Engineering Regeneration: Integrating Stem Cells and Biomaterial Scaffolds for Advanced Tissue Repair

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest strategies in tissue engineering that combine stem cells with advanced biomaterial scaffolds.

Engineering Regeneration: Integrating Stem Cells and Biomaterial Scaffolds for Advanced Tissue Repair

Abstract

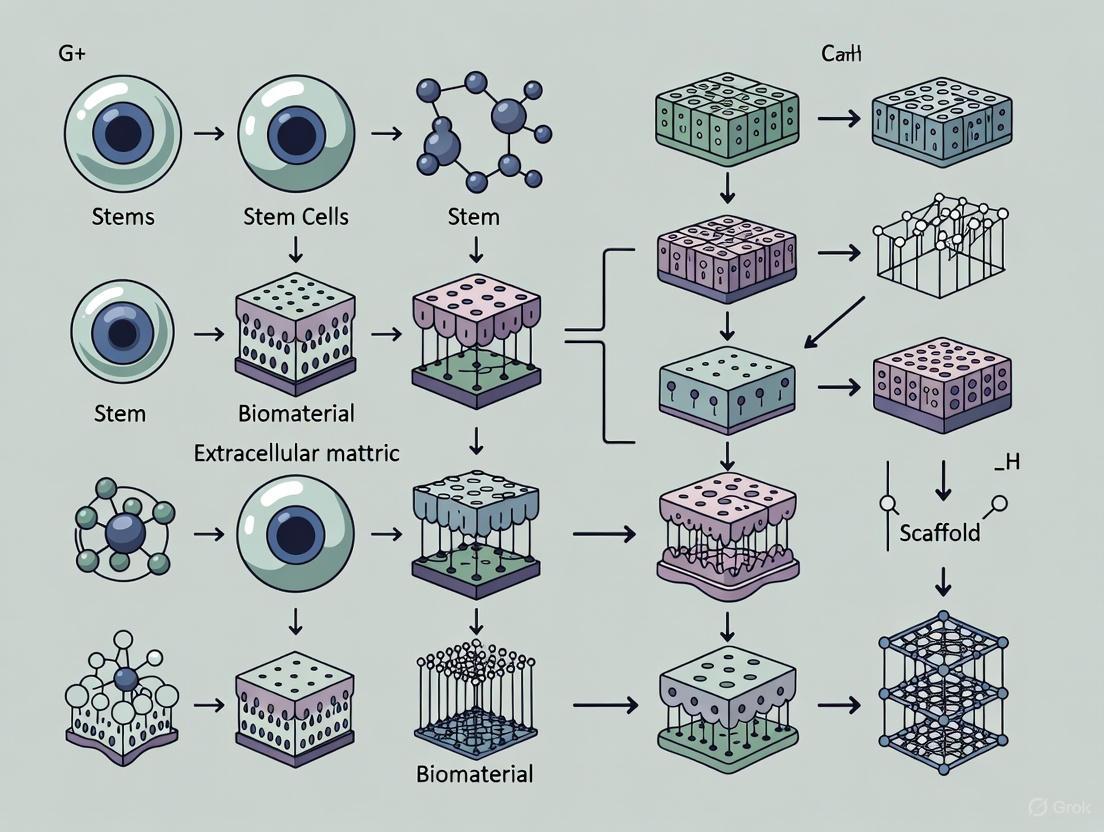

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest strategies in tissue engineering that combine stem cells with advanced biomaterial scaffolds. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology of stem cells and biomaterials, details cutting-edge methodological applications from 3D bioprinting to organoid development, addresses key challenges in cell viability and manufacturing, and evaluates the current regulatory and clinical trial landscape. By synthesizing information from recent market analyses and peer-reviewed studies (2024-2025), this review aims to serve as a critical resource for advancing therapeutic development and translational research in regenerative medicine.

The Biological and Material Foundation of Regenerative Engineering

Stem cells represent the foundational building blocks of regenerative medicine, offering unprecedented potential for repairing and regenerating damaged tissues and organs. These remarkable cells are defined by two fundamental characteristics: the capacity for self-renewal, allowing them to produce identical copies of themselves, and differentiation, enabling them to develop into specialized cell types [1] [2]. Within the context of tissue engineering, stem cells are increasingly combined with advanced biomaterial scaffolds to create powerful therapeutic strategies that address the limitations of traditional transplantation approaches. The integration of stem cell biology with biomaterial science has accelerated the development of innovative solutions for conditions ranging from neurodegenerative diseases to cardiovascular disorders and orthopedic injuries [3] [4].

The therapeutic application of stem cells extends beyond simple cell replacement, harnessing complex biological mechanisms including developmental signaling pathways, paracrine signaling, and metabolic reprogramming [1] [5]. By understanding and manipulating these mechanisms, researchers can optimize stem cell behavior for specific clinical applications. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for harnessing two key stem cell properties—pluripotency and paracrine signaling—within biomaterial-assisted tissue engineering frameworks, offering researchers standardized methodologies for advancing regenerative medicine applications.

Stem Cell Classification and Properties

Stem cells are classified based on their origin, differentiation potential (potency), and functional characteristics. Understanding these classifications is essential for selecting appropriate cell sources for specific tissue engineering applications.

Classification by Potency

The differentiation capacity of stem cells, referred to as potency, determines their therapeutic potential and application scope [1] [2].

Table 1: Classification of Stem Cells by Potency

| Potency Type | Differentiation Potential | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Totipotent | Can differentiate into all cell types, including extraembryonic tissues | Zygote (fertilized egg) |

| Pluripotent | Can differentiate into nearly all cell types derived from the three germ layers | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs), Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) |

| Multipotent | Can differentiate into a limited range of closely related cell types | Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs), Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) |

| Oligopotent | Can differentiate into only a few cell types | Lymphoid or myeloid stem cells |

| Unipotent | Can produce only one cell type but retain self-renewal capacity | Muscle stem cells |

Classification by Origin

Stem cells are also categorized based on their tissue source, which influences their availability, ethical considerations, and therapeutic properties [1] [4].

Table 2: Classification of Stem Cells by Origin

| Cell Type | Definition | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Pluripotent cells derived from the inner cell mass of a 4-5 day-old blastocyst | • Pluripotent differentiation capacity• Ethical controversies• Tumorigenic risk (teratoma formation) |

| Adult Stem Cells (ASCs) | Multipotent or unipotent cells found in various adult tissues | • Tissue-specific differentiation• Lower tumorigenic risk• Examples: HSCs, MSCs, neural stem cells |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Somatic cells reprogrammed into a pluripotent state via genetic manipulation | • Patient-specific (autologous)• Bypasses ethical concerns• Retain epigenetic "memory" of original tissue |

Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Key Therapeutic Player

Among adult stem cells, Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) have emerged as particularly valuable for regenerative applications due to their multipotency, immunomodulatory properties, and relative ease of isolation [6]. According to the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT), MSCs are defined by three key criteria: (1) adherence to plastic under standard culture conditions; (2) expression of specific surface markers (CD73, CD90, CD105 ≥95%) while lacking hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45, CD14 or CD11b, CD79α or CD19, HLA-DR ≤2%); and (3) capacity to differentiate into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages in vitro [6].

MSCs can be isolated from multiple tissue sources, each with distinctive properties:

- Bone Marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs): Most extensively studied, high differentiation potential, strong immunomodulatory effects [6]

- Adipose-derived MSCs (AD-MSCs): Easier to harvest in high yields, comparable therapeutic properties to BM-MSCs [6]

- Umbilical Cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs): Enhanced proliferation capacity, lower immunogenicity, suitable for allogeneic transplantation [2] [6]

The following diagram illustrates the relationships between different stem cell types and their key characteristics:

Pluripotency: Mechanisms and Experimental Manipulation

Molecular Regulation of Pluripotency

Pluripotency is maintained through complex transcriptional networks, epigenetic regulation, and signaling pathways. The core pluripotency network centers around transcription factors including Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (collectively known as OSKM), which maintain the undifferentiated state and self-renewal capacity [4]. These factors work in concert with epigenetic modifiers that establish permissive chromatin states, allowing broad developmental potential while preventing uncontrolled differentiation.

Key signaling pathways regulating pluripotency include:

- TGF-β/Activin/Nodal signaling: Supports self-renewal through SMAD2/3 activation

- Wnt/β-catenin pathway: Balanced activity maintains pluripotency; hyperactivation promotes differentiation

- FGF signaling: Regulates multiple aspects of pluripotent stem cell biology

- Hippo pathway: Influences cell proliferation and pluripotency through YAP/TAZ regulation

- BMP signaling: Promotes differentiation in human ESCs but supports self-renewal in mouse ESCs

External mechanical cues from the microenvironment also influence pluripotent stem cell fate through mechanotransduction pathways that ultimately converge on the transcriptional regulation of pluripotency factors [5].

Experimental Protocol: Biomaterial-Assisted Maintenance of Pluripotency

Title: Culture of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs) on Synthetic Thermoresponsive Scaffolds

Purpose: To maintain hPSCs in a pluripotent state using customizable synthetic terpolymer scaffolds, enabling robust expansion and subsequent differentiation.

Materials:

- Cell Source: Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) or human embryonic stem cells (hESCs)

- Synthetic Terpolymer Scaffold: Composed of N-isopropylacrylamide (NiPAAm), vinylphenylboronic acid (VPBA), and polyethylene glycol monomethyl ether monomethacrylate (PEGMMA) synthesized via free-radical polymerization [7]

- Functionalization Reagents: RGD peptides, vitronectin, fibronectin

- Culture Media: Commercially available defined hPSC maintenance medium

- Supplement: Appropriate growth factors for pluripotency maintenance

- Characterization Reagents: Antibodies for flow cytometry (e.g., against OCT4, SOX2, NANOG), immunofluorescence staining reagents

Methodology:

- Scaffold Preparation:

- Synthesize terpolymer via free-radical polymerization with varying molar ratios of NiPAAm, VPBA, and PEGMMA to optimize properties

- Functionalize polymer with bioactive molecules (RGD peptides, vitronectin, or fibronectin) by incorporating during synthesis or through post-synthesis conjugation

- Characterize scaffold properties: lower critical solution temperature (LCST ~37°C), mechanical stiffness (0.5-18 kPa), and transparency

Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Seed hPSCs at appropriate density (e.g., 10,000-50,000 cells/cm²) onto functionalized terpolymer scaffolds in both 2D and 3D configurations

- Maintain cultures in defined hPSC medium at 37°C with 5% CO₂

- Change medium daily and monitor cell morphology and confluence

Passaging:

- Utilize thermoresponsive properties of scaffold for gentle cell harvesting: reduce temperature below LCST to dissolve polymer-cell interactions

- Collect cells and reseed at appropriate splitting ratio onto fresh functionalized scaffolds

Pluripotency Assessment:

- Analyze pluripotency marker expression (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) via flow cytometry and immunofluorescence after multiple passages

- Evaluate genomic stability through karyotyping after long-term culture (e.g., 9 months)

- Assess in vitro differentiation potential by forming embryoid bodies and evaluating three-germ layer marker expression

Quality Control:

- Compare expansion rates and pluripotency maintenance against traditional matrices (Matrigel, Cultrex)

- Ensure >90% expression of pluripotency markers in cultured population

- Confirm absence of spontaneous differentiation in maintenance culture

The following diagram illustrates the regulatory network that maintains pluripotency in stem cells:

Paracrine Signaling: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Exploitation

The Paracrine Mechanism of Stem Cell Action

Rather than solely differentiating to replace damaged cells, stem cells—particularly MSCs—exert significant therapeutic effects through paracrine signaling, releasing bioactive molecules that modulate the local microenvironment and promote tissue repair [6]. This secretome includes growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular vesicles (exosomes) that collectively influence processes such as angiogenesis, immunomodulation, cell survival, and endogenous stem cell recruitment.

Key components of the MSC secretome include:

- Growth factors: VEGF (angiogenesis), HGF (anti-fibrotic, mitogenic), FGF2 (tissue repair), IGF-1 (cell survival)

- Immunomodulatory factors: PGE2, IDO, TGF-β, IL-10 (suppress excessive inflammation)

- Extracellular vesicles (exosomes): Carry proteins, lipids, mRNA, miRNA that influence recipient cell behavior

The paracrine activity of MSCs is not static but can be enhanced through preconditioning strategies including hypoxia, inflammatory cytokine exposure, 3D culture, and photobiomodulation [8].

Experimental Protocol: Enhancing MSC Paracrine Function via Photobiomodulation

Title: Photobiomodulation (PBM) Preconditioning of MSCs to Enhance Paracrine Secretion

Purpose: To augment the therapeutic potential of MSCs by using non-invasive photobiomodulation to enhance their paracrine functions, particularly for bone tissue engineering applications.

Materials:

- Cell Source: Human MSCs (bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord-derived)

- PBM Device: Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) system with appropriate wavelength (typically 600-900 nm)

- Culture Reagents: Standard MSC expansion medium, serum-free collection medium for conditioned media

- Analysis Reagents: ELISA kits for growth factors (VEGF, HGF, FGF2), multiplex cytokine array, materials for exosome isolation and characterization

Methodology:

- MSC Culture and Preparation:

- Culture MSCs under standard conditions (α-MEM with 10% FBS, 37°C, 5% CO₂)

- Harvest cells at 80-90% confluence using trypsin/EDTA

- Seed cells at appropriate density for PBM treatment (e.g., 10,000 cells/cm²)

Photobiomodulation Protocol:

- Determine optimal PBM parameters through dose-response studies:

- Wavelength: 630-660 nm (red light) or 810-850 nm (near-infrared)

- Energy density: 0.5-10 J/cm²

- Power density: 5-100 mW/cm²

- Irradiation time: Calculate based on energy density and power density

- Replace culture medium with serum-free medium before irradiation

- Apply PBM treatment using calibrated device at specified parameters

- Return cells to incubator following treatment

- Determine optimal PBM parameters through dose-response studies:

Conditioned Media Collection:

- Collect conditioned media at specific timepoints post-PBM (e.g., 24, 48, 72 hours)

- Concentrate conditioned media using centrifugal filters (3-10 kDa cutoff)

- Store at -80°C for subsequent analysis and functional assays

Paracrine Factor Analysis:

- Quantify secreted growth factors (VEGF, HGF, FGF2, IGF-1) using ELISA

- Analyze comprehensive cytokine/chemokine profiles using multiplex immunoassays

- Isolate and characterize exosomes via ultracentrifugation and nanoparticle tracking analysis

Functional Validation:

- Apply conditioned media to target cells (e.g., endothelial cells for angiogenesis assays, osteoblasts for bone formation assays)

- Assess functional outcomes: tube formation (angiogenesis), migration (wound healing), proliferation (MTT assay), differentiation (lineage-specific markers)

Optimization Notes:

- Conduct parameter optimization for each MSC source and specific application

- Consider multiple PBM treatments over several days for enhanced effect

- Monitor MSC viability and proliferation post-PBM to ensure non-cytotoxic parameters

The following diagram illustrates how paracrine signaling mediates therapeutic effects:

Biomaterial Integration and Tissue Engineering Applications

Biomaterial Strategies for Stem Cell Guidance

The integration of stem cells with biomaterial scaffolds represents a cornerstone of modern tissue engineering, addressing critical challenges in cell survival, integration, and functional tissue formation [4]. Biomaterials provide physical support and biochemical cues that mimic the native stem cell niche, enabling precise control over stem cell behavior.

Advanced biomaterial approaches include:

- "Bottom-up" design: Creating biomaterials based on fundamental stem cell biological needs rather than adapting cells to pre-existing materials [4]

- Mechanotransduction control: Using material stiffness, topography, and elasticity to direct stem cell fate through mechanical signaling [5]

- Dynamic scaffolds: Incorporating responsive elements (thermoresponsive, pH-sensitive, enzyme-degradable) that adapt to changing biological requirements

- Spatial patterning: Creating biomaterial gradients to establish organized tissue structures

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Stem Cell and Biomaterial Research

| Category | Specific Reagents | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Culture | Defined hPSC medium, MSC growth medium, Essential 8, mTeSR1 | Maintenance of pluripotency and expansion |

| Biomaterial Polymers | NiPAAm-VPBA-PEGMMA terpolymer [7], PEGDA, GelMA, chitosan, collagen, hyaluronic acid | Scaffold fabrication with tunable properties |

| Biofunctionalization | RGD peptides, vitronectin, fibronectin, laminin, YIGSR peptides | Enhancing cell-material interactions |

| Characterization Antibodies | CD73, CD90, CD105 (MSC markers); OCT4, SOX2, NANOG (pluripotency) | Cell phenotype verification |

| Secretome Analysis | VEGF, HGF, FGF2 ELISA kits; multiplex cytokine arrays; exosome isolation kits | Paracrine function assessment |

| Differentiation Inducers | Osteogenic: dexamethasone, β-glycerophosphate, ascorbic acid; Cardiogenic: BMP4, activin A, Wnt modulators | Lineage-specific differentiation |

Experimental Protocol: Biomaterial-Assisted Cardiac Differentiation

Title: Directed Differentiation of hPSCs to Cardiomyocytes using Synthetic Thermoresponsive Scaffolds

Purpose: To efficiently generate functional cardiomyocytes from hPSCs using bioactive molecule-functionalized synthetic scaffolds for cardiac regenerative applications.

