Combating Stem Cell Senescence: Molecular Mechanisms, Preventive Strategies, and Clinical Applications in Replicative Aging

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of stem cell senescence as a key driver of replicative aging and age-related dysfunction.

Combating Stem Cell Senescence: Molecular Mechanisms, Preventive Strategies, and Clinical Applications in Replicative Aging

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of stem cell senescence as a key driver of replicative aging and age-related dysfunction. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental molecular pathways including lysosomal dysfunction, epigenetic remodeling, and the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). The scope extends to cutting-edge interventional strategies such as senolytics, senomorphics, and niche modulation, while critically evaluating methodological challenges, optimization techniques, and comparative efficacy of therapeutic approaches. The synthesis of foundational science with translational applications offers a roadmap for developing effective anti-aging interventions and enhancing the efficacy of cell-based therapies.

Decoding the Hallmarks: Molecular Drivers and Biomarkers of Stem Cell Senescence

Technical Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: Our data shows that inhibiting lysosomal hyperacidicity in aged hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) does not consistently reduce interferon-inflammatory signatures. What could explain this?

- Potential Cause 1: Incomplete lysosomal suppression. The v-ATPase inhibitor concentration or exposure time may be insufficient. Lysosomal hyperacidity in aged HSCs is a robust phenotype, and partial inhibition may not adequately restore lysosomal integrity and downstream metabolic homeostasis [1] [2].

- Potential Cause 2: Persistent mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) leakage. The cGAS-STING pathway is triggered by misprocessed mtDNA. If lysosomal inhibition does not fully restore the processing of this DNA, inflammatory signaling may persist [1] [3].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm the efficacy of your v-ATPase inhibitor using a lysosomal pH indicator (e.g., LysoSensor) to ensure a consistent shift towards a more neutral pH in treated aged HSCs [4].

- Quantify the levels of cytosolic mtDNA via qPCR or immunofluorescence for double-stranded DNA in your treated samples to verify clearance.

- Use a specific STING inhibitor as a positive control to confirm that the inflammatory pathway is indeed cGAS-STING dependent.

Q2: When attempting to replicate the rejuvenation of aged HSCs via lysosomal inhibition, we observe high cell death ex vivo. How can the protocol be optimized?

- Potential Cause: Excessive lysosomal suppression. While slowing lysosomal degradation is beneficial, complete inhibition of this essential organelle is toxic. The "slow degradation" mode is crucial, not a full blockade [1] [2].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Perform a dose-response curve for the v-ATPase inhibitor. The goal is to find a concentration that reduces hyperacidity and inflammation without inducing widespread cell death.

- Shorten the treatment duration. The cited study achieved an over eightfold boost in repopulation capacity with ex vivo treatment before transplantation, suggesting a finite, pre-transplantation incubation period is sufficient [1] [2].

- Supplement the culture medium with growth factors and cytokines to support cell survival during the stress of lysosomal modulation.

Q3: How can we reliably distinguish lysosomal hyperactivation in aged stem cells from general autophagy upregulation?

- Solution: A multi-parametric assay is required, as hyperactivation is characterized by more than just increased degradative flux.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Measure Lysosomal Activity and pH: Use LysoTracker (stains active lysosomes) in conjunction with a pH-sensitive probe like LysoSensor. Aged HSCs show increased LysoTracker signal coupled with hyperacidity (lower pH) [1] [4].

- Assess Lysosomal Integrity: Evaluate lysosomal membrane permeabilization (e.g., via Galectin-3 puncta assay). Dysfunctional, hyperactive lysosomes in aged HSCs are more prone to damage and leakage [1].

- Analyze Autophagy Flux: Use an LC3 turnover assay (with and without bafilomycin A1). This helps determine if the observed lysosomal activity is coupled to complete autophagic degradation, which may be impaired despite lysosomal hyperactivation [5].

Q4: Are lysosomal dysfunctions consistent across different types of aged stem cells?

- Evidence from Other Systems: While the core principles may be shared, specific manifestations can vary. Research on Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) has also identified lysosomal acidification dysfunction as a key driver of senescence. In MSCs, this often presents as a loss of acidity and a decline in function, contrasting with the hyperacidity reported in HSCs [4]. This suggests stem cell type-specific contexts are critical.

- Recommendation: Always establish a baseline lysosomal phenotype (pH, activity, mass) for your specific stem cell population and age model before designing interventions.

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol: Assessing Lysosomal pH and Activity in Aged Stem Cells

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate lysosomal hyperacidity and hyperactivity in aged HSCs versus young controls.

Materials:

- Young and aged HSCs (e.g., from 2-3 month and 22-24 month old mice, respectively).

- LysoSensor Green DND-189 (or similar pH-sensitive dye).

- LysoTracker Red DND-99 (or similar acidotropic dye).

- Flow cytometry buffer.

- Flow cytometer.

Method:

- Isolate and purify HSCs (Lin− Sca1+ cKit+ CD48− CD150+ phenotype) from young and aged mice via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [1].

- Resuspend the HSCs in pre-warmed buffer.

- Load cells with LysoSensor Green (50 nM) and LysoTracker Red (50 nM) for 20-30 minutes at 37°C.

- Wash cells twice to remove excess dye.

- Analyze immediately via flow cytometry. Use the geometric mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for quantification.

- Expected Result: Aged HSCs will show a significantly higher LysoSensor signal (indicating lower pH) and an elevated LysoTracker signal (indicating increased lysosomal mass/activity) compared to young HSCs [1] [4].

Protocol: Evaluating Functional Rejuvenation via Transplantation Assay

Objective: To test the functional capacity of aged HSCs following lysosomal inhibition.

Materials:

- Aged HSCs (vehicle-treated control group).

- Aged HSCs treated with v-ATPase inhibitor (e.g., Bafilomycin A1 at optimized concentration).

- Young HSCs (positive control).

- Congenic recipient mice (e.g., CD45.1+).

Method:

- Treat aged HSCs with a v-ATPase inhibitor ex vivo for a defined period (e.g., 16-24 hours) [2].

- Mix treated aged HSCs, control aged HSCs, and young HSCs with competitor bone marrow cells.

- Transplant the mixture into lethally irradiated congenic recipient mice via intravenous injection.

- Monitor peripheral blood chimerism at 4, 8, 16, and 24 weeks post-transplantation using flow cytometry to detect donor-derived (e.g., CD45.2+) myeloid and lymphoid cells.

- Expected Result: The v-ATPase inhibitor-treated aged HSCs will show a significantly higher long-term repopulation capacity and a more balanced lineage output (improved lymphopoiesis) compared to the untreated aged HSCs, approaching the performance of young HSCs [1] [2].

The following table consolidates key quantitative findings from recent research on lysosomal dysfunction in aged hematopoietic stem cells.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings in Aged HSCs with Lysosomal Dysfunction

| Parameter | Change in Aged HSCs (vs. Young) | Functional Impact | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysosomal Acidity | Increased (Hyperacidic) | Disrupts metabolic/epigenetic homeostasis; triggers inflammation. | [1] [2] |

| Lysosomal Integrity | Decreased (Damaged/Leaky) | Impaired degradation capacity and organelle function. | [1] |

| cGAS-STING Signaling | Activated | Drives interferon-driven inflammatory programs. | [1] [3] |

| Repopulation Capacity | Decreased | Poor transplantation and self-renewal ability. | [1] |

| Repopulation Post v-ATPase inhibition | >8-fold increase | Restores regenerative potential and self-renewal. | [1] [2] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Lysosomal Dysfunction Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| V-ATPase Inhibitor (e.g., Bafilomycin A1) | Inhibits vacuolar (H+) ATPase proton pump. | Suppresses lysosomal hyperacidity to restore lysosomal integrity and metabolic homeostasis in aged HSCs [1] [2]. |

| LysoSensor Probes | pH-sensitive fluorescent dyes. | Quantitative measurement of lysosomal pH to identify hyperacidity in aged HSCs [4]. |

| LysoTracker Probes | Fluorescent dyes that accumulate in acidic organelles. | Staining and tracking of active lysosomes; indicates lysosomal mass and activity [1]. |

| cGAS/STING Inhibitors | Pharmacologically inhibits cGAS or STING proteins. | Validates the role of the mtDNA-cGAS-STING axis in driving age-related inflammation in HSCs [1] [3]. |

| Anti-CD150 Antibody | Recognizes SLAM family receptor CD150. | Identifies and isolates phenotypic long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs), which are enriched in aged mice [1]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

