The Bone Marrow Niche: Decoding the Hematopoietic Stem Cell Microenvironment for Therapeutic Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche within the bone marrow microenvironment, a dynamic and complex regulatory unit essential for lifelong blood production.

The Bone Marrow Niche: Decoding the Hematopoietic Stem Cell Microenvironment for Therapeutic Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche within the bone marrow microenvironment, a dynamic and complex regulatory unit essential for lifelong blood production. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the fundamental biology of niche components, from osteoblastic and vascular domains to perivascular stromal cells. The scope extends to cutting-edge methodologies for in vitro niche reconstruction, including 3D biomimetic models, organoids, and bone marrow-on-a-chip platforms. We further investigate the niche's role in disease pathogenesis, such as clonal hematopoiesis and myelodysplastic syndromes, and its emerging promise as a therapeutic target. Finally, we evaluate comparative and validation strategies that are refining our understanding of niche function in health and disease, offering a roadmap for translating basic science into clinical applications.

Deconstructing the HSC Niche: Cellular Architecture and Regulatory Mechanisms in Steady-State and Aging

The concept of the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche, first proposed by R. Schofield in 1978, represents a foundational pillar in our understanding of stem cell biology [1]. Schofield's hypothesis postulated that a stem cell's fundamental capacity for self-renewal is intrinsically dependent on its association with a specific cellular environment, or "niche," that determines its behavior [1] [2]. For nearly five decades, this concept has driven scientific inquiry, evolving from a theoretical construct to a well-defined anatomical and functional unit within the bone marrow. Recent research has progressively refined this model, revealing a dynamic, multi-component regulatory system that governs HSC fate. Contemporary studies demonstrate that the niche is not merely a passive housing structure but an active participant in regulating the critical balance between HSC quiescence, self-renewal, and differentiation [3] [4]. This in-depth technical guide synthesizes historical perspectives with cutting-edge research, providing a comprehensive resource for scientists and drug development professionals engaged in hematopoietic stem cell niche bone marrow microenvironment research.

Historical Development and Conceptual Framework

The intellectual genesis of the niche concept lies in the earlier theory of the "hemopoietic-inductive microenvironment" (HIM), which posited that specific local environments instruct hematopoietic cell development [1]. Schofield's seminal contribution was to crystallize this idea into the "stem cell niche" hypothesis, providing a specific framework to explain the dependence of stem cells on their microenvironment for maintaining self-renewal capacity [1] [2]. This hypothesis was initially supported by observations that transplanted HSCs would only engraft when niche space was made available through conditioning regimens like irradiation [5].

Over time, two predominant interpretations of the niche have emerged, reflecting the complexity uncovered by experimental evidence. The table below summarizes this conceptual evolution.

Table 1: Conceptual Evolution of the Stem Cell Niche Hypothesis

| Aspect | Schofield's Original Postulate (1978) | Orthodox Interpretation | Alternative/Dynamic Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | A cellular environment associating with stem cells to determine their behavior and self-renewal capacity [1]. | A confined anatomical site that supports self-renewal and maintains HSCs in a quiescent, undifferentiated state [1]. | A distinct, dynamic, hierarchical microenvironment regulating the balance between quiescence, proliferation, and differentiation of stem cells and progenitors [1]. |

| Primary Function | Maintain stem cell self-renewal and "stemness" [1]. | Retain HSCs in a quiescent state to protect the stem cell pool [1] [2]. | Instruct stem cell fate decisions dynamically in response to physiological demands and stressors [1] [4]. |

| Key Regulated Process | Self-renewal. | Quiescence maintenance. | Fate choice (quiescence, self-renewal, differentiation). |

The orthodox view emphasizes a static, protective role for the niche, primarily enforcing HSC quiescence. In contrast, the dynamic interpretation, supported by a growing body of evidence, recognizes the niche as a responsive entity that senses and reacts to changes such as injury, inflammation, and aging, thereby actively directing HSC fate [1] [4]. This evolution from a passive "space" to an active "instructional unit" marks a critical paradigm shift in the field.

Core Components and Regulatory Mechanisms of the HSC Niche

The bone marrow niche is a multicellular ensemble where diverse cell types coordinate to regulate HSCs. The major cellular constituents and their functional roles are detailed in the table below.

Table 2: Core Cellular Components of the Bone Marrow HSC Niche

| Cell Type | Key Identifiers/Markers | Primary Functions in Niche Regulation | Critical Secreted Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem/Progenitor Cells (MSPCs) | Nestin-GFP+, LEPR+, CXCL12-GFP+, CD51+CD140α+ [5] [6] [2] | Major source of CXCL12 and SCF; critical for HSC maintenance and retention; can differentiate into osteolineage cells [5] [6]. | CXCL12, SCF (Kitl), IL-7, Angiopoietin-1 [5] [6]. |

| Endothelial Cells (ECs) | CD31+, CD144+, SCA-1+ [5] [2] | Form vascular niches; regulate HSC quiescence and differentiation; facilitate homing and mobilization [3] [4]. | SCF, CXCL12, E-selectin [6] [2]. |

| Osteolineage Cells | Osteoblasts, osteocytes [2] | Historically considered a key niche component; contribute to endosteal niche; role in direct HSC maintenance is debated [6] [2]. | Osteopontin, Angiopoietin-1, Thrombopoietin [2]. |

| Sympathetic Nerves | N/A | Regulate HSC mobilization via circadian norepinephrine release; modulate CXCL12 expression; aid bone marrow regeneration [2]. | Norepinephrine [2]. |

| Megakaryocytes & Macrophages | N/A | Accessory niche cells; secrete factors that induce HSC quiescence [4]. | TGF-β, CXCL4 (PF-4) [4]. |

The signaling axis involving the C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) and its receptor C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) represents a cornerstone of niche regulation. This pathway is instrumental for HSC homing, retention, and quiescence [6]. CXCL12, produced predominantly by MSPCs and endothelial cells, acts as a potent chemoattractant for CXCR4-expressing HSCs. Beyond chemotaxis, CXCR4 signaling promotes HSC quiescence and facilitates access to other critical niche factors like Stem Cell Factor (SCF) [6]. The centrality of this pathway is highlighted by its additional role in guiding lymphoid progenitors to IL-7-producing niches for lymphopoiesis [6].

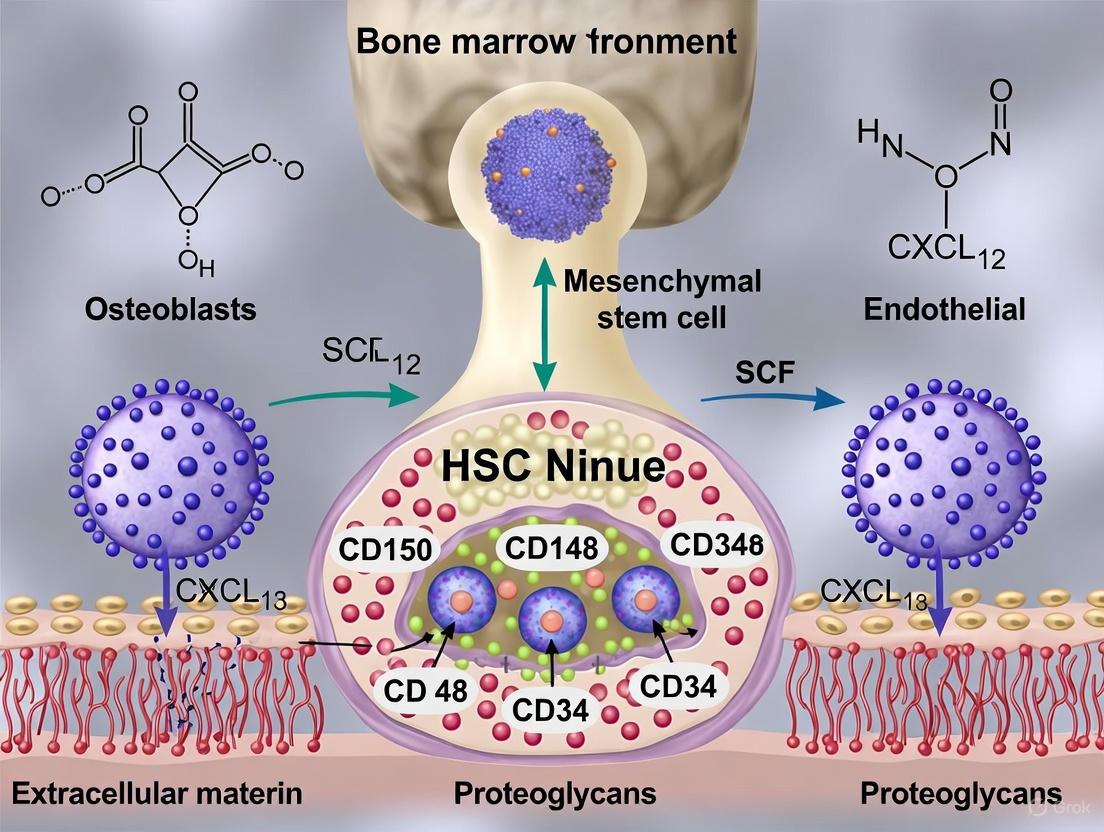

Diagram 1: Key Signaling in the HSC Niche.

