Disease Modeling with Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: From Fundamentals to Future Therapies

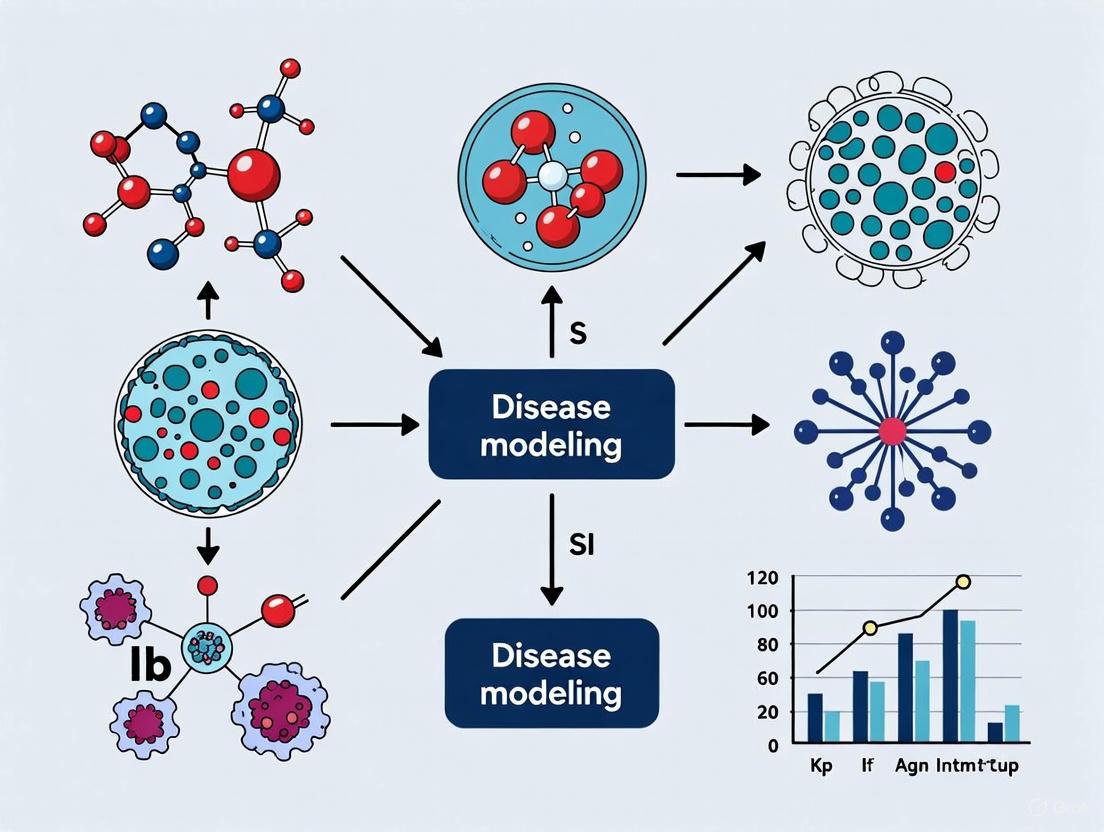

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are revolutionizing disease modeling and drug discovery.

Disease Modeling with Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: From Fundamentals to Future Therapies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are revolutionizing disease modeling and drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of iPSC technology, details advanced methodological applications from 2D cultures to 3D organoids, addresses key challenges such as cellular immaturity and technical variability, and validates the platform through comparisons with traditional models. By synthesizing the latest research, this review highlights the transformative potential of iPSCs in creating patient-specific disease models, enhancing drug screening accuracy, and paving the way for personalized regenerative therapies.

The iPSC Revolution: From Somatic Cells to Patient-Specific Disease Models

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) represent one of the most significant breakthroughs in modern regenerative medicine and biomedical research. These cells are generated by reprogramming adult somatic cells back to a pluripotent state, mimicking the key characteristics of embryonic stem cells (ESCs), including unlimited self-renewal and the capacity to differentiate into any cell type in the body [1]. The development of iPSC technology has provided researchers with an unprecedented tool for disease modeling, drug discovery, and the development of cell-based therapies, all within a patient-specific context [2] [3].

Framed within a broader thesis on disease modeling, the ability to reprogram somatic cells to pluripotency enables the creation of human-specific disease models that recapitulate pathological processes in vitro. This technical guide explores the core principles, molecular mechanisms, and methodologies underlying somatic cell reprogramming, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive foundation for applying iPSC technology to human disease research.

Historical Foundations and Key Discoveries

The conceptual foundation for cellular reprogramming was established through pioneering work in the mid-20th century. In 1962, John Gurdon demonstrated that the nucleus from a differentiated somatic cell of Xenopus laevis could be reprogrammed to a totipotent state when transplanted into an enucleated egg, giving rise to germline-competent organisms [1] [4]. This seminal somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) experiment proved that the genetic material in differentiated cells remains intact and can be reset to an embryonic state, challenging the prevailing view that cell differentiation was irreversible [5] [1].

The subsequent isolation of mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in 1981 by Evans and Kaufman and human ESCs by James Thomson in 1998 provided critical reference points for understanding pluripotency [5] [1]. Cell fusion experiments between ESCs and somatic cells further demonstrated that pluripotent cells contain factors capable of reprogramming somatic nuclei [5] [1].

The direct reprogramming breakthrough came in 2006 when Shinya Yamanaka and Kazutoshi Takahashi identified a combination of four transcription factors—Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM)—that could reprogram mouse fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells [3] [1]. This discovery, for which Yamanaka received the Nobel Prize in 2012, demonstrated that pluripotency could be induced without eggs or embryos, opening new avenues for patient-specific stem cell generation [3].

Molecular Mechanisms of Reprogramming

The Core Pluripotency Network

Reprogramming somatic cells to pluripotency involves reactivating the endogenous network of pluripotency genes while silencing somatic cell programs. At the heart of this network are key transcription factors that form an interconnected autoregulatory circuit:

- OCT4 (POU5F1): A POU-domain transcription factor essential for establishing and maintaining pluripotent identity [6] [1].

- SOX2: A high-mobility group (HMG) box transcription factor that partners with OCT4 to regulate many pluripotency-associated genes [6].

- NANOG: A homeodomain transcription factor that helps stabilize the pluripotent state by activating self-renewal genes and repressing differentiation pathways [6].

These core factors bind to and activate each other's promoters, creating a self-sustaining regulatory loop that maintains cells in a pluripotent state [6]. Additional ancillary factors including KLF4, c-MYC, LIN28, and REX1 further support and stabilize the pluripotency network [6] [1].

Epigenetic Remodeling During Reprogramming

Reprogramming requires extensive epigenetic remodeling to erase somatic cell memory and establish a pluripotent epigenome. This process involves:

- DNA demethylation: Active and passive removal of methylation marks from promoter regions of pluripotency genes like OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG [4].

- Histone modification: Changes in histone marks including increased H3K4me3 and H3K27ac at enhancers and promoters of pluripotency genes, and decreased H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 repressive marks [4].

- Chromatin reorganization: Transition from closed, heterochromatic regions to more open, accessible chromatin configurations permissive for transcription [1] [4].

- X chromosome reactivation: In female cells, reactivation of the somatically silenced X chromosome [4].

Recent research has identified factors such as Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) that may facilitate active DNA demethylation during reprogramming [5].

Phased Reprogramming Process

Reprogramming follows a sequential, multi-phase process characterized by distinct molecular and cellular events:

Figure 1: The phased process of somatic cell reprogramming showing transition from stochastic early events to deterministic late-phase events.

- Initiation Phase: Characterized by rapid proliferation, metabolic changes, and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), during which somatic genes are silenced and early pluripotency-associated genes show stochastic activation [1] [4].

- Maturation Phase: Progressive activation of pluripotency factors with ongoing epigenetic remodeling; cells begin to resemble ESCs morphologically but remain dependent on transgene expression [4].

- Stabilization Phase: Establishment of a self-sustaining pluripotency network with endogenous OCT4 and NANOG expression; cells become independent of exogenous factors and acquire stable pluripotency [4].

Single-cell analyses have revealed that the early phase is highly stochastic, with only a small fraction of cells successfully transitioning to the later, more deterministic phases where the core pluripotency network becomes stabilized [4].

Reprogramming Methodologies

Transcription Factor-Based Approaches

Various methods have been developed to deliver reprogramming factors to somatic cells, each with distinct advantages and limitations for research and clinical applications:

Table 1: Comparison of primary reprogramming methodologies

| Method | Mechanism | Efficiency | Genomic Integration | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral/Lentiviral | Integrates OSKM genes into host genome | 0.1-1% | Yes (permanent) | Basic research, proof-of-concept studies [3] [1] |

| Sendai Virus | RNA virus replicating in cytoplasm | 0.1-1% | No (transient) | Clinical applications, disease modeling [3] |

| Episomal Vectors | Non-integrating plasmid DNA | 0.001-0.1% | No | Clinical-grade iPSC generation [3] |

| Synthetic mRNA | Direct delivery of reprogramming factor mRNA | 1-4% | No | Clinical applications, high efficiency requirements [3] |

| Protein Transduction | Cell-penetrating reprogramming proteins | <0.001% | No | Applications requiring minimal genetic manipulation [3] |

Chemical Reprogramming

Small-molecule approaches offer a promising alternative to genetic reprogramming methods. Fully chemical reprogramming of murine fibroblasts using seven small-molecule compounds was first achieved in 2013, and similar approaches for human cells were subsequently developed [7] [1]. Chemical reprogramming involves three key molecular events:

- Erasure of somatic cell identity through disruption of fibroblast-specific programs

- Induction of an intermediate plastic state with similarities to regenerative progenitor cells

- Establishment of pluripotency through activation of the core pluripotency network [7]

This approach provides advantages including temporal control, reduced safety concerns, and potential for standardization, making it particularly attractive for clinical applications [7].

Alternative Nuclear Reprogramming Strategies

Beyond factor-based reprogramming, two historical methods demonstrate alternative approaches to resetting cellular identity:

- Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT): Transfer of a somatic nucleus into an enucleated oocyte, utilizing the oocyte's cytoplasmic factors to reprogram the somatic genome to totipotency [5] [1].

- Cell Fusion: Fusion of somatic cells with pluripotent stem cells (ESCs, EGCs, or ECs) generates hybrid cells where somatic nuclei are reprogrammed by trans-acting factors from the pluripotent partner [5].

While these methods have been instrumental in demonstrating nuclear plasticity, they present technical and ethical challenges that limit their application in disease modeling and regenerative medicine [5].

Experimental Protocols for iPSC Generation

Standard Fibroblast Reprogramming Protocol

The following protocol outlines a standard method for generating iPSCs from human dermal fibroblasts using non-integrating episomal vectors:

Day 0: Plating Fibroblasts

- Plate early-passage (P3-P6) human dermal fibroblasts at 5×10^4 cells per well in a 6-well plate in fibroblast medium (DMEM + 10% FBS + 1% GlutaMAX + 1% NEAA)

- Ensure cells are 70-80% confluent at time of transfection [3]

Day 1: Transfection

- Transfect fibroblasts with 1-2 μg of episomal vectors encoding OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, L-MYC, LIN28, and p53 shRNA using an appropriate transfection reagent

- Include fluorescent marker plasmid to monitor transfection efficiency [3]

Day 2: Medium Change

- Replace transfection medium with fresh fibroblast medium

Days 3-6: Transition to Pluripotency Medium

- Gradually transition cells to essential 8 (E8) medium or mTeSR1 pluripotency medium

- Continue daily medium changes [3]

Days 7-21: Emergence of iPSC Colonies

- Continue daily changes with pluripotency medium

- iPSC colonies typically begin to appear between days 14-28

- Monitor for colonies with sharp borders, high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, and prominent nucleoli [3]

Days 21-28: Colony Picking

- Manually pick well-defined iPSC colonies using a pipette tip or sterile needle

- Transfer colonies to Matrigel or laminin-521-coated plates with mTeSR1 medium containing 10 μM Y-27632 ROCK inhibitor [3]

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMC) Reprogramming

For PBMC reprogramming, a less invasive somatic cell source:

Day -4: PBMC Isolation and Activation

- Isolate PBMCs from whole blood using Ficoll density gradient centrifugation

- Culture PBMCs in ImmunoCult T Cell Activator medium for 3 days to stimulate proliferation [3]

Day 0: Transfection

- Transfect 1×10^5 activated PBMCs with synthetic mRNA encoding OSKM factors using lipid-based transfection reagent

- Repeat transfections daily for 12-16 days to maintain reprogramming factor expression [3]

Days 5-20: Colony Formation

- Transfer transfected cells to Matrigel-coated plates between days 5-7

- Continue daily mRNA transfections until colonies emerge

- Change medium daily with mTeSR1 supplemented with 100 ng/mL B18R protein to enhance mRNA transfection efficiency [3]

Advanced Genome Engineering in iPSCs

Recent advances in prime editing technology enable precise genetic modifications in iPSCs with reduced off-target effects compared to conventional CRISPR-Cas9 systems. Optimized prime editing in hPSCs involves:

- Stable genomic integration of prime editors via piggyBac transposon system for sustained expression

- Use of enhanced promoters (CAG) for high-level expression of prime editor components

- Lentiviral delivery of pegRNAs (prime editing guide RNAs) ensuring robust, ubiquitous expression [8]

This optimized system has achieved editing efficiencies of up to 50% in human pluripotent stem cells in both primed and naïve states, enabling precise disease modeling through introduction of patient-specific mutations [8].

Table 2: Essential research reagents for somatic cell reprogramming and iPSC culture

| Category | Specific Reagents | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM) | Core transcription factors inducing pluripotency | Initial fibroblast reprogramming [3] [1] |

| Alternative Factors | NANOG, LIN28 | Enhance reprogramming efficiency | Human iPSC generation [1] |

| Culture Matrices | Matrigel, Laminin-521, Vitronectin | Extracellular matrix supporting pluripotency | Feeder-free iPSC culture [3] |

| Pluripotency Media | mTeSR1, Essential 8 (E8), StemFlex | Chemically defined media formulations | Maintenance of undifferentiated iPSCs [3] |

| Small Molecules | Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor), SB431542, PD0325901 | Enhance survival and reprogramming efficiency | Improving clone recovery, supporting reprogramming [9] [3] |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-OCT4, Anti-NANOG, Anti-SSEA-4, Anti-TRA-1-60 | Detect pluripotency markers | Immunocytochemistry, flow cytometry [3] |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, Prime Editors, piggyBac transposon | Genetic modification of iPSCs | Disease modeling, gene correction [8] |

Quality Control and Characterization

Rigorous quality control is essential to confirm successful reprogramming and pluripotent status:

- Pluripotency Marker Expression: Assess by immunocytochemistry (OCT4, NANOG, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60) and flow cytometry (>85% positive for pluripotency markers) [3]

- Trilineage Differentiation Potential: Demonstrate in vitro differentiation into ectoderm (neurons, glia), mesoderm (cardiomyocytes, adipocytes), and endoderm (hepatocytes, pancreatic cells) [3]

- Karyotype Analysis: Verify genomic integrity through G-band karyotyping or SNP arrays [3]

- Pluripotency Gene Expression: Confirm by RT-PCR analysis of endogenous OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG expression [3]

- Teratoma Formation: Assess in vivo differentiation potential by subcutaneous injection into immunodeficient mice, with subsequent histological confirmation of three germ layers [3]

Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

The reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency has revolutionized approaches to studying human diseases. iPSC-based disease models offer several key advantages:

- Patient-Specific Models: iPSCs derived from patients with genetic disorders retain the disease-causing mutations, enabling modeling of monogenic and complex diseases in a human genetic background [3] [1]

- Differentiation into Affected Cell Types: Disease-specific iPSCs can be differentiated into cell types affected in the disorder, including neurons, cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, and others [3]

- Platform for Drug Screening: iPSC-derived cells provide human-relevant platforms for compound screening, toxicity testing, and drug development [3] [1]

- Pathogenesis Studies: Enable investigation of disease mechanisms and progression through isogenic pairs (patient-specific vs. gene-corrected iPSCs) [3]

Key signaling pathways and transcriptional networks are reactivated during the reprogramming process, which can be visualized through the following pathway diagram:

Figure 2: Key molecular and cellular events in somatic cell reprogramming, showing how OSKM factors trigger multiple parallel processes that converge on pluripotency establishment.

Neurodegenerative Disease Modeling

iPSCs have been particularly valuable for modeling neurodegenerative disorders, which are often challenging to study due to limited access to affected human tissues:

- Alzheimer's Disease: Patient-specific iPSCs differentiated into neurons and glia recapitulate disease hallmarks including tau hyperphosphorylation and β-amyloid deposition [3]

- Parkinson's Disease: iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons model degeneration of substantia nigra neurons and reveal the pathogenic role of α-synuclein aggregation [3]

- Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): iPSC-derived motor neurons enable identification of disease biomarkers and screening of therapeutic compounds [3]

Cardiovascular Disease Modeling

iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes have advanced the study of cardiac disorders:

- Arrhythmogenic Disorders: Modeling of congenital arrhythmias linked to ion channel mutations (e.g., KCNQ1 mutations) [3]

- Heart Failure: Patient-specific cardiomyocytes enable drug screening and mechanistic studies [3]

- Myocardial Injury: iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells explored for regenerative transplantation strategies [3]

The reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency represents a transformative technology with profound implications for disease modeling and therapeutic development. The core principles outlined in this technical guide—from molecular mechanisms to practical methodologies—provide researchers with the foundation needed to leverage iPSC technology effectively. As reprogramming methods continue to advance, with improvements in efficiency, safety, and standardization, iPSC-based disease models will play an increasingly central role in elucidating disease mechanisms, screening therapeutic compounds, and developing personalized medicine approaches. The integration of precise genome editing technologies with increasingly complex differentiation protocols promises to further enhance the fidelity of iPSC-based disease models, accelerating the translation of basic research findings into clinical applications.

Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research by enabling the development of human-specific disease models that overcome fundamental limitations inherent in traditional animal models. While animal studies have provided valuable insights, critical physiological differences between species often hinder their ability to accurately recapitulate human disease pathophysiology and predict drug responses. iPSCs, generated by reprogramming adult human somatic cells to a pluripotent state, provide unprecedented access to patient-specific human cells for disease modeling, drug screening, and therapeutic development. This whitepaper examines the key scientific advantages of iPSC-based models over traditional approaches, details experimental methodologies for implementing these systems, and discusses how this technology is transforming preclinical research and drug development pipelines.

Traditional animal models have long served as the cornerstone of biomedical research, yet they present significant challenges for accurately modeling human diseases and predicting clinical outcomes. These limitations stem from fundamental biological differences between species that can profoundly impact disease manifestation and therapeutic responses.

Physiological and Genetic Disparities: Numerous species-specific differences limit the translational relevance of animal models. For example, murine models of Fanconi anemia fail to develop the spontaneous bone marrow failure that is the hallmark of the human disease, despite carrying the same genetic deficiencies [10]. The heart rates of humans and mice differ by approximately ten-fold, which can lead to significantly different consequences from similar arrhythmias [10]. Additionally, mice engineered to be trisomic for genome sections orthologous to the human Down syndrome critical region failed to recapitulate human cranial abnormalities or neurodegeneration commonly associated with Down syndrome [10].

Drug Development Challenges: These species-specific differences contribute directly to the high failure rates of drugs in clinical development. It is estimated that 27%, 14%, and 7% of drugs fail in clinical trials due to adverse effects on the heart, liver, and central/peripheral nervous systems, respectively [11]. These failures often result from the inability of animal models to fully predict human-specific toxicities and efficacies.

Table 1: Fundamental Limitations of Traditional Animal Models

| Limitation Category | Specific Examples | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological Differences | Ten-fold difference in heart rate between humans and mice; Different drug metabolism pathways | Poor prediction of human drug responses and toxicity |

| Genetic & Genomic Differences | Lack of conservation of gene order; Different gene expression patterns; Inbred genetic backgrounds | Failure to recapitulate human disease phenotypes |

| Developmental Differences | Different brain architecture; Varied tissue composition | Limited relevance for neurodevelopmental disorders and tissue engineering |

| Disease Manifestation | Fanconi anemia models don't develop bone marrow failure; Down syndrome models lack characteristic neurodegeneration | Incomplete disease modeling missing key pathological features |

Fundamental Advantages of iPSC-Based Disease Models

Human Biological Context

iPSC technology enables researchers to study disease mechanisms and test therapeutic interventions within an authentically human cellular context. By reprogramming somatic cells from patients, iPSCs retain the complete genetic background of the donor, including all polymorphisms, epigenetic modifications, and disease-associated mutations [1]. This human origin eliminates the confounding variables introduced by cross-species differences when extrapolating from animal models to human patients.

The capacity of iPSCs to differentiate into virtually any cell type provides access to otherwise inaccessible human tissues, particularly for diseases affecting internal organs like the brain and heart [11]. For neurological disorders, this advantage is particularly significant as human brain development, architecture, and function differ substantially from even our closest primate relatives. iPSC-derived neurons and glial cells maintain human-specific characteristics in culture, enabling researchers to study disease processes in relevant cell types [1].

Genetic Fidelity and Patient Specificity

iPSCs capture the complete genetic identity of the donor, enabling the creation of disease models with unprecedented genetic accuracy. This includes not only the primary genetic lesion responsible for a disease but also the complete genetic background that modifies disease expression and progression [10]. This genetic fidelity enables two complementary approaches to disease modeling:

- Forward genetics: Starting with patients exhibiting a disease phenotype, then generating iPSCs to identify genetic contributors [10]

- Reverse genetics: Introducing specific, predefined mutations into well-characterized iPSC lines to study their functional consequences [10]

This patient-specific approach is particularly valuable for studying complex diseases where multiple genetic factors contribute to pathogenesis, as well as for understanding the variable expressivity of monogenic disorders [1]. Additionally, iPSCs enable research on human-specific aspects of biology that cannot be modeled in other species, such as unique gene isoforms, non-coding RNAs, and epigenetic regulation mechanisms.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Disease Modeling Platforms

| Characteristic | Traditional Animal Models | iPSC-Based Human Models |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Context | Species-specific genome with limited human gene orthology | Complete human genetic background with patient-specific variations |

| Physiological Relevance | Limited by cross-species differences in physiology and metabolism | Human-specific cellular physiology and signaling pathways |

| Experimental Accessibility | Limited access to disease-relevant tissues, especially for neurological disorders | Unlimited access to any cell type through directed differentiation |

| Personalization Potential | Low - requires genetic engineering for each variant | High - naturally captures individual genetic diversity |

| Throughput for Drug Screening | Moderate to low throughput, high cost | High throughput, scalable format |

| Temporal Resolution | Limited ability to observe cellular dynamics in real-time | Real-time monitoring of disease processes in live cells |

Developmental Modeling Capability

iPSC differentiation protocols recapitulate key aspects of human development, enabling researchers to study disease processes across the developmental timeline [1]. This "disease in a dish" approach allows observation of pathological changes as they unfold, from early cellular dysfunction to late-stage degeneration. For neurodevelopmental disorders like autism spectrum disorders and early-onset schizophrenia, this provides unprecedented access to the initial stages of disease manifestation that would be impossible to observe in human patients [1].

The ability to generate three-dimensional organoids from iPSCs further enhances their developmental modeling capabilities. These self-organizing structures mimic the complex architecture and cellular diversity of developing human tissues, enabling more sophisticated studies of cell-cell interactions, tissue patterning, and organ-level dysfunction [1]. Cerebral organoids, for instance, have been used to model microcephaly and other developmental brain disorders, revealing disease-specific alterations in progenitor cell populations and cortical organization that could not be observed in animal models [1].

Experimental Implementation: Methodologies and Protocols

iPSC Generation and Characterization

Reprogramming Methodologies: The foundational step in establishing iPSC-based disease models is the reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Several well-established methods exist, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Sendai Virus Reprogramming: This non-integrating RNA virus method is widely applied due to its high efficiency (approximately 0.1% for both fibroblasts and peripheral blood mononuclear cells) and safety profile, as the virus does not enter the nucleus or integrate into the host genome [11]. The protocol involves transducing somatic cells with Sendai virus vectors carrying the reprogramming factors (typically OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC), followed by culture in pluripotent stem cell conditions until iPSC colonies emerge (typically 3-4 weeks for human cells) [11].

Integration-Free Methods: For clinical applications, non-viral methods such as episomal plasmids, synthesized RNAs, and recombinant proteins offer alternatives that eliminate potential viral vector concerns [11]. The mRNA reprogramming method involves repeated transfections of synthetic mRNAs encoding reprogramming factors, typically over a 2-3 week period, resulting in footprint-free iPSCs [11].

Comprehensive Characterization: Newly established iPSC lines must undergo rigorous quality control assessment to confirm pluripotency and genomic integrity before use in disease modeling. Standard characterization includes:

- Pluripotency Marker Expression: Immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry for surface markers (TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81) and intracellular transcription factors (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2) [11]

- Trilineage Differentiation Potential: In vitro embryoid body formation followed by assessment of derivatives from all three germ layers, or in vivo teratoma formation in immunocompromised mice [11]

- Karyotype Analysis: G-band karyotyping or comparative genomic hybridization to detect chromosomal abnormalities acquired during reprogramming [11]

- Identity Confirmation: Short tandem repeat profiling to verify match with donor somatic cells [11]

- Microbiological Testing: Screening for mycoplasma and other potential contaminants [11]

Directed Differentiation to Relevant Cell Types

A critical advantage of iPSC technology is the ability to differentiate pluripotent cells into specific somatic cell types affected by disease. The following examples illustrate robust differentiation protocols for generating disease-relevant cells:

Cardiac Differentiation Protocol: iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) have become invaluable for modeling cardiac disorders and screening for cardiotoxicity. A standardized protocol involves:

- Mesoderm Induction: Treat iPSCs with 6-8 μM CHIR99021 (a GSK3β inhibitor) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with B-27 without insulin for 2 days [2]

- Cardiac Specification: Following mesoderm induction, add 2 μM Wnt-C59 (a Wnt inhibitor) in the same medium for 2 additional days to promote cardiac lineage specification [2]

- Metabolic Selection: From day 7 onward, switch to RPMI 1640 medium with B-27 complete supplement to support cardiomyocyte maturation [2]

- Functional Maturation Enhancement: To address the characteristic immature, fetal-like phenotype of iPSC-CMs, implement advanced maturation strategies:

- Co-culture Systems: Co-culture iPSC-CMs with iPSC-derived cardiac fibroblasts (iPSC-CFs) in a 2:1 ratio on micropatterned extracellular matrix substrates [2]

- 3D Hydrogel Culture: Encapsulate iPSC-CMs with human coronary artery endothelial cells in 3D gelatin methacryloyl hydrogels to better mimic cardiac tissue architecture [2]

Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Model Differentiation: iPSC-derived BBB models enable study of neurovascular disorders and drug penetration. A standardized protocol includes:

- Dual-SMAD Inhibition: Differentiate iPSCs using dual SMAD inhibition (10 μM SB431542 and 100 nM LDN193189) to induce neural and endothelial lineages simultaneously [12]

- Purification and Seeding: Purify endothelial cells and seed on collagen IV/fibronectin-coated transwell inserts (1×10^5 cells/cm²) [12]

- Barrier Maturation: Culture cells for at least 5 days in endothelial growth medium to establish tight junctions and mature barrier properties [12]

- Functional Validation: Measure transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) using an epithelial voltohmmeter, with values >1000 Ω×cm² indicating competent barrier function [12]

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for establishing human iPSC-based disease models, from somatic cell reprogramming to functional characterization.

Advanced Maturation and Microenvironment Engineering

A significant challenge in iPSC-based modeling is the characteristic immature phenotype of many differentiated cell types. Advanced culture systems have been developed to enhance functional maturation:

Cardiac Maturation via Co-culture: Research demonstrates that iPSC-derived cardiac fibroblasts (iPSC-CFs) significantly enhance the functional maturity of iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) through both paracrine signaling and direct cell-cell interactions [2]. In co-culture systems, iPSC-CMs exhibit:

- Larger contractile strain amplitude compared to monocultures

- Increased spontaneous contraction rates with faster kinetics

- Enhanced contractile anisotropy and myofibril alignment

- Improved calcium handling and electrophysiological properties

Three-Dimensional Microenvironment Engineering: 3D culture systems more accurately mimic native tissue architecture and significantly enhance cellular maturation:

- Hydrogel-Based Cultures: iPSC-CMs co-cultured with human coronary artery endothelial cells in 3D gelatin methacryloyl hydrogels show upregulated expression of cardiac maturation markers and reduced oxidative stress compared to 2D monocultures [2]

- Organoid Systems: Self-organizing 3D structures that recapitulate aspects of tissue development and organization, enabling study of complex cell-cell interactions and tissue-level phenotypes [1]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of iPSC-based disease modeling requires carefully selected reagents and specialized materials. The following table details essential components for establishing robust experimental systems:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC-Based Disease Modeling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Systems | Sendai virus vectors (CytoTune); Episomal plasmids; mRNA kits | Non-integrating delivery of reprogramming factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) to somatic cells |

| Pluripotency Maintenance | mTeSR1; StemFlex; Essential 8 Medium | Chemically defined media supporting iPSC self-renewal and genomic stability |

| Differentiation Inducers | CHIR99021 (GSK3 inhibitor); SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor); Retinoic acid | Small molecules directing lineage specification through targeted pathway modulation |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel; Geltrex; Laminin-521; Collagen IV/Fibronectin | Substrates mimicking native basement membrane to support cell attachment and polarization |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-OCT4, SOX2, NANOG; TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81; Lineage-specific markers | Validation of pluripotency and differentiation efficiency through immunocytochemistry |

| Functional Assay Kits | Calcium imaging dyes; MEA plates; TEER measurement systems | Assessment of functional maturation in neuronal, cardiac, and barrier models |

Technological Integration: Enhancing iPSC Models with Artificial Intelligence

The convergence of iPSC technology with artificial intelligence (AI) represents a transformative advancement in disease modeling and drug discovery. AI-based approaches are being deployed to address key challenges in iPSC research:

Image-Based Classification and Quality Control: Machine learning algorithms, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), can automatically identify and classify iPSC colonies based on morphology, predicting optimal colonies for expansion and differentiation [13] [14]. These systems can:

- Distinguish fully reprogrammed iPSCs from partially reprogrammed cells with >90% accuracy [14]

- Predict differentiation propensity based on colony morphology features [14]

- Identify subtle morphological changes indicative of genomic instability or culture adaptation [13]

Predictive Modeling of Differentiation Outcomes: AI approaches analyze high-content imaging data to forecast differentiation efficiency and functional maturation [13] [14]. For example:

- Morphological Descriptor Analysis: Quantitative analysis of cytoskeletal and nuclear features provides "barcode-like" identity to single cells, enabling prediction of lineage commitment [15]

- Time-Series Prediction Models: Hidden Markov Models can identify optimal time windows for colony selection and passage based on growth dynamics [14]

High-Content Phenotypic Screening: AI-enabled analysis of iPSC-derived cells facilitates high-throughput drug screening and toxicity assessment:

- Automated classification of cardiomyocyte beating patterns in response to pharmacological agents [13]

- Quantitative analysis of neurite outgrowth and synaptic connectivity in neuronal models [14]

- Prediction of complex disease phenotypes from simple morphological features [15]

Figure 2: Integration of artificial intelligence with iPSC technology enhances quality control, phenotypic analysis, and predictive modeling.

iPSC-based disease models represent a transformative approach that effectively overcomes the species-specific limitations inherent in traditional animal models. By providing a genetically accurate, human-specific experimental platform, iPSC technology enables researchers to study disease mechanisms, screen therapeutic compounds, and develop personalized treatment strategies with unprecedented relevance to human physiology and pathology. While challenges remain in achieving full functional maturation of some differentiated cell types, advanced culture systems and AI-enabled quality control are rapidly addressing these limitations.

The continued refinement of iPSC-based models, coupled with emerging technologies in genome editing, tissue engineering, and computational analysis, promises to further enhance their predictive validity and translational impact. As these human-specific models become increasingly sophisticated and accessible, they are positioned to significantly accelerate drug development, reduce reliance on animal studies, and ultimately enable more effective, personalized therapeutic interventions for complex human diseases.

The discovery of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology by Shinya Yamanaka in 2006 represents a watershed moment in regenerative medicine and disease modeling. This whitepaper traces the scientific journey from the initial reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts using defined factors to current innovations accelerating iPSC applications in pharmaceutical development and disease research. We examine the evolution of reprogramming methodologies, molecular mechanisms underlying somatic cell reprogramming, and the expanding toolkit for generating clinically relevant disease models. Within the context of disease modeling, we highlight how iPSC technology has enabled researchers to create patient-specific cellular models that recapitulate pathological features, facilitating drug discovery and therapeutic development. The integration of advanced gene editing, bioengineering, and computational approaches continues to address early challenges in reprogramming efficiency, safety, and standardization, positioning iPSC-based models as indispensable assets for researchers and drug development professionals.

The development of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has fundamentally transformed biomedical research and regenerative medicine prospects. iPSCs are laboratory-generated pluripotent stem cells produced by reprogramming somatic cells through the forced expression of specific pluripotency genes, effectively reversing the developmental clock without the ethical concerns associated with embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [16]. This breakthrough has created unprecedented opportunities for patient-specific disease modeling, drug screening platforms, and cell therapy development [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, iPSC technology provides a human-derived system to study disease mechanisms, test therapeutic candidates, and develop personalized medicine approaches, particularly for conditions where animal models fail to recapitulate human pathology [17] [1]. The capacity to differentiate iPSCs into virtually any somatic cell type enables the creation of human-relevant experimental models that mirror in vivo physiology and disease states with greater accuracy than traditional cell lines [18].

Historical Foundations

The conceptual foundation for iPSC technology extends back decades before its actualization. In 1962, John Gurdon's seminal somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) experiments in Xenopus laevis frogs demonstrated that a nucleus from a terminally differentiated somatic cell contained all genetic information needed to generate entire organisms when transplanted into an enucleated egg [1]. This landmark discovery refuted the prevailing notion that cell differentiation involved irreversible genetic changes, suggesting instead that epigenetic factors governed cellular specialization. The isolation of mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) by Martin Evans, Matthew Kaufman, and Gail Martin in 1981, followed by James Thomson's derivation of human ESCs in 1998, established pluripotent cells as powerful research tools [1]. Subsequent cell fusion experiments between ESCs and somatic cells revealed that ESC factors could reprogram somatic nuclei toward pluripotency, hinting at the potential for factor-based reprogramming [1].

The pivotal breakthrough came in 2006 when Shinya Yamanaka and Kazutoshi Takahashi systematically tested 24 candidate genes important for ESC function in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) [19] [1]. Through iterative testing, they identified four transcription factors—Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (collectively termed OSKM or Yamanaka factors)—sufficient to reprogram MEFs into pluripotent stem cells [19]. These mouse iPSCs exhibited morphology, growth properties, and marker gene expression similar to ESCs, could form teratomas containing tissues from all three germ layers, and contributed to embryonic development after blastocyst injection [19]. Just one year later, Yamanaka and James Thomson independently reported successful reprogramming of human fibroblasts, with Thomson's group using an alternative factor combination (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28) [1] [20]. These discoveries demonstrated that pluripotent stem cells could be generated directly from somatic cells without embryos, earning Gurdon and Yamanaka the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Table 1: Key Historical Developments in iPSC Technology

| Year | Discovery | Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Somatic cell nuclear transfer in frogs | John Gurdon | Demonstrated reversibility of cellular differentiation |

| 1981 | Isolation of mouse embryonic stem cells | Martin Evans, Matthew Kaufman | Established pluripotent cell culture |

| 1998 | Derivation of human embryonic stem cells | James Thomson | Enabled human pluripotent cell research |

| 2006 | First induced pluripotent stem cells from mouse fibroblasts | Shinya Yamanaka | Proof-of-concept for factor-based reprogramming |

| 2007 | Generation of human iPSCs | Yamanaka and Thomson groups | Extended technology to human cells |

| 2013 | First iPSC-derived cell transplantation in humans | Masayo Takahashi | Initiated clinical applications |

| 2016 | First formal clinical trial of allogeneic iPSC-derived product | Cynata Therapeutics | Advanced regulated clinical development |

Molecular Mechanisms of Reprogramming

The process of reprogramming somatic cells to pluripotency involves profound remodeling of cellular identity through specific molecular mechanisms. When pluripotent stem cells differentiate into somatic cells, they acquire stable epigenetic memory and undergo global chromatin changes that silence pluripotency genes while activating lineage-specific genes [1]. Reprogramming effectively reverses this process, erasing somatic epigenetic signatures and reestablishing the pluripotent state.

Reprogramming occurs in two broad phases: an early, stochastic phase followed by a late, deterministic phase [1]. During the early phase, somatic genes are silenced while early pluripotency-associated genes become activated in a heterogeneous, inefficient manner, likely due to variable accessibility of closed chromatin regions to the reprogramming factors [1]. The late phase involves more synchronized activation of the core pluripotency network, including establishment of autoregulatory loops that stabilize the pluripotent state. Throughout this process, cells undergo mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), a critical step particularly when reprogramming fibroblasts [1].

The reprogramming factors each play distinct but complementary roles. Oct4 and Sox2 function as pioneer factors that bind condensed chromatin and initiate epigenetic remodeling, while Klf4 assists in chromatin opening and c-Myc promotes global transcriptional activation and proliferation [18] [1]. The process involves comprehensive rewiring of epigenetic landscapes, including DNA demethylation at pluripotency gene promoters, histone modification changes, and three-dimensional chromatin restructuring [1]. Additionally, reprogramming triggers profound shifts in cellular metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation toward glycolysis, mirroring metabolic changes in normal pluripotent cells [1].

Diagram 1: Molecular reprogramming process from somatic cell to iPSC showing key transitional phases

Evolution of iPSC Reprogramming Methods

Since the original viral transduction method, iPSC generation techniques have evolved significantly to address safety concerns and improve efficiency. The table below summarizes major reprogramming methodologies that have been developed.

Table 2: Comparison of iPSC Reprogramming Methods

| Method | Key Features | Reprogramming Efficiency | Safety Concerns | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral Vectors (Original) | Stable integration, persistent transgene expression | Low (~0.01-0.1%) | High (insertional mutagenesis) | Basic research, proof-of-concept |

| Sendai Virus | Non-integrating, viral RNA-based | Moderate (~0.1%) | Low (cleared over passages) | Clinical applications, disease modeling |

| mRNA Transfection | Non-integrating, defined timing | High (~1-4%) | Low (immune response) | Clinical-grade iPSCs, GMP manufacturing |

| Episomal Vectors | Non-integrating, plasmid-based | Low (~0.001-0.01%) | Low (potential integration) | Clinical applications, biobanking |

| Small Molecules | Non-genetic, chemical-based | Variable (up to 0.1-1%) | Low (off-target effects) | Research, screening platforms |

Early reprogramming approaches relied on integrating retroviral vectors that posed significant safety risks due to potential insertional mutagenesis and reactivation of oncogenes like c-Myc [19] [1]. Subsequent advancements focused on non-integrating methods including Sendai virus (a cytoplasmic RNA virus that doesn't integrate into the host genome), mRNA transfection (introducing in vitro transcribed mRNAs encoding reprogramming factors), and episomal vectors [18]. More recently, small molecule-based reprogramming has emerged as a promising approach that eliminates the need for genetic manipulation entirely [18] [1]. These improved methods have enabled the generation of clinical-grade iPSCs while maintaining genomic integrity, a critical consideration for therapeutic applications.

Current innovations continue to refine reprogramming techniques. Machine learning algorithms now assist in quality control and colony selection, improving reproducibility [18]. The development of 3D reprogramming systems and the identification of more specific small molecule enhancers continue to increase efficiency while reducing heterogeneity in the resulting iPSC lines [18]. These advances collectively address earlier limitations and facilitate the reliable production of iPSCs suitable for disease modeling and drug screening applications.

Current Innovations in iPSC Technology

Gene Editing and iPSC Engineering

The convergence of iPSC technology with precise gene editing tools, particularly CRISPR-Cas9, has revolutionized disease modeling and therapeutic development [18]. Researchers can now introduce or correct disease-associated mutations in iPSCs from healthy donors, creating isogenic pairs that differ only at the locus of interest, thereby controlling for genetic background variability [18]. This approach enables more precise attribution of phenotypic differences to specific genetic changes in disease models. Newer CRISPR systems including base editors and prime editors allow even more precise genetic modifications without creating double-strand DNA breaks, reducing unintended mutations [18].

Gene-edited iPSCs serve multiple purposes in pharmaceutical development: creating humanized disease models for drug screening, correcting genetic defects in patient-derived iPSCs for autologous cell therapy, and introducing reporter genes for tracking differentiation efficiency or compound screening [18]. For example, Parkinson's disease-specific neurons derived from iPSCs can be genetically edited to investigate disease progression mechanisms and identify potential therapeutic targets [18]. Similarly, dystrophin gene correction in iPSCs from Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients represents a promising autologous cell therapy approach [18].

Advanced Differentiation and Disease Modeling

Innovations in differentiation protocols have significantly enhanced the efficiency and reproducibility of generating functionally mature cell types from iPSCs. Key signaling pathways—including BMP, Wnt, and TGF-β—are precisely manipulated through optimized timing and concentration of specific growth factors and small molecules to direct differentiation toward specific lineages [18]. These advances have enabled the routine production of cardiomyocytes, neurons, pancreatic β-cells, and hepatocytes with improved functional maturity [18].

The development of three-dimensional organoids represents a major advancement in disease modeling, creating complex tissue-like structures that better mimic human physiology than traditional two-dimensional cultures [18] [1]. These self-organizing structures contain multiple cell types and exhibit primitive tissue architecture, enabling modeling of higher-order cell-cell interactions and disease processes [1]. iPSC-derived organoids have been developed for brain, liver, kidney, and gastrointestinal tissues, providing powerful platforms for studying development, disease mechanisms, and drug responses [18].

Diagram 2: iPSC differentiation pathways showing 2D versus 3D modeling approaches

Immune Evasion Strategies

A significant challenge for allogeneic iPSC-based therapies is immune rejection, which has prompted the development of innovative immune evasion strategies. Researchers are employing CRISPR-Cas9 to engineer hypoimmunogenic iPSCs by deleting HLA class I and II molecules to reduce immune surveillance while adding immune modulators like PD-L1 to create universal cell products [18]. These approaches aim to develop "off-the-shelf" iPSC lines that can be transplanted without matching or intensive immunosuppression, potentially revolutionizing cell therapy scalability and accessibility [18].

Additional strategies include cell encapsulation in immune-protective materials and genetic modifications to enhance expression of immune suppressive molecules [18]. These innovations are particularly relevant for diseases like diabetes, where iPSC-derived β-cells could restore normal insulin production but face immune destruction in type 1 diabetes patients [21]. By combining immune evasion with precise differentiation protocols, researchers are moving closer to effective cell replacement therapies for multiple conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc | Initiate and maintain pluripotent state | Multiple factor combinations available; lab-specific optimization often required |

| Delivery Systems | Sendai virus, mRNA transfection, episomal plasmids | Introduce reprogramming factors | Choice depends on safety requirements and efficiency needs |

| Culture Media | mTeSR, E8, StemFlex | Support iPSC growth and maintenance | Defined, xeno-free formulations preferred for clinical applications |

| Differentiation Kits | Cardiomyocyte, neural, pancreatic β-cell kits | Direct lineage-specific differentiation | Protocol standardization enhances reproducibility across labs |

| Quality Control Assays | Pluritest, flow cytometry, karyotyping | Verify pluripotency and genomic integrity | Essential for confirming iPSC quality before downstream applications |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, base editors, prime editors | Introduce precise genetic modifications | Enables creation of disease models and correction of mutations |

The iPSC research workflow requires specialized reagents and methods at each stage. For reprogramming, Sendai virus systems and mRNA transfection kits are commercially available from suppliers like Thermo Fisher Scientific and Takara Bio, providing non-integrating options for clinical-grade iPSC generation [18] [16]. Culture systems have evolved from feeder-dependent setups to defined, xeno-free media like mTeSR and E8, which improve reproducibility and reduce variability [18].

For differentiation, numerous specialized kits and protocols are available for generating specific cell types, with companies like FUJIFILM CDI, REPROCELL, and Ncardia providing iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, neurons, and other lineages [16]. Quality control remains essential, with assays ranging from simple immunostaining for pluripotency markers (Oct4, Nanog, SSEA-4) to comprehensive genomic analyses to ensure genetic integrity [18] [22]. Advanced quality control methods include machine learning-based approaches for automated colony selection and DNA methylation profiling to verify complete reprogramming [18] [22].

Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

iPSC technology has enabled unprecedented advances in disease modeling and pharmaceutical development. The ability to generate patient-specific cell types has facilitated the creation of "disease-in-a-dish" models for conditions ranging from neurological disorders to cardiovascular diseases [17] [1]. For neurological conditions like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease, iPSC-derived neurons recapitulate key pathological features and enable screening of neuroprotective compounds [18] [1]. In cardiovascular research, iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes allow modeling of inherited arrhythmias and testing of drug cardiotoxicity [23]. Metabolic disorders like diabetes have been modeled using iPSC-derived pancreatic β-cells, enabling studies of β-cell dysfunction and survival [21].

The pharmaceutical industry has incorporated iPSC-derived cells into drug screening platforms, leveraging their human relevance for more predictive toxicity and efficacy assessment [17] [16]. The FDA Modernization Act 2.0, which permits cell-based assays as alternatives to animal testing for drug applications, has further accelerated adoption of iPSC-based screening platforms [16]. Companies like Evotec and BrainXell have developed industrialized iPSC platforms for high-throughput drug screening, providing specialized neural and cardiac cells to pharmaceutical companies [16].

iPSCs also enable personalized medicine approaches, where patient-specific cells can be used to predict individual drug responses or develop autologous therapies [16]. Clinical trials utilizing iPSC-derived cells are underway for conditions including macular degeneration, graft-versus-host disease, heart failure, and Parkinson's disease [17] [16]. While most current trials are early-phase investigations assessing safety, they represent critical steps toward realizing the clinical potential of iPSC technology.

The journey from Yamanaka's initial discovery to current innovations illustrates how iPSC technology has matured from a fundamental biological breakthrough to an indispensable tool for disease modeling and drug development. Current research focuses on enhancing the safety, efficiency, and scalability of iPSC generation and differentiation, while addressing challenges such as functional maturity of differentiated cells and standardization across laboratories [17] [18]. The integration of gene editing, bioengineering, and computational approaches continues to expand the capabilities of iPSC-based models.

For researchers and drug development professionals, iPSCs offer a uniquely versatile platform that bridges the gap between traditional cell lines and human physiology. The ability to model diseases in human cells with relevant genetic backgrounds, combined with advances in organoid and tissue engineering technologies, provides unprecedented opportunities for understanding disease mechanisms and developing novel therapeutics. As the field addresses remaining challenges in standardization and safety assessment, iPSC-based approaches are poised to become increasingly central to biomedical research and therapeutic development, ultimately fulfilling the promise of personalized regenerative medicine.

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) represent one of the most transformative breakthroughs in modern biomedical research, offering unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine. The utility of iPSCs fundamentally rests upon two defining biological characteristics: self-renewal—the ability to undergo numerous cell divisions while maintaining an undifferentiated state—and differentiation capacity—the potential to give rise to specialized cell types representing all three embryonic germ layers [3] [1]. These twin properties enable researchers to generate patient-specific cellular models that recapitulate disease pathophysiology in vitro, providing powerful platforms for investigating molecular mechanisms of disease pathogenesis and performing high-throughput drug screening [3] [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the molecular underpinnings and technical requirements for maintaining these essential characteristics is critical for exploiting the full potential of iPSC technology in both basic and translational research contexts.

The revolutionary discovery by Shinya Yamanaka and colleagues in 2006 demonstrated that somatic cells could be reprogrammed to a pluripotent state through the introduction of just four transcription factors: Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM) [3] [1]. This groundbreaking achievement, which earned Yamanaka the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2012, effectively bypassed the ethical concerns associated with embryonic stem cells while providing an unlimited source of patient-specific pluripotent cells [3]. Subsequent research has refined our understanding of the molecular mechanisms governing iPSC self-renewal and differentiation, leading to more robust protocols for maintaining these essential characteristics in vitro [24] [1].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

| Characteristic | Definition | Functional Significance | Key Molecular Regulators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Renewal | Capacity for extensive proliferation while maintaining undifferentiated state | Enables unlimited expansion and maintenance of pluripotent cell banks | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, KLF4, c-MYC [3] [1] |

| Pluripotency | Potential to differentiate into derivatives of all three germ layers | Forms basis for generating diverse disease-relevant cell types | Endogenous reactivation of OCT4 promoter, chromatin remodeling [3] |

| Genetic Stability | Maintenance of genomic integrity during culture | Critical for reliable disease modeling and clinical applications | Requires continuous genomic monitoring [3] |

| Epigenetic Memory | Retention of somatic cell epigenetic signatures | May influence differentiation efficiency; erased in fully reprogrammed iPSCs | DNA methylation resetting during reprogramming [1] |

Molecular Mechanisms Governing Self-Renewal

Transcriptional Networks and Epigenetic Regulation

The self-renewal capacity of iPSCs is maintained through an intricate network of transcriptional and epigenetic regulators that function cooperatively to sustain the pluripotent state. Core transcription factors, including OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, form a central autoregulatory loop that activates pluripotency-associated genes while simultaneously repressing differentiation genes [1]. OCT4 (encoded by POU5F1) serves as a master regulator of pluripotency, with precise expression levels critical for maintaining self-renewal—both deficiency and overexpression can trigger differentiation [3]. SOX2 cooperates with OCT4 to regulate numerous pluripotency genes, while NANOG provides stabilization to the network, enabling cytokine-independent self-renewal [1].

The reprogramming process involves profound epigenetic remodeling, including chromatin modification and DNA methylation resetting, which establishes the pluripotent state [3]. During the early phase of reprogramming, somatic genes are silenced while early pluripotency-associated genes are activated through predominantly stochastic mechanisms. The late phase involves more deterministic activation of the core pluripotency network and establishment of stable epigenetic patterns characteristic of embryonic stem cells [1]. This epigenetic reprogramming includes global DNA demethylation at pluripotency loci with concomitant increased methylation at somatic gene promoters, histone modifications that establish an open chromatin configuration at pluripotency genes, and reorganization of higher-order chromatin structure [3] [1].

The Stem Cell Niche: Microenvironmental Regulation of Self-Renewal

Self-renewal is profoundly influenced by the stem cell niche—a specialized microenvironment comprising supporting cells, extracellular matrix (ECM), and signaling molecules that collectively regulate stem cell behavior [25] [26]. The niche concept, first proposed by Schofield in 1978, posits that stem cell fate decisions are largely determined by extrinsic cues from their immediate microenvironment [25]. For iPSCs in culture, recreation of appropriate niche conditions is essential for maintaining self-renewal and pluripotency.

Early iPSC culture protocols employed feeder layers of mitotically inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts, which provided essential support through cell-cell contacts and secretion of supportive factors [3]. However, for enhanced reproducibility and clinical applications, feeder-free systems using defined extracellular matrix coatings such as Matrigel or recombinant human laminin have been developed [3]. These matrices provide not only structural support but also critical biochemical signaling through integrin-mediated pathways that regulate self-renewal [25]. The composition of the culture medium further contributes to niche recreation, with chemically defined formulations like mTeSR1 and E8 containing precise combinations of growth factors (e.g., FGF2) and pathway inhibitors (e.g., TGF-β/activin A) that maintain pluripotency while suppressing spontaneous differentiation [3].

Diagram 1: Regulatory Network Governing iPSC Self-Renewal. The stem cell niche provides critical extrinsic signals that interact with intrinsic transcriptional networks to maintain pluripotency.

Mechanisms of Differentiation Capacity

Developmental Principles and Directed Differentiation

The differentiation capacity of iPSCs mirrors that of embryonic stem cells, encompassing the potential to generate derivatives of all three germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm [3]. This developmental potential is harnessed through directed differentiation protocols that recapitulate key aspects of embryonic development in vitro, activating evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways in a precise temporal sequence to guide cells toward specific lineages [27]. Understanding the signaling pathways that orchestrate normal development has been instrumental in developing robust differentiation protocols, particularly for disease modeling applications where mature, functionally competent cell types are required [27].

Cardiac differentiation protocols, for example, have been informed by extensive research into heart development, which involves sequentially activated signaling pathways including Wnt, TGF-β, IGF, and retinoic acid [27]. Similarly, neural differentiation strategies often employ dual SMAD inhibition to promote ectodermal specification, followed by patterning factors that regionalize the neural tissue into specific neuronal subtypes [3]. The efficiency of differentiation protocols varies considerably depending on the target cell type, with some lineages (e.g., cardiomyocytes) achieving high efficiency (>80%) while others remain challenging [3] [27].

Mathematical Modeling of Differentiation Dynamics

Recent advances in the field include the development of mathematical models to predict and optimize differentiation protocols, reducing the need for extensive empirical experimentation [28]. These in silico approaches model population dynamics during differentiation, accounting for processes such as proliferation, differentiation, and cell death [28]. For example, modeling definitive endoderm differentiation from iPSCs has revealed that space-limited growth models (logistic and Gompertz) outperform exponential growth models in predicting cell population dynamics, with differentiation outpacing proliferation as the main driver of population changes during the initial differentiation period [28]. Such models can predict optimal differentiation timeframes (e.g., 1.9-2.4 days for definitive endoderm induction) and ideal seeding densities (e.g., 300,000 cells per well for endoderm differentiation), significantly accelerating protocol optimization [28].

Diagram 2: iPSC Differentiation Capacity and Disease Modeling Applications. iPSCs undergo germ layer specification followed by terminal differentiation into disease-relevant cell types for modeling human disorders.

Quantitative Analysis of Self-Renewal and Differentiation

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters of iPSC Self-Renewal and Differentiation

| Parameter | Typical Range/Value | Measurement Methods | Influence on Disease Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Efficiency | 0.1% to several percent [3] | Colony counting, pluripotency marker expression | Affects feasibility of generating patient-specific lines |

| Population Doubling Time | 15-24 hours [3] | Cell counting, metabolic assays | Determines expansion capability for large-scale studies |

| Karyotype Stability | Variable; requires monitoring every 10 passages [3] | Karyotyping, FISH, aCGH | Critical for genotype-phenotype correlations in disease models |

| Cardiac Differentiation Efficiency | Up to 80% for some protocols [27] | Flow cytometry for cardiac troponins | Determines yield of cardiomyocytes for disease modeling |

| Neural Differentiation Timeline | 30-60 days for mature neurons [3] | Immunostaining for neuronal markers | Impacts experimental planning for neurodegenerative disease models |

| Endoderm Differentiation Efficiency | ~70% CD117+CD184+ cells [28] | Flow cytometry for definitive endoderm markers | Affects yield of hepatic and pancreatic lineages |

Experimental Methodologies for Characterization

Assessing Pluripotency and Self-Renewal Capacity

Rigorous quality control is essential to verify the pluripotent state of iPSCs before their application in disease modeling. Standard characterization includes multiple complementary approaches to confirm both molecular and functional features of pluripotency [3]. Molecular analyses typically include PCR-based detection of endogenous pluripotency gene expression (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG), immunocytochemistry for pluripotency-associated proteins, and flow cytometry for surface markers such as TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81, and SSEA-4 [3]. Global gene expression profiling through microarray or RNA sequencing can further confirm similarity to reference embryonic stem cell lines.

Functional assessment of pluripotency represents the gold standard for confirming differentiation capacity. In vitro differentiation via embryoid body formation or directed differentiation followed by immunostaining for representatives of all three germ layers (e.g., β-III-tubulin for ectoderm, α-smooth muscle actin for mesoderm, and α-fetoprotein for endoderm) provides evidence of multilineage potential [3]. For the most stringent validation, teratoma formation assays involve injecting iPSCs into immunocompromised mice and subsequently examining the resulting tumors for the presence of differentiated tissues from all three germ layers [3]. Additionally, genomic integrity must be regularly evaluated through G-banding karyotyping or comparative genomic hybridization to detect chromosomal abnormalities that may compromise differentiation efficiency or predispose cells to malignant transformation [3].

Evaluating Differentiation Potential and Lineage Specification

The assessment of differentiation capacity requires specialized methodologies tailored to specific lineages of interest. For disease modeling applications, it is particularly important to confirm not only the presence of lineage-specific markers but also functional maturity of the differentiated cells [2]. Cardiac differentiation efficiency is typically quantified by flow cytometry analysis for cardiac troponins (cTnT) or myosin heavy chain (MHC), supplemented with functional assessments of spontaneous contraction, calcium transients, and electrophysiological properties using multi-electrode arrays [27]. Similarly, neuronal differentiation success is evaluated through a combination of morphological analysis (neurite outgrowth), immunostaining for neuronal markers (MAP2, NeuN), synaptic proteins (synapsin, PSD95), and functional assessments of electrophysiological activity using patch clamping or multi-electrode arrays [3].

Recent advances in differentiation protocol development have emphasized the importance of achieving not just lineage specification but functional maturation, as iPSC-derived cells often exhibit an immature, fetal-like phenotype [2]. Strategies to enhance maturation include extending culture duration, incorporating mechanical stimulation (e.g., cyclic stretch for cardiomyocytes), implementing three-dimensional culture systems, and developing co-culture models that better recapitulate the native tissue microenvironment [2]. For example, co-culture of iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes with cardiac fibroblasts has been shown to improve contractile function, increase spontaneous contraction rates, and enhance structural organization [2]. Similarly, three-dimensional gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel cultures promote cardiac maturation marker expression and reduce oxidative stress compared to traditional two-dimensional monocultures [2].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Characterization

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Vectors | Episomal plasmids, Sendai virus, mRNA [3] | Delivery of reprogramming factors | Non-integrating methods preferred for clinical applications |

| Culture Matrices | Matrigel, recombinant laminin-521 [3] | Provide structural support and signaling cues | Defined matrices reduce batch variability |

| Culture Media | mTeSR1, Essential 8 (E8) [3] | Maintain pluripotency and support self-renewal | Chemically defined formulations enhance reproducibility |

| Pluripotency Markers | Antibodies against OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, TRA-1-60 [3] | Characterization of undifferentiated state | Multiple verification methods recommended |

| Differentiation Kits | STEMdiff Definitive Endoderm Kit [28] | Directed differentiation to specific lineages | Improve protocol standardization across laboratories |

| Cell Dissociation Reagents | GCDR, dispase, EDTA [3] [28] | Passaging and harvesting of cells | Impact cell viability and recovery |

| Cryopreservation Reagents | DMSO-containing solutions [3] | Long-term storage of iPSC lines | Controlled-rate freezing improves post-thaw viability |

Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

The dual capacities of self-renewal and differentiation make iPSCs uniquely powerful for disease modeling and drug development applications. Patient-specific iPSCs can be differentiated into disease-relevant cell types that recapitulate pathological features in vitro, enabling investigation of disease mechanisms and high-throughput compound screening [3]. For neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease, iPSC-derived neuronal models have provided new insights into pathogenic mechanisms, including tau hyperphosphorylation, β-amyloid deposition, and α-synuclein aggregation [3]. Similarly, iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes have enabled the study of arrhythmogenic disorders and heart failure, with models of congenital arrhythmias linked to KCNQ1 mutations providing a basis for precision cardiology [3].

In metabolic disease modeling, iPSCs have been particularly valuable for studying genetic disorders such as cystic fibrosis, where iPSC-derived airway epithelial cells reproduce defective chloride transport caused by CFTR mutations, facilitating evaluation of targeted therapeutics like ivacaftor and lumacaftor [3]. For Duchenne muscular dystrophy, iPSC-derived myocytes enable mechanistic studies of muscle degeneration, while gene editing approaches have successfully restored dystrophin expression in vitro, highlighting the therapeutic potential of combining iPSC technology with genome editing [3].

The self-renewal capacity of iPSCs is especially important for drug discovery applications, as it enables the generation of virtually unlimited quantities of uniform, patient-specific cells for high-throughput screening [2]. This capability addresses a major limitation of primary human cells—their limited expansion potential—while providing human-relevant models that may more accurately predict drug efficacy and toxicity compared to animal models or transformed cell lines [3] [2]. Additionally, iPSC-based models support the development of personalized medicine approaches, as panels of iPSCs from patients with varying drug responses can be used to identify genetic determinants of treatment efficacy and toxicity [3].

The essential characteristics of self-renewal and differentiation capacity establish iPSCs as an indispensable platform for disease modeling and drug development. The molecular machinery governing these properties—including core pluripotency transcription factors, epigenetic regulators, and niche-derived signals—must be carefully maintained through optimized culture conditions and rigorous quality control. As differentiation protocols continue to improve through the application of developmental principles and mathematical modeling, and as culture systems evolve to better recapitulate native tissue microenvironments, iPSC-based disease models will become increasingly sophisticated and physiologically relevant. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the technical requirements for maintaining iPSC self-renewal while directing differentiation into functionally mature cell types is fundamental to harnessing the full potential of this transformative technology for understanding disease mechanisms and developing novel therapeutics.

The advent of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has fundamentally transformed the landscape of biomedical research, providing an unprecedented platform for studying human diseases in vitro. By enabling the generation of patient-specific pluripotent stem cells from somatic tissues, this technology offers a powerful pathway to bridge the gap between clinical phenotypes and molecular pathophysiology [2] [29]. The disease modeling pipeline, which encompasses the journey from patient biopsy to functionally differentiated cells, provides researchers with a system to elucidate disease mechanisms, screen potential therapeutic compounds, and develop personalized treatment strategies. This technical guide details the comprehensive pipeline, providing detailed methodologies, quantitative benchmarks, and standardized resources essential for establishing robust and reproducible patient-specific disease models.

The iPSC Generation Process: From Skin Biopsy to Pluripotency

Patient Biopsy and Fibroblast Derivation

The initial phase of establishing a patient-specific disease model involves obtaining somatic cells and reprogramming them into a pluripotent state. A common and minimally invasive approach is the skin biopsy procedure.

Materials for Skin Biopsy Procedure [29]:

- Biopsy Collect Medium: RPMI1640, 1× Anti-Anti.

- Disposable Biopsy Punches: Diameter 4 mm.

- Anesthetic: Xylocaine (lidocaine HCL and epinephrine injection, USP).

- Disinfectant: Povidone-iodine, USP swab stick.

- Suture: 5-0 VICRYL coated suture.

- Other Supplies: Sterile fenestrated towel, sterile gauze pad, autoclaved forceps, needle holder, scissors, 15 ml conical tube, Band-Aid.

Detailed Biopsy Protocol [29]:

- Site Preparation: The biopsy site, typically on the upper arm or thigh, is disinfected with 5% povidone-iodine twice using a circular motion from the center outward and allowed to air-dry.

- Anesthesia: The skin is anesthetized locally by subcutaneous injection of 1% lidocaine.

- Tissue Extraction: Using a sterile 4 mm skin punch, a full-thickness skin sample is obtained and cut at the base with sterile scissors.

- Collection: The tissue is immediately transferred using sterile forceps into a 15 ml tube containing 10 ml of biopsy collection medium and maintained at room temperature during transport.

- Wound Closure: The edges of the wound are sutured with dissolvable suture, and the site is covered with a Band-Aid.

Fibroblast Culture from Skin Biopsy [29]: The minced biopsy tissue is explanted onto a culture dish and secured under a sterile coverslip with silicone grease. It is cultured in biopsy plating medium (DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1× nucleosides, 1× L-glutamine, 1× non-essential amino acids, 1× Anti-Anti, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Fibroblasts typically migrate out from the tissue explants over 2-3 weeks. Upon reaching confluency, fibroblasts are harvested using trypsin-EDTA and expanded for reprogramming.

Reprogramming to Pluripotency

The critical step of converting patient-specific fibroblasts into iPSCs requires the introduction of reprogramming factors.

Reprogramming Materials [29]:

- Reprogramming Vector: CytoTune-iPS Sendai Virus Reprogramming Kit (footprint-free RNA virus).

- Reprogramming Medium: KO-DMEM, 15% KnockOut Serum Replacement, 1× L-glutamine, 1× non-essential amino acids, 1× penicillin-streptomycin, 0.1 mM β-Mercaptoethanol, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) 10 ng/ml.

- Support Cells: Mitomycin-C treated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) as feeders.

- ROCK Inhibitor: Y-27632, to enhance cell survival after passaging.

Detailed Reprogramming Protocol [29]: