Enhancing Stem Cell Integration with Host Tissue: Strategies for Improved Survival, Engraftment, and Therapeutic Efficacy

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to enhance the integration of transplanted stem cells with host tissues, a critical challenge in regenerative medicine.

Enhancing Stem Cell Integration with Host Tissue: Strategies for Improved Survival, Engraftment, and Therapeutic Efficacy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to enhance the integration of transplanted stem cells with host tissues, a critical challenge in regenerative medicine. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biological mechanisms of stem cell homing and engraftment, reviews advanced methodological approaches including biomaterial scaffolds and preconditioning strategies, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization hurdles such as poor cell survival and immune rejection, and evaluates validation techniques and comparative efficacy of different cell sources. The goal is to synthesize current scientific knowledge to guide the development of more effective and reliable stem cell-based therapies.

The Biological Blueprint: Understanding the Native Mechanisms of Stem Cell Homing and Engraftment

Stem Cell Integration Technical Support Center

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to assist researchers in navigating the complex process of stem cell integration, from initial engraftment to full functional reconstitution of host tissue.

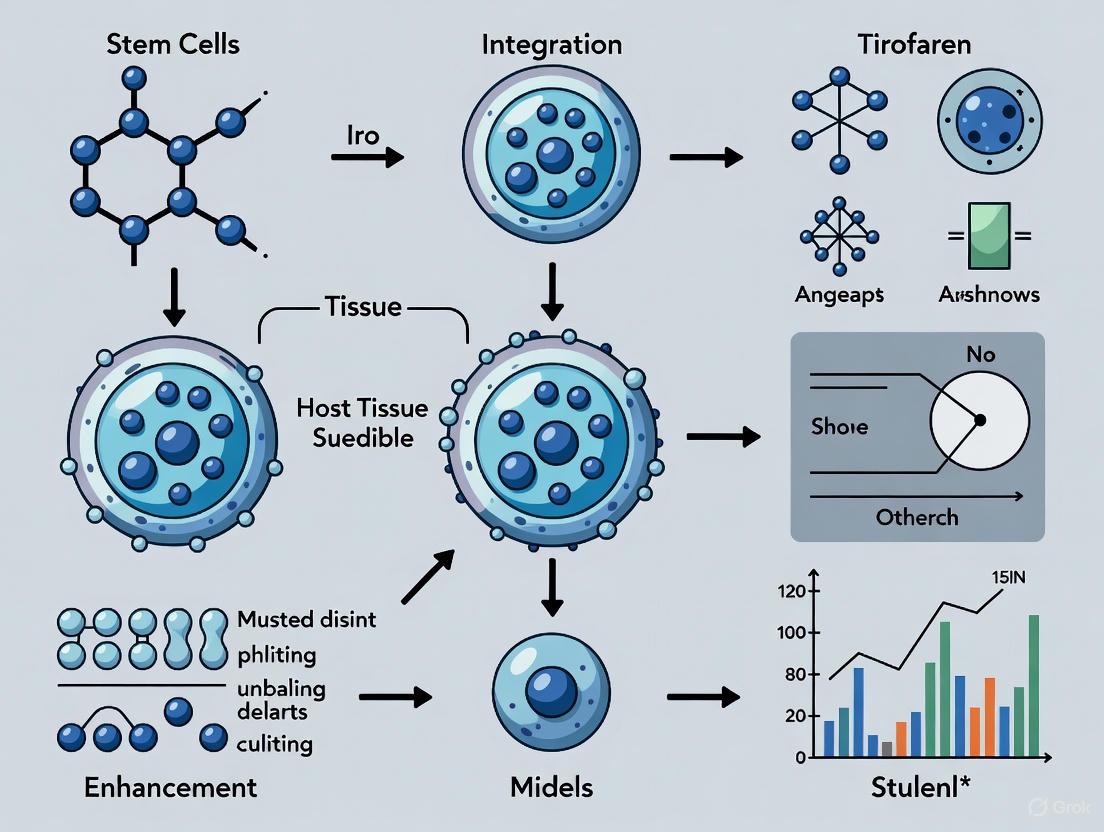

Core Concepts: The Stem Cell Integration Process

Stem cell integration is a multi-stage regenerative cascade where stem cells engraft, self-renew, and reconstitute damaged tissues to restore physiological function [1]. This process is crucial for developing stem cells as "living drugs" that can sense environmental cues, adapt to their microenvironment, and exert sustained therapeutic effects through differentiation, paracrine signaling, and immunomodulation [1].

Stem Cell Integration Pathway

The process begins when tissue injury triggers the release of Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) from damaged cells [2]. These endogenous molecules activate pattern recognition receptors, initiating inflammatory cascades and stem cell mobilization [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: Poor Stem Cell Engraftment Efficiency

Observed Issue: Less than 10% of administered stem cells successfully engraft in target tissues, with remaining cells trapped in reticuloendothelial organs or undergoing apoptosis [3].

Potential Solutions:

- Optimize delivery timing: Administer stem cells during the peak inflammatory phase when SDF-1 chemotactic gradients are strongest [2].

- Enhance vascular support: Implement VEGFR2 activation strategies to promote regeneration of sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs) essential for engraftment [4].

- Pre-condition stem cells: Expose cells to hypoxic conditions or inflammatory cytokines before transplantation to improve survival and homing capability.

- Utilize scaffold matrices: Provide structural support using biomaterial scaffolds that mimic native extracellular matrix.

Problem 2: Inadequate Functional Tissue Reconstitution

Observed Issue: Stem cells engraft but fail to restore physiological function due to poor differentiation, limited integration, or insufficient cell numbers.

Potential Solutions:

- Modulate microenvironment: Incorporate factors that replicate stem cell niche signaling (Wnt, Notch, BMP pathways) to guide proper differentiation [2].

- Ensure appropriate cell density: Plate at optimal densities to prevent spontaneous differentiation while maintaining proliferative potential [5].

- Monitor differentiation status: Remove areas of unwanted differentiation prior to passaging or transplantation [5].

- Employ combinatorial therapies: Combine stem cell delivery with growth factors or small molecules that enhance functional integration.

Problem 3: Limited Long-Term Cell Survival and Integration

Observed Issue: Transplanted cells show initial engraftment but rapidly decline or fail to integrate with host tissue architecture.

Potential Solutions:

- Address hostile microenvironment: Utilize ROCK inhibitors (Y27632) or RevitaCell Supplement during passaging to prevent extensive cell death [6] [5].

- Promote vascular integration: Enhance angiogenesis through co-delivery of endothelial progenitor cells or pro-angiogenic factors.

- Monitor cell health indicators: Passage cells upon reaching ~85% confluency and avoid overly confluent cultures which can result in poor cell survival [6].

- Implement real-time tracking: Use optoacoustic imaging with exogenous contrast agents to monitor cell distribution, migration, and long-term fate [3].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Integration

Protocol 1: Evaluating VEGFR2-Mediated Vascular Regeneration for Hematopoietic Reconstitution

Background: VEGFR2 activation is critical for regeneration of VEGFR3+Sca1- sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs) that are essential for engraftment and restoration of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) [4].

Methodology:

- Myelosuppression Model: Induce bone marrow suppression using:

- Chemotherapy: 5-Fluorouracil (5FU)

- Radiation: Sublethal (650 rad) or lethal (950 rad) irradiation

Bone Marrow Analysis:

- Process decalcified bone marrow sections for immunohistochemistry

- Perform polyvariate flow cytometry on crushed, enzymatically processed femurs

- Identify SECs using immunophenotypic signature: VE-cadherin+MECA32+CD31+VEGFR2+VEGFR3+Sca1-

- Identify arterioles as: VE-cadherin+MECA32+CD31+VEGFR2+VEGFR3−Sca1+

VEGFR2 Inhibition Studies:

- Use conditional VEGFR2 knockout mice

- Administer VEGFR2 signaling inhibitors in wild-type mice post-BMT

- Assess SEC reconstruction and HSPC engraftment at 7, 14, and 21 days

Quantitative Assessment Parameters:

- Percentage of SEC regression/regeneration

- HSPC counts (cKit+Lineage−Sca1+ cells)

- Hematopoietic recovery timelines

Protocol 2: Monitoring Stem Cell Migration and Engraftment via Optoacoustic Imaging

Background: Optoacoustic imaging (OAI) enables real-time tracking of stem cell distribution, migration, and engraftment at clinically relevant depths [3].

Methodology:

- Stem Cell Labeling:

- Incubate mesenchymal stem cells with exogenous contrast agents

- Optimize labeling efficiency by testing varying concentrations and incubation times

- Assess cytotoxicity impact on viability, differentiation, and function

In Vivo Tracking:

- Administer labeled cells via appropriate route (IV, local injection)

- Use multispectral optoacoustic tomography (MSOT) with multiple excitation wavelengths

- Acquire signals simultaneously from endogenous chromophores and exogenous contrast agents

- Perform imaging sessions at 24h, 72h, 1-week, and 2-week intervals

Spectral Unmixing Analysis:

- Separate contrast agent signals from background using characteristic spectral profiles

- Quantify inter- and intra-organ distribution of administered cells

- Correlate signal intensity with cell numbers using established calibration curves

Critical Parameters for Contrast Agent Selection:

- Biocompatibility and low toxicity

- Absorption coefficient at available laser wavelengths

- Narrow, characteristic spectral profile distinct from endogenous chromophores

- Efficient cellular uptake without affecting stem cell functionality

Quantitative Data: Integration Efficiency Parameters

Table 1: Stem Cell Integration Efficiency Benchmarks

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Suboptimal Indicators | Experimental Assessment Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engraftment Rate | >10% of administered cells | <1% successful engraftment | Optoacoustic imaging, bioluminescent tracking, histology [3] |

| Initial Cell Survival | >70% viability post-transplantation | <30% viability at 24 hours | Live/dead staining, metabolic activity assays [5] |

| Functional Duration | Sustained >4 weeks | Rapid decline within 7 days | Longitudinal imaging, functional recovery metrics [3] |

| VEGFR2-mediated SEC Regeneration | Complete by 14 days post-injury | Severe regression persisting >21 days | Immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry [4] |

| HSPC Reconstitution | Lineage-specific cells detectable by 7-10 days | Delayed beyond 21 days | Colony-forming unit assays, blood count monitoring [4] |

Table 2: VEGFR2-Dependent Hematopoietic Reconstitution Data

| Experimental Condition | SEC Regeneration | HSPC Engraftment | Hematopoietic Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady State (No injury) | Maintained VEGFR3+ SEC network | Normal HSPC maintenance | Homeostatic blood cell production |

| Sublethal Irradiation (650 rad) | Minor SEC regression with spontaneous regeneration | Transient decrease with full recovery | Complete recovery within 14 days |

| Lethal Irradiation (950 rad) + BMT | Severe SEC regression requiring VEGFR2 for regeneration | VEGFR2-dependent HSPC reconstitution | Complete recovery only with VEGFR2 signaling |

| Lethal Irradiation + VEGFR2 inhibition | Severely impaired SEC reconstruction | Blocked engraftment and HSPC reconstitution | Failure of hematopoietic recovery |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Stem Cell Integration Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Culture Media | mTeSR Plus, Essential 8 Medium, StemPro hESC SFM | Maintain pluripotency and viability | Use within 2 weeks when stored at 2-8°C; full media change daily [6] [5] |

| Passaging Reagents | ReLeSR, Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent, EDTA | Detach and subculture cells | Optimize incubation time (1-2 min adjustments) based on cell line sensitivity [5] |

| Viability Enhancers | ROCK inhibitor Y27632, RevitaCell Supplement | Improve survival after passaging/thawing | Include during passaging of confluent cultures; feed within 18-24h post-passaging [6] |

| Extracellular Matrices | Geltrex, VTN-N, Matrigel, Poly-L-ornithine/Laminin | Provide structural support and signaling cues | Ensure proper coating; use non-tissue culture-treated plates for some matrices [6] |

| VEGFR Signaling Modulators | VEGFR2 agonists/antagonists | Study vascular regeneration for engraftment | Critical for SEC reconstruction post-myeloablation [4] |

| Optoacoustic Contrast Agents | Engineered nanoparticles, dyes | Enable stem cell tracking via OAI | Must have high absorption coefficients and biocompatibility [3] |

VEGFR2 Signaling in Vascular Regeneration

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the critical relationship between vascular regeneration and stem cell engraftment? A: Research demonstrates that VEGFR2-mediated regeneration of sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs) is essential for hematopoietic stem cell engraftment. Without proper SEC reconstruction, even with bone marrow transplantation, engraftment and reconstitution of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells is severely impaired [4].

Q: Why do stem cells fail to integrate properly despite successful initial engraftment? A: Failed integration can result from multiple factors: hostile microenvironment at injury site, insufficient vascular support, inflammatory rejection, or lack of appropriate differentiation signals. Studies show less than 10% of administered cells typically achieve successful, lasting integration [3].

Q: What methods are available for real-time monitoring of stem cell integration in preclinical models? A: Optoacoustic imaging (OAI) with exogenous contrast agents enables real-time tracking of stem cell distribution, migration, and engraftment at clinically relevant depths. This provides advantages over MRI (better temporal resolution) and optical imaging (greater penetration depth) [3].

Q: How can I improve survival of stem cells after transplantation? A: Strategies include: using ROCK inhibitors during passaging, ensuring optimal cell density (passage at ~85% confluency), avoiding over-confluent cultures, proper matrix coating, and pre-conditioning cells to hostile microenvironments [6] [5].

Q: What are the key differences between stem cells as "living drugs" versus conventional pharmaceuticals? A: Unlike conventional drugs that are metabolized and excreted, living drugs become part of the damaged tissues, exerting longer-lasting effects. A single dose may have sustained impact, with cells actively homing to injury sites and integrating into tissues [1].

FAQs: Core Cellular Mechanisms

Q1: What are the key mechanisms by which Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells (MSCs) mediate their therapeutic effects? MSCs primarily mediate their therapeutic effects through three core mechanisms: multipotent differentiation, paracrine signaling, and immunomodulation.

- Differentiation: MSCs can differentiate into multiple cell lineages, including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes, to directly replace damaged cells [7].

- Paracrine Signaling: MSCs secrete a broad array of bioactive factors—such as growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular vesicles (exosomes)—that modulate the local microenvironment, promote tissue repair, and reduce inflammation. This is now considered a predominant mechanism of action [8] [9] [10].

- Immunomodulation: MSCs interact with both innate and adaptive immune cells (e.g., T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells) to suppress pro-inflammatory responses and promote anti-inflammatory, regenerative states. This occurs via soluble factors and direct cell-cell contact [11] [7].

Q2: How does the local microenvironment or "niche" influence stem cell behavior? The stem cell niche provides critical cues that determine cell fate [2]. Upon tissue injury, the niche is disrupted, leading to the release of Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) and pro-inflammatory cytokines [2]. This inflammatory microenvironment not only mobilizes stem cells but also licenses them, enhancing their paracrine and immunomodulatory activities. Key signals include IFN-γ and TNF-α, which induce MSCs to upregulate the production of immunosuppressive factors like PGE2 and IDO [11].

Q3: What is the clinical significance of the MSC secretome? The secretome—comprising all secreted factors and extracellular vesicles—is a major mediator of MSC therapy. Its clinical significance includes:

- Cell-Free Therapy: Using the secretome or isolated exosomes presents a cell-free therapeutic option, avoiding risks associated with whole-cell transplantation, such as pulmonary entrapment or cellular emboli [8] [10].

- Targeted Action: Secreted factors can be engineered or pre-conditioned to enhance specific therapeutic effects, such as amplifying anti-inflammatory responses in osteoarthritis or promoting angiogenesis in ischemic tissues [12] [10].

Q4: What are the primary soluble factors involved in MSC-mediated immunomodulation, and how do they work? MSCs employ a suite of soluble factors to suppress immune responses, particularly in inflammatory environments. The key factors and their mechanisms are summarized below.

Table: Key Soluble Immunomodulatory Factors from MSCs

| Factor | Primary Mechanism of Action | Therapeutic Context |

|---|---|---|

| Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) | Catalyzes tryptophan degradation into kynurenine, inhibiting T-cell proliferation and function [11]. | Graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), autoimmune disorders [11]. |

| Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) | Inhibits NF-κB nuclear translocation, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α) release. Promotes macrophage shift to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [11] [10]. | Osteoarthritis, inflammatory tissue damage [10]. |

| Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) | Suppresses T-cell and B-cell activity, promotes regulatory T-cell (Treg) generation [11]. | Tissue repair, fibrosis, immune tolerance [12]. |

| Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) | Modulates T-cell and dendritic cell function, supporting anti-inflammatory responses [11]. | Liver regeneration, inflammatory diseases [11]. |

| TNF-α-Stimulated Gene 6 (TSG-6) | Potent anti-inflammatory protein that inhibits NF-κB signaling and neutrophil migration [10]. | Osteoarthritis, degenerative disc disease [10]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: Issue - Poor survival or engraftment of transplanted stem cells.

- Potential Causes: Hostile inflammatory microenvironment, anoikis (detachment-induced cell death), inadequate vascularization, or improper delivery method leading to pulmonary entrapment (for intravenous administration) [8] [13].

- Solutions:

- Preconditioning: Treat MSCs with pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ) or hypoxia before transplantation to enhance their survival and potency [8] [12].

- Biomaterial Scaffolds: Use 3D biomaterial scaffolds to provide structural support, enhance retention, and protect cells from the hostile environment. These scaffolds can be engineered to deliver bioactive cues [8] [13].

- Optimized Delivery: For systemic administration, consider alternative routes to avoid lung entrapment. Local, direct injection into the target tissue is often more effective for engraftment [8].

Q2: Issue - Inconsistent or uncontrolled differentiation outcomes.

- Potential Causes: Uncontrolled microenvironment, heterogeneity in the starting stem cell population, or undefined culture components [5] [12].

- Solutions:

- Define Culture Conditions: Use fully defined, xeno-free culture media and matrices to reduce variability [5].

- Pharmacological Modulation: Apply small molecules to precisely modulate key signaling pathways (Wnt, TGF-β, BMP) that direct lineage specification [12].

- Biophysical Cues: Utilize engineered substrates with specific stiffness and topography to guide mechanotransduction and fate decisions [13].

Q3: Issue - Low homing efficiency of systemically administered MSCs to the target site.

- Potential Causes: The complex homing process involves mobilization, vascular adhesion, and transmigration, which can be inefficient [8].

- Solutions:

Q4: Issue - Variable immunomodulatory effects of MSCs between experiments.

- Potential Causes: MSC potency is highly dependent on the tissue source, donor variability, culture conditions, and the specific inflammatory signals present in the disease microenvironment [8] [11].

- Solutions:

- Standardize Characterization: Rigorously characterize MSCs using ISCT criteria (plastic adherence, trilineage differentiation, specific surface marker profile: CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, CD34-, CD45-, etc.) and assess their immunomodulatory potency in functional assays [8] [7].

- Inflammatory Priming: License MSCs by exposing them to a defined inflammatory cocktail (IFN-γ + TNF-α) to ensure a consistent, potent immunosuppressive phenotype before application [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Investigating Key MSC Mechanisms

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Culture Media (e.g., mTeSR) | Maintains pluripotency and supports consistent growth of human PSCs [5]. | Critical for eliminating variability from serum; less than 2 weeks old for optimal performance [5]. |

| Recombinant Cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α) | Used to "license" or precondition MSCs, enhancing their immunomodulatory capacity [11]. | A combination of IFN-γ and TNF-α is often used to maximally induce IDO and PGE2 expression [11]. |

| Small Molecule Pathway Modulators | Pharmacologically manipulate key stem cell signaling pathways (e.g., Wnt, TGF-β/SMAD, BMP) [12]. | Enables precise control over self-renewal and differentiation without genetic manipulation [12]. |

| Non-Enzymatic Passaging Reagents (e.g., ReLeSR) | Gentle dissociation of hPSC colonies into aggregates for subculturing [5]. | Incubation time must be optimized for each cell line to achieve ideal aggregate size (50-200 μm) [5]. |

| Biomaterial Scaffolds (2D & 3D) | Mimics the native extracellular matrix, providing mechanical support and biochemical cues [8] [13]. | 3D scaffolds better maintain cell-cell interaction and support differentiation compared to 2D [8]. |

| Surface Marker Antibodies (CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR) | Standardized identification and isolation of MSCs via flow cytometry [8] [7]. | Essential for quality control to ensure population purity according to ISCT criteria [7]. |

| Exosome Isolation Kits | Isolate extracellular vesicles from MSC-conditioned medium for paracrine studies [8] [10]. | Enables investigation of cell-free therapies and the specific cargo (miRNA, lncRNA) responsible for therapeutic effects [10]. |

Essential Signaling Pathway Diagrams

NF-κB Pathway in Inflammation

MSC Immunomodulation Mechanisms

Stem Cell Homing and Recruitment

Within the field of stem cell integration and host tissue enhancement, a profound understanding of the initial injury response cascade is paramount. This cascade, initiated by tissue damage, sets the stage for all subsequent repair and regenerative processes. Central to this event is the release of Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs), which activate innate immunity and establish chemotactic gradients, most notably of the cytokine Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1 (SDF-1/CXCL12). These gradients are critical for directing the homing and recruitment of various cell types, including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), neutrophils, and other progenitors, to the site of injury. This technical support document addresses key experimental challenges and provides foundational knowledge to optimize research in this domain, facilitating the development of advanced regenerative therapies.

Core Concepts FAQ

Q1: What initiates the cellular recruitment cascade following tissue injury? The cascade is initiated by the release of intracellular molecules known as Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) from necrotic or stressed cells. These molecules, which include ATP, HMGB1, extracellular DNA/RNA, and heat shock proteins, function as danger signals [2] [14]. They are recognized by Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE), on resident immune cells and tissue stromal cells [2]. This recognition triggers intracellular signaling pathways, primarily NF-κB, leading to the production and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including SDF-1, IL-8, and others, which establish the chemotactic gradients necessary for cell recruitment [2] [14].

Q2: What is the role of the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis in stem cell recruitment? The SDF-1 (CXCL12)/CXCR4 axis is one of the most well-characterized pathways governing stem cell homing. Under homeostatic conditions, SDF-1 secreted by bone marrow stromal cells helps retain stem cells within their niche via interaction with its receptor, CXCR4, expressed on stem cells [2]. Upon tissue injury, the damaged site exhibits a marked increase in SDF-1 production, creating a concentration gradient. Stem cells, including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), sense this gradient through the CXCR4 receptor and undergo a multistep recruitment process: mobilization from the bone marrow into circulation, vascular rolling and adhesion, transendothelial migration, and finally, migration through the extracellular matrix toward the injury site [2].

Q3: How do neutrophils and stem cells interact during the early injury response? Neutrophils are the first immune responders, arriving at the injury site within hours [15] [14]. Their early recruitment is also guided by DAMPs and chemokines like IL-8 [15]. Beyond their antimicrobial role, neutrophils are now recognized as active contributors to tissue repair. They help clear necrotic debris and, crucially, produce cytokines and factors that modify the microenvironment to support subsequent stem cell recruitment and activity [15]. For instance, our team recently discovered that neutrophils mediate the recruitment of stem cells in the early stages of bone regeneration, thereby triggering important repair processes [15]. The transition from neutrophil-dominated inflammation to a repair phase involving stem cells is a critical step for successful regeneration [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Challenge: Weak or Unreliable Stem Cell Migration in Chemotaxis Assays

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Degraded Chemotactic Gradient.

- Solution: The chemotactic gradient formed by SDF-1 bound to vascular and extracellular matrix glycosaminoglycans can extend up to 650 µm [15]. To maintain a stable gradient in vitro, use freshly prepared SDF-1α and ensure the assay chamber is properly sealed to prevent evaporation and convective flow. Consider using microfluidic-based systems that can generate and maintain more stable and complex gradients over longer periods.

Cause: Inappropriate Stem Cell Condition.

- Solution: The homing capacity of stem cells is dependent on their surface receptor expression. Ensure that your MSCs or other progenitor cells express functional CXCR4 receptors. Confirm this via flow cytometry. Passage number can affect receptor expression; use lower-passage cells and consider pre-activation with low-dose cytokines (e.g., IL-6 or SCF) to enhance CXCR4 expression if necessary.

Cause: Incorrect Gradient Concentration.

- Solution: The efficacy of a chemotactic cue is concentration-dependent. An appropriate concentration of IL-8 is required to induce polarization and recruitment of neutrophils; insufficient or excessive levels fail to guide regeneration or cause damage [15]. Systematically titrate the concentration of SDF-1 (e.g., from 10 ng/mL to 200 ng/mL) in your assay to establish the optimal dose for your specific cell type. A bell-shaped response curve is common in chemotaxis.

Challenge: Failure to Detect DAMP-Mediated Signaling in Vitro

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Non-Physiological DAMP Release.

- Solution: Simply adding recombinant DAMPs to culture media may not recapitulate the sterile injury context. Instead, induce sterile cellular damage in a feeder layer of primary cells (e.g., fibroblasts or keratinocytes) using methods like freeze-thaw cycles, mechanical scratch, or targeted irradiation to release a more physiological mixture of endogenous DAMPs [14].

Cause: Insufficient PRR Expression.

- Solution: The cellular response to DAMPs requires expression of relevant PRRs like TLRs and RAGE. Verify that your sensor cell line (e.g., reporter cells or resident macrophages) expresses the necessary receptors (e.g., TLR4 for HMGB1). If using a standard cell line, consider engineering a reporter system or using primary cells isolated from the target tissue.

Cause: Inadequate Readout of Pathway Activation.

- Solution: DAMP signaling often converges on the NF-κB pathway [2] [14]. Implement robust assays to detect NF-κB activation, such as phospho-specific antibodies for IκBα or p65 NF-κB via western blot, immunofluorescence to visualize p65 nuclear translocation, or using NF-κB luciferase reporter constructs.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Establishing a DAMP-Mediated Inflammatory Model In Vitro

Objective: To create a reliable in vitro system that mimics the sterile inflammatory response following tissue injury for studying downstream chemokine production and cell recruitment.

Materials:

- Primary fibroblasts or other relevant tissue-resident cells.

- Cell culture plates.

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Liquid nitrogen or a mechanical scratcher.

- ELISA kits for SDF-1, IL-8, and other chemokines.

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Seed a confluent monolayer of primary fibroblasts in a multi-well plate and allow them to adhere overnight.

- Induction of Injury:

- Option A (Freeze-Thaw): Wash the monolayer with PBS. Place the plate in a -80°C freezer for 30 minutes, then thaw at 37°C. Repeat for 2-3 cycles [14].

- Option B (Mechanical Scratch): Create a uniform scratch wound in the monolayer using a sterile pipette tip or cell scratcher.

- Conditioned Media Collection: After injury, add fresh serum-free medium and incubate the cells for 6-24 hours. Collect the supernatant (conditioned media) and centrifuge to remove cell debris. Aliquot and store at -80°C.

- Validation: Use the conditioned media to treat naïve reporter cells or to perform ELISA to quantify the release of SDF-1 and other DAMPs-induced chemokines.

Protocol: Quantifying Stem Cell Chemotaxis Using a Transwell System

Objective: To accurately measure the directed migration of stem cells toward an SDF-1 gradient.

Materials:

- Transwell plates with porous membranes (5-8 µm pore size).

- Serum-free basal medium.

- Recombinant SDF-1α.

- Cell staining solution (e.g., Crystal Violet or Calcein-AM).

- 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA).

Methodology:

- Gradient Establishment: Dilute recombinant SDF-1α in serum-free medium to the desired concentration (e.g., 50-100 ng/mL). Add this chemoattractant solution to the lower chamber of the Transwell plate. For a negative control, use serum-free medium only.

- Cell Seeding: Harvest and resuspend stem cells (e.g., MSCs) in serum-free medium. Seed a defined number of cells (e.g., 1x10^5) into the upper chamber of the Transwell insert.

- Incubation and Migration: Incubate the plate for 4-24 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator to allow cell migration.

- Quantification:

- After incubation, carefully remove the non-migrated cells from the top of the membrane with a cotton swab.

- Fix the migrated cells on the bottom side of the membrane with 4% PFA for 10 minutes.

- Stain the cells with Crystal Violet or Calcein-AM.

- Count the stained cells manually under a microscope or dissolve the stain and measure the absorbance for quantification.

Signaling Pathway Visualizations

DAMP Sensing and SDF-1 Production

Stem Cell Recruitment via SDF-1/CXCR4 Axis

Data Presentation: Key Chemoattractants in the Injury Cascade

Table 1: Major Chemoattractants and Their Roles in Cell Recruitment Following Injury.

| Chemoattractant | Primary Target Cell(s) | Key Receptor(s) | Core Function in Recruitment | Notes & Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDF-1 (CXCL12) | MSCs, HSCs, EPCs | CXCR4 | Guides stem/progenitor cell homing from bone marrow to injury site [2]. | The axis is a primary regulator of stem cell retention and mobilization. |

| IL-8 (CXCL8) | Neutrophils | CXCR1, CXCR2 | Primary neutrophil chemotactic factor; establishes a local chemotactic gradient [15]. | Concentration is critical; inappropriate levels can inhibit repair or cause damage [15]. |

| N-formyl peptides (e.g., fMLP) | Neutrophils | FPR1 | Potent bacterial-derived chemoattractant; also acts on mitochondria released from damaged cells [15] [16]. | Useful for inducing strong neutrophil chemotaxis in control experiments. |

| DAMPs (HMGB1, ATP) | Macrophages, Neutrophils, Dendritic Cells | TLRs (e.g., TLR4), RAGE, P2X/P2Y Receptors | Initiate the response by inducing production of other chemokines (SDF-1, IL-8) [2] [14]. | Represent the initial "danger" signal; use a mix for a physiologically relevant model. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Studying DAMPs and Chemotactic Gradients.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SDF-1α / IL-8 | To establish defined chemotactic gradients in Transwell or microfluidic assays. | Verify species specificity and bioactivity. Aliquot to avoid freeze-thaw cycles. |

| CXCR4 Antagonists (e.g., AMD3100) | To chemically inhibit the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis and confirm its specific role in migration. | Can be used to mobilize stem cells from bone marrow in vivo. |

| Anti-CXCR4 Antibody | For flow cytometric analysis of receptor expression on stem cells. | Critical for correlating migration efficiency with receptor presence. |

| TLR4 Agonists (LPS) & Antagonists (TAK-242) | To specifically activate or inhibit a major DAMP (HMGB1) sensing pathway. | Use ultrapure LPS to avoid confounding TLR2 responses. TAK-242 is a specific small-molecule inhibitor. |

| Phospho-specific NF-κB Antibodies | To detect activation of the key downstream signaling pathway of DAMP recognition. | Measures IκBα degradation or p65 phosphorylation/translocation. |

| Transwell Assay Plates | The standard workhorse for quantifying chemotaxis in a semi-in-vivo setting. | Choose membrane pore size (5-8 μm) appropriate for your cell type. |

Fundamental Concepts: The Stem Cell Niche

What is a stem cell niche?

A stem cell niche is a distinct, dynamic, and specialized microenvironment that provides a physical anchor for stem cells and regulates their fate through a complex set of biochemical, biophysical, and cellular cues [17] [18]. First proposed by R. Schofield in 1978 for hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), the niche concept explains how the local microenvironment maintains stem cell self-renewal, controls the balance between quiescence and proliferation, and guides differentiation and maturation [17]. Think of it as a dedicated "support system" that instructs stem cells on when to rest, divide, or specialize.

What are the core components of a niche?

The niche is an ensemble of multiple components that work in concert. The key elements include:

- Supporting Cells: Other cell types, such as mesenchymal stromal cells, osteoblasts, or endothelial cells, provide direct contact and secrete short-range signaling factors [17] [18].

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM): A sugar-rich, crosslinked gel network of structural proteins (e.g., collagens, laminin, fibronectin) and proteoglycans that provides structural support and biochemical signaling [18].

- Soluble Factors: Signaling molecules like growth factors, cytokines, and morphogens (e.g., WNTs, BMPs, FGFs) that can be freely diffusible or immobilized on the ECM [18].

- Physicochemical Cues: Parameters such as oxygen levels (hypoxia), metabolic signals (e.g., calcium ions, reactive oxygen species), and biomechanical forces [17] [18].

Why is understanding the niche critical for tissue regeneration and integration?

For a transplanted stem cell to successfully integrate into host tissue and restore function, it must receive the correct instructions from its new microenvironment [2] [1]. The niche provides the essential cues that direct stem cell homing, survival, fate decisions, and functional incorporation into the existing tissue architecture [2]. By recreating or manipulating these niche signals in vitro, we can pre-condition stem cells for enhanced in vivo integration potential and therapeutic efficacy [18].

Troubleshooting Guides for Niche-Based Experiments

Problem: Poor Survival or Integration of Transplanted Stem Cells

This is a common failure point in pre-clinical studies, often indicating a mismatch between the delivered cells and the host microenvironment.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Recommended Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Hostile host environment at the injury site (inflammation, fibrosis). | Pre-treat cells in vitro with pro-survival cytokines or use biomaterial scaffolds to shield cells. | Enhances cell resilience to inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress present in damaged tissue [1]. |

| Insufficient homing to the target tissue. | Pre-activate cells by priming with specific chemokines (e.g., SDF-1). | Upregulates homing receptors (e.g., CXCR4), improving navigation along chemotactic gradients to the injury site [2]. |

| Lack of essential niche signals for engraftment. | Co-transplant supportive niche cells (e.g., MSCs) or use ECM-based hydrogels. | Provides immediate, localized paracrine support and cell-matrix interactions that mimic a pro-regenerative niche [1] [18]. |

Problem: Uncontrolled Differentiation In Vitro

When stem cells differentiate unpredictably in culture, the niche-mimicking conditions are likely suboptimal.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Recommended Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent or low-quality stem cell starting population. | Rigorously remove differentiated areas before passaging and use controlled, high-quality cell lines as controls. | A homogeneous, pluripotent starting population is essential for reproducible response to differentiation cues [6] [5]. |

| Incorrect or uneven presentation of differentiation factors. | Use defined, immobilized growth factors instead of only soluble factors to better control concentration and localization. | Immobilizing morphogens (e.g., BMPs) on the ECM or culture surface more closely mimics the natural niche and prevents diffuse signaling [18]. |

| Suboptimal cell seeding density. | Standardize and optimize initial cell density for differentiation assays; both overly confluent and sparse cultures skew fate decisions. | Cell-cell contact is a critical niche signal; incorrect density disrupts endogenous signaling gradients and paracrine communication [6] [5]. |

Problem: Failure of 3D Niche Model Assembly (e.g., Organoids, Bone Marrow-on-a-Chip)

Advanced 3D models are prone to failure due to their complexity.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Recommended Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect ECM composition or stiffness. | Systematically test different ECM hydrogels (e.g., Matrigel, Geltrex, synthetic peptides) and mechanical properties. | Stem cell fate is profoundly influenced by ECM composition and matrix stiffness through integrin-mediated signaling [19] [18]. |

| Lack of essential cellular co-culture partners. | Introduce relevant supporting cells, such as endothelial cells for vascularization or MSCs for stromal support. | Niches are multi-cellular; the absence of key supporting cells fails to recapitulate essential paracrine and cell-contact signals [19] [17]. |

| Inadequate nutrient or oxygen diffusion. | Optimize the size of 3D constructs and consider using perfused microfluidic systems (organs-on-chips). | Central necrosis in large organoids indicates hypoxia and nutrient deprivation, which disrupts normal morphogenesis and niche function [19] [18]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How do niches influence stem cell fate decisions?

Niches regulate fate through an integrated signaling network. The diagram below summarizes the key regulatory pathways and their logical relationships within a stem cell niche.

What are the key differences betweenin vivoniches and currentin vitromodels?

While in vitro models have advanced significantly, key disparities remain.

| Feature | In Vivo Niche | Current In Vitro Models | Implication for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complexity | Highly complex, multi-cellular, and vascularized. | Simplified, often lacking full cellular repertoire and vasculature. | Models may miss critical signals from missing cell types or systemic inputs [19] [18]. |

| Dynamic Regulation | Signals change spatiotemporally in response to physiology and injury. | Often static; controlled delivery of multiple factors is challenging. | Fails to fully recapitulate the dynamic sequence of events during repair [2] [17]. |

| Biomechanics | Precise and tissue-specific mechanical properties. | Stiff plastic (2D) or variable hydrogel mechanics (3D). | Altered mechanotransduction can direct cells toward aberrant fates [18]. |

Can we target niches for therapeutic purposes?

Yes, this is a promising frontier. Instead of replacing cells, therapies can be designed to reactivate endogenous niches to enhance the body's own repair mechanisms [17]. For example, after a heart attack, delivering specific niche factors could potentially stimulate resident cardiac stem cells to proliferate and repair the damage, reducing the need for complex cell transplantation procedures [1].

How does the niche concept relate to cancer?

The concept of a "cancer stem cell niche" is critically important. Cancer stem cells are believed to reside in specialized microenvironments that protect them and sustain their self-renewal [18]. These niches can hijack normal signaling pathways to promote tumor growth and confer resistance to chemotherapy and radiation. Therefore, understanding and therapeutically disrupting the cancer stem cell niche is a major focus of oncology research [18].

Experimental Protocols: Key Workflows

Workflow: Establishing a Simplified 2D Niche Model to Study HSC-MSC Interactions

This protocol outlines the creation of a reductionist system to investigate how mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) influence hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) fate.

Detailed Methodology:

- Surface Preparation: Coat a tissue culture-treated plate with human fibronectin (5 µg/mL in PBS) for at least 1 hour at 37°C.

- Stromal Layer: Seed human bone marrow-derived MSCs at a density of 5,000-10,000 cells/cm² on the coated surface. Culture them in MSC growth medium until a confluent monolayer is formed.

- HSC Isolation: Isolate CD34+ HSCs from human umbilical cord blood using a clinical-grade immunomagnetic separation kit, following the manufacturer's instructions.

- Co-culture: Plate the isolated HSCs (at 1,000-5,000 cells/cm²) directly onto the pre-established MSC monolayer.

- Culture Conditions: Maintain the co-culture in a defined serum-free hematopoietic support medium, supplemented with key cytokines like Stem Cell Factor (SCF; 50 ng/mL) and FLT3-Ligand (FLT3-L; 50 ng/mL) [19].

- Analysis:

- Phenotype: After 7 days, harvest non-adherent and gently dissociated adherent cells. Analyze for HSC markers (e.g., CD34, CD90, CD45RA) via flow cytometry.

- Functionality: Perform colony-forming unit (CFU) assays in methylcellulose to assess multilineage differentiation potential.

Workflow: Testing the Role of immobilized vs. Soluble Cues on Neural Stem Cell (NSC) Fate

This protocol compares the effect of different growth factor presentations on NSC differentiation.

Detailed Methodology:

- Surface Functionalization:

- Arm 1 (Immobilized): Coat plates with a mixture of laminin (10 µg/mL) and FGF-2 (1 µg/mL) that has been chemically cross-linked to the surface using a sulfo-SANPAH crosslinker protocol [18].

- Arm 2 (Soluble) & Arm 3 (Control): Coat plates with laminin (10 µg/mL) only.

- NSC Culture: Seed human neural stem cells at a density of 2.5 x 10⁴ cells/cm² onto the prepared surfaces. Use fresh, pre-warmed neural induction medium.

- Factor Presentation:

- Arm 1: Use basal neural induction medium without added soluble FGF-2.

- Arm 2: Supplement the medium with soluble FGF-2 (20 ng/mL).

- Arm 3: Use basal medium without any FGF-2.

- Culture and Differentiation: Culture the cells for 7-10 days, changing the medium every other day.

- Analysis:

- Immunocytochemistry: Fix cells and stain for neural lineage markers: β-III-Tubulin (neurons), GFAP (astrocytes), and O4 (oligodendrocytes). Quantify the percentage of cells positive for each marker.

- qPCR: Analyze gene expression markers for the same lineages.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for studying and reconstructing stem cell niches in vitro.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Niche Research | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Culture Media (e.g., mTeSR Plus, Essential 8) | Maintain pluripotency of hPSCs in feeder-free conditions, providing a consistent basal medium for niche studies [6] [5]. | Ensure medium is fresh (<2 weeks old at 2-8°C) to prevent spontaneous differentiation. |

| ECM Hydrogels (e.g., Geltrex, Matrigel, Laminin, synthetic peptides) | Provide a biologically active 3D scaffold that mimics the in vivo ECM, presenting adhesion sites and immobilizing growth factors [6] [18]. | Different stem cell types may require specific ECMs (e.g., VTN-N for hPSCs, Laminin for NSCs). |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Improves survival of dissociated stem cells (especially hPSCs) after passaging or thawing by inhibiting apoptosis [6] [5]. | Use as a supplement for 18-24 hours post-passaging. Critical for single-cell seeding. |

| Cytokines & Growth Factors (e.g., SCF, BMPs, FGFs, WNTs) | Recreate key signaling pathways of the niche to direct self-renewal, differentiation, and maturation [2] [19]. | Consider immobilization strategies to mimic the natural, spatially restricted presentation in the niche [18]. |

| Small Molecule Agonists/Antagonists | Precisely control key signaling pathways (WNT, BMP, TGF-β) in a time-dependent manner to direct stem cell fate [18]. | Offer advantages over recombinant proteins, including stability, cost, and reversibility. |

| Chemokines (e.g., SDF-1/CXCL12) | Study and enhance the homing potential of stem cells by activating receptors like CXCR4, guiding cells to injury sites [2]. | Used for in vitro migration assays and pre-conditioning cells before transplantation. |

Quantitative Comparison of Stem Cell Types

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, integration mechanisms, and key challenges associated with Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs), and Tissue-Specific Stem Cells, providing a foundational comparison for researchers [20] [1] [21].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Stem Cell Types for Integrative Potential

| Feature | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Tissue-Specific Stem Cells (e.g., HSCs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potency & Differentiation | Multipotent (primarily mesodermal lineages: osteo-, chondro-, adipo-genic; reported transdifferentiation) [7] [21] | Pluripotent (can differentiate into all three germ layers) [20] [1] | Multipotent (typically limited to lineages of their tissue of origin) [1] |

| Primary Integration Mechanism | Predominantly paracrine signaling (trophic factors, extracellular vesicles); low-rate, transient engraftment [21] | Direct differentiation and replacement of damaged host cells; potential for functional engraftment [20] [1] | Direct engraftment, self-renewal, and reconstitution of host tissue lineages (e.g., blood, immune cells) [1] |

| Key Markers (Positive) | CD73, CD90, CD105 [7] | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG [20] [22] | Varies by tissue (e.g., CD34 for HSCs) [7] |

| Key Markers (Negative) | CD34, CD45, CD11b, CD19, HLA-DR [7] | - | - |

| Tumorigenic Risk | Low [20] [21] | High (due to reprogramming factors, genomic instability) [20] | Low (in their native context) |

| Immunogenicity | Low; immunomodulatory [7] [21] | Low for autologous use; potential immunogenicity from epigenetic aberrations [20] | High for allogeneic transplantation (requires matching) |

| Major Challenges | Functional heterogeneity, low engraftment efficiency, donor-dependent variations [21] | Tumorigenicity, immunogenicity, genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity [20] | Limited availability, expansion difficulties in vitro |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Integrative Potential

Protocol 1: Evaluating MSC Migration and Paracrine Activity

Objective: To assess the homing capability and secretome-mediated effects of MSCs, which are central to their integrative potential and therapeutic efficacy [2] [21].

Materials:

- Isolated MSCs (e.g., from bone marrow, umbilical cord, or adipose tissue) [7].

- Complete MSC growth medium (e.g., α-MEM supplemented with human platelet lysate) [20].

- Transwell migration chamber.

- Conditioned medium from MSC cultures.

- Target cells relevant to the disease model (e.g., cardiomyocytes for cardiac repair).

Methodology:

- Homing/Migration Assay: [2] [21]

- Place MSCs in the upper chamber of a Transwell insert.

- Add a chemotactic gradient of a known chemoattractant (e.g., SDF-1) to the lower chamber to simulate injury signals [2].

- Incubate for 6-24 hours under standard culture conditions.

- Fix and stain the cells that have migrated to the lower membrane surface.

- Count the cells under a microscope to quantify migratory capacity.

- Paracrine Effect Assay: [21]

- Culture MSCs until 70-80% confluency.

- Replace the medium with a serum-free option and incubate for 24-48 hours to collect conditioned medium (CM).

- Filter the CM to remove any cells or debris.

- Apply the CM to target cells (e.g., those subjected to oxidative stress or injury).

- Assess target cell viability (e.g., via MTT assay), apoptosis (e.g., caspase activity), and proliferation (e.g., Ki-67 staining) to measure the paracrine-mediated therapeutic effect.

Protocol 2: Assessing iPSC Differentiation and Functional Integration

Objective: To guide iPSCs to differentiate into specific lineages and verify their functional integration into host tissues, a key step for regenerative therapies [20] [1].

Materials:

- Validated iPSC line.

- Essential 8 Medium or similar feeder-free maintenance medium [6] [5].

- Differentiation kits or specific cytokine cocktails for target lineage (e.g., activin A for definitive endoderm).

- ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) for enhancing cell survival after passaging [6].

- Immunocytochemistry reagents for lineage-specific markers.

Methodology:

- iPSC Culture and Quality Control: [20] [5]

- Maintain iPSCs in a pluripotent state using defined media like Essential 8 on vitronectin (VTN-N)-coated plates.

- Monitor cultures daily for spontaneous differentiation. Remove differentiated areas manually or through selective passaging before starting differentiation protocols [5].

- Passage cells at ~85% confluency using EDTA or gentle dissociation reagents to maintain healthy, undifferentiated cultures [5].

Directed Differentiation: [20]

- Initiate differentiation by switching to specific induction media when iPSCs reach an optimal density.

- For robust results, include control cell lines (e.g., H9 or H7 ESC lines) to account for protocol variability and line-specific differentiation efficiency [6].

- Adjust cell seeding density and induction time based on the target lineage and the specific iPSC line used [6].

Verification of Integration and Function: [1]

- After differentiation, analyze the cells for expression of lineage-specific markers via immunostaining or flow cytometry.

- For in vivo integration studies, transplant the differentiated cells into appropriate animal models.

- Perform long-term follow-up to assess both functional improvement (e.g., motor function, electrical activity) and safety, specifically monitoring for tumor formation [20].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: How Can We Overcome the Low Engraftment Efficiency of MSCs in Host Tissue?

Challenge: A significant hurdle in MSC therapy is the low rate of cell retention and engraftment at the target site post-transplantation, which limits their direct regenerative contribution [21].

Solutions:

- Cell Priming/Preconditioning: Pre-treat MSCs with inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, TNF-α) or culture under hypoxic conditions before transplantation. This mimics the injury microenvironment, enhancing the cells' survival, homing, and paracrine activity [21].

- Genetic Modification: Engineer MSCs to overexpress homing-related receptors (e.g., CXCR4, the receptor for SDF-1) to improve their recruitment to injury sites [2] [21].

- Biomaterial-Assisted Delivery: Use hydrogel-based scaffolds or other biomaterials to encapsulate MSCs. These materials provide a protective niche, improve localization, and support cell survival and function at the transplantation site [21].

FAQ 2: What Are the Critical Steps to Minimize Tumorigenic Risk in iPSC-Derived Therapies?

Challenge: The use of iPSCs is associated with potential tumor formation, primarily due to residual undifferentiated cells or genetic abnormalities acquired during reprogramming and culture [20].

Solutions:

- Rigorous Purification: Implement stringent purification protocols post-differentiation to remove any residual pluripotent cells. This can be achieved using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with antibodies against pluripotency markers (e.g., TRA-1-60) or by using cell surface markers specific to the desired differentiated cell type.

- Vector-Free Reprogramming: Utilize non-integrating Sendai virus vectors or episomal plasmids for reprogramming to prevent insertional mutagenesis. For existing lines, ensure clearance of reprogramming vectors; for example, with the CytoTune-iPS Sendai 2.0 Kit, a temperature shift can be used to clear specific vectors after sufficient passages [6].

- Comprehensive Safety Monitoring: Employ genomic integrity assays (e.g., karyotyping, CNV analysis) throughout the culture and differentiation process. Always include long-term in vivo studies in animal models to monitor for teratoma or tumor formation before clinical application [20].

FAQ 3: How Can Heterogeneity in MSC Batches Be Controlled for Reproducible Experimental Outcomes?

Challenge: MSCs exhibit significant donor-to-donor and source-to-source variability, leading to inconsistent experimental and therapeutic results [21].

Solutions:

- Standardized Characterization: Adhere strictly to the updated International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT) criteria, which define markers and functional attributes for MSCs. Perform rigorous batch-level quality control, including trilineage differentiation assays and surface marker profiling [21].

- Use of Defined Culture Systems: Avoid using fetal bovine serum (FBS). Instead, use defined supplements like human platelet lysate (HPL) to reduce batch variability and the risk of xenogenic immune reactions [20] [21].

- Functional Potency Assays: Instead of relying solely on surface markers, implement quantitative functional assays tailored to the intended therapeutic mechanism (e.g., T-cell suppression assay for immunomodulation, angiogenesis tube formation assay for vascular repair) to ensure batch potency [21].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows for Stem Cell Integration

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the key signaling pathways and experimental workflows central to stem cell integration.

Diagram 1: SDF-1/CXCR4 Pathway in Stem Cell Homing

This diagram visualizes the SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling axis, a primary pathway responsible for mobilizing and recruiting stem cells to sites of injury [2]. Following tissue damage, the release of Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) triggers the production of the chemokine SDF-1, which creates a concentration gradient. Stem cells expressing the CXCR4 receptor sense this gradient, leading to their directed migration (homing) toward the injury site, a prerequisite for subsequent integration [2].

Diagram 2: Stem Cell Integration Workflow

This workflow outlines the general path from stem cell preparation to functional recovery in host tissue. It highlights the critical divergence in the mechanism of action post-homing: MSCs primarily exert effects via paracrine signaling, while iPSCs and Tissue-Specific Stem Cells like HSCs aim for direct integration and replacement of damaged cells [1] [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Stem Cell Integration Research

| Reagent | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Human Platelet Lysate (HPL) | A defined, xeno-free supplement for MSC culture; enhances cell growth and reduces variability compared to FBS [20]. | Can be gradually increased in concentration (e.g., in α-MEM) to accommodate and optimize cell growth [20]. |

| Essential 8 Medium | A defined, feeder-free culture medium designed for the maintenance of human pluripotent stem cells (hESCs and iPSCs) [6] [5]. | Allows for seamless transition of PSCs grown in other systems (e.g., mTeSR on Matrigel) when passaged with EDTA [6]. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | A small molecule that significantly improves the survival of human pluripotent stem cells after single-cell dissociation, cryopreservation, and passaging [6]. | Sold as RevitaCell Supplement. Critical for use during passaging, especially if cells are overly confluent [6] [5]. |

| Vitronectin (VTN-N) | A defined, recombinant substrate for feeder-free adhesion and culture of human pluripotent stem cells [6] [5]. | Used with Essential 8 Medium. Requires non-tissue culture-treated plates for effective coating [5]. |

| Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent | A non-enzymatic, gentle solution for passaging adherent pluripotent stem cells as small aggregates, minimizing differentiation [5]. | Preferable to enzymatic digestion for maintaining colony integrity; incubation time may require optimization per cell line [5]. |

Engineering Integration: Advanced Biomaterial and Delivery Strategies for Clinical Translation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Hydrogel-Based Scaffolds

Q1: What are the key advantages of using hydrogels as synthetic stem cell niches? Hydrogels are highly hydrated, microporous 3D scaffolds that provide an ideal microenvironment for stem cells. Their key advantages include the ability to stably encapsulate stem cells along with signaling molecules or growth factors, and to act as an immunological barrier that protects implanted cells from host immune attack while remaining permeable to therapeutic molecules [23]. They can be engineered with specific mechanical properties and degradation rates to match the target tissue.

Q2: How can I improve the survival and retention of stem cells delivered via hydrogel? Using specially designed, injectable hydrogels can significantly enhance cell retention. For instance, studies have shown that endothelial progenitor cells seeded into a hyaluronic acid (HA) shear-thinning hydrogel exhibited enhanced engraftment efficiency in rat hearts. Similarly, peptide amphiphile-based hydrogels have been shown to ensure growth factor retention, which increases the proliferation of encapsulated muscle stem cells [23].

Electrospun Fiber Scaffolds

Q3: Why are 3D electrospun scaffolds preferable to traditional 2D membranes for tissue engineering? Traditional 2D electrospun membranes are limited by their thinness and high packing density, which result in poor cellular infiltration and restricted nutrient diffusion [24]. Three-dimensional electrospun nanofiber-based scaffolds (3D ENF-S) overcome these limitations by providing a biomimetic 3D environment with significantly increased thickness and porosity. This architecture facilitates deep cell penetration, supports neo tissue development, and promotes higher genetic material expression related to ECM secretion and cell metabolism [24].

Q4: What are the primary methods for fabricating 3D electrospun nanofiber scaffolds? Fabrication methods can be classified into three main categories [24]:

- Electrospun Nanofiber 3D Scaffolds: Created via post-processing techniques (e.g., stacking, rolling, gas foaming) or by tuning collection techniques (e.g., using patterned collectors, cryogenic electrospinning).

- Electrospun Nanofiber/Hydrogel Composite 3D Scaffolds: Combine the fibrous structure of electrospinning with the high hydrability of hydrogels.

- Electrospun Nanofiber/Porous Matrix Composite 3D Scaffolds: Integrate fibers within other porous matrices to create composite structures.

3D Constructs and Host Integration

Q5: What is the concept of "in situ tissue regeneration" and how do scaffolds facilitate it? In situ tissue regeneration is an approach that bypasses extensive ex vivo cell manipulation by using a target-specific biomaterial scaffold to recruit the host's own endogenous stem or progenitor cells to the site of injury [25]. The implanted scaffold, often incorporating bioactive molecules, provides a template and appropriate microenvironment that guides these recruited cells to proliferate and differentiate into the desired tissue type, effectively regenerating damaged tissue without cell transplantation [25].

Q6: How do the physical properties of a biomaterial scaffold influence stem cell fate? The structural and mechanical properties of a scaffold are critical for regulating stem cell behavior and must be matched to the target tissue. For example, hard tissues like bone require scaffolds with relatively strong mechanical properties for load-bearing, whereas soft tissues like skin need porous, soft, and highly viscous biomaterials [23]. Properties such as surface charges, chemical compositions, and topography all play key roles in directing stem cell adhesion, survival, proliferation, and differentiation [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Cell Viability and Retention after Transplantation

Problem: Poor survival and rapid loss of transplanted stem cells at the injury site, with studies showing less than 5% cell retention on the first day after transplantation [23].

| Possible Cause | Solution | Experimental Example |

|---|---|---|

| Harsh microenvironment at injury site | Use a protective, biocompatible scaffold to shield cells. | Utilize a hyaluronic acid (HA) hydrogel to encapsulate cells, which acts as a physical barrier and improves the local microenvironment [23]. |

| Lack of proper cell-matrix interaction | Provide a 3D scaffold that mimics the native ECM. | Culture stem cells on a 3D electrospun nanofiber scaffold that recapitulates the fibrous structure of native ECM, promoting adhesion and survival [24]. |

| Inadequate pro-survival signaling | Co-deliver growth factors or incorporate bioactive peptides. | Incorporate the RGD peptide (a common cell-adhesion motif) into your hydrogel or fiber scaffold to enhance integrin-mediated cell survival signaling [23]. |

Poor Cellular Infiltration into Scaffolds

Problem: Cells remain on the surface of the scaffold and fail to migrate into its core, leading to limited tissue formation and potentially poor integration with the host.

| Possible Cause | Solution | Experimental Example |

|---|---|---|

| Small pore size and high packing density (common in 2D electrospinning) | Optimize fabrication to create larger, interconnected pores. | Employ cryogenic electrospinning, where ice crystals act as templates to create scaffolds with large pores (10-500 μm) [24]. |

| Insufficient bioactivity to guide cell migration | Functionalize the scaffold with chemoattractants. | Incorporate the neuropeptide Substance P (SP) into your scaffold. SP has been shown to effectively mobilize CD29+ MSC-like cells from bone marrow and drive their migration to injury sites [25]. |

| Scaffold's chemical composition is not conducive to cell attachment | Modify surface chemistry or use natural polymers. | Use natural polymers like collagen or chitosan, which inherently contain cell-binding domains, or coat synthetic scaffolds with these materials [26]. |

Inadequate Differentiation into Target Lineage

Problem: Stem cells within the scaffold do not efficiently differentiate into the desired functional cell type.

| Possible Cause | Solution | Experimental Example |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of specific differentiation cues | Sustained delivery of differentiation-inducing growth factors. | For neural differentiation, incorporate Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) or Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) via microspheres for controlled release within the scaffold [26]. |

| Mismatch between scaffold stiffness and target tissue | Tune the mechanical properties of your biomaterial. | For neural tissue engineering (a soft tissue), use soft hydrogels (~0.1-1 kPa) to promote neurogenesis, while for bone tissue, use stiffer scaffolds (>10 kPa) to promote osteogenesis [23]. |

| Uncontrolled differentiation (e.g., excessive spontaneous differentiation) | Ensure pre-differentiation culture conditions maintain cell potency and start with high-quality, undifferentiated cells. | Prior to seeding, ensure your stem cell cultures are healthy and undifferentiated. Refer to standard troubleshooting guides for hPSC culture to manage excessive differentiation [5]. |

Mechanical and Physical Properties of Common Biomaterial Polymers

Table 1: Key characteristics of natural and synthetic polymers used in scaffold fabrication.

| Polymer | Type | Key Properties | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen | Natural | Biocompatible, low immunogenicity, FDA-approved for some applications, can be processed into films, fibers, and sponges [25]. | Skin, bone, neural tissue regeneration [26] [25]. |

| Chitosan | Natural (Polysaccharide) | Biocompatible, biodegradable, antimicrobial properties [25]. | Nerve conduits, wound dressings [26]. |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Synthetic | Biodegradable, thermoplastic, tunable degradation rate, FDA-approved for sutures and devices [25]. | General tissue engineering, drug delivery [26] [25]. |

| Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) | Synthetic | Biodegradable, slow degradation, good mechanical strength [24]. | Long-term implantable scaffolds, bone, nerve guides [26] [24]. |

| Hyaluronic Acid | Natural (Glycosaminoglycan) | Highly hydrated, inherent cell signaling properties, can be modified to form hydrogels [23]. | Injectable hydrogels for cardiac, cartilage repair [23]. |

| Polyaniline (PANI) | Conductive Polymer | Conducts electricity, can help neurite outgrowth and cell activation by carrying electrical impulses [26]. | Neural tissue engineering, biosensors [26]. |

Performance Metrics of Advanced Scaffold Designs

Table 2: Documented outcomes of various scaffold-based strategies in experimental models.

| Scaffold Type | Cell Type | Key Outcome | Reference Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| HA Shear-Thinning Hydrogel | Endothelial Progenitor Cells | Enhanced engraftment efficiency and reduced myocardial fibrosis compared to saline-treated cells [23]. | Ischemic rat heart [23] |

| Peptide Amphiphile Hydrogel | Muscle Stem Cells | Ensured growth factor retention and increased proliferation of encapsulated cells [23]. | Injured mouse muscle [23] |

| 3D PCL with nHA Scaffold | (Not Specified) | Scaffold fabricated via mesh collector and layer-by-layer assembly for bone regeneration [24]. | Bone tissue engineering [24] |

| Cryogenic Electrospun PLLA | (Not Specified) | Produced scaffold with large pores (10-500 μm) facilitating cell infiltration [24]. | General tissue engineering [24] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a 3D Electrospun Nanofiber Scaffold via Gas Foaming

Objective: To transform a standard 2D electrospun nanofiber mat into a thick, porous 3D scaffold to enhance cell infiltration.

Materials:

- Electrospun nanofiber mat (e.g., Poly(ε-caprolactone) - PCL)

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) aqueous solutions [24] OR a chemical blowing agent like azodicarbonamide [24]

- Deionized water

- Laboratory oven

Method:

- Prepare Electrospun Mat: Fabricate a 2D electrospun PCL membrane using standard electrospinning techniques.

- Gas Foaming Treatment:

- Option A (NaBH4): Immerse the electrospun mat in an aqueous solution of NaBH4. The processing time in the solution directly controls the distribution of gap widths and layer thicknesses in the final scaffold [24].

- Option B (Azodicarbonamide): Incorporate azodicarbonamide into the polymer solution prior to electrospinning. After fiber deposition, expose the mat to a high temperature (e.g., 100°C for 2-3 seconds) to decompose the blowing agent and generate micro-sized pores [24].

- Rinsing and Drying: Thoroughly rinse the expanded scaffold with deionized water to remove any residual chemicals.

- Drying: Lyophilize or air-dry the scaffold to maintain its 3D porous structure.

- Sterilization: Sterilize the final 3D scaffold using ethylene oxide gas or ethanol immersion followed by UV exposure before cell culture.

Protocol: Functionalization of a Hydrogel with a Bioactive Peptide for Enhanced Cell Recruitment

Objective: To create a hydrogel scaffold that actively recruits host stem cells to a site of implantation for in situ tissue regeneration.

Materials:

- Hyaluronic acid (HA) hydrogel (or other injectable hydrogel)

- Substance P (SP) peptide [25]

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Sterile mixing vials

Method:

- Hydrogel Preparation: Prepare the precursor solution of your HA hydrogel according to the manufacturer's or standard protocol.

- Peptide Incorporation: Dissolve a determined concentration of Substance P (SP) in sterile PBS and mix it thoroughly into the HA precursor solution. The concentration should be optimized based on preliminary studies.

- Cross-linking and Implantation: Allow the hydrogel to cross-link, encapsulating the SP peptide. If using an injectable system, the solution can be gelled in situ.

- Implantation: Implant the functionalized hydrogel at the target injury site.

- Analysis: The sustained release of SP from the hydrogel will mobilize host MSC-like cells (e.g., CD29+ cells) from the bone marrow and recruit them to the implant site, where they can participate in the repair process [25].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram Title: In Situ Tissue Regeneration via Host Cell Recruitment

Diagram Title: Scaffold Mechanotransduction Signaling Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for biomaterial scaffold research.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | A widely used adult stem cell source with multipotent differentiation capability and immunomodulatory properties, derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord [23] [27]. |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Patient-specific pluripotent cells that can be differentiated into any cell type, offering a personalized and ethically non-contentious cell source [23]. |

| Collagen Type I | A natural polymer serving as a primary component of the ECM; used to create biocompatible scaffolds that promote cell attachment and growth [26] [25]. |

| Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) | A versatile, biodegradable synthetic polymer with tunable degradation rates, used for creating both scaffolds and controlled drug delivery systems [25]. |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | A natural glycosaminoglycan used to form highly hydrated hydrogels; particularly useful for creating injectable cell delivery systems and mimicking soft tissue environments [23]. |

| Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) | A neurotrophic factor used to direct stem cell differentiation towards neuronal lineages when incorporated into scaffolds for neural tissue engineering [26]. |

| Substance P (SP) | A neuropeptide used as a bioactive cue to functionalize scaffolds, enhancing the recruitment of host stem cells to the site of implantation for in situ regeneration [25]. |

| Electrospinning Apparatus | Standard equipment for generating nanofibrous scaffolds that morphologically mimic the native extracellular matrix [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary causes of mechanical stress on stem cells during delivery, and how do they impact cell survival?

Mechanical stress during delivery primarily arises from shear forces and fluid stretching experienced as cells pass through narrow-gauge needles. These forces can disrupt plasma membrane integrity, trigger apoptotic pathways, and significantly reduce viability. Studies show that delivering stem cells via needle injection of cell suspensions results in a survival rate of only ~30%. High cell mortality not only weakens therapeutic outcomes but can also trigger local immune responses and exacerbate damage to the injured tissue environment [28].

Q2: How do injectable and implantable systems differ in their approach to managing mechanical stress?

- Injectable Systems are typically low-viscosity solutions or shear-thinning hydrogels designed for minimally invasive delivery, often via syringe and needle. The main challenge is protecting cells from shear stress during the injection process. Strategies include optimizing delivery parameters and using bio-inks that lubricate cells [28].

- Implantable Systems often involve pre-formed, solid or semi-solid scaffolds (e.g., hydrogels, sponges) that are surgically placed. These systems avoid the high shear stress of injection but face different challenges related to surgical implantation and ensuring integration with host tissue. The mechanical stress is more related to compression and tension post-implantation [29].

Q3: What are the key signaling pathways activated by mechanical stress that affect stem cell viability?

A key pathway involves calcium (Ca²⁺) signaling. Mechanical stress can be converted into electrical signals via piezoelectric materials, which activate Piezo1 channels on the cell membrane. This leads to an influx of calcium ions, rapidly increasing intracellular free Ca²⁺ concentration. This Ca²⁺ surge triggers two critical mechanisms:

- Endogenous Membrane Repair: Ca²⁺ interacts with sensors like synaptotagmin VII and dysferlin to promote rapid resealing of damaged plasma membranes.

- Ca²⁺-triggered Actin Remodeling (CaAR): The increased Ca²⁺ stimulates actin polymerization and the formation of perinuclear actin rings, enhancing cellular stiffness and resistance to subsequent deformation [28].

Q4: What material strategies can be employed to shield cells from mechanical stress during injection?

Incorporating cells into protective hydrogels is a primary strategy. Ideal hydrogels for injectable delivery are:

- Shear-thinning: Their viscosity decreases under the shear stress of injection, reducing force on cells, and rapidly recovers once injected.

- Self-healing: Able to reform their structure after passing through a needle.

- Bioactive: Modified with peptides (e.g., RGD) to promote cell adhesion and survival.

- Piezoelectric: Can be engineered with nanoparticles like Barium Titanate (BTO) to convert harmful mechanical stress into beneficial electrical signals that actively protect cells [28].

Q5: How can I quantitatively assess cell viability and membrane damage after the delivery process?

Standard laboratory assays can be combined to evaluate delivery success:

- Cell Viability: Use live/dead staining (e.g., Calcein-AM for live cells, propidium iodide for dead cells) followed by fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry. A viability of >80% post-spraying has been achieved with optimized systems [29].

- Membrane Integrity: Perform an Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay. LDH is a cytosolic enzyme that leaks out upon membrane damage, providing a quantitative measure of cytotoxicity.

- Functional Assays: Follow up with tests for metabolic activity (e.g., MTT assay) and differentiation potential to ensure functionality is retained [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Cell Viability Post-Injection

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| >50% cell death after passing through needle. | Excessive shear stress from high injection speed or small needle diameter. | Optimize delivery parameters: Reduce injection speed, use a larger needle diameter (e.g., 0.45mm vs. 0.33mm), and ensure medium viscosity is appropriate [28]. |

| High LDH release indicating membrane damage. | Lack of physical protection for cells during injection. | Use a protective hydrogel carrier: Employ a shear-thinning hydrogel (e.g., RGD-OSA/HA-ADH) to lubricate and shield cells from direct fluid forces [28]. |

| Cells fail to engraft or proliferate after delivery. | Activation of apoptosis or loss of stemness due to stress. | Precondition or genetically modify cells: Prime MSCs before delivery to enhance stress resistance. Consider using a hydrogel with "electrical protection" that activates endogenous repair via Piezo1 channels [28] [21]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Cell Distribution and Retention

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Clumping of cells during delivery. | High cell density or aggregation in suspension. | Filter cells through a sterile cell strainer before loading into the delivery system. Optimize cell concentration for the chosen carrier [29]. |

| Cells leak from the implantation site. | Lack of a retaining matrix at the target tissue. | Switch to an in-situ gelling system: Use a hydrogel that is liquid during injection but solidifies in the body (e.g., via temperature, ionic crosslinking with Ca²⁺). Low-methyl pectin is one such material that gels upon contact with physiological Ca²⁺ [29]. |

| Poor integration with host tissue. | The delivery vehicle does not support cell-matrix interactions. | Use bioadhesive materials: Incorporate mucoadhesive polymers like pectin or functionalize hydrogels with RGD peptides to improve cell and host tissue adhesion [29]. |

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for different cell delivery methods and enhancement strategies as reported in recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Cell Delivery Systems and Strategies

| Delivery Method / Strategy | Reported Cell Viability | Key Measured Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Needle Injection (Cell Suspension) | ~30% | Baseline for high shear stress-induced mortality. | [28] |

| Spray Delivery (with syringe-driven device) | 80% - 90% | High viability with uniform cell distribution; suitable for covering surface wounds. | [29] |