Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds: Harnessing Native Microenvironments for Advanced Stem Cell Engraftment

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) as a biological scaffold for stem cell-driven tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds: Harnessing Native Microenvironments for Advanced Stem Cell Engraftment

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) as a biological scaffold for stem cell-driven tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational science behind dECM, detailing how its tissue-specific composition and structure provide a unique niche for controlling stem cell fate. The content systematically reviews current decellularization and recellularization methodologies, addresses critical challenges in scaffold optimization and biocompatibility, and evaluates the efficacy of dECM through comparative analyses with synthetic alternatives. By synthesizing current research and future directions, this resource aims to bridge translational gaps and inform the development of next-generation regenerative therapies and advanced in vitro models for drug discovery.

The Biological Blueprint: How Decellularized ECM Creates an Ideal Stem Cell Niche

Decellularization represents a cornerstone bioprocessing technique in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. It is defined as the process of removing all cellular and nuclear material from native tissues or organs while minimizing damage to the structural and functional components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) [1] [2]. The fundamental objective is to create a natural, bioactive scaffold that retains the intricate architecture and biochemical cues of the original tissue, thereby providing an optimal microenvironment for cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation [3].

The critical goal of preserving the native ECM cannot be overstated, as this complex three-dimensional network serves not merely as a passive structural support but as a dynamic regulator of cellular behavior [1]. A successfully decellularized ECM scaffold maintains tissue-specific biochemical composition—including collagens, elastin, glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), and growth factors—and biomechanical properties that are essential for guiding tissue-specific regeneration [1] [4]. Within the context of stem cell engraftment research, these preserved elements provide the necessary topological, mechanical, and biochemical signals that direct stem cell fate, integration, and functional tissue formation [5].

This Application Note delineates the core principles of decellularization, provides standardized protocols for quality assessment, and details experimental methodologies for creating ECM scaffolds that effectively support stem cell research and engraftment applications.

Core Principles and Quantitative Assessment of Decellularization

Effective decellularization hinges on balancing complete cell removal with maximal ECM preservation. The process must eliminate immunogenic cellular components—particularly DNA and cell membrane antigens—that could trigger adverse immune responses upon implantation [4]. Concurrently, it must conserve the native ECM's structural integrity and bioactive composition to facilitate constructive remodeling and stem cell integration [1].

Quantitative Metrics for Decellularization Efficacy

Rigorous assessment is mandatory to verify decellularization success. The table below summarizes the key quantitative and qualitative metrics used to evaluate decellularized scaffolds.

Table 1: Key Assessment Metrics for Decellularized ECM Scaffolds

| Assessment Category | Specific Metric | Target Value for Effective Decellularization | Analytical Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular Removal | Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) content | < 50 ng per mg of dry tissue weight [5] | DNA quantification assay (e.g., DNeasy Kit) [6] |

| DNA fragment length | < 200 base pairs [5] | Gel electrophoresis | |

| Visual absence of nuclear material | No visible nuclei in stained sections [7] | H&E staining, DAPI staining [7] [8] | |

| ECM Composition Preservation | Collagen content | Maintained relative to native tissue | Hydroxyproline assay, Sirius Red staining [8] |

| Glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content | Minimized loss (varies by protocol) | Dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) assay, Alcian blue staining [7] [8] | |

| Elastin and other structural proteins | Maintained architecture and content | Masson's Trichrome, Immunofluorescence [7] [6] | |

| Structural & Mechanical Integrity | Ultrastructure | Preserved microarchitecture (e.g., fibrillar collagen, lamellae) | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [7] [9] |

| Mechanical properties | Matches native tissue tensile/compressive strength | Uniaxial tensile testing, compression testing [8] [6] | |

| Biocompatibility | Cytotoxicity | No cytotoxic effects on seeded cells | MTT assay, Live/Dead staining [7] [8] |

| Cell adhesion and proliferation | Supportive of cell growth | Seeding with relevant cell types (e.g., stem cells) [8] |

Decellularization Methodologies and Comparative Analysis

Decellularization protocols typically integrate chemical, biological, and physical methods. The optimal combination is highly dependent on the tissue's intrinsic properties, such as cellular density, lipid content, and ECM density [1] [2].

Classification of Primary Decellularization Methods

Table 2: Comparison of Primary Decellularization Methodologies

| Method Type | Specific Agents | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | Disadvantages & ECM Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Detergents | ||||

| Ionic (e.g., SDS, SDC) [1] [2] | Solubilizes cell membranes and nuclear material by disrupting lipid-protein bonds. | Highly effective for dense tissues; robust cell removal [8] [6]. | Can denature proteins, damage ultrastructure, and remove GAGs; difficult to rinse out completely [1] [8]. | |

| Non-ionic (e.g., Triton X-100) [1] [2] | Disrupts lipid-lipid and lipid-protein interactions. | Gentler on ECM structure; preserves collagen alignment [8] [9]. | Less effective at removing nuclear material; may require combination with other agents [7]. | |

| Zwitterionic (e.g., CHAPS, SB-10) [2] [9] | Properties of both ionic and non-ionic detergents. | Can be effective for specific tissues like nerves. | May disrupt the basement membrane [2]. | |

| Biological Agents | ||||

| Nucleases (DNase, RNase) [2] [8] | Cleaves DNA and RNA bonds to remove residual nucleic acids. | Highly effective at degrading genetic material. | Requires subsequent washing to remove enzymes; ineffective on its own without prior cell lysis [1]. | |

| Trypsin [2] [7] | Proteolytic enzyme cleaves peptide bonds, dissociating cells from ECM. | Rapidly disrupts cell-ECM adhesion. | Prolonged exposure severely damages ECM proteins and structure [1] [8]. | |

| Physical Methods | ||||

| Freeze-Thaw Cycles [2] [3] | Intracellular ice crystals form, lysing cell membranes. | Simple, cost-effective; eliminates cellular content. | Does not remove cellular debris; can damage ECM if ice crystals are too large [3]. | |

| Agitation & Perfusion [1] [6] | Mechanical force assists in detergent penetration and debris removal. | Can be applied to whole organs via vascular conduits [6] [5]. | Perfusion requires intact vasculature; agitation may damage delicate structures. |

Protocol Performance in Different Tissues

The efficacy of a decellularization agent is highly tissue-dependent. The table below synthesizes data from comparative studies across various tissues.

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Decellularization Agents Across Different Tissues

| Tissue Type | Evaluated Protocols | Key Findings on Efficacy and ECM Preservation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Porcine Annulus Fibrosus | 1. Triton X-1002. SDS3. Trypsin | Triton X-100: Best overall; preserved concentric lamellar structure, collagen, highest GAG content, and mechanical properties.SDS: Removed cells but disturbed structure and decreased tensile strength.Trypsin: Disrupted tissue architecture. | [8] |

| Human Umbilical Cord | 1. Trypsin2. Triton X-1003. SDC4. Combined (Trypsin+Triton+SDC) | Combined Protocol: Most effective; removed most cellular components while retaining collagen, GAGs, and microstructure. Single-agent protocols were less effective or more damaging. | [7] |

| Rat Sciatic Nerve | 1. DN-P1 (TBP + PAA)2. DN-P2 (SB-10, Triton, SDS) | DN-P1: Better conservation of ultrastructure and ECM components; high biocompatibility.DN-P2: Caused moderate disruption of endoneurium and perineurium. | [9] |

| Human Digits | Perfusion with SDS + Triton X-100 | Successful decellularization of complex VCA; preserved vascular integrity, collagen, elastin, GAGs, and tendon mechanical strength. | [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Combined Chemical Decellularization of Human Umbilical Cord

This protocol, adapted from a 2024 study, demonstrates an effective short-term (5-hour) combined strategy for dense connective tissue [7].

Workflow Diagram: Combined Decellularization Protocol

Reagents and Materials:

- Trypsin-EDTA solution (0.025% w/v, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

- Triton X-100 (5% v/v, Macklin Inc.)

- Sodium Deoxycholate (SD) (4% w/v, Macklin Inc.)

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Deionized water

- Orbital shaker incubator capable of maintaining 37°C and 120 rpm

Procedure:

- Tissue Preparation: Slice fresh or thawed human umbilical cord tissue longitudinally into thin sections (e.g., 5 cm × 2 cm × 0.5 cm). Rinse sections in ultrapure water on a shaking bed (120 rpm) three times for 10 minutes each.

- Enzymatic Treatment (Step 1): Transfer tissue to 0.025% trypsin-EDTA solution. Agitate at 37°C and 120 rpm for 1.5 hours to dissociate cells from the ECM.

- First Detergent Wash (Step 2): Transfer tissue to a 5% v/v solution of Triton X-100. Agitate at room temperature, 120 rpm for 1.5 hours to lyse cells and solubilize membranes.