Materials:

- Cell Source: hPSCs (hiPSCs or hESCs) maintained in pluripotent state

- Scaffold Material: NiPAAm-VPBA-PEGMMA terpolymer functionalized with RGD peptides, vitronectin, and/or fibronectin [7]

- Differentiation Media: Cardiomyocyte differentiation kits or sequentially timed media with specific growth factors

- Characterization Reagents: Antibodies for cardiac troponin T (cTnT), cardiac troponin I (cTnI), α-actinin, MLC2v; calcium indicators for functional assessment

Methodology:

- Scaffold Preparation and Functionalization:

- Prepare terpolymer scaffolds with stiffness optimized for cardiac differentiation (∼10-15 kPa)

- Functionalize with RGD peptides (0.5-2 mM), vitronectin (0.5-1 μg/cm²), or fibronectin (1-2 μg/cm²)

- Characterize functionalization efficiency via ELISA or fluorescent tagging

Cardiac Differentiation Protocol:

- Seed hPSCs at high density (∼80% confluence) onto functionalized scaffolds

- Initiate differentiation using sequential media changes:

- Days 0-1: RPMI 1640 + B27 supplement (without insulin) + 6-8 μM CHIR99021 (Wnt activator)

- Days 2-3: RPMI 1640 + B27 supplement (without insulin) + 2-5 μM IWP2/Wnt-C59 (Wnt inhibitor)

- Days 4-7: RPMI 1640 + B27 supplement (without insulin)

- After Day 7: RPMI 1640 + complete B27 supplement (with insulin)

- Change media every 2-3 days throughout differentiation process

Functional Characterization:

- Assess cardiac-specific marker expression via flow cytometry (cTnT, cTnI) at day 15

- Evaluate structural maturation via immunofluorescence (sarcomeric organization using α-actinin)

- Measure spontaneous contraction rates and synchrony

- Assess electrophysiological properties using calcium imaging or patch clamping

Comparison with Traditional Methods:

- Compare differentiation efficiency against Matrigel, Cultrex, and VitroGel controls

- Quantify percentage of cTnT-positive cells and maturation markers

Expected Outcomes:

- ∼65% cTnT-positive cells and ∼25% cTnI-positive cells [7]

- Improved structural organization compared to traditional matrices

- Enhanced functional properties and maturation status

The strategic integration of stem cell biology with advanced biomaterial engineering represents the future of regenerative medicine. By harnessing both pluripotency and paracrine signaling mechanisms within tailored microenvironments, researchers can develop more effective and predictable therapeutic strategies. The protocols outlined herein provide standardized methodologies for manipulating these fundamental stem cell properties, offering researchers robust tools for advancing tissue engineering applications across multiple organ systems. As the field progresses, continued refinement of these approaches—particularly through the development of more sophisticated biomaterial systems that dynamically respond to biological cues—will further enhance our ability to direct stem cell fate and function for clinical applications.

The global demand for effective tissue regeneration strategies continues to rise due to the increasing burden of trauma, chronic diseases, and age-related tissue degeneration [9]. Biomaterial scaffolds, particularly hydrogels, have emerged as fundamental components in tissue engineering, serving as synthetic niches that mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM) to direct cellular behavior and support tissue formation [9] [10]. These three-dimensional frameworks provide not only structural support but also biochemical and mechanical cues that orchestrate regenerative processes, including cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, and differentiation [9] [11]. The design of ideal scaffolds requires careful balancing of multiple properties—mechanical, structural, and biological—to create environments that precisely control cell-matrix interactions through mechanotransduction while maintaining structural integrity under physiological loads [9] [12]. This document outlines the key properties of ideal scaffolds and hydrogels, provides detailed experimental protocols for their evaluation, and presents application-specific considerations for their use in tissue engineering contexts, framed within broader research combining stem cells with biomaterial scaffolds.

Properties of Ideal Scaffolds and Hydrogels

Mechanical Properties

The mechanical properties of scaffolds are critical determinants of their success in tissue engineering, as they directly govern cell–matrix interactions through mechanotransduction [9]. The stiffness and viscoelasticity of the scaffold influence cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, and lineage commitment, while adequate compressive strength and shear resistance are required to preserve structural integrity under physiological loads [9] [12]. Precise tuning of these parameters is essential to reproduce the biomechanical milieu of native tissues and to achieve functional regeneration.

Table 1: Key Mechanical Properties of Ideal Scaffolds and Their Functional Significance

| Property | Ideal Range/Target | Functional Significance | Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compressive Modulus | Tissue-specific: 0.02–1.16 MPa (superficial cartilage) to 6.44–7.75 MPa (deep zone cartilage) [12] | Withstands physiological loads; influences chondrocyte phenotype [12] | Uniaxial compression testing, AFM |

| Elasticity/Stiffness | Matches target tissue (e.g., neural: 0.1-1 kPa; bone: 10-30 kPa) [9] | Directs stem cell lineage specification; regulates cell spreading [9] | Rheometry, tensile testing |

| Viscoelasticity | Stress relaxation timescale similar to native ECM [9] | Enhances cell migration and proliferation; dissipates energy [9] | Dynamic mechanical analysis |

| Shear Resistance | Sufficient to maintain integrity during implantation [9] | Prevents scaffold failure during handling and implantation [9] | Rheometry, shear testing |

| Degradation Rate | Synchronized with tissue regeneration rate [13] | Maintains mechanical support during healing; prevents collapse or obstruction [13] | Mass loss measurement, GPC |

Biological and Structural Properties

Beyond mechanical properties, ideal scaffolds must possess specific biological and structural characteristics that support cellular activities and tissue development. These properties ensure the scaffold functions as a temporary ECM, providing both physical support and biological cues until the new tissue is fully formed [12] [10].

Table 2: Biological and Structural Properties of Ideal Scaffolds

| Property | Requirements | Significance in Tissue Regeneration |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | No immune rejection; non-toxic degradation products [12] [13] | Prevents adverse host responses; supports cell viability and function [12] |

| Porosity | High (>80%) with interconnected pores (typically 100-400 μm, tissue-dependent) [14] | Facilitates cell migration, vascularization, nutrient diffusion, and waste removal [14] |

| Bioactivity | Capacity to deliver growth factors, drugs, or genes [12] [13] | Promotes specific cellular responses (e.g., chondrogenesis, osteogenesis) [12] |

| Biodegradability | Rate matched to tissue regeneration; non-inflammatory byproducts [12] | Provides temporary support while gradually transferring load to new tissue [12] |

| Architectural Mimicry | Replicates tissue-specific hierarchical structure [10] | Recapitulates native tissue organization and function [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication and Characterization of Tunable Hydrogel Scaffolds

Objective: To synthesize hydrogel scaffolds with tunable mechanical properties and characterize their physical and biological performance.

Materials:

- Methacrylated gelatin (GelMA) or polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA)

- Photoinitiator (Irgacure 2959 or lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Primary cells or cell line relevant to target tissue

- Cell culture media and supplements

Procedure:

Hydrogel Precursor Preparation:

- Prepare GelMA or PEGDA solutions at concentrations ranging from 5-15% (w/v) in PBS.

- Add photoinitiator at 0.05-0.1% (w/v) and mix thoroughly until completely dissolved.

- Filter sterilize the solution using a 0.22 μm syringe filter for cell-laden hydrogels.

Scaffold Fabrication via Photocrosslinking:

- Transfer precursor solution to molds of desired dimensions (e.g., 8mm diameter, 2mm thickness for compression testing).

- Expose to UV light (365 nm, 5-10 mW/cm²) for 30-120 seconds based on crosslinking density requirements.

- For cell-laden constructs, maintain sterile conditions and limit UV exposure time to preserve cell viability.

Mechanical Characterization:

- Perform uniaxial compression testing using a materials testing system.

- Hydrate samples in PBS for 24 hours prior to testing.

- Apply displacement rate of 0.1 mm/min until 60% strain is reached.

- Calculate compressive modulus from the linear region of the stress-strain curve (typically 10-20% strain).

Biological Performance Assessment:

- Seed cells on hydrogel surfaces or encapsulate during fabrication at density of 1-5×10⁶ cells/mL.

- Culture for 1, 3, 7, and 14 days, assessing viability (Live/Dead staining), proliferation (DNA quantification), and tissue-specific differentiation (histology, immunohistochemistry, qPCR).

Protocol 2: 3D Bioprinting of Porous Scaffolds with Controlled Architecture

Objective: To fabricate scaffolds with precisely controlled porosity and internal architecture using 3D bioprinting technology.

Materials:

- Bioink (alginate, gelatin-fibrinogen, hyaluronic acid-based, or cell-laden hydrogels)

- 3D bioprinter with temperature-controlled printheads

- Crosslinking solution (CaCl₂ for alginate, thrombin for fibrin, or UV for photopolymerizable inks)

- CAD software for scaffold design

Procedure:

Scaffold Design:

- Design porous architecture using CAD software with pore sizes of 100-400 μm and 60-90% porosity.

- Incorporate interconnected channels to enhance nutrient diffusion.

- Generate G-code for printing path following a layer-by-layer approach.

Bioink Preparation:

- Mix polymer solution with cells if creating cell-laden constructs at density not exceeding 20×10⁶ cells/mL.

- Maintain bioink at appropriate temperature to balance viscosity and cell viability.

- Load bioink into sterile printing cartridges avoiding bubble formation.

Printing Process:

- Set printing parameters: pressure 20-80 kPa, nozzle speed 5-15 mm/s, nozzle diameter 100-400 μm.

- Maintain stage temperature at 4-10°C for thermal-sensitive bioinks.

- Print layer height set at 70-90% of nozzle diameter to ensure proper layer adhesion.

Crosslinking and Post-processing:

- Apply crosslinking solution immediately after printing each layer for ionic crosslinking.

- For photopolymerizable inks, expose each layer to UV light (365 nm, 3-5 mW/cm²) for 10-30 seconds.

- Transfer printed constructs to culture media and maintain under standard cell culture conditions.

Porosity Characterization:

- Quantify pore size, distribution, and interconnectivity using micro-CT imaging.

- Calculate porosity percentage using the formula: Porosity (%) = (1 - ρscaffold/ρmaterial) × 100, where ρ represents density.

- Assess permeability using fluid flow measurements.

Signaling Pathways in Scaffold-Cell Interactions

The following diagram illustrates key integrin-mediated signaling pathways through which biomaterial scaffolds influence cell behavior, a crucial mechanism in tissue engineering strategies.

Integrin-Mediated Cell-Scaffold Signaling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Scaffold Development and Evaluation

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Provide biocompatibility and bioactivity | Gelatin, collagen, hyaluronic acid, chitosan, silk fibroin [12] [13] |

| Synthetic Polymers | Offer tunable mechanical properties and degradation | PEG, PLGA, PCL, PLA [9] [15] |

| Crosslinkers | Enable mechanical stabilization | Genipin, glutaraldehyde, UV initiators (Irgacure 2959) [9] |

| Bioactive Factors | Enhance biological functionality | BMP-2 for bone, TGF-β for cartilage, VEGF for vascularization [12] [13] |

| Characterization Tools | Assess physical and mechanical properties | Rheometers, mechanical testers, micro-CT, SEM [9] [14] |

Application Notes

Bone Tissue Engineering

For bone regeneration, scaffolds require robust mechanical properties with compressive modulus matching cancellous bone (0.1-2 GPa) [15] [13]. Hydrogels for osteoporotic bone defects must address the pathological microenvironment characterized by chronic inflammation, impaired vascularization, and unbalanced bone remodeling [13]. Natural hydrogels like alginate and chitosan can be reinforced with bioceramics (hydroxyapatite) to improve osteoconductivity and mechanical strength [13]. Incorporating bioactive factors such as BMP-2 promotes osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells, while bisphosphonates can be loaded to inhibit osteoclast activity [13]. The degradation rate should be synchronized with new bone formation, typically over 4-12 weeks.

Cartilage Tissue Engineering

Articular cartilage repair demands scaffolds that withstand compressive loads while promoting chondrogenesis [12]. Ideal compressive modulus ranges from 0.02-1.16 MPa in superficial zones to 6.44-7.75 MPa in deep zones to maintain chondrocyte phenotype [12]. Natural polymer-based scaffolds (collagen, hyaluronic acid) provide excellent chondrocyte support, while composite hydrogels combining synthetic and natural polymers balance mechanical strength with bioactivity [12]. Incorporating TGF-β3 enhances chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Porosity of 80-90% with pore sizes of 100-300 μm facilitates cell migration and ECM production while maintaining structural integrity [12].

Skin Tissue Engineering

Hydrogel scaffolds for skin regeneration prioritize moisture retention, exudate absorption, and biocompatibility [9] [11]. Natural polymers like collagen, fibrin, and chitosan mimic the dermal ECM and promote fibroblast migration and angiogenesis [11]. The ideal scaffold should have moderate stiffness (5-20 kPa) to support fibroblast function while allowing epithelialization [9]. Incorporating antimicrobial agents (silver nanoparticles, antibiotics) helps prevent infection in wound environments [11]. Porous structures with gradient porosity support different cell types—denser layers for structural integrity, more porous layers for cell infiltration [11].

Advanced Fabrication Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for designing, fabricating, and evaluating biomaterial scaffolds, incorporating computational modeling and experimental validation.

Scaffold Design and Fabrication Workflow

Market Dynamics and Growth Drivers in Tissue Engineering

The global tissue engineering market is experiencing transformative growth, propelled by the convergence of rising clinical demand, technological innovation, and increasing investment in regenerative medicine. This expansion is fundamentally driven by the integration of advanced biomaterial scaffolds with stem cell technologies, creating powerful therapeutic platforms for tissue regeneration. With the market projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 12.1% to 20.0%, reaching values between $28.97 billion and $103.36 billion by 2032, the field represents a pivotal shift in therapeutic strategies for chronic diseases, traumatic injuries, and age-related tissue degeneration [16] [17] [18]. This growth is underpinned by sophisticated research protocols that combine biologically active scaffolds with stem cells to recreate functional tissue constructs, offering solutions to previously untreatable medical conditions while reducing dependency on organ transplantation.

Market Analysis and Quantitative Landscape

The tissue engineering market demonstrates robust expansion across all segments and regions, characterized by increasingly diverse applications and material technologies. The following tables provide a detailed quantitative breakdown of current market dynamics and future projections.

Table 1: Global Tissue Engineering Market Size and Growth Projections

| Market Aspect | 2024/2025 Base Values | 2030/2032 Projections | CAGR (%) | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Market Size | $13.02B (2025) [18], $19.6B (2024) [16], $29.63B (2025) [17] | $28.97B (2032) [18], $103.31B (2032) [16], $103.36B (2032) [17] | 12.1% - 20.0% | [16] [17] [18] |

| Tissue Engineering & Regeneration Submarket | $4.8B (2024) [19] | $9.8B (2030) [19] | 12.8% | [19] |

| Cardiac Tissue Engineering | $632.10M (2024) [20] | $2,943.92M (2034) [20] | 16.65% | [20] |

Table 2: Tissue Engineering Market Share by Segment (2024 Base Year)

| Segment | Leading Category | Market Share (%) | Fastest-Growing Category | Projected CAGR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material Type | Synthetic Polymers [21] | 54.64% [21] | Hybrid/Composite Materials [21] | 14.61% [21] |

| Application | Orthopedic & Musculoskeletal [21] | 42.12% [21] | Cardiovascular & Vascular [21] | 14.12% [21] |

| End User | Hospitals & ASCs [21] | 63.32% [21] | Specialty Regenerative Clinics [21] | 13.92% [21] |

| Region | North America [21] | 45.53% [21] | Asia-Pacific [21] | 14.34% [21] |

Primary Market Growth Engines

Clinical Demand Drivers

The rising global prevalence of chronic diseases and traumatic injuries establishes a substantial clinical foundation for tissue engineering adoption. Cardiovascular diseases alone account for approximately 17.9 million annual deaths worldwide, creating significant demand for vascularized tissue constructs [18]. Orthopedic and musculoskeletal applications dominate current market share (42.12%), driven by the increasing incidence of bone and joint disorders and an aging global population [16] [21]. Osteoarthritis affects approximately 595 million people worldwide, generating a substantial patient cohort for cartilage repair scaffolds and regenerative interventions [21]. The demographic shift toward older populations further accelerates demand, as age-related tissue degeneration creates need for regenerative solutions in joint reconstruction, wound care, and organ function restoration [18].

Technological Innovation Catalysts

Advanced manufacturing technologies are fundamentally transforming tissue engineering capabilities. 3D bioprinting enables precise fabrication of complex tissue architectures through layer-by-layer deposition of bioinks containing cells and biomaterials [20]. Innovations such as Stanford University's vascular network algorithm and the University of Pittsburgh's CHIPS system for perfusable scaffolds have compressed design-to-clinic timelines while enhancing reproducibility [21]. Stem cell technologies, particularly induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), provide ethically acceptable, patient-specific cardiomyocyte and vascular cell sources for engineered tissues [20]. Advanced scaffold materials, including smart scaffolds that respond to physiological stimuli, now provide not only structural support but also enhance cellular attachment, proliferation, and differentiation through controlled release of bioactive molecules [20].

Investment and Regulatory Landscape

Venture capital investment continues to bolster the tissue engineering ecosystem, supporting startups and biotech firms in research, product development, and commercialization initiatives [19]. Simultaneously, regulatory frameworks are evolving to accommodate innovative products, with the FDA's 2025 roadmap to phase out animal testing prioritizing organoid models and advanced computational methods that align with tissue engineering approaches [21]. Europe's ATMP regulation is gradually harmonizing dossier requirements, while Asia-Pacific regulators are clarifying product classifications to ease market entry barriers [21]. These coordinated advancements in both funding and regulatory pathways are significantly de-risking development processes and accelerating clinical translation.

Advanced Application Notes: Stem Cell-Seeded Biomaterial Scaffolds

Protocol: Fabrication of MSC-Seeded Nanofibrous Scaffolds for Skin Regeneration

Principle: This protocol details the fabrication of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-seeded electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for advanced wound healing applications, combining the regenerative capacity of MSCs with the structural guidance of biomaterial scaffolds.

Materials:

- Mesenchymal stem cells (bone marrow, adipose, or umbilical cord derived)

- Polycaprolactone (PCL) or poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)

- Hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) or trifluoroethanol (TFE)

- Fibronectin or collagen type I solution

- Cell culture media (DMEM/F12 supplemented with FBS and growth factors)

- Trypsin-EDTA solution for cell detachment

- Electrospinning apparatus with high-voltage power supply

- Syringe pump with metal needle

- Mandrel collector

Procedure:

Scaffold Fabrication (Day 1):

- Prepare polymer solution by dissolving PCL or PLGA in HFIP at 10-15% w/v concentration

- Stir the solution for 12 hours at room temperature until completely dissolved

- Load solution into syringe and mount onto syringe pump

- Set electrospinning parameters: flow rate 1.0 mL/h, voltage 15-20 kV, needle-to-collector distance 15 cm

- Collect fibers on rotating mandrel (500-1000 rpm) for 4-6 hours to achieve 100-200 μm thickness

- Vacuum-dry scaffolds for 48 hours to remove residual solvent

Surface Functionalization (Day 3):

- Treat scaffolds with oxygen plasma (100 W, 5 minutes) to enhance surface hydrophilicity

- Immerse in fibronectin solution (10 μg/mL in PBS) for 2 hours at 37°C

- Rinse with sterile PBS and UV sterilize for 30 minutes per side

Cell Seeding and Culture (Day 4):

- Trypsinize MSCs at 80% confluence and resuspend at 2×10^6 cells/mL

- Seed cells onto scaffolds at density of 1×10^5 cells/cm² using static seeding or perfusion bioreactor

- Allow cell attachment for 6 hours before adding complete culture media

- Culture for 7-14 days with media changes every 48 hours

- For 3D bioprinting applications, encapsulate MSCs in bioink (e.g., gelatin methacryloyl) at 5×10^6 cells/mL and print using pneumatic extrusion at 15-25°C

Quality Control:

- Verify scaffold morphology by SEM imaging (fiber diameter 500-1000 nm)

- Assess porosity (>90%) and pore interconnectivity using mercury porosimetry

- Confirm cell viability >95% post-seeding via live/dead staining

- Validate sterility through microbiological testing

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for fabricating MSC-seeded scaffolds

Mechanism of Action: Scaffold-Stem Cell Interactions in Wound Healing

The therapeutic efficacy of MSC-seeded scaffolds in wound healing operates through multiple coordinated mechanisms. MSCs secrete paracrine factors including exosomes that modulate key signaling pathways to promote tissue regeneration [22]. The scaffold serves as a temporary ECM mimic, providing mechanical support while enhancing MSC retention, viability, and directed differentiation at the wound site.

Diagram 2: Signaling mechanisms of MSC-seeded scaffolds in wound healing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Tissue Engineering Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Sources | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BM-MSCs, UC-MSCs, AT-MSCs) [23], Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [20] | Differentiation into target cell types; paracrine signaling; immunomodulation | UC-MSCs show higher proliferation and anti-inflammatory effects than other sources [23] |

| Scaffold Materials | Synthetic Polymers (PCL, PLGA) [21], Natural Polymers (Chitosan, Hyaluronic Acid, Collagen) [11] [24], Hybrid Composites [21] | 3D structural support; cell attachment; mechanical signaling; controlled degradation | Hybrid composites show fastest growth (14.61% CAGR) by merging synthetic durability with biologic cues [21] |

| Bioactive Molecules | Growth Factors (VEGF, FGF-2, TGF-β) [23], Exosomes [22], Signaling Peptides | Enhance angiogenesis; guide cell differentiation; modulate inflammation | MSC-derived exosomes activate PI3K/Akt and TGF-β/Smad pathways in skin regeneration [22] |

| 3D Bioprinting Systems | Bioprinters, Bioinks (Gelatin methacryloyl, Alginate) [16] | Fabrication of complex tissue architectures; cell encapsulation; patient-specific implants | Enables customized cardiac grafts with native tissue-like architecture [20] |

| Characterization Tools | SEM, Live/Dead Assays, ELISA, PCR | Assess scaffold morphology; cell viability; protein and gene expression | Essential for quality control and validation of tissue constructs |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

The tissue engineering field continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping its trajectory. Personalized medicine approaches are gaining prominence, leveraging patient-specific cells and 3D bioprinting technologies to create customized tissue constructs that minimize immune rejection [20]. Cell-free therapies utilizing exosomes and extracellular vesicles derived from MSCs represent a promising frontier, overcoming challenges related to cell survival and immunogenicity while maintaining therapeutic efficacy [22]. The integration of artificial intelligence in biomaterial discovery and scaffold design is accelerating R&D cycles while reducing development costs [19]. Additionally, decellularized extracellular matrix scaffolds from native tissues are emerging as biologically relevant platforms that provide innate signaling cues for enhanced tissue regeneration [21]. These innovations collectively address current limitations in scalability, functionality, and clinical translation while opening new therapeutic possibilities for complex tissue and organ regeneration.

The tissue engineering market demonstrates exceptional growth potential driven by substantive clinical needs and remarkable technological advancements. The strategic integration of stem cell biology with sophisticated biomaterial scaffolds represents the cornerstone of next-generation regenerative therapies, enabling researchers to address previously intractable medical challenges. As the field continues to mature, ongoing innovations in 3D bioprinting, smart material design, and stem cell engineering promise to further accelerate the development of functional tissue constructs that restore, maintain, or improve damaged tissue function. The convergence of increased research funding, regulatory pathway optimization, and cross-disciplinary collaboration positions tissue engineering as a transformative force in modern medicine, with the potential to fundamentally reshape therapeutic approaches across diverse clinical specialties.

The clinical translation of tissue-engineered constructs combining stem cells with biomaterial scaffolds consistently confronts a formidable obstacle: the hostile in vivo microenvironment at injury sites. This microenvironment represents a complex biological landscape that actively resists regenerative efforts through multiple synergistic mechanisms. Despite promising in vitro results demonstrating stem cell differentiation and biomaterial biocompatibility, the transition to clinical success remains limited by this biological barrier [24] [25].

The post-implantation microenvironment exhibits dynamic, multifactorial hostility characterized by oxidative stress, inflammatory signaling, pathological scarring, and excitotoxicity. These interconnected processes collectively establish a regeneration-inhibitory milieu that significantly compromises stem cell viability, integration, and functional efficacy [24]. In traumatic brain injury, for example, this microenvironment evolves through primary and secondary injury phases, creating self-perpetuating pathological cascades that actively suppress regenerative processes [24]. Understanding and addressing these barrier mechanisms is thus fundamental to advancing clinical outcomes in tissue engineering.

Key Barrier Mechanisms and Quantitative Profiling

Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Following implantation, tissue-engineered constructs encounter elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) that directly damage cellular components and disrupt signaling pathways. The oxidative stress microenvironment originates from mitochondrial dysfunction in compromised host tissues, where calcium ion influx triggers excessive mitochondrial calcium uptake, resulting in membrane permeabilization and electron transport chain disruption [24]. This process establishes a self-perpetuating cycle of ROS production and cellular damage.

Table 1: Quantitative Markers of Oxidative Stress in Hostile Microenvironments

| Marker Category | Specific Marker | Normal Range | Hostile Microenvironment Range | Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROS Species | Superoxide anion | 5-20 µM | 50-200 µM | Fluorescent probes (DHE, DCFH-DA) |

| Hydrogen peroxide | 0.1-1 µM | 5-50 µM | Amplex Red assay | |

| Hydroxyl radical | <0.1 µM | 1-10 µM | Electron spin resonance | |

| Oxidative Damage Markers | Lipid peroxidation (MDA) | 1-3 µM | 5-20 µM | TBARS assay |

| Protein carbonylation | 1-2 nmol/mg | 5-15 nmol/mg | DNPH assay | |

| 8-OHdG (DNA damage) | <5 ng/mL | 10-50 ng/mL | ELISA | |

| Antioxidant Defense | Glutathione (GSH) | 20-40 nmol/mg | 5-15 nmol/mg | Colorimetric assay |

| Superoxide dismutase | 10-30 U/mg | 3-10 U/mg | Spectrophotometric assay | |

| Catalase | 50-100 U/mg | 10-40 U/mg | Spectrophotometric assay |

Experimental Protocol 1: Quantifying Intracellular ROS in Implanted Stem Cells

Principle: This protocol measures ROS levels within stem cells after in vivo implantation using the oxidant-sensitive fluorescent probe DCFH-DA (2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate), which converts to fluorescent DCF upon oxidation.

Reagents:

- DCFH-DA solution (20 µM in PBS)

- Collagenase type IV (for construct retrieval)

- DNase I (0.1 mg/mL)

- Flow cytometry buffer (PBS with 2% FBS)

- Antioxidant standards (N-acetylcysteine, 10 mM)

Procedure:

- Construct Retrieval: At designated time points post-implantation (e.g., 6h, 24h, 72h), excise the tissue-engineered construct with surrounding host tissue (5mm margin).

- Tissue Dissociation: Mechanically mince tissue into 1-2mm³ fragments using sterile scalpels. Digest with collagenase IV (2 mg/mL) and DNase I (0.1 mg/mL) for 45 minutes at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Cell Isolation: Filter dissociated cells through 70µm cell strainer. Centrifuge at 400 × g for 5 minutes. Resuspend in flow cytometry buffer at 1×10⁶ cells/mL.

- DCFH-DA Staining: Incubate cells with 20 µM DCFH-DA for 30 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Wash cells twice with PBS. Analyze using flow cytometer with excitation at 485nm and emission at 535nm. Use unstained cells and antioxidant-treated controls for baseline fluorescence.

- Data Normalization: Express results as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) normalized to pre-implantation values or antioxidant-treated controls.

Technical Notes: Maintain samples on ice throughout processing to minimize artifactual ROS generation. Include viability dye (e.g., propidium iodide) to exclude dead cells from analysis. For spatial localization, cryosection constructs can be stained similarly for confocal microscopy imaging [24].

Figure 1: Oxidative Stress Pathway in Hostile Microenvironment. This pathway illustrates how calcium influx triggers mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to self-perpetuating ROS production that ultimately causes stem cell apoptosis.

Neuroinflammation and Glial Activation

The inflammatory component of the hostile microenvironment involves rapid activation of resident glial cells and infiltration of peripheral immune cells. Microglia transition to pro-inflammatory (M1) states, releasing cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 that create a toxic environment for implanted stem cells [24]. Astrocytes become reactive and contribute to glial scar formation through upregulation of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) that physically and chemically inhibit neurite outgrowth and stem cell integration [24] [26].

Table 2: Inflammatory Mediators in Hostile Microenvironments

| Inflammatory Component | Specific Marker | Baseline Expression | Hostile Microenvironment Expression | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-inflammatory Cytokines | TNF-α | 10-50 pg/mL | 200-1000 pg/mL | ELISA, multiplex immunoassay |

| IL-1β | 5-20 pg/mL | 100-500 pg/mL | ELISA, multiplex immunoassay | |

| IL-6 | 10-30 pg/mL | 150-800 pg/mL | ELISA, multiplex immunoassay | |

| Glial Activation Markers | Iba1 (microglia) | 1-2 fold | 5-15 fold | Immunohistochemistry, Western blot |

| GFAP (astrocytes) | 1-2 fold | 10-20 fold | Immunohistochemistry, Western blot | |

| CSPGs | Neurocan | 1-2 fold | 5-10 fold | Western blot, ELISA |

| Phosphacan | 1-2 fold | 5-10 fold | Western blot, ELISA | |

| NG2 | 1-2 fold | 8-15 fold | Western blot, immunohistochemistry |

Experimental Protocol 2: Flow Cytometric Analysis of Microenvironmental Inflammation

Principle: This protocol enables quantitative assessment of inflammatory cell populations and activation states within implanted tissue-engineered constructs using multiparametric flow cytometry.

Reagents:

- Fluorescently conjugated antibodies: CD45 (leukocyte marker), CD11b (microglia/macrophages), CD86 (M1 polarization), CD206 (M2 polarization), GFAP (astrocytes)

- Intracellular cytokine staining kit with brefeldin A

- Fixable viability dye eFluor 506

- Cell stimulation cocktail (PMA/ionomycin)

- Flow cytometry staining buffer (PBS with 2% FBS, 0.09% sodium azide)

- Fixation/Permeabilization solution

Procedure:

- Construct Processing: Harvest constructs at specified time points. Process immediately for single-cell suspension as described in Protocol 1.

- Viability Staining: Resuspend cells in PBS containing fixable viability dye (1:1000 dilution). Incubate 15 minutes at 4°C in the dark.

- Surface Marker Staining: Wash cells with flow cytometry buffer. Incubate with fluorochrome-conjugated surface antibodies (CD45, CD11b, CD86, CD206) for 30 minutes at 4°C in the dark.

- Fixation and Permeabilization: Wash cells, then fix and permeabilize using commercial fixation/permeabilization kit according to manufacturer instructions.

- Intracellular Staining: Incubate cells with intracellular antibodies (GFAP, cytokines) for 30 minutes at 4°C in the dark.

- Flow Cytometry Acquisition: Wash cells and resuspend in flow cytometry buffer. Acquire data using flow cytometer with appropriate laser and filter configurations. Collect at least 50,000 events per sample.

- Data Analysis: Use fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls for gating. Analyze using FlowJo software, employing sequential gating strategy: single cells → live cells → leukocytes (CD45+) → microglia/macrophages (CD11b+) → polarization states (CD86+/CD206+) [27].

Technical Notes: For cytokine detection, incubate cells with protein transport inhibitor (brefeldin A, 1µL/mL) for 4-6 hours before harvesting. Include isotype controls for each antibody to assess non-specific binding [27].

Glial Scar Formation and Physical Barriers

Reactive astrocytes form dense glial scars that create both physical and chemical barriers to regeneration. The scar tissue presents a dense meshwork of hypertrophic astrocyte processes enriched in inhibitory extracellular matrix molecules including CSPGs, which interact with neuronal receptors to collapse growth cones and inhibit stem cell migration [24]. The temporal progression of scar maturation correlates with declining regenerative capacity, creating a critical therapeutic window for intervention.

Excitotoxicity and Ionic Imbalance

The hostile microenvironment exhibits disrupted ionic homeostasis characterized by excessive glutamate release and subsequent hyperactivation of glutamate receptors. This excitotoxicity drives pathological calcium influx into cells, activating calcium-dependent proteases, phospholipases, and endonucleases that degrade cellular structures [26]. The resulting ionic imbalance further disrupts normal electrophysiological function and compromises stem cell integration and synaptic formation.

Advanced Analytical Approaches

Multiomics and Spatial Analysis of Microenvironments

Advanced analytical frameworks like MESA (multiomics and ecological spatial analysis) enable comprehensive characterization of hostile microenvironments by integrating spatial omics with single-cell multiomics data [28]. This approach adapts ecological diversity metrics to quantify cellular heterogeneity and spatial organization within tissue contexts, revealing patterns not discernible through conventional analysis.

Experimental Protocol 3: Spatial Analysis of Cellular Microenvironments Using MESA

Principle: This protocol applies ecological spatial analysis to quantify cellular diversity and organization within and around implanted tissue-engineered constructs, identifying pathological hot spots and interaction patterns.

Reagents:

- Multiplex immunohistochemistry/immunofluorescence antibody panels

- CODEX/COMET staining reagents

- Tissue clearing reagents (optional)

- Mounting medium for imaging

- DNA staining dye (DAPI, Hoechst)

Procedure:

- Tissue Preparation: Harvest construct with surrounding tissue at specified time points. Fix in 4% PFA for 24 hours at 4°C. Process for cryosectioning or paraffin embedding.

- Multiplex Staining: Perform cyclic immunofluorescence staining according to CODEX protocol or similar multiplex imaging approach. Include markers for key cell types (neurons, astrocytes, microglia, immune cells, implanted stem cells).

- Image Acquisition: Acquire whole-slide images using automated microscopy system with appropriate filter sets for each marker. Maintain consistent exposure across samples.

- Cell Segmentation and Phenotyping: Use automated cell segmentation algorithms (CellProfiler, Ilastik) to identify individual cells and assign marker expression profiles.

- Spatial Analysis Implementation:

- Apply MESA framework to calculate Multiscale Diversity Index (MDI) assessing cellular heterogeneity across spatial scales

- Compute Global Diversity Index (GDI) to evaluate whether patches of similar diversity cluster spatially

- Determine Local Diversity Index (LDI) to identify diversity "hot spots" and "cold spots"

- Calculate Diversity Proximity Index (DPI) to assess spatial relationships between identified spots

- Integration with Single-Cell Data: Map single-cell RNA sequencing data onto spatial coordinates using integration algorithms (MaxFuse) to create in silico multiomics profiles.

- Neighborhood Analysis: Define cellular neighborhoods based on local composition and multiomics profiles. Perform differential expression and ligand-receptor interaction analysis within identified neighborhoods [28].

Technical Notes: Optimal tissue thickness for spatial analysis is 5-10μm. Include controls for antibody cross-reactivity and autofluorescence. For 3D reconstruction, perform serial sectioning and alignment [28].

Figure 2: Spatial Microenvironment Analysis Workflow. This workflow integrates multiplex tissue staining with computational analysis to identify hostile cellular neighborhoods within tissue-engineered constructs.

Extracellular Vesicle Analysis from Native Microenvironments

Solid tissue-derived extracellular vesicles (ST-EVs) provide critical insights into intercellular signaling within hostile microenvironments. These vesicles carry molecular cargo that reflects the pathophysiological state of originating tissues and participate in creating regeneration-inhibitory niches [29].

Experimental Protocol 4: Isolation and Characterization of Solid Tissue-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

Principle: This protocol enables enrichment of extracellular vesicles directly from implanted tissue-engineered constructs and surrounding host tissue to analyze microenvironmental signaling molecules.

Reagents:

- Collagenase/hyaluronidase digestion cocktail

- Protease and phosphatase inhibitors

- OptiPrep density gradient medium

- PBS (calcium- and magnesium-free)

- Exosome-depleted FBS

- Antibodies for EV characterization (CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101)

- Negative control markers (calnexin, GM130)

Procedure:

- Tissue Collection and Processing: Harvest construct with 2-3mm margin of surrounding tissue. Rinse in cold PBS to remove blood contaminants. Mince into 1mm³ pieces using sterile scalpels.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Digest tissue fragments with collagenase IV (1mg/mL) and hyaluronidase (100U/mL) for 45 minutes at 37°C with gentle agitation. Neutralize with complete media containing 10% exosome-depleted FBS.

- Differential Centrifugation:

- Centrifuge at 300 × g for 10 minutes to remove cells

- Centrifuge supernatant at 2,000 × g for 20 minutes to remove cell debris

- Centrifuge supernatant at 10,000 × g for 30 minutes to remove apoptotic bodies and large vesicles

- Ultracentrifuge supernatant at 100,000 × g for 70 minutes to pellet EVs

- Density Gradient Purification: Resuspend EV pellet in PBS. Layer onto discontinuous iodixanol density gradient (5%, 10%, 20%, 40%). Ultracentrifuge at 100,000 × g for 18 hours. Collect EV-containing fractions (density 1.10-1.18 g/mL).

- EV Characterization:

- NTA: Dilute EVs 1:1000 in PBS, analyze using Nanosight NS300 for size distribution and concentration

- TEM: Adsorb EVs to formvar/carbon-coated grids, negative stain with 2% uranyl acetate, image at 80kV

- Western Blot: Analyze EV markers (CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101) and exclude contaminants (calnexin, GM130)

- Proteomic and RNA Analysis: Extract EV proteins and RNA for omics analysis to identify microenvironment-specific cargo [29].

Technical Notes: Process tissues immediately after collection or flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen. Include proteinase inhibitors throughout processing. Validate EV isolation efficiency using spiked-in reference particles [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microenvironment Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability/Cytotoxicity Assays | DCFH-DA, MitoSOX, CellROX | ROS detection and quantification | Measure multiple ROS species with different probes |

| Calcein-AM/EthD-1 (Live/Dead) | Cell viability assessment | Distinguish live/apoptotic/necrotic populations | |

| LDH cytotoxicity assay | Membrane integrity assessment | Correlate with histological damage | |

| Cytokine/Chemokine Analysis | Multiplex bead arrays (Luminex) | Simultaneous quantification of multiple inflammatory mediators | Requires small sample volumes |

| ELISA kits for TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 | Specific cytokine quantification | High sensitivity, established protocols | |

| Extracellular Matrix Analysis | CSPG detection antibodies (NG2, neurocan) | Inhibitory matrix component quantification | Critical for assessing glial scar maturation |

| Polarized light microscopy for collagen alignment | ECM organization assessment | Reveals structural barriers | |

| Ion/Neurotransmitter Sensing | Glutamate sensors (iGluSnFR) | Excitotoxicity assessment | Real-time monitoring possible |

| Calcium indicators (Fura-2, Fluo-4) | Calcium dyshomeostasis measurement | Rationetric vs. single-wavelength probes | |

| Spatial Analysis Tools | CODEX/COMET imaging systems | Highly multiplexed tissue imaging | Requires specialized instrumentation |

| GeoMx Digital Spatial Profiler | Region-specific RNA/protein analysis | Allows selection of specific microregions | |

| Single-Cell Analysis | 10x Genomics platform | Single-cell RNA sequencing | Reveals cellular heterogeneity |

| CITE-seq (cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes) | Combined protein and RNA at single-cell level | Correlates surface markers with transcriptome |

The hostile in vivo microenvironment presents multifaceted barriers to clinical success of tissue-engineered constructs through interconnected mechanisms of oxidative stress, inflammation, physical barrier formation, and excitotoxicity. Comprehensive characterization of these barriers using quantitative biochemical assays, spatial analysis frameworks, and extracellular vesicle profiling provides critical insights for developing targeted countermeasures. The experimental protocols detailed herein enable researchers to systematically dissect these microenvironmental challenges, forming a foundation for developing intervention strategies that can mitigate these barriers and enhance regenerative outcomes. Future advances will depend on integrating these analytical approaches with novel biomaterial designs and stem cell engineering strategies that collectively neutralize the hostile microenvironment while promoting regenerative processes.

Advanced Fabrication Techniques and Target Applications

Scaffold Design and 3D Bioprinting for Complex Tissue Architecture

Application Note: Integrating Vascularization in Scaffold Design

Core Challenge: The Vascularization-Osteogenesis Paradox

A primary obstacle in engineering large-segment bone defects is overcoming early ischemia and restricted nutrient diffusion, which can lead to cell apoptosis rates exceeding 60% within the scaffold core [30]. Successful regeneration hinges on dynamic crosstalk within the "vascular–osteogenic niche," where endothelial cells secrete osteogenic factors like PDGF-BB and VEGF, and nascent bone matrix releases chemokines such as SDF-1α to guide vascular ingrowth [30]. Scaffolds that provide only mechanical support without biological guidance are insufficient for complex tissue regeneration.

Strategic Solution: "Vascularization-Osteogenesis Integration" Paradigm

A transformative design paradigm involves combining 3D-printed scaffolds with vascularized bone substitutes to create a "scaffold plus vascular-pedicled flap" co-implantation system [30]. This strategy leverages microsurgery to create a functional microcirculation network ex vivo using an arteriovenous loop (AVL), bundle (AVB), flow-through (AVFT), or venous bundle (VB) within the scaffold, or by placing the graft in a muscle pouch (MP) [30]. This pre-vascularized network, when implanted, rapidly restores perfusion, establishes a co-culture microenvironment for endothelial cells and mesenchymal stem cells, and maximizes osteogenic and angiogenic efficiency, thereby accelerating defect repair [30].

Quantitative Analysis of 3D-Printing Technologies for Scaffold Fabrication

Table 1: Comparison of 3D-Printing Technologies for Bone Tissue Scaffolds [30]

| Technology | Suitable for Metal | Energy Source | Typical Materials | Mechanical Properties | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) | No | Laser | Polymers, Bioceramics | Moderate strength (non-load-bearing) | Customized bone tissue scaffolds |

| Selective Laser Melting (SLM) | Yes | Laser | Metal | High strength (load-bearing) | Load-bearing implants (e.g., hip joints) |

| Stereolithography (SLA) | No | UV Light | Photosensitive resins, Biohydrogels | Low-moderate (soft tissue) | Cartilage repair, craniofacial scaffolds |

| Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) | No | Thermal | PLA, PCL | Tunable | Prototyping, PLA-based scaffold research |

Protocol: Fabrication and Pre-vascularization of a Bioactive Composite Scaffold

Scaffold Design and Bioink Preparation

- Design Phase: Utilize CAD software to design a scaffold with hierarchical porosity, incorporating macro-pores (≥300 μm) to facilitate vascular ingrowth and cell proliferation, alongside micro-pores (<50 μm) to enhance cell adhesion and nutrient diffusion [31]. The design should aim for a total porosity ≥80% [32].

- Bioink Formulation: Prepare a composite bioink:

- Base Hydrogel: A gelatin-alginate blend provides a biocompatible, cell-friendly environment mimicking the native extracellular matrix (ECM) [33].

- Bioactive Additives: Incorporate gelatin microspheres for the sustained release (e.g., over 7 days) of deferoxamine (DFO), a pro-angiogenic factor that activates the HIF-1α pathway [30].

- Mechanical Reinforcement: Add 1 wt% halloysite nanotubes (HNTs) to synergistically enhance osteogenic differentiation and mechanical integrity [30].

Bioprinting Process

- Printer Setup: Employ a pneumatic or piston-driven extrusion bioprinting system equipped with a cooling stage (maintained at 4-10°C) and a UV light source for cross-linking [34].

- Printing Parameters: Use a nozzle diameter between 200-400 μm to balance printing resolution and minimizing shear stress on cells. Maintain a printing pressure and speed that ensures smooth filament extrusion without discontinuity [34].

- Cross-linking: Post-deposition, cross-link the structure by immersing in a calcium chloride solution (for ionic alginate cross-linking) and/or exposing to UV light (for methacrylated gelatin), depending on the bioink composition [34].

In-vitro Pre-vascularization

- Cell Seeding: Seed the sterilized scaffold with a co-culture of Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) and Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs) at an optimized ratio (e.g., 1:1) in an appropriate endothelial cell growth medium.

- Bioreactor Maturation: Culture the cell-seeded scaffold in a perfusion bioreactor for 7-14 days. The dynamic flow conditions enhance nutrient/waste exchange and promote the self-assembly of endothelial cells into capillary-like networks throughout the scaffold structure [30].

Surgical Implantation (Vascular-Pedicled Flap Co-implantation)

- Flap Harvest: In the recipient site, carefully raise a pedicled tissue flap (e.g., a muscle or fascia flap) with its intrinsic blood supply intact.

- Scaffold Implantation: Position the pre-vascularized scaffold into the bone defect.

- Anastomosis: Surgically anastomose (connect) the pedicle artery and vein of the flap to the pre-formed vascular network within the scaffold or place the scaffold in direct contact with the vascularized flap to facilitate rapid host vessel ingrowth [30]. This establishes immediate perfusion upon implantation.

Experimental Workflow for Bioprinted Construct Validation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated in-vitro and in-silico workflow for developing and validating a bioprinted tissue construct.

Reagent and Material Solutions for Research

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for 3D Bioprinting Complex Tissues

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin-Alginate Hydrogel | Serves as the primary bioink matrix; provides cell adhesion sites and enables gentle ionic/thermal cross-linking. | GelMA (Methacrylated Gelatin) for UV cross-linking [33]. |

| Deferoxamine (DFO) | Pro-angiogenic small molecule; loaded into microspheres for sustained release to activate HIF-1α pathway and promote vascularization [30]. | DFO@GMs (DFO-loaded Gelatin Microspheres) [30]. |

| Halloysite Nanotubes (HNTs) | Nanoscale additive; improves the composite scaffold's mechanical strength and synergistically enhances osteogenic differentiation [30]. | 1 wt% HNTs in a PCL composite [30]. |

| Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1α (SDF-1α) | Chemotactic cytokine; incorporated into scaffolds to actively recruit host mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to the defect site [30]. | H-BCP@SDF-1α/EPC composite scaffold [30]. |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Thermoplastic polymer for FDM printing; used to create scaffolds with high mechanical strength and complex geometries. | Hybrid Dome Face Centered Porous Structure (HDFCPS) designs [32]. |

| Endothelial & Stem Cells | Cellular components for pre-vascularization and osteogenesis; form the co-culture microenvironment critical for "vascularization-osteogenesis integration". | Co-culture of HUVECs and hMSCs [30]. |

Signaling Pathways in the Vascular-Osteogenic Niche

The following diagram summarizes the key biochemical crosstalk between endothelial and osteogenic cells within a successful bioactive scaffold.

Within the evolving field of tissue engineering, the combination of stem cells and biomaterial scaffolds represents a frontier for regenerative medicine. A critical factor for the success of these therapies is the survival and functional efficacy of the transplanted cells. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a cornerstone of this approach due to their multipotency, immunomodulatory properties, and pro-regenerative paracrine activity [3] [23]. However, upon transplantation, they face a hostile microenvironment characterized by inflammation, hypoxia, and oxidative stress, which severely compromises their therapeutic potential [35] [36] [37].

To address this limitation, preconditioning has emerged as a vital strategy. Preconditioning involves the in vitro exposure of MSCs to sublethal stresses or specific bioactive molecules, which "primes" the cells to better withstand the harsh in vivo conditions they will encounter post-transplantation [36]. This process acts as a form of cellular training, enhancing their resilience, improving their engraftment, and boosting their secretory profile. For tissue engineering applications, preconditioned MSCs, when integrated with supportive biomaterial scaffolds, show significantly improved outcomes in wound healing, neural repair, and organ regeneration [35] [24] [38].

This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for three core preconditioning strategies—hypoxic, cytokine, and pharmacological—framed within the context of advanced tissue engineering. It is designed to equip researchers and drug development professionals with standardized, actionable methodologies to enhance the therapeutic performance of stem cell-based constructs.

Hypoxic Preconditioning

Rationale and Mechanism

Hypoxic preconditioning moves MSCs from standard culture conditions (21% O₂) to a physiologically relevant low-oxygen environment (typically 1-5% O₂). This mimics the natural oxygen tension of stem cell niches and the ischemic conditions of damaged tissues [39]. This conditioning enhances MSC survival, paracrine function, and engraftment primarily through the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) pathway [37] [39]. Stabilization of HIF-1α triggers the upregulation of a suite of pro-survival and pro-angiogenic genes.

Key benefits of this approach include:

- Enhanced Cell Survival: Activation of Akt-dependent survival pathways reduces apoptosis [39].

- Improved Angiogenic Potential: Increased secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other pro-angiogenic factors [35] [39].

- Boosted Migration and Engraftment: Upregulation of the SDF-1/CXCR4/CXCR7 chemokine axis enhances homing to injury sites [37] [39].

Application Note: Hypoxic Preconditioning for Tissue-Engineered Constructs

In tissue engineering, hypoxic preconditioning is particularly valuable for therapies targeting ischemic tissues (e.g., myocardial infarction, diabetic wounds) or for cells destined for the interior of large, dense biomaterial scaffolds where nutrient and oxygen diffusion may be limited. Preconditioned MSCs exhibit greater resilience within these confined environments and can more effectively stimulate vascularization upon implantation, which is critical for the integration and longevity of the engineered tissue [38].

Protocol: Standardized Hypoxic Preconditioning of Adipose-Derived MSCs

Objective: To enhance the therapeutic potential of Adipose-Derived MSCs (ADSCs) through controlled hypoxic culture.

Materials:

- Cell Source: Human ADSCs (Passage 3-5)

- Base Medium: DMEM/F-12

- Supplements: 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin

- Hypoxia Chamber/Workstation: A tri-gas incubator capable of maintaining 1-5% O₂, 5% CO₂, and balance N₂.

- Analytical Reagents: Antibodies for Flow Cytometry (CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45); ELISA kits for VEGF and SDF-1; RNA isolation kit for PCR analysis of HIF-1α, VEGF, and CXCR4.

Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Expand ADSCs under standard conditions (37°C, 21% O₂, 5% CO₂) in complete medium until 70-80% confluence.

- Preconditioning Setup:

- Harvest and seed ADSCs at a density of 5,000 cells/cm² in standard culture flasks or plates.

- Once cells reach 60-70% confluence, place the culture vessels into the pre-equilibrated hypoxia chamber.

- Set and maintain the oxygen concentration at 2% O₂. The culture period should be 48-72 hours [39].

- Post-Preconditioning Handling:

- After the incubation period, harvest the preconditioned ADSCs for subsequent analysis or implantation.

- For use in tissue engineering, cells can be seeded directly onto biomaterial scaffolds (e.g., collagen hydrogels, PCL nanofiber meshes) either before or after the hypoxic exposure, depending on scaffold compatibility.

Quality Control:

- Validate preconditioning efficacy by quantifying VEGF and SDF-1 secretion in the conditioned medium via ELISA.

- Confirm upregulation of HIF-1α and CXCR4 gene expression using RT-qPCR.

- Verify that the cells maintain standard MSC surface marker expression (CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, CD34-, CD45-) via flow cytometry.

Signaling Pathway

Diagram Title: Hypoxic Preconditioning Activates the HIF-1α Signaling Pathway

Cytokine Preconditioning

Rationale and Mechanism

Cytokine preconditioning involves priming MSCs with specific inflammatory cytokines or growth factors to mimic the inflammatory disease microenvironment. This process enhances the cells' immunomodulatory capacity and primes them for robust paracrine activity. The approach is guided by the concept of Disease Microenvironment Preconditioning (DMP), where exposing MSCs to disease-specific signals improves their adaptability and therapeutic function upon transplantation [36].

Commonly used cytokines include:

- TNF-α and IFN-γ: Synergistically promote immunomodulation by inducing the expression of chemokines like CCL2 and anti-inflammatory factors [35] [37].

- IL-1β: Enhances MSC migration and promotes a anti-inflammatory macrophage polarization [40] [35].

- TGF-β1: Improves cell survival, engraftment, and reduces healing time in wound models [35] [37].

Application Note: Cytokine Preconditioning for Immunomodulation

This strategy is exceptionally powerful for designing cell-biomaterial systems aimed at treating inflammatory conditions, such as chronic wounds (e.g., diabetic foot ulcers), autoimmune diseases, or neural injuries characterized by intense neuroinflammation (e.g., Traumatic Brain Injury) [24] [36]. Cytokine-preconditioned MSCs seeded within a protective hydrogel can create a local immunomodulatory "hub" that actively suppresses detrimental inflammation and promotes a regenerative tissue environment.

Protocol: TNF-α and IFN-γ Preconditioning for Enhanced Immunomodulation

Objective: To prime MSCs for heightened immunomodulatory and reparative functions using a combination of TNF-α and IFN-γ.

Materials:

- Cell Source: Bone Marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) or Umbilical Cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs), Passage 3-5.

- Base Medium: α-MEM or DMEM.

- Supplements: 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin.

- Preconditioning Cytokines: Recombinant Human TNF-α and Recombinant Human IFN-γ.

- Analytical Reagents: Flow cytometry antibodies for IDO, TSG-6, and CCL2; ELISA kits for PGE2 and IL-6.

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Culture MSCs to 70% confluence in standard complete medium.

- Cytokine Treatment:

- Post-Preconditioning Processing:

- After incubation, carefully wash the cells with PBS to remove all cytokines.

- The preconditioned MSCs are now ready for harvest and subsequent use. They can be incorporated into biomaterial systems, such as injectable chitosan-based hydrogels, which provide a supportive matrix and can be delivered locally to the wound site [24] [38].

Quality Control: