Decoding the Balance: Molecular Mechanisms of Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Differentiation in Development and Disease

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sophisticated molecular networks governing the critical balance between stem cell self-renewal and differentiation.

Decoding the Balance: Molecular Mechanisms of Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Differentiation in Development and Disease

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sophisticated molecular networks governing the critical balance between stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational concepts with cutting-edge methodological applications. We explore intrinsic regulators like piRNAs and PIWI proteins, key signaling pathways including TGF-β, mTOR, and Notch, and the crucial role of niche communication. The content extends to troubleshooting in vitro culture challenges, optimizing differentiation protocols for clinical translation, and validating mechanisms through current FDA-approved therapies and clinical trials. By integrating basic science with therapeutic applications, this review serves as a strategic resource for advancing regenerative medicine and targeted drug discovery.

Core Principles and Key Molecular Regulators of Stem Cell Fate

Stem cell fate is governed by two primary division modes: symmetric cell division (SCD) and asymmetric cell division (ACD). These division patterns are fundamental to the processes of self-renewal and differentiation, balancing the maintenance of a stem cell reservoir with the generation of specialized tissues [1]. Self-renewal can be defined as the process by which a stem cell undergoes mitosis to produce at least one daughter cell possessing the same self-renewal and differentiation capacity, thereby creating a complete phenocopy [1]. The decision between symmetric and asymmetric division represents a crucial regulatory point in development, tissue homeostasis, and regeneration, with dysregulation potentially contributing to tumorigenesis [2] [3].

In the context of a broader thesis on stem cell self-renewal and differentiation mechanisms, understanding these division modes provides critical insight into how stem cells navigate fate decisions. ACD generates cellular diversity by producing two differentially fated daughter cells—one retaining stem cell identity and the other committing to differentiation [1] [2]. Conversely, SCD either expands the stem cell pool (symmetric self-renewal) or produces two differentiated progeny (symmetric differentiation) [1] [2]. Recent advances in genetic labeling and single-cell tracking have revealed that many mammalian stem cells exhibit remarkable plasticity, capable of switching between these division modes in response to physiological demands and microenvironmental cues [4] [2].

Core Concepts and Definitions

Characterizing Division Modes and Cell Fate Outcomes

The distinction between symmetric and asymmetric divisions lies in the fate of the daughter cells relative to their parent. The following table summarizes the key characteristics and outcomes of each division mode.

Table 1: Characteristics of Symmetric and Asymmetric Cell Divisions

| Feature | Symmetric Division | Asymmetric Division |

|---|---|---|

| Daughter Cell Fate | Two identical daughters | Two differentially fated daughters |

| Primary Role | Expansion or depletion of stem cell pool | Homeostatic maintenance of stem cell pool while generating differentiated progeny |

| Prevalence in Development | Early embryonic development (transient stem cells) [1] | Later embryonic stages and adult homeostasis (permanent stem cells) [1] |

| Fate Determinants Distribution | Equal distribution of cell fate determinants (e.g., transcription factors, organelles) [4] | Unequal (asymmetric) distribution of cell fate determinants [4] |

| Histone Variant Distribution | Symmetric (e.g., H3.1 and H3.3 in mouse muscle stem cells) [4] | Symmetric (observed in mouse muscle stem cells, unlike some invertebrate models) [4] |

| Spindle Orientation | Can be parallel or perpendicular to basement membrane, yielding symmetric outcomes [3] | Typically perpendicular to basement membrane, yielding asymmetric outcomes [3] |

Quantitative Analysis of Division Modes Across Biological Systems

The propensity for symmetric versus asymmetric division varies significantly across tissue types, developmental stages, and species. Quantitative data from lineage tracing and division tracking reveal this diversity.

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Division Modes in Different Biological Systems

| Biological System / Context | Symmetric Division Proportion | Asymmetric Division Proportion | Key Findings and Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Muscle Stem Cells (In Vivo) | Observed [4] | Observed [4] | Cells can switch from ACD to SCD ex vivo, indicating no obligate division mode [4]. |

| Developing Prostate Epithelium (Basal Cells, P15) | ~35% (Horizontal divisions) [3] | ~65% (Vertical divisions) [3] | Horizontal divisions yield two basal cells (symmetric); vertical divisions yield one basal and one luminal cell (asymmetric) [3]. |

| Mathematical Model of Mutagenesis | Variable parameter (θ) [2] | Variable parameter (1-θ) [2] | Symmetric divisions may generate double-hit mutants at a lower rate than asymmetric divisions, potentially delaying cancer onset [2]. |

| Prostate Luminal Cells (Developing) | ~100% [3] | ~0% [3] | Luminal cells divide almost exclusively symmetrically, with spindles horizontal to the basement membrane [3]. |

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Division Modes

Single-Cell Tracking and Clonogenic Tracing on Artificial Niches

This methodology enables the direct observation of stem cell division patterns and fate outcomes in a controlled environment.

Protocol Workflow:

- Cell Isolation and Labeling: Muscle stem cells (MuSCs) are isolated from reporter mice, for example, expressing fluorescently tagged proteins for key transcription factors (e.g., Pax7) or using a histone H3-SNAP-tag for tracking chromatin inheritance [4].

- Seeding on Artificial Niches: Single cells are plated at low density on engineered substrates that mimic the native stem cell niche, such as specific extracellular matrix (ECM) components like laminin or fibronectin, within micro-patterned wells or soft hydrogels [4].

- Time-Lapse Live-Cell Imaging: Cultures are placed under a live-cell imaging microscope, capturing phase-contrast and fluorescence channels at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-30 minutes) over several days to track cell divisions and movements [4].

- Lineage Tracing and Fate Analysis: The recorded videos are analyzed to construct lineage trees. Division symmetry is assessed by tracking the fate of each daughter cell—whether it remains a stem cell or initiates differentiation (e.g., by expressing Myogenin) over multiple generations [4].

- Quantification of Asymmetry: Asymmetry is quantified by measuring the differential distribution of fate determinants (e.g., fluorescence intensity of Pax7 between daughter cells) or old vs. new DNA strands using pulse-chase labeling [4].

In Vivo Lineage Tracing and Division Axis Analysis

This approach investigates division modes within the intact tissue context, preserving native niche interactions.

Protocol Workflow:

- Genetic Labeling: Use of inducible, cell-type-specific Cre-loxP systems in transgenic mice (e.g., K14CreER for basal cell lineage tracing) [3]. Administration of tamoxifen induces permanent fluorescent labeling (e.g., RFP) in a specific stem or progenitor population.

- Tissue Collection and Sectioning: Harvest tissues of interest (e.g., prostate) at defined time points post-induction. Tissues are fixed, processed, and sectioned for immunohistochemistry [3].

- Immunofluorescence and Spindle Orientation: Tissue sections are stained with antibodies against:

- Cell Lineage Markers: e.g., p63/CK5 for basal cells, CK8/CK18/AR for luminal cells [3].

- Mitotic and Polarity Markers: e.g., γ-tubulin (centrosomes), Survivin (midbody), Phospho-Histone H3 (mitotic cells), Par3/aPKC (cell polarity) [3].

- Junctional Markers: e.g., ZO-1 (tight junctions), E-cadherin (adherens junctions) [3].

- Confocal Microscopy and 3D Reconstruction: High-resolution z-stack images of mitotic cells are acquired using confocal microscopy. The angle of the mitotic spindle relative to the basement membrane is measured in 3D [3].

- Fate Mapping of Daughter Cells: The identity of newly formed daughter cells in anaphase/telophase is determined by colocalization of the midbody marker (Survivin) with lineage-specific markers (e.g., p63 and CK8), confirming whether the division was symmetric (daughters of same lineage) or asymmetric (daughters of different lineages) [3].

