Strategies for Preventing Teratoma Formation in Pluripotent Stem Cell Therapies: A 2025 Review of Safety Assessment and Risk Mitigation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of current strategies and emerging technologies for mitigating teratoma formation risk in human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC)-derived therapies.

Strategies for Preventing Teratoma Formation in Pluripotent Stem Cell Therapies: A 2025 Review of Safety Assessment and Risk Mitigation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of current strategies and emerging technologies for mitigating teratoma formation risk in human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC)-derived therapies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational biology of tumorigenic risk, explores innovative methods for eliminating residual undifferentiated hPSCs, addresses key challenges in safety assessment, and evaluates advanced validation techniques. The content synthesizes the latest 2025 consensus recommendations and research to offer a practical framework for enhancing the safety profile of hPSC-derived cell therapy products, supporting the advancement of rigorous, internationally harmonized safety protocols in regenerative medicine.

Understanding Teratoma Risk: The Biological Basis of Tumorigenicity in Pluripotent Stem Cells

Why are undifferentiated human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) considered tumorigenic?

The tumorigenic risk of hPSCs is intrinsically linked to the fundamental properties of pluripotency and self-renewal. The core issue is that even a small number of residual undifferentiated hPSCs in a differentiated cell product can form tumors upon transplantation [1] [2].

- Pluripotency and Tumorigenicity are Historically Linked: The earliest research on highly pluripotent stem cells was conducted on embryonic carcinoma cells (EC) derived from teratocarcinomas. When embryonic stem cells (ESCs) were later isolated, they shared not only pluripotency with these EC cells but also their robust tumorigenicity, as both readily form teratomas [1].

- The Teratoma Assay Paradox: The standard assay to demonstrate a cell's pluripotency—the teratoma assay—is itself a tumor formation assay. This underscores the strong biological link between "stemness" and tumorigenic potential. The formation of a benign teratoma from transplanted cells is clear evidence of their pluripotency but also highlights a significant safety risk for clinical applications [1].

- Minimal Cell Number Required: Preclinical models have shown that transplanting even 10,000 or fewer undifferentiated hPSCs can be sufficient to form a teratoma in vivo. When considering therapies where billions of differentiated cells are transplanted into a patient, even a tiny residual undifferentiated population of 0.001% could be therapeutically unacceptable, necessitating a depletion of undifferentiated hPSCs by a factor of 10,000 to 1,000,000 (5- to 6-log reduction) to ensure safety [2].

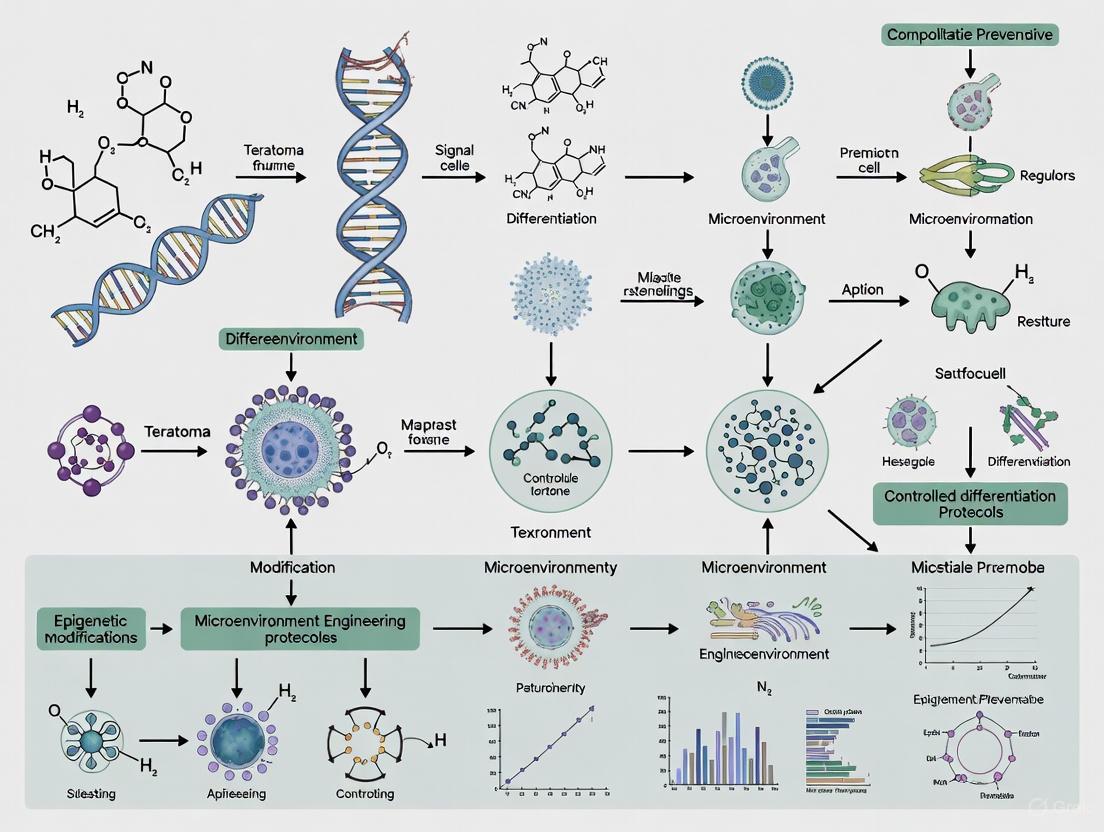

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationship between the defining properties of hPSCs and their clinical safety risk.

What is the molecular basis for the tumorigenicity of hPSCs?

The molecular programs that govern pluripotency and self-renewal in stem cells are co-opted in many human tumors. Key pluripotency transcription factors are either established oncogenes or are strongly linked to tumorigenesis [1].

Table 1: Key Molecular Links Between Pluripotency and Tumorigenicity

| Gene/Factor | Role in Pluripotency | Role in Tumorigenesis |

|---|---|---|

| c-MYC | Essential for normal signaling in mESC; dramatically boosts iPSC generation efficiency [1]. | A classic proto-oncogene; elevated expression may have a role in all human cancer [1]. |

| KLF4 | One of the four original Yamanaka factors for reprogramming; required for ESC pluripotency and self-renewal [1]. | An established oncogene in various contexts [1]. |

| NANOG | A master transcription factor critical for maintaining pluripotency [2]. | Linked to tumorigenesis; expressed in certain cancer cells [1]. |

| SOX2 | Essential transcription factor for the pluripotent state. | Linked to tumorigenesis in various cancers [1]. |

| OCT3/4 | Core pluripotency transcription factor. | Associated with tumorigenic processes [1]. |

This shared molecular machinery creates a significant challenge: reducing the tumorigenic potential of hPSCs by targeting these factors may inevitably reduce their essential "stemness" and pluripotency, which are the very properties needed for regenerative therapies [1].

What strategies exist to mitigate the risk of teratoma formation?

Mitigation strategies focus on two main areas: ensuring the purity of the differentiated cell product and developing safety switches to eliminate unwanted cells.

Table 2: Strategies for Mitigating hPSC Tumorigenicity

| Strategy Category | Specific Method | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Product Purity | Improved differentiation protocols | Reduces the number of residual undifferentiated hPSCs in the final therapeutic product. | Addresses the problem at its source. |

| Cell Surface Marker-Based Depletion | Antibody-mediated removal (e.g., against SSEA-3, TRA-1-60) [2]. | Physically removes undifferentiated hPSCs that express specific surface markers. | Well-established methodology. |

| Genetic Safety Switches | NANOG-promoter driven iCaspase9 [2] | A "suicide gene" is inserted into the NANOG locus. Undifferentiated cells expressing NANOG undergo apoptosis upon administration of a small molecule drug (AP20187). | Highly specific to the pluripotent state; achieves >1,000,000-fold depletion of hPSCs [2]. |

| Genetic Safety Switches | ACTB-promoter driven safety systems (e.g., iCaspase9, TK) [2]. | A suicide gene expressed in all cells derived from the engineered hPSC line. Allows elimination of the entire cell product if adverse events (e.g., tumors from mis-differentiated cells) occur. | Provides a broad "kill-switch" for the entire therapy if needed. |

The following workflow diagrams two key experimental approaches for implementing and validating these genetic safeguards.

What are the key experimental protocols for assessing tumorigenicity?

Teratoma Assay Protocol

The teratoma assay is the gold-standard functional test for both pluripotency and tumorigenic potential [1].

- Cell Preparation: Harvest the hPSC population or differentiated cell product to be tested. A positive control of known undifferentiated hPSCs and a negative control (e.g., fibroblasts) should be included.

- Transplantation: Inject cells into an immunodeficient mouse host (e.g., NSG or NOG mice). Common sites are the testis capsule, kidney capsule, or subcutaneous space.

- Monitoring: Palpate the injection site regularly for tumor formation over a period of 8-20 weeks.

- Histological Analysis:

- Sacrifice the animal and harvest the resulting tumor or graft.

- Fix the tissue in formalin and embed in paraffin.

- Section and stain with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E).

- Examine microscopically for the presence of differentiated tissues derived from all three embryonic germ layers: ectoderm (e.g., neural tissue, keratinocytes), mesoderm (e.g., cartilage, bone, muscle), and endoderm (e.g., gut-like epithelial tissues).

This protocol validates a specific safeguard to remove residual undifferentiated cells.

- Cell Line Engineering:

- Use CRISPR/Cas9 RNP and AAV6-based genome editing to knock-in an inducible Caspase9 (iCaspase9)-YFP cassette downstream of the stop codon in the NANOG gene, separated by T2A "self-cleaving" peptide sequences.

- Create a biallelic knock-in to prevent escape.

- Validate the knock-in and confirm normal pluripotency and karyotype.

- In Vitro Specificity and Potency Testing:

- Differentiate the engineered hPSCs into target lineages (e.g., liver progenitors, bone progenitors, forebrain progenitors).

- Treat both undifferentiated and differentiated cultures with the small molecule inducer AP20187 (at 1 nM concentration for 24 hours).

- Quantify cell death via flow cytometry (Annexin V/propidium iodide staining) or cell viability assays.

- Expected Outcome: >1,000,000-fold depletion of undifferentiated hPSCs, with >95% survival of the differentiated progeny.

- In Vivo Teratoma Prevention Assay:

- Mix a small number of undifferentiated NANOG-iCaspase9 hPSCs (e.g., 10,000) with a large number of their differentiated progeny.

- Transplant the mixture into immunodeficient mice.

- Administer AP20187 or a vehicle control to the animals.

- Monitor for teratoma formation over time. The experimental group receiving AP20187 should show a significant reduction or complete absence of teratomas compared to the control group.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying hPSC Tumorigenicity and Safety

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Surface Markers | Identification and sorting of undifferentiated hPSCs via flow cytometry or antibody-mediated depletion. | SSEA-3, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81 [2]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Genome editing to insert safety switches (e.g., iCaspase9) into specific genetic loci (e.g., NANOG). | Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) with AAV6 donor template [2]. |

| Inducible Safety Switches | Genetically encoded systems for targeted cell ablation. | iCaspase9 (activated by AP20187); Herpes Simplex Virus Thymidine Kinase (HSV-TK, activated by Ganciclovir) [2]. |

| Small Molecule Inducers | Activation of inducible safety switches in vitro and in vivo. | AP20187 (for iCaspase9); Ganciclovir (for HSV-TK) [2]. |

| Immunodeficient Mouse Models | In vivo hosts for teratoma formation assays and safety switch validation. | NSG (NOD-scid-gamma), NOG mice [1] [2]. |

| Clinical-Grade iPSC Lines | GMP-compliant, well-characterized starting material for therapy development, referenced in regulatory submissions. | StemRNA Clinical Seed iPSCs (REPROCELL) [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Are there any clinical data on the safety of hPSC-derived therapies regarding tumorigenicity? A: Yes, the clinical landscape is expanding. As of late 2024, a major review of 115 global clinical trials involving PSC-derived products, which had dosed over 1,200 patients, reported no significant class-wide safety concerns [3]. Specific trials, such as a Phase I/II trial of iPSC-derived dopaminergic progenitors for Parkinson's disease published in 2025, reported no tumor formation in patients [4]. This suggests that with careful manufacturing and quality control, the tumorigenicity risk can be managed.

Q: Can't we just use surface markers to remove all undifferentiated hPSCs from a cell product? A: While surface markers are a valuable tool, a significant challenge is specificity. Many surface markers traditionally used to identify undifferentiated hPSCs (e.g., SSEA-3, TRA-1-60) are also expressed at lower levels on various differentiated cell types that might be part of the therapeutic product [2]. Using these markers for negative selection could therefore inadvertently deplete a portion of the desired therapeutic cells. Genetic safeguards driven by highly specific pluripotency gene promoters (like NANOG) offer a more precise alternative for targeting the undifferentiated state.

Q: What is the difference between a teratoma and a malignant tumor? A: A teratoma is a benign tumor containing a disorganized mixture of tissues from all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm). It is the most common tumor type formed by pluripotent stem cells. However, hPSCs can also form malignant tumors, such as teratocarcinomas, which contain both differentiated tissues and undifferentiated, proliferative stem cells that can invade other tissues. Furthermore, if hPSCs acquire genetic abnormalities in culture, their differentiated progeny could potentially form other types of cancers [1] [2].

Q: Where can I find the latest best practices for developing hPSC-based therapies? A: The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) provides comprehensive and regularly updated guidance. Their "Best Practices for the Development of Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Therapies" document covers key principles from cell line selection and manufacturing to preclinical studies and regulatory considerations [5] [6]. This is an essential resource for any researcher translating hPSC science towards the clinic.

FAQs: Addressing Core Research Challenges

Q1: What is the primary cellular mechanism that initiates teratoma formation in hPSC-based therapies? Teratoma formation is primarily initiated by the presence of residual undifferentiated human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) within the differentiated cell product. Even very small quantities of these cells are sufficient; studies demonstrate that the transplantation of as few as 10,000 undifferentiated hPSCs can lead to teratoma formation in immunodeficient mouse models [7] [2]. These residual hPSCs escape differentiation protocols and, once transplanted, utilize their innate pluripotency to form complex tumors containing tissues from all three embryonic germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) [8].

Q2: How do the unique apoptotic pathways in hPSCs present a target for preventing teratomas? Research has revealed that hPSCs possess a unique apoptotic machinery characterized by a biased expression profile of pro- and anti-apoptotic genes. While many pro-apoptotic genes are upregulated, the survival of hPSCs is highly dependent on a few key anti-apoptotic factors, notably survivin (encoded by BIRC5) and Bcl10. These factors are highly expressed in undifferentiated hPSCs but are sharply downregulated upon differentiation. This dependency creates a vulnerability that can be therapeutically targeted. Using small-molecule inhibitors to block these anti-apoptotic factors selectively triggers the intrinsic apoptotic pathway in hPSCs, while sparing differentiated cells [9].

Q3: What are the most sensitive methods for detecting residual hPSCs in a cell therapy product? Sensitive detection is critical for risk assessment. Current consensus recommends in vitro assays over conventional in vivo teratoma assays due to their superior sensitivity and faster results. Key methods include:

- Digital PCR (dPCR) for hPSC-specific RNA: This method allows for the absolute quantification of pluripotency-associated transcripts with high precision.

- Highly Efficient Culture (HEC) Assay: This assay is designed to maximize the opportunity for any residual hPSC to proliferate and form colonies in culture, thereby confirming their presence. These in vitro methods provide a more practical and sensitive framework for evaluating the teratoma formation risk of hPSC-derived cell therapy products before clinical use [10] [11].

Q4: Can you provide a proven experimental protocol for evaluating teratoma risk in vivo? The in vivo teratoma assay remains a gold standard for demonstrating pluripotency and assessing tumorigenic risk.

- Cell Preparation: Prepare a monocellular suspension of your hPSC-derived cell product. It is crucial to include a positive control group of undifferentiated hPSCs.

- Animal Model: Use immunodeficient mice, such as NOD/SCID gamma (NSG) mice, to prevent immune rejection of the human cells.

- Transplantation: Systemically inject (e.g., intravenous) or inject the cells into an ectopic site (e.g., subcutaneous, intramuscular) [12] [8]. The number of cells injected should reflect the clinical dose.

- Monitoring: Observe the animals for a period of 12 to 24 weeks. Teratomas can form as early as 5 weeks post-injection [12].

- Endpoint Analysis: Perform necropsy on animals showing signs of tumor growth or at the study endpoint. Excised tumors are fixed, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological confirmation of trilineage differentiation (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent Results in Selective hPSC Elimination with Small Molecules

Problem: A researcher is using quercetin to eliminate residual hPSCs from a differentiated neuronal cell population, but the results are inconsistent, with some batches showing poor hPSC death.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Drug Exposure | - Check drug concentration and treatment duration.- Use a validated viability assay (e.g., flow cytometry for Annexin V/PI) on a defined co-culture of hPSCs and differentiated cells. | - Optimize the dose and duration. For quercetin, a single treatment sufficient to induce complete cell death of hPSCs is required [9]. |

| Variable Differentiation Efficiency | - Quantify the percentage of undifferentiated cells pre- and post-treatment using flow cytometry for pluripotency markers (OCT4, NANOG). | - Improve the differentiation protocol to minimize initial hPSC residue before applying the purge. |

| Loss of Differentiated Cell Function | - Assess the functionality of the differentiated neurons (e.g., electrophysiology, marker expression) post-treatment. | - Confirm the selective toxicity of the chosen molecule. Consider switching to another specific inhibitor like YM155 (survivin inhibitor) or digoxin (cardiac glycoside), which have shown minimal impact on certain differentiated cells [12] [7]. |

Issue: Failure to Prevent Teratoma Formation After Cell Transplantation

Problem: Despite a pre-transplantation purge step, teratomas still form in animal models after transplantation of an hPSC-derived hepatic progenitor product.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Purging Efficiency | - Spike a known number of luciferase-expressing hPSCs into your product, apply the purge, and use bioluminescence to quantify remaining cells. | - Increase the log-reduction capacity of your purge. A >5-log depletion of hPSCs is likely needed for a billion-cell product [2]. Consider orthogonal safeguards like a NANOG-iCaspase9 suicide gene system, which can achieve >1 million-fold depletion [2]. |

| Purging Method is Not Pluripotent-Specific | - Validate the expression profile of your target (e.g., survivin) in both hPSCs and the therapeutic hepatic progenitors. | - Use a target with higher specificity to the pluripotent state. NANOG is a more specific marker than survivin, which can be expressed in some differentiated progeny [2]. |

| Teratoma from Wrong Differentiated Lineage | - Perform detailed histopathology on the formed teratoma to confirm it originated from pluripotent cells (disorganized tissues) versus a monomorphic tumor from a progenitor. | - This indicates a differentiation protocol issue, not a purge failure. The solution is to improve the lineage specification and purity of the differentiated product [2]. |

Summarized Quantitative Data

Table 1: Efficacy of Small-Molecule Compounds in Selective hPSC Elimination

| Compound | Primary Target | Effective Concentration (in vitro) | hPSC Viability Reduction | Key Differentiated Cells Spared | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin | Survivin | Not fully quantified | Selective and complete cell death | Dopamine neurons, Smooth muscle cells | [9] |

| YM155 | Survivin | Not fully quantified | Efficient killing | Human CD34+ hematopoietic cells | [12] |

| Digoxin | Na+/K+-ATPase | 2.5 μM | ~70% (Annexin V/PI+) | Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (hBMMSCs), hESC-derived MSCs, neurons | [7] |

| Lanatoside C | Na+/K+-ATPase | 2.5 μM | ~82% (Annexin V/PI+) | Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (hBMMSCs), hESC-derived MSCs, neurons | [7] |

Table 2: Performance of Genetic Safeguard Systems for hPSC-Derived Therapies

| System Name | Genetic Basis | Inducing Molecule | Depletion Efficiency | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NANOG-iCaspase9 | iCaspase9 knocked into NANOG locus | AP20187 (1 nM) | 1.75 x 10^6-fold (>>5-log) | Extreme specificity and potency against undifferentiated state [2] |

| ACTB-iCaspase9 | iCaspase9 under constitutive ACTB promoter | AP20187 | Kills all engineered cells | "Global off-switch" for the entire cell product in case of adverse events [2] |

| Embryonic-specific TK | Thymidine Kinase under pmiR-302/367 promoter | Ganciclovir (GCV) | Less efficient than iCaspase-9 | Specific to pluripotent state [12] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Selective Elimination of Residual hPSCs using YM155

Application: Purging residual hiPSCs from a differentiated hematopoietic cell population before transplantation [12].

Materials:

- YM155 survivin inhibitor

- Differentiated cell population (e.g., hPSC-derived CD34+ cells)

- Appropriate cell culture medium (e.g., StemSpan for CD34+ cells)

- Flow cytometry equipment and antibodies for pluripotency markers (e.g., TRA-1-60, SSEA4)

Procedure:

- Harvest Cells: Gently harvest the differentiated cell population, which contains residual hiPSCs, into a single-cell suspension.

- Drug Treatment: Seed the cells in culture plates and add YM155 at the optimized concentration. A vehicle control (e.g., DMSO) must be included.

- Incubation: Incubate the cells with YM155 for a defined period (e.g., 24 hours). The specific duration and concentration require internal optimization.

- Assessment & Transplantation:

- Viability Check: Assess cell viability using trypan blue exclusion.

- Pluripotency Marker Analysis: Analyze the cells by flow cytometry for pluripotency surface markers (e.g., TRA-1-60) to quantify the reduction in the hPSC population.

- Functional Assay: The purged cell product is now ready for downstream functional assays or transplantation into animal models. Studies show this treatment eradicates teratoma formation in NSG mice without compromising the engraftment capacity of human CD34+ cells [12].

Protocol: Validating Purging Efficiency with a NANOG-iCaspase9 Safeguard System

Application: To achieve a ultra-high, specific log-reduction of undifferentiated hPSCs from any hPSC-derived cell product [2].

Materials:

- Genome-edited hPSC line with biallelic NANOG-iCaspase9 knock-in

- Inducer molecule AP20187

- Control differentiated cells (e.g., forebrain progenitors, bone progenitors, liver progenitors)

Procedure:

- Differentiate Engineered Cells: Differentiate the NANOG-iCaspase9 hPSCs into the desired therapeutic progenitor or cell type.

- Spike-in Experiment (Optional but recommended): For a rigorous validation, mix a known number of undifferentiated NANOG-iCaspase9 hPSCs (e.g., 1%) with the differentiated cell product.

- Inducer Treatment: Treat the cell mixture with 1 nM AP20187 for 24 hours.

- Quantify Depletion:

- In vitro Colony Assay: Plate the treated cells under hPSC-self-renewal conditions and count the number of alkaline phosphatase-positive colonies after 7-10 days. Compare to an untreated control.

- In vivo Teratoma Assay: Transplant the AP20187-treated cell product into immunodeficient mice. The result should be a complete absence of teratoma formation over the observation period, demonstrating the efficacy of the safeguard [2].

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

hPSC-Specific Apoptosis Pathway

Diagram 1: Molecular mechanism of small molecule-induced hPSC apoptosis.

Teratoma Risk Mitigation Workflow

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for teratoma risk mitigation.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Teratoma Prevention Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| YM155 | Small-molecule survivin inhibitor; selectively induces apoptosis in hPSCs. | Validated for purging hiPSCs from hematopoietic progenitors without toxicity to CD34+ cells [12]. |

| Digoxin | FDA-approved cardiac glycoside; inhibits Na+/K+-ATPase, cytotoxic to hPSCs. | Kills hESCs but spares differentiated MSCs and neurons; prevents teratoma formation in vivo [7]. |

| AP20187 | Dimerizing drug; induces apoptosis in cells engineered with iCaspase9. | Used with NANOG-iCaspase9 system for ultra-specific, high-efficiency hPSC depletion [2]. |

| Anti-TRA-1-60 Antibody | Cell surface marker for undifferentiated hPSCs; used for FACS analysis/sorting. | Critical for quantifying residual hPSC populations before and after purging interventions. |

| NSG (NOD/SCID/IL2rg-/-) Mice | Immunodeficient mouse model for in vivo teratoma assays. | The gold-standard model for assessing the tumorigenic potential of hPSC-derived products [12] [8]. |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | Highly sensitive nucleic acid quantification for detecting trace levels of hPSC-specific RNA. | An essential in vitro method with superior sensitivity for residual hPSC detection in final products [10] [11]. |

The Critical Role of Rigorous Safety Assessment in Clinical Translation

Technical Support Center: Preventing Teratoma Formation in Pluripotent Stem Cell Therapies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary safety concern associated with pluripotent stem cell-derived therapies? The primary safety concern is teratoma formation, a type of tumor arising from residual undifferentiated human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) that may persist in the differentiated cell product. Even a small number of residual hPSCs (10,000 or fewer) can form a teratoma in vivo [2]. Systemic injection of hiPSCs has been shown to produce multisite teratomas in immune-deficient mice in as little as 5 weeks [12].

FAQ 2: What methods can be used to purge residual undifferentiated hPSCs before transplantation? Two primary methods are compared in recent research:

- Suicide Gene Systems: These involve engineering hPSCs to express a suicide gene, such as inducible Caspase-9 (iCaspase-9), under the control of a pluripotency-specific promoter (e.g.,

pmiR-302/367orNANOG). Administration of a small molecule prodrug (AP20187) activates the suicide mechanism in undifferentiated cells [12] [2]. - Small Molecule Inhibitors: Using chemicals that specifically kill pluripotent cells, such as the survivin inhibitor YM155. This molecule exploits the fact that hiPSCs fully rely on survivin for survival [12].

FAQ 3: How efficient are these purging methods? Efficiency varies significantly between approaches:

- The NANOG-iCaspase-9 suicide gene system can deplete undifferentiated hPSCs by over 1.75 million-fold (10^6) in vitro [2].

- The survivin inhibitor YM155 was found to be more efficient at killing hiPSCs than the iCaspase-9/AP20187 system and fully eradicated teratoma formation in immune-deficient mice [12].

FAQ 4: Is there toxicity to therapeutic cells with these purging methods? Yes, this is a critical consideration. Research indicates:

- The iCaspase-9/AP20187 system showed nonspecific toxicity on human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells, strongly impairing their repopulation capability in adoptive transfers [12].

- In contrast, the survivin inhibitor YM155 demonstrated no toxicity on CD34+ cells, either in vitro or in adoptive transfers, making it a more suitable candidate for hematological applications [12].

FAQ 5: What are the best practices for detecting residual hPSCs in a cell therapy product? In vitro assays are increasingly favored for their sensitivity and efficiency.

- Digital PCR (dPCR) for detecting hPSC-specific RNA and the highly efficient culture (HEC) assay offer superior detection sensitivity compared to conventional in vivo teratoma assays in mice [10].

- Validating these in vitro assays for each specific product is essential for confident safety assessment [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Excessive differentiation in hPSC cultures, leading to heterogeneity and challenges in purifying the target cell type.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Old or improperly stored cell culture medium.

- Solution: Ensure complete cell culture medium (e.g., mTeSR Plus) kept at 2-8°C is less than 2 weeks old [13].

- Cause: Overgrown colonies or uneven cell aggregate sizes during passaging.

- Solution: Passage cultures when colonies are large and compact but before they overgrow. Ensure cell aggregates generated during passaging are evenly sized [13].

- Cause: Cultures are exposed to suboptimal conditions outside the incubator for extended periods.

- Solution: Minimize time culture plates are out of the incubator (aim for less than 15 minutes at a time) [13].

Problem 2: Differentiated cell product is still contaminated with residual pluripotent cells after a purging procedure.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: The purging method lacks sufficient specificity or efficiency for your cell line.

- Solution: Consider switching from a suicide gene/prodrug system to a small molecule inhibitor like YM155, which showed higher efficiency in killing hiPSCs without compromising therapeutic CD34+ cells [12]. Alternatively, implement a genome-edited orthogonal safeguard system that combines multiple safety switches for more robust control [2].

- Cause: The promoter driving the suicide gene is not sufficiently specific to the pluripotent state.

- Solution: Use a promoter with high specificity to undifferentiated cells, such as the NANOG promoter, which is sharply downregulated upon differentiation, unlike other potential markers [2].

Problem 3: Low cell viability or attachment after passaging and purging treatments.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Excessive manipulation or overly harsh dissociation reagents.

- Solution: Reduce pipetting of cell aggregates and optimize incubation time with passaging reagents (e.g., ReLeSR) for your specific cell line [13] [14].

- Cause: Nonspecific toxicity from the purging agent on differentiated cells.

- Solution: If using a suicide gene/prodrug, titrate the prodrug (e.g., AP20187) to the lowest effective concentration. For iCaspase-9, 1 nM AP20187 was optimal, as higher concentrations can downregulate NANOG and reduce system efficiency [2]. If toxicity persists, evaluate alternative agents like YM155 [12].

- Cause: Incorrect plating density or matrix coating.

- Solution: Plate a higher number of cell aggregates initially and ensure you are using the correct tissue culture-treated or non-treated plates for your specific coating matrix (e.g., Vitronectin XF, Matrigel) [13] [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Purging Methods for Residual Undifferentiated hPSCs

| Method | Mechanism | Reported Efficiency | Key Advantages | Key Limitations & Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivin Inhibitor (YM155) | Chemical inhibition of survivin, essential for hPSC survival. | More efficient than iCaspase-9/AP20187; eradicated teratomas in vivo [12]. | No toxicity on CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells; does not require genetic modification [12]. | Specificity for other therapeutically relevant differentiated cell types should be verified per product. |

| iCaspase-9 Suicide Gene | Genetically engineered iCaspase-9 under pluripotency promoter; activated by AP20187 prodrug. | >10^6-fold depletion of hPSCs in vitro with NANOG promoter [2]. | Highly specific and rapid apoptosis; potential for inducible control in vivo [2]. | Nonspecific toxicity of AP20187 prodrug on CD34+ cells, impairing hematopoiesis [12]. |

| Thymidine Kinase (TK) | Genetically engineered TK; activated by ganciclovir prodrug. | Less efficient and rapid than iCaspase-9 [12]. | Well-established "suicide gene" system. | Requires extended in vitro treatment; not suitable for all cell types. |

Table 2: Sensitivity of Assays for Detecting Residual Undifferentiated hPSCs

| Assay Type | Key Examples | Relative Sensitivity | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Assays | Digital PCR (dPCR) for hPSC-specific RNA; Highly Efficient Culture (HEC) Assay [10]. | Superior sensitivity compared to in vivo models [10]. | Requires rigorous validation for each product; faster and more cost-effective than in vivo studies [10]. |

| In Vivo Assays | Teratoma assay in immune-deficient mice (e.g., NSG, NOG) [12] [10]. | Conventional standard, but less sensitive than advanced in vitro methods [10]. | Time-consuming (can take 5+ weeks [12]), expensive, and has ethical considerations regarding animal use. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Purging of Residual hPSCs Using a Survivin Inhibitor This protocol is adapted from findings that YM155 efficiently kills hiPSCs without harming CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells [12].

- Preparation: Differentiate your hPSC line into the desired therapeutic cell population (e.g., hematopoietic progenitors).

- Treatment: At the final stage of differentiation, add the survivin inhibitor YM155 to the culture medium. The optimal concentration and duration must be determined empirically for your specific cell product but were effective in eliminating teratoma risk in pre-clinical models [12].

- Washing: After treatment, wash the cells thoroughly to remove the inhibitor.

- Assessment: Use a highly sensitive assay (e.g., digital PCR for pluripotency markers) to quantify the depletion of residual undifferentiated hPSCs. Validate the functional capacity of the purified therapeutic cell product (e.g., through colony-forming assays for hematopoietic cells).

Protocol 2: Validating a Genome-Edited Safety Switch (NANOG-iCaspase9) This protocol outlines the key steps for implementing and testing the orthogonal safeguard system described by [2].

- Cell Line Engineering:

- Use Cas9 RNP and AAV6-based genome editing to knock-in an iCaspase9 cassette and a fluorescent reporter (e.g., YFP) downstream of the stop codon in the NANOG gene locus, separated by T2A peptides.

- Generate a clonal hPSC line with biallelic integration to prevent escape.

- Validate the edited line for normal karyotype, pluripotency marker expression, and tri-lineage differentiation potential.

- In Vitro Purging Test:

- Differentiate the engineered hPSCs into your target cell type (e.g., liver, bone, or forebrain progenitors).

- Treat the differentiated cell population with 1 nM AP20187 for 24 hours to activate iCaspase9 in any residual NANOG-positive (undifferentiated) cells.

- Measure the depletion of undifferentiated hPSCs using flow cytometry for the reporter (YFP) or pluripotency markers. This system achieved a >10^6-fold depletion [2].

- In Vivo Safety Test:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Teratoma Risk Assessment and Mitigation

| Research Reagent | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Survivin Inhibitor (YM155) | Small molecule that selectively kills pluripotent stem cells by inhibiting survivin (BIRC5), a protein critical for hPSC survival [12]. | Purging residual hiPSCs from a differentiated hematopoietic cell product prior to transplantation [12]. |

| AP20187 | Small molecule dimerizer drug used to activate the inducible Caspase-9 (iCaspase-9) suicide gene system [12] [2]. | Eliminating undifferentiated hPSCs from a culture of NANOG-iCaspase9 engineered cells [2]. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Increases survival of dissociated hPSCs and improves cell viability after passaging or thawing [14]. | Adding to culture medium for 18-24 hours after passaging or thawing hPSCs to reduce apoptosis [14]. |

| Essential 8 Medium | A defined, feeder-free culture medium optimized for the growth and maintenance of human pluripotent stem cells [14]. | Routine culture of hiPSCs to maintain a pluripotent state before initiating differentiation protocols. |

| Geltrex / Matrigel / Vitronectin XF | Extracellular matrix proteins used to coat culture vessels, providing a substrate that supports hPSC attachment and growth in feeder-free conditions [13] [14]. | Coating tissue culture plates to create a suitable surface for plating and maintaining hPSCs. |

Experimental Workflow and Safety Switch Diagrams

Diagram 1: Teratoma risk mitigation workflow for hPSC therapies.

Diagram 2: Genome-edited safety switch mechanism for hPSC purge.

Current Regulatory Expectations for Tumorigenicity Risk Evaluation

Teratoma formation represents a significant safety concern in the development of pluripotent stem cell-derived therapies. As human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) can form these complex tumors containing multiple tissue types, regulatory agencies worldwide require rigorous assessment of tumorigenicity risk before clinical application. This technical support guide examines current regulatory expectations and provides practical methodologies for evaluating and mitigating teratoma formation risk in hPSC-derived cell therapy products (CTPs).

FAQ: Regulatory Framework and Testing Requirements

What is the current regulatory position on in vivo versus in vitro tumorigenicity testing?

Regulatory thinking has evolved significantly, with a 2025 consensus recommendation from the Health and Environmental Sciences Institute's International Cell Therapy Committee highlighting that in vitro assays such as digital PCR (dPCR) detection of hPSC-specific RNA and highly efficient culture (HEC) assays offer superior detection sensitivity compared to conventional in vivo models [10] [15] [11]. While traditional in vivo tumorigenicity assays in immunodeficient mice (e.g., NOD/SCID, NSG) remain part of some regulatory frameworks, there is growing recognition that these models have limitations in predicting human clinical outcomes [15].

How should we approach tumorigenicity testing for products targeting hematologic applications?

For hematologic applications, research demonstrates that systemic injection of hiPSCs produces multisite teratomas in immune-deficient mice as soon as 5 weeks after injection [12]. This finding underscores the critical importance of purging residual undifferentiated PSCs before administration. When considering purge strategies, studies indicate that survivin inhibitor YM155 was more efficient than AP20187/iCaspase-9 for killing hiPSCs without toxicity on CD34+ cells, both in vitro and in adoptive transfers [12].

What are the key regulatory guidelines governing stem cell-based medicinal products?

Regulatory agencies employ a risk-based approach that varies by region [16]. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines form the foundation, with recent updates including:

- ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice (effective July 2025 in EU) emphasizes risk-based quality management and technological innovation in clinical trials [17] [18] [19]

- Regional guidelines specific to advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) in the EU, regenerative medical products in Japan, and biological products in the US [16]

- Product-specific technical guidance for various hPSC-derived CTPs including retinal pigment epithelial cells and articular cartilage regeneration products [16]

Experimental Protocols for Tumorigenicity Assessment

Highly Efficient Culture (HEC) Assay for Residual Undifferentiated hPSCs

The HEC assay provides a sensitive in vitro method for detecting residual undifferentiated hPSCs in final products [10] [11].

Materials and Reagents:

- Rho kinase inhibitor (ROCKi) supplemented culture medium

- Matrigel-coated culture vessels

- Pluripotency markers (e.g., anti-TRA-1-60, anti-SSEA4 antibodies)

- Culture conditions optimized for hPSC growth (mTeSR or equivalent)

Procedure:

- Prepare serial dilutions of the test CTP sample

- Plate cells in ROCKi-supplemented medium on Matrigel-coated plates

- Culture for 14-21 days with regular medium changes

- Score colonies for pluripotent morphology and confirm with immunocytochemistry

- Calculate the frequency of undifferentiated hPSCs based on colony formation

Validation Parameters:

- Limit of detection (LOD) established using spiked samples

- Inter- and intra-assay precision

- Specificity against differentiated cell types

Digital PCR (dPCR) for hPSC-Specific Markers

dPCR offers a highly sensitive molecular method for quantifying residual undifferentiated hPSCs [10] [11].

Workflow:

Key Pluripotency Markers:

- mRNA transcripts: NANOG, POUSF1 (OCT4), SOX2

- Long non-coding RNAs: specific to pluripotent state

- Micro-RNAs: miR-302 family, miR-367

Validation Requirements:

- Establish detection limit with spike-in experiments

- Demonstrate specificity across differentiated lineages

- Determine linear dynamic range

- Assess interference from matrix effects

In Vivo Tumorigenicity Assay in Immunodeficient Mice

While in vitro methods are increasingly preferred, understanding traditional in vivo approaches remains important [10] [12] [20].

Animal Models:

- NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIL2rgtm1Wjl (NSG) mice

- NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIL2rgtm1Sug (NOG) mice

- Other severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) models

Experimental Design:

- Test groups: CTP, positive control (hPSCs), negative control (fully differentiated cells)

- Cell doses: Maximum feasible dose (MFD) plus lower doses

- Route of administration: product-specific (subcutaneous, intramuscular, intravenous)

- Observation period: minimum 12-16 weeks

- Endpoints: palpation, imaging, necropsy, histopathology

Comparative Analysis of Detection Methods

Table 1: Sensitivity Comparison of Tumorigenicity Assessment Methods

| Method | Detection Limit | Time Required | Key Advantages | Regulatory Acceptance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo tumorigenicity | ~1×10⁴ cells [20] | 12-16 weeks | Whole-system assessment | Traditional standard |

| Highly Efficient Culture (HEC) | ~1×10⁻⁶ [10] | 2-3 weeks | Functional assessment of pluripotency | Increasing acceptance |

| Digital PCR | ~1×10⁻⁶ [10] [11] | 2-3 days | Quantitative, high-throughput | Supported by recent consensus |

| Flow Cytometry | ~1×10⁻⁴ | Hours | Rapid, single-cell resolution | Complementary technique |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Tumorigenicity Risk Assessment

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Markers | Anti-TRA-1-60, Anti-SSEA4, Anti-OCT4 | Immunodetection of residual hPSCs | Specificity for undifferentiated state |

| Molecular Assays | dPCR assays for NANOG, POUSF1 | Quantitative residual hPSC detection | Primer/probe validation critical |

| Culture Reagents | ROCK inhibitor, mTeSR medium | HEC assay | Optimize for sensitive detection |

| Animal Models | NSG, NOG mice | In vivo tumorigenicity | Institutional animal care protocols |

| Control Materials | Reference hPSCs, Differentiated cells | Assay qualification | Well-characterized biospecimens |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Results in HEC Assay

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Variability in culture conditions

- Solution: Standardize matrix coating procedures and qualify all culture reagents

- Cause: Suboptimal ROCKi concentration

- Solution: Titrate ROCKi (typically 5-10 μM) using positive control hPSCs

- Cause: Overgrowth of differentiated cells

- Solution: Include selective agents or use morphological criteria early in culture

Problem: High Background in dPCR Assay

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: RNA degradation

- Solution: Implement rigorous RNA quality control (RIN >8.0)

- Cause: Non-specific amplification

- Solution: Optimize primer annealing temperature and validate specificity

- Cause: Inhibitors in sample matrix

- Solution: Include internal controls and optimize nucleic acid purification

Problem: Variable Teratoma Formation in Animal Models

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Immunodeficient mouse strain variability

- Solution: Use consistent strain source and monitor immune leakage

- Cause: Injection technique variability

- Solution: Standardize cell preparation and injection protocols across operators

- Cause: Cell viability issues

- Solution: Minimize time between cell preparation and implantation

Risk Mitigation Strategies

Genetic Safety Switches

Engineering hPSCs with suicide genes provides a safety strategy for eliminating teratoma-initiating cells [12] [20].

Approaches:

- Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) + ganciclovir [20]

- Integrated into NANOG locus via homologous recombination

- Enables selective elimination of undifferentiated cells

- Inducible caspase-9 (iCaspase-9) + AP20187 [12]

- Controlled by pluripotency-specific promoters (pmiR-302/367)

- Demonstrated efficacy in vitro but showed toxicity to CD34+ cells

Small Molecule Inhibitors

Survivin inhibitor YM155 [12]:

- Shows high efficiency in eliminating hiPSCs

- No observed toxicity to CD34+ hematopoietic cells

- Effectively prevents teratoma formation in immunodeficient mice

The regulatory landscape for tumorigenicity risk assessment of hPSC-derived therapies is rapidly evolving toward more sensitive, human-relevant in vitro methods. A comprehensive testing strategy should integrate orthogonal methods including highly sensitive molecular assays (dPCR), functional culture assays (HEC), and appropriate in vivo models when justified. Implementation of risk mitigation strategies such as genetic safety switches or small molecule purging approaches can further enhance product safety. As regulatory thinking continues to advance, maintaining awareness of updated guidelines and consensus recommendations is essential for successful development of safe hPSC-based therapies.

Proactive Prevention: Strategies for Eliminating Residual Pluripotent Stem Cells

Targeting hPSC-Specific Surface Markers for Selective Cell Removal

FAQ: Addressing Researcher Questions on PSC Removal Strategies

Q1: What are the key cell surface markers used to identify and target human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) for removal?

The most well-characterized cell surface markers for identifying undifferentiated hPSCs are the glycolipid antigens SSEA3 and SSEA4, and the glycoprotein antigens TRA-1-60 and TRA-1-81 [21] [22]. These markers were initially identified on human embryonic carcinoma cells and are also expressed by the inner cell mass of pre-implantation human embryos, providing a reliable signature of the pluripotent state [21]. Monitoring these markers provides a standardized measure of cell status and is fundamental for comparing different cell lines and culture conditions [22].

Q2: Why is it critical to remove residual undifferentiated hPSCs from differentiated cell populations intended for therapy?

Residual undifferentiated hPSCs possess unlimited self-renewal capacity and are intrinsically tumorigenic, capable of forming teratomas (benign tumors containing tissues from all three germ layers) upon transplantation [23] [10]. Studies have shown that even a very small number of residual undifferentiated cells—in some cases, as few as 20 to 100 undifferentiated stem cells within a population of differentiated cells—can eventually lead to teratoma formation [23] [12]. A clinical case report documented the occurrence of a rapidly growing, metastatic immature teratoma in a patient who received autologous iPSC-derived pancreatic beta cells, underscoring this critical safety risk [23].

Q3: What are the primary strategic approaches for eliminating residual hPSCs?

The main strategies can be categorized as follows:

- Pharmacological: Using small-molecule compounds that induce selective apoptosis in hPSCs.

- Immunological: Employing antibodies or antibody-drug conjugates that target hPSC-specific surface markers.

- Genetic: Engineering hPSCs with "safety switches" or suicide genes that can be activated to eliminate the cells.

- Physical Separation: Using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) to deplete marker-positive hPSCs from a mixed population [23] [12] [2].

Q4: What are common challenges when using cell surface markers for hPSC depletion, and how can they be troubleshooted?

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Purity Post-Depletion | Inefficient antibody binding; incomplete cell separation. | Optimize antibody concentration and incubation time; use a combination of markers (e.g., SSEA-3, TRA-1-60) for more robust depletion; validate separation efficiency with flow cytometry [12] [22]. |

| Low Viability of Target Cell Population | Excessive mechanical stress during FACS; cytotoxicity from the depletion method. | Use gentler sorting settings; consider magnetic bead-based separation (MACS) as a lower-stress alternative; test viability post-sorting and adjust protocols accordingly [12]. |

| Incomplete hPSC Elimination & Teratoma Formation | Low sensitivity of the detection or elimination method; presence of hPSCs that do not express the targeted marker. | Employ highly sensitive in vitro assays (e.g., digital PCR, highly efficient culture assays) to detect residual hPSCs; consider a multi-pronged approach combining surface marker depletion with a pharmacological agent [10]. |

| Unexpected Toxicity to Differentiated Cells | The targeted surface marker or pathway is also expressed at low levels in the therapeutic cell population. | Thoroughly validate marker specificity for undifferentiated cells across your specific differentiated cell types; consider alternative, more specific targets like Dsg2 [24] [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Issues in hPSC Removal

Problem: Inconsistent results in antibody-based targeting of hPSCs.

- Solution 1: Validate Antibody Specificity and Titer. Not all antibodies perform equally. Confirm the specificity of your antibody for the intended target (e.g., SSEA-4, TRA-1-60) using appropriate positive (undifferentiated hPSCs) and negative (fully differentiated somatic cells) controls. Perform a titration experiment to determine the optimal antibody concentration that maximizes signal-to-noise ratio [21] [22].

- Solution 2: Account for Pluripotency State Heterogeneity. hPSC cultures can contain subpopulations in different pluripotent states (naïve vs. primed), which express different surface markers. For instance, naïve hPSCs may express SSEA-4 differently than primed cells. Characterize your starting cell population and ensure your chosen markers are appropriate for the specific pluripotent state you are targeting [22] [25].

Problem: Differentiated cell product is compromised after hPSC removal treatment.

- Solution 1: Titrate Drug Concentrations and Exposure Time. When using small-molecule inhibitors or antibody-drug conjugates, a dose-response and time-course experiment is essential. The goal is to find a window where hPSCs are effectively killed while differentiated cells remain viable and functional [12] [24].

- Solution 2: Implement a "Safety Switch" as a Contingency. For critical applications, use hPSCs that have been genetically engineered with an inducible "safety switch," such as iCaspase9 under a pluripotency-specific promoter (e.g., NANOG). This provides a fail-safe mechanism to eliminate the entire cell product, including any potentially contaminating hPSCs, after transplantation if adverse events arise [2].

Experimental Protocol: Selective Elimination of hPSCs Using an Anti-Dsg2 Antibody-Drug Conjugate

This protocol is adapted from Park et al. (2020) and outlines a method for selectively eliminating undifferentiated hPSCs by targeting the highly specific surface marker Desmoglein 2 (Dsg2) with a doxorubicin (DOX) conjugate [24].

1. Principle The monoclonal antibody K6-1 specifically targets Dsg2, which is highly expressed on undifferentiated hPSCs but at low levels in differentiated somatic cells. Conjugating this antibody to the chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin creates a targeted delivery system (K6-1-DOX). The conjugate is selectively internalized by Dsg2-positive hPSCs, leading to intracellular DOX release and apoptosis, while sparing Dsg2-negative differentiated cells [24].

2. Reagents

- Purified Anti-Dsg2 Antibody (K6-1)

- Doxorubicin (DOX)

- Conjugation buffer

- hPSC culture (undifferentiated control)

- Differentiated somatic cell culture (negative control)

- Cell culture media

3. Step-by-Step Procedure 1. Preparation of ADC: Conjugate the K6-1 antibody to doxorubicin via a chemical linker. Purify the K6-1-DOX conjugate and characterize it using HPLC or SDS-PAGE to confirm conjugation efficiency and stability [24]. 2. In Vitro Treatment: * Culture undifferentiated hPSCs and the differentiated cell product of interest. * Treat cells with varying concentrations of K6-1-DOX (e.g., 0.1 - 10 µM) for 24-72 hours. * Include control groups: untreated cells, cells treated with unconjugated DOX, and cells treated with an irrelevant antibody-DOX conjugate. 3. Assessment of Cytotoxicity: * Measure cell viability using assays like MTT or CellTiter-Glo. * Analyze apoptosis via flow cytometry for Annexin V/propidium iodide staining. * Confirm selective elimination by quantifying the depletion of pluripotency marker-positive cells (e.g., via flow cytometry for OCT4 or NANOG) in the mixed population. 4. In Vivo Validation (Teratoma Assay): * Pre-treat a sample of hPSCs with K6-1-DOX or a control. * Inject the treated cells into immunodeficient mice (e.g., NSG). * Monitor the mice for teratoma formation over 8-16 weeks. Effective elimination should result in no teratomas in the K6-1-DOX group, while control groups should develop tumors [24].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for hPSC Removal Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-SSEA-3/-4, TRA-1-60/-81 Antibodies [21] | Immunophenotyping and physical depletion (FACS/MACS) of undifferentiated hPSCs. | Standard panel for defining pluripotent state; efficiency can be affected by marker heterogeneity. |

| Anti-Dsg2 Antibody (K6-1) [24] | Target for highly specific antibody-drug conjugates against hPSCs. | Reported to be highly differentially expressed in hPSCs vs. somatic tissues. |

| Survivin Inhibitor (YM155) [12] | Small molecule that induces selective apoptosis in hPSCs. | Can be toxic to some differentiated cell types (e.g., hematopoietic stem cells); requires careful titration [12] [2]. |

| Inducible Caspase 9 (iCasp9) System [2] | Genetically encoded "safety switch" activated by small molecule AP20187. | Can be placed under a pluripotency-specific promoter (e.g., NANOG) for selective killing or a ubiquitous promoter for total product elimination. |

| PluriTest Assay [cite[1]] | Bioinformatic tool to assess pluripotency and identity of hPSCs based on gene expression. | Useful for quality control and verifying the undifferentiated state of cells pre- and post-removal strategies. |

Workflow Diagram: Strategic Approaches to Eliminate Residual hPSCs

The diagram below illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting an hPSC removal strategy based on experimental or therapeutic goals.

Optimizing Differentiation Protocols to Minimize Undifferentiated Cell Populations

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why is it critical to minimize undifferentiated hPSC populations in cell therapy products? Even a small number of residual undifferentiated human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) can form teratomas in vivo. Studies have shown that as few as 10,000 undifferentiated hPSCs can generate these tumors, which presents a significant safety risk for clinical therapies. When transplanting billions of hPSC-derived cells, even a 0.001% residual undifferentiated cell contamination could be therapeutically unacceptable [2] [26].

FAQ 2: What are the primary methods for eliminating residual undifferentiated hPSCs? There are three predominant strategies:

- Physical separation based on pluripotent-specific cell surface antigens (e.g., depletion of SSEA-4+, TRA-1-60+ cells).

- Chemical elimination using small molecules that selectively induce apoptosis in pluripotent cells (e.g., survivin inhibitors like YM155).

- Genetic safeguards involving genome-edited suicide genes (e.g., inducible Caspase-9 under a NANOG promoter) that can be activated before transplantation [12] [2] [26].

FAQ 3: My hPSC cultures are showing excessive spontaneous differentiation (>20%). What could be the cause? Excessive differentiation in maintenance cultures can be caused by several factors:

- Using culture medium that has been stored at 2-8°C for more than two weeks.

- Allowing the culture plate to remain outside the incubator for extended periods (>15 minutes).

- Overgrown colonies or unevenly sized cell aggregates after passaging.

- Insufficient colony density after passaging [13].

- Cells located on the rim of colonies lacking cell-to-cell contact, which can trigger spontaneous differentiation [27].

FAQ 4: How can culture conditions influence the differentiation potential of PSCs? The culture medium can alter the differentiation potential of PSCs. Cells cultured in medium that supports the glycolytic pathway tend to maintain high expression of CHD7 and retain strong differentiation potential. In contrast, culture conditions that support mitochondrial function can reduce CHD7 levels and compromise differentiation capability [27].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Problem: Low cell attachment after passaging during differentiation protocols.

- Potential Solutions [13]:

- Plate a higher number of cell aggregates initially (e.g., 2-3 times higher) to maintain a more densely confluent culture.

- Work quickly after cells are treated with passaging reagents to minimize the duration that cell aggregates are in suspension.

- Reduce the incubation time with passaging reagents, as your specific cell line may be more sensitive.

- Do not excessively pipette to break up cell aggregates. Instead, increase the incubation time with the passaging reagent by 1-2 minutes to allow natural dissociation.

- Ensure you are using the correct culture plate type (non-tissue culture-treated for certain coatings like Vitronectin XF; tissue culture-treated for others like Matrigel).

Problem: Differentiated cells detach along with colonies when using passaging reagents like ReLeSR.

- Potential Solutions [13]:

- Decrease the incubation time with the reagent by 1-2 minutes.

- Decrease the incubation temperature to room temperature (15-25°C).

Problem: Cell aggregates obtained during passaging are too large for optimal differentiation.

- Potential Solutions [13]:

- Increase the incubation time with the dissociation reagent.

- Increase pipetting of the cell aggregates to break them up, but avoid generating a single-cell suspension.

- Add a wash step using D-PBS (without Ca++ and Mg++) before adding the non-enzymatic passaging reagents.

Quantitative Data & Safety Strategies

The following table summarizes and compares key strategies for eliminating tumorigenic hPSCs, a critical step for safe cell therapy [12] [2] [26].

Table 1: Comparison of Strategies for Eliminating Tumorigenic Pluripotent Stem Cells

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Reported Efficacy | Key Advantages | Key Limitations / Toxicities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivin Inhibition (YM155) | Chemical inhibitor of survivin (BIRC5), an protein essential for hPSC survival. | Efficiently kills hiPSCs; purge fully eradicated teratoma formation in mice [12]. | More efficient than iCaspase-9/AP20187 for killing hiPSCs; No toxicity on CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells in vitro and in adoptive transfers [12]. | Broad expression of survivin in some differentiated cell types may limit specificity [2]. |

| Inducible Caspase-9 (iCaspase-9) | Genetically engineered "suicide gene" activated by a small molecule (AP20187), triggering apoptosis. | >106-fold depletion of undifferentiated hPSCs [2]. | Highly specific, rapid, and irreversible apoptosis; Biallelic knock-in prevents escape [2]. | Nonspecific toxicity of prodrug AP20187 on some cell types (e.g., CD34+ cells), impairing human hematopoiesis [12]. Higher AP20187 concentrations can downregulate NANOG [2]. |

| Thymidine Kinase (TK) | Viral/ bacterial enzyme that converts prodrug ganciclovir (GCV) into a toxic nucleotide analog. | Successful ablation of teratomas in various models [12] [2]. | Well-established system. | Requires extended in vitro treatment for full efficacy; potential for bystander effect [12]. |

| NANOG-iCasp9 Orthogonal Safeguard | Genome-edited iCaspase-9 knocked into endogenous NANOG locus, specific to pluripotent state. | 1.75 x 106-fold depletion of undifferentiated hPSCs; prevented teratoma formation [2]. | Highly specific to undifferentiated state; faithful to endogenous NANOG downregulation; safeguards cannot be silenced without loss of pluripotency [2]. | Requires genome editing; optimal at low AP20187 doses (1 nM) [2]. |

Table 2: Key Reagents for Targeting Undifferentiated hPSCs

| Reagent / Method | Function in Elimination Strategy | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| YM155 | Small molecule survivin inhibitor; selectively induces apoptosis in undifferentiated hPSCs. | Demonstrated efficiency in purging hiPSCs without toxicity to CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells [12]. |

| AP20187 | Small molecule dimerizer drug; activates the inducible Caspase-9 (iCaspase-9) suicide gene. | Can exhibit non-specific toxicity on certain cell types, including hematopoietic CD34+ cells [12]. Optimal dose for NANOG-iCaspase9 is 1 nM [2]. |

| Ganciclovir (GCV) | Prodrug; converted to a toxic compound by thymidine kinase (TK), killing transduced cells. | Less efficient and rapid than iCaspase-9/AP20187 system; may require longer treatment duration [12]. |

| Anti-SSEA-4 / TRA-1-60 Antibodies | Antibodies for cell surface markers; used for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to deplete undifferentiated cells. | Results can be affected by gating strategy; procedure can be time-consuming and expensive, and may affect viability of therapeutic cells [12] [26]. |

| Geltrex/Matrigel | Extracellular matrix (ECM) coating; provides a more in vivo-like environment that can enhance differentiation efficiency. | Implementation of Geltrex in a pancreatic differentiation protocol significantly enhanced the expression of pancreatic markers in dental stem cells [28]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Purging Residual hPSCs with Survivin Inhibitor YM155

This protocol is adapted from methods used to eliminate hiPSCs before grafting in hematopoietic contexts [12].

- Preparation: Differentiate your hiPSCs toward the desired lineage using your established protocol.

- Treatment: At the end of the differentiation process, treat the heterogeneous cell population containing residual hiPSCs with a survivin inhibitor (e.g., YM155) at a determined optimal concentration.

- Note: The exact concentration and duration should be determined empirically for each cell line and differentiation protocol. In the cited study, YM155 was more efficient than AP20187/iCaspase-9 at killing hiPSCs.

- Assessment: After treatment, assess the viability of both the target differentiated cells and the residual hiPSCs.

Protocol 2: Using a Genome-Edited NANOG-iCaspase9 Safeguard

This protocol outlines the use of an orthogonal safety switch to selectively eliminate undifferentiated hPSCs [2].

- Cell Line Generation: Engineer hPSC lines to biallelically express an inducible Caspase9 (iCaspase9) cassette downstream of the endogenous NANOG coding sequence using CRISPR/Cas9 RNP and AAV6-mediated genome editing. The construct should use T2A peptides to separate NANOG, iCaspase9, and a fluorescent reporter (e.g., YFP).

- Validation: Validate the edited cell lines for normal pluripotency, karyotype, and differentiation potential. Confirm that YFP (reporting iCaspase9 expression) is uniformly expressed in undifferentiated cells and extinguished upon differentiation.

- Pre-transplantation Purging: Before transplanting differentiated cell products, treat the cell culture with 1 nM AP20187 for 12-24 hours to selectively eliminate any residual NANOG-positive (undifferentiated) cells.

- Confirmation: Confirm the depletion efficiency via flow cytometry for pluripotency markers and functional in vivo teratoma assays in immunodeficient mice.

Signaling Pathways & Experimental Workflows

Diagram: Orthogonal Safeguard Strategy for hPSC Therapy Safety

Diagram 1: Orthogonal Safeguard Strategy for hPSC Therapy Safety. This workflow shows two distinct, drug-inducible safety switches integrated into hPSCs. Strategy 1 (NANOG-iCaspase9) is activated before transplantation to selectively eliminate residual undifferentiated cells. Strategy 2 (ACTB-TK/iCaspase9) acts as a master "off-switch" for the entire graft if adverse events occur after transplantation [2].

Diagram: Strategic Workflow to Minimize Teratoma Risk

Diagram 2: Strategic Workflow to Minimize Teratoma Risk. A multi-step approach is critical for ensuring the safety of hPSC-derived therapies. This involves optimizing the initial differentiation, maintaining culture quality to prevent spontaneous differentiation, actively purging residual pluripotent cells, and rigorously validating the final product [12] [28] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Geltrex/Matrigel | Extracellular matrix providing a complex 3D environment for enhanced differentiation. | Significantly enhanced the expression of pancreatic markers (Foxa-2, Sox-17, PDX-1) in dental stem cell differentiation protocols [28]. |

| Survivin Inhibitor (YM155) | Small molecule that selectively targets survivin, a protein highly relied upon by hPSCs for survival. | A key chemical for purging residual hiPSCs; shown to be efficient and non-toxic to CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells [12]. |

| AP20187 | Bioactive dimerizer drug used to activate the inducible Caspase-9 (iCaspase9) suicide gene. | The optimal dose for systems like NANOG-iCaspase9 is 1 nM; higher concentrations can downregulate NANOG [2]. |

| Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent | Enzyme-free solution for passaging hPSCs as clumps, preserving cell viability and surface markers. | Critical for maintaining healthy cultures; over-incubation or excessive pipetting can result in overly small aggregates or single cells, which may not be ideal for some differentiation protocols [13]. |

| mTeSR Plus / Essential 8 Media | Defined, feeder-free culture media for the maintenance of undifferentiated hPSCs. | The quality and freshness of the culture medium is paramount; old medium can lead to excessive spontaneous differentiation [13] [27]. |

| Anti-Pluripotency Markers (SSEA-4, TRA-1-60) | Antibodies for detecting undifferentiated hPSCs via flow cytometry or immunocytochemistry. | Used for quality control to quantify residual undifferentiated cells before and after purging strategies. Results can be sensitive to gating strategies [12] [26]. |

FAQs: miRNA and Genetic Circuits in Teratoma Prevention

Q1: How do miRNA-based strategies specifically prevent teratoma formation in pluripotent stem cell therapies? miRNA-based strategies leverage the natural role of microRNAs in post-transcriptional regulation to eliminate residual undifferentiated human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) from differentiated cell therapy products. These strategies typically target hPSC-specific markers or pathways essential for pluripotency. For instance, introducing miRNAs that trigger the degradation of core pluripotency transcripts (like c-Myc) or promoting the expression of pro-differentiation miRNAs can selectively remove tumorigenic cells, thereby mitigating the risk of teratoma formation upon transplantation [30] [26].

Q2: What is the primary technical challenge in validating miRNA-target interactions for a novel genetic circuit? The primary challenge lies in the accurate prediction and experimental validation of miRNA-target interactions. Computational predictions suggest a single miRNA can regulate hundreds of mRNA molecules, but these interactions are highly dependent on cellular context, miRNA abundance, and the presence of competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs). False positives are common, and validation requires rigorous methodologies beyond bioinformatics, such as overexpression or knockdown experiments combined with high-throughput sequencing to confirm the specific degradation of the target transcript [31].

Q3: My genetic circuit for cell sorting shows perfect performance in vitro, but how do I assess its in vivo efficacy against teratoma formation? The most stringent assay for assessing teratoma risk is in vivo teratoma formation. This involves transplanting your cell therapy product into immunodeficient mouse models (e.g., SCID, NOD) and monitoring for tumor formation over time. This method provides a comprehensive, biologically relevant assessment of the product's safety. Additionally, highly sensitive in vitro assays like digital PCR (dPCR) for residual hPSC-specific RNA can be used to quantify the remaining undifferentiated cells in your product before transplantation, providing a complementary safety checkpoint [32] [10].

Q4: Why might my miRNA expression data from high-throughput sequencing be unreliable, and how can I improve it? RNA sequencing data for miRNA can be unreliable due to several factors:

- Low RNA Quality: Degraded RNA can generate fragments that are mis-annotated as miRNAs [31].

- Low Abundance Targets: miRNAs expressed at very low levels or in a temporally restricted manner may have few mapped reads, making their validation difficult [31].

- Inconsistent Processing Guidelines: Without stringent bioinformatics pipelines that check for features like 3' overhangs and 5' end compatibility with the miRNA processing machinery, many false-positive miRNAs can be annotated [31]. To improve reliability, ensure high-quality RNA input, use enrichment strategies for small RNAs, and adhere to established miRNA annotation guidelines that require multiple lines of evidence [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting miRNA Detection and Quantification

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low or no amplification signal for abundant miRNA targets. | Insufficient RNA input or suboptimal reverse transcription efficiency. | Titrate total RNA input up to 250 ng. Double the amount of reverse transcriptase enzyme to 6.6 U/µL [33]. |

| Multiple peaks in melt curve analysis (SYBR Green assays). | - Contaminating genomic DNA.- High primer concentration leading to primer-dimers.- Non-specific amplification. | - DNase-treat the RNA sample.- Optimize forward primer concentration to ~200 nM.- Check primer specificity and ensure a positive control is included [33]. |

| Amplification in No-Template Control (NTC) with Ct < 38. | - Reagent contamination.- Contamination from plasmids or artificial templates in the lab. | - Change reagents and use dedicated equipment.- Decontaminate surfaces with a DNA degradation solution. Work in a separate location if necessary [33]. |

| Inconsistent results from highly multiplexed miRNA profiling (e.g., Megaplex). | A subset of assays inherently exhibits lower NTC Ct values in large multiplex pools. | Consider these assays semi-quantitative in the multiplex format. Validate significant fold-changes using corresponding individual TaqMan MicroRNA Assays [33]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Genetic Circuit Performance

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic circuit fails to activate cell sorting mechanism in a subset of cells. | Heterogeneous expression of circuit components or variable cellular state. | Implement a dual-reporter system to identify and isolate cells with correct circuit function. Optimize delivery method (e.g., lentiviral vs. mRNA transfection) for more consistent expression. |

| High false-positive rate in cell sorting, removing differentiated cells. | Promoter leakiness or non-specific activity of the genetic circuit's sensor. | Use a more specific hPSC-specific promoter (e.g., with enhanced epigenetic silencing upon differentiation). Incorporate additional logic gates (AND gates) that require multiple hPSC markers for activation. |

| Differentiated cell product shows reduced viability or function after sorting. | Off-target effects of the cell-killing mechanism (e.g., toxin gene) or persistent low-level activity. | Employ a "suicide switch" that can be activated only for a limited time post-sorting. Validate the absence of off-target transcript degradation using RNA-Seq on the final product. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Highly SensitiveIn VitroDetection of Residual hPSCs

This protocol uses digital PCR (dPCR) to quantify trace amounts of residual undifferentiated hPSCs in a differentiated cell therapy product, a key safety assessment [10].

- RNA Extraction: Isolve total RNA from the cell therapy product using a column-based method that enriches for small RNAs. Determine RNA concentration and quality (e.g., RIN > 8.0).

- cDNA Synthesis: Convert RNA to cDNA using a reverse transcription kit suitable for a wide dynamic range. Include controls without reverse transcriptase (-RT) to detect genomic DNA contamination.

- dPCR Setup: Prepare the dPCR reaction mix using probes specific to hPSC markers (e.g., NANOG, POUSF1/OCT4). Include a reference gene for normalization.

- Partitioning and Amplification: Load the reaction mix into a dPCR chip or droplet generator to partition the sample into thousands of individual reactions. Perform PCR amplification.

- Analysis: Use the dPCR analyzer to count the positive and negative partitions. Calculate the absolute copy number of the hPSC-specific transcript and the reference gene per ng of total RNA. The limit of detection (LOD) for this method is superior to traditional qPCR [10].

Protocol 2:In VivoTeratoma Formation Assay

This is the "gold standard" assay to evaluate the tumorigenic potential of your cell product in an in vivo model [32].

- Cell Preparation: Harvest hPSCs or your final cell therapy product. Prepare a single-cell suspension in an appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS) mixed with Matrigel to enhance engraftment.

- Animal Model: Use immunodeficient mouse strains (e.g., Nu/Nu nude, NOD-SCID) to prevent immune rejection. Anesthetize the mice using an isoflurane system.

- Cell Transplantation: Inject cells subcutaneously, intramuscularly, or into an organ-specific site (e.g., intramyocardial). The critical cell number varies by site; for example, ~1×10⁵ cells may be needed for intramyocardial injection, while as few as 1×10⁴ may suffice for skeletal muscle [32].

- Monitoring: Monitor mice for teratoma formation over 12-20 weeks. For cells expressing reporters (e.g., luciferase), use bioluminescence imaging (BLI) for non-invasive, longitudinal tracking.

- Histological Analysis: Upon endpoint, resect the resulting teratomas. Fix, section, and stain with H&E. Confirm the presence of tissues derived from all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) to validate pluripotency [32].

Data Presentation

Table 3: Key RNA Degradation Pathways in Pluripotent Stem Cells

This table summarizes the core machinery that can be harnessed by miRNA strategies and genetic circuits to degrade pluripotency transcripts [30].

| Degradation Pathway | Key Complex/Enzyme | Direction | Primary Role in PSCs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deadenylation-dependent decay | CCR4-NOT, PAN2-PAN3 | 3' → 5' | Shortens the poly(A) tail, marking RNAs for decay; fine-tunes transcript abundance. |

| 5'→3' exonucleolytic decay | XRN1 (exonuclease), DCP1/DCP2 (decapping) | 5' → 3' | Mediates transcript clearance after decapping; maintains pluripotency network responsiveness. |

| 3'→5' decay (RNA exosome) | Exosome complex (with TRAMP/NEXT/PAXT) | 3' → 5' | Major nuclease for nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA surveillance; degrades misprocessed RNAs. |

| Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD) | UPF1, SMG1, SMG6 | Specialized | Quality control; also actively degrades transcripts of core pluripotency factors like c-Myc. |

| miRNA-mediated decay | RISC (Ago2, TRBP, Dicer) | Specialized | Selectively degrades or represses target mRNAs through sequence-specific binding. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: miRNA Biogenesis and Function

Diagram Title: miRNA Biogenesis, Processing, and Mechanism of Action

Diagram Title: Integrated Strategy for Teratoma Risk Mitigation

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| TaqMan MicroRNA Assays | For sensitive and specific quantification of individual mature miRNA levels from total RNA [33]. |

| NCode VILO miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit | A specialized kit for reverse transcribing miRNA, ideal for use with SYBR Green-based detection methods [33]. |

| Matrigel | Used to suspend cells for transplantation in teratoma formation assays, enhancing engraftment efficiency [32]. |

| Immunodeficient Mouse Models (e.g., Nu/Nu, SCID, NSG) | In vivo hosts for teratoma assays, as they do not reject transplanted human cells [32]. |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) Systems | Provides absolute quantification of residual hPSC-specific markers with high sensitivity, crucial for product safety release [10]. |

| Rho Kinase Inhibitor (ROCKi) | Improves the survival and viability of hPSCs during single-cell passaging and preparation for assays [10]. |

FAQs: Core Principles and Method Selection