Differentiation of iPSCs into Insulin-Producing Beta Cells: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Therapy Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the process to differentiate human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into functional, insulin-producing beta cells.

Differentiation of iPSCs into Insulin-Producing Beta Cells: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Therapy Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the process to differentiate human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into functional, insulin-producing beta cells. It covers the foundational biology of pancreatic development, details current multi-stage differentiation protocols utilizing growth factors and small molecules, and addresses key challenges including functional maturation, scalability, and tumorigenicity. The content also explores the application of iPSC-derived beta cells in disease modeling, drug screening, and cell replacement therapy, with a focus on validation techniques and comparative analysis against primary islets. Intended for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes recent advances and outlines future directions for translating this technology into clinical solutions for diabetes.

From Pluripotency to Pancreatic Fate: Understanding the Biological Blueprint

The Diabetes Burden and the Need for Beta Cell Replacement

Diabetes mellitus represents a global metabolic disease crisis, characterized by persistent hyperglycemia resulting from defects in insulin secretion or impaired insulin action [1] [2]. The International Diabetes Federation reports approximately 425 million adults aged 20-79 were living with diabetes in 2017, with projections indicating a rise to 629 million affected individuals by 2045 [1]. Over the past three decades, the global prevalence of diabetes has surged fourfold, establishing it as the ninth leading cause of reduced life expectancy worldwide [1]. This chronic condition not only requires lifelong management but significantly increases the risk of mortality from cardiovascular diseases, stroke, kidney damage, diabetic retinopathy, and neuropathy [3].

The pathophysiology differs between the two main forms of diabetes. Type 1 diabetes (T1D) involves autoimmune destruction of pancreatic β-cells leading to absolute insulin deficiency, while type 2 diabetes (T2D) features both functional decline of insulin-producing β-cells and systemic insulin resistance [1]. Current treatment strategies primarily involve continuous administration of exogenous insulin, which remains the only economical mode of treatment available for T1D and a common mainstay for T2D alongside pharmaceutical agents [4]. While whole pancreas transplantation and islet transplantation offer potential solutions, these approaches face significant limitations including scarcity of donor material, surgical risks, and the requirement for lifelong immunosuppression [1] [4]. The Edmonton protocol for islet cell transplantation, while showing improved outcomes achieving normoglycemia in 87.5% of patients at 1 year, still depends on limited cadaveric islet availability and carries risks of transplant rejection and complications from immunosuppression [1].

iPSC Technology: A Promising Solution

Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology, introduced by Shinya Yamanaka in 2006, represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine approaches to diabetes [3]. By reprogramming somatic cells to a pluripotent state through introduction of specific transcription factors (Yamanaka factors), iPSCs can differentiate into any cell type in the body while avoiding the ethical concerns associated with embryonic stem cells [3] [1]. The ability of iPSCs to differentiate into insulin-producing β-cells offers unprecedented opportunities for both disease modeling and cell replacement therapy for diabetes [3] [5].

Research in this field has demonstrated exponential growth from 2008 to 2021, with the United States leading in publications (28% of total), followed by China (13.8%), Japan (12.3%), the United Kingdom (4.1%), and Italy (3.9%) [3]. The United States not only leads in publication volume but also maintains a broader network of international collaborators, with 21.1% of its publications involving multi-country collaborations [3]. Current research hotspots include applying iPSCs to study pathological mechanisms of diabetes, disease modeling, drug screening, gene expression profiling, and investigating the degeneration process of β-cells [3].

Table 1: Global Research Output on iPSCs in Diabetes (2008-2025)

| Country | Publications (n) | Publication Percentage | Single Country Publications | Multi Country Publications | MCP Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 171 | 28.0% | 135 | 36 | 21.1% |

| China | 84 | 13.8% | 68 | 16 | 19.0% |

| Japan | 75 | 12.3% | 69 | 6 | 8.0% |

| United Kingdom | 25 | 4.1% | 11 | 14 | 56.0% |

| Italy | 24 | 3.9% | 17 | 7 | 29.2% |

Pancreatic Development: Insights for Protocol Design

The process of generating functional β-cells from iPSCs relies on recapitulating key stages of natural pancreatic embryogenesis [4]. Human pancreas specification begins from the foregut-midgut boundary, forming from anterior endoderm invagination during Carnegie Stage 10 [4]. During early CS13, the first signs of dorsal pancreas budding from the foregut endoderm begins, with the dorsal bud forming the pancreatic tail, neck and part of the pancreatic head, while the ventral bud forms the uncinate process and part of the pancreatic head [4].

Several transcription factors play crucial roles in pancreatic development. PDX1 (pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1) represents the most significant and earliest marker of pancreatic progenitor cells, essential for initiating formation of both ventral and dorsal pancreatic primordia and branching of the pancreatic buds [4]. NEUROG3 (neurogenin 3) initiates the endocrine program during pancreatic organogenesis by activating expression of downstream transcription factors responsible for maturation and lineage specification of endocrine precursors [4]. NKX6.1, a homeobox protein, plays an indispensable role during both early and late stages of pancreatic development [4]. Understanding these developmental mechanisms provides the foundation for designing effective differentiation protocols.

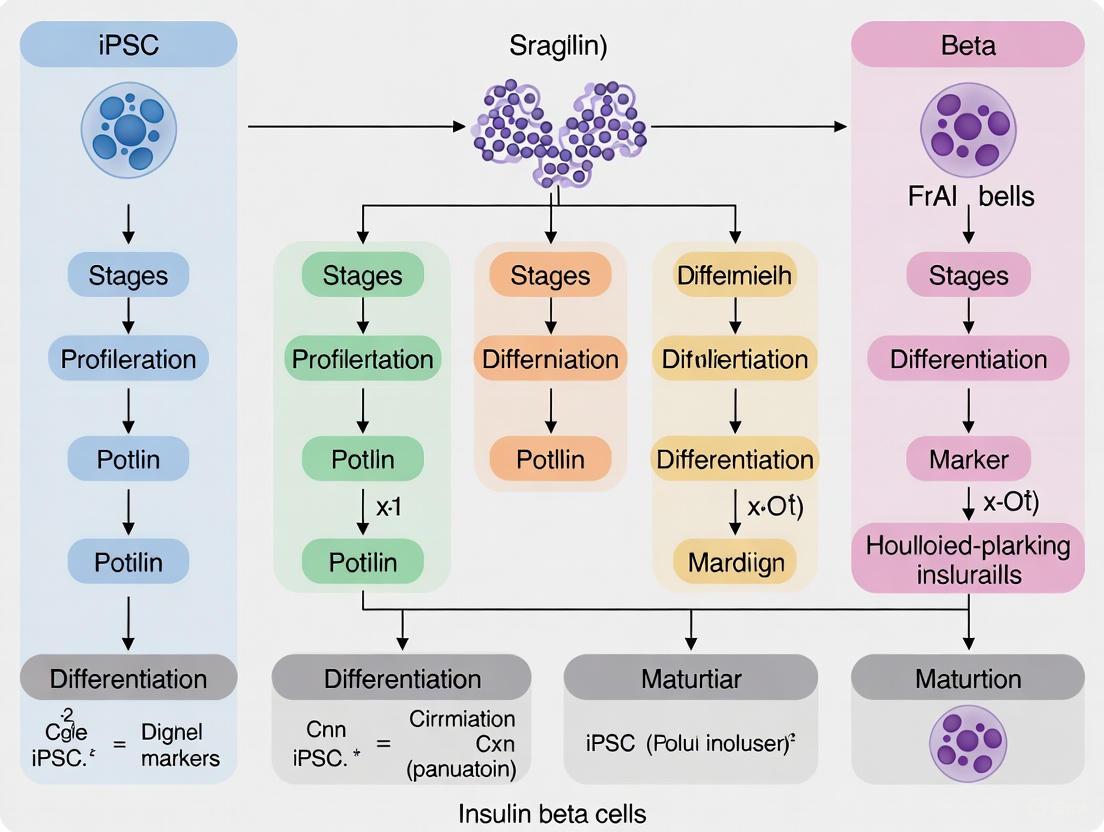

Figure 1: Stepwise Differentiation Protocol from iPSCs to Functional β-Cells

Application Notes: Differentiation Methodologies

2D vs. 3D Differentiation Systems

Current differentiation protocols employ either two-dimensional (2D) or three-dimensional (3D) culture systems, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The 3D environment allows better cell-to-cell communication and correct cellular polarization, which is crucial for proper islet architecture and β-cell functionality [6]. In static microwell systems, homogeneously small-sized islet-like aggregates can be obtained, while rotating suspension cultures often produce heterogeneous sizes with frequent aggregation clumping [6]. Research demonstrates that iPSCs differentiated with equal efficiency into β-cells in microwells compared to rotating suspension, but the former had a higher experimental success rate [6].

A critical advancement in disease modeling occurred with the development of 3D organotypic culture systems that facilitate better self-organization and lineage specification [6]. Natural scaffold-based strategies rely on laminin-rich Matrigel, pure laminins, collagens or other biomaterials which favor cell differentiation and functionality, though pure extracellular matrix proteins are costly and limit large-scale organoid production [6]. For large-scale production, β-cells can be differentiated in dynamic suspension cultures or bioreactors, though organoid formation and size control remains challenging [6].

