Ensuring Safety and Efficacy: A Comprehensive Guide to Genomic Stability Assessment in Stem Cells

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed overview of the critical methods for assessing genomic stability in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs).

Ensuring Safety and Efficacy: A Comprehensive Guide to Genomic Stability Assessment in Stem Cells

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed overview of the critical methods for assessing genomic stability in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). It covers the foundational knowledge of why hPSCs are prone to genetic alterations, explores the full spectrum of current detection methodologies—from karyotyping to next-generation sequencing and optical genome mapping—and offers practical guidelines for their application. Furthermore, it delivers comparative analyses to inform method selection, troubleshooting strategies for common challenges in quality control, and a forward-looking perspective on integrating these techniques to ensure the safety and efficacy of clinical-grade stem cell therapies.

The Genomic Stability Imperative: Why Stem Cells Acquire Variations and the Associated Clinical Risks

Genomic instability represents one of the most significant challenges in the application of stem cell technologies for research and clinical translation. The processes of cellular reprogramming to create induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and the subsequent long-term culture necessary for their expansion and differentiation can introduce genetic alterations that compromise both the functionality and safety of these cells. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the precise mechanisms behind this instability is crucial for developing robust quality control measures and safer stem cell-based therapies. This guide examines the key drivers of genomic instability by comparing the genetic alteration profiles across different stem cell technologies, with a particular focus on iPSCs and the newer conditional reprogramming (CR) technology, providing objective experimental data to inform model selection and quality assessment protocols.

Mechanisms and Origins of Genomic Instability

The genomic alterations observed in stem cells originate from multiple sources throughout the cell culture lifecycle. These variations can be categorized into three primary origins based on when they emerge during the cell processing pipeline.

Table 1: Origins of Genomic Variations in Stem Cells

| Origin Category | Description | Common Alterations |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-existing Variations [1] | Somatic mutations present in parental cells that are fixed and expanded during reprogramming due to the clonal nature of the process. | Single nucleotide variants (SNVs), Copy number variations (CNVs) |

| Reprogramming-Induced [1] [2] | Mutations acquired during the reprogramming process itself, attributed to the replicative stress and profound epigenetic remodeling involved. | Point mutations, Copy number alterations (CNAs) |

| Passage-Induced [1] [3] | Alterations that arise during extended in vitro culture, often providing a selective growth advantage that leads to their dominance in the culture. | Aneuploidy (e.g., Trisomy 12, X), Specific CNVs (e.g., 20q11.21 amplification) |

A key driver of passage-induced instability is the selective pressure that occurs during routine culture. Certain genetic abnormalities confer a growth advantage, allowing variant cells to outcompete their normal counterparts. For instance, amplifications of chromosome 20q11.21, a recurrent abnormality in pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), contain the BCL2L1 gene, an anti-apoptotic factor that enhances cell survival [3]. Similarly, trisomy 12 is frequently observed, potentially because this chromosome contains pluripotency-associated genes like NANOG that improve self-renewal [1].

Comparative Genomic Stability Across Cell Technologies

Different cell culture technologies exhibit varying propensities for genomic instability, a critical factor in model selection for research and therapy development.

Table 2: Technology Comparison of Genomic Stability and Features

| Feature | Transformed Cell Lines [4] | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [4] [1] | Conditionally Reprogrammed (CR) Cells [4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Success Rate | Medium | Medium | High |

| Genetic Stability | Low | Medium | High |

| Tissue Specificity | Low | Low | High |

| Heterogeneity | No | Medium | Medium |

| Tumorigenicity Risk | High | Medium (Teratoma/Tumor formation) [5] | Low (Form tumors in mice, but maintain original genetics) [4] [6] |

| Key Genetic Alterations | N/A | Trisomy 12, 20q11.21 amplification, TP53 mutations [1] [3] | Maintains original tumor genetics in early passages [6] |

The method used for reprogramming iPSCs also significantly impacts genomic stability. A systematic study comparing Sendai virus (SV) and episomal vector (Epi) methods found that all SV-iPS cell lines exhibited copy number alterations (CNAs) during reprogramming, compared to only 40% of Epi-iPS cells. Furthermore, single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) were observed exclusively in SV-derived cells during passaging and differentiation [2].

Conditional reprogramming (CR) presents an alternative with potentially higher genetic stability. This technology uses a Rho kinase inhibitor (Y-27632) and feeder cells to rapidly propagate primary epithelial cells without genetic manipulation [4]. Genomic studies have shown that early-passage CR cells from breast cancer patients maintained over 95% overlap in copy number alteration patterns with their original primary tumors and retained the same somatic mutations, demonstrating significant genomic fidelity [6].

Essential Experimental Assessment Methodologies

Rigorous and regular genomic assessment is mandatory for characterizing stem cell lines. The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) emphasizes the need for independent oversight, accountability, and transparency at each research stage [7]. A comprehensive genomic stability workflow should be implemented at multiple critical points.

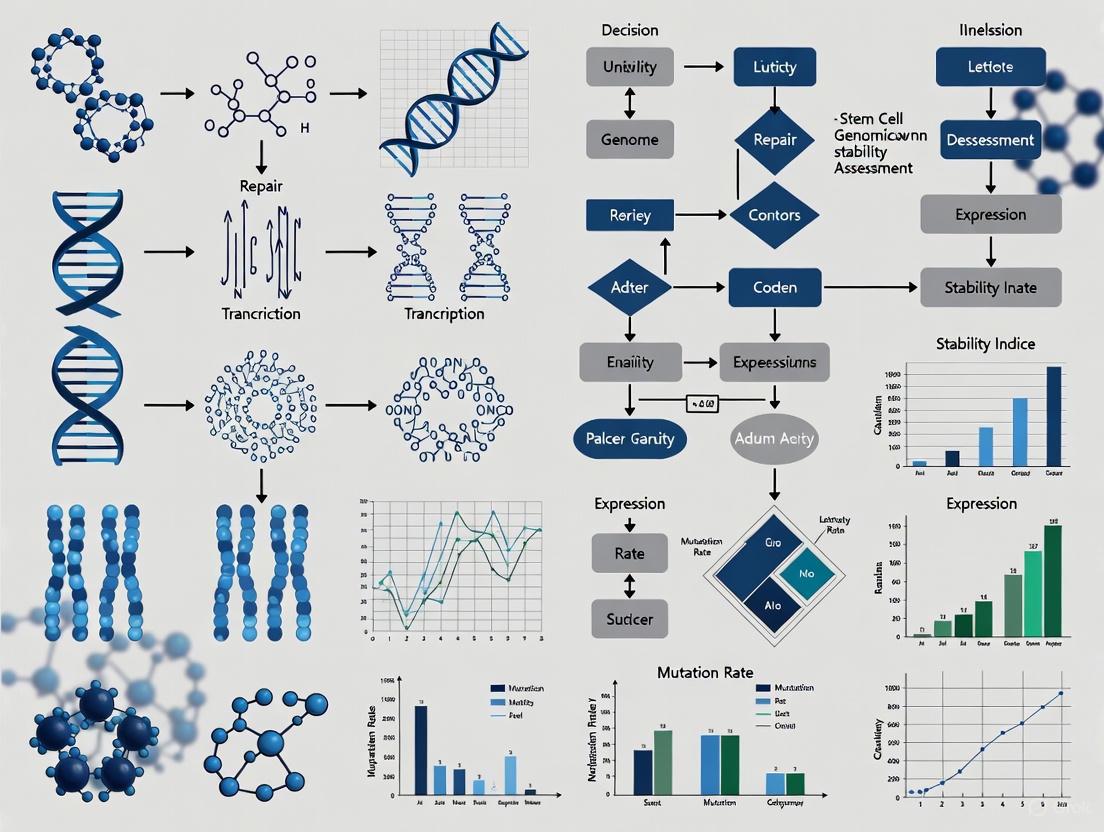

Figure: Genomic Stability Workflow. A practice-oriented testing pipeline for pluripotent stem cells, outlining key stages where genomic assessment is critical. Adapted from Stem Genomics recommendations [8].

