Overcoming Immune Rejection in Stem Cell Therapies: From Foundational Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

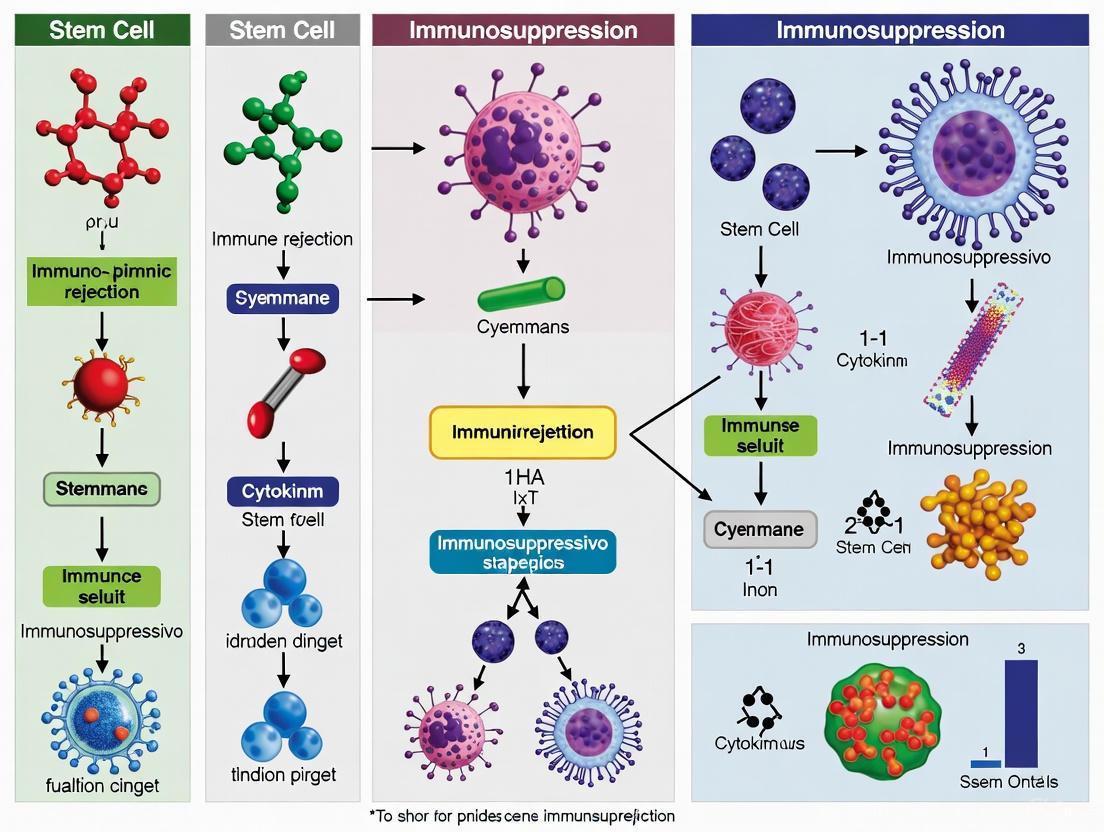

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the immunological barriers and evolving immunosuppression strategies in stem cell-based therapies.

Overcoming Immune Rejection in Stem Cell Therapies: From Foundational Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the immunological barriers and evolving immunosuppression strategies in stem cell-based therapies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational science on innate and adaptive immune drivers of graft rejection with cutting-edge methodological advances in genetic engineering and cell-based tolerance induction. The content explores troubleshooting for safety and optimization challenges, validates approaches through recent clinical trial data and comparative efficacy analyses, and outlines a translational roadmap for enhancing the survival and functional integration of regenerative cellular products.

The Immune Battlefield: Foundational Mechanisms of Stem Cell Graft Rejection

FAQ: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: In our mouse model of stem cell transplantation, we observe unexpected graft loss even with MHC-matched donors. What innate immune mechanisms could be responsible?

Unexpected graft loss in MHC-matched scenarios can often be attributed to innate immune triggers outside classical adaptive recognition pathways. Key players include:

- NK Cell "Missing-Self" Recognition: NK cells can become activated if the graft lacks host inhibitory MHC class I molecules, a scenario possible even with some MHC matching. This is mediated through killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) in humans and Ly49 receptors in mice. Educated NK cells, which have undergone maturation in the presence of self-MHC, are particularly responsive to this missing self, leading to graft injury through direct cytotoxicity and IFN-γ secretion [1].

- Complement System Activation: The complement cascade can be activated by ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) inherent to the transplantation process. DAMPs released from stressed or dying graft cells can trigger the lectin pathway, while natural antibodies may activate the classical pathway, even in the absence of high-titer donor-specific antibodies [2] [3]. The anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a generated during this process recruit and activate innate immune cells, exacerbating inflammation.

- Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC): The presence of low-level, pre-existing antibodies, potentially against non-HLA antigens, can bind to the graft. NK cells, via their FcγRIIIA (CD16) receptor, then recognize these antibody-coated cells and mediate ADCC, contributing to graft damage [1].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Experimental Check: Analyze your graft for the expression of ligands for NK cell activating receptors (e.g., MICA/B, ULBPs). Their upregulation under cellular stress can trigger NK cells independently of MHC.

- Model Validation: Confirm the specific MHC matching in your model. Use NK cell-depleting antibodies (e.g., anti-NK1.1, anti-asialo GM1) or complement inhibitors (e.g., C3aR/C5aR antagonists, soluble CR1) to test the functional role of these pathways.

- Readout Expansion: Beyond graft survival, include histology for NK cell infiltration (e.g., NKp46 staining) and complement deposition (e.g., C4d, C3d staining) to identify the involved mechanism.

FAQ 2: Our data on NK cells in graft rejection seem contradictory, with some studies showing a pro-tolerogenic role. How can we explain this duality?

NK cell function in transplantation is highly plastic and context-dependent, which explains apparent contradictions. Their role is dictated by a balance of signals and specific interactions.

- Checkpoint 1: Interaction with Donor Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs): A pivotal "checkpoint" is the early interaction between host NK cells and donor dendritic cells (DCs). If donor DCs are perceived as "missing self," NK cells can eliminate them via perforin-mediated killing. This reduces direct allorecognition by T-cells and can divert the immune response toward indirect presentation, which in some contexts promotes tolerance [4] [5].

- Checkpoint 2: Interaction with Host APCs: Conversely, NK cells can also license host DCs, enhancing their maturation and ability to prime alloreactive T-cells, thereby promoting rejection [4].

- Checkpoint 3: Direct Interaction with T-cells: NK cells can directly enhance T-cell responses via cytokine production (e.g., IFN-γ) or, alternatively, suppress them through direct killing of activated T-cells or secretion of immunoregulatory cytokines like IL-10 [4].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Timing is Critical: The net effect of NK cells can depend on the timing of their activation. Analyze their phenotype and function at different post-transplant periods (e.g., early vs. late).

- Microenvironment Matters: The cytokine milieu (e.g., levels of IL-15, IL-12, IL-18, TGF-β) can skew NK cell function. Profile the local cytokine environment in your graft.

- Define the Subset: Do not treat NK cells as a uniform population. Characterize the subsets involved (e.g., CD56bright vs. CD56dim in humans; CD27+ vs. CD11b+ in mice) as they have divergent functions.

FAQ 3: What are the primary experimental methods to differentiate between complement-mediated and NK cell-mediated damage in vivo?

Disentangling these pathways requires a combination of genetic, pharmacological, and analytical tools.

- Table 1: Key Experimental Approaches for Differentiating Innate Immune Pathways

Target Pathway Experimental Method Key Reagents / Models Readouts & Measurements NK Cell Activity Cell Depletion Anti-NK1.1 (mice), anti-asialo GM1 (mice/rats) Graft survival, histology for cytotoxicity, IFN-γ ELISpot Functional Blockade Anti-NKG2D, anti-CD16 (FcγRIII), anti-KIR antibodies Cytokine production, donor cell lysis in co-culture assays Genetic Models β2-microglobulin deficient grafts (lacks MHC I, "missing-self") Graft rejection kinetics, NK cell infiltration by flow cytometry Complement Activity Inhibitors C1-inhibitor, C3aR/C5aR antagonists, Cobra Venom Factor (CVF) Graft function, C3/C5a levels by ELISA, C4d deposition by IHC Genetic Models C3 knockout mice, Factor B knockout (blocks alternative pathway) Serum creatine (kidney), transaminases (liver), histology Integrated Analysis Multiplex Imaging Immunofluorescence (IF) for NKp46+ cells & C4d+ areas Spatial relationship between NK cells and complement deposition Transcriptomics RNA-seq of graft tissue Gene expression signatures for NK cell and complement pathways

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Specificity of Depletion/Inhibition: Always confirm the efficacy and specificity of your depletion/inhibition strategy. For example, ensure that anti-NK1.1 does not deplete NKT cells in your model.

- Combination Studies: To test for synergistic or additive effects, perform experiments combining NK cell depletion with complement inhibition.