- Second Detergent Wash (Step 3): Transfer tissue to a 4% w/v solution of Sodium Deoxycholate. Agitate at room temperature, 120 rpm for 2 hours to ensure complete removal of cellular debris.

- Washing: Thoroughly rinse the decellularized tissue with copious amounts of deionized water under agitation to remove all residual chemical reagents.

- Storage/Processing: The resulting dECM can be freeze-dried for storage or processed further into hydrogels or bioinks.

Quality Control: Confirm decellularization efficacy via H&E and DAPI staining (no visible nuclei), dsDNA quantification (<50 ng/mg dry weight), and ECM preservation via Masson's Trichrome (collagen), PAS staining (GAGs), and immunofluorescence [7].

Perfusion-Based Decellularization of Composite Tissues

For whole organs or complex vascularized composite allografts (VCAs) like human digits, perfusion decellularization is the preferred method as it utilizes the native vascular network to deliver decellularization agents [6] [5].

Workflow Diagram: Perfusion Decellularization Protocol

Reagents and Materials:

- Peristaltic pump system (e.g., Masterflex L/S digital drive)

- Pressure transducer (e.g., PT-F, Living Systems Instrumentation) for real-time pressure monitoring (target 40-60 mmHg)

- Bubble trap (e.g., Radnoti) to prevent vascular embolism

- SDS solution (0.2% w/v in deionized water)

- Triton X-100 solution (1% v/v in deionized water)

- Sterile Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

Procedure:

- Cannulation and Setup: Cannulate the main artery (e.g., digital artery) of the tissue or organ and secure the catheter. Connect the cannula to the perfusion system equipped with a pressure transducer and bubble trap.

- Initial Wash: Perfuse with PBS for 1 hour at a flow rate that maintains a physiological pressure (e.g., 40-60 mmHg) to clear the vasculature of blood and debris.

- Primary Decellularization: Perfuse with 0.2% SDS solution for 120 hours. Continuously monitor vascular resistance and adjust flow rate to maintain target pressure.

- Intermediate Wash: Perfuse with deionized water for 24 hours to help remove ionic detergents and cellular debris.

- Secondary Decellularization: Perfuse with 1% Triton X-100 solution for 24 hours to remove residual cellular material and SDS.

- Final Wash: Perfuse with PBS for 48 hours to thoroughly remove all residual detergents from the scaffold.

- Sterilization (Optional): Perfusion with 0.1% Peracetic Acid (PAA) can be incorporated for simultaneous sterilization [9].

Quality Control: Assess vascular integrity via contrast-enhanced X-ray. Evaluate decellularization by quantifying DNA in various tissue components (skin, vessel, muscle, nerve, bone) and confirm ECM preservation through histology and biochemical assays for collagen, elastin, and GAGs [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Decellularization

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Key Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Ionic detergent for efficient cell lysis and DNA removal in dense tissues. | Use minimal effective concentration and duration; requires extensive washing due to cytotoxicity and potential for ECM damage [1] [8]. |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent for gentle cell membrane disruption and lipid removal. | Better preserves ECM structure than SDS but may be insufficient as a standalone agent; often used in combination protocols [7] [8]. |

| Trypsin-EDTA | Proteolytic enzyme solution for dissociating cells from the ECM. | Exposure time is critical; prolonged use severely degrades ECM proteins like collagen and fibronectin [1] [8]. |

| DNase/RNase | Enzymes for digesting residual nucleic acid fragments post-cell lysis. | Essential for reducing fragment length and removing immunogenic DNA; used after initial detergent treatment [2] [8]. |

| Tri(n-butyl) phosphate (TBP) | Organic solvent for decellularizing compact tissues like tendons and nerves. | Can penetrate dense structures effectively; shown to preserve ultrastructure in nerve grafts [9]. |

| Peracetic Acid (PAA) | Oxidizing agent used for sterilization and to enhance tissue permeability. | Can be integrated into protocols to reduce detergent concentrations and simultaneously sterilize the scaffold [1] [9]. |

| Peristaltic Pump & Pressure Transducer | Enables perfusion decellularization of whole organs/VCAs via vascular conduits. | Critical for monitoring and maintaining physiological pressures to avoid damaging the delicate vascular network [6] [5]. |

Successful decellularization for stem cell engraftment research is a deliberate balancing act. The protocols and assessment metrics detailed in this application note provide a framework for generating high-quality, reproducible dECM scaffolds. The chosen method must be tailored to the specific tissue, with the unrelenting goal of preserving the native ECM's compositional, structural, and mechanical integrity. By adhering to these principles and rigorously validating scaffold quality, researchers can create powerful, biomimetic platforms that harness the innate signaling of the ECM to direct stem cell behavior, thereby advancing the frontiers of regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

In the field of regenerative medicine, decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) scaffolds have emerged as a premier biomaterial platform for stem cell engraftment research. These scaffolds are produced by removing all cellular components from native tissues while preserving the intricate structural and functional proteins of the native extracellular matrix (ECM). This process creates a natural, three-dimensional microenvironment that retains tissue-specific biological cues essential for guiding stem cell adhesion, proliferation, differentiation, and functional tissue formation [1] [10]. The preserved ECM components serve not only as a structural foundation but also as a biochemical signaling reservoir that closely mimics the native stem cell niche, making dECM scaffolds particularly valuable for studying and facilitating stem cell engraftment.

The critical importance of dECM scaffolds lies in their ability to provide a biomimetic microenvironment that synthetic scaffolds cannot fully replicate. By maintaining the complex architecture and bioactive composition of native ECM, these scaffolds create an inductive environment for stem cells. The preservation of key structural proteins and glycosaminoglycans allows researchers to investigate stem cell-ECM interactions under conditions that closely resemble in vivo physiology, providing critical insights for drug development and therapeutic applications [10] [11]. This application note details the core protein composition of acellular scaffolds and provides standardized protocols for their analysis in the context of stem cell research.

Core Structural and Functional Proteins

The functionality of acellular scaffolds in stem cell engraftment research depends on the preservation and composition of four key ECM components: collagens, elastin, laminin, and glycosaminoglycans. Each component contributes distinct structural and biological properties that collectively create a hospitable microenvironment for stem cells.

Quantitative Composition of Key ECM Proteins

Table 1: Core protein composition and functions in acellular scaffolds

| ECM Component | Primary Function | Key Characteristics | Role in Stem Cell Engraftment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen | Provides tensile strength and structural integrity [1] | Most abundant protein in human body (≈30% of total protein); multiple types (I, II, III, IV) with tissue-specific distribution [12] [11] | Guides cell adhesion through integrin binding; influences stem cell differentiation through mechanical signaling [1] [11] |

| Elastin | Confers elasticity and resilience to tissues [1] | Provides recoil in tissues subjected to repeated stretch (vessels, lungs, skin); extensive cross-linking via lysyl oxidase [12] [11] | Maintains tissue integrity during dynamic mechanical processes; important for vascular and pulmonary tissue engineering |

| Laminin | Basement membrane foundation; cell adhesion and signaling [12] | Cross-shaped glycoprotein; forms networks in basal laminae; essential for early embryonic development [12] [11] | Critical for epithelial and endothelial cell attachment; regulates stem cell survival, morphology, and differentiation [13] |

| Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) | Regulation of hydration, compressive resistance, and growth factor binding [1] | Highly negatively charged polysaccharides (heparan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, keratan sulfate, hyaluronic acid) [12] | Reservoir for growth factors and cytokines; modulates stem cell differentiation through controlled factor release [1] [10] |

Specialized ECM Components and Their Functions

Table 2: Additional ECM components with significant biological functions

| Component | Category | Function in Scaffold |

|---|---|---|

| Fibronectin | Glycoprotein | Connects cells with collagen fibers in ECM; facilitates cell movement; binds integrins and reorganizes cytoskeleton [12] [13] |

| Proteoglycans | Protein + GAGs | Control matrix hydration; establish permeability barriers; serve as reservoirs for growth factors and cytokines [1] [11] |

| Matrix-bound vesicles | Extracellular vesicles | Contain DNA, RNA, proteins, lipids; modify macrophage activation; alter cell proliferation and migration [12] |

| Growth Factors | Bioactive molecules | TGF-β, VEGF, FGF, BMPs stored in ECM; released during remodeling to guide angiogenesis and stem cell differentiation [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Scaffold Analysis

Protocol 1: DNA Quantification for Decellularization Verification

Purpose: To verify effective removal of cellular material by quantifying residual DNA content in dECM scaffolds, ensuring minimal immunogenicity for stem cell engraftment studies.