Table 3: Key Methods for Genomic Instability Detection

| Method | Detection Capability | Resolution | Best Use Case | Protocol Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karyotyping (G-banding) [1] [8] | Numerical and large structural chromosomal changes. | ~5-10 Mb | Initial and final cell line characterization. | Cells arrested in metaphase, dropped onto slides, Giemsa-stained, and chromosomes analyzed microscopically. |

| Digital PCR [8] | Targeted CNV detection (e.g., 20q11.21). | Single gene | High-frequency in-process monitoring and clone screening. | DNA partitioned into thousands of droplets; target amplification is measured absolutely to quantify copy number. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) [1] [8] | Genome-wide SNVs, Indels, and CNVs. | Single nucleotide | Comprehensive profiling at acquisition, banking, and pre-clinical stages. | Fragmented DNA is adapter-ligated, clonally amplified, and sequenced in parallel; data is aligned to a reference genome for variant calling. |

For specific applications like assessing DNA strand breaks under stress conditions, novel biosensors offer sensitive alternatives. One advanced method utilizes a TdT enzyme-Endo IV-fluorescent probe biosensor, which recognizes 3'-hydroxyl ends at DNA breakpoints, extends them to form a poly-A sequence, and cleaves a fluorescent probe for signal amplification, providing a parameter called the Mean number of DNA breakpoints (MDB) [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A selection of key reagents is fundamental for conducting research in stem cell genomic stability.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Kits

| Reagent/Kit Name | Primary Function | Key Application in Genomic Stability Research |

|---|---|---|

| Rho-Kinase (ROCK) Inhibitor (Y-27632) [4] | Inhibits ROCK-mediated apoptosis. | Essential for conditional reprogramming of primary cells; enhances survival of single cells. |

| Irradiated Swiss 3T3-J2 Fibroblasts [4] | Serves as feeder cells. | Provides necessary signaling and structural support for the growth of conditionally reprogrammed epithelial cells. |

| STEMdiff Mesenchymal Progenitor Kit [2] | Directed differentiation of iPSCs. | Generates iPS-derived mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (iMS cells) for studying genomic changes during differentiation. |

| TdT -Endo IV-Fluorescent Probe Biosensor [9] | Detects DNA strand breaks. | Quantifies DNA integrity in stem cells under stress (e.g., heat, cryopreservation) via a highly sensitive fluorescence signal. |

| CytoTune-iPS Sendai Reprogramming Kit [2] | Delivers reprogramming factors via non-integrating virus. | Generates iPSCs from somatic cells; used in comparative studies on reprogramming-induced genomic instability. |

The journey of a cell from its somatic state through reprogramming and prolonged culture is fraught with opportunities for genomic instability to arise, driven by factors from pre-existing mutations to culture-adapted selective advantages. A comparative analysis reveals that while no technology is immune to these changes, their nature and frequency vary significantly—iPSCs are susceptible to specific aneuploidies and mutations in genes like TP53, whereas CR cells demonstrate strong genomic fidelity to their tissue of origin, at least in early passages. For researchers and drug developers, this underscores the necessity of a rigorous, multi-stage quality control workflow that leverages complementary detection methods from karyotyping to NGS. The choice of cell technology and reprogramming method must be aligned with the application's specific needs, always balancing growth potential with genetic integrity to ensure the safety and efficacy of future stem cell-based applications.

The comprehensive assessment of genomic stability is a critical prerequisite for the clinical application of stem cells. Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) are susceptible to genomic instability throughout the reprogramming and extended culture processes, which poses a potential risk to the clinical application of cell-based therapies [10]. Genomic instability encompasses a spectrum of alterations, from single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) and small insertions and deletions (indels) to more complex rearrangements such as copy number variations (CNVs), structural variations (SVs), and whole-chromosome aneuploidies [10]. These alterations can originate from the initial cell state, emerge during reprogramming of somatic cells into iPSCs, or accumulate during subsequent amplification and cell banking [10].

The clinical implications of these genetic alterations are profound. Genomic instability not only affects the differentiation capacity of iPSCs but may also trigger safety issues such as tumorigenesis [10]. For example, chromosomal amplifications of oncogenes such as BCL2L1 and c-MYC, or mutation/loss of TP53, are associated with the transformation of transplanted iPSCs into tumor cells [10]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the detection methodologies for the full spectrum of genetic alterations in stem cells, providing researchers with experimental protocols and performance data for informed technology selection.

Classification and Characterization of Genetic Alterations

Structural Variants (SVs)

Structural variants represent genomic variations that involve breakage and rejoining of DNA segments ≥50 base pairs, potentially altering gene dosage, disrupting gene regulation, or creating novel fusion genes [11]. Based on their architectural features, SVs are classified into several categories. Simple SVs include deletions, duplications, insertions, and inversions, while complex structural variants involve combinations of multiple SV types with clustered breakpoints originating from a single event [12] [11]. Catastrophic genomic events like chromothripsis (localized chromosomal shattering and random reassembly), chromoplexy (interconnected inter- and intra-chromosomal translocations), and chromoanasynthesis (replication-based complex rearrangements with copy-number gains) represent the most complex categories [11].

The mutagenesis mechanisms underlying SVs vary considerably. Non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR) between low-copy repeats or segmental duplications leads to recurrent rearrangements with consistent breakpoints across individuals [11]. Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) repair double-strand breaks using little or short microhomologous sequences (5-25 bp), respectively [11]. Replication-based mechanisms like fork stalling and template switching (FoSTeS) and microhomology-mediated break-induced replication (MMBIR) contribute to complex rearrangements [11].

Copy Number Variations (CNVs) and Aneuploidy

CNVs are a subclass of SVs encompassing deletions or duplications/amplifications that typically range from 1 kilobase to several megabases [11]. These variants can be recurrent, with consistent size and breakpoints mediated by NAHR between segmental duplications, or non-recurrent, with varying sizes that share a minimal region of overlap encompassing dosage-sensitive genes [11].

Aneuploidy refers to the gain or loss of entire chromosomes, representing the most macroscopic form of genomic alteration. In stem cell cultures, specific recurrent aneuploidies such as gains of chromosomes 12, 17, and 20 provide selective growth advantages, leading to their overgrowth in culture conditions [10].

Single-Nucleotide Variations (SNVs) and Small Indels

SNVs and small insertions or deletions (indels) represent changes at the single-base-pair level. During iPSC culture, these mutations can accumulate over time, with some occurring in genes associated with tumors or diseases, such as CDH1 and BCOR [10]. The mutation rate and spectrum of these variations can be influenced by the reprogramming method and culture conditions [13].

Table 1: Spectrum of Genetic Alterations in Stem Cells

| Alteration Type | Size Range | Detection Methods | Common Genomic Locations | Functional Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aneuploidy | Entire chromosomes | Karyotyping, OGM | Chr12, 17, 20 gains | Altered gene dosage, growth advantage |

| CNVs (deletions/duplications) | 1 kb - several Mb | Microarray, OGM, WGS | Regions with segmental duplications | Gene dosage changes, gene disruption |

| Complex SVs | 50 bp - several Mb | OGM, long-read WGS | Multiple clusters | Gene fusions, regulatory rewiring |

| Simple SVs (inversions, translocations) | ≥50 bp | OGM, WGS | Genome-wide | Regulatory disruption, gene interruption |

| SNVs/Indels | 1 - 50 bp | WES, WGS | Coding regions, regulatory elements | Protein function changes, splice defects |

Detection Methodologies and Performance Comparison

Technological Platforms for Genetic Alteration Detection

Multiple technological platforms are employed for comprehensive genomic assessment, each with unique capabilities and limitations for detecting different classes of genetic alterations.

Karyotyping represents the traditional approach for identifying chromosomal anomalies in hiPSCs, yet it is limited to detecting alterations exceeding 5 Mb in size and lacks precision in pinpointing exact breakpoints [10]. The minimum mosaicism detected is 12% by routine analysis of 50 metaphase spreads [10].

Optical Genome Mapping (OGM) creates large-sized marked DNA fragments that can be assembled into whole-genome maps efficiently [10]. This technology can detect chromosomal structural variants with higher resolution than karyotyping (≥500 bp), and with higher accuracy than short-read next-generation sequencing techniques [10]. OGM effectively identifies SVs and CNVs below karyotyping resolution, particularly recurrent genome abnormalities such as gains on chr17q, chr12p, and chr20q [10].

Sequencing Technologies include whole-exome sequencing (WES) and whole-genome sequencing (WGS). WES and WGS are capable of detecting SNVs, Indels, and CNVs, though with limitations [10]. Short-read WGS has poor detection capabilities for low-frequency variants and SVs in repetitive regions, while long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., Pacific Biosciences) offer advantages for spanning complex structural variations but may have higher error rates for SNVs [14].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Genomic Assessment Technologies

| Technology | Resolution | SV Detection Capability | Aneuploidy Detection | SNV/Indel Detection | Throughput | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karyotyping | >5 Mb | Limited (large balanced) | Excellent | None | Low | Low |

| Chromosomal Microarray | >50 kb | CNVs only | Yes | None | Medium | Medium |

| Optical Genome Mapping | ≥500 bp | Excellent for CNVs, SVs | Yes | Limited | Medium | Medium |

| Short-read WGS | Single base | Moderate for small SVs | Possible | Excellent | High | High |

| Long-read WGS | Single base | Excellent for complex SVs | Possible | Good (higher error rate) | Medium | Highest |

| Whole Exome Sequencing | Single base | Limited | No | Excellent (coding only) | High | Medium |

Integrated Assessment Approaches

Research demonstrates that each method has unique detection capabilities and limitations, and only integrative approaches can comprehensively identify genomic abnormalities [10]. One study established a comprehensive strategy for evaluating the genetic stability of hiPSCs by integrating karyotyping, OGM, WES, and RNA-seq, which can be applied to scenarios such as hiPSC clone screening, establishment of cell bank passages, and quality control of hiPSC-derived products [10].

