From Bench to Bedside: The Historical Evolution of Stem Cells in Precision Medicine

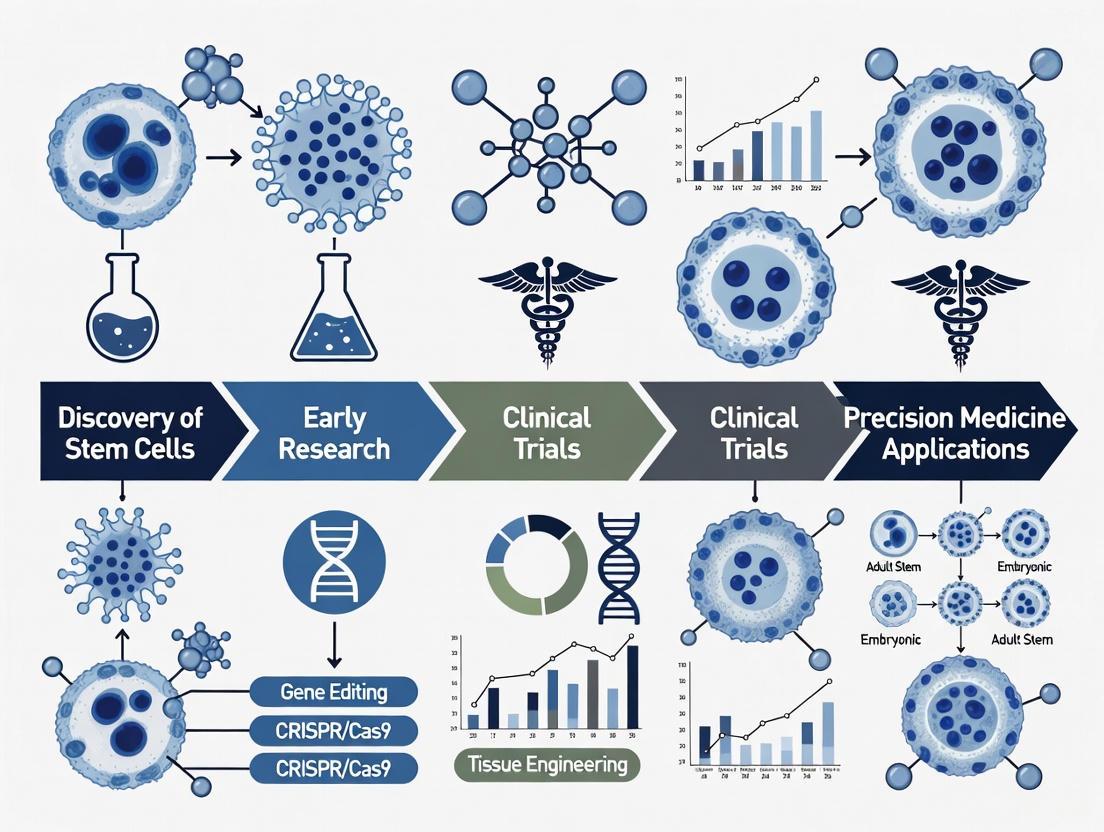

This article traces the transformative journey of stem cell technology and its integration into the paradigm of precision medicine.

From Bench to Bedside: The Historical Evolution of Stem Cells in Precision Medicine

Abstract

This article traces the transformative journey of stem cell technology and its integration into the paradigm of precision medicine. It explores the foundational discoveries, from early embryonic stem cell isolation to the revolutionary development of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which enabled patient-specific disease modeling. The review details methodological advances in stem cell engineering, including their application in targeted drug delivery, immune modulation, and the creation of sophisticated disease models for drug screening. It further addresses the critical challenges of tumorigenicity, immune rejection, and manufacturing scalability, while outlining the rigorous regulatory and clinical validation pathways. Finally, the article synthesizes how the convergence of stem cell biology with next-generation sequencing and gene-editing technologies is reshaping personalized therapeutic development for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Pioneering Discoveries: From Pluripotency to Patient-Specific Models

The isolation of the first human embryonic stem cell (hESC) line in 1998 marked a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine and biomedical research, establishing the conceptual and technical foundation for modern precision medicine approaches [1]. This breakthrough represented the culmination of decades of foundational work in cell biology and embryology, providing researchers with unprecedented access to the primitive cells that give rise to all human tissues. Pluripotency—the capacity of a single cell to differentiate into any of the approximately 200 specialized cell types that comprise the human body—emerged as the defining biological property that would captivate the scientific imagination and fuel two decades of intensive research [2]. For the first time, scientists could explore the intricate signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms that govern human development, disease progression, and tissue regeneration using an unlimited, genetically stable cell source [1].

The historical significance of this achievement extends beyond the laboratory, encompassing ethical considerations, political dimensions, and technological innovations that collectively shaped the trajectory of stem cell research. As Dr. James Thomson, who led the pioneering work, reflected: "For the first time, we had unlimited access to all of the basic cellular building blocks of the human body. And if you make an embryonic stem cell line, that's infinite. You can make as many cells as you want" [2]. This newfound capacity to maintain pluripotent cells in culture indefinitely while retaining their developmental potential created unprecedented opportunities for drug screening, disease modeling, and the development of cell-based therapies targeting conditions that had previously been considered untreatable [3] [1]. The following sections examine the historical context, methodological framework, and conceptual advances that defined this transformative period in stem cell biology.

Historical Context and Prelude to the 1998 Breakthrough

The conceptual foundation for stem cell biology emerged gradually over more than a century, with critical discoveries paving the way for the isolation of human embryonic stem cells. The term "stem cell" was first introduced in 1868 by German biologist Ernst Haeckel, who used "Stammzelle" (stem cell) to describe the unicellular ancestor from which all multicellular organisms evolved [3] [4]. This terminology was further refined in 1888 by zoologists Theodor Heinrich Boveri and Valentin Haecker, who identified a distinct cell population in embryos capable of differentiating into specialized cells [3]. The modern conceptualization of stem cells began to take shape in the early 20th century with Russian histologist Alexander Maksimov's proposal of hematopoietic stem cells in 1908 [4], followed by the first successful bone marrow transplant between identical twins by Dr. E. Donnall Thomas in 1956 to treat leukemia [5] [4].

The subsequent decades witnessed critical advances in understanding stem cell biology, including the seminal 1961 demonstration by Ernest McCulloch and James Till of self-renewing cells in bone marrow, which established the functional definition of stem cells [4]. Research progressed with the identification of mesenchymal stem cells by Alexander Friedenstein in 1970 [4], the discovery of hematopoietic stem cells in umbilical cord blood in 1974 [4], and the first isolation of embryonic stem cells from mouse embryos by Dr. Martin Evans and Matthew Kaufman in 1981 [4] [1]. This progression from conceptual framework to experimental validation in model systems set the stage for the landmark achievement in 1998, with each discovery building upon the previous to establish the methodological and theoretical principles necessary for working with human embryonic material.

Table: Major Historical Developments Preceding Human Embryonic Stem Cell Isolation

| Year | Discovery | Key Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1868 | First use of term "stem cell" | Ernst Haeckel | Introduced conceptual framework for ancestral cells |

| 1908 | Concept of hematopoietic stem cells | Alexander Maksimov | Proposed existence of blood-forming stem cells |

| 1956 | First successful bone marrow transplant | E. Donnall Thomas | Demonstrated therapeutic potential of stem cells |

| 1961 | Confirmation of self-renewing bone marrow cells | McCulloch and Till | Provided experimental evidence for stem cell theory |

| 1981 | Isolation of mouse embryonic stem cells | Evans and Kaufman | Established methodology for pluripotent cell culture |

The Landmark 1998 Isolation: Technical Methodology and Experimental Framework

Source Materials and Ethical Considerations

The derivation of the first human embryonic stem cell lines required meticulous attention to both technical and ethical considerations. Thomson's team utilized 36 surplus embryos from patients undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment, who provided explicit consent for research use of embryos that would otherwise have been discarded [1]. All embryos were donated voluntarily with informed consent, establishing an ethical framework that would become standard for subsequent hESC derivation [2]. The researchers worked with blastocyst-stage embryos (5-6 days post-fertilization), which contain approximately 100-200 cells organized into an outer trophectoderm layer and an inner cell mass (ICM)—the population of cells that would give rise to the embryonic stem cell lines [1]. This approach built upon previous experience with non-human primate models, as the same research team had successfully derived embryonic stem cells from rhesus macaque embryos in 1994, providing crucial technical expertise in primate stem cell culture [1].

Core Experimental Protocol: Immunosurgery and Pluripotent Cell Culture

The isolation and culture of hESCs followed a multi-stage protocol that required precise execution under sterile conditions. The complete methodology is summarized below.

Table: Detailed Protocol for Isolation and Culture of Human Embryonic Stem Cells

| Step | Procedure | Purpose | Key Reagents/Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Blastocyst Selection | Morphological assessment of embryo development | Identify viable blastocysts with distinct inner cell mass | Sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) |

| 2. Immunosurgery | Removal of trophectoderm using antibody-mediated complement lysis | Isolate intact inner cell mass | Anti-human whole antiserum, Guinea pig complement |

| 3. Plating | Transfer of ICM to culture dish | Initiate stem cell proliferation | Mitotically-inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder layer |

| 4. Initial Culture | Maintenance in specific media conditions | Support stem cell growth while preventing differentiation | KO-DMEM, FBS, L-glutamine, β-mercaptoethanol, Non-essential amino acids |

| 5. Passage | Mechanical dissociation of stem cell colonies | Expand cell lines while maintaining pluripotency | Collagenase IV, Mechanical scraping tools |

The critical innovation in the isolation process was immunosurgery, a technique that selectively removed the trophectoderm layer while preserving the intact inner cell mass [1]. This procedure involved incubating blastocysts with anti-human whole antiserum, followed by exposure to guinea pig complement, which selectively lysed the trophectoderm cells while leaving the ICM undamaged [1]. The intact ICM was then plated onto a feeder layer of mitotically-inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in a specific culture medium formulation that supported stem cell proliferation while inhibiting differentiation [2] [1].

The culture system represented a crucial advancement in maintaining pluripotency in vitro. The MEF feeder layer provided essential extracellular matrix components and signaling molecules that mimicked the natural stem cell niche, while the culture medium contained specific growth factors and nutrients optimized for undifferentiated cell growth [1]. Of the 14 inner cell masses successfully isolated through immunosurgery, five stable hESC lines were established that demonstrated long-term proliferative capacity while maintaining their developmental potential [1]. These lines, including the renowned H9 line that would later be used in clinical trials, could be continuously passaged while retaining normal karyotypes and pluripotent characteristics [1].

Characterization and Validation of Pluripotency

The researchers employed multiple validation strategies to confirm the pluripotent status of the derived cell lines. In vitro differentiation assays demonstrated the capacity of the cells to spontaneously generate derivatives of all three embryonic germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—when removed from supportive culture conditions [1]. Teratoma formation assays, conducted by injecting the cells into immunodeficient mice, confirmed their ability to generate complex tissues representative of multiple lineages, a gold standard test for pluripotency [1]. Additionally, the cells expressed characteristic molecular markers of pluripotency, including specific surface antigens and transcription factors that distinguished them from differentiated cell types [2].

Diagram Title: hESC Isolation and Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful derivation and maintenance of human embryonic stem cells depended on a carefully optimized system of reagents and culture conditions. The following table details the essential components required for hESC work during this pioneering period.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Human Embryonic Stem Cell Culture

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feeder Cells | Mitotically-inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) | Provide extracellular matrix and secreted factors that support pluripotency | Required inactivation by irradiation or mitomycin C; Batch variability concerns |

| Basal Media | KO-DMEM (Knockout Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium) | Nutrient foundation specifically formulated for pluripotent cells | Contains optimized glucose and nutrient concentrations |

| Serum Alternatives | Knockout Serum Replacement | Defined replacement for fetal bovine serum | Red variability and supports undifferentiated growth |

| Growth Factors | Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) | Key signaling molecule that maintains pluripotent state | Concentration critical (typically 4-20 ng/mL); Must be replenished frequently |

| Enzymatic Dissociation Agents | Collagenase IV, Trypsin/EDTA | Enable passage and expansion of cell colonies | Concentration and exposure time must be carefully controlled |

| Supplemental Factors | β-mercaptoethanol, Non-essential amino acids, L-glutamine | Reduce oxidative stress and support proliferation | Essential for cell viability during routine passage |

The feeder layer system represented a particularly critical component, with mouse embryonic fibroblasts providing not only physical support but also essential signaling molecules that maintained the stem cells in their undifferentiated state [1]. The culture medium formulation represented a significant advancement beyond previous systems used for animal stem cells, with KO-DMEM and serum replacement products specifically developed to support human pluripotent cells while reducing batch-to-batch variability [2]. Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) emerged as a crucial cytokine for maintaining self-renewal, with specific concentrations required to prevent spontaneous differentiation [1]. The mechanical and enzymatic methods for cell passage also required careful optimization, as stem cell colonies demonstrated particular sensitivity to dissociation methods, with approaches varying from precise mechanical dissection to controlled enzymatic treatment [2].

Classification Framework: Understanding Stem Cell Potency and Lineage

The isolation of human embryonic stem cells highlighted the importance of precise classification systems for understanding stem cell biology. Researchers established a hierarchical framework based on differentiation potential that remains fundamental to the field.

Table: Classification of Stem Cells by Differentiation Potential

| Potency Category | Differentiation Capacity | Representative Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Totipotent/Omnipotent | Can form all embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues | Fertilized oocyte (zygote), early blastomeres | Can generate a complete organism; Most undifferentiated cell type |

| Pluripotent | Can differentiate into all three embryonic germ layers | Embryonic stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells | Forms all body tissues but not extra-embryonic structures |

| Multipotent | Can differentiate into multiple cell types within a specific lineage | Hematopoietic stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells | Tissue-specific; Differentiation limited to related cell types |

| Oligopotent | Can differentiate into a few closely related cell types | Vascular stem cells, lymphoid stem cells | Further restricted differentiation capacity |

| Unipotent | Can produce only one cell type | Muscle stem cells, epidermal stem cells | Most restricted adult stem cell type |

This classification system provided critical context for understanding the unique position of embryonic stem cells in the developmental hierarchy [6] [5]. The pluripotent status of hESCs distinguished them from adult stem cells that had been previously characterized, explaining their broad developmental potential and unlimited self-renewal capacity [6]. This fundamental understanding of potency hierarchies would later prove essential for directing differentiation along specific pathways and for comparing the properties of various stem cell populations isolated from different sources [5] [7].

Diagram Title: Stem Cell Potency Hierarchy

Challenges and Limitations in Early Stem Cell Research

Despite the groundbreaking nature of the 1998 breakthrough, several significant challenges emerged that would require years of additional research to address. The dependence on mouse feeder layers raised concerns about potential xenogeneic contamination and the transfer of animal pathogens, limiting the clinical applicability of the cell lines [2] [1]. The initial culture systems also showed limited ability to precisely control differentiation, with spontaneous, heterogeneous differentiation occurring frequently and complicating efforts to generate pure populations of specific cell types [1]. Additionally, the ethical controversies surrounding the use of human embryos created significant political and funding challenges that would shape the regulatory landscape for years to come [6] [2].

The technical hurdles were equally substantial. The phenomenon of spontaneous differentiation presented a constant challenge for maintaining pure stem cell cultures, requiring meticulous daily attention to culture conditions and colony morphology [2]. As noted by Palmer Yu, a postdoctoral fellow in the Thomson lab: "It can be difficult to keep embryonic stem cells happy. They have the potential to differentiate to all the other cell types, and if you aren't careful, they'll start to spontaneously do so without direction from the scientist. It's actually a constant challenge for us to keep all cells in our culture, in a petri dish, in that undifferentiated state" [2]. Additionally, the field lacked standardized protocols for characterizing and quantifying pluripotency, making comparisons between different cell lines and research groups challenging [1].

The isolation of human embryonic stem cells in 1998 established a fundamentally new platform for understanding human development and disease, creating the technical and conceptual infrastructure that would enable the development of precision medicine approaches. This breakthrough provided researchers with their first unlimited access to the foundational cellular building blocks of the human body, opening unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug screening, and the development of cell-based therapies [2] [1]. The rigorous experimental methodologies established during this period—from immunosurgery techniques to defined culture systems—created standards that would guide subsequent innovations in the field.

The impact of this work extends far beyond the initial achievement, having spawned entirely new research domains including induced pluripotency, organoid technology, and cell-based therapeutic screening platforms. As Dr. Janet Rossant, Senior Scientist at SickKids, noted: "The transition from mouse embryonic stem cells to human embryonic stem cells was a big breakthrough and a fundamental shift. Now we have stem cells with this capacity to make every cell type in the body. Can we harness that capacity?" [2]. This fundamental shift continues to resonate through biomedical research, with the foundational principles established during the early years of stem cell isolation continuing to inform emerging technologies and clinical applications in regenerative medicine and precision therapeutics.

The development of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology represents a fundamental paradigm shift in regenerative medicine and biomedical research. This breakthrough, which demonstrated that terminally differentiated somatic cells could be reprogrammed to an embryonic-like pluripotent state, has fundamentally altered our approach to studying human development, disease modeling, and therapeutic development. The discovery by Shinya Yamanaka in 2006 that a small set of transcription factors could reverse the developmental clock provided researchers with a powerful new tool that bypassed the ethical concerns associated with embryonic stem cells while offering unprecedented opportunities for personalized medicine [8]. This technology has since become a cornerstone of precision medicine research, enabling the creation of patient-specific disease models and opening new avenues for drug discovery and regenerative therapies.

Historical Context: The Path to Reprogramming

The conceptual foundation for iPSC technology was built upon decades of pioneering research in cellular biology and development. The historical trajectory reveals how successive discoveries progressively challenged the dogma of irreversible cell differentiation:

Key Milestones in Stem Cell Research

Table 1: Historical Foundations of iPSC Technology

| Year | Discovery | Key Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) | John Gurdon [8] | Demonstrated nuclear totipotency; showed that differentiated cell nuclei could support embryonic development in Xenopus frogs |

| 1981 | Isolation of mouse Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Martin Evans, Matthew Kaufman, Gail Martin [8] | Established in vitro pluripotent cell culture systems |

| 1998 | Derivation of human ESCs | James Thomson [4] [8] | Provided human pluripotent cells for research and therapy |

| 2006 | Creation of mouse iPSCs | Shinya Yamanaka [9] [8] | First reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency using defined factors |

| 2007 | Generation of human iPSCs | Yamanaka and Thomson groups [9] [8] | Extended reprogramming technology to human cells |

The critical theoretical breakthrough came from John Gurdon's seminal SCNT experiments in 1962, which demonstrated that the nucleus of a differentiated somatic cell retained all the genetic information needed to generate an entire organism [8]. This discovery directly contradicted the prevailing Weissman barrier theory and Waddington's concept of irreversible epigenetic landscapes, suggesting instead that cell differentiation was reversible under appropriate conditions [8]. The subsequent isolation of embryonic stem cells from mice (1981) and humans (1998) provided the crucial reference point for what constituted a pluripotent state, while simultaneously highlighting the ethical and immunological challenges that would motivate the search for alternative approaches [4] [8].

The iPSC Breakthrough: Molecular Mechanisms

The Yamanaka Factors

Shinya Yamanaka's pioneering work began with a systematic screening of 24 candidate genes that were known to be important for maintaining pluripotency in embryonic stem cells [8]. Through iterative testing, his team made the remarkable discovery that only four transcription factors—Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (collectively known as OSKM or the Yamanaka factors)—were sufficient to reprogram mouse embryonic fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells [8]. The same factors (with Thomson's group demonstrating that Oct4, Sox2, NANOG, and LIN28 could also work) successfully generated human iPSCs in 2007 [10] [9] [8].

The reprogramming process initiates a profound transcriptional and epigenetic remodeling of somatic cells. The mechanism operates through distinct phases:

Evolving Reprogramming Methods

Since the initial viral vector approach, numerous reprogramming methods have been developed to enhance efficiency and safety:

Table 2: Evolution of iPSC Reprogramming Methodologies

| Method | Key Features | Efficiency | Safety Considerations | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral Vectors (Original) | Stable integration, high efficiency | Moderate | Insertional mutagenesis, oncogene activation | Basic research |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Can infect non-dividing cells | Moderate | Insertional mutagenesis | Basic research |

| Excisable Vectors | Allows removal after reprogramming | Moderate | Reduced long-term integration risk | Therapeutic applications |

| Non-integrating Episomes | No genomic integration | Low | Higher safety profile | Therapeutic applications |

| Sendai Virus | RNA-based, non-integrating | High | Cleared after reprogramming | Clinical applications |

| mRNA Transfection | No genetic material integration | Moderate | High safety, requires repeated transfection | Clinical applications |

| Protein Transduction | No genetic material | Low | Highest safety profile | Clinical applications |

| Small Molecule | Chemical induction only | Improving | High safety, easy delivery | Future clinical use |

The field has progressively moved toward integration-free methods such as Sendai virus, mRNA transfection, and small molecule approaches to enhance the safety profile of iPSCs for therapeutic applications [10]. Particularly noteworthy are advances in fully chemical reprogramming, first reported in 2013, which may eventually enable completely defined, xeno-free generation of clinical-grade iPSCs [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC Generation and Characterization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc (OSKM) or Oct4, Sox2, NANOG, LIN28 | Initiate and drive reprogramming process | Delivery via integrating/non-integrating vectors; chemical alternatives emerging |

| Culture Media | Pluripotent stem cell-specific media (e.g., mTeSR, StemFlex) | Maintain pluripotency and self-renewal | Defined, feeder-free systems preferred for reproducibility |

| Quality Control Assays | Pluripotency markers (Nanog, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60), Karyotyping, Short Tandem Repeat analysis | Verify pluripotent state and genetic integrity | Essential for confirming successful reprogramming |

| Differentiation Inducers | Specific growth factors, small molecules | Direct differentiation toward specific lineages | Protocol-dependent; often sequential activation/inhibition of key pathways |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs | Introduce or correct disease-relevant mutations | Enables creation of isogenic controls and disease models |

Applications in Precision Medicine and Drug Discovery

The integration of iPSC technology into precision medicine frameworks has created unprecedented opportunities for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapies.

Disease Modeling and Drug Screening

iPSCs have revolutionized disease modeling by enabling the creation of patient-specific cellular models that recapitulate pathological features in vitro. This "clinical trial in a dish" approach allows for studying disease mechanisms and screening therapeutic compounds in human genetic backgrounds [10]. Notable applications include:

- Neurological Disorders: Modeling of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and spinal muscular atrophy using patient-specific neurons [11]

- Cardiovascular Diseases: Creation of disease-specific cardiomyocytes for conditions like long QT syndrome, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [10]

- Drug Screening and Toxicity Testing: iPSC-derived cells provide human-relevant systems for evaluating drug efficacy and safety, with particular value in cardiotoxicity testing and hepatotoxicity assessment [12] [9]

The application of iPSC technology in drug discovery is exemplified by several clinical trials that have emerged from iPSC-based screening platforms, including trials of bosutinib, ropinirole, and ezogabine for ALS, and WVE-004 and BII078 for ALS/FTD [11].

Market Growth and Clinical Translation

Table 4: iPSC Market Outlook and Clinical Progress

| Parameter | Current Status | Projected Growth | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Market Value | $2.01 Billion (2024) | $4.69 Billion by 2033 [12] | Expanding applications in drug discovery and regenerative medicine |

| Compound Annual Growth Rate | — | 9.86% (2025-2033) [12] | Rising investments and technological advancements |

| Clinical Trial Stage | Phase 3 for osteoarthritis (CYP-004) [9] | Multiple Phase 2 and 3 trials anticipated | Demonstrated safety and efficacy in early trials |

| Key Companies | Fujifilm CDI, Evotec, Ncardia, Cynata Therapeutics [12] [9] | Increased strategic collaborations | Expanding product pipelines and therapeutic applications |

| Major Applications | Disease modeling, drug discovery, toxicology testing [12] [9] | Cell therapies, personalized medicine | Regulatory support (FDA Modernization Act 2.0) |

The clinical translation of iPSC technology reached a significant milestone in 2013 when the first iPSC-derived cell product was transplanted into a human patient for treating macular degeneration [9]. This was followed by Cynata Therapeutics receiving approval in 2016 for the first formal clinical trial of an allogeneic iPSC-derived cell product (CYP-001) for graft-versus-host disease [9]. The ongoing Phase 3 trial of Cynata's CYP-004 product for osteoarthritis represents the largest and most advanced clinical trial of an iPSC-derived therapeutic to date [9].

The discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells has fundamentally transformed biomedical research and regenerative medicine. By providing an unlimited source of patient-specific cells, iPSC technology has enabled unprecedented opportunities for modeling human diseases, screening drug candidates, and developing personalized cell therapies. The continued refinement of reprogramming methods, differentiation protocols, and genome editing technologies promises to further enhance the safety, efficiency, and applicability of iPSCs.

As the field progresses, key challenges remain, including the need for standardized quality control measures, improved differentiation efficiency, and addressing potential genomic instability during reprogramming [12] [8]. However, with the integration of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, organoid systems, and 3D bioprinting, iPSCs are poised to remain at the forefront of precision medicine initiatives, potentially enabling truly personalized treatments tailored to an individual's genetic makeup and disease characteristics [9] [11]. The paradigm shift initiated by Yamanaka's discovery continues to unfold, promising to reshape our approach to understanding and treating human diseases in the decades to come.

The historical evolution of precision medicine is deeply intertwined with advances in stem cell biology. The identification and characterization of distinct stem cell lineages—embryonic, adult, and perinatal—have provided researchers with a sophisticated toolkit for modeling human disease, screening therapeutic compounds, and developing regenerative therapies. These cellular tools exhibit fundamental differences in their developmental origins, differentiation potentials, and therapeutic applications, making them uniquely suited for specific research and clinical contexts. Embryonic stem cells (ESCs), derived from the inner cell mass of blastocysts, represent the foundational pluripotent platform capable of generating any cell type in the body [13]. Adult stem cells (ASCs), also known as somatic stem cells, are multipotent tissue-specific residents responsible for maintenance and repair [14]. Perinatal stem cells, harvested from birth-associated tissues such as umbilical cord and amniotic fluid, occupy a unique developmental intermediate position, often exhibiting enhanced plasticity and immunomodulatory properties compared to their adult counterparts [15] [16]. This technical guide examines the defining biological properties, experimental methodologies, and precision medicine applications of these three core stem cell lineages, providing researchers with a framework for their appropriate selection and utilization.

Defining the Core Stem Cell Lineages

Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs)

Key Characteristics: ESCs are defined by their pluripotent nature, enabling differentiation into any of the three germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm [13]. They are isolated from the inner cell mass of pre-implantation blastocysts through microsurgery or immunological targeting of trophoblast cells [13]. ESCs possess a virtually unlimited self-renewal capacity in culture, maintaining their undifferentiated state through specific signaling pathways and transcription factor networks [13]. Their primary research applications include disease modeling, drug discovery, and developmental biology studies, leveraging their broad differentiation potential [13].

Historical Context and Ethical Framework: The first human ESCs were isolated in 1998, marking a pivotal moment for regenerative medicine [17]. However, their use involves the destruction of human embryos, creating ongoing ethical considerations that have shaped research policies and funding landscapes worldwide [17]. These concerns directly motivated the development of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) as an alternative approach [17].

Adult Stem Cells (ASCs)

Key Characteristics: ASCs are multipotent stem cells found in various tissues of the adult organism, where they function in tissue maintenance, repair, and regeneration [14]. Unlike pluripotent ESCs, their differentiation potential is generally restricted to cell types within their tissue of origin [13] [14]. They reside in specific tniche microenvironments that regulate their quiescence, activation, and fate decisions [14]. ASCs can be harvested from multiple sources, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, dental pulp, and even salivary glands, making them accessible for autologous transplantation [14].

Major Subtypes and Functions:

- Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs): Located in bone marrow, HSCs give rise to all blood cell lineages and form the biological basis for bone marrow transplantation [13] [14].

- Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs): Initially isolated from bone marrow but present in all vascularized adult tissues, MSCs can differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondroblasts [18] [14]. Defined standards require them to express specific surface antigens (CD105, CD73, CD90) while lacking hematopoietic markers [14].

- Neural Stem Cells (NSCs): Found in specific brain regions, NSCs generate neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [14].

- Epithelial Stem Cells: Reside in the lining of the digestive tract and skin, enabling continuous renewal of these tissues [14].

Perinatal Stem Cells

Key Characteristics: Perinatal stem cells are derived from tissues associated with the prenatal and perinatal period, including umbilical cord blood, Wharton's jelly, amniotic membrane, amniotic fluid, and placenta [15] [16]. These cells exhibit multipotent capabilities but often demonstrate greater plasticity and proliferative capacity compared to adult stem cells [13]. Their collection is non-invasive and poses no ethical controversies, as the tissues are typically discarded after birth [15]. These cells also show reduced immunogenicity, making them promising candidates for allogeneic transplantation [19].

Research Trends and Therapeutic Promise: Bibliometric analysis reveals remarkable expansion in perinatal stem cell research, with over 33,273 publications appearing between 2000 and 2025 [15] [16]. The dominant research categories include hematology, immunology, cell biology, experimental medicine, and tissue engineering [15]. Recent studies highlight their potential in treating diabetic cardiomyopathy, generating hepatocyte-like cells, and repairing neurological damage [15] [16].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Stem Cell Lineages

| Characteristic | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) | Perinatal Stem Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental Origin | Inner cell mass of blastocyst | Various adult tissues (bone marrow, adipose, etc.) | Umbilical cord, placenta, amniotic fluid |

| Differentiation Potential | Pluripotent | Multipotent | Multipotent with enhanced plasticity |

| Self-Renewal Capacity | Virtually unlimited | Limited in vitro | Higher than ASCs |

| Ethical Considerations | Significant (embryo destruction) | Minimal | Minimal |

| Immunogenicity | High (allogeneic) | Low (autologous possible) | Reduced immunogenicity |

| Key Research Applications | Disease modeling, developmental biology, drug screening | Tissue repair, hematopoietic reconstitution, immunomodulation | Regenerative medicine, tissue engineering, immunomodulation |

| Primary In Vivo Role | Embryonic development | Tissue maintenance and repair | Fetal development |

Experimental Protocols for Lineage-Specific Analysis

iPSC Generation and Characterization

Reprogramming Methodology: The generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) represents a cornerstone technique for modern precision medicine, enabling the creation of patient-specific pluripotent cells without ethical concerns [17]. The standard protocol involves introducing the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC) into adult somatic cells, typically dermal fibroblasts or blood cells [17]. This can be achieved using viral vectors (retroviruses or lentiviruses) or non-integrating methods (episomal vectors, Sendai virus, or mRNA transfection) [17]. Following transduction, cells are transferred to ESC culture conditions and monitored for colony formation. Putative iPSC colonies are typically isolated 3-4 weeks post-transduction [17].

Characterization and Validation: Validated iPSC lines must demonstrate:

- Pluripotency Marker Expression: Immunocytochemistry for OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and SSEA-4 [17].

- Trilineage Differentiation Capacity: In vitro differentiation via embryoid body formation followed by analysis of germ layer markers [17].

- Genetic Stability: Karyotype analysis to confirm chromosomal integrity [17].

Precision Medicine Applications: iPSC technology enables the generation of patient-specific disease models, particularly for neurological disorders, cardiac conditions, and genetic diseases [17]. For example, researchers have successfully generated insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells from iPSCs for diabetes treatment [17].

MSC Isolation and Differentiation

Isolation Protocol: Mesenchymal stem cells can be isolated from multiple tissue sources using standardized protocols. For bone marrow-derived MSCs, aspirates are diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and separated via density gradient centrifugation [14]. The mononuclear cell fraction is plated in culture flasks with MSC-specific media, and non-adherent cells are removed after 48-72 hours [14]. Adipose-derived MSCs are isolated through enzymatic digestion (collagenase) of lipoaspirate samples, followed by centrifugation and plating [14]. Umbilical cord-derived MSCs are obtained through explant culture or enzymatic digestion of Wharton's jelly [14].

In Vitro Differentiation Assays:

- Osteogenic Differentiation: Culture in media containing β-glycerophosphate, ascorbic acid, and dexamethasone for 2-3 weeks; validate with Alizarin Red S staining for calcium deposits [14].

- Adipogenic Differentiation: Culture in media containing insulin, dexamethasone, indomethacin, and IBMX for 2-3 weeks; validate with Oil Red O staining for lipid vacuoles [14].

- Chondrogenic Differentiation: Pellet culture in media containing TGF-β3 for 3-4 weeks; validate with Alcian Blue staining for glycosaminoglycans [14].

Characterization Standards: According to International Society for Cellular Therapy guidelines, human MSCs must express CD105, CD73, and CD90 (≥95% positive), while lacking expression of CD45, CD34, CD14/CD11b, CD79a/CD19, and HLA-DR (≤2% positive) [14].

Organoid Generation from Pluripotent Stem Cells

Intestinal Organoid Protocol: Organoid technology represents a revolutionary approach for disease modeling and drug screening [20]. To generate intestinal organoids from iPSCs or ESCs, a stepwise differentiation protocol is employed:

- Definitive Endoderm Induction: Culture pluripotent stem cells in media containing Activin A for 3-5 days [20].

- Mid/Hindgut Specification: Transfer to media containing FGF4 and WNT3A to promote intestinal lineage commitment [20].

- 3D Matrigel Culture: Embed developing intestinal spheroids in Matrigel and culture in media containing EGF, Noggin, and R-spondin to promote crypt-villus structure formation [20].

- Maturation: Maintain organoids for 2-4 weeks with periodic passaging to allow structural maturation [20].

Advanced Co-culture Systems: To enhance physiological relevance, researchers have developed sophisticated co-culture systems:

- "Apical-out" Organoids: Reverse polarity to enable direct host-microbe interaction studies [20].

- Immune Cell Co-cultures: Incorporate macrophages or T cells to study epithelial-immune interactions [20].

- Neural Co-cultures: Combine intestinal organoids with enteric nervous system components to model gut-brain axis signaling [20].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) | Conversion of somatic cells to iPSCs |

| Culture Matrices | Matrigel, Laminin-521, Recombinant Vitronectin | Provide structural support for pluripotent stem cell growth |

| Lineage Tracing Systems | Cre-loxP, Dre-rox, Brainbow, R26R-Confetti | Fate mapping and clonal analysis |

| Differentiation Factors | Activin A, BMP4, FGFs, WNT agonists, Retinoic Acid | Direct differentiation toward specific lineages |

| Characterization Antibodies | CD105, CD73, CD90, OCT4, NANOG, SSEA-4 | Identification and validation of stem cell populations |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, ZFNs | Genetic modification for disease modeling |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Regulation

The distinct behaviors of different stem cell lineages are governed by specific signaling pathways and molecular networks. Understanding these regulatory mechanisms is essential for manipulating stem cell fate for precision medicine applications.

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways that regulate self-renewal and differentiation in pluripotent stem cells:

Diagram 1: Core signaling pathways regulating pluripotent stem cell fate. The diagram illustrates how external signals (LIF, BMP, WNT, FGF) activate intracellular pathways that ultimately influence the balance between self-renewal and differentiation.

In adult stem cells, niche-specific signals create localized microenvironments that maintain stem cell quiescence or activate proliferation and differentiation as needed. The following diagram depicts key niche signaling components:

Diagram 2: Niche signaling in adult stem cell regulation. The diagram shows how localized signals from the stem cell niche (Notch, TGFβ, WNT, FGF) influence the balance between quiescence and activation in adult stem cell populations.

For perinatal stem cells, particularly those with therapeutic applications in inflammatory conditions, immunomodulatory pathways play crucial roles. The following diagram outlines key molecular mechanisms involved in their therapeutic actions:

Diagram 3: Therapeutic signaling mechanisms of perinatal stem cells. The diagram illustrates molecular pathways (TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 and TGF-β/Smad) through which perinatal stem cells exert immunomodulatory and tissue repair effects, as demonstrated in models of diabetic cardiomyopathy [15].

Applications in Precision Medicine and Therapeutic Development

Disease Modeling and Drug Screening

Stem cell-based models have revolutionized preclinical drug development by providing human-relevant systems for efficacy and toxicity testing. iPSC-derived neurons, cardiomyocytes, and hepatocytes enable patient-specific drug response profiling and identification of subpopulation-specific toxicities [17] [20]. Organoid technology has been particularly transformative for studying complex diseases like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where patient-derived intestinal organoids retain disease-specific epigenetic and transcriptional signatures [20]. These models have enabled the identification of novel drug targets, such as components of the ATF6 pathway as a branch of the unfolded protein response [20]. Cerebral brain organoids co-cultured with microglia have provided unprecedented insights into neuroinflammatory processes in Parkinson's disease, demonstrating how mitochondrial stress-associated STING/IFN-I responses drive pathology [20].

Regenerative Medicine and Clinical Applications

The therapeutic application of stem cells represents a paradigm shift in treating degenerative conditions. The FDA-approved stem cell product landscape has expanded significantly between 2023-2025, with notable approvals including [18]:

- Omisirge (omidubicel): Approved in April 2023 for hematologic malignancies, this cord blood-derived hematopoietic progenitor cell product accelerates neutrophil recovery after transplantation [18].

- Lyfgenia (lovotibeglogene autotemcel): Approved in December 2023 as an autologous cell-based gene therapy for sickle cell disease, with 88% of patients achieving complete resolution of vaso-occlusive events in clinical trials [18].

- Ryoncil (remestemcel-L): Approved in December 2024 as the first MSC therapy for pediatric steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease [18].

Beyond these approved products, the clinical pipeline includes promising investigational therapies. Fertilo received FDA IND authorization in February 2025 as the first iPSC-based therapy to enter U.S. Phase III trials, using ovarian support cells derived from clinical-grade iPSCs to support ex vivo oocyte maturation [18]. Multiple iPSC-derived therapies targeting retinal degeneration (OpCT-001), systemic lupus erythematosus (FT819), and neurodegenerative conditions have received FDA clearance for clinical trials [18].

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The convergence of stem cell biology with bioengineering and gene editing technologies is creating unprecedented opportunities for precision medicine. Lineage tracing technologies have evolved from simple dye labeling to sophisticated genetic systems like Cre-loxP, Brainbow, and dual recombinase approaches (Cre-loxP/Dre-rox) that enable high-resolution fate mapping in developing tissues [21]. The integration of single-cell RNA sequencing with lineage tracing provides multidimensional data on cell fate decisions [21]. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing enables precise genetic correction in patient-specific iPSCs, creating autologous cell sources for transplantation without immune rejection concerns [13]. The development of direct reprogramming approaches that convert somatic cells between lineages without passing through a pluripotent state offers potentially safer and more efficient routes to therapeutic cell types [17]. As these technologies mature, they promise to accelerate the development of personalized regenerative therapies tailored to an individual's genetic makeup and disease characteristics.

The strategic integration of embryonic, adult, and perinatal stem cell lineages into the precision medicine toolkit has fundamentally transformed biomedical research and therapeutic development. Each lineage offers complementary strengths: ESCs provide the gold standard for pluripotency; ASCs enable tissue-specific regeneration with minimized ethical concerns; and perinatal stem cells offer an accessible, potent intermediate with unique immunomodulatory properties. The ongoing refinement of differentiation protocols, lineage tracing technologies, and genome editing tools continues to enhance the resolution at which we can manipulate cell fate for therapeutic benefit. As the field advances, the convergence of stem cell biology with bioengineering, genomics, and computational modeling promises to unlock increasingly sophisticated approaches for understanding human disease and developing personalized regenerative therapies. The historical evolution of stem cell applications in precision medicine reflects a journey from fundamental biological discovery to transformative clinical applications, with each stem cell lineage contributing unique capabilities to this rapidly advancing field.

Regenerative medicine represents a revolutionary frontier in medical science, aiming to repair, replace, and regenerate damaged tissues and organs [13]. This whitepaper examines the foundational role of stem cell biology in this field, framing it within the historical evolution toward precision medicine. We detail the core cell types driving these advances, provide actionable experimental protocols, and analyze the current clinical and regulatory landscape. Supported by quantitative data and technical workflows, this document serves as a guide for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the transition from foundational biology to therapeutic application.

Regenerative medicine is an emerging branch of medicine that leverages the body's innate repair mechanisms to address conditions previously considered incurable, such as organ failure, myocardial infarction, and neurodegenerative diseases [22]. Its potential to transform the treatment landscape for millions of patients worldwide is unprecedented [13]. Stem cells, with their dual capabilities of self-renewal and differentiation into specialized cell types, are the cornerstone of this field [13] [23]. The historical journey—from the early foundational work in the 19th and 20th centuries to the isolation of human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in 1998 and the landmark discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) in 2006—has set the stage for the current therapeutic revolution [13] [24] [25]. This document explores how these biological tools are being systematically bridged to clinical therapy, focusing on the technical methodologies, safety considerations, and regulatory frameworks that underpin this translation.

Stem Cell Types: Characteristics and Therapeutic Potential

Stem cells are broadly categorized based on their origin and differentiation potential. The following table summarizes the key types central to regenerative medicine.

Table 1: Key Stem Cell Types in Regenerative Medicine Research

| Stem Cell Type | Origin | Key Characteristics | Primary Research & Therapeutic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Inner cell mass of blastocysts [13] | Pluripotent; can differentiate into any cell type in the body [13] [23] | Disease modeling, drug testing and development, fundamental studies of development [13] |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Genetically reprogrammed somatic cells (e.g., skin, blood) [24] [23] | Pluripotent; avoid ethical concerns of ESCs; enable patient-specific modeling [24] [25] | Personalized disease modeling, drug screening, cell replacement therapies (e.g., Parkinson's, retinal diseases) [24] [18] |

| Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) | Various tissues (e.g., bone marrow, adipose, blood) [13] [23] | Multipotent; limited to differentiating into cell types of their tissue of origin [13] [23] | Tissue-specific regeneration; hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for blood cancers [13] [24] |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Tissues including bone marrow, umbilical cord, adipose [24] [23] | Multipotent; strong immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties [24] [23] | Treatment of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), inflammatory disorders, musculoskeletal repair [18] [23] |

Core Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Generating and Differentiating iPSCs

The creation of patient-specific iPSCs is a fundamental protocol enabling personalized regenerative medicine.

- Somatic Cell Isolation and Culture: Obtain somatic cells, typically dermal fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells, from the patient via biopsy or blood draw [24]. Culture and expand these cells under standard conditions.

- Reprogramming Factor Delivery: Introduce the four core transcription factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) into the somatic cells using a non-integrating method, such as Sendai virus or episomal vectors, to minimize the risk of tumorigenicity [24] [26].

- iPSC Colony Culture and Expansion: Transfer the transfected cells onto a feeder layer of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or a synthetic substrate. Culture in a defined medium that supports pluripotency. Colonies with embryonic stem cell-like morphology will appear in 2-4 weeks [24].

- Characterization of Pluripotency: Validate successful reprogramming through:

- Immunocytochemistry: Detection of pluripotency markers (e.g., Oct4, Sox2, Nanog).

- In vitro Differentiation: Formation of embryoid bodies and subsequent differentiation into cells of the three germ layers.

- Directed Differentiation: Differentiate the validated iPSCs into target cells (e.g., dopaminergic neurons, cardiomyocytes) using specific cytokine cocktails and small molecules to mimic developmental signaling pathways [24]. For example, to generate dopaminergic progenitors for Parkinson's disease, activation of the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) and Wnt pathways is critical [18].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of this protocol:

Diagram 1: iPSC Generation and Differentiation Workflow

Preclinical Assessment of Stem Cell-Based Therapies

Before clinical application, stem cell-derived products must undergo rigorous preclinical testing.

- In Vitro Functional Assays: Assess the functionality of differentiated cells. For iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, this includes measuring electrophysiological activity via patch clamping or microelectrode arrays. For dopaminergic neurons, measure dopamine release via HPLC [24] [23].

- In Vivo Transplantation and Tracking:

- Animal Models: Utilize immunodeficient rodent models (e.g., NSG mice) of human disease, such as a Parkinson's model induced by 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) [18].

- Cell Delivery: Transplant the stem cell-derived product (e.g., dopaminergic neural progenitors) into the target site (e.g., striatum) using stereotactic surgery.

- Outcome Measures: Monitor for functional recovery using behavioral tests (e.g., apomorphine-induced rotation). Post-mortem histological analysis confirms cell survival, maturation, and integration into host circuitry [18].

- Tumorigenicity Safety Assessment: A critical step is to monitor for aberrant growth. This involves long-term observation of transplanted animals and sensitive assays like PCR to detect any residual undifferentiated pluripotent cells in the final product [24] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful research in regenerative medicine relies on a suite of high-quality reagents and platforms.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Platform | Function in Research | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Vectors | Deliver transcription factors to somatic cells to induce pluripotency. | Non-integrating Sendai virus or episomal plasmids [24]. |

| Defined Culture Media | Support the growth and maintenance of stem cells or direct differentiation. | mTeSR1 for iPSC maintenance; media with activin A/BMP4 for mesoderm differentiation [24]. |

| GMP-Compliant iPSC Lines | Provide a standardized, clinically relevant starting material for therapy development. | StemRNA Clinical Seed iPSCs with an established Drug Master File (DMF) [18]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Enable precise genome editing for gene correction (e.g., in monogenic diseases) or insertion of therapeutic transgenes. | Used to correct mutations in iPSCs in diseases like sickle cell anemia [13] [24]. |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing | Characterize cellular heterogeneity, validate differentiation purity, and identify novel cell populations. | Critical for quality control of differentiated products and analyzing tumor microenvironment interactions [13] [27]. |

Clinical Translation and Regulatory Landscape

The transition from lab to clinic is a carefully regulated process. As of December 2024, 115 global clinical trials involving 83 distinct pluripotent stem cell (PSC)-derived products were identified, with over 1,200 patients dosed and no class-wide safety concerns reported [18]. The therapeutic areas of highest focus are ophthalmology, the central nervous system (CNS), and oncology [18].

Table 3: Select FDA-Approved and Late-Stage Stem Cell Therapies (2023-2025)

| Therapy / Product | Indication | Cell Type | Status & Key Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ryoncil | Pediatric steroid-refractory acute Graft-versus-Host Disease (SR-aGVHD) | Allogeneic bone marrow-derived MSCs | FDA Approved (Dec 2024). First MSC therapy approved in the U.S. [18]. |

| Lyfgenia | Sickle cell disease with history of vaso-occlusive events | Autologous hematopoietic stem cells (gene-modified) | FDA Approved (Dec 2023). One-time gene therapy that reduces red blood cell sickling [18]. |

| Omisirge | Hematologic malignancies (post-umbilical cord blood transplant) | Nicotinamide-modified umbilical cord blood-derived hematopoietic progenitor cells | FDA Approved (Apr 2023). Accelerates neutrophil recovery [18]. |

| Fertilo | Support for ex vivo oocyte maturation | iPSC-derived ovarian support cells (OSCs) | FDA IND Cleared (Feb 2025). First iPSC-based therapy to enter U.S. Phase III trials [18]. |

| OpCT-001 | Retinal degeneration (e.g., retinitis pigmentosa) | iPSC-derived therapy | FDA IND Cleared (Sep 2024) for Phase I/IIa trial targeting photoreceptor diseases [18]. |

It is critical to distinguish between FDA authorization for a clinical trial and full product approval. An Investigational New Drug (IND) application allows a company to begin human trials, whereas formal marketing approval requires a Biologics License Application (BLA) after successful trials demonstrate safety and efficacy [18]. Initiatives like the NIH's Regenerative Medicine Innovation Project (RMIP) are pivotal in accelerating progress by supporting clinical research on adult stem cells and promoting scientific rigor [28].

The future of regenerative medicine is being shaped by several converging technological trends. The integration of stem cells with gene-editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 allows for the precise correction of genetic defects in patient-specific iPSCs before therapy [13] [24]. The field is also advancing through the development of 3D bioprinting and organoid systems, which create more physiologically relevant models for drug screening and disease modeling, and may eventually serve as engineered tissue grafts [22] [26]. Furthermore, the combination of next-generation sequencing (NGS) with stem cell platforms enables deep molecular profiling of tumors and differentiated cells, refining patient selection and personalizing therapeutic interventions [27].

The initial foray into regenerative medicine has successfully bridged fundamental stem cell biology with tangible therapeutic strategies. The establishment of robust protocols for cell manipulation, coupled with a growing body of clinical evidence and a mature regulatory framework, has moved the field from theoretical promise to clinical reality. While challenges related to tumorigenicity, immunogenicity, and manufacturing scalability remain, the continuous refinement of gene-editing, delivery systems, and differentiation protocols is steadily addressing these hurdles. For researchers and drug developers, this era represents an unprecedented opportunity to contribute to a new therapeutic paradigm that moves beyond managing symptoms to achieving true tissue regeneration and cure.

Engineering Therapies: Stem Cells as Tools for Precision Targeting and Modeling

The historical journey of stem cell applications in precision medicine has witnessed a significant evolution, shifting from a primary focus on cell replacement to harnessing the sophisticated paracrine and immunomodulatory functions of specific stem cell types. Within this paradigm, Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) have emerged as a cornerstone for advanced therapeutic strategies. Initially identified in the bone marrow by Friedenstein and colleagues in the 1960s for their osteogenic potential, MSCs were primarily conceived as progenitor cells for skeletal tissues [29]. The contemporary understanding, however, recognizes MSCs as non-hematopoietic, multipotent stromal cells with potent capacities for immunomodulation and tissue repair, positioning them as powerful tools for treating a broad spectrum of human diseases [29] [30].

The therapeutic profile of MSCs is defined by their unique characteristics: the ability to self-renew, differentiate into multiple mesodermal lineages (osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes), and, most importantly, modulate the immune system [29]. According to the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT), MSCs are defined by their adherence to plastic, specific surface marker expression (CD73, CD90, CD105), and lack of hematopoietic marker expression (CD34, CD45, HLA-DR) [29]. Their effects are primarily mediated through the release of a diverse array of bioactive molecules—including growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles (EVs)—that orchestrate local tissue environments, promote repair, stimulate angiogenesis, and exert profound anti-inflammatory effects [29] [31]. This review delves into the molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of MSCs, framing their role within the next chapter of precision medicine aimed at harnessing innate biological systems for immunomodulation and tissue repair.

Molecular Mechanisms of Action

The therapeutic efficacy of MSCs is not attributed to a single action but to a multifaceted mechanism involving complex interactions with the host immune system and injured tissue. The primary pathways include direct cellular interactions, paracrine signaling, and the release of extracellular vesicles.

Immunomodulatory Properties and Immune Cell Interactions

MSCs possess a remarkable capacity to modulate both innate and adaptive immune responses. They interact with a wide range of immune cells, including T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and natural killer cells, through direct cell-to-cell contact and the release of soluble factors [29]. This immunomodulation is not constitutive but is licensed by inflammatory cytokines, such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), present in the injury microenvironment [32].

Upon activation, MSCs release a cocktail of immunoregulatory molecules. Key among these are:

- Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2): Promotes the polarization of macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype and inhibits the activity of natural killer (NK) cells [32].

- Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO): Catalyzes the degradation of tryptophan, which suppresses T-cell proliferation and effector functions [32].

- Tumor necrosis factor–stimulated gene 6 (TSG-6): Reduces the recruitment of monocytes and macrophages to sites of inflammation, thereby dampening the inflammatory response [32].

- Growth Factors (e.g., VEGF): Promote angiogenesis and endothelial cell function, which is crucial for supporting tissue repair [32].

The following diagram illustrates the key immunomodulatory pathways activated in MSCs within an inflammatory microenvironment:

Paracrine Signaling and Extracellular Vesicles

A pivotal shift in understanding MSC therapy has been the recognition that their benefits are largely mediated through paracrine effects rather than direct differentiation and engraftment [29] [31]. MSCs release a vast portfolio of bioactive factors, often referred to as the "secretome," which includes lipids, proteins, RNA, and entire organelles packaged into Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) [31].

MSC-derived EVs are emerging as a promising cell-free therapeutic alternative. These nanoscale vesicles can traverse biological barriers and deliver their cargo—including microRNAs, mRNAs, and proteins—to recipient cells, thereby modulating recipient cell behavior [31]. They exhibit strong anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, which are particularly relevant for treating neurodegenerative diseases and other inflammatory disorders [31]. Furthermore, EVs can be bioengineered to enhance brain targeting or drug loading, increasing their therapeutic potential and moving the field closer to clinical application [31].

Tissue Repair and Regenerative Capabilities

The role of MSCs in tissue repair is a coordinated process that integrates with the body's natural response to injury. The regenerative cascade begins with the release of Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) from injured cells, which act as distress signals [33]. These signals elicit an acute inflammatory response and mobilize stem cells from their niches.

A critical mechanism for MSC recruitment is the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis. Upon tissue injury, stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) is upregulated and creates a chemotactic gradient. MSCs, which express the CXCR4 receptor, follow this gradient, homing to the site of damage [33]. Once localized, MSCs contribute to tissue regeneration by:

- Reducing excessive inflammation via the immunomodulatory mechanisms described above.

- Secreting trophic factors that promote the survival and proliferation of resident progenitor cells.

- Stimulating the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) to restore blood supply.

- Remodeling the extracellular matrix (ECM) to support the formation of new, functional tissue [33].

Advanced Experimental Models and Protocols

Translating the therapeutic potential of MSCs into clinical reality requires robust and reproducible experimental models that closely mimic the in vivo environment. Traditional 2D culture systems often fail to capture the complexity of native tissues, leading to the development of more advanced 3D culture platforms.

3D Collagen Matrix Model for Assessing MSC Immunomodulation

A key protocol for investigating MSC function in a biomimetic environment involves embedding the cells within three-dimensional (3D) collagen hydrogels. This model allows researchers to study how physical parameters, such as matrix stiffness and cell density, influence MSC viability and immunomodulatory activity under inflammatory conditions [32].

Detailed Methodology:

- Hydrogel Preparation: A neutralized collagen solution is prepared from bovine dermis-derived atelocollagen. The solution is mixed with 10x DMEM, 7.5% NaHCO₃, 1M NaOH, and ultrapure water to achieve a physiologically neutral pH [32].

- Cell Encapsulation: Human MSCs are mixed with the neutralized collagen solution to achieve final cell densities typically ranging from 1x10⁶ to 7x10⁶ cells/mL. The mixture is dispensed into culture plates [32].

- Gelation: The plates are incubated at 37°C for 1 hour to allow the collagen-MSC mixture to form a solid hydrogel [32].

- Inflammatory Stimulation: The MSC-laden hydrogels are cultured in a medium supplemented with proinflammatory cytokines, specifically 10 ng/mL TNF-α and 25 ng/mL IFN-γ, to simulate an inflammatory microenvironment. The medium is replaced every two days [32].

- Analysis: Constructs are harvested for analysis at various time points (e.g., 24 hours and 5 days). Key readouts include:

- Gene Expression: Analysis of immunomodulatory genes (e.g., IDO, TSG-6) via qRT-PCR or RNA sequencing.

- Hydrogel Contraction: The surface area of the hydrogels is measured over time to quantify contraction, which is influenced by cell density and matrix stiffness.

- Cell Viability: Assessed using assays like CCK-8 or live/dead staining (e.g., calcein-AM/propidium iodide) [32].

The workflow for this essential experiment is outlined below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the aforementioned 3D collagen matrix model, along with their critical functions in the experimental protocol.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 3D MSC Immunomodulation Studies

| Research Reagent | Function and Application in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Bone Marrow-derived MSCs | Primary cellular component; sourced from human bone marrow and expanded in vitro to study their immunomodulatory behavior [32]. |

| Atelocollagen (Bovine Dermis) | Main structural polymer for forming the 3D hydrogel; provides a biomimetic extracellular matrix that supports cell adhesion and viability [32]. |

| Pro-inflammatory Cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ) | Used to simulate an inflammatory microenvironment in vitro; "license" the MSCs to activate their immunomodulatory gene expression and secretory profile [32]. |

| Cell Viability Assay (CCK-8) | Colorimetric assay used to quantify metabolic activity and estimate the number of viable cells within the hydrogel constructs at different time points [32]. |

| Live/Dead Staining (Calcein-AM/PI) | Fluorescent staining method that distinguishes live (green, calcein-AM) from dead (red, propidium iodide) cells, providing a visual assessment of cell viability and distribution in 3D [32]. |

MSC Biomarkers and Functional Characterization

Precise characterization is fundamental for ensuring the identity, purity, and functional competence of MSCs in both research and clinical settings. This is defined by specific surface markers and validated differentiation assays.

Table 2: Key Markers for the Identification and Characterization of MSCs

| Marker Category | Specific Markers | Significance and Function |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Surface Markers (≥95% Expression) | CD105, CD73, CD90 | CD105 is essential for angiogenesis; CD73 an enzyme producing anti-inflammatory adenosine; CD90 mediates cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesion [29]. |

| Negative Surface Markers (≤2% Expression) | CD34, CD45, CD14/CD11b, CD19/CD79α, HLA-DR | These are hematopoietic lineage markers (CD34, CD45, CD14, CD19) and an immunogenic MHC-II molecule (HLA-DR). Their absence confirms the non-hematopoietic nature of the MSC population [29]. |

| Functional Differentiation Potential | Osteogenic, Chondrogenic, Adipogenic | In vitro differentiation into these three mesodermal lineages is a mandatory functional criterion for defining MSCs, as per ISCT guidelines [29]. |

Clinical Translation and Delivery Strategies

A significant challenge in MSC therapy has been the poor retention and survival of transplanted cells at the target site, with studies indicating that less than 5% of administered cells remain viable hours after delivery [32]. To overcome this, biomaterial-based delivery systems, particularly hydrogels, have been developed to enhance therapeutic efficacy.

Hydrogel-Based Delivery Systems

Hydrogels are water-swollen, crosslinked polymer networks that closely mimic the physical and biochemical properties of the native ECM [34]. When used as MSC carriers, they provide a protective 3D microenvironment that supports cell viability, retention, and function upon transplantation [34] [32]. The properties of hydrogels can be finely tuned to modulate MSC behavior:

- Mechanical Properties: Substrate stiffness (elastic modulus) directs stem cell fate. Softer hydrogels (1–10 kPa) promote adipogenic/neurogenic differentiation, while stiffer matrices (25–40 kPa) favor osteogenic commitment [34].

- Biochemical Functionalization: Incorporation of bioactive molecules like RGD peptides (for adhesion), VEGF (for angiogenesis), or BMP-2 (for osteogenesis) can enhance MSC integration and direct therapeutic outcomes [34].

- Injectable Formulations: Hydrogels based on natural polymers (alginate, collagen, hyaluronic acid) can be designed to be injectable, allowing for minimally invasive administration and conformation to irregular defect geometries [34].

Recent advances include the development of "smart" hydrogels that respond to physiological stimuli (e.g., pH, enzymes) for controlled release, and bio-hybrid systems that combine decellularized ECM with synthetic polymers to couple biochemical functionality with structural stability [34]. Early-phase clinical trials have begun to support the feasibility, safety, and therapeutic potential of MSC-laden hydrogels, paving the way for broader clinical application [34].

The journey of MSCs from stromal progenitors to key mediators of immunomodulation and tissue repair mirrors the broader evolution of precision medicine towards biologically integrated therapies. The future of MSC-based therapeutics lies in moving beyond generic cell administration towards precision-engineered, patient-specific solutions. Key future directions include:

- Engineering and Delivery: Enhancing efficacy through advanced biomaterial scaffolds like tunable hydrogels and by developing engineered MSC-derived products, such as extracellular vesicles, which can be loaded with specific therapeutic cargo [34] [31].

- Combination with Advanced Technologies: Integrating MSC platforms with next-generation sequencing (NGS) and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq) to decipher patient-specific disease heterogeneity and identify novel targets, thereby enabling truly personalized treatment regimens [13] [27].

- Overcoming Translational Hurdles: Addressing challenges related to donor variability, scalable manufacturing, and standardized production to ensure consistent, safe, and potent therapeutic products [29] [31].

In conclusion, MSCs represent a paradigm-shifting tool with immense potential to treat a wide range of debilitating diseases. By continuing to unravel their molecular mechanisms and refining our ability to deliver and control their functions, MSC-based therapies are poised to become a cornerstone of next-generation precision regenerative medicine.

{#context}

Weapons Against Cancer: Engineered Stem Cells for Targeted Oncolytic Virotherapy and Drug Delivery

The historical evolution of stem cell applications in precision medicine has reached a pivotal convergence with oncolytic virotherapy, creating a novel therapeutic paradigm for cancer treatment. This synergy addresses one of the most significant challenges in oncology: the precise delivery of potent anticancer agents to tumor sites while sparing healthy tissues. Stem cells, with their innate tumor-homing properties and regenerative capacities, have emerged as sophisticated biological vehicles for oncolytic viruses (OVs), engineered pathogens designed to selectively replicate in and destroy cancer cells [13] [35]. This combination represents a monumental leap from early virotherapy concepts in the 20th century, when sporadic observations of tumor regression followed viral infections, to today's era of rationally designed, genetically engineered "soldiers" equipped with sophisticated "weapons" to combat cancer [36] [37].

The foundational principle of this approach leverages the unique biology of different stem cell types. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), for instance, are attracted to inflammatory and tumor microenvironments, making them ideal delivery vehicles [23]. When loaded with oncolytic viruses, these stem cells serve as protective trojan horses, shielding the therapeutic viruses from premature immune clearance while navigating them to metastatic and primary tumor sites [35]. Upon reaching the tumor, the stem cells release the oncolytic viruses, which then initiate a multi-mechanistic attack: direct lysis of cancer cells, induction of immunogenic cell death, and activation of systemic antitumor immunity [36] [37]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of this innovative platform, detailing the core stem cell and virus technologies, their mechanisms of action, essential research methodologies, and the translational pathway from laboratory research to clinical application.

Core Components: Stem Cell Vehicles and Oncolytic Payloads

Stem Cell Platforms: From MSCs to iPSCs

The selection of an appropriate stem cell vehicle is critical for the success of this therapeutic strategy. The most advanced platforms are derived from adult stem cells, which circumvent the ethical concerns and tumorigenicity risks associated with embryonic stem cells [23].

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs): Sourced from bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord, MSCs are the most extensively utilized cellular vehicle in clinical development [23] [18]. Their clinical appeal stems from three key properties: immunomodulatory capabilities that allow allogeneic use without severe rejection, inherent tumor-tropism driven by chemokine signaling in the tumor microenvironment, and a favorable safety profile [23]. The recent FDA approval of Ryoncil (remestemcel-L) for pediatric steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease in December 2024 validates the therapeutic potential of MSCs and paves the way for their use in advanced delivery systems [18].

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs): iPSCs represent a more recent, technologically advanced platform. These are adult somatic cells genetically reprogrammed to a pluripotent state, offering an unlimited, scalable source for deriving consistent, therapeutic-grade cells [13] [23]. iPSC-derived MSCs (iMSCs) are gaining momentum in regenerative medicine trials due to their enhanced consistency and scalability compared to primary MSCs [18]. For research and development, clinical-grade iPSC seed clones, such as the REPROCELL StemRNA Clinical iPSC Seed Clones, are now available with submitted Drug Master Files (DMF) to streamline regulatory submissions for clinical trials [18].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Stem Cell Platforms for OV Delivery

| Stem Cell Type | Sources | Key Advantages | Current Clinical Status | Primary Applications in OV Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Bone Marrow, Adipose Tissue, Umbilical Cord | Tumor-homing, immunomodulatory, allogeneic use, well-established safety profile [23] [18] | FDA-approved product (Ryoncil); Multiple clinical trials for OV delivery (e.g., CLD-201) [35] [18] | Protective vehicle for intravenous delivery; Modulates tumor immune microenvironment |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-derived MSCs (iMSCs) | Genetically reprogrammed somatic cells | Unlimited scalability, batch-to-batch consistency, avoids donor variation [18] | Early-phase clinical trials (e.g., CYP-001 for GvHD) [18] | Next-generation, standardized, off-the-shelf cellular vehicle production |

Oncolytic Virus Platforms and Engineering Strategies

Oncolytic viruses are the therapeutic payload carried by stem cells. They can be broadly classified into DNA and RNA viruses, each with distinct replication cycles, engineering capacities, and oncolytic mechanisms [36] [37].

Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV): A double-stranded DNA virus with a large genome (~150 kb), allowing for the insertion of large or multiple transgenes [36]. Its natural neurotropism can be harnessed for targeting brain tumors. Engineering typically involves deleting the ICP34.5 gene to reduce neurovirulence and enhance tumor-specific replication [36]. T-VEC (talimogene laherparepvec), an HSV-1 engineered to express GM-CSF, was the first OV approved by the FDA in 2015 for advanced melanoma [35] [36].