Adult Stem Cells from Somatic Tissues: A 2025 Guide to Bone Marrow and Adipose Sources for Research and Therapy

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of adult stem cells sourced from bone marrow and adipose tissue, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Adult Stem Cells from Somatic Tissues: A 2025 Guide to Bone Marrow and Adipose Sources for Research and Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of adult stem cells sourced from bone marrow and adipose tissue, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational biology and niches of these somatic stem cells, detailed methodologies for isolation and characterization, and strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing culture systems. The content also includes a critical validation and comparative analysis of Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs) and Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) from these sources, reviewing their therapeutic applications in approved treatments and ongoing clinical trials. The scope is designed to serve as a key resource for preclinical and translational research efforts.

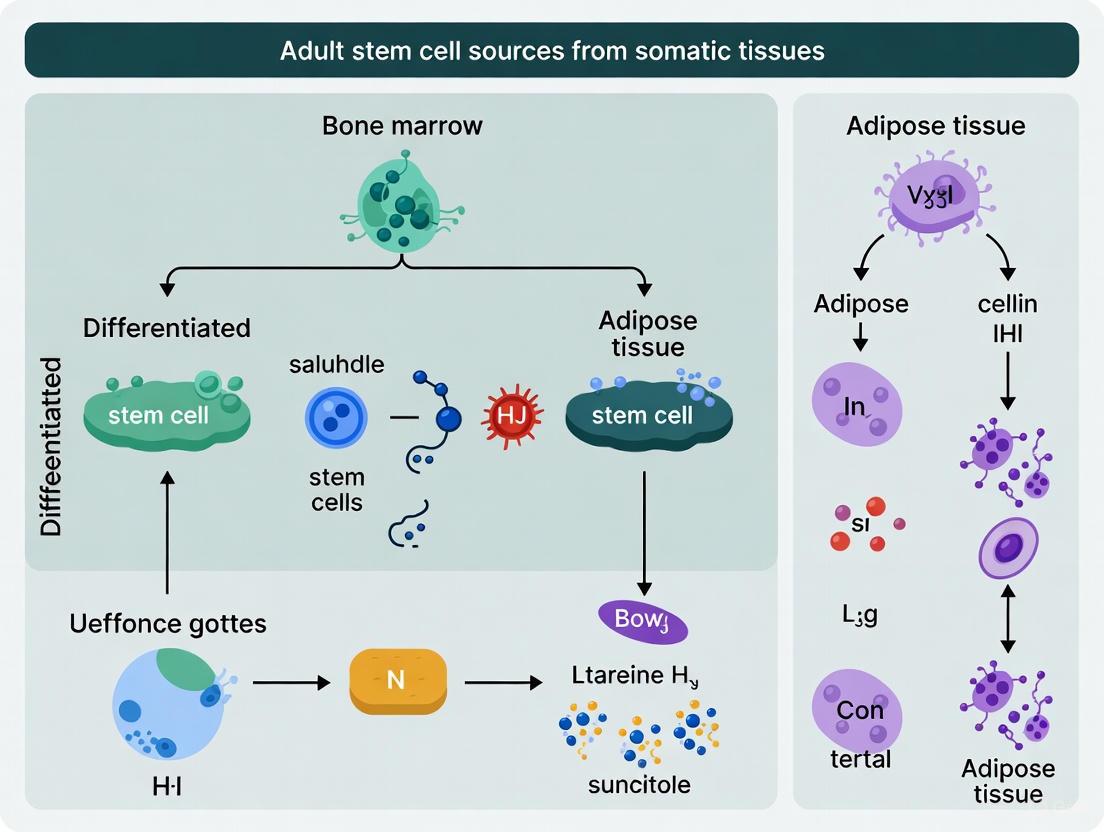

The Biology of Adult Stem Cells: Exploring Bone Marrow and Adipose Niches

Adult stem cells (ASCs), also known as somatic stem cells, are undifferentiated cells found throughout the body after embryonic development. These remarkable cells serve as a fundamental biological resource for tissue maintenance and repair, residing in specific niches within various vascularized organs and tissues [1]. Their primary function involves replacing cells lost through normal physiological turnover, injury, or disease, making them essential for long-term tissue homeostasis [1]. Unlike embryonic stem cells which are pluripotent, adult stem cells are generally considered multipotent, meaning they can differentiate into multiple—but not all—cell types, typically those related to their tissue of origin [2] [3].

The historical understanding of ASCs has evolved significantly, with their initial identification in tissues with high turnover rates like blood and skin. Contemporary research has revealed their presence in virtually all vascularized tissues, including those with limited regenerative capacity such as neural and cardiac tissues [1] [3]. This widespread distribution underscores their critical role in organismal maintenance and positions them as crucial therapeutic targets in regenerative medicine. ASCs maintain their populations through self-renewal while also producing progenitor cells that undergo differentiation to maintain tissue-specific cellular composition [1].

Defining Properties of Adult Stem Cells

Self-Renewal Capability

Self-renewal represents the capacity of adult stem cells to divide and generate identical copies of themselves throughout an organism's lifespan. This property allows ASC populations to maintain their numbers without depletion, ensuring a continuous reservoir for tissue maintenance [1]. The self-renewal process is tightly regulated by both intrinsic genetic programs and extrinsic signals from the specialized microenvironment, or niche, where these cells reside [1] [4].

The mechanism of stem cell division is particularly sophisticated. When ASCs divide, they can produce daughter cells that either become new stem cells (self-renewal) or specialized cells (differentiation) with tissue-specific functions [1]. This balance between self-renewal and differentiation is critical for tissue homeostasis, and its dysregulation can lead to either tissue degeneration or hyperproliferative disorders. While ASC populations are typically maintained throughout adulthood, research indicates that their function and numbers can decrease with advancing age, potentially impacting regenerative capacity [1].

Multipotency and Differentiation Capacity

Multipotency refers to the ability of adult stem cells to differentiate into multiple, but limited, specialized cell types within their lineage [2] [3]. This property distinguishes them from pluripotent embryonic stem cells, which can generate all cell types of the three germ layers. The differentiation potential of ASCs is typically restricted to cell types relevant to their tissue of origin, reflecting their specialized roles in tissue maintenance [3].

The multipotent nature of ASCs enables them to generate transit-amplifying cells—progeny that undergo several rounds of division before terminal differentiation [4]. This mechanism allows a single stem cell to produce numerous differentiated cells, efficiently maintaining or repairing tissues. The process of lineage commitment involves complex molecular regulation, with niche-derived signals playing instructive roles in fate determination [4]. For instance, in the Drosophila ovary model, Wnt and Hedgehog signaling pathways have been shown to coordinate progenitor cell fate decisions, demonstrating how extrinsic cues guide multipotent cells toward specific lineages [4].

Table 1: Core Functional Properties of Adult Stem Cells

| Property | Functional Significance | Biological Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Renewal | Maintains stem cell population throughout life | Asymmetric cell division; regulated by niche signals |

| Multipotency | Generates multiple cell types of native tissue | Lineage-restricted differentiation capacity |

| Quiescence | Prevents exhaustion of stem cell pool | Reversible cell cycle arrest; activated by damage signals |

| Niche Interaction | Regulates stem cell behavior and fate | Response to paracrine signaling and cell-cell contact |

Major Types and Locations of Adult Stem Cells

Adult stem cells reside in specific anatomical locations, or niches, within various tissues throughout the body. These specialized microenvironments provide the signals necessary to maintain stem cell properties while regulating their activity according to tissue needs [4]. Different types of ASCs exhibit distinct differentiation potentials tailored to their tissue contexts.

Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs)

Hematopoietic stem cells reside primarily in the bone marrow and are responsible for the continuous regeneration of all blood cell lineages throughout life [1] [2]. These cells represent one of the most thoroughly characterized adult stem cell populations and form the biological basis for bone marrow transplantation therapy. HSCs give rise to the complete repertoire of blood cells, including erythrocytes (red blood cells), leukocytes (white blood cells), and platelets [1] [3]. Their proper function is essential for immune competence, oxygen transport, and clotting mechanisms.

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)

Mesenchymal stem cells represent a heterogeneous population of stromal cells that can differentiate into various mesodermal lineages, including osteoblasts (bone cells), chondrocytes (cartilage cells), and adipocytes (fat cells) [1]. According to the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT), defining standards for human MSCs includes plastic adherence in standard culture, specific surface antigen expression (CD105+, CD73+, CD90+, with ≤2% expression of hematopoietic markers CD45, CD34, CD14 or CD11b, CD79a or CD19, and HLA-DR), and in vitro differentiation into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondroblasts [1]. MSCs have been isolated from multiple tissues, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, placenta, and dental pulp [1].

Tissue-Specific Stem Cells

Beyond HSCs and MSCs, numerous specialized adult stem cells exist in specific tissues:

- Neural Stem Cells (NSCs): Located in specific brain areas, including the hippocampus and subventricular zone, NSCs can generate the brain's major cell types: neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [1].

- Epithelial Stem Cells: Found in the lining of the digestive tract and the basal layer of the epidermis, these cells continually regenerate these protective barriers throughout life [1].

- Skeletal Muscle Stem Cells (Satellite Cells): Residing in a quiescent state beneath the basal lamina of muscle fibers, these cells activate in response to injury to repair and regenerate skeletal muscle [1].

- Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs): Located in fat tissue, ADSCs can differentiate into various cell types, including adipocytes, cartilage cells, and bone cells [1].

Table 2: Major Adult Stem Cell Types and Their Characteristics

| Stem Cell Type | Primary Location | Differentiation Potential | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic (HSCs) | Bone marrow, umbilical cord blood | All blood cell lineages | Immune cell production, oxygen transport |

| Mesenchymal (MSCs) | Bone marrow, adipose tissue, dental pulp | Osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes | Skeletal tissue maintenance, immunomodulation |

| Neural (NSCs) | Hippocampus, subventricular zone | Neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes | Limited neural repair, brain homeostasis |

| Epithelial | Skin basal layer, intestinal crypts | Keratinocytes, intestinal epithelial cells | Skin renewal, gut lining regeneration |

| Muscle Satellite | Skeletal muscle tissue | Myoblasts, muscle fibers | Muscle repair and regeneration |

Research Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Lineage Commitment Assessment

Advanced imaging and spectroscopic techniques enable researchers to characterize stem cell differentiation with minimal perturbation. Broadband Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering (BCARS) microscopy has emerged as a powerful label-free method for quantifying lineage commitment in individual stem cells [5]. This approach allows for non-invasive, quantitative characterization of stem cell differentiation without the need for fluorescent labels or cell destruction, preserving cellular integrity for further analysis.

The BCARS methodology involves several key steps. First, stem cells are cultured under differentiation-inducing conditions (e.g., adipogenic or osteogenic media) alongside controls in basal media. After a differentiation period (typically 2 weeks), cells are fixed and analyzed using BCARS microscopy, which provides hyperspectral imaging data with high spatial resolution [5]. The acquired spectra are processed through several computational steps: noise reduction via singular value decomposition, time-domain Kramers-Kronig transform to retrieve Raman susceptibility spectra, and calculation of second derivatives of individual spectra. This process generates chemical maps that reveal phenotypic commitment at single-cell resolution based on intrinsic biochemical composition [5].

Signaling Pathway Analysis

Understanding how niche signals coordinate adult stem cell fate decisions requires precise analysis of signaling pathway activity. Quantitative microscopy approaches using pathway-specific reporters enable researchers to monitor signaling dynamics in progenitor cells [4]. For example, in the Drosophila ovary model, reporters for Wnt, Hedgehog (Hh), and Notch pathways have revealed how multiple niche signals specify progenitor cell fate [4].

Experimental approaches for signaling analysis typically involve:

- Reporter constructs expressing fluorescent proteins under the control of pathway-responsive elements

- Quantitative image analysis of signal intensity and distribution within tissue contexts

- Genetic manipulation through loss-of-function and gain-of-function experiments

- Correlation with differentiation markers to establish causal relationships between signaling activity and cell fate decisions [4]

These methodologies have revealed that Wnt signaling transiently inhibits expression of the main body cell fate determinant Eya in the Drosophila ovary, biasing cells toward polar and stalk fates when hyperactivated. Meanwhile, Hh signaling independently controls the proliferation to differentiation transition, demonstrating how multiple niche signals coordinate to pattern cell fates [4].

Diagram 1: Niche signaling in stem cell fate. Multiple niche-derived signals (Wnt, Hh, Notch) act on stem and progenitor cells to coordinate self-renewal and differentiation decisions during tissue maintenance.

Advanced Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Essential Research Reagents

Cutting-edge research on adult stem cells requires specialized reagents and tools that enable precise manipulation and analysis. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for experimental work in this field:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Adult Stem Cell Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| BCARS Microscopy | Label-free chemical imaging based on Raman scattering | Quantifying lineage commitment in individual hMSCs [5] |

| Pathway Reporters (e.g., fz3-RFP) | Monitoring signaling pathway activity in live cells | Visualizing Wnt signaling gradients in germarium [4] |

| Defined Culture Media | Maintaining stemness or inducing specific differentiation | Adipogenic, osteogenic, and basal media for hMSC differentiation [5] |

| Surface Marker Antibodies | Identification and isolation of stem cell populations | CD105, CD73, CD90 for MSCs; CD45, CD34 negative selection [1] |

| Genetic Tools (RNAi, CRISPR) | Manipulating gene expression in stem cells | Knockdown of β-catenin to validate Wnt reporter specificity [4] |

Experimental Workflow

A typical experimental workflow for characterizing adult stem cell differentiation involves multiple coordinated steps from cell isolation through quantitative analysis. The following diagram illustrates a generalized approach for studying lineage commitment:

Diagram 2: Stem cell differentiation workflow. Key steps include cell isolation, expansion in culture, differentiation induction, and label-free analysis using BCARS microscopy, with validation through conventional staining methods.

Emerging Concepts and Clinical Relevance

Muse Cells: A Unique ASC Population

Recent research has identified a unique subpopulation of ASCs called Multilineage-differentiating stress-enduring (Muse) cells. These cells are naturally present in various connective tissues, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, dermis, and peripheral blood [6]. Muse cells exhibit several remarkable properties that distinguish them from conventional mesenchymal stromal cells, including stress tolerance, spontaneous differentiation into tri-germ layer lineages, and non-tumorigenicity [6].

Unlike induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) which require artificial reprogramming, Muse cells are naturally pluripotent-like without genetic modification. They demonstrate targeted homing to injured tissues through the S1P-S1PR2 axis, where they contribute to regeneration through direct differentiation and paracrine effects [6]. Clinical trials with Muse cells have shown promise for treating conditions including stroke, myocardial infarction, and osteoarthritis, highlighting their therapeutic potential while maintaining a favorable safety profile [6].

Therapeutic Mechanisms

Adult stem cells exert their therapeutic effects through multiple coordinated mechanisms [2]:

- Differentiation: Replacement of lost or damaged cells in diseased organs

- Paracrine signaling: Promotion of healing through secreted bioactive factors

- Immunomodulation: Control of autoimmune and inflammatory responses

- Homing & Migration: Targeted movement to sites of injury

- Engraftment & Integration: Functional incorporation into host tissues

- Anti-apoptotic & Anti-fibrotic: Reduction of cell death and pathological scarring

These mechanisms collectively enable ASCs to function as "biological drugs" with dynamic responsiveness to local environmental cues. Unlike conventional pharmaceuticals, stem cells can sense signals from injured tissues, adapt to their microenvironment, and execute appropriate regenerative responses [2]. This adaptability positions ASC-based therapies as promising approaches for conditions with complex pathologies, including neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and autoimmune conditions [2] [3].

Adult stem cells, defined by their capacities for self-renewal and multipotency, represent foundational components of tissue maintenance and repair throughout postnatal life. Residing in specialized niches within diverse somatic tissues, these cells respond to physiological demands and pathological challenges by generating appropriate progeny while maintaining their own populations. Ongoing research continues to elucidate the complex regulatory networks that control ASC behavior, including niche-derived signals, intracellular pathways, and systemic factors.

The characterization of various ASC populations—from well-established hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells to newly identified Muse cells—has revealed both shared principles and unique specializations. Advanced research methodologies, including label-free imaging and single-cell analysis, provide increasingly sophisticated tools for probing ASC biology with minimal perturbation. As our understanding of these remarkable cells deepens, so too does their potential for clinical application in regenerative medicine, offering promising avenues for addressing numerous debilitating conditions that currently lack effective treatments.

The bone marrow (BM) represents a quintessential adult stem cell somatic tissue source, harboring two primary populations: Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs) and Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs). These cells reside within a specialized microenvironment known as the "niche," a dynamic structural and functional unit that regulates stem cell fate decisions including quiescence, self-renewal, differentiation, and mobilization [7] [8]. The HSCs are rare, multipotent cells responsible for the lifelong production of all blood and immune cells, while MSCs are multipotent stromal cells that can differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes, and provide critical physical and metabolic support for hematopoiesis [8]. This intricate cellular cooperation establishes the bone marrow as a foundational reservoir in somatic stem cell biology with profound implications for regenerative medicine, disease pathogenesis, and therapeutic development.

Characterization of Bone Marrow Resident Stem Cells

Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs)

HSCs exist in a carefully regulated hierarchy within the bone marrow. Long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs) possess durable self-renewal capacity and offer lifelong multilineage reconstitution potential. These give rise to short-term HSCs (ST-HSCs), which exhibit limited self-renewal but robust short-term engraftment capacity. Further down the hierarchy are the multipotent progenitors (MPPs), which lack self-renewal capability but retain multilineage differentiation potential, eventually yielding lineage-restricted progenitors [8]. The functional integrity of HSCs is paramount for successful Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT), a curative treatment for genetic blood disorders and hematological malignancies [8].

Table 1: Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Populations

| Cell Population | Surface Phenotype | Function | Self-Renewal Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| LT-HSC | CD150+ CD48− Lin− Sca−1+ c-Kit+ [9] | Lifelong, multilineage reconstitution | High |

| ST-HSC | Lin− Sca-1+ c-Kit+ (LSK) [9] [8] | Short-term multilineage reconstitution | Limited |

| MPP | Lin− Sca-1+ c-Kit+ (LSK) [8] | Multilineage differentiation | None |

| CMP | Lin− CD127− Sca-1− c-Kit+ CD34+ FcγR− [9] | Myeloid lineage commitment | None |

| CLP | Lin− CD127+ Sca-1+ c-Kit+ [9] | Lymphoid lineage commitment | None |

Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs)

MSCs are an exceptionally rare cell population, comprising only 0.01% to 0.001% of the total cells in BM [8]. According to the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT), human MSCs must adhere to plastic under standard culture conditions; express surface antigens CD105, CD73, and CD90 (>95%); lack expression of CD45, CD34, CD14/CD11b, CD79α/CD19, and HLA-DR (<2%); and possess tri-lineage differentiation potential (adipogenic, osteogenic, chondrogenic) [10] [8]. Within the BM niche, two distinct MSC populations play complementary roles: Nestin-positive (Nestin⁺) MSCs, located in perivascular regions, are crucial for maintaining HSC quiescence and retention, while leptin receptor-positive (LepR⁺) MSCs constitute a significant portion of the adult BM stroma and support HSC homing, localization, and maintenance [8].

Table 2: Key Surface Markers for Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Characterization

| Surface Marker | Other Name | Expression in AD-MSCs | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD10 | MME | Positive [10] | Membrane metalloendopeptidase |

| CD13 | ANPEP | Positive [10] | Alanyl aminopeptidase |

| CD29 | ITGB1 | Positive [10] | Integrin subunit beta 1 (cell adhesion) |

| CD44 | CD44 | Positive [10] | Cell adhesion and migration |

| CD73 | NT5E | Positive [10] | 5'-nucleotidase ecto |

| CD90 | THY1 | Positive [10] | Thy-1 cell surface antigen |

| CD105 | ENG | Positive [10] | Endoglin |

| CD106 | VCAM1 | Positive [10] | Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| CD45 | PTPRC | Negative [10] [8] | Hematopoietic lineage marker |

| CD34 | CD34 | Variable (early culture) [10] | Hematopoietic progenitor marker |

The Bone Marrow Microenvironment: A Dynamic Interactive Niche

The bone marrow microenvironment is a complex, multi-cellular structure where various niche components secrete signaling molecules that collectively regulate HSC fate. The vascular niche,

involving sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs) and arterial endothelial cells (AECs), facilitates HSPC trafficking and maintains quiescence, respectively [8]. The perivascular niche,

anchored by MSCs, is a primary site for HSC maintenance. Key cellular components include:

- Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs): LepR⁺ MSCs are major producers of CXC-chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) and Stem Cell Factor (SCF), both essential for HSC maintenance [8].

- Endothelial Cells: Sinusoidal endothelial cells regulate HSPC trafficking, while arterial endothelial cells maintain HSPC quiescence and reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels [8].

- Osteoblasts: Bone-lining cells at the endosteum anchor HSPCs and secrete regulatory cytokines that enhance hematopoiesis [8].

- Sympathetic Nervous System: Innervates the BM, modulating osteoblast activity and CXCL12 expression to regulate HSPC dynamics, particularly in response to stress [8].

- Megakaryocytes: Platelet-producing cells that release factors like platelet factor 4 (PF4) and TGF-β1 to help maintain HSC quiescence [8].

Figure 1: Cellular Interactions in the Bone Marrow Niche. HSCs receive critical signals from various niche components including MSCs, osteoblasts, endothelial cells, megakaryocytes, and the sympathetic nervous system.

Recent Advances and Experimental Approaches

Reversal of HSC Aging through Lysosomal Targeting

A groundbreaking 2025 study revealed that aging in blood-forming stem cells is not irreversible. Researchers discovered that lysosomes in aged HSCs become hyper-acidic, depleted, damaged, and abnormally activated, disrupting metabolic and epigenetic stability. By suppressing this hyperactivation with a specific vacuolar ATPase inhibitor, lysosomal integrity and blood-forming stem cell function were restored. Remarkably, ex vivo treatment of old stem cells with this lysosomal inhibitor boosted their in vivo blood-forming capacity more than eightfold. This restoration also dampened harmful inflammatory pathways by improving lysosomal processing of mitochondrial DNA and reducing activation of the cGAS-STING immune signaling pathway, a key driver of inflammation and aging in stem cells [11].

Figure 2: HSC Aging Reversal via Lysosomal Modulation. Targeting lysosomal hyperactivity with a vacuolar ATPase inhibitor restores function in aged HSCs.

Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue as a Metabolic Regulator

Bone marrow adipose tissue (MAT) has emerged as a significant component of the hematopoietic microenvironment, remodeling in various metabolic conditions including obesity, diabetes, caloric restriction, and aging. MAT-derived Stem Cell Factor (SCF) is essential for hematopoiesis at steady state and upon metabolic stresses. Genetic ablation of the Kitl gene (encoding SCF) from adipocytes and bone marrow stroma cells using Adipoq-Cre and Osx1-Cre mouse models diminished hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and myeloid progenitors in the bone marrow, leading to macrocytic anemia. The composition and differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells dynamically responded to metabolic challenges including high-fat diet, β3-adrenergic activation, thermoneutrality, and aging, responses that were largely impaired in adipocyte-specific SCF knockout mice [9].

Novel Transplant Protocols Using Antibody-Based Conditioning

A Phase 1 clinical trial demonstrated a breakthrough in stem cell transplantation by replacing toxic chemotherapy or radiation with an antibody-based conditioning regimen. Patients received briquilimab, an antibody against CD117 (c-Kit) on the surface of blood-forming stem cells, which eliminated host HSCs without toxic side effects. This approach, combined with T-cell-depleted haploidentical transplants from parents, successfully treated three children with Fanconi anemia—a genetic disease that makes standard transplant extremely risky. All three patients achieved nearly 100% donor chimerism two years post-transplant, far exceeding the initial goal of 1% donor chimerism, demonstrating the efficacy of this less toxic approach [12].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bone Marrow Stem Cell Research

| Reagent/Cell Type | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Briquilimab (anti-CD117) | Antibody targeting c-Kit on HSCs; enables chemotherapy-free transplant conditioning [12] | Replaces toxic busulfan chemotherapy in stem cell transplantation protocols |

| Collagenase Type I | Enzyme for tissue dissociation during stromal vascular fraction (SVF) isolation [10] | Digestion of adipose tissue to isolate AD-MSCs from lipoaspirate |

| AMD3100 (Plerixafor) | CXCR4 receptor antagonist that mobilizes HSPCs from bone marrow [8] | Clinical mobilization of HSPCs for collection via apheresis |

| G-CSF | Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor cytokine [8] | Mobilization of HSPCs from bone marrow to peripheral blood |

| Vacuolar ATPase Inhibitor | Suppresses lysosomal hyperacidity in aged HSCs [11] | Ex vivo rejuvenation of aged hematopoietic stem cells |

| CD34+ Selection | Enrichment for blood-forming stem cells from donor tissue [12] | Generating stem cell-rich grafts for transplantation |

Experimental Protocols for Bone Marrow Stem Cell Research

Isolation and Culture of Adipose-Derived MSCs (AD-MSCs)

Protocol Source: [10]

- Tissue Harvesting: Collect adipose tissue during surgery or liposuction. Wash the tissue several times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Digestion: Digest the tissue at 37°C with 0.075% collagenase type I for approximately 30-60 minutes.

- Enzyme Neutralization: Neutralize collagenase activity with DMEM medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 1200× g for 10 minutes to obtain a high-density stromal vascular fraction (SVF) pellet.

- Red Blood Cell Lysis: Suspend the pellet in 160 mM NH4Cl and incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature to lyse red blood cells.

- Plating: Clean pellets by repeated centrifugation in neutralizing medium, then place in plastic culture flasks with appropriate medium (e.g., DMEM/F12 with 10% FBS).

- Expansion: Culture at 37°C with 5% CO2, changing medium every 2-3 days. AD-MSCs typically retain their phenotype until passage 6.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells

Protocol Source: [9]

- Bone Marrow Cell Isolation: Flush bone marrow from femurs in Ca2+ and Mg2+ free PBS with 1% heat-inactivated bovine serum.

- Cell Suspension Preparation: Dissociate cells to a single-cell suspension by gently passing through a 25-gauge needle and filtering through a 70-μm nylon mesh.

- Red Blood Cell Lysis: Remove red blood cells using ammonium-chloride-potassium lysing buffer.

- Antibody Staining: Stain cells with a cocktail of biotin-conjugated lineage antibodies (CD3e, B220, Ter119, Mac-1, Gr-1, CD4, CD5, CD8) followed by Streptavidin-AF488.

- Progenitor Panel Staining: Subsequently stain with CD127-APC, c-Kit-APC-eFluor780, Sca-1-Super Bright 436, CD34-PE, and FcγR-PerCP-eFluor710.

- HSC Staining: For LT-HSC identification, include CD150-BV605 and CD48-BUV395.

- Analysis: Perform multicolor analysis on a flow cytometer (e.g., BD LSRII). Identify populations as follows:

- HSPC: Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK)

- LT-HSC: CD150+CD48−Lin−Sca−1+c-Kit+

- Myeloid Progenitor: Lin−CD127−Sca-1−c-Kit+

- CLP: Lin−CD127+Sca-1+c-Kit+

Figure 3: Workflow for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Isolation. Complex multicolor flow cytometry enables identification of HSC subpopulations.

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

The interplay between HSCs and MSCs in the bone marrow reservoir has profound clinical implications. The ability to reverse HSC aging [11] and develop non-toxic conditioning regimens [12] opens new avenues for treating age-related blood disorders and making stem cell transplantation accessible to more vulnerable populations. Furthermore, understanding bone marrow adipose tissue as a metabolic sensor and regulator of hematopoiesis provides insights into the hematopoietic complications of metabolic diseases [9].

Ongoing research is exploring how lysosomal dysfunction in old stem cells may contribute to the formation of leukemic stem cells, potentially linking normal stem cell aging to cancer development [11]. The reauthorization of the Stem Cell Therapeutic and Research Act in 2025, with funding of $33 million annually for the C.W. Bill Young Cell Transplantation Program and $23 million annually for the National Cord Blood Inventory, ensures continued support for these life-saving programs and the research that underpins them [13].

As single-cell transcriptomic methods advance, they deliver unprecedented insight into gene expression profiles of individual cells, helping to deconstruct cellular hierarchy and differentiation trajectories, and to understand cell-cell interactions within the bone marrow microenvironment [14]. These technologies will further illuminate the complex dynamics of bone marrow as a stem cell reservoir, driving the next generation of somatic stem cell therapies.

Adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs), also referred to as adipose-derived adult stem (ADAS) cells, have emerged as a pivotal tool in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. As a type of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) residing in adipose tissue, ASCs fulfill the critical requirements for an ideal stem cell source: they are abundantly available, can be harvested with minimal morbidity, differentiate reliably down multiple pathways, and can be transplanted safely and efficiously [15]. Within the broader context of adult stem cell research, ASCs present a compelling alternative to bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), primarily due to their accessibility and superior yield from a readily available tissue source [16]. The ease of procurement via minimally invasive liposuction procedures, coupled with a differentiation capacity that is not adversely affected by donor age, positions ASCs as a frontrunner for autologous cell-based therapies [16] [17]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of ASC isolation, characterization, and comparative analysis with other somatic tissue sources, specifically tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Isolation of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells

The isolation of ASCs from adipose tissue is a standardized process that leverages their physiological presence within the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of fat. The procedure hinges on the breakdown of the extracellular matrix to release the cellular components, followed by their separation and culture.

Standard Enzymatic Isolation Protocol

The most widely utilized method for isolating ASCs relies on enzymatic digestion of lipoaspirated or excised adipose tissue [16] [17]. The following protocol is adapted from established methodologies [18] [19]:

- Tissue Collection and Washing: Subcutaneous adipose tissue is obtained via liposuction or direct surgical excision. The tissue is extensively washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing antibiotics (e.g., 1-5% penicillin/streptomycin) to remove blood cells and contaminants [19].

- Enzymatic Digestion: The washed adipose tissue is minced and digested with 0.1% to 0.2% collagenase type I (or type IV) in PBS for 30-60 minutes at 37°C with constant agitation. Collagenase hydrolyzes collagen, breaking down the tissue structure and releasing the cellular components [18] [19].

- Digestion Neutralization: The collagenase activity is neutralized by adding an equal volume of culture medium, typically Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) [19]. For clinical-scale expansion, FBS is often replaced with human platelet lysate (hPL) to avoid xenogeneic components and comply with Good Manufacturing Practice guidelines [16] [18].

- Centrifugation and Separation: The neutralized cell suspension is centrifuged (e.g., 1200-1800 rpm for 5-10 minutes). This separates the mixture into three layers: a top layer of mature adipocytes (floating), an intermediate aqueous layer, and a pellet containing the SVF cells, including ASCs, preadipocytes, endothelial cells, and pericytes [16] [17] [19].

- Pellet Washing and Plating: The SVF pellet is resuspended in culture medium, filtered through a 70-100 μm cell strainer to remove debris, and centrifuged again. The final pellet is resuspended and plated in culture flasks [19].

- In vitro Expansion: The plated cells are maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. After 24-48 hours, non-adherent cells are removed by washing with PBS. The adherent cells, which include the ASC population, are allowed to proliferate, with the medium changed twice weekly. Upon reaching 80-90% confluence, cells are passaged using trypsin/EDTA [18] [19].

The diagram below illustrates this core isolation workflow.

Characterization of ASCs

Proper characterization of ASCs is essential to confirm their identity and functional potency before experimental or clinical use. This involves assessing immunophenotype, differentiation potential, and proliferative capacity.

Immunophenotypic Characterization by Flow Cytometry

According to the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) criteria for MSCs, ASCs must express a specific set of surface markers and lack expression of hematopoietic markers [19]. Analysis is performed using flow cytometry on cells at passage 3-5.

- Cell Preparation: Harvest ASCs using trypsin/EDTA and wash with PBS. Use approximately 4 × 10^5 cells per sample [19].

- Staining: Incubate cells with fluorescently conjugated antibodies against target surface markers for 30 minutes in the dark at 4°C. Include unstained and isotype control samples for gating and background subtraction [18] [19].

- Analysis: Analyze the stained cells using a flow cytometer, collecting data for at least 50,000 events. The population of interest should demonstrate high expression (≥90%) of typical MSC markers and low expression (≤2%) of hematopoietic markers [19].

Table 1: Key Surface Markers for ASC Characterization

| Marker | Expression in ASCs | Function / Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD73 | Positive (≥90%) | Ecto-5'-nucleotidase; MSC-defining marker | [16] [19] |

| CD90 | Positive (≥90%) | Thy-1 cell surface antigen; MSC-defining marker | [16] [19] |

| CD105 | Positive (≥90%) | Endoglin; MSC-defining marker | [16] [19] |

| CD44 | Positive | Hyaluronic acid receptor | [16] |

| CD166 | Positive | Activated Leukocyte Cell Adhesion Molecule | [16] |

| CD34 | Variable/Low | Hematopoietic progenitor cell marker; often negative in cultured ASCs but present in SVF | [16] [17] [19] |

| CD45 | Negative (≤2%) | Pan-hematopoietic marker | [16] [19] |

| CD14 | Negative (≤2%) | Monocyte/macrophage marker | [19] |

| CD19 | Negative (≤2%) | B-cell marker | [19] |

| HLA-DR | Negative (≤2%) | Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II | [19] |

| Stro-1 | Low | Mesenchymal progenitor marker; often lower in ASCs vs. BMSCs | [19] |

| CD49d | High | Alpha-4 integrin; often higher in ASCs vs. BMSCs | [19] |

Tri-Lineage Differentiation Potential

A defining functional characteristic of ASCs is their ability to differentiate into multiple mesodermal lineages. The following protocols induce osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation.

- Baseline: Plate ASCs at a density of 3-5 x 10^3 cells/cm² in growth medium (DMEM + 10% FBS/hPL) for 24 hours before switching to differentiation media [18] [19].

- Staining and Analysis: Differentiated cells are fixed and stained after 14-21 days. Adipogenic cultures are stained with Oil Red O to visualize lipid vesicles. Osteogenic cultures are stained with Alizarin Red S to detect calcium deposits. Chondrogenic pellets are sectioned and stained with Alcian Blue or Safranin O to visualize sulfated glycosaminoglycans in the extracellular matrix [19]. Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) can be used to measure the expression of lineage-specific genes.

Table 2: Standard In vitro Differentiation Protocols for ASCs

| Lineage | Induction Medium Components | Key Markers / Stains | Incubation Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adipogenic | 0.5 mM IBMX, 1 μM dexamethasone, 10 μM insulin, 200 μM indomethacin [19] | Oil Red O (lipid vesicles), PPAR-γ, FABP4 [19] | 14-21 days |

| Osteogenic | 0.1 μM dexamethasone, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μM ascorbic acid-2-phosphate [19] | Alizarin Red S (calcium deposition), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) activity, Osteopontin, Runx2 [18] [19] | 14-21 days |

| Chondrogenic | Pellet culture in 0.1 μM dexamethasone, 1% ITS+ premix, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, 10 ng/mL TGF-β3, 40 μg/mL proline [19] | Alcian Blue / Safranin O (proteoglycans), Collagen type II, Aggrecan, SOX9 [19] | 21-28 days |

ASCs vs. Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs: A Donor-Matched Comparison

Within the landscape of adult stem cell sources, bone marrow has been the traditional gold standard. However, direct, donor-matched comparisons reveal critical biological differences that inform source selection for specific applications.

Table 3: Donor-Matched Comparison of ASCs and BMSCs [18] [19]

| Parameter | Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ASCs) | Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs (BMSCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Harvest | Minimally invasive (liposuction); abundant source [15] [16] | Highly invasive (bone marrow aspiration); limited source [16] [19] |

| Cell Yield | High (~500,000 stem cells per 1g of adipose tissue) [15] | Low (~100-1000 stem cells per 1mL of marrow) [19] |

| Proliferation Rate | Significantly higher population doublings [18] [19] | Lower proliferation capacity, higher senescence [16] [19] |

| Effect of Donor Age | No significant decline in proliferation with age [16] | Proliferation and differentiation potential decline with age [16] |

| Osteogenic Potential | Moderate | Superior (earlier/higher ALP activity, calcium deposition) [18] [19] |

| Chondrogenic Potential | Moderate | Superior (higher collagen type II production) [18] |

| Adipogenic Potential | Superior (more and larger lipid vesicles) [19] | Moderate |

| Immunomodulatory Effects | More potent inhibitory effects on immune cells [18] | Potent, but may be less so than ASCs in some assays [18] |

| Secretome Profile | Higher secretion of bFGF, IFN-γ, IGF-1 [18] | Higher secretion of HGF and SDF-1 [18] |

The following diagram summarizes the key comparative advantages of each cell source, derived from the donor-matched data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section details the key reagents and materials required for the isolation, expansion, and characterization of ASCs, forming a core toolkit for researchers in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ASC Isolation and Characterization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Notes & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Collagenase Type I/IV | Enzymatic digestion of adipose tissue to release the Stromal Vascular Fraction (SVF). | Concentration (0.1-0.2%) and incubation time (30-60 min) must be optimized to maximize cell viability and yield [18] [19]. |

| Culture Medium (DMEM) | Basal medium for cell growth and expansion. | Often supplemented with glucose and glutamine. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Standard serum supplement for in vitro cell culture, providing growth factors and adhesion factors. | Clinical Caution: Use of xenogeneic FBS is undesirable for clinical applications due to risk of pathogen transmission and immune reaction [18]. |

| Human Platelet Lysate (hPL) | Human-derived, xeno-free alternative to FBS for clinical-scale expansion. | Promotes faster proliferation; compliant with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines [16] [18]. |

| Antibiotics (Pen/Strep) | Added to wash buffers and media to prevent bacterial contamination during isolation and initial culture. | Typically used at 1% concentration. |

| Trypsin/EDTA | Enzymatic detachment of adherent cells for subculturing (passaging) and cell counting. | |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Immunophenotypic characterization of ASCs (e.g., CD73, CD90, CD105, CD45, CD34). | Crucial for confirming MSC identity as per ISCT criteria [19]. |

| Tri-lineage Differentiation Kits | Defined media supplements for inducing osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation. | Commercially available kits ensure reproducibility. Key components include dexamethasone, IBMX, insulin, ascorbic acid, and TGF-β3 [19]. |

| Lineage-Specific Stains | Histochemical validation of differentiation (Oil Red O, Alizarin Red S, Alcian Blue). | Allows for qualitative and semi-quantitative analysis of differentiation efficiency. |

Adipose tissue represents a highly accessible and abundant source of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells. The detailed protocols for isolation and characterization outlined in this guide provide a reliable foundation for research and development. The critical comparison with BMSCs underscores a fundamental principle: the choice of stem cell source must be systematically considered based on the specific clinical or experimental application [18]. ASCs hold distinct advantages in proliferative capacity, immunomodulatory function, and ease of harvest, making them particularly suitable for applications in soft tissue regeneration, immunomodulation, and chronic wound healing [15] [16]. The field continues to advance rapidly, with ongoing clinical trials exploring the efficacy of ASCs and their derivatives, such as the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) and exosomes, across a spectrum of medical conditions [20]. Future efforts must prioritize international collaboration, large-scale trials, and the resolution of standardization challenges to fully realize the therapeutic potential of ASCs in regenerative medicine [20].

The bone marrow (BM) microenvironment constitutes a sophisticated regulatory niche that is fundamental to the maintenance of adult stem cells, the support of hematopoiesis, and the regulation of bone remodeling. This specialized milieu facilitates intricate signaling crosstalk between hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), orchestrated by cytokines, growth factors, and extracellular matrix components [21]. Within this context, bone marrow adipose tissue (BMAT) has transitioned from being perceived as an inert space-filler to being recognized as a dynamic endocrine organ that actively participates in metabolic and regenerative processes [21] [22]. The bone marrow adipose tissue constitutes approximately 10% of total adipose mass and can occupy up to 70% of bone marrow volume in adults, underscoring its significant physical presence within the niche [21]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the bone marrow and adipose microenvironments, focusing on their anatomical and functional intricacies, with specific emphasis on their relevance to adult stem cell research for scientists and drug development professionals.

Anatomical and Functional Organization of Bone Marrow Niches

The bone marrow stroma is organized into distinct yet interconnected functional niches that regulate stem cell fate decisions through precise spatial positioning of signaling cues and cellular interactions.

Endosteal and Vascular Niches: Comparative Analysis

The endosteal and vascular niches represent two principal microenvironments within bone marrow that maintain HSCs through distinct mechanistic approaches.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Bone Marrow Niches

| Feature | Endosteal Niche | Vascular Niche |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Bone-lining surface | Surrounding arterioles and sinusoids |

| Oxygenation | Markedly hypoxic [21] | Relatively oxygen-rich [21] |

| Key Molecular Factors | HIF-1α, Osteopontin, Ang-1 [21] | CXCL12, SCF, Nitric Oxide, IL-6 [21] |

| Primary HSC Function | Maintenance in deep quiescence [21] | Cycling, differentiation, and mobilization [21] |

| Stromal Cell Types | Osteoblasts, bone-lining cells | LepR+ perivascular stromal cells, Endothelial cells [21] |

The vascular niche itself comprises specialized endothelial cell subpopulations, including type-L (sinusoidal), type-H (arteriole-associated), and arterial endothelial cells, which coordinate hematopoietic function through differential secretion of angiocrine factors [21]. Bone marrow adipocytes (BMAs) strategically position themselves between these regions, engaging with both niches and exhibiting remarkable functional plasticity depending on their specific location and physiological context [21].

Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue: A Unique Adipose Depot

Bone marrow adipose tissue exhibits distinct characteristics that differentiate it from classical white (WAT) or brown adipose tissue (BAT). BMAs demonstrate unique metabolic properties, including reduced insulin-stimulated glucose uptake due to lower GLUT4 expression and resistance to cold-induced glucose uptake [21]. During highly anabolic phases such as puberty or fracture repair, BMAs can transiently exhibit a brown adipocyte-like phenotype, expressing transcription factors such as PR domain-containing 16 (Prdm16) and Forkhead box C2, along with marker genes including PGC1α, Dio2, β3AR, and UCP1, thereby establishing a microenvironment conducive to osteogenesis [21].

Table 2: Functional Roles of Bone Marrow Adipocytes in Homeostasis

| Function | Mechanism | Impact on Niche |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Regulation | Lipolysis in response to metabolic stimuli; FFAs release via HSL and ATGL activation [21] | Systemic energy balance; local lipid availability |

| Osteogenic Modulation | Secretion of leptin and adiponectin (positive effect); RANKL secretion (negative effect) [21] | Context-dependent bone formation or resorption |

| Hematopoietic Support | Sequestration of excess lipids to reduce lipotoxic stress [21] | Protection of HSCs and osteoblasts from lipid-induced damage |

| Endocrine Signaling | Production of adipokines, cytokines, and chemokines [21] | Paracrine and systemic signaling |

Methodological Approaches for Investigating Bone Marrow Niches

Experimental Models and Isolation Techniques

Investigating the bone marrow microenvironment requires specialized methodological approaches that account for the unique properties of BMAs and their surrounding cellular constituents. The Bone Marrow Adiposity Society (BMAS) has highlighted the critical challenge of methodological variability and has established consensus recommendations to standardize isolation, storage, and characterization protocols for BMAT and bone marrow adipocytes (BMAds) [22]. Key considerations include:

- Site-Specificity: BMAT demonstrates significant heterogeneity across different skeletal sites (e.g., long bones vs. vertebrae) and between species, necessitating careful experimental design and interpretation [22].

- Isolation Techniques: Standardized protocols for BMAds isolation are essential for generating reproducible data in downstream applications, including high-throughput omics analyses [22].

- Functional Assays: Lipidomic analyses of BMAds in murine osteoporosis models have revealed significant alterations in lipid species, particularly increases in acylcarnitine and fatty acids (e.g., arachidonic acid), which contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction in neighboring cells [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Bone Marrow Adiposity Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Staining & Detection | Oil Red O (ORO), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E), Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) [23] | Visualization of lipids, osteogenic differentiation, general histology, senescence detection |

| Cell Culture Models | BMSC adipogenic/osteogenic induction, MC3T3-E1 osteoblast line [23] | In vitro modeling of differentiation and cell crosstalk |

| Molecular Probes | JC-1 (mitochondrial membrane potential), MitoSOX (mitochondrial superoxide) [23] | Assessment of mitochondrial function and oxidative stress |

| Lipid Modulators | GW1929 (fatty acid agonist), GW9662 (fatty acid antagonist) [23] | Experimental manipulation of lipid signaling pathways |

| Nanoparticle Systems | CZP@LC nanoplatform (Cu/Zn-ZIF8 loaded with PG3@LC) [23] | Targeted interference with adipocyte lipid metabolism |

Signaling Pathways in Bone Marrow Niches

The following diagrams, created using DOT language, illustrate key signaling pathways and experimental workflows relevant to bone marrow adipocyte research. The color palette adheres to the specified guidelines, ensuring sufficient contrast for readability.

Signaling Pathways Governing MSC Fate Decisions

Diagram 1: Aging skews MSC fate toward adipogenesis via altered Wnt/β-catenin and PPARγ signaling, exacerbated by oxidative stress and senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors [21].

BMAd Lipid Crosstalk Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for identifying and targeting BMAd-derived lipid crosstalk that induces osteoblast senescence in osteoporosis [23].

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Targeting

Dysregulation of the bone marrow microenvironment contributes significantly to disease pathogenesis, particularly in aging and metabolic disorders. Age-related transformations shift MSC differentiation from osteogenesis toward adipogenesis, altering secretory profiles and impairing endothelial function, which destabilizes the vascular niche and reduces hematopoietic stem cell support [21]. This culminates in clinical manifestations of bone fragility and disrupted hematopoiesis.

In osteoporosis, BMAds accumulate and secrete excessive lipids, including polyunsaturated fatty acids like arachidonic acid (AA). These lipids induce mitochondrial dysfunction and senescence in neighboring osteoblasts, creating a vicious cycle that further impairs bone formation [23]. Therapeutic strategies are emerging that target these pathological mechanisms. For instance, the CZP@LC nanoplatform—a polycation-loaded biomimetic dual-site framework—specifically targets BMAds in osteoporotic conditions to interfere with pathological lipid crosstalk [23]. This approach mitigates mitochondrial dysfunction in bone marrow cells, prevents senescence accumulation, and restores osteogenesis, demonstrating the potential of targeting BMAd-mediated pathways for therapeutic benefit [23].

The bone marrow and adipose microenvironments represent complex, dynamic niches where specialized anatomical structures govern stem cell fate through precise molecular signaling. Bone marrow adipocytes function as active participants in metabolic regulation, hematopoietic support, and bone homeostasis, rather than passive space-fillers. The ongoing standardization of experimental methods by organizations like BMAS, coupled with emerging technologies such as targeted nanotherapies that modulate adipocyte lipid metabolism, promises to accelerate both our fundamental understanding and therapeutic manipulation of these critical somatic stem cell niches. Future research focusing on the specific signaling molecules and metabolic pathways identified in this whitepaper will undoubtedly yield novel interventions for a range of degenerative, metabolic, and hematopoietic disorders.

Adult stem cells are undifferentiated cells found throughout the body after development, possessing the dual abilities of self-renewal and differentiation into specialized cell types [1]. They serve as fundamental units for maintaining tissue homeostasis and facilitating repair following injury. Within the context of somatic tissue sources, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from bone marrow (BM-MSCs) and adipose tissue (Adipose-Derived Stem Cells, ADSCs) represent two of the most extensively researched populations in regenerative medicine [1] [24]. These cells reside in highly specialized microenvironments known as stem cell niches, which integrate structural, biochemical, and mechanical cues to precisely regulate stem cell behavior, including quiescence, self-renewal, and differentiation [25]. The core functions of these adult stem cells—maintenance of tissue homeostasis, orchestration of repair processes, and dynamic immunomodulation—are not solely determined by their intrinsic genetic programs but are profoundly influenced by these niche interactions [25]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these core functions, framed within contemporary research on bone marrow and adipose-derived stem cells.

Core Functions of Adult Stem Cells

The therapeutic potential of BM-MSCs and ADSCs is realized through three principal, interconnected biological functions: sustained tissue homeostasis, coordinated response to injury, and sophisticated immunomodulation.

Tissue Homeostasis

The primary role of adult stem cells in healthy tissue is to maintain homeostasis by ensuring a continuous, balanced replacement of cells lost to normal turnover.

- Cell Replacement and Tissue Maintenance: Adult stem cells systematically replace cells lost through normal wear and tear, injury, or disease, thanks to their self-renewal and differentiation abilities [1]. This is essential for the homeostasis of organs with high turnover rates. For instance, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the bone marrow niche give rise to all blood cell lineages, thereby maintaining the circulatory system [1] [26].

- Metabolic and Endocrine Regulation: Beyond simple cell replacement, stem cells and their niche constituents actively participate in systemic metabolic regulation. Bone marrow adipocytes (BMAs), which share a common mesenchymal origin with BM-MSCs, are now recognized as a dynamic endocrine organ [26]. They secrete factors like adiponectin and free fatty acids (FFAs) that support HSC homeostasis and modulate bone metabolism [26].

- Niche Maintenance and Signaling: Stem cells also contribute to the integrity of their own niche. Through paracrine signaling and direct cell-cell contact, they help maintain the supportive function of neighboring cells, such as endothelial cells, osteoblasts, and immune cells, creating a stable microenvironment for sustained tissue function [25].

Tissue Repair and Regeneration

Upon tissue damage, the normally quiescent stem cell niche becomes activated, initiating a complex repair program.

- Activation and Proliferation: Signals from the injured microenvironment, including released cytokines and growth factors, activate resident stem cells, prompting them to exit quiescence and proliferate [1] [25].

- Differentiation and Matrix Remodeling: The progeny of activated stem cells differentiate to replace lost cell types. MSCs can differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes to repair mesodermal tissues [1]. Furthermore, they secrete enzymes and factors that remodel the extracellular matrix (ECM), clearing debris and facilitating the formation of new tissue scaffolding [24].

- Paracrine-Mediated Repair: A significant mechanism of stem cell-mediated repair is through robust paracrine activity. Stem cells secrete a cocktail of bioactive molecules—including growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines—that act on resident cells to promote angiogenesis, suppress apoptosis, and stimulate the proliferation of local progenitor cells [24]. This "bystander effect" is often more critical for repair than the direct differentiation of the stem cells themselves [24].

Immunomodulation

A defining feature of MSCs from both bone marrow and adipose tissue is their potent capacity to modulate immune responses, a function critical in both homeostasis and repair.

- Anti-inflammatory Effects: In inflammatory disease models, such as experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), administration of BM-MSCs, ADSCs, or the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) from adipose tissue significantly reduces serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IFNγ and IL-12 [27]. This indicates a systemic anti-inflammatory effect.

- Cell-to-Cell Immune Regulation: MSCs interact directly and indirectly with a wide range of immune cells. They can suppress the proliferation and activation of T-cells, inhibit B-cell function, modulate dendritic cell maturation, and drive macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotype [25] [27]. This re-establishment of a balanced immune environment is crucial for the resolution of inflammation and progression to the repair phase following injury.

- Dynamic Niche Interactions: The immunomodulatory function is not static; it is influenced by signals from the inflammatory niche. In turn, MSCs alter the niche through their secretome. For example, in obesity, adipose tissue macrophages shift toward a pro-inflammatory state, which disrupts the niche homeostasis. Weight loss can partially reverse this senescence and inflammation, demonstrating the dynamic reciprocity between stem cells, immune cells, and their niche [28].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Immunomodulatory Effects in an EAE Model

| Cell Therapy | Clinical Score Amelioration | Reduction in IFNγ | Reduction in IL-12 | Reduction in Inflammatory Infiltrates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow MSCs (BM-MSCs) | Significant | Comparable to other groups | Significant | Significant |

| Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ASCs) | Significant | Comparable to other groups | Significant | Significant |

| Stromal Vascular Fraction (SVF) | Significant (as effective as ASCs/BM-MSCs) | Comparable to other groups | Significant (more than BM-MSCs/ASCs) | Significant |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Investigating the core functions of adult stem cells requires robust and standardized experimental protocols. The following methodologies are central to the field.

Protocol 1: Comparative Functional Analysis in Disease Models

This protocol, adapted from a study comparing ADSCs and BM-MSCs in an EAE model, outlines the key steps for evaluating therapeutic efficacy [27].

Protocol 2: Isolation and Characterization of Bone Marrow Adipocytes

Studying the bone marrow niche requires specialized methods for isolating its most abundant cell type, the bone marrow adipocyte (BMA) [29] [22].

- Tissue Processing: Bone marrow samples are obtained from long bones (e.g., tibia, femur) or vertebrae. The marrow is flushed and subjected to collagenase digestion to liberate the cellular components.

- Adipocyte Isolation: The digested marrow is centrifuged. Mature adipocytes float to the top due to their high lipid content, forming a distinct layer that can be purified from the stromal vascular pellet [29].

- Characterization: Isolated BMAs are characterized using:

- Standardization Challenge: A key challenge in the field is the lack of widely adopted standardized protocols, which the Bone Marrow Adiposity Society (BMAS) is working to address [29] [22].

Key Signaling Pathways Regulating Stem Cell Fate

The core functions of adult stem cells are governed by a set of highly conserved signaling pathways. These pathways integrate signals from the niche to dictate cell fate decisions.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell Niche Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Collagenase Type I | Enzymatic digestion of tissues (adipose, bone marrow) to isolate stem cells and adipocytes [27]. |

| Stromal Vascular Fraction (SVF) | The heterogeneous, non-expanded cellular fraction from adipose tissue used directly in therapy, containing ADSCs, endothelial cells, and immune cells [27]. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | A key, though ill-defined, component of culture media for the ex vivo expansion of MSCs; subject to replacement efforts for clinical use [27]. |

| CD105, CD73, CD90 Antibodies | Surface antigen markers used for the immunophenotypic identification and definition of human MSCs via flow cytometry [1]. |

| Osteogenic/Adipogenic Induction Media | Defined media containing specific factors (e.g., dexamethasone, ascorbate for osteogenesis; insulin, IBMX for adipogenesis) to assess MSC multipotency in vitro [1]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | A high-resolution omics technology that maps gene expression data onto tissue architecture, allowing the study of cells within their native niche context [28]. |

BM-MSCs and ADSCs are central to a sophisticated biological system that maintains tissue integrity, responds to injury, and calibrates immune responses. Their core functions are inseparable from the dynamic regulatory control of their native niches in bone marrow and adipose tissue. While these cells share broad functional characteristics, critical differences in their abundance, accessibility, and specific responses to pathological cues make them uniquely suited for different therapeutic applications. The future of regenerative medicine lies in moving beyond a purely stem-cell-centric view. Success will depend on treating the stem cell and its niche as an inseparable therapeutic unit. Advancements in high-resolution niche mapping, the development of niche-mimetic engineered scaffolds, and the execution of niche-targeted clinical trials will be pivotal in unlocking the full regenerative potential of adult stem cells for treating degenerative diseases, injuries, and immune dysregulation.

From Lab to Clinic: Isolation, Characterization, and Therapeutic Applications

Within the context of research on adult stem cell somatic tissue sources, particularly bone marrow adipose tissue and subcutaneous adipose tissue, standardized and reproducible tissue processing is a critical foundation for experimental success. The isolation of specific cell populations, including mesenchymal stem cells and mature adipocytes, from these complex tissues is a fundamental step for investigating their role in physiology, disease, and regenerative medicine. The techniques of collagenase digestion and differential centrifugation form the cornerstone of this isolation process. This guide details the current, optimized protocols for processing adipose and bone marrow tissues, providing structured data, methodological details, and visual workflows to support researchers in generating high-quality, comparable data in the field of stem cell research.

Core Principles of Tissue Dissociation

The primary objective of tissue dissociation is to liberate individual cells from the dense extracellular matrix that holds them in place, while maximizing cell viability and preserving biological function. For adipose and bone marrow tissues, this presents unique challenges due to their high lipid content and complex stromal networks.

- Enzymatic Action: Collagenase, a matrix-degrading enzyme, specifically targets and hydrolyzes collagen, a major structural component of the extracellular matrix. This action disrupts the tissue architecture, releasing intact adipocytes, stromal cells, and the vascular fraction.

- Mechanical Assistance: Enzymatic digestion is typically augmented by mechanical disruption, such as mincing tissue with scissors, to increase the surface area for enzyme action and improve dissociation efficiency.

- Fractional Separation: Following dissociation, differential centrifugation exploits differences in cell size and density to separate buoyant adipocytes from the pelleted stromal vascular fraction, which contains a heterogeneous mix of cells including adipose-derived stem cells, endothelial cells, and immune cells.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Collagenase Digestion of Human Lipoaspirate

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the optimization of fat graft processing and is suitable for isolating cells from subcutaneous adipose tissue [30].

Materials:

- Tissue Source: Human lipoaspirate from elective liposuction procedures.

- Collagenase Solution: 0.1% (weight/volume) Collagenase Type I in a digestion buffer containing 2.5% BSA, 20 mM HEPES, and cations (e.g., CaCl₂) to maintain enzymatic activity.

- Equipment: 37°C water bath or incubator, centrifuge, sterile tubes and pipettes.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Tissue Preparation: Wash the lipoaspirate with phosphate-buffered saline to remove blood cell contaminants and local anesthetics.

- Digestion: Incubate the adipose tissue at a concentration of 1 g tissue per 1 mL of collagenase-containing digestion buffer.

- Agitation: Place the tissue-enzyme mixture in a 37°C water bath, agitating every 5 minutes to ensure uniform digestion.

- Digestion Duration: Digest for a standardized period. Studies indicate that a duration of 30 to 40 minutes is optimal, as longer digestion times (e.g., 60 minutes) significantly decrease the viability of both adipocytes and stromal cells [30].

- Reaction Termination: After digestion, wash the tissue digest three times with PBS to remove residual collagenase.

Differential Centrifugation for Cell Fractionation

Following collagenase digestion, differential centrifugation is used to separate different cell populations based on their buoyancy.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Initial Low-Speed Spin: Centrifuge the digested tissue mixture at a low g-force (e.g., 300 × g for 10 minutes) [30] [31].

- Fraction Separation: Following this spin, three distinct layers will form:

- Top Layer: Mature, lipid-filled adipocytes (floating).

- Middle Layer: Aqueous solution of collagenase and buffer.

- Bottom Pellet: The stromal vascular fraction, containing ADSCs, pericytes, endothelial cells, and immune cells.

- Pellet Washing: Carefully aspirate the supernatant and resuspend the SVF pellet in a wash buffer. Repeat centrifugation at the same low speed to remove remaining contaminants.

- High-Speed Clearing Spin: For protocols isolating extracellular vesicles from the digested supernatant, subsequent high-speed centrifugation (e.g., 2000 × g for 20 minutes) is used to remove cellular debris [31].

Isolation of Cells from Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue

Bone marrow adipose tissue presents distinct challenges due to its location and complex microenvironment. A perfusion-based dissociation is often required for intact tissue.

Key Considerations:

- Two-Step Perfusion: For intact bone or liver tissue, a two-step perfusion process is highly effective. The tissue is first perfused with a calcium-free buffer, followed by perfusion with a collagenase solution [31].

- Optimal Digestion Time: For mouse liver, an optimal treatment time for collagenase dissolution is 7 to 10 minutes. A shorter duration causes incomplete dissolution, while a longer duration may cause tissue damage [31].

- Standardization Need: The Bone Marrow Adiposity Society (BMAS) has highlighted that methods for isolating BMAT or bone marrow adipocytes are highly variable and has advocated for widely adopted standardized protocols to improve reproducibility [29].

Table 1: Impact of Collagenase Digestion Time on Cell Viability

| Digestion Time (Minutes) | Adipocyte Viability (Human) | Stromal Cell Viability (Human) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | High | High | Recommended starting point for optimal yield and viability [30] |

| 40 | High | High | Common clinical protocol duration; maintains high viability [32] |

| 50-60 | Significantly Decreased | Significantly Decreased | Prolonged exposure detrimental to both cell types [30] |

Table 2: Differential Centrifugation Parameters for Subcellular Fractionation

| Centrifugation Speed & Duration | Pelleted Components | Supernatant Contains | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 × g for 10 min [31] | Large cell clusters, undigested tissue | Single cells, small debris | Initial clarification of tissue digest |

| 300 × g for 10 min [30] [31] | Stromal Vascular Fraction (SVF) | Mature adipocytes, lipids | Standard SVF isolation from adipose tissue |

| 2000 × g for 20 min [31] | Cellular debris, apoptotic bodies | Smaller vesicles, organelles | Clearing supernatant for downstream EV isolation |

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from the literature to guide protocol optimization.

Table 3: Comparison of Tissue Digestion Protocols from Recent Research

| Tissue Type | Protocol Name/Type | Key Enzymes & Concentrations | Incubation Conditions | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Adipose Tissue | Standard Collagenase Digestion [30] | 0.1% Collagenase Type I | 37°C, 30-60 min | Digestion >50 min decreases adipocyte & stromal cell viability. |

| Gut Mucosa | One-Step Collagenase [33] | Collagenase (type not specified) | 37°C | Time-efficient; cell viability and composition comparable to gold standard. |

| Gut Mucosa | Two-Step Collagenase (Gold Standard) [33] | EDTA + Collagenase | 37°C (fraction-specific) | Sequential isolation of epithelial and lamina propria cells. |

| Human Breast Cancer Biopsy | Method 5 (Optimized) [34] | 1.6 mg/mL Collagenase IV + 0.14 mg/mL Hyaluronidase | Overnight, 37°C | Highly effective for establishing primary cell cultures. |

| Mouse Liver | Two-Step Perfusion [31] | Collagenase Type IV | 37°C, 7-10 min perfusion | Optimal for tissue dissociation and high EV yield. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists critical reagents and their functions for successfully executing these isolation protocols.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Tissue Dissociation and Cell Isolation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Collagenase Type I/IV | Enzymatic digestion of collagen in extracellular matrix. | Worthington Biochemical or Serva brands; type and concentration must be optimized per tissue [30] [34]. |

| Hyaluronidase | Degrades hyaluronic acid in the extracellular matrix. | Often used in combination with collagenase for enhanced tissue dissociation [34]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin | Acts as a carrier protein and reduces non-specific cell adhesion and enzyme inhibition. | Typically used at 2.5-5% in digestion buffers [30]. |

| HEPES Buffer | Maintains stable pH during the digestion process outside a CO₂ incubator. | Crucial for ensuring consistent enzyme activity [30]. |

| Calcium Chloride | Cofactor for collagenase enzyme activity. | Essential for maximal enzymatic efficiency [30]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline | Washing and dilution medium; maintains osmotic balance. | Used for washing tissue pre-digestion and terminating the reaction post-digestion. |

| DMEM/F12 Medium | Base medium for cell suspension and culture post-isolation. | Often supplemented with serum for initial plating of isolated cells [34]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the standard workflow for processing adipose tissue to isolate key cellular fractions, integrating both enzymatic and mechanical steps.

The following diagram outlines the hypothesized signaling pathways and cellular interactions within the bone marrow niche, based on current research.

The bone marrow stroma and adipose tissue represent two pivotal somatic tissue sources in adult stem cell research, harboring distinct yet crucial stem cell populations: mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). These cells are fundamental to regenerative medicine, tissue engineering, and therapeutic development. Their isolation and characterization rely heavily on the precise identification of unique cell surface antigen profiles. For researchers and drug development professionals, accurately defining these phenotypic markers is not merely a procedural step but a cornerstone for ensuring experimental reproducibility, therapeutic efficacy, and safety. The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) established minimal criteria to define human MSCs, requiring ≥95% of the population to express CD105, CD73, and CD90, while lacking expression of hematopoietic markers such as CD45, CD34, CD14, CD11b, and HLA-DR [35] [36]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the surface antigen profiles of MSCs and HSCs, focusing on their functional significance, standardized characterization methodologies, and critical considerations for research within the context of adult stem cell investigations involving bone marrow and adipose tissue.

Phenotypic Marker Profiles for Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs)

Core Positive Marker Definition and Functions

The triad of CD105, CD73, and CD90 forms the core of the immunophenotypic definition of culture-expanded MSCs as per ISCT guidelines. Their individual biological functions and expression patterns are detailed below.

Table 1: Core Positive Surface Markers for Human MSCs

| Marker | Alternative Name | Primary Function | Expression Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD105 | Endoglin | Accessory receptor for TGF-β superfamily ligands [37]. | Highly expressed on vascular endothelial cells; expressed at low levels on freshly isolated adipose-derived MSCs, increasing with culture [37]. |

| CD73 | Ecto-5'-nucleotidase | Converts extracellular AMP to adenosine [37]. | Expressed on lymphocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts; specific epitopes (SH3, SH4) may be MSC-specific [37]. |

| CD90 | Thy-1 | GPI-linked protein involved in cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions [37]. | Expressed on endothelial cells, fibroblasts, HSCs, and neurons; species-specific antibody reactivity is a concern [37]. |

In addition to the core positive markers, MSCs are also frequently characterized by the presence of other molecules, including CD44, CD29, CD166, and CD146 [35] [36]. It is critical to note that the expression of these markers can be dynamic. For instance, CD34 is a positive marker for native MSCs in adipose tissue's stromal vascular fraction and in bone marrow, but its expression is typically lost upon in vitro culture [38] [37] [35].

Essential Negative Markers and Hematopoietic Exclusion

The definitive immunophenotypic profile of MSCs requires the absence of markers associated with other lineages, particularly the hematopoietic lineage. This exclusion is vital for ensuring population purity in experimental and therapeutic applications.

Table 2: Key Negative Surface Markers for Human MSCs

| Marker | Typically Identifies | Importance in MSC Definition |

|---|---|---|

| CD45 | Pan-leukocyte marker [35] | Primary marker for excluding hematopoietic cells [39] [35]. |

| CD34 | Hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, endothelial cells [37] | A controversial marker; positive on native MSCs in some tissues (e.g., adipose) but generally negative on culture-expanded MSCs [38] [37]. |

| CD14/CD11b | Monocytes, macrophages, granulocytes [35] | Further excludes the myeloid lineage [36]. |

| CD19/CD79a | B cells [35] | Excludes the lymphoid B-cell lineage [36]. |

| HLA-DR | MHC Class II molecules | Indicates an immunologically activated state; should be absent on undifferentiated MSCs [35]. |

Tissue-Specific and Functional Subpopulation Markers

While the ISCT criteria provide a foundational definition, the MSC population is heterogeneous. Advanced research has identified additional markers that define functional subpopulations or indicate "stemness."

- STRO-1: This antigen, identified from CD34+ bone marrow cells, is used to isolate a primitive stromal precursor population but has been shown to be an endothelial antigen [37] [35].

- CD271 (LNGFR): The low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor is a marker for prospective isolation of bone marrow MSCs with high colony-forming efficiency [40].

- CD146 (MCAM): This marker identifies a perivascular subset of MSCs and is associated with in vivo bone formation potential [35] [40]. The ratio of CD271+/CD146+ and CD271+/CD146- subsets changes with donor age [40].

- SSEA-1 & CD49a: In mouse models, SSEA-1 identifies a primitive mesenchymal population, while CD49a is used for prospective isolation [35].

Phenotypic Marker Profiles for Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs)

Core Defining Markers for Human HSCs