Patient-Specific iPSCs for Neurodegenerative Disease: Modeling, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Discovery

Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are revolutionizing the study and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Patient-Specific iPSCs for Neurodegenerative Disease: Modeling, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Discovery

Abstract

Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are revolutionizing the study and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring how iPSC technology enables the creation of genetically accurate in vitro models of conditions like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). It covers foundational reprogramming mechanisms, advanced methodological applications in disease modeling and drug screening, critical troubleshooting for manufacturing and quality control, and rigorous validation against clinical outcomes. By synthesizing recent advances and practical strategies, this guide aims to accelerate the translation of patient-specific iPSC research into validated disease insights and effective therapeutic candidates.

The Foundation of Patient-Specific iPSCs: From Somatic Cell to Disease-Relevant Neuron

Core Principles of Somatic Cell Reprogramming and Pluripotency

The ability to reprogram somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) represents one of the most significant breakthroughs in modern regenerative medicine and disease modeling. Since the initial discovery by Takahashi and Yamanaka, iPSC technology has fundamentally transformed our approach to investigating human development and disease [1]. This technology allows for the generation of patient-specific pluripotent stem cells that can be differentiated into any cell type of the body, providing an unprecedented platform for studying neurodegenerative diseases, drug screening, and developing personalized therapeutic strategies [2] [3]. The core principle of somatic cell reprogramming involves reversing the epigenetic landscape to return differentiated cells to an embryonic-like pluripotent state, thereby erasing their specialized identity and restoring developmental potential [4] [5]. This technical guide examines the molecular mechanisms, methodologies, and applications of somatic cell reprogramming, with particular emphasis on its transformative role in neurodegenerative disease research.

Historical Foundations and Key Discoveries

The conceptual foundation for cellular reprogramming was established through decades of pioneering research that challenged the long-held belief that cell differentiation was an irreversible process. Conrad Waddington's classic "epigenetic landscape" metaphor depicted cell differentiation as a ball rolling downhill toward an increasingly restricted and terminal state [4]. The reversal of this process was first demonstrated by John Gurdon in 1962 through somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) experiments in Xenopus laevis frogs, showing that a nucleus from a terminally differentiated somatic cell could support the development of an entire organism when transplanted into an enucleated egg [1] [5]. This groundbreaking work revealed that the genetic material in specialized cells remains intact and can be reprogrammed to a embryonic state.

The isolation of mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in 1981 by Evans and Kaufman and human ESCs by Thomson in 1998 provided critical reference points for understanding pluripotency [1]. Subsequent cell fusion experiments between ESCs and somatic cells demonstrated that factors within ESCs could reprogram somatic nuclei to pluripotency, suggesting that the process was mediated by specific molecular determinants [1]. The field was revolutionized in 2006 when Takahashi and Yamanaka demonstrated that the forced expression of only four transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (collectively known as the OSKM or Yamanaka factors)—could reprogram mouse fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells [2] [1]. This discovery was rapidly extended to human cells in 2007 by both Yamanaka's group and Thomson's group, the latter using OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28 [2] [1]. These landmark studies earned Gurdon and Yamanaka the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and established the fundamental methodology for generating patient-specific pluripotent stem cells without embryonic destruction.

Molecular Mechanisms of Reprogramming

Epigenetic Remodeling and Transcriptional Regulation

The process of somatic cell reprogramming involves profound reorganization of the epigenetic and transcriptional landscape, effectively reversing the Waddington epigenetic landscape to push differentiated cells back up toward a pluripotent state [4] [5]. This complex process occurs through two broad phases: an early, stochastic phase where somatic genes are silenced and early pluripotency-associated genes are activated, followed by a more deterministic late phase where late pluripotency-associated genes are established [1]. The reprogramming factors initiate widespread changes in chromatin structure, DNA methylation patterns, and histone modifications that collectively erase the somatic epigenetic memory and establish a pluripotent state [1].

OCT4 and SOX2 serve as pioneer factors in this process, capable of binding to closed chromatin regions and initiating their opening [4]. These core factors activate endogenous pluripotency networks while repressing somatic-specific genes. KLF4 contributes to this process by regulating downstream targets including NANOG, another critical pluripotency factor [4]. c-MYC plays a distinct role by promoting global chromatin accessibility through histone acetylation and driving proliferation, though it is not absolutely essential for reprogramming [2] [4]. The mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) represents another critical event during early reprogramming, particularly when starting with fibroblast populations [1].

Table 1: Core Reprogramming Factors and Their Functions

| Factor | Primary Function | Essentiality | Alternative Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | Pioneer transcription factor; activates pluripotency network | Essential | NR5A2 [2] |

| SOX2 | Pioneer transcription factor; regulates embryonic development | Essential | SOX1, SOX3 [2] |

| KLF4 | Transcriptional regulator; activates NANOG | Non-essential | KLF2, KLF5 [2] |

| c-MYC | Global chromatin modifier; enhances proliferation | Non-essential | L-MYC, N-MYC [2] |

Alternative Reprogramming Factors and Pathways

Subsequent research has identified numerous alternative factors and pathways that can replace or supplement the original Yamanaka factors. The small molecule RepSox can replace SOX2 in reprogramming, while Esrrb and Glis1 can serve as alternatives to c-MYC [2]. Other studies have demonstrated that SALL4, combined with NANOG, Esrrb, and LIN28, can generate high-quality iPSCs [5]. In certain contexts, such as with human neural stem cells, expression of OCT4 alone has proven sufficient to generate iPSCs, highlighting the pivotal role of this factor and the varying requirements across different cell types [2].

Methodologies for Somatic Cell Reprogramming

Delivery Systems for Reprogramming Factors

The initial reprogramming methods relied on integrating viral vectors, particularly retroviruses and lentiviruses, which raised concerns about potential tumorigenesis due to insertional mutagenesis [2]. This limitation has driven the development of non-integrating delivery systems that improve the safety profile of iPSCs for clinical applications. Current delivery methods span multiple technological platforms, each with distinct advantages and limitations for research and therapeutic use.

Table 2: Comparison of Reprogramming Factor Delivery Systems

| Delivery System | Genetic Material | Genomic Integration | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retrovirus/Lentivirus | DNA | Yes | Basic research, proof-of-concept studies [2] |

| Sendai Virus | RNA | No | Clinical-grade iPSC generation [2] |

| Episomal Plasmid | DNA | No | Clinical applications, good manufacturing practice [2] |

| Synthetic mRNA | RNA | No | Clinical applications, high efficiency [2] |

| Recombinant Protein | Protein | No | Basic research, proof-of-concept [2] |

Chemical Reprogramming

A significant advancement in the field has been the development of fully chemical reprogramming approaches that use defined small-molecule combinations to induce pluripotency without genetic manipulation [2] [6]. This method offers a fundamentally different approach with enhanced safety profiles for clinical applications. Chemical reprogramming of human blood cells has been recently achieved with high efficiency, enabling robust generation of human chemically induced pluripotent stem (hCiPS) cells from both cord blood and adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells [6]. Notably, this approach has proven effective even with minimal starting material, generating over 100 hCiPS colonies from a single drop of fingerstick blood [6].

Chemical reprogramming follows a stepwise process with a distinct intermediate cell state that exhibits enhanced chromatin accessibility and activation of early embryonic developmental genes [2]. This transient state shows gene expression signatures analogous to those observed during initial limb regeneration in axolotls, suggesting the activation of conserved regenerative programs [2]. The chemical approach provides a more flexible and standardized platform for reprogramming, as small molecules are easily synthesized, quality-controlled, and administered without the complexities of genetic delivery systems [6].

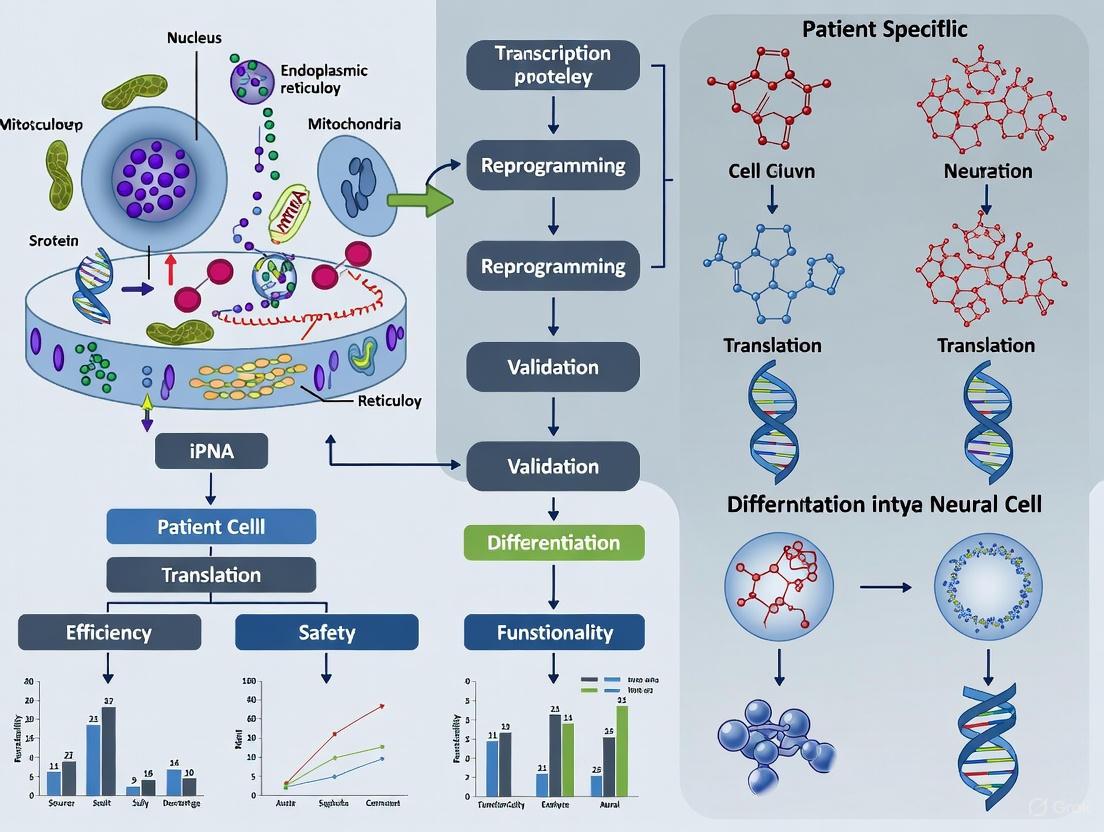

Figure 1: Chemical reprogramming workflow showing the transition from somatic cells to hCiPS cells through a highly plastic intermediate state, driven by small molecule cocktails that trigger epigenetic resetting and regenerative program activation [2] [6].

Enhancing Reprogramming Efficiency

Several strategies have been developed to improve the efficiency and kinetics of somatic cell reprogramming. Inhibition of the p53 tumor suppressor pathway significantly increases reprogramming efficiency, though this approach requires careful consideration due to potential cancer risks [2]. Additional epigenetic modulators, including DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (5-aza-cytidine, RG108), histone deacetylase inhibitors (sodium butyrate, trichostatin A, valproic acid), and the histone methylation regulator neplanocin A, have been shown to enhance reprogramming robustness [2]. The combination of 8-Bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cAMP) with valproic acid increased human fibroblast reprogramming efficiency by up to 6.5-fold [2]. MicroRNAs, particularly the miR-302/367 cluster and miR-372, also significantly improve reprogramming efficiency [2].

Experimental Protocols for iPSC Generation

Fibroblast Reprogramming Using Non-Integrating Methods

For generating clinical-grade iPSCs, non-integrating methods are preferred. The episomal plasmid system provides an effective approach: (1) Culture human dermal fibroblasts in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum; (2) At 60-70% confluency, transfect with episomal plasmids containing OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, L-MYC, LIN28, and p53 shRNA using electroporation; (3) After 48 hours, transfer cells to feeder-free culture conditions with essential 8 medium; (4) Change medium daily and monitor for emergence of embryonic stem cell-like colonies after 14-21 days; (5) Manually pick and expand individual colonies for characterization [2].

Chemical Reprogramming of Human Blood Cells

The chemical reprogramming of blood cells represents a recent advancement: (1) Isolate mononuclear cells from human cord blood or adult peripheral blood; (2) Expand cells in erythroid progenitor cell culture conditions; (3) Treat with a defined cocktail of small molecules targeting key epigenetic barriers and signaling pathways; (4) Transfer cells to adherent culture conditions and continue small molecule treatment; (5) Monitor for emergence of adherent colonies with embryonic stem cell morphology over 25-35 days; (6) Pick and expand hCiPS colonies in chemically defined medium [6]. This method has demonstrated higher efficiency compared to traditional OSKM-based approaches in blood cells and works effectively with both fresh and cryopreserved samples [6].

Characterization of Pluripotent Stem Cells

Validating fully reprogrammed iPSCs requires multiple lines of evidence: (1) Morphological assessment of embryonic stem cell-like colonies with high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio; (2) Immunocytochemistry for pluripotency markers including OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, TRA-1-60, and TRA-1-81; (3) RT-PCR analysis for endogenous pluripotency gene expression and silencing of transgenes if applicable; (4) In vitro differentiation through embryoid body formation followed by immunostaining for derivatives of all three germ layers; (5) Karyotype analysis to confirm genomic integrity; (6) Teratoma formation assay in immunodeficient mice to validate differentiation potential in vivo [6] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Reprogramming

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Somatic Cell Reprogramming

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC/L-MYC | Core transcription factors inducing pluripotency [2] |

| Epigenetic Modulators | VPA, Sodium Butyrate, Trichostatin A, 5-aza-cytidine | Enhance reprogramming efficiency by modifying chromatin structure [2] |

| Signaling Inhibitors | RepSox (TGF-β inhibitor), DMH1 (BMP inhibitor) | Replace transcription factors and promote MET [2] |

| Metabolic Regulators | 8-Br-cAMP | Enhances reprogramming efficiency through signaling activation [2] |

| Culture Matrices | Matrigel, Vitronectin, Laminin-521 | Provide substrate for pluripotent cell adhesion and expansion [6] |

| Pluripotency Media | Essential 8 Medium, mTeSR1 | Defined, xeno-free media supporting pluripotent state [6] |

| Blood Cell Culture Supplements | Erythropoietin, SCF, IL-3 | Support expansion of blood-derived progenitors for reprogramming [6] |

Applications in Neurodegenerative Disease Research

Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

iPSC technology has become an invaluable tool for investigating neurodegenerative diseases, particularly amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer's disease (AD), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) [2] [7] [8]. Patient-specific iPSCs enable researchers to generate neuronal models that recapitulate disease-specific pathology in vitro. iPSC-derived motor neurons (iPSC-MNs) from ALS patients provide a robust platform to investigate molecular mechanisms underpinning disease pathogenesis and accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic strategies [2]. Similarly, iPSC models of familial AD with mutations in PSEN1, PSEN2, or APP genes have demonstrated increased production of amyloid-β and altered Aβ42/40 ratios, confirming their utility in modeling disease mechanisms [3].

Several clinical trials based on iPSC research have been initiated for neurodegenerative diseases, including trials of bosutinib, ropinirole, and ezogabine for ALS, and WVE-004 and BII078 for ALS/FTD [7] [8]. iPSC-based screening platforms have identified compounds that target cholesterol metabolism to reduce phospho-Tau accumulation in AD models, revealing promising therapeutic avenues [3]. The integration of artificial intelligence with iPSC-based screening has further enhanced drug discovery efforts for neurodegenerative conditions [7] [8].

Three-Dimensional Models and Organoids

The development of three-dimensional cerebral organoids from patient-specific iPSCs has advanced modeling of neurodegenerative diseases by better recapitulating the complexity of the human brain [3]. For Alzheimer's disease research, cerebral organoids carrying PSEN1 mutations have been successfully established, exhibiting key pathological features including increased Aβ42/40 ratios and reduced synaptic proteins [3]. Similarly, iPSC-derived neurovascular unit models incorporating brain microvascular endothelial cells, astrocytes, and cortical projection neurons have been developed to study cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL), revealing impaired barrier function and disorganized tight junctions [3]. These advanced models provide more physiologically relevant systems for investigating disease mechanisms and screening therapeutic candidates.

Figure 2: Application of iPSC technology in neurodegenerative disease research, showing the pathway from patient samples to disease modeling and drug development through two-dimensional neuronal cultures and three-dimensional organoid systems [2] [3].

The core principles of somatic cell reprogramming and pluripotency have established a revolutionary platform for biomedical research and therapeutic development. The molecular mechanisms that govern the reversal of cellular differentiation involve sophisticated reprogramming of the epigenetic landscape, activation of endogenous pluripotency networks, and reorganization of cellular metabolism. Continued refinement of reprogramming methodologies, particularly the development of non-integrating delivery systems and fully chemical approaches, has enhanced the safety and efficiency of iPSC generation. In the context of neurodegenerative diseases, patient-specific iPSCs provide unprecedented opportunities to model pathogenesis, identify novel therapeutic targets, and screen candidate compounds in human neuronal systems. As the field advances, the integration of iPSC technology with emerging techniques in genome editing, three-dimensional organoid culture, and artificial intelligence promises to further accelerate progress toward effective treatments for currently incurable neurological disorders.

The discovery that somatic cells could be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) revolutionized biomedical research, creating unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling and regenerative medicine. This breakthrough, achieved by Shinya Yamanaka's team in 2006, demonstrated that the forced expression of four specific transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (collectively known as OSKM)—could revert adult cells to an embryonic-like pluripotent state [2] [1]. For neurodegenerative disease research, this technology offers a transformative approach: the ability to generate patient-specific neural cells in vitro, including the neurons and glial cells affected in conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer's, and Parkinson's diseases [2]. Patient-derived iPSCs provide a robust platform to recapitulate disease-specific pathology and investigate the molecular mechanisms underpinning these disorders, thereby accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic strategies [2]. The core of this technology lies in understanding the reprogramming factors—their functions, combinations, and delivery methods—which this review will explore in depth, with a specific focus on applications for neurodegenerative disease research.

Core OSKM Reprogramming Factors

The original OSKM factors were identified through a systematic screening of 24 genes known to be important for maintaining pluripotency in embryonic stem cells [1]. The successful reprogramming of both mouse and human fibroblasts using these factors established a new paradigm in cellular biology, proving that cell fate could be reversed without somatic cell nuclear transfer [1]. Each factor plays a distinct and critical role in the reprogramming process, as detailed below.

Table 1: Core OSKM Reprogramming Factors and Their Functions

| Factor | Full Name | Primary Function in Reprogramming | Key Target Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 | Master regulator of pluripotency; upregulates embryonic genes and inhibits differentiation genes [4]. | Activates pluripotency genes (e.g., NANOG); essential for stem cell maintenance [4]. |

| SOX2 | SRY (Sex determining region Y)-Box 2 | Partners with OCT4; regulates pluripotency gene expression and inhibits somatic gene programs [4]. | Works with OCT4 to co-activate pluripotency network; critical for early development [4]. |

| KLF4 | Krüppel-like factor 4 | Context-dependent transcriptional activator/suppressor; promotes mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) [2] [4]. | Regulates NANOG expression; can inhibit p53 to enhance reprogramming efficiency [4] [2]. |

| c-MYC | Cellular Myelocytomatosis | Global chromatin modifier; enhances proliferation and metabolism; increases efficiency but is not essential [4]. | Binds to ~15% of human genes; promotes expression of proliferation-related genes [4]. |

While OCT4 and SOX2 are considered the most essential core factors, KLF4 and c-MYC significantly enhance reprogramming efficiency. However, the use of the oncogene c-MYC poses significant safety risks for clinical applications, including tumorigenesis, which has driven the search for safer alternatives [2].

Alternative Reprogramming Factors and Small Molecules

Subsequent research has revealed that the OSKM combination is not rigid. Many factors can be substituted or supplemented to improve safety, efficiency, and applicability for different somatic cell sources. These alternatives are particularly valuable for generating clinical-grade iPSCs for therapeutic development.

Table 2: Alternative Reprogramming Factors and Small Molecules

| Category | Alternative to | Examples | Mechanism of Action / Rationale | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Substitutes | c-MYC | L-MYC, N-MYC [2] | Reduced tumorigenic risk compared to c-MYC while maintaining efficiency [2]. | L-MYC is often preferred for its superior safety profile. |

| KLF4 | KLF2, KLF5 [2] | Family members with similar functions can substitute for KLF4. | Most alternatives show lower efficiency than the original factor [2]. | |

| SOX2 | SOX1, SOX3, GLIS1 [2] | SOX family members can replace SOX2; GLIS1 acts as an alternative. | Small molecule RepSox can also replace SOX2 function [2]. | |

| OCT4 | NR5A2 [2] | Can substitute for OCT4 in combination with SOX2 and KLF4. | Demonstrates the flexibility of the core pluripotency network. | |

| Non-OSKM Factors | N/A | NANOG, LIN28 [4] [1] | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 (OSNL) form an alternative combination. | Used by Thomson et al. for human fibroblast reprogramming [4] [1]. |

| Efficiency Enhancers | N/A | miRNAs (e.g., miR-302/367, miR-372), LIN28 [2] | Improve reprogramming to pluripotency; regulate key developmental pathways. | Often used alongside transcription factors. |

| Epigenetic Modulators | N/A | VPA (HDAC inhibitor), Sodium Butyrate, 5-aza-cytidine [2] | Open chromatin structure, facilitating epigenetic remodeling during reprogramming. | Can increase iPSC generation efficiency by up to 6.5-fold when combined (e.g., 8-Br-cAMP + VPA) [2]. |

| Chemical Reprogramming | Genetic Factors | Specific small-molecule cocktails [2] [9] | Fully chemical reprogramming achieved without genetic manipulation, enhancing clinical safety [2]. | Significantly reduces tumorigenicity concerns; a major advance for clinical translation [10]. |

A notable advancement is the finding that the necessity of factors can vary by cell type. For instance, expressing OCT4 alone in human neural stem cells is sufficient to generate iPSCs, highlighting the pivotal role of OCT4 and the influence of the starting cell's epigenetic state [2].

Delivery Systems for Reprogramming Factors

The method used to deliver reprogramming factors is critical, as it impacts efficiency, genomic integrity, and the clinical potential of the resulting iPSCs. The ideal delivery system maximizes reprogramming efficiency while minimizing genomic alterations.

Table 3: Comparison of Reprogramming Factor Delivery Systems

| Vector/Platform | Genetic Material | Genomic Integration? | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrovirus | RNA | Yes | High efficiency; stable expression. | Integrates into genome; silenced in iPSCs; risk of insertional mutagenesis. |

| Lentivirus | RNA | Yes | Can infect non-dividing cells; high efficiency. | Integrates into genome; risk of insertional mutagenesis. |

| Sendai Virus | RNA | No | High efficiency; does not integrate; viral RNA degrades over time. | Requires effort to clear virus; potential immunogenicity. |

| Adenovirus | DNA | No | Does not integrate; lower immunogenicity than other viruses. | Lower reprogramming efficiency. |

| Episomal Plasmid | DNA | No | Non-viral; does not integrate; simple to use. | Low efficiency; requires repeated transfection. |

| PiggyBac Transposon | DNA | Yes, but reversible | Can be removed after integration; high cargo capacity. | Complex removal process; still involves temporary integration. |

| Synthetic mRNA | RNA | No | Non-viral, non-integrating; high efficiency; controlled dosing. | Can trigger innate immune response; requires multiple transfections. |

| Recombinant Protein | Protein | No | Completely non-genetic; highest safety profile. | Very low efficiency; difficult to produce and deliver. |

The field is increasingly moving toward non-integrating methods, such as Sendai virus, synthetic mRNA, and episomal plasmids, particularly for clinical applications where genomic integrity is paramount [2]. Furthermore, fully chemical reprogramming represents the ultimate safety goal, eliminating the need for genetic material altogether [2] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for iPSC Generation

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC Generation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|

| Core Transcription Factors | OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) factors | Ectopic expression reprograms somatic cells to pluripotency; the foundational components of the process. |

| Delivery Tools | Retroviral/Lentiviral vectors, Sendai virus, mRNA kits | Vehicles for introducing reprogramming factors into target somatic cells. |

| Efficiency Enhancers | Valproic Acid (VPA), Sodium Butyrate, 8-Br-cAMP | Small molecule compounds that increase reprogramming efficiency by modulating epigenetic states and signaling pathways [2]. |

| Cell Culture Media | DMEM/F12, specialized reprogramming media | Provides essential nutrients and a controlled environment to support cell survival and reprogramming. |

| Somatic Cell Sources | Skin fibroblasts, peripheral blood cells | Starting material for reprogramming; chosen for patient-specific applications and accessibility. |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-OCT4, Anti-SOX2, Anti-NANOG, Anti-SSEA4 | Used to confirm the successful establishment of pluripotency in resulting iPSC lines via immunostaining. |

The systematic identification and optimization of reprogramming factors have positioned iPSC technology as a cornerstone of modern biomedical research. The evolution from the canonical OSKM factors to safer, more efficient alternatives, including fully chemical reprogramming, has significantly enhanced the potential of this technology for clinical translation. For neurodegenerative diseases, where access to functional human neurons for study is severely limited, patient-specific iPSCs provide an unparalleled platform. These cells enable researchers to dissect disease mechanisms in relevant cell types, screen for novel therapeutic compounds, and develop autologous cell replacement strategies. As delivery methods become more refined and our understanding of the reprogramming epigenome deepens, the generation of clinical-grade iPSCs will become more standardized. The ongoing refinement of key reprogramming factors continues to push the field closer to its ultimate goal: leveraging a patient's own cells to understand and treat devastating neurodegenerative disorders.

The generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) represents a transformative advancement in regenerative medicine and disease modeling. By reprogramming adult somatic cells back to a pluripotent state, researchers can create patient-specific cell lines for studying disease mechanisms, drug screening, and developing cell-based therapies. The method used to deliver reprogramming factors significantly impacts the genomic integrity, safety profile, and clinical applicability of the resulting iPSCs. This technical guide provides a comprehensive comparison of integrating and non-integrating delivery systems, with particular emphasis on their applications in neurodegenerative disease research.

Core Principles of iPSC Reprogramming

iPSC reprogramming involves the forced expression of specific transcription factors to reverse the developmental clock of somatic cells. The original method utilized four core factors: OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (collectively known as OSKM) [11]. These factors work in concert to reactivate the endogenous pluripotency network while silencing somatic cell programs. The delivery method for introducing these factors into target cells represents a critical determinant of iPSC quality and safety, particularly for modeling complex neurodegenerative disorders where long-term culture and neuronal differentiation are required.

Integrating Delivery Systems: Methods and Limitations

Integrating delivery systems introduce reprogramming factors into the host cell genome, creating permanent genetic modifications. The primary methods include:

Retroviral Vectors

Retroviruses were used in the pioneering iPSC studies and remain efficient for reprogramming. These vectors require cell division for integration and are typically silenced in fully reprogrammed iPSCs, allowing endogenous pluripotency genes to take over [11]. However, the random nature of integration poses significant risks, including insertional mutagenesis and potential reactivation of transgenes in differentiated cells.

Lentiviral Vectors

Lentiviruses can infect both dividing and non-dividing cells, offering broader applicability than retroviruses. Like retroviral methods, they result in permanent genomic integration. Studies have reported reprogramming efficiencies of approximately 0.27% with lentiviral methods [12]. The major concern with both retroviral and lentiviral systems is the risk of oncogene activation, particularly when using potent factors like c-MYC, which is implicated in approximately 70% of human cancers [11].

Non-Integrating Delivery Systems: Techniques and Applications

Non-integrating methods provide transient expression of reprogramming factors, eliminating the risk of permanent genetic alterations. These approaches are particularly valuable for clinical applications and disease modeling where genomic integrity is paramount.

Sendai Virus (SeV)

Sendai virus is an RNA virus that replicates in the cytoplasm without integrating into the host genome. The CytoTune kit utilizing SeV demonstrates reprogramming efficiencies of approximately 0.077% [12]. A significant advantage is its high reliability, with success rates of 94% in generating multiple iPSC colonies [12]. However, the viral RNA must be actively diluted out through cell passaging, with studies showing 53.8% of lines clear the virus by passages 6-8, and only 21.2% remain positive by passages 9-11 [12].

Episomal Vectors (Epi)

Episomal vectors utilize Epstein-Barr virus-derived sequences that facilitate plasmid replication in dividing cells without genomic integration. These systems achieve reprogramming efficiencies of approximately 0.013% [12]. A concern with this method is the potential persistence of plasmids, with ~39.1% of early-passage iPSC lines retaining EBNA1 DNA, decreasing slowly to 33.3% at passages 9-11 [12]. Fluorescent tagging strategies have been developed to identify plasmid-retaining colonies [12].

mRNA Transfection

The mRNA method involves daily transfections of in vitro-transcribed mRNAs encoding reprogramming factors. This approach achieves the highest reprogramming efficiency at 2.1% but has a lower success rate of 27% due to massive cell death and detachment issues [12]. The method requires chemical measures to limit activation of the innate immune system by foreign nucleic acids. Success rates improve significantly to 73% when combined with microRNA transfections (miRNA + mRNA method) [12].

Additional Non-Integrating Methods

Other non-integrating approaches include adenoviral vectors, plasmid transfection, and protein transduction. Electroporation-based methods (Nucleofector, Neon systems) generally show higher reprogramming efficiency than chemical-based approaches like Lipofectamine 3000 [13]. Protein-induced pluripotent stem cells (piPSCs) generated through direct delivery of recombinant proteins represent perhaps the safest approach, completely avoiding genetic manipulation [14].

Quantitative Comparison of Reprogramming Methods

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of iPSC Reprogramming Methods

| Method | Reprogramming Efficiency (%) | Success Rate (%) | Aneuploidy Rate (%) | Hands-on Time (Hours) | Time to Colony Picking (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | 2.1 [12] | 27 [12] | 2.3 [12] | ~8 [12] | ~14 [12] |

| miRNA + mRNA | 0.19 [12] | 73 [12] | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Sendai Virus | 0.077 [12] | 94 [12] | 4.6 [12] | 3.5 [12] | ~26 [12] |

| Episomal | 0.013 [12] | 93 [12] | 11.5 [12] | ~4 [12] | ~20 [12] |

| Lentiviral | 0.27 [12] | 100 [12] | 4.5 [12] | N/A | N/A |

| Retroviral | N/A | N/A | 13.5 [12] | N/A | N/A |

Table 2: Genomic Integrity Assessment Across Reprogramming Methods

| Method | Copy Number Variation Burden | Likely Pathogenic CNVs | Single Nucleotide Variations | Mosaicism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrating Methods | Maximum CNV sizes 20x higher [15] | Elevated [15] | Increased [15] | More prevalent [15] |

| Non-Integrating Methods | Lower CNV burden [15] | Reduced [15] | Reduced [15] | Less prevalent [15] |

Impact on Genomic Stability and Pluripotency

The choice of reprogramming method significantly impacts the genomic stability of resulting iPSCs. Studies comparing integrating and non-integrating methods have revealed that integrating methods produce significantly larger copy number variations (CNVs) - with maximum sizes up to 20 times higher than non-integrating methods [15]. Additionally, integrating methods show higher numbers of novel CNVs and likely pathogenic CNVs overlapping with databases like ISCA [15].

Regarding pluripotency, all reprogramming methods can generate high-quality iPSCs expressing standard pluripotency markers including TRA160, NANOG, SSEA4, TRA181, OCT4, DNMT3B, SOX2, REX1, LIN28, and UTF1 [12]. However, some studies report differential expression of certain genes (TCERG1L, FAM19A5, MEG3/RIAN) in a subset of iPSC lines regardless of reprogramming method, suggesting additional factors influence complete reprogramming [12].

iPSC Reprogramming Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for generating and validating patient-specific iPSCs using non-integrating methods, with particular application to neurodegenerative disease modeling:

Application to Neurodegenerative Disease Research

The generation of patient-specific iPSCs has revolutionized neurodegenerative disease research by enabling the creation of in vitro models that capture patient-specific genetics. Large-scale studies have demonstrated the particular value of non-integrating methods for this application. For instance, in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) research, episomal reprogramming has been used to create iPSC libraries from 100 patients with sporadic ALS, enabling population-wide phenotypic screening and drug discovery [16].

These patient-derived models recapitulate key disease aspects including reduced motor neuron survival, accelerated neurite degeneration, and transcriptional dysregulation [16]. Importantly, the use of non-integrating methods ensures that observed phenotypes genuinely reflect the disease pathology rather than artifacts of genomic manipulation. This approach has enabled identification of potential combinatorial therapies (riluzole, memantine, and baricitinib) that rescue motor neuron survival across diverse SALS donors [16].

Similarly, iPSC-based epilepsy models derived from patients with CLCNKB mutations have revealed differentially expressed genes through RNA sequencing, providing insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets [17]. The ability to generate genetically accurate models of neurological disorders underscores the critical importance of selecting appropriate reprogramming methods that minimize genomic alterations while maintaining high reprogramming efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for iPSC Generation

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Generation and Characterization

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Kits | CytoTune-iPS Sendai Reprogramming Kit [12], Stemgent mRNA Reprogramming Kit [12] | Commercial systems for efficient non-integrating reprogramming |

| Delivery Systems | Neon Transfection System [13], Nucleofector System [13], Lipofectamine 3000 [13] | Electroporation and chemical-based methods for nucleic acid delivery |

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM) [11], OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 [11] | Core transcription factors to induce pluripotency |

| Culture Media | Knockout Serum Replacement (KSR) Medium [13], Fibroblast Medium [13] | Specialized media formulations for feeder-dependent iPSC culture |

| Pluripotency Markers | TRA160, TRA181, SSEA4, NANOG, OCT4 [12] [13] | Antibodies for immunocytochemical verification of pluripotency |

| Karyotyping Tools | KaryoLite BoBs [13], Affymetrix Cytoscan HD array [15] | Genomic tools for assessing chromosomal integrity and CNVs |

| Differentiation Factors | ChAT, MNX1/HB9, β-tubulin III (Tuj1) [16] | Markers for verifying neural differentiation potential |

Method Selection Framework for Neurodegenerative Disease Applications

The following decision diagram provides a structured approach for selecting the optimal reprogramming method based on research goals and technical constraints:

The selection between integrating and non-integrating reprogramming methods represents a critical decision point in experimental design for neurodegenerative disease research. While integrating methods offer established protocols and good efficiency, non-integrating approaches provide superior genomic integrity essential for clinical translation and accurate disease modeling. For most neurodegenerative disease applications requiring patient-specific iPSCs, Sendai virus and mRNA-based methods offer the optimal balance of efficiency, reliability, and safety. The continued refinement of non-integrating methods, coupled with rigorous genomic quality control, will further enhance our ability to model complex neurological disorders and develop effective therapeutic interventions.

The advent of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has revolutionized biomedical research, providing an unprecedented platform for disease modeling, drug screening, and therapeutic development. Within neurodegenerative disease research, patient-specific iPSCs offer the unique capacity to recapitulate disease pathophysiology in vitro, enabling the investigation of molecular mechanisms and personalized therapeutic interventions. The initial step in generating robust neurodegenerative disease models is the selection of an appropriate somatic cell source, a critical decision that directly influences reprogramming efficiency, genomic stability, and the fidelity of subsequent neuronal differentiation. This technical guide provides a comprehensive analysis of somatic cell sources for iPSC-based neurodegenerative disease modeling, detailing methodological considerations, quality control standards, and applications tailored to the requirements of research scientists and drug development professionals.

The choice of somatic cell source significantly impacts the efficiency and quality of resulting iPSC lines, particularly for neurological applications. Key somatic cell types vary in accessibility, reprogramming efficiency, and expansion capability.

Table 1: Characteristics of Somatic Cell Sources for iPSC Generation

| Cell Source | Accessibility | Reprogramming Efficiency | Key Advantages | Limitations for Neurological Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dermal Fibroblasts | Moderate (invasive skin biopsy required) | Variable (0.1%–1%) [18] | High genomic stability; well-established protocols; extensive banking potential [18] | Invasive collection; potential epigenetic memory bias |

| Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | High (minimally invasive blood draw) | Comparable to fibroblasts [18] | Minimal patient discomfort; renewable source (via blood draws); suitable for longitudinal studies [18] [19] | Lower cell yield per volume; requires specific reprogramming adjustments |

| Urinary Epithelial Cells | Very High (completely non-invasive collection) | Robust [18] | Completely non-invasive; easily repeatable sampling; suitable for pediatric and cognitively impaired patients [18] | Limited initial cell number; potentially higher microbial contamination risk |

| Keratinocytes | Moderate (hair pluck or skin biopsy) | Higher than fibroblasts [18] | Higher reprogramming efficiency than fibroblasts; accessible from minor biopsies [18] | Limited cell yield from plucked hairs; requires specialized culture conditions |

| Dental Pulp Stem Cells | Low (requires dental procedure) | High [18] | Neural crest origin; inherent neurogenic potential; high proliferation rate [18] | Limited availability; requires specialized dental procedures |

| Neural Stem/Progenitor Cells | Very Low (requires specialized tissue access) | High (endogenous expression of pluripotency factors) [19] | Inherent neurological commitment; reduced epigenetic barriers to neural differentiation [19] | Extremely limited accessibility from living donors; ethically complex |

Methodologies for Somatic Cell Reprogramming

Reprogramming Factor Combinations

The foundational reprogramming factors established by Yamanaka and colleagues (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) remain the benchmark for somatic cell reprogramming. However, subsequent refinements have enhanced safety and efficiency profiles.

Table 2: Reprogramming Factor Combinations and Their Applications

| Factor Combination | Components | Efficiency | Safety Profile | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSKM | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC [2] [1] | High | Lower (c-MYC oncogenic potential) [2] | Basic research with robust quality control |

| OSK | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 (c-MYC omitted) [2] | Moderate | Higher (eliminates c-MYC oncogene) [2] | Preclinical therapeutic development |

| OSNL | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 [2] [1] | Moderate to High | Higher (avoids c-MYC) [2] | Disease modeling and drug screening applications |

| Chemical Reprogramming | Small molecule cocktails (e.g., VPA, CHIR99021, A-83-01) [2] [19] | Lower initially, improving | Highest (non-integrating, transgene-free) [2] | Clinical translation and precision medicine |

Delivery Systems for Reprogramming Factors

The method of introducing reprogramming factors into somatic cells significantly influences genomic integrity and clinical applicability.

Non-integrating methods are strongly preferred for neurodegenerative disease modeling due to the need for genetically stable, clinically relevant models. Sendai virus systems offer an optimal balance of high efficiency and safety, while mRNA-based approaches provide a completely non-viral alternative with comparable safety profiles [18] [19].

Experimental Protocol: iPSC Generation from Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells

Materials Required:

- Ficoll-Paque PLUS density gradient medium

- PBMC isolation tubes

- StemSpan H3000 medium with cytokines (SCF, FLT-3 ligand, IL-3, IL-6)

- Sendai virus vectors encoding OSKM factors (CytoTune-iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming Kit)

- mTeSR1 or Essential 8 medium

- Matrigel-coated tissue culture plates

- Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor Y-27632

Procedure:

- PBMC Isolation: Collect peripheral blood via venipuncture in heparinized tubes. Isolate PBMCs using density gradient centrifugation with Ficoll-Paque [18].

- Expansion Culture: Resuspend PBMCs in StemSpan H3000 medium supplemented with cytokines. Culture for 5-7 days to expand progenitor populations [18].

- Reprogramming Transduction: On day 0, transduce 1×10^6 PBMCs with Sendai virus vectors at appropriate multiplicities of infection (MOI). Centrifuge plates at 1000×g for 30 minutes to enhance viral contact [19].

- Medium Transition: After 24 hours, replace virus-containing medium with fresh expansion medium. On day 7, transfer transduced cells to Matrigel-coated plates in mTeSR1 medium supplemented with ROCK inhibitor [19].

- Colony Selection: Between days 21-28, identify and manually pick embryonic stem cell-like colonies based on morphology (compact cells with defined borders, high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio). Expand selected clones for characterization [18].

Quality Control and Pluripotency Verification

Rigorous quality control is essential to ensure iPSC lines are suitable for neurodegenerative disease modeling. The verification process encompasses molecular characterization and functional assessment.

Key Quality Control Assays:

Pluripotency Marker Verification:

Trilineage Differentiation Potential:

- Embryoid Body Formation: Culture iPSCs in suspension to form embryoid bodies, then plate for spontaneous differentiation [20].

- Germ Layer Marker Analysis: Immunostain differentiated cells for ectoderm (β-III-tubulin), mesoderm (smooth muscle actin), and endoderm (alpha-fetoprotein) markers [20].

- In Vivo Teratoma Assay: Inject iPSCs into immunodeficient mice; analyze resulting teratomas for tissues derived from all three germ layers (requires 2-3 months) [20].

Genomic Integrity Assessment:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for iPSC Generation and Neural Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Vectors | CytoTune-iPS Sendai Virus, Episomal plasmids | Delivery of reprogramming factors | Sendai virus preferred for efficiency; episomal for clinical applications [18] [19] |

| Culture Media | mTeSR1, Essential 8, StemFlex | Maintenance of pluripotency | Chemically defined, xeno-free formulations enhance reproducibility [18] |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Laminin-521, Vitronectin | Substrate for feeder-free culture | Laminin-521 enhances attachment and survival of neural precursors [18] |

| Neural Induction Media | STEMdiff SMADi Neural Induction, N2/B27 supplements | Direct differentiation to neural lineages | Dual-SMAD inhibition protocol accelerates neural induction [19] |

| Neural Patterning Factors | Retinoic Acid, Sonic Hedgehog, BDNF, GDNF | Regional specification and maturation | Critical for generating disease-relevant neuronal subtypes [2] [21] |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems, PiggyBac transposons | Genetic modification for isogenic controls | Essential for correcting mutations or introducing disease variants [20] [19] |

Applications in Neurodegenerative Disease Modeling

Patient-specific iPSCs have enabled significant advances in modeling various neurodegenerative disorders, including Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer's Disease (AD), and Parkinson's Disease (PD).

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Modeling: iPSCs derived from familial and sporadic ALS patients have been successfully differentiated into motor neurons, recapitulating key disease pathologies including TDP-43 protein aggregation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neurite degeneration. A recent study utilizing 32 sALS patient-derived iPSC lines identified distinct patient clusters with varying drug responses, leading to the identification of ropinirole hydrochloride as a potential therapeutic candidate [21].

Parkinson's Disease (PD) Modeling: iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons from PD patients with LRRK2 or SNCA mutations have replicated disease-relevant phenotypes such as α-synuclein accumulation, mitochondrial impairment, and increased susceptibility to oxidative stress. These models have enabled high-throughput screening of compounds that reduce α-synuclein pathology [18] [20].

Alzheimer's Disease (AD) Modeling: iPSC-derived neurons and glial cells from familial AD patients have reproduced hallmark pathological features including β-amyloid deposition, tau hyperphosphorylation, and neuroinflammation. Co-culture systems incorporating microglia have enhanced the modeling of neuroimmune interactions in AD progression [18] [20].

Concluding Recommendations

Selecting the optimal somatic cell source for neurodegenerative disease modeling requires careful consideration of research objectives, patient population, and downstream applications. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells currently represent the optimal balance of accessibility, reprogramming efficiency, and clinical relevance for most neurodegenerative disease modeling applications. For studies requiring maximum neurological relevance, dermal fibroblasts remain valuable for their robust expansion and genomic stability. Emerging sources such as urinary epithelial cells offer particular promise for pediatric neurodegenerative disorders and longitudinal studies requiring repeated sampling.

The integration of advanced gene editing technologies, particularly CRISPR/Cas9, with patient-specific iPSCs enables the generation of isogenic control lines that are fundamental for distinguishing disease-specific phenotypes from background genetic variation. As the field progresses toward increasingly complex 3D model systems including cerebral organoids and assembloids, rigorous quality control of starting somatic cell populations and derived iPSCs becomes increasingly critical for generating physiologically relevant models of neurodegenerative pathogenesis.

Molecular and Epigenetic Remodeling During Neural Fate Acquisition

The process of neural fate acquisition, wherein naive cells are irrevocably committed to a neural lineage, is governed by a precise interplay of extrinsic signaling molecules and intrinsic epigenetic remodeling. This process is fundamental to embryogenesis and is recapitulated in vitro during the differentiation of pluripotent stem cells, including patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). The core molecular machinery involves the blockade of Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) signaling, which acts as a master switch to direct cell fate away from epidermal and towards neural lineages. Concurrently, dynamic chromatin modifications, orchestrated by complexes such as the Polycomb Repressor Complex (PRC), silence pluripotency genes and activate neural gene programs. This whitepaper provides a technical guide to the core mechanisms of neural induction, detailing the key signaling pathways, epigenetic regulators, and experimental protocols. Framed within the context of patient-specific iPSC models, this knowledge provides the foundation for advanced in vitro modeling of human neurodevelopment and neurodegenerative diseases, enabling novel drug discovery and therapeutic development.

Core Molecular Mechanisms of Neural Induction

Neural induction is the initial step in embryogenesis where naive cells are converted into committed neural cells [22]. The molecular pathways that govern this binary cell fate decision have been extensively studied and are leveraged in vitro to direct the differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into neural lineages.

The Central Role of BMP Signaling and Its Blockade

The default model of neural induction posits that the blockade of BMP signaling is the pivotal event that drives cells toward a neural fate. In the absence of exogenous inductive signals, mammalian pluripotent stem cells spontaneously differentiate into neural lineages [22]. The presence of BMP signaling promotes differentiation into non-neural ectoderm, characterized by the expression of genes like Id1 [22].

- Key Signaling Molecules: BMP2/4/7 ligands bind to BMP receptors, leading to the phosphorylation of the carboxyl-terminal serine residues of the SMAD1/5/8 proteins. This activated complex then translocates to the nucleus to activate the transcription of genes that promote non-neural fates [22].

- Extracellular Antagonists: Neural inducers such as Noggin, Chordin, and Follistatin are secreted proteins that bind directly to BMP ligands in the extracellular space, preventing them from interacting with their receptors and thus inhibiting the BMP signaling cascade [22].

- Convergence with FGF Signaling: Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) signaling also exhibits neural-inducing activity. One mechanism involves FGF promoting the phosphorylation of the intermediate linker domain of SMAD1, which restricts its activity and inhibits the BMP pathway. FGF may also directly induce the expression of neural genes through an independent pathway [22]. The combination of BMP inhibition and FGF signaling is essential for efficient neural induction in amniote embryos and stem cell systems [22].

Table 1: Core Signaling Pathways in Neural Fate Acquisition

| Pathway/Component | Role in Neural Induction | Key Effectors | Outcome of Pathway Activation | Outcome of Pathway Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP Signaling | Promotes non-neural (epidermal) fate | BMP2/4/7, BMP Receptors, p-SMAD1/5/8, ID1/ID3 | Differentiation into non-neural ectoderm | Neural fate specification |

| BMP Antagonists | Induces neural fate | Noggin, Chordin, Follistatin | - | Blocks BMP signaling, inducing neural genes |

| FGF Signaling | Supports neural induction | FGF ligands, FGF Receptors | Phosphorylation of SMAD1 linker region; direct neural gene induction | Perturbed neural differentiation |

The "Dual-SMAD Inhibition" Protocol

A widely adopted and efficient method for neural induction from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) is the "dual-SMAD inhibition" protocol [23]. This protocol utilizes small molecule inhibitors to simultaneously suppress both the BMP and TGFβ/Activin/Nodal branches of SMAD signaling.

- BMP Pathway Inhibition: Achieved using molecules like Dorsomorphin or its analogue LDN-193189, which act as BMP receptor kinase inhibitors.

- TGFβ/Activin/Nodal Pathway Inhibition: Achieved using SB431542, an inhibitor of the TGFβ type I receptor ALK5.

- Outcome: The combined inhibition results in highly efficient and rapid conversion of hPSCs into neuroepithelial cells, forming the basis for further differentiation into specific neural subtypes, such as cerebral cortex neural progenitor cells [23].

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway and its experimental inhibition that directs cells toward a neural fate.

Epigenetic Remodeling in Neural Commitment

The shift from a pluripotent to a neural-restricted state requires extensive reprogramming of the epigenetic landscape. This involves the silencing of pluripotency networks and the sequential opening of neural gene loci, a process tightly coupled with extrinsic signaling.

Chromatin Dynamics and Polycomb Complexes

As cells exit pluripotency, chromatin at pluripotent gene loci (e.g., Nanog, Rex) transitions from an open to a condensed, heterochromatic state through DNA methylation and histone modifications [22]. Concurrently, neural gene loci gradually acquire an open chromatin status [22].

- Polycomb Repressor Complexes (PRC): PRC1 and PRC2 are crucial chromatin-modifying complexes that mediate gene silencing through catalysis of specific histone marks.

- Dynamic Subunit Composition: The specificity and function of PRC1 are modulated by the exchange of its subunit components during differentiation. For instance, stem cell-enriched subunits like Cbx7 are replaced by neural progenitor cell (NPC)-enriched subunits like Cbx6, Cbx8, and Pcgf5, which is essential for proper neural differentiation [22].

Integration of Signaling and Epigenetics: The BMP-Phc1 Axis

A direct molecular link exists between the BMP signaling pathway and the epigenetic machinery. Research using mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells has demonstrated that BMP signaling regulates the expression of several PRC component genes, most notably Polyhomeotic Homolog 1 (Phc1) [22] [24].

- BMP Represses Phc1: BMP4 treatment during neural differentiation downregulates the expression of Phc1, a core component of cPRC1 [22].

- Phc1 is Essential for Neural Differentiation: Phc1-knockout (KO) ES cells fail to acquire a neural fate and remain in a pluripotent or primitive non-neural state. Chromatin accessibility analysis (ATAC-seq) revealed that Phc1 is essential for chromatin compaction at pluripotency gene loci during differentiation [22] [24].

- Feedback Loop: Aberrant upregulation of BMP signaling is observed in Phc1 mutant embryos, suggesting a feedback mechanism where the epigenetic regulator Phc1 is required to reinforce and maintain the BMP-inhibited state necessary for neural commitment [22].

The diagram below illustrates the critical role of this epigenetic regulator in neural fate acquisition.

Table 2: Key Epigenetic Regulators in Neural Induction

| Epigenetic Component | Complex/Function | Role in Neural Induction | Consequence of Loss-of-Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phc1 | Core component of canonical PRC1 | Essential for silencing pluripotency genes via chromatin compaction; regulated by BMP | Failure to differentiate into neural lineages; cells remain pluripotent [22] [24] |

| Pcgf5 | Component of non-canonical PRC1 | Enriched in NPCs; promotes neural differentiation | Prevents neural differentiation via aberrant SMAD2/TGF-β signaling [22] |

| Cbx7 | PRC1 subunit (Cbx protein) | Enriched in ESCs; maintains pluripotency | - (Subunit exchange during differentiation is crucial) |

| Cbx6/Cbx8 | PRC1 subunits (Cbx proteins) | Enriched in NPCs; promote neural differentiation | Mutants exhibit defective neural development [22] |

| EZH1/EZH2 | Catalytic core of PRC2 | Trimethylates H3K27 (H3K27me3) for gene silencing | Disruption of neural differentiation and patterning |

Experimental Protocols for Neural Differentiation

Standard 2D Cortical Neural Progenitor Differentiation

This protocol is designed for the highly efficient generation of dorsal forebrain neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and neurons from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) [23].

