In Vivo Stem Cell Tracking: Imaging Techniques for Monitoring Therapeutic Efficacy and Safety

Stem cell therapies hold immense clinical potential for treating conditions from cardiovascular disease to neurological disorders.

In Vivo Stem Cell Tracking: Imaging Techniques for Monitoring Therapeutic Efficacy and Safety

Abstract

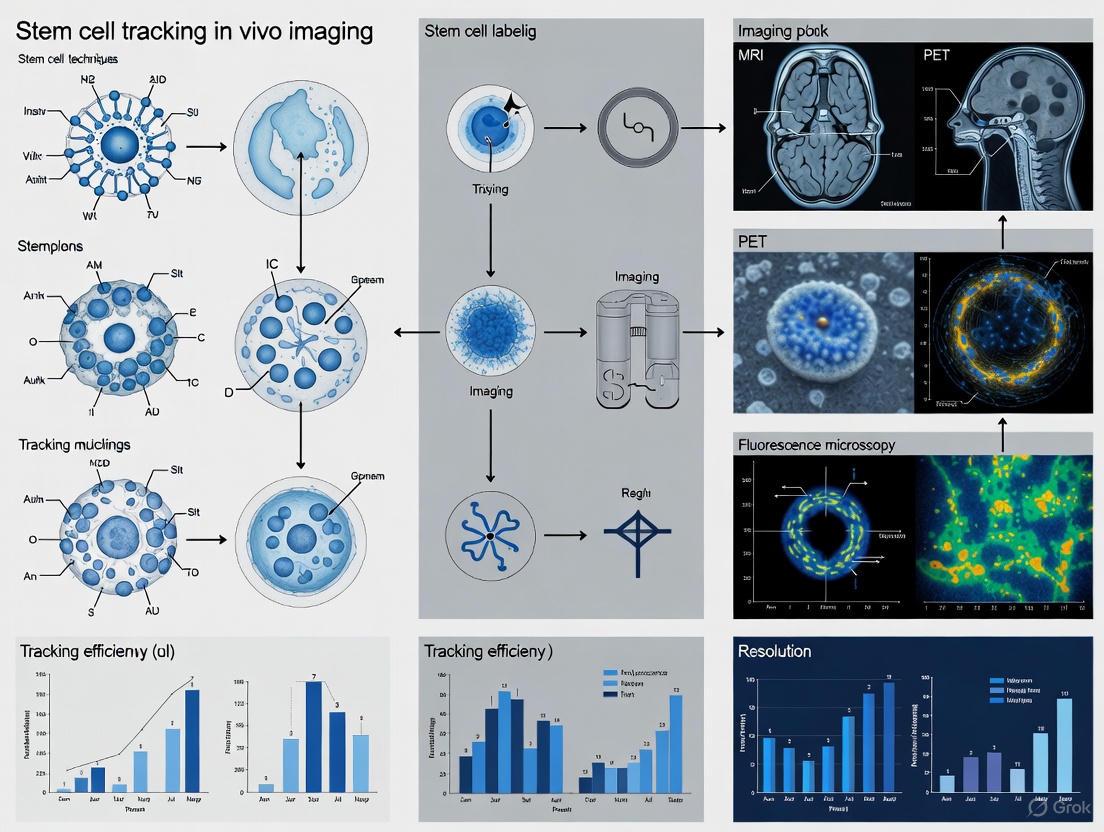

Stem cell therapies hold immense clinical potential for treating conditions from cardiovascular disease to neurological disorders. However, their clinical translation is hampered by an inability to non-invasively monitor transplanted cells in living subjects. This article provides a comprehensive overview of in vivo stem cell imaging techniques for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of cell labeling, details the methodology and applications of major imaging modalities like MRI, PET, SPECT, and optical imaging, addresses key technical challenges and optimization strategies, and offers a comparative analysis for validating and selecting the appropriate imaging approach. The integration of these imaging technologies is crucial for elucidating stem cell fate, optimizing therapeutic protocols, and accelerating the safe transition of stem cell therapies from the laboratory to the clinic.

The Why and How: Foundational Principles of Stem Cell Tracking

The Critical Need for In Vivo Monitoring in Stem Cell Therapies

The field of stem cell therapies is reaching a pivotal juncture, with several treatments achieving significant regulatory milestones. Between 2023 and 2025, the FDA approved therapies like Omisirge for accelerating neutrophil recovery, Lyfgenia for sickle cell disease, and in late 2024, Ryoncil as the first MSC therapy for pediatric steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease [1]. Simultaneously, the global clinical trial landscape for pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) has expanded, encompassing over 115 trials and more than 1,200 patients dosed by December 2024 [1]. This rapid clinical translation underscores an urgent and critical need: the development of reliable in vivo monitoring systems to track the fate, function, and efficacy of administered stem cells. In vivo monitoring is not merely a research tool but a fundamental component for ensuring patient safety, validating therapeutic mechanisms, and meeting the rigorous oversight demanded by international guidelines such as those from the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) [2]. Without precise tracking, the scientific community cannot adequately address central questions about cell survival, migration, engraftment, and potential off-target effects, which are essential for the responsible advancement of regenerative medicine.

Key Monitoring Modalities: Principles and Applications

A range of sophisticated imaging and tracking modalities has been developed, each with unique principles, advantages, and limitations. The choice of modality depends on the specific research question, balancing requirements for spatial resolution, temporal resolution, depth of penetration, and quantifiability. The table below provides a structured comparison of the primary methodologies used for in vivo stem cell tracking.

Table 1: Core In Vivo Stem Cell Tracking Modalities

| Modality | Core Principle | Key Applications | Spatial Resolution | Penetration Depth | Key Quantitative Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) [3] | Detects changes in T2 relaxation caused by internalized superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) | Tracking cell migration to injury sites; long-term engraftment studies | High (10-100 µm) | Unlimited | SPION density via voxel-based analysis of T2-weighted signal intensity |

| Positron Emission Tomography (PET) [3] | Detects gamma photons from positron-emitting radioisotopes (e.g., 18F-FDG, 64Cu) labeling cells | Real-time distribution and homing; cell viability via metabolic tracers | Low (1-2 mm) | Unlimited | Tracer uptake quantified as Standardized Uptake Value (SUV) in Region-of-Interest (ROI) |

| Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI) [3] | Detects photon emission from luciferase-expressing cells after substrate (luciferin) administration | Longitudinal cell survival and proliferation studies; high-throughput screening | Very Low (3-5 mm) | Limited (1-2 cm) | Photon flux (photons/second) measured by software like Living Image |

| Photoacoustic Imaging (PAI) [3] | Laser-pulsed contrast agents (e.g., gold nanorods) generate ultrasonic waves via thermoelastic expansion | Superficial structure imaging; tracking in highly vascularized tissues | Moderate (10-500 µm) | Limited (3-4 cm) | Signal amplitude correlating with density of labeled cells |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) [3] | Fluorescent semiconductor nanoparticles excited by external light source | High-resolution histological tracking; multicolor cell fate mapping | Very High (sub-cellular) | Very Limited | Fluorescence intensity analyzed via spectral unmixing |

Integrated Multi-Modality Imaging

No single modality provides a perfect solution; therefore, integrated approaches are increasingly employed to overcome individual limitations. For instance, a common strategy involves using PET/MRI with hybrid tracers like 64Cu-SPIONs [3]. This combination leverages the high sensitivity of PET for initial cell localization with the superior anatomical resolution and soft-tissue contrast of MRI for precise spatial mapping. Successful signal synchronization requires sophisticated voxel-wise co-registration algorithms and image fusion software (e.g., Amide, OsiriX) to align signal intensities temporally and spatially [3]. This multi-modality paradigm is becoming the gold standard for pre-clinical validation, providing a more comprehensive and reliable dataset on stem cell behavior in living organisms.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Modalities

Protocol: MRI Tracking with SPIONs

Objective: To track the in vivo migration and persistence of human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs) in a rodent model of cerebral ischemia using Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Materials:

- Cells: Human MSCs (e.g., from Lonza, passages 3-5).

- Labeling Agent: Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (SPIONs), e.g., Ferucarbotran.

- Transfection Agent: Protamine sulfate.

- Imaging Instrument: 7-Tesla or higher preclinical MRI scanner.

Methodology:

- Cell Labeling:

- Culture hMSCs to ~80% confluence in standard growth media.

- Incubate cells with a serum-free medium containing SPIONs (e.g., 50 µg Fe/mL) and protamine sulfate (1.5 µg/mL) for 4-6 hours at 37°C under 5% CO₂ [3].

- Remove labeling medium, wash cells three times with PBS to eliminate excess nanoparticles, and trypsinize for harvesting.

- Cell Transplantation:

- Induce cerebral ischemia in the rodent model using standard methods (e.g., transient middle cerebral artery occlusion).

- At the desired time post-injury, inject 1x10⁶ SPION-labeled hMSCs in 5 µL of PBS stereotactically into the ipsilateral striatum or via intracarotid injection [3].

- In Vivo MRI Acquisition:

- Anesthetize the animal and place it in the MRI scanner with a dedicated rodent head coil.

- Acquire T2-weighted fast spin-echo sequences or T2*-weighted gradient-echo sequences. SPIONs create localized magnetic field inhomogeneities, appearing as hypointense (dark) signals on these scans [3].

- Perform baseline imaging pre-injection and follow up at multiple time points (e.g., days 1, 3, 7, 14 post-transplantation).

- Data Quantification:

- Analyze MRI data using software like ImageJ or custom algorithms.

- Perform voxel-based analysis to quantify the hypointense volume and signal intensity in the region of interest, which correlates with the local density and distribution of SPION-labeled cells [3].

- Correlate signal changes over time with behavioral or histological outcomes.

Protocol: Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI) for Cell Survival

Objective: To longitudinally monitor the survival and proliferation of induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-derived neural progenitor cells in an immunodeficient mouse model.

Materials:

- Cells: iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells genetically modified to stably express firefly luciferase (FLuc) reporter gene.

- Substrate: D-Luciferin, potassium salt (15 mg/mL in PBS).

- Imaging Instrument: In vivo imaging system (IVIS) equipped with a highly sensitive CCD camera.

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation and Transplantation:

- Harvest luciferase-expressing neural progenitor cells.

- Transplant 1x10⁶ cells in 2 µL per site via stereotactic injection into the target brain region (e.g., striatum or hippocampus) [3].

- Image Acquisition:

- At each imaging time point (e.g., weekly), intraperitoneally inject the mouse with D-luciferin (150 mg/kg body weight) [3].

- After 10-12 minutes (to allow for systemic distribution and substrate conversion), anesthetize the animal and place it in the imaging chamber.

- Acquire a photographic image followed by a bioluminescence image using an exposure time of 1-60 seconds, depending on signal strength.

- Data Quantification:

- Use integrated software (e.g., Living Image) to quantify the total photon flux.

- Define a Region of Interest (ROI) over the injection site and measure the radiance in units of photons per second per steradian per square centimeter (p/s/sr/cm²) [3].

- Plot radiance over time to generate a kinetic curve of cell survival and proliferation. A decreasing signal indicates cell death, while an increasing signal suggests proliferation.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell Tracking

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (SPIONs) [3] | MRI contrast agent; internalized by cells for in vivo magnetic tracking. | Potential signal dilution upon cell division; degradation over time requires calibration; use of transfection agents (e.g., protamine) can enhance uptake. |

| Firefly Luciferase (FLuc) Reporter Gene [3] | Genetic label for bioluminescence imaging; enables monitoring of cell viability and location. | Requires genetic modification; signal is dependent on substrate (luciferin) bioavailability and cell metabolism; limited by tissue penetration depth. |

| Gold Nanorods [3] | Photoabsorbing contrast agent for Photoacoustic Imaging; converts light to sound. | Imaging efficacy is wavelength-dependent; allows for deeper tissue imaging than fluorescence. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) [3] | Fluorescent nanoparticles for high-resolution histological tracking and multicolor imaging. | Potential cytotoxicity; susceptible to photobleaching over time; ideal for ex vivo or superficial in vivo applications. |

| 64Cu-SPION Conjugates [3] | Hybrid tracer for dual-modality PET/MRI imaging. | Enables correlative imaging with high sensitivity (PET) and high resolution (MRI); requires careful management of tracer dose and stability. |

| StemRNA Clinical iPSC Seed Clones [1] | GMP-compliant, master cell bank for deriving consistent, clinically relevant cell types. | Submission of a Drug Master File (DMF) to FDA streamlines regulatory submissions for therapy developers. |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of stem cell monitoring is rapidly evolving beyond traditional tracking to include predictive functional assessment. A groundbreaking approach published in 2025 integrates quantitative phase imaging (QPI) with machine learning to forecast hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) diversity and functional quality [4]. This label-free technique analyzes temporal kinetic data—such as dry mass, sphericity, and division patterns—from individual live cells during ex vivo expansion. By applying a machine learning algorithm to this data, researchers can predict future stem cell function, such as lineage bias and long-term self-renewal capacity, based on past cellular behavior [4]. This represents a paradigm shift from static, snapshot identification to dynamic, predictive forecasting of stem cell potency.

Furthermore, advanced spectroscopic methods like Broadband Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering (BCARS) microscopy allow for quantitative, label-free characterization of stem cell lineage commitment. BCARS can chemically map hundreds of cells with high spatial resolution, revealing population heterogeneity by detecting intrinsic biochemical markers like lipids for adipocytes and minerals for osteoblasts [5]. These non-invasive technologies not only enhance the quality control of cell products prior to transplantation but also hold the potential to be adapted for in vivo sensing, paving the way for a new era of precision in regenerative medicine.

The successful clinical translation of stem cell therapies is inextricably linked to our ability to reliably monitor these living drugs within the patient. As evidenced by recent FDA approvals and the expanding clinical trial landscape, the field is maturing rapidly, making robust in vivo tracking a non-negotiable component of therapeutic development. The existing toolkit—spanning MRI, PET, BLI, and multi-modality approaches—provides powerful means to address critical questions of safety and efficacy. Meanwhile, emerging technologies like QPI-driven machine learning and advanced spectroscopy promise to further revolutionize the field by moving from simple location tracking to predictive functional assessment. Adherence to evolving international guidelines and the integration of these sophisticated monitoring protocols will ensure that the immense promise of stem cell therapies is realized safely, effectively, and ethically.

Visualized Workflows

Multi-Modality Cell Tracking Workflow

QPI-ML Predictive Analysis Pipeline

Tracking Cell Homing, Survival, Distribution, and Engraftment

The efficacy of stem cell therapies is fundamentally dependent on the successful journey of administered cells—their distribution throughout the body, targeted homing to sites of injury, subsequent survival in a hostile microenvironment, and long-term engraftment within the host tissue. Advanced in vivo imaging techniques are therefore indispensable for monitoring these dynamic processes non-invasively and longitudinally. These methodologies provide critical, quantitative data on cell fate, thereby accelerating the development and validation of regenerative therapies [6] [7]. This document outlines core protocols and application notes for tracking these critical cellular events, framed within the context of stem cell tracking for research and therapeutic development.

The selection of an appropriate imaging modality is a critical first step in experimental design, as each technology offers a unique balance of strengths and limitations. Key performance metrics include spatial resolution, temporal resolution, sensitivity, and depth penetration. The table below provides a comparative summary of major in vivo cell tracking techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Key In Vivo Cell Tracking Modalities

| Tracking Modality | Spatial Resolution | Sensitivity (Cell Number) | Tracking Duration | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) [6] [7] | 25-100 µm | 10⁵ - 10⁶ | Weeks to Months | High anatomical detail; No ionizing radiation | Low sensitivity; Signal dilution from cell division |

| Positron Emission Tomography (PET) [6] [7] | 1-2 mm | 10² - 10⁴ | Hours to Days (dictated by radioisotope half-life) | Very high sensitivity; Quantitative biodistribution data | Radiation exposure; Poor anatomical context (requires CT/MRI fusion) |

| Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI) [6] | 3-5 mm | 10² - 10⁴ | Unlimited (with substrate re-administration) | High sensitivity; Low background; Low cost | Limited tissue penetration; Semi-quantitative |

| Photoacoustic Imaging (PAI) [6] | 10-500 µm | N/A | Unlimited (with stable labels) | Good depth-to-resolution ratio; Functional imaging | Limited clinical translation for cell tracking |

| Computed Tomography (MicroCT) [7] | 10-100 µm | 10⁴ - 10⁵ | Months (with stable contrast agents) | High-resolution 3D anatomy; Quantitative | Generally lower sensitivity for cell tracking; Radiation dose |

The performance of cell therapies is often quantified by key metrics. For instance, studies have shown that the survival of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) in liver tissues can be less than 5% four weeks after transplantation, with a large number of cells dying within the first day [8]. Improving these metrics is a major focus of ongoing research.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics in Cell Therapy Efficiency

| Parameter | Typical Challenge/Value | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Survival in Liver Tissue [8] | < 5% at 4 weeks post-transplantation | Indicates massive cell attrition, a major bottleneck for therapy efficacy. |

| Early Cell Death [8] | Large-scale death within 1 day post-transplantation | Highlights the extreme sensitivity of cells to the in vivo environment after transplantation. |

| MSC Engraftment in Fibrotic Liver [8] | Surviving MSCs nearly completely disappear by 11 days | Underscores the need for strategies to enhance cell survival and retention. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Tracking Methodologies

MRI-Based Tracking with Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (SPIONs)

This protocol details the labeling of stem cells with SPIONs for non-invasive tracking using MRI, allowing for the visualization of cell migration and distribution within anatomical context [6] [7].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Stem Cells: (e.g., Mesenchymal Stem Cells, Neural Stem Cells).

- Labeling Agent: SPIO or USPIO nanoparticles (e.g., Ferucarbotran).

- Transfection Agent: Protamine sulfate (optional, to enhance uptake).

- Cell Culture Medium: Appropriate medium for the cell type.

- Imaging Instrument: Preclinical MRI system (e.g., 7T or higher).

Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Expand stem cells under standard conditions to 70-80% confluence.

- Labeling:

- Prepare a labeling medium by supplementing standard culture medium with SPIONs at a concentration of 25-100 µg Fe/mL.

- For difficult-to-label cells, add a transfection agent like protamine sulfate (0.5-1.5 µg/mL) to facilitate nanoparticle internalization.

- Incubate cells with the labeling medium for 12-48 hours.

- Washing and Harvesting:

- Remove the labeling medium and wash the cells thoroughly with PBS (3-5 times) to eliminate any non-internalized nanoparticles.

- Trypsinize the cells and resuspend in a suitable buffer (e.g., saline) for transplantation. Perform a cell count and viability assessment (e.g., Trypan Blue exclusion).

- Quality Control:

- Validate labeling efficiency by performing Prussian Blue staining on an aliquot of cells to confirm intracellular iron presence.

- Ensure labeled cells maintain normal viability, proliferation, and differentiation capacity.

- Transplantation: Administer the SPION-labeled cells into the animal model via the intended route (e.g., intravenous, intra-organ).

- In Vivo MRI:

- Anesthetize the animal and place it in the MRI scanner.

- Acquire T2-weighted or T2*-weighted sequences, where SPIONs create a hypointense (dark) signal.

- Conduct serial imaging over days or weeks to track cell migration and persistence.

- Data Analysis:

- Use software tools (e.g., ImageJ, OsiriX) to quantify the hypointense signal volume and its change over time.

- Correlate signal voids with anatomical location.

- Validation:

- After the final imaging time point, euthanize the animal and harvest tissues for histology.

- Confirm the presence of SPION-labeled cells using Perls' Prussian Blue staining co-localized with specific cell markers.

Radionuclide-Based Tracking for Biodistribution and Homing

This protocol uses radionuclides like ¹¹¹In to label cells for tracking with Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT), providing highly sensitive, quantitative data on whole-body biodistribution and homing to target tissues [7].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Stem Cells: (e.g., MSCs, dendritic cells).

- Radiotracer: ¹¹¹In-oxyquinoline (¹¹¹In-oxine).

- Radiation Safety Equipment: Shields, dosimeters, dedicated lab space.

- Imaging Instrument: Preclinical SPECT/CT scanner.

- Gamma Counter: For ex vivo tissue analysis.

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest cells and wash thoroughly. Resuspend the cell pellet (e.g., 10⁶ - 10⁷ cells) in a small volume (e.g., 100 µL) of saline or PBS without phenol red.

- Radiolabeling:

- Add ¹¹¹In-oxine (100-500 µCi) to the cell suspension and incubate for 15-20 minutes at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- The lipophilic ¹¹¹In-oxine complex diffuses across the cell membrane, where ¹¹¹In dissociates and binds to intracellular components.

- Washing and QC:

- Add excess cell medium to stop the reaction and pellet the cells by centrifugation.

- Carefully remove the supernatant (contains free radiotracer) and wash the cells twice with fresh medium.

- Resuspend the final cell pellet in transplantation buffer.

- Measure the radioactivity in the cell pellet and the combined washes to calculate labeling efficiency, which should typically be >70%.

- Cell Viability Check: Perform a rapid viability assay (e.g., Trypan Blue) post-labeling to ensure the process has not induced significant toxicity.

- Transplantation and Imaging:

- Inject the radiolabeled cells into the animal model.

- Acquire SPECT/CT images at multiple time points (e.g., 1h, 24h, 48h, 72h post-injection). The CT scan provides anatomical reference for the functional SPECT data.

- Quantitative Analysis:

- Use region-of-interest (ROI) analysis on the fused SPECT/CT images to quantify the percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g) in target organs (e.g., tumor, liver, spleen, lungs).

- Ex Vivo Validation:

- Euthanize the animal after the final scan and harvest major organs.

- Weigh the tissues and measure their radioactivity using a gamma counter to obtain a precise, high-sensitivity biodistribution profile.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful cell tracking relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The table below details essential components for the protocols described.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Cell Tracking Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (SPIONs) [6] [7] | MRI contrast agent. Internalized by cells, causing detectable darkening (T2 contrast) on MRI scans. | Ferucarbotran; Size: 50-500 nm; Incubation concentration: 25-100 µg Fe/mL. |

| ¹¹¹In-Oxyquinoline (¹¹¹In-oxine) [7] | Radiotracer for SPECT imaging and quantitative biodistribution studies. | Half-life: 2.8 days; Emits gamma photons; Used for labeling cells like MSCs and leukocytes. |

| Transfection Agents [6] | Enhance cellular uptake of labeling agents like SPIONs. | Protamine sulfate; Used at 0.5-1.5 µg/mL in labeling medium. |

| Luciferase Reporter Genes [6] | Genetic label for bioluminescence imaging (BLI). Cells express the enzyme luciferase. | Requires transfection (viral vectors); Substrate: D-luciferin; Provides high-sensitivity, longitudinal data on cell viability/location. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) [6] [7] | Fluorescent nanoparticles for high-resolution optical imaging and histology. | Semiconductor nanocrystals (2-5 nm); High resistance to photobleaching; Emission spectra are narrow and tunable. |

| Gold Nanorods [6] | Contrast agents for Photoacoustic Imaging (PAI). Absorb light and generate ultrasonic waves. | Strong absorption in the Near-Infrared (NIR) region; Allows for deeper tissue imaging. |

| Dual-Modality Tracers [6] | Allow cell tracking with two complementary techniques (e.g., PET and MRI). | Example: ⁶⁴Cu-SPION conjugates; Enable high-sensitivity detection (PET) with high anatomical resolution (MRI). |

In the field of regenerative medicine, stem cell therapy has emerged as a promising intervention for a wide range of diseases, including neurological, cardiovascular, and hematological disorders, through mechanisms such as cell replacement, paracrine factor secretion, and immune regulation [9] [10]. However, the clinical translation of these therapies faces a significant challenge: the inability to non-invasively monitor the transplanted cells in living subjects. The in vivo pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of stem cell therapy remain largely unclear, creating a critical knowledge gap in understanding stem cell fate, function, and efficacy [11] [10].

Molecular imaging bridges this gap by enabling longitudinal, non-invasive visualization of stem cell biological behaviors post-transplantation [9]. The fundamental approaches for stem cell tracking are categorized into two distinct strategies: direct and indirect labeling. Direct labeling involves incorporating detectable markers (fluorescent dyes, magnetic nanoparticles, or radiolabeled compounds) directly into cells prior to transplantation [12] [10]. In contrast, indirect labeling uses reporter genes transduced into stem cells, which are then visualized upon injection of specific probes [9] [12]. This dichotomy in strategy represents a core methodological consideration that influences every aspect of experimental design and data interpretation in stem cell research.

Core Principles: Direct versus Indirect Labeling

Direct Labeling Methodology

Direct labeling introduces labeling agents into cells through physical co-incubation or transfection methods before transplantation [12]. These agents become stably incorporated or attached to cellular components, allowing immediate detection post-transplantation. The method is technically straightforward and does not involve genetic modification of the target cells, reducing concerns about genetic responses and adverse events [9].

The underlying mechanism relies on transporting tracers into cells via endocytosis, transporter systems, or physical transfection, followed by intracellular retention through metabolic trapping or membrane anchoring [12]. For instance, 18F-FDG is taken up and retained in cells via glucose transporters and hexokinase-mediated phosphorylation, while 111In-oxine and 99mTc-HMPAO passively diffuse across cell membranes and are retained intracellularly [9]. Lipophilic compounds like hexadecyl-4-124I-iodobenzoate (124I-HIB) anchor efficiently into cellular membranes through simple incubation [9].

Indirect Labeling Methodology

Indirect labeling represents a genetically engineered approach where stem cells are modified to express reporter genes that produce detectable proteins or receptors [9] [12]. These reporter genes are integrated into the cellular genome using viral vectors, CRISPR/Cas9, or other gene-editing technologies, enabling permanent labeling that is passed to progeny cells [12] [13].

The imaging process requires administration of a specific probe or substrate that interacts with the reporter gene product. For example, cells expressing the herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase (HSV1-tk) reporter gene can be visualized after injecting radiolabeled substrates like 9-(4-[18F]fluoro-3-(hydroxymethyl)butyl)guanine ([18F]FHBG) [10]. Similarly, cells engineered with luciferase genes become detectable upon administration of luciferin substrate, generating bioluminescent signals [13].

Comparative Analysis: Strategic Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Direct and Indirect Labeling Methods

| Parameter | Direct Labeling | Indirect Labeling |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Physical incorporation of labels into cells [9] | Genetic engineering with reporter genes [9] |

| Typical Labels | Radionuclides (18F-FDG, 111In-oxine), SPIO, fluorescent dyes [9] [12] | Reporter genes (HSV1-tk, luciferase, GFP), receptor proteins [9] [13] |

| Cell Modification | No genetic modification required [9] | Permanent genetic modification necessary [12] |

| Signal Duration | Short-term (hours to days) [9] [12] | Long-term (weeks to months) [12] [10] |

| Signal & Cell Viability | Signal persists regardless of cell viability [12] | Signal correlates with viable, functional cells [11] |

| Proliferation Tracking | Label dilution with cell division [9] [12] | Stable inheritance by daughter cells [12] |

| Differentiation Monitoring | No specific differentiation insight [12] | Can use tissue-specific promoters [10] |

| Clinical Translation | Simpler regulatory pathway (no genetic modification) [9] | Complex regulatory pathway (genetic modification) [11] |

Table 2: Imaging Modalities and Their Applications in Stem Cell Tracking

| Imaging Modality | Direct Labeling Agents | Indirect Reporter Systems | Sensitivity | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET | 18F-FDG, 64Cu-PTSM, 124I-HIB [9] | HSV1-tk, sodium iodide symporter (NIS) [9] [10] | High (picomolar) [9] | 1-2 mm [9] | Minutes to hours [12] |

| SPECT | 111In-oxine, 99mTc-HMPAO [9] | NIS, other reporter genes [9] | High (picomolar) [9] | 1-2 mm [9] | Minutes to hours [12] |

| MRI | Superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) [9] [11] | Ferritin, β-galactosidase [13] | Low (micromolar) [11] | 25-100 μm [11] | Minutes [11] |

| Optical Imaging | Fluorescent dyes (Cy dyes, Alexa Fluor) [14] [13] | Luciferase, fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP) [10] [13] | High (femtomolar for bioluminescence) [13] | 2-3 mm (surface), >1 cm (deep tissue) [13] | Seconds to minutes [12] |

The strategic selection between direct and indirect labeling involves careful consideration of their respective advantages and limitations. Direct labeling offers immediate visualization post-transplantation, technical simplicity, and avoids genetic modification of cells [9]. However, this approach suffers from several fundamental constraints: signal dilution through cell division, inability to distinguish between living and dead cells, and limited long-term monitoring capability due to radiodecay or label efflux [9] [12]. For instance, 124I-HIB-labeled adipose-derived stem cells could only be tracked for 9 days in normal myocardium and 3 days in infarcted myocardium [9].

Indirect labeling addresses many limitations of direct approaches by providing permanent genetic labeling that is inherited by progeny cells, enabling long-term monitoring throughout the experiment duration [12] [10]. Since reporter gene expression requires viable, functionally active cells, the signal directly correlates with cell viability [11]. Furthermore, tissue-specific promoters can be incorporated to monitor differentiation status [10]. The primary limitations include potential immunogenicity of reporter proteins, more complex implementation requiring genetic engineering expertise, and variable transduction efficiency [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Direct Labeling with Radiolabeled Compounds

Objective: To track short-term distribution and homing of stem cells using direct radiolabeling.

Materials:

- Stem cells (e.g., mesenchymal stem cells, adipose-derived stem cells)

- Radiolabeling agent (e.g., 18F-FDG, 124I-HIB, 64Cu-PTSM)

- Cell culture medium and incubation equipment

- Radiation safety equipment

- PET/SPECT imaging system

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest stem cells at 70-80% confluency using standard trypsinization procedures. Wash cells with PBS and resuspend in appropriate medium at concentration of 1-5 × 10^6 cells/mL [9].

- Labeling Incubation: Incubate cells with radiolabeling agent (e.g., 18F-FDG, 37-74 MBq/10^6 cells) for 30-60 minutes at 37°C with gentle agitation [9].

- Washing: Centrifuge cells at 300 × g for 5 minutes and carefully remove supernatant containing unincorporated radiotracer. Repeat washing step twice with fresh medium to ensure complete removal of excess label [9].

- Quality Control: Measure radioactivity associated with cells using gamma counter. Determine labeling efficiency (typically 5-20% for 18F-FDG) and cell viability via trypan blue exclusion [9].

- Transplantation: Resuspend labeled cells in appropriate transplantation medium. Administer to experimental subject via predetermined route (intravenous, intramyocardial, etc.) [9].

- Imaging: Perform serial PET/SPECT imaging immediately post-transplantation and at predetermined timepoints. For 18F-FDG (t1/2 = 110 min), imaging is typically limited to first 6-8 hours [9].

Critical Considerations:

- Optimize labeling conditions to maintain cell viability (>90% post-labeling)

- Account for radionuclide physical half-life in experimental timeline

- Include controls for potential radiotracer leakage from dead cells

- For 124I-HIB (t1/2 = 4.2 days), tracking up to 9 days is feasible in normal tissue [9]

Protocol 2: Indirect Labeling with Reporter Genes

Objective: To monitor long-term viability, proliferation, and distribution of stem cells using reporter gene imaging.

Materials:

- Stem cells

- Reporter gene construct (e.g., triple fusion reporter: fluorescent protein/luciferase/HSV1-tk)

- Gene delivery system (lentiviral vectors, CRISPR/Cas9)

- Appropriate substrate (e.g., luciferin for bioluminescence, [18F]FHBG for PET)

- In vivo imaging system (bioluminescence, PET, or fluorescence)

Procedure:

- Genetic Modification:

- For viral transduction: Incubate stem cells with lentiviral vectors carrying reporter gene at appropriate MOI (typically 10-100) for 24-48 hours [13].

- For CRISPR/Cas9 integration: Transfect stem cells with plasmid containing reporter gene flanked by homology arms for specific genomic integration [13].

- Selection and Expansion: Apply selection pressure (e.g., antibiotics for resistance markers) for 1-2 weeks. Isolate single-cell clones and expand reporter-positive populations [13].

- Validation:

- Confirm reporter expression via fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry for fluorescent proteins.

- Validate functionality using substrate incubation (luciferin for bioluminescence assay).

- Assess stem cell properties (differentiation potential, surface markers) to ensure genetic modification hasn't altered fundamental characteristics [13].

- Transplantation: Administer validated reporter-expressing cells to experimental subjects via appropriate route [10].

- Longitudinal Imaging:

- For bioluminescence imaging: Inject D-luciferin (150 mg/kg intraperitoneally), image 10-20 minutes post-injection under anesthesia [13].

- For PET imaging: Inject reporter-specific probe (e.g., [18F]FHBG for HSV1-tk, 7.4 MBq intravenous), image 1-2 hours post-injection [10].

- Schedule imaging sessions at regular intervals (days to weeks) to monitor cell fate.

Critical Considerations:

- Monitor for potential immune responses against reporter proteins

- Validate stable reporter expression throughout experiment duration

- Use tissue-specific promoters to monitor differentiation (e.g., neuronal promoters for neural stem cells) [10]

- Triple fusion reporters enable multimodal imaging (fluorescence, bioluminescence, PET) [10]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell Tracking

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Labeling Agents | 18F-FDG, 111In-oxine, 99mTc-HMPAO [9] | Short-term cell labeling for nuclear imaging | Tracking initial cell distribution and homing [9] |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO), ferumoxytol [11] [10] | Cell labeling for MRI contrast | High-resolution anatomical localization [11] |

| Fluorescent Probes | Cy dyes, Alexa Fluor dyes, FITC [14] [13] | Direct fluorescence labeling | In vitro validation, histological analysis, in vivo surface imaging [14] |

| Reporter Gene Constructs | HSV1-tk, luciferase, GFP/RFP [9] [13] | Genetic cell labeling | Long-term viability and proliferation monitoring [10] |

| Reporter Substrates | [18F]FHBG, luciferin [10] [13] | Activation of reporter systems | PET and bioluminescence imaging of reporter genes [10] |

| Gene Delivery Systems | Lentiviral vectors, CRISPR/Cas9 [12] [13] | Stable integration of reporter genes | Creating constitutively expressing cell lines [13] |

Strategic Implementation and Decision Framework

Choosing between direct and indirect labeling strategies requires systematic consideration of research objectives, technical constraints, and biological questions. The following decision framework provides guidance for selecting the appropriate methodology:

Implementation Considerations:

Hybrid Approaches: Combined direct and indirect labeling can provide complementary information. For example, direct labeling with SPIO nanoparticles enables precise anatomical localization via MRI, while reporter genes allow long-term viability assessment [13].

Multimodal Imaging: Triple fusion reporter genes (e.g., combining fluorescent protein, luciferase, and PET reporter) enable correlation of multiple imaging modalities, enhancing data robustness [10].

Clinical Translation Pathway: For preclinical studies with clinical translation as the ultimate goal, consider regulatory pathways early. Direct labeling has simpler regulatory approval process, while indirect labeling faces additional hurdles due to genetic modification [11].

Troubleshooting Common Issues:

- For low signal in direct labeling: optimize labeling conditions (concentration, incubation time, temperature)

- For reporter gene silencing: use different promoters or gene integration methods

- For high background: adjust washing procedures (direct) or optimize substrate clearance time (indirect)

The strategic dichotomy between direct and indirect labeling methods represents a fundamental consideration in stem cell tracking research. Direct labeling offers simplicity and immediate applicability for short-term distribution studies, while indirect labeling provides powerful tools for long-term monitoring of cell viability, proliferation, and differentiation. The choice between these approaches ultimately depends on specific research questions, technical capabilities, and regulatory considerations.

As stem cell therapies continue to advance toward clinical application, molecular imaging through appropriate labeling strategies will play an increasingly critical role in understanding stem cell fate and function. Future developments will likely focus on improved multimodal approaches, more sensitive reporters, and clinical translation of these tracking methodologies. By strategically implementing either direct or indirect labeling—or combinations thereof—researchers can significantly enhance our understanding of stem cell biology and accelerate the development of effective regenerative therapies.

In the field of stem cell tracking for regenerative medicine, in vivo imaging is crucial for monitoring the distribution, migration, and survival of transplanted cells. Direct labeling stands as a fundamental approach for these studies, prized for its straightforward implementation compared to genetically-encoded indirect methods. This technique involves incorporating a labeling agent—such as a radionuclide, fluorescent dye, or magnetic nanoparticle—into cells prior to their transplantation [15] [9]. While this method offers significant advantages in simplicity and immediate applicability, it is inherently constrained by two major challenges: the dilution of the signal over time due to cell division and the potential for false positives caused by label leakage from dead cells. This application note details the principles, protocols, and critical considerations for employing direct labeling in stem cell tracking, providing researchers with a framework to optimize its use while mitigating its inherent limitations.

Core Principles and Key Challenges

The Mechanism of Direct Labeling

Direct cell labeling methods function by introducing a contrast agent or tracer into stem cells ex vivo. After the labeling procedure, these cells are administered to a recipient, enabling their detection through various imaging modalities [15]. The label is typically incorporated into cells through processes such as endocytosis, transporter-mediated uptake, or simple diffusion across the cell membrane, where it may be metabolically trapped [12]. This process allows for explicit detection and monitoring of the distribution of these cells in target organs [15].

Fundamental Limitations

The primary limitations of direct labeling stem from the biological orthogonality of the tracer and cell viability. The tracer itself does not replicate with the cell and is not passed on to daughter cells during division. This leads to two critical issues:

- Signal Dilution: With each cell division, the concentration of the labeling agent per cell is halved, leading to a progressive weakening of the detectable signal. This ultimately restricts long-term monitoring capabilities [9]. Furthermore, the labeled material can be asymmetrically distributed between progeny cells [15].

- False Positives: If a labeled cell dies, the contrast agent can be released into the extracellular space. It may then be phagocytosed by host macrophages or other non-target cells, or simply remain as background signal. This results in an imaging signal that no longer corresponds to the location or viability of the originally transplanted therapeutic cells [12].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of direct labeling and the emergence of its key challenges over time.

Quantitative Comparison of Direct Labeling Agents

The choice of labeling agent dictates the compatible imaging modality and influences the duration and reliability of tracking. The table below summarizes key characteristics of commonly used agents.

Table 1: Properties of Common Direct Labeling Agents for Stem Cell Tracking

| Labeling Agent | Imaging Modality | Key Feature | Typical Tracking Duration | Primary Cause of Signal Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., DiR) [15] | Optical Imaging | High sensitivity, real-time data | Days to a few weeks | Photobleaching, cell division, leakage |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) [15] | Optical Imaging | High resolution, multiplexing capability | Several weeks | Potential long-term toxicity, cell division |

| Polymer Dots (Pdots) [16] | Optical Imaging (NIR) | High brightness, low cytotoxicity | ~7 days (as demonstrated) | Cell division, clearance |

| Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (SPIONs) [15] [9] | Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | High spatial resolution, deep tissue penetration | 1-2 weeks (e.g., 8 weeks shown in SCI model [15]) | Cell division, iron metabolism |

| 18F-FDG [9] | Positron Emission Tomography (PET) | High sensitivity, quantitative | Hours (t1/2 = 110 min) | Radiodecay, leakage |

| 99mTc-HMPAO [9] | Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) | Clinical availability | Hours (t1/2 = 6 h) | Radiodecay, leakage |

| 111In-oxine [9] | SPECT | Longer half-life than 99mTc | Several days (t1/2 = 2.8 d) | Radiodecay, leakage |

| 124I-HIB [9] | PET | Membrane-anchored, longer tracking | Up to 9 days (demonstrated in normal myocardium) | Radiodecay, cell death |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Labeling Stem Cells with Near-Infrared Fluorescent Polymer Dots

This protocol is adapted from studies using semiconducting polymer dots (Pdots) for high-brightness cell tracking, which demonstrated effective monitoring of stem cell distribution for up to seven days in vivo [16].

4.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Pdots Labeling

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| NIR-Emitting Pdots | Fluorescent probe for tracking. | e.g., DFDBT/NIR800 blend, emission at 800 nm [16]. |

| Cell-Penetrating Peptide (CPP) | Enhates cellular uptake of Pdots. | e.g., TAT peptide (GRKKRRQRRRPQ) [16]. |

| Poly(styrene-co-maleic anhydride) (PSMA) | Functional copolymer for nanoparticle coating and stabilization. | Mn = 1700 [16]. |

| Stem Cell Line | Target cells for labeling and tracking. | e.g., Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs). |

| Appropriate Cell Culture Medium | Maintains cell viability during labeling. | Serum-free recommended during labeling. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Washing and dilution buffer. | |

| Flow Cytometer | Quantifying labeling efficiency and brightness. | |

| In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) | Non-invasive tracking of labeled cells in animal models. |

4.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

Pdots Preparation and Functionalization:

- Prepare Pdots using the nano-precipitation method. Mix the semiconducting polymers (e.g., DFDBT and NIR800) with the functional copolymer PSMA in THF.

- Vigorously inject the THF solution into ultrapure water and stir to allow nanoparticle self-assembly.

- Remove the organic solvent via dialysis or nitrogen purging.

- Conjugate the TAT cell-penetrating peptide to the surface of the Pdots via the amine-reactive chemistry of the PSMA copolymer. Purify the TAT-Pdots using size-exclusion chromatography or dialysis.

Cell Culture:

- Maintain stem cells (e.g., MSCs) in their recommended growth medium under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2).

- Harvest cells at 70-80% confluency using a standard trypsinization procedure. Wash cells once with PBS.

Cell Labeling:

- Resuspend the cell pellet in serum-free medium at a concentration of 1-5 x 10^6 cells/mL.

- Add the prepared TAT-Pdots solution to the cell suspension. The optimal working concentration should be determined empirically (e.g., 5-20 nM final Pdots concentration).

- Incubate the cell-Pdots mixture for 2-4 hours at 37°C with gentle agitation every 30 minutes.

Washing and Validation:

- After incubation, centrifuge the cell suspension (e.g., 300 x g for 5 minutes) and carefully remove the supernatant containing unincorporated Pdots.

- Wash the cells with PBS at least three times to ensure complete removal of free Pdots.

- Resuspend the labeled cells in PBS or complete medium for immediate use.

- Quantify Labeling Efficiency: Analyze an aliquot of the labeled cells using a flow cytometer. Compare the fluorescence intensity to unlabeled control cells. The protocol aims for a brightness increase of ~4 orders of magnitude [16].

- Assess Cell Viability: Perform a viability assay (e.g., trypan blue exclusion) post-labeling to ensure the procedure has not induced significant toxicity.

In Vivo Administration and Imaging:

- Transplant the Pdots-labeled stem cells into your animal model via the desired route (e.g., intravenous injection through the tail vein).

- Anesthetize the animals and image them using an in vivo imaging system (IVIS) with appropriate filters for NIR fluorescence (e.g., excitation 745 nm, emission 800 nm).

- Acquire images at predetermined time points (e.g., 1 hour, 1 day, 4 days, 7 days post-transplantation) to track cell distribution and persistence.

Protocol: Magnetic Resonance Imaging with SPIONs

This protocol outlines the labeling of stem cells with superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) for tracking via MRI, a method that has been used to monitor cells for up to 8 weeks in models of spinal cord injury [15].

4.2.1 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Cell Culture: Harvest and wash the target stem cells as described in section 4.1.2.

- SPIONs Labeling:

- Resuspend the cell pellet in culture medium containing SPIONs (e.g., Ferucarbotran). The typical iron concentration used ranges from 50 to 200 µg Fe/mL.

- To enhance labeling efficiency, add a transfection agent (e.g., poly-L-lysine) to the mixture according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Incubate the cells for 12-24 hours under standard culture conditions.

- Washing and Validation:

- After incubation, wash the cells thoroughly with PBS 3-5 times to remove any unincorporated nanoparticles.

- Confirm labeling efficiency via Prussian Blue staining for iron.

- Verify that stem cell viability and differentiation potential remain uncompromised post-labeling.

- In Vivo Administration and MRI:

- Transplant the SPIONs-labeled cells into the target tissue (e.g., intracardiac injection for myocardial infarction models or intraspinal injection for SCI models).

- Perform MRI scans at multiple time points using T2/T2*-weighted sequences. The labeled cells will appear as hypointense (dark) signal areas against the brighter background tissue [15].

Critical Interpretation of Data and Mitigating Pitfalls

The primary challenge in direct labeling is distinguishing true positive signals from false positives arising from label leakage. The diagram below outlines the decision process for data interpretation and validation.

To minimize misinterpretation, researchers should:

- Establish a Baseline: Understand the expected pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of the free label itself.

- Use Multiple Modalities: Correlate findings with a second, independent imaging technique where possible.

- Mandatory Post-Mortem Analysis: As shown in the diagram, histological validation is essential. Correlate the in vivo signal with ex vivo tissue analysis using specific cell markers and label-specific stains (e.g., Prussian Blue for iron) to confirm the cellular source of the signal [15] [17].

- Track Signal Kinetics: A rapidly disseminating or shifting signal, especially one accumulating in clearance organs like the liver and spleen, is a strong indicator of label leakage rather than viable cell migration [9].

Direct labeling remains a powerful and accessible technique for short- to medium-term tracking of stem cells in vivo, offering a straightforward path to answer critical questions about initial cell homing and early distribution. Its simplicity and relatively low technical barrier make it an excellent starting point for many preclinical studies. However, the inherent limitations of signal dilution upon cell division and the pervasive risk of false positives due to label leakage demand a cautious and critical approach to data interpretation. By selecting the appropriate label for the experimental timeframe and biological question, following optimized protocols to ensure cell health, and—most importantly—implementing rigorous histological validation, researchers can effectively leverage the simplicity of direct labeling while mitigating its drawbacks. For studies requiring long-term tracking or monitoring of cell proliferation, indirect reporter gene-based methods may be a more suitable, albeit more complex, alternative [12] [9].

In the field of stem cell tracking and regenerative medicine, understanding the long-term fate, proliferation, and differentiation of therapeutic cells is paramount. While direct labeling methods, which involve loading cells with contrast agents, are straightforward, they suffer from a critical limitation: the label dilutes with each cell division, causing the signal to fade and preventing long-term observation [18] [11]. Indirect reporter gene labeling overcomes this fundamental barrier. This technique involves genetically engineering cells to stably incorporate a reporter gene into their genome. The expression product of this gene—be it an enzyme, a receptor, or a transporter—can then interact with an externally administered probe to generate a detectable signal for non-invasive imaging [18] [19]. Because the reporter gene is integrated into the cell's DNA, it is passed on to all progeny, providing a heritable and permanent mark for long-term lineage tracing. This allows researchers to monitor the survival, migration, and differentiation of stem cells over weeks or months in living subjects, offering unparalleled insights into their in vivo biology and therapeutic efficacy [10] [19].

The following diagram illustrates the core principle of how indirect reporter gene labeling enables long-term lineage tracing, contrasting it with the limitation of direct labeling.

Molecular Principles and Key Reporter Gene Systems

The functionality of indirect reporter gene labeling hinges on the molecular biology of the reporter genes themselves. A typical construct consists of a regulatory response element (which controls when and where the gene is turned on) and the reporter gene itself, which produces a measurable signal [20]. When a therapeutic cell, such as a stem cell, is engineered to express such a construct, its activation leads to the production of a reporter protein. This protein then interacts with a compatible imaging probe, leading to signal generation that can be detected by various imaging modalities [18].

Reporter genes are broadly classified into three categories based on their mechanism of action: enzyme-based, receptor-based, and transporter-based systems [19]. Each class offers distinct advantages and is compatible with different imaging technologies. The choice of reporter depends on factors such as sensitivity, clinical translatability, and the need for multiplexing. The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of common biological activity methods, highlighting the position of reporter gene assays among other techniques.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Biological Activity Assay Methods

| Classification | Detection Method | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Dynamic Range | Intra-batch CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-based Activity Methods | Cell Proliferation Inhibition | ~10⁻⁹ – 10⁻¹² M | Varies (e.g., cell ratio dependent) | Below 10% |

| Cytotoxicity Assay | ~100 cells per test well | 10–90% cell death | Below 10% | |

| Transgenic Cell-based Methods | Reporter Gene Assay (RGA) | ~10⁻¹² M | 10² – 10⁶ relative light units | Below 10% |

| New Technology-based Methods | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | ~10⁻⁹ M | Wide (10⁴ – 10⁶) | ~1–5% |

| Homogeneous Time-Resolved Fluorescence (HTRF) | ~10⁻¹² M | Moderate (10² – 10⁴) | ~2–8% |

Data adapted from a 2025 review on biological activity methods [20]. CV: Coefficient of Variation.

Table 2: Key Reporter Gene Systems for In Vivo Imaging

| Reporter Gene Class | Reporter Name | Mechanism of Action | Imaging Modality | Example Imaging Probe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Thymidine Kinase (HSV1-tk) | Phosphorylates and traps probes inside cells | PET, SPECT | ¹²⁴I-FIAU, ¹⁸F-FHBG |

| Transporter | Sodium Iodide Symporter (NIS, SLC5A5) | Concentrates anions from extracellular space | PET, SPECT | ¹²⁴I⁻, ⁹⁹mTcO₄⁻ |

| Receptor | Dopamine D2 Receptor (D2R) | Binds specific ligands on cell surface | PET, SPECT | ¹⁸F-Fallypride |

| Light-Producing Enzyme | Firefly Luciferase (Fluc) | Catalyzes light-emitting reaction with substrate | Bioluminescence Imaging | D-luciferin |

| Fluorescent Protein | Green/Red Fluorescent Protein (GFP, RFP) | Fluoresces upon light excitation | Fluorescence Imaging | None (endogenous) |

Information synthesized from multiple sources on reporter gene technology [18] [19].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Stable Reporter Cell Line Using CRISPR/Cas9

The stability and reliability of lineage tracing data are highly dependent on the quality of the reporter cell line. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing allows for the rapid and precise insertion of a reporter gene cassette into a specific, defined genomic locus, known as a "safe harbor." This method ensures consistent and predictable transgene expression, which is critical for quantitative longitudinal studies [20].

Workflow Overview:

- Guide RNA (gRNA) and Donor Vector Design: Design gRNAs that target a safe harbor locus, such as the AAVS1 or ROSA26 locus. Synthesize a donor vector containing your reporter gene of choice (e.g., Fluc, eGFP) flanked by homology arms complementary to the target site.

- Cell Transfection/Transduction: Co-transfect/co-transduce the target cells (e.g., mesenchymal stem cells, T cells) with the plasmid or mRNA encoding the Cas9 nuclease, the gRNA, and the donor vector.

- Selection and Clonal Expansion: After transfection, apply the appropriate selection antibiotic (e.g., Puromycin) for 7-14 days to eliminate non-transfected cells. Subsequently, seed the cells at a very low density to allow for the isolation and expansion of single-cell-derived clones.

- Validation of Integration: Screen the expanded clones for successful reporter gene integration. Use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to confirm the correct 5' and 3' junction fragments. Further validate the clone with the strongest and most consistent signal via Western blot (to confirm reporter protein expression) and Sanger sequencing (to confirm the integrity of the integrated sequence).

Protocol 2: In Vivo Lineage Tracing of Stem Cells in a Murine Model

This protocol describes the use of an inducible Cre/loxP system for spatiotemporal control of reporter gene activation, enabling precise lineage tracing of specific stem cell populations in live mice [21].

Workflow Overview:

- Animal Model Preparation: Cross-breed two genetically engineered mouse lines: a) a driver mouse expressing CreER recombinase under a tissue-specific promoter (e.g., K14-CreER for skin stem cells), and b) a reporter mouse harboring a LoxP-STOP-LoxP (LSL) cassette upstream of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP, LacZ) at the ROSA26 locus [21] [22].

- Tamoxifen Induction for Sparse Labeling: To achieve clonal, single-cell resolution, administer a low dose of tamoxifen (e.g., 1-5 mg per 25 g body weight, intraperitoneally) to adult mice. Tamoxifen binds to CreER, causing its translocation to the nucleus where it excises the STOP cassette, thereby permanently activating the reporter gene in a sparse, random subset of stem cells [21].

- Long-Term In Vivo Imaging: Anesthetize the mouse and image it using the appropriate modality at regular intervals (e.g., weekly).

- For Fluorescence/Bioluminescence Imaging: Use a cooled CCD camera system. For bioluminescence, inject the substrate (e.g., D-luciferin, 150 mg/kg intraperitoneally) 10 minutes prior to imaging [18] [19].

- For PET/SPECT Imaging: Administer the radiolabeled probe (e.g., ¹⁸F-FHBG for HSV1-tk) intravenously. After a suitable uptake period (e.g., 60 minutes), anesthetize the animal and acquire a static scan [19].

- Data Analysis and Lineage Tree Reconstruction: Coregister images from different time points. Use software to track the spatial location, expansion, and migration of labeled clones over time. The hierarchical relationships between cells can be reconstructed into a lineage tree to visualize the progeny of a single labeled progenitor.

The following diagram maps out this integrated experimental workflow, from genetic engineering to in vivo analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of indirect reporter gene labeling requires a suite of well-characterized reagents. The table below details key materials and their functions in a typical lineage tracing experiment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Reporter Gene-Based Lineage Tracing

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Reporter Genes | Firefly Luciferase (Fluc), HSV1-thymidine kinase (HSV1-tk), Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) | Serves as the genetic marker; its expression produces a protein that generates the detectable signal for tracking cells and their progeny. |

| Inducible Systems | CreER, Tet-On/Off (rtTA/tTA) | Provides spatiotemporal control over reporter gene expression, allowing researchers to initiate labeling at a precise time during development or in response to a stimulus. |

| Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 system (Cas9 nuclease, gRNA) | Enables precise, site-specific integration of the reporter gene construct into the host cell genome, ensuring stable and consistent expression. |

| Imaging Probes | D-luciferin (for Fluc), ¹⁸F-FHBG (for HSV1-tk), ¹²⁴I⁻ (for NIS) | The substrate or ligand that interacts with the reporter protein to produce a signal (e.g., light or radioactivity) detectable by imaging equipment. |

| Cell Lineage Labels | Multicolor Confetti reporter, Brainbow cassette | Allows for the simultaneous tracking of multiple clones within the same organism by stochastically assigning one of several fluorescent colors to a cell and its descendants. |

Application Notes and Technical Considerations

Application in Stem Cell Therapy Monitoring

Indirect reporter gene labeling is indispensable for the preclinical development of stem cell therapies. It allows researchers to answer critical questions about the in vivo behavior of transplanted cells. For instance, in models of myocardial infarction, stem cells engineered with a triple-fusion reporter gene (e.g., combining Fluc, GFP, and HSV1-tk) have been tracked using bioluminescence imaging (BLI) and PET to confirm their engraftment, survival, and proliferation in the infarcted heart [10]. Similarly, in neurological disorders, the fate of transplanted human neural stem cells and their role in promoting brain repair has been elucidated using this technology [11]. The ability to longitudinally monitor the same cohort of animals reduces inter-subject variability and provides robust data on therapeutic cell kinetics.

Pitfalls and Optimization Strategies

- Immunogenicity: Reporter genes of non-human origin (e.g., Fluc, HSV1-tk) can elicit an immune response that leads to the elimination of the labeled cells, confounding long-term data. Strategy: Use human-derived reporter genes (e.g., human mitochondrial thymidine kinase 2 [hTK2], human deoxycytidine kinase [hdCK]) where possible to minimize immune recognition [19].

- Signal Dilution in Differentiating Cells: As stem cells differentiate, the promoter driving the reporter gene may become silenced, leading to signal loss that is not due to cell death. Strategy: Drive reporter expression with a ubiquitous and constitutive promoter (e.g., EF1α, CAG) to ensure expression in all progeny, regardless of differentiation state.

- Position Effect Variegation: Random integration of the reporter construct can lead to variable expression levels due to influences from surrounding chromatin. Strategy: Use CRISPR/Cas9 to target safe harbor loci (e.g., AAVS1, ROSA26), which provide a more predictable and consistent expression environment [20].

- Phototoxicity and Tissue Attenuation (Optical Imaging): Extended exposure to excitation light in fluorescence imaging can damage cells, and light scattering limits imaging in deep tissues. Strategy: For long-term live imaging, use bioluminescence or red-shifted fluorescent proteins, and optimize imaging intervals and exposure times to minimize photodamage [23].

The advancement of stem cell therapies hinges on the ability to non-invasively monitor administered cells in vivo. Molecular imaging serves as a powerful tool for examining complex cellular processes, understanding disease mechanisms, and evaluating the kinetics of cell therapies [24]. For researchers and drug development professionals, defining the ideal imaging agent is paramount. Such an agent must harmonize three core principles: biocompatibility (minimal impact on cell viability, function, and the host organism), specificity (accurate targeting and distinction from background signals), and sensitivity (detection of low cell numbers at high resolution) [24] [11]. This Application Note delineates these parameters within the context of stem cell tracking, providing structured data and detailed protocols to guide experimental design.

Core Principles of an Ideal Imaging Agent

The performance of an imaging agent is evaluated against a set of interdependent criteria. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of an ideal agent for stem cell tracking.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of an Ideal Imaging Agent for Stem Cell Tracking

| Characteristic | Description | Importance in Stem Cell Tracking |

|---|---|---|

| High Sensitivity | Ability to detect a small number of labeled cells [11]. | Enables monitoring of initial cell engraftment and long-term survival at low cell densities. |

| High Specificity | Clear distinction of the signal from the labeled cells against the biological background [24]. | Accurately determines cell location, migration, and homing to target tissues. |

| Excellent Biocompatibility | Non-toxic to the cell and the host, with no alteration of cell biology (e.g., viability, proliferation, differentiation potential) [24] [11]. | Ensures that the therapeutic effect is not compromised and that observed effects are due to the therapy, not the label. |

| Capacity for Long-Term Monitoring | The label is retained within the cell and remains detectable for the duration of the study [24]. | Allows for longitudinal studies in the same subject, tracking the entire fate of the administered cells. |

| Quantification Capability | The signal intensity should correlate with the number of labeled cells [25]. | Provides quantitative data on cell survival and proliferation over time. |

Comparative Analysis of Imaging Modalities

No single imaging modality excels in all categories; each presents a unique balance of strengths and weaknesses. The choice of modality depends on the specific research question, whether it is short-term homing or long-term viability and proliferation [11].

Table 2: Comparison of Imaging Modalities for Stem Cell Tracking

| Imaging Modality | Typical Spatial Resolution | Typical Penetration Depth | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages & Biocompatibility Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | 1 mm [26] / 25-100 µm [25] | 50 cm [26] | High spatial resolution; excellent soft-tissue contrast; deep penetration [24] [26]. | Low sensitivity, requiring high labeling agent load (e.g., SPIOs); potential impact of SPIOs and magnetic fields on stem cell biology (e.g., altered differentiation) [11]. |

| Positron Emission Tomography (PET) | 5 mm [26] / 1-2 mm [25] | 50 cm [26] | Very high sensitivity (picomolar); quantitative; deep penetration [24] [25]. | Use of ionizing radiation; limited spatial resolution; radiotracer half-life limits duration of tracking (hours to days) [24] [25]. |

| Optical Imaging (Bioluminescence/Fluorescence) | 1 mm [26] / 1 µm [25] | 1-2 mm [26] | High sensitivity; low cost; ease of use; suitable for reporter genes [25] [26]. | Limited tissue penetration due to light scattering; primarily suitable for small animals [25]. |

| Photoacoustic Tomography (PAT) | 0.1 mm [26] | 10 cm [26] | Good resolution at depth; high functional and chemical sensitivity [26]. | Relatively new technology; requires coupling medium; limited clinical translation [25] [26]. |

| Ultrasound (US) | 0.3 mm [26] | 10 cm [26] | Real-time imaging; high speed; deep penetration; safe and inexpensive [26]. | Low intrinsic sensitivity and chemical specificity for cell tracking; often requires contrast agents like microbubbles [26]. |

Experimental Protocols for Agent Evaluation

Protocol 1: Direct Labeling of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) with Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (SPIONs) for MRI

This protocol details the direct labeling of MSCs with SPIONs, a common approach for tracking cell delivery and short-term homing with MRI [24] [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Primary cell type for therapy and tracking studies [24]. |

| SPIONs (e.g., Ferucarbotran) | MRI contrast agent; shortens T2 relaxation time, creating dark contrast on T2-weighted images [25]. |

| Protamine Sulfate | Transfection agent; enhances cellular internalization of SPIONs via endocytosis [25]. |

| Cell Culture Medium (e.g., DMEM) | Provides nutrients and environment for maintaining cells during labeling. |

| Philips iU22 or GE Logiq E9 US System | For initial guidance of cell delivery, if required [27] [11]. |

| High-Field MRI Scanner (≥7T) | For high-resolution in vivo tracking of SPION-labeled cells [26]. |

Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Culture human MSCs in standard medium until 70-80% confluent [24].

- Labeling Complex Formation: Incubate SPIONs (e.g., 50-100 µg Fe/mL) with protamine sulfate (e.g., 5-10 µg/mL) in serum-free medium for 30-60 minutes at 37°C to form the labeling complex [25].

- Cell Labeling: Replace the culture medium with the SPION-protamine complex solution. Incubate cells for 4-24 hours under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂) [25].

- Washing and Harvesting: After incubation, wash cells thoroughly with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove excess particles. Harvest cells using standard trypsinization procedures [24].

- Quality Control: Determine labeling efficiency and iron load per cell using techniques like Prussian Blue staining or mass spectrometry [11]. Validate that labeling does not adversely affect cell viability (e.g., >95% via trypan blue exclusion) and key functions such as differentiation potential [11].

- In Vivo Imaging: Administer the labeled MSCs (e.g., via intramyocardial injection). Acquire T2*-weighted MRI sequences to track the cells as hypointense (dark) signals [25].

Protocol 2: Reporter Gene Imaging of Stem Cell Viability Using Bioluminescence

This protocol employs genetic engineering to express a reporter gene (luciferase), enabling long-term monitoring of cell viability and location via bioluminescence imaging (BLI) [25] [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Stem Cell Line (e.g., Neural Stem Cells) | Genetically modifiable cells for long-term tracking studies [11]. |

| Lentiviral Vector with Luciferase Reporter | Mediates stable integration of the luciferase gene into the host cell genome [25]. |

| D-Luciferin (Firefly substrate) | Enzyme substrate; produces bioluminescent light (photons) upon interaction with luciferase [25]. |

| In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) | Highly sensitive CCD camera for detecting low-light bioluminescence signals from live animals [25]. |

| Living Image Software | For quantifying photon flux (photons/second) as a measure of cell viability and number [25]. |

Methodology:

- Genetic Modification: Transduce stem cells with a lentiviral vector encoding the firefly luciferase (Fluc) reporter gene under a constitutive promoter. Select stable populations using an appropriate antibiotic (e.g., puromycin) [25].

- Validation: Confirm reporter gene expression and function in vitro by adding D-luciferin (e.g., 150 µg/mL) to culture media and detecting bioluminescence.

- Cell Transplantation: Administer the engineered stem cells into the target organ of an animal model (e.g., rat model of brain injury) [11].

- In Vivo Imaging: At designated time points, inject the animal intraperitoneally with D-luciferin (e.g., 150 mg/kg). Anesthetize the animal and place it in the IVIS chamber. Acquire images 10-20 minutes post-injection, using a 1-second to 5-minute acquisition time [25].

- Quantification and Analysis: Use software (e.g., Living Image) to define a region of interest (ROI) and quantify the total photon flux. Correlate signal intensity with cell viability and number [25] [11].

Decision Framework and Advanced Concepts

Choosing an Imaging Strategy

The decision between direct labeling and reporter gene imaging is fundamental. Direct labeling (e.g., with SPIONs, radionuclides, or quantum dots) is ideal for tracking the initial delivery and short-term homing of cells, as the signal is strong and immediate. However, the signal does not indicate cell viability and dilutes with cell division [24] [11]. Reporter gene imaging, while requiring genetic modification, is superior for long-term monitoring as the signal is directly tied to viable, functioning cells and is not diluted upon proliferation [11].

Mechanism of a Novel Bio-Responsive Imaging Agent

Innovative agents are being developed to detect specific pathophysiological conditions. The following diagram illustrates the mechanism of a dual 31P/19F-MR bio-responsive polymer probe designed to detect reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are abundant in inflammation and cancer [28].

The "ideal" imaging agent for stem cell tracking is context-dependent, defined by the specific therapeutic question. While direct labeling agents like SPIONs offer a practical solution for monitoring cell delivery, reporter genes provide unparalleled insight into long-term cell fate. The future of the field lies in the development of multimodal agents [24] [25] and smart, bio-responsive probes [28] that combine high sensitivity and specificity with the ability to report on the functional state of both the administered cells and their microenvironment. By adhering to the core principles of biocompatibility, specificity, and sensitivity, researchers can robustly track stem cells and accelerate the translation of regenerative therapies from the bench to the bedside.

The Imaging Toolkit: Modalities, Protocols, and Real-World Applications

The administration of exogenous stem cells offers significant promise for regenerating damaged organs, particularly in the context of cardiovascular disease and ischemic stroke [29] [30]. However, the failure of many cellular therapies in clinical trials can be attributed to uncertainties regarding stem cell fate post-transplantation, including their survival, migration, and engraftment at target sites [29] [31]. Non-invasive monitoring is therefore critical for optimizing therapeutic protocols. Among the available imaging modalities, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) provides high anatomical resolution and unlimited depth penetration, making it an ideal platform for tracking cells in vivo [32]. When combined with Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (SPIONs) as contrast agents, MRI enables the serial, non-invasive monitoring of accurately delivered cell therapeutics, offering profound insights into their biodistribution and persistence [29] [33]. This application note details the methodologies and protocols for utilizing SPIONs to track stem cells, framed within the broader thesis of advancing in vivo imaging techniques for regenerative medicine.

SPIONs as Contrast Agents

Mechanism of Action and Physicochemical Properties

SPIONs are composed of an iron oxide core, typically magnetite (Fe₃O₄) or maghemite (γ-Fe₂O₃), coated with a biocompatible polymer such as dextran, carboxydextran, or siloxanes [33] [34] [35]. Their superparamagnetic property means they become highly magnetic under an external magnetic field but retain no residual magnetism once the field is removed, which prevents aggregation and facilitates their use in biological systems [31]. As MRI contrast agents, SPIONs primarily act as potent T2 agents, creating strong local magnetic field inhomogeneities that dephase nearby water protons, resulting in a pronounced signal void (hypointensity) on T2- and T2*-weighted MR images [29] [33] [34]. This "blooming artifact" amplifies the detectable area beyond the physical volume of the nanoparticles themselves, significantly enhancing MRI sensitivity and allowing for the detection of single or small clusters of labeled cells [32].

Table 1: Commercially Available and Representative SPION Formulations for Cell Labeling

| Brand/Name | Coating Material | Hydrodynamic Size (nm) | Classification | Primary Application/Target | Relaxivity, r2 (mM⁻¹s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferumoxides (Feridex, Endorem) | Dextran | 120-180 | SPIO | Liver, Stem Cell Labeling | ~160 [33] |

| Ferucarbotran (Resovist) | Carboxydextran | ~60 | SPIO | Liver, Stem Cell Labeling | N/A |

| Ferumoxytol (Feraheme) | Carboxymethyl-dextran | ~30 | USPIO | Macrophage, Blood Pool | N/A |

| Sinerem (AMI-227) | Dextran | 15-30 | USPIO | Blood Pool, Lymph Node | N/A |

| ProMag (MPIO) | Polystyrene | 1000-1730 | MPIO | Cell Labeling | N/A |

| VivoTrax | Moldable | ~28 | SPIO | MPI/MRI Cell Tracking | N/A |

The surface engineering of SPIONs is paramount to their in vivo performance. The coating determines the particles' colloidal stability, circulation half-life, and ability to overcome biological barriers [35]. Furthermore, surface functionalization with cations or transfection agents facilitates the efficient internalization of SPIONs into non-phagocytic stem cells, such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and neural stem cells (NSCs) [29] [33].

Quantitative Performance of SPIONs

The effectiveness of SPIONs for cell tracking is quantified by their relaxivity (r2) and the achievable cellular iron load. These factors directly influence the minimum number of cells detectable by MRI.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics of Selected SPIONs for Stem Cell Labeling

| SPION Type / Formulation | Core Diameter (nm) | Overall Size (nm) | Zeta Potential (mV) | Typical Iron Load (pg Fe/Cell) | Approximate Detection Limit (Cells) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferumoxides-PLL [33] | 6.2 | N/A | -42 | 41.5 | ~10³ [32] |

| N-dodecyl-PEI2k/SPIO [33] | N/A | 54.7 | +40 | 7.1 | N/A |

| CMCS-SPIONs [33] | 6-10 | 55.4 | -21.4 | 26.7 | N/A |

| IONP-6PEG-HA [33] | 10 | 75 | -9.1 | ~14,590 | N/A |

| Synomag-D (in cells) [36] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1,000 (MPI) |

| ProMag (MPIO) (in cells) [36] | N/A | >1000 | N/A | N/A | 250 (MPI) |

Experimental Protocols for Stem Cell Labeling and Tracking

SPION Labeling of Stem Cells

Efficient labeling of stem cells is a prerequisite for successful tracking. The following protocols describe two established methods: magnetofection and magnetoelectroporation (MEP).