Beyond the Dish: Evaluating the Physiological Relevance of iPSC-Derived Tissues for Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of the physiological relevance of tissues derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for biomedical research.

Beyond the Dish: Evaluating the Physiological Relevance of iPSC-Derived Tissues for Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of the physiological relevance of tissues derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for biomedical research. It explores the foundational principles of iPSC technology, details advanced methodologies for generating physiologically representative models like engineered tissues and organoids, and addresses key challenges in maturation, reproducibility, and scalability. The content critically examines validation strategies, including comparative transcriptomic analyses and functional assays, to benchmark these models against native human physiology. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current advancements and persistent gaps, offering a roadmap for leveraging iPSC-derived tissues to enhance drug discovery and clinical translation.

The iPSC Revolution: Foundations for Modeling Human Physiology

The field of somatic cell reprogramming was revolutionized in 2006 when Takahashi and Yamanaka demonstrated that introducing four specific transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (collectively known as the OSKM factors)—could reprogram mouse fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [1] [2]. This groundbreaking discovery proved that mature, differentiated cells could be returned to a pluripotent state without controversial embryonic sources, earning Shinya Yamanaka and John Gurdon the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine [2]. The subsequent derivation of human iPSCs in 2007 opened unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine [3] [2].

The fundamental principle underlying reprogramming is that somatic cells maintain a complete genetic code despite differentiation, with cellular identity being determined by reversible epigenetic mechanisms rather than irreversible genetic changes [2] [4]. Reprogramming essentially reverses the developmental process, erasing somatic epigenetic memory and reestablishing the pluripotent state through profound remodeling of chromatin structure, DNA methylation patterns, and gene expression profiles [2]. This process involves two broad phases: an early stochastic phase where somatic genes are silenced and early pluripotency genes activated, followed by a more deterministic phase where late pluripotency genes are established [2].

Core Reprogramming Methodologies: A Comparative Analysis

Reprogramming Factor Combinations

The original OSKM factors remain the foundation for most reprogramming approaches, but significant optimizations have been developed to address safety concerns and improve efficiency. Research has revealed that the c-MYC component, while enhancing efficiency, acts as an oncogene and poses significant tumorigenic risks [1]. Subsequent studies have identified alternative factor combinations that minimize this risk while maintaining reprogramming capability.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Reprogramming Factor Combinations

| Factor Combination | Components | Efficiency | Safety Profile | Key Advantages | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSKM | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC | High | Lower (oncogenic c-MYC) | Gold standard, well-characterized | Basic research, early proof-of-concept studies |

| OSK | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 | Moderate | Higher (c-MYC free) | Reduced tumorigenic risk | Preclinical therapeutic development |

| OSNL | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 | Moderate | Higher (c-MYC free) | Alternative non-oncogenic combination | Disease modeling, therapeutic applications |

| L-Myc variant | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, L-MYC | High | Higher (reduced oncogenicity) | Family member with lower tumorigenic potential | Clinical translation, safety-sensitive applications |

| OCT4-only (specific contexts) | OCT4 alone in neural stem cells | Variable | High (minimal factors) | Demonstrates OCT4's pivotal role | Mechanistic studies, specialized applications |

Alternative factors have been identified that can substitute for components of the original OSKM combination. KLF2 and KLF5 can replace KLF4, while SOX1 and SOX3 can substitute for SOX2 [1]. Similarly, L-MYC and N-MYC can replace c-MYC with reduced oncogenic risk [1]. Beyond transcription factor family members, other genes and small molecules can enhance or replace core factors. Nuclear receptor NR5A2 can substitute for OCT4, while the small molecule RepSox can replace SOX2 in reprogramming cocktails [1]. Additional factors like Esrrb and Glis1 can serve as alternatives to c-MYC, addressing safety concerns while maintaining efficiency [1].

Delivery Systems for Reprogramming Factors

The method used to deliver reprogramming factors significantly impacts the genomic integrity, safety profile, and clinical potential of resulting iPSCs. Initial approaches relied on integrating viral vectors, raising concerns about insertional mutagenesis and tumorigenesis. The field has subsequently developed numerous non-integrating delivery methods to enhance safety profiles.

Table 2: Comparison of Reprogramming Factor Delivery Systems

| Delivery Method | Genetic Integration | Efficiency | Safety Profile | Technical Complexity | Clearance/Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrovirus | Yes (random) | High | Low (insertional mutagenesis) | Moderate | Persistent expression |

| Lentivirus | Yes (random) | High | Low (insertional mutagenesis) | Moderate | Persistent expression |

| Sendai Virus | No (episomal) | High | High | Moderate | Cleared by passage 10 [5] |

| Adenovirus | No (episomal) | Low | High | High | Transient (weeks) |

| Episomal Plasmid | No (episomal) | Low to moderate | High | Low | Lost with cell divisions |

| Synthetic mRNA | No | Moderate | High | High (requires multiple transfection) | Transient (days) |

| Recombinant Protein | No | Very low | High | High (requires multiple treatment) | Transient (hours/days) |

Integration-free methods like Sendai virus reprogramming have become particularly valuable for generating clinically relevant iPSCs. This approach preserves genomic integrity while maintaining high reprogramming efficiency, with the viral vector typically cleared by passage 10 [5]. The resulting iPSCs demonstrate normal karyotypes and proper differentiation into all three germ layers, making them suitable for regenerative medicine applications [5].

Chemical Reprogramming Approaches

A fundamentally different approach involves using only small molecules to induce pluripotency, eliminating the need for genetic manipulation entirely. Fully chemical reprogramming of murine fibroblasts was first achieved in 2013 using seven small-molecule compounds [2], and the approach has since been adapted for human cells.

Recent advances have demonstrated robust chemical reprogramming methods for human blood cells, achieving efficient generation of human chemically induced pluripotent stem (hCiPS) cells from both cord blood and adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells [6]. This method works with both fresh and cryopreserved blood cells across different donors and can generate over 100 hCiPS colonies from a single drop of fingerstick blood [6]. Chemical reprogramming operates through fundamentally different molecular pathways compared to transcription factor-based approaches, often involving a stepwise process with transient activation of regenerative programs that mimic a reversed developmental pathway [6].

Chemical reprogramming offers several advantages: small molecules are easily synthesized and standardized, the approach avoids genetic modification entirely, and it can achieve high efficiency with minimally invasive cell sources like blood [6]. These characteristics make chemical reprogramming particularly promising for clinical applications where safety and standardization are paramount.

Experimental Protocols for iPSC Generation and Validation

Sendai Virus Reprogramming Protocol

The Sendai virus (SeV) system represents one of the most widely used non-integrating methods for generating clinical-grade iPSCs. The following protocol outlines the key steps for efficient reprogramming of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs):

Initial Cell Preparation and Expansion

- Isolate PBMCs from whole blood using density gradient centrifugation

- Culture PBMCs in expansion medium supplemented with cytokines (SCF, IL-3, IL-6, EPO) for 7-10 days to establish erythroid progenitor cells (EPCs) [6]

- Maintain cells at a density of 0.5-1×10^6 cells/mL in tissue culture plates at 37°C, 5% CO₂

Viral Transduction

- Harvest expanded EPCs and seed at 1×10^5 cells per well in 6-well plates coated with retronectin

- Transduce cells with CytoTune-iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming Kit containing SeV vectors encoding OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC at an MOI of 3-5

- Centrifuge plates at 1000×g for 30 minutes to enhance viral attachment (spinoculation)

- Incubate at 37°C for 24 hours, then replace with fresh expansion medium

Transition to Pluripotency Conditions

- 24 hours post-transduction, transfer transduced cells to feeder-free culture vessels pre-coated with recombinant human vitronectin

- Transition culture medium to Essential 8 Flex medium supplemented with small molecule enhancers (e.g., 0.5mM sodium butyrate, 0.5mM valproic acid)

- Change medium daily and monitor for emergence of compact, ESC-like colonies (typically 14-21 days post-transduction)

Colony Picking and Expansion

- Manually pick individual iPSC colonies based on morphological criteria (high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, distinct borders) between days 21-28

- Transfer colonies to 96-well plates pre-coated with vitronectin using collagenase IV treatment

- Expand clonal lines through sequential passaging and bank at early passages (P3-P5)

Figure 1: Sendai Virus Reprogramming Workflow

Chemical Reprogramming Protocol for Blood Cells

For chemical reprogramming of human blood cells, the following optimized protocol has demonstrated high efficiency across multiple donors:

Blood Cell Preparation

- Isolate mononuclear cells from cord blood (CBMCs) or peripheral blood (PBMCs) using Ficoll density gradient centrifugation

- Culture cells in erythroid progenitor cell (EPC) medium consisting of StemSpan SFEM II supplemented with EPO (2 U/mL), SCF (100 ng/mL), IL-3 (10 ng/mL), and dexamethasone (1µM) for 7 days

- Passage cells every 2-3 days maintaining density at 0.5-1×10^6 cells/mL

Chemical Reprogramming Induction

- Seed 5×10^4 EPCs per well in 12-well plates pre-coated with laminin-521

- Initiate reprogramming using stage-specific small molecule combinations:

- Stage 1 (Days 0-7): VPA (0.5mM), CHIR99021 (3µM), 616452 (2µM), Forskolin (10µM) in EPC medium

- Stage 2 (Days 7-21): VPA (0.5mM), CHIR99021 (3µM), 616452 (2µM), Forskolin (10µM), DZNep (0.5µM), TTNPB (1µM) in pluripotency induction medium

- Stage 3 (Days 21+): VPA (0.5mM), CHIR99021 (3µM), 616452 (2µM) in Essential 8 Flex medium

- Change medium every other day and monitor for adherent cell emergence and colony formation

hCiPS Colony Expansion

- Manually pick emerging colonies between days 28-35 based on compact morphology and well-defined borders

- Transfer to vitronectin-coated plates in Essential 8 Flex medium

- Passage using EDTA solution (0.5mM) every 5-7 days at 70-80% confluence

Quality Control and Validation Assays

Rigorous characterization is essential to confirm pluripotency and genomic integrity of generated iPSCs:

Pluripotency Marker Validation

- Immunocytochemistry: Fix cells with 4% PFA, permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stain for nuclear pluripotency markers (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) and surface markers (SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81) [5]

- qPCR Analysis: Isolve RNA using TRIzol, synthesize cDNA, and perform quantitative PCR for endogenous pluripotency genes (POUSF1, SOX2, NANOG) with normalization to housekeeping genes (GAPDH, HPRT1)

Trilineage Differentiation Capacity

- Embryoid Body Formation: Harvest iPSCs with collagenase IV, culture in suspension in differentiation medium (DMEM/F12 with 20% FBS, 1% NEAA, 1mM L-glutamine) for 7 days

- Directed Differentiation: Differentiate iPSCs into representative lineages:

- Ectoderm: Neural induction using dual SMAD inhibition (dorsomorphin 1µM, SB431542 10µM) for 10 days, followed by immunostaining for PAX6 and NESTIN [5]

- Mesoderm: Mesodermal induction with BMP4 (50ng/mL) and Activin A (100ng/mL) for 5 days, analyze for BRACHYURY and NKX2.5 expression [5]

- Endoderm: Definitive endoderm differentiation using Activin A (100ng/mL) and CHIR99021 (3µM) for 5 days, validate with FOXA2 and SOX17 immunostaining [5]

Genomic Integrity Assessment

- Karyotype Analysis: Perform G-banding chromosomal analysis at 400-550 band resolution to confirm normal karyotype (46,XX or 46,XY) [5]

- Sendai Clearance Testing: Confirm absence of SeV genome by RT-PCR targeting SeV RNA using primers for the KOSM genes at passage 10 [5]

- Mycoplasma Testing: Regular mycoplasma screening using PCR-based detection methods

Molecular Mechanisms of Reprogramming

Signaling Pathways in Pluripotency Acquisition

The reprogramming process involves coordinated activation and suppression of multiple signaling pathways that collectively establish and maintain the pluripotent state. Understanding these pathways is essential for optimizing reprogramming efficiency and directing differentiation.

Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling The Wnt pathway plays a dual role in reprogramming, with precise temporal control being critical for success. In the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway, Wnt ligands bind to Frizzled receptors and LRP5/6 co-receptors, disrupting the β-catenin destruction complex (Axin, APC, GSK3β, CK1α) [7]. This prevents β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation, allowing its accumulation and translocation to the nucleus where it partners with TCF/LEF transcription factors to activate pluripotency genes [7]. Small molecule GSK3β inhibitors like CHIR99021 enhance reprogramming by stabilizing β-catenin, particularly during the early stages [1] [6].

TGF-β/SMAD Signaling The TGF-β pathway supports pluripotency through multiple mechanisms. Signaling through SMAD2/3 activated by TGF-β, Activin A, and Nodal supports self-renewal of primed pluripotent stem cells [8]. Simultaneously, BMP-activated SMAD1/5/8 signaling must be carefully balanced, as BMP promotes differentiation in most contexts but supports self-renewal in specific stem cell types [8]. Small molecule TGF-β pathway inhibitors (SB431542, A83-01) are commonly used in reprogramming to overcome epigenetic barriers and enhance mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) [1].

Additional Signaling Pathways Multiple other pathways contribute to establishing pluripotency. Hedgehog signaling can potentiate Wnt pathway activity and is essential for embryonic development [7]. Notch signaling regulates cell fate decisions through cell-cell communication and can influence reprogramming efficiency [8]. The Hippo pathway interacts with Wnt signaling through β-catenin and YAP/TAZ interactions, forming a complex regulatory network important for tissue size control and stem cell maintenance [7].

Figure 2: Key Signaling Pathways in Pluripotency

Epigenetic Remodeling During Reprogramming

Reprogramming involves comprehensive epigenetic remodeling to erase somatic memory and establish a pluripotent epigenome. Key changes include:

DNA Methylation Dynamics Pluripotent stem cells exhibit unique DNA methylation patterns characterized by global hypomethylation with focal hypermethylation at specific regulatory elements [4]. During reprogramming, somatic cell methylation patterns are erased through active and passive demethylation processes, followed by establishment of pluripotency-specific patterns. Studies comparing iPSCs from related donors demonstrate that iPSCs maintain donor-specific DNA methylation patterns even after reprogramming, indicating that some epigenetic variation persists despite comprehensive remodeling [4].

Histone Modification Changes The chromatin landscape undergoes dramatic reorganization during reprogramming. Somatic-specific histone marks (H3K9me3, H3K27me3) are removed from pluripotency genes, while activating marks (H3K4me3, H3K27ac) are established. Histone modifiers including SUV39H1, YY1, DOT1L, and Jhdm1a/1b significantly influence reprogramming efficiency [1]. Small molecule epigenetic modulators such as histone deacetylase inhibitors (valproic acid, sodium butyrate, trichostatin A) and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (5-aza-cytidine, RG108) enhance reprogramming by facilitating epigenetic plasticity [1].

Chromatin Accessibility Changes Reprogramming involves widespread alterations in chromatin accessibility, with closed chromatin regions in somatic cells becoming accessible in pluripotent states. ATAC-seq analyses reveal that epigenetic variation increases as cells differentiate, while the direct relationship with genetic variation becomes stronger in iPSCs compared to differentiated cells [4]. This suggests that reprogramming creates a ground state with stronger genetic control over epigenetic patterns, which then diversifies during differentiation.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC Generation and Characterization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC/L-MYC | Core transcription factors for pluripotency induction | L-MYC reduces tumorigenic risk compared to c-MYC [1] |

| Delivery Systems | CytoTune-iPS 2.0 Sendai Virus, Episomal plasmids, Synthetic mRNA | Factor delivery with varying integration profiles | Sendai virus offers high efficiency with clearance by passage 10 [5] |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | VPA, Sodium butyrate, Trichostatin A, CHIR99021, RepSox, 616452 | Epigenetic modulators and signaling pathway inhibitors | Significantly improve efficiency (up to 6.5-fold with VPA + 8-Br-cAMP) [1] |

| Culture Matrices | Vitronectin, Laminin-521, Matrigel | Extracellular matrix support for pluripotency | Defined matrices (vitronectin) preferred for clinical applications |

| Pluripotency Media | Essential 8, mTeSR1, Pluripotency induction medium | Support iPSC self-renewal and expansion | Chemically defined formulations enhance reproducibility |

| Characterization Antibodies | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81 | Pluripotency marker validation | Combined immunocytochemistry and flow cytometry for validation [5] |

| Differentiation Reagents | BMP4, Activin A, CHIR99021, dorsomorphin, SB431542 | Directed differentiation into three germ layers | SMAD inhibition critical for neural ectoderm differentiation [5] |

| Quality Control Assays | G-banding karyotyping, Mycoplasma PCR, SeV clearance testing | Genomic integrity and safety validation | Mandatory for clinical-grade iPSC lines [5] |

The journey from somatic cells to pluripotency has evolved dramatically since the initial discovery of iPSCs in 2006. The core reprogramming principles now encompass diverse methodologies including integration-free factor delivery, chemical reprogramming, and precise modulation of signaling pathways. Current approaches prioritize safety through non-integrating methods and reduced reliance on oncogenic factors while maintaining high efficiency through small molecule enhancers and optimized culture conditions.

The physiological relevance of iPSC-derived tissues continues to improve through better understanding of reprogramming mechanisms, particularly the epigenetic remodeling processes that create a authentic pluripotent state. As reprogramming protocols become more standardized and efficient, iPSC technology is poised to advance numerous applications including disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine. The ongoing development of chemically defined, xeno-free systems will further enhance the translational potential of iPSC-derived tissues for clinical applications.

The advent of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has revolutionized regenerative medicine and in vitro disease modeling. First introduced in 2006 by Shinya Yamanaka and colleagues, iPSCs are generated by reprogramming somatic cells to a pluripotent state through the transient overexpression of key transcription factors, most commonly Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM) [2] [9]. Unlike human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), iPSC derivation does not require the destruction of human embryos, circumventing ethical concerns while providing an invaluable reservoir of patient-specific pluripotent cells [10] [9]. However, the critical challenge remains thoroughly validating the pluripotency of the iPSC starting platform to ensure these cells possess the differentiation capacity and functional equivalence necessary for reliable research and clinical applications. This guide objectively compares the key markers and validation methodologies for confirming true pluripotent status in iPSCs, providing researchers with a framework for rigorous quality assessment.

Core Pluripotency Markers: Molecular Signatures of iPSCs

The molecular profile of fully reprogrammed iPSCs closely resembles that of hESCs, characterized by specific surface antigens, transcription factors, and enzymatic activities.

Table 1: Key Molecular Markers for Validating iPSC Pluripotency

| Marker Category | Specific Markers | Detection Method | Acceptance Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Antigens | SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81 [11] | Flow Cytometry, Immunocytochemistry | Expression on ≥75% of the cell population [12] |

| Transcription Factors | Oct3/4, Sox2, Nanog [9] [11] | Immunocytochemistry, RNA Analysis | Nuclear expression, significant transcriptional upregulation |

| Enzymatic Activity | Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) [9] | Colorimetric or Fluorescent Assay | High enzymatic activity visually detectable in colonies |

The expression of these core markers is regulated by an interconnected autoregulatory loop, with Oct4 and Sox2 playing particularly pivotal roles in establishing and maintaining the pluripotent state [9]. The validation of these markers should be performed using standardized assays. For flow cytometry, the use of a fluorescence minus one (FMO) control is advised to ensure accurate gating and control for fluorescent spread [12].

Functional Validation of Pluripotency: Beyond Molecular Markers

While molecular marker expression is necessary, it is insufficient alone to confirm full pluripotency. Functional assays are required to demonstrate the fundamental capacity of iPSCs to differentiate into derivatives of all three embryonic germ layers.

In Vitro Trilineage Differentiation

The gold standard in vitro assay involves differentiating iPSCs into ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm lineages, typically via embryoid body (EB) formation [10]. The directed differentiation potential can be assessed with a lineage scorecard, with a proposed detection limit of at least two out of three positive lineage-specific markers for each germ layer being a suitable criterion for validation [12].

In Vivo Teratoma Formation

The injection of iPSCs into immunodeficient mice leads to the formation of teratomas—complex tumors containing tissues from all three germ layers, such as neural tissue (ectoderm), cartilage (mesoderm), and epithelial structures (endoderm) [10]. This assay remains a rigorous, though time-consuming, test of functional pluripotency.

Epigenetic Landscape and Pluripotency Assessment

The reprogramming process involves profound remodeling of the epigenome to reset the somatic cell's epigenetic memory and establish a pluripotent state [2]. While global DNA methylation patterns between hiPSCs and hESCs are largely similar, studies have reported subtly different methylated regions [10]. Some differences are attributed to epigenetic memory—a persistence of epigenetic marks from the somatic cell of origin [10]. However, these differences tend to diminish with continuous cell passaging [10]. Analysis of global histone modification patterns (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27me3) provides additional insight into the epigenetic state of the pluripotency network.

iPSCs vs. ESCs: A Comparative Analysis of Pluripotency

The equivalence between iPSCs and the "gold standard" hESCs has been extensively debated. Overall, the molecular and functional profiles of iPSCs and hESCs are remarkably similar, though not always identical [10] [13].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Pluripotency in hESCs and hiPSCs

| Characteristic | Human Embryonic Stem Cells (hESCs) | Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (hiPSCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Inner cell mass of the blastocyst [10] | Reprogrammed somatic cells [9] |

| Ethical Considerations | Controversial due to embryo destruction [10] [9] | Ethically favorable; no embryos required [9] [11] |

| Genetic Background | Unique per line | Can be patient-specific [10] |

| Transcriptional Profile | Reference "gold standard" [10] | Largely similar, but subtle differences and increased variability reported [10] [13] |

| Epigenetic State | Established pluripotent epigenome | May retain epigenetic memory of cell of origin; can acquire aberrant methylation [10] |

| Functional Differentiation | Robust, high yield of differentiated progeny [10] | Can be variable and less efficient for some lineages (e.g., neural, cardiovascular) [10] |

| Tumorigenicity Risk | Teratoma formation | Teratoma formation; potential risk from integrating reprogramming vectors [9] |

Some studies comparing isogenic cell lines (those with the same genetic background) have found minimal differences in gene expression and methylation profiles between hiPSCs and hESCs, suggesting that many reported discrepancies may be due to genetic variation rather than the reprogramming process itself [14]. Furthermore, a 2017 study demonstrated equivalent neuronal differentiation potential between genetically unmatched hESCs and integration-free hiPSCs, with the derived motor neurons showing similar functionality in a neural muscular junction assay [13].

Quality Control in GMP-Compliant iPSC Production

For clinical applications, validation under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards is essential. Key validated parameters for GMP batch release include the absence of residual reprogramming vectors and demonstration of directed differentiation potential [12]. Screening for residual episomal vectors should occur between passages eight and ten, as testing at earlier passages might lead to unnecessary rejection of lines that have not yet fully cleared the vectors [12]. A minimum input of 20,000 cells (120 ng of genomic DNA) is recommended for the accurate determination of residual vectors [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for iPSC Validation

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Validation

| Reagent/Category | Example Product(s) | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Culture Medium | Essential 8, mTeSR Plus [11] | Maintains iPSCs in a stable, undifferentiated state for consistent analysis. |

| Extracellular Matrix | Vitronectin, ES-Matrigel [11] | Provides a defined, xeno-free substrate for robust iPSC growth. |

| Reprogramming Vectors | ReproRNA-OKSGM, Episomal Vectors [9] [15] | Non-integrating systems for footprint-free iPSC generation. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Anti-SSEA-4, Anti-TRA-1-60 [12] [11] | Quantifies expression of key pluripotency surface markers. |

| Immunocytochemistry Antibodies | Anti-OCT4, Anti-NANOG [13] [11] | Visualizes nuclear localization of core pluripotency factors. |

| Trilineage Differentiation Kits | Commercially available directed differentiation kits | Provides a standardized system for functional validation of differentiation potential. |

| qPCR Assays | Pluripotency TaqMan Gene Expression Panels | Enables quantitative transcriptional analysis of pluripotency genes. |

Critical Considerations for Robust Validation

- Reprogramming Method: The choice of reprogramming vector (integrating vs. non-integrating) can significantly impact the genomic integrity and transcriptional profile of the resulting iPSCs [9]. Non-integrating methods are preferred for clinical applications.

- Genetic Background: The donor's genetic background is a major source of variability. Using isogenic controls is ideal for comparative studies [10] [14].

- Clonal Variation: Not all iPSC clones from the same reprogramming experiment are equal. Multiple clones should be characterized to select the most suitable line [10].

- Passage Number: Epigenetic memory tends to fade with passaging, and residual reprogramming factors are diluted. Use mid-passage cells for validation to ensure a stable phenotype [10] [12].

Validating the pluripotent starting platform of iPSCs is a multi-faceted process that requires assessing molecular markers, functional differentiation capacity, and epigenetic status. While iPSCs demonstrate immense versatility and hold great promise for regenerative medicine and disease modeling, their equivalence to hESCs can be variable. A rigorous, standardized validation workflow incorporating the key markers and assays outlined in this guide is essential for researchers to ensure the quality and physiological relevance of their iPSC-derived tissues. As the field advances, the development of more refined "scorecards" and GMP-compliant quality control tests will further solidify iPSCs as a reliable and powerful tool for research and therapy.

A critical challenge in modern regenerative medicine and drug development is the efficient generation of physiologically relevant human tissues. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), with their capacity for unlimited self-renewal and ability to differentiate into any cell type, offer an unparalleled platform to address this challenge [2] [16]. However, the differentiation potential and functional maturity of the resulting tissues are highly dependent on the specific protocols and conditions employed. This guide objectively compares prominent differentiation strategies by analyzing key experimental data, providing researchers with a foundation for selecting and optimizing protocols for specific applications.

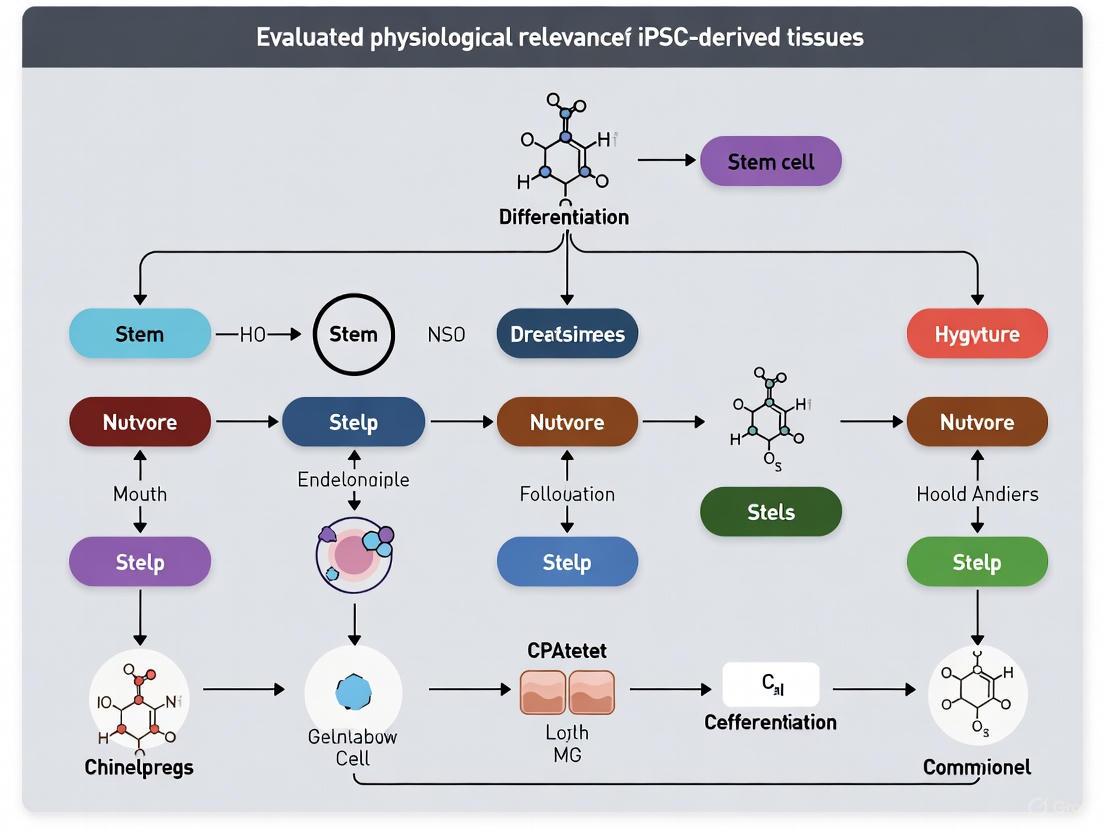

Key Signaling Pathways Governing iPSC Differentiation

The directed differentiation of iPSCs recapitulates embryonic development, relying on the precise activation or inhibition of key signaling pathways to guide cell fate. The following diagram illustrates the primary pathways involved in this process.

The activation of these pathways is context-dependent, varying with the timing, duration, and combination of signals. For example, BMP signaling has been identified as a key controller in the differentiation of neural crest cells and ectodermal placode cells, while FGF/BMP signaling cooperation is crucial for thyroid lineage specification [17] [18]. Similarly, Wnt and TGF-β signaling are instrumental in steering cells toward definitive endoderm, the precursor for liver, pancreas, and lung tissues [19].

Comparative Analysis of Cardiomyocyte Differentiation Protocols

The choice of pre-culture medium before initiating differentiation is a critical variable influencing the efficiency and outcome of iPSC-directed differentiation. Recent research has systematically evaluated this effect on the generation of cardiomyocytes.

Table 1: Impact of Pre-culture Medium on Cardiac Troponin T (cTnT) Positivity in Differentiated Cells

| Pre-culture Medium Type | Description | cTnT+ Cell Population (%) |

|---|---|---|

| StemFit AK03 (No. 1) | Standard pluripotency maintenance medium | 84% |

| Similar to E8 Medium (No. 3) | Low-nutrient, albumin-free formulation | 89% |

| Similar to E8 Medium (No. 2) | Low-nutrient, albumin-free formulation | 91% |

| Similar to EB Formation Medium (No. 5) | High-nutrient medium with KnockOut Serum Replacement (KOSR) | 95% |

Data adapted from a 2025 study investigating seven variations of pre-culture media [20].

The data demonstrates that medium composition directly impacts differentiation yield. Media approximating the high-nutrient environment of Embryoid Body (EB) Formation medium, which contains growth factors and proteins like albumin and transferrin, yielded the highest efficiency of cardiomyocyte differentiation (95% cTnT+ cells) [20]. This suggests that a nutrient-rich pre-culture environment may better prepare iPSCs for the subsequent stress of differentiation induction. Furthermore, the same study found that tissues derived using E8-like medium precursors exhibited higher protein expression levels of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), indicating not only higher yield but also enhanced tissue maturation [20].

Experimental Protocols for Directing iPSC Differentiation

Protocol 1: Directed Differentiation into Thyroid Follicular Cells

This protocol recapitulates developmental stages to derive thyroid follicular cells (TFCs) without exogenous transcription factors [18].

- Maintenance and Seeding: Culture human iPSCs on a suitable substrate (e.g., Matrigel) in a maintenance medium like mTeSR-1 or StemFit. Prior to differentiation, passage cells as single cells using an enzyme like TrypLE Select and plate them at an appropriate density, often with a Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632) to enhance survival.

- Definitive Endoderm Induction: Replace the maintenance medium with an endoderm induction medium. This typically involves activating key signaling pathways, notably WNT and TGF-β/Activin A signaling, for a defined period (e.g., 3-5 days) to specify the definitive endoderm lineage.

- Anterior Foregut Endoderm Induction: Following definitive endoderm formation, pattern the cells toward anterior foregut endoderm. This stage often uses a combination of growth factors and small-molecule inhibitors, such as BMP and TGF-β inhibitors, alongside FGF signaling activation.

- Thyroid Lineage Specification and Maturation: Specify the thyroid lineage using a combination of Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) and Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) signaling. Subsequent maturation into functional TFCs involves culture in a medium containing hormones such as TSH and IGF-1 to promote the formation of thyroid follicles capable of expressing thyroglobulin and thyroid hormones.

Protocol 2: Single-Step Direct Conversion into Functional Neurons

This alternative approach bypasses multi-stage differentiation by forced expression of a single neurogenic transcription factor, Neurogenin-2 (NGN2), to rapidly convert human ESCs and iPSCs into functional induced neuronal (iN) cells with nearly 100% yield and purity in under two weeks [21].

- Genetic Modification: Engineer the iPSC line to allow for inducible expression of the human NGN2 gene. This is typically achieved by lentiviral transduction or targeted integration of the NGN2 transgene under a doxycycline-inducible promoter.

- Induction and Culture: Initiate neuronal conversion by adding doxycycline to the culture medium. Cells are subsequently cultured in a neuronal induction medium supplemented with specific neurotrophic factors (e.g., BDNF, NT-3).

- Maturation and Purification: Within days, cells downregulate pluripotency markers and begin expressing neuronal proteins. After one week, cells can be replated onto supportive substrates (e.g., poly-D-lysine, laminin) and maintained in neuronal maturation media. The high purity of the culture often eliminates the need for further cell sorting.

This method produces neurons that form mature pre- and postsynaptic specializations, exhibit spontaneous network activity, and integrate synaptically upon transplantation into mouse brain [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for iPSC Differentiation

Successful differentiation relies on a core set of reagents and materials. The table below details essential components for the protocols discussed.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Differentiation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| StemFit AK03 / mTeSR Plus | Chemically defined medium for maintenance of iPSC pluripotency. | Pre-culture of iPSCs prior to initiation of differentiation [20]. |

| Essential 8 Medium | Low-nutrient, albumin-free medium for selective culture of iPSCs. | Pre-culture medium shown to support high-efficiency cardiac differentiation [20]. |

| iMatrix-511 / Laminin-521 | Recombinant laminin-based substrate for coating culture vessels. | Provides a defined surface for iPSC attachment and growth, supporting differentiation [20]. |

| Y-27632 (ROCK Inhibitor) | Small molecule that inhibits Rho-associated kinase. | Significantly improves survival of iPSCs after single-cell passaging [19]. |

| CHIR 99021 | Small molecule inhibitor of Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 (GSK-3). | Activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling; used in definitive endoderm and cardiomyocyte induction [20]. |

| Recombinant FGF2 (bFGF) | Growth factor that activates FGF signaling pathways. | Critical for maintaining pluripotency and for directing differentiation into mesoderm and endoderm lineages [18]. |

| Recombinant BMP4 | Growth factor that activates BMP signaling pathways. | Used in conjunction with FGF for thyroid lineage specification from anterior foregut endoderm [18]. |

| Doxycycline | Small molecule used for inducing gene expression. | Required for activating transgene expression (e.g., NGN2) in inducible direct conversion systems [21]. |

Enhancing Functional Maturity through Biomimetic Culture Systems

Achieving a mature, adult-like phenotype in iPSC-derived cells remains a significant hurdle. Simple 2D monocultures often yield immature, fetal-like cells. Advanced culture systems that better mimic the in vivo environment have shown great promise in overcoming this limitation.

- 3D Co-culture Systems: Research demonstrates that hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) co-cultured with human coronary artery endothelial cells in a 3D gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) hydrogel show significantly higher expression of cardiac maturation markers compared to standard 2D monocultures. Omics analysis confirmed the upregulation of pathways related to cardiac differentiation and contraction in the 3D system [22].

- Paracrine and Direct Contact Signaling: The functional maturation of hiPSC-CMs is further enhanced by co-culture with hiPSC-derived cardiac fibroblasts (hiPSC-CFs). This improvement is driven by a mechanism that requires both paracrine signaling (soluble factors) and direct cellular interactions. While conditioned medium from hiPSC-CFs improved some contractile properties, full functional maturation with enhanced contractile strain and kinetics required direct contact [22].

The following workflow summarizes the strategic options for generating functionally mature tissues from iPSCs, integrating the protocols and maturation strategies discussed.

The selection of a differentiation pathway is a fundamental decision that determines the physiological relevance and utility of the resulting iPSC-derived tissues. As the data indicates, protocol variables like pre-culture medium can alter differentiation efficiency by over 10% [20]. Furthermore, the choice between multi-stage directed differentiation and direct conversion trades off the recapitulation of development for speed and purity [18] [21]. For disease modeling and drug screening, the emergence of complex 3D co-culture systems is proving essential for driving cells beyond a fetal-like state into a more mature, adult phenotype that yields more predictive and translatable data [22]. By quantitatively comparing these approaches, researchers can make informed decisions to generate high-quality, functionally mature human tissues that advance the fields of regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

The advent of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized regenerative medicine and drug discovery by providing unprecedented access to human cell types for research and therapeutic applications. iPSCs are laboratory-made pluripotent stem cells produced by reprogramming somatic cells through the expression of specific pluripotency genes, a process first discovered in 2006 by Shinya Yamanaka's lab [23] [2]. Within this field, two distinct cellular source paradigms have emerged: patient-specific (autologous) approaches, which utilize cells derived from the same individual receiving the therapy, and allogeneic approaches, which employ cells from donor-derived sources manufactured for "off-the-shelf" use [24]. The choice between these paradigms represents a critical strategic decision for researchers and drug development professionals, with significant implications for physiological relevance, immune compatibility, manufacturing scalability, and clinical applicability. This comparison guide objectively examines the technical and practical considerations for both approaches within the context of evaluating physiological relevance in iPSC-derived tissue research.

Comparative Analysis: Key Parameters for Research and Development

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of patient-specific versus allogeneic iPSC sources across parameters critical for research and therapeutic development.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Patient-Specific and Allogeneic iPSC Sources

| Parameter | Patient-Specific (Autologous) iPSCs | Allogeneic iPSCs |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | iPSCs derived from and genetically identical to the patient/research subject [25] | iPSCs derived from a healthy donor, designed for universal application [24] |

| Immune Compatibility | High; minimal immune response upon transplantation [25] | Variable; requires immune suppression or HLA matching to prevent rejection [25] [26] |

| Physiological Relevance for Disease Modeling | Excellent for modeling patient-specific disease mechanisms and genetic backgrounds [23] [3] | Limited for personalized genetics; suitable for general disease mechanisms or when created with specific mutations [23] |

| Manufacturing Scalability | Low; individualized production runs are resource-intensive [24] | High; single, well-characterized cell bank can supply multiple patients or studies [26] [24] |

| Production Timeline & Cost | Timeline: Several months [24]Cost: High per unit [24] | Timeline: Immediate from cell bank [24]Cost: Lower per unit [24] |

| Batch-to-Batch Variability | High variability between individual patients/donors [26] | Low variability from a master cell bank [24] |

| Ideal Applications | Personalized medicine, disease modeling with patient genetics, cell therapies without immunosuppression [25] [3] | High-throughput drug screening, toxicology studies, off-the-shelf cell therapies [23] [26] |

Experimental Evidence: Immune Response and Functional Outcomes

Direct comparative studies, particularly in immunologically competent models, provide the most compelling data for evaluating these two cellular sources.

Key Findings from a Primate Transplantation Study

A seminal 2013 study directly compared autologous and allogeneic transplantation of iPSC-derived neurons into the brains of non-human primates without immunosuppression [25]. The experimental workflow and key outcomes of this critical study are detailed below.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow and key findings from the direct comparison of autologous and allogeneic iPSC-derived neural transplants in non-human primates [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Cell Source and iPSC Generation: Fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from four cynomolgus monkeys. iPSCs were generated using either retroviral vectors (for fibroblasts) or non-integrating episomal vectors (for PBMCs) [25].

Dopaminergic Neuron Differentiation: Selected iPSC clones were differentiated into neural cells using a growth factor-based protocol. Dissociated iPSCs were incubated in ultralow-attachment plates with BMP and Activin/NODAL signaling inhibitors to initiate neural induction. Midbrain dopaminergic (DA) neuron fate was induced by sequential addition of purmorphamine/FGF8 and FGF2/FGF20. The resulting cells expressed characteristic midbrain DA markers (LMX1A, FOXA2, TH, PITX3) [25].

Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) Mismatch Verification: Prior to transplantation, genotyping of MHC (Major Histocompatibility Complex) class I alleles was performed to confirm mismatch between donor and recipient animals in the allogeneic group [25].

Transplantation and Monitoring: Each animal received six stereotactic injections of iPSC-derived neural cells into the left striatum. Animals were observed for 3.5–4 months without immunosuppression. Monitoring included:

- PET imaging: Using [11C]PK11195 to visualize microglial activation [25].

- Serum cytokine analysis: Measuring IFN-γ levels as an indicator of systemic immune activation [25].

- Histological and immunofluorescence analysis: Post-mortem examination of graft survival and immune cell infiltration using markers for microglia (IBA-1), MHC class II, pan-leukocytes (CD45), T-cells (CD3), and cytotoxic T-cells (CD8) [25].

Quantitative Outcomes

The table below summarizes the key quantitative findings from this direct comparison study.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes from Primate iPSC-Derived Neuron Transplantation Study [25]

| Outcome Measure | Autologous Grafts | Allogeneic Grafts |

|---|---|---|

| Microglia Activation (IBA-1+ cells) | Minimal | Significantly higher |

| MHC Class II Expression | Low | Elevated, co-localized with host microglia |

| Leukocyte Infiltration (CD45+ cells) | Minimal | Significant accumulation |

| T-cell Infiltration (CD3+ cells) | Minimal | Present, ~60% were CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells |

| Dopaminergic Neuron Survival | 4,428 ± 1,130 neurons/tract | 2,247 ± 641 neurons/tract |

| PET [11C]PK11195 Uptake | No apparent uptake | Increased in 1 of 2 allografted animals at 3 months |

Implications for Research and Therapy

This direct comparison demonstrates that even in an immunologically privileged site like the brain, allogeneic grafts trigger a measurable acquired immune response that negatively impacts cell survival compared to autologous grafts [25]. For research requiring long-term engraftment or modeling of complex tissue environments, patient-specific cells may provide superior physiological relevance by avoiding these confounding immune responses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for iPSC Research

The table below catalogs key reagents and their applications in developing and differentiating patient-specific and allogeneic iPSCs.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC-Derived Tissue Research

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Convert somatic cells to pluripotent state | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM) [2] |

| Non-Integrating Vectors | Safer reprogramming for clinical applications | Sendai virus, episomal plasmids [3] |

| Neural Induction Media | Direct differentiation toward neural lineages | BMP/Activin/NODAL inhibitors [25] |

| Patterning Factors | Specify regional identity (e.g., midbrain) | Purmorphamine (SHH agonist), FGF8, FGF20 [25] |

| Cell Characterization Antibodies | Validate pluripotency and differentiation | Anti-OCT4, NANOG (pluripotency); Anti-TH, FOXA2, LMX1A (dopaminergic neurons) [25] |

| Immune Monitoring Reagents | Assess host immune response | Anti-IBA1 (microglia), anti-CD45 (leukocytes), anti-CD3 (T cells) [25] |

| GMP-Grade Materials | Clinical-grade manufacturing | cGMP-compliant cytokines, xeno-free matrices [24] |

Manufacturing and Scalability Considerations

The manufacturing pipeline differs significantly between patient-specific and allogeneic approaches, impacting their suitability for various research applications.

Figure 2: Comparative manufacturing workflows for patient-specific versus allogeneic iPSC-derived products, highlighting the scalability advantage of allogeneic approaches [24].

Manufacturing Protocols and Quality Control

Allogeneic iPSC Bank Establishment: For allogeneic products, a Master Cell Bank (MCB) is established from a single, well-characterized iPSC clone [24]. This process requires:

- Donor eligibility determination: Comprehensive health screening and infectious disease testing of the cell donor [24].

- Extensive characterization: Testing for sterility, mycoplasma, adventitious viruses, pluripotency, and genomic stability [24].

- cGMP compliance: All materials and processes must adhere to Current Good Manufacturing Practices, with animal-origin-free reagents preferred [24].

Patient-Specific iPSC Generation: For autologous products, the process begins anew for each patient/research subject, with more limited quality control focused on sterility, identity, and differentiation potential [24].

Purification Strategies: To ensure safety, particularly for removing residual undifferentiated iPSCs that could form teratomas, purification using specific surface markers is employed. Magnetic bead-based separation is often preferred over FACS for better compliance with closed-system manufacturing requirements [24].

The choice between patient-specific and allogeneic iPSC sources represents a fundamental trade-off between immune compatibility and manufacturing scalability. Patient-specific iPSCs offer the critical advantage of minimizing immune rejection, thereby providing more physiologically relevant models for long-term engraftment studies and enabling autologous therapies without immunosuppression [25]. Conversely, allogeneic iPSCs provide scalable, cost-effective "off-the-shelf" products suitable for high-throughput drug screening and broader therapeutic applications [23] [24].

Emerging technologies are blurring the distinction between these paradigms. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing enables correction of disease-causing mutations in patient-specific iPSCs [3], while also allowing creation of "universal donor" allogeneic cells through knockout of HLA genes [26]. Similarly, iPSC-derived organoids are being applied to both patient-specific disease modeling and allogeneic drug screening platforms [27]. The optimal choice depends fundamentally on the research question or clinical application, with the critical advantage going to patient-specific sources when immune compatibility is paramount, and to allogeneic sources when scalability and standardization are primary concerns.

Building Better Models: Advanced Fabrication of iPSC-Derived Tissues

The transition from two-dimensional (2D) to three-dimensional (3D) cellular models represents a paradigm shift in cardiovascular research, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine. While 2D cultures of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hPSC-CMs) have provided valuable insights, they inherently lack the structural complexity and cell-cell interactions found in native heart tissue [28]. This limitation has driven the development of more physiologically relevant models, primarily cardiac organoids and engineered heart tissues (EHTs), which better mimic the human heart's microenvironment.

The fundamental challenge in using hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes is their typically immature state, which limits their applications for disease modeling and drug screening [29]. Even extended culture periods up to one year fail to achieve maturity equivalent to in vivo conditions, indicating that either standard culture conditions are inhibitory or critical maturation stimuli are absent [29]. This maturation gap has significant implications for predicting human cardiac responses and remains a central consideration in evaluating the physiological relevance of iPSC-derived tissues.

Comparative Analysis of 3D Cardiac Models

Defining Characteristics and Applications

Cardiac organoids and EHTs represent complementary approaches with distinct design philosophies, fabrication methods, and application strengths, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of 3D Cardiac Models

| Feature | Cardiac Organoids | Engineered Heart Tissues (EHTs) |

|---|---|---|

| Formation Principle | Self-organization from stem/progenitor cells [30] | Bioengineering approaches with predefined architecture [28] [31] |

| Cellular Complexity | Multiple cardiac cell types (CMs, ECs, fibroblasts) [30] [29] | Primarily cardiomyocytes, often with engineered non-myocyte components [31] |

| Structural Fidelity | Recapitulates developmental cardiac structures [30] | Recapitulates adult cardiac tissue alignment and mechanics [31] |

| Primary Applications | Disease modeling, developmental biology, drug screening [30] | Drug safety testing (cardiotoxicity), regenerative therapy patches [28] [31] |

| Key Advantages | Patient-specific modeling, complex cell-cell interactions [30] | Controlled architecture, tunable mechanical properties, direct functional measurements [31] |

| Limitations | Size limitation due to lack of vasculature, variability [32] | Limited innate cellular complexity, requires external support [31] |

Quantitative Functional Comparison

Functional performance metrics provide critical insights for researchers selecting appropriate models for specific applications. Table 2 compares key parameters across different cardiac models.

Table 2: Quantitative Functional Comparison of Cardiac Models

| Parameter | 2D Cardiac Cultures | Cardiac Organoids | Engineered Heart Tissues | Native Adult Heart |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contractile Force | Not measurable | ~1-2 mN [29] | 1-5 mN [31] | >1000 mN |

| Maturation Markers (TNNI3/TNNI1 ratio) | <5% [29] | ~18% (SF-hCOs) to higher with directed maturation [29] | Varies with protocol, typically higher than 2D | ~100% |

| Spontaneous Beat Rate (bpm) | 30-60 [29] | 30-90 (DM-hCOs: reduced rate) [29] | 60-120 (often paced) | 60-100 (sinus rhythm) |

| Metabolic Capacity | Glycolytic dominance [29] | Intermediate, can be enhanced [29] | Can be enhanced via fatty acid supplementation [29] | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| Drug Response Predictive Value | Moderate (limited for chronic toxicity) [28] | High for disease-specific mechanisms [30] [29] | High for acute electrophysiology and contractility [28] | N/A |

Experimental Protocols for Advanced 3D Cardiac Models

Directed Maturation Protocol for Cardiac Organoids (DM-hCOs)

A recent breakthrough in cardiac organoid maturation addresses the critical limitation of immaturity in hPSC-derived models [29]. The directed maturation protocol incorporates specific pathway activators to drive cardiomyocytes toward a more adult-like state, as visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Directed maturation workflow for cardiac organoids. This protocol enhances maturity through transient activation of AMPK and ERR pathways [29].

The protocol builds upon a serum-free hCO foundation with two key additions:

- CHIR99021 (2 μM) during the first 2 days of hCO formation to enhance Wnt signaling

- Transient 4-day treatment with DY131 (3 μM) and MK8722 (10 μM) to activate estrogen-related receptors (ERR) and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), respectively [29]

This combinatorial approach induces metabolic switching to oxidative phosphorylation and enhances expression of mature sarcomeric proteins, including cardiac troponin I (cTnI). Phosphoproteomic analysis reveals that this treatment shares 48.2% of differentially regulated phosphosites with electrical pacing, including key cardiac regulators such as phospholamban (PLN S16/T17), which enhances sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium cycling [29].

Vascularized Cardiac Organoid Generation

A significant limitation of traditional organoids is the lack of functional vasculature, restricting their size and maturity. A recent Stanford Medicine protocol has overcome this challenge through optimized differentiation conditions that simultaneously generate multiple cardiac cell types [32].

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Vascularized Cardiac Organoid Formation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Protocol Timing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Maintenance | Small molecules for stem cell culture | Maintain starting cell pluripotency | Pre-differentiation |

| Mesoderm Induction | CHIR99021, BMP4 | Direct differentiation toward cardiac mesoderm | Days 0-3 |

| Cardiac Specification | Wnt inhibitors, FGFs | Promote cardiac progenitor formation | Days 3-5 |

| Vascular Induction | VEGFA, specific growth factor combinations | Enhance endothelial and smooth muscle differentiation | Days 5-10+ |

| Metabolic Maturation | Palmitate, linoleate, oleate | Promote oxidative metabolism | Days 17-22 |

| Maturation Agonists | DY131 (ERRβ/γ), MK8722 (AMPK) | Enhance transcriptional and metabolic maturity | Days 24-28 |

The winning "condition 32" from their screening of 34 different recipes produced organoids containing 15-17 different cell types, comparable to a six-week embryonic heart, with organized doughnut-shaped structures featuring cardiomyocytes and smooth muscle cells inside and an outer layer of endothelial cells forming branched, tubular vessels [32]. This self-organization approximates early embryonic development conditions, making these vascularized organoids valuable models for studying early human development.

3D Bioprinting of Engineered Heart Tissues

Bioprinting represents a bioengineering approach to creating EHTs with precise architectural control. The process involves several key stages, each with specific technical requirements, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: 3D bioprinting workflow for engineered heart tissues. Multiple printing modalities offer different trade-offs in resolution, speed, and biocompatibility [31].

Key bioprinting modalities each present distinct advantages for cardiac applications:

- Extrusion-based: Most common, good for high cell density, but lower resolution [31]

- Jetting-based (inkjet, laser-assisted, electrohydrodynamic): Higher resolution, suitable for precise cellular patterning [31]

- Light-based (stereolithography - SLA, digital light processing - DLP): High resolution, but potential UV toxicity [31]

- Volumetric: Emerging technique for rapid 3D fabrication [31]

Bioink design has evolved toward natural-synthetic hybrids combining bioactive components (decellularized extracellular matrix - dECM, collagen, fibrin) with synthetic tunability (gelatin methacryloyl - GelMA, polyethylene glycol - PEG, methacrylated hyaluronic acid - MeHA) [31]. Conductive components are often incorporated to enhance electrical coupling between cardiomyocytes.

Application Case Studies in Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

Modeling Inherited Cardiomyopathies

Cardiac organoids have demonstrated significant utility in modeling complex inherited heart diseases. When derived from human pluripotent stem cells with mutations in calsequestrin 2 (CASQ2) and ryanodine receptor 2 (RYR2), directed maturation hCOs (DM-hCOs) exhibit a pronounced pro-arrhythmia phenotype, effectively recapitulating key features of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) [29].

Similarly, modeling of cardiomyopathy caused by a desmoplakin (DSP) mutation resulted in fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction in DM-hCOs. This model led to the identification of INCB054329, a bromodomain and extra-terminal inhibitor, as a potential therapeutic compound mitigating the desmoplakin-related functional defect [29]. These findings establish matured cardiac organoids as versatile platforms for applications in cardiac biology, disease modeling, and drug screening.

Vascularized Organoids for Developmental Studies

The incorporation of functional vasculature enables novel applications in developmental biology and toxicology. When vascularized cardiac organoids were exposed to fentanyl, researchers observed increased blood vessel formation [32]. This finding demonstrates the potential of these models for studying how substances affect developing cardiovascular systems during early pregnancy, a period that is difficult to study in humans for ethical reasons.

The vascularized organoids also provide insights into diseases involving abnormal endothelial-epithelial interactions. For instance, using patient-derived iPSCs with FOXF1 mutations (causing alveolar capillary dysplasia with pulmonary venous misalignment), vascularized lung organoids revealed primary endothelial defects and secondary epithelial abnormalities that could not be modeled in traditional epithelial-only organoids [33].

Drug Screening and Cardiotoxicity Testing

Engineered heart tissues offer significant advantages for pharmaceutical screening through their reproducible contractile function and electrophysiological properties. Heart-on-a-chip (HoC) technologies developed using microfluidic chip-based platforms enable real-time monitoring of contraction and electrical activity, providing multifaceted information essential for capturing natural tissue responses to pharmacological compounds [28].

The enhanced maturation achieved in DM-hCOs makes them particularly valuable for drug testing, as they more accurately recapitulate adult human cardiac drug responses compared to traditional 2D cultures [29]. These advanced models can detect subtle contractile abnormalities and pro-arrhythmic effects that might be missed in less mature systems, potentially reducing late-stage drug attrition due to cardiotoxicity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 3D Cardiac Tissue Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Sources | Human iPSCs, ESCs | Starting cell material for differentiation | Patient-specific vs. standardized lines; genetic stability |

| Induction Factors | CHIR99021 (Wnt activator), BMP4 | Mesoderm induction and cardiac patterning | Concentration and timing critical for efficiency |

| Maturation Agonists | DY131 (ERRβ/γ), MK8722 (AMPK) | Enhance metabolic and functional maturity | Transient application sufficient for sustained effects |

| Metabolic Substrates | Palmitate, oleate, linoleate | Promote oxidative metabolic maturation | Fatty acid composition influences maturation outcomes |

| Matrix Materials | Matrigel, fibrin, collagen, synthetic hybrids | Provide 3D structural support | Defined vs. complex matrices; mechanical properties |

| Vascular Induction | VEGFA, FGF, specific combinatorial factors | Promote endothelial and smooth muscle differentiation | Multiple cell type coordination required |

| Functional Assessment | Calcium dyes, contractile force sensors | Evaluate electrophysiology and mechanical function | Real-time monitoring capabilities |

The evolution from 2D cultures to 3D cardiac organoids and engineered heart tissues represents significant progress in cardiovascular research. While both approaches enhance physiological relevance compared to traditional 2D systems, they offer complementary strengths: cardiac organoids excel in cellular complexity and disease modeling, whereas EHTs provide superior control over architecture and functional measurements.

Current research is focused on addressing remaining limitations, particularly in achieving full maturity and vascularization. The development of vascularized organoids that can connect to host circulation marks a critical step toward potential regenerative applications [32]. Similarly, directed maturation protocols that activate specific signaling pathways demonstrate that strategic interventions can substantially enhance functional maturity [29].

As these technologies continue to advance, they promise to accelerate drug discovery through more predictive human-relevant models and potentially enable patient-specific regenerative therapies for cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death worldwide [34]. The integration of these platforms with emerging technologies like 3D bioprinting, organ-on-chip systems, and single-cell genomics will further enhance their utility for both basic research and translational applications.

In the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, the extracellular matrix (ECM) serves as the fundamental architectural blueprint for cellular life. This non-cellular, three-dimensional network of macromolecules provides not only structural support but also critical biochemical and biomechanical cues that regulate cell behavior, signaling, and tissue development [35]. The growing emphasis on developing physiologically relevant human in vitro models, particularly those utilizing human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), has intensified the need for advanced scaffold systems that can accurately replicate the native ECM microenvironment [36]. Such systems are crucial for applications spanning drug development, disease modeling, and cellular therapeutics, where biological accuracy directly impacts translatability and predictive power.

The native ECM is a dynamic, complex structure whose composition varies across tissues and developmental stages. Its main components include collagens, elastin, laminin, fibronectin, proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans [35]. Furthermore, the ECM acts as a reservoir for various growth factors such as FGF, EGF, VEGF, and TGF-β, releasing them in a tightly regulated manner to guide processes including stem cell differentiation, angiogenesis, and tissue repair [35]. Beyond biochemistry, physical properties like ECM stiffness play a pivotal role in mechanotransduction, directly affecting cell fate decisions and lineage specification [35]. This multifaceted role makes the ECM an essential template for scaffold design, driving the development of innovative materials that can support the maintenance, expansion, and differentiation of hiPSCs in a biologically natural manner [36].

Categories of ECM-Mimetic Scaffolds

Scaffolds for tissue engineering are broadly classified into three categories based on their origin and composition: natural, synthetic, and hybrid. Each offers distinct advantages and limitations for replicating the native ECM.

Natural Scaffolds

Natural scaffolds are derived from biological sources and closely replicate the composition of native ECM, preserving structural integrity and biochemical cues essential for cellular functions [35].

- Decellularized ECM (dECM): Produced by removing cellular components and antigens from tissues or organs while preserving the native ECM structure and bioactive factors. This process minimizes immune and inflammatory responses while maintaining critical cues for cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [35]. Decellularization techniques include chemical, enzymatic, and physical methods [35].

- Matrigel: A basement membrane extract derived from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) mouse sarcoma, composed primarily of laminin, collagen IV, and entactin [37]. Despite its widespread use, Matrigel suffers from batch-to-batch variability, undefined composition, limited mechanical tunability, and ethical concerns regarding its tumor-derived, animal-based origin [37].

- Other Natural Polymers: Materials including hyaluronic acid, alginate, collagen, and chitosan are also used, but they often present challenges such as low mechanical strength, uncontrollable degradation, and potential immunogenicity [38].

Synthetic Scaffolds

Synthetic scaffolds are composed of lab-engineered polymers, enabling precise control over mechanical properties including strength, stiffness, elasticity, and porosity [35]. This category offers superior reproducibility, scalability, and tunability compared to natural materials.

- Thermoresponsive Polymers: Platforms such as poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (pNIPAM) allow for non-invasive cell harvesting through temperature-induced hydration changes, facilitating the creation of contiguous cell sheets with preserved cell-cell junctions and deposited ECM [39].

- Functionalized Synthetic Hydrogels: Customizable polymers can be engineered with specific bioactive motifs (e.g., RGD peptides, vitronectin, fibronectin) to enhance cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [40]. For example, a thermoresponsive terpolymer of NiPAAm, VPBA, and PEGMMA has demonstrated effective support for hiPSC pluripotency and robust cardiac differentiation [40].

- Conductive Polymers: Materials like polyaniline (PANI), polythiophene (PTh), and polypyrrole (PPy) can be used to create electroconductive scaffolds that regulate biological functions such as cell adhesion, migration, differentiation, and DNA synthesis, which is particularly beneficial for electrically excitable tissues [41].

Hybrid Scaffolds

Hybrid composites integrate both natural ECM components and synthetic materials, aiming to merge the bioactivity of biological components with the mechanical strength and processability of synthetic ones [35]. This approach offers a promising compromise for various tissue engineering applications.

- Nanomaterial-Enhanced Hydrogels: The integration of nanomaterials (e.g., carbon nanotubes, gold nanoparticles, graphene) into hydrogels can reinforce mechanical properties, enable conductivity, and introduce dynamic responsiveness [37].

- Functionalized Natural Scaffolds: Natural ECM scaffolds can be engineered with bioactive molecules to enhance their performance. For instance, collagen-based scaffolds have been functionalized with a dermatan sulfate molecule conjugated with collagen-binding and integrin-targeting peptides (LXW7-DS-SILY) to significantly improve endothelial progenitor cell attachment, growth, and neovascularization in diabetic wound healing [42].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Scaffold Categories for Tissue Engineering

| Category | Key Examples | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Scaffolds | Decellularized ECM (dECM), Matrigel, Collagen, Hyaluronic Acid | High bioactivity, innate cellular recognition, superior biocompatibility [35] | Batch-to-batch variability (e.g., Matrigel), poor mechanical properties, limited tunability, risk of immunogenicity [37] |

| Synthetic Scaffolds | pNIPAM, PEG-based hydrogels, Polyacrylamide, PANI-based polymers | Excellent reproducibility, tunable mechanical/chemical properties, scalable manufacturing [35] [40] | Typically lack innate bioactivity, may require complex functionalization, potential for inflammatory degradation by-products [35] [38] |

| Hybrid Scaffolds | Nano-enhanced hydrogels, peptide-functionalized ECM | Balanced bioactivity and mechanical control, customizable functionality [35] [37] | Increased complexity in design and fabrication, potential nanomaterial cytotoxicity, higher production costs [37] |

Key Scaffold Fabrication Techniques and Design Innovations

Multiple fabrication techniques are employed to create scaffolds that address specific mechanical, physicochemical, and biological requirements of target tissues [35].

Decellularization

This process involves the removal of cellular material from native tissues, leaving behind a complex, tissue-specific ECM scaffold. Techniques can be chemical, enzymatic, or physical, often used in combination [35]. A key advancement is the creation of ECM scaffolds with aligned microchannels (ECM-C) using sacrificial templates implanted in vivo. This method produces scaffolds with guided microchannels that promote oriented cell growth and enhanced vascularization upon implantation [38].

Electrospinning

This technique uses high voltage to fabricate micro- or nano-scale fibrous scaffolds that morphologically resemble native collagen fibers. It is applicable to a wide range of materials and produces scaffolds with a high surface-to-volume ratio and porosity, facilitating nutrient transport and cell-matrix communication [41]. For example, conductive nanofibrous scaffolds for skin tissue engineering have been created from polyaniline-grafted tragacanth gum and poly(vinyl alcohol) [41].

Multidimensional Bioprinting

3D, 4D, 5D, and 6D bioprinting technologies enable the layer-by-layer fabrication of complex structures using bioinks that incorporate ECM-derived components or synthetic polymers. This allows for precise spatial control over cell placement and scaffold architecture [35]. A significant challenge in this area is the limited availability of bioinks that adequately mimic the sophisticated biochemical and mechanical properties of the native ECM [43].

In Vivo Scaffold Engineering

An innovative approach involves using the body as a bioreactor. Sacrificial templates are implanted subcutaneously, where the host's body forms a vascularized tissue capsule around them. The template is then removed and the newly formed ECM is decellularized, resulting in an ECM scaffold with an innate and organized microarchitecture that supports cell infiltration and vascularization [38].

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Scaffold Platforms

Experimental data from recent studies provides a quantitative basis for comparing the performance of different scaffold platforms.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data of Selected Scaffold Systems

| Scaffold Type & Material | Key Experimental Findings | Cell Type / Assay | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Terpolymer (NiPAAm-based) | Cardiac differentiation efficiency: ~65% cTnT+ and ~25% cTnI+ cells; superior to Matrigel, Cultrex, and VitroGel controls [40] | hiPSCs / Flow Cytometry | [40] |

| ECM with Microchannels (ECM-C) | Porosity: 74.4 ± 2.1%; Anisotropy: 0.89 ± 0.12; Significant improvement in cell migration velocity and Euclidean distance vs. control scaffolds [38] | L6, RSC96, A10 cell lines / Cell Tracking | [38] |

| Conductive Nanofiber (TG-g-PANI/PVA) | Electrical Conductivity: 1.07 × 10⁻⁵ S/cm; Hemolysis Rate: <2%; HSA Protein Adsorption: 49 μg/mg [41] | L929 mouse fibroblasts / MTT, Hemolysis Assay | [41] |

| Functionalized SIS (LXW7-DS-SILY) | Significant improvement in wound healing, neovascularization, and collagen fibrillogenesis in a diabetic rat ischemic model vs. unfunctionalized SIS [42] | ZDF Rat EPCs / In Vivo Wound Model | [42] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide practical insights, here are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this guide.

Protocol: Evaluating hiPSC Cardiac Differentiation on Synthetic Terpolymers

This protocol is adapted from studies demonstrating enhanced cardiomyocyte differentiation using functionalized synthetic scaffolds [40].

- Scaffold Preparation and Functionalization: Synthesize the thermoresponsive terpolymer via free-radical polymerization of NiPAAm, VPBA, and PEGMMA monomers. Dissolve the sterile terpolymer in cold DI water to form a working solution. Coat culture surfaces and incubate at 37°C to form a stable layer. Functionalize by adsorbing bioactive molecules (e.g., RGD peptides, vitronectin, fibronectin) onto the polymer surface.

- hiPSC Culture and Seeding: Maintain hiPSCs in feeder-free conditions using defined culture media. Dissociate cells into a single-cell suspension and seed at an optimized density onto the functionalized terpolymer surfaces in culture media supplemented with a Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor.

- Cardiac Differentiation Induction: Upon reaching confluence, initiate differentiation using a standardized cardiac-directed protocol, such as sequential modulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway with CHIR99021 and IWP-4 small molecules in a defined, serum-free medium.

- Analysis of Differentiation Efficiency: Between days 10-15 of differentiation, harvest the cells for analysis.

- Flow Cytometry: Fix and permeabilize cells. Stain with fluorescently conjugated antibodies against cardiac-specific troponins (cTnT and cTnI). Analyze using flow cytometry to quantify the percentage of cardiomyocytes.

- Immunofluorescence: Fix cells and stain for cardiac markers (e.g., cTnT, α-actinin). Use DAPI for nuclear counterstaining. Image with confocal microscopy to assess sarcomeric organization and contractile structures.

- Gene Expression Analysis: Extract total RNA and perform reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) to evaluate the expression of key cardiac genes (e.g., NKX2-5, MYH6, TNNT2).

Protocol: Assessing Cell Guidance in ECM Scaffolds with Microchannels

This protocol outlines methods to quantify the guided cell behavior on anisotropic ECM-C scaffolds, as demonstrated in [38].

- Scaffold Preparation: Prepare ECM-C scaffolds using the in vivo sacrificial template method [38]. Briefly, implant aligned polycaprolactone (PCL) microfiber membranes subcutaneously in rats. After 4 weeks, explant the cellularized constructs, remove the PCL template by leaching, and decellularize using a combination of SDS and nucleases.

- Cell Seeding: Seed relevant cell types (e.g., skeletal muscle L6 cells, Schwann RSC96 cells, or vascular smooth muscle A10 cells) onto the ECM-C scaffolds and control scaffolds (e.g., non-porous decellularized capsules) at a defined density.

- Live-Cell Imaging and Tracking: 24 hours post-seeding, place the scaffolds in a live-cell imaging system maintained at 37°C and 5% CO₂. Acquire time-lapse images at regular intervals (e.g., every 10 minutes for 12-24 hours).

- Data Analysis: Track individual cell movements using cell tracking software.

- Velocity: Calculate the mean velocity of cells from their tracks.