- Functional Assays: Move beyond descriptive data. Use in vivo cytotoxicity assays to measure NK cell function and measure complement activation products (C3a, C5a, SC5b-9) in serum or graft tissue to confirm pathway engagement.

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Assessing NK Cell Cytotoxicity Against Donor Cells via In Vivo Rejection Assay

This protocol measures the ability of host NK cells to eliminate "missing self" target cells in vivo [1].

- Target Cell Preparation: Isolate splenocytes from a donor mouse strain that is MHC class I-deficient (e.g., β2m-/-) or has a specific MHC mismatch with the recipient. Label these cells with a high concentration of CFSE (e.g., 5 µM, CFSEhigh).

- Control Cell Preparation: Isolate splenocytes from a syngeneic host-type mouse. Label these cells with a low concentration of CFSE (e.g., 0.5 µM, CFSElow).

- Cell Injection: Mix the two populations at a 1:1 ratio and inject intravenously into the recipient mouse that has been transplanted or is undergoing a transplant experiment.

- NK Cell Depletion Control: In a parallel group of recipients, deplete NK cells using an appropriate antibody (e.g., anti-NK1.1) prior to target cell injection.

- Analysis: After 16-20 hours, harvest the recipient's spleen and analyze by flow cytometry. The ratio of CFSEhigh (donor) to CFSElow (host) cells is calculated. Specific rejection is indicated by a reduced donor-to-host ratio in the control group compared to the NK-depleted group.

Key Reagent Solutions:

- CFSE (Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester): A cell-permanent fluorescent dye for tracking cell division and fate.

- Anti-NK1.1 Antibody (PK136): For specific depletion of NK cells in C57BL/6 mice.

- β2-microglobulin deficient mice: A model to provide "missing self" target cells.

Protocol 2: Measuring Complement Activation in Graft Tissue by C4d Immunohistochemistry

C4d deposition is a stable marker of classical and lectin pathway activation and is a key diagnostic feature in antibody-mediated rejection [2] [1].

- Tissue Fixation and Sectioning: Fix graft tissue in formalin and embed in paraffin. Section at 4-5 µm thickness.

- Deparaffinization and Antigen Retrieval: Deparaffinize sections in xylene and rehydrate through a graded ethanol series. Perform heat-induced epitope retrieval using a citrate-based or EDTA-based buffer (pH 6.0 or 9.0) appropriate for your anti-C4d antibody.

- Blocking and Staining:

- Block endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% H₂O₂.

- Block non-specific binding with 10% normal serum from the species of your secondary antibody.

- Incubate with primary anti-C4d antibody (monoclonal or polyclonal) at the manufacturer's recommended dilution overnight at 4°C.

- Incubate with a biotinylated secondary antibody followed by an avidin-biotin-enzyme complex (ABC).

- Detection and Counterstaining:

- Develop the signal with 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate, which produces a brown precipitate.

- Counterstain with hematoxylin to visualize nuclei.

- Scoring: Analyze staining under a light microscope. C4d deposition is typically scored as positive when there is linear, diffuse staining along capillary endothelial cells. Scoring can be semi-quantitative (e.g., 0 to 3+) or based on the percentage of positive capillaries.

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Anti-C4d Antibody: Specific antibody for detecting the C4d fragment.

- ABC Kit (Avidin-Biotin Complex): A high-sensitivity detection system for immunohistochemistry.

- DAB Substrate Kit: A chromogen for producing a visible, insoluble reaction product.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: NK Cell Activation in Graft Recognition

Diagram 2: Complement Activation in Transplantation

Diagram 3: Experimental Workflow for Differentiating Innate Immune Damage

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

- Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Innate Immunity in Transplantation

Reagent / Model Category Primary Function in Experiments Anti-NK1.1 (PK136) Antibody Biological Tool Depletes NK cells in vivo in C57BL/6 mice to test their functional role. Anti-Asialo GM1 Antiserum Biological Tool Depletes NK cells and some T-cell subsets in vivo in various rodent models. Cobra Venom Factor (CVF) Biological Tool A potent and transient decomplementing agent that depletes C3, used to study the role of complement. C3a Receptor Antagonist (SB 290157) Pharmacological Inhibitor Specifically blocks the C3a-C3aR signaling axis, mitigating anaphylatoxin-mediated inflammation. β2-microglobulin KO Mice Genetic Model Provides grafts or cells that lack MHC class I, creating a "missing-self" scenario for NK cell studies. C3 Knockout Mice Genetic Model Allows for the study of transplantation in the absence of the central complement component C3. Recombinant Human IL-15 Cytokine Used to expand and activate NK cells in vitro and in vivo. Anti-C4d Antibody Analytical Reagent Critical for detecting classical/lectin pathway complement activation in graft tissue via IHC. Anti-NKG2D Blocking Antibody Biological Tool Inhibits a major NK cell activating receptor, used to test its contribution to rejection. Factor B Knockout Mice Genetic Model Specifically blocks the alternative pathway of complement activation.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: T-Cell Allorecognition Pathways

Q1: In our mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) assay, we observe unexpectedly high T-cell proliferation even with matched HLA-DR. Which allorecognition pathway is likely responsible and how can we confirm this?

A1: The semi-direct allorecognition pathway is the most probable cause. Donor antigen-presenting cells (APCs) can transfer intact Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules to recipient APCs via trogocytosis or exosomes, enabling recipient T-cells to see donor MHC peptides presented by self-MHC. To confirm:

- Perform an MLR using purified CD4+ T-cells as responders and recipient-derived, donor peptide-pulsed dendritic cells as stimulators.

- Use flow cytometry to detect the presence of donor MHC molecules on recipient APCs using specific antibodies.

- Employ transwell assays to physically separate cell populations and quantify cross-talk.

Q2: Our immunosuppressive drug effectively inhibits the direct pathway but graft rejection still occurs. What experimental approach can identify if the indirect pathway is active?

A2: This indicates a likely failure to control the indirect pathway. To investigate:

- ELISPOT Assay: Measure the frequency of recipient T-cells producing IFN-γ in response to donor-derived MHC peptides.

- Tetramer Staining: Use MHC class II tetramers loaded with donor-derived MHC peptides to identify and quantify T-cell clones specific for these indirectly presented antigens.

- Adoptive Transfer: Transfer T-cells from rejected hosts into naïve, matched hosts challenged with the same donor peptides to demonstrate pathogenicity.

Q3: We are developing a CAR-Treg therapy to suppress alloreactivity. Which allorecognition pathway should the CAR target for broad-spectrum efficacy?

A3: Targeting the semi-direct pathway may offer the broadest suppression. A CAR that recognizes a conserved region of donor MHC class I or II would allow Tregs to inhibit T-cell activation regardless of the presenting APC (donor for direct, recipient for indirect/semi-direct). This requires a CAR construct with a scFv domain specific for a non-polymorphic region of the MHC molecule.

Troubleshooting: B-Cell and Antibody Responses

Q4: In our stem cell transplant model, we detect high-titer donor-specific antibodies (DSAs) but cannot identify the immunizing source. How can we determine if T-cell help is coming from the direct or indirect pathway?

A4: This is a classic problem in chronic rejection. Use a two-pronged approach:

- Indirect Pathway Help: Isolate CD4+ T-cells from the recipient and test their proliferation and cytokine production (e.g., IL-21) in response to recipient APCs pulsed with donor MHC peptides.

- Direct/Semi-Direct Help: Co-culture recipient B-cells with donor-derived B-cells or recipient APCs that have acquired donor MHC (semi-direct) and measure B-cell activation and differentiation using CD86/CD69 upregulation.

Q5: Our protocol for detecting memory B-cells specific to donor HLA is yielding inconsistent results. What is a reliable method?

A5: Use an optimized Antigen-Specific Memory B-Cell ELISpot.

- Issue: Inconsistency often stems from suboptimal antigen coating or inadequate B-cell stimulation.

- Solution:

- Coat ELISpot plates with purified, recombinant donor HLA monomers (not multimers) to ensure correct conformation.

- Use a polyclonal stimulation cocktail (e.g., CpG + R848) for 4-6 days to differentiate memory B-cells into antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) in vitro before plating.

- Include positive controls (anti-Ig) and negative controls (irrelevant protein) in every assay.

Table 1: Frequency of Alloreactive T-Cells in Naïve Repertoire

| Allorecognition Pathway | Frequency of Precursor T-Cells | Primary MHC Restriction | Key Readout Assay |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | 1-10% of total T-cell pool | Donor MHC | Primary MLR, CFSE dilution |

| Indirect | 0.01-0.1% of total T-cell pool | Recipient MHC | Peptide-specific ELISpot, Tetramer staining |

| Semi-Direct | Not fully quantified (estimated <1%) | Recipient MHC | Flow cytometry for donor MHC on recipient APCs |

Table 2: Efficacy of Immunosuppressive Agents on Allorecognition Pathways

| Drug/Target | Direct Pathway Inhibition | Indirect Pathway Inhibition | Semi-Direct Pathway Inhibition | Effect on DSA Production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcineurin Inhibitors (Cyclosporin, Tacrolimus) | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| mTOR Inhibitors (Sirolimus) | Moderate | Strong | Strong (blocks exosome function) | Strong |

| Anti-CD25 (Basiliximab) | Strong (early) | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Co-stimulation Blockade (Belatacept) | Strong | Strong | Strong | Strong |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Distinguishing Direct vs. Indirect Allorecognition In Vitro

Title: MLR Co-culture Assay for Pathway Analysis

- Cell Isolation:

- Isolate CD4+ T-cells (responders) from recipient spleen or PBMCs using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS).

- Isolate APCs (stimulators) from donor (for direct pathway) and recipient (for indirect pathway) spleen. Irradiate (30 Gy) or treat with Mitomycin C to prevent proliferation.

- Antigen Pulsing (Indirect Pathway):

- Incubate recipient APCs with a panel of synthetic 15-mer peptides spanning the polymorphic regions of donor MHC class I and II (10 µg/mL) for 4-6 hours.

- Co-culture:

- Set up co-cultures in a 96-well U-bottom plate:

- Direct: Recipient T-cells + Donor APCs

- Indirect: Recipient T-cells + Recipient APCs (donor peptide-pulsed)

- Control: Recipient T-cells + Recipient APCs (unpulsed)

- Use a 1:1 responder:stimulator ratio (e.g., 1x10^5 cells each) in complete RPMI-1640 medium.

- Set up co-cultures in a 96-well U-bottom plate:

- Readout (Day 5-7):

- Proliferation: Add ³H-thymidine for the final 16-18 hours and measure incorporation.

- Cytokines: Collect supernatant for IFN-γ and IL-17 measurement by ELISA.

- Flow Cytometry: Use CFSE dilution to track proliferation divisions.

Protocol 2: Detection of Donor-Specific Antibodies (DSAs)

Title: Flow Cytometric Crossmatch (FCXM) for DSA Detection

- Target Cell Preparation:

- Isolate lymphocytes from donor spleen or use donor-derived cell lines expressing the relevant HLA.

- Wash cells twice with PBS + 1% BSA (FACS buffer). Adjust concentration to 5x10^6 cells/mL.

- Serum Incubation:

- Incubate 50 µL of donor cells with 50 µL of test recipient serum (heat-inactivated at 56°C for 30 mins) for 30 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

- Detection:

- Wash cells twice with FACS buffer to remove unbound antibody.

- Resuspend cell pellet in 100 µL of FACS buffer containing a fluorochrome-conjugated anti-human IgG antibody (e.g., F(ab')₂ fragment to avoid Fc receptor binding). Incubate for 30 minutes on ice in the dark.

- Analysis:

- Wash cells twice and resuspend in fixation buffer.

- Acquire data on a flow cytometer. Gate on lymphocytes and analyze the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the fluorochrome channel. A positive shift in MFI compared to a negative control serum indicates the presence of DSAs.

Pathway & Workflow Visualizations

Title: T-Cell Allorecognition Pathways

Title: B-Cell Alloantibody Production Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Alloimmunity Studies

| Research Reagent | Function & Application in the Field |

|---|---|

| Recombinant HLA Monomers/Tetramers | Used to identify and isolate T-cells specific for donor MHC or its peptides via flow cytometry. Critical for quantifying indirect pathway T-cells. |

| CFSE / Cell Proliferation Dyes | A fluorescent dye that dilutes with each cell division. Essential for tracking and quantifying T-cell and B-cell proliferation in MLR and other co-culture assays. |

| CpG ODN + R848 (Resiquimod) | Toll-like receptor agonists (TLR9 and TLR7/8) used in combination to polyclonally activate and differentiate human memory B-cells into ASCs for ELISpot assays. |

| Anti-CD40 Agonistic Antibody | Mimics T-cell help (CD40L) for B-cell activation, isotype switching, and germinal center formation in in vitro B-cell culture systems. |

| Transwell Inserts | Permeable supports for cell culture plates that allow physical separation of cell populations while permitting soluble factor exchange. Used to dissect cell-contact dependent vs. independent effects. |

| MHC-Specific Antibodies (One-HLA) | Antibodies that recognize a single allele of HLA. Used in flow cytometry and FCXM to confirm HLA expression and detect donor MHC on recipient APCs in the semi-direct pathway. |

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the core mechanisms by which an HLA mismatch leads to transplant rejection? An HLA mismatch triggers rejection through two primary immunological pathways:

- Direct Allorecognition: Recipient T cells directly recognize intact mismatched HLA molecules on the surface of donor antigen-presenting cells (APCs). This pathway is dominant in the early post-transplant period [6].

- Indirect Allorecognition: Recipient CD4+ T cells recognize peptides derived from donor HLA molecules that are presented by the recipient's own APCs. This pathway is operational throughout the life of the graft and is a potent inducer of allograft rejection via antibody-mediated and CD8+ T cell–mediated rejection [6].

FAQ 2: How does pre-sensitization occur, and why is it a major barrier to transplantation? Pre-sensitization refers to the pre-existence of anti-HLA antibodies in a transplant candidate's blood. Sensitizing events include [6]:

- Previous blood transfusions

- Pregnancies

- Previous organ transplants These pre-formed anti-HLA antibodies represent a significant immunological barrier because high-titer donor-specific HLA antibodies (DSA) can cause hyperacute antibody-mediated rejection (AMR), leading to rapid graft loss. Lower titer antibodies can also cause rejection via NK cell activation or endothelial cell proliferation [6].

FAQ 3: What is the difference between antigen-level and molecular-level HLA matching?

- Antigen-Level Matching: The conventional approach, which counts mismatches for HLA-A, -B, and -DR antigens. A "0-antigen mismatch" means no mismatch is detected for these loci at the antigen level [6] [7].

- Molecular-Level Matching (Eplet Matching): A more granular method that assesses mismatches at the level of small configurations of polymorphic amino acids called eplets, which are the actual targets for antibodies. An HLA antigen-mismatched graft could theoretically be matched at the eplet level, potentially reducing immunogenicity [8].

FAQ 4: My patient is highly sensitized with high PRA. What strategies can increase transplant opportunities?

- Advanced Histocompatibility Testing: Use single-antigen bead (SAB) assays to precisely define antibody specificities and identify "unacceptable" HLA antigens [6].

- Eplet-Based Matching: Use the HLAMatchmaker algorithm to assess donor-recipient compatibility at the epitope level, which can help identify acceptable donors among those who might appear mismatched at the antigen level [9] [8].

- Desensitization Protocols: Therapeutic options to reduce antibody levels prior to transplantation [6].

- Paired Donation Programs: Increase the pool of potential donors [7].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent or Ambiguous HLA Typing Results

- Potential Cause: Use of low-resolution typing methods that cannot distinguish between closely related alleles.

- Solution: Implement next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, such as single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing or Oxford Nanopore (ONT) sequencing. These third-generation systems analyze long-read sequences spanning entire intronic-exonic regions of HLA genes, effectively resolving ambiguity and phasing issues [10].

- Protocol: High-Resolution HLA Typing via NGS

- DNA Extraction: Obtain high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA.

- Target Amplification: Use locus-specific primers to amplify HLA genes of interest (e.g., HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, -DQB1, -DPB1).

- Library Preparation: Fragment amplicons and attach sequencing adapters.

- Sequencing: Run on a long-read sequencer (e.g., PacBio Sequel or Nanopore MinION).

- Data Analysis: Use specialized software (e.g., HLA Twin or specific NGS HLA typing suites) to align sequences and assign alleles based on the IMGT/HLA database.

Challenge 2: Differentiating Clinically Relevant Donor-Specific Antibodies (DSA) from Benign Signals

- Potential Cause: False positivity in single-antigen bead (SAB) assays, which are highly sensitive but can be prone to non-specific binding.

- Solution: Employ a multi-method verification approach. Do not rely on SAB results alone [6] [8].

- Protocol: Verification of Clinically Relevant HLA Antibodies

- Initial Screening: Use a solid-phase SAB assay to identify potential DSA.

- Cross-Correlation: Correlate SAB results with clinical history (e.g., known sensitizing events).

- Functional Assays: For antibodies detected by SAB, perform a complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) assay to confirm their ability to activate complement and cause cell lysis, which is a marker of clinical relevance [6].

- Antibody Verification (Research Setting): Use advanced techniques like site-directed mutagenesis of HLA molecules or cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to visualize the epitope-paratope interaction and confirm which specific amino acid residues are crucial for antibody binding [8].

Challenge 3: Investigating Antibody-Mediated Rejection (AMR) in a Patient with No Detectable DSA

- Potential Cause: Antibodies targeting non-HLA antigens or HLA epitopes not represented on standard SAB panels.

- Solution: Explore non-HLA pathways. Recent research highlights the role of innate immune mismatches, such as in the SIRPa-CD47 pathway [11].

- Protocol: Assessing Non-HLA SIRPa Mismatch

- Genotyping: Determine the SIRPa haplotypes (A or B) of both the donor and recipient using DNA from stored samples.

- Mismatch Directionality Analysis: Note that the immunogenic risk is particularly high when a recipient with SIRPa haplotype A receives an organ from a donor with SIRPa haplotype B [11].

- Functional Analysis (Research): In mouse models, blocking the SIRPa-CD47 interaction can prevent monocyte activation and subsequent chronic damage, providing mechanistic insight [11].

Data Presentation: HLA System in Transplantation

Table 1: Key HLA Loci and Their Characteristics in Transplantation [6] [10] [9]

| Locus Category | Loci | Polymorphism (Approx. Alleles) | Expression | Primary Role in Immune Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C | >7,500 known alleles | All nucleated cells | Present endogenous peptides to CD8+ cytotoxic T cells |

| Class II | HLA-DR, HLA-DQ, HLA-DP | High polymorphism | Antigen-presenting cells (B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells) | Present exogenous peptides to CD4+ helper T cells |

Table 2: Impact of HLA-A, -B, -DR Mismatch on Kidney Transplant Outcomes [7]

| Number of Mismatches (A, B, DR) | Incidence of Rejection (%) | 5-Year Graft Survival (%) | Key Contextual Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-2 | 4.4% | ~100% | Data from highly sensitized patients (PRA >80%) |

| 3-4 | 11.4% | ~81% | Data from highly sensitized patients (PRA >80%) |

| 5-6 | 31.3% | ~74% | Data from highly sensitized patients (PRA >80%) |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: HLA Antibody Screening and Characterization Using Single-Antigen Bead (SAB) Assay

Purpose: To detect and identify specific anti-HLA antibodies in a patient's serum to assess pre-sensitization risk. Workflow:

- Serum Preparation: Collect and heat-inactivate patient serum.

- Incubation: Mix serum with SAB panel. Each bead is coated with a single, purified HLA antigen.

- Detection: Add fluorescently labelled anti-human IgG antibody.

- Analysis: Run the bead mixture through a flow cytometry-based analyzer (e.g., Luminex). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) indicates the strength of antibody binding to each specific HLA antigen.

- Interpretation: Correlate reactive beads with the patient's HLA typing and potential donor HLA types to identify unacceptable antigens and potential DSA [6] [9].

Protocol 2: Eplet Mismatch Load Analysis Using HLAMatchmaker

Purpose: To provide a granular assessment of donor-recipient HLA compatibility beyond the antigen level, predicting the risk of de novo DSA development. Workflow:

- High-Resolution Typing: Obtain high-resolution (allele-level) HLA typing for both donor and recipient.

- Data Input: Enter the allele-level HLA types for both pairs into the HLAMatchmaker software.

- Analysis: The algorithm compares the amino acid sequences of the donor and recipient HLA molecules and counts the number of mismatched eplets—small, antibody-accessible configurations of polymorphic amino acids.

- Risk Stratification: A higher eplet mismatch load is associated with an increased risk of de novo DSA formation, rejection, and graft loss [8]. The analysis can inform on the immunogenic potential of a specific donor-recipient pair.

Visualization: Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: T Cell Allorecognition Pathways

Diagram 2: HLA Typing Technology Evolution

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Transplant Immunology Research

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Key Application in HLA/Rejection Research |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Antigen Bead (SAB) Kits | Multiplex detection of anti-HLA antibodies | Pre-transplant risk assessment; identification of DSA post-transplant [6] |

| Recombinant HLA Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) | Define specific HLA epitopes | Antibody verification; crucial for validating the immunogenicity of specific eplets [8] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Introduce specific point mutations in HLA genes | Determine the exact amino acid residues critical for antibody binding (epitope mapping) [8] |

| Anti-Thymocyte Globulin (ATG) | T-cell depleting induction therapy | Suppresses T-cell mediated rejection, particularly important in the context of HLA mismatch [6] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Gene editing in cell lines | Create knock-out or specific HLA-variant cell lines to study functional interactions (e.g., with KIRs) [8] |

The immunogenic potential of stem cells is a critical parameter determining their survival and efficacy upon transplantation. Different stem cell types exhibit distinct immunological properties due to variations in their expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and immunomodulatory factors. Understanding these profiles is essential for selecting appropriate cell types for specific therapeutic applications and for designing effective immunosuppression strategies.

Table 1: Immunogenicity and Immunomodulatory Properties of Major Stem Cell Types

| Stem Cell Type | Key MHC Expression Features | Immunogenic Potential | Immunomodulatory Properties | Primary Immune Evasion Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Low/absent MHC-I; negative for MHC-II [12]. | Low in undifferentiated state; potential increase upon differentiation [12] [13]. | Capable of immunosuppression via arginase I, preventing dendritic cell maturation, and up-regulating regulatory T cells [12]. | Low MHC profile reduces T-cell activation; soluble factors that suppress immune responses [12]. |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Low/absent MHC-I; negative for MHC-II; limited upregulation with IFN-γ [12]. | Conflicting in vivo reports; generally low in vitro [12]. | Potent immunomodulatory effects; can suppress T-cell proliferation more effectively than MSCs in some assays [12]. | Low antigen-presenting function; active suppression of responder immune cell proliferation [12] [14]. |

| Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs) | High MHC-I; low/negative MHC-II (can be upregulated by IFN-γ) [12]. | Low in autologous use; rejection reported in allogeneic settings [12]. | Significant; inhibit T-cell proliferation, alter dendritic cell maturation, induce regulatory lymphocytes [12]. | Dynamic immunophenotype; secretion of soluble immunosuppressive factors; lack of co-stimulatory molecules [12]. |

| iPSC-Derived Neural Stem/Progenitor Cells (NS/PCs) | Low HLA-DR (MHC-II) and co-stimulatory molecules, even with cytokine stimulation [14]. | Low, even in allogeneic HLA-mismatched settings [14]. | Suppressive effects on peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) proliferation [14]. | Low antigen-presenting function and active immunosuppression [14]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols for Immunogenicity Assessment

In Vitro Immunogenicity Assay (Modified Mixed Leukocyte Reaction - MLR)

The Mixed Leukocyte Reaction is a cornerstone assay for evaluating the immunogenic potential of stem cells by measuring T-cell proliferation in response to foreign antigens [12] [14].

Protocol Steps:

- Cell Preparation:

- Responder Leukocytes: Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or splenocytes from a donor. These represent the host's immune system [12] [14].

- Stimulator Cells: Use the stem cell population under investigation (e.g., iPSCs, MSCs, or differentiated progeny). These should be irradiated or treated with mitomycin-C to prevent their proliferation while retaining antigen-presenting capability [12].

- Controls: Include positive controls (MHC-mismatched leukocytes) and negative controls (MHC-matched leukocytes or self-leukocytes) [12].

Co-culture Setup:

- Culture responder and stimulator cells together in a culture plate for 5-7 days. A typical ratio is 1:1 (responder:stimulator), but dose-dependence should be tested (e.g., 1:1, 1:0.3, 1:0.1) [12] [14].

- Culture conditions: Use RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% human serum, L-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO₂ [12].

Proliferation Measurement:

- Assess T-cell proliferation after the culture period. Common methods include:

- ³H-thymidine incorporation: Add ³H-thymidine to the culture for the last 6-18 hours. Measure incorporated radioactivity using a beta-counter [12].

- CFSE dilution: Label responder cells with Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) prior to co-culture. Flow cytometry analysis of CFSE dilution in daughter cells indicates proliferation.

- Assess T-cell proliferation after the culture period. Common methods include:

Data Analysis:

- Compare the proliferation of responder cells when stimulated with test stem cells versus control stimulators.

- Significant proliferation in test groups compared to negative controls indicates immunogenicity.

- For immunomodulatory assessment, the suppression of proliferation in a standard MLR by the addition of stem cells is measured [12].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for a Mixed Leukocyte Reaction (MLR) assay to assess stem cell immunogenicity.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of MHC and Co-stimulatory Molecules

Quantifying the expression of immune-related surface markers is fundamental for profiling stem cells.

Protocol Steps:

- Cell Harvest: Gently dissociate stem cells into a single-cell suspension.

- Staining: Aliquot cells and incubate with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against target molecules (e.g., HLA-ABC (MHC-I), HLA-DR (MHC-II), CD80, CD86, CD40). Include isotype-matched control antibodies.

- Analysis: Analyze stained cells using a flow cytometer. The expression levels of MHC and co-stimulatory molecules are determined by the fluorescence intensity compared to the isotype control.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Stem Cell Immunogenicity Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Immunogenicity Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline-inducible Lentiviral Vectors | Delivery of reprogramming factors (e.g., OSKM) for iPSC generation [12]. | Creating isogenic iPSC lines for controlled differentiation and immunogenicity testing. |

| Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) | Proinflammatory cytokine used to mimic an inflammatory environment and test immune plasticity [12] [14]. | Upregulating MHC expression on stimulator cells in MLR assays or pre-treating stem cells. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Improves survival of dissociated human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) [15]. | Used during passaging or thawing of iPSCs/ESCs for MLR to maintain cell viability. |

| RevitaCell Supplement | A cocktail supplement containing a ROCK inhibitor, antioxidants, and other components to enhance cell recovery [15]. | Improving survival of single-cell clones after genetic modification of stem cells. |

| mTeSR Plus / Essential 8 Medium | Defined, feeder-free cell culture media for maintaining hPSCs in an undifferentiated state [15]. | Culturing iPSCs and ESCs to ensure a consistent, high-quality cell source for experiments. |

| Geltrex / Vitronectin (VTN-N) | Defined, xeno-free extracellular matrices for feeder-free culture of hPSCs [15]. | Coating cultureware for the adherent growth of iPSCs and ESCs under defined conditions. |

| Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) | Fluorescent cell dye for tracking cell division by flow cytometry [12]. | Labeling responder leukocytes in MLR to track and quantify T-cell proliferation. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Our iPSC lines show high variability in immunogenicity between different clones. How can we standardize our assessments? Answer: Clone-to-clone variation is a recognized challenge. To standardize assessments:

- Thorough Screening: Implement rigorous screening for genetic stability and karyotype abnormalities before immunogenicity testing [12].

- Isogenic Controls: Where possible, use isogenic controls (e.g., iPSCs derived from the same genetic background) to minimize genetic variability.

- Differentiation Status: Confirm the purity and maturity of your differentiated cell populations, as undifferentiated cells contaminating a culture can have different immune properties [15] [16].

- Internal Controls: Always include reference cell lines (e.g., a well-characterized MSC line) as an internal control across your MLR experiments to calibrate assay sensitivity [12].

FAQ 2: We are observing poor survival of our iPSCs in suspension during MLR setup, leading to inconclusive results. What can we do? Answer: Pluripotent stem cells are particularly sensitive to dissociation-induced apoptosis.

- Use ROCK Inhibitor: Include a ROCK inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632) at 10 µM in the culture medium during cell passaging, plating, and for the first 24 hours of the MLR assay to significantly improve cell survival [15] [16].

- Avoid Over-Dissociation: When preparing stimulator cells, avoid creating a single-cell suspension. Small, uniform cell aggregates survive better than single cells [16].

- Irradiation: Ensure proper irradiation of stimulator cells to prevent overgrowth, but optimize the dose to avoid excessive cellular stress.

FAQ 3: For regenerative neurology applications, is HLA-matching necessary for iPSC-derived neural stem/progenitor cells (NS/PCs)? Answer: Current in vitro evidence suggests that HLA-matching may be less critical for certain neural cells. Studies show that iPSC-derived NS/PCs have low expression of HLA-DR and co-stimulatory molecules even under inflammatory stimulation. Furthermore, they exhibit active immunosuppressive properties [14]. Modified MLR assays demonstrate similarly low allogeneic immune responses in both HLA-matched and mismatched settings for these cells [14]. However, these are in vitro findings, and their confirmation in clinical settings is crucial.

Troubleshooting Guide: Excessive Differentiation in Stem Cell Cultures Pre-Experiment

- Problem: Differentiated cells in your pluripotent stem cell culture can confound immunogenicity results.

- Solutions:

- Quality Control Media: Ensure culture medium (e.g., mTeSR Plus) is fresh and has been stored correctly at 2-8°C for less than two weeks [16].

- Manual Removal: Prior to passaging, manually remove areas of spontaneous differentiation under a microscope [16].

- Optimize Passaging: Passage cells when colonies are large and compact but before they overgrow and differentiate in the center. Ensure cell aggregates after passaging are evenly sized [15] [16].

- Limit Handling Time: Avoid having culture plates outside the incubator for extended periods (>15 minutes) [16].

Clinical Perspectives and Immunosuppression Strategies

Translating stem cell therapies from the lab to the clinic requires bridging in vitro findings with in vivo application. The choice of stem cell type and its inherent immunogenicity directly influences the immunosuppression regimen required.

Table 3: Clinical Immunosuppression Approaches in Stem Cell Trials

| Therapy / Cell Type | Common Immunosuppression Regimen | Clinical Context & Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| hESC-Derived Retinal Pigment Epithelial (RPE) Cells | Systemic: Tacrolimus + Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF), sometimes with corticosteroids. Local: Intravitreal fluocinolone acetonide implant [17]. | Used in trials for macular degeneration. No clear signs of immune rejection reported with these regimens. Adverse events include infections and GI symptoms [17]. |

| Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplants (Neural, Retinal) | Varies by trial; often a combination of Tacrolimus (targeting serum concentration), MMF, and steroids, tapered over months [17]. | Regimen aims to prevent acute rejection while allowing long-term graft survival. Some studies report long-term graft survival even after immunosuppression cessation [17]. |

| Future/Trial Strategies: T-regulatory cell (Treg) Therapy | Infusion of ex vivo expanded alloantigen-specific Tregs [18]. | Aims to induce immune tolerance, potentially eliminating need for chronic drug therapy. Early trials in organ transplantation and GVHD show safety and feasibility of this approach [18]. |

Diagram 2: The three-signal model of T-cell activation, a key pathway targeted by immunosuppressive strategies. Signal 1 (antigen recognition), Signal 2 (co-stimulation), and Signal 3 (cytokine differentiation) are all potential points for therapeutic intervention [19].

Armoring the Graft: Methodological Strategies for Immune Evasion and Tolerance

Pharmacologic immunosuppression is a critical component in clinical trials involving stem cell and gene therapies. It mitigates host immune rejection, promoting the survival and viability of transplanted cells. The strategies and regimens vary significantly depending on the target tissue, cell type, and the specific immune challenges posed by allogeneic or xenograft transplants. This technical resource summarizes key regimens and experimental protocols from recent clinical trials and preclinical studies, providing a structured reference for researchers developing therapies for neural, retinal, and other specialized cell types.

The table below summarizes immunosuppression regimens from key clinical trials in neural and retinal cell therapies, providing a comparison of drugs, durations, and applications [20].

| Therapy / Indication | Immunosuppression Regimen | Duration | Key Findings / Rationale | Clinical Trial Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retinal Cell Transplants [20] [21] | Systemic: Tacrolimus, Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF).Local: Corticosteroids (e.g., peri-ocular). | Short-term (tapering over weeks to months). | Grafted cells remained viable months to years after cessation. Local steroids manage intraocular inflammation. | Phase 1/2 trials for inherited retinal diseases (e.g., Retinitis Pigmentosa). |

| Spinal Cord Injury & ALS [20] | Multi-drug regimen: Tacrolimus, MMF, tapering corticosteroids. | Short-term course. | Detected immune responses in treated patients were rare. Regimen deemed efficacious for promoting graft survival. | Phase 1/2 trials for stem cell-derived neural precursor transplantation. |

| AAV Gene Therapy (Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy) [22] [23] | Standard: Systemic corticosteroids.Enhanced (under investigation): Addition of Sirolimus (pre- and post-infusion). | Corticosteroids: Before and after infusion.Sirolimus: 14 days prior to 12 weeks post-infusion. | Enhanced regimen aims to mitigate the risk of acute liver injury (ALI) and acute liver failure (ALF) associated with AAV vectors. | Phase 1b trial (ENDEAVOR Cohort 8) for non-ambulant patients. |

| Huntington's Disease Gene Therapy [24] | Optimized immunosuppression regimen (details not fully public). | Specific duration not disclosed; linked to one-time neurosurgical administration. | Protocol includes a dedicated cohort to investigate an optimized regimen for AAV-based therapy delivered directly to the brain. | Phase I/II clinical trial of AMT-130 (first gene therapy in HD). |

| Stem Cell Transplant (Fanconi Anemia) [25] | Non-Chemo Conditioning: Anti-CD117 antibody (Briquilimab) + immune-suppressing medications. | Antibody administered 12 days pre-transplant. | Replaced toxic busulfan chemotherapy/radiation. Achieved near 100% donor chimerism without graft rejection. | Phase 1 clinical trial for a genetic disease, enabling transplant from haploidentical donors. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the rationale behind using a multi-drug immunosuppression regimen in most cell therapy trials? Using a combination of drugs that target different pathways of the immune system allows for synergistic effects, enabling lower doses of each drug and potentially reducing individual drug-related toxicities. A common combination is Tacrolimus (a calcineurin inhibitor that suppresses T-cell activation) with Mycophenolate Mofetil (an antiproliferative agent that inhibits lymphocyte proliferation) [20]. This approach comprehensively targets both T-cell activation and expansion.

Q2: How long is immunosuppression typically maintained in retinal cell therapy trials? A short-term course is commonly employed. Evidence suggests that a tapering regimen over weeks to months can be efficacious, with some studies showing grafted cells remaining viable for months to years after immunosuppression has been stopped [20]. The "immune-privileged" status of the eye may contribute to this phenomenon, though local immunosuppression with steroids is also frequently used to control inflammation at the site [20] [21].

Q3: What are the key immune cell populations targeted by standard immunosuppressive drugs, and how are they monitored? The primary targets are T-lymphocytes. Tacrolimus inhibits calcineurin, blocking IL-2 production and T-cell activation. Mycophenolate Mofetil inhibits inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase, impairing lymphocyte proliferation. Sirolimus inhibits mTOR, disrupting T-cell activation and proliferation. Monitoring is critical and often involves [21]:

- Immunophenotyping: Using flow cytometry to track lymphocyte populations (e.g., T-helper, T-cytotoxic cells) in peripheral blood.

- Drug Level Monitoring: Using LC-MS to ensure therapeutic levels of drugs like tacrolimus are maintained.

- Cytokine Assays: Measuring pro-inflammatory cytokines to assess the overall immune state.

Q4: Our pre-clinical data shows graft rejection despite immunosuppression. What strategies can we investigate to induce immune tolerance? Beyond general immunosuppression, several advanced strategies are emerging:

- Engineered Immune Tolerance: Co-transplanting therapeutic cells with regulatory T-cells (Tregs) engineered to protect them. For example, beta cells engineered to express EGFRt can be protected by CAR-Tregs designed to recognize this tag, creating a "lock-and-key" system for local immune tolerance [26].

- Gene-Edited "Immune-Evasive" Cells: Using gene editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 to modify allogeneic cells, for example, by knocking out Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules to avoid T-cell recognition [27] [28].

- Novel Conditioning Regimens: Replacing toxic chemotherapies with targeted antibodies. Using an anti-CD117 antibody (e.g., Briquilimab) to clear host hematopoietic stem cells creates space for the donor graft without genotoxic side effects, which is particularly beneficial for fragile patients [25].

Q5: What are the primary safety concerns linked to prolonged immunosuppression in clinical trials? The main concerns are [20] [22]:

- Increased susceptibility to infections (including serious respiratory infections).

- Potential for organ toxicity (e.g., acute liver injury, nephrotoxicity from calcineurin inhibitors).

- Specific drug-related risks (e.g., sirolimus requires monitoring for metabolic issues and myelosuppression). Notably, in recent neural and retinal trials, side effects directly related to immunosuppression were reported to be uncommon [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Vitro Assessment of Immunosuppressant Toxicity on hESC-Derived Retinal Organoids (ROs)

This protocol is used to evaluate the direct effects of immunosuppressive drugs on the viability and function of candidate cell products before transplantation [21].

1. Materials

- hESC-derived Retinal Organoids (ROs) at relevant stages of differentiation.

- Immunosuppressant drugs: Tacrolimus (TAC), Mycophenolic Acid (MPA; the active metabolite of MMF).

- Culture medium suitable for ROs.

- qPCR system with primers for key retinal identity and differentiation markers (e.g., CRX, NRL, OPSIN).

- Functional and Structural Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) setup.

- Cell viability assay kit (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo).

2. Methodology

- Step 1: RO Exposure. Expose ROs to therapeutic concentrations of TAC, MPA, or a combination for 1-4 weeks. Refresh drugs and medium regularly.

- Step 2: Gene Expression Analysis (qPCR). Harvest ROs after exposure. Extract RNA, synthesize cDNA, and perform qPCR for retinal identity and photoreceptor-specific genes. Compare to untreated control ROs.

- Step 3: Metabolic Function Analysis (FLIM). Use FLIM to assess the metabolic activity of live ROs. The autofluorescence of metabolic co-enzymes (e.g., NAD(P)H) provides a readout of cellular metabolic states, which should remain unchanged if the drugs are non-toxic.

- Step 4: Structural and Viability Assessment. Perform immunohistochemistry on fixed ROs for standard retinal cell markers and synaptic proteins. Perform a cell viability assay to quantify potential cytotoxicity.

3. Expected Outcomes & Analysis A successful result shows no significant negative effects on RO gene expression, metabolic function, or structural integrity compared to controls. This data supports the tolerability of the proposed immunosuppression regimen for the retinal cells in a clinical setting [21].

Protocol: In Vivo Evaluation of Immunosuppression in an Immunocompetent Retinal Degeneration (RD) Model

This protocol outlines the steps to test the efficacy of a systemic immunosuppression regimen in preventing the rejection of a xenograft in a pre-clinical RD model [21].

1. Materials

- Animals: Immunocompetent retinal degenerate rats (e.g., SD-foxn1 Tg(S334ter)3Lav strain).

- Transplant: hESC-derived Retinal Organoid sheets.

- Drugs: Tacrolimus (TAC) pellets for sustained release, Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF) in chow.

- Analytical Tools: LC-MS for drug level monitoring, flow cytometer for immunophenotyping, ELISA kits for cytokines, Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) for in vivo imaging, Optokinetic Test (OKT) for visual function.

2. Methodology

- Step 1: Determine Minimum Effective Dosing. Administer TAC and MMF at varying doses to healthy immunocompetent rats. Use serial blood collection and LC-MS to establish pharmacokinetics. Use flow cytometry immunophenotyping to link drug levels to the degree of lymphocyte suppression, thereby defining the minimum effective dosing range.

- Step 2: Transplantation and Immunosuppression. Perform subretinal transplantation of RO sheets into RD rats. Implant TAC pellets and provide MMF-medicated chow to the treatment group starting at the time of surgery.

- Step 3: Post-Operative Monitoring.

- Drug Efficacy: Regularly collect blood for LC-MS (drug levels) and flow cytometry (T-cell, B-cell counts).

- Graft Survival: Use in vivo OCT imaging at defined intervals to monitor the presence and structure of the transplant.

- Visual Function: Assess visual acuity using OKT and electrophysiological recordings.

- Immune Activation: Measure serum cytokine levels (e.g., IFN-γ, TNF-α) post-surgery.

- Step 4: Endpoint Analysis. At study endpoint, perform immunohistochemistry on retinal sections to evaluate immune cell infiltration (e.g., with microglia/macrophage markers like IBA1) and assess donor photoreceptor integration into the host retina.

3. Expected Outcomes & Analysis Effective immunosuppression will result in significantly reduced immune cell infiltration into the graft, improved long-term graft survival, and significant visual improvement in OKT compared to non-immunosuppressed controls. This model helps characterize the critical immune populations involved in rejection and validates the efficacy of the chosen drug regimen [21].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

T-cell Activation and Immunosuppression Pathways

This diagram illustrates the mechanism of action of key immunosuppressant drugs on the T-cell activation pathway.

Pre-clinical In Vivo Immunosuppression Efficacy Workflow

This diagram outlines the logical workflow for evaluating an immunosuppression regimen in an immunocompetent animal model of retinal degeneration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key reagents and their functions for implementing the experimental protocols discussed [25] [21] [26].

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD117 Antibody (Briquilimab) | Targets and depletes host hematopoietic stem cells via the CD117 (c-Kit) receptor. | Replaces toxic chemotherapy/radiation in conditioning regimens for stem cell transplantation [25]. |

| Tacrolimus (FK-506) | Calcineruin inhibitor; blocks T-cell activation by suppressing IL-2 transcription. | Core component of systemic immunosuppression regimens in neural and retinal cell therapy trials [20] [21]. |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF) | Inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH); blocks lymphocyte proliferation. | Used in combination with Tacrolimus for multi-pathway immunosuppression [20] [21]. |

| Sirolimus (Rapamycin) | mTOR inhibitor; suppresses T-cell activation and proliferation. | Investigated in enhanced regimens for AAV gene therapy to mitigate liver toxicity [22] [23]. |

| Alpha/Beta T-Cell Depletion Kit | Immunomagnetic selection to remove αβ T-cells from a donor graft. | Reduces the risk of Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD) in haploidentical transplants, expanding donor pools [25]. |

| Engineered CAR-Treg Cells | Regulatory T-cells engineered with a Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) to target a specific tag (e.g., EGFRt) on co-transplanted cells. | Creates localized immune tolerance, protecting therapeutic cells from rejection without broad immunosuppression [26]. |

| hESC-Derived Retinal Organoids | 3D in vitro model containing laminated retinal layers and photoreceptors. | Used for pre-clinical safety testing of immunosuppressants and as a source for transplantation studies [21]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: General Concepts

Q1: Why target both CTLA4-Ig and PD-L1 for creating immune-privileged stem cells?

- A: These molecules target complementary pathways in T-cell activation. CTLA4-Ig acts early, blocking the CD28-B7 costimulatory signal required for naive T-cell activation. PD-L1 acts later, delivering an inhibitory signal to already-activated T-cells via PD-1, promoting tolerance and exhaustion. Combining them provides a multi-layered defense against immune rejection.

Q2: What is the primary advantage of a "knock-in" strategy over viral transduction?

- A: A knock-in strategy, using CRISPR/Cas9 for example, allows for targeted integration of the transgenes into a defined, active genomic "safe harbor" locus (e.g., AAVS1). This ensures consistent, stable, and physiological expression of CTLA4-Ig and PD-L1, avoiding the risks of insertional mutagenesis and transgene silencing associated with random viral integration.

Troubleshooting Guide: Molecular Cloning & Vector Design

Q1: Our donor vector for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in is yielding very low homologous recombination (HR) efficiency. What could be the issue?

- A: Low HR efficiency is common. Please check the following:

- Homology Arm Length: Ensure arms are sufficiently long (typically 800-1000 bp each).

- Donor Vector Concentration: Titrate the donor plasmid concentration; too high can be toxic, too low reduces HR events.

- sgRNA Efficiency: Validate that your sgRNA has high cutting efficiency using a T7E1 assay or next-generation sequencing.

- Cell Health: Use low-passage, healthy stem cells. Pre-treating cells with a small molecule like Alt-R HDR Enhancer can boost HR rates.

- A: Low HR efficiency is common. Please check the following:

Q2: We are concerned about off-target effects of CRISPR/Cas9. How can we mitigate this?

- A: Employ the following strategies:

- Use a high-fidelity Cas9 variant (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9).

- Design and validate multiple sgRNAs with high on-target scores using tools like CRISPRscan or ChopChop.

- Perform a computational prediction of off-target sites and sequence the top candidate loci in your final cell lines to confirm specificity.

- A: Employ the following strategies:

Troubleshooting Guide: Cell Culture & Selection

Q1: After transfection and selection, we see no surviving colonies. What steps should we take?

- A: This indicates potential cytotoxicity.

- Check Transfection Efficiency: Use a fluorescent reporter plasmid to determine your baseline transfection efficiency. If low, optimize your delivery method (electroporation parameters, lipofection reagent).

- Titrate Selection Antibiotic: Perform a kill curve assay on wild-type cells to determine the minimal effective concentration and optimal timing for antibiotic application post-transfection.

- Confirm Cas9 Activity: High levels of Cas9-induced double-strand breaks can be toxic. Consider using a lower concentration of Cas9 plasmid/RNP.

- A: This indicates potential cytotoxicity.

Q2: Our cloned stem cell colonies show heterogeneous transgene expression. How do we address this?

- A: Heterogeneity suggests variable integration or silencing.

- Single-Cell Cloning: Isolate single cells from a mixed population and expand them into clonal lines.

- Genomic Validation: Perform PCR and Southern blotting on clonal lines to confirm precise, mono-allelic or bi-allelic integration.

- Expression Analysis: Use flow cytometry (for surface PD-L1) and ELISA (for secreted CTLA4-Ig) to quantify expression levels across different clones and select high expressors.

- A: Heterogeneity suggests variable integration or silencing.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Knock-in into the AAVS1 Safe Harbor Locus

- sgRNA Design: Design an sgRNA targeting the human AAVS1 locus (PPP1R12C gene).

- Donor Vector Construction: Clone your expression cassettes (a constitutive promoter driving PD-L1 and a separate cassette for CTLA4-Ig, linked by a P2A self-cleaving peptide if desired) into a donor plasmid flanked by AAVS1-specific left and right homology arms (~800 bp each). Include a puromycin resistance gene flanked by loxP sites for selection and subsequent removal.

- Stem Cell Transfection: Co-transfect human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) with the donor vector and a plasmid encoding Cas9 and the AAVS1 sgRNA using a high-efficiency method like nucleofection.

- Selection and Expansion: 48 hours post-transfection, apply puromycin (e.g., 0.5-1.0 µg/mL) for 7-10 days. Manually pick and expand resistant colonies.

- Cre-Recombinase Excision: Transfer the puromycin-resistant clones with a Cre-recombinase plasmid to excise the selection cassette, leaving behind a single loxP site.

- Validation: Confirm correct integration via genomic PCR, Southern blot, and Sanger sequencing of the junction sites.

Protocol 2: In Vitro T-Cell Suppression Assay (Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction - MLR)

- Prepare Effector Cells: Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from a mismatched donor and label with CFSE.

- Prepare Target Cells: Differentiate your engineered and wild-type hPSCs into the desired cell type (e.g., cardiomyocytes, beta-cells). Irradiate them to prevent proliferation.

- Co-culture: Co-culture CFSE-labeled PBMCs (effectors) with the irradiated, differentiated cells (targets) at various ratios (e.g., 10:1, 5:1, 1:1) in a 96-well U-bottom plate for 5-7 days.

- Analysis: Harvest cells and analyze T-cell proliferation by flow cytometry, measuring CFSE dilution in the CD3+ T-cell population. Include wells with PBMCs alone (negative control) and PBMCs stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads (positive control).

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Key Immune Evasion Transgenes

| Transgene | Mechanism of Action | Expression Format | Key Interacting Partner |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTLA4-Ig | Soluble decoy receptor that blocks CD28 costimulation by binding CD80/CD86 on Antigen Presenting Cells (APCs). | Secreted | CD80 (B7-1), CD86 (B7-2) |

| PD-L1 | Membrane-bound ligand that engages PD-1 on activated T-cells, delivering an inhibitory signal. | Surface Membrane | PD-1 (Programmed Death-1) |

Table 2: Expected Outcomes from In Vitro T-Cell Suppression Assay

| Cell Type | Co-culture with Allogeneic PBMCs | Expected CFSE Proliferation Profile | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type Differentiated Cells | Yes | High % of CFSE-low proliferating T-cells | Strong immune rejection |

| CTLA4-Ig+PD-L1 Knock-in Differentiated Cells | Yes | Low % of CFSE-low proliferating T-cells; high % of CFSE-high non-proliferating T-cells | Significant immune evasion |

| Positive Control (anti-CD3/CD28) | N/A | Very high % of CFSE-low proliferating T-cells | Maximum T-cell activation |

| Negative Control (PBMCs only) | N/A | Very high % of CFSE-high non-proliferating T-cells | Baseline, no stimulation |

Diagrams

Diagram 1: T-cell Inhibition Pathways

Diagram 2: CRISPR Knock-in Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| AAVS1 Safe Harbor Targeting Kit | Pre-validated sgRNA and homology arm templates for reliable, safe integration. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Nuclease | Reduces off-target editing while maintaining high on-target activity. |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer | Small molecule that improves Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) efficiency. |

| Recombinant Human CTLA4-Ig Protein | Positive control for functional assays (e.g., ELISA, T-cell suppression). |

| Anti-PD-L1 Antibody (for flow cytometry) | Validates surface expression of the knocked-in PD-L1 transgene. |

| LIVE/DEAD Fixable Viability Dyes | Distinguishes live from dead cells in flow cytometry-based co-culture assays. |

| CFSE Cell Division Tracker | Fluorescent dye to monitor T-cell proliferation in suppression assays. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

This section addresses common technical challenges in the development and analysis of CHAR-Tregs and CAR-MSCs, providing evidence-based solutions.

Q1: My engineered CAR Tregs are losing their FoxP3 expression and suppressive function in long-term culture. What could be the cause and how can I prevent this?

A: Loss of FoxP3 expression and subsequent instability in CAR Tregs is a documented challenge. This can be caused by several factors:

- Cytokine Environment: Exposure to inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 can promote conversion to pro-inflammatory Th17-like cells [29].

- Costimulatory Domain Selection: The choice of intracellular signaling domains significantly impacts stability. CARs containing a CD28 domain have demonstrated superior stability and function in GvHD models compared to those with 4-1BB, which may exhibit decreased lineage stability [29].

- Mitigation Strategy: To enhance stability, consider transient exposure to mTOR inhibitors (e.g., rapamycin) and Vitamin C, which have been shown to improve the in vivo function and stability of 4-1BB-based CAR Tregs [29].

Q2: What are the primary mechanisms through which CAR-MSCs mediate immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment?

A: CAR-MSCs leverage both their engineered specificity and innate immunomodulatory capacities. Key mechanisms include:

- Precision Targeting: The CAR directs MSC homing to specific antigen-expressing cells within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [30].

- Secreted Factors: They can be engineered to secrete high levels of immunoregulatory factors like TRAIL (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) to induce apoptosis in target cells, or produce bispecific antibodies to engage immune effector cells [30].

- Immune Cell Modulation: CAR-MSCs can promote the induction of regulatory T cells (Tregs), thereby amplifying local immunosuppression [30].

- Bystander Suppression: Through their secretome, they can suppress immune responses in a non-antigen-specific manner within the local microenvironment [31].

Q3: How can I effectively monitor the persistence and in vivo functionality of administered CAR Tregs or CAR-MSCs?

A: A multi-parameter approach is recommended for accurate assessment.

- Phenotypic Tracking: For CAR Tregs, monitor canonical markers (CD4, CD25, FoxP3) alongside the CAR transgene to confirm stable identity [29].

- Functional Assays: Utilize multiplex immunoassays (e.g., Luminex technology) to quantify the profile of secreted cytokines in serum or tissue culture supernatant. This allows you to detect increases in suppressive cytokines like IL-10 and TGF-β, indicative of functional activity [32].

- Imaging and Biodistribution: For pre-clinical models, in vivo imaging can track cell homing, while PCR-based methods on explanted tissues can quantify cellular persistence [33].

Q4: What strategies can be employed to generate "off-the-shelf" hypoimmunogenic cell therapies to avoid host immune rejection?

A: Creating universal donor cells involves engineering to evade both T-cell and NK-cell surveillance. Key gene edits include:

- Abrogating T-cell Recognition: Knock out Beta-2 microglobulin (B2M) to prevent surface expression of HLA class I molecules [33].

- Evading NK-cell Mediated Lysis: To counter the "missing self" response from NK cells due to low HLA, overexpress CD47 (a "don't eat me" signal) and non-classical HLA molecules like HLA-G or HLA-E, which inhibit NK cell activity [33].

