Overcoming Immune Rejection in Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation: From Genetic Engineering to Clinical Applications

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation holds transformative potential for treating hematologic cancers and genetic disorders, but immune rejection remains a significant barrier to its broad application.

Overcoming Immune Rejection in Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation: From Genetic Engineering to Clinical Applications

Abstract

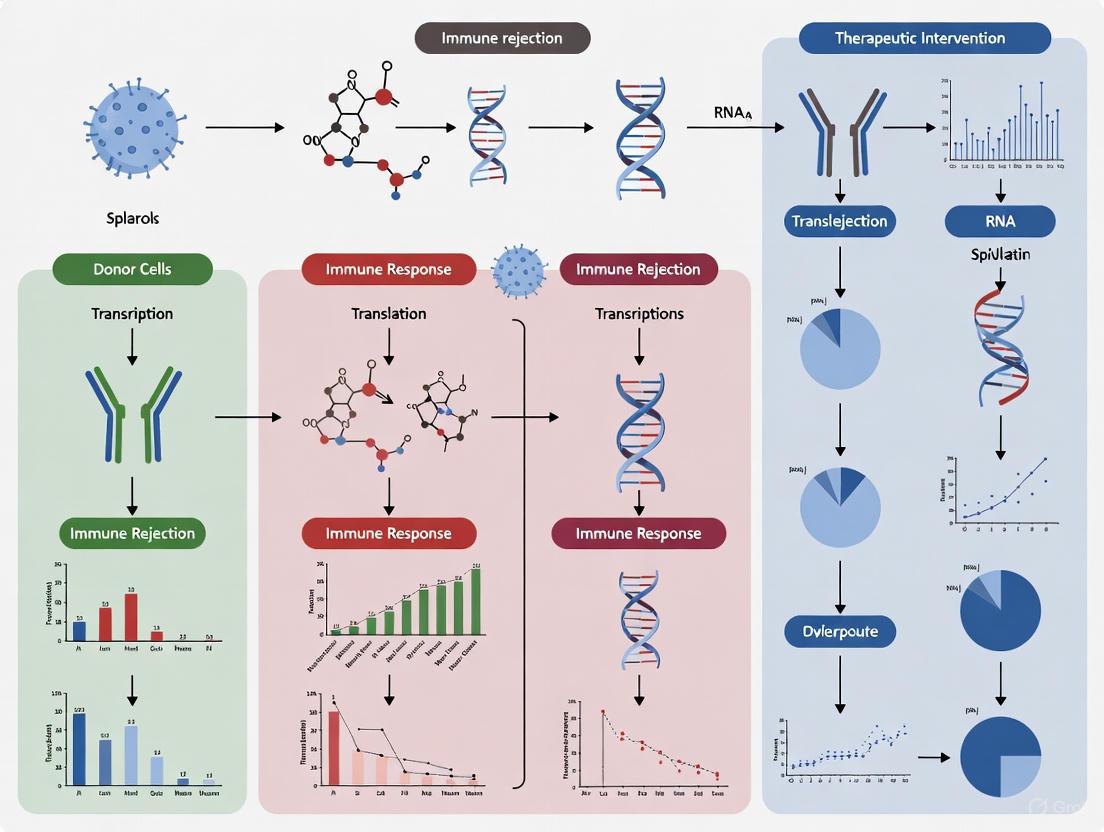

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation holds transformative potential for treating hematologic cancers and genetic disorders, but immune rejection remains a significant barrier to its broad application. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational immunology of graft rejection, innovative methodological advances in genetic engineering and conditioning regimens, strategies for troubleshooting innate immunity and optimizing persistence, and a comparative validation of emerging clinical data. By synthesizing the latest preclinical and clinical evidence, this review outlines a path toward universally applicable, off-the-shelf cellular therapies that do not require lifelong immunosuppression.

Decoding the Immune Barriers: Mechanisms of Allograft Rejection

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the primary immunological pathways responsible for allograft rejection? Allograft rejection is primarily driven by three pathways of allorecognition [1]:

- Direct Pathway: Donor Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs) migrate to recipient lymphoid organs and present donor-derived peptide-MHC complexes directly to recipient T cells. This is a dominant pathway in early acute rejection.

- Indirect Pathway: Recipient APCs process and present donor-derived peptides on self-MHC molecules to recipient T cells. This pathway is particularly important for chronic rejection and humoral responses.

- Semi-direct Pathway: Recipient APCs acquire intact donor peptide-MHC complexes from donor cells via extracellular vesicles (e.g., exosomes), allowing a single APC to activate both direct and indirect pathway T cells.

FAQ 2: Why are strategies that induce tolerance in rodent models often ineffective in humans? A key reason is the difference in T-cell memory compartments [2]. Laboratory rodents are typically specific pathogen-free (SPF) and have a T-cell profile similar to human neonates, with a high naïve-to-memory T cell ratio. In contrast, adult humans have a large pool of memory T cells generated through pathogen exposure. These memory T cells, including those generated via heterologous immunity, are more resistant to tolerance induction protocols.

FAQ 3: What are the major immune barriers to 'off-the-shelf' allogeneic cell therapies? The efficacy of allogeneic cell therapies, such as CAR-T or CAR-NK cells, is limited by host versus graft and graft versus host reactions [3] [4]:

- Host T-cell-mediated Rejection: Host CD8+ T cells recognize mismatched HLA class I molecules on the donor cells and eliminate them.

- Host NK-cell-mediated Rejection: Host NK cells attack donor cells that lack "self" HLA class I molecules, a phenomenon known as the "missing-self" response.

- Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD): Donor T cells within the therapeutic product recognize alloantigens on host tissues and cause pathology.

- Humoral Rejection: Pre-existing or de novo generated donor-specific antibodies (DSAs) can mediate rejection via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC).

FAQ 4: How does immune reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) influence clinical outcomes? The timing and quality of immune cell recovery post-HSCT are critical determinants of patient survival [5] [6]:

- Early Phase (First 100 days): Dominated by innate immunity and homeostatic peripheral expansion of memory T cells. Patients are highly susceptible to viral reactivations (e.g., CMV, EBV) and bacterial/fungal infections due to profound T-cell deficiency.

- Late Phase (Months to Years): Characterized by slow de novo generation of naïve T cells from the thymus and B cells from the bone marrow. Slow B-cell reconstitution and impaired class-switching lead to vulnerability to encapsulated bacteria and delayed humoral immunity.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Overcoming Host Rejection of Allogeneic Cell Therapies Problem: Adoptively transferred allogeneic T or NK cells are rapidly cleared by the host immune system. Solution: Employ gene editing to modulate the immunogenicity of the donor cells [3] [4].

- Step 1: Knock out the T-cell receptor (TCR) alpha constant (TRAC) locus to prevent GvHD. For a dual approach, simultaneously knock in the CAR gene at this locus.

- Step 2: Knock out Beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) to eliminate surface expression of HLA class I and evade host T-cell recognition.

- Step 3: To prevent the ensuing "missing-self" NK cell attack, co-express a single-chain, non-polymorphic HLA-E variant in the B2M locus. HLA-E engages the inhibitory receptor NKG2A on NK cells, suppressing their activation.

- Step 4: For additional persistence, overexpress CD47 ("don't eat me" signal) to inhibit phagocytosis by host macrophages.

Experimental Workflow for Engineering Allogeneic Cell Therapies

Challenge 2: Poor T-cell Persistence and Function in the Tumor Microenvironment (TME) Problem: Adoptively transferred cells become dysfunctional or exhausted within the immunosuppressive TME. Solution: Engineer cells to resist key suppressive mechanisms [3].

- Step 1: Express a dominant-negative TGF-β receptor II (dnTGFβRII) to block the immunosuppressive TGF-β signal.

- Step 2: Introduce a PD1:CD28 switch receptor. This chimeric receptor converts the inhibitory PD-1 signal from tumor PD-L1 into a co-stimulatory CD28 signal.

- Step 3: Co-express cytokines like IL-15 or membrane-bound IL-12 to promote sustained activation and survival in a cytokine-poor TME.

Challenge 3: Inducing Transplant Tolerance in Pre-clinical Models with High Memory T-cell Load Problem: Tolerance protocols fail in immunologically experienced hosts, limiting translational relevance. Solution: Utilize murine models that better mimic the human immune state and employ regulatory cell therapy [2].

- Step 1: Use "dirty" mice (pet store-derived or wildlings) that have a diverse microbial experience and a T-cell memory compartment similar to adult humans, rather than SPF-housed mice.

- Step 2: Generate and expand donor-specific regulatory T cells (Tregs) in vitro.

- Step 3: Infuse expanded Tregs along with the transplant under reduced immunosuppression. Tregs suppress effector T cell responses and promote a tolerogenic environment.

Quantitative Data on Post-Transplant Immune Reconstitution

The pace of immune recovery is a critical factor in managing post-transplant complications. The table below summarizes normative recovery timelines for key immune cells after allogeneic HSCT, which can serve as a benchmark for evaluating patient progress and identifying delays [5].

Table 1: Timelines for Key Immune Cell Recovery Post-Allogeneic HSCT

| Immune Cell Population | Time to Recovery | Key Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils (>0.5 × 10⁹/L) | ~14 days (PBSC), ~21 days (BM), ~30 days (CB) [5] | Protection against bacterial and fungal infections during the aplastic phase. |

| NK Cells | 30–100 days [5] | Early innate defense and anti-leukemic activity. |

| T Cells | ~100 days for initial recovery [5] | Control of viral reactivations (e.g., CMV, EBV); imbalance linked to GvHD and relapse. |

| CD4+ T Cells | Inversion of CD4/CD8 ratio common; numbers of ~200/μL by 3 months [5] | Critical for providing T-cell help; slow recovery correlates with opportunistic infections. |

| CD19+ B Cells | 1–2 years to reach normal numbers [5] | Defective humoral immunity; vulnerability to encapsulated bacteria (e.g., S. pneumoniae). |

| CD19+CD27+ Memory B Cells | Up to 5 years for complete reconstitution [5] | Delayed and restricted antibody repertoire; impaired response to vaccines. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating Alloreactivity and Tolerance

| Research Reagent | Primary Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Alemtuzumab (anti-CD52) | An anti-lymphocyte antibody used for in vivo or in vitro lymphodepletion. Knocking out CD52 in donor cells renders them resistant [4]. |

| Sirolimus (mTOR inhibitor) | Conditions recipient dendritic cells towards a tolerogenic profile, potentially inhibiting alloreactive T-cell survival and promoting tolerance [1]. |

| Anti-thymocyte Globulin (ATG) | Polyclonal T-cell-depleting antibody used in conditioning regimens to reduce host-versus-graft and graft-versus-host reactions [2]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Gene-editing tool for precise knockout (e.g., TRAC, B2M) or knock-in (e.g., CAR, HLA-E) to create immune-evasive allogeneic cell products [3] [4]. |

| Recombinant IL-2/IL-15 | Cytokines used to expand and maintain T cells and NK cells ex vivo, and to enhance their persistence and function in vivo [3]. |

| TGF-β Inhibitor / dnTGFβRII | Used to block the immunosuppressive effects of TGF-β in the tumor microenvironment, enhancing T-cell cytotoxicity [3]. |

Signaling Pathways in Alloreactive T-cell Activation

The activation of alloreactive T cells requires three distinct signals, which present multiple targets for immunosuppressive and tolerogenic strategies [1].

Diagram: Three-Signal Model of T-Cell Alloreactivity

FAQ: Resolving Key Experimental Challenges

1. In our in vitro cytotoxicity assays, we are not observing consistent NK cell activation against our allogeneic target cells, despite known HLA class I mismatches. What could be the cause?

Inconsistent NK cell activation often stems from an incomplete understanding of the "licensing" or "education" process. NK cell responsiveness is not universal; it is determined by the interaction between the recipient's inhibitory KIRs and their own HLA class I molecules during development. An NK cell that lacks an inhibitory receptor for self-HLA I may be unlicensed and hyporesponsive, even when encountering allogeneic target cells [7] [8].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify KIR-HLA Ligand Status: Genotype both the NK cell donor and the target cell donor for KIR genes and HLA-A, -B, and -C alleles. Focus on the major inhibitory KIR-ligand pairs: KIR2DL1 for HLA-C group 2 (C2), KIR2DL2/3 for HLA-C group 1 (C1), and KIR3DL1 for HLA-Bw4 [7] [8].

- Identify "Missing Self" Conditions: A functional "missing self" scenario exists when the target cell lacks the specific HLA I ligand for an inhibitory KIR expressed on the NK cell. For example, an NK cell expressing KIR2DL1 will be strongly activated by a target cell that is HLA-C2 negative, as the inhibitory signal is absent [7] [8].

- Use Positive Controls: Include a well-characterized target cell line known to be susceptible to NK cell lysis (e.g., K562) to confirm your NK cell effector function is intact.

2. We are investigating chronic rejection in a humanized mouse model of solid organ transplantation. We observe microvascular inflammation but cannot detect donor-specific antibodies (DSAs). What innate immune mechanisms should we explore?

Your observations are consistent with clinical findings where approximately 41% of kidney transplant patients with microvascular inflammation (MVI) do not have detectable DSAs [8]. This antibody-independent MVI is a hallmark of innate allorecognition, primarily driven by NK cells reacting to "missing self" on the graft endothelium [9] [8].

Experimental Investigation Plan:

- Histological Analysis: Perform immunohistochemistry on graft sections using an anti-NKp46 (in mice) or anti-CD56 (in humans) antibody to quantify NK cell infiltration within the microvasculature [8].

- Genetic Analysis: Confirm a mismatch between the donor's HLA I and the recipient's inhibitory KIR repertoire. This creates a "pseudo-missing self" situation where the graft endothelium expresses normal levels of HLA I, but these molecules cannot deliver an inhibitory signal to the recipient's educated NK cells [8].

- Pathway Inhibition: Treat your model with an mTOR inhibitor like rapamycin (sirolimus). Research has shown that the mTORC1 pathway in NK cells is mandatory for this type of endothelial damage, and rapamycin can prevent the development of these lesions [8].

3. Beyond NK cells, what other innate immune cells contribute to allorecognition, and how can we differentiate their roles in rejection?

Myeloid cells, particularly monocytes and macrophages, are now recognized as key players in innate allorecognition through mechanisms distinct from NK cells [10] [11]. They can directly recognize allogeneic non-self via specific receptor-ligand systems, leading to monocyte differentiation into mature dendritic cells and the acquisition of allocytotoxic functions by macrophages [10] [11].

Strategies to Differentiate Roles:

- Target Different Pathways: NK cell "missing self" recognition is primarily mediated by KIR-HLA I interactions. Myeloid allorecognition in mice involves paired immunoglobulin-like receptor type A (PIR-A) recognition of non-self MHC-I and the CD47-SIRPα axis, where polymorphisms in SIRPα trigger monocyte activation [10] [11]. Using blocking antibodies or genetic knockouts for these specific receptors can help isolate their effects.

- Cell Depletion Models: Use clodronate liposomes to deplete phagocytic myeloid cells or anti-asialo GM1 to deplete NK cells in animal models. Comparing rejection outcomes in these conditions can reveal the relative contribution of each cell type [11].

- Analyze Cytokine Profiles: NK cell responses are typically associated with high levels of IFN-γ. Myeloid cell activation, particularly monocyte differentiation into dendritic cells, is characterized by persistent production of IL-12, which drives a Th1 response [11].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: In Vitro Model of NK Cell "Missing Self" Activation

This protocol outlines a method to test the functional impact of KIR-HLA ligand mismatches on primary human NK cell activity.

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Ficoll-Paque | Density gradient medium for isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). |

| Human NK Cell Isolation Kit | Negative selection magnetic beads for untouched purification of NK cells. |

| IL-2 | Cytokine used to culture and maintain NK cell viability and activity. |

| K562 Cell Line | HLA class I-negative erythroleukemia cell line; used as a positive control for "missing self" lysis. |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Assay Kit | Measures LDH release from damaged target cells to quantify cytotoxicity. |

Methodology:

- Cell Isolation: Isolate PBMCs from the recipient (NK cell source) using Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation. Subsequently, isolate untouched NK cells from the PBMCs using a negative selection magnetic bead kit [7].

- NK Cell Culture: Culture the purified NK cells in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 500 IU/mL recombinant human IL-2 for 48-72 hours to pre-activate them [7].

- Target Cell Preparation: Culture allogeneic and syngeneic (control) target cells. These can be primary endothelial cells or cell lines with well-defined HLA class I types. Include K562 cells as a positive control.

- Cytotoxicity Assay: Co-culture effector NK cells with target cells at various effector-to-target (E:T) ratios (e.g., 10:1, 5:1, 1:1) in a 96-well plate. Incubate for 4-6 hours.

- Lysis Quantification: Use an LDH release assay according to the manufacturer's instructions. Measure the absorbance and calculate the percentage of specific cytotoxicity [7].

Protocol 2: Assessing Myeloid Allorecognition via the CD47-SIRPα Axis

This protocol uses a mouse model to study how SIRPα polymorphism drives monocyte infiltration and activation.

Workflow:

Methodology Details:

- Step 1: Mouse Strains. Utilize mice with known polymorphisms in the Sirpa gene, such as NOD (non-obese diabetic) and C57BL/6 (B6) strains. NOD SIRPα has a higher binding affinity for CD47 than the B6 variant [11].

- Step 2: Transplantation. Perform transplants (e.g., heart) from a donor of one strain into a RAG-/-γc-/- recipient of another strain. These recipients lack T, B, and NK cells, allowing you to isolate the innate myeloid response [10] [11].

- Steps 3-6: Graft Analysis. Harvest grafts at designated time points. Create a single-cell suspension and stain for monocytes and monocyte-derived dendritic cells (mo-DCs) using antibodies against CD11b, Ly6C, MHC class II (I-A/I-E), and CD80/86. Analyze via flow cytometry. Allogeneic grafts will show a significant and persistent infiltration of mature (MHC-IIhiCD80hi) host-derived mo-DCs compared to syngeneic controls [11].

- Steps 7-8: Mechanism Interrogation. To confirm the role of specific pathways, use congenic mouse strains to map the genetic locus responsible for the alloresponse (often the Sirpa locus) or administer blocking antibodies against CD47 or PIR-A to the recipients to inhibit the allorecognition response [11].

Signaling Pathways in Innate Allorecognition

Diagram 1: NK Cell "Missing Self" Activation Pathway

This diagram details the intracellular signaling events in an NK cell when it encounters a graft endothelial cell lacking self-HLA I.

Title: NK Cell Missing Self Signaling

Key Signaling Molecules:

- Inhibitory KIRs: Contain Immunoreceptor Tyrosine-based Inhibitory Motifs (ITIMs). When engaged by self-HLA I, they recruit phosphatases like SHP-1, which dephosphorylate activation pathway components, suppressing NK cell activity [7].

- Activating Receptors (e.g., NKG2D): Associate with adaptor proteins (DAP10/DAP12) containing Immunoreceptor Tyrosine-based Activation Motifs (ITAMs). Phosphorylated ITAMs recruit kinases like Syk and ZAP70 [7].

- Downstream Pathways (PLC-γ, PI3K, MAPK): These pathways integrate activating signals, leading to calcium flux, cytoskeletal polarization, and the release of perforin/granzyme-containing cytotoxic granules and cytokines like IFN-γ [7].

- mTORC1: This pathway is mandatory for NK cell-mediated endothelial damage in "missing self" responses. Its inhibition by rapamycin can prevent chronic vascular rejection [8].

Diagram 2: Myeloid Allorecognition via SIRPα-CD47

This diagram illustrates how polymorphism in the SIRPα protein on donor cells leads to monocyte activation in the recipient.

Title: Myeloid Allorecognition via SIRPα-CD47

Key Mechanism:

- In a syngeneic setting (donor and recipient have the same SIRPα variant), the bidirectional interaction between CD47 on the graft and SIRPα on the recipient monocyte is balanced. The affinity of binding is equal, resulting in a net inhibitory signal that prevents monocyte activation [11].

- In an allogeneic setting (donor expresses a different SIRPα variant), the affinity of the cross-interaction between donor SIRPα and recipient CD47 is altered. This imbalance upsets the steady-state signaling, leading to a net activating signal that drives monocyte differentiation into mature, IL-12-producing dendritic cells, which can prime naive T cells [11].

Table 1: Clinical Evidence for Antibody-Independent Microvascular Inflammation (MVI) [8]

| Patient Cohort | Prevalence of MVI | Circulating Anti-HLA Donor-Specific Antibodies (DSA) | NK Cell Infiltration in Graft | 5-Year Graft Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVI+ / DSA+ (C3d+) | 31% (40/129) | Present & Complement-Activating | Present | Lowest (Worst) |

| MVI+ / DSA+ (C3d-) | 23% (30/129) | Present & Non-Complement-Activating | Present | Intermediate |

| MVI+ / DSA- | 41% (53/129) | Absent | Present | Intermediate |

| MVI- / DSA- (Control) | N/A | Absent | Absent | Highest (Best) |

Table 2: Key Receptor-Ligand Pairs in Innate Allorecognition

| Receptor | Expression | Ligand | Function in Allorecognition | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitory KIR (e.g., KIR2DL1) | NK Cells | HLA-C (C2 group) | Inhibits NK cell cytotoxicity upon engagement; absence of ligand ("missing self") triggers activation [7] [8]. | Human |

| PIR-A | Monocytes, Macrophages | MHC Class I | Recognizes non-self MHC-I; engagement triggers monocyte/macrophage activation and memory [10] [11]. | Mouse |

| LILRs (PIR-A orthologs) | Monocytes, Macrophages | HLA Class I | Proposed human equivalent of PIR-A; likely involved in MHC-I allorecognition [11]. | Human |

| SIRPα | Myeloid Cells, Various Non-immune Cells | CD47 | Polymorphic protein; mismatched SIRPα between donor/recipient disrupts balanced signaling, initiating monocyte activation [11]. | Mouse/Human |

In allogeneic stem cell transplantation, the focus has long been on matching Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLA) to minimize immune rejection. However, even with perfect HLA matching, complications like Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD), graft rejection, and autoimmune phenomena persist. These events are largely driven by minor histocompatibility antigens (mHAgs) and disruptions in immune tolerance. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and experimental protocols to help researchers in the challenging field of transplant immunology overcome these barriers.

FAQs: Core Concepts for Researchers

1. What are minor histocompatibility antigens and why are they significant in transplantation?

Minor histocompatibility antigens (mHAgs) are immunogenic peptides presented by MHC molecules that can elicit T-cell immune responses between transplant recipients and donors who are matched at the HLA loci [12]. They are generated from polymorphic cellular proteins or peptides that differ between donor and recipient due to genetic variations like single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or insertions/deletions (indels) [12]. In HLA-matched sibling transplants, donor T cells recognize recipient mHAgs, contributing to both graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effects and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) [12].

2. What are the primary allorecognition pathways involved in transplant rejection?

The immune system uses three distinct pathways to recognize allografts as foreign [13] [14]:

- Direct Pathway: Recipient T cells directly recognize intact donor MHC molecules on the surface of donor antigen-presenting cells (APCs). This pathway is dominant in early acute rejection.

- Indirect Pathway: Recipient APCs process and present donor MHC molecules as peptides on recipient MHC molecules to recipient T cells. This pathway becomes more important over time and is involved in chronic rejection.

- Semi-direct Pathway: Recipient APCs capture intact donor MHC molecules and present them directly to recipient T cells.

3. How can autoimmune phenomena occur after an allogeneic stem cell transplant?

Autoimmune diseases (ADs) can occur after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) due to an imbalance in immune regulation, particularly involving the effect of T-regulatory lymphocytes on autoreactive T-lymphocytes [15]. The transfer of immune cells from the donor can also lead to the transfer of autoimmunity. This immune dysregulation can result in both hematological ADs and non-hematological ADs affecting organs like the thyroid, skin, liver, and nervous system [15]. Autoimmune cytopenias, such as autoimmune neutropenia (AIN), are documented rare complications, with one recent study reporting a cumulative incidence of 14.74% at 2 years post-HSCT in pediatric patients [16].

4. What is the emerging role of non-HLA antibodies in transplant rejection?

Beyond antibodies against HLA and mHAgs, immunity to non-HLA antigenic targets is increasingly recognized. A paradigm-changing example is immunity to the non-HLA angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) [17]. Antibodies against AT1R have been associated with antibody-mediated rejection and other vascular complications in transplantation. The successful detection and intervention for anti-AT1R antibodies provide a model for understanding the broader pathogenicity of non-HLA antibodies [17].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: Unexpected GVHD in HLA-Matched Animal Models

Observed Issue: Development of clinical or histopathological signs of GVHD in transplanted subjects despite full HLA compatibility.

Potential Root Causes:

- Presence of undiscovered mHAg mismatches.

- Incomplete immune suppression during the peri-transplant period.

- Underlying inflammatory conditions or infections triggering immune activation.

Investigative Steps:

- Confirm Histocompatibility: Re-genotype donor and recipient pairs to verify HLA identity and screen for known genetic disparities.

- Profile mHAgs: Utilize genomic approaches (see Experimental Protocol 1 below) to identify mismatched mHAgs.

- Monitor Immune Reconstitution: Use flow cytometry to track the expansion of alloreactive T-cell populations post-transplant.

- Control for Environment: Ensure sterile housing conditions and screen for common murine pathogens that can incite inflammation.

Solution: Incorporate high-throughput mHAg screening into your donor selection criteria. For established models, consider therapeutic strategies that target alloreactive T cells while preserving regulatory T-cell function.

Problem 2: Detecting Clinically Relevant mHAgs

Observed Issue: Difficulty in linking specific mHAgs to clinical outcomes like GVHD or relapse.

Potential Root Causes:

- Low precursor frequency of T cells for individual mHAgs.

- Lack of specific reagents (e.g., tetramers) for detecting mHAg-specific T cells.

- Heterogeneity in HLA restriction elements among study subjects.

Investigative Steps & Solution: Implement a genome-wide association study (GWAS) approach in well-defined transplant cohorts. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from such studies.

Table 1: Association between Genetic Mismatching and Clinical Outcomes in HLA-Matched Sibling HCT

| Study Cohort | Number of Sibling Pairs | Key Finding | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| FHCRC Discovery Cohort [12] | 824 HLA-A*02:01-positive pairs | Identification of recipient allele mismatch associations (RAMAs) with GVHD and relapse. | Analyzed via cause-specific hazard ratio (CSHR) |

| FHCRC Discovery Cohort [12] | 929 HLA-A02 supertype-negative pairs | Used as a control to test specificity of HLA-A*02:01-restricted associations. | Associations not replicated in this control group |

| CIBMTR Replication Cohort [12] | 838 HLA-A*02:01-positive pairs | Independent testing of RAMAs discovered in the FHCRC cohort. | Confirmed specific replicated associations |

Problem 3: Post-Transplant Autoimmune Cytopenia

Observed Issue: The patient develops isolated neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, or anemia after engraftment.

Potential Root Causes:

- Autoimmune neutropenia (AIN) or other autoimmune cytopenias (AIC).

- Drug toxicity from immunosuppressive agents.

- Viral reactivation (e.g., CMV, HHV-6).

- Incipient graft failure or disease relapse.

Investigative Steps:

- Confirm Diagnosis: For suspected AIN, obtain at least two consecutive absolute neutrophil counts (ANC) < 0.5 x 10⁹/L and test for anti-granulocyte antibodies via flow cytometry [16].

- Exclude Other Causes: Check donor chimerism to rule out graft failure. Test for viral DNA by PCR and review medication charts.

- Assess Clinical Context: Note that AIC often occurs during immunosuppression tapering and is associated with chronic GVHD [15] [16].

Solution: First-line treatment often involves corticosteroids or rituximab. For steroid-refractory cases, targeted therapies like JAK inhibitors (e.g., ruxolitinib) may be considered [14].

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol 1: Identification of mHAgs via Genomic Sequencing

Objective: To identify minor histocompatibility antigens in HLA-identical donor-recipient pairs.

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the major steps from sample preparation to statistical analysis.

Materials:

- Pre-transplant blood samples from donor and recipient.

- Genomic DNA extraction kits.

- Genotyping microarray or targeted sequencing platforms (e.g., Illumina MiSeq) [12].

- Bioinformatics pipelines for variant calling (e.g., GATK) and annotation (e.g., Ensembl VEP) [12].

- Computational tools for peptide-HLA binding prediction.

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from donor and recipient pre-transplant samples [12].

- Genotyping & Imputation: Genotype samples using a high-density SNP array or perform whole-exome/genome sequencing. Use imputation algorithms to fill in missing genotypes [12].

- Variant Annotation: Process variants with the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) to categorize them as "coding" (missense, frameshift, etc.) or "non-coding" [12].

- In Silico Prediction: For coding variants, use algorithms to predict whether the polymorphic peptides they generate will bind to the specific HLA allotypes present in the recipient [12].

- Statistical Analysis: Test for Recipient Allele Mismatch Associations (RAMAs) using Cox regression models, treating death as a competing risk. Compare outcomes between mismatched and non-mismatched pairs [12].

Protocol 2: Detecting Anti-Granulocyte Antibodies for AIN Diagnosis

Objective: To diagnose autoimmune neutropenia (AIN) post-HSCT by detecting anti-granulocyte antibodies.

Materials:

- Patient serum and EDTA blood samples.

- Flow cytometer (e.g., CytoFLEX, Beckman Coulter) [16].

- Antibodies for neutrophil labeling.

- Negative and positive control samples.

Method:

- Sample Collection: Collect patient blood when neutropenia (ANC < 0.5 x 10⁹/L) is observed.

- Direct Test (Detects cell-bound antibodies):

- Isolate neutrophils from the patient's blood.

- Incubate with a fluorescently-labeled anti-human immunoglobulin antibody.

- Analyze by flow cytometry. A positive result is a median fluorescence intensity (MFI) exceeding a validated laboratory cut-off [16].

- Indirect Test (Detects serum antibodies):

- Incubate healthy control neutrophils with the patient's serum.

- Wash and then incubate with a fluorescently-labeled anti-human immunoglobulin antibody.

- Analyze by flow cytometry. A positive result is an MFI at least twice that of a negative control [16].

- Interpretation: A positive result in either test, in the correct clinical context and after excluding other causes, supports a diagnosis of AIN [16].

Key Signaling Pathways in Rejection and Autoimmunity

Understanding these pathways is critical for developing targeted therapies. The diagram below illustrates two key pathways implicated in GVHD.

Pathway 1: JAK-STAT Signaling

- Role in GVHD: This pathway is a critical communication node activated by cytokines. It regulates the development and function of dendritic cells, T cells, and neutrophils, all of which are central to GVHD pathogenesis [14].

- Therapeutic Targeting: Inhibition of JAK signaling with drugs like ruxolitinib has been shown to reduce GVHD severity while potentially preserving graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) activity [14]. The US FDA has approved ruxolitinib for steroid-refractory acute GVHD.

Pathway 2: Notch Signaling

- Role in Rejection: This highly conserved pathway is crucial for innate and adaptive immune cell development and function. It is a key inflammatory pathway in T-cell alloreactivity [14].

- Therapeutic Targeting: Emerging evidence suggests that inhibiting the Notch pathway can prevent allograft rejection and may be beneficial for treating GVHD without interfering with GVL activity [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating mHAgs and Autoimmunity

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Microarray | Genome-wide SNP profiling | Initial screening for genetic disparities in donor-recipient pairs [12]. |

| GATK Pipeline | Variant calling from sequencing data | Joint genotyping of donor and recipient samples to identify mismatches [12]. |

| Ensembl VEP (Variant Effect Predictor) | Functional annotation of genetic variants | Categorizing variants as coding or non-coding to prioritize mHAg candidates [12]. |

| Peptide-HLA Binding Prediction Algorithms | In silico prediction of mHAg presentation | Predicting which polymorphic peptides will bind to a patient's specific HLA allotypes [12]. |

| Flow Cytometry with Anti-Human Ig | Detection of anti-granulocyte antibodies | Diagnosing Autoimmune Neutropenia (AIN) post-transplant [16]. |

| JAK Inhibitors (e.g., Ruxolitinib) | Inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling | Used in in vivo models or as a therapeutic to investigate pathway role in GVHD [14]. |

FAQ: Understanding IBMIR and Its Impact on Your Research

What is IBMIR and why is it a critical problem in cellular transplantation?

The Instant Blood-Mediated Inflammatory Reaction (IBMIR) is a rapid, innate immune response triggered when transplanted cells or tissues directly contact blood components. It is a major barrier to successful engraftment in intraportal islet transplantation, destroying up to approximately 60% of transplanted islet cells within hours by activating coagulation and complement cascades, inducing platelet activation, recruiting inflammatory cells, and promoting fibrin deposition around the graft [18] [19] [20]. This rapid graft loss severely compromises the initial engraftment and long-term function of transplanted cells.

How does IBMIR differ from other forms of immune rejection?

Unlike T-cell-mediated adaptive immune rejection, which occurs over days to weeks, IBMIR is an innate immune response that begins within minutes to hours of transplantation. Its key distinguishing feature is the simultaneous and powerful activation of both the coagulation system and the complement system, leading to immediate thrombosis and inflammation at the transplant site [18] [20]. This makes it a first-line barrier that must be overcome before addressing chronic rejection.

Which transplant sites are most susceptible to IBMIR?

The intraportal site (transplantation into the liver via the portal vein) is the most clinically established site for islet transplantation and is particularly susceptible to IBMIR [21] [19]. This is due to the direct exposure of islets to the bloodstream immediately upon infusion. Research into alternative sites, such as the subcutaneous space, aims to circumvent IBMIR, but no patient has yet been rendered insulin-free by cellular transplantation in a site other than the liver [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: Investigating and Mitigating IBMIR in Experimental Models

Problem: Poor Early Graft Survival In Vivo

Potential Cause: Uncontrolled IBMIR leading to massive early cell death.

Diagnostic Steps & Solutions:

- Monitor Coagulation Activation: Measure biomarkers like Thrombin-Antithrombin (TAT) complexes and β-thromboglobulin (β-TG). Elevated levels indicate strong coagulation activation and platelet activation, respectively [18].

- Assess Inflammatory Response: Analyze serum for pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and examine graft sites for inflammatory cell infiltration (e.g., neutrophils, macrophages) [18] [20].

- Histological Confirmation: Look for significant fibrin deposition and the formation of peri-graft microthrombi [18].

Recommended Interventions:

- Anticoagulant Therapy: Consider using direct thrombin inhibitors like Bivalirudin, which has been shown to more effectively reduce coagulation activation and inflammatory infiltration compared to unfractionated heparin in preclinical models [18].

- Multi-Target Therapy: Explore drugs with combined anti-inflammatory and anti-coagulant properties. For example, Xuebijing (XBJ) injection, a multi-component herbal medicine, has demonstrated efficacy in mitigating IBMIR by suppressing the NF-κB pathway, thereby reducing both thrombosis and inflammation [20].

Problem: Inconsistent IBMIR Readouts In Vitro

Potential Cause: Lack of a robust and standardized assay to model blood-cell interactions.

Solution: Implement a Standardized In Vitro IBMIR Assay. This assay incubates your cell product (e.g., isolated islets) with fresh human blood or plasma to simulate the initial contact [18] [20].

Key Parameters to Quantify:

- Coagulation Activation: Measure TAT complexes and platelet consumption.

- Complement Activation: Measure generation of complement split products like C3a and sC5b-9.

- Cell Activation and Death: Assess leukocyte infiltration and quantify apoptosis/necrosis in the cell product.

This assay provides a controlled system for pre-screening potential IBMIR-inhibiting strategies before moving to complex animal models.

Experimental Protocols: Core Methodologies for IBMIR Research

Detailed Protocol: Evaluating Anticoagulants in a Rodent Intraportal Transplantation Model

The following methodology is adapted from a 2025 study investigating bivalirudin [18].

1. Animal and Diabetes Model:

- Use male Wistar or Sprague Dawley rats (6-8 weeks old).

- Induce diabetes with a single intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (70 mg/kg for rats).

- Confirm diabetes by measuring blood glucose levels >300 mg/dL for two consecutive days prior to transplantation [18].

2. Islet Isolation and Preparation:

- Anesthetize donor SD rats and perform an abdominal laparotomy.

- Inject 8 ml of collagenase V (1 mg/ml) into the pancreatic common bile duct to distend the pancreas.

- Remove the enlarged pancreas and digest in a 37°C water bath for 5-6 minutes.

- Purify islets using density gradient centrifugation (e.g., with Histopaque 1077).

- Culture purified islets in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum.

- Count islets and determine islet equivalents (IEQ) using dithizone (DTZ) staining [18].

3. Experimental Groups and Dosing: The study design below is critical for a direct comparison of anticoagulants. The following table summarizes the dosing regimen for a rat model [18]:

Table 1: Experimental Groups and Anticoagulant Dosing for Rat Intraportal Islet Transplantation

| Group | Pre-Transplant Bolus (0.5 ml, i.v.) | Continuous Infusion (for 1 hour post-transplant) |

|---|---|---|

| Sham | Physiological Saline | 5 ml/(kg·h) Saline |

| Model (Control) | Physiological Saline | 5 ml/(kg·h) Saline |

| Bivalirudin (BT) | 50 mg/kg Bivalirudin | 70 mg/(kg·h) Bivalirudin |

| Heparin (HT) | 200 U/kg Heparin Sodium | 300 U/(kg·h) Heparin Sodium |

4. Transplantation and Assessment:

- Anesthetize recipient rats and expose the superior mesenteric vein and portal vein.

- Puncture the superior mesenteric vein with a 27G syringe and infuse the islet cells (2000 IEQ per 100g of recipient weight) into the liver.

- Administer treatments via tail vein infusion according to the group design.

- Collect blood via inferior vena cava puncture to assess anticoagulation function (e.g., APTT) and biomarkers (β-TG, TAT, TNF-α).

- Monitor graft function by tracking the time to achieve normoglycemia and the proportion of animals that become normoglycemic [18].

The following tables consolidate quantitative findings from key studies to aid in experimental planning and comparison.

Table 2: Efficacy of Bivalirudin vs. Heparin in Mitigating IBMIR Biomarkers [18]

| Biomarker / Outcome | Model (Saline) | Heparin Treatment (HT) | Bivalirudin Treatment (BT) | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coagulation (TAT complexes) | Baseline (High) | Reduced | Reduced more effectively than HT | BT showed superior anti-thrombotic activity [18] |

| Platelet Activation (β-TG) | Baseline (High) | Reduced | Reduced more effectively than HT | BT more effectively suppressed platelet activation [18] |

| Inflammation (TNF-α) | Baseline (High) | Attenuated | Attenuated, with more pronounced effects | BT demonstrated greater anti-inflammatory activity [18] |

| Graft Normoglycemia | Baseline (Low) | Higher proportion than model | Higher proportion than HT, with shorter time-to-normoglycemia | BT led to superior functional outcomes [18] |

Table 3: Multi-Target Effects of Xuebijing (XBJ) on IBMIR and Islet Function [20]

| Mechanism of Action | Observed Effect | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibition of NF-κB Pathway | Suppressed pro-inflammatory gene clusters and reduced inflammatory reaction. | Diabetic mouse transplantation model [20] |

| Direct Islet Protection | Protected islet cells against cytokine-induced apoptosis and restored glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. | Cytokine-stimulated mouse islets and β-cells in vitro [20] |

| Improved Transplantation Outcome | Mitigated IBMIR, led to a higher percentage of normoglycemia, and better graft survival. | Intrahepatic islet transplantation in diabetic mice [20] |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

IBMIR Mechanism and Therapeutic Blockade

This diagram illustrates the core mechanism of the Instant Blood-Mediated Inflammatory Reaction (IBMIR) and points where therapeutic agents can intervene.

In Vivo IBMIR Investigation Workflow

This diagram outlines a logical workflow for a standard preclinical experiment investigating IBMIR and potential therapeutics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for IBMIR Research

| Reagent | Function in IBMIR Research | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Bivalirudin | Direct thrombin inhibitor; anticoagulant. | Used to mitigate coagulation cascade activation; shown to be more effective than heparin in some models [18]. |

| Heparin Sodium | Indirect thrombin inhibitor (via antithrombin); anticoagulant. | Common clinical anticoagulant; used as a comparative control in IBMIR studies [18]. |

| Xuebijing (XBJ) Injection | Multi-component herbal medicine with anti-inflammatory and anti-coagulant properties. | Suppresses IBMIR via NF-κB pathway inhibition; offers a multi-target approach [20]. |

| Collagenase V | Enzyme for pancreatic digestion. | Critical for isolating islets from the pancreas for transplantation [18]. |

| Histopaque 1077 | Density gradient medium. | Used for purifying isolated islets from exocrine tissue after digestion [18]. |

| Dithizone (DTZ) | Zinc-chelating dye that stains islets red. | Essential for visualizing and counting islet equivalents (IEQ) pre-transplantation [18]. |

| Streptozotocin (STZ) | Chemical agent toxic to pancreatic beta cells. | Used to induce an experimental model of diabetes in rodents [18]. |

Engineering Immune Evasion: Strategies for Hypoimmunogenic Cell Therapies

Genetic Ablation of HLA Class I and II to Thwart T-cell Recognition

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on HLA Ablation

FAQ 1: My HLA-ablated cells are being killed by host natural killer (NK) cells after transplantation. How can I prevent this "missing-self" response?

Answer: The "missing-self" response occurs because host NK cells recognize and eliminate cells that lack surface expression of HLA class I molecules, a common outcome of B2M knockout [22] [3]. To overcome this, consider these strategies:

- Express Non-Polymorphic HLA Molecules: Introduce a single-chain HLA-E (SCE) gene or an HLA-E-B2M fusion gene into the B2M locus. HLA-E engages the inhibitory receptor NKG2A on NK cells, providing a "do not eat me" signal that inhibits NK cell-mediated killing [22] [23] [3].

- Use Specific shRNA for HLA-ABC: Employ shRNA (e.g., shRNA #1 from the literature) that selectively knocks down classical HLA-A, -B, and -C molecules without affecting HLA-E expression. This allows retention of HLA-E-mediated inhibition of NK cells while still evading T-cell recognition [23].

FAQ 2: After successful HLA class I ablation, my cellular product still faces rejection. What other immune mechanisms could be responsible?

Answer: Rejection despite HLA class I ablation suggests involvement of other immune components.

- HLA Class II Recognition: Host CD4+ T cells can recognize allogeneic HLA class II molecules. For complete immune evasion, disrupt the class II transactivator (CIITA) gene, which is the master regulator of HLA class II expression [22].

- Macrophage-Mediated Clearance: Host macrophages can phagocytose donor cells. To counter this, overexpress the CD47 protein on your cell product. CD47 binds to SIRPα on macrophages, delivering an inhibitory signal that prevents phagocytosis [3].

- Synapse Formation with Host Immune Cells: Genetic deletion of adhesion ligands CD54 (ICAM-1) and CD58 (LFA-3) can mitigate rejection by host NK cells, as it disrupts the formation of a functional immune synapse necessary for cytotoxicity [24].

FAQ 3: How can I ensure that genetic ablation of HLA does not impair the native therapeutic function of my cell product (e.g., Tregs, CAR cells)?

Answer: It is critical to perform comprehensive functional validation post-editing. Key assessments include:

- Phenotype Stability: Verify the stability of cell-specific surface markers and key transcription factors (e.g., FOXP3 for Tregs) via flow cytometry [22].

- In Vitro Functional Assays: Conduct suppression assays (for Tregs) or cytotoxic killing assays (for CAR cells) to confirm that the engineered cells retain their potent immunosuppressive or anti-tumor activity, comparable to unedited controls [22].

- Epigenetic Stability: For Tregs, assess the methylation status of the Treg-specific demethylation region (TSDR) in the FOXP3 locus. A low methylation state indicates stable FOXP3 expression and Treg lineage commitment [22].

FAQ 4: What is the advantage of using a single-vector system for creating hypo-immunogenic cells?

Answer: A single lentiviral vector that combines a CAR construct, an HLA-knockdown shRNA, and an immune checkpoint protein (e.g., PD-L1 or SCE) enables one-step construction of allogeneic cell products. This strategy simplifies manufacturing, improves efficiency, and ensures that all modifications are present in the final therapeutic product, facilitating clinical translation [23].

The tables below summarize key experimental data from recent studies on HLA engineering, providing a benchmark for expected outcomes.

Table 1: In Vivo Efficacy of HLA-Engineered Human Tregs in a Skin Graft Model [22]

| Treg Treatment Type | Median Graft Survival Time (Days) | Key Genetic Modification |

|---|---|---|

| Autologous Tregs | >100 days (control) | None |

| Allogeneic Tregs (Mismatched) | 24 - 27 days | None |

| HLA-Matched Tregs | >100 days | None |

| HLA-E KI / CIITA KO Tregs | Prolonged, comparable to autologous Tregs | B2M KO, HLA-E fusion knock-in, CIITA KO |

Table 2: Survival of Engineered Cells in Allogeneic Hosts Post-Transplantation [22] [23]

| Host Immune Cell Type | Effect on Unmodified Allogeneic Cells | Proposed Engineering Strategy to Evade Rejection | Outcome of Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host CD8+ T cells | Swift elimination via HLA mismatch | B2M KO or HLA-ABC-specific shRNA | Significant reduction in T-cell-mediated killing; improved cell persistence |

| Host NK cells | Elimination via "missing-self" recognition | HLA-E overexpression or HLA-E-B2M fusion knock-in | Protection from NK cell lysis; retained inhibition via NKG2A |

| Host Macrophages | Phagocytosis via SIRPα receptor | CD47 overexpression | Reduced phagocytosis; prolonged circulation time |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Multiplex CRISPR-Cas9 Editing for Generation of Hypo-immunogenic Tregs [22]

This protocol describes the generation of HLA class I/II deficient Tregs that incorporate an NK-inhibitory signal.

- Cell Isolation and Activation: Isolate CD4+CD25+ Tregs from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of healthy donors using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS). Activate the Tregs using anti-CD3/CD28 beads in the presence of IL-2.

- Electroporation with CRISPR RNP: On day 2-3 post-activation, electroporate Tregs with CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes.

- Target 1: B2M KO and HLA-E Knock-in: Use a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting the B2M gene, co-electroporated with a donor template plasmid containing an HLA-E-B2M fusion gene designed to integrate into the B2M locus via homology-directed repair (HDR).

- Target 2: CIITA KO: Use an sgRNA targeting the CIITA gene. This can be done concurrently or in a second editing step.

- Expansion and Validation: Culture the edited Tregs in expansion medium with IL-2 for 10-14 days.

- Validation of Editing: Use flow cytometry to confirm the loss of HLA class I (using an anti-HLA-ABC antibody) and HLA class II (using an anti-HLA-DR/DP/DQ antibody) surface expression. Verify HLA-E expression using a specific antibody.

- Functional Assay: Perform an in vitro suppression assay to confirm retained Treg function.

Protocol 2: One-Step Lentiviral Engineering of HLA-ABC-Knockdown CAR-NK Cells [23]

This protocol creates allogeneic CAR-NK cells resistant to T and NK cell attack using a single lentiviral vector.

- Lentiviral Vector Design: Construct a lentiviral vector encoding:

- A CAR transgene (e.g., anti-CD19 CAR).

- An shRNA (e.g., shRNA #1) under a U6 promoter for selective knockdown of HLA-A, -B, and -C.

- An immune checkpoint protein (e.g., PD-L1 or a single-chain HLA-E) linked via a P2A or T2A self-cleaving peptide.

- NK Cell Transduction: Isolve NK cells from donor PBMCs or use a cell line. Activate NK cells with IL-2 and IL-15. Transduce the activated NK cells with the lentiviral vector by spinfection.

- Expansion and Selection: Culture transduced NK cells in medium containing IL-2 and IL-15 for 10-14 days to allow expansion and transgene expression. If the vector contains a selection marker (e.g., puromycin resistance), apply selection pressure to enrich for transduced cells. Alternatively, sort cells based on a reporter gene (e.g., GFP).

- Validation:

- Phenotyping: Confirm CAR expression, reduced HLA-ABC expression, and increased PD-L1/SCE expression via flow cytometry.

- Cytotoxicity Assay: Validate anti-tumor function in a standard chromium-51 or luciferase-based killing assay against target tumor cells.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

CRISPR-Cas9 HLA Engineering Workflow

shRNA HLA Knockdown & CAR Engineering

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for HLA Ablation Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function in HLA Ablation Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Enables precise knockout of HLA-related genes (e.g., B2M, CIITA). | Disruption of B2M to eliminate surface HLA class I expression [22]. |

| Adenine Base Editor (ABE) | Allows precise single nucleotide changes without double-strand breaks; can be used to disrupt gene function. | Silencing of CIITA to ablate HLA class II expression [22]. |

| HLA-E-B2M Fusion Donor Template | A DNA template for HDR; replaces the endogenous B2M gene to express a non-polymorphic HLA-E fusion protein. | Knocked into the B2M locus to inhibit NK cells while avoiding T cell recognition [22]. |

| Lentiviral Vector with shRNA | Delivers genetic material for stable expression of CAR, shRNA, and other transgenes. | One-step generation of CAR-NK cells with shRNA-mediated HLA-ABC knockdown [23]. |

| Anti-HLA-ABC Antibody | Validates successful knockdown or knockout of HLA class I molecules. | Flow cytometry analysis of surface HLA-ABC post-editing [22] [23]. |

| Anti-HLA-DR/DP/DQ Antibody | Validates successful knockdown or knockout of HLA class II molecules. | Flow cytometry analysis of surface HLA class II post-CIITA editing [22]. |

| Recombinant IL-2 | Critical cytokine for the ex vivo expansion and survival of T cells, including Tregs. | Culture and expansion of edited Tregs [22]. |

A major frontier in regenerative medicine and allogeneic stem cell transplantation is overcoming the formidable challenge of immune rejection. The immune system is exceptionally skilled at distinguishing between self and non-self, leading to the rejection of transplanted allogeneic cells through multiple immune mechanisms [25]. These include recognition of highly polymorphic Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLAs), minor histocompatibility antigens (miHA), and newly acquired neoantigens (NA) that can arise during cell culture and differentiation [25].

To address this critical barrier, researchers are developing sophisticated "immune editing" strategies that armor therapeutic cells to evade immune detection. This technical support center focuses on three key immune checkpoint molecules—CD47, HLA-G, and PD-L1—that can be overexpressed to protect allogeneic cells. These strategies aim to create "hypoimmune" or "immune-evasive" cell products that can survive and function in allogeneic recipients without requiring broad immunosuppression, thereby enabling the development of scalable off-the-shelf cell therapies [26] [27].

Key Signaling Pathways and Their Experimental Evidence

Comparative Analysis of Checkpoint Overexpression Strategies

Different immune checkpoint overexpression strategies target distinct components of the immune system. The table below summarizes the function, mechanism, and experimental evidence for CD47, HLA-G, and PD-L1.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Immune Checkpoint Overexpression Strategies

| Checkpoint Molecule | Primary Function | Immune Mechanism Targeted | Key Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD47 | "Don't eat me" signal [28] | Innate immunity (macrophages, NK cells) [27] | HIP iPSCs survived 16 weeks in immunocompetent allogeneic rhesus macaques; CD47 protected HLA-deficient cells from NK cell killing [27]. |

| PD-L1 | T-cell inhibitory signal [29] | Adaptive immunity (T cells) [29] | Combined expression with CTLA4-Ig protected hESC-derived teratomas, fibroblasts, and cardiomyocytes from rejection in humanized mice [29]. |

| HLA-G | Tolerogenic HLA signal [27] | Both innate and adaptive immunity (NK cells, T cells) [27] | Engineered expression on K562 cells protected from ILT2+ NK cells but was ineffective against CD94+ NK cells, showing incomplete protection [27]. |

Quantitative Data from Pre-Clinical Models

The efficacy of combining these strategies has been quantified in several rigorous pre-clinical models, demonstrating significant improvements in cell survival.

Table 2: Quantitative Survival Outcomes of Engineered Cells in Pre-Clinical Models

| Cell Type | Engineering Strategy | Model System | Survival Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human iPSCs | B2M⁻/⁻ CIITA⁻/⁻ CD47⁺ (HIP) | Immunocompetent allogeneic rhesus macaques | Unrestricted survival for 16 weeks [27] | |

| Rhesus macaque primary islets | HIP editing (B2M⁻/⁻ CIITA⁻/⁻ CD47⁺) | Allogeneic rhesus macaque | Survival for 40 weeks without immunosuppression [27] | |

| Human ESC-derived cells | CTLA4-Ig + PD-L1 knock-in | Humanized mice (Hu-mice) | Effective protection of teratomas, fibroblasts, and cardiomyocytes from allogeneic rejection [29] | |

| Human HIP pancreatic islet cells | B2M⁻/⁻ CIITA⁻/⁻ CD47⁺ | Immunocompetent, allogeneic diabetic humanized mice | Survival for 4 weeks and amelioration of diabetes [27] |

Visualizing the Immune Checkpoint Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate how these overexpressed checkpoint molecules interact with immune cell receptors to suppress rejection.

CD47-SIRPα "Don't Eat Me" Signaling Pathway

Diagram 1: CD47-SIRPα Innate Immune Checkpoint. This diagram shows how donor cell surface CD47 binding to macrophage SIRPα receptors transmits an inhibitory signal that blocks phagocytosis [28] [27].

PD-L1/PD-1 T-Cell Inhibitory Signaling Pathway

Diagram 2: PD-L1/PD-1 Adaptive Immune Checkpoint. This shows how donor cell PD-L1 binding to T-cell PD-1 receptors inhibits T-cell activation and cytotoxic killing, a key adaptive immune evasion pathway [29] [30].

Integrated Hypoimmune Cell Engineering Strategy

Diagram 3: Integrated Hypoimmune Cell Engineering. A combined strategy shows that deleting HLA molecules prevents T-cell recognition via the missing MHC, while simultaneously overexpressing CD47 and/or PD-L1 provides active inhibition of innate and adaptive immunity [25] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Immune Checkpoint Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Example Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Gene knockout (e.g., B2M, CIITA) [25] | Creation of HLA class I/II deficient base lines in iPSCs [27] | Enables precise, permanent gene inactivation. Off-target effects must be assessed. |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Stable transgene overexpression (e.g., CD47, PD-L1) [27] | Constitutive expression of immune checkpoint modulators in stem cells and their derivatives. | Ensures transgene is passed to all progeny cells. Requires careful design to avoid insertional mutagenesis. |

| Bispecific Antibodies | Dual targeting of checkpoints (e.g., PD-L1 x CD47) [28] [31] | In vitro and in vivo validation of combined pathway blockade; potential therapeutic agent. | Affinity tuning is critical to minimize on-target, off-tumor toxicity (e.g., RBC binding). |

| Humanized Mouse Models (Hu-mice) | In vivo assessment of human immune rejection [29] [27] | Testing survival and immunogenicity of engineered human cell grafts in a functional human immune system. | Model must be robustly reconstituted with human immune cells for predictive results. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating Hypoimmune Pluripotent Stem Cells (HIP)

This protocol outlines the creation of a hypoimmune pluripotent stem cell line via combined gene knockout and overexpression, a foundational methodology in the field [27].

- Design gRNAs and Donor Template: Design CRISPR-Cas9 gRNAs targeting the B2M and CIITA genes to disrupt HLA class I and class II expression, respectively. Simultaneously, design a donor vector for the constitutive overexpression of CD47 (e.g., using a CAG or EF1α promoter).

- Stem Cell Transfection/Transduction: Co-transfect iPSCs with the CRISPR constructs and the CD47 donor vector. This can be achieved via electroporation or nucleofection.

- Single-Cell Cloning and Selection: Plate transfected cells at a very low density to derive single-cell clones. Expand individual clones.

- Genotypic Validation: Screen clones for successful B2M and CIITA knockout using sequencing (e.g., Sanger or NGS). Confirm the site-specific integration and expression of the CD47 transgene via PCR and flow cytometry.

- Phenotypic Validation (Flow Cytometry): Confirm the loss of HLA class I (using a pan-HLA class I antibody) and HLA class II (e.g., HLA-DR) surface expression. Confirm high surface expression of CD47.

- Functional Validation (In Vitro Assay): Co-culture engineered HIP cells with activated human natural killer (NK) cells from an allogeneic donor. Measure cell killing using real-time impedance assays (e.g., xCelligence) or flow cytometry-based cytotoxicity assays. Successful engineering should result in significant protection from NK cell killing.

Protocol 2: In Vivo Teratoma Formation Assay in Humanized Mice

This protocol is used to test the immune evasion capability of engineered stem cells and their differentiated progeny in a model with a functional human immune system [29].

- Prepare Humanized Mouse (Hu-mouse) Recipients: Reconstitute immunodeficient NSG or similar mice with a human immune system. Common methods include co-implantation of human fetal thymus tissue and fetal liver-derived CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (the BLT model) or injection of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) [29].

- Validate Immune Reconstitution: After 12-16 weeks, bleed the mice and use flow cytometry to confirm robust engraftment of human T cells, B cells, and other immune cell populations.

- Cell Transplantation: Harvest the engineered hPSCs (or their differentiated progeny) into a single-cell suspension. Subcutaneously inject a defined number of cells (e.g., 1-10 million) into the flank of the Hu-mice. The contralateral flank can be injected with wild-type control cells from the same genetic background as an internal control.

- Monitor Graft Survival: Monitor teratoma or graft formation weekly by palpation and caliper measurement. For cells engineered with a luciferase reporter, use bioluminescence imaging (BLI) to quantitatively track viable cell mass over time.

- Endpoint Analysis: After 4-8 weeks, harvest the teratomas/grafts. Compare the size, weight, and viable cell mass (via BLI) of experimental versus control grafts. Perform histological analysis to assess differentiation and immune cell infiltration (e.g., by H&E staining and immunohistochemistry for human CD45+ immune cells).

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is CD47 overexpression favored over HLA-G or PD-L1 alone for protecting HLA-deficient cells from innate immunity?

Answer: Comprehensive in vitro and in vivo studies comparing these strategies have shown that CD47 provides more robust protection. HLA-G only protects from the subset of NK cells expressing its specific receptor (ILT2), and PD-L1 only protects from PD-1+ NK cells, which are a minor population. In contrast, SIRPα, the receptor for CD47, is expressed on almost all macrophages and a majority of activated NK cells. Engineered cells overexpressing CD47 were comprehensively protected from killing by all NK cell subsets, whereas HLA-G and PD-L1 provided only partial protection [27].

FAQ 2: My HIP-edited cells are still being rejected in the Hu-mouse model. What could be the cause?

Answer: Consider these potential issues and troubleshooting steps:

- Incomplete HLA Knockout: Verify at the protein level that HLA class I and II are completely absent from your final differentiated cell product, as their expression can change during differentiation [25].

- Species-Specific CD47-SIRPα Interaction: The CD47-SIRPα interaction is species-specific. If using human cells in a mouse model reconstituted with a mouse immune system, you must use a CD47 transgene matching the recipient species (e.g., macaque CD47 for rhesus models) [27].

- Antibody-Mediated Rejection: While HIP editing removes major targets for donor-specific antibodies, check for pre-existing antibodies against other antigens. Ensure your HIP strategy includes broad disruption of HLA to prevent antibody binding [25].

- Insufficient CD47 Expression Levels: Quantify CD47 surface expression. There may be a threshold required for effective "don't eat me" signaling that your cells have not achieved.

FAQ 3: What are the primary safety concerns associated with overexpressing immune checkpoints like CD47 and PD-L1 in cell therapies?

Answer: The main concern is the potential for the engineered cells to evade immune surveillance in a way that could lead to tumorigenesis. If a pluripotent stem cell contaminates the final therapeutic product, its unchecked growth could form a teratoma that the immune system cannot clear. Furthermore, if the therapeutic cells themselves were to undergo malignant transformation, they might be shielded from anti-tumor immunity. Rigorous testing for residual undifferentiated cells and long-term follow-up in pre-clinical models are essential to quantify this risk [27]. For systemic therapies using bispecific antibodies targeting CD47, a major concern is hematological toxicity, such as anemia and thrombocytopenia, due to CD47's expression on red blood cells and platelets [28] [31]. This is often addressed by engineering lower affinity for CD47.

FAQ 4: Can I use a single immune checkpoint inhibitor, like anti-PD-L1, to protect my allogeneic graft?

Answer: Evidence suggests that single-agent checkpoint inhibition is often insufficient to prevent allograft rejection. Research in humanized mouse models demonstrated that combined expression of CTLA4-Ig and PD-L1 was required to protect hESC-derived cells; neither molecule was sufficient on its own [29]. The immune system has multiple redundant pathways for rejecting foreign cells. A successful strategy likely requires a multi-pronged approach that simultaneously addresses T-cell co-stimulation (e.g., via CTLA4-Ig), T-cell inhibition (e.g., via PD-L1), and innate immune cell clearance (e.g., via CD47) [25] [29].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

This guide addresses specific issues you might encounter while developing universal donor cells through multiplexed gene editing.

Table: Common Problems and Solutions in Gene Editing Experiments

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low editing efficiency [32] | Low transfection efficiency; difficult-to-edit locus. | Optimize transfection protocol; use antibiotic selection or FACS to enrich transfected cells [32]. |

| High off-target effects [32] | crRNA with homology to other genomic regions. | Carefully design crRNA target oligos to avoid off-target homology [32]. |

| No cleavage detected [32] | PAM site unavailable; nucleases cannot access target. | Design a new targeting strategy for a nearby sequence; use TAL effector-based nuclease as an alternative [32]. |

| No PCR product in cleavage detection [32] | Poor PCR primer design; GC-rich region. | Redesign primers (18–22 bp, 45–60% GC content, Tm 52–58°C); add GC Enhancer for GC-rich regions [32]. |

| Smear on cleavage detection gel [32] | Lysate is too concentrated. | Dilute the lysate 2- to 4-fold and repeat the PCR reaction [32]. |

| Immune escape after transplantation [33] | Activation of NK cell "missing-self" response due to absent HLA class I. | Co-express non-classical HLA molecules (e.g., HLA-E, HLA-G) to inhibit NK cell cytotoxicity [33] [34]. |

| Tumor formation from residual undifferentiated cells [33] | Persistence of pluripotent stem cells in the final product. | Implement safety mechanisms (e.g., suicide genes) to enable inactivation or removal of donor cells if needed [33]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary genetic targets for creating hypoimmunogenic pluripotent stem cells? The primary targets are genes within the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC). A common and effective strategy is the knockout of Beta-2 microglobulin (B2M), which is essential for the surface expression of all HLA class I molecules, thereby evading CD8+ T cell recognition [33] [25] [34]. To address the subsequent vulnerability to Natural Killer (NK) cell attack, a key strategy is the co-expression of non-classical HLA molecules like HLA-E or HLA-G [33] [34]. Furthermore, eliminating Class II Major Histocompatibility Complex Transactivator (CIITA) prevents the expression of HLA class II molecules, helping to evade CD4+ T cell responses [33] [34].

Q2: Our B2M-knockout cells are being rejected in vivo. What immune cells are likely responsible and how can we prevent this? This rejection is likely mediated by Natural Killer (NK) cells through the "missing-self" response [33] [35]. While B2M knockout removes the ligand for T-cell receptors, it also removes the ligands for inhibitory receptors on NK cells. To overcome this, engineer your cells to express HLA-E or HLA-G. These non-classical HLA molecules bind to inhibitory receptors (e.g., CD94/NKG2A) on NK cells and effectively suppress their cytotoxic activity [33] [34]. A proven method is the targeted knock-in of an HLA-E trimer at the B2M genomic locus, which simultaneously abolishes classical HLA expression and provides NK cell inhibition [34].

Q3: How can I improve the efficiency of my CRISPR/Cas9 editing in stem cells? Several parameters can be optimized:

- Enrich for Transfected Cells: Introduce antibiotic resistance genes alongside your CRISPR constructs and apply selection pressure. Alternatively, use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) if a fluorescent marker is co-expressed [32].

- Verify Oligonucleotide Design: For cloning into CRISPR vectors, ensure your single-stranded oligonucleotides contain the correct 5' or 3' nucleotide overhangs required by your specific kit (e.g.,

GTTTTon the 3' end for the top strand in some systems) [32]. - Handle Reagents Properly: Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of annealed oligonucleotides by creating aliquots and storing them at -20°C in an appropriate buffer [32].

Q4: What are the critical quality controls for a newly generated universal donor stem cell line? Beyond standard checks for pluripotency and karyotype, specific quality controls for hypoimmunogenic lines include:

- Genomic Quality Control: Perform rigorous sequencing to screen for and discard clones with undesired on-target or off-target mutations [34].

- Immune Evasion Verification:

- Use flow cytometry to confirm the absence of surface HLA class I and II molecules.

- Demonstrate resistance to allogeneic CD8+ T cell-mediated killing in co-culture assays [33].

- Demonstrate resistance to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity in co-culture assays, especially if HLA-E/G are expressed [33] [34].

- Functional Differentiation: Confirm that the edited cell line can differentiate normally into your desired therapeutic cell type (e.g., neural, cardiac) [34].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multiplexed KO of B2M and CIITA with HLA-E Knock-in

Objective: To generate a hypoimmunogenic hPSC line lacking T cell recognition (via B2M and CIITA KO) and protected from NK cells (via HLA-E knock-in).

Materials:

- Cell Line: Human ESCs or iPSCs.

- CRISPR System: Cas9 nuclease (mRNA or protein).

- Guide RNAs (gRNAs): Designed for B2M, CIITA, and for a safe harbor locus (e.g., AAVS1) or the B2M locus itself for knock-in.

- Repair Template: Donor vector containing a β2M-HLA-E single-chain trimer fusion gene, flanked by homology arms [33] [34].

- Transfection Reagent: Optimized for your stem cell line (e.g., Lipofectamine 3000).

- Selection Agent: Appropriate antibiotic if the repair template contains a resistance gene.

Methodology:

- Design and Preparation: Design high-efficiency gRNAs for B2M and CIITA. Clone the β2M-HLA-E fusion construct into a donor vector with homology arms.

- Transfection: Co-transfect the stem cells with the Cas9/gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for B2M, CIITA, and the donor vector.

- Selection and Cloning: Apply antibiotic selection (if applicable) 48-72 hours post-transfection. Manually pick single-cell-derived clones and expand them.

- Genotyping:

- Use PCR and sequencing to confirm biallelic knockout of B2M and CIITA.

- Use junction PCR and sequencing to verify targeted integration of the HLA-E trimer at the intended locus.

- Phenotypic Validation:

- Perform flow cytometry to confirm loss of surface HLA class I (using an antibody like W6/32) and HLA class II.

- Use a specific antibody to confirm surface expression of the HLA-E trimer [34].

- Functional Validation:

- Differentiate the edited clones and conduct in vitro immune cell co-culture assays with allogeneic CD8+ T cells and NK cells to demonstrate evasion of immune rejection [33].

Protocol 2: In Vitro Immune Cell Co-culture Assay

Objective: To quantitatively assess the survival of gene-edited hypoimmunogenic cells when confronted with allogeneic immune cells.

Materials:

- Target Cells: Differentiated progeny of your edited and control (unmodified) stem cells.

- Effector Cells: Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) from an allogeneic donor, or isolated CD8+ T cells and NK cells.

- Assay Plate: 96-well plate.

- Viability Assay: Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) release kit, or a flow cytometry-based assay using Annexin V/propidium iodide.

Methodology:

- Seed Target Cells: Plate differentiated target cells and allow them to adhere.

- Co-culture: Add allogeneic PBMCs or isolated immune cells at various effector-to-target (E:T) ratios.

- Incubate: Co-culture for 24-48 hours.

- Measure Cytotoxicity:

- LDH Assay: Measure the LDH enzyme released from the cytosol of damaged cells into the supernatant.

- Flow Cytometry: Harvest and stain cells to distinguish live, apoptotic, and dead target cells.

- Analysis: Calculate the percentage of specific lysis. Successful editing is indicated by significantly reduced lysis in edited cells compared to unmodified controls across all E:T ratios [35].

Key Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram: Strategies for Generating Universal Donor Cells

Diagram: Immune Recognition and Evasion Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Hypoimmunogenic Cell Generation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Precision genome editing for knocking out genes like B2M and CIITA [25]. | Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants to minimize off-target effects. RNP transfection is often highly efficient. |

| TALENs | Transcription activator-like effector nucleases; an alternative genome editing tool [32]. | Can be used when PAM sites for CRISPR are unavailable [32]. |

| HLA-E Single-Chain Trimer Donor Vector | Repair template for knock-in to confer NK cell resistance [34]. | Ensure the vector includes homology arms for the target locus (e.g., B2M) and a selectable marker. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Validation of surface protein expression (e.g., anti-HLA-ABC, anti-HLA-DR, anti-HLA-E). | Critical for confirming the knockout of immunogenic HLAs and expression of inhibitory HLAs. |

| In Vitro Immune Assay Kits (e.g., LDH Cytotoxicity) | Quantitative measurement of immune cell-mediated killing of edited cells [35]. | Perform with allogeneic PBMCs or purified immune cells at multiple effector-to-target ratios. |

| PureLink HQ Mini Plasmid Purification Kit | High-quality plasmid DNA preparation for sequencing or transfection [32]. | Using high-quality DNA is crucial for successful sequencing reactions and transfection efficiency. |

Core Concepts: Understanding the New Paradigm

This section answers fundamental questions about the purpose and components of these novel conditioning treatments.

FAQ: What is the primary goal of using non-genotoxic conditioning agents in allogeneic transplantation? The primary goal is to eliminate the need for traditional, DNA-damaging chemotherapy and radiation (genotoxic conditioning) that carries significant risks, including secondary malignancies, infections, and organ toxicity. Non-genotoxic conditioning aims to achieve targeted immunosuppression and create "space" for donor stem cell engraftment through highly specific mechanisms, thereby improving the safety profile of allogeneic stem cell transplantation [36] [37] [26].

FAQ: What are the key biological targets for these novel conditioning agents? The most advanced strategies focus on two key targets:

- CD117 (c-Kit): A receptor tyrosine kinase highly expressed on hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Depleting host HSCs with a CD117-targeting antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) creates a niche for donor HSC engraftment without genotoxicity [36] [37].

- TRBV9+ T Cells: A specific T-cell receptor beta variable gene segment identified as a driver in certain autoimmune diseases like ankylosing spondylitis. Targeted depletion of this T-cell subset can eliminate pathologic immune cells without causing broad immunosuppression [38].

FAQ: How does targeted T-cell depletion differ from traditional T-cell depletion? Traditional T-cell depletion is a broad, non-selective removal of all T-cells from a graft (pan-TCD) to prevent Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD). While effective at reducing GvHD, it increases risks of graft failure and disease relapse due to the loss of beneficial graft-versus-leukemia effects. In contrast, targeted T-cell depletion aims to remove only specific, disease-causing T-cell clones (e.g., TRBV9+ or PD-1+ alloreactive cells), preserving the broader T-cell repertoire to fight infection and cancer [39] [38] [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

This section provides solutions to common experimental and clinical challenges.

Challenge: Poor Donor Cell Engraftment

Problem: Despite conditioning, donor hematopoietic stem cells fail to engraft or show low-level, transient chimerism.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient host HSC clearance | Analyze bone marrow for residual host CD117+ HSCs post-conditioning. | Increase dose of CD117-ADC; combine with transient immunosuppression (e.g., anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD154 mAbs) [37]. |

| Resistant host immunity | Monitor T-cell chimerism; check for alloreactive T-cells. | Add short-course immunosuppressants (e.g., rapamycin) or target alloreactive T-cells (e.g., anti-PD-1 depletion) [37] [41]. |

| Inadequate cell dose | Quantify the number of donor HSCs infused. | Ensure transplanted cell dose is sufficient (>20 million total bone marrow cells in mouse models) [37]. |

Challenge: Disease Relapse or Autoimmune Symptom Return

Problem: Following initial successful treatment, the underlying malignancy or autoimmune pathology recurs.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|