Mycoplasma Contamination in Stem Cell Culture: Prevention, Detection, and Control Strategies for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing mycoplasma contamination in stem cell cultures.

Mycoplasma Contamination in Stem Cell Culture: Prevention, Detection, and Control Strategies for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing mycoplasma contamination in stem cell cultures. Covering the foundational biology and risks of these stealth contaminants, it details advanced detection methodologies like qPCR and next-generation sequencing. The content offers practical troubleshooting protocols for decontamination and outlines rigorous, phase-appropriate validation strategies to meet global pharmacopeia standards (USP, Ph. Eur., JP), ensuring data integrity, product safety, and regulatory compliance in both research and clinical applications.

The Stealth Contaminant: Understanding Mycoplasma Biology and Risks in Stem Cell Research

What Are Mycoplasmas? Defining the Cell Wall-Lacking Prokaryotes

Mycoplasmas represent a unique genus of bacteria that are a significant concern in cell culture laboratories worldwide. As prokaryotes that naturally lack a cell wall, they are resistant to many common antibiotics and can persistently contaminate cultures, leading to altered experimental outcomes and irreproducible data. This technical support center provides essential guides and FAQs to help researchers, particularly those in stem cell research, prevent, detect, and address mycoplasma contamination.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are mycoplasmas and why are they a problem in cell culture? Mycoplasmas are the smallest self-replicating bacteria, belonging to the class Mollicutes (meaning "soft skin") [1]. Their defining characteristic is the absence of a rigid cell wall [2] [3]. This makes them naturally resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics, such as penicillin, which target cell wall synthesis [2]. In cell culture, they are a major problem because they are difficult to detect visually, can significantly alter the physiology and metabolism of host cells, and are highly contagious, risking the contamination of entire laboratory cell stocks [4] [5].

How can I tell if my cell culture is contaminated with mycoplasma? Visual identification is nearly impossible as mycoplasma contamination does not cause media turbidity [6]. However, chronic signs may include subtle changes in cell growth rate, morphology, or overall cell health [4]. Definitive identification requires specific tests. The table below summarizes the common detection methods.

Table: Common Mycoplasma Detection Methods

| Method | Principle | Duration | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR-Based Assays | Amplifies specific mycoplasma DNA sequences [7] [3] | Hours to 1 day | Rapid, highly sensitive, can detect multiple species [5] | Does not distinguish between viable and non-viable organisms |

| DNA Staining (e.g., DAPI, Hoechst) | Stains extranuclear DNA in the cytoplasm of infected indicator cells [5] [6] | 1-2 days | Visually demonstrates contamination on cells | Requires experience to interpret, may have false positives |

| Microbiological Culture | Grows mycoplasma on agar plates; forms "fried-egg" colonies [1] [5] | Up to 4 weeks | The "gold standard" for viability confirmation [5] | Very slow, some species are difficult to culture |

| Enzymatic Assays | Detects specific mycoplasma enzymes (e.g., arginine deiminase) [5] | 1-2 days | Can be adapted for high-throughput | May be less sensitive than PCR or staining |

What are the most common sources of mycoplasma contamination in the lab? The primary sources are other contaminated cell cultures introduced into the laboratory, followed by laboratory personnel. Human-borne species like M. orale and M. fermentans can be introduced via poor aseptic technique [5]. While less common today, contaminated reagents like fetal bovine serum (source of M. arginini and A. laidlawii) or trypsin (source of M. hyorhinis) are also potential sources [5].

Table: Common Mycoplasma Species in Cell Culture and Their Sources

| Mycoplasma Species | Primary Source | Frequency in Cell Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Mycoplasma orale | Human oropharyngeal tract [5] | Very High |

| Mycoplasma fermentans | Human oropharyngeal tract [5] | High |

| Mycoplasma hyorhinis | Swine (via trypsin) [5] | Common |

| Mycoplasma arginini | Bovine serum [5] | Common |

| Acholeplasma laidlawii | Bovine serum [5] | Common |

My culture is contaminated. Can I eradicate mycoplasma, or must I discard the cells? Eradication is possible but should only be attempted for unique, irreplaceable cell lines due to the high risk of treatment failure and laboratory spread [5]. Standard practice is to discard contaminated cultures immediately [5]. If treatment is necessary, antibiotics like Plasmocin are added to the culture media for 1-2 weeks [4]. Following treatment, cells must be cultured antibiotic-free for 1-2 weeks and then rigorously re-tested to confirm eradication [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Preventing Mycoplasma Contamination

Prevention is the most effective and economical strategy for managing mycoplasma.

- Adhere to Strict Aseptic Technique: Always wear proper personal protective equipment (PPE) and use a biosafety cabinet correctly. Spray all items with 70% ethanol before introducing them into the cabinet, and avoid cluttering the work surface [4] [6].

- Implement a Quarantine System: All new cell lines arriving in the lab should be cultured in a separate incubator until they test negative for mycoplasma [4].

- Establish a Routine Testing Schedule: Test all active cell cultures for mycoplasma on a regular basis (e.g., monthly) and with every new cell stock frozen down [4] [5].

- Avoid Routine Use of Antibiotics: Using antibiotics in standard culture media can mask low-level contamination, allowing it to spread undetected and promoting the development of resistant strains [6].

- Maintain a Clean Incubator: Adhere to a strict schedule for cleaning and disinfecting incubators and water baths, as these are common cross-contamination points [4].

Guide 2: Detecting Mycoplasma Contamination

When contamination is suspected or as part of routine screening, follow this workflow for reliable detection.

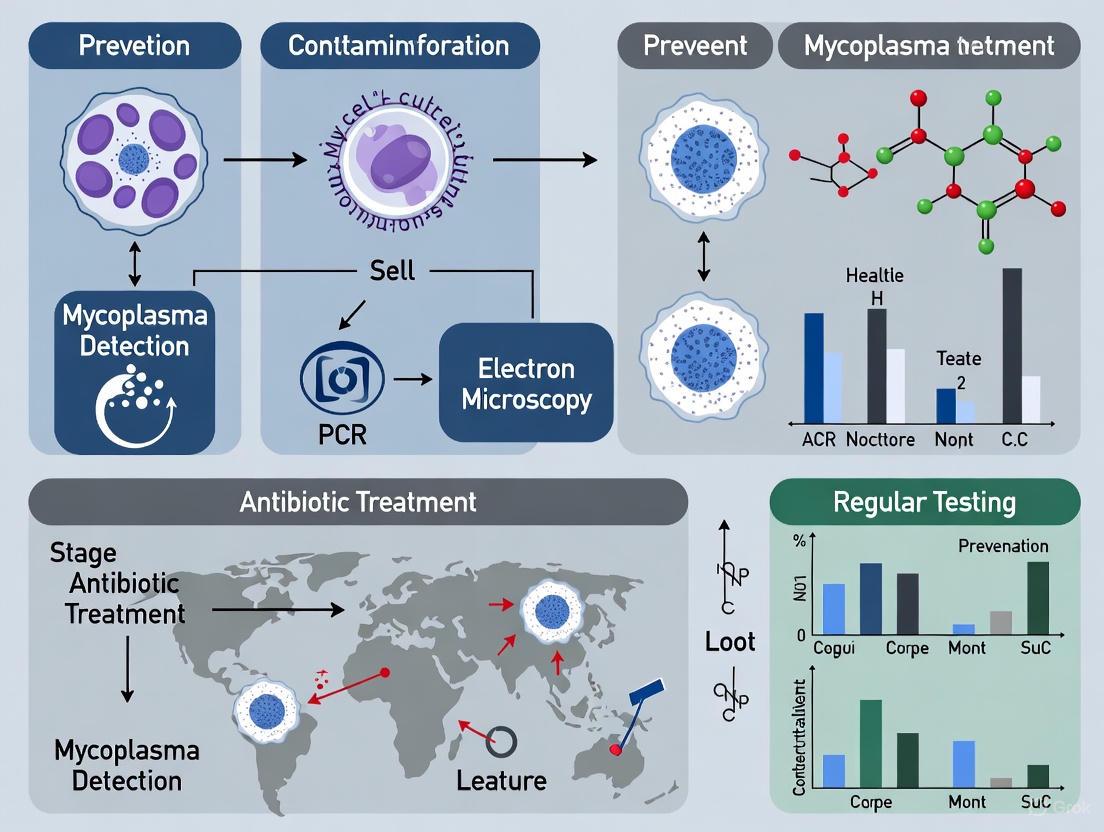

Diagram Title: Mycoplasma Detection Workflow

Experimental Protocol: DNA Staining for Mycoplasma Detection

This is a widely used, indirect method to visualize mycoplasma DNA adherent to host cells.

- Prepare Indicator Cells: Seed a sterile coverslip in a culture dish with an appropriate indicator cell line, such as Vero cells, and grow to 50-60% confluency.

- Inoculate with Test Sample: Add the sample to be tested (e.g., cell culture supernatant) to the indicator cells. Include a positive control (known mycoplasma-contaminated supernatant) and a negative control (known mycoplasma-free medium). Incubate for 3-5 days.

- Fix Cells: Aspirate the medium and wash the cells gently with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Fix the cells with a fresh mixture of acetic acid and methanol (1:3 ratio) for 10-15 minutes.

- Stain DNA: Prepare a DNA-binding fluorescent stain solution, such as Hoechst 33258 or DAPI, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Apply the stain to the fixed cells and incubate in the dark for 15-30 minutes.

- Mount and Visualize: Wash the coverslip with PBS to remove excess stain. Mount the coverslip on a microscope slide with a mounting medium. Examine the cells using a fluorescence microscope with the appropriate filter set.

- Interpret Results:

Guide 3: Eradicating Mycoplasma Contamination

This high-risk procedure should be performed in a dedicated quarantine space.

Experimental Protocol: Antibiotic Elimination of Mycoplasma

- Quarantine: Immediately move the contaminated culture to a separate, designated incubator and biosafety cabinet.

- Select an Antibiotic: Choose a proven anti-mycoplasma antibiotic, such as Plasmocin. Standard antibiotics like penicillin-streptomycin are ineffective [4].

- Treat Cells: Add the antibiotic to the culture medium at the recommended concentration (e.g., 25 μg/mL for Plasmocin). Culture the cells with the antibiotic for the prescribed duration, typically 1-2 weeks, with regular medium changes to maintain antibiotic activity [4].

- Passage without Antibiotics: After the treatment period, passage the cells into antibiotic-free medium and culture for a further 1-2 weeks. This "cure period" is crucial to ensure the bacteria are eliminated and not just suppressed.

- Validate Eradication: Test the cured cells for mycoplasma using at least two different methods (e.g., PCR and DNA staining) after the antibiotic-free period. If the tests are negative, the treatment was successful. If positive, consider a second, longer treatment cycle or discard the cells [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Mycoplasma Management

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmocin | A specialized antibiotic mixture used to treat mycoplasma-contaminated cell lines [4]. | Ineffective against all species; resistance can develop; treatment can stress cells. |

| Hoechst 33258 / DAPI Stains | Fluorescent DNA dyes used in indirect detection methods to visualize mycoplasma DNA on indicator cells [6]. | Requires fluorescence microscopy and experience to interpret; can produce false positives. |

| Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit | A commercially available kit for the highly sensitive and rapid detection of mycoplasma-specific DNA sequences [7]. | Does not confirm cell viability; can detect non-viable organism fragments. |

| 0.1 μm Pore Filter | Used for sterilizing solutions and media to physically remove mycoplasma [5] [6]. | Essential for filtering reagents; standard 0.22 μm filters are not sufficient. |

| Mycoplasma Experience Stock | A confirmed positive control culture used for validating detection assays and training personnel. | Must be handled with extreme caution in a quarantined area to prevent laboratory spread. |

Mycoplasma contamination represents one of the most significant yet stealthy challenges in cell culture laboratories. These bacteria, which lack a cell wall, are the smallest self-replicating organisms and can profoundly affect cell physiology and experimental outcomes without causing the obvious turbidity associated with common bacterial contaminants. For researchers in stem cell biology and drug development, where reproducibility and data accuracy are paramount, understanding and preventing mycoplasma contamination is not just good practice—it's essential for scientific integrity.

Prevalence and Resistance Patterns: The Quantitative Data

Mycoplasma contamination is widespread, affecting a substantial proportion of cell cultures globally. The tables below summarize key epidemiological and resistance data.

Table 1: Global Prevalence of Mycoplasma pneumoniae (MP) Infections and Resistance

| Location/Context | Prevalence/Resistance Rate | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Cell Cultures | 15-35% of continuous cultures [8] | Contamination rates can reach 65-80% in extreme cases; 8 species account for ~95% of contaminations. | |

| Southern Italy (Post-COVID) | 7.5% macrolide-resistant MP (MRMP) [9] | MRMP peaks at 12.6% in preadolescents (10-14 years); A2063G mutation predominates (96%). | |

| United States | <10% macrolide-resistant MP overall [10] | Higher resistance proportions (>20%) observed in the South and East, and within clusters. | |

| Europe | ~5% average macrolide-resistant MP [10] | Italy has a notably higher resistance rate, around 20%. | |

| Eastern China (Genital Mycoplasmas) | 43.74% infection rate in suspected cases [11] | High resistance to fluoroquinolones; Ureaplasma spp. most prevalent. |

Table 2: Impact of Mycoplasma Contamination on Cell Biology and Research

| Impact Area | Specific Consequences | Experimental Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Physiology | Chromosomal aberrations; disruption of nucleic acid synthesis; changes in membrane antigenicity [8]. | Compromised genetic studies; unreliable cell surface marker analysis. |

| Cell Growth & Metabolism | Inhibition of cell proliferation and metabolism; competition for essential nutrients (e.g., arginine) [5] [12]. | Altered growth curves; inconsistent cell counts; erroneous metabolic assays. |

| Gene Expression & Epigenetics | Dysregulation of hundreds of host genes; alteration of chromatin accessibility (affects ATAC-seq) [12]. | Misleading transcriptomics and epigenomics data; incorrect conclusions about treatment effects. |

| Virus Production & Transfection | Affects virus production; decreased transfection rates [8]. | Failed or inconsistent production of viral vectors; poor genetic manipulation efficiency. |

Detection and Diagnosis: Methodologies and Protocols

Routine testing is the cornerstone of mycoplasma contamination control. The following are established detection methods used in laboratories.

DNA Fluorescence Staining Method

This indirect method is a standard for many labs.

- Principle: Uses fluorescent dyes like Hoechst 33258 that bind to the A-T rich regions of DNA. In contaminated cultures, fluorescent spots appear in the cytoplasm around the host cell nuclei, which is the mycoplasma DNA [8] [13].

- Protocol: Culture cells on a sterile cover slip for 48-72 hours. Fix the cells with Carnoy's fixative (acetic acid:methanol, 1:3) and stain with Hoechst dye for 30 minutes. Examine under a fluorescence microscope [8].

- Advantages & Limitations: Relatively rapid (a few hours) but requires an indicator cell line and can sometimes yield false positives from apoptotic bodies or cellular debris.

PCR-Based Detection

PCR is one of the most sensitive, specific, and rapid methods.

- Principle: Universal PCR primers target the conserved 16S rRNA gene in the mycoplasma genome, allowing for the detection of over 60 species [8] [13].

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Incubate cell culture supernatant at 95°C for 5 minutes to inactivate nucleases [12].

- Amplification: Use specific primers (e.g., F: GGGAGCAAACAGGATTAGTATCCCT; R: TGCACCATCTGTCACTCTGTTAACCTC) in a touchdown PCR protocol to increase sensitivity [12] [8].

- Analysis: Run the PCR product on a 1.5% agarose gel. A positive result is indicated by a band of the expected size (e.g., ~500 bp) [12].

- Advantages & Limitations: Extremely sensitive and can provide results within 3-4 hours. However, it requires specialized equipment and can detect non-viable organisms.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Researchers

Q1: Our lab routinely uses penicillin/streptomycin in all cell cultures. Are we protected from mycoplasma contamination? No. Mycoplasmas lack a cell wall, rendering penicillin completely ineffective. While streptomycin may inhibit some strains, mycoplasmas are generally resistant to the antibiotic mixtures commonly used in cell culture [8] [14]. Reliance on antibiotics can mask low-level bacterial contamination and provide a false sense of security, allowing mycoplasma to spread undetected.

Q2: We are setting up a new stem cell culture lab. What are the most critical steps to prevent mycoplasma contamination? For a new stem cell lab, the following are crucial [12] [8] [14]:

- Source Cells Wisely: Only acquire cell lines from reputable sources that provide certification of being mycoplasma-free.

- Quarantine: Isolate and test all new cell lines in a designated incubator before introducing them to your main culture space.

- Aseptic Technique: Mandate strict use of personal protective equipment (PPE), minimize talking in the hood, and avoid working with multiple cell lines simultaneously.

- Routine Screening: Implement a policy of routine mycoplasma testing for all active cultures every 2 weeks to 3 months.

Q3: I suspect my precious, irreplaceable stem cell line is contaminated. Can it be saved? While the most recommended action is to discard contaminated cultures to prevent spread, eradication is sometimes attempted for unique or invaluable lines. Treatments can include specific antibiotics (e.g., plasmocin), fluoroquinolones, or macrolides, but success is not guaranteed [5]. Any "cured" cell line must be rigorously re-tested and its behavior closely monitored, as the eradication process and original contamination can alter its characteristics [5] [12].

Q4: How does mycoplasma contamination specifically impact high-throughput sequencing data in stem cell research? Mycoplasma contamination has severe effects on sequencing data:

- RNA-seq: Can dysregulate host gene expression profiles, leading to false interpretations of differential gene expression [12].

- ATAC-seq: Mycoplasma DNA, being prokaryotic, is highly accessible and will be preferentially tagmented by the Tn5 transposase. This can overwhelmingly dominate your sequencing library, drastically reducing the mapping rate to the host genome and invalidating the experiment [12].

- Genomic DNA-seq: Contaminating mycoplasma DNA can lead to misassembly and false alignment during analysis [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Problems Linked to Mycoplasma Contamination

| Problem | Potential Signs of Contamination | Recommended Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Cell Growth | Cells require frequent medium changes; reduced proliferation rate despite high confluence [13]. | Test for mycoplasma; check nutrient competition; review culture conditions. |

| Unexplained Changes in Cell Morphology | Increased granularity; unhealthy appearance without clear cause. | Perform DNA staining or PCR; check for contaminants affecting physiology. |

| Inconsistent Experimental Results | High variability in assays between passages; failure to replicate previous data. | Initiate systematic mycoplasma screening; authenticate cell lines. |

| Low Transfection/Virus Production Efficiency | Consistently low yields or efficiency despite protocol optimization. | Test for mycoplasma; known to disrupt transfection and viral production [8]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Mycoplasma Prevention, Detection, and Eradication

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Specific Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hoechst 33258 Stain | DNA-binding fluorescent dye for indirect detection. | Staining fixed cells on coverslips to visualize extranuclear mycoplasma DNA via fluorescence microscopy [8]. |

| Mycoplasma Detection PCR Kits | Contains primers targeting 16S rRNA for sensitive molecular identification. | Routine screening of cell culture supernatants; fast results (3-4 hours) with high specificity [12] [8]. |

| Mycoplasma Growth Supplement | Enriches broth and agar media for growing fastidious mycoplasma. | Used for the direct culture method, which is considered the gold standard for detection [8]. |

| Antibiotic/Eradication Reagents (e.g., Plasmocin) | Formulations specifically targeting mycoplasma metabolism. | Attempting to rescue unique, contaminated cell lines; not recommended for general use [5]. |

| Zell Shield | A cocktail of antibiotics, antifungals, and antimycoplasmal agents. | Added to media to protect against a broad spectrum of contaminants, though not a substitute for good technique [12]. |

Best Practices for Prevention

Preventing mycoplasma contamination is far more effective than dealing with its consequences. Key strategies include [12] [8] [14]:

- Strict Aseptic Technique: Always wear PPE, use a certified laminar flow hood, and disinfect all surfaces and equipment.

- Quarantine New Cell Lines: Isolate and test all new arrivals before integrating them with your main cell stock.

- Avoid Antibiotic Overreliance: Do not use antibiotics as a crutch; they can mask contamination.

- Maintain Good Record Keeping: Track cell lineages, test results, and contamination incidents.

- Routine Screening: Test all active cultures every few weeks and always before freezing or publishing.

In stem cell culture, even minor microbiological contamination can compromise research integrity and pose serious risks for clinical applications. Mycoplasma contamination, a particularly prevalent and stealthy threat, underscores the critical importance of understanding contamination pathways. This guide details common contamination sources and provides actionable protocols to safeguard your stem cell research.

1. What are the most common sources of mycoplasma contamination in a stem cell lab?

Mycoplasma contamination primarily originates from five key sources, each requiring specific control measures [15]:

- Laboratory Personnel: Technicians are a major source of human-origin mycoplasma species (e.g., M. orale, M. fermentans), often introduced via poor aseptic technique [5].

- Contaminated Culture Reagents: While less common with reputable suppliers, raw materials like fetal bovine serum (a source of M. arginini and A. laidlawii) and trypsin (a source of M. hyorhinis) can be vectors [5].

- Contaminated Cell Lines: The introduction of new, untested cell lines from other labs is currently a major route of contamination spread [5].

- Nonsterile Laboratory Equipment: Pipettes, water baths, and other equipment can harbor contaminants if not properly sterilized [15].

- Environmental Contamination: Mycoplasma can persist in the cell culture room, incubator, or biosafety cabinet, leading to cross-contamination across multiple cell lines [15].

2. How does contamination from personnel actually spread?

Mycoplasma spreads readily via aerosols and surface contact. A model demonstrated that after trypsinizing an infected culture in a laminar flow hood, live mycoplasma were found on the technician, the hemocytometer, pipettor, and the hood surface. Contamination persisted on the hood surface for up to six days, and a clean culture processed in the same hood weeks later became infected. This shows how a single contaminated culture can rapidly compromise an entire laboratory's work [5].

3. What is the documented rate of contamination in stem cell cultures?

Microbiological control programs in stem cell banks provide clear data on contamination rates. One study analyzing 32 stem cell and feeder cell lines over 158 passages found that 12% of passages were contaminated. The breakdown of contaminants is shown in the table below [16]:

Table 1: Contamination Profile in Stem Cell Cultures

| Contaminant Type | Number of Contaminated Passages | Percentage of Total Contaminants |

|---|---|---|

| Gram-Positive Cocci | 10 | 53% |

| Mycoplasma species | 7 | 37% |

| Gram-Negative Rods | 3 | 16% |

| Gram-Positive Rods | 2 | 11% |

| Note: Three passages had co-contamination with two microorganisms. |

4. Why is mycoplasma considered a more serious problem than bacterial contamination?

Mycoplasma is particularly problematic due to its subtle nature. Unlike bacteria, which often cause turbidity in the medium, mycoplasma does not typically kill the host cells or change the medium's appearance. It lacks a cell wall, making it resistant to common antibiotics like penicillin and allowing it to pass through standard 0.22µm filters. With a size of only 0.1-0.3 µm, it is impossible to detect with a regular microscope. Mycoplasma infection can chronically alter cell metabolism, growth, and gene expression, leading to unreliable and erroneous experimental results without any obvious signs of trouble [17] [5].

5. What are the best methods for detecting mycoplasma contamination?

Several methods are available, with varying levels of expertise and time required. The following table summarizes the common detection methodologies [15] [5]:

Table 2: Mycoplasma Detection Methods

| Method | Principle | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Culture-Based | Direct growth of mycoplasma on agar. | Considered the "gold standard" but can take weeks for results [15]. |

| DNA Staining (e.g., DAPI, Hoechst) | Fluorescent dyes bind to mycoplasma DNA attached to indicator cells, visible under a fluorescence microscope. | A common indirect method; requires an indicator cell line [17] [5]. |

| PCR and qPCR | Amplification of mycoplasma-specific DNA sequences. | Highly sensitive and fast; allows for specific identification of mycoplasma species [15]. |

| Enzymatic or Chemiluminescent Assays | Detection of an enzyme activity specific to mycoplasma. | Provides a robust and specific detection method [15]. |

The following workflow diagram outlines the strategic process for monitoring and responding to potential contamination:

Experimental Protocols for Prevention and Detection

Protocol 1: Routine Mycoplasma Detection via DNA Staining

This protocol uses fluorescent dyes to detect mycoplasma DNA adherent to host cells, a widely used and effective method [17].

Principle: DNA-binding dyes like DAPI or Hoechst stain both mammalian and mycoplasma DNA. Because mycoplasmas adhere to the cell surface and in the pericellular space, they appear as a characteristic particulate or filamentous staining pattern on the background of the larger host cell nuclei.

Materials:

- Indicator cells (e.g., Vero cells or the cells being tested) grown on a cover slip or in a chamber slide.

- DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) or Hoechst stain solution.

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

- Fixative solution (e.g., 3:1 Methanol:Acetic Acid or 4% Paraformaldehyde).

- Fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets.

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Grow indicator cells to about 50-70% confluency on a sterile cover slip placed in a culture dish. Alternatively, test the cells in question directly.

- Fixation: Aspirate the culture medium and wash the cells gently with PBS. Add the fixative solution and incubate for 15-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Staining: Aspirate the fixative, wash twice with PBS, and add the DAPI or Hoechst stain solution (diluted according to manufacturer's instructions). Incubate for 15-30 minutes in the dark.

- Washing and Mounting: Aspirate the stain and wash the cells thoroughly three times with PBS to remove unbound dye. If using a cover slip, mount it on a glass slide with a mounting medium.

- Microscopy: Observe the cells under a fluorescence microscope. A positive mycoplasma contamination is indicated by the presence of small, bright, particulate or filamentous staining in the intercellular spaces, in addition to the larger, well-defined nuclei of the host cells.

Protocol 2: Decontamination of Irreplaceable Cell Cultures

This protocol provides a stepwise procedure for attempting to salvage a valuable, contaminated cell line using antibiotics, noting that this is a last resort and carries risks of inducing resistance or cellular changes [18].

Principle: High doses of specific anti-mycoplasma antibiotics are applied to infected cultures for a limited time to eradicate the contaminant, followed by a rigorous validation period to confirm eradication.

Materials:

- Contaminated cell culture.

- Appropriate mycoplasma elimination reagent (e.g., antibiotic-based or non-antibiotic like membrane-active peptides) [15].

- Antibiotic-free culture medium.

- Multi-well culture plates or small flasks.

Methodology:

- Toxicity Test: Dissociate, count, and dilute the contaminated cells in antibiotic-free medium. Dispense the cell suspension into a multi-well plate. Add the elimination reagent to the wells in a range of concentrations. Observe the cells daily for signs of toxicity (e.g., sloughing, vacuolation, decreased confluency) over several days to determine the maximum non-toxic concentration [18].

- Treatment Phase: Culture the cells for 2-3 passages using the elimination reagent at a concentration one- to two-fold lower than the determined toxic level.

- Post-Treatment Validation: Culture the cells for one passage in antibiotic-free media. Then, culture the cells in antibiotic-free medium for 4-6 additional passages. At the end of this period, test the cells again for mycoplasma using a sensitive method (e.g., PCR) to confirm the contamination has been eliminated [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The following reagents are essential for the effective prevention, detection, and elimination of mycoplasma in stem cell cultures.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Mycoplasma Management

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mycoplasma Elimination Reagents | To treat and eradicate mycoplasma from contaminated cultures. | Includes DNA synthesis inhibitors (e.g., fluoroquinolones), protein synthesis inhibitors (e.g., macrolides), and non-antibiotic membrane disruptors. Alternating or combining agents is advised to prevent resistance [15]. |

| PCR or qPCR Detection Kit | Sensitive and specific molecular detection of mycoplasma DNA. | Ideal for routine screening; provides rapid results. Kits often include primers for common mycoplasma species [15]. |

| DNA Fluorescent Stains (DAPI/Hoechst) | Histochemical staining for microscopic visualization of mycoplasma. | A standard indirect method; requires indicator cells and fluorescence microscopy. Can yield false positives from cellular debris [17] [15]. |

| Mycoplasma Culture Kits | Gold-standard method based on microbial growth. | Used for definitive confirmation. Requires a long incubation time (several weeks) but is highly reliable [15]. |

| Validated Mycoplasma-Free FBS | Critical culture supplement certified to be free of mycoplasma and other viruses. | Sourcing from reputable suppliers who provide certification is a fundamental preventive measure [5] [19]. |

Effective control of contamination in stem cell research requires a proactive, multi-layered strategy. This involves rigorous environmental monitoring, strict adherence to aseptic technique, careful sourcing and quarantine of new cell lines and reagents, and implementing a routine, reliable testing schedule for mycoplasma. By understanding the common sources and integrating these troubleshooting guides and protocols into your daily practice, you can significantly mitigate risk and protect the integrity of your research and potential clinical products.

Mycoplasma contamination represents one of the most significant yet frequently overlooked challenges in stem cell research. Unlike bacterial or fungal contaminants that produce obvious turbidity or pH changes, mycoplasma contamination is covert, potentially lingering for extended periods without noticeable cell damage [5]. This hidden nature makes it particularly dangerous, as contaminated cultures can produce published data that are irreproducible, wasting valuable research resources and time [20].

The particular vulnerability of stem cell cultures to mycoplasma contamination necessitates specialized vigilance. Stem cells, with their unique metabolic profiles and pluripotent capabilities, respond differently to mycoplasma infection compared to traditional cell lines. The contamination can alter their differentiation potential, compromise their genetic integrity, and ultimately invalidate experimental results [20] [21]. This guide provides comprehensive troubleshooting resources to help researchers identify, address, and prevent mycoplasma contamination within the critical context of stem cell research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the specific effects of mycoplasma contamination on stem cell metabolism and gene expression?

Mycoplasma contamination systematically compromises fundamental cellular functions in stem cells through multiple mechanisms:

- Nutrient Competition: Mycoplasmas compete with stem cells for essential nutrients in the culture medium, particularly amino acids and nucleic acid precursors, leading to hindered cell growth and proliferation [20].

- Metabolic Interference: Mycoplasmas expose stem cells to unwanted metabolites and alter levels of protein, RNA, and DNA synthesis [20]. This metabolic stress can manifest as slowed proliferation and premature cell death [22].

- Gene Expression Alterations: Contamination induces significant changes in gene expression patterns and cell signaling pathways, potentially affecting stem cell differentiation and pluripotency markers [20].

- Genomic Impact: Mycoplasma infection can cause mutations and chromosomal changes, directly threatening genomic integrity [20]. Research has shown that transcription processes themselves can be sources of DNA damage, including double-strand breaks, which mycoplasma contamination may exacerbate [23].

Q2: Why is mycoplasma contamination particularly problematic for stem cell research and drug development?

Mycoplasma contamination poses unique threats to stem cell research and therapeutic development:

- Compromised Cellular Identity: Contamination alters gene expression, cell signaling, and morphology, potentially changing a stem cell's fundamental identity and differentiation capacity [20]. This is particularly critical for stem cells used in regenerative medicine.

- Irreproducible Results: Experiments conducted with contaminated cells often cannot be replicated with clean cells, and vice versa, leading to false interpretations and invalid conclusions [20].

- Therapeutic Safety Risks: For stem cell-based therapies, mycoplasma contamination presents direct patient safety concerns through altered cellular function and potential product contamination [24] [5].

- Regulatory Challenges: In GMP manufacturing, contamination can lead to batch failures, costly production delays, and regulatory scrutiny [24].

Q3: What are the most reliable methods for detecting mycoplasma contamination in stem cell cultures?

Detection methods vary in sensitivity, time requirements, and regulatory acceptance. The table below summarizes the primary detection approaches:

Table 1: Mycoplasma Detection Methods Comparison

| Method | Principle | Time Required | Sensitivity | Suitable for Stem Cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Agar Culture | Growth on specialized agar plates | 3-5 weeks | High (Gold Standard) | Yes, for definitive confirmation [20] |

| PCR-Based Tests | DNA amplification of mycoplasma-specific sequences | Hours to 1 day | High | Yes, for rapid screening [25] [20] |

| Fluorescence Staining | DNA-binding dyes (e.g., Hoechst) visualize mycoplasma DNA | 1-2 days | Moderate | Yes, with proper controls [22] |

| Enzyme Immunoassays | Detection of mycoplasma-specific enzymes | Several hours | Moderate | Yes, for high-throughput screening [22] |

| Indicator Cell Culture | Culture on Vero cells with DAPI staining | 1-2 weeks | High | Yes, but time-consuming [5] |

For stem cell research, a combination of PCR-based screening for regular monitoring and agar culture for definitive confirmation provides optimal security [20] [26].

Q4: Our lab follows aseptic techniques, yet we still experience mycoplasma contamination. What are we missing?

Even with proper aseptic technique, several overlooked factors can introduce mycoplasma:

- Cross-Contamination in Shared Spaces: Working with multiple cell lines simultaneously in the same biosafety cabinet significantly increases contamination risk [25] [26]. Implement a "one cell line at a time" policy in the hood.

- Inadequate Incubator Maintenance: Water baths and incubator water pans are common contamination reservoirs—clean these regularly and use antimicrobial solutions like Aquaguard [20].

- Improper Hood Management: Storing equipment or materials in the biosafety cabinet can disrupt laminar airflow, compromising sterility [25].

- Antibiotic Misuse: Routine antibiotic use in stem cell culture can mask low-level contamination and promote antibiotic resistance [25] [26]. Reserve antibiotics for specific, justified applications.

- Human Carriers: An estimated 80.6% of laboratory technicians are mycoplasma carriers [20]. Proper personal protective equipment, including lab coats dedicated to mammalian cell culture and gloves, is essential.

Troubleshooting Guides

Mycoplasma Contamination: Detection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a systematic approach to detecting mycoplasma contamination in stem cell cultures:

Systematic Prevention Strategy

Implementing a robust prevention strategy requires addressing multiple potential contamination sources simultaneously:

Quantitative Impact of Mycoplasma Contamination

The table below summarizes the documented effects of mycoplasma contamination on cellular systems:

Table 2: Documented Effects of Mycoplasma Contamination on Cellular Systems

| Affected System | Specific Effects | Experimental Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Metabolism | Competition for nucleic acid precursors and amino acids [20] | Altered metabolic profiling, reduced ATP production |

| Gene Expression | Changes in expression of up to 5-10% of mammalian genes [20] | False conclusions in transcriptome studies |

| Genomic Integrity | Chromosomal aberrations and mutations [20]; interference with DNA damage repair pathways [23] | Compromised genetic stability in stem cell lines |

| Proliferation Rate | Reduction in growth rate by 30-50% [22] | Extended experiment timelines, skewed population dynamics |

| Cell Physiology | Membrane damage, organelle dysfunction [20] | Abnormal response to differentiation signals |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Mycoplasma Prevention and Detection in Stem Cell Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Mycoplasma Management |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Kits | EZ-PCR Mycoplasma Detection Kit [25]; Sartorius MycoSEQ PCR kits [26] | Regular screening and confirmation of contamination |

| Disinfectants | Pharmacidal Spray [20]; 70% ethanol; bleach solutions | Surface decontamination of work areas and equipment |

| Water Pan Additives | Aquaguard Solutions 1 & 2 [20] | Prevention of microbial growth in incubator water reservoirs |

| Antibiotics for Eradication | Fluoroquinolones; Macrolides; Tetracyclines [20] [26] | Elimination of mycoplasma from irreplaceable cell lines |

| Cell Culture Media Components | Quality-controlled FBS; Antibiotic-free media [5] | Reducing introduction and masking of contaminants |

| Personal Protective Equipment | Dedicated lab coats; sterile gloves; masks [25] | Prevention of human-derived contamination |

Vigilance against mycoplasma contamination is not merely a technical consideration but a fundamental ethical responsibility in stem cell research. The hidden toll on cell metabolism, gene expression, and genomic integrity can compromise years of research and potentially endanger future therapeutic applications. By implementing the systematic detection, prevention, and troubleshooting strategies outlined in this guide, researchers can protect their valuable stem cell lines, ensure the validity of their findings, and contribute to the advancement of reproducible, high-quality science.

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the most critical ISSCR recommendations for preventing cell culture contamination? The ISSCR emphasizes that researchers must demonstrate and document that cell lines are free of microbial contamination [27]. Key recommendations include handling stem cell cultures aseptically, ideally without antibiotics to avoid hidden contaminations, and conducting daily microscopic observation of cultures to monitor for signs of infection such as cell death, turbidity, and color changes in culture media [27]. Robust microbiological testing of Master Cell Banks (MCBs) is strongly advised.

My cell culture shows no visible contamination but has a reduced growth rate. Could it be mycoplasma? Yes. Unlike other contaminants, mycoplasma contamination does not typically cause turbidity and is too small to be seen with regular microscopy [5] [28]. A reduced rate of cell proliferation is one of the first visible signs, as mycoplasmas compete with your cells for nutrients [28]. Other indications can include cell aggregation, morphological changes, and a sudden drop in transfection efficiency [28]. Specific testing is required for confirmation.

Are we obligated to test for mycoplasma even if our cells look healthy? Absolutely. The ISSCR recommends regular mycoplasma testing as part of good cell culture practice [29]. Mycoplasma contamination can persist without noticeable cell damage but can alter almost every aspect of cell physiology, leading to unreliable and erroneous results [5] [30]. Establishing a routine testing protocol (e.g., via PCR) for all cultures is essential for research integrity [29].

According to ISSCR, what should we do with a contaminated cell line? The ISSCR's general recommendation is that contaminated cell lines should be discarded, barring exceptional circumstances [27]. While methods to eliminate mycoplasma contamination exist and can be considered for unique, irreplaceable cultures, the safest and most standard practice to protect your other cell lines and the validity of your research is to dispose of the contaminated culture properly [5] [27].

What are the ethical implications of using contaminated cells in research? Using contaminated cells violates the core ethical principles of research integrity and transparency upheld by the ISSCR [31]. Data generated from contaminated cells is not trustworthy, as mycoplasma can profoundly alter cell physiology and metabolism [5]. This can lead to the publication of false and irreproducible results, wasting scientific resources and potentially misleading future research and clinical efforts, which is a breach of ethical scientific practice [31] [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Preventing Mycoplasma Contamination

Mycoplasma contamination is a serious problem in cell culture. The following diagram outlines the primary sources and pathways of contamination, which are critical to understand for effective prevention.

Workflow Overview: The diagram illustrates that contamination primarily originates from laboratory personnel, contaminated reagents, cross-contamination from infected cultures, and non-sterile supplies [5]. These sources introduce species like M. orale and M. arginini. The recommended prevention measures form a multi-layered defense to block these pathways [5] [29].

Detailed Prevention Protocols:

- Aseptic Technique: Maintain strict procedures and disinfect all surfaces with 70% ethanol/isopropanol. Avoid actions that can introduce contamination, such as talking or coughing near cultures [29].

- Quarantine New Cultures: Place all new cell sources in quarantine and perform quality control, including mycoplasma testing, before integrating them into your main laboratory workflow [29].

- Careful Reagent Handling: Use high-quality, well-screened reagents. Filter raw animal-derived sera and media with 0.1µm pore size filters, especially if sterility is dubious, as 0.2µm filters may not be sufficient under high pressure [5].

- Environmental Control: Keep the laboratory and laminar flow hoods clean and uncluttered. Regularly clean incubators and water baths [29].

- Antibiotic-Free Culture: Periodically culture cells for 2-3 weeks without antibiotics to reveal any hidden, low-level contaminations that antibiotics might be masking [29].

Guide 2: Detecting Mycoplasma Contamination

When contamination is suspected, a systematic approach to detection is required. The following workflow guides you through the process from observation to confirmation.

Workflow Overview: The detection process begins with observing subtle culture signs and proceeds to specific testing, as visual confirmation under a standard microscope is impossible [28]. A positive result typically leads to discarding the culture, with decontamination being a last resort for valuable lines [27].

Detailed Detection Methodologies: The ISSCR recommends robust testing and notes that different methods can be used [27]. The table below summarizes common techniques.

| Method | Principle | Duration | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR [30] | Amplifies mycoplasma-specific DNA sequences | ~1 day | High sensitivity, rapid, easy to establish in lab [30] [27] | Does not distinguish between viable and dead organisms |

| Microbiological Culture [30] | Grows mycoplasma on agar or in broth | 3-4 weeks | The "gold standard" for direct detection [30] | Very slow, requires specific culture conditions |

| DNA Fluorochrome Staining [30] [28] | Stains DNA on indicator cells; mycoplasma appear as fluorescent foci | 1-2 days | Detects a broad range of species visually | Requires fluorescence microscope, may have lower sensitivity |

Table: Comparison of major mycoplasma detection methods. It is recommended that two techniques be used, selected from a PCR-based method, indirect staining, and agar/broth culture [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Reagent / Material | Function in Prevention/Detection |

|---|---|

| 0.1µm Pore Filter | Sterilizing media and reagents; more effective at removing mycoplasma than standard 0.2µm filters [5]. |

| PCR Mycoplasma Test Kit | A rapid and sensitive method for routine screening of cell cultures for mycoplasma DNA [30] [29]. |

| DNA Staining Kit (e.g., Hoechst) | A fluorescent dye used in indirect staining methods to detect mycoplasma DNA on indicator cells [30]. |

| Mycoplasma Culture Media | Specialized agar and broth for the cultivation and direct detection of mycoplasma contaminants [30]. |

| 70% Ethanol/Isopropanol | A standard disinfectant for sterilizing surfaces, laminar flow hoods, and equipment to maintain an aseptic environment [29]. |

| Antibiotic-Free Medium | Used for routine culture to prevent the masking of low-level bacterial or mycoplasma contaminations [27] [29]. |

Navigating ISSCR Guidelines and Ethics

The ISSCR Guidelines stress that the primary mission of biomedical research is to alleviate human suffering, and this collective effort depends on public trust and rigorous ethical standards [31]. Contamination control is not just a technical issue but an ethical imperative directly tied to the core principles of:

- Integrity of the Research Enterprise: Ensuring that information obtained from research is trustworthy and reliable [31]. Data from contaminated cells is not, rendering subsequent experiments worthless [30].

- Transparency: Researchers are expected to share data and methods and communicate the state of the art, including uncertainties [31]. This includes being transparent about the quality control measures, like mycoplasma testing, applied to cell lines.

- Social Justice: Wasting resources on flawed research due to contamination diverts funds and effort from addressing unmet medical needs [31].

Furthermore, the ISSCR's clinical translation guidelines mandate that stem cell-based interventions must be processed with scrupulous oversight to ensure integrity, function, and safety before patient use [32]. Using a contaminated cell line in the development of a therapy introduces an unacceptable risk of pathogen transmission and invalidates preclinical safety data, constituting a serious breach of patient welfare [31] [32]. Adherence to these guidelines is fundamental to conducting scientifically sound and ethically responsible stem cell research.

Detection and Defense: Implementing Robust Mycoplasma Screening and Aseptic Protocols

Mycoplasma contamination represents a pervasive and serious threat to the integrity of stem cell research and the safety of resulting cellular therapies. These cell-wall-less bacteria can profoundly alter cell physiology and metabolism without causing visible turbidity in culture media, often going undetected for extended periods [5]. For stem cell lines, which are frequently cultured over long durations and exchanged between laboratories, the risk is particularly acute [14]. Compendial culture methods outlined in United States Pharmacopeia (USP) <63>, European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.) 2.6.7, and Japanese Pharmacopeia (JP) remain the regulatory gold standard for mycoplasma testing, providing the most comprehensive detection system despite the emergence of faster molecular alternatives [33] [34]. This guide details the implementation, troubleshooting, and contextual application of these mandated methods within a stem cell research environment.

Understanding the Compendial Framework: USP <63> and Ph. Eur. 2.6.7

What are the core principles of the compendial culture method?

The compendial culture method is a dual-phase enrichment and detection system designed to support the growth of a wide spectrum of fastidious Mollicutes. Its core principle is to provide both liquid and solid culture media that are exceptionally enriched with nutrients and growth factors to accommodate mycoplasmas' auxotrophic nature [33]. The method requires a substantial sample volume (typically ~15 mL) and an extended incubation period of 28 days to allow slow-growing contaminants to reach detectable levels [33] [34]. This prolonged incubation is necessary because mycoplasmas lack many biosynthetic pathways and are therefore fastidious, requiring complex media and extended incubation times [33].

Which mycoplasma species are targeted by these standards?

The pharmacopeias specify a panel of reference organisms that must be detected for a method to be considered valid. These organisms were selected based on their relevance as cell culture contaminants, their origin (human, bovine, or swine), and their clinical significance. The table below summarizes key indicator organisms.

Table 1: Key Mycoplasma Reference Strains in Compendial Testing

| Organism | Relevance in Pharmacopeia | Reported as Cell Culture Contaminant | Typical Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acholeplasma laidlawii | USP <63>, Ph. Eur. 2.6.7, JP XVIII [33] | Yes [33] [5] | Fetal Bovine Serum [5] |

| Mycoplasma fermentans | USP <63>, Ph. Eur. 2.6.7 [33] | Yes [33] | Laboratory Personnel [5] |

| Mycoplasma orale | USP <63>, Ph. Eur. 2.6.7, JP XVIII [33] | Yes [33] [5] | Laboratory Personnel (Human Oropharyngeal) [5] |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | USP <63>, Ph. Eur. 2.6.7, JP XVIII [33] | No [33] | Vaccines/Cell Banks for Human Use [33] |

| Mycoplasma hyorhinis | USP <63>, Ph. Eur. 2.6.7, JP XVIII [33] | Yes [33] [5] | Trypsin Solutions of Porcine Origin [5] |

It is important to note that some species, like Spiroplasma citri (or a genetically similar substitute), are also included to account for contaminants that may originate from insect or plant material used during production processes [33].

The Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram and protocol outline the standard compendial culture method as per USP <63> and Ph. Eur. 2.6.7.

Figure 1: Workflow of the compendial mycoplasma testing method as per USP <63> and Ph. Eur. 2.6.7, combining both broth/agar culture and indicator cell culture methods.

Detailed Methodology

- Sample Preparation: Aseptically collect at least 15 mL of the test cell culture supernatant [33]. The sample should be taken from a culture that has not received antibiotics for at least a week to avoid suppressing low-level contamination.

- Broth Inoculation and Incubation: Inoculate the sample into specialized, enriched broth media (e.g., Hayflick's broth or SP4 medium). The choice of medium may need to be optimized for certain fastidious species [33].

- Agar Subculture and Examination: On days 3, 7, and 14 of incubation, subculture a portion of the broth onto solid agar plates [33] [35].

- Wrap plates in parafilm to prevent drying and incubate under the same conditions as the broth [33].

- Periodically examine the agar plates under a dissection microscope (at up to 20x magnification) for the appearance of characteristic "fried egg" colonies, which result from central growth into the agar and superficial surface growth [34].

- Indicator Cell Culture Method (Parallel Test): As not all mycoplasma strains grow in artificial media, a parallel test is run. Inoculate a sample of the test material onto indicator cells (typically Vero cells) and culture for 3-5 days [34] [35]. The cells are then fixed and stained with a DNA-binding fluorochrome like Hoechst 33258 or DAPI. Under a fluorescence microscope, a mycoplasma-positive sample will show fluorescent staining not just in the cell nuclei, but also as a particulate or filamentous pattern on the cell surface due to the adhered mycoplasmas [34] [35].

A final negative result is only reported after a full 28-day incubation with no growth observed on agar plates and a negative indicator cell culture result [34] [35].

Troubleshooting Common Issues in Compendial Testing

What are the major limitations, and how can we address them?

The primary challenge of the compendial method is its 28-day duration, which is incompatible with biological products that have a short shelf-life, such as many cell therapy products (e.g., 48-72 hours) [33]. Furthermore, the method is technically demanding, labor-intensive, and requires a large sample volume [34] [36]. The following table outlines common problems and solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Compendial Culture Methods

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution & Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| No growth of positive control strains. | Improper media preparation, incorrect incubation conditions (temperature, CO₂), or excessive passaging of reference strains. | Use freshly prepared, validated media batches. Verify incubator settings. Keep reference strain passages below 15 from the original stock as per USP <63> [33]. |

| Contaminated test articles (other bacteria/fungi). | Non-sterile sample or technique. Overgrowth of contaminants can mask mycoplasma growth. | Ensure aseptic sampling technique. For non-sterile products, consider filtration or specific inactivating agents as described in the pharmacopeia. |

| Inconsistent results between tests. | Low-level or intermittent contamination, sample not representative, or technique variability. | Increase sample volume as per guidelines. Test cultures that are in the log phase of growth and have not been recently treated with antibiotics. Standardize protocols and analyst training. |

| Method is too slow for product release. | Inherent 28-day incubation period. | For short-shelf-life products, implement a validated, rapid molecular method (e.g., PCR) for product release, while using the compendial method for parallel validation and environmental monitoring [33] [34]. |

Comparison with Alternative Detection Methods

While the culture method is the gold standard, several other techniques are used, especially in time-sensitive R&D settings. The European and Japanese pharmacopeias accept validated molecular methods with a limit of detection of ≤10 CFU/mL as an alternative to culture [33]. The table below compares the primary methods.

Table 3: Comparison of Mycoplasma Detection Methods

| Method | Principle | Approx. Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compendial Culture [33] [34] | Growth in enriched broth/agar. | 28 days | Regarded as the gold standard; can detect viable organisms; high sensitivity when fully executed. | Very long turnaround time; labor-intensive; cannot detect non-cultivable species without indicator cell method. |

| DNA Staining [35] [28] | Staining with fluorescent DNA dyes (e.g., Hoechst). | 1-2 days | Rapid and relatively simple. | Low sensitivity; requires high level of contamination (~10⁶ CFU/mL); subjective interpretation; requires indicator cells. |

| PCR-Based Methods [33] [34] [35] | Amplification of conserved 16S rRNA gene sequences. | 2-5 hours | Very fast, highly sensitive, can detect a broad spectrum of species. Ideal for screening and short-shelf-life products [33]. | May detect non-viable DNA; requires rigorous validation to avoid false positives/negatives; considered an alternative method in the US [33]. |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) [36] | Detection of specific mycoplasma antigens. | 4-6 hours | Easy to perform, reproducible, and easily interpreted [36]. | Lower specificity and sensitivity compared to PCR and culture methods. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Compendial Testing

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Compendial Culture Methods

| Reagent/Item | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Enriched Broth Media | Supports the growth and metabolism of fastidious mycoplasma in liquid culture. | Hayflick's broth, SP4 broth [33]. The choice depends on the target species; SP4 is often used for more fastidious strains. |

| Enriched Solid Agar | Allows for the formation of characteristic mycoplasma colonies for visual identification. | Hayflick's agar, SP4 agar [33]. Must be sealed to prevent drying during long incubation. |

| Indicator Cell Line | Host cells for the detection of mycoplasma that do not grow in artificial culture media. | Vero cells (a mammalian cell line) [34]. |

| DNA Fluorochrome Stain | Binds to DNA, allowing visualization of mycoplasma adhered to indicator cells under fluorescence microscopy. | Hoechst 33258 or DAPI [34] [35]. |

| Reference Strains | Positive controls to validate that the media and methods are functioning correctly. | ATCC strains (e.g., M. pneumoniae ATCC 15531, A. laidlawii ATCC 23206) [33]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our stem cell therapies have a shelf-life of 48 hours. Is a 28-day test relevant?

This is a critical industry challenge. While the 28-day test is the regulatory ideal, it is impractical for product release. The current strategy is to use a rigorously validated, rapid method (like a validated PCR assay) for product release, while the compendial method is used for qualifying the manufacturing process, testing master cell banks, and ongoing system suitability [33]. The European Pharmacopoeia is currently being revised to better reflect this practice and the state of current technology [37].

Q2: Why is the sample volume requirement so large (~15 mL)?

The large volume is necessary to ensure a representative sample and to detect a low-level contamination. Mycoplasma contamination can be present at very low concentrations, and a large sample volume increases the probability of capturing the organism for detection, especially given the potential for uneven distribution in the culture [33].

Q3: Can we rely solely on PCR for our stem cell research?

For definitive product release in regulated environments, a validated PCR method may be acceptable as an alternative, but it requires extensive comparative validation against the compendial method to demonstrate equivalence as per USP <1223> [33]. For basic research, PCR is an excellent, highly sensitive tool for routine screening. However, it is crucial to remember that PCR detects DNA, not necessarily viability. A positive PCR result could be from dead organisms, while a culture-based method confirms the presence of viable, replicating mycoplasma.

Q4: What are the best practices for preventing mycoplasma contamination in a stem cell lab?

Prevention is paramount. Key tips include [14]:

- Routine Screening: Test all cells regularly, including all new cell lines entering the lab.

- Aseptic Technique: Use proper sterile technique, work with one cell line at a time, and keep all containers covered.

- Lab Hygiene: Sterilize work surfaces and equipment meticulously and regularly clean water baths and incubators.

- Antibiotic Responsibility: Avoid the routine use of antibiotics, as they can mask low-level bacterial contamination and are ineffective against mycoplasma, potentially leading to persistent, hidden infections [14].

- Good Record Keeping: Maintain thorough records of cell sources, test results, and contamination incidents for traceability.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common qPCR Issues in Mycoplasma Testing

This guide addresses specific qPCR issues you might encounter when testing for mycoplasma contamination in stem cell cultures, providing targeted solutions to ensure assay reliability.

Table 1: Common qPCR Abnormalities and Corrective Actions

| Problem Observed | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification in No Template Control (NTC) | Contamination from sample splashing, reagent contamination, or primer-dimer formation [38] [39]. | Clean work area and pipettes with 10% bleach or 70% ethanol; prepare fresh primer dilutions; spatially separate NTC wells on the plate; include a melt curve to detect primer-dimer [38] [39]. |

| Ct Values Too Early | Genomic DNA contamination in RNA samples, highly expressed transcript, or sample evaporation increasing concentration [38] [39]. | DNase treat samples prior to reverse transcription; ensure primers span an exon-exon junction; dilute template to an ideal Ct range [38] [39]. |

| Poor Replicate Reproducibility | Pipetting error, insufficient mixing of reaction solutions, or low copy number of the target [38] [40] [39]. | Calibrate pipettes; mix all solutions thoroughly; perform technical replicates; use positive-displacement pipettes and filtered tips [40] [39]. |

| Abnormal Melt Curve (Multiple Peaks) | Primer-dimer formation (if Tm <80°C) or non-specific amplification/gDNA contamination (if Tm >80°C) [40]. | Optimize primers and increase annealing temperature; Blast-check primer specificity; use a no-reverse-transcriptase control (NAC) to check for gDNA [40] [41]. |

| Low Amplification Efficiency (Slope > -3.1 or < -3.6) | Presence of PCR inhibitors, inaccurate dilutions for standard curve, or suboptimal primer design [38] [39] [41]. | Dilute template to reduce inhibitors; prepare standard curve fresh and accurately; redesign primers using specialized software [38] [41]. |

| No Amplification | Failed reverse transcription, reaction inhibitors, or incorrect instrument settings [42] [39]. | Check RNA quality and cDNA synthesis; verify correct dye and well selection in instrument software; run a positive control [42] [39]. |

| High Background Noise or Jagged Curves | Probe degradation, bubbles in the reaction well, or unstable fluorescence due to system inhibitors [40] [39]. | Ensure sufficient probe concentration; centrifuge plates to remove bubbles; improve template purity; calibrate the instrument [40] [39]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My No Template Control (NTC) is showing amplification. What does this mean and how can I resolve it? Amplification in your NTC indicates contamination of your reaction reagents or primer-dimer formation. This is a critical issue for mycoplasma testing as it can lead to false positives. To resolve it, decontaminate your work surface and pipettes with 10% bleach or 70% ethanol [39]. Prepare fresh primer and probe dilutions, and ensure you are using nuclease-free water [38]. When setting up your plate, position the NTC wells away from any sample wells to prevent splashing or aerosol contamination [38]. Finally, run a dissociation curve; a peak at a lower melting temperature (Tm) than your target amplicon typically indicates primer-dimer [40].

Q2: How can I prevent genomic DNA from causing false positives in my mycoplasma qPCR assay? Genomic DNA (gDNA) contamination is a common pitfall. The most effective strategy is to use primers that are designed to span an exon-exon junction, which will not efficiently amplify gDNA [38] [41]. Furthermore, you should always treat your RNA samples with DNase I prior to the reverse transcription step [38]. It is also crucial to include a mandatory "No Amplification Control" (NAC) or "No Reverse Transcriptase Control" (-RT control) in every experiment. This control contains all reaction components except the reverse transcriptase. Amplification in this control signals the presence of contaminating DNA [41].

Q3: My amplification curves for mycoplasma standards are inconsistent, with poor reproducibility between replicates. What should I check? Poor replicate reproducibility is often related to pipetting technique and reaction homogeneity. First, check the calibration of your micropipettes, as small volumetric errors can significantly impact qPCR results [38] [43]. Ensure all reaction components are mixed thoroughly but gently before plate loading [39]. For low-concentration targets, which can exhibit stochastic amplification, it is advisable to increase the number of technical replicates [40]. Using an automated liquid handler can dramatically improve precision and consistency by eliminating manual pipetting error [43].

Q4: My qPCR assay has low efficiency. How does this affect mycoplasma quantification, and how can I improve it? A qPCR reaction with low efficiency (slope > -3.1) will not double the product each cycle, leading to an underestimation of the target quantity and inaccurate quantification of mycoplasma load [41]. To improve efficiency, first verify the purity of your template, as PCR inhibitors from the cell culture medium can be carried over [38] [39]. Check your primer design for specificity and secondary structures, and consider optimizing their concentration [39] [41]. Finally, ensure that your standard curve is prepared from fresh, serial dilutions, as stored samples can evaporate and alter concentrations [38].

Experimental Workflow: qPCR for Mycoplasma Detection

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for detecting mycoplasma in stem cell cultures using qPCR, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Research Reagent Solutions for Mycoplasma qPCR

Table 2: Essential Reagents for qPCR-Based Mycoplasma Detection

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix | Fluorescent dye that binds double-stranded DNA, enabling real-time detection of amplified mycoplasma DNA [40]. | Check for compatibility with your qPCR instrument and the inclusion of a reference dye like ROX for well-to-well normalization [40] [41]. |

| Mycoplasma-Specific Primers | Oligonucleotides designed to anneal to a conserved, specific region of the mycoplasma genome [41]. | Specificity is critical. Validate primers with BLAST; design to generate a short amplicon (100-150 bp) for high efficiency [40] [39]. |

| No Template Control (NTC) | Critical control containing nuclease-free water instead of template to detect reagent or environmental contamination [39] [41]. | Must be included in every run. Any amplification in the NTC invalidates the experiment and necessitates decontamination [38]. |

| Positive Amplification Control (PAC) | A sample with known, low-level mycoplasma DNA to verify the assay is functioning with the expected sensitivity [39]. | Confirms that the entire qPCR system (reagents, thermal cycling, detection) is working correctly. |

| DNase I | Enzyme that degrades contaminating genomic DNA from host stem cells during RNA preparation [38]. | Essential for preventing false positives. Use prior to the reverse transcription step if detecting RNA, or as part of the DNA extraction for DNA-based tests. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | Precision instrument for dispensing small-volume reagents to minimize pipetting error and improve reproducibility [43]. | Highly recommended for high-throughput testing. Reduces human error and cross-contamination risk [43]. |

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with stem cells, the threat of contamination represents a significant risk to data integrity, experimental reproducibility, and patient safety in regenerative medicine. Mycoplasma contamination, in particular, is a pervasive and stealthy threat that can alter cell metabolism and gene expression without visible signs, potentially compromising years of research. This technical support center provides a comprehensive framework of aseptic techniques, troubleshooting guides, and frequently asked questions designed to fortify your laboratory's defense against contamination, with a specific focus on safeguarding precious stem cell cultures.

#1 Foundational Principles of Aseptic Technique

Aseptic technique is a set of procedures designed to create a barrier between microorganisms in the environment and your sterile cell culture. It is fundamentally different from sterilization, though the two concepts are complementary. Sterilization is a process that destroys or eliminates all forms of microbial life, creating an absolute state of being free from microorganisms. Aseptic technique, conversely, refers to the practices and procedures performed under controlled conditions to prevent contamination from microorganisms, thereby maintaining that sterile state [44] [45].

The core elements of aseptic technique are:

- A Sterile Work Area: Typically a biosafety cabinet (BSC) or laminar flow hood.

- Good Personal Hygiene: Including proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Sterile Reagents and Media: Ensuring all solutions and media are sterilized and properly handled.

- Sterile Handling: Manipulating cultures without introducing contaminants [44].

#2 The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for maintaining sterile stem cell cultures and addressing contamination issues.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 70% Ethanol | Surface disinfection for biosafety cabinets, gloves, and reagent bottles [44] [45]. | Effective concentration for microbial kill; allows for sufficient contact time. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Improves survival of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) after passaging or thawing [46] [47]. | Use at recommended concentrations; typically included for 18-24 hours post-dissociation. |

| Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent | Passages hPSCs into small, evenly-sized aggregates ideal for subsequent growth [47]. | Incubation time is cell line-dependent; avoid over-pipetting to prevent overly small clumps. |

| Mycoplasma Elimination Reagents (e.g., Mynox) | Rescues contaminated cultures by selectively disrupting mycoplasma membranes [48]. | Treatment can affect eukaryotic cells; goal is to rescue a subset of healthy cells for culture restart. |

| Validated Extracellular Matrices (e.g., Geltrex, Vitronectin) | Provides a defined, feeder-free substrate for hPSC attachment and growth [46] [47]. | Ensure correct plate coating (TC-treated vs. non-TC treated) per manufacturer's instructions. |

| B-27 Supplement | Serum-free supplement used in neural differentiation and other culture media [46]. | Check expiration; prepare fresh medium frequently; avoid repeated thawing/freezing of supplement. |

#3 Troubleshooting Common Stem Cell Culture Issues

This section addresses specific problems encountered during human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) culture.

Problem: Excessive Differentiation (>20%) in hPSC Cultures

- Ensure Medium Freshness: Use complete cell culture medium that is less than two weeks old when stored at 2-8°C [47].

- Remove Differentiated Areas: Manually scrape or pick off differentiated regions from colonies prior to passaging [47].

- Optimize Handling Time: Minimize the time culture plates are outside the incubator to less than 15 minutes at a time [47].

- Control Colony Density: Passage cultures when colonies are large and compact but before they overgrow. Plate fewer cell aggregates during passaging to decrease density [47].

- Check Passaging Parameters: For sensitive cell lines, reduce incubation time with passaging reagents like ReLeSR [47].

Problem: Low Cell Attachment After Passaging or Thawing

- Increase Seeding Density: Plate 2 to 3 times the normal number of cell aggregates initially to maintain a denser culture [47].

- Work Quickly: Minimize the time cell aggregates are in suspension after treatment with passaging reagents [47].

- Optimize Aggregate Size: Do not over-pipette to break up clumps. If aggregates are too large, slightly increase incubation time with the dissociation reagent by 1-2 minutes [47].

- Verify Coating and Plates: Use non-tissue culture-treated plates with Vitronectin XF and tissue culture-treated plates with Matrigel [47].

Problem: Suspected Microbial Contamination

The flowchart below outlines the logical decision-making process for identifying and addressing a contaminated culture.

Problem: Cell Aggregate Size After Passaging is Not Ideal

- If Aggregates Are Too Large (>200 µm): Gently pipette the mixture up and down (without creating single cells) and consider increasing incubation time with the passaging reagent by 1-2 minutes [47].

- If Aggregates Are Too Small (<50 µm): Minimize manipulation and pipetting of aggregates after dissociation and decrease the incubation time with the passaging reagent by 1-2 minutes [47].

#4 Aseptic Technique Checklist and Best Practices

A disciplined, zero-tolerance approach is the best defense against contamination. Adhere to the following protocols to maintain a sterile environment [44] [49].

Personal Hygiene and Preparation

- Wash Hands: Thoroughly with antiseptic soap and warm water before and after handling cultures [44] [50].

- Wear Appropriate PPE: Always wear a clean lab coat, sterile gloves, and safety glasses. Tie back long hair [44] [45] [49].

- Dedicated Lab Coats: Use separate lab coats for the cell culture room and other laboratory areas [49].

Workspace Management

- Biosafety Cabinet (BSC) Setup: Turn on the BSC for at least 15 minutes prior to use. Wipe all interior surfaces with 70% ethanol before and after work. Keep the work surface uncluttered [44] [45].

- Create a Sterile Field: Work in an area free from drafts, doors, and through traffic. When using a Bunsen burner (not inside a BSC), work within the sterile updraft of the flame [44] [50].

- Organize Materials Strategically: Arrange all necessary items in the BSC before starting. Place plates to your left, bottles/flasks in the center, and the Bunsen burner (if used) to your right [50].

Sterile Handling Procedures

- Disinfect Everything: Wipe gloved hands, the outside of all bottles, flasks, and equipment with 70% ethanol before introducing them to the work area [44] [45].

- Flame Bottle Necks: Briefly pass the necks of glass bottles and flasks through a Bunsen burner flame to create an upward convection current that prevents airborne contaminants from entering [50] [45].

- Cap Management: When setting a cap down, place it with the opening facing down on the sterile work surface. Never leave sterile containers uncovered [44].

- Pipetting Precautions: Use sterile pipettes and a pipettor for all liquids. Use each pipette only once to avoid cross-contamination. Never let the pipette tip touch anything non-sterile [44].

- Work Efficiently: Perform experiments as rapidly as possible to minimize exposure of sterile materials to the open environment [44].

#5 Mycoplasma Focus: Prevention, Detection, and Elimination

Mycoplasma contamination is a critical concern, as these bacteria are invisible under routine microscopy and are primarily spread from one culture to another by laboratory personnel [26].

Prevention and Detection Strategies

- Regular Testing: Implement a routine testing schedule using PCR-based methods, fluorescence staining, or culture on agar plates. PCR offers the fastest results [24] [26].

- Avoid Prophylactic Antibiotics: Do not use antibiotics in routine culture maintenance, as this can mask low-level contamination and lead to antibiotic resistance [26].

- Work on One Cell Line at a Time: This golden rule minimizes the risk of cross-contamination between cultures [26].

- Use Dedicated Media: Have separate media bottles for each cell line [26].

Mycoplasma Elimination Workflow

For irreplaceable, contaminated cell lines, a dedicated decontamination protocol can be attempted. The workflow below outlines the key steps for this rescue process.

#6 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most critical step of aseptic technique for cell culture? While all steps are important, the most critical element is the consistent and correct use of the biosafety cabinet, coupled with the meticulous disinfection of all surfaces and materials with 70% ethanol before starting work. This establishes the foundational sterile field for all subsequent manipulations [45].

Q2: My culture medium is cloudy. What does this mean? Cloudy or turbid media is a classic sign of bacterial contamination. You may also see a rapid shift in pH (color change in phenol red) or, under a microscope, tiny floating particles. Immediately quarantine and dispose of the contaminated culture following biosafety guidelines [24] [45].

Q3: Is it necessary to flame the neck of bottles during aseptic procedures? Yes, when working at an open bench with a Bunsen burner, flaming the neck of a sterile bottle or flask is a crucial step. The heat creates an upward convection current of sterile air, which prevents airborne microorganisms from falling into the container while it is open [45].

Q4: How can I prevent cross-contamination between my cell lines? Always work on one cell line at a time in the biosafety cabinet. Use dedicated media and reagents for each cell line whenever possible, and always change pipette tips between handling different cultures. Proper labeling and spatial separation of materials in the BSC are also essential [24] [26].