Protocol Efficiency and Characterization

Efficient differentiation protocols consistently generate pancreatic islet-like aggregates with yields of insulin-positive β-cells comparable to human islets [6]. Using optimized 7-stage protocols, research groups have reported final cell populations highly enriched for β-cells, with 75-80% of cells consistently staining double positive for the markers C-peptide and NKX6.1 [7]. Flow cytometry analysis typically shows 24±2% and 27±2% of cells co-expressing C-peptide+/NKX6.1+ for T1D and non-diabetic (ND) cells, respectively [8]. When analyzed with electron microscopy, both T1D and ND SC-β cells contain developing and mature insulin granules similar to β-cell granules [8].

Table 2: Characterization of iPSC-Derived β-Cells from Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Donors

| Parameter | T1D SC-β Cells | ND SC-β Cells | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-peptide+/NKX6-1+ cells | 24±2% | 27±2% | Flow cytometry |

| Insulin content | 210±40 μIU per 10³ cells | 220±20 μIU per 10³ cells | ELISA measurement |

| Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion | 2.0±0.4 μIU/10³ cells | 1.9±0.3 μIU/10³ cells | GSIS assay at 20mM glucose |

| Stimulation index | 1.9 | 2.2 | Ratio (20mM/2mM glucose) |

| Response to glucose challenges | 88% | 78% | Percentage of responsive batches |

Functional Validation In Vitro and In Vivo

In vitro functionality is typically assessed by glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS), NAD(P)H and calcium fluctuations [6]. Stage 7 aggregates generally show slight increases in insulin release in response to glucose in vitro [6]. However, extensive research indicates that in vitro differentiation typically generates aggregates lacking fully mature β-cell function, requiring in vivo maturation for complete functionality [6].

Transplantation studies under the kidney capsule of immunocompromised mice demonstrate that grafts develop glucose-responsiveness and maintain normoglycemia after streptozotocin injection [6]. After 2 weeks post-transplantation, graft function shows human insulin detection with glucose responsiveness in most mice (81% for T1D SC-β cells and 77% for ND SC-β cells) [8]. The ratio of insulin secretion after glucose challenge compared to before challenge averages 1.4 and 1.5 for T1D and ND SC-β cells, respectively [8]. Importantly, both T1D and ND SC-β cells continue to function for >5 months in vivo, maintaining fasting blood glucose <200 mg/dl, secreting human insulin in response to glucose injection, and rapidly clearing glucose after challenge [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC to β-Cell Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Differentiation |

|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Maintenance | mTeSR1 medium, Vitronectin XF, Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Maintain iPSCs in undifferentiated state, enhance survival after passaging |

| Definitive Endoderm Induction | Activin A, CHIR99021 (WNT agonist) | Direct differentiation toward definitive endoderm lineage |

| Pancreatic Progenitor Specification | FGF10, Retinoic acid, SANT-1 (Hedgehog inhibitor), Noggin (BMP antagonist) | Pattern definitive endoderm into pancreatic progenitors |

| Endocrine Commitment | TGF-β inhibitors (ALK5i), Thyroid hormone (T3), Nicotinamide | Promote endocrine differentiation and β-cell maturation |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-PDX1, Anti-NKX6.1, Anti-C-peptide, Anti-NEUROG3 | Identify specific differentiation stages by immunostaining |

| Functional Assay Reagents | Glucose solutions, Insulin ELISA kits, Calcium dyes | Assess β-cell function through GSIS and signaling assays |

Scaling Challenges and Manufacturing Solutions

Transitioning from laboratory-scale protocols to large-scale manufacturing presents significant challenges. Recent research has identified that stage time increase and limited media replenishing with lactate accumulation can increase the differentiation capacity of insulin-producing cells cultured in large-scale suspension environments [9]. A three-stage suspension manufacturing process has been developed, transitioning from adherent to suspension culture, with specialized media supporting iPSC growth during scaling [9].

Bioreactor systems using vertical wheel designs have demonstrated improved differentiation outcomes compared to traditional static cultures. Continuous bioreactor runs have been utilized to study nutrient and growth limitations and their impact on differentiation, showing metabolic shifts and a more β-cell-like differentiation profile compared to control media change bioreactors [9]. Importantly, cryopreserved aggregates harvested from these runs maintain viability and insulin secretion capacity post-recovery, indicating their potential for storage and future transplantation therapies [9].

Advanced monitoring systems incorporating daily sampling for cell counting, aggregate size analysis, and islet equivalency (IEQ) estimates have been implemented using flow cytometry and automated imaging systems [9]. Quantitative PCR analysis at different stages throughout culture time provides crucial quality control metrics, while flow cytometry testing at the end of each differentiation stage ensures consistent marker expression across batches [9].

Future Perspectives and Clinical Translation

The field of iPSC-derived β-cells continues to evolve rapidly, with more than hundred patients dosed in clinical trials with ESC-derived cells and a single trial of iPSC-derived cells [1]. A clinical trial presented at the 83rd Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association showcased VX-880, a stem cell-derived islet cell therapy, as a potential treatment for T1D, demonstrating restored insulin secretion, improved glycemic control, and elimination of severe hypoglycemic events in all six treated patients [9].

Emerging research directions include integrating immune evasion mechanisms and gene therapy, particularly by enhancing islet cell survival and function through immune regulation and genetic modification [3]. Epigenetic research has identified key regulators such as KDM4A, a histone demethylase, whose knockdown significantly reduces expression of pancreatic β-cell genes (PDX1, Nkx6.1, and Ins) by 50% and decreases glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by approximately 80% [10]. These findings emphasize the critical role of histone demethylation in hiPSC differentiation toward β-cells and suggest epigenetic modulation could enhance generation of functional β-cells for regenerative medicine in diabetes [10].

Despite these advancements, challenges remain in generating fully functional and mature β-cells from hPSCs, with protocol efficiency varying greatly among different hESC and hiPSC lines [4]. This variability poses a particular challenge for generating patient-specific β-cells. The ultimate goal remains developing a highly efficient directed differentiation protocol applicable across all genetic backgrounds of hPSCs, ensuring safety and efficacy of hPSC-derived pancreatic islets before widespread clinical utilization [4].

The field of regenerative medicine was transformed by the emergence of technologies to generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which represent a groundbreaking alternative to embryonic stem cells (ESCs). Pluripotent stem cells are defined by their capacity for unlimited self-renewal and their ability to differentiate into virtually any adult cell type [11]. Traditionally, human disorders were studied using animal models or patient-derived somatic cells, but these systems presented significant limitations for modeling many genetic diseases [11]. The isolation of human ESCs from the inner cell mass of blastocysts in 1998 provided a powerful new tool for developmental biology and disease modeling [12]. However, the use of human ESCs raised ethical concerns regarding embryo destruction and was subject to regulatory restrictions in many countries [11] [13].

The landmark discovery of iPSC technology by Shinya Yamanaka's lab in 2006 fundamentally changed the stem cell research landscape [12] [14]. Takahashi and Yamanaka demonstrated that the introduction of just four transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and Myc, collectively known as OSKM or Yamanaka factors) could reprogram mouse embryonic fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells [12]. This revolutionary finding was quickly followed in 2007 by the successful generation of human iPSCs by both Yamanaka and James Thomson's groups, the latter using a slightly different combination of factors (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28) [12] [14]. These discoveries revealed that somatic cell fate could be reversed through epigenetic reprogramming, earning Gurdon and Yamanaka the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and opening new avenues for disease modeling, drug screening, and cell-based therapies [12].

Molecular Principles of iPSC Induction

Historical Foundations of Nuclear Reprogramming

The conceptual foundation for iPSC technology was established through decades of pioneering research in nuclear reprogramming. In 1962, John Gurdon's seminal somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) experiments in Xenopus laevis frogs demonstrated that a nucleus isolated from a terminally differentiated intestinal epithelial cell could, when transplanted into an enucleated egg, support the development of germline-competent organisms [12]. This revolutionary finding established that the process of cell differentiation does not involve irreversible changes to the genetic material, but rather reversible epigenetic modifications that can be reset by factors present in the oocyte cytoplasm. The reversibility of the somatic cell state was further supported by cell fusion experiments in the early 2000s, which showed that fusion of mouse or human ESCs with somatic cells resulted in heterokaryons that were reprogrammed to pluripotency [12]. Concurrently, transdifferentiation experiments demonstrated that forced expression of lineage-specific transcription factors, such as C/EBPα/β, could directly convert B cells into macrophages, highlighting the power of transcription factors in reshaping cell identity [12].

The molecular basis of cellular plasticity lies in the epigenetic landscape that governs gene expression patterns. The Waddington epigenetic landscape model, proposed in 1957, conceptualized cell differentiation as a ball rolling downhill through branching valleys toward increasingly restricted and stable states [12]. In 1958, David Nanney proposed that while DNA sequence confers gene expression potential, phenotypic differences in genetically identical cells arise from "epigenetic" systems that regulate gene expression specificities [12]. We now understand that these epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin remodeling, and non-coding RNA regulation, which together establish and maintain cell type-specific gene expression patterns without altering the underlying DNA sequence. The process of reprogramming somatic cells to iPSCs involves the erasure of these somatic epigenetic signatures and their replacement with a pluripotency-associated epigenetic landscape [12].

