Modeling Amyloid-Beta Deposition with iPSC Technology: From Disease Mechanisms to Therapeutic Discovery

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have revolutionized the study of Alzheimer's disease (AD), enabling researchers to model amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposition in a patient-specific context.

Modeling Amyloid-Beta Deposition with iPSC Technology: From Disease Mechanisms to Therapeutic Discovery

Abstract

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have revolutionized the study of Alzheimer's disease (AD), enabling researchers to model amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposition in a patient-specific context. This article explores how iPSC-derived neurons, glia, and 3D organoids recapitulate key aspects of Aβ pathology, including the formation of seeding-active oligomers and plaque-associated axonal spheroids. We detail the integration of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing for manipulating AD-related genes and the use of these models for high-throughput drug screening. The content also addresses critical challenges in model fidelity and standardization, while highlighting the validation of iPSC findings against human postmortem data. This resource provides a comprehensive overview for scientists and drug development professionals seeking to leverage iPSC technology for AD research and therapy development.

Understanding Aβ Seeds and Early Deposition Mechanisms in Patient-Specific Models

The Central Role of Aβ Seeds in Alzheimer's Pathogenesis

For over three decades, the amyloid cascade hypothesis has positioned amyloid-β (Aβ) at the center of Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathogenesis, though not without controversy [1] [2]. Recent clinical successes with Aβ-targeting immunotherapies have revitalized this hypothesis, confirming Aβ's crucial role in AD progression [1] [2]. However, these treatments provide only modest clinical benefits, supporting a two-stage disease model: an early phase driven primarily by Aβ aggregation, followed by a later phase that progresses somewhat independently of Aβ accumulation [1]. This understanding has shifted research focus from terminal amyloid plaques to Aβ seeds—highly bioactive, prion-like assemblies that initiate and propagate the pathogenic cascade [1]. These seeds represent the smallest pathogenic units in Aβ aggregation, acting as templates that corrupt native Aβ monomers into pathological aggregates [1]. Evidence now confirms that Aβ seeds can transmit between humans through medical procedures, raising both therapeutic potential and biosafety concerns [1] [3]. This whitepaper examines the central role of Aβ seeds in Alzheimer's pathogenesis, with particular emphasis on how induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technologies are revolutionizing our ability to study these pathogenic entities.

Molecular Nature and Mechanisms of Aβ Seeds

The Biochemical Identity of Aβ Seeds

The precise molecular nature of Aβ seeds remains elusive, representing a significant challenge in the AD field [1]. Multiple Aβ aggregate forms demonstrate seeding capability, though with varying efficiency. Intracerebral Aβ aggregation can be induced by:

- Small, soluble Aβ seeds from brain parenchyma

- Aβ seeds isolated from various cellular compartments and intracellular membranes

- Purified Aβ fibrils from AD brain tissue

- Aggregated synthetic Aβ peptides [1]

While soluble oligomeric Aβ species appear to have particularly high seeding potency, no single specific conformation can currently be assigned to Aβ seeds [1]. What distinguishes these seeds is their remarkable resilience—they can persist in the living brain for months following exogenous injection, successfully evading endogenous degradation and clearance mechanisms [1]. This persistence underscores their pathogenic significance and represents a key therapeutic challenge.

Prion-like Propagation Mechanisms

Aβ misfolding propagates through the brain via a prion-like mechanism where seeding-active nuclei template the misfolding and aggregation of naïve Aβ monomers into higher aggregation states [1]. This process follows a nucleation-dependent polymerization model beginning with a lag phase during which seeding-active nuclei form, though detectable Aβ deposition has not yet occurred [1]. Consistent with this model, pre-amyloid Aβ seeds have been detected in transgenic mouse models overexpressing amyloid precursor protein (APP) [1]. The critical importance of targeting these early seeds is demonstrated by experiments showing that acute immunotherapy in pre-depositing APP transgenic mice significantly reduces Aβ deposition and associated neurodegeneration later in life [1].

Table 1: Characteristics of Different Aβ Aggregates in Alzheimer's Pathogenesis

| Aggregate Type | Size/State | Seeding Potency | Detection Methods | Therapeutic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ Seeds | Small, soluble oligomers | Very high | PMCA, RT-QuIC, seeding assays | Primary target for preventive therapies |

| Soluble Oligomers | Medium soluble aggregates | High | MSD immunoassays, Western blot | Target of Lecanemab immunotherapy |

| Insoluble Fibrils | Large aggregates | Moderate | Amyloid PET, immunohistochemistry | Target of Donanemab immunotherapy |

| Mature Plaques | Terminal deposits | Low | Histology, amyloid PET | Late-stage pathological hallmark |

Seeding Activity Across Disease Stages

Aβ aggregates from early amyloid stages demonstrate significantly higher seeding potency compared to those from later stages [1]. The seeding-active oligomers crucial for initial Aβ aggregation are termed "on-pathway" to distinguish them from "off-pathway" oligomers not involved in the aggregation process [1]. Importantly, soluble Aβ oligomers are present in both brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid of early-stage AD patients, though their seeding activity at this early stage requires further characterization [1]. The heightened seeding activity of early aggregates may explain why therapeutic interventions targeting Aβ are most effective when administered early in the disease course.

Modeling Aβ Pathology Using Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

Fundamentals of iPSC-Based AD Modeling

iPSC technology enables generation of human neurons containing the precise genome of cell donors, permitting creation of disease models from individuals with disease-associated genotypes [4]. This approach offers several key advantages:

- Provides unlimited supply of human neurons and glia expressing endogenous levels of disease proteins

- Enables study of patient-specific genetic backgrounds without overexpression artifacts

- Allows differentiation into specific vulnerable neuronal subtypes and glial cells

- Facilitates investigation of early pathogenic events in human cells [4] [5]

However, limitations exist, particularly regarding cellular maturity. The reprogramming process erases epigenetic signatures of aging—a significant consideration for age-related diseases like AD [4]. Despite this, iPSCs remain the only means to obtain unlimited patient-specific neurons and glia for mechanistic studies.

Recapitulating AD Pathologies in iPSC-Derived Models

iPSC-derived neurons from both familial and sporadic AD patients successfully recapitulate key disease pathologies. Neurons derived from fAD (PSEN1 mutations) and sAD patients show:

- Increased phosphorylation of TAU protein at multiple sites

- Elevated extracellular Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 levels

- Significantly increased Aβ1-42/Aβ1-40 ratios in fAD lines

- Increased active GSK3B, a physiological TAU kinase

- Significant upregulation of APP synthesis and cleavage

- Elevated sensitivity to oxidative stress induced by amyloid oligomers [5]

Notably, one of the first studies comparing fAD and sAD iPSC-derived neurons found no evident phenotypic differences except in secreted Aβ1-40 levels, demonstrating iPSC technology's suitability for modeling both AD forms [5].

Advanced 3D Organoid Models

Recent advances have developed more physiologically relevant vascularized neuroimmune organoids containing multiple cell types affected in AD brains: neurons, microglia, astrocytes, and blood vessels [6]. These complex models successfully recapitulate multiple AD pathologies when exposed to sAD brain extracts, including:

- Aβ plaque-like aggregates

- Tau tangle-like aggregates

- Neuroinflammation

- Elevated microglial synaptic pruning

- Synapse and neuronal loss

- Impaired neural network activity [6]

Importantly, these pathologies manifest within four weeks of exposure to AD brain extracts, compared to the months required in conventional organoid models [6]. This accelerated timeline makes these models particularly valuable for therapeutic screening.

Experimental Systems for Investigating Aβ Seeds

Detection and Characterization Methods

Significant challenges exist in studying Aβ seeds due to their presence at levels below detectability by routine methods [1]. Several specialized approaches have been developed:

Seeding Detection Assays:

- Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification (PMCA): Amplifies minute quantities of seeds to detectable levels

- Real-Time Quaking-Induced Conversion (RT-QuIC): Detects seeding activity through amyloid formation kinetics

- Transgenic Mouse Bioassays: Measure acceleration of amyloid pathology following inoculation with seed-containing extracts [1] [3]

Extraction Protocols: The method of Aβ extraction significantly impacts seeding activity. Gentle soaking protocols that minimize physical disruption produce "S extracts" containing readily diffusible Aβ species that demonstrate potent seeding activity and neuritotoxicity [3]. These extracts contain a broad range of Aβ assembly sizes and account for essentially all bioactivity present in homogenized extracts [3].

In Vivo Seeding Experiments

Animal studies demonstrate that intracerebral inoculation with Aβ-containing brain homogenates or extracts accelerates Aβ deposition in genetically modified mouse models [3]. Key findings include:

- A single inoculation with AD brain S extracts significantly perturbs learned behavior in AppNL-F/NL-F mice

- Accelerated cerebral amyloid deposition appears 10 months post-inoculation

- Accompanying pathologies include microgliosis, astrocytosis, neuronal dystrophy, and synaptic loss

- Control brain extracts induce none of these effects [3]

These results confirm that diffusible Aβ species from AD brains possess both acute toxicity and seeding activity that can be experimentally transmitted [3].

Table 2: Experimental Models for Studying Aβ Seeds

| Model System | Key Features | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| iPSC-Derived 2D Neuronal Cultures | Patient-specific genetic background, human physiology | Mechanistic studies, high-throughput screening | Limited cellular complexity, immature phenotypes |

| Vascularized Neuroimmune Organoids | Multiple CNS cell types, 3D architecture, vascularization | Modeling complex pathologies, therapeutic testing | Technical complexity, variability between organoids |

| Transgenic Mouse Models | Intact brain environment, behavioral readouts | In vivo seeding studies, pathology progression | Species differences, overexpression artifacts |

| Biochemical Assays (RT-QuIC/PMCA) | High sensitivity, quantitative detection | Seed detection and quantification, strain characterization | Does not capture cellular context |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Targeting Aβ Seeds for Therapy

The central role of Aβ seeds in initiating pathogenesis makes them attractive therapeutic targets. Several approaches show promise:

Immunotherapies: Recent successes with anti-Aβ immunotherapies represent a significant milestone, though their mechanisms continue to be refined [2] [7]. Lecanemab preferentially binds soluble Aβ protofibrils, while Donanemab targets deposited plaques [1] [2]. The finding that acute immunotherapy in pre-depositing mice reduces later pathology suggests that early targeting of Aβ seeds may represent the optimal therapeutic strategy [1].

Small Molecule Inhibitors: Compounds like CT1812 show promise for treating multiple dementia types by displacing toxic protein aggregates (both Aβ and α-synuclein) from synapses [7]. Phase 2 trials are currently evaluating its efficacy in early AD patients [7].

Biosafety Considerations

The prion-like transmission of Aβ seeds raises important biosafety concerns. Evidence of iatrogenic cerebral Aβ pathology in humans has been reported following administration of cadaver-sourced human growth hormone or dura mater grafts containing Aβ [3]. These observations emphasize the need to prevent accidental transmissions via medical and surgical procedures and highlight the importance of appropriate safety protocols when handling seed-containing samples [1].

iPSC-Based Drug Discovery Platform

iPSC models are increasingly integrated into drug discovery pipelines. Several clinical trials have been initiated based on iPSC research findings, including trials of bosutinib, ropinirole, and ezogabine for ALS, and WVE-004 and BIIB078 for ALS/FTD [8]. The combination of iPSC models with targeted mass spectrometry provides unprecedented insights into protein regulation, including:

- Protein isoform expression

- Relative levels of cleavage fragments

- Aggregated species

- Functionally critical post-translational modifications [4]

This approach enables determination of how closely iPSC-derived models recapitulate disease profiles observed in human brain [4].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Preparation of Diffusible Aβ-Enriched Extracts from Human Brain

Principle: Gently extract diffusible Aβ species from brain tissue while minimizing disruption of larger aggregates [3].

Procedure:

- Dissect gray matter and mince into small chunks using a McIlwain chopper

- Soak minced tissue in five volumes of ice-cold base artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) plus protease inhibitors at 4°C for 30 minutes with gentle mixing

- Centrifuge at 2,000 × g at 4°C for 10 minutes to remove cellular debris

- Collect upper 90% of supernatant and centrifuge at 200,000 × g for 110 minutes at 4°C

- Remove upper 90% of this second supernatant (designated as S extract)

- Dialyze against 100-fold excess fresh aCSF buffer with three changes over 72 hours using 2K MWCO dialysis cassettes

- Aliquot and store at -80°C until use

Validation: Characterize extracts for Aβ content using MSD immunoassays with m266 capture antibody and 2G3 detection antibody [3].

iPSC-Derived Neuronal Differentiation for AD Modeling

Principle: Generate cortical neurons from human iPSCs to study Aβ and tau pathology [5].

Procedure:

- Maintain iPSCs in pluripotency medium on feeder cells or Matrigel

- Induce neural differentiation using dual SMAD inhibition (SB43152 and Noggin)

- Pattern toward cortical fate using retinoid acid and Wnt inhibitors

- Expand neural progenitor cells (NPCs) in FGF2-containing medium

- Differentiate NPCs into mature cortical neurons by FGF2 withdrawal and addition of BDNF, GDNF, and cAMP

- Maintain neuronal cultures for 8-12 weeks to allow maturation and spontaneous pathology development

- Analyze cultures for AD pathologies:

- Extracellular Aβ levels by ELISA

- Tau phosphorylation by Western blotting

- Synaptic markers by immunocytochemistry

- Electrophysiological properties by multi-electrode arrays

Vascularized Neuroimmune Organoid Generation

Principle: Create 3D organoids containing neurons, microglia, astrocytes, and blood vessels for comprehensive AD modeling [6].

Procedure:

- Generate NPCs, primitive macrophage progenitors (PMPs), and vascular progenitors (VPs) from iPSCs

- Combine 30,000 NPCs, 12,000 PMPs, and 7,000 VPs to form organoids by spontaneous assembly

- Culture in proliferation medium with bFGF for 5 days to promote cellular expansion

- Transition to differentiation medium containing IL-34, VEGF, and neurotrophic factors

- Maintain organoids long-term (4+ weeks) with regular medium changes

- Treat with AD brain extracts to induce pathologies (typically 4-week exposure)

- Analyze resulting pathologies:

- Aβ and tau aggregates by immunohistochemistry

- Synaptic density by synaptophysin/PDS95 staining

- Microglial phagocytosis by synaptic marker internalization

- Neural network activity by calcium imaging

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Aβ Seeds Using iPSC Models

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| iPSC Lines | fAD (PSEN1/APP mutations), sAD, isogenic controls | Disease modeling, genetic studies | Provide patient-specific genetic background for in vitro models |

| Differentiation Kits | Neural induction media, patterning factors | Generation of disease-relevant cell types | Direct pluripotent stem cell differentiation to neural lineages |

| Aβ Detection Antibodies | m266 (capture), 2G3 (detection), 4G8, 6E10 | Aβ quantification, plaque detection | Recognize specific Aβ epitopes in immunoassays and imaging |

| Tau Phospho-Antibodies | AT8 (pS202/pT205), AT100 (pT212/pS214) | Tau pathology assessment | Detect hyperphosphorylated tau species in pathological aggregates |

| Cell Type Markers | PAX6/NESTIN (NPCs), CD43/CD235 (PMPs), CD31 (endothelial) | Cell identity validation | Confirm specific cell populations in mixed cultures and organoids |

| Seeding Assay Components | Recombinant Aβ monomer, thioflavin T, reaction buffers | Aβ seed detection | Enable amplification and detection of minute seed quantities |

| Cytokines/Growth Factors | IL-34 (microglia survival), VEGF (vascularization), BDNF (neuronal maturation) | Specialized culture support | Maintain specific cell types in complex co-culture systems |

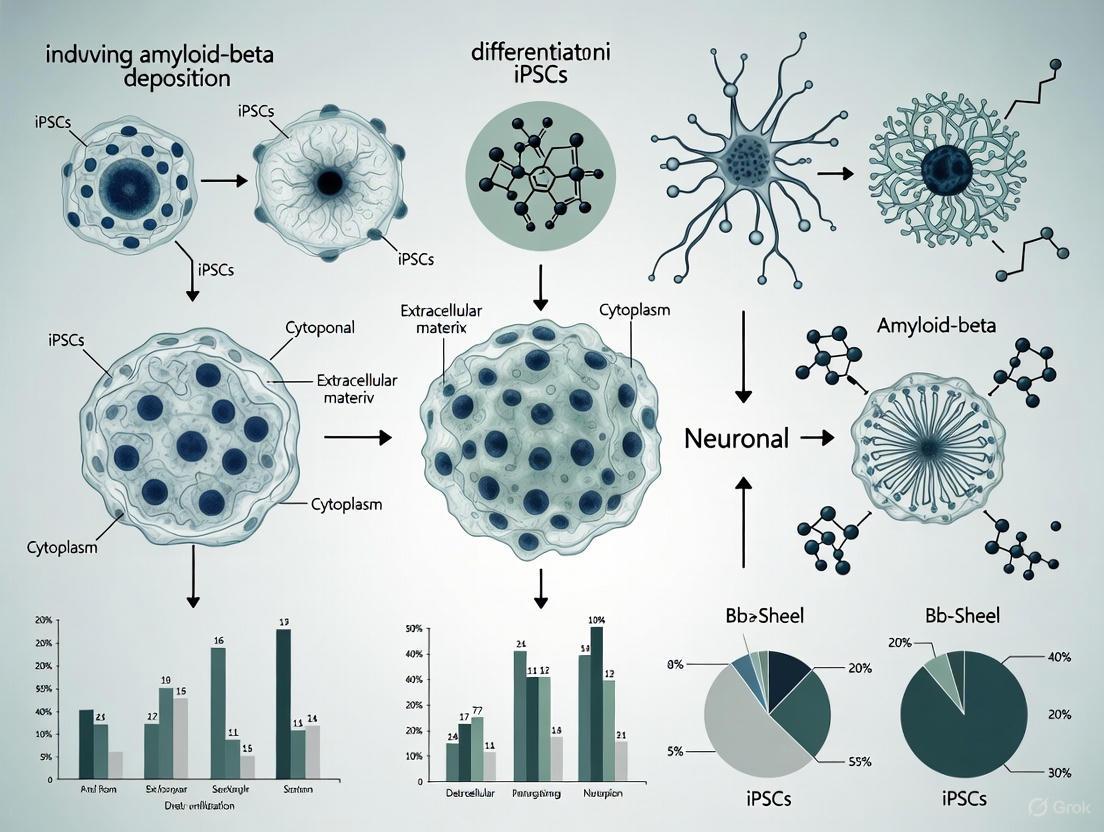

Visualizing Aβ Seed Pathogenesis and Research Workflows

Aβ Seed Pathogenesis Cascade

Figure 1: The central role of Aβ seeds in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. The cascade begins with amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing and Aβ monomer generation. Aβ seed formation represents a critical early event that enables prion-like spread throughout the brain, leading to oligomer formation, plaque deposition, and downstream pathological consequences including tau pathology, neuroinflammation, and synaptic dysfunction, ultimately resulting in neuronal loss.

iPSC Modeling of Aβ Pathology

Figure 2: Experimental workflows for modeling Aβ seed pathology using iPSC-based systems. Two-dimensional models (top) follow a sequential process from iPSC generation through therapeutic screening. Three-dimensional vascularized neuroimmune organoid models (bottom) incorporate additional complexity including vascularization and multiple cell type integration, enabling more comprehensive pathology assessment following exposure to AD brain extracts containing Aβ seeds.

Aβ seeds represent the earliest detectable molecular drivers of Alzheimer's pathogenesis, acting as critical instigators of the destructive cascade that culminates in dementia. Their prion-like propagation mechanisms, remarkable resilience to degradation, and ability to transmit between individuals underscore their central role in disease initiation and progression. The emergence of sophisticated iPSC-based models—particularly vascularized neuroimmune organoids that recapitulate multiple AD pathologies within a human cellular environment—provides unprecedented opportunities to dissect seed-mediated pathogenesis and develop targeted therapeutic strategies. As research continues to elucidate the precise molecular nature of these enigmatic seeds and optimize human cellular models for their study, we move closer to effective interventions that can disrupt the earliest events in Alzheimer's pathogenesis, potentially preventing the devastating consequences of this disease.

iPSC Models for Studying Familial vs. Sporadic Alzheimer's Disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) represents a profound public health challenge, with an estimated 7.1 million Americans currently living with symptoms and projections suggesting this will grow to 13.9 million by 2060 [7]. As the most common cause of dementia, AD pathology is characterized by the accumulation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tau tangles, leading to progressive cognitive decline [9]. Research has traditionally been hampered by models that fail to fully replicate human physiology and pathology. The advent of human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized AD research by enabling the generation of patient-derived neural cells that recapitulate human-specific disease mechanisms [10] [11].

iPSCs are particularly valuable for modeling the distinct pathogenic processes underlying familial AD (FAD) and sporadic AD (SAD). FAD accounts for less than 1% of all AD cases and is caused by fully penetrant autosomal dominant mutations in genes such as APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 [9] [11]. In contrast, SAD represents the vast majority of cases and involves complex interactions between genetic risk factors, aging, and environmental influences, with APOE ε4 being the strongest genetic risk factor, increasing late-onset AD risk by approximately three-fold for heterozygous carriers and 15-fold for homozygous carriers [9]. This technical guide examines how iPSC models are being leveraged to study amyloid-beta deposition across these AD forms, providing researchers with methodologies, applications, and future directions for this transformative technology.

Fundamental Differences Between Familial and Sporadic AD

The pathological distinction between FAD and SAD informs the design and interpretation of iPSC-based disease models. While both forms share hallmark Aβ and tau pathology, their underlying drivers and temporal progression differ significantly.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Familial vs. Sporadic AD

| Characteristic | Familial AD (FAD) | Sporadic AD (SAD) |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | <1% of all cases [11] | >95% of all cases [9] |

| Age of Onset | Early-onset (<60 years) [11] | Late-onset (>60 years) [9] |

| Inheritance | Autosomal dominant | Complex, polygenic |

| Primary Genetic Drivers | Mutations in APP, PSEN1, PSEN2 [9] | APOE ε4 allele and numerous risk genes (TREM2, BIN1, CLU, etc.) [9] [11] |

| Aβ Pathology Mechanism | Increased Aβ42 production or Aβ42/40 ratio [12] [11] | Impaired Aβ clearance and multiple pathways [9] |

| iPSC Modeling Approach | Introduce known pathogenic mutations | Focus on risk variants and polygenic contributions |

FAD mutations directly alter Aβ processing, typically by increasing the production of the more amyloidogenic Aβ42 peptide or the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio [11]. The seminal iPSC study of FAD by Yagi et al. demonstrated that neurons derived from patients with PS1 (A246E) and PS2 (N141I) mutations showed increased Aβ42 secretion, effectively recapitulating the molecular pathogenesis observed in patients [12]. In contrast, SAD involves more complex mechanisms, with genetic risk factors like APOE4 potentially impairing Aβ clearance rather than production [9]. Many SAD risk genes, including TREM2, CD33, and ABCA7, are highly expressed in glial cells (microglia and astrocytes), highlighting the importance of non-neuronal cells in SAD pathogenesis [9] [11].

iPSC Modeling Strategies for Alzheimer's Disease

Core iPSC Generation and Differentiation

The fundamental workflow for creating iPSC-based AD models begins with somatic cell reprogramming, followed by differentiation into disease-relevant neural cell types.

The core reprogramming process typically uses the OSKM factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) to convert patient somatic cells into iPSCs [11]. These iPSCs can then be differentiated into various neural lineages using established protocols. Critical advancements include improved differentiation methods for generating human astrocytes and microglia, which better recapitulate human-specific biology compared to rodent cells [11]. The National Alzheimer's Disease iPS Cell Bank managed by the UCI Alzheimer's Disease Research Center exemplifies institutional efforts to share these critical resources across the research community [13].

Genetic Engineering with CRISPR/Cas9

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing has become an indispensable tool for creating precise iPSC models of AD, particularly for generating isogenic control lines where disease-causing mutations are introduced into healthy iPSCs or corrected in patient-derived iPSCs [14]. This powerful approach enables researchers to study the specific effects of genetic alterations against identical genetic backgrounds.

The CRISPR/Cas9 system consists of two main components: a Cas9 nuclease that cleaves target DNA and a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs Cas9 to specific genomic sequences [14]. When applied to AD research, this technology enables targeted manipulation of pathogenic loci in genes such as APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, and APOE [14]. For example, Kwart et al. used CRISPR/Cas9 to alter Aβ production in mouse models with mutant APP, successfully reducing toxic Aβ peptides without impairing brain function [14]. The technology also facilitates multiplex gene editing by combining multiple sgRNAs in a single experiment, allowing simultaneous investigation of several genetic factors involved in AD pathogenesis [14].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

2D Monoculture and Co-culture Systems

Initial iPSC-based AD models primarily utilized 2D monocultures of neurons to study cell-autonomous disease mechanisms. The foundational study by Yagi et al. established that FAD-iPSC-derived neurons with PS1 and PS2 mutations demonstrated increased Aβ42 secretion and sharp response to γ-secretase inhibitors and modulators, validating this approach for drug screening applications [12]. However, the recognition that non-neuronal cells play crucial roles in AD pathogenesis has driven the development of more complex co-culture systems.

Table 2: Experimental Model Systems for iPSC-Based AD Research

| Model System | Components | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Monoculture | Single cell type (e.g., neurons) | Study of cell-autonomous mechanisms, high-content screening | Lacks cellular interactions, oversimplified |

| 2D Co-culture | Multiple cell types (e.g., neurons + astrocytes) | Investigation of cell-cell interactions, neuroinflammation | Limited tissue architecture, artificial interfaces |

| 3D Neural Organoids/Neurospheres | Self-organizing 3D structures with multiple neural cell types | Modeling tissue-level organization, complex cell interactions, amyloid plaque formation | Heterogeneity, necrotic cores, variable reproducibility |

| Assembled 3D Neurospheres | Defined ratios of iPSC-derived neurons, astrocytes, microglia | Controlled studies of specific cellular contributions, drug testing | Requires complex assembly, may lack native organization |

3D Organoid and Neurosphere Models

Three-dimensional model systems represent a significant advancement in iPSC-based AD modeling, as they better recapitulate the complex tissue architecture and cell-cell interactions of the human brain. Neural organoids are self-assembled three-dimensional aggregates that generate brain-like structures and recapitulate disease features from molecular to functional levels not fully reproduced by other culture systems [15].

A sophisticated 3D iPSC-derived neurosphere system developed by researchers incorporates neurons, astrocytes, and microglia to model cellular responses to chronic amyloidosis [16]. In this model, microglia demonstrated efficient phagocytosis of Aβ and significantly reduced neurotoxicity, mitigating amyloidosis-induced oxidative stress and neurodegeneration [16]. Furthermore, single-nuclei RNA sequencing revealed that the presence of microglia was essential for Aβ to upregulate AD-like gene expression signatures in astrocytes, including key genes such as APOE, CLU, LRP1, and VIM [16].

Live Human Brain Slice Cultures

Complementing iPSC-based models, live human brain slice cultures (HBSCs) provide a unique platform for validating findings in mature human tissue. Recent research using HBSCs has revealed divergent actions of physiological and pathological Aβ on synapses in live human brain tissue [17]. This approach has demonstrated that pharmacological manipulation of physiological Aβ in either direction results in loss of synaptophysin puncta, whereas treatment with pathological Aβ-containing AD brain extract causes post-synaptic Aβ uptake and pre-synaptic puncta loss without affecting synaptic transcripts [17].

Key Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC-Based AD Modeling

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) | Conversion of somatic cells to pluripotent state [11] |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9, sgRNAs | Introduction or correction of disease-associated mutations [14] |

| Neural Differentiation Media | Various specialized formulations | Direction of iPSC differentiation to neurons, astrocytes, microglia [16] |

| Cell Type Markers | MAP2, NeuN (neurons); GFAP (astrocytes); Iba1, P2RY12 (microglia) | Identification and validation of specific cell types [17] [16] |

| AD Pathological Assays | ELISAs for Aβ40, Aβ42, tau; Immunostaining for plaques and tangles | Quantification of disease-relevant biomarkers and pathology [12] [17] |

| Functional Assays | Calcium imaging (GCaMP6f), electrophysiology, oxidative stress sensors (roGFP1) | Assessment of neuronal activity, network function, and cellular stress [17] [16] |

Methodological Protocols for Key Experiments

Generating FAD iPSC Models with Known Mutations

To establish FAD iPSC models, researchers typically begin with dermal fibroblasts or blood samples from patients carrying known pathogenic mutations in APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2 [12] [13]. The standardized protocol involves:

- Reprogramming: Introduce the OSKM factors via non-integrating methods to generate iPSCs, with validation of pluripotency markers [11].

- Neural Differentiation: Differentiate iPSCs into neural progenitor cells (NPCs) using dual SMAD inhibition, then further differentiate into mature neurons using combinations of BDNF, NT-3, and cAMP [12] [16].

- Pathological Validation: Measure Aβ42 secretion and Aβ42/40 ratio via ELISA, expecting significant increases compared to control lines [12].

- Drug Response Testing: Expose neurons to γ-secretase inhibitors (e.g., DAPT) and modulators to validate the model's responsiveness, with FAD lines typically showing sharp concentration-dependent responses [12].

Establishing 3D Neurosphere Models with Chronic Amylosis

For the generation of 3D neurosphere models that replicate chronic amyloid exposure:

- Neurosphere Formation: Plate neural progenitor cells in AggreWell plates to initiate 3D aggregation, then transfer to orbital shakers for continued differentiation and maturation [16].

- Microglia Incorporation: Differentiate microglia separately and add to mature neurospheres, allowing infiltration for 7-10 days [16].

- Aβ Oligomer Treatment: Supplement culture media with synthetic Aβ1-42 oligomers for 3-5 weeks to model chronic amyloidosis [16].

- Functional Assessment: Monitor neuronal activity using GCaMP6f calcium imaging, oxidative stress with roGFP1, and neuronal death via lactate dehydrogenase release or live-dead assays [16].

- Transcriptional Analysis: Perform single-nuclei RNA sequencing to profile Aβ and microglia-driven transcriptional changes across different cell types [16].

CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing of APOE in iPSCs

For investigating the role of the major genetic risk factor APOE:

- sgRNA Design: Design sgRNAs targeting sequences near the APOE ε2/ε3/ε4 determinant residues (amino acids 112 and 158) [9] [14].

- Electroporation: Deliver Cas9 protein and sgRNAs as ribonucleoprotein complexes into iPSCs via electroporation [14].

- Isogenic Line Selection: Isolate single-cell clones and validate APOE genotype by sequencing, ensuring isogenicity with parent line [14].

- Phenotypic Characterization: Differentiate edited iPSCs into astrocytes and neurons to assess APOE secretion, Aβ aggregation, and neuronal vulnerability [9].

Current Applications and Future Directions

iPSC models of AD have become indispensable tools for both basic research and drug development. Bibliometric analysis reveals a steady increase in publications over 14 years, with research trends focusing on inflammation, astrocytes, microglia, apolipoprotein E (ApoE), and tau [10]. The United States leads in research contributions, followed by China, with prominent researchers including Li-Huei Tsai from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology [10].

These models are increasingly being used to:

- Elucidate cell-type-specific contributions to Aβ pathology [9] [16]

- Investigate the mechanistic roles of AD risk genes identified through GWAS studies [9]

- Screen and validate candidate therapeutics in human-relevant systems [12] [14]

- Model patient-specific responses to potential treatments [10]

Future directions for the field include addressing current limitations such as model heterogeneity, cellular immaturity, and the absence of aging components [15] [11]. Emerging strategies include the incorporation of additional cell types like vascular cells, development of more reproducible organoid systems, and integration of multi-omics approaches to comprehensively characterize disease mechanisms. As these technologies continue to mature, iPSC-based models hold considerable promise for advancing our understanding of AD pathogenesis and accelerating the development of effective therapeutics for both familial and sporadic forms of this devastating disorder.

The study of complex diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), requires models that accurately capture genetic susceptibility. Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS) have emerged as a powerful tool for quantifying an individual's genetic predisposition by aggregating the effects of numerous genetic variants across the genome [18]. When combined with advanced in vitro models like those utilizing human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), PRS provides a framework for stratifying biological risk and investigating molecular mechanisms underlying disease pathology. This integration is particularly potent in Alzheimer's research, where hiPSC-derived astrocytes and neurons enable the direct study of how genetic susceptibility influences cellular responses to pathological insults like amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposition [19] [20].

The power of PRS lies in its ability to move beyond single-gene effects to model the complex, polygenic nature of most common diseases. PRS are calculated as the sum of an individual's risk alleles for a phenotype, weighted by effect size estimates derived from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [18]. This individual-level genetic propensity score can then be used to stratify samples for experimental studies, including those using hiPSC-derived cell lines, to contrast biological processes between individuals at high and low genetic risk [18].

Computational Methodology for Polygenic Risk Score Calculation

Foundation of Polygenic Risk Scores

Polygenic Risk Scores provide an estimate of an individual's common genetic liability to a phenotype [18]. The standard PRS calculation involves summing risk alleles across many genetic variants, weighted by their effect sizes as estimated from large-scale GWAS. Formally, for an individual, the PRS is computed as:

[ PRSj = \sum{i=1}^{M} wi \times G{ij} ]

Where (PRSj) is the polygenic risk score for the (j)-th individual, (wi) is the weight (effect size) of the (i)-th single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) from base GWAS data, (G_{ij}) is the genotype of the (i)-th SNP for the (j)-th individual (coded as 0, 1, or 2 copies of the effect allele), and (M) is the total number of SNPs included in the score [18].

Quality Control Procedures for PRS Analysis

Robust PRS analysis requires stringent quality control of both base (GWAS summary statistics) and target (individual genotype) data. Key quality control measures include [18]:

- Base Data Quality Checks: Heritability check ((h_{snp}^2 > 0.05)), verification of effect allele identification, and standard GWAS quality control including genotyping rate > 0.99, minor allele frequency (MAF) > 1%, and imputation info score > 0.8.

- Target Data Requirements: Minimum sample size of 100 individuals, genotyping rate > 0.99, sample missingness < 0.02, heterozygosity P > 1×10⁻⁶, MAF > 1%, and careful handling of population structure.

- Data Harmonization: Ensuring consistent allele coding and strand orientation between base and target datasets to prevent spurious results.

Table 1: Key Quality Control Parameters for PRS Analysis

| Data Type | QC Parameter | Threshold | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base & Target | Genotyping rate | > 0.99 | Minimizes missing data |

| Base & Target | Minor allele frequency | > 1% | Filters rare variants |

| Base & Target | Imputation quality | > 0.8 | Ensures well-imputed SNPs |

| Base Data | Chip heritability | > 0.05 | Ensures sufficient genetic signal |

| Target Data | Sample size | ≥ 100 | Provides adequate power |

Advanced PRS Integration: Risk Factor PRS (RFPRS)

Recent methodologies have extended beyond disease-specific PRS to incorporate genetic susceptibility for risk factors. The Risk Factor Polygenic Risk Score (RFPRS) approach integrates genetic propensity for both disease and its risk factors, potentially enhancing predictive power [21]. This integrated RFDiseasemetaPRS combines information from multiple PRSs:

- Construction of Multiple RFPRSs: Generating PRS for various heritable risk factors (e.g., blood biochemistry, body composition, blood pressure) with SNP heritability > 10% [21].

- Association Screening: Testing associations between RFPRSs and a wide spectrum of diseases to identify significant relationships.

- Meta-Score Development: Combining disease PRS with relevant RFPRSs to create RFDiseasemetaPRS, which has demonstrated improved prediction performance for numerous diseases compared to standard PRS alone [21].

Experimental Integration: PRS with iPSC-Derived Cellular Models

hiPSC-Derived Astrocyte Model of Amyloid-Beta Pathology

The integration of PRS with hiPSC models enables the investigation of genetic risk in a human-relevant system. Key methodological aspects include:

- Astrocyte Differentiation: hiPSCs are differentiated into long-term neuroepithelial-like stem cells, which are then plated on poly-L-ornithine and laminin-coated surfaces in astrocyte differentiation medium containing growth factors (bFGF, heregulin, activin A, IGF-1, CNTF) for 30-66 days [19].

- Neuronal Differentiation: Parallel differentiation of hiPSCs into neurons using neuronal differentiation media with sequential media formulations to promote maturation over 30-66 days [19].

- Amyloid-Beta Exposure: Astrocytes are exposed to sonicated Aβ42 fibrils (200 nM for 2 days) to model pathological protein accumulation, followed by culture in Aβ-free medium for various durations (6-33 days) to study persistence effects [19] [20].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC-Amyloid Beta Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Example | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| hiPSC Line | Cntrl9 II cell line | Source for differentiated astrocytes and neurons |

| Differentiation Matrix | Poly-L-ornithine & Laminin | Surface coating for cell attachment and differentiation |

| Astrocyte Differentiation Factors | bFGF, Heregulin, Activin A, IGF-1, CNTF | Direct stem cell differentiation toward astrocytic lineage |

| Aβ Preparation | HiLyte Fluor 555 labeled Aβ42 monomers | Generation of sonicated fibrils for cellular uptake studies |

| Cell Culture Media | Advanced DMEM/F12 + supplements | Maintenance of differentiated astrocytes |

Functional Assessment of Aβ-Accumulating Astrocytes

Intracellular Aβ accumulation in astrocytes produces measurable functional consequences:

- Synaptic Dysregulation: Neurons co-cultured with Aβ-exposed astrocytes show significantly decreased frequency of excitatory post-synaptic currents, while conditioned media from these astrocytes induces synaptic hyperactivation [19].

- Sustained Cellular Stress: Aβ-containing astrocytes maintain markers of cellular reactivity and exhibit organelle abnormalities, including endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial swelling, even 10 weeks after initial exposure [20].

- Altered Secretory Profile: Aβ-accumulating astrocytes show modified cytokine secretion, including increased CCL2/MCP-1, and form pathological lipid structures, indicating broad metabolic disruption [20].

Visualizing Integrated Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate key experimental workflows and conceptual relationships in integrated PRS-iPSC research.

Integrated PRS-iPSC Experimental Workflow

Aβ-Induced Astrocyte Dysfunction Pathways

RFPRS Integration Strategy

Data Presentation and Analytical Outcomes

Quantitative Assessment of PRS Predictive Performance

Table 3: Performance Metrics for Standard PRS vs. RFDiseasemetaPRS

| Disease Category | Number of Diseases | Nagelkerke's Pseudo-R² | Odds Ratio per 1 SD | Net Reclassification Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard PRS Only | 70 diseases | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| RFDiseasemetaPRS | 31 diseases | Improved | Improved | Positive NRI values |

| Performance Gain | 44.3% of diseases | Significant increase | Significant increase | Better risk classification |

Experimental Outcomes of Aβ-Loaded Astrocytes

Table 4: Functional Consequences of Aβ Accumulation in hiPSC-Derived Astrocytes

| Experimental Measure | Control Astrocytes | Aβ-Exposed Astrocytes | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuronal Co-culture: EPSC Frequency | Normal pattern | Significantly decreased | Impaired synaptic support |

| Conditioned Media Effect on Neurons | Normal activation | Synaptic hyperactivation | Secreted factor alteration |

| Aβ Retention Duration | No accumulation | >10 weeks in LAMP1+ organelles | Long-term pathology |

| Cytokine Secretion Profile | Baseline levels | Elevated CCL2/MCP-1 | Chronic neuroinflammation |

| Organelle Integrity | Normal morphology | ER & mitochondrial swelling | Metabolic dysfunction |

Discussion: Implications for Drug Development and Personalized Medicine

The integration of polygenic risk modeling with hiPSC-based experimental systems represents a paradigm shift in how researchers can capture genetic susceptibility for complex diseases like Alzheimer's. The methodology enables:

- Stratified Experimental Models: Using PRS to select hiPSC donors at genetic extremes creates more biologically relevant models for therapeutic screening.

- Mechanistic Insight: The combination of genetic risk profiling with functional cellular assays reveals how polygenic susceptibility manifests in pathological processes like Aβ accumulation in astrocytes.

- Enhanced Predictive Power: RFDiseasemetaPRS approaches demonstrate that incorporating risk factor genetics alongside disease genetics improves prediction accuracy for a substantial proportion of diseases [21].

For drug development professionals, these approaches enable more targeted therapeutic strategies. The experimental evidence that Aβ-loaded astrocytes maintain long-term pathology and alter neuronal function provides specific cellular targets for intervention. Furthermore, the ability to stratify individuals by genetic risk enables development of more personalized therapeutic approaches, potentially targeting different biological pathways in high-risk versus low-risk populations.

The consistent observation that astrocytes store rather than degrade ingested Aβ [19] [20], resulting in sustained cellular stress and dysfunction, highlights the potential for targeting astrocyte-mediated clearance mechanisms as a therapeutic strategy. Combined with PRS-based patient stratification, this could enable preemptive interventions for individuals identified as high genetic risk before widespread neurodegeneration occurs.

Recapitulating Early Amyloid Pathology in Human Neurons

The pursuit of effective therapeutic interventions for Alzheimer's disease (AD) has been persistently hampered by the limited predictive validity of traditional model systems. Despite promising results in rodent models, countless candidate therapeutics have failed to benefit human patients, signaling a critical need for more human-relevant disease models [9]. The advent of human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized this landscape by providing unprecedented access to living human neurons and glial cells for pathological investigation. iPSC-derived models now serve as an essential bridge between animal studies and clinical trials, offering a platform that captures human-specific physiology and genetic diversity [22] [10].

The core pathological hallmark of AD—the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides—begins years before clinical symptoms emerge. Recapitulating these early stages of amyloid pathology in human neurons is therefore critical for understanding disease initiation and identifying therapeutic windows for intervention. This technical guide details established and emerging methodologies for modeling early amyloid pathology using human iPSC-derived neural cells, providing researchers with the experimental frameworks needed to advance our understanding of AD pathogenesis.

The Cellular Symphony in Amyloid Pathology: Beyond Neurons

While neuronal production of Aβ has been the historical focus of AD research, contemporary genetic and pathological evidence underscores the essential contributions of non-neuronal cell types to disease progression. Genome-wide association studies have identified numerous AD risk genes predominantly expressed in glial cells, shifting the research paradigm toward a more integrated view of AD pathophysiology [9].

Astrocytes: The Double-Edged Sword of Aβ Clearance and Storage

Astrocytes, crucial for maintaining brain homeostasis, exhibit a complex relationship with Aβ pathology. Human iPSC-derived astrocytes actively engulf large amounts of aggregated Aβ through phagocytic mechanisms. However, rather than effectively degrading this material, they store it within LAMP1-positive organelles for extended periods—at least 10 weeks in culture systems [20]. This incomplete processing has profound consequences for astrocyte function and neuronal health:

- Sustained cellular stress: Astrocytes with intracellular Aβ deposits exhibit persistent reactivity markers and an altered cytokine profile, particularly increased secretion of CCL2/MCP-1 [20].

- Organelle dysfunction: Aβ accumulation induces endoplasmic reticulum swelling, mitochondrial abnormalities, and the formation of pathological lipid structures [20].

- Synaptic impact: When co-cultured with Aβ-bearing astrocytes, neurons show significantly decreased frequency of excitatory post-synaptic currents, indicating impaired synaptic function [19].

- Contradictory signaling: Conditioned media from Aβ-exposed astrocytes paradoxically induces neuronal hyperactivity, suggesting the release of soluble factors that alter neuronal excitability [19].

Microglia: Inflammatory Mediators and Oxidative Stress Contributors

Microglia, the brain's resident immune cells, play pivotal roles in neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in AD. Human microglial models demonstrate elevated production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) when exposed to Aβ42, contributing to the oxidative damage observed in AD brains [23]. Recent advances in machine learning coupled with confocal microscopy have enabled sophisticated quantification of these ROS responses, providing new avenues for evaluating potential therapeutic compounds like cannabidiol for their anti-inflammatory properties [23].

Neuronal Senescence: The Emerging Pathway in AD Pathogenesis

Beyond traditional degeneration mechanisms, neurons exposed to Aβ enter a state of cellular senescence, termed "neurescence." Aβ42 oligomers significantly upregulate senescence markers (p21, PAI-1, SA-β-gal) in multiple human neuronal models, including SK-N-SH cells, SH-SY5Y cells, and neural stem cell-derived neurons [24]. This senescent state is characterized by:

- DNA damage response: Increased levels of 8-OHdG staining, histone variant H2AX phosphorylation (γ-H2AX), and genomic DNA lesions [24].

- SIRT1 suppression: Aβ exposure markedly suppresses sirtuin-1 (SIRT1), a critical regulator of aging, and exogenous SIRT1 expression alleviates Aβ-induced senescence phenotypes [24].

- Pharmacological rescue: Aspirin has been shown to rescue Aβ-induced cellular senescence至少部分通过其 regulation of SIRT1, suggesting potential therapeutic pathways [24].

Table 1: Key Cellular Contributors to Amyloid Pathology in Human iPSC Models

| Cell Type | Primary Role in Aβ Pathology | Functional Consequences | Key Experimental Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurons | Aβ production via APP processing; Vulnerability to oligomeric Aβ | Senescence induction; Synaptic dysfunction; Altered electrophysiology | p21, PAI-1, SA-β-gal; CDKN2D, ETS2 [24] [25] |

| Astrocytes | Aβ phagocytosis and storage; Trophic support | Incomplete degradation; Chronic reactivity; Altered cytokine secretion | GFAP; CCL2/MCP-1; LAMP1 [20] [19] |

| Microglia | Immune activation; ROS production | Neuroinflammation; Oxidative stress; Phagocytic clearance | ROS (CellROX); IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α [23] |

Experimental Framework: Methodologies for Modeling Amyloid Pathology

Generation of AD-Relevant Neural Cells from Human iPSCs

The successful recapitulation of early amyloid pathology begins with robust differentiation protocols for generating relevant neural cell types:

Forebrain Neuronal Differentiation:

- Utilize dual-SMAD inhibition in monolayer culture to direct differentiation toward cortical fates [22].

- Employ neuronal differentiation medium containing neurobasal medium with B27 supplement, CultureOne supplement, GlutaMAX, and ascorbic acid [24].

- Allow maturation for 30+ days in vitro to obtain functionally mature neurons capable of forming synaptic connections [19].

Astrocytic Differentiation:

- Differentiate long-term neuroepithelial-like stem cells in Advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with bFGF, heregulin, activin A, IGF-1, and CNTF [19].

- Culture for 30-66 days in vitro to achieve mature astrocytic properties, including phagocytic capability and cytokine secretion [19].

- Confirm functionality through phagocytosis assays and responsiveness to inflammatory stimuli.

Aβ Preparation and Exposure Protocols

Aβ42 Fibril Preparation:

- Dissolve synthetic Aβ42 peptides in hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) and dry overnight at room temperature [24].

- Resuspend in DMSO and dilute in phenol-red free DMEM/F12 medium to 100 μM concentration.

- Incubate at 4°C for 24 hours to form oligomers, or extend incubation to 4 days at 37°C with shaking to form fibrils [24] [19].

- Sonicate fibrils at 20% amplitude (1s on/off pulses for 1 minute) immediately before use to facilitate cellular uptake [19].

Cell Exposure Paradigms:

- For acute effects: Treat cells with 100-200 nM sonicated Aβ for 24-48 hours [24] [19].

- For long-term pathology modeling: Implement pulse-chase experiments with 2-day Aβ exposure followed by extended culture in Aβ-free medium (up to 10 weeks) to study retention and chronic effects [20].

Co-culture Systems for Cell-Cell Interaction Studies

To model the complex interactions between different brain cell types in AD:

- Establish neuronal cultures first (30 days maturation), then add astrocytes at a 1:10 ratio (astrocyte:neuron) [19].

- Maintain co-cultures in neuronal differentiation medium #2 (1:1 mix of neuronal differentiation medium and neurobasal medium with supplements) [19].

- Analyze effects after 7-33 days of co-culture depending on experimental endpoints.

Table 2: Quantitative Assessments of Aβ Effects in Human iPSC-Derived Neural Cells

| Experimental Measure | Control Conditions | Aβ-Exposed Conditions | Experimental Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ Retention in Astrocytes | Minimal intracellular Aβ | Persistent LAMP1+ inclusions after 10 weeks | 200 nM sonicated Aβ-fibrils, 2d exposure [20] |

| Senescence Markers in Neurons | Baseline p21, PAI-1 expression | Significant upregulation | 100 nM Aβ42 oligomers, 48h exposure [24] |

| Excitatory Post-synaptic Current Frequency | Normal synaptic activity | Significantly decreased | Co-culture with Aβ-exposed astrocytes [19] |

| ROS Production in Microglia | Baseline CellROX signal | Significantly increased | 100 nM Aβ42, 24h exposure [23] |

| SIRT1 Expression in Neurons | Normal SIRT1 levels | Markedly suppressed | 100 nM Aβ42 oligomers, 48h exposure [24] |

Advanced Methodologies: Screening and Discovery Platforms

iPSC-Based Compound Screening and Therapeutic Discovery

The use of iPSC-derived neurons has enabled new approaches to pharmaceutical screening:

- High-Content Phenotypic Screening: Rapid neuronal induction protocols allow screening of compound libraries for Aβ-lowering effects with nearly 100% pure neuronal cultures [26].

- Synergistic Combination Therapy: Identification of anti-Aβ cocktail (bromocriptine, cromolyn, and topiramate) that shows synergistic effects in reducing Aβ levels in familial and sporadic AD patient-derived neurons [26].

- Drug Repurposing Platforms: iPSC-based screening of existing pharmaceutical compounds can identify new applications for AD treatment, accelerating therapeutic development [26].

Machine Learning and Image Analysis in AD Research

Advanced computational methods are enhancing the quantification and interpretation of AD-related phenotypes:

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN): Deep learning models can predict ROS responses in microglia based on CellROX fluorescence images, enabling high-throughput screening of compound effects [23].

- Decision Tree Classification: Transcriptomic profiling identifies marker pairs (CDKN2D/ETS2) that accurately distinguish senescent neurons with 99% accuracy and 100% specificity [25].

- Eigengene Approaches: Integration of senescence gene panels (SenMayo, CSP, SIP) enables identification of "neurescent" cells from single-nucleus RNA sequencing data [25].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC-Based Amyloid Pathology Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| iPSC Differentiation Kits | Neural induction media; Patterning factors | Generation of disease-relevant cell types (forebrain neurons, astrocytes, microglia) | [22] [9] |

| Aβ Peptides | Aβ42 monomers (AnaSpec); HiLyte Fluor 555 labeled Aβ42 | Preparation of oligomeric and fibrillar Aβ for exposure studies | [24] [19] |

| Senescence Detection Kits | SA-β-gal assay; p21/PAI-1 antibodies | Identification of senescent neurons ("neurescence") | [24] [25] |

| Cellular Stress Indicators | CellROX Green/Live-act mCherry | Detection of reactive oxygen species in live cells | [23] |

| Lysosomal Markers | LAMP1 antibodies | Tracking intracellular Aβ storage in astrocytes | [20] |

| Electrophysiology Systems | Multi-electrode arrays; Patch clamp | Functional assessment of neuronal and synaptic activity | [19] |

| Cytokine/Chemokine Assays | CCL2/MCP-1 ELISAs; Multiplex cytokine panels | Quantifying inflammatory responses in glial cells | [20] |

Signaling Pathways in Aβ-Induced Pathology

The following diagram illustrates key signaling pathways involved in Aβ-induced neuronal senescence and cellular dysfunction:

Aβ-Induced Senescence Pathway

Experimental Workflow for Modeling Amyloid Pathology

This diagram outlines a comprehensive experimental workflow for recapitulating early amyloid pathology using human iPSC-derived models:

iPSC Amyloid Modeling Workflow

The development of robust protocols for recapitulating early amyloid pathology in human iPSC-derived neural cells represents a transformative advancement in Alzheimer's disease research. These models successfully capture key aspects of AD pathophysiology—including Aβ accumulation, neuronal senescence, glial activation, and synaptic dysfunction—within a genetically human context. The methodologies outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with comprehensive frameworks for establishing these models, enabling more physiologically relevant studies of disease mechanisms and therapeutic interventions.

As the field progresses, increasing model complexity through multi-cellular systems and organoid approaches will further enhance the physiological relevance of these platforms. Combined with advanced analytical techniques such as machine learning and high-content screening, human iPSC-based models promise to accelerate the development of effective therapies for Alzheimer's disease by bridging the critical gap between animal studies and human clinical response.

Advanced iPSC Platform Development for Aβ Pathology and Drug Screening

The study of complex neurological processes, such as amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposition in Alzheimer's Disease (AD), requires model systems that accurately recapitulate human neurobiology. Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized this field by enabling the generation of patient-specific neural cells and tissues. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of three primary iPSC-derived neural modeling systems—two-dimensional (2D) cultures, neurospheres, and brain organoids—within the specific context of Aβ pathology research. These systems offer varying levels of biological complexity, from basic cellular monolayers to sophisticated three-dimensional (3D) structures that mimic the human brain's cellular diversity, spatial organization, and functional connectivity [27] [28]. For AD research, particularly the study of Aβ deposition and clearance, the choice of model system significantly impacts the physiological relevance of findings and their translational potential for drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Neural Modeling Platforms

The selection of an appropriate neural model depends on the specific research questions, with each platform offering distinct advantages and limitations for studying Aβ pathology.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Neural Modeling Systems for Amyloid-Beta Research

| Model Characteristic | 2D Cultures | Neurospheres | Brain Organoids |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Complexity | Low (monolayer) | Intermediate (3D spheroid) | High (3D, self-organizing) |

| Cellular Diversity | Limited (typically 1-2 cell types) | Moderate (multiple neural cell types) | High (diverse neurons, glia, progenitors) [27] |

| Spatial Architecture | Absent | Limited organization | Recapitulates embryonic brain regions [28] |

| Physiological Relevance to Aβ Pathology | Basic cell-autonomous mechanisms | Improved cell-cell interactions | Human-relevant cell-cell interactions & tissue microenvironment [27] |

| Throughput for Drug Screening | High | Moderate | Moderate to Low [28] |

| Technical Reproducibility | High | Moderate | Variable (batch-to-batch heterogeneity) [28] |

| Modeling Aβ Deposition & Clearance | Limited to intracellular processes | Improved extracellular modeling | Captures extracellular aggregation & complex cell interactions [29] [28] |

| Suitability for BBB Interaction Studies | Limited (can model monolayers) | Limited | Enhanced (especially in vascularized or assembloid models) [27] [29] |

Table 2: Application-Specific Assessment for Aβ Research

| Research Application | Recommended Model | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Compound Screening | 2D Cultures | Superior throughput and reproducibility for initial screens [28] |

| Mechanistic Studies of Aβ Toxicity | 2D Cultures / Neurospheres | Controlled environment for dissecting specific pathways |

| Aβ Aggregation & Plaque Formation | Brain Organoids | 3D microenvironment promotes in vivo-like extracellular aggregation [28] |

| Cell-Type Specific Contributions to Aβ Pathology | Brain Organoids | Diverse cellular repertoire enables study of neuron-glia interactions |

| Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) & Aβ Clearance | BBB-specific Organoids / Assembloids | Models neurovascular unit interactions; demonstrates isoform-dependent Aβ clearance [29] |

| Genetic (APOE) Risk Factor Studies | Isogenic Brain Organoids | Controlled genetic background isolates isoform-specific effects on Aβ pathology [29] |

Experimental Protocols for Model Generation

Protocol 1: Generation of Cortical Brain Organoids for Aβ Pathology Modeling

This guided protocol generates region-specific cortical organoids suitable for studying Aβ deposition mechanisms.

Key Reagents:

- Basal Medium: DMEM/F12 [29]

- Neural Induction Supplements: N-2 Supplement, B-27 Supplement (serum-free) [29]

- Small Molecule Patterning Factors: SMAD inhibitors (e.g., Dorsomorphin, SB431542) [28], Retinoic Acid [29]

- Growth Factors: FGF-2 (basic fibroblast growth factor) [29]

- Extracellular Matrix: Matrigel or Geltrex for embedding [28]

Procedure:

- iPSC Maintenance: Culture human iPSCs on a Matrigel-coated surface in mTESR1 medium, passaging as clumps using EDTA or enzymatic dissociation to maintain pluripotency [29].

- Embryoid Body (EB) Formation: Dissociate iPSCs to single cells using Accutase and aggregate 9,000 cells per well in a 96-well U-bottom low-attachment plate in neural induction medium (DMEM/F12, N2, B27, FGF-2) supplemented with SMAD inhibitors [28].

- Neural Induction: Culture EBs for 5-7 days, with medium changes every other day, to form neuroepithelium.

- Matrigel Embedding and Guided Cortical Patterning: On day 7, individually embed EBs in Matrigel droplets. Transfer to orbital shaker and culture in neuronal differentiation medium (DMEM/F12, N2, B27) with dual SMAD inhibition and FGF-2 to promote telencephalic fate for an additional 7-10 days [28].

- Terminal Differentiation and Maturation: After 15-18 days total, transition organoids to a terminal differentiation medium (DMEM/F12, N2, B27, BDNF, GDNF) and culture for up to 3 months on an orbital shaker, with medium changes twice weekly, to promote neuronal maturation and network formation [28].

Protocol 2: Establishing a BBB Assay Using iPSC-Derived Cells for Aβ Clearance Studies

This protocol details the creation of a blood-brain barrier (BBB) model to investigate Aβ transcytosis, a critical clearance pathway [29].

Key Reagents:

- Basal Media: DMEM/F12, Knock-out DMEM [29]

- Specialized Media: Unconditioned Medium (UM), Human Endothelial Serum-Free Medium (hECSR) [29]

- Critical Factors: Retinoic Acid [29]

Procedure for Differentiating BMEC-like cells:

- iPSC Expansion: Culture and expand iPSCs on Matrigel in mTESR1 medium [29].

- Mesodermal Induction (6 days): Singularize iPSCs with Accutase and plate at 30,000 cells/cm². Induce differentiation by replacing mTESR1 with Unconditioned Medium (UM). Change UM daily for 6 days [29].

- Endothelial Patterning (2 days): On day 6, switch to hECSR medium supplemented with 10 µM retinoic acid to specify a brain microvascular endothelial cell (BMEC) fate. Culture for 48 hours [29].

- Cell Purification and Seeding: On day 8, purify BMEC-like cells using a CD271+ neural crest microbead kit or similar endothelial selection method. Seed the purified cells onto collagen IV-coated Transwell filters for permeability and transcytosis assays [29].

Aβ Transcytosis Assay:

- Seed purified BMEC-like cells onto collagen IV-coated Transwell inserts and culture until a tight monolayer forms, confirmed by Trans-Endothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) measurement.

- Add fluorescently labeled or otherwise detectable Aβ peptides (e.g., Aβ40 or Aβ42) to the upper (brain) chamber.

- Measure the rate of Aβ appearance in the lower (blood) chamber over time using an appropriate detection method (e.g., fluorescence, ELISA).

- To investigate specific pathways, inhibit key transporters like LRP1 or p-glycoprotein with pharmacological inhibitors and compare Aβ flux to untreated controls [29].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows in Organoid Modeling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for iPSC-Based Neural Modeling and Aβ Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Base Media | DMEM/F12, Knock-out DMEM, Essential 6 Medium [29] | Foundation for all culture and differentiation media. |

| Induction & Patterning Factors | SMAD Inhibitors (Dorsomorphin, SB431542), Retinoic Acid, FGF-2 [29] [28] | Direct pluripotent stem cell fate toward specific neural and regional identities. |

| Culture Supplements | N-2 Supplement, B-27 Supplement, BSA, Lipid Concentrate [29] | Provide essential nutrients, hormones, and lipids for cell survival and specialization. |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Geltrex, Collagen IV [29] [28] | Provide structural support and biochemical cues to mimic the native cellular microenvironment. |

| Dissociation Enzymes | Accutase, Collagenase/Dispase [29] | Gentle dissociation of cells for passaging and downstream analysis. |

| Differentiation Factors | BDNF, GDNTF [28] | Promote neuronal maturation, survival, and synaptic connectivity in later stages. |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems, Isogenic iPSC lines [30] [29] | Create precise disease models and isogenic controls to study specific genetic risk factors like APOE. |

| Analysis Kits & Assays | CellTiter-Glo 3D, ELISA kits for Aβ, TEER Measurement equipment [31] [29] | Assess viability, quantify Aβ peptides, and measure barrier integrity in 3D models and BBB assays. |

Alzheimer's disease (AD) research has entered a transformative phase with the recognition that neuroglial cells—microglia and astrocytes—are not passive bystanders but active contributors to disease pathogenesis. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified numerous AD risk genes highly expressed in microglia and astrocytes, highlighting their potential role in amyloid-β (Aβ) metabolism and clearance [32] [9] [33]. While microglia possess phagocytic capacity and have been implicated in Aβ clearance, accumulating evidence suggests their contribution to AD pathogenesis is more complex than initially anticipated [32]. Similarly, astrocytes, the most abundant glial cells in the brain, play crucial roles in maintaining brain homeostasis but become dysfunctional in AD, affecting Aβ production and clearance [33].

The limitations of traditional mouse models in fully recapitulating human AD pathology, combined with the failure of promising therapeutics in human clinical trials, have underscored the need for more physiologically relevant human cellular models [9]. The advent of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized AD research by providing a renewable source of human brain cells, including microglia and astrocytes [34] [22]. This technical guide explores the latest methodologies for generating and utilizing iPSC-derived microglia and astrocytes to study their complex roles in Aβ clearance, providing researchers with comprehensive protocols and analytical frameworks for advancing our understanding of AD pathophysiology.

Microglia in Aβ Clearance: Dual Roles in Protection and Pathogenesis

Developmental Ontogeny and Generation of iPSC-Derived Microglia

Microglia originate from yolk sac erythromyeloid progenitors (EMP) generated during primitive hematopoiesis, a developmental pathway that must be recapitulated for authentic iPSC differentiation [34]. A robust two-step protocol generates human microglial-like cells (iMGLs) from iPSCs in approximately five weeks [34]. The initial stage involves differentiating iPSCs to hematopoietic progenitors (iHPCs) representing early primitive hematopoietic cells, which are then cultured in serum-free differentiation medium containing critical cytokines—CSF-1, IL-34, and TGFβ1—to drive microglial commitment [34].

The resulting iMGLs closely resemble human fetal and adult microglia at the transcriptomic level, expressing canonical microglial genes including P2RY12, GPR34, C1Q, TREM2, and PROS1 [34]. Functional characterization confirms that iMGLs secrete cytokines in response to inflammatory stimuli, migrate, undergo calcium transients, and robustly phagocytose CNS substrates [34]. This protocol typically yields 30-40 million iMGLs from one million iPSCs, enabling scalable experiments including high-content screening applications [34].

Molecular Mechanisms of Microglial Aβ Clearance

Microglia interact with different forms of Aβ through distinct molecular mechanisms. Soluble Aβ is taken up through macropinocytosis and LDL receptor-related proteins (LRPs)-mediated pathways, while fibrillar Aβ interacts with cell surface innate immune receptor complexes that initiate intracellular signaling cascades stimulating phagocytosis [35]. Key receptors and signaling molecules involved in these processes include:

Table 1: Key Molecular Mediators of Microglial Aβ Clearance

| Molecule | Function in Aβ Clearance | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| TREM2 | Recognizes Aβ oligomers and fibrils; regulates phagocytosis; promotes microglial clustering around plaques | TREM2 deficiency enhances Aβ pathology; agonistic antibodies enhance phagocytosis [32] |

| SYK | Downstream signaling molecule necessary for Aβ uptake | SYK inhibition impairs microglial Aβ phagocytosis [32] |

| CD33 | Negatively regulates Aβ uptake by suppressing TREM2 signaling | CD33 overexpression reduces Aβ phagocytosis [32] |

| Axl/Mertk | Recognize phosphatidylserine co-deposited with amyloid plaques | TAM receptor family members facilitate Aβ clearance [32] |

| Piezo1 | Mechanosensing receptor recognizing plaque stiffness | Contributes to Aβ phagocytosis by sensing physical properties [32] |

| Scavenger Receptors | Multiple receptors (MSR1, CD36, SR-BI, RAGE) with Aβ binding capacity | Involvement in Aβ binding and internalization [32] |

The role of microglia in Aβ clearance appears to be context-dependent, varying with disease progression, genetic background, and experimental conditions [32]. Surprisingly, some microglial depletion experiments have resulted in unchanged or even decreased Aβ accumulation, challenging conventional views of their exclusively protective function [32]. This paradox may be explained by recent findings that microglia can promote parenchymal amyloid accumulation in early disease stages through mechanisms such as intracellular Aβ aggregation and release of pro-aggregation factors [32].

Signaling Pathways in Microglial Aβ Clearance

The following diagram illustrates the major receptors and signaling pathways involved in microglial Aβ clearance, highlighting potential therapeutic targets:

Astrocytes in Aβ Metabolism: Beyond Passive Support Cells

Generation and Characterization of iPSC-Derived Astrocytes

Human iPSC-derived astrocytes can be differentiated from long-term neuroepithelial-like stem (ltNES) cells through sequential treatment with specific growth factors including bFGF, heregulin, activin A, IGF-1, and CNTF [36]. The resulting astrocytes express characteristic markers and perform essential functions including trophic support, synapse formation, neurotransmission regulation, calcium homeostasis, and immune response control [33].

Notably, healthy hiPSC-derived astrocytes secrete β-amyloid (Aβ) and play important roles in APP processing, suggesting they have the potential to contribute to Aβ accumulation in AD brains [33]. Astrocytes derived from early-onset AD patients carrying the PSEN1ΔE9 mutation display AD hallmarks including increased Aβ and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, altered inflammatory responses, and dysregulated calcium homeostasis compared to isogenic control astrocytes [33].

Astrocyte Dysfunction in AD Pathogenesis

In AD, astrocytes undergo profound molecular, morphological, and functional alterations that arise at early stages and exacerbate as disease evolves [33]. Key aspects of astrocyte dysfunction include:

Table 2: Astrocyte Dysfunctions in Alzheimer's Disease

| Dysfunction Category | Specific Alterations | Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Aβ Metabolism | Increased Aβ secretion; impaired Aβ clearance | Contributes to amyloid accumulation; reduced plaque clearance |

| Lipid/Cholesterol Metabolism | Disrupted cholesterol biosynthesis and transport; APOE4-associated defects | Impaired neuronal support; enhanced Aβ aggregation |

| Inflammatory Response | Elevated proinflammatory cytokine secretion; C3 complement activation | Enhanced neuroinflammation; synaptic pruning defects |

| Calcium Homeostasis | Dysregulated calcium signaling | Disrupted neuron-astrocyte communication |

| Oxidative Stress | Increased ROS production | Neuronal damage; cellular stress |

APOE genotype profoundly influences astrocyte function in AD. Astrocytes are the major cell type expressing and producing Apolipoprotein E (APOE) in the brain, and the APOE4 variant confers the greatest genetic risk for late-onset AD [33]. iPSC-derived astrocytes carrying the APOE4 variant produce and secrete less APOE protein compared to APOE3 astrocytes, are less efficient at clearing extracellular Aβ, and show impaired lipid/cholesterol metabolism and increased inflammatory responses [33]. When co-cultured with neurons, APOE4 astrocytes provide less support for neuronal survival and synaptogenesis while exacerbating neuroinflammation [33].

Experimental Evidence of Astrocyte-Mediated Aβ Clearance Dysfunction

A critical study demonstrated that astrocytes exposed to sonicated Aβ42 fibrils develop intracellular Aβ deposits that severely impact their ability to support neuronal function [36]. Electrophysiological recordings revealed significantly decreased frequency of excitatory post-synaptic currents in neurons co-cultured with Aβ-exposed astrocytes, while conditioned media from these astrocytes had the opposite effect, resulting in synaptic hyperactivation [36]. This suggests that factors secreted from control, but not from Aβ-exposed astrocytes, benefit neuronal wellbeing, and that reactive astrocytes with Aβ inclusions fundamentally alter neuronal network activity [36].

Advanced iPSC-Based Model Systems for Studying Aβ Clearance

Monoculture vs. Co-culture Systems

Reductionist monoculture systems have provided valuable insights into cell-autonomous functions of microglia and astrocytes, but co-culture models better approximate the cellular crosstalk occurring in the AD brain:

- Microglia-Neuron Co-cultures: iMGLs can be co-cultured with iPSC-derived neurons to study synaptic pruning mechanisms and neuroinflammatory responses to Aβ pathology [34].

- Astrocyte-Neuron Co-cultures: Control astrocytes support neuronal survival and synaptogenesis, while Aβ-exposed astrocytes lead to decreased excitatory post-synaptic currents and compromised neuronal viability [36].

- Microglia-Astrocyte-Neuron Tri-cultures: Advanced tri-culture systems demonstrate that astrocyte-secreted interleukin-3 (IL-3) reprograms microglia, enhancing their capacity to cluster and clear Aβ and Tau aggregates [33]. Inflammatory conditions in tri-cultures also increase production of complement protein C3 through reciprocal astrocyte-microglia signaling [33].

3D Organoid and Cerebral Organoid Models

3D cerebral organoids generated from iPSCs represent a significant advancement, modeling early AD-like pathology in a more physiologically relevant context [15] [37]. These self-assembled structures recapitulate aspects of complex pathophysiology, including neuronal network dysfunction and accumulation of pathogenic proteins [15]. When exposed to Aβ, cerebral organoids show deposition in their outer layers, suppressed neural activity, and increased apoptotic signaling [37]. Notably, oxytocin demonstrated protective effects in these models, reducing Aβ deposition and apoptosis while enhancing microglial phagocytosis via OXTR and TREM2 upregulation [37].

Transplantation Models

iMGLs transplanted into transgenic mice and human brain organoids resemble microglia in vivo, providing a chimeric model system to study human microglial function in a more complex environment [34]. Similarly, transplantation of human astrocytes into AD model mouse brains offers unique opportunities to analyze human astrocyte dysfunction in vivo [33]. These chimeric approaches combine the strengths of in vitro and in vivo systems, allowing for investigation of human glial cell function within the context of a living brain.

Methodologies for Functional Assessment of Aβ Clearance

Experimental Protocols for Aβ Phagocytosis and Clearance Assays

Microglial Phagocytosis Assay:

- Generate iMGLs using the two-step differentiation protocol [34].

- Label Aβ42 monomers with HiLyte Fluor 555 and aggregate into insoluble fibrils by incubation on a shaker at 1500 rpm, 37°C for 4 days [36].

- Sonicate Aβ42 fibrils at 20% amplitude, 1s on/off pulses for 1 minute before use to facilitate cellular uptake [36].

- Expose iMGLs to 200 nM sonicated Aβ-F for 48 hours in serum-free differentiation medium.