2D vs 3D Cell Culture: A Comprehensive Efficacy Comparison for Predictive Preclinical Research

This article provides a systematic comparison of two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) cell culture systems, analyzing their efficacy in mimicking in vivo conditions for biomedical research and drug development.

2D vs 3D Cell Culture: A Comprehensive Efficacy Comparison for Predictive Preclinical Research

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) cell culture systems, analyzing their efficacy in mimicking in vivo conditions for biomedical research and drug development. It covers foundational biological differences, practical methodologies, key challenges with optimization strategies, and rigorous validation through comparative studies. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes current evidence demonstrating that 3D models more accurately recapitulate tissue architecture, cell-cell interactions, gene expression, and drug response, thereby offering more physiologically relevant and predictive data for reducing costly late-stage drug failures.

Beyond the Monolayer: How 3D Architecture Reshapes Cell Behavior and Biology

Core Principles and Fundamental Differences

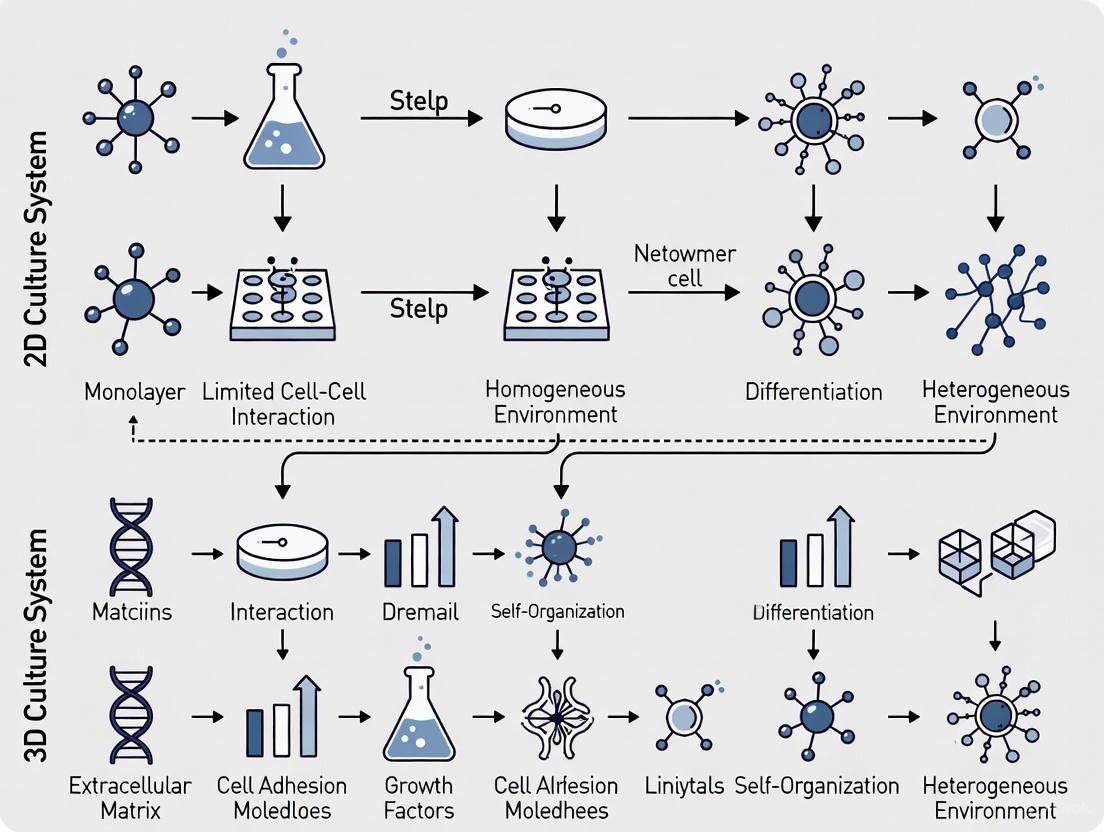

Cell culture is a foundational tool in biomedical research, and the choice between two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) systems fundamentally shapes experimental outcomes. A 2D culture involves growing cells as a single, adherent layer on a flat, rigid plastic or glass surface [1] [2]. This simple and reproducible method has been the standard for decades. In contrast, a 3D culture system allows cells to grow in all three spatial dimensions, facilitating cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions that more closely mimic the architectural and functional complexity of living tissues [1] [3].

The core principle distinguishing these models is their physiological relevance. In vivo, cells reside within a complex 3D microenvironment, surrounded by other cells and an ECM that provides biochemical and mechanical cues [4]. The spatial arrangement in 3D cultures influences critical processes such as cell differentiation, proliferation, gene expression, and responsiveness to stimuli—aspects that are fundamentally altered in 2D monolayers [1]. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each system.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of 2D and 3D Cell Culture Systems

| Characteristic | 2D Culture | 3D Culture | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Architecture | Monolayer; flat and spread | Multi-layered; tissue-like structure | [1] [2] |

| Cell-ECM Interactions | Disturbed; single plane of attachment | Physiologically representative; natural polarity | [1] [3] |

| Microenvironment | Uniform nutrient and oxygen access | Creates nutrient, oxygen, and metabolic gradients | [1] [5] |

| Gene & Protein Expression | Altered compared to in vivo | More closely resembles in vivo profiles | [1] [6] |

| Proliferation Rate | Generally high | Often reduced, more akin to in vivo tissues | [7] |

| Cost & Technical Ease | Low-cost, simple, highly reproducible | More expensive, time-consuming, and complex | [1] [8] |

| Throughput & Standardization | Excellent for high-throughput screening | Lower throughput; standardization can be challenging | [8] [4] |

Experimental Data and Efficacy Comparison

Drug Response and Resistance

A critical area where 2D and 3D models diverge significantly is in drug testing. Studies consistently show that 3D cultures exhibit higher innate resistance to both targeted therapies and classical chemotherapeutic agents, providing a more accurate prediction of clinical outcomes [7] [5].

In a pivotal study using HER2-positive breast cancer cell lines (BT474, HCC1954, EFM192A), researchers directly compared the efficacy of the targeted drug neratinib and the chemotherapeutic docetaxel in 2D versus 3D cultures (the latter formed using the poly-HEMA forced-floating method) [7]. The results were striking, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Comparative Drug Efficacy in 2D vs. 3D Breast Cancer Models (Data adapted from [7])

| Cell Line | Treatment | Cell Survival in 2D | Cell Survival in 3D | Difference (3D vs 2D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BT474 | Neratinib | 62.7% | 90.8% | +28.1% |

| HCC1954 | Neratinib | 64.7% | 77.3% | +12.6% |

| EFM192A | Neratinib | 59.7% | 86.8% | +27.1% |

| BT474 | Docetaxel | 60.3% | 91.0% | +30.7% |

| HCC1954 | Docetaxel | 52.3% | 101.6% | +49.0% |

| EFM192A | Docetaxel | 46.2% | 96.2% | +50.0% |

This innate resistance in 3D models is facilitated by several physiological factors:

- Altered Protein Expression: The study found increased expression of proteins involved in cell survival (e.g., Akt) and drug transporters associated with resistance in 3D cultures [7].

- Enhanced Drug Metabolism: Activity of the drug-metabolizing enzyme CYP3A4 was substantially increased in 3D cultures compared to their 2D counterparts [7].

- Diffusion Barriers: The compact architecture of 3D spheroids creates gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and waste, which can limit drug penetration to the core of the structure, mimicking the hypoxic core of solid tumors [1] [5].

Cell Viability and Morphology

The same breast cancer study also quantified fundamental differences in cell viability and morphology. After 6 days of culture, the viability of 3D spheroids was significantly lower than that of 2D monolayers: BT474 3D viability was 41.6% of its 2D control, HCC1954 was 18.4%, and EFM192A was 44.0% [7]. This reflects a more physiologically relevant proliferation rate.

Morphologically, cells in 3D culture form tight spheroids, often surrounded by a self-secreted extracellular matrix, which is a stark contrast to the flat, spread-out appearance of cells in 2D monolayers [7]. This restored 3D morphology directly impacts cellular signaling and function.

Experimental Workflow for Drug Efficacy

Methodologies for Key 3D Culture Techniques

The creation of 3D models can be broadly classified into scaffold-based and scaffold-free techniques, each with specific protocols and applications [5] [3].

Scaffold-Based Techniques

Scaffolds provide a physical 3D structure that supports cell attachment and growth.

