Embryonic vs Adult Stem Cells: A Comparative Analysis of Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and adult stem cells (ASCs) for researchers and drug development professionals.

Embryonic vs Adult Stem Cells: A Comparative Analysis of Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and adult stem cells (ASCs) for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational biology, distinct properties, and ethical considerations of each cell type. The scope extends to current methodological applications in regenerative medicine and disease modeling, alongside critical troubleshooting of optimization challenges such as tumorigenicity, immunogenicity, and manufacturing. The analysis validates therapeutic potential through clinical trial data and direct comparative assessment of efficacy, safety, and regulatory pathways, offering a strategic framework for selecting the appropriate stem cell type for specific therapeutic intents.

Understanding Stem Cell Biology: From Pluripotency to Tissue-Specific Function

Stem cells are fundamentally characterized by their dual capacities for self-renewal and differentiation [1]. The developmental potential of a stem cell—its "potency"—is the primary feature distinguishing its type and defining its therapeutic application. Pluripotency and multipotency represent two critical hierarchical levels within this spectrum. Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs), derived from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst, represent the gold standard for pluripotency, possessing the ability to differentiate into all cells of the three embryonic germ layers [2] [3] [4]. In contrast, Adult Stem Cells (ASCs), also known as somatic stem cells, are typically multipotent, with a more restricted differentiation capacity limited to the cell types of their tissue of origin [2] [1]. This guide provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of these cell types, framing their characteristics within the context of therapeutic development for researchers and drug development professionals.

Defining Pluripotency and Multipotency: A Hierarchical Comparison

Molecular and Functional Definitions

The distinction between pluripotency and multipotency is governed by distinct molecular networks and epigenetic landscapes, which directly translate to differing functional capabilities in research and therapy.

Core Pluripotency Network in ESCs: Pluripotency is maintained by a core transcriptional network. Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog form an autoregulatory loop, binding to each other's promoters to activate and sustain their own transcription, thereby preserving the undifferentiated state [3]. This network is active in the naïve pluripotent state of the pre-implantation embryo and can transition to a primed pluripotency state in the post-implantation epiblast, a distinction marked by changes in gene expression, metabolism, and signaling pathway dependence [3]. For instance, naïve mouse ESCs depend on Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) and Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP), whereas primed human ESCs and EpiSCs rely on Activin A/Nodal and Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 (FGF2) signaling [3].

Defining Multipotency in ASCs: Multipotent ASCs, such as Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), do not express the core pluripotency factors. Instead, they are identified by a specific set of surface markers (e.g., CD73, CD90, CD105 for MSCs) and are characterized by their capacity for self-renewal and differentiation into a limited range of lineages relevant to their tissue of origin [2] [5]. For example, adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) can differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes [5] but lack the capacity to form entire tissues derived from all three germ layers.

Table 1: Hierarchical Classification of Stem Cell Potency

| Potency Level | Defining Characteristic | Prototypical Cell Types | Key Molecular Regulators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency | Can differentiate into all derivatives of the three embryonic germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm). | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs), Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, Autocrine FGF signaling, specific epigenetic landscapes [3] [4]. |

| Multipotency | Can differentiate into multiple cell types, but restricted to a specific lineage or tissue of origin. | Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) including Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs), Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs). | Tissue-specific transcription factors (e.g., GATA factors in HSCs); surface markers like CD73, CD90, CD105 for MSCs [2] [5]. |

Comparative Analysis: ESCs vs. ASCs

Origin, Differentiation Potential, and Key Markers

The fundamental differences between ESCs and ASCs originate from their distinct biological niches and physiological roles.

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of ESCs and ASCs

| Characteristic | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Inner Cell Mass (ICM) of the blastocyst [3] [4]. | Various adult tissues (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue) [2] [5]. |

| Potency | Pluripotent [1]. | Multipotent (typically) [1]. |

| In Vivo Role | To form all tissues of the developing embryo. | Tissue maintenance, repair, and regeneration in the adult organism [2]. |

| Key Molecular Markers | Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, SSEA-3, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81 [3] [4]. | Varies by type; MSCs: CD73, CD90, CD105; lack Oct4/Nanog [2] [5]. |

| Self-Renewal Capacity | 理论上无限 in vitro [3]. | Limited in vitro, can enter senescence [2]. |

| Genetic Stability | Generally stable but can accumulate aberrations over long-term culture [6]. | Can be affected by donor age and health status (e.g., obesity reprograms ASC transcriptome) [7]. |

| Therapeutic Mechanisms | Primarily through direct differentiation into target cells for replacement [1]. | Primarily through paracrine signaling (secretion of growth factors, cytokines, exosomes), immunomodulation, and anti-apoptotic effects [5] [1]. |

| Major Advantages | Unlimited differentiation potential; model for early development; "gold standard" for pluripotency [8] [4]. | No ethical controversies; autologous transplantation possible; lower risk of teratoma formation; innate homing to injury sites [9] [5] [1]. |

| Major Challenges | Ethical controversies; risk of immune rejection; tumorigenicity (teratomas); complex differentiation protocols [9] [1]. | Limited differentiation potential; variability based on source and donor; lower expandability; potential functional impairment in disease [7] [1]. |

Experimental Data and Functional Evidence

Quantitative data from differentiation experiments and functional assays underscore the practical implications of these potency differences.

Differentiation Efficiency: A landmark study comparing the differentiation propensity of 20 hESC and 12 hiPSC lines found that, despite overall similarity, hiPSCs exhibited increased variation in the yield of neural progeny. The study developed a "lineage scorecard" based on the expression of 500 lineage-related genes, which highly correlated (Pearson's r = 0.87) with the observed efficiency of motor neuron differentiation [4]. This highlights that while pluripotent cells have broad potential, the efficiency of generating specific lineages can be variable and cell-line dependent.

Transcriptomic and Epigenetic Differences: Obesity serves as a model for how the ASC microenvironment impacts function. RNA sequencing of adipose-derived MSCs from lean (BMI <25) versus obese (BMI ≥35) donors revealed significant transcriptional reprogramming. In obese ASCs, 738 genes were significantly upregulated and 767 downregulated, with pathways related to extracellular matrix (ECM) organization, TGF-β signaling, and cell adhesion molecules being particularly affected [7]. This demonstrates that ASC function is not static but can be compromised by disease states, a crucial consideration for therapeutic development.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Potency

In Vitro Pluripotency Assay for ESCs

The standard in vitro method to confirm ESC pluripotency is the Embryoid Body (EB) Formation Assay.

- Culture and Detachment: Human ESCs are maintained on a feeder layer of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or in a feeder-free system on Matrigel or similar substrate. Colonies are treated with collagenase IV or dispase to detach them as small clumps [4].

- EB Formation: The clumps are transferred to non-adherent Petri dishes or U-bottom low-attachment plates in ESC medium without pluripotency factors (e.g., without bFGF). Under these conditions, cells aggregate to form 3D structures called embryoid bodies.

- Spontaneous Differentiation: EBs are cultured for 7-21 days, during which they spontaneously differentiate into cells representing all three germ layers.

- Analysis:

- Immunocytochemistry: EBs are plated on adhesive slides, fixed, and stained for germ layer-specific markers: β-III Tubulin (ectoderm), α-Smooth Muscle Actin (α-SMA) (mesoderm), and Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP) (endoderm).

- RT-qPCR: RNA is extracted from EBs and analyzed for the downregulation of pluripotency genes (OCT4, NANOG) and upregulation of differentiation markers from all three germ layers.

In Vitro Trilineage Differentiation Assay for ASCs (e.g., MSCs)

The gold standard for confirming the multipotency of MSCs is the Trilineage Differentiation Assay.

- Cell Source and Seeding: MSCs are isolated from tissue (e.g., adipose tissue via enzymatic digestion with collagenase to obtain the stromal vascular fraction) and characterized by flow cytometry for positive (CD73, CD90, CD105) and negative (CD34, CD45) markers [5]. For differentiation, cells are seeded at high density in multi-well plates.

- Osteogenic Differentiation: Cells are cultured in growth medium supplemented with 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 µM ascorbic acid, and 100 nM dexamethasone for 2-3 weeks. Differentiation is confirmed by Alizarin Red S staining, which detects calcium deposits in the extracellular matrix.

- Adipogenic Differentiation: Cells are cultured in medium supplemented with 1 µM dexamethasone, 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX), 10 µg/mL insulin, and 200 µM indomethacin for 1-3 weeks. Lipid vacuole accumulation is visualized by Oil Red O staining.

- Chondrogenic Differentiation: A pellet culture system is used. Approximately 2.5 x 10^5 cells are centrifuged to form a pellet, which is cultured in serum-free medium with 10 ng/mL TGF-β3, 100 nM dexamethasone, 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid, and 1x ITS (Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium) supplement for 3-4 weeks. The resulting pellet is sectioned and stained with Alcian Blue or Toluidine Blue to detect sulfated proteoglycans in the cartilage matrix.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Control

The maintenance of pluripotency and the induction of differentiation are controlled by intricate signaling networks. The core pluripotency circuitry, centered on the autoregulatory loop of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, integrates signals from key pathways like FGF, TGF-β/Activin A, and WNT. These signals help maintain the epigenetic landscape that defines the pluripotent state. In contrast, the multipotency of ASCs is regulated by a different set of context-dependent signals. For MSCs, pathways such as BMP for osteogenesis, TGF-β for chondrogenesis, and PPARγ for adipogenesis drive their lineage-specific differentiation. The primary cilium, a sensory organelle on ASCs, is a critical signaling hub; its dysfunction (e.g., in obesity, via downregulation of RFX2 and ADCY3) can impair ASC differentiation and regenerative capacity [7].

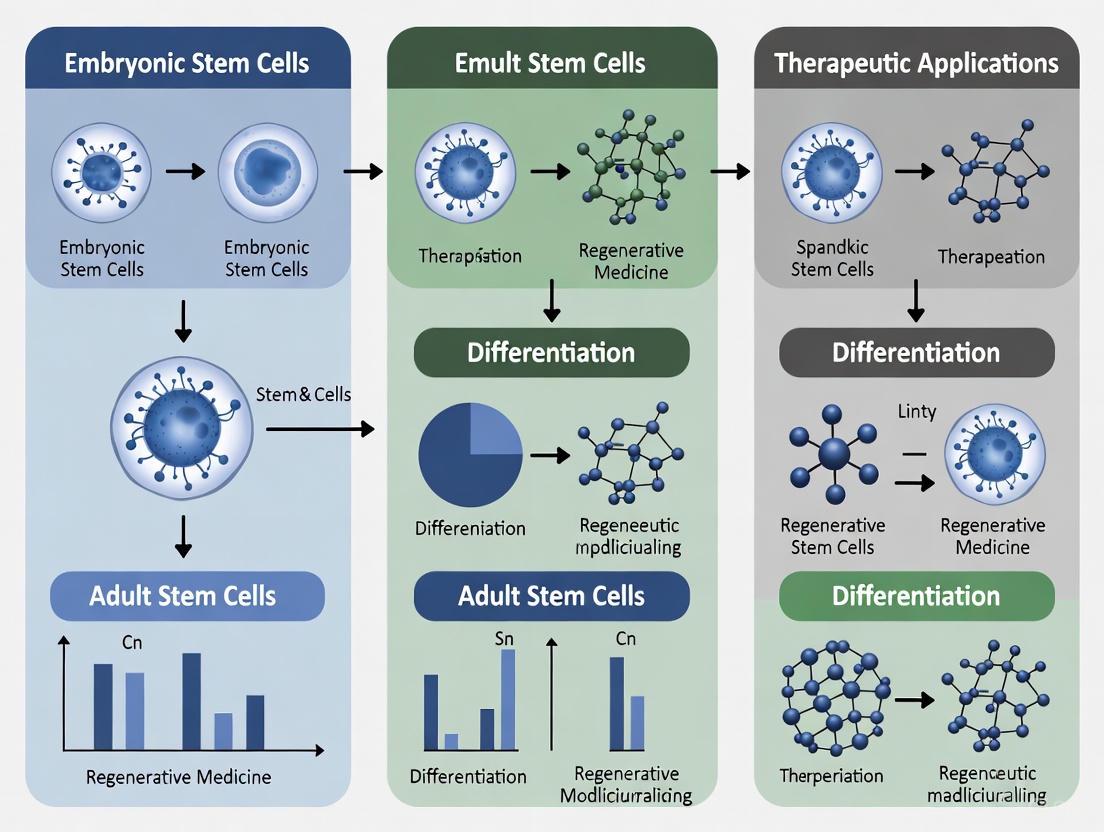

Diagram Title: Core Signaling in ESCs vs. ASCs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Stem Cell Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function in ESC Research | Function in ASC Research |

|---|---|---|

| Collagenase Type IV | Used for the mechanical dissociation of ESC colonies into clumps for passaging or EB formation [4]. | Critical for the enzymatic digestion of adipose tissue to isolate the Stromal Vascular Fraction (SVF) containing ASCs [5]. |

| Matrigel / Geltrex | A basement membrane matrix used as a feeder-free substrate for the attachment and growth of ESCs and iPSCs. | Used as a 3D scaffold for chondrogenic differentiation assays or in tissue engineering constructs. |

| Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF/FGF-2) | A key cytokine added to media to maintain hESC and hiPSC pluripotency in feeder-free cultures [3]. | Promotes ASC proliferation and is involved in wound healing applications by stimulating fibroblast growth and angiogenesis [5]. |

| Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Greatly improves the survival and cloning efficiency of single ESCs/iPSCs after dissociation (e.g., for transfection or subcloning). | Enhances the viability and recovery of ASCs after thawing from cryopreservation or during single-cell passaging. |

| Defined Culture Media | TeSR-E8, mTeSR: Chemically defined, xeno-free media for maintaining ESCs/iPSCs under standardized conditions. | MSCGM, StemPro: Specialty media formulations optimized for the expansion of MSCs while maintaining their multipotency. |

| Trilineage Differentiation Kits | Not typically used, as ESCs are assessed via EB formation and spontaneous differentiation into all germ layers. | Commercial kits (e.g., from MilliporeSigma, Thermo Fisher) provide optimized, pre-mixed media for robust osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs. |

The choice between ESCs and ASCs is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with research and therapeutic goals. ESCs, with their vast and well-defined pluripotency, are unparalleled tools for disease modeling (especially early developmental disorders), high-throughput drug screening, and generating cell types that are difficult to obtain from adult tissues, such as specific neuronal subtypes or cardiac cells [8] [1]. However, their clinical application is tempered by ethical considerations, immune rejection risks, and tumorigenicity.

Conversely, ASCs offer a more readily translatable path for autologous cell therapies and immunomodulation. Their inherent role in tissue repair and the ability to harness their paracrine functions make them ideal for treating inflammatory and degenerative conditions like osteoarthritis, wound healing, and graft-versus-host disease [5] [1]. The critical caveat is that their potency and function can be donor-dependent, influenced by age, health, and disease state, necessitating rigorous quality control [7]. As the field advances, the complementary use of both cell types—leveraging ESC-derived cells for complex disease models and ASCs for regenerative immunomodulation—will likely pave the way for a new era in regenerative medicine.

Stem cells are fundamental units of development and regeneration, characterized by their dual capacities for self-renewal and differentiation into specialized cell types [10]. Their potential, however, is profoundly influenced by their developmental origin. Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are derived from the inner cell mass of blastocysts, an early stage of embryonic development, and represent a state of developmental pluripotency [11] [10]. In contrast, adult stem cells (ASCs), also known as somatic stem cells, reside in specialized microenvironments known as niches within fully formed tissues and organs, where they function in maintenance and repair [12] [13]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these two distinct cellular populations, focusing on their biological characteristics, experimental handling, and therapeutic profiles for a research audience.

Core Biological Characteristics: A Comparative Analysis

The developmental origin of a stem cell dictates its fundamental biological properties, which in turn determine its suitability for specific research or therapeutic applications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Biological Characteristics

| Characteristic | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Origin | Inner Cell Mass (ICM) of the blastocyst [11] [14] | Specific niches in adult tissues (e.g., bone marrow, fat, brain) [13] |

| Key Defining Properties | Pluripotency, high self-renewal capacity [11] | Multipotency, role in tissue homeostasis [13] |

| Primary Functions | Generate all cell types of the developing fetus [11] [10] | Maintain and repair the tissue in which they reside [10] [13] |

| Differentiation Potential | Can differentiate into any of the three germ layers (Pluripotent) [11] [1] | Differentiate into a limited range of cell types within their tissue of origin (Multipotent) [13] [1] |

| Genomic Features | Exhibit a "naive" state; gold standard for pluripotency [15] | Somatic cell genome; may show age-associated alterations [10] |

A critical concept for ASCs is the stem cell niche, a specialized microenvironment that regulates their fate. Proposed by Schofield in 1978, the niche maintains stem cell self-renewal, guides differentiation, and responds to injury and microenvironmental cues such as oxygenation and mechanotransduction [12]. This dynamic regulatory system is absent in ESC cultures, which rely on defined in vitro conditions.

Experimental Protocols for Isolation and Culture

Methodologies for working with ESCs and ASCs differ significantly due to their distinct origins and biological properties. The workflows below outline the core experimental protocols.

Embryonic Stem Cell (ESC) Derivation and Culture

The following diagram illustrates the process of deriving and maintaining ESCs from a blastocyst.

Title: ESC Derivation and Culture Workflow

Detailed Protocol:

- Blastocyst Source: ESCs are derived from the inner cell mass (ICM) of a human blastocyst, typically from embryos created via in vitro fertilization (IVF) that are no longer needed [10].

- ICM Isolation: The ICM is isolated using microsurgery or a second approach involving antibody-mediated targeting of the surrounding trophoblast cells [11].

- Pluripotent Culture: The isolated cells are placed in a culture system designed to maintain pluripotency, often involving mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder layers or defined matrices with specific media containing growth factors like FGF-2 [11].

- Verification and Differentiation: Established cell lines are verified for pluripotency markers (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, NANOG). For differentiation, the culture conditions are altered to remove self-renewal signals and introduce cues (e.g., growth factors, cytokines) that guide the cells toward specific lineages (e.g., cardiomyocytes, neurons) [11] [15].

Adult Stem Cell (ASC) Isolation and Expansion

The process for isolating and studying ASCs from tissue sources is summarized below.

Title: ASC Isolation and Study Workflow

Detailed Protocol:

- Tissue Harvesting: ASCs are isolated from various adult tissues. Common sources include bone marrow (aspirated), adipose tissue (from lipoaspirate), and umbilical cord blood [13].

- Cell Isolation: The tissue is processed via enzymatic digestion (e.g., with collagenase) to create a single-cell suspension. Target cells can then be isolated using techniques like density gradient centrifugation or, for specific populations like MSCs, adherence to plastic in standard culture conditions [13].

- Characterization and Expansion: ASCs are expanded in culture. Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), a key ASC type, are defined by specific criteria: adherence to plastic, in vitro differentiation into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondroblasts, and expression of surface markers (CD105+, CD73+, CD90+) while lacking hematopoietic markers (CD45-, CD34-, etc.) [13].

- Functional Assays: The multipotent differentiation potential is confirmed using specific induction media. Their therapeutic potential is further investigated in animal models of disease, where mechanisms like immunomodulation and paracrine signaling can be studied [13] [1].

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Trial Data

The distinct biological properties of ESCs and ASCs translate into different therapeutic potentials and associated risks, as reflected in clinical trial outcomes.

Table 2: Comparative Therapeutic Profiles and Clinical Translation

| Parameter | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Potential | High versatility for regenerating diverse tissues [11] | Effective for tissue-specific repair and immunomodulation [13] [1] |

| Key Clinical Applications | ESC-derived RPE cells: Age-related macular degeneration (trials) [15]ESC-derived pancreatic cells: Type 1 diabetes (research) [16] | HSCs: Leukemia, lymphoma (standard of care) [11] [1]MSCs: Graft-versus-host disease, osteoarthritis, Crohn's disease (trials) [14] [1] |

| Clinical Trial Status | Mostly early-phase clinical trials [15] | Several established therapies; extensive ongoing trials [11] [1] |

| Major Safety Concerns | Tumorigenicity: Teratoma formation due to undifferentiated cells [11] [15]Immunological rejection upon allogeneic transplantation [10] | Lower tumorigenic risk compared to ESCs [17]Potential for irregularities from donor age/environment [10] |

| Key Advantages | Pluripotency: Can generate any cell type [17]High self-renewal: Unlimited expansion in culture [11] | Autologous transplantation is possible, avoiding rejection [13]Established safety profile in specific uses (e.g., HSC transplant) [1] |

| Primary Limitations | Ethical controversies regarding embryo destruction [10] [18]Safety concerns regarding tumorigenicity [11] | Limited differentiation potential (multipotent) [1]Decreased function and number with donor age [13] |

A promising development is the emergence of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs). These are adult somatic cells reprogrammed to an embryonic-like pluripotent state via the introduction of defined transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) [15] [16]. iPSCs bypass the ethical concerns of ESCs and allow for the creation of patient-specific cell lines, serving as powerful tools for disease modeling and drug screening, though concerns about tumorigenicity remain [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful research in this field relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for working with stem cells.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Yamanaka Factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) | Genetic reprogramming of somatic cells into iPSCs [15] [16] | iPSC generation; studying pluripotency |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Precise genome editing to correct disease-causing mutations or introduce reporters [11] [15] | Gene therapy in ESCs/iPSCs; functional genomics |

| Feeder Layers (e.g., Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts - MEFs) | Provide a supportive substrate and secrete factors that help maintain pluripotency [11] | Initial ESC and iPSC culture |

| Defined Culture Media (e.g., mTeSR, StemPro) | Serum-free media with precise formulations of growth factors (e.g., FGF-2) to maintain stemness or direct differentiation [11] | Long-term, reproducible ESC/iPSC culture |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies (e.g., CD105, CD73, CD90) | Identification and purification of specific stem cell populations based on surface marker expression [13] | Characterization and isolation of MSCs |

| Specific Induction Media | Contain cocktails of growth factors and chemicals to drive differentiation into specific lineages (e.g., bone, fat, cartilage) [13] | In vitro assessment of multipotency (e.g., for MSCs) |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | High-resolution analysis of cellular heterogeneity and transcriptional states within a stem cell population [11] | Profiling niche populations; characterizing differentiation cultures |

Self-Renewal Capacities and In Vitro Expansion Potential

The choice between embryonic and adult stem cells for therapeutic development hinges upon a fundamental understanding of their self-renewal and expansion capabilities. This guide provides a data-driven comparison of these core properties to inform preclinical research and protocol development.

Defining Stem Cell Properties

Stem cell potential is categorized by differentiation capacity and self-renewal mechanisms.

- Pluripotency: The ability to differentiate into any cell type from all three embryonic germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm). This is a defining characteristic of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [19] [20].

- Multipotency: The capacity to differentiate into multiple cell types, but within a specific lineage or tissue family (e.g., hematopoietic stem cells giving rise to various blood cells) [11] [21].

- Self-Renewal: The process by which a stem cell divides to produce at least one identical daughter stem cell, thereby maintaining the stem cell pool. This can occur through:

- Symmetric Division: One stem cell divides into two identical stem cells.

- Asymmetric Division: One stem cell divides into one identical stem cell and one differentiated progenitor cell [21].

Comparative Analysis: Embryonic vs. Adult Stem Cells

The table below summarizes the key characteristics governing the self-renewal and expansion potential of different stem cell types.

| Feature | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) - Hematopoietic Focus | Adult Stem Cells - Mesenchymal Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency/Multipotency | Pluripotent [19] [11] | Multipotent (blood lineage) [11] [21] | Multipotent (osteogenic, chondrogenic, adipogenic) [22] |

| Primary In Vivo Role | Form all tissues during embryonic development [19] | Maintain homeostasis and regeneration of the blood system [23] | Tissue maintenance and repair (e.g., bone, cartilage, fat) [11] [22] |

| In Vitro Self-Renewal | Unlimited with optimized protocols [19] | Limited; prone to exhaustion and differentiation in culture [24] | Senescence after prolonged passage [22] |

| Key Signaling Pathways | LIF/STAT3 (mouse), TGF-β/Activin A/Nodal (human), Wnt/β-Catenin, PI3K/AKT [19] | Wnt, Notch, BMP; largely quiescent in niche [21] [24] | Dependent on source; influenced by inflammatory and growth factors [22] |

| Cell Cycle Profile | Abbreviated or absent G1 phase; rapid cycling [24] | Predominantly quiescent (G0 phase); slow-cycling in vivo [24] | Varies with tissue source and donor age |

| Genetic Stability | High, but requires monitoring for karyotypic abnormalities over long-term culture [19] | Accumulates ~45 somatic mutations/year in mouse models; clonal evolution with age [23] | Generally stable, but potential for senescence-associated changes |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Self-Renewal

Clonal Colony-Forming Assays

Purpose: To quantify the frequency of cells within a population that can proliferate to form a colony, demonstrating self-renewal and proliferative capacity.

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Dissociate cells into a single-cell suspension and seed them at a very low density (e.g., 100-1,000 cells per well of a 6-well plate) to ensure colonies are clonal (derived from a single cell).

- Culture Conditions: Use optimized, feeder-free media conditions that support the stem cell type being tested. For human ESCs, this includes media containing TGF-β/Activin A and FGF2 [19]. For murine ESCs, media is supplemented with LIF and BMP4 [19].

- Feeder Layer (Optional): Some protocols use a layer of inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) to provide a supportive extracellular matrix and secreted factors.

- Culture Duration: Incubate for 7-14 days, with media changes every other day.

- Analysis: Colonies are fixed and stained with crystal violet or alkaline phosphatase. Only colonies exceeding a minimum threshold (e.g., >50 cells) are counted as positive. The colony-forming efficiency (CFE) is calculated as (Number of Colonies / Number of Cells Seeded) × 100%.

In Vivo Serial Transplantation Assay

Purpose: The gold-standard functional test for defining hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), assessing their long-term self-renewal ability in a living organism.

Detailed Methodology:

- Donor Cell Preparation: HSCs are isolated from the bone marrow of a donor mouse using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for specific surface markers (e.g., Lin⁻, Sca-1⁺, c-Kit⁺, CD150⁺, CD48⁻).

- Transplantation: The purified HSCs are transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice to eliminate the host's endogenous blood system. Supporting cells, such as competitor bone marrow cells, are co-transplanted to ensure short-term survival.

- Engraftment Analysis: After 4-6 months, peripheral blood and bone marrow from recipients are analyzed by flow cytometry to confirm multilineage engraftment (presence of myeloid, B-cell, and T-cell lineages) derived from the donor HSCs.

- Serial Transplantation: To stringently test self-renewal, bone marrow cells from the primary recipient are harvested and transplanted into a new set of lethally irradiated secondary recipients. The ability to reconstitute the blood system over multiple rounds indicates robust self-renewal capacity [23]. A recent 2025 study used whole-genome sequencing of single-cell-derived colonies from this assay to track somatic evolution and clonal dynamics over the mouse lifespan [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table lists essential reagents and their applications in stem cell self-renewal research.

| Research Reagent | Primary Function in Self-Renewal Research |

|---|---|

| LIF (Leukemia Inhibitory Factor) | Cytokine used to maintain self-renewal and pluripotency in murine ESCs by activating the STAT3 pathway [19]. |

| Activin A / TGF-β | Growth factors critical for sustaining human ESC pluripotency by activating Smad2/3 signaling and promoting Nanog expression [19]. |

| BMP4 (Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4) | In combination with LIF, supports murine ESC self-renewal by inhibiting ERK/MAPK differentiation signals and inducing Id genes [19]. |

| CHIR99021 | A small molecule GSK-3β inhibitor that activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling, used to support self-renewal and maintain stemness in various stem cell types [25]. |

| Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Improves the survival of single stem cells after passaging, thereby increasing cloning efficiency and reducing anoikis during subculture. |

| StemRNA Clinical Seed iPSCs | Clinical-grade, GMP-compliant induced pluripotent stem cell lines submitted to the FDA under a Drug Master File (DMF) for use in regulatory-compliant therapy development [26]. |

Signaling Pathways Governing Self-Renewal

The molecular regulation of self-renewal differs significantly between embryonic and adult stem cells. The following diagrams illustrate the core pathways.

Core Pluripotency Signaling Network

Diagram Title: Core Signaling in Embryonic Stem Cells

This network shows the key pathways that sustain ESC self-renewal. The LIF/STAT3 and TGF-β/Activin A/Smad2/3 pathways are central to activating core pluripotency transcription factors like Nanog and Sox2 [19]. Simultaneously, BMP signaling induces Id genes to suppress differentiation, while FGF/ERK signaling often promotes differentiation, creating a delicate balance that must be managed in culture [19].

Wnt Pathway in Stem Cell Fate

Diagram Title: Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway Logic

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is a master regulator of self-renewal in both embryonic and adult stem cells [21]. When the pathway is "OFF," a destruction complex targets β-catenin for proteasomal degradation. When Wnt signaling is "ON," the destruction complex is disrupted, allowing β-catenin to accumulate, enter the nucleus, and complex with Tcf/Lef transcription factors to activate the expression of self-renewal genes [21].

Research Implications and Future Directions

The distinct self-renewal properties of embryonic and adult stem cells present clear trade-offs for therapeutic development. ESCs and iPSCs offer unparalleled expansion potential for generating the vast cell numbers needed for therapies, but require precise control over differentiation and carry a risk of teratoma formation [19] [26]. Adult stem cells, particularly HSCs, have a proven record in clinical applications like bone marrow transplantation but are limited by donor availability, graft size, and age-related clonal evolution [11] [23].

Future research is focused on overcoming these limitations. Strategies include manipulating the cell cycle and signaling pathways to enhance the expansion of HSCs in culture [24], and developing novel cell types like Muse cells—naturally occurring, stress-resistant pluripotent-like cells found within mesenchymal tissues that show strong immunotolerance and tissue-reparative functions after intravenous injection [22]. Furthermore, the emergence of iPSC-derived MSCs (iMSCs) promises a more consistent and scalable source of mesenchymal cells for regenerative applications, potentially overcoming the heterogeneity and senescence of primary MSCs [26].

Stem cell research represents a revolutionary frontier in modern medicine, offering unprecedented potential to address a wide range of debilitating diseases and injuries [11]. This field is broadly divided between embryonic stem cell (ESC) research, which utilizes pluripotent cells derived from early-stage embryos, and adult stem cell research, which works with multipotent cells found in various tissues throughout the body [10] [13]. The ethical and regulatory considerations for these two pathways differ substantially, creating a complex landscape that researchers must navigate.

The distinctive properties of stem cells—their ability to self-renew and differentiate into specialized cell types—make them indispensable for regenerative medicine applications [11]. However, the very source of ESCs raises significant ethical questions that have shaped the regulatory environment. This guide objectively compares the ethical and regulatory frameworks governing embryonic versus adult stem cell research, providing researchers with the tools to conduct scientifically rigorous and ethically sound research.

Ethical Considerations: A Comparative Analysis

The ethical debate surrounding stem cell research primarily focuses on the moral status of the human embryo, creating a fundamental distinction between embryonic and adult stem cell approaches.

Embryonic Stem Cell Ethics

The derivation of human embryonic stem cells requires the destruction of human embryos, raising disputes about the onset of human personhood and the moral status of human embryos [18]. This has led to significant ethical controversies, particularly from religious and pro-life communities who argue that destroying embryos for research is morally wrong [27] [18].

- Moral Status of Embryos: The central ethical concern revolves around whether embryos deserve the same moral consideration as developed human beings [18].

- Source of Embryos: Most hESC lines are derived from embryos created through in vitro fertilization (IVF) that are no longer needed for reproductive purposes and would otherwise be discarded [10] [18].

- Informed Consent: Ethical guidelines require proper informed consent from donors for the use of these embryos in research [27] [10].

Adult Stem Cell Ethics

Adult stem cell research faces considerably fewer ethical objections as it does not involve the destruction of embryos [27] [18] [13]. These somatic stem cells are obtained from developed tissues such as bone marrow, adipose tissue, and other adult organs, bypassing the central ethical dilemma of embryonic research [13].

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells as an Ethical Alternative

The development of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has significantly altered the ethical landscape. These cells, generated by reprogramming adult somatic cells to a pluripotent state, offer similar research potential to ESCs without the ethical concerns specific to embryonic stem cell research [27] [18]. However, iPSCs are not without their own ethical considerations, including concerns about their safety and long-term effects, such as tumor formation [27].

Table: Comparative Ethical Analysis of Stem Cell Types

| Stem Cell Type | Ethical Concerns | Key Ethical Considerations | Primary Objections |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | High | Destruction of human embryos; Moral status of embryo; Informed consent for embryo donation | Strong opposition from religious and pro-life groups [27] [18] |

| Adult Stem Cells | Low | Informed consent for tissue donation; No destruction of embryos | Minimal ethical objections [27] [18] [13] |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Moderate | No embryo destruction; Potential for human cloning; Safety and long-term effects (e.g., tumorigenesis) | Some concerns about potential misuse and safety [27] |

Regulatory Frameworks and Guidelines

Regulatory frameworks for stem cell research have evolved to address both scientific advancement and ethical concerns, with significant international coordination.

International Guidelines: The ISSCR Framework

The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) provides comprehensive international guidelines that are regularly updated to reflect scientific advances. The most recent 2025 update specifically addresses stem cell-based embryo models (SCBEMs) [28] [29]. Key provisions include:

- Oversight Requirements: All 3D SCBEMs must have a clear scientific rationale, defined endpoint, and be subject to appropriate oversight mechanisms [28] [29].

- Research Boundaries: SCBEMs must not be transplanted to the uterus of a living animal or human host, and ex vivo culture is prohibited beyond the point of potential viability (ectogenesis) [28] [29].

- Fundamental Principles: The guidelines emphasize rigor, oversight, and transparency in all areas of practice, maintaining widely shared ethical principles in science [28].

United States Regulatory Landscape

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) plays a critical role in regulating regenerative medicine products, including stem cell therapies [27] [26]. The regulatory framework distinguishes between different categories of stem cell products:

- Minimally Manipulated Products: Human cells, tissues, and cellular and tissue-based products (HCT/Ps) that are minimally manipulated, intended for homologous use, and not combined with another article are regulated under Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act [27].

- More-Than-Minimally Manipulated Products: Stem cell products that undergo more than minimal manipulation, are intended for non-homologous use, or are combined with another article are regulated as drugs or biologics, requiring an Investigational New Drug (IND) application before clinical trials [27].

The FDA has established expedited programs such as the Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy (RMAT) designation to facilitate timely development of promising therapies while maintaining safety standards [27] [26].

Table: Recent FDA-Approved Stem Cell Products (2023-2025)

| Product Name | Approval Date | Stem Cell Type | Indication | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omisirge (omidubicel-onlv) | April 17, 2023 | Cord Blood-Derived Hematopoietic Progenitor Cells | Hematologic malignancies undergoing cord blood transplantation | Accelerates neutrophil recovery; Reduces infection risk post-myeloablative conditioning [26] |

| Lyfgenia (lovotibeglogene autotemcel) | December 8, 2023 | Autologous Cell-Based Gene Therapy | Sickle cell disease with history of vaso-occlusive events | One-time treatment; Modifies patient's own hematopoietic stem cells to produce HbAT87Q [26] |

| Ryoncil (remestemcel-L) | December 18, 2024 | Allogeneic Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs | Pediatric steroid-refractory acute Graft Versus Host Disease (SR-aGVHD) | First MSC therapy approved by FDA; Modulates immune response and mitigates inflammation [26] |

Regulatory Oversight Pathways for Stem Cell Research: This diagram illustrates the primary regulatory pathways for different stem cell research types, highlighting the more stringent requirements for embryonic stem cell research compared to certain adult stem cell applications.

Experimental Protocols and Research Applications

Embryonic Stem Cell Research Protocols

Research involving human embryonic stem cells requires specific protocols to maintain ethical standards while advancing scientific knowledge. The derivation of ESCs typically involves:

- Source Acquisition: hESCs are derived from the inner cell mass of blastocysts (3-5 day old embryos) obtained from in vitro fertilization clinics with informed donor consent [10].

- Isolation Techniques: Two primary methods are employed: microsurgical isolation of the inner cell mass or immunological dissection using antibodies to target trophoblast lineage cells [11].

- Culture Maintenance: ESCs are maintained in specialized culture conditions that preserve their pluripotent state while preventing spontaneous differentiation [10].

The ISSCR guidelines explicitly prohibit certain research applications, including:

- Human reproductive cloning

- Implantation of human embryos into non-human primate uteruses

- Breeding of animals into which human cells have been introduced at any stage of embryonic development

- Culture of human embryos beyond 14 days of development [28]

Stem Cell-Based Embryo Models (SCBEMs)

The 2025 ISSCR guidelines update specifically addresses stem cell-based embryo models, which are three-dimensional stem cell-derived structures that replicate key aspects of early embryonic development [29]. These innovative models offer unprecedented potential to enhance our understanding of human developmental biology while raising unique ethical considerations.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Stem Cell Research

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Genetic or chemical factors to induce pluripotency in somatic cells | Essential for iPSC generation; Includes OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC or alternative combinations [18] |

| StemRNA Clinical Seed iPSCs | GMP-compliant iPSC seed clones for therapeutic development | Subject to FDA Drug Master File (DMF) review; Provides standardized starting material [26] |

| Culture Media Systems | Specialized media formulations to maintain stem cell states | Formulations vary for ESCs, iPSCs, and adult stem cells; Often include specific growth factors [11] |

| Differentiation Induction Cocktails | Chemical and biological factors to direct lineage specification | Cell-type specific formulations (e.g., neural, cardiac, hepatic); Critical for functional cell generation [11] |

| Surface Marker Antibodies | Characterization of stem cell populations and differentiation status | CD105, CD73, CD90 for MSCs; CD45, CD34, CD14 negative selection; Pluripotency markers for ESCs/iPSCs [13] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Genome editing for disease modeling and functional studies | Enables precise genetic modifications; Requires careful ethical review for germline applications [11] |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Kits | High-resolution analysis of cell populations and differentiation trajectories | Reveals heterogeneity in stem cell populations; Identifies novel cell markers [11] |

The ethical and regulatory landscapes for embryonic and adult stem cell research present distinct pathways for scientific exploration. Embryonic stem cell research offers unparalleled pluripotency but operates within a tightly regulated framework to address significant ethical concerns. Adult stem cell research, while more limited in differentiation potential, faces fewer ethical hurdles and has already yielded multiple FDA-approved therapies.

The emergence of iPSC technology has created a middle ground, offering pluripotency without embryo destruction, though with its own regulatory considerations. The international regulatory environment, guided by organizations like the ISSCR and national bodies like the FDA, continues to evolve alongside scientific advancements.

Researchers must remain vigilant in adhering to both the technical and ethical standards of their respective fields, ensuring that stem cell research progresses in a manner that is both scientifically robust and socially responsible. The continued development of clear guidelines and oversight mechanisms provides the necessary framework to harness the full potential of stem cell research while maintaining public trust and ethical integrity.

Therapeutic Mechanisms and Clinical Applications in Regenerative Medicine

Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs), first isolated from human blastocysts in 1998, represent a foundational platform in stem cell biology due to their defining characteristics of sustained self-renewal and pluripotency—the ability to differentiate into all cell types in the body [11] [30]. These properties make ESCs uniquely suited for directed differentiation and disease modeling, enabling critical research into human development, disease mechanisms, and the development of new regenerative medicines [30]. This review objectively compares the performance of ESCs against other stem cell types, primarily adult stem cells (ASCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), within the broader thesis of evaluating therapeutic applications. We provide supporting experimental data and standardized protocols to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate stem cell platforms for specific applications.

Comparative Analysis of Stem Cell Types for Research and Therapy

The choice of stem cell type fundamentally influences experimental design, therapeutic potential, and clinical applicability. The following table summarizes the core characteristics of the major stem cell classes.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Stem Cell Types

| Feature | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency/Multipotency | Pluripotent (can form all embryonic germ layers) [11] [1] | Pluripotent (can form all embryonic germ layers) [15] [1] | Multipotent (limited to cell types of their tissue of origin) [11] [1] |

| Key Advantages | Gold standard for pluripotency; no epigenetic memory; clinically relevant protocols exist [30] [15] | Avoids ethical concerns of ESCs; enables patient-specific disease modeling [15] | No ethical concerns; limited tumorigenicity risk; used in established therapies (e.g., HSCT) [11] [1] |

| Primary Limitations | Ethical controversies; requires immunosuppression in allogeneic therapy [1] | Potential for epigenetic memory; tumorigenicity risk from reprogramming factors [15] | Limited differentiation capacity; difficult to isolate and expand in culture [11] |

| Therapeutic Use Example | Clinical trials for Parkinson's disease and age-related macular degeneration [30] | First iPSC-based therapy (Fertilo) in U.S. Phase III trials [26] | Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT) for blood cancers [1] |

Directed Differentiation of ESCs: Protocols and Performance Metrics

Directed differentiation protocols guide ESCs through specific developmental pathways to generate functional, specialized cell types. The reproducibility and efficiency of these protocols are critical for both research and clinical translation.

Experimental Protocol: Generation of Dopaminergic Neurons for Parkinson's Disease

This protocol is adapted from methods used in clinical trials for Parkinson's disease [26] [1].

- Maintenance of Undifferentiated hESCs: Culture hESCs on a feeder layer of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or on a defined substrate like Matrigel in feeder-free conditions. Maintain cells in pluripotency media containing basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF).

- Embryoid Body (EB) Formation: Detach hESC colonies and transfer to low-attachment plates to form aggregates known as Embryoid Bodies (EBs) in suspension culture. This initiates spontaneous differentiation into the three germ layers.

- Neural Induction: After 4-5 days, transfer EBs to culture dishes coated with poly-L-ornithine/laminin. Culture in neural induction media, typically containing dual SMAD signaling inhibitors (e.g., Noggin, SB431542) to promote neural ectoderm fate over mesoderm and endoderm.

- Dopaminergic Patterning: Once neural rosettes appear (around day 7-10 of differentiation), pattern the cells toward a midbrain dopaminergic phenotype. This is achieved by adding key morphogens such as Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) and Fibroblast Growth Factor 8 (FGF8) to the culture medium.

- Maturation and Purification: Over 4-6 weeks, mature the dopaminergic precursors by withdrawing mitogens and adding growth factors like BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor), GDNF (Glial Cell line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor), and ascorbic acid. Purification can be achieved using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for specific surface markers.

The workflow and key signaling molecules involved in this directed differentiation are summarized in the diagram below.

Quantitative Performance Data

The efficiency of differentiation protocols is a key performance indicator. The following table compares the output of ESC-derived dopaminergic neurons against other cell sources, based on data from preclinical and early clinical studies [26] [1].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Cell Sources for Dopaminergic Neuron Generation

| Cell Source | Differentiation Efficiency (%) | Time to Functional Maturity | In Vivo Functional Recovery in Rodent Models | Tumorigenicity Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESCs | 60-80% | 6-8 weeks | Significant motor improvement observed [1] | Low with optimized protocols [26] |

| iPSCs | 50-75% | 6-8 weeks | Significant motor improvement observed [1] | Moderate (varies with reprogramming method) [15] |

| Fetal Tissue | N/A (Primary cells) | N/A | Gold standard efficacy | None |

| ASCs (e.g., Mesenchymal) | Not possible to generate authentic dopaminergic neurons | N/A | Limited benefit, primarily via paracrine effects [1] | Very Low |

Disease Modeling with ESCs: From 2D to 3D Organoid Systems

While 2D cultures have been instrumental, the field is rapidly advancing toward 3D brain organoids to model the complexity of the human brain and its disorders more accurately [31] [32].

Experimental Protocol: Generating Cerebral Organoids to Model Neurodegeneration

This protocol is based on the landmark cerebral organoid generation method [31] [32].

- EB Formation and Neural Induction: Generate EBs from hESCs as in Step 3.1. Induce neural fate by culturing EBs in neural induction media.

- Embedding in ECM: After 5-7 days, embed the neuroectoderm-containing EBs in droplets of an extracellular matrix (ECM) substitute like Matrigel, which provides a 3D scaffold that supports complex tissue morphogenesis.

- Differentiation and Maturation in a Bioreactor: Transfer the Matrigel-embedded EBs to a spinning bioreactor. This dynamic culture system improves nutrient and oxygen exchange, allowing the organoids to grow larger and develop more complex tissue architectures over periods of 1-3 months.

- Disease Modeling and Analysis: To model a genetic neurodegenerative disease like Alzheimer's, ESCs with relevant mutations (e.g., in PSEN1 or APP) can be used. Alternatively, gene editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 can be used to introduce disease-causing mutations into wild-type ESCs. The resulting organoids can be analyzed for disease phenotypes, including protein aggregation (e.g., Aβ plaques), neuronal death, and electrophysiological abnormalities.

The workflow for generating these organoids is illustrated below.

Performance Comparison of Modeling Platforms

The physiological relevance of disease models is paramount for predictive drug discovery. The table below compares the capabilities of different stem cell-derived models for neurodegenerative disease modeling [31] [32] [15].

Table 3: Comparison of Stem Cell-Based Platforms for Modeling Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Model System | Physiological Relevance | Cellular Diversity | Ability to Model Complex Circuitry | Throughput for Drug Screening |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D ESC/iPSC Culture | Low (monolayer, simplified) | Low (limited co-cultures) | Very Low | High |

| ESC-Derived Brain Organoids | High (3D architecture, cell-cell interactions) | High (multiple neuronal and glial types) | Moderate (emerging regional connectivity) | Moderate |

| ASC Co-cultures | Low to Moderate | Very Low | Very Low | High |

| Animal Models | Moderate (species differences exist) [31] | N/A | High (intact brain) | Low |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for ESC Research

Successful directed differentiation and organoid generation rely on a suite of critical reagents and materials.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ESC Differentiation and Disease Modeling

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Matrigel / Basement Membrane Extract | Provides a 3D extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffold to support complex tissue organization [31] [32]. | Embedding for cerebral organoid generation [31]. |

| Dual SMAD Inhibitors (e.g., Noggin, SB431542) | Promotes neural induction by inhibiting BMP and TGF-β signaling pathways, steering differentiation toward neural ectoderm [31]. | Early-stage protocol for generating neural progenitor cells. |

| Morphogens (SHH, FGF8, WNT) | Patterning molecules that provide positional information to cells, directing them toward specific regional fates (e.g., midbrain, cortex) [31]. | Specifying dopaminergic neuron identity during differentiation. |

| Spinning Bioreactor | A dynamic culture system that enhances nutrient and oxygen diffusion to the core of 3D tissues, enabling larger and more mature organoids to form [31] [32]. | Long-term maturation of cerebral organoids. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | A precise gene-editing tool used to introduce or correct disease-associated mutations in wild-type ESCs, creating isogenic cell lines for disease modeling [15]. | Generating ESC lines with Alzheimer's-associated mutations for organoid studies. |

Within the broader context of stem cell therapeutic applications, ESCs maintain a critical and distinct role. Their definitive pluripotency and lack of epigenetic memory make them a powerful and standardized platform for directed differentiation, particularly for generating the complex cellular diversity needed to model neurological diseases in 3D organoids [31] [30]. While iPSCs offer an unparalleled advantage for patient-specific modeling and avoid ethical concerns, ESCs often serve as the gold-standard control for assessing the quality and functionality of iPSC-derived tissues [15]. In therapeutic applications, ESC-derived products are now demonstrating promising results in clinical trials for conditions like Parkinson's disease, underscoring their translational potential [26] [1]. The choice between ESCs, iPSCs, and ASCs is not a matter of superiority but of alignment with research goals, whether for foundational discovery, personalized disease modeling, or proven regenerative therapies.

The field of regenerative medicine is deeply engaged in the critical evaluation of embryonic versus adult stem cell therapeutic applications. Within this context, adult stem cells (ASCs), particularly mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), have emerged as a clinically viable and ethically less contentious alternative to embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [10] [11]. ESCs, while pluripotent and capable of generating any cell type in the body, face significant limitations including ethical concerns, potential for immune rejection, and tumorigenic risks [10] [11]. ASCs, harvested from adult tissues such as adipose tissue, bone marrow, and umbilical cord, offer a multipotent and more readily applicable solution for cell-based therapies [33] [34]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of ASC therapies, with a focused analysis on their performance in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), presenting key experimental data to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

MSCs derived from various tissues share core characteristics—they are adherent, possess multipotent differentiation potential, and express a typical surface marker profile (CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, CD34-, CD45-, HLA-DR-) [34]. However, parallel comparative studies reveal that their biological properties and functional efficacies are significantly influenced by their tissue of origin.

Comparative Analysis of Adipose and Umbilical Cord MSCs

A direct side-by-side analysis of human adipose tissue-derived MSCs (ASCs) and umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) from the same donors highlighted both similarities and critical differences [35]. Both cell types expressed characteristic MSC surface markers and could be induced to differentiate into adipocytes, osteoblasts, and neuronal phenotypes. However, quantitative differences in their capacities were evident:

- Adipogenesis: ASCs demonstrated more prominent and efficient adipogenic differentiation compared to UC-MSCs [35].

- Neurogenesis: ASCs responded better to neuronal induction, exhibiting a higher differentiation rate in a relatively shorter time [35].

- Cytokine Secretion: UC-MSCs exhibited a more prominent secretion profile of cytokines than ASCs [35].

This indicates that while ASCs and UC-MSCs share immunological phenotypes, their divergent biological strengths may suit them for different therapeutic applications.

Comparative Analysis of Adipose and Bone Marrow MSCs

When compared to the well-characterized bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs), ASCs demonstrate several superior regenerative attributes [36]. The table below summarizes key experimental findings from in vitro and in vivo studies.

Table 1: Comparative Biological Performance of ASCs vs. BM-MSCs

| Biological Characteristic | ASCs Performance | BM-MSCs Performance | Experimental Model/Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neovascularization | More effective, higher VEGF expression [36] | Less effective [36] | Rat hind-limb ischemia model; CD31/αSMA staining [36] |

| Resistance to Hypoxia | Higher (48.99% apoptosis) [36] | Lower (91.95% apoptosis) [36] | 1% O2 exposure for 24h; Annexin-V/PI staining [36] |

| Resistance to Oxidative Stress | Higher, maintained proliferation [36] | Lower, >90% senescence [36] | H2O2 treatment; SA-β-gal staining & MTT assay [36] |

| Proangiogenic Activity | More extensive tube networks [36] | Less extensive networks [36] | In vitro tube formation on Geltrex [36] |

| Telomerase Activity | Significantly higher [36] | Lower [36] | PCR-based TRAP assay [36] |

| Gene Expression (Oct4, VEGF) | Higher expression [36] | Lower expression [36] | Quantitative real-time PCR [36] |

These functional advantages are corroborated by unique biophysical properties. An analysis using a dielectrophoresis microfluidic platform revealed that ASCs display different traveling wave velocity and rotational speed compared to BM-MSCs, and remarkably, seem to develop an adaptive response when exposed to repeated electric field stimulation [36].

Experimental Protocols for Key Assessments

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear technical reference, detailed methodologies for critical experiments cited in the comparison tables are outlined below.

Protocol: In Vivo Neovascularization Potency (Hind-Limb Ischemia Model)

This protocol assesses the functional capacity of MSCs to promote blood vessel formation in a live animal model of ischemia [36].

- Animal Model Induction: Unilateral hind-limb ischemia is surgically induced in rats (e.g., via ligation of the femoral artery).

- Cell Administration: ASCs or BM-MSCs are administered via intramuscular injection into the ischemic gastrocnemius muscle. A control group receives a vehicle solution.

- Tissue Collection: After a set period (e.g., 3 weeks), muscle tissues are harvested.

- Histological Analysis:

- Fixation and Sectioning: Muscles are fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin for sectioning.

- Staining:

- H&E Staining: To assess overall muscle morphology, degeneration, and lymphocyte infiltration.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Sections are stained with antibodies against:

- CD31: Marker for endothelial cells (quantify vessel density).

- αSMA (Alpha-Smooth Muscle Actin): Marker for vascular smooth muscle cells (identifies mature vessels).

- VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor): Key pro-angiogenic growth factor.

- Quantification: The number of CD31-positive and αSMA-positive cells or structures per field of view is counted to quantify angiogenesis.

Diagram 1: In vivo neovascularization assessment workflow.

Protocol: In Vitro Proangiogenic Activity (Tube Formation Assay)

This assay evaluates the innate ability of MSCs to form capillary-like structures, a key indicator of their angiogenic support potential [36].

- Matrix Coating: A 96-well plate is coated with a solidified, growth factor-reduced basement membrane matrix (e.g., Geltrex or Matrigel) and allowed to polymerize.

- Cell Seeding: ASCs or BM-MSCs are harvested, counted, and seeded onto the surface of the polymerized matrix at a defined density (e.g., 1x10^4 cells/well) in a suitable endothelial or serum-supplemented medium.

- Incubation: The plate is incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for a defined period (e.g., 6-12 hours).

- Imaging and Quantification:

- After incubation, the formed networks are visualized using an inverted phase-contrast microscope.

- Images from multiple fields are captured.

- The extent of tube formation is quantified by measuring:

- The number of branching points per field.

- The total length of the tube structures.

- The number of closed meshes.

- Software-assisted image analysis (e.g., ImageJ with angiogenesis plugins) is recommended for objective quantification.

Protocol: Assessment of Hypoxia Resistance

This protocol measures cell survival under low-oxygen conditions, mimicking the stressful microenvironment of damaged tissues [36].

- Cell Culture: ASCs and BM-MSCs are cultured to 70-80% confluency.

- Hypoxic Exposure: Culture plates are placed in a hypoxic chamber flushed with a gas mixture containing 1% O2, 5% CO2, and balance N2. Control plates remain in a normoxic incubator (21% O2).

- Incubation Duration: Cells are exposed to hypoxia for a set period (e.g., 24-48 hours).

- Apoptosis Analysis (Flow Cytometry):

- Cells are collected by trypsinization.

- The cell pellet is resuspended in a binding buffer.

- Cells are stained with Annexin V-FITC and Propidium Iodide (PI) according to manufacturer's instructions.

- After incubation in the dark, the samples are analyzed by flow cytometry to distinguish:

- Viable cells (Annexin V-/PI-).

- Early apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI-).

- Late apoptotic/necrotic cells (Annexin V+/PI+).

Clinical Applications in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

HSCT is a cornerstone treatment for hematologic malignancies but is complicated by delayed engraftment and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). MSC co-infusion has been extensively investigated as a strategy to improve outcomes [37] [38] [33].

Efficacy in Promoting Engraftment

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of clinical trials demonstrate that MSC co-transplantation accelerates hematopoietic recovery after HSCT [37] [38]. The most consistent and significant benefit is observed in platelet engraftment [38]. The table below synthesizes clinical outcome data from controlled trials.

Table 2: Clinical Outcomes of MSC Co-Infusion in HSCT (Controlled Trials)

| Clinical Outcome | MSC Co-Infusion Group | Control Group (HSCT Alone) | Statistical Significance & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Neutrophil Engraftment (Days) | ~13.96 days [38] | Varies by study | Shorter (SMD: -1.20 in RCTs, -0.54 in nRCTs) [37] |

| Time to Platelet Engraftment (Days) | ~21.61 days [38] | Varies by study | More consistently and significantly shorter (SMD: -0.60 in RCTs, -0.70 in nRCTs) [37] [38] |

| Incidence of Chronic GVHD (cGVHD) | Lower [37] | Higher | Risk Ratio: 0.53 in RCTs, 0.50 in nRCTs [37] |

| Incidence of Acute GVHD (aGVHD) | Slightly positive trend [37] | - | Not statistically significant in meta-analysis [37] |

| Overall Survival (OS) & Relapse Rate (RR) | No significant difference [37] | No significant difference | MSC infusion did not increase mortality or relapse [37] |

| Non-Relapse Mortality (NRM) | Slightly positive trend [37] | - | Not statistically significant in meta-analysis [37] |

Subgroup analyses reveal that the benefits are most pronounced in specific patient populations. Children and adolescents, as well as patients receiving HLA-nonidentical HSCT, show more substantial improvements in engraftment and incidence of GVHD and NRM [37]. Conversely, a reduced overall survival was observed in adult patients with hematological malignancies undergoing HLA-identical HSCT, indicating the need for patient-stratified application [37].

Efficacy in Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD) Management

The potent immunomodulatory properties of MSCs make them a promising tool for managing GVHD [33] [34]. They suppress T-cell proliferation, inhibit B-cell and natural killer cell function, and modulate dendritic cell activity through cell-to-cell contact and secretion of soluble factors like TGF-β, HGF, and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase [34]. This translational potential culminated in the recent FDA approval of Ryoncil (remestemcel-L), an allogeneic bone marrow-derived MSC therapy, for the treatment of pediatric steroid-refractory acute GVHD (SR-aGVHD) in December 2024 [26]. This marks a significant regulatory milestone for MSC-based therapies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting the experiments described in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for MSC Research in HSCT Applications

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example(s) / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Collagenase Type I | Tissue digestion for primary isolation of MSCs from adipose tissue or umbilical cord Wharton's jelly [35]. | Critical for breaking down extracellular matrix to release cells. Concentration and incubation time vary by tissue [35]. |

| MSC Culture Medium | Ex vivo expansion and maintenance of MSCs. | Often includes a basal medium (e.g., DMEM/F12) supplemented with FBS and growth factors. Commercial serum-free MSC media are also available [35]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Immunophenotyping of MSCs to confirm identity per ISCT criteria. | Positive markers: CD73, CD90, CD105. Negative markers: CD34, CD45, HLA-DR [35] [34]. |

| Tri-lineage Differentiation Kits | In vitro validation of MSC multipotency (adiopgenic, osteogenic, chondrogenic). | Kits typically include induction and maintenance media with specific inducers like dexamethasone, indomethacin (adipo), and β-glycerophosphate (osteo) [35]. |

| Geltrex / Matrigel | Used for in vitro tube formation assays to assess proangiogenic potential [36]. | Provides a basement membrane matrix that supports cell attachment, migration, and tube formation. |

| Annexin V & Propidium Iodide (PI) | Flow cytometry-based detection of apoptosis and necrosis in hypoxia resistance assays [36]. | Distinguishes between viable (Annexin V-/PI-), early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-), and late apoptotic/necrotic (Annexin V+/PI+) cells. |

| Antibodies for IHC | Analysis of in vivo neovascularization and cell engraftment in animal models. | CD31: Endothelial cell marker. αSMA: Pericyte/vascular smooth muscle marker. VEGF: Growth factor expression [36]. |

| Hypoxic Chamber | Creating a controlled low-oxygen environment (e.g., 1% O2) to study hypoxia resistance [36]. | Essential for mimicking the ischemic tissue microenvironment in vitro. |

The accumulated experimental and clinical evidence solidifies the role of ASCs, particularly MSCs, as a powerful tool in regenerative medicine and HSCT. When compared to other MSC sources, ASCs demonstrate superior regenerative capacities, including enhanced resistance to stress, stronger proangiogenic activity, and more potent in vivo neovascularization [36]. While UC-MSCs may have a robust cytokine secretome [35], the functional advantages and easier accessibility of ASCs make them a highly attractive source.

In the clinical setting of HSCT, MSC co-infusion has transitioned from experimental to a recognized strategy to accelerate hematopoietic recovery (especially platelets) and reduce the incidence of chronic GVHD [37] [38] [33]. The recent FDA approval of Ryoncil for SR-aGVHD is a testament to this progress [26]. Future developments will focus on refining these therapies through the use of iPSC-derived MSCs (iMSCs) for improved consistency and scalability [26], and precision medicine approaches to identify patient subgroups that will benefit most, thereby optimizing the therapeutic landscape for ASCs in transplantation medicine.

Stem cell therapies represent a revolutionary frontier in regenerative medicine, offering potential treatments for a wide range of debilitating conditions from neurodegenerative diseases to cardiovascular disorders [11]. The therapeutic efficacy of these cells hinges on three primary mechanisms of action: differentiation into specialized cell types to replace damaged tissues, paracrine signaling through secreted factors that modulate the local microenvironment, and immunomodulation to regulate immune responses [14] [11]. Understanding how these mechanisms differ between embryonic and adult stem cells is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to develop targeted therapies.

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs), with their pluripotent nature, and adult stem cells (ASCs), including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), exhibit fundamental differences in their biological capabilities and therapeutic applications [39] [14]. This comparison guide objectively analyzes the mechanistic profiles of these distinct stem cell types, providing experimental data and methodologies relevant for preclinical research and clinical translation.

Comparative Mechanisms of Action

The therapeutic potential of stem cells is governed by their distinct biological capabilities, which vary significantly between embryonic and adult types. The following analysis compares their core mechanisms of action with supporting experimental data.

Table 1: Comparative Mechanisms of Action of Embryonic vs. Adult Stem Cells

| Mechanism | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Adult Stem Cells (ASCs/MSCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Differentiation Capacity | Pluripotent - Can differentiate into any cell type from all three germ layers [39] [10] | Multipotent - Limited to cell types of their tissue of origin (e.g., bone, cartilage, fat for MSCs) [39] [11] |

| Paracrine Signaling | Express developmental morphogens (Wnt, BMP, Nodal); crucial for patterning during differentiation [11] | Secrete VEGF, HGF, FGF; promote angiogenesis, reduce apoptosis, stimulate endogenous progenitor cells [14] [11] |

| Immunomodulation | High immunogenicity; require immunosuppression in allogeneic settings [39] [10] | Strong immunomodulatory properties; suppress T-cell proliferation, modulate dendritic cells and NK cells via PGE2, IDO, TGF-β [14] [11] |

| Primary Therapeutic Strategy | Cell replacement via directed differentiation [11] [26] | Trophic support and immune regulation [14] [11] |

| Key Evidence | Clinical trials for Parkinson's (dopaminergic neurons) and retinal diseases (RPE cells) [26] | FDA-approved for pediatric SR-aGVHD (Ryoncil); >1,200 patients dosed in PSC trials with encouraging safety [26] |

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Secreted Factors from Stem Cells

| Secreted Factor | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Adult Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF (pg/mL/10⁶ cells/24h) | 150-300 (from ESC-derived progenitors) | 500-2,000 | Angiogenesis, endothelial cell survival [11] |

| HGF (pg/mL/10⁶ cells/24h) | Low/Undetectable | 1,000-5,000 | Anti-fibrotic, mitogenic, morphogenic effects [11] |

| TGF-β (pg/mL/10⁶ cells/24h) | Variable during differentiation | 300-1,000 | Immunomodulation, extracellular matrix production [11] |

| FGF-2 (pg/mL/10⁶ cells/24h) | High during early differentiation | 500-1,500 | Cell proliferation, tissue repair [11] |

| PGE2 (ng/mL/10⁶ cells/24h) | Not typically measured | 1-10 | Macrophage polarization toward M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype [14] |

Experimental Analysis of Differentiation

Directed Differentiation of Embryonic Stem Cells

The differentiation capacity of ESCs is their most defining characteristic, enabling generation of any cell type for regenerative applications.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) into specialized cell types.

Protocol for ESC Directed Differentiation to Dopaminergic Neurons:

- Maintenance: Culture hESCs on feeder-free Matrigel matrix in mTeSR1 medium with daily medium changes [11].

- Embryoid Body Formation: Detach colonies using EDTA and transfer to low-attachment plates in suspension culture to form embryoid bodies for 4 days [11].

- Neural Induction: Transfer embryoid bodies to poly-ornithine/laminin-coated plates in N2 medium with dual SMAD inhibition (LDN-193189 100nM, SB431542 10μM) for 7-10 days [26].

- Patterning: Add sonic hedgehog (SHH C24II, 100ng/mL) and FGF8 (100ng/mL) for 14 days to specify dopaminergic fate [26].

- Maturation: Withdraw patterning factors and culture in BDNF, GDNF, ascorbic acid, and cAMP for 28+ days to generate functional dopaminergic neurons [26].

Validation: Immunocytochemistry for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), FOXA2, and β-tubulin III; HPLC for dopamine secretion in response to potassium chloride depolarization [26].

Spontaneous Differentiation of Embryonic Stem Cells

Embryoid Body Formation Assay Protocol:

- Preparation: Harvest ESC colonies using collagenase IV treatment.

- Suspension Culture: Transfer cell clusters to low-attachment plates in ESC medium without FGF2.

- Differentiation: Culture for 7-21 days with medium changes every 2-3 days.

- Analysis: Assess spontaneous differentiation into cell types representing all three germ layers via immunocytochemistry for β-tubulin III (ectoderm), α-fetoprotein (endoderm), and α-smooth muscle actin (mesoderm) [11].

Multipotent Differentiation of Adult Stem Cells

Trilineage Differentiation Assay for MSCs Protocol:

- Osteogenic Differentiation: Culture MSCs to confluence in growth medium, then switch to osteogenic induction medium (DMEM with 10% FBS, 0.1μM dexamethasone, 10mM β-glycerophosphate, 50μM ascorbic acid-2-phosphate) for 21 days. Validate with Alizarin Red S staining of mineralized matrix [14].

- Adipogenic Differentiation: Culture MSCs to confluence in growth medium, then cycle between adipogenic induction medium (DMEM with 10% FBS, 1μM dexamethasone, 0.5mM IBMX, 10μg/mL insulin, 100μM indomethacin) and maintenance medium (DMEM with 10% FBS, 10μg/mL insulin) for 14-21 days. Validate with Oil Red O staining of lipid droplets [14].

- Chondrogenic Differentiation: Pellet 2.5×10⁵ MSCs in conical tube and culture in chondrogenic induction medium (DMEM with 1% ITS+, 100nM dexamethasone, 50μg/mL ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, 40μg/mL proline, 10ng/mL TGF-β3) for 21-28 days. Validate with Alcian Blue staining of sulfated proteoglycans [14].

Analysis of Paracrine Signaling Mechanisms

Comparative Secretome Profiles

The therapeutic effects of both ESC-derived cells and MSCs are largely mediated by their secretome - the complex mixture of factors they release, including cytokines, growth factors, and extracellular vesicles.

Figure 2: Paracrine signaling mechanisms common to both embryonic and adult stem cells, mediating therapeutic effects.

Protocol for Secretome Analysis:

- Conditioned Medium Collection: Culture 80% confluent stem cells in serum-free medium for 24-48 hours. Collect conditioned medium and centrifuge at 2,000×g for 10 minutes to remove cells and debris [11].

- Extracellular Vesicle Isolation: Ultracentrifuge conditioned medium at 100,000×g for 70 minutes at 4°C. Wash pellet in PBS and repeat ultracentrifugation. Resolve EV pellet in appropriate buffer for downstream applications [11].

- Cytokine Array: Use Proteome Profiler Array kits to simultaneously detect multiple soluble factors in conditioned medium. Incubate array membrane with 1mL conditioned medium overnight at 4°C, followed by detection with streptavidin-HRP and chemiluminescence [11].

- Functional Validation - Scratch Assay: Seed endothelial cells in 24-well plates to form monolayers. Create scratch with p200 pipette tip. Treat with stem cell conditioned medium or control medium. Image at 0, 6, 12, and 24 hours to quantify migration [11].

ESC-Specific Paracrine Signaling in Development

ESCs and their differentiated progeny secrete developmental morphogens that establish positional information and tissue patterning.

Protocol for Studying ESC Morphogen Secretion:

- Directed Differentiation: Induce ESCs toward specific lineages using established protocols.

- Conditioned Medium Collection: Collect medium from differentiating ESCs at specific time points.