For clinical applications, the selection of healthy hiPSC clones with normal chromosomes and genomes at the source is crucial for downstream cell banking [10]. Determining the maximum number of permissible passages during continuous subculturing requires accurate and sensitive detection methods that can truly reflect genetic variations [10].

Figure 1: Integrated Workflow for Comprehensive Genetic Assessment. This workflow illustrates how different detection methods contribute to identifying the full spectrum of genetic alterations in stem cells.

Experimental Protocols for Genomic Assessment

Comprehensive Genomic Stability Assessment Protocol

A comprehensive protocol for assessing stem cell genomic stability involves multiple parallel analyses. Three hiPSC lines were continually cultured in vitro for 50 passages, with genome stability evaluated every 10 passages using the following integrated methodology [10]:

Karyotyping Protocol: Before cell harvesting, colchicine is added directly to the plate of cells achieving a final concentration of 100 ng/ml for 40 minutes. Cells are then trypsinized, treated with a hypotonic solution for 20 minutes, and fixed. Metaphases are spread on microscope slides and stained using the standard G-banding technique. For chromosomal number analysis, 500 metaphases are counted, then 50 metaphases are photographed and classified in accordance with the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature [10].

Optical Genome Mapping Protocol: Ultra-high molecular weight (UHMW) genomic DNA is extracted from 1.5 × 10^6 cells using the Prep SP-G2 Blood & Cell Culture DNA Isolation Kit. DNA quantification is performed using the Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit. A total of 750 ng of UHMW DNA is labeled using the Bionano Prep DLS-G2 Labeling Kit. The labeled UHMW DNA is quantified and loaded onto the Saphyr Chip G2.3 at a concentration of 4 to 15 ng/μL and run on a Bionano Saphyr Gen2 instrument. A total of 2,000 GB of data are collected per sample. DNA molecules with an average mapping rate greater than 70% and a minimum length of 150 kbp are selected for subsequent analysis using the Rare Variant Analysis pipeline in Bionano Solve version 3.6.1 [10].

Whole-Exome Sequencing Protocol: While the specific protocol was not detailed in the search results, WES typically involves capture of exonic regions followed by high-throughput sequencing. This method reveals coding mutations, including germline short variants and newly acquired somatic mutations [10].

RNA Sequencing Protocol: Total RNA is extracted from 2 × 10^6 cells using TRIzol reagent. After DNase I digestion, RNA concentration and integrity are detected using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Library preparation follows standard protocols for RNA sequencing [10].

Specialized Protocol for Detecting Complex Structural Variants

For comprehensive detection of complex de novo structural variants (dnSVs), specialized bioinformatics approaches are required. One study developed a rigorous pipeline to analyze an average of 13,980 candidate variants per proband, called using the Manta caller [12]. The protocol involves:

- Variant Calling: Initial identification of candidate SVs using specialized callers like Manta [12].

- Filtering and Classification: Application of stringent filters to remove false positives and classification of complex dnSVs into subtypes based on breakpoint architecture [12].

- Visual Inspection: Manual curation and visual inspection of all high-confidence dnSVs using integrative genomics viewers [12].

- Validation: Experimental validation using orthogonal methods such as long-read sequencing or array-based comparative genomic hybridization [12].

This approach identified 1,870 dnSVs in 13,698 offspring with rare diseases, with complex dnSVs (8.4%) emerging as the third most common type following simple deletions and duplications [12].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Genomic Stability Assessment

| Reagent/Kit | Manufacturer | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prep SP-G2 Blood & Cell Culture DNA Isolation Kit | Bionano Genomics | UHMW DNA extraction | Optical Genome Mapping |

| Bionano Prep DLS-G2 Labeling Kit | Bionano Genomics | DNA labeling for OGM | Structural variant detection |

| Saphyr Chip G2.3 | Bionano Genomics | Platform for OGM analysis | High-resolution genome mapping |

| CytoTune-iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | iPSC generation | Stem cell reprogramming |

| Episomal iPS Cell Reprogramming Vectors | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Non-viral iPSC generation | Footprint-free reprogramming |

| STEMdiff Mesenchymal Progenitor Kit | StemCell Technologies | MSC differentiation | Stem cell differentiation studies |

| mTeSR1 Medium | StemCell Technologies | iPSC maintenance | Pluripotent stem cell culture |

| MesenCult-ACF Medium | StemCell Technologies | MSC culture | Mesenchymal stem cell expansion |

Data Interpretation and Analytical Frameworks

Analytical Considerations for Different Alteration Types

The interpretation of genetic alterations requires different analytical frameworks depending on the variant type. For CNVs and SVs, researchers should cross-reference findings with population databases like the Database of Genomic Variants (DGV) and gnomAD-SV to distinguish common polymorphisms from potentially pathogenic alterations [11]. The clinical relevance should be evaluated based on the genomic content affected, including dosage-sensitive genes, regulatory regions, and topologically associating domains (TADs) [11].

For SNVs and small indels, annotation using tools like ANNOVAR or VEP followed by filtering against population frequency databases (e.g., gnomAD) is essential. Pathogenicity prediction scores (CADD, SIFT, PolyPhen-2) help prioritize potentially functional variants [10].

Complex structural variants require special attention as they may involve multiple breakpoints and different mutation mechanisms. The analysis should characterize the architecture, identify the involved genomic elements, and infer the potential mutational mechanism (e.g., FoSTeS/MMBIR for replication-based events) [12] [11].

Quality Control Metrics and Standards

The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) recommends establishing quality control metrics for stem cell-based model systems [15]. Key recommendations include:

- Characterization of Starting Material: Document the cell line or tissue of origin, isolation procedure, and culture conditions, as these can influence variability and reproducibility [15].

- Donor Information: Record sex, age, ethnic and genetic background, health status, and risk factors of the donor, where available and as permitted by regulations [15].

- Functional Validation: Demonstrate that cellular models are functionally and phenotypically representative of the native cell/tissue by multiple, appropriate criteria [15].

- Genetic Validation: Where assessing the impact of a known genotype, confirm the stem cell-derived disease model carries the expected genotype [15].

- Proper Controls: Use power analysis to determine sample size and include appropriate controls considering biological variability [15].

Figure 2: Structural Variant Interpretation Pipeline. This framework outlines the analytical process for classifying and determining the clinical significance of structural variants identified in stem cell genomes.

The comprehensive assessment of the genomic stability of stem cells requires a multi-technology approach, as each method offers unique capabilities and limitations. Karyotyping remains essential for detecting chromosomal-scale abnormalities, while optical genome mapping provides superior resolution for structural variants, and sequencing technologies enable base-pair level detection of small variants [10]. The integration of these methods is crucial for different applications in the stem cell pipeline, from clone selection and bank establishment to quality control of differentiated products [10].

Future directions in the field will likely focus on standardizing assessment protocols across laboratories, improving the resolution and throughput of long-read sequencing technologies, and developing better bioinformatic tools for complex variant interpretation. As the stem cell field advances toward clinical applications, robust genomic assessment will play an increasingly critical role in ensuring the safety and efficacy of stem cell-based therapies.

Chromosomal instability is a hallmark of genomic instability in cancer and a critical parameter in assessing the safety and efficacy of stem cell-based therapies. Specific recurrent abnormalities on chromosomes 1, 12, 17, and 20 serve as key markers of high-risk disease across multiple malignancies. This review systematically compares the clinical significance, frequency, and molecular pathways associated with these abnormalities, providing a comprehensive analysis of their roles in disease progression and treatment resistance. We further detail experimental methodologies for their detection and analysis, offering a standardized framework for genomic stability assessment in both clinical and research settings. Understanding these high-risk loci is paramount for developing targeted therapeutic strategies and improving risk-adapted treatment approaches.

Genomic instability represents a fundamental property of cancer cells and a significant concern in regenerative medicine, where it can compromise the safety of stem cell-based therapeutics [16]. Specific chromosomal loci are predisposed to recurrent abnormalities that drive oncogenesis, disease progression, and therapeutic resistance [17] [18]. Among these, chromosomes 1, 12, 17, and 20 harbor high-risk abnormalities that consistently emerge as markers of aggressive disease across diverse malignancies, including multiple myeloma, neuroblastoma, and various solid tumors.

The assessment of these chromosomal abnormalities provides critical insights into disease biology and patient prognosis. In multiple myeloma, for instance, cytogenetic abnormalities detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) represent the most widely accepted predictors for poor prognosis [17]. Similarly, in neuroblastoma, gain of chromosome 17q is recognized as the strongest indicator of adverse outcome [19]. These abnormalities not only serve as prognostic markers but also represent potential therapeutic targets, making their systematic characterization essential for advancing precision medicine approaches.

This review synthesizes current understanding of high-risk loci on chromosomes 1, 12, 17, and 20, comparing their pathological significance, frequency, and clinical implications across different disease contexts. We further elaborate standardized experimental protocols for their detection and analysis, providing researchers and clinicians with comprehensive methodological guidance for genomic stability assessment.

Comparative Analysis of High-Risk Chromosomal Abnormalities

Chromosome 1 Abnormalities

Chromosome 1 abnormalities represent some of the most frequent cytogenetic alterations in cancer, particularly in multiple myeloma, where they occur in approximately 40% of newly diagnosed cases [18]. The instability of chromosome 1 manifests primarily through copy number variations (CNV) and structural changes, with gain of 1q (+1q) and deletion of 1p (del(1p)) being the most clinically significant [17] [18].

Pathogenic Mechanisms and Clinical Impact: The 1q21 region contains several genes implicated in myeloma pathogenesis, including CKS1B, MCL-1, ADAR1, and IL-6R [18]. Gain of 1q leads to overexpression of these genes, driving tumor progression through multiple pathways: CKS1B promotes cell cycle progression by activating cyclin-dependent kinases and facilitating SKP2-mediated ubiquitination of the tumor suppressor p27Kip1 [18]; MCL-1 enhances survival by inhibiting apoptosis [18]; and ADAR1 contributes to malignant transformation through RNA editing mechanisms [18]. Clinically, +1q is associated with significantly worse overall survival (HR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.097–1.787) and progression-free survival (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.16–1.58) in multiple myeloma patients [20]. The adverse prognosis is further exacerbated when +1q co-occurs with other high-risk abnormalities such as del(17p), t(14;16), or del(13q) [20].

Copy Number Considerations: The prognostic impact of +1q varies with copy number burden. Patients are categorized as having gain(1q) (three total copies) or amp(1q) (four or more total copies) [18]. While some studies report worse outcomes with increasing copy number, others found no significant differences in progression-free or overall survival between patients with three versus four or more copies [20]. This suggests that the mere presence of +1q, rather than its magnitude, may be the primary determinant of adverse outcomes.

Chromosome 12 Abnormalities

Abnormalities of chromosome 12 are prominently associated with testicular germ cell tumors (GCTs) but also play significant roles in other malignancies, including inflammatory bowel disease and select solid tumors [21].

Isochromosome 12p in Germ Cell Tumors: The pathognomonic abnormality in malignant GCTs is increased representation of genetic material on chromosome 12p, either through gene amplification or formation of an isochromosome 12p [i(12p)] [21]. This abnormality is identified in nearly 100% of invasive malignant GCTs but appears normal in pre-invasive conditions like intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified (ITGCN), spermatocytic seminoma, and pediatric epidermoid cysts [21]. This specific association suggests a crucial role for genes on 12p in the transition from pre-invasive to invasive disease, though the specific driver genes remain unidentified.

Other Clinical Associations: Beyond GCTs, chromosome 12 harbors susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), particularly the IBD2 locus at 12q13-14 [21]. Linkage studies have demonstrated significant association between this region and ulcerative colitis, though the specific gene responsible remains elusive despite investigation of candidates including interferon gamma (IFNG), keratin 8 (KRT8), and natural-resistance-associated macrophage protein (NRAMP2) [21].

Chromosome 17 Abnormalities

Chromosome 17 abnormalities represent critical events in multiple cancer types, with distinct pathological implications depending on the specific region affected.

17p13 Deletions in Multiple Myeloma: Deletion of 17p13 [del(17p)], which encompasses the TP53 tumor suppressor gene, occurs in 5-10% of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma cases and confers particularly poor prognosis [17]. TP53 plays a central role in cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and DNA repair, and its loss confers resistance to conventional therapies and promotes genomic instability. The adverse impact of del(17p) is magnified when it co-occurs with other high-risk abnormalities, leading to significantly shorter survival [17].

17q Gains in Neuroblastoma: Gain of chromosome 17q is the most frequent genetic abnormality in neuroblastoma, present in 72% of cases, and represents the strongest independent indicator of adverse outcome [22] [19]. Research indicates that gain of chromosome 17 is an initial genetic event in neuroblastoma development, with additional copies of 17q acquired during clonal evolution in aggressive and metastatic disease [19]. The minimal common region of gain is 17q21-qter, and this abnormality is strongly associated with other unfavorable prognostic factors including 1p deletion, 11q deletion, and advanced disease stage [22].

Candidate Oncogenes on 17q: PPM1D (located at 17q22.3) has emerged as a strong candidate oncogene driving neuroblastoma progression [19]. PPM1D encodes a p53-inducible serine/threonine phosphatase that negatively regulates p53 activity, creating a negative feedback loop. Activation of PPM1D through segmental 17q gain, gene fusion, or gain-of-function mutations promotes tumor development and progression [19]. This makes PPM1D a promising therapeutic target in high-risk neuroblastoma.

17q12 Deletion Syndrome: Unlike the oncogenic implications of 17q gain, the recurrent 1.4-Mb heterozygous deletion at 17q12 causes a distinct multisystem disorder characterized by kidney abnormalities, maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 5 (MODY5), and neurodevelopmental conditions [23]. This condition underscores the diverse pathological consequences of chromosomal abnormalities depending on the specific genes affected.

Chromosome 20 Abnormalities

Mosaic Trisomy 20: Complete trisomy 20 is considered incompatible with life, but mosaic trisomy 20 (three chromosomes 20 in some cells) is compatible with survival and presents with highly variable phenotypes [24]. Clinical features may include craniofacial abnormalities, cutaneous manifestations, cardiovascular-pulmonary defects, gastrointestinal issues, endocrinological disturbances, reproductive anomalies, locomotor problems, and neurodevelopmental conditions [24]. Recent evidence indicates that neuropsychiatric manifestations may be more prevalent than previously recognized, with cases exhibiting complex neuropsychiatric presentations including self-injury, suicidal ideation, emotional dysregulation, and social difficulties [24].

Ring Chromosome 20 Syndrome: This rare condition results from deletion of the long arm of chromosome 20, forming a ring structure [25]. It presents with refractory epilepsy, characterized by nonconvulsive status epilepticus and brief motor seizures, typically beginning between ages 2 and 14 years [25]. Most cases are refractory to antiepileptic drugs, and patients often experience intellectual disability and behavioral regression [25].

Other Associations: Chromosome 20 also harbors the ADAM33 gene, identified as an asthma-associated gene expressed in lung fibroblasts and bronchial smooth muscle cells [25]. While its precise biological role remains unclear, ADAM33 is hypothesized to contribute to airway remodeling in asthma pathogenesis.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of High-Risk Chromosomal Abnormalities

| Chromosome | Abnormality | Frequency | Key Genes | Associated Cancers/Conditions | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gain(1q)/Amp(1q) | 35-40% of NDMM [18] | CKS1B, MCL-1, ADAR1, IL-6R [18] | Multiple myeloma | Independent risk factor for inferior OS (HR, 1.4) and PFS (HR, 1.36) [20] |

| 1 | Del(1p) | 20-30% of NDMM [17] | FAM46C, CDKN2C, TP73 [17] | Multiple myeloma | Associated with poor prognosis; compound effect with other HRCAs [17] |

| 12 | Isochromosome 12p | Nearly 100% of malignant GCTs [21] | Not fully characterized | Testicular germ cell tumors | Marker of invasive disease; not found in pre-invasive conditions [21] |

| 12 | IBD2 locus | Varied | Not fully characterized | Inflammatory bowel disease | Greater linkage to ulcerative colitis than Crohn's disease [21] |

| 17 | Del(17p) | 5-10% of NDMM [17] | TP53 [17] | Multiple myeloma, various cancers | High-risk feature; associated with early recurrence and resistance [17] |

| 17 | Gain(17q) | 72% of neuroblastoma [22] | PPM1D [19] | Neuroblastoma | Strongest indicator of adverse outcome; early event in tumorigenesis [22] [19] |

| 17 | 17q12 deletion | Rare (exact frequency unknown) | HNF1B [23] | 17q12 deletion syndrome | Multisystem disorder: kidney disease, MODY5, neurodevelopmental issues [23] |

| 20 | Mosaic trisomy 20 | Rare (16% of all mosaicisms) [24] | Multiple genes | Trisomy 20 mosaicism syndrome | Variable phenotype; neuropsychiatric manifestations increasingly recognized [24] |

| 20 | Ring chromosome 20 | Rare | Unknown | Epilepsy syndrome | Drug-resistant epilepsy, cognitive decline, behavioral issues [25] |

