Modeling Alzheimer's Disease Mechanisms with iPSCs: From Pathogenesis to Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) models are revolutionizing Alzheimer's disease (AD) research.

Modeling Alzheimer's Disease Mechanisms with iPSCs: From Pathogenesis to Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) models are revolutionizing Alzheimer's disease (AD) research. It explores the foundational mechanisms of AD, including Aβ and tau pathology, as revealed by patient-specific neurons. The content details methodological advances in creating high-fidelity cortical and motor neuron models, 3D systems, and their application in high-throughput drug screening. It addresses key challenges in model standardization and reproducibility while evaluating the validation of these models against traditional systems and their predictive power for clinical outcomes. Finally, it synthesizes how iPSC technology is paving the way for personalized medicine and identifying novel therapeutic combinations for this complex neurodegenerative disorder.

Decoding Alzheimer's Pathology: How iPSC Models Illuminate Aβ, Tau, and Neurodegenerative Mechanisms

Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia, presents a profound global health challenge with an estimated 7.1 million affected Americans and projections exceeding 13.9 million by 2060 [1]. For decades, Alzheimer's research has relied heavily on animal models, which often fail to fully recapitulate human-specific disease processes, contributing to the repeated failure of clinical trials [2] [3]. The discovery of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized this landscape, enabling researchers to generate patient-specific human neurons and glial cells that recapitulate the complex pathophysiology of AD in a dish [4] [2].

The core pathological hallmarks of AD—extracellular amyloid plaques composed primarily of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) consisting of hyperphosphorylated tau protein—have been exceptionally difficult to model in conventional systems [5] [3]. iPSC-derived models now provide an unprecedented platform to study the formation of these lesions, their cellular interactions, and their functional consequences in human cells with relevant genetic backgrounds [2]. This technical guide explores the current state of recapitulating amyloid and tau pathology in iPSC-derived neural models, providing methodologies, analytical approaches, and applications for drug discovery.

Alzheimer's Pathophysiology and iPSC Modeling Approaches

Amyloid and Tau Pathology

In the amyloidogenic pathway, the amyloid precursor protein (APP) undergoes sequential proteolytic cleavage by β-secretase (BACE1) and γ-secretase, generating Aβ peptides of varying lengths [4]. The Aβ1-42 isoform is particularly pathogenic due to its high self-aggregation propensity and central role in forming amyloid plaques [6] [4]. Meanwhile, tau, a microtubule-associated protein, becomes hyperphosphorylated at numerous serine and threonine residues in AD, leading to its dissociation from microtubules and aggregation into paired helical filaments and eventually NFTs [6]. This hyperphosphorylation is regulated by a balance between kinases such as glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3B) and phosphatases [6].

Familial vs. Sporadic AD Modeling

iPSC models have been developed for both familial AD (fAD) and sporadic AD (sAD). fAD models typically incorporate mutations in APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2 genes, which directly increase Aβ42 production or the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio [6] [3]. In contrast, sAD models leverage cells from patients without known familial mutations, often focusing on genetic risk factors such as the APOE ε4 allele, the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset AD [4] [3]. The ability to model both fAD and sAD using iPSC technology provides a platform for understanding shared and distinct pathomechanisms between these AD forms [6].

Beyond Neurons: The Role of Glial Cells

Recent advances have highlighted the importance of moving beyond neuron-centric models to incorporate glial cells. Microglia, the brain's resident immune cells, adopt distinct transcriptional states in AD, including a disease-associated microglia (DAM) phenotype enriched in neurodegenerative diseases [7]. Similarly, astrocytes contribute to Aβ clearance and neuroinflammation [4] [3]. The development of protocols to differentiate iPSCs into these cell types enables the creation of more complex co-culture systems that better mimic the brain environment [4] [3].

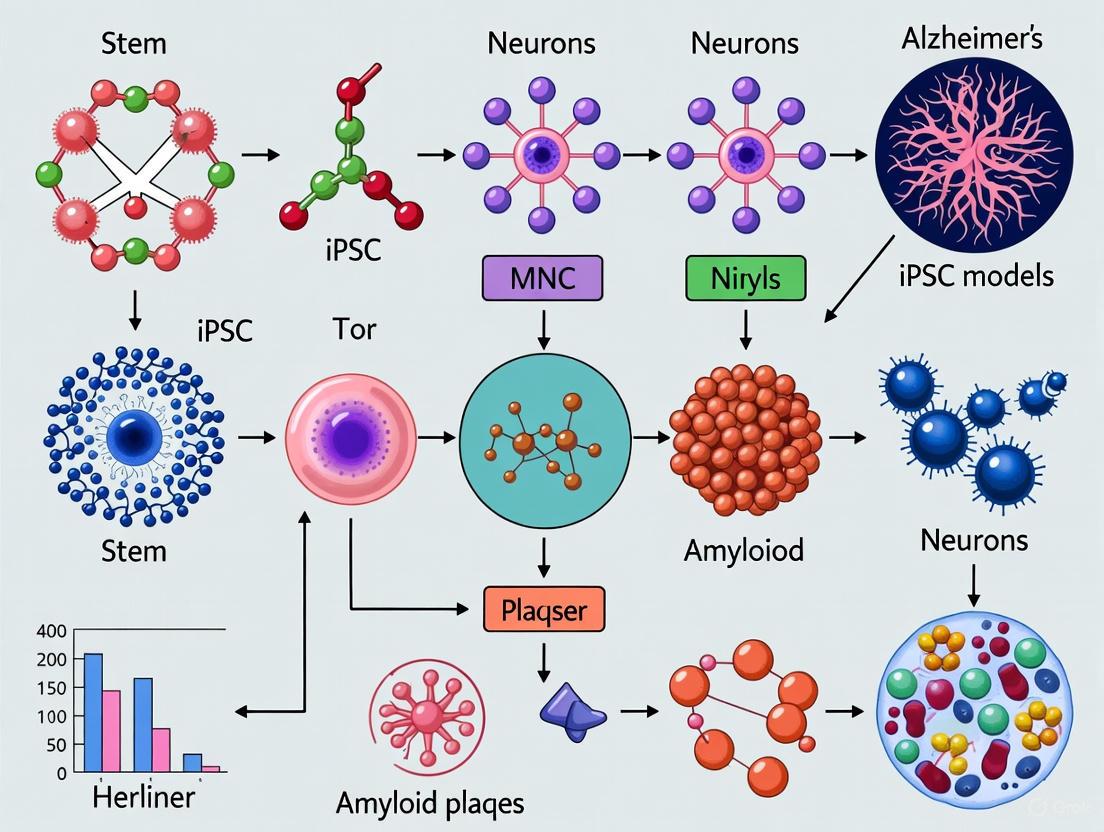

Figure 1: iPSC Modeling of Alzheimer's Disease Pathophysiology. This diagram illustrates how iPSCs can be differentiated into various neural cell types to model key AD pathologies, influenced by genetic and environmental risk factors.

Recapitulating Amyloid Pathology

Experimental Models and Methodologies

The recapitulation of amyloid pathology using iPSC-derived neurons typically involves differentiating control and AD-specific iPSCs into cortical neurons using established protocols. One common approach utilizes SMAD inhibition to direct cells toward a neural lineage, often through the formation of embryoid bodies or neural progenitor cells [2]. Neurons are then matured for several weeks to months to allow for the development of robust amyloid pathology.

For more physiologically relevant models, researchers are increasingly employing 3D culture systems such as cerebral organoids or hydrogel-based tissues that better mimic the brain's structural complexity [4] [8]. These 3D models demonstrate improved neuronal viability, network activity, and resemblance to in vivo disease pathology compared to 2D cultures [8]. A recent study described a 3D multi-electrode array (MEA) platform that enables non-invasive, real-time monitoring of extracellular field potentials throughout the entire depth of a 3D hydrogel-based neural tissue containing human iPSC-derived neurons and astrocytes [8].

Key Pathological Findings in iPSC-Derived Models

Studies using fAD iPSC-derived neurons consistently demonstrate elevated Aβ1-42 levels and increased Aβ1-42/Aβ1-40 ratios, consistent with the known effects of fAD mutations on γ-secretase processivity [6] [2]. For example, neurons with PSEN1 mutations (A246E, M146L) show significantly increased Aβ1-42/Aβ1-40 ratios compared to controls [2]. Similarly, sAD models have shown elevated levels of both extracellular Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42, though with less consistent effects on the Aβ1-42/Aβ1-40 ratio [6].

Additionally, AD neurons exhibit increased sensitivity to oxidative stress when exposed to amyloid oligomers or peroxide, suggesting a role for amyloid in mediating oxidative damage [6]. The table below summarizes key amyloid-related phenotypes reported in various iPSC-based AD studies.

Table 1: Amyloid-β Pathology in iPSC-Derived Neuronal Models of Alzheimer's Disease

| Study Model | Aβ1-40 | Aβ1-42 | Aβ42:40 Ratio | sAPPβ | Other Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fAD (PSEN1 A246E) [2] | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | Increased amyloidogenic processing | |

| fAD (PSEN1 M146L) [2] | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | - | NLRP2 inflammasome ↑ |

| fAD (APP V717L) [2] | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | Early endosomes ↑ | |

| sAD (APOE4) [2] | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | Secreted APOE ↑ |

| fAD & sAD Neurons [6] | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ (fAD only) | - | GSK3B activation; Oxidative stress sensitivity ↑ |

Analysis Methods for Amyloid Pathology

- ELISA: Quantifies absolute levels of Aβ1-40, Aβ1-42, and other Aβ species in conditioned media or cell lysates [6]

- Western Blotting: Detects APP and its processing fragments, including soluble APPβ (sAPPβ) and C-terminal fragments [6]

- Immunocytochemistry: Visualizes intracellular Aβ accumulation and APP distribution using antibodies against Aβ and APP [8]

- Electrophysiology: 3D multi-electrode arrays (MEAs) monitor network-level dysfunction resulting from amyloid pathology [8]

Modeling Tau Hyperphosphorylation and Tangle Formation

Experimental Approaches to Tau Pathology

iPSC-derived neurons have successfully recapitulated the hyperphosphorylation of tau at multiple AD-relevant epitopes. A seminal study comparing fAD and sAD iPSC-derived neurons found elevated tau phosphorylation at all investigated phosphorylation sites in both AD forms, with no evident difference in phenotype between fAD and sAD samples except for secreted Aβ1-40 levels [6]. This suggests that divergent upstream triggers (e.g., increased Aβ production in fAD vs. impaired clearance in sAD) may converge on similar tau pathology mechanisms.

Notably, the GSK3B kinase has been identified as a key driver of tau hyperphosphorylation in iPSC-derived AD models. Neurons from both fAD and sAD patients show increased levels of active GSK3B, providing a mechanistic link between amyloid pathology and tau hyperphosphorylation [6]. This is further supported by observations that Aβ accumulated in the AD brain can activate kinases that promote tau phosphorylation, including GSK3B [6].

Tau Pathology in 2D vs. 3D Models

While 2D cultures have proven valuable for studying basic mechanisms of tau phosphorylation, 3D models may offer advantages for observing more advanced tau aggregation. The development of neurofibrillary tangle-like structures in iPSC-derived models has been more challenging to achieve than amyloid deposition, typically requiring extended maturation periods or additional stressors. However, increasingly complex 3D models show promise for recapitulating later stages of tau pathology [4].

Regional identity of iPSC-derived neurons also influences tau pathology, with rostral (forebrain) neuronal cells showing higher tau levels than caudal cells when derived from the same patients, highlighting the importance of neuronal subtype specification in disease modeling [2].

Table 2: Tau Pathology in iPSC-Derived Neuronal Models of Alzheimer's Disease

| Study Model | p-TAU Sites | Total TAU | GSK3B Activation | Other Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fAD (PSEN1 A246E) [2] | ↑ | - | ↑ | - |

| fAD (PSEN1 V89L) [2] | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | Sensitivity to Aβ ↑ |

| sAD (APOE4) [2] | ↑ | ↑ | - | Synapse number ↑; Early endosomes ↑ |

| fAD & sAD Neurons [6] | ↑ at multiple sites | - | ↑ | Increased sensitivity to oxidative stress |

| MAPT Mutations [2] | ↑ | - | - | ROS ↑; Firing frequency ↑ |

Analysis Methods for Tau Pathology

- Western Blotting: Using phospho-specific tau antibodies (e.g., Thr181, Ser202, Thr231) to quantify phosphorylation levels at specific epitopes [6]

- Immunocytochemistry: Visualizes spatial distribution of phosphorylated tau within neurons and its potential co-localization with other pathological markers [8]

- ELISA: Quantitative measurement of specific phosphorylated tau species in cell lysates [6]

- Synaptosome Preparation: Isolates synaptic compartments to examine synaptic tau localization and phosphorylation [7]

Advanced Model Systems: Beyond Monocultures

Co-culture Systems and Microglial Contributions

The integration of microglia into iPSC-based AD models has revealed crucial insights into neuroinflammation and plaque clearance. A groundbreaking 2023 study established a platform for generating and manipulating diverse transcriptional states in iPSC-derived human microglia (iMGLs) by exposing them to various brain substrates [7]. When iMGLs were exposed to synaptosomes, myelin debris, apoptotic neurons, or synthetic Aβ fibrils, they adopted distinct transcriptional states that mapped to signatures identified in human brain microglia, including the DAM phenotype [7].

This study further demonstrated that the transcription factor MITF drives a disease-associated transcriptional signature and a highly phagocytic state in iMGLs [7]. The ability to model these microglial states in vitro provides a powerful tool for understanding how different neural cell types interact to shape AD pathology.

3D Organoid and Tissue Engineering Approaches

3D neural tissue models show enhanced maturation of neuronal networks and more physiologically relevant cell-cell interactions compared to 2D cultures. In one advanced platform, researchers created a 3D hydrogel-based neural tissue containing human iPSC-derived neurons and primary astrocytes cultured on a custom 3D multi-electrode array [8]. This system allowed for the analysis of functional neural network development over ~6.5 weeks, revealing distinct patterns of spiking activity, bursting, and network synchrony across different depths of the 3D tissue [8].

Such 3D systems demonstrate region-specific network compositions and differential sensitivity to GABAergic and glutamatergic antagonists throughout the tissue depth, providing unprecedented resolution for studying functional network consequences of AD pathology [8].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for iPSC-Based AD Modeling. This diagram outlines the progressive complexity in developing iPSC-derived Alzheimer's models, from basic 2D cultures to advanced 3D systems and their subsequent applications in functional characterization and drug discovery.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for iPSC-Based Alzheimer's Disease Research

| Reagent/Platform | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| iPSC Lines | Disease modeling with patient-specific genetics | fAD (PSEN1, APP mutations); sAD (APOE4 carriers); isogenic controls [6] [2] |

| Neural Differentiation Kits | Directing iPSC differentiation to neural lineages | SMAD inhibition protocols; Ngn2 direct induction; Embryoid body formation [2] |

| 3D Culture Matrices | Supporting three-dimensional neural tissue growth | Collagen-based hydrogels; ECM mixtures (e.g., Maxgel); Organoid culture platforms [8] |

| Aβ/Tau Assays | Quantifying amyloid and tau pathology | Aβ40/42 ELISAs; Phospho-tau Western antibodies (Thr231, Ser202); p-Tau ELISAs [6] |

| Microglia Differentiation Kits | Generating iPSC-derived microglia (iMGLs) | Protocol for iMGL generation and state manipulation [7] |

| 3D Multi-Electrode Arrays | Functional assessment of 3D neural networks | Custom 3D MEAs compatible with commercial systems (Multi Channel Systems MEA2100) [8] |

| Synaptosome Preparation Kits | Isolating synaptic fractions for pathway analysis | Synaptosome fractions for microglial state induction [7] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Tools | Gene editing for isogenic controls or novel mutations | Creating isogenic APOE3/APOE4 lines; introducing fAD mutations [2] |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

iPSC-derived AD models are playing an increasingly important role in drug discovery, with several candidates identified through iPSC-based screening advancing to clinical trials [9]. These include bosutinib, ropinirole, and ezogabine for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), demonstrating the broader applicability of iPSC-based screening for neurodegenerative diseases [9]. For AD specifically, iPSC models have been used to test γ-secretase modulators, Aβ aggregation inhibitors, and compounds targeting tau hyperphosphorylation [2].

The ability of iPSC models to recapitulate patient-specific pathophysiology enables a precision medicine approach to therapy development. For instance, a 2025 NIH report highlighted an epilepsy drug, levetiracetam, that may slow brain atrophy specifically in individuals without the APOE ε4 allele, demonstrating how treatments may work for some subpopulations but not others [1]. Similarly, the small molecule CT1812 shows promise for treating multiple types of dementia by displacing toxic protein aggregates at synapses [1].

High-throughput screening using iPSC-derived neurons and glia, sometimes combined with artificial intelligence approaches, represents the next frontier in AD drug discovery [9]. These platforms allow for the rapid testing of compound libraries on human cells with disease-relevant genetics, potentially accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic candidates.

iPSC-derived neuronal models have fundamentally transformed our approach to studying Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. The recapitulation of core AD hallmarks—amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles—in these human cell-based systems provides an unprecedented window into the molecular and cellular events driving neurodegeneration. While challenges remain in fully modeling the complexity of late-stage AD pathology in vitro, continued advancements in 3D culture systems, microglial incorporation, and functional assessment technologies are rapidly closing the gap between in vitro models and the human brain.

The application of these models to drug discovery holds particular promise for developing more effective, personalized therapies for this devastating disorder. As iPSC technology continues to evolve, it will undoubtedly play an increasingly central role in unraveling the mechanisms of Alzheimer's disease and developing interventions to combat it.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) represents a profound public health crisis, affecting millions worldwide without curative therapies. The disease is categorized into two primary forms: familial AD (FAD), a rare early-onset form caused by highly penetrant autosomal dominant mutations, and sporadic AD (sAD), a late-onset form with complex aetiologies involving polygenic risk and environmental factors [10]. Research into these distinct forms has been hampered by models that fail to recapitulate human-specific disease mechanisms, contributing to numerous failed clinical trials [11].

The advent of human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized AD research by enabling the generation of patient-specific neural cells and tissues. This platform provides an unprecedented opportunity to model both FAD and sAD under physiologically relevant human genetic backgrounds [12]. For FAD, iPSCs allow precise dissection of pathogenic mechanisms stemming from known mutations, while for sAD, they facilitate exploration of the complex interplay between polygenic risk profiles and environmental influences [13]. This technical guide examines current methodologies, experimental paradigms, and applications of iPSC-based models for both FAD and sAD, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of genetics and neurodegenerative disease.

Genetic Architecture of FAD and sAD

The genetic underpinnings of FAD and sAD display distinct patterns of inheritance, risk loci, and molecular mechanisms, necessitating different modeling approaches.

Familial AD (FAD) Genetics

FAD follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with nearly complete penetrance. It is primarily linked to mutations in three genes:

- APP (Amyloid Precursor Protein): Located on chromosome 21, with over 24 known pathogenic mutations that alter amyloid-beta production or aggregation properties [10].

- PSEN1 (Presenilin 1): Located on chromosome 14, with approximately 185 identified mutations that predominantly affect γ-secretase activity [10].

- PSEN2 (Presenilin 2): Located on chromosome 1, with at least 13 documented mutations that similarly dysregulate γ-secretase function [10].

A key unifying feature of FAD mutations is their common molecular phenotype: nearly all pathogenic variants in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 increase the Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio, promoting amyloid-beta aggregation and oligomerization [10].

Sporadic AD (sAD) Genetics

sAD exhibits a complex polygenic risk architecture influenced by numerous genetic variants with small effect sizes. The most significant genetic risk factor is the ε4 allele of APOE, which alone may account for up to 50% of sAD heritability [10]. Recent large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified over 70 genomic loci associated with sAD risk [14]. A 2025 multi-ancestry GWAS utilizing whole-genome sequencing data from diverse cohorts identified 16 novel AD loci, advocating for more genetically inclusive studies [14].

The emerging understanding of sAD genetics highlights the importance of polygenic risk scores (PRS) that aggregate the effects of many common variants. Research resources like the IPMAR Resource have established iPSC collections capturing extremes of global AD polygenic risk, including lines from high-risk late-onset AD, high-risk early-onset AD, and low-risk cognitively healthy controls [13].

Table 1: Key Genetic Features of FAD and sAD

| Feature | Familial AD (FAD) | Sporadic AD (sAD) |

|---|---|---|

| Heritability Pattern | Autosomal dominant | Polygenic, complex inheritance |

| Primary Genetic Drivers | Mutations in APP, PSEN1, PSEN2 | APOE ε4 allele + numerous risk loci |

| Age of Onset | Early-onset (<60 years) | Late-onset (≥65 years) |

| Proportion of Cases | ~5% | ~95% |

| Molecular Pathway | Altered Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio | Multiple pathways including lipid metabolism, immune response, endocytosis |

| iPSC Modeling Approach | Introduce known pathogenic mutations | Capture polygenic risk profiles; study gene-environment interactions |

iPSC Modeling Approaches for FAD and sAD

Establishing iPSC Models for FAD

FAD modeling leverages precise genome engineering to introduce specific pathogenic mutations into control iPSCs or utilizes iPSCs derived from FAD patients.

CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing: The CRISPR/Cas9 system enables targeted introduction of FAD-associated mutations into control iPSC lines. This approach involves:

- Design of sgRNAs targeting specific loci in APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2

- Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 components alongside donor DNA templates containing desired mutations

- Selection and validation of successfully edited clones through sequencing and functional assays [15]

Isogenic Control Generation: A critical aspect of FAD modeling is creating isogenic control lines where the pathogenic mutation is corrected in patient-derived iPSCs, ensuring that observed phenotypes are mutation-specific rather than due to background genetic variation [15].

Advanced Modeling Strategies for sAD

sAD modeling requires more complex approaches to capture its polygenic nature:

Polygenic Risk Score Stratification: Donor selection based on calculated PRS allows establishment of iPSC cohorts representing extremes of genetic risk. The IPMAR Resource, for instance, includes 90 iPSC lines with extremes of global AD polygenic risk and 19 lines with complement pathway-specific genetic risk [13].

Multi-ancestry Cohort Representation: Recent studies emphasize the importance of including diverse genetic backgrounds in sAD modeling, as novel risk loci have been identified through inclusion of non-European ancestry individuals [14].

Environmental Challenge Models: sAD iPSC models can be exposed to various environmental risk factors, including Aβ42 oligomers to simulate amyloid stress or other triggers that might unmask latent genetic risks [16].

Experimental Platforms and Phenotypic Assays

2D Cortical Neuronal Cultures

Two-dimensional cortical neuronal cultures derived from FAD or sAD iPSCs provide a platform for high-content screening and mechanistic studies.

Functional Assays Using Microelectrode Arrays (MEA): Patterned iPSC-derived cortical neurons integrated with MEAs enable measurement of long-term potentiation (LTP), a cellular correlate of learning and memory. This system effectively models early-stage AD dysfunction without significant neuronal death [16].

LTP Impairment and Rescue: Studies demonstrate that Aβ42 oligomers significantly reduce LTP maintenance in human cortical neurons, and this impairment can be rescued by AD therapeutics including Donepezil, Memantine, Rolipram, and Saracatinib [16].

Protocol: MEA-based LTP Assay

- Differentiate iPSCs to cortical neurons using dual-SMAD inhibition

- Plate neurons on patterned MEAs to form defined circuits (≥8 weeks maturation)

- Record baseline neural activity and network properties

- Induce LTP using tetanic electrical stimulation (e.g., 100 Hz, 1s duration)

- Monitor post-tetanic potentiation for ≥1 hour

- Challenge system with Aβ42 oligomers (500 nM-1 μM) with/without therapeutic compounds

- Quantify LTP maintenance as percentage of baseline response [16]

3D Brain Organoid Models

Three-dimensional brain organoids provide more physiologically relevant environments for AD modeling by incorporating multiple neural cell types and complex cell-cell interactions.

Vascularized Neuroimmune Organoids: Advanced organoid systems now incorporate neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and blood vessels, creating comprehensive models that better mimic the brain's cellular ecosystem. These complex organoids can be exposed to AD patient brain extracts containing proteopathic seeds to induce multiple AD pathologies within four weeks [11].

Pathology Induction in sAD Organoids: Exposure of vascularized neuroimmune organoids to sAD brain extracts induces:

- Aβ plaque-like aggregates

- Tau tangle-like aggregates

- Neuroinflammation with elevated microglial synaptic pruning

- Synapse and neuronal loss

- Impaired neural network activity [11]

Protocol: Vascularized Neuroimmune Organoid Generation

- Differentiate iPSCs to neural progenitor cells (NPCs), primitive macrophage progenitors (PMPs), and vascular progenitors (VPs)

- Combine progenitors at optimized ratios (30,000 NPCs:12,000 PMPs:7,000 VPs)

- Allow self-assembly into 3D organoids in low-attachment plates

- Culture with mitogens (bFGF) for 5 days (proliferation stage)

- Transition to differentiation medium with IL-34 and VEGF for long-term maturation

- At day 30-40, challenge with sAD brain extracts (10% v/v) for 4 weeks

- Analyze pathological hallmarks via immunostaining and functional assays [11]

Table 2: Comparison of iPSC-based Experimental Platforms for AD Research

| Platform | Key Features | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Cortical Cultures | Pure neuronal populations; amenable to high-content screening; MEA compatibility | Reductionist studies of neuronal vulnerability; electrophysiological characterization; HTS | Lacks cellular diversity; simplified connectivity |

| Conventional Brain Organoids | 3D architecture; multiple neural cell types; emergent network properties | Modeling neurodevelopment; compound screening; study of cell-cell interactions | Variable reproducibility; limited vascularization and immune components |

| Vascularized Neuroimmune Organoids | Includes neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and blood vessels; more complete brain mimicry | Modeling neuroinflammation; blood-brain barrier studies; sAD pathology induction | Technically challenging; longer maturation times; higher costs |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC-based AD Modeling

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Components | Cas9 nuclease, sgRNAs targeting APP/PSEN1/PSEN2, HDR templates | Introduction or correction of FAD-associated mutations; creation of isogenic controls |

| Differentiation Reagents | Dual-SMAD inhibitors (LDN193189, SB431542), N2/B27 supplements, BDNF, GDNF | Directed differentiation of iPSCs to cortical neurons, astrocytes, or other neural lineages |

| 3D Culture Systems | Matrigel, laminin, recombinant IL-34, VEGF, bFGF | Support for organoid formation and maturation; promotion of vascularization and microglial development |

| Pathology Inducers | Synthetic Aβ42 oligomers, tau fibrils, AD patient brain extracts | Induction of AD-like pathologies in otherwise healthy models; challenge tests for resilience |

| Functional Assay Tools | Microelectrode arrays, calcium indicators, patch-clamp systems | Measurement of neuronal activity, synaptic function, and network properties |

| Therapeutic Compounds | Donepezil, Memantine, Rolipram, Saracatinib, Lecanemab | Validation of models through rescue experiments; drug screening applications |

Signaling Pathways in Alzheimer's Disease Pathogenesis

The following diagram illustrates key signaling pathways dysregulated in Alzheimer's disease, highlighting potential therapeutic targets:

Applications in Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

iPSC models of both FAD and sAD have become invaluable platforms for drug discovery and validation, addressing critical gaps in traditional preclinical models.

Target Identification and Validation

Genetic Risk Locus Functionalization: iPSC models enable functional validation of newly identified genetic risk factors. For instance, a 2024 study identified a novel genetic locus on chromosome 2p22.2 (between CYP1B1 and RMDN2) associated with tau deposition that accounts for 4.3% of tau PET variation - surpassing even APOE4's contribution (3.6%) [17]. iPSC models provide a platform to investigate the functional consequences of such loci.

Pathway Analysis: Proteomic studies of AD iPSC models have revealed disrupted AD-related pathways beyond the canonical amyloid and tau pathways, including complement system, oxidative stress response, and mitochondrial function [11].

Compound Screening and Validation

Phenotypic Screening Platforms: iPSC-derived models serve in high-content therapeutic screening for both target-based and phenotypic approaches. The MEA-based LTP platform has been validated with four AD therapeutics (Donepezil, Memantine, Rolipram, and Saracatinib), demonstrating rescue of Aβ42-induced LTP impairment [16].

Drug Efficacy Testing: Complex vascularized neuroimmune organoids have been used to test FDA-approved therapies like Lecanemab, showing significant reduction of amyloid burden following treatment [11].

Clinical Trial Predictive Value: Several clinical trials have been initiated based on iPSC research findings, including trials of bosutinib, ropinirole, and ezogabine for ALS, and WVE-004 and BII078 for ALS/FTD, demonstrating the translational potential of these models [9].

iPSC-based modeling of both FAD and sAD has fundamentally advanced our ability to study Alzheimer's disease in human-specific systems that recapitulate key genetic and pathological features. The distinct approaches required for each form - precise genetic engineering for FAD versus polygenic risk capture and environmental challenge for sAD - highlight the complementary value of these models.

Future developments will likely focus on increasing model complexity through improved organoid systems with better vascularization and inclusion of additional cell types, enhancing maturation to better model late-onset processes, and incorporating high-content multi-omics readouts for comprehensive phenotyping. The integration of artificial intelligence with iPSC-based screening is already emerging as a powerful approach for pattern recognition and predictive modeling [9].

As these technologies continue to evolve, iPSC models of FAD and sAD will play an increasingly central role in bridging the gap between genetic discoveries and functional pathophysiology, ultimately accelerating the development of effective therapeutics for this devastating disorder. The ongoing creation of large-scale, well-characterized iPSC resources capturing the spectrum of AD genetic risk promises to provide the research community with powerful tools to dissect disease mechanisms and identify novel therapeutic interventions.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) research is undergoing a paradigm shift, moving beyond the neuron-centric view to embrace the critical contributions of glial cells in disease pathogenesis. While historical research emphasized amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles as the hallmark pathologies, recent genetic and molecular evidence reveals that non-neuronal cells play equally important roles in disease initiation and progression [18]. The emergence of human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has been instrumental in this reconceptualization, enabling researchers to model the complex cell-type-specific contributions to AD pathophysiology within a human context. iPSC-derived glial models provide unprecedented access to the human-specific aspects of neuroinflammation that cannot be adequately captured in rodent models [19].

The growing recognition that numerous AD risk genes identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are predominantly expressed in glia has further highlighted these cells as essential therapeutic targets [18]. Technologies such as iPSC differentiation and CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing have converged to create powerful platforms for investigating glial functions in AD, allowing researchers to dissect the roles of microglia and astrocytes in neuroinflammatory processes with human-specific relevance [20]. This technical guide explores how these advanced iPSC-based models are reshaping our understanding of AD mechanisms and accelerating the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

The Neuroinflammatory Landscape in Alzheimer's Disease

Central Players: Microglia and Astrocytes

In the central nervous system (CNS), microglia and astrocytes serve as the primary mediators of neuroinflammation, engaging in complex, dynamic responses to disease-related insults [19]. Rather than existing in simple binary states (e.g., resting/activated), these cells exhibit a spectrum of functional phenotypes that vary based on specific contextual signals.

Microglia, the brain's resident immune cells, constitute 0.5-16.6% of the total brain cell population depending on brain region, sex, and developmental stage [19]. In AD, microglia respond to damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as Aβ oligomers through pattern recognition receptors, triggering activation of NF-κB signaling pathways and subsequent release of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1α, TNF, and C1q [19]. These microglial-derived factors stimulate astrocytes to acquire a reactive phenotype, establishing a feedforward loop of neuroinflammatory signaling.

Astrocytes, the most abundant CNS glial cell type (17-61% of total brain cells), perform diverse functions including neurotransmitter recycling, metabolic support, and blood-brain barrier maintenance [19]. In AD, astrocytes become reactive, characterized by increased expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and morphological changes that correlate with patient clinical markers [21]. Reactive astrocytes contribute to AD pathogenesis through multiple mechanisms including disrupted glutamate homeostasis leading to excitotoxicity, impaired Aβ clearance, and secretion of inflammatory mediators that amplify neuroinflammatory responses [22].

Signaling Pathways in Glial-Driven Neuroinflammation

The following diagram illustrates key neuroinflammatory signaling pathways between microglia and astrocytes in Alzheimer's disease:

Figure 1: Neuroinflammatory Signaling in Alzheimer's Disease. This diagram illustrates how amyloid-β (Aβ) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) activate microglial NF-κB signaling, triggering cytokine release that induces astrocyte reactivity and contributes to synaptic and neuronal damage.

iPSC-Derived Glial Models: Methodological Approaches and Technical Considerations

Differentiation Strategies for Microglia and Astrocytes

Current protocols for generating microglia and astrocytes from human iPSCs generally follow one of two approaches: directed differentiation recapitulating developmental processes, or direct conversion using transcription factor programming [23]. The directed differentiation method sequentially mimics in vivo developmental stages through carefully timed exposure to specific growth factors and small molecules, while direct conversion approaches induce glial fates through overexpression of key transcription factors.

Microglia Differentiation: Protocols typically involve first generating hematopoietic progenitor cells, then maturing these precursors into microglia-like cells using combinations of cytokines including IL-34, M-CSF, GM-CSF, and TGF-β to promote microglial identity [19]. The resulting iPSC-derived microglia (iMG) exhibit characteristic ramified morphology, express canonical microglial markers (P2RY12, TMEM119, IBA1), and display functional properties including phagocytosis, cytokine secretion, and chemotaxis [24].

Astrocyte Differentiation: Most protocols begin with neural induction of iPSCs to generate neural progenitor cells (NPCs), followed by astrocyte specification using CNTF, BMPs, or LIF, with maturation requiring extended culture periods (often 60-180 days) [23]. The resulting iPSC-derived astrocytes express standard markers (GFAP, S100β, EAAT1/GLAST) and demonstrate functional properties including glutamate uptake, calcium signaling, and inflammatory responsiveness [21].

Table 1: Key Differentiation Factors for iPSC-Derived Glial Cells

| Cell Type | Key Differentiation Factors | Maturation Time | Characteristic Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microglia | IL-34, M-CSF, GM-CSF, TGF-β | 4-6 weeks | P2RY12, TMEM119, IBA1, CX3CR1 |

| Astrocytes | CNTF, BMP2/4, LIF, FGF2 | 8-26 weeks | GFAP, S100β, EAAT1/GLAST, EAAT2/GLT-1 |

Advanced Model Systems for Neuroinflammation Research

To better capture the complexity of CNS inflammation, researchers have developed increasingly sophisticated culture systems:

Monocultures: Single-cell type cultures enable reductionist studies of cell-autonomous responses but lack intercellular interactions [19].

Conditioned Media Transfer: This approach allows investigation of paracrine signaling without direct cell-cell contact by exposing one cell type to soluble factors secreted by another [19].

2D Co-culture Systems: Direct co-culture of multiple cell types (e.g., neurons with microglia or astrocytes) facilitates study of cell-contact-dependent signaling and bidirectional communication [19].

3D Organoid Systems: Cerebral organoids containing multiple CNS cell types self-organize into complex structures that more closely mimic the cellular diversity and organization of the developing brain [23].

Xenotransplantation Models: iPSC-derived human glia transplanted into mouse brains integrate into host circuits and adopt more mature phenotypes through exposure to the in vivo environment [19].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the process for establishing these diverse model systems:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for iPSC Glial Model Generation. This diagram outlines the differentiation of iPSCs into various neural lineages and the subsequent establishment of different model systems for neuroinflammation research.

Applications in Disease Modeling and Therapeutic Development

Modeling Patient-Specific Pathophysiology

iPSC-derived glial models demonstrate remarkable ability to recapitulate key features of individual patient pathophysiology. A compelling example comes from Rowland et al., who generated iPSC-derived astrocytes from AD patients stratified by levels of the inflammatory marker YKL-40 in cerebrospinal fluid [21]. Their research revealed that astrocyte morphological changes in response to Aβ oligomers correlated with patient clinical markers, with astrocytes from patients with lower CSF-YKL-40 levels and more protective APOE genotypes showing the greatest morphology changes [21]. This finding was subsequently verified using unbiased similarity learning approaches, highlighting how iPSC-derived glia capture biologically meaningful aspects of patient-specific disease phenotypes.

For modeling the complex genetics of sporadic AD, large-scale resources like the IPMAR Resource (iPSC Platform to Model Alzheimer's Disease Risk) have been developed, featuring over 100 iPSC lines capturing extremes of global AD polygenic risk as well as pathway-specific genetic risk (e.g., complement pathway) [13]. This collection includes lines from patients with high-risk early- and late-onset AD as well as low-risk cognitively healthy controls, many of whom have lived beyond the age of risk for disease development (>85 years) [13]. Such resources enable systematic investigation of how polygenic risk shapes glial contributions to AD pathogenesis.

High-Content Screening and Phenotypic Profiling

Advanced imaging and machine learning approaches are being leveraged to extract quantitative phenotypic information from iPSC-derived glial models. High-content imaging combined with deep learning algorithms enables unbiased quantification of morphological dynamics in glial cells following exposure to pathological insults [21]. These approaches can detect subtle, disease-relevant phenotypic changes that might be missed in conventional analyses, providing rich datasets for patient stratification and compound screening.

Table 2: Quantitative Assessments in iPSC-Glial Alzheimer's Models

| Parameter Measured | Experimental Approach | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Morphological Changes | High-content imaging, deep learning | Astrocyte morphology changes reflect patient clinical markers and APOE genotype [21] |

| Cytokine Secretion | Multiplex immunoassays (Luminex), ELISA | Distinct inflammatory profiles in high-risk vs. low-risk genotypes |

| Phagocytic Activity | pH-sensitive fluorescent beads, Aβ uptake assays | Impaired Aβ clearance in APOE4 genotypes |

| Calcium Signaling | GCaMP imaging, Fluo-4 assays | Aberrant calcium dynamics in reactive astrocytes |

| Metabolic Function | Seahorse assays, mitochondrial staining | Bioenergetic deficits in disease-associated glia |

Therapeutic Screening and Cell Engineering

iPSC-derived glial models are accelerating therapeutic development through multiple approaches:

Drug Screening: Glial models enable screening of compounds targeting neuroinflammatory processes. For instance, researchers are testing whether epilepsy drugs like levetiracetam might be repurposed for AD based on findings of abnormal electrical activity in AD brains [1]. Preliminary results suggest this approach may slow brain atrophy in individuals without the APOE ε4 allele, highlighting the importance of genotype-stratified therapeutic responses [1].

Cell Therapy Engineering: CRISPR-engineered iPSC-derived microglia are being developed as innovative therapeutic delivery vehicles. A groundbreaking study demonstrated that iPSC-microglia engineered to express the Aβ-degrading enzyme neprilysin under control of a plaque-responsive promoter (CD9) could reduce multiple biochemical measures of pathology in AD mice [24]. Both regional and CNS-wide engraftment approaches reduced Aβ pathology, but only widespread microglial engraftment achieved significant reductions in plaque load, dystrophic neurites, and astrogliosis while preserving neuronal density in plaque-dense regions [24].

Gene Editing: CRISPR/Cas9 enables precise manipulation of AD-related genes in iPSC-derived glia to study disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions. For example, editing of PSEN1 and PSEN2 in iPSC-derived cells has provided insights into how these mutations alter Aβ production and glial function [20]. Similar approaches targeting APOE have revealed allele-specific effects on Aβ clearance and neuroinflammatory responses [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC-Glial Neuroinflammation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Differentiation Factors | IL-34, M-CSF, GM-CSF, TGF-β, CNTF, BMP2/4 | Direct iPSC differentiation toward microglial or astrocytic lineages |

| Inflammatory Stimuli | Aβ oligomers, LPS, TNF-α, IL-1α/β, IFN-γ | Induction of neuroinflammatory responses in glial cultures |

| CRISPR Components | Cas9 nucleases, sgRNAs, HDR templates | Genetic engineering to introduce or correct AD-related mutations |

| Cell Surface Markers | Anti-CD11b, anti-TMEM119, anti-P2RY12 (microglia); anti-GFAP, anti-S100β (astrocytes) | Identification and purification of specific glial cell types |

| Cytokine Detection | Multiplex cytokine arrays, ELISA kits for TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β | Quantification of inflammatory mediator secretion |

Protocol: Modeling Aβ-Induced Neuroinflammation in iPSC-Derived Glial Co-cultures

Experimental Workflow:

- Differentiate iPSCs to microglia and astrocytes using established protocols [23]

- Establish co-culture systems by seeding iMG and iAstrocytes in optimized ratios (typically 1:2 to 1:5 microglia:astrocytes)

- Treat with Aβ oligomers (500 nM-2 μM) for 24-72 hours to induce AD-relevant neuroinflammation

- Implement experimental readouts including:

- High-content imaging for morphological analysis

- Multiplex cytokine profiling of conditioned media

- RNA sequencing for transcriptomic analysis

- Immunocytochemistry for marker expression and localization

- Functional assays (phagocytosis, glutamate uptake)

Key Technical Considerations:

- Include appropriate controls (vehicle-treated, monotherapy conditions)

- Use isogenic iPSC lines when possible to control for genetic background effects

- Validate Aβ oligomer preparation size and aggregation state using western blot or TEM

- Consider temporal dynamics of inflammatory responses through time-course experiments

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

The integration of iPSC-derived glial models into Alzheimer's disease research has fundamentally expanded our understanding of disease mechanisms, highlighting neuroinflammation as a central driver of pathogenesis rather than merely a secondary consequence. The development of increasingly complex culture systems, including multi-cell type co-cultures and region-specific organoids, will further enhance the physiological relevance of these models [23]. Meanwhile, advanced gene editing technologies like CRISPR/Cas9 enable precise dissection of how specific genetic variants contribute to glial dysfunction in AD [20].

Looking forward, several key areas will shape the next generation of iPSC-glial research. Multi-omics integration (transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics) applied to iPSC-derived glia from genetically stratified donors will reveal novel molecular pathways governing neuroinflammatory responses [13]. High-throughput screening platforms using iPSC-derived glia will accelerate the identification of compounds that modulate neuroinflammation in patient-specific contexts [21]. Finally, engineered glial cell therapies represent a promising frontier, with recent studies demonstrating the potential of iPSC-derived microglia to deliver therapeutic proteins throughout the CNS in a pathology-responsive manner [24].

As these technologies mature, iPSC-derived glial models will increasingly guide therapeutic development for Alzheimer's disease, enabling precision medicine approaches that account for individual genetic backgrounds and disease subtypes. By faithfully capturing the critical contributions of microglia and astrocytes to neuroinflammation, these human cellular models provide an essential bridge between basic research and clinical translation in the ongoing effort to develop effective Alzheimer's therapeutics.

Within the broader thesis on the mechanisms of Alzheimer's disease (AD) using induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) models, this whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of three critical downstream pathological pathways: synaptic dysfunction, oxidative stress, and axonal transport deficits. The advent of iPSC technology has revolutionized AD research by enabling the generation of patient-specific neural cells that recapitulate human disease pathophysiology in vitro [23] [25] [26]. These human cellular models are particularly valuable for investigating downstream events in AD pathogenesis, as they overcome limitations of animal models that often fail to fully mimic human disease processes [27]. iPSC-derived neurons from both familial and sporadic AD patients have been demonstrated to faithfully model key disease phenotypes, including elevated amyloid-β (Aβ) levels, TAU hyperphosphorylation, increased oxidative stress sensitivity, and impaired neuronal function [6] [26]. This technical guide summarizes current methodologies, quantitative findings, and experimental approaches for investigating these downstream pathways using iPSC-based AD models, providing researchers with practical tools for advancing therapeutic discovery.

Pathological Hallmarks in iPSC-Derived AD Models

iPSC-derived neural models successfully recapitulate the major pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease, providing a human-relevant platform for investigating disease mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. The table below summarizes key pathological phenotypes observed in iPSC-based AD models.

Table 1: Key Pathological Phenotypes in iPSC-Derived Alzheimer's Disease Models

| Pathological Hallmark | iPSC Model Findings | Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amyloid-β Pathology | Increased Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 levels; Elevated Aβ1–42/Aβ1–40 ratio in fAD | Recapitulates amyloid cascade hypothesis; Differentiates fAD from sAD | [6] [26] |

| TAU Hyperphosphorylation | Increased phosphorylation at multiple sites (Thr231, Ser396, etc.); GSK3B activation | Models neurofibrillary tangle formation; Links amyloid and tau pathology | [6] |

| Oxidative Stress Sensitivity | Enhanced vulnerability to amyloid oligomers and peroxide | Demonstrates increased oxidative stress susceptibility in AD neurons | [6] |

| Axonal Spheroid Formation | Plaque-associated axonal spheroids (PAAS) with disrupted conduction | Correlates with AD severity; disrupts neural circuits | [28] |

| Synaptic Dysfunction | Altered presynaptic (SNAP25, GAP43) and postsynaptic (NRGN) markers | Strongest structural correlate of cognitive deficits | [27] |

iPSC models have been particularly valuable for studying both familial (fAD) and sporadic (sAD) forms of Alzheimer's disease. Neurons derived from fAD patients (typically carrying PSEN1 mutations) and sAD patients show remarkably similar phenotypes, including increased phosphorylation of TAU protein at all investigated phosphorylation sites and higher levels of extracellular Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 [6]. However, the significantly increased Aβ1–42/Aβ1–40 ratio—a pathological marker of fAD—is observed primarily in fAD samples, highlighting both shared and distinct pathological mechanisms between AD forms [6]. These findings demonstrate that iPSC technology is suitable for modeling both fAD and sAD, providing a platform for developing novel treatment strategies for these conditions.

Synaptic Dysfunction in AD iPSC Models

Mechanisms and Pathological Features

Synaptic dysfunction represents the strongest structural correlate of cognitive deficits in Alzheimer's disease and is considered a central feature of AD pathogenesis [27]. iPSC-based studies have revealed that synaptic damage in AD involves multiple mechanisms, including local accumulation of Aβ around plaques causing localized damage to synapses of nearby neurons, thereby disturbing local neuronal networks [27]. Research using iPSC-derived neurons has demonstrated that high Aβ concentrations in and around plaques trigger damage to glutamatergic transmission and nearby synapses by targeting postsynaptic glutamatergic receptors in a calcium-dependent manner [27].

The analysis of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in AD patients has revealed specific alterations in synaptic proteins that can be modeled in iPSC systems. These include changes in presynaptic markers such as SNAP25 and GAP43 (involved in synaptic plasticity) and the postsynaptic marker neurogranin (NRGN, involved in long-term potentiation) [27]. These synaptic alterations are believed to contribute to memory dysfunction and disrupted default-mode network activity in the AD brain.

Experimental Assessment Protocols

Table 2: Methodologies for Assessing Synaptic Dysfunction in iPSC-Derived Neurons

| Method | Key Parameters | Technical Considerations | Applications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immuno-cytochemistry | Presynaptic (SNAP25, GAP43) and postsynaptic (PSD95, NRGN) marker localization and quantification | Requires high-resolution imaging (confocal/STED); Quantitative analysis of puncta density and size | Mapping spatial distribution of synaptic proteins; Assessing synapse density | [27] |

| Electro-physiology | Spontaneous postsynaptic currents; Network activity using MEA; Long-term potentiation (LTP) | Requires mature neuronal cultures (>60 days); Technical expertise in patch clamping | Functional assessment of synaptic transmission and plasticity | [29] |

| CSF Biomarker Analysis | Levels of SNAP25, GAP43, NRGN in conditioned media | Sensitivity of detection methods; Correlation with clinical biomarkers | Translational validation; Drug response assessment | [27] |

| Live-cell Imaging | Synaptic vesicle recycling (FM dyes); Calcium imaging | Temporal resolution; Phototoxicity considerations | Real-time monitoring of synaptic function and dynamics | [28] |

Oxidative Stress Mechanisms

Oxidative Stress in AD Pathogenesis

Oxidative stress represents a significant downstream pathway in Alzheimer's disease pathology, with iPSC-derived AD neurons demonstrating enhanced sensitivity to oxidative insults. Studies have shown that both fAD- and sAD-derived neurons exhibit elevated sensitivity to oxidative stress induced by amyloid oligomers or peroxide [6]. This increased vulnerability reflects the compromised antioxidant defense mechanisms and heightened oxidative damage observed in the AD brain.

The relationship between oxidative stress and other AD pathological features is complex and bidirectional. Aβ accumulation can induce oxidative stress by promoting mitochondrial dysfunction and generating reactive oxygen species (ROS). Conversely, oxidative stress can accelerate amyloidogenesis by enhancing β- and γ-secretase activities while inhibiting α-secretase processing of APP [6]. Additionally, oxidative stress can promote tau hyperphosphorylation by activating various kinases, including GSK3β, further connecting these pathological pathways.

Assessment Methodologies

The protocol for evaluating oxidative stress vulnerability in iPSC-derived AD neurons typically involves exposing mature neuronal cultures (60+ days of differentiation) to specific oxidative stressors, such as hydrogen peroxide or amyloid oligomers, followed by assessment of cell viability and metabolic function [6]. Additional measures include:

- ROS Detection: Using fluorescent probes like CM-H2DCFDA to measure intracellular ROS levels

- Mitochondrial Function Assessment: Utilizing JC-1 staining or TMRM to measure mitochondrial membrane potential

- Antioxidant Defense Evaluation: Quantifying expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, catalase, glutathione peroxidase)

- Lipid Peroxidation Measurement: Assessing levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) or 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE)

These approaches allow researchers to quantify the increased oxidative stress sensitivity observed in AD-derived neurons and evaluate potential therapeutic compounds that might mitigate this vulnerability.

Axonal Transport Deficits

Plaque-Associated Axonal Spheroids (PAAS)

A recent breakthrough in understanding axonal pathology in AD comes from the identification and characterization of plaque-associated axonal spheroids (PAAS) using iPSC models and proteomic approaches [28]. These dystrophic neurites are found around amyloid deposits in Alzheimer's disease, where they impair axonal electrical conduction, disrupt neural circuits, and correlate with AD severity [28]. Hundreds of axons near individual plaques develop enlarged spheroid-like structures that contain enlarged, enzyme-deficient endolysosomal vesicles and autophagosomes [28].

A proximity labeling proteomics approach has been developed to characterize the molecular composition of PAAS in postmortem AD human brains and iPSC-derived models [28]. This method utilizes PLD3, an endolysosomal protein highly abundant within PAAS, as a protein bait for proximity labeling. The approach involves sequential incubation with primary antibody against PLD3 and an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, followed by a peroxidation reaction with H2O2 and Biotin-XX-Tyramide, resulting in robust biotinylation of proteins within PAAS [28]. Proteomic analysis of these structures has revealed abnormalities in key biological processes, including protein turnover, cytoskeleton dynamics, and lipid transport.

mTOR Pathway in Axonal Pathology

Notably, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway—which regulates these processes—was found to be activated in spheroids, with phosphorylated mTOR levels in spheroids correlating with AD severity in humans [28]. This discovery has significant therapeutic implications, as mTOR inhibition in iPSC-derived neurons and mice ameliorated spheroid pathology [28]. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways involved in axonal spheroid formation and potential therapeutic targets:

Diagram Title: mTOR Pathway in Axonal Spheroid Formation

Experimental Protocols for iPSC-Based AD Research

Neural Differentiation Workflow

The investigation of downstream pathways in AD using iPSC models requires robust differentiation protocols to generate relevant neural cell types. The following diagram outlines a standardized workflow for generating AD-relevant neural cells from iPSCs:

Diagram Title: iPSC Neural Differentiation Workflow

The standard neural induction protocol typically employs dual SMAD inhibition using Noggin and SB431542 to efficiently direct differentiation toward neural fates [23]. This approach generates PAX6+ neural cells competent of rosette formation within approximately 11 days [23]. Neural rosettes can then be isolated and expanded as neural stem cells (NSCs), which can subsequently be differentiated into mature neuronal and glial cell types.

High-Content Phenotypic Screening

For drug discovery applications, high-content phenotypic screening platforms have been developed using iPSC-derived neurons. These typically involve:

- Longitudinal Live-cell Imaging: Automated imaging systems to monitor neuronal health and degeneration over time [29]

- Metabolic Assays: Measurement of cellular viability and metabolic function (e.g., MTT, ATP assays)

- Immunocytochemical Analysis: High-throughput staining and imaging of key pathological markers (Aβ, p-TAU, synaptic proteins)

- Multi-electrode Array (MEA): Functional assessment of neuronal network activity [29]

- Transcriptomic Analysis: RNA sequencing to evaluate pathway alterations and drug responses

These approaches have been validated in large-scale studies, such as a recent screen of 100 sporadic ALS iPSC lines (relevant to neurodegenerative disease mechanisms generally), which demonstrated the ability to recapitulate key disease phenotypes and identify potential therapeutic compounds [29].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below provides a comprehensive list of essential research reagents and their applications in iPSC-based AD research, compiled from the cited literature:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC-Based Alzheimer's Disease Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Induction Agents | Noggin, SB431542, LDN-193189 | Dual SMAD inhibition for efficient neural differentiation | [23] |

| Neural Maturation Factors | BDNF, GDNF, NT-3, cAMP, Ascorbic acid | Promote neuronal maturation and synaptic development | [23] [29] |

| Cell Type Markers | PAX6 (NSCs), Tuj1 (neurons), MAP2 (mature neurons), GFAP (astrocytes) | Identification and validation of specific neural cell types | [23] [29] |

| Pathological Antibodies | Anti-Aβ, Anti-phospho-TAU (Thr231, Ser396, etc.), Anti-GSK3B | Detection of AD pathological hallmarks | [28] [6] |

| Pathway Modulators | mTOR inhibitors (e.g., Rapamycin), GSK3B inhibitors, BACE1 inhibitors | Mechanistic studies and therapeutic target validation | [28] [6] |

| Proteomic Tools | PLD3 antibody, Biotin-XX-Tyramide, Streptavidin beads | Proximity labeling for subcellular proteomics | [28] |

| Vital Dyes & Reporters | CM-H2DCFDA (ROS), JC-1 (mitochondrial potential), Calcium indicators | Functional assessment of oxidative stress and signaling | [28] [6] |

iPSC-based models have emerged as powerful tools for investigating downstream pathways in Alzheimer's disease, including synaptic dysfunction, oxidative stress, and axonal transport deficits. These patient-derived cellular models recapitulate key aspects of AD pathology and provide a human-relevant platform for mechanistic studies and drug discovery. The integration of advanced techniques such as proximity labeling proteomics, high-content screening, and 3D organoid cultures has enabled unprecedented insights into the molecular mechanisms driving AD pathogenesis. Furthermore, the identification of potentially reversible pathways, such as mTOR activation in axonal spheroids, provides new hope for therapeutic interventions. As iPSC technology continues to evolve, it will undoubtedly play an increasingly central role in unraveling the complex mechanisms of Alzheimer's disease and developing effective treatments for this devastating disorder.

Uncovering Novel Therapeutic Targets through Genomic and Transcriptomic Analysis of iPSC-Derived Brain Cells

Alzheimer's disease (AD) remains a devastating neurodegenerative disorder with no cure, characterized by progressive cognitive decline and pathological hallmarks including amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles [20] [18]. The failure of countless therapeutics developed in traditional rodent models has highlighted the critical need for human-relevant model systems that better recapitulate human disease pathophysiology [18]. The advent of human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized AD research by enabling the generation of patient-specific brain cells, including neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and more complex 3D organoid systems [12] [11] [18].

Integrating genomic and transcriptomic analyses with these iPSC-derived models provides unprecedented opportunities to uncover novel therapeutic targets by directly linking human genetic risk factors to functional cellular and molecular phenotypes [30] [31]. This approach allows researchers to move beyond the limitations of familial AD models and investigate the complex polygenic nature of sporadic AD, which accounts for over 95% of cases [30] [11]. The ability to capture individual genetic backgrounds while manipulating specific risk genes through CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing further enables precise dissection of disease mechanisms [20] [15]. This technical guide outlines how these powerful technologies are being integrated to advance our understanding of AD pathogenesis and identify novel therapeutic intervention points.

Polygenic Risk Score Stratification in iPSC Cohorts

The complex genetic architecture of sporadic Alzheimer's disease necessitates iPSC resources that capture the polygenic nature of disease risk. The IPMAR Resource (iPSC Platform to Model Alzheimer's Disease Risk) represents a significant advancement, comprising 109 iPSC lines selected from extremes of global AD polygenic risk and complement pathway-specific genetic risk [30].

Table 1: IPMAR Resource Composition for Genomic Risk Modeling

| Risk Category | Donor Diagnosis | Number of Lines | Mean Polygenic Risk Score | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global AD Polygenic Risk | Late-onset AD (LOAD) | 34 | 2.2 ± 0.5 SD | Age of onset: 72 ± 6 years; 56% female |

| Global AD Polygenic Risk | Early-onset AD (EOAD) | 29 | 2.1 ± 0.4 SD | Age of onset: 51 ± 3 years; 55% female |

| Global AD Polygenic Risk | Cognitively healthy controls | 27 | -1.9 ± 0.4 SD | 59% female; elderly controls (>85 years) |

| Complement Pathway Risk | LOAD | 9 | 2.4 ± 0.3 SD | Age of onset: 71 ± 6 years; 78% female |

| Complement Pathway Risk | Cognitively healthy controls | 10 | -1.9 ± 0.2 SD | 70% female |

This resource enables researchers to investigate how aggregated genetic risk across the genome, quantified as polygenic risk scores (PRS), influences cellular phenotypes in human-derived neurons and glia [30]. The PRS approach aggregates information from all identified genetic variants known to impact overall AD risk, providing a personalized estimate of an individual's genetic susceptibility with 84% accuracy in predicting disease development [30].

APOE Isoform-Specific Modeling

Beyond polygenic risk scores, specific high-risk genetic factors can be modeled using isogenic iPSC lines. The APOE ε4 allele represents the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset AD, with APOE2 considered protective and APOE3 neutral [31] [18]. Researchers have generated iPSC-derived microglia with different APOE genotypes (APOE2, APOE3, APOE4, and APOE-knockout) transplanted into mouse brains to study microglial-autonomous effects [31].

Table 2: Key Genomic Targets in Alzheimer's Disease iPSC Modeling

| Gene/Pathway | Risk Allele/Variant | Associated AD Risk | Primary Cellular Functions | iPSC Modeling Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOE | APOE4 (vs. APOE3) | 3-fold (heterozygous) 15-fold (homozygous) | Lipid transport, Aβ clearance, immune regulation | Isogenic lines, xenotransplantation, transcriptomics |

| APOE | APOE2 (vs. APOE3) | Protective | Lipid transport, Aβ clearance, immune regulation | Isogenic lines, xenotransplantation, transcriptomics |

| APP | Multiple FAD mutations | Highly penetrant early-onset AD | Aβ production, synaptic function | CRISPR correction, pathogenic mutation introduction |

| PSEN1/PSEN2 | Multiple FAD mutations | Highly penetrant early-onset AD | γ-secretase activity, Aβ generation | CRISPR knockout, pathogenic mutation introduction |

| Complement Pathway | Multiple SNPs from GWAS | Modest individual effects, significant in aggregate | Immune clearance, synaptic pruning | Polygenic risk score stratification, pathway analysis |

RNA-seq and ATAC-seq analyses of these microglia revealed widespread transcriptomic and epigenomic differences dependent on APOE genotype, with the most significant differences observed between the protective APOE2 and risk-associated APOE4 isoforms [31]. APOE4 microglia showed impaired proliferation, migration, and immune responses, while APOE2 microglia exhibited enhanced phagocytic capabilities and unique vitamin D receptor signaling [31].

Transcriptomic Profiling of iPSC-Derived Brain Cells

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Complex Co-culture Systems

Advanced 3D model systems now enable transcriptomic profiling of multiple cell types in physiologically relevant contexts. A vascularized neuroimmune organoid model containing neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and blood vessels has been developed to study AD pathogenesis in a more complex human system [11]. When exposed to brain extracts from sporadic AD patients, these organoids develop multiple AD pathologies within four weeks, including Aβ plaque-like aggregates, tau tangle-like aggregates, neuroinflammation, synaptic loss, and impaired neural network activity [11].

Single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) of similar 3D neurosphere models has revealed how cellular interactions shape transcriptional responses to chronic amyloidosis [32]. In neurospheres containing neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, chronic exposure to Aβ oligomers induced significant transcriptional changes that were profoundly influenced by the presence of microglia [32]. Specifically, microglia were essential for the upregulation of AD-associated genes in astrocytes, including APOE, CLU, LRP1, and VIM, highlighting the critical role of intercellular signaling in shaping disease-relevant transcriptomic responses [32].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for transcriptomic analysis of iPSC-derived 3D neurospheres under chronic amyloidosis conditions.

Subcellular Proteomics of Disease-Associated Structures

Beyond transcriptomics, subcellular proteomic approaches have been developed to characterize the molecular composition of specific pathological structures in AD. Proximity labeling techniques using enzymes like horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated to antibodies against proteins enriched in pathological compartments enable proteomic profiling of these structures [28]. For example, targeting phospholipase D3 (PLD3), highly enriched in plaque-associated axonal spheroids (PAAS), has revealed the proteome of these dystrophic neurites [28].

This approach identified 821 proteins representing the PAAS proteome, with enrichment in biological processes including protein turnover, cytoskeleton dynamics, and lipid transport [28]. Notably, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway was activated in spheroids, and phosphorylated mTOR levels correlated with AD severity in humans [28]. Furthermore, mTOR inhibition in iPSC-derived neurons and mouse models ameliorated spheroid pathology, validating this pathway as a therapeutic target identified through subcellular proteomics [28].

Advanced 3D Model Systems for Pathological Recapitulation

Vascularized Neuroimmune Organoids

Recent advancements in 3D culture systems have enabled the development of more physiologically relevant models that incorporate multiple cell types affected in AD. Vascularized neuroimmune organoids contain human neurons, microglia, astrocytes, and blood vessels, providing a comprehensive system to study cellular interactions in AD pathogenesis [11]. These organoids exhibit functional blood vessels with endothelial cells and pericytes, as demonstrated by staining for CD31 (endothelial marker) and PDGFRβ (pericyte marker) [11].

When exposed to postmortem brain extracts from sporadic AD patients, these organoids develop multiple AD pathologies within four weeks, including:

- Aβ plaque-like aggregates and tau tangle-like aggregates

- Neuroinflammation with activated microglia

- Elevated microglial synaptic pruning

- Synapse and neuronal loss

- Impaired neural network activity [11]

This model also demonstrates utility for therapeutic testing, as treatment with Lecanemab, an FDA-approved anti-Aβ antibody, significantly reduced amyloid burden in AD brain extract-exposed organoids [11].

Chronic Amyloidosis Neurosphere Models

Another 3D approach uses iPSC-derived neurospheres containing neurons and astrocytes, with optional addition of microglia, to study cellular responses to chronic amyloidosis [32]. In this system, microglia efficiently phagocytose Aβ and significantly reduce neurotoxicity, mitigating amyloidosis-induced oxidative stress and neurodegeneration [32]. The neuroprotective effects conferred by microglia were associated with unique gene expression profiles in astrocytes and neurons, including several known AD-associated genes such as APOE [32].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC-Based Alzheimer's Disease Modeling

| Reagent/Cell Type | Specification | Function in Model System | Key Characterization Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Progenitor Cells (NPCs) | iPSC-derived, PAX6+/NESTIN+ | Foundation for neuronal and astrocyte differentiation | PAX6, NESTIN, SOX1, SOX2 |

| Primitive Macrophage Progenitors (PMPs) | iPSC-derived, CD235+/CD43+ | Source for microglia in co-culture systems | CD235, CD43, PU.1 |

| Vascular Progenitors (VPs) | iPSC-derived, CD31+ | Forms vascular structures in 3D organoids | CD31, PDGFRβ, Collagen IV |

| Brain Organoid Media | Supplemented with IL-34, VEGF, neurotrophic factors | Supports maturation of neuronal, microglial, and vascular components | N/A (culture medium) |

| Aβ Oligomers | Synthetic Aβ1-42 | Induces chronic amyloidosis pathology in 3D models | N/A (experimental treatment) |

This model provides a platform to study the protective functions of microglia and their role in shaping astrocyte and neuronal responses to Aβ, highlighting how different cell types interact to modify disease progression [32].

Therapeutic Target Validation and Screening

Target Identification Through Multi-Omic Integration

The integration of genomic and transcriptomic data from iPSC-derived brain cells has identified numerous potential therapeutic targets for AD. Key pathways emerging from these analyses include:

- mTOR Signaling: Subcellular proteomics of axonal spheroids identified mTOR activation as a key process in PAAS formation, with mTOR inhibition reducing spheroid pathology in iPSC-derived neurons and mouse models [28].

- APOE-Related Pathways: Transcriptomic profiling of APOE isoform-specific microglia revealed impaired proliferation, migration, and immune responses in APOE4 microglia, while APOE2 microglia showed enhanced phagocytic capability and unique vitamin D receptor signaling [31].

- Complement System: iPSC lines stratified by complement pathway-specific polygenic risk enable investigation of how genetic variation in this pathway influences neuroimmune function and AD susceptibility [30].

- Inflammatory Response: snRNA-seq of 3D neurosphere models revealed microglia-dependent upregulation of inflammatory genes in astrocytes, including APOE, CLU, LRP1, and VIM, in response to Aβ exposure [32].

Figure 2: Integrated workflow for therapeutic target discovery using iPSC models and multi-omic profiling.

Experimental Validation Approaches

Once potential therapeutic targets are identified through genomic and transcriptomic analyses, several experimental approaches enable validation:

CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing: CRISPR/Cas9 enables precise genetic modifications in key AD-related genes, such as APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, and APOE, in iPSC lines [20] [15]. This approach allows researchers to correct pathogenic mutations or introduce risk variants in isogenic backgrounds to study their specific effects on molecular and cellular phenotypes [20].

Pharmacological Screening: iPSC-derived neurons, glia, and 3D organoids provide human-relevant platforms for drug screening. For example, mTOR inhibition was shown to ameliorate axonal spheroid pathology in both iPSC-derived neurons and mouse models [28]. Similarly, Lecanemab treatment reduced amyloid burden in vascularized neuroimmune organoids exposed to AD brain extracts [11].

Functional Assays: Comprehensive functional characterization including electrophysiology, calcium imaging, phagocytosis assays, and neuronal activity measurements enables correlation of transcriptomic findings with functional outcomes [28] [32]. For instance, in 3D neurosphere models, microglia were shown to protect against Aβ-induced dysfunction of neuronal activity and oxidative stress [32].

Several clinical trials have been initiated based on findings from iPSC research, including trials of bosutinib, ropinirole, and ezogabine for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), demonstrating the translational potential of this approach [33]. Similar strategies are being applied to AD, with the goal of accelerating therapeutic development.

The integration of genomic and transcriptomic analyses with iPSC-derived brain models has transformed our ability to identify and validate novel therapeutic targets for Alzheimer's disease. These human-relevant systems capture the genetic complexity of AD and enable detailed investigation of disease mechanisms in precisely defined cellular contexts. As these technologies continue to advance—with improvements in 3D model complexity, single-cell multi-omic profiling, and genome editing—they hold considerable promise for delivering the next generation of AD therapeutics that have proven so elusive in traditional model systems. The ongoing development of large, genetically stratified iPSC resources, combined with advanced analytical approaches, will be critical to realizing the potential of personalized medicine for this devastating disorder.

Building Better Brain Models: iPSC Differentiation, High-Content Screening, and Drug Discovery Platforms

Protocols for Differentiating iPSCs into Functional Cortical Neurons and Motor Neurons

The development of robust protocols for differentiating induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into specific neuronal subtypes represents a cornerstone of modern neurological disease modeling, particularly for Alzheimer's disease (AD). Patient-derived iPSCs retain the individual's complete genetic background, enabling researchers to create human neuronal models that recapitulate disease-specific pathologies in vitro [34]. For AD research, the ability to generate cortical neurons—which are vulnerable to amyloid-beta and tau pathology—and motor neurons—relevant for understanding circuit dysfunction and axonal transport deficits—provides powerful platforms for investigating disease mechanisms and screening therapeutic candidates [12] [28]. This technical guide details established methodologies for generating these functionally mature neuronal populations, with specific consideration for their application in AD research.

Cortical Neuron Differentiation Protocols

Cortical neurons derived from human iPSCs provide essential models for studying AD-related pathologies, including amyloid plaque formation, tau hyperphosphorylation, and synaptic dysfunction observed in the cerebral cortex.

Defined Cortical Neuron Differentiation with Dual SMAD and Wnt Inhibition

A highly efficient 14-day protocol generates cortical neural stem cells (NSCs) using a defined, small molecule-based approach [35]. This method employs dual-SMAD inhibition combined with Wnt/β-Catenin inhibition to direct cells toward a dorsal cortical fate.

Key Protocol Steps:

- Neural Induction (Days 1-10): Culture iPSCs in Neural Induction Medium containing SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor), LDN193189 (BMP inhibitor), and XAV939 (Wnt inhibitor).

- Neural Maintenance (Days 10-14): Passage cells and culture in Neural Maintenance Medium to promote NSC expansion and neural rosette formation.