Cellular Adaptation to Hypoxia: Molecular Mechanisms, Therapeutic Strategies, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular pathways and therapeutic strategies for improving cell survival in hypoxic environments, a critical challenge in cancer biology, regenerative medicine, and ischemic...

Cellular Adaptation to Hypoxia: Molecular Mechanisms, Therapeutic Strategies, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular pathways and therapeutic strategies for improving cell survival in hypoxic environments, a critical challenge in cancer biology, regenerative medicine, and ischemic diseases. We explore foundational mechanisms including HIF-mediated signaling and metabolic reprogramming, examine methodological approaches for hypoxia targeting and imaging, discuss optimization strategies to overcome therapeutic resistance, and review validation techniques for assessing intervention efficacy. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current evidence from molecular pathways to clinical applications, offering insights for developing novel therapeutic interventions targeting hypoxic microenvironments.

Molecular Mechanisms of Cellular Adaptation to Hypoxia

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Why do I detect HIF-1α but not HIF-2α in my acute hypoxia experiments? This is likely due to the "HIF switch" – a temporal regulation where HIF-1α responds to acute hypoxia, while HIF-2α dominates during chronic hypoxia [1]. HIF-1α protein is rapidly stabilized under acute hypoxia (e.g., hours), driving the initial cellular response [1]. Confirm the duration of hypoxic exposure; HIF-2α stabilization often requires longer periods (e.g., 48-72 hours) [1].

Q2: My HIF-α western blots are inconclusive under normoxia. What could be wrong? Under normoxic conditions, HIF-α subunits have an extremely short half-life (approximately 5 to 8 minutes) due to continuous proteasomal degradation [1]. Inconclusive results are likely because the protein is degraded rapidly. To detect it, you must inhibit the degradation pathway. Use specific prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzyme inhibitors (e.g, FG-4592) or proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) in your normoxic cultures to artificially stabilize the HIF-α subunits for detection [1].

Q3: My cell viability decreases under hypoxia when I expect increased survival. Why? The role of HIF is highly context-dependent. While HIF can promote survival through metabolic reprogramming and angiogenesis, it can also directly induce apoptosis under certain conditions [2]. HIF-1α can upregulate pro-apoptotic genes like BNIP3 and modulate the BCL2 family proteins, activating both death receptor and mitochondrial apoptosis pathways [2]. Check the cell type, hypoxia severity, and duration. In some primary cells like fibroblasts, HIF-1α upregulation is a direct cause of apoptosis [2].

Q4: Why do I see different HIF target gene expression in different cell lines? HIF-1α and HIF-2α, while similar, have non-redundant and sometimes opposing functions and can regulate distinct sets of target genes [1] [3] [4]. This specificity arises from:

- Cell-type specific expression: HIF-2α expression is more cell-type-specific than HIF-1α [4].

- Different DNA binding preferences: HIF-1α tends to bind to HRE motifs near promoter regions, whereas HIF-2α binding is often more distal [1].

- Crosstalk and antagonism: In some immune cells, HIF-2α represses HIF-1α expression, and its deletion can lead to a hyper-inflammatory phenotype driven by HIF-1α [3].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor HIF-α detection in hypoxia | Inefficient hypoxia induction; degradation still occurring | Validate O₂ levels with an analyzer; use a chemical hypoxia mimetic like CoCl₂ [2]. |

| No upregulation of known HIF target genes | Inefficient HIF transcriptional activity; off-target effects | Check for functional HIF complex using a HRE-luciferase reporter assay; confirm siRNA/shRNA knockdown efficiency [2]. |

| Contradictory results in functional assays | Overlooked HIF-1α/HIF-2α specificity; non-canonical regulation | Analyze isoforms separately; test for oxygen-independent regulation (e.g., via inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α or IL-6) [1]. |

| Unstable Treg cell function in hypoxia studies | Disruption of HIF-2α, crucial for Treg suppressive function | Focus on HIF-2α specific knockout or inhibition; assess HIF-1α levels, as its upregulation can impair Treg function upon HIF-2α loss [3]. |

Key Quantitative Data on HIF Regulation

Table 1: Key Regulatory Proteins and Their Affinities for HIF-α Subunits

| Regulatory Protein / Enzyme | Primary Function | Notable Preference / Effect |

|---|---|---|

| PHD2 | Prolyl hydroxylation of HIF-α, targeting it for degradation | Primarily targets HIF-1α [1]. |

| PHD3 | Prolyl hydroxylation of HIF-α, targeting it for degradation | Displays greater affinity for HIF-2α than HIF-1α [1]. |

| FIH | Asparaginyl hydroxylation, inhibits HIF transactivation | Hydroxylates N803 in HIF-1α and N847 in HIF-2α [1]. |

| pVHL | E3 ubiquitin ligase recognizing hydroxylated HIF-α | Binds and ubiquitinates both HIF-1α and HIF-2α for proteasomal degradation [1]. |

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for HIF Stabilization and Detection

| Experimental Condition | HIF-1α Protein Half-Life | HIF-2α Protein Half-Life | Primary Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normoxia (21% O₂) | ~5-8 minutes [1] | ~5-8 minutes [1] | Rapid degradation, negligible activity. |

| Acute Hypoxia (2-24 h) | Rapidly stabilized, dominant isoform [1] | Lower levels | Metabolic shift to glycolysis; initiation of angiogenesis [1]. |

| Chronic Hypoxia (48-72 h) | Levels may decrease | Stabilized, dominant isoform [1] | Sustains vascular remodeling and maturation genes [1]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Analyzing HIF-1α-Induced Apoptosis

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating HIF-1α-mediated apoptosis in human uterosacral ligament fibroblasts (hUSLFs) [2].

Objective: To investigate the mechanisms of HIF-1α-induced apoptosis via both death receptor and mitochondrial pathways.

Materials:

- Cell Line: Primary human fibroblasts or other relevant cell type.

- HIF Inducer: Cobalt Chloride (CoCl₂), prepared in sterile PBS or culture medium.

- Gene Silencing: siRNA targeting HIF-1α and non-targeting negative control.

- Transfection Reagent: Lipofectamine 2000 or equivalent.

- Key Assays: MTT assay kit, Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit, JC-1 mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit, Western blot reagents.

- Antibodies for Western Blot: Anti-HIF-1α, Anti-Cleaved Caspase-3, -8, -9, Anti-BNIP3, Anti-Bcl-2, Anti-Bax, Anti-Cytochrome C.

Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Culture cells in appropriate medium. For hypoxia mimetic treatment, expose cells to a range of CoCl₂ concentrations (e.g., 0-300 μM) for 24-72 hours [2]. Determine the IC₅₀ using an MTT assay.

- Gene Silencing:

- Transfect cells with HIF-1α-specific siRNA or negative control siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions. Incubate for 24-48 hours before subsequent experiments [2].

- Measuring Apoptosis:

- Flow Cytometry: Use an Annexin V-FITC/PI staining kit. Analyze stained cells on a flow cytometer. HIF-1α induction should increase the percentage of Annexin V-positive cells [2].

- TUNEL Assay: Fix cells and incubate with TUNEL reaction mixture to label DNA strand breaks. Counterstain with DAPI and visualize under a fluorescence microscope [2].

- Analyzing Mitochondrial Pathway:

- Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm): Use the JC-1 dye. Healthy mitochondria with high ΔΨm show red fluorescence; apoptotic cells with low ΔΨm show green fluorescence. Measure the red/green fluorescence ratio. HIF-1α induction should decrease the ratio, indicating loss of ΔΨm [2].

- Western Blot: Analyze protein lysates for key mitochondrial pathway indicators: upregulation of BNIP3, Bax, and cytosolic Cytochrome C; downregulation of Bcl-2; and cleavage/activation of Caspase-9 [2].

- Analyzing Death Receptor Pathway:

- Western Blot: Analyze protein lysates for key death receptor pathway indicators: upregulation of TRAIL, DR5, and Fas; downregulation of c-FLIP and DcR2; and cleavage/activation of Caspase-8 [2].

- Execution Phase:

- Western Blot: Confirm the final stage of apoptosis by detecting cleaved Caspase-3 in all HIF-1α-induced samples. This effect should be reversed by HIF-1α knockdown [2].

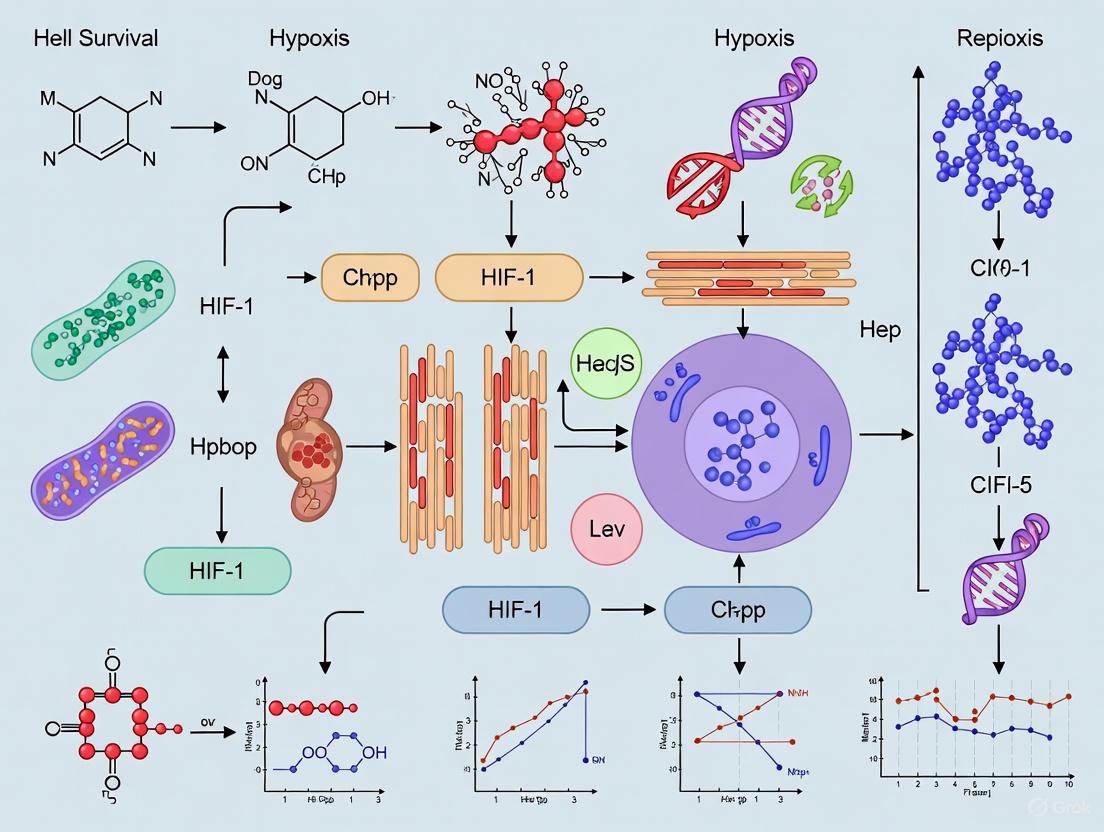

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for HIF Pathway Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Mechanism | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CoCl₂ (Cobalt Chloride) | Chemical hypoxia mimetic; inhibits PHD enzymes, stabilizing HIF-α [2]. | Inducing HIF-1α in cell culture (e.g., at 150-200 μM for 24h) to study apoptosis [2]. |

| siRNA / shRNA (HIF-1α or HIF-2α) | Isoform-specific gene silencing to delineate unique functions. | Validating the specific role of HIF-1α in apoptosis by knocking it down and observing rescued cell viability [2]. |

| PHD Inhibitors (e.g., FG-4592) | Selective inhibition of PHD enzymes, stabilizing HIF-α under normoxia. | Investigating the therapeutic potential of HIF stabilization, such as in erythropoiesis. |

| HIF-2α Specific Inhibitors | Pharmacological inhibition of HIF-2α activity (e.g., PT2385). | Selectively targeting HIF-2α in cancer models or to modulate Treg cell function [3]. |

| HRE-Luciferase Reporter | Plasmid containing HRE sequences driving luciferase gene; measures HIF transcriptional activity. | Quantifying the functional output of HIF stabilization in different cell types or under drug treatment. |

| Antibodies: HIF-1α / HIF-2α | Detecting protein levels and localization via Western Blot or IF. | Confirming HIF-α stabilization in hypoxia vs. normoxia and its knockdown efficiency. |

| Antibodies: Cleaved Caspases | Detecting activation of apoptosis executioners. | Confirming apoptosis induction via HIF-1α and identifying the pathway involved [2]. |

| JC-1 Dye | Fluorescent probe for measuring mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). | Demonstrating HIF-1α's role in initiating the intrinsic apoptosis pathway [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do cells shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis under hypoxic conditions? This metabolic reprogramming, known as the Warburg effect in cancer cells, occurs because oxygen availability becomes limited for efficient oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Cells adapt by upregulating glycolysis to generate ATP more rapidly, though less efficiently (2 ATP/glucose vs ~36 ATP/glucose via OXPHOS). This shift is primarily mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) that transcriptionally activate glycolytic enzymes and suppress mitochondrial activity [5] [6]. Glycolysis also provides metabolic intermediates for biosynthesis, supporting cell survival and proliferation in low-oxygen environments [5] [7].

Q2: What is the role of HIF-1α in hypoxic metabolic reprogramming? HIF-1α is the master regulator of cellular response to hypoxia. Under low oxygen:

- HIF-1α stabilizes and translocates to the nucleus

- Activates transcription of genes involved in glycolysis, angiogenesis, and cell survival

- Upregulates glucose transporters (GLUT1) and glycolytic enzymes (HK, PFK, LDHA)

- Suppresses mitochondrial metabolism by activating PDK1, which inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), reducing pyruvate entry into TCA cycle [6] [8] [7].

Q3: How do mitochondrial adaptations support cell survival during hypoxia? Mitochondria undergo functional adaptations to optimize limited oxygen utilization:

- Metabolic Flexibility: Shift to consuming alternative fuels like glutamine and fatty acids [7]

- Reduced ROS Production: Decreased electron transport chain activity lowers reactive oxygen species generation [8]

- Fission/Fusion Dynamics: Increased mitochondrial fission supports quality control and metabolic adaptation [5]

- Mitochondrial Biogenesis: In chronic hypoxia, sirtuin-mediated biogenesis helps maintain mitochondrial mass [9].

Q4: What experimental methods can assess metabolic shifts in hypoxic cells? Key methodologies include:

- Metabolomics: CE-TOFMS for comprehensive analysis of water-soluble metabolites [7]

- Seahorse Analyzer: Measures oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) in real-time

- Flow Cytometry: Evaluates mitochondrial membrane potential, ROS production, and surface marker expression [10]

- Transcriptomics: RNA sequencing identifies HIF-target genes and metabolic pathway alterations [10].

Q5: How can we therapeutically target hypoxic cells? Emerging strategies include:

- HIF Inhibitors: Direct targeting of HIF-1α stability or activity [6]

- Metabolic Modulators: PIM3 kinase inhibition reverses hypoxia-induced T-cell dysfunction [10]

- Combination Therapies: Glycolytic inhibitors with conventional chemotherapeutics [7]

- Hypoxia-Activated Prodrugs: Selective targeting of hypoxic tumor regions [6].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent metabolic responses in hypoxic cell cultures Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Oxygen Fluctuations: Use tri-gas incubators with continuous O₂ monitoring instead of anaerobic chambers [10]

- Improper Hypoxia Duration: Optimize exposure time (typically <48 hours for protective responses, avoiding senescence from prolonged exposure) [11]

- Cell Density Effects: Maintain consistent seeding density to prevent nutrient/gradient variations

- Validation Method: Verify hypoxia response via HIF-1α western blotting or HIF-reporter assays.

Problem: Poor cell survival post-hypoxic exposure Intervention Strategies:

- Preconditioning: Gradually acclimatize cells to hypoxia using stepped oxygen reduction [11]

- Metabolic Support: Supplement with pyruvate, glutamine, or fatty acids to support alternative energy pathways [7]

- Antioxidants: Add low-dose antioxidants to mitigate hypoxic burst of ROS during reoxygenation [8]

- Culture Optimization: Use specialized media formulations designed for hypoxic conditions.

Problem: Variable results in metabolic flux assays Technical Considerations:

- Normalization Issues: Normalize OCR/ECAR measurements to cell count, protein content, and mitochondrial DNA

- Substrate Concentration: Optimize glucose and glutamine concentrations in assay media [7]

- Hypoxia Equilibration: Allow sufficient time for medium gas equilibrium before assays (typically 2-4 hours)

- Control Validation: Include normoxic controls treated with HIF stabilizers (e.g., CoCl₂, DMOG) to distinguish HIF-specific effects.

Table 1: Metabolic Pathway Efficiency Comparison

| Parameter | Oxidative Phosphorylation | Glycolysis |

|---|---|---|

| ATP Yield per Glucose | ~36 molecules [5] | 2 molecules [5] |

| ATP Production Rate | Slower [5] | Faster [5] |

| Oxygen Requirement | High [8] | None [8] |

| Metabolic Intermediates | Limited | Abundant (for biosynthesis) [5] |

Table 2: Hypoxia-Induced Gene Expression Changes

| Gene | Function | Hypoxia Response | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIF-1α | Master hypoxia regulator | Stabilized/upregulated [11] [6] | Western blot, immunofluorescence [11] |

| VEGF | Angiogenesis | Upregulated [11] | ELISA, qPCR [11] |

| GLUT1 | Glucose transport | Upregulated [6] | Flow cytometry, glucose uptake assays [7] |

| PDK1 | Mitochondrial gatekeeper | Upregulated [7] | qPCR, enzyme activity assays [7] |

| BNIP3 | Mitophagy | Upregulated [5] | Immunoblotting, confocal microscopy [5] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: HIF-1α Stabilization and Detection

Based on mesenchymal stem cell preconditioning [11]

Materials:

- Tri-gas incubator (1-5% O₂, 5% CO₂, balance N₂)

- Anti-HIF-1α antibody (mouse monoclonal)

- Proteasome inhibitor (MG132, optional)

- Lysis buffer (RIPA with protease inhibitors)

Methodology:

- Culture cells to 70-80% confluence in standard conditions

- Transfer to hypoxic chamber (1-5% O₂) for 2-48 hours based on cell type optimization

- For protein detection, lyse cells directly in hypoxic workstation to prevent reoxygenation

- Perform western blotting with HIF-1α antibodies

- For immunofluorescence, fix cells immediately post-hypoxia with 4% PFA

Technical Notes:

- Include normoxic controls (21% O₂) cultured in parallel

- Use HIF-1α stabilizers (CoCl₂ 100-200μM) as positive controls

- Optimal hypoxia duration varies by cell type (MSCs: <48 hours [11])

Protocol 2: Metabolic Flux Analysis Under Hypoxia

Adapted from CAR-T cell studies [10]

Materials:

- Seahorse XF Analyzer with hypoxia module

- XF Glycolysis Stress Test Kit

- XF Mito Stress Test Kit

- Substrate-limited media (XF Base Medium)

Procedure:

- Culture cells under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 24-72 hours

- Seed 20,000-50,000 cells/well in Seahorse plates

- Equilibrate in non-buffered assay medium in hypoxic chamber (1% O₂) for 1 hour

- Load plates into hypoxia module maintaining 1% O₂ throughout assay

- For glycolysis stress test: sequentially inject glucose, oligomycin, and 2-DG

- For mitochondrial stress test: sequentially inject oligomycin, FCCP, and rotenone/antimycin A

Data Interpretation:

- Compare basal and maximal glycolytic capacity via ECAR

- Assess mitochondrial function through ATP-linked respiration and spare respiratory capacity via OCR

- Normalize data to protein content or cell number

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Hypoxia Metabolism Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIF Stabilizers | CoCl₂, DMOG, FG-4592 | Chemical hypoxia mimetics; induce HIF signaling without chamber | Concentration optimization critical; off-target effects possible [6] |

| Glycolytic Inhibitors | 2-DG, 3-bromopyruvate, WZB117 | Target glucose metabolism; probe glycolytic dependence | Compensatory OXPHOS upregulation may occur [7] |

| Mitochondrial Modulators | Oligomycin, FCCP, rotenone | Assess mitochondrial function in stress tests | Titrate carefully; cell type-specific toxicity [10] |

| Metabolic Sensors | MitoTracker Red, 2-NBDG, MitoSOX | Measure mitochondrial mass, glucose uptake, ROS | Validate with appropriate controls; consider probe stability in hypoxia [5] |

| Hypoxia Markers | Pimonidazole, HIF-1α antibodies | Detect hypoxic regions in tissues/cells | Pimonidazole requires in vivo injection; antibody validation essential [11] |

Metabolic Pathway Diagrams

HIF-1α Signaling Pathway in Hypoxia

Experimental Workflow for Metabolic Reprogramming Studies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core function of SREBP1 in cancer cells facing metabolic stress? A1: SREBP1 is a master transcription factor that orchestrates de novo lipogenesis, a critical adaptive response for cancer cell survival under stress conditions like hypoxia. It upregulates key enzymes for fatty acid synthesis, providing lipids for membrane biogenesis, energy production via Fatty Acid Oxidation (FAO), and protection from oxidative damage [12] [13] [14]. In hypoxic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), SREBP1-mediated lipogenesis and autophagy work together to promote cell survival by facilitating ATP production through FAO [13] [15].

Q2: Why is targeting SREBP1 a promising strategy against therapy-resistant cancers? A2: Research shows that resistant cancer cells often sustain SREBP1-dependent lipogenesis to maintain survival, irrespective of the original resistance mechanism. For example, in BRAF-therapy-resistant melanoma, resistant cells restore lipogenesis to protect from ROS-induced damage. Pharmacological inhibition of SREBP1 sensitizes these resistant cells to targeted therapy, highlighting its role as a key downstream mediator of resistance [14]. In TNBC, high SREBP1 expression is associated with a worse prognosis, further underscoring its therapeutic potential [13].

Q3: How does the hypoxic tumor microenvironment activate SREBP1? A3: Hypoxia can activate SREBP1 through multiple signaling pathways. Key upstream regulators include:

- PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway: Hyperactive Akt and mTORC1 can induce the synthesis and proteolytic activation of SREBP1, leading to lipid accumulation [12].

- EGFR Signaling: Promotes SCAP glycosylation, reducing its association with Insig proteins and leading to SREBP1 proteolytic activation [12].

- Transcriptional and Post-translational Regulation: Hypoxia can influence SREBP1 expression and activation via pathways involving HIF-1α, c-Myc, and O-GlcNAcylation [12] [16].

Q4: What are the key downstream effectors of SREBP1 that drive cancer progression? A4: SREBP1 transcriptionally activates a suite of lipogenic enzymes, including:

- ACLY (ATP Citrate Lyase): Generates acetyl-CoA in the cytoplasm.

- ACC (Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase): Catalyzes the first committed step in fatty acid synthesis.

- FASN (Fatty Acid Synthase): The rate-limiting enzyme for de novo fatty acid synthesis.

- SCD (Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase): Introduces double bonds into fatty acids, generating monounsaturated fatty acids critical for membrane fluidity and function [12] [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting SREBP1-Related Experiments

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low cell viability in hypoxic conditions despite SREBP1 activation. | Lipogenesis is occurring, but cells lack machinery to utilize lipids for energy. | Co-assess autophagy markers (e.g., LC3-I/II) and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) rates. Supplementing with an autophagy inducer (e.g., Rapamycin) may restore viability [13]. |

| Inconsistent SREBP1 target gene expression under hypoxia across cell lines. | Cell-type specific regulation; differences in culture conditions (e.g., serum concentration, cell density). | Standardize culture conditions. Use multiple cell models (e.g., TNBC vs. ER+). Confirm SREBP1 activation status via Western Blot for mature SREBP1 and not just mRNA [12] [16]. |

| Therapy-resistant cells remain viable after SREBP1 inhibition. | Existence of compensatory survival pathways or incomplete inhibition. | Combine SREBP1 inhibitors (e.g., Fatostatin) with other targeted agents (e.g., BRAF inhibitors). Validate inhibition by monitoring multiple downstream lipogenic enzymes [14]. |

| Failure to replicate hypoxic lipid droplet accumulation. | Insufficient hypoxic exposure; altered balance between lipid synthesis and uptake. | Ensure proper hypoxia induction (e.g., 1% O2 for 48 hours). Quantify lipid droplets with Nile Red staining and check expression of lipid uptake proteins like FABPs [13] [16]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Data on SREBP1 Inhibition in Hypoxic TNBC Models

| Experimental Metric | Normoxic MDA-MB-231 | Hypoxic MDA-MB-231 | Hypoxic MDA-MB-231 + SREBP1 Inhibition (Fatostatin/siRNA) | Restoration with Rapamycin (Autophagy Inducer) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Viability/Proliferation | Baseline | Markedly Increased [13] | Reduced [13] | Restored [13] |

| ATP Production | Baseline | Maintained or Increased | Reduced [13] | Restored [13] |

| Expression of Lipogenic Enzymes (e.g., FASN) | Baseline | Increased [13] | Decreased [13] | Not Reported |

| Expression of Autophagy Markers | Baseline | Increased [13] | Decreased [13] | Increased (by induction) |

| Fatty Acid Oxidation (FAO) | Baseline | Increased [13] | Decreased [13] | Not Reported |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing SREBP1 Function in Hypoxia-Induced Lipogenesis

Objective: To evaluate the role of SREBP1 in mediating lipogenesis and cell survival under hypoxic conditions. Materials:

- Cell lines: Triple-negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells [13].

- Reagents: SREBP1 inhibitor (e.g., Fatostatin, 5-15 µM), autophagy inducer (Rapamycin, 0.1-10 µM) [13].

- Equipment: Hypoxic chamber (1% O2, 5% CO2, 95% N2 at 37°C) [13].

Methodology:

- Hypoxia Induction: Culture MDA-MB-231 cells in a sealed hypoxic incubator chamber at 1% O2 for 48 hours. Maintain control cells under normoxia (21% O2) [13].

- Pharmacological Inhibition: Treat cells with Fatostatin or vehicle control under hypoxic conditions for 48 hours [13].

- Rescue Experiments: Co-treat hypoxic cells with Fatostatin and Rapamycin to test if inducing autophagy can bypass the need for SREBP1 [13].

- Downstream Analysis:

- Viability Assay: Use MTT or trypan blue exclusion assays to quantify cell viability and proliferation [13].

- Lipid Quantification: Stain neutral lipids with Nile Red and quantify via immunofluorescence [13].

- Gene Expression: Analyze mRNA levels of SREBP1 targets (ACLY, ACC, FASN, SCD) and FAO-related enzymes by RT-qPCR [13].

- Metabolic Analysis: Measure ATP production and FAO rates using specific commercial assay kits [13].

Protocol 2: Validating SREBP1 as a Target to Overcome Therapy Resistance

Objective: To determine if SREBP1 inhibition can re-sensitize therapy-resistant cancer cells to targeted agents. Materials:

- Cell lines: BRAF-mutant, therapy-resistant melanoma cell lines (e.g., 451lu R, M249 R) [14].

- Reagents: BRAF inhibitor (e.g., Vemurafenib), SREBP1 inhibitor (e.g., Fatostatin).

Methodology:

- Combination Treatment: Treat resistant cells with Vemurafenib, Fatostatin, or a combination thereof.

- Lipogenesis Measurement: Assess de novo lipogenesis by tracking 14C-acetate incorporation into lipids or using isotopomer spectral analysis for palmitate synthesis [14].

- Lipidomics: Perform mass spectrometry-based phospholipidome analysis to monitor shifts from saturated/mono-unsaturated to poly-unsaturated membrane lipids, a hallmark of lipogenesis inhibition [14].

- Viability & Apoptosis: Measure cell death and viability using Annexin V/PI staining and cell viability assays [14].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

SREBP1 Activation and Lipogenesis Signaling Pathway

Experimental Workflow for Hypoxia & SREBP1 Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SREBP1 and Lipogenesis Research

| Reagent Name | Function/Application | Example Usage in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Fatostatin | Chemical inhibitor of SREBP1 activation. | Used at 5-15 µM to block SREBP1 processing and function, validating its role in hypoxic survival and therapy resistance [13] [14]. |

| siRNA/shRNA vs. SREBP1 | Genetic tool for knocking down SREBP1 expression. | Confirms phenotypic effects of pharmacological inhibition and rules off-target effects [13]. |

| Rapamycin | Inducer of autophagy (mTORC1 inhibitor). | Used at 0.1-10 µM as a rescue agent to test if autophagy can compensate for loss of SREBP1-mediated lipogenesis [13]. |

| Vemurafenib | BRAF(V600E) inhibitor. | Used in melanoma studies to create therapeutic stress; combination with SREBP1 inhibitors overcomes resistance [14]. |

| Nile Red Stain | Fluorescent dye for neutral lipid detection. | Quantifies intracellular lipid droplet accumulation under hypoxia or after SREBP1 inhibition [13]. |

| Antibodies: mSREBP1, FASN, LC3 | Protein detection by Western Blot/IF. | mSREBP1 antibody detects the active, nuclear form. LC3 antibodies monitor autophagy activation [13] [14]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Hypoxia-Induced Autophagy

This guide addresses common experimental challenges in monitoring and modulating autophagy in hypoxic environments.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem & Phenomenon | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions & Verification Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent LC3B-II/I ratio (e.g., no change or decrease under hypoxia) [17]: Conflicting results in Western blot analysis of this key autophagy marker. | 1. Incomplete autophagy flux measurement.2. Hypoxia level or duration insufficient to trigger a response.3. Cell-type specific variations in autophagic response. | 1. Use lysosomal inhibitors (e.g., Chloroquine (CQ), Bafilomycin A1) to block degradation and measure accumulated LC3B-II [18].2. Verify HIF-1α stabilization as a positive control for hypoxia response [19].3. Titrate hypoxia exposure time and oxygen concentration (e.g., 1% O₂) [18]. |

| Lack of expected protective effect: Cell death occurs despite autophagy induction under hypoxia. | 1. Excessive or prolonged autophagy leading to autophagic cell death.2. Concurrent activation of apoptotic pathways.3. Autophagy is functioning as a survival mechanism for damaged cells that should be eliminated. | 1. Assess cell viability and apoptosis markers (e.g., caspase-3 cleavage) alongside autophagy markers [19].2. Modulate autophagy genetically (e.g., siRNA against ATG5/7) or pharmacologically to determine its precise role [20]. |

| Poor reproducibility of hypoxic conditions: Variable results between experiments or lab members. | 1. Inconsistent O₂ levels in hypoxic chambers.2. Variations in media pre-equilibration time.3. Differences in cell density affecting local oxygen microenvironments. | 1. Calibrate and log O₂ and CO₂ levels continuously using in-chamber sensors.2. Standardize protocol for media pre-equilibration in the hypoxic environment (e.g., 4-6 hours) [18].3. Maintain consistent cell seeding density and media volume across experiments. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Does hypoxia always activate autophagy in all cell types? No, the effect of hypoxia on autophagy is context-dependent. While hypoxia often induces autophagy as a pro-survival response, some studies report its attenuation. For instance, one study found that systemic hypoxia during exercise tended to attenuate the autophagy marker LC3B-II/I ratio in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [17]. The outcome depends on the cell type, severity and duration of hypoxia, and the overall cellular stress context [19] [20].

Q2: What is the most reliable method to confirm functional autophagy flux under hypoxia? The gold standard is to measure autophagy flux, not just marker levels. This involves comparing samples with and without lysosomal inhibitors. An increase in LC3B-II levels in inhibitor-treated samples confirms that autophagy is being initiated and that autophagosomes are being formed and degraded. Simply measuring a single LC3B-II value can be misleading [18] [20].

Q3: How does HIF-1α activation relate to autophagy induction under hypoxia? HIF-1α is a master regulator of the hypoxic response and can induce autophagy through several pathways. A key mechanism is the transcriptional upregulation of BNIP3 and BNIP3L/NIX. These proteins disrupt the inhibitory interaction between Bcl-2 and Beclin-1, freeing Beclin-1 to initiate autophagosome formation [19]. Furthermore, hypoxia and HIF-1α can inhibit mTOR, a major suppressor of autophagy [19] [20].

Q4: Why is autophagy considered a "double-edged sword" in hypoxic cancer environments? Autophagy can act as both a tumor suppressor and a tumor promoter. Initially, it can suppress tumorigenesis by removing damaged organelles and proteins. However, in established tumors, hypoxia-induced autophagy can be a critical survival mechanism for cancer cells, allowing them to recycle nutrients and survive low-oxygen conditions, thereby promoting tumor growth and resistance to therapy [19] [20].

Core Signaling Pathways & Experimental Workflows

Key Molecular Pathway of Hypoxia-Induced Autophagy

The following diagram illustrates the primary signaling pathway through which hypoxia activates autophagy, centered on HIF-1α stabilization.

Standard Experimental Workflow for Analysis

This workflow outlines a standard protocol for investigating hypoxia-induced autophagy in cell culture models.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Title: Assessing Autophagy Flux in Human Trophoblast Cells (HTR8/SVneo) Under Hypoxic Conditions.

Background: This protocol is adapted from a study investigating the protective role of autophagy in preeclampsia [18]. It details the use of chemical modulators to assess autophagic flux in response to hypoxia (1% O₂).

Materials:

- HTR8/SVneo cell line (or other relevant cell type)

- Hypoxic chamber/tri-gas incubator (for 1% O₂, 5% CO₂, balance N₂)

- Normoxic incubator (20% O₂, 5% CO₂)

- Chloroquine (CQ)

- Rapamycin (optional inducer)

- ox-LDL (optional stress inducer)

- Lysis buffer, reagents for Western Blot (antibodies against LC3B, p62, HIF-1α)

Method Steps:

- Cell Culture & Group Setup: Culture HTR8/SVneo cells in standard DMEM with 10% FBS. Seed cells at a consistent density and allow to adhere. Divide cells into the following experimental groups:

- Control: Normoxia

- Hypoxia: 1% O₂

- Hypoxia + CQ: 1% O₂ + 40 μM Chloroquine (12h incubation) [18]

- Normoxia + CQ: (Important control for basal flux)

- (Optional groups: Hypoxia + ox-LDL, Hypoxia + Rapamycin)

Hypoxia Exposure & Treatment: Place plates in the pre-equilibrated hypoxic chamber (1% O₂). Maintain control plates in the normoxic incubator (20% O₂). For CQ-treated groups, add the inhibitor for the final 12 hours of the hypoxia exposure period.

Sample Collection & Analysis: After the treatment period (e.g., 24-48h), lyse cells directly in the plate. Perform Western Blot analysis for:

- LC3B: Compare LC3B-II levels. A increase in the Hypoxia+CQ group vs. Hypoxia alone confirms increased autophagic flux.

- p62/SQSTM1: Levels should decrease with autophagy induction but accumulate when flux is blocked (e.g., in CQ groups).

- HIF-1α: Verify hypoxic response.

Key Quantitative Data from Reference Study [18]: Table: Autophagy Marker Changes in HTR8/SVneo Cells Under Hypoxia & Modulation

| Experimental Group | LC3B-II Protein Level (vs. Control) | p62 Protein Level (vs. Control) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia (1% O₂) | Increased | Decreased | Successful autophagy induction and flux. |

| Hypoxia + Chloroquine | Further Increased | Increased | Autophagic flux is blocked, confirming ongoing activity in hypoxia. |

| ox-LDL Treatment | Unchanged/Decreased | Increased | Impaired autophagy. |

| ox-LDL + Hypoxia | Increased | Decreased | Hypoxia rescues ox-LDL-impaired autophagy. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Studying Hypoxia and Autophagy

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Tri-Gas Incubator | Creates a controlled, sustained hypoxic environment (e.g., 1% O₂). | Essential for physiological studies vs. chemical hypoxia mimetics. Requires regular calibration [18]. |

| Cobalt Chloride (CoCl₂) | A chemical mimetic of hypoxia that stabilizes HIF-1α. | Useful for preliminary, low-cost screens but does not replicate all aspects of true hypoxia [19]. |

| Chloroquine (CQ) / Bafilomycin A1 | Lysosomal inhibitors that block autophagic degradation, allowing flux measurement. | Critical for distinguishing between increased autophagosome synthesis vs. blocked degradation [18]. |

| Antibody: LC3B | Detects the lipidated form (LC3B-II) associated with autophagosomes via Western Blot or IF. | Monitor the LC3B-II/I ratio and total LC3B-II levels with and without inhibitors [17]. |

| Antibody: HIF-1α | Confirms activation of the hypoxic response pathway. | Serves as a positive control for hypoxia experiments. Has a short half-life under normoxia [19]. |

| Antibody: p62/SQSTM1 | Marks cargo targeted for autophagy; levels typically inversely correlate with autophagic activity. | Accumulation indicates blocked autophagy; degradation suggests active flux. Always interpret with LC3B data [17] [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common histone modifications induced by hypoxia, and what are their functional outcomes? Hypoxia triggers specific, activating histone modifications. Key changes include increases in H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K14ac, and H3K27ac, which are associated with open chromatin and active gene transcription. In contrast, repressive marks like H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 often remain unchanged. These activating modifications are found within regulatory regions of genes essential for cellular adaptation, such as those involved in metabolism and fiber cell formation, and directly regulate their expression [21].

Q2: How does hypoxia lead to changes in transcription start site (TSS) selection, and what is the functional impact? Hypoxia causes pervasive transcription start site (TSS) switching, a process largely driven by changes in H3K4me3 distribution and nucleosome repositioning. This switching remodels the 5' untranslated region (5'UTR) of mRNAs, which in turn selectively alters their translation efficiency, independent of changes in the overall mRNA abundance. This mechanism enhances the synthesis of key proteins like pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1), which is crucial for metabolic adaptation to low oxygen [22].

Q3: Can hypoxia-induced epigenetic changes persist after normal oxygen levels are restored? Yes, hypoxic exposure can create a "hypoxic memory" where a subset of epigenetic alterations persists even after reoxygenation. These persistent changes, including stable DNA methylation patterns, histone modifications, and altered non-coding RNA expression, can drive long-term gene expression programs that contribute to the progression of chronic diseases, such as the transition from acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease [23].

Q4: What is the role of metabolic factors in hypoxia-induced epigenetic remodeling? Cellular metabolism and epigenetics are tightly intertwined. Key metabolites such as S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and acetyl-CoA serve as essential substrates for epigenetic enzymes. SAM is the primary methyl donor for DNA and histone methyltransferases, while acetyl-CoA is the acetyl group donor for histone acetyltransferases. In hypoxia, metabolic reprogramming can alter the availability of these metabolites, thereby directly influencing the epigenetic landscape and gene expression in cancer and other diseases [24].

Troubleshooting Experimental Challenges

Table: Common Issues in Hypoxia Epigenetics Research

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background in CUT&RUN | Non-specific antibody binding or incomplete washing. | Optimize antibody concentration and include high-stringency wash steps. Validate antibodies with relevant negative control regions [21]. |

| Poor Polysome Profile | Ribosome degradation or improper lysis buffer preparation. | Use fresh cycloheximide in experiments, prepare buffers fresh, and avoid RNA degradation by using RNase inhibitors [22]. |

| Low Cell Viability in Prolonged Hypoxia | Excessive metabolic stress or buildup of toxic metabolites. | Optimize the duration of hypoxia exposure and cell density. Consider using specialized media formulations designed for hypoxic culture [21] [22]. |

| Inconsistent H3K4me3 ChIP-qPCR Results | Variable cross-linking efficiency or chromatin fragmentation. | Standardize cross-linking time and temperature. Calibrate sonication conditions to achieve consistent fragment sizes (200–500 bp) [22]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Analyzing Histone Modifications in Hypoxia (Based on Chick Lens Model)

This protocol outlines the process for detecting global changes in histone modifications in response to hypoxia [21].

Cell Culture & Hypoxic Exposure:

- Culture E13 chick lenses or your chosen cell line.

- Place the experimental group in a hypoxic chamber set to 1% O₂, 5% CO₂, at 37°C. The control group remains in a normoxic incubator (21% O₂).

- Expose for the desired duration (e.g., 24-48 hours).

Acid Extraction of Histones:

- Wash cells with ice-cold PBS.

- Lyse cells in a suitable buffer and isolate nuclei.

- Resuspend the nuclear pellet in 0.2 M H₂SO₄ and incubate on a rotator at 4°C for 2-4 hours.

- Centrifuge at high speed. Collect the supernatant containing the acid-soluble histones.

- Precipitate histones by adding 100% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) to a final concentration of 25%. Incubate on ice for 1 hour.

- Pellet histones by centrifugation, wash with ice-cold acetone, and air-dry.

- Resuspend the histone pellet in nuclease-free water.

Analysis:

- Quantify histone modifications via Western Blotting using specific antibodies against H3K4me3, H3K27ac, etc., with total histone H3 as a loading control.

- For genome-wide localization, perform CUT&RUN or ChIP-seq using the extracted histones/chromatin.

Protocol 2: Profiling the Translatome Under Hypoxia

This protocol describes how to identify changes in mRNA translation efficiency during hypoxic stress [22].

Hypoxic Treatment and Lysate Preparation:

- Culture T47D or H9 cells. Treat experimental cells with hypoxia (0.5-1% O₂) for 24-48 hours, keeping controls in normoxia.

- Before harvesting, treat cells with 100 µg/mL cycloheximide for 10 minutes to arrest ribosomes.

- Wash, scrape, and lyse cells in a polysome lysis buffer containing cycloheximide and RNase inhibitors.

Polysome Profiling:

- Layer the lysate onto a 10-50% sucrose density gradient.

- Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 35,000 rpm in an SW41 rotor for 2-3 hours) to separate ribosomal complexes by size.

- Fractionate the gradient using a density gradient fractionation system while monitoring absorbance at 254 nm to obtain profiles of monosomes (80S) and polysomes.

RNA Extraction and Sequencing:

- Isolate total RNA from the "heavy polysome" fractions (typically >3 ribosomes) and from the total cell lysate input.

- Prepare libraries and perform RNA-seq on both the total and polysome-associated RNA samples.

Data Analysis:

- Use bioinformatics tools like anota2seq to compare total mRNA levels to polysome-associated mRNA levels. This identifies transcripts with altered translation efficiency ("translation" mode) or those where mRNA changes are buffered at the translational level ("offsetting" mode) [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential Reagents for Hypoxia Epigenetics

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Utility | Key Example |

|---|---|---|

| KDM5 Inhibitors | Pharmacologically inhibits H3K4 demethylases, mimicking hypoxia-induced H3K4me3 accumulation and TSS switching. | Used to demonstrate that H3K4me3 changes can drive 5'UTR remodeling independently of HIF [22]. |

| HDAC Inhibitors (HDACis) | Block histone deacetylase activity, leading to increased histone acetylation. Used to probe the role of acetylation in gene activation. | Vorinostat (FDA-approved for cancer); used in research to study PAH [23] [25]. |

| HAT Inhibitors | Inhibit histone acetyltransferases, preventing histone acetylation. Useful for establishing the necessity of acetylation for specific hypoxic responses. | Used to test the requirement for H3K27ac in hypoxia-induced gene expression [21]. |

| Hypoxia Mimetics | Chemicals that stabilize HIF-α (e.g., by inhibiting PHDs) to activate hypoxic signaling in normoxic conditions. | Cobalt chloride (CoCl₂), Dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG) [21]. |

| CUT&RUN / ChIP-seq Kits | For genome-wide mapping of histone modifications and transcription factor binding sites. | Used to identify hypoxia-specific localization of H3K4me3 and H3K27ac near gene promoters [21]. |

| nanoCAGE Sequencing | Precisely maps transcription start sites (TSS) and identifies 5'UTR isoforms, crucial for studying TSS switching. | Used to reveal pervasive 5'UTR remodeling under hypoxia in T47D and H9 cells [22]. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Hypoxia-Induced Chromatin Remodeling Pathway

Experimental Workflow for Hypoxia Epigenetics

Therapeutic Targeting and Intervention Strategies

This technical support center is designed for researchers investigating Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF) pathway inhibitors to enhance cell survival under hypoxic conditions. The HIF pathway serves as the master regulator of cellular adaptation to low oxygen, coordinating responses in angiogenesis, metabolic reprogramming, and cell survival [26] [27]. In the tumor microenvironment, hypoxia creates a stressful setting that triggers these adaptive changes, but prolonged hypoxia can lead to cell death [27]. Targeting this pathway requires precise methodological approaches and troubleshooting of common experimental challenges.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent HIF-α Stabilization in Normoxic Cell Cultures

Issue: Unexpected HIF-α subunit stabilization under normal oxygen conditions (21% O₂), complicating experimental results.

Explanation: While HIF-α is typically degraded under normoxia, several oxygen-independent mechanisms can trigger its stabilization, potentially confounding experimental outcomes in studies aimed at improving cell survival [28].

Solution:

- Verify Genetic Background: Check for mutations in key regulatory genes, particularly in renal carcinoma cell lines (e.g., 786-O, RCC4). Inactivation of the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene leads to constitutive HIF-α stabilization even under normoxia [29] [30]. Use VHL-deficient cells with and without functional VHL reintroduction for controlled experiments.

- Check Metabolite Accumulation: Assess the accumulation of metabolites that inhibit Prolyl Hydroxylase Domain (PHD) enzymes, such as fumarate, succinate, or (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate. These can result from mutations in genes like FH, SDH, or IDH1/2 [27] [28]. Metabolomic profiling can identify these interfering compounds.

- Confirm Pathway Activation Status: Investigate the activation of oncogenic signaling pathways. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK/ERK pathways can increase HIF-1α translation and protein levels independently of oxygen tension [29] [28]. Use specific pathway inhibitors as controls.

- Validate Hydroxylation Status: Employ hydroxylation-specific antibodies to distinguish between hydroxylated (targeted for degradation) and non-hydroxylated (stable) forms of HIF-α [28].

Problem 2: Off-Target Effects in HIF Inhibition Assays

Issue: Small molecule inhibitors intended to target HIF produce effects unrelated to HIF pathway inhibition.

Explanation: Many reported HIF inhibitors act through indirect or undetermined mechanisms, such as general effects on transcription, translation, or receptor tyrosine kinase signaling, rather than direct targeting of HIF subunits [26] [27].

Solution:

- Utilize Direct Binding Assays: For HIF-2α inhibitors (e.g., Belzutifan, PT2385), use AlphaScreen protein-protein interaction assays to confirm direct disruption of the HIF-2α/ARNT heterodimerization [30]. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) can quantitatively measure binding affinity to the HIF-2α PAS-B domain [30].

- Employ Comprehensive Controls: Include structurally related but inactive analogs as negative controls when available. For instance, use the inactive (S)-enantiomer of a compound to verify that observed effects are specific to the active (R)-enantiomer that binds the target [30].

- Perform Transcriptional Validation: Quantify mRNA expression of known HIF target genes (e.g., VEGFA, SLC2A1/GLUT1, BNIP3) via RT-qPCR to confirm that the inhibitor specifically blocks HIF-mediated transcription [26].

- Monitor Isoform Specificity: Differentiate between HIF-1 and HIF-2 inhibition. Use isoform-specific reporter gene assays and monitor expression of isoform-preferential target genes to determine selectivity and avoid misinterpretation of effects [26] [29].

Problem 3: Poor Cellular Activity in HIF-PHD Inhibitor Studies

Issue: HIF Prolyl Hydroxylase (HIF-PHD) inhibitors fail to stabilize HIF-α or induce target genes in cellular models.

Explanation: HIF-PHD inhibitors (e.g., Roxadustat, Vadadustat) are 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG) competitors and their efficacy can be reduced by high intracellular concentrations of 2-OG or insufficient cellular uptake [31] [32] [33].

Solution:

- Modify Cell Culture Conditions: Reduce the concentration of 2-OG and other TCA cycle intermediates (e.g., succinate, fumarate) in the culture medium, as they can compete with the inhibitor [27].

- Confirm Iron Availability: Ensure adequate intracellular Fe²⁺ levels, as PHDs are iron-dependent dioxygenases. Iron chelation can mimic hypoxia and confound results; conversely, iron supplementation may reduce inhibitor efficacy [27] [28].

- Use a Positive Hypoxia Control: Always include a hypoxic chamber (e.g., 1% O₂) or a known chemical hypoxia mimetic (e.g., CoCl₂, DMOG) as a positive control to verify the responsiveness of your cellular system.

- Optimize Dosing and Timing: Perform time-course and dose-response experiments. HIF-1α and HIF-2α have distinct stabilization kinetics—HIF-1α responds rapidly to acute hypoxia/HIF-PHD inhibition, while HIF-2α accumulates gradually during prolonged exposure [29].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key considerations for choosing between HIF-1 vs. HIF-2 selective inhibition?

A: The choice depends on your biological context and research goals. HIF-1α is often associated with acute hypoxia response, metabolic switch to glycolysis (regulating GLUT1, HK2), and cell autonomy, while HIF-2α is prominent in chronic hypoxia, erythropoiesis (regulating EPO), and specific cancers like ccRCC [29] [32] [30]. In ccRCC with VHL loss, HIF-2α often acts as the primary oncoprotein, making it a preferred target [26] [30]. For broader therapeutic impact in most cancers, dual inhibition may be desirable, but this must be balanced against potential safety concerns, as complete HIF pathway blockade could have systemic toxicities [26].

Q2: How do I validate the specificity of a direct HIF-2α inhibitor like Belzutifan in my experiments?

A: To validate specificity:

- Binding Site Mutants: Use cell lines engineered with point mutations in the HIF-2α PAS-B domain (e.g., Cys255, Asp237, Asno247, Met252, Met263, Gln277, Met279) that disrupt inhibitor binding. Resistance in these mutants indicates on-target activity [30].

- Heterodimerization Assays: Monitor the formation of the HIF-2α/ARNT complex via co-immunoprecipitation in the presence of the inhibitor. Effective compounds should disrupt this interaction without affecting the protein levels of individual subunits [30].

- Target Gene Analysis: Measure the transcript levels of HIF-2-preferential target genes (e.g., EPO, VEGFA, CCND1) versus HIF-1-preferential genes (e.g., PGK1, LDHA) to confirm selective HIF-2 blockade [26] [29].

Q3: What are the primary mechanisms of acquired resistance to HIF-2α inhibitors?

A: A key mechanism involves missense mutations in the HIF-2α PAS-B domain that sterically hinder drug binding while preserving the protein's ability to dimerize with ARNT and activate transcription [30]. Commonly reported mutations affect residues like Met252, Gln277, and Met279. Using second-generation inhibitors (e.g., PT2399, compound 12) with different binding modes or developing HIF-2α degraders (PROTACs) that operate independently of the binding pocket are potential strategies to overcome this resistance [30].

Q4: Can HIF-PHD inhibitors have effects beyond erythropoiesis that are relevant to cell survival research?

A: Yes. HIF-PHD inhibitors significantly reshape the immune landscape and modulate inflammation by stabilizing HIF-α in immune cells [32]. This includes recalibrating macrophage polarization from a pro-inflammatory M1 towards a pro-resolution M2 phenotype, altering neutrophil lifespan and function, and enhancing NK cell cytotoxicity [32]. These immunomodulatory effects can profoundly influence tumor cell survival and the response to immunotherapy in the hypoxic niche.

Table 1: Potency and Selectivity Profiles of Representative HIF-2α Inhibitors

| Compound Name | Chemical Class | Target | Binding Affinity (K_D) / Potency (IC₅₀) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belzutifan (PT2977) | Tetrazole | HIF-2α PAS-B | K_D: ~30 nM [30] | FDA-approved for ccRCC; disrupts heterodimerization with ARNT. |

| PT2385 | Tetrazole | HIF-2α PAS-B | K_D: ~90 nM [30] | First-generation inhibitor; predecessor to Belzutifan. |

| Compound 12 | Bicyclic | HIF-2α PAS-B | IC₅₀: 0.8 nM (AlphaScreen) [30] | High potency; structurally distinct from tetrazole series. |

| Compound 16 | Cycloalkyl[c]thiophene | HIF-2α PAS-B | IC₅₀: 2 nM (AlphaScreen) [30] | Developed via bioisosteric replacement of PT2385 scaffold. |

Table 2: Experimental Readouts for Verifying HIF Pathway Modulation

| Experimental Goal | Key Assays | Critical Controls | Potential Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confirm HIF-α Stabilization | Western Blot (whole cell lysates), Immunofluorescence | Normoxia (21% O₂) vs. Hypoxia (1% O₂); VHL-reconstituted cells [28]. | Poor antibody specificity; failure to detect rapid protein turnover. |

| Measure Transcriptional Activity | RT-qPCR of target genes (e.g., VEGFA, BNIP3), HRE-Luciferase Reporter Assay | Null-reporter (HRE-mutated); isoform-specific knockdown [26] [27]. | Non-specific effects on transcription/translation; hypoxia-mimicking conditions. |

| Validate Direct Target Engagement | AlphaScreen/Co-IP (heterodimer disruption), ITC, X-ray Crystallography | Binding-site mutants; inactive enantiomers [30]. | Compound aggregation; interference with assay components. |

| Assess Functional Outcome | Cell proliferation/apoptosis under hypoxia, Spheroid growth in 3D culture, Xenograft models | Paired isogenic cell lines; in vivo imaging [26] [27]. | Off-target effects dominating the phenotype; inadequate hypoxia models. |

HIF Signaling Pathway and Inhibitor Mechanisms

The diagram below illustrates the core HIF signaling pathway and the mechanisms of action for the main classes of inhibitors under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Direct HIF-2α Inhibitor Mechanism

Objective: Confirm that a candidate small molecule directly disrupts HIF-2α/ARNT heterodimerization.

Materials:

- Purified recombinant HIF-2α PAS-B domain protein and ARNT PAS-B domain protein.

- AlphaScreen His-Tag Detection Kit (PerkinElmer).

- Test compound (e.g., Belzutifan) and a structurally related inactive control.

- Plate reader capable of AlphaScreen measurement.

Method:

- Complex Formation: In a white opaque plate, mix His-tagged HIF-2α PAS-B domain and GST-tagged ARNT PAS-B domain at optimized concentrations in assay buffer.

- Inhibitor Incubation: Pre-incubate the HIF-2α protein with a serial dilution of the test compound or DMSO control for 60 minutes.

- Detection: Add the AlphaScreen donor and acceptor beads according to the manufacturer's protocol. Incubate the plate in the dark for 1-2 hours.

- Measurement: Read the AlphaScreen signal. A decrease in signal intensity relative to the DMSO control indicates disruption of the protein-protein interaction.

- Data Analysis: Plot signal vs. inhibitor concentration to calculate an IC₅₀ value. Compare the potency of your compound to a known inhibitor like PT2385 as a benchmark [30].

Protocol 2: Assessing HIF-Mediated Cell Survival Under Chronic Hypoxia

Objective: Quantify the effect of HIF pathway inhibition on cancer cell viability during prolonged hypoxia.

Materials:

- Appropriate cancer cell line (e.g., RCC4 for VHL-null, HCT116 for VHL-wildtype).

- Hypoxia workstation (capable of maintaining 0.5-1% O₂).

- HIF inhibitor (HIF-2α specific or HIF-PHD inhibitor) and vehicle control.

- Cell Titer-Glo 3D Cell Viability Assay (Promega).

Method:

- Culture Setup: Seed cells in 96-well plates at a density ensuring sub-confluence at the assay endpoint.

- Inhibitor Treatment: After cell attachment, add a dose range of the HIF inhibitor or vehicle control.

- Hypoxic Exposure: Transfer plates to the hypoxia workstation (0.5-1% O₂, 5% CO₂, balance N₂). Maintain a normoxic control plate in a standard incubator.

- Viability Assessment: After 72-96 hours, equilibrate plates to room temperature under hypoxia. Add Cell Titer-Glo reagent and measure luminescence according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Data Analysis: Normalize luminescence readings to the normoxic vehicle control. Plot dose-response curves to determine the inhibitor's effect on survival specifically under hypoxic stress [26] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for HIF Pathway Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines (VHL-deficient) | 786-O, RCC4 | Model constitutive HIF-2α stabilization; study oncogenic HIF signaling. |

| Cell Lines (Isogenic Pairs) | RCC4±VHL, HCT116±VHL | Control for genetic background; isolate VHL/HIF-specific phenotypes. |

| Direct HIF-2α Inhibitors | Belzutifan (PT2977), PT2385, PT2399 | Tool compounds for selective disruption of HIF-2α/ARNT dimerization. |

| HIF-PHD Inhibitors | Roxadustat (FG-4592), DMOG, IOX2 | Stabilize HIF-α pharmacologically; mimic hypoxic response in normoxia. |

| Hydroxylation-Specific Antibodies | Anti-HIF-1α (Pro402-OH), Anti-HIF-1α (Asn803-OH) | Distinguish active vs. inactive HIF-α; assess PHD/FIH activity. |

| HRE Reporter Constructs | HRE-Luciferase plasmids (pan-HIF, HIF-1 specific, HIF-2 specific) | Quantify HIF transcriptional activity and isoform specificity. |

| PROTAC Molecules | HIF-2α degraders (e.g., compound 25, 26) [30] | Induce targeted degradation of HIF-2α; useful for studying protein function and overcoming resistance. |

FAQs: Metabolic Modulation in Hypoxia Research

Q1: Why does hypoxia cause a metabolic shift away from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation? Under hypoxic conditions, the limited oxygen availability directly impairs the function of the electron transport chain (ETC), which relies on oxygen as the final electron acceptor. This disruption makes aerobic ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation inefficient. Consequently, cells undergo a metabolic reprogramming to prioritize ATP-generating pathways that are less dependent on oxygen, primarily through a shift to anaerobic glycolysis [8] [34].

Q2: What are the key metabolic differences between species adapted to high-altitude versus low-altitude habitats when exposed to hypoxia? Research on rodent species from different altitudes reveals distinct metabolic strategies for hypoxia adaptation. The high-altitude native Qinghai vole (Neodon fuscus) sustains its energy supply by regulating fatty acid oxidation under low-oxygen conditions. In contrast, species accustomed to lower altitudes, like the Brandt's vole (Lasiopodomys brandtii) and the Kunming mouse (Mus musculus), rely more on aerobic oxidation and anaerobic glycolysis of glucose, respectively, for energy maintenance during hypoxia [35].

Q3: How does an elevated NADH/NAD+ ratio under ETC dysfunction or hypoxia lead to metabolic derangements? Mitochondrial ETC dysfunction or hypoxia increases the cellular NADH/NAD+ ratio because the ETC is critical for oxidizing NADH back to NAD+. This elevated ratio inhibits key NADH-generating metabolic reactions. For instance, it can suppress the activity of enzymes like glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in glycolysis, causing a bottleneck and forcing a rewiring of glucose metabolism to regenerate NAD+ through pathways like lactate fermentation [36].

Q4: What is the role of HIF-1α in hypoxic metabolic reprogramming? Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) is a master regulator of the cellular response to low oxygen. Under hypoxia, HIF-1α stabilizes and orchestrates the transcription of genes that promote a shift toward glycolytic metabolism. This includes upregulating glucose transporters (GLUTs), glycolytic enzymes, and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1). PDK1 inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), thereby reducing the flow of pyruvate into the mitochondrial TCA cycle and favoring its conversion to lactate [37] [34].

Q5: Can modulating fatty acid oxidation be a viable strategy to improve cell survival in hypoxia? Evidence from naturally adapted high-altitude species suggests that yes, sustaining fatty acid oxidation (FAO) is a viable hypoxic survival strategy. In these species, a regulated FAO pathway appears to serve as an efficient energy source. Therefore, in a research context, promoting FAO—for example, by modulating key regulators like PPARα—could represent a therapeutic strategy to enhance cellular energy production and improve survival in low-oxygen environments [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Metabolic Shift to Glycolysis Under Experimental Hypoxia

Problem: Cells in your hypoxia model do not show a consistent or robust increase in glycolysis, as measured by extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) or lactate production.

- Potential Cause and Solution:

- Cause: Inadequate stabilization of HIF-1α. The hypoxic conditions might not be sufficiently low or prolonged to prevent HIF-1α degradation.

- Solution: Verify the oxygen concentration in your chamber (e.g., 1% O₂ or lower) and the duration of exposure. Confirm HIF-1α stabilization via Western blot [34].

- Cause: Cell-type specific responses. Some primary cells or differentiated tissues may have a less plastic metabolism.

- Solution: Include a positive control, such as a cancer cell line known to exhibit the Warburg effect. Consider using chemical HIF stabilizers (e.g., PHD inhibitors) to validate your setup [37].

Issue 2: Difficulty in Tracing Metabolic Rewiring Using Isotope-Labeled Glucose

Problem: When using ( [U^{-13}C] )-glucose or other labeled tracers in hypoxic cells, the expected labeling patterns in glycolytic intermediates or TCA cycle metabolites are not observed.

- Potential Cause and Solution:

- Cause: Insufficient tracer concentration or incubation time.

- Solution: Ensure the tracer fully replaces unlabeled glucose in the medium. Perform a time-course experiment to determine the optimal incubation period for label incorporation into your metabolites of interest [36].

- Cause: High background of unlabeled metabolites from internal stores (e.g., glycogen).

- Solution: Pre-incubate cells in glucose-free media for a period to deplete intracellular glycogen stores before adding the labeled glucose tracer [36].

Issue 3: Failure to Recapitulate High-Altitude Adaptation Phenotypes in Model Systems

Problem: Your cellular or animal model does not show the enhanced fatty acid oxidation capacity seen in high-altitude adapted species.

- Potential Cause and Solution:

- Cause: The model system lacks the genetic or regulatory architecture of adapted species.

- Solution: Consider a comparative approach using multiple cell types or species. Alternatively, use genetic engineering tools (e.g., CRISPR) to overexpress key regulatory genes identified in adapted species, such as those involved in fatty acid oxidation, in your model system [35].

- Cause: The acute hypoxia exposure time is too short to induce the adaptive metabolic pathway.

- Solution: Extend the duration of hypoxic exposure or consider using intermittent hypoxia protocols that may better mimic certain physiological conditions and induce adaptive responses [35].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Measuring the NADH/NAD+ Ratio and Rewiring of Glucose Metabolism in Hypoxic Cells

This protocol is adapted from methods used to analyze metabolic derangements resulting from ETC inhibition, which shares features with hypoxia [36].

Key Resources:

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| [4-(^2)H]-glucose | Cambridge Isotope laboratories | cat# DLM-9294-PK |

| [3-(^2)H]-glucose | Cambridge Isotope laboratories | cat# DLM-9294-PK |

| [U-(^{13})C]-glucose | Sigma-Aldrich | cat# 389374 |

| Antimycin A (ETC inhibitor) | Sigma-Aldrich | cat# A8674 |

| Extraction buffer | Prepared Fresh | 80% methanol |

Procedure:

- Preparation: Pre-condition cells in glucose-free medium if necessary. Prepare tracing media: glucose-free DMEM supplemented with 10% dialyzed FBS and 10 mM of the respective labeled glucose (( [U^{-13}C] ), ( [4-^2H] ), or ( [3-^2H] )) [36].

- Hypoxia & Tracer Incubation: Place cells in a hypoxia chamber (e.g., 1% O₂) with the prepared tracing medium. Include ETC inhibitors (e.g., Antimycin A) if used to exacerbate the hypoxic effect.

- Metabolite Extraction: After incubation (e.g., 24h), quickly remove media and wash cells with cold saline. Add pre-chilled 80% methanol extraction buffer to the cell plate, then scrape and collect the homogenate.

- Sample Processing: Incubate extracts on ice, then centrifuge at 15,000 g at 4°C for 20 min. Collect the supernatant and dilute if necessary before LC-MS/MS analysis [36].

- Data Analysis: The deuterium from ( [4-^2H] )-glucose traces electron transfer from glycolytic NADH, while ( [3-^2H] )-glucose traces the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway. ( [U^{-13}C] )-glucose is used to trace the fate of glucose carbons [36].

Protocol 2: Quasi-Targeted Metabolomics of Skeletal Muscle Under Hypoxia

This protocol is based on a study investigating metabolic patterns in rodent skeletal muscle under hypoxia [35].

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: After exposing animals to normoxia or hypoxia (e.g., 10% O₂ for 48h), dissect skeletal muscle tissues. Rinse with sterile saline, snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen, and store at -80°C.

- Metabolite Extraction: Homogenize 100 mg of frozen tissue in liquid nitrogen. Add 500 µL of pre-chilled 80% methanol with 0.1% formic acid, vortex thoroughly, and incubate on ice.

- Sample Processing: Centrifuge the homogenate at 15,000 g at 4°C for 20 min. Dilute a portion of the supernatant to a final methanol concentration of 53% using LC-MS-grade water. Centrifuge again and inject the supernatant into the LC-MS/MS system for analysis [35].

- Quality Control: Generate quality control (QC) samples by pooling equal volumes from each experimental sample to ensure analytical consistency [35].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Species-Specific Metabolic Adaptations to Hypoxia

Table summarizing the distinct metabolic strategies employed by three rodent species from different altitudes when exposed to hypoxia, based on transcriptomic and metabolomic data [35].

| Species | Native Altitude | Preferred Energy Pathway in Hypoxia | Key Adaptive Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qinghai vole (Neodon fuscus) | 3700-4800 m | Fatty Acid Oxidation | Superior adaptation to regulate fatty acid oxidation for energy. |

| Brandt's vole (Lasiopodomys brandtii) | < 2000 m | Aerobic Glucose Oxidation | Relies on more efficient aerobic mechanisms where possible. |

| Kunming mouse (Mus musculus) | Low altitude | Anaerobic Glycolysis | Shifts to glycolysis, leading to potential lactate accumulation. |

Table 2: Key Metabolites and Ratios as Indicators of NADH/NAD+ Redox State

Table listing metabolites that can serve as sensitive indicators of an elevated NADH/NAD+ ratio in tissues and plasma, useful for assessing hypoxic impact [36].

| Metabolite / Ratio | Direction of Change in High NADH/NAD+ | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Lactate/Pyruvate Ratio | Increases | A classic reflection of the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio. |

| α-Hydroxybutyrate | Increases | A sensitive marker of altered redox state and glutathione synthesis. |

| Alanine | Increases | Indicates a shift in aminotransferase reactions. |

| Aspartate | Decreases | Reflects inhibition of malate-aspartate shuttle activity. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Hypoxic Metabolism Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical ETC Inhibitors | To induce mitochondrial dysfunction and mimic/amplify hypoxic metabolic effects. | Antimycin A, Piericidin A [36]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Metabolites | To trace metabolic pathway fluxes and fates of nutrients (e.g., glucose, glutamine). | [U-(^{13})C]-Glucose, [4-(^2)H]-Glucose, [3-(^2)H]-Glucose [36]. |

| HIF Stabilizers (PHD Inhibitors) | To chemically simulate hypoxia by preventing HIF-1α degradation, independent of O₂ level. | Dimethyloxallylglycine (DMOG), Roxadustat. |

| NAD+/NADH Quantification Kits | To directly measure the cellular redox state, a central parameter in hypoxic metabolism. | Commercial colorimetric or LC-MS based kits [36]. |

| Extraction Buffers for Metabolomics | To quench metabolism and extract intracellular metabolites for LC-MS/MS analysis. | Pre-chilled 80% Methanol with 0.1% Formic Acid [35] [36]. |

Metabolic Pathway Visualizations

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Hypoxia-Activated Prodrugs (HAPs) Research

FAQ 1: Why does my HAP show high efficacy in vitro but fails in in vivo models?

Answer: This common issue often stems from inadequate consideration of the tumor microenvironment (TME) and pharmacokinetics.

- Potential Cause 1: Insufficient or heterogeneous hypoxia in the tumor model. HAPs require severe hypoxia (<1.3% O₂ or <10 mmHg) for efficient activation [38] [39]. The level and distribution of hypoxia can vary significantly between in vitro setups and in vivo tumors, and even between different in vivo models [40].

- Solution: Characterize the hypoxic fraction of your in vivo tumor model before initiating therapy. Use techniques like pimonidazole immunohistochemistry or [18F]-FAZA/[18F]-MISO PET imaging to confirm the presence and extent of hypoxia [41] [40].

- Potential Cause 2: Inadequate prodrug penetration or rapid systemic clearance. The disorganized tumor vasculature can hinder drug delivery to hypoxic regions, which are often distant from blood vessels [38].

- Solution: Investigate the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of your HAP. Consider modifying the dosing schedule or exploring formulations that enhance tumor delivery.

FAQ 2: My HAP is toxic to well-oxygenated cells in culture. What could be the reason?

Answer: Off-target, oxygen-independent activation is a frequent challenge.

- Potential Cause 1: Activation by reductases expressed in normoxic cells. Some prodrugs, like PR-104, can be activated by enzymes such as aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3) regardless of oxygen levels [38].

- Solution: Quantify the expression of potential activating reductases (e.g., AKR1C3, Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase) in your cell lines. Use inhibitors or genetic knockdown to confirm the specific reductase responsible for the off-target activation [38] [42].

- Potential Cause 2: The prodrug has a high K-value (oxygen concentration that halves its cytotoxic potency), meaning it is activated under moderately hypoxic conditions that might be present in some in vitro settings or even in normal tissues like the bone marrow [38].

- Solution: Determine the K-value for your HAP. A lower K-value indicates activation under more severe hypoxia and potentially a better therapeutic window [38].

FAQ 3: How can I enhance the efficacy of a HAP in a resistant tumor model?

Answer: Consider combination therapies that increase the hypoxic fraction or target complementary pathways.

- Strategy 1: Modulate Tumor Oxygenation. Use vasodilators (e.g., hydralazine) to induce a "vascular steal" effect, transiently reducing tumor blood flow and oxygen supply. Alternatively, use metabolic sensitizers (e.g., pyruvate) to increase cellular oxygen consumption, thereby expanding the hypoxic region [39].

- Solution Protocol: Administer the vasodilator or sensitizer shortly before the HAP to create a window of maximum hypoxia for prodrug activation. Mathematical modeling can help optimize the timing [39].

- Strategy 2: Combine with Conventional Therapies. HAPs target hypoxic cells that are resistant to radiotherapy and many chemotherapies. Combining a HAP with these agents can lead to synergistic cell killing [43] [42].

- Solution Protocol: Standard chemotherapeutics (e.g., gemcitabine, docetaxel, cisplatin) or radiotherapy can be administered in sequence with the HAP. This approach targets both the oxygenated and hypoxic compartments of the tumor [41] [43].

Experimental Protocols for Key HAP Assays

Protocol 1: Verifying Hypoxia-Selective Cytotoxicity In Vitro

Objective: To confirm that the cytotoxic activity of a prodrug is significantly enhanced under hypoxic conditions.

Materials:

- Hypoxia workstation/chamber for maintaining low O₂ (e.g., 0.1-1% O₂).

- Normoxic cell culture incubator (21% O₂).

- Appropriate cell lines.

- HAP stock solution and vehicle control.

- Cell viability assay kit (e.g., MTT, clonogenic assay).

Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in multiple well-plates at a density that will be sub-confluent at the time of analysis.

- Pre-equilibration: Place one set of plates in the hypoxic chamber and another in the normoxic incubator for 24 hours to pre-equilibrate the cells to their respective oxygen conditions.

- Drug Treatment: Add a range of HAP concentrations and controls to the plates inside the hypoxia chamber to avoid oxygen exposure. Transfer the hypoxic treatment plates back to the hypoxia chamber and the normoxic plates to the normoxic incubator.

- Incubation: Incubate for a predetermined time (e.g., 4-72 hours, depending on the drug and cell type).

- Viability Assessment:

- For acute cytotoxicity: Perform a viability assay (e.g., MTT) immediately after treatment.

- For long-term clonogenic survival: Trypsinize the cells, re-seed at low density in normoxic conditions, and allow colonies to form for 7-14 days before staining and counting.

- Data Analysis: Calculate IC₅₀ values for both hypoxic and normoxic conditions. A true HAP should show a significantly lower IC₅₀ (e.g., 10- to 100-fold) under hypoxia [43].

Protocol 2: Testing HAP Combination with Transient Hypoxia Modulators

Objective: To evaluate if a vasodilator or metabolic sensitizer can improve the efficacy of a HAP in an in vivo model.

Materials:

- Mouse tumor model (e.g., subcutaneous xenograft).

- HAP, Vasodilator (e.g., Hydralazine), Metabolic Sensitizer (e.g., Pyruvate).

- Pimonidazole HCl or access to hypoxia PET imaging.

Methodology:

- Tumor Hypoxia Characterization: Randomize tumor-bearing mice and use pimonidazole or PET imaging in a subset to establish baseline hypoxia.

- Treatment Groups: Divide mice into groups:

- Group 1: Vehicle control

- Group 2: HAP monotherapy

- Group 3: Vasodilator/Sensitizer monotherapy

- Group 4: HAP + Vasodilator/Sensitizer (with varying timings)

- Drug Administration:

- For vasodilator combination: Administer vasodilator intravenously 15-30 minutes before HAP injection. This timing allows for the reduction in tumor blood flow to establish hypoxia [39].

- For metabolic sensitizer combination: Administer sensitizer shortly (e.g., 5-15 minutes) before or concurrently with HAP to elevate oxygen consumption during drug exposure [39].

- Efficacy Endpoints: Monitor tumor growth over time. At endpoint, harvest tumors for analysis (e.g., immunohistochemistry for hypoxia markers, apoptosis, DNA damage).

Quantitative Data on Hypoxia-Activated Prodrugs

Table 1: Clinically Evaluated Hypoxia-Activated Prodrugs and Key Properties

| Prodrug (Class) | Active Cytotoxin | Mechanism of Action | Key Clinical Trial Findings & Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tirapazamine (TPZ) (Benzotriazine dioxide) | Oxidative radical | DNA single/double-strand breaks [42] | Phase III trials in HNSCC & NSCLC showed no overall survival benefit; hampered by toxicity (muscle cramps, ototoxicity) [38] [40]. |

| PR-104 (Dinitrobenzamide mustard) | DNA cross-linking nitrogen mustard | DNA interstrand cross-links [38] | Phase I/II trials showed dose-limiting myelosuppression (neutropenia, thrombocytopenia); activation by AKR1C3 causes off-target toxicity [38]. |

| Evofosfamide (TH-302) (2-Nitroimidazole mustard) | Bromo-isophosphoramide mustard (Br-IPM) | DNA cross-linking [43] | Phase III in pancreatic cancer & sarcoma failed primary survival endpoints; preclinical data shows strong hypoxia-selective cytotoxicity [38] [40] [43]. |

| AQ4N (Banoxantrone) (Aliphatic N-oxide) | AQ4 (topoisomerase II inhibitor) | DNA intercalation and topoisomerase II inhibition [42] | Early-phase trials demonstrated safety and evidence of hypoxia-targeted activation in tumors; limited single-agent efficacy [42]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for HAP Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia Markers (Exogenous) | Directly labels hypoxic cells in tissue sections for histological validation. | Pimonidazole, EF5 [41] [40] |

| Hypoxia PET Tracers | Non-invasive imaging to detect and quantify tumor hypoxia in vivo. | [18F]-FMISO, [18F]-FAZA, [18F]-HX4 [41] [40] |

| Hypoxia Gene Signatures | mRNA-based assessment of hypoxic tumor status from biopsy samples. | 15-gene signature, 26-gene signature [41] [40] |

| HIF-1α Inhibitors | Tool compounds to dissect the role of HIF-1 pathway in HAP response and resistance. | Chetomin (disrupts HIF-1α/p300 interaction) [41] |