Embryonic vs. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Disease Modeling

This article provides a comparative analysis of Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) for in vitro disease modeling, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Embryonic vs. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Disease Modeling

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) for in vitro disease modeling, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational biology and ethical considerations of both cell types, details methodological advances in reprogramming and differentiation, and examines their application in modeling neurological, cardiovascular, and metabolic disorders. The content addresses key challenges including genomic instability, tumorigenicity, and protocol standardization, while evaluating the comparative efficacy of each platform for phenotypic recapitulation, drug screening, and clinical translation. The synthesis aims to guide the selection of the optimal stem cell platform for specific research and therapeutic objectives.

Understanding Stem Cell Biology: From Pluripotency to Ethical Foundations

The advent of pluripotent stem cells has revolutionized biomedical research, offering unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine. Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs), derived from the inner cell mass of blastocysts, have long served as the gold standard for pluripotency [1]. The development of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) through somatic cell reprogramming provided an alternative that bypasses ethical concerns associated with embryo destruction [2]. While both cell types share defining characteristics of pluripotency—unlimited self-renewal capacity and the ability to differentiate into derivatives of all three germ layers—ongoing scientific debate questions whether these cell types are functionally equivalent [3] [4]. This guide provides an objective comparison of ESCs and iPSCs, highlighting key similarities and differences relevant to research applications.

Core Characteristics and Pluripotency: A Comparative Analysis

The following tables summarize the fundamental properties, molecular features, and functional applications of ESCs and iPSCs based on current research findings.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of ESCs and iPSCs

| Characteristic | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Inner cell mass of blastocyst-stage embryos [1] | Reprogrammed somatic cells (e.g., fibroblasts, blood cells) [2] |

| Derivation Process | Isolation from donated embryos [1] | Introduction of reprogramming factors (e.g., OSKM) into somatic cells [1] [5] |

| Ethical Considerations | Involves embryo destruction [3] | Avoids embryo destruction, fewer ethical barriers [3] |

| Immunogenicity | Risk of allogeneic immune rejection [6] | Potential for autologous transplantation, reduced rejection risk [2] |

| Key Advantages | Represent "native" pluripotent state; gold standard for comparison [4] | Patient-specific; enable disease modeling without genetic manipulation [3] [2] |

| Key Limitations | Ethical restrictions; limited genetic diversity [3] | Potential for genomic instability; epigenetic memory [3] [2] |

Table 2: Molecular and Functional Comparison

| Parameter | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Gene Network | Express core pluripotency factors (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) [7] | Re-activates core pluripotency network; may show subtle gene expression differences [7] [4] | Gene expression analysis, immunostaining [6] |

| Epigenetic Landscape | Characteristic hyperdynamic chromatin structure; specific DNA methylation patterns [7] | Epigenetic reprogramming occurs; may retain residual epigenetic memory of cell of origin [3] [7] | DNA methylation analysis, chromatin immunoprecipitation [7] |

| Proteomic Profile | Reference proteome for pluripotent state [8] | Highly similar to ESCs, but shows increased levels of cytoplasmic, mitochondrial, and secreted proteins [8] | Quantitative mass spectrometry [8] |

| Trilineage Differentiation | Can differentiate into ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm derivatives [1] | Demonstrated capacity for trilineage differentiation; efficiency may vary between lines [2] [6] | Embryoid body formation, directed differentiation, teratoma assays [6] |

| Metabolic Activity | Reference metabolic state [8] | Higher protein content, mitochondrial potential, and metabolic rates in some studies [8] | High-resolution respirometry, metabolic flux analysis [8] |

| Disease Modeling Applications | Ideal for early embryonic lethality (e.g., Turner syndrome) [3] | Superior for patient-specific disorders (e.g., Parkinson's, ALS) and drug screening [3] [2] | Directed differentiation into disease-relevant cell types [3] [2] |

Experimental Approaches for Characterization

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for rigorous comparison between ESCs and iPSCs. Key methodologies include:

1. Reprogramming and Pluripotency Induction

- Somatic Cell Reprogramming: Dermal fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells are transfected with reprogramming factors (typically OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC) using non-integrating methods such as Sendai virus or episomal vectors [2] [6]. The process involves global epigenetic remodeling, including DNA demethylation and chromatin reorganization, over several weeks [1] [7].

- Pluripotency Validation: Quality control assays confirm successful reprogramming. These include PCR and immunocytochemistry for pluripotency markers (OCT4, NANOG, SSEA-4), genomic integrity analysis via karyotyping, and functional assessment of differentiation potential through embryoid body formation and teratoma assays [2] [6].

2. Molecular and Functional Characterization

- Proteomic Analysis: Quantitative mass spectrometry using Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) labeling enables precise protein quantification. Data normalization with the "proteomic ruler" method reveals differences in absolute protein content, which may be masked by standard median normalization approaches [8].

- Raman Spectroscopy: This label-free technique detects biochemical differences based on inelastic light scattering. Studies have identified enriched nucleic acid content in iPSCs compared to ESCs, providing a non-biological method for discrimination [6].

- Directed Differentiation: Protocols using specific growth factors and small molecules guide ESCs and iPSCs toward defined lineages (e.g., neurons, cardiomyocytes). The efficiency and maturity of resulting cells are compared using lineage-specific markers and functional assays [3] [2].

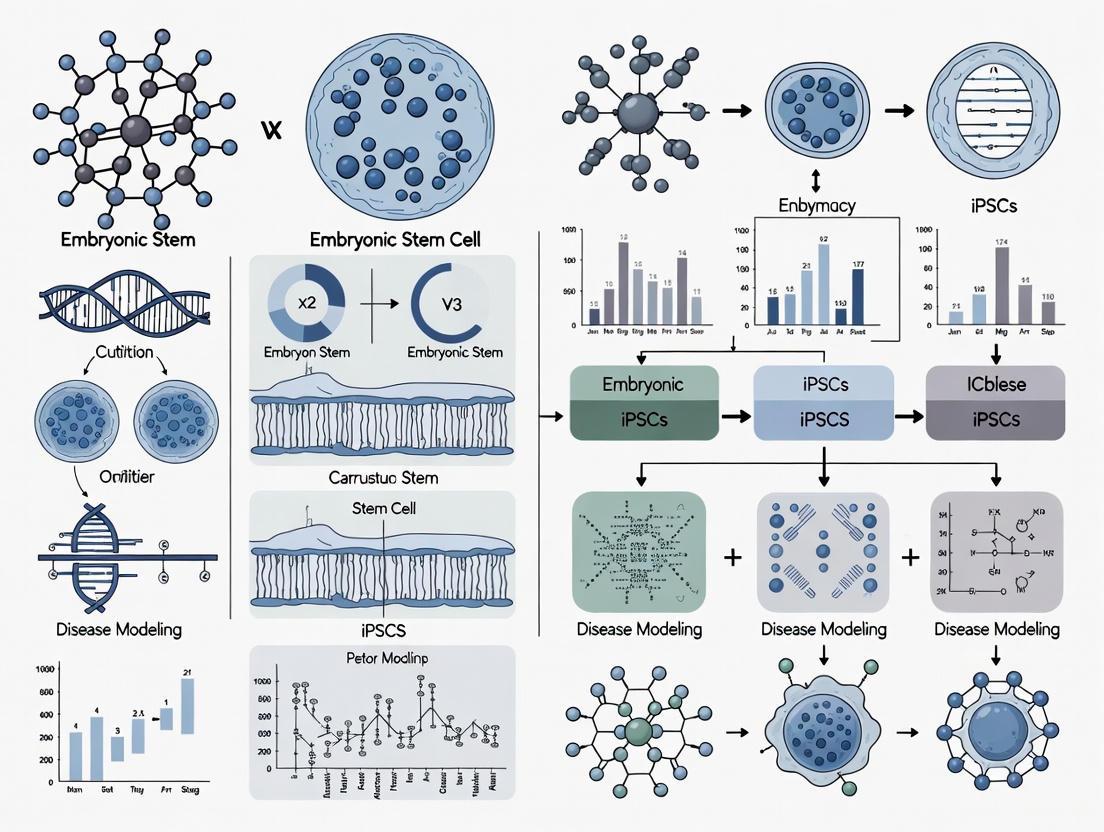

Experimental Workflow for Pluripotency Studies

Key Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The maintenance of pluripotency and execution of differentiation programs are governed by complex molecular networks.

Molecular Regulation of Pluripotency

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Pluripotent Stem Cell Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM); OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 (OSNL) [1] [5] | Induction of pluripotency in somatic cells; different combinations affect efficiency and iPSC quality |

| Culture Matrices | Matrigel, Laminin-521 [2] | Provides extracellular matrix support for feeder-free cell culture and maintenance of pluripotency |

| Culture Media | mTeSR1, Essential 8 (E8) medium [2] | Chemically defined formulations containing essential growth factors (e.g., FGF2) for maintaining pluripotent state |

| Pluripotency Markers | Antibodies against OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60 [6] | Validation of pluripotent state through immunocytochemistry, flow cytometry |

| Differentiation Inducers | Growth factors (BMP4, Activin A, FGFs), Small molecules (CHIR99021, SB431542) [3] [2] | Direct differentiation toward specific lineages (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) |

| Quality Control Assays | PluriTest, Karyotyping, Mycoplasma testing [2] [6] | Assessment of genomic integrity, pluripotency, and absence of contamination |

ESCs and iPSCs represent two sides of the pluripotency coin, each with distinct advantages and limitations. ESCs remain the gold standard reference for the pluripotent state, particularly valuable for studying early embryonic development and disorders involving embryonic lethality [3]. iPSCs offer unprecedented flexibility for patient-specific disease modeling, drug screening, and developing autologous cell therapies, though concerns regarding genomic stability and epigenetic memory warrant careful consideration [3] [2]. The choice between ESC and iPSC models should be guided by specific research objectives, with ESCs providing a foundational benchmark and iPSCs enabling personalized medical applications. As reprogramming technologies advance and our understanding of molecular differences deepens, both cell types will continue to be indispensable tools for unraveling developmental biology and developing novel therapeutics.

Biological Origins and Derivation Methods

Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) are pluripotent stem cells derived from the inner cell mass (ICM) of blastocyst-stage embryos [9] [10]. During mammalian development, the totipotent zygote undergoes multiple divisions to form a blastocyst, within which the first cell fate bifurcation occurs: the trophectoderm (TE) that will form extra-embryonic tissues, and the ICM that contains the pluripotent cells destined to form the embryo proper [9]. The ICM further segregates into primitive endoderm (PE) and epiblast (EPI) lineages, with EPI cells representing the primary source of true pluripotent cells [9]. The isolation of human ESCs (hESCs) was first achieved by James Thomson and colleagues in 1998, opening new avenues for studying human development and disease [1].

The derivation of ESCs requires precise methodological considerations to maintain the pluripotent state. Historically, the first ESCs were derived using culture conditions based on media for teratocarcinoma-derived embryonal carcinoma cells, including feeder layers and fetal calf serum [9]. Subsequent research revealed that these components could be substituted with leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and bone morphogenetic protein 4 (Bmp4) [9]. More recent advances utilize basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) to promote human ESC self-renewal [10]. Additional components required to maintain stem cell characteristics include cytokines (e.g., TGF-β, WNT3A), human serum albumin or serum replacement, and extracellular matrix components such as matrigel, fibronectin, or laminin [10].

ICM Isolation Techniques

The following diagram illustrates the primary methodological approaches for isolating the inner cell mass from blastocysts:

Two primary techniques have been developed for ICM isolation:

1. Immunosurgery: This traditional method involves removing the zona pellucida, then incubating blastocysts with antibodies that bind to trophectoderm cells, followed by complement-mediated lysis to selectively destroy the trophectoderm while leaving the ICM intact [11]. Although effective, this approach is time-consuming and carries a risk of contaminating ES cells with animal materials when used for therapeutic applications [11].

2. Microsurgical Technique: This improved mechanical method uses micromanipulators under an inverted microscope to physically separate the ICM [11]. The procedure involves: (1) anchoring the embryo on the ICM side with a holding needle using suction from a micrometer syringe; (2) cutting off the zona pellucida; and (3) tearing off the trophoblastic layer from the nudity blastocyst [11]. Comparative studies demonstrate that this microsurgical approach increases successful derivation rates compared to immunosurgery while eliminating potential animal material contamination [11].

Research Reagent Solutions for ESC Derivation

Table: Essential Research Reagents for ESC Derivation and Culture

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in ESC Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokines & Growth Factors | bFGF (FGF-2), LIF, TGF-β, WNT3A | Support self-renewal and maintenance of pluripotent state; bFGF particularly important for hESC self-renewal [10]. |

| Culture Supplements | Human serum albumin, Serum replacement | Provide essential nutrients and attachment factors while maintaining defined culture conditions [10]. |

| Extracellular Matrix | Matrigel, Fibronectin, Laminin | Provide structural support and signaling cues for cell attachment and proliferation [10]. |

| Signaling Inhibitors | MEK/ERK inhibitors, GSK3 inhibitors | Help maintain naive pluripotency states in combination with other factors [10]. |

| Metabolic Components | Glutamine, Lipid supplements | Support high metabolic demands of rapidly proliferating pluripotent cells [8]. |

Comparative Analysis: ESCs vs. iPSCs in Disease Modeling

The development of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) in 2006 by Shinya Yamanaka's lab provided an alternative pluripotent cell source [12] [1]. iPSCs are generated by reprogramming somatic cells through the overexpression of key transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC - OSKM factors) [1]. While both ESCs and iPSCs share the fundamental properties of pluripotency and self-renewal, significant functional differences impact their utility in disease modeling research.

Molecular and Functional Comparisons

Table: Experimental Comparison of ESCs and iPSCs in Disease Modeling

| Parameter | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Inner cell mass of blastocyst-stage embryos [9] [10] | Reprogrammed somatic cells (e.g., fibroblasts, blood cells) [12] [1] |

| Reprogramming Method | Natural embryonic development | Viral vectors (retrovirus, Sendai virus) or non-integrating methods (episomal vectors) [13] |

| Ethical Considerations | Controversial due to embryo destruction [3] | Non-controversial, no embryos required [3] |

| Genetic Background | Wild-type or specific mutations via PGD embryos [3] | Patient-specific, including disease-associated mutations [3] |

| Transcriptional Profile | Gold standard for pluripotency [14] | Near-identical to ESCs but with subtle differences [14] |

| DNA Methylation | Characteristic pluripotency signature [13] | Epigenetic memory of somatic cell origin; aberrant methylation patterns [14] [13] |

| Differentiation Propensity | Consistent across lines [14] | Variable yield of neural, cardiovascular progeny [14] |

| Disease Modeling Applications | Early embryonic lethality (e.g., Turner syndrome) [3] | Patient-specific diseases, late-onset disorders [3] |

Proteomic analyses reveal that while ESCs and iPSCs express a nearly identical set of proteins, they show consistent quantitative differences in expression levels [8]. iPSCs demonstrate increased total protein content (over 50% higher than ESCs), with significantly increased abundance of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial proteins required to sustain high growth rates, including nutrient transporters and metabolic proteins [8]. These molecular differences correlate with functional phenotypes, as iPSCs show increased glutamine uptake, enhanced lipid droplet formation, and elevated mitochondrial potential compared to ESCs [8].

Signaling Pathways Governing Pluripotency

The maintenance of pluripotency in ESCs is regulated by complex signaling networks that differ between species. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways involved in maintaining human ESCs:

The core pluripotency network in ESCs is governed by transcription factors including OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2 [9]. In mouse ESCs, LIF/Stat3 signaling is critical for maintaining pluripotency, while human ESCs rely more heavily on FGF signaling and TGF-β pathways [9] [10]. Inhibition of MEK/ERK and glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) signaling, combined with activation of Stat3 by LIF, was previously thought sufficient to promote the pluripotent ground state [10]. However, culture with basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) has proven more effective for promoting human ESC self-renewal [10].

Experimental Workflows in Disease Modeling

ESC-Based Disease Modeling Workflow

The following diagram outlines the generalized experimental workflow for creating and validating ESC-based disease models:

ESC-based disease models are generated through two primary approaches: (1) derivation from preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD)-identified mutant embryos, or (2) genetic manipulation of existing wild-type ESC lines using genome editing technologies [3]. The ICM is isolated via microsurgical techniques or immunosurgery, followed by ESC derivation under appropriate culture conditions [11]. Resulting lines must be validated for pluripotency through teratoma formation assays and marker expression analysis before directed differentiation into disease-relevant cell types [3].

Advantages and Limitations in Research Applications

Each cell type offers distinct advantages for specific research applications:

ESC-Based Models Excel For:

- Studying early embryonic lethal disorders (e.g., Turner syndrome) where ESCs better model embryonic phenotypes than iPSCs from surviving patients [3]

- Investigating placental development defects underlying early miscarriage [3]

- Research requiring consistent differentiation propensity across cell lines [14]

- Studies where epigenetic memory from somatic cells would confound results [3]

iPSC-Based Models Excel For:

- Patient-specific disease modeling with complete genetic background [3]

- Studying late-onset disorders and age-related diseases [1]

- Drug screening platforms using patient-specific cells [12]

- Applications where ethical considerations limit ESC use [3]

Notably, some disease phenotypes manifest differently in ESC versus iPSC models. For example, in Turner syndrome (XO karyotype), ESCs derived by screening for spontaneous X chromosome loss revealed significant effects on placental gene expression, suggesting abnormal placental development as the cause of early embryonic lethality [3]. In contrast, iPSCs derived from Turner syndrome patients showed minimal effects on placental gene expression, representing the rare surviving cases rather than the typical embryonic lethal phenotype [3].

Similarly, in Huntington's disease, an ESC-based model expressing mutant huntingtin with expanded polyglutamine repeats demonstrated protein aggregation, while iPSC-based models from patients did not consistently show this phenotype, suggesting differential vulnerability to proteostasis disruption between these cell types [3].

Both ESCs and iPSCs provide powerful platforms for disease modeling, each with distinct advantages and limitations. ESCs, derived from the ICM of blastocysts, remain the gold standard for pluripotency and are particularly valuable for studying early developmental disorders and establishing baseline molecular profiles. iPSCs offer unprecedented access to patient-specific genetic backgrounds and avoid ethical concerns associated with ESCs. The choice between ESC and iPSC models should be guided by the specific research question, with ESCs preferred for studies of early embryonic development and disorders causing embryonic lethality, and iPSCs optimal for modeling patient-specific diseases and developing personalized therapeutic approaches. Understanding the molecular and functional differences between these cell types enables researchers to select the most appropriate model system for their specific disease modeling applications.

The field of regenerative medicine and disease modeling was fundamentally reshaped by the advent of techniques to derive human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), which possess an unlimited self-renewal capacity and can differentiate into virtually any adult cell type [3] [15]. For decades, human Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs), isolated from the inner cell mass of blastocysts, served as the primary source of pluripotent cells for research [15]. However, their use is accompanied by ethical concerns and immunological rejection risks [16] [17]. A paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs), somatic cells reprogrammed to a pluripotent state through the introduction of specific transcription factors, most notably the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC) [18] [19]. This breakthrough offered a path to generate patient-specific cell lines without the ethical constraints of ESCs [17]. While theoretically similar in pluripotency, ESCs and iPSCs exhibit fundamental biological and practical differences that critically impact their efficacy in disease modeling, making the choice between them a strategic decision for researchers [3] [20]. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data and methodologies.

Core Technology Comparison: Derivation and Practical Considerations

The fundamental distinction between ESCs and iPSCs lies in their origin and derivation process, which directly translates into specific advantages and limitations for each system. The following table summarizes the core differentiators.

Table 1: Core Technology and Practical Considerations of ESCs vs. iPSCs

| Feature | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Inner cell mass of a blastocyst [15] | Reprogrammed somatic cells (e.g., skin fibroblasts, blood cells) [3] [19] |

| Key Derivation Method | Isolation via microsurgery or immunological targeting of trophoblast cells from donated embryos [15] | Viral (retrovirus, lentivirus) or non-viral delivery of reprogramming factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) [3] [21] |

| Ethical Status | Contentious; involves destruction of human embryos [3] [17] | Avoids ethical concerns associated with embryo use [16] [17] |

| Immunological Compatibility | Allogeneic; risk of immune rejection upon transplantation [16] | Autologous; potential for patient-specific cells, minimizing rejection [16] |

| Genetic Context | Wild-type or specific mutations via PGD; requires genetic manipulation for disease modeling [3] | Endogenously contains the patient's complete genetic background, including disease-causing mutations [3] [21] |

| Accessibility & Scalability | Limited to available embryos and associated with IVF units; restricted/banned in some countries [3] [16] | High; somatic cells are easily accessible from patients, enabling large-scale production of disease-specific lines [3] |

The derivation of mutated ESCs for disease modeling typically requires inefficient genome editing or derivation from affected embryos identified via Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis (PGD), which is limited to a small number of diseases [3] [20]. In contrast, iPSCs are derived by reprogramming a patient's somatic cells, inherently capturing the full genetic complexity of the disease and obviating the need for complex genetic engineering [21].

Comparative Efficacy in Disease Modeling: Experimental Evidence

While both cell types are pluripotent, their utility in accurately recapitulating disease phenotypes can vary significantly based on the specific disorder. The following experimental data highlights these nuances.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of ESC and iPSC Models in Specific Genetic Disorders

| Disease | ESC-Based Model Findings | iPSC-Based Model Findings | Comparative Efficacy Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turner Syndrome (XO Karyotype) | XO ESCs showed significant dysregulation of placental genes, suggesting a cause for the high rate of early embryonic lethality [3] [20]. | iPSCs from surviving patients showed minimal effect on placental gene expression, representing the rare surviving cases [3] [20]. | ESCs > iPSCs for studying early developmental lethality; iPSCs are suitable for studying postnatal phenotypes [3]. |

| Spinal Muscular Atrophy | Knockdown of SMN in ESCs successfully modeled the disease [3]. | iPSCs derived from patients recapitulated disease phenotypes [3]. | ESCs ≈ iPSCs; both systems effectively modeled the disorder [3]. |

| Fanconi Anemia | Gene targeting (e.g., TALEN) or knockdown of FANCA/FANCD2 used to create models [3]. | Reprogramming itself is challenging due to genomic instability; successful models have been generated [3]. | Context-dependent; the reprogramming process can be a hurdle for diseases with genomic instability [3]. |

| Long QT Syndrome | Gene targeting in ESCs successfully created disease models [3]. | Patient-specific iPSCs effectively modeled the cardiac electrical abnormality [3]. | ESCs ≈ iPSCs; both systems are effective for modeling this cardiac channelopathy [3]. |

| Huntington’s Disease | Overexpression of mutant HTT in ESCs led to the appearance of protein aggregates [3]. | Consortium studies generated iPSC models, but one study showed aggregates formed in the ESC model [3]. | ESCs > iPSCs in one study; potential differences in phenotypic penetrance [3]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Modeling Liver Disease from Pluripotent Stem Cells

A key application of hPSCs is generating disease-relevant cell types, such as hepatocytes for liver disease modeling. The following workflow, derived from a detailed differentiation roadmap, outlines the signals and markers for efficient liver progenitor generation from both ESCs and iPSCs [22].

Diagram 1: Directed Differentiation to Liver Cell Types.

This protocol emphasizes that liver commitment is executed by a temporally dynamic sequence of signaling events that suppress alternate fates (e.g., pancreas, intestines) across six consecutive lineage choices [22]. The efficiency of this process can be quantitatively tracked using cell-surface markers (e.g., CD99+CD184−CD10− for liver progenitors) [22].

Key Limitations of iPSC-Based Models

Despite their advantages, iPSCs have several documented limitations that can affect disease modeling fidelity:

- Incomplete Reprogramming and Epigenetic Memory: iPSCs may retain an epigenetic memory of their somatic cell origin, which can bias their differentiation potential [3] [20].

- Genomic Instability: The reprogramming process itself can introduce mutations or cause chromosomal instability, potentially confounding disease phenotypes [3] [20].

- Variable Reprogramming Efficiency: Certain genetic aberrations can significantly decrease the efficiency of generating iPSCs, creating a selection bias [3].

The Research Toolkit for Pluripotent Stem Cell Disease Modeling

A standardized set of reagents and tools is essential for the derivation, maintenance, and differentiation of hPSCs for disease modeling.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for hPSC Work

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Key Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Resets somatic cell identity to pluripotency. | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (Yamanaka factors); delivered via retrovirus, lentivirus, or Sendai virus [19] [21]. |

| Base Medium & Supplements | Supports hPSC self-renewal and expansion in culture. | Feeder-free media (e.g., mTeSR1); often contains FGF2 (bFGF) to maintain pluripotency [22]. |

| Inductive Growth Factors & Small Molecules | Directs differentiation toward specific lineages. | ACTIVIN/TGF-β (definitive endoderm), BMP4 & FGF (liver progenitors), Retinoic Acid (patterning), small molecule inhibitors (e.g., TGF-β inhibitor SB431542) [22]. |

| Characterization Antibodies | Confirms pluripotency and lineage-specific differentiation. | Pluripotency: OCT4, SOX2, NANOG; Endoderm: SOX17, FOXA2; Liver: HNF4A, TBX3, FAH, Albumin [22]. |

| Gene Editing Tools | Introduces or corrects mutations in ESCs or isogenic iPSC lines. | CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs; used for creating knockout models or generating genetically corrected controls [3] [15]. |

Emerging Trends and Regulatory Landscape

The field of hPSC research is rapidly evolving, with several key trends shaping its future. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are now being integrated to enhance iPSC technology, improving reprogramming efficiency, predicting optimal differentiation conditions, and automating quality control by analyzing colony morphology and multi-omics data [19]. Furthermore, the regulatory frameworks governing the clinical translation of these therapies vary significantly across leading research nations, influencing the pace of development [16]. The United States and Japan, with more flexible guidelines, are leading in the number of clinical trials, while the European Union maintains rigorous regulations that prioritize safety and ethics [16]. The number of clinical trials involving iPSCs has seen significant global growth since 2008, particularly targeting conditions of the cardiovascular and nervous systems [16].

Both ESCs and iPSCs are powerful and complementary tools for disease modeling. The choice between them is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with the research goal. iPSCs excel in modeling patient-specific, post-natal disease pathologies, drug screening, and personalized therapeutic discovery while avoiding ethical and immunological hurdles. In contrast, ESCs can be more effective for studying early embryonic lethal disorders, due to the potential selection bias in iPSCs derived from surviving patients, and in contexts where the genetic instability of the reprogramming process is a concern. The ongoing integration of AI and refined differentiation protocols promises to further enhance the precision and scalability of both systems, solidifying their role in advancing regenerative medicine and drug development.

The field of regenerative medicine has been profoundly shaped by two cornerstone cell types: Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs). ESCs, isolated from the inner cell mass of blastocysts, represent the gold standard for pluripotency but entail ethical controversies and allogeneic immune rejection concerns [23] [1]. In contrast, iPSCs, generated through the reprogramming of somatic cells, offer an autologous alternative while maintaining comparable differentiation potential [2] [1]. Understanding the nuanced molecular similarities and differences between these cell types is paramount for evaluating their comparative efficacy in disease modeling and therapeutic development. This guide provides a systematic comparison of the transcriptional networks and epigenetic landscapes that define ESCs and iPSCs, equipping researchers with the necessary framework to select the most appropriate cell type for specific biomedical applications.

Core Molecular Characteristics

Transcriptional Networks Governing Pluripotency

The pluripotent state in both ESCs and iPSCs is maintained by a core transcriptional network centered on key transcription factors. The canonical Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) form the foundation of iPSC induction, while ESCs endogenously express these and other critical regulators such as NANOG [2] [1] [24]. OCT4 (POU5F1) and SOX2 operate in a cooperative manner to activate pluripotency-associated genes while simultaneously repressing lineage-specific differentiation programs [1]. The stabilization of this network occurs through the endogenous reactivation of the OCT4 promoter, which serves as a central mechanism for establishing and maintaining the pluripotent state [2].

Recent investigations have revealed that while the core transcriptional circuitry is largely shared, subtle differences in gene expression profiles can persist in iPSCs compared to ESCs. These variations may stem from incomplete epigenetic resetting or the retention of a somatic memory reflective of the donor cell type [2] [25]. The transcriptional dynamics during reprogramming follow a biphasic pattern: an initial stochastic phase where somatic genes are silenced and early pluripotency genes are activated, followed by a more deterministic phase where late pluripotency-associated genes are established [1].

Table 1: Core Pluripotency Transcription Factors in ESCs and iPSCs

| Transcription Factor | Role in Pluripotency | Expression in ESCs | Expression in iPSCs | Functional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 (POU5F1) | Master regulator of pluripotency | High endogenous expression | Reactivated during reprogramming | Essential for establishment and maintenance of pluripotency; central stabilizer of pluripotent state [2] [1] |

| SOX2 | Partners with OCT4 in transcriptional regulation | High endogenous expression | Reactivated during reprogramming | Forms heterodimers with OCT4; regulates expression of multiple pluripotency genes [1] |

| NANOG | Stabilizes pluripotent state | High endogenous expression | Variable reactivation | Critical for preventing spontaneous differentiation; often included in alternative reprogramming factor cocktails [1] [24] |

| KLF4 | Promotes self-renewal | Expressed | Overexpressed during reprogramming | Can be substituted by KLF2 or KLF5 with reduced efficiency [24] |

| c-MYC | Enhances proliferation | Expressed | Overexpressed during reprogramming | Not strictly essential but significantly increases reprogramming efficiency; considered oncogenic [2] [24] |

| LIN28 | RNA-binding protein | Expressed | Used in alternative reprogramming (OSNL) | Promotes reprogramming through miRNA regulation; alternative to c-MYC [1] [24] |

Epigenetic Landscapes

The epigenetic landscape represents a crucial differentiator between ESCs and iPSCs. While both cell types share fundamental pluripotency features, iPSCs frequently retain epigenetic memories of their somatic cell origin, which can manifest as differential DNA methylation patterns and chromatin accessibility profiles [2] [25]. Research indicates that the relationship between genetic variation and epigenetic variation is most pronounced at the iPSC stage, with this association weakening following differentiation [25].

Reprogramming to pluripotency requires comprehensive epigenetic remodeling, including chromatin restructuring and DNA methylation resetting [2] [1]. However, this process is often incomplete, leading to aberrant epigenetic signatures in iPSCs. A comparative analysis has revealed that iPSCs generated through transcription factor overexpression harbor more epigenetic abnormalities compared to those produced via somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), suggesting that the reprogramming methodology itself significantly influences the resulting epigenetic landscape [26].

Notably, studies utilizing multiomics approaches have demonstrated that donor-specific epigenetic patterns are maintained in iPSCs, with lines from the same donor clustering together in principal component analyses of DNA methylation data [25]. This donor-specific epigenetic signature underscores the persistent influence of the original somatic epigenome, even after extensive reprogramming and passaging.

Table 2: Epigenetic Features of ESCs versus iPSCs

| Epigenetic Feature | ESCs | iPSCs | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Patterns | Established during embryonic development | Often retain somatic memory signatures | Can influence differentiation potential and disease modeling fidelity [25] |

| Chromatin Accessibility | Characteristic of native pluripotency | Resembles ESCs but with somatic cell-type specific variations | Affects transcription factor binding and gene expression profiles [1] [25] |

| Histone Modification Landscape | H3K4me3 at promoters of active genes; H3K27me3 at bivalent domains | Generally similar but may show variations at specific loci | Can create aberrant differentiation propensities in iPSCs [2] |

| X-Chromosome Inactivation | Inactivated in female lines | Variable reactivation and silencing patterns | Incomplete X-reactivation observed in female iPSC lines [27] |

| Imprinting Status | Normal parental-specific methylation | Frequent loss of imprinting (LOI) during reprogramming | Can affect growth and differentiation properties [27] |

| Relationship to Genetic Variation | Not applicable | Strong association in iPSCs, weakens after differentiation | Donor-specific patterns maintained despite reprogramming [25] |

Experimental Modeling and Data Generation

Methodologies for Molecular Profiling

Comprehensive molecular profiling of ESCs and iPSCs requires the integration of multiple experimental approaches to capture the complexity of their transcriptional and epigenetic states. The following protocols represent standardized methodologies for generating comparative data.

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Epigenetic Analysis of Pluripotent Cells

- Objective: To assess and compare the DNA methylation and chromatin accessibility landscapes of ESCs and iPSCs.

- Sample Preparation: Culture ESCs and iPSCs under identical conditions using defined media (e.g., mTeSR1 or E8) on recombinant laminin or Matrigel substrates. Maintain cells for a consistent number of passages (e.g., 10-20) to minimize culture-induced artifacts [2] [27].

- DNA Methylation Profiling (Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing):

- Extract high-molecular-weight genomic DNA using a commercial kit.

- Treat DNA with bisulfite to convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils.

- Prepare sequencing libraries and perform whole-genome sequencing on an Illumina platform to a recommended coverage of >30x.

- Align sequences to a reference genome and calculate methylation ratios for all cytosine positions [25].

- Chromatin Accessibility Profiling (ATAC-Seq):

- Harvest 50,000 viable cells per sample.

- Perform tagmentation reaction using hyperactive Tn5 transposase.

- Purify and amplify the tagmented DNA.

- Sequence libraries and map reads to the reference genome to identify regions of open chromatin [25].

- Data Analysis: Identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs) and differentially accessible peaks between ESC and iPSC lines. Integrate data with transcriptomic profiles to correlate epigenetic states with gene expression [25].

Protocol 2: Single-Cell Multiomics for Lineage Propensity Assessment

- Objective: To evaluate cellular heterogeneity and lineage-specific transcriptional and epigenetic states at single-cell resolution.

- Sample Preparation: Culture ESCs and iPSCs as described in Protocol 1. Include both undifferentiated populations and cells directed toward early differentiation (e.g., via embryoid body formation for 3-5 days) [27].

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq):

- Prepare single-cell suspensions with high viability (>90%).

- Partition cells into nanoliter-scale droplets using a platform such as the 10x Genomics Chromium Controller.

- Generate barcoded cDNA libraries and sequence to a depth of >50,000 reads per cell.

- Perform clustering analysis to identify distinct cell populations and lineage trajectories [27].

- Single-Cell ATAC Sequencing (scATAC-seq):

- Process cells in parallel using a commercial scATAC-seq kit.

- Sequence libraries and analyze fragment insert sizes to map nucleosome positions and transcription factor accessibility.

- Integrate with scRNA-seq data to link regulatory element activity with transcriptional outputs [27].

- Data Analysis: Compare the diversity of cell states and the frequency of spontaneous differentiation between ESC and iPSC cultures. Identify any residual somatic gene expression programs in iPSCs [25] [27].

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

The molecular pathways that govern pluripotency and reprogramming are complex. The following diagrams illustrate the core signaling networks and experimental workflows central to understanding ESC and iPSC biology.

Diagram 1: Key Pathways in Pluripotency and Reprogramming. The top section illustrates the multi-stage process of somatic cell reprogramming to iPSCs. The bottom section shows the core autoregulatory transcriptional network that maintains pluripotency in both ESCs and established iPSCs [2] [1].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Comparative Molecular Profiling. This diagram outlines the integrated multi-omics approach for generating comprehensive molecular data from ESCs and iPSCs, from sample preparation through data integration and analysis [25] [27].

Applications in Disease Modeling

The application of ESCs and iPSCs in disease modeling represents one of the most transformative advances in biomedical research. iPSCs offer a unique advantage through their ability to be derived from patients with specific genetic backgrounds, creating in vitro models that recapitulate disease pathophysiology [2] [1]. This has been particularly valuable for studying neurological disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and metabolic conditions.

Neurological Disease Models

iPSC-derived neuronal models have provided unprecedented insights into the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Patient-specific neurons enable the analysis of pathogenic mechanisms and the evaluation of pharmacological interventions [2]. For ALS, iPSC-derived motor neurons (iPSC-MNs) reproduce disease-specific pathology, including TDP-43 protein aggregation, and provide a platform for investigating molecular mechanisms and screening therapeutic compounds [24]. In PD models, iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons recapitulate the degeneration characteristic of the substantia nigra and have elucidated the role of α-synuclein aggregation in both sporadic and familial forms of the disease [2].

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disease Models

iPSCs differentiated into cardiomyocytes enable the study of arrhythmogenic disorders, heart failure, and myocardial injury. Models of congenital arrhythmias linked to mutations in genes such as KCNQ1 provide a foundation for precision cardiology [2]. In the realm of metabolic diseases, iPSCs preserve the patient's genotype in vitro, making them powerful tools for investigating conditions like cystic fibrosis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), and Wilson's disease [2]. For type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance, iPSC-derived hepatocytes, myocytes, and adipocytes allow researchers to study tissue-specific mechanisms of insulin resistance and screen for potential therapeutics [28].

Table 3: Disease Modeling Applications of ESCs and iPSCs

| Disease Category | Model System | Key Findings/Applications | Advantages of iPSCs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodegenerative (ALS) | iPSC-derived motor neurons | Recapitulate TDP-43 pathology; platform for drug screening [24] | Patient-specific genetic background; enable study of sporadic and familial forms |

| Neurodegenerative (PD) | iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons | Model α-synuclein aggregation; study dopaminergic neuron vulnerability [2] | Capture full genetic complexity of disease; useful for personalized therapeutic testing |

| Cardiovascular | iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes | Model channelopathies (e.g., KCNQ1); test drug-induced arrhythmogenesis [2] | Source of human cardiomyocytes for disease modeling and safety pharmacology |

| Metabolic (T2D/IR) | iPSC-derived hepatocytes, adipocytes, myocytes | Study tissue-specific insulin resistance mechanisms; drug screening [28] | Generate otherwise inaccessible human metabolic cell types with disease genotypes |

| Autoimmune (SLE) | iPSC-derived B and T lymphocytes | Recapitulate dysregulated signaling and autoantibody production [2] | Model complex immune cell interactions in a patient-specific context |

| Genetic (Cystic Fibrosis) | iPSC-derived airway epithelial cells | Reproduce defective chloride transport; evaluate CFTR correctors [2] | Platform for evaluating patient-specific responses to targeted therapies (e.g., ivacaftor) |

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful molecular profiling and disease modeling require access to high-quality, well-characterized reagents and cellular tools. The following table outlines essential materials for research in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Pluripotent Stem Cell Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations for ESC vs. iPSC Work |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OSKM factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC); OSNL factors (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28) | Induction of pluripotency in somatic cells | Delivery method (viral vs. non-viral) affects genomic integrity and safety profile [2] [24] |

| Culture Media | mTeSR1, E8 media, iPSC-Brew | Maintenance of undifferentiated pluripotent stem cells | Chemically defined media enhance reproducibility and minimize lot-to-lot variability [2] [27] |

| Culture Substrates | Matrigel, recombinant laminin-521, vitronectin | Extracellular matrix for feeder-free culture | Xeno-free substrates are preferred for clinical translation [2] |

| Differentiation Kits | Commercially available kits for cardiomyocytes, neurons, hepatocytes | Directed differentiation into specific lineages | Efficiency and purity of differentiation can vary between ESC and iPSC lines |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems, PiggyBac transposon | Genetic modification for disease modeling or gene correction | Isogenic controls are critical for confirming phenotype-genotype relationships |

| Quality Control Assays | Pluripotency marker antibodies (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG), karyotyping kits, mycoplasma tests | Validation of pluripotent state and genomic integrity | Regular monitoring is essential due to genomic instability risks in culture [2] [27] |

| iPSC Lines | Commercially available control lines (e.g., from FUJIFILM CDI, REPROCELL) | Standardized reference materials for assay development | Well-characterized lines reduce experimental variability [29] [12] |

The comparative analysis of transcriptional networks and epigenetic landscapes reveals both remarkable similarities and important distinctions between ESCs and iPSCs. While ESCs continue to serve as a fundamental reference for the pluripotent state, iPSCs offer unparalleled opportunities for patient-specific disease modeling and drug development. The persistent epigenetic memory observed in some iPSC lines, rather than being solely a limitation, also provides a window into the mechanisms of cellular identity and reprogramming. As reprogramming methodologies continue to advance—with improvements in non-integrating delivery systems, chemical induction protocols, and epigenetic resetting techniques—the functional equivalence between iPSCs and ESCs is expected to increase further. The choice between these cell types for specific research applications should be guided by the experimental question at hand, weighing the standardized properties of ESCs against the patient-specific relevance and ethical advantages of iPSCs. The ongoing development of comprehensive molecular datasets and standardized profiling protocols, as outlined in this guide, will continue to refine our understanding and utilization of these powerful tools in biomedical research.

The field of regenerative medicine and disease modeling is profoundly shaped by two cornerstone cell types: Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs). ESCs, derived from the inner cell mass of a blastocyst, represent the gold standard for pluripotency—the ability to differentiate into any cell type in the body [30]. Their discovery opened unprecedented avenues for studying human development and disease. In 2006, a paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of iPSCs—adult somatic cells reprogrammed back to an embryonic-like pluripotent state through the introduction of specific transcription factors [1] [2]. This breakthrough, earning Shinya Yamanaka the Nobel Prize in 2012, provided a powerful alternative that bypassed the primary ethical controversy associated with ESCs [31] [32]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the critical question is how these two cell types compare in practical application, particularly in the context of disease modeling research. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of their efficacy, focusing on scientific capabilities while acknowledging the ethical framework that underpins their use.

Ethical and Practical Foundations

The fundamental distinction between ESCs and iPSCs lies at the intersection of science and ethics.

The Ethical Divide

The derivation of ESCs requires the destruction of a human embryo, raising significant ethical concerns and debates about the moral status of the embryo [31] [32]. This has resulted in complex and varied regulatory landscapes across the globe, which can impact research funding and scope [32]. In contrast, iPSCs are derived from adult tissues, such as skin fibroblasts or peripheral blood cells, and do not involve the use of embryos, thus circumventing this primary ethical hurdle [31] [2]. However, iPSCs are not without their own ethical considerations, which include concerns about consent for tissue donation and the long-term safety of their clinical application, particularly the potential for tumor formation [31] [32].

Origin and Derivation

The following diagram illustrates the distinct origins and reprogramming pathways of ESCs and iPSCs.

Comparative Efficacy in Disease Modeling

For a researcher, the choice between ESCs and iPSCs often hinges on their functional performance in modeling diseases. The following table summarizes key comparative aspects based on current scientific evidence.

Table 1: Functional Comparison for Disease Modeling and Research Applications

| Aspect | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency | Gold standard; proven ability to differentiate into all three germ layers [30]. | Considered functionally equivalent to ESCs in their potential [4]. |

| Genetic Background | Heterogeneous; represents a unique genetic blueprint. | Patient-specific; can be derived from individuals with specific genetic diseases, enabling personalized disease modeling [33] [2]. |

| Disease Modeling Utility | Ideal for studying early human development and fundamental biology. | Superior for modeling genetically complex diseases, drug screening on patient-specific cells, and studying sporadic disease forms [33] [1] [2]. |

| Genomic Stability | Generally high stability. | Prone to genomic and epigenetic instability due to the reprogramming process and prolonged culture; requires rigorous monitoring [33] [2]. |

| Immunogenicity | Allogeneic; potential for immune rejection upon transplantation. | Autologous potential; derived from the patient's own cells, minimizing rejection risk [2]. |

| Differentiation Efficiency | Robust and well-established protocols. | Can be variable, influenced by the somatic cell source and reprogramming method [2]. |

Key Insights from Comparative Studies

A pivotal study from the Harvard Stem Cell Institute directly addressed the question of functional equivalence. Researchers used an experimental "trick" by first differentiating human ESCs into skin cells and then reprogramming those skin cells into iPSCs. This created genetically identical lines for a direct comparison. The study found that the gene expression profiles between the original ESCs and the newly created iPSCs were remarkably similar, with only about 50 differentially expressed genes out of thousands—a difference that may be negligible "transcriptional noise" [4]. Functionally, the ESCs and iPSCs demonstrated equivalent potential to differentiate into neural cells and other specialized lineages, leading the researchers to conclude that, within the parameters of their study, the two cell types are functionally equivalent [4].

Experimental Protocols for Equivalence and Disease Modeling

To ensure the reliable application of ESCs and iPSCs in research, standardized protocols for their evaluation are critical.

Protocol 1: Direct Functional Equivalence Testing

This protocol is based on the methodology used in the Harvard Stem Cell Institute study [4].

- Establish Baseline: Begin with a well-characterized human ESC line.

- In Vitro Differentiation: Differentiate the ESCs into a target somatic cell type (e.g., dermal fibroblasts or keratinocytes).

- Reprogramming: Reprogram the ESC-derived somatic cells into iPSCs using a non-integrating method, such as Sendai virus or episomal vectors expressing the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC).

- Molecular Characterization:

- RNA Sequencing: Perform whole-transcriptome RNA sequencing on the original ESC line and the derived iPSC line.

- Data Analysis: Compare gene expression profiles to identify differentially expressed genes. Functional equivalence is supported by minimal, biologically insignificant differences.

- Functional Validation:

- Directed Differentiation: Differentiate both the original ESCs and the derived iPSCs into a variety of lineages (e.g., neural ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm).

- Assessment: Use immunocytochemistry and functional assays to compare the efficiency and maturity of the differentiated cells.

Protocol 2: Patient-Specific Disease Modeling with iPSCs

This is a generalized workflow for creating a disease model using iPSCs, applicable to conditions like Parkinson's disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [33] [2].

- Somatic Cell Collection: Obtain somatic cells from a patient with the disease of interest and a healthy matched control. Common sources include:

- Reprogramming to iPSCs: Reprogram the somatic cells using integration-free methods (e.g., mRNA, Sendai virus) to generate patient-specific and control iPSC lines.

- Quality Control: Rigorously characterize iPSC lines for pluripotency (e.g., expression of OCT4, NANOG via immunocytochemistry or PCR) and genomic integrity (e.g., karyotyping) [2].

- Directed Differentiation: Differentiate the patient and control iPSCs into the relevant cell type(s) for the disease (e.g., dopaminergic neurons for Parkinson's disease).

- Phenotypic Screening: Analyze the diseased cells for known pathological hallmarks, such as protein aggregation, electrophysiological abnormalities, or metabolic dysfunction, and compare them to healthy controls.

- Drug Screening: Use the diseased cell model to test the efficacy and toxicity of potential therapeutic compounds.

The logical flow of this modeling and drug discovery process is depicted below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful experimentation with ESCs and iPSCs relies on a suite of specialized reagents. The following table details key solutions used in the featured protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Stem Cell Research

| Research Reagent | Function in Protocol | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Vectors | Deliver transcription factors to somatic cells to induce pluripotency [2]. | Non-Integrating Methods (Preferred): Sendai virus, episomal plasmids, synthetic mRNA. Integrating Methods: Retroviruses, lentiviruses (higher risk of insertional mutagenesis). |

| Chemically Defined Medium | Supports the growth and maintenance of pluripotent stem cells [2]. | mTeSR1, Essential 8 (E8) medium. These standardized, xeno-free formulations support feeder-free culture and enhance reproducibility. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Coats culture surfaces to support pluripotent cell adhesion and growth. | Matrigel, recombinant human laminin-521. Essential for feeder-free culture systems. |

| Pluripotency Markers | Used in quality control to confirm the pluripotent state of ESCs and iPSCs. | Antibodies against OCT4, SOX2, NANOG for immunocytochemistry; PCR kits for pluripotency gene analysis. |

| Differentiation Kits & Reagents | Directs pluripotent stem cells toward specific somatic cell fates. | Commercial kits available for neurons, cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, etc. Often use specific growth factors and small molecule inhibitors (e.g., TGF-β inhibitors, FGF2). |

| Genomic Integrity Assays | Monitors for chromosomal abnormalities acquired during reprogramming or culture. | Karyotyping (G-banding), Comparative Genomic Hybridization (CGH) arrays. Regular monitoring is crucial for iPSCs [2]. |

The objective comparison of ESCs and iPSCs reveals a landscape of functional equivalence tempered by distinct practical advantages. While ESCs remain a critical biological reference, iPSCs offer an unparalleled capacity for patient-specific disease modeling, which is accelerating research into complex neurological, cardiovascular, and metabolic disorders [33] [2]. The ethical simplicity of iPSCs further solidifies their role as the forefront technology for personalized medicine and drug discovery.

The future of the field lies in standardization and enhanced safety. Ongoing research focuses on addressing the challenges of genomic instability in iPSCs and developing more robust, chemically defined differentiation protocols [33] [34]. Furthermore, international consortia, like the one recently launched by the ISSCR, are working to establish guidelines for the widespread and responsible adoption of these powerful stem cell-derived models [34]. For the research scientist, the choice is no longer about which cell type is inherently "better," but which is the most fit-for-purpose for their specific scientific question, with iPSCs providing a powerful and ethically sound alternative that continues to close the gap with its embryonic counterpart.

Modeling Human Diseases: Techniques and Translational Applications

The advent of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has fundamentally transformed regenerative medicine and disease modeling research. This breakthrough, first achieved by Takahashi and Yamanaka in 2006, demonstrated that somatic cells could be reprogrammed into pluripotent stem cells through the ectopic expression of specific transcription factors [1]. The original methodology utilized retroviral vectors to deliver the reprogramming factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM) [35]. However, these pioneering methods raised significant safety concerns regarding insertional mutagenesis and transgene reactivation, particularly concerning the oncogenic potential of factors like c-Myc [36]. In response, the field has progressively evolved toward integration-free systems that minimize genomic alteration risks while maintaining reprogramming efficiency.

Within the broader context of comparing embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and iPSCs for disease modeling research, the choice of reprogramming methodology critically influences the validity and safety of the resulting cellular models. While ESCs historically provided the gold standard for pluripotency, they face ethical limitations and immunocompatibility challenges that iPSCs inherently overcome [35]. The progressive refinement of reprogramming methods has significantly enhanced the fidelity of iPSC disease models, positioning them as a powerful alternative to ESC-based systems for investigating disease mechanisms and screening therapeutic compounds.

Historical Development and Key Reprogramming Methods

Retroviral and Lentiviral Vector Systems

The first iPSC generation method employed retroviral vectors, which offered high transduction efficiency and stable transgene expression necessary for successful reprogramming. These vectors integrate into the host genome, enabling persistent expression of the OSKM factors throughout the reprogramming process [1]. A key limitation of simple retroviral vectors is their inability to transduce non-dividing cells, which constrained their application to certain cell types [36].

Lentiviral vectors, derived from HIV-1, emerged as an improvement, capable of infecting both dividing and non-dividing cells [37]. Scientists commonly used pantropic retroviral vectors pseudotyped with VSV-G protein to enhance transduction efficiency across diverse cell types [36]. The development of doxycycline-inducible systems represented another advancement, allowing temporal control of transgene expression after reprogramming was complete [35]. Despite these improvements, integrated vectors still posed risks of insertional mutagenesis and potential reactivation of oncogenic transgenes, particularly c-Myc, which was implicated in tumor formation in iPSC chimeric mice [36].

Table 1: Evolution of Viral Vector-Based Reprogramming Methods

| Vector Type | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral Vectors | Integrates into host genome; requires cell division for transduction | High efficiency for dividing cells; stable expression | Limited to dividing cells; insertional mutagenesis; transgene reactivation |

| Lentiviral Vectors | HIV-1 derived; integrates into host genome; transduces non-dividing cells | Broader cell type applicability; higher transduction efficiency | Insertional mutagenesis; complex vector design |

| Inducible Systems | Doxycycline-controlled transgene expression | Temporal control over reprogramming;可以减少持续性表达风险 | Leaky expression; incomplete silencing |

Integration-Free Reprogramming Systems

The recognition of risks associated with viral integration spurred development of non-integrating delivery systems. These methods aim to transiently express reprogramming factors without permanent genomic modification, generating footprint-free iPSCs more suitable for clinical applications [36].

Sendai virus, an RNA virus-based system, replicates in the cytoplasm without nuclear integration and is gradually diluted through cell divisions. Comparative studies show Sendai virus provides high reprogramming efficiency but may require extended culture periods to become vector-free [38]. Episomal plasmids are another non-integrating approach utilizing engineered DNA elements that replicate extrachromosomally. While these avoid integration, studies indicate they may confer a slightly higher incidence of karyotypic instability compared to other non-integrating methods [38].

Self-replicating RNA vectors and synthetic mRNA represent the most advanced non-integrating approaches. These systems enable high-efficiency reprogramming without nuclear entry and can be rapidly cleared from cells. However, RNA-based methods require careful optimization to minimize innate immune responses and can have lower overall success rates despite higher efficiency when successful [38] [36]. The RNA replicon system, based on a self-replicating RNA virus, has also been successfully employed to generate iPSCs without genomic integration [36].

Table 2: Comparison of Key Integration-Free Reprogramming Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Reprogramming Efficiency | Genomic Integration | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sendai Virus | Cytoplasmic RNA virus; diluted through cell divisions | Moderate to High | No | Broad cell type applications; clinical grade iPSC generation |

| Episomal Plasmids | Extrachromosomal replication; transient expression | Moderate | Low frequency | Patient-specific iPSC generation; disease modeling |

| Synthetic mRNA | Direct delivery of reprogramming factor mRNAs; daily transfections | High when successful | No | Clinical applications; high-quality iPSC lines |

| Protein Transduction | Cell-penetrating reprogramming proteins | Low | No | Proof-of-concept studies; mechanistic research |

Comparative Analysis of Reprogramming Method Efficacies

Efficiency and Kinetics Across Methodologies

Reprogramming efficiency varies substantially across different methodologies. Retroviral approaches typically achieve efficiencies ranging from 0.01% to 0.1% for human fibroblasts, with kinetics spanning 3-4 weeks for iPSC colony emergence [35]. The stochastic nature of early reprogramming events contributes to this relative inefficiency, with only a small fraction of transfected cells completing the full reprogramming process [1].

RNA-based reprogramming demonstrates the highest efficiency among non-integrating methods, potentially exceeding 1% under optimized conditions, though with variable success rates between cell types and laboratories [38]. Sendai virus systems offer more consistent results with efficiencies typically around 0.1%, while episomal plasmids generally yield lower efficiencies of approximately 0.001% [38] [36]. The reprogramming kinetics also differ, with RNA-based methods often producing colonies within 2-3 weeks, while episomal approaches may require 4-5 weeks.

Notably, the cell type being reprogrammed significantly influences efficiency. For instance, neural stem cells (NSCs) endogenously express high levels of Sox2 and c-Myc, enabling reprogramming with just a single factor (Oct4) [35]. Similarly, melanocytes express endogenous Sox2 and can be reprogrammed without this factor, though with reduced efficiency compared to using all four Yamanaka factors [35].

Molecular Mechanisms and Trajectories

The molecular journey from somatic cell to pluripotency involves profound epigenetic remodeling, metabolic reprogramming, and sequential activation of pluripotency networks [1]. Reprogramming occurs in two broad phases: an early, stochastic phase where somatic genes are silenced and early pluripotency-associated genes activate, followed by a late, deterministic phase where late pluripotency genes become established [1].

During the early phase, the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) represents a critical bottleneck, particularly for fibroblast reprogramming [1]. The chromatin state of the starting somatic cell significantly influences reprogramming efficiency, with more open chromatin configurations generally facilitating faster reprogramming. The process also involves global DNA demethylation, histone modification changes, and X chromosome reactivation in female cells [1].

Different reprogramming methods engage these molecular pathways with varying efficiencies. Viral methods providing sustained transgene expression may more effectively navigate epigenetic barriers, while transient methods like mRNA may require more precise timing to coordinate the complex molecular transitions.

Applications in Disease Modeling and Clinical Translation

Impact on Disease Modeling Research

The evolution of reprogramming methodologies has directly enhanced the utility of iPSCs in disease modeling and drug development. Early models utilizing integrating vectors faced concerns about genomic alterations confounding disease phenotypes, whereas modern integration-free systems generate more physiologically relevant models [33]. The ability to create patient-specific iPSCs from individuals with genetic disorders enables researchers to study disease mechanisms in human cells bearing the exact genetic background of interest [1].

iPSC-based disease models span diverse conditions including neurological disorders (Parkinson's disease, ALS), cardiac conditions (cardiomyopathies, channelopathies), ocular diseases, and metabolic disorders [39]. The development of three-dimensional organoid systems from iPSCs has been particularly transformative, enabling modeling of tissue-level architecture and cell-cell interactions not possible with traditional two-dimensional cultures [33]. For example, kidney organoids carrying PKD1 or PKD2 mutations recapitulate cyst formation seen in polycystic kidney disease, providing robust platforms for mechanistic studies and therapeutic screening [33].

Clinical Translation and Regulatory Landscape

The clinical application of iPSCs requires methods that meet regulatory standards for safety and quality. Current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP)-compliant reprogramming methods have been developed to support clinical trials [29]. As of 2025, systematic reviews identify 22 ongoing registered clinical trials utilizing iPSCs to treat conditions including cardiac disease, ocular disorders, cancer, and graft-versus-host disease [39].

Notable advancements in clinical translation include Fertilo, the first iPSC-based therapy to enter U.S. Phase III trials for supporting ex vivo oocyte maturation, and OpCT-001, an iPSC-derived therapy for retinal degeneration that received FDA IND clearance in 2024 [29]. Additionally, iPSC-derived dopaminergic neural progenitors for Parkinson's disease and iPSC-derived CD19-directed CAR natural killer cells for B-cell lymphoma have entered clinical testing [39].

The safety profile of iPSC-based therapies from early clinical trials appears encouraging, with a major review of global clinical trials identifying no class-wide safety concerns among over 1,200 patients dosed with PSC-derived products [29]. However, long-term monitoring continues to assess potential risks including tumorigenicity from residual undifferentiated cells or genetic abnormalities acquired during reprogramming [39].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC Generation and Characterization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming | Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc (OSKM); Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, Lin28 | Core transcription factors inducing pluripotency | Species-specific variants; alternative factor combinations for different cell types |

| Delivery Vectors | Retroviral/lentiviral particles; Sendai virus; episomal plasmids; synthetic mRNAs | Vehicle for introducing reprogramming factors into somatic cells | Integration vs. non-integrating; efficiency vs. safety; cell type compatibility |

| Culture Media | Fibroblast medium; OPC medium; pluripotent stem cell media | Support cell viability and growth during and after reprogramming | Stage-specific formulations; xeno-free requirements for clinical applications |

| Surface Coatings | Poly-L-ornithine/Laminin; Matrigel; recombinant vitronectin | Provide extracellular matrix support for cell attachment and growth | Defined vs. undefined matrices; compatibility with different cell types |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-Nanog, Oct4, SSEA-4, Tra-1-60 (pluripotency); lineage-specific markers | Verification of pluripotent state and differentiation potential | Species reactivity; validation for flow cytometry vs. immunocytochemistry |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Valproic acid; CHIR99021; PD0325901; ascorbic acid | Improve reprogramming efficiency and kinetics | Concentration optimization; potential synergistic effects |

The progression from retroviral vectors to integration-free systems represents a paradigm shift in cellular reprogramming methodologies. Each technological advancement has addressed specific limitations while introducing new considerations for researchers. The current landscape offers a diverse toolkit of reprogramming approaches, enabling selection based on specific research needs, from basic mechanistic studies to clinical-grade iPSC generation.

For disease modeling research, the choice of reprogramming method directly impacts the physiological relevance and safety of the resulting iPSC models. Integration-free methods now provide robust alternatives to ESCs without the ethical concerns, while generating genetically stable models that faithfully recapitulate disease phenotypes. As the field continues to mature, standardization of reprogramming protocols and characterization criteria will further enhance reproducibility and accelerate the therapeutic application of iPSC technology.

The ongoing clinical trials utilizing iPSCs derived through advanced reprogramming methods herald a new era in regenerative medicine, offering promising avenues for treating conditions that have previously proven intractable to conventional therapies.

The capacity of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), encompassing both human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), to differentiate into any cell type in the human body forms the cornerstone of modern regenerative medicine and disease modeling [40] [33]. The comparative efficacy of hESCs versus hiPSCs in generating functional somatic cells is a central question in biomedical research, with significant implications for both basic science and clinical translation. Directed differentiation protocols—sequential manipulation of culture conditions to mimic developmental signaling pathways—enable researchers to guide these pluripotent cells through specific lineage commitment steps into functional cell types [40] [41]. These protocols typically progress through defined stages, beginning with the induction of primitive germ layers (endoderm, mesoderm, or ectoderm), followed by lineage specification and terminal maturation into functional somatic cells such as cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, neurons, and retinal pigment epithelial cells [40].

The fundamental thesis underlying this comparative analysis is that while both hESC and hiPSC platforms demonstrate remarkable differentiation capacity, the choice of cell source, reprogramming method, and specific protocol optimization can significantly impact the efficiency, purity, and functional maturity of the resulting cell populations. This review systematically compares the performance of hESC and hiPSC differentiation across multiple lineages, providing experimental data and methodological details to inform researchers' decisions in disease modeling and drug development.

Comparative Efficacy of hESCs and hiPSCs in Lineage Specification

Experimental Evidence Across Multiple Lineages

A comprehensive study directly compared the differentiation potentials of three hESC lines, four retrovirally derived hiPSC lines, and one hiPSC line derived with non-integrating Sendai virus technology across four independent differentiation protocols: hepatocyte, cardiomyocyte, neuronal, and retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cell differentiation [40]. The findings revealed both significant functional similarities and crucial line-to-line variations.

Table 1: Comparative Differentiation Efficiency of hPSC Lines Across Lineages

| Cell Line Type | Hepatocyte Differentiation | Cardiomyocyte Differentiation | Neural Differentiation | RPE Differentiation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hESC Lines | Efficient definitive endoderm induction (CXCR4+ cells); Albumin secretion detected [40] | Beating cardiomyocytes observed; Expression of α-actinin, Troponin T, connexin-43 [40] | Active neuronal networks formed; Expression of MAP-2, GFAP [40] | Highly pigmented mature cells; Expression of BEST1, RLBP1 [40] |

| Retroviral hiPSC Lines | Variable efficiency; One line failed to produce hepatocytes [40] | Generally efficient; Similar gene expression patterns to hESCs [40] | Functional similarities observed; Comparable neuronal network activity [40] | Reactivation of transgenic OCT4 affected outcome in some lines [40] |

| Sendai Virus hiPSC Line | No transgene expression detected; Performance comparable to best hESC lines [40] | No transgene expression; Efficient cardiac differentiation [40] | No transgene-related issues detected [40] | Stable differentiation without transgene interference [40] |

The data indicate that overall, cells differentiated from hESCs and hiPSCs showed functional similarities and similar expression of genes characteristic of specific cell types [40]. However, critical differences emerged related to the reprogramming method, with residual transgene activity and epigenetic memory affecting some retrovirally derived hiPSC lines [40]. Specifically, reactivation of transgenic OCT4 was detected during RPE differentiation in retrovirally derived lines, potentially compromising differentiation outcomes [40]. One hiPSC line with incomplete silencing of exogenous KLF4 proved inferior across all differentiation directions and failed entirely to produce hepatocytes [40].

Quantitative Assessment of Differentiation Outcomes

Researchers employ multiple analytical methods to quantify differentiation efficiency and functional maturity of hPSC-derived cells. These include flow cytometry for surface markers (e.g., CXCR4+ for definitive endoderm), quantitative PCR for lineage-specific genes, immunocytochemistry for protein expression, and functional assays such as albumin secretion for hepatocytes, microelectrode array measurements for cardiomyocyte and neuronal activity, and morphological analysis of pigmentation for RPE cells [40].

Table 2: Characterization Methods for hPSC-Derived Cell Types

| Cell Type | Key Markers Analyzed | Functional Assays | Assessment Timepoints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatocyte-like Cells | SOX17, FOXA2, AFP, Albumin [40] | Albumin secretion (ELISA), Cytochrome P450 activity [40] | Day 7, 14, 21 of differentiation [40] |

| Cardiomyocytes | Brachyury T, NKX2.5, α-actinin, Troponin T [40] | Beating areas counting, Microelectrode array [40] | Day 0, 3, 6, 13, 30 [40] |

| Neural Cells | Musashi, NF-68, MAP-2, GFAP [40] | Time-lapse imaging, Microelectrode array for network activity [40] | 4 and 8 weeks [40] |

| RPE Cells | MITF, BEST1, RLBP1 [40] | Pigmentation monitoring, Morphological analysis [40] | Day 28, 52, 82, 116 [40] |

Molecular Mechanisms of Directed Differentiation

Signaling Pathways Governing Lineage Specification

The directed differentiation of hPSCs recapitulates embryonic development through the coordinated manipulation of key signaling pathways. The following diagram illustrates the major signaling pathways and their roles in guiding lineage specification:

Figure 1: Signaling pathways guiding hPSC differentiation. Directed differentiation protocols manipulate key developmental pathways to steer pluripotent cells through germ layer specification into terminal cell fates. Endoderm induction typically requires activation of TGFβ/Activin A and WNT signaling; mesoderm formation involves BMP and WNT pathways; ectoderm commitment necessitates inhibition of SMAD signaling alongside FGF activation [40] [41].

Experimental Workflows for Differentiation Studies