Recent Experimental Advances and Technical Approaches

Challenging the Niche Size Dogma: Systemic and Local Regulation

The classical model posits that HSC numbers are directly limited by available niche space. However, a groundbreaking 2025 study using a novel femur-transplantation system challenges this view [5]. Researchers subcutaneously transplanted wild-type femoral bones into non-conditioned host mice, creating additional functional niches with intact MSPCs and vasculature but devoid of host HSCs.

Table 3: Key Findings from Femur-Transplantation Studies [5]

| Experimental Condition | Observation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Addition of 6 femoral grafts | Total body HSC numbers did not increase. | A systemic mechanism overrides local niche availability to limit total HSC numbers. |

| Transplanted femurs in hosts with defective endogenous niches | HSC numbers in grafts did not exceed physiological levels. | Local restraint also operates, preventing niche saturation even when HSCs are mobilized and available. |

| Role of Thrombopoietin | Thrombopoietin is pivotal in setting the total HSC number. | A specific systemic factor (Thrombopoietin) is a key determinant of the HSC set-point, independent of niche number. |

This research demonstrates that HSC numbers are subject to dual restriction—both systemically (body-wide) and locally (within the bone marrow)—and are not solely defined by niche capacity [5]. The identification of thrombopoietin as a key systemic regulator provides a molecular handle for this previously elusive mechanism.

Protocol: Femur Transplantation for Niche Studies

The following methodology was used to investigate niche regulation [5]:

- Graft Preparation: Femurs are harvested from donor adult mice (e.g., wild-type, nestin-GFP, or CD45.1 mice).

- Transplantation: Grafts are implanted subcutaneously into non-conditioned, non-irradiated host mice (e.g., WT or CD45.2 mice). Up to six femurs can be transplanted per host.

- Validation of Niche Viability: Grafts are analyzed at multiple time points (e.g., 1, 3, 5 months). Persistence of graft-derived MSPCs (CD45−TER-119−CD31−CD51+CD140α+) and host-derived endothelial cells is confirmed by flow cytometry and imaging. Host-derived haematopoietic cell repopulation is assessed.

- Functional Assessment: At endpoint, HSC numbers in host bones, grafts, and non-skeletal sites are quantified by flow cytometry (phenotype: Lin−SCA-1+KIT+CD150+CD48−CD34−). Niche function is tested via competitive bone marrow reconstitution assays.

Visualizing Niche Dynamics: Single-Cell Localization and Cycling

To move beyond snapshots and understand HSC behavior dynamically, researchers employ sophisticated genetic models. One powerful system is the hCD34tTA/Tet-O-H2BGFP transgenic mouse, which allows tracking of HSC division history [4]. In this model, HSCs express a histone H2B-GFP fusion protein. Upon administration of doxycycline (Doxy), new GFP synthesis is suppressed, and GFP intensity halves with each cell division, enabling the identification of HSCs that have divided 0 to 4+ times (G0 to GFP4) [4].

Using this model in aged mice, studies reveal niche-specific proliferation dynamics: the majority of HSCs surrounding arterioles retain high GFP signal (G0, dormant/slow-cycling), while HSCs associated with venules/sinusoids rapidly lose GFP label, indicating active cycling and a bias toward differentiation [4]. This demonstrates that different vascular niches instruct distinct HSC fates.

Diagram 2: HSC Division Tracking via a Genetic Model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Cutting-edge research into the HSC niche relies on a suite of specialized reagents, animal models, and methodologies.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for HSC Niche Investigations

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Key Examples / Models |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Mouse Models | Lineage tracing, cell-specific ablation, and gene deletion in niche components. | Nestin-GFP [5] [2], Cxcl12-GFP [2], Lepr-Cre [6], Cdh5-creER (endothelial) [5], CD45.1/CD45.2 congenic [5]. |

| Cell Surface Markers for Isolation | Identification and purification of HSCs and niche cells by flow cytometry. | HSC (murine): Lin−SCA-1+KIT+CD150+CD48−CD34− [5]. MSPCs: CD45−TER-119−CD31−CD51+CD140α+ [5]. ECs: CD45−TER-119−CD31+ [5]. |

| In Vivo Functional Assays | Testing the long-term regenerative capacity and functional integrity of HSCs. | Competitive Bone Marrow Transplantation [5], Parabiosis [5]. |

| Mobilizing Agents | Studying HSC egress from the niche and the resulting compensatory mechanisms. | G-CSF [5]. |

| Advanced Microscopy & Lineage Tracing | Visualizing HSC location, division history, and niche interactions in real-time. | hCD34tTA/Tet-O-H2BGFP transgenic mice [4], multicolor confocal microscopy, intravital imaging. |

Fifty years after Schofield's prescient hypothesis, the field of HSC niche biology has matured from a theoretical model to a sophisticated understanding of a dynamic regulatory unit. The contemporary view defines the niche as a multi-tiered system employing local cellular cross-talk, systemic hormonal signals, and neural input to precisely control hematopoiesis. Recent discoveries of dual systemic/local HSC number control and niche-specific proliferation dynamics represent significant paradigm shifts [5] [4].

Despite these advances, the field faces challenges, including a lack of consensus on the precise definition and fundamental components of a "niche," which may be causing stagnation in conceptual progress [1]. Future research must leverage single-cell multi-omics and high-resolution spatiotemporal imaging to further deconstruct niche heterogeneity and plasticity. A major translational frontier lies in understanding how niches are corrupted in hematological malignancies and how to rebuild or modulate them for therapeutic benefit in regenerative medicine and stem cell transplantation. As we stand on the threshold of the 50th anniversary of Schofield's hypothesis, a concerted effort to integrate existing knowledge and standardize definitions will be crucial for the next generation of breakthroughs in this pivotal field [1].

The bone marrow microenvironment, or hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche, provides a specialized structural and functional unit essential for the maintenance, self-renewal, and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells. The classical model distinguishes three principal niche compartments: the osteoblastic niche situated at the endosteal bone surface, the vascular niche comprising sinusoidal and arteriolar networks, and the perivascular niche where mesenchymal stromal cells create a supportive microenvironment for HSCs [7] [8] [9]. These niches are not isolated entities but form a highly integrated and dynamic system. Recent research has challenged the oversimplified dichotomy of endosteal versus vascular niches, revealing a more complex reality where these compartments are structurally and functionally intertwined, particularly during early myelopoiesis [7]. The precise coordination between these niches ensures lifelong hematopoiesis, while disruptions in their function contribute to hematological disorders and age-related hematopoietic decline. This technical guide provides a comprehensive analysis of these key cellular components, their regulatory mechanisms, and the experimental approaches used to study them, framed within the context of advanced bone marrow microenvironment research.

The Osteoblastic Niche

Anatomical Location and Cellular Composition

The osteoblastic niche, also termed the endosteal niche, is localized at the inner bone surface, in close proximity to the endosteum. This niche is predominantly composed of osteoblasts (bone-forming cells) and other bone-lining cells that create a specialized microenvironment for HSC regulation [8]. Osteoblasts anchor HSCs near the endosteal region and enhance hematopoiesis through the secretion of regulatory cytokines and adhesion molecules, thereby facilitating HSC homing and retention [10]. The functional significance of osteoblasts is evidenced by studies showing that osteoblast number correlates with HSC population size; ablation of osteoblasts leads to HSC reduction, while increased osteoblast numbers boost HSC quantities [10]. Beyond osteoblasts, this niche also contains osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells) that regulate extracellular matrix turnover and release factors influencing HSC function and niche remodeling [8]. The coordinated activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts maintains bone marrow integrity and composition, essential for proper hematopoietic function.

Regulatory Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Osteoblasts regulate HSC function through multiple mechanisms, including direct cell-cell contact and paracrine signaling. They secrete key regulatory factors such as osteopontin and angiopoietin-1 that help maintain HSC quiescence [8]. Additionally, osteoblasts guide HSC differentiation through Wnt and Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) signaling pathways, thereby preserving hematopoietic regeneration capacity [8]. The angiopoietin-1/Tie2 receptor interaction is particularly crucial for maintaining HSC quiescence and adhesion within the niche [3]. Furthermore, osteoblasts produce thrombopoietin (TPO), a critical cytokine that promotes HSC maintenance and determines the total number of HSCs in the body, even in contexts of increased niche availability [5]. Recent evidence also highlights the role of osteoblast-derived SDF-1 (CXCL12) in preferentially regulating multipotent progenitors (MPP) and common lymphoid progenitors (CLP) retention [7].