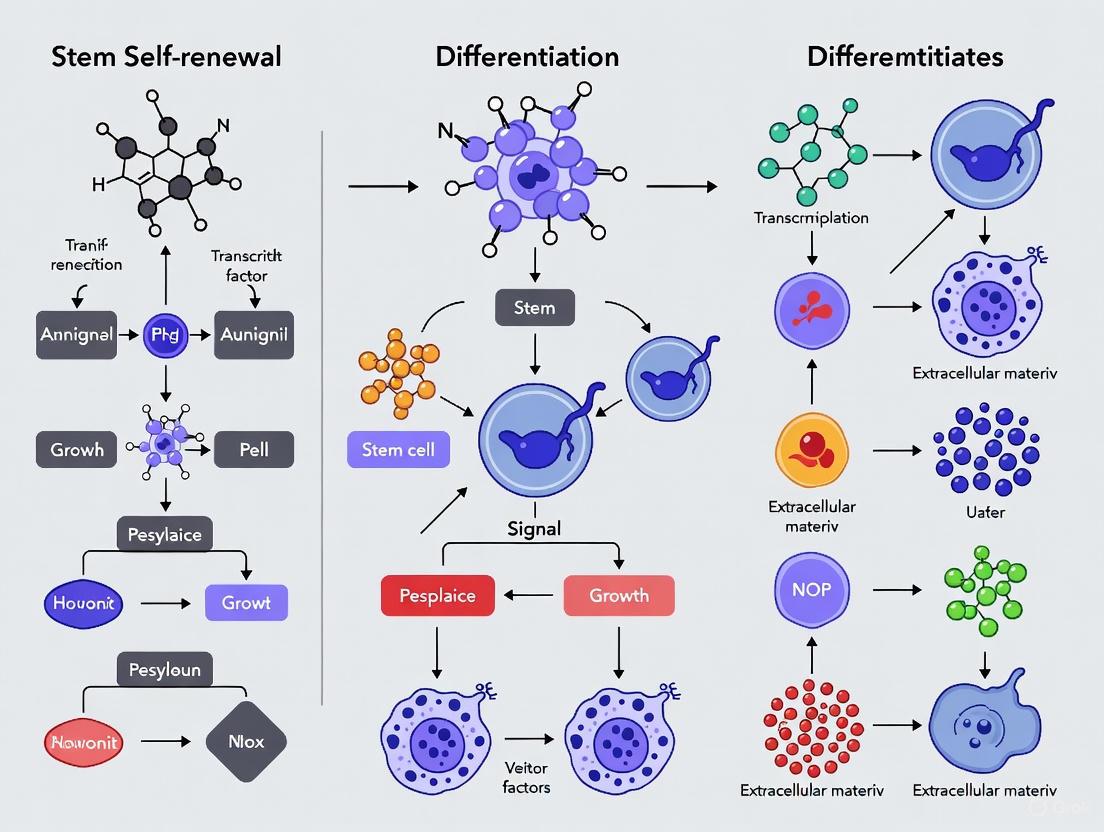

Diagram 1: Experimental workflows for analyzing stem cell division modes.

Molecular Regulators and Signaling Pathways

Key Molecular Players in Division Asymmetry

The execution of asymmetric cell division requires the coordinated action of several conserved molecular systems that establish cell polarity, orient the mitotic spindle, and ensure the asymmetric segregation of cell fate determinants.

Diagram 2: Molecular network regulating asymmetric and symmetric division.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Investigating stem cell division modes requires a specialized set of reagents and tools. The following table details key resources for designing experiments in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Stem Cell Division Modes

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Modified Mouse Models | Pax7-reporter mice; H3-SNAP-tag mice; K14CreER; RosaRFP (or RosaYFP/tdTomato) [4] [3] | Enables lineage tracing, fate mapping, and live imaging of specific stem cell populations and their progeny in vivo and ex vivo. |

| Cell Surface & Lineage Markers | CD73, CD90, CD105 (MSC positive); CD34, CD45 (MSC negative) [5]; p63, CK5 (basal); CK8, CK18, AR (luminal) [3] | Identifies and isolates pure populations of stem cells and their differentiated progeny via FACS or immunohistochemistry. |

| Polarity & Mitosis Protein Antibodies | Anti-Par3, Anti-aPKC, Anti-Gαi, Anti-LGN/Pins [3]; Anti-γ-tubulin, Anti-Survivin, Anti-Phospho-Histone H3 [3] | Visualizes the establishment of cell polarity and the orientation of the mitotic apparatus in fixed tissues. |

| Live-Cell Imaging Tools | SNAP-tag substrates (for histone pulse-chase) [4]; Fluorescent ubiquitination-based cell cycle indicator (FUCCI) | Tracks cell cycle progression, division kinetics, and the inheritance of cellular components in real time. |

| Artificial Niche Components | Laminin, Fibronectin, Collagen; Polyethylene glycol (PEG) hydrogels; Micropatterned surfaces [4] | Provides controlled extracellular environments (e.g., stiffness, ligand density) to study the impact of the niche on division mode. |

Discussion: Implications for Development, Regeneration, and Disease

The strategic balance between symmetric and asymmetric divisions has profound implications beyond basic development. From a therapeutic perspective, the ability of stem cells to switch from asymmetric to symmetric divisions, as observed in mouse muscle stem cells ex vivo, highlights a fundamental plasticity that could be harnessed for regenerative medicine [4]. Expanding stem cell populations through symmetric self-renewal is a critical step in generating sufficient material for cell-based therapies aimed at treating conditions like Parkinson's disease, diabetes, and liver disease [6].

Furthermore, the choice of division mode has significant consequences for tissue-level robustness and cancer risk. Theoretical modeling suggests that tissues relying on symmetric divisions may have a mechanism to delay the accumulation of oncogenic mutations, such as the two-hit process required for tumor suppressor gene inactivation [2]. This is because the stochastic fate decisions in a symmetrically-dividing population can lead to the passive loss of intermediate mutant clones, a phenomenon less likely in a rigidly asymmetric system where every stem cell division retains a stem daughter. This provides a potential evolutionary hypothesis for the prevalence of symmetric divisions in mammalian tissues [2].

Dysregulation of the molecular machinery governing asymmetric division is increasingly linked to tumorigenesis. In the prostate, for example, both basal and luminal cells can serve as cancer cells of origin, and the disruption of polarity proteins like PTEN, which interacts with the Par complex, is a common event [3]. This underscores the critical importance of understanding the molecular regulation of stem cell division modes not only for regenerative medicine but also for uncovering the fundamental origins of cancer and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Control Mechanisms

Stem cell fate, encompassing the fundamental processes of self-renewal and differentiation, is governed by a complex interplay of regulatory mechanisms that operate at multiple levels. Transcriptional control establishes the foundational gene expression programs through the action of transcription factors and epigenetic modifications, while post-transcriptional regulation provides a refined layer of control that fine-tunes protein synthesis in response to dynamic cellular cues. Operating as an integrated network, these mechanisms ensure precise temporal and spatial control of gene expression that is essential for maintaining pluripotency, directing lineage specification, and enabling stem cells to contribute to development, tissue homeostasis, and regeneration. A comprehensive understanding of these regulatory hierarchies is paramount for advancing stem cell biology and unlocking their therapeutic potential in regenerative medicine and drug development. This review synthesizes current knowledge of these control mechanisms, framing them within the context of stem cell self-renewal and differentiation, and provides detailed methodologies for their experimental investigation.

Transcriptional Control Mechanisms

Transcriptional regulation constitutes the primary tier of control in stem cell fate determination, establishing the specific gene expression patterns that define cell identity and potential.

Core Transcription Factor Networks

The maintenance of pluripotency in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) is orchestrated by a core set of transcription factors that form autoregulatory loops to sustain their undifferentiated state. These core pluripotency factors include OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, which collaboratively bind to and activate their own promoters as well as those of other genes essential for self-renewal, while simultaneously repressing genes involved in differentiation [7]. The forced expression of these and other factors (such as Klf4 and c-Myc) is sufficient to reprogram somatic cells into iPSCs, demonstrating their powerful role in establishing pluripotency [7]. In adult stem cell populations, transcription factor networks become more tissue-specific. For example, in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), a distinct set of transcription factors including PU.1, RUNX1, and GATA2 regulates the balance between self-renewal and differentiation into various blood lineages [8]. The directed manipulation of these networks is a primary strategy in controlling stem cell fate for therapeutic applications.

Epigenetic Regulation

Epigenetic modifications provide a heritable, yet reversible, layer of transcriptional control that does not alter the underlying DNA sequence. These mechanisms are critical for locking in cell fate decisions during differentiation.

- DNA Methylation: The addition of methyl groups to cytosine residues in CpG islands is generally associated with transcriptional repression. In stem cells, the promoters of developmental genes often exist in a "bivalent" state, bearing both activating and repressing histone marks, allowing them to be rapidly activated or permanently silenced upon differentiation cues. DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and TET proteins, which catalyze demethylation, are essential for these dynamic changes [8].

- Histone Modifications: Post-translational modifications of histone tails, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, alter chromatin structure and accessibility. For instance, histone acetylation by co-activators like p300 and CBP is typically linked to open chromatin and active transcription, as seen at pluripotency gene promoters in ESCs. Conversely, repressive complexes such as Polycomb group (PcG) proteins deposit H3K27me3 marks to silence developmental genes, maintaining them in a poised state until differentiation [9] [8].

Table 1: Key Transcriptional Regulators in Stem Cell Fate

| Regulator/Modification | Type | Function in Stem Cells | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4/SOX2/NANOG | Transcription Factor Network | Maintain pluripotency; form autoregulatory loops; repress differentiation genes. | iPSC generation; ChIP-seq shows co-occupancy at target promoters [7]. |

| Polycomb Repressive Complex (PRC2) | Chromatin Modifier | Catalyzes H3K27me3 for facultative heterochromatin formation, poising developmental genes for activation. | Loss-of-function leads to premature differentiation; ChIP-seq reveals bivalent domains [9]. |

| p300/CBP | Transcriptional Co-activator | Histone acetyltransferases that open chromatin; interact with β-catenin and other transcription factors. | Genetic ablation impairs self-renewal; regulates Wnt/β-catenin enhanceosome [10]. |

| BMP-SMAD | Signaling Pathway & Transcription Mediator | Promotes self-renewal in ESCs (via ID proteins) and differentiation in adult stem cells. | SMAD4 knockout ESCs show differentiation defects; phospho-SMAD1/5/8 ChIP [9]. |

Signaling Pathways and Transcriptional Integration

Extracellular signals from the stem cell niche are transduced to the nucleus and integrated by transcription factors to dictate cell fate. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is a quintessential example. In the absence of Wnt signaling ("OFF state"), a destruction complex containing AXIN, APC, CK1α, and GSK3β phosphorylates β-catenin, leading to its ubiquitination by SCF^β-TrCP and proteasomal degradation. Upon Wnt binding ("ON state"), the destruction complex is disassembled, allowing β-catenin to accumulate and translocate to the nucleus. There, it partners with transcription factors from the TCF/LEF family (and others like SOX factors) to form an enhanceosome that activates target genes such as MYC and CCND1, which promote self-renewal and proliferation [10] [11]. Other critical pathways include TGF-β/BMP, Notch, and Hedgehog, each engaging specific SMAD or other transcription factors to regulate distinct aspects of stem cell behavior, from maintaining quiescence to inducing lineage-specific differentiation [9].

Post-Transcriptional Control Mechanisms

After a gene is transcribed, its expression can be extensively modulated through a diverse array of post-transcriptional mechanisms. These controls are particularly critical in stem cells and during early development, where rapid and localized changes in protein synthesis are required in response to environmental signals.

mRNA Stability and Translation: The Role of the Poly(A) Tail

A major hub for post-transcriptional control is the 3' poly(A) tail of mRNAs. This tail interacts with the 5' cap structure to promote mRNA circularization and facilitate translation initiation. It also protects the mRNA from exonucleolytic degradation. The length of the poly(A) tail is dynamically regulated by opposing enzymes: poly(A) polymerases add adenosine residues, while deadenylases remove them [12]. Shortening of the tail (deadenylation) is often the first and rate-limiting step in mRNA decay but can also lead to translational repression without decay. Recent breakthroughs in high-throughput sequencing methods, such as those detailed by Miao et al., have enabled precise measurement of poly(A) tail lengths genome-wide, revealing the central role of this regulation in stem cell fate and early embryonic development [12]. Key deadenylase complexes, like the CCR4-NOT complex, are crucial for controlling mRNA turnover in developing systems, including early lymphocyte development [12].

RNA-Binding Proteins and Their Functions

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) are effectors of post-transcriptional control, recognizing specific sequences or structures in target mRNAs to influence their fate.

- Pumilio Proteins: These RBPs bind to the 3' untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNAs and typically repress their translation. In stem cells, different family members have distinct roles; PUM1 promotes differentiation, whereas PUM2 supports self-renewal by regulating the translation of a network of over a thousand mRNAs [13].

- PIWI Proteins and piRNAs: A novel layer of regulation involves PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), small non-coding RNAs that partner with PIWI proteins. These complexes are capable of silencing transposable elements and post-transcriptionally regulating mRNAs through endonucleolytic cleavage ("slicing"), thereby safeguarding the genomic integrity and functional repertoire of stem cells [13].

Table 2: Key Post-Transcriptional Regulators in Stem Cell Fate

| Regulator | Type | Mechanism of Action | Impact on Stem Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCR4-NOT Complex | Deadenylase Complex | Catalyzes mRNA deadenylation, leading to translational repression and/or decay. | Regulates early lymphocyte development; controls mRNA stability in stem cells [12]. |

| Pumilio (PUM1/PUM2) | RNA-Binding Protein (RBP) | Binds 3' UTRs to repress translation of target mRNAs. | PUM1 promotes differentiation; PUM2 enhances self-renewal [13]. |

| PIWI/piRNA Complex | Small Non-coding RNA & RBP | Binds piRNAs to degrade complementary mRNAs (e.g., transposons). | Maintains genome stability; novel regulatory pathway in stem cells [13]. |

| β-Catenin | Signaling Molecule & RBP Regulator | Can bind RNAs and influence pre-mRNA splicing (e.g., ER-β, PSA). | Non-canonical role beyond transcription; generates splice variants with altered function [10]. |

Alternative Splicing and Localization

Alternative splicing allows a single gene to produce multiple protein isoforms with distinct functions. Evidence suggests that even canonical transcriptional regulators can influence this process. For instance, β-catenin, the central effector of Wnt signaling, has been shown to modulate splice site selection. In HeLa cells, β-catenin transfection induced the expression of a specific estrogen receptor-β (ER-β) variant (ER-β Δ5-6) that acts as a dominant-negative isoform [10]. This indicates that signaling pathways can exert multifaceted control over gene expression by influencing both transcription and RNA processing. Furthermore, the subcellular localization of mRNAs, directed by RBPs, allows for localized protein synthesis, which is crucial in polarized cells such as neurons and during asymmetric stem cell divisions.

Integrated Experimental Analysis of Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Control

To fully understand gene regulation during stem cell differentiation, it is essential to employ integrated methodologies that capture both transcriptional and post-transcriptional events. A powerful approach involves combining total RNA-seq (reflecting the transcriptome) with polysome profiling (reflecting the translatome) [14].

Experimental Protocol: Polysome Profiling for Translational State Analysis

The following protocol, adapted from research published in BMC Genomics, allows for the separation and analysis of mRNAs based on their translational efficiency [14].

- Cell Culture and Differentiation: Human embryonic stem cells (e.g., H1 line) are cultured and induced to differentiate into the three germ layers (endoderm, mesoderm, neuroectoderm) using established monolayer protocols with specific factors (e.g., CHIR99021 and Activin A for endoderm) [14].

- Cycloheximide Treatment and Lysis: At desired time points (e.g., day 4 for endoderm), cells are treated with cycloheximide (0.1 mg/mL for 10 min) to arrest ribosomes on mRNA. Cells are then lysed in a buffer containing MgCl₂, NaCl, Triton X-100, and RNase inhibitors [14].

- Sucrose Gradient Centrifugation: The cell lysate is layered onto a 10-50% linear sucrose gradient and centrifuged at high speed (e.g., 270,000 × g for 120 min at 4°C) to separate ribosomal complexes based on density [14].

- Fractionation and RNA Isolation: The gradient is fractionated using a system that monitors UV absorbance at 254 nm. The resulting profile shows peaks for 40S/60S subunits, 80S monosomes, and polysomes (mRNAs bound by multiple ribosomes). Polysome-containing fractions are pooled, and RNA is extracted for subsequent sequencing [14].

- Data Analysis: Sequencing data from total RNA and polysome-bound RNA are analyzed (e.g., using HISAT2 for alignment and DESeq2 for differential expression). Comparing these datasets identifies genes subject to post-transcriptional regulation—e.g., those whose transcript levels remain unchanged but which show significant changes in polysome association [14].

This integrated analysis has revealed substantial post-transcriptional modulation during germ layer commitment, highlighting that the translatome captures regulatory nuances often missed by transcriptomics alone [14].

Visualization of an Integrated Regulatory Pathway

The diagram below synthesizes the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway with its non-canonical, post-transcriptional roles, illustrating the multi-level control it exerts on stem cell fate.

Diagram 1: The Wnt/β-catenin pathway integrates transcriptional and post-transcriptional control. In the "OFF" state, β-catenin is degraded, and TCF/LEF factors recruit repressors. In the "ON" state, stabilized β-catenin enters the nucleus to activate transcription. Non-canonically, nuclear β-catenin can also modulate pre-mRNA splicing and interact with RBPs, adding a layer of post-transcriptional regulation to its function in stem cell fate [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Gene Regulation in Stem Cells

| Reagent / Tool | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | Small molecule inhibitor of GSK3β; activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling. | Used in differentiation protocols (e.g., endoderm, mesoderm) to direct stem cell fate [14]. |

| Activin A | Cytokine; activates TGF-β/SMAD2/3 signaling pathway. | Key component in definitive endoderm differentiation from hESCs [14]. |

| Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Small molecule inhibitor of ROCK kinase; reduces apoptosis in single cells. | Improves survival of hESCs after passaging or thawing during experimental setup [14]. |

| Cycloheximide | Translation inhibitor; arrests ribosomes on mRNA. | Essential for polysome profiling experiments to "freeze" translating ribosomes [14]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Gene editing technology; enables knockout, knockin, or mutagenesis of specific genes. | Studying the functional role of transcription factors (e.g., OCT4) or RBPs in stem cell self-renewal and differentiation [9] [8]. |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | High-resolution profiling of gene expression in individual cells. | Resolving cellular heterogeneity in stem cell populations and identifying rare subpopulations [15] [7]. |

| Poly(A) Tail Sequencing Kits | High-throughput measurement of poly(A) tail length for transcriptome-wide analysis. | Investigating the role of deadenylation in mRNA stability during stem cell differentiation [12]. |

PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are a distinct class of 24-31 nucleotide small non-coding RNAs that form complexes with PIWI proteins to play multifaceted roles in epigenetic regulation and mRNA stability maintenance. Originally characterized in the germline for transposable element suppression, these molecules have emerged as critical regulators in stem cell biology, particularly in balancing self-renewal and differentiation. This technical review synthesizes current mechanistic insights into piRNA biogenesis, their epigenetic functions through DNA methylation and histone modifications, and their post-transcriptional regulatory roles via mRNA cleavage and translational control. Within the context of stem cell self-renewal and differentiation mechanisms, we detail experimental approaches for investigating piRNA pathways and provide key research tools. The growing evidence positions the PIWI/piRNA pathway as an essential epigenetic regulator in stem cell fate determination with significant implications for regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are single-stranded RNA molecules typically 24-31 nucleotides in length, making them the longest class of small non-coding RNAs [16]. They are distinguished from other small RNAs by their strong preference for a 5' uridine residue, 2'-O-methylation at their 3' terminus, and their Dicer-independent biogenesis pathway [17]. These molecules were initially discovered in Drosophila germline cells and have since been identified across diverse species, with approximately 30,000 piRNAs documented in the human genome [17].

piRNAs function through association with PIWI proteins, a conserved subfamily of Argonaute proteins predominantly expressed in germline cells [16] [18]. These PIWI/piRNA complexes form the core of a sophisticated genomic defense system that silences transposable elements (TEs) and regulates gene expression at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels [16]. The PIWI protein family includes multiple members across species: humans possess four PIWI proteins (PIWIL1/HIWI, PIWIL2/HILI, PIWIL3/HIWI3, and PIWIL4/HIWI2), while Drosophila has three (Piwi, Aubergine/Aub, and Argonaute 3/Ago3) [19].

Structurally, PIWI proteins contain four conserved domains: N-terminal, PAZ, MID, and PIWI domains, connected by L1 and L2 linkers [16]. The PIWI domain possesses endonucleolytic "slicer" activity mediated by a conserved catalytic triad that enables precise cleavage of RNA targets guided by bound piRNAs [16]. Beyond their canonical role in germline development, PIWI/piRNA pathways have gained significant attention for their functions in somatic stem cells and their dysregulation in various pathological conditions, including cancer [16] [20].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of piRNAs Compared to Other Small Non-Coding RNAs

| Feature | piRNA | miRNA | siRNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length (nt) | 24-31 | 19-25 | 20-25 |

| 5' End Bias | Uracil | None | None |

| 3' Modification | 2'-O-methylation | None | None |

| Biogenesis | Dicer-independent | Dicer-dependent | Dicer-dependent |

| Primary Function | TE silencing, gene regulation | mRNA degradation, translation repression | Viral defense, transgene silencing |

| Expression Pattern | Germline, somatic stem cells | Ubiquitous | Ubiquitous |

| Protein Partners | PIWI proteins | AGO proteins | AGO proteins |

piRNA Biogenesis Pathways

piRNA biogenesis occurs through two interconnected yet distinct pathways that ensure a diverse and abundant piRNA population: the primary processing pathway and the secondary "ping-pong" amplification pathway. Both pathways are essential for generating mature, functional piRNAs that maintain genome integrity and regulate gene expression.

Primary Biogenesis Pathway

The primary biogenesis pathway begins with the transcription of piRNA cluster regions in the genome by RNA polymerase II [16]. These piRNA clusters are specific genomic regions rich in transposable element fragments and can be either unistrand (transcribed from one strand) or dual-strand (transcribed from both strands) [19]. In Drosophila, dual-strand cluster transcription in germ cells depends on the Rhino-Deadlock-Cutoff (RDC) complex that recognizes H3K9me3 marks and facilitates non-canonical transcription [20]. In contrast, unistrand clusters in somatic cells are transcribed through canonical Pol II mechanisms dependent on the Cubitus interruptus transcription factor [20].

Following transcription, precursor transcripts are exported to the cytoplasm via specific nuclear export complexes (Nxf3-Nxt1 for germline clusters; Nxf1-Nxt1 for somatic clusters) [20]. These long precursor transcripts are processed at cytoplasmic perinuclear foci known as nuage in germ cells or Yb-bodies in somatic cells [21]. The endonuclease Zucchini (Zuc in Drosophila; PLD6 in mice) cleaves the precursor transcripts, generating pre-piRNAs with 5' monophosphate ends [16] [19]. These intermediates are then loaded onto PIWI proteins, after which their 3' ends are trimmed by the exonuclease Trimmer (PNLDC1) to achieve final length [16]. The mature piRNAs undergo 2'-O-methylation at their 3' terminus catalyzed by the methyltransferase Hen1, which enhances their stability [16] [19]. The resulting PIWI/piRNA complexes are then trafficked to their appropriate cellular compartments—nuclear localization for transcriptional silencing or cytoplasmic retention for post-transcriptional regulation.

Secondary Biogenesis and Ping-Pong Amplification

The secondary biogenesis pathway, known as the ping-pong cycle, amplifies piRNA populations through a reciprocal cleavage mechanism that occurs predominantly in germ cells [16] [21]. This cycle involves two cytoplasmic PIWI proteins: in Drosophila, Aub and Ago3 [21]. The cycle initiates when a primary piRNA bound to Aub (with antisense orientation to TEs) recognizes and cleaves complementary transposon transcripts. This cleavage generates the 5' end of a new piRNA fragment that is loaded onto Ago3 [21] [19]. The Ago3-bound piRNA (with sense orientation) then reciprocally cleaves precursor transcripts from piRNA clusters, generating the 5' end of a new Aub-bound piRNA [21]. This reciprocal relationship creates a self-sustaining amplification loop that efficiently targets active transposable elements.

A distinctive feature of ping-pong-derived piRNAs is their 10-nucleotide complementarity at the 5' ends—Aub-bound piRNAs typically begin with uridine (1U bias), while Ago3-bound piRNAs exhibit adenine at position 10 (10A bias) [21]. This signature results from the precise cleavage mechanism occurring 10 nucleotides upstream of the 5' end of the guiding piRNA [19]. The ping-pong cycle dramatically amplifies piRNA populations, enabling robust suppression of actively transposing elements while maintaining a diverse piRNA repertoire capable of recognizing emerging TE threats.

Epigenetic Regulation by piRNAs

The PIWI/piRNA pathway constitutes a major epigenetic regulatory system that maintains genome stability primarily through silencing transposable elements and regulating gene expression at the transcriptional level. This regulatory capacity is particularly critical in stem cell populations, where maintaining epigenetic integrity is essential for proper self-renewal and differentiation potential.

Transcriptional Gene Silencing Mechanisms

Nuclear-localized PIWI/piRNA complexes mediate transcriptional gene silencing through multiple interconnected epigenetic mechanisms. The best-characterized function involves repression of transposable elements through histone modifications and DNA methylation [19]. In Drosophila, the Piwi/piRNA complex recruits histone methyltransferases that catalyze H3K9 methylation, creating repressive chromatin marks that inhibit transcription initiation [18] [19]. This heterochromatin formation spreads to adjacent genomic regions, effectively silencing embedded transposable elements.

In mammalian systems, PIWI/piRNA complexes play a crucial role in guiding de novo DNA methylation during gametogenesis. The MIWI2/piRNA complex in mice interacts with SPOCD1 to recruit DNA methyltransferases to transposable element loci, establishing DNA methylation patterns that persist through development [19]. This DNA methylation-dependent silencing represents a more stable, long-term repression mechanism that is particularly important for maintaining germline genomic integrity across generations.

Beyond transposable element control, PIWI/piRNA complexes also regulate protein-coding genes through similar epigenetic mechanisms. In germline stem cells, Piwi-mediated silencing of key developmental regulators helps maintain the undifferentiated state by preventing premature expression of differentiation factors [18] [21]. The specificity of this regulation depends on sequence complementarity between piRNAs and target genomic loci, often involving piRNAs derived from specific regions of the genes they regulate.

Chromatin Remodeling and Organization

PIWI/piRNA complexes contribute to higher-order chromatin organization and nuclear architecture. By directing heterochromatin formation to specific genomic loci, these complexes help establish repressive nuclear compartments that limit accessibility of transcriptional machinery [18]. In germline stem cells, this chromatin remodeling function extends to the regulation of genes involved in self-renewal and differentiation decisions.

Recent evidence suggests that piRNAs can guide chromatin modifications beyond H3K9 methylation, including H3K27 methylation and histone deacetylation [19]. The combinatorial effect of these modifications creates a repressive chromatin state that is resistant to activation signals. Additionally, PIWI proteins interact with various chromatin remodeling complexes, facilitating nucleosome repositioning and chromatin compaction at target loci [18].

The epigenetic regulatory functions of PIWI/piRNA complexes exhibit remarkable adaptability, as the piRNA population can rapidly evolve to target newly active transposable elements or regulate different gene sets in response to developmental cues. This dynamic regulation is particularly important in stem cell niches, where epigenetic states must balance stability with plasticity to enable proper differentiation capacity.

Table 2: Epigenetic Modifications Mediated by PIWI/piRNA Complexes

| Epigenetic Modification | Molecular Mechanism | Biological Outcome | Stem Cell Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K9me3 | Recruitment of H3K9 methyltransferases | Heterochromatin formation, transcriptional repression | Maintains undifferentiated state by silencing differentiation genes |

| De novo DNA methylation | Recruitment of DNMTs via SPOCD1 | Stable long-term gene silencing | Imprints transposon silencing during germline development |

| Histone deacetylation | Recruitment of HDAC complexes | Chromatin compaction, reduced accessibility | Prevents premature activation of developmental genes |

| Chromatin remodeling | Interaction with remodeling complexes (SWI/SNF) | Altered nucleosome positioning | Regulates accessibility of self-renewal gene promoters |

piRNA-Mediated mRNA Stability and Translation Control

Beyond their nuclear functions in epigenetic regulation, PIWI/piRNA complexes play crucial roles in the cytoplasm through post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms that impact mRNA stability and translation. These functions are particularly important for the rapid gene expression changes required during stem cell differentiation and fate determination.

Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing

Cytoplasmic PIWI/piRNA complexes mediate post-transcriptional gene silencing through mechanisms analogous to RNA interference pathways. The endonucleolytic "slicer" activity of PIWI proteins enables direct cleavage of target mRNAs when guided by perfectly complementary piRNAs [22] [19]. This mechanism is particularly effective for degrading transposable element transcripts, preventing their translation and subsequent transposition [18].

In addition to direct cleavage, PIWI/piRNA complexes can recruit additional RNA degradation machinery to target transcripts. In Drosophila, Aub/piRNA complexes interact with the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex, leading to removal of the mRNA poly(A) tail and subsequent degradation [22] [18]. This mechanism allows for more regulated control of mRNA stability compared to direct cleavage and is employed for fine-tuning expression of protein-coding genes involved in stem cell maintenance and differentiation.

The ping-pong cycle itself represents a form of post-transcriptional regulation, as it directly consumes transposon transcripts to generate secondary piRNAs while simultaneously degrading these potentially harmful RNAs [21]. This dual functionality creates an efficient defense system that both neutralizes immediate threats and enhances future response capability through piRNA population amplification.

Translational Regulation

Emerging evidence indicates that PIWI/piRNA complexes can directly regulate translation of target mRNAs without necessarily inducing their degradation [21]. In germline stem cells, Aub/piRNA complexes have been shown to associate with specific mRNAs and either promote or repress their translation depending on cellular context and associated protein partners [21].

For instance, in Drosophila germline stem cells, Aub promotes translation of glycolytic enzymes by interacting with translation initiation factors, including PABP and eIF3 [21]. This enhanced glycolytic flux supports the unique metabolic state of stem cells. Conversely, Aub can repress translation of differentiation-promoting factors like Cbl through recruitment of translational repressors [21]. This dual capacity for activation and repression allows for precise control of the proteome in response to developmental signals.

The regulatory specificity of cytoplasmic PIWI/piRNA complexes is determined by both sequence complementarity between piRNAs and target mRNAs, and the particular suite of protein cofactors associated with the complex in different cellular contexts. This contextual regulation enables the same molecular machinery to produce opposing outcomes depending on the stem cell state, contributing to the delicate balance between self-renewal and differentiation.

piRNAs in Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Differentiation

The PIWI/piRNA pathway plays a pivotal role in regulating the balance between stem cell self-renewal and differentiation, particularly in germline stem cells (GSCs) where these molecules were first characterized. Recent evidence indicates similar functions in various somatic stem cell populations, highlighting the conserved importance of this regulatory system in stem cell biology.

Regulation of Germline Stem Cell Maintenance

In Drosophila germline stem cells, Piwi maintains the self-renewal capacity through both cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous mechanisms [18] [21]. Within GSCs, Piwi mediates transcriptional silencing of transposable elements and specific differentiation-promoting genes through epigenetic mechanisms, preserving genomic integrity and maintaining the undifferentiated state [18]. The loss of Piwi function leads to TE derepression, DNA damage accumulation, and eventual GSC depletion [18].

In somatic niche cells surrounding GSCs, Piwi regulates key signaling pathways that support stem cell maintenance. In escort cells, Piwi suppresses the expression of Dpp (BMP) signaling components, preventing excessive self-renewal signals that could disrupt the balance between stem cell maintenance and differentiation [18] [21]. Additionally, Piwi directly targets and cleaves c-Fos mRNA in niche cells, reducing AP-1 signaling and maintaining proper niche architecture and function [18].

The Aub protein contributes to GSC maintenance through translational control of metabolic regulators. Aub promotes translation of glycolytic enzymes in GSCs, supporting the glycol metabolic state characteristic of stem cells [21]. During differentiation, mitochondrial maturation facilitates a shift toward oxidative phosphorylation, and Aub-mediated translational control helps coordinate this metabolic transition.

Control of Differentiation Programs

As germline stem cells initiate differentiation, the PIWI/piRNA pathway facilitates this transition through regulated control of differentiation factors. Aub plays a particularly important role in promoting differentiation by modulating the expression of key differentiation regulators at both transcriptional and translational levels [18].

Aub directly regulates the expression of differentiation factors such as Bam (bag of marbles) through post-transcriptional mechanisms [18]. In GSCs, Aub represses Cbl mRNA via recruitment of the CCR4-NOT complex, but this repression is alleviated in cystoblasts, allowing increased Cbl expression that promotes differentiation [21]. This dynamic regulation enables precise control of the timing and progression of differentiation.

Beyond germline stem cells, PIWI/piRNA pathways function in various somatic stem cell populations. In Drosophila intestinal stem cells, Piwi regulates genome integrity and metabolic pathways that impact longevity and gut homeostasis [21]. In highly regenerative species like planarians, PIWI proteins are essential for somatic stem cell function and regenerative capacity [21]. These conserved functions highlight the broad importance of PIWI/piRNA pathways in stem cell biology across tissues and species.

Table 3: PIWI/piRNA Functions in Stem Cell Regulation

| PIWI Protein | Stem Cell Type | Molecular Function | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Piwi | Germline Stem Cells | Transcriptional silencing of TEs and differentiation genes | Maintains undifferentiated state, prevents premature differentiation |

| Piwi | Escort Cells (niche) | Repression of Dpp signaling, c-Fos mRNA cleavage | Regulates niche signaling, maintains proper stem cell niche architecture |

| Aubergine (Aub) | Germline Stem Cells | Translational activation of glycolytic enzymes | Supports stem cell metabolism, promotes self-renewal |

| Aubergine (Aub) | Cystoblasts | mRNA degradation of self-renewal factors | Promotes differentiation, prevents excessive self-renewal |

| PIWI proteins | Somatic Stem Cells | Genome stability maintenance, gene expression regulation | Supports regenerative capacity, tissue homeostasis |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Investigating PIWI/piRNA functions requires specialized methodological approaches tailored to their unique biogenesis, molecular interactions, and regulatory mechanisms. This section outlines key experimental protocols for studying piRNA biology in the context of stem cell research.

piRNA Identification and Characterization

Small RNA Sequencing: piRNA identification typically begins with small RNA sequencing using protocols that capture the 2'-O-methylated 3' terminus characteristic of mature piRNAs [23]. Standard small RNA-seq libraries should be prepared with 3' adapter ligation methods optimized for 2'-O-methylated RNAs. Bioinformatic analysis involves mapping sequences to piRNA clusters and transposable elements, with particular attention to the 1U/10A bias characteristic of ping-pong cycle products [24].

PIWI Protein Immunoprecipitation: PIWI/piRNA complexes can be isolated through immunoprecipitation using specific antibodies against PIWI proteins, followed by RNA extraction and sequencing to identify associated piRNAs [17]. This approach, often termed piRNA CLIP-seq, provides information about the specific piRNA repertoire associated with each PIWI protein and can reveal context-dependent binding patterns in different stem cell states.

In situ Hybridization and Localization: Cellular localization of piRNAs and PIWI proteins can be visualized using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for piRNAs combined with immunofluorescence for PIWI proteins [21]. This technique is particularly valuable for identifying subcellular compartments where piRNA biogenesis and function occur, such as nuage in germ cells or mitochondrial membranes where phased biogenesis takes place.

Functional Analysis of PIWI/piRNA Pathways

Genetic Manipulation: Loss-of-function studies using RNA interference or CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockout of PIWI genes remain the gold standard for determining PIWI/piRNA functions [18] [21]. In stem cell systems, inducible knockout systems allow temporal control of gene disruption to distinguish between developmental and maintenance functions. Transgenic rescue experiments with wild-type or mutant PIWI proteins can dissect functional domains required for specific activities.

Target Validation: Experimental validation of piRNA targets involves luciferase reporter assays with wild-type and mutant target sequences to confirm direct regulation through complementary base pairing [19]. For epigenetic targets, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for histone modifications or DNA methylation analysis can confirm transcriptional silencing at specific genomic loci.

Metabolic Labeling and Turnover Studies: Investigating piRNA effects on mRNA stability requires metabolic labeling approaches such as 4-thiouridine incorporation to measure transcript half-lives in the presence and absence of functional PIWI/piRNA pathways [18]. Similarly, ribosomal profiling can reveal translational regulation by providing snapshots of ribosome occupancy on target mRNAs under different conditions.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table compiles essential research tools and reagents for investigating PIWI/piRNA functions in stem cell systems, with particular emphasis on applications in self-renewal and differentiation research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for PIWI/piRNA Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PIWI Antibodies | Anti-PIWI, Anti-Aub, Anti-Ago3 (Drosophila); Anti-HIWI, Anti-HILI (Human) | Immunoprecipitation, Western blot, Immunofluorescence | Species specificity critical; validate in knockout controls |

| piRNA Detection | 3' 2'-O-methyl sensitive adapters, PANDH2 antibody | Small RNA library preparation, piRNA detection | Standard small RNA protocols may underrepresent piRNAs |

| Genetic Tools | PIWI mutant flies, Conditional knockout mice, RNAi lines | Loss-of-function studies | Consider functional redundancy between PIWI family members |

| Stem Cell Models | Germline stem cells, Embryonic stem cells, Planarian stem cells | Functional studies in stem cell context | Species-specific piRNA characteristics may limit generalizability |

| Bioinformatic Tools | piRNA cluster annotation, Ping-pong signature analysis, TE expression analysis | piRNA identification, functional annotation | Custom pipelines often needed for specific experimental designs |

| Reporters | Luciferase reporters with target 3'UTRs, Heterochromatin reporters | Target validation, Silencing quantification | Include mismatch controls to confirm specificity |

The PIWI/piRNA pathway represents a sophisticated regulatory system that integrates epigenetic and post-transcriptional control mechanisms to maintain genome stability and regulate gene expression programs. In stem cell biology, this pathway plays particularly important roles in balancing self-renewal and differentiation, with functions identified in both germline and somatic stem cell populations. The dual capacity of PIWI/piRNA complexes to enact stable epigenetic silencing through chromatin modifications and rapidly respond to cytoplasmic transcripts through slicer activity makes them uniquely suited to stem cell regulation.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the complete repertoire of piRNA functions in somatic stem cells, particularly in mammalian systems where these roles are less characterized. The development of more refined tools for piRNA detection and manipulation, especially in rare stem cell populations, will advance our understanding of their contributions to tissue homeostasis and regeneration. Additionally, the emerging connections between PIWI/piRNA pathways and cellular metabolism in stem cells warrant further investigation, as these links may reveal novel mechanisms coordinating metabolic state with fate decisions.

From a therapeutic perspective, the frequent dysregulation of PIWI/piRNA pathways in cancer and other diseases highlights their potential as therapeutic targets. The restricted expression of PIWI proteins in normal somatic tissues offers promising opportunities for targeted interventions with reduced off-target effects. As our understanding of PIWI/piRNA biology continues to expand, particularly in stem cell contexts, these insights will undoubtedly inform novel approaches to regenerative medicine, cancer therapy, and the manipulation of cell fate for therapeutic purposes.

Cellular quiescence, a reversible state of cell cycle arrest, is a fundamental property of stem cells that enables long-term tissue maintenance and regeneration. The precise control of quiescence is orchestrated by an intricate network of signaling pathways, with Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β), Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP), and the mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) representing central regulators. The TGF-β/BMP signaling pathway is involved in the vast majority of cellular processes and is fundamentally important during the entire life of all metazoans, with deregulation of TGF-β/BMP activity almost invariably leading to developmental defects and/or diseases, including cancer [25]. The proper functioning of the TGF-β/BMP pathway depends on its constitutive and extensive communication with other signaling pathways, leading to synergistic or antagonistic effects and eventually desirable biological outcomes [25]. In stem cell biology, these pathways collectively maintain the delicate balance between self-renewal and differentiation, ensuring a protected reservoir of stem cells capable of responding to physiological demands.

The interplay between these pathways creates a sophisticated signaling network that interprets both intracellular and extracellular cues to determine stem cell fate. This network exhibits tremendous complexity and context-dependency, with the nature of signaling cross-talk being overwhelmingly complex and highly context-dependent [25]. In the context of stem cell self-renewal and differentiation mechanisms research, understanding these signaling networks provides critical insights for regenerative medicine applications, including the development of stem cell-based therapies that harness the therapeutic potential of stem cells for treating numerous debilitating illnesses and injuries [15].

Pathway Fundamentals and Molecular Mechanisms

TGF-β Signaling Pathway

The TGF-β pathway operates through a canonical signaling cascade that transmits extracellular signals to the nucleus. Ligand binding to type II TGF-β receptors leads to recruitment and phosphorylation of type I receptors, which subsequently phosphorylate receptor-regulated SMADs (R-SMADs), specifically SMAD2 and SMAD3. These activated R-SMADs form complexes with the common mediator SMAD4 and translocate to the nucleus, where they regulate the transcription of target genes involved in cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and differentiation [25]. The pathway is tightly regulated by inhibitory SMADs (I-SMADs), including SMAD6 and SMAD7, which compete with R-SMADs for receptor binding or promote receptor degradation.

In stem cell quiescence, TGF-β signaling maintains hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in a reversible dormant state through transcriptional regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p15 and p21. The cytostatic function of TGF-β is mediated through its effects on cell cycle regulators, effectively preventing premature stem cell exhaustion while preserving genomic integrity. Research has shown that TGF-β signaling is crucial for preventing HSC exhaustion and maintaining their long-term repopulating capacity, highlighting its fundamental role in stem cell homeostasis.

BMP Signaling Pathway

As part of the TGF-β superfamily, BMP signaling follows a similar canonical pathway with distinct components and functional outcomes. BMP ligands bind to type II BMP receptors, which phosphorylate type I receptors (ALK1, ALK2, ALK3, ALK6). These activated receptors then phosphorylate R-SMADs 1, 5, and 8, which form complexes with SMAD4 and translocate to the nucleus to regulate transcription of target genes involved in differentiation, proliferation, and survival [25]. The BMP pathway exhibits significant cross-talk with other signaling pathways, creating a sophisticated regulatory network that controls stem cell behavior.

In stem cell biology, BMP signaling plays contrasting roles depending on cellular context. In neural stem cells, BMP promotes differentiation and suppresses self-renewal, while in embryonic stem cells, it supports pluripotency. This contextual functionality demonstrates the complexity of BMP signaling in maintaining quiescence and controlling cell fate decisions. The balance between BMP and TGF-β signaling is particularly important in stem cell niches, where these pathways often exert opposing effects to maintain tissue homeostasis.

mTOR Signaling Pathway

The mTOR pathway functions as a central regulator of cellular metabolism and growth in response to nutrient availability, energy status, and growth factors. mTOR exists in two distinct complexes: mTORC1, which is rapamycin-sensitive and regulates cell growth, autophagy, and protein synthesis through phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1; and mTORC2, which is rapamycin-insensitive and controls cell survival and metabolism through phosphorylation of AKT. The mTOR pathway integrates signals from multiple upstream regulators, including PI3K/AKT, AMPK, and growth factor receptors, to coordinate cellular processes with available resources.

In stem cell quiescence, mTOR activity is typically suppressed, reducing anabolic processes and conserving energy. Low mTORC1 activity is a hallmark of quiescent stem cells across multiple tissues, including HSCs, muscle stem cells, and neural stem cells. Activation of mTOR signaling drives stem cells out of quiescence and promotes proliferation and differentiation, making it a crucial switch in stem cell fate decisions. The careful regulation of mTOR activity ensures that stem cells remain protected from metabolic stress while maintaining their capacity for activation upon tissue demand.

Pathway Integration in Quiescence Regulation

The regulation of stem cell quiescence emerges from the sophisticated integration of TGF-β, BMP, and mTOR signaling pathways, which communicate through extensive cross-talk mechanisms. TGF-β/BMP signaling communicates with the Mitogen-activated protein kinase, phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt, Wnt, Hedgehog, Notch, and cytokine pathways, creating a network that determines stem cell fate decisions [25]. This cross-talk enables stem cells to respond appropriately to diverse environmental cues while maintaining the quiescent state.

A critical integration point occurs between TGF-β and mTOR signaling, where TGF-β can suppress mTORC1 activity through several mechanisms, including upregulation of negative regulators and modulation of AKT signaling. This suppression maintains stem cells in a quiescent, energy-conserving state. Conversely, BMP signaling often exhibits context-dependent interactions with mTOR, in some cases promoting mTOR activation to support stem cell differentiation. The interplay between these pathways creates a dynamic equilibrium that can be perturbed by changes in the microenvironment or systemic factors.

Table 1: Key Molecular Interactions in Quiescence Signaling Networks

| Pathway Interaction | Molecular Mechanism | Functional Outcome in Stem Cells |

|---|---|---|

| TGF-β to mTOR | SMAD-mediated transcription of mTOR inhibitors; regulation of AKT activity | Suppression of mTORC1; maintenance of quiescence |

| BMP to TGF-β | Competition for receptor complexes; modulation of I-SMAD expression | Context-dependent synergy or antagonism in fate decisions |

| mTOR to TGF-β/BMP | Regulation of SMAD phosphorylation and degradation; control of receptor expression | Modulation of pathway sensitivity and output |

| PI3K/AKT to mTOR | Direct activation of mTORC1 via TSC2 Rheb regulation | Exit from quiescence; promotion of proliferation |

The balance between these pathways is particularly important in the stem cell niche, where specialized microenvironmental cells provide precise combinations of ligands and regulators to maintain quiescence. In the bone marrow HSC niche, for example, TGF-β produced by niche cells maintains HSC quiescence, while BMP signaling contributes to the regulation of niche size and function. The integration of these signals with metabolic cues through mTOR allows stem cells to align their fate decisions with available resources and tissue needs.

Experimental Approaches for Signaling Network Analysis

Quantitative Proteomic and Phosphoproteomic Analysis

Advanced mass spectrometry-based techniques enable comprehensive quantification of signaling networks in stem cell populations. As demonstrated in studies of glioblastoma multiforme, quantitative proteomic and phosphoproteomic analysis can identify activated signaling networks from limited biological samples [26]. The experimental workflow involves:

Sample Preparation: Cells are homogenized in ice-cold 8M urea lysis buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein concentration is quantified using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay.

Protein Digestion: Proteins are reduced with 10mM DTT, alkylated with 50mM iodoacetamide, and digested with sequencing-grade trypsin at an enzyme-to-substrate ratio of 1:100.

Peptide Labeling: Peptides are labeled with isobaric tags (iTRAQ or TMT) to enable multiplexed quantification across multiple samples.

Phosphopeptide Enrichment: Phosphotyrosine peptides are enriched using a cocktail of anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies followed by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC).

Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Fractionated peptides are analyzed by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry.

Data Processing: Raw data are processed using specialized software to identify proteins and phosphorylation sites, with quantification based on reporter ion intensities.

This approach allows researchers to simultaneously monitor multiple signaling pathways and their activation states, providing a systems-level view of signaling networks in quiescent stem cells.

Organoid-Based Signaling Studies

Three-dimensional organoid cultures provide a physiologically relevant model system for investigating signaling pathways in stem cell biology. Organoids mimic human tissue architecture and function, making them particularly valuable for studying the role of TGF-β signaling in stem cell maintenance and differentiation [27]. The methodology for organoid-based signaling studies includes:

Organoid Generation: Stem cells are embedded in extracellular matrix hydrogels and cultured with specific growth factor combinations to promote self-organization.

Pathway Modulation: Small molecule inhibitors, recombinant proteins, or genetic approaches are used to selectively activate or inhibit specific signaling pathways.

Phenotypic Readouts: Organoids are analyzed using microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and single-cell RNA sequencing to assess morphological changes and differentiation status.

Signaling Analysis: Pathway activity is monitored through phospho-specific antibodies, reporter constructs, or transcriptional targets.

Organoid systems enable the study of TGF-β, BMP, and mTOR signaling in a context that preserves native cell-cell interactions and microenvironmental cues, providing insights that may be missed in traditional 2D culture systems.

Table 2: Experimental Models for Studying Quiescence Signaling Networks

| Experimental System | Key Applications | Technical Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Stem Cell Cultures | Direct analysis of quiescent stem cells; functional assays | Physiological relevance; maintenance of native properties | Limited expansion capacity; heterogeneity |

| Organoid Models | Study of niche interactions; tissue-level organization | 3D architecture; cell-cell interactions; long-term culture | Technical complexity; variable reproducibility |

| Genetically Engineered Models | In vivo pathway manipulation; lineage tracing | Physiological context; systemic factors examined | Compensatory mechanisms; developmental effects |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Quiescence Signaling Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Inhibitors | SB431542 (TGF-β RI inhibitor), LDN-193189 (BMP inhibitor), Rapamycin (mTOR inhibitor) | Acute pathway inhibition; functional validation | Specificity; off-target effects; dosage optimization |

| Recombinant Proteins | TGF-β1, BMP4, Noggin | Pathway activation; differentiation assays | Bioactivity verification; concentration optimization |

| Antibodies for Detection | Phospho-SMAD1/5/9, Phospho-SMAD2, Phospho-S6 Ribosomal Protein | Pathway activity assessment; immunohistochemistry | Specificity validation; application-specific optimization |

| Cell Surface Markers | CD34, CD45, CD73, CD90, CD105 [5] | Stem cell isolation and characterization | Context-dependent expression; species specificity |

| Reporters | SMAD-binding element luciferase, BRE-luciferase | Pathway activity quantification; high-throughput screening | Transduction efficiency; background signal |

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: TGF-β Signaling Pathway. This diagram illustrates the canonical TGF-β signaling cascade from ligand binding to target gene transcription.

Diagram 2: BMP Signaling Pathway. This diagram illustrates the canonical BMP signaling cascade, highlighting similarities and distinctions from TGF-β signaling.

Diagram 3: mTOR Signaling Pathway. This diagram illustrates the mTORC1 activation pathway in response to growth factors and nutrient availability.

Diagram 4: Quiescence Signaling Network Integration. This diagram illustrates the integrative network of TGF-β, BMP, and mTOR signaling in maintaining stem cell quiescence.

The signaling networks centered on TGF-β, BMP, and mTOR pathways represent a sophisticated control system that maintains stem cell quiescence and regulates the balance between self-renewal and differentiation. Understanding these networks at a quantitative level provides critical insights for both basic stem cell biology and therapeutic applications. As research in this field advances, several emerging areas hold particular promise:

First, the application of single-cell technologies will enable researchers to dissect the heterogeneity within stem cell populations and identify distinct quiescent states with different functional properties. Second, the integration of organoid models with CRISPR-based screening approaches will facilitate functional validation of pathway components in physiologically relevant contexts. Finally, the manipulation of these signaling pathways ex vivo could enable the expansion of therapeutic stem cell populations while maintaining their regenerative potential.

The comprehensive understanding of TGF-β, BMP, and mTOR signaling networks in quiescence will ultimately inform the development of novel regenerative medicine approaches [15] and therapeutic strategies for cancer and degenerative diseases where stem cell function is compromised. As these pathways continue to be elucidated in increasing detail, they offer promising targets for manipulating stem cell behavior in clinical applications.

Stem cell biology has evolved from a cell-centric view to a holistic understanding where the microenvironment, or stem cell niche, is recognized as a central determinant of cellular fate. The behavior of stem cells—including their self-renewal, quiescence, and differentiation—is governed not solely by intrinsic genetic programs but by highly specialized microenvironments that integrate structural, biochemical, and mechanical cues [28] [29]. The niche concept, first proposed by R. Schofield in 1978 for hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), posits that specific microenvironmental 'niches' maintain stem cell self-renewal, guide differentiation and maturation, and can even revert progenitor cells to an undifferentiated state [30]. These niches dynamically respond to injury, oxygen levels, mechanical forces, and signaling molecules, creating a dynamic regulatory system that is fundamental to tissue homeostasis and repair [30] [28].

This review delineates the architecture and function of stem cell niches within the broader context of stem cell self-renewal and differentiation mechanisms. We argue that successful regenerative interventions must treat stem cells and their microenvironment as an inseparable therapeutic unit [28] [29]. Emerging therapeutic strategies are now shifting the regenerative paradigm from a stem-cell-centric to a niche-centric model, which may unlock regenerative outcomes that surpass classical cell therapies [28].

The Architectural Blueprint of Stem Cell Niches

Stem-cell niches are anatomically discrete microenvironments where resident stem cells, their stromal neighbors, and a specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffold cooperate to balance quiescence, self-renewal, and lineage commitment [28].

Core Cellular and Extracellular Constituents

The functional unit of a niche comprises several core components that work in concert:

- Cellular Constituents: Immediate stromal neighbors—such as osteoblasts in bone marrow, fibroblasts in skin, and pancreatic telocytes—govern stem-cell fate through juxtacrine contacts and paracrine factors [28]. Accessory populations including endothelial cells, pericytes, macrophages, adipocytes, mast cells, and sympathetic neurons integrate systemic signals with local demands, modulating circadian mobilization or stress-induced recruitment [28].

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Scaffolds: The ECM provides both a structural lattice and a reservoir of biochemical and mechanical cues [28]. Laminin, collagen, fibronectin, and proteoglycans organize spatial relationships between niche residents, create morphogen gradients, and transmit force. Integrins and cadherins on the stem-cell surface translate ECM stiffness, viscoelasticity, and topography into intracellular signaling cascades that steer proliferation or differentiation [28].

Tissue-Specific Niche Architectures

Although built from similar building blocks, niche architecture diverges dramatically across organs to meet distinct regenerative demands. The table below summarizes key characteristics of major adult stem cell niches.

Table 1: Architecture and Characteristics of Major Adult Stem Cell Niches

| Tissue/Organ | Niche Location/Type | Stem Cell Types | Key Supporting Cells | Primary Regulatory Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow | Endosteal & Perivascular niches | Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs) | Osteoblasts, Endothelial cells, CAR cells | Maintains HSC quiescence (endosteal) and proliferation/differentiation (perivascular) [28]. |

| Skin | Hair follicle bulge, Interfollicular epidermis | Epithelial stem cells | Fibroblasts, Adipocytes | Regenerates epidermis, follicles, and sebaceous glands; maintains barrier function [28] [31]. |

| Intestine | Crypt base | Intestinal stem cells | Paneth cells, Stromal cells | Symmetric division expands pool; asymmetric division yields transit-amplifying cells for continuous renewal [28]. |

| Nervous System | Sub-ventricular zone, Sub-granular zone | Neural stem cells (NSCs) | Endothelial cells, Astrocytes | Maintains neurogenic capacity; interfaces with vasculature and cerebrospinal fluid [28]. |

| Skeletal Muscle | Beneath basal lamina | Satellite cells | Myofibers, Fibroblasts | Repairs muscle fibers after mechanical insult; maintained in quiescent state until activation [28]. |

Molecular Signaling Axes Governing Fate Decisions

Stem-cell self-renewal and lineage specification are regulated by a conserved set of signaling pathways that originate during embryogenesis and remain active throughout adult tissue maintenance [28]. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways and their primary functions in fate decisions.

Figure 1: Core Signaling Pathways in Stem Cell Fate Decisions. These evolutionarily conserved pathways integrate niche-derived cues to determine stem cell behavior.

Key Pathway Functions and Crosstalk

Wnt/β-catenin Pathway: This pathway plays a critical role in tissue homeostasis, supporting both stem cell self-renewal and differentiation, and is considered a key regulator of stem cell function [9] [28]. In the hematopoietic system, Wnt signaling promotes HSC maintenance and interacts with Notch signaling to support long-term self-renewal [28]. Similarly, in the epidermis and intestinal crypts, Wnt activity is critical for tissue homeostasis and cellular differentiation [28].

Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) Pathway: BMP signaling often counterbalances Wnt activity by imposing a quiescent state on stem cells [28]. This is particularly evident in the cycling of hair follicle stem cells where Wnt promotes entry into the growth phase while BMP maintains dormancy [28]. BMPs also play crucial roles in directing differentiation into specific lineages, including bone and cartilage formation [9].

Notch Signaling: The Notch pathway operates primarily through juxtacrine signaling between adjacent cells and plays a fundamental role in directing differentiation and maintaining the stem cell pool through lateral inhibition [9] [28]. In the hematopoietic system, Notch interacts with Wnt signaling to support stem cell maintenance [28].

Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) Signaling: The TGF-β superfamily consists of diverse proteins including TGF-β (1-3), activins, inhibits, and BMPs [9]. This pathway regulates tissue homeostasis, immune responses, extracellular matrix deposition, and cell differentiation [9]. TGF-β, along with Activin A and Nodal signaling pathways, is crucial for stimulating the self-renewal of primed pluripotent stem cells [9].

These pathways exhibit complex crosstalk, where modulation of one can influence others, providing multiple pharmacological entry points to fine-tune stem cell behavior for therapeutic purposes [9].

Quantitative Methodologies for Niche Analysis

Computational and Single-Cell Approaches

Advances in experimental and computational biology have dramatically improved our ability to resolve stem cell heterogeneity and niche interactions. The following table summarizes key quantitative methodologies and their applications in niche biology.

Table 2: Computational and Analytical Methods for Stem Cell Niche Research

| Methodology | Key Applications in Niche Biology | Resolution | Output Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) | Resolves transcriptional states of both stem and niche cells; identifies novel subtypes [32]. | Single-cell | Gene expression profiles, Cell type classification, Differential expression |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq) | Maps epigenetic landscape and transcription factor binding sites [32]. | Single-cell (newer methods) | Histone modifications, Transcription factor occupancy, Enhancer/promoter activity |

| Network Inference Algorithms | Reconstructs gene regulatory networks (GRNs) from expression data [32]. | Network-level | Regulatory interactions, Key transcription factors, Network topology |

| Machine Learning | Predicts stem cell fate outcomes; identifies novel regulatory elements [32]. | Predictive modeling | Fate prediction accuracy, Feature importance, Classification models |

| 3D Vertex Modeling | Simulates mechanical competition for space in epithelial tissues [31]. | Single-cell & tissue | Cell shape metrics, Division patterns, Fate outcomes |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol: scRNA-seq for Niche Deconstruction

Purpose: To resolve cellular heterogeneity within stem cell niches and characterize transcriptional states of both stem and supporting cells [32].

Workflow:

- Tissue Dissociation: Gentle enzymatic digestion to create single-cell suspension while preserving RNA integrity.

- Cell Sorting: Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to enrich for stem cell and niche cell populations using established surface markers.

- Library Preparation: Use droplet-based encapsulation systems (e.g., 10X Genomics) with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs).

- Sequencing: High-depth sequencing on Illumina platforms (recommended: ≥20,000 reads/cell).

- Computational Analysis:

- Quality control with FastQC [32].

- Alignment using STAR or CellRanger.

- Dimensionality reduction (PCA, UMAP).

- Cluster identification and marker gene detection.

- Trajectory inference (pseudotime) using Monocle or PAGA.

Key Reagents: Collagenase/Dispase for dissociation, FACS antibodies against niche-specific surface markers (e.g., CD34 for HSCs), single-cell RNAseq kit, bioinformatic tools (Seurat, Scanpy).

Protocol: Mechanical Fate Mapping in Epidermal Niches

Purpose: To quantify relationships between cell shape, mechanical forces, and fate decisions in skin epidermis [31].

Workflow:

- Tissue Preparation: Generate murine epidermal whole mounts or sectioned tissues.

- Immunofluorescence Staining: Label cell borders (E-cadherin), basement membrane (laminin), and nuclei (DAPI).

- Confocal Imaging: Acquire high-resolution z-stacks of interfollicular epidermis.

- 3D Segmentation: Use image analysis software (e.g., Imaris, MorphoGraphX) to extract cellular morphometrics.

- Shape Parameter Quantification: Measure cell height, cross-sectional area, basal surface area, and apical surface area.