondrogenic | TGF-β (e.g., TGF-β3), Dexamethasone, Ascorbate-2-phosphate, Proline [20]. | 21-28 days | Alcian Blue or Toluidine Blue staining of sulfated proteoglycans in pellet or micromass culture [20]. |

Functional Properties and Comparison with Other MSCs

AD-MSCs are not merely defined by their surface markers but by their potent functional capacities, which are central to their therapeutic application.

Paracrine Signaling and Exosome Biology

The therapeutic effects of AD-MSCs are now largely attributed to their paracrine activity rather than direct cell replacement [19] [18]. They secrete a complex mixture of bioactive molecules, collectively known as the secretome, which includes growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular vesicles (EVs) like exosomes [19]. AD-MSC-derived exosomes carry proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids (e.g., miRNAs) that can modulate recipient cell behavior, promoting processes such as angiogenesis, immunomodulation, and tissue repair [18]. This has led to the emergence of "stem cell-free" therapies utilizing the AD-MSC secretome or exosomes as a potentially safer and more controllable alternative to whole-cell transplants [19] [23].

Key Signaling Pathways

The regenerative and immunomodulatory functions of AD-MSCs are mediated through the activation or inhibition of multiple intracellular signaling pathways [21] [18].

AD-MSCs vs. Bone Marrow MSCs (BM-MSCs)

A donor-matched comparison of AD-MSCs and BM-MSCs reveals both similarities and critical, tissue-specific differences that influence their application [20].

Table: Donor-Matched Comparison of AD-MSCs and BM-MSCs

| Property | AD-MSCs | BM-MSCs | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Source & Accessibility | Abundant subcutaneous fat; minimally invasive harvest (liposuction) [18] [20]. | Iliac crest aspiration; more invasive and painful harvest [20]. | AD-MSCs are often preferred for autologous therapy due to easier access. |

| Cell Yield | High yield of cells per gram of tissue [18]. | Low frequency (0.001-0.01%) in bone marrow aspirate [20]. | AD-MSCs may require less in vitro expansion. |

| Proliferation Rate | Significantly higher proliferation capacity [20]. | Lower proliferation rate [20]. | AD-MSCs can be expanded more rapidly for clinical use. |

| Osteogenic Potential | Moderate | Superior (earlier and higher ALP activity, calcium deposition) [20]. | BM-MSCs may be preferred for bone tissue engineering. |

| Chondrogenic Potential | Moderate | Superior [20]. | BM-MSCs may be preferred for cartilage repair. |

| Adipogenic Potential | Superior (high lipid vesicle formation) [20]. | Moderate | AD-MSCs are inherently primed for adipogenesis. |

| Specific Marker Expression | High CD49d, Low Stro-1 [20]. | Low CD49d, High Stro-1 [20]. | Useful for distinguishing cell origin. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful isolation, culture, and differentiation of AD-MSCs require a suite of validated reagents and materials.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for AD-MSC Work

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Collagenase Type I/II | Enzymatic digestion of the extracellular matrix in adipose tissue to release the Stromal Vascular Fraction (SVF) [22]. | Collagenase from Clostridium histolyticum |

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) | Base nutrient medium for cell culture and expansion [22]. | Low-glucose DMEM |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Essential supplement for cell culture media, providing growth factors, hormones, and attachment factors [22]. | Qualified, lot-tested FBS |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Characterization of cell surface markers to confirm AD-MSC identity (positive and negative markers) [20]. | Antibodies against CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR |

| Trilineage Differentiation Kits | Defined media supplements to induce and support differentiation into adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes [20]. | StemPro Differentiation Kits |

| Trypsin/EDTA | Enzymatic detachment of adherent cells from culture plastic for passaging and sub-culturing [20]. | 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA |

| Dexamethasone | A synthetic glucocorticoid used as a key inductive factor in adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation media [20]. | -- |

The field of regenerative medicine has long relied on bone marrow (BM) and adipose tissue (AT) as primary sources for mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). These cells are defined by their adherence to plastic, specific surface marker expression (CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, CD34-, CD45-, HLA-DR-), and trilineage differentiation potential [2] [3]. However, the search for more accessible, potent, and less immunogenic alternatives has led researchers to investigate perinatal and adult biological materials previously considered medical waste. Umbilical cord (UC), placenta (PL), and menstrual blood-derived MSCs (MenSCs) represent promising alternatives with distinct biological advantages [3] [24] [25]. This review provides a technical comparison of these emerging MSC sources, detailing their isolation, characterization, and therapeutic mechanisms for researchers and drug development professionals.

Source-Specific Characterization and Isolation Protocols

Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells (UC-MSCs)

UC-MSCs are typically isolated from Wharton's jelly, the mucoid connective tissue surrounding the umbilical cord vessels [3]. This source provides a high concentration of MSCs with enhanced proliferative capacity compared to their bone marrow-derived counterparts [26].

Isolation Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Obtain informed consent and collect umbilical cord tissue (approx. 10-15 cm) post-delivery under sterile conditions. Transport in cold (4°C) saline solution supplemented with antibiotics (e.g., Penicillin-Streptomycin).

- Processing: Dissect cord segments to remove blood vessels. Mechanically mince Wharton's jelly into 2-3 mm³ explants.

- Explant Culture: Plate explants in culture-treated flasks with Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)/F12 supplemented with 10-15% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 1% L-glutamine, and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution.

- Outgrowth and Expansion: Maintain at 37°C with 5% CO₂. MSC outgrowth typically occurs within 7-14 days. Passage cells at 80-90% confluence using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA [3] [26].

Placental Mesenchymal Stem Cells (PMSCs)

The placenta contains MSCs within its amnion, chorionic frondosum, and basal decidua regions [3]. PMSCs may exhibit superior proliferative capacity compared to UC-MSCs and demonstrate pronounced immunosuppressive effects on dendritic cells and T cells [3].

Isolation Protocol:

- Tissue Processing: Collect placental tissue under sterile conditions. Separate amnion and chorion layers by blunt dissection.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Mince tissues and digest with 2 mg/mL collagenase type IV and 0.5 mg/mL hyaluronidase for 3-4 hours at 37°C with agitation.

- Cell Recovery: Neutralize enzymes with complete culture medium. Filter cell suspension through 100μm and 70μm cell strainers.

- Culture Establishment: Plate cells at 5×10⁴ cells/cm² in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 5 ng/mL bFGF, and antibiotics. Passage at 80% confluence [3].

Menstrual Blood-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MenSCs)

MenSCs are collected from menstrual effluent containing cellular material shed from the functionalis layer of the endometrium [27] [25]. These cells demonstrate a remarkably high proliferation rate, doubling approximately every 19.4 hours compared to 40-45 hours for BM-MSCs [27].

Isolation Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Utilize menstrual cup (e.g., DivaCup) or specialized collection device (e.g., Instead SoftCup) during first 2-3 days of menstruation.

- Transport Medium: Collect in sterile containers with transport medium containing antibiotics and antifungals.

- Processing: Dilute menstrual blood 1:1 with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Separate mononuclear cells using Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation (800×g for 30 minutes).

- Culture Establishment: Plate cells at 1×10⁵ cells/cm² in DMEM/F12 with 10% FBS, 1% antibiotic-antimycotic. Maintain at 37°C with 5% CO₂. First medium change after 48 hours to remove non-adherent cells [27] [25] [28].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Alternative MSC Sources

| Characteristic | UC-MSCs | PMSCs | MenSCs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Tissue Source | Wharton's Jelly | Amnion, Chorion, Decidua | Endometrial Functional Layer |

| Cell Yield | High (0.5-2×10⁶ cells/cm cord) | Moderate-High (Varies by region) | Moderate (1-5×10⁵ cells/mL effluent) |

| Population Doubling Time | ~30 hours | ~30-40 hours | ~19.4 hours |

| Unique Surface Markers | CD146+ [26] | HLA-G+ (reported in some studies) | Oct-4+, SOX2+, NANOG+ [27] |

| Key Secretory Factors | High HGF, FGF-2, NGF [26] | TGF-β, PGE2 | MMPs, VEGF, Angiogenin |

| Cryopreservation Recovery | >85% | >80% | >90% |

| Special Considerations | ISO/TS 22859-1:2022 standards [3] | Complex tissue composition requires careful isolation | Cyclical availability, can be collected repeatedly |

Experimental Workflow for MSC Characterization

The following diagram illustrates the standard experimental workflow for isolating and characterizing MSCs from alternative sources:

Diagram 1: MSC Isolation and Characterization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Alternative MSC Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | DMEM/F12, α-MEM, MSC-Qualified FBS | Supports MSC expansion while maintaining differentiation potential | UC-MSCs often require specialized supplements (bFGF) for optimal growth [26] |

| Dissociation Reagents | Collagenase Type IV, Hyaluronidase, Trypsin-EDTA | Tissue dissociation and cell passaging | Enzyme concentration and duration vary by tissue source (higher for placenta) |

| Characterization Antibodies | CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR | Flow cytometry immunophenotyping | Essential for ISCT compliance; MenSCs require additional pluripotency markers [2] [27] |

| Differentiation Kits | Osteo-, Chondro-, Adipogenic Induction Media | Trilineage differentiation potential assessment | Standardized kits ensure reproducible differentiation across laboratories |

| Extracellular Vesicle Isolation | Size Exclusion Chromatography, Differential Ultracentrifugation Kits | EV isolation for paracrine effect studies | Critical for investigating MSC-EV therapeutic applications [26] |

| Cryopreservation Solutions | DMSO-based cryoprotectant, Programmable freezer | Long-term cell storage | Maintains viability and functionality during long-term storage |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The therapeutic effects of alternative MSCs are mediated through complex signaling pathways that regulate tissue repair, immunomodulation, and angiogenesis. The following diagram illustrates key mechanistic pathways:

Diagram 2: MSC Therapeutic Mechanism Pathways

UC-MSCs secrete higher levels of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), basic fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), and nerve growth factor (NGF) compared to BM-MSCs and AD-MSCs [26]. HGF stimulates proliferation and exhibits anti-apoptotic and anti-fibrotic properties, while FGF-2 synergizes with VEGF to stimulate angiogenesis. MenSCs demonstrate upregulated expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and angiogenic factors that facilitate tissue remodeling and repair [27].

The immunomodulatory properties vary between sources. AD-MSCs show significantly higher indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and factor H expression, while BM-MSCs demonstrate higher CTLA-4 and IL-10 levels [29]. This suggests source-specific immunomodulatory profiles that may dictate therapeutic suitability for different conditions.

Functional Differences and Preclinical Applications

Table 3: Functional Properties and Research Applications

| Functional Attribute | UC-MSCs | PMSCs | MenSCs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunomodulatory Strength | Potent (low HLA-DR expression) [26] | Pronounced (DC and T-cell suppression) [3] | Moderate (low immunogenicity) [27] |

| Angiogenic Potential | High (VEGF, FGF-2 secretion) [26] | Moderate | High (uterine tissue remodeling) [28] |

| Migration Capacity | High (inflammatory homing) | Moderate | Exceptional (endometrial recruitment) |

| Key Research Applications | Cardiovascular repair, neurological disorders, GvHD [30] | Immune-mediated disorders, tissue engineering | Endometrial regeneration, ovarian restoration, Asherman's syndrome [25] [28] |

| EV Therapeutic Potential | High (similar to parent cells) [26] | Under investigation | High (wound healing, cardiac repair) [27] |

Umbilical cord, placental, and menstrual blood-derived MSCs represent scientifically valid and therapeutically promising alternatives to traditional BM and AT sources. Each source offers distinct advantages: UC-MSCs provide robust proliferation and potent immunomodulation; PMSCs offer unique immunosuppressive properties; and MenSCs deliver exceptional expansion capacity and endometrial homing capabilities [3] [27] [26].

Future research directions should focus on standardizing isolation and characterization protocols across laboratories, particularly for MenSCs and PMSCs where established standards are still evolving. The therapeutic potential of MSC-derived extracellular vesicles represents a particularly promising avenue, potentially offering similar efficacy with reduced regulatory hurdles [27] [26]. As the field advances, understanding the nuanced functional differences between these alternative MSC sources will enable researchers to select optimal cells for specific therapeutic applications, ultimately accelerating the development of effective regenerative therapies.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) represent a cornerstone of regenerative medicine, with their therapeutic potential primarily mediated through three core mechanisms: multipotent differentiation capacity, potent paracrine signaling, and immunomodulation. While bone marrow (BM) has traditionally been the primary source for MSC isolation, adipose tissue (AT) has emerged as a highly accessible and biologically distinct alternative. This technical review provides an in-depth analysis of these mechanistic pillars, presenting structured comparative data between BM-MSCs and AT-MSCs, detailed experimental protocols for functional validation, and visualizations of critical signaling pathways. The synthesis of current research underscores that the choice between MSC sources must be strategically aligned with the specific therapeutic application, whether the goal is tissue regeneration, immunomodulation, or trophic support.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), also termed mesenchymal stromal cells, are fibroblast-like, plastic-adherent cells with multipotent differentiation capacity [31] [32]. The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) has established minimal defining criteria: (1) expression of CD73, CD90, and CD105 surface markers in ≥95% of the population, combined with lack of expression (≤2%) of hematopoietic markers (CD45, CD34, CD14, CD11b, CD79α, CD19, and HLA-DR); (2) plastic adherence under standard culture conditions; and (3) ability to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondroblasts in vitro [20] [32]. While initially isolated from bone marrow, MSCs are now sourced from diverse tissues, including adipose tissue, umbilical cord, and dental pulp [32]. For clinical applications, bone marrow and adipose tissue remain the most extensively studied and utilized sources, each conferring distinct biological advantages and limitations that influence their therapeutic profile [33] [20].

Core Therapeutic Mechanism 1: Multipotent Differentiation

The capacity for trilineage mesodermal differentiation is a functional hallmark of MSCs. However, significant source-dependent variations in differentiation potency directly impact their suitability for specific regenerative applications.

Table 1: Comparative Differentiation Potential of BM-MSCs vs. AT-MSCs

| Differentiation Lineage | BM-MSC Performance | AT-MSC Performance | Key Comparative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osteogenic | High | Moderate | BM-MSCs demonstrate superior calcium deposition, higher Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) activity, and increased expression of osteogenesis-related genes (e.g., osteopontin) [33] [20]. |

| Chondrogenic | High | Moderate | BM-MSCs exhibit a greater capacity to form cartilage matrix and express chondrogenesis-related genes [33] [20]. |

| Adipogenic | Moderate | High | AT-MSCs show significantly greater potential, with more extensive lipid vesicle formation and higher expression of adipogenesis-related genes [33] [20]. |

Experimental Protocol: Trilineage Differentiation

The following standardized in vitro protocols are used to validate MSC multipotency [34].

1. Osteogenic Differentiation:

- Seeding: Plate MSCs at a density of 1.0 x 10^5 cells per well in a fibronectin-coated 6-well plate.

- Culture: Grow cells to 80-90% confluency in growth medium (e.g., MSC Growth Medium 2).

- Induction: Replace growth medium with Osteogenic Differentiation Medium (e.g., PromoCell C-28013), typically containing dexamethasone, ascorbate, and β-glycerophosphate.

- Maintenance: Differentiate for 12-14 days, changing the medium every 72 hours.

- Analysis: Fix cells and stain with Alizarin Red S to detect extracellular calcium deposits, which appear orange-red [34].

2. Adipogenic Differentiation:

- Seeding: Plate MSCs at a density of 1.0 x 10^5 cells per well.

- Culture: Grow to 80-90% confluency.

- Induction: Induce with Adipogenic Differentiation Medium (e.g., PromoCell C-28016), often containing insulin, indomethacin, and dexamethasone.

- Maintenance: Differentiate for 12-14 days, with medium changes every 3 days.

- Analysis: Fix cells and stain with Oil Red O to visualize intracellular lipid droplets, which stain bright red [34].

3. Chondrogenic Differentiation:

- Seeding: Pellet 2.0 x 10^5 MSCs in a 96-well U-bottom suspension plate.

- Spheroid Formation: Incubate for 24-48 hours to allow spontaneous spheroid (micromass) formation.

- Induction: Induce spheroids with Chondrogenic Differentiation Medium (e.g., PromoCell C-28012), typically containing TGF-β3.

- Maintenance: Differentiate for 21 days, changing medium every 3 days.

- Analysis: Fix spheroids and stain with Alcian Blue to detect sulfated proteoglycans in the cartilage matrix, which stain dark blue [34].

Diagram 1: Trilineage differentiation workflow for MSCs.

Core Therapeutic Mechanism 2: Paracrine Signaling

The primary therapeutic benefits of MSCs are now largely attributed to their potent paracrine activity, rather than direct engraftment and differentiation [31] [35]. MSCs secrete a complex mixture of bioactive factors—collectively known as the "secretome"—including growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular vesicles, which orchestrate tissue repair by modulating local cellular responses [31] [35].

Table 2: Key Secretome Factors and Their Therapeutic Roles

| Secreted Factor Category | Example Molecules | Primary Therapeutic Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Factors | HGF, bFGF, IGF-1, VEGF | Angiogenesis, anti-apoptosis, cell proliferation, and chemoattraction [33] [31]. |

| Cytokines | IL-6, IFN-γ | Immunomodulation, macrophage polarization [33] [36]. |

| Chemokines | SDF-1 | Stem cell homing and recruitment [33]. |

| Immunomodulatory Mediators | PGE2, IDO, TGF-β1 | Suppression of T-cell proliferation, induction of Tregs [32] [36]. |

The composition of the secretome is highly dynamic and influenced by the MSC tissue source and the local microenvironment. For instance, AT-MSCs secrete higher levels of bFGF, IFN-γ, and IGF-1, while BM-MSCs secrete more SDF-1 and HGF [33]. Furthermore, the secretome is not static; it is dynamically shaped by the inflammatory cues in the immediate tissue microenvironment, allowing MSCs to respond in a context-specific manner [35].

Core Therapeutic Mechanism 3: Immunomodulation

MSCs possess broad immunomodulatory properties that suppress adaptive and innate immune responses, making them potent therapeutic agents for autoimmune diseases and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) [37] [38] [36]. This immunomodulation is mediated through direct cell-cell contact and the secretion of soluble factors.

Mechanisms of Action on Immune Cells

- T-Lymphocytes: MSCs suppress the proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and shift the balance from a pro-inflammatory Th1 profile (IFN-γ) to an anti-inflammatory Th2 profile (IL-4) [32] [36]. A key mechanism is the promotion of Regulatory T cells (Tregs), which are induced by MSC-secreted factors like PGE2 and TGF-β, and via interactions with MSC-primed monocytes [36].

- Monocytes/Macrophages: MSCs drive the polarization of macrophages from a pro-inflammatory (M1) to an anti-inflammatory, tissue-reparative (M2) phenotype. This is achieved through the secretion of PGE2, IL-6, and IL-1RA [36]. Notably, even the phagocytosis of apoptotic or dead MSCs by monocytes can induce this anti-inflammatory polarization [38] [36].

- Dendritic Cells (DCs): MSCs inhibit the maturation and antigen-presenting capacity of DCs, reducing their ability to activate T cells [36].

- B-Lymphocytes and NK Cells: MSCs inhibit B cell proliferation and antibody production, and suppress the proliferation and cytotoxic activity of Natural Killer (NK) cells [32].

Viability-Independent Effects

Remarkably, the immunomodulatory function of MSCs is not solely dependent on cell viability. Apoptotic, metabolically inactivated, and fragmented MSCs have also demonstrated significant immunomodulatory potential, primarily through mechanisms involving phagocytosis by monocytes [38] [36]. This finding has important implications for safety and the development of cell-free therapeutic products.

Diagram 2: MSC immunomodulation mechanisms on innate and adaptive immunity.

Comparative Analysis: Bone Marrow vs. Adipose Tissue MSCs

Direct, donor-matched comparisons are essential for elucidating the intrinsic differences between BM-MSCs and AT-MSCs, minimizing donor-dependent variability [20].

Table 3: Head-to-Head Comparison of BM-MSCs and AT-MSCs

| Biological Characteristic | BM-MSCs | AT-MSCs | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source Availability | Limited, invasive harvest [20] | Abundant, minimally invasive harvest [20] [39] | AT-MSCs allow for larger cell yields with lower donor morbidity. |

| Proliferation Rate | Lower population doubling [33] | Significantly higher proliferative potential [33] [20] | AT-MSCs reach therapeutic cell numbers faster, advantageous for autologous therapy. |

| Immunophenotype (Typical) | CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, Stro-1+ [20] | CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, CD49d+, Stro-1low [20] | Surface marker Stro-1 and CD49d may be useful for source identification. |

| Osteogenic Potential | High [33] [20] | Moderate [33] [20] | BM-MSCs may be preferred for bone regeneration applications. |

| Chondrogenic Potential | High [33] [20] | Moderate [33] [20] | BM-MSCs may be superior for cartilage repair. |

| Adipogenic Potential | Moderate [33] [20] | High [33] [20] | AT-MSCs are the benchmark for adipogenic studies. |

| Immunomodulatory Capacity | Potent [33] | More potent in some studies [33] | AT-MSCs may offer enhanced suppression of immune responses. |

| Key Secreted Factors | Higher SDF-1, HGF [33] | Higher bFGF, IFN-γ, IGF-1 [33] | Secretome profile dictates suitability for specific paracrine applications. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for MSC Research

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Standard supplement for basal culture medium provides growth factors and adhesion factors [37]. | Routine expansion of MSCs. |

| Human Platelet Lysate (hPL) | Xeno-free, human-derived FBS alternative; enhances MSC proliferation and is suitable for clinical-grade expansion [33] [37]. | Clinical-scale expansion of MSCs for therapeutic applications. |

| Recombinant Human FGF-2 | Growth factor supplement that decreases population doubling time and increases expansion efficiency [37]. | Enhancing proliferation rates during in vitro culture. |

| Collagenase Type I/IV | Enzymatic digestion of tissues (e.g., adipose tissue, bone marrow) to isolate the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) containing MSCs [33] [20]. | Initial isolation of MSCs from raw tissue. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Characterization of MSC immunophenotype per ISCT criteria (CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, etc.) [33] [20]. | Quality control and validation of MSC identity. |

| Trilineage Differentiation Kits | Pre-formulated media containing inducters for osteogenesis, adipogenesis, and chondrogenesis [34]. | Functional validation of MSC multipotency. |

| Cell Culture-grade Heparin | Anticoagulant required for culture media supplemented with hPL to prevent gel formation [33]. | Essential when using hPL-supplemented media. |

The therapeutic efficacy of MSCs is a multifaceted interplay of their multipotent differentiation capacity, dynamic paracrine signaling, and context-dependent immunomodulation. The strategic choice between BM-MSCs and AT-MSCs is not a matter of superiority, but rather of matching the biological strengths of each cell source to the specific therapeutic goal. BM-MSCs, with their robust osteogenic and chondrogenic potential, may be the source of choice for orthopedic applications. In contrast, the high proliferative yield, potent immunomodulation, and strong adipogenic capacity of AT-MSCs make them an excellent candidate for treating inflammatory conditions and for soft tissue engineering. A deep understanding of these core mechanisms, coupled with standardized functional assays and a recognition of source-specific attributes, is paramount for advancing the next generation of MSC-based therapies from the laboratory to the clinic.

From Bench to Bedside: Isolation, Expansion, and Therapeutic Applications

Standardized Protocols for Isolating and Expanding BM-MSCs and AD-MSCs

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) have emerged as powerful tools in regenerative medicine due to their self-renewal capacity, multilineage differentiation potential, and immunomodulatory properties [2]. According to the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT), MSCs are defined by three key criteria: adherence to plastic under standard culture conditions; expression of specific surface markers (CD73, CD90, CD105 ≥95%; lack of hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45, CD14/CD11b, CD79α/CD19, HLA-DR ≤2%); and tri-lineage differentiation potential into osteocytes, adipocytes, and chondrocytes in vitro [2] [3]. While MSCs can be isolated from various tissues, including umbilical cord, placenta, and dental pulp, bone marrow and adipose tissue represent the most extensively studied and clinically utilized sources [9] [3]. This whitepaper provides a detailed technical guide to the standardized protocols for isolating and expanding bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) and adipose-derived MSCs (AD-MSCs), framing these methodologies within the broader context of MSC source selection for research and therapeutic development.

Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs (BM-MSCs): Isolation and Expansion

Isolation Techniques for BM-MSCs

Bone marrow represents the most established source of MSCs, though BM-MSCs are present at a low frequency of approximately 0.001%–0.01% of bone marrow mononuclear cells, necessitating effective isolation and expansion protocols [13]. The standard isolation approaches include:

- Bone Marrow Aspiration: Bone marrow is typically aspirated from the donor's posterior iliac crest using a Jamshidi needle into a heparin-containing syringe to prevent coagulation [40]. Aspiration volumes should be limited to approximately 2 mL per site to avoid peripheral blood dilution [40].

- Density Gradient Centrifugation: This method enriches the mononuclear cell fraction using media such as Ficoll or Percoll with densities of 1.073–1.077 g/mL [40] [9]. The automated Sepax cell separation system has demonstrated enhanced mononuclear cell recovery compared to manual Ficoll separation, improving standardization [40].

- Direct Plating Method: As an alternative to density gradient separation, the direct plating strategy separates plastic-adherent MSCs from non-adherent hematopoietic cells through adherence capability [40]. While this method often results in initial hematopoietic contamination, subsequent passaging efficiently removes non-MSC populations [40]. Recommended plating densities range from 4–22 × 10³ bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs)/cm² [40].

Table 1: Comparison of BM-MSC Isolation Methods

| Method | Procedure | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Gradient Centrifugation | Separation using Ficoll/Percoll | Reduces hematopoietic cell contamination | Requires additional equipment and processing time |

| Direct Plating | Immediate plating of BM aspirate | Simpler, fewer processing steps | Initial hematopoietic contamination |

| Whole Bone Marrow Culture | Culturing flushed marrow with fat mass [41] | Minimal disturbance to MSC niche | Specific to mouse model research |

For mouse BM-MSC isolation, a specialized protocol involves flushing bones with complete α-MEM medium and culturing the entire marrow content, including fat mass, without filtering or washing, thereby maintaining MSCs in their initial niche with minimal disturbance [41]. This method has demonstrated success across multiple mouse strains without requiring additional growth factors or cell sorting techniques [41].

Expansion and Culture of BM-MSCs

Once isolated, BM-MSCs require ex vivo expansion to achieve clinically relevant numbers. Key considerations for expansion include:

- Basal Media: Various basal media are employed, with α-MEM and DMEM being the most common [40] [13]. The critical component remains the serum supplement, which significantly influences MSC growth and functionality.

- Serum Considerations: Traditional MSC expansion relies on fetal bovine serum (FBS), though it presents significant safety concerns including risk of xenogenic immune reactions and transmission of infectious agents [40] [13]. Regulatory agencies increasingly discourage FBS use in clinical applications, driving the adoption of human alternatives like human platelet lysate (hPL), which demonstrates superior growth-promoting properties while mitigating xenogenic risks [40] [13].

- Serum-Free Media (SFM): Commercially available SFM formulations (e.g., StemMACS MSC XF, MSC NutriStem XF) support BM-MSC expansion while addressing regulatory concerns [13]. These defined media eliminate batch-to-batch variability and enhance manufacturing consistency, though they require validation for specific MSC sources and applications [13].

Table 2: BM-MSC Expansion Media Comparison

| Media Type | Examples | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Standard FBS | Well-characterized, widely used | Xenogenic risk, batch variability |

| Human Platelet Lysate (hPL) | PLTMax hPL | Human-derived, superior growth | Variable composition, requires pooling |

| Serum-Free/Xeno-Free Media | StemMACS MSC XF, MSC NutriStem XF | Defined composition, regulatory compliance | May require adaptation, cell-specific |

Research indicates that BM-MSCs expanded in SFM maintain characteristic surface marker expression, though parameters such as population doubling time, cell yield, differentiation potential, and immunosuppressive properties may vary between formulations [13]. BM-MSCs cultured in RoosterNourish (containing 1% FBS) and RoosterNourish-MSC XF typically appear spindle-shaped and elongated, while those in StemMACS MSC XF and MSC NutriStem XF present as spindle-shaped but shorter and thicker compared to control cultures [13].

Figure 1: BM-MSC Isolation and Expansion Workflow

Adipose-Derived MSCs (AD-MSCs): Isolation and Expansion

Isolation Techniques for AD-MSCs

Adipose tissue represents an abundant source of MSCs, with frequencies potentially 100–1,000 times higher than those in bone marrow [40]. The isolation process involves multiple steps:

- Tissue Harvesting: Adipose tissue is typically obtained through liposuction procedures, with smaller volumes collected via syringe aspiration or excision [40]. Tumescent liposuction involving pre-infusion of saline solutions with anesthetics and vasoconstrictors is common, though ultrasound-assisted liposuction may compromise MSC recovery and expansion capacity [40].

- Processing and Enzymatic Digestion: The lipoaspirate undergoes extensive washing to remove cellular debris, oil, blood cells, and extracellular matrix components [40]. The tissue is then digested with collagenase enzymes (typically 0.075% collagenase type I or II) at 37°C with agitation for 30-60 minutes [9].

- Stromal Vascular Fraction (SVF) Separation: Following digestion, the tissue is centrifuged to separate the mature adipocytes (floating layer) from the stromal vascular fraction (pellet) [40]. The SVF represents a heterogeneous cell mixture containing endothelial cells, pericytes, fibroblasts, and AD-MSCs [40].

- Plastic Adherence: The SVF is plated on culture vessels, allowing AD-MSCs to adhere while removing non-adherent cells through medium changes [40]. Approximately 1:1,000 cells within the SVF give rise to colony-forming units-fibroblastic (CFU-F), indicative of MSC frequency [40].

Automated closed systems have been developed for clinical-scale AD-MSC isolation, performing aspiration, washing, and SVF concentration at the patient's bedside, enhancing standardization and reducing contamination risk [40].

Expansion and Culture of AD-MSCs

AD-MSC expansion follows principles similar to BM-MSCs, with some distinct considerations:

- Culture Media: AD-MSCs proliferate effectively in standard MSC media such as DMEM or α-MEM supplemented with either FBS or human alternatives like platelet lysate [40]. Studies indicate that AD-MSCs from young, healthy donors can demonstrate rapid population doubling, potentially twice the rate observed in BM-MSCs [3].

- Morphological Characteristics: AD-MSCs typically exhibit a fibroblast-like, spindle-shaped morphology similar to BM-MSCs, though subtle differences in growth patterns and cell size may be observed [13].

- Donor Considerations: Unlike BM-MSCs, AD-MSC quantity and quality appear less affected by donor age and comorbidities such as obesity, renal failure, or vascular disease [40].

Figure 2: AD-MSC Isolation and Expansion Workflow

Comparative Analysis: BM-MSCs vs. AD-MSCs

Biological and Functional Comparisons

Understanding the relative advantages and limitations of BM-MSCs and AD-MSCs informs appropriate source selection for specific applications:

- Frequency and Accessibility: AD-MSCs exist at significantly higher frequencies in their native tissue compared to BM-MSCs (approximately 1-2% of nucleated cells in adipose tissue versus 0.001%-0.01% in bone marrow) [40] [13]. While AD-MSC harvesting is less invasive, bone marrow aspiration remains a well-tolerated procedure [16].

- Proliferation Capacity: Studies conflict regarding comparative proliferation rates, though some indicate AD-MSCs may proliferate faster than BM-MSCs, potentially reducing time to achieve target cell numbers [3] [16].

- Differentiation Potential: Both cell types demonstrate tri-lineage differentiation, though subtle lineage-specific biases exist. AD-MSCs may exhibit enhanced adipogenic propensity, while BM-MSCs often show superior osteogenic capacity [16].

- Immunomodulatory Properties: The immunomodulatory capacities of both MSC types are well-established, though direct comparative studies show conflicting results regarding their relative potency [16]. In vitro studies suggesting superior immunosuppression by AD-MSCs have not consistently translated to in vivo models [16].

- Transcriptional and Secretory Profiles: Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses reveal differences in gene expression patterns and secretory profiles between BM-MSCs and AD-MSCs, which may influence their functional applications [16].

Table 3: Functional Comparison of BM-MSCs and AD-MSCs

| Parameter | BM-MSCs | AD-MSCs |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Frequency | 0.001%-0.01% [13] | 1-2% (of nucleated cells) [40] |

| Harvesting Procedure | Bone marrow aspiration [40] | Liposuction/aspiration [40] |

| Osteogenic Potential | Strong [16] | Moderate [16] |

| Adipogenic Potential | Moderate [16] | Strong [16] |

| Clinical Trial Experience | Extensive (10 approved therapies) [3] | Limited (2 approved therapies) [3] |

| Regulatory Status | Well-established pathway [42] | Less established [16] |

Technical and Regulatory Considerations

From a technical and regulatory perspective, several factors distinguish these MSC sources:

- Manufacturing Standardization: BM-MSC manufacturing benefits from longer development history and established international standards (ISO/TS 24651:2022) [3]. Multiple clinical trials have successfully manufactured BM-MSCs according to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards for bone regeneration and other applications [42].

- Product Characterization: BM-MSCs typically demonstrate strong expression of standard MSC markers (CD44, CD90) with negative expression of hematopoietic markers (CD45, CD31) [41]. Both cell types must meet ISCT criteria for surface marker expression, though subtle differences in marker intensity or additional markers may occur.

- Donor Variability: BM-MSC quantity and quality are influenced by donor age, with younger donors generally providing more robust cells [3]. AD-MSCs appear less affected by donor age and comorbidities, potentially offering more consistent cell products across diverse donor populations [40].

- Therapeutic Applications: Sixteen MSC therapies have been approved worldwide: ten derived from bone marrow, three from umbilical cord, two from adipose tissue, and one from umbilical cord blood [3]. This disparity reflects both historical development and regulatory familiarity with BM-MSCs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for MSC Isolation and Expansion

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|