Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine: From Basic Science to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for researchers and drug development professionals.

Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine: From Basic Science to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational biology of MSCs, including their defining characteristics, sources, and therapeutic mechanisms such as immunomodulation and paracrine signaling. The review details methodological approaches for isolation and characterization, current clinical applications across various diseases, and the significant challenges in the field, including efficacy optimization and manufacturing heterogeneity. It further examines advanced strategies like genetic engineering and cell-free therapies to overcome these hurdles, culminating in an analysis of the clinical trial landscape, regulatory approvals, and evidence-based validation of MSC-based therapies.

The Biology of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Defining a Therapeutic Powerhouse

Historical Discoveries and Key Milestones in MSC Research

The field of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) research represents one of the most dynamic and transformative areas in regenerative medicine. From their initial identification as simple fibroblast-like cells to their current status as therapeutic agents with complex immunomodulatory capabilities, MSCs have undergone a remarkable evolution in scientific understanding. This whitepaper traces the critical discoveries and methodological advances that have shaped MSC research, providing scientists and drug development professionals with a comprehensive historical framework. The journey of MSC science reflects broader trends in cell biology, where initial focus on differentiation potential has progressively shifted toward paracrine-mediated mechanisms and clinical translation. Understanding this historical context is essential for appreciating current challenges and future directions in MSC-based therapeutics, particularly as the field moves toward more standardized and efficacious clinical applications [1] [2].

The Pioneering Era: Initial Discovery and Characterization

The foundational period of MSC research established the basic biological properties of these cells and set the stage for all subsequent investigations.

Early Discoveries (1960s-1970s)

The conceptual origins of MSCs date to the 1960s when Soviet scientist A. J. Friedenstein and his team conducted groundbreaking research demonstrating that bone marrow transplantation could yield osteoblast differentiation in vivo. Their experiments identified progenitor cells for both osteoblasts and hematopoietic cells, establishing the existence of a stromal component with regenerative potential within bone marrow. By 1974, Friedenstein and colleagues had successfully isolated a fibroblast-like cell from bone marrow via adherent culture that exhibited colony-forming units (CFU-F) capable of differentiating into osteoblasts and facilitating the formation of hematopoietic clones. This work established the fundamental principle that bone marrow contained not only hematopoietic elements but also stromal precursors with generative capacity—a revolutionary concept at the time [1].

A critical methodological insight from this period was the development of plastic adherence as a separation technique, which remains a defining characteristic of MSCs to this day. In 1987, Dr. Charbord provided further clarification by demonstrating that bone marrow stromal cells cultured in horse serum displayed notable differences in their uptake of serum proteins compared to bone marrow fibroblasts, establishing that MSCs represent a distinct cellular entity despite morphological similarities to fibroblasts in vitro [1].

Establishing Multipotency (1980s-1990s)

The 1980s witnessed crucial advances in understanding the differentiation potential of MSCs. Research in 1987 established that bone marrow stromal cells maintained differentiation potential even after 20–30 passages, retaining the ability to generate bone tissue after implantation in animal models. The pivotal recognition of MSC multipotency came in 1992 when J.N. Beresford and colleagues established that MSCs could differentiate into both adipocytes and osteoblasts, with differentiation pathways influenced by specific culture conditions and biochemical inducers [1].

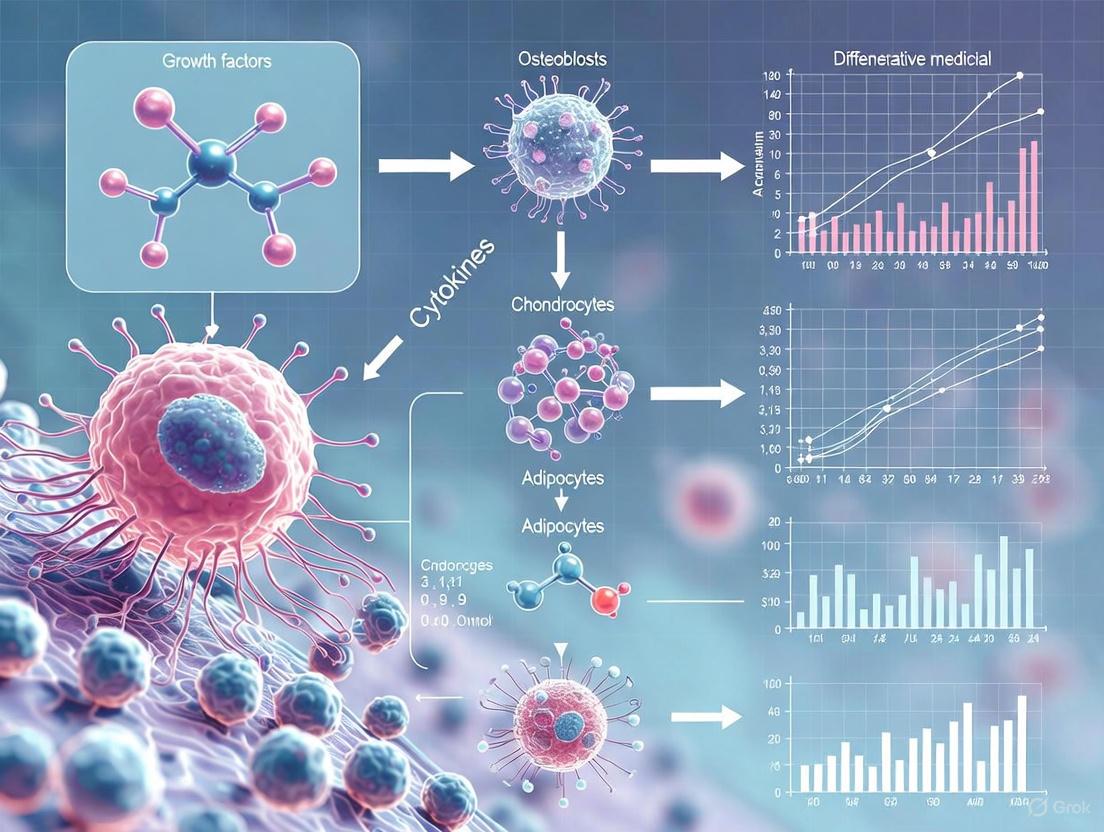

The formal naming of "mesenchymal stem cells" was proposed in 1991 by Dr. Arnold Caplan, who recognized their mesodermal origin and generative potential. This nomenclature systematized the field and provided a conceptual framework for subsequent research. The full demonstration of trilineage differentiation potential—the capacity to differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes—was definitively established in a landmark 1999 publication in Science, cementing the fundamental identity of MSCs and anticipating their significant contributions to regenerative medicine [1].

Table 1: Key Early Discoveries in MSC Research (1960s-1990s)

| Year | Discovery | Key Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s | Osteogenic potential of bone marrow transplants | Friedenstein et al. | First evidence of non-hematopoietic progenitor cells in bone marrow |

| 1974 | Isolation of plastic-adherent CFU-F | Friedenstein et al. | Established fundamental isolation method and colony-forming capability |

| 1987 | Distinction between MSCs and fibroblasts | Charbord | Clarified MSC as distinct cellular entity |

| 1991 | Proposal of "mesenchymal stem cell" term | Caplan | Standardized nomenclature and conceptual framework |

| 1992 | Confirmed adipogenic and osteogenic potential | Beresford et al. | Established dual differentiation pathways |

| 1999 | Demonstration of trilineage differentiation | Pittenger et al. | Defined fundamental multipotency of MSCs |

Methodological Advances: Isolation, Characterization and Standardization

The progression of MSC research has been inextricably linked to the development of increasingly sophisticated methodological approaches for isolation, characterization, and culture.

Initial MSC isolation relied exclusively on bone marrow aspiration, but methodological advances have dramatically expanded both sources and techniques. The classic isolation method developed by Friedenstein—plastic adherence in standard culture conditions—remains a cornerstone approach. However, this has been supplemented with specialized techniques for specific tissue sources, including enzymatic digestion (e.g., collagenase for adipose tissue) and mechanical fragmentation (explant methods) [3].

The discovery that MSCs could be isolated from diverse tissue sources represented a critical expansion of the field. In 1991, researchers successfully cultured MSCs from Wharton's jelly portion of the human umbilical cord via a tissue block culture technique. In 2000, a laboratory at the University of Chile isolated mononuclear cells from umbilical cord blood through adherent culture to obtain MSCs. Subsequently, MSCs have been isolated from numerous tissues including adipose tissue, amniotic membrane, gingiva, thymus, placenta, synovium, fetal blood, fetal liver, and fetal lungs [1].

