CRISPR-Cas9 and iPSCs: Revolutionizing Disease Modeling for Drug Discovery and Personalized Medicine

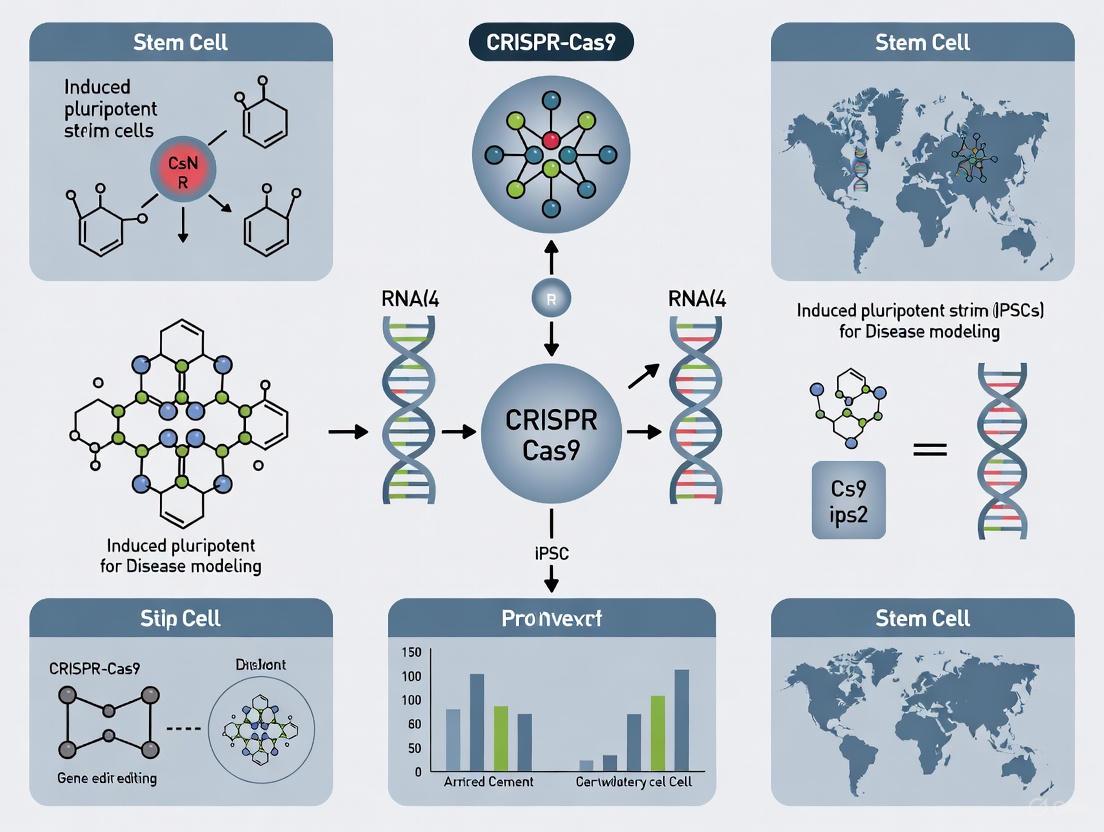

This article explores the powerful synergy between CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology, a combination that is revolutionizing disease modeling and therapeutic development.

CRISPR-Cas9 and iPSCs: Revolutionizing Disease Modeling for Drug Discovery and Personalized Medicine

Abstract

This article explores the powerful synergy between CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology, a combination that is revolutionizing disease modeling and therapeutic development. We provide a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of reprogramming somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells and the mechanics of CRISPR-Cas9. The article details advanced methodologies for creating precise genetic disease models, including isogenic cell lines and complex 3D organoids, and addresses critical troubleshooting strategies for overcoming challenges in editing efficiency and genomic stability. Finally, we examine the rigorous validation of these models through functional assays and their application in high-throughput drug screening, toxicology testing, and ongoing clinical trials, highlighting the transformative impact on biomedical research and the path toward clinical translation.

Building Blocks: Understanding iPSC Reprogramming and CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanics

The discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by Shinya Yamanaka in 2006 marked a transformative milestone in regenerative medicine and biological research. By introducing four specific transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (collectively known as the OSKM or Yamanaka factors)—his team demonstrated that somatic cells could be reprogrammed back to a pluripotent state [1]. This groundbreaking achievement proved that specialized adult cells carry the complete genetic code to revert to an embryonic-like state, capable of differentiating into virtually any cell type in the body [2] [3]. The iPSC technology effectively bypasses the ethical controversies associated with embryonic stem cells while providing an unlimited source of patient-specific cells for disease modeling, drug screening, and therapeutic development [3] [4].

The molecular machinery behind iPSC reprogramming involves profound remodeling of the epigenome. During the reprogramming process, somatic genes are progressively silenced while pluripotency-associated genes are activated through two major phases: an early stochastic phase and a late deterministic phase [1]. This process reverses the developmental clock, erasing somatic cell epigenetic memory and reestablishing the open chromatin configuration characteristic of pluripotent cells [1]. The resulting iPSCs closely resemble embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in their gene expression profiles, differentiation potential, and self-renewal capacity, making them invaluable tools for both basic research and clinical applications [3] [4].

Core Reprogramming Methodologies

Evolution of Reprogramming Factors

The original Yamanaka factors have undergone significant optimization to enhance safety and efficiency. Research has revealed that the oncogenic potential of c-MYC presents significant risks to iPSC stability and safety, prompting investigations into alternative factors [2]. Subsequent studies demonstrated that somatic cell reprogramming could be achieved using OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 without c-MYC, though with reduced efficiency [2]. Alternative factor combinations have also been successfully employed, including OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28 (OSNL), which eliminate c-MYC entirely [2] [1].

Factor substitution studies have identified several family members that can replace their original counterparts: KLF2 and KLF5 can substitute for KLF4; SOX1 and SOX3 can replace SOX2; and L-MYC and N-MYC can stand in for c-MYC [2]. Beyond direct family members, other genes and small molecules have shown reprogramming potential. For instance, NR5A2 can replace OCT4 when combined with SOX2 and KLF4, while the small molecule RepSox can effectively substitute for SOX2 [2]. Additional factors like Esrrb and Glis1 have also served as viable alternatives to c-MYC in somatic cell reprogramming [2].

Delivery Systems for Reprogramming

The method of introducing reprogramming factors into somatic cells significantly impacts the safety and quality of resulting iPSCs. Early approaches utilized integrating viral vectors, particularly retroviruses and lentiviruses, which raised concerns about insertional mutagenesis and tumorigenicity [3]. In response, researchers have developed numerous non-integrating delivery systems that minimize genomic alteration risks [3].

Table 1: Comparison of iPSC Reprogramming Delivery Systems

| Vector Type | Genetic Material | Genomic Integration | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrovirus | DNA | Yes | High efficiency | Integrates into genome; reactivation of transgenes |

| Lentivirus | DNA | Yes | Can infect non-dividing cells | Integration risks; variable silencing |

| Sendai Virus | RNA | No | High efficiency; non-integrating | Requires dilution; persistent for ~10 passages |

| Adenovirus | DNA | No | Non-integrating; good efficiency | Technically challenging; lower efficiency |

| Episomal Plasmid | DNA | No | Non-integrating; simple delivery | Low efficiency; requires multiple transfections |

| Synthetic mRNA | RNA | No | Non-integrating; high efficiency | Requires multiple transfections; immune stimulation |

| Recombinant Protein | Protein | No | Completely non-integrating | Very low efficiency; technically demanding |

Significant progress has been made in chemical reprogramming methods, which utilize defined small molecule combinations to induce pluripotency without genetic manipulation [2]. This approach represents a breakthrough in iPSC generation safety, substantially enhancing their clinical application potential. Chemical reprogramming activates early embryonic developmental genes and reveals a highly plastic intermediate cell state with enhanced chromatin accessibility [2].

Enhanced Reprogramming with Small Molecules

Small molecules that modulate epigenetic barriers and signaling pathways have proven highly effective in enhancing reprogramming efficiency. These compounds include DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (5-aza-cytidine, RG108), histone deacetylase inhibitors (sodium butyrate, trichostatin A, valproic acid), and histone methylation regulators (Neplanocin A) [2]. The combination of 8-Bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cAMP) with valproic acid has demonstrated a 6.5-fold increase in human fibroblast reprogramming efficiency [2].

Diagram 1: Key Molecular Transitions During iPSC Reprogramming

Integration of CRISPR-Cas9 with iPSC Technology

CRISPR-Cas9 Fundamentals for iPSC Engineering

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic engineering in iPSCs by providing a precise, efficient, and scalable platform for targeted genome modifications [5] [6]. This two-component system consists of a Cas9 nuclease and a synthetic guide RNA (sgRNA) containing a 20-base variable domain that mediates DNA-binding specificity [5]. When Cas9 scans the genome, the sgRNA base-pairs with complementary DNA sequences, and upon detecting a perfect match followed by a 3' protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), Cas9 creates a blunt-ended double-strand break three base pairs 5' to the PAM [5].

In iPSC research, CRISPR-Cas9 enables the creation of precise disease models through gene knock-outs, knock-ins, and point mutations [5] [6]. The technology facilitates the generation of isogenic cell lines—genetically identical except for specific disease-relevant mutations—which are critical for distinguishing phenotypic differences attributable to genetic variants from background genetic variability [5]. This precision makes CRISPR-edited iPSCs particularly valuable for disease modeling and drug discovery applications [6].

Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Knockout in iPSCs

Experimental Principle This protocol outlines the methodology for generating gene-specific knockouts in human iPSCs using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Gene knockout is achieved through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair of Cas9-induced double-strand breaks, which often introduces insertion/deletion (indel) mutations that disrupt gene function [5].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 in iPSCs

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Design Tools | CHOPCHOP, CRISPR Design Tool | Identifies optimal sgRNA sequences | Select guides with high on-target, low off-target activity |

| Expression Vectors | px330, pSpCas9(BB) | Delivers Cas9 and sgRNA to cells | May include selection markers (GFP, puromycin) |

| iPSC Culture Media | mTeSR, E8 medium | Maintains pluripotency during editing | Use defined, xeno-free formulations |

| Transfection Reagents | Lipofectamine Stem, Electroporation | Introduces CRISPR components into cells | Optimize for specific iPSC lines |

| Selection Agents | Puromycin, G418 | Enriches for successfully transfected cells | Determine kill curve for each cell line |

| Genomic DNA Extraction | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | Isolates DNA for genotyping | Critical for validation steps |

| Validation Primers | Target-specific designs | Amplifies edited genomic regions | Design flanking the target site |

| Sequencing Tools | Sanger sequencing, NGS | Confirms editing efficiency and specificity | Barcoded deep sequencing recommended |

Step-by-Step Procedure

sgRNA Design and Cloning

- Design sgRNAs using online tools (CHOPCHOP, CRISPR Design Tool) targeting early exons of the gene of interest

- Select guides with high predicted on-target activity and minimal off-target effects

- Clone validated sgRNA sequences into appropriate expression vectors (e.g., px330) containing Cas9 and selection markers

- Verify constructs by Sanger sequencing before transfection [5]

iPSC Culture and Transfection

- Maintain human iPSCs in feeder-free conditions using defined culture media (e.g., mTeSR or E8)

- Passage cells as small clumps using EDTA or enzyme-free dissociation reagents

- Transfect iPSCs at 70-80% confluence using optimized methods (lipofection or electroporation)

- Include untransfected controls and empty vector controls [5]

Selection and Single-Cell Cloning

- Begin antibiotic selection (e.g., 0.5-1 μg/mL puromycin) 48 hours post-transfection

- Maintain selection for 3-5 days until control cells are completely dead

- Harvest surviving cells and seed at clonal density (1-10 cells/cm²)

- Manually pick individual colonies after 10-14 days for expansion [5]

Genotype Validation

- Extract genomic DNA from expanded clones using commercial kits

- PCR-amplify the target region using flanking primers

- Analyze editing efficiency via T7E1 or SURVEYOR mismatch assays

- Confirm indels in candidate clones by Sanger sequencing

- Verify pluripotency maintenance through immunostaining for markers (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2) [5]

Troubleshooting Notes

- Low editing efficiency: Optimize sgRNA design and transfection parameters

- Poor clone survival: Reduce selection stringency and improve single-cell survival supplements

- Off-target effects: Design multiple sgRNAs and use validated controls

- Pluripotency loss: Regularly monitor stem cell morphology and marker expression

Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Protocol: Establishing iPSC-Derived Disease Models

Experimental Principle Patient-specific iPSCs can be differentiated into disease-relevant cell types to model human pathologies in vitro. When combined with CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, isogenic pairs of cell lines can be generated that differ only at the disease-causing locus, enabling precise mechanistic studies [5] [6].

Materials and Reagents

- Patient-derived iPSCs with disease-causing mutations

- CRISPR-Cas9 components for genetic correction

- Differentiation media specific to target cell type

- Cell type-specific antibodies for characterization

- Functional assay reagents (e.g., electrophysiology, calcium imaging)

Step-by-Step Procedure

iPSC Line Generation and Genetic Correction

- Derive iPSCs from patient somatic cells (fibroblasts or blood cells) using non-integrating methods

- Establish isogenic control line by correcting disease mutation using CRISPR-Cas9 with ssODN donor template

- Validate genetic correction through sequencing and off-target analysis

- Confirm pluripotency and normal karyotype before differentiation [6]

Directed Differentiation to Target Cell Type

- Adapt published differentiation protocols for specific cell types (neurons, cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes)

- Optimize timing and cytokine concentrations for your specific iPSC lines

- Monitor differentiation efficiency through time-course marker expression

- Purify target cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or magnetic sorting when possible

Phenotypic Characterization

- Assess disease-specific morphological changes through immunocytochemistry

- Evaluate functional deficits using cell-type appropriate assays

- Perform transcriptomic and proteomic analyses to identify molecular pathways

- Compare patient, corrected isogenic control, and healthy lines in parallel experiments

Application Example: Neurodegenerative Disease Modeling In Parkinson's disease research, iPSCs from patients carrying LRRK2 or PARK2 mutations have been differentiated into dopaminergic neurons. After CRISPR-mediated correction, the neurons exhibited improved mitochondrial function and nuclear envelope integrity, demonstrating the value of this approach for mechanistic studies [3]. Similarly, in Alzheimer's disease, researchers have used CRISPR to introduce PSEN1 E280A mutations into iPSCs, then differentiated them into neural cells to create precision models for AD research [6].

High-Throughput Drug Screening Platforms

iPSC-derived cellular models have become invaluable tools for drug discovery and toxicity testing. The ability to generate human cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, and neurons from iPSCs provides physiologically relevant systems for evaluating drug efficacy and safety [4] [6]. CRISPR-edited iPSCs further enhance these platforms by enabling the introduction of specific disease mutations or reporter genes that facilitate high-throughput screening [6].

Table 3: Applications of CRISPR-iPSC Platforms in Drug Development

| Application Area | iPSC-Derived Cell Type | CRISPR Modification | Readout | Notable Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiotoxicity Screening | Cardiomyocytes | Knock-in of calcium indicators | Calcium handling, beat rate | Identification of pro-arrhythmic compounds |

| Neurodegenerative Disease | Cortical neurons | Introduction of disease mutations | Tau phosphorylation, axon transport | Screening of tauopathy therapeutics |

| Metabolic Disorders | Hepatocytes | Reporter knock-in at metabolic genes | Lipid accumulation, glucose uptake | Steatosis drug screening |

| Monogenic Diseases | Disease-relevant cells | Correction of patient mutations | Functional rescue | Dyskeratosis congenita (PAPD5 inhibitors) |

| Cancer Immunotherapy | T-cells, NK cells | Knockout of immune checkpoints | Tumor cell killing | Hypoimmunogenic CAR-T cells |

A notable example of this approach comes from screening for dyskeratosis congenita (DC) therapeutics, where researchers used CRISPR-iPSC platforms to identify small-molecule PAPD5 inhibitors that restore telomerase activity in patient-derived cells [6]. Treatment with the inhibitor BCH001 demonstrated dose-dependent telomere extension in CRISPR knockout iPSCs, highlighting the power of this combined platform for discovering novel therapeutics [6].

Diagram 2: Integrated CRISPR-iPSC Workflow for Drug Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of iPSC and CRISPR technologies requires access to specialized reagents and platforms. The following table summarizes key solutions and their applications in iPSC-based research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC and CRISPR Work

| Reagent Category | Specific Product Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Kits | CytoTune Sendai Virus, Episomal Vectors | Somatic cell reprogramming to iPSCs | Non-integrating methods preferred for clinical applications |

| iPSC Culture Media | mTeSR, StemFlex, E8 medium | Maintain pluripotency and support expansion | Defined, xeno-free formulations ensure consistency |

| CRISPR Nucleases | Wild-type Cas9, HiFi Cas9, Cas12a | Induce targeted DNA breaks for genome editing | High-fidelity variants reduce off-target effects |

| Delivery Systems | Lipofectamine Stem, Neon Electroporation | Introduce CRISPR components into iPSCs | Optimized for sensitive stem cell lines |

| Differentiation Kits | Cardiomyocyte, Neural, Hepatocyte Kits | Direct iPSCs toward specific lineages | Protocol optimization often required for different lines |

| Characterization Antibodies | OCT4, NANOG, TRA-1-60, Cell-type markers | Assess pluripotency and differentiation | Essential for quality control throughout projects |

| Cell Banking Reagents | CryoStor, Synth-a-Freeze | Long-term preservation of edited lines | Use controlled-rate freezing for high viability |

Major market players have developed specialized platforms to support these research needs. FUJIFILM CDI (formerly Cellular Dynamics International) dominates as the world's largest manufacturer of human cells from iPSCs, while companies like REPROCELL, Evotec, and Ncardia provide specialized iPSC-derived cells and services [4]. For custom disease modeling, bit.bio offers opti-ox powered human-iPSC derived cells with specific mutations, providing consistent, defined products for drug discovery workflows [4].

Scaling and Automation in iPSC Production

The translation of iPSC technologies from research tools to clinical applications requires scalable manufacturing approaches that maintain quality and reproducibility [7]. Traditional manual iPSC production methods, while flexible and widely used in academic settings, are being supplemented and replaced by automated systems that enhance consistency and throughput [8].

Automated platforms integrate reprogramming, expansion, and differentiation into closed workflows that minimize human error and variability [7] [8]. These systems are particularly valuable for clinical-grade manufacturing where adherence to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards is essential [7]. The adoption of process analytical technologies (PAT) and quality by design (QbD) approaches further enhances the robustness of iPSC production processes [7].

The global iPSC production market reflects this transition, with automated platforms representing the fastest-growing product category [8]. Biotechnology companies and contract manufacturing organizations are increasingly implementing these systems to accelerate the translation of iPSC-based therapies from research to clinical applications [8]. This scalable manufacturing infrastructure will be critical for realizing the full potential of iPSC technologies in regenerative medicine and drug development.

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system constitutes a revolutionary gene-editing technology derived from a natural adaptive immune system in bacteria and archaea [9]. This powerful molecular machinery enables researchers to make precise, targeted modifications to DNA sequences across diverse biological systems, including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [10]. The core system consists of two fundamental components: the Cas9 nuclease, which acts as a molecular "scissors" to cut DNA, and a guide RNA (gRNA), which functions as a programmable "GPS" to direct Cas9 to specific genomic locations [9]. When combined with iPSC technology, CRISPR-Cas9 provides an unprecedented platform for creating highly accurate human disease models, facilitating drug discovery, and advancing personalized medicine approaches [11] [10].

The application of CRISPR-Cas9 in iPSC-based disease modeling has transformed biomedical research by enabling the creation of isogenic cell lines that differ only at specific pathogenic loci, thereby eliminating confounding genetic background effects [10]. This technical advancement is particularly valuable for studying neurological disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and rare genetic conditions where patient-derived cells may be difficult to obtain or maintain in culture [12] [10]. As the field progresses, understanding the core principles of gRNA design, Cas9 function, and subsequent DNA repair mechanisms becomes essential for optimizing editing efficiency and precision in iPSC-based research models.

Core Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

Guide RNA (gRNA)

The guide RNA is a synthetic fusion molecule comprising two distinct RNA components: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which contains a ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence complementary to the target DNA site, and the trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA), which serves as a scaffolding backbone that facilitates Cas9 binding [9]. These two elements are typically combined into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) for experimental simplicity. The sgRNA directs Cas9 to a specific genomic locus through Watson-Crick base pairing between its spacer sequence and the target DNA [9].

Critical design considerations for functional gRNAs include:

- Specificity: The 20-nucleotide targeting sequence must be unique to the intended genomic locus to minimize off-target effects

- Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM): The target site must be immediately adjacent to a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9)

- GC content: Optimal gRNAs typically contain 40-60% GC content for stable DNA binding

- Genomic context: Accessibility of the target chromatin region can significantly impact editing efficiency

Advances in computational tools and machine learning approaches have enhanced gRNA design parameters, leading to improved on-target efficiency and reduced off-target effects [13]. For iPSC applications, highly specific gRNAs are particularly critical due to the potential for clonal expansion and the need to maintain genomic integrity throughout differentiation protocols.

Cas9 Nuclease

The Cas9 protein is a multifunctional RNA-guided DNA endonuclease that induces double-strand breaks (DSBs) in target DNA sequences. Upon gRNA-mediated recognition of the target site, Cas9 undergoes conformational changes that position its nuclease domains (RuvC and HNH) to cleave opposite strands of the DNA duplex, generating blunt-ended DSBs approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [9].

Key Cas9 variants for specialized applications:

| Cas9 Variant | Attributes | Primary Applications in iPSC Research |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type SpCas9 | High activity, broad compatibility | General gene knockout studies |

| High-fidelity Cas9 (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) | Reduced off-target cleavage | Therapeutic modeling where specificity is critical |

| Catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) | DNA binding without cleavage | Gene regulation (CRISPRi/a), epigenetic editing |

| Nickase Cas9 (nCas9) | Single-strand DNA cleavage | Base editing with reduced indel formation |

| Artificial intelligence-designed editors (e.g., OpenCRISPR-1) | Enhanced specificity, novel PAM preferences | Expanding targetable genomic loci [13] |

The large size of Cas9 cDNA (~4.2 kb) presents challenges for delivery via size-constrained vectors such as adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), necessitating the use of alternative delivery methods or compact Cas variants in certain experimental contexts [9].

DNA Repair Pathways and Editing Outcomes

Following Cas9-mediated DNA cleavage, cellular repair mechanisms are activated to resolve the double-strand break. The competing pathways and their resulting outcomes determine the ultimate genetic modification achieved through CRISPR editing. In the context of iPSC disease modeling, understanding and controlling these pathways is essential for generating predictable editing results.

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

Non-homologous end joining is the dominant DNA repair pathway in mammalian cells, particularly in non-cycling cells. This error-prone mechanism directly ligates broken DNA ends without requiring a template, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site [9]. When these indels occur within protein-coding exons, they frequently produce frameshift mutations that disrupt gene function, making NHEJ particularly valuable for gene knockout studies in iPSC models [10].

Recent research has revealed that postmitotic cells, including neurons and cardiomyocytes derived from iPSCs, exhibit distinct NHEJ characteristics compared to dividing cells [12]. These nondividing cells demonstrate prolonged DSB repair kinetics, with indel accumulation continuing for up to two weeks post-editing, and favor classical NHEJ repair with a narrower distribution of smaller indels compared to their dividing counterparts [12] [14].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

Homology-directed repair is a precise, template-dependent repair pathway that operates primarily during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle. HDR requires a donor DNA template containing homologous sequences flanking the target site and can be harnessed to introduce specific nucleotide changes, insert reporter genes, or correct pathogenic mutations in iPSCs [9].

A significant challenge in HDR-based editing is the relatively low efficiency of this pathway compared to NHEJ, particularly in iPSCs. Researchers have developed several strategies to enhance HDR efficiency, including:

- Cell cycle synchronization to enrich for cells in S/G2 phase

- Timed delivery of CRISPR components during peak HDR activity

- Pharmacological inhibition of key NHEJ proteins (with important caveats regarding genomic integrity)

- Cas9 fusion proteins that recruit HDR-enhancing factors

It is important to note that recent studies have revealed that many strategies to enhance HDR, particularly pharmacological inhibition of DNA-PKcs, can inadvertently increase the frequency of large-scale structural variations, including kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations [15]. These findings highlight the critical need for comprehensive genomic integrity assessment following editing, especially for therapeutic applications.

Alternative Repair Pathways

Beyond classical NHEJ and HDR, mammalian cells employ additional repair mechanisms including microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) and single-strand annealing (SSA). These pathways are particularly relevant in dividing cells, where MMEJ contributes significantly to CRISPR editing outcomes [12]. Recent evidence indicates that postmitotic cells substantially downregulate MMEJ activity compared to their dividing counterparts, leading to different distributions of editing outcomes [12].

The following diagram illustrates the competitive relationship between these major DNA repair pathways following Cas9-induced double-strand breaks:

Competing DNA Repair Pathways After CRISPR-Cas9 Cleavage

Quantitative Analysis of CRISPR-Cas9 Editing Outcomes

Understanding the efficiency and distribution of editing outcomes is crucial for experimental design and interpretation in iPSC-based disease modeling. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent studies investigating CRISPR-Cas9 editing across different cellular contexts.

DNA Repair Kinetics in Dividing vs. Nondividing Cells

Recent research has revealed significant differences in how dividing and nondividing cells process CRISPR-induced DNA damage, with important implications for editing strategies in iPSC-derived differentiated cells [12].

| Cell Type | Repair Kinetics (Time to Indel Plateau) | Predominant Repair Pathway | Characteristic Indel Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dividing Cells (iPSCs, activated T cells) | 1-3 days | MMEJ > NHEJ | Broad range, larger deletions |

| Nondividing Cells (iPSC-derived neurons, cardiomyocytes, resting T cells) | Up to 14-16 days | NHEJ > MMEJ | Narrow distribution, smaller indels |

| Postmitotic Human Neurons | 2 weeks | NHEJ (95% of outcomes) | Small indels (<10 bp) predominant |

DNA Repair Pathway Manipulation Outcomes

Chemical and genetic manipulation of DNA repair pathways can shift editing outcomes, but these approaches must be used with caution due to potential genotoxic consequences [12] [15].

| Intervention | Intended Effect | Actual Outcome | Genomic Safety Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-PKcs inhibitors (e.g., AZD7648) | Enhance HDR by suppressing NHEJ | Increased kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions; thousand-fold increase in chromosomal translocations | High risk of extensive structural variations [15] |

| 53BP1 inhibition | Enhance HDR | Improved precise editing without increased translocation frequency | Lower genomic risk profile [15] |

| RRM2 inhibition (in neurons) | Shift outcome distribution | Increased deletion size and overall indel efficiency | Cell type-specific effects requiring validation [14] |

| p53 suppression | Reduce apoptosis in edited cells | Decreased large chromosomal aberrations | Potential selection for p53-deficient clones with oncogenic potential [15] |

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR-iPSC Disease Modeling

Protocol 1: Generation of Isogenic iPSC Lines via CRISPR-Cas9

This protocol describes the complete workflow for creating precisely edited iPSC lines for disease modeling applications, incorporating both HDR-based precise editing and NHEJ-mediated gene disruption approaches [10].

Materials Required:

- Human iPSCs (patient-derived or control lines)

- CRISPR-Cas9 components (Cas9 protein or expression vector, sgRNA)

- Electroporation system (e.g., Neon Transfection System)

- Single-cell dissociation reagent

- iPSC culture medium with Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor

- Genomic DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents and sequencing primers

- Purified donor template for HDR (ssODN or dsDNA)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

sgRNA Design and Validation (3-5 days)

- Design sgRNAs using computational tools (e.g., CRISPick, CHOPCHOP)

- Select target sites with high on-target and low off-target scores

- Validate sgRNA efficiency in a surrogate system (e.g., HEK293 cells) using T7E1 assay or next-generation sequencing

CRISPR Component Delivery (1 day)

- Prepare ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex by mixing 10 µg Cas9 protein with 5 µg sgRNA in opti-MEM, incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes

- Dissociate iPSCs to single cells using Accutase or similar enzyme

- Electroporate 1×10^6 iPSCs with RNP complex using manufacturer's recommended settings

- For HDR: Include 5 µL of 100 µM ssODN donor template in electroporation mixture

- Plate transfected cells at appropriate density in medium containing ROCK inhibitor

Clonal Isolation and Expansion (14-21 days)

- After 48-72 hours, dissociate and seed cells at low density (100-500 cells per 10 cm dish) for clonal formation

- Allow 10-14 days for distinct colony formation with regular medium changes

- Manually pick 96-192 well-isolated colonies using sterile pipette tips

- Transfer to 96-well plate format for expansion and screening

Genotypic Screening and Validation (7-10 days)

- Extract genomic DNA from expanded clones using commercial kits

- Perform PCR amplification of target region

- Analyze editing efficiency via Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing

- For HDR edits: Screen using restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) if possible, followed by sequencing confirmation

- Expand positively identified clones for banking and further characterization

Quality Control and Characterization (14-21 days)

- Validate pluripotency markers via immunocytochemistry (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG)

- Confirm normal karyotype via G-banding analysis

- Verify absence of off-target edits at top predicted sites

- Assess differentiation potential through embryoid body formation

Protocol 2: DNA Repair Pathway Analysis in iPSC-Derived Neurons

This specialized protocol addresses the unique challenges of CRISPR editing in postmitotic cells, based on recent findings of distinct repair mechanisms in nondividing cell types [12] [14].

Materials Required:

- iPSC-derived neurons (≥30 days differentiation)

- Virus-like particles (VLPs) containing Cas9 RNP (VSVG/BRL-pseudotyped)

- Neuronal culture medium

- DNA extraction kit suitable for low cell numbers

- Next-generation sequencing library preparation kit

- RNA extraction and qRT-PCR reagents

- RRM2 inhibitors (optional, for repair pathway modulation)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Neuronal Differentiation and Validation (30-60 days)

- Differentiate iPSCs to cortical neurons using established protocols

- Validate neuronal purity via immunostaining (NeuN, MAP2) and functional assays

- Confirm postmitotic status via Ki67 negativity

CRISPR Delivery via VLPs (1 day)

- Transduce neurons with VSVG/BRL-pseudotyped FMLV VLPs containing Cas9 RNP

- Use multiplicity of infection (MOI) optimized for >80% transduction efficiency

- Include untransduced controls and GFP-only VLP controls

Time-Course Analysis of Editing Outcomes (1-16 days)

- Harvest cells at multiple time points (days 1, 2, 4, 7, 11, 14, 16) post-transduction

- Extract genomic DNA and amplify target locus

- Prepare next-generation sequencing libraries

- Sequence with sufficient depth (>100,000 reads per sample) to detect rare variants

DNA Repair Pathway Characterization (3-7 days)

- Analyze sequencing data for indel spectrum and size distribution

- Quantify ratio of insertions to deletions as indicator of pathway bias

- Compare outcomes to isogenic dividing cells (iPSCs) edited with same sgRNA

- Perform transcriptomic analysis (RNA-seq) to identify differentially expressed DNA repair genes

Repair Pathway Modulation (Optional, 7-14 days)

- Treat neurons with RRM2 inhibitors (e.g., siRNAs) 24 hours pre-transduction

- Repeat editing and analysis to assess shifts in outcome distribution

- Evaluate effects on neuronal viability and functionality

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of CRISPR-iPSC disease modeling requires carefully selected reagents and tools. The following table summarizes essential materials and their applications.

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in CRISPR-iPSC Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | Wild-type SpCas9, HiFi Cas9, OpenCRISPR-1 [13] | Inducing targeted DNA breaks with varying specificity profiles |

| Delivery Tools | Electroporation systems, lipid nanoparticles [16], virus-like particles (VLPs) [12] | Introducing CRISPR components into hard-to-transfect iPSCs and neurons |

| iPSC Culture Reagents | mTeSR1 medium, Rho kinase inhibitor, recombinant laminin-521 | Maintaining pluripotency and supporting single-cell survival after editing |

| DNA Repair Modulators | DNA-PKcs inhibitors, 53BP1 inhibitors, RRM2 inhibitors [12] [15] | Shifting repair pathway balance (use with caution due to genotoxic risks) |

| Validation Tools | Next-generation sequencing kits, T7 endonuclease I, digital PCR systems | Assessing on-target efficiency, detecting off-target effects, and quantifying editing outcomes |

| iPSC Differentiation Kits | Commercial neuronal, cardiac, or hepatic differentiation kits | Generating disease-relevant cell types from edited iPSCs for phenotypic analysis |

| Control Reagents | Validated control gRNAs, isogenic control cell lines, targeting and non-targeting donors | Establishing experimental baselines and controlling for technical variability |

The integration of CRISPR-Cas9 technology with iPSC-based disease modeling has created unprecedented opportunities for studying human diseases in physiologically relevant systems. The core principles of gRNA design, Cas9 function, and DNA repair pathway manipulation form the foundation for generating accurate genetic models that recapitulate disease pathogenesis. Recent advances in understanding cell-type-specific repair mechanisms, particularly in nondividing cells like neurons, have highlighted the importance of tailoring editing strategies to specific experimental contexts [12] [14].

As the field progresses, several key considerations emerge for researchers employing CRISPR-iPSC platforms. First, the choice of editing approach (NHEJ-mediated knockout vs. HDR-mediated precise editing) must align with experimental goals while considering the inherent limitations of each method. Second, the delivery method must be optimized for the specific cell type, with virus-like particles showing particular promise for hard-to-transfect differentiated cells [12]. Third, comprehensive genotypic and phenotypic validation remains essential, especially given the potential for large structural variations that may escape detection by conventional screening methods [15].

The rapid evolution of CRISPR technology, including the development of AI-designed editors [13] and improved delivery systems [16], continues to expand the capabilities of iPSC-based disease modeling. By applying the core principles and protocols outlined in this document, researchers can leverage these powerful tools to advance our understanding of disease mechanisms and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

The convergence of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology and CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing represents a transformative paradigm in biomedical research and disease modeling. Both technologies are Nobel Prize-winning breakthroughs that have individually reshaped their respective fields. When combined, they create a powerful platform that addresses long-standing challenges in human disease modeling, particularly for neurological disorders, genetic diseases, and complex multifactorial conditions. This synergy enables researchers to establish isogenic cell lines that differ only in specific disease-causing mutations, providing unprecedented precision in unraveling disease mechanisms while controlling for genetic background variability [10] [17].

The fundamental compatibility between these technologies stems from their complementary strengths. iPSCs provide a patient-specific, ethically acceptable, and infinitely expandable source of human cells that can be differentiated into virtually any cell type, from neurons to cardiomyocytes [18] [6]. Meanwhile, CRISPR-Cas9 offers an efficient, highly precise, and programmable genome editing system that can introduce, correct, or study disease-relevant mutations in these patient-derived cells [19] [20]. This combination has accelerated the development of increasingly sophisticated disease models, from simple 2D cultures to complex 3D organoid systems that better recapitulate human tissue architecture and pathophysiology [11] [10].

Scientific Foundation: Core Technologies and Their Convergence

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)

iPSCs are reprogrammed somatic cells that have been returned to an embryonic-like pluripotent state, first generated by Dr. Shinya Yamanaka in 2006 [18] [1]. The reprogramming process involves introducing a specific set of pluripotency-related transcription factors - originally Oct4, Klf4, Sox2, and c-Myc (OKSM, known as Yamanaka factors) - into differentiated cells such as skin fibroblasts or blood cells [6] [1]. These reprogrammed cells acquire two essential characteristics: self-renewal capacity (the ability to divide indefinitely) and pluripotency (the potential to differentiate into any cell type of the body) [1].

The revolutionary aspect of iPSC technology lies in its ability to generate patient-specific stem cells without the ethical concerns associated with embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [18] [6]. From a disease modeling perspective, iPSCs offer two critical advantages: (1) they retain the complete genetic background of the donor, including all polymorphisms and variations that might influence disease manifestation; and (2) they can be differentiated into disease-relevant cell types that are otherwise inaccessible in living patients, such as specific neuronal subtypes, cardiomyocytes, or hepatocytes [1] [17]. This has been particularly valuable for studying neurological disorders, where primary human neural tissue is rarely available for research [17].

CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing System

The CRISPR-Cas9 system is an adaptive immune mechanism derived from bacteria that has been repurposed as a highly versatile genome editing tool [19] [20]. The system consists of two core components: the Cas9 nuclease, which creates double-strand breaks in DNA, and a guide RNA (gRNA), which directs Cas9 to a specific genomic sequence complementary to its 20-nucleotide targeting region [19]. The requirement for a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence immediately downstream of the target site ensures additional specificity [19].

When introduced into cells, the CRISPR-Cas9 complex induces double-strand breaks (DSBs) at predetermined genomic locations [20]. The cell then activates one of two primary DNA repair pathways: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function; or homology-directed repair (HDR), which uses a donor DNA template to precisely edit or introduce specific sequences [20]. The efficiency, simplicity, and low cost of CRISPR-Cas9 have made it the preferred genome editing technology for most research applications, superseding earlier methods like zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) [19] [18].

Technological Synergy for Disease Modeling

The powerful synergy between iPSCs and CRISPR emerges from their complementary capabilities in disease modeling applications. CRISPR-mediated genome editing addresses a fundamental limitation of patient-derived iPSCs: the genetic variability between different donor lines, which can confound the identification of phenotype-genotype relationships [10] [17]. By using CRISPR to introduce specific disease-causing mutations into healthy control iPSCs, or conversely to correct mutations in patient-derived iPSCs, researchers can create isogenic pairs that differ only at the locus of interest while sharing an identical genetic background [10] [17]. This precise control enables unambiguous attribution of observed phenotypic differences to the specific genetic manipulation [17].

Table 1: Advantages of Combining iPSC and CRISPR Technologies for Disease Modeling

| Aspect | iPSC Technology Contribution | CRISPR Technology Contribution | Combined Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Background | Provides patient-specific genetic context | Enables creation of isogenic controls | Isolates mutation-specific effects from background genetic variation |

| Disease Relevance | Retains complete patient genome with all disease-modifying variants | Allows introduction or correction of specific pathogenic mutations | Models both monogenic and complex polygenic disorders |

| Cell Source | Unlimited source of human cells; differentiation into relevant cell types | Permits genetic modification of otherwise inaccessible cell types | Humanized models of diseases affecting inaccessible tissues (e.g., brain, heart) |

| Experimental Scale | Suitable for high-throughput screening | Enables genome-wide CRISPR screens | Powerful platform for drug discovery and genetic screening |

| Therapeutic Development | Source for autologous cell therapy | Allows correction of mutations for regenerative medicine | Combined gene and cell therapy approaches |

Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Neurological Disorders

The CRISPR-iPSC platform has proven particularly valuable for modeling neurological disorders, which have been challenging to study due to limited access to human neuronal tissue and species-specific differences in brain physiology [19] [17]. iPSC-derived neurons, astrocytes, and brain organoids have been used to model a wide range of conditions, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), Huntington's disease (HD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and neurodevelopmental disorders [19] [21] [17].

For Alzheimer's disease research, CRISPR-iPSC approaches have been used to introduce mutations in genes such as APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 into control iPSCs, or to correct these mutations in patient-derived cells [6] [21]. These models have successfully recapitulated key aspects of AD pathology, including Aβ deposition, tau phosphorylation, and neuronal dysfunction [10] [21]. The 2021 Inducible Pluripotent Stem Cell Neurodegeneration Initiative (iNDI) represents a landmark large-scale application of this approach, generating 250 CRISPR-engineered iPSC clones to model Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) [6].

In Parkinson's disease research, isogenic iPSC lines have been created with mutations in the LRRK2 gene (including G2019S), which is associated with inherited forms of PD [6] [10]. These models have revealed disease-relevant phenotypes including mitochondrial dysfunction, dopaminergic neuron vulnerability, and impaired protein handling [10]. Similarly, for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, iPSC-derived motor neurons with mutations in SOD1, TARDBP, and C9orf72 genes have shown abnormalities in axonal transport, RNA homeostasis, and stress granule formation [10].

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases

CRISPR-iPSC technology has advanced the modeling of cardiovascular diseases by enabling the generation of human cardiomyocytes with specific disease-causing mutations [6]. These models have been particularly valuable for studying channelopathies such as long QT syndrome, where mutations in genes like KCNQ1 and SCN5A disrupt cardiac electrical activity [10]. iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes with these mutations recapitulate the prolonged action potential duration and arrhythmogenic potential observed in patients, providing a human-relevant platform for drug screening and safety assessment [6] [10].

In the metabolic disease domain, CRISPR-iPSC models have been applied to conditions such as familial hypercholesterolemia, Wilson's disease, and glycogen storage diseases [6] [10]. A proof-of-concept study in 2017 demonstrated that CRISPR-Cas9 could correct pathogenic mutations in the LDLR gene in iPSCs derived from patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HoFH) [6]. After differentiation into hepatocytes, the corrected cells showed normal function, suggesting potential for future regenerative medicine applications [6].

Rare Genetic Disorders

The precision of CRISPR editing makes the CRISPR-iPSC platform particularly suited for modeling rare genetic disorders, which often result from specific point mutations or small indels in single genes [20]. Notable examples include Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), sickle cell disease (SCD), β-thalassemia, and cystic fibrosis (CF) [20].

For Duchenne muscular dystrophy, researchers have used CRISPR in patient-derived iPSCs to implement exon skipping strategies that remove mutated exons and restore the reading frame of the dystrophin protein [20]. When differentiated into skeletal muscle progenitor cells, these edited cells expressed truncated but functional dystrophin and exhibited improved contractile function [20]. Similarly, for cystic fibrosis caused by the common ΔF508 mutation in the CFTR gene, CRISPR-mediated correction in iPSCs restored CFTR protein localization and chloride channel function in differentiated airway epithelial cells [20].

Table 2: Representative Disease Models Using CRISPR-iPSC Technology

| Disease Category | Target Genes | Cellular Model | Key Phenotypes Recapitulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease | APP, PSEN1, PSEN2 | Neurons, Brain Organoids | Aβ deposition, tau phosphorylation, neuronal dysfunction [6] [21] |

| Parkinson's Disease | LRRK2, GBA | Dopaminergic Neurons | Mitochondrial dysfunction, dopaminergic neuron vulnerability [6] [10] |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis | SOD1, TARDBP, C9orf72 | Motor Neurons | Axonal transport defects, RNA homeostasis abnormalities, stress granule formation [10] |

| Long QT Syndrome | KCNQ1, SCN5A | Cardiomyocytes | Prolonged action potential, arrhythmogenicity [10] |

| Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy | DMD | Skeletal Muscle Cells | Dystrophin deficiency, impaired contractile function [20] |

| Cystic Fibrosis | CFTR | Airway Epithelial Cells | Defective chloride channel function, mucus secretion abnormalities [20] |

| Hereditary Sensory & Autonomic Neuropathy | NTRK1 | Dorsal Root Ganglia Organoids | Reduced sensory neurons, premature gliogenesis, impaired axonal outgrowth [22] |

Drug Discovery and Development

The CRISPR-iPSC platform has transformed early-stage drug discovery by providing human-relevant disease models for target identification, compound screening, and toxicity assessment [10]. The ability to generate large libraries of iPSCs with specific genetic modifications enables high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns that identify potential therapeutic targets or compounds that reverse disease phenotypes [6] [10].

In one notable application, researchers used CRISPR-iPSC-derived neurons with GBA mutations (associated with Parkinson's disease) to screen for small molecules that could restore GCase enzyme activity and lysosomal function [10]. Identified hits showed efficacy in subsequent animal models, demonstrating the predictive value of this approach [10]. Similarly, in cystic fibrosis research, lung organoids derived from CFTR mutant iPSCs have been used to identify small molecules that correct the defective chloride channel function caused by the ΔF508 mutation [10].

The platform also excels in drug toxicity assessment, particularly for cardiotoxicity and hepatotoxicity [10]. iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes can be used to monitor changes in cardiac electrical activity in response to drug candidates, while iPSC-derived hepatocytes enable assessment of drug metabolism and toxicity accumulation [10]. By introducing polymorphisms in drug metabolism genes (such as CYP2D6 and CYP3A5) using CRISPR, researchers can further model how genetic variation affects drug responses across different individuals [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Generation of Isogenic iPSC Lines Using CRISPR-Cas9

The creation of isogenic iPSC lines is a fundamental application of CRISPR technology in disease modeling. The following protocol outlines the key steps for introducing a specific mutation into control iPSCs or correcting a mutation in patient-derived iPSCs [10] [20]:

gRNA Design and Synthesis: Design 2-3 gRNAs targeting the genomic region of interest. Select gRNAs with high on-target efficiency and minimal off-target potential using computational prediction tools. Synthesize gRNAs as chemically modified synthetic RNAs for enhanced stability [20].

Donor Template Design: For HDR-mediated precise editing, design a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) donor template containing the desired edit along with homologous arms (typically 90-120 nucleotides each). Incorporate silent mutations in the PAM sequence or protospacer to prevent re-cutting of edited alleles [20].

iPSC Culture and Preparation: Culture iPSCs in feeder-free conditions using defined essential 8 medium. Passage cells as small clumps using EDTA dissociation. One day before editing, passage cells as single cells using Accutase and seed at optimal density for transfection [18].

CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery: Transfect iPSCs with ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes formed by pre-incubating Cas9 protein with synthetic gRNA. Use electroporation systems optimized for stem cells (e.g., Neon Transfection System). Include the ssODN donor template for HDR-mediated editing [20].

Clonal Selection and Expansion: After transfection, allow cells to recover for 48 hours, then dissociate to single cells and seed at clonal density. Isolate individual colonies after 10-14 days and expand in 96-well plates [20].

Genotypic Validation: Screen clones by PCR amplification of the target region and Sanger sequencing. For comprehensive analysis, use next-generation sequencing of the target locus to identify on-target edits and rule out random integration of the donor template [20].

Off-Target Assessment: Perform off-target analysis using GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq for the selected gRNAs. Alternatively, whole-genome sequencing of edited clones provides the most comprehensive assessment of potential off-target effects [20].

Pluripotency and Karyotype Validation: Confirm that edited clones maintain pluripotency markers (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2) and normal karyotype before differentiation studies [20].

Differentiation into Disease-Relevant Cell Types

Following genetic modification, iPSCs are differentiated into cell types relevant to the disease being modeled. The following protocols describe differentiation into neuronal lineages and organoids, which are commonly used in neurological disease modeling [17]:

Neuronal Differentiation (2D Monoculture):

- Neural Induction: Transfer iPSCs to low-attachment plates to form embryoid bodies in neural induction medium containing dual SMAD inhibitors (LDN-193189 and SB431542) for 10-14 days [17].

- Neural Progenitor Cell (NPC) Expansion: Plate neural rosettes on poly-ornithine/laminin-coated dishes in NPC medium containing bFGF and EGF. Expand NPCs for 2-3 passages [17].

- Neuronal Differentiation: Dissociate NPCs and plate at high density in neuronal differentiation medium (NDM) containing BDNF, GDNF, cAMP, and ascorbic acid. Culture for 4-6 weeks with weekly half-medium changes, monitoring maturation by morphological changes and neuronal marker expression [17].

Cerebral Organoid Generation (3D Model):

- Embryoid Body Formation: Dissociate iPSCs to single cells and aggregate in low-attachment U-bottom plates in essential 6 medium with hLIF and CHIR99021 (4,000-10,000 cells per well) [17].

- Neural Induction: After 5 days, transfer embryoid bodies to Matrigel droplets in neural induction medium with dual SMAD inhibitors for 5 days [17].

- Organoid Maturation: Embed Matrigel-embedded organoids in spinning bioreactors or orbital shakers in neuronal differentiation medium. Culture for several months with regular medium changes, allowing complex neural tissue development [17].

Phenotypic Characterization and Functional Assays

Comprehensive phenotypic characterization is essential for validating disease models. The following assays are commonly used to assess pathological hallmarks in CRISPR-iPSC-derived models:

Molecular and Biochemical Assays:

- Immunocytochemistry: Fix cells with 4% PFA, permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stain with primary antibodies against cell-type-specific markers (e.g., TUJ1 for neurons, GFAP for astrocytes) and disease-relevant proteins (e.g., Aβ, p-tau) [21] [17].

- Western Blotting: Analyze protein expression and post-translational modifications using SDS-PAGE and specific antibodies. Particularly useful for quantifying pathogenic protein species (e.g., Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, phosphorylated tau) [21].

- ELISA: Quantify secreted factors or pathogenic proteins in conditioned media or cell lysates using commercial ELISA kits (e.g., for Aβ peptides) [21].

Functional Assays:

- Electrophysiology: Perform whole-cell patch clamping on neurons to assess action potential firing, synaptic activity, and channel function. For cardiomyocytes, use multi-electrode arrays (MEAs) to record field potentials and detect arrhythmogenic activity [10] [17].

- Calcium Imaging: Load cells with fluorescent calcium indicators (e.g., Fluo-4 AM) and monitor calcium transients using live-cell imaging to assess neural network activity or cardiomyocyte contraction [17].

- Metabolic Assays: Measure mitochondrial function using Seahorse Analyzer to assess oxygen consumption rates (OCR) and extracellular acidification rates (ECAR) [10] [21].

Research Reagent Solutions and Technical Tools

Successful implementation of CRISPR-iPSC disease modeling requires specific reagents and technical tools. The following table summarizes essential components and their functions in the experimental workflow:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for CRISPR-iPSC Disease Modeling

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| iPSC Culture | Essential 8 Medium, Matrigel, RevitaCell, Accutase | Maintenance of pluripotency, cell passaging, and recovery after editing | Use defined, xeno-free matrices and media for clinical relevance [18] |

| CRISPR Components | High-fidelity Cas9 (eSpCas9, HiFi-Cas9), synthetic sgRNA, ssODN donors | Genome editing with reduced off-target effects, precise HDR-mediated editing | RNP complexes show higher efficiency and reduced off-target effects compared to plasmid DNA [20] |

| Delivery Systems | Neon Transfection System, Amaxa Nucleofector | Efficient introduction of CRISPR components into iPSCs | Optimization of program settings and solution conditions is essential for high viability [20] |

| Differentiation Reagents | SMAD inhibitors (LDN-193189, SB431542), patterning factors (SHH, FGF8, BMP) | Directed differentiation into specific neural subtypes and regional identities | Concentration and timing of patterning factors determine regional specificity [17] |

| Characterization Tools | Pluripotency markers (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2), neuronal markers (TUJ1, MAP2), disease-relevant antibodies | Validation of pluripotency, differentiation efficiency, and disease phenotypes | Use multiple markers for comprehensive characterization [20] [17] |

| Quality Control Assays | Karyotyping, whole-genome sequencing, GUIDE-seq, mitochondrial sequencing | Assessment of genomic integrity, off-target effects, and genetic stability | Regular monitoring is essential for long-term culture and clinical applications [20] |

Technical Challenges and Solutions

Despite its transformative potential, the CRISPR-iPSC platform faces several technical challenges that researchers must address for robust experimental outcomes:

Editing Efficiency and HDR Limitations

A primary challenge in CRISPR-iPSC editing is the relatively low efficiency of homology-directed repair (HDR), which is necessary for precise gene correction or knock-in [18]. iPSCs predominantly use the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, especially outside the S/G2 phases of the cell cycle [18]. Several strategies can enhance HDR efficiency:

- Cell Cycle Synchronization: Treat iPSCs with cell cycle inhibitors such as nocodazole or thymidine to enrich for S/G2 phases where HDR is more active [18].

- Chemical Enhancers: Include small molecule HDR enhancers such as SCR7 (an NHEJ inhibitor) or RS-1 (a RAD51 stimulator) during and after editing [20].

- NHEJ Inhibition: Transiently inhibit key NHEJ factors such as DNA ligase IV using chemical inhibitors to shift the balance toward HDR [20].

- Cas9 Variants: Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants and optimize delivery as RNP complexes to reduce cytotoxicity and improve editing efficiency [20].

Off-Target Effects and Genomic Instability

Off-target effects remain a concern for CRISPR editing, particularly for therapeutic applications [10] [20]. Additionally, long-term culture of iPSCs can lead to genomic instability and the emergence of karyotypic abnormalities [20]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Computational gRNA Design: Use advanced algorithms to select gRNAs with minimal predicted off-target sites [20].

- High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Employ engineered Cas9 proteins with reduced off-target activity (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) [20].

- Comprehensive Off-Target Assessment: Implement high-throughput methods like GUIDE-seq, Digenome-seq, or CIRCLE-seq to empirically identify off-target sites [20].

- Regular Genomic Monitoring: Perform frequent karyotyping and genomic analysis to detect chromosomal abnormalities in cultured iPSCs [20].

Differentiation Variability and Model Maturation

iPSC differentiation protocols often yield heterogeneous cell populations with variable maturity, which can complicate phenotypic analysis [10] [17]. This is particularly challenging for neurological disease modeling, where human neurons require extended time to mature fully [17]. Addressing these challenges:

- Protocol Standardization: Use well-established, defined differentiation protocols with quality control checkpoints [17].

- Cell Sorting: Implement fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to purify specific cell populations using surface markers [17].

- Extended Maturation: Allow extended culture periods (3-6 months for neurons) to achieve more adult-like phenotypes [17].

- Assembloid Approaches: Combine region-specific organoids to create more complex models that better recapitulate tissue interactions [22] [17].

Visualization of Workflows and Signaling Pathways

CRISPR-iPSC Disease Modeling Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for creating disease models using CRISPR-edited iPSCs, from initial reprogramming to phenotypic analysis:

CRISPR-iPSC Disease Modeling Workflow

CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing Mechanism

This diagram details the molecular mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing and the two primary DNA repair pathways exploited for different types of genetic modifications:

CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing Mechanism

The convergence of iPSC and CRISPR technologies has fundamentally transformed disease modeling approaches, enabling unprecedented precision in studying human genetic disorders. The ability to create isogenic cell lines that differ only in specific disease-causing mutations has resolved the long-standing challenge of genetic background variability in human disease studies [10] [17]. This platform has proven particularly valuable for neurological disorders, where human-specific pathophysiology is difficult to recapitulate in animal models [21] [17].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on enhancing model complexity and physiological relevance through advanced 3D organoid and assembloid systems [22] [17]. The integration of multiple cell types (neurons, glia, vascular cells) in these models will better recapitulate the tissue microenvironment and enable study of cell-cell interactions in disease pathogenesis [22] [17]. Similarly, the development of cryopreserved, pre-differentiated cells and standardized differentiation protocols will improve reproducibility and accessibility of these models across research laboratories [10].

Technological advancements in genome editing will continue to expand the capabilities of the CRISPR-iPSC platform. Base editing and prime editing systems offer more precise genetic modifications without double-strand breaks, potentially reducing off-target effects and improving safety profiles [20]. The combination of CRISPR screening with iPSC-based disease models enables systematic functional genomics in disease-relevant human cell types, accelerating target identification and validation [10] [17].

From a therapeutic perspective, the path toward clinical translation of CRISPR-iPSC-based approaches is becoming increasingly clear. The recent development of hypoimmunogenic iPSCs that evade immune recognition brings "off-the-shelf" allogeneic cell therapies closer to reality [6]. As protocols for in vivo delivery of CRISPR components improve, the potential for direct therapeutic genome editing in human patients continues to grow [21] [20].

In conclusion, the powerful synergy between iPSC and CRISPR technologies has created a robust platform for disease modeling that combines human physiological relevance with genetic precision. This convergence has accelerated our understanding of disease mechanisms and continues to drive innovation in drug discovery and therapeutic development. As both technologies evolve and integrate with other emerging approaches like single-cell omics, artificial intelligence, and advanced bioengineering, they will undoubtedly remain at the forefront of biomedical research and precision medicine.

The discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) marked a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug discovery. This technology, which allows for the reprogramming of somatic cells into a pluripotent state, has evolved rapidly from a foundational scientific breakthrough to a platform for generating clinical-grade cell therapies. The convergence of iPSC technology with CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing has further revolutionized their application, enabling the creation of precise human disease models for research [1] [23]. This Application Note traces the key developmental milestones of iPSC technology and provides detailed protocols for their application in disease modeling research, specifically framed within the context of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing.

Historical Milestones in iPSC Technology

The development of iPSC technology represents a synthesis of decades of research in nuclear reprogramming, stem cell biology, and transcription factor function [24]. The key historical milestones are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in iPSC Development

| Year | Milestone | Key Finding/Outcome | Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) | John Gurdon demonstrated that a nucleus from a differentiated frog intestinal cell could support development of a tadpole. | Established that cellular differentiation involves reversible epigenetic changes, not irreversible genetic alterations. | [1] [24] |

| 1981 | Isolation of Mouse ESCs | Martin Evans, Matthew Kaufman, and Gail Martin isolated pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryos. | Provided the first in vitro model of pluripotency and a reference point for reprogramming. | [1] [24] |

| 1987 | Transcription Factor-Mediated Reprogramming | Ectopic expression of MyoD was shown to convert fibroblasts into myoblasts. | Established the principle that transcription factors are master regulators of cell fate. | [24] |

| 2006 | Discovery of Mouse iPSCs | Kazutoshi Takahashi and Shinya Yamanaka reprogrammed mouse fibroblasts to pluripotency using four factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, c-Myc, Klf4). | Demonstrated that pluripotency can be induced in somatic cells by defined factors. | [25] [1] |

| 2007 | Generation of Human iPSCs & Alternative Factors | Yamanaka's group and James Thomson's group independently generated human iPSCs using OSKM and OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28, respectively. | Made patient-specific human pluripotent stem cells a reality, avoiding ethical concerns of human ESCs. | [1] [23] |

| 2008-2013 | Development of Non-Integrating Methods | Successive development of methods using episomal vectors, Sendai virus, synthetic mRNA, and fully chemical reprogramming. | Addressed safety concerns of insertional mutagenesis, enabling a path toward clinical applications. | [23] |

| 2012-Present | Integration with CRISPR-Cas9 | CRISPR-Cas9 enabled precise gene editing in iPSCs for creating isogenic disease models and correcting mutations. | Powered highly accurate human disease modeling and the development of precision cell therapies. | [21] [10] [23] |

| 2014-Present | Clinical Trials & HLA-Haplobanks | Initiation of first-in-human iPSC clinical trial for macular degeneration and development of "haplobanks" of HLA-matched iPSCs. | Marked the transition of iPSC technology from the lab to the clinic, addressing immunocompatibility. | [26] [23] |

The intellectual framework for iPSC technology was built upon earlier pioneering work. The German evolutionary biologist August Weismann proposed that heritable information is irreversibly restricted during somatic cell development [1]. This view was famously illustrated by Conrad Waddington's "epigenetic landscape" model in 1957, which depicted cell differentiation as a ball rolling downhill into increasingly stable, specialized valleys [1]. The subsequent SCNT experiments by Gurdon directly challenged this notion of irreversibility, demonstrating that the genome of a specialized cell retains the totipotent capacity to direct embryonic development when exposed to the appropriate cytoplasmic environment of an oocyte [1] [24]. This established the principle of cellular plasticity, which is the fundamental concept underlying cellular reprogramming.

The subsequent derivation of embryonic stem cell (ESC) lines from mice and humans provided a critical in vitro system for studying pluripotency [1] [24]. Cell fusion experiments, in which somatic cells were fused with ESCs, yielded hybrid cells that were pluripotent, providing strong evidence that ESCs contained dominant factors capable of reprogramming a somatic cell nucleus [24]. The final conceptual piece was provided by transdifferentiation studies, which showed that the forced expression of lineage-specific transcription factors could directly convert one somatic cell type into another [24]. This established that transcription factors are powerful enough to override a cell's established epigenetic state and drive a new cell fate.

The pivotal 2006 discovery by Takahashi and Yamanaka synthesized these three principles [25]. They systematically tested 24 candidate genes important for ESC function and successfully narrowed down the minimal set required for reprogramming mouse fibroblasts to four transcription factors: Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM) [25] [1]. The resulting cells, termed induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), exhibited the morphology, gene expression, and functional capacity (including teratoma formation and germline transmission) of ESCs [25]. This work earned Shinya Yamanaka and John Gurdon the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for iPSC Research

The following table catalogs key reagents and materials essential for working with iPSCs, particularly in the context of gene editing and disease modeling.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Generation and Gene Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc (OSKM); OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 | Ectopic expression reprograms somatic cells to a pluripotent state. | Can be delivered via integrating (retrovirus, lentivirus) or non-integrating methods (Sendai virus, mRNA, episomal vectors). | [25] [1] [23] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Cas9 Nuclease, sgRNA, HDR donor template, Base Editors | Introduces or corrects disease-relevant mutations in iPSCs to create isogenic controls. | High-fidelity Cas variants reduce off-target effects. HDR is used for precise edits, while NHEJ creates knockouts. | [21] [10] [23] |

| Culture Matrices | Matrigel, Vitronectin, Laminin-521 | Provides a defined, xeno-free substrate for the attachment and growth of iPSCs and ESCs. | Critical for replacing mouse feeder cells (MEFs) to transition to clinically compliant cultures. | [27] [26] |

| Cell Culture Media | mTeSR, StemFit, Essential 8 | Chemically defined, feeder-free media formulations that support the self-renewal of iPSCs. | Maintains pluripotency and genomic stability over long-term culture. | [27] |

| Differentiation Induction Kits | Commercially available kits for neurons, cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes | Provides optimized protocols and reagents to direct iPSC differentiation into specific somatic lineages. | Ensures reproducibility and efficiency in generating disease-relevant cell types for modeling. | [28] [10] |

| Quality Control Assays | Karyotyping, Pluritest, Immunofluorescence (OCT4, NANOG, SSEA-4), Trilineage Differentiation In Vivo (Teratoma Assay) | Validates pluripotent state, genomic integrity, and differentiation potential of iPSC lines. | Mandatory for confirming the quality of parental and gene-edited clonal lines before experimentation. | [27] [23] |

Core Protocols for CRISPR-iPSC Disease Modeling

Protocol 1: Generation of Clinical-Grade iPSCs from Somatic Cells

This protocol outlines a method for generating integration-free human iPSCs using non-integrating vectors, suitable for subsequent clinical applications [27] [23].

Materials:

- Source Cells: Human dermal fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).

- Reprogramming Vector: CytoTune-iPS Sendai Virus Kit (non-integrating) or equivalent mRNA/episomal system.

- Culture Vessels: Matrigel-coated 6-well plates.

- Cell Culture Media: Fibroblast or PBMC growth medium, feeder-free iPSC maintenance medium (e.g., mTeSR1).

- Other Reagents: Rock inhibitor (Y-27632).

Procedure:

- Source Cell Preparation: Culture source cells to ~80% confluency. Ensure high viability (>90%).

- Viral Transduction: Calculate the appropriate multiplicity of infection (MOI). Add the Sendai virus vectors containing OSKM to the cell culture medium. Incubate for 24 hours.

- Media Change: After 24 hours, replace the virus-containing medium with fresh growth medium.

- Passaging and Plating: 5-7 days post-transduction, harvest the transduced cells using enzymatic dissociation. Plate the cells onto Matrigel-coated plates at a high density in medium supplemented with Rock inhibitor to enhance survival.

- Switch to iPSC Medium: 24 hours after replating, replace the growth medium with feeder-free iPSC maintenance medium. Continue feeding with iPSC medium every day.

- Colony Picking: After 3-4 weeks, distinct ESC-like colonies will emerge. Manually pick and expand individual clones into separate wells.

- Characterization: Validate bona fide iPSC status through immunocytochemistry (OCT4, NANOG, SSEA-4), PCR for the loss of the Sendai virus genome, and pluripotency tests (e.g., in vitro trilineage differentiation). Perform routine karyotyping.

Protocol 2: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Generation of Isogenic iPSC Lines

This protocol describes the use of CRISPR-Cas9 to correct a disease-causing mutation in patient-derived iPSCs, creating a genetically matched, isogenic control line [21] [10] [23].

Materials:

- Cells: Patient-derived iPSCs harboring a known pathogenic mutation.

- CRISPR Components: Plasmid or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex of Cas9 and target-specific sgRNA.

- Donor Template: Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) or double-stranded DNA donor containing the corrected sequence and silent restriction site.

- Transfection Reagent: Electroporation system (e.g., Neon) or chemical transfection reagent.

- Culture Media: iPSC maintenance medium with Rock inhibitor.

Procedure:

- Design and Preparation: Design sgRNA to target the genomic region near the mutation. Design an HDR donor template with the desired correction and a silent marker (e.g., novel restriction site).

- Delivery: Co-transfect patient iPSCs with the CRISPR-Cas9 complex (as plasmid or RNP) and the HDR donor template using electroporation.

- Recovery and Expansion: Plate transfected cells at low density in iPSC medium with Rock inhibitor. Allow cells to recover and expand for 5-7 days.

- Single-Cell Cloning: Harvest cells and seed at clonal density (<1 cell/well) in 96-well plates. Expand individual clones.

- Genotype Screening: Screen expanded clones by PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis (using the silent marker) to identify correctly edited clones.

- Sequence Validation: Sanger sequence the targeted genomic locus of candidate clones to confirm precise correction and rule off-target events.

- Quality Control: Bank the validated isogenic corrected clone and its mutant (parental) counterpart. Perform comparative karyotyping and pluripotency checks to ensure the editing process did not introduce unintended abnormalities.

Protocol 3: Phenotypic Screening of iPSC-Derived Neurons for Alzheimer's Disease Research

This protocol applies the isogenic iPSC lines to model Alzheimer's disease (AD) by differentiating them into neurons and assessing key pathological phenotypes [21] [28] [10].

Materials:

- iPSC Lines: Isogenic pair (e.g., with and without a mutation in APP or PSEN1).

- Differentiation Reagents: Neural induction medium, neuronal maturation supplements (e.g., BDNF, GDNF).

- Assay Kits: ELISA kits for Aβ40/42, antibodies for phospho-Tau and total Tau, immunocytochemistry reagents.

- Cell Culture: Matrigel-coated plates for 2D culture or low-attachment plates for 3D organoid formation.

Procedure:

- Neural Differentiation: Differentiate the isogenic iPSC pairs into cortical neurons using a standardized, multi-step protocol involving dual SMAD inhibition. For more complex modeling, generate 3D cerebral organoids.

- Sample Collection: Collect conditioned medium from mature neurons (e.g., at day 60-90 of differentiation) for secretome analysis.

- Aβ ELISA: Measure the concentration of Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides in the conditioned medium using commercial ELISA kits. Calculate the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, a key indicator of pathogenicity.

- Tau Phosphorylation Analysis: Lyse a parallel set of neurons. Perform western blotting or immunofluorescence using antibodies specific for phosphorylated Tau (e.g., at Ser202/Thr205) and total Tau. Quantify the ratio of p-Tau to total Tau.