Generating Kidney Organoids from iPSCs: A Comprehensive Guide for Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Kidney organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have emerged as a transformative platform for modeling renal development and disease.

Generating Kidney Organoids from iPSCs: A Comprehensive Guide for Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Abstract

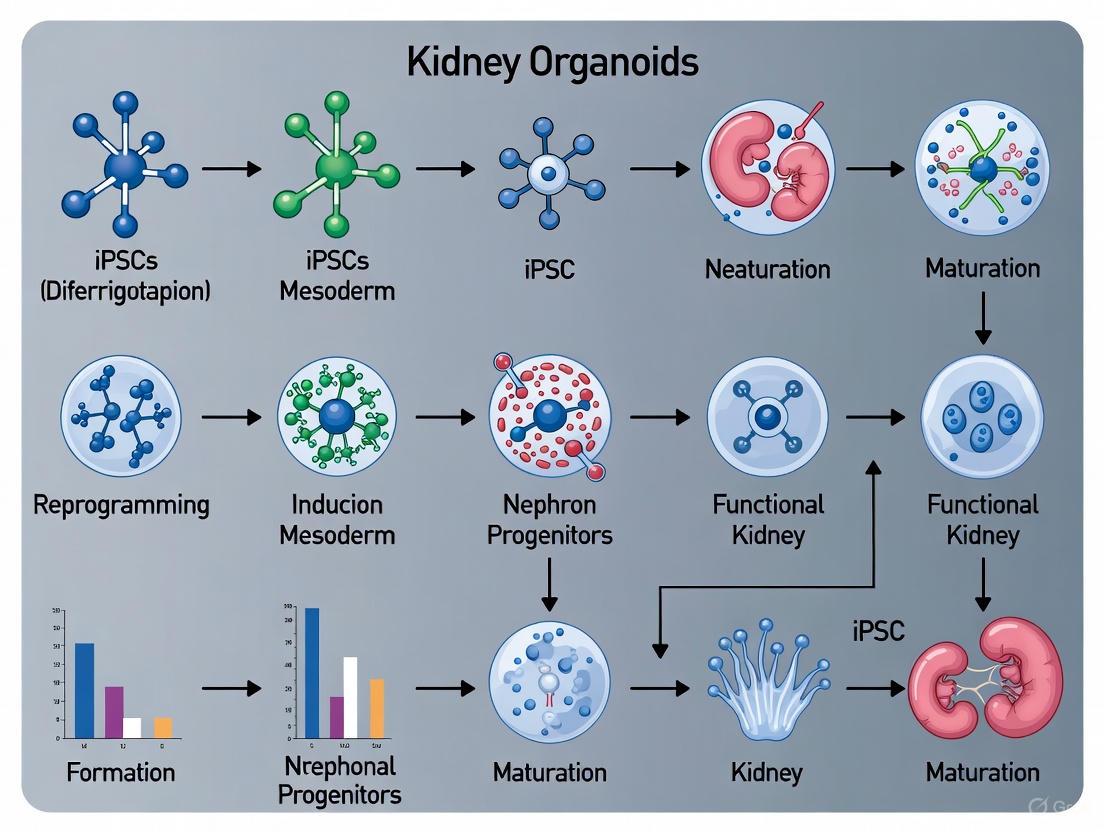

Kidney organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have emerged as a transformative platform for modeling renal development and disease. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of kidney organogenesis and iPSC biology. It details step-by-step differentiation protocols, explores their direct application in modeling hereditary diseases and nephrotoxicity, and addresses critical challenges such as cellular immaturity and off-target cells. Furthermore, it outlines advanced validation techniques using single-cell transcriptomics and functional assays, positioning kidney organoids as a powerful, human-relevant system for advancing mechanistic studies and therapeutic discovery.

The Foundation of Kidney Organoids: From iPSC Technology to Developmental Principles

Ethical and Practical Advantages of iPSCs

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) represent a pivotal innovation in regenerative medicine, offering a path to bypass the significant ethical controversies associated with embryonic stem cells (ESCs). The generation of ESCs requires the destruction of human embryos, raising profound ethical questions regarding the commencement of life and the moral status of the embryo [1] [2]. iPSC technology elegantly circumvents this issue by reprogramming adult somatic cells (e.g., from skin or blood) back into a pluripotent state, eliminating the need for embryos entirely [2]. This provides a less morally contentious source of pluripotent cells, aligning scientific progress with key ethical considerations [1] [2].

Beyond their ethical advantage, iPSCs offer substantial practical benefits for research and therapy. They enable the creation of patient-specific cell lines, which are invaluable for personalized disease modeling and can dramatically lower the risk of immune rejection in cell transplantation therapies [1] [2]. This contrasts with allogeneic ESC-derived cells, which face major immunological rejection challenges unless extensive HLA-matched donor banks are established [1].

Table 1: Key Comparisons Between iPSCs and Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs)

| Feature | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Source | Adult somatic cells (e.g., skin, blood) | Inner cell mass of a blastocyst-stage embryo [1] |

| Ethical Status | Avoids embryo destruction; considered ethically less contentious [2] | Involves destruction of human embryos; raises significant ethical debate [1] [2] |

| Immunological Compatibility | Can be generated from the patient for autologous use, minimizing rejection [1] | Typically allogeneic, requiring immunosuppression or HLA-matched banks [1] |

| Research & Therapeutic Applications | Disease modeling, drug screening, personalized cell therapy [1] | Disease modeling, drug screening, cell therapy (with limitations) [1] |

Protocols for Kidney Organoid Generation from iPSCs

The generation of kidney organoids from human iPSCs relies on protocols that mimic embryonic kidney development through stepwise manipulation of key signaling pathways. Below is a consolidated protocol based on established methods [3] [4].

Key Materials:

- Human iPSCs: Maintained in mTeSR1 medium on Geltrex-coated plates [3].

- Key Reagents: CHIR99021 (a GSK-3β inhibitor and WNT pathway agonist), FGF9, Heparin, Activin A [3].

- Basal Medium: Advanced RPMI 1640 supplemented with Glutamax [3].

Detailed Stepwise Protocol

- Maintenance of iPSCs: Culture human iPSCs in mTeSR medium on Geltrex-coated plates. For passaging, use Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent and maintain cells in small clumps [3].

- Induction of Intermediate Mesoderm: Differentiate iPSCs using 5–8 µM CHIR99021 in Advanced RPMI 1640 medium for 72–96 hours. This critical step activates the WNT pathway to specify the intermediate mesoderm lineage [3].

- Specification of Metanephric Cap Mesenchyme: Replace the medium with Activin A differentiation medium, containing 10 ng/ml Activin A, 200 ng/ml FGF9, and 1 µg/ml heparin, and culture for 24 hours [3].

- Formation of Kidney Progenitor Aggregates: Dissociate the cells using Accutase and re-aggregate them in a fresh medium containing 3 µM CHIR99021, 200 ng/ml FGF9, and 1 µg/ml heparin. For 3D organoid formation, transfer the cell suspension to a low-attachment 96-well U-bottom plate and culture for 5 days. This allows the cells to self-assemble into aggregates [3].

- Maturation of Kidney Organoids: Continue culturing the aggregates in a basal differentiation medium (without FGF9 and heparin) to promote spontaneous differentiation into tubules and glomerular-like structures. The entire process typically requires 18-25 days to form structured organoids [3] [4].

Applications in Disease Modeling

Kidney organoids derived from iPSCs provide a powerful platform for modeling human renal diseases, offering significant advantages over traditional 2D cultures and animal models. Their 3D, multicellular architecture allows for the study of complex disease mechanisms involving multiple cell types [4].

Modeling Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD)

ADPKD, caused by mutations in PKD1 or PKD2 genes, has been successfully modeled using iPSC-derived kidney organoids [5] [4].

- Protocol: Introduce biallelic loss-of-function mutations into the PKD1 or PKD2 genes in a control iPSC line using CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Differentiate these isogenic mutant iPSCs into kidney organoids alongside unedited controls [5].

- Phenotype: After about 35 days in culture, mutant organoids spontaneously develop fluid-filled cysts within the tubules, phenocopying the hallmark of ADPKD, while isogenic control organoids do not [4].

- Model Enhancement: Cystogenesis efficiency can be dramatically improved (from ~6% to ~75%) by growing the organoids in suspension culture using low-attachment plates instead of adherent culture conditions [4]. This system has been used to investigate the role of the extracellular matrix and has shown that embedding organoids in collagen droplets can reduce cyst formation [5].

Modeling Podocytopathies

Podocyte-specific diseases, such as those linked to podocalyxin (PODXL) mutations, can also be modeled.

- Protocol: Generate PODXL −/− iPSCs and corresponding isogenic controls via CRISPR-Cas9, then differentiate them into kidney organoids [5].

- Phenotype: Organoids with the knockout display defective podocyte formation, including failures in basal junctional assembly and microvilli formation, mirroring findings in PODXL-deficient mice and informing the mechanisms of human congenital nephrotic syndrome [5].