Mechanisms of Somatic Cell Reprogramming

The reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency involves profound remodeling of the epigenome and global changes in gene expression. When pluripotent stem cells differentiate into somatic cells, they acquire stable epigenetic memory and undergo chromatin conformation changes that inactivate pluripotency-specific genes while activating somatic cell-specific genes [12]. Reprogramming reverses this process, effectively "rewinding" the developmental clock through a sequence that partially mirrors developmental events in reverse [12].

Reprogramming occurs in two broad phases: an early, stochastic phase followed by a late, more deterministic phase [12]. During the early phase, somatic genes are silenced while early pluripotency-associated genes are activated. This initial phase is highly inefficient and stochastic, likely due to limited accessibility of closed chromatin regions to the reprogramming factors [12]. The late phase involves activation of late pluripotency-associated genes and establishment of a stable self-renewing pluripotent state. Universal aspects of reprogramming are accompanied by somatic cell type-specific reprogramming trajectories and transient events [12]. The process entails comprehensive remodeling of chromatin structure, epigenome, and multiple aspects of cell biology including metabolism, cell signaling, intracellular transport, and proteostasis [12]. Since fibroblasts are the most common starting cell type for reprogramming, mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) represents another critical event during iPSC generation [12].

Table 1: Key Molecular Events During Somatic Cell Reprogramming

| Reprogramming Phase | Epigenetic Changes | Transcriptional Changes | Cellular Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Phase (Stochastic) | Initiation of DNA demethylation at pluripotency loci; Early chromatin accessibility changes | Silencing of somatic genes; Activation of early pluripotency genes | MET; Changes in cell morphology; Initiation of proliferation changes |

| Late Phase (Deterministic) | Establishment of pluripotent epigenome; DNA methylation resetting; X chromosome reactivation | Activation of core pluripotency network (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2); Downregulation of lineage-specific factors | Metabolic shift to glycolysis; Acquisition of unlimited self-renewal capacity; Telomerase activation |

Methods for iPSC Generation and Characterization

Reprogramming Methods

Since the original description of iPSC generation using retroviral vectors, numerous technical approaches have been developed to improve the efficiency and safety of reprogramming. The choice of reprogramming method depends on the specific application, with integration-free methods being essential for clinical applications.

Table 2: Comparison of iPSC Reprogramming Methods

| Method | Key Features | Efficiency | Advantages | Disadvantages | Clinical Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrating Viruses (Retrovirus/Lentivirus) | Stable integration of reprogramming factors; OSKM expression | 0.01%-0.1% | High efficiency; Well-established protocol | Risk of insertional mutagenesis; Persistent transgene expression | Limited due to safety concerns |

| Non-integrating Viruses (Sendai Virus, Adenovirus) | RNA virus-based delivery; Non-integrating | 0.001%-0.01% | No genomic integration; Relatively efficient | Requires virus clearance; Potential immunogenicity | More suitable, with virus clearance |

| Episomal Vectors | OriP/EBNA1-based plasmids; Replicated in dividing cells | ~0.0005% | Non-integrating; Simple delivery | Low efficiency; Requires transfection | Suitable with careful screening |

| mRNA Reprogramming | Synthetic modified mRNAs; Daily transfections | ~1% | High efficiency; Non-integrating; Defined | Requires multiple transfections; Potential immune response | Highly suitable |

| Small Molecule Reprogramming | Chemical compounds that replace reprogramming factors | Varies by cocktail | Non-genetic; Cost-effective; Scalable | Often used to enhance other methods | Highly promising |

| Protein Reprogramming | Direct delivery of recombinant reprogramming proteins | Very low (<0.001%) | Non-genetic; Minimal safety concerns | Extremely low efficiency; Technically challenging | Theoretically ideal but impractical |

The original reprogramming factors identified by Yamanaka (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and MYC) remain the most widely used, though alternative combinations have been successfully employed, including Thomson's combination (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28) for human cell reprogramming [12]. OCT4 and SOX2 are considered core pluripotency factors, while KLF4 and MYC are thought to enhance reprogramming efficiency by promoting proliferation and epigenetic remodeling [12]. Small molecules have been increasingly incorporated into reprogramming protocols to enhance efficiency, replace certain transcription factors, or direct the reprogramming process. The first fully chemical reprogramming of murine fibroblasts using seven small-molecule compounds was reported in 2013 [12].

Characterization of Pluripotent Stem Cells

Both ESCs and iPSCs must be rigorously characterized to confirm their pluripotent identity and functional capacity. Standard characterization includes:

- Morphology: Pluripotent stem cells form compact colonies with well-defined borders and high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratios.

- Pluripotency Marker Expression: Immunocytochemistry and flow cytometry for core pluripotency transcription factors (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2) and surface markers (TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81, SSEA-3, SSEA-4).

- Gene Expression Analysis: RT-PCR or RNA-seq to detect expression of endogenous pluripotency genes and silence of reprogramming transgenes.

- Epigenetic Status: Assessment of DNA methylation status at key pluripotency gene promoters.

- In Vitro Differentiation: Formation of embryoid bodies and spontaneous differentiation into derivatives of all three germ layers.

- In Vivo Differentiation: Teratoma formation assay in immunocompromised mice, with histological confirmation of tissues representing all three germ layers.

- Karyotype Analysis: G-banding or spectral karyotyping to confirm genomic integrity.

While iPSCs and ESCs share fundamental characteristics of pluripotency, detailed comparisons have revealed subtle but potentially important differences. Proteomic analyses have shown that while hiPSCs and hESCs express a nearly identical set of proteins, they display consistent quantitative differences in protein expression levels [15]. iPSCs demonstrate increased total protein content, with elevated abundance of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial proteins required to sustain high growth rates, including nutrient transporters and metabolic enzymes [15]. These molecular differences correlate with functional phenotypes, including enhanced metabolic activity and increased production of secreted proteins including ECM components and growth factors [15].

Advantages of iPSCs over ESCs

iPSC technology offers several significant advantages over ESCs for research and therapeutic applications:

Ethical Advantages

iPSCs avoid the ethical controversies associated with the destruction of human embryos that has limited ESC research and led to regulatory restrictions in many countries [11] [13]. By enabling the generation of pluripotent stem cells from readily accessible somatic tissues, iPSC technology provides an ethically uncontroversial alternative that has expanded stem cell research globally.

Practical and Technical Advantages

From a practical standpoint, iPSCs offer numerous technical advantages. The derivation of mutant ESCs from affected embryos identified by preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) is limited to a small number of diseases and requires access to in vitro fertilization (IVF) facilities [11]. In contrast, iPSCs can be generated from patients with any genetic disorder, at any age, using minimally invasive procedures such as skin biopsy or blood draw. Furthermore, in ESC-based models, the correlation between genotype and phenotype may be obscured by protective genetic backgrounds, whereas patient-derived iPSCs naturally present the complete genetic context in which the disease manifests [11].

Personalized Medicine Applications

The ability to generate patient-specific iPSCs enables the development of truly personalized regenerative therapies. Autologous iPSC-derived cells should theoretically avoid immune rejection without requiring immunosuppression, though this advantage requires further validation [16]. Patient-specific iPSCs also facilitate the development of personalized disease models and drug screening platforms that account for individual genetic variability.

Applications in Diabetes Research: Differentiation into Insulin-Producing Beta Cells

Protocol for Differentiation of iPSCs to Pancreatic Beta Cells

The differentiation of iPSCs into functional insulin-producing beta cells represents a promising approach for cell replacement therapy for type 1 diabetes (T1D). T1D is characterized by autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells, resulting in absolute insulin deficiency [17]. Current treatment relies on exogenous insulin administration, which cannot perfectly replicate physiological glucose regulation and often leads to long-term complications [17]. Replacement of functional beta cells through transplantation of cadaveric islets has proven effective but is limited by donor scarcity and the need for lifelong immunosuppression [16] [17].

We detail a robust, six-stage planar differentiation protocol for generating SC-β cells that secrete high amounts of insulin in response to glucose stimulation [18]. This protocol generates SC-islets containing multiple endocrine cell types, including glucagon-producing alpha cells and somatostatin-producing delta cells, resembling native pancreatic islets [16].

Diagram 1: Differentiation protocol for generating SC-β cells from human iPSCs. Key signaling molecules are shown in blue ovals.

