Strategies for Improving Reprogramming Efficiency: From Somatic Cells to Functional iPSCs

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the latest strategies to enhance the efficiency and safety of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) generation.

Strategies for Improving Reprogramming Efficiency: From Somatic Cells to Functional iPSCs

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the latest strategies to enhance the efficiency and safety of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) generation. It covers foundational principles, including the core reprogramming factors and their mechanisms, explores advanced methodological approaches like non-integrating delivery systems and chemical reprogramming, and offers practical solutions for common troubleshooting and optimization challenges. Furthermore, it discusses critical validation frameworks and comparative analyses of different reprogramming techniques, synthesizing key insights to accelerate robust iPSC generation for research and clinical applications.

Decoding the Blueprint: Core Reprogramming Factors and Molecular Mechanisms

The Yamanaka Factors (OSKM) and Alternative Cocktails (OSNL)

Core Concepts: Understanding the Factors

What are the Yamanaka Factors (OSKM)?

The Yamanaka factors, officially known as the OSKM combination, are four transcription factors identified by Shinya Yamanaka and Kazutoshi Takahashi in 2006 as sufficient to reprogram somatic cells back into a pluripotent state. This groundbreaking discovery demonstrated that adult cells could be reprogrammed to behave like embryonic stem cells, creating what are known as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [1] [2] [3].

The OSKM acronym stands for:

- OCT4 (Octamer-binding transcription factor 3/4): A POU-family transcription factor critical for maintaining pluripotency and self-renewal. It inhibits the expression of genes associated with ESC differentiation [4] [5].

- SOX2 (SRY-box transcription factor 2): A high-mobility group (HMG) box transcription factor that works cooperatively with OCT4 to regulate pluripotency-associated genes [4] [5].

- KLF4 (Krüppel-like factor 4): A transcription factor with a dual role, both suppressing somatic cell-specific genes and activating pluripotency-associated genes [4] [5].

- c-MYC (Cellular Myelocytomatosis): A proto-oncogene that enhances reprogramming efficiency by promoting global histone acetylation, which facilitates the binding of OCT4 and SOX2 to their target loci. It also accelerates cell proliferation [4] [5].

What is the OSNL alternative cocktail?

In 2007, simultaneously with Yamanaka's human cell reprogramming, James Thomson's group identified an alternative combination of factors sufficient for reprogramming human somatic cells to pluripotency [4] [2] [5]. The OSNL cocktail consists of:

- OCT4: Serves the same critical pluripotency function as in the OSKM combination.

- SOX2: Functions identically to its role in the OSKM cocktail.

- NANOG: A homeodomain-containing transcription factor that functions as a key regulator for maintaining pluripotency alongside OCT4 and SOX2 [4] [5].

- LIN28: An RNA-binding protein that promotes cell proliferation during the early phase of iPSC generation, functioning similarly to c-MYC [4] [5].

Comparative Table: OSKM vs. OSNL Reprogramming Factors

| Factor | OSKM Cocktail | OSNL Cocktail | Primary Function | Safety Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | ✓ | ✓ | Master pluripotency regulator; inhibits differentiation genes | Essential for reprogramming |

| SOX2 | ✓ | ✓ | Partners with OCT4; maintains pluripotent state | Essential for reprogramming |

| KLF4 | ✓ | ✗ | Dual role: suppresses somatic genes, activates pluripotency | Generally safe |

| c-MYC | ✓ | ✗ | Promotes histone acetylation; accelerates cell proliferation | Proto-oncogene; tumor risk concern |

| NANOG | ✗ | ✓ | Reinforces pluripotency network; not strictly essential | Safe; enhances quality |

| LIN28 | ✗ | ✓ | Promotes proliferation; regulates microRNAs | Safer alternative to c-MYC |

Troubleshooting Common Reprogramming Issues

FAQ: Low Reprogramming Efficiency

Q: Our reprogramming efficiency remains consistently low despite using validated protocols. What factors should we investigate?

A: Low reprogramming efficiency can result from multiple factors. Consider these troubleshooting steps:

- Factor Stoichiometry: The ratio of reprogramming factors is critical. Research indicates that an OCT4highSOX2low stoichiometry is particularly important for efficient reprogramming [3]. Optimize your factor ratios rather than simply increasing total factor load.

- Cell Source Selection: The starting somatic cell type significantly impacts efficiency. Dermal fibroblasts remain the most common source, but peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) have shown excellent results with certain protocols [6]. Primary cells from older donors may require additional factors or longer reprogramming periods.

- Epigenetic Barriers: Enhance efficiency with epigenetic modifiers. Studies show that histone deacetylase inhibitors (e.g., Valproic Acid, Sodium Butyrate, Trichostatin A) and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (e.g., 5'-aza-cytidine) can significantly improve reprogramming rates [4]. For example, combining 8-Br-cAMP with Valproic Acid increased human fibroblast reprogramming efficiency by up to 6.5-fold [4].

- Metabolic Optimization: Ensure proper metabolic conditions. The transition from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis is a crucial early reprogramming event [3]. Maintain optimal nutrient conditions and consider hypoxia (5% O2) to enhance efficiency.

FAQ: Genomic Integration Concerns

Q: We need to minimize genomic integration of reprogramming factors for clinical applications. What delivery systems should we consider?

A: Safety concerns regarding genomic integration have prompted development of multiple non-integrating delivery systems:

- Episomal Plasmids: DNA-based vectors that remain separate from the host genome and are gradually diluted through cell divisions. Effective but typically lower efficiency than viral methods [4].

- Sendai Virus: An RNA virus that replicates in the cytoplasm without genomic integration. Provides high efficiency and is eventually cleared from the cells [4].

- Synthetic mRNA: In vitro transcribed mRNA that directly translates into protein without risk of integration. Requires careful optimization to avoid triggering innate immune responses [4].

- Recombinant Protein: Direct delivery of the reprogramming factors as proteins. Completely avoids genetic material but has very low efficiency [4].

For clinical applications, Sendai virus and synthetic mRNA systems currently offer the best balance of efficiency and safety.

FAQ: Teratoma Formation and Incomplete Differentiation

Q: Our iPSCs consistently form teratomas in differentiation assays or show incomplete differentiation. How can we address this?

A: Teratoma formation indicates persistent undifferentiated pluripotent cells:

- Improve Characterization: Implement rigorous pluripotency assessment beyond standard markers. Include transcriptional analysis, epigenetic profiling, and in vivo teratoma formation assays [6] [2].

- Enhance Differentiation Protocols: Implement sequential differentiation with stage-specific markers rather than direct differentiation. Consider 3D organoid systems that better recapitulate developmental cues [2].

- Cell Sorting: Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with surface markers specific to your target cell type to eliminate residual undifferentiated cells.

- Alternative Cocktails: Consider using the OSNL combination, which may produce higher-quality iPSCs in some systems, as NANOG enhances the stability of the pluripotency network [5].

Quantitative Data and Optimization Parameters

Table: Efficiency Comparison of Reprogramming Methods

| Delivery Method | Integration Risk | Relative Efficiency | Clearance Timeline | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrovirus | High (integrates) | High | Permanent | Basic research; robust cell lines |

| Lentivirus | Medium (integrates) | High | Permanent | Basic research; difficult-to-transfect cells |

| Sendai Virus | None (cytoplasmic) | High | 10-20 passages | Clinical applications; high-efficiency needs |

| Episomal Plasmids | Low (non-integrating) | Medium | 5-15 passages | Clinical applications; GMP production |

| Synthetic mRNA | None | Medium-High | 3-7 days | Clinical applications; minimal manipulation |

| Recombinant Protein | None | Low | Immediate | Specialized applications with efficiency concerns |

Table: Enhancing Reprogramming Efficiency with Small Molecules

| Small Molecule | Concentration Range | Mechanism of Action | Efficiency Improvement | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valproic Acid (VPA) | 0.5-2 mM | Histone deacetylase inhibitor | Up to 6.5-fold (with 8-Br-cAMP) [4] | Cytotoxic at high concentrations |

| Sodium Butyrate | 0.5-1 mM | Histone deacetylase inhibitor | Significant improvement | Requires concentration optimization |

| 5'-aza-cytidine | 0.5-5 µM | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor | Moderate improvement | Can induce genomic instability |

| RepSox | 2-10 µM | Replaces SOX2; TGF-β pathway inhibition | Enables factor minimization | Specific cell type responses vary |

| 8-Br-cAMP | 0.1-0.5 mM | cAMP analog; enhances signaling | 2-fold improvement alone [4] | Synergistic with other enhancers |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagents for iPSC Reprogramming

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Protocol Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OSKM, OSNL combinations | Induce pluripotency | Optimize ratios for specific cell types |

| Delivery Systems | Sendai virus, episomal plasmids, mRNA | Introduce factors into cells | Match to application (research vs. clinical) |

| Culture Media | mTeSR Plus, TeSR media | Maintain pluripotent state | Use consistently for reproducible results |

| Enhancement Molecules | Valproic Acid, Sodium Butyrate | Improve efficiency | Titrate carefully to avoid cytotoxicity |

| Characterization Tools | Pluripotency antibodies, PCR panels | Verify iPSC quality | Use multiple validation methods |

| Differentiation Media | STEMdiff systems | Direct lineage specification | Follow stage-specific protocols |

Experimental Workflows and Visualization

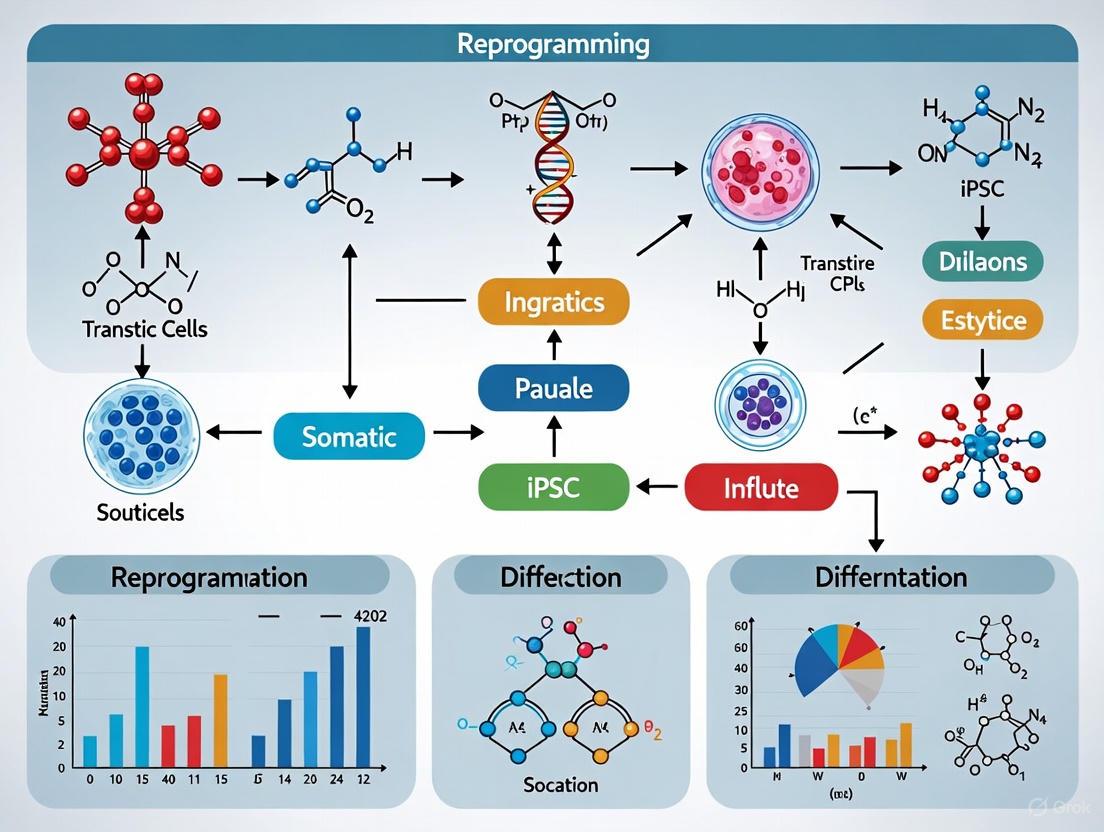

Diagram: OSKM Reprogramming Workflow and Mechanisms

Diagram: Molecular Mechanism of Yamanaka Factors

Advanced Technical Protocols

Detailed Methodology: mRNA-Based Reprogramming

For researchers requiring non-integrating methods suitable for clinical applications, synthetic mRNA reprogramming provides an excellent option:

Day 0: Plating Somatic Cells

- Isolate and culture source cells (e.g., fibroblasts or PBMCs) in appropriate medium

- Plate 5×10⁴ cells per well in a 6-well plate coated with suitable matrix

- Ensure cells are 70-80% confluent at time of transfection

Days 1-5: Daily mRNA Transfection

- Prepare mRNA cocktail containing OSKM or OSNL factors plus B18R protein

- Transfect using lipid-based transfection reagent optimized for mRNA

- Include modified nucleotides (e.g., pseudouridine) to reduce innate immune response

- Change medium 4-6 hours post-transfection to reduce cytotoxicity

Days 6-18: Transition and Colony Growth

- Reduce transfection frequency to every other day

- Switch to iPSC culture medium (e.g., mTeSR Plus or equivalent)

- Monitor for emergence of embryonic stem cell-like morphology

Days 19-30: Colony Picking and Expansion

- Manually pick well-defined colonies based on ESC-like morphology

- Transfer to feeder-free culture conditions

- Expand and bank validated iPSC lines

Critical Optimization Parameters:

- mRNA quality and purity is essential - use HPLC-purified transcripts

- Include B18R protein to suppress interferon response

- Maintain strict RNAse-free conditions throughout the process

- Monitor for complete mRNA clearance post-reprogramming (typically 3-7 days after final transfection)

Partial vs. Full Reprogramming for Different Applications

Recent advances have demonstrated that partial reprogramming through transient expression of Yamanaka factors can reverse age-associated phenotypes without completely resetting cell identity [1] [7]. This approach has shown promise in reversing epigenetic aging markers, restoring vision in old mice, and enhancing cognitive function in aged mouse models [1].

For full reprogramming to pluripotency, the complete epigenetic reset is necessary, making it ideal for disease modeling and differentiation to various cell types. The OSNL combination may produce higher-quality iPSCs for certain applications, particularly when avoiding proto-oncogenes like c-MYC is a priority [4] [5].

The choice between OSKM and OSNL, and between full versus partial reprogramming, should be guided by the specific research goals, with careful consideration of the trade-offs between efficiency, safety, and the desired cellular phenotype.

FAQ: Oncogenes in Cell Reprogramming

Q1: Why is c-Myc considered a liability in iPSC generation for therapeutic applications? c-Myc is a powerful transcription factor that acts as an oncogene, with its constitutive overexpression contributing to tumor formation. This poses significant risks to the long-term safety and stability of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), as it can enhance the tumorigenic potential of the resulting cells, making them unsuitable for clinical therapies [4] [8].

Q2: What are the primary strategies for reducing tumorigenic risk in reprogramming? The main strategies involve moving away from integrating viral vectors and finding substitutes for potentially oncogenic factors like c-Myc. Researchers focus on:

- Using non-integrating delivery systems (e.g., Sendai virus, episomal plasmids, synthetic mRNA).

- Employing safer factor combinations, such as replacing c-Myc with L-Myc or Glis1.

- Developing fully chemical reprogramming methods that avoid exogenous genetic material altogether [4] [8] [9].

Q3: Can pluripotency be achieved without using c-Myc? Yes, seminal work by Takahashi and Yamanaka demonstrated that somatic cell reprogramming into iPSCs could be achieved by expressing only OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4, without c-Myc, proving it is not an absolute requirement. However, its absence often results in lower reprogramming efficiency [4].

Q4: Besides L-Myc and Glis1, what other factors can replace c-Myc in reprogramming? Research has shown that other family members, such as N-Myc, can substitute for c-Myc. Furthermore, genes not belonging to the Myc family, including SALL4 and Esrrb, have also been identified as functional alternatives that can mitigate tumorigenic risk [4] [9].

Q5: How do the reprogramming efficiencies of safer alternatives compare to c-Myc? While most alternatives to c-Myc exhibit significantly lower reprogramming efficiency, specific optimizations can improve outcomes. For instance, L-Myc has been reported to maintain reprogramming efficiency while reducing the tumorigenic risk. The table below provides a comparative overview.

Table 1: Comparison of c-Myc and Safer Alternatives in iPSC Reprogramming

| Factor | Key Characteristics | Reported Impact on Efficiency | Tumorigenic Risk | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-Myc | Proto-oncogene; accelerates cell cycle; global histone acetylation | High | High | [4] [8] [5] |

| L-Myc | Myc family member; promotes reprogramming | Similar to c-Myc, with reports of high-quality iPSC generation | Lower | [4] [10] |

| Glis1 | Pioneer transcription factor; activates pluripotency genes | Promotes reprogramming; used in high-efficacy protocols | Lower | [4] [10] |

| SALL4 | Transcription factor; can replace c-Myc in OSKM combo | Successful reprogramming demonstrated | Lower | [4] |

| Esrrb | Nuclear receptor; can substitute for c-Myc | Comparable effectivity reported | Lower | [4] [9] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Reprogramming Efficiency After Replacing c-Myc

Problem: After substituting c-Myc with a safer alternative like L-Myc or Glis1, the number of successfully generated iPSC colonies is unacceptably low.

Solutions:

- Optimize Factor Ratios: The stoichiometry (ratio) of reprogramming factors is critical. Titrate the amounts of OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and your chosen c-Myc alternative. Research indicates that the specific ratio of SOX2 and OCT4 significantly affects both efficiency and colony quality [5].

- Combinatorial Approach: Use a combination of supplementary factors. For example, a protocol successfully used a cocktail including L-Myc, LIN28, and Glis1 alongside OSK to efficiently reprogram challenging senescent and pathologic human fibroblasts [10].

- Supplement with Small Molecules: Enhance efficiency by adding small molecules to the culture medium. Molecules like Valproic Acid (VPA) and 8-Bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cAMP) have been shown to increase reprogramming efficiency. One study found that combining 8-Br-cAMP with VPA increased human fibroblast reprogramming efficiency by up to 6.5-fold [4].

- Modulate p53 Activity: Transiently inhibiting the p53 pathway can boost efficiency, as p53 is a major barrier to reprogramming that eliminates cells with DNA damage. However, this must be done carefully. Research shows that overexpressing the p53 isoform Δ133p53 can both inhibit apoptosis and promote DNA repair during reprogramming, leading to a 4-fold increase in efficiency and better genetic quality in the resulting iPSCs [11].

Issue 2: Genomic Instability and Persistent Tumorigenic Concern

Problem: Even with non-integrating methods, the reprogramming process itself can induce DNA damage, leading to concerns about the genomic integrity of the final iPSCs.

Solutions:

- Employ Non-Integrating Delivery Systems: To avoid insertional mutagenesis, use methods such as Sendai virus, episomal plasmids, or synthetic self-replicating RNA. These systems do not integrate into the host genome and are gradually diluted out over cell divisions, producing "transgene-free" iPSCs [8] [12] [10].

- Monitor DNA Damage Response: Actively check for markers of DNA damage during reprogramming, such as γH2AX foci. Using factors that enhance DNA repair, like Δ133p53, can help maintain genomic stability. Overexpression of Δ133p53 was shown to promote DNA double-strand break repair and reduce chromosomal aberrations in resulting iPSC clones [11].

- Rigorous Post-Reprogramming Characterization: Implement thorough quality control checks, including karyotyping and whole-genome sequencing, to select iPSC clones without deleterious mutations for downstream applications [8] [11].

Experimental Protocol: High-Efficacy Reprogramming Using Safer Factors

This protocol is adapted from studies that successfully generated iPSCs from senescent and pathologic human cells using a optimized factor combination [10].

Objective: To generate integration-free human iPSCs from somatic fibroblasts using a cocktail of reprogramming factors that excludes c-Myc.

Materials and Reagents:

- Source Cells: Human dermal or myocardial fibroblasts.

- Reprogramming Factors: OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, L-MYC, LIN28, Glis1, and a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) for p53 knockdown.

- Delivery System: A non-integrating Sendai virus vector or episomal system to deliver the factor cocktail.

- Basal Medium: DMEM/F12 or equivalent.

- Essential Supplements: TGF-β or the TGF-β inhibitor SB431542, depending on the protocol phase.

- Characterization Reagents: Antibodies for TRA-1-60, alkaline phosphatase staining kit.

Method:

- Cell Seeding: Plate fibroblasts at an appropriate density and culture until they reach 70-80% confluency.

- Factor Transduction: Transfert the cells with the cocktail of reprogramming factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, L-MYC, LIN28, Glis1, sh-p53).

- Media Optimization:

- Protocol 1: Culture the transfected cells in medium containing TGF-β.

- Protocol 2 (Recommended): Culture the transfected cells in medium containing the TGF-β inhibitor SB431542 (without TGF-β). This protocol has demonstrated superior efficiency in generating iPSC colonies from aged and pathologic cells [10].

- Colony Expansion: Monitor for the emergence of embryonic stem cell-like colonies between days 14-28. Manually pick and expand candidate colonies.

- Validation: Confirm pluripotency through:

- Immunofluorescence staining for markers like TRA-1-60.

- Alkaline phosphatase staining.

- In vitro differentiation into all three germ layers.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The diagram below illustrates the core molecular interplay between the Yamanaka factors, the p53 pathway, and the role of safer alternatives like L-Myc and Glis1 during the reprogramming process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Oncogene-Safe iPSC Reprogramming

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Reprogramming | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Integrating Vectors | Delivers reprogramming factors without genomic integration, reducing mutagenesis risk. | Sendai Virus, Episomal Plasmids, Synthetic Self-Replicating RNA (e.g., VEE-RF RNA) [12] [10]. |

| Safer Factor Cocktails | Replaces oncogenic c-Myc to maintain efficiency while lowering tumorigenic potential. | Combinations including L-Myc, Glis1, LIN28, or SALL4 [4] [10]. |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Modulates signaling pathways and epigenetics to boost reprogramming efficiency. | Valproic Acid (VPA) (HDAC inhibitor), 8-Br-cAMP (signaling activator), SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor) [4] [10]. |

| p53 Pathway Modulators | Temporarily overcomes the p53-mediated barrier to reprogramming without permanent knockout. | shRNA for p53 knockdown, or overexpression of Δ133p53 to inhibit apoptosis and promote DNA repair [10] [11]. |

| Pluripotency Validation Kits | Confirms the successful generation and quality of iPSC colonies. | TRA-1-60 Antibody (surface marker), Alkaline Phosphatase Live Stain [10]. |

The reprogramming of somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) requires overcoming significant epigenetic barriers that stabilize the differentiated cell state. Chromatin remodeling—the dynamic alteration of chromatin structure—is a fundamental molecular mechanism that enables this dramatic cell fate change. This technical support center document details the key epigenetic barriers and provides troubleshooting guidance for researchers aiming to improve reprogramming efficiency.

FAQs: Core Concepts of Chromatin in Reprogramming

What are the main epigenetic barriers that resist reprogramming to pluripotency? The main epigenetic barriers include repressive histone modifications such as H3K9me3 (histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation) and H3K27me3 (histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation), which create condensed, inaccessible chromatin regions. These marks must be actively removed to activate the pluripotency network. Specifically, H3K9me3 constitutes a major barrier by locking somatic genes in an active state and silencing pluripotency genes. Similarly, DNA methylation patterns specific to the somatic cell type must be erased to allow for re-establishment of the pluripotent epigenome [13] [14].

What is the role of "pioneer factors" in initiating chromatin remodeling? Pioneer transcription factors, such as OCT4 and SOX2, are crucial for the initial steps of reprogramming. Unlike conventional transcription factors, they possess the unique ability to bind directly to condensed chromatin. Their binding initiates a series of chromatin remodeling events that lead to chromatin decondensation and increased accessibility. This process occurs progressively during cell division, exposing specific gene promoters and enabling other transcription factors to bind and activate the pluripotency network [15].

How does the chromatin state of a somatic cell influence the reprogramming trajectory? The initial chromatin state of the somatic cell determines the efficiency and kinetics with which reprogramming factors can access their target sites. Genes with an "open" chromatin state (e.g., with active H3K4me2/3 marks) are bound by reprogramming factors immediately. In contrast, core pluripotency genes like NANOG are often located in refractory heterochromatic regions enriched for repressive H3K9me3 marks, requiring extensive chromatin remodeling for activation. This creates a sequential and often inefficient reprogramming process [13].

What are the key chromatin-related checkmarks for high-quality iPSCs? High-quality iPSCs should exhibit:

- Erasure of Somatic Memory: Successful removal of repressive marks (e.g., H3K9me3, H3K27me3) from key pluripotency gene promoters.

- Establishment of Bivalent Domains: Presence of both activating (H3K4me3) and repressive (H3K27me3) marks at developmental gene promoters, poising them for future differentiation [13] [14].

- X-Chromosome Reactivation: In female somatic cells, the inactivated X chromosome should be reactivated [13].

- Activation of Endogenous Pluripotency Network: Sustained expression of core pluripotency factors like OCT4 and NANOG driven by their own promoters, without reliance on exogenous transgenes.

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming Epigenetic Barriers

Problem 1: Low Reprogramming Efficiency

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Reagents & Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Repressive H3K9me3 marks | Inhibit H3K9 methyltransferases (e.g., SUV39H1) or overexpress H3K9 demethylases (e.g., KDM4B). | KDM4B: Removes H3K9me3, facilitating the activation of pluripotency genes like NANOG [14]. |

| Closed chromatin at pluripotency loci | Utilize histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors to increase chromatin accessibility. | Valproic Acid (VPA): An HDAC inhibitor that increases global histone acetylation, promoting an open chromatin state and enhancing reprogramming efficiency [4] [14]. |

| Inefficient MET | Ensure the culture conditions support MET, an early reprogramming step. | The OSKM factors inherently drive MET; optimizing media (e.g., using specific growth factors) can support this transition [2]. |

| Inadequate pioneer factor activity | Use an optimized reprogramming factor cocktail that includes potent pioneer factors. | OCT4/SOX2: The core pioneer factors. SALL4 or NR5A2 can substitute for c-MYC or OCT4, respectively, in some cocktails to improve safety and efficiency [4] [15]. |

Problem 2: Incomplete Silencing of Somatic Genes

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Reagents & Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent active chromatin marks | Promote the activity of complexes that deposit repressive marks on somatic genes. | PRC2 Complex: Catalyzes H3K27me3, silencing somatic genes. Its recruitment is facilitated by OSKM factors [13]. |

| Insufficient DOT1L inhibition | Inhibit DOT1L, a histone methyltransferase that places the active H3K79me2/3 mark. | DOT1L Inhibitors: Loss of DOT1L enhances the downregulation of somatic genes early in reprogramming [13]. |

Problem 3: Heterogeneous iPSC Populations with Incomplete Pluripotency

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Reagents & Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete establishment of bivalent domains | Ensure culture conditions and factors support the function of chromatin modifiers that establish bivalency. | PRC2 and Trithorax Complexes: Work in concert to establish H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 marks, respectively, at developmental promoters. UTF1 has been implicated in regulating bivalency and can substitute for some reprogramming factors [13]. |

| Inadequate activation of core pluripotency genes | Extend the reprogramming timeline and confirm the activation of endogenous OCT4 and NANOG. | The switch from exogenous to endogenous factor expression is a key hallmark of successful, stable reprogramming [13]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Modifying Chromatin

The following table details key reagents used to manipulate the epigenetic landscape during reprogramming.

Table: Key Research Reagents for Epigenetic Modulation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Mechanism in Reprogramming | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Valproic Acid (VPA) | HDAC inhibitor; increases histone acetylation, promoting an open chromatin state. | Used in combination with reprogramming factors to significantly increase iPSC generation efficiency [4] [14]. |

| KDM4B | Histone demethylase; specifically removes repressive H3K9me3 marks. | Overexpression facilitates the activation of silenced pluripotency genes like NANOG [14]. |

| DOT1L Inhibitors | Inhibits H3K79 methylation, an active mark that maintains somatic gene expression. | Enhances the early phase of reprogramming by silencing the somatic program [13]. |

| RepSox | Small molecule; replaces SOX2 in the reprogramming cocktail by inhibiting TGF-β signaling. | Simplifies the reprogramming cocktail, potentially improving safety and efficiency [4]. |

| 5'-Azacytidine | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor; promotes DNA demethylation. | Can be used to erase somatic DNA methylation patterns, though requires careful titration due to toxicity [13]. |

| Pioneer Factors (OCT4, SOX2) | Initiate reprogramming by binding closed chromatin and initiating remodeling. | The foundational components of most reprogramming cocktails [15]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Assessing Chromatin Accessibility During Reprogramming via Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

This protocol is critical for troubleshooting epigenetic barriers by analyzing histone modifications at specific gene loci (e.g., NANOG promoter) during the reprogramming process.

Key Materials:

- Crosslinking Buffer (1% formaldehyde)

- Cell Lysis Buffer

- Micrococcal Nuclease (for enzymatic shearing) or Sonication equipment

- Protein A/G Magnetic Beads

- ChIP-validated Antibodies (e.g., anti-H3K9me3, anti-H3K4me3)

- DNA Purification Kit

- qPCR Primers for target genomic regions

Detailed Methodology:

- Crosslinking: Fix approximately 1-2 x 10^7 cells at your desired reprogramming time point with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to preserve protein-DNA interactions. Quench with glycine [16] [17].

- Cell Lysis: Harvest cells and lyse them using an appropriate ice-cold lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. Perform all steps at 4°C to prevent protein degradation [17].

- Chromatin Shearing (Fragmentation):

- Enzymatic Shearing (Recommended): Digest chromatin with Micrococcal Nuclease to yield fragments of 150-900 bp. This step must be optimized. Perform a pilot experiment with different enzyme concentrations to achieve the desired fragment size [16].

- Sonication: As an alternative, use a sonicator. Perform a time-course experiment to determine the optimal number of cycles/duration to achieve a DNA smear with the majority of fragments below 1 kb, avoiding over-sonication [16].

- Immunoprecipitation: Pre-clear the chromatin lysate with protein A/G beads. Incubate the pre-cleared chromatin (5-10 µg per reaction) with 3-5 µg of your target-specific antibody (e.g., anti-H3K9me3) and a control IgG overnight at 4°C with rotation. The next day, add beads to capture the antibody-chromatin complexes [16] [17].

- Washing and Elution: Wash the beads sequentially with low-salt, high-salt, and LiCl buffers, followed by a TE buffer to remove non-specifically bound chromatin. Elute the immunoprecipitated protein-DNA complexes from the beads [17].

- Reverse Crosslinking and DNA Purification: Reverse the crosslinks by incubating with NaCl at 65°C. Treat with RNAse A and Proteinase K. Purify the DNA using a commercial kit or phenol-chloroform extraction [16].

- Analysis: Analyze the purified DNA by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using primers specific for your genomic regions of interest. Compare the enrichment in your specific antibody sample to the control IgG sample.

Troubleshooting Common ChIP Issues:

- High Background: Ensure chromatin is properly fragmented. Add pre-clearing and additional wash steps. Optimize antibody concentration to prevent non-specific binding [17].

- Weak or No Signal: Confirm cell lysis is complete. Increase the amount of starting material and/or antibody. Verify the antibody is validated for ChIP and is suitable for the target [16] [17].

- Low DNA Recovery: Avoid over-crosslinking. Re-optimize cell lysis and fragmentation steps. Ensure you are using an effective ChIP-grade antibody with high affinity [17].

Workflow: A Strategic Roadmap for Enhancing Reprogramming Efficiency

The following diagram visualizes a logical workflow for diagnosing and overcoming epigenetic barriers in iPSC generation.

Diagram: A troubleshooting workflow for diagnosing and overcoming major epigenetic barriers to improve iPSC reprogramming efficiency.

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers overcome common challenges in improving the efficiency of somatic cell reprogramming to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ: My reprogramming efficiency remains low despite using the OSKM factors. What are the primary strategic enhancers I can use? The core OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) factors are often insufficient for high efficiency. You can augment them with three main classes of enhancers:

- Small Molecules: Compounds like Valproic Acid (VPA) and Sodium Butyrate (HDAC inhibitors) can increase efficiency by up to 6.5-fold when used in combination [4]. These modulators open chromatin structure, facilitating access to pluripotency genes.

- MicroRNAs (miRNAs): miRNAs such as the miR-302/367 cluster or gga-miR-1811 (in avian models) are potent enhancers. They promote critical steps like the Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition (MET), significantly boosting efficiency [4] [18].

- Epigenetic Modulators: Target repressive marks like H3K9me3. Using inhibitors for enzymes like SUV39H1 or overexpressing erasers like KDM4B can remove these barriers, resetting the epigenetic landscape to a pluripotent state [14] [19].

FAQ: How do I choose between a viral and non-viral reprogramming method for a therapy-oriented project? The choice is critical for clinical translation. Non-integrating methods are strongly recommended for therapeutic applications to avoid insertional mutagenesis.

- Sendai Virus (SeV): This is a non-integrating viral method that offers significantly higher reprogramming success rates compared to episomal methods [20]. A key advantage is that it is naturally diluted and cleared from the host cell over several passages.

- Episomal Vectors: These are non-integrating DNA-based methods but typically yield lower success rates than SeV [20]. They are a good choice when any viral component must be avoided.

- Chemical Reprogramming: This is a completely non-genetic method using only small molecules. Recent advances have drastically reduced the reprogramming timeline to as little as 16 days, making it a highly promising and safe alternative [21].

FAQ: I am observing high levels of differentiation in my emerging iPSC colonies. What could be the cause? This is often related to the balance of reprogramming factors and culture conditions.

- Factor Imbalance: The relative ratios of reprogramming factors are critical. Research indicates that specific ratios of SOX2 and OCT4 significantly impact both efficiency and final colony quality [5].

- Incomplete Epigenetic Remodeling: The persistence of repressive epigenetic marks (e.g., H3K27me3) can prevent full activation of the pluripotency network and lead to spontaneous differentiation. Ensure your protocol includes epigenetic enhancers like HDAC or DOT1L inhibitors [4] [14].

- Culture Conditions: Suboptimal feeding schedules, low colony density during passaging, or inadequate use of ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) during single-cell passaging can increase differentiation pressure [20].

Quantitative Data on Reprogramming Enhancers

The following tables summarize key quantitative data on various enhancers to aid in experimental design.

Table 1: Efficiency of Small Molecule and Epigenetic Enhancers

| Enhancer Class/Name | Specific Example | Reported Impact on Efficiency | Key Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDAC Inhibitor | Valproic Acid (VPA) | Up to 6.5-fold increase (with 8-Br-cAMP) [4] | Increases histone acetylation, opens chromatin |

| cAMP Activator | 8-Br-cAMP | 2-fold increase [4] | Activates cAMP signaling pathways |

| DNA Methylation Inhibitor | 5-aza-cytidine, RG108 | Enhances robustness [4] | Reduces DNA methylation, derepresses genes |

| H3K9me3 Targeting | SUV39H1 inhibition | Enhances induction efficiency [19] | Reduces repressive H3K9me3 chromatin mark |

Table 2: Comparison of Non-Integrating Reprogramming Methods

| Method | Type | Genomic Integration? | Relative Success Rate | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sendai Virus (SeV) | Viral | No | Significantly higher [20] | Effective, but requires clearance confirmation |

| Episomal Vectors | DNA/Vector | No | Lower [20] | Virus-free; lower efficiency |

| Chemical Reprogramming | Small Molecules | No | Highly efficient and rapid [21] | No genetic material; protocol can be complex |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Enhancing Reprogramming with HDAC Inhibitors This protocol uses Valproic Acid (VPA) to improve efficiency.

- Reprogramming Initiation: Transduce/transfect somatic cells (e.g., fibroblasts, PBMCs) with your chosen OSKM factor delivery system (e.g., Sendai virus, episomal vectors).

- VPA Treatment: 24-48 hours post-transduction, supplement the culture medium with 0.5 - 2 mM VPA. Prepare a 100 mM stock solution in DMSO and dilute in fresh medium.

- Medium Refreshment: Refresh the VPA-containing medium every day for the next 10-12 days.

- Monitoring: Observe for the appearance of compact, ESC-like colonies. The presence of VPA should increase the number of such colonies.

- Colony Picking: After 3-4 weeks, manually pick individual colonies for expansion and characterization.

Protocol 2: Confirmatory Assay for Pluripotency and Characterization Rigorous quality control is essential for any generated iPSC line.

- Immunofluorescence for Pluripotency Markers:

- Culture iPSCs on glass coverslips in a 12-well plate until ~70% confluent.

- Fix with 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 minutes.

- Permeabilize and block with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5% normal serum for 1 hour.

- Incubate with primary antibodies against OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG overnight at 4°C.

- The next day, incubate with fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Mount and image. Nuclei should show strong positive staining for these key pluripotency transcription factors [6].

- Sendai Virus Clearance Check (if applicable):

Molecular Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram 1: Molecular Mechanism of Epigenetic Enhancers in Reprogramming

Diagram 2: Enhanced Reprogramming Workflow with Key Checkpoints

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Item | Function in Reprogramming | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Sendai Virus (SeV) Vectors | Non-integrating delivery of OSKM factors. | Higher success rates than episomal methods [20]. |

| Valproic Acid (VPA) | HDAC inhibitor; opens chromatin. | Can dramatically improve efficiency in combination [4]. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Improves survival of dissociated iPSCs. | Critical during passaging and freezing [20]. |

| miR-302 Mimics | Promotes MET and enhances reprogramming. | Can be transfected alongside OSKM factors [4] [18]. |

| TeSR mTeSR Plus Medium | Defined, xeno-free medium for iPSC maintenance. | Supports robust growth of established lines [6]. |

| Antibodies (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) | Immunocytochemistry for pluripotency confirmation. | Essential part of quality control [6]. |

The Impact of Somatic Cell Source on Reprogramming Efficiency

The choice of somatic cell source is a critical experimental variable in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) research, significantly impacting reprogramming efficiency, kinetics, and the quality of resulting cell lines. Since the initial discovery that somatic cells could be reprogrammed into pluripotent stem cells using defined factors, researchers have explored a wide range of somatic cell types as starting materials [2]. The original iPSC studies utilized mouse and human fibroblasts reprogrammed with the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC) [5]. Since then, the field has expanded to include diverse somatic cell sources, each with distinct advantages and challenges for reprogramming experiments.

The developmental origin, epigenetic landscape, and proliferation capacity of the starting somatic cell population profoundly influence the reprogramming process [4]. Somatic cells can be obtained from various tissue sources, including skin, blood, and other accessible tissues, with varying levels of donor invasiveness during collection [22]. This technical resource provides troubleshooting guidance and detailed protocols to help researchers select and optimize somatic cell sources for their specific reprogramming applications, with the goal of maximizing efficiency and reproducibility while minimizing technical artifacts.

Quantitative Analysis of Reprogramming Efficiencies

Extensive research has revealed significant variations in reprogramming efficiency across different somatic cell types. The table below summarizes key efficiency data for commonly used somatic cell sources in iPSC generation:

Table 1: Reprogramming Efficiency Across Different Somatic Cell Sources

| Somatic Cell Source | Reprogramming Efficiency | Key Advantages | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Fibroblasts | Typically <1% of transfected cells [23] | Well-established protocols; Extensive characterization | Invasive collection; Slow proliferation |

| Human Cord Blood Cells | Highly efficient with optimized chemical methods [24] | Non-invasive collection; Immature epigenetics | Limited donor availability; Cord blood-specific |

| Human Peripheral Blood Cells | Efficient with chemical reprogramming; >100 hCiPS colonies from single fingerstick drop [24] | Minimally invasive; Renewable source | Lower efficiency with viral methods; Requires specific culture conditions |

| Mouse Spleen Leukocytes | ~30% of surviving cells after low pH stimulus (STAP) [25] | Rapid reprogramming with certain methods | High cell death with stimulus; Limited human application data |

| Neural Stem Cells | Achievable with OCT4 alone [4] | Endogenous stemness factors; High intrinsic plasticity | Limited availability; Specialized isolation requirements |

Beyond conventional cell sources, researchers have explored specialized somatic cells with unique reprogramming properties:

Neural Stem Cells: These cells represent a special case where exogenous expression of OCT4 alone can successfully generate iPSCs, highlighting the significant role of endogenous stemness factors in the reprogramming process [4]. This contrasts with most somatic cell types that require multiple transcription factors for efficient reprogramming.

Blood Cell Populations: Recent advances in chemical reprogramming have dramatically improved the efficiency of generating human chemically induced pluripotent stem (hCiPS) cells from blood sources [24]. This approach has demonstrated high reproducibility across different donors using both fresh and cryopreserved blood cells.

Multiple Murine Tissue Sources: Research on stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency (STAP) demonstrated that cells from diverse mouse tissues including brain, lung, muscle, adipose, liver, and cartilage could be reprogrammed with 10-30% efficiency among surviving cells after low-pH treatment [25].

Troubleshooting Guides: Cell Source-Specific Reprogramming Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why do my blood-derived reprogramming cultures show poor adherence and eventual senescence?

A: This common issue occurs when standard reprogramming conditions optimized for fibroblasts are applied to blood cells without modification. Blood cells require specific cytokine pre-treatment and culture conditions to enable successful reprogramming. Solution: Implement a 7-day expansion phase in erythroid progenitor cell (EPC) media containing SCF, EPO, IL-3, and IL-6 before initiating chemical reprogramming [24]. This preconditioning step promotes the transition from suspension to adherent culture and prevents senescence.

Q2: How can I improve the low efficiency of fibroblast reprogramming?

A: Fibroblast reprogramming efficiency can be enhanced through several strategies:

- Utilize small molecule enhancers such as 8-Bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cAMP), which can improve human fibroblast reprogramming efficiency by approximately 2-fold [4].

- Combine 8-Br-cAMP with valproic acid (VPA) to increase iPSC generation efficiency by up to 6.5-fold [4].

- Consider p53 inhibition in combination with different reprogramming factors, which has been shown to markedly increase iPSC generation efficiency [4].

Q3: What is the minimum blood volume required for successful reprogramming?

A: Recent chemical reprogramming advances have significantly reduced blood volume requirements. Studies demonstrate that a single drop of fingerstick blood (approximately 20-30 μL) is sufficient to generate an average of over 100 hCiPS colonies when using optimized chemical reprogramming methods [24]. This represents a substantial improvement over earlier blood reprogramming protocols that required larger venous blood draws.

Q4: How does donor age impact reprogramming efficiency across different cell sources?

A: Donor age inversely correlates with reprogramming efficiency for most somatic cell sources, though the magnitude of this effect varies:

- Fibroblasts from older donors typically show reduced reprogramming efficiency and slower kinetics compared to neonatal sources [5].

- Blood cells from older donors may require extended preconditioning or modified cytokine combinations to achieve efficiency comparable to cord blood sources [24].

- Optimization with alternative transcription factor combinations (e.g., OSKMNL with six factors) has demonstrated success in reprogramming fibroblasts from old donors where standard methods failed [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Chemical Reprogramming of Human Blood Cells

This protocol describes an optimized method for generating human chemically induced pluripotent stem (hCiPS) cells from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with high efficiency [24].

Table 2: Key Reagents for Blood Cell Chemical Reprogramming

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokines for Preconditioning | SCF, EPO, IL-3, IL-6 | Promote erythroid progenitor expansion and adherence |

| Epigenetic Modulators | Sodium butyrate, Trichostatin A, 5-aza-cytidine | Enhance chromatin accessibility; Facilitate epigenetic remodeling |

| Signaling Pathway Modulators | RepSox, CHIR99021, BMP4 | Regulate key reprogramming pathways; Replace transcription factors |

| Metabolic Regulators | 8-Br-cAMP, VPA | Alter cellular metabolism to support pluripotency acquisition |

Step-by-Step Workflow:

PBMC Isolation and Preconditioning

- Isolate mononuclear cells from fresh or cryopreserved peripheral blood using density gradient centrifugation.

- Culture PBMCs in EPC expansion medium containing SCF (100 ng/mL), EPO (10 U/mL), IL-3 (10 ng/mL), and IL-6 (10 ng/mL) for 7 days.

- Maintain cells at a density of 1-2×10^6 cells/mL in tissue culture-treated plates at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

Chemical Reprogramming Induction

- Plate preconditioned cells on Matrigel-coated plates at a density of 5×10^4 cells/cm² in chemical reprogramming medium.

- Implement a staged chemical cocktail approach with sequential exposure to specific small molecule combinations as detailed in recent studies [24].

- Replace medium every 2 days and monitor for morphological changes indicating transition to adherent state.

Emergence and Expansion of hCiPS Colonies

- First adherent colonies typically appear between day 10-14 of chemical treatment.

- Manually pick well-defined colonies with clear iPSC morphology between days 18-21.

- Transfer selected colonies to feeder-free culture conditions and expand using standard hPSC culture methods.

Quality Control and Characterization

- Confirm pluripotency marker expression (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81) via immunocytochemistry.

- Perform karyotype analysis to ensure genomic integrity.

- Validate trilineage differentiation potential through embryoid body formation assays.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for chemical reprogramming of human blood cells to pluripotency, highlighting key stages from cell isolation through quality control.

Fibroblast Reprogramming with Efficiency Enhancers

This protocol enhances standard fibroblast reprogramming through small molecule supplementation to significantly improve efficiency [4].

Enhanced Reprogramming Procedure:

Fibroblast Culture Preparation

- Culture human dermal fibroblasts in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% GlutaMAX.

- Plate fibroblasts at 70-80% confluence in tissue culture-treated dishes 24 hours before reprogramming initiation.

Factor Delivery with Small Molecule Enhancement

- Deliver OSKM factors using your preferred method (lentiviral, Sendai virus, or mRNA-based).

- Simultaneously add efficiency-enhancing small molecules:

- 8-Br-cAMP (250 µM) to improve reprogramming approximately 2-fold

- Valproic acid (0.5-1 mM) to potentially increase efficiency up to 6.5-fold when combined with 8-Br-cAMP

- Alternative epigenetic modulators such as Sodium butyrate (0.5 mM) or Trichostatin A (50 nM)

Monitoring and Colony Selection

- Monitor cultures for emergence of embryonic stem cell-like morphology beginning around day 7-10.

- Manually pick colonies based on compact morphology and well-defined borders between days 18-28.

- Expand colonies in feeder-free conditions for further characterization.

Figure 2: Key molecular events in enhanced fibroblast reprogramming showing how small molecule enhancers target specific stages of the process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Optimizing Reprogramming Efficiency

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Application Function | Cell Source Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM); OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 (OSNL) | Core transcription factor combinations for pluripotency induction | Universal application with efficiency variations |

| Chemical Enhancers | 8-Br-cAMP, Valproic acid, Sodium butyrate, RepSox, CHIR99021 | Improve efficiency; Replace transcription factors; Modulate signaling | Blood cells (8-Br-cAMP + VPA); Fibroblasts (all) |

| Cytokines/Growth Factors | SCF, EPO, IL-3, IL-6, FGF2, BMP4 | Preconditioning; Enhance survival and adherence | Blood cells (SCF, EPO, IL-3, IL-6); Universal (FGF2) |

| Culture Matrices | Matrigel, Vitronectin, Laminin-521 | Provide optimal substrate for reprogramming and iPSC expansion | Blood cells (Matrigel); Fibroblasts (all matrices) |

| Epigenetic Modulators | 5-aza-cytidine, RG108, Trichostatin A, DZNep | Facilitate epigenetic remodeling; Enhance chromatin accessibility | Universal application with concentration optimization needed |

| Metabolic Regulators | DMEM/F12, N2/B27 supplements, L-ascorbic acid | Support metabolic transition during reprogramming | Universal application |

The selection of an appropriate somatic cell source remains a fundamental decision in experimental design for iPSC generation, with significant implications for reprogramming efficiency, experimental timeline, and clinical applicability. Blood-derived cells have emerged as particularly promising starting materials due to their minimally invasive collection and recent efficiency improvements through chemical reprogramming methods [24]. Fibroblasts continue to be valuable for research applications, especially when enhanced with small molecule cocktails that address their inherent efficiency limitations [4].

Future directions in somatic cell source optimization include the development of universal chemical reprogramming platforms that can efficiently reprogram diverse cell types with minimal protocol modifications [26]. Additionally, research into the molecular mechanisms underlying the varying reprogramming competencies of different somatic cell types will continue to inform the rational selection of starting materials for specific applications [9]. As the field advances toward clinical translation, considerations of donor accessibility, scalability, and safety profiles will increasingly guide the selection of somatic cell sources for both basic research and therapeutic development [22] [5].

Advanced Reprogramming Technologies: Delivery Systems and Novel Platforms

The generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from somatic cells represents one of the most significant advancements in regenerative medicine and biomedical research. Since the initial discovery by Takahashi and Yamanaka that somatic cells could be reprogrammed using defined factors, the field has rapidly evolved to encompass numerous delivery strategies for introducing reprogramming factors into target cells. The core challenge lies in selecting an appropriate delivery system that balances reprogramming efficiency with safety profile, particularly regarding genomic integrity. This technical guide examines the spectrum of available delivery systems—from early integrating retroviruses to modern non-integrating methods—within the broader context of improving reprogramming efficiency for both basic research and clinical applications.

The fundamental process involves the ectopic expression of key pluripotency factors, typically OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-Myc (OSKM), though alternative combinations exist. The delivery method significantly influences not only the success rate but also the molecular characteristics of the resulting iPSCs, their differentiation potential, and ultimately their suitability for therapeutic use. This resource provides researchers with practical guidance for selecting, optimizing, and troubleshooting these critical methodologies.

The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of the primary delivery systems used in iPSC generation, summarizing key characteristics to guide method selection.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of iPSC Delivery Systems

| Delivery Method | Mechanism of Action | Reprogramming Efficiency | Genomic Integration | Primary Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMLV Retrovirus | Integrating viral vector | High [27] [28] | Yes | Efficient, stable transgene expression [28] | Insertional mutagenesis, transgene reactivation [29] [30] |

| Lentivirus | Integrating viral vector | High [27] | Yes | Infects dividing & non-dividing cells [27] | Insertional mutagenesis, residual expression [20] [30] |

| Sendai Virus (SeV) | Non-integrating RNA virus | Medium to High [20] [27] | No | High efficiency, no genomic integration [20] | Difficult to fully remove from cells [27] |

| Episomal Vectors | Non-integrating plasmid | Medium [20] [27] | No (Low risk) | Non-viral, simple to implement [27] | Low efficiency, requires verification of episome loss [20] |

| Adenovirus | Non-integrating viral vector | Low [27] [31] | No | No genomic integration, transgene-free cells [27] [31] | Very low reprogramming efficiency [31] |

| Synthetic mRNA | DNA-free RNA transfection | High [27] [32] | No | Highly safe, no genetic footprint [32] | Multiple transfections required, requires stringent culture [27] |

| Protein Transduction | Direct protein delivery | Low [27] [31] | No | Maximum safety, no genetic material [27] [31] | Very low efficiency, difficult protein purification [27] |

| piggyBac Transposon | Excisable integrating vector | Medium [27] | Yes (but excisable) | Footprint-free excision after reprogramming [27] [31] | Must verify excision didn't introduce mutations [27] |

Decision Framework: Selecting a Delivery System

The following workflow diagram outlines a logical decision-making process for selecting the most appropriate delivery system based on research goals and experimental constraints.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

This section addresses specific, frequently encountered problems during iPSC generation, providing evidence-based solutions to improve experimental outcomes.

FAQ 1: Low Viral Transduction Efficiency

- Problem: Low viral titer or poor infectivity leads to insufficient reprogramming factor delivery.

- Possible Causes:

- Suboptimal transfection efficiency in packaging cells.

- Low plasmid quality for virus production.

- Improper viral harvesting or storage conditions.

- Target cells not actively dividing (for retroviruses).

- Solutions:

- Optimize Packaging: Use high-quality, endotoxin-free plasmids and optimize transfection reagent ratios for packaging cells (e.g., HEK293T). [28]

- Concentrate Virus: Concentrate viral supernatant by ultracentrifugation or PEG precipitation to achieve a higher multiplicity of infection (MOI). [28]

- Enhance Infection: Use polybrene to facilitate viral entry. For difficult-to-transduce cells, use "spinoculation" (centrifugation during infection). [28] [30]

- Confirm Cell Status: Ensure target cells are healthy, low-passage, and actively proliferating at the time of transduction. [28]

FAQ 2: Poor Cell Survival Post-Transduction/Transfection

- Problem: Significant cell death occurs following the introduction of reprogramming factors.

- Possible Causes:

- Cytotoxicity from transfection reagents or viral particles.

- Stress induced by the reprogramming process itself.

- Over-proliferation and senescence triggered by oncogenic factors like c-Myc.

- Solutions:

- Use ROCK Inhibitor: Add a ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) to the culture medium for the first 24-48 hours post-transduction to enhance cell survival. [20] [28]

- Adjust Polybrene: Reduce polybrene concentration or shorten exposure time to minimize toxicity. [28]

- Co-culture with Feeders: For fragile cell types, use a feeder layer (e.g., irradiated MEFs) during the early stages of reprogramming for additional support. [28]

FAQ 3: Delayed or Absent Colony Formation

- Problem: Reprogramming colonies fail to appear or are significantly delayed beyond the expected timeframe (typically 3-4 weeks).

- Possible Causes:

- Insufficient expression of reprogramming factors.

- Epigenetic barriers in the starting somatic cell population.

- Suboptimal culture conditions.

- Solutions:

- Confirm Factor Expression: Use qPCR or immunostaining to verify the expression of OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-Myc. [28]

- Add Small Molecules: Enhance reprogramming efficiency by adding small-molecule enhancers such as valproic acid (VPA), sodium butyrate, or the GSK3 inhibitor CHIR99021. [4] [28]

- Modify Culture Conditions: Lower oxygen tension (to 5% O₂) to mimic physiological hypoxia, which can promote reprogramming. [28]

- Select Optimal Cells: Use starting somatic cells with high reprogrammability, such as keratinocytes or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), which can offer higher efficiency than fibroblasts. [29] [20]

FAQ 4: Partially Reprogrammed or Morphologically Abnormal Colonies

- Problem: Emerging colonies do not exhibit the tight, dome-shaped morphology of true iPSCs and may show signs of differentiation.

- Possible Causes:

- Incomplete epigenetic remodeling.

- Persistent expression or premature silencing of transgenes.

- Overgrowth and spontaneous differentiation.

- Solutions:

- Stringent Morphological Selection: Manually pick only colonies that are compact, with defined borders and a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. Avoid colonies with a flat or differentiated appearance. [28]

- Timely Passaging: Passage colonies before they become over-confluent and begin to differentiate in the center. [20] [28]

- Verify Pluripotency: Rigorously characterize candidate lines through immunostaining for pluripotency markers (OCT4, NANOG, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60) and trilineage differentiation assays. [20] [28]

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials critical for successful iPSC generation and culture, regardless of the delivery method chosen.

Table 2: Essential Reagent Toolkit for iPSC Generation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Packaging Cell Line | Produces viral particles for gene delivery. | HEK293T cells for lentiviral/retroviral production. [28] |

| Polybrene | A cationic polymer that enhances viral transduction efficiency. | Added to viral supernatant to neutralize charge repulsion between virus and cell membrane. [28] |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Improves survival of single pluripotent stem cells by inhibiting apoptosis. | Added to medium after passaging or thawing to increase cell survival. [20] [28] |

| bFGF (Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor) | Key cytokine for maintaining pluripotency and self-renewal in human iPSC culture. | Added daily to iPSC culture medium to sustain an undifferentiated state. [28] |

| Extracellular Matrix Substrates | Provides a scaffold for cell attachment and growth, replacing feeder layers. | Matrigel, Vitronectin, or Laminin-521 for feeder-free culture. [20] [28] |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Compounds that improve reprogramming efficiency by modulating signaling pathways and epigenetics. | Valproic acid (HDAC inhibitor), CHIR99021 (Wnt activator), RepSox (TGF-β inhibitor). [4] [31] |

| Pluripotency Marker Antibodies | Used to confirm the successful reprogramming to a pluripotent state via immunostaining or flow cytometry. | Antibodies against OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60. [20] [28] |

Core Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the generalized step-by-step workflow for generating iPSCs, highlighting stages that are common across most delivery methods and where key quality control checks should be implemented.

The evolution of iPSC delivery systems from integrating retroviruses to sophisticated non-integrating and footprint-free methods reflects the field's dual focus on enhancing efficiency and ensuring safety. The choice of delivery system remains a fundamental determinant of experimental success and clinical translatability. While retroviral and lentiviral systems offer robust efficiency for basic research, the clear trend is toward non-integrating methods like Sendai virus and synthetic mRNA for preclinical and therapeutic applications due to their superior safety profiles. [20] [32]

Future improvements will likely focus on standardizing protocols, further increasing the efficiency of non-integrating methods, and developing more sophisticated chemical reprogramming approaches that eliminate the need for genetic material altogether. [4] [2] By carefully considering the trade-offs between efficiency, safety, and practical experimental requirements outlined in this guide, researchers can strategically select and optimize their reprogramming methodology to advance both fundamental knowledge and therapeutic innovation.

Chemical reprogramming represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine, offering a fundamentally innovative approach for generating human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using small molecules instead of genetic factors. This non-genetic methodology provides a more flexible, standardized, and clinically promising pathway for cell fate manipulation. By targeting key signaling and epigenetic pathways, chemical reprogramming enables precise control over the pluripotency acquisition process while avoiding the risks associated with viral vectors and genomic integration. This technical support center guide addresses the most common experimental challenges and provides proven solutions to optimize chemical reprogramming protocols for somatic cells.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Encountered Issues and Solutions

Q: My somatic cells are not transitioning from suspension to an adherent state during the initial reprogramming phase. What could be causing this?

A: Failure of cellular adhesion often indicates suboptimal culture conditions or incorrect cell state. Research on blood cell reprogramming showed that standard erythroid progenitor cell (EPC) conditions failed to support adhesion, requiring protocol modification.

- Solution: Implement a "bridge" culture medium that transitions cells toward a mesenchymal state prior to reprogramming. For cord blood mononuclear cells (hCBMCs) or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), use specialized expansion media containing SCF, IL-3, and IL-6 for 7 days before applying chemical reprogramming cocktails [24].

- Additional verification: Ensure your starting cell population is viable and properly characterized. For blood cells, use fresh or properly cryopreserved samples with >90% viability [24].

Q: I observe extensive cellular senescence or apoptosis shortly after applying chemical reprogramming cocktails. How can I improve cell survival?

A: This common challenge occurs when somatic cells experience excessive stress during the initial reprogramming transition.

- Solution: Incorporate ROCK inhibitor (Y27632) or RevitaCell Supplement during the first 48-72 hours of reprogramming [33]. For confluent cultures (>85%), always include ROCK inhibitor during passaging.

- Protocol adjustment: For blood cell reprogramming, research indicates that inhibition of the H3K79 histone methyltransferase Dot1L – either via shRNA or small molecule inhibitors (EPZ004777) – can significantly reduce senescence barriers and enhance reprogramming efficiency [34].

- Timing consideration: Apply senescence-inhibiting treatments during the first week of reprogramming, as this window is critical for overcoming initial epigenetic barriers [34].

Q: The reprogramming efficiency is low compared to published results. Which factors most significantly impact efficiency?

A: Reprogramming efficiency depends on multiple interdependent variables that must be optimized for your specific cell type.

- Key efficiency enhancers:

- Epigenetic modulation: Dot1L inhibition increases reprogramming efficiency 3-6 fold across multiple human fibroblast lines (IMR-90, MRC-5) and can substitute for Klf4 and c-Myc in factor-based protocols [34].

- Cell density: Passage cells at 40-85% confluency. Overly confluent cultures demonstrate poor survival after passaging [33].

- Donor variability: Account for inherent differences between cell donors by including positive control lines (e.g., H9 or H7 ESC lines) in your experiments [33].

Q: How long should I maintain cells in reprogramming conditions before seeing iPSC colonies?

A: The timeline varies by cell type and protocol efficiency.

- Blood cells: Under optimized chemical conditions, initial adherent transitions appear within 2 weeks, with distinct hCiPS colonies emerging by week 3 [24].

- General indicators: Successful reprogramming shows accelerated emergence of Tra-1-60-positive cell clusters by days 10-14 when using optimized protocols [34].

- Troubleshooting: If no colonies appear after 4 weeks, verify your small molecule concentrations and refresh stocks, as some compounds degrade more quickly than others.

Advanced Technical Challenges

Q: Can I use cryopreserved cells for chemical reprogramming, and are there special considerations?

A: Yes, both fresh and cryopreserved cells can be successfully reprogrammed.

- Blood cells: The chemical reprogramming approach has been validated with both fresh and cryopreserved cord blood and peripheral blood cells across different donors [24].

- Best practices: Thaw cells quickly (<2 minutes at 37°C) and transfer to pre-rinsed tubes before adding medium drop-wise to prevent osmotic shock [33]. Do not use PBS, DPBS, or HBSS for rinsing as they lack necessary proteins.

- Viability check: Always count cell viability with trypan blue after thawing. For successful reprogramming, seed at least 1 × 10^5 viable cells/cm² for most somatic cell types [33].

Q: What are the critical quality control checkpoints for successful chemical reprogramming?

A: Implement these verification steps throughout your protocol:

- Starting material: Ensure your somatic cells have minimal differentiation and are proliferating normally before reprogramming initiation.

- Day 7-10: Check for morphological changes from suspension to adherent (for blood cells) or increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio (for fibroblasts).

- Day 14-21: Monitor for emergence of tight, dome-shaped colonies with defined borders.

- Endpoint validation: Verify pluripotency through immunostaining for OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, TRA-1-60, and TRA-1-81, followed by functional differentiation into all three germ layers [24] [34].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Key Small Molecule Cocktails for Enhanced Reprogramming

Table 1: Experimentally Validated Chemical Cocktails for Reprogramming Enhancement

| Component | Concentration Range | Primary Mechanism | Experimental Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dot1L Inhibitor (EPZ004777) | 1-10 μM | H3K79 histone methyltransferase inhibition | 3-4 fold increase in efficiency; enables OS (Oct4-Sox2) only reprogramming [34] |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y27632) | 10 μM | Inhibition of Rho-associated kinase; reduces apoptosis | Markedly improves cell survival during early reprogramming and single-cell passaging [33] |

| Valproic Acid | 0.5-2 mM | Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor | Enhances epigenetic remodeling; more effective with integrating viral systems [33] |

| Bridge Medium Components | Varies by protocol | Promotes mesenchymal transition | Enables blood cell adhesion and dramatically improves chemical reprogramming response [24] |

Optimized Chemical Reprogramming Workflow for Human Blood Cells

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials for Chemical Reprogramming Experiments

| Reagent/Cell Type | Specific Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Human Cord Blood Mononuclear Cells (hCBMCs) | Primary somatic cell source | Highly accessible; reprogramming efficiency confirmed across donors [24] |

| Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | Patient-specific cell source | Minimally invasive collection; compatible with fingerstick blood samples [24] |

| Essential 8 Medium | Feeder-free pluripotent stem cell culture | Supports chemical iPSC expansion and maintenance; compatible with VTN-N coating [33] |

| Geltrex Matrix | Basement membrane matrix for cell attachment | Provides optimal surface for adherent transition during reprogramming [33] |

| NCC Reporter System | Age and senescence monitoring | Distinguishes young/old cells via nucleocytoplasmic compartmentalization [35] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Pathway Diagrams

Epigenetic Regulation in Chemical Reprogramming

Critical Timing for Reprogramming Interventions

Table 3: Optimal Time Windows for Key Reprogramming Interventions

| Intervention | Critical Period | Observed Effect | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dot1L Inhibition | Days 1-14 | 3-fold enhancement; enables 2-factor (OS) reprogramming | Facilitates early epigenetic remodeling; loss of H3K79me from fibroblast-specific genes [34] |

| ROCK Inhibition | First 48 hours post-passaging | Significantly improves cell survival | Prevents anoikis during single-cell dissociation [33] |

| Bridge Culture Medium | 7 days pre-reprogramming | Enables blood cell adhesion and response | Promotes mesenchymal transition necessary for chemical reprogramming competence [24] |

| Temperature Shift (38-39°C) | After passage 10 (Sendai systems) | Clears residual c-Myc and KOS vectors | Exploits temperature-sensitive mutations in reprogramming vectors [33] |

Chemical reprogramming technology has evolved from a promising concept to a robust, clinically relevant platform for generating human iPSCs. The troubleshooting guidelines and experimental protocols outlined here address the most significant technical barriers to implementation. As research advances, further optimization of small molecule cocktails and timing regimens will continue to enhance efficiency and reliability. The non-genetic nature of this approach, combined with its compatibility with minimally invasive cell sources like blood, positions chemical reprogramming as a cornerstone technology for personalized regenerative medicine and drug development applications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the main advantages of using biomaterials over traditional viral methods for cell reprogramming? Biomaterial-based methods offer several key advantages over viral reprogramming. They avoid the risk of genomic integration and insertional mutagenesis associated with viral vectors, thereby enhancing the safety profile of the resulting induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [36]. Furthermore, engineered biomaterials provide a way to precisely control the biophysical and biochemical microenvironment, which can significantly improve reprogramming efficiency and guide more accurate cell fate transitions [23] [37].

FAQ 2: Why is the 3D genome structure important for generating high-quality iPSCs? Research indicates that the 3D folding of DNA within the nucleus (the genome's architecture) directly influences gene expression. High-resolution mapping has revealed that iPSCs do not always perfectly replicate the genome folding patterns found in gold-standard embryonic stem cells (ESCs). Instead, they can retain traces of the 3D configuration from the original somatic cell, a phenomenon linked to incomplete reprogramming and potential difficulties in subsequent differentiation. Modifying the culture environment, such as the growth medium, can help correct these folding patterns [38].

FAQ 3: My iPSC cultures are showing high levels of spontaneous differentiation (>20%). What could be the cause? Excessive differentiation in pluripotent stem cell cultures can be attributed to several factors related to culture conditions and handling. Using culture medium that has been stored for too long or allowing the culture plate to remain outside the incubator for extended periods can trigger differentiation. Additionally, allowing colonies to become over-confluent, generating uneven or overly large cell aggregates during passaging, and failing to physically remove differentiated areas before passaging are common procedural errors that contribute to this problem [39].

FAQ 4: How can synthetic polymer scaffolds address the limitations of natural matrices like Matrigel? Natural matrices suffer from batch-to-batch variability, undefined composition, and limited tunability, which hinder experimental reproducibility and clinical translation [40]. Synthetic scaffolds, such as thermoresponsive terpolymers, offer precisely controllable biochemical and mechanical properties. They ensure consistent quality, can be functionalized with specific bioactive peptides (e.g., RGD), and are scalable, providing a more reliable and customizable platform for stem cell expansion and differentiation [37] [40].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Low Reprogramming Efficiency

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Suboptimal Substrate Stiffness. The mechanical properties of the culture substrate are a critical factor in directing cell fate.

- Solution: Utilize biomaterials with a stiffness tailored for pluripotency. Research suggests that very soft substrates (e.g., around 0.1 kPa) can enhance the initiation of reprogramming to iPSCs [36]. Test a range of stiffnesses to optimize for your specific cell type and reprogramming method.

- Cause 2: Inconsistent Surface Topography. The physical nano- and micro-scale features of the culture surface influence cell signaling.

- Solution: Implement engineered surfaces with defined topographies. For example, nanogrooves have been shown to promote the direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into neurons [36]. Consistency in fabricating these topographical cues is key to achieving reproducible results.

- Cause 3: Inefficient Delivery of Reprogramming Factors. Viral methods, while efficient, pose safety risks.

- Solution: Adopt non-viral delivery systems. Techniques such as electroporation of mRNA or the use of chitosan nanoparticles and gold nanoparticles for delivering plasmid DNA have been successfully used for reprogramming somatic cells into iPSCs [36].

Problem: Differentiated Cells Exhibit Immature or Fetal-like Characteristics

Potential Causes and Solutions: