Ensuring iPSC Pluripotency: A Comprehensive Guide to Quality Control for Research and Translation

This article provides a comprehensive guide to quality control (QC) measures for ensuring induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) pluripotency, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Ensuring iPSC Pluripotency: A Comprehensive Guide to Quality Control for Research and Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to quality control (QC) measures for ensuring induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) pluripotency, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of pluripotency, detailing the core molecular network and the impact of reprogramming methods on QC outcomes. The methodological section explores a multi-parameter QC toolkit, including assays for genomic integrity, pluripotency verification, and functional differentiation potential. The guide also addresses critical troubleshooting strategies for common issues like genetic instability and differentiation variability, and concludes with a comparative analysis of validation frameworks and regulatory standards essential for preclinical and clinical translation. By synthesizing the latest advances and persistent challenges, this resource aims to support the development of safe, reproducible, and high-quality iPSC lines for research and therapy.

The Foundation of Pluripotency: Core Concepts and Molecular Mechanisms

Pluripotency is the defining characteristic of stem cells that allows them to self-renew indefinitely while maintaining the potential to differentiate into derivatives of all three embryonic germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. For researchers working with induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), rigorous verification of pluripotency is a critical quality control measure that ensures experimental integrity and reproducibility. This technical support center provides comprehensive guidance on key pluripotency markers, detailed experimental protocols for their analysis, and troubleshooting solutions for common challenges encountered in pluripotency assessment.

Key Pluripotency Markers: A Comprehensive Reference

Accurate assessment of pluripotency requires evaluating multiple marker categories through complementary techniques. The following tables summarize the essential markers for verifying the pluripotent state.

Table 1: Core Transcription Factors and Functional Indicators of Pluripotency

| Marker | Type | Function in Pluripotency | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 (POU5F1) | Transcription Factor | Maintains pluripotency by repressing differentiation pathways | qPCR, ICC, Western Blot |

| NANOG | Transcription Factor | Critical for self-renewal and suppression of differentiation | qPCR, ICC, Western Blot |

| SOX2 | Transcription Factor | Partners with OCT4 to sustain stemness | qPCR, ICC, Western Blot |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) | Functional Enzyme | High activity in undifferentiated cells | Enzymatic staining |

| Telomerase | Functional Enzyme | Maintains telomere length for self-renewal | TRAP assay, qPCR |

Table 2: Characteristic Surface Antigens of Pluripotent Stem Cells

| Marker | Type | Expression Pattern | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSEA-3 | Glycolipid Surface Antigen | Expressed in pluripotent cells | Flow Cytometry, ICC |

| SSEA-4 | Glycolipid Surface Antigen | Highly expressed in undifferentiated hPSCs | Flow Cytometry, ICC |

| TRA-1-60 | Proteoglycan Surface Antigen | Specific to pluripotent state | Flow Cytometry, ICC |

| TRA-1-81 | Proteoglycan Surface Antigen | Specific to pluripotent state | Flow Cytometry, ICC |

Recent research has identified additional genes with strong potential to discriminate between undifferentiated and differentiated states of iPSCs. Long-read nanopore transcriptome sequencing has revealed 172 genes potentially associated with differentiation states not addressed in current guidelines, with validated unique markers including CNMD, NANOG, and SPP1 for pluripotency [1].

Experimental Protocols for Pluripotency Assessment

RNA Extraction and qPCR Analysis Protocol

Principle: Quantify transcriptional signatures of core pluripotency factors to confirm stem cell status at the genetic level.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-quality RNA extraction kit (RNase-free)

- cDNA synthesis kit with reverse transcriptase

- qPCR reagents: SYBR Green Master Mix

- Pluripotency-specific primers (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2)

- Housekeeping gene primers (GAPDH, ACTB)

- Nuclease-free water and consumables

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Cell Preparation: Harvest PSCs at 70-80% confluency to avoid spontaneous differentiation. Use feeder-free or feeder-dependent cultures with compact colonies displaying high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratios [2].

RNA Extraction:

- Lyse cells using kit reagents under RNase-free conditions

- Bind RNA to purification columns

- Wash with appropriate buffers

- Elute with nuclease-free water

- Measure concentration and purity (A260/A280 ratio >1.8)

cDNA Synthesis:

- Use 0.5-1μg total RNA in reverse transcription reaction

- Follow kit protocol for reaction conditions

- Store synthesized cDNA at -20°C

qPCR Setup and Analysis:

- Prepare reaction mix: SYBR Green Master Mix, forward/reverse primers, cDNA template, nuclease-free water

- Run qPCR with appropriate cycling conditions

- Normalize results against housekeeping genes (GAPDH, ACTB)

- Interpret results: High OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG expression indicates pluripotency

Protein-Level Validation: Immunocytochemistry (ICC)

Principle: Visualize and localize pluripotency-associated proteins within cells to confirm expression and nuclear localization characteristic of undifferentiated states.

Materials and Reagents:

- Primary antibodies: Anti-OCT4, Anti-SOX2, Anti-NANOG, Anti-SSEA-4, Anti-TRA-1-60

- Fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies

- Fixative: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA)

- Permeabilization buffer: 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100

- Blocking solution: 1-5% BSA or serum in PBS

- Mounting medium with DAPI

- PBS buffer

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Cell Fixation:

- Aspirate culture medium from cells grown on coverslips or chamber slides

- Wash gently with PBS

- Fix with 4% PFA for 15-20 minutes at room temperature

- Wash 3 times with PBS

Permeabilization and Blocking:

- Permeabilize with 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 for 10-15 minutes (for intracellular markers)

- Wash with PBS

- Block with 1-5% BSA or appropriate serum for 30-60 minutes

Antibody Incubation:

- Incubate with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C

- Wash 3 times with PBS (5 minutes each)

- Incubate with fluorescent secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature (protected from light)

- Wash 3 times with PBS

Visualization and Analysis:

- Mount with DAPI-containing medium to counterstain nuclei

- Image with fluorescence or confocal microscopy

- Analyze for expected patterns: Nuclear staining for OCT4, SOX2, NANOG; cell surface for SSEA-4, TRA-1-60

Research Reagent Solutions for Pluripotency Analysis

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Pluripotency Marker Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Anti-OCT4, Anti-SOX2, Anti-NANOG, Anti-SSEA-4, Anti-TRA-1-60 | Specific binding to pluripotency markers for detection |

| Secondary Antibodies | Fluorescently labeled goat anti-mouse/anti-rabbit | Signal amplification and detection |

| Cell Culture Media | TeSR, mTeSR, ReproFF2, StemFit | Maintain pluripotent state during expansion |

| qPCR Reagents | SYBR Green Master Mix, RNA extraction kits, reverse transcriptase | Gene expression analysis at transcriptional level |

| Cell Dissociation | Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent, Accutase | Generate single-cell suspensions for analysis |

| Fixation/Permeabilization | Paraformaldehyde, Triton X-100 | Preserve cellular architecture and enable antibody access |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges and Solutions

FAQ: Addressing Frequent Pluripotency Assessment Issues

Q: How do I distinguish between fully reprogrammed and partially reprogrammed iPSCs?

A: Fully reprogrammed iPSCs express pluripotency markers at levels comparable to human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), with consistent expression across multiple detection methods (qPCR, ICC, flow cytometry). Partial reprogramming often shows incomplete marker profiles and reduced self-renewal capacity. Validate using a combination of transcriptional and protein-level analyses [2].

Q: What sample size is required for complete pluripotency marker profiling?

A: For a full multi-platform analysis, generally 1-2 million cells are recommended. However, with optimized protocols, analysis can be performed with as few as 200,000 cells using microfluidics and high-sensitivity antibody assays [2].

Q: How often should I validate pluripotency markers in my stem cell lines?

A: Validation every 3-5 passages is recommended, before differentiation experiments, or whenever cells undergo significant environmental changes (e.g., switch of feeder system, media brand, or culture substrate) [2].

Q: My PSCs appear negative for key markers despite proper culture conditions. What could be wrong?

A: This could result from partial differentiation, stress-induced gene downregulation, or culture adaptation. Reassess culture conditions and use fresh feeder layers or optimized feeder-free matrices. Supplement with small molecules (e.g., ROCK inhibitors) to stabilize pluripotency, and reduce passage numbers to maintain original stemness [2].

Q: What are the gold standard markers for definitive pluripotency validation?

A: The most widely accepted gold-standard markers are OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG at the transcriptional level, combined with surface markers such as SSEA-3/4 and TRA-1-60/TRA-1-81. Using a combination ensures robust and reproducible validation of pluripotency [2].

