Modeling Alzheimer's Risk: Investigating APOE Isoform-Specific Effects in Human iPSC-Derived Neurons and Brain Cell Types

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) have emerged as a transformative platform for investigating the mechanistic roles of Apolipoprotein E (APOE) isoforms in Alzheimer's Disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions.

Modeling Alzheimer's Risk: Investigating APOE Isoform-Specific Effects in Human iPSC-Derived Neurons and Brain Cell Types

Abstract

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) have emerged as a transformative platform for investigating the mechanistic roles of Apolipoprotein E (APOE) isoforms in Alzheimer's Disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions. This article synthesizes current research utilizing isogenic hiPSC models to dissect how APOE2, E3, and E4 differentially influence neuronal health, synaptic function, amyloid-β pathology, and blood-brain barrier integrity. We explore foundational APOE biology, methodological advances in stem cell differentiation and genome editing, troubleshooting of experimental challenges, and validation through comparison with clinical observations and animal models. This comprehensive analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with critical insights for developing targeted therapeutic strategies based on APOE genotype.

APOE Isoforms and Neurobiology: Establishing the Genetic Framework for Alzheimer's Disease

APOE Genotype as the Strongest Genetic Risk Factor for Late-Onset Alzheimer's Disease

The apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene is the most significant genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer's disease (LOAD). Among its three common isoforms, the APOE ε4 allele dramatically increases AD risk in a dose-dependent manner, while the APOE ε2 allele confers protection compared to the neutral APOE ε3 allele. This whitepaper delves into the molecular and cellular mechanisms through which APOE isoforms influence AD pathogenesis, with a particular emphasis on insights gained from human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) models. We review how APOE isoforms differentially regulate amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregation and clearance, tau pathology, neuroinflammation, lipid metabolism, and synaptic function. Furthermore, we summarize current therapeutic strategies targeting APOE pathways and provide a detailed toolkit for researchers, including standardized experimental protocols and reagents for modeling APOE in hiPSC-derived neural cells.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the most common cause of dementia worldwide. The APOE ε4 allele is the strongest genetic risk factor for LOAD, with individuals carrying one copy of ε4 having a 3-4 fold increased risk, and homozygotes facing a 12-15 fold increase compared to non-carriers [1] [2]. Conversely, the APOE ε2 allele is associated with a reduced risk of AD [2]. The APOE protein is a lipid-transport protein that is highly expressed in the brain, primarily by astrocytes and, to a lesser extent, by microglia [3] [4]. It plays a critical role in brain lipid homeostasis, synaptic integrity, and neuronal repair. The three APOE isoforms differ only by single amino acid substitutions at positions 112 and 158, yet these differences have profound impacts on protein structure and function, influencing AD risk through a complex interplay of Aβ-dependent and Aβ-independent mechanisms [2] [5].

The emergence of hiPSC technology has revolutionized the study of AD, allowing for the generation of patient-specific neural cells, including neurons, astrocytes, and microglia. This provides a critical humanized platform to investigate the isoform-specific effects of APOE in a physiologically relevant context, bridging the gap between animal models and human clinical disease [6].

APOE Genetics and Risk Quantification

Allelic Variants and Population Frequency

The human APOE gene is located on chromosome 19 and encodes three major alleles—ε2, ε3, and ε4—with a worldwide frequency of approximately 8.4%, 77.9%, and 13.7%, respectively [2]. These alleles give rise to three protein isoforms that differ at two key amino acid positions:

- APOE2: Cysteine-112, Cysteine-158

- APOE3: Cysteine-112, Arginine-158

- APOE4: Arginine-112, Arginine-158 [2]

Table 1: APOE Isoform Characteristics and Associated AD Risk

| APOE Isoform | Amino Acid Positions (112/158) | Relative AD Risk (vs. APOE3/3) | Approximate Allele Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| APOE2 | Cysteine/Cysteine | 0.6 (Reduced) | ~8% |

| APOE3 | Cysteine/Arginine | 1.0 (Neutral) | ~78% |

| APOE4 | Arginine/Arginine | 3-4 (Heterozygote), 12-15 (Homozygote) | ~14% |

Data synthesized from [1] [2] [5]

Dose-Dependent Effect of APOE4

The association between APOE4 and AD risk is dose-dependent. A large meta-analysis established that compared to the common ε3/ε3 genotype, the odds ratio for AD increases to 3.2 for ε3/ε4 heterozygotes and rises to 14.9 for ε4/ε4 homozygotes [2]. APOE4 is also associated with an earlier age of onset of AD [7] [2]. The protective effect of APOE2 is similarly dose-dependent, with ε2/ε3 heterozygotes showing reduced risk and ε2/ε2 homozygotes exhibiting the strongest protection [2] [5].

Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of APOE in AD

APOE isoforms influence AD pathogenesis through a multitude of mechanisms, which can be broadly categorized into Aβ-dependent and Aβ-independent pathways.

Aβ-Dependent Mechanisms

APOE isoforms differentially regulate Aβ metabolism, including its aggregation, deposition, and clearance.

- Amyloid Plaque Deposition: Human studies using amyloid PET imaging and post-mortem analysis consistently show that APOE4 carriers exhibit a significantly increased amyloid plaque burden compared to non-carriers, following an isoform-dependent pattern (E4 > E3 > E2) [3] [2]. The presence of APOE is required for the formation of amyloid plaques, as its absence in mouse models dramatically reduces Aβ deposition [3] [8].

- Aβ Clearance: APOE facilitates the cellular clearance of Aβ through receptor-mediated endocytosis. APOE4 is less effective than other isoforms in promoting Aβ clearance, potentially due to its impaired binding to certain receptors like LRP1 and its rapid degradation, which leads to its reduced levels in the brain [4] [2].

- Aβ Aggregation: In vitro studies suggest that APOE4 accelerates the fibrillization of Aβ into neurotoxic plaques compared to APOE2 and APOE3 [2].

Aβ-Independent Mechanisms

Significant evidence indicates that APOE4 contributes to AD pathology through mechanisms that operate independently of Aβ.

- Synaptic Dysfunction and Toxicity: APOE4 is associated with synaptic deficits both in humans and in animal models. APOE4-targeted replacement (TR) mice exhibit impairments in spatial learning, reduced dendritic spine density, and simpler dendritic arborization in the hippocampus and cortex, even in the absence of amyloid plaques [7] [8]. A recent mechanistic study revealed that APOE4 directly binds to the presynaptic protein VAMP2 with higher affinity than APOE3, thereby impairing the assembly of the SNARE complex and subsequent synaptic vesicle release, providing a direct molecular link to synaptic dysfunction [9].

- Tau Pathology: APOE4 exacerbates tau-mediated neurodegeneration and neurofibrillary tangle pathology. The interaction between APOE and tau appears to be independent of Aβ, and APOE4 drives a neuroinflammatory response that enhances tau pathology [4].

- Neuroinflammation: APOE isoforms differentially regulate the innate immune response in the brain. APOE4 tends to drive a pro-inflammatory state in microglia and astrocytes, which may contribute to neurodegeneration [3]. The interaction between APOE and microglial TREM2 is crucial for microglial function and response to neurodegeneration [3] [5].

- Endolysosomal Dysfunction: Enlarged endosomes represent an early pathological feature in AD neurons. Recent research using primary neurons indicates that APOE4 impairs endolysosomal function, leading to reduced degradative capacity and predisposing neurons to cholesterol accumulation over time [10].

- Cerebrovascular Deficits and Lipid Metabolism: APOE4 is associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) and impaired cerebrovascular function [2]. It also disrupts normal brain lipid homeostasis, leading to changes in neuronal lipid composition that can affect membrane integrity, synaptic signaling, and energy metabolism [4] [2]. APOE4 makes neurons more vulnerable to lipid peroxidation and subsequent ferroptotic cell death [4].

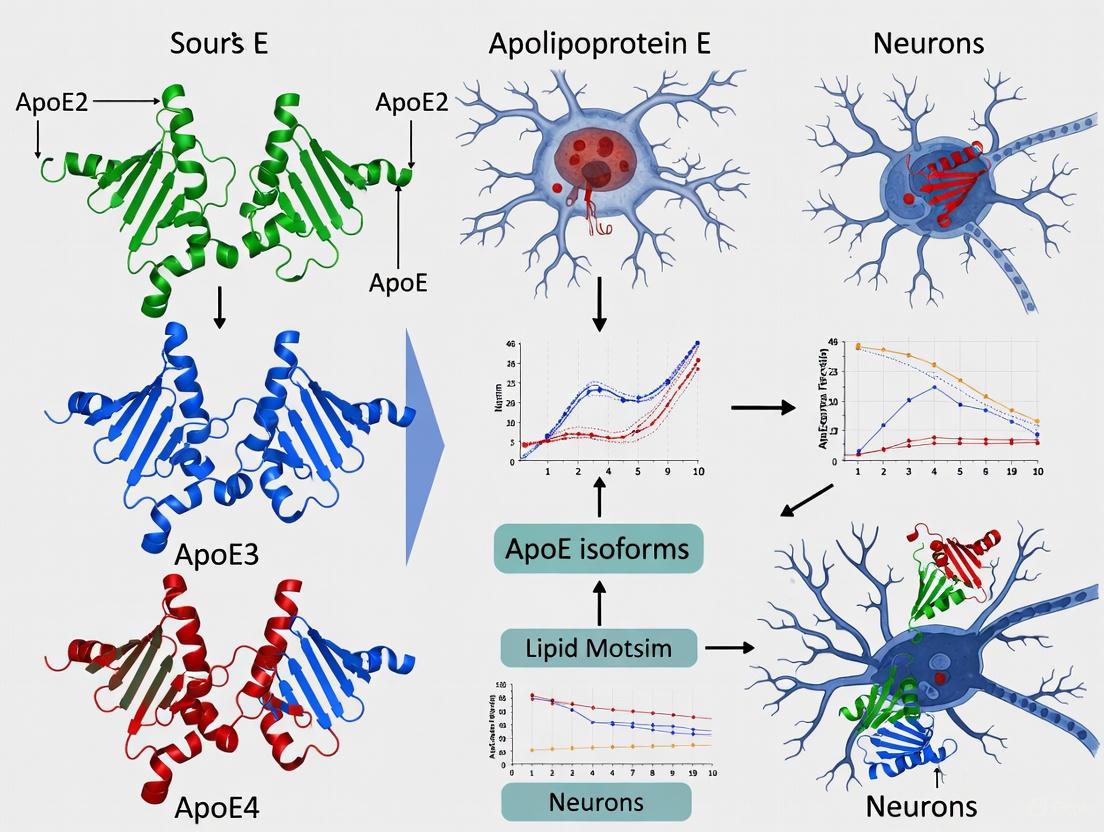

Diagram 1: APOE4 pathogenic mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease. The APOE4 isoform (red) drives pathology through multiple parallel pathways, including both amyloid-β-dependent and independent processes, which collectively contribute to disease progression.

APOE Research in hiPSC-Derived Models

hiPSC technology provides a powerful platform for studying the cell-type-specific effects of APOE isoforms in a human genetic background.

hiPSC Differentiation Protocols for Neural Cells

Table 2: Key hiPSC Differentiation Protocols for Neural Cells

| Target Cell Type | Key Patterning Factors/Signals | Key Markers | Primary Application in APOE/AD Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Neurons | Dual-SMAD inhibition (e.g., Noggin, SB431542); BDNF, GDNF [6] | MAP2, TBR1, CTIP2 | Study synaptic toxicity, tau pathology, and electrophysiological deficits. |

| Midbrain Dopaminergic Neurons | SHH, WNT, FGF8; Floor-plate based protocol [6] | TH, LMX1A, FOXA2, NURR1 | Model relevant for Parkinson's disease dementia and Lewy body dementia, also APOE-related risks. |

| Astrocytes | CNTF, LIF, NFIA; OR SOX9 overexpression [6] | GFAP, S100β | Investigate APOE secretion, lipid metabolism, and neuroinflammatory responses. |

| Microglia | BMP4, IL-3, IL-6, M-CSF, IL-34 [6] | P2RY12, TMEM119, IBA1 | Model neuroinflammation, Aβ phagocytosis, and TREM2-APOE interactions. |

2D vs. 3D Model Systems

- 2D Monocultures and Co-cultures: Simplified systems where a single cell type or a defined mix of cells (e.g., neurons and astrocytes) is differentiated. Ideal for high-throughput screening and mechanistic studies in a controlled environment [6].

- 3D Organoids and Tri-culture Systems: Cerebral organoids are self-organizing 3D structures that recapitulate some aspects of the brain's cellular diversity and complexity. Advanced 3D systems can incorporate neurons, astrocytes, and microglia to better model cell-cell interactions and disease pathology, such as microglial recruitment and neurotoxicity in an AD context [6].

Experimental Protocols for hiPSC-based APOE Research

Protocol: Generating and Differentiating APOE-isoform hiPSCs

This protocol outlines the generation of an APOE-isoform specific hiPSC model and differentiation into cortical neurons.

hiPSC Generation and Genotyping:

- Generate hiPSCs from patient fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) carrying specific APOE genotypes (ε2/ε2, ε3/ε3, ε4/ε4) using non-integrating reprogramming methods (e.g., Sendai virus or episomal vectors) [6].

- Confirm pluripotency (e.g., expression of OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) and perform karyotyping.

- Genotype the APOE locus to confirm the isoform status of the hiPSC lines.

Cortical Neuron Differentiation via Dual-SMAD Inhibition:

- Neural Induction: Culture hiPSCs until they reach 70-80% confluence. Treat with neural induction medium containing SMAD inhibitors (e.g., 10 µM SB431542 and 100 nM LDN-193189) for 10-14 days to generate neural progenitor cells (NPCs). Medium should be changed daily [6].

- NPC Expansion: Dissociate the neural rosettes and plate the NPCs on a suitable substrate (e.g., Matrigel). Expand NPCs in NPC medium containing FGF2.

- Neuronal Differentiation: Withdraw FGF2 and culture NPCs in neuronal differentiation medium supplemented with BDNF (20 ng/mL) and GDNF (20 ng/mL) for over 28 days to promote terminal differentiation into cortical neurons [6].

- Characterization: Validate neuronal identity by immunocytochemistry for MAP2, β-III-tubulin, and synapsin. Assess functionality via electrophysiology (patch-clamp).

Protocol: Assessing APOE4-induced Synaptic Defects via SNARE Complex Assembly

This protocol is based on a recent study investigating the presynaptic mechanism of APOE4 [9].

Treatment of Neuronal Cultures:

- Use primary hippocampal neurons from APOE knockout mice or human APOE-TR hiPSC-derived neurons.

- At Days In Vitro (DIV) 7, treat cultures with 10 µM of recombinant human APOE3 or APOE4 protein for 24 hours [9].

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and Western Blot:

- Harvest treated cells and lyse in IP buffer.

- Incubate lysates with an anti-APOE antibody (e.g., ab1906) overnight at 4°C.

- Add Protein A/G beads for 2 hours, wash complexes, and elute proteins.

- Analyze eluates and total lysates by Western blotting using antibodies against VAMP2, SNAP-25, syntaxin-1, and APOE to assess SNARE complex components and interactions [9].

Functional Assay: Synaptic Vesicle Release with FM4-64 Dye:

- Load mature neuronal cultures (e.g., from APOE3-TR or APOE4-TR mice) with FM4-64 dye by stimulating with high K+ solution.

- Wash the cultures extensively to remove excess dye.

- Image the synapses using live-cell microscopy. Stimulate the neurons again and measure the destaining kinetics (fluorescence loss) as an indicator of synaptic vesicle exocytosis [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for APOE and hiPSC Neuroscience Research

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| hiPSC Lines | APOE-genotyped patient-derived hiPSCs; CRISPR-edited isogenic APOE hiPSC lines (e.g., ε3/ε3 vs ε4/ε4) | Provide a physiologically relevant human model system to study isoform-specific effects on a controlled genetic background. |

| Differentiation Kits & Factors | SMAD inhibitors (LDN-193189, SB431542); BDNF, GDNF; SHH, Purmorphamine; IL-34, M-CSF | Direct efficient differentiation of hiPSCs into specific neural lineages (neurons, astrocytes, microglia). |

| Critical Antibodies | Anti-APOE (e.g., ab1906); Anti-MAP2; Anti-β-III-Tubulin; Anti-GFAP; Anti-VAMP2/Synaptobrevin-2; Anti-SNAP-25 | Characterize cell identity, protein expression, localization, and interactions (via ICC, Western Blot, Co-IP). |

| Recombinant Proteins | Recombinant human APOE3 and APOE4 (lipidated and non-lipidated) | Used for direct treatment of cultures to study acute, isoform-specific effects on neurons and glia. |

| Specialized Assays | FM4-64 dye (synaptic vesicle release); DQ-BSA (lysosomal degradation); ELISA/MSD for Aβ and phospho-tau | Functional readouts for synaptic function, endolysosomal activity, and AD-relevant biomarkers. |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Understanding the multifaceted roles of APOE has opened several promising therapeutic avenues.

- APOE-directed Therapeutics: Strategies include using anti-sense oligonucleotides (ASOs) to reduce APOE4 expression, developing APOE structure correctors to convert the APOE4 protein into a more APOE3-like conformation, and gene therapy to deliver the protective APOE2 allele to at-risk individuals [4].

- Leveraging Protective Variants: The study of naturally occurring protective variants like APOE Christchurch and the COLBOS variant of REELIN has revealed new mechanisms of resilience, such as reduced binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), which is associated with diminished tau pathology [4]. Mimicking these effects pharmacologically is an active area of research.

- Lipid Metabolism and Ferroptosis: Given APOE4's role in disrupting lipid metabolism and promoting lipid peroxidation, therapies targeting the ferroptosis pathway (e.g., ferrostatin-1) or enhancing lipid efflux are being explored [4].

- Immunomodulation: Targeting the APOE-TREM2 axis in microglia to modulate neuroinflammation and enhance clearance of pathological proteins represents another promising strategy [3] [5].

The APOE genotype remains the cornerstone of genetic risk for late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Its influence extends far beyond amyloid-β, impacting tau pathology, synaptic integrity, neuroinflammation, and cellular metabolism. The integration of hiPSC-derived models has been instrumental in elucidating these human-specific, cell-type-specific mechanisms in a controlled genetic environment. The future of AD therapy will likely include personalized approaches based on APOE status, with treatments aimed at mitigating the detrimental effects of APOE4 or harnessing the protective mechanisms of APOE2. Continued research using these advanced models is crucial for translating these mechanistic insights into effective disease-modifying treatments.

Structural and Functional Differences Between APOE2, E3, and E4 Isoforms

Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is a 34-kDa glycoprotein that plays a critical role in lipid metabolism, serving as a principal cholesterol carrier in the brain and periphery [11] [12]. The APOE gene exists as three major polymorphic alleles—ε2, ε3, and ε4—encoding protein isoforms that differ by single amino acid substitutions yet exhibit profoundly different functional impacts [11] [13]. Within the context of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) neuronal research, understanding these isoforms is paramount, as APOE4 represents the strongest genetic risk factor for sporadic Alzheimer's disease (AD), increasing risk by 3-fold in heterozygotes and up to 15-fold in homozygotes compared to the neutral APOE3 isoform, while APOE2 appears protective [14] [15] [13]. This technical guide comprehensively details the structural and functional differences between these isoforms, with specific emphasis on their implications for neurodegenerative disease research utilizing human iPSC-derived models.

Genetic and Protein Structure

Allelic Variation and Evolutionary Origins

The human APOE isoforms arose from sequential mutations over millions of years. APOE4 is the ancestral form, with the T61R mutation occurring in the human lineage after the primate-human split [16] [12]. Approximately 220,000 years ago, a Cys112Arg substitution in the APOE4 gene created the APOE3 allele, followed by an Arg158Cys substitution in APOE3 around 80,000 years ago that created the APOE2 allele [12]. These evolutionary changes resulted in the three major human isoforms characterized by specific amino acid combinations at positions 112 and 158, within the receptor-binding region of the N-terminal domain [11] [13].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Human APOE Isoforms

| Isoform | Amino Acid Position 112 | Amino Acid Position 158 | Worldwide Allele Frequency | AD Risk Relative to E3/E3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOE2 | Cysteine | Cysteine | 8.4% [12] | Reduced ~40% [13] |

| APOE3 | Cysteine | Arginine | 77.9% [12] | Neutral (reference) |

| APOE4 | Arginine | Arginine | 13.7% [12] | Heterozygous: 3-4× [14]; Homozygous: 12-15× [14] [13] |

Structural Conformations

ApoE is structured into two primary domains: an N-terminal domain (residues 1-167) containing the receptor-binding region (residues 136-150), and a C-terminal domain (residues 206-299) encompassing the lipid-binding site (residues 244-272), connected by a protease-sensitive hinge region [17] [14]. The single amino acid substitutions differentially affect the protein's conformation through domain interaction, a phenomenon particularly relevant to APOE4.

APOE4's structure (Arg112, Arg158) facilitates a pathological domain interaction where the Arg112 in the N-terminal domain interacts with Glu255 in the C-terminal domain, creating a more compact, unstable structure [17] [16]. This conformation alters the protein's lipid binding capacity, receptor interactions, and increases oligomerization propensity [13]. In contrast, APOE3 (Cys112, Arg158) and APOE2 (Cys112, Cys158) do not exhibit this domain interaction, with APOE2 showing impaired receptor binding due to the Cys158 substitution [11] [12].

Functional Consequences in the Central Nervous System

Lipid Metabolism and Synaptic Function

ApoE serves as the principal cholesterol carrier in the brain, mainly produced by astrocytes and, to a lesser extent, by microglia and stressed neurons [11] [13]. The isoforms differentially modulate lipid transport, with APOE4 exhibiting impaired lipid binding capacity and reduced ability to support synaptic maintenance and repair [13]. iPSC-derived astrocytes carrying APOE4 demonstrate impaired Aβ uptake and intracellular cholesterol accumulation compared to isogenic APOE3 counterparts [15].

Amyloid-β Pathology

APOE4 potently influences amyloid-β metabolism through multiple mechanisms, enhancing both production and impairing clearance of Aβ peptides [18]. Research using iPSC-derived cerebral organoids demonstrates that organoids from AD patients have increased levels of Aβ and phosphorylated tau compared to healthy subject-derived organoids, with APOE4 specifically exacerbating tau pathology [19]. APOE4 promotes APP expression and enhances BACE1 transcription and activity, thereby increasing amyloidogenic processing of APP [18]. Simultaneously, APOE4 inhibits insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) and neprilysin (NEP) expression, critical proteases for Aβ degradation, and impairs cellular clearance through disrupted endolysosomal trafficking and autophagy [18].

Tau Phosphorylation and Neurodegeneration

Beyond amyloid pathology, APOE4 exacerbates tau-mediated neurodegeneration. Cerebral organoids from AD patients carrying APOE4/4 show significantly greater apoptosis and decreased synaptic integrity compared to other genotypes [19]. APOE4 enhances tau phosphorylation through activation of oxidative stress pathways, disruption of lipid metabolism, and inflammatory signaling [18]. Isogenic conversion of APOE4 to APOE3 in iPSC-derived cerebral organoids from AD patients attenuates tau pathology and neurodegeneration, confirming the isoform-specific effect [19].

Neuroinflammation

APOE isoforms differentially regulate neuroinflammatory responses. Transcriptional profiling of iPSC-derived microglia-like cells reveals that APOE4 alters expression of immune response genes and reduces Aβ phagocytosis capacity [15]. APOE4 increases ROS production, activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, and modulates TREM2 signaling pathways, collectively amplifying neuroinflammatory states that contribute to neurodegeneration [18].

Energy Metabolism

APOE4 disrupts cerebral energy homeostasis, with carriers exhibiting impaired glucose metabolism detectable by FDG-PET imaging [14]. iPSC-based studies demonstrate that APOE4 competes for insulin receptors, inhibits key metabolic enzymes, and promotes lipid accumulation, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress [18]. These metabolic disturbances appear early in the disease process and contribute to synaptic dysfunction and neurodegeneration.

Table 2: Functional Consequences of APOE Isoforms in CNS Cell Types

| Cellular Function | APOE2 | APOE3 | APOE4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Binding & Cholesterol Transport | Moderate efficiency [13] | High efficiency [11] | Reduced efficiency; Cholesterol accumulation in astrocytes [15] |

| Aβ Clearance | Moderate [13] | Normal [18] | Impaired; Reduced phagocytosis by microglia [15] [18] |

| Tau Pathology | Not associated [13] | Baseline [19] | Exacerbated phosphorylation & aggregation [18] [19] |

| Synaptic Integrity | Protective effect [13] | Normal maintenance [19] | Decreased synaptophysin & PSD95; Increased synapse loss [19] |

| Neuroinflammation | Anti-inflammatory [13] | Moderate response [15] | Enhanced pro-inflammatory activation of microglia [15] [18] |

| Energy Metabolism | Not well characterized | Normal glucose metabolism [14] | Impaired mitochondrial function; Insulin resistance [14] [18] |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

iPSC-Derived Neuronal Models

The development of human iPSC models has revolutionized the study of APOE isoforms in a genetically defined, human-relevant system. Key methodological approaches include:

Isogenic iPSC Line Generation: CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing enables creation of isogenic iPSC lines differing only at APOE loci, controlling for background genetic variation [15]. The editing process involves introducing Cys112Arg substitution to convert APOE3 to APOE4, or the reverse to convert APOE4 to APOE3, with verification by Sanger sequencing and whole exome sequencing to confirm absence of off-target mutations [15].

Cerebral Organoid Differentiation: Cerebral organoids generated through embryoid body formation followed by neuroectodermal induction in Matrigel scaffolds recapitulate 3D cortical architecture with ventricular zones containing neural progenitors and outer layers with mature neurons and astrocytes [19]. These organoids demonstrate appropriate temporal development, with deep cortical layer neurons (Ctip2+) emerging by week 4 and superficial layer neurons (Satb2+) appearing by week 12, alongside astrocyte maturation and migration [19].

Phenotypic Assessment in iPSC Models

Comprehensive characterization of APOE isoform-specific effects in iPSC models includes:

Transcriptomic Profiling: RNA-sequencing of iPSC-derived neurons, astrocytes, and microglia reveals hundreds of differentially expressed genes between APOE3 and APOE4 genotypes, with neuronal signatures showing enrichment for synaptic function pathways and microglial signatures revealing immune response alterations [15]. Co-expression network analysis identifies genes co-regulated with APOE, with enrichment for lipid metabolism, immune response, and AD-associated pathways [15].

Pathological Assessment: Cerebral organoids analyzed at multiple timepoints (weeks 4, 8, 12) demonstrate APOE4-associated phenotypes including increased apoptosis (cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity), decreased synaptic markers (synaptophysin, PSD95), and elevated phosphorylated tau [19]. APOE4 also exacerbates Aβ-related pathology in AD patient-derived organoids [19].

Functional Assays: iPSC-derived astrocytes and microglia are assessed for Aβ phagocytosis capacity, cholesterol accumulation, and inflammatory cytokine secretion, with APOE4 consistently impairing homeostatic functions [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for APOE Isoform Studies in iPSC Models

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in APOE Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isogenic iPSC Lines | CRISPR/Cas9-edited APOE3/3, APOE4/4 [15] | Controlled genotype-phenotype studies | Enables comparison of isoform effects in identical genetic backgrounds |

| Differentiation Kits | Commercial neural induction kits; Neurogenin2 expression systems [15] | Generation of specific neural cell types | Produces neurons, astrocytes, microglia for cell-type-specific analyses |

| 3D Culture Systems | Matrigel scaffolds; Rotary orbital culture systems [19] | Cerebral organoid generation | Recapitulates complex tissue architecture and cell-cell interactions |

| APOE Detection Antibodies | Isoform-specific antibodies; Total APOE antibodies [19] | Protein expression quantification | Measures APOE secretion, cellular localization, and isoform-specific effects |

| Synaptic Markers | Anti-synaptophysin; Anti-PSD95 [19] | Synaptic integrity assessment | Quantifies APOE4-associated synaptic loss and therapeutic rescue |

| Pathology Assays | Aβ ELISAs; Phospho-tau antibodies (AT8, etc.); Cleaved caspase-3 antibodies [19] | Neurodegeneration pathway analysis | Evaluates amyloid, tau, and apoptotic pathology in isoform-specific models |

| Lipid Staining Dyes | Filipin; Bodipy-cholesterol; Oil Red O [15] | Cholesterol accumulation visualization | Detects APOE4-associated lipid metabolism defects |

| Transcriptomic Tools | RNA-sequencing platforms; Single-cell RNA-seq kits [15] | Genome-wide expression profiling | Identifies APOE-regulated pathways across neural cell types |

The structural differences between APOE isoforms, particularly the domain interaction unique to APOE4, propagate through multiple functional pathways to profoundly influence Alzheimer's disease risk and progression. Human iPSC-based models including cerebral organoids now provide unprecedented opportunities to study these isoform-specific effects in a genetically controlled, human-relevant system. The experimental methodologies and reagents outlined in this review provide a foundation for investigating APOE biology and developing isoform-targeted therapeutic strategies. Future research leveraging these approaches will be essential for elucidating the precise mechanisms by which APOE isoforms differentially contribute to neurodegeneration and for developing personalized medicine approaches for APOE-related Alzheimer's disease risk.

The apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, located on chromosome 19, is the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD). Its three common alleles—APOE2, APOE3, and APOE4—differ by single nucleotide polymorphisms resulting in amino acid substitutions at residues 112 and 158, and confer dramatically different AD risk profiles [20]. The APOE4 allele substantially increases AD risk in a dose-dependent manner, with heterozygous carriers facing a 3-4 fold increased risk and homozygous carriers facing a 9-15 fold increased risk compared to the most common APOE3 allele [20]. In contrast, the APOE2 allele demonstrates protective effects, reducing AD risk by approximately 40% and delaying disease onset [21] [20]. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms underlying these differential risk profiles within the context of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) neuronal research, providing a technical resource for researchers and drug development professionals working in neurodegenerative disease.

Table 1: APOE Genotype and Alzheimer's Disease Risk Profile

| Genotype | Relative Risk for AD | Compared To | Key Clinical Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| APOE2/2 | 0.13x (87% reduction) | APOE3/3 | Strongest protection, delayed onset [21] |

| APOE2/3 | ~0.5x (50% reduction) | APOE3/3 | Moderate protection [21] |

| APOE3/3 | 1.0x (reference) | - | Most common genotype, neutral risk [20] |

| APOE3/4 | 3-4x increased risk | APOE3/3 | Earlier onset by 5-10 years [22] |

| APOE4/4 | 9-15x increased risk | APOE3/3 | Earlier onset, potential distinct genetic form of AD [23] [20] |

Molecular Mechanisms of APOE Isoform Function

Protein Structure and Lipid Binding

The APOE protein is a 34 kDa glycoprotein comprising 299 amino acids with two primary structural domains: an N-terminal receptor-binding domain (residues 1-167) and a C-terminal lipid-binding domain (residues 206-299) [20]. The isoforms differ at two critical positions: APOE2 (Cys112, Cys158), APOE3 (Cys112, Arg158), and APOE4 (Arg112, Arg158) [14] [20]. These structural variations significantly impact APOE's binding affinity to lipids and receptors, particularly the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) [24]. APOE2 exhibits reduced binding affinity to LDLR compared to APOE3 and APOE4, which paradoxically contributes to its protective function by limiting lipid uptake and preventing lysosomal stress [24].

Lysosomal Function and Lipid Homeostasis

Recent research has revealed that APOE isoforms differentially impact lysosomal function through their interactions with LDLR. APOE4, with its high binding affinity to LDLR, promotes excessive uptake of lipidated APOE particles into lysosomes of astrocytes and neurons, leading to lysosomal stress and lipofuscin accumulation [24]. Lipofuscin, an autofluorescent pigment resulting from lipid peroxidation, is a hallmark of lysosomal dysfunction and cellular aging. The order of lipofuscin accumulation follows APOE4 > APOE3 > APOE2, directly correlating with AD risk [24]. APOE2's reduced binding to LDLR limits lysosomal lipid loading, thereby protecting against dysfunction. This mechanism is supported by the observation that the APOE3-Christchurch mutation, which similarly reduces LDLR binding, provides remarkable protection against AD despite high amyloid burden [24].

Brain Energy Metabolism

APOE isoforms differentially regulate brain energy homeostasis, particularly in aging neurons facing glucose hypometabolism. APOE3 facilitates neuronal utilization of long-chain fatty acids as an alternative energy source through interaction with the sortilin receptor [25]. This metabolic flexibility is crucial for neuronal survival when glucose availability declines. In contrast, APOE4 disrupts sortilin-mediated lipid uptake, creating an energy deficit in neurons and increasing their vulnerability to degeneration [25]. This APOE4-induced impairment in alternative fuel utilization represents a key non-amyloid mechanism contributing to AD pathogenesis.

Neuroinflammation and Immune Response

Substantial evidence indicates that APOE4 promotes pro-inflammatory states across neurodegenerative diseases. A comprehensive proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid and plasma revealed that APOE4 carriers exhibit a distinct inflammatory signature characterized by enrichment of viral processes, T-cell signaling, and pro-inflammatory pathways including Toll-like receptor, TNF, and IL-17 signaling [26]. This signature was consistent across AD, Parkinson's disease, and frontotemporal dementia, suggesting APOE4 confers a fundamental biological vulnerability through immune modulation rather than disease-specific mechanisms [26].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

APOE "Switch" Mouse Model

A groundbreaking approach to studying APOE isoform effects involves the inducible APOE4-to-APOE2 "switch" mouse model (APOE4s2) [27]. This knock-in model contains a floxed coding region of human APOE4 followed by exon 4 of human APOE2, allowing temporal induction of allele switching through tamoxifen-activated Cre recombinase.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for APOE Isoform Studies

| Research Tool | Application | Key Utility in APOE Research |

|---|---|---|

| APOE4s2 "Switch" Mice [27] | In vivo functional studies | Enables temporal control of APOE4 to APOE2 transition in adult mice |

| iPSC-Derived Human Neurons [25] | Human cellular models | Provides human-specific genetic background for studying isoform effects |

| Homogeneous Time-Resolved Fluorescence (HTRF) [24] | Protein-protein interaction | Quantifies lipAPOE-LDLR binding affinities |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [24] | Binding kinetics | Measures real-time binding affinity between APOE isoforms and LDLR |

| Single-cell RNA-seq [27] [28] | Transcriptomic profiling | Identifies cell-type-specific responses to APOE isoforms |

| ATAC-seq [28] | Epigenomic profiling | Maps chromatin accessibility changes in microglia with different APOE isoforms |

Experimental Protocol: APOE Allelic Switching and Phenotypic Assessment

- Animal Crossing: APOE4s2 mice are crossed with ROSA26-CreERT1 Cre drivers to generate floxed ROSA26-CreERT1(APOE4s2G) mice

- Switch Induction: 2-month-old APOE4s2G mice receive tamoxifen to activate Cre recombinase, inducing transition from APOE4 to APOE2 expression

- Efficiency Validation:

- qPCR: APOE mRNA expression analysis in liver and brain tissues confirms transition from APOE4 to APOE2 mRNA

- Mass Spectrometry: Proteomic analysis verifies replacement of ApoE4 protein with ApoE2 (92-99% efficiency in plasma)

- Phenotypic Assessment:

- Metabolic profiling: Plasma lipid measurements after Western diet challenge

- Cognitive testing: Behavioral assays in 5xFAD background mice

- Neuropathology: Amyloid burden, gliosis, and plaque-associated ApoE quantification [27]

Human iPSC-Derived Brain Cell Models

Protocol: Studying APOE-Mediated Lipid Metabolism in Human Neurons

- iPSC Differentiation: Generate astrocytes and neurons from human iPSCs carrying specific APOE genotypes

- Metabolic Stress Induction: Culture cells under glucose-deficient conditions to simulate aging-related metabolic stress

- Lipid Utilization Assessment:

- Treat cells with fluorescently-labeled long-chain fatty acids

- Measure fatty acid uptake in the presence of APOE3 vs. APOE4

- Evaluate sortilin receptor function through inhibition experiments

- Functional Rescue Experiments: Test metabolic rescue using bezafibrate to restore fatty acid oxidation [25]

Xenotransplantation of Human Microglia

Protocol: Microglial APOE Isoform Function in Amyloid Response

- Microglia Generation: Differentiate iPSC-derived human microglia with defined APOE genotypes (APOE2/0, APOE3/0, APOE4/0)

- Transplantation: Introduce human microglia into brains of AppNL-G-F mouse model of Alzheimer's disease

- Cell Isolation: At 12 months, isolate microglia by FACS using human-specific antibodies (CD11b + hCD45+)

- Multi-Omics Profiling:

- RNA-seq: Transcriptomic analysis to identify differentially expressed genes

- ATAC-seq: Epigenomic landscape assessment through chromatin accessibility mapping [28]

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Interactions

Diagram 1: APOE Isoform Signaling Pathways and Functional Consequences. This diagram illustrates the molecular mechanisms through which different APOE isoforms influence cellular processes relevant to Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. APOE2's reduced binding to LDLR limits lysosomal lipid loading and prevents lipofuscin accumulation. APOE3 enables normal lipid metabolism through sortilin interaction, maintaining energy homeostasis. APOE4 enhances LDLR binding leading to lysosomal dysfunction, disrupts sortilin-mediated lipid utilization, and promotes neuroinflammation, collectively increasing neuronal vulnerability.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for APOE Isoform Research in iPSC-Derived Models. This diagram outlines integrated experimental approaches for studying APOE isoform biology using human iPSC-derived cell models, combining in vitro systems with in vivo xenotransplantation and multi-omics analyses to identify therapeutic targets.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

APOE-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

Research elucidating the differential risk profiles of APOE isoforms has revealed several promising therapeutic approaches. APOE2-mimetic strategies represent a promising approach, with studies showing that astrocyte-specific switching from APOE4 to APOE2 in adult mice improves cognition, decreases amyloid pathology, reduces gliosis, and lowers plaque-associated ApoE [27]. Small molecule interventions targeting APOE4-induced metabolic deficits have also shown promise, with bezafibrate restoring fatty acid metabolism in APOE4-expressing neurons [25]. Additionally, liver X receptor agonists that reduce polyunsaturated fatty acid levels can inhibit lipofuscin accumulation and lysosomal degeneration in mouse models, offering another potential therapeutic avenue [24].

Personalized Medicine Approaches

The profound differences in AD risk mediated by APOE genotype underscore the importance of genotype-tailored prevention strategies [23]. APOE4 status modifies the relationship between numerous non-genetic risk factors and dementia, with stronger associations found for specific factors in carriers versus non-carriers [23]. Furthermore, the recent recognition that APOE4 homozygosity may represent a distinct genetic form of Alzheimer's disease [23] highlights the need for precision medicine approaches that consider APOE status in both clinical trial design and therapeutic development.

The dramatic differential risk profiles between APOE4 and APOE2 alleles—with APOE4 increasing AD risk 3-15 fold while APOE2 is protective—stem from fundamental differences in their effects on lysosomal function, lipid metabolism, energy homeostasis, and neuroinflammation. iPSC-based neuronal models combined with innovative experimental approaches like inducible allele switching and xenotransplantation have provided unprecedented insights into these mechanisms. These advances illuminate promising therapeutic strategies focused on converting APOE4 toxicity to APOE2-like protection, enhancing lysosomal function, and restoring metabolic flexibility. As our understanding of APOE biology continues to evolve, it creates exciting opportunities for developing targeted interventions that may fundamentally alter Alzheimer's disease treatment and prevention.

The Central Role of APOE in Brain Lipid Transport and Cholesterol Homeostasis

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) is a critical lipid transport protein in the central nervous system (CNS), serving as the primary coordinator of cholesterol homeostasis and lipid redistribution within the brain. As the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD), APOE exists as three major isoforms—APOE2, APOE3, and APOE4—that differentially influence brain physiology and disease pathogenesis. The brain is the most cholesterol-rich organ, containing approximately 30% of the body's cholesterol, yet it cannot import cholesterol from the periphery due to the blood-brain barrier. Instead, the brain relies entirely on local synthesis and sophisticated transport mechanisms, with APOE playing the central role in lipid trafficking and redistribution between cells. This whitepaper examines the structural and functional basis of APOE's role in brain lipid homeostasis, with particular emphasis on implications for iPSC-based neuronal models and therapeutic development.

Structural Basis of APOE Function

Domain Organization and Lipid Binding Properties

APOE is a 299-amino acid glycoprotein characterized by two distinct structural and functional domains separated by a protease-sensitive loop [29]. The N-terminal domain (residues 1-191) forms a four-helix bundle structure and contains the receptor-binding region (residues 136-150), while the C-terminal domain (residues 192-299) mediates primary lipid binding interactions [29] [4]. This two-domain organization enables APOE to exist in alternate lipid-free and lipid-associated states, functioning as a dynamic lipid carrier [29].

- Receptor Binding Domain: The N-terminal region contains the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) binding site, with critical basic residues between positions 136-150 that mediate interaction with LDLR family members [29] [4].

- Lipid Binding Domain: The C-terminal region (residues 244-272) features high hydrophobicity and mediates binding to phospholipids, cholesterol, and other lipids [4]. This domain drives APOE self-association in the lipid-free state and facilitates lipoprotein particle formation [29].

- Isoform-Specific Structural Variations: The three major APOE isoforms differ by single amino acid substitutions at positions 112 and 158, which profoundly influence structure and function [4]:

- APOE3: Cysteine112, Arginine158 (considered reference isoform)

- APOE2: Cysteine112, Cysteine158 (reduced receptor binding)

- APOE4: Arginine112, Arginine158 (domain interaction, altered lipid binding)

Table 1: APOE Isoform Characteristics and Functional Consequences

| Isoform | Amino Acid Positions | Structural Features | LDLR Binding | AD Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOE2 | Cys112, Cys158 | Altered salt bridge network | ~1% of APOE3 [29] | Protective [4] |

| APOE3 | Cys112, Arg158 | Reference structure | Normal (reference) | Neutral [4] |

| APOE4 | Arg112, Arg158 | Domain interaction, molten globule state [4] | Comparable to APOE3 [4] | High risk [4] |

Lipoprotein Particle Formation in CNS

In the brain, APOE is primarily secreted by astrocytes as discoidal lipoprotein particles resembling high-density lipoproteins (HDL) in the periphery [3]. These particles typically range from 8-20 nm in diameter, with the most common size being approximately 12.5 nm [3]. Structural studies using cryo-electron microscopy reveal that APOE forms antiparallel dimers within these lipoprotein particles, creating a structural framework for lipid incorporation and transport [3]. The lipidation state of APOE significantly influences its structure and receptor binding properties, with lipid-associated APOE exhibiting enhanced receptor binding capacity compared to lipid-free APOE [29].

APOE Isoforms in Neuronal Lipid Homeostasis

Cholesterol Transport and Metabolism

The maintenance of brain cholesterol homeostasis is crucial for neuronal function, as cholesterol is an essential component of cell membranes, contributes to synaptic integrity, and facilitates signal transduction. APOE serves as the principal carrier of cholesterol in the CNS, mediating its delivery to neurons via receptor-mediated endocytosis [4]. The differential effects of APOE isoforms on cholesterol homeostasis have profound implications for neuronal health and function:

- Receptor Binding Affinities: APOE isoforms exhibit markedly different binding affinities for members of the LDL receptor family. Surface plasmon resonance studies demonstrate that lipidated APOE3 and APOE4 bind LDLR with high affinity (16 nM and 9 nM, respectively), while APOE2 shows substantially weaker binding (approximately 800 nM) [4]. These differences significantly impact lipid delivery efficiency to neurons.

- Cellular Lipid Uptake: The APOE4 isoform demonstrates preferential binding to specific lipid species, including monosialotetrahexosylganglioside (GM1), with higher affinity than cholesterol [30]. This altered binding preference may contribute to cholesterol dysregulation in APOE4 carriers and promote amyloid-β oligomer aggregation, a key event in AD pathogenesis [30].

- Endolysosomal Processing: Recent investigations in primary neuronal models reveal that APOE4 impacts endolysosomal function in an age-dependent manner. With prolonged time in culture (serving as an aging proxy), APOE4-expressing neurons demonstrate reduced degradative capacity and decreased numbers of active lysosomal compartments [10]. When supplied with cholesterol, aged APOE4 neurons show a predisposition to accumulate cholesterol within the endolysosomal system, potentially disrupting cellular homeostasis [10].

Signaling Pathways and Receptor Interactions

APOE mediates its effects through interaction with multiple receptors in the CNS, activating diverse signaling pathways that influence neuronal function, survival, and plasticity. The major APOE receptors in the brain belong to the LDL receptor family and include LDLR, LRP1, VLDLR, and ApoER2 [4].

Diagram 1: APOE Receptor Interactions and Signaling Pathways (Max Width: 760px)

The diagram above illustrates the two major pathways through which APOE and its receptors influence neuronal function: (1) the lipid uptake pathway mediated primarily by LDLR and LRP1, and (2) the Reelin signaling pathway activated through VLDLR and ApoER2 binding. The Reelin pathway is particularly important for brain development, synaptic plasticity, and neuronal migration [4].

Experimental Approaches for iPSC Neuron Research

Methodologies for Investigating APOE Biology

The study of APOE isoforms in human neurons has been revolutionized by induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technologies, enabling the investigation of isoform-specific effects in genetically defined human neuronal systems. Key methodological approaches include:

APOE Genotyping and Isoform Expression Analysis

- Protocol: Genomic DNA extraction from iPSCs followed by APOE genotyping using PCR-RFLP or sequencing-based methods targeting residues 112 and 158. Confirm APOE expression at mRNA and protein levels in differentiated neurons using RT-qPCR and Western blotting [4].

- Application: Establish isogenic APOE iPSC lines expressing different APOE isoforms (E2/E3/E4) to control for genetic background effects when investigating isoform-specific phenotypes.

Lipid Uptake and Trafficking Assays

- Protocol: Differentiate iPSCs to cortical neurons using established protocols (e.g., dual SMAD inhibition). Incubate neurons with fluorescently labeled cholesterol (e.g., Bodipy-Cholesterol) or phospholipids complexed with recombinant APOE isoforms. Measure uptake kinetics using live-cell imaging and quantify intracellular distribution [30] [10].

- Application: Compare lipid internalization rates and subcellular localization between APOE isoforms. APOE4-expressing neurons typically show altered endocytic trafficking and delayed lysosomal processing.

Endolysosomal Function Assessment

- Protocol: Differentiate iPSCs to neurons and culture for extended periods (≥60 days) to model age-related effects. Assess endolysosomal pH using pH-sensitive dyes (e.g., LysoSensor), degradative capacity with DQ-BSA assay, and lysosomal enzyme activity [10].

- Application: APOE4 neurons demonstrate reduced degradative ability and decreased active lysosomal compartments with prolonged culture time, reflecting age-dependent dysfunction.

Lipidomic Profiling

- Protocol: Extract lipids from iPSC-derived neurons and analyze using LC-MS/MS. Focus on gangliosides (particularly GM1), cholesterol esters, and phospholipids. Monitor APOE-lipid interactions using microscale thermophoresis (MST) [30].

- Application: APOE4 shows preferential binding to GM1 over cholesterol, potentially explaining lipid trafficking alterations in APOE4 carriers.

Table 2: Quantitative Receptor Binding Affinities of APOE Isoforms

| APOE Isoform | LDLR Binding (Kd) | Relative Binding Efficiency | Lipid Preference | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOE2 | ~800 nM [4] | ~1% of APOE3 [29] | Altered specificity | Surface plasmon resonance [4] |

| APOE3 | 16 nM [4] | Reference (100%) | Balanced lipid binding | Surface plasmon resonance [4] |

| APOE4 | 9 nM [4] | Comparable to APOE3 | Preferential GM1 binding [30] | Surface plasmon resonance [4] |

APOE and Neuronal Endolysosomal Pathology

Research using primary neuronal cultures and iPSC-derived models has revealed that APOE4 significantly impacts endolysosomal function, particularly under aging-relevant conditions:

Diagram 2: Temporal Progression of APOE4-Induced Endolysosomal Alterations (Max Width: 760px)

The time-dependent emergence of APOE4-related endolysosomal dysfunction highlights the importance of modeling neuronal aging in iPSC systems. While young APOE4 neurons may show minimal phenotypic differences, prolonged culture reveals significant impairments in degradative capacity and lipid handling [10]. This has critical implications for experimental design in iPSC-based AD modeling, suggesting that extended maturation periods are necessary to capture APOE4-specific pathologies.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for APOE Lipid Transport Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| APOE Sources | Recombinant human APOE isoforms (E2, E3, E4); Conditioned media from APOE-expressing astrocytes | Lipid binding and uptake assays; Neuronal treatment studies | Ensure proper lipidation state; Lipid-free vs. lipid-associated APOE has different properties [29] |

| Lipid Probes | Bodipy-cholesterol, Bodipy-GM1, NBD-phospholipids, DQ-BSA | Tracking lipid uptake, trafficking, and degradation | Use complexed with APOE or liposomes; Consider fluorescent quenching approaches [30] [10] |

| Neuronal Markers | MAP2, NeuN, Tau, Synapsin-1 | Characterization of iPSC-derived neurons | Validate neuronal maturity and subtype specification (cortical vs. other regions) |

| Endolysosomal Markers | EEA1 (early endosomes), Rab7 (late endosomes), LAMP1 (lysosomes), Cathepsin D | Assessing endolysosomal morphology and function | Combine with functional assays (pH, degradation activity) [10] |

| Receptor Binding Tools | Recomceptor LDLR/LRP1 extracellular domains; Receptor antibodies | Surface plasmon resonance; Receptor binding assays | Account for isoform-specific binding differences; APOE2 has markedly reduced LDLR binding [4] |

APOE serves as the central coordinator of lipid transport and cholesterol homeostasis in the brain, with isoform-specific structural differences dictating functional consequences for neuronal health. The APOE4 isoform, the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer's disease, exhibits altered lipid binding preferences, impaired receptor interactions, and promotes endolysosomal dysfunction in an age-dependent manner. iPSC-based neuronal models provide powerful experimental systems for investigating these isoform-specific effects in human cells, particularly when combined with sophisticated lipid trafficking assays and appropriate aging protocols. Understanding the precise molecular mechanisms through which APOE isoforms influence neuronal lipid homeostasis will enable the development of targeted therapeutic strategies for APOE-related neurodegenerative disorders.

APOE Isoform Effects on Amyloid-β Aggregation, Clearance, and Plaque Deposition

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) is the strongest genetic risk modifier for late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD), with its three major isoforms—APOE2, APOE3, and APOE4—exerting profound effects on disease susceptibility and pathological progression [31] [13]. The primary physiological function of apoE is to mediate lipid transport in the brain and periphery, but it also significantly influences key AD pathological processes, particularly those involving amyloid-β (Aβ) [31] [13]. Inheritance of the APOE4 allele considerably increases AD risk in a dose-dependent manner, while the APOE2 allele confers protection relative to the common APOE3 allele [32] [13]. These differential risk profiles are intimately linked to how each isoform modulates the aggregation, clearance, and deposition of Aβ peptides in the brain. Understanding these isoform-specific mechanisms provides critical insights into AD pathogenesis and reveals potential therapeutic targets for this devastating neurodegenerative disorder.

APOE Isoforms: Structure, Function, and Expression

Structural Characteristics and Receptor Interactions

The APOE gene, located on chromosome 19, encodes a 299-amino acid glycoprotein that circulates as a 34-kDa glycosylated protein [3] [14]. The three major apoE isoforms differ by single amino acid substitutions at positions 112 and 158:

- APOE2: Cysteine112, Cysteine158

- APOE3: Cysteine112, Arginine158

- APOE4: Arginine112, Arginine158 [31] [32]

These single amino acid substitutions lead to significant structural alterations that profoundly influence protein function, stability, and receptor binding [31]. ApoE comprises two major structural domains: an N-terminal domain (residues 1-167) containing the receptor-binding region (residues 136-150), and a C-terminal domain (residues 206-299) containing the lipid-binding region (residues 244-272), connected by a hinge region [31] [13] [14]. The domain interaction between the N- and C-terminal regions is a key structural difference among isoforms, with apoE4 exhibiting a unique preference for such interactions that contribute to its pathological effects [13].

ApoE exerts its physiological effects by binding to several receptors from the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor family, including LDLR, LRP1, VLDLR, and ApoER2 (also known as LRP8), as well as heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) and the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) [31] [32] [3]. These receptor interactions exhibit remarkable isoform specificity, which significantly impacts Aβ metabolism and clearance.

Table 1: ApoE Receptor Binding Specificities and Functions

| Receptor | Isoform-Specific Binding | Lipidation Required | Primary Functions in AD |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDLR | Lipidated apoE: apoE2 << apoE3 = apoE4 [32] | Yes [32] | Mediates lipoprotein and Aβ clearance [31] [32] |

| LRP1 | Lipidated apoE: apoE2 < apoE3 = apoE4 [32] | Likely not required [32] | Mediates Aβ clearance; signal transduction; neurotrophic effects [31] [32] |

| VLDLR | Non-lipidated apoE: apoE2 = apoE3 = apoE4 [32] | No [32] | Mediates reelin signaling; lipoprotein clearance [31] [32] |

| ApoER2 | Non-lipidated apoE: apoE2 << apoE3 = apoE4 [32] | No [32] | Regulates reelin signaling; synaptic receptor trafficking [31] [32] |

| HSPG | Non-lipidated apoE: apoE2 < apoE3 < apoE4 [32] | No [32] | Facilitates lipoprotein and Aβ clearance; co-receptor for LRP1 [31] |

| TREM2 | Both lipidated and non-lipidated apoE: apoE2 = apoE3 = apoE4 [32] | No [32] | Mediates microglial phagocytosis of Aβ; maintains disease-associated microglia phenotype [32] |

Expression Patterns and Lipidation Status

In the central nervous system (CNS), apoE is primarily produced and secreted by astrocytes, with additional contributions from microglia and, under certain pathological conditions, neurons [31] [3] [13]. Peripheral and CNS pools of apoE are separated by the blood-brain barrier, with no exchange of apoE-containing lipoproteins between these compartments [32] [13]. The lipidation status of apoE significantly influences its function, with lipidated apoE representing the predominant form in the human CNS [33]. However, poorly- or non-lipidated apoE increases Aβ pathology and AD risk in both mouse models and humans [33].

ApoE isoform expression follows a distinct pattern, with apoE2 demonstrating greater stability and higher expression levels compared to apoE3 and apoE4. Human studies show that cortical apoE levels are highest in APOE2 carriers and lowest in APOE4 carriers [32], a pattern replicated in APOE-targeted replacement (APOE-TR) mice, where APOE2-TR mice exhibit higher levels of apoE in interstitial fluid and brain lysate than APOE3-TR mice, followed by APOE4-TR mice [32].

Differential Effects of APOE Isoforms on Aβ Aggregation

Modulation of Aβ Oligomerization and Fibrillation

ApoE isoforms differentially influence the aggregation kinetics of Aβ, with apoE4 promoting earlier and more abundant amyloid deposition compared to apoE3 and apoE2 [33] [13]. Recent single-molecule imaging studies reveal that all apoE isoforms associate with Aβ during the early stages of aggregation but dissociate as fibrillation proceeds [33]. These dynamic interactions significantly influence the size, composition, and pathogenicity of Aβ aggregates throughout the aggregation process.

Biophysical studies demonstrate that apoE binding to Aβ slows the oligomer growth and maintains a faster diffusion rate for Aβ peptides over time [34]. This inhibitory effect on oligomerization occurs in an isoform-dependent manner, with apoE4 exhibiting reduced capacity to prevent the formation of neurotoxic Aβ oligomers compared to apoE2 and apoE3 [34] [35]. The formation of soluble apoE/Aβ complexes represents a crucial mechanism modulating Aβ aggregation, with apoE4 forming less stable complexes with Aβ compared to apoE3, particularly in lipidated forms [35].

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of ApoE Isoforms on Aβ Aggregation and Deposition

| Parameter | APOE2 | APOE3 | APOE4 | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Aβ Deposition | Reduced | Intermediate | Significantly increased | [33] [3] |

| Soluble Oligomeric Aβ | Decreased | Intermediate | Increased | [35] |

| ApoE-Aβ Co-aggregate Size (Non-lipidated) | ~500-900 nm | ~500-900 nm | ~500-900 nm | [33] |

| ApoE-Aβ Co-aggregate Size (Lipidated) | ~200-250 nm | ~200-250 nm | ~200-250 nm | [33] |

| Rate of Aβ Fibril Formation (with lipidated apoE) | Slowed | Intermediate | Accelerated | [33] |

| Stability of ApoE/Aβ Complex | High | High (SDS-stable) | Low (SDS-labile) | [35] |

Co-aggregation and Plaque Formation

ApoE significantly co-deposits with Aβ in amyloid plaques in AD brains [33] [3]. The extent of co-aggregation varies by isoform, with apoE4 showing preferential association with Aβ deposits. Recent research utilizing single-molecule pull-down (SiMPull) technology demonstrates that apoE-Aβ co-aggregates account for approximately 50% of the mass of diffusible Aβ aggregates detected in the frontal cortices of APOE4 homozygotes [33]. These co-aggregates exhibit distinct physicochemical properties based on apoE lipidation status, with non-lipidated apoE forming larger co-aggregates with Aβ compared to lipidated apoE [33].

The isoform-specific effects on Aβ aggregation correlate with AD risk, as APOE4 carriers exhibit increased Aβ deposition, earlier amyloid positivity in life, and a faster-growing Aβ burden compared to non-carriers [33]. The presence of apoE is required for initial plaque formation during early stages of Aβ accumulation, potentially through its influence on Aβ fibrillogenesis and microglial uptake of Aβ [3].

Mechanisms of Aβ Clearance Modulated by APOE Isoforms

Receptor-Mediated Clearance Pathways

ApoE isoforms differentially regulate Aβ clearance through receptor-mediated pathways, with apoE4 being less efficient than apoE2 and apoE3 in facilitating Aβ removal [31] [13]. The major receptors involved in apoE-dependent Aβ clearance include LDLR, LRP1, and HSPGs [31] [32]. The binding affinity of apoE isoforms to these receptors directly influences their efficiency in Aβ clearance, with apoE4 exhibiting impaired receptor interactions compared to other isoforms.

The lipidation status of apoE critically affects its function in Aβ clearance, with lipidated apoE demonstrating enhanced efficiency in promoting Aβ clearance compared to poorly lipidated forms [33] [35]. ApoE4 is more prone to lipidation defects, contributing to its reduced capacity to facilitate Aβ clearance [35]. Additionally, apoE competes with Aβ for binding to clearance receptors, with apoE4 potentially exacerbating Aβ accumulation by outcompeting Aβ for receptor binding sites [33].

Glymphatic Clearance and Proteolytic Degradation

Beyond receptor-mediated pathways, apoE isoforms influence glymphatic clearance and proteolytic degradation of Aβ. The glymphatic system, a brain-wide perivascular network, facilitates the clearance of soluble proteins and metabolites from the CNS, and its function is impaired in AD [13]. ApoE isoforms differentially affect glymphatic function, with apoE4 associated with reduced clearance efficiency compared to other isoforms [13].

Several Aβ-degrading enzymes, including neprilysin and insulin-degrading enzyme, participate in Aβ proteolysis, and their activity appears to be modulated by apoE isoforms [13]. ApoE4 is associated with reduced expression and activity of these enzymes, further contributing to Aβ accumulation [13].

Experimental Approaches for Studying APOE-Aβ Interactions

Methodologies for Assessing ApoE-Aβ Complex Formation

Various experimental approaches have been developed to investigate the molecular interactions between apoE and Aβ, each with specific advantages and limitations:

1. Fluorescence Cross-Correlation Spectroscopy (FCCS): This single-molecule technique allows real-time observation of apoE-Aβ interactions in solution. Using alternating laser excitation FCCS (ALEX-FCCS), researchers can monitor the diffusion time of freely diffusing Aβ and its complexes with apoE, providing insights into oligomerization kinetics and complex stoichiometry [34]. This method revealed that apoE binding maintains a faster diffusion rate for Aβ over time, slowing its oligomerization [34].

2. Single-Molecule Pull-Down (SiMPull): This assay enables characterization of individual aggregates within heterogeneous populations. Aβ aggregates are captured using surface-tethered antibodies and imaged via two-color total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy after adding detector antibodies for Aβ and apoE [33]. This technique allows quantification of aggregate size, shape, and composition, revealing that apoE co-aggregates with Aβ in early aggregation stages but dissociates as fibrillation proceeds [33].

3. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and Western Blotting: These traditional biochemical methods assess apoE-Aβ complex formation under various conditions. The stringency of detection methods significantly affects results, with SDS-PAGE potentially disrupting less stable complexes (particularly apoE4-Aβ) [35]. The inclusion of reducing agents (β-mercaptoethanol, DTT) can disrupt both SDS-stable apoE3/Aβ and apoE4/Aβ complexes [35].

4. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): This technique quantitatively measures binding affinities between apoE isoforms and Aβ peptides. SPR studies have demonstrated isoform-specific differences in apoE binding to Aβ, with lipidated apoE3 showing more stable complex formation with Aβ compared to apoE4 [35].

Research Reagent Solutions for APOE-Aβ Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying APOE-Aβ Interactions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ApoE Proteins | Recombinant human apoE2, apoE3, apoE4; Lipidated vs. non-lipidated forms; Astrocyte-secreted apoE [33] [35] | In vitro aggregation assays; Receptor binding studies; Cellular uptake experiments | Lipidation status critically affects function; Source (recombinant vs. cell-secreted) influences physiological relevance |

| Aβ Peptides | Aβ(1-40), Aβ(1-42); Fluorescently-labeled (Atto 647N, Alexa Fluor); Pre-formed oligomers [34] [33] | Aggregation kinetics; Co-aggregation studies; Cellular toxicity assays | Peptide preparation method significantly affects aggregation state; Labeling position influences biological activity |

| Detection Antibodies | 6E10 (Aβ detection); EPR19392 (apoE detection); Isoform-specific apoE antibodies [33] | SiMPull; Immunoprecipitation; Immunohistochemistry; Western blotting | Antibody specificity crucial for accurate detection; Combination of multiple antibodies enhances validation |

| Cellular Models | APOE-TR mice; Primary astrocytes/microglia from TR mice; Human iPSC-derived neurons/glia [7] [32] [3] | Cellular uptake studies; Inflammatory response assessment; Drug screening | APOE-TR mice lack full AD pathology; iPSC models capture human genetic background but vary in differentiation efficiency |

| ApoE Receptors | Recombinant LDLR, LRP1, HSPG; Receptor-specific antibodies; Receptor-deficient cells [31] [32] | Receptor binding assays; Clearance pathway identification; Competitive inhibition studies | Receptor interactions are cell-type specific; Multiple receptors often involved in redundant pathways |

Implications for Therapeutic Development

ApoE-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

The isoform-specific effects of apoE on Aβ aggregation and clearance present promising opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Several strategic approaches have emerged:

1. ApoE Structure Correctors: Small molecules designed to disrupt the pathogenic domain interaction in apoE4, converting its structure and function to be more apoE3-like [13]. These compounds have shown promise in cell culture models, abolishing detrimental effects of apoE4 in cultured neurons [36].

2. ApoE Mimetic Peptides: Short peptides that mimic the receptor-binding region of apoE, enhancing Aβ clearance without isoform-specific detrimental effects [13]. These peptides have demonstrated efficacy in animal models, reducing Aβ pathology and improving cognitive function.

3. Immunotherapy Targeting ApoE-Aβ Complexes: Antibodies specifically targeting pathological apoE-Aβ complexes, particularly those involving apoE4 [33]. Selective removal of non-lipidated apoE4-Aβ co-aggregates has been shown to enhance clearance of toxic Aβ by glial cells and reduce secretion of inflammatory markers and membrane damage [33].

4. ApoE Lipidation Enhancers: Approaches to improve apoE lipidation, particularly for apoE4, including liver X receptor (LXR) agonists and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter activators [13]. Enhanced lipidation promotes Aβ clearance and reduces aggregation.

Integration with iPSC-Based Disease Modeling

The integration of APOE isoform studies with induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology provides a powerful platform for investigating human-specific disease mechanisms and screening therapeutic compounds. iPSC-derived neurons, astrocytes, and microglia from genotyped donors allow researchers to:

- Model human-specific pathophysiology in controlled genetic backgrounds

- Study cell-type-specific effects of apoE isoforms in relevant human CNS cells

- Screen therapeutic compounds for efficacy in humanized systems

- Investigate inflammatory responses in microglia with different APOE genotypes

Recent advances in iPSC differentiation protocols have enabled the generation of authentic brain cell types that recapitulate key aspects of AD pathology, providing valuable tools for validating findings from animal models and primary cell cultures [3].

APOE isoforms differentially influence Aβ aggregation, clearance, and plaque deposition through multiple interconnected mechanisms. APOE4 enhances AD risk by promoting Aβ aggregation into toxic oligomers and plaques while impairing clearance pathways, whereas APOE2 confers protection through opposite effects. The lipidation status of apoE significantly modulates these interactions, with lipidated apoE generally facilitating Aβ clearance while non-lipidated forms may promote pathogenic aggregation. Understanding these isoform-specific mechanisms at the molecular level provides critical insights for developing targeted therapies aimed at mitigating the detrimental effects of APOE4 while harnessing the protective mechanisms of APOE2. Future research integrating human iPSC models with advanced biophysical techniques will further elucidate these complex interactions and accelerate the development of effective APOE-targeted therapeutics for Alzheimer's disease.

Connections Between APOE and Tau Pathology, Neuroinflammation, and Synaptic Dysfunction

Apolipoprotein E (APOE), a lipid transport protein, exists in three major isoforms—APOE2, APOE3, and APOE4—with the APOE4 allele representing the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD), conferring up to a 10-15-fold increased risk in homozygous individuals [37]. While historically investigated for its role in amyloid-β (Aβ) pathology, contemporary research increasingly demonstrates that APOE4 exerts multifaceted pathogenic effects across several core AD pathways. This technical review synthesizes current evidence on how APOE4 directly and indirectly influences tau pathology, drives chronic neuroinflammation, and precipitates synaptic dysfunction, with particular emphasis on insights gained from human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) models. Understanding these interconnected mechanisms is paramount for developing targeted therapeutic strategies for APOE4-associated neurodegeneration.

APOE4 and Tau Pathology

The relationship between APOE4 and tau pathology extends beyond its established role in amyloid accumulation, representing a core pathogenic pathway independently linked to neurodegeneration and cognitive decline.

Direct Exacerbation of Tau Pathogenesis

Evidence from human iPSC-derived cerebral organoid models demonstrates that APOE4 significantly aggravates tau pathology. Cerebral organoids derived from AD patients carrying APOE ε4/ε4 show increased levels of phosphorylated tau compared to those with APOE ε3/ε3 genotype [19]. Importantly, this APOE4-related effect on tauopathy is observed in cerebral organoids from both healthy subjects and AD patients, suggesting its influence operates independently of disease status [19]. Isogenic conversion of APOE4 to APOE3 in these model systems attenuates tau pathology, providing causal validation of APOE4's role in tau hyperphosphorylation [19].

Mechanistically, APOE4 appears to accelerate early seeding of amyloid pathology, which subsequently facilitates tau spreading [38]. The presence of APOE4 also alters the relationship between tau pathology and synaptic density, with studies showing the associations between synaptic density and tau pathology are significantly regulated by APOE ε4 genotype [38]. This suggests APOE4 may lower the threshold for tau-mediated synaptic toxicity.

Biomarker Correlations

Postmortem brain studies reveal significant negative correlations between synaptic protein levels (including SV2A and synaptophysin) and phospho-tau concentrations, with these relationships being particularly pronounced in APOE ε4 carriers [39] [40]. Reductions in synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) are more severe in AD patients carrying APOE ε4, and these reductions correlate strongly with both Aβ and phospho-tau levels [39] [40]. This indicates that APOE4 amplifies the detrimental effects of tau pathology on synaptic integrity.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of APOE4 on Tau and Synaptic Pathology in Human Studies

| Study Model | Tau Pathology Measure | Effect of APOE4 | Technical Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| iPSC-derived cerebral organoids [19] | Phosphorylated tau levels | Significant increase in AD-E4 vs. AD-E3 organoids | Immunostaining, Western blot |

| Cognitively impaired participants [38] | Tau pathology mediation on synaptic density | APOE4 genotype regulates association between tau and synaptic density | PET imaging ([18F]SynVesT-1) |

| Postmortem human brain [39] [40] | Correlation with synaptic protein SV2A | Stronger negative correlation in APOE4 carriers | Mass spectrometry, IHC staining |

| Human brain-derived extracellular vesicles [40] | Phospho-tau levels in BDEVs | Significant negative correlation with SV2A in APOE4 carriers | LC-MS/MS proteomics |

APOE4 and Neuroinflammation

APOE4 fundamentally alters neuroimmune function, establishing a chronic pro-inflammatory state that contributes to neurodegeneration through multiple non-cell-autonomous mechanisms.

Glial Cell Dysregulation

Microglia and astrocytes, the primary immune cells of the central nervous system, express the majority of brain APOE and become progressively dysfunctional under APOE4 conditions [41] [42]. APOE4 disrupts their normal immunomodulatory functions, promoting a chronic inflammatory state that accelerates neurodegeneration [41]. Specifically, APOE4 exacerbates Aβ and tau burden-associated inflammation, creating a vicious cycle where pathology and neuroinflammation mutually reinforce each other [42].

Cell-specific APOE expression facilitates cross-talk between microglial and astroglial subsets, performing a diverse range of functions that become dysregulated in APOE4 carriers [42]. Under disease conditions, these immune cells show progressive dysfunction in regulating metabolic and immunoregulatory pathways, shifting from homeostatic functions toward pro-inflammatory states that damage neurons [41].

Systemic Inflammatory Signature

Recent large-scale proteomic profiling has revealed a conserved APOE ε4-associated pro-inflammatory immune signature persistent across brain, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and plasma, irrespective of specific neurodegenerative disease [26]. This signature is characterized by enrichment in pro-inflammatory immune and infection pathways, including T cell, B cell, and inflammatory signaling cascades such as Toll-like receptor (TLR), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-17 (IL-17), JAK/STAT, and NF-κB pathways [26].

Immune cell subtype enrichment analysis demonstrates that APOE ε4-associated proteins are most enriched in nonclassical and intermediate monocytes, memory CD8 T cells, Tregs, memory CD4 T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and γδ T cells [26]. This systemic inflammatory phenotype suggests APOE4 confers a fundamental biological vulnerability to neurodegeneration through immune modulation rather than disease-specific mechanisms.

Figure 1: APOE4-Induced Neuroinflammatory Signaling Pathways. APOE4 triggers glial cell dysregulation, activating multiple inflammatory signaling cascades and immune cell responses that drive chronic neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration.

APOE4 and Synaptic Dysfunction

Synaptic loss represents the strongest pathological correlate of cognitive decline in AD, and APOE4 significantly exacerbates this process through multiple interconnected mechanisms.

Synaptic Density and Protein Alterations

Quantitative neuroimaging studies using synaptic PET tracers demonstrate that APOE ε4 allele carriers exhibit significant synaptic loss in the medial temporal lobe compared to non-carriers [38]. This APOE4-associated synaptic depletion is mediated to different extents by both Aβ and tau pathology, with analyses suggesting these AD biomarkers partially explain the effect of APOE ε4 on synaptic density [38].

At the molecular level, APOE4 is associated with pronounced reductions in key synaptic proteins. Postmortem studies show significantly lower levels of synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) in AD patients, particularly in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, with APOE ε4 carriers showing further reductions compared to non-carriers [39] [40]. SV2A levels in brain-derived extracellular vesicles (BDEVs) and brain tissues positively correlate with synaptophysin levels and negatively correlate with Aβ and phospho-tau levels [40]. Reductions in SV2A are associated with decreased levels of other crucial synaptic proteins, including synaptotagmins, GAP43, and SNAP25, suggesting widespread disruption of the synaptic machinery in APOE4 carriers [40].

Metabolic Dysregulation at Synapses

Emerging research indicates that APOE4 impairs neuronal energy metabolism, indirectly disrupting synaptic function. Neurons exposed to APOE3 protein can utilize long-chain fatty acids as an alternative energy source when glucose is scarce, a critical adaptive mechanism in the aging brain [25]. However, this metabolic flexibility is impaired by APOE4, which disrupts the interaction with the sortilin receptor, preventing lipid uptake by neurons [25].

This metabolic disruption is particularly detrimental at synapses, which have high energy demands. The inability to switch to lipid metabolism when glucose availability declines likely compromises synaptic vesicle cycling, neurotransmitter release, and postsynaptic signaling, ultimately contributing to synaptic degeneration in APOE4 carriers [25].