2D vs 3D iPSC Models: A Strategic Guide for Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between two-dimensional (2D) monolayer and three-dimensional (3D) organoid models derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for researchers and drug development professionals.

2D vs 3D iPSC Models: A Strategic Guide for Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between two-dimensional (2D) monolayer and three-dimensional (3D) organoid models derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational biology of each system, detailing their technical establishment and key applications in disease modeling, drug screening, and toxicology evaluation. The content further delivers practical insights for model selection and troubleshooting, supported by direct experimental comparisons that validate the physiological relevance and predictive power of each approach. By synthesizing methodological, application, and validation data, this guide aims to inform strategic decisions in preclinical research, ultimately enhancing the efficiency and human relevance of therapeutic development.

Understanding the Core Biology: From Simple Monolayers to Complex Organoids

In the fields of regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug development, induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized our ability to study human biology and pathology in vitro. A critical decision in experimental design is the choice of culture model, which fundamentally shapes the resulting data and its biological relevance. The scientific community has largely transitioned from viewing these models as interchangeable to understanding them as complementary tools with distinct applications. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) monolayers and emerging three-dimensional (3D) organoids represent two fundamentally different approaches to cell culture, each with unique strengths, limitations, and physiological relevance [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison between 2D monolayer and 3D organoid iPSC models to help researchers select the appropriate system for their specific research objectives.

Model Definitions and Fundamental Characteristics

2D Monolayers

The 2D monolayer is the established, conventional cell culture system where cells grow as a single layer on a flat, rigid plastic or glass surface [1]. In this environment, cells adhere to the substrate, flattening and spreading to form a uniform monolayer. This system has been the foundation of cell biology for decades due to its simplicity, reproducibility, and ease of use. For iPSC research, this typically involves growing stem cells or their differentiated progeny on coated tissue culture plates where all cells have equal access to nutrients, oxygen, and experimental compounds in the culture medium [2]. The forced planar geometry, however, creates an artificial microenvironment that significantly alters native cell morphology and polarity.

3D Organoids

3D organoids are complex, self-organizing three-dimensional structures derived from stem cells (including iPSCs) that recapitulate key aspects of native tissue architecture and functionality [3] [4]. These miniaturized organ-like structures form through the remarkable self-renewal and spatial organization capabilities of stem cells when provided with an appropriate extracellular environment, typically using Matrigel or specially formulated collagen hydrogels [5]. Unlike simple 3D spheroids (which are cell aggregates lacking tissue-specific organization), organoids develop distinct regional patterns and contain multiple organ-specific cell types, mimicking the complex cellular ecology of real organs [5]. Their 3D architecture accommodates physiologically relevant features including hypoxic cores, proliferating and quiescent regions, and realistic cell-cell/cell-matrix interactions that more accurately mirror in vivo conditions [6].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of 2D vs. 3D Culture Models

| Characteristic | 2D Monolayers | 3D Organoids |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Architecture | Flat, monolayer | Three-dimensional, tissue-like |

| Cell Morphology | Altered, flattened | Physiological, natural shape |

| Cell-Cell Interactions | Limited to horizontal plane | Omnidirectional, more natural |

| Cell-Matrix Interactions | Artificial, with plastic surface | Physiological, with ECM proteins |

| Microenvironment | Homogeneous conditions | Gradients of nutrients, oxygen, signaling molecules |

| Physiological Relevance | Low to moderate | High |

| Technical Complexity | Low | High |

| Reproducibility | High | Variable, requires optimization |

| Cost | Low | High |

| Throughput Capacity | High | Moderate to low |

Methodological Approaches: From Setup to Analysis

Establishing 2D Monolayer Cultures

The protocol for 2D monolayer culture is well-standardized across laboratories. iPSCs are typically maintained on surface-treated tissue culture plastic in defined media supporting pluripotency or directed toward specific lineages. The process involves:

- Surface Coating: Application of substrate coatings (e.g., Matrigel, laminin, poly-ornithine) to promote cell attachment.

- Cell Seeding: Dissociation of iPSCs to single cells or small clusters followed by seeding onto coated surfaces at defined densities.

- Maintenance: Routine medium changes every 1-2 days until cells reach desired confluency.

- Passaging: Controlled detachment (typically using enzymatic digestion) and reseeding to maintain cultures or expand cell numbers.

The homogeneous nature of 2D cultures makes them ideal for many biochemical assays, high-resolution imaging, and genetic manipulations [2]. All cells are equally accessible to experimental compounds, and responses can be easily quantified using standard equipment.

Generating 3D Organoid Cultures

Organoid generation leverages the self-organizing capacity of stem cells. A representative protocol for generating intestinal epithelial monolayers from single-cell organoid suspensions illustrates key principles [7]:

- Starting Material: Use mouse intestinal organoids grown in 50 μL Matrigel drops in a 24-well plate.

- Cell Dissociation:

- Prepare cell dissociation solution containing Accumax, Chir-99021 (3 μM), and Y27632 (10 μM).

- Incubate organoids in dissociation solution for proper dissociation into single cells.

- Dissociation Termination:

- Use pre-warmed stop solution (DMEM F12-Glutamax with B27, Chir-99021, and Y27632).

- Add stop solution in a 2:1 ratio to dissociation solution.

- Cell Seeding:

- Seed dissociated cells onto polyacrylamide (PAA) gels coated with collagen type-I in glass-bottom dishes.

- Use plating medium (ENR medium with Chir-99021 and Y27632).

- Monolayer Formation:

- Culture cells in ENR-CNY medium for initial 48-72 hours to promote cell spreading and de novo crypt formation.

This process results in intestinal monolayers that can be subjected to additional analysis, including drug treatment, immunofluorescent staining, or live imaging [7]. The protocol highlights the higher technical complexity and specialized reagents required for 3D culture systems.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Model Systems

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function in Culture System |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Matrices | Matrigel, Collagen I, PEG-based hydrogels, polyacrylamide gels | Provide 3D scaffolding that mimics native extracellular matrix |

| Dissociation Agents | Accumax, Accutase, trypsin-EDTA | Break down cell-cell and cell-matrix connections for passaging or analysis |

| Signaling Pathway Modulators | Chir-99021 (Wnt activator), Y27632 (ROCK inhibitor), Noggin, R-spondin | Control stem cell self-renewal, differentiation, and survival |

| Media Supplements | B27, N2, N-acetylcysteine, growth factors (EGF, FGF) | Provide essential nutrients and signaling molecules for growth and maintenance |

Technical Workflow Comparison

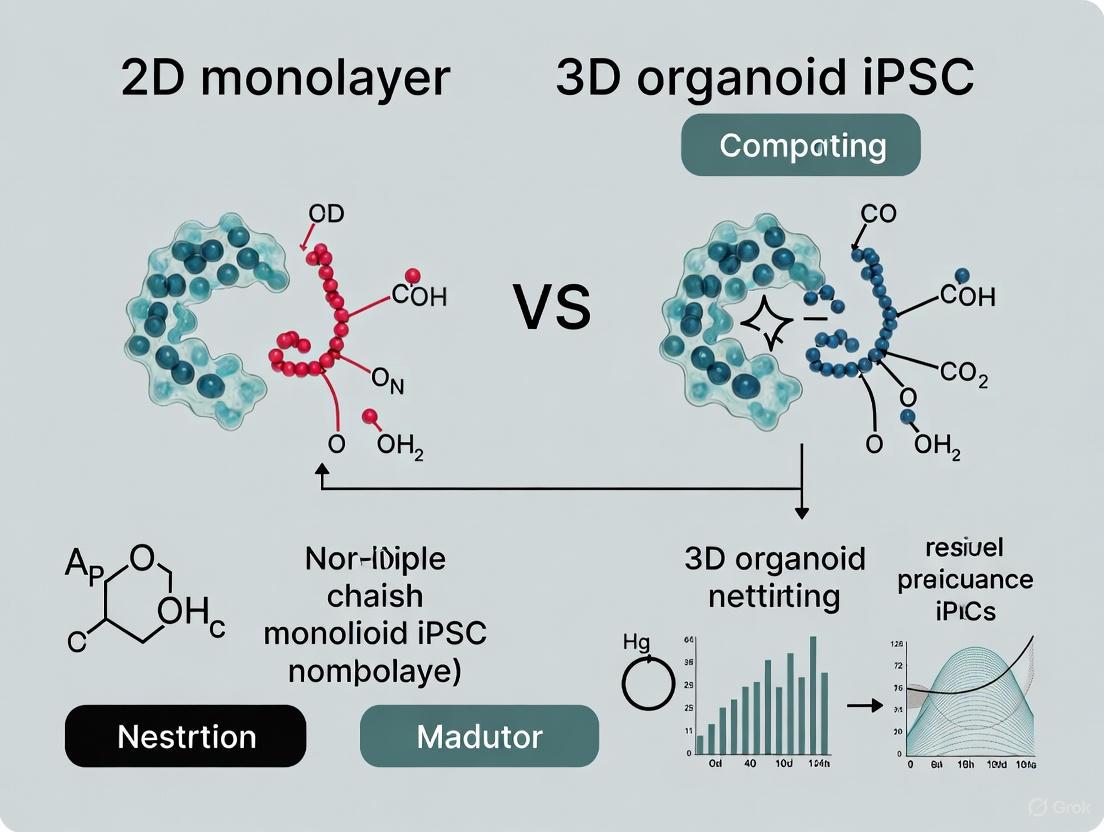

The diagram below illustrates the key procedural differences in establishing and maintaining 2D monolayer versus 3D organoid cultures:

Comparative Experimental Data: Functional Differences in Research Settings

Cellular Morphology and Architecture

Significant morphological differences exist between 2D and 3D cultures at both cellular and structural levels. In 2D monolayers, cells adopt flattened, spread morphologies unnatural to their in vivo counterparts, with forced apical-basal polarity aligned with the growth surface [1]. In contrast, 3D organoids exhibit proper cell polarization and tissue organization, with cells displaying natural cuboidal or columnar shapes arranged to form lumen, crypt-villus structures, or other organ-specific architectural features [7]. These structural differences directly impact cellular function, signaling, and response to external stimuli.

Proliferation and Viability Patterns

Comparative studies reveal fundamentally different growth dynamics between culture systems:

Table 3: Proliferation and Viability Assessment in 2D vs. 3D Systems

| Parameter | 2D Monolayer Findings | 3D Organoid Findings | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation Rate | Typically faster, more uniform | Slower, heterogeneous with proliferative zones | Cells in 3D displayed significant (p < 0.01) differences in proliferation patterns over time [6] |

| Cell Death Profile | More homogeneous apoptosis | Phased apoptosis with protective core regions | 3D cultures showed differences in cell death phase profiles [6] |

| Long-term Culture Stability | Limited (days to 1-2 weeks) | Extended (4-6 weeks or longer) | Cells in 3D tissues retain tissue-specific functions longer [2] |

| Metabolic Activity | Higher basal levels, more uniform | Gradients from periphery to core, more physiological | Metabolic heterogeneity observed in 3D systems [6] |

Gene Expression and Epigenetic Profiles

Transcriptomic and epigenetic analyses reveal striking molecular differences between culture models:

Transcriptomic Variations: RNA sequencing studies show significant (p-adj < 0.05) dissimilarity in gene expression profiles between 2D and 3D cultures, involving thousands of up/down-regulated genes across multiple pathways [6]. These differences affect critical processes including cell differentiation, metabolic pathways, and stress responses.

Epigenetic Patterns: 3D cultures more closely match the methylation patterns and microRNA expression profiles of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) patient samples, while 2D cells show elevated methylation rates and altered microRNA expression [6]. This suggests 3D systems better preserve physiological epigenetic regulation.

Pathway Activation: Key developmental signaling pathways (Wnt/β-catenin, BMP, Notch) show more physiological activation patterns in 3D organoids compared to 2D systems [5]. This has profound implications for studying development, tissue homeostasis, and disease mechanisms.

Drug Response and Predictive Value

Perhaps the most significant functional difference between models lies in drug screening applications:

Table 4: Drug Response Characteristics in 2D vs. 3D Systems

| Aspect | 2D Monolayer Response | 3D Organoid Response | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Penetration | Immediate, uniform access | Gradual, gradient-dependent | 3D models better predict antibiotic/chemotherapy efficacy [1] [5] |

| IC50 Values | Typically lower | Higher, more clinically relevant | 3D systems show increased resistance similar to in vivo tumors [8] |

| Resistance Mechanisms | Limited, primarily cellular | Complex, involving microenvironment | Better modeling of clinical drug resistance [6] |

| Tumor Modeling | Homogeneous response | Heterogeneous response mimicking in vivo tumors | 3D organoids preserve original tumor architecture and profiles [5] |

| Clinical Predictive Value | Often overestimates efficacy | Better correlation with clinical outcomes | Improved translation from in vitro to clinical settings [5] |

In a direct comparative study using colorectal cancer models, cells grown in 3D displayed significantly different responsiveness to chemotherapeutic agents including 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, and doxorubicin compared to 2D cultures [6]. This has critical implications for drug development, where 3D models may better predict clinical efficacy and toxicity.

Research Applications: Strategic Model Selection

When to Use 2D Monolayer Models

- High-Throughput Screening: Large-scale drug or genetic screens requiring 384/1536-well formats [2]

- Mechanistic Pathway Studies: Investigations of signaling pathways requiring uniform experimental conditions [2]

- Initial Characterization: Rapid assessment of cellular functions, transfection efficiency, or toxicity

- Live-Cell Imaging: Real-time visualization of dynamic processes using standard microscopy

- Educational Settings: Teaching basic cell culture techniques and experimental design

When to Use 3D Organoid Models

- Disease Modeling: Recapitulating human diseases requiring tissue context and cellular heterogeneity [3] [4]

- Drug Development: Preclinical assessment of drug efficacy, penetration, and toxicity in physiologically relevant systems [5]

- Developmental Biology: Studying tissue morphogenesis and organization [4]

- Personalized Medicine: Using patient-derived organoids for treatment selection and biomarker discovery [5]

- Host-Pathogen Interactions: Modeling infectious diseases affecting specialized tissue structures

Integrated Approach

Many sophisticated research programs employ both systems in a complementary strategy: using 2D monolayers for initial high-throughput screening and mechanistic studies, followed by validation in 3D organoids for physiological relevance and predictive value [1] [2]. This integrated approach maximizes both throughput and biological fidelity.

The choice between 2D monolayer and 3D organoid models represents a fundamental strategic decision in experimental design. 2D monolayers offer technical simplicity, reproducibility, and scalability ideal for reductionist approaches and high-throughput applications. 3D organoids provide superior physiological relevance, appropriate tissue context, and better predictive value for clinical translation, albeit with increased technical complexity and cost. The optimal model selection depends critically on the specific research question, required throughput, and available resources. As the field advances, the strategic integration of both approaches throughout the research pipeline—from discovery to validation—will maximize both efficiency and biological insight, ultimately accelerating progress toward understanding human biology and developing effective therapeutics.

The advent of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has revolutionized neuroscience, providing an unprecedented window into human brain development and disease. By reprogramming adult somatic cells into a pluripotent state, researchers can generate patient-specific neural cells for modeling neurological disorders, drug screening, and regenerative strategies. The journey from a somatic cell to a sophisticated neural model begins with two critical choices: the selection of the source cell type and the reprogramming method. These foundational decisions significantly impact the efficiency, fidelity, and functionality of the resulting iPSC-derived neurons and glia, ultimately influencing the success of downstream applications, particularly when comparing the output of two-dimensional (2D) monolayers versus three-dimensional (3D) organoid models. This guide provides a objective comparison of these initial building blocks, equipping researchers with the data needed to optimize their experimental pipelines.

Sourcing iPSCs: A Comparison of Starting Cell Types

The initial source of somatic cells used for reprogramming can influence the success rate, genetic stability, and even the differentiation propensity of the resulting iPSC line.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Somatic Cell Sources for iPSC Generation

| Cell Source | Reprogramming Success Rate | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Impact on Neural Differentiation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibroblasts | High with SeV method [9] | • Gold standard; well-established protocols• Easy to obtain via skin biopsy• High-quality, full karyotype data | • Invasive biopsy procedure• Slower proliferation rate | Well-characterized; reliable for generating various neuronal subtypes [10] |

| Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | High with SeV method [9] | • Minimally invasive collection• Scalable from blood donors• Rapid proliferation | • Limited starting material• Requires activation for reprogramming | Effective; may exhibit less somatic memory than fibroblasts [11] |

| Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines (LCLs) | Comparable between methods [9] | • Immortalized; unlimited source material• Often available from biobanks | • Requires establishment of cell line• Potential for genomic instability | Proven capability, though less studied than fibroblasts [9] |

| Adult Neuroprogenitor Cells (aNPCs) | Information Missing | • Endogenous expression of neural factors• Potentially higher neural differentiation efficiency | • Highly invasive sourcing from brain tissue• Limited availability | Shown to influence subsequent neuronal differentiation yield [12] |

Experimental Evidence on Cell Source Impact

A 2025 systematic study comparing non-integrating reprogramming methods across different source materials found that while the source material itself did not significantly impact the overall success rates of reprogramming, the Sendai virus (SeV) method yielded significantly higher success rates compared to the episomal method, regardless of whether the starting cells were fibroblasts, LCLs, or PBMCs [9]. This suggests that the choice of reprogramming method may be more critical than the cell source for simply generating an iPSC line.

However, the starting cell type can have a more nuanced effect on the iPSC's subsequent potential. For instance, a 2019 study demonstrated that the cell density of infected adult neuroprogenitor cells (aNPCs) during reprogramming confounded the efficiency of subsequent neuronal differentiation. iPSC clones derived from aNPCs plated at high density (iPSC-aNPCHigh) showed significantly higher neuronal differentiation efficiency compared to those from low density (iPSC-aNPCLow), highlighting that procedural variables coupled with cell source can influence the final model's performance [12].

Reprogramming Methods: Balancing Efficiency and Safety

The method used to deliver reprogramming factors is crucial, as it affects genomic integrity, a primary concern for both basic research and clinical applications.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Reprogramming Methods for iPSC Generation

| Reprogramming Method | Integration into Genome | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sendai Virus (SeV) | Non-integrating [9] [13] | • High reprogramming efficiency [9]• Dilutes out with cell passaging• Well-documented protocol | • Requires careful screening for clearance• Potential immune response | High-efficiency generation of research-grade lines; when source material is limited |

| Episomal Vectors | Non-integrating [9] [14] | • Non-viral, safer profile• Simple delivery (nucleofection) | • Lower efficiency than SeV [9]• Requires multiple vectors for factors | Clinical applications where viral vectors are a concern; footprint-free lines |

| Lentivirus | Integrating [9] [11] | • High efficiency• Stable transgene expression | • Risk of insertional mutagenesis• Persistent transgene expression | Largely superseded by non-integrating methods; specific research tools |

| mRNA Transfection | Non-integrating [14] | • Highly defined and virus-free• Rapid reprogramming | • Requires repeated transfections• Can trigger innate immune response | Clinical-grade iPSC generation; studies requiring minimal genetic manipulation |

Experimental Evidence on Reprogramming Methods

The shift from integrating to non-integrating methods has been a major focus in the field. A 2025 analysis confirms that methods like Sendai virus and episomal vectors are now predominant due to their significantly lower number of copy number variants (CNVs), single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and chromosomal mosaicism relative to older lentiviral methods [9]. This enhances the safety and reliability of the resulting iPSC lines.

Direct comparative data underscores the efficiency advantage of the Sendai virus approach. In a systematic evaluation, the Sendai virus reprogramming method yielded significantly higher success rates relative to the episomal reprogramming method across multiple source cell types [9]. This makes it a robust choice for projects where maximizing the yield of iPSC colonies from a precious sample is paramount.

Core Reprogramming Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The process of reprogramming somatic cells to pluripotency involves a profound reconfiguration of the cell's epigenetic landscape and gene expression network, largely driven by the core pluripotency factors.

The molecular mechanisms of induction involve a complex cascade. The overexpression of transcription factors like OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM) initiates a process that erases somatic cell identity and reactivates the pluripotency network [11]. This involves global remodeling of the epigenome, including DNA demethylation at pluripotency promoter sites, and a metabolic shift to glycolysis [11]. For neural induction, a critical subsequent step, the dual SMAD inhibition protocol—using Noggin (a BMP antagonist) and SB431542 (a TGFβ inhibitor)—is widely employed to rapidly and efficiently direct iPSCs toward a neural fate [15] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for iPSC Neural Modeling

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Generation and Neural Differentiation

| Reagent Category | Example Products | Critical Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Kits | CytoTune iPS Sendai Reprogramming Kit [13] | Delivers OSKM factors via non-integrating Sendai virus | High efficiency; requires screening for virus clearance. |

| Cell Culture Media | mTeSR1 [9], Knockout Serum Replacement [12] | Maintains pluripotency and supports iPSC growth | Chemically defined media ensures consistency and reproducibility. |

| Neural Induction Supplements | Noggin, SB431542 [15] [16] | Dual SMAD inhibition for efficient neural induction | Rapidly converts pluripotent cells to neuroepithelium. |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Poly-L-Ornithine/Laminin [15] [17] | Provides a substrate for cell adhesion and growth | Critical for polarity and organization; choice affects neurite outgrowth [18]. |

| Neural Patterning Factors | Retinoic Acid (RA), Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) [10] [16] | Patterns neural progenitor cells into specific subtypes | Generates region-specific neurons (e.g., cortical, motor, dopaminergic). |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-PAX6, SOX1, NESTIN, β3-Tubulin [15] [17] | Identifies neural progenitors and mature neurons | Essential for quality control via immunocytochemistry and flow cytometry. |

The Impact on 2D vs. 3D Neural Model Outcomes

The choices made during the sourcing and reprogramming stages have profound and often divergent consequences on the performance of 2D monolayer versus 3D organoid models.

Cellular Architecture and Polarity: 3D organoids spontaneously self-organize into a neuroepithelium with polarized radial glial cells (RGs), recapitulating an apical-basal axis similar to the developing cerebral cortex. In contrast, 2D monolayers lack this structural polarity, resulting in disorganized morphology [15]. This fundamental difference is rooted in cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions established during early differentiation.

Signaling and Neurogenesis: The preserved architecture in 3D organoids facilitates more efficient Notch signaling between adjacent RGs, which is crucial for the sequential generation of intermediate progenitors, outer RGs, and cortical neurons. Dissociation into 2D monolayers disrupts these contacts, suppressing Notch signaling and leading to impaired neurogenesis [15]. This is evidenced by organoids consistently producing TBR1+ (layer VI) and CTIP2+ (layer V) cortical neurons, while monolayers show lower and more variable yields [15].

Proliferation and Maturation: Cell dissociation for 2D culture induces a transient state of hyperproliferation, driven by increased integrin-ECM signaling [15]. Furthermore, 3D organoids exhibit continuous transcriptional evolution over time, progressively upregulating synaptic and neurotransmitter-related genes. Monolayers, however, become relatively static transcriptionally after initial differentiation, suggesting a maturation arrest [15].

Quantitative data reinforces these distinctions. A 2017 study directly comparing 2D and 3D neural induction found that the 3D method produced a significantly higher yield of PAX6+/NESTIN+ forebrain-type neural progenitor cells (NPCs). Moreover, neurons derived from these 3D-induced NPCs exhibited a significant increase in neurite length, a key morphological indicator of neuronal maturity and connectivity [17].

The journey to building a robust iPSC-derived neural model is paved with critical decisions at the very first steps. The evidence indicates that while the Sendai virus method offers superior reprogramming efficiency across multiple cell sources, the choice between a fibroblast or PBMC starting population may be guided by practical considerations of invasiveness and availability. The initial building blocks directly impact the performance of the final model: 3D organoids excel in recapitulating the complex cellular architecture, signaling, and developmental trajectory of the human brain, making them ideal for developmental studies and disease modeling requiring a tissue-like context. Conversely, 2D monolayers offer a simplified, more accessible system for high-throughput screening and electrophysiological analysis, albeit with limitations in maturity and network complexity. By aligning the choices of cell source and reprogramming method with the ultimate goal of the research, scientists can lay a solid foundation for generating predictive and physiologically relevant human neural models.

The transition from traditional two-dimensional (2D) monolayers to three-dimensional (3D) organoid models represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research. This comparison guide objectively evaluates these systems by focusing on their capacity to recapitulate the core architectural principles of native tissues: cell polarity, cell-cell interactions, and cell-matrix interactions. While 2D cultures offer simplicity and reproducibility, 3D organoid models, particularly those derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), exhibit superior physiological relevance by mimicking the complex structure and function of human organs. This analysis synthesizes experimental data and methodologies to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a clear framework for model selection based on specific scientific inquiries.

The architectural principles of tissues—cell polarity, cell-cell interactions, and cell-matrix interactions—are fundamental to cellular function, signaling, and response to external stimuli. Traditional 2D cell culture, where cells grow as a monolayer on a rigid plastic or glass surface, has been a cornerstone of biological research for decades due to its simplicity, low cost, and ease of use [19] [20]. However, this model presents a highly artificial environment that disrupts natural tissue architecture. Cells in 2D cultures experience supraphysiological mechanical signals from high-stiffness surfaces, undergo automatic apical-basal polarization constrained to a single plane, and lack the complex three-dimensional extracellular matrix (ECM) network [21]. Consequently, significant changes occur in cell morphology, gene expression, and differentiation, limiting the translational value of the data generated [19] [6].

In contrast, 3D organoid models are complex, multi-cellular microtissues derived from stem cells, including iPSCs, embryonic stem cells (ESCs), or adult stem cells (ASCs) [22] [23]. Through self-renewal and self-organization, organoids form structures that closely mimic the complexity, organization, and at least some functionality of native organs [22] [24]. Within a 3D ECM hydrogel, such as Matrigel, cells are free to establish proper polarity, form intricate cell-cell contacts, and interact with a biologically relevant matrix in all dimensions [21]. This environment allows for the emergence of tissue-like features, including gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and metabolic waste, which are critical for accurate disease modeling and drug screening [20]. The following sections provide a detailed, data-driven comparison of these two models.

Comparative Analysis of Architectural Principles

The following tables summarize the key differences between 2D and 3D iPSC models across critical parameters related to tissue architecture and their functional consequences.

Table 1: Direct Comparison of Architectural Features in 2D vs. 3D iPSC Models

| Architectural Feature | 2D Monolayer Culture | 3D Organoid Culture | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Polarity | Automatic, constrained to 2D plane; often disrupted [19]. | Spontaneously generated in 3D; resembles in vivo polarity [19] [21]. | Altered hepatocyte function & gene expression in 2D; proper polarization in 3D liver organoids [21]. |

| Cell-Cell Interactions | Limited to a flat monolayer; interactions are predominantly with the substrate [19]. | Multi-dimensional interactions dominate; formation of natural tissue layers and niches [19] [21]. | Transcriptomic studies show significant differences in pathways involving cell adhesion [6]. |

| Cell-Matrix Interactions | Interaction with rigid, non-physiological plastic/glass surface [21]. | Interaction with a tunable, soft, 3D ECM (e.g., Matrigel, collagen) [20] [21]. | Softer 3D matrices reduce proliferation, alter migration vs. 2D [21]. |

| Tissue Morphology | Flat, monolayer; unable to form complex structures [19]. | Spontaneous formation of 3D structures (e.g., tubes, spheres, branches) [21]. | Generation of optic cup structures and brain organoids with in-vivo-like architecture [21] [24]. |

| Mechanical Environment | High stiffness (GPa range), orders of magnitude higher than soft tissues [21]. | Tunable, low stiffness (kPa range), closely mimicking soft tissues [21]. | Altered cell adhesion, spreading, and differentiation in 2D due to high stiffness [21]. |

Table 2: Functional and Experimental Outcomes in 2D vs. 3D Models

| Performance Parameter | 2D Monolayer Culture | 3D Organoid Culture | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Relevance | Low; does not mimic natural tissue/tumor structure [19]. | High; mimics in vivo tissues and organs in 3D form [19] [23]. | |

| Gene Expression & Splicing | Altered; changes in topology and biochemistry of cells [19]. | Expression and splicing patterns more closely resemble in vivo [19]. | |

| Drug Response & Resistance | Often overestimates efficacy; lacks resistance mechanisms [20] [6]. | More accurately predicts in vivo efficacy and resistance; mirrors tumor drug response [20] [6]. | |

| Formation of Microenvironments | Absent; no environmental "niches" or gradients [19]. | Present; creates oxygen, nutrient, and metabolic waste gradients [20] [21]. | |

| Throughput & Cost | High throughput, low cost, simple protocols [19] [20]. | Lower throughput, more expensive, complex culture procedures [19] [20]. | |

| Imaging & Analysis | Simple and standardized [20]. | Challenging; requires confocal imaging and 3D analysis software [22]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for 3D Organoid Culture from iPSCs

The following workflow is a generalized protocol for generating iPSC-derived organoids, as detailed across multiple sources [22] [23].

Step 1: 2D Pre-culture and Differentiation iPSCs are maintained and expanded under standard 2D culture conditions. To initiate organoid formation, iPSCs are directed toward a specific lineage (e.g., neural, intestinal) using defined media containing specific growth factors and small molecules [22] [25].

Step 2: 3D Embedding and Structure Formation

- Single cells are harvested and premixed with a gel-like ECM substance, most commonly Matrigel [22].

- This cell-ECM mixture is plated as small droplets into a culture dish and incubated to form solid domes.

- Culture medium specific to the target organ (e.g., containing FGF, EGF, Noggin, R-spondin for intestinal organoids) is then overlaid to promote growth and differentiation [22] [23].

- Organoids typically form and mature over 7 to 21 days, with media changes every few days.

Step 3: Organoid Culture and Maintenance Organoid cultures are long-term processes that may involve several steps with different media compositions to guide maturation. Cell health and differentiation are monitored via microscopy and expression of cell-specific markers [22].

Step 4: Monitoring and Readouts Before experimentation, organoids are characterized to ensure appropriate tissue structure and differentiation. High-content confocal imaging is used for 3D reconstruction and analysis of organoid structure, cell morphology, viability, and marker expression [22].

Key Experimental Evidence: A Comparative Study

A 2023 study in Scientific Reports provides direct experimental data comparing 2D and 3D colorectal cancer models [6].

Objective: To comprehensively compare 2D and 3D culture models using colorectal cancer (CRC) cell lines and patient-derived FFPE samples.

Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Five different human CRC cell lines (Caco-2, HCT-116, etc.) were cultured in both 2D monolayers and as 3D spheroids in super-low attachment U-bottom 96-well plates.

- Proliferation: Measured using CellTiter 96 Aqueous MTS assay at desired time points.

- Apoptosis: Analyzed using FITC Annexin V/PI staining and flow cytometry after 24h (2D) and 72h (3D) of culture.

- Drug Response: Treated with 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, and doxorubicin. Viability was assessed post-treatment.

- Transcriptomic Analysis: RNA sequencing and bioinformatic analysis were performed to identify differentially expressed genes and pathways.

Key Findings:

- Proliferation & Death: Cells in 3D displayed a significantly different (p < 0.01) proliferation pattern and cell death profile compared to 2D.

- Drug Resistance: 3D cultures showed increased resistance to all three chemotherapeutics compared to 2D monolayers.

- Transcriptomics: RNA-seq revealed significant (p-adj < 0.05) dissimilarity, with thousands of genes up- or down-regulated in 3D versus 2D cultures, affecting multiple critical pathways.

- Conclusion: The 3D model more closely recapitulates the architecture, proliferation, and behavior of in vivo cells, invalidating the null hypothesis that there is no significant difference between the techniques [6].

Applications in Disease Research

The enhanced architectural fidelity of 3D organoids makes them invaluable for modeling diseases, particularly for studying neurotropic viruses and infectious diseases. Research utilizing these models has provided key insights that were unattainable with 2D models.

Table 3: Applications of 2D and 3D iPSC Models in Neurotropic Virus Research

| Virus | 2D Model Findings | 3D Organoid Model Findings | Architectural Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zika Virus (ZIKV) | Infects and damages iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) [25]. | Demonstrates tropism for outer radial glial cells, disrupting cortical layer formation and organoid size [25]. | 3D structure is essential for modeling developmental brain defects. |

| Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) | NPC infection impairs differentiation; mature neuron infection induces apoptosis [25]. | Disrupts Ca2+ signaling and cortical organoid cytoarchitecture; partial rescue with antiviral Maribavir [25]. | Organoids reveal structural and functional deficits from infection. |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Neurons with ApoE4 isoform are more susceptible; astrocytes increase neuronal infection [25]. | Neurotropism for choroid plexus epithelium; infection found in brain organoids [25]. | Models complex tissue tropism and host-genetic susceptibility. |

| Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV-1) | Lytic changes in patient iPSC-derived NPCs and neurons; used for drug screens [25]. | Latent reactivation is less efficient, mimicking in vivo models; infection induces microglial activation [25]. | 3D environment supports viral latency and neuro-immune interactions. |

The following diagram illustrates how architectural principles in 3D organoids enable advanced infectious disease modeling, a process poorly recapitulated in 2D.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful establishment and analysis of 2D and 3D models rely on a specific set of reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for organoid research.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Tools for iPSC and Organoid Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Foundational cell source capable of differentiating into any cell type; enables patient-specific modeling [25] [23]. | Starting material for generating organoids with a specific genetic background. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Hydrogels | Provides a 3D scaffold that mimics the native basement membrane; essential for organoid self-organization. | Matrigel is the "gold standard" for forming domes to support organoid growth [22] [23]. |

| Defined Growth Factors & Cytokines | Directs stem cell differentiation and maintains tissue-specific cell types in culture. | EGF, Noggin, and R-spondin are used to maintain and grow intestinal organoids [23]. |

| Low-Attachment Plates | Prevents cell adhesion to plastic, forcing cells to aggregate and form 3D spheroids. | Used for scaffold-free spheroid generation in U-bottom 96-well plates [19] [6]. |

| Confocal Imaging System | Enables high-resolution optical sectioning of 3D microtissues for accurate analysis. | Critical for capturing Z-stacks and performing 3D reconstruction of organoids [22]. |

| 3D Image Analysis Software | Quantifies complex parameters from 3D image data sets (e.g., volume, shape, cell counting). | Software like IN Carta is used to analyze organoid diameter and cell-specific markers [22]. |

The choice between 2D monolayer and 3D organoid models is fundamentally guided by the research question and the required level of physiological relevance. For high-throughput initial screens where simplicity and cost-effectiveness are paramount, 2D cultures remain a valuable tool. However, for studies where the core architectural principles of cell polarity, cell-cell interactions, and cell-matrix interactions are critical to the biological outcome—such as in disease modeling, drug efficacy and toxicity testing, and personalized medicine—3D organoid models are unequivocally superior. The experimental data clearly demonstrates that organoids more accurately mimic the in vivo tissue environment, leading to more physiologically relevant gene expression, drug responses, and disease phenotypes. As technologies for imaging, analysis, and high-throughput culturing of organoids continue to advance, their role in bridging the gap between traditional 2D culture and animal models will only become more pronounced, ultimately accelerating the drug discovery pipeline and enhancing the predictive power of preclinical research.

In the field of biomedical research, the choice between two-dimensional (2D) monolayers and three-dimensional (3D) organoid models is pivotal, particularly when using human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) to study complex biological processes. These culture systems differ profoundly in their ability to recapitulate the in vivo microenvironment, leading to significant functional differences in key signaling pathways that govern cellular behavior. Among these pathways, Notch signaling—a master regulator of cell fate determination and tissue patterning—and integrin signaling—a crucial mediator of cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions—exhibit fundamentally different activities between these models [15] [26]. Understanding these distinctions is not merely technical but essential for selecting the appropriate model system for studying neurodevelopment, disease mechanisms, and drug responses. This guide provides a detailed, evidence-based comparison of how these signaling pathways operate in 2D versus 3D cultures, empowering researchers to make informed decisions for their experimental designs.

Core Experimental Design

A seminal study directly comparing these systems employed a rigorous paired design, differentiating three biologically distinct iPSC lines into telencephalic organoids and monolayers in parallel, using identical culture media and conditions to isolate the effect of the culture dimensionality itself [15] [27]. The 3D organoids were generated by aggregating iPSCs into embryoid bodies, patterning them with inhibitors of BMP, TGFβ, and Wnt, and maintaining the neuroepithelium under 3D conditions. The 2D monolayers were created by dissociating the organoids at the terminal differentiation stage and plating the resulting neural progenitor cells (NPCs) onto poly-L-ornithine-laminin coated substrates [15]. This controlled approach allowed for direct comparison using transcriptomic, proteomic, and immunocytochemical analyses at multiple time points.

Key Workflow and Analytical Methods

The experimental workflow and key analytical methods used in such comparative studies are summarized below.

Differential Activation of Notch and Integrin Signaling

Notch Signaling is Suppressed in 2D Monolayers

The Notch pathway, a fundamental cell-cell communication system crucial for stem cell maintenance and differentiation, shows markedly different activity between culture models.

- Enhanced Signaling in 3D Organoids: In 3D organoids, preserved cell-cell adhesion enables efficient Notch signaling in ventricular radial glia [15]. This activation is critical for the subsequent generation of intermediate progenitors, outer radial glia, and cortical neurons, effectively recapitulating the cortical ontogenetic sequence [15] [26]. Network analyses of transcriptomic data revealed that genes related to cell adhesion and Notch signaling co-clustered in a module that was strongly downregulated in 2D monolayers [15].

- Suppressed Signaling and Premature Differentiation in 2D: In contrast, 2D monolayers exhibit suppressed Notch signaling and altered radial glia polarity [15] [27]. This suppression leads to impaired production of intermediate progenitors and cortical neurons. The dissociation process required to create 2D cultures disrupts the cell-to-cell contacts necessary for effective Notch ligand-receptor interaction, thereby disrupting this vital signaling axis [26].

Integrin Signaling is Hyperactive in 2D Monolayers

The integrin signaling pathway, which mediates cell-ECM interactions, is another major point of divergence.

- Balanced Signaling in 3D: 3D organoids provide a natural, cell-derived ECM environment. This allows for balanced integrin engagement and signaling, which supports normal cellular proliferation and polarity [15].

- Hyperproliferation from Increased Integrin Signaling in 2D: A key finding from the comparative study was that increased integrin signaling is the direct cause of hyperproliferation observed in 2D monolayers [15]. At an early differentiation time point (TD2), monolayers contained over 45% Ki67+ proliferating cells compared to only about 20% in organoids [15]. The artificial, high-density coating of ECM proteins (like laminin) on the 2D plastic surface creates a non-physiological over-stimulation of integrin receptors, driving this excessive proliferation.

Table 1: Quantitative and Functional Differences in Key Signaling Pathways

| Signaling Pathway | 2D Monolayer Model | 3D Organoid Model | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Notch Signaling | Suppressed [15] [27] | Enhanced/Efficient [15] [26] | Impaired generation of intermediate progenitors and cortical neurons in 2D; proper neuronal differentiation in 3D. |

| Integrin Signaling | Increased [15] | Balanced [15] | Hyperproliferation (45.65% Ki67+ cells) in 2D; normal proliferation (19.69% Ki67+ cells) in 3D. |

| Radial Glia Polarity | Disorganized [15] | Preserved, forming a structured layer [15] | Disrupted tissue architecture and neuronal migration in 2D; recapitulation of in vivo-like tissue organization in 3D. |

| Transcriptional Dynamics | Relatively static (296 DEGs between TD11 and TD31) [15] | Highly dynamic (1,175 DEGs between TD11 and TD31) [15] | 3D models continue to mature and develop; 2D models show limited evolutionary trajectory. |

The interplay of these signaling pathways and their differential activation in 2D versus 3D cultures is illustrated below.

Impact on Neurogenesis and Model Validation

Downstream Effects on Cortical Development

The disruption of Notch and integrin signaling in 2D monolayers translates directly into deficient models of cortical development. At day 31 of differentiation, 3D organoids consistently generated TBR1+ (layer 6) and CTIP2+ (layer 5) cortical neurons across different cell lines. In stark contrast, 2D monolayers produced lower and highly variable counts of these cortical neurons [15]. Furthermore, the generation of GABAergic inhibitory neurons was significantly impaired in 2D, as shown by very low levels of GAD67 or GABA compared to the reproducible ~5% found in organoids [15].

Validation through Reaggregation Experiments

The critical role of 3D architecture and cell adhesion was confirmed through elegant reaggregation experiments. When dissociated monolayer cells were reaggregated and cultured under 3D conditions, the hyperproliferation phenotype was partially reversed, and some deficits in cell fate were corrected [15]. This demonstrates that the signaling and developmental impairments in 2D are not entirely irreversible and are largely a consequence of the disrupted microenvironment.

Table 2: Phenotypic Outcomes in Neural Differentiation Models

| Developmental Readout | 2D Monolayer Model | 3D Organoid Model | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radial Glia Markers (SOX1+) | 12% ± 3.49% of cells | 25% ± 0.69% of cells | [15] |

| Proliferation (Ki67+ at TD2) | 45.65% ± 5.06% | 19.69% ± 1.64% | [15] |

| Cortical Neuron Generation | Lower and highly variable | Consistent and reproducible | [15] |

| GABAergic Neuron Generation | Very low (~0%) | Reproducible (~5% GAD67+) | [15] |

| Transcriptional Dynamics | Fewer DEGs over time; static | More DEGs over time; dynamic | [15] |

| Neuronal Subtype Specificity | Enriched with glutamatergic neurons | Higher prevalence of GABAergic neurons | [28] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table lists essential reagents and materials used in the featured experiments for establishing and analyzing these models.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC-based Neural Models

| Reagent/Category | Specific Example | Function in the Protocol | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| iPSC Lines | Biologically distinct cell lines (e.g., 3 different lines) | Provides genetic diversity and controls for line-specific artifacts. | [15] [27] |

| ECM Coating | Poly-L-ornithine, Laminin | Creates an artificial 2D adhesive surface for monolayer culture. | [15] |

| Patterning Molecules | Noggin, BMP/TGFβ/Wnt inhibitors | Patterns pluripotent cells toward a telencephalic neural fate. | [15] |

| Proliferation Marker | Anti-Ki67 antibody | Identifies and quantifies actively proliferating cells. | [15] |

| Neural Progenitor Markers | Anti-SOX1, Anti-PAX6 antibodies | Labels radial glia and neural progenitor cells. | [15] |

| Cortical Neuron Markers | Anti-TBR1 (Layer VI), Anti-CTIP2 (Layer V) antibodies | Identifies specific subtypes of deep-layer cortical neurons. | [15] |

| Inhibitory Neuron Marker | Anti-GAD67 antibody | Labels GABAergic inhibitory neurons. | [15] |

| Transcriptomic Analysis | High-throughput RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) | Provides global, unbiased data on gene expression differences. | [15] [28] |

The choice between 2D monolayer and 3D organoid models is far from trivial, as it fundamentally alters core signaling pathways that direct cellular behavior. Experimental evidence demonstrates that 3D organoids maintain physiological Notch and integrin signaling, leading to robust, in vivo-like neurogenesis and tissue architecture. In contrast, 2D monolayers are characterized by suppressed Notch signaling and hyperactive integrin signaling, resulting in hyperproliferation, disorganized polarity, and impaired neuronal differentiation. While 2D systems offer simplicity and throughput, 3D organoids provide superior physiological relevance for studying developmental processes, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic interventions where these pathways are critical. Researchers should therefore align their model choice with their specific research questions, prioritizing 3D systems for investigations requiring faithful recapitulation of tissue-level signaling and organization.

Inherent Strengths and Limitations of Each System's Design

The choice between two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures and three-dimensional (3D) induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived organoids represents a critical decision point in experimental design for drug discovery and disease modeling. While 2D systems offer simplicity, standardization, and high-throughput compatibility, 3D organoids better recapitulate in vivo physiology, cellular complexity, and tissue-level responses. This guide provides an objective comparison of these systems' performance characteristics, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols, to inform selection criteria for specific research applications.

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have revolutionized biomedical research by providing a patient-specific, ethically acceptable platform for disease modeling and drug development [29] [25]. These pluripotent cells can be differentiated into virtually any cell type using either two-dimensional (2D) monolayer systems or three-dimensional (3D) organoid cultures, each with distinct technical considerations and biological implications.

2D monolayer cultures involve growing cells on flat, rigid plastic surfaces in a single layer, representing the traditional standard for in vitro experimentation [30]. These systems provide a simplified, controlled environment that enables straightforward manipulation, imaging, and analysis. In contrast, 3D organoids are complex, self-organizing microtissues that develop from stem cells or organ progenitors and mimic the architectural, functional, and biological complexity of in vivo organs [3] [31] [24]. These miniature organ-like structures contain multiple cell types arranged in a spatially organized manner similar to their in vivo counterparts, creating a more physiologically relevant microenvironment for studying human biology and disease [29] [23].

The fundamental distinction between these systems lies in their spatial organization and resulting biological complexity. While 2D cultures offer practical advantages for high-throughput applications, 3D organoids bridge the gap between traditional cell culture and animal models by preserving tissue-specific characteristics more accurately [24].

Technical Comparison of System Designs

Core Architectural Differences

Figure 1: Architectural comparison between 2D monolayer and 3D organoid culture systems highlighting fundamental design differences.

Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of 2D monolayer vs. 3D organoid system performance

| Performance Parameter | 2D Monolayer Systems | 3D Organoid Systems | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Relevance | Low: Lacks 3D architecture and tissue-specific mechanical cues [31] [30] | High: Recapitulates tissue organization and cell-matrix interactions [3] [32] | 3D colon cancer HCT-116 cells show chemoresistance patterns matching in vivo responses, unlike 2D cultures [31] |

| Throughput Capability | High throughput; compatible with HTS/HCS [31] [32] | Low to medium throughput; challenging for HTS [31] | 2D systems enable screening of thousands of compounds weekly; 3D systems limited by complexity and cost [32] [30] |

| Reproducibility | High with standardized protocols [32] | Variable with batch-to-batch heterogeneity [31] [32] | Coefficient of variation (CV) for midbrain organoid uniformity reported at 20-30% [32] |

| Culture Duration | Days to weeks [25] | Weeks to months (40-70 days for maturation) [32] | Midbrain organoids require 40-50 days for functional maturation [32] |

| Cost Efficiency | Low cost per sample [32] | High cost due to matrices and extended culture [32] | Organoids require expensive ECM components and specialized media [24] |

| Disease Modeling Fidelity | Limited for complex diseases [31] | High for spontaneous disease phenotype observation [32] | Midbrain organoids recapitulate Parkinson's α-synuclein aggregation without artificial induction [32] |

| Cellular Complexity | Typically single cell type or simple co-cultures [30] | Multiple cell types with native ratios [3] [24] | Intestinal organoids contain enterocytes, goblet, Paneth and enteroendocrine cells [33] |

| Drug Response Prediction | Often overestimates efficacy [31] | Better predicts clinical response including resistance [3] [31] | Colon cancer cells in 3D show resistance to fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan matching in vivo patterns [31] |

Table 2: Functional assessment of neuronal models in Parkinson's disease research

| Aspect | 2D Models | 3D Midbrain Organoids | PD Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine Neuron Survival | Variable, protocol-dependent | ~50-60% at maturity [32] | MOs better model SNpc vulnerability |

| α-Synuclein Pathology | Requires artificial induction | Spontaneous aggregation and Lewy-like pathology [32] | MOs capture natural protein aggregation dynamics |

| Hypoxia Artifacts | Absent | Present in cores (>200μm) [32] | MOs may overrepresent hypoxic stress |

| Neural Circuitry | Limited local connections | Local synapses only, no long-range connections [32] | Both require additional engineering for nigrostriatal pathway |

| Throughput for Drug Screening | High throughput feasible [32] | Low throughput; high cost [32] | 2D better for initial screening campaigns |

| Reproducibility | High with established protocols [32] | Variable batch-to-batch heterogeneity [32] | 2D more reliable for standardized toxicity assays |

Methodological Approaches

Experimental Workflows

Figure 2: Comparative experimental workflows for 2D monolayer and 3D organoid differentiation from human iPSCs.

Detailed Methodologies

Intestinal Organoid Generation from iPSCs

The establishment of functional intestinal monolayers from iPSC-derived organoids involves a multi-step process [33]:

Definitive Endoderm Induction: Human iPSCs are differentiated toward definitive endoderm using Activin A treatment in low-serum conditions for 5-7 days.

Intestinal Progenitor Specification: Cells are patterned toward an intestinal fate using FGF4 and WNT3a signaling activation for 10-14 days.

3D Organoid Formation: Intestinal progenitor cells are embedded in Matrigel domes and cultured in organoid medium containing EGF, Noggin, and R-spondin to promote 3D self-organization.

Monolayer Generation: Organoids are dissociated into single cells and seeded on Matrigel-coated permeable filters at high density (5.0 × 10⁵ cells/well) to form polarized monolayers within 3-7 days.

Functional Maturation: Monolayers are maintained in intestinal maturation medium containing growth factors and small molecules to enhance CYP450 enzyme activity and transporter expression.

This methodology yields intestinal epithelial monolayers with high CYP3A4 activity comparable to primary human small intestinal cells, along with functional P-glycoprotein and BCRP transporter activities [33].

Midbrain Organoid Protocol for Parkinson's Modeling

The generation of region-specific midbrain organoids follows a patterning-based approach [32]:

Embryoid Body Formation: iPSCs are dissociated and aggregated in low-attachment plates to form uniform embryoid bodies.

Neural Induction: Dual-SMAD inhibition using SB431542 and LDN193189 for 5-7 days to direct neural ectoderm differentiation.

Midbrain Patterning: Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) activation and WNT pathway modulation using CHIR99021 for 10-12 days to specify midbrain floor plate progenitors.

3D Matrigel Embedding: Patterned neural progenitors are embedded in Matrigel droplets to support complex tissue architecture.

Long-term Maturation: Organoids are maintained in rotating bioreactors or orbital shakers for 40-70 days with BDNF, GDNF, and ascorbic acid supplementation to promote dopaminergic neuron maturation.

This protocol generates organoids containing up to 60% tyrosine hydroxylase-positive dopaminergic neurons with evidence of spontaneous electrical activity, neuromelanin production, and disease-relevant protein aggregation [32].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents for 2D and 3D iPSC culture systems

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECM Substrates | Matrigel, Collagen I, Laminin-511 | Provide structural support and biochemical cues | Matrigel concentration (5-20%) affects organoid complexity and maturation [24] [33] |

| Patterning Factors | Recombinant WNT3a, SHH, FGF8, BMP4 | Direct regional specification and differentiation | Concentration gradients critical for proper tissue patterning in 3D systems [32] |

| Maintenance Media | mTeSR, StemFit, Organoid Specialty Media | Support pluripotency or differentiated state | 3D media often requires additional supplements and growth factors [33] |

| Maturation Factors | BDNF, GDNF, cAMP, Ascorbic Acid | Promote terminal differentiation and functionality | Essential for achieving electrophysiologically active neurons in both systems [32] |

| Dissociation Reagents | Accutase, TrypLE, Collagenase | Enable passaging and monolayer formation | Gentle dissociation critical for maintaining viability in 3D systems [33] |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | CHIR99021, SB431542, LDN193189 | Modulate key signaling pathways | Concentration optimization more critical in 3D systems due to diffusion limitations [32] |

Signaling Pathways in System Development

Figure 3: Signaling pathways governing neural differentiation in 2D versus 3D culture systems.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Disease Modeling

Infectious Disease Modeling

The application of iPSC-derived models to study neurotropic viruses illustrates the complementary strengths of both systems [25] [23]. In 2D models, HIV infection of iPSC-derived microglia produces inflammatory cytokines and dysregulates EIF2 signaling across co-cultured cell types [25]. For SARS-CoV-2 research, 2D models demonstrated that astrocytes increase infection of neurons and that remdesivir inhibits infection of both cell types [25]. However, 3D organoids revealed additional complexities, showing that SARS-CoV-2 exhibits tropism for choroid plexus and that ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are expressed at higher levels in cerebral organoids compared to 2D neuronal cultures [25].

Neurodegenerative Disease Research

In Parkinson's disease modeling, 3D midbrain organoids have demonstrated particular utility in recapitulating key pathological hallmarks [32]. Organoids carrying LRRK2 G2019S mutations show increased dopaminergic neuron death (up to 20% reduction) and have identified TXNIP as a mediator of G2019S pathology [32]. Similarly, GBA1-deficient organoids with α-synuclein triplication exhibit impaired autophagy and mitochondrial dysfunction, providing insights into disease mechanisms [32]. These complex phenotypes are challenging to observe in 2D systems, which lack the cellular diversity and tissue context of organoids.

Drug Screening Applications

The performance differences between 2D and 3D systems become particularly evident in drug screening contexts [31] [30]. For chemotherapeutic testing, colon cancer HCT-116 cells in 3D culture demonstrate enhanced resistance to melphalan, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan compared to 2D cultures, mirroring in vivo chemoresistance patterns [31]. This enhanced predictive value of 3D systems extends to drug metabolism studies, where intestinal organoid-derived monolayers exhibit CYP3A4 activity comparable to primary human small intestinal cells, surpassing the performance of traditional Caco-2 models [33].

The choice between 2D monolayer and 3D organoid systems depends primarily on research objectives, with each platform offering distinct advantages. 2D monolayer cultures provide superior throughput, reproducibility, and experimental control for reductionist studies, target validation, and initial compound screening. 3D organoid systems deliver enhanced physiological relevance, better preservation of native tissue architecture, and improved predictive value for complex biological processes and therapeutic responses.

For comprehensive research programs, a sequential approach leveraging both systems often proves most effective: utilizing 2D platforms for initial high-throughput screening followed by 3D models for lead optimization and mechanistic studies. As organoid technology continues to advance—with improvements in vascularization, reproducibility, and throughput—these 3D systems are positioned to increasingly bridge the gap between traditional in vitro models and clinical research, potentially transforming drug discovery and personalized medicine approaches.

From Bench to Application: Establishing and Utilizing 2D and 3D iPSC Models

The transition from conventional two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures to three-dimensional (3D) models represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, particularly for induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) studies. Traditional 2D cell culture systems, while foundational to cellular research, suffer from critical limitations as they lack the spatial, mechanical, and biochemical complexity of native tissues [34] [35]. This discrepancy often results in poor translation of preclinical findings to clinical success, with compounds effective in 2D cultures frequently failing in animal models or human patients [34].

In contrast, 3D culture systems enable cells to grow in a more physiologically relevant context, mimicking the architectural, mechanical, and biochemical characteristics of in vivo tissues [35] [36]. These advanced models are particularly valuable for cancer research, drug discovery, and developmental biology, providing crucial insights into cellular behavior, drug responses, and disease mechanisms [36] [37]. Within the iPSC research landscape, 3D cultures facilitate the development of organoids—miniature, self-organizing structures that recapitulate key aspects of human organ development and function [38] [39].

This technical guide systematically compares scaffold-free and scaffold-based 3D culture methodologies, providing researchers with standardized protocols, analytical frameworks, and practical implementation strategies to advance their investigative programs.

Fundamental Differences Between 2D and 3D Culture Systems

The transition from 2D to 3D culture environments fundamentally alters cellular behavior and characteristics. Understanding these differences is essential for selecting the appropriate model system for specific research applications.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of 2D vs. 3D Culture Systems

| Parameter | 2D Monolayer Culture | 3D Culture Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Architecture | Flat, monolayer organization | Three-dimensional structure with depth |

| Cell Morphology | Flattened, stretched morphology | Natural, in vivo-like morphology |

| Cell-Cell Interactions | Limited to peripheral contact | Enhanced, multi-directional interactions |

| Cell-ECM Interactions | Polarized, ventral surface only | Uniform distribution across cell surface |

| Nutrient/Gradient Formation | Uniform exposure | Physiological gradients (oxygen, nutrients) |

| Gene Expression Profile | Altered due to forced adhesion | More physiologically relevant expression |

| Drug Response | Typically more sensitive | More resistant, clinically relevant |

| Stem Cell Maintenance | Limited self-renewal capacity | Enhanced stemness preservation |

Cells cultured in 2D systems undergo forced flattening and remodeling of their internal cytoskeleton, which significantly alters gene expression patterns and cellular function [35]. The polarization of binding proteins to the ventral surface where they attach to tissue culture plastic further distorts natural cellular behavior [35]. In 3D environments, however, receptors and adhesion molecules distribute more evenly over the cell surface, fostering more natural signaling pathways and cellular responses [35].

The physiological relevance of 3D cultures is particularly evident in drug screening applications. For instance, Loessner et al. demonstrated that ovarian cancer spheroids showed higher survival rates after exposure to paclitaxel compared to 2D monolayers, better simulating in vivo chemosensitivity [36]. Similarly, osteosarcoma spheroids displayed enhanced resistance to standard chemotherapeutic agents like doxorubicin and cisplatin, providing more clinically predictive data for therapeutic development [34].

Scaffold-Free 3D Culture Systems

Scaffold-free 3D culture systems rely on the innate ability of cells to self-assemble into three-dimensional aggregates without external supporting materials. The most common scaffold-free models include spheroids and organoids, which form through cell-cell interactions and endogenous extracellular matrix production [34] [40]. These systems are characterized by their simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and ability to generate complex multicellular structures that mimic key aspects of in vivo tissue organization [41].

Spheroids are typically spherical clusters of cells that form under conditions preventing surface adhesion, while organoids represent more sophisticated structures that self-organize to recapitulate aspects of native organ architecture and functionality [40]. The formation of scaffold-free structures occurs through a self-assembly process driven by cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion and the production of endogenous ECM components [35].

Establishment Protocols

Hanging Drop Method

The hanging drop technique creates gravity-enforced cellular aggregates by suspending droplets of cell suspension on the lid of a culture dish [35] [40].

Procedure:

- Prepare a single-cell suspension of iPSCs or differentiated cells at appropriate density (typically 1.0×10^4 to 5.0×10^4 cells/mL)

- Pipette 20-50 μL droplets of cell suspension onto the inner surface of a culture dish lid

- Carefully invert the lid and place it over a dish filled with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to maintain humidity

- Incubate at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 48-72 hours to allow spheroid formation

- Carefully transfer formed spheroids to ultra-low attachment plates for long-term culture

Advantages: Uniform spheroid size, minimal equipment requirements, cost-effective Limitations: Low throughput, difficult media exchange, limited long-term culture capability

Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) Surfaces

Commercially available ULA plates (e.g., Corning Spheroid Microplates, Elplasia plates) feature covalently bound hydrogel coatings that prevent cell attachment, forcing cells to aggregate [41] [42].

Procedure:

- Pre-equilibrate ULA plates with appropriate culture medium for 30 minutes at 37°C

- Prepare single-cell suspension at optimized density (e.g., 5.0×10^3 to 1.0×10^5 cells/mL depending on plate format and spheroid size requirements)

- Seed cell suspension into ULA plates following recommended volumes for specific plate format

- Centrifuge plates at 100-300 × g for 3-5 minutes to enhance cell aggregation (for forced-floating method)

- Incubate at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 24-72 hours, monitoring spheroid formation

- Exchange 50-70% of media carefully every 2-3 days to avoid disrupting spheroids

Advantages: Reproducible, scalable, compatible with high-throughput screening, enables long-term culture Limitations: Potential size variability, specialized equipment required

Agitation-Based Methods

Bioreactors with constant rotational agitation (e.g., spinner flasks, rotary cell culture systems) maintain cells in suspension, promoting aggregation through continuous movement [34] [40].

Procedure:

- Prepare single-cell suspension at optimized density (typically 2.5×10^5 to 1.0×10^6 cells/mL)

- Transfer cell suspension to bioreactor vessel following manufacturer's instructions

- Set agitation speed to maintain cells in suspension without excessive shear stress (typically 40-80 rpm)

- Culture for 3-7 days, monitoring aggregation daily

- Harvest spheroids once desired size is achieved (typically 100-300 μm diameter)

Advantages: High yield, uniform oxygenation, suitable for large-scale production Limitations: Specialized equipment required, potential for mechanical damage to cells

Applications and Case Studies

Scaffold-free systems have demonstrated particular utility in cancer research, stem cell biology, and drug screening applications. For instance, Ohya et al. utilized MG-63 osteosarcoma spheroids cultured under serum-free, non-adhesive conditions to evaluate KCa1.1 channel inhibition, which enhanced spheroid sensitivity to paclitaxel, doxorubicin, and cisplatin [34]. Similarly, Ozturk et al. demonstrated that scaffold-free spheroids derived from Soas-2 osteosarcoma stem cells preserved stem-like properties longer than monolayer cultures, providing a more relevant platform for assessing drug responses against cancer stem cell populations [34].

In iPSC research, scaffold-free cerebral organoids have enabled groundbreaking studies of human brain development and neurological disorders. Lancaster et al. developed a method where embryoid bodies from iPSCs were embedded in Matrigel and cultured with specific growth factors, resulting in complex cerebral organoids containing various neural cell types organized into discrete regions [38].

Scaffold-Based 3D Culture Systems

Scaffold-based 3D culture systems utilize biocompatible materials to provide structural support that mimics the native extracellular matrix (ECM), enabling cells to grow in a three-dimensional environment that more closely resembles in vivo conditions [34] [36]. These systems physically reinforce cell growth in a spatially organized manner, facilitate extracellular matrix deposition, and enhance cell survival and function through provision of appropriate mechanical and biochemical cues [34].

The fundamental principle underlying scaffold-based systems is the recreation of key aspects of the tumor microenvironment (TME) or tissue-specific niche, including biomechanical properties, biochemical signaling, and spatial architecture [36]. Scaffolds can be fabricated from natural, synthetic, or hybrid materials, each offering distinct advantages for specific applications [41] [40].

Scaffold Types and Properties

Table 2: Comparison of Scaffold Types for 3D Cell Culture

| Scaffold Type | Examples | Advantages | Limitations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Hydrogels | Matrigel, collagen, fibrin, alginate, hyaluronic acid | Bioactive, biocompatible, tissue-like stiffness | Batch-to-batch variability, poor mechanical strength | Organoid culture, epithelial morphogenesis, angiogenesis studies |

| Synthetic Hydrogels | PEG, PLA, polyamide | High consistency, tunable properties, reproducible | Lack native bioactive motifs, may require functionalization | Mechanotransduction studies, controlled microenvironments |

| Hard Polymers | Polystyrene, polycaprolactone | Excellent mechanical properties, high cell recovery | Limited biodegradability, may not mimic soft tissues | Tissue engineering, bone models, tumor cell treatments |

| Decellularized ECM | Tissue-derived scaffolds | Native composition and architecture, tissue-specific cues | Complex processing, potential immunogenicity | Tissue-specific models, regenerative medicine studies |

| Composite Materials | Alginate-polymer blends, polymer-ceramic composites | Tailored mechanical and biological properties | Complex fabrication, characterization challenges | Complex tissue models, load-bearing applications |

Establishment Protocols

Hydrogel-Based 3D Culture

Natural hydrogels like Corning Matrigel Matrix remain the gold standard for many organoid and 3D culture applications, particularly for epithelial and iPSC-derived cultures [41] [42].

Procedure for Matrigel-Based iPSC Organoid Culture:

- Thaw Matrigel on ice overnight at 4°C; pre-chill pipette tips and tubes

- Harvest iPSCs as single cells or small clusters using appropriate dissociation reagent

- Centrifuge cells and resuspend in appropriate culture medium at desired density (typically 1.0×10^4 to 1.0×10^6 cells/mL)

- Mix cell suspension with cold Matrigel at appropriate ratio (typically 1:1 to 1:3)

- Pipette cell-Matrigel mixture into pre-warmed culture plates (10-50 μL drops per well for 24-48 well plates)

- Incubate at 37°C for 20-30 minutes to allow hydrogel polymerization

- Carefully overlay with appropriate pre-warmed culture medium

- Culture with regular medium changes (every 2-4 days) based on specific protocol requirements

Considerations: Matrigel concentration, cell density, and medium composition must be optimized for specific cell types and applications. ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) is often included for the first 24-48 hours to enhance cell survival after dissociation [42].

Synthetic Scaffold Systems

Synthetic scaffolds like Corning Synthegel 3D matrix kits offer defined composition with minimal batch-to-batch variability, supporting growth of iPSCs, cancer spheroids, and other 3D cultures [41].

Procedure for Synthetic Scaffold Culture:

- Prepare synthetic scaffold according to manufacturer's instructions

- Seed cells directly onto pre-formed scaffolds or mix with scaffold precursors before polymerization

- For in situ polymerization systems, induce crosslinking through appropriate method (photoinitiation, ionic crosslinking, thermal initiation)

- Culture with appropriate medium, ensuring sufficient nutrient penetration throughout scaffold

- Monitor cell growth and distribution within scaffold using microscopy techniques

Advantages: Reproducible composition, tunable mechanical properties, controlled degradation profiles Limitations: May lack native bioactive motifs, often requires functionalization with adhesion peptides

Applications and Case Studies

Scaffold-based systems have demonstrated exceptional utility in creating physiologically relevant models for studying human development, disease mechanisms, and drug responses. Romero-López et al. utilized decellularized ECM scaffolds from normal and tumor tissues to demonstrate how tissue-specific ECM composition influences cancer cell growth, metabolic state, and vascular network formation [36]. Their findings revealed that cells seeded in tumor ECM exhibited elevated glycolytic rates compared to those in normal ECM, highlighting the significant influence of ECM on cancer cell behavior.

In iPSC research, scaffold-based systems have been instrumental in generating complex, region-specific organoids. For example, Qian et al. developed a method for generating cortical organoids from iPSCs using a combination of Matrigel embedding and specific growth factor supplementation, resulting in structures that mimic the six-layer organization of human cortical tissue [38]. These organoids contained neural progenitor cells, intermediate progenitors, GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons, and glial cells that formed functional neural networks, providing unprecedented opportunities for studying human brain development and disorders.

Direct Comparison: Scaffold-Free vs. Scaffold-Based Systems

Technical and Performance Comparison

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Scaffold-Free and Scaffold-Based 3D Culture Systems

| Parameter | Scaffold-Free Systems | Scaffold-Based Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Complexity of Setup | Low to moderate | Moderate to high |

| Cost Considerations | Lower cost, minimal specialized materials | Higher cost, specialized scaffolds required |

| Reproducibility | Moderate (size variability can occur) | High with synthetic scaffolds, variable with natural materials |

| Throughput Capacity | High (compatible with screening platforms) | Moderate to high (depends on scaffold format) |

| ECM Control | Limited to endogenous production | Precise control over composition and mechanics |

| Cell-Cell Interactions | High (direct contact promoted) | Variable (depends on scaffold density) |

| Cell-ECM Interactions | Limited endogenous production | Extensive, tunable interactions |