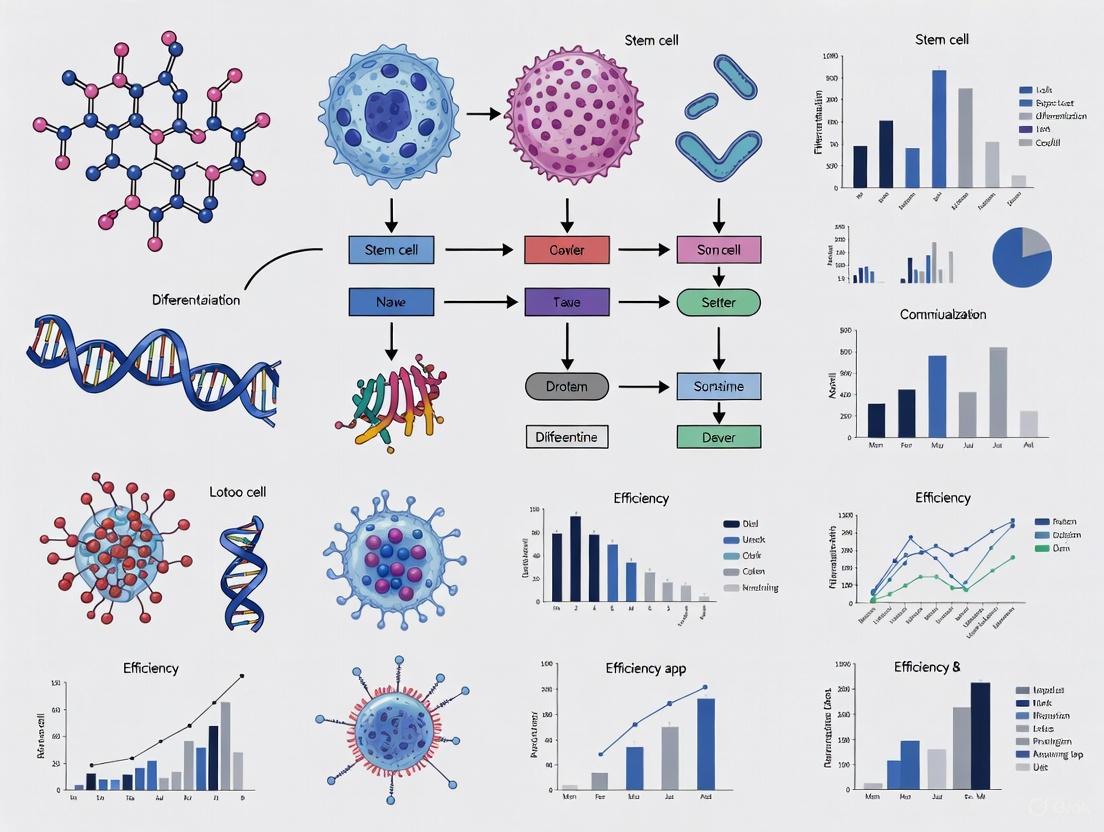

Optimizing Stem Cell Differentiation Efficiency: Foundational Principles, Advanced Methods, and AI-Driven Solutions

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing stem cell differentiation efficiency, a critical bottleneck in regenerative medicine and disease modeling.

Optimizing Stem Cell Differentiation Efficiency: Foundational Principles, Advanced Methods, and AI-Driven Solutions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing stem cell differentiation efficiency, a critical bottleneck in regenerative medicine and disease modeling. It explores the foundational biological principles governing cell fate, details established and emerging differentiation protocols for key cell lineages like hepatic, hematopoietic, and neural cells, and addresses major challenges such as protocol reproducibility and long differentiation timelines. Crucially, it highlights innovative troubleshooting strategies, including the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning for non-destructive quality prediction and protocol optimization. The scope also covers rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of differentiation methods to ensure the generation of high-quality, clinically relevant cell populations.

Understanding the Blueprint: Core Principles of Stem Cell Fate and Differentiation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My stem cell differentiation yields highly heterogeneous cultures. Is this a sign of a failed protocol? Not necessarily. Heterogeneity is an inherent property of stem cell populations and can emerge from high-dimensional gene-regulatory networks [1]. Rather than indicating failure, this may reflect a diverse differentiation landscape. To assess your protocol, use single-cell RNA sequencing to characterize the distribution of cell states and confirm the presence of your target progenitors [2].

Q2: How can I improve the low transduction efficiency in my liver progenitor cell models? Your choice of delivery method is critical. Research shows that using recombinant adeno-associated viral (rAAV) vectors, particularly serotype 2/2 at a high multiplicity of infection (MOI of 100,000), can achieve transduction efficiencies over 90% in liver progenitor cells. For non-viral methods, electroporation can achieve moderate efficiency (around 54%) [3]. Optimize your viral titer or electroporation parameters specific to your cell line.

Q3: Can physical cues alone direct stem cell fate decisions? Yes. Surface topography is a powerful cue. Hierarchical micro-nano topographies can maintain mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) viability while significantly enhancing osteogenic differentiation, even without biochemical inducers. These physical features modulate focal adhesions, triggering downstream signaling that influences cell morphology, migration, and lineage commitment [4].

Q4: My primary hepatocytes dedifferentiate rapidly in 2D culture. What are more robust models for liver disease research? This is a common challenge. Consider moving to 3D organoid cultures derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These models better maintain functional properties and cellular characteristics of liver tissue. We recommend using optimized directed differentiation protocols to generate bipotent liver progenitor cells (LPCs) that can self-renew and differentiate into both hepatocyte- and cholangiocyte-like cells [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Differentiation Efficiency into Target Lineage

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Signaling Molecule Concentration | Review protocol logs; check reagent preparation and storage. | Standardize concentrations of small molecules/growth factors (e.g., CHIR99021, Activin A, BMP4) to reduce need for line-specific optimization [3]. |

| Inaccurate Developmental Timing | Perform single-cell RNA-seq at multiple time points to map trajectory [2]. | Strictly adhere to timed media changes; use a detailed differentiation workflow chart for reference. |

| Unsuitable Extracellular Matrix | Immunofluorescence for pluripotency markers (OCT-4, NANOG) post-seeding. | Use Matrigel-coated plates for hiPSC maintenance and differentiation initiation [3] [2]. |

Issue 2: High Bacterial Contamination in Implant Co-culture Studies

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-sterile Implant Surface | Standard microbiological culture tests. | Use polymers (PDMS, PMMA) with integrated mechano-bactericidal nanotopographies like Moth-Eye nanocones to physically kill bacteria [4]. |

| Ineffective Antibiotic Prophylaxis | Check for antibiotic resistance in contaminants. | Combine hierarchical micro-nano topographies with a short, targeted course of antibiotics [4]. |

Issue 3: Low Transduction Efficiency in Progenitor Cells

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal Transgene Delivery Method | Titrate viral vectors; test electroporation parameters on a small scale. | For high efficiency (>90%), use rAAV serotype 2/2. For non-viral delivery, use optimized electroporation protocols (~54% efficiency) [3]. |

| Incorrect Cell State/Health | Check viability and marker expression (e.g., FOXA2 for LPCs) pre-transduction. | Transduce during the progenitor cell stage; ensure >80% confluent monolayer at induction [3]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Optimized Directed Differentiation of hiPSCs to Liver Progenitor Cells (LPCs)

This protocol is optimized for rapid, cost-effective, and straightforward generation of LPCs with high marker expression efficiency [3].

Key Materials:

- Cell Line: Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs)

- Basal Medium: RPMI 1640, 1% B-27 supplement (without Vitamin A), 1% Glutamax, 1% sodium pyruvate [3].

- Small Molecules/Growth Factors: CHIR99021, Activin A, FGFβ, FGF10, SB431542, Retinoic acid, BMP4 [3].

- Coating Material: Matrigel-coated plates [3].

Methodology:

- Maintenance: Culture hiPSCs on Matrigel-coated plates in mTeSR1 medium [2].

- Initiation (Day -1): Harvest hiPSCs and seed at high density (100,000 cells per cm²) in mTeSR1 with ROCK inhibitor [3].

- Definitive Endoderm (Day 0-3):

- Days 0-1: Switch to basal medium supplemented with 100 ng/mL Activin A and 3 µM CHIR99021.

- Days 1-3: Change to basal medium with 100 ng/mL Activin A and 10 ng/mL FGFβ. Change media daily [3].

- Anteroposterior Foregut (Day 3-5): Change to basal medium supplemented with 50 ng/mL FGF10, 10 µM SB431542, and 10 µM retinoic acid. Change media daily [3].

- Liver Progenitor Cells (Day 5+): Culture in basal medium with 50 ng/mL FGF10 and 10 µM BMP4 to obtain LPCs [3].

Table 1: Comparison of transgene delivery methods in Liver Progenitor Cells.

| Delivery Method | Specific Type | Key Parameter (MOI) | Average Efficiency | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral (rAAV) | Serotype 2/2 | 100,000 | 93.6% | High-efficiency gene delivery for therapy [3] |

| Non-Viral | Electroporation | N/A | 54.3% | Gene delivery avoiding viral vectors [3] |

Signaling Pathway Perturbation in Mesendoderm Differentiation

This methodology uses single-cell RNA sequencing to study the role of specific signaling pathways during differentiation [2].

Methodology:

- Differentiate hiPSCs towards mesendoderm for 2 days (as in the protocol above).

- On day 2, apply signaling perturbations by adding small molecules or recombinant proteins (e.g., targeting WNT, BMP4, VEGF pathways) to the culture medium.

- Remove the perturbation agents on day 5.

- Collect cells for scRNA-seq at baseline (day 2), progenitor (day 5), and committed stages (day 9) to analyze the effects [2].

Table 2: Key research reagents for stem cell differentiation and manipulation.

| Reagent / Solution | Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | Small Molecule | GSK-3 inhibitor; activates WNT signaling to initiate differentiation [3] [2] |

| Activin A | Growth Factor | Promotes differentiation into definitive endoderm lineage [3] |

| BMP4 | Growth Factor | Signals for hepatic specification from foregut [3] |

| ROCK Inhibitor | Small Molecule | Improves survival of dissociated single hiPSCs during passaging [3] |

| rAAV Vectors | Viral Delivery | High-efficiency tool for introducing transgenes into progenitor cells [3] |

| Matrigel | Extracellular Matrix | Provides a basement membrane matrix for cell attachment and polarization [3] [2] |

| SB431542 | Small Molecule | TGF-β inhibitor; used in foregut patterning [3] |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Stem Cell Differentiation State Space

hiPSC to Liver Progenitor Workflow

Signaling Perturbation Experimental Design

Stem cell differentiation is a tightly regulated process orchestrated by key signaling pathways. Among these, the Wnt, BMP (Bone Morphogenetic Protein), and FGF (Fibroblast Growth Factor) pathways play particularly critical and interconnected roles in determining cell fate. In the context of stem cell differentiation efficiency optimization, precise control of these pathways is paramount. These pathways do not function in isolation; they engage in complex crosstalk that can either promote or constrain differentiation toward specific lineages, influencing the overall success and reproducibility of experimental protocols [5] [6]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate the challenges associated with manipulating these pathways for robust stem cell differentiation.

Pathway Diagrams and Crosstalk

The following diagrams illustrate the core components and transduction mechanisms of the Wnt, BMP, and FGF signaling pathways, which are frequently manipulated in differentiation protocols.

Canonical Wnt/β-catenin Signaling Pathway

Wnt signaling is categorized into canonical (β-catenin-dependent) and non-canonical (β-catenin-independent) pathways [7]. The canonical pathway, crucial for lineage specification, is activated when Wnt ligands bind to Frizzled receptors and LRP5/6 co-receptors. This disrupts the β-catenin destruction complex, preventing β-catenin degradation and allowing its nuclear translocation to activate target genes via TCF/LEF transcription factors [7] [8]. In stem cell differentiation, this pathway must be temporally controlled, often initially activated to induce mesoderm, then inhibited to promote cardiac specification [8].

BMP Signaling Pathway

BMP signaling is initiated when BMP ligands form a complex with type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors, leading to the phosphorylation of R-SMADs (1/5/8) [5] [9]. These then complex with SMAD4 and translocate to the nucleus to regulate gene expression alongside lineage-specific transcription factors like NKX2.5 and Hand1 [5]. The pathway is finely tuned by extracellular antagonists (e.g., Noggin, Chordin) and inhibitory SMADs (6/7) [5] [9]. BMP signaling promotes differentiation by antagonizing pluripotency and is essential for mesoderm and cardiac lineage commitment [5] [10].

FGF Signaling Pathway

FGF signaling begins with FGF ligands binding to FGFRs (Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptors), a process facilitated by heparan sulfate proteoglycans [5] [11]. Receptor activation triggers intracellular signaling through several downstream cascades, including RAS-MAPK, PI3K-AKT, PLCγ, and STAT pathways [5] [11] [12]. These effectors regulate fundamental processes like proliferation, survival, and differentiation. The role of FGF signaling is highly context-dependent, exhibiting biphasic effects where early activation promotes cardiac mesoderm formation, but continued signaling can inhibit further cardiomyocyte differentiation [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: Addressing Low Differentiation Efficiency

Q1: My stem cells are not efficiently differentiating into the target lineage (e.g., cardiomyocytes). What could be wrong?

A: Low differentiation efficiency often stems from improper temporal control of signaling pathways. Consider these factors:

- Check Wnt Pathway Timing: For cardiac differentiation, the initial activation of Wnt signaling via CHIR99021 is crucial for mesoderm induction. However, premature or delayed inhibition can drastically reduce efficiency. Adhere strictly to the optimal window for adding Wnt inhibitors like IWP-2 [8].

- Optimize BMP Concentration: BMP signaling levels are dose-sensitive. Low concentrations may favor intermediate mesoderm, while higher concentrations promote lateral plate mesoderm and cardiomyocyte differentiation [13]. Titrate BMP4 concentrations (e.g., 4-100 ng/mL) to find the optimal level for your target lineage [13].

- Account for Pathway Crosstalk: Be aware that activating one pathway can cross-activate others. For instance, BMP signaling can cross-activate FGF, Nodal, and Wnt pathways, which may divert cells from the intended totipotent or differentiation state [6]. Using specific inhibitors for these cross-activated pathways might be necessary to enhance target population proportions.

Q2: I observe high variability between differentiation experiments. How can I improve reproducibility?

A: Variability often arises from inconsistent cell culture practices and reagent handling.

- Standardize Cell Confluency: Initiate differentiation at a consistent and recommended cell confluency (e.g., 70-90%). High confluency can lead to spontaneous differentiation, while low density can result in poor survival and differentiation [8].

- Quality Control of Critical Reagents: Test the activity of small molecules like CHIR99021 and recombinant proteins like BMP4 in a pilot assay. Use the same batch of Matrigel and growth factor-reduced media for a series of experiments to minimize lot-to-lot variability [13] [8].

- Monitor Pluripotency State: The starting state of pluripotent stem cells (naïve vs. primed) significantly impacts differentiation competency. Use standardized conditions and validated markers (e.g., Oct4, Sox2, Nanog) to ensure a consistent starting population [11].

Q3: My differentiated cultures are contaminated with off-target cell types. How can I enhance purity?

A: Purity issues suggest incomplete lineage specification or the presence of signaling factors promoting alternative fates.

- Fine-tune Wnt Inhibition: The choice and combination of Wnt inhibitors (e.g., IWP-2 + IWR-1-endo vs. IWP-2 + XAV939) can influence the balance between cardiomyocytes and other mesodermal derivatives like smooth muscle cells [8].

- Apply Selective Pressure: Use metabolic selection (e.g., lactate purification) or antibiotic resistance genes driven by cardiac-specific promoters (e.g., α-MHC) to enrich for the target cardiomyocyte population.

- Re-evaluate BMP and FGF Signaling: BMP levels must be precisely controlled, as incorrect concentrations can promote alternative mesodermal lineages instead of cardiac [13]. Similarly, the duration of FGF signaling should be limited, as its prolonged activity can inhibit terminal cardiomyocyte differentiation [5].

Quantitative Data for Protocol Optimization

Table 1: Key signaling pathway modulators used in stem cell differentiation protocols.

| Pathway | Modulator | Common Concentrations | Function in Differentiation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt | CHIR99021 (Agonist) | 3-6 µM [13] [8] | Induces mesoderm progenitor formation (e.g., TBXT+/MIXL1+ cells) [13]. | Concentration and exposure time are critical; excess can inhibit cardiac specification. |

| IWP-2/IWR-1 (Inhibitor) | 3-5 µM [8] | Inhibits Wnt production/response to promote cardiac specification from mesoderm. | Often used after initial Wnt activation; choice of inhibitor can affect maturation [8]. | |

| BMP | BMP4 | 4-100 ng/mL [13] | Promotes mesoderm and cardiac lineage commitment; concentration dictates lineage specificity [13]. | Low concentrations may favor IM; higher concentrations favor LPM and CMs [13]. |

| Noggin (Inhibitor) | Varies | Extracellular antagonist that binds BMP ligands, preventing receptor activation. | Can be used to block endogenous BMP signaling that may cause heterogeneity. | |

| FGF | FGF2 (bFGF) | Varies (e.g., 100 ng/mL [13]) | Supports pluripotency in hPSCs; roles in differentiation are context and stage-dependent. | Required for maintaining primed pluripotency; its role in differentiation is complex [11]. |

Comparison of Differentiation Protocol Schedules

Table 2: Impact of temporal control on differentiation outcomes based on optimized protocols.

| Differentiation Schedule | Key Steps | Reported Outcome | Maturation State of Derived Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| "2 + 2" Schedule [8] | 2 days CHIR99021 → 2 days IWP-2 + IWR-1-endo. | High efficiency (>80% TNNT2+ CMs) [8]. | Improved structural and metabolic maturation compared to some other schedules [8]. |

| "1 + 2 + 2" Schedule [8] | 1 day CHIR -> 2 days medium -> 2 days IWP-2 + XAV939. | High efficiency (>80% TNNT2+ CMs) [8]. | Altered gene expression profiles related to maturation; may yield less mature CMs [8]. |

| IM Differentiation Protocol [13] | 2 days CHIR99021 → 2 days CHIR99021 + BMP4. | Generation of OSR1+/GATA3+/PAX2+ intermediate mesoderm (IM) cells [13]. | Used for generating precursors for urogenital system organoids. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Pathway Manipulation

Table 3: Essential reagents for studying Wnt, BMP, and FGF signaling in differentiation.

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Agonists | CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor) [13] [8] | Activates canonical Wnt signaling by stabilizing β-catenin, used for mesoderm induction. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | IWP-2, IWR-1-endo, XAV939 (Wnt inhibitors) [8] | Blocks Wnt ligand secretion or response, crucial for cardiac specification after mesoderm induction. |

| Recombinant Growth Factors | BMP4, BMP2, BMP7, BMP9 (Osteogenic) [5] [13] [14] | Activates BMP signaling to promote mesodermal and osteogenic differentiation. Concentration is critical for lineage direction. |

| FGF2 (bFGF), FGF4, FGF10 [5] [11] | Activates FGF signaling. Roles vary from maintaining pluripotency to promoting specific differentiation stages. | |

| Extracellular Antagonists | Noggin, Chordin [5] | Binds to BMP ligands in the extracellular space, preventing them from activating receptors. |

| Cell Culture Supplements | Heparin [13] | Used with FGFs to stabilize ligand-receptor interaction and enhance FGF signaling efficiency. |

Advanced Technical Guide: Optimizing a Cardiac Differentiation Protocol

The following workflow summarizes an optimized protocol for generating cardiomyocytes, highlighting the critical control points for the key signaling pathways.

Experimental Workflow for Cardiac Differentiation

Detailed Methodology:

Starting Cell Preparation: Culture human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) in defined conditions (e.g., mTeSR or E8 medium) on Matrigel-coated plates. Passage cells at 70-90% confluency, as this is critical for achieving reproducible differentiation [8]. Accurately count cells and ensure >90% viability.

Mesoderm Induction (Day 0): Initiate differentiation by adding CHIR99021 (3-6 µM) in a chemically defined medium like CDM3 [8]. This activation of Wnt signaling is essential for directing cells toward a mesodermal fate (inducing TBXT+/MIXL1+ mesoderm progenitors) [13] [8]. The optimal concentration may vary between cell lines and should be determined empirically.

Cardiac Specification (Day 2-4): After precisely 48 hours, replace the medium containing CHIR99021 with fresh medium containing a combination of Wnt inhibitors, such as IWP-2 and IWR-1-endo (5 µM each) [8]. This inhibition of Wnt signaling is the key step that drives the specified mesoderm to commit to the cardiac lineage. The "2 + 2" schedule (2 days agonist, 2 days inhibitor) has been shown to yield high-purity cardiomyocyte cultures with improved maturation traits [8].

Culture and Maturation (Day 4+): After 48 hours of Wnt inhibition, transition to a basal medium (e.g., CDM3 or RPMI supplemented with B27) without small molecules, refreshing the medium every 2-3 days [8]. Spontaneously contracting areas typically appear between days 8-10.

Analysis and Validation (Day 10+): Assess differentiation efficiency by analyzing the percentage of cells expressing cardiac troponin T (TNNT2) via flow cytometry or immunocytochemistry [8]. Evaluate functional maturity through calcium transient imaging, metabolic assays (shift from glycolysis to fatty acid oxidation), and analysis of sarcomeric structure (e.g., via α-actinin staining) [8].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the core transcription factors (TFs) in pluripotency, and how do they interact? A core network of transcription factors, including OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, stabilizes the pluripotent state in stem cells through a positive feedback loop. These TFs activate their own expression and each other's, creating a robust network that maintains stem cell identity [15] [16]. This network represses the expression of differentiation-promoting genes. The stability of this state is influenced by the intrinsic half-life of its components, such as NANOG, which helps the network filter out short-lived stochastic fluctuations in gene expression and only respond to sustained differentiation signals [16].

Q2: How can a single transcription factor induce differentiation? Lineage-specific transcription factors can drive differentiation by competing with and destabilizing the core pluripotency network. A key mechanism is transcription factor competition [16]. For example, during neural differentiation, the pro-neural factor BRN2 (an OCT4 homolog) competes with OCT4 for binding to SOX2 [16]. Successful competition disrupts the OCT4-SOX2-NANOG pluripotency complex, leading to its destabilization and initiating a neural differentiation program [16]. Similar competition mechanisms govern other lineage choices, such as endoderm differentiation [16].

Q3: What is the role of epigenetics beyond transcription factors in directing cell fate? While TFs initiate gene expression changes, epigenetic mechanisms provide a crucial layer of regulation that stabilizes cell fate decisions by modifying chromatin structure without altering the DNA sequence itself [17]. These modifications create heritable patterns of gene expression and include:

- DNA Methylation: The addition of methyl groups to DNA, typically repressing transcription of genes, including tumor suppressor genes in cancer [17].

- Histone Modifications: A variety of chemical modifications (e.g., acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation) to histone proteins that can either activate or repress gene transcription depending on the specific modification and genomic context [17].

- Non-coding RNAs: RNA molecules that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally and are implicated in diverse cellular processes [17]. These epigenetic marks are dynamically regulated by "writer," "eraser," and "reader" enzymes, and their widespread dysregulation is highly correlated with malignant phenotypes and therapy resistance in cancer [17].

Q4: How can I identify the right transcription factors to differentiate stem cells into a specific target cell type? High-throughput, unbiased screening of transcription factor libraries is a powerful method for this. A state-of-the-art approach involves:

- Creating a Library: Generate a comprehensive, barcoded library of human TF open reading frames (ORFs) or splice isoforms [18] [19].

- Pooled Transfection: Transfect this library into human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) in a pooled format.

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Use scRNA-seq to profile the gene expression of the transfected cells and simultaneously detect which TF(s) each cell received via barcode sequencing [18].

- Data Analysis: Computational analysis identifies TFs or TF combinations that drive the expression profile closest to your target cell type [18] [19]. This method has been successfully used to identify TF combinations for generating microglia and many other cell types [18] [19].

Q5: Why does my transcription factor-driven differentiation protocol yield heterogeneous or incomplete cell types? This common challenge arises from several factors:

- Insufficient TF Combination: A single TF may be insufficient. Many cell types require a specific combination of TFs to fully suppress the original cell identity and activate the complete new genetic program [18]. For example, generating microglia-like cells required a combination of six TFs (SPI1, CEBPA, FLI1, MEF2C, CEBPB, and IRF8) [18].

- Incomplete Maturation: The induced cells may lack the necessary epigenetic landscape or proper cellular microenvironment (niche) signals to reach full maturity [20]. The new cell state must be stabilized through epigenetic remodeling [15] [17].

- Off-Target Effects: Exogenous expression of TFs can have unintended binding and activation effects, leading to a mixture of cell fates [20]. Using inducible systems and optimizing the timing of TF expression can help improve synchrony.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Efficiency in Transcription Factor-Driven Differentiation

| Potential Cause | Investigation Method | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient TF delivery/expression | Quantify vector copy number per cell via qPCR (as in [18]); Check exogenous TF expression via barcode-amplification from cDNA [18]. | Optimize DNA dose during transfection to ensure single-digit copy number of multiple TFs per cell [18]. |

| Suboptimal TF combination | Perform iterative TF screening; use scRNA-seq to rank TFs by their ability to drive target gene expression [18]. | Employ a polycistronic vector to ensure co-expression and co-delivery of multiple TFs. Test different gene orders in the cassette, as this affects expression levels [18]. |

| Incorrect culture conditions | Analyze expression of maturity markers (electrophysiology for neurons, phagocytosis for microglia). | Review literature for target-cell specific soluble factors (e.g., TGF-β for tissue-resident memory T cells [21]). Co-culture with supportive cell types may be necessary. |

Issue 2: Poor Reproducibility Across Different Stem Cell Lines

| Potential Cause | Investigation Method | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Variable epigenetic background | Perform multi-omics profiling (e.g., scATAC-seq) to compare chromatin accessibility between cell lines [21]. | Pre-screen iPSC lines for differentiation competence. Consider using an intermediate progenitor cell bank (e.g., neuronal progenitors) as a more uniform starting population [22]. |

| Heterogeneous transgene integration | Use FACS to select a population with homogeneously integrated inducible TF cassettes [22]. | Utilize site-specific integration systems (e.g., PiggyBac transposase [18]) instead of random integration to minimize position effects. |

| Inconsistent cell state at start | Monitor key pluripotency markers (e.g., NANOG) before induction. | Standardize passaging and maintenance protocols rigorously. Ensure cells are in a consistent, healthy pluripotent state at the initiation of differentiation. |

Key Experimental Data and Protocols

Table 1: Transcription Factor Screening Data for Directed Differentiation

| Target Cell Type | Key Identified Transcription Factors (TFs) | Number of TFs Screened | Protocol Duration | Key Functional Validation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microglia-like cells (TFiMGL) | SPI1, CEBPA, FLI1, MEF2C, CEBPB, IRF8 | 40 (initial screen) | 4 days | Phagocytosis, cytokine response, transcriptional similarity to primary microglia [18] | [18] |

| Various Cell Types | 290 TFs (e.g., for neural progenitors, trophoblasts) | 3,548 (all human TF isoforms) | Varies by target | Matching to reference cell type expression profiles from single-cell RNA-seq atlas [19] | [19] |

| Neurons (iGluNeurons) | Neurogenin-2 (NGN2) | N/A (Literature-based) | N/A | Single-cell and network electrophysiological recordings [22] | [22] |

Table 2: Major Epigenetic Modifications and Their Roles in Cell State Regulation

| Epigenetic Modification | Key Enzymes (Examples) | Primary Function | Role in Cell State/Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation | DNA methyltransferases (Writers), TET proteins (Erasers) | Transcriptional repression of genes, including tumor suppressors; genome stability [17]. | Widespread dysregulation (hypermethylation of promoters); contributor to therapy resistance [17]. |

| Histone Acetylation | HATs (Writers), HDACs (Erasers) | Generally associated with open, active chromatin and gene activation [17]. | Aberrantly activated oncogenes or repressed differentiation programs; target of epigenetic drugs [17]. |

| Histone Methylation | KMTs (Writers), KDMs (Erasers) | Can be activating or repressing depending on the modified residue (e.g., H3K4me3 active, H3K27me3 repressive) [17]. | Altered in tumors; can maintain cells in a stem-like, undifferentiated state [17]. |

| N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA Modification | METTL3/14 (Writers), FTO/ALKBH5 (Erasers) | Regulates mRNA stability, translation efficiency, and splicing [17]. | Affects tumor proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and immune evasion [17]. |

This protocol enables the identification of optimal TF combinations for differentiating iPSCs into a target cell type.

Key Reagents:

- Cell Line: Human iPSCs (e.g., PGP1).

- TF Library: A custom barcoded library of 40 TF clones in a doxycycline-inducible PiggyBac vector (pBAN2).

- Transfection Reagent: PiggyBac Transposase.

- Culture Media: Standard iPSC media and differentiation media.

Workflow:

- Clone & Barcode: Clone each TF from the selected library into the pBAN2 vector. Incorporate a unique 20-nucleotide barcode between the stop codon and poly-A sequence of each TF for tracking.

- Transfect & Integrate: Co-transfect the TF library and PiggyBac transposase into iPSCs at a 4:1 mass ratio. Determine the optimal DNA dose (e.g., 5 µg) to achieve a single-digit copy number of multiple TFs per cell.

- Select & Induce: Select for successfully transfected cells using puromycin. Induce TF expression by adding doxycycline (Dox) to the culture medium for 4 days to initiate differentiation.

- Sort & Sequence: Use Fluorescent Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to sort differentiated cells (e.g., TRA-1-60 negative). Perform single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on the sorted population.

- Analyze & Rank: From the scRNA-seq data, quantify exogenous TF expression via barcode amplicon sequencing. Correlate TF presence with the expression of target cell-type-specific genes (e.g., ITGAM, P2RY12 for microglia). Rank TFs based on their ability to induce the desired gene signature.

- Iterate & Validate: For complex lineages, a second round of screening with the top TFs from the first round may be necessary. Validate the final TF combination by testing its ability to generate cells with the correct molecular and functional properties of the target cell.

Figure 1: Core Gene Regulatory Network Logic. The pluripotency network (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) maintains the stem cell state via mutual activation. A sustained differentiation signal induces a lineage-specific TF, which competes with and disrupts the pluripotency network, allowing activation of a new differentiation gene program [15] [16].

Figure 2: Iterative Transcription Factor Screening Workflow. This high-throughput screening method involves multiple rounds of transfection, induction, and single-cell analysis to efficiently identify optimal TF combinations for generating specific cell types from iPSCs [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Key Features & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded TF ORF Library [18] [19] | Comprehensive screening of transcription factor effects. | Contains thousands of human TF isoforms; each TF has a unique nucleotide barcode for tracking in pooled screens; often in inducible vectors. |

| Inducible Expression System (e.g., Dox-inducible) [18] | Precise temporal control over TF expression. | Allows separation of transfection/integration from differentiation induction; enables testing of duration thresholds for TF activity [16]. |

| Polycistronic Vector (2A peptide-linked) [18] | Co-expression of multiple TFs from a single transcript. | Ensures delivery of all required TFs to a cell; gene order matters for expression levels and must be optimized. |

| PiggyBac Transposon System [18] | High-efficiency genomic integration of large DNA cargo. | Provides stable, long-term expression; preferred over random plasmid integration for higher consistency. |

| Single-Cell Multi-Omics (scRNA-seq + scATAC-seq) [21] | Simultaneous profiling of gene expression and chromatin accessibility. | Reveals enhancer-driven gene regulatory networks and the epigenetic state of differentiating cells. |

| Dominant-Negative REST (DN:REST) [23] | Tool to block activity of the transcriptional repressor REST. | Used to dissect the role of REST-mediated repression in maintaining stem cell states or blocking differentiation. |

Within stem cell research and regenerative medicine, a central challenge persists: the inherent limitations of native biological systems. Primary cells, isolated directly from living tissue, are the gold standard for physiological relevance but suffer from finite lifespans and a strong tendency to dedifferentiate—lose their specialized characteristics—in culture. This instability drives the need for robust, standardized models that can reliably generate high-quality, functional cells for disease modeling, drug screening, and therapeutic development. This technical support center is framed within the broader thesis of optimizing stem cell differentiation efficiency, providing actionable solutions to common pitfalls.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the main advantage of using primary cells over cell lines? Primary cells are isolated directly from tissues (e.g., blood, bone marrow, skin) and are therefore more representative of the in vivo physiological state of that tissue compared to immortalized cell lines. Data generated from primary cells has increased physiological relevance, making them an ideal model for investigative research [24] [25].

2. Why do my primary cells keep dedifferentiating or losing their phenotype in culture? Dedifferentiation is a common challenge. Primary cells have a finite lifespan and a limited number of population doublings before they enter senescence. This process can be accelerated by:

- Over-confluence: Culturing cells beyond 100% confluence can trigger differentiation and slow proliferation [25].

- Sub-optimal culture medium: The lack of tissue-specific cytokines and growth factors fails to maintain the specialized phenotype [25].

- Extended culture time: Primary cells should not be maintained for extended periods; for example, plateable cryopreserved hepatocytes are generally not recommended for culture beyond five days [26].

3. My stem cell differentiation efficiency is low and variable. What are the common causes? Low and variable differentiation efficiency is a widely recognized hurdle. Key causes include:

- Inconsistent Starting Material: The genetic and epigenetic state of human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) clones can vary, impacting their differentiation potential [27] [28].

- Protocol Variability: Slight changes in seeding cell number, growth factor composition, or timing can lead to marked differences in the resulting cultures [29].

- Insufficient Characterization: Many protocols fail to fully characterize the intermediate progenitor cells, leading to heterogeneous final populations [29] [27].

- Incorrect Primitive Streak Patterning: For mesoderm and endoderm differentiation, the specific subtype of primitive streak induced (anterior, mid, posterior) dictates the downstream cell types that can be formed. Using broad markers like BRACHYURY is insufficient to ensure the correct intermediate has been generated [27].

4. How can I improve the reproducibility of my differentiation protocols?

- Use 3D Embryoid Body (EB)-based Systems: EB formation can improve differentiation efficiency for many cell lineages and allows for early prediction of differentiation potential by analyzing gene expression markers like SALL3 [30].

- Ensure High-Quality hPSCs: Before neural induction, remove any differentiated or partially differentiated hPSCs. Cell counting is also recommended to ensure optimal seeding density, as too low or too high confluency will reduce induction efficiency [31].

- Employ Early Prediction Tools: Emerging technologies using phase-contrast imaging and machine learning can predict the final differentiation efficiency of induced muscle stem cells (MuSCs) as early as 50 days before the end of the induction period, allowing for early sample selection [28].

5. What are the key considerations for choosing between 2D and 3D culture systems? Both systems have distinct advantages. While 2D culture is simpler, 3D embryoid body (EB)-based suspension culture systems often demonstrate higher stable differentiation efficiency and are better suited for generating complex organoids that mimic human organs [30]. The choice depends on the target cell type and the research application.

Table 1: Common Primary Cell Culture Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low post-thaw viability | Improper thawing technique, rough handling | Thaw cells rapidly (<2 mins at 37°C). Use wide-bore pipette tips and mix slowly [26]. |

| Poor cell attachment | Coating matrix dried, suboptimal substratum | Shorten time between coating and cell seeding. Use appropriate extracellular matrix (e.g., Matrigel, Collagen I) [26] [25]. |

| Excessive differentiation in hPSC cultures | Old culture medium, overgrown colonies | Use fresh medium (<2 weeks old). Remove differentiated areas before passaging. Do not allow colonies to overgrow [31]. |

| Heterogeneous differentiation outcomes | Inconsistent cell aggregate size during passaging | Ensure cell aggregates are evenly sized. Avoid generating a single-cell suspension for protocols requiring clump passaging [31]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inefficient Neural Differentiation from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs)

Possible Causes and Recommendations:

- Cause: Low-quality starting hPSCs.

- Recommendation: Regularly characterize hPSCs for pluripotency markers and genomic integrity. Remove any differentiated regions from the culture before initiating differentiation [31].

- Cause: Incorrect seeding density for induction.

- Recommendation: Perform cell counting before plating. The recommended plating density for neural induction is often in the range of 2–2.5 x 10^4 cells/cm². Plating cells as small clumps, not as a single-cell suspension, can also improve efficiency [26].

- Cause: Sub-optimal or expired differentiation supplements.

- Recommendation: Check the expiration date of all supplements. For example, B-27 Supplement, once thawed, should be stored at 4°C and used within one week. Prepared medium supplemented with B-27 is stable for only two weeks at 4°C [26].

Problem: Low Attachment Efficiency in Primary Cells

Possible Causes and Recommendations:

- Cause: Improper thawing technique.

- Cause: Inadequate or dried-out extracellular matrix coating.

- Recommendation: Ensure the culture vessel is coated with the appropriate attachment factor (e.g., Collagen, Matrigel, Vitronectin). Do not let the coating solution dry out. Work with a few wells at a time to prevent drying during the coating process [26].

- Cause: Seeding density is too low.

- Recommendation: Check the lot-specific specification sheet for the recommended seeding density. Observe cells under a microscope after seeding to ensure appropriate density [26].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell Differentiation

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Factors (e.g., FGF, BMP, SHH) | Mimic developmental signaling to direct lineage specification. | SHH and FGF8 are used for ventral patterning in dopaminergic neuron differentiation [29]. |

| Small Molecule Agonists/Antagonists | Precisely control key signaling pathways (Wnt, TGF-β). | A Wnt agonist is used at high concentration to induce dermomyotome cells from hiPSCs [28]. |

| EB-Based 3D Culture Systems | Improve differentiation efficiency and stability for various lineages. | Used for robust differentiation into neural, hepatic, and cardiac cells [30]. |

| Defined Culture Media & Supplements | Provide tailored nutrients and factors for specific cell types. | B-27 Supplement is critical for neuronal cell culture and health; its quality must be assured [26]. |

| Lineage Reporter Systems | Enable real-time tracking of differentiation efficiency. | MYF5-tdTomato reporter hiPSCs allow for flow cytometry analysis of muscle stem cell induction efficiency [28]. |

Detailed Methodology: Early Prediction of Muscle Stem Cell (MuSC) Differentiation Efficiency

This protocol, based on a 2025 study, outlines a non-destructive method to predict the final differentiation efficiency of hiPSC-derived MuSCs approximately 50 days in advance [28].

1. Cell Line and Differentiation:

- Use MYF5-tdTomato reporter hiPSCs.

- Induce MuSC differentiation using a directed protocol:

- Days 0-14: Treat with a high concentration of a Wnt agonist to generate dermomyotome cells.

- Days 14-38: Treat with growth factors (IGF-1, HGF, bFGF) to promote myogenic differentiation (myogenic induction phase).

- Days 38-82: Switch to a muscle culture medium with low-concentration horse serum for maturation.

2. Image Acquisition and Feature Extraction:

- Between days 14 and 38, capture phase-contrast images of the cells in culture.

- Apply Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to each image to obtain a power spectrum.

- Perform shell integration on the power spectrum to generate a 100-dimensional, rotation-invariant feature vector that captures cell morphology characteristics.

3. Machine Learning and Classification:

- Use a random forest classifier trained on the feature vectors from days 14-38.

- The model predicts the final MYF5+ percentage (measured by flow cytometry on day 82).

- Key Finding: Samples with high and low induction efficiency can be predicted from images taken on day 34 and day 24, respectively.

Signaling Pathways in Directed Differentiation

The following diagram illustrates the critical initial stages of germ layer differentiation from hPSCs, highlighting the importance of precise primitive streak patterning.

Diagram 1: Pathway to Germ Layer Formation. Successful differentiation requires inducing the correct primitive streak subtype, as each has restricted lineage potential [27].

Table 3: Correlation Between Early Markers and Final Differentiation Efficiency in MuSC Induction [28]

| Day of Induction | Marker Analyzed | Marker Type | Correlation with Final MYF5+ % (Day 82) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 7 | T (Brachyury) | Gene Expression (qRT-PCR) | Not Significant |

| Day 14 | PAX3 | Gene Expression (qRT-PCR) | Not Significant |

| Day 38 | MYH3 | Gene Expression (qRT-PCR) | Significant Positive |

| Day 38 | MYOD1 | Gene Expression (qRT-PCR) | Significant Positive |

| Day 38 | Myosin Heavy Chain (MHC) | Protein (Immunocytochemistry) | Significant Positive |

```

This technical support content underscores that overcoming the challenges of primary cell dedifferentiation and variable differentiation requires a multi-faceted approach. By integrating robust, standardized protocols, rigorous quality control of starting materials, and the adoption of advanced predictive technologies, researchers can generate more reliable and physiologically relevant models to advance the field of regenerative medicine.

From Theory to Practice: Protocols for Differentiating Hepatic, Hematopoietic, and Mesenchymal Lineages

Directed Differentiation of iPSCs into Liver Progenitor Cells and Organoids

This technical support center is designed within the context of ongoing research to optimize the efficiency and reproducibility of stem cell differentiation. It addresses frequent experimental challenges encountered when differentiating induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) into liver progenitor cells (LPCs) and subsequent 3D hepatic organoids. The following FAQs, troubleshooting guides, and summarized data are compiled to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in standardizing protocols and achieving robust, high-quality results for downstream applications in disease modeling, drug screening, and toxicology studies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Protocol Efficiency and Differentiation Success

Q1: What is a typical differentiation efficiency for obtaining definitive endoderm (DE) and hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs) from iPSCs?

Achieving high differentiation efficiency is a primary goal in optimization research. Performance can vary based on the specific protocol and cell line used. The table below summarizes key efficiency metrics from established methods.

Table 1: Typical Differentiation Efficiencies for Key Stages

| Differentiation Stage | Typical Efficiency | Measurement Method | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definitive Endoderm (DE) | Up to 97% | Sox17-positive cells (Immunofluorescence) [32] | |

| Liver Progenitor Cells (LPCs) | High-level expression achieved | Expression of specific LPC markers [3] | |

| Hepatocyte-like Cells (HLCs) | Up to 94% | HNF4α-positive cells (Immunofluorescence) [32] | |

| Transduction of LPCs | 93.6% | eGFP expression using rAAV serotype 2/2 [3] | |

| Transfection of LPCs | 54.3% | eGFP expression using electroporation [3] |

Q2: My differentiation efficiency is low. What are the most critical steps to optimize?

Low efficiency often stems from inconsistencies in early stages. The most critical steps include:

- Accurate Cell Counting: The initial seeding density of iPSCs is paramount. Inaccurate counts can severely impact yield. It is recommended to use a hemocytometer/Bürker chamber for validation, especially when setting up an automated cell counter [32].

- Strict Protocol Adherence: Small deviations, such as delayed medium changes, can significantly affect the functionality of the final hepatocytes. Adhere strictly to the timing and formulation of media changes [32].

- Cell Line Variability: Different iPSC lines have inherent variations in differentiation potential. One study found that a self-reprogrammed hiPSC line had a higher differentiation tendency than a commercially sourced line [33]. Protocol optimization for each specific cell line may be necessary.

Q3: Can the definitive endoderm (DE) or hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs) be expanded or cryopreserved for later use?

- Definitive Endoderm (DE): Yes, DE cells can be dissociated, cryopreserved using a provided protocol, and later reseeded for differentiation [32]. Some protocols also support the expansion of DE/foregut endoderm cells [32].

- Hepatocyte-like Cells (HLCs): Differentiated hepatocytes are generally terminally differentiated and cannot be expanded [32]. While custom protocols for dissociation and cryopreservation of HLCs exist as customized solutions [32], it is noted that differentiated hepatic organoid cultures cannot be passaged or cryopreserved [34].

Organoid Culture and 3D Modeling

Q4: What seeding density is recommended for forming hepatic organoids, and why is high density often used?

Seeding at higher densities is recommended for two primary reasons:

- Improved Formation Probability: Not every single cell or fragment will develop into an organoid; higher densities increase the chances of successful establishment.

- Paracrine Signaling: Liver organoids benefit from "neighboring cells," as paracrine signaling between them supports growth and health [34]. A common recommendation for differentiation experiments is to seed approximately ~2000 fragments between 30 - 100 µm in size [34]. It is crucial to avoid overseeding, as this can negatively affect culture quality and viability.

Q5: How long can hepatic organoids be maintained in culture, and what is a typical passage number?

Human hepatic organoid expansion cultures can be maintained long-term. One established protocol maintains cultures up to passage 14 - 15 with the potential for indefinite culture [34]. The ability to culture long-term is a key advantage for generating a sustainable cell model.

Q6: My organoids show high heterogeneity in size. Is this normal, and how can it be controlled?

Heterogeneity in organoid size is normal, especially if the fragments generated during passaging are not uniform [34]. To standardize size:

- Generate Uniform Fragments: Aim for fragments between 30 - 100 µm during passaging.

- Use Strainers: Employ reversible strainers to generate more uniformly sized fragment suspensions [34].

- Control Final Size: Actively maintain organoids under 500 µm in diameter. Larger organoids risk core cell death due to limited oxygen and nutrient diffusion in the absence of a vascular system [35].

Characterization and Functional Validation

Q7: What key hepatic functions should I validate in my differentiated HLCs or organoids?

To confirm successful differentiation and maturation, researchers should assess a panel of classic hepatic functions. The table below lists key functions and common assessment methods.

Table 2: Key Hepatic Functions for Model Validation

| Hepatic Function | Description | Common Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|

| Albumin Secretion | Major plasma protein synthesized by hepatocytes | ELISA on culture supernatant [34] |

| CYP450 Enzyme Activity | Critical for drug metabolism (e.g., CYP3A4, CYP1A2) | P450-Glo Assay or LC/MS [34] [32] |

| Urea Synthesis | Key metabolic function of hepatocytes | Colorimetric assay [34] |

| Bile Acid Production | Indicator of hepatocyte metabolic function | Total bile acid assay [34] |

| LDL Uptake | Functional receptor-mediated endocytosis | Fluorescent LDL uptake assay [32] |

Q8: Do hepatic organoids contain non-parenchymal cells (e.g., stellate, Kupffer cells)?

Most standard protocols for deriving hepatic organoids from iPSCs focus on the parenchymal lineage (hepatocytes and cholangiocytes). One FAQ explicitly states, "We have not looked for the presence of non-parenchymal cells in human hepatic organoids" [34]. However, one optimized protocol reported the establishment of a 2D culture comprising stellate-like cells alongside the organoid cultures, suggesting that with specific protocol modifications, certain non-parenchymal cell types can be obtained [3].

Essential Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Optimized Differentiation Workflow

The following diagram outlines a generalized and optimized workflow for the directed differentiation of iPSCs into liver progenitor cells and subsequent 2D or 3D cultures, integrating steps from multiple sources [3] [36] [32].

Key Signaling Pathways for Directed Differentiation

The directed differentiation of iPSCs into liver cell fates is achieved by sequentially modulating key signaling pathways to mimic embryonic liver development. The following diagram summarizes the critical factors and their roles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A successful differentiation experiment relies on a suite of high-quality reagents. The following table details essential materials and their functions as cited in the literature.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for iPSC to Hepatic Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Basal Media | RPMI 1640, Advanced DMEM | Serves as the base for differentiation media formulations [3]. |

| Critical Growth Factors & Cytokines | Activin A, BMP4, FGF10, FGFβ, HGF, KGF, OSM | Key signaling molecules that direct each stage of differentiation from definitive endoderm to hepatocyte maturation [3] [33]. |

| Small Molecules & Pathway Modulators | CHIR99021 (WNT agonist), SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor), Retinoic Acid | Precisely controls developmental signaling pathways to steer cell fate [3]. |

| 3D Culture Matrix | Matrigel, synthetic hydrogels, recombinant protein gels | Provides a scaffold for 3D organoid formation, mimicking the native extracellular matrix [3] [35]. |

| Specialized Organoid Media | HepatiCult Organoid Growth & Differentiation Media | Commercially available, optimized media systems for robust expansion and maturation of hepatic organoids [34] [3]. |

| Cell Dissociation Reagents | TrypLE, Versen solution | Enzymatic or non-enzymatic solutions for passaging organoids and dissociating cells during protocol steps [34] [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is stromal cell seeding density critical in co-culture systems? The initial seeding density of stromal cells directly influences the efficiency of stem cell differentiation. An optimal density creates the correct cellular microenvironment and signaling gradients needed to direct differentiation, while suboptimal densities can lead to reduced efficiency or incorrect cell fate specification [37] [38]. For example, in OP9-hESC co-cultures for hematopoietic differentiation, a precise density of 10.4 × 10⁴ cells/cm² achieved high efficiency five days faster than traditional overgrown cultures [37].

2. What are common signs of suboptimal co-culture conditions? Common indicators include low expression of target differentiation markers (e.g., CD34 for hematopoietic cells), delayed appearance of differentiated cell populations, and inconsistent results across experimental replicates [37] [28]. For instance, prolonged differentiation timelines (14-18 days) with variable CD34+ cell yields can signal inefficient OP9 stromal preparation [37].

3. How can I non-destructively monitor differentiation efficiency early in the process? Phase-contrast imaging combined with machine learning algorithms can predict final differentiation efficiency long before traditional marker analysis. One system using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based feature extraction from images successfully predicted muscle stem cell differentiation efficiency approximately 50 days before the end of the induction period [28].

4. What are the key differences between research-grade and GMP-grade stromal cells? The isolation process and quality control criteria are often similar, but GMP-grade cells require manufacturing in B-grade clean rooms, more comprehensive documentation, and additional testing for chromosomal stability [39]. Both types should be negative for hematopoietic markers (CD45, CD34, CD14) and positive for typical mesenchymal markers (CD105, CD73, CD90) [39].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Hematopoietic Differentiation Efficiency in OP9 Co-culture Systems

Symptoms: Reduced CD34+ cell yield, prolonged differentiation time (exceeding 14 days), inconsistent results between batches [37].

Solution: Optimize OP9 stromal cell preparation method and density.

- Step 1: Replace the traditional 4-day overgrowth protocol with a 24-hour pre-culture of OP9 cells at optimal density [37].

- Step 2: Plate OP9 cells at (10.4 \times 10^4) cells/cm² in a 6-well plate format [37].

- Step 3: Co-culture with hESCs after exactly 24 hours of OP9 cell attachment.

- Step 4: Evaluate CD34+ cell appearance by flow cytometry on day 8-10, expecting peak efficiency 2 days earlier than traditional methods [37].

Prevention: Use low-passage OP9 cells (passages 3-15) and maintain consistent culture conditions. Pre-test different OP9 cell batches for differentiation-supporting capability [37].

Problem: Variable Efficiency in Long-Term Differentiation Protocols

Symptoms: High well-to-well variability in final differentiation outcomes, inefficient use of resources due to long protocol durations (up to 80+ days) [28].

Solution: Implement early prediction systems to identify high-efficiency cultures.

- Step 1: Capture phase-contrast images during the early differentiation phase (days 14-38 for an 82-day protocol) [28].

- Step 2: Apply Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) feature extraction to generate rotation-invariant feature vectors from images [28].

- Step 3: Use machine learning classification (e.g., Random Forest) to predict high and low-efficiency samples [28].

- Step 4: Focus resources on cultures predicted to have high differentiation efficiency, discarding low-performing samples early.

Validation: Correlation between early image-based predictions and late-stage marker expression (e.g., MYF5+% or CDH13+% for MuSCs) should be established for each protocol [28].

Problem: Poor Factor Diffusion in Filter-Based Co-culture Systems

Symptoms: Inadequate paracrine signaling between cell types, reduced co-culture effect, inconsistent results across the culture area [40].

Solution: Ensure proper filter preparation and adequate culture volumes.

- Step 1: Degas filters thoroughly before use to remove air trapped in pores [40].

- Step 2: Pre-treat filters by washing with pure water, followed by 100% ethanol for 1 minute, then PBS before assembling the co-culture plate [40].

- Step 3: Use sufficient culture medium volume to ensure complete contact with the filter surface [40].

- Step 4: For extracellular vesicle studies, note that proteins and vesicles may adhere to filters, requiring optimization of recovery methods [40].

Table 1: Optimized Seeding Densities for Various Co-culture Applications

| Cell Type/System | Optimal Seeding Density | Culture Format | Key Efficiency Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OP9 stromal cells (for hESC hematopoietic differentiation) | (10.4 \times 10^4) cells/cm² (total (1.0 \times 10^6) cells/well) | 6-well plate | CD34+ cells appeared 2 days earlier; Same efficiency achieved 5 days faster | [37] |

| Adipose-derived Stem Cells (ASCs for epithelial differentiation) | (5.0 \times 10^6) cells/cm² | Composite scaffold | Highest expression of epithelial markers; Supported further air-liquid interface culture | [38] |

| Primary Endometrial Stromal Cells (for tissue modeling) | Tissue explants method-dependent | 6-cm culture dish | Successful outgrowth in 2-3 days; 75-80% confluency for passaging | [41] |

Table 2: Comparison of Stromal Cell Preparation Methods

| Parameter | Traditional Overgrowth Method | Optimized Density Method | Advantage of Optimization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preparation Time | 4 days | 24 hours | Reduces total process time by 3 days | [37] |

| Cell State at Co-culture | Overgrown, confluent | Log-phase growth | Better recapitulates physiological stromal signaling | [37] |

| Differentiation Timeline | 14-18 days | 9-13 days | Achieves peak CD34+ population 2 days earlier | [37] [42] |

| Reproducibility | Variable between batches | Higher consistency | Standardized density reduces experimental variability | [37] [28] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimized OP9 Stromal Cell Preparation for Hematopoietic Differentiation

Materials:

- OP9 mouse stromal cell line (passages 3-15 recommended)

- α-MEM medium supplemented with 15% FBS

- 0.1% gelatin-coated 6-well plates

- hPSC medium (mTeSR1 or equivalent)

- Differentiation medium: α-MEM with 10% FBS and 100 μmol/L monothioglycerol (MTG)

Method:

- Thawing and Maintenance: Culture OP9 cells on gelatin-coated plates in α-MEM/15% FBS until 70-80% confluent. Use 0.25% trypsin for passaging (1 minute at 37°C) [37].

- Experimental Seeding: Harvest OP9 cells and seed at exactly (10.4 \times 10^4) cells/cm² in 6-well plates [37].

- Pre-culture Incubation: Incubate OP9 cells for 24 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂ [37].

- hESC Preparation: Harvest hESCs using 2 mg/ml dispase, maintaining cells in small clumps. Plate at (0.7-1.0 \times 10^6) cells per well onto OP9 monolayer [37].

- Co-culture Maintenance: Culture in differentiation medium with complete medium change on day 1 and half-medium changes on days 4, 6, 8, and 10 [37].

- Efficiency Assessment: Harvest co-culture cells by 20-minute trypsinization on days 8, 10, and 12. Analyze CD34+ population by flow cytometry using PE-Cy5.5 anti-human CD34 and APC-human TRA-1-85 antibodies [37].

Protocol 2: Early Efficiency Prediction via Imaging and Machine Learning

Materials:

- Phase-contrast microscope with digital camera

- MYF5-tdTomato reporter hiPSCs (for MuSC differentiation)

- Computational resources for image analysis

- Python/R with machine learning libraries (e.g., scikit-learn)

Method:

- Image Acquisition: Capture phase-contrast images during early differentiation phase (days 14-38 for an 82-day protocol) [28].

- Feature Extraction: Process images using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to generate power spectra. Apply shell integration to create 100-dimensional, rotation-invariant feature vectors [28].

- Model Training: Label images based on final differentiation efficiency (e.g., MYF5+% on day 82). Train a Random Forest classifier using feature vectors from multiple independent experiments [28].

- Prediction Application: Use the trained model to classify new cultures based on early images. For MuSC differentiation, images from days 24-34 were most predictive [28].

- Decision Making: Prioritize cultures predicted to have high efficiency for further experimentation and resource allocation.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Cell Line | Function in Co-culture Systems | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| OP9 Mouse Stromal Cells | Supports hematopoietic differentiation from hPSCs; provides critical microenvironmental signals | Use passages 3-15; pre-test differentiation support capability; culture on gelatin-coated surfaces [37] |

| Fibrin Sealant (Tisseel) | Bioengineered scaffold for 3D co-culture; enhances cell attachment and tissue ingrowth | Composed of fibrinogen, thrombin, factor XIII, CaCl₂, and aprotinin; forms gel when combined; FDA-approved [38] |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Multipotent stromal cells with immunomodulatory properties; can differentiate into multiple lineages | Source matters (bone marrow, umbilical cord, adipose); characterized by CD105+, CD73+, CD90+ and lack of hematopoietic markers [39] |

| Defined Xeno-Free Media | Clinically relevant culture conditions without animal components; reduces variability | Essential for GMP-compliant processes; supports MSC expansion and differentiation without FBS [39] |

| Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) Systems | Promotes epithelial differentiation and maturation; mimics physiological tissue interfaces | Requires specialized culture inserts; enables study of polarization and specialized cell functions [38] |

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

Co-culture Optimization Workflow

Stromal Cell Signaling in Co-culture Systems

Selecting the appropriate cell culture model is a critical strategic decision in stem cell differentiation efficiency optimization research. While two-dimensional (2D) cultures have been the laboratory standard for decades, three-dimensional (3D) cultures are emerging as a powerful tool for their ability to better mimic the in vivo microenvironment. This technical support center guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a practical framework for choosing between these models, troubleshooting common experimental issues, and implementing protocols that enhance the reliability and predictive power of their work in stem cell research.

Model Comparison: 2D vs. 3D at a Glance

The choice between 2D and 3D culture models involves balancing practical considerations with physiological relevance. The following table summarizes their core characteristics based on current literature [43] [44].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of 2D and 3D Cell Culture Models

| Feature | 2D Cell Culture | 3D Cell Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Pattern | Monolayer on a flat plastic surface [44] | Cells grow in all directions, forming structures like spheroids and organoids [43] |

| In Vivo Imitation | Does not mimic the natural 3D structure of tissues [44] | Better mimics the natural morphology and architecture of tissues and organs [43] [44] |

| Cell Interactions | Limited cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions; no in vivo-like microenvironment [44] | Proper cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions; creates environmental "niches" [43] [44] |

| Cell Morphology & Polarity | Altered morphology; loss of native phenotype and polarity [44] | Preserved native morphology, diverse phenotype, and polarity [43] [44] |

| Gradients (Oxygen, Nutrients) | Unlimited access to oxygen, nutrients, and signaling molecules [44] | Variable access, creating natural gradients (e.g., hypoxic cores) as found in vivo [43] [44] |

| Gene Expression & Biochemistry | Changes in gene expression, splicing, and biochemistry compared to in vivo [44] | Gene expression, splicing, and biochemistry more closely resemble in vivo conditions [43] [44] |

| Cost & Infrastructure | Simple, low-cost maintenance; well-established protocols [43] [45] | More expensive, time-consuming; fewer commercially available standardized tests [44] |

| Throughput & Ease of Use | High performance, reproducibility; easy to culture and interpret; compatible with High-Throughput Screening (HTS) [43] [44] | Often more cumbersome; can be difficult to interpret and maintain; throughput is improving with new technologies [44] [45] |

Table 2: Strategic Application of Culture Models in Stem Cell Research

| Research Objective | Recommended Model | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Drug Screening (Early Stage) | 2D | Allows for quick, inexpensive screening of thousands of compounds due to simplicity and compatibility with HTS formats [43]. |

| Basic Genetic Manipulations (e.g., CRISPR) | 2D | Well-established, straightforward protocols for genetic modifications in a controlled environment [43]. |

| Stem Cell Differentiation & Protocol Optimization | 3D | Provides a more physiologically relevant context for differentiation, leading to more mature and accurate cell phenotypes [43] [28]. |

| Disease Modeling (e.g., Cancer, Neurodegenerative) | 3D | Captures complex tissue architecture and cell interactions crucial for understanding disease mechanisms [43] [46]. |

| Personalized Therapy Testing | 3D (Patient-Derived Organoids) | Enables the creation of patient-specific models for predicting individual treatment responses [43]. |

| Toxicology & Safety Pharmacology | 3D | Offers more accurate prediction of drug toxicity and metabolism due to better preservation of tissue-specific functions [43]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Differentiation Efficiency in 3D Cultures

Problem: The differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) into target cells (e.g., muscle stem cells) is inefficient and highly variable, leading to unreliable results and wasted resources.

Investigation & Solution:

- Monitor Early Differentiation Markers: Biological analyses suggest that the efficiency of muscle stem cell (MuSC) differentiation on day 82 can be predicted by assessing the expression of skeletal muscle markers (like MYH3, MYOD1, and MYOG) around day 38 [28]. Implement non-destructive quality checks during early induction phases.

- Implement Early Prediction Systems: Adopt machine learning-based prediction systems that use phase-contrast imaging and feature analysis (e.g., Fast Fourier transform) during the early stages of differentiation (e.g., days 14-38). This non-destructive method can forecast final induction efficiency approximately 50 days before the end of the protocol, allowing for early intervention or termination of poorly differentiating samples [28].

- Verify Pluripotency Status: Ensure that the starting hiPSCs have a high, homogeneous expression of established undifferentiated stem cell markers. Using a cost-effective flow cytometry protocol to verify pluripotency before initiating differentiation can help reduce line-to-line variability [47].

Issue 2: Choosing Between 2D and 3D for a Specific Project

Problem: A researcher is unsure whether to use a 2D or 3D culture system for a new project, balancing the need for physiological relevance with practical constraints like budget, time, and throughput.

Investigation & Solution:

- Define the Primary Research Question:

- Is the goal high-speed screening of many compounds? → Choose 2D for its speed, low cost, and compatibility with HTS [43] [45].

- Is the goal to understand a complex biological process where tissue architecture and cell-ECM interactions are critical? → Choose 3D for its physiological relevance [43] [46].

- Adopt a Tiered Workflow: Many advanced labs use a hybrid approach. Start with 2D to rapidly screen and eliminate a large number of candidates. Then, validate the shortlisted candidates in more physiologically relevant 3D models (e.g., spheroids, organoids) for better predictive power [43].

- Consider the Endpoint Analysis: If the required readout (e.g., high-resolution microscopy, protein isolation) is not yet fully optimized for 3D models, a 2D system might be more practical. However, technologies for 3D analysis are rapidly improving [45].

Issue 3: Challenges with 3D Culture Analysis and Throughput

Problem: 3D cultures are perceived as cumbersome, difficult to analyze with standard equipment, and low-throughput, making them unsuitable for large-scale screening projects.

Investigation & Solution:

- Address Throughput with Advanced Plates: Use modern microfluidic 3D culture plates, such as the OrganoPlate, which are based on standard 384-well plate formats. These are specifically designed to provide the high throughput needed for large-scale drug screening and research [45].

- Simplify Microscopy and Assays: Select 3D systems that are engineered to allow for easy microscopy, assays, and readouts. The architecture of these systems is designed to overcome the challenges of light penetration and focus in thicker 3D structures [45].

- Leverage AI-Driven Image Analysis: Implement artificial intelligence (AI) tools for the analysis of 3D cultures. AI can enable predictive analytics and non-destructive assessment of complex parameters like differentiation efficiency from simple phase-contrast images, reducing the reliance on complex, low-throughput assays [28] [46].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Early, Non-Destructive Prediction of hiPSC Differentiation Efficiency

This protocol is adapted from Saware et al. and demonstrates how to predict the final differentiation efficiency of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) into muscle stem cells (MuSCs) long before the protocol is complete, using imaging and machine learning [28].

Application: Optimizing and screening long-term hiPSC differentiation protocols non-destructively.

Workflow Diagram:

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for the Prediction Protocol

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| MYF5-tdTomato Reporter hiPSC Line | Allows for quantification of final MuSC induction efficiency via flow cytometry by expressing a fluorescent protein under a muscle-specific promoter [28]. | Custom-generated cell line. |

| Phase Contrast Microscope | For non-destructive, daily imaging of cell cultures during the differentiation induction period [28]. | Standard equipment. |

| Directed Differentiation Media | Specific combinations of growth factors and small molecules to direct hiPSCs toward the muscle lineage. | Includes Wnt agonist, IGF-1, HGF, and bFGF [28]. |

| Flow Cytometer | For final analysis of differentiation efficiency on day 82 by measuring the percentage of MYF5-tdTomato positive cells [28]. | e.g., FACSCalibur. |

| Machine Learning Software | For analyzing extracted image features (FFT data) and building a predictive classification model [28]. | Random Forest classifier used in the study. |

Protocol 2: Flow Cytometry Analysis of Pluripotency Markers in hiPSCs

This protocol, based on Saware et al., outlines a cost-effective method to verify the pluripotent status of hiPSCs before beginning differentiation experiments, which is crucial for ensuring consistent and high-quality starting material [47].

Application: Defining the pluripotency status of hiPSC cultures by evaluating the expression of surface and intracellular undifferentiated stem cell markers.

Workflow Diagram:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between 2D and 3D cell culture? The fundamental difference lies in the growth environment. In 2D culture, cells grow as a monolayer attached to a flat plastic surface (e.g., flask, Petri dish). In 3D culture, cells are allowed to grow in three dimensions, expanding in all directions to form tissue-like structures such as spheroids, organoids, or cells embedded within an extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffold. This 3D architecture more closely mimics the natural tissue environment [43] [44].

Q2: My 2D culture results are inconsistent when transitioning to a new cell line. Could the culture model be the issue? Yes. While 2D cultures are simple, they are known for altering cell morphology, polarity, and gene expression. Different cell lines can respond uniquely to the artificial 2D environment, leading to variability. Furthermore, the lack of a natural 3D microenvironment in 2D culture means that critical cell-ECM and complex cell-cell interactions are absent, which can significantly impact differentiation capacity and other cellular functions. For sensitive work like stem cell differentiation, moving to a 3D system might provide more consistent and physiologically relevant results across different cell lines [44].

Q3: Are there any scenarios where 2D culture is still the preferred or recommended method? Absolutely. 2D culture is not obsolete. It remains the preferred method for:

- High-throughput screening (HTS) applications where thousands of compounds need to be tested quickly and cost-effectively [43].

- Basic cytotoxicity assays and initial genetic manipulations (e.g., CRISPR knockouts) due to its simplicity and well-standardized protocols [43].

- Projects with significant budget or time constraints, or when a vast amount of comparative historical data from 2D models exists [45].

Q4: What are the main practical challenges when starting with 3D cell cultures, and how can I overcome them? The main challenges include:

- Cost and Infrastructure: 3D cultures are generally more expensive and may require specialized materials (e.g., ECM hydrogels, specialized plates) [44].

- Protocol Standardization: Protocols can be less standardized and more time-consuming than for 2D [44].

- Analysis Complexity: Analyzing 3D structures can be difficult with standard microscopy and biochemical assays [45].

- Solution: Begin with well-established 3D protocols for your cell type. Invest in technologies designed for 3D throughput and analysis (e.g., microfluidic plates). Leverage AI and advanced imaging techniques to simplify data extraction from complex 3D models [46] [45].

Q5: How is AI being integrated with 3D cell culture models to advance drug discovery? AI is playing a transformative role by:

- Enabling Predictive Analytics: Machine learning models can analyze data from 3D cultures (e.g., imaging, gene expression) to predict outcomes like drug efficacy or toxicity with high accuracy [46].

- Automating Image Analysis: AI can non-destructively assess complex parameters in 3D cultures, such as predicting future differentiation efficiency from simple phase-contrast images, which is a major bottleneck in protocol optimization [28].

- Facilitating Personalized Medicine: AI can help analyze data from patient-derived 3D organoids to identify personalized therapeutic regimens [43] [46].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues & Solutions

Problem 1: Low Differentiation Efficiency and High Variability

| Problem Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Reagents & Concentrations |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent starting cell quality [47] [48] | Verify pluripotency status of hiPSCs prior to differentiation using flow cytometry for established undifferentiated stem cell markers (e.g., OCT4, SOX2). [47] | Flow cytometry antibodies panel for pluripotency markers. [47] |

| Suboptimal cell seeding density [48] | Accurately count cells and plate at protocol-specific density. For neural induction, a density of 2–2.5 x 10⁴ cells/cm² is often recommended. [48] | ROCK inhibitor (Y27632, 10 µM) to improve cell survival after passaging. [48] [49] |

| Spontaneous differentiation in culture [31] [50] | Remove differentiated areas from hPSC cultures before induction. Maintain cultures by passaging when colonies are large and compact, avoiding overgrowth. [31] | N/A |

| Inherent line-to-line variability [47] [50] | Include a control hPSC line (e.g., H9 or H7) as a positive control in differentiation experiments. Adjust cell density or extend induction time for difficult lines. [48] | N/A |

Problem 2: Inconsistent Cell Aggregate Size During Passaging