Standardizing Differentiation Efficiency in Patient-Specific Stem Cell Lines: From Foundational Challenges to Clinical Translation

This article addresses the critical challenge of variability in differentiation efficiency across patient-specific stem cell lines, a major bottleneck in regenerative medicine and drug development.

Standardizing Differentiation Efficiency in Patient-Specific Stem Cell Lines: From Foundational Challenges to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of variability in differentiation efficiency across patient-specific stem cell lines, a major bottleneck in regenerative medicine and drug development. We explore the foundational sources of variability, from genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity to technical protocol inconsistencies. The piece delves into cutting-edge methodological solutions, including non-destructive imaging and machine learning for early prediction, alongside optimization strategies like protocol harmonization and advanced genome editing. Finally, we examine validation frameworks and global regulatory landscapes essential for translating standardized, reproducible stem cell products from the laboratory to the clinic, providing a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals.

Understanding the Bottleneck: Why Differentiation Efficiency Varies in Patient-Specific Lines

The Critical Need for Standardization in Translational Stem Cell Research

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Fundamental Concepts and Standards

Q1: Why is standardization so critical in translational stem cell research?

Standardization is the cornerstone of transforming stem cell research from a promising scientific field into reliable, clinically applicable therapies. Without it, significant variability is introduced from multiple sources, including donor genetic background, culture conditions, reagent inconsistencies, and protocol differences [1]. This variability frustrates attempts to compare results across labs, collaborate effectively, and scale up for translational work. The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) and other regulatory bodies emphasize that standards help enable collaborations, support efficient clinical translation, reduce costs, and engender trust among patients [2] [3]. Ultimately, standardization moves the field toward workflows that produce consistent, day-after-day results, which is a prerequisite for developing safe and efficacious cell therapies [4] [1] [5].

Q2: What are the key areas where standards are needed?

The ISSCR highlights numerous areas where standards development would greatly advance stem cell science and its clinical application [2]. Key opportunities include:

- Source Materials: Standards for consent, procurement, manufacturing regulations, and cell potency assays.

- Process Controls: Standards for biobanking, minimally acceptable changes during cell culture, reporting of animal experiments, and trial design.

- Analytical Methods & Data Processing: Standards for characterizing cells and reporting data to ensure reproducibility.

Q3: What is the difference between assessing pluripotency as a "state" versus a "function"?

This is a crucial distinction in cell characterization [6].

- Pluripotency as a State: This involves identifying molecular signatures commonly observed in pluripotent populations, such as the expression of key transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) and cell surface markers (SSEA-4, TRA-1-60) via immunocytochemistry or flow cytometry [6]. While important, these markers in isolation do not necessarily confirm the cell's functional capacity to differentiate.

- Pluripotency as a Function (Developmental Potency): This assesses the actual differentiation capacity of a stem cell population. Assays like the teratoma formation assay (in vivo) or embryoid body formation (in vitro) are used to empirically prove that the cells can generate differentiated progeny from all three developmental germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) [6].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q4: My differentiation yields are low and variable. What could be the cause?

Low and variable differentiation efficiency is a common challenge, often stemming from inconsistencies in the starting cell population or differentiation process. Key factors to investigate are:

- Quality of Starting Cells: Ensure your pluripotent stem cells are healthy, free of spontaneous differentiation, and have been properly characterized for pluripotency and genomic integrity [7]. Passaging cells at very high density or when they are over-confluent can reduce their differentiation potential.

- Cell Cluster Size in 3D Differentiation: For protocols involving embryoid body (EB) formation, the size of the cell clusters has a significant impact on differentiation efficiency. EBs that are too large can develop a hypoxic core, leading to cell death and haphazard organization [6] [8]. Using cell cluster sorting or standardized aggregation methods can produce EBs of a defined size, improving reproducibility and yield [8].

- Reagent Consistency: Inconsistencies in growth factors, cytokines, or small molecule inducers between batches can derail a protocol. Using well-validated, GMP-grade reagents where possible helps minimize this variability [1].

Q5: How can I reduce technician-to-technician variability in my stem cell culture and differentiation workflows?

Human handling is a major source of variation. Strategies to mitigate this include:

- Detailed, Validated Protocols: Start with established guidelines from trusted sources like the ISSCR and document every procedural detail, from seeding density and passage number to the exact timing of media changes [1].

- Automation: Implementing automated liquid handling systems for cell passaging, feeding, and differentiation can drastically reduce human error and improve inter-technician consistency [8] [1]. Automated platforms can maintain iPS cells in an undifferentiated state for long periods and ensure highly parallelized processing [8].

- Adoption of Defined Culture Systems: Moving away from poorly defined components like animal feeder layers and serum toward feeder-free, xeno-free, and GMP-grade media and substrates eliminates batch inconsistency associated with biological materials [1].

Q6: I am concerned about genomic instability in my stem cell lines. What are the risks and how can I monitor them?

Stem cells are subject to the acquisition of genetic changes in culture, which can confer a growth advantage and alter the cell's phenotype and behavior [7]. These changes can impact the reproducibility of your results and the safety of any derived therapies.

- Risks: Genetic alterations can affect the differentiation capacity of the stem cells and the functional properties of the cells derived from them.

- Monitoring: Regular genomic characterization is essential. Karyotyping is a standard method to assess chromosome number and integrity [6]. For higher resolution, more sensitive detection methods like genomic sequencing can be employed to identify subtle genetic variants that may not be visible by karyotyping [7].

Analytical and Reporting Standards

Q7: What are the minimal criteria I should report when publishing results with human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs)?

To ensure reproducibility, published papers should include detailed information on key parameters [7]. The ISSCR Standards provide comprehensive guidance, which includes:

- Basic Characterization: Cell line origin, culture conditions, and mycoplasma status.

- Status of the Undifferentiated State: Evidence of pluripotency, including marker expression and, ideally, a functional assessment of differentiation potential.

- Genomic Characterization: Results of karyotyping or other genetic analysis to confirm genomic integrity.

- Details of Stem Cell-Based Model Systems: For differentiated models, a thorough description of the protocol and characterization of the resulting cells.

- Reporting: Detailed methodology to allow other labs to replicate the work.

Q8: The teratoma assay is considered a gold standard, but what are its limitations?

While the teratoma formation assay is considered a rigorous in vivo method to confirm pluripotency, it has several significant disadvantages [6]:

- Practical Constraints: It is labour-intensive, time-consuming (taking several weeks to months), and expensive due to animal care and maintenance.

- Ethical Considerations: The use of immunocompromised animals raises ethical issues.

- Technical and Analytical Challenges: The assay suffers from protocol variation between laboratories, which impacts tumour differentiation. The analysis is primarily qualitative (morphological identification of tissues) and can be subject to interpretation, with significant inter-tumour heterogeneity. There are also few universally accepted reporting standards for the assay.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Differentiation Efficiency | - Poor starting cell quality- Inconsistent EB/organoid size- Unoptimized cytokine/growth factor concentrations- High spontaneous differentiation in PSC culture | - Characterize PSCs for pluripotency before differentiation [7]- Use cell cluster sorting for defined EB size [8]- Perform dose-response experiments for signaling molecules [9]- Improve routine PSC culture; use Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor for single-cell survival [10] |

| High Variability Between Replicates/Experiments | - Technician handling differences- Batch-to-batch reagent variability- Inconsistent cell passaging- Fluctuations in incubation conditions (CO₂, temperature) | - Automate key culture and differentiation steps [8] [1]- Source GMP-grade or highly validated reagents [1]- Standardize passaging criteria and methods (e.g., consistent pipetting cycles) [8]- Regularly calibrate incubators and equipment |

| Contamination of Differentiated Cultures with Undifferentiated Cells | - Incomplete differentiation- Lack of selection methods for target cells | - Optimize differentiation protocol timing and factor combinations [10] [9]- Include a passage or freezing step post-differentiation to reduce undifferentiated cells [10]- Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to purify target population |

| Genomic Instabilities in PSC Lines | - Culture-adapted mutations- High passage number- Stress from suboptimal culture conditions | - Regularly karyotype cells and use more sensitive genomic assays [6] [7]- Use low-passage cell banks for experiments- Culture cells in defined, physiologically optimized conditions [1] |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Automated Workflow for Clonal iPS Cell Line Establishment and Defined EB Formation

This protocol, adapted from Ma et al. (2022), integrates automation and cell cluster sorting to enhance reproducibility [8].

Key Materials:

- Liquid Handling Unit (LHU): Hamilton STARlet or equivalent.

- Cell Cluster Sorter: Union Biometrica's BioSorter or equivalent.

- iPS Cells: Cultured on MEF feeders or feeder-free.

- Reagents: Collagenase IV, appropriate iPS cell culture media.

Methodology:

- Automated iPS Cell Culture: Maintain iPS cells on the automated platform, with regular feeding and monitoring via integrated microscopy.

- Passaging and Cluster Size Control: Dissociate iPS cell colonies using Collagenase IV. Use the LHU to resuspend the colonies with a predefined number of pipetting cycles (e.g., 5-8 cycles) to break them into uniformly sized clusters.

- Cell Cluster Sorting for Cloning: Analyze and sort the cell clusters using the BioSorter. Individual clusters of 5-10 cells are sorted into individual wells of a 96-well plate to establish clonal iPS cell lines.

- EB Formation of Defined Size: For differentiation, sort larger, defined clusters (e.g., 100-150 µm in diameter) into low-attachment plates to initiate homogeneous EB formation.

- Differentiation: Proceed with directed hematopoietic or other differentiation protocols using these standardized EBs.

Protocol 2: Time-Efficient Differentiation and Cryopreservation of Pancreatic Progenitors

This protocol, based on the work of Lucar et al. (2024), shortens the differentiation timeline and enables banking of intermediate cells [10].

Key Materials:

- iPS Cells: Patient-specific iPS cells.

- Cytokines and Small Molecules: Activin A, CHIR99021, FGF-7, cyclopamine, noggin, all-trans retinoic acid, GLP-1, nicotinamide.

- Media: RPMI 1640, StemMACS iPS-Brew XF.

- Matrix: Matrigel.

Methodology:

- Directed Differentiation:

- Stage I - Definitive Endoderm (4 days): Differentiate iPS cells using Activin A (100 ng/mL) and CHIR99021 (3 µM).

- Stage II - Primitive Gut Tube (3 days): Pattern endoderm with FGF-7 (50 ng/mL).

- Stage III - Pancreatic Progenitors (3 days): Induce pancreatic fate with cyclopamine (0.25 µM), noggin (50 ng/mL), and all-trans retinoic acid (2 µM).

- Cryopreservation of Progenitors: At the end of Stage III, harvest pancreatic progenitor cells. Cryopreserve them in appropriate freezing medium. Upon thawing, the cells can be replated and expanded.

- Final Differentiation and Analysis:

- Stage IV - Pancreatic Exocrine Cells (4-20 days): Differentiate thawed or freshly derived progenitors using FGF-7, GLP-1, and nicotinamide.

- Characterization: Assess efficiency by qPCR (for PDX1, AMY2A/B) and immunofluorescence (for PDX1 and amylase proteins). A reduction in stemness markers like OCT4 and NANOG after passaging or freezing indicates a purer pancreatic cell population [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Rationale for Use in Standardized Workflows |

|---|---|---|

| GMP-Grade Media | Provides nutrients and signaling milieu for cell growth/differentiation | Minimizes batch-to-batch variability; supports clinical translation [1] |

| Feeder-Free Matrix | Provides a defined substrate for cell attachment and growth | Eliminates inconsistency and contamination risk from animal feeder cells [1] |

| Validated Antibodies | Detects key pluripotency (OCT4, SOX2) and differentiation (PDX1, Amylase) markers | Critical for accurate characterization; poor antibodies are a major source of irreproducibility [1] |

| Cell Cluster Sorter | Analyzes and sorts cell clusters/EBs by size and fluorescence | Enables production of uniformly sized EBs, critical for reproducible differentiation [8] |

| Liquid Handling Robot | Automates repetitive tasks (media changes, passaging) | Reduces human error and inter-technician variability, enhancing reproducibility [8] [1] |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Improves survival of single pluripotent stem cells | Increases plating efficiency after passaging or thawing, standardizing initial cell numbers [10] |

Standardized Assessment Workflow

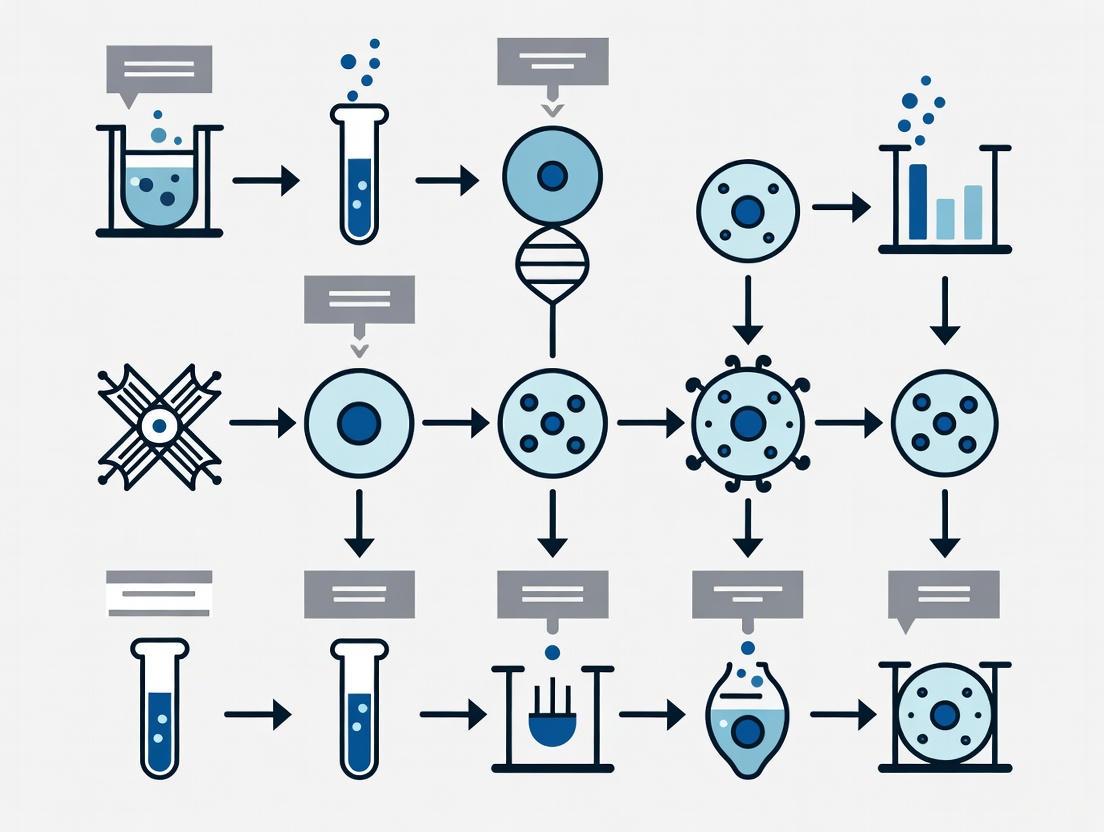

This diagram illustrates a comprehensive, standardized workflow for the characterization of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), integrating assessments of both their "state" and "function" as recommended by the ISSCR [6] [7].

Framework for Standardization

This diagram outlines the multi-level framework necessary for achieving standardization in translational stem cell research, from foundational materials to final application.

What are the primary genetic variations found in iPSCs and how do they originate?

Genetic variations in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can originate from multiple sources and manifest as different types of abnormalities. The main types include aneuploidy (abnormal chromosome numbers) and subchromosomal copy number variations (CNVs) [11].

Table 1: Sources and Types of Genetic Variations in iPSCs

| Variation Type | Common Examples | Primary Sources | Frequency/Occurrence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aneuploidy (Whole chromosome gains/losses) | Trisomy 12 (most common), Trisomy 8, Trisomy X [11] | - Innate instability of in vitro pluripotent state [11]- Prolonged culture (adaptive selection) [11]- Inherited from aneuploid source cells [11] | ~13-33% of hESC/hiPSC cultures [11] |

| Subchromosomal CNVs (Mb-scale deletions/duplications) | Variations around genes like NANOG (Chr. 12), DNMT3B (Chr. 20) [11] | - Reprogramming process (replication stress) [11]- Pre-existing mosaicism in source cells [11]- Prolonged culture [11] | High frequency noted in early-passage iPSCs (deletions often lost through passaging) [11] |

| Single Nucleotide Variations (SNVs) | Point mutations [11] | - Reprogramming-induced mutations [11]- Carried over from source cells [11] | Fewer de novo SNVs detected by sequencing studies [11] |

These variations are significant because they can confer a growth advantage under culture conditions, alter stem cell phenotype and behavior, and impact the reproducibility of downstream differentiation experiments [11] [7].

How does epigenetic variation affect the differentiation capacity of patient-specific iPSC lines?

Epigenetic variation is a strong indicator and determinant of a cell line's ability to differentiate into specific lineages. Donor-specific epigenetic patterns are maintained in iPSCs after reprogramming, creating a "molecular memory" that influences differentiation potential [12] [13].

Key Findings:

- Predictive Epigenetic Marks: Studies integrating molecular signatures with differentiation performance have found that hematopoietic commitment capacity correlates with IGF2 expression levels, which itself depends on signaling-dependent chromatin accessibility. Furthermore, the maturation capacity of derived blood cells is associated with specific patterns of DNA methylation acquired during reprogramming [13].

- Dynamic Relationship with Genetic Variation: The relationship between genetic variation and epigenetic variation is strongest at the iPSC stage. While iPSCs from the same donor cluster closely based on DNA methylation patterns, this donor-dependency decreases after differentiation. Epigenetic variation increases significantly in differentiated cell types, and the donor of origin becomes a less dominant contributor, suggesting cell-type-specific cues override some genetic influences [12].

- Impact on Reproducibility: This inherent epigenetic variation between lines is a major source of heterogeneity in differentiation yields and can affect the purity and functionality of the resulting differentiated cell populations [6] [13].

What are the standard methods for assessing pluripotency and differentiation potential, and what are their limitations?

Confirming pluripotency—the ability to differentiate into all three germ layers—is crucial. Assays are categorized as assessing pluripotency as a "state" (marker expression) or as a "function" (differentiation capacity) [6].

Table 2: Standard Assays for Assessing Pluripotency and Differentiation Potential

| Technique | Key Aspect | Advantages | Disadvantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunocytochemistry/Flow Cytometry | Detects protein markers of pluripotency (e.g., Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60) [6] | Accessible, provides data on colony homogeneity [6] | Marker expression does not confirm functional differentiation capacity [6] |

| Trilineage Spontaneous Differentiation In Vitro | Formation of embryoid bodies (EBs) containing cells from ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm [6] | Inexpensive, accessible, can reveal lineage biases [6] | Produces immature, haphazardly organized tissues; may not reflect full capacity [6] |

| Teratoma Assay In Vivo | Injection of PSCs into immunodeficient mice forms a benign tumour (teratoma) with complex, mature tissues from the three germ layers [6] | Considered the "gold standard"; provides empirical proof of pluripotency and tests for malignancy [6] | Labour-intensive, expensive, ethical concerns, qualitative, protocol variation between labs [6] |

| Modern 3D Cell Culture Technology | Directed differentiation in 3D to form specific tissue rudiments or organoids [6] | Can generate complex structures; avoids animal use; highly customizable [6] | Requires technical skill and optimization; not yet standardized for routine pluripotency assessment [6] |

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Experimental Challenges

Issue: Poor or Inefficient Differentiation Across Multiple Patient-Specific iPSC Lines

Potential Causes and Data-Driven Solutions:

Underlying Genetic or Epigenetic Variation

- Cause: Inherent genetic (e.g., CNVs) and epigenetic differences between donor lines can lead to significant variation in differentiation efficiency, a phenomenon called "differential capacity" [13].

- Solution:

- Characterize and Select Lines: Perform integrative molecular analysis to pre-screen lines. Lines with epigenetic features conducive to your target lineage (e.g., specific chromatin accessibility at key genes) should be selected for differentiation experiments [13].

- Use a Positive Control: Always include a well-characterized control PSC line (e.g., H9 or H7 ESC line) in your differentiation experiments to benchmark performance [14].

- Adjust Protocol Parameters: For difficult-to-differentiate iPSC lines, troubleshoot by adjusting cell seeding density or extending the induction time of your differentiation protocol [14].

Inadequate Characterization of Starting Population

- Cause: The pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) used to initiate differentiation are partially differentiated, genetically abnormal, or not maintained in an optimal state, leading to unpredictable results [14] [7].

- Solution:

- Rigorously Characterize hPSCs: Before differentiation, ensure your starting population is fully characterized. This includes confirming morphology, pluripotency marker expression (via flow cytometry/immunocytochemistry), and genomic integrity (e.g., karyotyping) [6] [7].

- Remove Differentiated Cells: Before starting neural induction or other differentiations, carefully remove any differentiated cells observed in the PSC culture [14].

- Monitor Culture Confluency: Prevent routine passaging at high confluency, as this can negatively impact cell health and subsequent differentiation potential [14].

Issue: Low Cell Viability During Differentiation or After Thawing Cryopreserved Cells

Potential Causes and Data-Driven Solutions:

Cryopreservation and Thawing Techniques

- Cause: Incorrect thawing of cryopreserved neural stem cells (NSCs) or other progenitor cells can cause severe osmotic shock and cell death [14].

- Solution:

- Thaw Rapidly and Gently: Do not thaw cells for longer than 2 minutes at 37°C. After thawing, transfer cells to a pre-rinsed tube and add pre-warmed complete medium drop-wise (about one drop per second) while gently swirling the tube. Do not add a large volume of medium at once [14].

- Avoid Centrifugation: For extremely fragile cells like primary neurons, avoid centrifugation upon thawing [14].

- Check Seeding Density: Ensure you are seeding at the recommended density (e.g., >1x10^5 viable cells/cm² for H9-derived NSCs) [14].

Passaging and Apoptosis

- Cause: Passaging PSCs as single cells can induce significant apoptosis, reducing the number of healthy cells available for differentiation.

- Solution:

- Use a ROCK Inhibitor: Include a ROCK inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632) in the culture medium for 18-24 hours after passaging cells. This is critical for improving cell survival after single-cell dissociation [14].

Issue: Failure of Specific Differentiation Protocols (e.g., Neural Induction)

Potential Causes and Data-Driven Solutions:

Suboptimal Initial Conditions

- Cause: The quality of the starting PSCs and the initial seeding conditions are critical for successful neural induction [14].

- Solution:

- Ensure High hPSC Quality: Use a high-quality, fully characterized PSC population and remove any differentiated portions before induction [14].

- Optimize Seeding Confluency: Plate cells at the recommended density. For neural induction, a density of 2–2.5x10^4 cells/cm² is often recommended. Both too low and too high confluency will reduce efficiency [14].

- Plate as Cell Clumps: For some protocols, plating hPSCs as small clumps rather than a single-cell suspension can improve induction efficiency [14].

- Use ROCK Inhibitor at Induction: To prevent extensive cell death at the start of induction, consider overnight treatment with 10 µM ROCK inhibitor Y27632 after splitting hPSCs for the induction protocol [14].

Incorrect Reagent Handling

- Cause: The differentiation medium or critical supplements may have been prepared or stored incorrectly.

- Solution:

- Verify Supplement Usage: For neural differentiation, check that the correct B-27 Supplement is used. It should be a transparent yellow liquid; a green color indicates degradation [14].

- Ensure Reagent Freshness: B-27-supplemented medium is stable for only 2 weeks at 4°C. Thawed B-27 supplement should be stored at 4°C and used within one week, without repeated freeze-thaw cycles [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell Research and Differentiation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Significantly improves cell survival after single-cell passaging, thawing, and during the initiation of differentiations [14]. | Use at 10 µM concentration; typically included in medium for 18-24 hours post-disruption [14]. |

| Essential 8 Medium | A feeder-free, defined culture medium for the maintenance of human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) [14]. | Allows for transition of PSCs from other media systems (e.g., mTeSR) or feeder-dependent cultures [14]. |

| Geltrex / Matrigel / VTN-N | Extracellular matrix proteins used to coat culture vessels, providing a substrate for PSC attachment and growth in feeder-free conditions [14]. | Proper coating is critical for cell health and preventing spontaneous differentiation. |

| B-27 Supplement | A serum-free supplement essential for the survival and growth of post-mitotic neurons and neural differentiation protocols [14]. | Handle with care: stable for 2 weeks at 4°C after preparation; avoid excessive heat and freeze-thaw cycles [14]. |

| StemRNA Clinical Seed iPSCs | Commercially available, clinically compliant iPSC master cell lines. Used as a consistent starting source for deriving differentiated cells for therapy development [15]. | A Drug Master File (DMF) submission to regulators facilitates their use in clinical trial applications [15]. |

| Stemdiff Differentiation Kits | Commercially available, standardized kits for directed differentiation of PSCs into specific lineages (e.g., midbrain organoids, neural precursors) [7]. | Promotes protocol reproducibility and saves optimization time compared to in-house protocol development. |

Experimental Workflows & Molecular Relationships

Workflow for Addressing Differentiation Variability

This diagram outlines a systematic troubleshooting approach when facing inconsistent differentiation results across iPSC lines.

This diagram illustrates the primary origins of genetic and epigenetic variability in iPSCs and how these factors interact to influence differentiation outcomes.

Impact of Donor-Specific Differences on Reproducibility and Experimental Outcomes

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the primary donor-related factors that cause variability in stem cell differentiation outcomes?

Donor-specific differences significantly impact the reproducibility of experimental outcomes in stem cell research. The key factors contributing to this variability include:

- Donor Age: Younger donors often exhibit higher cell proliferation rates and greater regenerative potential. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from older donors may show reduced viability and differentiation capacity [16] [17].

- Donor Health Status: Underlying conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and systemic inflammation can impair ASC functionality and alter the adipose tissue microenvironment [16].

- Genetic Background: Genetic variations, including single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes encoding critical receptors, can alter cell expression profiles and functional capacity. This is well-documented in NK cells and solid organ transplantation outcomes [18] [19].

- Sex and Hormonal Influences: Functional differences in cells derived from male and female donors have been observed, potentially due to hormonal influences on cellular environments [16].

- Anatomical Source: The cellular composition, vascularity, and stem cell content of tissue harvested from different body regions can vary, affecting graft viability and integration [16].

FAQ 2: Why do my differentiation results remain inconsistent even when using the same protocol?

Persistent inconsistency, even with standardized protocols, is a common challenge often stemming from these root causes:

- Inherent Donor Variability: The genetic and epigenetic individuality of each donor creates a fundamental baseline variability. Studies on NK cells show marked inter-donor differences in proliferation and receptor expression even under identical culture conditions [19].

- Source Cell Heterogeneity: Using non-clonal induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines means you are working with a mixed population of cells. A clonal iPSC line, derived from a single reprogrammed cell, provides a genetically uniform population, drastically improving reproducibility [20].

- Protocol Drift and Handling Differences: Subtle differences in reagent batches, operator technique, or cell passaging schedules can introduce variability. The complexity of some differentiation protocols makes them particularly susceptible to this [21].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the reproducibility of my experiments involving donor-derived cells?

Implementing the following strategies can significantly enhance reproducibility:

- Utilize Clonal Cell Lines: For iPSC work, start with clonal lines. The Jackson Laboratory, for instance, offers genetically engineered iPSC lines derived from a characterized clonal parental line (KOLF2.1J), ensuring a uniform genetic baseline [20].

- Adopt Standardized Practices: Follow established guidelines like the ISSCR's "Standards for Human Stem Cell Use in Research" and principles of Good Cell Culture Practice (GCCP) to instill quality in daily cell handling [21].

- Implement Rigorous Quality Control: Perform comprehensive cell characterization (e.g., flow cytometry, karyotyping, RNA sequencing) and establish quality acceptance criteria for every batch of cells used [21] [17].

- Control for Donor Factors: When designing experiments, deliberately account for donor age, sex, and health status. For autologous therapies, strategies like adipose tissue cryopreservation can help mitigate variability related to donor age [16].

- Report Detailed Metadata: Promote transparency by thoroughly documenting donor information, cell handling procedures, and any protocol adjustments [22].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High Variability in MSC Differentiation Outcomes

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Donor Selection | Older donor or donor with underlying health condition(s) | Where possible, characterize cells from multiple donors and select those with robust growth kinetics and differentiation potential [17]. |

| Culture Model | Reliance solely on 2D differentiation protocols | Incorporate 3D biomaterial-based culture models (e.g., alginate hydrogels for chondrogenesis), as standard 2D models cannot predict MSC capacity in 3D [23]. |

| Quality Control | Inconsistent cell populations at differentiation start | Implement pre-differentiation checks for viability (e.g., >85% post-thaw), plating efficiency, and surface marker expression [17]. |

Problem: Low Yield or Functionality in Differentiated β-Cells from iPSCs

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Material | Use of a non-clonal, heterogeneous iPSC line | Use a clonal, genetically stable iPSC line to ensure a uniform population is directed toward differentiation [20]. |

| Differentiation Protocol | Generation of functionally immature β-cells | Optimize protocol using factors like triiodothyronine (T3), vitamin C (Vc), and adenoviral vectors encoding key transcription factors (Pdx1, Ngn3, MafA) to enhance maturity [24]. |

| Functional Validation | Assays only measure insulin presence | Include glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) assays to test functional maturity, as insulin+ cells may not respond properly to glucose [24]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1. Documented Impact of Donor Variability Across Cell Types

| Cell Type | Key Variable Measured | Range of Variability | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow-MSCs | Post-thaw viability | 42.8% to 84.2% | Clinical doses for ARDS trial [17] |

| Bone Marrow-MSCs | Plating efficiency | 44% to 100% | Clinical doses for ARDS trial [17] |

| Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells (ASCs) | Graft retention rate (clinical) | 10% to 80% within first year | Autologous fat grafting [16] |

| NK Cells | Proliferation & receptor expression | Marked inter-donor differences | Expansion under IL-2 stimulation [19] |

Detailed Protocol: Assessing Donor Variability in MSC Differentiation

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating donor-driven differences in differentiation potential across multiple lineages [23].

Objective: To evaluate and compare the differentiation capacity of MSCs from different human donors using both standard and 3D culture models.

Materials:

- Primary Cells: MSCs from at least 3-6 different human donors.

- Control Cells: A well-characterized MSC line can serve as a reference.

- Chondrogenic Differentiation: Pellet culture system or alginate hydrogels.

- Osteogenic Differentiation: Standard 2D culture or gelatin microribbon (µRB) hydrogels.

- Adipogenic Differentiation: Standard 2D culture or gelatin microribbon (µRB) hydrogels.

- Lineage-Specific Stains: Alcian Blue (chondrogenesis), Alizarin Red (osteogenesis), Oil Red O (adipogenesis).

Methodology:

- Cell Expansion and Seeding:

- Expand MSCs from each donor to the same passage number.

- For each differentiation lineage, seed cells from all donors in parallel at identical densities.

- Tri-lineage Differentiation:

- Chondrogenesis: For each donor, create pellet cultures or encapsulate cells in alginate hydrogels. Culture in chondrogenic induction media for 21-28 days.

- Osteogenesis: Seed cells in 2D or 3D µRB hydrogels. Culture in osteogenic induction media for 14-21 days.

- Adipogenesis: Seed cells in 2D or 3D µRB hydrogels. Culture in adipogenic induction media for 14-21 days.

- Maintain control cultures in base media without induction factors.

- Analysis:

- Quantitative Analysis: Perform quantitative analysis on the stains (e.g., dye elution and spectrophotometry) or measure gene expression (qPCR) for key lineage-specific markers.

- Statistical Comparison: Compare the differentiation outcomes across donors using statistical tests (e.g., ANOVA). Significant inter-donor variability is expected across all three lineages.

Workflow Diagram: Integrating Genetic and Phenotypic Analysis

This diagram outlines an integrated approach to dissect the contributions of genetic and non-genetic factors to donor variability, as applied in NK cell studies [19].

Diagram 1: Integrated analysis workflow for identifying variability drivers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2. Essential Materials and Tools for Managing Donor Variability

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Clonal iPSC Lines (e.g., KOLF2.1J) | Provides a genetically uniform starting population for differentiation and disease modeling, reducing intrinsic noise. | Ensure lines are stable over extended culture (>25 passages) and thoroughly characterized [20]. |

| Deterministic Programming (opti-ox) | Overcomes stochastic differentiation by precisely driving iPSCs to a chosen cell type using transcription factors. | Enables production of highly consistent, defined human cells (e.g., ioCells) with high lot-to-lot uniformity [21]. |

| 3D Biomaterial Scaffolds (e.g., Alginate hydrogels, µRB) | Provides structural support and biochemical cues that more closely mimic the in vivo environment for differentiation. | Significantly influences differentiation outcomes; standard 2D models cannot predict 3D capacity [23]. |

| RosetteSep NK Cell Enrichment Cocktail | Isolation of NK cells directly from donor buffy coats for functional studies. | Used in conjunction with density-gradient centrifugation to study donor variability in immune cell expansion [19]. |

| G-Rex Culture System | A gas-permeable culture platform for scalable in vitro expansion of cells like NK cells. | Enhances nutrient availability and gas exchange, supporting efficient expansion and reducing culture-induced stress [19]. |

The Clinical and Commercial Consequences of Uncontrolled Variability

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center provides resources for researchers addressing variability in stem cell differentiation. The guides below focus on standardizing differentiation efficiency in patient-specific stem cell lines.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary sources of uncontrolled variability in stem cell differentiation protocols? Uncontrolled variability arises from multiple sources, broadly categorized as biological, technical, and procedural. Biological sources include genetic heterogeneity in starting patient cell lines and epigenetic memory from the original somatic cell type, which can create lineage-specific biases [6] [25]. Technical sources encompass inconsistencies in reprogramming efficiency for iPSCs, batch-to-batch variability in critical reagents like growth factors and Matrigel, and suboptimal cell culture conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, CO₂) [6]. Procedural sources involve poorly standardized or complex differentiation protocols and a lack of robust, quantitative potency assays to characterize the starting cell population [6].

2. How can I determine if my differentiation protocol is producing uncontrolled variation? Monitor for these key indicators: high levels of heterogeneity in marker expression within your differentiated cell populations (e.g., mixed cell types when a pure population is expected), significant run-to-run variation in the yield of your target cell type, and poor reproducibility of differentiation outcomes between different technicians or laboratory sites [6]. A well-controlled process should produce consistent, predictable results.

3. My differentiation efficiency is inconsistent between different patient-specific iPSC lines. Is this normal, and how can I address it? Yes, heterogeneity in differentiation capacity between different iPSC lines is a well-documented challenge due to their unique genetic and epigenetic backgrounds [6]. To address this, implement a robust pre-screening process where you characterize the differentiation propensity of new iPSC lines before large-scale experiments. You can also consider developing line-specific "training" protocols that adjust morphogen concentrations or timing based on initial performance. Furthermore, using integrated reporter cell lines to track the expression of key differentiation markers in real-time can help optimize conditions for each specific line [25].

4. What are the clinical and commercial risks of failing to control this variability? Uncontrolled variability poses severe clinical and commercial consequences. Clinically, it can lead to incomplete or incorrect differentiation, raising the risk of tumor formation from residual undifferentiated pluripotent cells or poor therapeutic efficacy of the final cell product [25]. Commercially, variability results in unreliable manufacturing, low batch success rates, and extremely high costs, making therapies economically unviable. It also causes regulatory hurdles, as agencies like the FDA require stringent proof of product consistency, potency, and safety, which is impossible without a controlled process [25].

Troubleshooting Guide: Inconsistent Differentiation Yields

Use this guide to diagnose and resolve common issues leading to variable differentiation outcomes.

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| High heterogeneity in final cell population. | Spontaneous differentiation due to suboptimal pluripotency maintenance before differentiation initiation. | Confirm pluripotency marker expression (e.g., Oct4, Nanog) via flow cytometry prior to starting differentiation. Improve passaging technique to maintain healthy, undifferentiated colonies [6]. |

| Significant batch-to-batch variation. | Uncontrolled variability in reagent quality or cell culture conditions. | Implement a rigorous reagent quality control system. Use large, master batches of critical reagents. Strictly monitor and log incubator conditions (temperature, CO₂, humidity). Standardize cell culture handling procedures across all lab personnel [25]. |

| Differentiation fails or is inefficient in a new iPSC line. | Inherent line-to-line variation in differentiation potential. | Do not assume a one-size-fits-all protocol. Perform a small-scale pilot differentiation to "profile" the new line's response. Titrate key morphogens and growth factors to establish a line-specific optimized protocol [6]. |

| Differentiated cells lack mature function. | Protocol may generate immature progenitors but not fully mature, functional cells. | Extend the differentiation timeline. Incorporate maturation factors in the later stages. Consider using advanced 3D culture systems or organoid platforms that better mimic the in vivo microenvironment for terminal maturation [6] [26]. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Pluripotency and Differentiation

Standardized characterization of starting stem cell lines is critical for understanding differentiation variability. The table below summarizes key methods for assessing pluripotency as a state (marker expression) and as a function (differentiation capacity) [6].

Table 1: Methods for Assessing Pluripotent State and Function

| Method | Key Aspect | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Cytometry | Quantifies expression of multiple pluripotency markers (e.g., Oct4, SSEA-4). | High-throughput, quantitative, accounts for population heterogeneity. | Marker expression does not confirm functional pluripotency [6]. |

| Embryoid Body (EB) Formation | 3D aggregates that spontaneously differentiate into cell types of the three germ layers. | Accessible, inexpensive, indicates broad differentiation capacity. | Structures are immature and disorganized; not a stringent assay [6]. |

| Teratoma Assay | In vivo assay where cells form a benign tumor containing complex, mature tissues from all three germ layers. | Historically the "gold standard"; provides conclusive proof of functional pluripotency. | Labor-intensive, expensive, ethically contentious, primarily qualitative, and protocol variation is high [6]. |

| Modern 3D Organoid Differentiation | Directed differentiation in 3D culture to generate complex, tissue-specific structures. | Mimics organ development; can produce mature, functional cell types; avoids animal use. | Technically challenging to optimize; can be expensive; not yet standardized for all cell types [6] [26]. |

Detailed Protocol: Quantitative Analysis of Differentiation Efficiency via Flow Cytometry

This protocol provides a method to quantitatively assess the purity and efficiency of differentiation toward a specific mesodermal lineage (e.g., cardiomyocytes), a common source of variability.

1. Sample Preparation:

- Differentiate your iPSCs toward the target cell type using your established protocol.

- At the endpoint of differentiation, harvest cells using a gentle cell dissociation reagent to preserve surface markers.

- For intracellular markers (e.g., transcription factors), fix and permeabilize cells using a commercial fixation/permeabilization kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2. Staining:

- Prepare antibody master mixes in FACS buffer (e.g., PBS with 1-2% FBS). Include appropriate isotype controls and single-color controls for compensation.

- Resuspend cell pellets in the antibody mix and incubate for 30-60 minutes at 4°C in the dark.

- Wash cells twice with FACS buffer to remove unbound antibody.

3. Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Resuspend cells in FACS buffer and filter through a cell strainer cap into FACS tubes.

- Acquire data on a flow cytometer, collecting a minimum of 10,000 events per sample.

- Use the unstained and isotype controls to set negative gates. Analyze the percentage of positively stained cells for your target marker (e.g., TNNT2 for cardiomyocytes) to determine differentiation efficiency.

Visualization of Key Concepts

Pluripotency Assay Workflow

This diagram outlines the logical decision process for selecting and implementing assays to confirm pluripotency.

This diagram maps the primary sources of variability in stem cell differentiation experiments and their relationships.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

A critical step in reducing variability is the consistent use of high-quality, well-defined reagents. The table below lists essential materials for stem cell maintenance and differentiation.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Standardized Stem Cell Research

| Item | Function | Key Considerations for Reducing Variability |

|---|---|---|

| Basal Media (e.g., DMEM/F12, Neurobasal) | Foundation for culture and differentiation media. | Use a single, validated supplier. Pre-mix large batches from a single lot number for long-term projects. |

| Essential Growth Factors (e.g., FGF-2, TGF-β, BMP4) | Direct stem cell fate toward specific lineages. | Source recombinant proteins from reliable vendors. Aliquot upon arrival to avoid freeze-thaw cycles. Perform dose-response titrations for each new lot. |

| Small Molecule Inducers/Inhibitors (e.g., CHIR99021, SB431542) | Chemically define differentiation protocols and improve efficiency. | Verify chemical stability and storage conditions. Prepare concentrated stock solutions in the correct solvent (e.g., DMSO) and use consistent aliquots. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) (e.g., Matrigel, Laminin-521) | Provides physical and chemical cues for cell attachment, survival, and differentiation. | This is a major source of variability. Use a dedicated, large batch for a single project. Thoroughly test dilution factors and polymerization times for consistency. |

| Cell Dissociation Reagents (e.g., EDTA, Accutase) | Used for passaging and harvesting cells. | Standardize concentration, volume, and incubation time to minimize stress and selective pressure on subpopulations. |

| Quality Control Assays (e.g., Mycoplasma tests, Karyotyping G-banding) | Ensures cell culture health and genomic integrity. | Perform tests regularly (e.g., monthly for mycoplasma) and with each new cell line thawed. Document all results. |

Innovative Methods for Monitoring and Controlling Differentiation Outcomes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is non-destructive monitoring, and why is it critical for stem cell research? Non-destructive monitoring uses imaging and sensing techniques to assess cell status without harming or destroying the samples. This is vital for stem cell research because it allows researchers to monitor the same population of cells throughout a long-term differentiation process, enabling early prediction of efficiency and the selection of high-quality cultures for downstream applications [27] [28].

Q2: My differentiation protocol takes over 80 days. How early can efficiency be predicted? Research on muscle stem cell (MuSC) differentiation from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) has demonstrated that samples with high and low final induction efficiency can be predicted approximately 50 days before the end of the induction period. Specifically, predictions for low-efficiency samples were possible from day 24, and for high-efficiency samples from days 31-34 of an 82-day protocol [27].

Q3: What are the limitations of traditional methods for assessing differentiation? Traditional methods, such as quantitative PCR (qPCR), immunocytochemistry, and flow cytometry, are often:

- Destructive, requiring sample fixation or lysis.

- Time-consuming and require skilled techniques.

- Costly and provide only a single time-point snapshot [27] [6]. While the teratoma assay is a gold standard for assessing pluripotency, it is labor-intensive, time-consuming, expensive, and raises ethical concerns due to its use of animal hosts [6].

Q4: Which machine learning model is best for this task? The "best" model depends on your data and specific goal. Different models have shown success:

- Random Forest was effectively used for classifying differentiation efficiency from phase-contrast image features [27].

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are powerful for automatically learning complex features directly from images and have been used for tasks like predicting firmness in agricultural products and analyzing SERS spectra [28] [29].

- Support Vector Machines (SVM) and XGBoost are also commonly applied [29] [30]. It is advisable to test and compare multiple models.

Q5: Our phase-contrast images look similar between efficient and inefficient differentiations. What features can machine learning detect? The human eye may miss subtle, quantitative morphological patterns. Machine learning can analyze features that are not immediately obvious, such as:

- Texture and spatial patterns extracted via Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) [27].

- Complex morphological characteristics learned directly by deep learning models from raw pixels [29].

- Biochemical signatures from the culture medium analyzed via Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Correlation Between Early Images and Final Differentiation Outcomes

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect Timing: The chosen imaging window may not capture the critical decision point in the differentiation pathway.

- Solution: Conduct a correlation study early in your protocol development. Measure key marker expressions (e.g., via qPCR or ICC) at intermediate time points and correlate them with your final efficiency metric to identify the predictive window [27].

- Insufficient Features: The features you are extracting (manually or automatically) may not be discriminatory.

- Solution:

- For traditional ML: Explore different feature extraction methods. The study on hiPSC-MuSC differentiation found that a 100-dimensional, rotation-invariant feature vector generated from the FFT power spectrum was effective [27].

- For deep learning: Use a pre-trained CNN (e.g., ResNet) to leverage its ability to extract rich, hierarchical features automatically [29] [30].

- Solution:

- Model Overfitting: The model performs well on training data but poorly on new data.

- Solution: Increase your dataset size using data augmentation (e.g., rotation, flipping, scaling). Ensure you are using proper validation techniques like k-fold cross-validation and evaluate the model on a completely held-out test set [29].

Issue 2: Inconsistent Model Performance Across Different Cell Lines

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cell Line-Specific Bias: The model has learned features specific to the genetic background of the cell lines it was trained on.

- Batch Effects: Variations in culture conditions, media lots, or operator technique can introduce noise.

- Solution: Standardize protocols as much as possible. Document all conditions meticulously. Techniques like batch effect correction algorithms can be applied to the feature data before model training [4].

Issue 3: The "Black Box" Problem – Lack of Interpretability in Predictions

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Complex Models: Deep learning models, in particular, are often not intrinsically interpretable.

- Solution: Employ Explainable AI (XAI) techniques.

- LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations): Can highlight which regions of an input image were most influential for a specific prediction [29].

- SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations): Helps explain the output of any machine learning model [30].

- Using these tools can build trust in the model and provide biological insights by revealing what the model is "seeing" [29].

- Solution: Employ Explainable AI (XAI) techniques.

Experimental Protocol: Early Prediction of hiPSC Differentiation Efficiency

The following methodology is adapted from a published study that successfully predicted muscle stem cell (MuSC) differentiation efficiency [27].

Cell Culture and Differentiation

- Cell Line: Use a reporter hiPSC line (e.g., MYF5-tdTomato) for accurate quantification of final efficiency via flow cytometry.

- Differentiation Protocol: Induce MuSCs from hiPSCs using a directed differentiation protocol. The example protocol involves:

- Days 0-14: Induce dermomyotome cells with a Wnt agonist.

- Days 14-38: Promote myogenic differentiation with growth factors (IGF-1, HGF, bFGF).

- Days 38-82: Mature myotubes in a low-concentration horse serum medium.

- Day 82: Analyze final MuSC induction efficiency (MYF5+ %) by flow cytometry.

Image Acquisition

- Instrument: Standard phase-contrast microscope.

- Schedule: Capture images of cells in multiple wells from the predictive window (days 14-38).

- Dataset: The referenced study used 5,712 images from 34 wells across six independent experiments [27].

Feature Extraction: Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)

This step converts the image into a format that captures its spatial frequency characteristics.

- Procedure:

- Apply FFT to each pre-processed (e.g., cropped, normalized) phase-contrast image.

- Obtain the power spectrum from the FFT output.

- Perform shell integration on the power spectrum to create a 100-dimensional, rotation-invariant feature vector for each image. This vector captures the distribution of spatial frequencies, which correlate with cell morphology.

Machine Learning Classification

- Model: Use a Random Forest classifier.

- Training: Train the model using the feature vectors from days 14-38 as input and the final day-82 efficiency classification (e.g., "High" or "Low") as the target output.

- Validation: Validate model performance using a held-out test set or cross-validation.

Key Quantitative Findings from the Referenced Study

Table 1: Correlation of Mid-Protocol Markers with Final MuSC Efficiency

| Time Point | Marker Type | Marker Name | Correlation with Day 82 Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 38 | Gene Expression (qPCR) | MYH3 | Significant Positive |

| Day 38 | Gene Expression (qPCR) | MYOD1 | Significant Positive |

| Day 38 | Gene Expression (qPCR) | MYOG | Significant Positive |

| Day 38 | Protein (ICC) | MHC-positive area | Significant Positive |

| Days 7 & 14 | Various | T, TBX6, SIX1, DMRT2, PAX3 | No Significant Correlation |

Table 2: Prediction Performance Using FFT and Random Forest

| Prediction For | Effective Prediction Day | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Low Efficiency Samples | Day 24 | Early identification of failing differentiations |

| High Efficiency Samples | Days 31-34 | Reliable selection of high-yield cultures |

| Overall Workflow | Day 24 & 34 | 43.7% reduction in defective sample rate; 72% increase in good samples |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Implementation

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Reporter hiPSC Line | Enables precise, quantitative measurement of target cell population at the end of differentiation. | e.g., MYF5-tdTomato for muscle stem cells [27]. |

| Directed Differentiation Factors | Drives cells toward the desired lineage in a controlled, step-wise manner. | Wnt agonist, IGF-1, HGF, bFGF (for MuSC protocol) [27]. |

| Quality Control Reagents | Ensures the integrity, function, and safety of cells. Critical for clinical translation. | Karyotyping kits, pathogen tests, pluripotency marker antibodies [31] [4]. |

| SERS-Active Substrate | For SERS-based monitoring; enhances Raman signal from the culture medium for sensitive detection. | Periodical gold gratings on polymer substrates [28]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Experimental Workflow for Early Prediction

hiPSC to Muscle Stem Cell Differentiation Signaling

Machine Learning Model Training Pipeline

Leveraging Prime Editing and CRISPR for Precision Control in hPSCs

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), including embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells, represent a cornerstone for regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug development due to their capacity for unlimited self-renewal and differentiation into any cell type [32] [33]. The precision manipulation of their genome is crucial for studying gene function, correcting disease-causing mutations, and standardizing differentiation efficiency for patient-specific therapies. While traditional CRISPR-Cas9 systems have enabled targeted gene disruption, their reliance on double-strand breaks (DSBs) leads to undesirable consequences in hPSCs, including p53-mediated apoptosis, chromosomal rearrangements, and low editing efficiency [34] [33]. Prime editing has emerged as a transformative "search-and-replace" technology that directly writes genetic information into target DNA sites without creating DSBs, offering exceptional versatility, specificity, and precision for hPSC engineering [34] [35].

Prime Editing System: Components and Mechanism

Core Components

The prime editing system consists of two primary components:

- Prime Editor (PE) Protein: A fusion of a Cas9 nickase (H840A mutant that cuts only one DNA strand) and an engineered reverse transcriptase (RT) from the Moloney murine leukemia virus [34] [35]. Advanced versions like PEmax feature an optimized architecture for improved nuclear localization and expression in human cells [36].

- Prime Editing Guide RNA (pegRNA): A specially engineered guide RNA that both specifies the target genomic locus and templates the desired edit. Its complex structure includes [35]:

- Spacer Sequence: A ~20-nucleotide region complementary to the target DNA site.

- Scaffold: Binds the Cas9 nickase.

- Reverse Transcription Template (RTT): Encodes the desired genetic alteration (typically 10-25 nucleotides).

- Primer Binding Site (PBS): A ~13-nucleotide sequence that anneals to the nicked DNA strand to initiate reverse transcription.

Mechanism of Action

The following diagram illustrates the multi-step mechanism of prime editing, from target recognition to the completion of the edit.

Step 1: Target Recognition and Strand Nicking: The PE-pegRNA complex binds to the target DNA site via complementary base pairing. The Cas9 nickase domain creates a single-strand cut (nick) in the DNA strand containing the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence, releasing a 3' DNA end [34] [35].

Step 2: Primer Binding and Reverse Transcription: The liberated 3' DNA end hybridizes with the PBS on the pegRNA. The reverse transcriptase then uses the RTT as a template to synthesize a new DNA strand that contains the desired edit, creating a 3' "edited flap" [34] [35].

Step 3: Edited Flap Incorporation: The newly synthesized 3' edited flap competes with the original 5' non-edited flap. Cellular repair machinery typically favors the 3' flap, ligating the edited strand into the genome. This results in a heteroduplex DNA molecule where one strand carries the new edit and the other retains the original sequence [34] [35].

Step 4: Heteroduplex Resolution (PE2): In the PE2 system, cellular DNA repair or replication processes eventually resolve the heteroduplex, copying the edit to the complementary strand to make the change permanent. However, the mismatch repair (MMR) pathway can sometimes reverse the edit, lowering efficiency [34] [36].

Step 5: Complementary Strand Nicking (PE3/PE3b): In the more advanced PE3 and PE3b systems, a second, standard sgRNA is used to direct the prime editor to nick the non-edited strand. This nick tricks the cell's repair system into using the edited strand as a template, significantly increasing the likelihood that both DNA strands will permanently incorporate the desired change [34] [35].

Optimizing Prime Editing Efficiency in hPSCs

Achieving high editing efficiency in hPSCs is challenging due to their low transfection efficiency and robust DNA repair mechanisms [32]. The following table summarizes key optimization strategies and their quantitative impact on editing efficiency, primarily derived from studies in hPSCs.

Table 1: Optimization Strategies for Prime Editing in hPSCs

| Strategy | Description | Impact on Efficiency | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibit Mismatch Repair (MMR) [36] | Co-express a dominant-negative MLH1 (MLH1dn) to suppress the MMR pathway, which often reverses prime edits. | ~1.4x increase (e.g., from 4.2% to 5.7% for a 2nt deletion at HEK3 site) [36] | Part of the PE4/PE4max and PE5/PE5max systems. Most effective for substitutions and small indels [36]. |

| Inhibit p53 [36] | Co-express a dominant-negative p53 (P53DD) to dampen p53-mediated stress responses activated by editing. | Substantial increase for larger edits (e.g., 30nt deletion: 3.1% to 12.1%; 34nt insertion: 7.9% to 24.3%) [36] | Particularly beneficial for larger edits and in sensitive cell lines. |

| Use Engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) [36] | Incorporate stabilizing RNA motifs (e.g., tev or tmp) at the 3' end of the pegRNA to enhance its stability. |

~2x increase (e.g., from 8.4% to ~18-19% when combined with PE4max) [36] | Improves pegRNA half-life, leading to more consistent and robust editing. |

| Employ the PEmax Editor [36] | Use an optimized prime editor with improved nuclear localization and codon usage for human cells. | Synergistic improvement with other strategies (e.g., PE2max + P53DD reached 29.2% in a reporter assay) [36] | Considered a superior backbone for all prime editing experiments. |

| Combine Optimizations [36] | Integrate PEmax, MLH1dn, P53DD, and epegRNA into a single "PE-Plus" system. | ~3x increase over baseline PE4max (e.g., from 8.4% to 24-27%) [36] | Represents the current state-of-the-art for achieving maximal editing efficiency in hPSCs. |

The "PE-Plus" System: A Case Study in Optimization

A comprehensive study systematically compared prime editing configurations in hPSCs and developed a highly efficient "PE-Plus" system. The results demonstrate the additive effect of combining multiple optimizations, as shown in the following workflow diagram.

This integrated approach, combining an optimized editor (PEmax), MMR inhibition (MLH1dn), p53 suppression (P53DD), and stable epegRNAs, resulted in editing efficiencies exceeding 50% in a reporter assay and enabled efficient creation of disease-relevant mutations [36].

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My prime editing efficiency in hPSCs is consistently low. What are the primary factors I should optimize first? A: Low efficiency is common. Prioritize these steps based on the optimization table (Table 1) [36]:

- pegRNA Design: Systematically test pegRNAs with different PBS lengths (typically 10-15 nt) and RTT lengths. Use online design tools (e.g., PE-Designer) and validate multiple designs [32].

- Editor Selection: Switch from PE2 to the PEmax backbone for improved performance [36].

- Cellular Defense Bypass: Co-deliver MMR and p53 inhibitors (MLH1dn and P53DD) to prevent the reversal of edits and reduce stress-induced cell death [36].

Q2: I am observing high background and unintended edits in my edited hPSC pools. How can I improve editing purity? A: Unintended byproducts can arise from several sources:

- pegRNA-independent off-targets: Reassuringly, prime editors (unlike some base editors) do not cause widespread, guide-independent off-target mutations, as confirmed by whole-genome sequencing [33].

- Incorrect flap resolution: To improve purity, use the PE3b system, which employs a nicking sgRNA designed to avoid the edited strand, reducing unwanted indels [34] [35].

- Transfection contamination: Ensure you are working with single-cell clones after editing. When using cleavage selection systems, high background can occur due to plasmid contamination; picking single clones can mitigate this [37].

Q3: What is the best method for delivering prime editing components into hPSCs? A: The delivery method critically impacts efficiency.

- Electroporation of RNP complexes is highly recommended for its high efficiency and transient delivery, which minimizes off-target effects [32]. Deliver the pegRNA as a synthetic nucleic acid alongside mRNA encoding the prime editor protein.

- Plasmid DNA transfection is less efficient in hPSCs due to the need for nuclear entry and transcription [32].

- All-in-one systems stably integrated into a safe-harbor locus (like AAVS1) with inducible expression (e.g., using doxycycline) offer controlled editing and high efficiency, as demonstrated by the iPE-Plus platform [36].

Troubleshooting Table for Common Experimental Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Prime Editing Problems in hPSCs

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No editing detected | Poor pegRNA design or activity [32] | Redesign pegRNA with different PBS/RTT. Test multiple targets. Use epegRNAs. |

| Low transfection efficiency [32] | Optimize delivery method (use electroporation). Use a fluorescent reporter to monitor efficiency. | |

| Inefficient nicking or RT activity | Use a more active editor (PEmax) and ensure proper cellular conditions. | |

| Low editing efficiency | MMR reversal of edits [36] | Use PE4/PE5 systems with MLH1dn. |

| p53-mediated stress response [36] | Co-express P53DD during editing. | |

| Unstable pegRNA [36] | Use engineered epegRNAs with stabilizing motifs. | |

| High indel byproducts | Use of basic PE3 system [34] | Switch to the PE3b system, which uses a more specific nicking sgRNA. |

| Overly long transfection/expression | Use transient delivery methods (RNP electroporation) instead of plasmids. | |

| Difficulty isolating edited clones | Low initial efficiency or cell death | Increase starting cell numbers. Optimize post-transfection recovery by using ROCK inhibitor [33]. Use the "PE-Plus" system for higher efficiency. |

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Prime Editing in hPSCs

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Optimized Prime Editors | Core enzyme for editing. | PEmax: An optimized version of PE2 with improved nuclear localization and expression for higher efficiency in human cells [36]. |

| Stable hPSC Lines | Provides controlled, inducible editor expression. | iPE-Plus (AAVS1-integrated): A cell line with the "PE-Plus" system integrated into the AAVS1 safe-harbor locus, allowing for doxycycline-inducible editing [36]. |

| MMR Inhibitor | Blocks the mismatch repair pathway to prevent edit reversal. | MLH1dn: A dominant-negative version of the MLH1 protein, key to the PE4/PE5 systems [36]. |

| p53 Inhibitor | Reduces p53-mediated cellular stress response to editing. | P53DD: A dominant-negative p53 domain that improves editing efficiency, especially for larger edits [36]. |

| Engineered pegRNAs | Increases the stability and half-life of the pegRNA. | epegRNA: pegRNAs with added RNA motifs (e.g., tev or tmp) at the 3' end to protect against degradation [36]. |

| Delivery Method | Method for introducing editing components into cells. | Electroporation of RNP/mRNA: Preferred method for hPSCs due to high efficiency and transient activity. The NEON system is commonly used [33]. |

| Design Software | Computational tools for designing effective pegRNAs. | PE-Designer, pegFinder: Web-based resources to design and optimize pegRNA and nicking sgRNA sequences [32]. |

Standard Experimental Protocol: Prime Editing hPSCs using an All-in-One System

This protocol details the steps for using an inducible, integrated prime editor system (e.g., iPE-Plus) in hPSCs, based on published methodologies [36] [33].

Key Steps:

- Cell Culture Preparation: Maintain iPE-Plus hPSCs in Essential 8 (E8) medium on a suitable matrix (e.g., iMatrix-511). Passage cells using a gentle dissociation reagent like ReLeSR and ensure cells are in a log phase of growth with >90% viability before starting [33].

- Editor Induction: Treat cells with 1 µg/mL doxycycline for 24-48 hours to induce the expression of the prime editor protein [36] [33].

- pegRNA/sgRNA Delivery:

- Prepare a single-cell suspension using Accutase.

- For electroporation, mix 1x10^5 cells with 250-750 ng of pegRNA-encoding plasmid and, for PE3/PE3b systems, 83 ng of nicking sgRNA plasmid.

- Electroporate using a system like the Neon Transfection System (e.g., 1050V, 30ms, 2 pulses) [33].

- Post-Transfection Recovery: Seed the electroporated cells in E8 medium supplemented with a 10 µM ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) for the first 24 hours to enhance cell survival [33].

- Harvest and Analysis: Culture cells for 3-7 days post-transfection, then harvest for genomic DNA extraction. Analyze editing efficiency via targeted next-generation sequencing (e.g., MiSeq) of PCR-amplified target sites [33].

- Clone Isolation: For clonal isolation, re-seed transfected cells at low density. Pick individual colonies, expand them, and screen by sequencing to identify isogenic clones with the desired edit [36].

Implementing ISSCR Standards for Cell Line Characterization and Banking

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical first steps for implementing ISSCR standards when acquiring a new cell line?

The most critical first steps involve proper documentation and legal compliance. Before beginning any experiments, researchers must read and understand the Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) or similar agreement, as it captures all donor consent provisions, supplier restrictions, and licensing requirements [38]. Failure to do so could result in violation of donor consent obligations, wasted resources, invalid research, or inability to publish [38]. Additionally, you should establish a Master Cell Bank (MCB) from the earliest possible passage of the established cell line prior to any experimental use or distribution [38]. This MCB should be characterized post-thaw and created as a single homogenous lot by pooling expanded cells prior to cryopreservation to ensure consistency of materials [38].

Q2: How often should I authenticate my cell lines, and what methods are recommended?

Cells for experimental use should be authenticated, with Short Tandem Repeat (STR) analysis recommended as the preferred method [38]. STR analysis has been formally developed into an internationally recognized consensus standard for human cell line authentication and offers advantages including cost efficiency, reproducibility, comparability across platforms, and ability to detect multiple cell sources within a culture [38]. When authenticating cells, a reference sample from the original donor should be used for confirmation of origin where possible [38]. Funding agencies and journals are increasingly requiring evidence of cell line authentication, placing the onus on researchers to properly identify materials used within their laboratory [38].

Q3: What genetic monitoring is required for stem cell cultures according to ISSCR standards?

Cultures should be monitored for culture-acquired genetic changes as these can have irreversible effects on stem cells and their differentiated progeny [39]. The ISSCR recommends a comprehensive genetic monitoring approach:

Table: Recommended Genetic Monitoring Methods

| Method | Detects | Sensitivity for Mosaicism | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| G-banded Karyotyping | Large chromosomal abnormalities >5Mb (aneuploidies, translocations) | 10-20% of cell population [40] | Baseline monitoring for major chromosomal changes [40] |

| 20q11.21 (BCL2L1) FISH | Specific, common CNVs in hPSCs (0.55-4.6Mb duplications) | 5-10% of cell population [40] | Detecting recurrent hPSC changes missed by karyotyping [40] |

| Higher Resolution Methods | Small CNVs, single nucleotide variants (e.g., in TP53) | Varies by method | When karyotype is normal but cell behavior has changed [39] |

Genetic abnormalities are common in hPSC cultures, with studies indicating 30-35% of cultures analyzed by G-banding harbor a genetic abnormality [40]. Commonly observed abnormalities include gains in chromosomal regions such as 1q, 12p, and 20q11.21, which harbor genes associated with increased proliferation or resistance to apoptosis [40].

Q4: At what timepoints should genetic monitoring be performed?

The ISSCR recommends genetic monitoring at multiple critical stages [39] [40]:

- Before starting experiments: Master and Working Cell Banks should be evaluated to determine their genetic status [39]

- During experiments: Approximately every 10 passages to detect culture-acquired abnormalities early [40]

- After major culture bottlenecks: Events like cloning or genetic modifications increase risk of clonal expansion [40]

- When changes in cell traits are observed: Altered growth or differentiation may indicate genetic changes [39]

- At the end of experiments: To confirm genetic integrity throughout the study period [39]

Cells carrying variants with selective advantage can overtake a culture rapidly, often within 5-10 passages [39]. Not using cells drawn from tested banks beyond passage 10 after thawing significantly decreases risks of genetic drift [39].

Q5: What are the essential elements to report in publications using stem cell lines?

Published reports must include sufficient information to ensure reproducibility [41]:

- Cell line source and derivation details: Include unique cell line identifier, registry number, and specific source [41]

- Complete culture methods: Detailed protocols for maintenance, preservation, passaging, freezing, and thawing [41]

- Passage documentation: Population doublings of cryopreserved MCB or WCB stocks, and number of subsequent passages during experimentation [41]

- Genotyping methodology: Specific methods, timing, and relationship to key experiments [41]

- Pluripotency assessment: Thorough description of assays, reagents, readouts, and quantitation [41]

- Experimental unit definition: Clear explanation of what constitutes n (cell lines, organoids, batches, etc.) [41]

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Differentiation Efficiency and High Variability

Problem: Directed differentiation protocols show low reproducibility and robustness, with efficiency varying between hiPSC clones, experimental batches, and even wells in the same plate [27].

Solutions:

Implement early prediction systems: Recent research demonstrates that machine learning analysis of phase contrast images can predict final differentiation efficiency approximately 50 days before the end of induction for long protocols [27]. For muscle stem cell differentiation, samples with high and low induction efficiency could be predicted using images from days 24-34 of an 82-day protocol [27].

Standardize differentiation protocols: Use standardized differentiation kits that contain optimized reagents and succinct protocols to improve yield, minimize time, and provide more reproducible methods compared to "home-brew" protocols that piece together reagents from multiple vendors [42].

Characterize intermediate stages: For MuSC differentiation, significant positive correlations were detected between the expression of skeletal muscle markers (MYH3, MYOD1, MYOG) on day 38 and final efficiency on day 82 [27]. Identify and monitor similar critical checkpoints in your specific differentiation protocol.

Consider 3D culture systems: Implement three-dimensional co-culture systems and microfluidics to control feeding cycles and growth factor gradients, which have been reported to improve differentiation efficiency [43].

Issue: Suspected Cell Line Misidentification or Cross-Contamination

Problem: Uncertain whether cells in culture are the expected line or may have been cross-contaminated.

Solutions:

Perform regular authentication: Implement STR profiling as recommended by ISSCR standards [38]. This is particularly important for cell lines that can be passaged indefinitely, as misidentified lines could corrupt research data on an international basis [38].

Maintain rigorous documentation: Ensure all work is traceable with well-documented routine laboratory protocols [38]. While rigorous documentation by centralized cell banks can reduce potential for misidentification at sourcing, the onus still lies with the end researcher to authenticate materials used within the laboratory [38].