Hydrogel Scaffolds for Stem Cell Delivery: Engineering the Microenvironment for Enhanced Regenerative Therapy

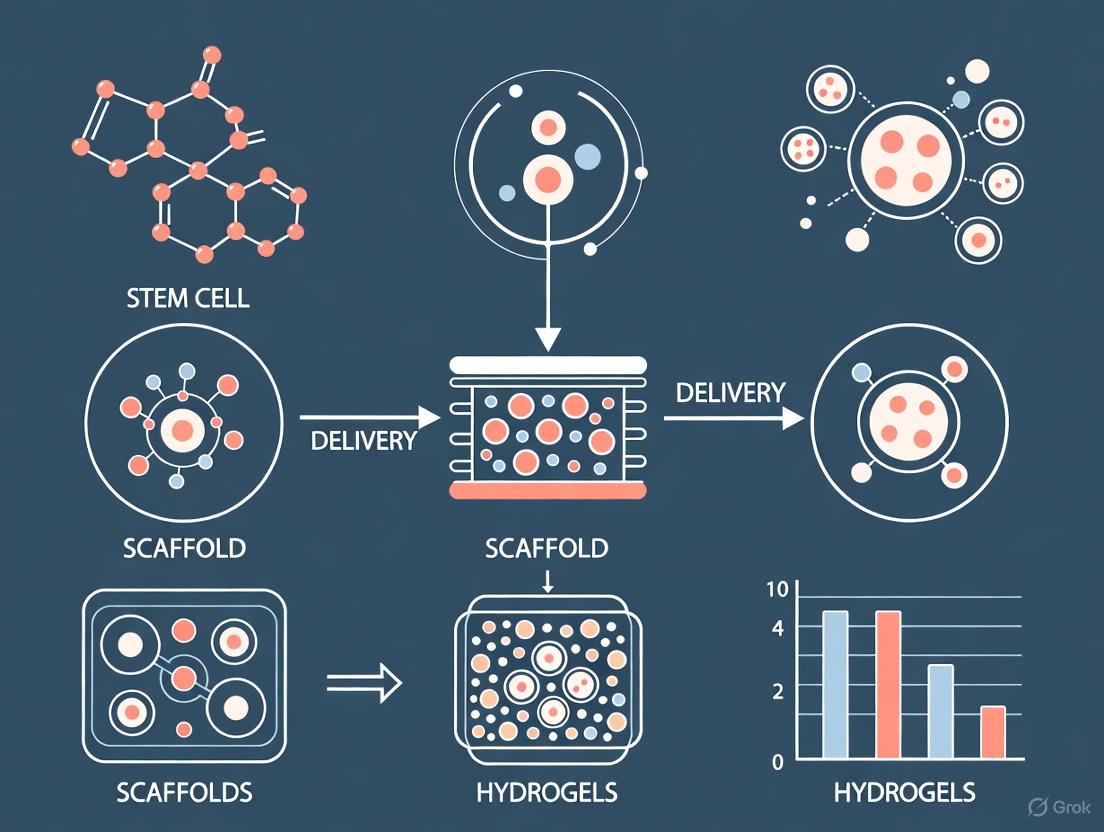

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of hydrogel-based scaffolds as advanced delivery systems for stem cells in regenerative medicine.

Hydrogel Scaffolds for Stem Cell Delivery: Engineering the Microenvironment for Enhanced Regenerative Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of hydrogel-based scaffolds as advanced delivery systems for stem cells in regenerative medicine. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of hydrogel design, including tunable mechanical properties and biomimicry of the native extracellular matrix. The scope extends to methodological advances in 3D bioprinting and application-specific formulations for musculoskeletal, neural, and dermal repair. It further addresses critical challenges in cell viability, immunogenicity, and manufacturing, while evaluating preclinical and clinical validation strategies. By synthesizing current research and future trajectories, this review serves as a strategic guide for overcoming translational barriers and harnessing the full potential of cell-laden hydrogels.

The Hydrogel-Stem Cell Nexus: Principles of a Biomimetic Microenvironment

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is far more than a passive scaffold for cells; it is a dynamic, instructive microenvironment that actively regulates cell behavior, fate, and function [1] [2]. For stem cell research, particularly in the development of delivery methods and scaffolds, recreating this complex niche is paramount to controlling stem cell survival, retention, and therapeutic efficacy post-transplantation [3]. Hydrogels—three-dimensional networks of hydrophilic polymers that imbibe large quantities of water—have emerged as the leading platform for mimicking the native ECM [2]. They provide a physiologically relevant 3D environment that can be engineered with tunable biochemical and biophysical properties, offering a superior alternative to traditional two-dimensional culture systems and enabling significant advances in stem cell delivery for regenerative medicine [1] [3].

Key Properties of the Native ECM to Be Replicated

To design effective hydrogels, one must first understand the key properties of the native ECM that govern cell behavior. These can be categorized into three main groups:

- Biochemical Composition: The ECM is composed of a complex mixture of proteins (e.g., collagens, elastin, fibronectin, laminin) and polysaccharides (e.g., hyaluronic acid) [1] [4]. These components provide specific cell-adhesion motifs and act as reservoirs for growth factors.

- Structural Properties: The ECM possesses a distinct architecture, often fibrous, with defined pore sizes and topography that influence cell migration, nutrient diffusion, and tissue organization [1].

- Mechanical Properties: Tissues exhibit unique mechanical behaviors, including specific stiffness (elastic modulus), viscoelasticity (a combination of solid- and fluid-like behavior), and non-linear stress-strain relationships [1] [5]. Cells sense these mechanical cues through a process called mechanotransduction.

The following table summarizes target properties for engineering hydrogels.

Table 1: Key Native ECM Properties and Their Roles in Guiding Cell Behavior

| ECM Property Category | Specific Parameters | Impact on Cell Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Biochemical | Presence of adhesion motifs (e.g., RGD) | Supports cell attachment, survival, and prevents anoikis [2] |

| Tissue-specific composition (e.g., laminin) | Directs tissue-specific differentiation and function [6] | |

| Structural | Pore size and porosity | Governs cell migration, nutrient diffusion, and waste removal [3] |

| Fiber topography and (an)isotropy | Influences cell polarity, migration, and cytoskeletal organization [1] | |

| Mechanical | Stiffness (Elastic Modulus) | Directs stem cell lineage commitment [3] |

| Viscoelasticity | Affects cell spreading, proliferation, and mechanosensing [1] [5] |

Designing Biomimetic Hydrogels: From Concept to Application

The rational design of hydrogels involves the strategic incorporation of specific biochemical and biophysical cues to replicate the native ECM microenvironment. The logical workflow for designing such hydrogels is outlined below.

Incorporating Biochemical Cues

To make synthetic hydrogels bioactive, they must be functionalized with molecules that facilitate cell adhesion and signaling.

- Cell-Adhesive Peptides: The most common strategy is incorporating the arginine-glycine-aspartate (RGD) peptide sequence, a universal integrin-binding domain found in many ECM proteins like fibronectin [2] [4]. This is essential for the survival of anchorage-dependent cells.

- Proteoglycan Mimetics: Molecules like heparin and chondroitin sulfate can be incorporated to mimic the function of native ECM proteoglycans. They sequester and release growth factors (e.g., VEGF, BMP-2), providing localized biochemical signaling to encapsulated stem cells [3] [2].

- Engineered Proteins: Advanced strategies involve designing novel biofunctional components. For example, a genetically engineered Link module (LinkCFQ) can be used to crosslink hyaluronan and gelatin, creating an ECM-inspired hydrogel with high biocompatibility and degradability [7].

Tuning Structural and Mechanical Properties

The physical parameters of a hydrogel are critical determinants of stem cell fate.

- Mechanical Properties: Hydrogel stiffness is a primary regulator of mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) differentiation. Softer hydrogels (1–10 kPa) promote neurogenic and adipogenic lineages, while stiffer matrices (25–40 kPa) favor osteogenic commitment [3]. Furthermore, the viscoelasticity (the ability to dissipate energy, like native tissues) of hydrogels has been shown to significantly impact cell spreading and proliferation [1] [5].

- Structural Properties: Parameters like polymer molecular weight, concentration, and crosslinking density determine the hydrogel's pore size and fiber architecture [1]. This microstructure governs the diffusion of nutrients and oxygen, as well as the migration of cells within the 3D construct [3].

Table 2: Targeting Mechanical Properties for Stem Cell Differentiation

| Target Cell Fate | Optimal Hydrogel Stiffness | Key ECM Components to Mimic |

|---|---|---|

| Adipogenic / Neurogenic | 1 - 10 kPa | Soft adipose tissue / brain ECM [3] |

| Musculoskeletal | 25 - 40 kPa | Stiffer collagenous matrix of bone [3] |

| Cartilaginous | Variable (Viscoelastic) | Collagen II, Hyaluronic Acid networks [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Fabrication and Characterization of a Biofunctionalized PEG-Based Hydrogel

This protocol details the creation of a synthetic hydrogel functionalized with RGD peptides to support MSC encapsulation.

Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Essential Materials for PEG-RGD Hydrogel Formation

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| 4-Arm PEG-Acrylate (PEG-AC) | Synthetic polymer backbone that forms the hydrogel network via crosslinking. |

| RGD-Adhesive Peptide (e.g., GCGYGRGDSPG) | Contains the integrin-binding RGD sequence and a cysteine residue for covalent conjugation. |

| Protease-Degradable Crosslinker (e.g., KCGPQG↓IWGQCK) | Forms degradable bonds within the hydrogel, allowing cell-mediated remodeling. |

| Triethanolamine (TEA) Buffer, pH 8 | Creates a basic environment for the Michael-type addition reaction. |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Primary cells to be encapsulated and studied. |

Part A: Conjugation of RGD Peptide to PEG-AC

- Prepare Reaction Mixture: Dissolve 4-arm PEG-AC (100 mg) in 1 mL of 0.1 M TEA buffer, pH 8.

- Add Peptide: Add a molar excess of the cysteine-terminated RGD peptide (e.g., 1.2x molar ratio per acrylate group) to the PEG solution.

- React: Allow the reaction to proceed for 2 hours at room temperature under gentle agitation, protected from light.

- Purify: Dialyze the resulting PEG-RGD macromer against deionized water for 48 hours to remove unreacted peptide. Lyophilize and store at -20°C.

Part B: Encapsulation of MSCs and Hydrogel Formation

- Prepare Precursor Solution: Dissolve the purified PEG-RGD macromer and the protease-degradable crosslinker in a cell-compatible buffer (e.g., PBS). Sterilize the solution by passing it through a 0.22 µm filter.

- Cell Suspension: Trypsinize, count, and centrifuge the MSCs. Resuspend the cell pellet in a small volume of culture medium to create a concentrated cell suspension.

- Mixing: Gently mix the cell suspension with the sterile hydrogel precursor solution to achieve a final density of 5-10 million cells/mL.

- Gelation: Pipet the cell-polymer mixture into the desired mold (e.g., a silicone mold or multi-well plate). Incubate at 37°C for 20-45 minutes to allow for complete crosslinking and hydrogel formation.

- Culture: After gelation, carefully add culture medium to cover the hydrogel and place the construct in a cell culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂).

Characterization Workflow:

- Mechanical Testing: Use a rheometer to measure the storage (G') and loss (G'') moduli of the hydrogel to confirm its stiffness and viscoelastic properties.

- Cell Viability Assay: At 24 hours post-encapsulation, assess cell viability using a Live/Dead assay kit following the manufacturer's instructions.

Protocol 2: Forming and Assessing a Human Tissue-Derived ECM Hydrogel

This protocol utilizes decellularized ECM from human tissues to create a biologically complex scaffold [6].

Part A: Preparation of ECM Hydrogel from Decellularized Powder

- Source ECM: Obtain decellularized ECM powder from a certified supplier (e.g., human skin, bone, fat, or birth tissue) [6].

- Digest: Suspend the ECM powder at a concentration of 10-30 mg/mL in a pepsin solution (0.1 M HCl) and stir for 48-72 hours at 4°C until the solution becomes viscous and homogeneous.

- Neutralize: Neutralize the digest with 0.1 M NaOH and add a 10x concentrated PBS solution and culture medium to achieve physiological pH and salt concentration. Keep the neutralized ECM solution on ice to prevent premature gelation.

Part B: Gelation Kinetics and Stability Analysis

- Gelation Time: Transfer the neutralized ECM solution to a pre-chilled rheometer plate and initiate a time sweep at 37°C. The gelation point (tgel) is defined as the time when the storage modulus (G') crosses over and exceeds the loss modulus (G'') [6].

- Compressive Modulus: Form cylindrical ECM hydrogels and allow them to set at 37°C. Using a universal testing machine, perform unconfined compression tests on the hydrated gels at a constant strain rate. Calculate the compressive modulus from the linear region of the resulting stress-strain curve.

- Stability Study: Weigh pre-formed ECM hydrogels (Wi), incubate them in PBS or culture medium at 37°C, and record their wet weight (Wf) over 4 weeks. Calculate the percentage of mass remaining as (Wf / Wi) * 100.

Advanced Material Platforms and Future Directions

The field is moving beyond simple homogeneous gels toward more sophisticated, functional platforms.

- ECM-Mimetic Hydrogel Nanocomposites: Incorporating nanomaterials (e.g., carbon nanotubes, gold nanoparticles) can enhance mechanical strength, introduce electrical conductivity, and create stimuli-responsiveness (e.g., to magnetic fields or light) for advanced applications in bioelectronics and 4D bioprinting [4].

- "Smart" and Shape-Memory Hydrogels: These materials can change their properties in response to physiological stimuli (e.g., pH, enzymes) or recover a pre-defined shape after injection. This is highly relevant for minimally invasive delivery of stem cells and for creating complex 3D structures in situ [3] [8].

- Decellularized ECM (dECM) Hydrogels: dECM hydrogels, derived from actual human tissues, preserve the complex, tissue-specific biochemical composition of the native ECM. Studies show that hydrogels derived from different human tissues (e.g., skin, birth) have distinct physicochemical properties and differentially support stem cell metabolic activity, underscoring the importance of selecting the appropriate tissue source for specific regenerative applications [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for ECM-Mimetic Hydrogel Research

| Category & Reagent | Key Function in Hydrogel Design |

|---|---|

| Synthetic Polymers | |

| Poly(Ethylene Glycol) (PEG) | Biologically inert "blank slate" backbone; highly tunable mechanical properties [2] [4]. |

| Poly(Acrylamide) (PAm) | Allows precise control over substrate stiffness for mechanobiology studies [2]. |

| Natural Polymers | |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | Major ECM glycosaminoglycan; promotes cell migration and proliferation [2] [7]. |

| Collagen Type I | Most abundant ECM protein; offers innate bioactivity and self-assembling properties [1] [6]. |

| Functionalization Agents | |

| RGD Peptide | Critical integrin-binding ligand for enabling cell adhesion to synthetic hydrogels [2] [4]. |

| Heparin | Glycosaminoglycan mimetic; binds and sequesters growth factors for localized delivery [3] [2]. |

| Crosslinking Enzymes | |

| Microbial Transglutaminase (MTG) | Catalyzes stable isopeptide bonds between proteins; used in biofabrication [7]. |

| Advanced Materials | |

| Decellularized ECM (dECM) | Provides a tissue-specific complex mixture of native ECM proteins and factors [6]. |

| Self-Assembling Peptides (e.g., RADA16) | Form nanofibrous structures mimicking native ECM architecture [5]. |

Hydrogels, three-dimensional (3D) cross-linked polymer networks capable of absorbing and retaining large amounts of water, have emerged as fundamental biomaterials in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering [9] [10]. Their high water content, biocompatibility, and tunable physical and chemical properties make them exceptionally suitable for creating supportive microenvironments for stem cell delivery and tissue regeneration [3]. Based on their origin, hydrogel polymers are broadly classified into natural, synthetic, and hybrid categories, each offering distinct advantages and limitations for designing stem cell delivery scaffolds [9] [11]. Natural polymers provide inherent bioactivity and cellular recognition, synthetic polymers offer mechanical robustness and high tunability, while hybrid systems aim to synergistically combine the benefits of both [9]. The selection of the core material class directly influences critical scaffold properties such as mechanical strength, degradation kinetics, and bioactivity, thereby dictating the success of the stem cell therapy by modulating cell viability, retention, and function post-transplantation [3].

Core Material Classes: Properties and Characteristics

The distinct properties of natural, synthetic, and hybrid hydrogels determine their specific applicability in stem cell delivery. The table below provides a comparative summary of these core material classes.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Natural, Synthetic, and Hybrid Hydrogel Polymers for Stem Cell Delivery

| Feature | Natural Polymer Hydrogels | Synthetic Polymer Hydrogels | Hybrid (Natural/Synthetic) Hydrogels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Example Polymers | Alginate, Chitosan, Gelatin Methacrylate (GelMA), Hyaluronic Acid, Collagen [9] [11] [10] | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA), Polyacrylamide (PAAm) [9] [10] | PVA/Sodium Alginate, PEG-graft-Chitosan, Alginate-CMC-GelMA composites [9] [12] [10] |

| Key Advantages | High biocompatibility, inherent biodegradability, presence of cell-adhesive motifs (e.g., RGD), intrinsic bioactivity [9] [11] | Excellent mechanical strength, high durability, slow degradation rate, highly tunable properties (e.g., stiffness, degradation) [9] [3] | Combines biocompatibility of natural polymers with mechanical strength and tunability of synthetic polymers; enables advanced properties like self-healing and conductivity [9] |

| Key Limitations | Poor mechanical properties, high batch-to-batch variability, rapid and unpredictable degradation rates [9] [11] | Lack of intrinsic bioactivity, potential for inflammatory responses due to degradation by-products, limited cell-interactive functions [9] [11] | Increased complexity in synthesis and characterization; optimization of component interactions is challenging [9] |

| Stem Cell Function Influence | Support high cell viability and direct stem cell fate through native biochemical cues [3] [13]. | Provide controlled mechanical cues (e.g., matrix stiffness) to guide stem cell differentiation [3]. | Allows for simultaneous tuning of biochemical and mechanical signals to precisely modulate stem cell behavior [9] [3]. |

Application Notes in Stem Cell Delivery and Tissue Engineering

The application of these material classes is exemplified in specific tissue engineering contexts, demonstrating their critical role in advancing regenerative medicine.