Technical Issue Resolution

Table 4: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low-quality RNA leading to poor qPCR amplification | RNase contamination, suboptimal cell lysis, degraded samples | Use RNase-free consumables with inhibitors; confirm RNA integrity; store at -80°C [2] |

| Weak ICC staining or non-specific background | Suboptimal antibody concentration, cross-reactivity, expired antibodies | Test multiple antibody clones; optimize dilutions with titration; validate with positive controls [2] |

| Variable flow cytometry results | Poor sample preparation, dead cells, antibody aggregation | Filter cells to remove clumps; incorporate viability dyes; vortex antibody solutions before use [2] |

| Spontaneous differentiation in culture | Over-confluence, suboptimal passaging, poor quality matrices | Passage at 70-80% confluency; use appropriate matrices; remove differentiated areas before analysis [3] |

| Inconsistent results across detection methods | Method-specific limitations, sample heterogeneity | Employ orthogonal validation methods; ensure consistent sample processing; use multiple detection techniques [1] [2] |

Advanced Techniques and Emerging Markers

While traditional markers remain essential for pluripotency verification, recent advances in sequencing technologies have revealed additional genes with strong potential to discriminate between undifferentiated and differentiated states. Long-read nanopore transcriptome sequencing has identified 172 genes potentially associated with differentiation states not addressed in current guidelines, with validated unique markers for pluripotency including CNMD, NANOG, and SPP1 [1].

Machine learning-based scoring systems such as "hiPSCore" have been developed using these refined marker panels, trained on multiple iPSC lines and demonstrating accurate classification of undifferentiated and differentiated cells [1]. These approaches enhance the standardization of pluripotency assessment while reducing time, subjectivity, and resource requirements.

For comprehensive pluripotency assessment within quality control frameworks, researchers should integrate both established marker analysis and emerging technologies to ensure robust characterization of iPSC lines for research and therapeutic applications.

The core pluripotency network, orchestrated by the transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, governs the remarkable capacity of pluripotent stem cells to self-renew and differentiate into any cell type in the body. This regulatory circuitry is fundamental to embryonic development and serves as the cornerstone for generating induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [4] [5]. In iPSC research, stringent quality control measures are essential to ensure the faithful reprogramming of somatic cells and the maintenance of authentic pluripotent states. Understanding the precise roles, expression levels, and interactions of these core factors is therefore not merely of biological interest but a critical practical requirement for generating reliable, clinically relevant cell models [6] [7]. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate the specific experimental challenges associated with assessing and maintaining this core network.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential reagents used in the study and manipulation of the core pluripotency network, with explanations of their primary functions in an experimental context.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Pluripotency Network Analysis

| Research Reagent | Function and Application in Pluripotency Research |

|---|---|

| Yamanaka Factors (OSKM) | A set of four transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) used for somatic cell reprogramming to generate iPSCs [6] [7]. |

| bFGF (Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor) | A critical growth factor for maintaining pluripotency in human ESCs and iPSCs, primarily through activation of the MAPK signaling pathway [8]. |

| LIF (Leukemia Inhibitory Factor) | A cytokine used to maintain pluripotency in mouse ESCs through activation of the Jak/Stat3 signaling pathway; not typically required for human ESCs [4]. |

| 2i Inhibitors (ERK1/2 + GSK3β) | A combination of small-molecule inhibitors that safeguard mouse ESCs in a "ground state" of pluripotency by suppressing differentiation signals [4]. |

| BMP4 (Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4) | A signaling molecule that, in combination with LIF, helps maintain mouse ESC pluripotency by inducing Id genes. Its role is complex and context-dependent in human ESCs [4] [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What are the distinct functional roles of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG in human pluripotent stem cells?

While OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG form a core cooperative network, each factor has unique, non-overlapping functions in lineage specification. Understanding these distinct roles is crucial for interpreting differentiation outcomes.

- OCT4's Role in Lineage Specification: OCT4 level is a critical determinant of cell fate and interacts with external signaling pathways like BMP4. Research shows that high OCT4 levels enable self-renewal in the absence of BMP4 but specify mesendoderm in its presence. Conversely, low OCT4 levels induce embryonic ectoderm differentiation without BMP4 but specify extraembryonic lineages with BMP4 [9].

- NANOG as a Specific Repressor: NANOG primarily functions as a repressor of neuroectoderm and neural crest lineages. It does not act as a pan-repressor of all differentiation pathways but is specifically critical for preventing this particular fate [9].

- SOX2/SOX3 Redundancy in Repression: SOX2, along with its family member SOX3, functions redundantly to repress primitive streak differentiation and mesendoderm specification [9].

FAQ 2: How can we experimentally assess the protein interaction and genomic binding of the core pluripotency factors?

A common experimental workflow involves Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) to map the genomic binding sites of these factors and identify their target genes.

Experimental Protocol: ChIP-seq for Core Pluripotency Factors

- Cross-linking: Fix cells (e.g., iPSCs) with formaldehyde to covalently link transcription factors like OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG to their DNA binding sites.

- Cell Lysis and Chromatin Shearing: Lyse cells and fragment the chromatin into small pieces (200–500 bp) using sonication.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the sheared chromatin with a specific, validated antibody against your target protein (e.g., anti-OCT4). Use Protein A/G beads to pull down the antibody-protein-DNA complexes.

- Washing and Elution: Wash the beads stringently to remove non-specifically bound chromatin. Elute the bound complexes from the beads and reverse the cross-links to free the DNA.

- DNA Purification: Purify the immunoprecipitated DNA.

- Library Prep and Sequencing: Prepare a sequencing library from the purified DNA and perform high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq).

- Data Analysis: Map the sequenced reads to the reference genome to identify peaks of enrichment, which represent genomic regions bound by the transcription factor. Co-occupancy of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG on target gene promoters is a hallmark of the core pluripotency network [4] [5].

FAQ 3: Our iPSCs show spontaneous differentiation. How do we troubleshoot issues with the core pluripotency network?

Spontaneous differentiation often indicates a failure to maintain the core pluripotency network. The table below outlines common problems and their solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Spontaneous Differentiation in iPSC Cultures

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous expression of OCT4/NANOG, with patches of differentiated cells. | Inconsistent culture conditions: Fluctuations in key signaling pathways (e.g., FGF, TGF-β). | Standardize feeding schedules. Use fresh, pre-warmed media. For human cells, ensure consistent high concentration of bFGF (e.g., 100 ng/mL) to maintain MAPK signaling [8]. |

| Rapid loss of pluripotency markers after passaging. | Passaging-induced stress leading to apoptosis or initiation of differentiation. | Use a Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632) for 24 hours post-passaging to improve cell survival [8]. Optimize passaging method and frequency. |

| Uniform differentiation toward a specific lineage. | Imbalanced core factor expression. Low OCT4 can drive neuroectoderm differentiation; high OCT4 with BMP4 can push mesendoderm. | Monitor and control OCT4 expression levels. Review differentiation protocols to ensure no inducing factors are present in the maintenance medium. Check for adequate NANOG expression to repress neuroectoderm [9]. |

| Failure to silence exogenous reprogramming factors in established iPSCs. | Incomplete reprogramming or use of integrating vectors that remain active. | Use non-integrating reprogramming methods (e.g., Sendai virus, episomal plasmids, mRNA) [7]. Perform qRT-PCR to confirm silencing of exogenous transgenes and activation of endogenous pluripotency genes. |

FAQ 4: What signaling pathways are critical for maintaining the core pluripotency network, and how do they interact with it?

The core transcription factors are regulated by and interact with specific external signaling pathways to maintain pluripotency. The required pathways differ between species.

- Mouse ESC Signaling: Relies on LIF (activating Jak/Stat3) and BMP4 (inducing Id genes) signaling. Pluripotency can also be maintained in a "ground state" using small-molecule inhibitors ("2i") against ERK1/2 and GSK3β [4].

- Human ESC/iPSC Signaling: Depends on FGF (particularly bFGF) and TGF-β/Activin/Nodal signaling pathways [4] [8]. Withdrawing bFGF leads to downregulation of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG and initiates differentiation, primarily toward the ectoderm lineage, accompanied by a decrease in MAPK pathway activity [8].

FAQ 5: What are the key quality control checks for the core pluripotency network in a new iPSC line?

Rigorous quality control is mandatory for any newly derived or acquired iPSC line. The assessment should include multiple layers of validation.

- Expression Analysis: Confirm the expression of endogenous OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG at the mRNA level (via qRT-PCR) and protein level (via immunocytochemistry). Ensure that transgenes used for reprogramming have been silenced in integration-free lines [7].

- Functional Genomic Assessment: Perform ChIP-seq to validate that the core factors bind to their known target genomic sites, confirming a properly wired regulatory network [4] [5].

- Pluripotency Validation: Demonstrate the capacity for in vitro differentiation into cell types of all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) via directed differentiation or teratoma formation assays.

- Karyotyping and Genetic Stability: Perform G-banding karyotyping or higher-resolution genetic analysis to ensure the cell line has a normal, stable karyotype, as prolonged culture can lead to chromosomal abnormalities.

- Mycoplasma Testing: Routinely test for mycoplasma contamination, which can alter cell physiology and differentiation potential without causing overt turbidity in the culture medium.

The choice of reprogramming method is a critical initial step in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) generation, with significant implications for quality control (QC), downstream applications, and clinical translation. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of major integrating and non-integrating approaches.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major iPSC Reprogramming Methods

| Method Type | Specific Method | Genetic Integration | Reprogramming Efficiency | Key Safety Considerations | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrating | Retroviral/Lentiviral Vectors | Yes (Random) | High (e.g., ~0.01% for retroviral [10]) | Insertional mutagenesis, transgene reactivation [11] [12] | Basic research, disease modeling [12] |

| Non-Integrating | Sendai Virus (SeV) | No (Cytoplasmic) | High (e.g., ~0.05% [10]) | Requires dilution over passages to clear viral vectors [11] | Disease modeling, drug screening, clinical applications [13] [10] |

| Non-Integrating | Episomal Vectors | No | Low to Moderate (e.g., ~0.05% [10]; ~0.0006% [11]) | Rapid transgene clearance (typically 17-21 days) [11] | Clinical-grade iPSC generation, biobanking [11] [13] |

| Non-Integrating | Synthetic mRNA | No | High (with repeated transfections) | Labor-intensive; potential interferon response [11] [14] | Clinical-grade iPSC generation [14] |

The following workflow outlines the key decision points when selecting a reprogramming method based on research goals and QC priorities.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What is the single most important QC differentiator between integrating and non-integrating methods?

The most critical differentiator is genomic integration and the associated risk of insertional mutagenesis. Integrating methods, such as those using retroviruses, permanently insert the reprogramming transgenes into the host cell's genome. This can disrupt tumor suppressor genes or activate oncogenes, posing a significant tumorigenicity risk for clinical applications [11] [12]. Non-integrating methods avoid this risk by ensuring transient expression of the reprogramming factors.

FAQ 2: Our lab uses Sendai virus reprogramming. A QC check shows residual viral vectors at passage 5. Is this normal?

Yes, this is an expected finding. Sendai virus vectors are cytoplasmic and are gradually diluted out as cells divide. However, their clearance requires a sufficient number of cell passages. It is recommended to perform passaging until the vectors are undetectable by PCR. One study notes that a "far greater number of cell divisions are required to dilute the cell line free of contaminating viral proteins and the vector" [11]. You should establish a QC protocol to routinely test for viral clearance at later passages (e.g., passage 10 or beyond) before using the iPSC line for critical experiments.

FAQ 3: We are struggling with the low efficiency of episomal reprogramming. How can we improve our success rate without compromising safety?

The low efficiency of episomal reprogramming is a known challenge [11]. You can consider these troubleshooting strategies without reverting to integrating methods:

- Optimize your starting cell type. Fibroblasts, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), and cord blood cells have been successfully reprogrammed with episomal vectors [11] [13].

- Use small molecules. Supplementing the culture with small molecules like RepSox, valproic acid (VPA), or sodium butyrate can enhance reprogramming efficiency significantly [15] [12]. For instance, one study found that combining 8-Br-cAMP with VPA increased efficiency by up to 6.5-fold [15].

- Validate your nucleofection protocol. For episomal vectors, efficient delivery via nucleofection is crucial. Ensure you are using the correct program and conditions for your specific cell type [13].

FAQ 4: Do different reprogramming methods create inherent functional differences in the final iPSC line?

Evidence suggests that once fully reprogrammed and quality-controlled, iPSCs exhibit similar pluripotency profiles regardless of the reprogramming method used. A comparative study that analyzed the gene expression profiles of iPSCs derived via retroviral, Sendai virus, and episomal methods found no significant differences attributable to the reprogramming technique [10]. The critical factor is that the lines are fully reprogrammed to a bona fide pluripotent state. Variability is more likely due to the genetic background of the donor or technical handling.

Essential Experimental Protocols for QC

Protocol: Confirming Absence of Reprogramming Transgenes in Non-Integrating iPSC Lines

Purpose: To ensure that iPSC lines generated with non-integrating methods (e.g., Sendai virus, episomal vectors) are free of residual reprogramming vectors, a key safety QC test.

Materials:

- iPSC genomic DNA (minimally 100 ng)

- PCR primers specific for the reprogramming factors (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) and the specific vector backbone (e.g., SeV genome, Epstein-Barr virus OriP/EBNA1 for episomes)

- Positive control (e.g., DNA from the original transfected/transduced cells)

- Negative control (e.g., DNA from a known negative cell line or nuclease-free water)

- PCR Master Mix

- Thermo-cycler and gel electrophoresis equipment

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from the candidate iPSC line at a minimum of passage 10. Earlier passages are likely to yield positive results and are not conclusive [11].

- PCR Setup: Set up PCR reactions for each reprogramming factor/vector-specific primer set. Include positive and negative controls in every run.

- Amplification: Run the PCR using optimized cycling conditions for your primers.

- Analysis: Resolve the PCR products on an agarose gel. A line is considered clear of vectors if no PCR product is amplified with the vector-specific primers, while the positive control shows a clear band.

Troubleshooting: If the result is positive, continue passaging the cells and re-test at a later passage. For Sendai virus, specific kits are available (e.g., CytoTune Sendai Virus Detection Kit) to facilitate this QC step.

Protocol: Validating Pluripotency via Embryoid Body (EB) Formation

Purpose: This in vitro assay tests the differentiation capacity of iPSCs into derivatives of all three germ layers, a core QC metric for pluripotency [10].

Materials:

- Confluent well of iPSCs in a 6-well plate

- Dispase or Collagenase IV solution

- iPSC medium without bFGF

- Low-attachment 6-well plate or Petri dish

- Cultureware coated with Poly-L-Ornithine/Laminin or Gelatin for EB plating

- RT-PCR reagents and primers for germ layer markers

Procedure:

- EB Formation: Harvest iPSCs by enzymatic digestion to create small clumps. Resuspend the cell clumps in iPSC medium without bFGF and transfer to a low-attachment plate to prevent adhesion. Culture for 7-10 days, allowing EBs (3D spherical structures) to form.

- EB Plating: After 7-10 days, transfer the EBs to a standard culture plate coated with Poly-L-Ornithine/Laminin or Gelatin. Continue culture for an additional 7-14 days in the same medium, allowing cells to migrate and differentiate out of the EBs.

- Analysis: After the differentiation period, analyze the outgrowths.

- Immunofluorescence: Stain for specific protein markers: ECTODERM (β-III-Tubulin), MESODERM (α-Smooth Muscle Actin), and ENDODERM (Alpha-Fetoprotein).

- qRT-PCR: Analyze the expression of key genes: ECTODERM (PAX6), MESODERM (MSX1), and ENDODERM (SOX17) [10].

Troubleshooting: If spontaneous differentiation is inefficient, consider adding differentiation-inducing agents like retinoic acid to the medium.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for iPSC Reprogramming and QC

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming/QC |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM); OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 (OSNL) [15] [16] | Core transcription factors that induce pluripotency in somatic cells. |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Valproic Acid (VPA), Sodium Butyrate, RepSox, 8-Br-cAMP [15] [12] | Improve reprogramming efficiency by modulating epigenetic marks and signaling pathways. |

| Non-Integrating Vectors | CytoTune Sendai Virus Kit, Episomal plasmids (e.g., pCE-epi vector system) [11] [13] | Delivery systems for transient expression of reprogramming factors, enhancing safety profile. |

| Pluripotency Markers | Antibodies against OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, SSEA4, TRA-1-60 [13] [10] | Used in immunostaining and flow cytometry to confirm the undifferentiated state of iPSCs. |

| Germ Layer Markers | Antibodies against β-III-Tubulin, α-SMA, AFP; PCR primers for PAX6, MSX1, SOX17 [10] | Critical for validating pluripotency via EB assays, confirming trilineage differentiation potential. |

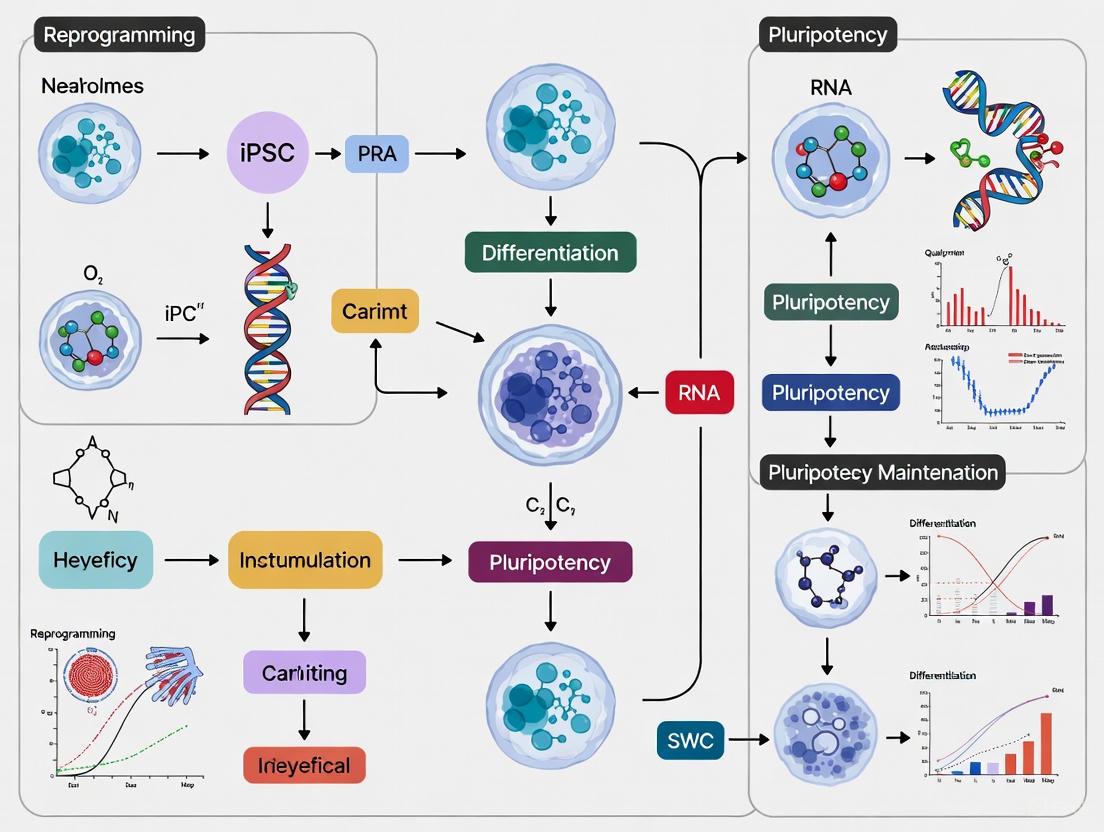

The following diagram summarizes the multi-stage quality control pipeline for validating iPSC lines, from the initial reprogramming event to final confirmation of pluripotency and safety.

The Role of Epigenetic Remodeling in Establishing Pluripotency

Core Concepts: Epigenetic Reprogramming to Pluripotency

What is the fundamental role of epigenetic remodeling in establishing pluripotency? Reprogramming somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) requires profound alterations in the epigenetic landscape to reset gene expression and stabilize self-renewal. This process reverses the epigenetic modifications that occur during cellular differentiation, transforming a specialized cell with restricted potential into a pluripotent one with broad developmental capacity [17] [6].

What are the key epigenetic changes during this process?

- DNA Methylation: Somatic cells exhibit stable, tissue-specific DNA methylation patterns that must be reset. During reprogramming, pluripotency gene promoters (like OCT4 and NANOG) undergo demethylation to become active again, while somatic cell-specific genes are silenced through hypermethylation [17].

- Histone Modifications: Pluripotent stem cells possess a unique epigenetic profile enriched for open, active chromatin modifications (H3K4me3, H3K36me3, histone acetylation). Reprogramming establishes these marks at pluripotency genes and creates bivalent domains (H3K4me3 and H3K27me3) at differentiation-related genes, keeping them in a "poised" state for future development [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Epigenetic Barriers in iPSC Generation

Problem 1: Low Reprogramming Efficiency

Potential Cause: Epigenetic barriers are hindering the reprogramming process. Solutions:

- Utilize epigenetic modifiers: Treatment with DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (e.g., 5-aza-cytidine) or histone deacetylase inhibitors (e.g., Valproic Acid, Sodium butyrate, Trichostatin A) can increase reprogramming efficiency by opening condensed chromatin [15] [17].

- Target specific epigenetic enzymes: Knockdown of Dot1l (H3K79 methyltransferase) or Suv39H1/2 (H3K9 methyltransferases) facilitates reprogramming by reducing repressive heterochromatin [15] [17].

- Enhance activating marks: Overexpression of Jhdm1b (H3K36me demethylase) or Ezh2 (PRC2 component for H3K27 methylation) has been shown to enhance reprogramming efficiency [17].

Problem 2: Incomplete Reprogramming (Partially Reprogrammed Cells)

Potential Cause: Failure to fully reset the epigenetic landscape, particularly at key pluripotency loci. Solutions:

- Demethylation agents: Treatment with agents like 5-aza-cytidine facilitates the transition of partially reprogrammed cells into a full state of pluripotency [17].

- Activate specific factors: Overexpression of Kdm4b (H3K9 demethylase) promotes conversion from pre-iPSCs to iPSCs [17].

- Ensure complete MET: The Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition is a critical early event; optimize culture conditions to support this process [6].

Problem 3: Genomic Instability and Aberrant Karyotypes

Potential Cause: Epigenetic dysregulation during reprogramming and in vitro culture can lead to chromosomal abnormalities. Solutions:

- Implement rigorous quality control: Regularly monitor chromosomal stability using G-banding karyotyping (detects larger structural abnormalities >5-10 Mb) and SNP array analysis (detects smaller copy number variations >350 kb and loss of heterozygosity) [18].

- Monitor common anomalies: Pay particular attention to common hPSC abnormalities involving chromosomes 12, 17, 20 (especially 20q11.21 amplification), and X [18].

- Maintain reference standards: Compare iPSC epigenetic profiles (DNA methylation patterns, histone marks) to embryonic stem cells as a reference for complete reprogramming [17].

Epigenetic Modifiers in Reprogramming

Table 1: Key Epigenetic Modifiers That Influence Reprogramming Efficiency

| Epigenetic Modifier | Function | Effect on Reprogramming | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hdac inhibitors (VPA, Sodium butyrate) | Histone deacetylase inhibitor | Increases efficiency [17] | Opens chromatin structure |

| 5-aza-cytidine | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor | Increases efficiency [17] | Demethylates pluripotency gene promoters |

| Dot1l | H3K79 methyltransferase | Silencing facilitates reprogramming [15] [17] | Reduces repressive histone methylation |

| Suv39H1/2 | H3K9 methyltransferase | Downregulation increases reprogramming [15] [17] | Decreases heterochromatin formation |

| Ezh2 (PRC2) | H3K27 methyltransferase | Overexpression enhances reprogramming [17] | Establishes repressive marks on somatic genes |

| Kdm4b | H3K9 demethylase | Overexpression promotes conversion from pre-iPSCs [17] | Removes repressive histone marks |

| Wdr5 (Set/Mll complex) | H3K4 methyltransferase complex | Knockdown decreases reprogramming [17] | Reduces active chromatin marks |

| Mbd3 (NuRD complex) | Chromatin remodeling | Conflicting reports; may be indispensable [17] | Complex role in chromatin regulation |

Experimental Protocols for Quality Control

Protocol 1: Assessing DNA Methylation Reprogramming

Purpose: Verify complete epigenetic resetting at pluripotency gene promoters. Methodology:

- Bisulfite Sequencing: Treat DNA with bisulfite to convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils, then sequence key pluripotency gene promoters (e.g., OCT4, NANOG).

- Global Methylation Analysis: Use methods like MethylC-Seq for genome-wide DNA methylation profiling at single-base resolution.

- Comparison to ESCs: Compare iPSC methylation patterns with embryonic stem cells as a reference standard [17].

Expected Results: Successfully reprogrammed iPSCs should show hypomethylation at pluripotency gene promoters similar to ESCs, with establishment of non-CG methylation patterns characteristic of pluripotent cells [17].

Protocol 2: Monitoring Histone Modification Patterns

Purpose: Confirm establishment of pluripotent-appropriate chromatin state. Methodology:

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP): Use antibodies specific for histone modifications (H3K4me3, H3K27me3, H3K9me3) followed by sequencing.

- Focus on Key Loci: Assess bivalent domains at developmental gene promoters and active marks at pluripotency genes.

- Validate with Functional Assays: Correlate epigenetic patterns with gene expression (RNA-seq) and functional pluripotency assays [17].

Protocol 3: Chromosomal Integrity Assessment

Purpose: Ensure genomic stability after reprogramming. Methodology:

- G-banding Karyotyping: Analyze at least 20 metaphases with 300-500 band resolution to detect larger structural abnormalities (>5-10 Mb).

- SNP Array Analysis: Use platforms like Illumina's Global Screening Array to detect smaller copy number variations (>350 kb) and copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity.

- Regular Monitoring: Perform these assessments every 10-15 passages, as abnormal clones can overtake a culture in less than five passages [18].

Epigenetic Reprogramming Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Epigenetic Quality Control

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Quality Control |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Inhibitors | 5-aza-cytidine, RG108 | Improve reprogramming efficiency; verify methylation role [15] [17] |

| Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors | Valproic Acid, Sodium butyrate, Trichostatin A | Enhance reprogramming; modulate chromatin accessibility [15] [17] |

| Chromatin Remodeling Modulators | RepSox, Neplanocin A | Improve reprogramming robustness; study chromatin dynamics [15] |

| Pluripotency Media | mTeSR Plus, mTeSR1 | Maintain pluripotent state; ensure consistent culture conditions [19] |

| Passaging Reagents | ReLeSR, Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent | Maintain epigenetic state during subculture; minimize stress [19] |

| Extracellular Matrices | Vitronectin XF, Corning Matrigel | Provide appropriate signaling context for pluripotency maintenance [19] |

| SNP Array Platforms | Illumina Global Screening Array | Detect chromosomal abnormalities and copy number variations [18] |

| Epigenetic Editing Tools | CRISPR-dCas9 fusion systems | Precisely manipulate specific epigenetic marks for functional studies [15] |

Frequently Asked Questions

How can we distinguish complete versus partial epigenetic reprogramming? Complete reprogramming is characterized by: (1) Global DNA methylation patterns resembling embryonic stem cells, including establishment of non-CG methylation; (2) Demethylation of pluripotency gene promoters (OCT4, NANOG); (3) Appropriate histone modification patterns including bivalent domains at developmental genes; and (4) Stable expression of pluripotency markers without spontaneous differentiation [17].

Why do we observe donor-specific epigenetic variation in iPSCs? iPSCs maintain some donor-specific epigenetic patterns even after reprogramming due to underlying genetic variation. Studies show that epigenetic variation is most strongly associated with genetic variation at the iPSC stage, though this relationship weakens after differentiation. This reflects the complex interaction between genotype and epigenome that persists through reprogramming [20].

What are the most critical quality control checkpoints for epigenetically stable iPSCs?

- Regular karyotyping (every 10-15 passages) to detect chromosomal abnormalities [18]

- DNA methylation profiling at key pluripotency loci to confirm complete reprogramming [17]

- Expression analysis of pluripotency markers and spontaneous differentiation potential [19]

- Epigenetic stability monitoring across passages to ensure maintenance of pluripotent state [20]

How does partial reprogramming for rejuvenation differ from complete reprogramming? Partial reprogramming involves transient expression of Yamanaka factors (OSKM) long enough to produce epigenetic rejuvenation (restoration of youthful gene expression patterns) but not long enough to fully dedifferentiate cells into iPSCs. This approach aims to refresh cellular function while maintaining cell identity, though it requires precise control to avoid tumor formation or loss of cellular identity [21].

The Pillars of Pluripotency QC

Robust quality control (QC) for induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) research extends beyond routine checks; it requires a deep understanding of the molecular foundations of pluripotency. The core properties defining pluripotent stem cells are self-renewal, the ability to divide indefinitely, and potency, the capacity to differentiate into all cells derived from the three germ layers (ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm) [22]. Effective QC verifies that your iPSC lines consistently demonstrate these two traits. The following table outlines the essential pillars of pluripotency QC.

| QC Pillar | Key Indicators | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Renewal | Consistent expression of pluripotency factors (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, NANOG); Stable karyotype and proliferation rate | Confirms genetic stability and unlimited expansion capacity in culture [22]. |

| Pluripotency | In vitro: Spontaneous differentiation via embryoid body formation; In vivo: Teratoma formation with tissues from three germ layers | Provides functional evidence of the ability to differentiate into any somatic cell type [22]. |

| Epigenetic State | Specific epigenetic landscape (e.g., open chromatin, DNA methylation patterns); Reactivation of endogenous pluripotency genes | Validates complete reprogramming and a stable, ESC-like epigenetic signature [6]. |

Troubleshooting Common iPSC QC Challenges

Q1: Our iPSC colonies appear heterogeneous, with some cells spontaneously differentiating. What is the cause, and how can we achieve a more homogeneous culture?

This indicates your cells are in a "metastable" state. The solution often lies in refining your culture conditions to promote a "ground state" of pluripotency.

- Root Cause: Standard culture media containing serum introduces undefined factors that can prod cells toward differentiation. Fluctuations in the expression of pluripotency and lineage-specific factors lead to heterogeneity [22].

- QC Solution: Transition to a defined, serum-free culture system using small-molecule inhibitors. The "2i" system, comprising PD0325901 (a MEK inhibitor) and CHIR99021 (a GSK3 inhibitor), blocks prodifferentiation signals. This promotes a uniform "ground state" of pluripotency, resulting in morphologically homogeneous colonies and a more consistent gene expression profile [22].

- Protocol:

- Passage your iPSCs into pre-coated culture vessels.

- Replace the standard medium with a defined base medium (e.g., N2B27) supplemented with 1 µM PD0325901 and 3 µM CHIR99021.

- Change the medium daily and passage cells every 3-4 days.

- Monitor colony morphology for a more uniform, compact appearance.

Q2: We confirmed the expression of key pluripotency markers, but the cells fail to form robust teratomas in vivo. What might be wrong?

This suggests incomplete or unstable reprogramming.

- Root Cause: The reprogramming process is inefficient and occurs in distinct phases. An early, stochastic phase can yield cells that express core pluripotency markers but have not fully stabilized their epigenetic landscape, preventing robust multi-lineage differentiation [6].

- QC Solution: Do not rely on a single QC assay. Your QC workflow must be multi-faceted. Combine pluripotency marker analysis (e.g., immunostaining for OCT4) with functional assays like embryoid body (EB) formation in vitro and the gold-standard teratoma assay in vivo. Furthermore, assess the epigenetic status, such as the methylation state of pluripotency gene promoters, to ensure complete epigenetic reprogramming [6] [22].

- Protocol: Embryoid Body (EB) Formation for In Vitro Differentiation

- Harvest iPSCs using gentle enzymatic dissociation to create small clumps.

- Transfer cell clumps to a low-attachment culture plate in a medium that does not contain pluripotency-sustaining factors (e.g., no bFGF or 2i).

- Allow EBs to form over 3-5 days, changing the medium every other day.

- Plate EBs onto gelatin-coated tissue culture dishes and continue culture for another 10-14 days.

- Analyze the outgrowths for markers of the three germ layers (e.g., β-III tubulin for ectoderm, α-fetoprotein for endoderm, and smooth muscle actin for mesoderm) via immunocytochemistry.

Foundational Signaling Pathways in Pluripotency

A deep understanding of the signaling pathways that maintain or disrupt pluripotency is non-negotiable for effective QC. The following diagrams map the critical networks you must monitor.

LIF/Stat3 Signaling for Self-Renewal

FGF4-Driven Differentiation Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions for Pluripotency QC

A consistent and well-defined set of reagents is the bedrock of reproducible QC. The table below details essential materials for foundational pluripotency experiments.

| Reagent / Material | Function in QC | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Small-Molecule Inhibitors (2i) | Maintains "ground state" pluripotency by suppressing differentiation signals. | PD0325901 (MEK inhibitor) and CHIR99021 (GSK3 inhibitor). Used in serum-free media for homogeneous, naive pluripotent cultures [22]. |

| Cytokines for Self-Renewal | Supports pluripotency in mouse iPSC cultures via specific signaling pathways. | Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF). Activates the JAK/STAT3 pathway. Often used with Serum or BMP4 in traditional mouse iPSC culture [22]. |

| Feeder Cells | Provides a supportive extracellular matrix and factors for cell growth. | Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs). Mitotically inactivated. Can introduce variability; feeder-free cultures on defined substrates (e.g., Geltrex) are preferred for consistency [22]. |

| Pluripotency Marker Antibodies | Detects the presence and intracellular location of key pluripotency transcription factors. | Anti-OCT4, Anti-SOX2, Anti-NANOG. Critical for immunocytochemistry and confirming the molecular signature of pluripotency. |

| Karyotyping Kits | Monitors genomic integrity after reprogramming and long-term culture. | G-banding analysis or SKY FISH kits. Aneuploidy can occur in culture; regular screening is essential for credible research [22]. |

| In Vivo Teratoma Assay Components | The gold-standard functional test for pluripotency. | Immunodeficient Mice (e.g., NOD/SCID). Subcutaneous injection of iPSCs should yield a tumor with tissues from the three germ layers within 8-12 weeks [22]. |

The iPSC QC Toolkit: Essential Assays and Analytical Methods

Regular visual inspection of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) colonies is a fundamental and rapid quality control method for any pluripotency research program. Morphology serves as a sensitive, real-time indicator of cellular health and pluripotent status. Careful daily monitoring under a phase-contrast microscope allows researchers to identify early signs of differentiation or culture decline, often before these changes are detected by molecular assays. This non-invasive assessment is crucial for maintaining the integrity of experiments and ensuring the reproducibility of results, forming the first line of defense in a comprehensive quality control strategy.

