Comparative Biodistribution of Cell Therapies: Analytical Methods, Regulatory Insights, and Clinical Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of comparative biodistribution assessment for cell therapy products (CTPs), a critical component for evaluating their safety and efficacy.

Comparative Biodistribution of Cell Therapies: Analytical Methods, Regulatory Insights, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of comparative biodistribution assessment for cell therapy products (CTPs), a critical component for evaluating their safety and efficacy. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational regulatory requirements from agencies like the FDA, EMA, and PMDA, compares established and emerging analytical methodologies such as qPCR, ddPCR, and imaging techniques, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges in delivery and dosing, and outlines validation strategies for robust, multi-site studies. By synthesizing current trends and best practices, this review serves as a vital resource for the non-clinical and clinical development of CTPs.

The Critical Role of Biodistribution in Cell Therapy: Purposes and Regulatory Landscapes

Biodistribution studies are a cornerstone in the preclinical development of Cell Therapy Products (CTPs), providing critical data on the in vivo journey of therapeutic cells post-administration. These studies assess the distribution, persistence, and clearance of a cellular agent from the administration site to both targeted and non-targeted tissues and biological fluids [1]. For CTPs, often called "living drugs," understanding this cellular kinetics is not merely a regulatory checkbox but a fundamental component for interpreting pharmacological responses, potential toxicities, and overall efficacy [2]. The biodistribution profile of adoptive T cell therapies, for instance, has been shown to directly influence clinical outcomes, highlighting its pivotal role in translating promising laboratory research into safe and effective patient treatments [2].

The regulatory requirement for these studies is driven by the need to ensure patient safety. By identifying off-target tissue accumulation and assessing the risk of germline transmission, biodistribution studies help de-risk clinical trials [3] [1]. Furthermore, they provide essential context for interpreting findings from other preclinical studies, such as toxicology and pharmacology, creating a comprehensive safety profile for new CTPs [3].

Regulatory Framework and Guidelines

The regulatory landscape for biodistribution studies of CTPs is complex and evolving, with guidelines issued by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). These guidelines generally advise a per-product approach, meaning the specific requirements are tailored to the unique aspects of each therapy [3]. Generally, biodistribution studies are required for CTPs to initiate first-in-human studies, especially when they involve new cell types, significant formulation changes, or novel routes of administration [3] [1].

Regulatory bodies strongly advise developers to request assistance before initiating preclinical studies [3]. The goal of these studies is to characterize the presence, persistence, and clearance of the drug product at a molecular level in both target and non-target tissues [3]. While not always mandatory, assessing the distribution of the therapeutic cells, their carrier/delivery system, and individual components may be requested [3]. Although these studies do not always have to comply with Good Laboratory Practice (GLP), the analytical techniques used, such as quantitative PCR (qPCR), must be rigorously validated to ensure data reliability [3] [1].

Table 1: Key Regulatory Considerations for Biodistribution Studies

| Aspect | Regulatory Consideration | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| General Requirement | Often required for CTPs; decided on a per-product basis. | [3] [1] |

| Study Goal | Characterize presence, persistence, and clearance in target and non-target tissues. | [3] |

| Animal Model | Should be as relevant as possible to the expected human situation. | [3] |

| GLP Compliance | Preclinical biodistribution studies do not have to comply with GLP. | [3] |

| Data Reliance | Studies may be avoided by referring to previous data for identical components. | [3] |

Key Methodologies for Biodistribution Assessment

A multi-faceted approach is required to fully characterize the biodistribution of CTPs. The current gold standard and most widely recommended method by the FDA is the quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay [1]. This method sensitively quantifies the number of vector copies (for gene therapies) or human cell DNA (for cellular therapies) present in animal tissue samples and biological fluids.

Core Workflow: qPCR for Biodistribution

The standard workflow involves several critical steps, from sample collection to data analysis, each contributing to the final biodistribution profile.

Diagram 1: Experimental qPCR Workflow

- CTP Administration and Tissue Harvesting: The CTP is administered to animal models via the intended clinical route. At predetermined time points, animals are sacrificed, and a wide panel of tissues (e.g., target organs, liver, spleen, gonads) and biological fluids (e.g., blood, urine, saliva) are collected [1].

- DNA Isolation: Genomic DNA is isolated from all collected samples. The DNA extraction method must be evaluated for its recovery rate and potential PCR inhibition effects to ensure accurate quantification [1].

- qPCR Analysis: The isolated DNA is used as a template in a qPCR reaction with primers and a probe specific to the therapeutic vector or human-specific DNA sequences (e.g., Alu repeats). The assay must be developed and validated for sensitivity and target-specificity. The FDA often requires a sensitivity of ≤ 50 copies per microgram of host DNA [1].

- Absolute Quantification: The quantity of the therapeutic agent in each sample is determined using a standard curve. For gene therapies, this reports the viral copy number per microgram of genomic DNA. For cell therapies, it quantifies the number of human cells distributed to animal organs [1].

Complementary and Emerging Techniques

While qPCR is a powerful and sensitive tool for quantifying DNA, it primarily confirms the physical presence of the therapeutic agent's genetic material. It does not directly confirm cell viability, protein expression, or functional activity. Therefore, a layered approach using complementary techniques is often necessary.

- Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-qPCR): This technique is used for transgene expression profiling in tissues. It requires RNA isolation and converts RNA into cDNA, allowing for the quantification of mRNA expression levels, providing insight into whether the delivered genetic material is functionally active [1].

- Imaging Techniques: Modalities like in vivo fluorescence imaging (FLI) and bioluminescence imaging (BLI) offer real-time, non-invasive spatial data on cell location and persistence. These are invaluable for longitudinal studies within the same animal but may offer less quantitative granularity than qPCR [3].

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): MS-based assays can detect and quantify the therapeutic protein product encoded by the mRNA or transgene, moving beyond genetic material to assess functional output [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Biodistribution Assessment Techniques

| Technique | Measured Analyte | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| qPCR | DNA (Vector or human-specific) | High sensitivity, quantitative, gold standard, GLP-validatable. | Does not confirm cell viability or protein expression. |

| RT-qPCR | RNA (Transgene expression) | Assesses functional activity (transcription). | Does not confirm protein translation or function. |

| In Vivo Imaging | Light-emitting probes | Real-time, longitudinal, non-invasive, provides spatial context. | Lower resolution and quantitative precision compared to qPCR. |

| Mass Spectrometry | Protein product | Directly quantifies the functional protein product. | Complex method development; may have lower sensitivity for some targets. |

Comparative Analysis of Cell Therapy Products

Biodistribution profiles are not one-size-fits-all; they vary significantly between different types of CTPs. Understanding these differences is crucial for product development and regulatory strategy.

Adoptive T Cell Therapies vs. Stem Cell Therapies

Adoptive T cell therapies (such as CAR-T) and stem cell therapies (like MSCs) represent two major classes of CTPs with distinct biological functions and, consequently, different biodistribution fates. CAR-T cells are engineered to target specific antigens, ideally leading to their accumulation and expansion in tissues where that antigen is expressed, such as tumor sites [2]. In contrast, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are often attracted to sites of inflammation and tissue injury, and a significant portion intravenously administered is often initially trapped in the lungs before redistributing to organs like the liver and spleen [1].

The persistence of these cells also differs markedly. CAR-T cells can persist for years in the host, leading to durable remissions, a phenomenon directly linked to their clinical efficacy [2]. MSCs, however, are often short-lived and may not engraft long-term, which can be a limitation for chronic conditions but may be sufficient for their primary mechanism of action via transient immunomodulation and paracrine signaling.

Impact of Administration Route

The route of administration is a critical factor shaping the biodistribution profile. The following diagram illustrates how different routes dictate the initial journey and eventual fate of a CTP within the body.

Diagram 2: Administration Route Impact

- Intravenous (IV) Injection: This leads to the most widespread distribution. Cells enter the systemic circulation, often resulting in initial accumulation in filtering organs like the lungs, liver, and spleen. This is common for CAR-T therapies targeting hematological malignancies [2] [1].

- Local/Intratumoral (IT) Injection: This route aims to maximize delivery to the target site (e.g., a solid tumor) while minimizing systemic exposure and off-target effects. However, some leakage into the circulation is often still detectable [2].

- Intraperitoneal (IP) Injection: This results in regional distribution within the peritoneal cavity, making it relevant for cancers like ovarian cancer. Cells may subsequently drain via the portal system to the liver [1].

Successfully conducting a biodistribution study requires a suite of specialized reagents and instruments. The following table details key solutions and their functions in a typical qPCR-based workflow.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biodistribution Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Biodistribution Studies |

|---|---|

| qPCR Instrument | Precisely amplifies and quantifies target DNA sequences in real-time. Instruments like the QuantStudio 6 Flex are capable of high-throughput 384-well analyses [1]. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers & Probes | Bind exclusively to the therapeutic vector's DNA or human-specific DNA sequences (e.g., Alu repeats), enabling specific detection of the CTP against the background of host animal DNA [1]. |

| DNA Standards for Quantification | Serially diluted plasmid DNA (for vector copies) or human cell DNA (for cell counts) used to generate a standard curve. This curve allows for the absolute quantification of the target in unknown samples [1]. |

| DNA/RNA Isolation Kits | Specialized kits for the efficient extraction of high-quality, inhibitor-free nucleic acids from a wide variety of tissue types and biological fluids [1]. |

| Animal Disease Models | Relevant in vivo models (e.g., immunodeficient mice for human cell tracking) that mimic the human disease state are crucial for generating clinically predictive biodistribution data [3]. |

Biodistribution studies provide an indispensable roadmap of CTP fate in the body, directly informing safety and efficacy from the lab to the clinic. A thorough understanding of regulatory guidelines, a strategic choice of sensitive and validated methodologies like qPCR, and the use of relevant animal models are all critical. As the CTP landscape expands into new territories, particularly solid tumors, the insights gained from sophisticated biodistribution assessments will be paramount in overcoming biological barriers, enhancing tumor penetration, and ultimately engineering the next generation of effective and safe "living drugs."

The development of advanced therapies, including cell and gene therapies, is a rapidly evolving field that presents unique regulatory challenges. Regulatory agencies worldwide have established specific frameworks to ensure the safety, quality, and efficacy of these innovative products while facilitating their development for serious conditions with unmet medical needs. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and Japan's Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) represent three major regulatory systems with distinct yet increasingly convergent approaches to overseeing advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs). Understanding the similarities and differences among these frameworks is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in the global landscape, particularly in critical areas like biodistribution assessment which directly informs product safety and biological activity.

The regulatory environment for these therapies continues to evolve rapidly. As of 2025, both the FDA and Japan have introduced significant updates to their regulatory guidance. The FDA has issued new draft guidance on expedited programs for regenerative medicine therapies, while Japan has amended its Act on the Safety of Regenerative Medicine to expand its scope to include in vivo gene therapy, with these changes taking effect in May 2025 [4] [5]. This dynamic regulatory landscape necessitates ongoing attention from researchers and developers in the field of cell and gene therapies.

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Frameworks

Each regulatory agency operates within its distinct legal framework and utilizes specific terminology for advanced therapies. The FDA regulates these products as cellular and gene therapy (CGT) products under the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) [6]. The EMA classifies them as advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs), which include gene therapy medicines, somatic-cell therapy medicines, and tissue-engineered medicines [7] [8]. Japan's PMDA operates under a dual framework consisting of the Act on the Safety of Regenerative Medicine (ASRM), which governs the provision of regenerative medicine, and the Pharmaceuticals, Medical Devices, and Other Therapeutic Products Act (PMD Act), which regulates the commercialization of regenerative medical products [9]. Japan defines regenerative medical products as processed live human/animal cells (beyond minimal manipulation) intended for reconstruction/repair of body structures/functions or treatment/prevention of disease, plus gene therapy products (excluding prophylactic vaccines against infectious diseases) [9].

Table 1: Fundamental Regulatory Characteristics of FDA, EMA, and PMDA

| Characteristic | FDA (USA) | EMA (Europe) | PMDA (Japan) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Legal Framework | Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act; Public Health Service Act | European Union Directives and Regulations | Act on the Safety of Regenerative Medicine (ASRM) & Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Act (PMD Act) |

| Product Category | Cellular and Gene Therapy (CGT) Products | Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) | Regenerative Medical Products |

| Risk Classification | Case-based risk assessment | Case-based risk assessment | Three-tiered classification (Class I-III, with Class I highest risk) |

| Expedited Programs | Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy (RMAT) | Priority Medicines (PRIME) | Conditional/Time-limited Approval, Priority Review |

| Key Recent Updates | New draft guidances (2025) on expedited programs, innovative trial designs, and postapproval data collection [6] [5] | New multidisciplinary guideline on clinical-stage ATMPs effective July 2025 [10] | Amended ASRM effective May 2025, expanding scope to include in vivo gene therapy in Class I [4] |

Early-Phase Clinical Trial Design Considerations

The approach to early-phase clinical trials for advanced therapies reveals both convergence and unique regional emphases among the three agencies. A comparative analysis of guidelines reveals that all three agencies share common objectives for early-phase trials: safety evaluation, preliminary evidence of effectiveness gathering, and dose exploration [8]. The FDA additionally emphasizes feasibility assessment of the product administration process [8]. Regarding safety considerations specific to CGT products, the FDA provides the most detailed guidance, highlighting potential issues such as delayed infusion reactions, autoimmunity, graft failure, graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), new malignancies, transmission of infectious agents from a donor, and viral reactivation [8].

For monitoring and follow-up, both the FDA and EMA emphasize the need for long-term follow-up due to the potential for delayed adverse events. The FDA recommends at least one year or more of follow-up for each subject in early-phase trials, while the PMDA advises setting an appropriate follow-up period based on the type of gene therapy product, with specific mention that products with chromosomal integration vectors warrant particularly extended observation [8]. The FDA's 2025 draft guidance on "Innovative Designs for Clinical Trials of Cellular and Gene Therapy Products in Small Populations" further encourages flexibility in trial design for rare diseases, including the use of innovative designs comparing multiple investigational agents and the potential use of natural history data as historical controls when populations are adequately matched [11] [5].

Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) Requirements

CMC requirements represent a critical component of advanced therapy development, with significant regulatory convergence but also important distinctions. The FDA generally adopts a graduated, phase-appropriate approach to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) compliance, with full verification typically occurring during pre-license inspection [10]. In contrast, the EMA's guideline on clinical-stage ATMPs emphasizes that GMP compliance is a prerequisite for clinical trials at both exploratory and pivotal stages, achieved partly through mandatory self-inspections [10].

For allogeneic donor eligibility determination, the FDA maintains more prescriptive requirements regarding donor screening and testing for infectious diseases, including specified tests, laboratory qualifications, and restrictions on pooling human cells or tissue from multiple donors [10]. The EMA acknowledges the importance of guarding against communicable disease transmission but provides more general guidance, reminding sponsors that requirements must comply with relevant EU and member state-specific legal requirements [10]. This divergence can create challenges for global developers using cellular starting materials obtained from donors screened under one jurisdiction's requirements for development in another region.

Table 2: Key CMC and Non-Clinical Requirements Across Agencies

| Requirement Area | FDA | EMA | PMDA |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMP Compliance | Phase-appropriate approach; verification at BLA stage | Prerequisite for clinical trials; mandatory self-inspections | Alignment with international standards; specific quality and safety guidelines |

| Donor Eligibility | Prescriptive requirements for screening and testing; restrictions on donor pooling | Compliance with EU and member state laws; general guidance on risk management | Detailed standards for biological raw materials; specific guidelines for different cell types |

| Potency Assurance | Dedicated guidance (2023) on demonstrating potency | Covered in overarching ATMP guidelines; product-specific requirements | Integrated into product-specific guidelines; focus on quantitative metrics |

| Biodistribution Assessment | Required as part of nonclinical assessment; long-term monitoring | ICH S12 guideline on nonclinical biodistribution | Required in nonclinical studies; tumorigenicity assessment for iPSC-derived products |

| Tumorigenicity Testing | Recommended for relevant cell types (e.g., pluripotent cells) | Addressed in reflection papers on stem cells and genetically modified cells | Detailed points to consider document for iPSC-based products |

Biodistribution Assessment in Regulatory Context

Regulatory Expectations for Biodistribution Studies

Biodistribution assessment represents a critical component of the nonclinical safety evaluation for advanced therapies, particularly within the context of comparative analysis across regulatory agencies. These studies are essential for understanding the migration, persistence, and fate of cellular products within the body, directly informing potential safety concerns such as ectopic tissue formation or unwanted engraftment [12]. The EMA has established a dedicated guideline (ICH S12) on nonclinical biodistribution considerations for gene therapy products, providing specific recommendations for these products [7]. While the FDA and PMDA may not have standalone biodistribution guidelines, they address these requirements within broader nonclinical guidance documents.

The PMDA has published specific "Points to consider" documents for efficient conduct of consultations on quality and safety from the early stages of development for both cellular and tissue-based products and gene therapy products [9]. These documents highlight the importance of biodistribution assessment, particularly for products with potential for widespread distribution or persistence. Furthermore, the PMDA emphasizes the need for tumorigenicity testing and genomic stability evaluation for human cell-based therapeutic products, especially those derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [9]. The FDA's guidance on "Preclinical Assessment of Investigational Cellular and Gene Therapy Products" outlines similar expectations for biodistribution studies to support initial clinical trials.

Methodologies for Biodistribution Assessment

Regulatory agencies generally accept multiple methodological approaches for assessing biodistribution, with the choice dependent on product characteristics and scientific rationale. Commonly employed techniques include quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) for sensitive detection of cell-specific DNA sequences and imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to monitor spatial distribution and persistence over time [12]. These methodologies enable researchers to track the movement and fate of administered cellular products in relevant animal models.

The design of biodistribution studies should incorporate multiple time points to understand both short-term trafficking and long-term persistence patterns. For products with potential for integration or genotoxic effects, longer duration studies may be necessary to assess potential risks. The selection of animal models should be scientifically justified, considering factors such as immunocompatibility with the human cell product and biological relevance to the intended clinical application. Immunodeficient animal models are often employed to permit engraftment and persistence of human cells, enabling more meaningful assessment of distribution patterns [12].

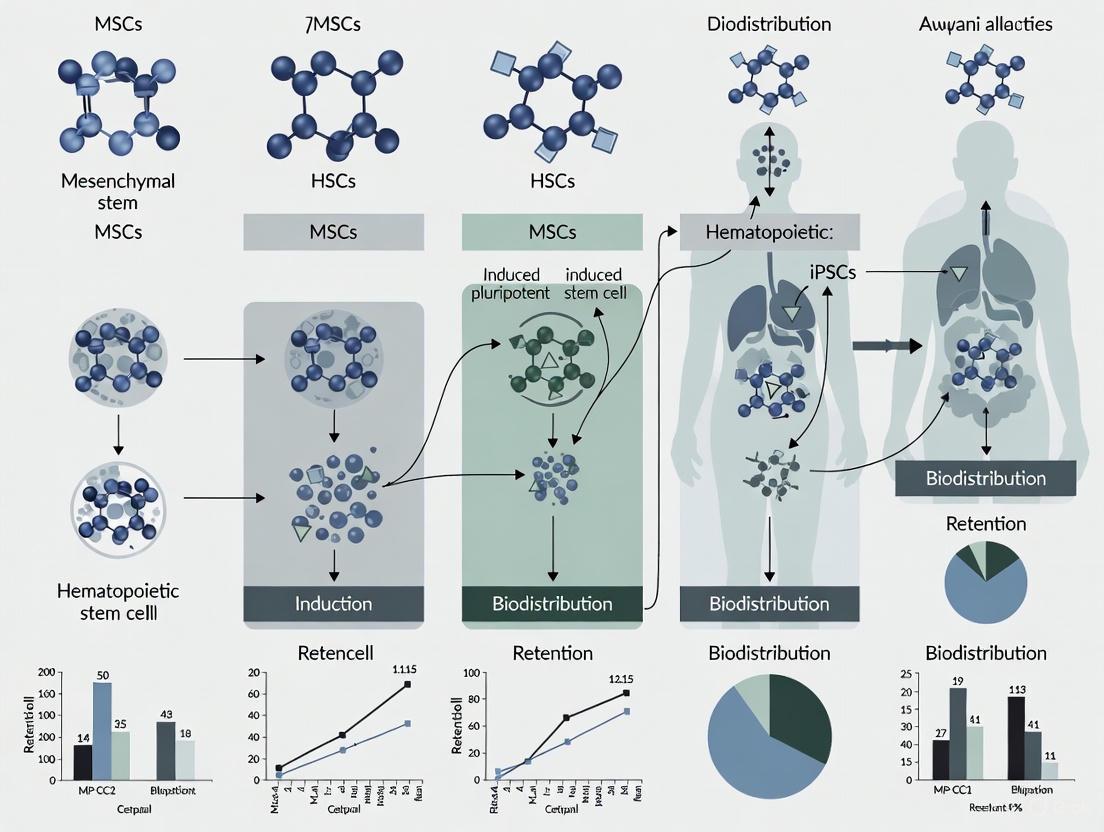

Figure 1: Biodistribution Assessment Workflow - This diagram illustrates the key stages in designing and conducting biodistribution studies for regulatory submissions, from initial model selection through data integration.

Comparative Analysis of Biodistribution Requirements

When comparing biodistribution requirements across regulatory agencies, a pattern of general alignment with regional nuances emerges. All three major agencies recognize the fundamental importance of understanding the in vivo distribution and persistence of cell-based products. However, the degree of specificity and emphasis on particular aspects may vary based on the product type and previous regulatory experience with similar modalities.

The FDA typically expects sponsors to provide comprehensive biodistribution data as part of the nonclinical package supporting initial clinical trials, with particular attention to products with potential for widespread distribution or targeting sensitive tissues. The EMA's ICH S12 guideline provides more detailed recommendations specific to gene therapy products, including considerations for vector shedding and environmental risk assessment [7]. Japan's PMDA incorporates biodistribution assessment within its broader framework for ensuring quality and safety of regenerative medical products, with specific considerations for products derived from iPSCs and other pluripotent cell sources [9]. For these higher-risk products, the PMDA emphasizes the need for thorough assessment of oncogenic potential and teratogenic effects, particularly when working with pluripotent cells that have the capacity to differentiate into various tissue types [12].

Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

The conduct of robust biodistribution studies and other critical nonclinical assessments requires specialized research reagents and methodologies. The selection and validation of these tools are essential for generating reliable data acceptable to regulatory agencies. The following section outlines key components of the "scientist's toolkit" for biodistribution assessment and related safety studies, with particular relevance to comparative regulatory analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Biodistribution & Safety Assessment

| Reagent/Methodology | Primary Function | Regulatory Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Sensitive detection of cell-specific DNA sequences to quantify biodistribution | Tracking and persistence of human cells in animal models; required by all agencies | Target human-specific sequences (e.g., Alu repeats); establish detection limits |

| Molecular Imaging Agents | Enable non-invasive monitoring of spatial and temporal distribution | Longitudinal assessment without sacrificing animals; accepted across agencies | Consider label stability, effect on cell viability/function |

| Immunodeficient Animal Models | Permit engraftment and persistence of human cells | Essential for meaningful biodistribution studies; used for all agencies | Select appropriate level of immunodeficiency; consider biological relevance |

| Flow Cytometry Reagents | Characterize cell identity, viability, and phenotypic changes | Product quality assessment; potency; immunogenicity evaluation | Validate antibody panels for specific cell types; include viability markers |

| Cytokine Analysis Kits | Quantify immune responses and inflammatory mediators | Immunogenicity assessment; safety pharmacology; required by all agencies | Multiplex platforms efficient for comprehensive profiling |

| Genomic Stability Assays | Detect chromosomal abnormalities and genetic changes | Tumorigenicity risk assessment; especially critical for PMDA for iPSC products | Karyotyping, FISH, CNV analysis; multiple methods recommended |

The selection of appropriate analytical methods should be guided by phase-appropriate validation principles, with increasing rigor required as product development advances. Regulatory agencies emphasize the importance of assay validation according to International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, including parameters such as accuracy, precision, linearity, range, specificity, and robustness [12]. For cell-specific assays, additional considerations include matrix effects from biological specimens and stability of cellular analytes under various storage and processing conditions. The implementation of quality-by-design principles in assay development helps ensure reproducible and reliable data across the product development lifecycle.

The comparative analysis of FDA, EMA, and PMDA guidelines for advanced therapies reveals a landscape of significant convergence with persistent regional distinctions. All three agencies have established specialized frameworks to address the unique challenges posed by cell and gene therapies, with particular attention to nonclinical safety assessment including biodistribution, tumorigenicity, and long-term monitoring. The ongoing revisions to regulatory guidelines across these jurisdictions demonstrate a responsive approach to the rapid scientific advancements in this field.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding both the commonalities and differences among these regulatory systems is essential for efficient global development strategy. Key areas of alignment include the general principles for biodistribution assessment, the importance of phase-appropriate product characterization, and the need for long-term follow-up to monitor delayed adverse events. Remaining differences in areas such as donor eligibility requirements and the timing of GMP compliance necessitate strategic planning for global development programs. As the field continues to evolve, ongoing regulatory convergence initiatives and increased international harmonization offer the promise of more efficient development pathways for these innovative therapies, potentially accelerating patient access to transformative treatments for serious conditions with unmet medical needs.

Biodistribution assessment is a cornerstone in the safety evaluation of cell-based therapies, providing critical insights into the travel and fate of therapeutic cells within a recipient's body. This distribution pattern is fundamentally linked to two paramount safety concerns: tumorigenicity and off-target effects. Tumorigenicity refers to the potential of administered cells to form abnormal growths, including teratomas or malignant tumors [12] [13]. Off-target effects, on the other hand, encompass unintended consequences in tissues other than the target organ, which can result from misplaced cell differentiation or inappropriate paracrine signaling [14]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this link is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for de-risking novel therapies. A therapy's biodistribution profile directly influences its risk blueprint; cells that migrate to or persist in sensitive anatomical compartments can pose significantly different safety challenges than those confined to the target site. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how different cell therapy platforms manage these interconnected risks, supported by experimental data and methodologies essential for robust preclinical safety assessment.

Comparative Analysis of Biodistribution-Linked Risks Across Cell Therapy Platforms

The inherent biological properties of different cell types dictate their biodistribution after administration and, consequently, their unique risk profiles. The table below provides a structured comparison of major cell therapy classes, highlighting how their distribution patterns correlate with specific safety concerns.

Table 1: Comparative Biodistribution and Linked Critical Risks of Cell Therapies

| Cell Therapy Platform | Primary Biodistribution Pattern | Linked Tumorigenicity Risk | Linked Off-Target/Immunogenicity Risk | Supporting Evidence Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs/ESCs) | Widespread dissemination possible; potential for ectopic engraftment in organs like liver, spleen, and gonads [12]. | High due to potential residual undifferentiated cells with uncontrolled proliferative capacity [13]. | Risk of aberrant differentiation in non-target tissues (teratogenicity) [12]. | |

| Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells (MSCs) | Often initially trapped in lungs post-IV injection; can home to sites of inflammation or injury [12]. | Low to Moderate; some reports of spontaneous transformation in long-term cultures, but generally considered low risk [12]. | Potential for off-target immunomodulation; may support tumor growth in microenvironment [12]. | |

| CAR-T Cells | Predominantly in lymphoid tissues, bone marrow, and sites of target antigen expression (e.g., tumors) [15]. | Low (Direct) but emerging concern for secondary T-cell cancers potentially linked to viral vector integration [15]. | High (On-target, off-tumor) toxicity if target antigen is expressed on healthy tissues [15]. | |

| Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs) | Primary engraftment in bone marrow niche following intravenous infusion [12]. | Low for properly differentiated and characterized products. | Graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) from allogeneic transplants is a major immunogenic risk [12]. |

Essential Experimental Methodologies for Risk Assessment

A thorough investigation of the biodistribution-tumorigenicity axis requires a suite of complementary experimental protocols. The following section details key methodologies cited in recent literature and regulatory guidelines.

Quantitative Biodistribution Assessment

Objective: To quantitatively track the movement, persistence, and accumulation of therapeutic cells in target and non-target tissues over a defined period.

Protocol Details:

- Technology: Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) is a gold standard, especially for human-specific Alu sequences or other unique genetic markers in animal models [12].

- Procedure:

- Administration: The cell therapy product is administered to immunocompromised animal models (e.g., NSG mice) via the intended clinical route (e.g., intravenous, intramuscular).

- Tissue Collection: At predetermined timepoints (e.g., 24 hours, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months), animals are euthanized, and a comprehensive panel of organs (e.g., liver, lungs, spleen, gonads, brain, and injection site) is harvested.

- DNA Extraction: Genomic DNA is isolated from each tissue sample using validated kits.

- qPCR Analysis: DNA samples are analyzed via qPCR using primers and probes specific to the human genetic marker. A standard curve is generated from known quantities of the cell product to allow absolute quantification.

- Data Expression: Results are typically reported as vector genomes or cell equivalents per microgram of total DNA [12].

Supporting Imaging Techniques:

- Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI): Requires cells engineered to express luciferase. After injection of the substrate (e.g., D-luciferin), light emission is captured, providing a semi-quantitative, whole-body view of cell location and viability over time [12].

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET) / Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Used for deeper tissue imaging. Cells can be labeled with radioactive tracers (e.g., [18F]FDG for PET) or superparamagnetic iron oxide particles (for MRI) to monitor their homing and distribution non-invasively [12] [16].

Tumorigenicity and Oncogenicity Testing

Objective: To evaluate the potential of the cell product to form tumors in vivo, either from overgrowth or from malignant transformation.

Protocol Details:

- In Vivo Models: The most definitive assessments require long-term studies in immunodeficient animals with compromised abilities to reject human cells (e.g., NOD-scid IL2Rγnull mice) [12] [13].

- Study Design:

- Groups: Animals are divided into at least three groups: test article (the cell therapy product), a negative control (e.g., fully differentiated cells), and a positive control (e.g., undifferentiated pluripotent cells known to form teratomas).

- Administration: Cells are implanted at a high dose, often via a route that ensures high local concentration, such as subcutaneous or intramuscular injection.

- Observation Period: Animals are monitored for an extended period, typically 6-12 months, for palpable mass formation or signs of ill health.

- Necropsy and Histopathology: A full necropsy is performed. Tissues are examined grossly and microscopically (histopathology) for evidence of tumor formation. Suspected tumors are analyzed to determine their cell origin (host vs. donor) and histological type [13].

Supporting In Vitro Assays:

- Soft Agar Colony Formation Assay: Tests for anchorage-independent growth, a hallmark of cellular transformation.

- Karyotyping and Genomic Stability Analysis: Identifies chromosomal abnormalities that could predispose cells to tumorigenicity [12].

Investigating Off-Target Effects and Immunogenicity

Objective: To identify unintended biological consequences in non-target tissues and assess immune responses triggered by the therapy.

Protocol Details:

- For Off-Target Toxicity:

- Clinical Observations: Animals in biodistribution and tumorigenicity studies are closely monitored for behavioral changes, weight loss, and other signs of toxicity.

- Clinical Pathology: Blood samples are analyzed for hematology and clinical chemistry parameters (e.g., liver enzymes like ALT and AST, kidney markers like creatinine and BUN) to detect organ dysfunction [12].

- Histopathology: A comprehensive histological examination of all major organs is conducted to identify any cellular damage, inflammation, or abnormal tissue architecture not related to tumor formation [12].

- For Immunogenicity:

- Cytokine Profiling: Serum or plasma is analyzed using multiplex immunoassays (e.g., Luminex) to measure levels of cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IFN-γ) associated with immune activation, such as Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) [14].

- Immune Cell Phenotyping: Flow cytometry is performed on blood or tissue samples to characterize immune cell populations (e.g., T-cells, NK cells, macrophages) and their activation states in response to the therapy [12].

Figure 1: Integrated experimental workflow for assessing biodistribution-linked critical risks, showing the parallel evaluation pathways that feed into a comprehensive risk assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of the aforementioned experimental protocols relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The table below catalogs essential solutions for researchers in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Biodistribution and Risk Assessment Studies

| Research Reagent / Solution | Primary Function | Key Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Immunodeficient Mouse Models (e.g., NSG, NOG) | In vivo host for human cell engraftment and tumorigenicity studies. | Degree of immunodeficiency (T, B, NK cell deficiency), lifespan, cost, and susceptibility to radiation. |

| qPCR Kits for Human-Specific Sequences (e.g., Alu, LINE-1) | Quantitative biodistribution analysis in animal tissues. | Specificity for human DNA, sensitivity (limit of detection), and efficiency on complex tissue lysates. |

| Bioluminescence/Luciferase Reporter Systems | Non-invasive, longitudinal tracking of cell fate in vivo. | Signal brightness, stability in cell type, potential immunogenicity in immunocompetent models. |

| MRI Contrast Agents (e.g., SPIO nanoparticles) | Deep-tissue anatomical imaging and cell tracking via MRI. | Biocompatibility, labeling efficiency, persistence in cells, and potential impact on cell function. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibody Panels | Immunophenotyping of donor and host immune cells. | Multiplexing capability, host (e.g., mouse) cross-reactivity, and specificity for activation markers. |

| Cytokine Multiplex Assays | Profiling a broad spectrum of inflammatory mediators in serum/plasma. | Number of analytes, dynamic range, sample volume requirements, and species specificity. |

The relationship between biodistribution and critical safety risks is a fundamental aspect of cell therapy development that cannot be overlooked. As the data and methodologies outlined in this guide demonstrate, a proactive and integrated safety assessment strategy is paramount. This involves employing quantitative biodistribution studies (e.g., qPCR, imaging) in tandem with sensitive tumorigenicity assays and comprehensive off-target effect analyses from the earliest stages of product development. The field is evolving towards more predictive tools, including AI-driven safety modeling and advanced molecular assays for detecting genotoxicity [14] [17]. Furthermore, regulatory expectations are intensifying globally, emphasizing the need for standardized, rigorous approaches to these evaluations [13] [17]. For researchers, mastering the link between where cells go and what risks they may pose is not just about ensuring regulatory approval; it is about building a solid scientific foundation for the next generation of safe and effective cell therapies.

In the field of cell therapy, successful treatment outcomes hinge on the dynamic behaviors of administered therapeutic cells. Survival, engraftment, proliferation, and migration represent four fundamental parameters that collectively determine the efficacy and safety of cell-based therapies. These interconnected processes govern the journey of therapeutic cells from administration to functional integration within target tissues. A comprehensive understanding of these parameters enables researchers to optimize therapeutic protocols, predict clinical outcomes, and design more effective cell therapy products. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these essential parameters across different cell types, supported by experimental data and methodological insights crucial for drug development professionals.

Parameter Definitions and Biological Significance

Cell Survival

Cell survival refers to the viability and persistence of administered therapeutic cells in the host environment following transplantation. This parameter is crucial because acute donor cell death significantly limits therapeutic efficacy across multiple cell types [18]. The survival capacity varies substantially between cell types, with studies showing that within the first 3 weeks post-transplantation, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), skeletal myoblasts (SkMb), and fibroblasts (Fibro) experience significant cell death, while bone marrow mononuclear cells (MN) demonstrate more favorable survival patterns [18]. For MSCs specifically, studies in fibrotic liver models show that a large number die within 1 day after transplantation, with surviving cells nearly completely disappearing within 11 days [19]. Improving cell survival remains a primary focus in cell therapy optimization, as survival rates directly impact the number of cells available for engraftment and subsequent therapeutic functions.

Engraftment

Engraftment describes the process by which transplanted cells integrate structurally and functionally into the host tissue, establishing a stable presence. This parameter is distinct from mere survival as it involves successful incorporation into the tissue architecture. Engraftment efficiency is closely tied to cell survival, as only surviving cells can successfully engraft [19]. Research indicates that engraftment plateaus can occur at higher transplantation doses, where the total number of engrafted human cells never exceeds the initial dose, suggesting that donor cell expansion is inversely regulated by target niche parameters and/or transplantation density [20]. The relationship between administration route and engraftment efficiency is particularly important in systemic delivery, where cells must navigate through the circulation to reach target tissues.

Proliferation

Proliferation encompasses the capacity of transplanted cells to divide and expand their population after administration. This parameter is critical for achieving sufficient cell numbers to exert therapeutic effects, especially when initial engraftment numbers are low. However, studies have revealed an inverse correlation between transplantation dose and donor cell proliferation, suggesting that proliferation is tightly regulated by microenvironmental factors and niche availability [20]. Regardless of transplantation dose, research on human neural stem cells indicates that only a small proportion of transplanted cells remain mitotic after engraftment [20]. This highlights the complex balance between achieving therapeutic cell numbers and avoiding uncontrolled expansion that could lead to tumorigenicity.

Migration

Migration refers to the directed movement of transplanted cells from the administration site to target tissues, a process particularly crucial for systemically administered therapies. Also described as "homing," this parameter involves a coordinated multi-step process similar to leukocyte migration to inflammatory sites [19]. The migration process can be divided into distinct phases: rolling, activation, adhesion, crawling, and transendothelial migration [19]. Different cell types utilize various molecular mechanisms for migration; for instance, MSC rolling is facilitated by CD24 as a P-selectin ligand and CD29/VCAM-1 interactions with liver sinusoidal endothelial cells [19]. Effective migration ensures that sufficient numbers of therapeutic cells reach the intended site of injury or disease to exert their beneficial effects.

Comparative Analysis Across Cell Types

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Different Cell Types in Cardiac Therapy Models

| Cell Type | Survival Pattern | Engraftment Efficiency | Proliferation Capacity | Migration/Homing | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cells (MN) | Significantly better; cardiac signals present at 6 weeks [18] | Favorable; confirmed by TaqMan PCR [18] | Not specifically reported | Not specifically reported | Significant preservation of fractional shortening, least ventricular dilatation [18] |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC) | Significant death within 3 weeks [18] | Limited by poor survival [18] | Not specifically reported | Depends on CD29/VCAM-1 interactions [19] | Less robust functional preservation compared to MN [18] |

| Skeletal Myoblasts (SkMb) | Significant death within 3 weeks [18] | Limited by poor survival [18] | Can proliferate but risk of uncontrolled growth [21] | Not specifically reported | Limited functional preservation [18] |

| Fibroblasts (Fibro) | Significant death within 3 weeks [18] | Limited by poor survival [18] | Not specifically reported | Not specifically reported | Limited functional preservation [18] |

| Neural Stem Cells (NSC) | Varies with transplantation niche [20] | Plateaus at higher doses [20] | Inversely correlated with transplantation dose [20] | Not specifically reported | Not specifically reported |

Table 2: Key Molecular Mechanisms Governing Cell Behavior

| Parameter | Critical Molecular Mediators | Function in Cell Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Survival | Oxidative stress resistance pathways [19] | Determines initial cell retention and persistence |

| Engraftment | Integrins, adhesion molecules [19] | Enables structural integration into host tissue |

| Proliferation | Mitotic signaling pathways [20] | Controls population expansion post-transplantation |

| Migration/Homing | Selectins (P-selectin), chemokine receptors (CXCR4), adhesion molecules (VCAM-1/CD29) [19] | Directs cells to target tissues following systemic administration |

Methodologies for Assessment

Tracking Cell Survival

- Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI): Non-invasive, quantitative method using firefly luciferase (Fluc) reporter genes; validated with strong correlation between Fluc expression and cell number (r² > 0.93) [18]

- TaqMan PCR: Ex vivo quantification using species-specific or sex-specific genetic markers (e.g., male-derived cells in female recipients via Sry gene detection) [18]

- Reporter Gene Imaging: Includes bioluminescence and fluorescence proteins for repetitive, non-invasive monitoring of cell viability [22]

Assessing Engraftment and Proliferation

- Droplet Digital PCR: Highly sensitive method for quantifying donor cell presence in host tissues; validated for biodistribution studies [23]

- Histological Analysis: Direct visualization of engrafted cells in tissue sections using immunohistochemistry or fluorescence tagging [18]

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Standard regulatory-recommended method for biodistribution studies; can detect ≤50 copies/μg host DNA [24] [25]

Monitoring Migration and Biodistribution

- Radionuclide Imaging (PET/SPECT): High sensitivity tracking using 111In-oxyquinoline or 99mTc-labeled cells; allows clinical translation [22]

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Uses superparamagnetic iron oxide particles for anatomical localization; suitable for 3D imaging [22]

- Spatial Multiomics: Emerging technology enabling detection of multiple RNA and protein targets simultaneously in tissue sections; useful for characterizing migratory cells [26]

Visualizing the Integrated Cell Journey

The following diagram illustrates the sequential relationship between the four key parameters in determining ultimate therapy efficacy:

Diagram 1: The sequential relationship between key parameters in cell therapy efficacy. The journey begins with cell survival and migration, which enable engraftment, creating a foundation for proliferation that collectively determines therapeutic efficacy.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Parameter Assessment

| Reagent/Technology | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Firefly Luciferase (Fluc)/GFP Reporter System [18] | Longitudinal survival tracking | Enables non-invasive bioluminescence imaging and histological validation |

| Droplet Digital PCR [23] | Sensitive biodistribution quantification | Absolute quantification without standard curves; high precision |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) [24] [25] | Biodistribution and engraftment assessment | Regulatory-accepted; detects low copy numbers (≤50 copies/μg DNA) |

| Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Particles [22] | MRI-based cell tracking | Suitable for 3D anatomical localization; low concentration detection |

| Radionuclide Tracers (111In-oxine, 99mTc) [22] | Clinical cell tracking | High sensitivity; clinically translatable |

| RNAscope Multiomic LS Assay [26] | Spatial characterization of migrated cells | Multiplex RNA/protein detection in tissue sections |

The comparative analysis of survival, engraftment, proliferation, and migration across different cell types reveals distinct advantages and limitations that inform therapeutic applications. Bone marrow mononuclear cells demonstrate superior survival characteristics translating to enhanced functional preservation in cardiac models, while other cell types face significant attrition barriers. The inverse relationship between transplantation dose and proliferation observed in neural stem cells highlights the complex regulation of cell expansion post-administration. Effective migration relies on conserved molecular mechanisms including selectin-mediated rolling and chemokine-directed activation. The integrated assessment of these four parameters through advanced imaging, molecular, and spatial technologies provides the comprehensive understanding necessary to optimize cell therapy products and predict their clinical behavior. As the field advances, strategies to enhance cell survival and direct migratory potential will be crucial for maximizing therapeutic efficacy across diverse medical applications.

Analytical Toolkits for Biodistribution: From qPCR to Advanced Imaging

Evaluating the biodistribution (BD) of cell therapy products (CTPs) is a critical component of non-clinical safety and efficacy assessment. BD data clarify cell survival time, engraftment, and distribution sites after administration, providing vital insights for predicting clinical outcomes [27]. Among the techniques available for this purpose, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) have emerged as powerful tools for the sensitive detection and quantification of nucleic acids from administered CTPs within host tissues. These molecular biology tools are employed throughout the development pipeline, from preclinical bio-distribution studies for gene therapies to corresponding clinical development such as shedding and cellular kinetics [28]. This guide provides an objective comparison of qPCR and ddPCR performance, supported by experimental data relevant to biodistribution assessment.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Quantitative PCR (qPCR), also known as real-time PCR, has been the gold standard for nucleic acid detection and quantification for years. It is a relative quantification method that monitors the amplification of a target DNA sequence in real time using fluorescent reporters. The quantification cycle (Cq) at which the fluorescence crosses a threshold is used, in conjunction with a standard curve, to determine the initial template concentration [29]. This method is valued for its speed, sensitivity, ease of use, and well-established guidelines.

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR)

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) is a more recent technology that provides absolute quantification of nucleic acid molecules without the need for a standard curve. The reaction mixture is partitioned into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets, and PCR amplification occurs within each individual droplet. After endpoint PCR, droplets are analyzed to count the positive and negative reactions, allowing for absolute quantification of the target molecule using Poisson statistics [30] [31]. This partitioning makes ddPCR less susceptible to PCR inhibitors and capable of higher precision, especially for low-abundance targets [29].

Direct Performance Comparison: Experimental Data

Multiple studies have directly compared the performance of qPCR and ddPCR, providing robust data to inform platform selection. The table below summarizes key performance characteristics based on empirical evidence.

Table 1: Experimental Performance Comparison of qPCR and ddPCR

| Performance Characteristic | qPCR | Droplet Digital PCR | Supporting Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Method | Relative (ΔΔCq); requires standard curve [29] | Absolute (copies per μL); no standard curve [29] [30] | Fundamental operational difference |

| Detection Sensitivity | Best for moderate-to-high abundance targets (Cq < 30-35) [29] | Superior for low-abundance targets (down to ~0.5 copies/μL) [29] [31] | LOD for ndPCR: 0.39 copies/μL; ddPCR: 0.17 copies/μL [31] |

| Precision | Good for mid/high expression levels (>twofold changes) [29] | Higher precision; reliable detection of <1.5-fold changes [29] | CVs for ddPCR: 6-13%; qPCR: generally higher for low-abundance targets [31] |

| Accuracy in BD Studies | Accurate within a dynamic range, but relative | High accuracy for absolute copy number | In vitro BD validation showed accuracy (relative error) generally within ±50% for both [27] |

| Impact of Inhibitors | Susceptible; may require extra optimization [29] | More resilient due to endpoint analysis [29] | dPCR is less affected by PCR inhibitors in complex matrices like respiratory samples [32] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Requires validation for matched amplification efficiency [29] | Simplified multiplex development; minimal optimization [29] | Both platforms demonstrated robust performance in singleplex and multiplex formats [29] |

Further data from a gene expression study highlights ddPCR's advantage in detecting subtle changes. When measuring the low-abundance target BCL2, qPCR did not identify a statistically significant fold change, whereas ddPCR resolved a significant 2.07-fold difference with tighter error bars, demonstrating greater precision and sensitivity [29].

In the critical context of biodistribution, a multi-facility study demonstrated that both qPCR and ddPCR are fit-for-purpose. The study, which used the primate-specific Alu gene to track human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) in immunodeficient mice, found that both methods exhibited similar accuracy (relative error generally within ±50%) and precision (coefficient of variation generally less than 50%). The resulting tissue distribution profiles were consistent across all facilities, identifying the lungs as the site of highest cell distribution [27].

Experimental Protocols for Biodistribution Analysis

The following workflow outlines a typical protocol for a biodistribution study of human cells in a mouse model using qPCR and ddPCR. This methodology is adapted from a study that successfully compared both techniques across multiple facilities [27].

Detailed Methodology

1. In Vivo Administration and Sample Collection:

- Animal Model: Immunodeficient mice are commonly used in non-clinical tumorigenicity and biodistribution studies to prevent rejection of human-derived CTPs [27].

- Cell Administration: A known number of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) or other CTPs are administered via a defined route (e.g., intravenous) [27].

- Tissue Harvest: At predetermined time points post-administration (e.g., 1, 4, and 24 hours), target tissues (e.g., lungs, liver, spleen, gonads) are collected. All tissues should be snap-frozen or preserved appropriately to prevent nucleic acid degradation.

2. Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Homogenization: Tissues are homogenized in lysis buffer using bead-beating or other mechanical methods to ensure complete cell disruption.

- DNA Extraction: Genomic DNA is purified from the homogenates using commercial kits (e.g., MagMax Viral/Pathogen kit on a KingFisher Flex system) [32]. The extraction should include an RNase step if quantifying DNA targets. The quality and concentration of the extracted DNA should be assessed via spectrophotometry or fluorometry.

3. Assay Setup and Partitioning:

- Primer/Probe Design: Assays must be specific to the administered CTP and not cross-react with the host's genome. A common approach is to target a species-specific sequence, such as the primate-specific Alu gene for human cells in a rodent background [27]. Software is typically used for design, focusing on creating primers/probes that span a unique modification junction for maximum specificity.

- Reaction Setup:

- For qPCR, the reaction mix contains DNA template, primer-probe mix, and a master mix suitable for real-time PCR. The mix is loaded directly into a qPCR plate.

- For ddPCR, an analogous reaction mix is prepared. This mix is then loaded into a droplet generator (e.g., Bio-Rad's QX200) which partitions the sample into ~20,000 nanoliter-sized droplets, or into a nanoplate-based system (e.g., QIAGEN's QIAcuity) [32] [31].

4. Amplification and Analysis:

- Amplification:

- qPCR is run on a real-time thermocycler (e.g., Bio-Rad CFX Opus). The amplification is monitored in real-time, and Cq values are determined by the instrument's software [29].

- ddPCR involves endpoint PCR on a thermal cycler. After cycling, the plate or droplets are transferred to a reader that counts the positive and negative partitions [31].

- Quantification and Normalization:

- qPCR relies on a standard curve, created from serially diluted samples with known copy numbers, to convert Cq values into relative quantities. Data are often normalized to a reference gene [29].

- ddPCR uses Poisson statistics to calculate the absolute concentration in copies per microliter of input directly from the fraction of positive partitions, without a standard curve [30]. Results can be reported as copies per microgram of total DNA to normalize for tissue input differences.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key reagents and materials required for implementing these assays, particularly in a biodistribution context.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for qPCR/ddPCR Biodistribution Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Products / Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Species-Specific Primers/Probes | Enables specific detection of administered CTPs in a host background by targeting unique genomic sequences. | Primate-specific Alu sequence for human cells in mouse tissues [27] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | For purification of high-quality, inhibitor-free DNA from complex tissue matrices; critical for assay robustness. | MagMax Viral/Pathogen kit (Thermo Fisher) [32]; High Pure Viral Nucleic Acid Kit (Roche) [33] |

| PCR Master Mixes | Optimized buffers, enzymes, and dNTPs tailored for either qPCR or ddPCR workflows. | Bio-Rad ddPCR Supermix; QIAGEN QIAcuity Probe PCR Kit; various RT-qPCR buffers [29] [33] |

| Digital PCR Partitioning Systems | Creates thousands of individual reactions for absolute quantification. | Droplet-based (Bio-Rad QX200); Nanoplate-based (QIAGEN QIAcuity) [32] [31] |

| Reference Gene Assays | Used for normalization in qPCR to account for variations in DNA input and extraction efficiency. | Pre-optimized assays for genes like ACTB, PGK1 (e.g., Bio-Rad PrimePCR Reference Gene Panel) [29] |

| Positive Control Templates | Synthetic DNA or plasmid containing the target sequence, used for standard curves (qPCR) and assay validation. | Synthesized DNA fragments [30]; Plasmid DNA controls |

The choice between qPCR and ddPCR for biodistribution studies is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific experimental question and context.

- qPCR remains a powerful and efficient choice for moderate-to-high abundance targets where sample throughput and established workflows are priorities. Its reliance on a standard curve is manageable when suitable reference materials are available [29].

- ddPCR offers distinct advantages for applications requiring absolute quantification, high precision for low-abundance targets, or detection of subtle fold-changes (e.g., less than two-fold). Its resilience to inhibitors and simplified multiplexing are significant benefits when working with complex tissue samples [29] [30].

For cell therapy biodistribution, where quantifying low levels of engraftment in distant tissues is often the goal, ddPCR's superior sensitivity and precision make it an increasingly attractive platform. However, as demonstrated in multi-facility studies, both methods can generate reliable and comparable biodistribution profiles when properly validated [27]. The decision should be guided by the required level of sensitivity, the available sample quantity and quality, and the specific regulatory and project needs.

The development of effective cell therapies hinges on the ability to non-invasively monitor the fate of administered cells in living subjects. Biodistribution studies, which track the journey, persistence, and localization of therapeutic cells, are essential for predicting and assessing both the efficacy and toxicity of Cell Therapy Products (CTPs) [24]. Without this capability, the post-administration phase becomes a "black box," making it difficult to understand inconsistent clinical results, optimize delivery methods, or determine why some patients respond to treatment while others do not [34] [35]. Molecular imaging provides a powerful solution to this challenge by enabling the real-time, quantitative tracking of cells in vivo. This guide objectively compares the performance of four primary imaging modalities—PET, SPECT, MRI, and Optical Imaging—within the context of comparative biodistribution assessment for cell therapy research.

Comparative Analysis of Imaging Modalities

The table below provides a quantitative comparison of the key technical and performance characteristics of each imaging modality for cell tracking.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of In Vivo Imaging Modalities for Cell Tracking

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Detection Sensitivity | Tissue Penetration | Quantitative Ability | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET | 1-2 mm [34] | High (picomolar) [36] | Unlimited | Excellent, absolute quantification possible [37] | Whole-body scanning, high sensitivity, quantifiable, clinically translatable [36] | Radiation exposure, requires cyclotron, lower spatial resolution than MRI [38] |

| SPECT | 1-2 mm [34] | High (picomolar) [36] | Unlimited | Good | Multiple probe imaging, clinically translatable [36] | Radiation exposure, generally lower resolution and sensitivity than PET [39] |

| MRI | 25-100 µm [40] | Low (micromolar); requires 10³ - 10⁴ cells [40] | Unlimited | Challenging for direct labels | Excellent soft-tissue contrast, high spatial resolution, anatomical and functional data [40] | Low sensitivity for cell detection, potential contrast agent artifacts, contraindicated for patients with implants [34] |

| Optical Imaging | 2-3 mm [36] | High (nanomolar for fluorescence) [36] | Limited (1-2 cm) [22] | Semi-quantitative | High throughput, low cost, versatile probe options [36] | Limited tissue penetration, significant light scatter, primarily preclinical use [22] [36] |

Experimental Protocols for Cell Tracking

Understanding the practical implementation of each modality is crucial for experimental design. The following section details standard methodologies for labeling and tracking cells in vivo.

Radionuclide Imaging (PET/SPECT)

Radionuclide imaging uses radioactive isotopes to label cells, allowing for highly sensitive detection after administration.

Cell Labeling Protocol (Direct Labeling):

- Isolate and culture the therapeutic cells of interest (e.g., T cells, mesenchymal stem cells).

- Incubate cells with the radiotracer in a buffered solution. Common tracers include:

- Wash cells thoroughly to remove unincorporated radioactivity.

- Resuspend in administration medium and validate cell viability and function post-labeling.

In Vivo Tracking:

- Administer labeled cells to the subject via the chosen route (e.g., intravenous, intracoronary).

- Image at multiple time points using a PET or SPECT scanner, often co-registered with CT for anatomical reference.

- Key Data Output: Quantification of percentage injected dose (%ID) retained in target tissues (e.g., 4.7% of injected endothelial progenitor cells in infarcted myocardium [34]) and longitudinal biodistribution maps.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI tracks cells by detecting contrast agents that alter the magnetic properties of water protons in tissues.

Cell Labeling Protocol (Direct Labeling with SPIOs):

- Isolate and culture target cells.

- Introduce contrast agents via co-incubation, often with transfection agents to boost uptake. Common agents are:

- Wash and resuspend cells for administration.

In Vivo Tracking:

- Image subjects using T2/T2*-weighted sequences for SPIO-labeled cells. The "blooming artifact" of the dark signal amplifies detectability, allowing for the visualization of as few as 10³ cells [40].

- Key Data Output: High-resolution 3D anatomical maps showing the location of cell clusters as hypointense signal regions. The number of cells required for detection is typically higher than for nuclear methods (e.g., 10⁷ to 10⁸ for confident detection in swine hearts [34]).

Optical Imaging

Optical imaging uses light-emitting probes to track cells, but its use in humans is limited by tissue penetration.

Cell Labeling Protocol:

- Label cells ex vivo using one of two primary methods:

- Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., DiR, Cy5.5): Cells are incubated with lipophilic dyes that incorporate into cell membranes [36].

- Reporter Genes (e.g., Firefly Luciferase): Cells are genetically engineered to express light-producing enzymes. The substrate (e.g., D-luciferin) is administered systemically before imaging [22].

- Wash and administer the labeled cells.

- Label cells ex vivo using one of two primary methods:

In Vivo Tracking:

- For fluorescence imaging, illuminate the subject at the specific excitation wavelength and detect the emitted light. Near-infrared (NIR) dyes are preferred for deeper tissue penetration [36].

- For bioluminescence imaging, administer the substrate and detect the resulting bioluminescent signal without the need for excitation light, resulting in very low background [36].

- Key Data Output: 2D images showing relative signal intensity, which can be quantified as photons/second or radiant efficiency to estimate cell location and number, albeit with limited depth information.

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for labeling and tracking cells, which is common across modalities, while highlighting specific agent-modality pairings.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful cell tracking experiments rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The table below lists key solutions and their functions in the context of biodistribution studies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Tracking Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Cell Tracking | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide (SPIO) | MRI contrast agent for direct cell labeling; creates negative contrast. | Feridex; high sensitivity but causes "blooming" artifact on images [34] [40]. |

| Radionuclide Tracers | Direct cell labeling for PET/SPECT imaging; provides high detection sensitivity. | [¹¹¹In]Oxyquinoline, ⁹⁹mTc-HMPAO, ¹⁸F-FDG; potential radiotoxic effects on cell function must be assessed [34] [22]. |

| Reporter Genes | Genetic constructs for indirect, long-term cell labeling; signal correlates with cell number/viability. | Firefly Luciferase (bioluminescence), Herpes Simplex Virus Thymidine Kinase (HSV-tk for PET); requires genetic modification [22]. |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Dyes | Fluorescent probes for direct optical cell labeling; deeper tissue penetration than visible light. | DiR, Cy5.5, Cy7; used for in vivo and ex vivo validation imaging [41] [36]. |

| Transfection Agents | Enhance uptake of labeling agents (e.g., SPIOs) into cells during ex vivo culture. | Cationic liposomes or polymers; improves labeling efficiency but requires toxicity testing [40]. |

| Multimodal Nanoparticles | Single agent enabling detection by multiple modalities (e.g., MRI + fluorescence). | Perfluorocarbon (PFC) nanoparticles visible via ¹⁹F MRI and fluorescence; reduces regulatory burden [35]. |

No single imaging modality is perfect for all cell tracking scenarios. The choice depends on the specific research question, balancing the need for sensitivity, resolution, quantification, depth penetration, and clinical translation. MRI excels in providing high-resolution anatomical context for localized cell grafts. PET offers superior quantitative sensitivity for whole-body biodistribution and tracking over days to weeks. SPECT allows for simultaneous tracking of multiple probes. Optical Imaging remains a powerful, cost-effective tool for preclinical proof-of-concept studies.

The future of cell tracking lies in multimodal imaging and the development of novel, versatile agents. Combining modalities, such as PET-MRI or agents visible in both MRI and optical imaging, leverages the strengths of each technology [37] [35]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence for image analysis and partial volume correction is set to improve the quantitative accuracy of techniques like PET and SPECT [39]. As cell therapies continue to evolve, robust, broadly applicable imaging platforms will be indispensable for optimizing their design, validating their efficacy, and ensuring their safety in patients.

The comparative assessment of biodistribution is a critical component in the non-clinical safety and efficacy evaluation of cell therapy products (CTPs). It clarifies the cell survival time, engraftment, and distribution site, which are crucial for predicting clinical outcomes based on non-clinical studies [27]. However, the absence of a standardized international protocol for these assessments leads to methodological variability, posing significant challenges in the drug approval process [23]. This guide provides an objective comparison of two principal quantitative methods—quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR)—used in biodistribution studies, focusing on their sensitivity, specificity, and throughput. The analysis is framed within a broader thesis on comparative biodistribution assessment, offering researchers a data-driven framework for method selection in the development of CTPs, such as induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived pancreatic islet cells [23].

Biodistribution studies are pivotal for elucidating the fate and tumorigenicity risk of CTPs. The fundamental goal is to detect and quantify the presence of human-derived cells within various mouse tissues following administration. The lack of standardized protocols can result in inconsistent and unreliable data, complicating the interpretation of results and hindering regulatory approval [23]. Two primary nucleic acid amplification techniques have been adapted to meet this challenge:

- Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR): This method relies on the relative quantification of a target DNA sequence against a standard curve. It provides amplification data in real-time, allowing for the quantification of the initial amount of target DNA in a sample. Its established workflow and higher throughput make it a common choice in many laboratories.

- Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR): This is an absolute quantification method that partitions a single PCR reaction into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets. Each droplet acts as an individual PCR reactor. By counting the positive and negative droplets at the end of the amplification, the initial concentration of the target DNA can be calculated without the need for a standard curve, potentially offering greater precision and sensitivity for low-abundance targets.

The selection between these methods directly impacts the reliability of biodistribution data, influencing critical decisions on product safety and clinical translation.

Performance Comparison: qPCR vs. ddPCR

A direct comparison of qPCR and ddPCR performance is essential for informed method selection. The following table summarizes their key characteristics based on standardized evaluations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of qPCR and ddPCR in Biodistribution Studies

| Performance Metric | qPCR | ddPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Principle | Relative (requires standard curve) | Absolute (no standard curve) |

| Accuracy (Relative Error) | Generally within ±50% [27] | Generally within ±50% [27] |

| Precision (Coefficient of Variation) | Generally <50% [27] | Generally <50% [27] |

| Sensitivity | High | Potentially higher for low-copy targets |

| Tolerance to PCR Inhibitors | Moderate | High |

| Throughput | Higher | Lower |

| Multiplexing Capability | Well-established | Developing |

| Data Output | Cq (Cycle of quantification) value | Copy number per microliter |

The table indicates that while both methods demonstrated comparable accuracy and precision in a multi-facility validation study, their underlying principles and operational strengths differ [27]. The choice between them often involves a trade-off between the absolute quantification and inhibitor tolerance of ddPCR and the higher throughput and easier multiplexing of qPCR.

Supporting Experimental Data

A key multi-facility study provides concrete experimental data supporting this comparison. The study aimed to standardize biodistribution assays and conducted in vivo BD studies after the intravenous administration of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) to immunodeficient mice [27].

- Experimental Findings: The biodistribution of hMSCs was evaluated at seven facilities (qPCR at three facilities; ddPCR at four facilities). The results revealed similar tissue distribution profiles across all facilities, irrespective of the quantification method used. The lungs showed the highest cell distribution among the tissues tested, a finding consistently reported by both qPCR and ddPCR platforms [27].

- Interpretation: This demonstrates that both methods can generate congruent biodistribution profiles in a real-world research setting. The conclusion was that both qPCR and ddPCR methods, using a protocol targeting primate-specific Alu sequences, are suitable for the BD evaluation of CTPs [27].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and reliability in biodistribution studies, detailed and standardized protocols are necessary. The following workflows outline the core methodologies for both qPCR and ddPCR, from sample preparation to data analysis.

Core Workflow for Biodistribution Assessment

The general process for conducting a biodistribution study is method-agnostic in its initial stages. The diagram below illustrates the shared workflow.

Diagram 1: Generic BD Study Workflow.

qPCR Experimental Protocol

The qPCR method provides relative quantification based on a standard curve. The specific protocol is detailed below.

Diagram 2: qPCR Quantification Workflow.

Detailed Methodology:

- Standard Curve Preparation: A standard is created using a known number of human cells spiked into control mouse tissues. Genomic DNA (gDNA) is extracted, and a series of dilutions is prepared to generate a standard curve for relative quantification [27].

- qPCR Reaction Setup: The reaction mix includes the gDNA sample, primers and a probe specific to a human-specific repetitive element (e.g., LINE1 [23] or Alu [27]), and a qPCR master mix containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer.