Taming Variability: A Researcher's Guide to Robust and Reproducible Stem Cell-Derived Organoid Models

Stem cell-derived organoids have emerged as transformative tools for disease modeling and drug development, yet their potential is often hampered by variability and reproducibility challenges.

Taming Variability: A Researcher's Guide to Robust and Reproducible Stem Cell-Derived Organoid Models

Abstract

Stem cell-derived organoids have emerged as transformative tools for disease modeling and drug development, yet their potential is often hampered by variability and reproducibility challenges. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, addressing the core issue of variability from foundational principles to advanced applications. We explore the intrinsic sources of variation stemming from different stem cell sources and culture components, detail methodological best practices for establishing standardized protocols, and offer a systematic troubleshooting framework for common technical pitfalls. Finally, we present validation strategies and comparative analyses to benchmark organoid performance against traditional models, empowering scientists to generate more robust, reliable, and clinically predictive organoid systems for precision medicine.

Understanding the Roots: Deconstructing the Intrinsic and Extrinsic Sources of Organoid Variability

Organoid technology represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, providing three-dimensional (3D) in vitro models that mimic the structural and functional complexity of human organs. These advanced models are primarily derived from two principal stem cell sources: Pluripotent Stem Cells (PSCs), including Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) and induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs), and Adult Stem Cells (aSCs), also known as tissue-specific stem cells [1] [2]. A critical challenge across all organoid systems is managing the inherent variability, which is profoundly influenced by the choice of stem cell source. This technical support center provides a comprehensive troubleshooting guide to help researchers identify, understand, and mitigate the specific sources of variability associated with iPSC, ESC, and aSC-derived organoids, thereby enhancing the reliability and reproducibility of their experimental outcomes.

The choice of stem cell source dictates fundamental aspects of your organoid model, including its developmental representation, cellular complexity, and key variability challenges.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Variability of Different Stem Cell Sources for Organoids

| Stem Cell Source | Developmental Stage Modeled | Cellular Complexity | Primary Advantages | Inherent Variability Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Early organogenesis and fetal development [1] [2] | Multi-lineage, can include multiple tissue-specific cell types [1] | Model genetic disorders; patient-specific; no ethical concerns of ESCs [1] [3] | Donor-specific genetic background; reprogramming method; differentiation efficiency [4] |

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Early organogenesis and fetal development [2] | Multi-lineage, can include multiple tissue-specific cell types [2] | High pluripotency; considered the "gold standard" for PSCs [2] | Ethical constraints; limited donor diversity; line-to-line differences [2] |

| Adult Stem Cells (aSCs) | Adult tissue homeostasis and repair [1] [2] | Typically single epithelial lineage, lacks mesenchymal components [4] [2] | High fidelity to native adult tissue; faster protocol; genetically stable [1] [5] | Inter-donor genetic heterogeneity; tissue availability and quality [5] [4] |

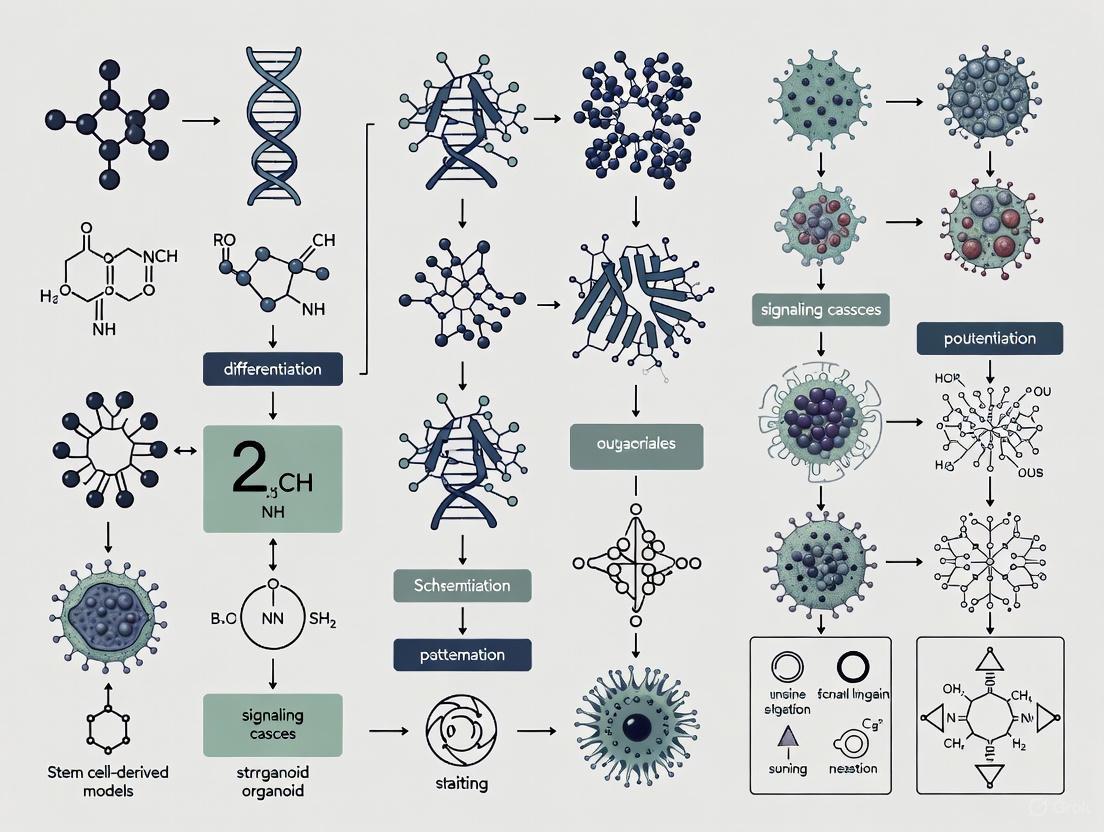

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental workflows and sources of variability for organoids derived from these different stem cell sources.

Troubleshooting FAQ: Addressing Common Variability Issues

Q1: Our iPSC-derived neural organoids show high levels of cell stress and death after 30 days in culture. What could be causing this?

A: Hypoxia and necrosis in the organoid core are common limitations in PSC-derived organoid models, particularly in large, dense structures like neural organoids [6]. The absence of a vascular system limits oxygen and nutrient diffusion to the interior cells.

- Solution: Implement the slicing method. Transferring organoids to a slice culture system can dramatically increase oxygen permeability and reduce central necrosis [6].

- Proactive Strategy: Consider using smaller organoids or bioreactors that enhance medium perfusion. Regularly monitor organoid size and consider dissociation and re-aggregation for long-term cultures.

Q2: Our patient-derived intestinal organoid lines from different donors show vastly different growth rates and morphologies, complicoring our drug screening assay. How can we normalize this?

A: This inter-donor genetic heterogeneity is an inherent feature of aSC-derived organoids, but it can be managed [5] [4].

- Solution: Increase sample size and stratify. For drug screening, ensure you are using a sufficiently large biobank of patient-derived organoids (PDOs) and group them based on known genetic biomarkers (e.g., mutation status) relevant to your study [5].

- Standardization Tactic: Meticulously standardize the tissue procurement and initial processing steps. Use a larger initial biopsy size if possible and follow a strict protocol from the moment of collection to minimize technical variability amplifying biological differences [5].

Q3: We observe inconsistent regional patterning and cell type composition in our cerebral organoids between differentiations. How can we improve reproducibility?

A: High variability is a hallmark of unguided, self-patterning cerebral organoid protocols [7].

- Solution: Switch to a regionally-directed differentiation protocol. Using small molecules or recombinant proteins to precisely modulate key developmental signaling pathways (e.g., Wnt, BMP, SHH) can generate more consistent regional identities (e.g., forebrain, midbrain) [6] [7].

- QC Measure: Implement regular quality control checks using transcriptional analysis (e.g., qPCR for region-specific markers) and immunohistochemistry to validate the consistent presence of desired cell populations across different batches.

Q4: Our kidney organoids lack maturity and display immature fetal-like characteristics, limiting their use for modeling adult kidney disease. What are the options for improvement?

A: It is a fundamental characteristic of PSC-derived organoids to model fetal, not adult, tissues. iPSC-derived kidney organoids, for example, resemble the first trimester of human fetal kidney [1].

- Solution: Extend the differentiation timeline and investigate post-maturation media containing hormones and signaling molecules that promote adult cell state transitions.

- Advanced Strategy: Consider co-culture systems. Incorporating other cell types, such as endothelial cells or fibroblasts, may provide critical maturation cues that are missing in standard protocols [4].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing and Controlling Variability

Protocol: Standardized Tissue Processing for aSC-Derived Organoids

Minimizing pre-culture variability is critical for generating reproducible aSC-derived organoids, especially from colorectal tissues [5].