Table 1: Key Signaling Molecules in the Osteoblastic Niche

| Signaling Molecule | Cellular Source | Function in HSC Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Osteopontin | Osteoblasts | Regulates HSC quiescence and pool size |

| Angiopoietin-1 | Osteoblasts | Promotes HSC quiescence via Tie2 receptor interaction |

| Thrombopoietin (TPO) | Osteoblasts | Critical for HSC maintenance and determination of total HSC numbers |

| CXCL12 (SDF-1) | Osteolineage cells | Regulates retention of multipotent progenitors and lymphoid progenitors |

| Wnt Proteins | Osteoblasts | Guides HSC differentiation and self-renewal |

| BMP Signals | Osteoblasts | Influences HSC fate decisions |

Diagram 1: Osteoblastic niche signaling pathways regulating HSC fate.

The Vascular Niche

Sinusoidal and Arteriolar Compartments

The vascular niche encompasses the blood vessel networks within the bone marrow, primarily consisting of sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs) and arteriolar endothelial cells (AECs). These two endothelial subtypes create distinct microenvironments that differentially regulate HSC function [10]. Sinusoidal vessels are characterized by their permeable, dilated structure and support HSC activation, trafficking, and mobilization into circulation [10]. In contrast, arteriolar vessels are surrounded by smooth muscle cells and non-myelinating Schwann cells, creating a niche that maintains HSC quiescence and protects against oxidative stress [10] [9]. The spatial distribution of HSCs within these vascular compartments correlates with functional states; HSCs in perisinusoidal areas are often more primed for differentiation and mobilization, while those associated with arterioles maintain greater quiescence [11]. This compartmentalization allows for precise regulation of hematopoietic output based on physiological demands.

Endothelial Cell Regulation of Hematopoiesis

Endothelial cells form the structural basis of the vascular niche and actively regulate HSC migration, maintenance, and activation through multiple mechanisms. They produce angiocrine factors—including VEGF, Notch ligands, and CXCL12—that directly influence HSC behavior [8]. The CXCL12/CXCR4 axis is particularly critical for HSC retention within the niche, with endothelial-derived SCF being specifically required for HSC maintenance and quiescence [7] [12]. Recent research has demonstrated that endothelial barrier integrity, controlled by FGF and CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling, is essential for HSC retention and metabolic stability [10]. Disruption of endothelial function leads to increased HSC mobilization, apoptosis, and reduced regenerative potential, highlighting the dynamic role of ECs in both stem cell maintenance and clinical mobilization strategies. The differential roles of endothelial subtypes are further emphasized by their distinct responses to stress and contribution to hematopoietic recovery.

Table 2: Functional Characteristics of Vascular Niche Components

| Vascular Component | Structural Features | HSC Functions Supported | Key Signaling Molecules |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells (SECs) | Permeable, dilated structure with discontinuous basement membrane | HSC activation, trafficking, and mobilization; more permeable to circulating plasma | CXCL12, SCF, VEGF |

| Arteriolar Endothelial Cells (AECs) | Continuous basement membrane, surrounded by smooth muscle cells | HSC quiescence maintenance, protection from oxidative stress | Notch ligands, CXCL12, SCF |

| Type H Vessels | Specific endothelial subtype found in metaphysis | Association with osteogenesis, reduced in aged BM | Notch signaling components |

The Perivascular Niche

Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Populations

The perivascular niche represents a critical functional compartment where mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) create a supportive microenvironment for HSCs. Two principal MSC populations have been identified: Nestin-positive (Nestin⁺) MSCs and leptin receptor-positive (LepR⁺) MSCs, also known as CXCL12-abundant reticular (CAR) cells [12] [10] [9]. These perivascular stromal cells are strategically positioned around blood vessels and constitute the major cellular component of niches for HSCs and hematopoiesis in the bone marrow [9]. Nestin⁺ MSCs, predominantly located in perivascular regions in close association with sympathetic nerve fibers, are crucial for maintaining HSC quiescence and retention through the secretion of key factors such as CXCL12 and SCF [10] [9]. Conversely, LepR⁺ (CAR) cells constitute a significant portion of the adult BM stromal population and are instrumental in supporting hematopoiesis by contributing significantly to HSC homing, localization, and maintenance [10]. These cells also contribute to bone formation and adipogenesis, particularly during stress responses and following chemotherapy-induced damage.

Regulatory Functions of Perivascular Cells

Perivascular MSCs support hematopoiesis through multiple mechanisms, including the creation of a specialized extracellular matrix and provision of essential signaling cues. Through the secretion of key ECM proteins and cell adhesion molecules, MSCs regulate HSPC proliferation, differentiation, homing, retention, and maintain the quiescence necessary for effective hematopoiesis [10]. CAR/LepR⁺ cells have been demonstrated as the major cellular component of niches for HSCs, with approximately 97% of LT-HSCs in contact with these cells [9]. These perivascular cells produce critical niche factors including CXCL12, stem cell factor (SCF), VCAM-1, and Angpt1 [5]. The functional output of these signaling pathways is highly specific; for instance, although SCF is secreted by multiple stromal cells, HSC maintenance specifically relies on the endothelial source, demonstrating the precision of cellular crosstalk within the niche [7]. Furthermore, perivascular cells exhibit phenotypic and functional changes during aging, with increased expression of senescence markers like p16 and IL-1β, contributing to age-related hematopoietic decline [9].

Diagram 2: Perivascular MSC populations and their regulatory functions.

Integrated View of Niche Interactions

Cellular Crosstalk and Signaling Networks

The bone marrow niche operates as an integrated system where continuous crosstalk between cellular components ensures precise regulation of hematopoiesis. This complex multicellular communication involves not only the primary niche cells but also hematopoietic progeny and neural components that actively modulate niche function. Megakaryocytes, for example, regulate bone marrow hematopoiesis by secreting key cytokines such as TPO, CXCL4, and TGF-β to directly promote HSC maintenance, while also physically interacting with niche cells like osteomacs, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts to modulate their support of HSCs [7]. Similarly, sympathetic nerve fibers interact directly with MSCs, influencing the production of essential niche factors such as CXCL12, SCF, and VCAM-1, all critical for HSPC maintenance [10]. Recent research has uncovered novel regulatory mechanisms whereby dopamine, secreted by sympathetic nerves, promotes HSPC proliferation through upregulation of tyrosine-protein kinase Lck, which subsequently activates the MAPK pathway [10]. Additionally, regulatory T cells (Tregs) and cytotoxic T cells regulate the hematopoietic microenvironment via cytokines IL-10 and IFN-γ, respectively, and Tregs may engage in direct interactions with HSCs to establish a survival-promoting niche for aged HSCs [7].

Biophysical Properties of the Niche

Beyond biochemical signaling, the mechanical properties of cells, extracellular matrix (ECM), and tissues act as fundamental physical regulators within the bone marrow hematopoietic microenvironment. Key biophysical parameters such as stiffness, viscoelasticity, 3D topological architecture, and dynamic fluid shear stress critically regulate HSC quiescence, differentiation, migration, and apoptosis [7]. The ECM, secreted by niche cells, predominantly comprises structural proteins including type I and IV collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, alongside glycosaminoglycans such as hyaluronic acid and heparan sulfate proteoglycans [7] [12]. Matrix stiffness within the HSC niche is heterogeneous: the endosteal niche exhibits a relatively rigid matrix exceeding 35 kPa, whereas the vascular niche is characterized by softer matrices—approximately 0.3 kPa in bone marrow, 0.5–2 kPa in endothelium, and 5–8 kPa in vascular walls [7]. HSCs perceive ECM mechanical cues via mechanosensitive receptors, notably integrins, ion channels, and primary cilia, which collectively maintain functional homeostasis and precisely govern stem cell fate decisions [7]. Furthermore, specialized capillaries within the bone marrow regulate HSC survival via shear stress, with blood flow-induced shear stress activating specific signaling pathways in endothelial cells that influence HSC behavior.

Experimental Methodologies for Niche Analysis

Advanced Imaging and Modeling Techniques

Research on HSC niches employs sophisticated methodologies that enable high-resolution analysis of niche architecture and function. The iFAST3D imaging protocol allows high-resolution imaging of HSCs and their niche components within intact mouse tissues while preserving their spatial organization [11]. This technique involves sample preparation where bones are harvested and fixed, followed by shaving with a cryotome until the bone marrow is fully exposed to ensure optimal antibody penetration. After immunofluorescence staining with antibodies targeting HSC markers and niche components, imaging is performed using confocal laser scanning microscopy to capture z-stack images for 3D reconstruction and quantification of HSC size, shape, and spatial positioning relative to niche structures [11]. For in vitro modeling, 3D culture systems using biomimetic hydrogel scaffolds facilitate long-term HSC expansion and directed differentiation by establishing a three-dimensional niche architecture [7]. Microfluidic devices emulating vascular and osteogenic niches recreate the dynamic HSC microenvironment, offering platforms for in vitro modeling of hematological disorders and enabling high-throughput drug screening [7]. Additionally, bone transplantation models have been developed to rigorously define the role of niche size in regulating HSC numbers, enabling researchers to augment overall niche availability in vivo and assess the impact on HSC populations [5].

Molecular and Cellular Analysis

Single-cell technologies have revolutionized niche research by providing unprecedented resolution of cellular heterogeneity and molecular regulation. Single-cell RNA sequencing enables the identification of novel molecular regulators of HSC emergence and resolves cellular heterogeneity during hematopoietic development [13]. Flow cytometry-based size analysis determines the absolute size of individual HSPC populations from young and aged mice using forward scatter measurements calibrated with reference size beads [11]. To assess HSC polarity, the CellDetail analysis method involves immunofluorescence staining of FACS-isolated and fixed HSCs, followed by epifluorescence or confocal microscopy to capture subcellular high-resolution images of spatial distribution of proteins like Tubulin and Cdc42 within the cells [11]. For studying niche cell secretions, conditioned media collection from in vitro HSC niche models allows comparison of how young versus old niche environments affect hematopoietic cell development and function [14]. These complementary approaches provide comprehensive insights into niche function at molecular, cellular, and tissue levels.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Tools for Niche Studies

| Research Tool | Application | Key Features/Components |

|---|---|---|

| iFAST3D Imaging | 3D spatial analysis of HSCs in intact bone marrow | Preserves spatial organization; uses antibodies against CD150, CD48, sinusoids, arterioles |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing | Molecular profiling of niche and HSC heterogeneity | Identifies novel regulators; resolves transitional cellular states |

| Conditioned Media from Niche Models | Analysis of secretory profiles from young vs. aged niches | Contains adipokines (e.g., adiponectin); reveals age-related inflammatory changes |

| Reference Size Beads | Flow cytometry-based HSC size measurement | Enables calibration with 7µm, 10µm, 16µm standards for precise sizing |

| Bone Transplantation System | In vivo niche expansion studies | Provides additional functional niches without adding HSCs |

| 3D Biomimetic Hydrogels | In vitro niche reconstruction | Replicates mechanical properties; supports long-term HSC culture |

The osteoblastic, vascular, and perivascular niches represent functionally distinct but highly integrated compartments that collectively regulate hematopoietic stem cell fate through complex biochemical and biophysical signals. Understanding the precise cellular composition, regulatory mechanisms, and dynamic interactions within these niches provides critical insights for both basic hematopoiesis research and clinical applications. Recent advancements in single-cell technologies, high-resolution imaging, and sophisticated in vitro models have progressively enhanced our understanding of niche biology, revealing unprecedented complexity in cellular crosstalk and microenvironmental regulation. These findings have important implications for developing novel therapeutic strategies for hematological disorders, improving hematopoietic stem cell transplantation outcomes, and addressing age-related hematopoietic decline. Future research focusing on the dynamic regulation of these niche components during homeostasis, stress, and aging will further advance our understanding of the bone marrow microenvironment and its role in health and disease.

Long-term hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs) maintain lifelong blood production by residing in a state of quiescence within the hypoxic bone marrow niche. This in-depth technical guide explores the central role of hypoxia and the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) in enforcing a metabolic program essential for LT-HSC quiescence and functional preservation. We delineate how the hypoxic niche, through HIF-1α signaling, promotes a glycolytic metabolic phenotype and actively suppresses oxidative phosphorylation to minimize the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby protecting stem cell integrity. This review is framed within the broader context of bone marrow microenvironment research, synthesizing current molecular insights, experimental methodologies, and technical approaches relevant for scientists and drug development professionals working in hematopoiesis, stem cell biology, and regenerative medicine.

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are multipotent cells responsible for the lifelong regeneration of all blood cell lineages. The long-term self-renewing HSCs (LT-HSCs), which serve as the cornerstone of hematopoiesis, predominantly exist in a quiescent state (G0 phase of the cell cycle) within the bone marrow [15] [3]. This quiescence is a crucial mechanism to protect LT-HSCs from proliferative and genotoxic stress, thereby preserving their self-renewal capacity and preventing exhaustion [16] [15].

The bone marrow microenvironment, or "niche," is a complex, multicellular tissue where hematopoiesis occurs. A defining characteristic of this niche, particularly in the perisinusoidal regions where LT-HSCs are thought to reside, is its low oxygen tension (hypoxia) [15]. This hypoxic environment is not merely a passive condition but an active regulator of HSC function. Emerging evidence positions cellular metabolism as a fundamental determinant of HSC fate, with the hypoxic niche imparting specific metabolic characteristics that are integral to the maintenance of stemness [16] [15].

Metabolic Programming of Quiescent LT-HSCs

Quiescent LT-HSCs exhibit a distinct metabolic profile characterized by a reliance on anaerobic glycolysis for energy production, coupled with restrained mitochondrial activity. This bioenergetic configuration is a key adaptation to their hypoxic residence and is essential for their functional integrity.

Table 1: Metabolic Characteristics of Quiescent vs. Differentiating HSCs

| Metabolic Parameter | Quiescent LT-HSCs | Differentiating/Activated HSCs |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Energy Pathway | Anaerobic Glycolysis [16] [15] | Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation [16] |

| Mitochondrial Activity | Low membrane potential, inactive [16] [15] | High membrane potential, active [16] |

| Oxygen Consumption | Low [16] | High [16] |

| ROS Levels | Low (physiological) [16] [15] | Elevated [16] |

| ATP Levels | Lower [16] | Higher |

The preference for glycolysis over the more energy-efficient mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) is a critical feature of stem cell maintenance. While OXPHOS generates more ATP per glucose molecule, it also produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) as byproducts. Elevated ROS levels can cause oxidative damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids, leading to impaired self-renewal capacity, loss of functionality, and accelerated HSC exhaustion [16] [15]. Therefore, the glycolytic metabolism of LT-HSCs serves to minimize ROS production, thus preserving genomic integrity and long-term regenerative potential [16]. This metabolic state, involving reduced oxidative capacity and lower mitochondrial activity, is considered a marker of "stemness" [16].

Central Role of HIF-1α in Metabolic Regulation

The transcription factor Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α (HIF-1α) is the master regulator mediating the adaptation of LT-HSCs to the hypoxic niche and enforcing their quiescent metabolic state.

Regulation of HIF-1α Stability

HIF-1α is highly elevated in LT-HSCs, partly through transcriptional regulation by Meis homeobox 1 (Meis1) [15]. The stability of the HIF-1α protein is exquisitely controlled by cellular oxygen levels:

- Under normoxic conditions: HIF-1α is continuously synthesized but rapidly ubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome. This process is mediated by prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzymes, which hydroxylate HIF-1α in the presence of oxygen, marking it for recognition by the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [15].

- Under hypoxic conditions: PHD enzyme activity is inhibited, preventing HIF-1α hydroxylation. This stabilizes HIF-1α, allowing it to translocate to the nucleus, dimerize with its constitutive partner HIF-1β, and bind to Hypoxia-Response Elements (HREs) in the promoter regions of target genes [15].

HIF-1α Target Genes and Metabolic Control

Active HIF-1 orchestrates a metabolic switch by regulating a suite of genes that promote glycolysis and suppress mitochondrial OXPHOS.

- Promotion of Glycolysis: HIF-1 upregulates the expression of key glycolytic enzymes and glucose transporters, increasing the flux of glucose through the glycolytic pathway. This includes rate-limiting catalysts like phosphofructokinase-1 (Pfk-1) [15].

- Suppression of OXPHOS: A pivotal mechanism involves the HIF-1-mediated transactivation of genes encoding pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK1-4). PDK phosphorylates and inactivates the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) enzyme. This critical step shunts glucose-derived pyruvate away from the mitochondria, preventing its conversion to acetyl-CoA and subsequent entry into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. This effectively decouples glycolysis from mitochondrial respiration, limiting oxygen consumption and ROS generation [15].

The following diagram illustrates the core HIF-1α signaling pathway and its key metabolic functions in a hypoxic LT-HSC:

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Investigating the interplay between hypoxia, HIF-1α, and HSC biology requires a combination of genetic models, precise functional assays, and advanced analytical techniques.

Key Genetic Models and Functional Assays

Table 2: Experimental Models for Studying HSC Metabolism

| Model/Assay | Key Feature | Application & Functional Readout |

|---|---|---|

| HIF-1α Deletion/Modulation | Loss-of-function in HSCs or niche cells [15] [17]. | Assesses cell-autonomous vs. non-autonomous roles in HSC maintenance, quiescence, and metabolic programming. |

| P2H1Ad.Cortex Mouse Model | Adrenocortical-specific HIF1α deletion, causing chronic systemic elevation of glucocorticoids [17]. | Mimics chronic stress; used to study systemic hormonal influence on HSC quiescence and function. |

| Competitive Transplantation | Transplanting test HSCs (e.g., KO) with wild-type competitor cells into lethally irradiated recipients [15] [17]. | Gold-standard assay for evaluating long-term self-renewal and regenerative capacity in vivo. |

| Bone Marrow Niche Modeling (3D Cultures) | Co-culture of HSCs with stromal cells (MSCs) in hydrogels/scaffolds mimicking ECM [18]. | Enables dissection of cell-cell interactions and testing niche influences on HSC fate ex vivo. |

The experimental workflow for validating the role of a specific gene in HSC metabolism often follows a multi-step process, as visualized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for HSC Metabolism Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Application in HSC Research |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | High-speed cell sorting and analysis. | Isolation of pure LT-HSC populations (e.g., Lin−Kit+Sca-1+CD48−CD150+) from murine bone marrow for functional and molecular analysis [15] [17]. |

| Antibody Panels for HSC Phenotyping | Surface markers: Lineage, c-Kit, Sca-1, CD48, CD150. | Identification and quantification of HSCs and progenitor subpopulations by flow cytometry [17]. |

| HIF-1α Stabilizers (e.g., PHD Inhibitors) | Chemical inhibition of PHD enzymes. | Experimentally mimic hypoxia and activate HIF-1α signaling in vitro to study downstream metabolic and functional effects [15]. |

| Seahorse Extracellular Flux Analyzer | Real-time measurement of OCR and ECAR. | Direct functional assessment of mitochondrial respiration (OXPHOS) and glycolytic flux in live HSCs [15]. |

| MitoTracker / MitoSOX Dyes | Fluorescent probes for mitochondrial mass and ROS. | Flow cytometry or microscopy-based quantification of mitochondrial content and superoxide production in HSCs [16] [15]. |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | Genome-wide expression profiling at single-cell resolution. | Unraveling HSC heterogeneity, identifying novel subpopulations, and mapping transcriptional states of niche cells [19] [20]. |

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Perspectives

Dysregulation of the finely tuned metabolic and signaling networks in LT-HSCs has significant consequences for disease pathogenesis and offers potential therapeutic avenues.

- Leukemogenesis: The metabolic dysregulation seen in leukemia often represents a corrupted version of stem cell metabolism. For instance, gain-of-function mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1/2) genes, found in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), lead to production of the oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG). This metabolite inhibits enzymes like TET2, leading to epigenetic alterations that block differentiation and promote leukemogenesis [16]. Furthermore, chronic inflammation, as studied in models of clonal hematopoiesis (CHIP) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), can rewire the bone marrow niche. The emergence of inflammatory mesenchymal stromal cells (iMSCs) creates a self-reinforcing inflammatory loop that disrupts normal hematopoiesis and favors the expansion of mutant HSC clones, acting as a precursor to frank leukemia [19] [21].

- Aging and the Niche: The aged bone marrow microenvironment exhibits chronic, low-grade inflammation ("inflammaging"), characterized by elevated levels of cytokines like CCL5 and IL-1β [20]. This inflammatory state can impose metabolic stress on HSCs, driving a myeloid bias and potentially selecting for clones with pre-leukemic mutations, thereby linking niche aging to increased cancer risk [20] [21].

- Therapeutic Implications: Understanding HIF-1α-mediated metabolic regulation opens promising strategies. HIF stabilizers are being explored for their therapeutic potential [17]. Targeting the inflammatory bone marrow niche in pre-leukemic conditions like CHIP and MDS represents a novel preventive approach to intercept disease progression before leukemia develops [19] [21].

The maintenance of LT-HSC quiescence is a metabolically active process critically dependent on the hypoxic bone marrow niche and the transcriptional activity of HIF-1α. By enforcing a glycolytic metabolic state and suppressing mitochondrial OXPHOS, the HIF-1α pathway minimizes ROS production and protects the long-term self-renewal capacity of the stem cell pool. This mechanistic insight is fundamental to understanding both normal hematopoietic homeostasis and the pathophysiological processes of aging and malignant transformation. Future research, leveraging advanced genetic models, single-cell technologies, and sophisticated ex vivo niche systems, will continue to decipher the complex dialogue between HSCs and their microenvironment, paving the way for novel microenvironment-directed therapies for hematologic disorders.

The bone marrow microenvironment, or HSC niche, is a highly organized and dynamic structure essential for the lifelong maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). This niche provides precise regulatory signals that control HSC quiescence, self-renewal, and differentiation to maintain blood and immune system homeostasis [18]. During aging, this carefully tuned microenvironment undergoes profound functional and structural remodeling, which is now recognized as a critical driver of hematopoietic decline. The aged niche is characterized by a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation termed "inflammaging," which promotes a shift in HSC differentiation potential toward the myeloid lineage (myeloid bias) and impairs fundamental HSC functions [22] [23]. This transformation of the bone marrow landscape creates a self-reinforcing cycle that not only compromises normal hematopoiesis but also increases susceptibility to hematologic malignancies and other age-related pathologies [19]. Understanding the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying niche aging is therefore paramount for developing therapeutic strategies to counteract age-related hematopoietic decline.

The Molecular and Cellular Hallmarks of the Aged Niche

Inflammaging and Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP)

Inflammaging describes the persistent, low-grade inflammation that characterizes the aging process. This phenomenon is driven by the accumulation of senescent cells within the bone marrow microenvironment. These cells exhibit a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), releasing a plethora of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors [22] [23]. Key SASP factors include IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and TGF-β, which create a chronically inflamed milieu that disrupts normal niche function [22] [23]. The production of these factors can be triggered by various sources of age-associated damage, including genomic instability, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress [22]. This inflammatory signaling is not a passive consequence of aging but an active driver of hematopoietic dysfunction, establishing a vicious cycle where inflammation promotes further senescence and niche deterioration.

Table 1: Key Inflammatory Mediators in the Aged Bone Marrow Niche

| Mediator | Primary Cellular Source | Major Functional Impact on HSCs/Niche |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | Senescent stromal cells, Myeloid cells | Promotes myeloid-biased differentiation, Impairs self-renewal [23] |

| IL-1β | Myeloid cells, Senescent stromal cells | Expands pro-inflammatory neutrophil subsets, Drives HSC proliferation and myeloid skewing [20] |

| TNF-α | Immune cells, Senescent stromal cells | Contributes to chronic inflammatory signaling, Alters HSC differentiation potential [23] |

| TGF-β | Multiple niche cells | Associated with megakaryocytic differentiation bias; its neutralization can restore lymphoid potential [23] |

| Ccl5 (RANTES) | Aged microenvironment | Induces myeloid bias in young HSCs via mTOR pathway activation [20] |

Remodeling of the Cellular Niche

The functional decline of the aged HSC niche is driven by fundamental changes in its cellular composition. A critical transformation involves the replacement of normal, supportive mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) with inflammatory MSCs (iMSCs) [19]. These iMSCs secrete high levels of interferon-induced cytokines and chemokines, which recruit and activate T cells. These T cells then amplify the inflammatory signal, creating a feed-forward loop that sustains chronic inflammation, suppresses healthy hematopoiesis, and promotes vascular remodeling [19]. This process is evident in pre-malignant conditions like clonal hematopoiesis (CHIP), where inflammatory remodeling begins long before overt disease develops [19].

Concurrently, there is a documented expansion of megakaryocytes and megakaryocyte progenitors in the aged bone marrow [20]. While megakaryocytes are a normal component of the HSC niche and help regulate HSC quiescence via factors like CXCL4, their age-related expansion is thought to contribute to the dysregulation of HSC behavior, though the spatial relationship between HSCs and megakaryocytes during aging remains an active area of research [20]. The net effect of this cellular remodeling is the creation of a microenvironment that is inherently pro-inflammatory and selectively supportive of altered HSC function.

Myeloid Bias and Lineage Skewing

One of the most prominent functional consequences of an aged niche is the myeloid bias in HSC differentiation. Aging is associated with an increase in the proportion of myeloid-biased HSCs (my-HSCs) within the total HSC pool [24] [20]. This shift is driven by both cell-intrinsic changes in HSCs and powerful extrinsic pressures from the inflamed microenvironment. The molecular basis for this bias involves the epigenetic silencing of lymphoid-affiliated genes (e.g., EBF1, PAX5) and the upregulation of myeloid-specifying genes [25]. Furthermore, exposure of young HSCs to aged systemic factors or specific inflammatory cytokines like Ccl5 is sufficient to induce a myeloid-skewed output, demonstrating the instructive role of the extrinsic milieu [20]. This bias results in diminished lymphopoiesis—particularly a reduction in B cell production—and an expansion of myeloid cells, which contributes to weakened adaptive immunity and increased incidence of myeloid malignancies in the elderly [24] [20].

