Safeguarding iPSC Integrity: Strategies to Prevent Genomic Instability in Long-Term Culture

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing genomic instability in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) during extended culture.

Safeguarding iPSC Integrity: Strategies to Prevent Genomic Instability in Long-Term Culture

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing genomic instability in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) during extended culture. It explores the fundamental causes and consequences of karyotypic abnormalities, details practical methodologies for routine monitoring and stable culture maintenance, offers troubleshooting and optimization strategies to minimize variability, and establishes validation frameworks for ensuring iPSC quality. By synthesizing recent advances, this resource aims to enhance the reliability of iPSC models for disease research, drug discovery, and clinical applications.

Understanding Genomic Instability: The Silent Challenge in iPSC Culture

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) hold transformative potential for disease modeling, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine. However, their clinical application is significantly challenged by genomic instability, which can arise during reprogramming, long-term culture, and differentiation processes. This technical support center provides a comprehensive guide to identifying, troubleshooting, and preventing the genetic alterations that compromise iPSC quality and safety, framed within a broader thesis on maintaining genomic integrity in long-term iPSC culture research.

FAQs: Understanding Genomic Instability in iPSCs

1. What types of genomic instability are most commonly observed in iPSC cultures? iPSC cultures frequently acquire both numerical and structural chromosomal abnormalities. Common findings include trisomy of chromosomes 12, 17, 20, and 8, and gains of chromosomal regions 1q and 20q11.21 [1] [2]. Structural alterations such as acentric fragments, chromosomal fusions, double minutes, radial figures, ring chromosomes, and inversions are also regularly detected [3]. The frequency of karyotype abnormalities in iPSC lines has been reported to be approximately 21-23%, with some studies observing rates as high as 80% in prolonged passaging [2].

2. At what stage does genomic instability typically arise? Genetic variations can originate from multiple stages:

- Pre-existing variations in parental somatic cells that are clonally expanded during reprogramming [1].

- Reprogramming-induced mutations that occur during the reprogramming process itself [1].

- Passage-induced mutations that accumulate during prolonged in vitro culture [1]. Studies note that abnormal clones can emerge or be selected over time, generating altered lineages, with aberrations becoming more common in later passages [3].

3. Does the reprogramming method influence genomic instability? Yes, the choice of reprogramming method significantly impacts genomic instability. Recent research comparing Sendai virus (SV) and episomal vector (Epi) methods found that all SV-iPS cell lines exhibited copy number alterations (CNAs) during reprogramming, while only 40% of Epi-iPS cells showed such alterations. Additionally, single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) were observed exclusively in SV-derived cells during passaging and differentiation [4].

4. How does long-term culture affect genomic stability? Prolonged passaging selectively enriches for clones with growth advantages, often through specific chromosomal gains. The percentage of abnormal samples increases with passage number. One study analyzing passages P6 to P34 found that while abnormal clones can emerge early, they become increasingly prevalent in later passages [3]. Another study noted that the frequency of clonal aberrations in lines from healthy donors increased from 2 out of 10 to 4 out of 10 when re-karyotyped at later passages [2].

5. Can genomic instability be transmitted during differentiation? Yes, genomic alterations can persist or newly arise during differentiation into downstream lineages. Studies have identified copy number alterations (CNAs) and single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) during the differentiation of iPSCs into induced mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (iMS cells) [4]. Additionally, genomic abnormalities may appear as a result of in vitro differentiation protocols, highlighting the importance of monitoring both pluripotent cells and their differentiated progeny [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Excessive Differentiation in Cultures

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Overgrown colonies or suboptimal culture conditions.

- Solution: Ensure cultures are passaged when majority of colonies are large and compact with dense centers. Remove differentiated areas prior to passaging [6].

- Cause: Old or degraded culture medium.

- Solution: Use complete cell culture medium less than 2 weeks old when stored at 2-8°C [6].

- Cause: Prolonged exposure to non-incubator conditions.

- Solution: Minimize time culture plates remain outside the incubator to less than 15 minutes [6].

- Cause: Inappropriate colony density.

- Solution: Decrease colony density by plating fewer cell aggregates during passaging [6].

Problem 2: Declining Cell Viability After Passaging

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Over-confluent cultures at time of passaging.

- Solution: Passage cells at 40-85% confluency for optimal health. Avoid routine passaging at high confluencies [7].

- Cause: Inadequate protection during single-cell passaging.

- Solution: Include ROCK inhibitor (e.g., RevitaCell Supplement) during passaging, especially for sensitive lines or when cultures are overly confluent [7].

- Cause: Excessive manipulation of cell aggregates.

- Solution: Minimize pipetting and manipulation of cell aggregates after dissociation to maintain proper cluster size [6].

Problem 3: Low Cell Attachment After Plating

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Insufficient initial cell density.

- Solution: Plate 2-3 times higher number of cell aggregates initially and maintain more densely confluent culture [6].

- Cause: Prolonged suspension of cell aggregates.

- Solution: Work quickly after treatment with passaging reagents to minimize time aggregates spend in suspension [6].

- Cause: Incorrect plate coating or handling.

- Solution: Ensure non-tissue culture-treated plates are used when coating with Vitronectin XF; use tissue culture-treated plates when coating with Corning Matrigel [6].

Problem 4: Suspected Genetic Instability in Established Lines

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Accumulation of mutations during prolonged culture.

- Solution: Implement regular genomic monitoring at key passages (e.g., P10, P20, P30) using G-banding karyotyping and higher-resolution methods [3] [1].

- Cause: Selective pressure favoring abnormal clones.

- Solution: Maintain lower passage stock banks and avoid extended culture beyond 30-40 passages when possible [3] [2].

- Cause: Reprogramming method-related instability.

- Solution: Consider episomal vector methods if Sendai virus-derived lines show persistent instability [4].

Quantitative Data on Genomic Instability

Table 1: Frequency and Types of Chromosomal Aberrations in iPSC Cultures

| Aberration Type | Specific Alterations | Frequency/Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Karyotype Abnormalities | Any clonal aberration | 21-23% of cell lines (increasing to 80% with prolonged passaging) | [2] |

| Common Trisomies | Trisomy 12, 17, 20, 8 | Most recurrent aneuploidies | [1] [2] |

| CNV Hotspots | 20q11.21 amplification | Most recurrent CNV; contains DNMT3B, ID1, BCL2L1 genes | [1] |

| Structural Rearrangements | 1q duplications, translocations | Most frequently affected region in structural changes | [2] |

| Method-Specific Instability | Sendai virus vs. episomal | 100% of SV-iPS vs. 40% of Epi-iPS showed CNAs during reprogramming | [4] |

Table 2: Detection Methods for Genomic Instability

| Method | Resolution | Key Applications | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| G-banding Karyotyping | ~5-10 Mb | Detection of numerical and large structural abnormalities | Low cost, detects low-level mosaicism (>5%); cannot detect small alterations [3] [1] |

| Array-based Technologies (aCGH, SNP array) | ~kb level | Genome-wide CNV detection | Higher resolution than karyotyping; cannot detect balanced translocations [1] [5] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (WGS, WES) | Single nucleotide | Comprehensive SNV and CNV detection | Highest resolution, detects low-frequency variants; higher cost and computational requirements [1] [4] |

| M-FISH | Chromosomal arm level | Detection of complex structural rearrangements | Visualizes multiple chromosomes simultaneously; lower resolution than arrays [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Monitoring Genomic Instability

Materials:

- KaryoMAX Colcemid (Life Technologies)

- Hypotonic solution (0.075 M KCl with HEPES)

- Fixative (methanol-acetic acid 3:1)

- Trypsin and Giemsa stain

- Microscope with image capture capability (e.g., Leica DM Microscope)

Method:

- Harvest chromosomes when cultures reach 60-80% confluence.

- Incubate with 0.1 µg/ml Colcemid for one hour at 37°C.

- Trypsinize cells and add to 6 ml of hypotonic solution.

- Fix cells with methanol-acetic acid solution (3:1).

- Prepare slides by dropping cell suspension onto pre-warmed slides.

- Perform G-banding using trypsin and Giemsa staining.

- Analyze at least 20 metaphases per sample.

- For clonal definition: same structural aberration or chromosome gain must be present in ≥2 metaphases; chromosome loss must be detected in ≥3 cells.

Background: Residual reprogramming vectors can contribute to genomic instability.

Method:

- After 10+ passages, perform RT-PCR to confirm absence of Klf4 vector.

- If only c-Myc and KOS vectors remain, incubate iPSCs at 38-39°C for 5 days.

- Confirm clearance with subsequent RT-PCR testing.

- Note: Only perform temperature shift with sensitive lines and after appropriate validation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Genomic Stability Maintenance

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function/Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Systems | CytoTune-iPS Sendai Reprogramming Kit; Episomal vectors | Non-integrating reprogramming; Episomal methods show lower instability | [3] [4] [7] |

| Culture Media | mTeSR Plus, Essential 8 Medium | Feeder-free culture maintenance | [6] [7] |

| Passaging Reagents | ReLeSR, Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent, EDTA | Enzymatic and non-enzymatic passaging | [6] [7] |

| Genomic Stability Enhancers | ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632), RevitaCell Supplement | Improves cell survival after passaging, reduces selective pressure | [7] |

| Extracellular Matrices | Vitronectin XF, Geltrex, Matrigel | Defined substrates for feeder-free culture | [6] [7] |

Maintaining genomic stability in iPSCs requires a multifaceted approach encompassing careful reprogramming method selection, controlled culture conditions, regular monitoring, and appropriate troubleshooting. By implementing the guidelines and protocols outlined in this technical support center, researchers can significantly improve the genetic quality of their iPSC lines, enabling more reliable research outcomes and advancing the path toward safe clinical applications. Regular genomic surveillance using the described methodologies should be integrated as a standard practice in any iPSC research program focused on long-term culture maintenance.

For researchers working with induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), genomic instability presents a critical challenge that can compromise experimental results and therapeutic applications. Karyotypic changes—including aneuploidies, copy number variations (CNVs), and structural chromosomal aberrations—can arise from two primary stressors: the reprogramming process itself and prolonged in vitro passaging [8] [1]. Understanding these drivers is essential for developing robust protocols that maintain genetic integrity throughout your experiments.

This technical support guide provides targeted troubleshooting advice and FAQs to help you identify, prevent, and manage karyotypic instability in your iPSC research. The strategies outlined below are framed within a comprehensive approach to preserving genomic stability in long-term iPSC cultures.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common karyotypic abnormalities observed in iPSC cultures, and how frequently do they occur?

The following table summarizes the frequency and types of genetic variations commonly detected in iPSC cultures:

Table 1: Common Genetic Variations in iPSC Cultures

| Variation Type | Specific Examples | Reported Frequency | Potential Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aneuploidy | Trisomy 12, Trisomy 8, Trisomy X [8] [1] | ~13-33% of hESC/hiPSC lines [8] | Confers growth advantage; alters pluripotency gene dosage (e.g., NANOG on Chr12) [8] |

| Subchromosomal CNVs | Amplification of 20q11.21 [8] [1] | Frequently recurrent [1] | Enriches genes associated with pluripotency and anti-apoptosis (e.g., DNMT3B, BCL2L1) [1] |

| Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) | Point mutations in protein-coding regions [1] | ~10 mutations per line (WGS/WES data) [1] | Can introduce aberrant or immunogenic proteins [9] |

| Chromosomal Aberrations | Translocations, inversions, breaks [10] | 6.12% of new iPS clones (in one study) [10] | May compromise differentiation potential or lead to tumorigenesis [10] |

Q2: Does the choice of reprogramming method influence genomic instability?

Yes, the reprogramming method is a significant factor. Studies comparing Sendai virus (SV) and episomal vector (Epi) methods have found clear differences:

- Sendai Virus (SV): A higher frequency of copy number alterations (CNAs) was observed during the reprogramming phase in all SV-iPS cell lines. Furthermore, single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) were detected exclusively in SV-derived cells during subsequent passaging and differentiation [4].

- Episomal Vectors (Epi): Only 40% of Epi-iPS cell lines showed CNAs during reprogramming, and no SNVs were detected in Epi-derived lines during passaging and differentiation [4]. Gene expression analysis also revealed upregulation of chromosomal instability-related genes in late-passage SV-iPSCs, further indicating increased genomic instability with this method [4].

Q3: How does extended cell passaging contribute to genomic instability?

Prolonged culturing introduces or selects for genetic alterations that facilitate cell propagation, a process known as culture adaptation [8]. The frequency of recurrent aneuploidy generally increases with continuous passaging, as subpopulations with growth-advantageous mutations (like Trisomy 12) expand [8]. Furthermore, long-term culture can lead to the accumulation of genetic mutations due to errors in DNA replication and oxidative stress [9]. One study also demonstrated that even long-term cryopreservation (e.g., 10 years) can lead to genomic instability, causing variability in chromosome number and random chromosomal rearrangements upon thawing and subsequent culturing [11].

Q4: What are the practical consequences of these karyotypic changes for my research?

Karyotypic instability can directly impact your experimental outcomes and the safety of potential therapies.

- Altered Cell Behavior: Genetic changes can affect differentiation potential, proliferation rates, and cellular function [12] [10].

- Immunogenicity: Mutations can lead to the production of altered or new proteins that may be recognized as foreign by the immune system, triggering rejection even in autologous transplantation settings [9].

- Tumorigenic Risk: The presence of mutations in tumor suppressor genes (e.g., TP53) or amplification of oncogenic regions raises serious safety concerns for clinical applications [1] [4] [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Incidence of Karyotypic Abnormalities in Newly Generated iPSC Clones

Potential Cause: Reprogramming-induced replication stress and oxidative damage.

Solution: Mitigate the stress encountered by cells during reprogramming.

- Experimental Protocol: Limiting Replication Stress

- Nucleoside Supplementation: Add a nucleoside supplement to the culture medium during the reprogramming process. This provides the raw materials for DNA synthesis and has been shown to reduce the load of DNA damage and genomic rearrangements in resulting iPSCs [14].

- Antioxidant Treatment: Include the antioxidant N-Acetyl-Cysteine (NAC) in the culture medium for the first few days of reprogramming. This has been proven to effectively reduce the occurrence of chromosomal aberrations at this critical early stage [10].

- Modulate Reprogramming Factors: Be cautious with the dosage and combination of reprogramming factors. High expression of factors like cMYC can exacerbate replication stress. Using a cocktail that excludes cMYC or using small molecules to enhance reprogramming efficiency can be beneficial [14] [9].

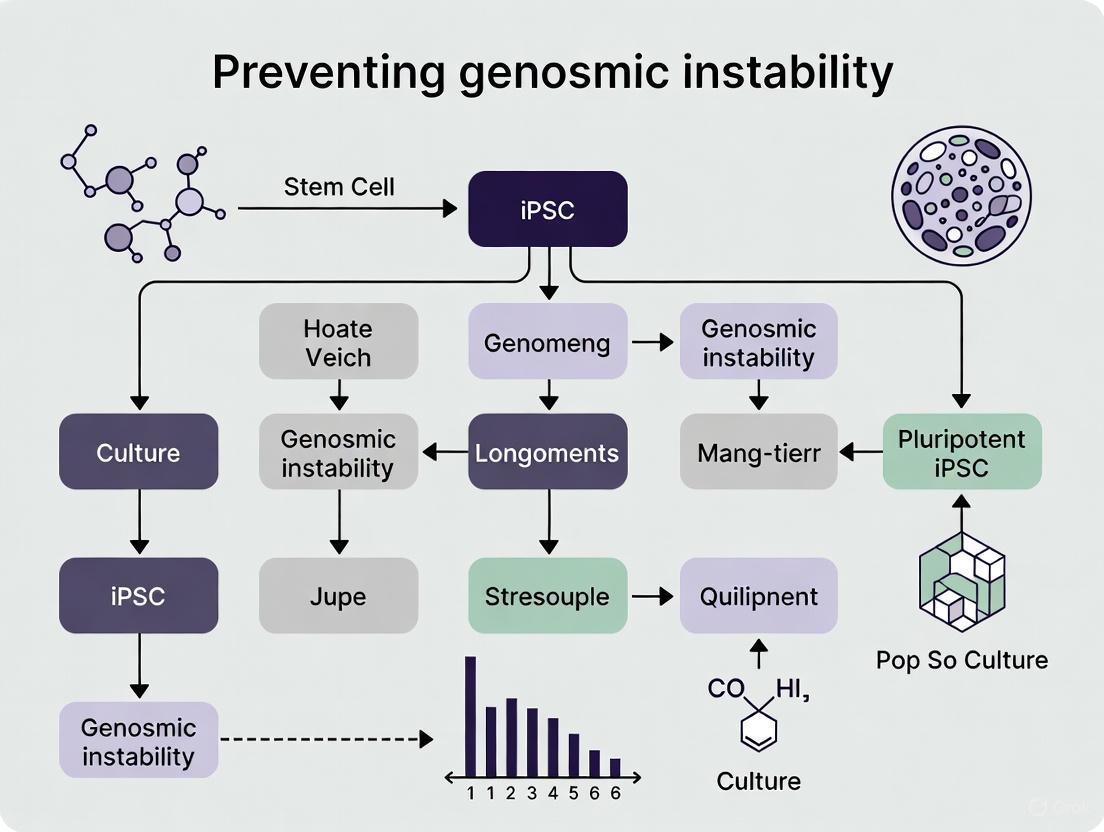

The diagram below illustrates how reprogramming factors induce replication stress and two effective strategies to mitigate it.

Issue 2: Emergence of Genomic Instability During Long-Term Culture and Differentiation

Potential Cause: Culture adaptation and selective pressure.

Solution: Implement rigorous monitoring and optimized culture conditions.

- Experimental Protocol: Routine Genomic Surveillance

- Regular Karyotyping: Perform G-banded karyotyping every 10-15 passages to screen for gross chromosomal abnormalities and aneuploidy [1]. This is a basic but essential requirement.

- High-Resolution CNV Detection: Use higher-resolution technologies like SNP arrays or array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH) to detect subchromosomal CNVs, particularly in regions like 20q11.21 [8] [1].

- Sequencing-Based Screening: For the most comprehensive assessment, employ whole-genome sequencing (WGS) or whole-exome sequencing (WES) to identify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and low-frequency pre-existing variations that might be captured during cloning [1].

- Limit Passages: As a general practice, establish a master cell bank and working cell bank system. Use cells within a strictly defined passage range (e.g., below passage 20-30) for key experiments and differentiation protocols to minimize the impact of culture-accumulated variations [8] [11].

Issue 3: Genomic Instability in Differentiated Cell Products (e.g., iMS Cells)

Potential Cause: Mutations carried over from the parent iPSC line or acquired during differentiation.

Solution: Ensure the genetic integrity of the starting material and the differentiation process.

- Experimental Protocol: Ensuring Genomic Stability of Final Products

- Source Cell Validation: Only begin differentiation with iPSC lines that have recently been confirmed as karyotypically normal and genetically stable via the surveillance methods described above.

- Clonal Selection: Select specific, well-characterized iPSC clones for differentiation rather than using a mixed population, which may contain subclones with heterogeneous genetic aberrations [4].

- Monitor Differentiation: Perform genetic analysis on the final differentiated cell product (e.g., iMS cells) to confirm the absence of major de novo abnormalities, especially if the cells are intended for therapeutic use [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Managing Genomic Instability

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| N-Acetyl-Cysteine (NAC) [10] | Antioxidant that reduces oxidative stress and chromosomal breaks. | Added to medium during the first few days of reprogramming. |

| Nucleoside Supplement [14] | Provides substrates (dNTPs) for DNA synthesis, alleviating replication stress. | Added to medium during the reprogramming process. |

| CHK1 Expression Vector [14] | Genetically increases levels of the checkpoint kinase 1, which stabilizes replication forks. | Used to generate cells with enhanced ability to cope with replication stress. |

| Non-Integrating Reprogramming Vectors (e.g., Episomal, mRNA) [4] [9] | Deliver reprogramming factors without integrating into the host genome, reducing mutation risk. | Preferred method for generating clinical-grade iPSCs. |

| Giemsa (G) Banding Kit [1] | Standard cytogenetic method for detecting numerical and large structural chromosomal changes. | Routine karyotyping of iPSC cultures. |

| SNP/Array CGH Platform [1] [12] | High-resolution detection of copy number variations (CNVs) across the genome. | Identifying subchromosomal gains/losses. |

| Next-Generation Sequencer | Enables whole genome/exome sequencing to detect SNVs and low-frequency variants. | Comprehensive genomic profiling of master cell banks and final products. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What types of genomic abnormalities are most commonly found in iPSCs, and how do they originate? Genomic instability in iPSCs manifests in several forms, which can originate from different stages of cell handling. The table below summarizes the primary types and their origins.

Table 1: Common Genomic Abnormalities in iPSCs

| Abnormality Type | Description | Primary Origins |

|---|---|---|

| Chromosomal Aberrations | Gains or losses of entire chromosomes (aneuploidy). Recurrent examples include trisomy of chromosomes 12, 8, 17, and X [15] [1]. | Acquired during long-term culture; can provide a selective growth advantage [15] [1]. |

| Copy Number Variations (CNVs) | Deletions or duplications of DNA sections, ranging from kilobases to megabases. A recurrent hotspot is amplification of 20q11.21 [15] [1]. | Pre-existing as low-frequency variants in the parental somatic cell population that are fixed during reprogramming, or acquired de novo during reprogramming [15] [1]. |

| Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) | Single point mutations in the protein-coding regions. iPSC lines can contain an average of 6-12 such mutations [15] [1]. | A combination of pre-existing mutations in parental somatic cells and mutations acquired during the reprogramming process itself [15] [1]. |

| Uniparental Disomy (UPD) | Inheritance of two copies of a chromosome from one parent and none from the other, leading to loss of heterozygosity [15]. | Can occur during the reprogramming process, sometimes as a compensatory mechanism to correct a chromosomal aberration [15]. |

FAQ 2: Can you provide a specific example of how a somatic mutation directly derails a differentiation protocol? Yes. A large-scale study differentiating 238 iPSC lines into dopaminergic neurons found that loss-of-function mutations in the BCOR gene were strongly associated with differentiation failure [16]. BCOR is a key developmental gene. Lines with deleterious BCOR mutations produced significantly fewer dopaminergic neurons and exhibited a larger proliferation rate in culture, indicating that the mutation disrupted the normal developmental pathway and inhibited successful neurogenesis [16]. This is a clear example where a single mutation can compromise an entire disease-modeling experiment.

FAQ 3: What are the best methods to detect these abnormalities in my iPSC lines? Detection methods vary in resolution and what they can find. A combination of techniques is often necessary for comprehensive quality control.

Table 2: Genomic Instability Detection Methods

| Technique | What It Detects | Resolution/Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| G-banding Karyotyping | Numerical abnormalities (aneuploidy) and large structural chromosomal changes [1]. | Low resolution; cannot detect small CNVs or SNVs [15]. |

| SNP Array / CGH Array | Copy Number Variations (CNVs) and Loss of Heterozygosity (LOH), which can indicate UPD [15] [1]. | Kilobase resolution. Cannot detect balanced translocations or single nucleotide variants [15] [1]. |

| Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing (WES/WGS) | Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions across the entire exome or genome [1]. | Single-nucleotide resolution. Essential for a complete picture of genomic integrity [1]. |

FAQ 4: How can I adjust my culture practices to minimize the acquisition of genomic abnormalities? Proper culture techniques are crucial for maintaining genomic integrity. The table below outlines common problems and their solutions based on established protocols.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for iPSC Culture to Maintain Genomic Integrity

| Problem | Potential Impact on Genomic Integrity | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive Differentiation in Cultures | Differentiated cells may overgrow and outcompete pluripotent cells, potentially selecting for aberrant clones. | Remove differentiated areas before passaging. Do not allow cultures to overgrow. Plate evenly sized aggregates and optimize passage timing [6]. |

| Prolonged Culture & Over-confluence | Increases selective pressure for mutations that confer growth advantage (e.g., trisomy 12, 20q11.21 amplification) [15] [1]. | Avoid excessive passaging. Use low-density freezing stocks to minimize long-term culture. Passage cultures when colonies are large and dense but before multi-layering [6] [17]. |

| Low Cell Survival After Passaging | Can selectively pressure the survival of a small number of potentially abnormal cells that are more resistant to stress. | Use a Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor to improve survival. Plate a higher density of cell aggregates and work quickly with passaging reagents [6] [17]. |

| Switching to Feeder-Free Conditions | Adaptation stress can induce apoptosis and differentiation, potentially allowing minor abnormal populations to expand. | Proceed carefully. Test different matrices (e.g., Geltrex, Matrigel, Laminin-521) and media (e.g., mTeSR Plus, StemFlex) to find the optimal condition for your line to minimize stress [17]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents are critical for the successful culture, quality control, and adaptation of iPSC lines.

Table 4: Key Reagents for iPSC Culture and Genomic Integrity Monitoring

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Improves cell survival after passaging and thawing by inhibiting apoptosis, helping to maintain a representative cell population [17]. | Stemgent; available from various suppliers. |

| Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent | A non-enzymatic reagent for passaging cells in aggregates, minimizing DNA damage and stress compared to traditional trypsinization [6] [17]. | STEMCELL Technologies. |

| Defined Matrices for Feeder-Free Culture | Provide a consistent, xeno-free substrate for iPSC attachment and growth, reducing variability and contamination risk. | Geltrex (Thermo Fisher), Matrigel (Corning), Laminin-521 (Thermo Fisher) [17]. |

| High-Quality Culture Media | Specially formulated media support pluripotency and healthy growth under feeder-free conditions. | mTeSR Plus, StemFlex (STEMCELL Technologies) [6] [17]. |

| SNP Microarray Kits | For high-resolution detection of CNVs and LOH (UPD) as part of routine genomic quality control [15] [18]. | Affymetrix, Illumina. |

| Whole Exome Sequencing Services | For comprehensive detection of single nucleotide variants and small indels in the coding regions of the genome [1] [16]. | Various commercial and core facility providers. |

Experimental Protocols for Monitoring Genomic Integrity

Protocol 1: Routine Karyotyping and SNP Analysis for iPSC Lines Objective: To screen for gross chromosomal abnormalities and sub-chromosomal CNVs. Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest a confluent well of a 6-well plate of iPSCs during an active log-phase growth period.

- Karyotyping: Submit cells to a cytogenetics core facility for G-banding analysis. A minimum of 20 metaphase spreads are typically analyzed to confirm a normal karyotype [1].

- SNP Genotyping: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from iPSCs. Use a commercial SNP array platform according to the manufacturer's instructions. This will identify CNVs and regions of LOH that are invisible to karyotyping [15] [18]. Frequency: This analysis should be performed when establishing a new master cell bank and periodically (e.g., every 10-15 passages) on working cell banks, especially if cells are maintained in long-term culture.

Protocol 2: Assessing Differentiation Capacity via Directed Differentiation Objective: To functionally validate that an iPSC line has not acquired mutations that impair its ability to differentiate into a specific lineage. Methodology (Example: Dopaminergic Neurons):

- Base Protocol: Follow an established, robust protocol for the differentiation of iPSCs into dopaminergic neurons [16].

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): At key time points during differentiation (e.g., day 11, 30, and 52), harvest cells and perform scRNA-seq.

- Data Analysis: Use computational clustering to identify the different cell types present in the culture. Quantify the proportion of cells that have successfully reached the desired dopaminergic neuron fate.

- Correlation with Genomics: Compare the differentiation efficiency (percentage of target cells) across multiple lines. Lines that consistently fail to differentiate, like those with BCOR mutations, should be subjected to whole-exome sequencing to identify potential causative mutations [16]. Application: This functional test is critical for ensuring that iPSC-based disease models will yield relevant and reproducible results.

Visualizing the Origins and Impacts of Genomic Instability

The following diagram illustrates the pathways through which genomic abnormalities arise and how they ultimately compromise research outcomes.

FAQ: Understanding Karyotypic Abnormalities in iPSC Cultures

What are the most common karyotypic abnormalities found in human iPSC lines?

The most frequently observed karyotypic abnormalities in human iPSC lines are recurrent gains of entire chromosomes or specific chromosomal regions. These changes confer a selective growth advantage under standard culture conditions. The table below summarizes the most common recurrent abnormalities.

Table 1: Recurrent Karyotypic Abnormalities in Human iPSCs

| Abnormality Type | Specific Chromosomal Region | Reported Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Chromosome Gain | Trisomy 20 | 8.6% of all tests, 38.5% of unique aberrant lines [19] |

| Whole Chromosome Gain | Trisomy 8 | 2.9% of all tests, 15.4% of unique aberrant lines [19] |

| Partial Chromosome Gain | Gain of 1q arm | 7.2% of all tests, 30.8% of unique aberrant lines [19] |

| Partial Chromosome Gain | Gain of 20q | A recurrent CNV hotspot [1] |

| Partial Chromosome Gain | Gain of 12p | Associated with prolonged culture [1] |

| Whole Chromosome Loss | Loss of Chromosome 18 | A well-recognized recurrent loss [19] |

| Whole Chromosome Loss | Loss of Chromosome 10 | A well-recognized recurrent loss [19] |

Why do these specific abnormalities keep appearing?

These recurrent aberrations are not random. They undergo selection in vitro because the genetic changes they confer improve the cells' ability to survive and proliferate in the artificial culture environment, a process known as culture adaptation [19]. For example:

- Trisomy 12 is recurrent because chromosome 12 contains pluripotency-associated genes like NANOG and other cell cycle-related genes, which boost proliferation and reprogramming efficiency [1].

- Gain of 20q11.21 is a common CNV hotspot enriched with genes that support pluripotency and inhibit apoptosis (such as BCL2L1), favoring survival after single-cell passaging [19] [1].

- Gain of the 1q arm has been associated with feeder-free and high-density cell culture protocols [19].

How does the reprogramming process itself contribute to genomic instability?

The cellular stress of reprogramming, coupled with the unique physiology of pluripotent cells, creates a perfect storm for genomic instability. Key factors include [19] [14]:

- Reprogramming-Induced Replication Stress: The forced expression of reprogramming factors (like OSKM) can induce replication stress, leading to DNA breakage, similar to the phenomenon of oncogene-induced replication stress in cancer [14].

- Low Mitotic Fidelity & Relaxed Checkpoint Control: Pluripotent stem cells have relaxed cell cycle checkpoints, which can allow errors to propagate [19].

- Basal Levels of Replication Stress: iPSCs inherently have high basal levels of replication stress, predisposing them to damage at fragile sites in the DNA [19].

The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms and outcomes of genomic instability in iPSCs.

Troubleshooting Guide: Preventing and Managing Genomic Instability

How can I reduce the occurrence of genomic instability during reprogramming?

Evidence suggests that mitigating replication stress during the reprogramming process can significantly reduce DNA damage and resultant genomic rearrangements [14].

Table 2: Strategies to Limit Reprogramming-Induced Instability

| Strategy | Method | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleoside Supplementation | Adding nucleosides to the culture medium during reprogramming. | Increases nucleotide pool, reduces replication stress, DNA damage, and de novo CNVs [14]. |

| Checkpoint Kinase 1 (CHK1) Overexpression | Genetically increasing levels of the CHK1 kinase. | Limits replication stress and increases reprogramming efficiency [14]. |

| Choosing a Low-Stress Reprogramming Method | Using non-integrating methods (e.g., Sendai virus, episomal vectors). | Minimizes risk of insertional mutagenesis and associated DNA damage [19] [20]. |

What is the recommended schedule for karyotypic monitoring of my iPSC cultures?

Regular monitoring is a cornerstone of quality control. The following workflow provides a robust strategy for maintaining genetic integrity.

Which techniques should I use to detect different types of genetic variations?

No single method captures all genomic aberrations. A combination of techniques is recommended for comprehensive quality control [15] [1].

Table 3: Genomic Integrity Assessment Toolkit

| Technique | Primary Use | Detects | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| G-Banding Karyotyping | Initial screening for large-scale abnormalities. | Aneuploidy, translocations, large deletions/duplications (>5-10 Mb). | Limited resolution; cannot detect small CNVs or SNVs [1] [21]. |

| SNP Array / CGH Array | Higher-resolution screening for sub-chromosomal changes. | Copy Number Variations (CNVs) at kilobase resolution. | Cannot detect balanced translocations or low-level mosaicism reliably [15] [1]. |

| Whole Genome/Exome Sequencing | Most comprehensive analysis of the genome. | Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs), small insertions/deletions, and CNVs. | Higher cost and complex data analysis; may not detect low-frequency mosaicism [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents for Genetic Stability Workflows

| Reagent / Material | Function in iPSC Culture & Quality Control |

|---|---|

| Nucleoside Supplement | Chemical means to reduce replication stress during reprogramming and culture, limiting DNA damage and CNVs [14]. |

| Versene (EDTA Solution) | A non-enzymatic, gentle method for dissociating iPSCs, improving cell survival and reducing stress during passaging [20]. |

| Matrigel / Geltrex / Laminin-521 | Defined extracellular matrix coatings for feeder-free culture, supporting cell attachment and expansion while reducing variability [20]. |

| Essential 8 (E8) Medium | A chemically defined, xeno-free medium that provides a simpler and more controlled environment for hiPSC propagation [20]. |

| Giemsa Stain | The standard dye used in G-banding karyotyping to produce a distinct banding pattern for chromosome identification [21]. |

Genomic instability is a critical factor that can compromise the validity of disease models and the reproducibility of preclinical data. In the context of long-term cell culture, particularly with sensitive models like induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), accumulated genetic alterations can lead to inconsistent differentiation, functional deficiencies, and unreliable experimental results. This guide provides troubleshooting and best practices for researchers to identify, monitor, and prevent genomic instability in their experiments.

Troubleshooting Common Genomic Instability Issues

FAQ 1: My iPSC culture shows inconsistent differentiation into the target cell type. Could genomic instability be the cause?

Yes, this is a common consequence of genomic instability. Alterations in the expression of genes that maintain pluripotency and control differentiation pathways can directly impair an iPSC line's ability to differentiate reliably into specific cell types [22]. This inconsistency undermines the reliability of downstream assay data.

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Karyotype Analysis: Perform G-banding to check for large-scale chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., trisomy 12 or 20) that are known to provide a growth advantage and alter differentiation potential [1].

- Functional Assay: Differentiate the suspect iPSC line in parallel with a low-passage, well-characterized control line. Compare the efficiency and purity of the resulting differentiated cells using cell-type-specific markers.

- Solution: Implement a routine genetic integrity check. If abnormalities are found, thaw an earlier, validated stock of the cell line with a known stable differentiation profile.

FAQ 2: After several passages, my cell line's growth rate and functional characteristics have changed. What should I do?

Genetic alterations acquired during prolonged culture (passage-induced mutations) can affect proliferation rates, viability, and functional characteristics [1] [22]. This is a typical sign of genomic instability and has been documented even in widely used lines like Jurkat cells, leading to marked variations in immunophenotype and cytokine production between laboratories [23].

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Monitor Proliferation: Keep detailed records of population doubling times and confluency at each passage. A significant increase in growth rate can indicate the expansion of a clone with a selective advantage, such as a gain of chromosome 12p or the 20q11.21 region [1].

- Genetic Screening: Use a high-resolution method like SNP array or whole-genome sequencing to identify copy number variations (CNVs) and single nucleotide variants (SNVs) that may have arisen during culture [1] [23].

- Solution: Establish a strict cell culture policy: avoid culturing cells for excessive passages, create large master banks of low-passage stocks, and routinely authenticate and characterize cell lines to prevent the dominance of genetically variant subpopulations.

FAQ 3: My experimental results are not reproducible between different stocks of the same cell line. How can I troubleshoot this?

Substantial genomic heterogeneity both between and within cell lines is a major source of irreproducibility. Genomic instability leads to a heterogeneous population of cells with different functional characteristics, growth rates, and differentiation potentials [22] [23].

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Cell Line Authentication: Use Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling to confirm the identity of your cell lines and rule out cross-contamination [23].

- Multi-Omic Comparison: For critical cell lines, compare the genomic (karyotype, CNVs), transcriptomic (RNA-seq), and functional (e.g., cytokine production, surface marker expression) profiles of the different stocks [23].

- Solution: Standardize cell culture protocols across laboratories. Replace old, high-passage cell stocks with newly authenticated, low-passage stocks from a reliable source. Clearly document the passage number and culture history for all experiments.

FAQ 4: How can I determine if a detected genetic variation in my iPSCs poses a safety risk for clinical applications?

It remains challenging to distinguish between innocuous genomic aberrations and those that may cause adverse effects like malignant transformation [1] [18]. However, certain mutations are considered higher risk.

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Focus on Hotspots: Prioritize the screening for mutations in known cancer-driver genes and recurrent CNV hotspots like 20q11.21, which contains anti-apoptosis and pluripotency-associated genes like BCL2L1 [1].

- Functional Validation: Conduct in vitro tumorigenicity assays (e.g., soft agar colony formation) and in vivo teratoma formation assays to assess the malignant potential of iPSC-derived cells.

- Solution: Employ high-resolution monitoring (e.g., SNP genotyping) throughout the preparation of cells for transplant [18]. Regulatory agencies typically require comprehensive genetic analysis, including karyotyping and higher-resolution methods like array genomic hybridization (AGH), to identify microdeletions before clinical use [22].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Monitoring Genomic Instability

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Genetic Integrity Workflow for iPSCs

This workflow combines multiple techniques to detect different types of genomic instability at various scales.

Table 1: Methods for Detecting Genomic Instability in Cell Cultures

| Method | Detects | Resolution | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karyotyping (G-banding) [1] | Numerical & large structural chromosomal changes (aneuploidy, translocations) | ~5-10 Mb | Routine quality control, gold standard for regulatory submissions [22] | Low resolution; cannot detect small CNVs or SNVs |

| Array Genomic Hybridization (AGH) [22] | Copy Number Variations (CNVs) | Kilobase level | Identifying microdeletions and recurrent CNV hotspots (e.g., 20q11.21) [1] | Cannot detect balanced translocations or low-frequency mosaicism [1] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) [1] | Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs), CNVs, structural variants | Single nucleotide | Most comprehensive profiling; identifying low-frequency variants and mutations of unknown origin [1] | Higher cost and complex data analysis |

Workflow Diagram: Genetic Integrity Monitoring Pathway

Protocol 2: Assessing Functional Consequences of Instability

Genomic instability must be linked to phenotypic outcomes. This protocol assesses the functional impact on a model T-cell line (Jurkat), but the principles are applicable to other cell types.

Method:

- Cell Stimulation: Stimulate cells from different laboratory stocks or passages in parallel. For Jurkat cells, use CD3/CD28 Dynabeads or PMA/Ionomycin [23].

- Phenotypic Analysis by Flow Cytometry: At 24 hours post-stimulation, analyze the cells for activation markers (e.g., CD69, CD25) to detect immunophenotype variations [23].

- Cytokine Production Profiling: Collect supernatant at 6-24 hours post-stimulation. Use a multiplex cytokine bead array (e.g., for IL-2, IFN-γ) to quantify functional output [23].

- Correlation with Genomic Data: Integrate functional data with genomic data (e.g., from WES or CMA) to link specific mutations or karyotypic changes to the observed phenotypic variations [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Genomic Instability Research

| Item | Function | Example Product(s) | Specific Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Karyotyping Kit | Detects chromosomal aberrations via G-banding | Giemsa Stain | Routine cytogenetic analysis required by regulatory agencies for cell therapy applications [22]. |

| CGH/SNP Array | High-resolution detection of CNVs | Agilent GenetiSure Cyto CGH + SNP array [23] | Identifying recurrent CNV hotspots in iPSCs (e.g., 20q11.21) and confirming karyotype results [1] [23]. |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kit | Detects mycoplasma contamination | MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit [23] | Essential quality control step, as mycoplasma infection can induce chromosomal abnormalities and alter gene expression, confounding results [23]. |

| T-cell Activation Reagents | Functional assessment of immune cells | Human T-activator CD3/CD28 Dynabeads, PMA/Ionomycin [23] | Testing the functional impact of genomic instability in T-cell models like Jurkat cells by measuring activation and cytokine production [23]. |

| Multiplex Cytokine Assay | Quantifies multiple cytokines simultaneously | Multiplex cytokine bead array (e.g., for IL-2, IFN-γ) [23] | Profiling functional changes in cell secretome due to accumulated mutations, linking genotype to phenotype [23]. |

Workflow Diagram: From Instability to Functional Deficit

Practical Monitoring: Essential Tools for Detecting Genomic Drift

In long-term induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) culture research, maintaining genomic integrity is not optional—it is foundational. iPSCs possess an inherent propensity for genomic instability, with studies revealing that a genetically abnormal clone can overtake a culture in less than five passages [24]. This technical support guide provides a comprehensive framework for establishing a routine karyotyping schedule, a critical component in preventing genomic instability and ensuring the validity of your research and the safety of future therapeutic applications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is routine karyotyping non-negotiable in iPSC research? Karyotyping is a primary quality control measure because chromosomal abnormalities frequently arise during reprogramming, gene editing, and maintenance cultivation [24]. These aberrations can compromise differentiation efficiency, alter cellular function, and pose significant safety risks in cell replacement therapies [24]. Routine monitoring is the only way to catch these changes early.

2. What is the recommended baseline schedule for karyotyping my iPSC lines? A proactive schedule is essential for catching genomic drift before it compromises your cell lines. The following table summarizes the key timepoints:

| Cell Culture Stage | Recommended Action | Rationale & Supporting Data |

|---|---|---|

| Newly Established Line | Perform initial karyotyping at early passage (Passage 7-10) [20]. | Establishes a genomic baseline for the line post-reprogramming. |

| During Routine Maintenance | Karyotype every 10-15 passages during propagation [20]. | Monitors for instability acquired during long-term culture. |

| Pre-Differentiation | Validate karyotype before initiating major differentiation protocols [4]. | Ensures genomic integrity of the starting material for downstream experiments. |

| Post-Gene Editing | Karyotype after selection and expansion of edited clones [24]. | Confirms that the editing process has not introduced chromosomal aberrations. |

| After Cell Line Recovery | Karyotype after re-expansion from cryopreserved stocks [20]. | Verifies stability after the freeze-thaw cycle. |

3. What are the most common chromosomal abnormalities I should look for in iPSCs? Research has identified a consistent bias in the genetic changes acquired in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). The most frequent anomalies involve [24] [15]:

- Trisomy of chromosome 12, 17, or X.

- Amplification of specific regions like chromosome 1, 12p, 17q, or 20q11.21.

4. My karyotype results are normal. Are my cells genetically pristine? Not necessarily. A normal karyotype is crucial but does not guarantee full genomic integrity. Traditional G-banding karyotyping has a resolution of 5-10 Mb, meaning smaller abnormalities can be missed [24]. It also cannot detect copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity (CN-LOH) or single point mutations [24] [15]. A comprehensive quality control panel should include additional assays like SNP arrays or sequencing.

Troubleshooting Guide: Interpreting Karyotyping Results

Problem: A suspected chromosomal abnormality is reported. Solution:

- Verify the Nomenclature: Ensure you understand the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN). Common symbols include [25] [26]:

- del: Deletion

- t: Translocation

- inv: Inversion

- + / -: Gain or loss of a chromosome

- i: Isochromosome

- mar: Marker chromosome

- dn: De novo (not inherited from parents)

- Correlate with Biology: Determine if the abnormality is a known, culture-adapted mutation (e.g., gain of 20q11.21) that provides a growth advantage [24].

- Action: Discard the affected iPSC clone. The identified abnormality is likely to confer a selective advantage and may impact your research outcomes [20].

Problem: Subclonal abnormalities or mosaic cells are detected. Solution:

- Understand the Limitation: Karyotyping has a limited ability to identify sub-clonal populations; its sensitivity depends on the proportion of the abnormal cells and the number of metaphases analyzed [24].

- Action: If a minor sideline is detected, it is a strong indicator of emerging genomic instability. The culture should be considered compromised and regenerated from an earlier, fully characterized stock.

Problem: The karyotype is normal, but the cell line shows poor differentiation performance. Solution:

- Investigate Further: A normal karyotype rules out large chromosomal aberrations, but not smaller genetic lesions.

- Employ Higher-Resolution Techniques: Use SNP array analysis to detect copy number variations (CNVs) and copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity (CN-LOH) as small as 350 kb [24]. Consider whole-exome sequencing to identify single point mutations that can accumulate in iPSCs [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and kits are essential for establishing and monitoring iPSC genomic integrity.

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Application in Genomic Health Checks |

|---|---|---|

| Colcemid | Inhibits spindle fiber formation, arresting cells in metaphase. | Used in the preparation of samples for G-banding karyotype analysis to obtain analyzable metaphase spreads [24]. |

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit | Extracts high-quality genomic DNA from cell samples. | Prepares DNA for high-resolution analysis techniques like SNP arrays or next-generation sequencing (NGS) [24]. |

| Illumina Global Screening Array | A single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping platform. | Used for molecular karyotyping to sensitively detect CNVs and CN-LOH with high resolution [24]. |

| STEMdiff Mesenchymal Progenitor Kit | Differentiates iPSCs into mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (iMS cells). | Used in studies to trace genomic instability from the iPSC stage through differentiation, a key quality control step [4]. |

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Genomic Screening

The diagram below illustrates a multi-tiered experimental workflow for monitoring genomic integrity in iPSCs, integrating both routine checks and higher-resolution follow-up analyses.

Figure 1: A tiered workflow for genomic health checks in iPSC cultures, from routine karyotyping to advanced molecular analysis.

Leveraging Targeted qPCR Assays for Rapid, Cost-Effective Screening of Common Abnormalities

The utility of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) in research and regenerative medicine is often compromised by genomic instability that arises during reprogramming and long-term culture. This instability can manifest as copy number variations (CNVs), single nucleotide variants (SNVs), and chromosomal aberrations, which collectively impact the reliability and safety of iPSC-based models and therapies [1]. Targeted qPCR assays offer a rapid and cost-effective solution for routine monitoring of the most common karyotypic abnormalities, serving as a critical quality control checkpoint to ensure genomic integrity in iPSC cultures [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is genomic instability a particular concern in long-term iPSC culture? Genomic instability in iPSCs originates from multiple sources: pre-existing variations in parental somatic cells, reprogramming-induced mutations, and passage-induced mutations acquired during prolonged culture [1]. Certain abnormalities, such as gains on chromosome 12 or 20q11.21, confer a selective growth advantage, allowing affected cells to overtake the culture over time and leading to reduced differentiation capacity and increased neoplastic risk [1] [27].

2. How does targeted qPCR compare to other methods like karyotyping or aCGH for abnormality screening? While traditional karyotyping and array-based methods like aCGH provide broad genomic coverage, they are often lower in resolution, more time-consuming, and costlier. Targeted qPCR is specifically designed for high-throughput, rapid screening of known common abnormality hotspots. It offers a practical solution for frequent monitoring, allowing researchers to identify problematic cultures early before committing resources to extensive differentiations [27].

3. My iPSC line shows a common abnormality. Should I immediately discard it? The decision depends on the specific abnormality and your research application. Gains in regions like 20q11.21 are well-documented to impair differentiation potential and increase tumorigenicity [1] [27]. For most therapeutic or rigorous preclinical studies, discarding the line is the safest course. For basic research, you might proceed with extreme caution and clear documentation, but be aware that results may be irreproducible or misleading.

4. Can the reprogramming method influence the genomic instability of the resulting iPSCs? Yes. Reprogramming methods that utilize integrating vectors or specific oncogenes (e.g., c-MYC) can contribute to genomic instability [28]. Non-integrating methods, such as episomal vectors or Sendai virus, are generally preferred for generating clinical-grade iPSCs as they lower the risk of insertional mutagenesis and viral immunogenicity [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Differentiation Outcomes

- Symptoms: High variability in differentiation efficiency and purity between passages or batches of the same iPSC line. Presence of non-target cell types or abnormal cellular morphology [27].

- Potential Cause: The accumulation of genomic abnormalities in the iPSC master cell bank or during culture expansion. Common abnormalities like trisomy 12 or 20q11.21 amplification can directly alter differentiation capacity [27].

- Solutions:

- Implement Routine Screening: Integrate a targeted qPCR assay for common karyotypic abnormalities as a mandatory quality control check before initiating any differentiation experiment.

- Monitor Culture Passages: Assess genomic stability at key passages (e.g., every 10 passages) to track the emergence of abnormalities over time.

- Establish Clear Thresholds: Define acceptable cut-off values for chromosomal copy number (e.g., 1.5 to 2.5 for autosomes) based on your assay validation data. Discard lines that fall outside this range [27].

Problem 2: Amplification in No Template Control (NTC)

- Symptoms: The NTC well, which contains all qPCR reagents except the nucleic acid template, shows amplification and a Ct value [29] [30].

- Potential Causes:

- Contamination: Aerosol contamination from amplified PCR products or concentrated positive control templates in the lab environment [29].

- Primer-Dimer Formation: The forward and reverse primers anneal to each other and are amplified, typically resulting in a low efficiency reaction and a melt curve peak at a lower temperature than the specific product [30].

- Solutions:

- Prevent Contamination: Use separate physical areas for reagent preparation, sample handling, and post-amplification analysis. Clean workspaces and pipettes with 10% bleach or 70% ethanol [29].

- Use a Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG) System: Employ a master mix containing dUTP and UDG. This enzyme will degrade any contaminating amplicons from previous PCRs before the new reaction begins [29].

- Optimize Primer Design: Re-design primers to avoid self-complementarity and check for dimer formation using oligonucleotide analysis tools. Increase the annealing temperature during the qPCR cycle to discourage non-specific binding [31] [30].

- Physical Separation: Place NTC wells away from high-concentration sample wells on the qPCR plate to prevent splashing or aerosol cross-contamination [30].

Problem 3: Poor qPCR Assay Efficiency or Non-Specific Amplification

- Symptoms: A standard curve with an efficiency below 90% or above 110%, or a melt curve with multiple peaks indicating non-specific products [30].

- Potential Causes: Suboptimal primer/probe design, incorrect annealing temperature, or contaminated reagents [31] [29].

- Solutions:

- Verify Oligo Design: Ensure primers and probes meet optimal design criteria (see Table 2). Use tools like IDT's OligoAnalyzer to check for secondary structures and dimer formation [31].

- Perform BLAST Analysis: Confirm that your primer sequences are unique to the intended target to avoid amplifying non-specific genomic regions [31].

- Optimize Annealing Temperature: Perform a temperature gradient experiment to determine the ideal annealing temperature for your specific assay [31].

- Use High-Purity Reagents: Source oligonucleotides from manufacturers that take steps to prevent bacterial DNA contamination during synthesis and purification [29].

Common Karyotypic Abnormalities in iPSCs

The following table summarizes the most frequent genomic abnormalities identified in human iPSCs, which are ideal targets for a focused qPCR screening panel [1] [27].