- Tissue Procurement: Collect human tissue samples under sterile conditions immediately after colonoscopy or surgical resection. Place in a 15 mL tube with 5-10 mL of cold Advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with antibiotics (e.g., Penicillin-Streptomycin) [5].

- Critical Step - Timely Processing: Process tissue immediately. Delays reduce cell viability and organoid formation efficiency.

- If processing within 6-10 hours: Wash tissue with antibiotic solution and store at 4°C in DMEM/F12 with antibiotics [5].

- If delay exceeds 14 hours: Cryopreservation is preferred. Wash tissue and cryopreserve using a freezing medium (e.g., 10% FBS, 10% DMSO in 50% L-WRN conditioned medium) [5]. Note: A 20-30% variability in live-cell viability can be expected between these two preservation methods [5].

- Tissue Dissociation: Mechanically and enzymatically dissociate the tissue to isolate intact crypts or single cells, depending on the protocol.

- Embedding and Culture: Resuspend the cell pellet in a reduced-growth factor basement membrane extract (e.g., Matrigel) and plate as droplets. Overlay with a defined, tissue-specific medium containing essential niche factors (e.g., EGF, Noggin, R-spondin for intestine) [5] [4].

Protocol: Quality Control for iPSC Line Karyotype and Pluripotency

Ensuring the genetic integrity and pluripotency of your starting iPSC population is essential for reducing downstream variability.

- Pre-Differentiation Check:

- Pluripotency Validation: Confirm the expression of core pluripotency markers (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) via immunocytochemistry or flow cytometry.

- Karyotype Analysis: Perform G-banding karyotyping or higher-resolution CNV analysis to detect gross chromosomal abnormalities that can accumulate during reprogramming or prolonged culture.

- Line Authentication: Use STR profiling to confirm cell line identity and avoid cross-contamination.

- Post-Differentiation Analysis:

- Germ Layer Marker Expression: Differentiate iPSCs as 2D embryoid bodies and assess for the presence of markers from all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) to confirm trilineage differentiation potential.

- Mycoplasma Testing: Regularly test cell cultures for mycoplasma contamination.

Key Signaling Pathways Governing Organoid Development and Patterning

The differentiation of PSCs into specific organoid types is directed by the precise manipulation of a small number of evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways. The diagram below summarizes how these pathways are utilized to guide lineage commitment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Organoid Culture

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Basement Membrane Extract (e.g., Matrigel) | Provides a 3D scaffold that mimics the extracellular matrix; contains essential basement membrane proteins and growth factors. | Standard embedding matrix for both PSC- and aSC-derived organoids to support 3D structure [5] [4]. |

| Niche Factor Cocktails | Defined combinations of growth factors that re-create the stem cell niche. | aSC Culture: EGF, Noggin, R-spondin (for intestinal organoids) [4]. PSC Differentiation: Wnts, FGFs, BMPs, Retinoic Acid to guide lineage specification [1]. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Inhibits Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase; reduces anoikis (cell death after detachment). | Significantly improves cell survival after passaging, thawing, or single-cell dissociation of organoids [5]. |

| L-WRN Conditioned Medium | Conditioned medium from a cell line secreting Wnt3a, R-spondin 3, and Noggin. | Provides a consistent and potent source of key niche factors for growing aSC-derived organoids, particularly from the intestine [5]. |

| CHIR99021 | A potent and selective GSK-3 inhibitor that activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling. | Used in PSC differentiation protocols to direct mesodermal and endodermal fates [1]. |

| BMP4 / Noggin | Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4 (BMP4) and its antagonist Noggin. Used to manipulate BMP signaling. | BMP4 promotes dorsal-ventral patterning. Noggin (BMP inhibition) is essential for neural ectoderm induction and intestinal organoid culture [1] [6]. |

The journey to mastering organoid technology is a process of actively managing variability, not eliminating it. Success hinges on a strategic approach: select the stem cell source that best aligns with your research question—aSCs for adult tissue physiology and personalized medicine, and PSCs for developmental studies and inaccessible tissues like the brain. Once selected, rigorous standardization of protocols, from tissue procurement to differentiation, is non-negotiable. Finally, implement the quality control measures and troubleshooting strategies outlined in this guide to diagnose sources of inconsistency. By understanding and controlling for these factors, researchers can fully leverage the power of organoids to advance our understanding of human biology and disease.

What is the core "Matrix Effect" problem in organoid research? The "Matrix Effect" refers to the significant technical variability and challenges in experimental reproducibility introduced by the use of naturally-sourced extracellular matrices (ECMs), primarily Matrigel. This effect stems from the inherent batch-to-batch variability in the composition, structure, and mechanical properties of these matrices, which are critical determinants of cell behavior. When organoids are cultured in different batches of ECM, these variations can lead to inconsistent organoid morphology, growth rates, differentiation potential, and ultimately, experimental outcomes [8] [9].

Why is this a critical issue for the organoid research community? Achieving reproducibility is a cornerstone of the scientific method. For organoid models to fulfill their promise in drug development, disease modeling, and personalized medicine, results must be consistent and reliable across experiments, time, and laboratories. The undefined nature and variability of traditional matrices like Matrigel directly undermine this reproducibility, making it difficult to compare data, validate findings, and translate discoveries into clinical applications [8] [10]. Troubleshooting this variability is therefore essential for advancing the field.

Technical FAQs: Understanding ECM Variability

Q1: What specific components in Matrigel contribute to its batch-to-batch variability? Matrigel is a complex basement membrane extract derived from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) mouse sarcoma. Its variability arises from its multifaceted composition, which includes:

- Structural Proteins: Laminin (a major component), collagen type IV, and entactin/nidogen form the primary structural network [9].

- Growth Factors: Matrigel contains variable levels of embedded growth factors such as epidermal growth factor (EGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) [9]. A "growth factor-reduced" formulation is available, though it may not completely eliminate all factors like TGF-β [9].

- Complex Proteome: Proteomic analyses have identified over 1,800 proteins in Matrigel, including numerous intracellular proteins from the source tumor tissue. This immense complexity makes full standardization practically impossible [11] [9].

Q2: How do batch variations concretely affect my organoid cultures and experimental data? Variations in ECM batches can manifest in several critical aspects of your organoid models:

- Organoid Morphology and Architecture: Changes in matrix stiffness and ligand density can alter the self-organization process, leading to irregular organoid size, shape, and internal structure (e.g., disrupted lumens, bud formation) [8].

- Growth and Viability: Inconsistent presentation of adhesive ligands and growth factors can result in unpredictable cell proliferation rates and survival, affecting the efficiency of organoid formation and expansion [8] [12].

- Differentiation and Function: Biochemical and mechanical cues from the ECM direct cell fate. Variations can skew lineage specification, leading to an imbalance in cell types within the organoid and impairing its functional maturity [8] [13].

- Drug Response Data: Altered TME mimicry can change how organoids respond to therapeutic agents, generating unreliable drug screening data [8] [5].

- Proteomic Analysis: Insufficient removal of Matrigel during sample preparation can lead to contamination, wasting mass spectrometry scans on matrix proteins and causing misidentification or biased quantification of organoid proteins [11].

Q3: Are there any best practices for characterizing a new batch of Matrigel before experimental use? Yes, implementing a Quality Control (QC) protocol for each new batch is highly recommended. While comprehensive characterization can be demanding, accessible steps include:

- Rheology: Measure the storage and loss moduli (G' and G") to determine the mechanical stiffness and gelation kinetics of the matrix.

- Proteomic Analysis: If resources allow, running a simple SDS-PAGE gel can reveal gross differences in protein composition and concentration between batches.

- Pilot Culture: The most critical step is to culture a well-characterized, standard organoid line (e.g., a control line you use frequently) in the new batch. Compare key metrics like organoid formation efficiency, diameter, and morphology to cultures in your previous batch [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing ECM-Related Issues in Organoid Cultures

| Symptom | Potential ECM-Related Cause | Next Steps for Investigation |

|---|---|---|

| Poor organoid formation efficiency | Suboptimal mechanical properties (too soft/too stiff); insufficient cell-adhesive ligands | Test a different batch of ECM; check lot-specific concentration recommendations. |

| Irregular organoid morphology/size | Altered microstructure and ligand presentation | Perform detailed morphological analysis (e.g., circularity, area measurements) comparing old and new batches. |

| Spontaneous differentiation or incorrect lineage specification | Changes in growth factor content or matrix stiffness driving aberrant signaling | Check marker expression via immunofluorescence; consider using growth factor-reduced Matrigel. |

| High cell death in fresh cultures | Toxic contaminants or improper gelation | Ensure proper, cold handling of ECM during plating; test viability with a live/dead assay. |

| Inconsistent results in high-throughput screening | Significant functional batch-to-batch variation | Standardize screening campaigns to a single, large batch; implement rigorous pilot QC. |

Guide 2: Quantitative Comparison of Matrigel Dissolving Methods for Downstream Analysis

A key step in many protocols is the dissociation of organoids from the surrounding Matrigel for passaging or analysis. The chosen method can significantly impact the purity of your sample, especially for proteomics.

Table: Evaluation of Matrigel Dissolving Methods for Proteomic Sample Preparation [11]

| Method | Mechanism | Peptide Yield | SILAC Incorporation Ratio | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dispase | Enzymatic digestion | Highest | 97.1% | Minimal Matrigel contamination; high sample purity | Enzymatic activity must be quenched |

| Cell Recovery Solution | Non-enzymatic, chemical dissolution | Intermediate | Lower (due to contamination) | Simple protocol | Highest level of Matrigel contaminants |

| PBS-EDTA Buffer | Chemical chelation | Lowest | Lower (due to contamination) | Mild, non-enzymatic | Less effective dissolution, leading to contamination |

Conclusion: For proteomic and other molecular analyses where sample purity is paramount, dispase is the recommended method to minimize interference from undissolved Matrigel contaminants [11].

Guide 3: Transitioning to Defined Matrices to Mitigate Batch Effects

For long-term projects requiring high reproducibility, consider moving away from poorly-defined matrices.

Table: Strategies for Improving Reproducibility through Matrix Choices

| Strategy | Description | Impact on Reproducibility | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Batch Purchasing | Purchasing a large quantity of a single Matrigel lot for a long-term project. | Medium-High (for that project) | Costly; requires adequate storage capacity. |

| In-house QC Protocol | Establishing standardized pilot tests for each new batch (see FAQ III). | Medium | Adds time but is essential for identifying problematic batches. |

| Engineered Synthetic Matrices | Using chemically-defined hydrogels with tunable properties (e.g., PEG-based). | High | Requires optimization for specific organoid types; commercially available. |

| ECM-derived Biomaterials | Using decellularized ECM from specific tissues as a more native, yet more defined, scaffold. | Medium-High | Better recapitulates native niche; composition is more defined than Matrigel [14] [13]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Addressing ECM Variability

| Reagent / Material | Function in Troubleshooting ECM Variability | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Enhances cell survival after dissociation and plating, mitigating variability in initial seeding efficiency [5] [12]. | Added to culture medium for the first 2-3 days after passaging. |

| Dispase | Enzymatic solution for efficient dissociation of organoids from Matrigel with minimal contamination for downstream omics studies [11]. | Preferable to trypsin or cell recovery solution for proteomic work. |

| Synthetic ECM Hydrogels | Provides a chemically-defined, xeno-free, and tunable alternative to Matrigel to eliminate batch effects [8] [15]. | e.g., PEG-based, peptide-functionalized hydrogels. Allows independent tuning of stiffness and ligand density. |

| Decellularized ECM (dECM) | Bioactive scaffold derived from native tissues that offers a more physiologically relevant and compositionally defined niche than Matrigel [14] [13]. | Can be sourced from specific organs (e.g., liver, intestine) for tissue-specific modeling. |

| Structured Reporting Checklist | A lab-developed template for meticulously documenting ECM details in experiments. | Should include: Product (Matrigel), Manufacturer, Catalog #, Lot #, Concentration, Date of Use. |

Visual Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: ECM Signaling Pathways in Organoid Development

This diagram illustrates how variable ECM components directly influence key intracellular signaling pathways that dictate organoid fate, linking batch differences to phenotypic outcomes.

Diagram 2: Experimental QC Workflow for New ECM Batches

This workflow provides a step-by-step guide for researchers to qualify a new batch of ECM before committing critical experiments to it.

Foundational Concepts: Soluble Factors and Their Mechanisms of Action

What are soluble cytokine and growth factor receptors, and how do they influence signaling?

Soluble cytokine and growth factor receptors are typically the extracellular ligand-binding domains of membrane-bound receptors that have been released into the extracellular space. They add substantial complexity to cell signaling through several mechanisms [16]:

- Decoy Function: They can compete with membrane-bound receptors for ligand binding, thereby attenuating signaling.

- Ligand Stabilization: Conversely, they can bind to and stabilize ligands, potentially enhancing signaling.

- Remote Signaling: Their soluble nature allows them to exert biological effects away from their production site, enabling inter-organ and inter-cellular communication.

These soluble receptors are generated through three primary mechanisms [16]:

- Proteolytic Cleavage (Ectodomain Shedding): Enzymes like ADAM17 and ADAM10 cleave membrane receptors near their transmembrane domains.

- Alternative mRNA Splicing: Results in the synthesis and secretion of soluble receptor isoforms lacking transmembrane domains.

- Extracellular Vesicle Release: Membrane receptors on exosomes are released into circulation.

Table: Key Soluble Receptor Generation Mechanisms

| Generation Mechanism | Key Enzymes/Processes | Example Receptors |

|---|---|---|

| Proteolytic Cleavage | ADAM17, ADAM10 | IL-6R, TNFR1, CXCR2 |

| Alternative Splicing | mRNA processing | IL-4Rα, IL-5Rα, IL-15Rα |

| Vesicle Release | Exosome formation | Various transmembrane receptors |

Diagram: Soluble Receptor Generation Mechanisms and Functional Consequences

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: Soluble Factor Stability and Composition

How long do recombinant growth factors remain stable in culture media? Growth factor stability varies significantly by type. Recent stability testing in HEK293T conditioned media at 37°C shows substantial differences [17]:

Table: Growth Factor and Cytokine Stability Profiles

| Factor | Stability Duration | Bioactivity Retention | Key Stability Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| FGF-2 (WT) | <2 days | Significant loss after 2 days | Requires daily media changes for consistent signaling |

| FGF-2 (G3) | >7 days | Maintained >7 days | Engineered thermostable variant enables weekend-free culture |

| GM-CSF | 7 days | EC50: 38.3→47.8 ng/ml | Stable protein with minimal bioactivity loss |

| IL-6 | 7 days | EC50: 2.5→1.8 ng/ml | Maintains structural integrity and function |

| IGF-1 | 7 days | EC50: 11.2→17.2 ng/ml | Retains activity despite known instability in cultures |

| BMP-4 | 7 days | EC50: 51.2→40 pM | Highly stable with consistent dose-response |

| TGF-β1 | 7 days | EC50: 28.3→23 pg/ml | Maintains picomolar potency throughout testing period |

| GDNF | 7 days | EC50: 20.1→8.2 ng/ml | Progressive protein degradation but retained bioactivity |

What causes variability in conditioned media composition? Conditioned media (CM) composition is influenced by multiple factors [18]:

- Cell Source: MSC-derived CM from umbilical cord shows highest cytokine levels compared to adipose, bone marrow, gingiva, or placenta sources.

- Culture Format: 3D spheroid cultures produce different secretome profiles compared to 2D monolayers.

- Time in Culture: Secretome composition changes with culture duration, typically analyzed after set periods (e.g., 3 days).

- Donor Heterogeneity: Individual genetic and physiological differences affect soluble factor secretion.

How does phenotypic drift manifest in organoid cultures? Phenotypic drift refers to gradual changes in organoid characteristics over passages [4] [19]:

- Morphological Changes: Organoids may show altered growth patterns, including shortened cycles or rapid proliferation.

- Genetic Instability: Accumulation of mutations during passaging can change behavior.

- Differentiation Shifts: Changes in lineage commitment and cellular composition.

- Functional Alterations: Modified responses to stimuli and drugs.

FAQ: Experimental Design and Troubleshooting

How can researchers minimize phenotypic drift caused by soluble factor variability?

- Limit Passaging: Restrict organoid passaging to 2-3 generations (maximum 5) to minimize genetic and phenotypic changes [19].

- Standardize Media Formulations: Use consistent, quality-tested growth factor batches with known stability profiles [17].

- Monitor Stability: Implement regular quality control checks for growth factor activity in conditioned or supplemented media.

- Cryopreserve Early Passages: Bank organoids at passage 2-5 (P2-P5) when viability and differentiation potential are optimal [19].

What are the critical steps for establishing consistent organoid cultures?

- Tissue Processing: Process samples within 2-4 hours post-collection under cold conditions (∼4°C) to maintain viability [5] [19].

- Contamination Control: Pre-treat tissues with PBS containing double antibiotics (1-5% depending on tissue exposure) [19].

- Matrix Selection: Use consistent extracellular matrix lots (Matrigel or alternatives) to minimize variability [19].

- Size Control: Maintain organoids under 500μm diameter to prevent central necrosis due to diffusion limitations [19].

How can researchers troubleshoot inconsistent organoid growth?

- Check Factor Stability: Test growth factor activity after different media storage durations [17].

- Assess Contamination: Look for fast-growing contaminating cells (e.g., fibroblasts) via histological staining [19].

- Verify Media Composition: Ensure consistent growth factor concentrations and avoid lot-to-lot variability.

- Monitor Passage Effects: Compare early and late passage organoids for genetic and phenotypic changes.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Assessing Growth Factor Stability in Conditioned Media

Objective: Determine the stability and bioactivity retention of recombinant growth factors in conditioned media under standard culture conditions [17].

Materials:

- HEK293T conditioned media (DMEM + 10% FBS, conditioned for 72 hours)

- Recombinant growth factors (GM-CSF, IL-6, IGF-1, BMP-4, TGF-β1, etc.)

- Appropriate reconstitution buffers (PBS or HCl buffer)

- 37°C CO2 incubator

- SDS-PAGE equipment

- Cell-based bioassay systems (luciferase reporter or proliferation assays)

Procedure:

- Preparation: Reconstitute growth factors at 1 mg/ml in appropriate buffers.

- Dilution: Dilute to 0.5 mg/ml in PBS, then further dilute in HEK293T conditioned media.

- Incubation: Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 0, 1, 2, 5, and 7 days.

- Analysis:

- Structural Integrity: Run SDS-PAGE at each time point to assess protein degradation.

- Bioactivity: Use appropriate bioassays:

- Luciferase reporter assays for IL-6, IGF-1, BMP-4, TGF-β1

- Cell proliferation assays (TF-1 cells for GM-CSF, SH-SY5Y for GDNF)

- Quantification: Calculate EC50 values at each time point and compare to day 0 controls.

Diagram: Growth Factor Stability Assessment Workflow

Protocol: Standardized Organoid Culture Establishment

Objective: Establish reproducible organoid cultures while minimizing variability from soluble factors [5].

Critical Steps:

- Tissue Procurement: Collect human colorectal tissue samples under sterile conditions immediately following procedures. Transfer in cold Advanced DMEM/F12 with antibiotics.

- Tissue Preservation Options:

- Short-term: Refrigerated storage at 4°C in DMEM/F12 with antibiotics (≤6-10 hours delay)

- Long-term: Cryopreservation in 10% FBS, 10% DMSO in 50% L-WRN conditioned medium

- Crypt Isolation: Enzymatic digestion and mechanical dissociation to isolate crypt structures.

- Matrix Embedding: Resuspend in extracellular matrix (Matrigel or alternatives) and plate as domes.

- Media Supplementation: Use defined media with consistent growth factor batches:

- EGF, Noggin, R-spondin for intestinal organoids

- Monitor growth factor stability and replace accordingly

Troubleshooting:

- Low Viability: Reduce processing time; optimize preservation method

- Contamination: Increase antibiotic concentration for externally-exposed tissues

- Poor Growth: Verify growth factor activity; check matrix quality

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Soluble Factor Research

Table: Key Research Reagents for Soluble Factor Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Growth Factor Variants | FGF2-G3 (thermostable) | Weekend-free culture protocols | Maintains bioactivity >7 days vs. <2 days for wild type [17] |

| Cytokine Standards | GM-CSF, IL-6, TGF-β1 | Bioactivity calibration and assay controls | Lot-to-lot consistency critical for reproducibility [17] |

| Protease Inhibitors | TAPI-1, TAPI-2 | Inhibit ADAM proteases to reduce ectodomain shedding | Modulates soluble receptor generation [16] |

| Extracellular Matrix | Matrigel, Cultrex, synthetic hydrogels | 3D structural support for organoids | Batch variability affects growth factor diffusion [19] |

| Conditioned Media Components | L-WRN (Wnt3a, R-spondin, Noggin) | Stem cell niche signaling | Quality control essential for consistent self-renewal [5] |

| Stability Testing Reagents | Luciferase reporter systems, CellTiter-Glo | Quantifying growth factor bioactivity over time | Enables evidence-based media change schedules [17] |

Quality Control Recommendations

- Growth Factor Activity Testing: Implement regular bioassays to verify functional activity, not just protein concentration.

- Stability Monitoring: Track lot-specific stability data for each growth factor under actual culture conditions.

- Documentation: Maintain detailed records of growth factor lots, reconstitution dates, and performance characteristics.

- Validation: Correlate growth factor activity with organoid phenotypic outcomes to establish acceptable activity ranges.

By implementing these standardized protocols, troubleshooting guides, and quality control measures, researchers can significantly reduce variability introduced by soluble factors and improve the reproducibility of organoid-based research.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting hPSC Culture Variability

This guide addresses common issues that can compromise the genetic and epigenetic fidelity of your human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) cultures, which are the foundation of organoid models.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive differentiation (>20%) in cultures [20] | - Degraded culture medium- Overgrown colonies- Prolonged exposure outside incubator | - Use fresh culture medium less than 2 weeks old [20]- Passage cultures when colonies are large and dense, before overgrowth [20]- Limit time outside incubator to less than 15 minutes [20] |

| Low cell attachment after passaging [20] | - Low initial cell density- Over-manipulation of cell aggregates- Incorrect plate coating | - Plate 2-3 times more cell aggregates; maintain denser culture [20]- Minimize pipetting to avoid breaking up aggregates [20]- Use non-tissue culture-treated plates with Vitronectin XF [20] |

| Inconsistent cell aggregate size [20] | - Suboptimal passaging reagent incubation time- Improper pipetting technique | - For large aggregates (>200µm): Increase incubation time 1-2 minutes and pipette mixture up and down [20]- For small aggregates (<50µm): Decrease incubation time 1-2 minutes and minimize manipulation [20] |

| Presence of differentiated cells in passage [20] | - Colony not adequately purified before passaging- Over-incubation with passaging reagent | - Manually remove differentiated areas before passaging [20]- Decrease incubation time with reagent (e.g., ReLeSR) by 1-2 minutes or lower temperature to 15-25°C [20] |

Troubleshooting Organoid Model Fidelity

This guide focuses on issues related to the maintenance of donor-specific genetic and epigenetic signatures in organoid models.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Failure to recapitulate injury or disease signatures [21] | - Culture conditions only support homeostatic, not regenerative, states- Lack of key epigenetic modulators | - Utilize specialized media (e.g., 8-component system with VPA, EPZ6438) to induce regenerative/hyperplastic states [21] |

| Limited maturation or incorrect lineage specification [22] | - Incomplete differentiation protocol- Lack of essential morphogens or growth factors | - For cholinergic neurons: Ensure sequential use of RA, SHH, FGF8, BDNF, and NGF; consider transcription factor (LHX8, GBX1) transfection [22] |

| Loss of patient-specific drug response [23] | - Gradual genetic drift in culture- Overgrowth by non-representative cell populations | - Regularly characterize organoids (genomics, transcriptomics) between passages [23]- Use lower passage cultures for drug screening assays [23] |

| High batch-to-batch variability [23] | - Unstandardized differentiation protocols- Variable raw materials | - Adopt automated, high-throughput systems where possible [23]- Rigorously quality-control all reagents and cell sources [23] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Model Fidelity

Q1: What are the primary sources of genetic and epigenetic variability in stem cell-derived organoid models? Variability arises from multiple sources: the genetic background of the donor [23] [24], the specific reprogramming method used to generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [22], the efficiency and protocol of differentiation [22], and the culture conditions themselves (e.g., 2D vs. 3D, media components) [23] [21]. Even between organoids from the same donor, differences can emerge due to stochastic events during self-organization.

Q2: How can I assess whether my organoid model accurately retains the donor's epigenetic age? This is a complex challenge. While reprogramming to iPSCs is known to cause significant epigenetic rejuvenation [24], subsequent differentiation can re-establish some age-associated signatures. Techniques include:

- DNA Methylation Clocks: Using established epigenetic clocks (e.g., Horvath's clock) to analyze the methylation status of your organoids [24].

- Transcriptomic Analysis: Comparing your organoid's RNA-seq data with public datasets of aged primary tissues.

- Functional Assays: Measuring biomarkers of senescence (e.g., SA-β-Gal activity, p16 expression) or assessing responses to age-relevant stressors [24].

Q3: Why do my organoids sometimes fail to model specific disease pathologies seen in the donor? The disease phenotype might require specific environmental triggers, a longer time to manifest, or cellular components absent in a pure epithelial organoid (e.g., immune cells, stroma, vasculature) [23]. Consider:

- Incorporating the microenvironment: Using co-culture systems or organoid-on-chip technologies to introduce missing cell types [23].

- Inducing stress: Applying chemical, mechanical, or metabolic stress to unmask latent vulnerabilities [21].

- Extending maturation: Prolonging the culture time or using protocols that enhance terminal maturation [22].

Technical and Methodological Concerns

Q4: What are the critical checkpoints for ensuring differentiation protocol efficiency? A robust differentiation requires validation at multiple levels [22]:

- Morphology: Microscopic observation of expected structural formation (e.g., neural rosettes, budding cysts).

- Gene Expression: qRT-PCR or RNA-seq to confirm the upregulation of key lineage-specific markers and downregulation of pluripotency genes.

- Protein Expression: Immunofluorescence or flow cytometry for protein-level validation of target cell types.

- Functionality: Electrophysiology for neurons, albumin production for hepatocytes, contractility for cardiomyocytes, etc.

Q5: When should I use a 2D differentiation system versus 3D organoids? The choice depends on the research question:

- Use 2D for: High-throughput screens, simpler readouts, easy genetic manipulation, and when studying cell-autonomous mechanisms [23].

- Use 3D Organoids for: Modeling tissue architecture, cell-cell interactions, complex disease pathologies (e.g., tumor heterogeneity), and when spatial context is critical [23] [25].

Q6: How can I reduce the batch-to-batch variability of my organoid cultures? Standardization is key [23]:

- Cell Source: Use well-characterized, low-passage starter cells.

- Reagents: Use defined, high-quality matrices and media components, and batch-test critical growth factors.

- Protocols: Automate dissociation and passaging steps where possible. Pre-define and strictly adhere to criteria for when to passage.

- Quality Control: Implement routine genomic and phenotypic checks to monitor stability across batches.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Establishing Hyperplastic Intestinal Organoids to Model Epithelial Regeneration

This protocol is adapted from a study that created "Hyper-organoids" to mimic injury-responsive epithelium, which is not captured by conventional (ENR) culture [21].

Background: Standard intestinal organoid media (e.g., ENR: EGF, Noggin, R-Spondin 1) supports homeostasis. To model regeneration, a defined 8-component (8C) system was developed to enrich for injury-responsive stem cells (e.g., Clu+ revival stem cells) by inducing a hyperplastic state [21].

Methodology:

- Base Medium Preparation: Start with advanced DMEM/F-12 as a base.

- Add 8C Components: Supplement the base medium with the following critical factors [21]:

- Small Molecules: LDN193189 (BMP inhibitor), GSK-3 Inhibitor XV (Wnt activator), Pexmetinib (MAPK inhibitor), VPA (HDAC inhibitor, epigenetic modulator), EPZ6438 (EZH2 inhibitor, epigenetic modulator).

- Growth Factors: EGF, R-Spondin 1 conditioned medium (Wnt activator), bFGF.

- Culture: Embed intestinal crypts or single stem cells in Matrigel and overlay with the 8C medium.

- Maintenance: Culture for over 20 passages, with medium changes every 2-3 days and routine passaging.

- Validation:

- Morphology: Confirm larger organoid size and more complex crypt-villus structures compared to ENR controls [21].

- Markers: Validate by immunofluorescence or flow cytometry for high expression of injury/regeneration markers (SCA1, ANXA1, REG3B, CLU) [21].

- Transcriptomics: Perform RNA-seq to confirm enrichment of injury-associated and fetal intestinal gene signatures [21].

Protocol 2: Differentiating Forebrain Cholinergic Neurons for Disease Modeling

This protocol outlines key steps for generating basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (BFCNs), relevant for Alzheimer's disease research, highlighting factors that influence fate specification [22].

Background: BFCN development in vivo relies on specific morphogen gradients. Recapitulating this in vitro requires precise timing and combination of signaling molecules to achieve correct anterior/ventral patterning [22].

Methodology:

- Neural Induction: Begin with hPSCs and form embryoid bodies, then neural rosettes to generate neural precursor cells (NPCs).

- Anterior Patterning: Treat NPCs with low doses of Wnt inhibitors to promote forebrain (anterior) identity, marked by FOXG1 expression.

- Ventralization: Add Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) to direct cells toward a ventral telencephalic fate, inducing NKX2.1 expression characteristic of the medial ganglionic eminence (MGE).

- Cholinergic Specification: Further mature the cells using a combination of growth factors:

- Optional Enhancement: For higher purity (>94%), consider transfection with transcription factors LHX8 and GBX1, followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [22].

- Validation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Vitronectin XF | Defined, xeno-free substrate for feeder-free hPSC culture [20]. | Requires use on non-tissue culture-treated plates. Promotes consistent attachment and pluripotency. |

| LDN193189 | Small molecule inhibitor of BMP signaling [21]. | Critical in neural induction and in the 8C hyperplastic organoid medium to suppress dorsal differentiation. |

| VPA (Valproic Acid) | Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor; broad epigenetic modulator [21]. | In hyperplastic organoid medium, it reprograms the epigenome, working synergistically with EPZ6438 to promote a regenerative state. |

| EPZ6438 | Small molecule inhibitor of EZH2 (catalytic subunit of PRC2); epigenetic modulator [21]. | Blocks H3K27me3 repressive mark. Essential for inducing injury-associated signatures in organoids. |

| R-Spondin 1 | Protein that enhances Wnt/β-catenin signaling [21]. | Crucial for intestinal and other stem cell growth. Often used as a conditioned medium. |

| Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) | Morphogen for ventral patterning of the neural tube [22]. | Concentration and timing are critical for specific neuronal fates (e.g., midbrain dopaminergic vs. forebrain cholinergic). |

| ReLeSR | Non-enzymatic passaging reagent for hPSCs [20]. | Sensitivity varies by cell line; incubation time and temperature may need optimization to control aggregate size and remove differentiated cells. |

FAQ: What are the key dimensions for assessing organoid maturity and success?

A physiologically relevant organoid must be evaluated across multiple, complementary dimensions. Success is not defined by a single parameter but by a combination of structural, cellular, and functional characteristics that collectively demonstrate the model's fidelity to native human tissue.

Core Assessment Dimensions:

- Structural Architecture: This involves the examination of the organoid's physical organization. Key benchmarks include the presence of region-specific cytoarchitecture (such as cortical layering in brain organoids), the formation of functional synaptic connections, and the development of essential barrier structures like a rudimentary glia limitans or blood-brain barrier unit [26].

- Cellular Diversity: A successful organoid contains a heterogeneous mix of cell types that appropriately reflect its target organ. This includes not only various neuronal subtypes (e.g., glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons) but also crucial supportive cells like astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, identified by specific molecular markers [26].

- Functional Maturation: The ultimate test of an organoid's relevance is its function. This encompasses the emergence of electrophysiologically active neurons and synchronized neural network activity, which can be measured by techniques such as multielectrode arrays (MEAs) and calcium imaging. Additionally, the functional maturation of non-neuronal cells, such as astrocyte-mediated homeostatic processes, is a critical advanced benchmark [26].

- Molecular and Metabolic Profiling: Confirmation at the molecular level is essential. Techniques like single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) validate cellular heterogeneity and identity by revealing transcriptome-wide profiles, ensuring the organoid's gene expression aligns with expected developmental stages [26].

FAQ: What specific markers and methods are used to evaluate these dimensions?

Evaluating organoid maturity requires a toolkit of specific reagents and established experimental protocols. The table below summarizes key benchmarks and their corresponding detection methods.

Table 1: Key Benchmarks and Methods for Assessing Organoid Maturity

| Assessment Dimension | Specific Benchmark | Target/Marker | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Architecture | Cortical Layering | SATB2 (upper layers), TBR1, CTIP2 (deep layers) [26] | Immunofluorescence (IF), Immunohistochemistry (IHC) [26] |

| Synapse Formation | SYB2 (presynaptic), PSD-95 (postsynaptic) [26] | IF, IHC, Electron Microscopy (EM) [26] | |

| Barrier Formation | Aquaporin 4 (glia limitans), CD31/PDGFRβ/GFAP (BBB units) [26] | IF, IHC, Confocal Microscopy [26] | |

| Cellular Diversity | Neuronal Populations | NEUN (mature neurons), DCX (immature neurons) [26] | IF, Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) [26] |

| Neurotransmitter Identity | VGLUT1 (glutamatergic), GAD65/67 (GABAergic) [26] | IF, FACS [26] | |

| Non-Neuronal Cells | GFAP, S100β (astrocytes); MBP, O4 (oligodendrocytes) [26] | IF, FACS [26] | |

| Functional Maturation | Network Activity | Synchronized action potentials, γ-band oscillations [26] | Multielectrode Arrays (MEAs) [26] |

| Calcium Dynamics | GCaMP reporters (in neurons/astrocytes) [26] | Calcium Imaging [26] | |

| Live-cell Dynamics | Intracellular motion patterns [27] | Dynamic Contrast OCT (DyC-OCT) [27] |

Experimental Protocol: Immunofluorescence for Structural and Cellular Assessment

This is a core protocol for validating organoid structure and cellular composition [26] [5].

- Fixation: Immerse organoids in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24-48 hours at 4°C to ensure complete penetration and preservation of the 3D structure.

- Cryopreservation and Sectioning: Transfer organoids to a 30% sucrose solution for cryoprotection until they sink. Embed organoids in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound and section them into 10-20 μm thick slices using a cryostat.

- Staining:

- Permeabilize sections with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 15-20 minutes.

- Block non-specific binding with 5-10% normal serum (from the host species of the secondary antibody) for 1 hour.

- Incubate with primary antibodies (e.g., anti-SATB2, anti-GFAP) diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4°C.

- Wash thoroughly and incubate with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Include counterstains like DAPI for nuclei.

- Imaging and Analysis: Mount sections and image using a confocal microscope to achieve high-resolution z-stacks for 3D reconstruction. Analyze images for marker expression, co-localization, and spatial distribution.

Experimental Protocol: Functional Assessment using Multielectrode Arrays (MEAs)

MEAs are used to record spontaneous and evoked electrical activity from entire organoids, providing a readout of functional network maturation [26].

- Preparation: Transfer the organoid to the MEA chamber in the recording medium. Ensure the organoid is positioned to make good contact with multiple electrodes.

- Acclimation: Allow the organoid to acclimate to the chamber for at least 30 minutes under culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂ if possible) to stabilize physiological activity.

- Recording: Record extracellular field potentials for a minimum of 10 minutes. To assess network robustness, perform multiple recordings.

- Data Analysis: Use specialized software to analyze parameters including:

- Mean Firing Rate: The average rate of action potentials across the network.

- Burst Detection: Identification of synchronized periods of high-frequency activity, a key indicator of network maturity.

- Oscillation Analysis: Detection of rhythmic network activity in specific frequency bands (e.g., gamma oscillations).

Diagram 1: Organoid maturity is determined by integrating multiple assessment dimensions, from structure to function.

FAQ: How can I troubleshoot variability and incomplete maturation in my organoid cultures?

Variability and developmental arrest are common bottlenecks. The table below outlines major challenges and their targeted solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Organoid Variability and Immaturity

| Challenge | Root Cause | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Necrotic Core & Hypoxia | Limited nutrient/O₂ diffusion in large 3D structures [26] [28]. | Bioengineering: Integrate with organ-on-chip microfluidic systems to enhance perfusion [26] [28] [29]. Cellular: Co-culture with endothelial cells to promote vascularization [26] [28]. Culture: Use stirred bioreactors to improve diffusion [28]. |

| Incomplete Maturation (Fetal Phenotype) | Lack of adult-like physiological cues; extended culture times (≥6 months) needed for late-stage markers [26] [28]. | Active Acceleration: Apply bioengineering cues like electrical stimulation [26]. Chronological Optimization: Use vascularized co-cultures to support long-term health and maturation [26]. Cell Source: Consider Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) from adult tissue for modeling adult diseases [28]. |

| Batch-to-Batch Variability & Low Reproducibility | Manual protocols; inconsistent starting materials; lack of control over organoid size/shape [28]. | Automation & AI: Implement automated systems for standardized organoid generation and analysis to remove human bias [28]. Validated Reagents: Use assay-ready, validated models and GMP-grade matrices where possible [28]. Protocol Standardization: Adopt detailed, step-by-step protocols with strict quality control during tissue processing [5]. |

Experimental Protocol: Enhancing Maturation via Organoid-Vascularization Co-culture

A key strategy to overcome necrosis and promote maturity is to facilitate vascularization [26] [28].

- Co-culture Setup: Isolate human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and pericytes. Seed them in a 3:1 ratio (HUVECs:Pericytes) and pre-assemble them into microvessel fragments in a fibrin gel.

- Organoid Integration: Embed the day 30-60 brain organoid into the fibrin gel containing the pre-assembled microvessels.

- Culture Maintenance: Culture the co-culture system in a specialized medium that supports both neural and endothelial cell types. For advanced models, transfer the co-culture to a microfluidic organ-on-chip device to introduce physiological fluid flow and shear stress.

- Validation: After 4-6 weeks, fix and stain the co-culture for endothelial markers (CD31), pericyte markers (PDGFRβ), and astrocytic endfeet (GFAP, Aquaporin-4) to visualize the formation of organoid-integrated vascular networks and barrier structures [26].

Diagram 2: Bioengineering strategies target diffusion limits to resolve necrosis and improve maturity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table compiles key reagents and materials critical for successful organoid research, as derived from the cited methodologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Organoid Work

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Provides a 3D scaffold for organoid growth and self-organization. | Matrigel is widely used; research focuses on GMP-grade and defined synthetic matrices for standardization [5] [28]. |

| Niche Factor Supplements | Mimics the stem cell niche to guide differentiation and growth. | Essential components include EGF, Noggin, R-spondin, and Wnt3a for intestinal organoids; FGFs and BMP inhibitors for other types [5]. |

| Cell Sources | Starting material for generating patient-specific or disease-specific models. | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs), Adult Stem Cells (e.g., Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells), Patient-Derived Tumor Tissues [5] [23]. |

| Molecular Markers (Antibodies) | Characterization of structural, cellular, and functional maturity via IF/IHC. | See Table 1 for specific markers like SATB2, GFAP, NEUN, and VGLUT1 [26]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Genome editing for introducing disease mutations or creating reporter lines. | Used in organoids to study mutational signatures and disease mechanisms [5] [23]. |

| Microfluidic Chips | Provides dynamic culture conditions, perfusion, and co-culture capabilities. | Organ-on-chip platforms integrate fluid flow and mechanical cues to enhance organoid polarity and function [28] [29]. |

Building Consistency: Standardized Protocols and Advanced Culture Systems for Reliable Organoid Generation

Within stem cell-derived organoid research, achieving experimental reproducibility is a significant hurdle. Protocol variability across laboratories, combined with the inherent biological complexity of three-dimensional culture systems, introduces substantial challenges in comparing results and validating findings. This technical support guide provides a standardized workflow for establishing intestinal organoid cultures—from tissue procurement to long-term maintenance—with an integrated troubleshooting framework designed to systematically identify and correct common experimental pitfalls. By adopting this structured approach, researchers can enhance the reliability of their organoid models and strengthen the overall validity of their research conclusions.

Standardized Workflow: From Tissue to Organoid

The following section outlines a comprehensive, step-by-step protocol for generating and maintaining intestinal organoids. Adherence to each critical step is essential for maximizing cell viability and culture success.

Tissue Procurement and Initial Processing

Proper handling of the starting tissue specimen is the most critical determinant of overall success.

- Sample Collection: Human colorectal tissue samples should be collected under sterile conditions immediately following a colonoscopy or surgical resection, in accordance with approved Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols and patient informed consent. Transfer samples in a 15 mL Falcon tube containing 5–10 mL of cold Advanced DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with antibiotics (e.g., penicillin-streptomycin) to maintain sterility during transit [5].

- CRITICAL STEP: Minimize processing delays. Reduced cell viability and organoid formation efficiency are directly correlated with prolonged time between tissue collection and processing [5].

- Addressing Processing Delays: When same-day processing is not feasible, employ one of two validated preservation methods, the choice of which depends on the anticipated delay, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Guidance for Tissue Preservation Based on Anticipated Processing Delay

| Anticipated Delay | Recommended Method | Protocol | Impact on Viability |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 6-10 hours | Short-term refrigerated storage [5] | Wash tissue with antibiotic solution and store at 4°C in DMEM/F12 medium with antibiotics. | Lower impact, but not quantified |

| > 14 hours | Cryopreservation [5] | Wash tissue with antibiotic solution; cryopreserve using a freezing medium (e.g., 10% FBS, 10% DMSO in 50% L-WRN conditioned medium). | 20-30% variability in live-cell viability compared to short-term storage |

Crypt Isolation and Plating

This phase involves liberating the intestinal crypts—which contain the stem cells—and embedding them in a 3D matrix to initiate culture.

- Crypt Isolation: Isolate crypts from the washed intestinal tissue through chelation (e.g., with EDTA) and mechanical dissociation. For mouse intestine, extensive washing is crucial [30].

- CRITICAL STEP: When harvesting mouse intestine, "remove the mesentery (the membrane attaching the intestine to the abdominal wall) prior to cutting the section. If it is not removed first, it will be difficult to spin it out during subsequent washing steps" [30].

- Washing: "After cutting the intestine into 2 mm segments, 15 - 20 rounds of washing in PBS are necessary" to remove toxic matter from the intestinal folds, which would otherwise inhibit organoid growth [30]. Let pieces settle by gravity during washes, as centrifugation can pellet impurities and reduce crypt recovery [30].

- Plating: Resuspend the isolated crypts in an ice-cold extracellular matrix (ECM) like Matrigel and plate as small droplets onto pre-warmed tissue culture plates.

- CRITICAL STEP: Use pre-warmed plates and ice-cold Matrigel to keep crypts in suspension. If crypts settle and stick to the plate surface, they will undergo differentiation instead of forming organoids [30].

- CRITICAL STEP: After the Matrigel dome solidifies at 37°C, "add IntestiCult medium to the well along the side of the wall. If medium is added directly onto the drop of Matrigel, the force of the liquid will disrupt the Matrigel dome." Ensure the dome is completely covered by medium [30].

- Seeding Density: Plate crypts at multiple densities (e.g., 3 different densities). Both the medium and the organoids themselves produce necessary paracrine factors. If seeded too densely, nutrients are depleted; if seeded too sparsely, survival factors become insufficient [30].

Long-Term Culture and Passaging

Organoids require regular maintenance and passaging to remain healthy and proliferative.

- Monitoring Culture Health: Organoids begin as simple, spherical structures and progressively develop into more complex, budded architectures. "As organoids begin to bud, the mature epithelial cells shed into the lumen. Ensure that organoid cultures are passaged before the lumen gets too dark" [30].

- Passaging Protocol: To passage, mechanically break up organoids or use dissociation reagents like Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent (GCDR) or ACCUTASE to break up the organoids into smaller fragments or single cells [30] [31].

- CRITICAL STEP: Dissociation involves both incubation time in the dissociation reagent and mechanical agitation. "If the organoids are over-incubated... or too aggressively agitated, there will be more single cells, which is not desirable" [30]. The goal is to generate small fragments for efficient re-plating.

- Recovery: For cultures passaged into single cells, adding a ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) to the medium for the first 1-2 days post-passaging can significantly improve cell survival and organoid re-formation [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful organoid culture relies on a defined set of reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Intestinal Organoid Culture

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Examples & Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Basal Medium | Nutrient foundation for culture medium. | Advanced DMEM/F12 is commonly used [5] [12]. |

| Niche Factors | Promote stem cell survival and proliferation. | EGF, Noggin, R-spondin, Wnt3a. Often used as conditioned medium (e.g., L-WRN) [5] [32]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | 3D scaffold providing structural support and biochemical cues. | Matrigel (GFR, phenol red-free). Must be kept on ice; use pre-chilled tips [32] [12]. |

| Dissociation Reagent | Breaks down ECM and dissociates organoids for passaging. | ACCUTASE [31], Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent (GCDR) [30], or TrypLE [32]. |

| ROCK Inhibitor | Enhances survival of single cells post-passaging. | Y-27632. Typically used for 24-48 hours after dissociation to single cells [31]. |

| Antibiotics | Prevents microbial contamination during initial processing. | Penicillin-Streptomycin. Note: Not recommended for routine culture of established organoids as they can mask low-level contamination [12]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section directly addresses the most common challenges encountered during organoid culture.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why did my organoids fail to form after plating, and only a few simple spheres are visible? A1: This is often a seeding density issue. If crypts were seeded too sparsely, there are insufficient organoid-derived factors to support growth. If seeded too densely, nutrients are rapidly depleted. Consistently plate at multiple densities to determine the optimum for your specific setup [30].

Q2: My organoids look dark and necrotic in the center. What is the cause and how can I fix it? A2: This is a classic sign of hypoxia and necrosis due to limited diffusion of oxygen and nutrients into the organoid core, especially as organoids grow larger. To mitigate this, ensure timely passaging before the lumen becomes overly dark [30]. For advanced models, consider transitioning to organoid slice cultures, which increase oxygen and nutrient permeability and significantly reduce central cell death [6].

Q3: After passaging, my organoids are not regrowing. What went wrong? A3: This typically stems from the passaging technique. There are two key variables: incubation time in the dissociation reagent and the force of mechanical agitation.

- Problem: Over-incubation or overly aggressive pipetting generates excessive single cells, which have lower viability than small fragments.

- Solution: Optimize the balance between enzymatic incubation and gentle manual trituration to generate small clusters of cells (10-20 cells) rather than a single-cell suspension [30]. If working with single cells, always supplement the medium with a ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) for the first 1-2 days post-passaging [31].

Q4: My organoids are differentiating prematurely instead of maintaining a proliferative, budded state. Why? A4: The most common cause is crypts or organoid fragments making direct contact with the plastic surface of the culture dish, which triggers differentiation.

- Prevention: Always use ice-cold Matrigel and pre-warmed culture plates. This combination helps keep the cells in suspension within the Matrigel dome, preventing them from settling and sticking [30].

- Check: Ensure your Matrigel droplets are firm and fully set before carefully overlaying with medium along the side of the well.

Advanced Technique: CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing in Organoids

Integrating genetic manipulation with organoid models is a powerful approach for functional studies. The following workflow, based on ribonucleoprotein (RNP) electroporation, minimizes off-target effects and is highly effective [31] [33].

Key Steps for CRISPR Editing:

- Preparation: Dissociate organoids into a high-viability single-cell suspension using ACCUTASE [31].

- RNP Complex Formation: Pre-complex the purified Cas9 protein with synthetic single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to form the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. This RNP system acts quickly and degrades rapidly, reducing off-target editing compared to plasmid-based methods [31] [33].

- Delivery: Introduce the RNP complex into the single cells via electroporation (e.g., using Neon or 4D-Nucleofector systems) [31].

- Recovery and Clonal Expansion: Plate the transfected cells in Matrigel with medium containing a ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) to support survival. To generate clonal knockout lines, single cells can be sorted into individual wells and expanded before validation [33].

- Validation: Confirm successful gene knockout using Western blot analysis or DNA sequencing [33].

FAQs: Addressing Common Organoid Culture Challenges

FAQ 1: What are the essential core components in a typical intestinal organoid medium, and what is their specific function?

The foundational recipe for culturing many epithelial organoids, particularly those from the intestine, is known as the "ENR" medium, which contains Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF), Noggin, and R-spondin [34] [35].

- R-spondin: This growth factor is a critical potentiator of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. It functions by binding to and removing the negative regulators RNF43 and ZNRF3 from the cell surface. This removal prevents the degradation of Wnt receptors, thereby enhancing Wnt signaling activity which is essential for stem cell maintenance and proliferation [36] [37].

- Noggin: This molecule is a Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) signaling antagonist. By inhibiting BMP signaling, Noggin prevents the differentiation of stem cells, thereby supporting their self-renewal and maintaining the stem cell niche within the organoid culture [36] [35].

- EGF: The Epidermal Growth Factor stimulates epithelial cell proliferation by binding to its receptor (EGFR), directly supporting tissue growth and renewal [34] [35].

FAQ 2: Our organoid growth is inconsistent between batches. What could be causing this variability?

Batch-to-batch variability is a common challenge, often originating from two key sources: the growth factors and the extracellular matrix.

- Growth Factor Sourcing and Activity: Using conditioned media as a source for growth factors like R-spondin and Noggin can introduce inconsistency, as the concentration and activity of the growth factors, as well as other secreted proteins, can vary between batches [36]. To ensure reproducibility, consider using highly pure recombinant growth factors with defined cellular activity [36]. Always aliquot reconstituted growth factors to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Tissue Processing Timing: The viability of starting tissue significantly impacts success. Delays in processing can reduce cell viability and organoid formation efficiency. If processing immediately is not possible, for short delays (≤6-10 hours), store the tissue at 4°C in DMEM/F12 with antibiotics. For longer delays, cryopreservation is recommended, though a 20-30% reduction in viability should be anticipated [5].

- Extracellular Matrix (Matrigel): Matrigel is a complex and undefined mixture. Batch-to-batch differences in its composition can greatly affect organoid growth. Test new batches alongside a current batch before fully switching, and always keep the Matrigel on ice after thawing to prevent premature polymerization [12] [35].

FAQ 3: Are the expensive growth factors like R-spondin and Noggin always necessary for all organoid types?

Not always. Recent research indicates that some cancer-derived organoids, particularly colorectal cancer organoids (CRCOs), can be maintained in reduced growth factor conditions. One study showed that the activation of Wnt and EGF signaling and inhibition of BMP signaling are non-essential for the survival of most CRCOs. A modified medium containing FGF10, A83-01, SB202190, gastrin, and nicotinamide was sufficient to maintain tumor features in long-term culture, offering a more economical and defined strategy [38]. This highlights the importance of tailoring the medium to your specific organoid type and research question.

Quantitative Data: Medium Formulations and Growth Factor Activity

| Component | Colon | Esophageal | Pancreatic | Mammary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noggin | 100 ng/mL | 100 ng/mL | 100 ng/mL | 100 ng/mL |

| R-spondin1 CM | 20% | 20% | 10% | 10% |

| EGF | 50 ng/mL | 50 ng/mL | 50 ng/mL | 5 ng/mL |

| Wnt-3A CM | Not included | 50% | 50% | Not included |

| FGF-10 | Not included | 100 ng/mL | 100 ng/mL | 20 ng/mL |

| FGF-7 | Not included | Not included | Not included | 5 ng/mL |

| A83-01 | 500 nM | 500 nM | 500 nM | 500 nM |

| Nicotinamide | 10 mM | 10 mM | 10 mM | 10 mM |

| N-Acetyl cysteine | 1 mM | 1 mM | 1.25 mM | 1.25 mM |

| SB202190 | 10 μM | 10 μM | Not included | 1.2 μM |

| Gastrin | Not included | Not included | 10 nM | Not included |

| B-27 supplement | 1X | 1X | 1X | 1X |

CM: Conditioned Medium

| Growth Factor | Cellular Activity (IC50/WPC50) | Typical Use Concentration in Organoid Media | Relative Cost per Litre of Media (vs. Bacterial) | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-spondin 1 | 4.0 ± 0.53 nM (Bacterial, post-SEC) | 25 nM | >£5,000 (Commercial) | Potentiates Wnt signaling by antagonizing RNF43/ZNRF3 [36] [37] |

| Gremlin 1 | 6.4 ± 0.65 nM (Bacterial) | 25 nM | >£3,500 (Commercial) | Inhibits BMP signaling, supporting stem cell maintenance [36] |

Experimental Protocols: Key Workflows

Protocol: Production of Bacterially-Derived R-spondin 1 with Defined Activity [36]

Objective: To produce highly pure, cost-effective R-spondin 1 with minimal endotoxin levels and defined cellular activity, overcoming batch-to-batch variation.

Workflow Diagram: R-spondin 1 Production

Methodology:

- Expression: Use an expression vector for an Avi-tagged MBP-R-spondin 1 fusion protein in NEB Shuffle T7 E. coli, a strain engineered for enhanced disulphide bond formation in the cytoplasm [36].

- Purification: After bacterial lysis, perform initial purification using Nickel-NTA agarose, leveraging the histidine tag [36].

- Refolding: Subject the protein to an in vitro "disulphide shuffling" step using reduced and oxidized glutathione to ensure correct disulphide bond formation, which is critical for R-spondin's activity [36].

- Polishing: Apply Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC). This step removes ~60% of inactive protein aggregates and yields a single band of pure MBP-R-spondin 1 on an SDS-PAGE gel. The cellular activity (WPC50) increases over 10-fold after this step [36].

- Tag Removal (Optional): The MBP tag can be cleaved off using thrombin, followed by cation exchange chromatography to obtain pure R-spondin 1, with a similar WPC50 to the tagged version [36].

Quality Control:

- Activity Assay: The cellular activity is measured as the WPC50 (half-maximal Wnt potentiation concentration) using a reporter cell line [36].

- Endotoxin Testing: Ensure endotoxin levels are low (>20-fold less than the limit of concern of 0.5 EU/ml when diluted in culture media) [36].

Signaling Pathways: The Rationale Behind the Recipes

The core growth factors in organoid media directly manipulate key signaling pathways that govern stem cell fate in vivo. Understanding these pathways is key to effective troubleshooting.

Diagram: Core Signaling Pathways in Intestinal Organoid Culture

Pathway Descriptions:

Wnt/β-catenin Pathway: This is the master regulator of stem cell proliferation and self-renewal in the intestine. R-spondin is not a direct activator but a powerful potentiator of this pathway. It works by binding to the E3 ubiquitin ligases ZNRF3/RNF43 and their co-receptors LGR4/5/6, leading to the removal of these ligases from the cell surface. This stabilizes Wnt receptors, making cells more responsive to ambient Wnt signals and driving the expression of stem cell genes like Lgr5 [34] [37].

BMP (Bone Morphogenetic Protein) Pathway: The BMP pathway acts as a counterbalance to Wnt, promoting cellular differentiation. In the intestinal crypt, BMP signaling is naturally suppressed. In organoid culture, this inhibition is replicated by adding recombinant Noggin or Gremlin 1. By blocking BMP signaling, these factors prevent the premature differentiation of stem cells, allowing for their expansion and the formation of undifferentiated organoid structures [36] [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Organoid Culture and Troubleshooting

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Core Growth Factors | Recombinant R-spondin 1, Noggin/Gremlin 1, EGF | Define the stem cell niche; essential for proliferation and self-renewal [36] [12]. |

| Signaling Modulators | A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor), SB202190 (p38 MAPK inhibitor), CHIR99021 (GSK3 inhibitor) | Fine-tune signaling pathways beyond core Wnt/BMP to support specific tissues or cancer models [12] [38] [35]. |

| Extracellular Matrix | Matrigel, Synthetic Hydrogels | Provides a 3D scaffold that mimics the native basement membrane, crucial for structural organization [12] [35]. |

| Cell Survival Aids | Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Improves survival of dissociated single cells and cryopreserved organoids by inhibiting anoikis [12] [35]. |

| Medium Supplements | B-27, N-Acetylcysteine, Nicotinamide | Provides essential nutrients, antioxidants, and supports overall cell health and growth [12] [38]. |

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Category 1: Microfluidic Device Operation & Integration

Q: My organoids are forming inconsistently across different channels in the same device. What could be the cause?

- A: This is often due to uneven flow rates or blockages. First, check for microbubbles, which are a common culprit. Ensure all your solutions are properly degassed before loading. Second, verify that the pump calibration is consistent across all channels. Particulate matter in your cell suspension or hydrogel precursor can also cause blockages; always centrifuge and filter (e.g., 40µm strainer) your cell-laden hydrogel solution before loading.

Q: I'm observing high cell death within the microfluidic device shortly after seeding. How can I resolve this?

- A: Sudden cell death is typically related to shear stress or nutrient deprivation.

- Shear Stress: Review your flow rate. For delicate stem cell-derived cultures, a continuous low flow rate (e.g., 0.1-5 µL/h) is preferable to high, pulsatile flows. Use a ramp-up protocol to gradually introduce flow after cell seeding.

- Nutrient Deprivation: Ensure your medium reservoir is adequately filled and that the device is in a humidified incubator to prevent evaporation. Confirm that your device material (e.g., PDMS) is not absorbing critical small molecules from your culture medium; consider using alternative polymers or pre-conditioning channels by soaking in medium overnight.

- A: Sudden cell death is typically related to shear stress or nutrient deprivation.

Category 2: Synthetic Hydrogel Properties & Handling

Q: The stiffness of my synthetic hydrogel (e.g., PEG, HA) is inconsistent between batches, leading to variable organoid morphology. How can I improve reproducibility?

- A: Hydrogel stiffness is primarily controlled by the crosslinking density. To ensure consistency:

- Precise Weighing: Use an analytical balance for all polymer and crosslinker components.

- Controlled Gelation: Standardize gelation time and temperature. Use a photoinitiator (e.g., LAP) at a consistent concentration and ensure UV light intensity and exposure time are uniform across all samples. A light meter can calibrate your UV source.

- Quality Control: Perform rheology on a small sample from each hydrogel batch to confirm the storage modulus (G').

- A: Hydrogel stiffness is primarily controlled by the crosslinking density. To ensure consistency:

Q: My cells are not encapsulating evenly within the hydrogel; they clump or settle. What is the proper technique?

- A: This requires optimizing the hydrogel precursor solution viscosity and working speed.

- Keep the cell-polymer mix on ice until ready to polymerize to slow down premature crosslinking.

- Mix the cell suspension and hydrogel precursor solution gently but thoroughly by pipetting up and down a minimum number of times (e.g., 10-15x) to avoid introducing air bubbles or shearing cells.

- Immediately load the mixture into your device or mold. The working time (e.g., before gelation) should be less than 5 minutes to prevent sedimentation.

- A: This requires optimizing the hydrogel precursor solution viscosity and working speed.

Category 3: Biological Performance & Readouts

- Q: My organoids show high levels of spontaneous differentiation or necrosis in the core. How can I enhance viability and direct differentiation?

- A: This indicates a limitation in nutrient/waste diffusion and/or a lack of specific morphogenetic cues.

- Diffusion Limits: Design your organoid size to be below the diffusion limit (~200-500 µm). The microfluidic flow should be optimized to deliver nutrients and remove waste without applying excessive shear.

- Controlled Differentiation: Integrate micropatterning within the hydrogel to create controlled gradients of morphogens. Use your microfluidic device to establish stable, defined concentration profiles of growth factors (e.g., Wnt, BMP, FGF) instead of relying on bulk addition.

- A: This indicates a limitation in nutrient/waste diffusion and/or a lack of specific morphogenetic cues.