- Hydrogel-Based Cultures: Hydrogels are water-swollen polymer networks that mimic the native ECM [3]. A common protocol using Matrigel involves liquefying the Matrigel on ice, mixing it with a cell suspension, and then plating the mixture. Upon incubation at 37°C, the Matrigel solidifies, embedding the cells in a 3D protein-rich environment [1]. Natural hydrogels (e.g., collagen, alginate) and synthetic hydrogels (e.g., Polyethylene Glycol - PEG) are also widely used, with the latter offering greater control over mechanical properties [6] [3].

- Polymeric Hard Material-Based Scaffolds: These are rigid, porous structures made from biodegradable materials like polylactic acid (PLA) or polycaprolactone (PCL) [6] [3]. Cells are seeded onto these scaffolds and migrate into the pores, where they attach, grow, and form 3D tissues.

Scaffold-Free Techniques

These methods rely on the innate ability of cells to self-assemble.

- The Hanging Drop Method: This technique involves suspending a droplet of cell culture medium, containing a known number of cells, from the lid of a culture dish. Gravity causes the cells to aggregate at the bottom of the droplet, forming a single spheroid [5].

- Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) Plates: These plates are manufactured with a covalently bound hydrogel surface that prevents protein and cell attachment. When seeded into ULA plates, cells are forced to aggregate and form spheroids [1] [5].

- Magnetic Levitation: In this advanced technique, cells are first incubated with magnetic nanoparticles. When exposed to an external magnetic field, the cells are levitated and gathered to form a dense 3D spheroid at the air-media interface [5].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 3D Cell Culture (Compiled from [1] [6] [9])

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in 3D Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Hydrogels | Matrigel, Collagen, Alginate, Fibrin | Provide a biologically active, ECM-like matrix for cell embedding and growth. |

| Synthetic Hydrogels | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), PLA, PCL | Offer tunable stiffness and porosity with minimal batch-to-batch variability. |

| Scaffold Materials | Polymeric scaffolds (e.g., PCL, PLA), Glass microfibers | Provide a rigid, porous 3D structure for cell attachment and tissue formation. |

| Specialized Cultureware | Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) Plates, Hanging Drop Plates | Prevent cell adhesion, forcing cells to self-assemble into spheroids. |

| Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting | Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA), Alginate-based bioinks, Cell-laden hydrogels | Serve as printable materials for the precise spatial patterning of cells and biomaterials. |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The differential response to drugs and stimuli in 2D versus 3D systems is rooted in profound changes at the molecular level. The 3D architecture restores physiological signaling that is lost in 2D monolayers.

Molecular Basis for Drug Resistance in 3D Models

Key molecular differences include:

- Gene Expression and Splicing: Cells in 3D culture exhibit gene expression and mRNA splicing patterns that are more representative of in vivo tissues, unlike the altered profiles found in 2D cultures [1].

- Activation of Survival Pathways: Research has demonstrated that components of critical cell survival pathways, such as Akt and Erk, show increased expression in 3D cultures compared to 2D, contributing to enhanced cell survival and drug resistance [7].

- Metabolic Changes: The gradient-driven microenvironment within 3D spheroids can lead to areas of hypoxia, which alters cellular metabolism and further contributes to a drug-resistant phenotype [5].

The choice between 2D and 3D culture systems is not a matter of one being universally superior, but of selecting the appropriate tool for the research question. 2D cultures remain invaluable for high-throughput screening, genetic manipulations, and basic research where simplicity, low cost, and reproducibility are paramount [8]. However, the evidence is clear that 3D culture systems provide a superior model for preclinical research demanding physiological accuracy, particularly in drug discovery, cancer biology, and personalized medicine [7] [5] [3]. Their ability to mimic the tissue microenvironment, including critical cell-ECM interactions, gradient formation, and more in vivo-like molecular profiles, makes them indispensable for bridging the translational gap between traditional cell culture and animal models, ultimately leading to more predictive and successful clinical outcomes.

Cell culture systems are indispensable tools in basic and clinical in vitro research. The classically preferred model is a static dish culture system which mainly generates adherent two-dimensional (2D) cell monolayers [2]. However, such culture systems do not reflect the situation in vivo, where cells grow within a complex three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment and where vascular perfusion continuously supplies and removes metabolites and catabolites, respectively [2]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions within these fundamentally different culture environments, framing the analysis within the broader context of efficacy comparison for research and drug development applications.

It is now well-established that cells behave structurally and functionally different when seeded on thin 2D surface-coated substrate versus a thick layer of polymeric 3D molecules, which more closely mimics their natural environment [2]. The spatial arrangement of cells significantly affects how they interact with each other and their surroundings, ultimately influencing experimental outcomes in drug discovery, toxicity testing, and basic biological research [7]. This comparison aims to objectively evaluate the performance of both systems based on current scientific evidence.

Core Biological Differences: Interaction Complexities in 2D vs 3D Environments

Fundamental Architecture and Cellular Interactions

The fundamental distinction between these culture systems lies in their spatial organization and the resulting biological interactions. In 2D cultures, cells are grown attached to tissue culture-grade plastic as a single layer, which imposes artificial polarity and limits natural cell-cell contacts [2] [8]. Conversely, 3D cultures allow cells to grow in all directions, enabling them to form more physiologically relevant structures such as spheroids and organoids [8].

Cell-cell interactions in these systems differ substantially. In 3D environments, cells exhibit proximity to other cells on all sides, creating more natural communication networks through direct contact and signaling molecules [2]. These interactions are mediated by transmembrane adhesion receptors that bind to specific extracellular ligand partners and link receptor cytoplasmic domains to intracellular cytoskeletal systems via protein complexes [10]. The spatial arrangement in 3D cultures facilitates the formation of more natural cell adhesion complexes, including adherens junctions, desmosomes, and gap junctions, which are critical for tissue function [11].

Cell-ECM interactions represent another crucial distinction. In vivo, cells interact continuously with a complex ECM that regulates essential biological functions like cell migration, apoptosis, transcription regulation, and receptor expression [6]. While 3D cultures replicate these interactions through natural or synthetic matrices, 2D cultures provide only a flat, rigid surface that fundamentally alters how cells engage with their substrate [2] [6]. This difference significantly impacts cytoskeletal organization, mechanical signaling, and overall cell behavior.

Molecular and Structural Implications

The dimensional context profoundly influences molecular and structural characteristics at the cellular level. Research demonstrates that cells in 3D culture exhibit more authentic gene expression profiles and protein expression patterns compared to their 2D counterparts [6]. For example, immortalized human hepatocyte HepG2 cells grown in traditional 2D culture lose substantial amounts of CYP450 enzyme mRNA and activity—critical components for drug metabolism—while 3D culture using an ECM hydrogel restores these phenotypic characteristics [7].

Structural complexity also markedly differs between the systems. Three-dimensional cultures exhibit a higher degree of structural organization and homeostasis analogous to tissues and organs in vivo [2]. This includes the development of natural gradients of oxygen, pH, and nutrients that influence cellular behavior and drug responses [8]. The cytoarchitecture in 3D cultures more accurately represents in vivo conditions, with cells establishing more natural polarity and functional organization [2].

Diagram 1: Comparative molecular pathways in 2D versus 3D culture systems showing how the initial environment leads to fundamentally different cellular outcomes.

Experimental Data Comparison: Quantitative Performance Metrics

Drug Response and Resistance Profiles

Substantial evidence demonstrates that 3D cell cultures exhibit drug response profiles that more closely resemble in vivo conditions compared to 2D models. This is particularly evident in cancer research, where 3D models better replicate the resistance mechanisms observed in solid tumors.

A study using HER2-positive breast cancer cell lines (BT474, HCC1954, EFM192A) revealed significant differences in response to both targeted therapy and classical chemotherapy between 2D and 3D cultures [7]. When treated with the HER-targeted drug neratinib, 2D cultured cells showed significantly reduced cell survival (62.7±1.2% for BT474) compared to 3D cultures (90.8±4.5% for BT474), indicating substantially increased resistance in the 3D models [7]. Similarly, when exposed to the chemotherapeutic agent docetaxel, 2D cultures of BT474 cells demonstrated 60.3±8.7% survival compared to 91±5.9% in 3D cultures [7].

