Karyotype Monitoring in Stem Cells: A Comprehensive Guide to Detecting and Managing Genetic Instability for Research and Therapy

Genetic instability in stem cells, particularly induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), poses a significant challenge to their research validity and therapeutic safety.

Karyotype Monitoring in Stem Cells: A Comprehensive Guide to Detecting and Managing Genetic Instability for Research and Therapy

Abstract

Genetic instability in stem cells, particularly induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), poses a significant challenge to their research validity and therapeutic safety. This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of the causes, consequences, and monitoring solutions for karyotypic abnormalities. We explore the foundational biology of genetic instability, detail current and emerging karyotyping methodologies, offer troubleshooting strategies for culture optimization, and present a comparative analysis of validation techniques. By synthesizing the latest research and regulatory perspectives, this guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to ensure genomic integrity in stem cell applications, from basic research to clinical translation.

The Unstable Core: Understanding the Causes and Consequences of Genetic Instability in Stem Cells

FAQs: Core Concepts and Best Practices

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between chromosomal aberrations and copy number variations (CNVs) in the context of stem cell genetic instability?

Chromosomal aberrations are large-scale abnormalities that can be observed under a microscope using traditional karyotyping methods. They include changes in chromosome number (aneuploidy) and large structural rearrangements such as translocations, inversions, and large deletions/duplications, typically larger than 5-10 megabases (Mb) [1]. In contrast, Copy Number Variations (CNVs) are sub-microscopic changes in the DNA sequence, defined as DNA segments of one kilobase or larger that are present at a variable copy number compared to a reference genome [2]. These smaller alterations (often ranging from 1 Kb to several Mb) require higher-resolution molecular techniques for detection but can have dramatic effects on gene expression and tumorigenic potential in stem cells [3].

Q2: Why is regular genetic monitoring absolutely essential for maintaining stem cell cultures in research and drug development?

Stem cells grown in culture are exposed to strong selection pressures that often result in genomic alterations [4]. These genetic changes can confer a selective advantage to subpopulations of cells, allowing them to rapidly take over the culture within very few passages. The consequences are severe and multifaceted:

- Compromised Research Validity: Genetic aberrations affect differentiation capacity, stem cell identity, and cellular behavior, jeopardizing the accuracy and reproducibility of basic research and disease modeling [1] [4].

- Tumorigenicity Risk: Aneuploidy and structural variations are hallmarks of cancer. Genetically abnormal stem cells may generate more aggressive teratomas and pose significant safety risks for therapeutic applications [4] [5].

- Regulatory Compliance: Stem cells intended for translational research or clinical use must meet rigorous genetic characterization release criteria. Regulatory bodies like the FDA emphasize comprehensive cytogenetic analysis for Investigational New Drug (IND) applications [1].

Q3: When should researchers perform genetic stability checks on their stem cell cultures?

Regular characterization is recommended at specific critical points to ensure culture integrity [1]:

- Establishment of a new cell line or upon acquisition from external sources

- Before establishing a master cell bank

- At the start of significant experimental protocols

- At regular intervals during prolonged culture (recommended every 10 passages)

- Before publishing results or concluding major experiments

- Prior to any clinical application

Q4: Can digital PCR (dPCR) replace traditional karyotype analysis for comprehensive genetic assessment?

No, dPCR should be viewed as complementary to karyotype analysis rather than a replacement [1]. While dPCR is faster and can detect small-scale genetic changes in known targets (point mutations, specific copy number variations), it cannot detect unknown abnormalities or identify large-scale structural abnormalities such as balanced translocations and aneuploidies. The most common aberrations found in genetically unstable cells—aneuploidy and large-scale structural rearrangements—would be missed by relying solely on dPCR, potentially compromising research findings and safety [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconclusive or Suboptimal Karyotyping Results

Problem: Poor chromosome spreading, weak banding patterns, or inability to obtain sufficient metaphase cells for G-banded karyotype analysis.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal cell culture conditions | Ensure cells are in log-phase growth and healthy. Use pre-warmed media and avoid over-confluence. |

| Incorrect mitotic arrest timing | Optimize colchicine/colcemid concentration and exposure time (typically 1-4 hours). Too short: insufficient metaphases; too long: over-contracted chromosomes. |

| Inadequate hypotonic treatment | Freshly prepare hypotonic solution (e.g., potassium chloride) and optimize incubation time (usually 15-30 minutes at 37°C). |

| Poor slide preparation | Ensure slides are clean and use controlled dropping technique. Adjust humidity and temperature during spreading. Age slides appropriately before staining. |

Protocol: Standard G-Banded Karyotyping for Stem Cells [1]

- Culture Preparation: Grow stem cells to 60-80% confluence in log-phase growth.

- Mitotic Arrest: Add colcemid to culture medium (final concentration 0.1 µg/mL) and incubate for 1-4 hours at 37°C.

- Harvesting: Trypsinize cells and collect by centrifugation.

- Hypotonic Treatment: Resuspend cell pellet in pre-warmed 0.075M KCl and incubate for 15-30 minutes at 37°C.

- Fixation: Gradually add fresh methanol:acetic acid (3:1) fixative while gently vortexing. Repeat centrifugation and fixation 2-3 times.

- Slide Preparation: Drop cell suspension onto clean, wet slides and air dry.

- G-Banding: Age slides, then treat with trypsin and stain with Giemsa or Leishman's stain.

- Analysis: Examine 15-20 metaphase spreads under microscope for chromosomal abnormalities >5-10 Mb.

Issue 2: Discrepant Findings Between Different Genetic Assessment Methods

Problem: Karyotype analysis appears normal but other methods (e.g., aCGH, RNA-Seq) suggest genetic abnormalities, or vice versa.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Resolution limitations | Karyotyping detects >5-10 Mb changes. Use higher-resolution methods (aCGH, SNP array) for submicroscopic CNVs. |

| Mosaicism below detection threshold | Karyotyping examines 15-20 cells; abnormalities in <10-20% of population may be missed. Increase the number of cells analyzed or use DNA-based methods. |

| Method-specific blind spots | Karyotyping detects balanced translocations; aCGH cannot. Use orthogonal methods for comprehensive assessment. |

| Culture heterogeneity | Subpopulations with different genetic profiles may exist. Isclone single-cell clones for pure populations. |

Protocol: High-Resolution aCGH for CNV Detection in Stem Cells [3]

- DNA Isolation: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from stem cells using phenol-chloroform or column-based methods. Assess purity (A260/280 ratio ~1.8).

- DNA Labeling: Denature 500 ng of test DNA and sex-matched reference DNA, then label with Cy3-dUTP and Cy5-dUTP respectively using random primers.

- Hybridization: Combine labeled samples with Cot-1 DNA and hybridization buffer. Apply to 135K StemArray microarray and hybridize at 42°C for 72 hours.

- Washing and Scanning: Wash slides stringently and scan at 2µm resolution using a microarray scanner.

- Data Analysis: Extract and normalize data using specialized software (e.g., NimbleScan). Call aberrations using segmentation algorithms (e.g., FASST2) with minimum of 4 probes, log2 ratio ≥0.3 for gains, ≤-0.3 for losses.

Issue 3: Detecting Genetic Abnormalities in Differentiated Cell Populations

Problem: Standard e-Karyotyping methods become noisy when analyzing differentiated cells due to gene expression changes.

Solution: Implement eSNP-Karyotyping, which utilizes allelic bias in RNA-Seq data rather than overall expression levels [6].

Protocol: eSNP-Karyotyping for Detecting Chromosomal Aberrations [6]

- RNA Sequencing: Extract high-quality RNA and prepare sequencing libraries. Sequence to sufficient depth (recommended 15-20 million mapped reads).

- SNP Calling: Identify single nucleotide polymorphisms from RNA-Seq data using GATK HaplotypeCaller.

- SNP Filtering: Filter SNPs with coverage <20 reads and minor allele frequency <0.2 to eliminate technical artifacts.

- Allelic Ratio Analysis: For each SNP, calculate the ratio of reads between the more-expressed allele and less-expressed allele.

- Aberration Detection: Order SNPs by chromosomal location and identify regions with statistically significant deviations from the expected 1:1 allelic ratio using moving average plots and t-tests with FDR correction.

Technical Data and Method Comparisons

Comparison of Genetic Instability Assessment Methods

| Method | Resolution | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-Banded Karyotyping [1] | 5-10 Mb | Gold standard; detects balanced and unbalanced large abnormalities; provides whole-genome view | Requires live, dividing cells; labor-intensive; low resolution | Routine monitoring; regulatory compliance; initial characterization |

| aCGH [3] [4] | 15 Kb - 1 Mb | High resolution for CNVs; automated; no cell culture required | Cannot detect balanced rearrangements or polyploidy | Identifying submicroscopic CNVs; detailed characterization |

| SNP Array [4] | 20 Kb - 1 Mb | Detects CNVs + loss of heterozygosity (LOH); can detect polyploidy | Cannot detect balanced translocations | Population diversity studies; LOH detection |

| RNA-Seq eSNP-Karyotyping [6] | Gene-level | Uses existing expression data; no reference sample needed; detects gains/losses | Requires heterozygous SNPs; depends on expression | Analysis of differentiated cells; secondary use of RNA-Seq data |

| Whole Genome Sequencing [4] | Single-base | Highest resolution; detects all variant types | Expensive; computationally intensive; complex analysis | Comprehensive characterization; research studies |

Common Recurrent Genetic Abnormalities in Cultured Stem Cells

| Chromosomal Region | Type of Abnormality | Associated Genes | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trisomy 12 [3] [6] | Aneuploidy | Multiple genes | Enhanced self-renewal, competitive growth advantage |

| Trisomy 17 [3] | Aneuploidy | Multiple genes | Culture adaptation, potential tumorigenicity |

| 20q11.21 amplification [6] [5] | CNV gain | BCL2L1 (Bcl-xL) | Anti-apoptotic, survival advantage |

| 3q13.13 amplification [3] | CNV gain (~595 Kb) | DPPA2, DPPA4 | Pluripotency marker amplification, possible selective advantage |

| 16q23.3 deletion [3] | CNV loss (~285 Kb) | CDH13 | Increased growth, reduced apoptosis (tumor suppressor loss) |

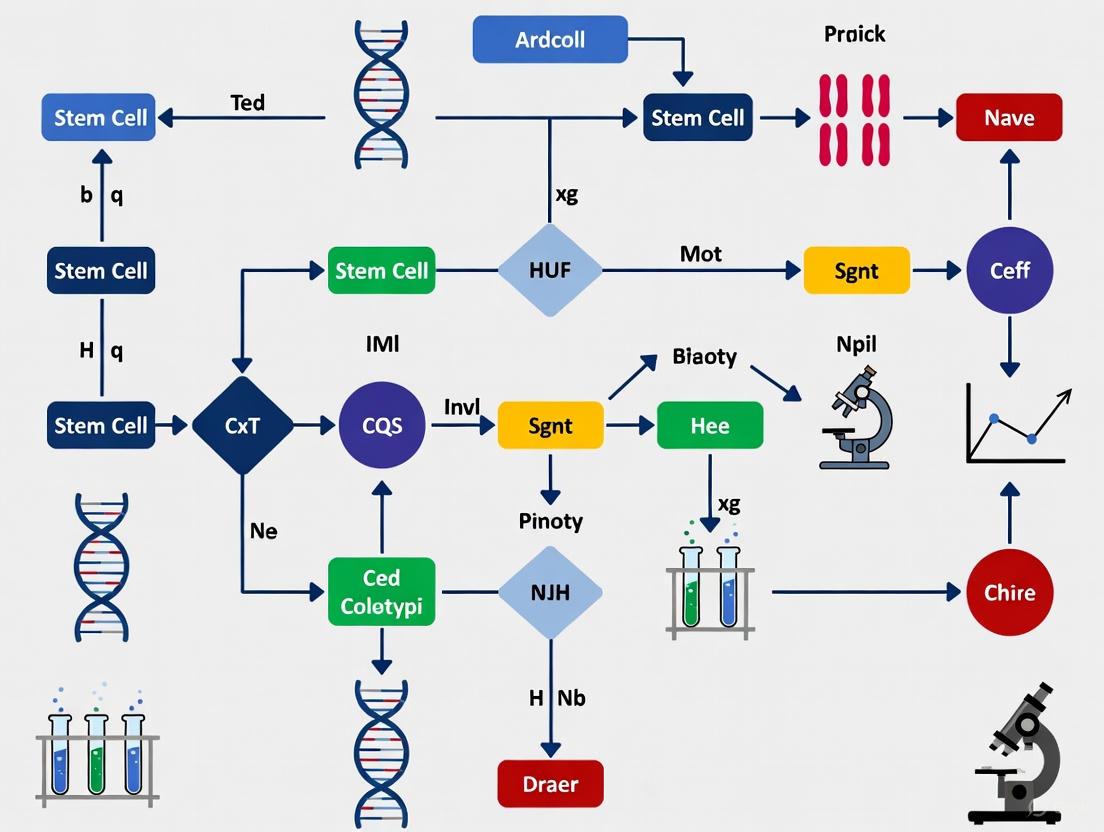

Visualized Workflows and Pathways

Genetic Instability Monitoring Workflow

Method Selection Decision Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Genetic Instability Assessment

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Mitotic Arrest Agents | Colchicine, Colcemid, Demecolcine | Arrests cells in metaphase for chromosome analysis in karyotyping [1] |

| Hypotonic Solutions | 0.075M Potassium Chloride | Swells cells to separate chromosomes for better spreading [1] |

| Fixatives | Methanol:Acetic Acid (3:1) | Preserves chromosome structure and morphology for analysis [1] |

| Staining Reagents | Giemsa stain, Leishman's stain | Creates G-banding patterns for chromosome identification [1] |

| aCGH Microarrays | 135K StemArray, Whole-genome arrays | High-resolution platform for detecting copy number variations [3] |

| DNA Labeling Kits | Cy3-dUTP, Cy5-dUTP labeling kits | Fluorescent labeling for comparative genomic hybridization [3] |

| SNP Array Platforms | Illumina, Affymetrix arrays | Genotype analysis and loss of heterozygosity detection [4] |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | RNA-Seq, WGS library preparation | Preparation of sequencing libraries for high-resolution analysis [6] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | GATK HaplotypeCaller, NimbleScan, Nexus Copy Number | Data analysis for variant calling and aberration detection [3] [6] |

Stem cell cultures are vital tools for studying development, disease, and creating cell-based therapies. However, their genetic integrity is constantly threatened by reprogramming stress and the pressures of in vitro culture. These stressors can induce genetic abnormalities that compromise research validity, disease modeling accuracy, and patient safety in therapeutic applications [1]. This technical support center outlines the primary drivers of this instability and provides actionable troubleshooting guides to help researchers maintain genetically stable cell lines.

Understanding the Stressors: FAQs on Drivers of Instability

FAQ 1: What are the fundamental types of stress that lead to genetic instability?

- Reprogramming Stress: The process of converting somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) forces a massive transcriptional rewiring. This process can disrupt cellular metabolism, leading to NADH reductive stress, where an accumulation of NADH drives harmful metabolic reprogramming and increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [7].

- Culture-Induced Stress: The in vitro environment is inherently stressful. Key stressors include:

- Proteostatic Stress: The high demand for protein synthesis in rapidly dividing cultures can overwhelm the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), leading to ER stress and the unfolded protein response (UPR). Persistent UPR activation can trigger apoptosis [8].

- Oxidative Stress: Metabolic imbalances in culture can generate excess ROS, causing DNA damage and genomic lesions [8].

- Suboptimal Culture Conditions: Factors like high cell density, over-confluence during passaging, and enzymatic dissociation can inflict mechanical and chemical stress, selectively favoring the growth of abnormal cells [9] [10].

FAQ 2: What are the most common genetic abnormalities acquired in culture?

The most frequent abnormalities are aneuploidies (gains or losses of whole chromosomes) and large-scale structural rearrangements such as translocations, inversions, and duplications or deletions larger than 5-10 megabases. Chromosome region 9p21 is a known hotspot for such aberrations [1].

FAQ 3: How do metabolic stresses like NADH reductive stress connect to genetic damage?

NADH reductive stress is often a consequence of mitochondrial dysfunction, nutrient overload, or hypoxia. It serves as a central mediator in disease pathways by enhancing ROS production and reducing ATP levels. The resulting oxidative stress can directly damage DNA, while the energy deficit can impair crucial DNA repair mechanisms, creating a permissive environment for mutations to arise and persist [7].

Troubleshooting Common Culture Problems

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive Differentiation (>20%) [9] | Old culture medium; over-confluent cultures; prolonged time outside incubator. | Use fresh medium (<2 weeks old); remove differentiated areas before passaging; passage before over-confluence; limit plate handling to <15 minutes. |

| Low Cell Attachment After Passaging [9] [10] | Over-sensitive to passaging reagent; low initial seeding density; incorrect cultureware. | Reduce incubation time with passaging reagent; plate 2-3x more cell aggregates; ensure use of non-tissue culture-treated plates with Vitronectin XF. |

| Poor Neural Induction Efficiency [10] | Low-quality hPSCs; incorrect plating density; single-cell suspension. | Use high-quality, undifferentiated hPSCs; plate cell clumps (not single cells) at 2–2.5 x 10⁴ cells/cm²; consider 10 µM ROCK inhibitor at passage. |

| Unexpected Cell Death/ Cytotoxicity [10] | Normal post-transduction effect during reprogramming; overly confluent at passaging. | Continue culture per protocol; if passaging overly confluent cells, use a ROCK inhibitor (e.g., Y27632) to improve survival. |

| Inconsistent Experimental Results [1] | Undetected genetic abnormalities in stem cell line; phenotype drift. | Implement regular genetic monitoring (e.g., karyotyping); establish a robust quality control system with standardized protocols. |

Genetic Monitoring: Protocols and Schedules

Regular genetic characterization is non-negotiable for ensuring culture integrity. G-banded karyotyping is the gold standard for detecting large-scale abnormalities [1].

| Key Event or Milestone | Monitoring Action |

|---|---|

| Acquisition or Derivation of a new cell line | Perform initial karyotyping to establish a genomic profile. |

| Initial Biobanking for future use/distribution | Confirm genetic identity and stability before creating a master cell bank. |

| Start of a Critical Experimental Protocol | Verify genetic integrity to ensure a valid starting point. |

| During Long-Term Culture (In-Process Control) | Monitor genomic stability at regular intervals (e.g., every 10 passages). |

| Conclusion of Experiments / Prior to Publication | Confirm the genetic identity and integrity of the cell line used. |

Note: While digital PCR (dPCR) is useful for detecting known, small-scale mutations, it cannot replace karyotyping, as it will miss unknown abnormalities and large-scale structural changes like translocations [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y27632) [10] | Improves survival of single cells and cryo-recovered cells by inhibiting apoptosis; used during passaging and thawing. |

| Essential 8 Medium [10] | A defined, feeder-free culture medium designed for the maintenance and expansion of human PSCs. |

| Vitronectin (VTN-N) [10] | A defined, recombinant substrate used for feeder-free culture of human PSCs, providing an attachment surface. |

| ReLeSR / Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent [9] | Non-enzymatic reagents for passaging PSCs as cell aggregates, minimizing mechanical and enzymatic stress. |

| Geltrex / Matrigel [10] | A basement membrane matrix extract used as a substrate to coat cultureware for plating and maintaining various cell types, including NSCs. |

| B-27 Supplement [10] | A serum-free supplement essential for the long-term survival and growth of neuronal cells in culture. |

| Collagenase/Dispase Enzymes [11] | Enzymatic cocktails used for the gentle dissociation of tissues to isolate primary cells. |

| Cryo-SFM Plus [12] | An advanced cryopreservation medium designed to maintain high cell viability and integrity during frozen storage. |

Visualizing Stress Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Cellular Stress Signaling Pathways

Genetic Integrity Monitoring Workflow

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), including both embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells, are invaluable tools for developmental studies, disease modeling, and regenerative medicine. However, long-term culture of these cells is associated with the accumulation of karyotypic abnormalities that may change their developmental potential, malignant capacity, and therapeutic safety. The genomic integrity of hPSC lines requires routine monitoring, as reprogramming and prolonged in vitro cultivation can induce genetic instability. Research has revealed that chromosomal aberrations in hPSCs occur in a non-random, sporadic manner, with particularly recurrent abnormalities involving chromosomes 1, 12, 17, 20, and X. These recurrent changes are observed in both research-grade and clinically-oriented stem cell lines, raising significant concerns for their application in translational medicine and drug development.

Cataloging the Recurrent Chromosomal Hotspots

Large-scale studies on thousands of hPSC samples have identified that the most common karyotypic abnormalities involve partial or whole gains of chromosomes 12, 17, 20, and X. These recurrent abnormalities provide a selective advantage to the cells in culture, leading to their outcompetition of karyotypically normal cells over successive passages.

Comprehensive Table of Recurrent Aberrations

Table 1: Recurrent chromosomal aberrations in human pluripotent stem cells

| Chromosome | Specific Abnormality | Frequency | Key Genes Involved | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | Trisomy 12 (whole-chromosome gain) | High | Numerous pluripotency-associated genes | Enhanced self-renewal, reduced differentiation potential |

| 17 | Trisomy 17, gain of 17q25 | High | TP53 | Altered apoptosis, selective growth advantage |

| 20 | Gain of 20q11.21 | Very High | BCL2L1 (BCL-XL) | Anti-apoptotic effect, proliferation advantage |

| 1 | Trisomy 1q | Moderate | Multiple oncogenes | Increased proliferation rates |

| X | Trisomy X (in female lines) | Moderate | X-linked regulators | Altered differentiation capacity |

The recurrence of these specific abnormalities across independent cell lines and laboratories suggests strong selective pressures in culture conditions that favor cells with these genetic changes. These alterations frequently involve genes that provide survival advantages, such as anti-apoptotic genes or genes that enhance proliferation rates.

Technical FAQs: Addressing Researcher Questions on Aberration Detection

Q1: What is the detection limit for mosaicism in hPSC cultures using standard karyotyping methods? Conventional G-banding karyotyping can typically detect mosaicism at levels of approximately 10-20%. More sensitive methods like digital PCR (dPCR) can detect lower levels of mosaicism for specific known targets, but cannot identify unknown or structural abnormalities. Recognition of this detection limit is crucial for developing strategies for routine laboratory practice and regulation for the use of hPSCs in regenerative medicine [13].

Q2: How do culture conditions affect the acquisition of chromosomal abnormalities in hPSCs? Studies involving over 100 continuous passages have demonstrated that single-cell passaging and feeder-free conditions are associated with a higher incidence of cytogenetic changes. hPSCs cultured as single-cells displayed increased rates of cell proliferation and persistence of pluripotency markers in differentiation assays. This emphasizes the need to meticulously evaluate the effects of new media types, substrates, and passaging methods on hPSC stability, particularly for cultures intended for clinical use [13].

Q3: Why do karyotypically abnormal hPSCs often overtake cultures? Karyotypically abnormal hPSCs can bypass developmental restrictions that limit the growth of normal cells. Research has identified a series of bottlenecks that restrict the growth of karyotypically normal hPSCs when seeded as single-cells. A large proportion of normal cells die shortly after plating, and those that survive often fail to re-enter the cell cycle. In contrast, karyotypically abnormal hPSCs successfully bypass these bottlenecks, providing them with a competitive advantage in standard culture conditions [13].

Q4: What are the safety concerns regarding these recurrent abnormalities? The recurrent abnormalities identified in hPSCs are also frequently observed in human cancers, raising significant safety concerns for using these cells in therapeutic applications. Specifically, gains of chromosomes 12, 17, and 20, as well as duplication of 20q11.21 containing the BCL2L1 anti-apoptotic gene, are associated with increased growth rates and survival advantages reminiscent of cancer cells [13].

Methodologies for Detecting Chromosomal Aberrations

Multiple complementary techniques are available for detecting chromosomal abnormalities in hPSCs, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and appropriate applications in quality control pipelines.

Comparative Table of Detection Methods

Table 2: Techniques for detecting chromosomal aberrations in stem cells

| Method | Resolution | Key Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-banding Karyotyping | ~5-10 Mb | Comprehensive genome view, detects balanced/unbalanced rearrangements, gold standard | Requires skilled interpretation, needs actively dividing cells | Routine quality control, regulatory compliance |

| FISH | 50-500 kb | Targeted analysis, works on interphase cells, quantitative | Limited to pre-selected targets | Confirming specific suspected abnormalities |

| SNP Arrays | <50 kb | Genome-wide coverage, detects copy number variations and UPD | Cannot detect balanced rearrangements | High-resolution screening of genomic imbalances |

| aCGH | <50 kb | Genome-wide coverage, sensitive for copy number changes | Cannot detect balanced rearrangements or low-level mosaicism | Comprehensive copy number analysis |

| RNA-Seq eSNP-Karyotyping | Variable | Uses existing transcriptome data, no separate DNA analysis needed | Limited to expressed regions, requires sufficient coverage | Integrated analysis when RNA-Seq data is available |

| KaryoLite BoBs | Arm-level | High-throughput, cost-effective, simple data analysis | Limited to chromosome arm-level resolution | Rapid screening of common aneuploidies |

Experimental Protocol: G-Banded Karyotyping for hPSCs

Regular karyotyping is essential for monitoring hPSC genomic integrity. The following protocol outlines the standard procedure for G-banded karyotype analysis:

Cell Preparation and Harvest:

- Culture hPSCs to 60-80% confluence in appropriate conditions.

- Add mitotic arresting agent (colchicine, colcemid, or demecolcine) to actively dividing cells for 4-6 hours.

- Dissociate cells using enzyme-free dissociation buffer or gentle enzymatic treatment.

- Transfer cell suspension to centrifuge tubes and pellet cells at 1000 rpm for 8 minutes.

Hypotonic Treatment and Fixation:

- Resuscell pellet in pre-warmed 0.075M KCl hypotonic solution and incubate at 37°C for 20 minutes.

- Add freshly prepared methanol:acetic acid (3:1) fixative slowly while gently mixing.

- Centrifuge and repeat fixation twice with fresh fixative.

- Drop cell suspension onto clean, wet microscope slides and air dry.

G-Banding and Analysis:

- Age slides overnight at 60°C or use chemical aging methods.

- Treat slides with trypsin solution followed by Leishman's stain [14] [1].

- Examine under high-resolution microscope and capture images of 20+ metaphase spreads.

- Arrange chromosomes into karyogram using specialized software.

- Analyze for numerical and structural abnormalities according to ISCN nomenclature.

Diagram: Karyotyping workflow for genetic monitoring

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful karyotype monitoring requires specific reagents and materials designed for stem cell culture and cytogenetic analysis. The following table outlines essential solutions for establishing a robust genetic monitoring pipeline.

Table 3: Essential research reagents for karyotype analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| KaryoLite BoBs | High-throughput molecular karyotyping using BAC probes on beads | Rapid screening of common aneuploidies in multiple cell lines | Detects arm-level abnormalities with 100 ng DNA input [15] |

| Leishman's Stain | G-banding chromosome staining for microscopic analysis | Conventional karyotyping following standard protocols | Provides characteristic banding patterns for chromosome identification [14] |

| Colcemid | Mitotic arresting agent | Metaphase chromosome preparation | Optimize concentration and exposure time for optimal chromosome spreading |

| mTeSR1 Medium | Defined, feeder-free culture medium | Maintenance of hPSCs prior to karyotype analysis | Provides consistent culture conditions minimizing selective pressures [16] |

| Matrigel Matrix | Extracellular matrix for cell attachment | Feeder-free culture substrate for hPSCs | Batch-to-batch variation may affect culture stability |

| Sendai Virus Vectors | Non-integrating reprogramming method | Generation of iPSC lines | Associated with higher genetic instability compared to episomal vectors [16] |

| Episomal Vectors | Non-viral reprogramming method | Generation of integration-free iPSC lines | Lower frequency of copy number alterations compared to viral methods [16] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Researchers frequently encounter specific technical challenges when monitoring chromosomal stability in hPSCs. The following troubleshooting guide addresses the most common issues and provides evidence-based solutions.

Problem: Inadequate metaphase spreads for karyotyping Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient cell division: Ensure cells are in log-phase growth before harvesting. Optimize culture conditions to promote proliferation.

- Suboptimal hypotonic treatment: Adjust KCl concentration and incubation time based on cell type. Test different durations (15-25 minutes).

- Poor slide preparation: Adjust humidity, temperature, and dropping height during slide preparation. Ensure fixative is freshly prepared.

Problem: Inconsistent detection of low-level mosaicism Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Limited sample size: Increase the number of metaphases analyzed from 20 to 50+ to improve detection sensitivity.

- Methodological limitations: Employ orthogonal methods such as FISH to confirm suspected mosaicism detected by karyotyping.

- Suboptimal culture sampling: Sample multiple culture vessels and different passage numbers to comprehensively assess mosaicism.

Problem: Culture adaptation and emergence of abnormal clones Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Selective pressure in culture: Avoid over-trypsinization and extreme dilution cloning. Use bulk passaging methods when possible.

- Suboptimal culture conditions: Regular quality control of culture reagents. Avoid frequent changes in media formulation or substrate.

- Extended passaging: Establish early passage master cell banks and limit experimental use to lower passage numbers.

Diagram: Method selection for chromosomal analysis

Quality Control Recommendations and Regulatory Considerations

Establishing a systematic approach to karyotypic monitoring is essential for maintaining hPSC quality and ensuring regulatory compliance, particularly for cells intended for therapeutic applications.

Strategic Timing for Karyotype Analysis

Regular karyotyping should be performed at specific milestones in the stem cell culture lifecycle [1]:

- At the acquisition or derivation of a new cell line

- During initial biobanking and master cell bank establishment

- At the start of experimental protocols or differentiation studies

- As an in-process control every 10 passages during extended culture

- At the conclusion of major experiments prior to publication

- Before creating working cell banks for distribution

Addressing Regulatory Requirements

For stem cells intended for clinical applications, regulatory bodies like the FDA emphasize comprehensive cytogenetic analysis using validated methods. Investigational New Drug (IND) applications and Biologics License Applications (BLA) require detailed information on genetic stability, including data from cytogenetic testing. G-banded karyotyping remains widely recognized across the stem cell community and by regulatory bodies as the "gold standard" measurement for genetic stability, providing a comprehensive visual overview of the entire chromosome complement [1].

The recurrent chromosomal aberrations affecting chromosomes 1, 12, 17, 20, and X represent a significant challenge in hPSC research and application. Understanding these hotspots, their functional consequences, and methods for their detection is essential for producing robust, reproducible research and developing safe therapeutic products. By implementing systematic karyotype monitoring protocols at critical culture milestones, employing appropriate detection methods based on specific research needs, and understanding the technical challenges associated with cytogenetic analysis, researchers can better ensure the genetic integrity of their stem cell lines. This comprehensive approach to genomic monitoring supports both basic research quality and the translational pathway for stem cell-based therapies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common genetic abnormalities found in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) during routine culture?

hPSCs, including both embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells, are prone to acquiring recurrent genetic abnormalities during prolonged in vitro culturing. The most frequently observed aberrations are specific chromosomal gains and mutations in key tumor suppressor genes [17] [18].

- Common Chromosomal Gains: Recurrent aneuploidies often involve gains of whole chromosomes or specific chromosomal arms. The most prevalent include chromosomes 20, 1q, 12, 17, and 8 [17] [18] [19]. For instance, gain of 20q11.21 is one of the most frequently reported anomalies in hPSC cultures [19].

- Common Gene Mutations: Pathogenic single nucleotide variants (SNVs) are often found in cancer-associated genes. The most commonly mutated gene is TP53, a critical tumor suppressor. Other less frequent mutations occur in genes like EGFR and CDK12 [17].

FAQ 2: How do genetic abnormalities directly impact the differentiation potential of hPSCs?

Culture-acquired genetic alterations can significantly compromise the utility of hPSCs by affecting their fundamental properties, including their capacity to differentiate into specialized cell types [18]. Abnormalities can alter the efficiency of differentiation protocols and the functionality of the resulting differentiated cells [19]. For example, studies have shown that cell lines with specific genetic aberrations can exhibit altered proliferation and differentiation capacities, which would negatively impact their use in generating specific cell types for research or therapy [17].

FAQ 3: What is the link between culture-adapted hPSCs and increased tumorigenic risk?

Prolonged culture can lead to "culture adaptation," where hPSCs with specific genetic aberrations that confer a growth advantage (like anti-apoptotic mutations) outcompete normal cells [17]. These culture-adapted cells are not just genetically different; they also display more aggressive tumorigenic potential.

- From Teratoma to Teratocarcinoma: While normal hPSCs typically form benign teratomas, culture-adapted cells with specific aberrations have been shown to form more malignant, teratocarcinoma-like tumors. These immature tumors contain undifferentiated, cancerous cells in addition to the differentiated tissues found in teratomas, representing a significantly higher safety risk [17].

- Aggressive Tumor Growth: The genetic aberrations acquired during culture are closely linked to an increase in "tumorigenic aggressiveness" [17].

FAQ 4: Can genetic testing predict the formation of abnormal tissues in animal models?

Yes, specific types of genetic tests can be highly predictive. Research has shown that analyzing Copy Number Variants (CNVs) is a more reliable predictor of abnormal tissue formation after transplantation of iPSC-derivatives into immunodeficient mice than looking for single nucleotide variants (SNVs) [20].

- Low Predictivity of SNVs: The presence of SNVs or small deletions in cancer-related genes showed no strong positive correlation with abnormal tissue formation, with an overall predictivity of only 29% [20].

- High Predictivity of CNVs: In contrast, a copy number higher than 3 in a genomic region was strongly correlated with abnormal tissue formation, with an overall predictivity of 86%. This suggests that CNV analysis is a powerful tool for risk assessment in preclinical safety evaluations [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Managing Genetic Abnormalities

Problem: Suspected genetic overgrowth in your hPSC culture. Solution: Implement a regular and rigorous genomic quality control (QC) strategy.

Step 1: Routine Monitoring

Regular testing is crucial because a genetically abnormal clone can completely overtake a culture in as little as five passages [19].

- Action: Perform routine karyotyping at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-15 passages) and after critical manipulations like reprogramming or gene editing [19].

- Method Selection: The table below compares common QC methods.

| Method | Key Function | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| G-banding Karyotyping [19] | Detects large-scale chromosomal aberrations (≥5-10 Mb). | Genome-wide view; can detect balanced translocations. | Low resolution; requires living, dividing cells. |

| SNP Array Analysis [19] | Detects copy number variants (CNVs) and loss of heterozygosity (LOH). | Higher resolution (~350 kb); detects CN-LOH. | Cannot detect balanced translocations. |

| Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing [17] | Identifies single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions. | Base-pair resolution of coding (exome) or entire (genome) sequences. | More expensive; data analysis is complex. |

Step 2: Interpretation of Results

Compare your QC data against known recurrent abnormalities.

- Action: If analysis reveals a known high-risk aberration (e.g., gain of 1q, 12p, 17q, or 20q; or a TP53 mutation), the cell line should be discarded for clinical purposes and used for research only with extreme caution [17] [19].

- Quantitative Data: The table below summarizes the frequency and functional impact of the most common abnormalities.

| Genetic Abnormality | Approximate Frequency in Studies | Impact on Pluripotency | Impact on Tumorigenicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gain of 20q/20q11.21 [17] [18] [19] | Very common (e.g., 8.6% of lines in one study [18]) | Confers growth advantage; linked to anti-apoptotic gene BCL2L1 [17]. | Increases tumorigenic aggressiveness [17]. |

| Gain of 1q [18] [19] | Very common (e.g., 7.2% of tests [18]) | Associated with feeder-free and high-density culture [18]. | Increases tumorigenic aggressiveness [17]. |

| TP53 mutations [17] [16] | Very common (e.g., >30% of samples in one analysis [17]) | Provides selective growth advantage in culture [17]. | Strongly linked to cancer; dramatically increases risk [17]. |

| Trisomy 8 [18] | Less common (e.g., 2.9% of tests [18]) | Confers a growth advantage in culture. | Increases tumorigenic aggressiveness [17]. |

Step 3: Preventive Measures

- Culture Practices: Avoid extended passaging and minimize stress by using gentle, defined passaging methods. Be aware that some aberrations, like 1q gain, are associated with specific culture conditions like feeder-free systems [18].

- Banking: Create early-passage master cell banks and perform comprehensive QC (karyotyping and SNP array) on the banked cells to ensure a baseline of genetic normality.

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: SNP Array Analysis for High-Resolution CNV Detection

This protocol provides a practical guide for using SNP arrays for quality control, based on the method described by [19].

1. DNA Extraction:

- Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from hPSCs using a commercial kit (e.g., QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit). Ensure DNA integrity and concentration.

2. Array Processing:

- Process the DNA on a commercial SNP array platform (e.g., Illumina Global Screening Array).

- The protocol uses allele-specific primer extension (ASPE) and single-base extension (SBE) on fluorescence-labeled BeadChips to genotype hundreds of thousands of SNPs across the genome.

3. Data Analysis with GenomeStudio:

- Load the scanned data into Illumina's GenomeStudio software with the cnvPartition plug-in.

- Key QC Metrics:

- Call Rate: The percentage of successfully genotyped SNPs. An acceptable call rate is typically >95% [19].

- CNV Detection: The software algorithm (cnvPartition) will automatically call CNVs (gains and losses) and regions of Loss of Heterozygosity (LOH) based on deviations from expected signal intensities and allele frequencies.

4. Interpretation:

- Visually inspect the genome-wide plots for large-scale aberrations.

- Cross-reference any called CNVs with databases of known recurrent hPSC aberrations (e.g., 20q11.21, 1q).

Protocol 2: The Teratoma Assay for Assessing Pluripotency and Tumorigenicity

The teratoma assay is the gold-standard in vivo test for pluripotency and a key assessment of tumorigenic potential [17] [21].

1. Cell Preparation:

- Harvest undifferentiated hPSCs. A common injection dose is 1x10^6 to 2x10^6 cells per site [16].

- Resuspend the cell pellet in an appropriate buffer, often mixed with an extracellular matrix like Matrigel to enhance engraftment.

2. Animal Transplantation:

- Inject the cell suspension subcutaneously, intramuscularly, or under the testis capsule of immunodeficient mice (e.g., NOD/SCID mice). The subcutaneous dorsal flank is a common site [16].

3. Observation and Tumor Harvest:

- Monitor mice for tumor formation over 8-16 weeks [16].

- Excise the resulting teratoma and fix it in formalin for histological processing.

4. Histological Analysis:

- Embed the fixed teratoma in paraffin and section it.

- Stain sections with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E).

- Examine the tissue for the presence of differentiated structures representing all three embryonic germ layers:

- Ectoderm (e.g., neural rosettes, pigmented cells, keratinocytes)

- Mesoderm (e.g., cartilage, bone, muscle, adipose tissue)

- Endoderm (e.g., gut-like epithelial structures, respiratory epithelium)

Signaling Pathways and Logical Relationships

Teratoma Formation Mechanism

The following diagram summarizes the key factors and mechanisms that contribute to teratoma formation from transplanted hPSCs, integrating genetic, cellular, and host-related factors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This table lists key materials and reagents essential for the experiments and quality control procedures discussed in this guide.

| Item | Specific Example(s) | Function in Experiment/QC |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Vectors | Sendai Virus (CytoTune-iPS), Episomal Vectors [16] | Non-integrating methods to generate integration-free iPSCs from somatic cells. |

| hPSC Culture Medium | mTeSR1 [16] | Defined, feeder-free medium for the maintenance of undifferentiated hPSCs. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit [19] | Isolates high-quality genomic DNA for downstream genetic analysis (e.g., SNP array, sequencing). |

| SNP Array Platform | Illumina Global Screening Array [19] | High-resolution platform for genome-wide detection of CNVs and LOH. |

| Analysis Software | GenomeStudio with cnvPartition [19] | Software for analyzing SNP array data to automatically call CNVs and assess quality metrics. |

| Immunodeficient Mice | NOD/SCID mice [16] [21] | In vivo host for the teratoma assay, preventing immune rejection of transplanted human cells. |

| Extracellular Matrix | Matrigel [16] | Used as a scaffold mixed with hPSCs for transplantation to support engraftment and teratoma formation. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why do we observe a rapid takeover of cultures by genetically variant human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs)?

A1: The rapid overgrowth, or selective advantage, occurs when genetically variant hPSC populations have intrinsic properties that differ from wild-type cells. Research indicates these variants often exhibit a higher proliferative rate or a more favorable response to the specific culture environment. Computational modeling has identified three critical process parameters that drive this phenomenon when variants are present: total culture density, initial proportion of variant cells, and the degree of variant cell overgrowth [22].

Q2: During which stages of iPS cell generation and differentiation are we most likely to see the emergence of genetically variant cells?

A2: Genomic alterations can occur at multiple stages. One systematic investigation observed a total of ten copy number alterations (CNAs) and five single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) across the phases of reprogramming, differentiation, and passaging. The study found that the reprogramming method matters; iPS cells generated using the Sendai virus (SV) method showed a higher frequency of CNAs and SNVs during the reprogramming phase compared to those generated with episomal vectors (Epi) [23].

Q3: What are the critical consequences of this selective advantage for manufacturing cell-based products?

A3: The primary consequence is the potential impact on Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) of the final product. Genetic variations can alter the differentiation potential of hPSCs or cause phenotypic variation in the resulting differentiated cells. For products that specify a maximum allowable proportion of variant cells, understanding and controlling the growth dynamics between wild-type and variant populations is essential for ensuring product quality, safety, and efficacy [22].

Q4: What key signaling pathways are often disrupted in cells that gain a selective advantage?

A4: While specific pathways can vary, the TP53 tumor suppressor pathway is frequently implicated. Studies on iPS cell genomic instability have identified TP53 mutations as a key vulnerability, underscoring the need for careful genomic scrutiny. Furthermore, gene expression analysis has revealed upregulation of chromosomal instability-related genes in late-passage cells that exhibit genomic instability, pointing to broader disruptions in cell cycle control and DNA damage response pathways [23].

Experimental Protocols for Monitoring Selective Advantage

Protocol 1: Longitudinal Genomic Instability Assessment during iMS Cell Differentiation

This protocol is designed to trace genomic alterations from the initiation of iPS cells through to induced Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem (iMS) cell differentiation [23].

Key Steps:

- Reprogramming: Generate integration-free iPS cell lines from human dermal fibroblasts using either Sendai virus (SV) vectors (CytoTune-iPS 2.0 kit) or non-viral episomal plasmid vectors.

- Characterization: Validate iPS cell colonies through Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) staining, immunocytochemistry for pluripotency markers (e.g., Oct3/4, Nanog, Tra-1-81), and teratoma formation assays.

- Differentiation: Differentiate validated iPS cells into iMS cells using appropriate differentiation media and conditions.

- Passaging: Maintain and passage both iPS cells and derived iMS cells according to standard protocols (e.g., manual passaging every 5-7 days for iPS cells).

- Genomic Analysis: At each key phase (reprogramming, passaging, differentiation), perform comprehensive genomic analysis. The cited study used:

- Chromosomal Microarray Analysis (CMA) for Copy Number Alterations (CNAs).

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for Single Nucleotide Variations (SNVs).

- Conventional chromosome analysis.

Objective: To define the genomic scenarios and identify the specific stages (reprogramming, passaging, or differentiation) where genetically variant clones emerge and persist.

Protocol 2: Computational Modeling of Variant-Wild-Type Growth Dynamics

This methodology uses a computational model to mathematically describe and predict the growth dynamics between genetically variant and wild-type hPSCs in co-culture systems [22].

Key Steps:

- Model Formulation: Develop a mathematical model that describes the growth behaviors of wild-type and variant hPSCs, both in individual and co-culture systems.

- Parameter Identification: Use the model to identify Critical Process Parameters (CPPs). The cited research pinpointed three key CPPs:

- Total culture density.

- The initial proportion of variant cells within the culture system.

- The specific overgrowth rate of the variant cells.

- Model Validation: Calibrate and validate the model's predictions against empirical data from actual co-culture experiments.

- Scenario Prediction: Use the validated model to run simulations predicting how variability in the CPPs (like different seeding densities or initial variant proportions) affects the prevalence of both cell populations over time.

Objective: To identify opportunities for manufacturing process control by predicting the conditions that favor variant overgrowth, allowing for proactive process adjustments.

Quantitative Data on Genomic Instability

Table 1: Frequency of Genomic Alterations in iPS Cells During Reprogramming and Differentiation [23]

| Reprogramming Method | Phase | Cell Lines with Copy Number Alterations (CNAs) | Cell Lines with Single Nucleotide Variations (SNVs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sendai Virus (SV) | Reprogramming | 100% (All lines) | Information Not Specified |

| Episomal Vectors (Epi) | Reprogramming | 40% | Information Not Specified |

| Sendai Virus (SV) | Passaging & Differentiation | Observed | Exclusively Observed in SV-derived cells |

| Episomal Vectors (Epi) | Passaging & Differentiation | Observed | None Detected |

Table 2: Critical Process Parameters Driving Selective Advantage of Variant hPSCs [22]

| Critical Process Parameter (CPP) | Impact on Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) |

|---|---|

| Total Culture Density | Impacts the overall growth dynamics and competition for resources between variant and wild-type cells. |

| Initial Proportion of Variant Cells | A higher starting proportion can lead to a more rapid dominance of the culture by the variant population. |

| Variant Cell Overgrowth Rate | The intrinsic growth rate advantage of the variant clone is a direct driver of its prevalence in the culture. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Selective Advantage in Stem Cells

| Research Reagent | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| CytoTune-iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming Kit | For integrating reprogramming factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) via Sendai virus vector to generate iPS cells. | Used to create SV-iPS cells for genomic instability studies [23]. |

| Episomal iPS Reprogramming Vectors | For non-viral, integration-free reprogramming using plasmids encoding factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, l-Myc, Lin28A, shp53). | Used to create Epi-iPS cells for comparative genomic analysis [23]. |

| mTeSR1 Medium | A defined, feeder-free culture medium for the maintenance and expansion of human pluripotent stem cells. | Used for culturing established iPS cell colonies [23]. |

| Chromosomal Microarray Analysis (CMA) | A high-resolution technique for genome-wide detection of copy number variations (CNVs) and copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity. | Used to identify copy number alterations (CNAs) in iPS and iMS cells [23]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | A high-throughput sequencing technology for comprehensive detection of single nucleotide variations (SNVs) and other sequence-level changes. | Used to identify single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) during passaging and differentiation [23]. |

Visualizing Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Selective advantage in stem cell culture.

Diagram 2: Mechanisms for selective advantage.

The Karyotyping Toolkit: From Gold-Standard G-Banding to Cutting-Edge Genomic Technologies

G-banding, or Giemsa banding, is a fundamental cytogenetic technique and the gold-standard method for obtaining a whole-genome overview of chromosomal integrity in a single assay. It is particularly vital in stem cell research, where genomic instability can arise during reprogramming, in vitro cultivation, and differentiation. Genetically abnormal clones can overtake a human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) culture in less than five passages, making routine monitoring essential for valid research and safe clinical applications [19]. By providing a macroscopic analysis of the genome, G-banding allows researchers to identify significant chromosomal abnormalities that could compromise experimental results and therapeutic potential [24] [25].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the core principle behind G-banding?

G-banding is a DNA staining technique that investigates the structure of condensed chromosomes. The Giemsa stain binds specifically to the phosphate groups of DNA, attaching more readily to regions rich in adenine-thymine (A-T) base pairs. These regions appear as dark bands. Conversely, less condensed chromatin, which tends to be richer in guanine-cytosine (G-C), incorporates less stain and appears as light bands. The result is a unique, chromosome-specific pattern of light and dark bands called a karyogram [26] [24] [25].

Why is G-banding considered the gold standard?

G-banding remains the gold standard because it provides a whole-genome overview in a single assay and is the only method that can detect balanced structural aberrations, such as reciprocal translocations and inversions, which do not involve a change in DNA copy number. This is crucial for a comprehensive assessment of genomic stability [19].

What are the most common chromosomal aberrations found in hPSCs using G-banding?

Studies of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have shown a pattern of recurrent, culture-acquired abnormalities. In one karyotypic analysis of 65 iPSC lines, the overall frequency of abnormalities was 23%. The most frequent recurrent aberrations were gains of chromosome 20 or 20q, and gains of the 1q arm [18]. These recurrent changes are thought to provide a selective growth advantage in culture [18] [25].

Table 1: Recurrent Karyotype Abnormalities in iPSCs (from a study of 65 lines) [18]

| Abnormality | Type | Percentage of Unique Aberrant Lines |

|---|---|---|

| Trisomy 20 / i(20q) | Whole or partial chromosome gain | 38.5% |

| 1q duplication / translocation-duplication | Partial chromosome gain | 30.8% |

| Trisomy 8 | Whole chromosome gain | 15.4% |

| Balanced translocation | Structural rearrangement | 23.1% |

What is the main limitation of G-banding?

The primary limitation of G-banding is its limited resolution, typically detecting only larger-scale aberrations of 5–10 Mb or greater [24] [19] [25]. This means smaller genetic alterations, such as the common and clinically significant 20q11.21 amplification in hPSCs, often fall below its detection limit [25]. Furthermore, the technique requires living, actively dividing cells and significant expertise to perform and interpret accurately [24] [19].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem 1: Poor Chromosome Spreading and Morphology

- Issue: Overlapping or poorly spread metaphase chromosomes, or insufficient metaphase cells for analysis.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect colcemid concentration or exposure time: Optimize the concentration and duration of colcemid treatment to arrest a sufficient number of cells in metaphase without over-condensing the chromosomes. A typical protocol uses 0.04 μg/mL colcemid for 2 hours [19].

- Low mitotic index: Ensure cells are in a log phase of growth and healthy before harvesting. Use cells at an appropriate confluence.

- Suboptimal hypotonic treatment: The hypotonic solution (e.g., 0.075M KCl) swells the cells, helping to spread the chromosomes. Adjust the incubation time and temperature (e.g., 37°C for 60 minutes) for optimal results [19].

- Fixation issues: Use a fresh, chilled methanol:acetic acid fixative (3:1 ratio) and ensure the fixation steps are performed correctly to preserve chromosome structure [24].

Problem 2: Weak or Blurry G-Banding Patterns

- Issue: Bands lack contrast, appear fuzzy, or are indistinct, making chromosome identification difficult.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Incomplete trypsin digestion: Over-digestion with trypsin leads to pale, "ghost-like" chromosomes. Under-digestion results in uniformly dark, non-banded chromosomes. Precisely calibrate the trypsin incubation time for your specific cell type and conditions [24].

- Suboptimal Giemsa staining: Ensure the Giemsa stain is fresh and properly filtered. Optimize the staining time and concentration.

- Aged microscope slides: Use freshly prepared slides. Slides that have been stored for too long may produce poor banding.

- Poor-quality metaphase spreads: Refer to solutions in Problem 1 to improve chromosome morphology.

Problem 3: Inconsistent Results Between Analyses

- Issue: Variable detection of abnormalities or differing karyotype interpretations.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cell culture-induced instability: Be aware that chromosomal aberrations can arise and expand during passaging. Karyotype at consistent, early passages and monitor frequently. A genetically abnormal clone can overtake a culture very rapidly [19].

- Technical subjectivity: G-banding interpretation requires a high level of expertise. Ensure analysis is performed by a trained cytogeneticist and that a sufficient number of metaphases (e.g., at least 20) are evaluated [19].

- Methodological variability: Strictly adhere to a standardized laboratory protocol for cell harvesting, slide preparation, and banding to improve reproducibility.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for G-Banding Karyotyping of hPSCs

The following workflow details the key steps for preparing metaphase chromosomes for G-banding analysis from human pluripotent stem cells.

- Cell Culture and Mitotic Arrest: Grow hPSCs to a healthy, sub-confluent state in log-phase growth. Add colcemid (a mitotic spindle inhibitor) to the culture medium at a final concentration of 0.04 μg/mL and incubate for 2 hours at 37°C. This arrests dividing cells at metaphase, when chromosomes are most condensed [19].

- Cell Harvest and Hypotonic Treatment: Harvest cells using trypsin or Accutase to create a single-cell suspension. Centrifuge and subject the cell pellet to a hypotonic solution (commonly 0.075M KCl, sometimes mixed with sodium citrate). Incubate at 37°C for 60 minutes. This causes the cells to swell, which helps spread the chromosomes upon slide preparation [19].

- Fixation: Centrifuge the cells and carefully remove the hypotonic solution. Resuspend the pellet in a freshly prepared, chilled fixative solution (3:1 methanol to acetic acid). Repeat the centrifugation and resuspension in fresh fixative several times (typically 3-4) to thoroughly clean and fix the cells [24] [19].

- Slide Preparation: Drop the fixed cell suspension onto clean, wet microscope slides from a height of about 30-50 cm. Allow the slides to air dry. Proper technique is critical for achieving well-spread metaphase chromosomes. Examine slides under a phase-contrast microscope to assess chromosome spread and density [24].

- Aging and Banding: Age the slides, either by incubating at 60°C overnight or at 90°C for about one hour. Treat the slides briefly with a trypsin solution to digest chromosomal proteins. The time and concentration must be carefully optimized. Stain the slides with a filtered Giemsa stain for 5-10 minutes, then rinse and air dry [24].

- Analysis and Reporting: Analyze the G-banded metaphase spreads under a bright-field microscope at 100x oil immersion. A minimum of 20 metaphase cells should be structurally evaluated. Chromosomes are identified by their characteristic banding patterns and arranged into a karyogram. The final report is generated according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN) [24] [19].

Comparison of Karyotyping Methods

While G-banding is the gold standard for a macroscopic overview, other technologies offer complementary capabilities. The table below compares key methods used in hPSC research.

Table 2: Comparison of Common Karyotyping Methods in Stem Cell Research [26] [19] [25]

| Method | Resolution | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-Banding | 5 - 10 Mb | Gold standard; detects balanced structural rearrangements; whole-genome view. | Low resolution; requires live, dividing cells; subjective. | Initial, macroscopic genome screening. |

| SNP Array | ~350 kb - 2 Mb | High resolution; detects CNVs, CN-LOH; automated analysis. | Cannot detect balanced translocations. | High-resolution CNV and LOH detection. |

| Array CGH (e.g., KaryoStat+) | >1 - 2 Mb | Whole-genome coverage for CNVs; improved resolution over G-banding. | Cannot detect balanced rearrangements or CN-LOH. | Sensitive, genome-wide CNV screening. |

| ddPCR | Single gene/region | Extremely sensitive; absolute quantification; detects low-level mosaicism. | Targeted analysis only (e.g., 24 hotspots); not a whole-genome method. | Validating and monitoring specific, common aberrations (e.g., 20q11.21). |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | 1 bp (but limited for large SVs) | Single-base resolution; detects SNVs and CNVs. | High cost; complex data analysis; may miss large SVs. | Most comprehensive detection of SNVs and CNVs. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for G-Banding Karyotyping [24] [19]

| Reagent / Material | Function | Notes for Experimental Success |

|---|---|---|

| Colcemid | A mitotic inhibitor that disrupts spindle formation, arresting cells in metaphase. | Concentration and incubation time are critical to obtain sufficient metaphase spreads without over-condensing chromosomes. |

| Hypotonic Solution (KCl) | Causes cells to swell, separating the chromosomes for clearer analysis. | Must be pre-warmed and used immediately after preparation for consistent results. |

| Methanol:Acetic Acid Fixative | Preserves the chromosomal structure and removes cytoplasmic debris. | Must be prepared fresh and kept cold for optimal fixation. |

| Trypsin | Digestive enzyme used in controlled amounts to treat slides, enabling the Giemsa stain to produce banding patterns. | The most sensitive step; requires precise calibration for clear, high-contrast bands. |

| Giemsa Stain | DNA-specific dye that binds preferentially to A-T rich regions, creating the characteristic light and dark banding pattern. | Should be filtered before use to remove particulates that can cause uneven staining. |

| Microscope Slides | Surface for metaphase chromosome spreading. | Must be clean and often used slightly wet ("breathing" on them) to facilitate chromosome spreading during dropping. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the core differences between aCGH and SNP arrays in detecting CNVs?

Answer: While both are high-resolution array technologies, their primary differences lie in the type of genetic variants they detect and their underlying principles.

- Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH): This technique is designed specifically to detect copy number variations (CNVs) by performing a competitive hybridization between a test and a reference DNA sample, both labeled with different fluorescent dyes (e.g., Cyanine 3 and Cyanine 5) [27]. It provides a direct, quantitative measure of DNA copy number differences between the two samples but cannot detect copy-number neutral events like loss of heterozygosity (LOH) or identify ploidy status.

- Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Arrays: SNP arrays can also detect CNVs but do so by comparing the intensity of sample hybridization to a reference set, not through a direct competitive hybridization [1]. A key advantage is their ability to simultaneously detect CNVs, LOH, and uniparental disomy (UPD) because they genotype hundreds of thousands of specific SNP loci across the genome.

What is the typical resolution and detection limit of these array technologies?

Answer: The resolution is determined by the number and density of probes on the array. Higher-density arrays offer greater resolution for detecting smaller aberrations.

- Common Array Formats:

- Mosaicism Detection: Genomic aberrations smaller than 10 Mb can be successfully detected in samples with as low as 10% mosaicism using optimized aCGH protocols [27]. This is significantly more sensitive than traditional G-banded karyotyping, which typically detects mosaicism at levels exceeding 10-20% [28].

My aCGH data shows a "wave effect." What causes this and how can it be mitigated?

Answer: A wavy pattern of hybridization intensities along the chromosome is a known technical artifact [27].

- Primary Causes:

- GC content bias: Probes with high GC content can hybridize differently.

- DNA isolation bias: Inefficiencies during DNA extraction can contribute.

- Solutions:

When should I use aCGH or SNP array over other techniques like karyotyping or FISH?

Answer: The choice of technique depends on your research question, required resolution, and the need for genome-wide versus targeted analysis. The following table compares key characteristics:

| Feature | G-banded Karyotyping | FISH (20q11.21 example) | aCGH | SNP Array |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | >5-10 Mb [28] [1] | ~0.55-4.6 Mb (for 20q11.21) [28] | High (probe-dependent) [27] | High (probe-dependent) [1] |

| Primary Use | Genome-wide, large structural changes [1] | Targeted, submicroscopic CNVs [28] | Genome-wide CNV detection [27] | Genome-wide CNV, LOH, and ploidy [1] |

| Best for Detecting | Aneuploidy, translocations, large inversions/deletions [28] | Low-level mosaicism, specific recurrent CNVs (e.g., BCL2L1) [28] | Submicroscopic CNVs across the entire genome [27] | CNVs, regions of homozygosity (LOH), UPD [1] |

| Throughput | Low | Low | Medium to High | Medium to High |

For stem cell research, the ISSCR standards recommend routine genetic monitoring. Karyotyping provides a baseline for large-scale integrity, while aCGH and SNP arrays are essential for high-resolution, genome-wide screening of culture-acquired CNVs that karyotyping will miss [28] [29].

What are the critical quality control metrics for a successful aCGH experiment?

Answer: Rigorous QC is essential for generating reliable and reproducible data. Key metrics to check after probe labeling and hybridization include:

Table: Essential aCGH Quality Control Metrics

| Metric | Description | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Yield | Total amount of labeled DNA generated. | >5.0 µg (for 4x180k arrays) [27] |

| Dye Incorporation | pmol of dye incorporated per reaction. | Cy3: ≥300 pmol; Cy5: ≥200 pmol [27] |

| Specific Activity | pmol of dye incorporated per µg of DNA. | Cy3: ≥60 pmol/µg; Cy5: ≥40 pmol/µg [27] |

| Signal Intensity | Overall fluorescence intensity measurement. | >200 [27] |

| Background Noise | Standard deviation of negative control probes. | <25 [27] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Ratio of probe signal to background noise. | >30 [27] |

| Derivative Log Ratio (DLR) | Measure of variation of signal around the mean. | <0.2 [27] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio

A low signal-to-noise ratio can obscure true genetic alterations and lead to inaccurate data interpretation.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Poor DNA quality.

- Solution: Check DNA purity via spectrophotometry (A260/280 >1.8; A260/230 2.0-2.2) and integrity via gel electrophoresis. Re-purify if necessary [27].

- Cause: Inefficient labeling reaction.

- Solution: Adhere strictly to labeling protocol incubation times and temperatures. Do not shorten the denaturation or primer extension steps [27].

- Cause: Suboptimal hybridization conditions.

- Solution: Ensure the correct buffer stringency, temperature, and amount of Cot-1 DNA are used [27].

- Cause: High background noise.

- Solution: Protect Cyanine dyes from light during all steps. Check that the array itself is not contaminated [27].

- Cause: Poor DNA quality.

Problem: Dye Bias in aCGH

Dye bias occurs when one fluorescent dye (e.g., Cy3 or Cy5) consistently shows higher intensity than the other, independent of actual copy number changes.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inefficient or unequal dye incorporation.

- Solution: Check dye incorporation and specific activity metrics via NanoDrop. Ensure labeling reactions for both test and reference samples are performed identically and with fresh reagents [27].

- Cause: Environmental factors.

- Solution: Be aware that Cy5 is more sensitive to ozone degradation than Cy3. Perform hybridizations in a controlled environment, and consider using an ozone scrubber if necessary [27].

- Confirmatory Test: Perform a "dye swap" experiment, where the dyes used to label the reference and test DNA are switched. A true genetic anomaly will be consistent, while a dye-specific artifact will reverse with the dyes [27].

- Cause: Inefficient or unequal dye incorporation.

Problem: Detecting Mosaicism in hPSC Cultures

Subpopulations of genetically distinct cells (mosaicism) can be missed if the detection method lacks sensitivity.

- Guidance:

- Understand Sensitivity Limits: No technique can detect mosaicism at 0%. Digital PCR (dPCR) is highly sensitive for known targets, while arrays can detect ~10% mosaicism for smaller aberrations [28] [27].

- Use Orthogonal Techniques: No single method is perfect. A combined approach is most effective. The following diagram illustrates a recommended testing strategy for comprehensive genomic stability monitoring in hPSCs:

Problem: High Derivative Log Ratio (DLR)

A high DLR value (>0.2) indicates excessive noise in the array data, reducing confidence in CNV calls.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Poor DNA quality or integrity.

- Solution: This is the most common cause. Re-check DNA quality and use high molecular weight DNA for all labeling reactions [27].

- Cause: Inefficient labeling.

- Solution: Verify that the labeling reaction produced sufficient DNA yield and dye incorporation, as outlined in the QC table above [27].

- Cause: Bubbles or scratches on the array.

- Solution: Handle arrays carefully during hybridization and washing steps. Ensure the hybridization chamber is properly sealed [27].

- Cause: Poor DNA quality or integrity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for aCGH and Genetic Monitoring

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| CGH Labeling Kit (e.g., CYTAG TotalCGH) | Incorporates fluorescent dyes (Cy3/Cy5) into test and reference DNA via random priming. | Choose based on needs: SNP compatibility, or low input (e.g., 50 ng) with kits like CYTAG SuperCGH [27]. |

| Cot-1 DNA | Blocks non-specific hybridization of repetitive DNA sequences, reducing background noise. | The amount used is critical to prevent "wave effect" artifacts [27]. |

| Purification Columns (e.g., silica membrane-based) | Removes unincorporated dyes, enzymes, and salts after the labeling reaction. | Included in many commercial kits. Alternative purification methods include ethanol precipitation [27]. |

| Microarray Platform | The slide containing thousands of immobilized DNA probes for hybridization. | Select format based on required resolution (60K vs. 180K) and number of samples per run [27]. |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) Assay | A highly sensitive targeted method to quantify specific, recurrent CNVs (e.g., 20q11.21). | Not a substitute for karyotyping or arrays, but an excellent complementary tool for monitoring common hPSC abnormalities [29]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Wet Lab and Library Preparation

Q1: My NGS run failed during initialization with a "W1 pH out of range" error. What should I do?

This error on the Ion PGM System indicates the pH of the W1 solution is out of range or the volume is insufficient. First, check that at least 200 mL of solution remains in the W1 bottle and that all sippers and bottles are securely attached. Press "Start" to restart the measurement. If the error persists, discard the solution in the W1 bottle, prepare a fresh solution with 350 µL of 100 mM NaOH, and restart the initialization process. If issues continue, detach and clean the reagent bottles, check for line blockages, and inspect the chip port for standing solution, replacing the chip if necessary [30].

Q2: How can I address library preparation failures that lead to low cluster density or poor sequencing yield?

Library preparation issues often stem from suboptimal DNA quality, quantity, or fragmentation. Verify the quantity and quality of your input DNA using fluorometric methods. Ensure the library preparation protocol, including fragmentation and adapter ligation, is meticulously followed. For GC-rich or difficult templates, use polymerases optimized for high-GC content and consider PCR additives. Incorporating unique dual indexes during library preparation can help identify and filter index-hopped reads in multiplexed samples, providing higher confidence in your results [31] [32].

Instrumentation and Run Monitoring

Q3: The instrument displays a "Chip Not Detected" error on my Ion S5 system. What are the likely causes?

This error typically arises from a clamp not being fully closed, a chip that is not properly seated, or a damaged chip. Open the chip clamp, remove the chip, and inspect for physical damage or signs of moisture outside the flow cell. If damaged, replace it with a new chip. Ensure the chip is correctly positioned, close the clamp firmly, and run the Chip Check again. If the error persists, the issue may lie with the chip socket, and you should contact Technical Support [30].

Q4: My sequencer shows connectivity issues with the server. How can I resolve this?

For "No Connectivity to Torrent Server" errors on Ion S5 systems, first disconnect and then re-connect the Ethernet cable. Confirm that your router and network are operational. If the problem is not resolved, a system restart may be necessary. From the Main Menu, select Tools > Shut Down, wait 30 seconds, and then power the instrument back on. If connectivity alarms continue, contact Technical Support [30].

Data Analysis and Variant Calling

Q5: My data analysis reveals a high number of false-positive variant calls, particularly indels in homopolymer regions. How can I improve specificity?

This is a common challenge with some sequencing technologies. To improve variant calling accuracy:

- Increase Sequencing Depth: Ensure sufficient coverage (e.g., >100x for heterogeneous samples) to distinguish true low-frequency variants from errors [33].

- Apply Bioinformatics Filters: Use quality scores (Q-scores), strand bias filters, and remove variants located in homopolymer stretches or other problematic genomic regions [33] [34].

- Utilize Unique Dual Indexes: This allows for the computational identification and removal of reads that have experienced index hopping, a common source of sample cross-contamination [31].

- Benchmark with Proficiency Testing: Leverage insights from proficiency testing programs, which highlight that homopolymer regions and genes with high GC-content are frequent sources of false positives and require special attention during assay validation [32].

Q6: What are the primary sources of uncertainty in NGS variant calling, and how can they be mitigated?

Uncertainty in NGS data arises from several sources, including sequencing errors, misalignments, and amplification biases. Key mitigation strategies are summarized in the table below [33] [34].

Table 1: Common Sources of Uncertainty in NGS Data and Mitigation Strategies

| Source of Uncertainty | Description | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Errors | Platform-specific errors (e.g., indels in homopolymers for Ion Torrent, substitutions for Illumina) [33]. | Apply base quality recalibration and platform-specific error correction algorithms. |

| Alignment Ambiguity | Reads misaligned, especially in repetitive regions or for indels [33]. | Use optimized aligners; perform manual review of aligned reads in a genomic viewer. |

| Amplification Bias | Duplicated reads from PCR over-amplification skew variant allele frequencies [33]. | Use PCR-free library prep where possible; mark/remove duplicate reads. |

| Low Coverage | Regions with insufficient reads prevent confident variant calling [34]. | Design experiments to ensure adequate mean coverage and uniform coverage distribution. |

Stem Cell Research-Specific Considerations

Q7: Within the context of stem cell genetic instability research, how does NGS complement traditional karyotyping?