hiPSCs in Cardiovascular Disease Modeling: From Patient-Specific Cells to Precision Drug Discovery

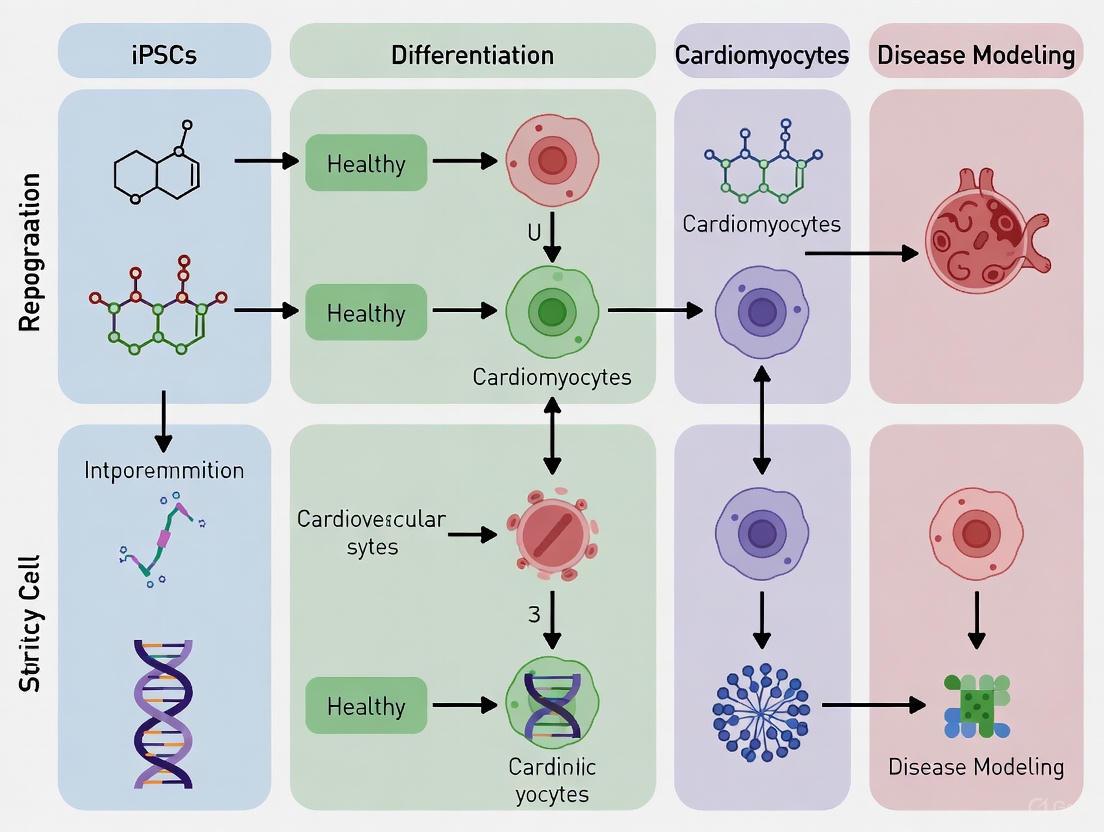

Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) are revolutionizing cardiovascular research by providing a patient-specific, human-relevant platform for disease modeling and drug development.

hiPSCs in Cardiovascular Disease Modeling: From Patient-Specific Cells to Precision Drug Discovery

Abstract

Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) are revolutionizing cardiovascular research by providing a patient-specific, human-relevant platform for disease modeling and drug development. This article explores the foundational principles of hiPSC technology, detailing the reprogramming of somatic cells and their differentiation into cardiomyocytes. It examines advanced methodological applications in modeling inherited arrhythmias, cardiomyopathies, and drug-induced cardiotoxicity, while also addressing key challenges such as cellular immaturity and phenotypic variability. Furthermore, it validates hiPSC-CMs against traditional models, highlighting their superior predictive value for human physiology. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current advancements and future directions, underscoring the role of hiPSCs in advancing personalized medicine and improving the efficacy and safety of cardiovascular therapeutics.

The Foundation of iPSC Technology: Reprogramming and Cardiac Differentiation

The discovery that somatic cells can be reprogrammed to a pluripotent state represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine and biomedical research. In 2006, Shinya Yamanaka and his team demonstrated that the forced expression of four specific transcription factors—Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (collectively known as the Yamanaka factors)—could convert specialized adult cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [1]. This groundbreaking work, which earned Yamanaka the Nobel Prize in 2012, demonstrated that cellular differentiation is not a unidirectional process and that epigenetic fate can be reversed through specific molecular interventions [2].

In the context of cardiovascular disease research, iPSC technology offers unprecedented opportunities. Scientists can now generate patient-specific cardiomyocytes in vitro, enabling the study of disease mechanisms, cardiotoxicity testing, and the development of personalized therapeutic approaches [3]. This technical guide explores the core principles of somatic cell reprogramming using Yamanaka factors, with specific emphasis on methodologies and applications relevant to cardiovascular disease modeling.

Molecular Mechanisms of the Yamanaka Factors

Core Pluripotency Network

The Yamanaka factors function as master regulators of pluripotency by activating a self-reinforcing transcriptional network that silences somatic cell identity genes while activating embryonic stem cell programs. These four transcription factors work in concert to reshape the epigenetic landscape and initiate the reprogramming cascade [4].

Table 1: Core Yamanaka Factors and Their Functions in Reprogramming

| Transcription Factor | Primary Function in Reprogramming | Role in Pluripotency Maintenance | Associated Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oct4 (Pou5f1) | Establishes and maintains pluripotency; essential for inner cell mass development | Forms core regulatory circuit with Sox2 and Nanog; regulates pluripotency-associated genes | Over-expression causes differentiation; depletion blocks reprogramming |

| Sox2 | Partners with Oct4 to regulate key pluripotency genes | Maintains self-renewal; cooperates with Oct4 in transcriptional activation | Expressed in neural stem cells; implicated in some cancers |

| Klf4 | Facilitates epigenetic remodeling; activates Nanog expression | Enhances core pluripotency factors for developmental regulation; contains zinc-finger DNA-binding domains | Can function as both oncogene and tumor suppressor depending on context |

| c-Myc | Promotes chromatin accessibility; regulates metabolic switching | Orchestrates proliferation and metabolism; distinct role from other factors | Potent oncogene; increases tumorigenesis risk in iPSC-derived tissues |

Mechanism of Action

The reprogramming process initiates when the Yamanaka factors are introduced into somatic cells. c-Myc functions as a pioneer factor that opens chromatin structure by binding to methylated regions, making previously inaccessible genetic sequences available for transcriptional activation [4]. Subsequently, Oct4 and Sox2 interact with enhancers and promoters of genes involved in somatic cell identity and pluripotency, forming heterodimers that recognize composite SOX-OCT binding sites in the genome [5] [4].

This transcription factor partnership creates a self-reinforcing interconnected loop that activates their own promoters along with those of other pluripotency-associated genes such as Nanog [4]. During this process, mesenchymal genes are silenced while epithelial genes such as Cdh1, Epcam, and Ocln are upregulated, facilitating the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition that characterizes early reprogramming stages [4]. The Yamanaka factors collectively regulate a developmental signaling network composed of at least 16 crucial developmental signaling pathways to maintain pluripotency, including previously unknown pathways in ES cells such as apoptosis and cell-cycle regulation [5].

Figure 1: Molecular Reprogramming Cascade by Yamanaka Factors

Reprogramming Methodologies and Protocols

Delivery Systems for Reprogramming Factors

Multiple delivery systems have been developed to introduce the Yamanaka factors into somatic cells, each with distinct advantages and limitations for research and clinical applications.

Table 2: Comparison of Yamanaka Factor Delivery Methods

| Delivery Method | Integration into Genome | Reprogramming Efficiency | Safety Profile | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral/Lentiviral | Yes (Random integration) | High | Low (Oncogenic risk) | Basic research, difficult-to-reprogram cells |

| Sendai Virus | No (Non-integrating RNA virus) | High | Moderate (Viral persistence concerns) | Clinical applications, disease modeling |

| Episomal Vectors | No (Extrachromosomal) | Low to moderate | High | Clinical applications, GMP compliance |

| Synthetic mRNA | No (Transient expression) | High with optimization | High | Clinical applications, personalized medicine |

| Small Molecules | No (Chemical induction) | Low to moderate | High (But specificity challenges) | Research, safety-sensitive applications |

Detailed Reprogramming Protocol Using mRNA Technology

The synthetic mRNA reprogramming method represents one of the safest and most efficient approaches for generating clinical-grade iPSCs, particularly for cardiovascular applications where genetic stability is paramount [6] [7].

Protocol: mRNA-Based Reprogramming of Human Fibroblasts

Day 0: Target Cell Seeding

- Plate human dermal fibroblasts or cardiac fibroblasts in 6-well plates at optimal seeding density (1×10^5 to 1×10^6 cells per well) to achieve 60-80% confluency after 24 hours [7].

Day 1: B18R Protein Pretreatment and mRNA Transfection

- Pretreat cells with 200 ng/mL B18R protein in DMEM for 2 hours to inhibit innate immune responses against introduced RNA [7].

- Prepare transfection complex: Combine 0.5 μL VEE-OKS-iG RNA (encoding OCT4, KLF4, SOX2), 0.5 μL B18R RNA, and 4.0 μL RiboJuice mRNA transfection reagent in 250 μL Opti-MEM medium [7].

- Add RNA-transfection reagent complexes dropwise to cells and incubate for 4 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂ [7].

- Replace with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1X glutamine, and 200 ng/mL B18R protein [7].

Days 2-11: Puromycin Selection and Daily Transfections

- Replace medium daily with fresh DMEM containing 200 ng/mL B18R protein and puromycin at the optimal selection concentration (determined empirically for each cell line) [7].

- Monitor cell death and morphology changes; by days 4-5, approximately 30-60% cell death should be observable [7].

- Continue daily transfections and puromycin selection until day 11 [7].

Days 11-18: Replating and Expansion

- When puromycin-resistant cells reach 70-90% confluency (typically between days 9-18), replate them onto Matrigel-coated plates or inactivated MEF feeders [7].

- Culture in MEF-conditioned medium supplemented with 10 ng/mL bFGF, 1X human iPSC reprogramming enhancer, and 200 ng/mL B18R protein [7].

Days 18-30: iPSC Colony Picking and Expansion

- Monitor for emergence of compact colonies with defined borders, typically appearing between days 15-20 [7].

- Pick individual colonies when they reach approximately 200 cells and transfer to PluriSTEM Human ES/iPSC medium for further expansion and characterization [7].

Figure 2: mRNA Reprogramming Workflow Timeline

Enhanced Protocol for Senescent and Pathologic Cells

Reprogramming efficiency decreases significantly when working with senescent or pathologic cells, which is particularly relevant for cardiovascular disease modeling where patient-specific cells often come from elderly individuals or those with chronic conditions [8]. An enhanced protocol has been developed specifically for such challenging cases:

Enhanced Protocol for Senescent Cardiac Fibroblasts

- Use protocol modifications including culture medium supplemented with SB431542 (a TGF-β inhibitor) instead of TGF-β [8].

- Employ an expanded factor combination including OCT3/4, short hairpin p53, SOX2, KLF4, LIN28, L-MYC, Glis-1, and Tet-1 [8].

- This approach successfully generated iPSCs from myocardial fibroblasts isolated from all four chambers of a pathologic heart from a heart transplant recipient with dilated cardiomyopathy, whereas conventional protocols failed [8].

Applications in Cardiovascular Disease Modeling

iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes for Disease Modeling

The generation of human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) has created unprecedented opportunities for cardiovascular disease modeling and drug discovery. Cardiovascular diseases cause approximately 19.8 million deaths annually, ranking as the leading cause of death worldwide, yet the number of new cardiovascular drugs has been steadily decreasing [3]. This decline is partly attributable to the lack of preclinical models that accurately evaluate therapeutic efficacy and safety in humans [3].

hiPSC-CMs enable researchers to reproduce disease-specific characteristics in culture dishes, offering several advantages over traditional models:

- Species-specific relevance: Animal models have limited predictive value due to differences in cardiac biology between species (e.g., mouse heart rate is approximately eight times higher than humans, with different ion current dependencies) [3].

- Patient-specific modeling: hiPSCs can be generated from patients with specific genetic cardiovascular disorders, creating personalized disease models [3].

- Unlimited expansion potential: Unlike primary human cardiomyocytes that dedifferentiate in culture, hiPSCs offer a renewable cell source [3].

Current Limitations and Maturation Challenges

Despite their promise, hiPSC-CMs exhibit an immature phenotype similar to fetal cardiomyocytes, which limits their application in disease modeling and drug discovery [3]. Key differences between hiPSC-CMs and adult human cardiomyocytes include:

Table 3: Immaturity of hiPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes and Functional Consequences

| Characteristic | hiPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes | Adult Human Cardiomyocytes | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Morphology | Small (3000-6000 μm³), rounded shape | Cylindrical (∼40,000 μm³) | Reduced contractile force generation |

| Sarcomere Organization | Poorly organized, randomly oriented | Form myofibrils parallel to entire cell | Impaired coordinated contraction |

| Sarcomere Isoforms | Express fetal isoforms (αMHC, MLC2a, ssTnI) | Express adult isoforms (βMHC, MLC2v, cTnI) | Altered contractile kinetics and calcium sensitivity |

| T-Tubules | Rarely observed | Well-developed regular T-tubule network | Delayed calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) |

| Metabolism | Primarily glycolytic | Primarily oxidative phosphorylation | Different energy utilization and stress responses |

| Electrophysiology | Fetal-like ion channel expression | Adult-specific ion channel patterns | Different repolarization properties and drug responses |

Maturation Strategies for Enhanced Disease Modeling

Multiple strategies have been developed to enhance the maturation of hiPSC-CMs to better model adult cardiovascular diseases:

- Long-term culture: Extended culture duration (up to 120 days) promotes structural and functional maturation [3].

- Biochemical stimulation: Treatment with thyroid hormone (T3), glucocorticoids, and cAMP inducers promotes adult-like gene expression patterns [3].

- Biophysical stimulation: Application of mechanical stretch, electrical pacing, and substrate stiffness tuning enhances structural alignment and maturation [3].

- 3D tissue engineering: Creating engineered heart tissues using biomaterial scaffolds and multicellular compositions improves tissue-level organization and function [3].

- Metabolic manipulation: Shifting culture conditions to promote fatty acid oxidation instead of glycolysis drives metabolic maturation [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Yamanaka Factor Reprogramming

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | VEE-OKS-iG RNA (OCT4, KLF4, SOX2); c-Myc expression vector | Core transcription factors inducing pluripotency | Optimal ratio crucial for efficiency; c-Myc can be omitted but reduces efficiency |

| Immune Suppressors | B18R protein | Inhibits innate immune response against introduced RNA | Critical for mRNA-based methods; improves cell survival during transfection |

| Delivery Reagents | RiboJuice mRNA transfection reagent; Lipofectamine STEM | Facilitates cellular uptake of reprogramming factors | Optimization required for different cell types; can impact cytotoxicity |

| Selection Agents | Puromycin; Geneticin (G418) | Selects for successfully transfected cells | Concentration must be empirically determined for each cell type |

| Culture Media | PluriSTEM Human ES/iPSC medium; MEF-conditioned medium | Supports pluripotent stem cell growth and maintenance | Often requires supplementation with bFGF for optimal results |

| Enhanced Factors | LIN28, L-MYC, Glis-1, Tet-1 | Improves reprogramming efficiency in difficult cells | Particularly valuable for senescent or pathologic somatic cells |

| Signaling Modulators | SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor); Ascorbic acid | Enhances reprogramming efficiency; reduces senescence | Context-dependent effects; optimal concentration varies by cell type |

Reprogramming somatic cells using Yamanaka factors has revolutionized cardiovascular research by enabling the generation of patient-specific iPSCs that can be differentiated into cardiomyocytes for disease modeling and drug screening. The continued refinement of reprogramming methodologies—particularly the development of non-integrating delivery systems and enhanced protocols for senescent cells—has improved the safety and efficiency of iPSC generation.

Future directions in this field include the development of more precise temporal control over factor expression, further reduction in genomic instability risks, and the creation of increasingly mature cardiomyocyte models that better recapitulate adult heart physiology. As these technologies converge with advances in gene editing, tissue engineering, and machine learning, iPSC-based cardiovascular disease modeling is poised to become an indispensable tool for drug discovery and personalized medicine, potentially transforming how we understand and treat the world's leading cause of mortality.

The selection of an appropriate somatic cell source is a critical first step in the successful generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for cardiovascular disease modeling. This initial decision directly influences reprogramming efficiency, the quality of the resulting iPSC lines, and their subsequent applicability in downstream research and potential therapies [9]. The ability to derive patient-specific cardiomyocytes from iPSCs has provided an unprecedented platform for modeling inherited cardiac disorders, screening pharmacological compounds, and developing personalized therapeutic strategies [10]. Since the groundbreaking discovery of iPSC technology by Shinya Yamanaka in 2006, which demonstrated that somatic cells could be reprogrammed into a pluripotent state using defined factors, the field has rapidly diversified the types of somatic cells used for reprogramming [11] [12]. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of three prominent somatic cell sources—dermal fibroblasts, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and urine-derived renal epithelial cells—within the specific context of cardiovascular research applications. We evaluate these sources based on quantitative metrics, detail optimized experimental protocols, and discuss their relative advantages and limitations for generating iPSC-derived cardiovascular cells.

The ideal somatic cell source for iPSC generation balances reprogramming efficiency, patient convenience, scalability, and genomic stability. The table below provides a systematic comparison of the three primary cell sources evaluated in this guide.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Somatic Cell Sources for iPSC Generation

| Parameter | Dermal Fibroblasts | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | Urine-Derived Renal Epithelial Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Efficiency | Moderate | Comparable to fibroblasts [9] | Robust [9] |

| Invasiveness of Collection | Invasive (skin biopsy) [9] | Minimally invasive (blood draw) [9] | Non-invasive (urine sample) [9] |

| Cell Yield | Readily expanded [9] | Varies by donor | Sufficient for multiple reprogramming cycles [9] |

| Genomic Stability | High [9] | High | Not Specified |

| Reprogramming Factors | OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) [9] | OSKM [9] | OSKM [9] |

| Key Advantages | High genomic stability, reliable protocol [9] | Minimally invasive, established immune cell protocols [9] | Completely non-invasive, easily repeatable sampling [9] |

| Primary Limitations | Invasive collection, requires tissue culture expansion [9] | Lower yield for some blood cell types, requires specific mobilization in some cases | Lower initial cell number, requires optimized culture conditions |

Detailed Methodologies for Cell Isolation and Reprogramming

Somatic Cell Isolation and Culture

Dermal Fibroblasts: Fibroblasts are typically obtained via a 3-4 mm punch biopsy from the dermis. The tissue explant is minced and cultured in fibroblast medium (e.g., Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10-15% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin) [9]. Explants are maintained at 37°C with 5% CO₂, and outgrowing fibroblasts are passaged upon reaching 70-80% confluence using trypsin-EDTA. Early-passage fibroblasts (passages 3-5) are optimal for reprogramming to minimize the accumulation of epigenetic alterations [9].

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs): Blood samples are collected in anticoagulant-treated tubes (e.g., EDTA or heparin). PBMCs are isolated via density-gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque. For T lymphocyte reprogramming, cells can be stimulated with cytokines like IL-7 and stem cell factor [9]. Alternatively, erythroblasts expanded in specific cytokine cocktails (e.g., SCF, EPO, IL-3, IL-6, and dexamethasone) can serve as an efficient starting population [9].

Urine-Derived Renal Epithelial Cells: Mid-stream urine samples (typically 100-200 mL) are collected in sterile containers. Cells are harvested by centrifugation and initially cultured in specialized media such as REGM (Renal Epithelial Cell Growth Medium) or a defined cocktail of keratinocyte serum-free medium (KSFM) and fibroblast medium [9]. The initial emergence of epithelial-like colonies usually occurs within 5-10 days, after which they can be expanded for reprogramming.

Reprogramming to Pluripotency

The core reprogramming process involves the introduction of specific transcription factors to revert somatic cells to a pluripotent state. The original Yamanaka factors (OSKM: Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) remain a standard combination [9] [13] [12]. Multiple delivery systems have been developed, each with distinct advantages for safety and efficiency, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Delivery Systems for Reprogramming Factors

| Vector/Platform | Genetic Material | Genomic Integration | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retrovirus | RNA | Yes | High efficiency, but silencing required; risk of insertional mutagenesis [9] [13]. |

| Lentivirus | RNA | Yes | Can infect non-dividing cells; risk of insertional mutagenesis [9]. |

| Sendai Virus | RNA | No | High efficiency, non-integrating; diluted out over passaging [9] [13]. |

| Episomal Plasmid | DNA | No | Integration-free; low efficiency, requires repeated transfection [9] [13]. |

| Synthetic mRNA | RNA | No | Non-integrating, high efficiency; can trigger immune responses [9] [13]. |

| Recombinant Protein | Protein | No | Highest safety profile; very low efficiency and technically challenging [9] [13]. |

The reprogramming workflow follows a characteristic sequence, beginning with the silencing of somatic cell genes, followed by the activation of pluripotency networks, and culminating in the emergence of stable iPSC colonies [12].

Diagram 1: The sequential process of somatic cell reprogramming to iPSCs.

Following reprogramming, iPSCs require rigorous quality control before differentiation. This includes verification of pluripotency marker expression (e.g., Oct4, Nanog via PCR or immunostaining) and functional assessment of differentiation potential into the three germ layers [9]. Genomic integrity must be confirmed through karyotyping and other analyses to ensure the cells are free of reprogramming-induced mutations [9].

Cardiac Differentiation and Maturation from iPSCs

Directed Cardiac Differentiation

The most common method for differentiating iPSCs into cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) is via modulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [14]. This highly efficient protocol can be performed in both monolayer and suspension culture formats.

Diagram 2: Key stages of cardiac differentiation via Wnt pathway modulation.

Bioreactor Suspension Differentiation Protocol: Recent advances have optimized cardiac differentiation in stirred suspension bioreactors, which offer superior scalability, reproducibility, and maturation compared to traditional monolayer cultures [14]. The optimized workflow is as follows:

- Input Cell Quality Control: Use quality-controlled master cell banks of iPSCs. High pluripotency marker SSEA4 (>70% by FACS) is correlated with successful differentiation [14].

- Embryoid Body (EB) Formation: Culture hiPSCs in suspension to form EBs. Monitor EB diameter, targeting ~100 µm at the time of Wnt activation for optimal efficiency [14].

- Cardiac Differentiation: Initiate mesoderm differentiation by adding 7 µM CHIR99021 (a GSK-3β inhibitor) for 24 hours. After a 24-hour gap, add 5 µM IWR-1 (a Wnt inhibitor) for 48 hours to specify cardiac mesoderm [14].

- Maintenance and Harvesting: Continue culture in RPMI + B27 supplement (with insulin). Spontaneous contractions typically appear by differentiation day 5 [14].

- Cryopreservation: Cells can be cryopreserved at day 15 post-differentiation with high viability (>90%) upon thawing [14].

This protocol consistently yields ~1.2 million cells per mL with high purity (~94% Troponin T-positive cells) and predominantly ventricular identity [14].

Enhancing Cardiomyocyte Maturity

iPSC-CMs are typically immature, resembling fetal rather than adult cardiomyocytes. Enhancing maturity is crucial for accurate disease modeling. Key strategies include:

- Advanced 3D Culture: Engineering bioactive, anisotropic extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffolds derived from human iPSC-cardiac fibroblasts (hiPSC-CFs) provides a physiologically relevant microenvironment that promotes structural and functional maturation of iPSC-CMs, leading to improved contractile properties and electrophysiology [15].

- Co-culture Systems: Co-culturing iPSC-CMs with hiPSC-CFs in engineered platforms significantly enhances CM contractile strain, organization, and contraction kinetics. This enhancement is mediated by both paracrine signaling and direct cell-cell contact [16].

- Metabolic Maturation: Shifting the culture medium to lactate-based metabolism enriches for cardiomyocytes and promotes a more adult-like metabolic phenotype [14].

- Chronic Stimulation: Applying mechanical stretch [15] and electrical pacing [16] to iPSC-CMs can drive further structural and functional maturation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for iPSC-CV Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC and Cardiac Differentiation Workflows

| Reagent/Category | Example Products | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Vectors | CytoTune-iPS Sendai Virus Reprogramming Kit, Episomal plasmids | Safe and efficient delivery of OSKM reprogramming factors. |

| Cell Culture Media | mTeSR1, StemFlex, Essential 8 (E8) | Maintenance of pluripotent stem cells in defined, feeder-free conditions. |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Recombinant Laminin-521 | Coating substrate for adherent culture of iPSCs. |

| Cardiac Differentiation Kits | Gibco PSC Cardiomyocyte Differentiation Kit, STEMdiff Cardiomyocyte Kit | Directed differentiation of iPSCs to cardiomyocytes using optimized protocols. |

| Small Molecule Inducers | CHIR99021 (Wnt activator), IWP-2/IWR-1 (Wnt inhibitors) | Critical for modulating Wnt signaling to drive cardiac differentiation. |

| Cell Culture Supplements | B-27 Supplement, Insulin | Serum-free supplements for cardiomyocyte maintenance and maturation. |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-cTnT (Cardiac Troponin T), Anti-α-Actinin, Anti-MLC2v | Immunostaining to confirm cardiomyocyte identity and subtype (ventricular). |

The choice of somatic cell source for iPSC generation is a fundamental decision that shapes the entire trajectory of cardiovascular disease modeling research. Dermal fibroblasts offer a well-established, genomically stable starting material. Peripheral blood cells provide a less invasive alternative with robust reprogramming efficiency, making them suitable for large-scale donor collections. Urine-derived cells present a completely non-invasive option that is easily repeatable, facilitating longitudinal studies from the same donor. The selection should be guided by the specific requirements of the research project, weighing factors such as invasiveness, scalability, and reprogramming efficiency. When combined with advanced cardiac differentiation protocols—particularly scalable suspension systems—and strategies to enhance cardiomyocyte maturity, iPSCs from any of these sources form a powerful platform for elucidating disease mechanisms, accelerating drug discovery, and advancing personalized cardiovascular medicine.

The advent of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized biomedical research, offering unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine. In cardiovascular research, the ability to derive patient-specific cardiomyocytes from iPSCs has enabled the precise in vitro modeling of cardiac diseases and the screening of potential therapeutics [9] [3]. The foundation of this technology lies in reprogramming somatic cells to a pluripotent state by introducing specific transcription factors, predominantly OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM) [12]. The choice of delivery method for these reprogramming factors is crucial, as it directly impacts the genomic integrity, functional fidelity, and clinical applicability of the resulting iPSCs. This technical guide comprehensively examines the evolution of iPSC delivery methods, from early integrating vectors to contemporary non-integrating platforms, with specific emphasis on their utility in cardiovascular disease modeling research.

Historical Development and Core Principles

The conceptual foundation for iPSC technology was established through seminal experiments demonstrating that cellular identity is maintained by reversible epigenetic mechanisms. John Gurdon's seminal somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) experiments in 1962 demonstrated that a nucleus from a differentiated somatic cell could support the development of an entire organism when transferred into an enucleated egg [12]. This pivotal finding established that genetic information remains intact during development and that epigenetic regulation is reversible. The direct reprogramming of somatic cells became feasible with the groundbreaking work of Shinya Yamanaka, who identified that retroviral-mediated expression of four transcription factors—Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc—could reprogram mouse fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells [12]. This discovery unlocked the potential to create patient-specific pluripotent cells without embryonic sources, with Yamanaka receiving the Nobel Prize in 2012 for this transformative achievement.

The reprogramming process involves profound epigenetic remodeling and transcriptional reorganization, reverting somatic cells to a pluripotent state through a partially stochastic process [12]. Successful reprogramming entails silencing somatic genes while activating the endogenous pluripotency network, with the endogenous reactivation of the Oct4 promoter serving as a critical stabilization point for the pluripotent state [9]. The initial methods using integrating viral vectors raised significant safety concerns for clinical applications, driving the development of non-integrating alternatives that minimize the risk of insertional mutagenesis and oncogene reactivation [9] [17].

Comparative Analysis of Delivery Methods

Integrating Delivery Methods

Retroviral and Lentiviral Vectors

Early iPSC generation relied heavily on integrating viral vectors, particularly gamma-retroviruses and lentiviruses, which offer high reprogramming efficiency through stable genomic integration of the transgenes [17]. Retroviral vectors (e.g., pMXs) efficiently infect dividing cells but are prone to incomplete transgene silencing after reprogramming, which can interfere with differentiation [17]. Lentiviral vectors provide the advantage of infecting both dividing and non-dividing cells and can accommodate polycistronic cassettes expressing multiple factors from a single promoter [17].

However, the primary safety concern with these methods is insertional mutagenesis, where random integration disrupts tumor suppressor genes or activates oncogenes, potentially leading to malignant transformation [9] [17]. Additionally, persistent expression or reactivation of reprogramming factors, particularly the oncogene c-MYC, can compromise differentiation and increase tumorigenic risk in derived cells [18] [17]. While excisable systems using Cre-lox technology or piggyBac transposons mitigate these concerns, they still leave genetic scars and require careful sequencing to verify complete removal [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Integrating Delivery Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Efficiency | Advantages | Disadvantages | Cardiovascular Research Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral Vectors | Genomic integration via reverse transcription | High | High efficiency; stable expression | Only infects dividing cells; insertional mutagenesis; incomplete silencing | Limited due to safety concerns; historical significance |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Genomic integration | High | Infects dividing & non-dividing cells; larger cargo capacity | Insertional mutagenesis; heterogeneous clones | Improved with excisable systems but largely superseded |

| piggyBac Transposon | "Cut-and-paste" transposition | Medium | Excisable system; large cargo capacity | Need to verify excision; potential for genomic alterations | Research tool for generating footprint-free lines |

Non-Integrating and DNA-Free Methods

Sendai Viral Vectors

Sendai virus (SeV) vectors represent a highly efficient non-integrating RNA-based system derived from a murine paramyxovirus [17] [19]. As an RNA replication-competent vector that operates entirely in the cytoplasm, SeV poses minimal risk of genomic integration [19]. These vectors provide robust, transient transgene expression ideal for reprogramming, and can be engineered with temperature-sensitive mutations to facilitate eventual clearance from the cell population [17] [19].

In proof-of-concept studies, SeV vectors have successfully generated transgene-free iPSCs from patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, including an 85-year-old individual, demonstrating their applicability to aged and diseased somatic cells [19]. The SeV system induces endogenous pluripotency genes while suppressing senescence pathways, facilitating efficient reprogramming [19]. A minor limitation is the potential difficulty in completely clearing the virus from all cells, though temperature-sensitive variants and prolonged passaging achieve elimination in most cases [17].

mRNA-Based Reprogramming

Synthetic mRNA reprogramming represents the safest approach, completely eliminating risks associated with viral vectors and genomic integration [17]. This method involves repeated transfection of cells with modified mRNAs encoding the reprogramming factors, typically with nucleoside modifications to reduce innate immune recognition and improve stability [17]. The protocol requires daily transfections over approximately two weeks, followed by picking of emerging iPSC colonies [17].

While this method offers superior safety profile and high efficiency, it requires multiple transfections and sophisticated mRNA engineering to minimize cellular immune responses [17]. The completely defined, vector-free nature of mRNA-derived iPSCs makes them particularly valuable for clinical applications, including the generation of cardiomyocytes for regenerative therapies [17].

Other Non-Integrating Methods

Additional non-integrating approaches include episomal plasmids, which replicate extrachromosomally and are gradually diluted through cell divisions, and adenoviral vectors, which remain episomal but typically show lower reprogramming efficiencies [17]. Minicircle DNA vectors, devoid of bacterial plasmid backbone sequences, offer enhanced transfection efficiency and prolonged transgene expression compared to conventional plasmids [17]. Protein-based reprogramming represents the ultimate in safety by directly delivering reprogramming factors, though it suffers from low efficiency and practical challenges in protein production and delivery [17].

Table 2: Comparison of Non-Integrating and DNA-Free Delivery Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Efficiency | Advantages | Disadvantages | Cardiovascular Research Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sendai Virus (SeV) | Cytoplasmic RNA virus | Medium-High | Non-integrating; broad cell tropism; high efficiency | Can be difficult to clear completely; screening needed | Excellent for research and clinical applications |

| Synthetic mRNA | Direct delivery of modified mRNA | High | DNA-free; no integration risk; high efficiency | Multiple transfections; immune response concerns | Preferred for clinical-grade cardiomyocyte derivation |

| Episomal Plasmids | Extra-chromosomal replication | Medium | Non-integrating; simple production | Low efficiency; potential for integration | Research applications with verification needed |

| Adenovirus | Episomal DNA vector | Low | Non-integrating; broad tropism | Low efficiency; immune response | Limited utility due to low efficiency |

| Protein Delivery | Direct protein transduction | Low | Completely DNA-free; maximal safety | Very low efficiency; difficult protein production | Research tool with limited practical application |

Methodological Protocols

Sendai Virus Reprogramming Protocol

For cardiovascular disease modeling, the generation of iPSCs using Sendai virus vectors follows a standardized protocol. Begin with somatic cell isolation—dermal fibroblasts from skin punch biopsies or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected via venipuncture represent the most common sources [9]. PBMCs are increasingly favored for their minimally invasive collection [9].

Day 0: Plate 5×10^4 to 1×10^5 somatic cells in appropriate medium. Day 1: Infect cells with SeV vectors expressing OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC using MOI (Multiplicity of Infection) of 3-5 for each vector in serum-free medium. After 2 hours, add complete medium. Days 2-6: Change medium daily. Day 7: Transfer transduced cells onto irradiated mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder layers or Matrigel-coated plates in human iPSC medium. Days 8-20: Continue daily medium changes. Days 21-30: Pick emerging iPSC colonies based on embryonic stem cell-like morphology and transfer to new culture vessels [19].

Monitor SeV clearance via PCR or immunostaining for viral genes. Most lines lose the viral genome by passages 8-12. For temperature-sensitive SeV variants, shifting culture temperature to 38°C can accelerate clearance [19].

mRNA Reprogramming Protocol

The mRNA reprogramming protocol requires stringent aseptic technique and daily transfections. Day 0: Plate 5×10^4 fibroblasts in 6-well plates. Days 1-16: Transfect daily with a cocktail of modified mRNAs encoding OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, LIN28, and NANOG using lipid-based transfection reagents. Include B18R protein in the medium to enhance mRNA stability and reduce immune responses. Days 17-30: Monitor for emerging iPSC colonies and pick for expansion [17].

Application in Cardiovascular Disease Modeling

The selection of reprogramming method directly influences the suitability of resulting iPSCs for cardiovascular disease modeling and therapeutic development. Current clinical trials using iPSC-derived cells prioritize non-integrating methods like Sendai virus and mRNA to minimize oncogenic risks [18]. In cardiovascular research, iPSCs are differentiated into cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) that recapitulate disease phenotypes for conditions including arrhythmogenic disorders, heart failure, and myocardial injury [9] [3].

For instance, models of congenital arrhythmias linked to KCNQ1 mutations provide platforms for precision cardiology and drug testing [9]. However, a significant limitation remains the immature phenotype of iPSC-CMs, which resemble fetal rather than adult cardiomyocytes in their structure, metabolism, and electrophysiology [3]. Advanced engineering approaches, including 3D tissue constructs and engineered cardiac tissues (ECTs), enhance maturation and improve physiological relevance for disease modeling and drug screening applications [20].

Diagram 1: iPSC Generation and Cardiovascular Application Workflow. This diagram illustrates the complete workflow from somatic cell isolation to cardiovascular disease modeling, highlighting key viral and non-viral reprogramming methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of iPSC technology for cardiovascular research requires specific reagents and systems tailored to different reprogramming methods.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC Generation

| Reagent/System | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sendai Virus Vectors (Cytotune iPS 2.0) | Delivery of OSKM factors | Temperature-sensitive variants available; monitor clearance via RT-PCR |

| mRNA Reprogramming Kit (StemRNA NP) | Modified mRNA for reprogramming | Includes immune suppressor; requires daily transfections |

| Episomal Plasmids (pCEP4-EO2S-EN2L) | Non-integrating DNA vectors | EBNA1-based system for episomal maintenance |

| Lentiviral Vectors (pSIN) | Integrating delivery | Useful for difficult-to-reprogram cells; excisable versions available |

| Yamanaka Factor Cocktail | Core reprogramming factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM) essential for all methods |

| Matrigel/Laminin-521 | Extracellular matrix coating | Supports iPSC colony attachment and growth in feeder-free systems |

| mTeSR1/E8 Medium | Defined culture medium | Chemically formulated for feeder-free iPSC maintenance |

| Small Molecule Enhancers (e.g., Sodium Butyrate) | Epigenetic modifiers | Enhance reprogramming efficiency across multiple methods |

Diagram 2: Molecular Dynamics of Cellular Reprogramming. This diagram illustrates the key molecular and cellular events during reprogramming, highlighting the transition from early stochastic phases to late deterministic events that establish a stable pluripotent state.

The evolution of iPSC delivery methods from integrating lentiviruses to non-integrating Sendai virus and mRNA platforms reflects the field's progression toward safer, clinically applicable technologies. For cardiovascular disease modeling, the selection of reprogramming method represents a critical decision point balancing efficiency, safety, and practical considerations. While integrating methods retain utility for certain research applications, non-integrating approaches—particularly Sendai virus and synthetic mRNA—offer distinct advantages for generating clinical-grade iPSCs and their cardiovascular derivatives. Continued refinement of these technologies, coupled with advanced cardiac differentiation and tissue engineering strategies, will enhance the fidelity of iPSC-based cardiovascular disease models and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics for cardiac disorders.

The pursuit of robust in vitro models for cardiovascular disease research and drug discovery has positioned induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived cardiomyocytes at the forefront of cardiac regenerative medicine. The differentiation of these cells mirrors embryonic heart development, a process orchestrated by precise temporal activation and inhibition of conserved signaling pathways [21] [22]. Among these, the Wnt/β-catenin, Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP), and Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β) pathways form a critical signaling nexus that directs iPSCs through mesoderm specification, cardiac progenitor formation, and ultimately functional cardiomyocyte maturation [23] [24]. Understanding and manipulating these pathways is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental requirement for generating clinically relevant cardiomyocytes for disease modeling, drug screening, and therapeutic applications. This technical guide explores the mechanistic roles of these pathways and provides a practical framework for their exploitation in directing cardiac differentiation, with particular emphasis on their application within iPSC-based cardiovascular disease modeling research.

Core Signaling Pathways in Cardiac Differentiation

Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling: A Biphasic Regulator

The Wnt/β-catenin, or canonical Wnt pathway, exhibits a temporally sensitive, biphasic role in cardiac differentiation, which explains earlier seemingly contradictory findings about its function [24] [25].

- Early Activation Promotes Mesoderm Commitment: During the initial stages of differentiation, activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is essential for mesoderm induction. Secreted Wnt ligands, such as Wnt3a, bind to Frizzled receptors and LRP5/6 co-receptors, preventing the destruction complex from targeting β-catenin for degradation. The stabilized β-catenin translocates to the nucleus, forming a complex with TCF/LEF transcription factors to activate target genes like Brachyury, which drives mesoderm formation [24]. Inhibition of this endogenous Wnt activity at this stage with antagonists like Dikkopf-1 (Dkk1) markedly reduces cardiac differentiation efficiency [24] [25].

- Late Inhibition Enhances Cardiogenesis: After mesoderm specification, continued Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibits cardiac differentiation. Antagonism of the pathway during this later stage promotes the transition from cardiac progenitors to definitive cardiomyocytes [24]. This biphasic mechanism is harnessed in directed differentiation protocols, where GSK3β inhibitors like CHIR99021 are used for initial activation, followed by later inhibition using small molecules like IWP2 or IWR1 [26].

Table 1: Biphasic Role of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Cardiac Differentiation

| Differentiation Phase | Signaling Status | Key Effect | Experimental Manipulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early (Mesoderm Induction) | Activation | Promotes formation of mesoderm and cardiac progenitors [24] [25] | Add GSK3β inhibitor (e.g., CHIR99021) or Wnt3a [26] |

| Late (Cardiac Specification) | Inhibition | Enhances differentiation of progenitors into contracting cardiomyocytes [24] | Add Wnt inhibitors (e.g., IWP2, IWR1, Dkk1) [24] |

The following diagram illustrates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway mechanism and its biphasic role in cardiac differentiation:

BMP Signaling: Driving Cardiac Progenitor Specification

BMP signaling works in concert with Wnt signaling to promote cardiac mesoderm formation and specification [23] [21].

- Mechanism: BMP ligands (e.g., BMP2, BMP4) bind to type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors, leading to the phosphorylation of receptor-regulated SMADs (R-SMADs: SMAD1/5/8). These phosphorylated R-SMADs form a complex with the common mediator SMAD4, which translocates to the nucleus to regulate the transcription of key cardiac genes [23].

- Key Roles in Cardiac Differentiation:

- Synergy with Activin/Nodal: BMP signaling works synergistically with Activin A (a TGF-β family member) to pattern the mesoderm toward a cardiac fate. This combination is a cornerstone of many efficient cardiomyocyte differentiation protocols [24] [25].

- Regulation of Cardiac Transcription Factors: BMP signaling directly regulates the expression of core cardiac transcription factors, including NKX2-5, ISL1, and HAND1. The SMAD complex can bind to regulatory elements of these genes, and SMAD4 interacts with NKX2-5 to promote its nuclear localization [23].

- Crosstalk with Other Pathways: A crucial crosstalk exists between BMP and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is required for SMAD1 activation by BMP4, indicating that Wnt signaling primes the cells for BMP activity during early mesoderm induction [24] [25].

TGF-β/Activin A Signaling: Patterning the Primitive Streak

The TGF-β pathway, particularly through Activin A and Nodal signaling, is instrumental in the initial stages of differentiation for priming pluripotent cells toward a mesendodermal lineage [24] [22].

- Mechanism: Similar to BMP signaling, Activin A binds to type I (ALK4/5/7) and type II receptors, leading to the phosphorylation of R-SMADs (SMAD2/3). The SMAD2/3-SMAD4 complex then translocates to the nucleus to direct gene expression.

- Role in Primitive Streak Patterning: Activin A signaling promotes the formation of the primitive streak and directs cells toward a definitive mesoderm fate, which is a prerequisite for cardiac specification [24]. In standard cardiac differentiation protocols, Activin A is often applied first to induce a primitive streak-like state, followed by BMP4 to drive cardiac mesoderm specification [24] [25].

The following workflow summarizes a standard protocol harnessing these pathways for cardiac differentiation:

Experimental Protocols for Directed Cardiac Differentiation

This section details a standard, highly efficient protocol for differentiating human iPSCs into cardiomyocytes by sequentially manipulating the Wnt, BMP, and TGF-β pathways, based on the activin A/BMP4 method [24] [25].

Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Cardiac Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Differentiation | Mechanistic Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokines/Growth Factors | Activin A [24] [25] | Initiates primitive streak patterning; induces definitive mesoderm [24] | TGF-β/Activin Pathway (SMAD2/3) |

| BMP4 [24] [25] | Specifies cardiac mesoderm; promotes cardiac progenitor formation [23] [24] | BMP Pathway (SMAD1/5/8) | |

| Wnt3a [24] [25] | Enhances mesoderm induction when added early [24] | Canonical Wnt/β-catenin Pathway | |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | CHIR99021 [26] | GSK3β inhibitor; activates Wnt signaling for mesoderm induction [26] | Wnt/β-catenin Pathway (GSK3β) |

| IWP2 / IWR1 [24] | Wnt production/inhibition; suppresses Wnt signaling to enhance cardiogenesis [24] | Wnt/β-catenin Pathway | |

| Dkk1 [24] [25] | Secreted Wnt antagonist; inhibits early Wnt signaling and cardiogenesis [24] | Wnt/β-catenin Pathway (LRP5/6) | |

| Cell Culture Reagents | RPMI 1640 Medium [24] | Base medium for differentiation | N/A |

| B-27 Supplement (without insulin) [24] | Chemically defined supplement supporting cardiomyocyte survival | N/A | |

| Matrigel or Vitronectin [26] | Extracellular matrix for pluripotent stem cell attachment and survival | Integrin-mediated signaling |

Step-by-Step Differentiation Protocol

- Initial Cell Preparation: Culture human iPSCs to high confluence (≈80-90%) in a defined, feeder-free system, such as on Matrigel-coated plates.

- Day 0: Mesoderm Induction (Activin A): Replace the maintenance medium with differentiation medium (e.g., RPMI 1640 supplemented with B-27 minus insulin) containing Activin A (100 ng/mL). This 24-hour exposure initiates TGF-β/Activin signaling, priming cells for mesoderm formation [24] [25].

- Day 1: Cardiac Mesoderm Specification (BMP4 + Wnt Activation): Change the medium to fresh differentiation medium containing BMP4 (10 ng/mL). The protocol can be enhanced by also adding Wnt3a (10 ng/mL) or the GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021 (2-6 µM) at this stage to further boost Wnt signaling and cardiac mesoderm specification [24] [25].

- Days 3-5: Spontaneous or Directed Wnt Inhibition: Allow the cells to develop in a basal differentiation medium without cytokines. Endogenous Wnt production typically declines in successful differentiations. Alternatively, to robustly enhance cardiomyocyte yield, add a Wnt inhibitor such as IWP2 (2 µM) or IWR1 (5 µM) between days 3 and 5 to block late Wnt signaling and promote cardiac progenitor differentiation [24].

- Days 5-14: Maturation and Beating: Continue culture in basal differentiation medium, changing the medium every 2-3 days. Spontaneously contracting clusters are typically observed between days 8 and 10.

- Day 14+: Metabolic Selection and Maintenance: From approximately day 14, replace the medium with RPMI 1640 containing B-27 Supplement (with insulin) to support long-term culture. To enrich for cardiomyocytes, a metabolic selection method using glucose-depleted lactate medium can be employed between days 10-14, which selectively supports the survival of cardiomyocytes [3].

Applications in iPSC-Based Cardiovascular Disease Modeling

The ability to generate patient-specific iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) has revolutionized cardiovascular disease modeling and drug discovery, directly building upon the principles of directed differentiation [18] [3].

- Disease Modeling and Mechanism Elucidation: hiPSC-CMs allow for the reproduction of disease-specific phenotypes in a culture dish. This is particularly valuable for studying inherited cardiomyopathies (e.g., hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) and channelopathies, where patient-specific cells can reveal underlying pathological mechanisms [26]. Genome-editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 enable the creation of isogenic control lines, confirming the causality of specific genetic mutations [26].

- Drug Discovery and Cardiotoxicity Screening: hiPSC-CMs provide a human-relevant platform for evaluating drug efficacy and safety. They can be used to assess the therapeutic potential of new compounds and are increasingly employed in preclinical cardiotoxicity screening to detect dangerous side effects like drug-induced arrhythmias, a major cause of drug attrition [3] [27]. This addresses the limitations of animal models, which often fail to predict human-specific cardiac responses due to species differences in ion channels and cardiac physiology [3].

- Clinical Trials and Regenerative Medicine: iPSC-derived cells are emerging as a promising cell-based therapy. A 2025 systematic review identified 10 published clinical studies and 22 ongoing registered trials using iPSCs to treat a range of conditions, including cardiac diseases [18]. These early studies, while small and uncontrolled, pave the way for using iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes or their secreted factors for cardiac repair in heart failure patients [18].

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant progress, the field faces a major hurdle: the relative immaturity of hiPSC-CMs compared to adult human cardiomyocytes [3] [27]. hiPSC-CMs typically exhibit a fetal-like phenotype, with rounded morphology, disorganized sarcomeres, absent T-tubules, immature electrophysiology, and preferential reliance on glycolytic metabolism rather than mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [3] [27]. This immaturity can limit their accuracy in modeling adult-onset cardiovascular diseases.

Future research is focused on developing maturation strategies that better recapitulate the adult cardiac environment. These include:

- Advanced Engineered Microenvironments: Using biomaterials like tunable hydrogels to provide physiologically relevant mechanical cues and 3D structural support that promote maturation through mechanotransduction pathways [26].

- Metabolic Manipulation: Shifting the metabolic profile of hiPSC-CMs from glycolysis to fatty acid oxidation, the primary energy source in the adult heart [3].

- Long-Term Culture and Electromechanical Stimulation: Subjecting hiPSC-CMs to prolonged culture periods and applying rhythmic electrical pacing or mechanical load to drive structural and functional maturation [26].

Overcoming the challenge of immaturity will be paramount for fully realizing the potential of hiPSC-CMs in accurately modeling cardiovascular diseases, predicting drug responses, and ultimately achieving success in regenerative therapy.

The discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) marked a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine and biomedical research, offering unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug discovery, and cell replacement therapies. Within cardiovascular research, iPSC technology has emerged as a particularly powerful platform for studying disease mechanisms and developing therapeutic interventions. This technical guide traces the key milestones in iPSC development from fundamental discovery to clinical-grade cell line generation, with specific emphasis on applications in cardiovascular disease modeling. The journey from basic reprogramming to clinical implementation represents a remarkable scientific achievement that has transformed our approach to understanding and treating cardiac disorders [1] [28].

The reprogramming of somatic cells to a pluripotent state fundamentally altered the stem cell research landscape, providing a patient-specific cell source without the ethical concerns associated with embryonic stem cells. For cardiovascular researchers, this technology enables generation of patient-specific cardiomyocytes that recapitulate disease phenotypes in vitro, facilitating mechanistic studies and drug screening platforms. The evolution of iPSC technology has progressed through distinct phases—from initial discovery to refinement of reprogramming methods, standardization of differentiation protocols, and ultimately development of clinical-grade cell lines compliant with regulatory standards [28].

Historical Trajectory of iPSC Technology

The foundation of iPSC technology builds upon decades of developmental biology research, with seminal discoveries paving the way for cellular reprogramming. Key historical milestones established the conceptual and technical framework that eventually enabled the generation of iPSCs:

Figure 1: Historical progression of key reprogramming milestones from early nuclear transfer to clinical application of iPSC technology.

The transformative breakthrough came in 2006 when Shinya Yamanaka's laboratory demonstrated that introducing four transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (collectively known as OSKM)—could reprogram mouse fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells [1] [28]. This discovery was rapidly extended to human cells in 2007 by both Yamanaka and James Thomson, generating human iPSCs from adult fibroblasts [1]. The original reprogramming approach utilized retroviral vectors that integrated into the host genome, raising concerns about potential tumorigenicity, particularly from the oncogene c-MYC [28] [29].

The mechanistic basis of reprogramming involves extensive transcriptional and epigenetic remodeling through distinct phases. Initially, somatic identity is suppressed during an initial phase, followed by stabilization of the pluripotency network. This process involves chromatin reorganization with activating histone marks (H3K4me3) enriched at pluripotency loci and reduction of repressive marks (H3K27me3). SOX2 facilitates chromatin opening and demethylation, while TET enzymes promote DNA demethylation at key regulatory genes. Signaling pathways including BMP, Wnt, and TGF-β modulate critical transitions such as the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), which is essential for successful reprogramming [28].

Table 1: Evolution of Reprogramming Methods for iPSC Generation

| Method | Key Features | Integration Profile | Efficiency | Safety Considerations | Clinical Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral Vectors | Original Yamanaka factors (OSKM) | Integrating | Low | High tumor risk, especially with c-MYC | Limited |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Can reprogram non-dividing cells | Integrating | Moderate | Insertional mutagenesis concerns | Limited |

| Sendai Virus | RNA virus, remains cytoplasmic | Non-integrating | High | Replicates in cytoplasm, eventually diluted | Good |

| Episomal Plasmids | DNA-based, Epstein-Barr origin | Non-integrating | Low to moderate | No viral elements, but low efficiency | Good |

| Synthetic mRNA | Modified to evade immune recognition | Non-integrating | Moderate | Requires repeated transfection | Excellent |

| CRISPR Activation | Targeted activation of endogenous genes | Can be integrating or non-integrating | Varies | Depends on delivery method | Emerging |

The progression toward clinical application has driven development of non-integrating reprogramming methods including Sendai virus, episomal plasmids, synthetic mRNAs, and CRISPR-based activation systems. These approaches significantly reduce the risk of insertional mutagenesis and improve the safety profile of clinical-grade iPSCs [28]. Small molecules such as CHIR99021 (a GSK3β inhibitor) and valproic acid (a histone deacetylase inhibitor) have been shown to enhance reprogramming efficiency by modulating metabolic activity and chromatin structure, further advancing the field toward robust clinical-grade cell production [28].

Progression to Clinical Applications

The translation of iPSC technology from research tool to clinical intervention has progressed rapidly, with landmark trials establishing the therapeutic potential of iPSC-derived cells. The timeline from initial discovery to clinical application has been remarkably accelerated compared to other biotechnological breakthroughs:

Table 2: Key Milestones in Clinical Translation of iPSC Technology

| Year | Milestone | Significance | Field/Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | Discovery of mouse iPSCs | Proof-of-concept for somatic cell reprogramming | Basic Research |

| 2007 | Generation of human iPSCs | Extension to human cells, patient-specific models | Disease Modeling |

| 2013 | First human transplantation of iPSC-derived cells | iPSC-derived retinal sheets for macular degeneration | Ophthalmology |

| 2016 | First formal clinical trial of allogeneic iPSC-derived product (Cynata CYP-001) | Approval for GvHD treatment | Immunology |

| 2018 | First Parkinson's disease trial with iPSC-derived dopaminergic progenitors | Neurodegenerative disease application | Neurology |

| 2023 | Initiation of first Phase 3 iPSC trial (Cynata CYP-004) | Landmark large-scale trial for osteoarthritis | Regenerative Medicine |

| 2024 | IND approval for Eyecyte-RPE in India | Regulatory milestone for geographic atrophy | Ophthalmology |

| 2025 | Phase I/II trial of allogeneic iPSC-derived dopaminergic progenitors for Parkinson's | Demonstrated survival, dopamine production, no tumors | Neurology |

The first clinical application of iPSC-derived cells occurred in 2013 at the RIKEN Center in Kobe, Japan, led by Dr. Masayo Takahashi. This pioneering study investigated the safety of iPSC-derived retinal cell sheets in patients with age-related macular degeneration [1]. Shortly thereafter, in 2016, Cynata Therapeutics received approval to launch the first formal clinical trial of an allogeneic iPSC-derived cell product (CYP-001) for treating graft-versus-host disease (GvHD). This historic trial met its clinical endpoints and produced positive safety and efficacy data [1].

The field has now advanced to Phase 3 clinical trials, with Cynata's iPSC-derived mesenchymal stem cell product (CYP-004) being evaluated in 440 patients with osteoarthritis. This represents both the first Phase 3 clinical trial involving an iPSC-derived cell therapeutic product and the largest such trial completed to date [1]. Concurrently, numerous clinical trials are underway that do not involve transplantation but instead focus on creating and evaluating iPSC lines from specific patient populations to develop disease models [1].

Recent clinical advances include a Phase I/II trial published in 2025 reporting that allogeneic iPSC-derived dopaminergic progenitors survived transplantation, produced dopamine, and did not form tumors in Parkinson's patients [28]. Additionally, an ongoing autologous iPSC-derived dopamine neuron trial at Mass General Brigham is pioneering the use of a patient's own blood-derived iPSCs in Parkinson's disease, eliminating the need for immune suppression [28].

iPSC-Cardiomyocyte Differentiation Methodologies

The application of iPSC technology to cardiovascular disease modeling has driven development of robust cardiac differentiation protocols that generate functionally relevant cardiomyocytes. The evolution of these methods has progressed from spontaneous differentiation in embryoid bodies to highly efficient, directed differentiation protocols:

Figure 2: Evolution of cardiac differentiation protocols from initial embryoid body methods to contemporary bioreactor systems.

Initial cardiac differentiation protocols relied on spontaneous differentiation of iPSCs aggregated into embryoid bodies in KO-DMEM with 20% fetal bovine serum, yielding approximately 8% contracting embryoid bodies [30]. These were followed by co-culture systems that provided platforms for early cardiomyocyte generation without precise control of differentiation parameters, resulting in low yields and purity [30]. The field advanced significantly with the introduction of directed differentiation protocols informed by developmental biology cues, utilizing specific growth factors including activin A, FGF2, and BMP4 to improve efficiency in both embryoid body and monolayer formats [30].

The contemporary paradigm for cardiac differentiation employs sequential modulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, typically using small molecule inhibitors and activators. This approach begins with Wnt activation using compounds such as CHIR99021 (a GSK3β inhibitor), followed by Wnt inhibition using molecules such as IWR-1 or IWP-2 [30] [14]. This method has become the dominant approach for hiPSC-CM differentiation due to its relative simplicity and high efficiency, making it suitable for both disease modeling and therapeutic applications [14].

Recent advances have optimized suspension culture cardiac differentiation protocols to address challenges with quality, inter-batch consistency, cryopreservation, and scale that have historically reduced experimental reproducibility and clinical translation [14]. Modern bioreactor-based approaches can produce approximately 1.2 million cardiomyocytes per milliliter with ~94% purity across multiple iPSC lines. These bioreactor-differentiated cardiomyocytes (bCMs) demonstrate high viability after cryopreservation (>90%), predominantly ventricular identity, and more mature functional properties compared to standard monolayer-differentiated cardiomyocytes (mCMs) [14].

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Cardiac Differentiation Platforms

| Parameter | Traditional Monolayer | Advanced Suspension Bioreactor |

|---|---|---|

| Scalability | Limited, linear scaling with plate area | High, efficient scaling to large volumes |

| Yield | Variable, typically lower | ~1.2E6 cells/mL, consistent |

| Purity | Variable (often <90%) | High (~94% TNNT2+) |

| Batch-to-Batch Variation | Significant | Minimal |

| Functional Maturity | Less mature phenotypes | Enhanced maturity metrics |

| Cryopreservation Recovery | Reduced viability and function | High viability (>90%) with retained function |

| Resource Requirements | Labor-intensive | More efficient at scale |

| Cost at Scale | Higher | Lower per cell |

| Clinical Translation Potential | Limited | Substantially better |

The development of stirred suspension systems represents a significant advancement in producing high-quality cardiomyocytes with reduced variability. These systems provide continuous monitoring and adjustment of temperature, O2, CO2, and pH, while constant mixing ensures optimal distribution of nutrients and differentiation factors [14]. This approach has demonstrated applicability across diverse patient-specific, gene-edited, and commercially available iPSC lines, facilitating robust cardiovascular disease modeling [14].

Technical Protocols for Cardiac Disease Modeling

Bioreactor-Based Cardiac Differentiation

An optimized suspension culture cardiac differentiation protocol developed by Fiedler et al. (2024) enables large-scale production of high-quality iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) with enhanced maturity and reduced batch-to-batch variability [14]. The protocol incorporates several critical advancements:

Quality-Controlled Input Cells: Establishment of master cell banks with comprehensive quality control including karyotyping and mycoplasma testing. Pluripotency marker SSEA4 is monitored by FACS, with >70% SSEA4 positivity correlating with successful differentiations (>90% TNNT2+ cells) [14].

Stirred Bioreactor System: Utilization of bioreactors that continuously monitor and adjust temperature, O2, CO2, and pH parameters throughout differentiation [14].

Small Molecule-Based Differentiation: Employment of small molecules rather than growth factors to guide differentiation, reducing costs and lot-to-lot variability [14].

Optimized Timing: Precise optimization of the initiation time point for Wnt activation based on embryoid body diameter (targeting 100μm), duration of Wnt activation (24 hours with CHIR99021), and timing of Wnt inhibition (48 hours with IWR-1 following a 24-hour gap) [14].

The protocol generates predominantly ventricular cardiomyocytes, as evidenced by high expression of ventricular markers MYH7, MYL2, and MYL3, with 83.4% of cells positive for ventricular myosin light chain (MLC2v) by flow cytometry. These cardiomyocytes demonstrate functional properties with contraction onset at differentiation day 5, earlier than monolayer-differentiated counterparts [14].

Cardiac Organoid Generation in Suspension Culture

The same research group has adapted their bioreactor protocol to generate 3D cardiac organoids entirely in suspension culture, representing the first cardiac organoid model completely generated under these conditions [14]. These organoids primarily consist of cardiomyocytes and model ventricular wall and chamber formation, similar to previously published cardiac organoid models generated in static culture. The suspension approach enables scalable production of organoids for disease modeling and drug screening applications [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Successful implementation of iPSC-based cardiovascular disease modeling requires specific reagents, tools, and methodologies carefully selected for their reliability and effectiveness:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC-Based Cardiac Disease Modeling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Systems | Sendai Virus, Episomal Plasmids, mRNA | Somatic cell reprogramming | Non-integrating methods preferred for clinical applications |

| Cell Culture Media | Essential-8, mTeSR1, StemFlex | iPSC maintenance | Chemically defined, xeno-free formulations |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Geltrex, Vitronectin | iPSC attachment and growth | Specific coatings support pluripotency |

| Cardiac Differentiation Agents | CHIR99021, IWR-1, BMP4, Activin A | Directed cardiac differentiation | Wnt pathway modulation is central |

| Cell Characterization Tools | Flow cytometry antibodies (TNNT2, MLC2v) | Cardiomyocyte identification and purity assessment | Quality control checkpoints |

| Functional Assay Reagents | Calcium indicators, MEA plates, Contractility sensors | Functional assessment of cardiomyocytes | Key for disease phenotyping |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems, Homology-directed repair templates | Introduction or correction of disease mutations | Isogenic control generation |

| Cryopreservation Solutions | DMSO-based cryomedium with controlled rate freezing | Cell storage and banking | Critical for maintaining viability |

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning methodologies represents an emerging tool in the iPSC workflow. These technologies enable automated colony morphology classification, differentiation outcome prediction, and enhanced standardization in iPSC manufacturing [28]. AI-guided approaches are increasingly applied to optimize culture conditions for large-scale iPSC production and analyze genetic and omics data to uncover biological patterns relevant to personalized medicine applications [29].

CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has become an indispensable tool for creating precise disease models and conducting mechanistic studies. In cardiovascular research, CRISPR enables introduction of specific disease-associated mutations into healthy iPSC lines or correction of mutations in patient-derived iPSCs, generating isogenic control lines that are genetically identical except for the mutation of interest [28] [31]. This approach controls for genetic background variability and strengthens conclusions about genotype-phenotype relationships.

The progression from the initial discovery of iPSCs to the development of clinical-grade cell lines represents a remarkable scientific achievement that has fundamentally transformed cardiovascular research and regenerative medicine. Key milestones including the refinement of reprogramming methods, standardization of cardiac differentiation protocols, implementation of quality control measures, and execution of pioneering clinical trials have established iPSC technology as a cornerstone of modern biomedical science. For cardiovascular disease modeling specifically, advances in bioreactor-based differentiation and organoid generation have enabled production of high-quality, clinically relevant cardiomyocytes at scales necessary for drug screening and therapeutic applications. Despite substantial progress, challenges remain in achieving full maturation of iPSC-cardiomyocytes, ensuring genomic stability, and scaling manufacturing processes to meet clinical demand. The ongoing integration of enabling technologies such as CRISPR gene editing, single-cell omics, and artificial intelligence promises to further advance the field toward robust clinical implementation and personalized cardiovascular medicine.

Advanced hiPSC-CM Applications: Disease Modeling and Drug Screening

The advent of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has revolutionized the study of inherited cardiac channelopathies by providing a uniquely human, patient-specific model system that bridges the gap between traditional animal models and human pathophysiology [32] [33]. These cells, generated through the reprogramming of somatic cells such as dermal fibroblasts or peripheral blood cells, possess the critical advantage of maintaining the complete genetic background of the donor, including all disease-causing mutations and genetic modifiers [34] [33]. For complex arrhythmia syndromes such as Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) and Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC), iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) enable researchers to move beyond mere phenotypic recapitulation to mechanistic interrogation of disease processes in a controlled human cellular environment [32]. This technological advancement is particularly valuable for cardiovascular disease modeling because it bypasses the limitations of primary human cardiomyocytes, which are difficult to obtain and expand, while also overcoming the species-specific differences that often render animal models inadequate for predicting human cardiac electrophysiology and drug responses [33] [35].

Within the broader context of cardiovascular disease modeling research, iPSC systems now occupy a critical role in bridging basic discovery with translational applications [32]. They have enabled unprecedented insight into human-specific disease mechanisms, including the role of splice variants, transcriptional regulation, and mitochondrial stress in arrhythmogenesis [32]. Furthermore, the ability to integrate iPSC technology with genome editing tools such as CRISPR/Cas9 has empowered researchers to establish definitive causal links between genetic variants and cellular phenotypes, particularly for variants of uncertain significance (VUS) that present diagnostic challenges in clinical practice [33]. As the field progresses, advances in directed differentiation now permit chamber-specific cardiac cell generation, allowing for more precise atrial and ventricular disease modeling and revealing critical cell-cell interactions that contribute to arrhythmogenesis [32]. These developments position iPSC technology as an indispensable component of the modern cardiovascular researcher's toolkit, contributing significantly to personalizing care and advancing therapeutics in inherited arrhythmic syndromes [32].

Disease Modeling: Long QT Syndrome and ARVC

Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) Modeling with iPSC-CMs

Long QT Syndrome represents a group of inherited cardiac arrhythmogenic disorders characterized by prolonged ventricular repolarization, reflected in a lengthened QT interval on the surface electrocardiogram, and an increased risk of potentially fatal ventricular tachyarrhythmias [33] [35]. iPSC-based modeling has been particularly instrumental in advancing our understanding of specific LQTS subtypes, with research revealing novel disease mechanisms beyond simple ion channel loss-of-function.

For LQT2, caused by mutations in KCNH2 encoding the hERG potassium channel, iPSC studies have uncovered the significant role of alternative splicing in disease pathogenesis [33]. Research using patient-specific iPSCs harboring the H70R mutation within the hERG N-terminal PAS domain demonstrated not only impaired channel trafficking of the hERG1a isoform but also a compensatory increase in hERG1b mRNA levels and an altered hERG1b/hERG1a ratio [33]. This altered ratio leads to faster deactivation of IKr and longer repolarization times, revealing a dual pathogenic mechanism that expands our understanding beyond simple haploinsufficiency [33]. Similarly, studies of Timothy Syndrome (LQT8), caused by mutations in CACNA1C encoding the L-type calcium channel, have utilized patient-specific iPSCs to identify novel therapeutic approaches. Yazawa et al. demonstrated that roscovitine, which enhances voltage-dependent inactivation of CaV1.2, could restore electrical and Ca2+ signaling properties of patient-specific iPSC-CMs, with subsequent mechanistic studies revealing that this effect occurs through partial inhibition of CDK5 to regulate CaV1.2 [33].

iPSC models have also proven invaluable for interrogating variants of uncertain significance (VUS) in LQTS genes. Terrenoire et al. investigated familial LQTS using patient-specific iPSCs harboring two VUS from both SCN5A (F1473C) and KCNH2 (K897T) [33]. Patch-clamp recordings revealed that enhanced late Na+ current (INaL) driven by the SCN5A polymorphism was primarily responsible for the LQT3 phenotype, while the KCNH2-K897T variant showed normal current density, enabling more accurate variant classification according to ACMG guidelines [33].

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC) Modeling with iPSC-CMs

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy is characterized by progressive replacement of ventricular myocardium with fibrofatty tissue, ventricular arrhythmias, and an increased risk of sudden cardiac death [33]. While traditionally considered a structural disorder, iPSC models have revealed important electrophysiological alterations that contribute to its arrhythmogenic potential.