Materials and Reagents:

- DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit

- Nanodrop spectrophotometer or equivalent

- Microbalance (0.1 mg sensitivity)

- PBS buffer (pH 7.4)

- Liquid nitrogen and mortar/pestle

Procedure:

- Obtain 25 mg biopsy samples from multiple regions of the decellularized scaffold (center and periphery)

- Homogenize tissue samples using liquid nitrogen and mortar/pestle

- Extract DNA using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit according to manufacturer's protocol

- Quantify purified DNA using absorbance at 260 nm with Nanodrop

- Calculate DNA content as weight of DNA per weight of wet tissue (ng/mg)

- Compare against established criteria for acellular scaffolds (<50 ng/mg) [14] [15]

Quality Control: Include positive control (native tissue) and negative control (reagent only) in each assay batch. Effective decellularization should reduce DNA content by >95% compared to native tissue.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Glycosaminoglycan (GAG) Assay

Purpose: To quantify GAG retention in dECM scaffolds, as GAGs are critical for growth factor binding and stem cell differentiation signaling.

Materials and Reagents:

- Papain digestion solution (100 mM phosphate buffer, 10 mM cysteine HCl, 10 mM EDTA, pH 6.5)

- Papain enzyme (20 μg/mL final concentration)

- Dimethylene blue dye solution

- Chondroitin sulfate standards (0-100 μg/mL)

- Spectrophotometer or microplate reader

Procedure:

- Digest 10 mg scaffold samples in papain solution at 60°C for 18 hours

- Centrifuge digested samples at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes

- Aliquot supernatant and mix with dimethylene blue dye solution

- Measure absorbance at 525 nm immediately after mixing

- Calculate GAG content from standard curve using chondroitin sulfate

- Express results as μg GAG per mg wet weight of tissue [14]

Applications: GAG content correlates with scaffold bioactivity and growth factor retention capacity, important predictors of stem cell engraftment success.

Protocol 3: Immunohistochemical Analysis of ECM Proteins

Purpose: To visualize and semi-quantitatively analyze spatial distribution of key ECM proteins in dECM scaffolds.

Materials and Reagents:

- 10% neutral buffered formalin

- Paraffin embedding system

- Microtome

- Primary antibodies: collagen I, collagen IV, elastin, laminin

- HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies

- DAB peroxidase substrate

- Hematoxylin counterstain

Procedure:

- Fix scaffold samples in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours

- Process tissues through graded ethanol series and embed in paraffin

- Section tissues at 5 μm thickness using microtome

- Deparaffinize and rehydrate sections through xylene and graded ethanol series

- Perform antigen retrieval using appropriate buffer (citrate or EDTA)

- Block endogenous peroxidase activity and nonspecific binding sites

- Incubate with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C

- Detect with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and DAB substrate

- Counterstain with hematoxylin, dehydrate, and mount

- Image using digital slide scanner and analyze protein distribution [14]

Signaling Pathways in Stem Cell-ECM Interactions

The interaction between stem cells and acellular scaffolds activates multiple signaling pathways that direct stem cell fate decisions. These pathways are primarily triggered through integrin-mediated recognition of ECM components and subsequent mechanotransduction events.

ECM-Stem Cell Signaling Pathways

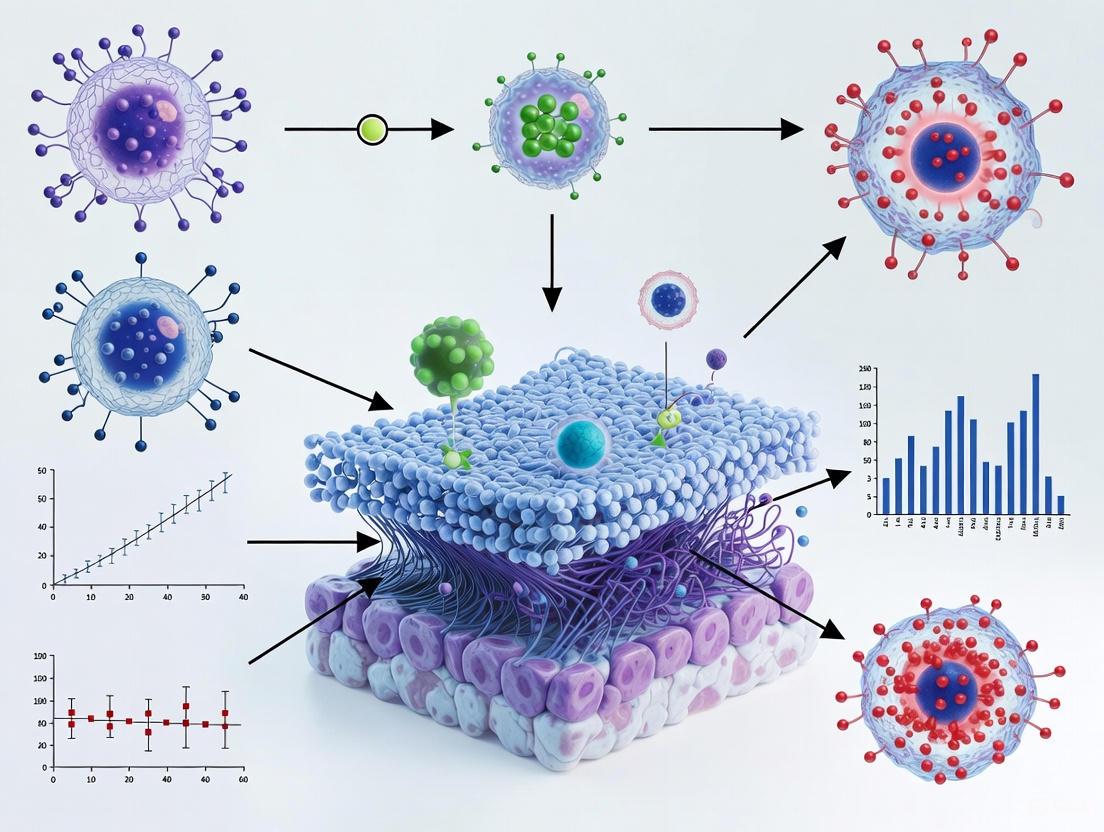

The diagram illustrates two primary mechanisms of stem cell-ECM interaction: biochemical signaling initiated when integrin receptors recognize ECM ligands such as collagen, laminin, and fibronectin, and mechanotransduction where cells sense mechanical properties of the ECM including stiffness and elasticity. These signals converge to regulate gene expression programs that ultimately determine stem cell fate decisions including proliferation, migration, and differentiation [1] [11]. The integrin-FAK signaling axis activates both MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways, while mechanical cues influence gene expression through cytoskeletal reorganization and YAP/TAZ translocation [12] [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents for dECM scaffold analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decellularization Agents | Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), Triton X-100, Triton X-200, Sodium deoxycholate [1] [10] | Scaffold preparation | Remove cellular components while preserving ECM structure and bioactivity |

| DNA Quantification Kits | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit [14] | Quality control | Assess decellularization efficiency by measuring residual DNA content |

| Histological Stains | Hematoxylin & Eosin, Masson's Trichrome, Van Gieson's stain [14] | Structural analysis | Visualize tissue architecture, collagen distribution, and elastic fibers |

| ECM Component Assays | Total Collagen Assay Kit, Dimethylene Blue GAG Assay [14] | Quantitative analysis | Measure specific ECM component retention after decellularization |

| Growth Factor Arrays | RayBio Human Growth Factor Antibody Array [14] | Bioactivity assessment | Profile retained growth factors (VEGF, FGF, TGF-β) in dECM scaffolds |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Endothelial cells, muscle stem cells, Schwann cells [15] [16] | Functional assessment | Evaluate scaffold biocompatibility and stem cell engraftment potential |

The core structural and functional proteins preserved in acellular scaffolds—collagen, elastin, laminin, and glycosaminoglycans—collectively create a biomimetic microenvironment that is indispensable for advancing stem cell engraftment research. These components provide not only the structural foundation for tissue development but also the critical biochemical and biophysical cues that direct stem cell fate decisions. The experimental protocols outlined in this application note provide standardized methodologies for characterizing these key components, ensuring that researchers can consistently evaluate and qualify dECM scaffolds for stem cell research applications. As tissue engineering and regenerative medicine continue to evolve, understanding and optimizing the composition of acellular scaffolds will remain fundamental to developing effective stem cell-based therapies and advancing drug development platforms.

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is far more than a passive, structural scaffold for tissues; it is a dynamic, information-rich environment that actively directs stem cell fate. Within the context of regenerative medicine and decellularized tissues, understanding how matrix-bound cues guide stem cell behavior is paramount for developing effective therapies. Decellularized ECM (dECM) serves as an ideal biomimetic platform, retaining the complex biochemical composition and three-dimensional architecture of native tissue, thereby providing a multitude of physical and chemical signals. These signals are interpreted by stem cells through a process known as mechanotransduction, influencing critical cellular decisions including adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [17] [18]. This application note details the mechanisms by which these matrix-bound cues exert their effects and provides standardized protocols for investigating these phenomena in a research setting, with a specific focus on applications within dECM scaffold technology.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative data on how specific matrix properties influence mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) behavior, serving as a critical reference for designing experiments with dECM scaffolds.

Table 1: Influence of Substrate Stiffness on MSC Lineage Specification

| Target Lineage | Substrate Stiffness Range | Key Morphological and Molecular Markers | Reference Model Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurogenic | 0.1 - 1 kPa | Branched, filopodia-rich morphology; expression of neuronal precursors | Brain [17] [19] [20] |

| Myogenic | 8 - 17 kPa | Elongated, spindle-shaped morphology; expression of MyoD | Muscle [17] [19] |

| Chondrogenic | 20 - 25 kPa (3D) | Round cell morphology; expression of chondrogenic markers | Cartilage [20] |

| Osteogenic | 25 - 40 kPa (2D) | Spread, polygonal morphology; expression of Runx-2, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | Collagenous bone [17] [19] [20] |

Table 2: Impact of Scaffold Biophysical Cues on MSC Behavior

| Biophysical Cue | Parameter Range | Impact on MSC Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Shape / Micropatterning | Small islands (<1600 μm²) vs. Large islands | Round shape promotes adipogenesis; spread shape promotes osteogenesis [17] |

| Cell Density | Low vs. High Density | Low density promotes osteogenesis (ALP expression); high density promotes adipogenesis [17] |

| Aspect Ratio | 1:1 vs. 4:1 (constant area) | ∼20% higher osteogenesis on 4:1 aspect ratio patterns [17] |

| Edge Curvature | High curvature (flower) vs. Straight edges (star) | High curvature promotes adipogenesis; straight edges stimulate osteogenic differentiation [17] |

Key Mechanotransduction Signaling Pathways

Cells perceive mechanical cues from the dECM through surface receptors, primarily integrins, which cluster to form focal adhesions. These structures act as bidirectional mechanical links, transmitting forces from the ECM to the intracellular cytoskeleton and vice versa. The resulting cytoskeletal tension, generated by actin-myosin contractility, activates downstream signaling pathways that ultimately lead to transcriptional changes in the nucleus.

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 4.1: Preparation and Characterization of Decellularized ECM (dECM) Scaffolds

This protocol outlines a standard method for preparing dECM from soft tissues (e.g., cartilage, testis) using a combination of physical and chemical decellularization, as validated in recent studies [21] [22].

Workflow Diagram:

Materials:

- Native Tissue Source: (e.g., Porcine aorta, rat testis, bovine cartilage).

- Detergents: 1% Triton X-100, 1% Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), or 0.5% Sodium lauryl ether sulfate (SLES).

- Buffers: Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), DNase/RNase solution.

- Equipment: Biological shaker or magnetic stirrer, -80°C freezer.

Procedure:

- Physical Pre-treatment: Rinse the tissue in PBS and puncture the capsule if present. Subject the tissue to at least three cycles of freezing at -80°C and thawing at room temperature. This process forms ice crystals that lyse cells [22].

- Chemical Decellularization:

- Washing: Wash the decellularized tissue in sterile PBS for a minimum of 3 hours, with multiple buffer changes, to thoroughly remove all residual detergents.

- Sterilization & Storage: Store the dECM scaffolds in sterile PBS at 4°C for immediate use, or freeze at -80°C for long-term storage.

Validation & Quality Control:

- Histology: Perform Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and Hoechst staining to confirm the absence of visible cell nuclei [21] [22].

- DNA Quantification: Use a DNA quantification kit. A successful decellularization should show a significant reduction in DNA content compared to native tissue [22].

- ECM Composition: Use staining (e.g., Masson's Trichrome for collagen, Alcian Blue for glycosaminoglycans (GAGs)) and immunohistochemistry (e.g., for Collagen I, IV) to confirm the retention of key ECM components [21] [22].

Protocol 4.2: Functionalization of dECM with Bioactive Factors

To enhance the therapeutic potential of dECM, it can be functionalized with specific growth factors. This protocol describes a method for incorporating factors like Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) into MSC spheroid-derived dECM, leveraging its endogenous GAGs for sustained release [23].

Procedure:

- Prepare MSC Spheroid-derived dECM: Assemble MSCs into 3D spheroids and decellularize using a mild surfactant (0.5% Triton X-100) to preserve endogenous GAGs [23].

- Growth Factor Incorporation: Incubate the 3D dECM constructs in a solution containing the desired growth factor (e.g., 100 ng/mL BDNF) for 24 hours at 4°C under gentle agitation. The preserved GAGs in the gently decellularized matrix will naturally sequester the growth factors without the need for chemical crosslinkers [23].

- Washing and Use: Gently rinse the functionalized dECM with buffer to remove unbound factor before cell seeding or implantation.

Protocol 4.3: Evaluating Stem Cell Response to dECM Scaffolds

This protocol describes how to seed and culture stem cells on dECM scaffolds and assess key outcomes: adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation.

Materials:

- Stem Cells: Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs), induced MSCs (hiMSCs), or other relevant progenitor cells.

- Culture Medium: Appropriate basal medium (e.g., DMEM) with necessary supplements (e.g., FBS). For differentiation, use defined induction media.

- dECM Scaffolds: Prepared and sterilized as per Protocol 4.1.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells onto the dECM scaffold at a desired density (e.g., 1-5 x 10⁵ cells/scaffold) using a static or dynamic seeding method. Allow 2-4 hours for initial attachment before adding culture medium.

- Culture: Maintain cell-scaffold constructs in standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂). Change the medium every 2-3 days.

Analysis and Readouts:

- Cell Viability and Proliferation:

- Live/Dead Assay: Use calcein-AM (labels live cells green) and ethidium homodimer-1 (labels dead cells red) to visualize and quantify cell viability after 1, 3, and 7 days in culture [21].

- Metabolic Activity Assays: Use AlamarBlue or MTT assays at multiple time points to track proliferative activity.

- Cell Morphology and Adhesion:

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Fix constructs, dehydrate, and sputter-coat with gold to visualize cell morphology and attachment to the ECM fibers [22].

- Differentiation Analysis:

- Gene Expression: Use RT-qPCR to measure the expression of lineage-specific markers (e.g., Runx2 for osteogenesis, SOX9 for chondrogenesis, PPARγ for adipogenesis) after 7-21 days in culture.

- Histological Staining: For chondrogenic differentiation, fix constructs, section, and stain with Alcian Blue to detect sulfated GAG deposition, a key marker of cartilage matrix production [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for dECM and Stem Cell Guidance Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Triton X-100 (Detergent) | Mild, non-ionic detergent for gentle cell membrane solubilization. | Decellularization of cell spheroids to preserve endogenous GAGs and growth factors [23]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Strong ionic detergent for efficient nuclear and cytoplasmic material removal. | Decellularization of dense tissues; requires careful optimization to avoid ECM damage [21] [22]. |

| Gellan Gum | Biocompatible polysaccharide hydrogel for 3D bioprinting and cartilage engineering. | Used as a base bioink mixed with dECM to improve printability and provide cartilage-like environment [21]. |

| Perfluorocarbons (PFCs) | Synthetic oxygen carriers with high oxygen solubility. | Incorporated into hydrogels to enhance oxygen supply and improve stem cell survival in hypoxic transplantation sites [24]. |

| Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) | Neurotrophic growth factor crucial for neuronal survival and outgrowth. | Loaded into MSC spheroid-derived dECM to create a pro-regenerative scaffold for brain repair [23]. |

| Dolichos Biflorus Agglutinin (DBA) | Lectin that binds specifically to spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs). | Used to identify and isolate SSCs for seeding onto decellularized testicular scaffolds [22]. |

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a complex, three-dimensional network of proteins and carbohydrates that provides not only structural support but also critical biochemical and biomechanical cues to resident cells. Decellularized ECM (dECM) represents this native architecture after cellular components have been removed, preserving tissue-specific signaling motifs that guide cell behavior, differentiation, and function. The fundamental hypothesis driving dECM research posits that the unique compositional and structural properties of ECM from different tissues—such as liver, nerve, and cardiac—create distinct microenvironments that elicit specific cellular responses crucial for tissue regeneration [25].

The therapeutic potential of dECM is particularly valuable in the context of stem cell engraftment, where the goal is to enhance cell survival, integration, and functional tissue repair. Traditional synthetic biomaterials often lack the biological complexity required to direct sophisticated cellular processes. In contrast, tissue-specific dECM bioinks and scaffolds replicate native conditions more faithfully, making them superior substrates for regenerative applications [25]. This application note details the unique properties of liver, nerve, and cardiac dECM and provides standardized protocols for their use in stem cell research.

Comparative Analysis of Tissue-Specific dECM Compositions and Effects

The compositional profile of dECM varies significantly between tissues, directly influencing its functional properties and subsequent cellular interactions. The table below summarizes key characteristics and documented cellular responses for liver, nerve, and cardiac dECM.

Table 1: Quantitative and Functional Characteristics of Tissue-Specific dECM

| Tissue dECM | Key ECM Components | Documented Stem Cell Responses | Differentiation & Functional Markers Observed | Noted Advantages in Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver dECM | Collagens, Glycosaminoglycans, Laminin [25] | Enhanced hepatocyte function; Stem cell differentiation into hepatocyte-like cells [25] | Increased albumin production, urea synthesis, and cytochrome P450 activity [25] | Retains tissue-specific biochemical cues; Promotes rapid and enhanced hepatic function [25] |

| Nerve dECM | Laminin, Fibronectin, Collagens [26] [27] | MSC secretion of neurotrophic factors; Enhanced axon regeneration and myelination [26] [27] [28] | Increased expression of S100, GFAP, p75 NTR (Schwann cell-like markers) [27] | Provides a supportive microenvironment for axonal growth; Enhances functional motor recovery [26] [28] |

| Cardiac dECM | (Information not explicitly covered in search results) | (Information not explicitly covered in search results) | (Information not explicitly covered in search results) | (Information not explicitly covered in search results) |

Table 2: Experimental Outcomes in Preclinical Models Using Tissue-Specific Approaches

| Tissue System | Model Used | Key Functional Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver dECM Bioink | 3D cell printing of HepG2 cells and stem cells [25] | Cell viability, metabolic function (e.g., albumin secretion), and gene expression of hepatic markers [25] | Superior enhancement of hepatocyte function and stem cell differentiation compared to standard collagen bioinks [25] |

| Nerve Repair with MSC-Seeded Grafts | Rat sciatic nerve 10mm defect [26] [27] | Isometric tetanic force (ITF), compound muscle action potential (CMAP), muscle mass, histology [26] [27] | Significantly improved ITF and CMAP at 12 weeks compared to acellular allografts; Outcomes comparable to autografts by 16 weeks [26] [27] |

Experimental Protocols for dECM Utilization

Protocol: Fabrication of Liver dECM Bioink for 3D Cell Printing

This protocol outlines the process for creating a bioink from liver-derived dECM, suitable for 3D bioprinting of liver tissue constructs [25].

Step 1: Tissue Decellularization

- Obtain fresh liver tissue from an approved source (e.g., porcine or rodent).

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water to remove blood residues.

- Treat the tissue with a series of detergent solutions (e.g., 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, SDS) under constant agitation to lyse cells and remove cellular debris.

- Wash extensively with deionized water and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to eliminate all traces of detergent.

- Verify decellularization by quantifying DNA content (should be <50 ng/mg of tissue dry weight) and staining for residual nuclei (e.g., DAPI).

Step 2: dECM Digestion and Bioink Formation

- Mince the acellular dECM matrix into small pieces (< 1 mm³).

- Digest the ECM material in a 0.1% pepsin solution in 0.1M HCl under constant agitation for approximately 48-72 hours until a viscous, homogeneous solution is formed.

- Neutralize the pH to 7.4 using 1M NaOH and dilute the pre-gel solution to the desired working concentration (e.g., 3-5 mg/ml) using PBS on ice to prevent premature gelation.

- The resulting liquid is the liver dECM bioink, ready for cell mixing and printing.

Step 3: 3D Bioprinting and Gelation

- Keep the bioink on ice throughout the printing process.

- Mix the bioink with the target cell population (e.g., HepG2 cells, MSCs, or primary hepatocytes) at a concentration of 1-10 million cells/mL.

- Load the cell-bioink mixture into a sterile printing cartridge.

- Print the construct using a 3D bioprinter onto a substrate maintained at 37°C to induce thermal gelation.

- Culture the printed constructs in appropriate media for downstream application or analysis.

Protocol: Seeding MSCs onto Decellularized Nerve Allografts

This protocol describes a dynamic seeding method to adhere Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) onto decellularized nerve allografts for peripheral nerve repair [26] [27].

Step 1: Preparation of Decellularized Nerve Allografts

- Harvest nerve tissue (e.g., sciatic nerve) and decellularize using a validated protocol involving detergents, enzymes, and washes to remove immunogenic cellular material while preserving the basal lamina structure.

- Sterilize the decellularized allografts using gamma irradiation and store in PBS at 4°C until use.

Step 2: MSC Culture and Optional Differentiation

- Isolate MSCs from a relevant source (e.g., rat adipose tissue or human bone marrow).

- Culture MSCs in growth medium (e.g., α-MEM supplemented with 5% platelet lysate and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin).

- For differentiation into Schwann cell-like cells (optional):

- Upon reaching 70-80% confluence, replace the growth medium with a differentiation cocktail containing Forskolin, bFGF, PDGF-AA, and Neuregulin-1 ß1.

- Culture the cells in this medium for approximately 10-14 days, confirming differentiation via immunocytochemistry for markers like S100, GFAP, and p75 NTR [27].

Step 3: Dynamic Seeding of MSCs onto Allografts

- Trypsinize the undifferentiated or differentiated MSCs and resuspend them in growth medium. A typical seeding density is 1 x 10^6 cells in 10 mL of medium per graft [27].

- Place a single decellularized nerve allograft into a conical tube containing the cell suspension.

- Secure the tube on a bioreactor rotator and place it in an incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) for 12 hours to allow for dynamic, uniform cell adhesion.

- After rotation, remove the seeded graft from the tube. The graft is now ready for immediate implantation.

Signaling Pathways in Tissue-Specific Stem Cell Niches

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways and cellular crosstalk within a stem cell niche supported by tissue-specific dECM. The dECM provides a complex scaffold that presents specific signals to resident or transplanted stem cells, guiding their fate.

Diagram 1: Stem Cell Niche Signaling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation with dECM requires specific reagents and materials. The following table lists key solutions used in the protocols and literature cited herein.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for dECM and Stem Cell Work

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Protocols / Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Ionic detergent for effective cell lysis and removal during tissue decellularization. | Used in liver dECM protocol for decellularization [25]. |

| Pepsin | Proteolytic enzyme used to digest the solid dECM matrix into a liquid pre-gel form for bioink. | Used to solubilize liver dECM in 0.1M HCl [25]. |

| Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1 (SDF-1/CXCL12) | Key chemokine for stem cell homing; binds to CXCR4 receptor on MSCs. | Critical for MSC homing to injured liver; its receptor CXCR4 can be overexpressed to enhance engraftment [29] [30]. |

| Differentiation Cocktail (Forskolin, bFGF, PDGF-AA, NRG-1β1) | A defined set of factors to induce MSC differentiation into a Schwann cell-like phenotype in vitro. | Used to pre-differentiate MSCs before seeding onto nerve allografts [27]. |

| Platelet Lysate | A source of growth factors and proteins used as a serum supplement for robust MSC culture. | Component of the growth medium for expanding MSCs [27]. |

| Decellularized Nerve Allograft | Provides a natural, conductive scaffold for axonal regeneration in peripheral nerve defects. | Serves as a physical scaffold and cell carrier for MSCs in rat sciatic nerve model [26] [27]. |

The evidence underscores a clear principle: tissue-specific dECM provides a uniquely advantageous microenvironment that cannot be replicated by generic or synthetic scaffolds alone. Liver dECM bioink enhances hepatocyte function and stem cell differentiation, while nerve-specific dECM scaffolds seeded with MSCs create a permissive environment for functional axonal regeneration. The provided protocols and analytical tools offer a foundation for researchers to further explore and harness the distinct biological cues of cardiac and other tissue-specific dECMs. Advancing this field requires a commitment to standardized decellularization, rigorous characterization of ECM composition, and validation in physiologically relevant models to fully unlock the potential of dECMs in regenerative medicine and drug development.

From Protocol to Practice: Decellularization Techniques and Recellularization Strategies for Functional Tissue Engineering

Within the field of regenerative medicine, decellularized extracellular matrix (ECM) has emerged as a pivotal biological scaffold for stem cell engraftment research. The process of decellularization aims to remove all cellular material from native tissues while preserving the intricate composition and three-dimensional architecture of the native ECM [31] [10]. This resulting acellular scaffold provides a biomimetic niche that is critical for supporting the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of transplanted stem cells [24] [22]. The efficacy of a decellularization protocol is therefore measured not only by its removal of immunogenic cellular components but also by its retention of the ECM's biological and mechanical properties, which are essential for creating a hospitable microenvironment for stem cell engraftment [3] [32].

Decellularization techniques are broadly categorized into physical, chemical, and enzymatic methods, each with distinct mechanisms, advantages, and drawbacks. The selection and optimization of these methods are crucial, as they directly impact the scaffold's ability to support subsequent stem cell repopulation [3] [10]. Physical methods often serve as an initial step to lyse cells, while chemical and enzymatic agents are employed to remove cellular debris and nuclear material. However, the agents used, particularly ionic detergents, can disrupt ECM integrity, thereby diminishing the scaffold's bioactivity and potential for successful stem cell therapy [31] [33]. This document provides a comparative analysis of decellularization agents and detailed protocols, framed within the context of enhancing stem cell engraftment on decellularized tissues.

Comparative Analysis of Decellularization Agents

The choice of decellularization agent significantly influences the final scaffold's properties. The following sections and tables provide a detailed comparison of the various agents used.

Physical Methods

Physical methods are frequently used as a preliminary step to disrupt cell membranes and facilitate the penetration of subsequent chemical or enzymatic agents [3] [34]. They offer the advantage of avoiding residual toxic chemicals, which is beneficial for maintaining scaffold biocompatibility [31].

Table 1: Physical Decellularization Methods

| Method | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantages | Key Limitations/Damage | Typical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freeze-Thaw (Thermal Shock) | Forms intracellular ice crystals that disrupt cell membranes [3] [34]. | Maintains mechanical properties; minimizes ECM disruption; reduces immune response [31] [3]. | Incomplete decellularization alone (up to 88% DNA may remain); ice crystal size must be controlled to prevent ECM damage [3] [34]. | 8 cycles of freezing in N₂ (15 min) and thawing at 60°C (15 min) [31]. |

| Ultrasound/Sonication | Applies mechanical sound waves to lyse cell walls [31] [3]. | Even distribution; effective for cell lysis and debris removal [31] [3]. | Standardized parameters not established; potential for ECM damage if over-applied [34]. | 70% power, 20 kHz wavelength, pulsed for 45 min [31]. |

| High Hydrostatic Pressure (HHP) | Applies extreme pressure (hundreds of MPa) to disrupt cell ultrastructure [3]. | Reduces decellularization time; retains ECM structure and immunocompatibility [3]. | Can induce ice crystal damage; requires combination treatments; limited to less compact tissues [3]. | ~980 MPa for 10 min [3]. |

| Mechanical Agitation | Uses physical movement to dislodge cells and debris [34]. | Simple to implement; assists chemical and enzymatic penetration [34]. | Aggressive agitation can damage ECM architecture; speed and time are tissue-dependent [34]. | Use of orbital shakers or rollers; parameters vary [34]. |

Chemical and Enzymatic Methods

Chemical and enzymatic agents are the workhorses of decellularization, responsible for solubilizing lipid membranes and degrading nucleic acids. Their efficacy and cytotoxicity are primary considerations for stem cell viability post-recellularization.

Table 2: Chemical and Enzymatic Decellularization Agents

| Agent Category | Specific Agent | Mechanism of Action | Impact on ECM & Stem Cell Engraftment | Residual DNA Post-Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Detergents | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) [10] [33] | Solubilizes lipid membranes and cytoplasmic components; disrupts DNA-protein interactions [10]. | High Disruption: Damages collagen integrity; significantly reduces GAGs and growth factors; detrimental to recellularization [31] [10] [33]. | Highly effective removal, but can leave residual nuclear cages [31]. |

| Non-Ionic Detergents | Triton X-100 [10] [33] | Disrupts lipid-lipid and lipid-protein interactions, but not protein-protein bonds [10]. | Moderate Disruption: Less effective cell lysis; tissue-dependent efficacy; better preservation of ECM structure than SDS [10]. | Less effective than SDS; may require combination with other agents [10]. |

| Zwitterionic Detergents | CHAPS [10] | Combines properties of ionic and non-ionic detergents [10]. | Lower Disruption: Better preservation of ECM structure and composition compared to ionic detergents [10]. | Effective cell removal while preserving ECM [10]. |

| Enzymes | Trypsin [31] [33] | Cleaves peptide bonds, disrupting transmembrane proteins and cell-ECM adhesion [31]. | Can damage ECM proteins like collagen and GAGs if overused; concentration and time critical [31] [33]. | Effective at removing cellular proteins, but does not degrade DNA. |

| Nucleases | DNase, RNase [33] | Degrades nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) after cell lysis. | Essential for removing immunogenic genetic material; minimal direct impact on ECM proteins [33]. | Critical for reducing DNA to negligible levels [33]. |

| Hyper/Hypotonic Solutions | Sterile Water [35], 10% NaCl [35] | Induces osmotic shock to lyse cells. | Can effectively decellularize thin membranes like anterior lens capsules with good ECM preservation [35]. | Effective for specific, thin tissues [35]. |

Detailed Decellularization Protocols

This section outlines specific, reproducible protocols that have been successfully employed for various tissues, with a focus on preserving ECM integrity for stem cell research.

This protocol highlights a chemical-free approach, ideal for generating highly biocompatible scaffolds.

- Tissue Preparation: Obtain fresh bovine tracheal cartilage. Remove adipose tissue and perichondrium, and cut into ~1 mm² fragments.

- Hypotonic Incubation: Immerse cartilage fragments in a hypotonic Tris-HCL solution (pH 8).

- Freeze-Thaw Cycles: Subject the tissues to eight cycles of freezing in liquid nitrogen for 15 minutes, followed by thawing at 60°C for 15 minutes.

- Ultrasonic Treatment: Place samples in PBS and sonicate using a homogenizer (e.g., BANDELIN SONOPULS HD 2070) at 70% power with a 20 kHz wavelength in pulse mode for 45 minutes.

- Enzymatic Wash: Immerse and agitate tissues in 0.25% trypsin for 24 hours in a shaker incubator, changing the solution every 8 hours.

- Final Wash and Storage: Wash samples thoroughly with PBS to remove debris. The decellularized scaffolds can be freeze-dried and stored at -20°C.

This protocol demonstrates the optimization of detergent and enzyme use to minimize ECM damage.

- Tissue Preparation: Acquire fresh porcine aortic or pulmonary valves.

- Detergent Wash: Treat valves with a non-ionic detergent, specifically Tergitol (a substitute for Triton X-100), for a specified duration. Note: This protocol intentionally omits harsh ionic detergents like SDS.

- Enzymatic Treatment: Incubate with a low concentration of trypsin to disrupt cell-ECM adhesion, followed by treatment with a high concentration of DNase and RNase to thoroughly degrade nucleic acids.

- Confirmation: DNA quantification should show a reduction to nearly untraceable levels. The valves should appear off-white, without shrinkage or swelling, and maintain mechanical properties equivalent to native valves.

Workflow Diagram of Decellularization Strategies

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting and combining decellularization methods to create an optimal scaffold for stem cell engraftment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key reagents and their critical functions in the decellularization and stem cell engraftment pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Decellularization and Recellularization Workflows

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Contextual Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tergitol | Non-ionic detergent for cell membrane disruption [33]. | An eco-friendly alternative to Triton X-100; reduces ECM damage [33]. |

| DNase & RNase | Enzymatic degradation of nucleic acids to minimize immunogenicity [33]. | High concentrations are crucial for reducing DNA to untraceable levels [33]. |

| Trypsin | Proteolytic enzyme for disrupting cell-ECM adhesion [31]. | Use lower concentrations to minimize damage to ECM proteins like collagen [31] [33]. |

| Perfluorocarbons (PFCs) | Oxygen carriers in recellularization scaffolds [24]. | Enhance stem cell survival post-transplantation by mitigating ischemic stress in the hostile microenvironment [24]. |

| Calcium Peroxide (CaO₂) | Solid peroxide for sustained oxygen release in scaffolds [24]. | Used in oxygen-generating systems to support cell viability prior to neovascularization [24]. |

| Sodium Chloride (10%) | Hypertonic solution for osmotic shock [35]. | Effective for decellularizing thin basement membranes (e.g., anterior lens capsules) with good ECM preservation [35]. |

| Tris-HCL Buffer | Common buffer for hypotonic solutions and maintaining pH [31]. | Used in physical decellularization protocols to create a hypotonic environment for cell lysis [31]. |

The strategic selection and combination of decellularization agents are paramount to producing scaffolds that are not only acellular but also functionally competent for stem cell engraftment. Physical methods provide a gentle foundation, while the careful choice of chemical and enzymatic agents—favoring non-ionic over ionic detergents and optimizing nuclease concentrations—is critical for preserving the bioactive ECM niche. The protocols and data summarized herein provide a framework for researchers to design decellularization strategies that maximize scaffold biocompatibility and bioactivity, thereby addressing a key challenge in regenerative medicine: the creation of a hospitable microenvironment for transplanted stem cells. Future efforts must focus on the standardization of these protocols and rigorous in vivo validation of the engraftment efficiency and functional outcomes of stem cells seeded on these optimized scaffolds.

In the field of regenerative medicine, decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) has emerged as a uniquely promising scaffold for stem cell engraftment research. Unlike synthetic alternatives, dECM preserves the natural microenvironment—a complex three-dimensional architecture of structural proteins, glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), and growth factors that are essential for guiding stem cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation [1] [2]. The process of decellularization removes cellular and immunogenic components from native tissues while aiming to preserve these critical ECM components [3] [36]. The success of this process fundamentally hinges on selecting the appropriate decellularization strategy, primarily categorized into perfusion-based and immersion-based techniques. The choice between these methods carries profound implications for the resulting scaffold's quality and its subsequent performance in stem cell engraftment studies. Perfusion decellularization, which involves circulating solutions through the native vasculature, is generally the method of choice for whole organs or thick tissues, as it achieves more uniform cell removal and better preservation of complex ECM architectures [37] [38]. In contrast, immersion decellularization, where tissues are simply submerged in detergent solutions with agitation, can be sufficient for thin or simple tissues but often struggles with scalability and completeness [14] [38]. This application note provides a structured comparison of these two foundational approaches, supported by quantitative data and detailed protocols, to guide researchers in selecting the optimal strategy for generating high-quality scaffolds conducive to stem cell research and engraftment.

Technical Comparison: Perfusion vs. Immersion Decellularization

The efficacy of a decellularization protocol is typically evaluated against three key criteria: the efficiency of cellular content removal, the preservation of essential ECM components, and the retention of mechanical and structural integrity. The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison between perfusion and immersion techniques based on these parameters.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Decellularization Efficacy: Perfusion vs. Immersion

| Evaluation Parameter | Perfusion Decellularization | Immersion Decellularization | Significance for Stem Cell Engraftment |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Removal (Residual DNA) | < 50 ng/mg of dry tissue [38]; as low as 3.7 ng/mg in optimized gravity-fed systems [38]. | Can exceed 200 ng/mg [38]; often fails to meet the sub-50 ng/mg benchmark [37]. | Residual DNA is highly immunogenic and can trigger a host immune response, jeopardizing stem cell survival and integration [36] [2]. |

| ECM Component Preservation | Superior retention of collagen, glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), and fibronectin [37] [38]. Architecture of delicate vascular networks is maintained [14]. | Significant loss of GAGs and other core ECM proteins due to prolonged detergent exposure [37]. Structure is often disrupted. | GAGs and fibrous proteins are crucial for binding growth factors and mediating stem cell adhesion, differentiation, and tissue remodeling [1] [23]. |

| Structural & Mechanical Integrity | Maintains original 3D organ architecture and vasculature; mechanical properties (tensile strength) closely match native tissue [37] [14]. | Often results in edema, disruption of ultrastructure, and loss of mechanical strength [37]. | A biomechanically matched scaffold provides the necessary physical cues for stem cell differentiation and functional tissue formation [36] [1]. |

| Uniformity of Decellularization | High uniformity throughout the entire organ scaffold, including the core [38]. | Often incomplete and non-uniform, with cellular remnants frequently found in the tissue core [38]. | A uniform scaffold ensures predictable stem cell behavior and integration throughout the entire construct, which is vital for engineering functional tissue. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decisive factors and outcomes when choosing between perfusion and immersion decellularization strategies.

Diagram 1: Decision Workflow for Decellularization Strategy Selection

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Gravity-Assisted Perfusion Decellularization for Whole Organs

This protocol describes a cost-effective and reproducible method for decellularizing whole organs, such as the liver, using gravity-driven flow instead of mechanical pumps. This approach has been shown to produce high-quality, acellular scaffolds with well-preserved ECM, ideal for subsequent stem cell engraftment studies [38].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Perfusion Decellularization

| Reagent/Solution | Concentration & Formula | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heparinized Saline | 15 UI/mL in PBS [14] | Pre-clotting flush; prevents coagulation in vasculature during harvest. | Ensures vascular patency for uniform detergent distribution. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | 1% (w/v) in dH₂O [14] [38] | Ionic detergent; efficiently lyses cells and solubilizes nuclear & cytoplasmic membranes. | Strong detergent that can damage ECM if overused; requires thorough washing [36] [2]. |

| Triton X-100 | 1% (v/v) in dH₂O or PBS [14] | Non-ionic detergent; disrupts lipid-lipid and lipid-protein bonds; helps rinse out SDS and cellular debris. | Gentler on ECM structure than SDS but less effective at nuclear removal [36] [2]. |

| Deionized Water (dH₂O) | N/A | Wash step; creates osmotic shock to lyse remaining cells. | |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | 1X | Final wash; removes residual detergents and prepares scaffold for storage or sterilization. | Extensive washing is critical to eliminate cytotoxic detergent traces [2]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Organ Harvest and Cannulation: Excise the target organ (e.g., liver) with utmost care to preserve the main vascular pedicle (e.g., portal vein, inferior vena cava). Cannulate the primary artery or vein with appropriate tubing. Gently flush with 500 mL of ice-cold Heparinized Saline to remove blood and prevent clotting [14] [38].

- Gravity-Driven Perfusion Setup: Connect the cannula to a solution reservoir elevated 60-100 cm above the organ. This height provides a hydrostatic pressure of approximately 44-74 mmHg, which is sufficient for gentle perfusion without causing ECM damage [38].

- Decellularization Cycle: Perfuse the organ sequentially with the following solutions at a controlled flow rate (e.g., 5-10 mL/min) at room temperature:

- 1% SDS Solution: Perfuse for approximately 24-48 hours, or until the organ becomes translucent and no visible cellular material is flushed out. This step is responsible for the bulk of cell lysis [38].

- dH₂O Wash: Perfuse for 6-12 hours to remove SDS and induce osmotic shock.

- 1% Triton X-100 Solution: Perfuse for 12-24 hours to remove residual SDS and lipid debris.

- PBS Wash: Perfuse extensively for 24-48 hours to ensure complete removal of all detergent traces [38].

- Sterilization and Storage: The resulting acellular scaffold can be sterilized using 0.1% Peracetic Acid [1] or gamma irradiation [3]. Scaffolds should be stored in PBS at 4°C for short-term use or frozen for long-term preservation.

Protocol 2: Immersion-Based Decellularization for Simple Tissues

This protocol is suitable for thin tissues (e.g., dermis, pericardium, small intestine submucosa) or tissue slices where perfusion is not feasible. While simpler, it requires careful optimization to minimize ECM damage [14].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Tissue Preparation: Aseptically dissect the tissue into thin sections (e.g., 1-2 mm thick) to facilitate detergent penetration. The surface area to volume ratio is critical for success [37] [2].

- Agitation-Based Decellularization: Immerse the tissue samples in a large volume (typically 10:1 v/w) of decellularization solutions under constant agitation on an orbital shaker. Change solutions at intervals as follows:

- Hypotonic/Tris Buffer: Agitate for 24 hours.

- Detergent Solution (SDS or SDC): Agitate for 48-72 hours. Monitor tissue transparency. Agitation is crucial for forcing detergents into the tissue matrix [37] [2].

- DNase/RNase Solution (Optional): Incubate in an enzymatic solution (e.g., 100 U/mL DNase) for 6-12 hours to digest residual nucleic acid fragments [36].

- Wash Steps: Rinse repeatedly with dH₂O and PBS over 48-72 hours to remove cellular debris and detergents [37].

- Termination and Storage: Once acellular, store the scaffolds in PBS or sterilize as described in the perfusion protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below expands on the key reagents used in decellularization, detailing their mechanisms and trade-offs.

Table 3: Essential Reagent Toolkit for Decellularization Protocols

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Mechanism of Action | Advantages & Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Detergents | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), Sodium Deoxycholate (SDC) | Powerful solubilization of cell membranes and nuclear material by disrupting hydrophobic-hydrophilic bonds [36] [2]. | Adv: Highly effective for dense tissues. Disadv: Harsh; can denature ECM proteins (e.g., collagen) and deplete GAGs [36] [1]. |

| Non-Ionic Detergents | Triton X-100, Tween-20 | Disrupts lipid-lipid and lipid-protein interactions; gentler on ECM structure [37] [36]. | Adv: Better preservation of ECM ultrastructure and growth factors. Disadv: Less effective for nuclear material removal; may require combination therapies [37] [36]. |

| Zwitterionic Detergents | CHAPS | Combines properties of ionic and non-ionic detergents; effective at disrupting protein-protein interactions [37] [36]. | Adv: Can maintain structural ECM proteins. Disadv: May disrupt the basement membrane and leave cytoplasmic proteins [36]. |

| Enzymatic Agents | Trypsin, DNase, RNase | Target specific components: Trypsin cleaves peptide bonds, while nucleases digest genetic material [36] [2]. | Adv: Highly specific. Disadv: Trypsin can damage ECM if overused; typically used as a supplement to detergent methods [36]. |

| Acids & Bases | Peracetic Acid (PAA), Ammonium Hydroxide | Solubilize cytoplasmic components and degrade nucleic acids; PAA also provides sterilization [1] [2]. | Adv: Effective for sterilization and nucleic acid removal. Disadv: Can damage ECM architecture and alter mechanical properties (e.g., increase stiffness) [36] [1]. |

Strategic Application for Stem Cell Research

The ultimate success of a decellularized scaffold in stem cell engraftment research depends on its bioactivity and capacity to direct cell fate. The ECM is not a passive scaffold but an active signaling platform. The diagram below illustrates how a well-preserved dECM influences stem cell behavior through key signaling pathways.

Diagram 2: dECM-Stem Cell Crosstalk Signaling Pathways

As shown, a high-quality scaffold orchestrates stem cell behavior through multiple synchronized cues:

- Adhesion and Survival: Structural proteins like fibronectin and laminin promote stem cell adhesion via integrins, activating pro-survival pathways such as PI3K/Akt and MAPK [1].

- Differentiation: GAGs like heparan sulfate bind and present growth factors (e.g., FGF, BMP) to their receptors, activating signaling cascades that drive lineage-specific differentiation [1] [23].

- Mechanotransduction: The physical stiffness and topography of the ECM are sensed by cells through the cytoskeleton, regulating fate decisions via effectors like YAP/TAZ [1].

Therefore, the choice of decellularization method directly impacts this signaling potential. Perfusion, by better preserving the native ECM composition and 3D architecture, provides a more holistic and potent microenvironment for guiding stem cell engraftment and functional tissue formation compared to immersion [37] [38].

Within regenerative medicine and stem cell research, the scaffold serves as a critical cornerstone, providing the essential three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment that directs cell fate. For research focused on decellularized tissues for stem cell engraftment, the physical format of the scaffold is a primary determinant of its experimental utility and eventual therapeutic application. These formats—ranging from intact preserved 3D structures to versatile powders, customizable hydrogels, and advanced bioinks for 3D printing—each offer distinct advantages and limitations for directing stem cell behavior.

This document provides detailed application notes and standardized protocols for these key scaffold formats. The guidance is designed to equip researchers with the practical methodologies necessary to effectively utilize these materials in studies aimed at understanding and enhancing stem cell engraftment, proliferation, and differentiation.

The selection of an appropriate scaffold format is guided by the specific requirements of the stem cell research project, including the desired level of structural mimicry, need for customization, and the mode of delivery. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and primary applications of each format to aid in selection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Scaffold Formats for Stem Cell Research

| Scaffold Format | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages | Typical Applications in Stem Cell Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preserved 3D Structures [39] [40] | Intact, organ-scale architecture; Native biomechanical cues. | High biological fidelity; Preserved native vasculature. | Limited customizability; Potential for immunogenicity. | Whole-organ regeneration models; Studying cell-ECM interactions in a native context. |

| Powders [41] | Lyophilized and milled dECM; Highly soluble. | Versatile application; Ease of storage and handling; Can be formed into other formats. | Lacks macroscopic structure; Requires processing for 3D culture. | Supplementation of 2D cultures; Formulation of hydrogels and bioinks; Injectable cell delivery systems. |

| Hydrogels [42] [43] | Hydrated polymer networks; Tunable mechanical properties. | High biocompatibility; Can be injected or cast in situ. | Often requires chemical cross-linking; Limited mechanical strength. | 3D stem cell encapsulation; Differentiation studies; Soft tissue regeneration models. |

| Bioinks [42] [44] | Hydrogels optimized for 3D printing; Often cell-laden. | High architectural control; Customizable, complex geometries. | Requires specialized bioprinting equipment; Can exert shear stress on cells. | Fabrication of complex, patient-specific tissue constructs; High-throughput tissue modeling. |

Detailed Protocols for Scaffold Format Application

Protocol: Preparation and Recellularization of Preserved 3D Decellularized Scaffolds

Application Note: This protocol is fundamental for leveraging the full biological complexity of native organ structures for stem cell engraftment research, such as in studies involving decellularized liver, heart, or kidney scaffolds [40].

Materials & Reagents:

- Decellularized organ scaffold (e.g., rodent liver)

- Recellularization cell suspension (e.g., stem cells)

- Bioreactor system with perfusion capabilities

- Sterile PBS

- Cell culture medium

Procedure:

- Scaffold Sterilization and Hydration: Subject the decellularized scaffold to gamma irradiation or peracetic acid treatment. Rinse thoroughly with sterile PBS and hydrate in culture medium for 24-48 hours prior to recellularization [39].

- Cell Preparation: Prepare a high-density suspension (e.g., 1-10 x 10^6 cells/mL) of the stem cell population intended for engraftment.

- Perfusion Recellularization:

- Cannulate the scaffold's primary vasculature (e.g., portal vein for liver).

- Connect the cannula to a perfusion bioreactor.

- Slowly perfuse the cell suspension through the vascular network at a low flow rate (e.g., 1-3 mL/min) to facilitate cell attachment and distribution [40].

- Gradually increase flow rates over several days to condition the cells to fluid shear stress.

- Static Maturation: Following initial perfusion seeding, the construct may be maintained under static or low-flow conditions in a bioreactor to promote further cell engraftment, proliferation, and functional maturation for up to several weeks.

- Assessment: Analyze cell viability, distribution (via histology), and markers of differentiation and function (e.g., albumin secretion for hepatocytes, contractile proteins for cardiomyocytes).

Protocol: Fabrication and Use of dECM Hydrogels

Application Note: dECM hydrogels provide a biocompatible, bioactive environment ideal for 3D stem cell culture and soft tissue engineering, balancing biological cues with practical handling [41].

Materials & Reagents:

- dECM in powder form

- Pepsin

- Dilute acidic solution (e.g., 0.1M HCl)

- Neutralizing solution (e.g., 0.1M NaOH)

- PBS and cell culture medium

- Stem cells for encapsulation

Procedure:

- Digestion: Suspend dECM powder at a concentration of 10-30 mg/mL in a pepsin solution (0.1 mg/mL in 0.1M HCl). Stir continuously at 4°C for 48-72 hours until a viscous, homogeneous solution is formed.

- Neutralization and Gelation:

- Neutralize the pre-gel solution on ice using 0.1M NaOH and pre-chilled PBS (10X concentration). The optimal ratio is typically 8:1:1 (pre-gel: PBS: NaOH). Keep the solution on ice to prevent premature gelling.

- To encapsulate cells, mix the neutralized pre-gel with a cell suspension to achieve the desired final cell density.

- Pipette the cell-pregel mixture into the desired cultureware and incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes to induce thermogelation into a solid hydrogel [41].

- Culture and Analysis: After gelation, carefully overlay the hydrogel with cell culture medium. Refresh the medium regularly and assess stem cell viability, morphology (e.g., via phalloidin staining), and differentiation (via immunocytochemistry for lineage-specific markers).

Protocol: 3D Bioprinting with dECM-Based Bioinks

Application Note: This protocol enables the fabrication of complex, architecturally defined constructs for creating sophisticated stem cell niche models or tissue grafts [42] [44].

Materials & Reagents:

- dECM-based bioink (prepared as in Protocol 3.2)

- Support bath or crosslinking agent (e.g., CaCl₂ for alginate-blended inks)

- Extrusion-based 3D bioprinter

- Sterile printing substrates (e.g., glass coverslips, multi-well plates)

Procedure:

- Bioink Preparation and Cell Loading: Prepare a dECM bioink as described in Protocol 3.2, ensuring viscosity is appropriate for printing. Mix the neutralized, ice-cold bioink with a stem cell suspension to create a cell-laden bioink. Maintain the bioink on ice throughout the printing process to prevent clogging.

- Printer Setup: Load the cell-laden bioink into a sterile printing cartridge. Fit the cartridge with a nozzle of appropriate diameter (e.g., 22G-27G). Calibrate the printer for the printing surface.

- Printing Parameters: Set the printing pressure and speed empirically. Typical pressures range from 20-700 kPa and speeds from 1-20 mm/s, depending on the bioink viscosity and nozzle size [45] [44]. Higher pressures and smaller nozzles increase shear stress, which can compromise cell viability.

- Cross-linking and Post-Printing Culture:

- For pure dECM bioinks, the primary cross-linking mechanism is thermal gelation at 37°C.

- For composite bioinks (e.g., with alginate), immediate post-printing immersion in a cross-linking solution (e.g., 100mM CaCl₂) may be required to stabilize the structure.

- After printing and cross-linking, transfer the constructs to an incubator and culture under standard conditions, with regular medium changes.

Table 2: Key Parameters for Extrusion-based Bioprinting of Hydrogel Bioinks

| Parameter | Typical Range | Impact on Print Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Nozzle Diameter | 150 - 410 μm (27G - 22G) | Smaller diameter improves resolution but increases shear stress. |

| Printing Pressure | 20 - 700 kPa | Must be optimized for specific bioink viscosity to ensure continuous flow. |

| Print Speed | 1 - 20 mm/s | Must be synchronized with flow rate for consistent filament deposition. |

| Bioink Viscosity | Shear-thinning properties | High viscosity improves shape fidelity but requires higher extrusion pressure. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials