iPSC Disease Modeling for Rare Genetic Disorders: From Patient Cells to Precision Therapies

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on utilizing induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to model rare genetic diseases.

iPSC Disease Modeling for Rare Genetic Disorders: From Patient Cells to Precision Therapies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on utilizing induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to model rare genetic diseases. It covers the foundational rationale for iPSC use, given that over 80% of rare diseases have a genetic origin and fewer than 10% have approved therapies. The content details methodological advances in reprogramming, 2D/3D differentiation, and organoid generation, illustrated with case studies across neurological, renal, and cardiovascular disciplines. It further addresses critical troubleshooting aspects, such as managing genomic instability and optimizing cell maturation, and evaluates the validation and comparative power of iPSC models against traditional methods. Finally, it discusses the integration of these models into drug discovery pipelines and their growing utility in the wake of regulatory shifts like the FDA Modernization Act 2.0.

The Imperative for iPSCs in Tackling the Rare Disease Challenge

Rare diseases, though individually uncommon, collectively represent a significant global health challenge affecting hundreds of millions of people worldwide. These conditions are characterized by their diversity, complexity, and the substantial diagnostic and therapeutic gaps that plague the rare disease community. With the recent declaration of rare diseases as a global health priority by the World Health Assembly, there is renewed impetus to address the unmet needs of this population [1]. This whitepaper examines the current landscape of rare diseases, focusing on their collective prevalence, phenotypic and genotypic diversity, and the critical shortage of effective treatments. Against this backdrop, we explore the emerging role of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology as a transformative platform for rare disease research and therapeutic development.

The Scale and Impact of Rare Diseases

Global Prevalence and Definition

While definitions vary globally, rare diseases are universally recognized by their low prevalence, with estimates ranging from 40-50 cases per 100,000 people depending on the jurisdiction [2]. The collective burden, however, is substantial, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Global Rare Disease Burden and Characteristics

| Metric | Global Statistics | References |

|---|---|---|

| Total Number of Distinct Rare Diseases | 7,000 - 10,000 | [3] [4] |

| Global Prevalence | 263 - 446 million people (3.5% - 5.9% of world population) | [1] [3] [2] |

| Diseases with Genetic Origin | Approximately 80% | [3] [4] |

| Diseases with Pediatric Onset | 50% - 75% | [2] |

| Diseases with Approved Therapies | Less than 10% | [3] [4] [5] |

The recent adoption of the first-ever rare diseases resolution by the World Health Assembly marks a landmark recognition of this public health issue, urging countries to integrate rare diseases into national health planning and accelerate research and innovation [1].

Socioeconomic and Healthcare Burden

The impact of rare diseases extends far beyond prevalence statistics, creating profound challenges for patients, healthcare systems, and societies:

- Diagnostic Odyssey: Patients typically experience diagnostic delays of 5-7.6 years, consulting with an average of 8 physicians and receiving 2-3 misdiagnoses before obtaining a correct diagnosis [2]. In Europe, 25% of patients wait between 5 and 30 years from symptom onset to diagnosis [2].

- Economic Impact: Rare diseases exert a significant financial burden on healthcare systems globally, with per-patient-per-year healthcare costs up to 10 times greater than for more common diseases [3] [4]. Orphan drugs are reported to be as high as 13.8 times more expensive than conventional medications [2].

- Psychosocial Consequences: The various disabilities arising from these conditions lead to significant physical, emotional, and financial hardship for patients and families [1]. Stigma, discrimination, and social isolation are commonly reported by both patients and caregivers [2].

The Therapeutic Gap and Research Challenges

Despite affecting hundreds of millions globally, the rare disease community faces a vast therapeutic gap, with fewer than 10% of diagnosed rare diseases having suitable drug treatments [3] [4] [5]. This gap stems from multiple fundamental research challenges:

- Small Patient Populations: Limited numbers of patients for clinical studies complicate traditional research approaches and drug development pathways [6].

- Limited Biological Samples: Access to patient-derived biological materials for research is often severely restricted [6].

- Inadequate Disease Models: Many rare diseases lack physiologically relevant models that accurately recapitulate human disease pathophysiology [6].

- Economic Disincentives: The small market opportunity for each individual rare disease provides limited commercial incentive for biopharmaceutical investment [2].

The recent FDA Modernization Act 2.0, which allows therapeutics to be tested in cell-based assays without mandatory animal testing, has created new opportunities for innovative approaches to rare disease research, particularly favoring human-relevant models like iPSCs [3] [4].

iPSC-Based Disease Modeling: A Path Forward

Foundations of iPSC Technology for Rare Diseases

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are adult somatic cells that have been reprogrammed to a pluripotent state, capable of differentiating into virtually any cell type in the human body [7]. For rare diseases, approximately 80% of which have genetic origins, patient-derived iPSCs and their isogenic controls represent unique model systems for mechanistic studies and therapeutic development [3] [4].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC-Based Rare Disease Modeling

| Research Reagent | Function in Rare Disease Research |

|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Introduce pluripotency (e.g., via Sendai virus or mRNA) to convert patient somatic cells to iPSCs. |

| Differentiation Kits | Direct iPSCs toward specific lineages (e.g., neuronal, cardiac, renal) affected by rare diseases. |

| Gene Editing Tools | Create isogenic controls (CRISPR-Cas9) or introduce specific mutations into control iPSC lines. |

| Extracellular Matrix | Provide physiological scaffolding for 2D culture or 3D organoid formation (e.g., Matrigel). |

| Cytokines/Growth Factors | Pattern iPSC differentiation toward specific tissue fates through controlled signaling exposure. |

The utility of iPSC-based models spans multiple research applications, including disease mechanism elucidation, drug screening and toxicity studies, and the development of personalized therapeutic approaches [3] [4] [7].

Experimental Design and Workflow

A robust iPSC-based disease modeling workflow requires careful experimental design, particularly regarding the number of biological replicates needed to achieve statistically significant results. Recent empirical evidence using RNA sequencing data from Lesch-Nyhan disease models suggests that optimal results are obtained with iPSC lines from 3-4 unique individuals per group, with 2 lines per individual recommended without statistical corrections for multiple lines from the same donor [8].

The workflow begins with obtaining patient somatic cells (typically through skin biopsy or blood draw), followed by reprogramming using defined factors to generate iPSCs. These iPSCs are then expanded and characterized before being directed toward disease-relevant cell types using specific differentiation protocols. The resulting models enable various research applications, including mechanistic studies, drug screening, and personalized medicine approaches [8] [3] [4].

Applications in Specific Rare Diseases

iPSC-based models have demonstrated particular utility for studying rare diseases affecting tissues and organs that are difficult to access in patients. Notable examples include:

- Juvenile Nephronophthisis (NPH): Researchers developed the first human NPH disease models using patient-derived iPSCs and gene-edited iPSCs differentiated into kidney organoids. These models demonstrated that NPHP1-deficient cells exhibit abnormal cell proliferation, primary cilia abnormalities, and renal cyst formation - key disease phenotypes that were reversed upon NPHP1 reintroduction [3] [4].

- RDH12-associated Retinitis Pigmentosa: Retinal organoids derived from patient iPSCs carrying dominant RDH12 mutations showed reduced photoreceptor numbers, shortened photoreceptor length, and disruptions in the vitamin A pathway, replicating features of the human disease [3] [4].

- Lesch-Nyhan Disease: Transcriptomic analysis of iPSC models revealed disease-relevant changes in gene expression patterns, providing insights into underlying molecular mechanisms [8].

Integrating iPSC Models with Advanced Computational Approaches

The convergence of iPSC technology with advanced computational methods represents the next frontier in rare disease research. In silico technologies - including mechanistic models, machine learning, and digital twins - offer scalable tools for disease characterization, drug discovery, and virtual trials that complement experimental approaches [6]. These computational methods are particularly valuable for rare diseases, where limited patient numbers constrain traditional research.

This integrated approach enables a bidirectional workflow where standardized data from iPSC models parameterize computational models, and model predictions subsequently guide the next round of experimental investigation. This creates a virtuous cycle that maximizes the utility of scarce patient-derived materials and accelerates therapeutic development [6].

Addressing Diversity and Equity in Rare Disease Research

Despite technological advances, significant challenges remain in ensuring equitable representation in rare disease research. Patients from historically marginalized communities face additional barriers to diagnosis and care, and are often underrepresented in research studies [5]. This lack of diversity has implications for the generalizability of findings and the effectiveness of therapies across populations.

Recent initiatives like the Rare Disease Diversity Coalition (RDDC) are working to address these disparities through systemic change focused on diversity in research and clinical trials, improving the patient and caregiver journey, and advocating for supportive legislation [5]. The development of updated demographic categories that better capture global diversity in rare disease patient registries represents another step toward more inclusive research practices [9].

A 2025 probability-based national survey in the United States found that 8% of U.S. adults report living in a household affected by rare disease, with an additional 7% living with undiagnosed illnesses [10]. These households are more likely to adopt innovative healthcare technologies, including telehealth (63% vs. 45% in non-rare disease households) and AI tools for health information (38% vs. 21%), demonstrating their role as early adopters in the healthcare ecosystem [10].

The global burden of rare diseases represents a critical challenge and opportunity for the biomedical research community. While the therapeutic gap remains substantial, emerging technologies like iPSC-based disease models offer unprecedented opportunities to understand disease mechanisms and develop new treatments. The recent policy recognition of rare diseases as a global health priority, combined with scientific advances in stem cell biology and computational medicine, creates a fertile environment for progress.

Future directions for the field include developing more sophisticated differentiation protocols to generate mature cell types that better reflect adult disease states, improving 3D organoid systems to capture tissue-level complexity, and strengthening international collaboration to share resources and data. As these efforts advance, iPSC-based approaches are poised to play an increasingly central role in narrowing the therapeutic gap for the hundreds of millions affected by rare diseases worldwide.

Rare diseases present a formidable challenge to the global healthcare system. With an estimated 7,000–10,000 distinct rare diseases identified, their collective prevalence is substantial, affecting between 263–446 million individuals worldwide [4]. Approximately 80% of these conditions have a genetic origin, yet less than 10% have approved therapies, creating a significant therapeutic gap [4]. Traditional research models, including animal studies and immortalized cell lines, have proven insufficient for addressing these conditions due to species-specific differences, limited availability of patient biological samples, and inability to recapitulate human pathophysiology accurately [11]. The emergence of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has introduced a powerful platform that directly addresses these challenges through patient-specific, scalable, and physiologically relevant human disease models.

iPSCs are adult somatic cells that have been reprogrammed to a pluripotent state, capable of differentiating into virtually any cell type in the human body [12]. This breakthrough technology, first developed by Takahashi and Yamanaka in 2006, has since evolved into a sophisticated tool for disease modeling, drug discovery, and therapeutic development [12]. For rare genetic disorders specifically, iPSC-based models offer unique advantages that are transforming our approach to understanding disease mechanisms and developing effective treatments.

Core Advantages of iPSC Technology

Patient-Specificity

The genetic makeup of iPSCs mirrors that of the donor, making them exceptionally valuable for studying genetic rare diseases. Researchers can generate iPSCs directly from patients with rare genetic conditions, creating cell lines that carry the exact mutations responsible for the disease [11] [7]. This patient-specificity enables several critical applications:

Accurate Disease Modeling: iPSCs derived from patients with known genetic mutations allow researchers to study disease mechanisms in a human genetic context. For example, in a study of Lesch-Nyhan disease (caused by mutations in the HPRT1 gene), patient-derived iPSCs provided crucial insights into disease-relevant changes in gene expression [8].

Isogenic Controls: Through CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, researchers can correct disease-causing mutations in patient-derived iPSCs to create genetically matched control lines [12] [13]. This powerful approach allows for precise comparison between diseased and corrected cells, eliminating the confounding effects of genetic background variability. This methodology has been successfully applied in disease modeling for Parkinson's disease, where the A53T SNCA mutation was corrected in patient-derived iPSCs for mechanistic studies [12].

Personalized Therapeutic Screening: Patient-specific iPSC models enable drug testing on the exact genetic background of an individual, allowing for personalized assessment of therapeutic efficacy and toxicity [7].

A significant challenge in rare disease research is the limited availability of biological samples from affected patients. iPSC technology fundamentally addresses this limitation through:

Indefinite Expansion: Once established, iPSC lines can be expanded indefinitely in culture, providing a renewable source of biological material for research [14]. This is particularly crucial for rare diseases, where patient numbers are small and primary tissue samples are extremely scarce.

High-Throughput Applications: Differentiated iPSC-derived cells can be scaled for drug discovery efforts, including high-throughput screening campaigns. These cells can be plated in 384- or 1536-well formats, imaged automatically, and analyzed using high-content imaging systems to extract rich phenotypic data at scale [14].

Biobanking: iPSCs from patients with rare genotypes/phenotypes can be stored in biobanks as a resource for genotype/phenotype correlation analyses, study of rare mutations, and development of precision medicine applications [11].

Table 1: Scalability Applications of iPSC Technology in Rare Disease Research

| Application | Scale | Utility | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Screening | 384- to 1536-well plates | High-throughput compound testing | Identification of compounds rescuing neuronal function in neurodegenerative diseases [14] |

| Biobanking | Multiple cell lines from various patients | Resource for rare disease research | Storage of patient-specific iPSCs for genotype/phenotype studies [11] |

| Clinical Translation | GMP-manufactured cell batches | Therapeutic development | Manufacturing of clinical-grade iPSC-derived products for transplantation [15] |

Physiological Relevance

iPSC-derived models offer unprecedented physiological relevance compared to traditional in vitro systems:

Human Biology: iPSC-derived cells maintain human genotype and often demonstrate complex functional behaviors that immortalized lines cannot replicate, such as spontaneous contraction in cardiomyocytes or synaptic firing in neurons [14].

2D vs. 3D Model Systems: iPSCs can be differentiated into both two-dimensional monolayer cultures and three-dimensional organoids, each offering distinct advantages for disease modeling. While 2D cultures are cost-effective and easily manageable for initial drug assessment, 3D organoids offer a more natural environment with cell-to-cell and cell-to-extracellular matrix interactions that better mimic human organ/tissue architecture [11].

Disease-Relevant Phenotypes: iPSC-derived models successfully replicate key disease features. For instance, in Juvenile Nephronophthisis (NPH), NPHP1-deficient iPSCs exhibited abnormal cell proliferation, abnormalities in primary cilia, and renal cyst formation in iPSC-derived kidney organoids – all clinically relevant phenotypes [4]. Similarly, in a rare form of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (RDH12-AD), retinal organoids exhibited reduced photoreceptor number, shortened photoreceptor length, and disruptions in the vitamin A pathway, reflecting the disease course seen in patients [4].

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Establishing Robust iPSC-Based Rare Disease Models

Creating reliable iPSC models for rare diseases requires careful experimental design. A 2025 study on Lesch-Nyhan disease used gene expression profiles determined by RNA sequencing to empirically evaluate the impact of the number of unique individuals and replicate iPSC lines needed for robust results [8]. The findings provide crucial guidance for the field:

Optimal Line Numbers: The best results were obtained with iPSC lines from 3-4 unique individuals per group, with 2 lines per individual [8]. This approach helps account for both inter-individual genetic variability and technical reproducibility.

Technical Variance Management: The study revealed that when all lines were produced in parallel using the same methods, most variance in gene expression came from technical factors unrelated to the individual from whom the iPSC lines were prepared [8]. This highlights the importance of standardizing reprogramming and differentiation protocols.

Analytical Considerations: Results for detecting disease-relevant changes in gene expression depended on the analytical method employed, emphasizing the need for appropriate statistical approaches in experimental design [8].

iPSC Reprogramming and Differentiation Workflows

The fundamental process of creating iPSC-based disease models involves multiple critical steps, each requiring specific reagents and quality control measures:

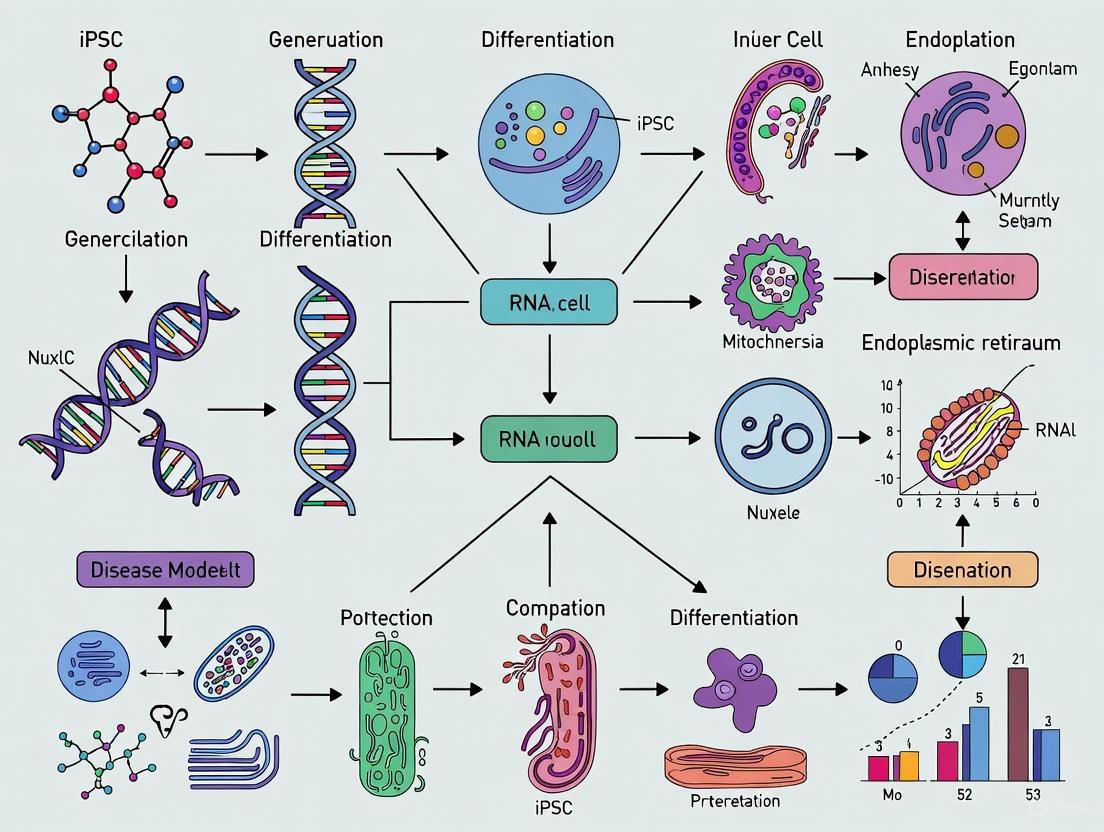

Diagram 1: iPSC Modeling Workflow

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC-Based Rare Disease Modeling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM) | Dedifferentiation of somatic cells to pluripotent state | Non-integrating delivery methods (episomal plasmids, mRNA) preferred for clinical translation [12] |

| Extracellular Matrices | Laminin-521, Matrigel | Provide structural support and biochemical cues for cell growth and differentiation | Laminin-521 used in clinical-grade process development [16] |

| Differentiation Factors | Tissue-specific growth factors, small molecules | Direct lineage-specific differentiation | BMP4, activin A for germ layer specification; protocol-specific factors for target tissues [11] |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Create isogenic controls through precise genetic modification | Enables correction of disease-causing mutations in patient-derived iPSCs [12] [13] |

| Analytical Tools | Single-cell RNA sequencing, high-content imaging | Quality control and phenotypic assessment | scRNA-seq used to demonstrate consistency of cellular outcomes [16] |

Advanced 3D Model Development

For many rare diseases, 3D organoid models provide superior physiological relevance compared to traditional 2D cultures. The general procedure for generating organoids involves:

Germ Layer Specification: iPSCs are directed toward a specific embryonic germ layer (ectoderm, mesoderm, or endoderm) using selected factors that activate cell differentiation commitment, such as WNT, BMP4, and activin A [11].

Tissue-Specific Differentiation: Cells are differentiated into the target tissue/organ through the addition of tissue-specific growth factors and small molecules [11].

3D Structure Formation: Cells are embedded in an ECM gel or aggregated in a 3D structure using scaffold-forming external biomaterials to allow self-organization [11].

This approach has been successfully applied to model rare neurological disorders, such as Hereditary Sensory and Autonomic Neuropathy Type IV (HSAN IV), using dorsal root ganglia (DRG) organoids derived from patient-specific iPSCs [13]. These organoids revealed that NTRK1 mutations disrupt the balance of neuronal and glial differentiation in human DRG during development, providing crucial insights into disease mechanisms [13].

Applications in Rare Disease Research and Drug Development

Disease Mechanism Elucidation

iPSC-based models have enabled groundbreaking insights into the pathophysiology of numerous rare diseases:

Juvenile Nephronophthisis (NPH): Using patient-derived iPSCs and kidney organoids, researchers demonstrated that NPHP1 deficiency leads to abnormal cell proliferation, primary cilia abnormalities, and renal cyst formation. Importantly, reintroduction of NPHP1 expression reversed cyst formation, confirming the gene's role in disease pathogenesis and validating the model system [4].

Neurexin 1 (NRXN1)-Related Disorders: To study the influence of the same mutation in different genetic backgrounds, researchers developed "village editing" – CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in a cell village format – generating NRXN1 knockouts in iPSC lines from 15 donors with varying polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia. This approach demonstrated that genetic background deeply influences gene expression changes in NRXN1 knockout neurons [13].

Usher Syndrome and Marfan Syndrome: Comprehensive reviews highlight how iPSC-based models have advanced understanding of these rare conditions, offering valuable insights into disease mechanisms and potential for discovering new therapies [4].

Drug Discovery and Toxicity Testing

iPSC-based models are increasingly integrated into drug development pipelines for rare diseases:

Cardiac Safety Screening: iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes are now used routinely to screen for drug-induced arrhythmia risk and have been integrated into regulatory safety initiatives like CiPA (Comprehensive in vitro Proarrhythmia Assay) [14].

Phenotypic Screening: iPSC-derived neurons from patients with Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and ALS are used in phenotypic screens that have identified compounds capable of rescuing neuronal function in vitro [14]. Similar approaches are being applied to rare diseases.

Drug Repurposing: iPSC-derived hepatocyte-like cells have been used to model familial hypercholesterolemia, revealing that cardiac glycosides reduced ApoB secretion – identifying a potential drug repurposing opportunity [14].

The regulatory landscape is also evolving to support these applications. The FDA Modernization Act 2.0 allows therapeutics to be tested in cell-based assays without the need for animal testing for progression to clinical trials, which is likely to further drive interest in iPSC-based models for rare disease studies [4].

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the considerable promise of iPSC technology, several challenges remain to be addressed:

Maturation Limitations: Many iPSC differentiation protocols yield cells with fetal-like phenotypes, which may not fully recapitulate late-onset disease aspects [14]. Developing novel technologies to precisely control the maturation of specific cell types is crucial for both drug screening and mechanistic studies [4].

Standardization and Reproducibility: Protocols for iPSC culture and differentiation are improving but still not uniform across laboratories. Efforts to benchmark electrophysiological performance or gene expression signatures are underway but not yet universal [14].

Technical Demands and Cost: iPSC models are technically demanding to create and maintain, with media, reagents, and culture time contributing to significant costs, particularly for HTS-scale assays [14] [7].

Model Complexity: While 3D organoids better recapitulate tissue architecture, they often lack proper vascularization, resulting in necrosis and apoptosis of some cells [11]. They also show considerable variation from batch to batch, limiting reproducibility [11].

Future advancements are likely to focus on enhancing model complexity through the development of assembloids (connecting organoids of different lineages), improving vascularization, and integrating immune system components. Additionally, the combination of iPSC technology with artificial intelligence and machine learning for automated colony morphology classification and differentiation outcome prediction will enhance standardization, quality control, and reproducibility in iPSC manufacturing [12].

iPSC-based model systems represent a transformative approach for rare disease research, addressing fundamental limitations of traditional models through their unique combination of patient-specificity, scalability, and physiological relevance. As the technology continues to evolve with improvements in gene editing, differentiation protocols, and analytical techniques, iPSCs are poised to accelerate our understanding of rare disease mechanisms and the development of effective treatments. For the 94% of rare diseases that currently lack approved therapies, these advances offer renewed hope for patients and researchers alike [4]. The ongoing collaboration between clinicians, geneticists, and stem cell biologists will be essential to fully realize the potential of iPSC technology in overcoming the challenges of rare disease research.

Rare diseases, often perceived as a collection of isolated medical curiosities, represent a significant and cumulative global health challenge. While individually defined by their low prevalence—affecting fewer than 5 in 10,000 people in Europe or fewer than 200,000 people in the United States—they are collectively common [17]. Recent epidemiological studies estimate that there are between 7,000 and 10,000 distinct rare diseases, cumulatively affecting 263–446 million individuals worldwide, which corresponds to a global prevalence of 3.5–6% [3]. This substantial burden is further magnified by a critical therapeutic gap; less than 10% of these diseases have approved therapies, leaving the vast majority of patients without effective treatment options [3] [17]. Moreover, rare diseases exert a significant financial strain on healthcare systems, as the per-patient-per-year healthcare cost can be up to 10 times greater than that of more common diseases [3].

The exploration of this therapeutic chasm is tightly linked to the fundamental genetic origin of these conditions. Approximately 80% of rare diseases have a genetic basis, with a majority being monogenic—caused by defects in a single gene [3] [17]. This high degree of genetic determinism, while complicating the clinical landscape, provides a clear scientific entry point for research. It creates an ideal scenario for modeling diseases in vitro, as the pathogenic trigger can often be traced to a specific, identifiable genetic variant. The discovery of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has therefore revolutionized the field, offering a patient-specific, scalable, and physiologically relevant preclinical model system to elucidate disease mechanisms and screen potential therapeutics [3] [18]. This whitepaper details how the genetic architecture of rare diseases makes iPSCs an unparalleled model system for accelerating research and drug development.

The Genetic Landscape of Rare Diseases

The following table summarizes the key epidemiological and genetic characteristics that define the challenge of rare diseases and highlight the rationale for iPSC-based modeling.

Table 1: Epidemiological and Genetic Landscape of Rare Diseases

| Aspect | Global Statistics | Implication for Disease Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Total Number of Diseases | 7,000 - 10,000 distinct conditions [3] | Vast diversity requires scalable and flexible research models. |

| Cumulative Prevalence | 263 - 446 million people affected (3.5-6% global prevalence) [3] | Significant collective health impact justifies major research investment. |

| Genetic Origin | ~80% are genetic, mostly monogenic [3] [17] | Provides a direct and traceable target for mechanistic studies. |

| Therapeutic Gap | >90% of rare diseases lack an approved therapy [3] | Highlights a critical unmet medical need and a large field for drug discovery. |

| Economic Burden | Per-patient costs can be up to 10x higher than common diseases [3] | Underlines the economic incentive for developing effective treatments. |

The Imperative for Advanced Model Systems

The predominance of genetic drivers in rare diseases necessitates biological models that can accurately recapitulate human pathophysiology. Traditional approaches, including animal models and immortalized cell lines, have provided valuable insights but are often hampered by substantial limitations. Animal models may not fully replicate human disease due to anatomic, embryonic, and metabolic differences between species, leading to difficulties in translating therapeutic discoveries to clinical trials [17]. Immortalized cell lines, on the other hand, are often not an accurate reflection of primary patient cells and cannot model the developmental context of many congenital disorders [17].

The high genetic component of rare diseases creates a precise and testable hypothesis: that introducing a patient-specific mutation into a pluripotent cell capable of differentiation will result in a cellular model that manifests key aspects of the disease phenotype. This is the fundamental promise of iPSC technology. By capturing an individual's entire genomic background, including modifiers and polymorphisms, patient-derived iPSCs offer a unique system to study not only the primary genetic lesion but also the complex interplay of genetic factors that influence disease severity and presentation [17] [19]. This is particularly crucial for the nearly 50% of rare diseases that manifest in children and are a leading cause of infant mortality [17].

iPSC Technology: A Primer for Rare Disease Research

Historical Development and Core Methodology

The field of cellular reprogramming was built upon foundational work demonstrating the reversibility of cell fate. John Gurdon's seminal somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) experiments in 1962 showed that a nucleus from a differentiated somatic cell could support the development of an entire organism, proving that genetic information remains intact during differentiation [18]. This concept of epigenetic reversibility was later catalyzed into a practical technology by Shinya Yamanaka and colleagues, who discovered in 2006 that the forced expression of four transcription factors—Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and Myc (OSKM)—could reprogram mouse somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells [17] [18]. This breakthrough was rapidly extended to human cells in 2007 by both Yamanaka's group (using OSKM) and James Thomson's group (using OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28) [20] [18].

The core experimental protocol for generating patient-derived iPSCs involves several key steps, which can be achieved through clinically compliant processes [20] [21]:

- Somatic Cell Isolation: Fibroblasts from skin biopsies or mononuclear cells from peripheral blood are the most common starting materials. For example, researchers at Nationwide Children's Hospital successfully used skin fibroblasts from patients with prune belly syndrome and posterior cloaca to generate iPSC lines [21].

- Reprogramming Factor Delivery: The genes encoding the reprogramming factors are introduced into the somatic cells. While early methods used integrating retroviral vectors, current best practices employ non-integrating methods such as episomal plasmids [20], Sendai virus, or mRNA transfection to minimize the risk of genomic alterations.

- Pluripotency Induction and Culture: Following transduction, cells are cultured under conditions that promote the emergence and expansion of iPSC colonies, which are identified by their characteristic compact, embryonic stem cell-like morphology.

- Validation and Characterization: Established clones are rigorously tested for pluripotency. Key assays include:

- Immunocytochemistry for pluripotency-associated proteins (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) [21].

- Transcriptomic analysis to confirm the activation of pluripotency networks.

- In vitro differentiation into cells of all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) [21].

- Karyotyping to ensure genomic integrity [21].

Key Research Reagents and Tools for iPSC Modeling

The standardized workflow for iPSC generation and disease modeling relies on a suite of essential reagents and tools, as detailed below.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Toolkit for iPSC-Based Rare Disease Modeling

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Vectors | Episomal plasmids (e.g., pEB-Tg), Sendai virus, mRNA cocktails [20] | Non-integrating delivery of OSKM/L transcription factors to initiate reprogramming. |

| Cell Culture Media | Priming medium (IMDM/Ham's F12 base), essential supplements (Lipids, BSA, ITS-X) [20] | Supports expansion of somatic cells (e.g., CD34+ cells) and the reprogramming process. |

| Cytokines & Growth Factors | rhSCF, rhFlt3-ligand, rhThrombopoietin, IL-3 [20] | Enhances reprogramming efficiency when used during somatic cell expansion. |

| Pluripotency Validation Antibodies | Anti-OCT4, Anti-SOX2, Anti-NANOG, Anti-SSEA-4 | Immunocytochemical confirmation of successful reprogramming to a pluripotent state. |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems (e.g., SpCas9), HDR donors, sgRNAs [17] [19] | Creation of isogenic controls via precise genetic correction or introduction of mutations. |

| Lineage-Specific Differentiation Kits | Commercially available kits for neurons, cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, etc. | Directs iPSCs toward disease-relevant cell types for phenotypic analysis. |

The Strategic Fit: Genetic Rare Diseases and iPSC Models

Unprecedented Access to Affected Cell Types

A paramount challenge in researching many rare genetic diseases is the inability to safely access and study the affected human tissues, such as neurons, cardiomyocytes, or specific renal cell types. iPSC technology directly overcomes this barrier. By differentiating patient-derived iPSCs into the relevant affected cell types, researchers can generate an unlimited supply of living human cells that carry the disease-causing mutation for in-depth analysis [17]. For instance, studies on Juvenile Nephronophthisis (NPH), a genetic kidney disease, have utilized patient-derived iPSCs differentiated into kidney organoids. These organoids successfully recapitulated disease-specific phenotypes, including abnormal cell proliferation and renal cyst formation, providing a novel human model for mechanistic studies [3]. Similarly, iPSC-derived retinal organoids have been used to model a rare form of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa, revealing a reduction in photoreceptor number and disrupted retinol biosynthesis over time [3].

Isogenic Controls and the Power of CRISPR Gene Editing

The combination of iPSC technology with CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing represents a particularly powerful approach for rare disease research. A central challenge in interpreting disease phenotypes in patient-derived cells is controlling for the immense genetic variability between human individuals. To address this, researchers can use CRISPR/Cas9 to correct the disease-causing mutation in a patient-derived iPSC line, thereby generating an isogenic control line that is genetically identical except for the pathogenic variant [3] [19]. The reverse is also possible: introducing a specific mutation into a healthy control iPSC line.

This workflow allows for ultra-precise causal inference. Any phenotypic differences observed between the diseased and the corrected isogenic control lines can be confidently attributed to the specific genetic mutation under investigation, as the confounding effect of background genetic variation is eliminated. For example, in the NPH kidney organoid model, the reintroduction of the corrected NPHP1 gene was shown to reverse cyst formation, directly demonstrating the gene's role in the pathological phenotype [3]. This pairing of iPSCs and CRISPR provides a level of experimental control that is unattainable with patient biopsies or animal models.

From 2D Cultures to 3D Organoid Systems

The initial application of iPSCs in disease modeling primarily involved two-dimensional (2D) monocultures. While valuable, these systems lack the cellular complexity and tissue-level architecture of human organs. The field has since evolved to develop three-dimensional (3D) organoids, which are self-organizing structures that mimic the multicellular composition and spatial organization of native tissues [17] [18].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from patient cell to 2D and 3D disease models, highlighting key steps and technology integrations.

Organoids have been successfully generated for a wide range of tissues, including the cerebrum, retina, inner ear, stomach, liver, and kidney [17]. For rare diseases, these 3D models offer a more physiologically relevant context to study complex pathological processes like cyst formation in kidney diseases, photoreceptor degeneration in retinal diseases, and interneuron migration defects in neurodevelopmental disorders [3] [17]. The fusion of organoids modeling different brain regions has even enabled the study of interneuron migration defects in Timothy syndrome, a rare neurodevelopmental disorder, providing insights with broader implications for autism spectrum disorder [17].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The therapeutic deficit in rare diseases creates an urgent need for efficient drug discovery pipelines. iPSC-derived disease models are increasingly being deployed in high-throughput screening (HTS) platforms to identify novel therapeutic compounds. These human cell-based assays provide a more physiologically relevant and predictive system compared to traditional immortalized cell lines or animal models [18]. Furthermore, the FDA Modernization Act 2.0, which now allows cell-based assays to be used for investigational new drug applications without mandatory animal testing, is likely to drive further interest in iPSC-based models for rare disease drug development [3].

Beyond small-molecule screening, iPSCs also form the foundation for a new generation of cell replacement therapies. For rare diseases characterized by specific cellular loss or dysfunction, such as certain forms of blindness or muscular degeneration, iPSCs can be differentiated in vitro into the required cell type and then transplanted back into the patient (autologous therapy) or a matched recipient (allogeneic therapy) [3] [17]. While this application faces challenges related to safety, manufacturing, and efficacy, early-stage clinical trials, such as those using iPSC-derived retinal pigment epithelium for macular degeneration, provide hope for the future of regenerative medicine for rare disorders [17].

The convergence of two key facts—that approximately 80% of rare diseases are genetic in origin, and that human iPSCs can be differentiated into virtually any affected cell type—has created an unparalleled synergy for biomedical research. iPSC-based models directly address the core challenges of rare disease research: the inaccessibility of human tissues, the lack of relevant animal models, and the critical need for patient-specific therapeutic strategies. By providing a scalable, patient-derived, and genetically tractable platform, iPSC technology has moved rare disease research from the periphery to the forefront of precision medicine. As differentiation protocols become more sophisticated, genome editing more precise, and high-throughput screening more automated, the role of iPSCs will only expand, accelerating the path from genetic understanding to effective therapies for the millions of patients affected by these conditions.

Rare genetic diseases collectively affect an estimated 263–446 million people worldwide, yet approximately 94% of these conditions lack approved therapies, creating a significant unmet medical need. Traditional research approaches have been hampered by two fundamental constraints: the scarcity of patient samples and the poor predictive validity of animal models that often fail to recapitulate human disease pathophysiology. This whitepaper examines how induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology is revolutionizing rare disease research by overcoming these historical hurdles. We present a comprehensive technical framework encompassing optimized study designs, advanced differentiation protocols, and integrated computational approaches that enable robust disease modeling and drug discovery. The validated methodologies and experimental workflows detailed herein provide researchers with a strategic roadmap for advancing therapeutic development for rare genetic disorders.

Rare diseases present a formidable research challenge due to their low individual prevalence, genetic heterogeneity, and limited availability of biological samples. With 80% having a genetic origin and less than 10% having approved therapies, these conditions represent a significant frontier in biomedical science [4] [3]. Traditional research paradigms relying on animal models have proven inadequate for many rare diseases due to fundamental species-specific differences in physiology and genetics that limit their translational relevance [22]. The emergence of iPSC technology has initiated a paradigm shift in rare disease research, enabling the generation of patient-specific cellular models that faithfully recapitulate human disease mechanisms.

Induced pluripotent stem cells, first developed by Takahashi and Yamanaka in 2006, allow for the reprogramming of adult somatic cells into a pluripotent state capable of differentiating into virtually any cell type [12]. This breakthrough has created unprecedented opportunities for studying rare genetic disorders in human cells, facilitating both mechanistic studies and drug discovery efforts. The subsequent refinement of iPSC technologies, including non-integrating reprogramming methods, CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, and advanced differentiation protocols, has further enhanced their utility for modeling rare diseases [12] [23]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to leveraging iPSC-based systems to overcome the traditional bottlenecks in rare disease research.

Establishing Robust iPSC Study Designs for Rare Diseases

Determining Optimal Experimental Scale

A critical consideration in iPSC-based rare disease research is determining the appropriate number of cell lines and donors required to generate statistically robust and reproducible results. Empirical studies using Lesch-Nyhan disease as a model have provided valuable insights into optimal study design, revealing that best results were obtained with iPSC lines from 3-4 unique individuals per group, with 2 lines per individual [24] [8]. This finding challenges earlier recommendations that advocated for studying a single iPSC line from at least 4 unrelated individuals and demonstrates that technical variance can outweigh inter-individual variance when standardized protocols are implemented.

For diseases with particularly heterogeneous presentations or genetic backgrounds, larger sample sizes may be necessary. A groundbreaking study on sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) demonstrated the power of large-scale approaches by establishing an iPSC library from 100 patients, enabling population-wide phenotypic screening and identification of therapeutic candidates effective across diverse genetic backgrounds [25]. This scale represents a significant advance beyond traditional rare disease studies, which typically included only 1-3 unique cases, often with just 1-2 sublines per case [24].

Table 1: Recommended iPSC Line Numbers for Rare Disease Studies

| Study Type | Recommended Unique Donors | Recommended Lines Per Donor | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proof-of-Concept | 3-4 | 2 | Balance statistical power with practical constraints [24] |

| Population-Based Screening | 10+ | 1-2 | Capture clinical and genetic heterogeneity [25] |

| Drug Discovery | 5-8 | 2 | Identify compounds effective across multiple genetic backgrounds [25] |

| Mechanistic Studies | 3-4 | 2-3 | Control for technical variability while maintaining biological relevance [24] |

Addressing Technical Variability

A key finding from optimized iPSC studies is that when all lines are produced in parallel using the same methods, most variance in gene expression profiles comes from technical factors unrelated to the individual from whom the iPSC lines were prepared [24] [8]. This highlights the critical importance of standardizing reprogramming, differentiation, and analytical protocols across all samples in a study. Implementing automated robotics platforms for reprogramming and differentiation can significantly enhance uniformity and reduce batch effects, as demonstrated in the large-scale ALS study where fibroblasts were reprogrammed with non-integrating episomal vectors using an automated system [25].

Statistical approaches also play a crucial role in managing technical variability. Studies have shown that results for detecting disease-relevant changes in gene expression depend on the analytical method employed and whether statistical procedures are used to address multiple iPSC lines from the same individual [24]. Mixed-effects models that account for the nested structure of the data (multiple lines per donor) often provide the most appropriate analytical framework for iPSC studies.

Advanced iPSC Modeling Platforms and Methodologies

Two-Dimensional versus Three-Dimensional Modeling Systems

iPSC-based modeling platforms have evolved from simple two-dimensional (2D) monocultures to complex three-dimensional (3D) organoid systems that better recapitulate tissue architecture and cellular interactions. Both approaches offer distinct advantages and are suited to different research applications.

Table 2: Comparison of 2D and 3D iPSC-Based Modeling Systems

| Characteristic | 2D Models | 3D Organoid Models |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | High-throughput screening compatible [23] | Medium-throughput, improving with automation [22] |

| Complexity | Reduced system, minimal cell-cell interactions | Recapitulates tissue architecture, cellular heterogeneity [4] |

| Differentiation Efficiency | Typically high, homogeneous | Variable between organoids, protocol-dependent |

| Physiological Relevance | Limited tissue context | Enhanced; exhibits functional tissue units [22] |

| Applications | Initial drug screening, electrophysiology, mechanistic studies [23] | Disease modeling requiring tissue context, developmental studies [4] |

The selection between 2D and 3D systems should be guided by research objectives. For high-throughput drug screening or detailed electrophysiological studies, 2D models offer practical advantages. For investigating diseases with complex tissue pathology or developmental origins, 3D organoids provide superior physiological relevance. Recent advances in organoid technology have enabled the generation of kidney organoids to model Juvenile Nephronophthisis [4] [3] and retinal organoids to study inherited retinitis pigmentosa [4] [3], demonstrating the utility of these systems for rare disease research.

Integrating Gene Editing for Isogenic Controls

CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has become an essential tool in iPSC-based disease modeling, enabling the creation of isogenic control lines that are genetically identical to patient-derived iPSCs except for the disease-causing mutation [12] [23]. This approach powerfully controls for individual genetic background effects, allowing researchers to confidently attribute observed phenotypes to specific mutations. Two primary strategies are employed:

- Disease Correction: Repairing the disease-causing mutation in patient-derived iPSCs to generate genetically matched controls [12]

- Disease Introduction: Introducing specific mutations into healthy control iPSCs to establish causal relationships between genotypes and phenotypes [23]

The generation of isogenic controls has proven particularly valuable for studying rare diseases where access to multiple patients with identical mutations is limited. For example, in Parkinson's disease research, CRISPR has been used to correct the A53T SNCA mutation in patient-derived iPSCs, creating isogenic lines that enabled clear dissection of disease mechanisms [12]. Similarly, gene editing has been employed to investigate Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy type 1 (EDMD1) by introducing EMD mutations into control lines [23].

Technical Workflows for iPSC-Based Disease Modeling

iPSC Generation and Quality Control Workflow

Diagram 1: iPSC Line Generation and Validation Workflow

The initial generation and validation of iPSC lines represents a critical foundation for reliable disease modeling. Best practices include:

Reprogramming Method Selection: Use non-integrating methods such as episomal plasmids, Sendai virus vectors, or synthetic mRNAs to avoid insertional mutagenesis and ensure clinical translatability [12]. The large-scale ALS study utilized non-integrating episomal vectors reprogrammed using an automated robotics platform to maximize output and uniformity [25].

Comprehensive Pluripotency Assessment: Employ multiple validation methods including immunostaining for pluripotency markers (SSEA3, SSEA4, TRA1-60, TRA1-81, NANOG), gene expression profiling of pluripotency genes, and PluriTest pluripotency scores derived from RNA sequencing data [24].

Genomic Integrity Monitoring: Perform karyotype analysis of a minimum of 20 metaphase cells at 400 band resolution to exclude relevant abnormalities, and conduct regular monitoring for genomic mutations that may arise during culture [24].

Trilineage Differentiation Potential: Verify differentiation capacity using established protocols such as the STEMdiff Trilineage Differentiation Kit, with immunostaining for ectoderm (PAX6, NESTIN), endoderm (SOX17, FOXA2), and mesoderm (brachyury, NCAM) markers [24].

Mutation Confirmation: Confirm the presence of disease-causing mutations through RT-PCR and visualization in RNA sequencing read alignments using tools such as the Integrative Genomics Viewer [24].

Directed Differentiation and Phenotypic Screening Pipeline

Diagram 2: Differentiation and Phenotypic Screening Pipeline

The differentiation of iPSCs into disease-relevant cell types followed by comprehensive phenotyping represents the core of iPSC-based disease modeling. Key technical considerations include:

Protocol Optimization: Adapt established differentiation protocols to maximize purity and maturation. The ALS study utilized a five-stage protocol adapted from established spinal motor neuron differentiation methods with extensively optimized maturation and screening conditions capable of discriminating between healthy control and diseased motor neurons [25]. This protocol generated cultures with 92.44% ± 1.66% motor neurons, demonstrating the high purity achievable with optimized methods.

Longitudinal Live-Cell Imaging: Implement automated live-cell imaging systems to monitor cell health and degeneration over time. The ALS study developed a robust pipeline using daily live-cell imaging with a virally delivered non-integrating motor neuron-specific reporter (HB9-turbo) to quantitatively assess motor neuron survival and neurite degeneration [25]. This approach enabled the identification of significant survival deficits in patient-derived neurons that correlated with donor survival.

Multi-Omics Profiling: Integrate transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic analyses to comprehensively characterize molecular phenotypes. RNA sequencing provides a wealth of information regarding the condition of the cells and has standardized metrics for quality control [24]. Studies should target sufficient sequencing depth (e.g., 50 million paired-end reads) and implement strategies to mitigate technical batch effects by processing all samples in a single batch when possible [24].

Functional Validation: Include electrophysiological assessments, calcium imaging, or other functional assays appropriate to the cell type being studied. In the ALS model, pharmacological testing with riluzole not only rescued motor neuron survival but also reversed electrophysiological abnormalities, demonstrating functional restoration [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for iPSC-Based Rare Disease Modeling

| Category | Specific Tools | Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Systems | Episomal plasmids, Sendai virus vectors, synthetic mRNAs [12] | Footprint-free iPSC generation | Non-integrating methods preferred for clinical translation |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems [12] [23] | Isogenic control generation, mutation correction | Enables causal relationship establishment between genotype and phenotype |

| Differentiation Kits | STEMdiff Trilineage Differentiation Kit [24] | Pluripotency validation, directed differentiation | Standardized protocols enhance reproducibility |

| Quality Control Assays | Karyotyping, immunostaining, RNA sequencing [24] | Line validation, pluripotency confirmation | Regular genomic integrity monitoring essential |

| Phenotyping Platforms | Live-cell imaging systems, electrophysiology platforms, multi-omics technologies [25] | Disease phenotype characterization | Longitudinal assessment captures progressive phenotypes |

| Analytical Tools | RNAseq analysis pipelines, variant interpretation algorithms [24] [6] | Data integration, pathogenicity prediction | Computational methods enhance diagnostic accuracy |

Integrated Computational-Experimental Approaches

The integration of in silico technologies with iPSC-based experimental models represents a powerful frontier in rare disease research. Computational approaches can enhance the design and interpretation of iPSC studies through several key applications:

Variant Interpretation: AI-enhanced pipelines leverage whole-genome and exome sequencing combined with phenotype extraction from electronic health records to improve diagnostic accuracy for rare diseases [6]. Tools such as REVEL, MutPred, and SpliceAI provide scalable assessment of variant pathogenicity, though performance on ultra-rare variants remains challenging [6].

Drug Repurposing: Network-based algorithms and virtual screening platforms can identify potential therapeutic candidates from existing compound libraries, significantly accelerating drug discovery for rare diseases [6]. This approach is particularly valuable given that approximately 94% of rare diseases lack approved treatments [3].

Clinical Trial Simulation: Pharmacokinetic models and virtual trial platforms help optimize clinical trial designs for small patient populations, addressing a fundamental challenge in rare disease therapeutic development [6]. These approaches support model-informed drug development and facilitate regulatory submissions.

The convergence of iPSC-based experimental models with in silico technologies creates a powerful framework for rare disease research, enabling more efficient use of limited patient-derived materials and enhancing the predictive validity of preclinical studies.

iPSC-based disease modeling has fundamentally transformed the research landscape for rare genetic disorders, providing solutions to the historical challenges of sample scarcity and inadequate animal models. Through optimized study designs incorporating 3-4 unique donors with 2 lines per individual, advanced differentiation protocols generating highly pure cell populations, and integration of gene editing for isogenic controls, researchers can now generate robust, reproducible disease models that faithfully recapitulate human pathophysiology. The convergence of these experimental approaches with computational technologies and the implementation of large-scale iPSC libraries enables comprehensive disease modeling and therapeutic discovery even for ultra-rare conditions. As these technologies continue to evolve, they promise to accelerate the development of effective treatments for the millions of patients affected by rare genetic diseases worldwide.

Building Better Models: From Somatic Cell to Complex Organoid

The foundation of robust induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-based disease modeling lies in the selection of an appropriate somatic cell source for reprogramming. This choice directly influences reprogramming efficiency, the quality of the resulting iPSC lines, and their subsequent applicability in mechanistic studies and drug discovery [26]. For research into rare genetic disorders, where patient samples are often scarce and precious, this decision is paramount. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of three primary somatic cell sources: dermal fibroblasts, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), and urinary epithelial cells. We evaluate these sources within the specific context of building reproducible and clinically relevant in vitro models for rare diseases, focusing on practical methodologies, quantitative performance metrics, and integration into a scalable research pipeline.

The initial step in iPSC generation is the isolation of somatic cells from a donor. The chosen cell source impacts the reprogramming trajectory, the epigenetic landscape of the iPSCs, and the overall experimental timeline [26] [27]. Below, we detail the three most common starting materials.

Dermal Fibroblasts: Historically the first cell type used for iPSC generation, fibroblasts are typically obtained via skin punch biopsy [26]. This method provides a high yield of genomically stable cells that can be readily expanded and banked, making them a reliable source [26] [27]. However, the collection procedure is invasive, requires medical personnel, and may result in minor patient discomfort or scarring.

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs): PBMCs, isolated from whole blood samples, offer a less invasive alternative to skin biopsy [26]. Blood collection is a routine clinical procedure, allowing for easier serial sampling from the same donor. PBMCs demonstrate comparable reprogramming efficiency to fibroblasts and are increasingly favored in translational studies [26] [28]. A key consideration is the need for stimulation to activate proliferation in certain blood cell populations before reprogramming can be initiated.

Urinary Epithelial Cells: Cells isolated from urine samples, including renal epithelial cells and urine-derived stem cells (USCs), represent a completely non-invasive, patient-friendly, and easily repeatable method of sample acquisition [26] [29]. Urine-derived cells can be collected without any clinical procedure, facilitating the generation of multiple iPSC lines from the same donor within a short timeframe [26] [29]. Notably, due to their epithelial origin, these cells reprogram more efficiently and rapidly than fibroblasts, as the process eliminates the need for a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) [29]. One study reported a transduction rate of 80% and the emergence of distinct iPSC colonies expressing pluripotency markers within 7 days, compared to 28 days for some mesenchymal cell-derived lines [29].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Somatic Cell Sources for iPSC Generation

| Parameter | Dermal Fibroblasts | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | Urinary Epithelial Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collection Method | Skin punch biopsy [26] | Venipuncture (blood draw) [26] | Non-invasive urine collection [26] [29] |

| Invasiveness | Invasive | Minimally invasive | Non-invasive |

| Reprogramming Efficiency | Variable, can be low [26] | Comparable to fibroblasts [26] | High; more efficient and rapid than fibroblasts [29] |

| Key Advantages | High genomic stability, reliable, well-established protocols [26] [27] | Minimally invasive collection, accessible, suitable for serial sampling [26] | Completely non-invasive, high patient compliance, rapid reprogramming, no MET required [26] [29] |

| Key Limitations | Invasive collection, potential for scarring, requires clinical personnel for collection [26] | Requires stimulation for some cell types, finite expansion potential ex vivo [28] | Lower initial cell yield, requires optimization for consistent culture [29] |

| Ideal Use Case | Foundational research, biobanking, when maximum genomic stability is prioritized | Large-scale cohort studies, longitudinal monitoring, hematological disorders | Pediatric studies, fragile patients, serial sampling, urological and renal disease modeling |

Experimental Protocols for Cell Isolation and Reprogramming

Isolation and Culture of Primary Cells

Dermal Fibroblasts: A skin punch biopsy (3-4 mm) is cleaned to remove adipose tissue and minced into ~1 mm³ pieces. Explants are placed on a culture dish and maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10-20% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Fibroblasts migrate from the explants over 1-3 weeks and are expanded through serial passaging using trypsin/EDTA [26] [27].

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs): Whole blood is collected in anticoagulant tubes (e.g., EDTA or heparin). PBMCs are isolated via density-gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque. The mononuclear cell layer is carefully extracted, washed, and resuspended in a suitable medium, such as RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS. For reprogramming, cells may be stimulated with cytokines (e.g., SCF, IL-3, IL-6) or mitogens to promote proliferation [26] [28].

Urinary Epithelial Cells / Urine-Derived Stem Cells (USCs): A mid-stream urine sample (50-200 ml) is collected in a sterile container. Cells are collected by centrifugation and resuspended in a specialized culture medium, such as Keratinocyte Serum-Free Medium (KSFM) or REGM, supplemented with growth factors (e.g., EGF, BPE). The cell pellet is resuspended and plated. Medium is changed periodically to selectively favor the growth of USCs or epithelial cells over contaminating cells [29]. The isolated cells exhibit high proliferative capacity and can be expanded for subsequent reprogramming.

Reprogramming to Pluripotency

Reprogramming involves resetting the epigenetic and transcriptional state of a somatic cell to a pluripotent state, typically via the introduction of key transcription factors. The original Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) remain a standard combination [26] [27]. The delivery method is critical for the safety and quality of the resulting iPSCs.

Table 2: Common Reprogramming Methods for iPSC Generation

| Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages | Suitability for Rare Disease Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral/Lentiviral Vectors | Genomic integration of transgenes [26] [27] | High efficiency, robust [27] | Risk of insertional mutagenesis, transgene reactivation [26] [27] | Lower suitability due to safety concerns for future therapies; useful for basic research [26] |

| Sendai Virus | RNA virus-based, non-integrating, replication-incompetent [26] [27] | High efficiency, non-integrating, can be cleared from cells [27] | Requires diligence to confirm viral clearance, biosafety level considerations [27] [28] | High suitability; widely used for generating clinical-grade iPSCs [28] |

| Episomal Vectors | Non-integrating plasmid DNA with Epstein-Barr virus elements [27] | Non-integrating, cost-effective [27] | Lower reprogramming efficiency, requires daily transfection for some protocols [27] | Good suitability; balance of safety and accessibility [26] [29] |

| Synthetic mRNA | Direct delivery of reprogramming factor mRNAs [28] | Non-integrating, high efficiency, no vector to clear [28] | Can trigger innate immune response, requires multiple transfections [28] | Excellent suitability; emerging as a leading method for footprint-free iPSCs [28] |

Emerging Protocol: Synthetic RNA Reprogramming of PBMCs A recent advanced protocol demonstrates the generation of iPSCs from PBMCs using synthetic RNA [28]. The process involves mixing the PBMC suspension, reprogramming medium (e.g., StemFit AK03N without bFGF), synthetic RNAs encoding the reprogramming factors (e.g., StemRNA 3rd Gen Reprogramming Kit), a transfection reagent, and iMatrix-511, then seeding them together in a single step. This approach allows RNA delivery from the entire cell surface, enhancing efficiency. Co-transfection with MDM4 mRNA, a suppressor of p53 function, has been shown to significantly boost reprogramming efficiency in PBMCs by mitigating stress-induced p53 activation [28]. iPSC-like colonies typically emerge around 14 days post-transfection and can be picked and expanded under standard feeder-free conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for iPSC Workflows

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Generation and Culture

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| StemRNA 3rd Gen Reprogramming Kit (REPROCELL) | Synthetic mRNAs for OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, LIN28, and miR-302/367 cluster for footprint-free reprogramming [28] | Primary reprogramming of fibroblasts and PBMCs [28] |

| iMatrix-511 (Laminin-511 E8 fragment) | Recombinant human protein substrate for feeder-free culture; supports iPSC attachment, survival, and self-renewal [28] | Coating culture vessels for both reprogramming and maintenance of established iPSCs [28] |

| StemFit AK03N / Essential 8 (E8) Medium | Chemically defined, xeno-free medium formulations optimized for iPSC growth; contain essential growth factors like FGF2 and TGF-β/Activin A [26] [28] | Maintenance of pluripotency during routine culture and in some reprogramming protocols [26] |

| Yamanaka Factor Lentivirus / Sendai Virus | Viral particles for delivering OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC to somatic cells. | Standard, high-efficiency reprogramming of various somatic cell types. |

| mTeSR1 / mTeSR Plus | Chemically defined, serum-free media widely used for the maintenance of human iPSCs in feeder-free conditions. | Routine culture and expansion of established iPSC lines. |

Quality Control and Characterization of Generated iPSCs

Rigorous quality control is imperative to confirm the successful generation of high-quality iPSCs, especially for modeling rare diseases where phenotypic accuracy is crucial.

- Pluripotency Marker Analysis: Expression of canonical pluripotency-associated transcription factors and surface antigens (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, TRA-1-60, SSEA-4) must be confirmed. This is typically done via immunocytochemistry, flow cytometry, or PCR-based assays [26].

- Genomic Integrity Assessment: Reprogramming can introduce chromosomal abnormalities or mutations. Karyotyping and whole-genome sequencing should be performed to ensure genomic integrity [26] [30]. One study noted that iPSCs maintain donor-specific epigenetic patterns, and while the relationship between genetic and epigenetic variation is strongest in iPSCs, epigenetic variation increases upon differentiation [30].

- Functional Pluripotency Assay: The gold standard is in vivo teratoma formation in immunodeficient mice, where iPSCs should form differentiated tissues from all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm). A more practical in vitro alternative is directed differentiation into representatives of the three germ layers, followed by analysis of lineage-specific markers [26].

The selection of a somatic cell source for iPSC generation is a strategic decision that balances practical collection logistics, reprogramming efficiency, and the specific requirements of the rare disease under investigation. Dermal fibroblasts remain a robust, genomically stable option. PBMCs offer a minimally invasive path suitable for large-scale studies. Urinary epithelial cells stand out for their completely non-invasive collection and high reprogramming efficiency, making them ideal for vulnerable patient populations and longitudinal studies. As reprogramming technologies, particularly non-integrating methods like synthetic mRNA, continue to advance, the barrier to generating high-fidelity iPSC models from even the most accessible cell sources will continue to diminish. This progress promises to accelerate the use of patient-specific iPSCs in elucidating the pathogenesis of rare genetic disorders and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Appendix: Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

IPSC Generation Workflow: This diagram illustrates the workflow for generating iPSC-based disease models from three patient cell sources.

MET Bypass in Reprogramming: This diagram shows the key difference in reprogramming mesenchymal versus epithelial cells, highlighting the MET bypass that makes urinary cells more efficient. MET = Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition.

The advent of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized biomedical research, offering unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine. For rare genetic disorders research, where patient samples are scarce and disease mechanisms are often poorly understood, iPSCs provide a uniquely powerful platform for generating patient-specific cellular models [4]. The foundation of this technology rests on reprogramming somatic cells to a pluripotent state by reactivating endogenous transcriptional networks governing self-renewal and differentiation potential [18].

A critical consideration in iPSC generation is the choice of reprogramming method, particularly regarding genomic integration of exogenous genetic material. Early approaches utilizing integrating viral vectors, while efficient, carried risks of insertional mutagenesis and altered cellular behavior, posing significant concerns for both basic research and clinical applications [26] [31]. Consequently, integration-free methods have been developed to mitigate these risks while maintaining high reprogramming efficiency.

This technical guide provides an in-depth evaluation of two leading integration-free reprogramming methods—episomal vectors and Sendai virus—within the context of iPSC disease modeling for rare genetic disorders. We examine their molecular mechanisms, practical implementation, and comparative performance characteristics to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate reprogramming strategies for their specific research objectives.

Molecular Mechanisms of Integration-Free Reprogramming

Somatic cell reprogramming to pluripotency involves profound reorganization of epigenetic landscapes, gene expression networks, and cellular metabolism. The process typically occurs in two broad phases: an initial stochastic phase where somatic genes are silenced and early pluripotency-associated genes are activated, followed by a more deterministic phase where late pluripotency genes are activated and a stable pluripotent state is established [18]. Throughout this process, cells undergo metabolic reprogramming from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), particularly when fibroblasts serve as the starting population [18].

The Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, MYC) function as pioneer factors that initiate chromatin remodeling at pluripotency loci, while simultaneously repressing somatic cell-specific transcriptional programs [26]. OCT4 and SOX2 play particularly crucial roles in activating the core pluripotency network, while MYC enhances chromatin accessibility and promotes global transcriptional amplification [18].

Episomal Vector Mechanisms

Episomal vectors are plasmid-based systems that utilize elements from the Epstein-Barr (EB) virus for extrachromosomal maintenance and replication. These vectors contain the origin of viral replication (oriP) and EB nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) gene, which together enable nuclear retention and once-per-cell-cycle replication of the plasmid without integration into the host genome [32]. The EBNA1 protein facilitates nuclear import and retention of the vector through binding to oriP, while also contributing to transcriptional activation of other reprogramming factors [32].

A key advantage of episomal vectors is their natural loss over time during cell division (at a rate of approximately 5% per cell cycle), eventually yielding iPSC lines free of exogenous genetic material without requiring additional manipulation [32]. Vectors incorporating the spleen focus-forming virus U3 (SFFV) promoter, which exhibits strong activity in hematopoietic cells, have demonstrated enhanced reprogramming efficiency for blood-derived cells [33].

Table 1: Key Components of Episomal Reprogramming Systems

| Component | Function | Variations/Improvements |

|---|---|---|

| oriP/EBNA-1 | Enables episomal replication and nuclear retention | Fundamental to all EBV-based episomal systems |

| SFFV U3 promoter | Strong promoter activity in hematopoietic cells | Enhances PBMC reprogramming efficiency |

| 2A "self-cleaving" peptides | Enables equimolar expression of multiple genes from single transcript | E2A, P2A, T2A sequences link OCT4-SOX2 |

| BCL-XL | Anti-apoptotic factor enhances cell survival during reprogramming | Particularly valuable for difficult-to-reprogram cells |

| SV40LT | Immortalizing factor that enhances reprogramming efficiency | Used in some systems but raises safety concerns |

Sendai Virus Mechanisms

Sendai virus is a non-integrating RNA virus belonging to the paramyxovirus family that replicates in the cytoplasm of infected cells without transitioning through a DNA intermediate [34]. The cytoplasmic replication mechanism fundamentally prevents genomic integration, making it a safe choice for generating integration-free iPSCs [32]. The virus exhibits high infectivity for numerous cell types, including difficult-to-transfect cells such as peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [34].

Sendai virus-based reprogramming systems deliver the Yamanaka factors as separate viral particles or as a polystronic construct, allowing control over the stoichiometry of reprogramming factor expression [34]. Like episomal vectors, Sendai virus is gradually diluted out of cells during repeated passaging, though the clearance process may require extended culture time or temperature-sensitive mutants that facilitate more rapid elimination at non-permissive temperatures [34].

Figure 1: Workflow of Integration-Free iPSC Reprogramming. Both episomal vector and Sendai virus methods progress through distinct reprogramming phases before yielding integration-free iPSCs.

Technical Comparison of Integration-Free Methods

Efficiency and Performance Characteristics

Reprogramming efficiency varies considerably between methods and depends on multiple factors, including cell source, donor characteristics, and technical execution. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for episomal vector and Sendai virus reprogramming systems based on current literature.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Integration-Free Reprogramming Methods

| Parameter | Episomal Vectors | Sendai Virus |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Efficiency | ~20-30 colonies/1×10^6 PBMCs [33]; >100-fold improvement with optimized vectors [33] | High efficiency; 1 kit can generate up to 60,000 colonies from 2×10^6 fibroblasts [34] |

| Time to iPSC Colony Emergence | 3-4 weeks | 2-3 weeks |

| Genomic Integration Risk | Low but occasional integration reported [31] | No integration (cytoplasmic replication) [35] |

| Clearance Timeline | Gradual loss over passages; ~70 days without intervention [31] | Temperature-sensitive mutants accelerate clearance; otherwise gradual dilution |

| Cost Considerations | Low cost after initial setup [33] | Higher reagent cost but can be aliquoted for multiple experiments [34] |