Comparative studies have revealed significant functional differences between MSCs from various sources. For instance, dental pulp-derived MSCs (DPSCs) demonstrate consistently smaller cell size, Nestin positivity, and higher proliferation rates compared to adipose-derived MSCs (ADSCs), while also showing a diminished capacity for adipogenic differentiation. Similarly, ADSCs obtained through different extraction methods (enzymatic digestion versus mechanical fragmentation) exhibit variations in secretome profiles, highlighting how isolation methodology can influence biological properties [3].

Characterization and Standardization

The development of standardized characterization criteria has been essential for advancing MSC research and clinical translation. In 2006, the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) established minimal criteria for defining human MSCs, creating a unified framework for the field. These criteria include: (1) adherence to plastic under standard culture conditions; (2) specific surface marker expression (≥95% positive for CD105, CD73, and CD90; ≤2% positive for CD45, CD34, CD14/CD11b, CD79α/CD19, and HLA-DR); and (3) capacity for trilineage differentiation into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages under in vitro conditions [1] [4].

The functional significance of these surface markers reflects the biological identity of MSCs: CD105 (endoglin) is a type I membrane glycoprotein essential for cell migration and angiogenesis; CD90 (Thy-1) mediates cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions; and CD73 functions as a 5'-exonuclease that catalyzes the hydrolysis of adenosine monophosphate, playing a role in cell signaling within bone marrow. The negative markers primarily exclude hematopoietic lineages (CD45, CD34), monocyte/macrophage cells (CD14/CD11b), B cells (CD79α/CD19), and potent antigen-presenting cells (HLA-DR) [1].

Diagram Title: MSC Characterization Workflow

Table 2: Standard MSC Characterization Markers and Their Significance

| Marker | Expression | Biological Function | Significance in MSC Identity |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD105 | Positive (≥95%) | Type I membrane glycoprotein; essential for cell migration and angiogenesis | Core MSC marker; critical for regenerative function |

| CD73 | Positive (≥95%) | 5'-exonuclease; catalyzes AMP hydrolysis to adenosine | Core MSC marker; mediates purinergic signaling |

| CD90 | Positive (≥95%) | Cell adhesion molecule; mediates cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions | Core MSC marker; facilitates tissue integration |

| CD45 | Negative (≤2%) | Protein tyrosine phosphatase; marker for all leukocytes | Excludes hematopoietic lineage contamination |

| CD34 | Negative (≤2%) | Cell adhesion factor; marker for hematopoietic stem cells | Excludes hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells |

| HLA-DR | Negative (≤2%) | MHC class II cell surface receptor; antigen presentation | Confirms low immunogenicity; excludes antigen-presenting cells |

Conceptual Evolution: From Differentiation to Paracrine Mechanisms

A fundamental shift in the understanding of MSC therapeutic mechanisms has marked the maturation of the field, moving from a direct differentiation hypothesis to a more complex paracrine model.

The Trophic Shift

By the mid-2000s, research began to challenge the initial assumption that MSCs primarily functioned through direct differentiation and replacement of damaged tissues. Instead, evidence accumulated supporting the concept of "trophism" - that MSCs act as medicinal signaling cells that create a regenerative microenvironment through secreted factors. This paradigmatic shift recognized that MSC therapeutic effects are mediated largely through the release of bioactive molecules including growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular vesicles (EVs) that modulate the local cellular environment, promote tissue repair, stimulate angiogenesis, enhance cell survival, and exert anti-inflammatory effects [1] [2].

The recognition of extracellular vesicles as key mediators of MSC effects further refined this paracrine hypothesis. MSC-derived EVs—including exosomes (30-200 nm), microvesicles (100-1000 nm), and apoptotic bodies (0.5-2 microns)—contain diverse biomolecular cargo including metabolites, proteins, nucleic acids (microRNAs, noncoding RNAs), and even organelles such as mitochondria. These EVs function as sophisticated intercellular communication vehicles, delivering therapeutic payloads to recipient cells and demonstrating bioactivity capable of reducing fibrosis, promoting tissue regeneration, and modulating inflammation [5] [2].

Immunomodulatory Capabilities

Parallel to the understanding of trophic mechanisms, research illuminated the profound immunomodulatory capacities of MSCs. MSCs interact with diverse immune cells including T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages, modulating immune responses through both direct cell-cell contacts and release of immunoregulatory molecules. These interactions can suppress activation and maturation of innate immune cells while skewing early innate reactions toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype, making MSCs particularly attractive for treating immune-mediated conditions [1] [2].

This immunomodulatory function forms the basis for the first FDA-approved MSC product, Ryoncil (remestemcel-L), approved in December 2024 for treating steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease (SR-aGVHD) in children. This approval validated decades of research into MSC immunobiology and established a regulatory precedent for future MSC-based therapies [6] [7].

Diagram Title: MSC Therapeutic Mechanisms Evolution

Clinical Translation: From Bench to Bedside

The progression of MSCs from laboratory curiosities to clinically implemented therapeutics represents a landmark achievement in regenerative medicine, though this journey has faced significant challenges.

Regulatory Milestones and Approved Therapies

The clinical translation of MSCs began with trials in the 1990s and achieved its most significant regulatory milestone with the December 2024 FDA approval of Ryoncil (remestemcel-L) for pediatric steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. This approval marked a watershed moment for the field, validating the scientific consensus regarding MSC potential and contributing to renewed activity in MSC clinical development [6] [7].

Globally, multiple MSC therapies have received regulatory approval in various jurisdictions. As of 2025, sixteen MSC therapies have been approved worldwide: ten derived from bone marrow, three from umbilical cord, two from adipose tissue, and one from umbilical cord blood. These approved therapies target conditions including acute graft-versus-host disease, acute myocardial infarction, complex anal fistulas in Crohn's disease, osteoarthritis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [4].

Clinical Trial Landscape

The clinical trial landscape for MSCs has expanded dramatically, reflecting both scientific interest and therapeutic potential. As of October 2024, a query of ClinicalTrials.gov revealed 567 registered studies for "mesenchymal stromal cells" and 1,506 results for "mesenchymal stem cells," including 339 Phase 1, 280 Phase 2, 36 Phase 3, and 7 Phase 4 registered studies. However, this enthusiasm must be balanced against the reality that an overwhelming majority (94%) of registered trials did not report results, highlighting ongoing challenges in clinical translation and data dissemination [2].

The therapeutic applications of MSCs in clinical trials span a remarkable range, including autoimmune diseases (lupus, Crohn's disease, multiple sclerosis), inflammatory disorders (GVHD), neurodegenerative diseases, orthopedic injuries, cardiovascular conditions, and gynecological disorders. Recent trials have demonstrated particular promise in areas where inflammation plays a central role, leveraging the potent immunomodulatory properties of MSCs [1] [8] [4].

Table 3: Clinically Approved MSC Therapies (As of 2025)

| Product Name | Tissue Source | Approval Region | Indication | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ryoncil | Bone marrow | United States (FDA) | Pediatric steroid-refractory acute GVHD | 2024 |

| Alofisel | Adipose tissue | European Union | Complex perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease | 2018 |

| Temcell | Bone marrow | Japan | Acute GVHD | 2015 |

| Prochymal | Bone marrow | Canada, New Zealand | Pediatric acute GVHD | 2012, 2015 |

| Cupistem | Adipose tissue | South Korea | Crohn's fistula, Anal fistula | 2012, 2021 |

| Cellgram | Bone marrow | South Korea | Acute myocardial infarction | 2011 |

| Cartistem | Umbilical cord | South Korea | Knee articular cartilage defects | 2012 |

| Neuronata-R | Bone marrow | South Korea | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 2014 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Advancing MSC research requires specialized reagents and methodological approaches that have been refined through decades of investigation.

Standard Experimental Protocols

Trilineage Differentiation Assay: The fundamental protocol for demonstrating MSC multipotency involves inducing differentiation toward osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages using specific induction media. For osteogenic differentiation, cells are cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 50μM ascorbic acid-2 phosphate, 10mM β-glycerophosphate, and 0.1μM dexamethasone for 21 days, with mineralization detected by Alizarin Red staining. Adipogenic differentiation uses DMEM with 10% FBS, 1μM dexamethasone, 0.5mM isobutylmethylxanthine, 10μg/ml insulin, and 200μM indomethacin for 14-21 days, with lipid accumulation visualized by Oil Red O staining. Chondrogenic differentiation typically employs pellet culture systems in serum-free DMEM with 1% ITS+ premix, 100nM dexamethasone, 50μg/ml ascorbic acid-2 phosphate, and 10ng/ml TGF-β3 for 21-28 days, with sulfated proteoglycans detected by Alcian Blue or Safranin O staining [3].

Flow Cytometric Immunophenotyping: Standardized characterization of MSC surface markers requires flow cytometric analysis using antibodies against positive markers (CD73, CD90, CD105) and negative markers (CD34, CD45, CD14/CD11b, CD79α/CD19, HLA-DR). Cells are typically harvested using non-enzymatic cell dissociation buffer to preserve surface epitopes, incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies, and analyzed on a flow cytometer. The ISCT criteria require ≥95% positivity for CD73, CD90, and CD105, and ≤2% positivity for hematopoietic markers [1] [4].

Conditioned Media Collection and Secretome Analysis: For paracrine studies, MSC-conditioned media is collected from subconfluent cultures (typically 70-80% confluence) after 24-48 hours in serum-free conditions to avoid fetal bovine serum contamination. The conditioned media is concentrated using centrifugal filters (3-10 kDa cutoff) and analyzed via ELISA/multiplex arrays for cytokines/growth factors, nanoparticle tracking analysis for extracellular vesicles, and mass spectrometry/microRNA sequencing for comprehensive molecular profiling [5] [3].

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for MSC Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Reagents | Collagenase Type I/II, Ficoll-Paque, RBC lysis buffer, Plastic cultureware | Primary MSC isolation from tissue sources | Tissue-specific enzyme cocktails; adherence separation requires 3-7 days |

| Culture Media | αMEM/DMEM, Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), L-glutamine, Penicillin/Streptomycin | MSC expansion and maintenance | Serum screening essential for batch consistency; antibiotic-free for therapy |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR (fluorochrome-conjugated) | Flow cytometric immunophenotyping | Use non-enzymatic detachment to preserve epitopes; include isotype controls |

| Differentiation Inducers | Dexamethasone, IBMX, Indomethacin, Ascorbic acid, TGF-β3, BMPs | Trilineage differentiation assessment | Lineage-specific induction cocktails; differentiation requires 2-4 weeks |

| Secretome Analysis Tools | ELISA kits, Multiplex arrays, Exosome isolation kits, miRNA sequencing reagents | Paracrine mechanism investigation | Serum-free conditioning; protease inhibitors for protein analysis |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite substantial progress, the MSC field faces persistent challenges that must be addressed to fully realize the therapeutic potential of these remarkable cells.

Manufacturing and Standardization Hurdles

A primary challenge in MSC translation remains the inherent variability of primary cell products. MSCs exhibit considerable heterogeneity based on tissue source, donor characteristics (age, health status), isolation method, and culture conditions. This biological variability introduces significant challenges in manufacturing consistent therapeutic products. Additionally, scaling MSC production while maintaining quality presents substantial technical obstacles, as MSCs have a limited number of passages before losing potency or undergoing senescence [6] [2].

Efforts to address these challenges include advances in automation and analytical development that help standardize how MSCs are produced and evaluated. The implementation of robust release criteria and potency assays represents a critical step forward in ensuring consistency and quality. The development of master and working cell banks has allowed for more consistent yields at scale while preserving cellular potency. Additionally, optimized cryopreservation and transport protocols help extend shelf life and simplify logistics for these living therapies [6].

Emerging Frontiers

Several innovative approaches are shaping the future of MSC research and clinical application. iPSC-derived MSCs (iMSCs) offer enhanced consistency, scalability, and reduced donor variability compared to primary MSCs. While not yet FDA-approved, iMSCs are gaining momentum in regenerative medicine trials targeting conditions such as osteoarthritis and graft-versus-host disease [7].

The field is also increasingly exploring cell-free approaches utilizing MSC-derived extracellular vesicles and conditioned media. These strategies potentially offer similar therapeutic benefits with improved safety profiles, easier storage and handling, and potentially fewer regulatory hurdles. MSC-derived EVs are being investigated for applications including COVID-19-related lung injury, chronic wound healing, and neuroinflammation [5] [8].

Genetic engineering of MSCs represents another frontier, with CRISPR-edited lines being tailored for enhanced immunomodulation, targeted delivery, and improved survivability post-transplantation. These approaches may address current limitations in homing efficiency and therapeutic potency [8].

Finally, the discovery of Multilineage-differentiating stress-enduring (Muse) cells within MSC populations has opened new research directions. These endogenous, reparative cells exhibit selective migration to damaged tissues, phagocytic capability, and pluripotent-like differentiation, potentially explaining some of the therapeutic effects observed in MSC administration [5].

The historical journey of MSC research demonstrates a remarkable evolution from basic biological discovery to clinical implementation. The field has progressed from initial observations of bone marrow stromal cells to a sophisticated understanding of multipotent cells with complex immunomodulatory and trophic functions. Key milestones including the standardization of characterization criteria, recognition of paracrine mechanisms, and recent regulatory approvals have established MSCs as legitimate therapeutic agents. However, challenges in manufacturing consistency, clinical efficacy demonstration, and mechanistic understanding remain active areas of investigation. The continued evolution of MSC science—including emerging approaches with iMSCs, engineered cells, and cell-free derivatives—promises to further transform the landscape of regenerative medicine. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this historical context provides essential insights for navigating both current challenges and future opportunities in this dynamic field.

In regenerative medicine, the therapeutic potential of Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells (MSCs) has garnered significant attention for their ability to self-renew, differentiate into multiple lineages, and modulate immune responses [1]. However, the initial lack of a universal definition for these cells led to substantial inconsistencies in research findings and clinical trial outcomes. To address this, the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT) established a set of minimal defining criteria for human MSCs, which have become the foundational standard for the field [1]. These criteria ensure that cells characterized as MSCs across different laboratories and clinical studies possess comparable biological properties, thereby enabling the reproducibility of scientific data and the meaningful comparison of clinical results. This standardization is crucial for the rigorous development of MSC-based therapies, facilitating their successful transition from basic science to clinical applications aimed at addressing unmet medical needs [9] [1].

The Core ISCT Defining Criteria

The ISCT standards, established to create a unified framework for the field, specify that MSCs must be defined by a combination of three fundamental criteria [1].

- Plastic Adherence: When cultured under standard conditions, MSCs must adhere to a plastic surface. This is a primary, functional characteristic used to separate MSCs from non-adherent cell populations in the initial isolate, such as hematopoietic cells.

- Specific Surface Marker Expression: MSCs must express a defined set of positive and negative surface antigens, as determined by flow cytometry. To be considered MSCs, a population must exhibit high expression (≥95% positive) of specific markers and similarly high lack of expression (≤2% positive) of others.

- Multilineage Differentiation Potential: Under standard in vitro induction conditions, MSCs must possess the capacity to differentiate into cells of the mesodermal lineage—specifically osteoblasts (bone), adipocytes (fat), and chondrocytes (cartilage). This functional property confirms their stem cell nature.

The table below summarizes these core criteria.

Table 1: Core ISCT Defining Criteria for Human MSCs

| Criterion | Requirement | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Plastic Adherence | Must adhere to plastic culture surfaces under standard conditions. | A primary, functional characteristic used for initial isolation. |

| Positive Surface Marker Expression (≥95%) | CD73, CD90, CD105. | CD73 functions as a 5'-exonuclease; CD90 mediates cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions; CD105 is essential for angiogenesis [1]. |

| Negative Surface Marker Expression (≤2%) | CD34, CD45, CD14 or CD11b, CD79α or CD19, HLA-DR. | CD34 is a marker for hematopoietic stem cells; CD45 for white blood cells; CD14/CD11b for monocytes/macrophages; CD79α/CD19 for B cells; HLA-DR is a strongly immunogenic MHC-II molecule [1]. |

| Trilineage Differentiation Potential | Must differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes in vitro. | Confirmation requires specific staining: Mineral deposits (e.g., Alizarin Red S) for osteogenesis, lipid vacuoles (e.g., Oil Red O) for adipogenesis, and proteoglycans (e.g., Alcian Blue) for chondrogenesis. |

Experimental Protocols for MSC Characterization

This section provides detailed methodologies for verifying the three core ISCT criteria, with a focus on the critical assays for surface marker profiling and differentiation potential.

Surface Marker Analysis by Flow Cytometry

The immunophenotype of MSCs is typically confirmed using flow cytometry. The following protocol outlines the key steps for this analysis.

Workflow for Surface Marker Analysis

Protocol:

- Cell Harvesting: Wash adherent MSC cultures with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and detach cells using a trypsin-EDTA solution. Neutralize the trypsin with complete culture medium.

- Cell Preparation: Wash the cell pellet with a flow cytometry staining buffer (e.g., PBS containing 1-2% fetal bovine serum). Filter the cells through a 70μm strainer to obtain a single-cell suspension and perform a cell count.

- Staining: Aliquot approximately 1x10^5 to 5x10^5 cells into separate tubes for unstained, isotype control, and experimental antibody staining. Resuspend cell pellets in staining buffer containing the fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against the target markers (e.g., CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR). Incubate for 30-60 minutes in the dark at 4°C.

- Washing and Analysis: Wash the cells twice with staining buffer to remove unbound antibody. Resuspend the final pellet in a suitable buffer for flow cytometry acquisition.

- Data Interpretation: Analyze the data using flow cytometry software. The cell population is considered positive for a marker if the fluorescence intensity is greater than 99% of the isotype control. The population must meet the ISCT thresholds [1].

Trilineage Differentiation Assays

The functional capacity of MSCs is confirmed by inducing differentiation down osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic lineages. The diagram below outlines the general workflow, and the table in Section 4 lists the key reagents.

Workflow for Trilineage Differentiation

Protocols:

- Osteogenic Differentiation: Seed MSCs at a defined density (e.g., 2x10^4 cells/cm²). Once cells reach 70% confluency, replace the growth medium with osteogenic induction medium. Culture for 2-4 weeks, refreshing the medium every 3-4 days. To confirm differentiation, fix the cells and stain with 2% Alizarin Red S (pH 4.1-4.3) to detect calcium phosphate deposits, which appear as bright red/orange nodules [10] [1].

- Adipogenic Differentiation: Seed MSCs at a high density (e.g., 2x10^4 cells/cm²). At 100% confluency, stimulate the cells with adipogenic induction medium for 2-3 days, followed by a switch to adipogenic maintenance medium for 1-2 days. Repeat this cycle for 2-3 weeks. To confirm differentiation, fix the cells and stain with Oil Red O working solution to detect intracellular lipid vacuoles, which stain red [10] [1].

- Chondrogenic Differentiation: Pellet 2.5x10^5 MSCs by centrifugation in a conical tube. Culture the pellet in chondrogenic induction medium containing TGF-β (e.g., TGF-β1 or β3) for 3-4 weeks. To confirm differentiation, fix the pellet, embed it in paraffin, section it, and stain with Alcian Blue (pH 2.5) to detect sulfated proteoglycans in the extracellular matrix, which stain blue-green [10] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below details the key reagents and materials required for the characterization of MSCs according to ISCT standards.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for MSC Characterization

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application in MSC Research |

|---|---|

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Panels for positive (CD73, CD90, CD105) and negative (CD34, CD45, CD11b, CD19, HLA-DR) markers are essential for immunophenotyping and confirming ISCT identity [1]. |

| Osteogenic Induction Medium | Typically contains Dexamethasone, Ascorbic Acid, and β-Glycerophosphate to drive MSC differentiation into osteoblasts and mineral matrix formation [10] [1]. |

| Adipogenic Induction Medium | Typically contains Insulin, Indomethacin, IBMX, and Dexamethasone to stimulate MSC differentiation into adipocytes and lipid accumulation [10] [1]. |

| Chondrogenic Induction Medium | Typically contains TGF-β (e.g., TGF-β1), Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium (ITS), and Ascorbic Acid to promote pellet-based differentiation into chondrocytes and cartilage matrix formation [10] [1]. |

| Histological Stains (Alizarin Red S, Oil Red O, Alcian Blue) | Used for the visual confirmation of successful differentiation: Alizarin Red S for calcium (osteogenesis), Oil Red O for lipids (adipogenesis), and Alcian Blue for proteoglycans (chondrogenesis) [10] [1]. |

| Standard Culture Medium | Typically consists of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) or α-MEM, supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic for routine MSC expansion [10]. |

| Trypsin-EDTA Solution | A protease solution used to detach adherent MSCs from plastic culture surfaces for subculturing or preparing cells for analysis [10]. |

While the ISCT criteria provide a minimal definition, it is critical to recognize that MSCs derived from different tissue sources exhibit unique biological properties that can influence their therapeutic application [10] [1].

- Bone Marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs): The most extensively studied type, known for their high differentiation potential and strong immunomodulatory effects [1].

- Adipose Tissue-derived MSCs (AD-MSCs): Easier to harvest in large quantities and yield more cells, with comparable therapeutic properties to BM-MSCs [1].

- Umbilical Cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs): Exhibit enhanced proliferation, lower immunogenicity, and longer culture times, making them suitable for allogeneic transplantation [10] [1].

These variations in properties mean that the choice of MSC source is a key strategic decision in both basic research and clinical trial design for regenerative medicine [10].

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) represent a cornerstone of regenerative medicine, prized for their self-renewal, multipotent differentiation, and potent immunomodulatory capabilities. While the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) sets minimum criteria for their definition, MSCs derived from different anatomical niches exhibit profound functional and molecular heterogeneity. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of MSCs isolated from bone marrow (BM-MSCs), adipose tissue (ADSCs), umbilical cord (UC-MSCs), and dental pulp (DPSCs). We dissect the critical influence of tissue origin on cellular phenotype, proliferation, differentiation potential, and secretome composition, underscoring the necessity of a precise, source-aware approach in both basic research and clinical protocol development. Understanding these differences is paramount for harnessing their full therapeutic potential, as the choice of MSC source is not merely a logistical consideration but a fundamental determinant of biological activity and clinical application.

The tissue microenvironment, or niche, from which MSCs are isolated imprints a distinct identity on the cells, influencing their functional characteristics for therapeutic use [11] [12]. The following table summarizes the core biological and functional properties of MSCs from the four key sources.

Table 1: Functional and Biological Characteristics of MSCs from Different Sources

| Characteristic | Bone Marrow (BM-MSCs) | Adipose Tissue (ADSCs) | Umbilical Cord (UC-MSCs) | Dental Pulp (DPSCs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation & Availability | Invasive harvest; low yield (0.01-0.001% of nucleated cells) [4] | Minimally invasive (e.g., liposuction); high yield [4] | Non-invasive; ethically favorable; readily available [1] [4] | Minimally invasive from medical waste (e.g., third molars) [13] |

| Proliferation & Senescence | Moderate proliferation; higher senescence with age and passage [14] | Moderate proliferation; donor age-dependent [14] | Highest proliferation rate; lowest expression of senescence markers (p53, p21, p16) [4] [14] | High proliferation rate; nestin-positive [13] |

| Tri-Lineage Differentiation | Osteogenic, Chondrogenic, Adipogenic [1] | Osteogenic, Chondrogenic, Adipogenic [1] | Osteogenic, Chondrogenic, Adipogenic [14] | Osteogenic, Chondrogenic; Limited/No Adipogenic [13] |

| Immunophenotype (ISCT) | CD73+, CD90+, CD105+; CD34-, CD45-, HLA-DR- [1] [4] | CD73+, CD90+, CD105+; CD34-, CD45-, HLA-DR- [1] [4] | CD73+, CD90+, CD105+; CD34-, CD45-, HLA-DR- [14] | CD73+, CD90+, CD105+; CD34-, CD45-, HLA-DR- [13] |

| Secretome Profile | Broad range of immunomodulatory and trophic factors [1] | Pro-angiogenic and immunomodulatory factors; specific miRNA sets regulating cell cycle/proliferation [13] | Potent anti-inflammatory (e.g., via Angiopoietin-1) [14] | Specific miRNA sets involved in oxidative stress and apoptosis pathways [13] |

| Key Advantages | Most extensively studied; strong immunomodulation [1] | High cell yield per gram of tissue; ease of harvest [4] | Biologically primitive; high proliferative capacity; low immunogenicity [4] [14] | High accessibility; neural crest origin; high neuro-regenerative potential [13] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for MSC Characterization

Standardized experimental protocols are critical for the accurate characterization and functional validation of MSCs from any source. The methodologies below are foundational to MSC biology.

Isolation and Culture of Adipose-Derived MSCs (ADSCs)

Objective: To isolate and expand mesenchymal stromal cells from human adipose tissue using two distinct methods: enzymatic digestion and mechanical fragmentation [13].

Materials:

- Tissue Source: Discarded abdominal adipose tissue (e.g., from lipoaspirate).

- Reagents:

- LIPOGEMS system or equivalent for initial tissue processing.

- Basic Medium (BM): αMEM supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin.

- Enzyme Solution: Collagenase 1A for enzymatic digestion.

- Serum: Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS).

- Trypsin-EDTA for cell detachment.

Protocol:

- Processing: The harvested adipose tissue is processed to remove contaminants like oil and erythrocytes, retaining the intact adipose tissue layer.

- Mechanical Fragmentation (MF):

- A portion of the processed tissue is placed in a culture dish with BM supplemented with 20% FBS.

- Within two weeks, ADSCs migrate from the tissue fragments, adhere to the plastic, and proliferate.

- At 80% confluence, cells are detached with trypsin-EDTA and subcultured for expansion.

- Enzymatic Digestion (Stromal Vascular Fraction - SVF):

- The remaining tissue is washed with DPBS and digested overnight with collagenase 1A at 37°C.

- The digested material is centrifuged, and the cell pellet (the stromal vascular fraction) is plated in BM with 10% FBS.

- At 80% confluence, cells are detached and subcultured.

- Expansion: Cells from both methods are maintained in BM with 10% FBS and used for experiments between passages 4-6.

Trilineage Differentiation Assay

Objective: To confirm the multipotent differentiation capacity of MSCs into osteocytes, adipocytes, and chondrocytes in vitro [13] [1].

Materials:

- Induction Media: Commercially available or laboratory-formulated osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation media.

- Staining Reagents:

- Osteogenesis: Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) stain or Alizarin Red S (for calcium deposition).

- Adipogenesis: Oil Red O (for lipid droplets).

- Chondrogenesis: Safranin O (for proteoglycans) [14].

Protocol:

- Seeding: MSCs are seeded at a standardized density (e.g., 3x10³ cells/well in 48-well plates for osteogenesis and adipogenesis). Chondrogenesis often uses a pelleted micromass culture system.

- Induction: After cell attachment, the standard growth medium is replaced with specific differentiation induction media. Control wells are maintained in standard growth medium.

- Maintenance: Media is changed every 2-3 days for 2-4 weeks.

- Analysis: Differentiation is confirmed by:

- Histochemical Staining: Cells are fixed and stained with lineage-specific dyes (ALP, Oil Red O, Safranin O).

- Gene Expression: Quantitative PCR analysis of lineage-specific markers (e.g., Runx2 for osteogenesis, PPARγ for adipogenesis, SOX9 for chondrogenesis).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for MSC Isolation, Culture, and Characterization

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Collagenase (Type IA) | Enzymatic digestion of tissues (e.g., adipose, umbilical cord) to release stromal cells. | Isolation of ADSCs via the Stromal Vascular Fraction (SVF) method [13]. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Critical supplement for basal culture media, providing essential growth factors and adhesion proteins for MSC expansion. | Used in basic medium (BM) for the culture of ADSCs and DPSCs [13]. |

| Trypsin-EDTA | Proteolytic enzyme solution used to detach adherent cells from culture plastic for subculturing and propagation. | Standard reagent for passaging all MSC types upon reaching 80% confluence [13]. |

| Defined Induction Media | Media cocktails containing specific factors (e.g., dexamethasone, ascorbate, insulin) to direct MSC differentiation. | Used in trilineage assays to induce osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic fates [13] [1]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies (CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR) | Immunophenotyping to confirm MSC identity per ISCT criteria (≥95% positive for CD73, CD90, CD105; ≤2% positive for hematopoietic/endothelial markers). | Essential for the characterization of all MSC populations before experimental use [13] [4] [14]. |

| Cell Culture Tested FN | Coating protein for surfaces; its organization influences stromal cell phenotype and niche engineering. | Used in bioengineered niches to control extracellular matrix presentation and support stem cell maintenance [15]. |

Signaling Pathways and Functional Mechanisms

The therapeutic effects of MSCs are largely mediated through complex paracrine signaling and direct cell-cell interactions, which are influenced by the tissue of origin. The following diagram synthesizes key pathways and functional outcomes, particularly highlighting the immunomodulatory axis.

Discussion: Implications for Research and Therapy

The functional disparities among MSC sources have direct and significant implications for their clinical translation. The recent FDA approval of Ryoncil (remestemcel-L), an allogeneic bone marrow-derived MSC therapy for pediatric steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease (SR-aGVHD), underscores the therapeutic viability of MSCs [7]. However, the selection of a cell source must be disease-specific. For instance, UC-MSCs, with their potent anti-inflammatory activity mediated by factors like Angiopoietin-1, may be superior for modulating overwhelming immune responses [14]. Conversely, DPSCs, which secrete microRNAs targeting oxidative stress and apoptosis pathways, might offer unique advantages for treating neurodegenerative conditions or dental pulp regeneration [13].

A major challenge in the field is donor heterogeneity and the lack of standardized isolation and expansion protocols. As research advances, new frontiers are emerging, including the use of iPSC-derived MSCs (iMSCs) to overcome limitations of cell source availability and consistency, and the engineering of biomimetic niches that control ECM organization to better maintain stem cell potency ex vivo [7] [15]. Ultimately, treating the stem cell and its microenvironment as an inseparable unit will be key to unlocking the full regenerative potential of MSC-based therapies [11].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are adult, multipotent stromal cells with the capacity to differentiate into various cell types of mesodermal origin, most notably osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes [16] [1] [17]. This trilineage differentiation potential represents a cornerstone of their application in regenerative medicine, enabling the repair and regeneration of diverse tissues such as bone, cartilage, and fat [1]. Initially discovered in the bone marrow by Friedenstein and colleagues in the 1960s, MSCs have since been isolated from numerous other tissues, including adipose tissue, umbilical cord, placenta, and dental pulp [16] [1]. The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) has established minimal criteria for defining MSCs, which include: (1) adherence to plastic under standard culture conditions; (2) specific surface marker expression (CD105, CD73, CD90 ≥95%; CD45, CD34, CD14/CD11b, CD79α/CD19, HLA-DR ≤2%); and (3) ability to differentiate into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages in vitro [1] [17]. Beyond their differentiation capabilities, MSCs exhibit immunomodulatory properties and secrete bioactive factors that contribute to tissue repair, making them highly attractive for therapeutic development [1]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the molecular regulators, signaling pathways, and experimental methodologies underlying the osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic differentiation of MSCs, contextualized within the framework of basic science for regenerative medicine research.

Molecular Regulation of Trilineage Differentiation

The commitment of MSCs to a specific lineage is governed by a complex network of transcription factors, signaling pathways, and epigenetic modifications. These molecular drivers often operate in a mutually exclusive manner, where activation of one lineage program simultaneously suppresses alternative fates [17].

Key Transcription Factors and Signaling Pathways

Table 1: Core Transcription Factors Regulating MSC Trilineage Differentiation

| Lineage | Master Transcription Factors | Key Signaling Pathways | Critical Downstream Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osteogenic | Runx2, Osterix (Osx) [16] | Wnt/β-catenin, BMP, FGF-2 [16] | Collagen I, Alkaline Phosphatase, Osteocalcin [16] |

| Chondrogenic | SOX9 [16] | TGF-β, BMP [16] | Collagen II, Aggrecan, SOX5, SOX6 [16] |

| Adipogenic | PPARγ, C/EBPα [17] | Insulin, Glucocorticoids [17] | FABP4, Leptin, Adiponectin [17] |

The osteogenic differentiation of MSCs is primarily regulated by the transcription factor Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2), which is indispensable for osteoblast commitment [16]. Studies on Runx2-deficient mice have demonstrated a complete absence of osteoblasts and bone formation, underscoring its pivotal role [16]. Runx2 operates downstream of multiple signaling pathways, including bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which critically enhance osteoblast differentiation [16]. Osterix (Osx) acts downstream of Runx2, and its deficiency also results in a lack of osteoblast formation [16]. For chondrogenic differentiation, SRY-related high-mobility-group (HMG) box transcription factor 9 (SOX9) is the major regulatory factor involved [16]. SOX9 coordinates the expression of essential extracellular matrix components such as collagen type II and aggrecan, which are fundamental to cartilage structure and function [16]. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) superfamily members are potent inducers of SOX9 and chondrogenesis [16]. Adipogenic differentiation is coordinated by a cascade of transcription factors, culminating in the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (C/EBPα) [17]. These factors promote the expression of adipocyte-specific genes, including those encoding fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4), leptin, and adiponectin [17]. The balance between adipogenesis and osteogenesis is particularly critical in bone marrow homeostasis, where an imbalance favoring adipogenesis is associated with bone loss in conditions like osteoporosis [17].

Pathway Interactions and Cross-Regulation

A key feature of MSC lineage commitment is the cross-antagonism between these regulatory pathways. For instance, factors and pathways that stimulate adipogenesis typically inhibit osteogenesis, and vice versa [17]. PPARγ activation not only promotes adipogenesis but also suppresses osteoblast differentiation by inhibiting Runx2 activity [17]. Conversely, Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes osteogenesis while simultaneously suppressing adipogenesis by downregulating PPARγ [17]. This reciprocal relationship ensures that MSCs commit to a single lineage rather than intermediate states. The molecular basis for this cross-regulation involves direct transcriptional repression, competition for coactivators, and epigenetic modifications that create mutually exclusive chromatin configurations at lineage-specific gene promoters.

Experimental Protocols forIn VitroDifferentiation

Standardized in vitro differentiation protocols are essential for investigating MSC multipotency and for potential therapeutic applications. The following sections detail established methodologies for inducing and assessing trilineage differentiation.

Osteogenic Differentiation Protocol

Induction Medium Composition:

- Base medium: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) - high glucose

- Supplements: 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS)

- Dexamethasone: 100 nM (acts as a synthetic glucocorticoid to promote differentiation)

- Ascorbic acid: 50-100 μM (essential for collagen matrix formation)

- β-glycerophosphate: 10 mM (provides a source of organic phosphate for matrix mineralization) [16]

Procedure:

- Seed MSCs at a density of 5,000-10,000 cells/cm² in standard growth medium.

- At 60-70% confluence, replace growth medium with osteogenic induction medium.

- Refresh the induction medium every 2-3 days for 21-28 days.

- Differentiated osteoblasts will deposit a mineralized extracellular matrix detectable by staining.

Assessment Methods:

- Alizarin Red S Staining: Stains calcium deposits in the mineralized matrix bright orange-red. Quantification can be performed by eluting the dye and measuring absorbance.

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity: Early marker of osteoblast differentiation, measurable using enzymatic assays.

- Gene Expression Analysis: qRT-PCR for osteogenic markers such as Runx2, Osterix, Osteocalcin, and Collagen I [16].

Chondrogenic Differentiation Protocol

Induction Medium Composition:

- Base medium: DMEM - high glucose

- Supplements: 1% ITS+ Premix (Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium)

- Dexamethasone: 100 nM

- Ascorbic acid: 50 μM

- Sodium pyruvate: 100 μg/mL

- Proline: 40 μg/mL

- TGF-β3: 10 ng/mL (key inductive factor for chondrogenesis) [16]

Procedure (Micromass Culture):

- Resuspend MSCs at a high density (5-10 million cells/mL) in induction medium.

- Place 5-10 μL droplets of cell suspension in the center of culture wells and allow cells to adhere for 2-3 hours in a humidified incubator.

- Gently add induction medium to the wells without dislodging the micromass.

- Culture for 21-28 days, refreshing medium every 2-3 days.

- This high-density culture mimics the condensed mesenchyme during embryonic cartilage development.

Assessment Methods:

- Histological Staining: Safranin O or Alcian Blue staining detects sulfated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in the cartilage matrix.

- Immunohistochemistry: For collagen type II, the main collagenous component of cartilage.

- Gene Expression Analysis: qRT-PCR for chondrogenic markers including SOX9, Aggrecan, and Collagen II [16].

Adipogenic Differentiation Protocol

Induction Medium Composition:

- Base medium: DMEM - high glucose

- Supplements: 10% FBS

- Dexamethasone: 1 μM

- Isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX): 0.5 mM (phosphodiesterase inhibitor that increases intracellular cAMP)

- Indomethacin: 200 μM (cyclooxygenase inhibitor that promotes adipogenesis)

- Insulin: 10 μg/mL [17]

Procedure (Two-Step Induction):

- Seed MSCs at 20,000-30,000 cells/cm² and allow to reach 100% confluence.

- Initiate differentiation by adding adipogenic induction medium for 3-5 days.

- Replace with adipogenic maintenance medium (identical to induction medium but without IBMX and indomethacin) for 2-3 days.

- Repeat this cycle 2-3 times over 14-21 days to achieve mature adipocytes with lipid vacuoles.

Assessment Methods:

- Oil Red O Staining: Lipophilic dye that stains intracellular lipid droplets red. Can be quantified after elution.

- Gene Expression Analysis: qRT-PCR for adipogenic markers such as PPARγ, C/EBPα, FABP4 (aP2), and Leptin [17].

Table 2: Standard Staining Methods for Assessing Trilineage Differentiation

| Lineage | Staining Method | Target | Appearance | Time Point |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteogenic | Alizarin Red S | Calcium deposits | Orange-Red | 21-28 days |

| Chondrogenic | Alcian Blue or Safranin O | Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) | Blue/Green or Orange-Red | 21-28 days |

| Adipogenic | Oil Red O | Intracellular lipid droplets | Red | 14-21 days |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful investigation of MSC differentiation requires a carefully selected set of reagents and tools. The following table compiles essential solutions for studying multipotency.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying MSC Trilineage Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Differentiation |

|---|---|---|

| Induction Factors | Dexamethasone, TGF-β3, BMP-2, IBMX, Indomethacin, Insulin | Activate specific signaling pathways to initiate and drive lineage commitment [16] [17]. |

| Serum & Supplements | Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), ITS+ Premix (Insulin, Transferrin, Selenium) | Provide essential nutrients, hormones, and attachment factors for cell survival and differentiation [16]. |

| Surface Markers | CD105, CD73, CD90 (Positive); CD45, CD34, HLA-DR (Negative) | Identify and purify MSCs via flow cytometry; confirm cell population purity before differentiation [1] [17]. |

| Staining Kits | Alizarin Red S, Oil Red O, Alcian Blue | Detect and quantify differentiation endpoints (mineralization, lipids, GAGs) [16] [17]. |

| Antibodies | Anti-Collagen I, Anti-Osteocalcin, Anti-Collagen II, Anti-SOX9, Anti-PPARγ | Confirm protein-level expression of lineage-specific markers via immunohistochemistry or Western blot [16] [17]. |

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the key signaling pathways and molecular relationships governing MSC differentiation.

Osteogenic Signaling Pathway

Chondrogenic Signaling Pathway

Adipogenic Signaling Pathway

MSC Lineage Commitment Relationships

Advanced Research Applications and Methodologies

Contemporary MSC research employs sophisticated technologies to unravel the complexity of differentiation processes and overcome challenges in therapeutic applications.

Transcriptomic Approaches to Differentiation

High-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized our understanding of the molecular events during MSC differentiation [17]. This approach enables comprehensive profiling of mRNA, microRNA, circular RNA, and long non-coding RNA expression patterns at different time points throughout adipogenesis, osteogenesis, and chondrogenesis [17]. Transcriptome analyses have revealed that the differentiation processes involve complex temporal regulation of gene networks governing cell cycle, metabolism, and extracellular matrix organization. For instance, during osteogenesis, there is sequential activation of genes involved in cell proliferation, followed by matrix maturation and finally mineralization. Similarly, adipogenesis involves coordinated induction of lipid metabolism genes and suppression of osteogenic genes, reflecting the reciprocal relationship between these lineages [17].

Deep Learning for Predicting Differentiation Potential

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have introduced novel approaches for assessing MSC quality and differentiation potential. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) can predict the multipotency of human MSCs based on cellular morphology with high accuracy (85.98% in one study) [18]. This non-invasive method utilizes bright-field or immunofluorescence images of single cells to classify their differentiation capacity without requiring destructive assays [18]. The implementation of deep learning models such as DenseNet121, VGG19, and InceptionV3 enables researchers to perform quantitative, single-cell characterization of live stem cells, offering significant potential for improved quality control in clinical cell therapies [18]. This approach is particularly valuable for addressing donor-dependent variation in MSC differentiation capacity, which has been a major challenge in clinical applications [18].

Quantitative Lineage Tracing Strategies

Rigorous assessment of MSC differentiation potential at the single-cell level requires sophisticated lineage tracing methodologies [19]. Recent developments include statistical analysis of multicolor lineage tracing and lineage tracing at saturation, which allow researchers to determine multipotency potential with high confidence and assess the fate of all stem cells within a given lineage [19]. These methods provide a framework to resolve whether tissue-specific stem cells are truly multipotent or composed of mixtures of unipotent progenitors—a question of fundamental importance in developmental biology [19]. For MSCs, such approaches could help clarify the heterogeneity within populations and identify subpopulations with enhanced therapeutic potential for specific applications.

The multipotent differentiation potential of MSCs toward osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages represents a fundamental biological property with tremendous implications for regenerative medicine. The molecular regulation of these processes, centered around master transcription factors Runx2, SOX9, and PPARγ for the respective lineages, involves complex signaling networks that ensure proper lineage commitment. Standardized in vitro protocols enable researchers to direct MSC differentiation for both investigative and therapeutic purposes. Contemporary research employs advanced transcriptomic analyses, deep learning algorithms, and sophisticated lineage tracing strategies to deepen our understanding of these processes and address challenges such as donor variability and population heterogeneity. As basic science continues to elucidate the intricate mechanisms governing MSC multipotency, the translation of this knowledge to clinical applications holds promise for developing effective cell-based therapies for a wide range of degenerative diseases, orthopedic injuries, and other conditions requiring tissue repair and regeneration.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have emerged as a highly promising therapeutic strategy in regenerative medicine due to their unique multifunctional capabilities [1]. These non-hematopoietic, multipotent stromal cells possess three fundamental biological properties that underpin their clinical potential: immunomodulation, paracrine activity, and trophic support [20] [21]. Originally identified in bone marrow, MSCs have since been isolated from diverse tissues including adipose tissue, umbilical cord, placental tissue, and dental pulp [1]. The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) defines MSCs based on three key criteria: adherence to plastic under standard culture conditions; specific surface marker expression (CD73, CD90, CD105 ≥95%; CD34, CD45, CD14, CD19, HLA-DR ≤2%); and tri-lineage differentiation potential into osteocytes, chondrocytes, and adipocytes in vitro [1]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the core therapeutic mechanisms of MSCs, framed within the context of basic science and translational research applications for scientific and drug development professionals.

Immunomodulatory Mechanisms

Cell-to-Cell Contact-Dependent Immunomodulation

MSCs participate in both innate and adaptive immunity through direct cellular interactions [20]. These contact-dependent mechanisms involve precise molecular engagements with various immune cell populations:

T-cell Regulation: MSCs inhibit naive and memory T-cell responses through upregulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), which are critical for T-cell activation and leukocyte recruitment [20]. MSC co-culture with CD4+ T-cells activates the Notch1/forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) pathway, increasing the percentage of CD4+CD25 FOXP3+ regulatory T-cells (Tregs) [20]. Galectin-1, abundantly expressed on MSC surfaces, plays a crucial role in T-cell modulation, as knockdown results in restored CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation [20]. Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and PD-L2 expression on placental MSCs further inhibits T-cell proliferation through cell cycle arrest [20].

B-cell Interactions: Adipose-derived MSCs (A-MSCs) increase survival of quiescent B-cells via contact-dependent mechanisms and facilitate B-cell differentiation independently of T-cells [20]. MSC-mediated inhibition of Caspase 3-mediated B-cell apoptosis occurs through vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) upregulation, while proliferation inhibition involves cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 phase mediated by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways [20].

Innate Immune Cell Engagement: MSC interactions with natural killer (NK) cells result in suppressed granule polarization, indicating differential crosstalk between MSCs and cytotoxic NK cells [20]. MSCs prevent neutrophil apoptosis via ICAM-1-dependent mechanisms, exerting tissue-protective effects [20]. Monocytes phagocytose infused MSCs, inducing phenotypical and functional changes that subsequently modulate adaptive immune responses [20].

Table 1: Cell Contact-Dependent Immunomodulatory Mechanisms

| Immune Cell Type | Molecular Mechanisms | Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| T-cells | ICAM-1/VCAM-1 upregulation, Notch1/FOXP3 pathway activation, PD-L1/PD-L2 expression | Inhibition of proliferation, increased Treg induction, cell cycle arrest |

| B-cells | VEGF-mediated anti-apoptosis, p38 MAPK pathway activation | Enhanced survival of quiescent cells, cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 phase |

| NK cells | Suppression of granule polarization | Reduced cytotoxic activity |

| Monocytes/Macrophages | Phagocytosis of MSCs, PGE2-mediated switching | Phenotypical and functional changes, M1 to M2 phenotype transition |

| Neutrophils | ICAM-1-dependent anti-apoptosis | Enhanced survival, tissue-protective effects |

Soluble Factor-Mediated Immunomodulation

The MSC secretome contains a diverse repertoire of immunomodulatory molecules that exert potent paracrine effects on immune effector cells [20] [21]:

Cytokine Networks: MSCs secrete transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which collectively inhibit T helper 17 cell (Th17) differentiation while promoting Treg induction [20]. These factors work in concert to inhibit IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ production while inducing IL-10 secretion [20]. The IL-25/STAT3/PD-L1 axis has been identified as a key pathway through which MSCs suppress Th17 responses [20].

Extracellular Vesicles: MSC-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) and exosomes (30-150 nm diameter) represent important vehicles for immunomodulatory factor delivery [22]. These vesicles contain proteins, mRNAs, and microRNAs that mirror parent MSC immunoregulatory functions while offering advantages including low immunogenicity, enhanced stability, and reduced risks of tumorigenesis or thrombosis compared to whole-cell therapies [22].

Paracrine Signaling and Secretome

Composition and Biological Activity

The MSC paracrine secretome represents a complex mixture of bioactive factors that mediate therapeutic effects without requiring direct cellular differentiation or engraftment [1] [20]:

Growth Factors and Cytokines: MSC secretome includes stem cell factor (SCF), thrombopoietin (TPO), IL-6, TGF-β, FGF, HGF, and VEGF, which collectively promote angiogenesis, support bone marrow niche function, and modulate T-cell-mediated responses [23]. These factors work in concert to create a regenerative microenvironment conducive to tissue repair.

Extracellular Vesicle Cargo: MSC-EVs contain specific protein and nucleic acid cargo that varies depending on MSC tissue source and culture conditions [22]. EV contents include immunomodulatory miRNAs, growth factors, and enzymes that can reprogram recipient cells through horizontal transfer of biological information [22].

Table 2: Key Paracrine Factors in MSC Secretome

| Factor Category | Specific Components | Primary Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Factors | VEGF, FGF, HGF, TGF-β1 | Angiogenesis promotion, fibroblast proliferation, hepatocyte growth, immunomodulation |

| Cytokines | IL-6, IL-10, IL-1RA, SCF, TPO | Hematopoietic support, anti-inflammatory signaling, immunoregulation |

| Lipid Mediators | PGE2 | Macrophage polarization to M2 phenotype, T-cell suppression |

| Enzymes | IDO | Tryptophan catabolism, T-cell proliferation inhibition |

| Extracellular Vesicles | Exosomes, microvesicles | Horizontal transfer of miRNAs, proteins, and lipids to recipient cells |

Tissue Source Variability and Standardization Challenges

The biological functions and characteristics of MSC secretomes vary significantly depending on tissue source, creating both opportunities and challenges for therapeutic development [22]:

Source-Specific Variations: Bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) demonstrate high differentiation potential and strong immunomodulatory effects [1]. Adipose-derived MSCs (AD-MSCs) yield higher cell quantities and exert potent immunomodulatory effects, potentially superior to BM-MSCs for some applications [1] [20]. Umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) exhibit enhanced proliferation capacity, lower immunogenicity, and minimal risk of initiating allogeneic immune responses [1] [20].

Standardization Deficits: While procedures for MSC isolation, expansion, and therapeutic use have been standardized according to ISCT guidelines, standardized protocols for MSC-EV isolation and purification remain lacking [22]. Significant variations in EV characterization, dose units, and outcome measures across clinical trials underscore the need for harmonized reporting standards [22].

Trophic Support Mechanisms

Hematopoietic Support and Bone Marrow Niche

MSCs provide crucial trophic support for hematopoietic recovery, particularly following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) [23]:

Engraftment Acceleration: Systematic review of 47 clinical studies involving 1,777 patients demonstrated that MSC co-infusion accelerates hematopoietic recovery after HSCT, with particularly consistent benefits for platelet engraftment [23]. MSC recipients showed average neutrophil and platelet engraftment times of 13.96 and 21.61 days, respectively, with approximately 79% of studies reporting enhanced engraftment [23].

Mechanisms of Hematopoietic Support: MSCs contribute to hematopoietic recovery through secretion of cytokines including SCF, TPO, IL-6, and TGF-β, promotion of angiogenesis, support of bone marrow niche integrity, and modulation of T-cell-mediated responses [23]. These effects facilitate engraftment and mitigate graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in high-risk transplantation settings [23].

Tissue Repair and Regenerative Support

The trophic functions of MSCs extend beyond hematopoietic support to broader tissue repair and regeneration:

Anti-apoptotic Effects: MSCs secrete factors that inhibit programmed cell death in vulnerable cell populations, particularly in ischemic, inflammatory, or mechanically stressed tissues [1] [20]. These anti-apoptotic signals enhance survival of parenchymal cells during injury and recovery phases.

Angiogenic Induction: Through VEGF, FGF, and other angiogenic factor secretion, MSCs promote neovascularization in damaged tissues, restoring perfusion and nutrient delivery to compromised regions [1] [23].

Fibrosis Reduction: MSC trophic factors modulate extracellular matrix remodeling, reducing excessive scar formation while promoting functional tissue restoration [20].

Bacterial Clearance: MSCs enhance phagocytic activity of innate immune cells and may directly secrete antimicrobial peptides, contributing to infection resolution in injured tissues [20].

Experimental Methodologies

MSC-EV Isolation and Characterization Protocols

Standardized methodologies for extracellular vesicle isolation and characterization are critical for research reproducibility and therapeutic development:

Isolation Techniques: Differential centrifugation remains the most common approach, involving sequential centrifugation steps at 300 × g (10 minutes) to remove cells, 2,000 × g (10 minutes) to remove debris, 10,000 × g (30 minutes) to remove larger vesicles, and final ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g (70 minutes) to pellet EVs [22]. Alternative methods include size-exclusion chromatography, polymer-based precipitation, and immunoaffinity capture.

Characterization Standards: Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) determines particle size distribution and concentration [22]. Flow cytometry confirms surface marker expression (CD63, CD81, CD9) while transmission electron microscopy visualizes vesicle morphology [22]. Western blotting confirms presence of EV-associated proteins (Alix, TSG101) and absence of contaminants (calnexin, GM130).

Immunomodulation Assay Systems

T-cell Proliferation Assays: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are labeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and activated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies in the presence or absence of MSCs (typically 1:10 to 1:100 MSC:PBMC ratios) [20]. After 3-5 days, CFSE dilution in CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells is measured by flow cytometry to determine proliferation inhibition.

Macrophage Polarization Assays: Human monocytes are differentiated to M1 macrophages with GM-CSF (50 ng/mL) and polarized with IFN-γ (20 ng/mL) plus LPS (100 ng/mL), or to M2 macrophages with M-CSF (50 ng/mL) and IL-4 (20 ng/mL) [20]. MSCs are added in transwell systems or conditioned media is applied. M1 (CD80, CD86, HLA-DR) and M2 (CD206, CD163) marker expression is quantified by flow cytometry after 48 hours.

Table 3: In Vitro Functional Assays for MSC Characterization

| Assay Type | Key Reagents | Readout Parameters | Typical Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-cell Suppression | CFSE, anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies, PBMCs | CFSE dilution, cytokine secretion (IFN-γ, IL-17), Treg induction | 3-5 days |

| Macrophage Polarization | GM-CSF, M-CSF, IFN-γ, LPS, IL-4 | Surface markers (CD80/86, CD206/163), cytokine secretion (TNF-α, IL-10) | 2-3 days |

| IDO Activity | L-tryptophan, kynurenine standard | Kynurenine production (spectrophotometry, 490 nm) | 24-48 hours |

| Angiogenesis Assay | HUVECs, Matrigel, VEGF | Tube formation (branch points, tube length) | 4-18 hours |

| Hematopoietic Support | CD34+ cells, methylcellulose media | CFU-GM, BFU-E, CFU-GEMM colonies | 14 days |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for MSC Mechanism Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Marker Antibodies | CD73, CD90, CD105 (positive); CD34, CD45, HLA-DR (negative) | MSC characterization and purity assessment according to ISCT criteria |

| Differentiation Media | Osteogenic: Dexamethasone, β-glycerophosphate, ascorbic acid; Adipogenic: IBMX, indomethacin, insulin; Chondrogenic: TGF-β3, BMP-6 | Tri-lineage differentiation potential verification |

| Cytokine/Chemokine Arrays | TGF-β1, PGE2, IDO, HGF, VEGF detection systems | Secretome analysis and paracrine factor quantification |

| EV Isolation Kits | Ultracentrifugation reagents, size-exclusion columns, polymer-based precipitation kits | Extracellular vesicle isolation and purification |

| Cell Culture Supplements | FBS alternatives (xeno-free), hypoxia-mimetic agents, inflammatory priming cocktails (IFN-γ, TNF-α) | MSC preconditioning to enhance therapeutic potency |

| Flow Cytometry Panels | T-cell (CD4, CD8, CD25, FOXP3), B-cell (CD19, CD20), macrophage (CD80, CD86, CD206) markers | Immunomodulation mechanism analysis |

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Applications

Current Clinical Evidence

MSC-based therapies have demonstrated potential across diverse clinical applications, supported by accumulating clinical evidence:

Hematopoietic Recovery: Comprehensive systematic review of clinical studies (2000-2025) confirms MSC co-infusion accelerates hematopoietic recovery after transplantation, with platelet engraftment showing the most consistent benefit [23]. MSC therapy demonstrated safety with no major adverse events reported across 47 studies and 1,777 patients [23].

Disease Applications: Clinical trials have explored MSC therapies for autoimmune diseases, inflammatory disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, orthopedic injuries, cardiovascular diseases, and graft-versus-host disease [1] [20]. MSC administration has shown potential efficacy in treating several conditions that resist standard treatment approaches [21].

Dose Optimization Challenges

Clinical translation faces significant dose optimization challenges, particularly for MSC-derived products:

Route-Dependent Dosing: Dose-effect relationships reveal that nebulization therapy achieves therapeutic effects at doses around 10^8 particles, significantly lower than required for intravenous routes, suggesting a narrow and route-dependent effective dose window [22].

Standardization Deficits: Large variations in EV characterization, dose units, and outcome measures across clinical trials underscore the lack of harmonized reporting standards [22]. The field urgently requires standardized dosing frameworks, potency assays, and harmonized clinical protocols to advance safe and effective translation.

The therapeutic potential of MSCs in regenerative medicine is fundamentally underpinned by three core mechanisms: sophisticated immunomodulation through both contact-dependent and soluble factor-mediated pathways, comprehensive paracrine activity via diverse secretome components, and multifaceted trophic support promoting tissue repair and regeneration. The convergence of these mechanisms enables MSCs to coordinate complex tissue responses to injury, inflammation, and degeneration. Current research challenges include standardization of MSC-EV characterization, optimization of dosing parameters across different administration routes, and development of potency assays that reliably predict clinical efficacy. Future directions will likely focus on MSC engineering strategies to enhance homing, increase immunomodulatory potency, and improve therapeutic consistency. As the field advances, understanding the intricate interplay between immunomodulation, paracrine signaling, and trophic support will be essential for developing next-generation MSC-based therapies with enhanced precision and efficacy for clinical applications.

From Bench to Bedside: MSC Applications and Therapeutic Strategies

Standardized Protocols for MSC Isolation, Expansion, and Characterization

Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells (MSCs) have emerged as a cornerstone of regenerative medicine and cell-based therapy due to their unique properties, including self-renewal capacity, multipotent differentiation potential, and immunomodulatory functions [1]. These adult stem cells, first identified in bone marrow, can be isolated from various tissues and possess the ability to modulate the immune system and differentiate into multiple cell lineages, including osteocytes, chondrocytes, and adipocytes [24]. The therapeutic potential of MSCs extends across a broad spectrum of human diseases, from autoimmune and inflammatory disorders to neurodegenerative diseases and orthopedic injuries [1]. Their effects are primarily mediated through the release of bioactive molecules such as growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles, which play crucial roles in modulating the local cellular environment, promoting tissue repair, angiogenesis, and exerting anti-inflammatory effects [1].

The International Society for Cell and Gene Therapy (ISCT) has established minimum criteria for defining MSCs, which include: (1) adherence to plastic under standard culture conditions; (2) expression of specific surface markers (CD73, CD90, CD105) while lacking expression of hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45, CD14 or CD11b, CD79α or CD19, HLA-DR); and (3) capacity to differentiate into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages in vitro [1] [25]. These criteria provide a foundational standard for the field, though heterogeneity exists between MSCs from different tissue sources and even between clonal populations from the same source [26].

This technical guide provides comprehensive, standardized protocols for the isolation, expansion, and characterization of MSCs, framed within the context of basic science research to support their therapeutic application in regenerative medicine.

MSCs can be isolated from various somatic and perinatal tissues, each requiring specific isolation techniques. The most common sources include adipose tissue, bone marrow, umbilical cord, and cord blood [27]. The methodology varies depending on the tissue structure and cellular composition, with enzymatic digestion and density gradient centrifugation being the most widely employed techniques [27].

Isolation from Adipose Tissue

Adipose tissue represents a rich source of MSCs, with higher yields compared to bone marrow [1]. Two primary methods have been standardized for isolating adipose-derived MSCs (AD-MSCs):

Standard Isolation Protocol:

- Tissue Processing: Wash approximately 250mL of fat tissue 3-5 times with PBS for 5 minutes each wash, discarding the lower phase until clear [24].

- Enzymatic Digestion: Add collagenase and incubate for 1-4 hours at 37°C on a shaker [24].

- Enzyme Neutralization: Add 10% FBS to neutralize collagenase activity [24].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge digested fat at 800×g for 10 minutes to separate the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) pellet from floating adipocytes, lipids, and liquid [24].

- Red Blood Cell Lysis: Resuspend SVF pellet in 160mM NH₄Cl and incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature [24].

- Gradient Separation: Layer cells on Percoll or Histopaque gradient and centrifuge at 1000×g for 30 minutes at room temperature [24].

- Cell Filtration: Wash cells twice with PBS, then resuspend cell pellet in PBS and filter sequentially through 100μm and 40μm nylon mesh [24].

- Plating: Resuspend final cell pellet in 40% FBS/DMEM and plate in culture vessels incubated at 37°C, 5% CO₂ [24].

Rapid Isolation Protocol:

- Aspiration: Transfer blood/saline containing adipose tissue into a 50mL conical tube [24].