- Core Principle: Dual-SMAD inhibition.

- Base Medium: Chemically defined medium such as GFCDM (growth factor-free chemically defined medium) to allow precise evaluation of exogenous factors [22].

- Key Steps:

- Initiation of Differentiation: hPSCs are dissociated and plated as a monolayer. From day 0, the medium is supplemented with SMAD inhibitors:

- SB431542 (10 µM): A TGFβ receptor inhibitor.

- LDN-193189 (100 nM): A BMP receptor inhibitor.

- Neural Progenitor Expansion: The dual-SMAD inhibitors are maintained for 10-14 days. During this period, cells efficiently differentiate into PAX6+ neuroepithelial cells. The medium can be further supplemented with FGF2 (20 ng/mL) to support progenitor proliferation.

- Patterning and Maturation: To generate specific neuronal subtypes, patterning factors are added. For cortical neurons, SMAD inhibition is continued, and the culture can be transitioned to a medium containing BDNF, GDNF, and ascorbic acid to support neuronal maturation over several weeks. The protocol generates deep-layer neurons followed by upper-layer neurons and astrocytes, recapitulating in vivo corticogenesis [23].

- Initiation of Differentiation: hPSCs are dissociated and plated as a monolayer. From day 0, the medium is supplemented with SMAD inhibitors:

Spinal Motor Neuron Differentiation

This protocol is optimized for generating spinal motor neurons (MNs), which are relevant for diseases like Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) [16].

- Core Principle: Sequential activation and inhibition of key developmental pathways to pattern the cells toward a caudal spinal cord fate.

- Key Steps:

- Neural Induction: Similar to the cortical protocol, often using dual-SMAD inhibition for the first 1-2 weeks to generate neuroepithelium.

- Caudalization: To specify a spinal cord identity, cells are treated with a Wnt agonist (e.g., CHIR99021) and retinoic acid (RA). This combination promotes a posterior neural fate.

- Ventralization: To generate motor neuron progenitors, the culture is treated with a Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) pathway agonist (e.g., Purmorphamine or SAG). This ventralizes the neural tube to a pMN progenitor domain.

- Maturation: Progenitors are then differentiated into post-mitotic motor neurons expressing markers like HB9 (MNX1) and ChAT in the presence of neurotrophic factors (BDNF, GDNF, CNTF). The entire process from hPSC to mature MNs typically takes 5-7 weeks [16].

Applications in Neurodegenerative Disease Research

Patient-specific iPSCs have revolutionized the modeling of neurodegenerative diseases, providing access to live, human neurons that carry the genetic blueprint of the patient.

Disease Modeling with Patient-Specific iPSCs

iPSC-derived neural models have been generated for all major neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinson's disease (PD; dopaminergic neurons), Alzheimer's disease (AD; cortical and hippocampal neurons), Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS; motor neurons), and Huntington's disease (HD; striatal neurons) [25] [26]. A key advancement is the ability to model sporadic diseases, which account for over 90% of cases.

- Sporadic ALS Modeling: A landmark study generated an iPSC library from 100 sporadic ALS (SALS) patients. Motor neurons derived from these lines recapitulated key disease pathologies, including reduced survival and accelerated neurite degeneration. The severity of in vitro neurodegeneration correlated with the donor's clinical survival time, validating the model's pathophysiological relevance [16].

- Recapitulating Disease Hallmarks: iPSC-derived neurons from patients with monogenic and sporadic diseases often exhibit disease-specific phenotypes such as protein aggregation (e.g., TDP-43 in ALS), transcriptional dysregulation, and increased susceptibility to cellular stressors [25] [16].

Drug Screening and Therapeutic Discovery

The reproducibility and scalability of iPSC-derived neural models make them ideal for high-throughput drug screening.

- Phenotypic Screening: The SALS motor neuron model was used to screen over 100 drugs that had previously been tested in ALS clinical trials. The model showed a 97% failure rate, accurately reflecting the clinical trial outcomes and validating the model's predictive power [16].

- Identification of Combinatorial Therapies: The same screen identified that a combination of Riluzole (an approved ALS drug), Memantine (an NMDA receptor antagonist), and Baricitinib (a JAK inhibitor) significantly increased the survival of SALS motor neurons, offering a promising new therapeutic avenue [16].

Table 3: Clinical Trial Landscape for Stem Cell Therapies in Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Disease | Total Stem Cell Trials (n=94) | Furthest Clinical Phase | Key Cell Types Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | ~65% of total participants | Phase 2 (Ongoing) | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), Neural Stem Cells (NSCs) [26] |

| Parkinson's Disease (PD) | - | Phase 2 (Completed & Ongoing) | iPSCs, ESCs, MSCs [26] |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) | - | Phase 3 (Completed & Ongoing) | MSCs, NSCs [26] |

| Huntington's Disease (HD) | - | Phase 3 (Ongoing) | MSCs [26] |

Data adapted from a systematic review of 94 clinical trials [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Neural Differentiation and Characterization

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Specific Example(s) | Function in Neural Fate Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMAD Inhibitors | Small Molecules | LDN-193189 (BMP inhibitor), SB431542 (TGFβ inhibitor) | Core of "dual-SMAD inhibition"; induces efficient neural induction from PSCs [23] |

| Patterning Molecules | Small Molecules/Growth Factors | CHIR99021 (Wnt agonist), Retinoic Acid, Purmorphamine (SHH agonist) | Specifies regional identity (e.g., caudal spinal cord, ventral motor neurons) [16] |

| Growth Factors | Proteins | FGF2, EGF, BDNF, GDNF | Supports neural progenitor proliferation and neuronal maturation/survival [22] [23] |

| Lineage Reporters | Viral Vectors/Reporter Lines | HB9::GFP, PAX6::tdTomato | Enables live-cell tracking and purification of specific neural populations (e.g., motor neurons) [16] |

| Epigenetic Assays | Kits/Reagents for | ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq (H3K27me3, H2AK119ub) | Profiles chromatin accessibility and histone modifications to map epigenetic remodeling [22] [24] |

Technical Considerations and Variability

A significant challenge in using PSC-derived neural models is the inherent variability in differentiation outcomes.

- Sources of Variation: Analysis of 162 differentiations from 61 hPSC lines revealed that variation occurs primarily along developmental spatial axes (dorsoventral and rostrocaudal) [23]. This variation can be line-independent (stochastic) or line-dependent.

- Endogenous Signaling: Line-dependent variation is largely driven by differences in endogenous signaling pathway activity, most notably Wnt/β-catenin signaling [23].

- Correcting Variability: This bias is not insurmountable. Studies show that modulating the Wnt pathway with exogenous agonists or antagonists during a specific critical window early in differentiation can correct these biases and reduce line-to-line variability, ensuring more consistent and reproducible results [23].

Advanced Methodologies and Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

Protocols for Differentiating iPSCs into Key Neural Lineages (Neurons, Microglia, Astrocytes)

The discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by Takahashi and Yamanaka in 2006 represented a paradigm shift in biomedical research, enabling the generation of patient-specific pluripotent stem cells from somatic cells [1] [18]. This technology has profound implications for neurodegenerative disease research, as it allows investigators to create patient-specific neural cells that harbor the exact genetic background of individuals with conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [27] [2] [28]. Unlike embryonic stem cells, iPSCs are derived from readily accessible adult tissues—including skin fibroblasts, peripheral blood cells, or urinary epithelial cells—circumventing ethical concerns while providing an unlimited source of cells for disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative approaches [27] [18].

The fundamental principle underlying iPSC technology is cellular reprogramming, typically achieved through the introduction of key transcription factors—most commonly OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM)—which collectively reset the epigenetic landscape of somatic cells to a pluripotent state [2] [1] [18]. These iPSCs can subsequently be differentiated into virtually any cell type in the body, including the diverse neural lineages of the central nervous system [1] [29]. For neurodegenerative disease research, the ability to generate human neurons, microglia, and astrocytes from patients with specific genetic vulnerabilities provides an unprecedented opportunity to study disease mechanisms in physiologically relevant human cells, identify novel therapeutic targets, and test candidate drugs in a patient-specific context [29] [28].

Fundamental Principles of iPSC Neural Differentiation

The differentiation of iPSCs into neural lineages recapitulates aspects of embryonic development, guided by the sequential activation and inhibition of key signaling pathways [1] [29]. The process typically begins with the transition from pluripotency to neural progenitor cells (NPCs), which subsequently give rise to the specific neural cell types through the action of regionalizing factors [30].

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways in Neural Differentiation

| Pathway | Role in Neural Differentiation | Common Modulators |

|---|---|---|

| TGF-β/Activin A | Supports pluripotency; inhibition promotes neural induction | SB431542, A83-01 |

| BMP | Inhibition is required for neural induction | Noggin, DMH1, LDN-193189 |

| WNT/β-catenin | Regulates patterning; precise temporal control required | CHIR99021 (activator), IWR-1 (inhibitor) |

| FGF | Promotes neural proliferation and survival | FGF2 (basic FGF) |

| SHH | Ventralizes neural tissue; critical for specific neuronal subtypes | Purmorphamine, SAG (agonists) |

| RA | Posteriorizes neural tissue; promotes neuronal differentiation | Retinoic acid |

The molecular dynamics of differentiation involve profound epigenetic remodeling and changes to almost every aspect of cell biology, including metabolism, cell signaling, and proteostasis [1]. During the early phase of differentiation, pluripotency genes such as NANOG and OCT4 are silenced, while early neural markers like SOX1 and PAX6 are activated [1] [30]. The late phase involves the activation of lineage-specific genes that define mature neuronal and glial identities, such as MAP2 for neurons, GFAP for astrocytes, and TMEM119 or P2RY12 for microglia [31] [29] [32].

Differentiation Protocols for Specific Neural Lineages

iPSC-Derived Neurons

The generation of cortical neurons from iPSCs can be significantly accelerated through the overexpression of the transcription factor Neurogenin 2 (NGN2), which can produce functional neurons within just 3-4 weeks [31]. This method yields a highly pure population of glutamatergic neurons, providing a robust system for disease modeling and drug screening applications.

Key Protocol Steps:

- iPSC Culture and Maintenance: Maintain iPSCs in feeder-free conditions using defined media such as mTeSR or E8 on matrix-coated plates (e.g., Matrigel, laminin) [18].

- Lentiviral Transduction: Introduce a doxycycline-inducible NGN2 expression system into iPSCs using lentiviral vectors.

- Neural Induction: Upon doxycycline addition, NGN2 expression drives neuronal differentiation. Cells are typically cultured in neural medium supplemented with growth factors (BDNF, NT-3) and small molecules (e.g., dorsomorphin to inhibit BMP signaling) [31].

- Maturation: After 1-2 weeks, cells are replated onto surfaces coated with poly-D-lysine and laminin to promote neurite outgrowth and synaptic formation, with full maturation occurring within 3-4 weeks [31].

For dopaminergic neurons—particularly relevant for Parkinson's disease research—protocols typically employ dual SMAD inhibition combined with ventralization factors. The CORIN sorting strategy has emerged as a milestone for enriching mesencephalic dopaminergic progenitors while eliminating serotonergic neurons and tumorigenic precursors [28].

iPSC-Derived Astrocytes

The directed differentiation of iPSCs into astrocytes employs a developmental approach that passes through a neural progenitor cell (NPC) stage, with protocols typically requiring 60-90 days to generate functional astrocytes [31] [29].

Key Protocol Steps:

- Neural Induction: Use dual SMAD inhibition (SB431542 and LDN-193189) for 10-12 days to convert iPSCs to NPCs.

- NPC Expansion: Expand NPCs in media containing FGF2 to maintain progenitor status.

- Astroglial Specification: Transition cells to astrocyte differentiation medium containing CNTF, BMP4, or LIF to promote glial fate. The transcription factors SOX9 and NFIB can be introduced to accelerate maturation [31].

- Maturation: Maintain cells for 60-90 days to allow for complete maturation, characterized by typical astrocytic morphology and expression of markers including GFAP, S100β, and EAAT1 [29].

Recent advances have significantly shortened this timeline through the use of defined transcription factors, with some protocols generating astrocytes within 20 days post-thaw of pre-differentiated cells [31].

iPSC-Derived Microglia

Microglia differentiation protocols uniquely recapitulate yolk sac hematopoiesis, as microglia originate from primitive macrophages rather than definitive hematopoietic stem cells [29] [32].

Key Protocol Steps:

- Hematopoietic Progenitor Induction: Differentiate iPSCs for 8-10 days in serum-free media with BMP4, VEGF, SCF, and TPO to generate primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) [31] [32].

- Myeloid Specification: Transfer floating HPCs to media containing IL-34, M-CSF, and TGF-β to drive microglial identity.

- Maturation and Expansion: Culture cells for an additional 2-4 weeks to allow for maturation, characterized by expression of microglial markers including TMEM119, P2RY12, and IBA1, and the development of characteristic ramified morphologies [32].

Table 2: Key Markers for Characterizing Neural Lineages

| Cell Type | Pluripotency/ Progenitor Markers | Early Differentiation Markers | Mature Cell Markers | Functional Assays |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPSCs | OCT4, NANOG, SOX2, SSEA-4 | - | - | Pluripotency: Teratoma formation, trilineage differentiation |

| Neural Progenitor Cells (NPCs) | SOX2, NESTIN | PAX6, SOX1 | - | Self-renewal, multipotency |

| Neurons | - | βIII-TUBULIN | MAP2, SYN1, VGLUT1 | Electrophysiology (patch clamp), calcium imaging, synaptic activity |

| Astrocytes | - | S100β | GFAP, EAAT1, GLT-1 | Glutamate uptake, calcium signaling, inflammatory response (cytokine release) |

| Microglia | - | CD11b, IBA1 | TMEM119, P2RY12, CX3CR1 | Phagocytosis, chemotaxis, inflammatory response (LPS stimulation) |

Advanced Co-culture Models and Their Applications

The true power of iPSC-derived neural lineages emerges when these cells are combined to create more physiologically relevant systems that capture the complex cell-cell interactions within the brain. A robust triculture system incorporating iPSC-derived neurons, astrocytes, and microglia (iNs, iAs, iMGs) has been developed that enables the study of neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative mechanisms in a controlled human cellular environment [31].

Triculture Protocol Workflow:

- Independent Differentiation: Differentiate iNs, iAs, and iMGs separately using the protocols outlined above.

- Cryopreservation and Quality Control: Cryopreserve each cell type independently, allowing for quality control assessments before triculture assembly.

- Co-culture Assembly: Plate iAs and iMGs onto established iNs at defined ratios (typically 1:1:1) in a optimized triculture medium (TCM).

- Maintenance and Analysis: Maintain co-cultures for 7-20 days before analysis, during which cells develop mature interactions and phenotypes [31].

This triculture system has demonstrated remarkable utility in modeling neurodegenerative disease mechanisms. For example, when microglia are co-cultured with astrocytes and neurons, they exhibit upregulated expression of disease-associated microglia (DAM) genes, including TREM2, APOE, SPP1, and GPNMB—a transcriptional signature observed in Alzheimer's disease brains [31]. Furthermore, when this system incorporates neurons carrying familial Alzheimer's disease (fAD) mutations, the DAM signature is significantly dampened, revealing how disease-specific genetic backgrounds disrupt neuron-glial communication [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful differentiation and maintenance of iPSC-derived neural lineages requires carefully selected reagents and culture components. The following table summarizes essential materials and their functions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC Neural Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM) | Reprogram somatic cells to pluripotency | Non-integrating methods (episomal, mRNA, Sendai virus) preferred for clinical applications [2] [33] |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor), LDN-193189 (BMP inhibitor), CHIR99021 (GSK-3β inhibitor) | Direct cell fate by modulating signaling pathways | Dual SMAD inhibition critical for efficient neural induction [1] [29] |

| Growth Factors & Cytokines | FGF2, EGF, BDNF, GDNF, IL-34, M-CSF, TGF-β | Support proliferation, survival, and specification | M-CSF and IL-34 essential for microglia differentiation and survival [31] [32] |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Laminin-521, Poly-D-lysine | Provide structural support and biochemical cues | Laminin-511/521 supports iPSC expansion and neural differentiation [18] [30] |

| Cell Culture Media | mTeSR, Neural Base Medium, BrainPhys | Provide nutrients and defined environment | BrainPhys optimized for neuronal activity and network formation [31] [18] |

| Cell Sorting Markers | CORIN, PSA-NCAM, CD44 | Isolate specific neural populations | CORIN sorting enriches for dopaminergic progenitors in Parkinson's applications [28] |

Quality Control and Characterization Techniques

Rigorous quality control is essential throughout the differentiation process to ensure the generation of high-quality, lineage-specific cells. Key characterization approaches include:

- Pluripotency Assessment: Confirm the starting iPSC population expresses canonical markers (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2) via immunocytochemistry or flow cytometry, and demonstrate trilineage differentiation potential [18].