Table 3: Six-Stage Planar Differentiation Protocol for Generating SC-β Cells from iPSCs

| Stage | Duration | Key Signaling Molecules | Target Cell Population | Characteristic Markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: Definitive Endoderm Induction | 3 days | Activin A, CHIR99021 (Wnt activator) | Definitive endoderm | SOX17, FOXA2, CXCR4 |

| Stage 2: Primitive Gut Tube Formation | 2 days | Keratinocyte Growth Factor (KGF) | Primitive gut tube | HNF1B, HNF4A, PDX1 (low) |

| Stage 3: Posterior Foregut Patterning | 5 days | SANT1 (Hedgehog inhibitor), TPPB (PKC activator), LDN193189 (BMP inhibitor), Retinoic Acid | Posterior foregut | PDX1, NKX6-1, SOX9 |

| Stage 4: Pancreatic Progenitor Specification | 7-9 days | Continued from Stage 3 with adjusted concentrations | Pancreatic progenitors | PDX1+/NKX6-1+ |

| Stage 5: Endocrine Progenitor Induction | 7 days | Latrunculin A (cytoskeletal modulator), XXI, T3, ALK5 inhibitor II, SANT1, Retinoic Acid | Endocrine progenitors | NEUROG3, INS, GCG |

| Stage 6: SC-β Cell Maturation | 7-14 days | Basal media with low glucose | SC-β cells and islet-like clusters | NKX6-1/C-Peptide+, MAFA, Glucose-responsive insulin secretion |

This protocol eliminates the need for 3D culture during endocrine induction, simplifying the methodology while generating highly functional SC-β cells [18]. The resulting SC-β cells and other endocrine cell types can be aggregated into islet-like clusters for analysis and transplantation [18]. The entire process requires approximately 34 days to generate functional SC-β cells, plus an additional 1-2 weeks for initial stem cell expansion and final cell assessment [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for iPSC Differentiation

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC to Beta Cell Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Differentiation |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, MYC (OSKM); OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 | Induction of pluripotency in somatic cells |

| Basal Media | mTeSR, E8 medium | Maintenance of pluripotent stem cells |

| Growth Factors | Activin A, Keratinocyte Growth Factor (KGF) | Definitive endoderm induction; primitive gut tube formation |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | CHIR99021 (Wnt activator), SANT1 (Hedgehog inhibitor), LDN193189 (BMP inhibitor), ALK5 inhibitor II (TGF-β inhibitor) | Pathway modulation to direct pancreatic differentiation |

| Signaling Molecules | Retinoic Acid, T3 (thyroid hormone) | Patterning and maturation of pancreatic endocrine cells |

| Cytoskeletal Modulators | Latrunculin A | Enhancement of endocrine differentiation efficiency |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-OCT4, SOX17, FOXA2, PDX1, NKX6-1, C-Peptide, Insulin | Identification of specific cell populations during differentiation |

| Functional Assays | Glucose Stimulated Insulin Secretion (GSIS); ELISA for C-peptide/insulin; Electrophysiology | Validation of SC-β cell function |

Disease Modeling and Drug Screening Applications

iPSC technology has enabled the generation of patient-specific beta cells for modeling various forms of diabetes, including type 1 diabetes (T1D), type 2 diabetes (T2D), monogenic diabetes (MD), and cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) [16]. These disease-specific iPSC-derived beta cells allow researchers to study disease mechanisms, progression, and potential therapeutic interventions in a human-relevant system [16]. The combination of disease modeling with gene editing technologies such as CRISPR-Cas9 enables the correction of diabetes-causing mutations, providing both insights into disease mechanisms and a potential pathway for autologous cell therapy [16].

For drug development, iPSC-derived beta cells offer a physiologically relevant human cell system for identifying and validating drug targets, screening compounds for efficacy, and conducting toxicology studies [14] [19]. The availability of patient-specific cells enables the development of personalized medicine approaches, where drug responses can be tested in vitro before administration to patients [14]. The adoption of the FDA Modernization Act 2.0, which permits cell-based assays as alternatives to animal testing for drug applications, has further accelerated the use of iPSC-derived cells in pharmaceutical development [14].

iPSC technology has revolutionized stem cell research and regenerative medicine by providing an ethically acceptable, patient-specific source of pluripotent stem cells. While ESCs and iPSCs share fundamental properties of pluripotency, quantitative proteomic analyses have revealed consistent differences in protein expression patterns, particularly in metabolic and secretory pathways [15]. These differences may reflect the reprogramming process or the distinct developmental origins of these cells and warrant consideration when selecting a stem cell platform for specific applications.

In the context of diabetes research, iPSC technology offers unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug screening, and cell replacement therapy. The development of robust differentiation protocols for generating glucose-responsive SC-β cells from patient-specific iPSCs represents a major advancement toward personalized cell therapy for diabetes [16] [18]. Ongoing efforts focus on improving the maturation and function of SC-β cells, enhancing their engraftment and survival after transplantation, and developing strategies to protect them from autoimmune rejection [16] [17].

The iPSC field continues to evolve rapidly, with advances in reprogramming technologies, differentiation protocols, gene editing, and tissue engineering. The global iPSC market is projected to grow significantly, reaching USD 4.69-5.12 billion by 2033-2034, driven by increasing demand for patient-specific cell therapies and disease models [20] [19]. As the technology matures and overcomes current challenges in manufacturing, safety, and regulatory approval, iPSC-based therapies hold immense promise for transforming the treatment of diabetes and other degenerative diseases.

Recapitulating Embryonic Pancreas Development In Vitro

The in vitro recapitulation of embryonic pancreas development is a cornerstone of modern regenerative medicine strategies for diabetes. This process aims to generate functional, insulin-producing β-cells from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by meticulously mimicking the sequential stages of natural organogenesis [1] [21]. Success in this endeavor holds the potential to provide an unlimited cell source for transplantation, moving beyond the limitations of donor pancreata and lifelong immunosuppression [1] [3]. The foundation of all contemporary differentiation protocols lies in a deep understanding of the spatiotemporal cues and transcriptional networks that guide pancreatic progenitor cells toward a mature endocrine fate in the embryo [1] [22]. This document provides a detailed experimental framework for modeling early human pancreas development using iPSC-based organoid systems, designed for researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of developmental biology and disease modeling.

Key Findings from Recent Investigations

Recent single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) studies of human embryonic pancreas between post-conception weeks (PCW) 4 and 11 have provided an unprecedented view of early development. These analyses reveal a complex cellular heterogeneity and distinct lineage trajectories for dorsal and ventral multipotent progenitor (MP) cells [22].

- Dorsal vs. Ventral MP Cells: Dorsal MP cells express

NR2F1and are associated with Wnt signaling and cell junction assembly. In contrast, ventral MP cells expressTBX3andSOX11and are linked to ribosome assembly and muscle tissue development [22]. - Signaling from Mesenchyme: Notch and MAPK signals from surrounding mesenchymal cells have been identified as critical regulators directing the differentiation of multipotent cells into trunk and ductal lineages [22].

- Identification of Procr-like Cells: A recent investigation identified a

Procr-like cell population in the mouse and human embryonic pancreas, which shares a transcriptional signature with a putative adult progenitor population. These cells areNeurog3negative and display a profile that includesRspo1,Dcn, andUpk3b, suggesting a potential, though debated, role in developmental or regenerative processes [23].

Table 1: Key Transcription Factors in Pancreatic Development and Differentiation

| Gene | Function in Development | Role in iPSC Differentiation |

|---|---|---|

| PDX1 | Master regulator of pancreatic progenitor specification; expressed in early buds [1] [22] | Critical initial checkpoint for definitive pancreatic fate [1] [21] |

| PTF1A | Specific to pancreatic progenitors; promotes tip cell and acinar fate [1] [22] | Used to specify pancreatic progenitor population [21] |

| NKX6.1 | Regulates trunk cell fate and β-cell precursor maintenance/maturation [1] [22] | Essential for functional β-cell maturation; a key marker for polyhormonal vs. monohormonal fate [21] [7] |

| NEUROG3 | Master regulator of endocrine differentiation; drives delamination of endocrine progenitors [22] | Induces endocrine commitment; its expression is transiently activated [21] |

| SOX9 | Expressed in multipotent progenitor cells and ductal cells [1] [22] | Marker for multipotent and bipotent progenitor stages [21] |

| MAFA | Regulates final β-cell maturation and insulin production [1] | Late-stage marker indicating functional maturation of derived β-cells [1] |

Table 2: Characterization of Major Cell Types During Early Human Pancreas Development (PCW 4-11)

| Cell Type | Key Markers | Developmental Timeline (PCW) | Function/Fate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multipotent Progenitor (MP) | PDX1+, PTF1A+, NKX6.1+, FOXA2+ [22] |

4-5 | Founder population for all pancreatic epithelial lineages |

| Dorsal MP | NR2F1+ [22] |

4-5 | Gives rise to dorsal bud lineages |

| Ventral MP | TBX3+, SOX11+ [22] |

4-5 | Gives rise to ventral bud lineages; shares origin with pancreato-biliary progenitors |

| Tip / Acinar Progenitor | CPA2+, RBPJL+, CTRB2+ [22] |

Emerges from ~PCW 7 | Committed to exocrine/acinar differentiation |

| Trunk / Bipotent Progenitor | HES4+, DCDC2+ [22] |

Emerges from ~PCW 7 | Gives rise to both ductal and endocrine lineages |

| Endocrine Progenitor (EP) | NEUROG3+ [22] |

Peaks after PCW 8 | Transient population committed to endocrine cell fate |

| Immature β-cell | INS+, NKX6.1+, MAFA- [1] |

Appears after PCW 8 | Immature insulin-producing cell; requires further maturation |

Experimental Protocols

hPSC-Based Matrigel-Overlay Organoid Differentiation

This protocol outlines a robust method for generating key pancreatic cell types, including multipotent progenitors, endocrine progenitors, and hormone-producing cells, within a 3D organoid structure [21].

Key Materials:

- Cells: Human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs), including iPSCs or ESCs.

- Basal Media: DMEM/F12 or other defined base medium.

- Induction Factors: Recombinant growth factors and small molecules (see Table 4).

- 3D Matrix: Matrigel, Growth Factor Reduced.

- Culture Vessels: Multi-well plates for monolayer and 3D culture.

Detailed Procedure:

Pre-culture of hPSCs as a 2D Monolayer:

- Maintain hPSCs in a feeder-free culture system using essential media like mTeSR or StemFlex.

- Culture cells on tissue culture plates coated with a suitable substrate (e.g., Matrigel, Geltrex).

- Passage cells at 70-80% confluence using a gentle cell dissociation reagent. Ensure cells maintain a high pluripotency status (e.g., >90% OCT4-positive) before initiating differentiation.

Definitive Endoderm (DE) Induction (Days 1-3):

- Day 0: When hPSCs reach ~80% confluence, switch to a definitive endoderm induction medium.

- Base Medium: RPMI 1640.

- Key Inducers: Add 100 ng/mL Activin A and 3 µM CHIR99021 (a GSK-3β inhibitor activating WNT signaling) [21].

- Serum Gradient: On Day 1, use 0% FBS; on Day 2, switch to 0.2% FBS.

- Quality Control: Assess efficiency by flow cytometry for DE markers SOX17 and FOXA2. A successful induction should yield >80% double-positive cells.

Primitive Gut Tube (PGT) and Posterior Foregut (PF) Induction (Days 4-6):

- Day 4-5 (PGT): Change medium to DMEM with 2% FBS, supplemented with 50 ng/mL FGF7 (KGF).

- Day 6 (PF): Switch to a medium that promotes posterior foregut fate. A common formulation includes DMEM with 1% B27, 0.5 µM Retinoic Acid (RA), 500 nM LDN193189 (a BMP inhibitor), and 200 nM Sant1 (a Sonic Hedgehog inhibitor) [21].

Application of Matrigel Overlay and Pancreatic Progenitor (PP) Induction (Days 7-12):

- Day 7: This is a critical step for establishing the 3D niche. Gently overlay the cells with a thin layer of cold, diluted Matrigel (e.g., a 1:1 mix of Matrigel and culture medium).

- Pancreatic Induction Medium: Use DMEM with 1% B27, and continue supplementation with 0.5 µM RA, 200 nM Sant1, and 50 ng/mL FGF7. Additional factors like 10 µM Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) can be added to support cell survival during this transition.

- Culture: Maintain the cells with this 3D Matrigel overlay, changing the medium every 2-3 days.

- Monitoring: By Day 12, the cells should form distinct 3D epithelial structures. Analyze for co-expression of PDX1 and NKX6.1 via immunostaining to confirm successful pancreatic progenitor specification.

Endocrine Progenitor (EP) and Hormone-Producing Cell Induction (Days 13-20+):

- Day 13-17 (EP): Switch to an endocrine induction medium. This often involves DMEM with 1% B27, 10 µM ALK5 inhibitor II (to reduce TGF-β signaling), 10 µM T3 (Thyroid Hormone), and 100 nM Gamma-secretase inhibitor XX (to modulate Notch signaling and promote endocrine differentiation).

- Day 18+ (Endocrine Maturation): For final maturation into hormone-expressing cells, use a basal medium like CMRL with 1% B27, 10 µM T3, and 10 µM ALK5 inhibitor II. This stage can be extended for several weeks to promote functional maturation, marked by the acquisition of MAFA expression in INS+/NKX6.1+ β-cells [21].

3D Culture of Mouse Embryonic Pancreas Progenitors

This protocol summarizes a method for the extensive expansion and self-organization of dispersed mouse embryonic pancreatic progenitor cells within a 3D Matrigel scaffold [24].

Key Steps:

- Tissue Isolation: Dissect the dorsal pancreatic bud from E10.5-E11.5 mouse embryos in cold PBS or DMEM.

- Tissue Dissociation: Mechanically dissociate and incubate the tissue with collagenase to obtain a single-cell suspension.

- 3D Embedding: Resuspend the dispersed cells in liquid Matrigel and plate droplets onto a pre-warmed culture dish to polymerize.

- Culture: Overlay the Matrigel droplets with a defined medium. The composition of the medium can be manipulated:

- For progenitor expansion, use a medium favoring proliferation (e.g., with FGF10).

- For differentiated organoids, use a medium containing serum, which supports differentiation into acinar, ductal, and endocrine cells, and spontaneous self-organization into branched structures [24].

Signaling Pathways and Logical Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the key signaling pathways and experimental workflows for recapitulating pancreatic development in vitro.

Diagram 1: Core Signaling Pathways in Pancreatic Progenitor Specification

Core Signaling Pathways in Pancreatic Progenitor Specification

Diagram 2: Organoid Differentiation Workflow

Organoid Differentiation Workflow

Diagram 3: PI3K-AKT-FoxO1 Pathway in Beta Cells

PI3K-AKT-FoxO1 Pathway in Beta Cells

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for In Vitro Pancreas Differentiation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Application Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Activin A | TGF-β family ligand; induces definitive endoderm differentiation. | Used in high concentration (100 ng/mL) in the first stage to direct hPSCs to SOX17+/FOXA2+ endoderm [21]. |

| CHIR99021 | GSK-3β inhibitor; activates WNT signaling. | Paired with Activin A during definitive endoderm induction to enhance efficiency [21]. |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | Morphogen; patterns the posterior foregut and specifies pancreatic identity. | Critical component at the posterior foregut to pancreatic progenitor transition (e.g., 0.5 µM) [21]. |

| LDN193189 | Small molecule inhibitor of BMP signaling. | Used during posterior foregut and pancreatic specification to block non-pancreatic fates [21]. |

| Sant1 | Small molecule antagonist of Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling. | Applied during pancreatic specification to inhibit SHH, which is necessary for pancreatic commitment [21]. |

| FGF7 (KGF) | Growth factor; promotes growth and patterning of gut endoderm. | Used during primitive gut tube and pancreatic progenitor stages to support progenitor growth [21]. |

| Matrigel | Basement membrane extract providing a 3D scaffold. | Used as an overlay to create a 3D epithelial niche that supports morphogenesis and polarity [24] [21]. |

| Y-27632 (ROCKi) | ROCK inhibitor; reduces apoptosis in dissociating cells. | Often added during passaging or the transition to 3D culture to improve cell survival [21]. |

| ALK5 Inhibitor II | Small molecule inhibitor of TGF-β receptor ALK5. | Used during endocrine differentiation to reduce TGF-β signaling, which can inhibit endocrine fate [21]. |

| Gamma-Secretase Inhibitor | Inhibits Notch signaling, promoting endocrine differentiation. | Applied to endocrine progenitor stage to derepress NEUROG3 and allow endocrine lineage commitment [21]. |

Table 5: Comparison of 3D Culture Systems for Pancreatic Cells

| Characteristic | Matrigel-Embedded Organoids | Alginate-Encapsulation | Scaffold-Free Spheroids |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Cells embedded in a complex 3D ECM scaffold [24] [21] | Single cells or clusters encapsulated in a semi-permeable hydrogel [25] | Cells self-aggregate in non-adherent conditions [25] |

| Key Advantages | Supports complex morphogenesis, cell polarity, and self-organization; recapitulates tissue architecture [24] | Immunoisolation potential for transplantation; tunable mechanical properties [25] | Simplicity; strong cell-cell contacts; no foreign material [25] |

| Reported Outcomes | Generation of multipotent progenitors, endocrine cells, and branched structures [24] [21] | Enhanced GSIS and PDX1 expression via PI3K/AKT/FoxO1 pathway vs. 2D [25] | Improved GSIS and viability over 2D; but may be inferior to alginate in some functional measures [25] |

| Primary Application | Modeling development and disease; studying morphogenesis [21] | Cell transplantation and therapy [25] | Drug screening; basic islet function studies [25] |

Key Transcription Factors and Signaling Pathways in Beta Cell Differentiation (PDX1, NGN3, NKX6.1, MAFA)

The differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into functional, glucose-responsive beta cells represents a transformative strategy for disease modeling, drug screening, and cell replacement therapy for diabetes [3] [6]. Central to this process are key transcription factors that orchestrate pancreatic development and beta cell maturation. Among these, PDX1 (Pancreas/Duodenum Homeobox Protein 1), NEUROG3 (Neurogenin-3, also abbreviated as NGN3), NKX6.1, and MAFA (Musculoaponeurotic Fibrosarcoma Oncogene Homolog A) form a critical regulatory network guiding cellular identity and function [26] [27]. This application note details the roles of these factors within the context of iPSC differentiation, provides quantitative data on their expression and function, and outlines detailed experimental protocols for their manipulation and assessment. The content is framed for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to implement or optimize beta cell differentiation protocols, with a focus on generating functionally mature insulin-producing cells.

Roles of Key Transcription Factors

The differentiation of iPSCs into beta cells follows a developmental pathway mimicking in vivo pancreatic organogenesis, requiring precisely timed expression of specific transcription factors.

Table 1: Key Transcription Factors in Beta Cell Differentiation

| Transcription Factor | Primary Role in Development | Expression Timing | Target Genes/Pathways | Human Disease Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDX1 | Pancreatic progenitor formation, beta cell maturation and function [26] [27] | Early: Human gestational week 4; sustained in mature beta cells [27] | Insulin, MAFA, Glucokinase [26] | MODY4, Pancreatic Agenesis [26] [27] |

| NEUROG3 (NGN3) | Endocrine progenitor specification, master regulator of islet cell fate [26] | Mid-gestation; peaks and declines before hormone expression [26] | NEUROD1, INSM1 [26] | Permanent Neonatal Diabetes [26] |

| NKX6.1 | Beta cell specification and maturation; often co-expressed with PDX1 [28] | Following pancreatic specification in PDX1+ progenitors [28] | Unknown direct targets, essential for functional maturation [28] | Associated with T2D risk [27] |

| MAFA | Beta cell terminal maturation and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) [26] | Late gestation; increases after birth [26] | Insulin, Genes for glucose sensing and exocytosis [26] | Polymorphisms linked to T1D and T2D [26] |

The following diagram illustrates the temporal sequence and functional relationships of these key transcription factors during the differentiation process:

Figure 1: Simplified workflow of iPSC differentiation into beta cells, showing key transitional stages and the corresponding core transcription factors.

Functional Interactions and Chromatin Regulation

The transcription factors PDX1, NEUROG3, and MAFA do not operate in isolation but form a tightly regulated network. PDX1 is critical for initiating the pancreatic program and, in mature beta cells, binds to and activates the insulin gene [26]. It also regulates the expression of NEUROG3, thereby controlling the emergence of the endocrine lineage [26]. NEUROG3 acts as a pro-endocrine "master regulator" and is essential for the differentiation of all islet cell types, including beta cells [26]. Finally, MAFA is a key integrator of beta cell maturity, exclusively expressed in beta cells and vital for activating insulin gene expression in response to glucose [26].

Successful differentiation requires not only the presence of these factors but also profound remodeling of the chromatin landscape. Studies have shown that the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, particularly its BRG1 and BRM subunits, is essential for proper endocrine cell expansion and differentiation. Loss of SWI/SNF function in endocrine progenitors leads to reduced expression of Mafa, Ins1, and Ins2, and compromises beta cell differentiation capacity [29]. Furthermore, the removal of Polycomb-mediated repression is a key mechanism for activating stage-specific genes during pancreatic differentiation of human ESCs. Inefficient removal of this repression in in vitro-differentiated endocrine cells is associated with their functional immaturity [30].

Experimental Protocols for Beta Cell Differentiation and Analysis

This section provides detailed methodologies for differentiating iPSCs into beta-like cells and for assessing the resulting cells' function and molecular profile.

Protocol 1: Forward Programming of hiPSCs Using Inducible Transcription Factors

This protocol, adapted from a 2024 study, uses inducible lentiviral vectors to drive the expression of NGN3, PDX1, and MAFA (NPM factors) to accelerate beta cell differentiation [28].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Inducible Lentiviral System: A two-vector system is used. The first vector, pLentiEF1a-rtTABsdR, provides a blasticidin-resistant transactivator. The second, pLentiTRE-NPMHygR, contains the NGN3, PDX1, and MAFA genes under a doxycycline-inducible promoter and confers hygromycin resistance [28].

- Cell Line: Human iPSCs.

- Culture Medium: Pancreatic progenitor induction medium, typically containing factors like Activin A, FGF, and Retinoic Acid to support pancreatic lineage commitment.

- Induction Agent: Doxycycline (1-2 µg/mL) to activate transgene expression.

Procedure:

- Lentiviral Transduction: Sequentially transduce hiPSCs with the EF1a-rtTABsdR lentivirus and then the TRE-NPMHygR lentivirus.

- Selection: Select successfully transduced cells using blasticidin (1.0 µg/mL for 5 days) and hygromycin B (25.0 µg/mL for 6 days). The resulting cell line is termed rtTA-NPM hiPSCs.

- Differentiation Induction: Seed rtTA-NPM hiPSCs and culture them in pancreatic progenitor induction medium supplemented with doxycycline for 5-10 days to induce transgene expression and initiate differentiation.

- 3D Aggregation (Optional): For further maturation, dissociate the cells and aggregate them into 3D spheroids using platforms like AggreWell plates or rotating suspension cultures.

- Analysis: Assess the expression of key markers (PDX1, NKX6.1, MAFA, Insulin) via qPCR and immunofluorescence. Evaluate functionality using Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion (GSIS) assays.

Expected Outcomes: Cells should show upregulated expression of pancreatic and beta cell markers within five days of induction. In vitro GSIS response may be limited, often resembling a fetal, rather than adult, functional profile [28].

Protocol 2: Directed Differentiation in 3D Culture

This protocol is based on a widely used, multi-stage directed differentiation approach, with a focus on generating homogenous 3D islet-like aggregates to enhance maturation [6].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Basal Media: DMEM, F12, or other specialized base media.

- Key Signaling Molecules: A sequence of growth factors and small molecules, including Activin A (for definitive endoderm), KGF (for foregut/pancreatic progenitors), Retinoic Acid (for pancreatic specification), and TPB (a PKC activator for endocrine maturation).

- 3D Culture Platform: Static microwells (e.g., AggreWell400) or rotating suspension bioreactors.

Procedure:

- Staged Differentiation (Stages 1-4): Differentiate iPSCs in a 2D monolayer through sequential stages to generate definitive endoderm, primitive gut tube, and posterior foregut/PDX1+ pancreatic progenitor cells.

- 3D Aggregation (Stage 5): At the pancreatic progenitor stage, dissociate cells and transfer to a 3D culture system. Aggregation in static microwells at a density of 750 cells/microwell is recommended to generate uniform, small-sized aggregates and prevent central necrosis.

- Endocrine Induction and Maturation (Stages 6-7): Continue culture in media containing endocrine induction and maturation factors (e.g., TPB, Aldosterone, Thyroid hormone) for several weeks.

- In Vivo Maturation (Optional): Transplant aggregates under the kidney capsule of immunodeficient mice (e.g., NOD-SCID). Grafts typically acquire more mature functional characteristics within 2-3 months post-transplantation [6].

Expected Outcomes: The resulting 3D aggregates should contain insulin-positive cells with a yield comparable to human islets. While they may show only a slight glucose response in vitro, they become highly glucose-responsive and can maintain normoglycemia in diabetic mice after transplantation [6].

Table 2: Quantitative Functional Comparison of Beta Cells from Different Protocols

| Characteristic | Forward Programming (2D) [28] | Directed 3D Differentiation (In Vitro) [6] | Directed 3D + In Vivo Maturation [6] | Primary Human Islets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timeline | 10-14 days | ~4-6 weeks | 3-4 months (incl. transplant) | N/A |

| Insulin+ Cells | Low (marker expression) | High (comparable to human islets) | High | Benchmark |

| In Vitro GSIS | Limited, fetal-like | Slight increase | Not Tested (graft removed) | Strong response |

| In Vivo Function | Not Tested | Not Applicable | Restores normoglycemia in mice | Benchmark |

| Key Markers | NGN3, PDX1, MAFA (mRNA) | PDX1, NKX6.1, MAFA, Insulin (protein) | PDX1, NKX6.1, MAFA, Insulin (protein) | All mature markers |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table compiles key reagents and tools critical for research in this field, as derived from the cited protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Beta Cell Differentiation Studies

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factor Tools | Inducible lentiviral vectors for NGN3, PDX1, MAFA [28]; CRISPR/dCas9-P300core for epigenetic activation [31] | Driving beta cell fate through overexpression or targeted gene activation. |

| Cell Culture Media & Supplements | Activin A, FGF, Retinoic Acid, KGF, TPB, Aldosterone, Thyroid Hormone (T3) [6] [28] | Mimicking developmental signaling to guide stepwise differentiation. |

| 3D Culture Systems | AggreWell plates (static microwells) [6]; Rotating suspension bioreactors [6] | Promoting cell-cell interactions and organoid formation for enhanced maturation. |

| Key Antibodies for Characterization | Anti-PDX1, Anti-NKX6.1, Anti-NEUROG3, Anti-MAFA, Anti-Insulin, Anti-C-Peptide [27] [6] | Confirming protein expression and identity of progenitors and mature beta cells via immunofluorescence. |

| Functional Assay Kits | Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion (GSIS) Assay; ELISA for Human Insulin/C-Peptide; Calcium Flux Assay Kits [6] | Quantifying dynamic insulin release and beta cell functional maturity. |

The coordinated actions of PDX1, NEUROG3, NKX6.1, and MAFA are indispensable for the successful generation of functional beta cells from iPSCs. While current protocols can produce insulin-producing cells, achieving a fully mature adult phenotype remains a challenge. The experimental approaches detailed here, from forward programming to sophisticated 3D differentiation, provide a robust foundation for researchers. Future work must focus on refining the temporal control of these transcription factors and optimizing the epigenetic landscape to generate beta cells that are functionally indistinguishable from their native human counterparts, thereby unlocking their full potential for therapeutic applications.

The Definitive Endoderm as a Critical First Step

The differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) into insulin-producing beta cells represents a transformative strategy for cell therapy in diabetes. Within this multi-stage process, the precise specification of definitive endoderm (DE) is the indispensable foundational step, forming the embryonic germ layer from which the pancreas, liver, lungs, and intestines develop [32] [33]. This stage establishes the cellular context for all subsequent lineage decisions, and its efficiency directly dictates the yield and purity of the final beta cell product. Current research focuses on refining DE induction protocols to achieve high efficiency and reproducibility using both growth factor-based and novel chemically-defined systems [33] [34]. This application note details the critical methodologies and quality control measures for successful DE specification, framed within the broader objective of generating functional, transplantable beta cells for diabetes treatment.

Key Signaling Pathways in DE Specification

The in vitro specification of DE from hiPSCs aims to recapitulate the embryonic gastrulation events governed by key signaling pathways. The Nodal/Activin A signaling pathway, a branch of the Transforming Growth Factor-Beta (TGF-β) family, is the primary driver of endodermal fate [35]. Concurrent activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is crucial as it enhances the expression of key transcription factors and potentiates the response to Nodal/Activin signaling [36]. Recent studies have highlighted the role of GRP94, an endoplasmic reticulum chaperone, in regulating the WNT/β-catenin pathway during this process. GRP94 depletion has been shown to hinder DE specification by reducing WNT signaling activation and promoting ER stress-induced cell death [36]. Furthermore, a novel chemically defined system has identified TEAD3 as a key regulator, working alongside pioneers like GATA4 to reconfigure chromatin architecture, making it accessible for DE-associated transcription factors such as SOX17 and FOXA2 [34]. The following diagram illustrates the logical progression of signaling events and transcriptional activation during this critical phase.

Comparative Analysis of DE Induction Methods

Two primary methodological approaches are widely used for DE induction: the Growth Factor (GF) Protocol and the Small Molecule (SM) Protocol [33]. The GF approach utilizes recombinant proteins, primarily Activin A and Wnt3a, to directly activate the key signaling pathways. In contrast, the SM approach employs a GSK-3 inhibitor, CHIR99021, to modulate the Wnt pathway and endogenous Nodal gene expression as a single agent. A comparative study demonstrated that both protocols produce DE with similar high efficiency, morphological phenotype, and expression of hallmark markers (SOX17, FOXA2, CXCR4) [33]. However, divergence in subsequent lineage specification, such as hepatic commitment, has been observed, underscoring the importance of selecting an induction method aligned with the target endodermal derivative [33]. More recently, a fully chemically defined, growth factor-free system (termed "4C") has been developed, enabling highly efficient DE specification without recombinant proteins, thereby enhancing scalability and reducing costs for clinical translation [34].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Definitive Endoderm Induction Protocols

| Protocol Feature | Growth Factor (GF) Protocol | Small Molecule (SM) Protocol | Chemically Defined (4C) System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Inducing Factors | Activin A (100 ng/mL), Wnt3a (25 ng/mL) [33] [35] | CHIR99021 (3-6 µM) [33] [34] | Combination of 4 small molecules [34] |

| Base Media | RPMI 1640 [33] [35] | RPMI 1640 [33] | Chemically defined [34] |

| Duration | 3 days [33] [35] | 3-4 days [33] [34] | Not specified |

| Key Markers Post-Differentiation | SOX17, FOXA2, CXCR4 [33] | SOX17, FOXA2, CXCR4 [33] | SOX17, FOXA2 [34] |

| Reported Efficiency | High (>80% SOX17+) [33] [35] | High (>80% SOX17+) [33] | Highly efficient [34] |

| Primary Advantage | Established, direct pathway activation | Cost-effective, simplified formulation [33] [34] | Growth factor-free, scalable for manufacture [34] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for DE Induction

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for DE Differentiation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Product / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Human iPSCs | Starting cell population for differentiation | Patient-specific or banked iPSC lines [33] |

| Matrigel / Vitronectin | Extracellular matrix coating for cell adhesion | L7 hPSC Matrix [37] or Vitronectin (Qk120) [35] |

| Activin A | TGF-β family ligand; primary inducer of DE fate | Recombinant Human Activin A [33] [35] |

| CHIR99021 | GSK-3 inhibitor; activates Wnt signaling | Stemolecule CHIR99021 [33] [35] |

| BMP4 | Bone Morphogenetic Protein; aids initial specification | Recombinant Human BMP4 [35] |

| FGF-2 (bFGF) | Fibroblast Growth Factor; supports DE specification | Qkine FGF2-G3 (Qk053) [35] |

| LY294002 | PI3K inhibitor; enhances DE purity | LY294002 [35] |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Prevents anoikis in single-cell passaging | Y-27632 [38] [35] [37] |

| Anti-SOX17 Antibody | Immunocytochemistry for DE marker | R&D systems, AF1924 [37] |

| Anti-FOXA2 Antibody | Immunocytochemistry for DE marker | Abcam, ab108422 [37] |

Step-by-Step Workflow

The following protocol is adapted from established methodologies [33] [35] [37] and is designed for a 6-well plate format.

Day 0: Seeding hiPSCs

- Preparation: Coat culture plates with Matrigel (or equivalent like vitronectin) according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Cell Dissociation: Detach hiPSCs using Accutase or EDTA to create a single-cell suspension.

- Seeding: Seed cells at a density of 0.25 - 1.0 x 10^6 cells per well in complete hiPSC maintenance medium (e.g., mTeSR1 or E8) supplemented with 10 µM Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) to enhance survival [35] [37].

- Incubation: Place cells in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO₂.

Day 1: Initiating Differentiation

- Media Change: Aspirate the maintenance medium.

- Induction Medium: Add DE 1 medium. For a GF protocol, this typically consists of RPMI 1640 base supplemented with 100 ng/mL Activin A, 25 ng/mL Wnt3a (optional for Day 1 only), 80 ng/mL FGF-2, 10 ng/mL BMP4, and 10 µM LY294002 [35]. For an SM protocol, use RPMI/B27 with 6 µM CHIR99021 [33].

Day 2: Continuing Induction

Day 3: Final Day of Induction

Day 4: Analysis and Harvest

- Assessment: Differentiated DE cells can be harvested for downstream differentiation or analyzed for quality control on Day 4 or 5.

- Quality Control (QC): Fix a representative sample of cells for immunocytochemical analysis of DE markers SOX17 and FOXA2.

Quality Control and Validation

Rigorous quality control is essential to confirm successful DE specification before proceeding to subsequent stages like pancreatic progenitor induction. The primary method for validation is the assessment of protein and gene expression for hallmark DE markers.

- Immunocytochemistry (ICC): This is the gold standard for visualizing DE markers. A successful differentiation will show high co-expression of the transcription factors SOX17 and FOXA2 in the cell nuclei, typically exceeding 80% of the cell population [33] [35] [37]. The surface marker CXCR4 (CD184) is also commonly used in conjunction with intracellular markers for flow cytometry analysis [38] [33].

- Flow Cytometry: This method allows for the quantitative assessment of differentiation efficiency. Cells can be stained for surface CXCR4 and intracellular SOX17/FOXA2. High-quality DE populations should demonstrate a high percentage of double-positive cells (e.g., SOX17+/FOXA2+ or CXCR4+/SOX17+).

- qPCR: Gene expression analysis can confirm the upregulation of key DE-associated genes (SOX17, FOXA2, CXCR4, GATA4) and the concomitant downregulation of pluripotency markers (OCT4, NANOG).

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- Low Differentiation Efficiency: If SOX17/FOXA2 expression is low (<70%), verify the activity and concentration of the primary inducing factors (Activin A, CHIR99021). Ensure consistent and timely media changes. Check the pluripotency and health of the starting hiPSC population.

- High Cell Death: This is common during the first 24 hours of differentiation. Ensure the use of a ROCK inhibitor during the initial cell seeding. Confirm that the cell seeding density is optimal, as both overly confluent and sparse cultures can lead to poor outcomes. Mathematical modeling suggests plating populations closer to 300,000 cells per well can optimize yield efficiency [38].

- Batch-to-Batch Variability: To minimize variability, use high-quality, animal origin-free recombinant proteins and small molecules. Standardize the passage number and maintenance conditions of the parent hiPSC line. Consider adopting a completely chemically defined system like the 4C protocol to reduce reliance on recombinant proteins [34].

- Scale-Up Considerations: For manufacturing scales, transitioning from planar culture to suspension bioreactors (e.g., Vertical Wheel bioreactors) can enable uniform, large-scale production of DE with minimal variability and reduced cell loss [39].

Protocols and Applications: From Bench to Bedside

Diabetes mellitus (DM), a metabolic disorder characterized by chronic hyperglycemia, affects millions of adults worldwide, with projections estimating 700 million cases by 2045 [32] [17]. Type 1 diabetes (T1D) results from autoimmune destruction of pancreatic β-cells, leading to absolute insulin deficiency [32]. Current treatment paradigms, primarily lifelong insulin injections, face significant limitations in mimicking physiological insulin secretion kinetics and preventing secondary complications [17]. Allogeneic pancreatic islet transplantation, particularly under the Edmonton protocol, has demonstrated therapeutic success but remains constrained by donor scarcity and risks of immunosuppression [32] [17].

Differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into insulin-producing cells (IPCs) represents a promising alternative that could overcome these limitations [32]. Patient-specific iPSCs, obtained via reprogramming of somatic cells, offer the potential for autologous transplantation while avoiding immune rejection [32]. Contemporary differentiation protocols emulate natural pancreatic embryogenesis through sophisticated multi-stage approaches, activating specific signaling pathways with precise temporal control [32] [4]. This protocol analysis examines the stepwise differentiation of human iPSCs into functional pancreatic β-cells, detailing the morphological changes, key signaling pathways, and quality control checkpoints at each developmental stage.

Stage-by-Stage Differentiation Protocol

The differentiation of iPSCs into functional pancreatic β-cells recapitulates in vivo pancreatic development, progressing through definitive endoderm, primitive gut tube, pancreatic progenitor, endocrine progenitor, and finally mature β-cell stages [40]. Each transition is controlled by specific signaling molecules and growth factors that direct cellular fate toward the pancreatic lineage.

Detailed Stage Analysis and Experimental Methodologies

Stage 1: Definitive Endoderm Induction (Days 0-3)

The initial differentiation stage directs pluripotent cells toward definitive endoderm, the embryonic germ layer that gives rise to pancreatic tissue. This process mimics gastrulation events, where epiblast cells undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition to form primitive streak and subsequently definitive endoderm.

Key Signaling Pathways: TGF-β/Nodal/Activin A signaling combined with WNT pathway activation serves as the primary inducer of definitive endoderm [40]. High concentrations of Activin A (100 ng/mL) activate Nodal-like signaling, while WNT3A or GSK3-β inhibitors (CHIR99021, 3-6 μM) enhance primitive streak formation [40]. PI3K inhibitors (LY294002 or Wortmannin) and JNK-JUN signaling inhibition improve definitive endoderm yield by blocking alternative differentiation paths [40].

Experimental Protocol:

- Culture Preparation: Plate human iPSCs at high density (∼85% confluence) on Matrigel-coated plates in mTeSR1 medium 24 hours before differentiation.

- Day 0-1 Medium: RPMI 1640 supplemented with Activin A (100 ng/mL), CHIR99021 (3 μM), and 0.2% FBS. Incubate for 24 hours.

- Day 1-2 Medium: Replace with RPMI 1640 containing Activin A (100 ng/mL) with 0.2% FBS.

- Day 2-3 Medium: Replace with RPMI 1640 containing Activin A (100 ng/mL) with 2% FBS.

- Quality Control: Assess efficiency via flow cytometry for CXCR4, SOX17, and FOXA2. Target >90% positive cells [40]. CD177-positive subpopulations show enhanced pancreatic commitment [40].

Stage 2: Primitive Gut Tube Formation (Days 3-5)

Following definitive endoderm specification, cells progress toward a primitive gut tube phenotype, with particular emphasis on posterior foregut development where pancreatic buds emerge.

Key Signaling Pathways: Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling, particularly through FGF10 (50 ng/mL) or keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), promotes gut tube formation and inhibits hepatic differentiation [40]. BMP signaling modulation helps pattern the gut tube along the anterior-posterior axis.

Experimental Protocol:

- Days 3-5 Medium: DMEM supplemented with FGF10 (50 ng/mL) or KGF (50 ng/mL), with 1% B27 supplement.

- Culture Conditions: Maintain cells in adherent culture with daily medium changes.

- Quality Control: Verify emergence of gut tube morphology and expression of HNF1β, HNF4α, and additional endodermal markers.

Stage 3: Pancreatic Progenitor Specification (Days 5-12)

This critical stage establishes pancreatic commitment with the emergence of PDX1-positive progenitor cells that possess both endocrine and exocrine potential.

Key Signaling Pathways: Retinoic acid (RA, 0.5-2 μM) synergizes with FGF10 (50 ng/mL) to promote pancreatic specification [40]. Sonic hedgehog (SHH) inhibition (using cyclopamine, 0.25-1 μM) enhances dorsal pancreatic fate. BMP signaling requires careful modulation, with initial inhibition followed by low-level activation.

Experimental Protocol:

- Days 5-8 Medium: DMEM with FGF10 (50 ng/mL), RA (0.5-2 μM), cyclopamine (0.25-1 μM), and Noggin (50 ng/mL) for BMP inhibition.

- Days 8-12 Medium: Transition to DMEM with FGF10 (50 ng/mL), RA (0.5-2 μM), and Noggin (50 ng/mL), gradually reducing FGF10 concentration.

- Quality Control: Assess PDX1 and NKX6.1 co-expression via immunostaining. Target >80% PDX1+ cells with substantial NKX6.1+ population [4]. PDX1+/NKX6.1+ progenitors demonstrate strong β-cell commitment potential.

Stage 4: Endocrine Progenitor Induction (Days 12-18)

Pancreatic progenitors transition to endocrine-committed progenitors under Notch signaling inhibition, enabling endocrine differentiation.

Key Signaling Pathways: Notch pathway inhibition (using DAPT, 10 μM) initiates endocrine differentiation by lifting lateral inhibition [4]. BMP signaling inhibition continues during early endocrine specification. Thyroid hormone (T3, 1 nM) promotes endocrine maturation.

Experimental Protocol:

- Days 12-15 Medium: DMEM with DAPT (10 μM), Noggin (50 ng/mL), and T3 (1 nM).

- Days 15-18 Medium: DMEM with ALK5 inhibitor II (10 μM), T3 (1 nM), and γ-secretase inhibitor (10 μM).

- Quality Control: Monitor NGN3 (NEUROG3) expression as a marker of endocrine commitment [4]. Assess emergence of endocrine hormones (insulin, glucagon) via immunocytochemistry.

Stage 5: β-Cell Maturation (Days 18-30+)

The final stage focuses on functional maturation of immature β-cells into glucose-responsive endocrine cells capable of dynamic insulin secretion.

Key Signaling Pathways: TGF-β signaling inhibition (ALK5i, 10 μM) promotes endocrine differentiation [4]. Thyroid hormone (T3) supports metabolic maturation. Cell aggregation into islet-like clusters enhances maturation through cell-cell contact and 3D architecture.

Experimental Protocol:

- Days 18-21 Medium: CMRL medium with ALK5 inhibitor II (10 μM), T3 (1 nM), and γ-secretase inhibitor (10 μM).

- Days 21-30+ Medium: Maturation medium containing T3 (1 nM), R428 (1 μM), N-acetyl cysteine (10 μM), and 10% FBS.

- 3D Culture: Detach cells and culture in suspension to form islet-like aggregates using low-adhesion plates.

- Quality Control: Evaluate insulin content (≥0.5-1 μg/μg DNA), glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) with stimulation index ≥2, and expression of mature β-cell markers (MAFA, UCN3) [4].

Key Transcription Factor Expression Profile

The progression through differentiation stages correlates with specific transcription factor expression patterns that define cell identity and developmental progression.

Table 1: Key Transcription Factors in Pancreatic β-Cell Differentiation

| Developmental Stage | Key Transcription Factors | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG | Maintain pluripotent state |

| Definitive Endoderm | SOX17, FOXA2, CXCR4 | Endoderm specification and migration |

| Pancreatic Progenitors | PDX1, PTF1A, SOX9 | Pancreatic commitment and proliferation |

| Endocrine Progenitors | NEUROG3, NEUROD1, PAX4 | Endocrine lineage specification |

| Immature β-Cells | NKX6.1, NKX2.2, PAX6 | β-cell identity and differentiation |

| Mature β-Cells | MAFA, PDX1, NEUROD1, UCN3 | Functional maturation and glucose responsiveness |

PDX1 represents the cornerstone of pancreatic organogenesis, essential for both initial pancreatic specification and mature β-cell function [4]. NEUROG3 serves as the master regulator of endocrine commitment, activating downstream transcription factors including NEUROD1 and NKX6.1 [4]. NEUROD1 maintains the mature phenotype of pancreatic β-cells and regulates insulin gene expression [4]. NKX6.1 plays an indispensable role during both early and late stages of pancreatic development, with sustained expression critical for functional β-cell identity [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful differentiation requires precise combination of signaling molecules, growth factors, and culture supplements at specific developmental timepoints.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC to β-Cell Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Typical Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|