Mesenchymal Stromal Cell (MSC) Delivery for Musculoskeletal Repair: Hydrogel-based delivery systems are a promising strategy to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs [3]. Bioactive natural polymers like chitosan and hyaluronic acid mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM), supporting MSC viability and paracrine signaling. Furthermore, the mechanical properties of hydrogels can be tuned to guide MSC differentiation; for instance, stiffer matrices (25–40 kPa) promote osteogenic commitment, which is crucial for bone tissue engineering [3].

3D Bioprinting of Stem Cell-Laden Constructs: In extrusion-based 3D bioprinting, bioinks must balance printability, stability, and biocompatibility [12]. Hybrid hydrogel systems are particularly advantageous. A notable example is a composite bioink of Alginate, Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC), and GelMA, which leverages a dual-crosslinking mechanism (ionic with CaCl₂ for Alginate and covalent with UV for GelMA) to achieve excellent printability and long-term mechanical stability, supporting enhanced cell proliferation for gradient tissue regeneration [12].

Neural Stem/Progenitor Cell (NSPC) Delivery for Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): Biomaterial scaffolds like hydrogels are essential for repairing the complex microenvironment of TBI [14]. Chitosan-based hydrogels, known for their non-toxicity, biodegradability, and biocompatibility, can be used to deliver NSPCs or bioactive molecules to the injury site. They provide structural support, modulate local inflammation, and guide axonal regeneration, thereby enhancing the potential for functional recovery [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Formulation and Evaluation of a Hybrid Hydrogel Bioink

This protocol details the synthesis and characterization of a tri-component hybrid bioink (Alginate-CMC-GelMA) for extrusion-based bioprinting of stem cell-laden constructs, based on established methodologies [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Hybrid Bioink Formulation

| Item Name | Function / Role in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Sodium Alginate (Alg) | Natural polysaccharide polymer; provides shear-thinning behavior and enables ionic cross-linking for structural integrity [12]. |

| Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC) | Natural polymer derivative; enhances viscosity and improves the rheological properties and printability of the bioink [12]. |

| Gelatin Methacrylate (GelMA) | Photo-crosslinkable natural polymer; provides thermoresponsive behavior and cell-adhesive RGD motifs, supporting long-term stability and biocompatibility [12]. |

| Photoinitiator (e.g., LAP) | Initiates radical polymerization upon UV light exposure, leading to covalent cross-linking of the GelMA network [12]. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) Solution | Ionic cross-linker for alginate chains; enables rapid initial stabilization of the printed structure [12]. |

| Primary Cells (e.g., MSCs) | The biological payload; encapsulated within the bioink to create living tissue constructs [3] [12]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Part A: Polymer Solution Preparation

- Prepare Alginate and CMC Solution: Dissolve 4g of sodium alginate and 10g of carboxymethyl cellulose in 100mL of sterile, cell-culture grade phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Stir continuously at room temperature until the polymers are fully dissolved and a homogeneous, viscous solution is formed.

- Prepare GelMA Solution: Separately, dissolve GelMA at the desired concentration (e.g., 8%, 12%, or 16% w/v) in PBS at 37°C. Add a photoinitiator (e.g., 0.25% w/v Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate - LAP) and ensure it is completely dissolved while protecting the solution from light.

- Formulate Hybrid Bioink: Combine the Alginate-CMC solution with the GelMA solution in a 1:1 volume ratio. Mix them thoroughly but gently at a temperature above the gelation point of Gelatin (e.g., 37°C) to avoid premature setting. The final formulation is designated as 4% Alg–10% CMC–GelMA.

Part B: Rheological and Printability Assessment

- Rheological Testing: Perform rotational and oscillatory rheometry on the bioink.

- Flow Sweep Test: Measure viscosity over a shear rate range (e.g., 0.1 to 100 s⁻¹) to confirm shear-thinning behavior, which is essential for extrudability.

- Amplitude Sweep Test: Determine the linear viscoelastic region (LVE) and yield stress, which correlates to the minimum extrusion pressure required.

- Temperature Ramp Test: Monitor storage (G′) and loss (G″) moduli while cooling from 37°C to 15°C to characterize thermoresponsive gelation.

- Thixotropy Test: Apply alternating low and high shear strains to assess the bioink's self-recovery capability after extrusion.

- Printability Evaluation: Load the bioink into a sterile cartridge and perform extrusion printing using a calibrated bioprinter. Assess printability by quantifying the fiber diameter, filament uniformity, and ability to form stable 3D structures (e.g., a grid). A dimensionless printability value (Pr) can be calculated from these parameters.

Part C: Cell Encapsulation, Bioprinting, and Post-Printing Analysis

- Cell Mixing: Gently mix a suspension of MSCs with the prepared hybrid bioink at a temperature of 37°C to achieve a final desired cell density (e.g., 1-10 million cells/mL). Avoid introducing air bubbles.

- Extrusion Bioprinting: Print the cell-laden bioink under sterile conditions using optimized parameters (e.g., nozzle diameter, pressure, print speed, and bed temperature of 15°C).

- Dual Cross-Linking:

- Ionic Cross-linking: Immediately after deposition, mist the printed construct with a sterile 100-200 mM CaCl₂ solution.

- Photo-Cross-linking: Following ionic stabilization, expose the entire construct to UV light (e.g., 365 nm wavelength) for a determined time (e.g., 30-60 seconds) to cross-link the GelMA network.

- Post-Printing Culture and Evaluation:

- Transfer the cross-linked constructs to cell culture media.

- Mechanical Stability Test: Perform an oscillatory time sweep test over 21 days to monitor the evolution of the storage modulus (G′) and assess long-term stability.

- Biocompatibility Assay: At predetermined time points (e.g., days 1, 7, 14), assess cell viability using a Live/Dead assay and quantify metabolic activity using an AlamarBlue or MTS assay.

Diagram 1: Hybrid bioink workflow from formulation to analysis.

Pathway and Decision Logic for Material Selection

The selection of an appropriate hydrogel class for a specific stem cell delivery application is guided by the key functional requirements of the target tissue. The following decision logic outlines this process.

Diagram 2: Decision logic for hydrogel class selection.

The field of stem cell research is undergoing a paradigm shift, moving beyond a purely biochemical perspective to embrace the critical role of physical cues in directing cell fate. The mechanical properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM)—particularly stiffness and elasticity—are now recognized as powerful directives that govern stem cell behavior, including differentiation, proliferation, and morphogenesis [15] [16]. This application note details how researchers can harness these mechanical cues within hydrogel-based scaffold systems to precisely control stem cell fate for regenerative medicine and drug development applications. The fundamental principle underlying this approach is mechanotransduction, the process by which cells convert mechanical stimuli from their environment into biochemical signals [17] [16]. When stem cells adhere to a substrate, they exert contractile forces through their cytoskeleton. The resistance they encounter, determined by the substrate's stiffness, triggers intracellular signaling cascades that ultimately lead to specific transcriptional programs and lineage commitment [17]. By engineering hydrogels with tunable mechanical properties, we can therefore create artificial niches that guide stem cells toward desired phenotypes without relying exclusively on soluble factors.

Core Concepts: Stiffness as a Fate Determinant

The Stiffness-Differentiation Relationship

A foundational discovery in mechanobiology is that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) sense matrix stiffness and differentiate accordingly. The following table summarizes the well-established relationship between substrate stiffness and lineage specification for MSCs.

Table 1: Matrix Stiffness as a Determinant of MSC Differentiation Lineage

| Target Tissue | Approximate Stiffness Range | Primary Differentiation Outcome | Key Regulatory Pathways/Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Tissue | 0.1 - 1 kPa [17] | Neurogenic differentiation [17] | Not Specified |

| Muscle Tissue | 8 - 17 kPa [17] | Myogenic differentiation [17] | Not Specified |

| Adipose Tissue | ~2 - 10 kPa [18] | Adipogenic differentiation [18] | Low YAP/TAZ activity [18] |

| Bone Tissue | >34 kPa [17] | Osteogenic differentiation [17] [18] | High YAP/TAZ activity [18] |

This relationship is not merely a passive response but is governed by sophisticated mechanotransduction pathways. Yes-associated protein (YAP) and its transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) are key nuclear effectors. On stiff matrices, YAP/TAZ translocate to the nucleus to promote the expression of osteogenic genes, whereas on soft matrices, they remain cytoplasmic, permitting adipogenesis [18]. Inhibition of YAP has been shown to significantly downregulate osteogenic markers even in stiff 3D-bioprinted constructs, confirming its central role [18].

