hiPSC Models in Alzheimer's Disease: Bridging the Gap Between Familial and Sporadic Pathologies for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) models for both familial (FAD) and sporadic (SAD) Alzheimer's disease.

hiPSC Models in Alzheimer's Disease: Bridging the Gap Between Familial and Sporadic Pathologies for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) models for both familial (FAD) and sporadic (SAD) Alzheimer's disease. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology of AD, detailing established and emerging methodologies for generating neurons, microglia, and astrocytes from patient-derived hiPSCs. The content further addresses critical challenges in model optimization, including achieving cellular maturity and recapitulating sporadic disease. Finally, it examines the application of these models in high-throughput drug screening and validation, highlighting their growing role in de-risicking clinical trials and advancing personalized therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative disorders.

Decoding Alzheimer's Heterogeneity: Etiology and Pathophysiology in Familial vs. Sporadic Forms

Alzheimer's disease (AD) presents a genetic landscape of striking contrast, characterized by rare, highly penetrant monogenic drivers in familial forms (FAD) and a complex polygenic risk architecture in sporadic forms (SAD). This dichotomy represents a critical framework for understanding disease etiology and developing targeted therapeutic interventions. While FAD accounts for less than 1-5% of all cases and typically presents with early onset (before age 65), SAD constitutes the overwhelming majority (95%) of AD cases and usually manifests later in life [1] [2]. Despite their differing genetic foundations, both forms share core neuropathological features, including extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein [1]. Advances in genetic technologies, particularly genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and next-generation sequencing, have progressively refined our understanding of this architecture, revealing both expected divisions and surprising overlaps between these AD forms [3]. For research and drug development, this distinction is paramount, as it necessitates different modeling approaches: FAD can be recapitulated through specific pathogenic mutations, whereas SAD requires accounting for the cumulative burden of numerous risk variants and their interaction with environmental factors.

Monogenic Drivers in Familial Alzheimer's Disease (FAD)

Familial Alzheimer's Disease follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and is primarily caused by highly penetrant, pathogenic mutations in three genes: APP (amyloid precursor protein), PSEN1 (presenilin 1), and PSEN2 (presenilin 2). These mutations are sufficient to cause disease, often with onset before age 65 [1].

Causative Genes and Pathogenic Mechanisms

The table below summarizes the key features of the three major FAD genes.

Table 1: Monogenic Drivers in Familial Alzheimer's Disease

| Gene | Chromosome Location | Protein Function | Number of Known Pathogenic Mutations | Mechanistic Consequence of Mutation | Prevalence in FAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APP | 21q.21 | Amyloid precursor protein; cleaved to produce Aβ peptide | >50 [1] | Alters APP processing, increasing total Aβ production or aggregation-prone Aβ42/Aβ43 species [1] | ~10-15% of monogenic cases [4] |

| PSEN1 | 14q.29.2 | Catalytic subunit of γ-secretase complex | >350 (some of unclear pathogenicity) [1] | Disrupts γ-secretase activity, increasing ratio of longer, aggregation-prone Aβ42/Aβ40 peptides [1] | ~80% of monogenic cases [1] |

| PSEN2 | 1q.31-q42 | Catalytic subunit of γ-secretase complex | ~30 [1] | Alters γ-secretase activity, increasing Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio; effect is more variable than PSEN1 [1] | ~5% of monogenic cases [1] |

Mutations in these genes converge on a common pathophysiological pathway: the altered processing of APP and the consequent accumulation of amyloidogenic Aβ peptides, forming the biochemical foundation of the amyloid cascade hypothesis [1] [5]. This hypothesis posits that amyloid deposition is an initial, causative event in a cascade that leads to tau pathology, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline. The discovery of a protective mutation in APP (A673T) in the Icelandic population, which reduces amyloidogenic peptide formation by approximately 40%, provides compelling genetic support for this hypothesis [1].

Experimental Protocols for Monogenic FAD Research

Protocol 1: Cellular Modeling of FAD using hiPSCs

- hiPSC Generation: Derive hiPSCs from fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of FAD patients carrying specific APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2 mutations using non-integrating reprogramming methods (e.g., Sendai virus or episomal vectors) [6] [5].

- Genome Editing for Isogenic Controls: Use CRISPR/Cas9 to correct the pathogenic mutation in patient-derived hiPSCs or introduce it into control hiPSC lines to generate genetically matched, isogenic control lines—a critical step for attributing phenotypes specifically to the mutation [5].

- Neuronal Differentiation: Differentiate hiPSCs into cortical neurons using dual-SMAD inhibition protocols (e.g., using small molecule inhibitors for TGF-β and BMP signaling). This typically involves generating neural progenitor cells (NPCs) followed by terminal differentiation over 8-12 weeks [5].

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Aβ Profiling: Measure levels of Aβ40, Aβ42, and the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio in conditioned media using ELISA or mass spectrometry. FAD models typically show an increased Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio [5].

- Pathological Assessment: Immunocytochemistry for amyloid plaque-like aggregates and hyperphosphorylated tau (e.g., using antibodies against p-tau181, p-tau231) [5].

- Functional Assays: Perform electrophysiology (e.g., multi-electrode arrays) to assess neuronal network dysfunction and calcium imaging to measure aberrant neuronal activity [5].

Protocol 2: In Vivo Validation in Animal Models

- Model Selection: Utilize transgenic mice overexpressing human FAD mutant genes (e.g., 5xFAD, APP/PS1 models). The 5xFAD model expresses five FAD mutations (Swedish (K670N/M671L), Florida (I716V), and London (V717I) in APP, and M146L and L286V in PSEN1) under the neuron-specific Thy1 promoter [5].

- Longitudinal Phenotyping: Monitor animals for the development of Aβ plaques (e.g., via in vivo imaging or post-mortem immunohistochemistry with antibodies like 6E10), cognitive deficits (e.g., Morris water maze, contextual fear conditioning), and synaptic loss.

- Intervention Studies: Test potential therapeutics by administering compounds and assessing their impact on pathology and behavior.

Polygenic Risk in Sporadic Alzheimer's Disease (SAD)

Sporadic Alzheimer's Disease, representing over 95% of cases, does not exhibit a simple Mendelian inheritance pattern. Instead, its genetic architecture is complex and polygenic, involving a combination of common risk variants with small effect sizes, rare variants with moderate to large effects, and the influential APOE genotype [2] [3].

TheAPOELocus and GWAS-Derived Risk Loci

The apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele is the most potent genetic risk factor for SAD. Compared to the common ε3 allele, the ε4 allele confers a ~3-4 fold increased risk for heterozygotes and a 12-15 fold increased risk for homozygotes, while the ε2 allele is protective [1] [5]. The APOE genotype is estimated to explain 20-25% of the heritability of SAD. Beyond APOE, large-scale GWAS meta-analyses, such as those by the International Genomics of Alzheimer's Project (IGAP) and the European Alzheimer & Dementia Biobank (EADB), have identified over 90 genomic regions associated with AD risk [3]. The table below summarizes the primary categories of genetic risk factors in SAD.

Table 2: Key Genetic Risk Factors in Sporadic Alzheimer's Disease

| Risk Category | Representative Genes/Loci | Strength of Effect (Odds Ratio) | Primary Implicated Cell Type / Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Risk Locus | APOE ε4 allele | 3-4 (heterozygous), 12-15 (homozygous) [5] | Lipid metabolism, Aβ clearance, innate immunity |

| Common Risk Variants (GWAS) | BIN1, CLU, ABCA7, CR1, PICALM, TREM2, CD33, SORL1 [3] | 1.05 - 1.25 per allele | Myeloid cells/immunity, endocytosis, lipid metabolism |

| Rare Coding Variants (Large Effect) | TREM2 (R47H), SORL1, ABCA7 [3] | 2 - 5 (e.g., TREM2 R47H ~3-5) [3] | Myeloid cells/immunity, endosomal trafficking |

Notably, the common risk variants identified through GWAS are not randomly distributed but are significantly enriched in regulatory elements active in myeloid cells (e.g., microglia), implicating neuroinflammation and innate immunity as central processes in SAD etiology [1] [3].

Polygenic Risk Scores and Shared Genetic Architecture

A Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) aggregates the effects of many common risk alleles (both risk-increasing and protective) into a single numeric score, estimating an individual's genetic predisposition to a disease. Research has demonstrated a significant overlap in the genetic architecture across different AD classifications. A pivotal study found that a PRS derived from late-onset AD (LOAD) GWAS was associated with risk not only in sporadic LOAD but also in familial LOAD (fLOAD) and sporadic early-onset AD (sEOAD) [7] [8]. The highest association was observed in sEOAD (OR = 2.27), followed by fLOAD (OR = 1.75) and sLOAD (OR = 1.40), indicating that the burden of common risk variants is associated with familial clustering and an earlier age of onset [7] [8]. Furthermore, in autosomal dominant early-onset AD (eADAD) caused by APP/PSEN1/PSEN2 mutations, the PRS was not associated with disease risk but was associated with cerebrospinal fluid biomarker levels (ptau181/Aβ42), suggesting it may modulate the age at onset or disease penetrance [7] [8].

Experimental Protocols for Polygenic SAD Research

Protocol 1: Constructing and Applying a Polygenic Risk Score

- Base Data: Obtain summary statistics from a large-scale AD GWAS meta-analysis (e.g., from IGAP or EADB) [3].

- Clumping and Thresholding: Prune single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for linkage disequilibrium (LD) to ensure independence. Generate scores at multiple p-value thresholds (e.g., PT < 0.001, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1) to determine the most predictive set of variants for the target dataset.

- Score Calculation: In the target genotype dataset, for each individual, calculate the PRS as the sum of risk alleles they carry, weighted by the effect size (log(odds ratio)) from the base GWAS. The formula is: ( PRS = \sum{i} (\betai \times Gi) ), where ( \betai ) is the effect size of SNP i and ( G_i ) is the genotype dosage (0, 1, 2) [7].

- Validation: Test the association between the PRS and disease status in the target cohort using logistic regression, adjusting for covariates like age, sex, and genetic principal components.

Protocol 2: Modeling Polygenic Risk in hiPSC Cohorts

- Cohort Selection: Assemble a diverse hiPSC bank from dozens to hundreds of cognitively assessed healthy elderly and SAD patients, with whole-genome sequencing data available [6].

- Stratification by PRS: Calculate PRS for each hiPSC line and stratify lines into "High-PRS" (e.g., top quartile) and "Low-PRS" (e.g., bottom quartile) groups.

- Differentiation and Multi-cell Culture: Differentiate hiPSCs into relevant brain cell types (neurons, astrocytes, microglia). For more physiological models, generate 2D co-cultures or 3D cerebral organoids containing multiple cell types [6] [5].

- Phenotypic Interrogation: Challenge the models (e.g., with Aβ oligomers, inflammatory stimuli) and assay for SAD-relevant phenotypes: transcriptomic profiles, Aβ and tau pathology, phagocytic capacity of microglia, and neuronal network activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating AD Genetic Architecture

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| hiPSCs (patient-derived) | Foundation for in vitro disease modeling; retain donor-specific genetic background. | Generating neuronal and glial cells to study patient-specific pathophysiology [6] [5]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Precision genome editing for introducing or correcting mutations. | Creating isogenic control lines for FAD studies or introducing risk variants into low-PRS control lines [5]. |

| Differentiation Kits (Neuronal, Microglial) | Standardized protocols to generate specific brain cell types from hiPSCs. | Producing consistent, reproducible cultures of neurons and microglia for pathway and functional analysis [5]. |

| Anti-Aβ & Anti-p-Tau Antibodies | Detection and quantification of key AD pathologies via immunofluorescence, ELISA, and Western blot. | Staining for amyloid plaques (e.g., 6E10) and neurofibrillary tangles (e.g., AT8 for p-tau) in hiPSC-derived cultures or tissue [5]. |

| Cytokine & Chemokine Panels | Profiling inflammatory mediators secreted by glial cells. | Measuring neuroinflammatory responses in microglia and astrocyte cultures derived from High-PRS vs. Low-PRS lines [6]. |

| Multi-Electrode Arrays (MEAs) | Functional assessment of neuronal network activity and synchronization. | Detecting hyperexcitability or network dysfunction in FAD- or SAD-patient neurons [5]. |

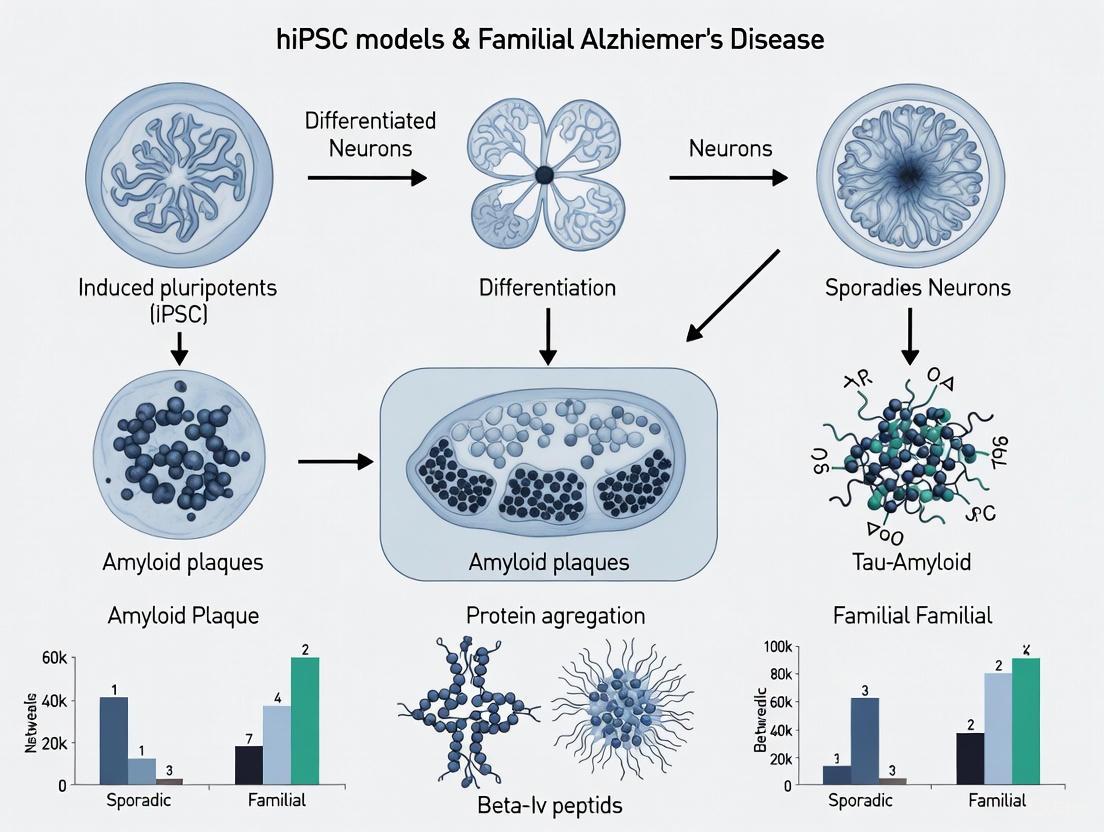

Visualizing Genetic Architecture and Research Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core genetic concepts and experimental approaches discussed in this whitepaper.

Genetic Architecture of FAD vs. SAD

hiPSC Modeling Workflow for FAD and SAD

The genetic architecture of Alzheimer's disease is defined by a clear dichotomy between monogenic drivers in FAD and polygenic risk in SAD, yet modern research reveals a shared pathophysiological ground and significant overlap in their underlying genetic risk factors. This understanding directly informs the use of hiPSC models in research and drug development. For FAD, the strategy involves precise modeling of specific pathogenic mutations with isogenic controls to dissect causal mechanisms. For SAD, the approach requires cohort-based studies that capture polygenic risk, focusing on the interplay between multiple risk variants, with a particular emphasis on non-neuronal cell types like microglia. As the field moves forward, integrating genetic findings from diverse ancestries, exploring the role of somatic mutations, and leveraging complex hiPSC-based systems like organoids and microfluidic chips will be crucial for bridging the gap between genetic insight and effective, personalized therapeutic interventions.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the most common cause of dementia globally, characterized by a devastating decline in memory and cognitive function. The pathological diagnosis of AD relies on the presence of three core hallmarks: amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques, neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), and sustained neuroinflammatory responses [9] [10]. For decades, research has been hampered by the inability to model the human brain's complexity and the distinct characteristics of sporadic versus familial AD. The advent of human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) technology has revolutionized this landscape, enabling the generation of patient-specific brain cells that recapitulate both familial and sporadic disease pathologies in vitro [11] [5] [6]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the three core pathological hallmarks and details how hiPSC models are elucidating their roles in AD pathogenesis.

Amyloid-β Plaques

Pathological Basis

Amyloid-β plaques are extracellular deposits primarily composed of Aβ peptides, which are generated through the sequential proteolytic cleavage of the Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) by β-secretase (BACE1) and γ-secretase complexes [5]. The γ-secretase complex, which includes Presenilin 1 (PSEN1) and Presenilin 2 (PSEN2), produces Aβ peptides of varying lengths, with Aβ42 being more aggregation-prone due to its hydrophobicity [5]. In the dominant amyloid cascade hypothesis, an imbalance between Aβ production and clearance leads to the accumulation of Aβ oligomers and ultimately the formation of insoluble plaques, triggering a pathogenic cascade that results in synaptic dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and neuronal death [5] [12].

Insights from hiPSC Models

hiPSC-derived neurons from patients with familial AD (fAD), such as those with APP gene duplications (APPDp) or PSEN1 mutations, faithfully replicate key aspects of amyloid pathology. These models demonstrate significantly higher levels of secreted Aβ(1–40) and increased Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios compared to neurons from non-demented controls [11] [5]. Crucially, hiPSC models have also proven valuable for studying sporadic AD (sAD), with neurons from some sAD patients exhibiting amyloidogenic phenotypes similar to fAD models, including elevated Aβ and large RAB5-positive early endosomes, suggesting convergent pathological mechanisms [11]. Furthermore, isogenic hiPSC lines, where AD-related mutations are introduced via CRISPR/Cas9, allow for controlled studies of specific genetic contributions.

Table 1: Amyloid-β Pathology in hiPSC-Derived Neurons

| hiPSC Model Type | Key Amyloid-Related Phenotypes | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Familial AD (APPDp) | ↑ APP mRNA, ↑ Secreted Aβ(1–40), ↑ RAB5+ early endosomes [11] | Confirms causative role of APP dosage in amyloidosis |

| Familial AD (PSEN1 ΔE9) | ↑ Aβ secretion, altered inflammatory response [13] | Demonstrates mutation-specific effects on γ-secretase function |

| Sporadic AD (sAD) | Elevated Aβ, phospho-Tau, active GSK-3β in a subset of patients [11] | Proves sporadic cases can exhibit amyloid-driven phenotypes |

Neurofibrillary Tangles

Pathological Basis

Neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) are intraneuronal aggregates consisting of hyperphosphorylated forms of the microtubule-associated protein tau [9]. In its normal state, tau promotes the assembly and stabilization of microtubules, which are critical for maintaining cell structure and facilitating axonal transport [9] [10]. In AD, tau becomes abnormally phosphorylated at multiple sites, which reduces its affinity for microtubules and promotes its self-assembly into paired helical filaments (PHFs) and eventually NFTs [9] [14]. This process compromises microtubule integrity, impairs axonal transport, and is strongly correlated with neuronal loss and cognitive decline [9] [10].

Insights from hiPSC Models

hiPSC-derived neurons have been instrumental in probing the relationship between amyloid and tau pathology. Neurons from both fAD (APPDp) and sAD patients show significantly elevated levels of phospho-tau (Thr231) and active glycogen synthase kinase-3β (aGSK-3β), a key kinase that phosphorylates tau [11]. A critical experiment using these models revealed that β-secretase (BACE) inhibition, but not γ-secretase inhibition, significantly reduced levels of phospho-Tau(Thr231) and aGSK-3β [11]. This finding suggests a direct relationship between APP proteolytic processing (but not necessarily the Aβ peptide itself) and the activation of pathways leading to tau phosphorylation in human neurons, offering a new perspective on the amyloid-tau nexus.

Neuroinflammation

Pathological Basis

Neuroinflammation is now recognized as a third core hallmark of AD, driven primarily by the activation of glial cells in the central nervous system [9] [14]. Microglia, the brain's resident immune cells, and astrocytes become reactive in response to damage signals like Aβ oligomers and NFTs [9]. This activation triggers the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), chemokines, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [9] [14]. While an acute inflammatory response can be protective, chronic glial activation creates a toxic environment that drives neurodegeneration. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have solidified the role of neuroinflammation by identifying numerous AD risk genes that are highly expressed in microglia and astrocytes (e.g., TREM2, APOE) [9] [5] [13].

Insights from hiPSC Models

hiPSC technology enables the generation of all major brain cell types, allowing for the creation of sophisticated co-culture systems to study neuroinflammation.

- Astrocyte Dysfunction: hiPSC-derived astrocytes carrying the APOE4 allele—the strongest genetic risk factor for sAD—display impaired Aβ clearance, disrupted cholesterol metabolism, and heightened pro-inflammatory responses compared to their APOE3 counterparts [13]. When co-cultured with neurons, APOE4 astrocytes provide less synaptic support and exacerbate neuroinflammation [13].

- Microglial Activation: Tri-culture systems incorporating hiPSC-derived neurons, astrocytes, and microglia model immune cross-talk. In such models, microglia respond to Aβ and tau aggregates, but their function is modulated by other cells. For instance, astrocyte-derived * interleukin-3 (IL-3)* can reprogram microglia to enhance their capacity to cluster and clear Aβ and Tau aggregates [13].

- Complement System: Tri-culture models have shown that under inflammatory conditions, reciprocal signaling between astrocytes and microglia drives the overproduction of the complement protein C3, a key player in synapse elimination, with this effect being amplified in AD cultures [13].

Table 2: Glial Dysfunction in hiPSC Models of Alzheimer's Disease

| Cell Type | AD-Associated Dysfunction | hiPSC Model Insights |

|---|---|---|

| Astrocytes | ↓ Aβ clearance, ↑ inflammation, ↓ synaptic support, metabolic disruption [13] | APOE4 astrocytes are intrinsically pro-inflammatory and less supportive of neurons [13]. |

| Microglia | Chronic activation, altered phagocytosis, pro-inflammatory cytokine release [9] [5] | In tri-cultures, microglia can be "reprogrammed" by astrocyte signals to improve aggregate clearance [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for hiPSC-Based AD Research

Neuronal Differentiation and Phenotypic Analysis

A standardized protocol for generating and analyzing neurons from hiPSCs involves the following key steps [11]:

- hiPSC Generation and Culture: Fibroblasts from fAD, sAD, and non-demented control donors are reprogrammed into hiPSCs using non-integrating methods (e.g., Sendai virus) expressing OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC. Multiple clonal lines are maintained and validated for pluripotency markers and karyotypic stability.

- Neural Induction and Progenitor Expansion: hiPSCs are differentiated into neural progenitor cells (NPCs) via embryoid body formation or dual SMAD inhibition. NPCs are purified using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with surface markers (CD184+/CD15+/CD44−/CD271−) and expanded in culture.

- Neuronal Differentiation and Purification: NPCs are differentiated for 3-5 weeks into heterogeneous neuronal cultures. Neurons are then purified to near homogeneity (>90%) using FACS for CD24+/CD184−/CD44− immunoreactivity.

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Biochemical Assays: ELISA or MSD assays on cell lysates and media to quantify Aβ species (Aβ40, Aβ42) and phosphorylated tau (e.g., Thr231).

- Immunocytochemistry: To visualize and quantify intracellular proteins like MAP2, βIII-tubulin, RAB5, and phospho-tau.

- Electrophysiology: Whole-cell patch-clamp recording to confirm functional neuronal properties, including action potential generation and synaptic activity.

Advanced Co-culture Systems

To model neuroinflammation, more complex 2D and 3D systems are employed [13]:

- Tri-culture System: hiPSC-derived neurons, astrocytes, and microglia are combined in a defined ratio.

- Treatment and Analysis: Cultures are exposed to aggregated Aβ or pro-inflammatory cytokines. The culture medium is analyzed for secreted factors (cytokines, complement proteins), and cells are fixed for immunostaining to analyze glial activation, phagocytosis of Aβ, and neuronal health.

Visualizing Pathological Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Core AD pathology cascade.

Diagram 2: hiPSC modeling workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for hiPSC-based Alzheimer's Disease Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| hiPSC Lines | Patient-specific disease modeling | Isogenic lines with edited APOE or PSEN1 alleles to study specific mutations [5] [13]. |

| Neural Differentiation Kits | Directing cell fate to neural lineages | Commercial kits (e.g., STEMdiff) for consistent generation of NPCs and neurons. |

| FACS Antibodies | Purification of specific cell populations | Anti-CD24, CD184, CD44, CD15 for isolating neurons and NPCs [11]. |

| Aβ ELISA/MSD Kits | Quantifying Aβ peptides from media | Measuring Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio in neuronal culture supernatants [11]. |

| Phospho-Tau Antibodies | Detecting tau pathology | Immunostaining or Western Blot for p-Tau (Thr231) [11]. |

| Cytokine Profiling Arrays | Assessing neuroinflammatory states | Quantifying TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β from co-culture media [9] [13]. |

| γ-/β-Secretase Inhibitors | Probing amyloidogenic pathway | Testing effect on Aβ production and downstream tau phosphorylation [11]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Genome editing for functional studies | Creating isogenic controls or introducing risk variants (e.g., APOE4) [13]. |

The amyloid cascade hypothesis (ACH), which posits amyloid-β (Aβ) accumulation as the initiating trigger of Alzheimer's disease (AD), has dominantly influenced research and drug development for decades. The advent of human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) technology provides a revolutionary platform for reevaluating this hypothesis using patient-derived neurons. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence from hiPSC models, demonstrating how they elucidate shared and distinct pathophysiological endotypes across familial (fAD) and sporadic (sAD) forms of the disease. We detail critical experimental protocols, present quantitative data, and visualize core signaling pathways, offering a refined, hiPSC-informed perspective on AD pathogenesis and therapeutic targeting.

The amyloid cascade hypothesis, formally articulated in 1992, proposes that AD pathogenesis is initiated by an imbalance in Aβ production and clearance, leading to Aβ aggregation into oligomers and plaques. This, in turn, is hypothesized to trigger tau pathology, neuroinflammation, synaptic dysfunction, and eventual neuronal loss [15]. Despite its longevity, the hypothesis faces significant challenges, including the poor correlation between amyloid plaque burden and cognitive decline, and the limited clinical efficacy of anti-amyloid therapies [16] [17].

hiPSC technology, pioneered by Shinya Yamanaka, enables the generation of patient-specific neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, offering a human-relevant system to model AD [6] [18]. Bibliometric analysis reveals a steady increase in hiPSC-AD publications over the past 14 years, with research trends focusing on inflammation, astrocytes, microglia, apolipoprotein E (ApoE), and tau [6]. This resource allows for the direct interrogation of the ACH in a human neuronal context, capturing patient-specific genetic backgrounds and the complexity of sAD, which constitutes the majority of cases.

hiPSC Models Differentiate and Refine Amyloid-Associated Mechanisms

hiPSC models have been instrumental in moving beyond a simplistic view of the ACH, revealing subtler dysregulations in amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing and its downstream consequences.

Familial AD Models: Beyond Aβ42

In fAD, caused by mutations in PSEN1, PSEN2, or APP, hiPSC-derived neurons have validated the shift in γ-secretase activity toward the production of longer, more aggregation-prone Aβ peptides (e.g., Aβ42) [19] [20]. However, multi-omics studies on hiPSC-derived neurons harboring PSEN1A79V, PSEN2N141I, and APPV717I mutations reveal that common disease endotypes extend far beyond Aβ. These include:

- Dedifferentiation: A reversion to a less-differentiated cellular state.

- Synaptic Signaling Dysregulation: Repression of genes critical for synaptic function.

- Mitochondrial Repression: Downregulation of oxidative phosphorylation and metabolic pathways.

- Inflammation: Activation of pro-inflammatory pathways [20]. This indicates that fAD mutations trigger a broad pathogenic network where altered Aβ production is one component of a multifaceted cellular crisis.

Sporadic AD Models: Polygenic Risk and Cellular Vulnerability

Modeling sAD requires capturing its polygenic nature. Recent resources like the IPMAR Resource have created a collection of over 100 hiPSC lines from donors with extremes of global AD polygenic risk scores (PRS) and complement pathway-specific PRS [21]. This allows researchers to study the molecular consequences of genetic risk in a controlled in vitro setting. Furthermore, a groundbreaking study using wild-type murine neurons identified a unique subpopulation that spontaneously recapitulates fAD phenotypes, including inefficient γ-secretase activity, endo-lysosomal abnormalities, and increased vulnerability to toxic insults [19]. This suggests that sAD may involve the selective vulnerability of specific neuronal populations due to intrinsic variability in proteostatic mechanisms, rather than a deterministic genetic mutation.

Experimental Protocols for hiPSC-Based AD Research

Protocol 1: Generating and Differentiating Cortical Neurons from hiPSCs

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in foundational hiPSC-AD studies [20].

- Reprogramming: Dermal fibroblasts from patients and non-demented controls are reprogrammed into hiPSCs using non-integrating methods (e.g., episomal vectors) to minimize genomic alterations.

- Neural Induction: hiPSCs are co-cultured with PA6 stromal cells to induce neural differentiation. To enhance neural induction, cultures are treated with 5 μM dorsomorphin (a BMP inhibitor) and 10 μM SB431542 (a TGF-β inhibitor) for the first 6 days.

- Neural Stem Cell (NSC) Expansion: On day 12, NSCs are isolated by Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) using a cell surface signature (CD24+/CD184+/CD44−/CD271−). NSCs are expanded in NSC growth medium supplemented with 20 ng/mL human basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF-2).

- Neuronal Differentiation: Upon reaching 80% confluence, the medium is switched to neuron differentiation medium (lacking bFGF-2) for 3 weeks to promote terminal differentiation into cortical neurons.

- Neuronal Purification: Differentiated cultures are dissociated and magnetically purified using anti-PE conjugated magnetic beads after incubation with antibodies against CD184 and CD44. The supernatant, containing purified CD184−/CD44− neurons, is collected for downstream applications [20].

Protocol 2: Fluorescence Imaging and FACS of Neurons with Altered γ-Secretase Activity

This protocol enables the identification and isolation of neurons with inherent vulnerabilities [19].

- Biosensor Expression: Primary wild-type or hiPSC-derived neurons are transduced with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) packaging a FRET-based γ-secretase biosensor (e.g., C99 Y-T) under a neuron-specific promoter (e.g., human synapsin, hSyn).

- Confocal Microscopy & FRET Imaging: Live neurons are imaged using a confocal microscope equipped with environmental control (CO2 and temperature). The biosensor is excited with a 405 nm laser, and emissions are detected simultaneously at 460–480 nm (donor, mTurquoise-GL) and 520–540 nm (acceptor, YPet). The FRET ratio (YPet/mTurquoise-GL) is calculated on a cell-by-cell basis, with a lower ratio indicating diminished γ-secretase endopeptidase-like activity.

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): For live-cell sorting, neurons are stained with Propidium Iodide (PI) to exclude dead cells. Neurons expressing the biosensor are excited with a 405 nm laser, and emissions are collected in the 425–475 nm and 500–550 nm channels. The designated 20% of neurons with the lowest FRET ratios (diminished activity) and the 20% with the highest ratios (control) are sorted into separate populations for subsequent molecular and functional analyses [19].

Quantitative Data and Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Key hiPSC Lines for Modeling Genetic Risk in Alzheimer's Disease

| Resource Name | Description of hiPSC Lines | Key Genetic Features | Associated Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPMAR Resource [21] | >100 lines from donors with extremes of polygenic risk. | • 34 lines: High global PRS (Late-Onset AD)• 29 lines: High global PRS (Early-Onset AD)• 27 lines: Low global PRS (Control)• 19 lines: Extremes of complement pathway PRS | Clinical, longitudinal, and genetic datasets. Available via EBiSC and DPUK. |

| FAD Multi-omics Study [20] | Isogenic and patient-derived lines. | • PSEN1A79V (fAD)• PSEN2N141I (fAD)• APPV717I (fAD)• Non-demented controls (NDC) | RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and proteomic data on purified neurons. |

Table 2: Phenotypic Characterization of Neuronal Subpopulations with Altered γ-Secretase Activity [19]

| Assay Type | Parameter Measured | Neurons with Low γ-Secretase Activity | Control Neurons (High Activity) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical | Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio | ↑ Increased | Normal |

| Cellular Imaging | Endo-lysosomal morphology | Abnormally enlarged | Normal |

| Functional Assay | Viability after oxidative stress (DTDP) | ↓ Significantly decreased | More resistant |

| Functional Assay | Viability after excitotoxicity (Glutamate) | ↓ Significantly decreased | More resistant |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for hiPSC-based AD Mechanistic Studies

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Dorsomorphin & SB431542 [20] | Small molecule inhibitors for highly efficient neural induction from hiPSCs. | Directing hiPSCs toward a neural lineage during co-culture with PA6 cells. |

| FRET-based γ-secretase biosensor (C99 Y-T) [19] | Visualizing and quantifying endogenous γ-secretase activity in live neurons. | Identifying neuronal subpopulations with inherently inefficient γ-secretase function via live-cell imaging or FACS. |

| Magnetic Cell Sorting Kits (e.g., anti-PE beads) [20] | Purifying specific cell populations (e.g., neurons) from heterogeneous cultures. | Isolating CD184-/CD44- neurons from differentiated hiPSC cultures for clean omics analysis. |

| Human Aβ38 & Aβ42 ELISA Kits [19] | Quantifying specific Aβ peptide species from conditioned media or cell lysates. | Confirming a pathological shift in Aβ production in FAD lines or sorted neuronal populations. |

| LysoPrime Green & Propidium Iodide (PI) [19] | Staining acidic organelles (endo-lysosomes) and identifying dead cells, respectively. | Assessing endo-lysosomal morphology and quantifying cell viability in health and after insult. |

Visualizing Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: The Expanded Amyloid Cascade in hiPSC Models. hiPSC studies show FAD mutations initiate a cascade that extends beyond Aβ to fundamental cellular dysfunctions.

Diagram 2: hiPSC Experimental Workflows for sAD and fAD. Complementary approaches for modeling polygenic risk and investigating intrinsic neuronal vulnerability.

hiPSC models have provided an indispensable, human-relevant platform for a rigorous re-evaluation of the amyloid cascade hypothesis. The evidence compels a move from a linear, Aβ-centric view to a complex model where amyloid dysregulation is one critical node within a broader network of cellular pathology. Key insights include the identification of common molecular endotypes across genetic forms of AD and the existence of vulnerable neuronal subpopulations in sporadic contexts. Future research must leverage large-scale hiPSC resources, such as those capturing polygenic risk, and continue to develop more complex co-culture and organoid systems to unravel the interplay between amyloid, tau, glial cells, and neuroinflammation. This hiPSC-refined understanding is crucial for developing therapeutics that target the core cellular vulnerabilities in AD, moving beyond the sole removal of amyloid.

The pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Alzheimer's disease (AD), has historically focused on neuronal pathology. However, emerging research highlights the critical roles of glial cells—microglia and astrocytes—as active contributors to disease mechanisms. This whitepaper examines how these resident immune cells transition from homeostatic supporters to pathogenic drivers in neurodegenerative processes, with a specific focus on insights gained from human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) models. The integration of hiPSC technology has been crucial for dissecting cell-intrinsic pathologies, revealing distinct glial phenotypes in familial versus sporadic AD, and identifying novel therapeutic targets. By leveraging patient-specific hiPSCs, researchers can now model the complex interplay of genetics and cellular pathology, providing unprecedented opportunities for drug development and personalized medicine approaches in neurological disorders.

The central nervous system (CNS) operates through sophisticated interactions between neurons and glial cells, with microglia and astrocytes serving as essential components of the neuroimmune interface. Microglia, the resident immune macrophages of the CNS, and astrocytes, the predominant homeostatic support cells, collectively maintain brain homeostasis through surveillance, metabolic support, synaptic regulation, and inflammatory modulation [22] [23]. In Alzheimer's disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions, these glial cells undergo functional transformation, contributing to neuroinflammation, synaptic dysfunction, and protein aggregation pathologies.

The advent of human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) technology has revolutionized our ability to model these complex glial-neuronal interactions in patient-specific contexts. Bibliometric analysis reveals a steady increase in hiPSC-AD publications over the past 14 years, with the United States and China leading research contributions [6]. Current research trends have particularly focused on neuroinflammation, astrocytes, microglia, apolipoprotein E (ApoE), and tau pathology, highlighting the growing recognition of glial mechanisms in AD pathogenesis [6]. This whitepaper synthesizes current understanding of microglial and astrocytic pathophysiology in neurodegenerative disease, with emphasis on findings from hiPSC models that distinguish sporadic from familial disease mechanisms.

Pathological Transformation of Microglia

Physiological Functions and Phenotypic Heterogeneity

Under homeostatic conditions, microglia exhibit a highly ramified morphology with extensive branching processes that continuously surveil the CNS microenvironment. These dynamic sentinel cells perform essential functions including phagocytosis of cellular debris, clearance of pathological protein aggregates, and regulation of synaptic plasticity through direct interactions with neurons [22] [24]. Microglia display remarkable heterogeneity and phenotypic plasticity, transitioning along a functional spectrum in response to microenvironmental cues. The traditional M1 (pro-inflammatory)/M2 (anti-inflammatory) classification has been superseded by recognition of disease-specific activation states identified through single-cell transcriptomics [22].

Microglial activation states are tightly regulated by complex receptor networks that sense environmental changes. Key receptors include Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 (TREM2), immunomodulatory receptors (CD33), pattern recognition receptors (Toll-like receptors, NLRs), scavenger receptors (SR-A, CD36), and TAM family tyrosine kinases (Tyro3, Axl, MerTK) [24]. These receptors enable microglia to detect damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), and neurodegenerative disease-related proteins such as amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau.

Mechanisms in Neurodegenerative Pathogenesis

In Alzheimer's disease, microglia demonstrate dual roles that can both ameliorate and exacerbate pathology. Initially, microglia attempt to clear Aβ deposits through phagocytic activity, with TREM2 playing a critical role in promoting microglial survival, proliferation, and phagocytic function [24]. However, genetic variants in microglia-associated genes, including TREM2, CD33, and MS4A, significantly elevate AD risk and impair these protective functions [22]. The R47H mutation in TREM2, for instance, diminishes microglial capacity to phagocytose Aβ, contributing to plaque accumulation [24].

Sustained microglial activation leads to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α) and chemokines that establish chronic neuroinflammation, ultimately driving synaptic loss and neuronal damage [24]. Microglia also contribute to neurodegeneration through immunometabolic reprogramming, with disruptions in glucose, lipid, and amino acid metabolism influencing their functional states [22]. Recent research has identified ferroptosis—an iron-dependent form of cell death—as a particularly vulnerable pathway in microglia, with iron overload inducing inflammatory phenotypes and contributing to neurotoxicity [25].

Table 1: Key Microglial Receptors in Alzheimer's Disease Pathogenesis

| Receptor | Primary Ligands | Signaling Pathways | Functional Role in AD |

|---|---|---|---|

| TREM2 | Aβ, ApoE, apoptotic cells | DAP12/SYK | Phagocytosis, cell survival, metabolic regulation |

| CD33 | Sialic acid residues | Unknown | Inhibits phagocytosis; risk gene for AD |

| TLR4 | Aβ, LPS | NF-κB, MAPK | Pro-inflammatory activation |

| CX3CR1 | Fractalkine (CX3CL1) | Various | Microglia-neuron communication; neuroprotection |

| CD36 | Aβ, oxidized LDL | NF-κB, NLRP3 inflammasome | Aβ uptake; pro-inflammatory response |

Astrocytic Contributions to Disease Progression

Homeostatic Functions and Reactive Transformation

Astrocytes constitute the most abundant glial cell type in the CNS and perform diverse homeostatic functions essential for neuronal health. These include regulation of ionic balance (particularly K⁺ and Ca²⁺), metabolic support through the glutamate-glutamine cycle and lactate shuttle, neurotransmitter recycling, synaptic modulation, and blood-brain barrier maintenance [23]. Under pathological conditions, astrocytes undergo reactive transformation characterized by morphological changes (hypertrophy, process swelling), molecular alterations (increased GFAP expression), and functional reprogramming.

Reactive astrocytes are broadly categorized into neurotoxic (A1) and neuroprotective (A2) phenotypes, though this classification represents a simplification of a continuous functional spectrum [23]. The A1 phenotype is induced by activated microglia releasing IL-1α, TNF-α, and C1q, leading to production of inflammatory mediators and loss of normal homeostatic functions. Conversely, A2 astrocytes upregulate neurotrophic factors and anti-inflammatory cytokines that support neuronal survival and tissue repair [23].

Pathogenic Mechanisms in Neurodegeneration

In Alzheimer's disease, astrocytes respond to Aβ deposition by releasing pro-inflammatory factors that exacerbate neuroinflammation [23]. Astrocyte dysfunction also contributes to AD pathology through metabolic disturbances, including lipid droplet accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress imbalance [23]. Recent research has identified a failed astrocyte stress response to Aβ as an early inducer of amyloid and tau pathology through activation of δ-secretase, a stress-induced protease implicated in both amyloidogenic and tau-related proteolytic processing [26].

Experimental models demonstrate that astrocytes with diminished stress response capabilities (via SORCS2 deficiency) exhibit heightened sensitivity to Aβ-induced stress, resulting in massive amyloid and tau pathologies [26]. These findings position astrocyte distress as a potential mechanism linking amyloid and tau comorbidities in AD. Additional astrocytic contributions to neurodegeneration include disruption of synaptic function through impaired glutamate clearance and release of synaptotoxic factors, as well as blood-brain barrier dysfunction that compromises CNS integrity [23].

Table 2: Astrocyte Dysfunctions in Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Pathogenic Mechanism | Functional Consequences | Associated Diseases |

|---|---|---|

| A1 Reactive Polarization | Neuroinflammation, synaptotoxicity, oxidative stress | AD, PD, ALS |

| Metabolic Reprogramming | Lipid droplet accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress | AD, PD, MS |

| Glutamate Dysregulation | Excitotoxicity, synaptic impairment | AD, ALS, epilepsy |

| Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption | Enhanced CNS permeability, immune cell infiltration | AD, MS, stroke |

| δ-secretase Activation | Enhanced Aβ and tau proteolytic processing | AD |

hiPSC Models for Dissecting Sporadic versus Familial Alzheimer's Disease

hiPSC Technology Platform

Human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) technology has emerged as a transformative platform for disease modeling, enabling generation of patient-specific neurons, glia, and three-dimensional organoid systems that recapitulate human physiology and pathology [6] [27]. The technology involves reprogramming somatic cells (typically fibroblasts or blood cells) into pluripotent stem cells through expression of defined transcription factors, followed by differentiation into disease-relevant cell types [6]. This approach allows researchers to investigate intrinsic cellular pathologies independent of confounding factors such as peripheral immunity or aging environments.

HiPSC models offer particular advantages for studying glial cells in neurodegenerative diseases, as they retain donor-specific genetic and molecular signatures, enabling modeling of patient-specific phenotypes [6]. The ability to differentiate hiPSCs into purified populations of microglia-like cells and astrocytes has facilitated investigation of cell-autonomous contributions to disease pathogenesis, as well as cell-cell interactions in more complex co-culture systems [28].

Modeling Familial versus Sporadic AD

A significant application of hiPSC technology involves distinguishing pathological mechanisms between familial (autosomal dominant) and sporadic (polygenic) forms of Alzheimer's disease. Familial AD models typically utilize hiPSCs from patients with mutations in APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2 genes, which directly impact Aβ production and processing. In contrast, modeling sporadic AD requires capture of the complex polygenic risk architecture through several approaches:

Polygenic Risk Score Stratification: Researchers have created hiPSC collections capturing extremes of global AD polygenic risk, including lines from high-risk late-onset AD (34 lines), high-risk early-onset AD (29 lines), and low-risk control donors (27 lines) [21]. This IPMAR Resource (iPSC Platform to Model Alzheimer's Disease Risk) enables systematic investigation of how polygenic risk converges on specific cellular phenotypes.

Pathway-Specific Genetic Risk: Some resources focus on specific pathways, such as complement system biology, with hiPSC lines selected for extremes of complement pathway-specific genetic risk (9 high-risk AD, 10 low-risk controls) [21].

Endophenotype Analysis: hiPSC models reveal distinct glial-intrinsic phenotypes across neurodegenerative diseases. In multiple sclerosis, for example, hiPSC-derived cultures from people with primary progressive MS (PPMS) contain fewer oligodendrocytes and show increased expression of immune and inflammatory genes in oligodendrocyte lineage cells and astrocytes, matching glial profiles from MS postmortem brains [28].

These approaches demonstrate that hiPSC models can capture disease-relevant cellular phenotypes independent of extrinsic factors, providing platforms for dissecting fundamental disease mechanisms and screening therapeutic interventions.

Experimental Protocols for hiPSC-Based Glial Research

hiPSC Differentiation to Glial Cells

Protocol: Generation of Microglia-Enriched Cultures from hiPSCs

- Maintenance of hiPSCs: Culture hiPSCs on Matrigel-coated plates in mTeSR Plus medium with daily medium changes until 70-80% confluency.

- Mesodermal Induction: Dissociate hiPSCs with Accutase and transfer to low-attachment plates in differentiation medium containing BMP4, VEGF, SCF, and IL-3 to form embryoid bodies.

- Myeloid Progenitor Expansion: After 10 days, transfer embryoid bodies to Matrigel-coated plates in medium containing M-CSF, IL-3, and GM-CSF to promote hematopoietic progenitor expansion.

- Microglial Differentiation: Harvest floating progenitors and culture in medium containing IL-34, GM-CSF, and TGF-β to induce microglial fate for 14-21 days.

- Characterization: Analyze cells for expression of microglial markers (IBA1, TMEM119, P2RY12) using flow cytometry and immunocytochemistry.

Protocol: Astrocyte Differentiation from hiPSCs

- Neural Induction: Differentiate hiPSCs to neural progenitor cells (NPCs) using dual SMAD inhibition (LDN193189, SB431542) for 10-14 days.

- NPC Expansion: Culture NPCs in neural expansion medium containing EGF and FGF2 for 2-3 passages.

- Astrocyte Differentiation: Switch NPCs to astrocyte differentiation medium (DMEM/F12, N2 supplement, 1% FBS) for 30-45 days.

- Astrocyte Maturation: Culture in CNTF, BMP4, or LIF-containing medium for additional 14-21 days to promote maturation.

- Characterization: Verify astrocyte identity using markers (GFAP, S100β, AQP4) and functional assays (glutamate uptake, calcium imaging).

Functional Assays for Glial Phenotyping

Microglial Phagocytosis Assay

- Incubate hiPSC-derived microglia with pHrodo Red-conjugated Aβ42 fibrils (1 µg/mL) for 2 hours

- Fix cells with 4% PFA and counterstain with DAPI

- Quantify phagocytosed Aβ using fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry

- Include control wells with cytochalasin D (phagocytosis inhibitor)

Astrocyte Neurotoxicity Assay

- Culture hiPSC-derived astrocytes in serum-free medium for 24 hours to collect conditioned medium

- Apply astrocyte-conditioned medium to hiPSC-derived cortical neurons

- Assess neuronal viability after 48 hours using MTT assay or Live/Dead staining

- Measure LDH release as indicator of cytotoxicity

Multi-electrode Array (MEA) for Network Activity

- Plate hiPSC-derived neurons and astrocytes (1:1 ratio) on MEA plates

- Record spontaneous electrical activity for 10 minutes weekly

- Analyze firing rate, burst frequency, and network synchronization

- Challenge with glutamate or Aβ to assess functional responses

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for hiPSC Glial Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Systems | CytoTune iPSC Sendai Reprogramming Kit, Episomal vectors | Footprint-free reprogramming of somatic cells to hiPSCs |

| Differentiation Kits | STEMdiff Astrocyte Differentiation Kit, Microglia Differentiation Kit | Standardized differentiation protocols for glial cells |

| Cell Type Markers | Anti-GFAP (astrocytes), Anti-IBA1/TMEM119 (microglia), Anti-MBP (oligodendrocytes) | Identification and purification of specific glial cell types |

| Cytokines/Growth Factors | IL-34, M-CSF (microglia), CNTF, BMP4 (astrocytes) | Directional differentiation and maintenance of glial phenotypes |

| Functional Assay Kits pHrodo Aβ Phagocytosis Assay, Glutamate Uptake Assay Kit | Quantification of glial-specific functional capacities | |

| Single-Cell RNA Seq | 10x Genomics Chromium System, SMART-seq reagents | Transcriptional profiling of glial heterogeneity |

Signaling Pathways in Glial Pathogenesis

Microglial Receptor Signaling Network

Microglial Receptor Signaling: This diagram illustrates key receptor-mediated pathways in microglial activation. TREM2 signaling through DAP12/SYK promotes phagocytosis and cell survival, while TLR4 and CD36 activate inflammatory responses and pyroptosis through NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome pathways, respectively.

Astrocyte Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration

Astrocyte Dysfunction Pathways: This diagram summarizes molecular pathways driving astrocyte dysfunction in neurodegeneration. Aβ and microglial signals promote the neurotoxic A1 phenotype, while SORCS2 deficiency enables δ-secretase activation, linking amyloid and tau pathologies. Metabolic dysfunction contributes directly to neuronal death.

Future Directions and Therapeutic Implications

The expanding knowledge of glial pathophysiology in neurodegenerative diseases has opened new avenues for therapeutic development. Several promising strategies are emerging:

Microglia-Targeted Therapies: Approaches include TREM2 agonism to enhance phagocytic function, CD33 antagonism to reduce inhibitory signaling, and modulation of immunometabolic pathways to reprogram microglial phenotypes [22] [24]. Targeting microglial ferroptosis represents another novel strategy for neuroprotection [25].

Astrocyte-Directed Interventions: Potential therapies include modulation of astrocyte polarization toward neuroprotective A2 phenotypes, metabolic reprogramming to address bioenergetic deficits, and inhibition of pathogenic pathways such as δ-secretase activation [23] [26].

Gene Therapy Approaches: CRISPR-based and viral vector-mediated interventions could correct glial-specific genetic risk factors or enhance protective functions in both microglia and astrocytes.

Advanced hiPSC Applications: Future research will leverage multi-omics integration, three-dimensional organoid systems, and machine learning approaches to decipher the complex spatiotemporal dynamics of glial responses across disease stages [27]. These technologies will enhance prediction of therapeutic responses and identification of patient-specific treatment strategies.

The continued refinement of hiPSC models that accurately capture the genetic diversity of sporadic Alzheimer's disease will be essential for translating glial biology into effective clinical interventions. By focusing on the expanding roles of microglia and astrocytes in disease pathogenesis, researchers and drug development professionals can identify novel therapeutic targets that address the multifaceted nature of neurodegenerative processes.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder that represents the most common cause of dementia worldwide. While early-onset familial AD (FAD) accounts for less than 5% of cases and is caused by fully penetrant mutations in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 genes, the overwhelming majority of cases are sporadic late-onset AD (LOAD) with a complex, polygenic etiology [5] [2]. The heritability of LOAD is estimated to be as high as 80%, underscoring the critical importance of genetic risk factors in disease pathogenesis [29]. For nearly three decades, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have served as a powerful, hypothesis-free approach for identifying genetic variants that contribute to LOAD risk. Since the initial discovery of APOE as the strongest genetic risk factor for sporadic AD in 1993, GWAS has identified numerous additional susceptibility loci, revealing novel biological pathways and potential therapeutic targets [30] [29]. This review synthesizes current knowledge of GWAS-identified genetic risk factors for sporadic AD, with particular emphasis on their functional validation using human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) models, which offer unprecedented opportunities for studying AD pathogenesis in human-derived neurons and glial cells.

The APOE Locus: The Preeminent Genetic Risk Factor for Sporadic AD

APOE Genotype and AD Risk Spectrum

The APOE ε4 allele remains the strongest genetic risk factor for sporadic Alzheimer's disease, while the APOE ε2 allele provides the strongest genetic protection, as confirmed by multiple large-scale GWAS and meta-analyses [30]. The three common APOE alleles (ε2, ε3, and ε4) encode protein isoforms that differ at amino acid positions 112 and 158, resulting in significant functional consequences for AD pathogenesis [31]. The population distribution of these alleles creates a remarkable risk spectrum, with APOE ε4 homozygotes facing up to a 15-fold increased risk of developing AD compared to the most common ε3/ε3 genotype, while APOE ε2 carriers enjoy significantly reduced risk [5] [31]. This dose-dependent effect of APOE ε4 underscores its central role in AD pathophysiology.

Table 1: APOE Genotype and Associated Alzheimer's Disease Risk

| Genotype | Prevalence in General Population | Relative Risk for AD | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ε2/ε2 | ~1% | 0.13 OR | Strongest protection, associated with longevity |

| ε2/ε3 | ~11% | 0.39 OR | Protective effect relative to ε3/ε3 |

| ε3/ε3 | ~60% | Reference (1.0) | Most common genotype |

| ε3/ε4 | ~23% | ~3-fold increase | Intermediate risk |

| ε4/ε4 | ~2% | 8-15-fold increase | Highest genetic risk for sporadic AD |

Differential Pathological Mechanisms of APOE Isoforms

APOE isoforms differentially impact multiple AD-related pathological processes beyond their well-established effects on amyloid-β metabolism and clearance. APOE4 significantly increases Aβ aggregation and deposition, reduces Aβ clearance, exacerbates tau pathology and neurofibrillary tangle formation, amplifies neuroinflammatory responses, and disrupts blood-brain barrier integrity [30] [31]. In contrast, APOE2 demonstrates protective effects across these same pathways. The recently identified APOE3-Christchurch (R136S) mutation, discovered in a woman resistant to autosomal dominant AD despite carrying a PSEN1 E280A mutation, appears to inhibit Aβ oligomerization and disrupt APOE binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans and LDL receptor family members, providing insights into potential protective mechanisms [30]. These isoform-specific effects highlight the complex multifactorial nature of APOE's contribution to AD pathogenesis.

GWAS-Identified Genetic Risk Loci Beyond APOE

Evolution of GWAS Findings in Alzheimer's Disease

GWAS of Alzheimer's disease began in 2007 with initial studies that primarily confirmed the overwhelming association of APOE with disease risk [29]. These early studies, though limited in sample size and genotyping density, established GWAS as a valuable approach for identifying AD susceptibility genes. Technological advances and international collaborations have dramatically expanded GWAS scope and power, with current studies incorporating hundreds of thousands of participants and millions of genetic variants. The largest recent GWAS meta-analysis, published in 2022, identified 75 risk loci for AD, including 42 new loci not previously associated with the disease [32]. This expanding genetic landscape reveals the extraordinary polygenic nature of sporadic AD and implicates diverse biological pathways in disease pathogenesis.

Table 2: Key GWAS-Identified Risk Loci for Sporadic Alzheimer's Disease

| Gene/Locus | Year Identified | Primary Function | Contribution to AD Pathogenesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIN1 | 2010 | Membrane trafficking, endocytosis | Modulates tau pathology, influences amyloid processing |

| CLU | 2009 | Chaperone, complement pathway | Aβ clearance, synaptic function, inflammation |

| ABCA7 | 2011 | Lipid transporter, phagocytosis | Aβ clearance, microglial function |

| PICALM | 2009 | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | Aβ internalization, blood-brain barrier integrity |

| CR1 | 2009 | Complement activation | Inflammation, synaptic pruning |

| SORL1 | 2013 | APP trafficking, endosomal function | Aβ production, endosomal dysfunction |

| TREM2 | 2012 | Microglial signaling, phagocytosis | Neuroinflammation, plaque encapsulation |

| MS4A | 2011 | Immune signaling, calcium homeostasis | B-cell function, microglial activation |

| CD33 | 2011 | Sialic acid binding, innate immunity | Microglial phagocytosis, inflammation |

| EPHA1 | 2011 | Tyrosine kinase receptor, cell signaling | Immune response, synaptic plasticity |

Functional Categorization of Risk Genes and Pathways

The GWAS-identified risk genes can be broadly categorized into several biological pathways, with immune response and microglial function representing the most prominent category. Genes such as TREM2, CR1, ABCA7, and MS4A cluster within this pathway, highlighting the critical importance of neuroinflammation in AD pathogenesis [32]. A second major category includes genes involved in endosomal trafficking and protein sorting, including BIN1, PICALM, and SORL1, which influence APP processing and Aβ generation [29]. Lipid metabolism and transport represent a third significant pathway, with APOE serving as the cornerstone but joined by other lipid-related genes. Additional pathways include synaptic function, protein degradation, and vascular biology, reflecting the multifactorial nature of AD pathophysiology [32]. The preponderance of immune-related genes identified by GWAS has fundamentally shifted AD research toward greater emphasis on neuroimmune mechanisms.

hiPSC Models for Functional Validation of GWAS Findings

hiPSC Technology: Advantages and Applications in AD Research

Human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) technology has emerged as a transformative approach for studying sporadic Alzheimer's disease, addressing critical limitations of traditional animal models that often fail to fully recapitulate human-specific pathophysiology [6] [5]. By reprogramming somatic cells from individuals with specific genetic backgrounds into pluripotent stem cells, researchers can generate patient-derived neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and other brain cell types that retain the donor's complete genetic risk profile [6]. This platform enables: (1) isogenic comparison of risk variants by genome editing, (2) investigation of cell-type-specific effects, (3) modeling of human-specific disease processes, and (4) screening of therapeutic compounds in a human genetic context. Bibliometric analysis reveals rapidly growing application of hiPSC models in AD research, with annual publications increasing significantly since 2015 and research trends focusing on inflammation, astrocytes, microglia, APOE, and tau [6].

Experimental Workflow for hiPSC-Based Functional Validation

Key Methodologies for hiPSC-Based AD Research

Patient Recruitment and hiPSC Line Generation

The initial step involves careful selection of donors representing specific genetic backgrounds, typically including individuals carrying high-risk alleles (e.g., APOE ε4/ε4), protective alleles (e.g., APOE ε2/ε2), and appropriate controls (e.g., APOE ε3/ε3) [6]. Skin biopsies or blood samples are collected, and somatic cells (typically fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells) are reprogrammed into hiPSCs using non-integrating Sendai virus or episomal vectors expressing the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) [6]. Multiple clonal lines are established and rigorously characterized for pluripotency markers (OCT4, NANOG, SSEA-4), karyotypic normality, and differentiation potential before experimental use.

Genome Editing for Isogenic Comparisons

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing enables creation of isogenic hiPSC lines that differ exclusively at specific risk variants, allowing researchers to isolate the functional consequences of individual polymorphisms [5]. Common strategies include: (1) introducing protective mutations into high-risk genetic backgrounds (e.g., converting APOE4 to APOE3), (2) introducing risk variants into neutral genetic backgrounds, and (3) knocking out risk genes to establish their necessity for observed phenotypes. Precise editing is verified by Sanger sequencing, off-target effects are assessed by whole-genome sequencing, and multiple independently edited clones are characterized to control for clonal variation.

Neural Differentiation and Co-culture Systems

hiPSCs are differentiated into relevant neural cell types using established protocols. Cortical neurons are generated through dual SMAD inhibition, while astrocytes are differentiated through neural progenitor expansion and glial induction [33]. Microglial precursors are generated using specific cytokine cocktails and matured in the presence of IL-34 and CSF-1. For more complex modeling, 2D co-culture systems and 3D cerebral organoids are established to investigate cell-cell interactions. These systems recapitulate key AD pathological features, including Aβ accumulation, tau phosphorylation, and neuroinflammatory responses in a human genetic context [5].

Signaling Pathways Implicated by GWAS in Sporadic AD

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for hiPSC-Based AD Modeling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| hiPSC Lines | APOE3/3, APOE4/4, APOE2/2 hiPSCs; isogenic edited lines | Isogenic comparison of genetic risk variants | Verify pluripotency, karyotype stability, genetic background |

| Differentiation Kits | Commercial neural induction kits; astrocyte differentiation media | Generation of relevant neural cell types | Optimize protocol efficiency; assess functional maturity |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems; base editors; prime editors | Introduction of specific risk/protective variants | Monitor off-target effects; use multiple independent clones |

| Cell Type Markers | Anti-MAP2 (neurons); Anti-GFAP (astrocytes); Anti-IBA1 (microglia) | Characterization of differentiated cells | Use multiple markers; confirm functional properties |

| Pathological Assays | ELISA for Aβ42/40; Western for p-Tau; Phos-tag gels | Quantification of AD-related pathologies | Standardize culture conditions; use appropriate controls |

| Functional Assays | Multi-electrode arrays; calcium imaging; synaptic dye uptake | Assessment of neuronal network activity | Control for cell density; use appropriate analysis methods |

| Co-culture Systems | Transwell inserts; microfluidic devices; 3D organoid platforms | Modeling cell-cell interactions | Optimize cell ratios; validate system reproducibility |

GWAS has fundamentally expanded our understanding of the genetic architecture of sporadic Alzheimer's disease, moving beyond APOE to identify numerous susceptibility loci that converge on distinct biological pathways. The integration of these GWAS findings with hiPSC-based disease models represents a powerful approach for functional validation and mechanistic exploration of how these genetic variants contribute to disease pathogenesis. Current evidence strongly supports a central role for immune-related processes, lipid metabolism, and endosomal trafficking in AD pathophysiology, with APOE serving as a critical node connecting these pathways. Future research directions should include: (1) development of more complex multi-cell type systems to better model in vivo interactions, (2) integration of additional AD risk factors such as aging and environmental influences, (3) application of single-cell omics technologies to identify cell-type-specific effects of risk variants, and (4) leveraging hiPSC-based models for high-throughput therapeutic screening. The continued synergy between large-scale genetic studies and human cellular models holds exceptional promise for elucidating the fundamental mechanisms underlying sporadic AD and developing effective, genetically-informed therapeutic strategies.

Building Better Brain Models: hiPSC Differentiation, Co-cultures, and 3D Systems

The generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) from somatic cells represents a cornerstone of modern biomedical research, providing an unparalleled tool for disease modeling and therapeutic development. Within Alzheimer's disease (AD) research, this technology has enabled the creation of patient-specific neural models that capture the complex genetic architecture of both familial and sporadic disease forms [6] [34]. The reprogramming of somatic cells to a pluripotent state fundamentally rewrites cellular identity through epigenetic remodeling, reversing the process of developmental specialization [35]. This technical guide examines contemporary reprogramming methodologies and donor selection strategies, with particular emphasis on their application in developing physiologically relevant hiPSC models for AD research. The critical interplay between reprogramming techniques and careful donor selection enables researchers to create platforms that accurately recapitulate the polygenic nature of common AD, thereby facilitating drug discovery and mechanistic studies [36] [37].

Molecular Mechanisms of Somatic Cell Reprogramming

Historical Foundations and Key Discoveries

The conceptual foundation for cellular reprogramming was established through pioneering nuclear transfer experiments by John Gurdon in 1962, demonstrating that the somatic cell nucleus retains the genetic completeness required for embryonic development [34] [35]. This discovery of epigenetic plasticity was later validated through cell fusion experiments showing that mouse and human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) could reprogram somatic cells within heterokaryons [34]. The field transformed in 2006 when Shinya Yamanaka identified a minimal set of transcription factors—Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM)—sufficient to reprogram mouse fibroblasts to pluripotency [6] [34] [18]. The subsequent generation of human iPSCs by Yamanaka and James Thomson's groups in 2007 established the core technology now widely applied in disease modeling [34].

Epigenetic Remodeling During Reprogramming

Reprogramming somatic cells to pluripotency involves profound epigenetic reorganization that occurs in distinct phases. The early phase is characterized by stochastic silencing of somatic genes and initial activation of early pluripotency-associated genes, while the late phase involves more deterministic activation of the core pluripotency network [34]. Critical epigenetic modifications include:

- DNA Demethylation: Promoter regions of key pluripotency genes (OCT4, SOX2) are heavily methylated in somatic cells but undergo demethylation during reprogramming, facilitated by agents like 5-azacytidine that enhance reprogramming efficiency [38].

- Histone Modification: Somatic cells typically exhibit hypoacetylated histone H4 and specific methylation patterns (H3K9me) that must be reversed to a pluripotent state. Histone deacetylase inhibitors like valproic acid and modulation of H3K79 methylation by Dot1L improve reprogramming efficiency [38] [34].

- Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition (MET): Reprogramming requires MET, accomplished by suppressing EMT mediators (TGFβ1, TGFβR2, Smad) and activating E-cadherin through epigenetic regulation of relevant promoters [38].

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular transitions during somatic cell reprogramming:

Mathematical Models of Reprogramming

The stochastic nature of early reprogramming has been formalized through mathematical models that predict efficiency and kinetics. The model f(Cd, k) describes reprogramming as a function of cell divisions (Cd) and cell-intrinsic reprogramming rate (k) [38]. This framework explains how factors like p53/p21 inhibition accelerate reprogramming by increasing division rates, thereby making stochastic events occur earlier. Another model, V(S) = f (gene regulatory architecture, culture conditions), conceptualizes reprogramming as overcoming "energy barriers" between cellular states [38].

Reprogramming Techniques and Methodologies

Factor-Based Reprogramming Strategies

Multiple approaches have been developed for delivering reprogramming factors to somatic cells, each with distinct advantages and limitations for AD research applications:

- Integrating Viral Vectors: Early reprogramming methods used retroviruses or lentiviruses to deliver OSKM factors, providing high efficiency but risking insertional mutagenesis and transgene reactivation [34].

- Non-Integrating Methods: Episomal vectors, Sendai virus, and mRNA transfection offer non-integrating alternatives that generate footprint-free iPSCs, essential for clinical applications and accurate disease modeling [34].

- Chemical Reprogramming: Fully chemical reprogramming using seven small-molecule compounds was demonstrated in 2013, providing a completely non-genetic approach [34].

Enhancing Reprogramming Efficiency

Several strategies have been identified to improve the efficiency and quality of iPSC generation:

- Small Molecule Enhancers: Vitamin C enhances reprogramming by facilitating histone demethylase Jhdm1a/1b function, which suppresses senescence regulator Ink4a/Arf [38].

- Senescence Bypass: Disruption of the p53 network and other senescence pathways significantly enhances iPSC production efficiency [38].

- microRNA-mediated Reprogramming: microRNAs like the 302-367 cluster can remove epigenetic repressors from pluripotency gene promoters and enable reprogramming without additional transcription factors [38].

Donor Selection Strategies for Alzheimer's Disease Research

Genetic Considerations for AD Modeling

Donor selection represents a critical consideration for generating clinically relevant hiPSC models of Alzheimer's disease. AD exists along a spectrum from rare autosomal-dominant familial forms (FAD) to common sporadic cases (sAD) with complex genetic architecture:

- Familial AD Donors: Characterized by highly penetrant mutations in APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2 genes, suitable for modeling monogenic disease mechanisms [39].

- Sporadic AD Donors: Involve polygenic risk influenced by APOE genotype and numerous other genetic variants identified through genome-wide association studies [36].

Polygenic Risk Score-Based Donor Selection

The IPMAR resource (iPSC Platform to Model Alzheimer's Disease Risk) exemplifies a sophisticated donor selection strategy that captures extremes of polygenic risk for common AD [36] [21] [37]. This resource includes:

- 90 iPSC lines with extremes of global AD polygenic risk: 34 from high-risk late-onset AD donors, 29 from high-risk early-onset AD donors, and 27 from low-risk cognitively healthy controls [36].

- 19 iPSC lines with complement pathway-specific polygenic risk: 9 from high-risk AD donors and 10 from low-risk controls [36].

- Comprehensive associated data: All lines have associated clinical, longitudinal, and genetic datasets available through cell and data repositories [21].

Table 1: IPMAR Resource Donor Stratification Based on Polygenic Risk Scores

| Donor Category | Number of iPSC Lines | Mean Global PRS (SD) | Mean Complement PRS (SD) | Age of Onset (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late-Onset AD (High Global PRS) | 34 | 2.2 (±0.5) | N/A | 72 (±6) |

| Early-Onset AD (High Global PRS) | 29 | 2.1 (±0.4) | N/A | 51 (±3) |

| Healthy Controls (Low Global PRS) | 27 | -1.9 (±0.4) | N/A | N/A |

| AD (High Complement PRS) | 9 | N/A | 2.4 (±0.3) | 71 (±6) |

| Healthy Controls (Low Complement PRS) | 10 | N/A | -1.9 (±0.2) | N/A |

APOE Genotype Considerations

The APOE ε4 allele remains the most significant genetic risk factor for sporadic AD, with odds ratios between 3.62 and 34.3 depending on population [36]. Donor selection should carefully consider APOE genotype alongside polygenic risk scores to accurately model the genetic complexity of AD.

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

IPSC Generation and Quality Control Protocol

The generation of the IPMAR resource exemplifies a robust workflow for creating genetically stratified iPSC banks:

- Donor Selection: Identify donors from well-characterized cohorts using polygenic risk scoring from genome-wide association data [36].

- Somatic Cell Collection: Obtain peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or skin fibroblasts from selected donors, prioritizing recent donations [36].

- Reprogramming: Transform somatic cells using non-integrating methods to generate footprint-free iPSCs.

- Quality Control: Perform comprehensive characterization including pluripotency marker expression, karyotyping, and differentiation potential [36].

- Banking and Distribution: Cryopreserve validated lines and make them available through repositories like EBiSC and DPUK [37].

Vascularized Neuroimmune Organoid Generation

Advanced disease modeling employs complex 3D organoid systems that incorporate multiple cell types affected in AD:

- Progenitor Generation: Derive neural progenitor cells (NPCs), primitive macrophage progenitors (PMPs), and vascular progenitors (VPs) from hiPSCs [40].

- 3D Co-culture: Combine NPCs, PMPs, and VPs at optimized ratios (30,000:12,000:7,000) to facilitate self-organization into organoids [40].

- Maturation Culture: Maintain organoids in neural differentiation medium supplemented with IL-34, VEGF, and other factors to support neuronal, microglial, and vascular maturation [40].

- Disease Modeling: Expose organoids to AD brain extracts to induce multiple pathologies including Aβ plaques, tau tangles, and neuroinflammation within four weeks [40].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for hiPSC-based Alzheimer's Disease Modeling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM) | Induction of pluripotency in somatic cells |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Vitamin C, Valproic acid, 5-azacytidine | Improve reprogramming efficiency through epigenetic modulation |