Biomaterial Scaffolds for Stem Cell Delivery: Engineering the Niche for Regenerative Medicine

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in biomaterial scaffolds for stem cell delivery, a cornerstone of regenerative medicine.

Biomaterial Scaffolds for Stem Cell Delivery: Engineering the Niche for Regenerative Medicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in biomaterial scaffolds for stem cell delivery, a cornerstone of regenerative medicine. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of creating cell-instructive microenvironments. It delves into the diverse portfolio of natural, synthetic, and composite biomaterials, their applications in bone, wound, and neural tissue engineering, and the critical challenges of ensuring cell survival, integration, and safety. The content further synthesizes validation strategies and comparative study outcomes, offering a roadmap for translating scaffold-based stem cell therapies from the laboratory to the clinic.

The Blueprint of Life: How Biomaterial Scaffolds Create Stem Cell Niches

The stem cell niche constitutes a specialized temporal and spatial organization that provides the anatomical and functional interactions critical for stem cell fate determination [1] [2]. This dynamic microenvironment integrates cellular contacts, molecular signals, and biophysical cues to regulate stem cell self-renewal, quiescence, and differentiation [1]. Within the context of biomaterial scaffolds for therapeutic delivery, understanding native niche biology provides an essential blueprint for engineering synthetic microenvironments that can maintain stem cell potency and function after transplantation. This application note delineates the core components of physiological stem cell niches and provides detailed protocols for their replication in biomaterial design, offering researchers a framework for developing more effective stem cell-based therapies.

The concept of the stem cell niche was first hypothesized by Schofield as a specialized microenvironment required for stem cell maintenance [2]. The initial experimental demonstration emerged from studies of the C. elegans distal tip cell (DTC), a single mesenchymal cell that provides the essential microenvironment for germline stem cell (GSC) maintenance through Notch signaling [2]. This foundational concept has since expanded to encompass diverse tissue systems, with niches identified in bone marrow, intestinal crypts, skeletal muscle, and neural tissues [1] [2] [3].

Stem cell niches function not merely as passive support structures but as active agents of feedback control and coordination among tissue compartments [2]. They protect stem cells from damage while enabling responsiveness to physiological demands for cell replacement and repair. The emerging understanding of niche biology reveals that aged or altered niches significantly contribute to the decline in stem cell function associated with aging and disease, highlighting the therapeutic potential of niche-targeted interventions [1].

Table 1: Core Components of the Stem Cell Niche

| Component Category | Specific Elements | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Elements | Mesenchymal, endothelial, immune cells, Paneth cells (intestine) | Structural support, secretion of regulatory factors, immune modulation [1] [2] |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Integrins, laminin, fibronectin, collagen, proteoglycans | Structural scaffolding, mechanical cues, growth factor reservoir [1] [3] |

| Signaling Molecules | Wnt, Notch, TGF-β, FGF, chemokines | Regulation of self-renewal, quiescence, differentiation decisions [1] [2] |

| Biophysical Cues | Matrix stiffness, shear stress, oxygen tension, temperature | Influence on stem cell metabolism, proliferation, and lineage commitment [1] |

Analytical Methods for Niche Characterization

Protocol: Isolation of Niche-Specific Stem Cells and Stromal Components

This protocol details the isolation of Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells and their associated Paneth cells, which constitute a well-defined niche unit [2].

Materials and Reagents

- Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Stock #008875) - for identification of Lgr5+ stem cells

- Collagenase/Dispase solution (1-2 mg/mL in PBS) - for tissue dissociation

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffers (PBS with 2% FBS)

- Anti-CD24 antibody (eBioscience, cat. #11-0242-82) - for Paneth cell identification

- Intestinal epithelial cell culture medium:

- Advanced DMEM/F12

- 1x N2 supplement

- 1x B27 supplement

- 1mM N-acetylcysteine

- 50 ng/mL EGF

Procedure

Tissue Harvest and Dissociation:

- Euthanize Lgr5-EGFP mouse and immediately extract small intestine.

- Open intestine longitudinally, wash with cold PBS, and mince into 2-4 mm fragments.

- Incubate tissue fragments in collagenase/dispase solution for 30-45 minutes at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Pipette tissue digest vigorously every 10 minutes to facilitate dissociation.

- Pass cell suspension through 70μm cell strainer to remove undigested fragments.

Cell Sorting:

- Centrifuge cell suspension at 400 x g for 5 minutes and resuspend in FACS buffer.

- Incubate with anti-CD24 antibody (1:100 dilution) for 20 minutes on ice.

- Wash cells twice with FACS buffer and resuspend at 10-20 x 10⁶ cells/mL.

- Sort using FACS:

- Lgr5+ stem cells: EGFP+ CD24- population

- Paneth cells: EGFP- CD24hi population

- Collect sorted populations in ice-cooled collection tubes containing culture medium.

Validation:

- Assess purity by re-analyzing sorted populations.

- Confirm functional capacity of Lgr5+ cells by organoid formation assay.

Technical Notes

- Maintain cells at 4°C throughout the isolation process when possible to preserve viability.

- For optimal organoid formation, plate Lgr5+ cells in combination with Paneth cells (1:1 ratio) in Matrigel.

- This protocol can be adapted for other niche systems by modifying dissociation enzymes and surface markers.

Protocol: 3D Co-culture System for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Niche Modeling

This protocol establishes a biomimetic microenvironment for studying human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) and mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) [4].

Materials and Reagents

- Porous poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) scaffolds (prepared by thermal fiber bonding) [5]

- Human bone marrow-derived MSCs (Lonza, cat. #PT-2501)

- Human CD34+ HSPCs (StemCell Technologies, cat. #70002)

- HSC expansion medium:

- StemSpan SFEM II

- 100 ng/mL SCF

- 100 ng/mL TPO

- 50 ng/mL FGF-2

- 3D bioreactor system (optional, for perfusion culture)

Procedure

Scaffold Preparation:

- Sterilize PCL scaffolds (5mm diameter x 2mm thickness) in 70% ethanol for 30 minutes.

- Wash thoroughly with PBS and pre-condition in expansion medium for 2 hours at 37°C.

Cell Seeding:

- Seed MSCs at density of 1x10⁵ cells/scaffold and culture for 7 days to establish stromal layer.

- Subsequently seed CD34+ HSPCs at density of 5x10⁴ cells/scaffold.

- Maintain co-cultures in expansion medium with medium changes every 2-3 days.

Analysis:

- After 14 days, assess HSPC expansion by flow cytometry using CD34 and CD45 markers.

- Evaluate colony-forming potential by methylcellulose assay.

- Analyze spatial organization by confocal microscopy of immunostained scaffolds.

Technical Notes

- Scaffold porosity and stiffness can be modified to mimic specific niche properties.

- Incorporation of niche-specific cytokines (e.g., CXCL12) can enhance niche functionality.

- This 3D co-culture system more accurately recapitulates the bone marrow microenvironment compared to traditional 2D cultures.

Biomaterial Scaffolds as Synthetic Niches

The translation of stem cell therapies faces significant challenges, including poor cell survival, limited engraftment, and phenotypic instability following transplantation [5] [6]. Biomaterial scaffolds designed to replicate key aspects of native niches offer promising solutions to these limitations by providing tailored microenvironments that support stem cell function.

Table 2: Biomaterial Classes for Synthetic Niche Engineering

| Biomaterial Class | Examples | Advantages | Stem Cell Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Collagen, chitosan, alginate, hyaluronan, gelatin, silk fibroin | Innate biocompatibility, bioactive motifs, enzymatic degradation [5] | Neural repair, mesenchymal stem cell delivery, cartilage regeneration [5] |

| Synthetic Biodegradable Polymers | Poly(L-lactic acid), poly(glycolic acid), polycaprolactone, polyphosphoester | Tunable mechanical properties, controlled degradation rates, reproducible manufacture [5] | Hematopoietic stem cell expansion, cardiac tissue engineering [4] |

| Conductive Polymers | Polypyrrole, polythiophene, polyaniline | Electrical signal conduction, enhanced neurite outgrowth, neural cell activation [5] | Neural tissue engineering, rehabilitation after nerve injury [5] |

| Hybrid Systems | Protein-functionalized synthetic polymers, polymer-ceramic composites | Combinatorial advantages, multifunctionality, graded properties | Bone regeneration, osteogenic differentiation [6] |

Diagram: Native vs. Engineered Niche Signaling Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Stem Cell Niche Research and Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Markers | Lgr5-EGFP mice, CD34 antibodies, Pax7 antibodies | Identification and isolation of specific stem cell populations [2] [3] |

| Niche Signaling Modulators | Recombinant Wnt3a, Dll4-Fc, R-spondin-1, Noggin | Activation or inhibition of key niche signaling pathways [2] |

| Matrix Proteins | Laminin-521, Collagen IV, Fibronectin, Matrigel | Recreation of basal lamina components for stem cell support [1] [3] |

| Biomaterial Polymers | Polycaprolactone, chitosan, alginate, hyaluronic acid | Scaffold fabrication with tunable physical and biochemical properties [5] |

| Protease-Sensitive Linkers | MMP-cleavable peptides, heparin-binding domains | Creation of dynamically responsive matrices that remodel with cells [6] |

| Cytokine Delivery Systems | PLGA microparticles, affinity-based release systems | Spatiotemporal control of morphogen presentation in synthetic niches [6] |

Application Notes for Therapeutic Scaffold Design

Protocol: Biomaterial Scaffold for Neural Stem Cell Delivery

This protocol details the fabrication of an electrically conductive scaffold for neural stem cell (NSC) delivery to overcome limitations in neural repair [5].

Materials and Reagents

- Polycaprolactone (PCL) (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. #440744) - structural polymer

- Polypyrrole (PPy) (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. #577030) - conductive component

- Nerve growth factor (NGF) (PeproTech, cat. #450-01) - neurotrophic factor

- Electrospinning apparatus with high-voltage power supply

- Neural stem cell culture derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells

Procedure

Polymer Solution Preparation:

- Prepare 12% (w/v) PCL solution in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol.

- Add 3% (w/w) PPy relative to PCL mass and stir for 24 hours to ensure complete dissolution.

- Incorporate NGF (50 μg/mL) into the polymer solution immediately before electrospinning.

Scaffold Fabrication:

- Load polymer solution into 5mL syringe with 21G blunt needle.

- Set electrospinning parameters:

- Flow rate: 1.0 mL/hour

- Voltage: 15 kV

- Collector distance: 15 cm

- Collector rotation speed: 1000 rpm

- Collect aligned nanofibers on mandrel collector for 4 hours.

- Cross-link scaffolds with genipin (0.5% w/v) for 12 hours to stabilize structure.

Cell Seeding and Implantation:

- Sterilize scaffolds in 70% ethanol for 2 hours and UV irradiate for 30 minutes per side.

- Seed NSCs at density of 1x10⁶ cells/scaffold in neuronal differentiation medium.

- Culture for 7 days with medium changes every 2 days before in vivo implantation.

- For neural injury models, implant NSC-seeded scaffolds at lesion site using microsurgical techniques.

Technical Notes

- Scaffold conductivity can be modulated by varying PPy content (1-5% w/w).

- Alignment of nanofibers guides directional neurite outgrowth.

- Controlled release of NGF enhances NSC survival and differentiation.

- This scaffold design has applications in spinal cord injury and neurodegenerative disease models.

Developmental Transitions in Niche Composition

Understanding how niches change during development provides critical insights for designing age-appropriate therapeutic scaffolds. The transition from emerging fetal niches to adult niches involves significant changes in ECM composition, signaling networks, and cellular interactions [3].

Application in Aging and Disease

Aged niches display altered signaling profiles, modified ECM composition, and chronic inflammatory states that contribute to declining stem cell function [1]. Niche-targeted interventions represent promising strategies for rejuvenating stem cell function in age-related diseases. Biomaterial scaffolds can be designed to counteract age-related niche dysfunction through:

Delivery of Youthful Systemic Factors: Scaffolds can release factors present in young niches but diminished in aged environments.

Reduction of Senescent Cells: Incorporation of senolytics or modifiers of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).

ECM Rejuvenation: Provision of embryonic ECM components that restore regenerative capacity [3].

Inflammation Modulation: Controlled release of anti-inflammatory cytokines to counteract chronic inflammation in aged niches.

The stem cell niche represents a dynamic, multi-component signaling center that exerts precise control over stem cell fate decisions. As a design template, native niche biology informs the development of biomaterial scaffolds that can maintain stem cell potency and direct therapeutic outcomes after transplantation. The protocols and application notes provided here offer researchers a foundation for designing synthetic niches tailored to specific stem cell types and therapeutic applications.

Future directions in the field include the development of four-dimensional scaffolds that dynamically change their properties in response to environmental cues, the integration of multiple niche cells to recreate tissue-level complexity, and the personalization of scaffolds based on patient-specific niche characteristics. As understanding of niche biology continues to evolve, so too will the sophistication of biomaterial scaffolds, ultimately enhancing the efficacy and reliability of stem cell-based therapies.

Core Principles of the Bottom-Up Approach

The "bottom-up" paradigm in biomaterial design represents a fundamental shift from traditional methods. This approach prioritizes a deep understanding of the fundamental biological properties and microenvironmental needs of stem cells first, then engineering cell-instructive biomaterials specifically to support them [7]. Unlike conventional strategies that adapt cells to pre-existing materials, this framework designs biomaterials from the molecular level upward to address critical clinical translation challenges [7]. These challenges include differentiation variability, incomplete matching of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to somatic counterparts, functional maturity of derived cells, and poor survival of therapeutic cell populations like endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs) and multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) in hostile in vivo niches [7].

The "bottom" refers to the essential biological and microenvironmental requirements of stem cells, such as specific mechanical cues (e.g., matrix stiffness), biochemical gradients (e.g., morphogens), and precise cell-cell interactions [7]. The "up" represents the subsequent development of biomaterial platforms tailored to these specific requirements. By mirroring native stem cell niches, these tailored biomaterials significantly enhance differentiation fidelity, reprogramming efficiency, and functional tissue integration, offering a transformative roadmap for regenerative medicine [7].

Quantitative Characterization of Scaffolds and Cellular Response

A critical component of the bottom-up approach is the rigorous, quantitative characterization of both the scaffold's physical properties and the biological response of the encapsulated cells. The tables below summarize key parameters and methods.

Table 1: Quantitative Characterization of 3D Scaffold Architecture via Micro-CT

| Parameter | Description | Significance for Bone Tissue Engineering | Example Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macropore Size | Primary pore diameter; spherical pores ~500 µm in bioactive glass foams [8]. | Provides space for cell migration, tissue ingrowth, and vascularization [8]. | >500 µm [8] |

| Interconnect Size | Diameter of windows connecting adjacent macropores; distinct from pore throats [8]. | Dominates nutrient diffusion, cell communication, and tissue perfusion; critical for viability [8]. | >100 µm (minimum for bone ingrowth) [8] |

| Percentage Porosity | Volume fraction of void space within the scaffold [8]. | Influences total cell loading capacity and ultimate tissue volume [8]. | 85-92% (e.g., bioactive glass scaffolds) [8] |

| Permeability | Measure of fluid flow through the porous network; can be predicted from µCT data [8]. | Informs optimization of bioreactor conditions for cell culture and nutrient delivery [8]. | Modeled from 3D pore structure [8] |

Table 2: Direct Quantitative Analysis of Cells within 3D Scaffolds

| Analysis Type | Measured Parameter | Technical Basis | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Density/Distribution [9] | Number of cells per mm³ of scaffold; spatial distribution. | Fluorescence staining of nuclei (Hoechst 33342) and wide-field microscopy with Z-stack imaging [9]. | Direct cell counting within the intact 3D structure, avoiding destructive processing and associated cell loss [9]. |

| Proliferative Activity [9] | Dynamics of cell population growth over time. | Time-course analysis of cell nucleus counts within scaffold fragments using the above method [9]. | Enables assessment of cell cycle progression and expansion potential within the actual 3D microenvironment [9]. |

| Cell Viability [9] | Ratio of live to dead cells. | Sequential use of membrane-permeant (Hoechst 33342) and membrane-impermeant (Propidium Iodide) DNA dyes [9]. | Provides a direct viability metric within the scaffold, superior to indirect metabolic assays like MTT [9]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Non-Destructive 3D Analysis of Scaffold Architecture using Micro-CT

This protocol enables the quantitative, non-destructive 3D analysis of pore and interconnect size distributions, which are critical parameters for scaffold design [8].

- Step 1: Image Acquisition. Scaffolds are imaged using high-resolution X-ray micro-computed tomography (μCT). Acquire 3D images of the scaffold structure with sufficient resolution to resolve the smallest interconnects of interest (e.g., ~100 µm) [8].

- Step 2: Image Thresholding. Process the μCT images to distinguish between the solid scaffold material and the pore space. Apply a global threshold to create a binary (black and white) 3D image [8].

- Step 3: Pore & Interconnect Identification. Apply custom algorithms to the binary 3D image stack.

- Pore Identification: Use a combination of 3D distance mapping and watershed segmentation to identify and label individual pore cavities [8].

- Interconnect Identification: Apply a separate algorithm to detect the regions of open space that connect adjacent pores, treating them as distinct structural features [8].

- Step 4: Size Distribution Calculation. For each identified pore and interconnect, calculate its size. Generate full distributions (e.g., pore diameter, interconnect length) for the entire scaffold volume [8].

- Step 5: Validation. Validate the μCT-based size distributions against established methods such as mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) and manual 3D image analysis to ensure accuracy [8].

Micro-CT Analysis Workflow

Protocol: Direct Quantitative Analysis of Cells within a 3D Scaffold

This method allows for the direct counting of cell nuclei within an opaque, 3D scaffold, enabling accurate assessment of cell density, distribution, proliferation, and viability without destructive processing [9].

- Step 1: Sample Preparation and Staining.

- Place a scaffold fragment (≥ 0.64 cm²) into a well of a 24-well fluorescence plate with opaque walls.

- Add 1 µL of Hoechst 33342 solution (10 µg/mL) per 2 mL of culture medium in the well.

- Incubate for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Remove the dye medium and wash the scaffold fragment twice with PBS (2 mL per wash, 10-minute incubations) [9].

- Step 2: Data Visualization and Z-Stack Acquisition.

- Add 0.3-1.0 mL of PBS to the well to prevent drying.

- Transfer the plate to a wide-field fluorescence imager (e.g., Cytation 5) equipped with a Z-stack function.

- For each field of view, acquire images at multiple focal planes along the Z-axis to a depth of ≤ 530 µm. Use a 4x or 10x objective.

- The instrument software synthesizes the in-focus portions of each layer into a single, fully focused "stitched" Z-stack image for each field of view. Acquire at least 10 such images per sample [9].

- Step 3: Image Processing and Nuclei Counting.

- Process the stitched Z-stack images using image analysis software (e.g., Gen5).

- Apply a fluorescence intensity threshold filter (e.g., >7000 relative units) to count only brightly stained nuclei and to help separate closely spaced nuclei.

- Apply an object area filter (e.g., <30 µm²) to exclude non-nuclear artifacts or unseparated clusters.

- Visually confirm via a "mask" function that all nuclei are counted correctly and adjust filter thresholds if necessary for new scaffold types [9].

- Step 4: Quantitative Analysis.

- For each sample, calculate the average number of cells (N) from the ≥10 stitched Z-stack images.

- Calculate the number of cells per mm³ (K) using the formula: K = N / (B * C * D * 10⁻⁹) where B, C, and D are the dimensions (in µm) of the analyzed field of view along the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively [9].

- Step 5: Assessing Viability (Optional).

- Follow the staining procedure using a combination of Hoechst 33342 (stains all nuclei) and Propidium Iodide (PI, stains only nuclei of dead cells with compromised membranes).

- Acquire Z-stacks for both fluorescence channels and count the total nuclei (Hoechst) and dead nuclei (PI). Calculate viability as: (Total Nuclei - PI-positive Nuclei) / Total Nuclei [9].

Cell Quantification Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Bottom-Up Scaffold Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Hoechst 33342 [9] | Cell-permeant fluorescent dye that binds double-stranded DNA. | Enables live-cell nuclear staining for direct quantification within intact 3D scaffolds without the need for fixation [9]. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) [9] | Cell-impermeant fluorescent DNA dye. | Used in conjunction with Hoechst to identify dead cells with compromised plasma membranes in viability assays [9]. |

| Bioactive Glass (70S30C) [8] | Sol-gel derived foam scaffold (70 mol% SiO₂, 30 mol% CaO). | Example of an osteoconductive and bioactive scaffold material that stimulates bone cell activity and bonds to bone [8]. |

| Wide-Field Fluorescence Imager with Z-Stack [9] | Microscope system capable of acquiring images at multiple Z-planes and synthesizing fully focused images. | Essential for quantitative analysis in opaque 3D scaffolds, as it overcomes the limitations of light microscopy through optical sectioning [9]. |

| Image Analysis Software (e.g., Gen5) [9] | Software for processing stitched Z-stack images and applying counting filters. | Allows for automated, high-throughput counting using customizable filters for fluorescence intensity and object area to ensure accuracy [9]. |

The field of regenerative medicine is increasingly focused on combining advanced stem cell types with sophisticated biomaterial scaffolds to direct tissue repair and regeneration. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the unique properties and clinical translation pathways of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs) is crucial for designing next-generation therapies. These cells represent the most promising "key players" in clinical development, each offering distinct advantages and facing specific challenges. Critically, their therapeutic potential is profoundly influenced by their interaction with the three-dimensional biomaterial scaffold microenvironment, which provides essential physical and biochemical cues for cell survival, differentiation, and functional integration. This application note provides a structured comparison of these cell types, detailed experimental protocols aligned with their clinical applications, and essential tools for integrating them with scaffold-based delivery systems.

Stem Cell Profiles at a Glance

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Stem Cell Players for Scaffold-Based Therapies

| Feature | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells (ECFCs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Reprogrammed somatic cells (e.g., skin fibroblasts) [10] | Multiple tissues: bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord [11] [12] | Cord blood, peripheral blood, vessel wall [13] |

| Key Markers | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (reprogramming factors) [10] | CD73, CD90, CD105+; CD34, CD45, HLA-DR- [11] [12] | CD34, CD31, VEGFR2+; CD45, CD14- [13] |

| Differentiation Potential | Pluripotent (all three germ layers) [10] | Multipotent (mesodermal lineages: osteo-, chondro-, adipo-genic) [11] | Committed progenitor (endothelial lineage) [13] |

| Primary Mechanism of Action | Cell replacement via differentiation into target somatic cells [14] [10] | Paracrine signaling (growth factors, extracellular vesicles), immunomodulation [11] [15] | Blood vessel formation and direct vascular integration [13] [16] |

| Clinical Trial Landscape | 10 published studies, 22 ongoing trials (cardiac, ocular, cancer) [14] [10] | Over 10 approved therapies globally (GVHD, Crohn's, osteoarthritis) [11] [12] | No clinical trials to date; promising preclinical data [13] |

| Key Challenge for Delivery | Tumorigenicity risk from undifferentiated cells; need for precise lineage commitment within scaffold [10] | Variable potency based on donor age and tissue source; ensuring retention and survival post-transplantation [11] [12] | Very low frequency in blood; maintaining robust angiogenic function in diseased microenvironments [13] [16] |

| Scaffold Design Implication | Requires sophisticated, spatially defined cues for precise differentiation. | Ideal for incorporation into hydrogels and 3D-printed scaffolds that enhance paracrine effects. | Needs pro-angiogenic microenvironments and micro-patterning to guide vascular network formation. |

Detailed Clinical Applications & Experimental Protocols

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)

iPSCs are reprogrammed adult cells that have been returned to an embryonic-like pluripotent state, capable of differentiating into any cell type in the body [10]. Their application is emerging in clinical trials for conditions like cardiac disease, ocular disorders, and cancer, with 10 published clinical studies and 22 ongoing registered trials as of early 2025 [14] [10]. A primary challenge is the risk of tumorigenicity, which necessitates rigorous purification of the differentiated cell product before transplantation [10].

Protocol 1: In Vitro Differentiation of iPSCs into Cardiomyocytes for Cardiac Patch Therapy This protocol is adapted from preclinical studies underpinning current clinical efforts for heart failure [17] [10].

- Objective: To generate a functional cardiac patch by seeding iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes onto a biomimetic scaffold.

- Materials:

- Cells: Human iPSC line.

- Basal Medium: RPMI 1640.

- Small Molecules: CHIR99021 (GSK-3 inhibitor), IWP-4 (Wnt inhibitor).

- Supplements: B-27 Supplement (with and without insulin).

- Scaffold: 3D porous elastomer patch (e.g., PGS/GelMA composite).

- Procedure:

- Maintenance: Culture iPSCs in essential 8 medium on Matrigel-coated plates until 80-90% confluent.

- Mesoderm Induction (Day 0-2): Dissociate iPSCs into single cells and seed onto the 3D scaffold at a high density (5-10 x 10^6 cells/cm³). Switch to RPMI/B-27 minus insulin medium supplemented with 6-12 µM CHIR99021.

- Cardiac Progenitor Induction (Day 2-5): Replace medium with RPMI/B-27 minus insulin containing 5 µM IWP-4.

- Cardiomyocyte Maturation (Day 5-30+): On day 5, change to RPMI/B-27 with insulin. Refresh the medium every 2-3 days. Spontaneous contractions are typically observed between days 8-12. Maintain the construct for up to 30 days to promote metabolic and functional maturation.

- Quality Control: Analyze by flow cytometry for cardiac Troponin T (cTnT) expression (>80% purity expected). Perform electrophysiological assessment via patch clamp or microelectrode array (MEA).

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)

MSCs are multipotent stromal cells with potent immunomodulatory and tissue-repair capabilities, primarily mediated through paracrine secretion of bioactive molecules and extracellular vesicles [11] [15]. With over ten approved therapies worldwide for conditions like graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and Crohn's disease fistulas, they are the most clinically advanced cell type discussed here [11] [12].

Protocol 2: Seeding and Tri-Lineage Differentiation of MSCs in a 3D Biomimetic Scaffold This protocol is foundational for bone and soft tissue engineering applications [18] [19].

- Objective: To evaluate the multipotency of MSCs within a 3D scaffold environment by inducing osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic differentiation.

- Materials:

- Cells: Bone marrow-derived MSCs (BMSCs).

- Scaffold: 3D-printed bilayered scaffold (e.g., vECM/GelMA/SF bioink) [19].

- Basal Medium: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS.

- Induction Media: Commercial osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic differentiation kits.

- Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Trypsinize P3-P5 BMSCs and resuspend in basal medium. Seed cells drop-wise onto the sterilized 3D scaffold at a density of 1x10^6 cells/cm³. Allow 4 hours for attachment in an incubator before adding more medium.

- Osteogenic Differentiation: Culture scaffold in osteogenic medium for 21 days. Refresh medium twice weekly. Analysis: Fix and stain with 2% Alizarin Red S to detect calcium deposits.

- Chondrogenic Differentiation: Culture scaffold in chondrogenic medium in a pellet culture system for 21 days. Analysis: Fix, section, and stain with 1% Alcian Blue to detect sulfated glycosaminoglycans.

- Adipogenic Differentiation: Culture scaffold in adipogenic medium for 21 days. Refresh medium twice weekly. Analysis: Fix and stain with 0.5% Oil Red O to visualize lipid vacuoles.

- Quality Control: Confirm MSC phenotype prior to seeding via flow cytometry for CD73, CD90, CD105 (≥95% positive) and CD34, CD45, HLA-DR (≤2% positive) [11] [12].

Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells (ECFCs)

ECFCs are true endothelial progenitors with high proliferative potential and the ability to form de novo blood vessels in vivo [13]. They are a promising tool for vascularizing engineered tissues, though no clinical trials have been conducted yet. A major barrier is their low frequency in peripheral blood (approximately 1.7 cells per 10^8 mononuclear cells) and donor-specific heterogeneity [13] [16].

Protocol 3: Isolation, Expansion, and Tubulogenesis Assay of ECFCs for Vascularization This protocol is critical for pre-clinical assessment of ECFC functionality in creating vascular networks [13].

- Objective: To isolate ECFCs from human umbilical cord blood and evaluate their in vitro vessel-forming capability on a basement membrane matrix.

- Materials:

- Cell Source: Human umbilical cord blood collected in CPDA-1 bags.

- Coating Substrate: Rat tail collagen I.

- Culture Medium: EGM-2 MV BulletKit (Lonza).

- Tubulogenesis Substrate: Growth Factor Reduced (GFR) Matrigel.

- Antibodies: for flow cytometry (CD31, CD34, CD45, CD14, VEGFR2).

- Procedure:

- Isolation: Isolate mononuclear cells from cord blood via density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque). Plate 1-5x10^7 cells per well of a collagen I-coated 6-well plate in EGM-2 medium.

- Expansion: After 24 hours, gently wash away non-adherent cells. Refresh medium daily for the first week, then every other day thereafter. Colonies with cobblestone morphology (ECFCs) appear in 5-14 days. Expand by trypsinizing and re-plating at 1:3 ratio.

- Phenotyping: Characterize cells at P2-P4 by flow cytometry. ECFCs should be >95% positive for CD31, CD34, and VEGFR2, and >95% negative for CD45 and CD14 [13].

- Tubulogenesis Assay: Thaw GFR Matrigel on ice and coat a 96-well plate (50 µL/well). Polymerize at 37°C for 30 min. Seed 1x10^4 ECFCs per well in EGM-2. Incubate for 6-18 hours and image under a microscope. Quantify total tube length, number of branches, and meshes per field.

- Quality Control: Only use ECFCs with a confirmed phenotype and high tubulogenesis capacity (e.g., >5000 µm total tube length per field) for scaffold vascularization studies.

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow

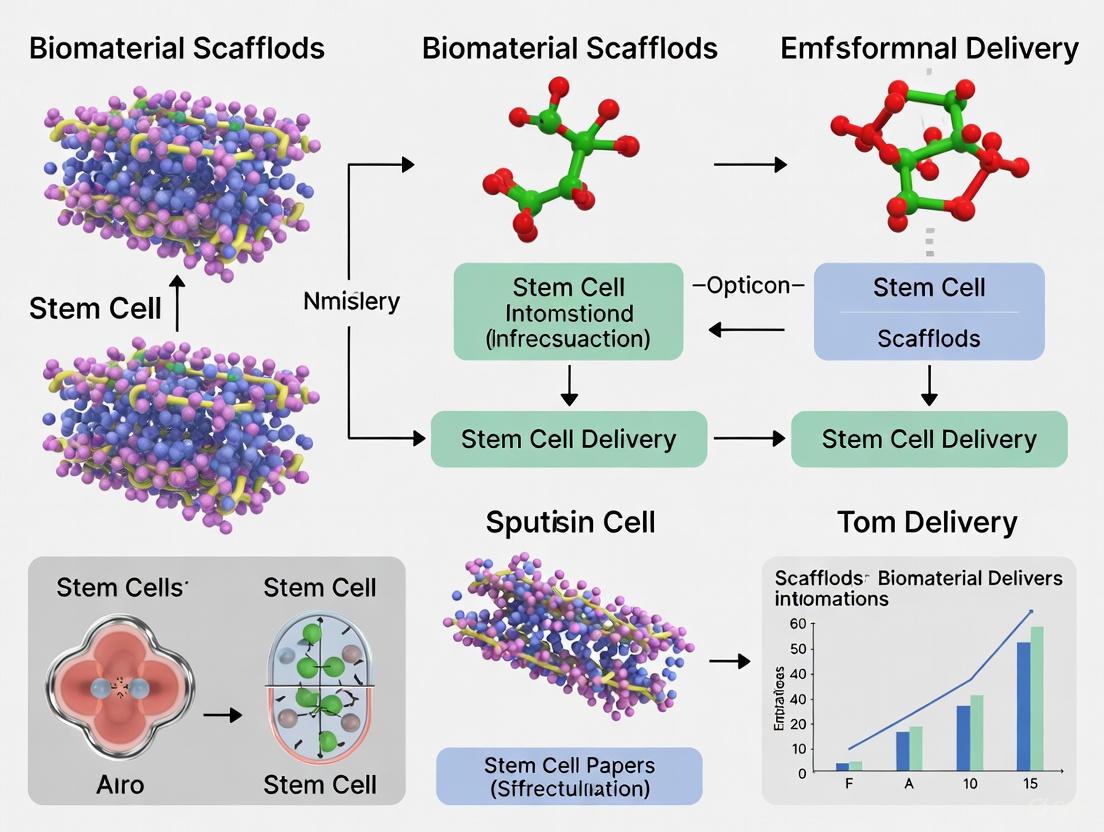

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for developing a stem cell-based tissue construct, integrating the protocols for iPSCs, MSCs, and ECFCs.

Diagram 1: Stem Cell-Based Construct Development Workflow (52 characters)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell and Scaffold Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen I | Substrate for cell adhesion and culture; promotes ECFC isolation and expansion. | Coating culture flasks for primary ECFC isolation from blood [13]. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photocrosslinkable hydrogel; provides tunable mechanical properties and bioactivity for 3D printing. | Component of bioink for 3D-printed bilayered vaginal scaffolds [19]. |

| Decellularized Extracellular Matrix (dECM) | Provides native tissue-specific biochemical and structural cues to scaffolds. | Porcine vaginal ECM (vECM) used in composite bioinks to mimic native tissue microenvironment [19]. |

| EGM-2 MV BulletKit | Specialized medium optimized for growth and maintenance of microvascular endothelial cells. | Culture and expansion of ECFCs after isolation [13]. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors (CHIR99021, IWP-4) | Direct stem cell differentiation by modulating key signaling pathways (e.g., Wnt). | Sequential use for directed differentiation of iPSCs to cardiomyocytes [10]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies (CD73, CD90, CD105, CD31, CD34, CD45) | Cell surface marker identification for phenotypic characterization and purity assessment. | Confirming MSC (CD73+/CD90+/CD105+) and ECFC (CD31+/CD34+/CD45-) phenotypes [11] [12] [13]. |

| Alizarin Red S, Alcian Blue, Oil Red O | Histochemical stains for detecting calcium (bone), proteoglycans (cartilage), and lipids (fat). | Assessing tri-lineage differentiation potential of MSCs in 2D or 3D culture [19]. |

iPSCs, MSCs, and ECFCs each offer a unique and powerful set of tools for addressing different challenges in regenerative medicine. The successful clinical translation of these cells is inextricably linked to their effective integration with advanced biomaterial scaffolds. These scaffolds are not merely passive carriers; they are active microenvironments that can be engineered to enhance cell survival, direct fate, and ultimately, improve therapeutic outcomes. By leveraging the structured data, detailed protocols, and reagent guidance provided, researchers can accelerate the development of sophisticated, safe, and effective stem cell-scaffold therapies for a wide range of debilitating diseases.

In the field of regenerative medicine and stem cell delivery, biomaterial scaffolds serve a dual purpose that extends far beyond passive structural support. While their three-dimensional architecture provides the physical framework for cell attachment and tissue formation, emerging research reveals their equally critical role in active biological signaling. These dynamic scaffolds modulate cellular behavior by presenting precise biochemical and biophysical cues that guide stem cell survival, proliferation, migration, and differentiation [5] [20]. This complex functionality makes scaffolds indispensable for overcoming the significant challenges in therapeutic stem cell delivery, including poor cell survival, limited retention at target sites, and uncontrolled differentiation [21] [22]. The evolution of scaffold design now focuses on engineering these materials to replicate key aspects of the native extracellular matrix, creating microenvironments that can direct stem cell fate toward specific therapeutic outcomes for conditions ranging from spinal cord injury to retinal degeneration [5] [21].

Core Scaffold Functions

Structural Support Functions

The structural properties of scaffolds establish the fundamental basis for their performance in stem cell delivery applications. These physical characteristics determine how scaffolds interact with both host tissues and delivered cells.

Table 1: Essential Structural Properties of Biomaterial Scaffolds for Stem Cell Delivery

| Property | Functional Role | Ideal Parameters | Impact on Stem Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | Enables integration without adverse immune response | Non-toxic, non-immunogenic | Supports cell survival and function [20] |

| Biodegradability | Temporary support that transfers load to new tissue | Rate matches tissue regeneration | Prevents long-term interference with regenerated tissue [20] |

| Mechanical Strength | Withstands physiological forces during healing | Similar to target tissue | Influences stem cell differentiation pathways [20] |

| Porosity & Pore Size | Enables cell infiltration, vascularization, nutrient waste exchange | High interconnectivity, tissue-specific pore size (e.g., ~95μm for neural repair) | Facilitates 3D colonization, tissue integration [20] [22] |

The interconnected porosity of scaffolds is particularly critical for stem cell applications, as it enables three-dimensional cell distribution, vascular ingrowth, and efficient diffusion of nutrients and signaling molecules [20]. For example, porous collagen-based scaffolds (PCSs) with mean pore diameters of approximately 95μm have demonstrated excellent support for neural stem cell infiltration and distribution in spinal cord injury models [22]. The mechanical properties of scaffolds must be carefully matched to the target tissue, as these physical cues significantly influence stem cell differentiation decisions through mechanotransduction pathways [5].

Dynamic Signaling Functions

Beyond physical support, advanced scaffolds actively participate in biological signaling through multiple mechanisms. These dynamic functions enable precise control over stem cell behavior and tissue regeneration processes.

Table 2: Scaffold-Mediated Signaling Mechanisms in Stem Cell Delivery

| Signaling Mechanism | Key Components | Biological Effects | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Signaling | Incorporated growth factors, adhesion peptides (RGD), glycosaminoglycans (Chondroitin-6-sulfate) | Enhanced neuronal differentiation of NSCs; guided axonal elongation [22] | |

| Electroconductive Signaling | Polypyrrole, Polyaniline, Polythiophene polymers | Enhanced neurite outgrowth; improved nerve signal propagation [5] | |

| Mechanotransduction | Stiffness-tuned matrices, surface topography | Regulation of neurite repair via TRPV1, Piezo, VGCC ion channels [5] | |

| Immunomodulation | Controlled cytokine release (IL-4, IL-13), scaffold microstructure | Polarization of macrophages to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype; reduced astrogliosis [6] [22] |

Scaffolds functionalized with specific biochemical cues can significantly enhance therapeutic outcomes. For instance, collagen-glycosaminoglycan (CG) scaffolds containing chondroitin-6-sulfate promoted significantly greater oligodendrocyte differentiation from neural stem cells compared to two-dimensional culture controls (36.3% vs 23.0%) [22]. Similarly, electroconductive polymers like polypyrrole facilitate electrical signal propagation that enhances neurite outgrowth and neuronal activation, making them particularly valuable for neural tissue engineering applications [5].

The integration of these signaling modalities enables scaffolds to function as sophisticated extracellular matrix analogs that can dynamically regulate the stem cell microenvironment. This is particularly evident in immune cell engineering, where scaffold properties can be tuned to control the polarization of therapeutic macrophages or enhance the persistence of delivered T-cells in cancer immunotherapy [6].

Application Notes: Scaffold Design for Specific Therapeutic Applications

Neural Tissue Engineering

In neural repair, scaffold design requires careful consideration of both the inhibitory CNS environment and the specific needs of neuronal cell types. Porous collagen-based scaffolds have demonstrated remarkable success in promoting recovery after spinal cord injury, with studies showing that mice receiving NSC-seeded PCS grafts achieved locomotion performance statistically indistinguishable from uninjured animals within 12 weeks post-injury [22]. The porous architecture of these scaffolds enables robust axonal elongation through the lesion site while reducing inhibitory astrogliosis. Furthermore, the inclusion of glycosaminoglycans like chondroitin-6-sulfate in scaffold composition significantly influences neural stem cell differentiation patterns, promoting oligodendrocyte lineage commitment which is crucial for remyelination strategies [22].

Retinal Tissue Engineering

Retinal repair presents unique challenges due to the delicate sensory tissue structure and the need for precise cellular layering. Scaffolds for retinal progenitor cell (RPC) delivery have evolved into three principal designs: microcylinder scaffolds that mimic vertical retinal organization, fibrous scaffolds that replicate extracellular matrix microstructure, and hydrogel scaffolds that match retinal mechanical properties [21]. Thin microcylinder scaffolds (5-6μm thickness) with precisely engineered pores (10-25μm diameter) have demonstrated 20-fold increases in transplanted cell retention compared to non-structured films while minimizing retinal deformation during implantation [21]. Biodegradable polyesters like PLGA, PCL, and PGS are particularly advantageous for subretinal implantation due to their tunable degradation profiles, with PGS offering superior mechanical matching to native retinal tissue [21].

Immune Cell Engineering

Scaffolds have emerged as powerful platforms for enhancing the efficacy of adoptive immune cell therapies, including CAR-T cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages. Biomaterial scaffolds can address critical limitations in these living drugs by providing localized delivery, maintaining therapeutic phenotypes, and enhancing cell viability [6]. For example, alginate-based hydrogels have been used to create injectable scaffolds that support dendritic cell survival and function for vaccination applications, while porous polymer scaffolds can enhance CAR-T cell expansion and persistence through sustained cytokine presentation [6]. The scaffold microenvironment can be precisely engineered to control immune cell polarization, as demonstrated by decellularized matrix scaffolds that drive macrophages toward regenerative phenotypes for spinal cord repair [6].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Neural Stem Cell Seeding and Differentiation in Porous Collagen Scaffolds

This protocol describes the methodology for preparing, seeding, and differentiating neural stem cells within porous collagen-based scaffolds (PCS) for neural tissue engineering applications, based on established procedures with demonstrated efficacy in spinal cord injury models [22].

Materials Required

- Porous collagen or collagen-glycosaminoglycan scaffolds (0.5% mass fraction, ~95μm mean pore diameter)

- Embryonic neural stem cells (NSCs)

- Poly-D-lysine and laminin for 2D control surfaces

- Complete NSC medium: DMEM/F-12 supplemented with B27, N2, EGF (20ng/mL), FGF2 (20ng/mL)

- Differentiation medium: DMEM/F-12 with B27, N2, 1% FBS, BDNF (10ng/mL), GDNF (10ng/mL)

- Fixation solution: 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS

- Immunostaining antibodies: Nestin, Tuj1 (neurons), GFAP (astrocytes), Olig2 (oligodendrocytes)

Procedure

- Scaffold Preparation: Hydrate sterile PCS samples in PBS for 2 hours, then equilibrate in complete medium for 24 hours before cell seeding.

- NSC Expansion: Culture NSCs as neurospheres in complete medium for 5-7 days, then dissociate to single-cell suspension using Accutase.

- 3D Seeding: pipette 50μL of NSC suspension (5×10^6 cells/mL) onto each hydrated PCS (5mm diameter × 2mm thickness). Centrifuge at 300×g for 5 minutes to enhance cell infiltration into scaffold pores.

- Pre-implantation Culture: Maintain seeded scaffolds in complete medium for 3 days to allow cell attachment and initial proliferation.

- Differentiation Induction: Switch to differentiation medium for 4-7 days, refreshing medium every 2-3 days.

- Analysis: Fix constructs with 4% PFA for immunostaining and confocal microscopy analysis.

Technical Notes

- Seeding efficiency typically exceeds 80% with the centrifugation method.

- Scaffold degradation should be minimal during the 7-10 day culture period.

- >99% of cells should express nestin at 3 days post-seeding, confirming maintenance of stemness.

Protocol: Retinal Progenitor Cell Delivery Using Thin Microcylinder Scaffolds

This protocol details the fabrication, cell seeding, and subretinal implantation of thin microcylinder scaffolds for retinal progenitor cell delivery, optimized to minimize retinal damage while maximizing cell retention and integration [21].

Materials Required

- Polycaprolactone (PCL) or poly(glycerol sebacate) (PGS) resin

- Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) negative molds with microcylinder architecture

- Retinal progenitor cells (RPCs) or photoreceptor precursors

- Poly-D-lysine and laminin coating solutions

- Subretinal implantation surgical instruments

- Animal model (e.g., rhodopsin knockout mice for degeneration models)

Procedure

- Scaffold Fabrication: Create PCL scaffolds by solvent casting over PDMS negatives with 25μm diameter pores. For PGS scaffolds, cure pre-polymer at 120°C under vacuum using PDMS molds with 50μm diameter pores separated 175μm apart.

- Surface Modification: Treat scaffolds with oxygen plasma, then coat with poly-D-lysine (50μg/mL, 2 hours) followed by laminin (10μg/mL, 4 hours) to enhance cell adhesion.

- Cell Seeding: Apply RPC suspension (10μL at 1×10^5 cells/μL) to scaffold surface, then centrifuge at 200×g for 3 minutes to drive cells into pores.

- Pre-implantation Culture: Maintain seeded scaffolds in retinal differentiation medium for 5-7 days before implantation.

- Scaffold Implantation: For PGS scaffolds, roll the flexible scaffold and load into a 1mm internal diameter needle for subretinal injection. For rigid scaffolds, use specialized implantation tools.

- Outcome Assessment: Evaluate cell integration, photoreceptor outer segment formation, and functional recovery at 4-8 weeks post-implantation.

Technical Notes

- Scaffold thickness should not exceed 50μm to minimize retinal detachment and damage.

- PGS scaffolds offer superior mechanical compatibility with retinal tissue but require laminin coating for cell adhesion.

- Expect 20-fold increases in cell retention compared to bolus injection methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Scaffold-Based Stem Cell Research

| Category/Reagent | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Collagen, Chitosan, Alginate, Hyaluronan, Silk Fibroin, Gelatin | Biocompatible ECM analogs; support cell adhesion and infiltration | Batch variability; potential immunogenicity; tunable degradation [5] [20] |

| Synthetic Polymers | PLA, PLGA, PCL, Polyphosphoester, Polyurethane | Reproducible properties; controllable biodegradation; mechanical strength | Hydrophobicity may require surface modification [5] [20] |

| Conductive Polymers | Polypyrrole, Polyaniline, Polythiophene | Enhance neurite outgrowth; support electrical signaling in neural tissues | Requires composite formation for biodegradability [5] |

| Surface Modifiers | Poly-D-Lysine, Laminin, RGD Peptides | Enhance cell-scaffold adhesion; promote specific integrin signaling | Coating density affects cell behavior; stability concerns [21] [22] |

| Fabrication Technologies | Solvent Casting/Particle Leaching, Electrospinning, Freeze Drying, 3D Printing | Create controlled pore architectures; nanofibrous structures; patient-specific designs | Equipment cost; resolution limitations; scalability challenges [23] |

The selection of appropriate biomaterials and fabrication methods is critical for developing effective scaffold-based stem cell delivery systems. Natural polymers like collagen and chitosan offer excellent biocompatibility and biological recognition but may exhibit batch-to-batch variability. Synthetic polymers such as PLGA and PCL provide more consistent mechanical and degradation properties but often require surface modification to enhance cell adhesion [5] [20]. Conductive polymers represent a specialized class of materials particularly valuable for neural applications, where they support the electrical activity essential for neuronal function and network formation [5]. Surface modification with adhesion proteins like laminin is frequently necessary to promote sufficient stem cell attachment and retention, especially for synthetic materials [21] [22].

A Materials Toolkit: From Natural Polymers to 3D-Printed Constructs

The development of biomaterial scaffolds for stem cell delivery represents a cornerstone of modern regenerative medicine. Among the various options, natural biomaterials—specifically collagen, fibrin, and decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM)—provide unparalleled advantages as they inherently recapitulate critical aspects of the native tissue microenvironment. These materials are not merely passive structural supports but active participants in regulating stem cell behavior through tissue-specific biochemical composition, mechanical cues, and spatial organization. The integration of stem cells with these biomaterials aims to overcome significant clinical translation challenges, including poor cell survival post-transplantation, insufficient control over differentiation, and limited functional integration with host tissues [24] [25].

Decellularized ECM scaffolds, in particular, have emerged as a premier platform because they preserve the complex tapestry of native tissue structure, including a diverse array of collagens, proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), and sequestered growth factors [26] [27]. This preserved complexity creates a biomimetic template that promotes cell integration, immunomodulation, and constructive tissue remodeling, making it ideally suited for hosting and delivering therapeutic stem cells [26]. This application note provides a current overview of the properties and applications of these key natural biomaterials, with a specific focus on dECM, and details standardized protocols for their utilization in stem cell research.

Application Notes: Properties and Comparative Analysis

Key Characteristics of Natural Biomaterials

Decellularized Extracellular Matrix (dECM) is derived from tissues or organs through processes that remove cellular material while preserving the intricate native ECM structure and composition. The primary strength of dECM lies in its tissue-specific bioactivity; it naturally contains a complex mixture of structural proteins (e.g., collagens, elastin), proteoglycans, and signaling molecules (e.g., growth factors) that mimic the in vivo stem cell niche [26] [27]. This composition provides inherent cell-instructive cues that can direct stem cell fate. However, a common limitation of pure dECM is its inherent mechanical weakness and poor tunability, which can be addressed through crosslinking or combination with synthetic materials [26] [28].

Collagen, particularly Type I, is the most abundant protein in the human ECM and a fundamental component of many tissues. It is highly biocompatible, biodegradable, and contains cell adhesion motifs (e.g., RGD sequences) that support cell attachment and proliferation [29]. While collagen hydrogels can self-assemble, they often lack the mechanical strength and complexity of full native ECM.

Fibrin is a natural polymer formed from fibrinogen and thrombin during the wound healing process. It serves as an excellent provisional matrix and is widely used as a clinical sealant. Fibrin's key advantages include its injectability and its role in promoting cell migration and angiogenesis. However, its rapid degradation rate and relatively weak mechanics often require stabilization.

Quantitative Comparison of Biomaterial Properties

The following table summarizes the key properties of these natural biomaterials, with a specific focus on data derived from dECM sources.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Natural Biomaterials for Stem Cell Delivery

| Property | Decellularized ECM (dECM) | Collagen (Type I) | Fibrin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Composition | Complex, tissue-specific mix of collagens, GAGs, proteoglycans, glycoproteins, growth factors [26] [27] | Primarily collagen type I fibrils [29] | Fibrin polymer network |

| Mechanical Properties (Elastic Modulus) | Wide range, tissue-dependent (e.g., Skin ECM ~highest; Birth ECM ~lowest) [29] | Tunable, typically lower; varies with concentration & crosslinking | Soft, weak; degrades rapidly |

| Gelation Kinetics | Significantly slower than pure collagen control [29] | Rapid, temperature-dependent self-assembly | Very rapid, enzyme-mediated (thrombin) |

| Degradation Profile | Biodegradable; rate depends on tissue source, crosslinking [26] | Biodegradable via collagenases; rate is tunable | Rapid; requires protease inhibitors (e.g., aprotinin) for stabilization |

| Key Advantages | Tissue-specific bioactivity, inherent complexity, immunomodulatory potential [26] [25] | Excellent biocompatibility, well-established protocols, abundant cell adhesion sites | Injectable, promotes angiogenesis, clinically approved as sealant |

Tissue-Specific dECM Composition and Applications

dECM is not a single material but a class of materials whose properties vary significantly with the tissue of origin. This tissue-specificity is crucial for selecting the appropriate scaffold for a given stem cell application.

Table 2: Tissue-Specific Properties and Applications of dECM Scaffolds

| Tissue Source | Key ECM Components | Stem Cell Applications | Notable Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tendon | ~70% Collagen I (dry weight); Decorin, Fibromodulin, COMP, Tenascin-C [27] | Tendon stem/progenitor cell delivery for musculoskeletal repair | Promotes directional cell alignment and tenogenic differentiation; composite dECM-hydrogels enhance injectability and mechanical recovery in rabbit Achilles tendon models [27]. |

| Skin | Collagen I, III; High elastin content [29] | Mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) delivery for wound healing | Skin-derived Methacryloyl-functionalized dECM (MA-dECM) showed a 30-fold increase in elastic modulus and significantly accelerated wound closure and vascularization in mice [28]. |

| Skeletal Muscle | Collagen IV, Laminin, Fibronectin [30] | Satellite cell or myoblast delivery for volumetric muscle loss (VML) | Heparinized muscle dECM scaffolds enabled sustained release of PDGF, FGF, and VEGF from PRP, enhancing angiogenesis and host cell migration in a VML model [30]. |

| Birth Tissues (e.g., Umbilical Cord) | Collagen content comparable to pure collagen control [29] | Cord-tissue MSC (CMSC) encapsulation and delivery | Birth ECM hydrogels supported the highest metabolic activity of encapsulated CMSCs compared to other human ECM sources [29]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Granular MA-dECM Hydrogels for 3D Bioprinting

This protocol describes the modification of skin-derived dECM into a photo-crosslinkable, granular hydrogel compatible with extrusion 3D printing and stem cell encapsulation, based on a recent study [28].

Workflow Overview:

Materials & Reagents:

- Acellular dECM: Derived from porcine or human skin, solubilized via enzymatic digestion.

- Methacrylic anhydride (MA): For introducing photo-crosslinkable functional groups.

- Photoinitiator: Irgacure 2959 or Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP).

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS): For washing and solution preparation.

- UV Light Source: (365-405 nm) for crosslinking.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Methacryloyl Functionalization: React the solubilized dECM solution with methacrylic anhydride (e.g., 0.5% v/v) under controlled pH (e.g., 8.0) for several hours at 4°C. Terminate the reaction and dialyze extensively against distilled water to remove unreacted monomers. Lyophilize the resulting MA-dECMA to a porous foam for storage.

- Precursor Hydrogel Formation: Dissolve the lyophilized MA-dECM powder in a cell culture-compatible solvent (e.g., PBS) at a desired concentration (e.g., 3-5% w/v). Add the photoinitiator (e.g., 0.1% w/v LAP) and sterilize the solution by filtration.

- Primary Crosslinking & Granulation: Expose the MA-dECM precursor solution to UV light (e.g., 5-10 mW/cm² for 1-5 minutes) to form a bulk hydrogel. Mechanically fragment this bulk hydrogel through a mesh or sieve to create a slurry of granular microgels.

- 3D Bioprinting and Cell Encapsulation:

- Option A (Cell Seeding on Scaffold): Seed the granular hydrogel with a suspension of stem cells (e.g., MSCs, endothelial colony-forming cells) and allow for cell attachment.

- Option B (Cell Encapsulation in Bulk): Mix the stem cell suspension directly with the MA-dECM precursor solution before primary crosslinking in step 3.

- Load the cell-laden granular hydrogel or precursor into a bioprinter cartridge. Extrude the material through a nozzle to create 3D structures.

- Secondary Stabilization: After printing, expose the entire construct to a second, longer UV crosslinking cycle (e.g., 10-20 mW/cm² for 5-10 minutes) to stabilize the structure and fuse the microgels.

Notes: The granular form exhibits shear-thinning behavior, enabling smooth extrusion, and self-heals after the shear force is removed. The mechanical properties of the final construct can be tuned by varying the MA-dECM concentration, UV intensity, and exposure time [28].

Protocol 2: Heparinization of dECM Scaffolds for Sustained Growth Factor Delivery

This protocol outlines a method to functionalize dECM scaffolds with heparin, creating an affinity-based system for the controlled release of growth factors, which can be used to enhance the paracrine signaling of delivered stem cells or recruit host cells [30].

Workflow Overview:

Materials & Reagents:

- Macroporous dECM Scaffold: Fabricated from skeletal muscle or other tissues via decellularization, freeze-drying, and crosslinking.

- Heparin Sodium: From porcine intestinal mucosa or other biological sources.

- Crosslinkers: 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS).

- Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) or EVs: As a source of growth factors (e.g., PDGF, FGF, VEGF).

- Toluidine Blue: For qualitative assessment of heparin conjugation.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Scaffold Fabrication: Decellularize the source tissue (e.g., skeletal muscle) using a combination of detergents (e.g., SDS, Triton X-100), enzymes, and washes. Confirm decellularization by quantifying DNA content (<50 ng/mg dry tissue) and preserving ECM components like collagen and GAGs. Create a macroporous scaffold using a freeze-drying technique.

- EDC/NHS Crosslinking: Hydrate the dECM scaffold in a MES buffer solution. Incubate the scaffold with a fresh EDC/NHS solution (e.g., 20mM EDC, 10mM NHS) for 2-4 hours at room temperature to activate carboxyl groups on the ECM. Rinse thoroughly to remove excess crosslinkers.

- Heparin Conjugation: Transfer the activated scaffold to a heparin solution (e.g., 1 mg/mL in PBS). Incubate for 12-24 hours at 4°C to allow covalent conjugation between the amine groups on heparin and the activated carboxyl groups on the scaffold. Wash extensively with PBS to remove unbound heparin.

- Verification of Heparinization: Qualitatively confirm successful conjugation using Toluidine Blue staining. Heparin-bound scaffolds (DSMS-H) will show a deeper blue color compared to the background color of control scaffolds (DSMS) [30].

- Loading of Bioactive Molecules: Incubate the heparinized scaffold (DSMS-H) with the growth factor source, such as PRP or a solution of extracellular vesicles (EVs). The negatively charged heparin molecules will electrostatically bind and retain positively charged growth factors.

- Release Kinetics Assessment: To characterize the release profile, immerse the loaded scaffold in PBS at 37°C under gentle agitation. Collect supernatant at predetermined time points and quantify the concentration of specific growth factors (e.g., PDGF-BB, FGF2, VEGF) using ELISA. The heparinized scaffold is expected to show a significantly reduced burst release and a more sustained release profile over several days compared to a non-heparinized control [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for dECM and Stem Cell Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Ionic detergent for effective decellularization; disrupts lipid membranes and dissociates DNA from proteins [26] | Primary detergent in tissue decellularization protocols (e.g., for skeletal muscle, tendon). Requires careful concentration control and thorough washing to avoid cytotoxicity [30] [31]. |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent for delipidation and removal of residual ionic detergents [26] | Used in sequence with SDS for more complete decellularization and removal of detergent residues [31]. |

| Methacrylic Anhydride (MA) | Introduces photo-polymerizable methacryloyl groups into biomolecules like dECM or gelatin [28] | Key reagent for creating MA-dECM or GelMA, enabling UV-light-mediated crosslinking for mechanical tunability and shape fidelity in 3D bioprinting [28]. |

| EDC / NHS Crosslinker | Zero-length crosslinker that forms amide bonds between carboxyl and amine groups without becoming part of the linkage [30] | Used to enhance the mechanical integrity of dECM scaffolds and to conjugate molecules (e.g., heparin) to the dECM by targeting their amine groups [30]. |

| Heparin Sodium | Highly sulfated glycosaminoglycan with high affinity for a wide range of growth factors [30] | Immobilized on dECM scaffolds to create an affinity-based system for the sustained and controlled delivery of growth factors from PRP or other sources [30]. |

| Irgacure 2959 / LAP | Photoinitiators that generate radicals upon UV/Violet light exposure to initiate polymerization [28] | Essential for crosslinking methacrylated materials (MA-dECM, GelMA). LAP offers better water solubility and biocompatibility than Irgacure 2959. |

Signaling Pathways in Biomaterial-Stem Cell Interactions

The therapeutic success of stem cell-laden biomaterials is largely governed by the activation of specific intracellular signaling pathways triggered by cell-material interactions. The following diagram summarizes the key pathways involved.

Key Signaling Pathways Activated by Natural Biomaterials:

Pathway Description: Stem cells adhere to natural biomaterials primarily via integrin receptors that recognize specific ligands (e.g., RGD sequences) present in the scaffold [26]. This adhesion leads to the formation of focal adhesion complexes and the activation of Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK). FAK activation initiates several downstream pathways:

- The MAPK/ERK pathway is crucial for promoting cell proliferation and survival [26].

- The PI3K/Akt pathway further enhances survival signals and plays a key role in lineage specification and differentiation [26] [24].

- Mechanotransduction pathways are activated as cells sense and respond to the mechanical properties (e.g., elasticity, stiffness) of the biomaterial scaffold, directly influencing stem cell fate decisions and guiding cytoskeletal organization [26] [25].

Furthermore, growth factors sequestered and presented by the dECM (e.g., VEGF, TGF-β, FGF) bind to their respective tyrosine kinase receptors, synergizing with integrin signaling to amplify these pro-regenerative signals and guide functional tissue formation [26] [30].

The regeneration of critical-sized bone defects remains a significant clinical challenge, with an estimated 2.2 million bone graft procedures performed annually worldwide [32]. Within the context of biomaterial scaffolds for stem cell delivery research, synthetic and ceramic scaffolds provide an essential foundation for bone tissue engineering. These constructs address the limitations of natural bone grafts by offering tunable properties, consistent quality, and osteoconductive surfaces that guide cellular behavior and tissue formation [33] [32].

Synthetic polymers, particularly poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), provide exceptional versatility through tunable mechanical properties, degradation rates, and scaffold architecture. When combined with osteoconductive ceramic materials such as hydroxyapatite (HA) and β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), these composite scaffolds create a biomimetic microenvironment that supports stem cell viability, differentiation, and ultimately, functional bone regeneration [34]. This application note details the quantitative performance, experimental protocols, and biological mechanisms of these advanced scaffold systems to facilitate their effective implementation in regenerative medicine research.

Quantitative Performance of Composite Scaffolds

The performance of composite scaffolds is critically dependent on their composition and fabrication methodology. The quantitative data below highlight the impact of material selection and production technique on key scaffold properties.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Bone Graft Materials and Scaffolds

| Material Type | Osteoconductivity | Osteoinductivity | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Degradation Time | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autograft | High | High | N/A (Native Tissue) | N/A | Gold standard, biological properties |

| Allograft | Moderate | Variable | Variable | 6-18 months | Availability |

| β-TCP Ceramics | High | Moderate | 1-10 [32] | 6-24 months [32] | Bioresorbable, osteoconductive |

| PLGA Polymers | Low | Low | 0.5-5 [34] | 1-12 months [34] | Tunable degradation |

| PLGA-HA Composite | High | Enhanced | 2-15 [34] | 3-18 months | Balanced properties |

Advanced fabrication technologies significantly impact scaffold characteristics and performance. Automated manufacturing methods, particularly 3D bioprinting, have demonstrated substantial improvements over traditional approaches.

Table 2: Impact of Fabrication Method on PLGA-HA Scaffold Properties

| Parameter | Manual Casting | Automated 3D Bioprinting | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Processing Time (per scaffold) | 10 min 51 sec | 2 min [34] | 5.4x faster |

| Material Retention (average weight) | 0.01169 g [34] | 0.02354 g [34] | 2x greater |

| Inter-batch Reproducibility | Low [34] | High [34] | Significant improvement |

| Structural Complexity | Limited [34] | High (controlled porosity) [34] | Enhanced design control |

| Coating Uniformity | Variable [34] | Consistent [34] | Improved homogeneity |

Experimental Protocols

Automated Fabrication of PLGA-HA Composite Scaffolds

This protocol describes the automated fabrication of PLGA-HA composite scaffolds using 3D bioprinting technology, enabling high reproducibility and precise architectural control [34].

Materials Required

- Poly(dl-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA)

- Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (nHA)

- Chloroform

- Borosilicate glass vials with polypropylene lids

- Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) filament for mold printing

- Lulzbot bioprinter with 2.5 mL and 5 mL syringes

- Autodesk Inventor software

- CURA Lulzbot Edition slicer software

- Bambu Carbon X1 3D printer

- Precision laboratory scale

- Magnetic stirrer

- Probe sonicator

Procedure

PVA Mold Fabrication

- Design the scaffold mold using CAD software (e.g., Autodesk Inventor)

- Generate G-code and fabricate PVA molds using an Ender 3D printer

- Store PVA molds under controlled humidity conditions

- Weigh and record individual mold weights before use

PLGA-HA Solution Preparation

- Calibrate an empty borosilicate glass vial on a precision scale

- Add chloroform (5.92 g) to the vial, accounting for evaporation

- Weigh 100 mg of PLGA (stored at -15 to -18°C) and add to chloroform

- Insert magnetic stirring bar and seal vial with parafilm

- Stir on a magnetic stirrer (without heat) for ≥3 hours until complete dissolution

- Slowly add hydroxyapatite nanoparticles while dispersing with a probe sonicator for 2-3 minutes to ensure even distribution

Automated Casting via 3D Bioprinting

- Design the casting path using 3D CAD software

- Load PLGA-HA solution into bioprinter syringe (2.5 mL or 5 mL capacity)

- Calibrate the Lulzbot bioprinter

- Set extrusion parameters: rate of 4 mm/s, layer height of 2 mm

- Execute automated casting process (approximately 5 min 11 sec for 4 molds with 2.5 mL syringe; 3 min 46 sec with 5 mL syringe)

- Allow solvent evaporation under controlled conditions

Quality Assessment

- Verify chemical composition using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

- Analyze pore structure and morphology using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

- Assess mechanical properties through compression testing

Troubleshooting Notes

- Chloroform volatility: Use weight-based measurements instead of volume-based

- Material handling: Use borosilicate glass and polypropylene to prevent chemical reactions

- Scalability: Implement 3D-printed mesh filters for high-throughput experimentation

In Vitro Assessment of Scaffold-Cell Interactions

This protocol details the evaluation of cell-scaffold interactions using mesenchymal stem cells, critical for assessing the regenerative potential of fabricated constructs [35] [36].

Materials Required

- Mesenchymal stem cells (bone marrow, adipose, or umbilical cord-derived)

- Cell culture media (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium with 10% FBS)

- Resazurin sodium salt (for viability assay)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Fixation solution (2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer)

- Primary antibodies (CD73, CD90, CD105 for MSC characterization)

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) equipment

Procedure

Cell Seeding on Scaffolds

- Sterilize scaffolds (UV irradiation or ethanol treatment)

- Pre-wet scaffolds in culture media for 2-4 hours

- Seed MSCs at density of 50,000-100,000 cells per scaffold

- Allow cell attachment for 4-6 hours before adding additional media

Viability and Proliferation Assessment

- Prepare resazurin working solution (10% in culture media)

- Incubate cell-scaffold constructs with resazurin for 2-4 hours at 37°C

- Measure fluorescence (560EX/590EM) at 24, 48, and 72 hours

- Calculate cell numbers based on standard curve

Immunophenotyping via Flow Cytometry

- Harvest cells from scaffolds using collagenase/trypsin treatment

- Wash cells with PBS and aliquot 100,000 cells per tube

- Incubate with antibodies against CD73, CD90, CD105 (positive markers) and CD34, CD45 (negative markers)

- Fix cells with 2% paraformaldehyde

- Analyze using flow cytometry to confirm MSC phenotype

Microscopic Evaluation

- Fix cell-scaffold constructs with 2.5% glutaraldehyde

- Process for SEM: dehydrate through ethanol series, critical point dry, sputter coat with gold/palladium

- Image using SEM to assess cell morphology and integration

Biological Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The regenerative capacity of composite scaffolds is mediated through specific biological mechanisms that direct cellular behavior and tissue formation. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways activated by synthetic and ceramic scaffolds to promote osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells.

Diagram 1: Signaling pathways in scaffold-mediated bone regeneration. Ceramic components (HA/β-TCP) promote osteoconduction and BMP-2 upregulation, driving MSC differentiation toward osteogenic lineage through RUNX2 activation. Tunable polymers enhance cell adhesion and modulate degradation, influencing the RANKL/OPG balance critical for bone remodeling. β-TCP additionally promotes macrophage polarization toward anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, creating a favorable regenerative microenvironment.

The molecular mechanisms underlying scaffold-mediated osteogenesis involve complex interactions between multiple signaling pathways. HA and β-TCP ceramics directly stimulate osteogenic differentiation by activating the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway, particularly upregulating BMP-2 expression [32]. This activation occurs through calcium-sensing receptors (CaSR) on mesenchymal stem cells, leading to downstream SMAD phosphorylation and translocation to the nucleus where they activate transcription of osteogenic genes including RUNX2, the master regulator of osteoblast differentiation [32] [36].

Simultaneously, scaffold topography and mechanical properties activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which synergizes with BMP signaling to enhance osteogenic commitment while suppressing adipogenic differentiation [32]. The controlled degradation of polymer components regulates the local release of calcium and phosphate ions, which further promotes osteoblast mineralization through activation of calcium-sensing receptors and alkaline phosphatase activity [32].

An additional crucial mechanism involves immunomodulation, where β-TCP scaffolds promote the polarization of macrophages toward the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [32]. This transition from pro-inflammatory M1 to regenerative M2 macrophages enhances BMP-2 expression while reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine production, creating a microenvironment conducive to bone formation rather than fibrosis [32] [36].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated experimental approach for developing and evaluating synthetic and ceramic scaffolds for bone regeneration applications.

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for scaffold development and evaluation. The process begins with strategic material selection and scaffold design, proceeds through automated or manual fabrication, and culminates in comprehensive physical, biological, and molecular characterization to optimize scaffold performance for bone regeneration applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of scaffold-based bone regeneration research requires specific materials and reagents with defined functions. The following table details essential components for designing, fabricating, and evaluating synthetic and ceramic scaffolds.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Scaffold-Based Bone Regeneration Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Materials | PLGA, PCL, PEG | Structural scaffold matrix; tunable degradation | Varying copolymer ratios affect degradation rate [34] |

| Ceramic Components | Hydroxyapatite (HA), β-TCP | Osteoconduction; enhancing compressive strength | Nanoparticles improve distribution [32] [34] |

| Solvents | Chloroform, Hexafluoroisopropanol | Polymer dissolution for processing | Weight-based measurement improves accuracy [34] |

| Fabrication Aids | PVA (mold material), Borosilicate glass vials | Support structures; chemical compatibility | Prevents reaction with solvents [34] |