Modeling Parkinson's Disease: How iPSC Technology is Unraveling Pathogenesis and Accelerating Therapy

This article provides a comprehensive overview of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) models and their transformative role in Parkinson's disease (PD) research.

Modeling Parkinson's Disease: How iPSC Technology is Unraveling Pathogenesis and Accelerating Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) models and their transformative role in Parkinson's disease (PD) research. It covers the foundational principles of recapitulating PD pathology in patient-specific neurons, explores advanced methodological applications in disease modeling and drug screening, addresses key challenges and optimization strategies for robust model systems, and validates iPSC models against traditional preclinical approaches. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current evidence and highlights the direct clinical translation of these technologies, including recent trial results, to illustrate their potential in creating a new paradigm for understanding and treating PD.

Recapitulating Parkinson's Pathology: From Patient Cells to Disease-Relevant Neurons

The pursuit of effective treatments for Parkinson's disease (PD) has been persistently hampered by the inadequacy of animal models to fully recapitulate human-specific disease pathogenesis. The emergence of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has inaugurated a transformative era in neurodegenerative disease research. This whitepaper delineates the core challenge of modeling PD and elaborates on how patient-specific iPSCs are being leveraged to create human-relevant models for investigating disease mechanisms and advancing drug discovery. We detail experimental methodologies for generating and characterizing iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons, present quantitative data from recent pioneering clinical trials, and provide a curated toolkit of essential research reagents. By integrating advanced genomic engineering with complex culture systems, iPSC-based models are overcoming traditional species barriers, offering an unprecedented platform for elucidating the human-specific pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease.

Parkinson's disease stands as the second most common neurodegenerative disorder worldwide, affecting millions and posing an escalating societal burden as global populations age [1] [2]. The core pathological hallmark of PD is the progressive loss of dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta, leading to the characteristic motor symptoms of tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability [3] [4]. A critical barrier to developing disease-modifying therapies has been the lack of accurate models that capture the human-specific complexities of PD pathogenesis. Traditional animal models, while valuable for studying certain aspects of disease, fail to replicate the unique vulnerabilities of human neurons and the multifaceted interplay of genetic and environmental factors that drive disease progression in humans [3].

The discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by Shinya Yamanaka and colleagues established a watershed moment, creating new possibilities for modeling human diseases [5] [3]. iPSCs are generated by reprogramming patient-specific somatic cells back to a pluripotent state through the introduction of key transcription factors, notably OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC [5] [3]. These patient-derived cells offer two profound advantages: they circumvent the ethical concerns associated with human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), and they provide a platform for studying disease processes in the exact genetic background of patients [4]. For a complex, multifactorial disorder like Parkinson's disease, where both genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures contribute to pathogenesis, iPSC technology represents a paradigm shift for creating human-specific disease models that can bridge the translational gap between preclinical research and effective clinical therapeutics [1] [3].

Foundations of iPSC Technology

Generation of Footprint-Free iPSCs

The initial methods for generating iPSCs relied on integrating viral vectors, such as retroviruses or lentiviruses, which carried the risk of insertional mutagenesis and oncogenic transformation, particularly concerning since c-MYC and KLF4 are known oncogenes [3]. To overcome these limitations for both research and clinical applications, significant efforts have been directed at developing non-integrating, "footprint-free" reprogramming methods that leave the genome intact [3]. The following table summarizes the primary approaches:

Table 1: Footprint-Free Reprogramming Methods for iPSC Generation

| Method | Mechanism | Key Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Episomal Plasmids | Non-integrating plasmids that support prolonged transgene expression. | Simple, robust; plasmids are gradually diluted and lost during cell divisions. | [3] |

| Sendai Virus (SeV) | RNA virus that replicates in the cytoplasm without integrating into the host genome. | Highly efficient; virus is gradually diluted and degraded with cell division. | [3] |

| Synthetic mRNA | Modified mRNAs encoding reprogramming factors are transfected into cells. | High efficiency; requires repeated transfections and careful control of immune response. | [3] |

| Recombinant Proteins | Reprogramming factors fused with cell-penetrating peptides (e.g., TAT) are delivered directly. | No genetic material introduced; efficiency can be lower. | [3] |

Characterization and Validation of Pluripotency

Following reprogramming, putative iPSC colonies must be rigorously characterized to confirm their pluripotent state. This involves a multi-faceted approach assessing key markers and functional capacities [5]:

- Morphology: Colonies should exhibit classic embryonic stem cell-like morphology, with a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio and prominent nucleoli.

- Surface Marker Expression: Flow cytometry or immunocytochemistry confirms the expression of characteristic pluripotency antigens such as SSEA-4 and TRA-1-80 [5].

- Pluripotency Potential: The gold standard functional test is the demonstration of differentiation into derivatives of all three germ layers. This can be assessed in vitro via spontaneous formation of embryoid bodies (EBs), with subsequent immunostaining for markers like alpha-fetoprotein (AFP, endoderm), β-III-tubulin (B-III-TUB, ectoderm), and smooth-muscle antibody (SMA, mesoderm) [5]. Alternatively, the in vivo teratoma formation test can be used, wherein iPSCs are injected into immunocompromised mice and the resulting tumors are examined for tissues from all three germ layers [5].

Modeling Parkinson's Disease with iPSC-Derived Neurons

Differentiation into Midbrain Dopaminergic Neurons

A critical step in modeling PD is the efficient and specific differentiation of iPSCs into authentic midbrain-like DA neurons. Protocols have evolved significantly from early methods that involved embryoid body formation or stromal cell co-culture (PA6/SDIA) [4]. The current state-of-the-art leverages knowledge of developmental biology to direct differentiation through a floor-plate intermediate, mimicking the natural origin of these neurons in the embryo [6] [7].

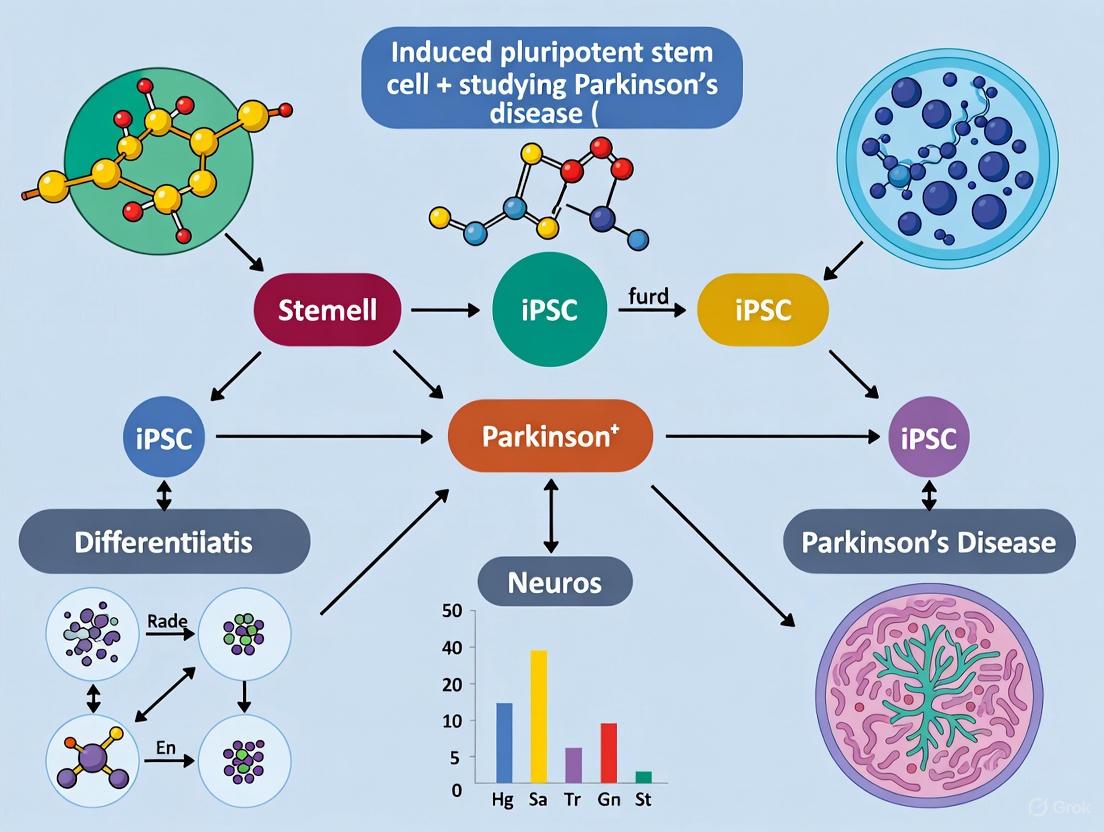

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for the generation and application of iPSC-derived DA neurons for Parkinson's disease research:

Diagram 1: Workflow for iPSC-Derived PD Modeling

Detailed Protocol for DA Neuron Differentiation: A typical protocol involves several key stages [4]:

- Neural Induction and Patterning (Days 1-12): iPSCs are transitioned to neural medium. To specify a midbrain fate, key developmental morphogens are added. Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) is used to ventralize the neural tissue, while FGF8 acts as a caudalizing factor, together patterning the cells toward a midbrain floor-plate identity. This stage can be monitored by the emergence of markers like FOXA2 and LMX1A.

- Progenitor Expansion (Days 12-20): The neural progenitor cells are maintained and expanded in the presence of SHH and FGF8, along with Ascorbic Acid (AA), which promotes progenitor survival and dopaminergic fate.

- Terminal Differentiation (Days 20+): Cells are dissociated and replated. Morphogens are withdrawn, and the culture is switched to a terminal differentiation medium containing neurotrophic factors such as Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF), and TGF-β3, as well as cAMP. These factors support the maturation, survival, and phenotypic stability of the emerging DA neurons, which begin expressing tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis, and other markers like NURR1 and PITX3.

To enrich for the correct population, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) can be used to select cells expressing the surface marker CORIN, a floor-plate marker, thereby purifying the DA progenitor pool before final differentiation [6].

Advanced Model Systems: From 2D to 3D and Co-cultures

While 2D monolayers of iPSC-derived DA neurons are valuable, the brain is a complex 3D environment with multiple interacting cell types. To better model PD pathogenesis, the field is advancing toward more sophisticated systems [1] [5]:

- Co-culture Systems: Culturing iPSC-derived neurons alongside iPSC-derived astrocytes or microglia provides critical insights into cell-cell interactions, neuroinflammation, and non-cell-autonomous mechanisms of neurodegeneration [1] [8]. For instance, microglia derived from PD patients may have impaired phagocytosis of alpha-synuclein or may release pro-inflammatory cytokines that exacerbate neuronal damage.

- 3D Organoids: These self-organizing, three-dimensional structures more closely mimic the cellular diversity and spatial organization of the human brain. Brain region-specific organoids can model interregional disease processes and network-level dysfunctions observed in PD [1]. The integration of midbrain-specific organoids with other regions like the cortex or striatum in assembloids is a cutting-edge approach to study circuit-level vulnerabilities.

Phenotypic Analysis and Key Pathogenic Insights

iPSC-derived DA neurons from patients with both familial and sporadic forms of PD have successfully recapitulated key aspects of the disease pathology, validating their use for mechanistic studies. The following table summarizes major phenotypes observed in models based on specific genetic mutations:

Table 2: Key Phenotypes in iPSC-Derived DA Neurons from Familial PD Patients

| Gene/Protein | Mutation | Observed Phenotypes in iPSC-Derived DA Neurons | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-synuclein (SNCA) | A53T / Triplication | Elevated α-synuclein levels, endoplasmic reticulum stress, nitrosative stress, increased reactive oxygen species, reduced neurite outgrowth. | [3] |

| LRRK2 | G2019S | Elevated α-synuclein, increased susceptibility to oxidative stress (H₂O₂), impaired neurite outgrowth, mitochondrial dysfunction, delayed initiation of mitophagy. | [3] |

| Parkin (PARK2) | Deletions (Exon 3/5) | Mitochondrial dysfunction, increased sensitivity to cellular stress. | [3] |

| PINK1 | Point Mutations | Mitochondrial impairments, similar to Parkin mutations, consistent with their shared pathway in mitophagy. | [3] |

These convergent phenotypes, particularly around mitochondrial health and protein homeostasis, across multiple genetic forms of PD point toward shared downstream pathogenic pathways, offering validated targets for therapeutic intervention.

Clinical Translation and Validation

The ultimate validation of iPSC-based models comes from their successful translation into clinical therapies. Recent landmark clinical trials have demonstrated the safety and potential efficacy of transplanting iPSC-derived dopaminergic progenitors into PD patients, marking a historic milestone for the field.

Table 3: Summary of Recent Stem Cell-Based Clinical Trials for Parkinson's Disease

| Trial Parameter | Kyoto University Trial (iPSC-Derived) | Bemdaneprocel Trial (hESC-Derived) |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Source | Allogeneic iPSCs from HLA-homozygous donor | Human Embryonic Stem Cells (hESCs) |

| Study Phase | Phase I/II | Phase I |

| Patients Enrolled | 7 (for safety), 6 (for efficacy) | 12 |

| Dosing | Low: 2.1-2.6 million cells/hemisphereHigh: 5.3-5.5 million cells/hemisphere | Low: 0.9 million cells/putamenHigh: 2.7 million cells/putamen |

| Immunosuppression | Tacrolimus (15 months) | 1 year (Basiliximab, steroids, tacrolimus) |

| Primary Safety Outcome | No serious adverse events; 73 mild-moderate events. | No adverse events related to cell product; 2 serious AEs (seizure, COVID-19) unrelated to cells. |

| Efficacy Signal (Motor) | MDS-UPDRS Part III OFF score improved by 9.5 pts (20.4%) on average at 24 months. | MDS-UPDRS Part III OFF score improved by 23 pts on average in high-dose cohort at 18 months. |

| Dopamine Production | 18F-DOPA PET Ki values increased by 44.7% in putamen. | Increased 18F-DOPA PET uptake in putamen at 18 months. |

| Reference | [6] | [7] |

These trials confirm that stem cell-derived dopaminergic progenitors can survive engraftment, produce dopamine, and improve motor function in patients without forming tumors, providing a powerful proof-of-concept for the entire iPSC modeling and drug discovery pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and tools essential for conducting research using iPSC models of Parkinson's disease.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC-based PD Modeling

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (Yamanaka factors) | Epigenetic reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. |

| Neural Patterning Factors | Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), FGF8, CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor) | Directs differentiation toward midbrain floor-plate and dopaminergic progenitor fate. |

| Neuronal Maturation Factors | BDNF, GDNF, Ascorbic Acid (AA), TGF-β3, cAMP | Supports survival, maturation, and phenotypic stability of dopaminergic neurons. |

| Cell Sorting Markers | CORIN, LMX1A, FOXA2 | Identification and purification of dopaminergic progenitors via FACS. |

| Characterization Antibodies | Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH), NURR1, β-III-Tubulin, MAP2 | Immunocytochemical validation of dopaminergic neuronal identity and maturity. |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, gRNA designs | Creation of isogenic control lines; introduction or correction of disease-associated mutations. |

The core challenge of modeling a human-specific neurodegenerative disease like Parkinson's is being met through the continuous refinement of iPSC-based technologies. Future directions will focus on increasing model complexity and physiological relevance. This includes the development of more sophisticated blood-brain barrier (BBB) models to study toxin permeability and drug delivery, the integration of advanced omics technologies (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to deconstruct disease pathways, and the application of high-content imaging and electrophysiology to quantify dynamic disease phenotypes in real-time [1] [8]. Furthermore, the combination of iPSCs with gene editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 allows for the creation of isogenic control lines—genetically identical cells where only the disease-causing mutation has been corrected—which serve as the perfect experimental control for discerning true disease-related phenotypes from background genetic noise [5] [3].

In conclusion, iPSC technology has fundamentally altered the landscape of Parkinson's disease research. By providing a patient-specific, human-relevant platform, it overcomes the longstanding limitations of animal models. The successful differentiation of iPSCs into vulnerable midbrain dopaminergic neurons, the recapitulation of key pathological features in vitro, and the recent triumphant translation into early-stage clinical trials collectively affirm that iPSC models are an indispensable tool for unraveling pathogenesis and accelerating the development of much-needed therapeutic interventions for Parkinson's disease.

The advent of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has revolutionized biomedical research, providing an unprecedented platform for studying human development, disease modeling, and developing regenerative therapies. This technology enables the reprogramming of somatic cells back to a pluripotent state, allowing them to differentiate into any cell type in the body. For research on Parkinson's disease (PD) pathogenesis, iPSC technology offers a powerful tool to generate patient-specific dopaminergic neurons, the primary cells affected in PD, facilitating the study of disease mechanisms in a human-relevant context [9] [10]. This technical guide details the fundamental principles, methods, and applications of somatic cell reprogramming, with a specific focus on its critical role in advancing PD research.

Historical Foundation and Core Principles

The conceptual foundation for iPSC technology was laid by pioneering work in nuclear reprogramming. John Gurdon's seminal somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) experiments in 1962 demonstrated that a nucleus from a differentiated somatic cell could be reprogrammed to support the development of an entire organism, proving that the genetic material in somatic cells remains intact and could be reversed to an embryonic state [11]. This established the principle of cellular plasticity – that cell fate is not irreversible but can be altered by factors in the cellular environment.

The direct generation of iPSCs was achieved by Shinya Yamanaka's team in 2006. Through a systematic screening of factors important for maintaining embryonic stem cell (ESC) identity, they identified four key transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (collectively known as the OSKM or Yamanaka factors)—that were sufficient to reprogram mouse fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells [12] [11]. This groundbreaking discovery was rapidly followed in 2007 with the successful generation of human iPSCs, both by Yamanaka's group using the OSKM factors and by James Thomson's team using an alternative combination: OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28 [12] [11]. These breakthroughs opened the door to creating patient-specific pluripotent cells without the ethical concerns associated with human embryos.

The reprogramming process involves a profound epigenetic remodeling, where the somatic cell's gene expression pattern is erased and replaced with a pluripotency network. This process occurs in phases: an early, stochastic phase where somatic genes are silenced and early pluripotency genes are activated, followed by a more deterministic late phase where the stable pluripotent state is established [11]. A key morphological event during fibroblast reprogramming is the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), which is critical for establishing the epithelial characteristics of pluripotent stem cells [11].

Molecular Mechanisms of Reprogramming

The reprogramming of a somatic cell to a pluripotent state is driven by the coordinated action of the Yamanaka factors, which function to dismantle the somatic gene expression program and activate the endogenous pluripotency network.

- Core Pluripotency Factors: OCT4 (encoded by POU5F1) and SOX2 are central transcription factors that form a core regulatory circuit to activate the expression of genes essential for self-renewal and pluripotency, while simultaneously repressing genes involved in differentiation [12] [13]. They play non-redundant roles, and neither can be omitted from the reprogramming cocktail.

- Supporting Factors: KLF4 assists in the activation of pluripotency genes and contributes to the MET process. c-MYC, a potent oncogene, primarily enhances reprogramming efficiency by promoting widespread changes in chromatin structure and boosting cell proliferation, thereby facilitating the access of other factors to their target genes [12] [13]. Due to its tumorigenic potential, c-MYC is often considered dispensable, and safer family members like L-MYC can be used as substitutes [12].

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular stages and signaling pathways involved in the reprogramming process:

Reprogramming Methods and Delivery Systems

A critical aspect of iPSC generation is the method used to deliver the reprogramming factors into the somatic cell. Each method balances reprogramming efficiency with safety concerns, particularly the risk of genomic integration and potential tumorigenesis.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Reprogramming Factor Delivery Systems

| Delivery System | Genetic Material | Genomic Integration | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrovirus | DNA | Yes | High efficiency; Robust reprogramming | Integrates into genome; Reactivation of transgenes [12] [13] |

| Lentivirus | DNA | Yes | Can infect non-dividing cells; High efficiency | Integrates into genome; Complex production [13] |

| Sendai Virus | RNA | No | High efficiency; Non-integrating; Can be diluted out | Viral clearance required; Immunogenic potential [13] |

| Episomal Plasmid | DNA | No (typically) | Non-integrating; Simple production | Low efficiency; Requires repeated transfection [13] |

| Synthetic mRNA | RNA | No | High efficiency; Non-integrating; Controlled timing | Immunogenic; Requires daily transfection [13] |

| Recombinant Protein | Protein | No | Non-integrating; No genetic material | Very low efficiency; Technically challenging [12] |

Beyond the original Yamanaka factors, research has identified numerous alternative reprogramming factors and small molecules that can enhance efficiency and safety. Factors like SALL4, NR5A2, and GLIS1 can substitute for core factors or complement the OSKM combination [12] [13]. Small molecule compounds have been used to replace specific transcription factors; for example, RepSox can replace Sox2 [12]. Furthermore, fully chemical reprogramming using defined small molecule cocktails has been achieved, representing a completely non-genetic approach to generating iPSCs [12] [11]. Epigenetic modulators such as valproic acid (VPA), sodium butyrate, and trichostatin A can significantly enhance reprogramming efficiency by opening chromatin structure and facilitating the activation of pluripotency genes [12] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for iPSC Generation

Successful reprogramming requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key components of a researcher's toolkit for generating and validating iPSCs.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Generation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|

| Core Reprogramming Factors | OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) or OSNL (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28) cocktails | Initiate and drive the epigenetic and transcriptional remodeling toward pluripotency [12] [11] |

| Efficiency Enhancers | Valproic Acid (VPA), Sodium Butyrate, Trichostatin A, 5'-azacytidine | Histone deacetylase inhibitors and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors that open chromatin to improve factor access [12] [13] |

| Signaling Pathway Modulators | CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor), A-83-01 (TGF-β receptor inhibitor), PD0325901 (MEK inhibitor) | Enhance reprogramming efficiency by modulating key signaling pathways like WNT and TGF-β [13] |

| Source Somatic Cells | Dermal fibroblasts, Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs), Renal epithelial cells from urine | Provide the starting genetic material for reprogramming; choice affects efficiency and practicality [13] |

| Pluripotency Validation | Antibodies against OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60 | Used in immunocytochemistry or flow cytometry to confirm protein expression of pluripotency markers [11] |

Application to Parkinson's Disease Research

The ability to generate iPSCs from PD patients and differentiate them into dopaminergic neurons has transformed the landscape of PD research. Patient-specific iPSCs capture the individual's entire genetic background, including mutations in genes like SNCA (encoding α-synuclein) and LRRK2 that are linked to PD, thereby providing a unique humanized model to study the disease [14] [9] [10].

The standard workflow involves:

- Reprogramming: Generating iPSCs from a PD patient's somatic cells (e.g., skin fibroblasts or blood cells) using a non-integrating method like Sendai virus or episomal plasmids for clinical relevance [13].

- Directed Differentiation: Differentiating the iPSCs into midbrain dopaminergic neurons. This is achieved by mimicking embryonic development through the sequential use of small molecules and growth factors that activate specific signaling pathways, such as SMAD inhibition, followed by SHH activation and WNT activation to pattern the cells toward a midbrain fate [15] [10]. Key transcription factors like LMX1A and FOXA2 are critical markers of successful differentiation.

- Disease Modeling and Drug Screening: The resulting dopaminergic neurons can be used to investigate disease-specific phenotypes, such as α-synuclein aggregation (a key component of Lewy bodies), mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuronal vulnerability [14] [9]. These cells serve as a platform for high-throughput drug screening to identify compounds that can mitigate the observed pathological features.

The following diagram outlines this applied workflow for Parkinson's disease research:

Furthermore, the integration of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing allows for the correction of disease-causing mutations in patient-derived iPSCs, creating isogenic control lines that are genetically identical except for the mutation of interest. This powerful approach enables researchers to conclusively link observed cellular pathologies to specific genetic defects [13]. The emergence of 3D organoid models from iPSCs offers an even more sophisticated system, allowing for the study of dopaminergic neurons in a tissue-like context that includes other cell types, such as glia, potentially revealing novel cell-cell interactions critical to PD pathogenesis [15] [10].

The fundamental technology of reprogramming somatic cells to pluripotence has evolved from a groundbreaking discovery into a robust and essential tool for modern biological research. A deep understanding of the molecular mechanisms, delivery methods, and reagent options is crucial for the effective generation and application of iPSCs. In the specific context of Parkinson's disease research, this technology provides a unparalleled human model system to deconstruct the molecular pathways leading to dopaminergic neuron degeneration. It accelerates the path from basic scientific discovery to therapeutic intervention, enabling mechanistic studies, target validation, and pre-clinical drug screening in a patient-specific context, thereby holding immense promise for unlocking the mysteries of PD and developing much-needed disease-modifying therapies.

The pathological hallmarks of Parkinson's disease (PD), primarily the aggregation of α-synuclein protein and the formation of Lewy bodies, have been notoriously difficult to recapitulate in traditional laboratory models. This challenge has significantly hindered the understanding of disease mechanisms and the development of effective therapies. The advent of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized this landscape. By enabling the generation of patient-specific neural cells and complex three-dimensional midbrain organoids, iPSCs provide a human-relevant system to model the intricate pathophysiology of PD in a dish [16] [13]. This technical guide details how these advanced in vitro models are being leveraged to investigate alpha-synuclein aggregation and Lewy body-like inclusions, framing these approaches within the broader thesis that iPSC-based systems are indispensable for elucidating Parkinson's disease pathogenesis.

Modeling Alpha-Synuclein Aggregation

The propensity of alpha-synuclein to misfold and aggregate is a central event in Parkinson's disease. Conventional cell cultures and animal models often fail to replicate the spontaneous and progressive nature of this process within a human neuronal context. iPSC-derived models have overcome this barrier through several innovative strategies.

Genetic Predisposition Models

A primary method involves introducing key genetic risk factors associated with PD into iPSC-derived neurons and organoids.

- GBA1 Mutations: Studies using human midbrain-like organoids (hMLOs) generated from GBA1 knockout isogenic cell lines have demonstrated that the loss of glucocerebrosidase function, especially when coupled with wild-type α-synuclein overexpression, results in a substantial accumulation of detergent-resistant, β-sheet–rich α-syn aggregates [17]. This model directly links a common genetic risk factor to a core pathological phenotype.

- SNCA Triplication: Patient-derived iPSCs carrying a triplication of the SNCA gene (which encodes α-synuclein) provide a model for familial PD. These cells inherently overproduce α-synuclein, leading to its aggregation. Research has shown that impairing glucocerebrosidase function in these patient-derived organoids further promotes the formation of Lewy body-like inclusions, highlighting an interaction between genetic risk factors [17].

Table 1: Genetic Perturbations for Modeling α-Synuclein Aggregation

| Genetic Perturbation | Model System | Key Pathological Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| GBA1-/- + SNCA OE | Isogenic hMLOs | Substantial accumulation of detergent-resistant, β-sheet-rich α-syn aggregates [17] |

| SNCA Triplication | Patient-derived hMLOs | α-syn aggregation; LB-like inclusion formation enhanced by impaired GCase function [17] |

| LRRK2 Mutations | iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons | Increased susceptibility to proteostatic stress and aggregation (Based on established PD risk genes) |

Optogenetics-Assisted Induction System (OASIS)

To overcome the slow and variable timeline of spontaneous aggregation, researchers have developed an optogenetics-assisted α-synuclein aggregation induction system [18]. This system uses a blue light-sensitive protein domain fused to α-synuclein, allowing for the precise and rapid induction of aggregation in PD hiPSC-derived midbrain dopaminergic neurons and organoids upon light stimulation.

- Protocol Overview:

- Cell Line Generation: Engineer hiPSCs to express a fusion protein of α-synuclein and a photosensitive domain (e.g., cry2olig).

- Neural Differentiation: Differentiate the engineered hiPSCs into midbrain dopaminergic neurons or generate midbrain organoids using established protocols.

- Aggregation Induction: Expose the cultures to blue light pulses (e.g., 1-5 Hz frequency) for a defined period (minutes to hours) to trigger the oligomerization of the fusion protein.

- Phenotype Validation: Confirm aggregation via immunofluorescence using antibodies against phosphorylated α-synuclein and assess neuronal toxicity through viability assays.

- Utility: The OASIS model enables high-throughput, reproducible induction of pathology, making it particularly suitable for primary drug screening and mechanistic studies over short timelines [18].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for the Optogenetics-Assisted α-synuclein Aggregation Induction System (OASIS), enabling rapid and controlled pathology generation.

Recapitulating Lewy Body-like Inclusions

Lewy bodies are intraneuronal inclusions that represent the definitive pathognomonic sign of Parkinson's disease. Reproducing these complex structures in vitro has been a major goal for the field.

Key Experimental Protocol: Generating hMLOs with Dual Perturbations

The following detailed methodology is adapted from research that successfully generated Lewy body-like inclusions in human midbrain-like organoids (hMLOs) [17].

- Objective: To investigate the combined effect of GBA1 deficiency and α-synuclein overexpression on Lewy body formation.

- Materials and Methods:

- Cell Line Generation:

- Generate GBA1−/− human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) or iPSCs using CRISPR/Cas9 with a guide RNA targeting exon 4 of the GBA1 gene.

- Create a separate isogenic line with a doxycycline-inducible SNCA (α-synuclein) overexpression construct.

- Dual Perturbation Model: Cross these lines or use co-transduction to create a dual-perturbation hPSC line.

- hMLO Generation:

- Dissociate hPSCs and plate them in 96-well culture plates in neuronal induction medium.

- On day 3, switch to floor plate induction medium.

- On day 7, embed the forming organoids in reduced growth factor Matrigel.

- Transfer organoids to an orbital shaker and culture them in tissue growth medium (Neurobasal medium supplemented with growth factors like BDNF, GDNF, and ascorbic acid), with medium changes every 3-4 days.

- For the inducible SNCA line, add doxycycline to the culture medium to trigger α-synuclein overexpression during the maturation phase (e.g., from day 30 onwards).

- Phenotypic Analysis (after ~60-80 days of maturation):

- Immunohistochemistry: Fix hMLOs with 4% PFA, embed in paraffin, and section. Stain sections with antibodies against α-synuclein and ubiquitin. Lewy body-like inclusions are identified as spherically symmetric structures with an eosinophilic core that are positive for both markers.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Fix hMLOs with 2% PFA/3% glutaraldehyde, post-fix with 1% OsO4, and process through dehydration and resin embedding. Ultrathin sections can be used to visualize the dense fibrillar structure of the inclusions.

- Cell Line Generation:

- Key Findings: This protocol reliably produces Lewy body-like inclusions that morphologically resemble those found in post-mortem PD brains and are positive for α-synuclein and ubiquitin [17].

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Pathological Phenotypes in iPSC-PD Models

| Pathological Readout | Measurement Technique | Exemplary Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Synuclein Aggregation | Immunostaining (pS129-α-syn); FRET/Flow Cytometry | Detergent-resistant, β-sheet-rich aggregates in GBA1−/−/SNCA OE hMLOs [17] | Confirms key pathological protein state |

| Lewy Body-like Inclusions | IHC (H&E, α-syn/Ubiquitin); Transmission Electron Microscopy | Spherical inclusions with eosinophilic core, positive for α-syn and ubiquitin [17] | Recapitulates definitive PD pathology |

| Neuronal Loss | Immunostaining (TH+, NeuN+ cells); Viability Assays | ~40% loss of mDA neurons in OASIS midbrain organoids over 21 days [18] | Models neurodegeneration |

| Dopaminergic Function | HPLC, FSCV, Electrophysiology | Reduced dopamine release; Altered neuronal firing [19] | Links pathology to functional deficits |

| Mitochondrial Dysfunction | Seahorse Assay, JC-1/TMRM Staining | Decreased ATP production; Reduced mitochondrial membrane potential [19] | Captures key downstream cellular stress |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successfully modeling PD pathology requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC-based PD Modeling

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| iPSC Lines | Foundation for disease modeling; provide patient-specific or genetically engineered background. | Patient-derived (e.g., GBA1 N370S, SNCA triplication); Isogenic CRISPR-edited lines (e.g., GBA1−/−) [17]. |

| Neural Differentiation Kits | Direct differentiation of iPSCs into relevant neural cell types. | Commercial kits available for midbrain dopaminergic neurons; Protocols for floorplate-mediated induction [17] [4]. |

| Cerebral Organoid Media | Support the complex 3D growth and maturation of brain-like tissues. | Neuronal induction, floor plate induction, and tissue growth media with supplements (BDNF, GDNF, AA, cAMP) [17]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | For precise genome editing to introduce or correct mutations. | Used to generate GBA1−/− lines and other isogenic controls [17] [13]. |

| Optogenetic Constructs | Enable controlled, light-induced protein aggregation. | cry2olig-α-syn fusion gene for OASIS model [18]. |

| Key Antibodies | Critical for identifying and characterizing cells and pathology. | TH (dopaminergic neurons); pS129-α-syn (pathological α-syn); Ubiquitin (LBs); CORIN/FOXA2 (midbrain progenitors) [17] [6]. |

| Small Molecule Modulators | Probe pathways and rescue phenotypes in drug screens. | Rapamycin (induces autophagy, shown to rescue α-syn pathology [19]); Conduritol-β-epoxide (chemical inhibition of GCase [17]). |

The ability to model key pathological hallmarks of Parkinson's disease—specifically, alpha-synuclein aggregation and Lewy body-like inclusions—in iPSC-derived neuronal systems marks a transformative advance in neuroscience research. The integration of patient-specific genetics, CRISPR genome editing, 3D organoid technology, and innovative tools like optogenetics has created tractable and human-relevant models that bridge the gap between traditional models and the complex human disease state. These systems provide an unparalleled platform for deconstructing disease mechanisms, exploring genotype-phenotype relationships, and, most importantly, conducting high-throughput screening for novel therapeutic candidates that can mitigate or prevent the underlying pathology of Parkinson's disease.

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, characterized by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and the presence of Lewy bodies in surviving neurons [20] [3]. The etiological landscape of PD encompasses both sporadic (approximately 85-90% of cases) and familial (approximately 10-15% of cases) forms, though this distinction has become increasingly blurred with advancing genetic research [21]. The emergence of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized PD research by enabling the generation of patient-specific neural cells, providing unprecedented opportunities to model disease pathogenesis and investigate the functional consequences of genetic mutations in a human cellular context [16] [13].

Within the framework of iPSC-based disease modeling, four genes have garnered significant research attention: SNCA, LRRK2, GBA, and PINK1. These genes represent different inheritance patterns and molecular mechanisms contributing to PD pathogenesis. SNCA and LRRK2 are primarily associated with autosomal dominant forms, while PINK1 follows autosomal recessive inheritance. GBA mutations are considered the most significant genetic risk factor for PD [22] [23]. This technical guide examines the roles of these key genes in PD pathogenesis through the lens of contemporary iPSC research, providing a comprehensive resource for investigators utilizing these models to unravel disease mechanisms and develop novel therapeutic strategies.

Genetic Foundations of PD: Key Genes and Mutations

Understanding the genetic architecture of Parkinson's disease is fundamental to utilizing iPSC models effectively. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the four focal genes in this review:

Table 1: Key Genetic Factors in Parkinson's Disease

| Gene | Inheritance Pattern | Protein Function | Common Mutations | Prevalence in PD | Key Cellular Pathways Affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNCA | Autosomal dominant | Synaptic function, neurotransmitter release | A53T, A30P, E46K, gene multiplications | ~0.3% of all PD [24] [21] | α-synuclein aggregation, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress |

| LRRK2 | Autosomal dominant | Kinase signaling, membrane trafficking | G2019S, R1441C, R1441G | 1-2% of all PD; higher in specific populations [23] | Lysosomal function, mitochondrial homeostasis, neurite outgrowth |

| GBA | Risk factor | Lysosomal enzyme (glucocerebrosidase) | N370S, L444P, E326K | Most common genetic risk factor [22] [23] | Lysosomal-autophagic function, α-synuclein metabolism |

| PINK1 | Autosomal recessive | Mitochondrial quality control | Point mutations, deletions | ~0.3% of all PD [21] | Mitophagy, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress response |

The prevalence estimates demonstrate that known causal mutations are relatively rare in the overall PD population, with the collective frequency of mutations in established PD genes occurring in less than 2% of patients [21]. However, these genetic variants provide crucial insights into pathogenic mechanisms relevant to both familial and sporadic disease forms. iPSC models have been particularly valuable in exploring these mechanisms while controlling for individual genetic background through the use of isogenic controls generated via CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing [20] [13].

SNCA (α-Synuclein): From Protein Aggregation to Cellular Dysfunction

Genetic and Molecular Background

The SNCA gene encodes α-synuclein, a 144-amino acid protein that is the primary structural component of Lewy bodies, the pathognomonic proteinaceous inclusions found in PD brains [24] [20]. SNCA was the first gene linked to familial PD, with the identification of the A53T missense mutation in a large Italian family [24]. Since this discovery, additional point mutations (A30P, E46K, H50Q, G51D, A53E) as well as gene multiplications (duplications and triplications) have been associated with autosomal dominant PD [20]. The dosage effect observed with SNCA multiplications provides compelling evidence that increased expression of wild-type α-synuclein is sufficient to cause PD, with triplication carriers developing more severe disease than duplication carriers [24] [20].

Pathogenic Mechanisms Elucidated by iPSC Models

iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons from patients with SNCA triplication have been particularly informative for studying α-synuclein pathogenesis. These cells exhibit a two-fold increase in α-synuclein protein levels and a six-fold increase in mRNA levels, successfully modeling the protein accumulation observed in PD brains [20]. Key pathological features observed in these models include:

- Oxidative Stress: SNCA triplication iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons demonstrate elevated oxidative stress markers and increased sensitivity to peroxide-induced oxidation. This phenotype can be reversed by knocking out endogenous α-synuclein, confirming the central role of α-synuclein in driving oxidative damage [20].

- Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Transcriptomic analyses of purified SNCA triplication iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons revealed perturbations in genes associated with mitochondrial function. At the functional level, these cells exhibit morphological changes in mitochondria, decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, and disrupted endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial associations that impact Ca²⁺ homeostasis and ATP production [20].

- Lysosomal Dysfunction: Accumulated α-synuclein disrupts RAB1a-mediated hydrolase transport from the Golgi apparatus to lysosomes, reducing lysosomal function. Overexpression of RAB1a restores Golgi structure, improves hydrolase transport and activity, and reduces pathological α-synuclein accumulation [20].

- Nuclear Toxicity: Under conditions of oxidative stress, C-terminal fragments of α-synuclein translocate to the nucleus where they can bind to chromatin and activate DNA damage responses. SNCA triplication iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells demonstrate accelerated senescence and impaired genomic integrity [20].

Experimental Protocols for SNCA Modeling

The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for generating and analyzing SNCA mutant iPSC-derived neuronal models:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for SNCA iPSC model generation and analysis

LRRK2: Kinase Function and Converging Pathogenic Pathways

Genetic and Molecular Background

LRRK2 (leucine-rich repeat kinase 2) mutations represent the most common genetic cause of autosomal dominant PD, with the G2019S mutation accounting for approximately 1-2% of all PD cases and higher percentages in specific ethnic populations such as Ashkenazi Jewish and North African Berber descendants [23]. The LRRK2 gene encodes a large multi-domain protein containing both GTPase and kinase activities. The G2019S mutation, located in the kinase domain, enhances kinase activity and is considered a key driver of pathogenesis [20] [23].

Pathogenic Mechanisms Elucidated by iPSC Models

iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons from LRRK2 G2019S mutation carriers have revealed several consistent pathological phenotypes:

- Elevated α-Synuclein Levels: Similar to SNCA mutant models, LRRK2 G2019S iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons demonstrate increased α-synuclein accumulation, suggesting a convergence of pathogenic mechanisms on this key protein [3].

- Mitochondrial Dysfunction: LRRK2 G2019S neurons exhibit increased mitochondrial DNA damage and delayed initiation of mitophagy, the selective autophagy of damaged mitochondria [3]. These cells also show abnormalities in mitochondrial morphology and distribution.

- Neurite Outgrowth Deficits: Multiple studies have reported reduced neurite complexity and branching in LRRK2 G2019S iPSC-derived neurons, suggesting disruptions in neuronal connectivity and function [3].

- Lysosomal Impairment: LRRK2 mutations impact lysosomal function by altering the activity of key lysosomal proteins, including transcription factor EB (TFEB), a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis [20].

Experimental Protocols for LRRK2 Modeling

The standard approach for evaluating LRRK2 pathogenesis in iPSC models includes:

Table 2: Key Assays for LRRK2 Pathogenesis Evaluation

| Assay Category | Specific Assays | Key Readouts | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinase Activity | In vitro kinase assays, Phospho-substrate detection | LRRK2 autophosphorylation, RAB10 phosphorylation | Use specific LRRK2 inhibitors (e.g., LRRK2-IN-1) as controls |

| Neurite Morphology | High-content imaging of neuronal cultures | Neurite length, branching complexity, Sholl analysis | Analyze at multiple time points during maturation |

| Mitochondrial Function | Seahorse extracellular flux analysis, Live imaging with mito-trackers | OCR, ECAR, mitochondrial membrane potential, motility | Combine functional assays with morphological assessment |

| Lysosomal Function LysoTracker staining, Cathepsin activity assays | Lysosomal pH, proteolytic activity, TFEB localization | Monitor acute response to lysosomal stressors (e.g., chloroquine) | |

| Protein Aggregation FRET-based α-synuclein sensors, Filter trap assay | α-synuclein oligomerization, insoluble protein accumulation | Compare baseline levels and stress-induced aggregation |

GBA: Linking Lysosomal Function and Synucleinopathology

Genetic and Molecular Background

GBA mutations, which encoding the lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase (GCase), represent the most common genetic risk factor for PD [22] [23]. While GBA mutations cause Gaucher's disease in a recessive manner, heterozygous mutations significantly increase the risk of developing PD by 5-8 fold [21]. The most common GBA mutations associated with PD are N370S and L444P, though numerous other variants have been identified [22].

Pathogenic Mechanisms Elucidated by iPSC Models

iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons from GBA mutation carriers have revealed a bidirectional relationship between GCase dysfunction and α-synuclein pathology:

- Reduced GCase Activity: GBA mutant neurons exhibit decreased GCase enzyme activity and impaired lysosomal function, leading to the accumulation of glycosphingolipids that promote α-synuclein aggregation [20] [23].

- α-Synuclein Accumulation: Impaired lysosomal clearance of α-synuclein in GBA mutant neurons leads to increased α-synuclein levels and aggregation, which in turn further inhibits GCase activity, creating a pathogenic feedback loop [20].

- Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Similar to other genetic forms of PD, GBA mutant neurons demonstrate mitochondrial impairments, including reduced membrane potential and altered morphology [20].

PINK1: Mitochondrial Quality Control and Recessive PD

Genetic and Molecular Background

PINK1 (PTEN-induced putative kinase 1) mutations cause autosomal recessive early-onset PD [20]. PINK1 encodes a serine/threonine kinase localized to mitochondria that plays a critical role in mitochondrial quality control. Together with Parkin (encoded by PRKN), PINK1 functions in a pathway to identify and eliminate damaged mitochondria through mitophagy [20] [23].

Pathogenic Mechanisms Elucidated by iPSC Models

iPSC models of PINK1 deficiency have provided crucial insights into mitochondrial pathophysiology in PD:

- Mitophagic Impairment: PINK1 mutant iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons exhibit defective mitophagy, with impaired recruitment of Parkin to damaged mitochondria and subsequent failure to clear dysfunctional organelles [20] [3].

- Mitochondrial Dysfunction: These cells demonstrate multiple mitochondrial abnormalities, including reduced ATP production, increased oxidative stress, and altered morphology [20].

- Enhanced Vulnerability: PINK1 deficient neurons show increased sensitivity to mitochondrial stressors such as CCCP and rotenone, confirming the importance of PINK1 in mitochondrial stress response [20].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for iPSC-Based PD Modeling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (Yamanaka factors) | iPSC generation from somatic cells | Non-integrating methods (Sendai virus, episomal vectors) preferred [13] |

| Neural Induction Supplements | SB431542, LDN193189, Noggin | Dual SMAD inhibition for neural induction | Critical for efficient neural conversion [13] |

| Midbrain Patterning Factors | SHH, FGF8, CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor) | Dopaminergic neuron specification | CHIR99021 activates Wnt signaling for floor plate induction [3] |

| Neuronal Maturation Factors | BDNF, GDNF, TGF-β3, DBC, ascorbic acid | Dopaminergic neuron maturation & maintenance | Essential for functional maturation and long-term survival [3] |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Generation of isogenic controls | Critical for controlling for genetic background [20] [13] |

| Key Antibodies | Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), FOXA2, LMX1A, α-synuclein | Cell characterization and pathology assessment | Validate for human-specific epitopes where available |

| Pathway Reporters | MitoTimer, LC3-GFP, ROS-sensitive dyes | Dynamic assessment of cellular pathways | Enable live-cell imaging of pathological processes |

iPSC-Based Therapeutic Development and Clinical Translation

The therapeutic implications of iPSC-based PD research extend from drug discovery to cell replacement strategies. The pathological mechanisms identified in genetic iPSC models have revealed novel therapeutic targets, including LRRK2 kinase activity, GCase function, and mitochondrial quality control pathways [20] [23]. Furthermore, iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons provide a human-relevant platform for high-throughput drug screening and validation.

Notably, iPSC technology has advanced to clinical applications for PD. A recent phase I/II trial demonstrated the safety and potential efficacy of allogeneic iPSC-derived dopaminergic progenitors transplanted into the putamen of PD patients [6]. This study reported no serious adverse events over 24 months, increased dopamine production in the putamen (as measured by 18F-DOPA PET), and improvements in motor symptoms in several patients [6]. This pioneering trial establishes a foundation for cell replacement therapies in PD and validates the utility of iPSC-based approaches for developing clinically viable treatments.

iPSC-based modeling has fundamentally advanced our understanding of Parkinson's disease pathogenesis, particularly through the study of key genes such as SNCA, LRRK2, GBA, and PINK1. These models have revealed converging pathogenic pathways—including mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired protein homeostasis, and lysosomal abnormalities—that connect diverse genetic forms of PD and likely extend to sporadic disease. The continued refinement of iPSC differentiation protocols, combined with advanced gene editing and multi-omics approaches, will further enhance the physiological relevance of these models. As the field progresses, iPSC-based studies will play an increasingly central role in validating therapeutic targets, screening candidate compounds, and developing personalized approaches for treating this complex neurodegenerative disorder.

While the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra remains the cardinal pathological feature of Parkinson's disease, emerging research underscores the indispensable role of glial cells in disease pathogenesis. This whitepaper explores how microglia and astrocytes contribute to PD progression through neuroinflammatory signaling, impaired neuronal support, and dysfunctional protein clearance. Within the context of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) modeling, we detail how advanced co-culture systems and organoid technologies are revealing novel glial-mediated mechanisms and creating more physiologically relevant platforms for therapeutic development. The integration of glial cells into PD models represents a paradigm shift in our approach to understanding disease mechanisms and developing effective interventions.

The historical neuron-centric view of Parkinson's disease has progressively evolved to acknowledge the essential contributions of non-neuronal cells in disease pathogenesis. Glial cells, particularly microglia and astrocytes, are now recognized as active participants in PD pathology rather than passive bystanders. These cells contribute to multiple aspects of disease progression, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, protein aggregation, and neuronal dysfunction [25]. The advent of human iPSC-derived cellular models has been instrumental in advancing this understanding, enabling researchers to study human-specific glial biology and its contribution to PD mechanisms in unprecedented detail.

The limitations of traditional model systems in recapitulating human neuroinflammatory pathways have further highlighted the necessity of human iPSC-based approaches. Mouse models, though valuable, are unable to faithfully replicate human neuroinflammatory responses due to species-specific differences in immune system architecture and signalling pathways [25]. For instance, mouse astrocytes, but not human astrocytes, respond to the glycolipid lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a commonly used experimental neuroinflammatory activator [25]. This species divergence underscores the critical importance of human iPSC-derived models for studying glial functions in PD.

Glial Cell Types and Their Pathogenic Roles in PD

Microglia: The CNS Immune Sentinels

Table 1: Key Microglial Pathogenic Functions in Parkinson's Disease

| Function | Role in Homeostasis | Dysregulation in PD | Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immune Surveillance | Constant monitoring of CNS environment through ramified processes [25] | Chronic activation via DAMPs, PAMPs, and NAMPs [25] | Sustained neuroinflammatory response |

| Phagocytosis | Clearance of cellular debris and unwanted synapses [25] | Impaired clearance of α-synuclein aggregates [26] | Accumulation of pathological protein aggregates |

| Cytokine Signaling | Balanced release of pro- and anti-inflammatory factors [25] | Persistent pro-inflammatory cytokine release (IL-1α, TNF, C1q) [25] | Neuronal damage and astrocyte activation |

| Metabolic Support | Trophic support for neuronal health | Transition to disease-associated microglia (DAM) phenotype [25] | Altered lipid metabolism and phagocytic activity |

Microglia, the primary immune cells of the central nervous system, constitute between 0.5% and 16.6% of the total brain cell population, varying by anatomical region, sex, and developmental stage [25]. In PD, microglia undergo phenotypic changes in response to damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and neurodegeneration-associated molecular patterns (NAMPs) released from damaged neurons and protein aggregates [25]. The nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway serves as a pleiotropic regulator of microglial inflammatory responses to these stimuli [25].

The chronic activation of microglia in PD contributes to the phenomenon of "inflammaging" – a low-grade chronic inflammation that characterizes both aging and neurodegenerative diseases [26]. Inflammaging is driven by factors such as mitochondrial dysfunction, elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS), and proteotoxicity associated with overloaded protein degradation systems [26]. Inflammatory markers including IL-6 and IL-8 also contribute to the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which can induce cellular senescence in neighboring cells [26]. The sustained release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines creates a toxic environment that exacerbates neuronal vulnerability, particularly for metabolically active dopaminergic neurons [26].

Astrocytes: Multifunctional CNS Support Cells

Table 2: Astrocytic Functions and Dysfunctions in Parkinson's Disease

| Function | Role in Homeostasis | Dysregulation in PD | Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate Homeostasis | Uptake of synaptic glutamate via transporters [25] | Reduced glutamate clearance | Excitotoxicity and neuronal damage |

| Metabolic Support | Nutrient provision to neurons | Impaired energy metabolism | Increased neuronal vulnerability |

| Blood-Brain Barrier | Maintenance of BBB integrity [25] | Compromised BBB function | Increased CNS exposure to peripheral insults |

| Inflammatory Regulation | Balanced immune signaling | Reactive astrogliosis and SASP secretion [26] | Chronic neuroinflammation |

| Trophic Support | Release of neurotrophic factors | Reduced neurotrophic support | Compromised neuronal maintenance |

Astrocytes represent the most prevalent glial cell type, comprising 17-61% of total CNS cells [25]. These highly heterogeneous cells display diverse densities, morphologies, gene expression profiles, and proliferation rates depending on brain region and disease state [25]. In PD, astrocytes contribute to disease pathogenesis through multiple mechanisms, including the propagation of neuroinflammation, failure to support neuronal health, and impaired clearance of pathological proteins.

Reactive astrocytes in PD exhibit increased expression of glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) and undergo hypertrophy and proliferation, a phenomenon known as astrogliosis [25]. These reactive astrocytes cluster and integrate with extracellular matrix components to form glial scars, which physically shield injured regions from healthy tissue but may also impede regeneration [25]. Critically, reactive astrocytes activate NF-κB signaling and produce various chemokines (e.g., CCL2, CXC3L1, CXCL1) that attract immune cells, as well as cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-12, TNF, IL-10, TGF-β) that propagate immune responses by stimulating neighboring glia [25].

The communication between microglia and astrocytes represents a crucial axis in PD neuroinflammation. Upon detecting insults, microglial secretion of inflammatory factors (e.g., IL-1α, TNF, and C1q) stimulates astrocytes to acquire a more reactive, inflammatory phenotype [25]. In turn, reactive astrocytes secrete additional factors that affect microglial-mediated neuroinflammatory behaviors, creating a feed-forward cycle of inflammation [27].

iPSC-Derived Glial Models: Methodological Approaches

Generation of iPSC-Derived Glial Cells

The development of reliable protocols for differentiating human iPSCs into microglia and astrocytes has revolutionized the study of glial pathophysiology in PD. Several methodological approaches exist for generating iPSC-derived glial cells, each with distinct advantages and applications.

iPSC Reprogramming Methods:

- Non-integrating Viral Approaches: Sendai virus vectors demonstrate high efficiency and safety as RNA viruses can be completely eliminated from iPSCs, reducing genomic integration risks [28].

- DNA-Based Methods: Episomal plasmids, PiggyBac transposons, and minicircle vectors offer reduced risks of genomic instability, though with variable reprogramming efficiencies [28].

- RNA Delivery: mRNA transfection presents lower mutagenic risk and high efficiency, though currently limited to specific cell types like fibroblasts and peripheral blood cells [28].

Differentiation Protocols: Microglia differentiation protocols typically involve directing iPSCs through hematopoietic progenitor stages using cytokines like IL-34, CSF-1, and TGF-β to generate cells that express characteristic microglial markers (IBA1, TMEM119, P2RY12) and exhibit functional properties including phagocytosis, cytokine secretion, and process motility [25].

Astrocyte differentiation protocols generally involve neural induction through dual SMAD inhibition, followed by glial specification using CNTF, BMPs, or LIF, resulting in cells expressing GFAP, S100β, and EAAT1, and exhibiting typical astrocytic functions such as glutamate uptake and synaptic modulation [25].

Advanced Model Systems for Neuroinflammation Research

Table 3: iPSC-Based Model Systems for Studying Neuroinflammation in PD

| Model Type | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monocultures | Single cell type (microglia or astrocytes) in 2D culture | High throughput, simplified experimental variables | Lacks cell-cell interactions |

| Conditioned Media Transfer | Media from one cell type transferred to another | Reveals paracrine signaling effects | Removes physical cell contacts |

| 2D Co-culture Systems | Multiple cell types cultured together | Enables study of direct cell-cell interactions | May lack tissue architecture |

| 3D Organoids | Self-organizing 3D structures containing multiple CNS cell types | Recapitulates tissue complexity and architecture | Potential heterogeneity between organoids |

| Xenotransplantation | Human iPSC-derived glia transplanted into mouse brain | Provides in vivo environment for maturation | Species-specific environmental differences |

Each model system offers distinct advantages for investigating specific aspects of neuroinflammation. While monocultures enable high-throughput screening, co-culture systems and organoids provide more physiologically relevant contexts for studying cell-cell interactions [25]. The neuroinflammatory response in vivo involves numerous complex interactions between multiple brain cell types, and consequently, inflammatory responses are likely to be more physiologically relevant with increasing culture complexity [25].

Experimental Workflow for iPSC Glial Studies

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for establishing and utilizing iPSC-derived glial models for Parkinson's disease research:

Key Pathogenic Mechanisms and Experimental Findings

Neuroinflammation Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates key neuroinflammatory signaling pathways in glial cells that contribute to Parkinson's disease pathogenesis:

Glial Dysfunction in Genetic PD Forms

iPSC models of genetic Parkinson's disease have revealed important glial contributions to disease pathogenesis:

GBA Mutations: Mutations in the GBA gene, which encodes the lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase, represent one of the most common genetic risk factors for PD. iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons from patients with GBA mutations demonstrate elevated extracellular α-synuclein levels, suggesting impaired lysosomal function and protein clearance [29]. This pathological α-synuclein accumulation can subsequently activate glial cells, creating a feed-forward cycle of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration.

LRRK2 Mutations: iPSC-derived astrocytes from patients carrying the G2019S LRRK2 mutation show downregulation of MMP2 and TGFB1, indicating altered extracellular matrix remodeling and trophic support [29]. These dysfunctional astrocytes may fail to provide adequate neuronal support and contribute to a toxic microenvironment for dopaminergic neurons.

SNCA Mutations: Microglia-like macrophages derived from iPSCs of patients with SNCA triplication demonstrate reduced phagocytic capability and impaired degradation of α-synuclein [30]. These cells release significantly more α-synuclein into the extracellular environment, potentially promoting the spread of pathology throughout the brain.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for iPSC Glial PD Modeling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (Yamanaka factors) [28] | iPSC generation from somatic cells | Induction of pluripotency |

| Alternative Factors | OCT3/4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 [28] | iPSC generation | Maintenance of pluripotency |

| Differentiation Cytokines | IL-34, CSF-1, TGF-β (microglia) [25]; CNTF, BMP, LIF (astrocytes) [25] | Glial cell differentiation from iPSCs | Directional specification of glial lineages |

| Neuroinflammatory Inducers | LPS, IL-1α, TNF, C1q [25]; pre-formed α-syn fibrils (PFFs) [27] | Modeling neuroinflammatory activation | Triggering glial inflammatory responses |

| Senescence Inducers | Chemically induced ageing methods (e.g., SLO cocktail) [26] | Modeling age-related aspects of PD | Induction of senescence phenotypes |

| Cell Sorting Markers | CORIN (floor plate marker) [6] | Enrichment of specific progenitor populations | Purification of target cell types |

| Key Antibodies | IBA1, TMEM119 (microglia); GFAP, S100β (astrocytes); TH (dopaminergic neurons) [6] [25] | Cell characterization and identification | Cell type-specific marker detection |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: Establishing iPSC-Derived Microglia-Astrocyte Co-cultures

Objective: To generate a physiologically relevant neuroinflammatory model system for studying glial interactions in PD.

Materials:

- Established human iPSC lines (patient-derived or isogenic controls)

- Microglia differentiation media: Advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with IL-34 (100 ng/mL), CSF-1 (100 ng/mL), TGF-β (50 ng/mL) [25]

- Astrocyte differentiation media: DMEM supplemented with CNTF (20 ng/mL) and BMP-4 (10 ng/mL) [25]

- Co-culture media: 1:1 mixture of microglia and astrocyte media

- Matrigel-coated plates for co-culture

- Recombinant human α-synuclein pre-formed fibrils (PFFs)

Procedure:

- Differentiate iPSCs into microglial precursors using a standardized 30-day protocol with staged addition of cytokines [25].

- Differentiate iPSCs into astrocytes using a 60-day neural induction and glial specification protocol [25].

- Harvest mature microglia and astrocytes using gentle enzymatic dissociation.

- Plate cells in Matrigel-coated plates at a 1:1 ratio (100,000 cells each per cm²) in co-culture media.

- Allow cells to stabilize for 48 hours before experimental manipulations.

- For disease modeling, treat co-cultures with α-syn PFFs (1-5 μg/mL) for 24-72 hours to induce neuroinflammatory responses.

Validation Measures:

- Immunocytochemistry for microglial markers (IBA1, TMEM119) and astrocyte markers (GFAP, S100β)

- ELISA quantification of cytokine secretion (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β) in conditioned media

- Phagocytosis assays using pHrodo-labeled α-syn fibrils

- RNA sequencing for transcriptional profiling of inflammatory pathways

Protocol: Assessing Neuroinflammatory Responses in Glial Cells

Objective: To quantify neuroinflammatory activation in iPSC-derived glial cells following exposure to PD-relevant stimuli.

Materials:

- iPSC-derived microglia and/or astrocytes

- Stimuli: LPS (100 ng/mL), IL-1α/TNF/C1q combination (each at 10 ng/mL), α-syn PFFs (5 μg/mL)

- RNA extraction kit and qPCR reagents

- ELISA kits for human IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, CCL2

- NF-κB pathway inhibitors (e.g., BAY-11-7082)

Procedure:

- Plate iPSC-derived glial cells in 96-well or 24-well plates at appropriate densities.

- Treat cells with inflammatory stimuli for 6-24 hours (time course dependent on readout).

- For inhibitor studies, pre-treat cells with NF-κB inhibitors for 2 hours before stimulation.

- For transcriptional analysis: Harvest RNA at 6 hours post-stimulation, perform qPCR for key inflammatory genes (IL6, TNF, IL1B, CCL2, NFKBIA).

- For protein secretion analysis: Collect conditioned media at 24 hours post-stimulation, perform ELISA for inflammatory cytokines.

- For pathway activation analysis: Fix cells and perform immunocytochemistry for NF-κB nuclear translocation or Western blotting for phospho-proteins.

Data Analysis:

- Normalize cytokine secretion to cell number (determined by parallel MTS assays or DNA quantification)

- Calculate fold-change relative to unstimulated controls

- Perform statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc testing for multiple comparisons

Future Directions and Therapeutic Implications

The growing recognition of glial contributions to PD pathogenesis opens new avenues for therapeutic development. Several promising approaches are emerging:

Targeting Neuroinflammation: Compounds that modulate microglial activation or astrocyte reactivity represent promising candidates for disease modification. The development of small molecules that specifically target pathogenic glial states without compromising homeostatic functions is an active area of investigation.

Enhancing Protein Clearance: Strategies to boost lysosomal function in glial cells, particularly for GBA-related PD, may reduce α-synuclein accumulation and spread. Activators of glucocerebrosidase activity or TFEB-mediated lysosomal biogenesis are being explored [30].

Senotherapeutics: Given the role of cellular senescence in PD pathogenesis, senolytic compounds that selectively eliminate senescent glial cells or senomorphics that suppress SASP secretion represent novel therapeutic approaches [26].

Cell Replacement Therapies: As cell therapies progress toward clinical application, consideration of glial interactions becomes essential. Recent clinical trials of iPSC-derived dopaminergic progenitors have shown promise, with no tumor formation and evidence of functional integration [6]. Understanding how grafted neurons interact with host glia will be crucial for optimizing therapeutic outcomes.

The continued refinement of iPSC-derived glial models, including the development of more complex multi-culture systems and region-specific brain organoids, will further enhance our understanding of glial contributions to PD and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

The integration of glial cells into our conceptual and experimental frameworks for understanding Parkinson's disease represents a critical advancement in the field. iPSC-derived models have been instrumental in revealing the active contributions of microglia and astrocytes to neuroinflammation, protein aggregation, and neuronal vulnerability in PD. As these models continue to increase in complexity and physiological relevance, they offer unprecedented opportunities to unravel disease mechanisms and develop targeted therapies that address both neuronal and glial aspects of PD pathogenesis. The future of PD research lies in embracing this cellular complexity to develop comprehensive treatments that can truly modify disease progression.

Advanced iPSC Platforms for Mechanistic Insights and High-Throughput Screening

The investigation of Parkinson's disease pathogenesis has been transformed by the advent of induced pluripotent stem cell technology. Patient-specific iPSCs provide a unique platform for in vitro disease modeling, enabling researchers to study pathological mechanisms in disease-relevant cells with a patient's complete genomic background [20] [31]. For Parkinson's disease research, this is particularly crucial as dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra are the predominant brain cells affected but are inaccessible in live patients [32]. Early models relied on two-dimensional monocultures, which, despite their utility, lack the cytoarchitecture and cellular interactions essential for comprehensive disease modeling [33]. The emergence of three-dimensional brain organoid technology addresses these limitations by recapitulating more complex tissue architecture, cellular diversity, and cell-cell interactions observed in the human brain [33] [34]. This technical guide examines the evolution from 2D monocultures to 3D organoids, with a specific focus on developing brain region-specific models for Parkinson's disease research.

Fundamental Principles of iPSC Technology

iPSC Generation and Reprogramming

Induced pluripotent stem cells are generated by reprogramming somatic cells to an embryonic-like state through the forced expression of specific transcription factors. The original method established by Takahashi and Yamanaka utilizes OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM) [13]. These factors perform distinct yet complementary roles: OCT3/4, SOX2, and KLF4 maintain pluripotency and inhibit differentiation, while c-MYC enhances reprogramming efficiency and promotes cell proliferation [13]. Alternative factor combinations include OCT3/4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28, where NANOG regulates stem cell self-renewal and LIN28 modulates RNA modification and expression [13].

Table 1: Comparison of iPSC Reprogramming Methods

| Method | Key Factors/Components | Advantages | Disadvantages | Reprogramming Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral Methods | Retroviral/lentiviral delivery of OSKM factors | High efficiency, robust | Risk of transgene reactivation, genomic integration | High |

| Non-Viral Methods | Episomal plasmids, mRNA transfection | Reduced integration risk, safer for clinical applications | Lower efficiency, technically challenging | Moderate to Low |

| Chemical Reprogramming | CHALP cocktail (CHIR99021, PD0325901, LIF, A-83-01, bFGF, HA-100) | No genetic modification, defined conditions | Complex optimization, variable between cell types | Variable |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | VPA, AZA, trichostatin A, BIX-01294 | Enhance efficiency, can replace some transcription factors | Potential off-target effects | Moderate |

Various somatic cell sources can be reprogrammed, with skin fibroblasts, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and renal epithelial cells being among the most common due to their accessibility and reprogramming efficiency [13]. The choice of reprogramming method and cell source depends on the specific application, with non-integrating methods preferred for clinical applications to minimize genomic alteration risks.

Neural Induction and Patterning

The differentiation of iPSCs into neural lineages typically begins with neural induction, most commonly achieved through dual SMAD inhibition. This approach promotes neural fate selection by preventing iPSCs from adopting alternative somatic or extraembryonic fates via inhibition of TGF-β and BMP signaling at early differentiation stages [35]. In the absence of additional patterning signals, this default pathway typically yields forebrain-type neural progenitors [34].

To generate specific neuronal subtypes relevant to Parkinson's disease, particularly midbrain dopaminergic neurons, additional patterning is required. The current state-of-the-art employs specific signaling molecules to direct anterior-posterior and dorso-ventral patterning:

- WNT Activation: Canonical WNT signaling activation using GSK3β inhibitors like CHIR99021 imposes midbrain regional identity by mimicking WNT1 signaling from the isthmic organizer [35]

- SHH Pathway Activation: Sonic hedgehog signaling ventralizes cells to induce LMX1A+/FOXA2+/OTX2+ ventral midbrain floor plate progenitors [35]

- FGF8 Signaling: Often applied together with WNT activation to reinforce midbrain patterning [35]

An alternative patterning approach utilizes retinoic acid signaling, where the duration of exposure rather than concentration determines mesencephalic specification. This concentration-insensitive method provides robustness and reduces protocol adjustments between different iPSC lines [35].

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for 2D and 3D Neural Differentiation from iPSCs

2D Monoculture Models for Parkinson's Research

Generation of Dopaminergic Neurons in 2D

Two-dimensional monocultures represent the foundational approach for generating Parkinson's-relevant cell types. The original protocol for deriving dopaminergic neurons from iPSCs relied on small molecules and took more than two months to achieve mature neurons [32]. These protocols typically involve stepwise differentiation through neural progenitor cells into post-mitotic neurons.

More recent approaches utilize transcription-factor-mediated direct differentiation to accelerate the process and improve purity. Key transcription factors include:

- ASCL1: A DNA-binding transcription factor that accesses closed chromatin to allow other factors to bind and activate neural pathways [32]

- NURR1: An orphan nuclear receptor critical for dopaminergic neuronal development, regulating tyrosine hydroxylase expression, dopamine metabolism, and neuronal survival [32]

- LMX1A: A LIM homeobox transcription factor that induces msh homeobox 1 (Msh1) and activates Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2), promoting neuronal differentiation and suppressing alternate ventral cell fates [32]