Table 1: Comparative Drug Response in 2D vs 3D Breast Cancer Cultures

| Cell Line | Drug Treatment | Cell Survival in 2D (%) | Cell Survival in 3D (%) | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BT474 | Neratinib | 62.7 ± 1.2 | 90.8 ± 4.5 | 28.1 ± 5.4 |

| BT474 | Docetaxel | 60.3 ± 8.7 | 91.0 ± 5.9 | 30.7 ± 2.8 |

| HCC1954 | Neratinib | 64.7 ± 3.9 | 77.3 ± 6.9 | 12.6 ± 5.3 |

| HCC1954 | Docetaxel | 52.3 ± 8.5 | 101.6 ± 5.7 | 49.0 ± 3.1 |

| EFM192A | Neratinib | 59.7 ± 2.1 | 86.8 ± 0.6 | 27.1 ± 2.7 |

| EFM192A | Docetaxel | 46.2 ± 2.6 | 96.2 ± 1.9 | 50.0 ± 2.5 |

The increased resistance observed in 3D cultures has been attributed to several factors, including altered expression of proteins involved in cell survival, increased activity of drug transporters associated with resistance, and enhanced drug metabolizing enzyme activity [7]. Specifically, research shows that activity of CYP3A4, a crucial drug-metabolizing enzyme, is substantially increased in 3D compared to 2D cultures [7].

Viability, Phenotypic, and Functional Comparisons

Beyond drug response, significant differences exist in basic cellular functions between 2D and 3D systems. Studies consistently show that cell viability measures differ substantially between the two formats, with 3D cultures often exhibiting lower ATP levels—a standard viability metric—compared to 2D cultures when measured at the same time points [7].

After 6 days of culture seeded at identical densities, BT474 3D cell viability was only 41.6±5.9% of that measured in BT474 2D cells. Similarly, HCC1954 3D cell viability was only 18.4±1.5% of that measured in 2D cultures, and EFM192A 3D cell viability was 44±3.7% of their 2D counterparts [7]. These differences likely reflect distinct metabolic states and proliferation rates rather than simply indicating poorer health in 3D cultures.

Morphological examinations using scanning electron microscopy reveal substantial differences between 2D and 3D cultured cells [7]. While cells in 2D culture typically spread out to form monolayers with characteristic flattened morphology, the same cells grown in 3D conditions form structured spheroids with complex surface features. Some cell lines in 3D culture appear to secrete significant extracellular matrix that smoothens the spheroid surface and creates pores, making individual cells difficult to distinguish—a characteristic more reminiscent of in vivo tissue architecture [7].

Table 2: Functional and Structural Comparison of 2D vs 3D Culture Systems

| Parameter | 2D Culture | 3D Culture | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Viability (ATP levels) | Higher (reference) | 18-44% of 2D levels [7] | Different metabolic state in 3D |

| Drug Metabolizing Enzyme Activity | Reduced CYP activity | Substantially increased CYP3A4 [7] | Better prediction of drug metabolism |

| Expression of Survival Proteins | Lower | Increased Akt expression [7] | Enhanced survival signaling in 3D |

| Cell Morphology | Flat, spread monolayers | Structured spheroids with ECM [7] | Better tissue representation |

| Gene Expression Profile | Artificial | More physiologically relevant [6] | Better translational potential |

| Spatial Organization | Single layer, artificial polarity | Natural architecture, gradients [8] | Recreation of tissue context |

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Implementation

3D Culture Techniques and Technologies

Three-dimensional cell culture technologies can be broadly divided into two categories: scaffold-based and scaffold-free techniques [6]. The choice between these approaches depends on several parameters, including the nature of the cells (cell line vs primary cells, tissue origin) and the research objectives.

Scaffold-based techniques utilize supportive matrices that facilitate three-dimensional growth. These include:

- Hydrogel-based scaffolds: Natural or synthetic polymer networks that swell in water, allowing cell embedding or surface coating. These can be further categorized as ECM protein-based hydrogels (e.g., Matrigel, collagen), natural hydrogels (e.g., alginate, chitosan), or synthetic hydrogels (e.g., PEG-based) [6].

- Polymeric hard material-based scaffolds: Fibrous or spongeous structures made from materials such as polystyrene (ideal for imaging due to transparency) or biodegradable polymers like polycaprolactone [6].

Scaffold-free techniques rely on cellular self-assembly to form structures known as spheroids—non-adherent cell aggregates that mimic solid tissues [6]. These systems enable cells to secrete their own ECM and establish natural nutrient and oxygen gradients. Scaffold-free approaches include:

- Hanging drop methods: Utilizing gravitational forces and surface tension to encourage cell aggregation [8].

- Ultra-low attachment plates: Specially treated surfaces that prevent cell adhesion, promoting spheroid formation [8].

- Rotary bioreactors: Systems that use continuous motion to maintain cells in suspension, facilitating aggregate formation [2].

Diagram 2: Decision pathway for selecting appropriate 3D culture methodologies based on research objectives and technical requirements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Implementing robust 3D culture systems requires specific reagents and materials that differ from traditional 2D approaches. The following table details key solutions and their applications in establishing physiologically relevant 3D microenvironments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 3D Cell Culture Applications

| Reagent/Material | Type | Primary Function | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly-HEMA | Scaffold-free | Prevents cell adhesion to promote spheroid formation [7] | Forced-floating 3D culture methods |

| Basement Membrane Extracts (e.g., Matrigel) | ECM-based hydrogel | Provides complex ECM environment for cell embedding | Organoid culture, angiogenesis assays |

| Alginate Hydrogels | Natural hydrogel | Tunable 3D matrix for cell encapsulation | Cell migration studies, tissue engineering |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Hydrogels | Synthetic hydrogel | Defined, customizable ECM microenvironment | Mechanobiology studies, drug screening |

| Ultra-Low Attachment Plates | Scaffold-free surface | Prevents cell attachment, enables spheroid formation | High-throughput drug screening, toxicity testing |

| Hanging Drop Plates | Scaffold-free platform | Gravity-assisted spheroid formation | Multicellular tumor spheroid generation |

| Rotary Wall Vessels | Bioreactor system | Maintains cells in suspension by constant motion | Large-scale 3D culture, tissue modeling |

Research Applications: Context-Specific System Selection

Appropriate Use Cases for 2D Culture Systems

Despite the physiological advantages of 3D models, 2D culture systems remain valuable for specific research applications where their simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and compatibility with high-throughput workflows provide practical benefits [8].

Appropriate use cases for 2D culture include:

- High-throughput screening (HTS) applications: Early-stage compound screening where thousands of molecules need rapid evaluation [8].

- Basic cytotoxicity assessments: Initial evaluation of compound toxicity using standardized protocols [8].

- Genetic manipulation studies: Techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing where accessibility and efficiency are prioritized [8].

- Receptor-ligand interaction studies: Investigation of specific molecular interactions without complex tissue context [8].

- Large-scale cell production: Applications requiring substantial biomass where cost and scalability are primary concerns.

A tiered approach is often most efficient, using 2D systems for initial screening followed by 3D models for validation and more sophisticated studies [8]. This strategy leverages the strengths of both systems while managing resource constraints.

Applications Benefitting from 3D Culture Models

Three-dimensional culture systems provide particular value in research contexts where tissue architecture, cell-cell interactions, and physiological gradients significantly influence biological outcomes [8]. These applications typically prioritize physiological relevance over throughput and cost considerations.

Key applications where 3D cultures excel include:

- Cancer research and drug development: Especially for solid tumors where the microenvironment influences drug penetration, resistance mechanisms, and cellular responses [8] [7].

- Stem cell differentiation and organoid development: Where three-dimensional context supports proper tissue-specific differentiation and function [8].

- Toxicology and safety pharmacology: Particularly for organs like the liver where metabolizing enzyme function is crucial and better maintained in 3D cultures [6] [7].

- Infectious disease modeling: Studying host-pathogen interactions in tissue-like environments [8].

- Personalized medicine approaches: Using patient-derived organoids to match therapies to individual patients, as demonstrated by institutions like Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [8].

Leading research organizations and pharmaceutical companies have incorporated 3D models into their workflows. For example, Roche uses 3D tumor spheroids to model hypoxic tumor cores and test immunotherapies, while Emulate Inc. deploys liver-on-chip platforms for preclinical hepatotoxicity screening [8].

The comparison between 2D and 3D culture systems reveals a complex landscape where each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations. Two-dimensional cultures provide simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and compatibility with high-throughput workflows, making them suitable for initial screening and specific molecular studies. However, their limitations in replicating in vivo physiology, particularly regarding cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions, can compromise translational relevance.

Three-dimensional culture systems demonstrate superior performance in modeling tissue architecture, drug resistance, metabolic function, and cellular differentiation. The experimental data clearly shows that 3D models generate different—and often more physiologically relevant—responses to therapeutic agents, gene expression profiles, and functional outcomes. These advantages come with increased complexity, cost, and technical challenges that must be considered in experimental planning.

The evolving landscape of cell culture technologies suggests a future of integrated approaches rather than exclusive adoption of either system. Hybrid workflows that strategically employ both 2D and 3D models at different stages of research, combined with advanced analytics and possibly AI integration, represent the most promising path forward [8]. As regulatory bodies increasingly recognize data from 3D models in drug submissions, the strategic implementation of these physiologically relevant systems will continue to grow in importance throughout biomedical research and drug development.

For decades, two-dimensional (2D) cell culture has been a fundamental tool in biological research, yet it imposes artificial constraints that fundamentally alter cellular architecture. In traditional 2D systems, cells are forced to adhere and spread on rigid, flat plastic or glass surfaces, resulting in unnatural flattened morphologies and disrupted polarity [8] [12]. This environment fails to recapitulate the complex three-dimensional architecture of living tissues, where cells interact with neighbors and the extracellular matrix (ECM) in all dimensions.

The shift to three-dimensional (3D) cell culture represents a paradigm shift in experimental biology. These systems allow cells to grow and interact in a spatial context that closely mimics the in vivo microenvironment, thereby preserving essential morphological characteristics and establishing proper apical-basal polarity found in native tissues [13] [12]. This guide provides an objective comparison of how 3D culture systems maintain natural cellular structure compared to traditional 2D methods, supported by experimental data and protocols for researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Differences in Cellular Architecture

Morphological Characteristics Across Culture Models

The table below summarizes the key differences in cellular morphology and polarity between 2D and 3D culture systems.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Cellular Morphology and Polarity in 2D vs. 3D Culture Systems

| Feature | 2D Culture | 3D Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Shape | Flattened, stretched morphology [8] | Natural, tissue-like 3D architecture [13] |

| Polarity | Often disrupted or partially formed [12] | Proper apical-basal polarization [12] |

| Cell-Cell Interactions | Limited to peripheral contacts [12] | Multi-faceted, natural adhesion patterns [14] |

| Cell-ECM Interactions | Single plane, unnatural binding [15] | Natural, spatially organized ECM binding [13] |

| Spatial Organization | Monolayer, forced 2D arrangement [8] | Self-organizing, tissue-like structures [14] |

| Gene Expression | Altered due to unnatural substrate [8] | In vivo-like expression profiles [8] |

| Proliferation Rate | Typically faster, unregulated [12] | Physiologically relevant rates [12] |

| Nutrient/Oxygen Access | Uniform, non-physiological [14] | Gradient-dependent, physiologically accurate [8] |

Quantitative Assessment of Structural Features

Experimental data reveals measurable differences in structural preservation between culture systems.

Table 2: Experimental Measurements of Structural Preservation in Culture Models

| Parameter | 2D Culture Findings | 3D Culture Findings | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeletal Organization | Stress fibers prominent; abnormal actin distribution [12] | Natural cytoskeletal arrangement; tissue-specific architecture [12] | Immunofluorescence imaging [12] |

| Differentiation Markers | Reduced expression of tissue-specific markers [15] | Enhanced expression of functional differentiation markers [15] | Gene expression analysis (qPCR) [8] |

| Cell Viability in Core | Not applicable (monolayer) | Viable cells throughout structure with possible necrotic core in large spheroids (>300μm) [16] | Live/dead staining and confocal microscopy [16] |

| Drug Penetration | Uniform access; overestimated efficacy [8] | Gradient penetration; predictive of in vivo response [8] | Chemotherapy drug testing in cancer spheroids [8] |

| Tight Junction Formation | Irregular junctional protein localization [12] | Proper tight junction assembly and function [12] | Transmission electron microscopy [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Structural Analysis

Protocol 1: 3D Spheroid Formation and Morphological Analysis

Objective: To generate and characterize 3D spheroids using scaffold-free methods for morphological assessment.

Materials:

- Nunclon Sphera 96-well U-bottom plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) [16]

- Appropriate cell culture medium (e.g., Gibco 3D culture media) [16]

- Cell lines of interest (e.g., HepG2, A549) [16]

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Centrifuge

- Inverted microscope or high-content analysis system (e.g., CellInsight CX7) [16]

Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Prepare single-cell suspension at optimal density (e.g., 5,000 cells/well for A549 in 96-well plate) [16].

- Spheroid Formation: Centrifuge plate at low speed (300-500 × g) for 5 minutes to aggregate cells at well bottom [16].

- Culture Maintenance: Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for 3-7 days, with half-medium changes every 2-3 days [16].

- Morphological Assessment:

- Image spheroids daily using brightfield microscopy to monitor size and structure [16].

- For detailed analysis, use high-content imaging systems to measure diameter, volume, and circularity [16].

- For internal structure analysis, use clearing reagents (e.g., CytoVista) followed by fluorescence imaging [16].

Expected Results: Formation of compact, spherical structures with cell-cell interactions throughout. Size depends on initial seeding density and culture duration.

Protocol 2: Immunofluorescence Analysis of Cell Polarity in 3D Models

Objective: To visualize and quantify establishment of apical-basal polarity in 3D cultures.

Materials:

- 3D spheroids/organoids (7-14 days in culture)

- Fixation solution (e.g., 4% paraformaldehyde)

- Permeabilization buffer (e.g., 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100)

- Blocking solution (e.g., 1-5% BSA in PBS)

- Primary antibodies for polarity markers (e.g., ZO-1, Par3, aPKC)

- Fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies

- Nuclear stain (e.g., DAPI)

- Mounting medium (e.g., ProLong Glass Antifade Mountant) [16]

- Confocal microscope

Methodology:

- Fixation: Fix spheroids with 4% PFA for 30-60 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilization and Blocking: Permeabilize with 0.3% Triton X-15 for 30 minutes, then block with 3% BSA for 2 hours.

- Antibody Staining: Incubate with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by secondary antibodies for 2-4 hours at room temperature.

- Mounting and Imaging: Mount spheroids using anti-fade mounting medium and image using confocal microscopy with z-stack acquisition [16].

Expected Results: Distinct localization of polarity proteins at appropriate membrane domains, demonstrating proper apical-basal polarization in 3D models compared to disrupted patterns in 2D cultures.

Research Reagent Solutions for 3D Culture

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 3D Cell Culture and Structural Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function in 3D Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Systems | Matrigel, Geltrex, Collagen, VitroGel [16] [17] | Provides extracellular matrix mimicry for cell attachment and morphogenesis |

| Scaffold-Free Platforms | Nunclon Sphera plates, Hanging drop plates, Ultra-low attachment surfaces [16] | Enables self-assembly of spheroids through minimized cell-surface adhesion |

| Specialized Media | Gibco 3D culture media, Organoid differentiation media [16] | Provides optimized nutrients and signaling molecules for 3D growth |

| Imaging Reagents | CytoVista 3D Culture Clearing Agent, ProLong Glass Antifade Mountant [16] | Enables deep imaging within 3D structures by reducing light scattering |

| Analysis Tools | CellInsight CX7 HCA System, EVOS cell imaging systems [16] | Allows quantitative analysis of size, morphology, and protein localization |

Signaling Pathways in Morphology and Polarity Establishment

The following diagram illustrates key signaling pathways regulating morphology and polarity in 3D cultures, highlighting differences from 2D systems.

Impact on Predictive Value in Drug Development

The preservation of natural morphology and polarity in 3D cultures significantly enhances their predictive value in pharmaceutical research. Cells cultured in 3D exhibit more physiological gene expression profiles, drug metabolism, and toxicity responses compared to 2D cultures [8] [15]. For instance, hepatocytes in 3D culture maintain cytochrome P450 expression and metabolic function that rapidly declines in 2D conditions [15]. This preservation of tissue-specific functionality makes 3D models particularly valuable for preclinical testing.

In cancer research, 3D tumor spheroids develop physiological barriers to drug penetration, including hypoxic cores and compact tissue architecture, providing more accurate prediction of chemotherapeutic efficacy [8] [18]. Studies have demonstrated that drugs showing promise in 2D models often fail in clinical trials due to this discrepancy, with 3D cultures potentially bridging this translational gap [8].

The evidence comprehensively demonstrates that 3D cell culture systems preserve natural cellular morphology and polarity far more effectively than traditional 2D methods. By enabling cells to establish proper three-dimensional architecture, cell-cell interactions, and apical-basal polarization, these systems provide more physiologically relevant models for basic research and drug development. While 2D cultures remain valuable for high-throughput screening and certain mechanistic studies, 3D systems offer superior structural and functional mimicry of in vivo tissues.

The research community is increasingly adopting hybrid approaches, leveraging the strengths of both systems while recognizing that 3D culture represents a fundamental advancement in preserving natural cellular structure. As technologies mature and become more accessible, 3D culture systems are poised to significantly enhance the predictive power of in vitro research and accelerate the development of more effective therapeutics.

In the realm of cancer biology and drug development, the transition from two-dimensional (2D) to three-dimensional (3D) cell culture systems represents a critical advancement in preclinical modeling. While traditional 2D monolayers have served as fundamental tools for decades, they lack the architectural complexity and microenvironmental cues present in living tissues [1]. Nutrient and oxygen gradients emerge as defining characteristics of 3D spheroids, creating physiological heterogeneity that closely mimics the avascular regions of solid tumors [19] [20].

These gradients are not merely technical observations; they are fundamental to recapitulating the tumor microenvironment (TME). In vivo, tumors develop complex spatial organizations where access to oxygen and nutrients varies significantly from the well-perfused periphery to the often nutrient-deprived and hypoxic core [19]. This spatial heterogeneity drives differential cellular behaviors, gene expression profiles, and drug responses—none of which can be adequately modeled in 2D cultures where cells experience uniform exposure to media components [8] [1]. The emergence of these natural gradients in 3D spheroids enables researchers to study critical phenomena such as drug penetration, hypoxia-induced signaling, and the development of therapeutic resistance mechanisms that mirror clinical responses [19] [7].

This guide objectively compares the capabilities of 2D and 3D culture systems in modeling these vital physiological parameters, providing experimental data and methodologies that highlight the superior predictive power of gradient-containing 3D models in preclinical research.

Comparative Analysis of 2D and 3D Culture Systems

Fundamental Structural Differences

The structural basis for gradient formation fundamentally differs between 2D and 3D culture systems, originating from their distinct spatial organizations:

- 2D Monolayers: Cells grow as a single layer attached to a flat plastic or glass surface, with uniform access to oxygen and nutrients dissolved in the culture medium [1]. This homogeneous environment fails to create the variable conditions that cells experience in solid tissues and tumors.

- 3D Spheroids: Cells aggregate into three-dimensional structures, typically ranging from hundreds to thousands of cells. In these configurations, the physical limitations of diffusion create natural gradients from the periphery to the core [19] [20]. Cells in outer regions experience higher concentrations of oxygen and nutrients, while those in inner regions progressively encounter metabolic waste accumulation, nutrient deprivation, and hypoxia [19].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between 2D and 3D Culture Systems

| Feature | 2D Culture System | 3D Spheroid System |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Architecture | Monolayer; flat morphology | Three-dimensional; tissue-like structure |

| Gradient Formation | Uniform nutrient/oxygen access | Physiological nutrient/oxygen gradients |

| Cell-Cell Interactions | Limited to peripheral contacts in a single plane | Extensive, multi-directional interactions mimicking tissues |

| Cell-ECM Interactions | Limited to 2D surface binding | Natural 3D ECM integration and remodeling |

| Proliferation Patterns | Homogeneous proliferation throughout | Zonal proliferation (outer layer) and quiescence (inner layer) |

| Drug Penetration | Immediate, uniform drug access | Limited, gradient-dependent penetration mimicking in vivo tumors |

| Gene Expression Profile | Often altered, less representative of in vivo tissue | Better preserves in vivo-like gene expression patterns |

| Predictive Value for Drug Response | Limited; overestimates efficacy | Higher; better predicts clinical drug responses including resistance |

Quantitative Comparison of Microenvironmental Parameters

The structural differences between 2D and 3D systems translate into quantitatively distinct microenvironmental conditions that significantly impact cellular behavior and drug response. Research has systematically documented these variations:

Table 2: Quantitative Differences in Microenvironment and Drug Response Between 2D and 3D Cultures

| Parameter | 2D Culture | 3D Spheroid | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Gradient | Homogeneous distribution | Hypoxic core (<3% O₂); normoxic periphery | Spheroids cultured at 3% O₂ exhibited reduced dimensions and increased necrosis [21] |

| Glucose Concentration Threshold for Necrosis | Not applicable | ~0.08 mM (critical threshold for necrosis) | COMSOL-based multiphysics model of HER2-positive BT-474 spheroids identified this critical threshold [22] |

| Drug Resistance (Docetaxel) | 40-54% cell survival reduction | Minimal reduction (4-9% survival reduction) | HER2-positive breast cancer cell lines showed significantly reduced efficacy in 3D systems [7] |

| Drug Resistance (Neratinib) | 37-40% cell survival reduction | 9-23% survival reduction | Targeted therapy showed reduced efficacy in 3D cultures of HER2-positive breast cancer cells [7] |

| Cell Viability (ATP levels) | 100% (reference) | 18-44% of 2D levels | Significantly lower metabolic activity in 3D cultures across multiple cell lines [7] |

| CYP3A4 Enzyme Activity | Lower baseline activity | Substantially increased activity | Enhanced drug metabolism capability in 3D cultures better mimicking hepatic function [7] |

The data demonstrate that 3D spheroids develop a heterogeneous cellular landscape with distinct zonation: an outer proliferative zone, an intermediate quiescent zone, and an inner necrotic core, each characterized by unique microenvironmental conditions and cellular behaviors [19] [20]. This architectural complexity directly contributes to the enhanced drug resistance observed in 3D systems, more accurately reflecting clinical treatment challenges.

Experimental Evidence: Gradient Formation and Impact

Methodologies for Studying Gradients in 3D Spheroids

Spheroid Formation Techniques

Researchers employ various established methods to generate 3D spheroids for gradient studies:

- Hanging Drop Technique: Cells aggregate spontaneously in liquid droplets suspended from plate lids, forming uniform spheroids without external scaffold interference [8] [23].

- Ultra-Low Attachment Plates: Specialized polymer-coated surfaces prevent cell attachment, forcing cells to aggregate in the well bottom under standard culture conditions [18] [23].

- Agitation-Based Methods: Bioreactors with constant rotation maintain cells in suspension, promoting aggregation through continuous gentle mixing [23].

- Scaffold-Based Systems: Natural (e.g., Matrigel, collagen) or synthetic polymers provide structural support that facilitates 3D organization and cell-ECM interactions [24] [23].

Gradient Visualization and Quantification Methods

Advanced technologies enable direct observation and measurement of gradients:

- Time-Lapse Microscopy with Viability Stains: Fluorescent markers (e.g., propidium iodide for necrosis, Calcein-AM for viability) track spheroid development and zone formation over time [21] [20].

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Reveals differential gene expression across spheroid zones, identifying upregulation of hypoxia-responsive genes (e.g., HIF-1α) and extracellular matrix components in inner regions [21].

- Microfluidic Chemotaxis Chambers: Specialized devices generate controlled nutrient gradients, allowing real-time monitoring of spheroid responses to defined microenvironmental conditions [20].

- Multiphysics Computational Modeling: COMSOL-based simulations integrate growth dynamics, nutrient diffusion, uptake kinetics, and porosity evolution to predict gradient formation and its effects [22].

Impact of Culture Conditions on Gradient Formation

Experimental evidence demonstrates that specific culture parameters significantly influence gradient development and spheroid characteristics:

- Oxygen Concentration: Spheroids cultured at 3% O₂ exhibited reduced dimensions and increased necrosis compared to those under standard oxygen conditions [21].

- Serum Concentration: Serum levels above 10% promoted dense spheroid formation with distinct necrotic and proliferative zones, while serum-free conditions led to spheroid shrinkage and increased cell detachment [21].

- Initial Seeding Density: The number of cells initially seeded directly correlates with final spheroid size, impacting nutrient diffusion distances and consequent gradient steepness [21].