Table 2: Kidney Disease Models Using iPSC-Derived Organoids

| Disease Modeled | Genetic Target | Method of Modeling | Key Phenotype in Organoids |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD) | PKD1, PKD2 | CRISPR-Cas9 knockout in control iPSCs [5] [4] | Tubular cyst formation [5] [4] |

| Podocytopathy (e.g., FSGS, Nephrotic Syndrome) | PODXL | CRISPR-Cas9 knockout in control iPSCs [5] | Defects in podocyte foot process assembly and junctional migration [5] |

| Drug-Induced Kidney Injury | N/A (Wild-type organoids) | Treatment with nephrotoxins (e.g., Cisplatin, Gentamicin) [4] | Specific expression of injury markers (KIM-1) in tubular cells; Caspase-3 activation [4] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful generation and application of kidney organoids require a suite of specialized reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Kidney Organoid Generation and Application

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Usage in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | GSK-3β inhibitor; activates WNT signaling to induce intermediate mesoderm [3] [4]. | Used at 5-8 µM for initial differentiation (3-4 days) [3]. |

| FGF9 & Heparin | Promotes survival and specification of kidney progenitor cells (metanephric mesenchyme) [3]. | Used at 200 ng/ml (FGF9) with 1 µg/ml heparin after CHIR99021 treatment [3]. |

| Low-Attachment Plates | Facilitates 3D self-assembly of cells into organoids and improves cystogenesis in disease modeling [5] [3]. | Used for 3D aggregation and maturation of kidney progenitor cells [3]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Genome editing tool for introducing disease-causing mutations or correcting them in iPSCs [5] [4]. | Used to create isogenic mutant lines (e.g., PKD1/PKD2 KO) for disease modeling [5]. |

| DMOG (Dimethyloxallyl Glycine) | HIF-1α stabilizer; promotes vascularization and cell survival under hypoxia in organoids [3]. | Treated at 10 µM to enhance endothelial network formation [3]. |

| Cisplatin | Chemotherapeutic agent and nephrotoxin; used to model acute kidney injury in organoids [4]. | Used at ~10 µM to induce tubular cell injury and apoptosis for toxicity studies [3] [4]. |

The development of the mammalian kidney is a classic model of reciprocal tissue interactions, driven by reciprocal signaling between two key embryonic progenitor tissues: the metanephric mesenchyme (MM) and the ureteric bud (UB) [6] [7]. The UB, an epithelial outgrowth from the Wolffian duct, invades the MM, a population of mesoderm-derived cells. This invasion initiates a sophisticated developmental program wherein the UB undergoes iterative branching morphogenesis to form the collecting duct system, while the MM, in response to signals from the UB, condenses and undergoes mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) to form the nephrons, the functional filtration units of the kidney [6] [8].

Recapitulating these interactions in vitro is the cornerstone of generating kidney organoids from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These organoids provide an unprecedented platform for disease modeling, drug toxicity screening, and exploring the principles of regenerative medicine [7]. The fidelity of these models hinges on successfully mimicking the complex, stage-specific crosstalk that occurs between the MM and UB during embryonic development. This document details the core signaling pathways, provides protocols for generating UB and MM lineages, and explores advanced assembloid models that capture the essence of kidney organogenesis for research applications.

Key Signaling Pathways in MM-UB Crosstalk

The dialogue between the MM and UB is mediated by a well-orchestrated set of signaling pathways. The diagrams below summarize the core signaling interactions and the critical pathway that drives nephron formation.

Figure 1: Core Signaling in Kidney Organogenesis. The MM secretes GDNF, which binds to the RET receptor on the UB epithelium, inducing branching morphogenesis. In response, the UB secretes signals like WNT9b and FGFs, which promote survival of the MM and induce the WNT4-mediated MET critical for nephron formation [6] [7] [8].

Figure 2: The WNT4 Autocrine Loop for Nephrogenesis. A key event in nephron formation is the autoinduction of WNT4 within the MM. UB-derived WNT9b triggers the expression of WNT4 in the MM, which then acts as an autocrine signal to drive the subsequent steps of MET, leading to the formation of a nephron [8].

Quantitative Data on MM-UB Interactions

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from MM and UB Interaction Studies

| Finding | Quantitative Result | Experimental Model | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Branching Efficiency | UB branching can occur without MM contact, but requires MM for vectorial elongation and stalk tapering [6]. | Isolated rat UB culture & recombination with MM [6]. | MM provides essential contact-dependent cues for proper 3D architecture. |

| Functional Maturation | Co-cultured UB+MM tissue expressed OAT1, Na-Pi2, AVP receptor, resembling E19 kidney [6]. | Rat UB+MM recombinant [6]. | Contact with MM promotes functional maturation of proximal tubule and collecting duct segments. |

| Progenitor Induction Efficiency | Protocol achieves ~90% efficiency in generating PAX2+/GATA3+ pronephric intermediate mesoderm [9]. | Human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) differentiation [9]. | Highly efficient starting point for generating UB organoids. |

| Collecting Duct Purity | UB organoids differentiate into CD organoids containing >95% principal and intercalated cells [9]. | hPSC-derived UB organoids (scRNA-seq) [9]. | Enables high-fidelity modeling of the collecting system. |

| Patterning Correction | MM can normalize "branchless" UB morphology induced by growth factors like FGF7/heregulin [6]. | Dysmorphic UB cultured with MM [6]. | MM has a "quality control" or sculpting role, ensuring robust branching patterns. |

Table 2: Protocols for Deriving Kidney Lineages from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs)

| Protocol Step | Objective | Key Signaling Factors & Media | Duration | Outcome / Markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Primitive Streak Induction | Specify mesendodermal fate. | CHIR99021 (WNT agonist), FGF2, BMP4, Activin A [9]. | 30 hours [9]. | >95% TBXT+ cells [9]. |

| 2. Intermediate Mesoderm (IM) Specification | Generate anterior/pronephric IM. | Retinoic Acid (RA), FGF2, LDN193189 (BMP inhibitor), A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor) [10] [9]. | 48 hours [9]. | ~90% PAX2+/GATA3+ cells; LHX1+, HOXB7+ [9]. |

| 3. Nephric Duct (ND) Spheroid Formation | Promote 3D organization and early UB lineage commitment. | Aggregate cells; culture with RA, FGF9, GDNF [10] [9]. | 4 days [9]. | Spheroids expressing PAX2, GATA3, RET, EMX2 [9]. |

| 4. UB Organoid & Branching Morphogenesis | Initiate branching morphogenesis. | Embed ND spheroids in extracellular matrix (e.g., Matrigel) [10] [9]. | 7 days [10]. | Branched, RET+ tip-domain structures [9]. |

| 5. Collecting Duct (CD) Differentiation | Generate functional principal and intercalated cells. | Mature in specialized medium; for ICs, induce FOXI1 expression [9]. | 7-10 days [10]. | Functional ENaC+ principal cells and V-ATPase+ intercalated cells [9]. |

| MM / Nephron Progenitor Differentiation | Generate nephron-forming MM. | CHIR99021, then FGF9 with or without BMP7 [7]. | 7-10 days [7]. | SIX2+ nephron progenitors; WT1+, PAX2+ structures [7]. |

Advanced Model Systems: Kidney Assembloids

While individual UB or nephron organoids are valuable, the most physiologically relevant models combine these lineages to form kidney progenitor assembloids (KPAs). These systems more faithfully recapitulate the spatial patterning and reciprocal interactions of the developing kidney [11].

In a KPA, hPSC-derived induced ureteric progenitor cells (iUPCs) and induced nephron progenitor cells (iNPCs) are combined. The iUPCs self-organize into a central, branching UB-like structure, while the iNPCs form renal vesicles (RVs) and nascent nephrons that polarize around and fuse with the central "collecting duct" [11]. This self-organization mirrors the in vivo process of nephron formation and connection to the excretory system. These assembloids show dramatically improved cellular complexity and maturity, and have been successfully used to model human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), recapitulating cyst formation and complex cell-cell interactions in vivo [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Kidney Organoid and Assembloid Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Protocol | Key Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | Direct cell fate by modulating key signaling pathways. | CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor, activates WNT); LDN193189 (BMP inhibitor); A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor) [10] [9]. |

| Growth Factors | Provide mitogenic and patterning signals for progenitor expansion and differentiation. | FGF2/FGF9 (IM specification, NPC maintenance); GDNF (UB growth/branching); BMP7 (supports MM survival) [6] [7] [9]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Provides a 3D scaffold that supports tissue organization and morphogenesis. | Growth Factor-Reduced Matrigel [6] [9]. |

| Reporter Cell Lines | Enables tracking and purification of specific progenitor populations. | GATA3-mScarlet (labels pronephric IM, ND, and UB lineages) [9]. |

| Gene Editing Tools | For disease modeling and functional studies. | CRISPR-Cas9 (e.g., for generating PKD2-/- models in assembloids) [11]. |

Troubleshooting and Protocol Optimization

A common challenge in kidney organoid differentiation is the appearance of off-target cell types, such as chondrocytes, which can proliferate with extended culture [12]. Recent research has shown that this can be mitigated by modifying the standard protocol.

- Problem: Appearance of Alcian Blue-positive cartilage in organoids after day 18-25 of culture, correlated with increased expression of SOX9, COL2A1, and ACAN [12].

- Solution: Extend the supplementation of FGF9 in the culture medium. Maintaining FGF9 for one additional week (e.g., until day 12 of the protocol) significantly reduces chondrocyte formation without adversely affecting renal structures like glomeruli and tubules [12].

- Rationale: FGF9 is crucial for normal kidney development and has been shown to suppress chondrocyte differentiation in other systems, helping to maintain renal progenitor identity [12].

Application in Disease Modeling

The primary application of these sophisticated organoid and assembloid systems is the modeling of human kidney diseases. iPSCs derived from patients with genetic disorders can be differentiated into kidney lineages to study disease mechanisms in vitro.

- Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD): The KPA platform has been successfully used to model ADPKD. Genome-edited PKD2-/- human KPAs grown in vivo robustly recapitulate the cystic phenotype, revealing complex interactions between cyst-lining epithelium, stroma, and macrophages [11].

- Chronic Disease Modeling: Kidney organoids (iTubuloids) can be subjected to repetitive injury, such as multiple rounds of hypoxia, to model chronic kidney disease. After one injury, organoids recover efficiently, but after three rounds, they express markers of maladaptive repair (SAA1, SAA2, S100A8/A9), mimicking the progression to chronic disease [13].

The process of kidney organogenesis, centered on the reciprocal induction between the MM and UB, provides the essential blueprint for generating in vitro models of the kidney. By meticulously applying developmental principles, researchers can now direct hPSCs through the intermediate mesoderm stage to form self-organizing UB organoids, nephron-containing MM organoids, and, most powerfully, assembloids that combine these lineages. These models, which are becoming increasingly structurally complex and functionally mature, offer a powerful path for mechanistic studies of kidney development, accurate disease modeling, and high-throughput toxicology screening, thereby accelerating the pace of discovery in nephrology.

The generation of kidney organoids from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) recapitulates the complex process of embryonic kidney development, providing an unprecedented platform for disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine research. Central to this process are three key signaling pathways—WNT, FGF, and BMP—that act in concert to orchestrate the spatial and temporal differentiation of nephron progenitors into segmented nephron structures [14]. These pathways form an integrated signaling network that directs the patterning of the proximal-distal axis of the nephron, ultimately yielding specialized renal cell types including podocytes, proximal tubules, and distal tubules [15]. Understanding and manipulating these pathways is fundamental to generating high-fidelity kidney organoids that accurately model human kidney physiology and disease. This application note details the specific roles of WNT, FGF, and BMP signaling in kidney organoid differentiation, providing structured protocols, quantitative data, and practical reagent solutions to empower researchers in optimizing their organoid generation workflows.

Pathway Functions and Experimental Manipulation

The following table summarizes the core functions, key ligands, and experimental manipulation strategies for each critical signaling pathway in kidney organoid differentiation.

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Kidney Organoid Differentiation

| Pathway | Primary Roles in Kidney Organogenesis | Key Ligands & Receptors | Activation Methods | Inhibition Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WNT/β-catenin | Initiates nephrogenesis; drives PTA formation; controls PD axial patterning; dosage determines proximal/distal fate [15] [16]. | WNT9B, WNT4 [16] [14]; Receptor: Frizzled, LRP5/6 [16] | CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor) [14] [17] [18] | IWP-2, DKK1 [16] |

| BMP | Supports MM survival/proliferation; integrates with WNT/FGF to tune PD patterning; required for proximal fate [15] [14]. | BMP2, BMP4, BMP7 [19] [14]; Receptors: ALK2, ALK3, ALK6, BMPR2 [19] | Recombinant BMP proteins (e.g., BMP2, BMP4, BMP7) [14] [18] | DMH1, LDN-193189, Noggin, Gremlin [15] [19] |

| FGF | Promotes UB branching and NPC differentiation; sustains NPC population; crucial for distal nephron and loop of Henle maturation [15] [12] [14]. | FGF8, FGF9 [15] [14]; Receptors: FGFR1, FGFR2 [12] | Recombinant FGF proteins (e.g., FGF9, FGF2) [12] [14] [18] | BGJ398, AZD4547 |

Experimental Workflow for Signaling Pathway Modulation

The sequential and combinatorial manipulation of WNT, BMP, and FGF signaling is critical for directing the differentiation of iPSCs through key developmental stages toward functional kidney organoids. The diagram below illustrates a generalized experimental workflow, which can be modified to achieve specific patterning outcomes.

Protocol: Generating Proximal-Biased Kidney Organoids

Recent research highlights the critical challenge of generating mature proximal tubule cells in kidney organoids, which are essential for modeling tubular injury and drug toxicity. The following protocol details a method to generate proximal-biased (PB) organoids by modulating signaling pathways to mimic in vivo development [20].

- Key Principle: Transient PI3K inhibition during early nephrogenesis activates Notch signaling, shifting nephron axial differentiation toward proximal precursor states that mature into functional proximal convoluted tubule cells [20].

- Differentiation Baseline: Begin with a standard kidney organoid differentiation protocol, such as a modified Takasato protocol, to generate nephron progenitor aggregates [15] [20].

- Intervention Window: Apply a PI3K inhibitor (e.g., LY294002) at the pretubular aggregate (PTA) to early renal vesicle (RV) transition stage, typically around differentiation days 10-12 [20].

- Mechanistic Insight: PI3K inhibition drives cells through a JAG1+/HNF1B+ medial fate, culminating in the expansion of HNF4A+ proximal tubule precursors. This bypasses an abnormal triple-positive (HNF1B+/HNF4A+/JAG1+) cell state commonly observed in standard organoid protocols [20].

- Outcome Validation: Successful differentiation yields organoids with homogenous proximal tubule structures broadly expressing solute carriers (SLCs). These organoids demonstrate functional albumin and dextran transport and exhibit characteristic KIM1/HAVCR1 upregulation and SOX9 induction upon nephrotoxic injury [20].

Protocol: Inducing Distal Nephron Fate and Plasticity

The plasticity of nephron patterning can be exploited to generate distal nephron segments, including the thick ascending loop of Henle.

- Key Principle: A WNTON/BMPOFF state established during axial symmetry breaking establishes a distal nephron identity [15].

- Intervention: At the PTA/RV stage (e.g., differentiation day 10), maintain WNT signaling (e.g., via CHIR99021) while simultaneously inhibiting BMP signaling (e.g., with DMH-1 or LDN-193189) [15].

- Maturation: The imposed distal identity can mature into thick ascending loop of Henle cells by endogenously activating FGF signaling [15].

- Fate Switching: Remarkably, distal-fated nephron cells devoid of FGF signaling can revert to a proximal cell state. This transformation is itself dependent on BMP signal transduction, demonstrating high plasticity and tunability [15].

Quantitative Data and Phenotypic Outcomes

The effects of signaling pathway modulation can be quantified by measuring changes in key marker genes and cellular outcomes. The following table compiles experimental data from recent studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of Pathway Modulation in Kidney Organoids

| Experimental Condition | Key Marker Changes | Phenotypic Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| WNTON / BMPOFF | ↑ HNF1B, ↑ POU3F3, ↑ TFAP2A | Enhanced distal nephron fate specification; maturation into thick ascending loop of Henle cells [15]. | [15] |

| BMPON / FGFOFF (in distal-fated cells) | ↓ Distal markers, ↑ HNF4A, ↑ JAG1 | Fate switching from distal to proximal nephron cell states [15]. | |

| Transient PI3Ki (Proximal Biasing) | Expansion of HNF4A+ precursors; ↑ Expression of SLC transporters | Proximal-biased organoids with enhanced maturity and nephrotoxin response [20]. | [20] |

| FGF9 Extension (Day 5 to Day 12) | ↓ SOX9, ↓ COL2A1, ↓ ACAN | Significant reduction in off-target chondrocyte population; improved renal purity [12]. | [12] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Manipulating Key Signaling Pathways

| Reagent | Primary Function | Application in Kidney Organoid Differentiation |

|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | Potent and selective GSK-3 inhibitor; activates canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling [14] [17]. | Used in initial primitive streak induction and subsequent patterning stages. Dosage and timing are critical for proximal/distal patterning [15] [18]. |

| Recombinant FGF9 | Ligand for FGF receptors; key mesoderm inducer and NPC maintenance factor [14] [17]. | Critical for intermediate mesoderm induction and sustaining nephron progenitors. Extended treatment (up to day 12) reduces off-target chondrogenesis [12]. |

| Recombinant BMP4/BMP7 | Ligands for BMP receptors; involved in mesoderm patterning and MM survival [14] [18]. | Used in conjunction with FGF9 for IM induction (BMP4) and for supporting MM (BMP7). Essential for establishing proximal nephron fate [15] [14]. |

| DMH-1 | Selective inhibitor of BMP type I receptor ALK2 [15]. | Used to create a "BMPOFF" state during patterning to promote distal nephron fates [15]. |

| LY294002 | Potent and selective PI3K inhibitor [20]. | Applied transiently at PTA/RV stage to drive proximal tubule development via Notch activation [20]. |

Integrated Pathway Logic and Crosstalk

The WNT, FGF, and BMP pathways do not function in isolation but form a complex, integrated signaling network. The logic of their interactions is fundamental to achieving specific organoid patterning goals.

Mastery of the WNT, FGF, and BMP signaling pathways is indispensable for the precise engineering of kidney organoids from iPSCs. As research progresses, the move beyond simple activation and inhibition toward fine-tuned, spatiotemporal control of these pathways will be crucial. This includes optimizing the precise dosage, sequence, and duration of pathway modulation to enhance the maturation and functionality of organoids. Furthermore, integrating these strategies with advanced culture systems such as bioreactors, microfluidic chips, and vascularization techniques will help overcome current limitations. The protocols and data outlined herein provide a foundational framework for researchers to manipulate these core pathways, thereby generating more physiologically relevant kidney organoids for robust disease modeling and drug screening applications.

The Self-Organizing Potential of Pluripotent Stem Cells into 3D Renal Structures

The generation of three-dimensional kidney organoids from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), represents a transformative advancement in nephrology research. These organoids are in vitro models that recapitulate key aspects of kidney development, structure, and function, providing a promising platform for investigating disease mechanisms, performing drug screening, and developing regenerative therapies [7] [18]. The self-organization of PSCs into renal structures mirrors embryonic kidney development, where sequential signaling cues drive the differentiation of intermediate mesoderm into nephron progenitors that subsequently form intricate, segmented nephron-like structures [7] [14]. Within the context of disease modeling research, patient-specific iPSC-derived kidney organoids offer unprecedented opportunities to study genetic kidney diseases such as polycystic kidney disease and congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) [7] [14]. Despite remarkable progress, challenges remain in achieving full structural and functional maturation, necessitating continued refinement of differentiation protocols and integration of bioengineering strategies to enhance physiological relevance [21] [22].

Key Signaling Pathways in Kidney Organoid Development

The self-organization of pluripotent stem cells into kidney organoids recapitulates embryonic kidney development, which is orchestrated by precisely timed signaling interactions. Understanding these pathways is essential for optimizing differentiation protocols and generating physiologically relevant 3D renal structures for disease modeling.

Figure 1. Key signaling pathways directing kidney organoid differentiation from pluripotent stem cells. The diagram illustrates the sequential developmental stages and the primary signaling molecules required at each transition point, based on established differentiation protocols [7] [18] [14].

The differentiation process follows a conserved developmental trajectory, beginning with the induction of posterior primitive streak through WNT activation via GSK3β inhibitors such as CHIR99021 [7] [14]. Subsequent patterning into intermediate mesoderm requires fibroblast growth factor 9 (FGF9) and, in some protocols, bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP7) [7] [14]. The metanephric mesenchyme stage is characterized by the emergence of nephron progenitor cells (NPCs) expressing key transcription factors including SIX2, WT1, PAX2, and OSR1, which are maintained and expanded through continued FGF9 exposure [7] [18]. These NPCs ultimately undergo mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) to form nephron-like structures containing glomerular, proximal tubular, and distal tubular segments [7] [14]. The temporal integration of these signaling pathways regulates the formation of nephrons, with WNT signaling (WNT4, WNT9b) being essential for MET and nephron induction, while Notch signaling contributes to nephron segmentation and fate specification [7] [14].

Comparative Analysis of Kidney Organoid Differentiation Protocols

Several research groups have established core protocols for generating kidney organoids from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), each with distinct advantages and limitations for disease modeling applications. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of four principal methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Kidney Organoid Differentiation Protocols

| Protocol | Cell Source | Key Signaling Molecules | Efficiency of NPC Generation | Major Cellular Components | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taguchi et al. [18] | Mouse ESC/hiPSCs | BMP4, Activin A, FGF2, CHIR, Retinoic Acid | 20–70% | Wt1/nephrin+ glomeruli; cadherin6+ proximal tubules; E-cadherin+ distal tubules | Foundational step toward kidney reconstruction | Requires coculture with mouse embryonic spinal cords; lower efficiency; immaturity |

| Morizane et al. [18] | hESCs/hiPSCs | CHIR99021, Activin A, FGF9 | 80–90% | Multi-segmented nephron structures with podocytes, proximal tubules, loops of Henle, and distal tubules | Uses fully defined medium; higher efficiency; suitable for chemical screening | Differentiation efficiency affected by hPSC line variability; no collecting duct structures |

| Freedman et al. [18] | hESCs/hiPSCs | CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibition only) | Not specified | Segmented nephron structures with proximal tubules, podocytes, and endothelial cells | No exogenous FGF2, Activin, or BMP; low cost; high throughput; simple steps | Organoids random in size; no collecting duct structure; more off-target cells |

| Little's Team [18] | iPSC/hESC | CHIR99021, FGF9 | Not specified | Multiple nephrons surrounded by endothelial and stromal populations | Higher cell yield; low cost; specifies intermediate mesoderm before aggregate formation | Immaturity comparable to other protocols |

Each protocol employs a multi-step approach that mirrors kidney development. The Morizane protocol generates NPCs through 8-9 days of differentiation, beginning with induction of late primitive streak via WNT signaling regulation, followed by exposure to activin A to form posterior intermediate mesoderm, and finally treatment with FGF9 to generate NPCs [18]. These NPCs can then form kidney organoids in 96-well plates suitable for chemical screening. In contrast, the Freedman protocol utilizes a two-step approach that forms spheroids first followed by GSK3β inhibition, requiring no exogenous addition of FGF2, activin, or BMP [18]. Little's team employs a suspension culture method that increases final cell yield by 3-4 folds compared to static culture, thereby reducing costs while maintaining transcriptional equivalence of renal cell types [18].

Advanced Protocol: Monocyte-Enhanced Kidney Organoid Differentiation

Recent research has revealed that incorporating immune cell components, particularly monocytes, can significantly improve the efficiency and quality of kidney organoid differentiation. The following protocol integrates monocyte co-culture to enhance organoid development for disease modeling applications.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Monocyte-Enhanced Kidney Organoid Differentiation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Base Cell Line | Human Episomal iPSC Line (e.g., ThermoFisher Gibco A18945) | Starting cellular material for organoid differentiation |

| Basal Medium | Advanced RPMI 1640 with L-Glutamine | Foundation for differentiation media formulations |

| Key Signaling Molecules | CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor, 10 μM), Noggin (5 ng/mL), Activin A (10 ng/mL) | Sequential induction of primitive streak, intermediate mesoderm, and nephron progenitors |

| Monocyte Isolation | Classical Monocyte Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) | Isolation of CD14+CD16– monocytes from human peripheral blood |

| Monocyte Culture | M-CSF (20 ng/mL), IFNγ (20 ng/mL) + LPS (20 ng/mL), IL-4 (20 ng/mL) | Monocyte differentiation and polarization into M1/M2 macrophages |

| Apoptosis/Autophagy Modulation | Rapamycin (mTOR inhibitor) | Activation of autophagy to prevent CHIR-induced apoptosis |

| Analysis Reagents | Cell counting kit 8, Autophagy detection kit, Antibodies for cleaved Caspase 3, PARP-1, TBX6, OSR1, Nephrin, E-Cadherin | Assessment of cell survival, autophagy, and differentiation markers |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Day -7 to Day 0: Monocyte Preparation

- Isolate human CD14+CD16– monocytes from peripheral blood buffy coats using a Classical Monocyte Isolation Kit according to manufacturer's instructions.

- For functionality testing, treat monocytes with 20 ng/mL M-CSF for 7 days to differentiate into macrophages, then polarize using either:

- M1 polarization: 20 ng/mL IFNγ + 20 ng/mL LPS for 24 hours

- M2 polarization: 20 ng/mL IL-4 for 24 hours

- Verify polarization success by assessing expression of IL-6, IL-10, and TNFα.

Day 0: iPSC Seeding

- Culture human iPSCs in StemFlex medium on Geltrex-coated cell culture plates.

- Seed iPSCs at a density of 0.75 × 10^6 cells/cm² for differentiation.

Day 1-4: Mesoderm Induction

- Replace culture medium with Basal Medium (Advanced RPMI 1640 with 200 μM L-Glutamine and 0.5% KnockOut Serum Replacement) supplemented with 10 μM CHIR99021 and 5 ng/mL noggin.

- Refresh the medium after 2 days with the same components.

- Optional rapamycin treatment: Add rapamycin during this stage to activate autophagy and reduce CHIR-induced apoptosis.

Day 4-7: Intermediate Mesoderm Formation

- Change to Basal Medium supplemented with 10 ng/mL Activin A.

- Culture for 3 days with medium refreshment on day 5-6.

Day 7-9+: Organoid Formation and Monocyte Co-culture

- Begin indirect co-culture with prepared monocytes or iPSC-derived macrophages using a transwell system.

- Continue culture with appropriate kidney organoid differentiation medium (specific factors depend on base protocol used – Morizane et al. recommended).

- Refresh medium every 2-3 days and monitor organoid development.

- Harvest organoids for analysis between days 24-26.

Critical Protocol Notes

- Monocytes prevent CHIR-induced apoptosis through release of extracellular vesicles and induction of autophagy, significantly improving organoid differentiation efficiency [23].

- The co-culture system should use functionally validated monocytes that have demonstrated proper differentiation and polarization capacity.

- Rapamycin treatment alone improves iPSC survival during CHIR treatment but does not enhance differentiation; monocytes provide both survival and differentiation benefits [23].

- This protocol can be adapted for both adherent culture and 3D organoid formation formats.

Engineering Innovations for Enhanced Organoid Maturation

Recent bioengineering approaches have addressed key limitations in kidney organoid technology, particularly regarding structural maturity, reproducibility, and scalability for disease modeling research. These innovations include sophisticated culture platforms, bioprinting technologies, and vascularization strategies.

Advanced Culture Platforms

The UniMat (Uniform and Mature organoid culture platform) represents a significant advancement in organoid culture technology. This system features a 3D geometrically-engineered, permeable membrane that provides both geometrical constraints for uniformity and unrestricted supply of soluble factors for maturation [22]. Fabricated from electrospun polycaprolactone (PCL) and Pluronic F108 nanofibers, the UniMat creates a porous, hydrophilic environment that enhances nutrient exchange and gas permeability while promoting cell aggregation through its V-shaped microwell design [22]. When used for kidney organoid culture, the UniMat platform achieves approximately 87% efficiency in generating nephron-like structures with improved uniformity and enhanced maturation, including increased expression of nephron transcripts, more in vivo-like cell-type balance, and better long-term stability [22].

3D Bioprinting Applications

Extrusion-based 3D bioprinting has emerged as a powerful tool for scalable production of kidney organoids. This technology enables automated fabrication of self-organizing kidney organoids with high reproducibility in cell number and viability [24] [25]. The process involves creating a wet cell paste from differentiated nephron progenitor cells, which is then loaded into a bioprinter for precise deposition onto Transwell filters [25]. Bioprinting facilitates rapid generation of organoids (approximately one micromass every 3 seconds) with minimal size variation (coefficient of variation 1-4%) and allows scaling from 6-well to 96-well formats for high-throughput drug screening [25]. Modifications to printing parameters can manipulate organoid biophysical properties, including size, cell number, and conformation, with specific configurations substantially increasing nephron yield per starting cell number [25].

Figure 2. Workflow for 3D bioprinting of kidney organoids and their research applications. The process begins with nephron progenitor cells, which are processed into a cell paste for bioprinting, followed by extended culture to form mature structures suitable for various research applications [24] [25].

Vascularization and Structural Complexity

Enhancing vascularization remains a critical challenge in kidney organoid maturation. Millifluidic culture systems that cultivate kidney organoids under flow conditions have demonstrated expansion of endogenous endothelial progenitor pools and production of vascular networks with perfusable lumens surrounded by mural cells [18]. Additionally, protocols for generating ureteral organoids from PSCs have been developed, combining induced stromal progenitors with ureteric bud epithelia to create ureter-like spherical organoids [26]. These advancements in modeling different renal components contribute to more physiologically relevant systems for disease modeling and therapeutic screening.

Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Kidney organoids derived from iPSCs have demonstrated significant utility in modeling genetic kidney diseases and screening for nephrotoxic compounds, providing valuable platforms for both basic research and pharmaceutical development.

Genetic Disease Modeling

iPSC-derived kidney organoids offer particular promise for studying genetic kidney diseases such as polycystic kidney disease (PKD) and congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) [7] [14]. By using patient-specific iPSCs, researchers can generate organoids that recapitulate key pathological features of these diseases, enabling investigation of disease mechanisms and high-throughput screening of potential therapeutics [7]. For example, organoids with PKD-associated mutations develop cyst-like structures that can be quantified and manipulated to test intervention strategies [7] [22]. Similarly, disease modeling using organoids generated from patients with TBX18 mutations has successfully replicated pathological features associated with ureteral developmental defects [26].

Nephrotoxicity Screening

The pharmaceutical industry has embraced kidney organoids for preclinical nephrotoxicity screening, addressing a critical need in drug development. Bioprinted organoids in 96-well formats have been validated for compound testing, demonstrating reproducible responses to known nephrotoxins [25]. For instance, treatment with aminoglycoside antibiotics or the chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin produces dose-dependent injury responses in specific renal cell types within organoids [25]. Organoids exposed to doxorubicin show specific activation of caspase 3 and loss of MAFB staining within podocytes, along with upregulation of the kidney injury molecule KIM1 (HAVCR1) [25]. These models provide more human-relevant toxicity data compared to traditional 2D renal cell cultures or animal models, potentially improving drug safety prediction.

The self-organizing potential of pluripotent stem cells into 3D renal structures has established a powerful platform for kidney disease modeling research. Through continued refinement of differentiation protocols, integration of immune components, and application of bioengineering innovations, kidney organoids are becoming increasingly physiologically relevant and technically reproducible. The ongoing development of more complex systems incorporating vascularization, ureteral components, and improved maturation will further enhance their utility in both basic research and translational applications. As these technologies continue to evolve, iPSC-derived kidney organoids promise to accelerate our understanding of renal development and disease mechanisms while improving the efficiency and safety of drug development pipelines.

Protocols and Applications: A Stepwise Guide to Generating and Utilizing Kidney Organoids

The advent of three-dimensional kidney organoid technology represents a transformative advance in nephrology, offering an unprecedented in vitro platform to study human kidney development, model disease, and screen therapeutics [7]. Kidney organoids, primarily derived from human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and embryonic stem cells (ESCs), are capable of self-organizing into nephron-like structures that recapitulate key aspects of early kidney development [7] [27]. This application note provides a comparative analysis of four pioneering differentiation protocols—Taguchi, Morizane, Takasato, and Freedman—framed within the context of generating kidney organoids from iPSCs for disease modeling research. We summarize quantitative data in structured tables, detail methodological workflows, and visualize signaling pathways to serve as a practical resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Protocol Comparison

The stepwise differentiation of human PSCs to kidney organoids is designed to recapitulate embryonic kidney development, progressing through primitive streak, intermediate mesoderm, and metanephric mesoderm stages before forming self-organizing, three-dimensional renal tissues [7] [27]. Below, we compare the defining characteristics of four foundational protocols.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Kidney Organoid Differentiation Protocols

| Protocol | Starting Cell Format | Key Inducing Factors | Major Renal Progenitors Generated | Time to Nephron Structures | Reported Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taguchi et al. | Embryoid bodies | CHIR99021, FGF2, Retinoic Acid | Metanephric mesenchyme (MM) only | ~20 days | High efficiency for MM [7] |

| Morizane et al. | Monolayer | CHIR99021, FGF9, BMP7 | Primarily MM, some ureteric epithelium | 10-12 days for progenitor populations; ~25 days for organoids [28] [29] | ~90% efficiency for MM [27] |

| Takasato et al. | Monolayer → 3D aggregate | CHIR99021, FGF9, BMP7 (varies) | MM, ureteric epithelium, interstitial, endothelial progenitors | 18-21 days for segmented nephrons [7] [27] [20] | Diverse renal lineages [27] |

| Freedman et al. | hPSC-derived epiblast spheroids in Matrigel | CHIR99021, FGF9, BMP7 | Nephron tubules, glomeruli, endothelial cells [27] | Not explicitly stated in provided context | Generates renal tubules, glomeruli, endothelial cells [27] |

Table 2: Functional Outputs and Limitations of Kidney Organoid Protocols

| Protocol | Nephron Segments Present | Off-Target Cell Types Reported | Documented Functional Assays | Noted Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taguchi et al. | Glomeruli, renal tubules | Not specified in provided context | Forms nephrons when combined with Wnt signals [7] | Lacks collecting ducts and other renal lineages [27] |

| Morizane et al. | Podocytes, tubular epithelia | Neuronal clusters, muscle cells [29] | Response to nephrotoxicants (cisplatin, gentamicin) [27] | Limited heterogeneity; contains off-target cells [29] |

| Takasato et al. | Glomeruli, proximal tubules, distal tubules, loops of Henle | Neuronal clusters, melanocyte-like cells [29] | Megalin/cubilin-mediated endocytosis; cisplatin response [27] [20] | 10-20% non-renal cells; immature proximal tubules [29] [20] |

| Freedman et al. | Renal tubules, glomeruli | Not specified in provided context | Not specified in provided context | Not specified in provided context |

Detailed Methodologies

Taguchi and Nishinakamura Protocol

This protocol employs an embryoid body-based approach guided by insights from mouse embryology to generate metanephric mesenchyme [7] [27].

Key Steps:

- Embryoid Body Formation: Aggregate iPSCs to form embryoid bodies in low-adhesion plates.

- Posterior Primitive Streak Induction: Treat embryoid bodies with CHIR99021 (a GSK3β inhibitor and WNT agonist) for 4 days.

- Intermediate Mesoderm Induction: Culture with FGF2 and retinoic acid for further differentiation.

- Metanephric Mesenchyme Specification: Cells express markers of metanephric mesenchyme (e.g., SIX2, PAX2, WT1).

- Nephron Formation: Combine induced metanephric mesenchyme cells with mouse dorsal spinal cord or activate WNT signaling using CHIR99021 to induce nephron formation, resulting in glomerular and tubular structures [7] [27].

Critical Notes: This protocol focuses exclusively on generating the metanephric mesenchyme and its nephron derivatives, without inducing collecting duct, renal interstitial, or endothelial cells [27]. The resulting nephrons can become vascularized when transplanted under a mouse renal capsule [27].

Morizane and Bonventre Protocol

This monolayer-based protocol emphasizes generating a homogeneous nephron progenitor population with high efficiency [7] [29].

Key Steps:

- Primitive Streak Induction: Culture iPSCs as a monolayer and activate WNT signaling with CHIR99021 for 3-4 days to induce posterior primitive streak.

- Intermediate Mesoderm Induction: Pattern posterior primitive streak toward intermediate mesoderm using FGF9 and BMP7 for several days.

- Nephron Progenitor Expansion: Maintain and expand nephron progenitor populations with FGF9.

- 3D Aggregation and Differentiation: Dissociate cells and aggregate into 3D spheroids in low-adhesion plates or transwell filters. Continue culture for ~18 days to allow self-organization into nephron structures [7] [28] [29].

Critical Notes: This protocol generates kidney organoids relatively quickly and cost-effectively, making it well-suited for large-scale assays such as drug screening [28]. Single-cell RNA-seq analysis reveals this protocol produces a high proportion of podocytes but also contains off-target neuronal and muscle cells [29].

Takasato Protocol

This comprehensive protocol simultaneously induces multiple renal progenitor populations to generate kidney organoids containing nephrons connected to collecting ducts and surrounded by renal interstitium and endothelial networks [27].

Key Steps:

- Monolayer Differentiation (7 days):

- Days 1-4: Induce posterior primitive streak in iPSC monolayer using CHIR99021.

- Days 4-7: Differentiate posterior primitive streak into intermediate mesoderm using FGF9.

- 3D Culture (18 days):

- Monolayer Differentiation (7 days):

Critical Notes: This protocol generates the broadest diversity of renal cell types, including glomerular podocytes (expressing PODXL, NPHS1), proximal tubules (LTL+, SLC3A1+), distal tubules, and collecting duct cells, as well as renal interstitial cells and an endothelial network [7] [27]. However, proximal tubule maturation remains incomplete, with low expression of key solute carriers under standard conditions [20]. A recent refinement using transient PI3K inhibition during early nephrogenesis can shift differentiation toward proximal tubule fates, creating "proximal-biased" organoids with enhanced functional maturity [20].

Freedman Protocol

This approach utilizes a unique starting point with hPSC-derived epiblast spheroids embedded in Matrigel to generate kidney organoids.

Key Steps:

- Epiblast Spheroid Formation: Create hPSC-derived epiblast spheroids by sandwiching hPSCs between two layers of dilute Matrigel.

- Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition: Spheroids undergo EMT to form a monolayer.

- Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition: Cells are reaggregated, prompting MET and resulting in formation of renal tubules, glomeruli, and endothelial cells [27].

Critical Notes: This method generates nephron structures including glomeruli and renal tubules along with endothelial cells, but detailed characterization of all renal lineages produced is not provided in the available context [27].

Signaling Pathways in Kidney Organoid Differentiation

The differentiation of kidney organoids relies on precise temporal activation of key developmental signaling pathways. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling events and their temporal sequence across major differentiation protocols.

The directed differentiation of kidney organoids recapitulates embryonic kidney development through sequential activation of conserved signaling pathways [7] [27]. Canonical WNT signaling, typically activated by the GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021, drives the initial specification of posterior primitive streak, which represents the progenitor population for all mesoderm, including kidney lineages [7] [27]. Subsequently, FGF9 signaling promotes patterning of the posterior primitive streak toward intermediate mesoderm, with some protocols incorporating BMP7 to enhance this process [7] [27] [30]. Continued FGF9 signaling supports the maintenance and expansion of nephron progenitor populations within the metanephric mesenchyme [7]. Finally, a secondary WNT signal, potentially through CHIR99021 activation or endogenous WNT production, triggers mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition and nephron formation [7] [27]. Additional pathways including BMP, Notch, and retinoic acid signaling contribute to nephron segmentation and cell fate specification in a protocol-dependent manner [7] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Kidney Organoid Differentiation

| Reagent/Category | Protocol Applications | Function in Differentiation |

|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | Taguchi, Morizane, Takasato, Freedman | GSK3β inhibitor that activates canonical WNT signaling; induces posterior primitive streak [7] [27] |

| FGF9 (Fibroblast Growth Factor 9) | Morizane, Takasato, Freedman | Patterns posterior primitive streak to intermediate mesoderm; maintains nephron progenitors [7] [27] [30] |

| BMP7 (Bone Morphogenetic Protein 7) | Morizane, Takasato (some variations) | Enhances intermediate mesoderm induction; supports progenitor survival/proliferation [7] |

| FGF2 (Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor) | Taguchi | Promotes intermediate mesoderm induction in embryoid body protocol [27] |

| Retinoic Acid | Taguchi | Promotes intermediate mesoderm induction in embryoid body protocol [27] |

| Matrigel | Freedman | Provides 3D extracellular matrix environment for epiblast spheroid formation and differentiation [27] |

| Transwell Filters | Takasato, Morizane (some applications) | Provides air-media interface for 3D organoid culture, enhancing tissue organization [27] [30] |

Applications in Disease Modeling and Limitations

Disease Modeling Applications

Kidney organoids generated using these protocols have been widely applied to model genetic kidney diseases such as polycystic kidney disease (PKD), congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT), and nephrotic syndrome [7] [31]. Patient-specific iPSC-derived organoids offer a unique platform for analyzing disease pathophysiology and performing therapeutic screening [7] [31]. For instance, organoids with HNF1B deletion, linked to congenital kidney defects, have been used to validate experimental systems for studying renal developmental biology [30]. Similarly, organoids have been employed to model ciliopathic renal phenotypes and podocyte injury [31].

Functional Assessment and Toxicity Screening

Kidney organoids demonstrate clinically relevant functions, particularly in nephrotoxicity testing. Proximal tubules within organoids display megalin- and cubilin-mediated endocytosis and respond to nephrotoxicants like cisplatin by undergoing specific apoptosis [27]. This response is attributed to the presence of basolateral organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2) and copper transporter 1 (CTR1) that mediate cisplatin uptake [27]. The development of "proximal-biased" organoids with enhanced expression of solute carriers has further improved the utility of organoids for studying proximal nephrotoxicity and tubulopathies [20].

Current Limitations and Refinement Strategies

Despite their promise, kidney organoids face several limitations. They generally represent fetal rather than adult kidney tissue, with incomplete maturation and lack of full nephron segmentation [7] [28] [20]. Organoids typically contain 10-20% non-renal cell types, including neuronal and muscle cells, which reflect incomplete lineage specification [29]. Vascularization is limited under standard culture conditions, though co-culture with endothelial cells or transplantation into immunodeficient mice can enhance vascular integration [7]. Recent innovations aim to address these limitations through bioengineering strategies such as microfluidic organ-on-a-chip platforms, 3D bioprinting, and optimized differentiation protocols that reduce off-target cells and enhance functional maturation [7] [31] [20].

The Taguchi, Morizane, Takasato, and Freedman protocols each offer distinct approaches to kidney organoid generation, with trade-offs in cellular diversity, protocol complexity, and applicability to specific research questions. The Taguchi protocol provides a focused model of metanephric mesenchyme and nephron formation, while the Takasato protocol generates the broadest spectrum of renal cell types, including nephrons connected to collecting ducts. The Morizane protocol balances efficiency and reproducibility, making it suitable for larger-scale applications. Continued refinement of these protocols through bioengineering, single-cell technologies, and signaling pathway manipulation will further enhance the physiological relevance and translational potential of kidney organoids for disease modeling and drug discovery.

The generation of kidney organoids from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) represents a transformative approach in biomedical research, offering unprecedented opportunities for studying renal development, disease modeling, and drug screening. This protocol is framed within a broader thesis on leveraging hiPSC-derived kidney organoids for disease modeling research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed roadmap for in vitro nephrogenesis. The fundamental strategy involves recapitulating key milestones of embryonic kidney development through directed differentiation, which proceeds through three critical phases: primitive streak induction, intermediate mesoderm patterning, and nephron progenitor formation [32]. Each of these stages must be precisely controlled through specific signaling pathway activation to generate kidney organoids containing functional nephron structures.

The kidney develops from the intermediate mesoderm, which gives rise to two key progenitor populations: the metanephric mesenchyme (MM) and the ureteric bud (UB). The MM contains self-renewing nephron progenitor cells (NPCs) that express critical transcription factors including SIX2, WT1, PAX2, and OSR1 [7]. These NPCs ultimately form all epithelial components of the nephron except the collecting duct through a process of mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) [7]. Successful duplication of this process in vitro requires meticulous control of developmental signaling pathways, including WNT, BMP, FGF, and RA signaling, at specific timepoints and concentrations [33]. The protocols outlined below synthesize established methodologies from leading research groups to provide a comprehensive framework for generating kidney organoids with robust nephron structures for research applications.

Developmental Biology Principles

Embryonic Origins of Kidney Structures

Understanding the embryonic origins of renal structures is essential for designing effective differentiation protocols. The adult kidney derives from the metanephros, which begins development through reciprocal inductive signaling between two key embryonic tissues: the ureteric bud (UB) and the metanephric mesenchyme (MM) [7]. The UB evaginates from the posterior portion of the Wolffian duct and undergoes repeated branching to form the collecting duct system, while the MM contains nephron progenitor cells that differentiate into all nephron segments including glomeruli, proximal tubules, loops of Henle, and distal tubules [7] [34]. This developmental process is orchestrated by precisely timed signaling interactions, with WNT signaling (particularly WNT9b and WNT4) being essential for MET and nephron induction [7]. BMP7 supports MM survival and proliferation, while FGF signaling (especially FGF8 and FGF9) promotes cell differentiation and UB branching [7]. Notch signaling contributes to nephron segmentation and fate specification, ensuring the proper formation of distinct nephron regions [7].

Developmental Timeline and Signaling

Table: Key Developmental Stages and Their In Vitro Recapitulation

| Developmental Stage | In Vivo Timing (Human) | Key Signaling Pathways | Major Markers | In Vitro Equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primitive Streak | Week 2-3 | WNT, Nodal/Activin, BMP | Brachyury (T), MIXL1 | CHIR99021 treatment |

| Intermediate Mesoderm | Week 3-4 | WNT, FGF, BMP | OSR1, PAX2, LHX1 | FGF9 ± BMP7 treatment |

| Metanephric Mesenchyme | Week 4-5 | FGF9, WNT, RA | SIX2, WT1, SAL11 | 3D aggregation + FGF9 |

| Nephron Formation | Week 5+ | WNT, Notch, FGF | NPHS1, LTL, ECAD | Spontaneous in organoids |

Experimental Protocols

Primitive Streak Induction

The initial step in kidney organoid differentiation involves guiding hiPSCs toward primitive streak identity, which represents the developmental stage preceding mesoderm formation. This is typically achieved through transient activation of the canonical WNT signaling pathway using GSK3β inhibitors.

Detailed Protocol:

- Culture hiPSCs to approximately 70-80% confluence in feeder-free conditions using essential stem cell maintenance medium such as mTeSR or StemFlex.

- Initiate differentiation by switching to a basal medium such as Advanced RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1-2% GlutaMax and 1-2% penicillin-streptomycin.

- Add CHIR99021 at optimized concentrations ranging from 3-12 µM (typically 8-10 µM for most cell lines) for 24-48 hours [7] [18]. The optimal concentration and duration must be determined empirically for specific hiPSC lines, as prolonged WNT activation promotes more posterior fates [34].

- Monitor morphological changes including the transition from compact colonies to more dispersed, elongated cells with mesenchymal appearance.

- Confirm successful induction by assessing expression of primitive streak markers Brachyury (T) and MIXL1 via immunocytochemistry or qPCR, typically visible within 24-48 hours.

Critical Considerations:

- The concentration and duration of CHIR99021 treatment significantly influence the resulting cell fate, with longer exposures promoting posterior primitive streak fates that give rise to kidney lineages [34].

- Cell density at differentiation initiation critically affects efficiency, with optimal results typically achieved at 70-80% confluence.

- Batch-to-batch variability in CHIR99021 activity necessitates quality control measures for reproducible results.

Intermediate Mesoderm Patterning

Following primitive streak induction, cells must be guided toward intermediate mesoderm identity, the direct precursor to kidney lineages. This stage requires precise manipulation of WNT, FGF, and BMP signaling.

Detailed Protocol:

- Following primitive streak induction (typically 24-48 hours), replace medium containing CHIR99021 with fresh basal medium.

- Add patterning factors including FGF9 (50-100 ng/mL) with or without BMP7 (10-50 ng/mL) for 3-5 days [7] [18]. Some protocols incorporate retinoic acid (RA) at this stage to support posterior IM patterning [18].

- Consider aggregate formation by transferring cells to low-attachment plates or using forced aggregation methods to promote 3D organization, which enhances IM patterning.

- Monitor for IM markers including OSR1, PAX2, and LHX1 via immunostaining or qPCR, typically emerging within 2-3 days of patterning factor addition.

- Assess morphology characterized by compact, epithelial-like clusters emerging within the more dispersed mesenchymal population.

Critical Considerations:

- The transition from primitive streak to IM represents a critical fate decision point, with anterior IM giving rise to ureteric bud lineages and posterior IM forming metanephric mesenchyme [32].

- The combination of FGF9 with BMP7 enhances the efficiency of IM induction in some protocols, while others achieve successful differentiation with FGF9 alone [18].

- The duration of WNT activation during the previous stage influences the response to patterning factors, with appropriate posteriorization being essential for kidney lineage specification.

Nephron Progenitor Formation and Organoid Generation

The final differentiation step involves expanding and maintaining nephron progenitor populations, followed by 3D organoid formation to support self-organization into nephron structures.

Detailed Protocol:

- After IM patterning (typically 4-6 days total differentiation), continue culture with FGF9 (50-100 ng/mL) to support nephron progenitor expansion.

- Transfer to 3D culture by forming aggregates in low-adhesion plates or embedding in extracellular matrix such as Matrigel to promote tissue-level organization [34].

- Maintain in 3D culture for 10-21 days, with medium changes every 2-3 days using renal organoid medium typically containing FGF9 alone or in combination with other factors such as BMP4, RA, or CHIR99021 at lower concentrations [18].

- Monitor nephron formation evidenced by the emergence of distinct morphological regions including cyst-like structures, tubular extensions, and dense glomerular clusters.

- Validate organoid identity through immunostaining for nephron progenitor markers (SIX2, CITED1), podocyte markers (WT1, NPHS1, PODXL), proximal tubule markers (LTL, CUBN), and distal tubule markers (ECAD, SLC12A1) [7].

Critical Considerations:

- The efficiency of NPC generation varies significantly between protocols, with Morizane's protocol reporting 80-90% SIX2+ cells compared to 20-70% in Taguchi's approach [18].

- Organoids generated using standard protocols typically exhibit fetal-like characteristics, resembling first-trimester human kidney more than adult tissue [34].

- Significant protocol-dependent variability exists in off-target cell types, with some protocols generating 10-20% non-renal cells [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Kidney Organoid Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Typical Concentrations |

|---|---|---|---|

| WNT Agonists | CHIR99021 | GSK3β inhibitor inducing primitive streak and posterior mesoderm | 3-12 µM (stage-dependent) |

| Growth Factors | FGF9 | Supports IM patterning and nephron progenitor maintenance | 50-100 ng/mL |

| Morphogens | BMP4, BMP7 | Promotes mesoderm formation and IM patterning | 10-50 ng/mL |

| Retinoids | Retinoic Acid (RA) | Patterns IM and supports nephron segmentation | 0.1-1 µM |

| Basal Media | Advanced RPMI 1640 | Base medium for differentiation | 100% |

| 3D Culture | Matrigel, AggreWell | Provides scaffold for 3D organization | Varies by system |

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Diagram Title: Kidney Organoid Differentiation Workflow

Diagram Title: Signaling Pathways in Kidney Organogenesis

Protocol Variations and Comparative Analysis

Several research groups have established distinct but overlapping protocols for kidney organoid generation, each with specific advantages and limitations. The table below summarizes key protocol variations from leading research groups, enabling researchers to select approaches most appropriate for their specific applications.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Kidney Organoid Differentiation Protocols

| Protocol Parameter | Taguchi et al. | Morizane et al. | Freedman et al. | Little Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Primitive Streak Induction | BMP4 (24h) → Activin A + FGF2 (48h) | CHIR99021 (monolayer) | Spheroid formation → CHIR99021 | CHIR99021 (suspension) |

| IM Patterning | BMP4 + high CHIR (10µM, 6 days) → Activin A + BMP4 + CHIR (3µM) + RA (2 days) | CHIR99021 → Activin A → FGF9 | Single-step CHIR99021 without exogenous FGF2/Activin/BMP | Modified CHIR99021 and growth factor timing |

| NPC Generation Efficiency | 20-70% SIX2+ cells | 80-90% SIX2+ cells | Not specified | Not specified |

| 3D Culture Method | Coculture with mouse spinal cord | Aggregation in low-adhesion plates | Matrigel sandwich | Suspension culture |

| Key Cell Types Generated | Glomeruli, proximal and distal tubules | Multi-segmented nephrons (podocytes, PT, LoH, DT) | Podocytes, proximal tubules, endothelial cells | Multiple nephrons with endothelial and stromal cells |

| Unique Advantages | Forms glomerular structures | Defined medium, high NPC efficiency | Simple, cost-effective, high-throughput | High cell yield, reduced costs |

| Major Limitations | Requires non-human tissue, lower efficiency | Line-dependent variability, no collecting duct | Random organoid size, no collecting duct | Immaturity similar to other protocols |

Technical Considerations and Troubleshooting

Optimization Strategies

Successful kidney organoid generation requires careful optimization of several parameters. Key considerations include:

- hiPSC Line Variability: Different hiPSC lines exhibit substantial variation in differentiation efficiency. Preliminary testing with multiple lines or CRISPR-edded isogenic controls is recommended for critical applications [18].

- Temporal Precision: The timing of growth factor addition is critical, with even 4-6 hour deviations potentially altering differentiation outcomes. Establish strict medium change schedules.

- 3D Culture Configuration: The method of 3D aggregation significantly influences organoid development. Forced aggregation using microwell plates (e.g., AggreWell) improves uniformity compared to spontaneous aggregation [35].

- Maturation Limitations: Standard protocol-generated organoids typically resemble first-trimester fetal kidney [34]. Enhanced maturation may require extended culture, specialized culture conditions such as air-liquid interface [35], or transplantation into animal hosts.

Quality Assessment Metrics

Rigorous quality control is essential for generating reproducible, high-quality kidney organoids. Key assessment metrics include:

- Molecular Characterization: Immunofluorescence analysis for segment-specific markers (podocytes: NPHS1, WT1; proximal tubule: LTL; distal tubule: ECAD) at day 18-21 of differentiation.

- Structural Assessment: Light microscopic evaluation for the presence of distinct glomerular-like bodies connected to tubular structures.

- Purity Evaluation: Quantification of off-target cell types (typically 10-20% in most protocols) using specific neural and muscle markers [18].

- Functional Assessment: For advanced applications, evaluate tubular function through dextran uptake assays or glomerular function through albumin retention.

Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Kidney organoids generated using these protocols serve as valuable tools for modeling genetic kidney diseases, including polycystic kidney disease (PKD) and congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) [7]. The patient-specific nature of hiPSC-derived organoids enables creation of personalized disease models that recapitulate individual genetic backgrounds. For drug development applications, kidney organoids provide human-relevant systems for nephrotoxicity screening and efficacy testing, addressing limitations of animal models and traditional 2D culture systems [36]. Recent advances in organoid culture, including microfluidic systems [7] and air-liquid interface approaches [35], further enhance the physiological relevance and scalability of these models for preclinical research.

The advent of kidney organoids derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has revolutionized the study of human renal diseases in a controlled, accessible in vitro environment. These three-dimensional structures recapitulate key aspects of kidney development, architecture, and function, providing researchers with unprecedented opportunities to model hereditary and acquired kidney diseases [7] [14]. For diseases like polycystic kidney disease (PKD), Alport syndrome, and acute kidney injury (AKI), kidney organoids have emerged as powerful platforms for elucidating pathological mechanisms, validating genetic findings, and screening potential therapeutic compounds [4] [37]. This application note details successful protocols and case studies demonstrating how iPSC-derived kidney organoids are advancing our understanding of these conditions, providing researchers with practical methodologies for implementing these models in their investigative workflows.

Kidney Organoid Generation from iPSCs

The foundation of effective disease modeling lies in the robust differentiation of iPSCs into kidney organoids. The following protocol, adapted from established methods, outlines the key steps for generating kidney organoids containing segmented nephron-like structures [7] [14].

Protocol: Directed Differentiation of iPSCs into Kidney Organoids

Key Reagents Required:

- Human iPSCs (healthy or patient-derived)

- CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor)

- Recombinant Human FGF9

- Recombinant Human BMP7

- Matrigel or Geltrex

- Advanced RPMI 1640 Medium

Procedure:

Intermediate Mesoderm Induction (Days 0-4):

- Culture iPSCs to 70-80% confluence in a defined, feeder-free system.

- Initiate differentiation by switching to advanced RPMI 1640 medium containing 8-12 µM CHIR99021.

- Culture for 4 days, changing medium every 48 hours. CHIR99021 activates WNT signaling, driving cells toward a posterior primitive streak and intermediate mesoderm fate [7] [14].

Nephron Progenitor Cell Specification (Days 4-9):

- On day 4, replace medium with advanced RPMI 1640 containing FGF9 (200 ng/mL).

- Culture for 5 days with medium changes every 2-3 days. FGF9 supports the maintenance and expansion of nephron progenitor populations [7].

3D Aggregation and Nephron Formation (Days 9-26):

- On day 9, dissociate cells into single cells using Accutase.

- Resuspend cells in differentiation medium containing FGF9 and transfer to low-attachment plates or specialized platforms like the UniMat system to promote 3D aggregation [22].

- Culture for 14-18 days, allowing for self-organization into nephron-like structures. Medium should be changed every 3-4 days.

Quality Control:

- Monitor for the emergence of tubular and glomerular-like structures.

- Validate differentiation by immunostaining for segment-specific markers: PODXL (podocytes), LTL (proximal tubules), CDH1 (distal tubules) [22].

- Use single-cell RNA sequencing to assess cell type composition and purity if available [7].

Table 1: Key Markers for Characterizing Kidney Organoid Differentiation

| Nephron Segment | Marker | Expected Expression Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Podocytes | PODXL, NPHS1, WT1 | Glomerular-like structures |

| Proximal Tubule | LTL, CUBN, SLC3A1 | Tubular structures with brush border |

| Distal Tubule | CDH1, SLC12A1 | Tubular structures |

| Stromal Cells | FOXD1, PDGFRβ | Interstitial areas |

Disease Modeling Applications

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD)

ADPKD, caused primarily by mutations in PKD1 or PKD2 genes, leads to progressive cyst formation and renal function decline. iPSC-derived kidney organoids have successfully modeled key aspects of ADPKD pathogenesis, including cystogenesis and the "second hit" hypothesis [38] [4].

Experimental Workflow for ADPKD Modeling:

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for generating and analyzing ADPKD kidney organoids:

Protocol: Modeling Cystogenesis in ADPKD Organoids

Genetic Manipulation:

Organoid Generation:

- Differentiate both mutant and control iPSCs into kidney organoids using the protocol in Section 2.1.

Cyst Induction:

- On day 18-21 of differentiation, supplement medium with 10-20 µM forskolin (an adenylate cyclase activator) or 10 µM nifedipine (an L-type calcium channel blocker) to stimulate cyst formation [38].

- Treat for 10-14 days, refreshing compounds every 2-3 days.

Phenotypic Analysis:

- Quantify cyst number and size using brightfield or phase-contrast microscopy.

- Employ automated image analysis platforms like OrganoID for high-throughput quantification [39].

- Assess intracellular cAMP levels via ELISA.

- Evaluate renin expression in cystic epithelium via immunostaining or RNA analysis, as ectopic renin expression is a hallmark of ADPKD organoids [38].

Key Findings:

- ADPKD organoids recapitulate elevated cAMP levels and abnormal calcium signaling central to cyst pathogenesis [38].

- Cyst formation often requires a "second hit" beyond genetic mutation, mimicked by forskolin or nifedipine treatment [38].

- Aberrant activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) has been observed in ADPKD organoids, with ectopic renin expression detected in the cystic epithelium [38].

Alport Syndrome

Alport Syndrome results from mutations in COL4A3, COL4A4, or COL4A5 genes, encoding type IV collagen chains essential for glomerular basement membrane (GBM) integrity [40]. While modeling the structural GBM defects in organoids remains challenging, they offer potential for studying disease mechanisms and screening therapeutic interventions.

Protocol: Modeling Alport Syndrome in Kidney Organoids

iPSC Generation:

- Generate iPSCs from Alport Syndrome patients with confirmed COL4A3, COL4A4, or COL4A5 mutations.

- Create gene-corrected isogenic controls using CRISPR/Cas9.

Organoid Differentiation: