CRISPR-Engineered Stem Cells: Revolutionizing Therapeutic Development and Disease Modeling

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the integration of CRISPR gene editing with stem cell technology, a frontier that is reshaping biomedical research and therapeutic development.

CRISPR-Engineered Stem Cells: Revolutionizing Therapeutic Development and Disease Modeling

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the integration of CRISPR gene editing with stem cell technology, a frontier that is reshaping biomedical research and therapeutic development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of CRISPR-Cas systems and stem cell biology, detailing advanced methodologies for creating precise cellular models. The content delves into critical challenges such as off-target effects, delivery efficiency, and immune responses, offering troubleshooting and optimization strategies grounded in recent studies. Furthermore, it presents a rigorous validation and comparative framework, evaluating CRISPR against traditional editing platforms and highlighting successful clinical applications. By synthesizing insights from current literature and clinical trials, this article serves as a strategic resource for advancing the translation of CRISPR-engineered stem cells from the laboratory to the clinic.

The Confluence of CRISPR and Stem Cells: Building the Bedrock of Modern Therapies

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins constitute an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes that has been repurposed as a revolutionary genome-editing technology. This system provides bacteria and archaea with sequence-specific defense against invading mobile genetic elements such as viruses and plasmids. The transition from a bacterial immune mechanism to a programmable genome-editing tool represents one of the most significant breakthroughs in modern biotechnology, enabling precise modifications to genetic information across diverse organisms and cell types.

The fundamental CRISPR-Cas system consists of CRISPR arrays—short repetitive DNA sequences interspersed with unique "spacer" sequences derived from previous invaders—and adjacent Cas genes encoding the protein machinery for immune function [1]. These systems are categorized into two classes: Class 1 (types I, III, and IV) utilize multi-protein effector complexes, while Class 2 (types II, V, and VI) employ a single large Cas protein such as Cas9, Cas12, or Cas13 [1]. The Type II CRISPR-Cas9 system, in particular, has been engineered into a versatile platform for genome editing, comprising the Cas9 endonuclease and a synthetic single-guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs Cas9 to specific DNA sequences [1].

Fundamental Mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas Systems

Native Biological Function in Prokaryotes

In its native context, CRISPR-Cas functions as an adaptive immune system through three distinct stages: adaptation, expression, and interference. During adaptation, specialized Cas1-Cas2 integrase complexes capture short fragments of foreign DNA (protospacers) and integrate them as new spacers into the CRISPR array, creating a genetic record of infection [1]. In the expression phase, the CRISPR array is transcribed and processed into small CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs). Finally, during interference, these crRNAs assemble with Cas proteins to form effector complexes that recognize and cleave complementary nucleic acids of invading pathogens, thereby neutralizing the threat [1].

CRISPR arrays provide remarkable insights into the dynamics of host-pathogen interactions. Spacer acquisition typically occurs at the leader end of arrays, with trailer-end repeats generally representing older sequences [2]. Analysis of CRISPR arrays in Bacteroides fragilis populations from human gut microbiomes has revealed three distinct system types (I-B, II-C, and III-B) with varying prevalence and activity levels between individuals, highlighting the dynamic nature of these systems in natural environments [3].

Molecular Mechanisms of Genome Editing

The repurposing of CRISPR-Cas systems for genome editing leverages the interference stage of the native immune response. When deployed in non-native contexts, the CRISPR-Cas9 system creates targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA approximately 3 base pairs upstream of a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence [4]. These breaks are subsequently repaired by the cell's endogenous DNA repair mechanisms, primarily either Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) or Homology-Directed Repair (HDR).

NHEJ is an error-prone repair pathway that often results in insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt gene function, making it suitable for gene knockout applications. In contrast, HDR uses a donor DNA template to enable precise genetic modifications, including nucleotide substitutions, gene insertions, or conditional alleles [4]. The efficiency of HDR remains a significant challenge in CRISPR applications, as NHEJ typically dominates the repair process in most cell types.

Table 1: CRISPR-Cas System Classification and Key Characteristics

| Class | Type | Signature Protein | Target | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | I | Cas3 | DNA | Multi-protein effector complex |

| Class 1 | III | Cas10 | DNA/RNA | Targets both DNA and RNA |

| Class 1 | IV | Unknown | Unknown | Function not fully characterized |

| Class 2 | II | Cas9 | DNA | Single effector protein; most widely used |

| Class 2 | V | Cas12 | DNA | Single effector protein; different PAM requirements |

| Class 2 | VI | Cas13 | RNA | RNA-targeting capability |

Applications in Stem Cell Genetic Engineering

Disease Modeling and Therapeutic Development

CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized stem cell research by enabling precise genetic modifications in pluripotent stem cells. In Alzheimer's disease (AD) research, human induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (hiPSCs) derived from patients can be reprogrammed into neurons and glial cells that recapitulate core pathological features of AD, including amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles [5]. CRISPR-Cas9 facilitates the introduction of pathogenic mutations in genes such as APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 into hiPSCs, creating isogenic cell lines that allow researchers to study disease mechanisms in a controlled genetic background [5].

These engineered stem cell models provide platforms for high-throughput drug screening, enabling identification of compounds that modulate β- and γ-secretase activity to reduce Aβ formation [5]. Additionally, CRISPR-edited stem cells offer potential for cell replacement therapies, where gene-corrected autologous cells could be transplanted to restore function in neurodegenerative conditions.

Protocol: Generating Conditional Knockout Models in Stem Cells

The generation of conditional knockout (cKO) models using stem cells requires precise integration of recombinase recognition sites (e.g., loxP sites) flanking critical exons of target genes. The following protocol outlines key steps for efficient homology-directed repair in stem cells:

Guide RNA Design: Design two crRNAs targeting sequences flanking the exon of interest. In vivo studies demonstrate that targeting the antisense strand with two crRNAs improves HDR precision compared to other strategies [4].

Donor DNA Template Design: Create a donor template with homologous arms (60-80 bp) flanking the loxP sites. Incorporation of 5'-end modifications (biotin or C3 spacer) significantly enhances HDR efficiency. 5'-biotin modification increases single-copy integration up to 8-fold, while 5'-C3 spacer modification produces up to a 20-fold rise in correctly edited cells [4].

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Formation: Combine Cas9 protein with sgRNAs to form RNP complexes. Delivery as RNP complexes rather than plasmid DNA reduces off-target effects and improves editing efficiency.

Stem Cell Transfection: Transfect stem cells using optimized electroporation parameters. For challenging cell types, perform extensive optimization—testing up to 200 conditions in parallel can identify parameters that increase editing efficiency from 7% to over 80% [6].

Validation and Screening: Isolate single-cell clones and validate correct integration via PCR, Southern blotting, and sequencing. Functional validation through differentiation and gene expression analysis confirms the conditional nature of the knockout.

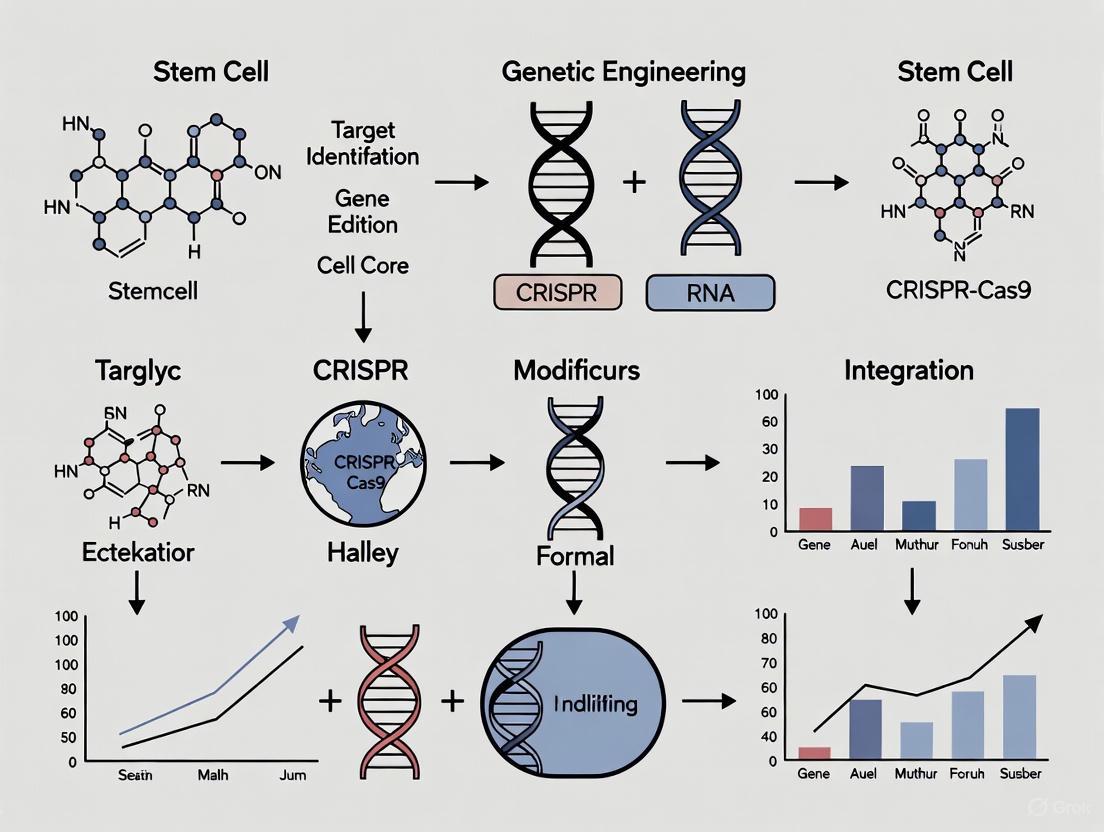

Diagram 1: Workflow for Generating Conditional Knockout Stem Cell Models

Advanced Genome Engineering Technologies

CRISPR-Assisted Transposase Systems

Recent advances have integrated CRISPR systems with transposase enzymes to enable precise, large-scale DNA integration without relying on endogenous DNA repair mechanisms. CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems combine RNA-guided DNA targeting with transposase-mediated DNA insertion, enabling integration of large genetic elements (up to 30 kb) into specific genomic loci [7].

Type I-F CAST systems utilize Cas6, Cas7, and Cas8 proteins forming the Cascade complex, which directs target DNA recognition, while TnsA, TnsB, and TnsC form a heteromeric transposase complex that catalyzes DNA cleavage and transposition [7]. Type V-K CAST systems employ the single-effector protein Cas12k, with DNA integration occurring 60-66 base pairs downstream of the PAM site [7]. These systems have demonstrated nearly complete insertion efficiency in prokaryotic hosts and are being adapted for eukaryotic and mammalian cell applications.

Prime Editing and Precision Modifications

Prime editing represents a versatile "search-and-replace" genome editing technology that enables precise base conversions, small insertions, and deletions without requiring double-strand breaks or donor DNA templates. This system uses a catalytically impaired Cas9 endonuclease fused to an engineered reverse transcriptase enzyme, programmed with a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that specifies the target site and encodes the desired edit [7].

The development of prime editing addresses significant limitations of conventional CRISPR-Cas9 systems, particularly off-target effects and the low efficiency of HDR in post-mitotic cells, including neurons derived from stem cells. This technology shows particular promise for correcting point mutations associated with neurodegenerative diseases in stem cell models.

Table 2: Advanced CRISPR Technologies for Stem Cell Engineering

| Technology | Mechanism | Editing Capacity | Key Advantages | Current Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 HDR | Double-strand break with donor template | < 2 kb | High efficiency knockouts | Low HDR efficiency; off-target effects |

| Base Editing | Chemical modification without DSB | Single nucleotide | High precision; no DSBs | Limited to specific base changes |

| Prime Editing | Reverse transcription without DSB | < 100 bp | Versatile; minimal off-targets | Complex system design |

| CAST Systems | Transposase-mediated integration | Up to 30 kb | Large payload capacity | Early development for eukaryotic cells |

| HITI | NHEJ-mediated integration | 1-5 kb | Works in non-dividing cells | High indel frequency |

Optimization Strategies for Enhanced Efficiency

Improving Homology-Directed Repair

Enhancing HDR efficiency remains a critical focus for precise genome editing applications in stem cells. Recent research has identified several key factors that significantly improve HDR outcomes:

Donor DNA Modifications: Denaturation of long 5'-monophosphorylated double-stranded DNA templates enhances precise editing and reduces unwanted template multiplications. 5'-biotin modification increases single-copy integration up to 8-fold, while 5'-C3 spacer modification produces up to a 20-fold rise in correctly edited cells [4].

Protein Cofactors: Supplementation with RAD52 protein increases single-stranded DNA integration nearly 4-fold, though accompanied by higher template multiplication. This approach demonstrates a 13-fold increase in correct modification compared to dsDNA alone when combined with denatured DNA templates [4].

Strand Targeting: Targeting the antisense strand with two CRISPR RNAs improves HDR precision compared to sense strand targeting, particularly in transcriptionally active genes [4].

Protocol: High-Efficiency Transfection Optimization

Achieving high editing efficiency in stem cells requires careful optimization of transfection parameters. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach:

Cell Line Preparation: Culture stem cells in optimal conditions to ensure >90% viability before transfection. Use early passage cells whenever possible.

Positive Controls: Include species-specific positive controls to distinguish between guide RNA failures and optimization parameter issues [6].

Multi-Parameter Testing: Test an average of seven different transfection conditions, systematically varying parameters such as voltage, pulse length, and reagent concentrations. Advanced platforms can test up to 200 conditions in parallel to identify optimal parameters [6].

Editing Assessment: Measure editing efficiency through genotyping rather than relying solely on transfection efficiency metrics, as successful transfection does not guarantee efficient editing [6].

Balance Optimization: Balance high editing efficiency with cell viability, as there is no benefit to achieving 99% editing efficiency if all edited cells undergo cell death [6].

Diagram 2: Strategies for Enhancing HDR Efficiency in Stem Cells

Clinical Applications and Therapeutic Translation

Current Clinical Landscape

CRISPR-based therapies have begun demonstrating remarkable success in clinical trials, with the first CRISPR-based medicine, Casgevy, receiving approval for treating sickle cell disease (SCD) and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia (TBT) [8]. This ex vivo therapy involves harvesting a patient's hematopoietic stem cells, editing them to reactivate fetal hemoglobin production, and reinfusing them after myeloablative conditioning.

Recent advances include the development of personalized in vivo CRISPR treatments. In a landmark 2025 case, an infant with CPS1 deficiency received a bespoke in vivo CRISPR therapy developed and delivered in just six months [8]. The treatment utilized lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for delivery and was administered via IV infusion, with the patient safely receiving multiple doses that progressively reduced symptoms. This case establishes a regulatory pathway for rapid approval of platform therapies and demonstrates the potential for treating rare genetic diseases.

Protocol: Rapid Screening of Gene Editing Outcomes

Monitoring editing outcomes is essential for both research and clinical applications. The following protocol enables rapid screening of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing outcomes using fluorescent protein conversion:

Generate Reporter Cell Line: Create enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (eGFP)-positive cells via lentiviral transduction [9].

Design Editing Strategy: Design gRNAs to convert eGFP to Blue Fluorescent Protein (BFP) through specific nucleotide changes. The HDR-mediated conversion to BFP indicates precise editing, while NHEJ-mediated disruption leads to loss of fluorescence [9].

Transfection and Culture: Transfect editing reagents into eGFP-positive cells and culture for sufficient time for protein turnover.

Flow Cytometry Analysis: Analyze cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to quantify the percentages of BFP-positive (HDR), eGFP-positive (unedited), and non-fluorescent (NHEJ) populations [9].

Data Interpretation: Calculate HDR and NHEJ efficiencies based on fluorescence patterns. This system enables high-throughput, scalable assessment of gene editing techniques and optimization of editing conditions [9].

Table 3: Quantitative Analysis of HDR Enhancement Strategies

| Strategy | Condition | HDR Efficiency | Template Multiplication | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor Type | dsDNA | 2% | 34% | Baseline efficiency |

| Donor Type | Denatured DNA | 8% | 17% | 4-fold HDR increase |

| Protein Addition | RAD52 + ssDNA | 26% | 30% | 13-fold HDR increase |

| 5' Modification | 5'-C3 spacer | 40% | 9% | 20-fold HDR increase |

| 5' Modification | 5'-biotin | 14% | 5% | 8-fold HDR increase |

| Strand Targeting | Antisense + ssDNA | 8% | 5% | Improved precision |

Computational Tools and Future Directions

AI-Powered CRISPR Design

Artificial intelligence tools are revolutionizing experimental design in CRISPR applications. CRISPR-GPT, a large language model developed at Stanford Medicine, functions as a gene-editing "copilot" that assists researchers in generating designs, analyzing data, and troubleshooting flaws [10]. This AI tool leverages 11 years of published experimental data and expert discussions to hone experimental designs, predict off-target effects, and recommend optimization strategies.

The system offers multiple interaction modes: beginner mode provides explanations for recommendations, expert mode collaborates on complex problems without additional context, and Q&A mode addresses specific technical questions [10]. In practice, researchers have used CRISPR-GPT to successfully design experiments on their first attempt, significantly reducing the trial-and-error period typically required for CRISPR experiment optimization.

CRISPR Array Analysis Tools

Bioinformatic tools enable detailed analysis of CRISPR system dynamics in natural environments. The CRISPR Comparison Toolkit (CCTK) provides resources for identifying relationships between CRISPR arrays through several steps [2]:

Array Identification: CCTK Minced identifies CRISPR arrays using a sliding window search to identify regularly spaced repeats without requiring prior knowledge of CRISPR subtypes.

Relationship Analysis: CRISPRdiff visualizes arrays and highlights similarities between them, assigning unique color combinations to spacers present in multiple arrays.

Evolutionary Analysis: CRISPRtree infers phylogenetic relationships between arrays using a maximum parsimony approach, presenting hypotheses about evolutionary history based on spacer patterns.

These tools facilitate exploration of how CRISPR systems evolve in response to environmental pressures, providing insights that can inform engineering of improved CRISPR systems for biotechnological applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Stem Cell Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | Cas9, Cas12a, Cas12k, Nickase variants | DNA cleavage at target sites | Cas9 most widely validated; Cas12k for CAST systems |

| Guide RNA Formats | Synthetic sgRNA, crRNA:tracrRNA duplex | Target specification | Synthetic sgRNA most common for stem cells |

| Donor DNA Templates | dsDNA, ssDNA, 5'-modified donors | HDR template | 5'-biotin or C3 spacer enhances efficiency 8-20x |

| Enhanced HDR Reagents | RAD52, small molecule inhibitors | Increase HDR efficiency | RAD52 increases ssDNA integration 4-fold |

| Delivery Systems | Lipid nanoparticles, Electroporation | Introduce editing components | LNPs enable in vivo delivery and redosing |

| Stem Cell Media | Essential 8, mTeSR, StemFlex | Maintain pluripotency | Varies by stem cell type and application |

| Editing Assessment | T7E1, TIDE, NGS, Flow cytometry | Measure editing outcomes | Fluorescent conversion enables rapid screening |

The journey of CRISPR-Cas systems from bacterial immunity mechanisms to programmable genome editing tools represents one of the most transformative developments in modern biotechnology. As research continues to refine these systems, improve delivery methods, and enhance precision, the applications in stem cell genetic engineering continue to expand. The integration of CRISPR technology with stem cell biology has created unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug discovery, and therapeutic development.

Current challenges, including editing efficiency, off-target effects, and safe delivery in vivo, are being addressed through continued innovation in protein engineering, delivery technologies, and computational design tools. The recent success of clinical trials and the emergence of personalized CRISPR treatments highlight the tremendous potential of these technologies to revolutionize medicine and provide new hope for patients with genetic disorders.

As the field progresses, the combination of stem cell technology and CRISPR genome editing promises to enable increasingly sophisticated approaches to understanding and treating human disease, ultimately fulfilling the promise of personalized regenerative medicine.

Stem cell research has profoundly transformed the landscape of regenerative medicine and therapeutic development. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs), and neural stem cells (NSCs) represent three distinct yet complementary therapeutic vessels with immense potential for treating a wide spectrum of diseases. The convergence of these cell-based approaches with precision gene-editing technologies, particularly CRISPR/Cas9, has opened unprecedented opportunities for modeling human diseases, screening therapeutic compounds, and developing innovative cell therapies. This article provides a comprehensive overview of these stem cell types, their therapeutic applications, and detailed experimental protocols within the context of advanced genetic engineering research.

Stem Cell Characteristics and Therapeutic Potential

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)

iPSCs are reprogrammed somatic cells that have regained pluripotency through the ectopic expression of specific transcription factors. The groundbreaking discovery by Takahashi and Yamanaka in 2006 demonstrated that mouse fibroblasts could be reprogrammed into pluripotent stem cells using four factors: Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and Myc (OSKM) [11]. This was subsequently extended to human cells in 2007, with Thomson's group using a different combination: OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28 [11] [12]. The molecular reprogramming process occurs in two phases: an early stochastic phase where somatic genes are silenced and early pluripotency genes are activated, followed by a deterministic phase where late pluripotency-associated genes are activated [11].

Table 1: iPSC Reprogramming Methods and Efficiencies

| Reprogramming Method | Key Features | Reprogramming Efficiency | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral/Lentiviral | Original method using OSKM factors | 0.01-0.1% [12] | Well-established, efficient | Integration into genome, tumorigenicity concerns |

| Sendai Virus | RNA virus that does not enter nucleus | 0.1-1% [12] | Non-integrating, high protein production | Requires ~10 passages to dilute out virus |

| mRNA Transfection | Daily transfection of reprogramming mRNAs | 1.4-4.4% [12] | Footprint-free, defined method | Labor-intensive, requires multiple transfections |

| PiggyBac Transposition | Mobile genetic element with excision capability | 0.02% in human MSCs [12] | Footprint-free after excision | Lower efficiency in human cells |

| Protein Transduction | Direct delivery of reprogramming proteins | 0.001-0.006% [12] | Completely DNA-free | Very low efficiency, technically challenging |

| miRNA Transfection | Uses microRNAs to enhance or induce reprogramming | Up to 10% reported [12] | Can enhance efficiency | Not consistently replicated |

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)

MSCs are multipotent adult stromal cells capable of self-renewal and differentiation into multiple lineages, including osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes [13] [14]. According to International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) guidelines, MSCs must express specific surface markers (CD105, CD73, CD90) while lacking hematopoietic markers (CD45, CD34, CD14, CD11b, CD79α, CD19, and HLA-DR) [13] [14]. MSCs can be isolated from various tissues, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, and placenta [13] [15]. The therapeutic effects of MSCs are primarily attributed to their immunomodulatory properties and paracrine actions rather than their differentiation potential [14].

Table 2: MSC Sources and Their Characteristics

| Tissue Source | Isolation Method | Key Markers | Differentiation Potential | Therapeutic Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow | Enzymatic digestion or explant culture | CD105+, CD73+, CD90+, CD271+ [15] [14] | High osteogenic potential [15] | Standard source, well-characterized |

| Adipose Tissue | Enzymatic digestion | CD105+, CD73+, CD90+, CD36+ [15] | High adipogenic potential [15] | Easily accessible, abundant supply |

| Umbilical Cord | Explant culture or enzymatic digestion | CD105+, CD73+, CD90+, CD45- [15] | High osteogenic, low adipogenic potential [15] | High proliferation, potent immunomodulation |

| Placenta | Enzymatic digestion | CD105+, CD73+, CD90+, CD146+ [14] | Multilineage differentiation | Available as medical waste, primitive properties |

Neural Stem Cells (NSCs)

NSCs are multipotent cells capable of self-renewal and differentiation into the three major central nervous system (CNS) lineages: neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [16]. In the mature mammalian CNS, NSCs are primarily localized to two key regions: the subventricular zone (SVZ) lining the lateral ventricles of the forebrain, and the subgranular layer of the dentate gyrus in the hippocampal formation [16]. NSCs can be isolated from embryonic, postnatal, or adult CNS tissue, or generated from PSCs through neural induction protocols [16]. The therapeutic potential of NSCs lies in their ability to replace damaged neurons and glial cells, provide neurotrophic support, and modulate the inflammatory environment in neurological disorders.

CRISPR/Cas9 Applications in Stem Cell Engineering

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has revolutionized stem cell research by enabling precise genetic modifications in stem cells for disease modeling and therapy development. This RNA-guided gene-editing tool consists of two main components: a Cas9 nuclease that cleaves target DNA and a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs Cas9 to specific genomic sequences [17].

CRISPR/Cas9 in iPSC Research

CRISPR/Cas9 technology allows for precise genetic modifications in iPSCs, making it invaluable for disease modeling and therapeutic applications. In Alzheimer's disease research, CRISPR/Cas9 has been used to introduce or correct mutations in genes such as APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 in iPSCs, enabling the study of disease mechanisms and screening of potential therapeutics [17]. For monogenic disorders like thalassemia, CRISPR/Cas9 can correct disease-causing mutations in patient-derived iPSCs, which can then be differentiated into hematopoietic stem cells for autologous transplantation [18]. This approach offers a potential cure by addressing the genetic root cause of the disease.

CRISPR/Cas9 in MSC Research

While MSCs are already used therapeutically for their immunomodulatory properties, CRISPR/Cas9 can enhance their therapeutic potential through genetic engineering. This includes modifying MSCs to enhance their homing capabilities, increase their secretion of therapeutic factors, or improve their resistance to inflammatory environments [18]. Additionally, CRISPR/Cas9 can be used to study the mechanisms underlying MSC biology, such as the genes involved in their differentiation potential or immunomodulatory functions.

Experimental Protocols

iPSC Generation and Characterization Protocol

Reprogramming Human Fibroblasts to iPSCs Using the PiggyBac Transposition System

Materials:

- Human dermal fibroblasts (commercially available or patient-derived)

- PB-Tre-h4F, PB-Tre-hRL, PB-Tre-P2F, EF1α, and Pbase plasmids [19]

- STO feeder cells

- M15 medium supplemented with doxycycline (1.0 μg/mL)

- mTeSR medium (STEMCELL Technologies, #85850)

- Vitronectin (VTN)-coated plates (Gibco A14700)

Methodology:

- Transfection: Prepare a DNA mixture containing 3.0 μg PB-Tre-h4F, 1.0 μg PB-Tre-hRL, 1.0 μg PB-Tre-P2F, 1.0 μg EF1α, and 1.0 μg Pbase. Transfect into 1.0 × 10^6 fibroblasts using preferred method [19].

- Seeding and Initial Culture: Seed transfected cells on STO feeder cells in a 10-cm dish with M15 medium supplemented with doxycycline (1.0 μg/mL) [19].

- Doxycycline Removal: At day 14 post-transfection, remove doxycycline and switch culture medium to mTeSR [19].

- iPSC Expansion: Monitor cultures for emergence of iPSC colonies. Manually pick and expand colonies to establish stable iPSC lines on VTN-coated plates in mTeSR medium [19].

Characterization Assays:

- Alkaline Phosphatase Staining: Fix cells in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes, then incubate with AP staining solution. Pluripotent cells show strong AP activity [19].

- Immunofluorescence Analysis: Stain for pluripotency markers (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) using specific antibodies. Analyze using confocal microscopy [19].

- Karyotyping: Treat cells with 0.2 μg/mL colchicine for 2.5 hours. Process cells through hypotonic treatment, fixation, and Giemsa staining. Analyze chromosomes for numerical and structural abnormalities [19].

- Teratoma Formation: Inject iPSCs into immunodeficient mice. After 8-12 weeks, analyze formed teratomas histologically for presence of tissues from all three germ layers [13].

MSC Isolation and Differentiation Protocol

Isolation and Osteogenic/Adipogenic Differentiation of MSCs

Materials:

- Tissue source (bone marrow aspirate, adipose tissue, umbilical cord)

- Collagenase type I for enzymatic digestion

- Growth medium (EGM-2 kit or DMEM with 10% FBS)

- Adipogenic differentiation medium (Cyagen Biosciences, #GUXMX-90031)

- Osteogenic differentiation medium (Cyagen Biosciences, #GUXMX-90021)

- Oil Red O stain (Sigma-Aldrich)

- Alizarin Red S stain (Sigma-Aldrich)

Methodology:

Isolation from Umbilical Cord Tissue:

- Cut umbilical cord tissue into 1-2 mm³ pieces.

- Enzymatically digest with 3 mg/mL type I collagenase for 3-4 hours at 37°C.

- Culture digested tissue in growth medium, changing medium every 2-3 days [15].

Flow Cytometry Characterization:

Adipogenic Differentiation:

- Culture MSCs in adipogenic differentiation medium for 3 weeks, changing medium twice weekly.

- Fix cells and stain with Oil Red O to visualize lipid vacuoles [15].

Osteogenic Differentiation:

- Culture MSCs in osteogenic differentiation medium for 3 weeks, changing medium twice weekly.

- Fix cells and stain with Alizarin Red S to detect calcium deposition, or use von Kossa staining for mineralization [15].

NSC Differentiation and Deep Learning-Based Identification Protocol

Generation of NSCs from iPSCs and Early Fate Identification

Materials:

- Established iPSC lines

- Neural induction medium

- Imageable flow cytometer

- Specific markers: NeuN (neurons), GFAP (astrocytes), Olig2 (oligodendrocytes) [20]

- Deep learning computational setup

Methodology:

Neural Induction from iPSCs:

- Induce neural differentiation using established protocols (embryoid body or monolayer system).

- Identify and isolate neural rosettes containing NPCs [16].

Lineage-Specific Differentiation:

- For neuronal differentiation: Culture NSCs in neuron differentiation medium with retinoic acid (RA) and sonic hedgehog (SHH) for 1-5 days [20].

- For astrocyte differentiation: Culture NSCs in astrocyte differentiation medium for 0.5-2 days [20].

- For oligodendrocyte differentiation: Culture NSCs in oligodendrocyte differentiation medium for 1-3 days [20].

Deep Learning-Based Identification:

- Collect brightfield images of differentiating NSCs using imageable flow cytometry.

- Train a convolutional neural network (CNN) with annotated single-cell images.

- Use the trained model to identify differentiated cell types from brightfield images alone, enabling early prediction of NSC fate [20].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

iPSC Reprogramming Mechanisms

The reprogramming of somatic cells to iPSCs involves profound remodeling of the epigenome and global changes in chromatin structure. The process begins with the silencing of somatic genes and activation of early pluripotency-associated genes, followed by activation of late pluripotency genes [11]. Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) is a critical early event in reprogramming when starting from fibroblast populations [11]. Signaling pathways such as Wnt play crucial roles in establishing and maintaining pluripotency [19].

MSC Therapeutic Action Mechanisms

MSCs exert their therapeutic effects primarily through paracrine actions rather than differentiation and engraftment. The secretion profile of MSCs includes growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, extracellular matrix components, and metabolic products that contribute to immune modulation, tissue remodeling, and cellular homeostasis during regeneration [14]. MSCs can modulate immune responses by inhibiting T lymphocyte proliferation, inducing cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis [14]. They also express a wide array of chemokines and receptors that form a chemotactic network for guiding circulating cells to injury sites [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Stem Cell Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, NANOG, LIN28 | Induction of pluripotency | Multiple combinations effective; viral and non-viral delivery methods [11] [12] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Components | Cas9 nuclease, sgRNA, HDR donors | Precision gene editing | Enable specific genetic modifications in stem cells [18] [17] |

| Cell Culture Media | mTeSR, E8, MSC growth media | Maintenance and expansion | Defined media preferred for reproducibility [19] |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, CD105, CD73, CD90, NeuN, GFAP, Olig2 | Cell type identification | Essential for validating stem cell identity and differentiation [15] [20] [14] |

| Differentiation Inducers | Retinoic acid, SHH, BMPs, specific cytokine cocktails | Lineage-specific differentiation | Direct stem cells toward specific fates [20] [16] |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | IWR1 (Wnt inhibitor), SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor) | Pathway modulation | Enhance reprogramming or direct differentiation [13] [19] |

iPSCs, MSCs, and NSCs represent powerful therapeutic vessels with complementary strengths and applications. iPSCs offer unlimited expansion potential and the ability to model human diseases, MSCs provide potent immunomodulatory and trophic support, while NSCs hold promise for treating neurological disorders. The integration of CRISPR/Cas9 technology with these stem cell platforms has accelerated disease modeling, drug screening, and the development of novel cell therapies. As research continues to address challenges such as tumorigenicity, genomic stability, and functional maturation, stem cell-based therapies are poised to transform treatment paradigms for a wide range of diseases.

The convergence of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 technology with stem cell biology represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research and therapeutic development. This powerful synergy leverages the precision of programmable genome editing with the pluripotency and self-renewal capabilities of stem cells. The CRISPR-Cas system functions as a bacterial adaptive immune system that has been repurposed as a highly specific gene-editing tool, utilizing a guide RNA (gRNA) to direct the Cas9 nuclease to create targeted double-strand breaks in DNA [21]. When applied to stem cells—including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), embryonic stem cells (ESCs), and adult stem cells—this combination enables unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine.

The molecular architecture of the CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of two key components: the Cas9 enzyme, which acts as molecular scissors to cut DNA, and a customizable gRNA that directs Cas9 to a specific genomic locus. This creates a double-strand break that activates the cell's native DNA repair mechanisms: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) for gene disruption or homology-directed repair (HDR) for precise gene correction [21]. When deployed in stem cells, these precise genetic modifications can be perpetuated through cell divisions and differentiation processes, creating durable cellular platforms for both research and clinical applications.

Application Notes: Research and Clinical Applications

Disease Modeling and Drug Screening

The combination of CRISPR and stem cell technologies has revolutionized disease modeling by enabling the creation of genetically accurate cellular models that recapitulate human disease pathophysiology. Researchers can introduce patient-specific mutations into healthy iPSCs or correct disease-causing mutations in patient-derived iPSCs to establish isogenic control lines. These paired cell lines provide genetically matched systems for identifying phenotype-specific differences, dramatically improving the signal-to-noise ratio in disease mechanism studies [21].

Table 1: CRISPR-Generated Stem Cell Models for Disease Research

| Disease Category | Stem Cell Type | Genetic Modification | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodegenerative Disorders | iPSCs | Introduction of PARK2 mutations | Parkinson's disease pathogenesis studies [22] |

| Hematologic Disorders | Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs) | BCL11A enhancer editing | Sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia modeling [8] |

| Cardiac Diseases | iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes | Editing of sarcomere protein genes | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy drug screening [22] |

| Metabolic Disorders | iPSC-derived hepatocytes | CPS1 deficiency correction | Urea cycle disorder modeling and therapeutic testing [8] |

| Retinal Disorders | iPSC-derived retinal cells | Correction of photoreceptor genes | Inherited blindness studies and gene therapy development [22] |

For drug screening applications, CRISPR-edited stem cells enable high-throughput compound testing in disease-relevant human cell types. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying candidate therapeutics for monogenic disorders, as demonstrated by screens using iPSC-derived motor neurons for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and iPSC-derived microglia for Alzheimer's disease research. The precision of CRISPR editing allows for the incorporation of reporter constructs and biosensors into safe-harbor loci, facilitating real-time monitoring of disease-associated cellular phenotypes in response to compound libraries.

Cell Therapy Manufacturing and Engineering

CRISPR-Cas9 has transformed cell therapy manufacturing by enabling precise engineering of therapeutic stem cell products with enhanced functionality and safety profiles. In allogeneic cell therapies, CRISPR is utilized to create immune-evasive stem cells through knockout of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes, reducing host rejection without the need for toxic immunosuppression. This approach is being applied to develop hypoimmune stem cell lines for regenerative medicine applications, including type 1 diabetes (T1D) treatment [23].

Table 2: CRISPR-Engineered Stem Cell Therapies in Clinical Development

| Therapeutic Product | Stem Cell Type | Genetic Modification | Clinical Indication | Development Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASGEVY (exa-cel) | Autologous HSCs | BCL11A enhancer disruption | Sickle cell disease, Transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia | FDA Approved [8] [23] |

| CTX112 | Allogeneic CAR-T cells | CD19 targeting + immune evasion edits | B-cell malignancies, Autoimmune diseases | Phase 1/2 [23] |

| CTX211 | Allogeneic stem cell-derived pancreatic islets | Hypoimmune edits + enhanced fitness | Type 1 diabetes | Phase 1 [23] |

| Hypoimmune hiPSC Lines | Induced pluripotent stem cells | MHC class I/II knockout | Multiple regenerative applications | Preclinical [24] |

The manufacturing process for these therapies involves multiplexed genome editing, where multiple genetic modifications are introduced simultaneously to enhance therapeutic properties. For example, CAR-T cell products incorporate edits to improve potency, reduce exhaustion, and prevent fratricide (killing of fellow therapeutic cells) [23]. For stem cell-derived therapies, additional edits can promote differentiation efficiency, engraftment capability, and long-term persistence of the therapeutic cells in the recipient.

In Vivo and In Vivo Regenerative Applications

CRISPR-edited stem cells are advancing regenerative medicine through both ex vivo and in vivo approaches. In ex vivo applications, stem cells are genetically modified outside the body before transplantation, as exemplified by CASGEVY, where a patient's own hematopoietic stem cells are edited to reactivate fetal hemoglobin production [8]. This approach avoids immune rejection concerns but requires complex manufacturing logistics.

Emerging in vivo strategies directly deliver CRISPR components to stem cells within the body using advanced delivery systems such as lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). The recent landmark case of an infant with CPS1 deficiency who received a personalized in vivo CRISPR therapy demonstrates the potential of this approach [8]. The therapy was developed in just six months and delivered systemically via LNPs, with the patient safely receiving multiple doses that each provided additional therapeutic benefit. This case establishes a precedent for on-demand gene editing therapies for rare genetic diseases and highlights the advantage of LNP delivery, which doesn't trigger the same immune responses as viral vectors and allows for potential redosing [8].

Diagram 1: CRISPR-Stem Cell Synergy Workflow. This diagram illustrates the integration of diverse stem cell sources with CRISPR engineering strategies to generate various therapeutic applications.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Generation of CRISPR-Edited iPSCs for Disease Modeling

This protocol describes the complete workflow for creating genetically engineered induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using CRISPR-Cas9, from guide RNA design to validation of edited clones.

Materials and Reagents

- Human iPSCs (commercially available or patient-derived)

- CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex

- Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX or Neon Transfection System

- mTeSR Plus maintenance medium

- Recombinant laminin-521 or Matrigel

- CloneR supplement for enhanced clonal survival

- Puromycin or other appropriate selection antibiotic

- QuickExtract DNA solution for genotyping

- PCR reagents and Sanger sequencing primers

- T7 Endonuclease I or Surveyor mutation detection assay

Procedure

Guide RNA Design and Synthesis

- Identify target genomic sequence using reference databases (e.g., UCSC Genome Browser)

- Design 3-5 gRNAs targeting your locus of interest using CRISPR design tools (e.g., CRISPick, CHOPCHOP)

- Synthesize gRNAs as chemically modified synthetic RNAs or clone into appropriate expression vectors

- Validate gRNA efficiency using predictive scoring algorithms and in vitro cleavage assays

CRISPR Delivery to iPSCs

- Culture iPSCs in essential 8 medium on recombinant laminin-521-coated plates until 60-70% confluent

- Prepare CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex by combining 10μg Cas9 protein with 5μg synthetic gRNA, incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes

- Dissociate iPSCs to single cells using Accutase and resuspend at 1×10^7 cells/mL in electroporation buffer

- Add RNP complex to cell suspension and electroporate using Neon Transfection System (1200V, 20ms, 2 pulses)

- Alternatively, use lipid-based transfection with CRISPRMAX according to manufacturer's protocol

Isolation and Expansion of Clones

- 48 hours post-transfection, dissociate cells to single cells and plate at clonal density (500-1000 cells/10cm plate) in mTeSR Plus supplemented with CloneR

- After 10-14 days, manually pick individual colonies using a pipette tip under microscope guidance

- Transfer each colony to a separate well of a 96-well plate pre-coated with laminin-521

- Expand clones through 24-well and 12-well plates before transferring to 6-well format

Genotypic Validation

- At 70-80% confluence in 6-well plates, harvest portion of cells for genomic DNA extraction using QuickExtract solution

- Perform PCR amplification of the target genomic region using flanking primers

- Analyze editing efficiency using T7 Endonuclease I assay or Surveyor mutation detection kit

- For precise edits, clone PCR products and sequence 10-20 colonies or use next-generation sequencing

- Screen for potential off-target effects at predicted off-target sites

Characterization of Edited Clones

- Confirm pluripotency maintenance through flow cytometry for pluripotency markers (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG)

- Perform karyotype analysis to ensure genomic integrity

- Bank validated clones in liquid nitrogen with appropriate documentation

Timeline: This complete protocol requires approximately 8-10 weeks from CRISPR delivery to validated banked clones.

Protocol: In Vivo Delivery of CRISPR-Edited Stem Cells

This protocol describes the administration of CRISPR-edited stem cells for in vivo therapeutic applications, using hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) for hematologic disorders as a model system.

Materials and Reagents

- CRISPR-edited CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells

- Cryopreservation media (e.g., CryoStor CS10)

- Pre-transplantation conditioning regimen reagents (e.g., busulfan)

- Sterile saline for infusion

- Patient monitoring equipment

- Flow cytometry reagents for engraftment analysis

Procedure

Pre-transplantation Processing

- Thaw CRISPR-edited CD34+ HSCs rapidly at 37°C and transfer to pre-warmed transplant media

- Wash cells to remove cryopreservatives and resuspend in sterile saline at appropriate concentration

- Perform quality control assessments: viability (trypan blue exclusion), cell count, and sterility testing

- Confirm editing efficiency in the final product via PCR and sequencing of a representative sample

Patient Conditioning

- Administer myeloablative conditioning regimen (e.g., busulfan) according to established protocols

- Monitor patient for conditioning-related toxicities and provide supportive care as needed

- Confirm adequate myeloablation before stem cell infusion

Stem Cell Infusion

- Transport cell product to bedside in approved transport container maintaining appropriate temperature

- Pre-medicate patient with antipyretics and antihistamines per institutional standards

- Administer cell product via central venous catheter using a syringe pump over appropriate duration

- Monitor patient closely during infusion for adverse reactions (fever, hypersensitivity, etc.)

Post-Transplantation Monitoring

- Monitor hematologic recovery through daily complete blood counts

- Assess engraftment starting around day +14 via chimerism analysis (STR-PCR or FISH)

- Evaluate editing persistence in peripheral blood cells at regular intervals (1, 3, 6, and 12 months)

- Monitor for potential off-target effects through comprehensive metabolic panels and organ function tests

- Document therapeutic efficacy through disease-specific parameters (e.g., hemoglobin electrophoresis for hemoglobinopathies)

Safety Considerations

- Monitor for insertional oncogenesis through periodic blood tests and clinical evaluation

- Screen for immune responses to CRISPR components or edited cells

- Implement long-term follow-up according to FDA guidance for gene therapy products [22]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Stem Cell Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | SpCas9, HiFi Cas9, Cas12a | Create targeted DNA double-strand breaks | High-fidelity variants reduce off-target effects in sensitive stem cell applications |

| Delivery Systems | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), Electroporation, AAV vectors | Deliver CRISPR components to cells | LNPs show promise for in vivo delivery; electroporation works well for ex vivo editing [8] |

| Stem Cell Culture Reagents | mTeSR, Essential 8, Laminin-521 | Maintain pluripotency during editing | Xen-free systems recommended for clinical applications |

| Editing Enhancers | HDR enhancers (e.g., RS-1, L755507), NHEJ inhibitors | Bias DNA repair toward desired pathway | Improve efficiency of precise gene correction in slow-dividing stem cells |

| Selection Markers | Puromycin, GFP, antibiotic resistance genes | Enrich for successfully edited cells | Fluorescent reporters enable sorting without antibiotics |

| Analytical Tools | T7E1 assay, Next-generation sequencing, Digital PCR | Validate editing efficiency and specificity | NGS provides comprehensive assessment of on-target and potential off-target edits |

Diagram 2: CRISPR-Stem Cell Experimental Decision Pathway. This diagram outlines the key decision points when designing CRISPR-stem cell experiments, from strategic approach selection through validation tiers.

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite the remarkable progress in CRISPR-stem cell applications, several significant challenges remain. Delivery efficiency continues to be a primary obstacle, particularly for in vivo applications where reaching the target stem cell population with sufficient editing components remains difficult [8] [21]. The field is actively addressing this through advances in lipid nanoparticle (LNP) technology and novel viral vectors with improved tissue tropism.

Off-target effects present another critical challenge, as unintended edits could potentially lead to oncogenesis or other pathological consequences [21]. The development of high-fidelity Cas variants and improved computational prediction tools has substantially mitigated this risk, but comprehensive off-target assessment remains essential, particularly for clinical applications. Immunogenicity of bacterial-derived Cas proteins represents an additional concern, especially for in vivo applications where pre-existing immunity could limit efficacy or cause adverse reactions [21].

The regulatory landscape for CRISPR-edited stem cell therapies is rapidly evolving. The FDA has established specific guidance documents including "Human Gene Therapy Products Incorporating Human Genome Editing" and "Studying Multiple Versions of a Cellular or Gene Therapy Product in an Early-Phase Clinical Trial" that provide frameworks for development [25] [22]. The recent establishment of the Office of Therapeutic Products (OTP) within the FDA has created a specialized pathway for reviewing these complex biologics, with increased staffing and expertise in cell and gene therapy products [25].

Future directions for the field include the development of next-generation editing platforms such as base editing and prime editing that offer more precise genetic modifications without creating double-strand breaks. The combination of hypoimmune stem cells with precision editing could enable true off-the-shelf regenerative therapies that avoid immune rejection [24] [23]. Additionally, the success of personalized CRISPR therapies, such as the recent case of an infant with CPS1 deficiency, points toward a future of bespoke genetic medicines for rare disorders [8].

As the field advances, balancing innovation with safety remains paramount. The extraordinary synergistic potential of CRISPR and stem cells continues to drive transformative advances across biomedical research and clinical medicine, offering new hope for addressing previously untreatable genetic diseases.

Key Historical Milestones and Ethical Touchstones in the Field

The convergence of stem cell biology and CRISPR-based genome editing represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research and therapeutic development [26]. This synergy creates a powerful platform for disease modeling, drug discovery, and the development of novel cell-based therapies for a range of intractable conditions, from genetic disorders to neurodegenerative diseases [26] [27]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the integrated historical trajectory and the evolving ethical landscape is crucial for navigating this rapidly advancing field. This application note provides a detailed overview of key milestones, ethical frameworks, and standardized experimental protocols that form the foundation of responsible and effective research in stem cell genetic engineering.

Historical Milestones in Stem Cell Research and CRISPR Technology

The following table summarizes the pivotal discoveries that have shaped the fields of stem cell research and genome editing, leading to their powerful integration.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Stem Cell Research and CRISPR Technology

| Year | Milestone | Key Researchers/Entity | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Identification of blood-forming (hematopoietic) stem cells [28] [27] | McCulloch and Till | Provided the first definitive evidence for the existence of stem cells, laying the groundwork for bone marrow transplantation. |

| 1981 | Isolation of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) from mouse embryos [28] | N/A | Established the first in vitro models for studying early mammalian development. |

| 1998 | Derivation of the first human embryonic stem cell (hESC) lines [28] [29] [27] | James Thomson | Opened new avenues for studying human development and regenerative medicine, though raising significant ethical questions [30]. |

| 2006 | Discovery of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [28] [27] | Shinya Yamanaka | Developed a method to reprogram adult somatic cells into a pluripotent state, offering an ethical alternative to hESCs and enabling patient-specific disease modeling [26] [27]. |

| 2012 | Characterization of CRISPR-Cas9 for programmable genome editing [31] | Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna | Demonstrated a highly specific and easily programmable system for editing genes in their natural chromosomal context, revolutionizing genetic engineering. |

| 2023 | First regulatory approval of a CRISPR-based therapy (Casgevy for sickle cell disease and TBT) [31] [8] | FDA/EMA | Marked the transition of CRISPR from a research tool to an approved clinical modality, validating its therapeutic potential. |

| 2025 | First personalized in vivo CRISPR therapy for a rare genetic disease (CPS1 deficiency) [8] | Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI) and collaborators | Demonstrated the feasibility of rapidly developing and deploying bespoke CRISPR therapies for individuals with ultrarare diseases, setting a new regulatory precedent. |

Ethical Touchstones and Regulatory Framework

The powerful capabilities of stem cell genetic engineering necessitate a robust ethical and regulatory framework. The core ethical principles for research, as outlined by organizations like the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR), include integrity, transparency, and a primary duty of care to patient welfare [29]. The following diagram illustrates the key ethical considerations and their interrelationships that researchers must navigate.

Diagram 1: Key Ethical Considerations. This map outlines the primary ethical domains (yellow) and their associated specific concerns (red) that arise from the use of genome editing and stem cell technologies.

Key Ethical Considerations

- Safety and Unintended Outcomes: A primary concern is the risk of off-target effects, where CRISPR edits occur at unintended sites in the genome, potentially leading to harmful mutations [31] [32]. Similarly, on-target effects can include unwanted edits at the intended target, and the long-term safety of edited cells, including tumorigenicity, must be rigorously assessed [32] [27].

- Access and Justice: The high cost of emerging therapies (e.g., over $2 million per patient) raises significant concerns about equitable access [32]. There is a tangible risk that these treatments could exacerbate existing health disparities both within and between countries, making justice a central ethical touchstone [28] [32] [29].

- Germline Editing: Modifying the human germline (sperm, eggs, or embryos) to create heritable genetic changes is widely considered an ethical red line [32]. Such interventions would permanently alter the human gene pool and raise profound questions about consent of future generations. The ISSCR guidelines explicitly prohibit the clinical use of germline editing [29].

- Informed Consent and Therapeutic Misconception: Obtaining valid informed consent is particularly challenging in this field. Patients with serious illnesses may be vulnerable to "therapeutic misconception," where they conflate experimental research with proven treatment [28]. Researchers must clearly communicate the experimental nature, potential risks, and uncertain benefits of these interventions [28] [29].

Experimental Protocols for Stem Cell Genetic Engineering

This section details a standard workflow for incorporating CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing into stem cell research, using the generation of a gene-corrected neuronal model from patient-specific iPSCs as an example.

Protocol: Gene Correction in iPSCs for Disease Modeling

Application: Modeling and rescuing pathogenic mutations in neurological disorders such as Familial Alzheimer's Disease (caused by mutations in APP, PSEN1, PSEN2) [26].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key stages for generating gene-corrected disease models using patient-derived iPSCs.

Step 1: iPSC Generation and Culture

- Methodology: Maintain patient-derived iPSCs in feeder-free culture using essential media such as mTeSR or StemFlex on a suitable substrate (e.g., Geltrex or Matrigel). Culture cells in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO₂. Passage cells using EDTA or enzyme-free dissociation reagents to maintain pluripotency, confirmed by regular checks for marker expression (e.g., OCT4, NANOG, SOX2) and karyotype stability [26] [27].

Step 2: gRNA Design and Vector Construction

- Methodology: Design a target-specific guide RNA (gRNA) using online in silico tools (e.g., from IDT or Broad Institute) to minimize potential off-target effects [31]. For non-viral delivery, clone the gRNA sequence and the Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 coding sequence into a single plasmid vector under a U6 and Cbh promoter, respectively. Include a donor DNA template containing the desired corrective sequence with homologous arms (~800 bp) if performing HDR [26].

Step 3: Delivery of CRISPR Components

- Methodology: Deliver the CRISPR plasmid or, for higher efficiency and reduced off-target effects, a pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex [31]. Use an electroporation-based system (e.g., Neon Transfection System) with optimized parameters for iPSCs. A typical reaction uses 1-2 million cells, 10-20 µg of RNP complex, and a pulse voltage of 1100-1300 V for 20-30 ms. Alternatively, use a non-viral delivery method to mitigate immune response risks associated with viral vectors [31] [8].

Step 4: Isolation and Expansion of Edited Clones

- Methodology: Post-transfection, allow cells to recover for 48-72 hours before applying appropriate antibiotic selection (e.g., Puromycin) for 5-7 days if a selection marker was co-delivered. Then, manually pick and expand single-cell-derived clonal colonies in 96-well plates. This step is critical for ensuring a homogeneously edited population [26].

Step 5: Genotypic Validation of Edited Clones

- Methodology: Extract genomic DNA from expanded clonal lines. Screen for successful editing using a mismatch detection assay (e.g., T7 Endonuclease I or TIDE analysis). Confirm the precise genetic correction in positive clones by Sanger sequencing of the target locus. Perform whole-genome sequencing on at least one correctly edited clone to assess potential off-target effects [31] [26].

Step 6: Functional Differentiation and Analysis

- Methodology: Differentiate the validated, gene-corrected iPSC clones and the original (un-corrected) patient iPSCs into the relevant cell type (e.g., neurons) using a standardized protocol. Compare the isogenic cell lines to assess functional rescue of the disease phenotype. For an AD model, this would involve quantifying the reduction of Aβ plaques and phosphorylated tau protein, as well as evaluating the rescue of electrophysiological function and synaptic activity [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell Genetic Engineering

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Human iPSCs | Patient-specific disease modeling; source for gene-edited therapeutic cells [26] [27]. | Check for stable karyotype and pluripotency markers; use low-passage stocks. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Introduction of targeted double-strand breaks in the DNA for gene knockout or correction. | RNP delivery is preferred for reduced off-target effects and shorter cellular exposure [31]. |

| gRNA | Guides the Cas9 nuclease to the specific genomic target sequence. | Must be designed using in silico tools to predict and minimize off-target activity [31]. |

| Electroporation System | Efficient delivery of CRISPR components (RNP or plasmid) into hard-to-transfect iPSCs. | Optimization of voltage and pulse duration is critical for high efficiency and low cytotoxicity. |

| Cytokines & Small Molecules | Direct differentiation of iPSCs into specific somatic cell lineages (e.g., neurons, cardiomyocytes). | Quality and batch consistency are paramount for reproducible differentiation protocols. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo delivery vehicle for CRISPR components; shows promise for liver-targeted therapies [8]. | Enables in vivo editing and allows for potential re-dosing due to low immunogenicity [8]. |

Current Clinical Applications and Future Outlook

The clinical translation of integrated stem cell and CRISPR technologies is advancing rapidly. The first approved CRISPR therapy, Casgevy, is an ex vivo application where a patient's hematopoietic stem cells are edited outside the body to treat sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia [8]. The field is now moving towards more complex in vivo applications and allogeneic (off-the-shelf) cell therapies.

Promising clinical targets include:

- Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis (hATTR): NTLA-2001 (Intellia Therapeutics) is an in vivo CRISPR therapy that knocks out the TTR gene in the liver, showing sustained protein reduction in clinical trials [8] [33].

- Neurodegenerative Disease: Research is focused on using gene-edited stem cells to deliver neurotrophic factors or correct mutations in models of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease [26].

- Cardiovascular Disease: Base editing therapies like VERVE-101 and VERVE-102 aim to permanently inactivate the PCSK9 gene in the liver to lower cholesterol [33].

Future developments will depend on overcoming key challenges in delivery, particularly improving the targeting of LNPs and other vectors to organs beyond the liver [8] [34]. Furthermore, the high cost of therapies necessitates the development of scalable manufacturing processes and innovative financing models to ensure equitable access, aligning with the core ethical principle of distributive justice [32] [29].

From Bench to Bedside: Methodologies and Translational Applications in Disease Modeling and Therapy

The field of stem cell genetic engineering has been revolutionized by CRISPR-based genome editing technologies, which provide unprecedented precision for modeling human diseases and developing regenerative therapies. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the transition from traditional knockout techniques to advanced base editing is crucial for tackling complex genetic diseases. These workflows enable precise genetic modifications in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), allowing for the creation of more accurate disease models and the development of potentially curative therapies. The integration of these technologies into stem cell research has accelerated our understanding of developmental biology and opened new avenues for personalized medicine, particularly through the creation of patient-specific stem cell lines with targeted genetic corrections.

Core Genome Editing Technologies

CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Workflows

CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene knockout remains the foundational workflow in genome engineering, primarily utilized for loss-of-function studies. This technology creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA at sequence-specific locations, which are then repaired by the cell's error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, resulting in insertion/deletion mutations (indels) that disrupt gene function [7]. The simplicity and efficiency of this approach have made it the most widely used CRISPR method, with approximately 45-54% of researchers in both commercial and non-commercial institutions reporting knockouts as their primary type of CRISPR edit [35].

The standard knockout workflow begins with careful single guide RNA (sgRNA) design targeting the early exons of the gene of interest to maximize the likelihood of generating frameshift mutations. The editing components are then delivered to cells, typically via electroporation or viral vectors, with subsequent steps involving clonal isolation, expansion, and genotypic validation. A critical consideration for stem cell researchers is that CRISPR editing in human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells predominantly produces homozygous rather than heterozygous modifications, with frequent identical indels occurring in both alleles of target genes [36]. This property has important implications for therapeutic genome editing applications and requires careful experimental design.

Recent advancements have enhanced traditional knockout approaches. For instance, the development of CRISPRgenee, a dual-action gene-editing system that combines CRISPR-Cas9 knockout with epigenetic silencing using truncated guide RNAs, demonstrates improved gene depletion efficiency while reducing sgRNA performance variance compared to conventional CRISPR approaches [36]. This is particularly valuable in stem cell research where complete gene ablation is often necessary to study developmental pathways.

Table: Comparison of Primary CRISPR Modification Methods Among Researchers

| Editing Method | Commercial Institutions | Non-Commercial Institutions |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Knockout | 54% | 45% |

| RNAi | 32.2% | 34.6% |

| Base Editing | Comparable to knock-ins | Comparable to knock-ins |

| CRISPRa/i | Comparable to knock-ins | Comparable to knock-ins |

Base Editing Technologies and Workflows

Base editing represents a significant advancement beyond traditional CRISPR-Cas9 systems by enabling precise, irreversible single-nucleotide changes without creating double-stranded DNA breaks [37]. This technology utilizes engineered fusion proteins consisting of a catalytically impaired Cas nuclease (nickase) linked to a deaminase enzyme, which directly converts one DNA base to another within a small editing window [38]. The two primary classes of base editors are cytosine base editors (CBEs), which convert C•G to T•A base pairs, and adenine base editors (ABEs), which convert A•T to G•C base pairs [39].

The base editing workflow shares initial steps with traditional CRISPR approaches, beginning with careful gRNA design to position the target nucleotide within the effective editing window of the base editor. However, unlike knockout approaches, base editing requires consideration of additional parameters including protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) compatibility, editing window position, and potential bystander edits. After delivery of the base editing components to cells, the process achieves precise nucleotide conversion through a series of enzymatic steps: the Cas nickase moiety binds to the target DNA without creating a DSB, the deaminase enzyme catalyzes the base conversion, and cellular mismatch repair mechanisms complete the permanent genetic change.

Recent research demonstrates the remarkable therapeutic potential of base editing in stem cell applications. A landmark study published in November 2025 reported using adenine base editors to precisely repair two of the most common severe β-thalassaemia mutations (CD39 and IVS2-1), restoring adult haemoglobin production in patient blood stem cells with high correction rates (98% for CD39 and 90% for IVS2-1) and an encouraging safety profile [39]. This approach demonstrated restored HBB transcripts and β-globin protein accompanied by a more balanced α/non-α globin ratio, reduced erythroid apoptosis, and improved maturation. The study confirmed the safety of highly processive ABE8e usage in patients' hematopoietic stem cells in terms of genotoxicity and specificity, with no detectable increase in mutation burden and preserved stem-cell diversity based on whole-exome sequencing and clonal analyses [39].

Table: Base Editing Efficiency in Preclinical Disease Models

| Disease Model | Editor Type | Editing Efficiency | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Thalassaemia (CD39 mutation) | ABE8e | ~98% correction | Restored β-globin production, improved erythroid maturation |

| β-Thalassaemia (IVS2-1 mutation) | ABE8e | ~90% correction | Balanced α/non-α globin ratio, reduced apoptosis |

| Sickle cell-β-thalassaemia | ABE8e | Substantial phenotype correction | Reduced sickling, levels lower than asymptomatic carriers |

Advanced Editing Technologies

Beyond base editing, several advanced CRISPR technologies are expanding the capabilities of stem cell genetic engineering. Prime editing represents a more versatile precise editing technology that can install all possible transition and transversion mutations, as well as small insertions and deletions, without requiring double-strand breaks or donor DNA templates [7]. This "search-and-replace" editing approach uses a catalytically impaired Cas9 nickase fused to a reverse transcriptase enzyme and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that specifies both the target site and the desired edit.

Epigenome editing technologies, particularly CRISPR activation (CRISPRa), have proven valuable for stem cell research applications. A protocol published in October 2025 detailed using CRISPRa to rapidly verify silent gene reporters in human pluripotent stem cells, providing a method to validate reporter knockins at unexpressed loci without requiring time-consuming cell state transitions [40]. This approach enables efficient transcriptional activation of silent genes in hPSCs through designed single-guide RNA (sgRNA) and delivery of CRISPRa components, allowing for rapid functional assessment of genetic modifications.

For large-scale DNA engineering, CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems enable targeted integration of large genetic elements without creating double-strand breaks [7]. These systems are particularly valuable for introducing complex genetic circuits or synthetic genes into stem cells for therapeutic applications. While currently more efficient in prokaryotic systems, where they enable stable integration of donor sequences up to approximately 15.4 kb with type I-F CAST and up to 30 kb using type V-K variants, ongoing development is improving their efficiency in mammalian cells [7].

Application Notes for Stem Cell Research

Workflow Design and Optimization

Implementing robust genome editing workflows in stem cell systems requires careful consideration of several technical parameters. Research indicates that the entire CRISPR workflow, from guide design to clonal isolation, typically requires repetition 3 times (median value) before researchers achieve their desired edit, with the total process taking approximately 3 months for generating knockouts and 6 months for generating knock-ins [35]. This timeline highlights the importance of systematic optimization and validation in stem cell editing projects.

The choice of cell model significantly impacts editing efficiency and experimental difficulty. Primary cells, including stem cells, present greater challenges compared to immortalized cell lines, with survey data showing that among researchers who found CRISPR "easy," only 16.2% worked in primary T cells, while among those who answered "difficult," 50% worked on primary T cells [35]. This differential difficulty underscores the need for protocol optimization when working with sensitive stem cell populations.

Delivery method selection represents another critical parameter. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have emerged as a promising delivery vehicle for CRISPR components, particularly for in vivo applications, due to their favorable safety profile and potential for redosing [8]. Unlike viral vectors, which typically trigger immune responses that prevent repeated administration, LNPs don't trigger the immune system similarly, enabling multiple doses as demonstrated in both Intellia Therapeutics' hATTR trial and the personalized CRISPR treatment for infant KJ with CPS1 deficiency [8].

Recent advances in automated editing and analysis are addressing workflow challenges. Japanese researchers have developed a high-throughput robotic method for isolating and analyzing genome-edited human iPS cell clones, overcoming the challenge of single-cell survival in these fragile cells [36]. This approach enables more efficient processing of the over 1,000 clones often necessary to identify correctly edited stem cell lines, significantly accelerating the research timeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced Genome Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo delivery of CRISPR components | Favorable safety profile, enables redosing; natural affinity for liver; researchers developing versions with affinity for other organs [8] |

| Adenine Base Editor (ABE8e) | A•T to G•C base conversions | High-processivity editor used in β-thalassaemia correction; demonstrated high correction rates with preserved stem-cell diversity [39] |

| Hypo-immunogenic Tregs | Universal allogeneic cell therapy | Created by disrupting HLA class I/II genes while inserting HLA-E fusion protein using CRISPR; evades both T and NK cell rejection [34] |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) enzyme | Alternative to Cas9 for gene editing | Used in Edge's AsCas12a-based system for HBG1/2 editing; different PAM requirements than Cas9 [36] |

| dCas9-epigenetic modifiers | Targeted epigenetic manipulation | Enables precise DNA methylation or histone modification; used in breast cancer epigenetic therapy research [36] |

| Programmable phages | Antimicrobial therapy | CRISPR-armed bacteriophages target dangerous bacterial infections; SNIPR001 in Phase 1b trials for hematological cancer patients [8] |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Base Editing in Hematopoietic Stem Cells for β-Thalassaemia

This protocol outlines the adenine base editing approach for correcting prevalent β-thalassaemia mutations (CD39 and IVS2-1) in patient-derived hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), based on recently published research [39].

Materials:

- Patient-derived CD34+ HSPCs carrying β-thalassaemia mutations

- ABE8e base editor components (plasmid or mRNA)

- Guide RNA targeting the CD39 or IVS2-1 mutation site

- Cell culture media for HSPC maintenance and differentiation

- Electroporation system

- Genotyping primers for HBB locus

- Antibodies for flow cytometry analysis of erythroid differentiation

- RNA extraction kit and RT-PCR reagents for HBB transcript analysis

Procedure:

- Guide RNA Design: Design guide RNAs matched to the CD39 or IVS2-1 target sites, ensuring the pathogenic nucleotide falls within the editing window of the ABE8e base editor (typically positions 4-8 in the protospacer).

- Stem Cell Preparation: Isolate and expand CD34+ HSPCs from patient samples using cytokine-supported serum-free media. Maintain cells at appropriate densities to preserve stemness.

- Electroporation: Deliver the ABE8e base editor (as mRNA or plasmid) and guide RNA to HSPCs via electroporation. Optimize voltage and pulse parameters for minimal cell toxicity.

- Erythroid Differentiation: Culture edited HSPCs in erythroid differentiation medium containing SCF, IL-3, and erythropoietin for 14-21 days to generate erythroblasts.

- Editing Efficiency Assessment: After 72 hours, harvest a subset of cells for genotypic analysis. Use PCR amplification of the HBB locus followed by Sanger sequencing and tracking of indels by decomposition (TIDE) analysis to quantify base conversion efficiency.

- Functional Validation: Differentiate another portion of edited HSPCs along the erythroid lineage. Analyze for restoration of β-globin production via RT-PCR and Western blot at days 7, 14, and 21 of differentiation.

- Phenotypic Rescue Assessment: Evaluate improved erythroid maturation by flow cytometry analysis of CD71/GPA expression, assess reduction in apoptosis via Annexin V staining, and measure α/non-α globin ratio by HPLC.