Table 2: Association of Chromosome 1q Gain with Other High-Risk Cytogenetic Abnormalities in Multiple Myeloma

| Co-existing Abnormality | Impact on PFS | Impact on OS | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| t(14;16) | Reduced | Reduced | Significant for both PFS and OS [20] |

| del(17p) | Reduced | Reduced | Significant for both PFS and OS [20] |

| del(13q) | Reduced | Reduced | Significant for both PFS and OS [20] |

| del(1p) | Not significant | Reduced | Significant only for OS [20] |

Experimental Methodologies for Detection and Analysis

Standard Cytogenetic Techniques

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH): FISH represents the gold standard for detecting recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities in clinical practice, particularly for malignancies like multiple myeloma where plasma cells have low proliferative rates [17] [18]. The protocol involves: (1) Preparation of metaphase chromosomes or interphase nuclei from patient samples (bone marrow aspirate); (2) Denaturation of DNA to generate single-stranded targets; (3) Hybridization with fluorochrome-labeled DNA probes specific to regions of interest (e.g., 1q21, 17p13); (4) Washing to remove non-specifically bound probes; (5) Counterstaining with DAPI and visualization using fluorescence microscopy [17] [18]. FISH allows specific detection of abnormalities like +1q, del(17p), and IGH translocations with high sensitivity and reproducibility, making it indispensable for risk stratification.

Chromosomal Microarray (CMA): CMA provides genome-wide assessment of copy number variations and is particularly valuable for detecting microdeletions/duplications beyond the resolution of conventional karyotyping [23]. The methodology involves: (1) Extraction of genomic DNA from patient and reference samples; (2) Fragmentation and labeling with different fluorescent dyes; (3) Competitive hybridization to a microarray containing thousands of oligonucleotide probes; (4) Scanning and analysis of fluorescence intensity ratios to identify copy number changes [23]. CMA is the preferred technique for diagnosing conditions like 17q12 recurrent deletion syndrome, reliably detecting the characteristic 1.4-Mb heterozygous deletion [23].

Advanced Genomic Approaches

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): NGS technologies, including whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing, provide comprehensive characterization of genomic alterations at base-pair resolution. These approaches enable simultaneous detection of point mutations, copy number variations, and structural variants, offering a complete genomic profile [23]. For copy number variant detection, specialized bioinformatic algorithms must be applied to NGS data [23]. In neuroblastoma research, NGS approaches have been instrumental in identifying PPM1D as a candidate oncogene on 17q and characterizing its activation through various mechanisms including gene fusion and gain-of-function mutations [19].

Comparative Genomic Hybridization (CGH): CGH allows genome-wide screening of DNA copy number variations without requiring cell culture [22]. The technique involves: (1) Extraction of test (tumor) and reference (normal) DNA; (2) Differential labeling with distinct fluorochromes; (3) Competitive hybridization to normal metaphase chromosomes or oligonucleotide arrays; (4) Quantitative analysis of fluorescence ratios along chromosomes to identify regions of gain or loss [22]. CGH has been particularly valuable in neuroblastoma research, where it first identified gain of chromosome 17q as the most frequent abnormality [22].

Single-Cell Sequencing: Emerging single-cell RNA and DNA sequencing technologies enable characterization of genomic aberrations and transcriptional patterns at single-cell resolution, allowing mapping of clonal evolution and heterogeneity within tumors [19]. In neuroblastoma, these approaches have revealed how additional copies of chromosome 17q are acquired during clonal evolution in aggressive disease [19].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Chromosomal Abnormality Detection. This diagram illustrates the integrated approaches for identifying high-risk chromosomal abnormalities, from sample processing through detection methods to clinical and research applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chromosomal Abnormality Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specific Examples | Application | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| FISH Probes | 1q21 (CKS1B), 17p13 (TP53), 13q14 (RB1), IGH breakapart | Fluorescence in situ hybridization | Targeted detection of specific chromosomal abnormalities in interphase or metaphase cells |

| Microarray Platforms | Oligonucleotide arrays, SNP genotyping arrays | Chromosomal microarray analysis | Genome-wide detection of copy number variations and loss of heterozygosity |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kits | Whole-genome sequencing, whole-exome sequencing, targeted panels | Comprehensive genomic analysis | Detection of point mutations, structural variants, and copy number changes |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Cytokines, stromal co-culture systems | Plasma cell culture | Supporting in vitro growth of low-proliferative cells for metaphase analysis |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Phenol-chloroform, column-based methods | Nucleic acid purification | High-quality DNA preparation for microarray and sequencing applications |

| Fluorescence Microscopy Systems | Epifluorescence microscopes with filter sets | FISH visualization | Imaging of hybridized probes for abnormality detection and quantification |

| Bioinformatic Tools | CNV calling algorithms, segmentation analysis | Data analysis | Interpretation of sequencing and microarray data for abnormality identification |

High-risk chromosomal abnormalities on chromosomes 1, 12, 17, and 20 represent critical determinants of disease behavior across multiple malignancies. Their systematic identification and characterization are essential for accurate risk stratification, treatment selection, and therapeutic development. The consistent association of these abnormalities with aggressive disease phenotypes and poor clinical outcomes underscores the importance of robust detection methods and standardized reporting in both clinical and research settings.

Advancements in genomic technologies continue to refine our understanding of these high-risk loci, revealing complex pathogenic mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. The integration of FISH, chromosomal microarray, and next-generation sequencing provides complementary approaches for comprehensive genomic assessment, enabling both targeted analysis and genome-wide discovery. As stem cell-based therapies advance, rigorous assessment of genomic stability using these methodologies will be paramount for ensuring patient safety and therapeutic efficacy.

Future directions will likely focus on developing targeted interventions for specific high-risk abnormalities, elucidating the complex interactions between co-occurring abnormalities, and translating genomic insights into improved risk-adapted treatment strategies. The continued refinement of detection methodologies and analytical frameworks will further enhance our ability to identify and characterize these critical genomic alterations across diverse disease contexts.

Genomic instability, a hallmark of cancer, is defined as an increased tendency for genomic alterations to accumulate during cell division [26] [27]. In the context of stem cell biology and tumorigenesis, this phenomenon presents a complex paradox. While genomic instability drives malignant transformation by fueling tumor evolution and heterogeneity, it can also trigger potent immune surveillance mechanisms that eliminate damaged cells [26]. The intricate relationship between genomic instability and impaired cellular differentiation represents a critical nexus in understanding cancer pathogenesis, particularly concerning cancer stem cells (CSCs) that exhibit stem-like properties including self-renewal capacity, differentiation potential, and enhanced therapy resistance [28].

Recent research has revealed that true cancer stem cells may exhibit surprising genomic stability alongside dormancy, distinguishing them from the more proliferative, genomically unstable cells that constitute the bulk of tumors [29]. This discovery highlights the sophisticated hierarchy within tumors and suggests that genomic stability in the CSC subpopulation may be a protective mechanism for long-term survival and repopulation potential. Understanding the mechanisms connecting genomic instability to disrupted differentiation programs is therefore essential for developing targeted therapeutic strategies that can effectively eradicate the root of tumorigenesis, including the elusive CSC population responsible for disease recurrence.

Molecular Mechanisms: Connecting Genomic Instability to Differentiation Failure

Forms of Genomic Instability and Their Biological Consequences

Genomic instability manifests through multiple mechanisms that collectively drive tumorigenesis by altering the normal differentiation trajectories of cells. The primary forms include DNA repair deficiencies, chromosomal instability, and telomere dysfunction, each contributing distinctly to the acquisition of malignant phenotypes.

Table 1: Forms and Consequences of Genomic Instability in Tumorigenesis

| Form of Instability | Molecular Defect | Impact on Differentiation | Associated Cancers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mismatch Repair (MMR) Deficiency | Loss of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 | HyperMutation, increased neoantigens, immune activation | Colorectal, Endometrial, Gastric [26] |

| Homologous Recombination (HR) Deficiency | Mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM | Accumulation of DSBs, complex genomic rearrangements | Breast, Ovarian, Pancreatic, Prostate [26] |

| Chromosomal Instability (CIN) | Errors in chromosome segregation | Aneuploidy, gene dosage alterations, metabolic stress | >90% of solid tumors and blood cancers [30] |

| Telomere Dysfunction | Critical telomere shortening | Chromosomal end-to-end fusions, senescence bypass | Various cancers with alternative lengthening mechanisms [27] |

Chromosomal instability (CIN), particularly prevalent in human cancers, exists as both structural and numerical forms [30]. Structural CIN involves amplifications, deletions, or rearrangements of chromosomal segments, while numerical CIN entails gains or losses of entire chromosomes. Both forms disrupt the precise gene expression networks required for normal differentiation, potentially locking cells in a progenitor-like state. The resulting aneuploidy generates significant intracellular stress, including proteotoxic stress, metabolic alteration, and DNA damage, which can further impede differentiation processes [30].

Signaling Pathways Linking Instability to Differentiation Impairment

The cGAS-STING pathway represents a crucial connector between genomic instability and immune recognition, creating a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Chromosomal missegregation can lead to micronuclei formation, which upon nuclear envelope rupture, exposes self-DNA to the cytosol where it activates the cGAS-STING pathway [31]. This triggers type I interferon signaling and inflammatory cytokine production, potentially attracting immune cells and eliminating unstable cells. However, tumors can co-opt this pathway to promote chronic inflammation that fuels progression and impairs differentiation of tumor-infiltrating immune cells.

Beyond immune activation, genomic instability directly disrupts differentiation through p53-dependent senescence pathways, altered epigenetic landscapes, and disrupted niche signaling. The DNA damage response (DDR) can activate cell cycle checkpoints that prevent progenitor cells from entering differentiation pathways, effectively maintaining them in a stem-like state. Additionally, large-scale chromosomal alterations can disrupt the coordinated gene expression programs required for lineage commitment, particularly when master transcriptional regulators are affected by copy number alterations [30].

Experimental Approaches: Assessing Genomic Instability in Stem Cell Populations

The MAGIC Platform: Tracking De Novo Chromosomal Abnormalities

The Machine-learning-assisted Genomics and Imaging Convergence (MAGIC) platform represents a cutting-edge approach for investigating chromosomal instability dynamics in live cells [31]. This autonomously operated platform integrates live-cell imaging of micronucleated cells, machine learning on-the-fly, and single-cell genomics to systematically investigate chromosomal abnormality (CA) formation.

Table 2: MAGIC Platform Workflow and Applications

| Step | Technology | Function | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Tracking | H2B-Dendra2 photolabelling | Fluorescent nuclear labeling | Enables precise tracking of individual cells across divisions [31] |

| Phenotype Detection | Machine learning classifier (XGBoost) | Automated micronuclei identification | Achieves 90% precision, 50% recall in identifying nuclear atypia [31] |

| Cell Isolation | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) | Target cell purification | Efficient recovery of photolabelled cells with nuclear defects [31] |

| Genomic Analysis | Single-cell template-strand sequencing (Strand-seq) | CA detection & sister cell relationship mapping | Identifies de novo CAs, reveals 5-fold enrichment in micronucleated cells [31] |

The MAGIC platform has revealed that dicentric chromosomes frequently initiate CAs, and that chromosome losses arise more frequently than gains in non-transformed cell lines. TP53-deficient cells show an approximately doubled CA mutation rate, highlighting the importance of p53 in maintaining genomic stability. Furthermore, targeted induction of DNA double-strand breaks using CRISPR-Cas9 demonstrated that break location influences the spectrum of resulting CAs, with complex rearrangements often mapping to a single homologue [31].

Identifying Dormant, Genomically Stable Cancer Stem Cells

Contrary to conventional models that might assume CSCs harbor significant genomic instability, recent research has identified a subpopulation of true cancer stem cells that exhibit both dormancy and genomic stability [29]. Using a human PDX model (Mary-X) that expresses a strong cancer stem cell phenotype, researchers employed GFP-labelled retroviral transfection and fluorescent microsphere uptake studies to distinguish proliferating from dormant cells.

The experimental approach involved:

- Retroviral GFP transfection to label proliferating cells

- Fluorescent microsphere uptake to identify dormant, non-phagocytic cells

- Array CGH to identify regions of amplifications and deletions

- FISH with derived probes on individual cells to identify genomically stable subpopulations

This methodology revealed that while 97-99% of cells expressed retroviral GFP and showed numerous gene amplifications and deletions, approximately 1-3% of cells exhibited the opposite pattern - retaining fluorescent microspheres and demonstrating genomic stability [29]. This subpopulation was significantly smaller in size than their GFP-expressing, genomically unstable counterparts and could be further enriched by sorting for established CSC markers (CD133 or ALDH positivity). These findings indicate that a truly biological cancer stem cell subpopulation exists that exhibits both dormancy and genomic stability, representing a hierarchical stem cell population capable of only unidirectional differentiation.

Comparative Analysis: Experimental Models for Studying Genomic Instability

Model Systems for Genomic Instability Research

Various model systems have been developed to study the relationship between genomic instability and tumorigenesis, each offering distinct advantages and limitations for investigating different aspects of this complex relationship.

Table 3: Experimental Models for Genomic Instability and Tumorigenesis Studies

| Model System | Key Features | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Transformed Cell Lines (MCF10A, RPE-1) | Near-diploid, non-transformed | Baseline CA mutation rates, early tumorigenesis events | May not fully capture tumor microenvironment [31] |

| Bioengineered Niche Models | Recapitulate physiological ECM organization | LT-HSC maintenance, stem cell-niche interactions | Technical complexity in recreation of native niche [32] |

| Patient-Derived Xenografts (e.g., Mary-X) | Preserves tumor heterogeneity | CSC dormancy studies, therapeutic response testing | Limited human immune component, host microenvironment differences [29] |

| CIN Mouse Models | In vivo CIN investigation | Tumor progression, metastasis, therapeutic testing | Species-specific differences in cancer biology [30] |

Bioengineered niches that recreate physiological extracellular matrix organization have emerged as particularly valuable tools for studying stem cell behavior in controlled microenvironments. These systems use soft collagen type-I hydrogels to drive nestin expression in perivascular stromal cells (PerSCs), creating an environment that supports long-term haematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs) [32]. The induction of nestin, which is expressed by HSC-supportive bone marrow stromal cells, appears cytoprotective and regulates metabolism in PerSCs, influencing HIF-1α expression - a critical factor in maintaining LT-HSCs. Such bioengineered systems enable researchers to dissect the specific contributions of microenvironmental factors to genomic stability and differentiation potential.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Investigating the connection between genomic instability and impaired differentiation requires specialized research tools and reagents designed to detect, quantify, and manipulate genomic integrity in stem and progenitor cells.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Genomic Instability Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| H2B-Dendra2 Protein | Photoconvertible fluorescent histone label | Live-cell tracking of nuclear morphology and cell division [31] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Targeted DNA double-strand break induction | Studying specific CA formation processes [31] |

| Strand-seq Reagents | Single-cell template-strand sequencing | Sister chromatid exchange detection, CA mapping [31] |

| Fluorescent Microspheres | Non-dividing cell population identification | Dormant CSC isolation and characterization [29] |

| Soft Collagen Hydrogels | Physiological ECM stiffness recreation | Bioengineered stem cell niche development [32] |

| Nestin Expression Markers | Perivascular stromal cell phenotype detection | HSC-supportive niche identification and analysis [32] |

Advanced imaging dyes represent critical components of the genomic instability researcher's toolkit. The development of photo-activatable tracking dyes like DACT-1 enables cell tracking without genetic manipulation, bypassing potential artifacts associated with fluorescent protein expression [31]. Similarly, the H2B-Dendra2 system allows precise photolabelling of nuclei with a 22-fold increase in red fluorescence after illumination, facilitating automated cell sorting without detectable phototoxicity. These tools enable the precise isolation and tracking of cells with specific nuclear abnormalities, connecting morphological phenotypes with underlying genomic alterations.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The investigation into genomic instability and its relationship with impaired differentiation has yielded significant insights for therapeutic development. The paradoxical nature of CIN - where moderate levels promote tumor evolution while excessive instability leads to cell death - presents a promising therapeutic avenue known as the "just-right" model of CIN [30]. Therapeutic strategies that push tumor cells beyond their tolerable threshold of genomic instability could effectively induce lethal amounts of DNA damage and mitotic catastrophe.

Emerging approaches include:

- Centrosome declustering agents to induce multipolar divisions in cells with supernumerary centrosomes [27]

- Dual metabolic inhibition strategies targeting the metabolic plasticity of CSCs [28]

- CAR-T cells targeting CSC-specific surface markers like EpCAM to eliminate therapy-resistant subpopulations [28]

- Synthetic lethal interactions with specific DNA repair deficiencies, such as PARP inhibitors in HR-deficient tumors [26]

The discovery that true CSCs may possess relative genomic stability [29] necessitates a re-evaluation of therapeutic strategies that predominantly target rapidly dividing, genomically unstable cells. Future efforts must develop approaches to target the dormant, stable CSC subpopulation that may survive conventional genotoxic therapies and drive disease recurrence. Combining conventional therapies with agents that specifically target CSCs or force their exit from dormancy represents a promising direction for achieving more durable remissions and overcoming therapeutic resistance in advanced cancers.

The Quality Control Toolbox: From Karyotyping to NGS for Detecting Genetic Variants

In the field of stem cell research and therapeutic development, assessing genomic stability is paramount for ensuring both safety and efficacy. Karyotyping, particularly G-banding analysis, remains a cornerstone technique for visualizing chromosomal number and large-scale structural abnormalities at single-cell resolution. This methodology provides a comprehensive genome-wide view that can detect balanced structural rearrangements and mosaic abnormalities that often elude higher-resolution molecular techniques [33]. For stem cell biologists and drug development professionals, maintaining chromosomal integrity in cell lines is crucial, as acquired genetic abnormalities can compromise therapeutic utility and potentially introduce oncogenic risk [16].

While newer technologies like next-generation sequencing (NGS) and chromosomal microarray (CMA) offer enhanced resolution for specific applications, G-banding karyotyping maintains its fundamental role in the initial screening and validation of stem cell lines. Its ability to provide a simultaneous assessment of all chromosomes without prior knowledge of potential abnormalities makes it particularly valuable for detecting unexpected chromosomal changes that may occur during extended cell culture or genetic manipulation [34]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of G-banding with contemporary cytogenetic methods, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols relevant to stem cell genomic stability assessment.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Execution

The G-Banding Technique

G-banding (Giemsa banding) is a cytogenetic technique that produces a visible karyotype by staining condensed chromosomes with Giemsa stain after trypsin digestion. The distinct patterns of Giemsa-dark and light bands observed on chromosomes reflect regional differences in chromatin structure and composition [35]. These banding patterns are unique to each chromosome pair, enabling the identification of both numerical and structural aberrations through microscopic analysis [36]. The technique relies on the differential binding of Giemsa stain to chromosomal regions with varying base pair compositions, with constitutive heterochromatin typically staining more darkly due to its AT-rich nature.

The standard G-banding protocol involves several critical steps that must be carefully optimized for reliable results [37]:

- Specimen preparation: Cells are arrested in metaphase when chromosomes are most condensed, then subjected to hypotonic treatment and fixation.

- Slide preparation: Fixed cells are dropped onto slides and aged to achieve optimal chromosome spreading.

- Trypsin digestion: Slides are treated with trypsin (typically 0.025% at pH 7.2-7.4) for approximately 1 minute, with exact timing determined empirically based on specimen age and environmental conditions.

- Staining: Giemsa staining for 10 minutes followed by rinsing and drying.

- Microscopic examination: Banding quality is assessed under high magnification, with clear, distinct bands indicating successful processing.

The quality of G-banding is highly dependent on technical factors including trypsin concentration, digestion time, temperature, and specimen age. Older specimens generally require longer trypsin exposure, while very fresh specimens may produce fuzzy chromosomal morphology [37].

Advancements in Karyotyping Technologies

Traditional manual karyotyping has evolved significantly with the introduction of automated imaging systems and, more recently, artificial intelligence (AI)-guided analysis [35]. These systems have transformed the labor-intensive process of metaphase spread identification, chromosome segmentation, and karyogram assembly. Currently, four commercially available AI-based chromosome analysis systems (from Applied Spectral Imaging, BioView, Diagens, and MetaSystems) utilize deep learning algorithms to streamline karyotyping workflows [35] [36].

AI-guided karyotyping systems demonstrate impressive efficiency gains, reducing average analysis time from approximately 33.9 minutes with conventional methods to just 6.5 minutes for 70 metaphases [33]. Following AI analysis, technologists typically spend about 7 minutes reviewing 15 representative karyotypes, significantly accelerating turnaround times while maintaining diagnostic accuracy [33]. Clinical validation studies report that AI-assisted karyotyping with manual correction achieves 97% accuracy, 98% sensitivity, and 96% specificity compared to conventional karyotyping [33].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Cytogenetic Techniques

Technical Capabilities and Limitations

Table 1: Comparison of Key Cytogenetic Techniques for Genomic Stability Assessment

| Parameter | G-Banding Karyotyping | Chromosomal Microarray (CMA) | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | ~5-10 Mb (at 550-band level) | >100 kb (SNP arrays); >30 kb (aCGH) | >1 bp (varies with coverage) |

| Numerical Abnormalities | Excellent detection | Limited detection (except polyploidy) | Excellent detection |

| Balanced Structural Rearrangements | Excellent detection | Cannot detect | Limited detection |

| Unbalanced Structural Rearrangements | Detection >5-10 Mb | Excellent detection | Excellent detection |

| Polyploidy Detection | Excellent | Limited with some arrays | Limited |

| Single Cell Analysis | Yes | No (bulk analysis) | Limited (requires single-cell WGA) |

| Mosaicism Detection | Sensitivity ~10-20% | Sensitivity ~5-30% (depends on array) | Sensitivity ~1-5% (varies with depth) |

| Turnaround Time | 7-14 days (culture-dependent) | 3-7 days (no culture required) | 5-21 days (varies with approach) |

| Stem Cell Applications | Routine genomic stability screening, MSC characterization | Comprehensive CNV profiling, iPSC line validation | Comprehensive mutation profiling, off-target editing assessment |

Diagnostic Performance in Research Settings

Prospective comparative studies demonstrate significant differences in the diagnostic performance of various cytogenetic techniques. In the analysis of products of conception (POC), NGS-based approaches presumed the cause of miscarriage in 75.0% of cases, significantly outperforming G-banding's diagnostic rate of 42.5% [38]. This performance disparity was particularly pronounced in early gestation losses before 12 weeks, where NGS identified causal abnormalities in 73.5% of cases compared to 44.1% with G-banding [38].

A critical factor influencing this performance difference is the culture failure rate associated with G-banding. In prospective analyses, G-banding could only analyze 67.5% of submitted samples due to culture failure, while NGS successfully analyzed 100% of samples [38]. This technical limitation significantly impacts the utility of G-banding for samples with limited viability or contamination.

Table 2: Experimental Success Rates and Diagnostic Yield Across Techniques

| Performance Metric | G-Banding Karyotyping | Chromosomal Microarray | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Success Rate | 67.5% (27/40 samples) [38] | >95% [39] | 100% (40/40 samples) [38] |

| Diagnostic Yield (POC Analysis) | 42.5% (17/40 cases) [38] | Not specified | 75.0% (30/40 cases) [38] |

| Early Gestation Diagnostic Yield | 44.1% (15/34 cases) [38] | Not specified | 73.5% (25/34 cases) [38] |

| Successful Analysis Among Cultured Samples | 62.9% (17/27 cases) [38] | Not specified | 70.3% (19/27 cases) [38] |

| Polyploidy Detection | Excellent [38] | Limited [39] | Limited [38] |

| Balanced Rearrangements | Excellent [33] | Cannot detect [33] | Limited [38] |

Experimental Design and Workflow Integration

G-Banding Protocol for Stem Cell Characterization

For stem cell research applications, the G-banding protocol requires specific modifications to optimize results with cultured cells [37]:

- Cell Culture and Harvesting: Grow stem cells to 60-80% confluence. Add colcemid (0.02 μg/mL) for 45-60 minutes to arrest cells in metaphase. Collect cells using trypsinization or scraping.

- Hypotonic Treatment: Resuspend cell pellet in pre-warmed 0.075M KCl solution and incubate for 20 minutes at 37°C.

- Fixation: Gradually add fresh methanol:acetic acid (3:1) fixative while gently mixing. Perform three fixation changes, each with 15-minute intervals.

- Slide Preparation: Drop cell suspension onto clean, wet slides and air dry. Age slides at 60°C overnight or at 72-75°C for 3 hours.

- Trypsinization and Staining: Treat slides with 0.025% trypsin for 30-90 seconds. Rinse in saline and stain with 2% Giemsa solution for 5-8 minutes.

- Analysis: Examine under 100x oil immersion objective. Count 15-20 metaphases and fully analyze 5-10 cells for karyotyping.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete G-banding procedure for stem cell genomic assessment:

Strategic Workflow Integration for Comprehensive Genomic Assessment

For comprehensive stem cell genomic stability assessment, integrating multiple complementary techniques provides the most rigorous evaluation. The following workflow demonstrates how G-banding fits within a broader analytical strategy:

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for G-Banding Karyotyping

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Colcemid | Metaphase arrest inhibitor | Concentration and exposure time optimization critical for chromosome spreading |

| Trypsin Solution | Chromosome protein digestion | Concentration (typically 0.025%) and digestion time must be empirically determined |

| Giemsa Stain | Chromosome banding pattern visualization | Standardized solution (2-4%) provides consistent G-banding patterns |

| Hypotonic Solution (KCl) | Cellular swelling and chromosome spreading | 0.075M concentration standard; temperature and timing affect spreading quality |

| Methanol:Acetic Acid Fixative | Cellular preservation and chromosome fixation | Fresh 3:1 ratio required for each experiment; multiple changes improve morphology |

| Microscopy Slides | Chromosome presentation | Pre-cleaned and chilled slides enhance chromosome spreading |

| Cell Culture Media | Stem cell maintenance and proliferation | Culture conditions must maintain stemness while allowing cell cycle progression |

G-banding karyotyping remains an essential component of comprehensive stem cell genomic assessment, providing unique capabilities for detecting balanced chromosomal rearrangements and mosaic abnormalities at single-cell resolution. While newer technologies like CMA and NGS offer superior resolution for detecting specific abnormalities, G-banding's genome-wide screening capability without prior knowledge of potential abnormalities maintains its relevance in stem cell research and characterization.

The integration of AI-guided analysis has significantly enhanced the efficiency and standardization of karyotyping, reducing turnaround times while maintaining diagnostic accuracy [35] [33]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a strategic combination of G-banding with higher-resolution techniques provides the most comprehensive approach to ensuring stem cell genomic integrity, ultimately supporting the development of safe and effective cell-based therapies.

Optical Genome Mapping (OGM) is an advanced genomic imaging technology that enables the comprehensive detection of structural variants (SVs) and copy number variants (CNVs) across the entire genome. This innovative methodology utilizes ultra-high molecular weight (UHMW) DNA to perform an unbiased assessment of genomic rearrangements with a resolution that far exceeds conventional cytogenetic approaches [40]. Unlike sequencing-based methods that infer structure from sequence data, OGM directly visualizes the physical architecture of DNA molecules by converting them into fluorescent barcode patterns that can be digitally analyzed and compared to reference genomes [41].

The application of OGM is particularly valuable in the context of stem cell genomic stability assessment, where unintended genetic modifications during differentiation and proliferation can compromise therapeutic safety and efficacy [42]. As regulatory agencies increasingly emphasize the importance of genetic stability testing for stem cell-based products, OGM offers a powerful solution for identifying cryptic rearrangements and complex variants that may escape detection by traditional methodologies [42] [43].

Fundamental Principles of OGM

The OGM workflow begins with the isolation of UHMW DNA using specialized extraction protocols that minimize DNA shearing, typically yielding fragments of 150 kilobases to megabases in size - substantially longer than conventional DNA isolation techniques [41]. This DNA is then fluorescently labeled at specific CTTAAG hexamer motifs, creating a unique labeling pattern across the genome with approximately 14-17 labels per 100kb [41]. The labeled DNA molecules are linearized in nanochannels, imaged, and digitized to generate consensus maps of 500 kb to megabase-sized segments that are computationally compared to reference genome labeling patterns [40] [41].

This imaging-based approach converts DNA into a "barcode" whose labeling profile and characteristics can sensitively and specifically resolve copy number and structural variation without requiring nucleotide-level sequence data [41]. The technology can detect a wide range of variant types including copy number gains/losses, balanced and unbalanced translocations, insertions, and inversions [41].

Performance Comparison with Conventional Cytogenetic Methods

Table 1: Comparative analysis of OGM versus conventional cytogenetic methods for structural variant detection

| Method | Resolution | SV Types Detected | Genome Coverage | Specimen Requirements | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome Banding Analysis | >5-10 Mb | CNVs, balanced SVs | Genome-wide | Viable cells | Low resolution, subjective interpretation [41] |

| Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) | ~70 kb - 1 Mb | CNVs, specific SVs | Targeted | Viable or fixed cells | Limited to targeted regions, requires prior knowledge of targets [40] [41] |

| Chromosomal Microarray (CMA) | >5 kb - 200 kb | CNVs, AOH (SNP arrays) | Genome-wide | Viable or fixed cells | Cannot detect balanced SVs, provides no structural information for gains [43] [41] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Single nucleotide | SNVs, CNVs, some SVs | Genome-wide | Viable or fixed cells | Challenging for complex regions, specialized algorithms needed for different SV types [40] |

| Optical Genome Mapping | ~500 bp - 5 kb | CNVs, balanced SVs, AOH | Genome-wide | Viable cells (can be frozen) | Requires UHMW DNA, not suitable for fixed specimens [41] |

Table 2: Diagnostic performance of OGM in hematologic malignancies

| Study Focus | Concordance with Standard Methods | Additional SVs Detected by OGM | Clinical Impact of Additional Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) [41] | >95% | 34% of cases | Changed risk assessment in 17% of patients |

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) [41] | >95% | 12-23% of cases | Altered clinical management or trial eligibility |

| Acute Leukemia (467 cases) [44] | 88.1% overall concordance with RNA-seq | 15.8% uniquely detected by OGM | Identification of cryptic, enhancer-driven events |

| B- and T-ALL [41] | Superior to combined CBA, FISH, MLPA | 20% increased detection of risk groups | Improved risk stratification |

Recent studies have demonstrated that OGM reliably detects all forms of clinically significant SVs identified by standard testing methods with greater than 95% concordance [41]. The discordances primarily involve low-level whole chromosome aneuploidies present in less than 5% of nuclei, which may fall below the reliable detection threshold of OGM [41]. Importantly, conventional diagnostic standards for SV detection fail to recognize clinically relevant aberrations at significant rates, with OGM identifying previously cryptic SVs in 34% of MDS cases and 12-23% of AML cases that would have altered clinical management [41].

Comparison with Sequencing-Based Approaches

When compared to targeted RNA sequencing in acute leukemia, OGM demonstrated complementary strengths. In a study of 467 acute leukemia cases, the overall concordance rate between a 108-gene RNA-seq panel and OGM was 88.1% for detected gene/rearrangement fusions [44]. However, significant differences emerged in their ability to detect specific variant types: OGM uniquely identified 15.8% of clinically relevant rearrangements, while RNA-seq exclusively detected 9.4% [44].

The technologies showed particularly divergent performance for specific variant categories. OGM significantly outperformed RNA-seq in detecting enhancer-hijacking lesions (including MECOM, BCL11B, and IGH rearrangements), with a markedly lower concordance of 20.6% compared to 93.1% for all other aberrations [44]. Conversely, RNA-seq slightly outperformed OGM for fusions arising from intrachromosomal deletions that were sometimes labeled by OGM as simple deletions [44]. This demonstrates that while RNA-seq is more sensitive for detecting expressed chimeric fusions, OGM is superior for identifying cryptic, enhancer-driven events that do not generate fusion transcripts [44].

Experimental Data and Validation Studies

OGM in Constitutional Disorder Diagnosis

In constitutional genetic disorder diagnosis, OGM has demonstrated significant utility in resolving complex rearrangements that challenge conventional methods. A key application is the characterization of copy-number gains, which frequently present interpretation challenges when detected by chromosomal microarray (CMA) [43]. In a comprehensive study of 4073 CMA cases, copy-number gains were significantly more likely to be classified as variants of uncertain significance (VUS) compared to losses (70.9% vs 44.1%, p<0.001) [43]. This "VUS burden" stems from CMA's inability to provide structural information about the location and orientation of multiplied regions, which is critical for determining their functional consequences [43].

When OGM was applied to 33 VUS gains involving disease-associated genes, it successfully determined the genomic structure in all cases, revealing that 26 of 33 were tandem duplications while 7 of 33 were complex rearrangements [43]. This structural information facilitated more conclusive clinical interpretation in the majority of cases, supporting benign classification for 27 of 33 gains and potentially preventing unnecessary follow-up testing and patient concern [43]. The study estimated that approximately 20% of reported VUS gains would not have been reportable if OGM data had been available initially [43].

Resolution of Complex Structural Variants