- Expressing Local Immunosuppressants: Engineer cells to overexpress surface immunomodulators like PD-L1 (Programmed Death-Ligand 1), which engages PD-1 on activated T cells to induce tolerance [33].

Key Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol: In Vitro Suppression Assay for CAR Tregs

This protocol is used to quantify the antigen-specific suppressive function of engineered CAR Tregs.

- Prepare Responder T Cells (Tresps): Isolate CD4+ CD25- T cells from human PBMCs and label them with a cell division tracker like CFSE.

- Stimulate Tresps: Co-culture the labeled Tresps with anti-CD3/CD28 activation beads or antigen-presenting cells (APCs).

- Set Up Co-culture: Add your engineered CAR Tregs to the stimulated Tresps at various ratios (e.g., 1:1, 1:2, 1:4 Treg:Tresp). Include controls with no Tregs (maximal proliferation) and no stimulation (background).

- Provide Antigen Specificity: Ensure the co-culture contains the target antigen recognized by the CAR (e.g., a peptide or expressed on APCs) to activate the CAR Tregs specifically.

- Incubate and Analyze: After 3-5 days, analyze Tresp proliferation by flow cytometry via CFSE dilution. The suppressive capacity is calculated as the percentage reduction in proliferation compared to the maximal proliferation control [29].

Protocol: Assessing CAR-MSC Mediated Treg Induction

This protocol evaluates the ability of CAR-MSCs to promote the differentiation of regulatory T cells.

- Co-culture Setup: Isolate naive CD4+ T cells from human PBMCs. Co-culture them with your CAR-MSCs (or control MSCs) in the presence of the target antigen and T-cell activation stimuli (e.g., soluble anti-CD3/CD28).

- Polarizing Conditions: Include TGF-β in the medium to favor Treg differentiation.

- Analysis by Flow Cytometry: After 5-7 days, harvest the T cells and stain for Treg markers, primarily CD4, CD25, and the transcription factor FoxP3.

- Functional Validation: To confirm functionality, the induced Tregs can be isolated and tested in a standard in vitro suppression assay as described above [30].

The tables below consolidate key quantitative findings from the literature on CAR Tregs and CAR-MSCs.

Table 1: Comparison of CAR Treg Costimulatory Domains and Functional Outcomes

| CAR Generation | Costimulatory Domain(s) | Model System | Key Functional Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Generation | CD28 | Human, GvHD | Significant prevention of GvHD; enhanced suppressive efficacy. | [29] |

| Second Generation | 4-1BB | Human, GvHD | Prevention of GvHD, but with decreased lineage stability. | [29] |

| Second Generation | CD28 | Human, Skin Allograft | Suppressed HLA-mismatched immune responses; preserved human skin grafts for 100 days. | [29] |

| Second Generation | CD28 | Murine, Islet Allograft | Prolonged survival of pancreatic islet allografts. | [29] |

Table 2: Documented Clinical and Preclinical Efficacy of MSCs and CAR-MSCs

| Cell Type | Disease / Model | Key Efficacy Metric | Outcome / Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Third-party MSCs | Steroid-resistant aGVHD (Clinical trial, n=47) | Treatment Response Rate | 75.0% response in MSC group vs. 42.1% in control. | [31] |

| Third-party MSCs | Haploidentical HSCT (Clinical, n=50) | Hematopoietic Reconstitution | Rapid, stable engraftment; median neutrophil (12d) and platelet (15d) recovery. | [31] |

| CAR-MSCs | Glioblastoma, Ewing's Sarcoma (Preclinical) | Tumor Suppression | Mediated via TRAIL secretion and induction of local Tregs. | [30] |

| MSC + IL-37b gene | DSS-induced Colitis (Murine) | Therapeutic Efficacy | Gene-modified MSCs alleviated colitis by inducing regulatory T cells. | [34] |

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

CAR Treg Signaling and Stability Pathway

This diagram illustrates the intracellular signaling within a CAR Treg and the factors influencing its stability.

Title: CAR Treg Signaling and Stability Regulation

CAR-MSC Immunomodulation Mechanism

This diagram outlines the multi-modal mechanisms by which CAR-MSCs exert targeted immunosuppression.

Title: CAR-MSC Mechanisms of Targeted Immunomodulation

Workflow for Generating Hypoimmunogenic "Off-the-Shelf" Cells

This flowchart details the genetic engineering steps required to create universal donor cells resistant to immune rejection.

Title: Engineering Workflow for Hypoimmunogenic Cells

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key reagents and tools essential for research and development in engineered cell-based immunomodulation.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CHAR-Treg and CAR-MSC Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Luminex Multiplex Immunoassays | Simultaneously quantify up to 50 soluble analytes (e.g., cytokines, chemokines) from a single small sample volume [32]. | Profiling suppressive cytokine secretion (IL-10, TGF-β) by CAR Tregs or CAR-MSCs in culture supernatant. |

| Lentiviral / Retroviral Vectors | Efficient and stable gene delivery for the expression of CAR constructs or gene-editing tools in primary immune cells and stem cells [29]. | Engineering CAR Tregs with antigen-specific receptors or creating hypoimmunogenic MSCs via gene overexpression. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Precision gene-editing technology for targeted knock-out (e.g., B2M) or knock-in (e.g., CAR into TCR locus) [29]. | Generating universal donor cells by disrupting HLA genes or creating stable, potent CAR Tregs. |

| Anti-human CD4, CD25, FoxP3 Antibodies | Flow cytometry antibodies for the identification, isolation, and purity check of Treg populations by surface and intracellular staining [29]. | Characterizing the phenotype of engineered CAR Tregs before and after in vitro or in vivo experiments. |

| Recombinant Immunomodulatory Proteins (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β) | Recombinant cytokines used to polarize T cells towards a regulatory phenotype or to test the functionality of engineered cells in suppression assays [29]. | Differentiating naive T cells into iTregs for subsequent CAR engineering or as positive controls in functional assays. |

| Treg Isolation Kits (e.g., CD4+CD25+) | Magnetic or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) kits for the high-purity isolation of Tregs from PBMCs as a starting population for engineering [29]. | Obtaining a pure population of primary human Tregs for CAR transduction to ensure a well-defined cellular product. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Mixed Chimerism and Tolerance Induction

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between graft acceptance and true transplant tolerance? Graft acceptance is often a transient state of immune nonresponsiveness, commonly achieved by immunosuppression and can be reversible. In contrast, true transplant tolerance is an active immunological process of mutual education between two immune systems to accept donor antigenic makeups, requiring either modulation of central selection or institution of indefinite peripheral suppression. It is characterized by specific unresponsiveness to donor alloantigens without ongoing immunosuppressive treatment [35].

Q2: Why is mixed chimerism preferred over complete chimerism for tolerance induction in solid organ transplantation? Mixed chimerism (coexistence of donor and host immune cells) induces true immune tolerance through central and peripheral mechanisms, with minimal risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Complete chimerism (full replacement of recipient hematopoiesis with donor cells), typically requiring myeloablative conditioning, carries significant risks including GVHD, infections, and is considered overly toxic for organ transplant recipients without underlying malignancy [36] [37].

Q3: Is stable, long-term mixed chimerism always necessary for sustained organ graft tolerance? No. Studies in large animal models and some clinical cases demonstrate that transient mixed chimerism can be sufficient for long-term graft acceptance. In MHC-mismatched transplantation in non-human primates, loss of detectable chimerism after several weeks did not preclude maintained renal allograft function without immunosuppression, suggesting that a limited period of chimerism may adequately "reset" the immune system [36].

HLA Matching and Stem Cell Banking

Q4: What are the current standardized HLA matching recommendations for different donor types? The Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) has established evidence-based guidelines for donor HLA assessment [38]:

Table: Standardized HLA Matching Recommendations for Allogeneic Transplantation

| Donor Type | Minimum HLA Matching Requirement | Key Loci Assessed |

|---|---|---|

| Matched Sibling | 6/6 match | HLA-A, -B (intermediate/high resolution), -DRB1 (high resolution) |

| 1 Antigen Mismatched Related | 7/8 match | HLA-A, -B, -C (intermediate/high resolution), -DRB1 (high resolution) |

| Haploidentical Related | ≥4/8 match | HLA-A, -B, -C (intermediate/high resolution), -DRB1 (high resolution) |

| Adult Unrelated Donor | 8/8 match preferred | HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1 (all high resolution) |

| Umbilical Cord Blood | ≥4/6 match | HLA-A, -B (intermediate resolution), -DRB1 (high resolution) |

Q5: What are the critical quality control checkpoints when establishing a stem cell bank for clinical applications? The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) recommends a two-tiered banking system with rigorous characterization [39]:

Table: Characterization Testing for Stem Cell Banks

| Characteristic | Master Cell Bank | Working Cell Bank |

|---|---|---|

| Post-thaw viability | ||

| Authentication (donor match) | ||

| Sterility (mycoplasma, adventitious agents) | ||

| Genomic stability | ||

| Gene/marker expression (undifferentiated status) | ||

| Functional pluripotency |

Technical and Translational Challenges