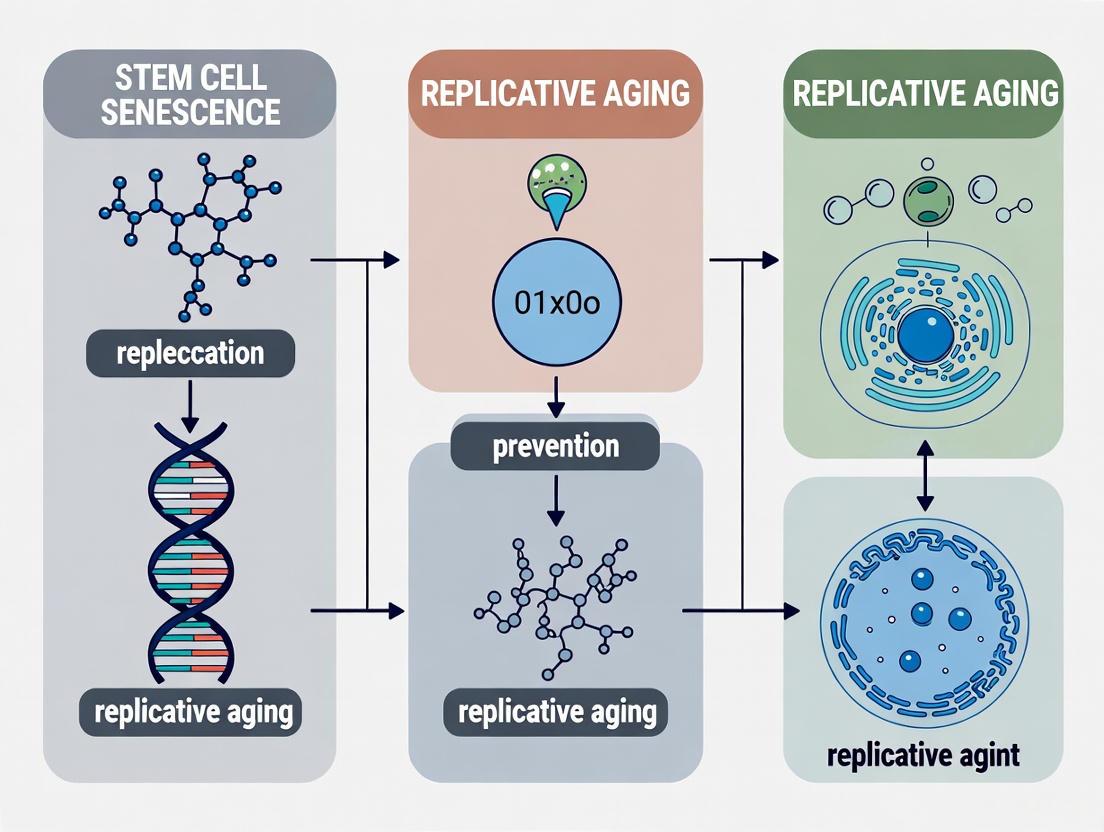

Diagram 1: Lysosomal Dysfunction Drives HSC Aging via cGAS-STING

Diagram 2: Workflow for Reversing HSC Aging

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges in Senescence Research

This guide addresses frequent issues researchers encounter when studying senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF) and the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).

Table 1: Troubleshooting SAHF and SASP Analysis

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak or absent SAHF formation | Incorrect senescence model (e.g., using RS in mouse fibroblasts); Insufficient senescence induction time. | Validate senescence with multiple markers (SA-β-Gal, p16, p21). Use OIS models (e.g., oncogenic RAS in IMR90) for robust SAHF. Ensure adequate induction time (days for OIS, weeks for RS). | [6] [7] [8] |

| Inconsistent SASP expression | Heterogeneous senescent cell populations; Variability between senescence inducers (OIS vs. RS). | Use FACS to sort for SA-β-Gal+ cells. Characterize the specific SASP profile for your model via cytokine array. Confirm NF-κB and C/EBPβ activation. | [6] [9] [10] |

| Difficulty visualizing cytoplasmic chromatin fragments (CCFs) | Low sensitivity of DNA staining; CCFs degraded during protocol. | Use high-sensitivity immunofluorescence (IF) for cytoplasmic DNA. Combine with cGAS/STING pathway markers for functional validation. | [6] [10] |

| SAHF formation but no SASP upregulation | SASP gene loci incorporated into repressive SAHF. | Verify exclusion of key SASP loci (e.g., IL6, IL8) from SAHF via immuno-FISH. Check HMGB2 levels, as its depletion can silence SASP genes. | [6] [9] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Are SAHF required for the stable cell cycle arrest in senescence? No, SAHF are not strictly necessary for growth arrest. While they help silence proliferation-promoting genes like CCNA2 and CDK1, the arrest is primarily enforced by the p53/p21 and p16/Rb pathways. Disrupting SAHF via HIRA depletion can impair the SASP without fully reversing arrest [6] [10].

Q2: Why do my primary mouse fibroblasts not form punctate SAHF upon senescence induction? Robust, punctate SAHF are primarily a feature of oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) in human fibroblast lines like IMR90 and WI-38. Mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) and replicative senescence (RS) models often fail to form them, instead showing other heterochromatin rearrangements like senescence-associated distension of satellites (SADS) [6] [8].

Q3: What is the functional connection between cytoplasmic chromatin fragments (CCFs) and the SASP? CCFs are released from the nucleus of senescent cells into the cytoplasm. There, they are recognized by the innate immune DNA sensor cGAS. This activates the STING pathway, leading to the induction of the transcription factor NF-κB, a master regulator of the inflammatory SASP [6] [9] [10].

Q4: How can I specifically inhibit the SASP without affecting the senescence growth arrest? This is the goal of senomorphic therapies. Potential strategies include:

- Using small-molecule inhibitors of key SASP regulators like the NF-κB or p38 MAPK pathways.

- Targeting upstream regulators like the cGAS-STING axis [9].

- Inhibiting chromatin regulators that specifically control SASP genes, such as the H3K4 methyltransferase MLL1 [9].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying SAHF via Immunofluorescence and Image Analysis

This protocol is optimized for OIS in IMR90 human lung fibroblasts.

- Key Reagents: Antibodies against H3K9me3 (constitutive heterochromatin core) and H3K27me3 (facultative heterochromatin ring) [7].

- Procedure:

- Induce Senescence: Transduce cells with a vector expressing oncogenic HRAS (e.g., HRASG12V).

- Fix and Permeabilize: At day 6-8 post-induction, fix cells with 4% PFA and permeabilize with 0.5% Triton X-100.

- Stain Chromatin: Incubate with primary antibodies (anti-H3K9me3 and anti-H3K27me3), followed by fluorescent secondary antibodies. Counterstain DNA with DAPI.

- Image and Analyze: Acquire high-resolution confocal images. Quantify the percentage of cells with >5 distinct, DAPI-dense nuclear foci that show the characteristic concentric structure (H3K9me3 core, H3K27me3 ring) [7] [8].

Protocol 2: Inhibiting SASP via MLL1 Inhibition

This protocol tests the role of H3K4me3 in SASP regulation.

- Key Reagents: MLL1 complex inhibitor (e.g., MI-2-2) [9].

- Procedure:

- Induce Senescence: Establish OIS or TIS (e.g., 10 µM Etoposide for 72 hours) in IMR90 cells.

- Apply Inhibitor: Treat senescent cells with the MLL1 inhibitor (e.g., 1-10 µM MI-2-2) for 48 hours. Include a DMSO vehicle control.

- Assay SASP Output:

- Molecular: Perform ChIP-qPCR for H3K4me3 at SASP gene promoters (e.g., IL6, IL8). Expect a significant reduction with inhibitor treatment.

- Secreted: Collect conditioned media and analyze IL-6 and IL-8 levels by ELISA.

- Functional: Test the conditioned media on a cancer cell line (e.g., BJeH) invasion assay; media from inhibitor-treated senescent cells should have reduced pro-invasive capacity [9].

Visualizing Key Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram 1: Chromatin Reorganization and SASP Regulation in Senescence

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for SASP Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Studying Senescence Epigenetics

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Application in Senescence Research | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIRA sh/siRNA | Depletes HIRA histone chaperone | Disrupts SAHF formation; used to study SAHF's role in SASP and arrest [6]. | siRNA pools |

| HMGB2 Antibody | Detects/Depletes HMGB2 protein | Used in IF, WB; depletion studies show its role in protecting SASP genes from heterochromatin silencing [6] [7]. | Commercial mAb |

| cGAS/STING Inhibitors | Inhibits cytoplasmic DNA sensing | Tests the contribution of the cGAS-STING pathway to SASP initiation (e.g., H-151 for STING) [6] [9]. | H-151, RU.521 |

| MLL1 Inhibitor | Inhibits H3K4 methylation | Specifically reduces H3K4me3 at SASP gene promoters, suppressing their expression (senomorphic effect) [9]. | MI-2-2 |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Inhibits histone deacetylases | Induces a SASP independent of DNA breaks; used to study chromatin-based SASP regulation [10] [11]. | Trichostatin A |

| Antibody: H3K9me3 | Marks constitutive heterochromatin | Key marker for IF analysis of SAHF core structure [6] [7]. | Commercial mAb |

| Antibody: H3K27me3 | Marks facultative heterochromatin | Key marker for IF analysis of SAHF outer ring [6] [7]. | Commercial mAb |

FAQs on Core Concepts & Mechanisms

Q1: How does telomere attrition lead to genomic instability in aging stem cells?

Telomere attrition acts as a persistent form of DNA damage that triggers genomic instability. Telomeres are protective caps at chromosome ends, and their shortening occurs with each cell division in the absence of telomerase. Critically short telomeres are recognized by the cell as double-strand breaks, initiating a DNA damage response (DDR). This can lead to cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, or cellular senescence. In stem cells, this process depletes the functional reservoir, impairing tissue maintenance and regeneration [12]. The dysfunctional telomeres also lose the protection of the shelterin complex, leading to end-to-end chromosome fusions and genomic rearrangements that further drive instability [13].

Q2: What is the role of the cGAS-STING pathway in sensing genomic instability?