Diagram 1: Impact of culture conditions on spheroid gradient formation and functional outcomes. External factors influence microgradient development, which establishes distinct structural zones that ultimately drive clinically relevant functional outcomes.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Establishing reliable 3D spheroid models requires specific materials and approaches designed to support three-dimensional growth and gradient formation. The following table summarizes key solutions and their applications in spheroid research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Spheroid Gradient Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Spheroid Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Low Attachment Plates | Prevents cell adhesion, promotes 3D aggregation | Polystyrene plates with covalently bound hydrogel coating; essential for scaffold-free spheroid formation [1] [23] |

| Basement Membrane Matrix (e.g., Matrigel) | Provides natural scaffold for cell invasion and signaling | Contains endogenous bioactive factors; influences spheroid morphology and gene expression [24] [23] |

| Natural Hydrogels (Collagen, Alginate) | Creates 3D ECM-mimetic environment for spheroid embedding | Collagen I at 2mg/mL concentration used in chemotaxis chambers to study invasion [20] |

| Synthetic Hydrogels (PEG, PLA) | Provides defined, customizable scaffold with controlled properties | Offers higher consistency and reproducibility than natural hydrogels; minimal bioactive interference [23] |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Source of growth factors and chemoattractants | Concentrations of 10-20% promote dense spheroid formation; serum-free conditions induce shrinkage [21] [20] |

| Chemotaxis Chambers | Generates stable nutrient gradients for invasion studies | Microfluidic devices with porous membranes create controlled FBS gradients (0-100%) [20] |

| Viability Assay Kits | Quantifies live/dead cells across spheroid zones | ATP-based assays show 60-80% lower viability in 3D vs 2D cultures [8] [7] |

Standardized Protocol: Establishing Gradient-Containing Spheroids

Based on methodologies from the cited research, the following protocol represents a standardized approach for generating spheroids with physiological nutrient and oxygen gradients:

- Coating Preparation: Create a 1% agarose solution in ultrapure water and add to 48-well plates (100μL/well). Allow polymerization at room temperature to form non-adhesive surfaces.

- Cell Seeding: Harvest and count cells from 2D cultures. Seed at optimized density (e.g., 2×10³ cells/well for CT26 colon carcinoma cells) in complete medium.

- Spheroid Formation: Incubate plates under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂) for 5-7 days without disturbance to allow compact spheroid formation.

- Medium Optimization: Use medium with 10% FBS for optimal structure; adjust glucose concentration to physiological levels (5.5 mM) rather than standard high-glucose formulations.

- Gradient Development: Monitor daily until spheroids reach 200-500μm diameter, indicating established nutrient/oxygen gradients.

Gradient Quantification and Validation

- Viability Staining: Incubate spheroids with propidium iodide (necrotic core) and Calcein-AM (viable cells) for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Image Analysis: Capture fluorescent images using confocal microscopy; quantify spatial distribution of live/dead cells using software like AnaSP [21].

- Oxygen Gradient Confirmation: Measure hypoxia using HIF-1α immunostaining or hypoxyprobe markers.

- Gene Expression Analysis: Process spheroids for single-cell RNA sequencing to identify gradient-dependent gene expression patterns (e.g., ECM genes COL18A1, MUC5B in inner zones) [21].

The evidence comprehensively demonstrates that nutrient and oxygen gradients in 3D spheroids are not experimental artifacts but rather defining features that create physiological heterogeneity mirroring in vivo conditions. These gradients drive the formation of distinct cellular zones with divergent proliferation profiles, metabolic activities, and drug sensitivities—fundamental characteristics of solid tumors that cannot be recaptured in 2D monolayers [19] [20].

The functional significance of these gradients extends beyond morphological mimicry to enhanced predictive validity in drug development. The dramatically different drug responses observed between 2D and 3D systems, with 3D spheroids consistently showing greater resistance to both targeted therapies and classical chemotherapeutics, directly reflect the gradient-induced heterogeneity that complicates clinical cancer treatment [7]. Furthermore, the preservation of more physiological gene expression patterns, metabolic enzyme activity, and cellular signaling pathways in 3D gradient systems underscores their superior biological relevance [21] [7].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the implication is clear: incorporating 3D spheroid models with established nutrient and oxygen gradients provides essential preclinical data that better predicts clinical outcomes. While 2D systems retain value for high-throughput initial screening, gradient-containing 3D models offer indispensable insight into drug penetration, mechanism of action in heterogeneous microenvironments, and resistance development—ultimately strengthening the translational pipeline and potentially reducing late-stage drug attrition rates.

For decades, two-dimensional (2D) cell culture has been a fundamental workhorse in biological research, providing a straightforward and low-cost method to maintain cells and perform experiments [8]. However, this approach involves growing cells in a single layer on flat surfaces, which does not reflect the essential features of tumor tissues found in living organisms [25]. The limitations of 2D culture have prompted the development of three-dimensional (3D) models that more accurately mimic the complex and dynamic cell-cell communications and cell-matrix interactions occurring in native tissue microenvironments [2] [25].

The transition from 2D to 3D culture systems represents more than just a technical shift—it introduces a fundamental biological variable that significantly influences cellular behavior, particularly gene expression and splicing patterns. Cells in the body naturally reside within a complex three-dimensional architecture where they interact with their surroundings on all sides, creating gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and signaling molecules [2]. This spatial organization is crucial for maintaining proper cellular function and tissue homeostasis, elements that are largely lost in traditional 2D cultures.

This comparison guide examines the profound transcriptomic shifts that occur when cells transition from 2D to 3D microenvironments, providing researchers with an evidence-based framework for selecting appropriate culture systems based on their experimental goals. We present quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and practical resources to support informed decision-making in cancer research and drug development.

Fundamental Differences Between 2D and 3D Culture Systems

Structural and Microenvironmental Contrasts

The structural differences between 2D and 3D culture systems create fundamentally distinct microenvironments that dramatically influence cellular behavior. In 2D cultures, cells are forced to adapt to an unnatural flat, rigid surface where they form monolayers with disrupted cell polarity and altered morphology [26]. This environment exposes the entire cell surface to the culture medium, creating uniform conditions without gradients. In contrast, 3D cultures allow cells to grow in all directions, forming complex structures that more closely resemble native tissues [2] [27].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of 2D vs. 3D Culture Systems

| Feature | 2D Culture | 3D Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Pattern | Monolayer on flat surfaces | Multilayer, expanding in all directions |

| Cell-Matrix Interactions | Limited, unnatural adhesion | Complex, biomimetic adhesion |

| Spatial Organization | Uniform, two-dimensional | Three-dimensional with spatial gradients |

| Cell-Cell Contacts | Limited to peripheral contacts | Omni-directional, as found in vivo |

| Microenvironment | Homogeneous nutrient and oxygen distribution | Heterogeneous, creating nutrient/oxygen gradients |

| Physiological Relevance | Low, does not reflect natural tissue architecture | High, better mimics native tissue organization |

The 3D microenvironment enables the formation of critical physiological features such as oxygen gradients, pH gradients, and nutrient gradients that significantly influence cellular behavior and gene expression profiles [8]. These gradients are particularly important in cancer research, as they recreate the conditions found in solid tumors, including hypoxic regions that drive tumor progression and drug resistance [25].

Technical Implementation of 3D Culture Systems

Three-dimensional cultures can be established using several technical approaches, each with distinct advantages and applications:

- Scaffold-based methods: Utilize biological or synthetic materials to provide structural support. These include hydrogels, polymeric hard materials, and decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) scaffolds that provide mechanical support and cell adhesion sites [28] [27].

- Scaffold-free methods: Rely on the self-aggregation properties of cells. The hanging drop technique is a well-established scaffold-free approach that uses gravitational and surface tension forces to facilitate natural cellular aggregate formation [8] [27].

- Bioreactor systems: Employ dynamic culture conditions to enhance nutrient distribution and waste removal. Examples include spinner flasks, rotating wall vessels, and orbital shakers that prevent cells from adhering to surfaces, keeping cells and spheroids in suspension [27] [25].

- Microfluidic platforms: Create precisely controlled microenvironments for culturing organoids and other 3D structures, allowing for sophisticated manipulation of culture conditions [29].

Transcriptomic Differences Between 2D and 3D Cultures

Gene Expression and Splicing Alterations

The structural and microenvironmental differences between 2D and 3D culture systems trigger profound transcriptomic changes that significantly impact cellular function and drug response. Cells in 3D cultures exhibit gene expression profiles that more closely resemble in vivo conditions compared to their 2D counterparts [8].

Table 2: Transcriptomic Differences Between 2D and 3D Cultures

| Transcriptomic Feature | 2D Culture Characteristics | 3D Culture Characteristics | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Fidelity | Altered gene expression patterns compared to in vivo [2] | Better gene expression profiles resembling in vivo conditions [8] | More clinically relevant drug response predictions |

| DNA Damage Response Pathways | Standard response to DNA damage | Upregulation of MRE11 and associated DNA damage repair pathways [30] | Enhanced genomic stability mechanisms |

| Metabolic Pathway Activity | Uniform metabolic activity | Increased metabolic activity at center of microregions [31] | Better modeling of tumor metabolic heterogeneity |

| Immune-Related Signaling | Limited immune marker expression | Increased antigen presentation along microregion edges [31] | More accurate immunotherapy response modeling |

| Oncogenic Pathway Activation | Altered oncogene expression | Differential activity in pathways like MYC [31] | Better recapitulation of cancer driver mechanisms |

| Alternative Splicing Patterns | Simplified splicing profiles | Complex, tissue-specific splicing patterns | Enhanced functional proteome diversity |

Research has demonstrated that 3D cultures exhibit a higher degree of structural complexity and homeostasis analogous to tissues and organs [2]. A comprehensive study examining 131 tumour sections across 6 cancer types using spatial transcriptomics revealed that tumor microregions show distinct spatial organization with varied genetic activities, including increased metabolic activity at the center and elevated antigen presentation along the leading edges [31]. These patterns are not observed in 2D systems due to their uniform microenvironment.

Key Molecular Pathways Differentially Regulated in 3D Microenvironments

The transcriptomic shifts in 3D environments activate several crucial molecular pathways with significant implications for cancer biology and therapeutic development:

Diagram 1: Transcriptomic Pathways in 3D Microenvironments. This diagram illustrates key molecular pathways differentially regulated in 3D culture systems, showing how microenvironment-induced changes in gene expression and splicing influence clinically relevant cellular behaviors.

One particularly important pathway differentially regulated in 3D environments involves MRE11, a critical component of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex responsible for recognizing and repairing DNA double-strand breaks [30]. Studies in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have demonstrated that high MRE11 expression is strongly associated with poor prognosis and regulates immune responses within the tumor microenvironment, facilitating immune evasion via the cGAS-STING pathway and HGF-MET axis [30]. This pathway activation is more accurately modeled in 3D culture systems that maintain appropriate cell-cell interactions and spatial organization.

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols for Transcriptomic Analysis

To accurately assess transcriptomic differences between 2D and 3D culture systems, researchers employ several sophisticated methodological approaches:

Spatial Transcriptomics Protocol:

- Tissue Preparation: Fresh tumor tissues are collected and embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound for cryosectioning [31].

- Sectioning: Tissues are cut into thin sections (typically 10-20 μm) and placed on specialized glass slides containing barcoded capture areas.

- Staining and Imaging: Sections are stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for histological analysis and imaged [31].

- Permeabilization: Tissue sections are permeabilized to release mRNA molecules which bind to spatially barcoded capture probes.

- Library Preparation: cDNA libraries are synthesized, amplified, and prepared for sequencing.

- Sequencing and Data Analysis: Libraries are sequenced, and bioinformatic tools are used to map transcriptomic data back to spatial locations.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Protocol:

- Cell Dissociation: 3D structures are dissociated into single-cell suspensions using enzymatic and mechanical methods [30].

- Cell Viability Assessment: Cell viability is confirmed using trypan blue exclusion or similar methods.

- Single-Cell Capture: Cells are loaded into microfluidic devices for single-cell barcoding.

- Reverse Transcription and Amplification: mRNA is reverse transcribed and cDNA is amplified.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Libraries are prepared using platform-specific protocols and sequenced.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Data processing, normalization, clustering, and trajectory inference are performed.

3D Culture Models for Drug Response Evaluation:

- Model Establishment: Patient-derived cancer cells (PDCCs) are cultured in 3D matrices such as decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) scaffolds [28] or as organoids [29].

- Drug Treatment: Compounds are applied at clinically relevant concentrations, often in gradient doses.

- Viability Assessment: Cell viability is measured using assays optimized for 3D structures (e.g., ATP-based assays, resazurin reduction).

- Transcriptomic Analysis: Treated and control samples are processed for bulk or single-cell RNA sequencing.

- Pathway Analysis: Differentially expressed genes are analyzed for enriched pathways and biological processes.

Quantitative Evidence from Comparative Studies

Substantial experimental evidence demonstrates the profound transcriptomic differences between 2D and 3D culture systems:

Drug Resistance Mechanisms: Transcriptomic analysis of 3D tumor models reveals upregulation of multidrug resistance (MDR) proteins through specific cellular signaling pathways, including those activated by hypoxia, low nutrient supply, and low pH [25]. These conditions are naturally recreated in 3D models but are largely absent in 2D systems.

Tumor Microregion Heterogeneity: Spatial transcriptomic studies of 3D tumor models have identified distinct "tumor microregions" - spatially distinct cancer cell clusters separated by stromal areas that vary in size and density among cancer types [31]. These microregions exhibit differential gene expression patterns, with increased metabolic activity at the center and increased antigen presentation along the leading edges.

Immune Interaction Signatures: Analysis of 3D tumor models co-cultured with immune cells has revealed dynamic remodeling of the tumor microenvironment under immunotherapy, with high MRE11 expression facilitating epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and extensive remodeling of the tumor microenvironment [30].

Implications for Drug Discovery and Development

Drug Response and Resistance Mechanisms

The transcriptomic shifts observed in 3D culture systems have profound implications for drug discovery and development, particularly in predicting clinical efficacy:

Table 3: Drug Response Differences Between 2D and 3D Cultures

| Parameter | 2D Culture Response | 3D Culture Response | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Sensitivity | Generally hypersensitive | More resistant, resembling in vivo responses | Better prediction of clinical efficacy |

| Drug Penetration | Uniform exposure throughout cells | Gradient penetration, creating sanctuary sites | Models physiological drug distribution barriers |

| IC50 Values | Typically lower | Higher, more clinically relevant | Improved dose selection for clinical trials |

| Multidrug Resistance | Limited expression of MDR proteins | Upregulated MDR expression in hypoxic regions | Recapitulates clinical resistance mechanisms |

| Combination Therapy Effects | Often overestimated | More predictive of clinical outcomes | Better prioritization of combination regimens |

| Immunotherapy Response | Limited predictive value | Models immune-tumor interactions | Enhanced immuno-oncology drug screening |

Compared to 2D cultures, cells in 3D generally exhibit a reduced sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents, providing a more accurate prediction of clinical drug response [25]. This difference stems from multiple factors, including the presence of physiological barriers to drug penetration, altered proliferation kinetics, and the development of microenvironment-induced resistance mechanisms.

Applications in Personalized Medicine

The enhanced physiological relevance of 3D culture systems, particularly those derived from patient samples, enables more effective personalized medicine approaches:

Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs): These 3D structures retain the genetic and phenotypic characteristics of the patient's original tumor and can more accurately reflect tumor biology than traditional cell lines [29]. They allow for functional testing of patients' cancer cells against various therapeutic options.

Therapeutic Biomarker Discovery: The transcriptomic profiles generated from 3D cultures have proven more reliable for identifying predictive biomarkers of drug response. For instance, MRE11 expression patterns in 3D hepatocellular carcinoma models have been identified as promising biomarkers for diagnosis and potential targets for personalized immunotherapy [30].

Treatment Selection Guidance: Prominent cancer centers like Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) now use patient-derived organoids to match therapies to drug-resistant pancreatic cancer patients, demonstrating the clinical utility of 3D culture systems [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Implementing robust comparisons between 2D and 3D culture systems requires specific reagents and technical platforms:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Transcriptomic Studies

| Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Application in Transcriptomic Studies |

|---|---|---|

| 3D Scaffold Systems | Decellularized ECM (dECM) scaffolds [28], Hydrogels (Matrigel, collagen) | Provide biomechanical and biochemical cues for proper 3D gene expression |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | 10X Genomics Visium, Nanostring GeoMx | Enable spatial mapping of gene expression patterns in 3D structures |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing | 10X Genomics Chromium, BD Rhapsody | Resolve cellular heterogeneity within 3D cultures |

| Cell Culture Platforms | Ultra-low attachment plates, Hanging drop plates, Microfluidic chips (OrganoPlate) | Facilitate formation and maintenance of 3D structures |

| Extracellular Matrix Components | Laminin, Fibronectin, Collagen I/IV | Recreate tissue-specific microenvironment for proper signaling |

| Analysis Tools | Seurat, Scanpy, stCancer package, GEPIA2 | Process and interpret transcriptomic data from 3D models |

The selection of appropriate reagents and platforms is critical for generating reliable, reproducible data when comparing 2D and 3D systems. For instance, decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) scaffolds have been shown to create complex microenvironments that better maintain native gene expression profiles compared to basic protein matrices typically employed in 2D or simpler 3D culture systems [28].

The transition from 2D to 3D cell culture systems represents far more than a technical advancement—it constitutes a fundamental shift in how researchers model biological systems. The transcriptomic differences between these systems are profound and well-documented, with 3D environments promoting gene expression and splicing patterns that more closely resemble in vivo conditions. These differences significantly impact drug response profiles, mechanistic studies of disease processes, and the predictive accuracy of preclinical models.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between 2D and 3D culture systems should be guided by specific research objectives. While 2D systems remain valuable for high-throughput screening and certain reductionist experimental approaches, 3D models provide essential physiological context for studies requiring clinical relevance. The optimal approach for many research programs involves a complementary strategy, using 2D systems for initial screening followed by 3D models for validation and mechanistic studies.

As technological advancements continue to improve the accessibility and reproducibility of 3D culture systems, their adoption is expected to grow, ultimately enhancing the translation of basic research findings into clinical applications. Strategic integration of 3D models into research workflows will support both improved understanding of disease mechanisms and the discovery of more effective, personalized therapeutic interventions.

Implementing 3D Models: Techniques and Their Transformative Applications in Biomedicine

The transition from traditional two-dimensional (2D) to three-dimensional (3D) cell culture represents a fundamental evolution in biomedical research. While 2D cultures, where cells grow as monolayers on flat plastic surfaces, have been the workhorse of laboratories for decades, they present significant limitations [2]. Cells in 2D exhibit altered gene expression, increased drug sensitivity, and cannot replicate the complex architecture and cell-cell interactions found in living tissues [2] [32]. In contrast, 3D cell culture systems bridge the gap between simple 2D cultures and complex in vivo environments, enabling cells to grow in all directions, form natural gradients of oxygen and nutrients, and establish cell-matrix interactions that closely mimic the physiological conditions of human tissues and organs [2] [33]. This enhanced biological relevance is crucial for applications in drug discovery, disease modeling, and regenerative medicine [32].

The foundation of most 3D culture systems is the scaffold—a material that provides structural and biochemical support for cell attachment, proliferation, and organization. This guide objectively compares the performance of the predominant scaffold-based techniques: the naturally-derived Matrigel, various hydrogel systems, and emerging synthetic polymer scaffolds, providing a clear analysis of their efficacy within the broader thesis of 2D versus 3D culture system research.

The Gold Standard and Its Limitations: Matrigel

Matrigel, a basement membrane matrix extracted from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) mouse sarcoma, has been the "gold standard" scaffold for 3D cell culture for over four decades [34] [35]. Its main components are laminin (~60%), collagen IV (~30%), entactin (~8%), and the heparin sulfate proteoglycan perlecan [34]. This composition, rich in bioactive molecules like laminin-derived peptides IKVAV and YIGSR, provides a naturally favorable environment for a myriad of applications, including stem cell culture, regenerative medicine, and organoid assembly [34] [35]. Matrigel is a thermosensitive hydrogel, existing as a liquid at 4°C and forming a gel at 37°C, facilitating easy cell encapsulation [36].

Documented Limitations and Performance Issues

Despite its widespread use, Matrigel's suitability for rigorous, reproducible research is hampered by several critical limitations:

- Complex and Ill-Defined Composition: Matrigel contains a complex mixture of over 1,800 proteins, including growth factors (e.g., TGF-β, FGFs) and enzymes (e.g., MMPs), which vary between batches and are not fully characterized [34] [35]. This introduces significant experimental uncertainty.

- Batch-to-Batch Variability: Variations in the mechanical and biochemical properties within a single batch and between different batches lead to a lack of reproducibility in cell culture experiments [34] [35] [37].

- Animal-Derived Nature: As a murine sarcoma-derived product, Matrigel presents a risk of xenogenic contaminants, limiting its use for therapeutic cell manufacturing and raising concerns for clinical translation [34] [37].

- Limited Tunability: Its composition is not conducive to physical or biochemical manipulation, making it difficult to fine-tune the matrix to probe specific cell behaviors or achieve defined biological outcomes [34] [35].

Synthetic Scaffold Alternatives: A Designed Approach

To overcome the limitations of Matrigel, significant research efforts have focused on developing synthetic and defined scaffolds. These materials aim to provide a xenogenic-free, chemically defined, and highly tunable environment for 3D cell culture [34] [35].

Synthetic Hydrogels

Synthetic hydrogels are three-dimensional networks of hydrophilic polymers that absorb large amounts of water, mimicking the natural extracellular matrix (ECM) [38]. They are highly designable and can be classified by their source (natural, synthetic, semi-synthetic), durability (durable, biodegradable), and responsiveness to environmental stimuli (smart hydrogels) [38]. Common synthetic polymers include polyethylene glycol (PEG), polyacrylamide (PAA), and PLGA-PEG-PLGA triblock copolymers [34] [37] [39].

- Advantages: Their primary advantage is the independent control over mechanical properties (e.g., stiffness, viscoelasticity) and biochemical cues (e.g., adhesion ligands, growth factors) [40] [39]. For instance, PEG hydrogels functionalized with RGD peptides (a common cell-adhesion motif) have been successfully used for intestinal organoid culture and to study cancer cell dissemination [34] [40].

- Performance Data: A 2025 study developed a fully synthetic injectable gel scaffold (PLGA-PEG-PLGA/LAPONITE/L-Arg@NU-1000) for skeletal muscle regeneration. In vivo experiments demonstrated that its tissue regeneration efficiency was higher than that of Matrigel, as judged by histological analysis including MYH3 immunofluorescent staining [37].

Recombinant Protein and Peptide Hydrogels

These scaffolds strive to combine the bioactivity of natural components with the definition and reproducibility of synthetic systems.

- Recombinant Protein Hydrogels: These are composed of engineered proteins, such as recombinant elastin or laminin, produced in controlled systems (e.g., E. coli), ensuring a defined and consistent composition [36].

- Self-Assembling Peptide (SAP) Hydrogels: These are made from short peptide sequences that spontaneously organize into nanofibers under specific physiological conditions, forming a hydrogel scaffold [36]. They can be functionalized with bioactive epitopes (e.g., IKVAV) to direct cell behavior [34].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of Matrigel, synthetic hydrogels, and peptide-based scaffolds, highlighting their comparative efficacy.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Scaffold-Based 3D Culture Techniques

| Feature | Matrigel | Synthetic Hydrogels (e.g., PEG, PAA) | Peptide Hydrogels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composition & Definition | Complex, ill-defined, >1800 proteins [34] [35] | Chemically defined, reproducible [34] | Chemically defined, reproducible [36] |

| Batch-to-Batch Variability | High, a major source of irreproducibility [34] [35] | Low, highly reproducible [34] | Very low, highly reproducible [36] |

| Origin & Safety | Mouse sarcoma, xenogenic, not clinically translatable [34] [37] | Synthetic, xenogenic-free, better clinical potential [34] [37] | Synthetic, xenogenic-free, good clinical potential [36] |

| Tunability of Properties | Very low, difficult to manipulate [34] | Very high, independent control over mechanics and biochemistry [40] [39] | High, can engineer peptide sequences [34] |

| Bioactivity | High, but uncontrolled and variable [34] | Customizable via incorporation of specific ligands (e.g., RGD, IKVAV) [34] [40] | Customizable via peptide design [34] |

| Typical Applications | Stem cell culture, organoids, angiogenesis assays [34] [35] | Organoid culture, regenerative medicine, mechanistic studies [34] [37] [39] | Neural tissue engineering, 3D cell culture [34] |

| Documented Performance | Excellent growth but inconsistent results; promotes epithelial dissemination in cancer models [40] | Equivalent or superior to Matrigel in stem cell culture and organoid formation; induced dissemination at intermediate adhesion/rigidity [34] [40] [37] | Promotes neural stem cell differentiation; can direct specific cell behaviors [34] |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental logical relationship between the choice of scaffold material and the key considerations in 3D cell culture.

Diagram 1: Scaffold Selection Logic

Experimental Protocols and Data Generation

Example Protocol: Culturing Intestinal Organoids in PEG-Based Hydrogels

The following workflow details a method for creating synthetic hydrogel environments for organoid culture, as an alternative to Matrigel [34].

Table 2: Key Reagents for PEG Hydrogel Organoid Culture

| Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| 4-Arm PEG-VS (PEG-vinyl sulfone) | Macromer that forms the backbone of the hydrogel network through covalent crosslinking. |

| Peptide Crosslinker (e.g., GCGPQG↓IWGQCG) | MMP-degradable crosslinker; allows cells to remodel and invade the matrix. |

| Adhesion Peptide (e.g., CRGDS) | Provides integrin-binding sites for cell attachment and survival. |

| Laminin-Derived Peptides | Provides specific bioactive cues to support stemness and differentiation. |

| Factor XIIIa | Enzyme that catalyzes the crosslinking reaction between PEG-VS and peptides. |

| Intestinal Stem Cells | Primary cells or progenitor cells used to generate organoids. |

Step-by-Step Workflow: