Mitigating Teratoma Risk in Stem Cell Therapies: 2025 Strategies for Detection and Safety

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of teratoma formation, a critical tumorigenicity risk associated with pluripotent stem cell (PSC)-derived therapies.

Mitigating Teratoma Risk in Stem Cell Therapies: 2025 Strategies for Detection and Safety

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of teratoma formation, a critical tumorigenicity risk associated with pluripotent stem cell (PSC)-derived therapies. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational biology of teratomas, explores advanced in vitro and in vivo methodologies for residual PSC detection, discusses optimization strategies for risk reduction, and delivers a comparative validation of emerging technologies against conventional assays. Synthesizing the latest 2025 consensus recommendations, the content serves as a strategic guide for developing safer cell therapy products through internationally harmonized safety protocols.

Understanding the Teratoma Challenge: Biology, Ethics, and Pluripotency

The same pluripotent characteristic that makes human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs) a powerful tool in regenerative medicine also creates their most significant clinical hurdle: the risk of teratoma formation [1]. A teratoma is a benign tumor characterized by rapid growth in vivo and a haphazard mixture of tissues derived from multiple embryonic germ layers, often with semi-semblances of organs, teeth, hair, muscle, cartilage, and bone [1]. This intrinsic link exists because the core definition of pluripotency—the ability to differentiate into cell types representing all three embryonic germ layers—is functionally tested in vivo via the teratoma formation assay, which remains the "gold standard" for assessing pluripotency [2] [1] [3]. When a small number of undifferentiated hPSCs escape differentiation protocols and are transplanted into a patient, they can find themselves in an appropriate in vivo microenvironment that allows them to undergo spontaneous, uncontrolled differentiation, leading to a teratoma [3]. This guide addresses the specific issues researchers encounter when working to mitigate this risk.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is a teratoma and why does it form from hPSCs?

A teratoma is a benign tumor composed of a disorganized mixture of tissues foreign to the site in which it arises. The term itself comes from the Greek words "teras" (monster) and "onkoma" (swelling or tumor) [2]. For researchers, a teratoma is best defined as a benign tumor composed of mature somatic tissues arranged in a disorderly manner [2]. They form from hPSCs because pluripotency is the ability of a single cell to give rise to all embryonic germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) and their derivatives. When hPSCs are placed in an in vivo environment, such as an immunocompromised mouse or an unintended human transplantation site, they can exploit this developmental potential in an unregulated fashion, spontaneously differentiating into various tissues in a chaotic, tumor-like mass [1] [3]. This is why the teratoma assay is considered the most stringent test of pluripotency.

Q2: How many undifferentiated hPSCs are needed to form a teratoma?

The minimum cell number required is context-dependent, but studies have shown that the "critical threshold" can be surprisingly low. The table below summarizes key findings from the literature on the relationship between cell number and teratoma formation risk.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Teratoma Formation Risk

| Injection Site | Minimum Cell Number for Teratoma Formation | Experimental Model | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intramyocardial | ~1 × 10⁵ cells | Immunodeficient mice | [1] |

| Skeletal muscles | ~1 × 10⁴ cells | Immunodeficient mice | [1] |

| Subcutaneous dorsal region | As few as 0.5 × 10³ - 1 × 10³ cells | Immunodeficient mice | [1] |

| General risk threshold | 10,000 or even fewer hPSCs can form a teratoma in vivo | Preclinical hPSC-derived cell populations | [4] [1] |

Q3: What are the main safety risks for hPSC-based cell therapies?

The safety risks fall into two main categories [4]:

- Teratoma Formation from Residual Undifferentiated hPSCs: Differentiation protocols often yield heterogeneous cell populations. Even a tiny fraction (e.g., 0.001%) of residual undifferentiated hPSCs in a billion-cell therapeutic product can be sufficient to form a teratoma in vivo [4]. This necessitates a depletion of undifferentiated hPSCs by 5-logs or more to ensure safety [4].

- Tumors or Unwanted Tissues from Wrong Lineages: Differentiated cell-types of the wrong lineage can, upon transplantation, generate tumors or unwanted tissues. For example, transplantation of PSC-derived neural populations has, in some cases, generated tumors or cysts in animal models [4].

Q4: What strategies can prevent teratoma formation in therapeutic products?

Multiple advanced strategies are being developed to mitigate teratoma risk. The most promising approaches are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Strategies for Teratoma Prevention and Risk Mitigation

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Key Findings/Agents | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small-Molecule Inhibition | Targets and inhibits hPSC-specific antiapoptotic factors (e.g., Survivin), selectively eliminating undifferentiated cells via apoptosis. | Quercetin, YM155. One treatment caused selective and complete cell death of undifferentiated hPSCs while sparing differentiated progeny. | [5] |

| Genome-Edited Safeguards | Genetic insertion of "safety switches" into the genome of hPSC lines that allow for selective elimination of undifferentiated cells or the entire therapeutic product. | NANOG-iCaspase9: A system knocked into the NANOG locus that eliminates hPSCs >10⁶-fold upon addition of a small molecule (AP20187). ACTB-iCaspase9/ACTB-TK: Systems that allow elimination of all hPSC-derived cells if adverse events occur. | [4] |

| Advanced In Vitro Assays | Using highly sensitive methods to detect residual undifferentiated cells in the final product before transplantation. | Droplet digital PCR (dPCR) and Highly Efficient Culture (HEC) assays offer greater sensitivity and reproducibility than traditional in vivo teratoma assays for quality control. | [6] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Excessive Differentiation in hPSC Cultures Leading to Heterogeneous Populations

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Old or improperly stored culture medium.

- Solution: Ensure complete cell culture medium (e.g., mTeSR Plus) kept at 2-8°C is less than two weeks old [7].

- Cause: Overgrowth of colonies or uneven colony size during passaging.

- Solution: Passage cultures when colonies are large and compact but before they overgrow. Ensure cell aggregates generated after passaging are evenly sized [7].

- Cause: Cultures exposed to suboptimal conditions.

- Solution: Avoid having the culture plate out of the incubator for more than 15 minutes at a time. Manually remove areas of differentiation prior to passaging [7].

Problem: Low or No Teratoma Formation in Validation Assays

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Poor cell viability at the time of injection.

- Solution: Confirm stem cells are ≥90% viable and free of mycoplasma prior to injection [3].

- Cause: Suboptimal injection site, technique, or cell number.

- Cause: Host immune rejection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Immunocompromised Mice | In vivo host for teratoma formation assays to avoid immune rejection of xenografted human cells. | NOD/SCID, NSG, BALB/c nude mice [1] [3]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Provides structural support and signaling cues for injected cells; enhances teratoma take rate and vascularization. | Growth factor-reduced Matrigel [1] [3]. |

| Defined Culture Medium | Maintains hPSCs in a pluripotent state for pre-injection expansion. | mTeSR1, mTeSR Plus [7] [1]. |

| Passaging Reagents | Gently dissociates hPSC colonies into aggregates for propagation or preparation for injection. | ReLeSR, Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent, Collagenase Type IV [7] [1] [8]. |

| Histology Reagents | For analysis of harvested teratomas to confirm pluripotency via identification of three germ layers. | H&E Staining: General tissue morphology. IHC Antibodies: Lineage-specific markers for precise germ layer identification [2] [3]. |

| Small-Molecule Inhibitors | Selective elimination of undifferentiated hPSCs from a differentiated cell population. | Quercetin, YM155 (target Survivin) [5]. |

| Reporter Genes | Enables non-invasive, longitudinal imaging of cell survival, migration, and teratoma growth in vivo. | Firefly luciferase (Fluc) for bioluminescence imaging (BLI); fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP, mRFP) for fluorescence imaging [1]. |

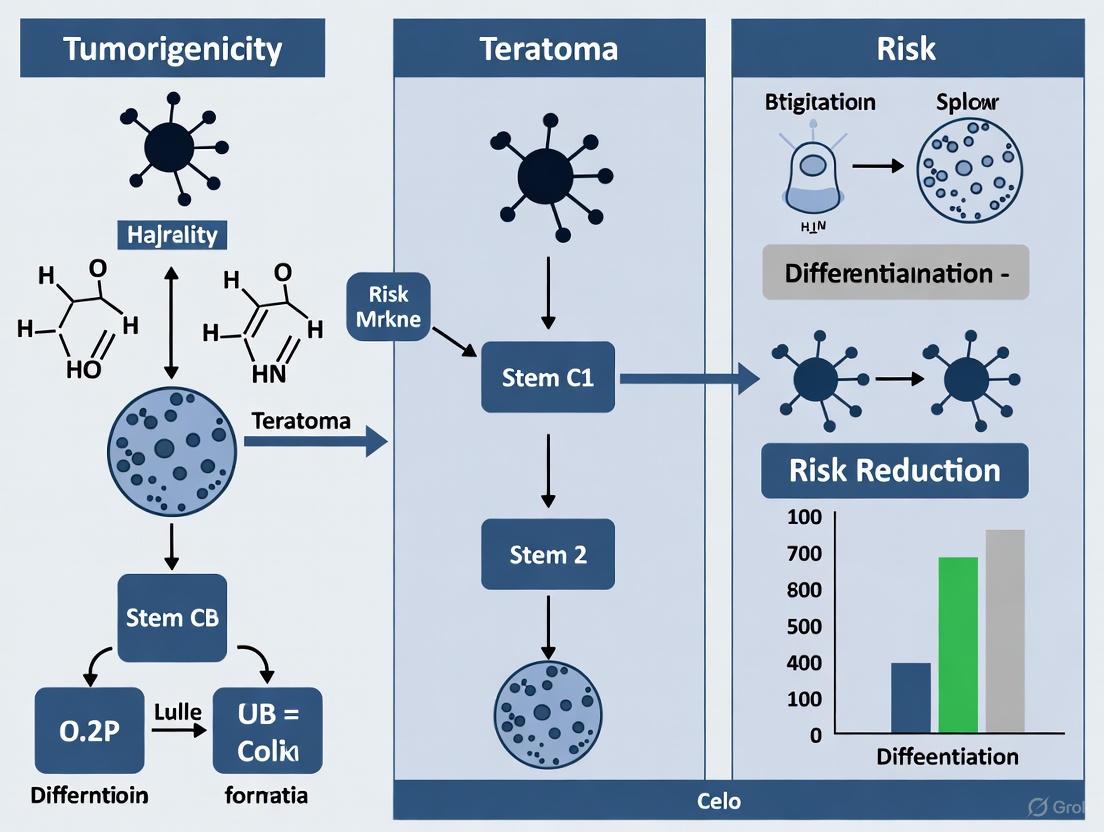

Visualizing the Link: From Pluripotency to Teratoma

The following diagram illustrates the core biological pathway that links the intrinsic property of pluripotency to the formation of a teratoma.

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Assays

Protocol 1: Standard In Vivo Teratoma Formation Assay

This protocol is used to validate the pluripotency of hPSC lines or to test the tumorigenicity of their therapeutic derivatives [1] [3].

Stem Cell Preparation:

- Expand pluripotent stem cells under conditions that maintain pluripotency (e.g., feeder-free, xeno-free) [3].

- Verify cell quality via pluripotency markers (OCT4, NANOG, SSEA4) before harvesting [3].

- Harvest cells during the logarithmic growth phase. For injection, resuspend cells in an appropriate buffer, often mixed with an ECM like Matrigel to enhance engraftment [1] [3].

Animal Preparation and Injection:

- Use immunocompromised mice (e.g., NOD/SCID, NSG) aged 6-8 weeks, maintained in sterile, pathogen-free housing [1] [3].

- Anesthetize the mouse according to institutional guidelines. Shave and disinfect the injection site (common sites include subcutaneous, intramuscular, or under the testis capsule) [1].

- Load a fine-gauge syringe (e.g., 28.5 gauge insulin syringe) with the cell suspension. The typical cell number ranges from 1x10⁵ to 1x10⁷ per injection site [1] [3].

- Slowly inject the cells into the chosen site. Gently withdraw the needle and apply slight pressure to prevent leakage. Monitor the animal until it recovers from anesthesia [3].

Teratoma Monitoring and Analysis:

- Observe mice weekly. Palpate injection sites for nodules, which are typically visible within 6-12 weeks [3].

- Monitor tumor size with calipers. Pre-define humane endpoints (e.g., tumor diameter of 1.0–1.5 cm) to prevent animal distress [3].

- When endpoints are reached, sacrifice the animal and carefully excise the teratoma.

- Fix the teratoma in 10% formalin for 24-48 hours, then embed in paraffin and section at 5-10 µm thickness [3].

- Stain sections with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and evaluate under a microscope for the presence of tissues derived from all three germ layers (e.g., neural rosettes for ectoderm; cartilage or muscle for mesoderm; gut-like epithelium for endoderm) [2] [3]. Immunohistochemistry with lineage-specific markers can provide further confirmation.

Protocol 2: Selective Elimination of Undifferentiated hPSCs Using Small Molecules

This protocol is used to pre-treat a differentiated cell population to remove residual pluripotent cells prior to transplantation [5].

Procedure:

- Generate your differentiated cell product from hPSCs using your standard protocol.

- Treat the mixed cell population with a small-molecule inhibitor. For example, a single treatment with Quercetin (which targets the antiapoptotic factor Survivin) can be used [5].

- The treatment selectively induces mitochondrial accumulation of p53 and apoptotic cell death in undifferentiated hPSCs, while sparing differentiated cell types like dopamine neurons and smooth-muscle cells [5].

- After treatment, the differentiated cell product can be washed and prepared for transplantation. This pre-treatment has been shown to be sufficient to prevent teratoma formation in subsequent transplantation experiments [5].

FAQs on Teratoma Composition and Analysis

FAQ 1: What defines a teratoma in the context of pluripotent stem cell research?

A teratoma is a benign tumor composed of tissues representing all three embryonic germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—when pluripotent stem cells are xenografted into immunodeficient mice. The ability to form teratomas is a defining characteristic (sine qua non) of pluripotent stem cells and is considered the "gold-standard" assay to confirm pluripotency. These tumors contain complex, disorganized structures with differentiated tissues such as neural tissue (ectoderm), cartilage or muscle (mesoderm), and epithelial structures (endoderm) [9] [10] [11].

FAQ 2: How does the transplantation site affect teratoma formation efficiency and composition?

The site of implantation significantly influences the efficiency of teratoma formation, but histological composition across sites is generally consistent. The table below summarizes key findings from site-dependent studies:

Table: Teratoma Formation Efficiency by Injection Site

| Injection Site | Formation Efficiency | Key Observations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney Capsule | 100% | Often used for its high efficiency. | [12] |

| Subcutaneous (with Matrigel) | 80-100% | Easy to monitor and remove; larger proportion of solid tissues. | [9] [11] |

| Intratesticular | 60-94% | High efficiency, but slightly longer latency. | [9] [11] |

| Intramuscular | 12.5% | Reported as most convenient and reproducible in one study. | [9] [12] |

While the efficiency and growth latency vary, site-specific differences in the histological composition of the resulting teratomas are generally not observed [9] [11]. Subcutaneous teratomas are often distinct, easier to remove, and cause minimal discomfort to the animal model [9].

FAQ 3: What factors can lead to failed or inconsistent teratoma formation?

Failed teratoma formation can often be traced back to issues with the stem cells or the experimental procedure. Here is a troubleshooting guide based on common problems:

Table: Troubleshooting Teratoma Formation Experiments

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No teratoma formation | Low cell viability or insufficient cell number. | Ensure high cell viability (>90%) and use at least 1x10^6 cells per injection [10] [11]. |

| Suboptimal injection site. | Switch to a higher-efficiency site like subcutaneous with Matrigel or kidney capsule [9] [12]. | |

| Excessive differentiation in starting culture | Stem cell culture is not fully undifferentiated. | Maintain cultures by removing differentiated areas before passaging and avoid overgrowth [7]. |

| High variability in teratoma growth | Inconsistent cell handling. | Minimize time culture plates are out of the incubator; ensure cell aggregates for injection are evenly sized [7]. |

| Low cell attachment post-passaging | Over-dissociation of cells. | Reduce pipetting and incubation time with dissociation reagents to avoid generating overly small aggregates [7]. |

FAQ 4: What are the primary strategies to eliminate the tumorigenic risk of residual pluripotent stem cells in cell therapy products?

The primary challenge for clinical applications is that even a few contaminating undifferentiated hPSCs within differentiated derivatives can form teratomas after transplantation [13] [14]. Strategies focus on targeting unique properties of pluripotent cells:

- Genetic Modification with Suicide Genes: A highly specific strategy involves inserting a suicide gene, like the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK), into a pluripotency-specific genetic locus such as NANOG via homologous recombination. When exposed to a prodrug like ganciclovir (GCV), only the undifferentiated cells expressing the TK gene are eliminated, leaving the differentiated therapeutic cell population unharmed [13].

- Antibody-Based Cell Depletion: This method uses antibodies against hPSC-specific surface markers (e.g., SSEA-5) to identify and remove undifferentiated cells from a mixed population through immunodepletion or cytotoxic killing [13].

- Small Molecule Inhibitors: Certain small molecules can selectively induce cell death in pluripotent stem cells without harming differentiated progeny, offering a non-genetic alternative for risk reduction [14].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Standardized Teratoma Formation Assay

This protocol is adapted from established methods for assessing the pluripotency and tumorigenic potential of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) [9] [11].

- Cell Preparation:

- Culture hPSCs under standard, feeder-free conditions (e.g., on Matrigel-coated plates in mTesR1 medium) to maintain undifferentiated state [13] [7].

- At ~80% confluence, harvest cells using a gentle dissociation reagent like TrypLE or collagenase. Ensure cells are in a single-cell suspension or small, uniform clumps.

- Wash cells twice with PBS and resuspend in an appropriate injection solution, typically PBS mixed with 30% Matrigel, to enhance teratoma formation efficiency [9] [11]. Keep the cell suspension on ice until injection.

- Animal Model and Injection:

- Use immunodeficient mice such as NOD/SCID IL2Rγ⁻⁄⁻ or SCID/beige mice aged 6-8 weeks.

- For subcutaneous injection, slowly inject 1-5 million cells in a 200 µL volume into the hind leg or flank region using a 27-gauge needle [13] [11].

- Monitor animals regularly for teratoma formation. Growth latency typically ranges from 6 to 12 weeks.

- Tissue Harvesting and Analysis:

- Surgically remove teratomas once they reach a predetermined size (e.g., 1.5 cm diameter).

- Fix teratomas in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24-48 hours.

- Process fixed tissues through a standard ethanol dehydration series, embed in paraffin, and section at 5-10 µm thickness.

- Stain sections with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for general histology.

- Analyze multiple sections from different parts of the teratoma to identify representative tissues from all three germ layers (e.g., neural rosettes for ectoderm, cartilage for mesoderm, gut-like epithelium for endoderm) [9] [15].

Protocol 2: Validating Pluripotent Cell Elimination via Suicide Gene Strategy

This protocol describes how to test the effectiveness of a genetic safety switch, such as the TK/GCV system, both in vitro and in vivo [13].

- In Vitro Validation:

- Culture genetically modified hPSCs (e.g., NANOG-TK knock-in) alongside wild-type controls.

- Differentiate a portion of the TK-modified cells into the desired cell type (e.g., neural progenitor cells or cardiomyocytes).

- Treat undifferentiated TK-hPSCs, differentiated TK-cell derivatives, and wild-type controls with Ganciclovir (GCV) at varying concentrations (e.g., 1-10 µM) for several days.

- Assess cell viability using assays like ATP-based luminescence or flow cytometry. The expected outcome is selective death of undifferentiated TK-hPSCs, while their differentiated progeny and wild-type cells remain viable [13].

- In Vivo Validation (Preventing Teratoma Formation):

- Inject TK-modified hPSCs subcutaneously into immunodeficient mice as described in Protocol 1.

- One day post-injection, administer GCV to the mice via intraperitoneal injection (e.g., 10 mg/kg/day) for 1-2 weeks.

- Monitor the injection sites for teratoma growth over 12-16 weeks. Effective elimination should result in a significant reduction or complete absence of teratoma formation in the GCV-treated group compared to the untreated control group [13].

- In Vivo Validation (Aborting Established Teratomas):

- Allow teratomas to establish from TK-modified hPSCs for 6-8 weeks.

- Administer GCV for 1-2 weeks.

- Analyze harvested teratomas for extensive apoptosis (e.g., via TUNEL assay) and regression, confirming the functionality of the suicide gene in an in vivo setting [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in teratoma formation and analysis studies.

Table: Key Reagents for Teratoma Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Matrigel | Basement membrane extract; enhances teratoma formation efficiency and provides structural support for injected cells. | Mixed with cell suspension in PBS at 30% concentration for subcutaneous injection [9] [11]. |

| Immunodeficient Mice (e.g., NOD/SCID IL2Rγ⁻⁄⁻) | Host organism that does not reject transplanted human cells, allowing teratoma growth. | Used as the in vivo model for teratoma formation assays [13] [11]. |

| mTeSR1 / mTeSR Plus | Defined, feeder-free culture medium; maintains human PSCs in a pluripotent state. | Used for culturing hPSCs prior to harvesting for injection [13] [7]. |

| Ganciclovir (GCV) | Antiviral prodrug; selectively kills cells expressing the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) suicide gene. | Administered via intraperitoneal injection to mice to eliminate TK-expressing undifferentiated stem cells [13]. |

| Anti-GFP Antibody | Immunohistochemical detection; identifies GFP-tagged cancer cells in co-culture or invasion studies within teratomas. | Used to track invasion of GFP-expressing tumor cells into human teratoma-derived tissues [15]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Diagrams and Workflows

Teratoma Assay Workflow

This diagram illustrates the standard experimental workflow for performing a teratoma formation assay.

Safety Strategy: Suicide Gene Mechanism

This diagram outlines the genetic strategy for eliminating residual pluripotent stem cells to enhance the safety of cell therapies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Is VEGF absolutely essential for all types of teratoma growth? No, the essentiality of VEGF depends on the cellular context. Research demonstrates that teratomas derived from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), such as embryonic stem cells (ESCs), are highly dependent on VEGF for angiogenesis and growth. Genetically disrupting the VEGF gene in these cells completely abrogates their tumorigenic potential. In contrast, certain oncogene-driven tumors (e.g., from ras or neu-transformed adult fibroblasts) can form aggressive, angiogenic tumors even when they are VEGF-null, utilizing VEGF-independent pathways [16].

Q2: What are the primary mechanisms of VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling in teratoma angiogenesis? VEGF-A binding to VEGFR2 initiates a critical signaling cascade that promotes teratoma angiogenesis. The key steps include:

- Receptor Dimerization & Autophosphorylation: VEGF binding induces VEGFR2 dimerization and autophosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues within its intracellular domain [17] [18].

- Downstream Pathway Activation: This activates major downstream signaling pathways, including:

- RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK: Promotes endothelial cell proliferation and differentiation.

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR: Enhances endothelial cell survival.

- p38/MAPK: Regulates endothelial cell migration and tube formation [18]. These signals drive endothelial cell proliferation, migration, survival, and ultimately, the formation of new blood vessels to support teratoma growth [17] [18].

Q3: What are the best strategies to eliminate residual undifferentiated PSCs and reduce teratoma risk? Multiple strategies have been developed to purge residual teratoma-initiating cells:

- Antibody-Based Cell Removal: Using monoclonal antibodies against cell surface markers highly specific to undifferentiated PSCs (e.g., SSEA-5) for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) to deplete them prior to transplantation [19].

- Small Molecule Inhibitors: Treating cell populations with inhibitors like YM155, a survivin inhibitor, which selectively kills pluripotent stem cells while sparing differentiated progeny like CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells [20].

- Suicide Gene Strategies: Engineering PSCs to express a suicide gene (e.g., inducible caspase-9) under the control of a pluripotency-specific promoter, allowing for selective elimination of undifferentiated cells upon administration of a prodrug [20].

Q4: Why might anti-VEGF therapies fail, and what are potential combination strategies? Anti-VEGF monotherapy can fail due to compensatory angiogenic signaling. Tumors may upregulate alternative pro-angiogenic factors such as FGF-2 [21]. FGF-2 can recruit pericytes via a PDGFRβ-dependent mechanism, stabilizing vessels and conferring resistance to VEGF inhibition [21]. Combination therapy, such as dual inhibition of VEGF and PDGF signaling, has been shown to overcome this resistance and produce a superior antitumor effect in resistant models [21].

Troubleshooting Experimental Challenges

Challenge: Variable Teratoma Formation in Xenograft Models

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent numbers of residual undifferentiated PSCs in the graft.

- Solutions:

- Implement a rigorous pre-transplantation purification step using validated surface markers (e.g., SSEA-5, TRA-1-60) to remove undifferentiated cells [19].

- Use a highly sensitive assay, such as digital PCR, to quantify residual undifferentiated PSCs in your final cell product to better correlate cell dose with tumorigenic risk [22].

- Standardize the differentiation protocol and use highly efficient culture assays to ensure minimal pluripotent cell contamination [22].

Challenge: Inconsistent Response to VEGFR2 Inhibitor Treatment

- Potential Cause: Activation of alternative pro-angiogenic pathways (e.g., FGF-2, PDGF) bypassing VEGF blockade [16] [21].

- Solutions:

- Profile the tumor's expression of multiple angiogenic factors (VEGF, FGF-2, PDGF) post-treatment to identify potential resistance mechanisms.

- Consider combination therapy targeting multiple pathways simultaneously, such as using a VEGFR2 inhibitor alongside a PDGFRβ inhibitor [21].

Quantitative Data on VEGF and Teratoma Formation

Table 1: Tumorigenicity of VEGF-Deficient Cells in Different Contexts

| Cell Type | Genetic Alteration | VEGF Status | Tumorigenic Outcome | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Stem (ES) Cells | None (Teratoma model) | VEGF -/- | No tumor formation (for at least 50 days) | VEGF is indispensable for ES cell-derived teratoma angiogenesis [16]. |

| Adult Dermal Fibroblasts | Transformed with ras or neu oncogene | VEGF -/- | Aggressive tumor formation (100% take rate) | Oncogene-driven tumorigenesis can proceed via VEGF-independent angiogenesis [16]. |

Table 2: Strategies for Eliminating Teratoma-Forming Cells

| Strategy | Method | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Marker Depletion [19] | FACS/MACS with anti-SSEA-5 | Physical removal of undifferentiated cells | Non-invasive; uses intrinsic cell markers |

| Small Molecule Inhibition [20] | Treatment with YM155 | Inhibits survivin, killing pluripotent cells | More efficient than some suicide genes; low toxicity to HSCs |

| Suicide Gene [20] | iCaspase-9 + AP20187 prodrug | Induces apoptosis in undifferentiated cells | Can be used pre- or post-transplantation |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Validating VEGFR2 Signaling Inhibition In Vitro

Objective: To assess the efficacy and specificity of a VEGFR2 inhibitor on downstream signaling pathways in endothelial cells.

Materials:

- Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs)

- VEGFR2 inhibitor (e.g., Sunitinib, Sorafenib)

- Recombinant Human VEGF-A

- Cell culture medium and supplements

- Lysis Buffer (containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors)

- Antibodies for Western Blot: anti-phospho-VEGFR2 (Tyr1175), anti-VEGFR2, anti-phospho-ERK, anti-ERK, anti-β-Actin.

Method:

- Cell Preparation: Seed HUVECs in culture plates and serum-starve them for 4-6 hours to quiesce the cells.

- Inhibitor Pre-treatment: Pre-treat cells with a range of concentrations of the VEGFR2 inhibitor (e.g., 0.1 µM, 1 µM, 10 µM) or a vehicle control (DMSO) for 1-2 hours.

- Stimulation: Stimulate the cells with VEGF-A (e.g., 50 ng/mL) for 10-15 minutes.

- Cell Lysis: Lyse the cells immediately on ice using ice-cold lysis buffer.

- Western Blot Analysis:

- Determine protein concentration of the lysates.

- Separate equal amounts of protein by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a PVDF membrane.

- Probe the membrane with the specified antibodies.

- Key Validation: Successful inhibition is confirmed by a dose-dependent decrease in phosphorylated VEGFR2 and its downstream effector, ERK, in response to VEGF stimulation, without a change in total protein levels.

Protocol: In Vivo Teratoma Assay with Anti-Angiogenic Treatment

Objective: To evaluate the effect of VEGFR2 blockade on the growth and vascularization of PSC-derived teratomas.

Materials:

- Immunodeficient mice (e.g., NOD-SCID or NSG)

- Undifferentiated PSCs or differentiated cell product.

- VEGFR2 neutralizing antibody (e.g., DC101 for mouse models) or small molecule inhibitor.

- Matrigel for cell suspension.

- In vivo imaging system (if using luciferase-expressing cells).

Method:

- Cell Transplantation: Harvest PSCs and resuspend in a 1:1 mixture of culture medium and Matrigel. Inject cells subcutaneously or under the testis capsule of anesthetized mice.

- Treatment Regimen: Randomize mice into treatment and control groups.

- Treatment Group: Administer VEGFR2 blocking agent (e.g., DC101 antibody at 20-40 mg/kg, i.p., twice weekly).

- Control Group: Administer isotype control antibody or vehicle.

- Tumor Monitoring: Monitor tumor formation weekly by palpation and/or bioluminescent imaging. Record tumor volume.

- Endpoint Analysis: At the experimental endpoint, harvest tumors.

- Weigh and measure tumors.

- Process for histology: Fix tumors, embed in paraffin, and section. Perform immunohistochemistry for CD31 (vascular endothelial marker) to quantify microvessel density and assess vascular morphology [16].

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

VEGFR2 Signaling Pathway in Angiogenesis

Experimental Workflow for Validating Anti-Angiogenic Therapy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying VEGF/VEGFR2 in Teratomas

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Example Product(s) | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGFR2 Neutralizing Antibody | Blocks ligand binding to VEGFR2 | DC101 (anti-mouse VEGFR2) | In vivo inhibition of angiogenesis in mouse teratoma models [16]. |

| VEGFR2 Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor | Small molecule inhibiting VEGFR2 kinase activity | Sunitinib (Type I), Sorafenib (Type II) | Pharmacological blockade of VEGFR2 signaling; can be used in vitro and in vivo [18]. |

| Anti-Human Pluripotency Marker Antibodies | Binds surface markers on undifferentiated PSCs | Anti-SSEA-5, Anti-TRA-1-60 | Identification and removal of teratoma-initiating cells via FACS/MACS [19]. |

| Anti-CD31 (PECAM-1) Antibody | Labels vascular endothelial cells | Anti-CD31 for IHC/IF | Histological quantification of tumor microvessel density (angiogenesis) [16]. |

| Survivin Inhibitor | Selectively induces apoptosis in PSCs | YM155 | Purging residual undifferentiated cells from differentiated cell populations pre-transplantation [20]. |

| Recombinant VEGF Protein | Activates VEGFR2 signaling | Recombinant Human VEGF-A165 | Positive control for stimulating angiogenesis in in vitro assays. |

FAQ: Ethical Considerations in Stem Cell Research

Q1: What are the primary ethical advantages of using iPSCs over ESCs in research? The primary ethical advantage of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) over embryonic stem cells (ESCs) is that their generation does not require the destruction of human embryos, which is a central point of ethical debate for ESCs [23] [24]. Furthermore, iPSC technology avoids the ethical concerns related to egg donation, including the health risks to women from invasive procedures and issues regarding appropriate compensation for donors [24]. This removes a significant burden from women and circumvents the ethical debate about the commodification of human body parts [24].

Q2: Do iPSCs fully resolve all ethical issues associated with stem cell research? No, the generation of iPSCs does not resolve all ethical issues. While they circumvent concerns about embryo destruction, they introduce other ethical considerations [24] [25]. These include:

- Potential for Human Cloning: If iPSCs were reprogrammed to full embryonic potential, the technology could be used for reproductive cloning [24].

- Genetic Manipulation: The use of genetically altered cells in therapies raises concerns about unintended consequences of modifying the human genome [24] [25].

- Chimera Formation: The use of iPSCs to create chimeras (organisms with cells from different species) raises ethical questions about the boundaries of scientific intervention in nature [24].

- Justice and Access: There are concerns about the equitable distribution of and access to potentially expensive iPSC-derived therapies [24].

Q3: What is the significance of the NANOG locus in improving the safety of stem cell therapies? The NANOG locus is highly specific to pluripotent stem cells and is rapidly downregulated when these cells differentiate [13] [4]. This makes it an ideal genetic "safe harbor" for introducing suicide genes. By placing an inducible suicide gene, such as herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (TK) or inducible Caspase 9 (iCasp9), into this locus via homologous recombination, researchers can create stem cell lines where undifferentiated cells—and only undifferentiated cells—can be selectively eliminated before or after transplantation, thereby preventing teratoma formation [13] [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Teratoma Risk Mitigation

Problem: Teratoma Formation from Residual Undifferentiated PSCs in Therapeutic Cell Products

Background: Even a small number of residual undifferentiated pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) within a differentiated cell product can lead to teratoma formation after transplantation. This is a major safety hurdle for clinical applications [26] [4].

Solution 1: Genetic Modification with a Suicide Gene This strategy involves engineering a "safety switch" into the PSCs that allows for the selective elimination of undifferentiated cells.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Targeting Vector Design: Construct a targeting vector containing a suicide gene cassette (e.g., HSV-TK or iCasp9) flanked by long homology arms specific to the 3'-untranslated region (UTR) of the endogenous NANOG gene [13] [4].

- Stem Cell Transfection: Introduce the targeting vector into your pluripotent stem cell line (e.g., via electroporation).

- Selection and Screening: Select for successfully transfected cells (e.g., using puromycin resistance if included in the cassette). Screen clones for correct homologous recombination at the NANOG locus using techniques like Southern blotting or PCR [13].

- Validation: Validate that the engineered cell line maintains normal pluripotency, karyotype, and differentiation potential [4].

- Application:

- In vitro: Differentiate the engineered PSCs into your desired therapeutic cell type. Before transplantation, treat the cell population with the pro-drug ganciclovir (if using TK) or the small molecule AP20187 (if using iCasp9) to activate the suicide gene and eliminate any remaining NANOG-positive, undifferentiated PSCs [13] [4].

- In vivo: If a teratoma is detected post-transplantation, administering the pro-drug can eliminate the contaminating pluripotent cells [13].

Solution 2: Small Molecule-Based Depletion This approach uses small molecules that are selectively toxic to undifferentiated PSCs.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Establish your differentiated cell population from PSCs.

- Compound Administration: Treat the mixed cell culture with a small molecule that targets undifferentiated cells. Examples include the survivin inhibitor YM155, though its specificity should be verified for your specific cell types [4].

- Dosage and Timing Optimization: Determine the optimal concentration and duration of treatment that maximizes the killing of undifferentiated PSCs while minimizing damage to the differentiated therapeutic cells. This requires careful dose-response assays [4].

- Validation: After treatment, assess the viability of both the differentiated target cells and the undifferentiated PSCs. Use flow cytometry for pluripotency markers (e.g., TRA-1-60, SSEA4) to confirm the depletion of undifferentiated cells [26].

Diagram: Suicide Gene Strategy for Teratoma Prevention

This diagram illustrates the genetic strategy for eliminating undifferentiated pluripotent stem cells to prevent teratoma formation.

Problem: Assessing Pluripotency and Tumorigenicity of Novel Cell Lines

Background: Researchers developing new PSC lines or differentiation protocols need robust methods to validate pluripotency and rule out malignancy.

Solution: Standardized Teratoma Assay The teratoma assay is the gold standard for testing pluripotency and assessing malignancy potential in vivo [27] [28].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest undifferentiated PSCs. A typical injection uses 5-10 million cells resuspended in Matrigel/PBS [27].

- Animal Model: Use immunodeficient mice (e.g., NOD/SCID, Rag2-/-;γc-/-). The injection site (subcutaneous, intramuscular, under the kidney capsule) should be reported as it can influence assay outcomes [27] [28].

- Monitoring and Endpoint: Monitor mice for teratoma formation. The assay typically runs for 8-12 weeks, or until tumors reach a predefined size limit. Record the time to tumor appearance and growth kinetics [27].

- Histological Analysis: Extract teratomas, fix, section, and stain with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). A qualified pathologist should examine the sections for the presence of differentiated tissues from all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) to confirm pluripotency. The teratoma should also be scrutinized for "embryonal carcinoma elements" or undifferentiated tissues, which indicate malignancy [28].

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Lack of Standardization: The teratoma assay suffers from a lack of standardization across labs. It is critical to report detailed methods, including the animal strain, sex, age, number of cells injected, injection site, and assay duration to ensure reproducibility [28].

- In Vitro Alternatives: In vitro assays like ScoreCard and PluriTest can assess pluripotency but are generally not accepted by regulatory authorities as standalone tests for the safety of clinical-grade cell products. They are useful for preliminary screening [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Teratoma Risk Reduction Strategies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| NANOG-targeting Vector [13] [4] | Knocks in suicide gene into the NANOG locus for specific targeting of undifferentiated PSCs. | High specificity for pluripotent state; use homologous recombination for precise genomic integration. |

| Inducible Caspase 9 (iCasp9) [4] | Safety switch; dimerizing drug AP20187 induces apoptosis in cells expressing the construct. | Highly potent and sensitive; allows for >1 million-fold depletion of undifferentiated hPSCs. |

| Herpes Simplex Virus Thymidine Kinase (HSV-TK) [13] | Safety switch; converts prodrug ganciclovir into a toxic compound, killing dividing cells. | Well-established system; FDA-approved drugs available for activation. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors (e.g., YM155) [4] | Selectively toxic to undifferentiated PSCs in a mixed culture. | Must be rigorously validated for specificity to avoid harming differentiated cell product. |

| Immunodeficient Mice (e.g., NOD/SCID) [27] [28] | In vivo host for teratoma assay to validate pluripotency and assess tumorigenicity. | Strain, cell number, and injection site can affect results and require standardization. |

| Pluripotency Markers (TRA-1-60, SSEA-4) [28] | Flow cytometry or immunocytochemistry to identify and quantify residual undifferentiated PSCs. | Essential for quality control before and after safety procedures. |

FAQ: What is the fundamental clinical threat posed by residual undifferentiated hPSCs?

Residual undifferentiated human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) present a direct risk of iatrogenic tumorigenesis in cell therapy recipients. The core of the threat is their capacity to form teratomas—benign tumors containing tissues from all three embryonic germ layers. These tumors can arise from even very small numbers of undifferentiated cells that contaminate a differentiated cell product intended for therapy. Studies have demonstrated that the systemic injection of hPSCs can produce multisite teratomas in immune-deficient animal models in as little as 5 weeks [20]. This risk is a major limitation hindering the widespread clinical application of hPSC-derived therapies across various medical fields, including hematology, neurology, and diabetes treatment [20] [14] [29].

FAQ: How can a small number of residual cells cause a tumor?

hPSCs are defined by their abilities of self-renewal and pluripotency. Unlike therapeutic differentiated cells, which have a limited lifespan and a defined function, undifferentiated hPSCs retain the capacity for unlimited division and can generate any cell type in the body. When transplanted into a permissive in vivo environment, a single residual hPSC can clonally expand and spontaneously differentiate in a disorganized fashion, leading to the formation of a teratoma. The minimum number of cells required to form a teratoma can be as low as 10,000 cells, and since clinical doses can be in the range of billions of cells, even a contamination level of 0.001% could be therapeutically unacceptable [4] [29].

FAQ: What are the primary strategies to eliminate residual hPSCs?

Researchers have developed multiple strategies to purge undifferentiated hPSCs from final cell products. The table below summarizes the main approaches:

Table 1: Strategies for Eliminating Residual Undifferentiated hPSCs

| Strategy | Mechanism | Key Example(s) | Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Separation | Sorting cells based on pluripotency-specific surface antigens (e.g., SSEA-4, TRA-1-60). | Flow cytometry or magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) [20]. | Limitation: Can affect cell viability; results affected by gating; not all pluripotent cells may express the marker [20]. |

| Suicide Gene Therapy | Genetically engineering hPSCs with a "kill-switch" activated by a small molecule. | iCaspase-9/AP20187: Induces apoptosis in cells expressing the transgene [20] [4]. | Advantage: Can be very specific and efficient.Limitation: Requires genetic modification; potential toxicity of prodrugs to therapeutic cells (e.g., CD34+ HSCs) [20]. |

| Small Molecule Inhibition | Using chemicals that selectively induce apoptosis in pluripotent cells. | YM155 (Survivin inhibitor): Targets survivin, a protein hPSCs rely on for survival [20]. | Advantage: High efficiency; no genetic modification needed; shown to be non-toxic to some therapeutic cells like CD34+ HSCs [20]. |

| Genome-Edited Safeguards | Inserting drug-inducible safety switches into endogenous pluripotency genes. | NANOG-iCaspase9: Knocks-in iCaspase9 into the NANOG locus, which is highly specific to the pluripotent state [4]. | Advantage: Highly specific (>1 million-fold depletion); cannot be silenced without loss of pluripotency [4]. |

FAQ: How do we detect and quantify residual undifferentiated cells for quality control?

Sensitive and specific assays are critical for quantifying residual hPSCs in a final cell product to assess teratoma risk. The required sensitivity is extremely high, needing to detect as few as 1 undifferentiated cell in 1,000,000 to 100,000,000 differentiated cells [29]. The table below compares key detection methodologies.

Table 2: Methods for Detecting Residual Undifferentiated hPSCs

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Throughput & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Teratoma Assay | Injecting cells into immunodeficient mice and monitoring for tumor formation [29]. | High (biological readout) | Time-consuming (weeks to months), costly, and low-throughput. Used as a gold-standard functional test [29]. |

| Flow Cytometry | Detecting cell surface markers of pluripotency (e.g., TRA-1-60) via antibodies [29]. | ~0.01% | Rapid but limited sensitivity. Affected by gating strategies and marker specificity [29] [30]. |

| RT-qPCR | Measuring mRNA levels of pluripotency-associated genes. | ~0.01% [30] | Moderately sensitive and high-throughput. Sensitivity can be insufficient for large cell doses; relies on good marker genes [29] [30]. |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Absolutely quantifying nucleic acid copies by partitioning a sample into thousands of droplets. | ~0.001% (1 in 105 cells) or better [29] [30] | Highly sensitive, precise, and reproducible. Ideal for quality control. Targets can include LIN28A or specific long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) like LNCPRESS2 [29] [30]. |

| High-Efficiency Culture (HEC) | Culturing the cell product under conditions that favor hPSC growth over differentiated cells. | Can reach 0.00002% with MACS pre-enrichment [29] | Very sensitive but labor-intensive and time-consuming (weeks in culture) [29]. |

Experimental Protocol: Detection of Residual hiPSCs using LIN28/ddPCR

This protocol allows for the highly sensitive quantification of residual undifferentiated hiPSCs in a background of differentiated cells, such as cardiomyocytes [30].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a mixture of your hPSC-derived cell product. As a control, create a standard curve by spiking known numbers of undifferentiated hiPSCs (e.g., 10, 100, 1000 cells) into a fixed number of the target differentiated cell type (e.g., 1 x 10^6 cells).

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA from the test sample and standard curve samples using a standard phenol-chloroform extraction method (e.g., TRIzol) or a commercial kit. Treat samples with DNase to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- Reverse Transcription: Convert equal amounts of total RNA (e.g., 500 ng) into cDNA using a reverse transcriptase enzyme and oligo(dT) or random hexamer primers.

- Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR):

- Prepare a 20 µL reaction mixture containing the cDNA template, ddPCR supermix, and a TaqMan probe and primer set specific for LIN28A (or another highly specific marker like an lncRNA).

- Generate droplets from the reaction mixture using a droplet generator (~20,000 droplets per sample).

- Perform PCR amplification on the droplet emulsion using the following cycling conditions (optimized for the LIN28-1 probe/primer set [30]):

- 95°C for 10 minutes (enzyme activation)

- 40 cycles of:

- 94°C for 30 seconds (denaturation)

- 64°C for 60 seconds (annealing/extension)

- 98°C for 10 minutes (enzyme deactivation)

- 4°C hold

- Droplet Reading and Analysis: Read the droplets using a droplet reader that measures fluorescence in each droplet. The software will count the number of fluorescence-positive (containing the target) and negative droplets.

- Quantification: The concentration of the target LIN28A mRNA in the original sample is calculated automatically by the software using Poisson statistics. The number of residual undifferentiated cells can be extrapolated from the standard curve.

FAQ: Are markers like OCT4 and NANOG sufficient to define pluripotency and risk?

No. While markers like OCT4 (POU5F1) and NANOG are strongly associated with the undifferentiated state, their expression alone does not demonstrate functional pluripotency. It is critical to understand that:

- They are markers of the "undifferentiated state," not "pluripotency." Nullipotent cells (which cannot differentiate) from certain tumors can also express these markers [31].

- They can be expressed in some differentiated cell types, leading to potential false positives if used for purging [4].

- Functional pluripotency must be demonstrated through rigorous differentiation assays that show the ability to generate cells of all three germ layers [31]. For safety purposes, the most reliable systems for eliminating hPSCs use genes with expression highly restricted to the pluripotent state, such as NANOG, for driving suicide genes [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying hPSC Tumorigenicity Risk

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example & Key Detail |

|---|---|---|

| Survivin Inhibitor | Selective small molecule for eliminating hPSCs by inducing apoptosis. | YM155: A chemical survivin inhibitor; shown to be more efficient than suicide gene/prodrug systems and non-toxic to human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells [20]. |

| Inducible Caspase-9 (iCaspase-9) System | Genetically encoded suicide gene for targeted cell ablation. | AP20187: The small molecule dimerizer drug that activates iCaspase-9, triggering rapid apoptosis in cells expressing the transgene [20] [4]. |

| hPSC-Specific Marker Antibodies | Identification and depletion of undifferentiated cells via flow cytometry. | Anti-TRA-1-60 & Anti-SSEA-4: Antibodies against common surface markers used for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) [20] [29]. |

| Digital PCR Reagents | Ultra-sensitive detection and absolute quantification of residual hPSCs. | LIN28A TaqMan Assay: Probe and primer set for quantifying the pluripotency-associated gene LIN28A via ddPCR. Can detect 1 hiPSC in 100,000 cardiomyocytes [30]. |

| Long-Term Culture Media | Enrichment and expansion of potential residual hPSCs from a cell product. | Laminin-521 & Essential 8 Medium: Components of a high-efficiency culture (HEC) system used to detect rare residual hPSCs by providing an optimal environment for their growth [29]. |

Visual Guide: The Pathway from Residual Cell to Clinical Risk

The following diagram illustrates the core safety problem and the strategic points for intervention.

Visual Guide: Mechanism of a Genome-Edited Safety Switch

This diagram details the structure and function of a sophisticated genetic safeguard against teratoma formation.

Advanced Assays for Teratoma Risk Assessment: From In Vivo to In Vitro Platforms

The SCID mouse teratoma assay remains a cornerstone for evaluating the pluripotency and tumorigenic risk of human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs) and their derivatives in regenerative medicine. By transplanting hPSCs into immunodeficient mice, this assay tests their ability to form teratomas—benign tumors containing tissues from all three embryonic germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) [32] [33]. For cell therapy products, it is a critical biosafety test to ensure that no residual undifferentiated cells with tumorigenic potential remain in a differentiated cell population destined for clinical use [22] [34]. Despite its status as a historical "gold standard," the assay faces significant challenges regarding standardization, sensitivity, and ethical use of animals, driving the development of robust in vitro alternatives [33] [35] [36].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What is the minimum number of cells required to form a teratoma, and how can I improve the sensitivity of my assay?

The minimum number of cells needed can vary significantly based on the assay protocol. A standardized subcutaneous assay co-injecting hESCs with mitotically inactivated feeders and Matrigel has demonstrated high sensitivity [34].

Table 1: Teratoma Formation Sensitivity Based on Cell Number

| Number of hESCs Injected | Teratoma Formation Efficiency | Time to Teratoma Formation |

|---|---|---|

| 5 x 10⁵ and 1 x 10⁵ | 100% efficiency | 6-8 weeks [34] |

| 1 x 10³ | Variable | Longer follow-up required [34] |

| 1 x 10² | Possible, but inconsistent | Requires larger number of animals and extended follow-up (>12 weeks) [34] |

Troubleshooting Low Engraftment:

- Problem: Low teratoma formation rates, especially with low cell numbers.

- Solution:

- Use a Support Matrix: Co-inject cells with Matrigel or similar basement membrane extracts. This provides a scaffold that enhances cell survival and engraftment [32] [34].

- Co-transplant with Feeders: Mitotically inactivated feeder cells (e.g., Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts - MEFs) provide crucial supportive signals for undifferentiated hPSCs. This has been shown to significantly improve the assay's sensitivity [34].

- Add ROCK Inhibitor: Supplement the cell suspension with a Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase (ROCK) inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632) prior to transplantation. This increases hPSC survival after single-cell dissociation [34].

- Optimize Injection Site: The intra-muscular route (e.g., gastrocnemius muscle) is highly vascularized and easy to access, leading to high teratoma formation efficiency (95-100%) [32].

FAQ 2: My teratoma assay results are inconsistent between experiments. How can I standardize my protocol?

Lack of standardization is a widely recognized issue that compromises data comparability [35] [36]. Key variables to control are listed in the table below.

Table 2: Key Parameters for Teratoma Assay Standardization

| Parameter | Recommended Standardization | Impact on Variability |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Preparation | Use a consistent dissociation method. Define cell viability thresholds. Pre-treat with ROCK inhibitor [34]. | Cell health and aggregation affect engraftment. |

| Injection Site | Choose one site (e.g., subcutaneous, intramuscular) and stick to it across all experiments [32] [34]. | Different sites have varying vascularization and microenvironmental cues, affecting teratoma growth and composition [33]. |

| Cell Number | Use a defined, quantified cell number for injection. For sensitivity assays, a titration series is recommended [34]. | The primary variable for determining tumorigenic potential. |

| Support Matrix | Always use the same lot and concentration of Matrigel or equivalent [32] [34]. | Provides a consistent extracellular environment for cell growth. |

| Mouse Strain | Use immunodeficient mice with a consistent genetic background (e.g., NOD/SCID, NSG). Report the strain used [32] [36]. | Different strains have varying levels of immune leakage, affecting teratoma acceptance and growth. |

| Assay Duration | Monitor until teratoma reaches ~1 cm³ or for a pre-defined period (e.g., 12-20 weeks). Do not allow overgrowth [32] [33]. | Under-grown teratomas may not show all germ layers; over-growth causes animal distress. |

FAQ 3: What are the definitive criteria for a successful pluripotency assay, and how do I distinguish a teratoma from a malignant tumor?

A successful assay for pluripotency requires definitive histological evidence of tissues derived from all three embryonic germ layers [32] [34].

- Ectoderm: Look for neural tissues (e.g., rosettes, pigmented cells, neural epithelium) or stratified squamous epithelium [32].

- Mesoderm: Look for cartilage, bone, muscle (smooth or striated), or adipose tissue [32].

- Endoderm: Look for respiratory epithelium (ciliated), intestinal epithelium (with goblet cells), or glandular structures [32].

Troubleshooting Malignancy Concerns:

- Problem: Distinguishing a benign teratoma from a malignant teratocarcinoma.

- Solution: A true teratoma is a benign, multi-layered tumor. The presence of embryonal carcinoma (EC) elements—poorly differentiated, rapidly dividing cells that resemble embryonic carcinoma cells—indicates malignancy and classifies the tumor as a teratocarcinoma [33] [36]. These EC elements are highly undifferentiated and can be metastatic. Their presence in a cell therapy product would lead to its exclusion from clinical use [33]. Histopathological analysis must be performed by a trained pathologist to make this critical distinction.

FAQ 4: Are there animal-free alternatives to the teratoma assay that are accepted by regulators?

While the teratoma assay is still required by many regulatory authorities for final safety assessment of clinical products, several in vitro alternatives are gaining traction for research and characterization [22] [36].

Troubleshooting the Need for an Alternative:

- Problem: The teratoma assay is time-consuming, costly, raises ethical concerns, and is poorly standardized.

- Solution: Implement orthogonal in vitro assays to complement or, in some contexts, replace the in vivo assay.

- Highly Efficient Culture Assays (HEC): These sensitive in vitro assays can detect very low numbers of residual undifferentiated hPSCs within a differentiated population, often with superior sensitivity compared to in vivo assays [22].

- Molecular Assays: Digital PCR (dPCR) can be used to detect and quantify RNA transcripts specific to undifferentiated hPSCs, offering a highly sensitive and quantitative readout for residual pluripotent cells [22].

- Bioinformatic Assays: Tools like PluriTest use transcriptomic data from the test cell line to compute a "pluripotency score" and a "novelty score" by comparing it to a large reference database of validated pluripotent cell lines [35] [36]. ScoreCard is another assay that quantitatively evaluates the differentiation potential by analyzing germ layer-specific gene expression patterns after spontaneous or directed differentiation [35] [36].

Experimental Workflow & Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in performing a standardized teratoma assay and the critical decision points for data interpretation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for a Standardized Teratoma Assay

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Immunodeficient Mice (e.g., NOD/SCID, NSG) | In vivo host for teratoma formation. Prevents immune rejection of human cells [32] [34]. | Maintain in specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions. Strain choice impacts engraftment efficiency. |

| Basement Membrane Matrix (e.g., Matrigel) | Extracellular matrix scaffold. Enhances cell survival, engraftment, and teratoma formation [32] [34]. | Keep on ice to prevent polymerization. Use consistent lots for reproducibility. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632) | Small molecule that inhibits Rho-associated kinase. Dramatically improves survival of dissociated hPSCs [34]. | Add to cell suspension medium prior to injection. |

| Mitotically Inactivated Feeders (e.g., MEFs) | Provide essential supportive signals for the survival and growth of undifferentiated hPSCs post-transplantation [34]. | Co-injection significantly increases assay sensitivity. |

| Defined hPSC Culture Media | Maintains cells in a pluripotent state prior to harvest and injection. | Use consistent, high-quality media to ensure cell health and genetic stability. |

| Histology Reagents (Paraformaldehyde, Paraffin, H&E Stain) | For tissue preservation, sectioning, and staining to visualize teratoma morphology and germ layer differentiation [32]. | Essential for final analysis. H&E is the standard stain for initial germ layer identification. |

The SCID mouse teratoma assay remains a critical, though imperfect, tool for assessing the functional pluripotency and tumorigenic risk of hPSCs. Its successful implementation hinges on careful standardization of protocols, particularly in cell preparation, injection method, and histological analysis. While it continues to be a requirement for the safety assessment of clinical-grade cell products, the field is actively developing and validating sophisticated in vitro molecular and bioinformatic assays [22] [35]. These alternatives promise to reduce animal use, increase throughput, and improve quantitative accuracy, ultimately supporting the safer clinical translation of stem cell-based therapies.

This technical support resource addresses key challenges in detecting residual human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) in therapeutic products. The content focuses on applying digital PCR (dPCR) for sensitive identification of hPSC-specific RNA biomarkers to mitigate teratoma formation risk, a major safety concern in regenerative medicine. The guidance is framed within the context of stem cell tumorigenicity and teratoma formation risk reduction research.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the key advantages of digital PCR over qPCR for residual hPSC detection?

Digital PCR (dPCR) provides several critical advantages for detecting trace levels of undifferentiated hPSCs in differentiated cell products.

- Absolute Quantification Without Standards: dPCR does not require a standard calibration curve, enabling direct nucleic acid concentration measurement. This eliminates variability introduced by external calibrators, which can be unstable and cause day-to-day variability in qPCR [37] [38].

- Superior Sensitivity and Tolerance: dPCR is more robust against PCR inhibitors present in complex biological samples and offers high sensitivity, which is crucial for detecting extremely rare events like residual hPSCs [37] [39].

- Precision for Rare Targets: By partitioning a sample into thousands of individual reactions, dPCR allows for the detection of a single molecule of the target RNA, making it ideal for identifying minute quantities of pluripotency markers amidst a background of differentiated cells [38] [40].

FAQ 2: Which RNA biomarkers are most effective for sensitive hPSC detection?

The most effective biomarkers are those with high expression in hPSCs and near-undetectable expression in the differentiated cell therapy product. The optimal choice can depend on the specific hPSC line and its differentiated progeny.

- Traditional Protein-Coding Genes: LIN28 is a highly sensitive marker. A ddPCR assay using LIN28 was able to detect 0.001% undifferentiated hPSCs spiked into cardiomyocytes [40].

- Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs): Emerging research identifies lncRNAs as excellent biomarkers due to their often higher specificity. A 2023 study identified LNCPRESS2, LINC00678, and LOC105370482 as highly specific markers for human chemically induced PSCs (hCiPSCs). A ddPCR assay using these could detect 1 to 3 residual hPSCs in a background of 1 million islet cells [29].

- Marker Selection Strategy: A 2025 review emphasizes that biomarker expression must be rigorously validated across multiple hPSC lines and the final differentiated cell product to ensure specificity. RNA-seq is a powerful tool for discovering differentially expressed transcripts [22] [29].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Biomarkers for Residual hPSC Detection via dPCR

| Biomarker | Type | Reported Sensitivity | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIN28 | mRNA | 0.001% (1 in 10⁵ cells) [40] | Well-characterized, high expression in hPSCs |

| LNCPRESS2 | lncRNA | 0.0001% (1 in 10⁶ cells) [29] | High specificity, low expression in differentiated cells |

| LINC00678 | lncRNA | 0.0001% (1 in 10⁶ cells) [29] | High specificity, low expression in differentiated cells |

| NANOG | mRNA | Varies with assay | Core pluripotency factor; requires careful validation for specificity [4] |

FAQ 3: What is a detailed protocol for setting up a ddPCR assay for hPSC-specific lncRNAs?

The following protocol is adapted from a 2023 study that successfully detected residual hCiPSCs in derived islet cells [29].

Workflow: Detection of Residual hPSCs using ddPCR

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction:

cDNA Synthesis:

- Reverse-transcribe the extracted RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit.

- Use random hexamer primers to ensure comprehensive conversion of all RNA species, including lncRNAs [29].

ddPCR Reaction Setup:

- Prepare the ddPCR reaction mix containing:

- ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTP).

- Target-specific FAM-labeled TaqMan assay (primers and probe) for the lncRNA (e.g., LNCPRESS2).

- A HEX-labeled assay for a reference gene for normalization (if required).

- The synthesized cDNA template.

- A sample volume of 20 µL is standard for systems like the QX200 Droplet Digital PCR system [29] [40].

- Prepare the ddPCR reaction mix containing:

Droplet Generation and PCR Amplification:

Droplet Reading and Data Analysis:

- Place the plate in a droplet reader, which counts the fluorescent-positive and negative droplets for each sample.

- The concentration of the target lncRNA (in copies/µL) is calculated automatically from the fraction of positive droplets using Poisson statistics [37] [38].

- The result can be used to back-calculate the number of residual hPSCs in the original sample based on the measured lncRNA copies per cell.

FAQ 4: How can I troubleshoot high background noise or false positives in my dPCR assay?

High background can arise from several sources. The table below outlines common issues and solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for dPCR Assays in hPSC Detection

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High false-positive droplet count | Non-specific amplification or probe degradation [39]. | Redesign primers/probe to improve specificity; aliquot and store probes correctly. |

| Poor partition resolution (rain) | Suboptimal PCR efficiency or inhibitor carryover [37]. | Re-optimize annealing temperature; ensure high-quality, inhibitor-free RNA/cDNA. |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Inaccurate droplet generation or pipetting errors [38]. | Check droplet generator for faults; use calibrated pipettes and master mixes. |

| Low or no positive signal | cDNA synthesis failure or incorrect assay design for the specific hPSC line. | Check cDNA synthesis with a positive control; validate biomarker expression in your cells [22] [29]. |

FAQ 5: What are the critical validation steps for ensuring an accurate and sensitive dPCR assay?

Robust assay validation is required for quality control. Key steps include:

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Sensitivity: Determine the lowest number of hPSCs that can be reliably detected. Perform spike-in experiments where known numbers of hPSCs (e.g., 1, 10, 100) are mixed with a large number of differentiated cells (e.g., 10^6 or 10^7) and processed through the entire workflow. This confirms the assay's ability to detect contaminants at the 0.0001% level [22] [29].

- Specificity Testing: Verify that the signal from your biomarker is specific to undifferentiated hPSCs. Test the assay on RNA extracted from the final differentiated cell product (with no residual hPSCs) to ensure no background signal. Also, test on various other cell types that might be present [4] [29].

- Linearity and Dynamic Range: Create a standard curve by testing serial dilutions of hPSC RNA in differentiated cell RNA. The measured concentration should correlate linearly with the expected input [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for dPCR-based hPSC Detection

| Item | Function/Description | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Droplet Digital PCR System | Platform for partitioning samples, amplifying targets, and reading results. | Bio-Rad QX200 Droplet Digital PCR System [37] |

| ddPCR Supermix for Probes | Optimized reaction mix for probe-based assays in droplet formats. | Bio-Rad ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTP) |

| TaqMan Assay for lncRNA | Primer and probe set designed specifically for the target hPSC biomarker. | Custom-designed assays for LNCPRESS2, LINC00678, etc. [29] |

| RNA Extraction Kit | For high-quality, contaminant-free total RNA isolation from cell pellets. | PureLink RNA Mini Kit [29] [39] |

| cDNA Synthesis Kit | For efficient reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA, including lncRNAs. | High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit [29] |

Technology Comparison and Decision Framework

The following diagram illustrates the position of dPCR among other key methodologies for detecting residual hPSCs, highlighting its role in balancing sensitivity, specificity, and practicality.

The Highly Efficient Culture (HEC) assay represents a significant advancement in the safety assessment of human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC)-derived therapies. As hPSCs hold immense promise for regenerative medicine due to their ability to differentiate into any cell type, they simultaneously pose a substantial safety risk through potential teratoma formation if residual undifferentiated cells remain in cell therapy products (CTPs) [22] [41]. The HEC assay has been developed as a robust in vitro method to detect these residual hPSCs with superior sensitivity and reproducibility compared to traditional in vivo teratoma assays [42] [6].

International multi-site studies coordinated by the Health and Environmental Sciences Institute's Cell Therapy-TRAcking, Circulation & Safety (CGT-TRACS) Committee have validated the HEC assay as a sensitive tool for tumorigenicity evaluation of hPSC-derived products [42] [43]. This technical guide provides comprehensive troubleshooting and procedural support to ensure optimal implementation of HEC assays in quality control frameworks for cell therapy development.

Key Concepts and Definitions

Pluripotent Stem Cells (PSCs): Cells with the capacity to differentiate into all derivatives of the three primary germ layers (ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm). Includes both embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [44] [45].

Teratoma: A type of tumor consisting of multiple tissue types that can form when pluripotent stem cells are transplanted into immunodeficient mice. While often benign, their formation in patients receiving cell therapies is unacceptable [44] [28].

Tumorigenicity: The ability of cells to cause tumor formation, a key safety concern for hPSC-derived products [43] [41].

Residual Undifferentiated Cells: Pluripotent stem cells that remain in a differentiated cell therapy product, posing a potential tumorigenicity risk [42] [41].

Limit of Detection (LOD): The lowest number of PSCs that can be reliably detected in a background of differentiated cells [42].

Experimental Protocol: HEC Assay Implementation

Principle

The HEC assay functions by creating optimal culture conditions that selectively promote the expansion of potentially contaminating residual undifferentiated pluripotent stem cells within a differentiated cell product. These conditions enable even trace numbers of PSCs to form detectable colonies, providing a highly sensitive in vitro method for tumorigenicity risk assessment [42].

Step-by-Step Workflow

Step 1: Sample Preparation and Spike-in Controls

- Prepare differentiated cell product (e.g., iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes) as the background matrix [42]

- Establish spike-in controls by adding known numbers of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) into the differentiated cell population

- Recommended spike-in levels: 5-100 hiPSCs per 1 million differentiated cells to validate assay sensitivity [42]

Step 2: HEC Culture Setup

- Plate cells in culture conditions optimized for pluripotent stem cell growth

- Include Rho kinase inhibitor (ROCKi) to enhance PSC survival and clonogenicity [42]

- Use appropriate feeder cells or extracellular matrix components (e.g., Matrigel)

- Maintain cultures in PSC-specific medium supporting undifferentiated growth

Step 3: Culture Monitoring and Maintenance

- Incubate cultures for 14-21 days to allow colony formation [42]

- Monitor regularly for emergence of characteristic PSC colonies

- Perform medium changes every 48 hours to maintain optimal nutrient supply

- Document colony appearance and growth patterns

Step 4: Colony Identification and Analysis

- Identify undifferentiated stem cell colonies by morphological characteristics (compact, dome-shaped colonies with defined borders)

- Confirm pluripotency through immunocytochemistry for markers (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2, TRA-1-60) [42] [28]

- Count colonies to determine detection sensitivity

Step 5: Data Interpretation

- Calculate True Positive Rate (TPR) across multiple replicates [42]

- Determine Limit of Detection (LOD) based on lowest spike-in level consistently detected

- Establish assay reproducibility through statistical analysis of inter-laboratory results

Performance Specifications

Table 1: HEC Assay Performance Metrics from International Validation Studies

| Parameter | Performance Value | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Sensitivity | 5 hiPSCs in 1 million cardiomyocytes | All participating facilities detected colonies at this spike-in level [42] |

| Assay Duration | 14-21 days | Time required for colony formation from trace PSCs [42] |

| True Positive Rate (TPR) | High (exact values in publication) | Rate of correct detection of spiked hiPSCs [42] |

| Reproducibility | High between facilities | Majority of variance attributed to repeatability rather than inter-site differences [42] |

| Comparison to in vivo | Superior sensitivity | More sensitive than traditional teratoma assays in mice [6] |

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Issues and Solutions

Table 2: HEC Assay Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low colony formation efficiency | Suboptimal culture conditions | Include ROCKi in initial plating; Verify matrix quality; Confirm medium freshness | Quality test all reagents with known PSC lines before use |

| High background differentiation | Inadequate PSC-supportive conditions | Optimize seeding density; Use freshly prepared cytokines; Validate feeder cell activity | Pre-qualify lots of critical reagents; Maintain consistent culture handling |

| Variable results between replicates | Inconsistent cell handling | Standardize cell counting methods; Use single-cell suspensions; Ensure even distribution | Train multiple operators on standardized protocols; Use automated cell counters |

| Failure to detect low spike-in levels | Inhibitors in differentiated cell population | Incorporate additional washing steps; Adjust initial cell plating density | Characterize matrix effects from specific differentiated cell types |

| Contamination in long cultures | Aseptic technique issues | Implement antibiotic/antimycotic regimen; Regular mycoplasma testing | Use dedicated incubators for long-term cultures; Regular cleaning schedules |

Advanced Technical Challenges

Matrix Effects from Differentiated Cell Products:

- Different target cell types may secrete factors that inhibit or promote PSC growth

- Solution: Conduct matrix-specific validation for each CTP type

- Include additional controls with conditioned media from target cells

Assay Transferability Between Laboratories:

- Standardize critical reagents and cell lines across sites

- Establish shared training protocols for colony identification

- Implement cross-validation studies before technology transfer

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for HEC Assay Implementation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in HEC Assay | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitors | Rho kinase inhibitor (ROCKi) | Enhances single-cell survival and clonogenicity of PSCs [42] | Use at optimal concentration; Prepare fresh stock solutions |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Laminin-521 | Provides structural support mimicking stem cell niche | Batch variability requires pre-qualification for PSC support |

| Culture Media | mTeSR, Essential 8 | Maintains pluripotent state; Supports undifferentiated growth | Quality check each lot for consistent performance |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-OCT4, Anti-SOX2, Anti-NANOG, Anti-TRA-1-60 | Confirms pluripotent identity of colonies [28] | Validate specificity and appropriate dilutions |

| Cell Viability Reagents | Trypan blue, Calcein-AM | Assesses initial cell quality and viability | Standardize counting methods across operators |

| Feeder Cells | Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) | Secretes supportive factors for PSC growth | Irradiate properly to prevent overgrowth; Quality test support capability |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How does the sensitivity of the HEC assay compare to traditional in vivo teratoma assays?

The HEC assay demonstrates superior sensitivity compared to traditional in vivo teratoma assays. International validation studies have shown that the HEC assay can detect as few as 5 residual hiPSCs in a background of 1 million differentiated cells, a detection level that exceeds the sensitivity of in vivo models [42] [6]. Additionally, the HEC assay provides quantitative results with greater reproducibility across different laboratories.

Q2: What is the appropriate duration for HEC assays, and how is the endpoint determined?