The cGAS-STING pathway is a major cytosolic DNA sensor that connects genomic instability to inflammatory signaling. When genomic or mitochondrial DNA leaks into the cytoplasm—a common consequence of DNA damage and nuclear envelope rupture in micronuclei—it is bound by cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase (cGAS). cGAS produces the second messenger 2'3'-cGAMP, which activates STING (Stimulator of Interferon Genes). Activated STING triggers TBK1 and IRF3 phosphorylation, leading to the production of type I interferons and other pro-inflammatory cytokines. This establishes a link between DNA damage, innate immunity, and the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [14] [15] [16].

Q3: What are the primary sources of cytosolic DNA that activate cGAS in senescent cells?

The two major sources are:

- Micronuclei: These are small, DNA-containing organelles that form due to chromosome missegregation or fragmentation after genotoxic stress. The nuclear envelope of micronuclei is fragile and often ruptures, exposing self-DNA to the cytosol where it is sensed by cGAS [14].

- Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA): Mitochondrial dysfunction, a hallmark of aging, can lead to permeability of the mitochondrial membrane and release of mtDNA into the cytoplasm. This has been identified as a key driver of cGAS-STING activation, particularly in aged microglia and other cell types [15] [16].

Q4: How does replication stress contribute to the aging process?

Replication stress refers to the slowing or stalling of DNA replication forks. It is a potent source of genomic instability because stalled forks can collapse into double-strand breaks. This stress is a key driver of cellular senescence, and hereditary premature aging disorders (e.g., Werner syndrome, Bloom syndrome) often involve mutations in genes that help resolve replication stress (e.g., RECQ helicases). Replication stress contributes to multiple hallmarks of aging, including telomere attrition, stem cell exhaustion, and mitochondrial dysfunction [13].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Research Challenges

Challenge: Detecting cGAS-STING Activation in Aged Stem Cell Cultures

Problem: A researcher is unable to consistently detect markers of cGAS-STING pathway activation in a culture of aged mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), despite signs of senescence.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiment | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low basal pathway activity | Measure cytosolic cGAMP levels via ELISA or LC-MS [15]. | Pre-treat cells with a low dose of DNA-damaging agent (e.g., 50 µM Etoposide, 24h) to induce cytoplasmic DNA. |

| Compensatory degradation of cGAMP | Quantify expression of enzymes like ENPP1 that hydrolyze cGAMP. | Use a STING agonist (e.g., 2'3'-cGAMP, 2-5 µg/mL) as a positive control to bypass cGAS. |

| Insensitive readout | Perform a time-course analysis of p-STING and p-TBK1 by Western blot in addition to IFN-β mRNA. | Include multiple readouts: qPCR for ISGs (e.g., ISG15, MX1) and ELISA for secreted CXCL10. |

Recommended Workflow:

- Induction: Treat aged MSCs with a STING agonist (e.g., 2'3'-cGAMP) for 6 hours as a positive control.

- Lysis: Harvest cells for RNA extraction (qPCR) and protein extraction (Western blot).

- Analysis:

- qPCR: Analyze expression of IFN-β, ISG15, and CXCL10.

- Western Blot: Probe for total STING, phosphorylated STING (Ser365), and phosphorylated TBK1 (Ser172).

- ELISA: Measure cGAMP from cell lysates or CXCL10 from culture supernatants.

Challenge: Differentiating Senescence-Associated cGAS Signaling from Infection-Related Signaling

Problem: An experiment involves a stem cell model exposed to both genotoxic stress and low levels of environmental microbes, making it difficult to attribute cGAS-STING activation specifically to genomic instability.

| Feature | Senescence-Associated Signaling | Infection-Associated Signaling |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Source | Self-DNA (micronuclei, mtDNA) [14] [15] | Foreign microbial DNA |

| Onset & Duration | Chronic, low-grade, persistent [16] | Acute, strong, typically resolved |

| Key Cytokines | SASP factors (IL-6, IL-8), Type I IFNs [14] [16] | High levels of Type I IFNs, pro-inflammatory cytokines |

| Experimental Inhibition | VDAC inhibitors (e.g., VBIT-4) block mtDNA release [15]. | Antimicrobial agents will prevent signaling. |

Diagnostic Strategy:

- Visualize the Source: Perform immunofluorescence staining for cGAS and γH2AX (DNA damage marker) along with a DNA stain. The co-localization of cGAS with micronuclei is indicative of senescence-associated activation [14].

- Inhibit Specific Sources: Treat cells with VBIT-4 (1-2 µM, 48h), an inhibitor of mitochondrial VDAC oligomerization that blocks mtDNA release. A reduction in signaling implicates mtDNA as a key driver [15].

- Profile the Secretome: Use a multiplex cytokine array. A SASP-rich profile (IL-6, IL-8, MMPs) alongside moderate IFN-β suggests senescence, while a very high IFN-β/IFN-α ratio is more typical of viral infection.

Challenge: High Variability in Telomere Length Measurements

Problem: A team observes unacceptably high variability in telomere length data from qPCR-based assays across replicates of the same primary stem cell population.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiment | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Variable DNA quality/quantity | Run all samples on a bioanalyzer to assess DNA integrity and precise concentration. | Use a fluorometric method for DNA quantification and standardize input DNA mass. |

| Primer/dye inefficiency | Check primer dimer formation with no-template controls and analyze amplification efficiency curves. | Optimize primer annealing temperatures and use intercalating dyes specific for dsDNA. |

| Heterogeneous cell population | Analyze cell surface markers via FACS to confirm population purity before extraction. | Use single-cell telomere length measurement techniques, such as quantitative FISH (qFISH). |

Optimal Protocol Checklist:

- DNA Quality: Ensure all DNA samples have an A260/A280 ratio between 1.8-2.0 and are run on a gel or bioanalyzer to confirm high molecular weight and lack of degradation.

- qPCR Validation: Validate primer sets for a single-copy reference gene (e.g., 36B4) and telomere repeats. Ensure amplification efficiencies for both are between 90-110% and within 5% of each other.

- Controls: Include a reference DNA sample in every assay plate to allow for inter-plate normalization and correct for run-to-run variation.

Table 1: Key Markers of Genomic Instability and Associated Pathways

| Marker/Parameter | Young/Healthy Cells | Aged/Senescent Cells | Detection Method | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telomere Length | >10 kbp | <6 kbp [12] | qPCR, TRF, STELA | Indicator of replicative history and onset of senescence. |

| γH2AX Foci | Low (<5 foci/nucleus) | High (>10 foci/nucleus) [17] | Immunofluorescence | Marker of DNA double-strand breaks. |

| Cytosolic cGAMP | Low/Undetectable | Robustly increased [15] | ELISA, LC-MS | Direct indicator of cGAS enzyme activity. |

| p-STING (Ser365) | Low/Undetectable | Elevated [15] | Western Blot | Marker of STING pathway activation. |

| Micronuclei Frequency | Low (<2%) | High (>10%) [14] | Microscopy (DAPI) | Indicator of chromosomal instability and cGAS activator. |

Table 2: Reagents for Modulating the cGAS-STING Pathway in Aging Research

| Reagent | Function | Example Use in Senescence Research | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| H-151 | Potent and selective STING inhibitor | Suppresses SASP and age-related inflammation in vivo; 1-5 µM in vitro. | [15] |

| 2'3'-cGAMP | STING agonist | Positive control for pathway activation; 2-5 µg/mL in vitro. | [14] [16] |

| VBIT-4 | Inhibitor of VDAC oligomerization | Blocks mtDNA release and subsequent cGAS activation; 1-2 µM. | [15] |

| TREX1 | Cytosolic DNA exonuclease | Ectopic expression degrades cytosolic DNA, suppressing cGAS activation. | [16] |

Essential Signaling Pathways & Workflows

Diagram 1: cGAS-STING Pathway in Aging. This diagram illustrates how triggers of genomic instability (telomere attrition, DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction) lead to the accumulation of cytosolic DNA, which activates the cGAS-STING innate immune pathway. This drives the production of pro-inflammatory SASP factors and type I interferons, promoting cellular senescence and tissue aging [14] [15] [16].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for cGAS-STING in Senescence. A generalized workflow for investigating the role of the cGAS-STING pathway in cellular senescence models. The process involves priming cells into senescence, modulating the pathway with specific tools, and analyzing a multi-faceted set of readouts to confirm the relationship [14] [15] [13].

Within the context of stem cell senescence and replicative aging prevention research, mitochondrial dysfunction has emerged as a critical pathophysiological hub. Mitochondria are not only the powerhouses of the cell but also central signaling organelles whose functional decline directly triggers and amplifies the senescent phenotype [18] [19]. In replicative aging, particularly in stem cell populations like mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), this dysfunction manifests as a self-reinforcing cycle of bioenergetic compromise, metabolic imbalance, and eventual proliferative arrest [20]. The ensuing metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to inefficient glycolysis further depletes the regenerative capacity of stem cell pools, creating a significant barrier to therapeutic application [20]. Understanding the precise mechanistic links between mitochondrial energetics and senescence-associated biomarkers is therefore paramount for developing effective interventions to maintain stemness and combat age-related functional decline.

FAQ: Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Stem Cell Senescence

Q1: How does mitochondrial dysfunction directly trigger a senescent phenotype in human stem cells? Mitochondrial dysfunction induces senescence through several interconnected mechanisms in stem cells. Primarily, it causes a definitive decrease in respiratory capacity per mitochondrion and a lowered mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) at steady state [19]. This energy crisis is compounded by increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which accelerates damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA, thereby activating persistent DNA damage response pathways that initiate growth arrest [19] [21]. Furthermore, dysfunctional mitochondria in stem cells exhibit specific metabolic alterations, such as a lowered NAD+/NADH ratio. This shift activates AMPK and subsequently p53, establishing a distinct form of growth arrest known as Mitochondrial Dysfunction-Associated Senescence (MiDAS) [22]. The accumulation of damaged mitochondria due to impaired mitophagy further stabil the senescent state [19] [23].

Q2: What are the key mitochondrial biomarkers I should monitor in replicative aging studies? Key mitochondrial proteins serving as reliable biomarkers for cellular senescence include proteins involved in dynamics, quality control, and apoptosis. Analysis of these biomarkers provides valuable information on cellular state at various aging stages [23] [24].

Table: Key Mitochondrial Biomarkers in Cellular Senescence

| Biomarker | Primary Function | Senescence-Associated Change |

|---|---|---|

| DRP1 (Dynamin-related protein 1) | Triggers mitochondrial fission [18] [21]. | Altered expression/activity disrupts mitochondrial network balance [23] [24]. |

| PINK1-Parkin | Initiates mitophagy (clearance of damaged mitochondria) [18]. | Impaired pathway leads to accumulation of dysfunctional organelles [23] [24]. |

| Prohibitin | Regulates mitochondrial respiratory activity and mtDNA stability [24]. | Loss contributes to oxidative stress and functional decline [24]. |

| MFF (Mitochondrial Fission Factor) | Recruits DRP1 to mitochondria to promote fission [21]. | Involved in fission induced by membrane potential loss [24]. |

| VDAC (Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel) | Forms channels in the outer membrane; triggers apoptosis [24]. | Participates in release of pro-apoptotic factors and mtDNA [25] [24]. |

Q3: Why do my late-passage MSCs show a shift from osteogenic to adipogenic differentiation potential? This "osteogenic to adipogenic shift" is a classic hallmark of MSC senescence and is intrinsically linked to mitochondrial metabolic status [20]. As MSCs approach replicative senescence, their mitochondrial function declines, leading to a compensatory increase in mitochondrial mass, but with lower overall efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) [19] [20]. This bioenergetic crisis favors a metabolic shift towards glycolysis, which is less efficient at generating ATP but is the preferred metabolic pathway for adipogenesis. In contrast, robust OXPHOS is required to meet the high energy demands of osteogenic differentiation. Therefore, the senescence-associated metabolic reprogramming directly biases stem cell fate towards the less energy-intensive adipogenic lineage, limiting their utility in bone regeneration therapies [20].

Q4: Can mitochondrial transfer or transplantation techniques prevent stem cell senescence? Yes, mitochondrial transplantation represents an advanced and promising therapeutic strategy in regenerative medicine. Preclinical studies have shown that transferring functionally intact mitochondria from healthy donor cells into metabolically compromised recipient cells can reconstitute mitochondrial bioenergetics and rescue cellular function [18]. This approach has demonstrated promise in various disease models and has even been used in pediatric patients receiving ECMO support [18]. For senescent stem cells, this horizontal transfer of healthy organelles could potentially reverse the energetic deficits that underlie the senescent phenotype, thereby restoring proliferative capacity and differentiation potential. However, clinical translation faces challenges, including maintaining mitochondrial vitality post-isolation, ensuring efficient cellular internalization, and achieving sustained therapeutic effects [18].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Inconsistent Senescence Induction via Mitochondrial Disruption

- Potential Cause: Heterogeneous cellular response to the stressor (e.g., oligomycin, rotenone) due to variations in baseline metabolic states.

- Solution: Pre-condition cells in a low-nutrient or uniform metabolic state before induction. Use a combination of biochemical (e.g., mtDNA depletion) and pharmacological stressors for a more synchronized arrest. Always validate induction by measuring multiple senescence markers (SA-β-Gal, p21, Lamin B1) in conjunction with mitochondrial parameters (MMP, ROS) [19] [22].

Problem 2: Failure to Detect mtDNA Release into Cytosol

- Potential Cause: Inefficient cell fractionation methodology or insufficiently sensitive detection assays.

- Solution: Optimize the digitonin-based permeabilization protocol for selective plasma membrane disruption while keeping mitochondrial membranes intact. Use a combination of immunofluorescence for cytosolic mtDNA and highly sensitive qPCR with primers specific for mitochondrial genes (e.g., CYTB, ND1) rather than nuclear DNA to confirm cytosolic presence [25].

Problem 3: Unclear or Weak Mitophagy Flux Data

- Potential Cause: Inadequate inhibition of lysosomal degradation or poor temporal resolution of the assay.

- Solution: Employ a tandem-fluorescent reporter (e.g., mt-Keima, mCherry-GFP-FIS1) that can distinguish neutral (GFP+/mCherry+) from acidic (GFP-/mCherry+) organelles. For pharmacological approaches, use a combination of lysosomal inhibitors (e.g., Bafilomycin A1) and monitor the accumulation of PINK1 and Parkin on mitochondria over a detailed time course [23].

Problem 4: MSC Differentiation Potential is Lost Before Replicative Senescence is Evident

- Potential Cause: Early and subtle mitochondrial dysfunction that precedes overt growth arrest and SA-β-Gal expression.

- Solution: Routinely monitor functional mitochondrial parameters from early passages, including the Respiratory Control Ratio (RCR) in permeabilized cells and NAD+/NADH ratio. Implement interventions like Nrf2 activators or SIRT1 modulators early in the expansion phase to maintain mitochondrial health and stemness [20].

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Assessing Mitochondrial Function in Live Stem Cells via Seahorse XF Analyzer This protocol measures key parameters of mitochondrial function in intact, living MSCs, providing a real-time bioenergetic profile.

- Cell Seeding: Seed 20,000-80,000 early or late-passage MSCs per well in a Seahorse XF cell culture microplate 24 hours before the assay. Use appropriate growth medium.

- Assay Medium Preparation: On the day of the assay, replace growth medium with Seahorse XF Base Medium (supplemented with 1 mM pyruvate, 2 mM glutamine, and 10 mM glucose, pH 7.4) and incubate cells for 1 hour at 37°C in a non-CO2 incubator.

- Sensor Cartridge Loading: Load the Seahorse XFp Sensor Cartridge with modulators:

- Port A: 1.5 µM Oligomycin (ATP synthase inhibitor) to measure ATP-linked respiration.

- Port B: 1.0 µM FCCP (uncoupler) to measure maximal respiratory capacity.

- Port C: 0.5 µM Rotenone & Antimycin A (Complex I & III inhibitors) to measure non-mitochondrial respiration.

- Run the Assay: Place the cell culture plate and sensor cartridge in the XF Analyzer. The instrument will perform a series of mix, wait, and measure cycles to calculate the Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) and Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR) under basal conditions and after each injection.

- Data Analysis: Calculate key parameters from the OCR profile: Basal Respiration, ATP Production, Maximal Respiration, Proton Leak, and Spare Respiratory Capacity. Normalize all data to total protein content per well [19].

Protocol 2: Quantifying Cytosolic mtDNA Release as a DAMP Signal This protocol details a method to detect the release of mitochondrial DNA into the cytosol, a potent trigger of the innate immune response and SASP.

- Cell Fractionation:

- Harvest 1-5 x 10^6 senescent and control MSCs by trypsinization and wash with PBS.

- Resuspend the cell pellet in 1 mL of ice-cold Digitonin Lysis Buffer (50 µg/mL digitonin in PBS with protease inhibitors).

- Incubate on ice for 10 minutes with gentle tapping. Digitonin selectively perforates the cholesterol-rich plasma membrane while leaving organelle membranes intact.

- Centrifuge at 2,000 x g for 5 minutes at 4°C to pellet the nuclei and intact cells.

- Transfer the supernatant (cytosolic fraction) to a new tube and centrifuge at 16,000 x g for 20 minutes at 4°C to pellet any remaining organelles, including mitochondria.

- Carefully transfer the final supernatant (clean cytosolic fraction) to a new tube.

- DNA Isolation and DNase Treatment: Isolve DNA from the cytosolic fraction using a commercial kit. To ensure the DNA is from within mitochondria and not bound to the outer membrane, treat an aliquot of the fraction with 20 U of DNase I for 1 hour at 37°C before DNA isolation. The DNase will degrade any externally exposed DNA.

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Perform qPCR on the isolated DNA using primers specific for a mitochondrial gene (e.g., ND1) and a nuclear gene (e.g., 18S rRNA or B2M). The absence of the nuclear gene signal confirms the purity of the cytosolic fraction. A significant increase in the mtDNA/nuclear DNA ratio in the cytosolic fraction of senescent cells compared to controls indicates mtDNA release [25].

Key Signaling Pathways in Mitochondria-Driven Senescence

The transition of stem cells to a senescent state is orchestrated by specific mitochondrial-driven signaling cascades. The diagram below illustrates the core pathway linking mitochondrial dysfunction to the MiDAS phenotype and the release of mitochondrial DAMPs that promote a pro-inflammatory environment.

Diagram 1: Signaling from mitochondrial dysfunction to senescence. Mitochondrial dysfunction triggers senescence via AMPK-p53 activation from NAD+ decline and ROS-induced DNA damage. Concurrently, released mtDNA activates cGAS-STING, driving a pro-inflammatory SASP [19] [25] [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Studying Mitochondria in Senescence

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Example Use in Senescence Research |

|---|---|---|

| MitoTEMPO | Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant (scavenges mtROS) | Testing the causal role of mtROS in initiating senescence; reduces DNA damage and p53 activation [21]. |

| Oligomycin | ATP synthase (Complex V) inhibitor | Inducing metabolic stress and MiDAS; used in Seahorse assays to measure ATP-linked respiration [19] [22]. |

| Nicotinamide Riboside (NR) | NAD+ precursor | Boosting NAD+ levels to counteract the NAD+ decline in senescence, potentially delaying the onset of MiDAS [18]. |

| PINK1 siRNA/shRNA | Gene knockdown of PINK1 kinase | Investigating the role of impaired mitophagy in senescence; knockdown leads to accumulation of damaged mitochondria [23] [24]. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | V-ATPase inhibitor (blocks lysosomal degradation) | Measuring mitophagy flux in conjunction with LC3-II or PINK1/Parkin markers; distinguishes between increased initiation vs. blocked degradation [23]. |

| MitoTracker Red CMXRos | Fluorescent dye that stains active mitochondria (ΔΨm-dependent) | Visualizing mitochondrial mass and membrane potential in live cells; often shows a hyperfused but depolarized network in senescence [19]. |

| JC-1 Dye | Potentiometric fluorescent dye for ΔΨm | Quantifying mitochondrial membrane potential; shift from red (J-aggregates) to green (monomers) indicates depolarization, a hallmark of dysfunction [19]. |

| Coenzyme Q10 | Electron carrier in ETC; antioxidant | Testing therapeutic intervention to improve ETC efficiency and reduce oxidative stress in aging stem cells [18] [26]. |

Cellular senescence is a state of irreversible growth arrest that occurs in response to various stressors, including DNA damage, oxidative stress, and oncogenic activation [27]. A defining feature of senescent cells is the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP), a complex secretome comprising pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and proteases [28]. In the context of stem cell research and replicative aging prevention, the SASP is a critical therapeutic target. While transient SASP activity can aid tissue remodeling and wound healing, its chronic activation drives inflammation, fibrosis, and tissue dysfunction [27]. In mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), the accumulation of senescent cells and the persistent SASP secretion can severely impair regenerative potential, immunomodulatory functions, and overall therapeutic efficacy [29]. This technical support guide provides a detailed resource for researchers investigating the profibrotic and pro-inflammatory components of the SASP, with a specific focus on mitigating its effects in stem cell-based therapies and aging research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the core profibrotic and pro-inflammatory components of the SASP most relevant to stem cell aging? The SASP is highly heterogeneous, but several core factors are consistently implicated in driving profibrotic and pro-inflammatory pathways in aging stem cells. Key components include:

- Pro-inflammatory Cytokines: IL-6, IL-8 (CXCL8), IL-1β, and TNF-α. These factors establish a chronic low-grade inflammatory state, often termed "inflammaging," which disrupts the stem cell niche [27] [30].

- Profibrotic Factors: Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β), IL-11, and SERPINE1 (PAI-1). These molecules directly activate fibroblasts and promote the excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM), leading to tissue fibrosis [27] [31].

- Matrix Remodeling Enzymes: Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) like MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-9, along with their inhibitors (TIMPs). They alter the tissue architecture and stem cell microenvironment [28] [27].

- Growth Factors: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Insulin-like Growth Factor-Binding Proteins (IGFBPs). These can paradoxically impair tissue repair and promote senescence in neighboring cells [27].

FAQ 2: How does the SASP contribute to the decline in MSC functionality during in vitro expansion? During serial passaging, MSCs undergo replicative senescence, characterized by an irreversible growth arrest [32]. Senescent MSCs develop a robust SASP, which creates an unfavorable microenvironment through several mechanisms:

- Autocrine and Paracrine Senescence: The SASP factors can reinforce the senescent state in the producing cell and spread senescence to nearby young MSCs and other progenitor cells through the "bystander effect" [29].

- Impaired Immunomodulation: The SASP alters the critical immunomodulatory functions of MSCs. For instance, senescent MSCs may fail to properly suppress T lymphocyte proliferation or promote the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs), undermining their therapeutic utility [29].

- Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Replicative senescence in MSCs is closely linked to mitochondrial defects, including increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. This oxidative stress is both a cause and a consequence of the SASP, creating a vicious cycle that accelerates functional decline [32].

FAQ 3: What techniques are recommended for a comprehensive quantification of the SASP in my stem cell models? Accurately measuring the SASP requires a multiparametric approach across different biological levels. The table below summarizes the principal methodologies.

Table 1: Techniques for SASP Quantification

Molecular Level Technique Sample Type Key Applications RNA qRT-PCR Cell culture, tissue Targeted quantification of IL-6, IL-8 transcripts [28] RNA-seq Cell culture, tissue Unbiased discovery of SASP "Atlas"; diversity across cell types [28] Protein ELISA Cell culture, plasma, serum Quantifying specific proteins like IL-6, IL-8 in conditioned media [28] Western Blotting Cell culture, tissue lysate Detecting protein expression and activation states (e.g., mTOR phosphorylation) [28] [32] Multiplex Immunoassays (Luminex, MSD) Cell culture, tissue, plasma Simultaneously measuring dozens of SASP factors in precious samples; used in human studies [28] [33] Mass Spectrometry Cell culture, plasma, serum Comprehensive, unbiased profiling of the SASP secretome [28] Localization Immunofluorescence (IF) Cells, tissues Spatial detection of SASP factors (e.g., IL-6) and co-localization with senescence markers [28] RNA In Situ Hybridization Tissue (fixed sections) Spatial localization of specific SASP factor mRNAs [28]

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Inconsistent SASP Measurement in Conditioned Media from Senescent MSC Cultures.

- Potential Cause: The heterogeneity of senescent cell populations and variability in the timing of SASP peak expression.

- Solution:

- Standardize Senescence Induction and Validation: Use a combination of biomarkers to confirm a senescent state prior to SASP measurement. This includes Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining [32], and detection of cell cycle inhibitors like p21 and p16 via Western Blot [32].

- Normalize Data: Always normalize SASP protein concentrations (e.g., from ELISA or multiplex assays) to the total cell number or total protein content of the culture.

- Use Multiplex Assays: Employ multiplex platforms (Luminex, MSD) to profile a panel of SASP factors from a single sample to capture the complexity and reduce inter-assay variability [28].

- Collect Time-Course Data: The SASP is dynamic. Collect conditioned media at multiple time points after the induction of senescence to capture its temporal evolution.

Problem 2: Difficulty in Distinguishing SASP-Driven Inflammation from General Inflammatory Responses.

- Potential Cause: Overlap between SASP factors and classic inflammatory cytokines produced during infections or other immune responses.

- Solution:

- Profile Multi-Marker Signatures: Do not rely on a single cytokine like IL-6. Instead, look for a co-expression pattern that is characteristic of senescence, such as the persistent simultaneous upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8), extracellular matrix modulators (MMPs, TIMPs), and growth regulators (IGFBPs) [28].

- Correlate with Senescence Markers: Directly correlate the levels of suspected SASP factors with established cellular senescence markers in your samples (e.g., via combined IF for p21 and IL-6) [28].

- Utilize Published Gene Signatures: Leverage established senescence gene panels, such as the SenMayo gene list, to analyze your transcriptomic data and confirm a senescence-specific signature [34].

Problem 3: Poor Efficacy of Senomorphic Compounds in Suppressing the SASP in Aged MSCs.

- Potential Cause: Inadequate targeting of upstream regulators of the SASP or compound toxicity.

- Solution:

- Target Multiple Pathways: The SASP is regulated by multiple interconnected pathways (NF-κB, C/EBPβ, p38MAPK, cGAS-STING). Consider using a combination of low-dose inhibitors or target a master regulator upstream [27].

- Assess Lysosomal Function: Recent research highlights lysosomal dysfunction as a key driver of stem cell aging. Targeting lysosomal hyperacidity has been shown to reverse age-related defects in hematopoietic stem cells, including reducing inflammatory signaling [2]. Evaluate lysosomal activity (e.g., LysoTracker staining) and consider interventions to restore lysosomal function.

- Check for Iron Accumulation: Iron accumulation has been identified as a key driver of senescence and the SASP in fibrotic diseases [31]. Measure intracellular iron levels (e.g., Perl's Prussian blue staining) and consider iron chelation as an experimental intervention to modulate the SASP.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Inducing and Validating Replicative Senescence in Human MSCs

This protocol outlines the serial passaging of MSCs to induce replicative senescence in vitro, a key model for studying aging [32].

Materials:

- Human bone marrow-derived MSCs (bMSCs)

- Complete culture medium (e.g., DMEM with 20% FBS, glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin)

- Trypsin-EDTA solution

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- SA-β-gal staining kit

- RIPA lysis buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors

- Antibodies for p21, p16, and GAPDH

Method:

- Cell Culture and Passaging: Culture bMSCs under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2). Serially passage cells at a defined split ratio (e.g., 1:3) upon reaching 80-90% confluence. Record the population doubling level (PDL) at each passage.

- Senescence Validation (at desired PDLs, e.g., P4, P11, P16):

- SA-β-gal Staining: Seed cells on a 24-well plate. Once attached, wash with PBS, fix, and incubate overnight with the X-Gal staining solution at 37°C (without CO2). Count the percentage of blue-stained cells under a bright-field microscope [32].

- Western Blot for Cell Cycle Inhibitors: Lyse cells and extract protein. Perform Western blotting for p21 and p16, using GAPDH as a loading control. A significant increase in these proteins indicates senescence [32].

- Morphological Analysis: Observe cells under a microscope. Senescent MSCs often appear enlarged, flattened, and granular.

Protocol: Quantifying SASP Factors via Multiplex Immunoassay

This protocol describes a method for simultaneously measuring multiple SASP proteins from conditioned media.

Materials:

- Conditioned media from senescent and control MSCs (centrifuged to remove debris)

- Human SASP multiplex assay kit (e.g., from Luminex or MSD)

- Wash buffer

- Microplate reader compatible with the kit

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Collect conditioned media after 24-48 hours of culture in serum-free medium to avoid interference. Clarify by centrifugation and store at -80°C.

- Assay Procedure: Follow the manufacturer's instructions precisely. Typically, this involves:

- Incubating samples with antibody-coated beads or spots.

- Washing to remove unbound proteins.

- Adding a biotinylated detection antibody mixture.

- Adding a streptavidin-conjugated reporter.

- Reading the plate with the appropriate instrument.

- Data Analysis: Use the instrument's software to calculate protein concentrations from standard curves. Normalize values to the total cell count or protein concentration from the corresponding culture well.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Regulation

The core SASP is primarily regulated by the synergistic activation of the NF-κB and C/EBPβ pathways [27]. DNA damage, oxidative stress, and other senescence triggers activate the cGAS-STING pathway in response to cytosolic DNA, which further potentiates NF-κB activity. The p38 MAPK pathway also plays a key role in SASP regulation. Furthermore, mTOR signaling promotes SASP translation, and its inhibition (e.g., with rapamycin) can suppress the SASP. A critical connection has been established between iron accumulation and the SASP, where iron fuels ROS production, exacerbating the inflammatory secretome [31]. The diagram below illustrates these key regulatory interactions.

SASP Regulatory Network

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for SASP and Senescence Research

| Reagent / Assay | Primary Function | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Senescence Inducers | To trigger cellular senescence in vitro for experimental models. | Bleomycin: Induces DNA damage. Hydrogen Peroxide: Induces oxidative stress. Etoposide: DNA topoisomerase inhibitor [27] [31]. |

| SASP Modulators (Senomorphics) | To inhibit the production or secretion of SASP factors. | Rapamycin: mTOR inhibitor. Dasatinib + Quercetin: A senolytic cocktail with senomorphic properties. Vacuolar ATPase Inhibitors: Target lysosomal acidity to reduce SASP [27] [2]. |

| Cytokine Multiplex Assays | To simultaneously quantify multiple SASP proteins from a single sample. | Luminex xMAP & Meso Scale Discovery (MSD): Ideal for profiling conditioned media or plasma. Validate panels for key targets like IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, TNF-α, TGF-β [28] [33]. |

| SA-β-gal Staining Kit | A histochemical marker for detecting senescent cells. | Available from various suppliers (e.g., Sigma, Cell Signaling). Optimal for cells and frozen sections; requires careful pH control [32]. |

| Antibodies for Senescence Markers | For protein-level detection of key senescence effectors via Western Blot or IF. | p21 (CDKN1A), p16 (CDKN2A): Core cell cycle inhibitors. Lamin B1: Often downregulated in senescence. γH2AX: Marker for DNA damage [32]. |

| Lysosomal Probes | To assess lysosomal function and mass, which is often dysregulated in senescence. | LysoTracker: Stains acidic compartments. LysoSensor: Probes lysosomal pH. Useful for investigating the link between lysosomal dysfunction and SASP [2]. |

| Iron Chelators & Sensors | To manipulate and detect intracellular iron, a key SASP driver. | Deferoxamine (DFO): An iron chelator. FerroOrange, FeRhoNox-1: Fluorescent probes for labile iron [31]. |

Therapeutic Arsenal: From Senolytics to Rejuvenation Strategies in Preclinical and Clinical Development

Cellular senescence, a state of irreversible cell cycle arrest, is a fundamental mechanism in aging and a significant contributor to age-related dysfunction. In the context of stem cell research, the accumulation of senescent cells compromises tissue regeneration, impairs stem cell function, and promotes chronic inflammation through the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [35] [36]. Senolytic therapies have emerged as promising interventions to eliminate these senescent cells, thereby potentially extending healthspan and mitigating age-related degenerative pathologies [37] [38].

Senotherapeutic agents are broadly classified into two categories: senolytics, which selectively induce apoptosis in senescent cells, and senomorphics, which suppress the deleterious effects of the SASP without eliminating the cells [39] [36]. For research focused on preserving stem cell pools and function, senolytics offer a direct strategy to reduce the senescent burden and create a more hospitable microenvironment for regeneration. This technical support center provides detailed methodologies, troubleshooting guides, and essential resource information for researchers investigating these compounds in models of stem cell senescence and replicative aging.

Detailed Agent Profiles & Quantitative Data

Core Senolytic Classes and Mechanisms

The following table summarizes the primary senolytic agents, their molecular targets, and key functional characteristics relevant to experimental design.

Table 1: Core Senolytic Agent Profiles

| Senolytic Class / Agent | Primary Molecular Targets | Key Mechanisms of Action | Reported Efficacy in Senescent Cells | Key Limitations & Toxicities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCL-2 Family Inhibitors (e.g., Navitoclax/ABT-263) | BCL-2, BCL-xL, BCL-w [36] [38] | Blocks anti-apoptotic proteins, sensitizing senescent cells to intrinsic apoptosis [36] [38]. | Broad-acting across multiple senescent cell types [36]. | Dose-limiting thrombocytopenia due to BCL-xL inhibition in platelets [36] [38]. |

| Dasatinib + Quercetin (D+Q) | Dasatinib: Src family kinases, Eph receptors. Quercetin: PI3K/AKT, BCL-2 family [40] [36]. | Inhibits overlapping pro-survival pathways (SCAPs); broader efficacy in combination [40] [36] [41]. | Effective in senescent preadipocytes, endothelial cells, and VSMCs; reduces p16INK4a, SASP in vivo [40] [41]. | Cell-type specificity; potential for transient chromatin alterations in young cells [40]. |

| Natural Polyphenols (e.g., Fisetin) | PI3K/AKT, NF-κB, ROS pathways; p16–CDK6 interaction [36] [42] [38]. | Induces apoptosis via oxidative stress and suppression of anti-apoptotic signaling; acts as senomorphic [36] [42]. | Reduces senescence markers in multiple tissues; extended lifespan in old mice [38] [43]. | Variable potency; poor bioavailability; extensive first-pass metabolism [42]. |

Quantitative Data for Experimental Planning

Table 2: Experimentally-Validated Dosing and Treatment Schedules

| Experimental Model | Agent | Concentration / Dosage | Treatment Schedule & Duration | Key Outcomes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human VSMCs (in vitro) | D+Q | Dasatinib: 100 nM; Quercetin: 5 µM [40] | 48-hour treatment, with or without 24-hour recovery [40]. | Altered chromatin structure; some "rejuvenation" in senescent cells [40]. | [40] |

| Aged Mice (in vivo) | D+Q | Dasatinib: 5 mg/kg; Quercetin: 50 mg/kg [41] | Weekly intraperitoneal injection; treatment initiated at 6, 14, or 18 months; analysis at 23 months [41]. | Ameliorated disc degeneration; decreased p16INK4a, p19ARF, SASP; preserved cell viability [41]. | [41] |

| Progeroid Mice (in vivo) | Fisetin | Not specified in results | Not specified in results | Reduced senescent cell burden across tissues; extended median and maximum lifespan [38]. | [38] |

| Human Clinical Pilot | D+Q | Dasatinib: 50 mg; Quercetin: 500 mg [43] | Oral administration over 6 months [43]. | Increased epigenetic age acceleration at 3 months (mitigated by Fisetin co-administration) [43]. | [43] |

Key Signaling Pathways in Senescence and Senolysis

The efficacy of senolytic agents hinges on targeting specific pro-survival pathways that are upregulated in senescent cells. The diagram below illustrates the key molecular pathways involved in cellular senescence and the points of intervention for major senolytic classes.

Diagram 1: Senescence Signaling and Senolytic Intervention. Key pathways (p53/p21 and p16/RB) establish growth arrest. Senescent cells activate Senescent Cell Anti-apoptotic Pathways (SCAPs) for survival. Senolytics target SCAPs or related nodes to induce apoptosis.

Experimental Protocols for Stem Cell Senescence Research

Protocol: Inducing and Quantifying Replicative Senescence in Stem Cells

This protocol outlines the process of inducing replicative senescence in human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs), a common model in aging research, and the subsequent validation of the senescent state.

1. Induction of Replicative Senescence:

- Cell Culture: Culture hMSCs (e.g., from bone marrow or adipose tissue) in standard growth medium. Use cells from low passages (e.g., passage 3-5) as "young" controls.

- Serial Passaging: Continuously passage cells at a standardized seeding density (e.g., 4,000 cells/cm²) until they approach replicative exhaustion [40]. Passage cells when they reach 70-80% confluency.

- Senescence Trigger (Optional): To accelerate senescence, sub-lethal stress can be applied at intermediate passages. Common triggers include:

- Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂): Treat with 50-200 µM H₂O₂ for 1-2 hours, then replace with fresh medium [39].

- Ionizing Radiation: A single dose of 5-10 Gy.

2. Validation of Senescent Phenotype: A senescent population should be confirmed using at least two of the following assays before senolytic testing:

- Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) Staining: Fix cells and incubate with X-Gal staining solution at pH 6.0 overnight at 37°C (non-CO₂ conditions) [40] [35]. A population is considered senescent when >70% of cells stain positive (blue-green cytoplasm) [40].

- Proliferation Assay:

- BrdU Incorporation: Measure 5-bromo-2'-deoxyuridine incorporation via immunodetection. A senescent population should have <30% BrdU-positive cells [40].

- Ki67 Staining: Immunofluorescence for the proliferation marker Ki67 should show a significant decrease in senescent cells compared to young controls [41].

- Western Blot or qPCR for Senescence Markers: Confirm upregulated expression of key markers like p16INK4a, p21CIP1, and p53 in senescent cells compared to young controls [41] [44].

- SASP Analysis: Use ELISA or multiplex immunoassays (e.g., Luminex) to detect increased secretion of SASP factors (e.g., IL-6, IL-1β, MMP-13) in the conditioned medium of senescent cultures [41].

Protocol: Testing Senolytic Efficacy In Vitro

1. Treatment of Senescent Stem Cells:

- Agent Preparation:

- Dasatinib: Prepare a stock solution in DMSO. Use working concentrations in the range of 50-200 nM [40].

- Quercetin/Fisetin: Prepare stock solutions in DMSO or ethanol. Use working concentrations of 5-20 µM [40] [38].

- Navitoclax (ABT-263): Prepare stock in DMSO. Use working concentrations of 1-10 µM [36].

- Include vehicle control (e.g., DMSO at the same dilution) for all experiments.

- Treatment Schedule:

2. Assessment of Senolytic Action:

- Viability/Cytotoxicity Assays:

- MTT/XTT Assay: Measure metabolic activity as a proxy for cell viability post-treatment. A successful senolytic will show a significant reduction in viability in senescent cultures but minimal effect in young cultures.

- ATP-based Assays (e.g., CellTiter-Glo): Provide a sensitive measure of viable cell number.

- Apoptosis Assays:

- Caspase-3/7 Activity: Use a luminescent or fluorescent caspase assay to confirm apoptosis is the mechanism of cell death.

- Annexin V/Propidium Iodide (PI) Staining: Perform flow cytometry to quantify early (Annexin V+/PI-) and late (Annexin V+/PI+) apoptotic cells.

- Clearance Confirmation:

- Re-stain for SA-β-Gal after treatment and recovery. A successful treatment should significantly reduce the percentage of SA-β-Gal-positive cells.

- Measure SASP factors in the conditioned medium after treatment. Effective senolysis should lead to a reduction in SASP.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Senescence and Senolytic Research

| Reagent / Assay | Specific Example(s) | Primary Function in Research | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SA-β-Gal Staining Kit | Commercial kits (e.g., Cell Signaling Technology #9860) | Histochemical detection of senescent cells via lysosomal β-galactosidase activity at pH 6.0 [35]. | Standard benchmark; can be combined with immunofluorescence. Not entirely specific [44]. |

| Anti-p16INK4a Antibody | Recombinant monoclonal antibodies for WB, IF, IHC | Protein-level detection of a key cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor driving senescence [41] [44]. | Critical marker for validation; confirm specificity with knockout controls. |

| Anti-p21CIP1 Antibody | Recombinant monoclonal antibodies for WB, IF, IHC | Protein-level detection of a p53-target gene enforcing cell cycle arrest [44]. | Upstream regulation differs from p16; provides complementary data. |

| SASP Panel | Luminex or ELISA Panels (e.g., IL-6, IL-1α/β, MMP-3, MMP-13) | Multiplexed quantification of soluble SASP factors in cell culture supernatant or serum [41]. | Essential for assessing paracrine effects and senomorphic activity. |

| BCL-2 Family Inhibitors | Navitoclax (ABT-263), ABT-737 | Tool compounds for inducing apoptosis in senescent cells dependent on BCL-2/BCL-xL for survival [36] [38]. | Monitor platelet toxicity in vivo; use as a positive control in vitro. |

| Natural Polyphenols | Fisetin (≥98% purity), Quercetin (≥95% purity) | Tool compounds for studying natural product-mediated senolysis/senomorphics [42] [38]. | Address poor solubility and bioavailability with vehicle optimization (e.g., cyclodextrins) [42]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My senolytic treatment (D+Q) is also killing a significant portion of my young, proliferating stem cells. What could be the cause?

- A: This is a recognized challenge. Evidence shows D+Q can cause transient, reversible chromatin changes in young cells that resemble senescence [40]. To troubleshoot:

- Confirm Senescence Status: Ensure your "young" cell population has a low baseline senescence (<5% SA-β-Gal+, high proliferation). Use early passage cells.

- Titrate Concentration: Perform a dose-response curve. The effective senolytic concentration may be lower than cytotoxic concentrations for young cells. Start with lower doses (e.g., 50 nM Dasatinib + 5 µM Quercetin) [40].

- Shorten Exposure: Reduce treatment time from 48 to 24 hours and include a recovery period to assess if effects on young cells are transient [40].

- Agent Specificity: Consider that your stem cell type might be inherently sensitive to one agent. Test Dasatinib and Quercetin separately to identify the primary driver of toxicity.

Q2: I am not observing a significant reduction in SA-β-Gal positive cells after Navitoclax treatment, despite seeing cell death. Why?

- A: This can occur due to the kinetics of the assay. SA-β-Gal staining is a marker of the senescent state, but its disappearance lags behind actual cell death. The dead cells (which may have been SA-β-Gal+) detach and are washed away during staining, leaving behind the viable, untreated senescent cells. To confirm efficacy:

- Quantify Absolute Cell Death: Use a viability assay (e.g., CellTiter-Glo) and normalize to the total DNA content or protein pre-treatment.

- Measure Apoptosis Directly: Use Annexin V/PI flow cytometry to confirm the induction of apoptosis specifically in the senescent population.

- Use Complementary Markers: Assess clearance by measuring a reduction in other markers, such as p16INK4a protein levels via Western blot or a reduction in SASP factors in the conditioned media, which may provide a more quantitative readout [41].

Q3: The in vitro senolytic efficacy of Fisetin is promising, but I see no effect in my mouse model of stem cell aging. What are potential reasons?

- A: This is a common translational hurdle, primarily attributed to pharmacokinetics and bioavailability.

- Bioavailability: Natural polyphenols like Fisetin have poor oral bioavailability and undergo extensive first-pass metabolism into inactive conjugates [42].

- Solution: Investigate different administration routes (e.g., intraperitoneal injection) or formulated versions of Fisetin designed to enhance bioavailability (e.g., nanoparticles, liposomal carriers, or cyclodextrin complexes) [42].

- Dosing Schedule: The intermittent senolytic dosing used for D+Q (e.g., once weekly) may not be optimal for Fisetin. Explore more frequent dosing or a loading-dose strategy based on published in vivo studies [38].

- Confirm Target Engagement: Analyze the senescent cell burden in the specific tissue of interest (e.g., bone marrow, muscle stem cell niche) after treatment to ensure the compound is reaching its target.

Q4: What are the best practices for defining a cell population as "senescent" for a senolytic experiment?

- A: Relying on a single marker is insufficient due to senescence heterogeneity [37] [44]. A rigorous definition requires a multi-parameter approach:

- Mandatory: Growth Arrest + at least one other marker.

- Gold Standard Panel:

- Proliferation Halt: Demonstrated by <30% BrdU+ or Ki67+ cells [40].

- SA-β-Gal Activity: >70% positive cells is a common benchmark [40].

- Key Marker Upregulation: Elevated protein or mRNA levels of p16INK4a and/or p21CIP1 [41] [44].

- Functional Secretory Phenotype: Increased secretion of SASP factors (e.g., IL-6) [41].

- Emerging Tools: For RNA-seq data, consider using established senescence gene signatures like SenMayo to quantitatively assess senescent burden before and after treatment [44].

FAQ: Core Concepts and Definitions

What is the primary goal of a senomorphic intervention compared to a senolytic? Senomorphic interventions aim to suppress the deleterious effects of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) without killing the senescent cell. In contrast, senolytics selectively induce apoptosis in senescent cells to remove them entirely. Senomorphics are particularly valuable in contexts where complete cell clearance is undesirable or when targeting the inflammatory SASP is the primary therapeutic objective. [36] [45]

Why is the SASP considered a "double-edged sword" in stem cell biology and cancer? The SASP has a dual role. Initially, it can facilitate tissue repair and act as a tumor-suppressive barrier by attracting immune cells. However, the chronic presence of SASP factors (cytokines, chemokines, growth factors) creates a pro-inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic microenvironment. In stem cell niches, this can disrupt tissue regeneration, while in cancer, it promotes therapy resistance, metastasis, and immunosenescence. [36] [46] [47]

How do the mTOR, JAK/STAT, and NF-κB pathways interact in regulating the SASP? These pathways form a core signaling network controlling SASP. The DNA damage response often initiates SASP, leading to NF-κB activation. NF-κB and JAK/STAT are primary transcription regulators for many SASP components. mTOR signaling integrates environmental cues to amplify SASP production. There is significant crosstalk; for instance, mTOR can regulate translation of SASP factors, and JAK/STAT can be activated by SASP cytokines in a feed-forward loop. [36] [46] [47]

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Failure to Observe Significant SASP Suppression

- Potential Cause: Inadequate pathway inhibition or off-target effects.