Key Morphological Features of Undifferentiated iPSCs

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of high-quality, undifferentiated iPSC colonies and contrasts them with features indicating poor cell quality.

Table 1: Morphological Features of Undifferentiated vs. Differentiating iPSC Colonies

| Feature | High-Quality, Undifferentiated Colonies | Poor Quality or Differentiating Colonies |

|---|---|---|

| Colony Shape | Relatively round and symmetrical [23] | Irregular, asymmetric, or loss of border integrity [23] |

| Cell Packing | Tightly packed cells with a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio; very dense colony centers [23] | Loosely packed cells with visible phase-bright gaps between them [23] |

| Nucleoli | Prominent nucleoli [23] | Not specified in search results |

| Phase Brightness | Colony centers appear phase-bright under phase contrast [23] | Phase-brightness that appears "mottled," sporadic, and not localized to the center [23] |

| Spontaneous Differentiation | Low levels (5-10%) are normal [23] | Increased areas (>10%) of spontaneous differentiation [23] |

Diagram 1: Visual Assessment Workflow for iPSC Morphology.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My colonies have developed "spiky" or irregular edges a few days after passaging. Does this indicate differentiation? Not necessarily. For the first few days after passaging (up to 4 days), colonies may exhibit looser packing and "spiky" edges as they spread out and become established. This is often a normal variation. The density and robustness of the colonies should increase rapidly after this timepoint. If the spiky edges and loose packing persist or worsen as the colonies grow, it may then indicate a decrease in cell quality [23].

Q2: What does it mean if the centers of my colonies appear very phase-bright? Phase-bright colony centers are a characteristic of high-quality, densely packed human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) and are typically observed near the optimal time for passaging. This is a sign of healthy, proliferative cells. However, you should be concerned if the phase-brightness appears "mottled," sporadic, and is not localized to the center of the colony, as this can be an indicator of poor cell quality [23].

Q3: Is it normal for colonies to merge, and what is the impact? Yes, it is normal for colonies to merge, especially as they expand and toward the time of passaging. This can also occur if aggregates are seeded at a low density and are not well-dispersed. Merging itself is not typically a cause for concern. However, very large, merged colonies may begin to spontaneously differentiate in the center due to nutrient gradients or contact inhibition. Maintaining an appropriate seeding density to achieve well-separated colonies is considered best practice [23].

Q4: How does the culture substrate affect colony morphology? The physical and chemical properties of the culture substrate can significantly influence colony morphology. Studies have shown that groove-ridge structures with submicrometer periodicity can induce elongation of iPSC colonies, guide the orientation of apical actin fibers, and direct the plane of cell division [24]. Furthermore, the symmetry of colonies can vary between different extracellular matrices (e.g., Vitronectin XF vs. Matrigel) [23].

Essential Protocols for Morphological Assessment

Daily Observation Protocol

Objective: To routinely monitor the health, density, and undifferentiated status of iPSC cultures. Materials: Phase-contrast microscope, cell culture vessel. Procedure:

- Frequency: Examine cultures daily using a phase-contrast microscope, both before and after feeding [23] [25].

- Assessment: Systematically scan the entire surface of the culture vessel. Evaluate the following:

- Colony Density and Distribution: Determine if the culture is ready to be passaged.

- Morphology: Check for the key features of undifferentiated colonies listed in Table 1.

- Differentiation: Identify and estimate the percentage of the culture surface showing signs of spontaneous differentiation (e.g., changes in cell morphology, loose packing). A low amount (5-10%) is normal, but an increase indicates a need for action [23].

- Contamination: Look for any signs of microbial contamination.

Documentation Protocol

Objective: To maintain a visual record of culture status over time for tracking quality and experimental reproducibility. Materials: Phase-contrast microscope with a digital camera. Procedure:

- Image Capture: Take representative, high-resolution images of colonies at regular intervals (e.g., daily or at each passage) using consistent magnification and lighting.

- Annotation: Label each image with the cell line name, passage number, date, and any relevant culture conditions.

- Storage: Archive images in a structured database for future reference and comparison.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials used in the culture and quality assessment of iPSCs.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for iPSC Culture and Quality Control

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Culture Medium | Provides essential nutrients, growth factors, and signals to maintain self-renewal and pluripotency. | mTeSR Plus, mTeSR1 [23] |

| Cell Culture Substrate | A defined extracellular matrix that supports iPSC attachment, colony formation, and expansion. | Vitronectin XF, Corning Matrigel [23] |

| Passaging Reagent | Enzymatic or non-enzymatic solution used to dissociate colonies for sub-culturing. | Accutase, ReLeSR (for clump passaging) [25] |

| ROCK Inhibitor | A small molecule that increases single-cell survival and cloning efficiency post-passage by inhibiting apoptosis. | Y-27632, used when passaging as single cells [25] |

| Pluripotency Markers | Antibodies for key transcription factors and cell surface antigens to confirm undifferentiated status. | Antibodies against Oct3/4, Nanog, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81 [26] |

Diagram 2: Simplified Mechanotransduction Pathway in iPSCs.

Within the framework of a thesis on quality control for induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) research, rigorous validation of pluripotency markers is non-negotiable. This technical support center addresses common pitfalls in Immunocytochemistry (ICC), Flow Cytometry, and quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR), providing targeted solutions to ensure data integrity and reproducibility.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Immunocytochemistry (ICC)

Q1: My ICC staining for OCT4 shows high background noise, obscuring the nuclear signal. What can I do? A: High background is often due to non-specific antibody binding or inadequate blocking.

- Solution: Increase the concentration of your blocking serum (e.g., from 5% to 10%) and extend the blocking time to 1 hour at room temperature. Include a detergent like 0.1% Triton X-100 in your blocking and antibody dilution buffers to reduce non-specific hydrophobic interactions. Re-titrate your primary antibody to find the lowest effective concentration.

Q2: I am not detecting any signal for my pluripotency marker NANOG. My positive control works. What is wrong? A: This typically indicates an issue with antibody penetration or antigen accessibility.

- Solution: Ensure your permeabilization step is sufficient. For nuclear markers like NANOG, use a stronger permeabilization agent (e.g., 0.5% Triton X-100 for 20 minutes) or consider a methanol fixation step (-20°C methanol for 10 minutes), which simultaneously fixes and permeabilizes cells. Verify that your primary antibody is validated for ICC.

Flow Cytometry

Q3: My flow cytometry data for SOX2 shows a large spread in fluorescence intensity and poor separation between the positive and negative populations. A: This can be caused by cell clumping, improper voltage settings, or high background.

- Solution:

- Cell Preparation: Filter cells through a 35-40 µm cell strainer immediately before analysis to remove clumps.

- Voltage/Gain: Use an unstained control and a single-color control (e.g., IgG isotype control) to set the voltage on the relevant detector. Adjust the voltage so that the negative population is in the first decade of the log scale.

- Gating: Use a sequential gating strategy: first, gate on FSC-A vs. SSC-A to select live, single cells; then, gate on FSC-A vs. FSC-H to exclude doublets.

Q4: What is an acceptable percentage of positive cells for a core pluripotency marker in a high-quality iPSC line? A: For a well-characterized iPSC line, the expression of core transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) should be highly homogeneous.

Table 1: Expected Pluripotency Marker Expression in a High-Quality iPSC Line via Flow Cytometry

| Pluripotency Marker | Expected % Positive Cells | Acceptable Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| OCT3/4 | >90% | >85% |

| SOX2 | >90% | >85% |

| NANOG | >85% | >80% |

| SSEA-4 | >95% | >90% |

qRT-PCR

Q5: My qRT-PCR results show high Ct values for the housekeeping gene GAPDH in my iPSC samples. What does this indicate? A: High Ct values for a stable housekeeping gene suggest poor RNA quality or quantity.

- Solution: Check RNA integrity using an instrument like a Bioanalyzer. A RNA Integrity Number (RIN) >9.5 is ideal for iPSCs. Ensure you are using a minimum of 50-100 ng of high-quality RNA per reaction. Re-evaluate your choice of housekeeping gene; β-actin or GAPDH are commonly used, but 18S rRNA or TBP may be more stable in some stem cell contexts.

Q6: How do I calculate the relative fold-change in gene expression for my pluripotency markers? A: The most common method is the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method.

- Solution:

- Calculate ΔCt: ΔCt = Ct(Target Gene) - Ct(Housekeeping Gene) for each sample.

- Calculate ΔΔCt: ΔΔCt = ΔCt(Test Sample) - ΔCt(Calibrator Sample). The calibrator is often the undifferentiated iPSC control.

- Calculate Fold-Change: Fold-change = 2^(-ΔΔCt).

Table 2: Example qRT-PCR Data Analysis for Pluripotency Markers

| Sample | Gene | Ct Value | ΔCt | ΔΔCt | Fold-Change vs. Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPSC Control | OCT4 | 24.5 | 24.5 - 18.0 = 6.5 | 6.5 - 6.5 = 0.0 | 2^0 = 1.0 |

| GAPDH | 18.0 | ||||

| Differentiated Cells | OCT4 | 29.0 | 29.0 - 18.2 = 10.8 | 10.8 - 6.5 = 4.3 | 2^(-4.3) ≈ 0.05 |

| GAPDH | 18.2 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Immunocytochemistry for Pluripotency Markers

- Culture & Fixation: Culture iPSCs on Matrigel-coated coverslips. At ~70% confluence, aspirate media and fix with 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 minutes at room temperature (RT).

- Permeabilization & Blocking: Wash 3x with PBS. Permeabilize and block with a solution of 5% normal serum (e.g., goat serum) and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 hour at RT.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubate with primary antibody (e.g., Anti-OCT4, 1:200) diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4°C.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Wash 3x with PBS. Incubate with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500) diluted in blocking solution for 1 hour at RT in the dark.

- Counterstaining & Mounting: Wash 3x with PBS. Incubate with DAPI (1 µg/mL) for 5 minutes. Wash and mount coverslip onto a slide using an anti-fade mounting medium.

Protocol 2: Flow Cytometry Analysis of Pluripotency Markers

- Cell Harvest & Fixation: Dissociate iPSCs into a single-cell suspension using Accutase. Centrifuge and resuspend ~1x10^6 cells in 4% PFA. Fix for 20 minutes at RT.

- Permeabilization: Centrifuge, wash with PBS, and resuspend in ice-cold 90% methanol for 30 minutes on ice. (This step is crucial for intracellular markers like OCT4 and NANOG).

- Staining: Centrifuge and wash with FACS Buffer (PBS + 2% FBS). Resuspend cell pellet in 100 µL FACS Buffer containing the primary antibody or isotype control. Incubate for 1 hour at RT in the dark.

- Analysis: Wash cells twice with FACS Buffer. If using a directly conjugated antibody, resuspend in FACS Buffer and analyze immediately on a flow cytometer. If using an unconjugated primary, perform a secondary antibody incubation step first.

Protocol 3: RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR for Pluripotency Markers

- RNA Extraction: Lyse cells directly in a culture plate using TRIzol reagent or a commercial silica-membrane column kit. Include a DNase I digestion step to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- cDNA Synthesis: Quantify RNA concentration. Use 1 µg of total RNA for reverse transcription with a kit using random hexamers and M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase.

- qPCR Setup: Prepare a master mix containing SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, forward and reverse primers (e.g., for OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and a housekeeping gene), and nuclease-free water. Add cDNA template. Run in triplicate on a real-time PCR instrument.

- Data Analysis: Use the instrument software to determine Ct values. Export data and calculate relative fold-change using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method.

Visualizations

Title: ICC Experimental Workflow

Title: Flow Cytometry Gating Strategy

Title: qRT-PCR Fold-Change Calculation

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pluripotency Marker Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative that preserves cellular architecture for ICC and Flow Cytometry. |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent used to permeabilize cell membranes, allowing antibodies to access intracellular targets. |

| Normal Serum (e.g., Goat Serum) | Used for blocking to prevent non-specific binding of antibodies to cells or tissue. |

| Fluorophore-Conjugated Antibodies | Antibodies tagged with a fluorescent dye (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488) for detection in ICC and Flow Cytometry. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | A reagent used in qRT-PCR that fluoresces when bound to double-stranded DNA, allowing for quantification of amplified PCR products. |

| DNase I | Enzyme that degrades genomic DNA during RNA preparation to prevent false-positive signals in qRT-PCR. |

| Matrigel | Basement membrane matrix used to coat culture surfaces, providing a substrate that supports iPSC attachment and pluripotency. |

The teratoma formation assay is a critical in vivo functional test used to confirm the pluripotency of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), including both embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). This assay provides the most stringent validation of a cell line's capacity to differentiate into derivatives of all three embryonic germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—within an in vivo environment [27] [28].

For researchers in the field of iPSC quality control, this assay serves a dual purpose: it not only confirms developmental potential but also provides crucial safety data by assessing tumorigenic risk. The same pluripotent characteristic that makes hPSCs powerful tools in regenerative medicine also creates major clinical hurdles, highlighting the fine line that both separates and connects pluripotency and tumorigenicity [27]. Despite being time-consuming and requiring animal models, it remains the gold standard for pluripotency assessment, particularly for pre-clinical safety evaluation of hPSC-derived cell therapy products [29] [30].

Key Principles and Biological Basis

What is a Teratoma?

Teratomas are benign tumors characterized by rapid growth in vivo and their haphazard mixture of tissues, often containing semi-semblances of organs, teeth, hair, muscle, cartilage, and bone [27]. The presence of multiple tissue types derived from all three germ layers provides definitive evidence of robust pluripotency [27] [31].

When these tumors contain undifferentiated "embryonal carcinoma elements," they are classified as teratocarcinomas, indicating malignant potential [29]. The distinction is critical for safety assessment, as the presence of undifferentiated cells in a therapeutic product poses significant tumorigenicity risks [29] [30].

Why Use the Teratoma Assay?

While in vitro alternatives exist—such as embryoid body formation, directed differentiation, and bioinformatic tools like PluriTest—the teratoma assay offers unique advantages [28] [31]:

- Provides a more physiologically relevant environment compared to artificial petri dish conditions

- Allows assessment of both pluripotency and malignant potential simultaneously

- Remains the preferred method for detecting undifferentiated cells in differentiated cell products intended for transplantation

- Is generally required by regulatory authorities for pre-clinical safety assessment of hPSC-derived therapies [29] [30]

Experimental Design and Protocols

Essential Materials and Reagents

The following research reagents are fundamental for executing a proper teratoma formation assay:

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Teratoma Formation Assays

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples & Details | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| hPSC Lines | H7, H9 (WA07, WA09), or validated iPSC lines; optionally with reporter genes (Fluc, mRFP, HSVtk) | Starting cellular material for implantation [27] |

| Cell Culture | Gelatin, Matrigel, mTESR-1 hES Growth Medium, Collagenase Type IV | Maintenance and preparation of undifferentiated hPSCs [27] |

| Animal Models | Immunodeficient mice (Nu/Nu nude, SCID, NOD/SCID, NSG) | Host organisms that allow hPSC engraftment without rejection [27] [30] |

| Injection Supplies | 28.5 gauge insulin syringes, Matrigel for cell suspension | Delivery of cells to implantation site [27] |

| Anesthesia & Support | Isoflurane vapor system, 37°C heat pad | Animal comfort and physiological support during procedures [27] |

Critical Experimental Parameters

Multiple factors significantly influence teratoma formation efficiency and must be carefully controlled:

Table: Key Experimental Parameters Affecting Teratoma Formation

| Parameter | Options/Recommended Values | Impact on Assay Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Injection Site | Subcutaneous, intramuscular, kidney capsule, intratesticular | Affects teratoma formation efficiency and differentiation patterns [27] [32] |

| Cell Number | 1×10^4 to 1×10^6 cells (site-dependent); ~1×10^5 for intramyocardial | Must exceed critical threshold for teratoma formation; too high increases malignancy risk [27] |

| Animal Strain | Immunocompromised strains (Nu/Nu, SCID, NOD/SCID, NSG) | Prevents xenogeneic rejection of human cells [27] [30] |

| Assay Duration | 6-20 weeks (cell line and site dependent) | Must allow sufficient time for teratoma development and tissue differentiation [29] |

Standardized Workflow Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for conducting a teratoma formation assay:

Detailed Methodological Steps

Cell Preparation and Injection

- Culture hPSCs: Maintain undifferentiated hPSCs on feeder layers or in feeder-free conditions using validated media [27].

- Harvest cells: Use collagenase Type IV or manual scraping to create cell aggregates or single-cell suspensions [27].

- Prepare injection sample: Resuspend cells in an appropriate buffer, often mixed with Matrigel (approximately 1:1 ratio) to enhance cell survival and engraftment [27].

- Load syringes: Use 28.5 gauge insulin syringes for precise delivery while maintaining cell viability [27].

Animal Procedures and Monitoring

- Anesthetize mice: Use isoflurane vapor in oxygen for safe and reversible anesthesia [27].

- Inject cells: Administer cell suspension to selected site (subcutaneous, intramuscular, or kidney capsule) [27].

- Post-operative care: Provide analgesic if needed and monitor recovery on a 37°C heat pad [27].

- Longitudinal monitoring: Palpate weekly for tumor formation; utilize non-invasive imaging (BLI, MRI) if cells express reporter genes [27].

Tissue Harvest and Analysis

- Harvest tumors: Euthanize mice at predetermined endpoints (typically 8-20 weeks) or when tumors reach 1-2 cm in diameter [27] [32].

- Process tissue: Fix teratomas in formalin, embed in paraffin, and section for staining [27].

- Histological analysis: Stain sections with H&E and examine for tissues representing all three germ layers [27] [31].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: What should I do if no teratoma forms after injection?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient cell number: Ensure you're injecting at or above the critical threshold (typically >10,000 cells, depending on site) [27]. Consider creating a cell number titration series.

- Suboptimal injection site: Test multiple sites (subcutaneous, intramuscular, kidney capsule) as efficiency varies [27] [32].

- Cell quality: Verify pluripotency status prior to injection using flow cytometry for markers (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, TRA-1-60) [33].

- Animal model issues: Confirm immunodeficient status of mice and use younger animals (6-8 weeks) for better engraftment [27] [32].

FAQ 2: Why does my teratoma show incomplete differentiation or lacks all three germ layers?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient growth time: Allow more time for differentiation (extend to 12-20 weeks) as different lineages appear at different rates [29].

- Excessive cell number: Very high cell numbers can sometimes lead to poor differentiation; try reducing cell number by 50% [27].

- Sampling error: Ensure thorough sectioning and sampling of the entire teratoma, as germ layer distribution can be heterogeneous [31].

- Cell line variability: Acknowledge that different hPSC lines have varying differentiation biases [27] [28].

FAQ 3: How can I distinguish between a benign teratoma and a malignant teratocarcinoma?

Key Distinguishing Features:

- Benign teratomas contain only well-differentiated tissues from the three germ layers without undifferentiated components [29] [32].

- Teratocarcinomas contain undifferentiated "embryonal carcinoma" cells in addition to differentiated tissues, indicating malignant potential [29] [32].

- Histopathological analysis by an experienced pathologist is essential for accurate classification [29].

- Additional indicators of malignancy include invasive growth, high proliferation index (Ki67 staining), and metastasis [32].

FAQ 4: What are the ethical considerations and alternatives to reduce animal use?

Ethical Framework and Alternatives:

- Follow 3Rs principles: Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement as outlined in EU Directive 2010/63/EU [32].

- Implement humane endpoints: Establish clear tumor size limits (typically 1-2 cm diameter or 10% body weight) to prevent suffering [32].

- Consider in vitro alternatives: For initial screening, use embryoid body formation, directed differentiation, or bioinformatic tools (PluriTest, ScoreCard) [28] [31] [32].

- Maximize data obtained: Combine endpoints where possible and share data to avoid duplication of experiments [32].

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Histopathological Assessment

Proper analysis requires systematic examination of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections for well-differentiated tissues representing:

- Ectoderm: Neural tissue (rosettes, pigment epithelium), stratified squamous epithelium, glial cells [27] [31]

- Mesoderm: Cartilage, bone, muscle (skeletal, smooth), adipose tissue, connective tissue [27] [31]

- Endoderm: Respiratory epithelium, intestinal epithelium, glandular structures [27] [31]

Documentation should include high-quality photomicrographs with scale bars and clear tissue identification.

Quantitative and Semi-Quantitative Approaches

While traditional teratoma assessment is qualitative, newer approaches provide more objective measures:

- TeratoScore: A computational method that quantifies differential gene expression in teratoma tissue to provide quantitative assessment of differentiation capacity [28].

- Scoring systems: Some laboratories implement semi-quantitative scoring based on tissue diversity, organization, and maturity [31].

The following decision diagram guides the interpretation of teratoma assay results:

Current Methodological Innovations and Future Directions

The field continues to evolve with several important developments:

- Enhanced sensitivity assays: Digital PCR and highly efficient culture (HEC) assays now offer superior detection sensitivity for residual undifferentiated hPSCs in differentiated products [30].

- Standardization efforts: Recent consensus recommendations from the Health and Environmental Sciences Institute's International Cell Therapy Committee aim to harmonize evaluation procedures globally [30].

- Imaging advancements: Non-invasive longitudinal imaging with reporter gene-expressing cells allows monitoring of teratoma development without sacrificing animals at multiple timepoints [27].

- In vitro alternatives: While not yet replacing teratoma assays for safety assessment, improved 3D culture systems and organoid technologies show promise for reducing animal use in the future [31] [32].

For drug development professionals and researchers, understanding both the power and limitations of the teratoma assay remains essential for proper preclinical assessment of hPSC-based therapies. While the assay continues to be required by regulatory authorities for clinical applications, employing complementary in vitro methods during early development can enhance efficiency and reduce animal use [30] [32].

Troubleshooting FAQ: Common Issues in Directed Differentiation

FAQ 1: What are the most common causes of low differentiation efficiency across all three germ layers?

Low differentiation efficiency often stems from issues with starting cell quality, inappropriate signaling molecule concentration, or suboptimal culture conditions. Ensure your iPSCs are fully pluripotent and undifferentiated before beginning, with >75% expression of key markers like NANOG, OCT4, SSEA4, TRA-1-60, and TRA-1-81 [33] [34]. Other factors include incorrect timing of growth factor addition, poor cell density optimization, and variability between cell lines. Always include positive controls and validate with multiple pluripotency markers to confirm starting cell quality [35] [34].

FAQ 2: How can I troubleshoot high background staining during immunocytochemical analysis of germ layer markers?

High background staining in immunocytochemistry can result from multiple factors. To reduce nonspecific background: quench endogenous peroxidases with 3% H₂O₂ in methanol, block endogenous biotin using avidin/biotin blocking solutions, optimize primary antibody concentration to prevent nonspecific binding, and add NaCl (0.15-0.6 M) to antibody diluents to reduce ionic interactions [36]. For fluorescent detection, address autofluorescence by testing different fixatives or using near-infrared fluorescent dyes that don't compete with tissue autofluorescence [36].

FAQ 3: What quality control standards should be implemented for clinical-grade iPSC differentiation?

For clinical-grade applications, implement rigorous quality control tests validated under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards. These include: residual episomal vector screening (minimum 20,000 cells/120 ng genomic DNA), pluripotency marker assessment (>75% expression of at least three markers), and differentiation potential verification (positive for at least two lineage-specific markers per germ layer) [34] [37]. Testing should occur between passages 8-10 to avoid unnecessary rejection of lines still losing reprogramming vectors [34].

FAQ 4: How does extracellular matrix affect definitive endoderm differentiation efficiency?

Substrate properties significantly influence definitive endoderm differentiation. Research demonstrates that synthetic PEG-based hydrogels presenting cyclic RGD peptides support efficient DE differentiation when combined with appropriate soluble factors [38]. Increasing substrate stiffness (G' = 1.0-4.0 kPa) produces a linear increase in DE differentiation efficiency, with focal adhesion kinase activity regulating both iPSC growth and DE differentiation outcomes [38]. This fully defined synthetic matrix offers a clinically translatable alternative to poorly-defined xenogeneic substrates like Matrigel [38].

FAQ 5: What are the key signaling pathways to manipulate for specific germ layer specification?

Germ layer specification requires precise manipulation of evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways. For mesendoderm (precursor to both mesoderm and endoderm), TGF-β family signals (particularly Nodal/Activin) are crucial [39] [40]. For ectoderm specification, TGF-β signaling must be attenuated, a process mediated by factors like Ectodermin, a Smad4 ubiquitin ligase that restricts mesoderm-inducing signals [40]. Mesoderm formation requires synergistic activity of FGF signaling with TGF-β signals, while definitive endoderm specification relies on high levels of Activin/Nodal signaling [39] [38].

Quantitative Standards for Germ Layer Differentiation Validation

Table 1: Minimum Acceptance Criteria for Successful Germ Layer Differentiation [34]

| Parameter | Minimum Acceptance Criteria | Testing Method |

|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Starting Population | ≥75% expression of at least 3 pluripotency markers | Flow cytometry, immunocytochemistry |

| Ectoderm Confirmation | Positive for ≥2 of: PAX6, SOX1, Nestin, βIII-tubulin | Immunocytochemistry, qRT-PCR |

| Mesoderm Confirmation | Positive for ≥2 of: Brachyury, SMA, Desmin, CD31 | Immunocytochemistry, qRT-PCR |

| Endoderm Confirmation | Positive for ≥2 of: SOX17, FOXA2, CXCR4, AFP | Immunocytochemistry, qRT-PCR |

| Genetic Stability | Normal karyotype maintained post-differentiation | Karyotype analysis, SNP array |