Bridging the Gap: Validating iPSC Disease Phenotypes with Clinical Data for Robust Disease Modeling and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the strategies and challenges in validating disease phenotypes in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) models against real-world clinical data.

Bridging the Gap: Validating iPSC Disease Phenotypes with Clinical Data for Robust Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the strategies and challenges in validating disease phenotypes in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) models against real-world clinical data. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of iPSC-based disease modeling, details advanced methodological approaches for creating clinically relevant phenotypes, and addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges. Furthermore, it examines cutting-edge validation frameworks, including the use of AI and large-scale clinical data, to enhance the predictive accuracy and translational value of iPSC models for therapeutic discovery and personalized medicine.

The Foundation of iPSC Disease Modeling: From Cellular Reprogramming to Clinical Phenotypes

The development of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology represents a transformative breakthrough in regenerative medicine and disease modeling. iPSCs are a type of pluripotent stem cell generated directly from somatic cells through the introduction of specific reprogramming factors, effectively reversing the developmental clock of specialized cells back to an embryonic-like state [1] [2]. This technology, pioneered by Shinya Yamanaka and Kazutoshi Takahashi in 2006, demonstrated that the forced expression of four transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc, collectively known as Yamanaka factors or OSKM) could convert mouse fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells [1] [3] [2].

The core principle of iPSC generation rests on the fundamental understanding that while somatic cells harbor complete genetic information, phenotypic diversity is achieved through reversible epigenetic mechanisms rather than irreversible genetic changes [1]. This concept was initially demonstrated through seminal somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) experiments by John Gurdon, which showed that nuclei from differentiated cells could support full embryonic development when transferred into enucleated eggs [1] [3]. The iPSC technology builds upon this principle, offering a powerful platform for disease modeling, drug screening, and cell therapy applications while bypassing the ethical concerns associated with embryonic stem cells [1] [3] [2].

Molecular Mechanisms of Reprogramming

Key Transcription Factors and Their Roles

The reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency involves profound remodeling of chromatin structure and the epigenome, orchestrated by core transcription factors [1] [3]. Each factor plays distinct yet interconnected roles in resetting cellular identity:

- Oct4 (Pou5f1): A POU-family transcription factor crucial for maintaining pluripotency. Oct4 deletion leads to spontaneous differentiation into trophoblast cells, demonstrating its essential role in preserving the pluripotent state [2]. It forms core regulatory circuits with Sox2 and Nanog to activate pluripotency-associated genes [3].

- Sox2: An SRY-box transcription factor that partners with Oct4 to bind composite SOX-OCT motifs in enhancers and promoters of pluripotency genes. This partnership enables the activation of a broad network of genes essential for establishing pluripotency [3] [2].

- Klf4: A Krüppel-like factor that supports reprogramming through multiple mechanisms, including activation of epithelial genes during mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) and reinforcement of the pluripotency network through interaction with Oct4 and Sox2 [3].

- c-Myc: A proto-oncogene that enhances reprogramming efficiency by binding broadly to somatic genome regions with open chromatin, facilitating access for other reprogramming factors to their target genes. It primarily promotes cell cycle progression and metabolic changes conducive to reprogramming [3].

Alternative factor combinations have also proven effective, with Thomson and colleagues demonstrating successful reprogramming using OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28 [1] [2]. The specific combination used can influence reprogramming efficiency and the quality of resulting iPSCs.

Phases of Reprogramming

The process of somatic cell reprogramming occurs through a sequential series of molecular events characterized by two main transcriptional waves [1] [3]:

Early Phase Events: The initial reprogramming stage begins with OSKM factors binding to somatic cell genomes, where c-Myc facilitates access to closed chromatin regions [3]. This binding initiates:

- Silencing of somatic genes including Thy1, Snai1, Snai2, Zeb1, and Zeb2 surface markers [3]

- Activation of early pluripotency-associated genes [1]

- Initiation of mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), characterized by upregulation of epithelial genes (Cdh1, Epcam, Ocln) and downregulation of mesenchymal markers [1] [3]

Late Phase Events: The subsequent stage establishes stable pluripotency through:

- Activation of core pluripotency circuitry including Nanog, Sall4, Utf1, and endogenous Sox2 [3]

- Epigenetic resetting with establishment of ESC-like chromatin modifications [1] [3]

- Morphological transformation into compact, ESC-like colonies with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios [1]

- Formation of autoregulatory loops that maintain the pluripotent state without continuous transgene expression [3]

The complete reprogramming process is typically slow and inefficient, taking 3-4 weeks for human cells with efficiencies around 0.01-0.1% for most methods [2]. The low efficiency reflects significant barriers including activation of p53-dependent senescence pathways and the stochastic nature of epigenetic remodeling [3].

Comparative Analysis of Reprogramming Methods

Integration-Based vs. Non-Integration Methods

Various reprogramming methods have been developed, each with distinct advantages and limitations for research and therapeutic applications. These methods can be broadly categorized into integrating and non-integrating systems [3].

Quantitative Comparison of Major Non-Integrating Methods

Recent comparative studies have provided quantitative data on the performance of the most commonly used non-integrating reprogramming methods [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Non-Integrating Reprogramming Methods

| Method | Reprogramming Efficiency* | Key Factors Delivered | Genomic Integration | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sendai Virus (SeV) | 0.1-1% | OSKM | No | High efficiency, works with multiple cell types, well-defined clearance | Viral method, potential immunogenicity |

| Episomal Vectors | 0.04-0.3% | Oct4, Sox2, Lin28, Klf4, L-Myc (+ p53 suppression) | No (extra-chromosomal) | Virus-free, transgene-free iPSCs | Lower efficiency, requires electroporation |

| Synthetic mRNA | 0.5-2% | OSKM modified mRNAs | No | High efficiency, precise control, no vector design needed | Requires multiple transfections, potential immune activation |

| Protein Transduction | <0.001% | Recombinant OSKM proteins | No | Completely footprint-free, minimal safety concerns | Very low efficiency, technically challenging |

*Efficiency range represents percentage of starting somatic cells that become iPSC colonies [5] [4]

A 2025 comparative analysis examining reprogramming success rates across different source materials found that Sendai virus reprogramming yielded significantly higher success rates compared to episomal methods [4]. The study also demonstrated that source material (fibroblasts, LCLs, or PBMCs) did not significantly impact success rates, highlighting the robustness of viral delivery systems [4].

Experimental Protocols for iPSC Generation

Sendai Virus Reprogramming Protocol

The Sendai virus (SeV) system represents one of the most efficient non-integrating reprogramming methods. Below is a detailed protocol based on the CytoTune Sendai Reprogramming Kit [4]:

Day 0: Preparation and Plating

- Culture source cells (e.g., fibroblasts, PBMCs) in appropriate medium

- Ensure cells are 70-90% confluent at time of transduction

- Prepare essential supplements including 10μM Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor)

Day 1: Viral Transduction

- Dilute CytoTune viruses in appropriate culture medium

- Remove culture medium from cells and add virus-containing medium

- Incubate cells for 24 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2

Day 2: Medium Replacement

- Remove virus-containing medium and replace with fresh culture medium

- Culture cells for additional 6 days with medium changes every other day

- Monitor transduction efficiency via GFP expression if using reporter constructs

Day 7: Harvest and Replate

- Harvest transduced cells using appropriate dissociation reagent

- Replate cells onto feeder layers or extracellular matrix-coated plates (e.g., Matrigel)

- Switch to hiPSC culture medium supplemented with ROCK inhibitor

Days 10-30: Colony Selection and Expansion

- Continue culture with daily medium changes

- Monitor emergence of ESC-like colonies with defined borders, high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio

- Mechanically pick individual colonies between days 21-30

- Expand clonal lines and validate pluripotency

Episomal Reprogramming Protocol

The episomal reprogramming method provides a non-viral alternative for generating footprint-free iPSCs [5]:

Day 0: Nucleofection Preparation

- Culture source cells to 75-90% confluency

- Prepare episomal vector mixture containing OCT4, SOX2, LIN28, KLF4, L-MYC, and p53 suppression factors [5]

- Harvest cells and resuspend in nucleofection solution

Day 1: Nucleofection

- Perform nucleofection using Amaxa Nucleofector II device (Program U-015 for LCLs, U-023 for fibroblasts) [4]

- Plate transfected cells in culture medium

- Culture under hypoxic conditions (5% O2) to enhance efficiency [4]

Days 2-7: Post-Transfection Culture

- Change medium every other day

- Monitor transfection efficiency via GFP expression if using reporter constructs

- Avoid antibiotic use during this critical period [5]

Days 7-14: Replating

- Harvest transfected cells and replate at appropriate density on feeder cells or extracellular matrix

- Switch to hiPSC culture medium

Days 14-35: Colony Selection

- Identify and manually pick at least 24 candidate colonies for expansion [4]

- Expand clonal lines and confirm loss of episomal vectors (typically after ~5 passages) [5]

- Validate pluripotency markers and differentiation potential

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for iPSC Generation and Characterization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | CytoTune Sendai Viruses, Epi5 Episomal Vectors [5] [4] | Deliver OSKM transcription factors | Sendai: high efficiency; Episomal: integration-free |

| Cell Culture Media | mTeSR1, Essential 8, DMEM/F12 with KSR | Support iPSC growth and maintenance | Defined, xeno-free formulations preferred |

| Culture Supplements | Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor), bFGF, L-ascorbic acid | Enhance cell survival, promote pluripotency | ROCK inhibitor critical post-thaw and during passaging |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Geltrex, Vitronectin, Laminin-521 | Provide substrate for feeder-free culture | Mimic basement membrane for cell attachment |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60 | Confirm pluripotency marker expression | Essential for quality control of iPSC lines |

| Differentiation Inducers | BMP4, Activin A, CHIR99021, Retinoic acid | Direct differentiation to specific lineages | Used for functional validation of pluripotency |

| Quality Control Assays | Karyotyping, STR profiling, Mycoplasma testing | Ensure genetic integrity and sterility | Critical for biobanking and therapeutic applications |

Applications in Disease Modeling and Clinical Validation

iPSC technology has revolutionized approaches to disease modeling and drug discovery by enabling the generation of patient-specific disease models [1] [3]. The ability to differentiate iPSCs into various cell types allows researchers to recapitulate disease phenotypes in vitro, providing powerful platforms for:

Mechanistic Studies of Pathogenesis: iPSCs derived from patients with genetic disorders can be differentiated into affected cell types to study disease mechanisms. For example, iPSCs from spinal muscular atrophy patients have been differentiated into neurons to model disease-specific phenotypes [3]. Similarly, iPSCs have been extensively applied to study diabetes pathogenesis through differentiation into pancreatic β-cells [6].

Drug Screening and Toxicity Testing: iPSC-derived cells enable high-throughput screening of compound libraries using human cells with disease-relevant genetic backgrounds. This approach is particularly valuable for neurological disorders and cardiac conditions, where species-specific differences limit the predictive value of animal models [1].

Clinical Applications and Cell Therapy: The potential to generate autologous cells for transplantation represents one of the most promising applications of iPSC technology. Significant progress has been made in developing iPSC-derived cells for retinal diseases, Parkinson's disease, and myocardial infarction [1]. A 2020 review highlighted successes in animal models, including correction of sickle cell anemia in mice through autologous iPSC therapy [3].

The integration of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing with iPSC technology has further enhanced its utility by enabling precise genetic corrections in patient-specific iPSCs, facilitating both functional studies and development of therapeutic approaches [3]. As the field advances, the validation of iPSC disease phenotypes with clinical data remains essential for establishing the relevance and predictive value of these innovative cellular models [6].

The Promise of Patient-Specific iPSCs for Disease Modeling and Personalized Medicine

The advent of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has catalyzed a transformative shift in biomedical research and therapeutic development. First established by Shinya Yamanaka and colleagues in 2006, iPSC technology enables the reprogramming of adult somatic cells into a pluripotent state through the introduction of specific transcription factors, classically OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM) [1] [7]. This groundbreaking discovery, which earned Yamanaka the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2012, provided an ethically acceptable alternative to embryonic stem cells while offering unprecedented access to patient-specific human cells for research [8]. The fundamental promise of patient-specific iPSCs lies in their capacity to capture the unique genetic background of individual patients, thereby enabling the development of personalized disease models that more accurately recapitulate human pathophysiology than traditional animal models or immortalized cell lines [9].

The application of iPSC technology within personalized medicine represents a convergence of stem cell biology, genomics, and drug discovery. By generating pluripotent stem cells from patients with known genetic variants and clinical histories, researchers can differentiate these cells into the specific cell types affected in various diseases—neurons for neurodegenerative disorders, cardiomyocytes for cardiac conditions, or hepatocytes for metabolic diseases [8] [1]. These patient-derived cellular models retain the donor's complete genetic information, providing a powerful platform for elucidating disease mechanisms, identifying novel therapeutic targets, screening drug candidates, and developing personalized treatment strategies [8] [10] [9]. This approach is particularly valuable for rare genetic diseases, which collectively affect millions worldwide but often lack adequate models for research and therapeutic development [11].

This review will objectively compare the performance of iPSC-based disease modeling against traditional approaches, examining its validation against clinical data across multiple disease contexts. We will present structured experimental data, detailed methodologies, and analytical frameworks that demonstrate how patient-specific iPSCs are reshaping our approach to understanding and treating human disease.

Comparative Analysis of Disease Modeling Platforms

To objectively evaluate the performance of patient-specific iPSCs against traditional disease modeling approaches, we have summarized key comparative metrics across multiple dimensions in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Disease Modeling Platforms

| Model Characteristic | Patient-Specific iPSCs | Animal Models | Immortalized Cell Lines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Relevance | Carries patient's complete genotype; preserves disease-associated variants [9] | Species-specific genetic background; human transgenes often overexpressed [12] | Cancer-derived; extensively mutated; non-physiological gene expression [9] |

| Phenotypic Predictive Value | Recapitulates patient-specific disease phenotypes (e.g., neuronal degeneration, cardiac arrhythmia) [12] | Limited translation of therapeutic efficacy (∼95% failure rate in ALS trials) [12] | Poor correlation with human tissue responses; missing complex physiology [9] |

| Scalability for Screening | Indefinite expansion potential; compatible with HTS formats (384-/1536-well plates) [9] | Low-throughput; time-consuming and expensive | High-throughput capable but physiologically irrelevant [9] |

| Clinical Correlation | Transcriptomic profiles match human post-mortem tissue; donor phenotype correlations [12] | Species-specific pathophysiology; different drug metabolism [13] | No clinical correlation possible |

| Temporal Resolution | Enables longitudinal monitoring of disease progression in human cells [12] | Requires terminal timepoints; limited longitudinal assessment | Continuous culture but non-physiological aging |

| Multi-system Modeling | Emerging 3D organoid systems with multiple cell types [1] [11] | Intact organism with systemic physiology | Limited to single cell types |

The comparative advantage of iPSC-based models is particularly evident in their ability to model complex, sporadic diseases that have proven resistant to traditional modeling approaches. A landmark study utilizing a library of iPSCs from 100 patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (SALS) demonstrated that patient-derived motor neurons recapitulated key disease features including reduced survival and accelerated neurite degeneration that correlated with donor survival time—a critical validation against clinical data [12]. This model also successfully predicted the clinical failure of 97% of drugs previously tested in ALS trials, demonstrating superior predictive validity compared to traditional transgenic models [12].

Similarly, in cardiovascular disease, iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes from patients with hereditary arrhythmogenic disorders have replicated electrophysiological abnormalities observed in patients, enabling both mechanistic studies and drug screening [8] [7]. The capacity to capture patient-specific drug responses represents a particular strength of iPSC technology, addressing a fundamental limitation of traditional one-size-fits-all therapeutic development [10].

Experimental Validation of iPSC Disease Models

The scientific credibility of iPSC-based disease modeling depends on rigorous validation against clinical data. The table below summarizes key validation approaches and representative findings from recent studies across multiple disease contexts.

Table 2: Experimental Validation of iPSC Disease Models Against Clinical Data

| Disease Area | Validation Methodology | Key Correlation with Clinical Data | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sporadic ALS | Longitudinal survival analysis of motor neurons from 100 SALS patients | Neurite degeneration rate correlated with donor survival time (p<0.001) [12] | [12] |

| Epilepsy | RNA-seq of CLCNKB-mutant iPSCs vs. control lines | Identification of differentially expressed genes previously implicated in epilepsy phenotypes [14] | [14] |

| Parkinson's Disease | Transplantation of iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons in clinical trials | Graft survival, dopamine production, and absence of tumors in patients (Phase I/II) [7] | [7] |

| Cardiovascular Disease | Drug screening using iPSC-cardiomyocytes from congenital arrhythmia patients | Recapitulation of patient-specific drug responses (e.g., KCNQ1 mutation responses) [8] | [8] [10] |

| Diabetes | Differentiation of iPSCs to insulin-producing β-cells | Reversal of hyperglycemia in animal models; recapitulation of autoimmune destruction with T-cells [8] [6] | [8] [6] |

| Rare Diseases (NPH) | Kidney organoids from NPHP1-deficient iPSCs | Cyst formation consistent with patient renal pathology; reversal with gene correction [11] | [11] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Large-Scale Drug Screening in iPSC-Derived Motor Neurons

To illustrate the methodological rigor required for robust iPSC-based disease modeling, we detail the experimental protocol from the landmark SALS study [12], which exemplifies the comprehensive approach needed to validate disease phenotypes against clinical data:

1. iPSC Library Generation and Quality Control

- Somatic Cell Source: Dermal fibroblasts isolated from skin biopsies of 100 SALS patients and 25 healthy controls [12]

- Reprogramming Method: Non-integrating episomal vectors delivered via automated robotics platform to maximize uniformity [12]

- Quality Control Measures: Genomic integrity verification (karyotyping), pluripotency confirmation (immunocytochemistry for canonical markers), and trilineage differentiation potential [12]

- Clinical Annotation: Comprehensive donor clinical data including ALS subtype, site of onset, age of onset, ALSFRS-R progression rate, and survival time [12]

2. Motor Neuron Differentiation and Characterization

- Protocol: Five-stage spinal motor neuron differentiation adapted from established protocols with optimized maturation conditions [12]

- Purity Assessment: Immunocytochemistry for cell-type-specific markers demonstrating >92% purity for motor neurons (ChAT+, MNX1/HB9+, Tuj1+) with minimal contamination from astrocytes (<0.12%) and microglia (<0.04%) [12]

- Functional Assessment: Electrophysiological measurements to confirm neuronal activity and pharmacological response to riluzole [12]

3. Phenotypic Screening and Longitudinal Analysis

- Live-Cell Imaging: Daily monitoring using virally delivered motor neuron-specific reporter (HB9-turbo) in conjunction with automated image acquisition [12]

- Quantitative Metrics: Survival curves, neurite degeneration rates, and correlation with donor clinical parameters [12]

- Transcriptomic Profiling: RNA sequencing to compare SALS motor neurons with controls and post-mortem spinal cord tissue [12]

4. Drug Screening and Validation

- Compound Library: >100 drugs previously tested in ALS clinical trials [12]

- Screening Format: High-throughput assessment of motor neuron survival [12]

- Hit Validation: Combinatorial testing of effective drugs across multiple SALS donors to account for population heterogeneity [12]

This comprehensive protocol demonstrates the multi-layered validation approach required to establish iPSC-based models with strong clinical correlation. The study's findings were particularly significant for demonstrating that only 3% of drugs that showed efficacy in traditional ALS models rescued motor neuron survival across the SALS donor population, mirroring the high failure rate of these compounds in clinical trials [12].

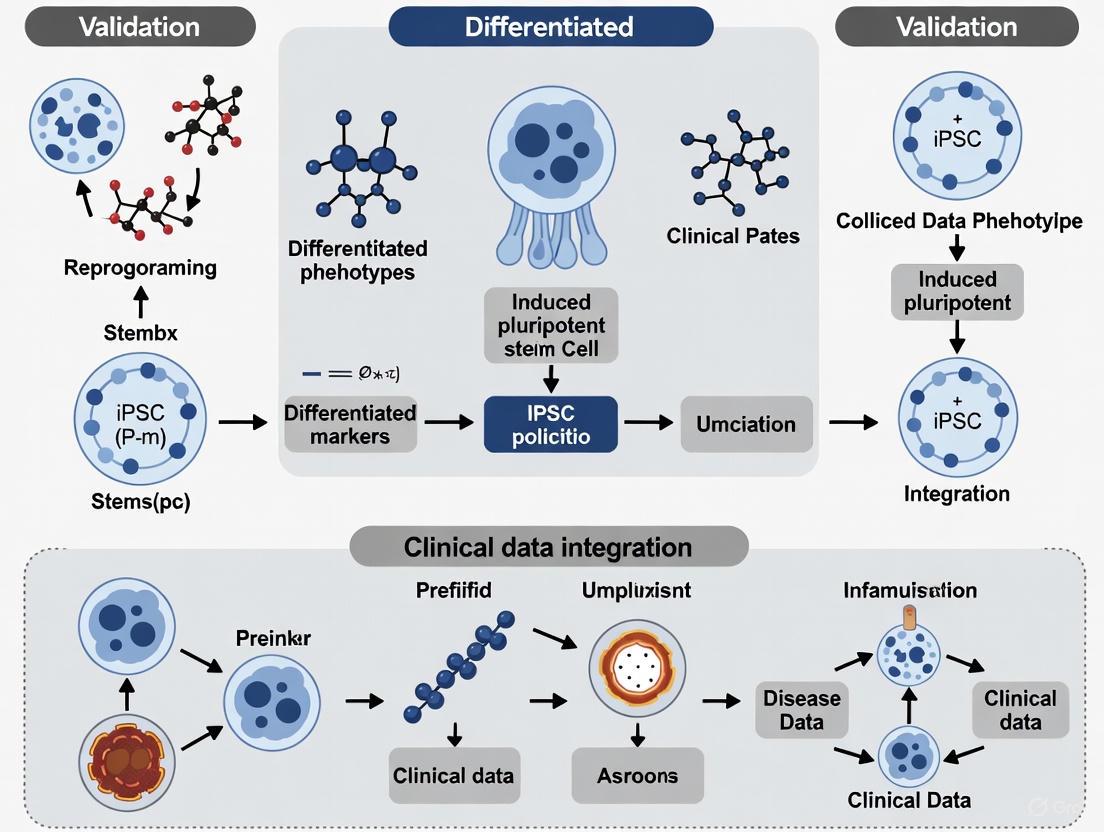

Visualization of iPSC Workflow and Signaling

To better understand the technical workflow and molecular mechanisms underlying iPSC-based disease modeling, the following diagrams provide visual representations of key processes.

Diagram 1: iPSC Technology Workflow from Somatic Cells to Disease Modeling. This diagram illustrates the sequential process of generating patient-specific disease models, beginning with somatic cell isolation from various accessible tissues, through reprogramming using OSKM factors or non-integrating methods, expansion of pluripotent cells, and directed differentiation into disease-relevant cell types for modeling and therapeutic development [8] [1] [7].

Diagram 2: Molecular Mechanisms of Somatic Cell Reprogramming. This diagram outlines the key molecular events during iPSC generation, highlighting the two-phase process where early reprogramming involves stochastic silencing of somatic genes and chromatin remodeling, while late reprogramming features deterministic activation of the pluripotency network and epigenetic resetting, culminating in stabilization of the pluripotent state [1].

Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC-Based Disease Modeling

The successful implementation of iPSC technology requires specialized reagents and platforms. The table below details essential research tools and their applications in patient-specific disease modeling.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for iPSC-Based Disease Modeling

| Reagent Category | Specific Product/Platform | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Systems | CytoTune-iPS Sendai Reprogramming Kit [14] | Non-integrating reprogramming of somatic cells | Leave-no-trace methodology; high efficiency [7] |

| Culture Systems | mTeSR1/Matrigel culture system [14] | Maintenance of pluripotent iPSCs | Defined, feeder-free conditions; enhanced reproducibility [8] |

| Differentiation Kits | iCell Cardiomyocytes [13] | Directed differentiation to specific lineages | High-purity, functionally mature cells; batch consistency [13] |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems [7] | Generation of isogenic controls; disease mutation correction | Precise genetic modification; creation of paired cell lines [7] |

| Characterization Assays | Pluripotency marker antibodies [8] | Quality control of iPSCs and differentiated cells | Verification of pluripotent state (OCT4, NANOG) [8] |

| Specialized Media | Maturation supplements for cardiomyocytes [9] | Enhanced functional maturation of differentiated cells | Promotion of adult-like phenotypes; improved drug response [9] |

| Automation Platforms | opti-ox precision cell programming [13] | Large-scale, consistent differentiation | Industrial-scale production; exceptional purity [13] |

The selection of appropriate reagents and platforms is critical for generating reproducible, high-quality iPSC models. Commercial providers have optimized systems for specific applications, such as Ncardia's cardiomyocytes for cardiac safety pharmacology, FUJIFILM CDI's iCell products for various lineages, and bit.bio's opti-ox technology for consistent differentiation at scale [13]. These standardized platforms are increasingly important for reducing technical variability and enabling more direct comparison of results across different laboratories and studies.

For genetic studies, CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing systems have become indispensable for generating isogenic control lines—where disease-causing mutations are corrected in patient-derived iPSCs or introduced into healthy iPSCs [7]. This powerful approach controls for genetic background variability and enables definitive establishment of genotype-phenotype relationships, as demonstrated in studies of Parkinson's disease where correction of LRRK2 mutations rescued mitochondrial dysfunction in patient-derived neurons [7].

Patient-specific iPSCs have emerged as a transformative platform for disease modeling and therapeutic development, offering unprecedented ability to capture human genetic diversity and recapitulate disease pathophysiology in vitro. The rigorous validation of iPSC-derived disease models against clinical data—as demonstrated by correlations between in vitro phenotypes and patient outcomes—establishes their growing value in the biomedical research toolkit [12] [14].

While challenges remain in standardization, functional maturation, and cost, the continuous refinement of differentiation protocols, the development of more complex multi-cellular systems including organoids, and the integration of emerging technologies like AI-guided differentiation and high-content screening are rapidly advancing the field [7] [9]. The ongoing clinical translation of iPSC-based therapies for conditions like Parkinson's disease and geographic atrophy further validates the fundamental utility of this platform [7].

As the field progresses toward more physiologically relevant in vitro models and larger-scale biobanking efforts, patient-specific iPSCs are poised to become an increasingly central component of personalized medicine, enabling not only improved drug development efficiency but ultimately the creation of truly individualized therapeutic approaches based on a patient's unique cellular responses.

Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized biomedical research by providing a platform for creating patient-specific disease models. By reprogramming somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells, researchers can generate disease-relevant cell types to study pathogenesis and test therapeutic interventions. This guide compares the application of iPSC technology across three key disease areas—neurological, cardiac, and metabolic disorders—highlighting successful studies that have bridged the gap between in vitro modeling and clinical validation.

Neurological Disorders: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

A landmark 2025 study established a robust framework for modeling sporadic ALS (SALS) using iPSCs [12]. Researchers generated an iPSC library from 100 SALS patients and 25 healthy controls. A five-stage protocol differentiated iPSCs into spinal motor neurons with high purity (92.44% ± 1.66%) [12]. Key steps included:

- Fibroblast Isolation and Reprogramming: Skin biopsies from donors were reprogrammed using non-integrating episomal vectors on an automated robotics platform to ensure uniformity [12].

- Motor Neuron Differentiation: Adapted from an established spinal motor neuron differentiation protocol with optimized maturation conditions [12].

- Phenotypic Screening: Cultures were monitored daily using live-cell imaging with a motor neuron-specific reporter (HB9-turboGFP) [12].

- Longitudinal Analysis: Automated image analysis quantified motor neuron survival and neurite degeneration over time [12].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this large-scale screening approach:

Key Findings and Clinical Validation

This study demonstrated that SALS motor neurons recapitulated key disease features, including reduced survival and accelerated neurite degeneration that correlated with donor survival time [12]. Transcriptional profiling aligned with postmortem spinal cord tissues from ALS patients, validating the model's pathophysiological relevance [12].

In drug screening, the model showed remarkable predictive value for clinical outcomes. When testing over 100 drugs previously evaluated in ALS clinical trials, 97% failed to rescue motor neuron survival, mirroring their clinical trial failures [12]. The study identified a promising therapeutic combination of baricitinib, memantine, and riluzole that significantly improved motor neuron survival across the heterogeneous SALS donor population [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagents for iPSC-Based ALS Modeling

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Example Product/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Non-integrating Episomal Vectors | Reprogramming somatic cells without genomic integration | Episomal plasmids containing OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC [12] |

| Motor Neuron Differentiation Kit | Directing iPSCs toward spinal motor neuron fate | Commercial kits or established 5-stage protocols [12] |

| HB9-turboGFP Reporter | Labeling motor neurons for live-cell imaging | Viral vector with motor neuron-specific promoter [12] |

| Cell Culture Matrices | Providing substrate for cell attachment and growth | Matrigel-coated plates [15] |

| Neuronal Maintenance Media | Supporting motor neuron survival and maturation | Optimized culture medium with specific growth factors [12] |

Metabolic Disorders: Fatty Acid Oxidation Disorders & Barth Syndrome

Experimental Approach

iPSC models have advanced the study of metabolic cardiomyopathies, particularly long-chain fatty acid oxidation disorders (lcFAODs) and Barth syndrome (BTHS) [16]. These disorders disrupt cardiac energy metabolism through three primary mechanisms: toxic metabolite accumulation, excessive substrate storage, and energy deficiency [16]. Research protocols typically involve:

- Patient iPSC Generation: Somatic cells from patients with specific mutations are reprogrammed to iPSCs [16].

- Cardiomyocyte Differentiation: iPSCs are differentiated into cardiomyocytes using specific biochemical cues [16].

- Metabolic and Functional Analysis: Researchers assess mitochondrial function, fatty acid oxidation rates, and contractile properties [16].

The diagram below illustrates how inherited metabolic defects lead to cardiac dysfunction:

Disease Modeling Successes

iPSC-cardiomyocytes from lcFAOD patients have revealed disease-specific alterations in mitochondrial morphology and function, enabling drug screening to identify compounds that restore metabolic balance [16]. For Barth syndrome, caused by TAFAZZIN mutations, iPSC models have elucidated the link between defective cardiolipin remodeling and mitochondrial inefficiency, providing a platform for testing potential interventions [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Metabolic Cardiomyopathy Research

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Definitive Endoderm Induction Kits | First step in cardiac differentiation | STEMdiff Definitive Endoderm Kit [15] |

| Cardiac Differentiation Media | Directing iPSCs to cardiomyocyte lineage | Media with stage-specific growth factors [16] |

| Metabolic Substrates | Assessing energy pathway function | Labeled fatty acids for oxidation studies [16] |

| Mitochondrial Dyes | Visualizing and quantifying mitochondrial function | TMRE, JC-1 for membrane potential [16] |

| Calcium Indicators | Measuring calcium handling in cardiomyocytes | Fura-2, Fluo-4 for functional assessment [16] |

Cardiac Disorders: Disease Modeling & Drug Screening

Methodological Advances

iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes have become valuable for modeling inherited cardiac conditions and screening for drug-induced toxicity [17]. Key methodological considerations include:

- Maturation Strategies: iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes often resemble neonatal cells, requiring advanced maturation protocols to better model adult disease [17].

- 3D Culture Systems: Engineered heart tissues provide more physiological relevance than 2D cultures [17].

- Metabolic Maturation: Optimizing culture conditions to promote adult-like metabolic phenotypes [16].

Applications and Outcomes

In drug discovery, iPSC-cardiomyocytes have been extensively used for preclinical cardiotoxicity screening, particularly for predicting arrhythmogenic potential [13]. Companies like Fujifilm CDI and Ncardia have industrialized iPSC-derived cardiomyocyte production for high-throughput safety pharmacology [13]. For disease modeling, iPSC-cardiomyocytes from patients with hereditary cardiomyopathies have revealed disease mechanisms and enabled patient-specific drug testing [16].

Comparative Analysis of iPSC Models Across Disease Areas

Table: Quantitative Comparison of iPSC Disease Modeling Success

| Parameter | Neurological (ALS) | Metabolic (lcFAODs/BTHS) | Cardiac (Channelopathies/CM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size in Key Studies | 100 SALS patients [12] | Multiple cell lines per disorder [16] | Varies (often 5-20 patients) [17] |

| Differentiation Efficiency | 92.44% ± 1.66% motor neurons [12] | High purity achievable [16] | High purity, but maturation limited [17] |

| Key Phenotypes Recapitulated | Reduced survival, neurite degeneration [12] | Mitochondrial dysfunction, metabolic alterations [16] | Arrhythmias, contractile dysfunction [17] |

| Clinical Predictive Value | 97% accurate for clinical trial failures [12] | Pathophysiological mechanisms confirmed [16] | Strong for cardiotoxicity prediction [13] |

| Therapeutic Discovery | Identified effective drug combination [12] | Targets for metabolic correction identified [16] | Patient-specific drug responses [16] |

iPSC technology has generated clinically relevant models across neurological, cardiac, and metabolic disorders, with the most compelling successes emerging from studies that incorporate large patient cohorts and rigorous clinical validation. The SALS model demonstrates the power of iPSCs to predict clinical trial outcomes and identify new therapeutic combinations. In metabolic and cardiac disorders, iPSCs have uncovered disease mechanisms and provided platforms for drug screening. Future directions include improving cellular maturation, developing more complex multicellular models, and integrating artificial intelligence to enhance phenotypic analysis and predictive accuracy [18]. As these technologies advance, iPSC-based disease models will play an increasingly central role in bridging the gap between preclinical research and clinical application.

In the decade and a half since their discovery, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have revolutionized biomedical research, offering unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine [1]. The ability to reprogram adult somatic cells into a pluripotent state and differentiate them into virtually any cell type provides a powerful platform for studying human diseases in vitro [19]. However, as the field matures and approaches clinical translation, a critical validation gap has emerged: the disconnect between iPSC-derived disease phenotypes observed in laboratory settings and the actual clinical manifestations in human patients. This gap represents a significant challenge for realizing the full potential of iPSC technology in therapeutic development, necessitating robust strategies to ensure that in vitro models faithfully recapitulate in vivo disease biology.

The Nature of the Validation Gap in iPSC Research

The validation gap in iPSC research stems from multiple technical and biological challenges that limit the physiological relevance of iPSC-derived models. A primary concern is the immaturity of iPSC-derived cells, which often resemble fetal rather than adult phenotypes, posing particular challenges for modeling late-onset diseases like neurodegenerative disorders [20]. This cellular immaturity means that disease-relevant pathways active in adult patients may not be fully functional in vitro, potentially leading to false negatives in drug screening or incomplete disease modeling.

Another significant factor is the inherent variability in iPSC models. Research has demonstrated that genetic background differences between iPSC donors contribute substantial variation, which can obscure disease-specific phenotypes [21]. This problem is exacerbated by differences in reprogramming methods, differentiation protocols, and culture conditions across laboratories. A power analysis of published iPSC studies reveals that many are underpowered to detect realistic effect sizes given this variability, leading to unreliable results and difficulties in replicating findings [21].

The structural simplicity of many iPSC models further contributes to the validation gap. While 2D monocultures offer experimental convenience, they lack the cellular diversity and complex tissue architecture of human organs [22]. This limitation is particularly relevant for diseases where non-cell-autonomous mechanisms—interactions between different cell types—play crucial roles in pathogenesis.

Table 1: Key Factors Contributing to the Validation Gap in iPSC Disease Modeling

| Factor | Impact on Validation | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Immaturity | Limited relevance for late-onset diseases; incomplete phenotype development | Prolonged culture, metabolic maturation, 3D culture systems |

| Donor Variability | Difficulty distinguishing disease-specific effects from background genetic variation | Isogenic controls, larger cohort sizes, multi-line studies |

| Model Simplicity | Inability to capture tissue-level and non-cell-autonomous disease mechanisms | Co-culture systems, 3D organoids, engineered microenvironments |

| Technical Variability | Poor reproducibility across laboratories and experiments | Standardized protocols, quality control metrics, automated systems |

Quantitative Evidence of the Validation Challenge

Recent systematic analyses have quantified the scope of the validation challenge in iPSC-based modeling. A 2023 study examining statistical power in iPSC-based brain disease research found that most published case-control studies are significantly underpowered due to high variability between lines [21]. The analysis demonstrated that for a realistic effect size (Cohen's d = 1.0) with data variance similar to actual iPSC-derived neurons, a case-control study would require approximately 20 lines per group to achieve 80% power—far more than the typical 3-10 lines used in most published studies.

This power analysis further revealed that studies using isogenic lines consistently demonstrate higher statistical power than case-control designs comparing unrelated patients and controls [21]. For the same effect size, an isogenic pair design might require only 5-7 pairs to achieve similar power, representing a 3-4 fold increase in efficiency. This finding highlights the importance of appropriate experimental design in bridging the validation gap.

Table 2: Statistical Power Comparison for Different iPSC Study Designs

| Study Design | Sample Size Required for 80% Power | Relative Efficiency | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case-Control (Unrelated Lines) | ~20 lines per group | 1x | High genetic background variation |

| Single Isogenic Pair | 1 pair (2 lines) | Limited generalizability | Restricted to single genetic context |

| Multiple Isogenic Pairs | ~5-7 pairs | 3-4x | Requires gene editing for each pair |

Strategies for Bridging the Validation Gap

Isogenic Controls as a Validation Tool

The use of isogenic controls represents one of the most powerful approaches for addressing the validation gap. By comparing iPSC-derived cells that differ only at a specific disease-relevant locus, researchers can isolate the effects of a particular mutation while controlling for background genetic variation [21]. This strategy was effectively demonstrated in a Huntington's disease model where introduction of a 50 CAG repeat expansion in the HTT gene of a control line enabled clear identification of disease-related phenotypes, including transcriptional changes and electrophysiological abnormalities [23].

The generation of isogenic lines typically involves CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to introduce or correct disease-associated mutations in well-characterized iPSC lines [7]. This approach has been successfully applied to numerous conditions, including Parkinson's disease, where correction of the A53T SNCA mutation in patient-derived iPSCs enabled researchers to confirm that observed pathological features were mutation-dependent [7].

Advanced Model Systems: From 2D to 3D

Bridging the validation gap requires moving beyond simple 2D cultures to more physiologically relevant model systems. Cerebral organoids have emerged as a promising platform that better recapitulates the cellular diversity and spatial organization of human tissues [22]. These 3D structures contain multiple neural cell types and have demonstrated the ability to model disease features not observable in 2D cultures, such as the neurofibrillary tangles and β-amyloid plaques characteristic of Alzheimer's disease pathology [22].

The development of co-culture systems further addresses the validation gap by enabling investigation of non-cell-autonomous disease mechanisms [22]. For example, wild-type neural progenitor cells show reduced proliferation when co-cultured with PS1-mutant microglia compared to wild-type microglia, demonstrating how intercellular interactions contribute to Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis [22].

Multi-Omics and Phenotypic Characterization

Comprehensive validation requires thorough molecular and functional characterization of iPSC-derived models. Multi-omics approaches—including transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenomics—provide robust benchmarks for assessing how closely iPSC-derived cells resemble their in vivo counterparts [21]. For instance, proteomic analysis of iPSC-derived neurons has revealed significant variation between lines, highlighting the importance of thorough characterization [21].

Functional validation through electrophysiological analysis remains crucial for neuronal models. In the validated Huntington's model, multi-electrode array (MEA) measurements demonstrated altered neuronal activity in HTT-mutant neurons compared to isogenic controls, providing functional correlation with molecular changes [23].

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Workflow for Validating iPSC Disease Models. This workflow integrates isogenic control generation, advanced model systems, multi-omics characterization, and clinical correlation to bridge the validation gap.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Generation and Validation of Isogenic Pairs

- Starting Material Selection: Begin with a well-characterized, high-quality iPSC line with normal karyotype and robust differentiation potential [23].

- CRISPR-Cas9 Design: Design guide RNAs targeting the locus of interest with minimal off-target effects. Include repair templates with desired modifications and appropriate selection markers.

- Electroporation: Deliver CRISPR components to iPSCs using nucleofection under optimized conditions.

- Clonal Selection: Isolate single cells and expand clonal lines. Screen for successful editing using PCR, sequencing, and functional assays.

- Off-Target Assessment: Perform whole-genome sequencing or targeted analysis of predicted off-target sites to confirm specificity.

- Pluripotency Confirmation: Verify that edited lines maintain pluripotency markers and differentiation potential.

- Banking: Create master and working cell banks of validated isogenic pairs.

Protocol 2: Multi-Omics Characterization of Disease Phenotypes

- Sample Preparation: Differentiate isogenic control and disease lines simultaneously using standardized protocols with appropriate sample replication.

- Transcriptomic Analysis:

- RNA extraction with quality control (RIN > 8.0)

- Bulk or single-cell RNA sequencing with minimum 20 million reads per sample

- Differential expression analysis with correction for multiple comparisons

- Proteomic Profiling:

- Protein extraction and quantification

- LC-MS/MS analysis using SWATH or label-free quantification

- Pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed proteins

- Functional Validation:

- Electrophysiological assessment (patch clamp or MEA for neuronal models)

- Metabolic assays (ATP production, mitochondrial function)

- Cellular imaging (immunocytochemistry, live-cell imaging)

- Data Integration: Correlate omics datasets with functional measurements to identify coherent disease signatures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Model Validation

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Precise genome editing | Generation of isogenic controls; introduction of disease mutations |

| Non-integrating Reprogramming Vectors (e.g., Sendai virus, mRNA) | Footprint-free iPSC generation | Production of clinically relevant iPSC lines with minimal genomic alterations |

| Defined Differentiation Kits | Directed differentiation to specific lineages | Standardized production of target cell types across experiments |

| Organoid Culture Matrices (e.g., Matrigel) | 3D support structure | Generation of complex tissue models with improved physiological relevance |

| Multi-Electrode Arrays (MEA) | Network-level electrophysiological recording | Functional validation of neuronal models |

| Multiplex Immunocytochemistry Antibody Panels | Protein expression analysis | Characterization of cellular identity and maturity |

| Bulk/Single-cell RNA-seq Kits | Transcriptomic profiling | Molecular validation of disease phenotypes |

As iPSC technology continues to evolve, several emerging approaches show promise for further bridging the validation gap. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are being applied to improve differentiation protocols, predict cellular behavior, and identify subtle disease phenotypes that might escape conventional analysis [24]. These computational approaches can extract more information from complex datasets, enhancing the predictive value of iPSC models.

The integration of high-content screening with multi-omics readouts enables comprehensive phenotyping that captures the multidimensional nature of human diseases [24]. As these technologies become more accessible, they will support more rigorous validation of iPSC models against clinical benchmarks.

Furthermore, the establishment of standardized validation frameworks across the field will promote consistency and reproducibility. Organizations like the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) provide guidelines for stem cell research and clinical translation that emphasize rigor, oversight, and transparency [25]. Adherence to these principles strengthens the validity of iPSC-based findings.

In conclusion, while a significant validation gap currently exists between iPSC disease models and clinical reality, the research community has developed powerful strategies to address this challenge. Through the implementation of isogenic controls, advanced model systems, comprehensive molecular and functional characterization, and correlation with clinical data, researchers can enhance the predictive value of iPSC models. As these approaches become standardized and widely adopted, iPSC technology will increasingly fulfill its promise to accelerate drug discovery and development, ultimately leading to more effective therapies for patients.

Methodologies for Generating and Characterizing Clinically Relevant iPSC Phenotypes

The generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) represents one of the most significant breakthroughs in modern regenerative medicine and disease modeling. Since the pioneering work of Takahashi and Yamanaka in 2006-2007, the field has evolved from a basic proof-of-concept to a sophisticated technological platform with profound implications for drug discovery and therapeutic development [1] [7]. The core challenge in iPSC generation has centered on optimizing the balance between two critical parameters: reprogramming efficiency (the percentage of somatic cells successfully converted to pluripotency) and safety profile (minimizing risks associated with genomic instability and tumorigenicity) [26] [27]. This comparison guide provides an objective analysis of contemporary reprogramming methodologies, their performance metrics, and their application in validating disease phenotypes against clinical data—a crucial consideration for researchers and drug development professionals seeking physiologically relevant models.

Comparative Analysis of Reprogramming Techniques

Current reprogramming methods span multiple technological approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations for clinical translation and disease modeling applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Reprogramming Techniques

| Method | Reprogramming Factors Delivered | Efficiency Range | Genomic Integration | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral/Lentiviral | OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) [1] | 0.01%-0.1% [26] | Yes | High efficiency for difficult-to-reprogram cells; well-established protocol | Significant tumorigenicity risk; silencing issues; unsuitable for clinical applications |

| Episomal Vectors | OSKM, sometimes with additional factors (e.g., LIN28, NANOG) [7] | ~0.001% [7] | No | Non-integrating; relatively simple implementation | Low efficiency; potential vector persistence in some cells |

| Sendai Virus | OSKM [7] | 0.1%-1% [7] | No | High efficiency; robust reprogramming; cytoplasmic RNA virus | Viral vector requires dilution through cell division; potential immunogenicity |

| mRNA Reprogramming | OSKMNL (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc, Nanog, Lin28) with immune evasion factors [27] | Up to 4% (fibroblasts); 0.5% (PBMCs) [27] | No | Highest safety profile; precise temporal control; xeno-free conditions | Requires daily transfections; potential immune activation without modifiers |

| Chemical Reprogramming | Small molecule cocktails [1] [28] | Not fully quantified | No | Completely non-genetic; potentially scalable | Complex multi-stage process; efficiency optimization ongoing |

The data reveals a clear inverse relationship between integration risk and reprogramming efficiency in earlier methods, with newer approaches like mRNA reprogramming successfully breaking this trade-off by achieving both high efficiency and excellent safety profiles [27].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics in Disease Modeling Applications

| Method | Typical Reprogramming Time | Teratoma Formation Risk | Genetic Stability | Suitable for Clinical Applications | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral/Lentiviral | 2-3 weeks [1] | High | Low due to insertional mutagenesis | No | Basic research; mechanistic studies |

| Episomal Vectors | 3-4 weeks [7] | Moderate | Moderate | Preclinical | Disease modeling with isogenic controls |

| Sendai Virus | 3-4 weeks [7] | Low | High | With rigorous clearance testing | Disease modeling; drug screening |

| mRNA Reprogramming | 10-14 days [27] | Very Low | Very High | Yes, with GMP compliance | Clinical-grade iPSCs; personalized medicine |

| Chemical Reprogramming | Not fully established | Potentially Low | Potentially High | Under investigation | Future therapeutic applications |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The reprogramming process involves profound remodeling of the chromatin structure and epigenome, transitioning through distinct molecular phases [1]. The early phase is characterized by the silencing of somatic genes and activation of early pluripotency-associated genes, while the late phase involves stabilization of the pluripotency network [1]. Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) represents a critical bottleneck in this process, coordinated by suppression of pro-epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) signals like TGF-β signaling [26].

The molecular roadmap above illustrates the phased progression from somatic to pluripotent state, highlighting key barriers and enhancers that impact efficiency. Research has identified specific strategies to modulate these pathways, including depletion of barriers like p53, p21, and Mbd3, or overexpression of enhancing genes such as FOXH1 and GLIS1 [26]. Understanding these mechanisms enables researchers to select reprogramming methods that optimally navigate this complex landscape.

Experimental Protocols for High-Efficiency Reprogramming

mRNA Reprogramming Protocol

The mRNA reprogramming approach represents one of the most advanced methods for generating clinical-grade iPSCs, combining high efficiency with an excellent safety profile [27]. The following protocol is adapted from commercial mRNA reprogramming kits with optimization for research applications:

Day 0: Plate neonatal or adult human fibroblasts on iMatrix-511-coated wells at a density of 10,000-20,000 cells per cm² in fibroblast culture medium [27].

Days 1-4: Perform daily transfections with StemRNA 3rd Gen Reprogramming Factor mRNAs (OSKMNL - Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc, Nanog, Lin28) combined with immune evasion factors (EKB) using a suitable transfection reagent. Incubate cells in NutriStem hPSC XF medium at 37°C with 5% O₂ (hypoxic conditions) to enhance colony yields [27].

Days 5-14: Change medium daily without additional transfections. Monitor emerging iPSC colonies daily for morphology changes characteristic of pluripotent cells [27].

Days 10-14: Identify and manually pick compact iPSC colonies with defined borders and high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio for further expansion and characterization [27].

Protocol for Enhancing Reprogramming Efficiency

Several strategic enhancements can significantly improve reprogramming outcomes across different methods:

Hypoxic Conditions: Maintain cultures at 5% O₂ throughout reprogramming to enhance colony yields by reducing oxidative stress [27].

Small Molecule Supplementation: Add vitamin C (ascorbic acid) to culture media to enhance reprogramming efficiency through epigenetic modulation, particularly as a co-factor for histone and DNA demethylases [26].

Barrier Inhibition: Implement transient inhibition of reprogramming barriers such as p53 or TGF-β signaling using small molecule inhibitors (e.g., A83-01 for TGF-β inhibition) during early reprogramming phases to enhance efficiency [26].

MET Promotion: Enhance mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition by supplementing with small molecules that promote this critical early reprogramming event [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Advanced Reprogramming

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | StemRNA 3rd Gen mRNA cocktail (OSKMNL + EKB) [27] | Core factors inducing pluripotency; immune evasion | Enables high-efficiency, integration-free reprogramming |

| Culture Matrices | iMatrix-511, Corning Matrigel [27] | Provides extracellular matrix support for cell attachment and signaling | Critical for colony formation and expansion |

| Culture Media | NutriStem hPSC XF Medium [27] | Defined, xeno-free medium supporting reprogramming and pluripotency | Eliminates batch-to-batch variability |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Vitamin C, TGF-β inhibitors, MAPK inhibitors [26] | Modulates signaling pathways to enhance efficiency | Particularly valuable for difficult-to-reprogram cell types |

| Efficiency Reporters | Fbxo15-β-gal/neo reporter system [1] | Enables quantification and selection of reprogrammed cells | Essential for method optimization and quality control |

Disease Modeling Applications and Clinical Validation

Advanced reprogramming techniques have enabled unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling and drug discovery. The capacity to generate patient-specific iPSCs provides a biologically matched resource for studying disease mechanisms and screening therapeutic compounds [19] [29].

The workflow above illustrates how advanced reprogramming enables the generation of disease models that can be rigorously validated against clinical data. A landmark study demonstrating this approach involved generating an iPSC library from 100 sporadic ALS (SALS) patients and conducting population-wide phenotypic screening [12]. The resulting motor neurons recapitulated key disease aspects including reduced survival, accelerated neurite degeneration correlating with donor survival, transcriptional dysregulation, and appropriate pharmacological rescue by riluzole [12]. This validation against clinical outcomes establishes the pathophysiological relevance of iPSC models for drug development.

Similar approaches have been successfully applied across numerous disease areas:

Neurological Disorders: iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons from Parkinson's patients show impaired mitochondrial function, increased oxidative stress, and α-synuclein accumulation [29].

Cardiac Diseases: iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes from patients with familial long-QT syndrome demonstrate prolonged action potentials, mirroring the clinical electrophysiological abnormality [19].

Metabolic Disorders: Hepatocyte-like cells derived from patients with α1-antitrypsin deficiency recapitulate the pathological phenotype with aggregation of misfolded protein in the endoplasmic reticulum [29].

The field of iPSC reprogramming continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping future applications. Partial reprogramming approaches are gaining attention for their potential to achieve cellular rejuvenation without complete dedifferentiation, potentially offering therapeutic applications for age-related diseases [28]. Chemical reprogramming using entirely non-genetic methods represents another frontier, though efficiency and protocol standardization remain challenging [28]. For disease modeling, the progression from two-dimensional cultures to complex three-dimensional organoids and multi-organ systems enables more physiologically relevant studies of tissue-level interactions and disease pathophysiology [19] [29].

The integration of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing with iPSC technology has further enhanced disease modeling capabilities, allowing creation of isogenic controls that differ only at disease-relevant loci, thereby eliminating confounding genetic background effects [7] [29]. Additionally, artificial intelligence and machine learning are being applied to improve standardization, quality control, and differentiation outcome prediction in iPSC manufacturing [7].

In conclusion, the ongoing refinement of reprogramming techniques has progressively enhanced both efficiency and safety profiles, with mRNA reprogramming currently representing the optimal balance for many research and clinical applications. The rigorous validation of disease phenotypes against clinical data ensures the physiological relevance of iPSC models, positioning this technology as an indispensable platform for drug discovery and the development of personalized medicine approaches. As standardization improves and protocols become more accessible, these advanced reprogramming techniques will continue to transform our approach to disease modeling and therapeutic development.

The advent of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized regenerative medicine by providing a platform for disease modeling, drug screening, and potential cell therapies. A critical challenge in this field is achieving precision differentiation—generating functionally mature, patient-specific somatic cells that accurately recapitulate native physiology and disease phenotypes. This guide provides a comparative analysis of experimental protocols for differentiating iPSCs into three therapeutically crucial cell types: cardiomyocytes, neurons, and pancreatic beta-cells, with a specific focus on validating resulting disease models against clinical data.

Experimental Protocols for Precision Differentiation

Cardiomyocyte Differentiation

Overview: Efficient cardiac differentiation requires stage-specific manipulation of developmental signaling pathways to guide iPSCs through mesoderm, cardiac mesoderm, and cardiomyocyte progenitor stages, ultimately yielding functional cardiomyocytes.

- Key Signaling Pathways: The Wnt/β-catenin pathway requires precise temporal regulation—initial activation promotes mesoderm commitment, while subsequent inhibition drives cardiac specification. Concurrent BMP (Bone Morphogenetic Protein) and Nodal/Activin A signaling further enhance cardiac progenitor formation [30] [31].

- Maturation Challenges: hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) typically exhibit an immature fetal-like phenotype, characterized by a rounded morphology, poorly organized sarcomeres, lack of T-tubules, and a reliance on glycolytic metabolism rather than mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [30].

- Advanced Maturation Protocol: A robust method for enhancing maturation involves culturing cells on a biomimetic fibronectin-Matrigel composite extracellular matrix (ECM). This is combined with precise small-molecule modulation of key signaling pathways, resulting in significantly improved sarcomere organization, contractile function, and electrophysiological properties that more closely resemble adult cardiomyocytes [32].

Neuronal Differentiation

Overview: Neuronal differentiation leverages fundamental developmental principles, where morphogen gradients pattern iPSCs toward specific neural fates, followed by terminal differentiation into diverse neuronal subtypes.

- Dual Strategies: Two primary methods exist:

- Transcription Factor Overexpression: Direct introduction of lineage-specific transcription factors (e.g., Ngn2 for motor neurons) instructs rapid neuronal conversion [33].

- Small Molecule-Mediated Induction: Sequential use of small molecules modulates key pathways (SMAD, Wnt, SHH) to direct neural induction and subtype specification in a more scalable manner [33] [1].

- Subtype Specification: The specific combination of morphogens determines the neuronal subtype. For example, dopaminergic neurons require activation of SHH (Sonic Hedgehog) and FGF8 (Fibroblast Growth Factor 8) to establish a midbrain identity, while motor neuron generation depends on caudalizing (retinoic acid) and ventralizing (SHH) signals [33].

- Current Challenges: Key hurdles include achieving high purity and functional maturity of specific neuronal subtypes, and ensuring the long-term survival and functional integration of transplanted neurons in vivo [33].

Pancreatic Beta-Cell Differentiation

Overview: Generating glucose-responsive insulin-producing cells (IPCs) involves mimicking pancreatic organogenesis by guiding iPSCs through definitive endoderm, primitive gut tube, pancreatic progenitor, and endocrine progenitor stages.

- Key Markers and Real-Time Monitoring: A powerful approach for protocol optimization involves using a Pdx1-mRFP/Insulin-hrGFP dual-reporter iPSC line. This allows for real-time monitoring of two key transcription factors: Pdx1 (pancreatic progenitor marker) and Insulin (beta-cell hormone) [34].

- Protocol Enhancements: Studies demonstrate that 3D induction protocols significantly improve the efficiency of pancreatic progenitor specification and yield more mature IPCs compared to traditional 2D cultures. Furthermore, treatments that promote DNA demethylation can enhance differentiation efficiency by remodeling the epigenetic landscape [34].

- Functional Maturity: The ultimate goal is to generate beta-cells that exhibit glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, express key maturity markers (e.g., MAFA, NKX6.1), and contain insulin granules, achieving functional parity with primary human islet beta-cells [34].

The diagram below summarizes the core signaling pathways and key markers involved in differentiating iPSCs into these three target cell types.

Comparative Analysis of Differentiation Outcomes and Functional Validation

The table below provides a detailed, quantitative comparison of the typical yields, key maturity markers, and functional characteristics achieved by contemporary differentiation protocols for each target cell type.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of iPSC Differentiation Outcomes

| Differentiation Aspect | Cardiomyocytes | Neurons (Dopaminergic) | Beta-Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differentiation Efficiency | High purity: >90% cTnT+ reported [30] | ~50-80% TUJ1+; ~30-60% TH+ for dopaminergic [33] | Variable; 10-30% Insulin+ without sorting [34] |

| Key Structural Markers | cTnT, α-actinin, MLC2v, βMHC [30] | TUJ1, MAP2, Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH) [33] | PDX1, NKX6.1, C-peptide, Insulin [34] |

| Critical Functional Assays | Contractility analysis, Ca2+ transients, MEA for electrophysiology [30] [32] | Electrophysiology (patch clamp), dopamine release, synaptic activity [33] | Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion (GSIS), C-peptide secretion [34] |

| In Vivo Validation | Engraftment in rodent/ primate MI models; EHM allografts in macaques/human [31] | Functional improvement in PD rodent/ primate models; dopamine release [35] [36] | Glucose correction in diabetic rodent models; reversal of hyperglycemia [34] |

| Primary Limitation | Immature phenotype, fetal gene expression, lack of T-tubules [30] [31] | Subtype purity, functional integration post-transplantation, synaptic complexity [33] | Functional immaturity, inconsistent GSIS, polyhormonal cells [34] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful precision differentiation relies on a core set of high-quality reagents and tools. The following table details essential components for establishing these protocols in a research setting.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Differentiation

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Application Across Cell Types |

|---|---|---|

| Yamanaka Factor Reprogramming Tools | Non-integrating methods (e.g., Sendai virus, mRNA) to generate clinical-grade iPSCs [37] [36] | Foundational step for creating patient-specific lines for all cell types. |

| Small Molecule Pathway Modulators | Precise temporal control of key pathways (Wnt, BMP, TGF-β, SHH, RA) [33] [1] [32] | Core component of all differentiation protocols (e.g., CHIR99021 for Wnt activation). |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Components | Provide biophysical and biochemical cues for cell adhesion, survival, and differentiation (e.g., Vitronectin, Matrigel, Fibronectin composites) [32] | Used in all protocols; composite matrices enhance cardiomyocyte maturation [32]. |

| Reporter Cell Lines | Enable real-time monitoring of differentiation efficiency via lineage-specific fluorescent proteins (e.g., PDX1-mRFP/Insulin-hrGFP) [34] | Critical for protocol optimization, especially for beta-cells and neuronal subtypes. |

| Cell Surface Markers for Purification | Antibodies against proteins like CD34 (hematopoietic) or CD142 (pancreatic progenitors) for isolating specific populations [38] | Used to enrich target populations (e.g., CD34+ progenitors) to increase purity. |

The precision differentiation of iPSCs into cardiomyocytes, neurons, and beta-cells has progressed remarkably, moving from proof-of-concept to the development of sophisticated protocols capable of generating cells with increasing structural and functional maturity. The consistent theme across all three lineages is that functional maturation remains the primary bottleneck, whether it involves achieving adult-like metabolic and electrophysiological properties in cardiomyocytes, robust synaptic integration of neurons, or fully glucose-responsive insulin secretion in beta-cells. Overcoming these hurdles requires a multi-faceted approach, integrating advanced engineering strategies like 3D culture, biochemical stimulation, and genetic tools to guide cells toward a more complete mature state. As these technologies mature and converge with advancements in gene editing and biomaterials, the path toward clinically relevant disease modeling, high-fidelity drug screening, and effective autologous cell therapies becomes increasingly attainable.

In the landscape of modern biomedical research, the quest for physiologically relevant models that narrow the divide between conventional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures and dynamic living systems has driven the rise of organoid technology [39]. Traditional 2D culture systems, while simple and cost-effective, differ substantially from original tumors in various aspects, including the tumor microenvironment, cell metabolism, and gene expression profiles [40]. These models fail to faithfully recapitulate human-specific responses, leading to poor predictive value and high attrition rates in clinical trials [41]. For many years, scientists have recognized that depending on the physiological processes studied, these simplified models often lack the intricate interactions found in native tissues, such as tissue-specific architecture, cell-extracellular matrix interactions, spatial organization, and diversity of cell types that are essential for tissue functionality [42].

Three-dimensional organoids represent a revolutionary advancement in disease modeling, offering miniature, in vitro models of human organs grown from stem cells or tissue samples [39] [43]. These systems preserve patient-specific genetic, epigenetic, and phenotypic features, providing unprecedented opportunities for personalized disease modeling and drug response prediction [41]. The convergence of stem cell and organoid technologies has catalyzed the emergence of next-generation preclinical platforms, particularly in the context of precision medicine and the validation of iPSC disease phenotypes against clinical data [41] [44]. As the field progresses, organoids are rapidly becoming indispensable tools for researchers seeking to bridge the translational gap between preclinical findings and clinical applications.

Fundamental Differences Between 2D and 3D Model Systems

Structural and Functional Limitations of 2D Cultures

Conventional 2D cell cultures, in which cells grow as a flat monolayer on plastic surfaces, present several critical limitations for disease modeling and drug development. The artificial environment fails to replicate the complex three-dimensional architecture of human tissues, leading to altered cell morphology, polarization, and signaling [40] [42]. In 2D systems, cell-extracellular matrix interactions are fundamentally different, gene expression profiles are significantly altered, and critical tissue-specific functions are often lost [40]. These limitations substantially reduce the predictive power of 2D models for human physiological responses.

The simplification of the cellular environment in 2D cultures results in abnormal cell differentiation, proliferation, and drug metabolism patterns. For instance, 2D-cultured cells typically exhibit uniform exposure to oxygen, nutrients, and therapeutic agents—a condition rarely found in human tissues or tumors where gradient distributions create microenvironments with distinct cellular behaviors [42]. This lack of physiological relevance contributes to the high failure rates observed in drug development, where promising results from 2D models frequently fail to translate to clinical success [41].

Advantages of 3D Organoid Models

Organoids are three-dimensional, self-organizing structures derived from stem cells that closely mimic the cytoarchitecture and functional characteristics of native human organs [41]. These advanced models offer several significant advantages over traditional 2D systems:

- Architectural Complexity: Organoids replicate the spatial organization, cellular heterogeneity, and tissue-specific structures of original organs, including crypt-villus architecture in intestinal organoids and bile canaliculi in hepatic organoids [41].

- Functional Fidelity: They preserve key physiological functions, such as polarized secretion, metabolic activity, and electrical signaling patterns, more accurately reflecting in vivo conditions [43].

- Patient Specificity: Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) retain the genetic, epigenetic, and phenotypic features of the donor tissue, enabling personalized disease modeling and drug testing [39] [41].

- Microenvironment Recapitulation: 3D organoids better model the tumor microenvironment, including gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and therapeutic agents that influence drug penetration and efficacy [40] [42].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of 2D vs. 3D Organoid Culture Systems

| Characteristic | 2D Culture Systems | 3D Organoid Models |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Architecture | Monolayer, flat growth | 3D structure, tissue-like organization |

| Cell-Cell Interactions | Limited to horizontal contacts | Multi-directional, physiologically relevant |

| Extracellular Matrix | Artificial or absent | Natural or biomimetic matrix present |

| Proliferation Patterns | Uniform | Heterogeneous, with growth gradients |

| Gene Expression | Altered, dedifferentiated | Tissue-specific, differentiated |

| Drug Response | Typically more sensitive | More physiologically relevant resistance |

| Metabolic Activity | Homogeneous | Zoned, with metabolic heterogeneity |

| Predictive Value for Clinical Response | Limited (~5% translation) | Enhanced, with demonstrated correlation |

Experimental Validation: Direct Comparisons of 2D and 3D Systems

Methodological Approaches for Comparative Studies

Robust comparative analyses between 2D and 3D models require standardized protocols for generating and evaluating both systems. For pancreatic cancer research, studies have established conditionally reprogrammed cell (CRC) lines under 2D conditions before transitioning to 3D organoid cultures using a Matrigel-based platform without organoid-specific medium components to preserve intrinsic molecular subtypes [40]. This approach allows direct comparison using isogenic cell populations, eliminating genetic variability as a confounding factor.

Key methodological considerations include:

- Matrix Selection: Matrigel is commonly used for 3D organoid culture, providing a basement membrane-rich environment that supports self-organization and polarity [40].