Key Mechanotransduction Pathways

The journey from a mechanical cue to a change in cell fate involves a well-defined signaling cascade. The following diagram illustrates the core mechanotransduction pathway initiated by hydrogel stiffness.

Diagram 1: Core mechanotransduction pathway from matrix stiffness to cell fate (based on [17] [16] [18])

Advanced Material Systems and Protocols

Protocol: Fabricating Stiffness-Tuned Alginate-Gelatin (Alg-Gel) Hydrogels for 3D Bioprinting

This protocol describes the synthesis of Alg-Gel composite hydrogels with decoupled stiffness and porosity for 3D bioprinting applications, adapted from a 2020 study [18].

Objective: To create 3D-bioprinted hydrogel constructs with defined stiffness to study MSC differentiation in a controlled microenvironment.

Materials:

- Sodium Alginate (120–190 kDa, 39% guluronic acid)

- Gelatin (Type B, 40–100 kDa)

- Ultrapure Water

- Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) Solution (2.5% w/v for crosslinking)

- Mouse MSCs (e.g., isolated from C57BL/6 mice)

- MesenCult Expansion Medium

- Osteogenic/Adipogenic (O/A) Induction Medium (for differentiation assays)

- 3D Bioprinter with temperature-controlled printhead and crosslinking system

Procedure:

- Hydrogel Preparation:

- Prepare Alg-Gel precursor solutions according to Table 2 to achieve different stiffness levels. For example, to make the "1A3G" formulation, dissolve 1g of sodium alginate and 3g of gelatin in 100 mL of ultrapure water.

- Stir the mixture in a sealed container at 60°C for 12 hours until fully dissolved.

- Sterilize the solution by pasteurization or filtration.

- Store the sterile Alg-Gel bioink at 4°C until use.

Cell Harvesting and Encapsulation:

- Culture and expand MSCs in MesenCult Expansion Medium.

- Trypsinize MSCs at ~80% confluence and resuspend in the sterile, cold Alg-Gel bioink to a final density of 5-10 × 10^6 cells/mL. Maintain the bioink-cell suspension on ice to prevent premature gelation.

3D Bioprinting and Crosslinking:

- Load the cell-laden bioink into a temperature-controlled printhead cartridge (maintained at ~18-22°C).

- Print the constructs into a desired 3D architecture (e.g., a grid structure) directly into a bath of 2.5% CaCl₂ solution.

- Allow the printed constructs to crosslink in the CaCl₂ bath for 10-15 minutes to ensure ionic gelation of the alginate.

Post-Printing Culture and Differentiation:

- Carefully transfer the crosslinked constructs to cell culture plates.

- Culture the constructs in either standard growth medium (DMEM) or O/A Induction Medium. Refresh the medium every 2-3 days.

- The constructs can be cultured for up to 21 days for differentiation analysis.

Validation and Analysis:

- Mechanical Testing: Confirm the Young's modulus of each hydrogel formulation using a compression test, selecting the first 10% of the stress-strain curve for calculation [18].

- Viability: Assess cell viability at 24 and 72 hours post-printing using Live/Dead staining. Viability should exceed 95% [19].

- Differentiation Assay: After 14-21 days, fix constructs and co-stain for alkaline phosphatase (ALP, osteogenic marker) and Oil Red O (lipid droplets, adipogenic marker). Perform qPCR to analyze gene expression of ALP and LPL (lipoprotein lipase) as early as day 3 [18].

- Pathway Inhibition: To confirm the role of YAP/TAZ, treat a set of constructs with a YAP inhibitor (e.g., Verteporfin) and observe the downregulation of differentiation markers [18].

Innovative System: Shell-Hardened Macroporous Hydrogels for Bone Regeneration

For challenging applications like bone regeneration, where mechanical integrity must be maintained during degradation, advanced hydrogel designs are required. A 2025 study introduced a macroporous hydrogel with spatiotemporally programmed mechanical properties [19].

Design Principle: A soft-templating technique using liquid-liquid phase separation between polyethylene glycol (PEG) and dextran creates a macroporous structure. Preassembled, acryl-modified lysozyme nanofibers self-assemble at the liquid-liquid interface, forming a rigid, protein-fiber-coated shell around each pore [19].

Experimental Workflow:

- Phase Separation: Create a phase-separated mixture of PEG and dextran in water. The dextran phase forms non-percolating droplets that act as soft templates for macropores.

- Interfacial Self-Assembly: Add acryl-modified lysozyme nanofibers to the system. The fibers migrate to and stabilize the PEG-dextran interface.

- Copolymerization: Incorporate polymerizable monomers (e.g., acrylamide), degradable and non-degradable PEG crosslinkers (PEG-ACLT and PEG-ACA), and an acrylated RGD peptide into the PEG phase.

- Gelation and Encapsulation: Initiate free-radical polymerization under blue light (405 nm) with a photoinitiator (Lap) to form the final hydrogel. Encapsulate stem cells by adding their suspension to the dextran phase prior to polymerization [19].

Key Advantages:

- The macroporous structure (pores ~50 μm) prevents contact inhibition during cell proliferation.

- The rigid pore shell provides sustained mechanical cues for osteodifferentiation, protecting cells from mechanical loads even as the softer hydrogel matrix degrades.

- Tunable degradation is achieved by adjusting the ratio of degradable to non-degradable PEG crosslinkers, potentially synchronizing with new tissue deposition.

- This system has demonstrated efficacy in bone regeneration in both rabbit and porcine models [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mechanobiology Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Polyacrylamide (PAA) | Synthetic hydrogel for 2D and 3D culture with widely tunable stiffness (2 Pa - 55 kPa) [20]. | Fundamental studies on stiffness-mediated fate decisions [21] [17]. |

| Alginate-Gelatin (Alg-Gel) | Composite bioink for 3D bioprinting; stiffness tuned via concentration and ionic crosslinking [18]. | 3D-bioprinted constructs for studying MSC differentiation in a controlled porosity environment [18]. |

| PEG-based Crosslinkers | (e.g., PEG-ACLT (degradable) and PEG-ACA (non-degradable)): Create hydrogel networks with programmable mechanics and degradation [19]. | Fabricating hydrogels with spatiotemporally controlled mechanical properties [19]. |

| Acrylated RGD Peptide | Synthetic peptide grafted into hydrogels to facilitate integrin-mediated cell adhesion [19]. | Providing essential biochemical adhesion cues in synthetic hydrogels that lack natural cell-binding domains [19]. |

| YAP/TAZ Inhibitor | (e.g., Verteporfin): Pharmacological inhibitor to probe the role of the YAP/TAZ pathway in mechanotransduction. | Validating the necessity of YAP/TAZ signaling in stiffness-directed differentiation [18]. |

The precise engineering of hydrogel stiffness and architecture provides a powerful, non-biological method for directing stem cell fate. The protocols and material systems outlined here—from straightforward stiffness-tuned Alg-Gel bioinks for 3D bioprinting to sophisticated shell-hardened macroporous hydrogels—offer researchers a toolkit to recreate critical aspects of the native stem cell niche. As the field progresses, the integration of other mechanical properties like viscoelasticity [17] [20] and the use of piezoelectric materials to provide endogenous electrical stimulation in response to mechanical loading [22] will further enhance the complexity and fidelity of these artificial microenvironments. By mastering these mechanical directives, scientists and drug developers can advance the development of more effective and predictive in vitro models and accelerate the translation of stem cell-based therapies for regenerative medicine.

Within the field of regenerative medicine, the efficacy of stem cell-based therapies is profoundly influenced by the design of the delivery scaffold. A critical triad of architectural properties—porosity, topography, and nutrient diffusion—dictates the success of these constructs by directly modulating key cellular processes, including viability, adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [23] [24]. This Application Note delineates the quantitative relationships between these scaffold parameters and stem cell behavior, providing validated experimental protocols to guide the development of advanced hydrogel-based delivery systems for research and therapeutic applications.

Background and Significance

Stem cell-laden hydrogels function as synthetic extracellular matrices (ECMs), providing a three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment that instructs cellular fate. The architecture of this microenvironment is not a passive backdrop but an active instructor of cell behavior [3] [25]. Porosity and pore interconnectivity are fundamental for the diffusion of nutrients and oxygen, as well as the removal of metabolic waste, which are essential for maintaining cell viability throughout the scaffold volume [23] [24]. Simultaneously, the topographical orientation of scaffold fibers—whether random or aligned—provides "contact guidance" cues that direct cell morphology, migration, and tissue-specific organization [26]. Mastering the interplay of these properties is therefore crucial for creating scaffolds that not only support stem cell survival but also guide functional tissue regeneration.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Influence of Pore Architecture on Cellular Processes

The following table summarizes the effects of specific pore architectural parameters on stem cell behavior and scaffold functionality, as established in current literature.

Table 1: Influence of Scaffold Pore Architecture on Stem Cell Behavior and Scaffold Function

| Architectural Parameter | Targeted Tissues & Cell Behaviors | Impact on Scaffold Function & Cellular Response |

|---|---|---|

| Pore Size [23] | • Bone: 300-600 µm• Cartilage: 100-200 µm• Skin & General Tissue: 50-150 µm | • Regulates cell infiltration, migration, and spatial organization.• Larger pores enhance vascularization; specific sizes can promote lineage commitment. |

| High Interconnectivity [23] [24] | • All tissues, especially thick constructs. | • Ensures efficient nutrient/waste exchange, preventing necrotic cores.• Enables uniform cell distribution and colony formation. |

| Aligned Topography [26] | • Neural, Muscular, Tendon/Ligament (Anisotropic tissues). | • Provides "contact guidance" for directional cell growth and matrix deposition.• Enhances mechanical strength in the direction of alignment. |

Hydrogel Composition and Resulting Physicochemical Properties

The properties of a hydrogel scaffold are directly determined by its composition and crosslinking method. The table below compares common hydrogel systems used in stem cell delivery.

Table 2: Comparison of Hydrogel Systems for Stem Cell Delivery

| Hydrogel System | Gelation Mechanism | Key Advantages | Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharide-Based (e.g., Chitosan, Alginate) [27] [28] | Ionic (e.g., Ca²⁺), Schiff base, Physical crosslinking. | Excellent biocompatibility; biodegradable; tunable mechanical properties. | Batch-to-batch variability (natural sources); limited bioactivity without modification. |

| Synthetic (e.g., PEG derivatives) [29] [25] | Chemical crosslinking (e.g., photo-polymerization). | High reproducibility; precise control over mechanical properties. | Often lacks intrinsic bioactivity; requires functionalization (e.g., with RGD peptides). |

| Hybrid/Composite [3] [25] | Combination of multiple mechanisms. | Couples bioactivity of natural polymers with tunable mechanics of synthetic polymers. | Optimization of multiple components can be complex. |

| Stimuli-Responsive "Smart" Hydrogels [3] [25] | pH, temperature, enzymatic activity. | Enables controlled release of cells/bioactive factors in response to local physiological cues. | Requires careful design to match the specific stimuli at the target site. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of Aligned Fibrous Scaffolds via Electrospinning

Principle: A high-voltage electrostatic field is applied to a polymer solution to generate a charged jet, which is collected on a rotating mandrel. The speed of the mandrel determines the degree of fiber alignment [26].

Materials:

- Polymer (e.g., PCL, PLGA, or a blended natural/synthetic polymer)

- Suitable solvent (e.g., chloroform, DMF)

- Electrospinning apparatus (syringe pump, high-voltage power supply, collector)

- Rotating mandrel collector

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve the polymer in the appropriate solvent at a concentration of 5-15% (w/v). Stir until a homogeneous solution is achieved.

- Apparatus Setup: Load the solution into a syringe. Set the flow rate to 0.5-2.0 mL/h. Set the tip-to-collector distance to 10-20 cm. Connect the high-voltage power supply (10-20 kV).

- Fiber Collection: For aligned fibers, set the rotating mandrel speed to a high velocity (≥1300 rpm or ≥3.0 m/s) [26]. For random fibers, use a stationary or slowly rotating (∼300 rpm) flat collector.

- Post-processing: Dry the collected fibrous scaffolds under vacuum for 24 hours to remove residual solvent.

Validation:

- Characterization: Use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to confirm fiber morphology and alignment. Analyze SEM images with software (e.g., ImageJ) to determine average fiber diameter and orientation distribution.

Protocol: Fabrication of Porous Hydrogels via Particulate Leaching

Principle: A sacrificial porogen (e.g., salt crystals) of a defined size is mixed with a polymer solution. After the polymer solidifies, the porogen is dissolved, leaving behind a porous network [23].

Materials:

- Hydrogel precursor (e.g., methacrylated alginate, gelatin, or PEG)

- Salt crystals (NaCl) sieved to specific size ranges (e.g., 150-250 µm, 250-425 µm)

- Crosslinking initiator (e.g., photo-initiator Irgacure 2959 for UV crosslinking)

- Deionized water

Procedure:

- Porogen Mixing: Mix the sieved salt particles with the hydrogel precursor solution at a predetermined weight ratio (e.g., 70-90% porogen) to achieve the desired porosity.

- Crosslinking: Transfer the mixture into a mold. For photopolymerizable hydrogels, expose to UV light (λ = 365 nm, intensity = 5-10 mW/cm²) for 3-10 minutes.

- Porogen Leaching: Immerse the crosslinked hydrogel in a large volume of deionized water. Change the water 3-5 times daily for 2-3 days to completely dissolve the salt.

- Hydration & Storage: Rinse the porous hydrogel with PBS and store at 4°C until use.

Validation:

- Characterization: Use SEM to visualize pore size, morphology, and interconnectivity. Measure the equilibrium swelling ratio to assess porosity.

Protocol: Evaluating Nutrient Diffusion and Cell Viability in 3D Constructs

Principle: This protocol assesses the functional outcome of scaffold porosity by monitoring the diffusion of a fluorescent glucose analog (2-NBDG) and quantifying live/dead cell distribution throughout the scaffold.

Materials:

- Cell-laden porous scaffold

- Fluorescent glucose analog (2-NBDG)

- Live/Dead viability/cytotoxicity kit (e.g., Calcein AM / Propidium Iodide)

- Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM)

- Image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, Imaris)

Procedure:

- Scaffold Seeding: Encapsulate human adipose-derived stem cells (hADSCs) or other relevant stem cells within the hydrogel at a density of 1-5 million cells/mL during the fabrication process [27].

- Culture: Maintain the cell-laden constructs in standard culture conditions for the duration of the experiment.

- Diffusion Assay: At the desired time point (e.g., day 1, 3, 7), incubate scaffolds in culture medium containing 2-NBDG (e.g., 100 µM) for 1-2 hours.

- Viability Staining: Rinse scaffolds with PBS and incubate with Calcein AM (2 µM) and Propidium Iodide (4 µM) in PBS for 30-45 minutes.

- Imaging: Image the entire scaffold thickness using CLSM. Acquire Z-stacks from the top to the bottom of the scaffold.

Analysis:

- Diffusion Profile: Plot the fluorescence intensity of 2-NBDG as a function of scaffold depth. A uniform profile indicates effective diffusion.

- Viability Quantification: Calculate the percentage of live cells (Calcein AM positive) and dead cells (Propidium Iodide positive) in multiple regions, including the core of the scaffold. High core viability (>80%) indicates sufficient nutrient diffusion [27].

Signaling Pathways and Conceptual Workflows

Scaffold Architecture to Cell Fate Signaling Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the mechanotransduction signaling pathway through which architectural cues from the scaffold are converted into biochemical signals that direct stem cell fate.

Diagram Title: Scaffold Architecture to Cell Fate Signaling Pathway

Integrated Experimental Workflow for Scaffold Evaluation

This workflow outlines the key steps for designing, fabricating, and characterizing a stem cell-laden hydrogel scaffold.

Diagram Title: Integrated Scaffold Evaluation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Hydrogel-Based Stem Cell Research

| Category / Item | Function / Application | Example Formulations / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Provide biocompatibility and bioactivity; mimic the native ECM. | Hyaluronic Acid (HA): Major ECM component; can be modified (e.g., Ald-HA) for crosslinking [27].Chitosan/Na-Alginate: Forms gentle ionic-crosslinked gels; versatile for cell encapsulation [27] [28]. |

| Synthetic Polymers | Offer precise control over mechanical and chemical properties. | Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG): "Gold standard" for highly tunable, bio-inert hydrogels; requires functionalization with adhesion peptides (e.g., RGD) [29] [25]. |

| Crosslinkers & Initiators | Enable hydrogel formation and control gelation kinetics. | Photo-initiators (Irgacure 2959): For UV-induced gelation of methacrylated polymers.Divalent Cations (CaCl₂): For ionic crosslinking of alginate.Oxidizing Agents (NaIO₄): To create aldehyde groups on polysaccharides for Schiff base crosslinking [27] [28]. |

| Bioactive Additives | Enhance biological function and guide stem cell fate. | RGD Peptide: Promotes integrin-mediated cell adhesion.Growth Factors (BMP-2, VEGF): Can be encapsulated to direct osteogenesis or vascularization [3] [25]. |

| Characterization Tools | Assess scaffold physical properties and biological response. | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): For pore size, morphology, and fiber diameter.Rheometer: For measuring storage (G') and loss (G") moduli.Confocal Microscopy: For 3D cell viability, distribution, and differentiation analysis. |

The transition from traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell culture to three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment modeling represents a fundamental paradigm shift in regenerative medicine and stem cell research. While 2D cultures on plastic surfaces have been the standard methodology for decades, they fail to recapitulate the complex architecture and signaling environments found in native tissues [30]. This limitation has profound implications for stem cell biology, particularly in the context of therapeutic applications where the microenvironment directly controls cell fate and function [31].

The native stem cell niche is a specialized, physiologically 3D microenvironment that immediately surrounds cells in living tissue, providing structural, biochemical, mechanical, and stimulatory cues necessary for appropriate functioning during homeostasis and in response to physiological change [31]. When stem cells are removed from this 3D context, they exhibit altered functionality, phenotype, and responsiveness to environmental cues, creating significant challenges for clinical translation [31]. The development of hydrogel-based delivery systems has emerged as a promising strategy to overcome these limitations by providing biomimetic 3D platforms that recapitulate key features of the native extracellular matrix (ECM), supporting cell viability, retention, and function upon transplantation [3].

Fundamental Limitations of 2D Culture Systems

Traditional 2D culture systems, while convenient and cost-effective, introduce artificial constraints that dramatically alter cellular behavior. The fundamental differences between 2D and 3D environments are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of 2D vs. 3D Cell Culture Systems

| Parameter | 2D Culture Systems | 3D Culture Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Architecture | Flat, monolayer growth with unnatural polarization | Physiologically relevant 3D organization with natural cell-cell interactions |

| Cell Morphology | Forced spreading and flattening | Natural, unconstrained shape and volume |

| Nutrient/Gas Exchange | Direct, uniform access | Gradient-dependent, mimicking in vivo conditions |

| Mechanical Cues | Rigid, non-compliant substrates | Tunable stiffness matching native tissues |

| Gene Expression Profiles | Altered, non-physiological patterns | In vivo-like expression patterns |

| Drug Response | Often inaccurate prediction of efficacy | Clinically relevant drug sensitivity |

| Stem Cell Differentiation | Directed primarily by soluble factors only | Integrated cues from matrix, mechanics, and topology |

Cells cultured in 2D systems lack the complex architectural context found in living tissues, leading to altered morphology, polarity, and signaling pathways [30]. This artificial environment generates data with limited predictive value for in vivo responses, particularly regarding drug efficacy and stem cell differentiation potential [30]. The forced polarization of cells on 2D substrates creates an unnatural mechanical environment that strongly influences cytoskeletal organization and mechanotransduction pathways, which cannot be decoupled from other experimental parameters [32].

Perhaps most critically for stem cell research, 2D culture environments fail to support the balanced differentiation and self-renewal behavior characteristic of native stem cell niches. The spatial positioning, cell-ECM interactions, and mechanical cues that collectively regulate stem cell fate in vivo are largely absent in traditional 2D systems [31].

The Critical Importance of 3D Microenvironments for Stem Cell Function

Recapitulating Native Stem Cell Niches

Three-dimensional microenvironments provide essential cues that regulate fundamental stem cell behaviors, including self-renewal, differentiation, and paracrine signaling. The 3D niche comprises multiple integrated components that collectively influence cell fate:

Diagram 1: Components of the 3D stem cell microenvironment. The integrated nature of these cues directs stem cell fate decisions.

The extracellular matrix (ECM) in 3D environments not only provides structural and organizational guidance for tissue development but also actively defines and maintains cellular phenotype and drives cell fate decisions [31]. Cells within 3D matrices are surrounded by a complex architecture of proteins, polysaccharides, and proteoglycans that undergo dynamic change through assembly, remodeling, and degradation events. Adhesion to specific ECM components via integrins, cadherins, and discoidin domain receptors activates signaling programs sensitive to the composition and orientation of the ECM [31].

The Impact of Geometry and Mechanical Cues in 3D

Advanced 3D culture systems have revealed the profound influence of geometrical and mechanical cues on stem cell behavior. In pioneering research using 3D microniches to control individual human mesenchymal stem cell volume and shape, studies demonstrated that actin filament organization, focal adhesions, nuclear shape, YAP/TAZ localization, cell contractility, and lineage selection are all sensitive to cell volume and geometry [32].

The mechanical properties of the 3D microenvironment, particularly matrix stiffness, have been shown to direct stem cell differentiation along specific lineages. For example, softer hydrogels with elastic moduli in the range of 1–10 kPa promote adipogenic or neurogenic differentiation, whereas stiffer matrices ranging from 25 to 40 kPa favor osteogenic commitment [3]. This mechanosensitivity underscores the importance of substrate stiffness in guiding stem cell fate decisions, with 3D environments providing the necessary context for these mechanical signals to be properly interpreted.

Table 2: Matrix Stiffness and Corresponding Stem Cell Differentiation Outcomes

| Matrix Stiffness Range | Primary Lineage Commitment | Representative Native Tissues |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1-1 kPa | Neural | Brain tissue, neural matter |

| 1-10 kPa | Adipogenic, Neurogenic | Adipose tissue, spinal cord |

| 10-25 kPa | Musculoskeletal | Muscle, connective tissue |

| 25-40 kPa | Osteogenic | Pre-mineralized bone, cartilage |

| >40 kPa | Highly mineralized tissues | Mature bone, calcified tissues |

Furthermore, pore architecture within 3D hydrogels significantly affects nutrient diffusion, waste elimination, and cell migration—all essential for maintaining a viable and functionally active stem cell population in situ [3]. Complementing these internal features, hydrogel surface geometry—including roughness, curvature, and micro- or nano-topography—plays a critical role in modulating stem cell adhesion, proliferation, and lineage commitment [3].

Hydrogel-Based 3D Microenvironments for Stem Cell Delivery

Hydrogels as Biomimetic Platforms

Hydrogels have emerged as ideal platforms for creating 3D microenvironments for stem cell delivery due to their unique properties that closely mimic the physical and biochemical characteristics of native ECM. These water-swollen, crosslinked polymer networks provide biocompatibility, tunable mechanical strength, and the ability to encapsulate and release cells or bioactive molecules [3]. The combination of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) and hydrogels has gained considerable attention in regenerative medicine, offering a synergistic approach to enhance tissue regeneration [3].

Injectable hydrogels, including those based on natural polymers such as alginate, collagen, gelatin, or hyaluronic acid, enable minimally invasive administration, in situ gelation, and conformation to irregular defect geometries. This ensures precise stem cell localization, retention, and protection within injured tissues [3]. Synthetic variants such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) offer improved mechanical tunability and reproducibility, though often at the expense of bioactivity. Composite hydrogels combining natural and synthetic components aim to leverage the advantages of both material classes [3].

Advanced Hydrogel Design Strategies

Recent advances in hydrogel design include the development of "smart" hydrogels responsive to physiological stimuli, enabling controlled release of encapsulated cells or bioactive molecules in response to local cues [3]. These dynamic hydrogels can prolong therapeutic action, support tissue remodeling, and potentially provide on-demand modulation of stem cell activity.

A promising strategy to further refine hydrogel bioactivity involves engineering matrices with controlled surface or volumetric charge to non-covalently sequester nucleic acids (microRNA, mRNA, plasmid DNA). Such gene-activated hydrogels can prolong local factor residence, protect labile cargos from degradation, and enable cell-responsive release, thereby extending and amplifying stem cell paracrine activity in vivo [3].

Hydrogels derived from decellularized ECM have also gained increasing attention as stem cell carriers. These biomaterials closely mimic the native biochemical composition and architecture of tissues, thereby providing a bioactive microenvironment that promotes cell adhesion, survival, and lineage-specific differentiation [3]. However, the intrinsic mechanical weakness and batch-to-batch variability of pure ECM hydrogels may limit their translational application, leading to the development of bio-hybrid systems combining ECM components with synthetic polymers [3].

Experimental Protocol: Establishing a Simplified 3D Collagen Hydrogel System for Stem Cell Culture

This protocol describes the establishment of a cost-effective and mechanically robust 3D collagen hydrogel system suitable for stem cell culture, enabling physiologically relevant in vitro modeling of cell-matrix interactions. The system utilizes rat tail type I collagen to form a stable 3D network that supports stem cell viability and function, providing a simplified alternative to complex bioprinting methods [33].

The fundamental principle involves the self-assembling fibrillogenesis of type I collagen under neutral pH and physiological temperature (37°C) to form an interwoven 3D network with tunable stiffness and porosity. This scaffold provides a supportive microenvironment for stem cell proliferation and differentiation while maintaining crucial biomechanical cues absent in 2D systems [33].

Diagram 2: Workflow for 3D collagen hydrogel preparation. Sequential mixing with maintained order is critical for uniform gel formation.

Materials and Reagent Preparation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 3D Collagen Hydrogel System

| Reagent/Component | Specifications | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Rat Tail Type I Collagen | 5 mg/ml concentration, sterile | Primary matrix-forming polymer providing structural foundation |

| 10x Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Sterile, isotonic | Provides physiological ionic strength for fibrillogenesis |

| 0.1 mol/L Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Sterile filtered | Neutralizes acidic collagen solution to initiate gelation |

| Complete Culture Medium | With serum and supplements | Maintains cell viability during gel formation |

| Cell Suspension | 85-95% confluency, 1.3 × 10^6 cells/ml | Cellular component for encapsulation |

| Type I Collagenase | 1 mg/ml in DMEM/F-12 | Enzymatic digestion for cell recovery from hydrogels |

| 24-Well Plates | Standard tissue culture treated | Molds for uniform gel column formation |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Component Preparation

- Pre-cool the mouse tail type I collagen solution (5 mg/ml) on ice

- Prepare cell suspension at 85-95% confluency (approximately 8 × 10^6 cells), trypsinize, and resuspend in 6 ml complete culture medium

- Ensure all reagents are sterile and at appropriate temperatures

Sequential Mixing (Critical Order)

- Add 42 μl of 10x PBS to each well of a 24-well plate

- Add 18 μl of 0.1 mol/L NaOH to each well

- Add 300 μl of mouse tail type I collagen (5 mg/ml) to each well

- Add 1 ml of cell suspension in complete medium

- Mix by pipetting up and down exactly five times

- Note: Maintain this exact order—premature addition of NaOH to acidic collagen results in uneven gel formation

Gelation and Incubation

- Transfer the 24-well plate to a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2

- Incubate for 10 minutes for complete gel formation

- Validate successful gelation by semi-transparent appearance with pale orange color and pH of 7.3–7.4

Cell Adaptation Period

- Allow cells to adapt to the 3D gel environment for 6–8 hours

- Maintain standard culture conditions during this stabilization period

Experimental Applications

- Proceed with planned experiments including viability assessment, differentiation studies, or mechanical testing

- For cell recovery: Digest gels with 1 mg/ml collagenase solution at 37°C with gentle shaking for 20 minutes

Quality Control and Validation

- Structural Integrity: The resultant gel should maintain structural stability for 24 hours during culture and remain stable for up to 4 days

- Morphological Assessment: Scanning electron microscopy should reveal a consistent nanofiber network with uniform porosity

- Cell Viability: Assess via live/dead staining; >90% viability should be maintained at 24 hours

- Mechanical Properties: The gel should resist deformation under mechanical loading up to 30 mmHg pressure

Applications in Regenerative Medicine and Disease Modeling

The implementation of 3D microenvironment systems has demonstrated significant potential across multiple regenerative medicine applications. In musculoskeletal diseases, MSC-laden hydrogels have shown enhanced therapeutic effects, with the 3D environment supporting both differentiation capacity and paracrine factor secretion [34]. For neural disorders, injectable microgel scaffolds have been developed to support neural progenitor cell transplantation and vascularization after stroke, addressing critical limitations in cell survival and integration within ischemic microenvironments [35].

In spinal cord injury treatment, hydrogels serve as both delivery systems and scaffolds, providing structural support while inhibiting the progression of secondary injury through localized delivery of bioactive factors [36]. The 3D architecture enables unidirectional growth of nerve cells while delivering therapeutic agents in situ, demonstrating how dimensional context directly influences regenerative outcomes.

The application of 3D models extends beyond regenerative medicine to disease modeling and drug discovery. Cancer research has particularly benefited from 3D culture systems that accurately mimic tumor microenvironments, providing insights into morphological and cellular changes associated with disease progression and enabling more predictive drug screening platforms [30].

The shift from 2D to 3D microenvironments represents more than a technical advancement—it constitutes a fundamental requirement for meaningful stem cell research and therapeutic development. The evidence consistently demonstrates that the dimensional context in which cells are cultured profoundly influences their behavior, gene expression, differentiation potential, and therapeutic efficacy. As regenerative medicine advances toward clinical applications, embracing the complexity of 3D microenvironments will be essential for developing truly effective stem cell-based therapies.

The continued refinement of hydrogel-based 3D culture systems, including the development of stimuli-responsive matrices, decellularized ECM platforms, and tunable synthetic hybrids, promises to further enhance our ability to mimic native stem cell niches. These advanced platforms will not only accelerate therapeutic development but also deepen our fundamental understanding of stem cell biology within its proper physiological context.

Fabrication and Translation: From 3D Bioprinting to Targeted Tissue Regeneration

Three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting has emerged as a revolutionary additive manufacturing technology for fabricating complex, cell-laden tissue constructs with the potential to address critical challenges in regenerative medicine and drug development. This technology enables the precise spatial patterning of living cells, biomaterials, and biological molecules to create tissue-like structures that mimic native extracellular matrix (ECM) environments [37]. The convergence of 3D bioprinting with stem cell research has created a powerful paradigm for producing patient-specific tissue models and regenerative scaffolds, leveraging the multi-lineage differentiation potential and self-renewal capacity of stem cells [38]. More recently, four-dimensional (4D) bioprinting has expanded these capabilities by introducing dynamic, time-dependent transformations in printed structures in response to specific stimuli, offering new avenues for creating more biologically relevant tissues [39].

This article details advanced protocols and application notes for the fabrication of stem cell-laden constructs, framed within the broader context of developing improved stem cell delivery systems. We provide a comprehensive scientific toolkit containing optimized bioink formulations, detailed procedural protocols, and standardized evaluation metrics tailored for researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of biofabrication and regenerative medicine.

Bioprinting Technology Landscape

The selection of an appropriate bioprinting technology is fundamental to project success, as each method offers distinct advantages and limitations regarding resolution, cell viability, and compatible materials. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of major bioprinting platforms:

Table 1: Comparison of Bioprinting Technologies

| Bioprinter Type | Resolution | Cell Viability | Speed | Cost | Suitable Bioink Viscosities | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrusion-Based [39] [40] | 50-1000 μm [40] | 40-90% [39] | Slow [39] | Medium [39] | 30 mPa·s to >6×10⁷ mPa·s [39] [40] | Bone, cartilage, muscle, vascular tissues [41] [37] |

| Inkjet-Based [37] [39] | High [39] | 80-95% [39] | Fast [39] | Low [39] | 3.5-12 mPa·s [39] | Skin, thin tissues, neuronal networks [37] |

| Laser-Assisted [37] [42] | High [39] | >85% [39] | Medium [39] | High [39] | 1-300 mPa·s [39] | High-precision patterning, vascular structures [37] |

| Stereolithography/DLP [43] [42] | High [39] | >85% [39] | Fast [39] | Low [39] | No limitation [39] | Complex 3D architectures, dentin, neovascular structures [44] |

Technology Selection Guidelines

Extrusion-based bioprinting remains the most widely used approach for creating dense, cell-laden constructs for tissue regeneration, particularly advantageous for printing high-viscosity bioinks and high cell densities [40] [42]. Its versatility makes it suitable for fabricating constructs for skeletal and locomotor systems such as bone, cartilage, and skeletal muscle [41]. Inkjet bioprinting offers superior cell viability and speed but is limited to low-viscosity bioinks, making it ideal for thin tissues and precise cellular patterning [37] [39]. Laser-assisted bioprinting provides nozzle-free operation and excellent viability but at higher equipment costs [42]. Digital Light Processing (DLP) technologies, including stereolithography, enable high-resolution fabrication of complex structures through photopolymerization, with recent advances demonstrating the creation of stem cell spheroids within hydrogel constructs [44] [42].

Bioink Design and Formulation

Bioinks represent the cornerstone of successful bioprinting, requiring careful balancing of mechanical, structural, and biological properties to support both printability and cell functionality. The concept of the "biofabrication window" describes the compromise between printability and cell viability that must be optimized for each application [40].

Essential Bioink Properties

Ideal bioinks must possess several key characteristics: Shear-thinning behavior to reduce viscosity under extrusion stress and protect cells during printing; Yield stress to prevent spreading after deposition; Self-healing capability to recover viscosity post-extrusion; controlled Crosslinking kinetics for stabilization; and appropriate Degradability with non-toxic byproducts [43] [40]. These properties collectively ensure that bioinks can be smoothly extruded while maintaining structural fidelity and supporting long-term cell survival and function.

Bioink Formulations for Stem Cell Delivery

Table 2: Advanced Bioink Formulations for Stem Cell Delivery

| Bioink Composition | Crosslinking Method | Mechanical Properties | Stem Cell Compatibility | Key Applications | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GelMA-Sodium Alginate-Bioactive Glass (BGM) [45] | Ionic (Ca²⁺) + Photocrosslinking | Enhanced compressive modulus | mBMSCs, DPSCs [45] [44] | Periodontal tissue, bone regeneration | Significantly improved osteogenic differentiation and apatite formation [45] |

| GelMA-Dextran Emulsion [44] | Photocrosslinking | Tunable mechanical support | DPSCs, MSC spheroids [44] | Dentin, neovascular structures | Enables in-situ stem cell spheroid formation with enhanced differentiation [44] |

| Hyaluronic Acid-GelMA [37] | Photocrosslinking | Cartilage-like mechanical properties | MSCs [37] | Cartilage reconstruction | Direct reconstruction of cartilage in sheep models [37] |

| Decellularized ECM (dECM) Bioinks [38] | Thermal | Tissue-specific biochemical cues | hiPSCs, various stem cells [38] | Organ-specific models | Provides tissue-specific niche for enhanced differentiation [38] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Bioprinting Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) [40] [45] | Photocrosslinkable hydrogel base with inherent cell adhesion motifs | Various bloom strengths; typically modified with methacrylic anhydride [40] |

| Sodium Alginate [43] [45] | Ionic-crosslinkable polysaccharide for rapid stabilization | Often combined with GelMA or other polymers to improve printability [45] |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) Diacrylate (PEGDA) [37] [39] | Synthetic, biologically inert "blank slate" polymer | Highly tunable mechanical properties; requires bioactive functionalization [40] |

| Bioactive Glass Microspheres (BGM) [45] | Osteogenic and angiogenic bioactive filler | SiO₂-CaO-P₂O₅ composition enhances bioactivity and mechanical properties [45] |

| Photoinitiator 2959 [45] | UV-activated crosslinking initiator for cytocompatible polymerization | Critical concentration optimization required for cell viability [45] |

| Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP)-Sensitive Peptides [40] | Enables cell-mediated hydrogel remodeling | Essential for stem cell migration and matrix invasion [40] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Bioactive Composite Scaffolds for Periodontal Regeneration

This protocol details the fabrication of GelMA-SA-BGM composite scaffolds laden with mesenchymal stem cells and growth factors for complex tissue regeneration, based on the work of [45].

Materials Preparation:

- Synthesize GelMA using standard methacrylation protocols [45]

- Prepare bioactive glass microspheres (BGM) with composition 60% SiO₂, 36% CaO, 4% P₂O₅ via sol-gel method [45]

- Dissolve GelMA (10% w/v) and sodium alginate (4% w/v) in PBS at 37°C

- Suspend BGM (2% w/v) in the polymer solution and mix thoroughly

- Add photoinitiator (PI-2959, 0.5% w/v) to the bioink

- Isolate and expand mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (mBMSCs) or human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) [45] [44]

Bioprinting Procedure:

- Mix the bioink with mBMSCs or DPSCs at a density of 5×10⁶ cells/mL

- Add growth factors (BMP-2 for osteogenesis, PDGF for soft tissue repair) at 100 ng/mL each

- Load the cell-laden bioink into a temperature-controlled extrusion cartridge (maintained at 22-25°C)

- Print through a 22G-27G nozzle (200-400 μm diameter) at 5-15 kPa pressure

- Deposit layers onto a print bed maintained at 10°C

- Apply ionic crosslinking with 2% CaCl₂ solution for 5 minutes post-printing

- Perform photocurring with UV light (365 nm, 5-10 mW/cm²) for 60 seconds to achieve final stabilization

Culture and Evaluation:

- Maintain constructs in osteogenic media (DMEM with 10% FBS, β-glycerophosphate, ascorbic acid, and dexamethasone) [45]

- Assess cell viability using Live/Dead staining at 1, 3, and 7 days post-printing

- Evaluate osteogenic differentiation via ALP activity at 7 days and Alizarin Red staining at 21 days

- For in vivo evaluation, implant in Beagle dog periodontal defects for 8 weeks followed by histological analysis [45]

Protocol 2: DLP Bioprinting for In-Situ Stem Cell Spheroid Formation

This protocol describes a advanced DLP-based approach for creating stem cell spheroids within high-performance hydrogel constructs, adapted from [44].

Materials Preparation:

- Prepare GelMA solution (15% w/v) in PBS

- Dissolve dextran (20% w/v) in culture media

- Isolate and concentrate dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) or mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)

Spheroid Formation and Bioprinting:

- Create cell/dextran microdroplets by mixing DPSCs (10×10⁶ cells/mL) with dextran solution

- Emulsify the cell/dextran mixture within the GelMA precursor solution

- Load the emulsion into a DLP bioprinter reservoir

- Project 405 nm light with 20 mW/cm² intensity in 5-10 second exposures per 100 μm layer

- Culture the printed constructs in standard growth media

- Allow dextran to leach out over 24-48 hours, creating cavities that promote cell aggregation and spheroid formation

Characterization:

- Monitor spheroid formation over 3-7 days using phase-contrast microscopy

- Assess stemness maintenance via immunostaining for Nestin, Oct4, and Sox2

- Evaluate differentiation potential by transferring to appropriate inductive media

- For in vivo evaluation, implant in dentin regeneration models and assess for vascularized tissue formation after 4 weeks [44]

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for stem cell bioprinting, covering critical stages from bioink design to functional evaluation.

Evaluation and Optimization Methods

Assessing Geometrical Fidelity and Cell Viability

Maintaining high post-printing cell viability while achieving desired structural fidelity represents a central challenge in bioprinting. The following table summarizes key evaluation parameters and their optimization strategies:

Table 4: Critical Evaluation Metrics and Optimization Approaches

| Evaluation Parameter | Optimal Range | Measurement Techniques | Optimization Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Viability [42] | >80% (short-term), >70% (long-term) | Live/Dead assay, Calcein AM/Propidium Iodide [45] [42] | Optimize nozzle diameter, pressure, crosslinking duration; incorporate shear-thinning modifiers [40] [42] |

| Geometrical Fidelity [46] | <10% deviation from design [46] | Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), micro-CT [46] | Implement iterative feedback bio-printing (IFBP); optimize bioink viscosity and gelation kinetics [46] |

| Mechanical Properties [40] | Tissue-matched modulus | Compression testing, rheology | Adjust polymer concentration, crosslinking density, composite reinforcement [40] [45] |

| Metabolic Activity [45] | Continuous increase over 7+ days | AlamarBlue assay, glucose consumption | Ensure appropriate bioink degradability, porosity, and nutrient diffusion [40] [45] |

| Lineage-Specific Differentiation [45] [44] | Marker expression 2-3x baseline | qPCR, immunostaining, histology | Incorporate bioactive cues (BGM, growth factors); control spheroid size [45] [44] |

Iterative Feedback Bio-Printing for Quality Control

The Iterative Feedback Bio-Printing (IFBP) approach leverages Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) for non-destructive, 3D quantification of printed scaffolds, enabling significant improvements in geometrical fidelity. This method involves:

- Printing an initial set of calibration scaffolds with varying design parameters

- 3D imaging and quantitative analysis using OCT to characterize actual pore size, strut size, and volume porosity

- Establishing linear correlation models between designed and printed parameters

- Adjusting design parameters based on empirical formulas to compensate for systematic deviations

- Re-printing with optimized parameters to achieve geometrical mismatches below 7% (compared to 30-40% without optimization) [46]

This approach has demonstrated significant improvements in biological outcomes, including enhanced cell viability, proliferation, and tissue-specific function (e.g., hepatocyte markers CYP3A4 and albumin in liver models) [46].

Diagram 2: 4D bioprinting pathways showing how external stimuli trigger structural and biological transformations in printed constructs over time.

Applications in Stem Cell Research and Regenerative Medicine

Tissue-Specific Applications

Periodontal Tissue Regeneration: The GelMA-SA-BGM composite bioink has demonstrated significant regeneration of gingival tissue, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone in Beagle dog models. Scaffolds laden with mBMSCs and growth factors (BMP-2 and PDGF) achieved reconstructed periodontal structures within 8 weeks post-implantation [45].

Dentin and Vascularized Tissue Regeneration: DLP-bioprinted GelMA-dextran constructs supporting DPSC spheroid formation have shown capability to regenerate dentin and neovascular-like structures in vivo. The in-situ spheroid formation enhances stem cell differentiation potential and supports complex tissue morphogenesis [44].

Cartilage Reconstruction: Extrusion-printed HA-GelMA scaffolds laden with MSCs have successfully demonstrated direct reconstruction of cartilage in sheep models, with enhanced expression of cartilage-specific genes and improved mechanical properties resembling native tissue [37].

Cardiac Tissue Engineering: 3D-bioprinted endothelialized myocardium patches have been fabricated using GelMA hydrogels containing HUVECs and cardiac progenitor cells. These constructs exhibited functional properties, including spontaneous contraction and formation of vessel-like structures, showing promise for myocardial repair [37] [38].

Emerging Frontiers: 4D Bioprinting and Organ-on-Chip Applications

Four-dimensional bioprinting introduces dynamic temporal dimension to biofabrication, creating structures that evolve their shape or functionality in response to environmental stimuli. This approach leverages smart materials that respond to temperature, pH, light, or magnetic fields to achieve post-printing morphological changes [39]. These4D systems are particularly valuable for creating self-assembling tissue structures and adapting to in vivo environments after implantation.

The integration of 3D-bioprinted tissues with microfluidic systems has advanced the development of sophisticated organ-on-chip models for drug development and disease modeling. These systems enable precise control over biochemical and mechanical microenvironments, allowing for high-fidelity modeling of human physiology and disease pathways while reducing reliance on animal models [39].

The convergence of 3D/4D bioprinting technologies with advanced stem cell biology has created unprecedented opportunities for fabricating functional tissue constructs with complex architectural and biological features. The protocols and formulations detailed in this application note provide a robust foundation for researchers developing next-generation stem cell delivery systems and tissue models. As bioink designs continue to evolve toward greater biomimicry and intelligence, and as bioprinting technologies offer enhanced resolution and viability, the field moves closer to achieving the ultimate goal of fabricating clinically relevant tissues and organs for regenerative medicine and drug development applications.

Injectable Hydrogels for Minimally Invasive Delivery and In Situ Gelation