Osteogenic, Chondrogenic, and Adipogenic Differentiation of Stem Cells: Mechanisms, Methods, and Clinical Translation

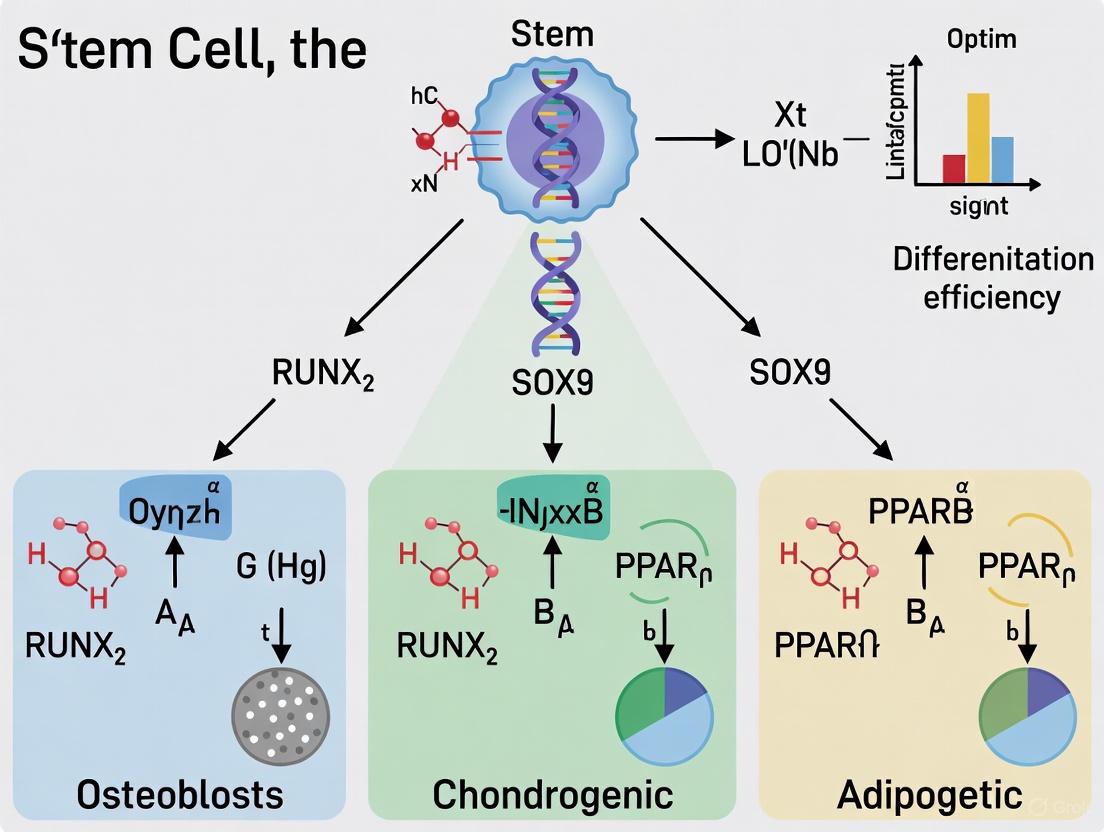

This comprehensive review synthesizes current advancements in steering mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) differentiation towards osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages.

Osteogenic, Chondrogenic, and Adipogenic Differentiation of Stem Cells: Mechanisms, Methods, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current advancements in steering mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) differentiation towards osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages. It explores the foundational biology, including key transcription factors and signaling pathways, and details innovative methodological approaches such as 3D bioprinting, advanced biomaterials, and machine learning for predicting differentiation. The article also addresses critical challenges in optimization and standardization, provides a comparative analysis of MSC sources, and discusses validation strategies for clinical application. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource bridges fundamental research with translational medicine, offering insights for regenerative therapies in orthopedics and beyond.

The Biological Blueprint: Unraveling Lineage-Specific Pathways and Transcriptional Networks

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have emerged as a highly promising strategy in regenerative medicine due to their self-renewal, pluripotency, and immunomodulatory properties [1]. These non-hematopoietic, multipotent stem cells were first identified in bone marrow and can differentiate into various mesodermal lineages while modulating the immune system [1]. The therapeutic potential of MSCs from different tissues has been widely explored in preclinical models and clinical trials for human diseases, ranging from autoimmune and inflammatory disorders to neurodegenerative diseases and orthopedic injuries [1]. According to the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT), MSCs are defined by three key criteria: adherence to plastic under standard culture conditions; expression of specific surface markers (CD73, CD90, and CD105 ≥95%) while lacking hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45, CD14/CD11b, CD79α/CD19, HLA-DR ≤2%); and capacity to differentiate into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages in vitro [1] [2]. Originally termed "mesenchymal stem cells" by Dr. Arnold Caplan in 1991, the nomenclature has evolved, with the ISCT now officially defining them as "Mesenchymal Stromal Cells" to reflect their tissue-supporting and immunomodulatory functions [3] [4].

Defining Characteristics: Surface Markers and Identification

The precise identification of MSCs relies on a specific immunophenotypic profile established by international standards. The positive and negative marker expression provides a critical framework for researchers to validate MSC populations before experimental or therapeutic application.

Table 1: Essential Surface Markers for MSC Identification According to ISCT Criteria

| Marker Category | Specific Markers | Expression Requirement | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Markers | CD105 (Endoglin) | ≥95% expression | Type I membrane glycoprotein essential for cell migration and angiogenesis [1]. |

| CD73 (5'-ectonucleotidase) | ≥95% expression | Catalyzes AMP hydrolysis to adenosine; role in cell signaling within bone marrow [1]. | |

| CD90 (Thy-1) | ≥95% expression | GPI-anchored protein mediating cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions; contributes to adhesion and migration [1]. | |

| Negative Markers | CD45, CD34 | ≤2% expression | CD45: marker for white blood cells; CD34: biomarker for hematopoietic stem cells [1]. |

| CD14/CD11b | ≤2% expression | Expressed on monocytes and macrophages [1]. | |

| CD79α/CD19 | ≤2% expression | Markers of B cells [1]. | |

| HLA-DR | ≤2% expression | MHC class II molecule with strong immunogenic properties [1]. |

The adherence to these marker criteria is crucial for ensuring population purity and distinguishing MSCs from hematopoietic cells. Additional markers like STRO-1, CD146, and CD29 are often used in research to identify subpopulations with enhanced stemness, but the core ISCT panel remains the standard for minimal definition [5]. The expression profile must be confirmed using techniques such as flow cytometry, and researchers should note that marker expression can be influenced by factors like passage number and culture conditions [5].

MSCs can be isolated from a remarkable variety of adult and perinatal tissues, each source offering distinct advantages and challenges. The selection of a source material is a critical first step that influences the yield, proliferation rate, and potential application of the derived MSCs.

Table 2: Comparison of Primary Mesenchymal Stem Cell Sources

| Tissue Source | Isolation Yield & Key Features | Primary Isolation Methods | Research & Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow (BM-MSCs) | Limited yield (0.01-0.001% of nucleated cells); considered the "gold standard" [2]. | Bone marrow aspirate followed by density gradient centrifugation (e.g., Ficoll-Paque) and adherence culture [3]. | Most extensively studied source; used in 10 approved therapies; requires invasive harvest [1] [2]. |

| Adipose Tissue (AD-MSCs) | High yield (up to 1 billion cells from 300g tissue); less invasive harvest [2]. | Lipoaspirate processed via enzymatic digestion (e.g., collagenase) and red blood cell lysis [3] [4]. | Abundant source; advantages in bone regeneration and skin healing; three approved therapies [2]. |

| Umbilical Cord (UC-MSCs) | High concentration in Wharton's Jelly; enhanced proliferation, low immunogenicity [1] [2]. | Enzymatic digestion of cord tissue or explant culture; ISO/TS 22859-1:2022 standard exists [2] [3]. | Ideal for allogeneic transplantation; three approved therapies [2]. |

| Umbilical Cord Blood (UCB-MSCs) | Contains MSCs alongside hematopoietic stem cells; lower yield than UC [2]. | Density gradient centrifugation of cord blood to isolate mononuclear cells [2] [3]. | High proliferation and clonogenic rates; delayed senescence [2]. |

| Placenta (P-MSCs) | Complex organ with high MSC concentration; superior proliferative capacity [2]. | Surgical dissection of specific regions (amnion, chorion) followed by enzymatic digestion [3]. | Exhibits pronounced immunosuppressive effects; isolation challenged by complex composition [2]. |

| Menstrual Blood/Endometrium (MenSCs/eMSCs) | Easy, non-invasive collection; rapid doubling time (~20 hours) [2]. | Collection and processing of menstrual effluent or endometrial biopsy via adherence [2]. | Promising for gynecological applications; no clinical trials to date [2]. |

Detailed Protocol: Isolation of Human Umbilical Cord MSCs (Wharton's Jelly Derivation)

Principle: This protocol utilizes enzymatic digestion to efficiently release MSCs from the Wharton's Jelly matrix of the human umbilical cord, providing a high yield of cells suitable for allogeneic therapies [2] [3].

Reagents and Materials:

- Fresh human umbilical cord (full-term, maternal consent obtained)

- Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS), sterile

- Antibiotic-Antimycotic solution (100X)

- Collagenase Type I or Type IV (e.g., 1-2 mg/mL working concentration)

- Hyaluronidase (optional, to enhance digestion)

- Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) to quench digestion

- Complete culture medium: α-MEM or DMEM/F12, 10% FBS, 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic

- Tissue culture plasticware (flasks, plates)

- Surgical scissors, forceps, scalpels

Procedure:

- Transport and Washing: Transport the umbilical cord to the lab in a sterile container with cold DPBS containing 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic. Wash thoroughly in fresh DPBS to remove residual blood.

- Vessel Removal: Using sterile instruments, dissect the cord to remove the two arteries and one vein.

- Tissue Mincing: Chop the remaining Wharton's Jelly tissue into small fragments (~1-2 mm³).

- Enzymatic Digestion: Incubate the tissue fragments in a collagenase solution (1-2 mg/mL in DPBS) for 3-6 hours at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Digestion Quenching: Add an equal volume of complete culture medium containing 10% FBS to stop the enzymatic reaction.

- Filtration and Centrifugation: Filter the cell suspension through a 100μm cell strainer to remove undigested tissue. Centrifuge the filtrate at 300-400 x g for 10 minutes.

- Plating and Culture: Resuspend the cell pellet in complete culture medium and plate in a tissue culture flask. Maintain at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ humidified incubator.

- Medium Changes: Perform the first medium change after 48-72 hours to remove non-adherent cells, then change the medium every 3-4 days thereafter.

- Passaging: Passage cells at 70-80% confluence using standard trypsin/EDTA digestion.

Notes: The isolated cells should be characterized according to ISCT criteria (Section 2) before experimental use. The international standard ISO/TS 22859-1:2022 provides further technical specifications for hUC-MSCs [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for MSC Research and Their Applications

| Reagent / Material | Function in MSC Research | Example Application & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Provides essential growth factors, hormones, and nutrients for in vitro cell growth. | Standard component (typically 10-20%) of basal MSC culture medium. Batch variability is a significant concern; screening is recommended. |

| Collagenase Type I/IV | Enzyme that degrades collagen, a major ECM component, to dissociate cells from tissues. | Critical for isolating MSCs from adipose tissue (lipoaspirate) and umbilical cord [3]. |

| Ficoll-Paque Premium | Density gradient medium for isolating mononuclear cells from bone marrow or cord blood. | Enriches for MSCs by separating them from red blood cells and granulocytes [3]. |

| Trypsin-EDTA Solution | Proteolytic enzyme (Trypsin) chelates calcium (EDTA) to dissociate adherent cells for passaging. | Standard reagent for detaching adherent MSCs from culture plastic for subculturing. |

| CD105, CD73, CD90 Antibodies | Conjugated antibodies for flow cytometry to confirm the positive marker profile of MSCs. | Required for immunophenotypic characterization per ISCT guidelines. |

| Osteo-/Chondro-/Adipo-Induction Media | Specialized media containing specific inducing factors to drive MSC differentiation. | Used to validate MSC multipotency in vitro (see Section 5). |

| Acrylate-based Functionalized Substrates | Synthetic polymer supports grafted with biomolecules (gelatin, heparin) to study cell-biomaterial interactions. | Used in advanced research to direct MSC fate and for bone tissue engineering applications [6]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Gene editing tool to create specific genetic modifications in MSCs for functional studies. | Used to investigate gene function, e.g., role of XYLT1 in chondrogenic differentiation [7]. |

Multipotency: Trilineage Differentiation Potential

The defining functional characteristic of MSCs is their ability to differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes in vitro. This trilineage potential is not only a validation criterion but also the foundation of their application in regenerative medicine. The differentiation processes are governed by complex and highly regulated transcriptional networks [5].

Detailed Protocol: Standard In Vitro Trilineage Differentiation Assay

Principle: This protocol provides a standardized method to induce and validate the adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs in vitro, fulfilling a core defining criterion [1] [5].

Reagents and Materials:

- Validated MSCs (Passage 2-4, ~70-80% confluence)

- Basal medium: DMEM high glucose, 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin

- Adipogenic Induction Medium: Basal medium supplemented with 0.5 mM IBMX, 1 μM Dexamethasone, 10 μM Insulin, 200 μM Indomethacin.

- Adipogenic Maintenance Medium: Basal medium supplemented with 10 μM Insulin.

- Osteogenic Induction Medium: Basal medium supplemented with 0.1 μM Dexamethasone, 10 mM β-Glycerophosphate, 50 μM Ascorbic Acid-2-Phosphate.

- Chondrogenic Induction Medium: Serum-free DMEM high glucose supplemented with 1% ITS+ Premix, 0.1 μM Dexamethasone, 50 μM Ascorbic Acid-2-Phosphate, 40 μg/mL Proline, and 10 ng/mL TGF-β3.

- Oil Red O staining solution

- Alizarin Red S staining solution

- Alcian Blue staining solution

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding:

- Adipogenesis/Osteogenesis: Seed MSCs in 12- or 24-well plates at a standard density (e.g., 2.1 x 10⁴ cells/cm² for adipogenesis, 3.1 x 10⁴ cells/cm² for osteogenesis). Allow cells to adhere for 24 hours.

- Chondrogenesis: Pellet 2.5 x 10⁵ MSCs in a 15 mL polypropylene tube by centrifugation (500 x g for 5 minutes). Culture the pellet in the tube.

Induction:

- Adipogenesis: Once cells are 100% confluent, replace the basal medium with Adipogenic Induction Medium. After 3 days, switch to Adipogenic Maintenance Medium for 24 hours. Repeat this cycle 3-4 times. Finally, maintain cells in Maintenance Medium for an additional 4-7 days, changing medium every 2-3 days.

- Osteogenesis: Once cells are 70-80% confluent, replace the basal medium with Osteogenic Induction Medium. Maintain for 21 days, changing the medium every 3-4 days.

- Chondrogenesis: Loosen the cell pellet by gently tapping the tube and add Chondrogenic Induction Medium. Incubate for 21-28 days, changing the medium every 2-3 days. The pellet will form a spherical micromass.

Staining and Analysis:

- Adipogenesis: Fix differentiated cells with 4% PFA for 20 minutes. Stain with Oil Red O (working solution) for 30-60 minutes to visualize intracellular lipid droplets. Quantify by eluting the stain with isopropanol and measuring absorbance at 520 nm.

- Osteogenesis: Fix cells with 4% PFA for 20 minutes. Stain with 2% Alizarin Red S (pH 4.1-4.3) for 20-30 minutes to detect calcium deposits.

- Chondrogenesis: Fix the micromass pellet with 4% PFA, process for paraffin embedding, and section. Stain sections with Alcian Blue (pH 2.5) for 30 minutes to visualize sulfated proteoglycans in the extracellular matrix.

Troubleshooting: Lack of differentiation may indicate over-passaged MSCs, suboptimal inducer concentrations, or poor initial cell quality. Always include undifferentiated controls (cultured in basal medium) for comparison. For molecular validation, perform RT-qPCR for lineage-specific markers (Figure 2).

Clinical Applications and Future Perspectives

The therapeutic application of MSCs has expanded dramatically, with over ten approved MSC-based therapies marketed worldwide and hundreds of clinical trials ongoing [2] [8]. The initial focus on their regenerative potential via direct differentiation has shifted towards appreciating their potent paracrine effects. MSCs release a diverse array of bioactive molecules, including growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles (EVs), which play crucial roles in modulating the local cellular environment, promoting tissue repair, angiogenesis, and exerting anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects [1] [8] [4].

Approved MSC therapies primarily address conditions like complex perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [8]. In gynecology, MSC therapies for uterine adhesions and early-onset ovarian failure have progressed to clinical application, demonstrating notable efficacy [2]. However, the field faces challenges, including inconsistent efficacy in clinical trials, product heterogeneity, and a lack of standardized manufacturing and delivery protocols [8] [4]. Future directions involve overcoming these hurdles through strategies like genetic modification, preconditioning ("priming") of MSCs, and a growing interest in cell-free therapies utilizing MSC-derived extracellular vesicles [4]. A deeper understanding of MSC biology, differentiation pathways, and mechanisms of action will undoubtedly pave the way for more effective and reliable regenerative therapies.

Osteogenic differentiation is a sophisticated, multi-step process through which mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) commit to the osteoblast lineage, ultimately producing bone-forming cells responsible for bone matrix synthesis and mineralization. This process is governed by a precise transcriptional hierarchy and influenced by several key signaling pathways. Understanding this regulatory network is paramount for advancing bone tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, and developing therapeutics for bone loss diseases such as osteoporosis. The master transcription factor Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) initiates the osteogenic program, while the zinc-finger transcription factor Osterix (Osx) acts downstream as an essential regulator for osteoblast maturation and bone matrix deposition [9] [10]. The differentiation process is further fine-tuned by major signaling pathways, notably the Wnt/β-catenin and Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP)/Smad pathways, which integrate external cues to regulate the activity of these core transcription factors [11] [12] [13]. This application note provides a detailed overview of these regulators, their functional crosstalk, and standard experimental protocols for investigating osteogenic differentiation in vitro.

Master Transcriptional Regulators of Osteogenesis

Runx2: The Master Switch of Osteoblast Lineage

Runx2 is a transcription factor belonging to the runt homology domain protein family and is widely recognized as the master regulator of osteoblast differentiation [9] [14].

- Function and Expression: Runx2 is expressed early in cells prefiguring the skeleton and is essential for directing MSCs into the osteoblast lineage. It controls the expression of major bone matrix protein genes by binding to the osteoblast-specific cis-acting element (OSE2) in the promoters of genes such as osteocalcin (OC), osteopontin (OPN), bone sialoprotein (BSP), and collagen type I alpha 1 (Col1A1) [9]. Its expression and transcriptional activity must be precisely regulated, as both deficiency and overexpression lead to bone defects. Homozygous loss of Runx2 in mice results in a complete lack of bone formation due to maturational arrest of osteoblasts [9]. In humans, haploinsufficiency of RUNX2 causes cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD), characterized by hypoplastic/aplastic clavicles and open fontanelles [9] [14] [10].

- Regulation by Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): Runx2 activity is intricately controlled by PTMs, including phosphorylation, prolyl isomerization, acetylation, and ubiquitination [14]. For instance, FGF signaling activates ERK and p38 MAPKs, which phosphorylate Runx2. This phosphorylation facilitates prolyl isomerization by PIN1, which in turn exposes lysine residues for acetylation by p300. Acetylation stabilizes Runx2 by protecting it from ubiquitin-mediated degradation, thereby enhancing its transactivation potential [14].

Osterix (Osx): The Gatekeeper of Osteoblast Maturation

Osterix (Osx or Sp7) is a zinc finger-containing transcription factor that acts downstream of Runx2 and is indispensable for osteoblast maturation [9] [10].

- Function and Expression: Mice lacking Osx completely fail to form bone and are devoid of mature osteoblasts, demonstrating its non-redundant role [9] [10]. Osx is required for the differentiation of preosteoblasts into fully functional osteoblasts and osteocytes. It regulates a suite of genes involved in the final stages of osteogenic differentiation and bone matrix production.

- Interaction with Runx2 and PPARγ: Osx and Runx2 can functionally interact to cooperatively induce the expression of osteogenic genes like Col1a1 and Ibsp. This cooperation is mediated by their binding to adjacent Sp1 and Runx sites on target gene enhancers and is regulated by MAPK signaling [15]. Beyond its osteogenic role, Osx also represses adipogenesis by directly interacting with the ligand-binding domain of PPARγ, the master regulator of adipogenesis. This interaction inhibits PPARγ's transcriptional activity, thereby suppressing fat cell differentiation and promoting a commitment to the osteoblastic lineage [16].

Table 1: Key Master Transcription Factors in Osteogenic Differentiation

| Transcription Factor | Key Function | Genetic Evidence (Loss-of-Function) | Key Downstream Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Runx2 | Master regulator; initiates osteoblast lineage commitment from MSCs. | Complete lack of bone formation; arrested osteoblast maturation [9]. | Osteocalcin (OC), Osteopontin (OPN), Bone Sialoprotein (BSP), Collagen type I (Col1A1) [9]. |

| Osterix (Osx) | Essential for osteoblast maturation and bone matrix deposition. | No bone formation; complete absence of mature osteoblasts [9] [10]. | A repertoire of genes for osteoblast maturation and matrix mineralization [10]. |

Key Signaling Pathways in Osteogenic Differentiation

Wnt/β-catenin Signaling Pathway

The canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway is a critical regulator of bone mass and osteoblastogenesis [11] [12] [17].

- Mechanism: In the absence of a Wnt ligand, a cytoplasmic "destruction complex" (containing Axin, APC, GSK-3β, and CK1) phosphorylates β-catenin, targeting it for proteasomal degradation. When Wnt ligands (e.g., Wnt1, Wnt3a) bind to the Frizzled (Fzd) receptor and LRP5/6 co-receptor, this complex is disrupted. This leads to the stabilization and accumulation of β-catenin in the cytoplasm, followed by its translocation to the nucleus. Inside the nucleus, β-catenin partners with TCF/LEF transcription factors to activate the expression of target genes, including those critical for osteoblast differentiation and proliferation [11] [17].

- Role in Osteogenesis: Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes MSC commitment to the osteoblast lineage and simultaneously inhibits differentiation into the adipocyte and chondrocyte lineages [12]. Activation of this pathway results in increased bone mass and bone formation strength in vivo [12].

BMP/Smad Signaling Pathway

The BMP pathway is a potent osteoinductive signal that works in concert with other pathways to drive bone formation [12] [13].

- Mechanism: BMP ligands (e.g., BMP2, BMP4, BMP7) bind to a heterodimeric complex of type I and type II BMP transmembrane serine/threonine kinase receptors. This binding leads to the phosphorylation of receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads: Smad1, Smad5, Smad8). The phosphorylated R-Smads then form a complex with the common mediator Smad4 (Co-Smad). This trimeric complex translocates into the nucleus, where it regulates the transcription of target genes, including Runx2 [12] [13].

- Role in Osteogenesis: BMP signaling is a key upstream activator of the osteogenic transcription factor cascade. It stimulates the expression of Runx2, which in turn drives the entire osteogenic program. The pathway is tightly controlled by inhibitory Smads (I-Smads), such as Smad6 and Smad7, which provide a negative feedback loop to prevent over-signaling [13].

Crosstalk Between Signaling Pathways

A critical aspect of osteogenic control is the crosstalk between different signaling pathways. The Wnt/β-catenin and BMP/Smad pathways, while distinct, do not operate in isolation. They exhibit significant functional synergy to promote robust osteogenic differentiation [12]. Active Wnt/β-catenin signaling can promote the expression of downstream targets of the BMP signaling pathway, creating a reinforced pro-osteogenic network. This integration ensures that MSCs receive coordinated signals to commit to the bone lineage effectively.

Experimental Protocols for Studying OsteogenesisIn Vitro

Standard Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)

This protocol outlines the basic methodology for inducing and assessing osteogenic differentiation in MSCs in vitro.

- Cell Culture: Seed human bone marrow-derived MSCs (BMSCs) or an appropriate MSC line at a density of 5,000 - 10,000 cells/cm² in basal growth medium (e.g., α-MEM or DMEM) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

- Osteogenic Induction: Once cells reach 80-90% confluence, replace the growth medium with osteogenic induction medium. The basal medium is supplemented with:

- 50-100 µM Ascorbic Acid-2-phosphate: Promotes collagen matrix synthesis.

- 10 mM β-glycerophosphate: Provides a source of organic phosphate for matrix mineralization.

- 10-100 nM Dexamethasone: A synthetic glucocorticoid that promotes osteoblast differentiation by modulating transcription factors like Runx2 [9].

- Maintenance: Culture the cells for 21-28 days, changing the osteogenic medium every 2-3 days.

Modulating Signaling Pathways: Application of Recombinant Proteins and Inhibitors

To investigate the role of specific pathways, the osteogenic medium can be supplemented with activating or inhibiting agents.

Table 2: Reagents for Modulating Key Osteogenic Pathways

| Target Pathway | Reagent Example | Concentration Range | Function / Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMP Signaling | Recombinant human BMP-2 | 50-100 ng/mL [18] | Potent osteoinductive factor; activates BMP-Smad signaling to induce Runx2 expression. |

| Wnt/β-catenin Signaling | Recombinant Wnt3a | 10-100 ng/mL | Activates canonical Wnt signaling to promote osteoblast lineage commitment. |

| CHIR99021 (GSK-3β inhibitor) | 3-10 µM | Chemical activator of Wnt signaling by inhibiting β-catenin degradation. | |

| FGF Signaling | Basic FGF (bFGF/FGF-2) | 5-20 ng/mL [18] | Mitogen for MSCs; its effect on osteogenesis is stage-dependent (inhibitory early, promotive later). |

| TGF-β Signaling | Recombinant TGF-β1 | 1-5 ng/mL [18] | Low concentrations (e.g., 1 ng/mL) may promote osteogenesis, while high concentrations inhibit it. |

Assessment of Osteogenic Differentiation

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity: Measure ALP activity (an early osteoblast marker) around day 7-10 using a colorimetric assay (e.g., with p-nitrophenyl phosphate) and normalize to total protein content.

- Matrix Mineralization (Alizarin Red S Staining): After 21-28 days, fix cells and stain with 2% Alizarin Red S (pH 4.2) to detect calcium deposits. Stained mineralized nodules can be quantified by eluting the dye and measuring absorbance or by image analysis.

- Gene Expression Analysis (qRT-PCR): Isolate RNA at specific time points (e.g., days 7, 14, 21). Analyze the expression of osteogenic markers:

- Early: Runx2, ALP

- Mid/Late: Osterix (Sp7), Osteopontin (SPP1), Bone Sialoprotein (BSP)

- Late: Osteocalcin (OC)

- Protein Analysis (Western Blot/Immunofluorescence): Confirm the expression and localization of key proteins like Runx2, Osterix, and phosphorylated Smads (p-Smad1/5/8).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Osteogenesis Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Primary model system for in vitro osteogenesis. | Human Bone Marrow MSCs (hBM-MSCs), Adipose-derived MSCs (ADSCs), or cell lines like C3H10T1/2 or MC3T3-E1. |

| Osteogenic Induction Supplements | Core components to induce differentiation in basal medium. | Ascorbic Acid, β-Glycerophosphate, and Dexamethasone. Available as pre-mixed supplements from various suppliers. |

| Recombinant Growth Factors | To activate specific pro-osteogenic signaling pathways. | Recombinant Human BMP-2, Wnt3a, FGF-2, TGF-β1. Use at optimized concentrations to avoid off-target effects. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | To chemically perturb pathways and study their function. | CHIR99021 (Wnt activator), SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor), Dorsomorphin (BMP inhibitor). |

| Histological Stains | To detect and quantify terminal differentiation markers. | Alizarin Red S (mineralization), Oil Red O (lipid droplets, for adipogenesis control), Von Kossa (calcium phosphate). |

| Antibodies | For protein-level analysis of transcription factors and signaling molecules. | Anti-Runx2, Anti-Osterix, Anti-p-Smad1/5/8, Anti-β-catenin. Validate for application (WB, IF). |

Integrated Osteogenic Regulatory Network

The following diagram synthesizes the key regulators and their interactions described in this note into a cohesive osteogenic differentiation network.

Chondrogenic differentiation, the process by which progenitor cells differentiate into chondrocytes to form cartilage, is a critical pathway in skeletal development, adult homeostasis, and tissue regeneration. This process is tightly regulated by a complex interplay of transcription factors and extracellular cues from the cellular microenvironment, or niche. The transcription factor SRY-box transcription factor 9 (Sox9) is the undisputed master regulator of this pathway, essential for directing mesenchymal progenitor cells toward a chondrogenic fate. Its activity, in combination with other SOX proteins and in response to specific signaling pathways, orchestrates the expression of key cartilage-specific extracellular matrix (ECM) components. Beyond intracellular regulators, the cartilage niche—comprising the native cellular environment, structural components, and physicochemical signals—plays a decisive role in determining the ultimate phenotype and stability of the differentiated cartilage. This application note details the core mechanisms of Sox9 action and the influential role of the niche, providing structured data and validated protocols to support research and development in cartilage biology and regenerative medicine.

Key Players & Molecular Mechanisms

The Sox Trio and Transcriptional Regulation

The core transcriptional machinery driving chondrogenesis is the Sox Trio, consisting of Sox9, L-Sox5 (Sox5), and Sox6. These factors cooperate to activate the gene expression program essential for chondrocyte differentiation and cartilage matrix synthesis [19] [20].

- Sox9: Functions as the master transcription factor. It binds to the consensus DNA sequence (A/T)(A/T)CAA(A/T)G in the enhancer regions of its target genes. It is indispensable for the initiation of chondrogenesis and for the expression of key ECM genes like type II collagen (COL2A1) and aggrecan (ACAN) [19] [20]. Mutations in SOX9 cause campomelic dysplasia, a severe skeletal dysplasia syndrome, underscoring its non-redundant role [19].

- L-Sox5 and Sox6: These structurally related proteins lack a transactivation domain but potentiate the function of Sox9. They bind to adjacent DNA sites, facilitating the assembly of a more robust enhanceosome complex that dramatically boosts the transcription of cartilage-specific genes [20].

Sox9's activity is itself regulated by multiple mechanisms, including phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, interaction with co-activators like CREB-binding protein (CBP)/p300, and modulation by signaling pathways such as BMP/TGF-β via Smad proteins [19] [20].

Biphasic Expression and Novel Functions of Sox9

Recent research has revealed that Sox9 expression during chondrogenic differentiation is biphasic [19]. An immediate, transient early phase is followed by a later, sustained phase associated with active ECM synthesis. While the late phase is linked to canonical matrix production, the early phase is crucial for preparing the cell for the demanding differentiative process. A seminal study identified a novel essential function for Sox9 during this early phase: the regulation of translational capacity [19].

Early Sox9 knockdown was shown to:

- Severely inhibit chondrogenic differentiation weeks later.

- Downregulate the expression of ribosome biogenesis factors and ribosomal protein subunits.

- Decrease the cell's overall translational capacity, correlating with lower amounts of active mono- and polysomes.

- Alter the mode of translation initiation (cap- vs. IRES-mediated) [19].

This demonstrates that beyond its well-known transcriptional role, Sox9 primes the cellular machinery for the high levels of protein synthesis required for subsequent proliferation and massive ECM production.

The Deterministic Role of the Cartilage Niche

The local microenvironment, or niche, is a dominant factor in specifying the type of cartilage regenerated by stem cells. A systematic in vivo study demonstrated that the native cartilage niche overrides instructively biomimetic scaffolds and co-cultured chondrocytes to determine the final cartilage phenotype [21].

- Key Finding: When BMSCs were implanted into specific native cartilage niches (ear or articular), the type of cartilage regenerated was always consistent with the implantation site, regardless of the type of acellular cartilage sheet (ACS) scaffold or the source of co-cultured chondrocytes used [21].

- Niche-Specific Outcomes:

- The articular cartilage niche regulated BMSCs to regenerate hyaline-like cartilage.

- The ear cartilage niche regulated BMSCs to regenerate elastic cartilage, characterized by elastin expression [21].

This work provides compelling evidence that for clinical translation, strategies must not only focus on inducing chondrogenesis but also on recapitulating or harnessing niche-specific signals to achieve a functionally appropriate and stable cartilage type.

Summarized Quantitative Data

| Experimental Manipulation | Time of Analysis | Key Quantitative Findings & Impact on Chondrogenesis |

|---|---|---|

| Sox9 siRNA Knockdown (prior to differentiation) | 2 hours & 7 days | Severe inhibition of late differentiation (weeks later).↓ Expression of ribosome biogenesis factors and ribosomal proteins.↓ Total translational capacity (SuNSET assay).↓ Amount of active mono- and polysomes (polysome profiling).Altered cap- vs. IRES-mediated translation (bicistronic reporter). |

| Sox9 Overexpression (Lentiviral) | Various time points | Reciprocal effects to knockdown; enhanced chondrogenic capacity. |

| Implanted Construct | Native Niche for Implantation | Resulting Cartilage Type Regenerated by BMSCs |

|---|---|---|

| BMSC + Ear ACS (EACS) | Ear Cartilage | Elastic Cartilage |

| BMSC + Articular ACS (AACS) | Articular Cartilage | Hyaline-like Cartilage |

| BMSC + AACS | Ear Cartilage | Elastic Cartilage |

| BMSC + EACS | Articular Cartilage | Hyaline-like Cartilage |

| BMSC + AACS + Articular Chondrocytes | Ear Cartilage | Elastic Cartilage |

| BMSC + EACS + Ear Chondrocytes | Articular Cartilage | Hyaline-like Cartilage |

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol: Investigating the Early Role of Sox9 via Knockdown in ATDC5 Cells

This protocol is adapted from methods used to elucidate Sox9's novel role in regulating translational capacity [19].

Objective: To ablate early Sox9 expression and analyze its effects on the transcriptome, proteome, and translational machinery during chondrogenic differentiation.

Materials:

- Cell Line: ATDC5 murine progenitor cells.

- Culture Media: DMEM/F12 + 5% FBS + 1% Antibiotic/Antimycotic + 1% NEAA.

- Differentiation Supplements: 10 µg/mL insulin, 10 µg/mL transferrin, 30 nM sodium selenite.

- Sox9 siRNA: Duplex sequence: sense 5'-GACUCACAUCUCUCCUAAUTT-3', antisense 5'-AUUAGGAGAGAUGUGAGUCTT-3'.

- Control siRNA: Scrambled sequence.

- Transfection Reagent: HiPerFECT or equivalent.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Plate ATDC5 cells at a density of 20,000 cells/cm² in standard growth media.

- Transfection: 24 hours after seeding, transfert cells with 100 nM Sox9 siRNA or Control siRNA using the manufacturer's protocol for HiPerFECT.

- Induction of Differentiation: 24 hours post-transfection, initiate chondrogenic differentiation by replacing the media with culture media containing the differentiation supplements (insulin, transferrin, selenite).

- Harvesting: Harvest samples for analysis at critical time points (e.g., 2 hours for early transcriptomic changes, 7 days for proteomic and differentiation markers).

- RNA-seq: Isolate total RNA using TRIzol for transcriptome analysis.

- Label-free Proteomics: Prepare cell lysates for proteomic analysis.

- Functional Assays:

- SuNSET Assay: Incorporate puromycin to measure de novo protein synthesis.

- Polysome Profiling: Lyse cells and separate ribosomal fractions by sucrose density gradient centrifugation to assess ribosome activity.

- Bicistronic Reporter Assay: Transfect a reporter plasmid to determine the mode of translation initiation.

Protocol: Assessing Niche-Directed Chondrogenesis of BMSCs In Vivo

This protocol outlines the approach for demonstrating the deterministic role of the native cartilage niche [21].

Objective: To test whether a specific native cartilage microenvironment can direct BMSCs to regenerate a matching cartilage type, overriding other biomimetic cues.

Materials:

- Cells: GFP-labeled Bone Marrow Stromal Cells (BMSCs), ear chondrocytes (EACs), articular chondrocytes (ARCs).

- Scaffolds: Acellular Cartilage Sheets (ACS) from ear (EACS) and articular (AACS) cartilage.

- Animals: Immunocompetent large animal model (e.g., pig).

Procedure:

- Construct Preparation:

- Prepare two types of ACSs (EACS and AACS) via decellularization of tissue sheets.

- Seed GFP-BMSCs onto the ACSs alone, or in a "sandwich" model with corresponding chondrocytes (e.g., BMSCs + AACS + ARCs).

- Experimental Groups & Implantation:

- Niche-Matched: Implant BMSC-EACS into ear cartilage niche; BMSC-AACS into articular cartilage niche.

- ACS Niche-Mismatched: Implant BMSC-AACS into ear niche; BMSC-EACS into articular niche.

- Biomimetic Niche-Mismatched: Implant BMSC-AACS-ARC into ear niche; BMSC-EACS-EAC into articular niche.

- In Vivo Culture: Allow constructs to develop in vivo for an extended period (e.g., one year).

- Analysis:

- Cell Tracking: Identify the origin of regenerating cells via GFP fluorescence.

- Histology & Immunohistochemistry: Assess cartilage type using specific markers:

- Hyaline Cartilage: Type II Collagen (Col II), Proteoglycans (Safranin O staining).

- Elastic Cartilage: Elastin.

- Articular Surface Marker: PRG4 (Lubricin).

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Sox9 in Chondrogenic Differentiation

Experimental Workflow for Niche Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Chondrogenesis and Niche Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| ATDC5 Progenitor Cell Line | A well-established in vitro model for studying the stepwise process of chondrogenic differentiation. | Used to delineate the early vs. late roles of Sox9 [19]. |

| Sox9 siRNA & Lentiviral Overexpression Constructs | For precise loss-of-function (knockdown) and gain-of-function studies to interrogate Sox9's necessity and sufficiency. | Custom siRNA and pLVX-EIF1α-mSox9-IRES-puro lentivirus used in [19]. |

| Chondrogenic Differentiation Media Supplements | Defined components (Insulin, Transferrin, Selenium - ITS) to induce and maintain chondrogenic differentiation in progenitor cells. | 10 µg/ml insulin, 10 µg/ml transferrin, 30 nM sodium selenite used for ATDC5 differentiation [19]. |

| Acellular Cartilage Sheets (ACS) | Scaffolds derived from native cartilage that retain tissue-specific structure and components, providing a biomimetic environment for seeded cells. | Ear (EACS) and Articular (AACS) sheets used to test niche-mimetic properties [21]. |

| Bone Marrow Stromal Cells (BMSCs) | A primary multipotent mesenchymal cell source with high clinical relevance for cartilage regeneration studies. | GFP-labeled porcine BMSCs used for in vivo fate tracking [21]. |

| Assays for Translational Capacity | Functional assays to measure global protein synthesis and ribosome activity, beyond transcriptomics. | SuNSET assay and Polysome profiling [19]. |

Within the broader context of stem cell differentiation research, understanding the specific molecular pathways governing adipogenic lineage commitment is fundamental for advancing regenerative medicine and metabolic disease therapeutics. The process of adipogenesis, through which multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) differentiate into mature adipocytes, is primarily orchestrated by a core transcriptional cascade. This cascade is dominated by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) and the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) family of transcription factors. These factors do not operate in isolation; they engage in a robust cross-regulatory network that amplifies and stabilizes the differentiation program. Furthermore, this transcriptional core is increasingly understood to be under precise epigenetic control, adding another layer of regulatory complexity. This application note details the molecular mechanisms of this transcriptional control and provides standardized protocols for investigating adipogenic differentiation in vitro, providing researchers with the tools to explore fat cell development in health and disease.

Core Transcriptional Mechanisms

The Master Regulatory Loop: PPAR-γ and C/EBPα

The feed-forward loop between PPAR-γ and C/EBPα is a critical circuit for lineage commitment during adipocytic differentiation. This reciprocal relationship ensures the initiation and maintenance of the adipogenic gene expression program.

- Positive Cross-Regulation: PPAR-γ and C/EBPα positively regulate each other's expression. This mutual reinforcement locks the cell into the adipogenic pathway and maintains the differentiated state [22] [23].

- PPAR-γ as the Proximal Effector: While both factors are essential, PPAR-γ is the indispensable, non-redundant master regulator. Critical loss-of-function experiments demonstrate that C/EBPα has no ability to promote adipogenesis in PPAR-γ-deficient fibroblasts. In contrast, PPAR-γ can induce adipogenesis in C/EBPα-deficient cells, establishing a hierarchical relationship where C/EBPα functions largely through its ability to induce and maintain PPAR-γ expression [24] [25].

- Genome-Wide Cooperativity: On a genomic scale, PPAR-γ and C/EBP factors cooperate extensively. Chromatin immunoprecipitation studies have revealed that in adipocytes, PPAR-γ binds to thousands of genomic sites, and the vast majority of these locations also contain binding motifs for C/EBP factors. Physical colocalization of C/EBPα is observed at a majority of these PPAR-γ-binding regions, and most adipocyte-specific genes are coregulated by both factors, indicating a cooperative orchestration of the adipocyte transcriptome [23].

The following diagram illustrates the core transcriptional network and its regulatory interactions.

Figure 1: The Core Transcriptional Network and its Epigenetic Regulation in Adipogenesis. Early factors C/EBPβ/δ initiate PPAR-γ and C/EBPα expression, which then engage in a positive feed-forward loop to drive the adipogenic program. The methyltransferase PRMT6 represses this loop in precursors via H3R2me2a.

Epigenetic Control of the Transcriptional Circuit

The PPAR-γ–C/EBPα feed-forward loop is repressed in progenitor cells by epigenetic mechanisms, ensuring differentiation only proceeds upon appropriate stimulation.

- PRMT6 as a Key Corepressor: Protein arginine methyltransferase 6 (PRMT6) associates with PPAR-γ on the promoters of both Ppar-γ and C/ebpα in pre-adipocytes, contributing to the repression of their expression. This repressive function is mediated, in part, through PRMT6's ability to deposit the repressive histone mark H3R2me2a, which counteracts activating epigenetic modifications [26].

- Release from Repression upon Differentiation: During the induction of adipocyte differentiation, Prmt6 expression is reduced, and the methyltransferase dissociates from the target promoters. This release of repression allows for the upregulation of PPAR-γ and C/EBPα, thereby establishing the adipocytic gene expression program. Pharmacological inhibition of PRMT6 enhances adipogenesis, highlighting its role as a molecular brake on differentiation [26].

Experimental Protocols for Adipogenic Differentiation

This section provides a detailed methodology for inducing and analyzing adipogenic differentiation in vitro using mesenchymal stromal cells.

Standard Adipogenic Differentiation Protocol

The following protocol is adapted from established methods for inducing adipogenesis in MSC cultures like ST2 or 3T3-L1 cell lines [26].

Materials:

- Cells: Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (e.g., ST2 cells, 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes, or primary MSCs).

- Basal Medium: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) GlutaMAX, supplemented with 10% Fetal Calf Serum (FCS) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin.

- Adipogenic Induction Cocktail:

- 250 nM Dexamethasone

- 450 µM IBMX (3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine)

- 1 µM Rosiglitazone (a PPAR-γ agonist)

- 5 µg/ml Insulin

- Maintenance Medium: DMEM with 10% FCS and 5 µg/ml Insulin.

- Reagents for Analysis: Oil-Red-O working solution, 4% Formaldehyde, RNA extraction kit, antibodies for immunoblotting.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells at a density of 15,000 cells per cm² in standard growth medium and allow them to reach 100% confluency.

- Induction Phase: Replace the growth medium with Adipogenic Induction Medium (basal medium supplemented with the induction cocktail).

- Differentiation Schedule: Culture the cells in induction medium for 3-4 days. This period initiates the transcriptional cascade.

- Maintenance Phase: After the induction phase, switch the culture to Adipogenic Maintenance Medium. Refresh the maintenance medium every 2-3 days.

- Maturation: Continue the culture for a total of 14-21 days to allow for full maturation, including significant lipid accumulation.

Key Considerations:

- The protocol can be adapted for Wharton's Jelly MSCs (WJ-MSCs), though their intrinsic adipogenic potential is lower than that of adipose tissue-derived MSCs (AT-MSCs) [27].

- Optimization may be required for different cell types. For WJ-MSCs, supplementation with 100 µM oleic acid during induction can significantly enhance lipid droplet formation and bring their adipogenic capacity closer to that of AT-MSCs [27].

Protocol for Genetic and Pharmacological Manipulation

To probe the specific roles of transcriptional regulators, genetic and pharmacological tools can be integrated into the differentiation protocol.

- PRMT6 Inhibition: To assess the effect of releasing epigenetic repression, add the selective PRMT6 inhibitor SGC6870 (e.g., at 5 µM concentration) to the induction and/or maintenance medium. A control compound (SGC6870N) should be used in parallel [26].

- Ectopic Gene Expression: To test the sufficiency of a transcription factor, cells can be transduced with retroviruses or lentiviruses expressing the gene of interest (e.g., PPAR-γ or C/EBPα) prior to the induction of differentiation. For example, ectopic expression of PPAR-γ can rescue adipogenesis in PPAR-γ-deficient cells [24] [25].

- Gene Knockdown/Knockout: To test necessity, cells can be transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing specific gRNAs (e.g., in a lentiCRISPRv2 backbone) to knock out genes of interest, followed by selection and differentiation [26].

Analysis of Differentiation Efficiency

Rigorous assessment of adipogenic differentiation is crucial. The table below summarizes the key methods and their applications.

Table 1: Standard Methods for Assessing Adipogenic Differentiation

| Method | Target / Principle | Procedure Summary | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oil-Red-O Staining | Staining of neutral lipid droplets in fixed cells. | Fix cells (4% formaldehyde), stain with Oil-Red-O solution, wash, and image. For quantification, elute dye with isopropanol and measure absorbance at 500 nm [26]. | Qualitative visualization and quantitative measurement of lipid accumulation. |

| Triglyceride (TG) Content Assay | Quantitative measurement of intracellular TG. | Use commercial kits based on enzymatic reactions to solubilize and measure TG content, normalized to total cellular protein [27]. | Quantitative, normalized data on lipid storage. |

| Gene Expression Analysis (RT-qPCR) | mRNA levels of adipogenic markers. | Extract RNA, synthesize cDNA, perform qPCR with gene-specific primers. Normalize to housekeeping genes (e.g., TBP) and analyze via ΔΔCT method [26]. | Expression dynamics of key transcriptional regulators and adipocyte genes. |

| Protein Analysis (Immunoblotting) | Protein levels of key transcription factors. | Prepare whole-cell extracts, separate proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to membrane, and probe with specific antibodies (e.g., for PPAR-γ, C/EBPα) [26] [24]. | Confirmation of protein expression and post-translational modifications. |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) | Transcription factor binding and histone modifications at genomic loci. | Cross-link proteins to DNA, shear chromatin, immunoprecipitate with specific antibody (e.g., anti-PPAR-γ, anti-H3R2me2a), reverse cross-links, and purify DNA for qPCR or sequencing [26] [23]. | Direct evidence of in vivo transcription factor occupancy and epigenetic states. |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Adipogenesis Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Adipogenesis Research | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PPAR-γ Agonists | Potent chemical inducers of differentiation; activate the master regulator. | Rosiglitazone and Troglitazone are commonly used. Rosiglitazone is included in standard induction cocktails [26] [24]. |

| Small Molecule Inducers | Activate early signaling pathways that initiate the transcriptional cascade. | Dexamethasone (glucocorticoid receptor agonist), IBMX (phosphodiesterase inhibitor that elevates cAMP) [26] [27]. |

| Key Antibodies | Detection of proteins via immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, or ChIP. | Anti-PPAR-γ, Anti-C/EBPα, Anti-FABP4/aP2 (mature adipocyte marker), Anti-PRMT6, Anti-H3R2me2a [26] [23]. |

| Genetic Tools | For gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies. | Lentiviral/Retroviral Vectors for overexpression (e.g., of PPAR-γ) [24] [25] or CRISPR-Cas9 systems for gene knockout (e.g., using lentiCRISPRv2) [26]. |

| Epigenetic Inhibitors | To probe the role of specific epigenetic modifiers. | SGC6870: A selective, small-molecule inhibitor of PRMT6 [26]. |

Advanced Applications and Protocol Optimization

Understanding the core pathway enables researchers to optimize protocols for specific applications and cell types.

- Optimizing WJ-MSC Differentiation: The intrinsic lipid profile of MSCs can influence their differentiation potential. Lipidomic analysis reveals that WJ-MSCs have a different triglyceride profile compared to AT-MSCs. Supplementing the standard adipogenic induction medium with 100 µM oleic acid (OA), a mono-unsaturated fatty acid, significantly enhances lipid droplet formation and upregulates adipogenic markers in WJ-MSCs, making their differentiation efficiency more comparable to AT-MSCs [27].

- Transcriptome Analysis: For a systems-level understanding, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) can be employed to analyze the global gene expression profile during differentiation. This approach has been instrumental in identifying key molecules, signaling pathways, and biological processes at different time points of adipogenesis [28].

- Lineage Commitment Studies: The commitment of MSCs to adipogenic or osteogenic lineages is a tightly balanced process. Inhibition of the ERK signaling pathway, for instance, can block osteogenic differentiation and simultaneously promote adipogenic differentiation, indicating that molecular switches can redirect cell fate [29].

The following workflow diagram integrates both standard and advanced approaches to studying adipogenesis.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Adipogenesis Research. The core differentiation protocol can be complemented with genetic, epigenetic, and media optimization strategies to address specific research questions.

The transcriptional control of adipogenesis via PPAR-γ and C/EBPs represents a paradigm of cell lineage specification. The precise interplay between these transcription factors, fine-tuned by epigenetic regulators like PRMT6, ensures proper fat cell development. The protocols and tools detailed in this application note provide a robust foundation for researchers to investigate this process, from foundational mechanistic studies to the development of novel therapeutic strategies for metabolic disease and the advancement of soft tissue engineering in regenerative medicine.

The lineage commitment of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to either osteogenic or adipogenic fates represents a critically balanced process in skeletal homeostasis and whole-body metabolism [30]. As common progenitor cells, MSCs undergo delicately regulated differentiation programs where activation of one lineage often occurs at the expense of the other [31] [30]. This reciprocal relationship is maintained through an intricate network of transcription factors, signaling pathways, and epigenetic modifications that collectively determine cellular fate decisions.

Understanding this balance has significant pathophysiological implications. Aging, obesity, and osteoporosis are frequently characterized by a shift in this equilibrium, with increased bone marrow adiposity coinciding with decreased bone formation [30] [32]. The molecular machinery governing this switch involves core transcription factors including PPARγ2 for adipogenesis and Runx2 for osteogenesis, which often exhibit mutually antagonistic relationships [31]. Additionally, key signaling pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin, BMP, and TGF-β play pivotal roles in directing MSC fate commitment [33] [34].

This application note provides a comprehensive overview of the molecular regulation of osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation, detailed experimental protocols for studying these processes, and key methodological considerations for researchers investigating MSC lineage specification.

Molecular Mechanisms Governing Lineage Specification

Core Transcription Factors and Their Cross-Regulation

The differentiation of MSCs into osteoblasts and adipocytes is governed by two master transcription factors that demonstrate a mutually antagonistic relationship.

Table 1: Core Transcription Factors in Osteogenesis and Adipogenesis

| Transcription Factor | Primary Lineage | Key Target Genes | Antagonistic Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Runx2 | Osteogenesis | Osteocalcin (OC), Bone Sialoprotein (BSP), Alkaline Phosphatase (APL) | Suppresses PPARγ2 transactivation; induces osteogenic genes |

| PPARγ2 | Adipogenesis | Fatty Acid-Binding Protein 4 (FABP4), Lipoprotein Lipase (LPL) | Inhibits Runx2-mediated transcription of osteocalcin |

| sLZIP | Regulatory | HDAC3, PPARγ2 complex | Interacts with PPARγ2 and HDAC3 to suppress PPARγ2 activity while enhancing Runx2 |

The PPARγ2-Runx2 axis forms the core regulatory circuit governing the adipogenesis-osteogenesis balance [31]. PPARγ2 activation not only promotes adipogenic differentiation but also directly inhibits osteoblast differentiation by suppressing Runx2 transcriptional activity [31]. Conversely, Runx2 expression inhibits adipogenesis by interfering with PPARγ2 function. This reciprocal inhibition ensures that MSCs commit predominantly to one lineage.

Recent research has identified regulatory proteins that modulate this core circuit. The small leucine zipper protein (sLZIP) acts as a novel PPARγ2 modulator by interacting with PPARγ2 and recruiting histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) to form a corepressor complex [31]. This complex suppresses PPARγ2 transcriptional activity, thereby inhibiting adipogenesis while simultaneously promoting osteogenesis through enhanced Runx2 activity [31]. Transgenic mice overexpressing sLZIP demonstrate enhanced bone mass and density, confirming its role in directing MSC fate toward osteogenesis.

Signaling Pathways in Lineage Determination

Multiple evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways interact to fine-tune the balance between osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation.

Table 2: Signaling Pathways in MSC Lineage Specification

| Signaling Pathway | Effect on Osteogenesis | Effect on Adipogenesis | Key Molecular Mediators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt/β-catenin | Promotes | Inhibits | LRP5/6, β-catenin, GSK3β, TAZ |

| TGF-β/BMP | Context-dependent promotion | Context-dependent inhibition | Smads, MAPK, Runx2, PPARγ |

| Hedgehog | Promotes | Inhibits | Gli proteins, Smo, Ptch |

| Notch | Complex (inhibitory or promotional) | Inhibits | Hes, Hey, PPARγ |

Wnt/β-catenin Signaling

The canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway serves as a potent promoter of osteogenesis while simultaneously inhibiting adipogenesis [30]. Wnt ligands binding to Frizzled receptors and LRP5/6 co-receptors stabilize β-catenin, which translocates to the nucleus and activates osteogenic target genes including Runx2 [34]. Additionally, Wnt signaling activates the transcriptional coactivator TAZ, which enhances Runx2-dependent gene transcription while suppressing PPARγ-mediated adipogenic differentiation [30]. Recent research has identified Mapk7 as a novel activator of Wnt signaling, which enhances osteogenesis and suppresses adipogenesis by phosphorylating Lrp6 at Ser1490, thereby stabilizing β-catenin [32].

TGF-β/BMP Signaling

The TGF-β/BMP pathway exhibits complex, context-dependent effects on MSC differentiation [33]. BMP2 demonstrates concentration-dependent effects: at low doses (50 ng/mL) it can promote adipogenesis, while at higher doses (500 ng/mL) it strongly promotes osteogenic differentiation [30] [33]. TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 generally inhibit adipogenic differentiation while promoting chondrogenesis [33]. The adipogenesis inhibition occurs primarily through Smad3, which associates with C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ to suppress PPARγ expression [33].

Figure 1: Molecular regulation of the adipogenesis-osteogenesis balance. Key transcription factors PPARγ and Runx2 demonstrate mutual inhibition, while signaling pathways exert directional control on lineage commitment.

Epigenetic Regulation and Omics Characteristics

Epigenetic modifications play a pivotal role in mediating heritable changes in gene expression without altering the DNA sequence during MSC differentiation [35]. Advances in omics technologies have enhanced our understanding of ADSC molecular profiles through transcriptomic, proteomic, and lipidomic analyses [35].

Transcriptomic studies using single-cell RNA sequencing have revealed considerable heterogeneity within ADSC populations [35]. Distinct subpopulations exhibit different lineage commitment capabilities, with one subcluster expressing high levels of adipogenic markers (Pparg, Cd36) representing committed preadipocytes, while another fraction characterized by Cd142 and Abcg1 expression negatively regulates adipogenesis through paracrine mechanisms [35].

Proteomic analyses have identified distinct protein expression patterns between ADSCs and BMSCs. ADSCs exhibit proteins associated with biological oxidation, nucleobase biosynthesis, and vitamin metabolism, suggesting higher basal metabolic activity, while BMSCs show elevated expression of proteins involved in extracellular matrix organization and cell-matrix interactions [35].

Lipidomics studies have revealed that ADSCs possess a distinctive and more diverse phospholipid profile compared to other cell types, with specific species such as phosphatidylglycerol (PG) 40:7 and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) O-36:3 detected exclusively in ADSCs [35]. Sphingomyelins (SMs) are also predominantly present in ADSCs, suggesting potential roles for phospholipids and sphingolipids in regulating ADSC biology [35].

Experimental Models and Methodological Approaches

In Vitro Differentiation Protocols

Standardized protocols for inducing and assessing osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation are essential for studying MSC fate decisions.

Osteogenic Differentiation Protocol

Materials:

- C3H10T1/2 MSC line or primary MSCs

- Osteogenic Induction Medium (OIM): DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μM ascorbate-2-phosphate, and 100 nM dexamethasone

- 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for fixation

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) staining solution

- Alizarin Red S (ARS) staining solution (2%, pH 4.2)

Procedure:

- Seed MSCs at a density of 10,000 cells/cm² in growth medium and culture until 80% confluent.

- Replace growth medium with Osteogenic Induction Medium (OIM).

- Change the induction medium every 3-4 days for up to 21 days.

- For alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining, after 7 days of induction, rinse cells with PBS, fix with 4% PFA for 10 minutes, and incubate with ALP staining solution until desired color development [32].

- For mineralization assessment (Alizarin Red S staining), after 21 days of induction, fix cells with 4% PFA for 15 minutes, then stain with 2% ARS solution (pH 4.2) for 20 minutes [32].

- For quantitative analysis, dissolve calcium nodules in DMSO and measure absorbance at 405 nm [32].

Adipogenic Differentiation Protocol

Materials:

- C3H10T1/2 MSC line or primary MSCs

- Adipogenic Induction Medium (AIM): DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), 1 μM dexamethasone, 10 μM insulin, and 200 μM indomethacin

- Oil Red O (ORO) staining solution (0.5% in isopropanol)

- 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for fixation

Procedure:

- Seed MSCs at a density of 20,000 cells/cm² in growth medium until 100% confluent.

- Maintain at confluence for 2-3 days (post-confluence stage).

- Replace growth medium with Adipogenic Induction Medium (AIM).

- After 3-5 days of induction, change to adipogenic maintenance medium (DMEM with 10% FBS and 10 μM insulin) for 2-3 days.

- Repeat induction/maintenance cycles 2-3 times over 10-14 days.

- For lipid droplet visualization, fix cells with 4% PFA for 15 minutes and stain with filtered Oil Red O working solution for 30-60 minutes [36].

- For quantitative analysis, extract stained lipid droplets with 100% isopropanol and measure absorbance at 510 nm [32].

Modulation of Signaling Pathways

Experimental manipulation of key signaling pathways allows researchers to direct MSC fate decisions.

Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation:

- Add 10 nM CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor) to differentiation medium [32]

- Co-culture with L Wnt-3A cells using trans-well systems [32]

- Use recombinant Wnt3a protein (50-100 ng/mL)

TGF-β/BMP pathway modulation:

- For osteogenesis: BMP2 at 500 ng/mL [33]

- For adipogenesis: BMP2 at 50 ng/mL with PPARγ activator [33]

- TGF-β1 at 10 ng/mL for chondrogenesis or adipogenesis inhibition [33]

Mapk7 manipulation:

- Knockout models: Prx1-Cre; Mapk7flox/flox mice [32]

- Overexpression studies using viral vectors

Analysis Methods for Differentiation Assessment

Table 3: Analytical Methods for Assessing MSC Differentiation

| Analysis Type | Method | Key Markers/Targets | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression | RT-qPCR | Osteogenesis: Runx2, ALP, OCN, Osterix Adipogenesis: PPARγ, C/EBPα, FABP4, adiponectin | Quantitative assessment of lineage-specific gene expression |

| Protein Analysis | Western Blot, Immunofluorescence | Osteogenesis: Runx2, Osterix, Osteocalcin Adipogenesis: PPARγ, FABP4, ACC | Protein level confirmation of differentiation |

| Histochemical Staining | ALP, ARS, ORO | ALP activity (early osteogenesis), Calcium deposition (late osteogenesis), Lipid accumulation (adipogenesis) | Qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of differentiation extent |

| Flow Cytometry | Surface marker analysis | CD73, CD90, CD105 (positive); CD34, CD45 (negative) | MSC phenotype verification before differentiation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Adipogenesis and Osteogenesis Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | C3H10T1/2, 3T3-L1, Primary MSCs | In vitro differentiation models | Primary MSCs require phenotype verification via flow cytometry |

| Induction Cocktails | Dexamethasone, IBMX, Insulin, Indomethacin, β-glycerophosphate, Ascorbate-2-phosphate | Direct lineage-specific differentiation | Cyclic induction recommended for adipogenesis (3-5 day cycles) |

| Signaling Modulators | CHIR99021 (Wnt activator), Recombinant BMP2/TGF-β, SOST antibodies | Pathway-specific manipulation | Concentration-dependent effects observed with BMP2 |

| Staining Reagents | Alizarin Red S, Oil Red O, Alkaline Phosphatase staining kits | Differentiation endpoint assessment | Quantitative extraction protocols available for mineralization and lipid content |

| Antibodies | Anti-Runx2, Anti-PPARγ, Anti-Osteocalcin, Anti-FABP4 | Protein-level confirmation of differentiation | Essential for Western blot and immunofluorescence validation |

Applications and Research Implications

Disease Modeling and Pathophysiological Insights

The inverse relationship between osteogenesis and adipogenesis has significant implications for understanding and treating metabolic bone diseases. In osteoporosis, increased bone marrow adiposity coincides with decreased bone formation, representing a shift in MSC lineage commitment [30] [32]. Similarly, in obesity and type 2 diabetes, dysfunction in ADSC differentiation potential contributes to impaired adipose tissue plasticity and metabolic complications [37].

Notably, the unique regenerative capacity of Acomys cahirinus (spiny mice) provides intriguing insights into MSC biology. ADSCs from Acomys cahirinus exhibit enhanced osteogenesis and suppressed adipogenesis compared to Mus musculus, which is linked to their exceptional tissue regeneration capabilities but potentially limits their adipose tissue self-renewal [37]. This model system offers opportunities to identify novel regulatory mechanisms that could be therapeutically targeted.

Therapeutic Targeting and Tissue Engineering

Understanding the molecular basis of the adipogenesis-osteogenesis balance enables development of targeted therapeutic strategies. Several approaches show promise:

Wnt pathway modulation:

- Anti-SOST antibodies (Romosozumab, Blosozumab) to enhance bone formation [34]

- Small molecule GSK3β inhibitors to stabilize β-catenin [32]

Transcription factor modulation:

- PPARγ partial agonists to minimize adverse effects on bone [31]

- sLZIP-based approaches to simultaneously inhibit adipogenesis and promote osteogenesis [31]

Biomaterial applications:

- Surface topography engineering with specific ridge patterns (2 μm ridges enhance osteogenesis, 15 μm ridges increase adipogenesis) [38]

- Nanostructured substrates (650 nm periodicity) that enhance both osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation when combined with induction media [38]

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for studying adipogenesis-osteogenesis balance. A comprehensive approach combining differentiation assays with pathway modulation and multi-modal analysis enables mechanistic insights.

Concluding Remarks

The reciprocal relationship between osteogenesis and adipogenesis represents a fundamental aspect of MSC biology with far-reaching implications for regenerative medicine, metabolic disease treatment, and tissue engineering. The core regulatory circuit centered on PPARγ2 and Runx2 antagonism, modulated by various signaling pathways and epigenetic mechanisms, provides a sophisticated control system for MSC fate decisions.

Methodologically, robust protocols for inducing and assessing differentiation, combined with targeted pathway modulation approaches, enable detailed investigation of this balance. The continued development of specific reagents and advanced biomaterials that can direct MSC lineage commitment holds promise for novel therapeutic strategies for conditions characterized by disruption of the adipogenesis-osteogenesis equilibrium, such as osteoporosis, obesity, and diabetes.

Future research directions should focus on understanding the temporal dynamics of lineage commitment decisions, the role of epigenetic memory in MSC differentiation, and the development of spatiotemporal control systems for precise regulation of MSC fate in therapeutic contexts.

Application Notes

Stem cell differentiation into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages is a tightly regulated process guided by dynamic changes in the transcriptome. The emergence of high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technologies, particularly single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq), has revolutionized our ability to decode these complex molecular events. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), once considered "genomic junk," are now recognized as vital regulators of gene expression during cell fate determination. This article explores how transcriptomic insights, especially those concerning non-coding RNAs, are shaping our understanding of lineage commitment in stem cell biology, with significant implications for regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

The Transcriptomic Landscape of Stem Cell Differentiation

Transcriptome analysis during stem cell differentiation reveals precisely timed molecular programs that guide lineage specification. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) possess the capacity to differentiate into adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic lineages when stimulated under appropriate conditions, making them a primary model for studying lineage commitment [28]. The transcriptome of a stem cell represents the complete set of RNA molecules that dictate its functional state, with lineage commitment directed by specific gene expression profiles and their complex interactions [28].

Single-cell transcriptomic analyses have been particularly transformative, revealing that exit from pluripotency marks the start of a lineage transition accompanied by a transient phase of increased susceptibility to lineage-specifying signals [39]. During retinoic acid-driven differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs), researchers observed a sharp increase in gene expression variability between 24-48 hours of exposure, coinciding with the exit from pluripotency and the beginning of lineage commitment [39]. This period of increased transcriptional heterogeneity may represent a critical window where cell fate decisions are most malleable to external cues.

Non-Coding RNAs as Master Regulators of Cell Fate

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), defined as RNA transcripts exceeding 200 nucleotides without protein-coding capacity, have emerged as crucial regulators of stem cell pluripotency and differentiation [40] [41]. These molecules exert their regulatory effects through diverse mechanisms depending on their subcellular localization and interacting partners.

In the cytoplasm, lncRNAs typically regulate mRNA stability, mediate translation, and function as competing endogenous RNAs. In contrast, nuclear lncRNAs more commonly influence chromatin architecture and transcriptional activity through interactions with DNA, RNA, and proteins [40]. For example, XIST lncRNA recruits polycomb repressive complexes to trigger histone modifications that silence gene transcription, while MALAT1 functions as a scaffold molecule in nuclear speckles to regulate splicing [40].

During embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte differentiation, lncRNAs demonstrate highly dynamic expression patterns, with the largest group enriched specifically in ESCs [40]. Systematic analysis of lncRNA expression across four critical developmental stages revealed that differentially expressed lncRNAs group into six distinct clusters, suggesting specialized functions at different differentiation timepoints [40].

Epitranscriptomic Modifications Fine-Tune LncRNA Function

The regulatory capacity of lncRNAs is further refined by post-transcriptional modifications, particularly N6-methyladenosine (m6A) - the most abundant RNA modification identified in mRNA [40]. This modification can significantly influence lncRNA functionality by recruiting specific "reader" proteins.

Research has demonstrated that m6A residues on lncRNAs recruit nuclear reader proteins like YTH domain containing 1 (YTHDC1), which is required for XIST-mediated transcriptional silencing [40]. During ESC differentiation, a subset of lncRNAs shows significant m6A modification and direct interaction with YTHDC1 [40]. Notably, the ESC-specific lncRNA Gm2379 is dramatically upregulated in response to m6A or Ythdc1 depletion, and its own depletion dysregulates pluripotency genes and those required for germ layer formation [40]. This epitranscriptomic regulation represents an additional layer of control in stem cell fate decisions.

Signaling Pathways in Lineage Commitment

The integration of external and internal signals guides fate commitment in differentiating pluripotent cells [39]. The MAPK signaling pathway, particularly ERK activation, plays a pivotal role in determining whether human MSCs commit to osteogenic or adipogenic lineages [29].

During osteogenic differentiation, treatment with osteogenic supplements induces a sustained phase of ERK activation from day 7 to day 11 that coincides with differentiation, before decreasing to basal levels [29]. JNK activation occurs later (day 13-17) and associates with extracellular matrix synthesis and calcium deposition - hallmark processes of bone formation [29]. Significantly, inhibition of ERK activation blocks osteogenic differentiation in a dose-dependent manner and redirects fate toward adipogenic differentiation [29]. This demonstrates how the same signaling pathway can act as a molecular switch between alternative lineage commitments.

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Mesenchymal Stem Cell Lineage Commitment

| Pathway | Role in Osteogenesis | Role in Adipogenesis | Key Regulators |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAPK/ERK | Sustained activation promotes differentiation [29] | Inhibition redirects from osteogenesis [29] | ERK, JNK, p38 |

| Retinoic Acid | Induces neuroectodermal and XEN lineages [39] | Suppresses mesodermal genes [39] | RA receptors |

| m6A Modification | Regulates lncRNAs guiding lineage commitment [40] | Potential role through lncRNA regulation [40] | METTL3, YTHDC1 |

Technological Advances in Transcriptome Analysis

The evolution from hybridization-based microarrays to next-generation RNA sequencing has dramatically enhanced our ability to study stem cell differentiation [28]. RNA-seq provides precise measurements of transcript abundance with single-base resolution, can distinguish splicing isoforms, and does not require prior knowledge of genes present in the analyzed genome [28]. This technological advancement has been particularly valuable for identifying novel non-coding RNA species, including various classes of regulatory lncRNAs [28].

Single-cell RNA sequencing has further revolutionized the field by enabling researchers to characterize heterogeneity within stem cell populations and trace transcriptional dynamics during lineage commitment [39] [42]. This approach has revealed that cells in the neural stem cell lineage exist on a continuum through activation and differentiation processes, with rare intermediate states possessing distinct molecular profiles [42]. Pseudotemporal ordering of scRNA-seq data can reconstruct developmental trajectories and identify putative regulators of cell fate decisions [42].

More recently, high-resolution spatial transcriptomics has enabled molecular identification of cell types based on spatially resolved gene expression profiles in developing tissues [43]. Integrating scRNA-seq with spatial transcriptomics during craniofacial development has revealed that mesenchymal lineage establishment occurs prior to anatomical structure formation, with heterogeneous progenitor populations already activating early lineage-specific markers at the onset of development [43].

Table 2: Transcriptomic Technologies for Studying Lineage Commitment

| Technology | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk RNA-seq | Population-level expression profiling [28] | Detects overall expression patterns; cost-effective [28] | Masks cellular heterogeneity [39] |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | Resolving cellular heterogeneity; trajectory inference [39] [42] | Reveals rare cell states; reconstructs differentiation paths [42] | Higher cost; technical noise [39] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Mapping gene expression to tissue location [43] | Preserves spatial context; links location to fate [43] | Lower resolution than scRNA-seq [43] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Differentiation of Human MSCs into Osteogenic, Chondrogenic, and Adipogenic Lineages

This protocol describes standard methods for differentiating bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) into three key mesodermal lineages, based on established characterization criteria that include plastic-adherence capacity, defined epitope profile, and multipotent differentiation capability [44].

Materials

- Human BM-MSCs: Isolated from bone marrow aspirates

- Basal medium: α-MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin

- Osteogenic supplements: 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μM ascorbic acid, and 100 nM dexamethasone

- Adipogenic supplements: 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), 1 μM dexamethasone, 10 μM insulin, and 200 μM indomethacin

- Chondrogenic supplements: 10 ng/mL TGF-β3, 100 nM dexamethasone, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, 40 μg/mL proline, and 1% ITS+ premix

Osteogenic Differentiation Procedure