- Solution:

- Verify Target Engagement: Use phospho-specific antibodies (e.g., p-S6K for mTOR, p-STAT3 for JAK/STAT, p-p65 for NF-κB) in western blotting to confirm pathway inhibition. [48] [49]

- Titrate Inhibitor Concentration: Start with established IC50 values and perform a dose-response curve. Consider that some senomorphic effects require sub-apoptotic or non-cytotoxic doses. [45]

- Check Senescence Induction: Confirm the senescence model is robust using multiple markers (SA-β-Gal, p16INK4a, p21CIP1). [36] [46]

Issue 2: High Cytotoxicity or Unintended Senolysis

- Potential Cause: Inhibitor concentration is too high, or the compound has off-target senolytic activity.

- Solution:

- Reduce Dosage: Screen lower concentrations and shorten treatment duration. Senomorphics are often effective at non-toxic doses. [45]

- Monitor Viability: Use real-time cell viability assays alongside SASP readouts.

- Select Specific Inhibitors: For mTOR inhibition, consider rapalogs (e.g., Everolimus) which may have a better therapeutic window than pan-inhibitors. [36]

Issue 3: Inconsistent SASP Profiling Results

- Potential Cause: The dynamic and heterogeneous nature of SASP; inappropriate time-points for analysis.

- Solution:

- Multi-timepoint Analysis: SASP composition evolves. Conduct time-course experiments post-senescence induction and after treatment. [46]

- Use a Multi-analyte Approach: Do not rely on a single SASP factor. Use ELISA panels or multiplex assays to profile a suite of key cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-8, IL-1α/β, GM-CSF). [46] [47]

- Standardize Conditions: Use consistent serum concentrations in media, as serum can contain variable levels of cytokines and growth factors. [46]

Experimental Protocols for Key Senomorphic Assays

Protocol: Assessing SASP Suppression via Cytokine Array

Objective: To quantitatively measure the effect of senomorphic compounds on the secretion of key SASP factors.

Materials:

- Conditioned media from senescent cells (48-72 hour collection).

- Human Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Panel or equivalent ELISA kits.

- Senomorphic compounds (e.g., Rapamycin, Ruxolitinib, BAY 11-7082).

- Multiplex analyzer or plate reader.

Methodology:

- Induce Senescence: Establish a senescence model (e.g., etoposide treatment, irradiation, replicative exhaustion) in your stem cell line. Validate with SA-β-Gal staining and p16/p21 western blot. [36]

- Treat with Senomorphics: After senescence establishment, treat cells with optimized concentrations of senomorphic inhibitors for 48-72 hours.

- Collect Conditioned Media: Aspirate media, wash cells with PBS, and add fresh serum-free media. Collect conditioned media after 24-48 hours. Centrifuge to remove cell debris.

- Perform Multiplex Immunoassay: Follow manufacturer's instructions for the cytokine array. Key analytes should include IL-6, IL-8 (CXCL8), IL-1β, CCL2 (MCP-1), and VEGF. [46] [47]

- Data Analysis: Normalize cytokine concentrations to total cellular protein or cell count. Compare treated senescent cells to untreated senescent and non-senescent controls.

Protocol: Validating Pathway Inhibition via Western Blot

Objective: To confirm the on-target activity of senomorphic compounds by analyzing key phosphorylation sites.

Materials:

- RIPA Lysis Buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Antibodies: p-STAT3 (Tyr705), total STAT3, p-S6 Ribosomal Protein (Ser235/236), total S6, p-NF-κB p65 (Ser536), total p65, β-Actin.

- SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting equipment.

Methodology:

- Cell Lysis: Lyse treated and control cells directly in RIPA buffer. Determine protein concentration.

- Western Blotting: Separate 20-30 µg of protein by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a PVDF membrane.

- Immunoblotting: Probe membranes with phospho-specific antibodies first. After imaging, strip and re-probe with total protein antibodies to assess total protein levels and loading control (β-Actin).

- Expected Outcomes:

Table 1: Key SASP Components and Their Regulation by Target Pathways. This table summarizes core SASP factors that can be used as readouts for senomorphic efficacy.

| SASP Factor | Function | Regulating Pathways | Common Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | Pro-inflammatory cytokine; promotes chronic inflammation and tumor growth. | NF-κB, JAK/STAT | ELISA, Multiplex Assay |

| IL-8 (CXCL8) | Chemokine; recruits neutrophils, promotes angiogenesis. | NF-κB, JAK/STAT | ELISA, Multiplex Assay |

| IL-1α/β | Pro-inflammatory cytokines; key initiators of inflammaging. | NF-κB | ELISA, Multiplex Assay |

| VEGF | Growth factor; stimulates angiogenesis. | mTOR, NF-κB | ELISA, Multiplex Assay |

| MMP2/MMP9 | Proteases; degrade extracellular matrix, facilitate invasion. | NF-κB, MAPK | Zymography, Western Blot |

| CCL2 (MCP-1) | Chemokine; recruits monocytes/macrophages. | NF-κB | ELISA, Multiplex Assay |

Table 2: Representative Senomorphic Compounds and Their Experimental Use.

| Compound | Primary Target | Common In Vitro Concentration | Key Considerations & Off-Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapamycin | mTORC1 (via FKBP12) | 10 - 100 nM | Long pre-treatment may be needed; can affect autophagy. [36] [45] |

| Ruxolitinib | JAK1/JAK2 | 1 - 5 µM | Can affect immune cell function; check viability. [48] [49] |

| BAY 11-7082 | IKK/NF-κB | 5 - 10 µM | Can induce apoptosis at higher doses; use short treatments. [46] |

| Tocilizumab (mAb) | IL-6 Receptor | 10 - 100 µg/mL | Neutralizes extracellular IL-6; does not affect production. [46] |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Core SASP Signaling Network and Senomorphic Inhibition. This diagram illustrates the interplay between the NF-κB, JAK/STAT, and mTOR pathways in SASP production and the points of inhibition for key senomorphic compounds.

Diagram 2: Senomorphic Assay Validation Workflow. A step-by-step guide for evaluating the efficacy of senomorphic compounds in vitro.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Senomorphic Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Product Types |

|---|---|---|

| Senescence Inducers | To establish in vitro senescence models. | Etoposide, Doxorubicin, Hydrogen Peroxide, Irradiation. |

| Pathway Inhibitors | To selectively target senomorphic pathways. | Rapamycin (mTOR), Ruxolitinib (JAK), BAY 11-7082 (NF-κB). |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | To validate on-target inhibition via Western Blot. | Anti-p-S6 (S235/236), Anti-p-STAT3 (Y705), Anti-p-NF-κB p65 (S536). |

| Cytokine Detection Kits | To quantify SASP factor secretion. | Luminex Multiplex Panels, ELLA Automated Immunoassay, ELISA Kits (IL-6, IL-8). |

| SA-β-Gal Staining Kit | A foundational marker for identifying senescent cells. | Commercial kits (e.g., Cell Signaling #9860) or prepared solutions. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | To analyze senescence and SASP markers at single-cell level. | Anti-p16INK4a, Anti-p21CIP1, surface-bound SASP factors (e.g., ICAM-1). |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is lysosomal hyperactivity in the context of stem cell aging? Lysosomal hyperactivity is a recently identified aging hallmark where lysosomes in aged stem cells become hyperacidic (excessively acidic), depleted, damaged, and abnormally activated. This disrupts the cell's metabolic and epigenetic stability, leading to a loss of regenerative capacity. It is more than just a passive decline; it is an active driver of the aging process in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) [2] [3].

Q2: How does lysosomal dysfunction contribute to stem cell aging and inflammation? Dysfunctional lysosomes in aged HSCs fail to properly process damaged mitochondria. This leads to the leakage of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) into the cell's cytosol. The cell mistakes this mtDNA for a foreign invader, activating the cGAS-STING immune signaling pathway. This, in turn, triggers harmful inflammatory and interferon-driven responses, which are key drivers of inflammation and aging in stem cells [2] [50] [3].

Q3: Can lysosomal-targeted intervention actually reverse aging in stem cells? Yes, recent evidence demonstrates that aging in blood stem cells is not irreversible. By suppressing lysosomal hyperactivation with a specific v-ATPase inhibitor (ConA), researchers were able to restore lysosomal integrity, renew metabolic and mitochondrial function, and improve the epigenome in aged HSCs. This intervention successfully reset aged stem cells to a younger, healthier state, significantly improving their ability to regenerate blood and immune cells [2] [50].

Q4: What is the key signaling pathway involved in this lysosome-driven aging? The primary pathway is the cGAS-STING pathway. It is activated by cytosolic mtDNA that accumulates due to impaired lysosomal processing in old HSCs. Targeting lysosomal hyperactivity dampens this pathway, reducing inflammation and restoring stem cell function [2] [3].