Table 1: Common Genomic Abnormalities in Human iPSCs

| Chromosomal Abnormality | Functional Consequence | Impact on Differentiation |

|---|---|---|

| Trisomy 12 | Contains pluripotency genes (e.g., NANOG); confers selective growth advantage [1]. | Recurrent aneuploidy; alters pluripotency network. |

| Amplification of 20q11.21 | Harbors anti-apoptosis (BCL2L1) and pluripotency-associated genes (DNMT3B, ID1) [1]. | Well-documented to reduce differentiation capacity and purity [27]. |

| Trisomy 8 | Another recurrent aneuploidy observed in both iPSCs and ESCs [1]. | Can alter differentiation propensity and culture stability. |

| Trisomy X (in female lines) | A common sex chromosome aneuploidy [1]. | Effect on differentiation requires further study. |

Experimental Protocol: Targeted qPCR Screening for Common iPSC Abnormalities

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for using a bulk qPCR assay to screen for common karyotypic abnormalities in human iPSCs, based on the approach validated in scientific studies [27].

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- Cell Lysis: Harvest a minimum of 1x10^6 iPSCs. Extract high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA using a silica column-based kit to minimize inhibitor carryover.

- DNA Quantification: Precisely quantify the DNA using a fluorometer. Normalize all samples to the same concentration (e.g., 10 ng/µL) in nuclease-free water.

Primer and Probe Design

- Target Selection: Design assays to target the nine most common karyotypic abnormalities in human iPSCs (e.g., chromosomes 1, 8, 12, 17, 20, and X) [27].

- Reference Genes: Include at least two reference assays targeting genomically stable regions on different chromosomes (e.g., chromosome 14).

- Design Parameters:

- Amplicon Length: 70–150 bp.

- Tm: Primers: 60–64°C; Probes: 5–10°C higher than primers.

- GC Content: 35–65% for both primers and probes.

- Specificity: Ensure primers span an exon-exon junction if targeting an RNA sequence for reverse-transcribed samples, and run a BLAST analysis for specificity [31].

qPCR Setup and Run

- Reaction Mix: Prepare a master mix for each sample containing:

- 1X double-quenched probe master mix (e.g., TaqMan).

- Primers and probe for the target abnormality.

- Primers and probe for the reference gene.

- 50 ng of normalized genomic DNA.

- Controls:

- No Template Control (NTC): Contains all reaction components except DNA.

- Positive Control: Genomic DNA from a cell line with a known, validated abnormality.

- Negative Control: Genomic DNA from a confirmed karyotypically normal cell line.

- Cycling Conditions:

- UDG incubation (if using): 50°C for 2 minutes.

- Polymerase activation: 95°C for 20 seconds.

- 40 cycles of: Denature at 95°C for 3 seconds, Anneal/Extend at 60°C for 30 seconds.

Data Analysis

- Copy Number Calculation: Use the ΔΔCt method. Normalize the Ct of the target assay to the reference assay in the test sample and a diploid control sample.

- Copy Number = 2 × 2^(–ΔΔCt)

- Interpretation:

- Normal: Copy number between 1.5 and 2.5 for autosomes (or 0.7-1.3 for chromosome X in male lines).

- Abnormal: Copy number ≤ 1.5 or ≥ 2.5 (for autosomes) indicates a potential deletion or amplification, respectively [27].

The workflow for this screening process is outlined below.

Best Practices for qPCR Assay Design and Validation

Adhering to established design principles is crucial for developing a robust and reliable targeted qPCR assay.

Table 2: qPCR Primer and Probe Design Guidelines [31]

| Parameter | Recommended Guideline | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18–30 bases | Balances specificity and binding efficiency. |

| Primer Tm | 60–64°C (ideal: 62°C); pair within 2°C | Ensures simultaneous and efficient binding of both primers. |

| Probe Tm | 5–10°C higher than primers | Ensures probe is bound before primer extension. |

| GC Content | 35–65% (ideal: 50%) | Provides sequence complexity while avoiding stable secondary structures. |

| Amplicon Length | 70–150 bp | Ideal for efficient amplification under standard cycling conditions. |

| Specificity Check | BLAST analysis; avoid poly-G sequences | Confirms uniqueness to the target and prevents G-quadruplex formation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Targeted Genomic Screening

| Item | Function | Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies target sequences with low error rates. | Essential for accurate quantification in pre-amplification steps, if used. |

| Double-Quenched Probes | Provides specific signal detection during qPCR. | Lowers background fluorescence, increasing signal-to-noise ratio compared to single-quenched probes [31]. |

| dUTP/UDG Master Mix | Prevents carryover contamination from previous PCR products. | UDG enzymatically degrades uracil-containing amplicons before PCR begins [29]. |

| Commercial gDNA Extraction Kits | Isolates high-purity, inhibitor-free genomic DNA. | Silica-column based kits are preferred for removing PCR inhibitors. |

| Predesigned Assay Panels | Targets the most common iPSC abnormalities. | Available from vendors like STEMCELL Technologies; saves development time [27]. |

| Nucleoside Supplements | Reduces replication stress during reprogramming/culture. | Adding nucleosides to culture media can decrease DNA damage and CNV load in resulting iPSCs [14]. |

The diagram below illustrates how replication stress from reprogramming can lead to genomic instability and how targeted screening and mitigation strategies form a complete quality control cycle.

Foundational Principles and Applications in iPSC Research

What are the fundamental principles distinguishing SNP microarray and aCGH?

SNP microarray and aCGH are powerful genomic profiling technologies, but they operate on different principles and are suited for detecting distinct types of genomic aberrations.

Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH) is primarily designed to detect copy number variations (CNVs), which are gains or losses of genomic DNA. Its principle is based on a competitive hybridization between a test DNA and a reference DNA, each labeled with different fluorescent dyes (typically Cyanine 3 for test and Cyanine 5 for reference). The mixture is applied to a microarray chip containing thousands of known DNA probes. The resulting color at each probe spot reveals the copy number: a green-to-red ratio indicates equal copy number, a shift towards red suggests a loss in the test sample, and a shift towards green indicates a gain [32].

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Microarray is designed to detect single nucleotide polymorphisms and can also infer copy number. Its principle is based on hybridizing a single sample's DNA to a chip containing probes for known SNP loci. By measuring the hybridization signal intensity and, crucially, the allelic composition (the "B allele frequency"), it can determine both the copy number at each locus and the genotype (e.g., AA, AB, BB). This dual measurement allows SNP microarrays to detect not only CNVs but also copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity (LOH), a change in the genome where both copies of a gene are from one parent, without a change in copy number [33] [34].

Table 1: Core Differences Between aCGH and SNP Microarray

| Feature | aCGH | SNP Microarray |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Principle | Competitive, two-color hybridization | Single-sample hybridization with intensity and allelic ratio measurement |

| Detects CNVs | Yes | Yes |

| Detects SNPs & Genotypes | No | Yes |

| Detects Copy-Neutral LOH | No | Yes |

| Key Outputs | Log R ratio (intensity) | Log R ratio (intensity) & B Allele Frequency |

Why are these techniques critical for monitoring genomic instability in iPSC cultures?

Genomic instability is a major concern in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) research, potentially compromising their use in disease modeling and regenerative medicine. SNP microarrays and aCGH are essential for identifying the following types of genetic alterations that arise during reprogramming and long-term culture [1] [22]:

- Copy Number Variations (CNVs): These are recurrently observed in iPSCs. A common hotspot is an amplification of 20q11.21, a region containing genes associated with pluripotency and anti-apoptosis (e.g., DNMT3B, BCL2L1), which can provide a selective growth advantage [1].

- Chromosomal Aberrations: Aneuploidy, particularly gains of chromosomes 12, 8, and X, is frequently reported in both iPSCs and ESCs, likely conferring a proliferative advantage [1].

- Copy-Neutral Loss of Heterozygosity (LOH): This can unmask recessive mutations and is implicated in tumorigenesis. SNP arrays are uniquely capable of detecting this abnormality, which aCGH cannot [33] [34].

These aberrations originate from multiple sources: pre-existing mutations in parental somatic cells that are clonally expanded during reprogramming; reprogramming-induced mutations caused by replication stress from the forced expression of factors like OCT4 and c-MYC; and passage-induced mutations accumulated during prolonged culture [1] [14] [22]. Routine screening with these technologies is therefore paramount for quality control in iPSC banking and for ensuring the safety of future cell therapies.

Troubleshooting Guides

Our aCGH data shows high background noise and poor signal-to-noise ratio. What steps can we take?

Poor data quality in aCGH often stems from suboptimal sample preparation or hybridization conditions. Follow this checklist to resolve these issues [32]:

Table 2: Troubleshooting aCGH Quality Control Metrics

| QC Metric | Target Value | Problem | Potential Causes & Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Background Noise | < 25 | High Background | Cause: Contaminated DNA, inefficient washing, or incorrect hybridization stringency.Solution: Re-purify DNA using columns or ethanol precipitation. Ensure wash buffers are fresh and follow washing protocols strictly. Verify hybridization temperature and buffer composition. |

| Signal Intensity | > 200 | Low Signal | Cause: Inefficient fluorescent labeling or degraded DNA.Solution: Check DNA integrity via gel electrophoresis. Ensure the labeling reaction is performed at the correct temperature and for the full recommended duration. Do not shorten the primer extension step. |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | > 30 | Low Ratio | Cause: Combination of high background and low signal.Solution: Address both issues above. Also, verify the amount of Cot-1 DNA in the hybridization mix, as it blocks non-specific binding of repetitive sequences. |

| Derivative Log Ratio (DLR) | < 0.2 | High DLR | Cause: Poor DNA quality and/or inefficient labeling efficiency. A high DLR indicates high noise, reducing the ability to call CNVs accurately.Solution: Start with high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA (A260/280 > 1.8; A260/230 ~2.0-2.2). Re-check the labeling reaction efficiency using a NanoDrop before hybridizing to the expensive chip. |

Our SNP microarray results show unusual clustering or a high failure rate. How can we improve this?

Unusual clustering in SNP genotyping can arise from several technical and biological factors [35].

Problem: Trailing or Multiple Clusters

- Cause 1 (Technical): Variation in gDNA quality or concentration across samples. This is a common cause of "trailing" where data points smear between clusters.

- Solution: Accurately quantify all DNA samples and use a standardized, high-quality isolation method to ensure consistent purity and integrity. Avoid degraded DNA [35].

- Cause 2 (Biological): A hidden SNP under the probe or primer binding site.

- Solution: Query the dbSNP database for other known polymorphisms near your target SNP. If found, redesign the assay to avoid this region by masking the position as an "N" in the design tool [35].

- Cause 3 (Biological): The genomic region being assayed is within a copy number variation.

- Solution: Evaluate the sample with a dedicated TaqMan Copy Number Assay to confirm if the region is amplified or deleted, which would explain the abnormal genotype clustering [35].

Problem: No Amplification or High Failure Rate

- Cause: Inaccurate DNA quantitation, degraded DNA, or the presence of PCR inhibitors in the sample.

- Solution: Re-quantify DNA using a fluorescence-based method for higher accuracy. Check DNA integrity on a gel. If inhibitors are suspected, clean up the DNA sample with a purification column [35].

How can we mitigate replication stress during iPSC reprogramming to reduce genomic instability?

A key driver of genomic instability during iPSC generation is replication stress, triggered by the expression of reprogramming factors. Proactively reducing this stress leads to iPSC lines with fewer genetic alterations [14].

- Chemical Mitigation: Supplement the reprogramming medium with nucleosides. This provides the raw materials for DNA synthesis, alleviating the nucleotide depletion that contributes to replication stress. Studies show this treatment reduces the load of DNA damage (γH2AX foci) and lowers the number of de novo CNVs in the resulting iPSC lines without increasing reprogramming efficiency [14].

- Genetic Mitigation: Increasing the levels of the checkpoint kinase CHK1, a key regulator of the replication stress response, has been shown to reduce reprogramming-induced DNA damage. While this is often done genetically, it underscores the importance of the CHK1 pathway in maintaining genomic integrity during reprogramming [14].

Detailed Methodologies

What is a standardized workflow for performing SNP microarray analysis?

The general workflow for SNP microarray is robust and can be broken down into several key stages [33]:

- Chip Fabrication: Predesigned oligonucleotide probes, specific to the target SNP loci, are synthesized and arranged in a high-density pattern on a solid glass carrier. Technologies like Affymetrix's GeneChip allow for in-situ oligonucleotide synthesis with extreme density [33].

- Sample Preparation: High-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA is isolated from the sample (e.g., iPSCs). The concentration and purity (A260/280 > 1.8) are critically important. The DNA is then fluorescently labeled [33].

- Hybridization: The labeled DNA is denatured and applied to the SNP microarray chip under controlled conditions of temperature, salt concentration, and time to allow for specific hybridization between the sample DNA and the complementary probes on the array [33].

- Washing and Scanning: After hybridization, the chip is washed stringently to remove any non-specifically bound DNA. It is then scanned with a high-resolution fluorescence scanner to detect the signal at each probe [33].

- Data Analysis: Specialized software analyzes the scanned image, extracting raw signal data. This data is processed to generate the two key values for each SNP: the Log R Ratio (normalized intensity for copy number) and the B Allele Frequency (allelic ratio for genotype). These are plotted along the genome for visualization and detection of aberrations [33] [34].

What is the detailed protocol for aCGH in profiling iPSC lines?

For reliable aCGH results, meticulous attention to protocol details is required [32]:

- Step 1: DNA Quality Control. Isolate genomic DNA from your iPSC line and a reference control. Assess purity by spectrophotometry (A260/280 ~1.8; A260/230 ~2.0-2.2) and check integrity by gel electrophoresis (should be a high molecular weight band). Store DNA at 4°C to avoid freeze-thaw cycle-induced breaks.

- Step 2: Fluorescent Labeling. Label 1 µg of test and reference DNA with different cyanine dyes (e.g., Cy3 and Cy5) using a validated labeling kit (e.g., Enzo's CYTAG series). The reaction, based on random priming and primer extension, must be performed at the correct temperature and for the full duration to ensure efficient dye incorporation.

- Step 3: Probe Purification and Quality Check. Purify the labeled DNA to remove unincorporated nucleotides, using silica columns or ethanol precipitation. Check the labeling efficiency with a NanoDrop: for a 4x180k array, aim for a DNA yield >5.0 µg, with specific activity of at least ~60 pmol/µg for Cy3 and ~40 pmol/µg for Cy5.

- Step 4: Hybridization. Mix the labeled test and reference DNA with Cot-1 DNA (to block repetitive sequences) and hybridization buffer. Denature the mixture and apply it to the aCGH microarray. Incubate in a hybridization chamber at the recommended temperature and duration (typically ~24-40 hours).

- Step 5: Washing, Scanning, and Analysis. After hybridization, wash the array according to the manufacturer's protocol to remove non-specific binding. Scan the slide with a dual-laser scanner and extract the log2 ratio of test/reference signal for each probe using the appropriate software. Aberrations are called when the log2 ratio significantly deviates from zero.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Genomic Analysis

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CYTAG TotalCGH Labeling Kit | Fluorescent labeling of DNA for aCGH. | Allows for SNP arrays in addition to standard CGH, providing flexibility [32]. |

| CYTAG SuperCGH Labeling Kit | Fluorescent labeling for limited DNA input. | Designed for samples with as little as 50 ng of starting DNA, crucial for rare iPSC clones [32]. |

| Infinium Whole-Genome Genotyping BeadChip | High-density SNP genotyping platform. | Available in various densities (e.g., 109K, 317K SNPs); enables simultaneous measurement of intensity and allelic ratios [34]. |

| Nucleoside Supplement | Chemical mitigation of replication stress. | Adding to reprogramming media reduces DNA damage and CNVs in resulting iPSCs [14]. |

| PCR & Gel Clean-up Kit | Purification of labeled DNA probes. | Typically included in labeling kits to remove unincorporated dyes and nucleotides post-labeling [32]. |

| Cot-1 DNA | Blocking of repetitive genomic sequences. | Added in excess to the hybridization mix to prevent non-specific binding and reduce background "wave effects" [32]. |

Integrating Genomic Stability Assessment into Standard iPSC Culture Workflows

FAQs on Genomic Instability in iPSC Cultures

What types of genomic abnormalities are most common in iPSCs?

The most frequent genomic abnormalities in iPSCs are copy number variations (CNVs) and single nucleotide variants (SNVs) [36]. CNVs are deletions or amplifications of DNA sections that often confer a selective advantage for proliferation and survival, while SNVs can disrupt differentiation capacities and increase the risk of malignant transformation [36]. Specific recurrent abnormalities include:

- Trisomy of chromosome 12, 17, or X [15]

- Amplification of 20q11.21, a region containing pluripotency and anti-apoptosis genes [1]

- Uniparental disomy (UPD), where both copies of a chromosome come from a single parent [15]

When should I test my iPSC cultures for genomic instability?

Regular monitoring at key process stages is essential for maintaining genomic integrity [36]:

| Testing Stage | Purpose | Recommended Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition of a new line | Establish baseline genomic stability | G-banding + digital PCR or NGS [36] |

| After reprogramming/gene editing | Screen for procedure-induced aberrations | Digital PCR for clone screening [36] |

| During cell amplification & maintenance | Monitor for culture-acquired defects | Digital PCR every 5-10 passages [36] |