Functional Consequences of Niche Aging on Hematopoiesis

HSC Functional Decline

The aged bone marrow niche directly impairs the core functional properties of HSCs. Despite an overall increase in the phenotypic number of HSCs with age, these cells exhibit a reduced long-term self-renewal capacity and diminished functional competence in transplantation assays [24] [26]. This paradox—increased numbers but decreased quality—highlights the profound impact of aging on HSC biology. The aged niche contributes to this decline by disrupting the signals that normally maintain HSC quiescence. For instance, aged HSCs show impaired homing and engraftment capabilities, which is critical for successful bone marrow transplantation [26]. This homing defect is linked to alterations in the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis, a key pathway for HSC retention and maintenance within the niche [23]. The chronic inflammatory signaling also induces metabolic shifts in HSCs, forcing them to rely more on oxidative respiration than glycolysis, which in turn leads to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and increased DNA damage [23].

Table 2: Functional Alterations in Aged HSCs and Myeloid Cells

| Cell Type | Key Age-Related Functional Alterations | Underlying Mechanisms/Mediators |

|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic Stem Cell (HSC) | Reduced self-renewal and engraftment potential [26] | Altered CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling, Accumulated DNA damage, Increased ROS [23] |

| Myeloid-biased differentiation [24] [27] | Epigenetic repression of lymphoid genes (e.g., EBF1, PAX5), Inflammatory cytokine signaling (e.g., IL-1, IL-6) [25] [23] | |

| Impaired homing to bone marrow [26] | Reduced response to homing signals, Altered adhesion molecule expression | |

| Neutrophil | Decreased phagocytic capacity, Abnormal chemotaxis [23] | Downregulation of CXCR2 receptor, Altered TLR function [23] |

| Increased pro-inflammatory subsets (IL-1β+) [20] | Exposure to aged bone marrow microenvironment | |

| Macrophage | Reduced efferocytosis (clearance of apoptotic cells) [20] | Diminished autophagy, Dysregulated cytokine secretion (e.g., reduced IL-10) [23] |

| Increased SASP factor secretion (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) [23] | Accumulation of senescent cells, Chronic inflammatory signaling |

Immunosenescence and Inflammaging Loop

The functional decline of HSCs and the myeloid skewing of hematopoiesis directly lead to immunosenescence—the aging of the immune system. This is characterized by a shrinking pool of naïve T and B cells, a restricted T-cell receptor repertoire, and weakened responses to new antigens, resulting in reduced vaccine efficacy and increased susceptibility to infections [24] [20]. The aged niche fuels a vicious cycle: the immune cells it produces are dysfunctional and themselves contribute to inflammaging by secreting more pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1) [20]. This creates a self-reinforcing "inflammaging loop" where the inflammatory microenvironment produces defective immune cells, which in turn fail to resolve inflammation and adequately clear senescent cells, further exacerbating the inflammatory state of the niche [23] [20]. For example, aged macrophages show reduced phagocytic activity and efferocytosis, leading to the accumulation of cellular debris that further fuels inflammation [23].

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Studying the Aged Niche

Key Experimental Models

Heterochronic Transplantation

This gold-standard experiment involves transplanting HSCs from a donor of one age into a recipient of a different age, allowing researchers to disentangle the contributions of cell-intrinsic versus niche-extrinsic factors in HSC aging [20].

- Protocol:

- HSC Isolation: Harvest bone marrow from young (e.g., 2-3 month) and old (e.g., >20 month) mice. Enrich for HSCs using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for the Lineage⁻Sca-1⁺c-Kit⁺ (LSK) CD150⁺CD48⁻ phenotype.

- Recipient Conditioning: Irradiate young and old recipient mice with a lethal dose to ablate endogenous hematopoiesis.

- Transplantation: Intravenously inject purified young HSCs into conditioned young and old recipients, and old HSCs into young and old recipients. Include competitor cells to fairly assess repopulation potential.

- Analysis: Monitor peripheral blood chimerism over 16+ weeks. Analyze lineage output (myeloid vs. lymphoid), conduct secondary transplants to assess self-renewal, and examine HSC homing and localization within the niche [20].

Single-Cell Multi-Omics Analysis

This approach provides an unbiased, high-resolution view of the cellular and molecular changes in the aged niche.

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Obtain bone marrow from young and old donors (human or murine). Create a single-cell suspension.

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): Use a platform to capture thousands of individual cells and generate transcriptomic libraries. This identifies distinct cell populations (HSCs, MSCs, immune cells) and their inflammatory states [19] [27].

- Computational Analysis:

- Cluster Identification: Identify all cell types present in the bone marrow microenvironment.

- Differential Expression: Compare gene expression profiles between young and old cells to identify inflammaging signatures.

- Cell-Cell Communication: Infer altered signaling pathways between niche cells and HSCs [19].

- Spatial Validation: Validate findings using imaging techniques (e.g., immunofluorescence, imaging mass cytometry) on bone marrow biopsies to confirm changes in the spatial organization of the niche [19].

In Vitro Niche Reconstruction

Advanced 3D culture systems are being developed to model the complexity of the bone marrow niche in vitro for controlled studies of aging.

- Protocol:

- Scaffold Selection: Choose a biomaterial (e.g., gelatin-methacrylamide hydrogel, porous scaffolds) that mimics the physical and chemical properties of the native bone marrow extracellular matrix.

- Cellular Composition: Co-culture primary or induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived HSCs with key niche cells, such as mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), endothelial cells, and osteoblasts.

- Inflammatory Priming: To model inflammaging, treat the culture with a cocktail of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6).

- Functional Readouts:

- Assess HSC long-term culture-initiating cell (LTC-IC) capacity.

- Analyze differentiation bias by quantifying myeloid vs. lymphoid progeny.

- Measure transcriptomic and epigenetic changes in HSCs [28].

Diagram 1: The Inflammaging Signaling Cascade in the Aged Niche. This pathway illustrates how aging stressors trigger a self-reinforcing inflammatory loop that impairs HSC function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Models

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Studying the Aged HSC Niche

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cxcl5 Knockout (KO) Mice | To study the role of specific chemokines in niche-mediated lineage skewing. | Demonstrating that aged HSCs transplanted into Ccl5 KO recipients show reduced myeloid bias [20]. |

| SpliceUp Computational Tool | To identify cells with somatic mutations from single-cell RNA-seq data based on aberrant splicing. | Distinguishing mutant from non-mutant cells in clonal hematopoiesis (CHIP) and MDS samples to study niche interactions [19]. |

| CD49b Surface Marker | To prospectively isolate lymphoid-biased (CD49b+) and myeloid-biased (CD49b-) HSC subsets via FACS. | Investigating intrinsic age-related changes in functionally distinct HSC subpopulations [27]. |

| 3D Bone Marrow-on-a-Chip | To create a biomimetic in vitro model of the bone marrow niche with controlled fluid flow and cell-cell interactions. | Modeling the effects of chronic inflammatory cytokine exposure on HSC fate in a controlled system [28]. |

| Heterochronic Transplantation Model | To dissect cell-intrinsic (HSC) vs. extrinsic (niche) contributions to hematopoietic aging. | Transplanting young HSCs into aged recipients to test the rejuvenating effect of a young niche [20]. |

Diagram 2: Heterochronic Transplantation Experimental Workflow. This experimental design is fundamental for deconvoluting the intrinsic (HSC) and extrinsic (niche) contributions to hematopoietic aging.

The aged bone marrow niche is an active driver of hematopoietic decline, characterized by a self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation (inflammaging), cellular remodeling, and altered signaling that collectively promote myeloid bias and impair HSC function. Moving forward, research must focus on translating this mechanistic understanding into therapeutic strategies. Promising avenues include pharmacological inhibition of specific inflammatory pathways (e.g., IL-1 signaling), metabolic reprogramming of aged HSCs and niche cells, and epigenetic interventions to reverse myeloid-skewing gene expression programs [25] [26]. Furthermore, the development of increasingly sophisticated in vitro models, such as patient-specific bone marrow organoids, will enable high-throughput screening of rejuvenating compounds [28]. Ultimately, targeting the aged niche itself offers a powerful, complementary approach to direct HSC manipulation for preventing and treating age-related hematopoietic disorders and improving immune health in the elderly.

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) is an age-related condition characterized by the expansion of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) bearing somatic mutations in genes associated with hematologic malignancies. While intrinsic driver mutations confer a selective advantage to HSCs, a growing body of evidence indicates that the bone marrow microenvironment, or HSC niche, plays a critical role in promoting the emergence and expansion of these pre-malignant clones. This review synthesizes current research on how age-related alterations in the HSC niche—including vascular dysfunction, increased adiposity, dampened DNA damage response, and pro-inflammatory signaling—create a permissive environment for clonal selection. We detail the molecular mechanisms underpinning this relationship and provide a comprehensive toolkit for researchers, including standardized experimental protocols, key reagent solutions, and visual schematics of critical pathways. Understanding these niche-driven dynamics is paramount for developing novel therapeutic strategies to mitigate the risk of malignant progression and associated morbidities in CHIP.

Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) describes a prevalent, age-associated state in which a genetically distinct subpopulation of blood cells, derived from a single hematopoietic stem or progenitor cell, expands within the bone marrow compartment [29] [30]. The defining criterion for Clonal Hematopoiesis of Indeterminate Potential (CHIP) is the presence of somatic mutations in genes recurrently mutated in hematologic malignancies at a variant allele frequency (VAF) of ≥2% in the absence of definitive diagnostic criteria for a hematologic neoplasm [29] [31]. The incidence of CHIP rises dramatically with age, affecting less than 1% of the population under 40 but 10-20% of individuals over 70 [30]. While often asymptomatic, CHIP confers an elevated, albeit low absolute, risk of progression to overt hematologic cancer and is strongly associated with increased all-cause mortality and non-malignant conditions, particularly cardiovascular disease [29] [32] [30].

The traditional understanding of CHIP has focused on the acquisition of driver mutations—such as in DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1, and splicing factors—that confer a fitness advantage to HSCs, leading to their clonal expansion [29] [31]. However, the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche, a complex microenvironmental network in the bone marrow, is now recognized as an equally critical determinant. With aging, this niche undergoes profound functional and phenotypic changes that can selectively support the expansion of mutant HSCs, thereby fueling pre-malignant progression [33] [34]. This review examines the mechanistic links between the aged HSC niche and CHIP, framing CH not merely as a cell-autonomous process but as a ecosystem-level phenomenon driven by a deteriorating microenvironment.

The Aged Hematopoietic Stem Cell Niche: A Permissive Environment

The HSC niche is a multi-component system essential for HSC maintenance, quiescence, and regenerative potential. Its age-related degeneration creates a permissive soil for the seeds of clonal hematopoiesis. Key alterations include:

- Cellular Composition Shifts: Aging is associated with a significant accumulation of bone marrow adipocytes [33] [34] [35]. This shift alters the secretory profile of the niche, increasing pro-inflammatory adipokines like adiponectin, which can dysregulate immune cell development and function [35]. Furthermore, the supportive osteolineage cells and mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) decline in function, impairing their ability to maintain HSC quiescence [33].

- Vascular Dysfunction: The vascular component of the niche, critical for HSC homeostasis, deteriorates with age. This manifests as increased vascular permeability (leakiness) and vessel dilation, driven by a loss of key regulatory factors like Netrin-1 from perivascular LepR+ cells [34]. This compromised integrity disrupts the hypoxic, protective milieu required for HSC dormancy.

- Altered Neural Regulation: The sympathetic nervous system, which innervates the niche to regulate HSC mobilization and maintenance, exhibits abnormal activity with age. Denervation or impaired nerve function can force HSCs out of their quiescent state and into active cell cycle, increasing their susceptibility to stress and potentially favoring clones resilient to such activation [33].

- Accumulation of DNA Damage: A fundamentally conserved attribute of aging niche cells (MSCs, endothelial cells) and HSCs is a dampened DNA damage response (DDR) and the accrual of DNA damage. This genomic instability creates a pro-mutagenic environment and compromises the functional potential of both the niche and the HSCs it supports [34].

Table 1: Hallmark Changes in the Aged HSC Niche and Their Functional Consequences

| Niche Component | Age-Associated Change | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs) | Impaired function, increased adipogenic differentiation [34] | Reduced support for HSC quiescence, altered cytokine secretion (e.g., SCF, CXCL12) [33] |

| Vascular Endothelium | Increased permeability, vessel dilation [34] | Loss of HSC dormancy, altered HSC distribution [33] |

| Adipocytes | Expansion in bone marrow cavity [33] [35] | Secretion of pro-inflammatory adipokines (e.g., adiponectin), dysregulation of DC and HSC function [35] |

| Sympathetic Nerves | Abnormal nerve activity [33] | Disrupted HSC mobilization and maintenance of quiescence [33] |

| Global Niche | Attenuated DNA Damage Response (DDR) [34] | Accumulation of DNA damage in niche and HSCs, reduced regenerative capacity [34] |

Molecular Mechanisms Linking the Aged Niche to Clonal Expansion

The aged niche does not passively deteriorate; it actively selects for and promotes the growth of HSCs with specific mutations through several interconnected mechanisms.

Inflammation as a Central Driver

A bidirectional, self-reinforcing relationship exists between CHIP and inflammation. The aged niche is characterized by a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation ("inflammaging") [31] [35]. CHIP clones, particularly those with loss-of-function mutations in TET2 or DNMT3A, can contribute to this inflammation by producing macrophages and other immune cells that secrete elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα [31]. In a vicious cycle, this inflammatory milieu then selectively promotes the proliferation and survival of the mutant HSCs over their wild-type counterparts. For instance, HSCs with Tet2 or Dnmt3a mutations proliferate disproportionately when exposed to inflammatory signals like LPS or TNFα, leading to clonal expansion [29] [31].

Figure 1: The Vicious Cycle of Inflammation and Clonal Expansion. Inflammatory signals from the aged niche select for and promote the expansion of CH clones, whose mutant immune progeny in turn secrete more inflammatory cytokines, reinforcing the cycle and driving end-organ disease [29] [31].

Dysregulated Stem Cell-Niche Attachment

A mathematical modeling approach has illuminated how interactions with the niche directly influence clonal fitness [36]. This model posits that HSCs attached to the niche are quiescent. Upon detachment, they become activated and can either divide or differentiate. The progeny from division must reattach to the niche to maintain stemness. In this framework, the attachment and detachment rates are critical parameters determining a clone's long-term persistence. An aged niche, with its altered expression of adhesion molecules and chemokines (e.g., CXCL12), may disproportionately favor the attachment and retention of mutant clones, giving them a competitive edge over wild-type HSCs [36]. The model further suggests that the abundance of a clone in peripheral blood may not reflect its abundance in the niche, highlighting the diagnostic limitation of relying solely on blood samples [36].

Netrin-1 and DNA Damage Resolution

Recent research has identified Netrin-1 (NTN1) as a critical factor secreted by niche cells (MSCs and endothelial cells) that maintains niche and HSC fitness [34]. NTN1 plays an essential role in sustaining an active DNA damage response. With age, a decline in niche-derived NTN1 leads to the accumulation of DNA damage in both niche cells and HSCs. Remarkably, supplementation of aged mice with recombinant Netrin-1 was sufficient to rejuvenate the aged BM vascular niche, resolve accrued DNA damage, and restore the competitive fitness of aged HSCs to youthful levels [34]. This demonstrates that targeting specific deficiencies in the aged niche can directly counteract the functional decline that permits pre-malignant expansion.

Figure 2: Netrin-1 Mediated Niche Rejuvenation. Age-related decline in niche-derived Netrin-1 leads to a dampened DNA Damage Response (DDR) and accrued DNA damage, creating a permissive environment for CH. Exogenous NTN1 supplementation reactivates the DDR, restoring niche and HSC function [34].

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Niche-CHIP Investigation

In Vitro Modeling of the Aged HSC Niche

Objective: To simulate the secretory profile of young and aged HSC niches to study their effects on hematopoietic cell differentiation and function [35].

Protocol:

- Isolate Bone Marrow (BM) Cells: Harvest BM from the femurs, tibiae, humeri, ilia, and vertebrae of young (e.g., 2-3 months) and aged (e.g., 24 months) mice.

- Establish Long-Term Cultures: Resuspend viable BM cells in complete long-term culture medium (LTCM, e.g., MyeloCult M5300 with hydrocortisone). Seed cells at a density of 1.1 x 10^6 cells/cm² in culture flasks.

- Maintain Cultures: Culture cells for 4 weeks at 33°C with 5% CO2. Replace half of the medium with fresh LTCM weekly, taking care not to disturb the adherent layer.

- Generate Conditioned Media (CM): After 4 weeks, discard all LTCM, wash adherent cells with PBS, and add fresh supernatant media (e.g., RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS). After 48 hours, collect the CM.

- Process CM: Centrifuge CM at 1000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove cellular debris. Aliquot and store at -80°C. Pooling CM from multiple mice per age group is common to obtain sufficient volume and capture general trends [35].

- Functional Assays: Use the young and aged niche CM to differentiate BM-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) or other hematopoietic progenitors. Analyze outcomes including:

- Cell Phenotype: Flow cytometry for maturation markers (e.g., MHC Class II, CD86).

- Functional Capacity: Mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) to assess T-cell stimulatory capacity.

- Cytokine Secretion: ELISA or multiplex assays to quantify secreted factors (e.g., IL-6) [35].

Genetic Mouse Models for Niche-Specific Manipulation

Objective: To delineate the role of specific niche-derived factors in HSC function and clonal hematopoiesis in vivo.

Protocol (Example: Netrin-1):

- Model Generation:

- Niche Phenotyping: Analyze the bone marrow of knockout and control littermates for:

- Hematopoietic Assessment:

- Flow Cytometry: Quantify frequencies of HSCs (Lin−cKIT+SCA1+CD150+CD48−) and multipotent progenitors (MPPs) in the BM [34].

- Functional Assays: Perform competitive repopulation assays to test the long-term engraftment and lineage output of HSCs from mutant niches [34].

- DNA Damage Analysis: Immunofluorescence for γH2AX or other DNA damage markers in HSCs and niche cells [34].

Mathematical Modeling of Clonal Dynamics

Objective: To quantify the impact of niche-mediated processes (attachment, detachment, proliferation) on the clonal composition of the stem cell compartment [36].

Framework:

- A published model uses a system of ordinary differential equations to track quiescent (niche-bound), active, and inactive HSC populations, alongside empty niche spaces [36].

- Key Parameters: Clone fitness is determined by its specific set of parameters: detachment rate, attachment rate, proliferation rate, and differentiation rate [36].

- Simulation: The model can be parameterized with data from mouse experiments and used to simulate clinical scenarios like bone marrow transplantation, clonal competition, and response to therapy. It can predict whether a clone will expand, go extinct, or coexist with others based on its interaction parameters with the niche [36].

Table 2: Key Quantitative Associations in CHIP and the Aged Niche

| Parameter | Observation/Measurement | Experimental/Clinical Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHIP Prevalence | <1% (age <40) → 10-20% (age >70) | Analysis of large-scale human sequencing studies | [30] |

| Mortality Hazard Ratio | ~1.4 (all-cause mortality) | Meta-analysis of individuals with CHIP | [29] |

| Inflammatory Cytokines | Elevated IL-6, IL-8, TNFα | Plasma levels in individuals with CHIP, particularly with TET2 and DNMT3A mutations | [31] |

| Netrin-1 Rejuvenation | Restores competitive fitness of aged HSCs | In vivo treatment of aged mice with recombinant Netrin-1 | [34] |

| Clonal Abundance | Discrepancy between niche and blood | Predictions from mathematical modeling of HSC-niche interactions | [36] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating the Niche-CHIP Axis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Conditional Knockout Mice (e.g., LepR-Cre, Cdh5-CreERT2) | Enables cell-type-specific gene deletion in niche cells (MSCs, ECs). | Studying the role of niche-specific factors like Netrin-1 [34]. |

| Recombinant Netrin-1 | Recombinant protein for supplementation studies in vitro and in vivo. | Testing niche rejuvenation strategies in aged mouse models [34]. |

| MyeloCult M5300 Medium | Specialized medium for long-term culture of hematopoietic cells, supporting the growth of niche-forming stromal cells. | Generating in vitro models of the young and old HSC niche [35]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibody Panels (e.g., Lin−, c-Kit+, Sca-1+, CD150+, CD48−) | Identification and isolation of pure populations of HSCs and progenitors by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). | Quantifying HSC frequencies and analyzing cell surface phenotype in different niche conditions [34]. |

| Digital Droplet PCR (ddPCR) | Ultra-sensitive and absolute quantification of low-frequency somatic mutations. | Detecting and tracking CHIP clones at very low Variant Allele Frequencies (<0.1%) [30]. |

| Cytokine Profiling Arrays | Multiplexed measurement of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNFα, etc.) in conditioned media or serum. | Characterizing the inflammatory secretome of young vs. aged niche models or CHIP subjects [31] [35]. |

The pre-malignant expansion of HSCs in CHIP is a paradigm of how age-related ecosystem failure drives disease. The aged HSC niche is not a neutral bystander but an active accomplice, fostering clonal hematopoiesis through inflammatory signaling, dysfunctional cell-adhesion dynamics, and failure to maintain genomic integrity. The mechanistic insights linking niche-derived factors like Netrin-1 to DNA damage resolution offer a promising therapeutic avenue.

Future research must focus on translating these pre-clinical findings. This includes:

- Developing humanized mouse models to validate niche pathways in a human context.

- Conducting longitudinal clinical studies to correlate niche imaging parameters (e.g., BM adiposity) with CHIP clone dynamics.

- Launching clinical trials testing niche-directed therapies, such as anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors) or factors like Netrin-1, to suppress clonal expansion or mitigate its non-hematological consequences. By shifting the therapeutic focus from the mutant HSC alone to the dysfunctional niche that sustains it, we open a new frontier for preventing the progression of CHIP to malignancy and related morbidities.

Engineering the Niche: Advanced Models for Disease Modeling, Drug Screening, and Regenerative Therapy

The bone marrow (BM) microenvironment, or niche, is a complex physiological system indispensable for the maintenance, self-renewal, and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). This niche not only supports hematopoietic homeostasis but also plays a significant role in the etiology of various hematological disorders [7]. For decades, research and drug development for blood cancers and disorders have relied on conventional two-dimensional (2D) culture systems and animal models. However, 2D cultures fail to replicate the spatial, metabolic, and cellular complexity of human bone marrow, while animal models are limited by significant species-specific differences in cellular composition, signaling molecules, and markers of the hematopoietic microenvironment [7] [37]. This lack of physiologically relevant models has hindered the development of effective treatments and accurate prediction of drug efficacy and toxicity.

The transition to three-dimensional (3D) biomimetic models represents a paradigm shift in hematopoietic research. These advanced systems aim to faithfully recapitulate the native BM architecture, incorporating critical elements such as stromal and vascular networks, hypoxic gradients, and extracellular matrix (ECM) components. Framed within the broader context of HSC niche research, these models are revolutionizing our fundamental understanding of hematopoiesis, disease pathogenesis, and the development of novel cell-based therapies [7] [38]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the core principles, methodologies, and applications of these transformative technologies.

Core Components of the Native and Engineered HSC Niche

Physiological Anatomy and Key Niches

In vivo, the HSC niche is a highly complex and dynamically regulated microenvironment. It is traditionally categorized into two primary, yet integrated, compartments:

- The endosteal niche, located near the bone surface, is rich in osteoblasts and osteolineage cells. It is characterized by a relatively stiffer matrix (exceeding 35 kPa) and is believed to host and maintain quiescent long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs) [7] [39].

- The vascular niche, associated with sinusoidal blood vessels and arterioles, comprises endothelial cells, perivascular stromal cells, and adipocytes. This region features a softer matrix (approximately 0.3 kPa in the marrow) and supports more active HSCs and progenitors [7] [40].

Emerging evidence indicates that these niches are highly integrated in both structure and function. The endosteal region is richly vascularized, forming a functional "arterial–endosteal niche" critical for early myelopoiesis [7]. Beyond cellular and biochemical components, the biophysical properties of the niche—including stiffness, viscoelasticity, 3D topology, and fluid shear stress—are fundamental physical regulators of HSC fate [7].

Critical Biochemical and Biophysical Cues

Successful in vitro reconstruction of the HSC niche requires the integration of specific biochemical and biophysical signals.

Table 1: Key Cues for Reconstructing the HSC Niche In Vitro

| Cue Category | Specific Factor/Property | Function in HSC Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Signals | CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 axis | Guides HSC homing, retention, and survival [7] [40]. |

| Stem Cell Factor (SCF) | Critical for HSC maintenance and quiescence; specifically requires endothelial source [7]. | |

| VLA-4/VCAM-1 interaction | Mediates firm adhesion of HSCs to the niche, facilitating extravasation and lodging [40]. | |

| Biophysical Properties | Matrix Stiffness | Heterogeneous (0.3 - 40 kPa); directs HSC lineage commitment (e.g., softer matrices promote erythroid differentiation) [7] [41]. |

| Matrix Viscoelasticity | Influences HSC stemness and lineage-specific differentiation via mechanotransduction [7]. | |

| Oxygen Tension (pO₂) | Hypoxic conditions in specific zones help maintain HSC quiescence and stemness [39] [41]. | |

| Fluid Shear Stress | Activates signaling pathways in endothelial cells and HSCs, influencing survival and homing [7]. | |

| ECM Architecture | Fibrillar Fibronectin | Prevalent in the endosteal niche; presents growth factors and supports adhesion [39]. |

| Collagen I & IV, Laminin | Provide structural integrity and topological cues; distribution varies between niche sub-compartments [41]. |

Figure 1: Key Signaling Pathways and Microenvironmental Cues Regulating HSC Fate. The diagram illustrates how biochemical signals, biophysical cues, and ECM architecture from the bone marrow niche collectively regulate critical HSC functions like homing, quiescence, and differentiation.

Leading-Edge 3D Biomimetic Platforms and Methodologies

Biomimetic Scaffolds and Hydrogel Systems

A primary approach involves using 3D scaffolds, particularly hydrogels, to mimic the native ECM. These systems are functionalized with specific physical and biochemical cues to direct HSC behavior.